BEAUTIFUL BIRDS

BEAUTIFUL BIRDS

BY

EDMUND SELOUS

AUTHOR OF “TOMMY SMITH'S ANIMALS”

WITH MANY ILLUSTRATIONS BY

HUBERT D. ASTLEY

1901

LONDON: J. M. DENT & CO.

29 & 30 BEDFORD STREET, W.C.

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Why Beautiful Birds are Killed | 1 |

| II. | Birds of Paradise | 20 |

| III. | The Great Bird of Paradise | 35 |

| IV. | The Red Bird of Paradise | 56 |

| V. | The Lesser, Black, Blue, and Golden Birds of Paradise | 67 |

| VI. | About all Birds of Paradise, and some Explanations | 93 |

| VII. | About Humming-Birds, and some more Explanations | 108 |

| VIII. | Some very Bright Humming-Birds | 129 |

| IX. | Hermit Humming-Birds and Two Other Ones | 151 |

| X. | The Cock-of-the-Rock and the Lyre-Bird | 164 |

| XI. | The Resplendent Trogon and the Argus Pheasant | 179 |

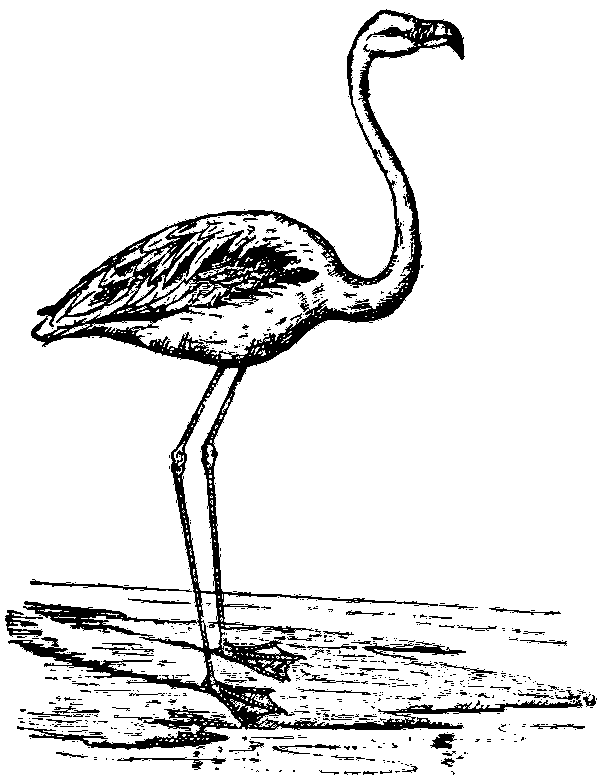

| XII. | White Egrets, “Ospreys,” and Ostrich-Feathers | 203 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

