The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

A Ride through Syria to Damascus and Baalbec,

and Ascent of Mount Hermon

— Contents. —

| Page | |

| Jaffa to Tiberias | 3 |

| Tiberias to Hasbêya | 10 |

| Mount Hermon and The Druses | 19 |

| Damascus | 27 |

| The Anti-Lebanon | 37 |

| Baalbec and The Bukâa | 45 |

| Beyrût to Boulogne | 52 |

| The Bedaween and Fellaheen | 55 |

| ————————— | |

| Index | 61 |

ILLUSTRATIONS.

| Map of Palestine | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

| Joppa, and House of Simon the Tanner | 5 |

| Mount Carmel | 9 |

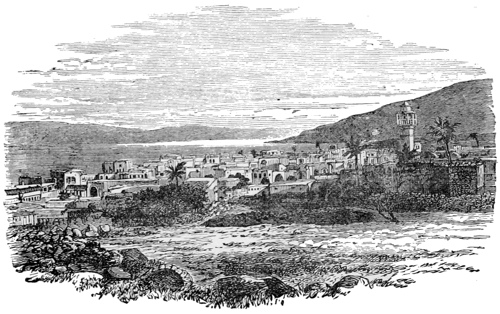

| Tiberias | 26 |

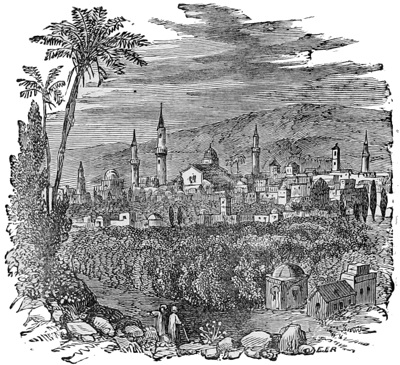

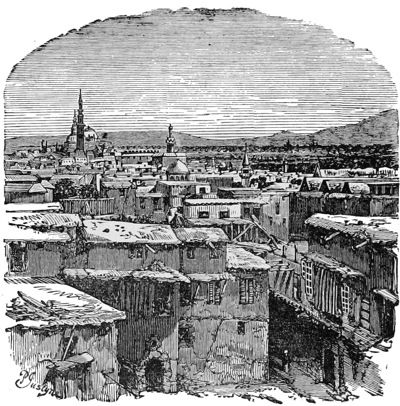

| Damascus | 33 |

| Damascus | 35 |

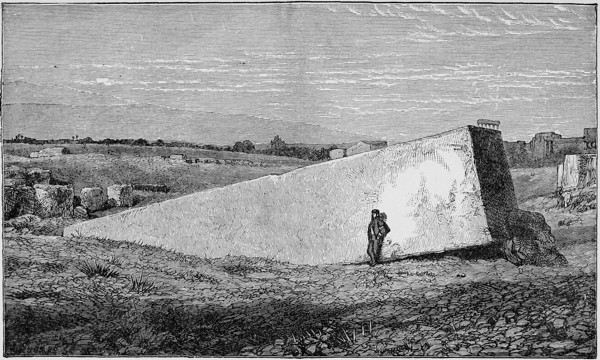

| Baalbec—Great Stone and Quarry | 42 |

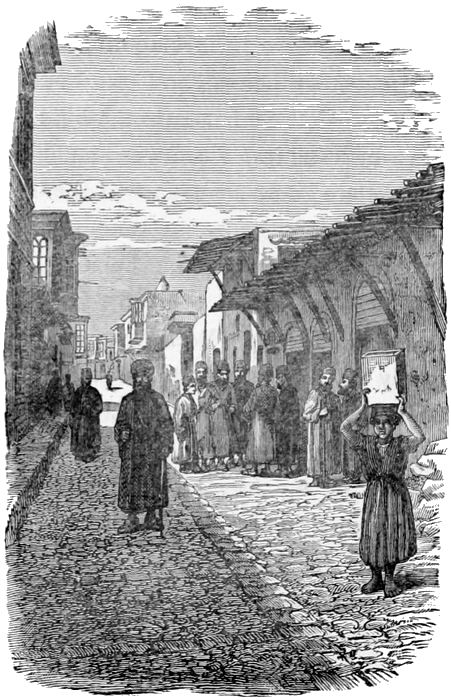

| Damascus—Street called “Straight” | 44 |

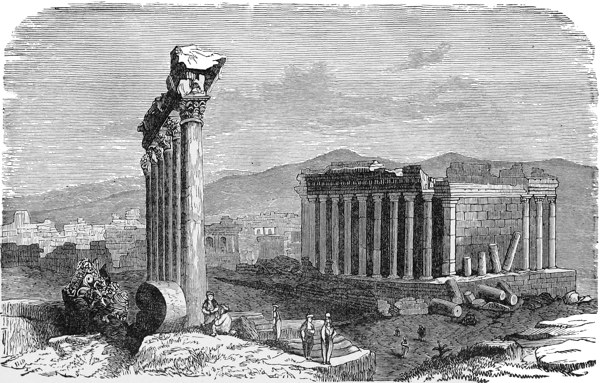

| Baalbec—General View of Ruins | 48 |

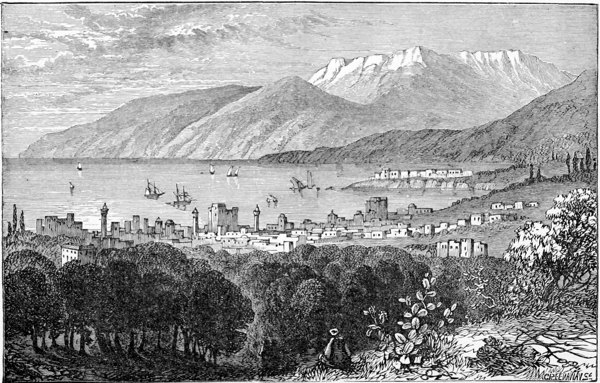

| Beyrût and the Lebanon | 51 |

| Cyprus—Larnaca | 52 |

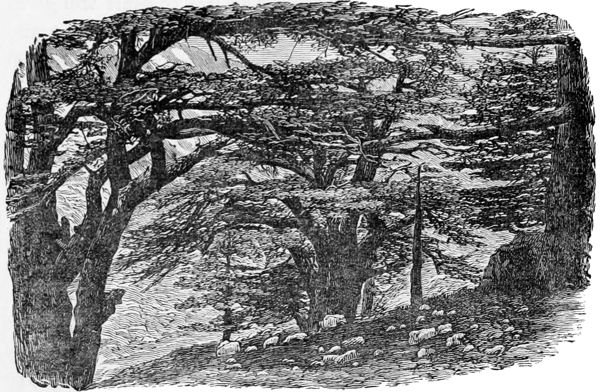

| Cedars of Lebanon | 54 |

A Ride

Through

Syria.

CHAPTER I.—Jaffa to Tiberias.

Our “Ride through Palestine” did not exhaust our enthusiasm for the East; we were not, as some travellers have been, disappointed with “The Holy Land,” because we did not expect to find it still, as in ancient days, a “land of milk and honey.” The cisterns are broken and the waters run to waste, the walls of the vineyards are cast down, the very soil has disappeared from the once fertile terraced heights, the wine presses are covered with weeds, the defenced cities are all a ruin; but, in spite of all this desolation, the Land of our Lord will always have an overwhelming interest for the thoughtful traveller who wishes to trace out on the spot the history of the oldest and most interesting people of the world.

Having on the former occasion travelled by the beaten track, viâ Jerusalem, we this time try a new and unfrequented route. Our objective points are the plains of Sharon and 4Esdraelon, sighting that mighty headland, “the excellency of Carmel,” with its numerous reminiscences of Elijah, and Baal, that “glory of Lebanon,” Hermon with its traditional snow-clad summit and verdure-vested slopes—the sacred sources of the Jordan, and of Pharpar and Abana, which one thought “better than all the rivers of Israel”—onward then to Damascus with its “straight street” and memories of Abram, Saul of Tarsus, Ananias, and Naaman—then onward again to the reputed tombs of the early patriarchs, and lastly—Baalbec with its massive Hivite and beautiful Roman remains. This is a short sketch of the tour we purpose describing in the following pages.

Joppa—With the House of Simon the Tanner on the Sea shore.