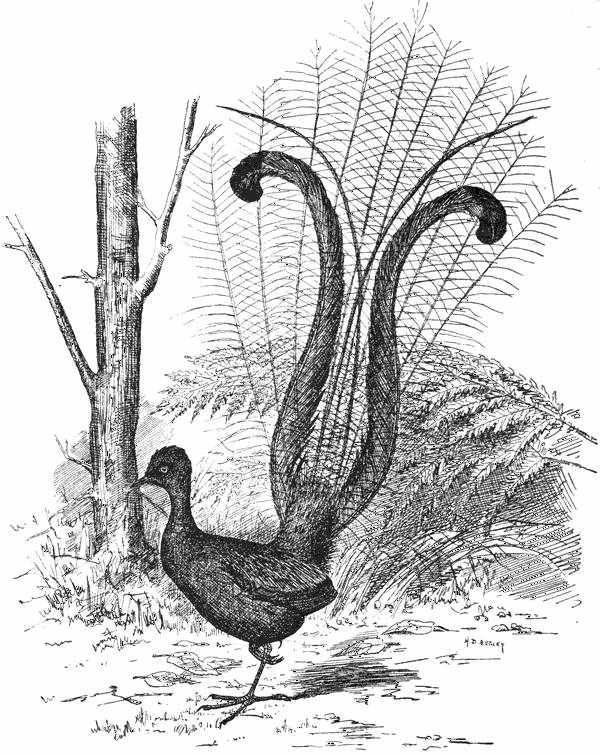

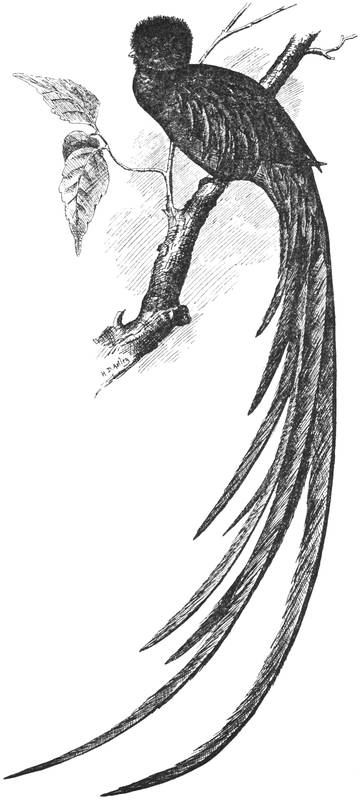

| Lyre-Bird | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

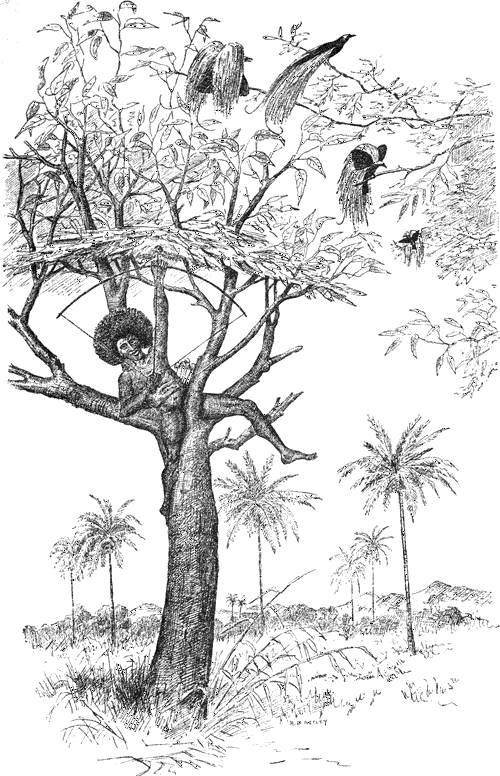

| Papuan shooting Birds of Paradise | 49 |

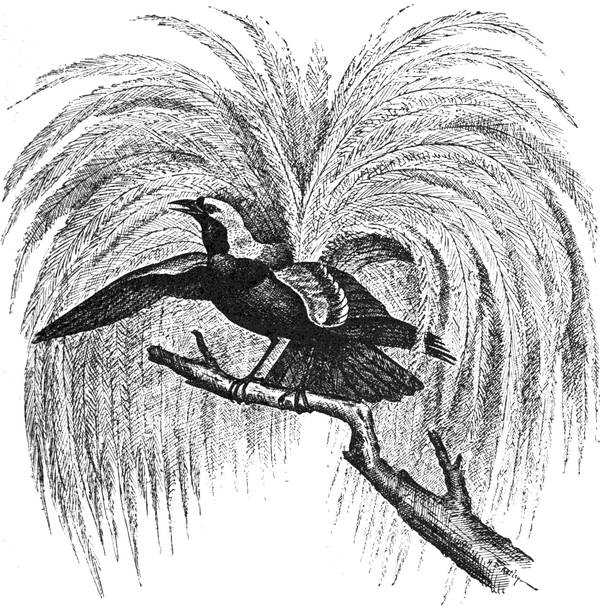

| Lesser Bird of Paradise | 69 |

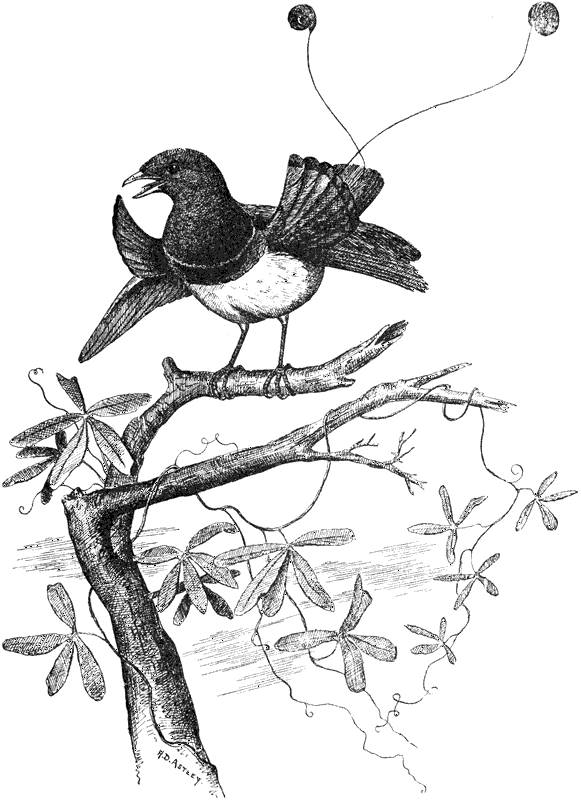

| King Bird of Paradise | 77 |

| Golden-winged Bird of Paradise | 89 |

| Racquet-tailed Humming-Bird | 113 |

| Plover-crest Humming-Bird | 125 |

| Train-bearer Humming-Bird | 131 |

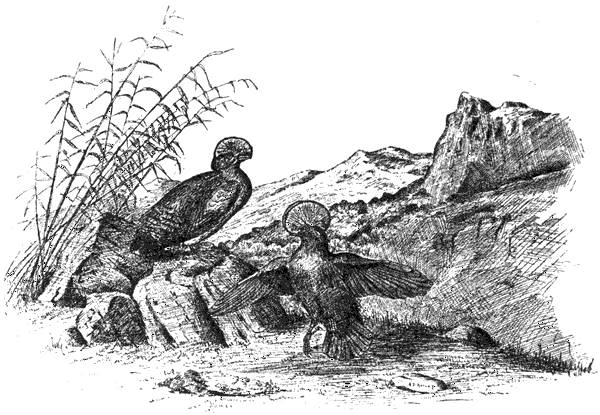

| Cock-of-the-Rock | 168 |

| Resplendent Trogon | 187 |

| Argus Pheasant | 195 |

| White Egret | 205 |

| End Piece | 225 |

BEAUTIFUL BIRDS.

CHAPTER I

Why Beautiful Birds

are Killed

What beautiful things birds are! Can you think of any other creatures that are quite so beautiful? I know you will say “Butterflies,” and perhaps it is a race between the birds and the butterflies, but I think the birds win it even here in England. Just think of the Kingfisher, that bird that is like a little live chip of the blue sky, flying about all by itself, and doing just what it likes. The Sky-blue Butterfly is like that too, I know, but then it is a much smaller chip, and does not shine in the sun in such a wonderful way as the Kingfisher does. Neither, I think, does the Peacock-Butterfly, or the Red Admiral, or the Painted Lady, or the Greater or Lesser Tortoise-shell; and, besides, they none of them go so fast. Yes, all those butterflies are beautiful, very, very beautiful. But now, supposing they were all flying[Pg 2] about in a field that a river was winding through, and, supposing you were sitting there too, amongst the daisies and buttercups in the bright summer sunshine, and looking at them, and supposing all at once there was a little dancing dot of light far away down the river, and that it came gleaming and gleaming along, getting nearer and nearer and keeping just in the middle all the time, till it passed you like a sapphire sunbeam, like a star upon a bird's wings, then I am sure you would look and look at it all the time it was coming, and look and look after it all the time it was going away, and when at last it was quite gone you would sit wondering, forgetting about the butterflies, and thinking only of that star-bird, that little jewelly gem. But, perhaps, if you were to see a Purple Emperor sweeping along—ah, he is a very magnificent butterfly, is the purple emperor. You can tell that from his name, but whether he is quite so magnificent as a star-bird (for that is what we will call the Kingfisher)—well, it is not so easy to decide. The birds and the butterflies are both beautiful, there is no doubt about that, only this little book is about beautiful birds, and perhaps afterwards there will be another one about beautiful butterflies. That will be quite fair to both.

The birds, then! We will talk about them. I am going to tell you about some of the most beau[Pg 3]tiful ones that there are, and to describe them to you, so that you will know something about what they are like. But perhaps you think that you know that already because you have seen them, so that you could tell me what they are like. There is the star-bird that we have been talking about, and then there is the Thrush and the Blackbird. What two more beautiful birds could you see than they, as they hop about over the lawn of your garden in the early dewy morning? The Blackbird is all over of such a dark, glossy, velvety black, and his bill is such a lovely, deep, orangy gold. It would be difficult, surely, to find a handsomer bird, but the Thrush, with his lovely speckled breast, is just as handsome. Then the Robin with his crimson breast, and his little round ball of a body—what bird could be prettier? Or the Chaffinch, or Greenfinch, or Linnet? Or the Bullfinch, surely he is handsomer than all of them (except the star-bird), with his beautiful mauve-peach-cherry-crimson breast, and his coal-black head and nice fat beak, and that pleasant, saucy look that he has. Yes, he is the handsomest, unless—oh, just fancy! we were actually leaving out the Goldfinch. He has crimson on each side of his face, and a black velvet cap on his head, whilst on both his wings he has feathers of a beautiful, bright, golden yellow. I think he must be the handsomest, unless it is the[Pg 4] Brambling, who is dressed all in russet and gold. And then there is the Yellow-Wagtail! Could one think of a prettier little bird than he is—unless one tried a good deal? To be a wagtail at all is something, but to be not only a Wagtail but yellow all over as well, that does make a pretty little bird! And I daresay you have seen him running about on your lawn, too, at the same time as the thrush and the blackbird. And there is another bird, one that you do not see running or hopping over your lawn, but flying over it, sometimes far above it, when the sky is blue and the insects are high in the air, sometimes just skimming it when it is dull and cloudy and the insects are flying low. You know what bird it is I mean, now—the Swallow. I need not say how beautiful he is.

So, as you have seen all these pretty birds, and a good many others too—at least if you live in the country and not in London—perhaps you think that there cannot be many, or perhaps any, that are so very much prettier. Ah, but do not be too sure about that. You must never think that because something is very beautiful there can be nothing still more beautiful. You may not be able to imagine anything more beautiful, but that may be only because your imagination is not strong enough to do it. It may be a very good imagination in its way,[Pg 5] better than mine perhaps, or a great many other people's, but still it is not good enough. In fact there is not one of us who has an imagination which is good enough to do things like that. We could never have imagined birds which are still more beautiful than those we have been talking about. Indeed we could never have imagined those that we have been talking about. Only Dame Nature has been able to imagine them both.

She can imagine anything, and the funny thing is that as she imagines it, there it is—just as if she had cut it out with a pair of scissors. Perhaps she does do that. She is a lady—Dame Nature, you know—so she would know how to use a pair of scissors. But what her scissors are like and how she uses them and what sort of stuff it is that she cuts things out of, those are things which nobody knows. Only, there are the birds, not only the beautiful ones that you have seen, but a very great many others which you have never seen, and which are so very much more beautiful than the ones you have, that if you were to see those beside them, they would look quite—well no, not ugly—thrushes and blackbirds and swallows and robin-redbreasts could not look that—but insignificant—in comparison.

Now it is about some of those birds—the very beautiful birds of all, the most beautiful ones in the[Pg 6] whole world—that I am going to tell you; but all the while I am telling you, you must remember that they—these very beautiful birds—do not sing, whilst our birds—the insignificant-looking ones—do. So you must not think poorly of our birds because their colours are plain or even dingy—I mean in comparison with these other ones—for if they have not the great beauty of plumage, they have the great beauty of song. And perhaps you would not so very much mind growing up plain, like a lark or a nightingale (which would not be so very, very plain), if you could sing like a lark or a nightingale—as perhaps one day you will.

Indeed, I sometimes wish that those very beautiful birds were not quite so beautiful as they are. You will think that a funny wish to have, but there is a sensible reason for it, which I will explain to you. Perhaps if they were not quite so beautiful, not quite so many of them would be killed. For, strange as it may seem to you—and I know it will seem strange—it is just because the birds are beautiful that hundreds and hundreds, yes, and thousands and thousands, of them are being killed every day. Yes, it is quite true. I wish it were not, but I am sorry to say it is. People kill the birds because they are beautiful. But is not that cruel? Yes, indeed it is, very, very cruel. It is cruel for two reasons: first, because to kill them gives them pain; and secondly, because their life is so[Pg 7] happy. Can anything be happier than the life of a bird? Surely not. Only to fly, just think how delightful that must be, and then to be always living in green, leafy palaces under the bright, warm sun and the blue sky. For I must tell you that these birds we are going to talk about live where the trees are always leafy, where the sun is always bright and the sky always blue. So they are always happy. Even if a bird could be unhappy in winter—which I am not at all sure about—there is no winter there. Now the happier any creature is the more cruel it is to kill it and take that happiness away from it. I am sure you will understand that. If you were carrying a very heavy weight, which tired you and made you stoop and gave you no pleasure at all, and some one were to come and take it away from you, you would not think that so very cruel. You would have nothing now, it is true, but then all you had had was that weight, which was so heavy and made you stoop. But, now, if you were carrying a beautiful bunch of flowers which smelt sweetly and weighed just nothing at all, and some one were to take that away, you would think that cruel, I am sure. A bird's life is like that bunch of flowers. How cruel, then, it must be to take it away from any bird. We should think it very wrong if some one were to kill us. Yet it is not always a bunch of flowers that we are carrying.