Again we have the good fortune, by the courtesy of the director, to obtain a passage in the French China Mail, from Marseilles to Port Said, so arrive in the Holy Land eight and a half days after leaving the Crusaders’ old haunt in London. Favoured with fine weather, we sail north of Sardinia, and sighting Elba and Monte Christo, in two days pass by Ischia into the beautiful bay of Naples. We find the pretty Chiaja much enlarged, planted, and generally improved, and are pleased to see the graceful palm trees in thriving condition. In the Museo Nazionale, ever so interesting, we come to the same conclusion as Solomon as to nothing being new under the sun, for there, if we mistake not, on well-preserved fresco, we see our old friend the sea-serpent and a lady, very much like Britannia ruling the waves on a half-penny. But the sun is setting on Sorrento, Virgil’s tomb is already in the shade, the ship’s bell is summoning strangers to depart, and passengers to dress for dinner, so we must bid adieu to Naples and proceed again en voyage. Capri stands out grandly and gloomily in the twilight; Vesuvius is quiet, scarcely keeping up appearances: we gaze at it until the giant form dies away in the dim distance, and then—go down to 5dinner. Early next morning we pass Stromboli, and in the Straits of Messina Ætna, but both are “still and silent as the grave,” in fact on the latter summit, if we mistake not, we see the dark black lava spotted with bright white snow. On the far horizon we sight the distant cliffs of Crete, and two days later find ourselves entering Port Said, where we tranship ourselves to the Austrian steamer for Jaffa, are off in an hour and arrive early next morning. We elect to go to Syria by way of Palestine, but by a different route, in order that we may visit certain interesting districts which lay out of our line on our former visit.

We commence our ride from Jaffa by a two days journey across the plains of Sharon and Esdraelon to Nazareth. This route, being very open to the attacks of predatory Bedouins, is never attempted by travellers, the all but trackless paths over the vast plains being but little known even to the native.

We engage a picturesque Bedouin Sheik (“as mild a looking man as ever cut a throat”) for a guard and guide; two other Arabs join us for company or safety’s sake. This force a small party of Bedouins would not care to face, and a large party would not attempt it, as they would be discovered by their numbers, and vengeance would soon follow, so we pass the Bedouin camps without any interference.

The ride from Jaffa to Nazareth, viâ Jerusalem, is reckoned three good days; but by our new route we only take two, and pushing briskly forward run it in about eighteen hours—hard work rather to begin with, and the Sirocco blowing hot and dry from the Syrian desert into the bargain. We vary the monotony of the journey over the dusty plains with several little races with our Bedouin guard, who does his best to ride us down; but fails to do so, much to the delight of our old Shikarri (muleteer), whose face, by-the-bye, was of such an 6Assyrian type that he seemed to have started out from the has reliefs of Birs Nimroud. But á route we ride across the Plain of Sharon, passing many hills crowned with villages and capped with ruined churches and fortresses mostly mediæval or Saracenic. It was in this plain that Richard Cœur-de-Lion gained a great victory over Saladin.

We halt for lunch at El Tireth (from the name, probably once a fortified town), and, after a ride of eleven hours, halt for the night at a Mahommedan village called Baka, which probably now for the first time receives a European guest (as even my guides had not been there before): the sun being already set, it is the only refuge near us. It is built of mud on the slope of a hill near an old ruined fountain enclosed in massive masonry. Most of the wells and fountains we see on the way had been similarly well cared for in ancient times, but are now fast falling into decay. We will give you a little idea of an Eastern village:—Place a honeycomb with the cells perpendicular, cover the top of some of the cubes to represent a flat mud roof, leave others open to represent small stable yards for all the domestic animals in creation, camels included, and you have an Arab village of one-storeyed huts, scarcely distinguishable at a distance from the hillside on which it is plastered. The Sheiks’ houses have an additional storey, a guest-chamber built on the wall. One of these we occupy, not a pane of glass in the place and quite innocent of any furniture whatever, which is perhaps an advantage, considering the creeping things innumerable which abound in Eastern villages. Our guard and other retainers sleep in the open yard with the horses, and leave their weapons with us for safe custody, so for the time I am the custos custodum, but our quarters are inviolable, as for the nonce we are the guests of the village. A few crossed sticks in the corner of the yard form the nearest approach to a fire-place.

7We start early next morning over the low Samarian hills of Manasseh, which fall into the sea at Carmel, take a hasty glance at El Mahrakah, or the Rock of Sacrifice, where Elijah slaughtered the Priests of Baal, and enter the vast plain of Esdraelon, between one of the feeders or lower sources of Kishon and Megiddo, at which latter place it will be remembered Barak and his men of Manasseh defeated the hosts of Jabin, King of Hazor, under Sisera, who fled on foot to the tents of Heber the Kenite and was treacherously murdered there by Jael. The Kenites’ home was at Kedes, three days’ journey off in the mountains. It is not probable that Sisera could have fled on foot so far; it is more probable that Heber was pasturing his flocks in the fertile plains of Esdraelon, and that Jabin’s captain took refuge in their tents, then not far off. At Megiddo also, Ahaziah died of the wounds he received from Jehu, and near this spot, in modern times, Napoleon inflicted on the Turkish levies a defeat somewhat similar to that which Barak inflicted on Sisera, but Sir Sydney Smith, holding Acre in his rear, rendered his victory of but little value except to secure a safe retreat to the sea.

After traversing the great plain of Esdraelon for some hours, crossing it in almost a direct line, we leave the level ground again, and ascending the little hills of Lower Galilee, mount up to Nazareth (described in our “Ride through Palestine”) and obtain a lodging at the Latin Monastery, finding in residence the same good Father, quite pleased at seeing us again, so seldom does he see the same visitor twice. Next day we leave Nazareth early, taste the waters of the fountain of the Virgin, at which our Saviour must often have drunk, and soon on our left see Jiptah or Gath-Hepher, the reputed birth-place of Jonah, and on our right, the battle-field where the Crusaders gained their last victory over the Saracens. A few hours later on at Kurun, (the horns of 8Hattin, we pass the battle-field where shortly after under Guy of Lusignan in 1187 the Crusaders suffered their last defeat, their power in Palestine being then for ever crushed by Saladin. In the meantime, we have also sighted Sepphoris or Sefûrieh, the Apollonia of Josephus, and ridden through Kefr Kenna (Cana of Galilee) where on a previous visit, we were shown the miraculous waterpots which must have been very fortunate indeed to have survived the crash of so many ages. This is rather a dangerous ride for small parties like ours, and at one place where the path is very narrow, we think that we shall have to fight our way through. About six wild Moabite Bedouins, from the other side of Jordan, had planted themselves each side of the narrow way on a slight eminence, completely commanding us; we determine to pass through in Indian file, with the length of a pistol shot between us, so that we cannot both be attacked at the same time. They, perhaps, were peaceably disposed, but it is wise in such a wild country to be cautious: anyhow, they do not molest us. They were all on foot, and seemed quite dead-beat by the sun, and were without water, which we were unable to give them, not having any ourselves. Arabs do not give away water when on the march, as the fountains are so few and far between, and want of water in the sun-stricken wilderness means weariness, distress, and death, so graphically described in the pathetic story of Hagar and Ishmael.

After a pleasant ride, skirting the plain of El Buttauf, we halt for tiffin in the pleasant orange grove of Lubieh, where in 1799 the French, under Junot, held their own against a vastly superior army of Turks, and succeeded in reaching Tabor just in time to fall on the rear of the force then pressing hard upon the main body under Napoleon. Soon after, we catch a glimpse of the little lake of Galilee or Tiberias, at one time, in the bright sunshine, looking like an emerald in a golden 9setting, and at another time, when a passing cloud veils the God of day, like a jasper diamond set in an agate frame. We put up at the Latin Monastery in Tiberias or Tabarea, where we are entertained by the Father Superior hospitably as we were on a former occasion. Before leaving Tiberias, we trot along the shore to visit the hot Sulphur Springs and old Roman Baths, which are still greatly used.

The tombs of Jethro and Habbakuk are said to be in the hills above the town.

Mount Carmel.

CHAPTER II.—Tiberias to Hâsbeyâ.

Tiberias was our last halting place. After a grateful dip in the buoyant lake waters we leave early next day for Safed, the highest inhabited place in Galilee, said to be the “city on a hill that cannot be hid,” for it is situated so high that it is visible far and wide, but the term ‘city on a hill’ might almost equally well apply to Bethlehem, the “city of our Lord.” In the distance the snow-white houses of Safed glisten on the dark mountain side like diamonds set in the breast-plate of a mighty giant. Leaving the Latin Convent of Tiberias, we ride along the shore of the Sea of Galilee for about an hour, until we reach Medjil, or Magdala, the home of the Magdalene, now a collection of wretched mud hovels, then across the fertile but neglected plain of Gennesaret, in the midst of which we see a fine stone circular fountain, evidently once the centre of a great city, considered by some to be Capernaum; it is now overgrown with vegetation and the centre of a wilderness, no other trace of a town near. We pause awhile to think of those great cities which in our Saviour’s time lined the shores of the lake, and see how thoroughly their doom has been fulfilled. Tyre still exists as a place to dry nets on, and Sidon as a habitation for fishermen; but Chorazin, Capernaum, the two Bethsaidas 11and the other great lake cities—where are they? Their very sites are not a certainty, and on the lake, where the Romans once fought a great naval battle with the Jews, are now only three wretched fishing boats, in one of which we take a voyage. They were “exalted to heaven,” they are indeed “brought down to hell.” We leave the sites of these formerly great cities on our right, and soon after pass along sloping ground where there is much grass (here, in all probability, Christ miraculously fed the multitude). A mountain near by was in the middle ages known as Mensa, alluding perhaps to the place where our Saviour made a table for the multitude in the wilderness. We lunch at Ain-et-Tabighah, a pleasant spring in the mountains, said to be the site of Bethsaida (there are ruins near by), and starting again skirt the Wady-el-Hamân, or Valley of Doves, and soon after find ourselves high up in the mountains of Naphtali, near Safed; we ascend the hill behind the city to the ruins of the old Crusaders’ Castle, whence we obtain one of the finest views of Palestine. To the east we look over the Sea of Galilee, across Basan and the wild Hauran, almost into the Arabian Desert, taking in, in the far south-east, the mountains of Moab and Ammon, with a long stretch of the Jordan Valley—on the south and south-west we see Carmel and Tabor—on the west the sea-coast—on the north the view is bounded by the high mountains of Lebanon. We hire a Moslem house for the night, after, of course, being asked for a month’s rent; we put our horses in the basement and sleep in the upper room, as usual without any kind of furniture or glass window, and the floor a mud one, but the view from it is magnificent. The Jews cook for us, but are so fanatical that they will not taste the food they themselves have prepared for us. Our bed is a stone ledge a few feet from the floor, but better however than we have in many other places; we soon learn the 12way of making ourselves as comfortable as circumstances will permit, sleeping often sounder on our stony couches than many do on down beds. My dragoman shares my apartment, the others sleep outside in the open. It is 5 a.m. when the Muzeddin, from the summit of the minaret chants out the first hour of prayer, and we set about enjoying our frugal Frühstück, as the Polish Jews here call it, and soon after are in the saddle.

Safed Olim Saphet, one of the four sacred cities of the Jews, is built on terraces one above the other on the side of the mountain, so that the flat roofs of one terrace serve very well as promenades for the houses immediately above, also affording extra facilities for cats and pariah dogs, jackals, &c., to intrude upon our nocturnal privacy. From Safed we travel up and down the mountains, having beautiful views of the plain where Jabin of Hazor gathered together his iron chariots against Joshua; of the waters of Merom (Lake Huleh), and the swamps and jungles of the Jordan, with herds of half wild buffaloes almost hidden in the high rushes. On our left we pass a large khan, built to accommodate the Circassian cut-throats, exiled for committing the Bulgarian atrocities; then on our right is a rock-hewn cistern of vast size, evidently made for some other purpose than to supply a few sheep here in the wilderness.

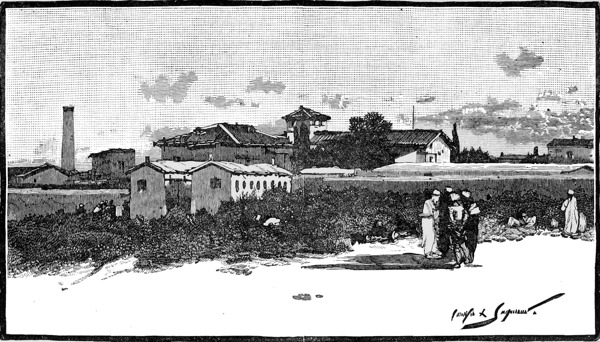

Deshun, an African colony sent from Algeria when the French conquered that country, is next reached; the people seem to be industrious and prosperous. We observe that their houses are detached and have sloping roofs, seldom seen in this country except in European settlements, and altogether they appear more civilised than the Arab inhabitants around them. About noon we pass the site of Hazor, whose kings we hear of in Holy Writ under the common name of Jabin, which was probably the hereditary title of their kings, as 13Hazael of Syria, Hiram of Tyre, Pharaoh of Egypt, &c. After a ride of about 11 miles, we halt for tiffin in the olive grove of Kedes, (Kadesh Naphtali) one of the cities of refuge, and the home, it will be remembered, of Barak, as also of Heber the Kenite. It was one of the royal cities of the Canaanites. There are great masses of débris and ruins here, and some fine single and double sarcophagi lying about. The Turkish people are excavating huge trenches and digging out large quantities of ancient worked stones, not however, with any love or regard for archæology, for they are at once utilised to erect modern buildings or burnt for lime. We acquire a very ancient lamp for about three half-pence. Our zeal for antiquities a Turk or Arab does not understand; he will sooner build a bizarre new mosque (as at Cairo) than repair the grand old one next door; if a building goes to ruin, he says resignedly “Mâshâllah” (God wills it), and leaves it to decay.

Lake Huleh (Semachonitis), which lies under Mount Hermon, is between four and five miles long and about four miles broad. Nebu Husha, or the tomb of Joshua, looks down upon it. The views all along the shores (where the hills of Naphtali and Basan close upon the lake) and the vista of the Jordan valley and mountains beyond, especially Hermon, are very fine. We now, as there is a deal of ground to cover before sundown, try a short cut into the valley without going by Hunin, the usual way. We hear of a path from the Bedouin, and after some difficulty find it. It is not known to the travellers’ guides, and it is just as well that it should not be, for it is a difficult dangerous descent, and one of our horses slipping in a bad place, very nearly brings great grief, both to himself, his rider, and the writer, who suddenly finds himself, with a frightened horse in front slipping, falling, and struggling, wedged in a track so narrow and precipitous 14that it is difficult to find room to dismount; once off, we do not remount until we reach the plain, and no greater damage is done than the loss of a bridle, but a halter is almost as good for an Arab horse. The animal bolted after his fall but we managed to catch him. The path afterwards, when we could find one, being little better than a goat track, we have some trouble to get the horses to face the steep descents. It saves however some hours of time, and is of immense service to us, as otherwise we should have been benighted in the difficult, dangerous, rough and swampy country at the head of the Jordan valley. As it is we are out 11½ hours in an almost tropical country, and do not get into Banias until after sunset, a bad time to enter any Eastern town, and then have to look for a lodging. But to go back a little, we get down into the Jordan valley, near Ain Belat, at the tents of the Ghawarineh Arabs. “Rob Roy” gives them a bad character, and says they attacked him, but they give us water and behave civilly. However we should not trust them too far, nor after dark. We are so glad to get down to level ground, so severe is the descent, that we think little of any danger from the wild denizens we drop down on. The scene here is remarkable, the black Bedouin tents, the dusky herds of buffaloes roaming among the marshes, the impenetrable jungles, the almost naked swarthy barbarians, together with the intense heat, make us imagine ourselves to be in the midst of the dark continent. Our advice to travellers going from Safed by Kedes to Banias, is to make a two day’s trip of it, and not one as we did, and then to keep up on the mountain, and descend by Hunin to the plain.

Hunin, which we pass under, was the Beth-rehob of Joshua, the limit of the land searched by the spies, for here Syria may be said to begin on the slopes of the Anti-lebanon. We now cross the Hasbâny, the most northerly source of the Jordan, 15by an old ruined Roman bridge, Jisl-el-Ghugar, where my men dismount again, but I have more confidence in my horses hoofs than my own boots, and stop in the saddle, and the surefooted sagacious animal carries me over the holes and boulders safely, whereat I score a point against the dragoman, and now after another rough ride for about three miles over stones and swamps, at length we reach Tell-el-Kadi, the (fertile) hill of the Judge or Dan, which in the Hebrew also signifies Judge.

Dan, it will be remembered, was the extreme northern limit of the promised Land, as Beersheba was the most southern. Its Canaanitish name was Laish, it was a colony of Sidon, and dated back to the days of Abraham. The Danites took it easily by surprise, as the inhabitants were a peaceable people devoted to commerce and the manufacture of pottery. It was always a “high place” or sacred city with the Phœnicians, who called it Balinas, or the city of Baal, as later on with Jeroboam, whose Calf was a venerated idol with the local heathen of that day, as it is still curiously with the native ignorant Druse peasants at the present day. When cursed by a Mahommedan they are often called “Sons of a Calf,” as we ourselves heard: so Jeroboam did not necessarily take his idea from the golden calf of Mosaic times, but may have simply adopted the indigenous idolatry; yet “Calfolatry” may have originally come from Egypt, as Dan, being a city of palm trees and water, was a favourite trysting place for the Egyptian as well as the Assyrian, being on the road to Damascus, which was the objective point of every invader, whether warrior or merchant.

Dan is now a mound some 500 feet or so long, and 40 feet high, visible for a long distance over the low plain; here, under a fine oak tree, near a grotto sacred to Pan, is another most copious source of the Jordan, forming a large stream 16immediately it springs from the ground, said to be the largest source of any river in the world, as it forms a good flowing river at once. It is called by Josephus the Little Jordan, and is considered by many the chief source, but it is not the most northerly. We get a grand view here of the great Jordan Valley, looking down upon a sea of waving corn, spread out in one vast field, almost as far as the eye can reach. A long ride through lanes and pleasant wooded country, the road often paved with ruined pillars and old Phœnician worked stones, brings us at last to Banias, the site of ancient Cæsarea Philippi, so called Cæsarea by Philip the Tetrarch, in honour of Tiberius Cæsar, the agnomen Philippi being added by the same gentleman in honour of himself, and to distinguish it from Cæsarea on the coast near Jaffa. Agrippa II. called it Neronias in honour of Nero, but in later times it regained its original name Paneas (which it took from the Temple of Pan then there), and that was easily corrupted to its present name Banias. It was once at least visited by Christ (Matt. xvi.).