So, as it is cruel to kill the birds, and as they are not nearly so beautiful when they are dead as they are when they are alive, and as the world is full of tender-hearted women to love them and plead for them and to say, “Do not kill them,” perhaps you will wonder why it is that they are killed. I will tell you how it has come about. When Dame Nature had imagined all her beautiful birds, and then cut them out of that wonderful stuff of hers—the stuff of life—with her marvellous pair of scissors, she said to her eldest daughter—whose name is Truth—“Now I will leave them and go away for a little, for there are other places where I must imagine things and cut them out with my scissors.” Truth said, “Do not leave the birds, for there are men in the world with hard hearts and a film over their eyes. They will see the birds, but not their beauty, because of the film, and they will kill them because of their hearts, which are like marble or rock or stone.” “They are, it is true,” said Dame Nature,[Pg 9] “and indeed it was of some such material that I cut them out. I had my reasons, but you would never understand them, so I shall not tell you what they were. But there are not only my men in the world; there are my women too. I cut them out of something very different. It was soft and yielding, and that part that went to make the heart was like water—like soft water. I made them, too, to have influence over the men, and I put no film over their eyes. They will see how beautiful my birds are, and they will know that they are more beautiful alive than dead. And because of this and their soft hearts they will not kill them, and to the men they will say, ‘Do not kill them,’ and my beautiful birds will live. Women will spare them because they have pity, and men because women ask them to. And to make it still more certain, see yonder on that hill sits the Goddess of Pity. She has come from heaven to help me, and has promised to stay till I return. It is from her that pity goes into all those hearts that have it, and because she is a goddess, she sends most of it into the hearts of women. Have no fear, then, for until the Goddess of Pity falls asleep my birds are safe.” “But may she not fall asleep?” said Truth. But Dame Nature had hurried away with her scissors, and was out of hearing.

As soon as she was gone, there crept out of a dark cave, where he had been hiding, an ugly little mannikin, who hated Dame Nature and her daughter Truth, and did everything he could to spite them both. Their very names made him angry. He was a demon, really, and ugly, as I say. But he did not look ugly, because nobody saw him. All that people saw when they looked at him was a suit of clothes, and this suit of clothes was so well made and so[Pg 10] fashionable, and fitted him so well, that they always thought the ugly demon inside it was just what he ought to be. So, of course, as every one had different ideas as to what he ought to be, he seemed different to different people. One person looked at the clothes, and thought him quite remarkable, another one looked at them and thought him ordinary and commonplace, and so on. Only every one was pleased, because, whatever else he seemed, he always seemed just what he ought to be. So, when two people both found that he was that, they each of them thought that he looked the same to the other. Of course the clothes were enchanted, really, only nobody knew it, and if any one had been told that it was the clothes and not the demon inside them they were looking at, he would not have believed it. It was only Dame Nature and her daughter Truth who could look at those clothes and see the little demon inside them, just as he really was. That was why he hated them, and never liked to hear their names.

This ugly little demon crept up to the Goddess of Pity, who looked at the clothes and was not even able to pity him; and, when he saw that he had her good opinion, he began to repeat a sort of charm to send her to sleep, for he knew that when once the Goddess of Pity was asleep he might do whatever he liked.

These were the words of the charm:—

Under the influence of this drowsy charm—which, of course, had no meaning in it whatever—the Goddess of Pity began to nod, and nodded and nodded till, on the last line, she went fast asleep, with a pleased smile on her face.

Then the wicked little demon took from one of the pockets in the suit of clothes that charmed everybody two little bottles that contained two different sorts of powders, one hot like pepper, and the other cold like ice, but both of them so fine that they were quite invisible. He took a pinch of the hot powder which was labelled “Vanity,” and blew it upon the heads of all the women, and the instant it touched them they all looked pleased, and you could see that they were thinking only of how they looked, though they talked in a very different way. It was funny that they all looked pleased, because a great many—in fact, most of them—were plain, not pretty, and yet they looked[Pg 12] pleased too, as well as the others. But, you see, it was all done by magic. Then from the other little bottle, which was labelled “Apathy,” the demon took a pinch of the cold powder and blew it on the women's hearts, and as soon as it fell on them they became frozen, so that all the pity that had been in them before was frozen, too. Frozen pity, you know, is of no good whatever. You can no more be kind with it in that state than you can bathe in frozen water. So now there was nothing but vanity in the women's heads, and no pity in their hearts, and as the Goddess of Pity was fast asleep, it was not possible for any more to be put into them until she woke up. Nobody could tell when that would be. Gods and goddesses sometimes sleep for a long time, and very soundly. Besides, you know, this was a charmed sleep.

So, now, what happened after the wicked little demon had behaved in this wicked way? Why, the women whose hearts he had frozen began to kill the poor, beautiful birds, those birds that Dame Nature loved so, and had taken such pains to keep alive. I do not mean that they killed them themselves with their own hands. No, they did not do that, for they had not enough time to go to the countries where the beautiful birds lived, which were often a long way off as well as being very[Pg 13] unhealthy. You see they were wanted at home, and so to have gone away from home into unhealthy countries to kill birds would have been selfish, and one should never be that. So instead of killing them themselves the women sent men to kill them for them, for they could be spared much better, and if they should not come back they would not be nearly so much missed. And the women said to the men, “Kill the birds and tear off their wings, their tails, their bright breasts and heads to sew into our hats or onto the sleeves and collars of our gowns and mantles. Kill them and bring them to us, that you may think us even more lovely than you have done before, when you compare our beauty with theirs and find that ours is the greater. Let us shine down the birds, for they are conceited and think themselves our rivals. Then kill them. Kill, kill, kill, kill, kill them.” Then the men, whose hearts had always been hard, and over whose eyes there was a film, went forth into the world and began to kill the poor, beautiful birds wherever they could find them. Everywhere the earth was stained with their blood, and the air thick with floating feathers that had been torn from their poor, wounded bodies. It was full, too, of their frightened cries, and of the wails of their starving young ones for the parents who were dead and could not[Pg 14] feed them any more. For it is just at the time when the birds lay their eggs and rear their young ones that their plumage is most beautiful—most exquisitely beautiful—and it was just this most exquisitely beautiful plumage that the women, whose hearts the wicked little demon had frozen, wanted to put into their hats. They knew that to get it the young fledgling birds must starve in their nests. But they did not mind that now, their hearts were frozen and the Goddess of Pity was asleep.