Banias is beautifully situated on a spur of Hermon, on the direct road to Damascus, which we do not intend to take, preferring to go two days longer journey round to visit the less frequented parts of Syria. We are received into a Mahommedan house, and have, as usual, the upper chamber allotted to us; and have, what is not usual, the daughter of the house to attend upon us. Veils are dispensed with in this establishment, except by the mother, who after a while thinks it proper to drape up the lower part of her face which somewhat improves her appearance. The accommodation is the same old story, four bare walls. It is quite an Oriental scene at night. The moon shines brightly on the one-storeyed flat mud-roofed huts. On the top of each are the members of the various families sleeping al fresco. Some more 17fastidious or important personages rig themselves up a leafy bower on four supports about three or four feet from the roof—a cool retreat undoubtedly, forming little tents such as might have been seen in ancient Jerusalem during the feast of Tabernacles. A cat or two of course come in through the paneless windows during the night in search of our saddle bags, but a heavy boot well shot at an Oriental cat helps him out quite as quickly as it would one of our own domestic favourites. One time, however it misses the mark and alights on our sleeping dragoman. It was at Banias, by-the-bye, that Titus celebrated with gladiatorial games the capture of Jerusalem, and many thousand prisoners perished in the “Sports.”

Early next morning we visit the massive ruins of the old gate, the grotto of Pan, which gave the name to the city, and the Banias fountains of the Jordan. The rocks just above the latter are sculptured with shrines and niches in which statues once stood; there are also Greek inscriptions which are not very legible.

We now leave Banias by the old western gate, and riding over a slope of Hermon enter Syria proper. The whole country including Palestine is often described as Syria, and was all under one Pashalic so called until lately—Palestine originally included only the country of the Philistines. We breakfast in a poplar grove in the prosperous Christian village of Rasheyat el Fûkhar, celebrated for its pottery, which it supplies to the whole of the northern part of Palestine and Syria, as far as Damascus. It is refreshing to come across an industrious manufacturing population, so rare in Palestine except at Gaza and Ramleh in the south, where jars and lamps are made, and at Nablous (ancient Shechem), where a coarse native soap is made of olive oil, and exported as far as Egypt. The Germans at Caifa (under 18Mount Carmel) are cultivating this industry also, and turn out a much finer article, which finds a sale in America, but has not yet made a market in Palestine, which prefers its native make to that of the Feringhee. We next descend the mountains by a precipitous path, a new one not tried before by our guide, down which we with great difficulty drag our horses to Hibberiyeh, prettily situated in one of the western gorges of Hermon: here we visit a very ancient well-preserved temple built of Phœnician bevelled stones principally, but curiously with pilasters and columns having Ionic capitals—an old Sidonian shrine to Baal probably (as it faced his temple on the summit of Mount Hermon) altered by the Greeks to accommodate one of their own deities. The valley is remarkably a Valley of Rocks; some isolated ones seem to have been formerly sculptured to imitate the human form divine. The ascent up the other side of the valley we find very laborious, having again to lead or rather drag our horses, until at length we arrive at Hâsbeyâ, our quarters for the night, of which more in our next. The shortest way to Damascus is that through the wilderness of Damascus by which St. Paul travelled; but the most beautiful road is that we select, which leads round the slopes of Hermon.

CHAPTER III.—Hasbêya to Mount Hermon.

Hasbêya is a small town beautifully situated some 2,000 feet above the sea, on the western side of Hermon, in an amphitheatre of hills well cultivated and inhabited by Maronite Christians, Druses and Moslems, all very fanatical, hating and fearing each other intensely, and not, as far as the Christians are concerned, without cause, for here they were treacherously massacred by the Druses in 1860. They were decoyed into the Konak, or Governor’s Castle, by the Turkish commander under pretence of protection, induced to part with their arms, and then the Druses being admitted men women and children were massacred without mercy. The French army of the Lebanon avenged these cowardly murders partially, and but for the milder (and doubtfully humane) counsels of the English, would have done so effectually. We saved the Druse scoundrels from their just fate then, and consequently they are quite ready to repeat the crime now. This our rulers would do well to remember that maudlin sentimentality is often another name for weakness and not true mercy which is frequently obliged “to be cruel to be kind.” Orientals do not practice and do not understand undeserved clemency. The Christians in the Anti-Lebanon feel the effects of a too 20lenient policy, and are periodically in a panic about their ruffianly neighbours, and the Moslem feeling too is often inflamed against Christians, the old rumour that the five kings of Europe (as the great powers are called) are about to depose the Sultan and upset Islamism, being for fanatical purposes often revived. This rumour was one of the causes which led to the rebellion of Arabi in Egypt. If Arabi had not been crushed, there would probably have been a general rising of Arabic Islam against the Ottoman Caliphate and European interference—and it may come yet. The Ottomans are no longer a nation—they are quite effete—but the Arabs are as vigorous a race as they were in the days of Alexander the Great and Mahomet. The Arabs and the Jews, the children of Abram’s two sons, are destined to endure for ever distinct races in the midst of a heterogeneous world, everlasting monuments of the truth of the Bible story.

Hasbêya is thought by many to be the Hermon and Baal-Gad of the Bible, but others identify the latter with Baalbec. We will not attempt to decide that on which many doctors differ. We lodge in one of the best houses at the head of the valley, near the Konak. A sort of stretcher, much resembling an oriental bier, is hastily run up for us as a place to sleep on. Round the room and in the courtyard below we see ranged a number of immense jars, each large enough to contain one of the “forty thieves,” some in fact could have accommodated two. We find them to be mostly full of new wine, which is rather too rich and luscious to take much of. Just as the day is dawning an oriental maiden enters our room and makes for one of the jars (to get something out of it) and we are forcibly reminded that we are in the land of the “Arabian Nights.” Next day, after about three hours toiling over mountain paths, we pass the mouth of the Wady-et-Teim, in which is the source of the Hasbâny, the highest and most northerly 21source of the Jordan, the Banias and Dan branches of which it joins just above the waters of Merom, or Lake Huleh, after running almost parallel with them for some distance. We crossed this stream lower down by an old Roman bridge on our way from Kadesh to Dan and Banias.

THE DRUSES.

The Druses make the Hasbâny Valley their religious centre, as their prophet, Ed Darazi, is supposed to have been born there. Their religious books having been lost (or rather stolen by the Egyptians), their religion, which is of more recent origin than Mahometanism, is traditional only, and it is difficult to say what it really is, but it seems to have been founded on an ancient form of freemasonry. It consists of several degrees. The Druses hate Moslem and Christian pretty equally, but are more tolerant of the former, with whom they often associate for the purpose of plunder, but they would murder either without compunction. At the same time, with an appreciable regard to expediency, their religion allows them to live under whatever creed is supreme. They have, since the 1860 massacres, migrated in large numbers from the Lebanon to the Hauran, east of Jordan, which they hold practically independent of any Government whatever, although nominally subject to the Turkish Sultan. They are distinguished by white turbans. Lebanon being now a separate pashalic, under a Christian governor with a native Christian army, the Druses would find it more difficult to occupy that district now than they did in 1860; but in Anti-Lebanon they are more formidable. When a fanatical Mahommedan wishes to annoy a Druse (as was done by our muleteer in our presence) he calls him “a worshipper of the calf.” This is curious, as the golden calf set up at Dan was only a day’s march from here. The Druses have no mosques 22or temples, but worship in a room outside a village, and only the higher initiated members are admitted to the whole performance or allowed to learn what is known of their sacred records, which are imparted by oral instruction only, and never reduced to writing. Very few indeed are acquainted with all the mysteries of their religion, and to the higher degrees no man under 30 is ever admitted, the women, we think, never. The most sacred shrine of the Druses is a secluded cave half-way up Hermon, and there only the most secret rites are performed. A pretty ride of about six hours brings us to Rashêya.

Rashêya, the Syrian Heliopolis, or City of the Sun, is finely and healthily situated high up on the slope of Hermon. I have never been mobbed in any Eastern town as I was here, a European being quite a rara avis. Men women and children cluster round me, and even crowd into my little room to stare at me and touch my clothes, prompted, I suppose, by either curiosity or superstition or both; many seem to think me a medicine man, and bringing sick children ask me to touch them; but unfortunately I am not a doctor. A few of the younger women, having confidence in their good appearance, beg of me to draw their portraits, but my first sketch soon puts the other fair candidates to flight. Two or three enterprising young ladies, clasping my hand in theirs, entreat me to take them back with me to England and make them members of my family. I have to explain to them that the social system of the West does not allow of any such extensive adoption as that of the East. We have often been asked by mothers to take their children and bring them up as Feringhees, but think that in most cases this is done to frighten the children. The Rashêya folk are strong healthy-looking people, but have a barbarous habit of tattooing their bodies (which is seldom seen in the East), the hands especially with stripes 23looking like the seams of gloves. We have, as usual, the floor only to sit and sleep on. We are beginning to be quite clever at squatting à la Turc, but must admit that we think chairs, tables and beds more comfortable. The Rashêya Christians in 1860, were, as in Hasbêya, decoyed into the castle by the Turks, and by them basely betrayed to the Maronite Druses, who massacred man, woman and child.