So the birds were killed, and the lovely, painted feathers that had lighted up whole forests or made a country beautiful, were pressed close together into dark ugly boxes—or things like boxes—called “crates” (large it is true, but not quite so large as a forest or a country), and then brought over the seas in ships, to dark, ugly houses, where they were taken out and flung in a great heap on the floor. Soon they were sewn into hats which were set out in the windows of milliners' shops for the women with the frozen hearts to buy. You may see such hats now, any time you walk about the streets of London—or of Paris or Vienna, if you go there—for the Goddess of Pity is still sleeping, she has not woken up yet. There you will see them, and outside the window, looking at them—sometimes in a great crowd—you will see those poor women that the demon has treated so badly. There[Pg 15] they stand, looking and looking, ravenous, hungry—you would almost say they were—longing to buy them, even though they have new ones of the same sort on their head. Ah, if they could see those birds as they looked when they were shot, before they were dressed and cleaned and made to look so smart and fashionable! If they could see them with the blood-stains upon them, the wet, warm drops running down over the bright breasts—perhaps onto the little ones underneath them—the poor, broken wings dragging over the ground and trying to rise into the air, through which they had once flown so easily, the flapping, the struggling! If they could see all this, and much more that had been done—that had to be done—before there was that nice, gay, elegant shop-window for them to look into, would it not be different then, would not the vain heads begin to think a little and the frozen hearts to melt? No, I do not think so, because of the ugly little demon in the correct suit of clothes. They would look in at the window and go in at the door still, and—shall I tell you something?—it would be the same, just the same, if all those bright feathers in every one of the hats had been stripped, not from the birds' but from the angels' wings. Those who could wear the one could wear the other, and if angels were to come down[Pg 16] here I should not wonder if angel-hats were to get to be quite the fashion. Only first, of course, angels would have to come down here. I do not think they are so very likely to.

And the worst of it is that not only the pretty women wear the beautiful birds in their hats, but the plain ones do too, which makes so many more of them to be killed. If it was only the pretty women who wore them it would not be quite so bad, but the wicked little demon was much too clever to arrange it like that. He did not wish any of the birds to escape, and I cannot tell you how many millions of them would escape if only the pretty women were to wear their feathers.

But now, how are the birds to be saved—for we want them all to escape—and how are the women to be saved? That is another thing. You know it is not their fault. They were kind and pitiful till the wicked little demon blew his powder into their hearts. It is his fault. You may be angry with him as much as you like, but you must not think of being angry with the women. Indeed, you should be sorry for them, more even than for the birds, for it is much worse to be a woman with a frozen heart than to be a bird and be shot. Oh, poor, frozen-hearted women, who would be so kind and so pitiful if only they were allowed to be, if only the wicked[Pg 17] little demon would go away, and the Goddess of Pity would wake up!

Then is there no way of saving them both, the poor birds and the poor women? Yes, there is a way, and it is you—the children—who are to find it out. Listen. It is so simple. All you have to do is to ask these women (these poor women) not to wear the hats that have feathers, that have birds' lives in them, and they will not do so any more. They will listen to you. There is nobody else they would listen to, but they will to you—the children. Perhaps you think that funny. Listen and I will explain it. When the wicked little demon blew his powder called “Apathy” into the hearts of the women, it froze them all up, as I have told you, but there was just one little spot in every one of their hearts that it was not able to freeze. That was the spot called Motherly Love, which every woman has in her heart, and which is the softest spot of all, if only a little child presses it—and especially if it is her own little child. So I want you—the little children who read this little book—to press that spot and to save the birds from being killed. Nobody can do it but you, nobody even can find that spot except you, but you will find it directly. And you are to press it in this way. Throw, each one of you, your arms round your mother's neck, kiss her and ask her not[Pg 18] to kill the birds, not to wear the hats that make the birds be killed. And if you do that and really mean what you say, if you are really sorry for the birds and have real tears in your eyes (or at least in your hearts), then your mother will do as you have asked her, for you will have pressed that spot, that soft spot, that spot that even the wicked little demon, try as he might, could not freeze, could not make hard. And as you press it, the whole heart that has been frozen will become warm again, and the powder of the demon will go out of it, and the Goddess of Pity will wake up. You will do this, will you not? It is only asking, and what can be easier than to ask something of your mother? But you must make her promise. Never, never leave off asking her till you have got her to promise.

And if some of you have mothers who do not kill the birds, who do not wear the hats that have birds' lives sewn into them, well it will do them no harm to promise too. Then they never will wear them, and if they should never mean to wear them, they will be all the more ready to promise not to. Only in that case you might put your arms round the neck of some other woman that you have seen wearing those hats and kiss her and ask her to promise. And she will, you will have touched that spot because you are a little child, even though you are not her own little[Pg 19] child. Perhaps you will remind her of a little child that was hers once.

Now I am going to tell you about some of the most beautiful birds that there are in the world, but you must remember that they are being killed so fast every day that, unless you get that promise from your mother very quickly, there will soon be no more of them left; as soon as she promises it will be all right, for of course it will not be only your mother who will have promised, but the mother of every other little girl all over the country, and as the birds were only being killed to put into their hats, they will be let alone now, for now no more hats like that will be wanted. No one will wear hats that have birds' lives sewn into them, any more.

So the beautiful birds will go on living and flying about in the world and making it beautiful, too. You will have saved them—you the children will have saved them—and no grown-up person will have done anything to be more proud about. I daresay a grown-up person would be more proud about what he had done, even if it was nothing very particular; but that is another matter.

Now we will begin, and as we come to one bird after another, you shall make your mother promise not to wear it in her hat.

CHAPTER II

Birds of Paradise

First I will tell you about the Birds of Paradise. You have heard of them perhaps, and how beautiful they are, but you may have thought that birds with a name like that did not live here at all. For the Emperor of China lives in China, and if the Emperor of China lives in China, the Birds of Paradise ought, one would think, to live in Paradise. But that is not the case—not now at any rate. They live a very long way off, it is true, right over at the other side of the world, but it is not quite so far off as Paradise is. No, it cannot be there that they live, because if you were to leave England in a ship and sail always in the right direction, you would come at last to the very place, instead of coming right round to England again, which is what you would do if you were to sail for Paradise—for you know, of course, that the earth is round. But why, then, are they called Birds of Paradise if they live here on the earth? Well, there are two ways of explaining it. I will tell you[Pg 21] first one and then the other, and you can choose the way you like best. The first way is this.

A long time ago—but long after the little demon had crept out of his cave—the early Portuguese voyagers (whom your mother will tell you about), when they came to the Moluccas to get spices, were shown the dried skins of beautiful birds which were called by the natives “Manuk dewata,” which means “God's birds.” There were no wings or feet to the skins, and the natives told the Portuguese that these birds had never had any, but that they lived always in the air, never coming down to settle on the earth, and keeping themselves all the while turned towards the sun. One would have thought they must have wanted wings, at any rate, to be always in the air, but that is what the natives said. So the Portuguese, who did not quite know what to make of it, called them “Passaros de Sol,” which means “Sun-birds” or “Birds-of-the-Sun,” because of their always turning towards him. Some time after that, a learned Dutchman who wrote in Latin (just think!), called these birds “Aves Paradisei”—Paradise Birds or Birds of Paradise—and he told every one that they had never been seen alive by anybody, but only after they had fallen down dead out of the clouds, when they were picked up without wings or feet, and still lying with their heads towards the sun in the way they had fallen.[Pg 22] So, after that these wonderful birds were always called “Birds of Paradise.” That is one way of explaining how they got their names, but the other way, and perhaps you will think it a little more probable, is this.

Once the Birds of Paradise were really Birds of Paradise, for they lived there and were ever so much more beautiful than they are now, though perhaps, if you were to see them flying about in their native forests, you would hardly believe that possible. That is because you cannot imagine how beautiful real Birds of Paradise are, for these Birds of Paradise were not more beautiful than the other ones that lived there. All were as beautiful as each other though in different ways, and it was just that which made these Birds of Paradise discontented. “If we go down to earth,” said they, “the birds of all the world will do homage to us on account of our superior beauty, for there will be none to equal us. So we shall reign over them and be their King. Here we are only like all the others. None of them fly to the tree on which we are sitting to do us homage.” “Do not be foolish,” said the tree (for in Paradise trees and all can speak).[Pg 23] “The homage which you desire you would soon weary of, and the beauty which you enjoy here would, on earth, be only a pain to you, for it would remind you of the Paradise you had left but could never enter again. For those who once leave Paradise can never more return to it. Therefore be wise and stay, for if you go you will repent, but then it will be too late.” And all the birds around said, “Stay,” and then they raised their voices, which were lovelier than you can imagine, in a song of joy—of joy that they were in Paradise and not on earth. And the Birds of Paradise sang too, their voices were as sweet as any, but they had envy and discontent in their hearts. “Our singing cannot be surpassed, it is true,” thought they, “but it is equalled by that of every other bird. We sing in a chorus merely. It would not be so on earth. We should be ‘prima donnas’ there.” (Your mother will tell you what a prima donna is as well as what doing homage means.)

So, when the song was over, they flew to the Phenix, who was the most important and powerful bird of all the birds that were in Paradise. I have told you that all the birds there were equal, and so they were, only, you see, the Phenix was a little more equal than the others. One cannot be a Phenix for nothing. Now it was only the Phenix who could open the gate of Paradise, and let any bird in or out of it. He was not obliged to let them in, and there were very few birds (who were not there already) that he ever did let in. Many and many a bird fluttered and fluttered outside the door, that had to[Pg 24] fly away again. But if a bird that was in Paradise wanted to go out of it, then the Phenix had to open the door and let it out, because if it had stayed it would have been discontented, and birds that are discontented cannot stay in Paradise. It would not be Paradise for long if they could. So when the Birds of Paradise said to the Phenix, “Let us out, for we are tired of being here, where all are equal, and wish to be kings and ‘prima donnas’ on earth,” he had to do it, only he warned them as the tree had done, that if they once left Paradise they could never come back to it again. “The door of Paradise,” said he, “may be passed through twice, but only entered once. When you pass through it the second time, it is to go out of it, and when you are once out of it, out of it you must remain. You can never come in again; you can only flutter at the gate.”

“We shall never do that,” said the proud Birds of Paradise. “We shall stay down on earth and be kings and ‘prima donnas’ amongst the other birds.” So the Phenix let them out, and they flew down through the warm summer sky, looking like soft suns or trembling stars or colours out of the sunrise or sunset, they were so beautiful.

Then the birds of earth flew around them and did them homage, and, when they sang, the nightingale stood silent and hid her head for shame, and would[Pg 25] never sing in the daytime any more, but only at night when the beautiful strangers were asleep. That is why the nightingale sings by night and not by day—only since the Birds of Paradise have lost their voice (which I am going to tell you about) she does sing in the daytime sometimes, just a little.