Mount Hermon, we believe, has not been ascended to the summit by any Englishman for some years. It is called by the Arabs the Snowy Mountain: misled probably by this the text books on the subject boldly assert that its summit is perpetually covered with snow, but this is not the case, nor is it so even with the loftier peaks of Lebanon, on the opposite side of the plain. From Hermon the snow disappears some two months at least, and although we find it cold there is not a trace of snow anywhere. The bare white limestone sides of mountains are often mistaken at a distance for snow, but few travellers ever attain the summit, and hence the perpetuation of the perpetual snow fable.

ASCENT OF MOUNT HERMON.

Hermon, being isolated from the Anti-Lebanon, and the three peaks rising abruptly some 3,000 feet above the lower ridges, has an apparent altitude much greater than many higher mountains. The grandeur of the Matterhorn, for instance, although a monarch of mountains, is diminished by the magnitude of its mighty neighbours, Monte Rosa and the Breithorn (which latter we ascended a few years since, so can judge from experience). The Matterhorn is a giant among giants, a king of kings; but Hermon stands alone in its glory—is, as it were, a sturgeon amongst minnows, and owes its prestige, not to its height, which is under 10,000 feet, but to its isolated position and abrupt elevation; and the same 24may be said of Carmel, which Swiss travellers would scarcely dignify with the name of a mountain at all.

Hermon, the Sirion of the Sidonians, and Shenir of the Amorites, is called by the Arabs, Jebel el Sheikh, the Monarch of Mountains; it was once encircled by shrines to the Sun God, Baal, all facing the great central temple on the summit of the southern peak; there is only one of these remaining now, between Banias and Hasbêya, which we have already described.

Baal, literally interpreted Lord, was probably applied first to the greatest hero, then to the favourite deity of the day. We hear of it as Bel applied to Nimrod; and we trace it in many other names, such as Bel Shazzar, which means King under the Lord Baal, a sort of divine right we suppose. The Phœnicians generally patronised the Sun, the Israelites probably called their golden calf Baal. After the Greek conquest, Baal and the other Gods were very much mixed up, and the Romans later on, to appease the conquered Syrians, identified their Jupiter with Baal, and their Venus with Astarte, or Ashtaroth. It may be interesting to note here that a memorial of Sun worship survives in Scotland in the Bel tane (Bel’s fire) fair still held at Peebles. It is commemorated on May-day morning. Our actual ascent of the mountain is without much interest, except that on the way we pass a very well-preserved wine press, hewn out of the solid rock. The horses are at the door at four a.m., but not until six can we venture out, for Hermon is veiled in dark cloud, and over the Rashêyan Valley bursts a terrific thunderstorm, the thunder reverberating grandly among the mountains. A continuous bombardment by the biggest guns ever launched from Woolwich would have been infants’ rattles compared to it. At six a.m. a ray of sunshine breaks through the black firmament above, and we set out briskly, 25and in about four hours scramble up to the southern—the highest peak—where we find extensive and massive remains of two temples, dedicated to Baal, also a large cave in which we tiffin. Time and space would fail to describe the grand panoramic picture displayed from this sacred summit, no high peaks near to intercept the view. During the ascent, to the summit, which is some 5,000 feet above Rashêya, we have a fine sight of the coast from Carmel to Tyre, but on the summit, the greater part of Palestine and Syria are opened out as a map—to the west, the Mediterranean coast; to the north, the ranges of the Lebanon stand boldly out; the plain of Damascus, bounded by the six day’s desert, flanked by Abana and Pharpar, is in the extreme north-west; Dan, Cæsarea Philippi, Kadesh Naphtali, Safed, &c., nestle beneath on the near south-east; further south the broad waters of Merom, and the silver streak of the Jordan glisten in the noon-day sun, and in the far east the lofty plains of Basan and the Mountains of Moab bound the distant horizon; on the south, Mount Tabor raises its beautifully wooded crest over Nazareth; Gilboa near by seems lost in the plains of Esdraelon; and further west, in the dim distance on the coast, Carmel slopes away to the sea. We enjoy the view only a short time, as a blinding hailstorm comes down and causes us to beat a very precipitate retreat; but as the black thunder clouds gather above and beneath us, and the sun at intervals shines through and upon them, the mélange of earth and sky, sunshine and cloud, gold and colour, is grand in the extreme. Mountain and meadow bathed in black and gold, here and there mellowed with the most delicate tinges of purple green and orange, form an effect, which if fixed on the canvas, would be called an impossible picture, and we could now well understand and feel that enthusiastic praise so often in the Bible bestowed on Hermon, “that Tower of Lebanon 26which looketh towards Damascus.” The ascent is neither difficult nor dangerous to a careful and vigorous climber, but extremely laborious, being a steady steep and continuous scramble over loose stones, on which it is difficult to retain a footing; there is no defined path to the summit, and it should not be attempted without a local guide, as the clouds gather round and envelope Hermon very quickly, and sleet or snow may come on suddenly, in which case there would be but little chance for any but the most experienced guides. Hermon is thought by some to have been the scene of the transfiguration as Banias, where our Saviour started from, is near by. On our way up we try to track a bear, but fortunately fail to find him. If our curiosity had been gratified, we probably should not have written this account.

Tiberias.

CHAPTER IV.—Damascus.

Rasheya is again our resting place after our descent from Hermon, and next morning we make an early start for Damascus. In about 40 minutes we arrive at Rûkleh where there are ruins of temples, and a mountain ride of another two hours brings us to Deir-el-Ashair, where again, on a small elevated plateau, we see extensive and massive remains of ancient temples with fragments of Ionic columns. After a short ride we now reach the French diligence road, the only decent bit of road in Syria, over this the French have a monopoly of wheeled traffic and transport for nearly 99 years, riding horses pass free, but all pack animals and caravans have to pay, which however the native caravans evade by still using the old track up and down the mountains which runs almost parallel. The ride through the Abana, or Barada Valley, for the last three hours is very pleasant, being well watered, wooded, and sheltered from the sun—a most agreeable contrast to the dreary desert of Sahira, through which we have to ride some two hours to reach it. We may here remark that Sahira in the Koran is the Arabic term used for Hell, and anyone who has been in the burning desert at noontide (the hot dry wind making the skin like parchment and drying up all moisture in 28the lips and body) will have an idea that any kind of Hell must be a most uncomfortably hot place, life being in the burning desert a burden almost unbearable. The first sight of Damascus, unlike that of Jerusalem, realises all we have heard of it, it is indeed magnificently situated in the midst of an extensive plain, intersected in all directions by the rills of the rivers Pharpar and Abana, which mæander through and round the whole city, and finally lose themselves in the meadow lakes beyond.

We see the Wali, or Governor, Hallett Pasha, sitting alone on a chair by the river side enjoying otium sine dignitate; his guards at a distance standing by their horses ready to look after him, if necessary. He politely returns our passing salute in true Parisian style. Like all other Turkish Pashas he will have to make hay while the sun shines and be sharp about it. His predecessor, Midhat Pasha (of mournful memory) did not enjoy the sunshine long, and Hallett’s may be a similarly short summer. It costs money to be a Damascus Pasha, some £4000 has to be first found for the Palace Cabal at Stamboul. The official pay of the appointment is under £3000 a year, so the moment a Pasha gets to his government he has to set to squeezing; he squeezes backsheesh out of the higher officials, and they squeeze the lower and the public, who are fair game for all. Justice, not at all blind here, is continually looking out for the dollars. But to return to Damascus. The plain in which it is situated is surrounded on three sides by mountains, Lebanon, Anti-Lebanon and Hermon; on the east it is bounded by the Syrian desert, in the midst of which is the city of palm trees, Palmyra, the ancient Tadmor, the city of Zenobia, the Boadicea of the Syrians. Well might the Moslem, arrived in this ever-verdant plain, after six days dreary riding across the desert, when he came across this city embosomed in beautiful gardens and 29orchards, when he saw the rills of living water flowing in all directions and rising in fountains in the very court-yards of the houses, well might he imagine that he had lighted at last upon the Garden of Eden. We find comfortable quarters at Demetri’s, the only Frank hotel, and are glad again to see some signs of western civilisation.

My flying visit here without tents, traversing the country by little known paths, creates some curiosity, even among the Europeans, who wish to know if I am travelling under diplomatic orders; a negative answer to such a question is not, of course, worth much. The Turkish police give vent to their curiosity by visiting me in my bedroom and cross-examining my dragoman as to my intents and purposes, position in life, &c., &c. Things are rather strained here. The attitude of the allied Powers to Turkey makes this fanatical people never well disposed to Christians, now still less so, and to make matters worse, Arab placards have been posted here and at Beyrût in the Bazaars, summoning the natives to revolt against the Turks, asking reasonably what common interest the Arabs have with their now imbecile and insolent conquerors, the Osmanli usurpers of the Khalifate, who monopolise all place and power, using them only to oppress the people, whose language they do not even understand, and whose lives, liberties, and properties they either cannot or do not care to protect. This is a sign of the times—a writing on the wall to warn the feeble despots of Stamboul of their doom. This movement has since developed into an organised Arab League, following the example of the Albanians. An Armenian League probably is not far behind. The collapse of the rule of the Osmanlis is merely a matter of time. They may retain Asia Minor for the present (if England does not seize it to save it from Russia), but they will have to clear out of Europe, and Syria, Lebanon and Palestine must ere 30long be like Egypt, semi-independent vice-royalties under European protection, or they will become Russian and French appanages. The Turkish Government have authorised their postmasters in Syria to detain telegrams and open letters at their pleasure. A remedy for that is to give the letters to the Consul who forwards them in his bag. The Consul here lives in a hired house liable to a notice to quit at any moment. What a pity that our Government does not buy itself a consular residence in such an important post as this? It is so undignified for an English Consul to have to turn out at the bidding of a Moslem landlord, and troublesome in the extreme to have to move all the archives every few years; and in case of an intrigue, which is not uncommon in these parts, we might find it difficult to find a suitable place for the Consul at all. In one of the squares we see a crowd and several soldiers looking at the dead body of an Arab. This poor fellow was, with others, in charge of a caravan of camels, some Druses swooped upon them within only a few hours of Damascus, all ran except the murdered man, who stuck to his post; they of course soon killed him and cleared off with the camels. This is the security for life and property which Turkey provides for its subjects in the neighbourhood of a great city. We will now take a stroll through this thoroughly Eastern city, where the far East and the far West meet more than in any other city in the world, more so even than in Tanjiers and Tunis. Here we see English tourists in tweed suits, black-coated Americans in tall hats, Bedouins in dirty bornous, Druses with white turbans and blood-stained hands, Turks in officials fezzes, orthodox Moslems in flowing robes and showy green turbans, Circassians with breast full of cartridges (murderous looking rascals), Kurds in rough sheep skin cloaks, Persians, Afghans, Pariahs and Parsees, slipshod veiled Eastern women, gorgeous Jewesses and smartly dressed 31Parisian dames, all these meet together in this metropolis of the East, jostling each other in the narrow unpaved bazaars. Camels also, and mules, horses and donkeys, with perhaps a drove of long-tailed sheep, from the far steppes of Turkestan, press on amidst this motley crew, “Oua garda”—take care, take care, get out of the way quickly! A pack mule is no respecter of persons, he cares not for your Consul, and over you go if you do not get out of his way, unless by a vigorous shove you send him over, just as in self-defence we were obliged to do once. A pack mule on his back, legs up in the air, is a helpless, pitiable spectacle.

Metropolis did I call Damascus? Indeed it is rightly so called, for is it not the mother of all cities, the oldest living city in the world? (not even excepting Hebron), for here Abraham’s steward Eliezer lived; these streets the patriarch himself must often have traversed as a trader in flocks and herds, and through these lanes, once at all events, he drove the Hivite Kings of Hermon before his avenging spear, for near here he rescued Lot and the King of Sodom from their Syrian captors. It was conquered by David after a protracted struggle, but recovered its independence in the reign of Solomon. It was subsequently subdued by the Assyrians. Rome may call itself, Damascus is the Eternal City, founded probably soon after the flood by a Semitic grandson of Noah. Damascus has never ceased to exist as a great city, and from its unique position, probably never will. The prey of every ambitious conqueror, it has seen the rise and survived the fall of every great empire. Assyrian, Persian, Greek, Roman, Crusader and Saracen, each in turn have dominated the garden city—and died—but Damascus still lives and has out-lived all its rivals of every age. Sidon, Tyre, Antioch and Tarsus survive only as uninteresting towns, Babylon, Palmyra and Nineveh are no more, but Damascus is still the 32“Head of Syria” as it was in the days of Abraham—Damascus a green island in the midst of a golden sea of sand, bounded by the desert, surrounded by its rivers, has always been and must for ever remain the mother city of the world.

To brace ourselves up for our rambles, we now take a bath in the waters of the Abana, which are, as its Syrian name Barada indicates, remarkably cool and pleasant. Having tried Jordan too, we must endorse Naaman’s opinion, that the bathing in the former is decidedly the best. In the midst of the city, we are shown a sycamore tree, 42 feet in girth; certainly a curiosity in any city, but especially so in a Mahommedan one, where the process of destruction is carried on by man and that of re-construction or re-placement left to “Allah.” We also see another tree in the horse market close by, used as a gallows, but public executions are very rare in Turkey. A good Moslem is peculiarly sensitive—he does not object to strangle a wife or two quietly at home if they are annoying, but he objects to a fellow male Moslem being publicly executed even for a murder. We look into the great mosque; in its courtyard are the remains of a small ancient temple to the sun—it was once a Roman temple, then a Greek basilica, and was in more ancient times probably the site of the very temple in which Naaman bowed the knee to Rimmon, when his master worshipped there. We found it easier to enter St. Sophia at Stamboul, the mosque of Omar at Jerusalem, and the grand mosque at Cairo, than this, the people being so fanatical. St. Sophia, in fact, we got into by only paying a few francs to the door-keeper, but here it costs a lot to get in. We are next shown the tomb of the great Saladin, who died 1193, but as it is very sacred, cannot view the interior. We now come to the street called “Straight,” above a mile long, running through the city east to west, and on our way we call at the traditional 33house of Ananias, now a small Latin Church; then just outside the east gate we pass the reputed house of Naaman, now appropriately a leper hospital, and come upon that part of the wall from which it is said St. Paul was let down in a basket at the time when Aretas, the Petræan ruler of Arabia, was King. Aretas was the name of the dynasty, like, Ptolemy and Pharaoh of Egypt, Candace of Ethiopia, &c. The conversion of St. Paul is said to have taken place just outside the city—the spot is shown: bright indeed must have been the light before which an eastern sun at mid-day paled. A walled up gate is also shewn as that by which St. Paul entered the city.

Damascus.

The Bazaars are very interesting, here is to be found merchandise collected by caravans from all corners of the earth; Merchants from Manchester, Paris, Vienna, Constantinople, Aleppo, Bagdad, Persia, Afghanistan, India, Egypt, Nubia, and Arabia as far as Mecca, crowd its exchanges. The native manufactures are chiefly silk, leather and metal work; the population is principally Moslem. We 34of course pay a visit to old Abu Antika (father of antiquities), and possess ourselves of a Damascus blade. A friend of ours, an artist, was about to give 100 francs for one at Cairo, we asked to look at it, and saw engraved on it “warranted best steel.” We asked the old Arab swindler what language it was; he unblushingly answered “Arabic”! my answer induced him to hastily put away the Damascus blade and my friend put his 100 francs back into his pocket. Tricks are sometimes played upon travellers. We see in old Abu Antika’s booth an English Countess wasting a lot of money on spurious antiquities, we did not know her then so could not interfere, but she introduced herself to us later on and was a very pleasant and intelligent fellow traveller. The houses of the rich Damascenes are very handsomely fitted up; on visiting one, we enter by an archway into a great open courtyard, with a fountain in the centre and trees and plants all around. A divan, roofed in, but open to the courtyard at one end, is fitted with a luxurious lounge; this serves as a public reception room. On each side of the court is a large room, one used as a Summer and the other as a Winter sitting room, according to the seasons. All are magnificently decorated with marble and mirrors. The sleeping rooms are on the first floor and are entered from a verandah above. Running water from the Abana flows through all the best houses. The public buildings and barracks built during the Egyptian occupation are very good for a Turkish city, and the citadel, an old mediæval castle, is interesting, but access is not allowed to it. Abdel-Kader, who so long kept the French at bay in North Africa, lived in Damascus, and had a quarter allotted to him and his Algerian fellow exiles. Damascus is not the dirty city it once was. Midhat Pasha greatly improved it in that respect, and also in other ways, for we see a large quarter of Damascus in ruins 35and are told that it was set fire to by Midhat Pasha (after the fashion of Nero) to make room for a new wide street. This is a much shorter and more economical way (to the government) of making street improvements than that we have in England, but as no notice of the contemplated improvement is given, it must be rather inconvenient to the inhabitants. Damascus is called by the Arabs El Sham, and in the eyes of the Moslem world is second in sanctity only to Mecca.

Damascus.

CHAPTER V.—The Anti-Lebanon.