So the Birds of Paradise were kings and “prima donnas” amongst the birds of earth, and they were happy—for a time. They were not quite so happy after a little while, for they got tired of hearing the birds praise them, and, wherever they looked, they saw nothing to give them pleasure. The earth, indeed, was beautiful, but they remembered Paradise, and that made it seem ugly. There was nothing for them to see that was worth the seeing, or to hear that was worth the listening to, except their own beauty and their own song. But that reminded them of Paradise, and they could not bear to be reminded of it now that they had lost it for ever. In fact they were miserable, and it was not long before they were all fluttering outside the gates of Paradise, and begging the Phenix to let them in. But the Phenix said,[Pg 26] “No, I cannot. I warned you that the gates of Paradise could only be passed twice, once in and once out, and then no more. I tried to keep you from going, but you chose to go, and now you must stay outside. You can never enter Paradise again.” “If we cannot enter it,” said the poor Birds of Paradise, “let us at least forget it. Take away our beautiful voices, so that, when we sing, we shall not think of all the joys we have lost. Let our song be no more than the lark's or the nightingale's, or make us only able to twitter, and not sing at all. Then we can listen to the lark and the nightingale, and perhaps, in time, we may grow to admire them. As it is, we must either sing or be silent. We do not like to sit silent, and when we sing we think only of Paradise.” “Yes,” said the Phenix, “I will take your voice, your beautiful voice of song.” So he took it, and that is why the Birds of Paradise never sing at all now, not even as the lark and the nightingale sing.

After that they were happier, but still they had their great beauty, their glorious, glorious plumage, and when they looked at each other they felt sad and hung their heads, for still they thought of Paradise. “You have taken our song from us,” they said (for they were soon there at the gate again), “but still our beauty remains. Take that also, that, when we look at each other, we may not think of the Paradise we have lost, and be wretched.” “Fly back to earth,” said the Phenix,[Pg 27] “and when you are a little way off I will open the gates of Paradise wide, and the brightness that is in it will stream out and scorch your feathers, and you will be beautiful no more. Only you must fly fast, and you must not turn to look, for if you do, the brightness will blind you. You could bear it once when you lived in it and had known nothing else, but now that you have lived on earth you cannot. It would only blind you now.” So the Birds of Paradise flew towards the earth, and, when they had got a little way, the Phenix opened the gates (he had only been speaking to them through the keyhole), and, as the splendour of Paradise streamed forth and fell upon them, their feathers were scorched in its excessive brightness, all except a few tufts and plumes which were not quite destroyed, because, you see, they were getting farther away every second. A little of their beauty was left, and that was enough to make them the most beautiful birds on earth (till we come to the Humming-birds), but they are very ugly compared to what they once were when they lived in Paradise. Think then, what the real Birds of Paradise must be like when those that have left it, and have had their plumage scorched and spoilt, are so very beautiful. That is the other way of explaining how there come to be Birds of Paradise living on the earth, and I think you will say that it is the more sensible way of the two. For as for people having ever believed that there were birds who had no feet or wings, and that lived always in the air with[Pg 28] their heads turned towards the sun, why, that does not seem possible. Nobody could have believed in a thing like that, but here is a natural explanation.

But now you must not think that the Birds of Paradise which are in the world to-day, are the very same ones that used to live in Paradise, and that had their feathers scorched. Oh no, you must not think that. Those old Birds of Paradise died (for, of course, as soon as they came to earth they became mortal, they had been immortal before), but before they died they had laid a great many eggs, and reared a great many young ones, and these young ones, as soon as they were grown up, laid other eggs, and the birds that came out of those eggs laid others, and so it has been going on for hundreds of thousands of years, right up to now. And now, if you were to ask a Bird of Paradise where it was he used to live, and why he had lost his voice and got his feathers scorched, he would not know one bit what you were talking about. In hundreds of thousands of years a great many things are forgotten, and the Birds of Paradise of to-day are quite happy. The earth is quite good enough for them, and if they were not shot and put into hats for the women with the frozen hearts to wear, they would have nothing to complain of. They have something to complain of now, but you must remember your promise,[Pg 29] and then, perhaps, they will not be shot any more.

Now, the Birds of Paradise that live on the earth to-day do not live all over it, as they used to do in those old days when they could hear the lark and the nightingale. It is only a very small part of the world that they live in now—small, I mean, compared to the rest of it—and there are no larks or nightingales there. I will tell you where it is. Far away over the deep sea, farther than Africa, farther than India, farther even than Burma or Siam, there are a number of great islands and small islands and middling-sized islands, which lie between Asia and Australia, and all of these together are called the Malay Archipelago. The largest of all these islands, and the one that is farthest away too, is called New Guinea, and it is a very large island indeed, the largest, in fact, in the world after Australia, which, as you know, is so large that we call it a continent. Round about this great island of New Guinea, and not very far from its shores, there are some other islands which are quite tiny in comparison, and it is here, just in this one great island and in these few small islands near it, that the Birds of Paradise live. They do not live in any of the other islands of the Malay Archipelago, but only just here in the ones that are farthest away of all.

It would take you weeks to go in a steamer to where the Birds of Paradise live, and if you were to go, not in a steamer but in a ship with sails, it would take you longer still. But when you got there you would not see the Birds of Paradise flying all about, as soon as you went ashore out of the ship or the steamer, as you would see sparrows here. Oh no, Birds of Paradise are not so common as that, even in their own country. They do not come into the towns, like sparrows, either, but live in the great forests where people do not often go, and even when one does go into them, it is difficult to see them amongst the great tall trees and the broad-fronded ferns and the long, hanging creepers that make a tangle from one tree to another.