Damascus must now be left behind, adieu, we wish we could say au revoir to its lovely lanes and pleasant orchards, its curious motley crowded bazaars, its marble palaces and murmuring waters, and its grand associations with all time—for did not through Damascus pass those archaic caravans whose descendants colonised the four quarters of the globe? Shem probably here said goodbye to Ham on his way to Africa, and both bade God-speed to Japhet, in quest of a new world farther north; and Noah himself—did not he pass here on his way to leave his bones as near as possible to Eden; and are we not shown his tomb, and that of Adam, Abel and Seth, cum multis aliis near here even to this day? Adieu also to the comfortable hotel of Demetri, an oasis in the desert of barbarism we pass through. We follow back the diligence road a few miles as far as Dummar, and then start upon the upper road to Baalbec, viâ Zebedâni, one of the prettiest rides in Syria; but first to get a zest for better things we pass across the arid desert of Sahrâ. We see on the way several rock-cut tombs, and soon enter the upper part of the Abana watershed, which might well be called the “Happy Valley,” in this part of the world where there is so much desert and wilderness. We pass several Mohammedan villages having a clean prosperous 37appearance, the women looking better and healthier than any we have yet seen. We now enter the narrow gorge of the Abana, a very romantic looking defile, and soon after about five hours from Damascus, come upon Ain El Fijeh (one of the principal tributaries of the Barada), a little river which springs up suddenly from the earth so abundantly as at once to form a large stream, which, although not broad, is very deep. It must be, we should think, the shortest river in the world. Over these springs, half-hidden by the beautiful foliage of the fig and pomegranate, rise the massive remains of two temples, one across the stream, one in it, all around is a grand luxurious grove; this is a fine halting spot and a good place for a bath. Fruit trees of all kinds—walnut, fig and orange, mulberry, vine and lemon line the banks of this most lovely little stream, and where its crystal current mixes with the turbid Barada, there is a “Meeting of the Waters,” more beautiful even than the “Moore” famed meeting of the Avonbeg and Avonmore in the once picturesque Vale of Avoca. Here the giant poplar, the graceful palm, the spreading sycamore, the sombre cypress and the stately oak, are found forming little forests wherever a rill of living water can force its way. If the ruined aqueducts of Tyrian and Roman times were only, and they could easily be, reformed, the whole land would again laugh and sing, and paradises as of old, would replace the present deserts. God made the land a garden of Eden, man, by neglecting the watercourses, has turned it into a wilderness. We continue our journey, following the course of the Barada for some two hours, having a succession of pretty woodland views until we come to Sûk Wady Barada, supposed to be the site of the ancient Abila, the chief town of the district of Abilene, of which (according to St. Luke) Lysanias was tetrarch in the reign, of Tiberius Cæsar.

38Abila is said to derive it name from Abel, who according to tradition was here slain by Cain. A Wely on an overhanging height (Neby Hâbyl) is pointed out as Abel’s tomb. This first murder, according to tradition was avenged by Lamech, who slew Cain on Mount Carmel, not far from Mahrakah the rock of sacrifice, where Elijah slaughtered the prophets of Baal. We now reach the narrowest part of the Barada gorge, where the river descending in small cataracts is spanned by a very tumbledown bridge, attributed by some writers to Zenobia, but more probably the work of the Roman engineers who built the aqueducts and cut out the corniche roads.

In the cliff above—now inaccessible—we see numerous rock-cut tombs, tunnels which once contained an aqueduct, and the remains of a high-level mountain road, works well worthy the finest engineering of the West. Here by the stream, near a murmuring waterfall we spread our carpet for tiffin, the lofty overhanging cliffs, the rushing eddying waters, the greensward and cool shade of trees (all so uncommon at this season in the East), combining to make it a very delightful resting place. On resuming our ride we pass some fine waterfalls and ruined bridges, and then enter the mountain-girt grass plain of Zebedâni, one of the most fertile in the land, well watered and well cultivated; then, after passing some more ruins, we ride through some pretty English-like lanes to the town, which is the half-way halting place between Damascus and Baalbec. The population is chiefly Moslem, but there are many Maronites also. We lodge with the chief priest. We may here remark that the Maronites are a primitive community of Christians who acknowledge the Roman Pontiff as their nominal head, but cannot be called orthodox Roman Catholics, for they are really ruled by their own patriarch and do not carry out the Roman ritual. They 39might almost equally well acknowledge the Archbishop of Canterbury as their chief. The Maronite women are distinguished by a black band on the forehead.

Zebedâni is a small town, finely situated in the midst of most luxurious vegetation, and almost surrounded by mountains. It boasts a small Bazaar. Its low mud houses are built closely together, only one or two having a first floor; most have a small courtyard, into which the goats and cattle are driven at night. The low flat roofs of the houses are used much more for getting about the village than the dark, dirty ill-paved lanes; and, as in other villages, the people sleep in the open on the roof; and when in the early morning sleeper after sleeper raised his or her head from beneath the coverlet, gave a yawn and a stretch and tried to escape from dreamland, the effect was comical in the extreme. All turned out at dawn of day—lodgers on the cold ground are as a rule early risers. The room we have is clean, contains the usual curtained recesses in the walls for cupboards, and a wooden ledge round top of room for stores, and, what is the only piece of furniture ever seen in these parts, a large damasceened chest for the valuables of the household. The mural decorations consist of English willow pattern plates cemented into the walls—this is a decided improvement on hanging them up by wires, as they are not liable to be broken by domestic dusting. We have seen the outside as well as the inside of dwellings decorated in this manner, and our Western sisters are long forestalled in this kind of mural ornaments by their barbaric sisters in the East. Our worthy host is rather nervous about being massacred by Druses, and we try to reassure him by saying that times are changed since 1860, and that there is not any occasion to fear; but we should not like to back this opinion too heavily, for we believe that the fanatical Moslems and Druses are as 40bloodthirsty against Christians as ever they were; soon after writing above there was a collision between Moslems and Christians at Beyrût, and several of the latter were massacred. There was also an attack on Christians in the Hauran by the Druses. A Turk only recently said to me what Froude said in September, 1880, in his admirable article on Ireland: “The idea of Government had almost ceased to exist, and that every one had to look after his own immediate interest,” and in the case of a collapse of Turkish rule (not unlikely), Arabs would swarm in from the desert like locusts, murder all round, and in all probability permanently occupy the whole country. When we mount our horses at daybreak the summits of the hills are brightly gilded with the rising sun. No poetical expression, no fancy pen-picture this gilding of the hills—far too beautiful to be expressed in language, far too bright to be pictured in painting, is the grand mise-en-scène of black and gold set in silver frame produced by the rays of the rising sun mingling with the disappearing darkness. We have seen it also on many former occasions; once notably when after sleeping 10,000 feet high in the Théodule hut under the Matterhorn we saw the Italian mountains literally bathed in the brightest gold as the sun climbed up to the summits of the highest peaks and crept down the opposite sides into the valley.

At Zebedâni, by-the-bye, we have a good opportunity of seeing the Syrian sheep, remarkable for their tremendous tails, and watch the women stuffing the vine leaves down the sleepy animals’ throats, for the purpose of creating the enormous quantity of fat, which flies to the tail and is used to fatten the frugal dish of sour milk and rice, which, with a salad of olives, fruit and vegetables, all jumbled together into one great hotch-pot, form their staff of life called (as our German friends would say aptly) Leben. To this meat is 41added in times of plenty. We soon leave the lovely valley of Zebedâni behind, and passing under Bludàn, the summer residence of the European Consuls, arrive at the upper source of the Barada, near the watershed of the Anti-Lebanon, the streams now flowing towards Damascus south-east, and towards the Bukâa and Lebanon north-west. The first fountain on the northern slope is that of Eve, in whose transparent waters the mother of all was, according to poetical tradition, admiring herself when her future lord and master (as he is euphemistically called) first caught sight of her. We infer from the Bible description that the Garden of Eden was by no means a small one, and must have included all Syria Mesopotamia, Palestine and Egypt, if not the whole of the world. As we are soon leaving Anti-Lebanon, we may observe that this mountain range extends from Banias, at the head of the Jordan Valley, to the plains of the Bukâa, in which is Baalbec. Hermon is sometimes reckoned as part of it, but on account of its almost isolated position, is often considered to be as a mountain in business for itself. On our way we cross two Roman bridges, now on their last legs, but they have done well to have lasted 1800 years.

Baalbec—The Great Stone in the Quarry.

Between Rashêya and this place we have seen two ancient wine presses, hewn out of the solid rock; they date over 2,000 perhaps 3,000 years back; they enable one to understand what building a wine press meant, and what a terrible loss and disappointment it would be to the builder, if, when he “looked for grapes, he found but wild grapes.” The Cactus hedges too, with which the vineyards are surrounded to keep out the “little foxes that spoil the vines,” also take great trouble and many years before they form that impenetrable barrier through which even the wild boar cannot break his way. We pass through Surghaya and halt for lunch in the Wady Yafûfeh, on the banks of the Saradah, which we cross 42by a single arched Saracenic bridge, and on resuming our journey leave on our left Nadu Shays, the reputed tomb of Seth. Ham is said to be buried a little further east. A beautiful panorama of Lebanon now bursts upon our view, separated from us by the great plain of the Bukâa, or valley of the Litany (the accursed river). We next pass near the village of Brêethen, thought to be the Beroshai of Samuel, and soon come in sight of the many-rilled orchard gardens and grand Acropolis of Baalbec, the great ancient shrine of Baal in Phœnicia, the Heliopolis, or City of the Sun of the Greeks and Romans, and the Baal-gad, according to many, of Joshua, formerly a station like Palmyra on the great caravan road from Tyre to India, which we may mention was the original overland route, and if history repeats itself will be so again. What shorter route to India can there be than rail to Brindisi, steamer to Corinth through the canal now being made to Piræus, across the Ægean, to Smyrna, and thence all the way by rail through the iron gates of Cilicia, viâ the two Antiochs, Syria, Mesopotamia, Persia and Afghanistan, to India—there are no difficulties which modern engineers could not overcome. But perhaps we are waiting for the French or Germans to show the way.[1] Before entering the town we visit the ancient quarries out of which were hewn the enormous Cyclopean stones which formed the very ancient Phœnician or Hittite foundation. One block lies there already hewn but not quite separated from the quarry, it is about 70 feet long, 14 feet wide and 14 high, weighing some 10,000 tons; other large stones are seen lying about partially hewn—why they were thus left unfinished in the workshop—whether it was an Assyrian or Persian invader who made the busy mason so suddenly throw away the 43gavel to seize the sword will now never be known. We put up at a small hotel facing the ruins, and find it fairly comfortable; but are quite alone in our glory until late in the evening, when an English countess and her niece come in with two Turkish guards as guides, with whom they can only converse in the primitive language of signs—the result being that when next morning they want to see the ruins, they are taken from them, to a hill some miles off, where they see them—from a distance—a fine effect probably, but not what was wanted. However, we coming to the rescue, they get a closer inspection in the afternoon, and having previously gone through it all ourselves, are quite eloquent in dragomanic descriptions. Their guides, if not useful as Cicerones, were we must admit extremely picturesque and pleasant barbarians. The younger lady has we believe by this time immortalized them and the ruins on canvas, and we hope with supreme effect, for we planted the fair artist on a high pinnacle of the Temple from which the coup d’oeil was magnificent.

1. Since writing the above we hear that the Porte are about to grant a firman to make a railway from Ismid to Bagdad.

Soon after, we see another instance of the inconvenience of having a guide whose language is unintelligible. On our way to Beyrût we meet a man and his horse at cross purposes, endeavouring in vain to find out the reason from his Arab guide. He appeals to us; “Well,” we say, “you and your horse certainly do not appear to be friends.” “No,” the traveller replies, “he does not understand me, and I do not understand my guide, who only speaks Arabic; my horse is a brute.” “Not so, my friend,” we rejoin, “you are riding him with an Arab bridle in English fashion.” He was, in fact, unknowingly the greater brute of the two, for he was torturing the poor beast, and the injured animal might, if he had been so gifted as the Scriptural ass, have appropriately replied, “Tu quoque brute.” The Arab bit is in the shape of a gridiron (minus interior bars), a ring hangs from the flat 44broad end of it, in which the lower jaw of the animal is placed the handle of the gridiron is in the mouth, and by a pull of the reins is forced up into the roof of the mouth, causing considerable pain; the reins are bunched in the hand, and the animal is guided by laying the left rein across the neck when wishing to go to the right, and vice versâ. Pulling the rein English fashion would simply hurt and puzzle the animal. We explain the process and leave the man and his beast better friends; they now understand each other. (How many of us would also like each other better if we were less impatient, and took more trouble to understand). Horse and rider now go on their way as reconciled to one another as Balaam to the ass after the departure of the Angel.

A Street called “Straight,” Damascus.

CHAPTER VI.—Baalbec.

Baalbec, more correctly, we believe, Baalbak, is situated about forty-five miles north of Damascus but slightly to the west, on the lowest slope of Anti-Lebanon, near the source of the Leontes or Litany. The Litany and Orontes rivers rise six miles west from Baalbec within one mile of each other. The Litany runs west down the Bukâa or Cœlesyria, and falls into the sea between Sidon and Beyrût. The Orontes, El Asi or rebellious river, so called because it changes its course in a remarkable manner, flows north and falls into the Gulf of Antioch. Baalbec is the point where the great roads from Damascus, Tyre, Beyrût and Tripoli converge, hence probably its great ancient importance, and it was also the entrance gate to Padan Aram or Upper Syria where Terah lived, whence Abram emigrated and whither Jacob went to seek a wife among the daughters of his uncle Laban, who was also his cousin and subsequently his father-in-law, a very mixed up series of relationships; even more puzzling than that which befell the proverbial American who married his stepmother’s mother, and was driven to despair, insanity and death, because he never could make out what relation he was to himself.

The ancient city of Baalbec must have been between two and three miles in circumference. Some learned writers 46attribute its foundation to Solomon, arguing that the colossal stones used in the substructure, of which we will speak more in detail hereafter, are similar in size and bevel to those in the temple foundations at Jerusalem. They identify it with Baalath, which Solomon is recorded in I. Kings, IX., to have built at the same time as Tadmor (by them supposed to be Palmyra), in the wilderness. Now it must be noted that Solomon lost Damascus to the Syrians, which David his father had taken from them. It is not likely that having so lost Damascus, he held Baalbec to the north of it, and built Palmyra six days journey in the desert beyond it, neither would he if he dominated the cedar country have troubled Hiram to send him cedars for the Temple. We may also observe that Baalaath and Tadmor are described as being built along with Gezer, Megiddo, and other cities in the land, i.e., Solomon’s own land of Israel, where these last cities undoubtedly were, in the plain of Esdraelon, &c. Baalaath is more likely to have been Banias, and as for Tadmor, the city of palms, there are plenty of palm trees and wildernesses in Palestine without locating Tadmor in the great Syrian desert, then held by the hostile kings of Syria; and further, we are informed that Solomon gave Hiram, king of Phœnician Tyre, certain Galilean cities which he named “Cabul,” Solomon could surely have much better spared, if he had had them to give, Baalbec and Phœnician cities, further beyond his base of operations, but equally conveniently situated for Hiram and much more acceptable to him. Baalbec was probably a Hittite fortress anterior to the time of Hiram, who however might have added to it. The similarity of some of the stones to those in Jerusalem is easily explained by the historical fact that Solomon employed Hiram’s Phœnician workmen to prepare the Temple materials, the woodwork of which was undoubtedly, and the stonework perhaps too, obtained from 47the Anti-Lebanon mountains of Tyre, and floated down along the coast on rafts to Joppa. But we will now visit the celebrated ruins, the grandest probably in the world, only approached in sublimity of position, but not equalled by those on the Acropolis at Athens. We first see just outside the village a beautiful little Temple of Venus, called by the natives Barbara el Ahkah, quite a gem of architecture, semicircular in shape, the architraves, cornices, &c., richly ornamented with the fair goddess, doves, and flowers. It has a peristyle of eight Corinthian columns, each made of a monolith. It was last used as a Greek church, to which era the trace of frescoes still remaining must be attributed. Near by are the remains of a large mosque, which looks very like having been built from the ruins of Constantine’s basilica and other temples previously existing—the capitals and columns being terribly mixed up, one or other being always too large or too small. Some of the porphyry pillars must have been very fine.

The great Trilithon Temple, the Acropolis of Baalbec, and its massive, mighty ruins are now before us—they have been so often pictured by the painter that their external appearance must be familiar to many. We enter from the east, where once was the principal entrance, a noble flight of steps ascending to a colonnade supported by twelve mighty columns. This grand approach was destroyed by the Turks when they converted the Acropolis into a fortress. Passing under this, through a portico, we find ourselves in a long lofty corridor, richly ornamented; facing us are three large doors, the centre, 23 feet wide, brings us into an outer court of hexagonal form about 190 feet long and 240 wide; three gates again from this leading to the grand court, about 440 feet long and 370 wide; on the north and south sides are vast somewhat semicircular alcoves, with three Exedrae, 48rectangular recesses on each side with arched roofs, but open to the central court; these are elaborately decorated with niches, Corinthian pillars, shrines, &c., the various designs of ornament on the latter scrolls, birds, flowers, &c., being very beautiful and still in fine preservation, so numerous and varied that it has been said that it would take an artist a lifetime to copy them in detail. This court leads us up to what was once the great Temple, at first dedicated to Baal and then to all the gods, so as not to offend any. The only remains of this Temple are six magnificent columns of the peristyle, each 60 feet high and 7½ feet in diameter; they are visible at a great distance in the plain below, and have a very grand impressive effect, especially when seen from below at a distance standing out boldly in an evening sky.

Baalbec—General View of Ruins.