Ah, those are wonderful forests, those forests far away over the seas! Some of the trees have trunks so thick that a dozen men—or perhaps twenty—would not be able to circle them round by joining their hands together, and so tall that when you looked up you would not be able to see their tops. They would go shooting up and up like the spires of great cathedrals, till at last they would be lost in a green sky, not the real sky, the blue one—that would be higher up still—but a green sky of leaves made by all the trees themselves, and in this sky of leaves there would be flower-stars almost as bright and as[Pg 31] beautiful as the real stars of the real sky. Then there are other trees that have their roots growing right out of the ground, and going up more than a hundred feet high into the air. At the top of them is the tree itself, going up another hundred feet, or perhaps more, so that the real tree—the trunk at any rate—begins in the air, and before you could climb it, you would have to climb its roots, which does seem funny. And there are palm-trees with long, tall, slender trunks, smooth and shining, crowned with leaves that are like large green fans; and rattan-palms, which are quite different, for instead of being straight, their trunks twist round and round the trunks of other trees, going right up to their very tops, and raising their own most beautiful feathery ones above theirs. Sometimes they will climb first up one tree and then down it again, and up another, and then down that, till they have climbed up and down several trees, all of them very, very tall. How tall—or rather how long—they must be you may think. We say that a snake is so many feet long, not tall, and these rattan-palms are palm-creepers, great vegetable serpents, that twist and coil as they grow, and hug the forest in their great coils, which are larger and more powerful than those of any python or boa-constrictor. A python or a boa-constrictor could not kill a very large animal, but the[Pg 32] great palm-snakes will crawl up the largest tree, and crush it and squeeze it till at last it dies and comes thundering down in the forest, and then they will crawl along the ground to another, and hug that to death, too. Then there are tree-ferns, which are ferns that have trunks like trees, which are sometimes thirty feet high, with fronds growing from their tops, so broad and tall that a number of people could sit underneath them in their cool, deep shade, as if they were a tent. And there are wonderful flowers in these forests, such as you only see here in botanical gardens or in the conservatories of rich people, orchids and pitcher-plants, and others with Latin names that one forgets. Some of them are flower-trees, or tree-flowers, as high as the trees are, and with hundreds of large, crimson blossoms glowing out like stars from their trunks. When you come upon them all at once in the gloom of the forest, it almost looks as if some of the trees were on fire.

Other flowers are golden like the sun and grow all together in clusters, whilst others, again, grow on the branches of trees and hang down from them by long stalks which are like threads, each thread-stalk strung with flowers, as a thread is strung with beads. Only these flower-beads are as large as sunflowers, with colours varying from orange to red, and with beautiful, deep, purple-red spots upon them.

But if you had wings like the Birds of Paradise, and could fly over the tops of the trees that make the forest, and look down into a leafy meadow instead of up into a leafy sky, then you would see the most gloriously beautiful flowers growing in that meadow, just as the daisies and buttercups grow in the meadows that you run over, here. For flowers love the light of the sun, and they struggle up into it through the leaves that keep it out. To them the leaves are not as the sky, but as the clouds that shut the sky out, and as they are clouds that will never roll away (even though they may fall sometimes in a rain of leaves), the only thing for them to do is to climb up to them and pierce them, and see the sky, with the sun shining in it, on the other side. So whilst a few flowers stay in the shade below, most of them grow and struggle up into the light and air above, and they are all in such a hurry to get there that every one tries to grow faster than all the others. Ah! what a race it is, a race to reach the sun. You have heard of all sorts of races, and some, perhaps, you have seen; running-races, races in sacks, boat-races, horse-races (though those, I hope, you never have and never will see), but you never either saw or heard of a fairer, lovelier, more delicate race than a race of flowers to reach the sun. Think[Pg 34] of it, all over those great, wide, far-stretching forests, forests stretching away like the sea, and only bounded by the sea! Think of all the millions of flowers there must be in them, with all their delicate shapes, and rich, fragrant scents and glorious colours, and then think of them all growing up together, each trying to be the first to see the sun. So eager they all are, but so gentle. There is no pushing, nothing rude or rough. But as the leaves grow thinner, and the light shines more and more through them, they tremble and sigh with joy, and one says to another, “We are getting nearer—nearer. I can see him almost; we shall soon be bathed in his light.” And so they all grow and grow till at last they gleam softly through the soft leaves, and see the beautiful deep blue sky and the glorious, golden sun. Yes, that is a lovely race indeed—as anything to do with flowers is lovely—and it is a race upwards, to the sky and to the sun. Not all races are of that kind.

It is in forests like those that the Birds of Paradise live; and now that we know something about where they live, we will find out something about them.

CHAPTER III

The Great Bird of Paradise

The Great Bird of Paradise lives in the middle of the great island called New Guinea, and all over some quite little islands close to it which are called the Aru Islands. He is the largest of the Birds of Paradise, and perhaps he is the most beautiful, but it is not so easy to be sure about that. However, we shall see what you think of him. His body and wings and tail are brown. “What, only brown?” you cry. “That is like a sparrow.” Ah, but wait. It is not quite like a sparrow. It is a beautiful, rich, coffee-brown, and on the breast it deepens into a most lovely, dark, purple-violet brown. There! That is different to being just brown like a sparrow, is it not? Then the head and neck are yellow, not a common yellow, but a very pretty, light, delicate yellow, like straw. Sometimes ladies have hair of that colour, and when they have, then people look at them and say, “What beautiful hair!” which is just what they themselves say,[Pg 36] sometimes, when they look in the glass. These feathers are very short and set closely together, which makes them look like plush or velvet, so you can think how handsome they must be. What would you think if you were to go out for a walk and see a bird flying about with a yellow plush or yellow velvet head? But the throat is handsomer still. That is a glorious, gleaming, metallic green. Some feathers are called “metallic,” because when the light shines on them they flash it back again just as a bright piece of metal does; a helmet or a breastplate, for instance. You know how they flash and gleam in the sunshine when the Horse-Guards ride by. At least, if you have seen the Horse-Guards, you do, and if you have not, well, I daresay you have seen it in a dish-cover or a bright coal-scuttle. But fancy feathers as soft as velvet, gleaming as if they were polished metal, but gleaming all emerald green as if they were jewels—emeralds—too! Then on the forehead and the chin of this bird—by which I mean just under the beak—there are glossy velvety plumes of a deeper green colour. The other is emerald. These are like the deep, lovely greens that one sees sometimes in the fiery opal or the mother-of-pearl. What jewellery! and out of it all flash two other jewels—the bird's two eyes—which are of a beautiful bright yellow colour to match with the yellow[Pg 37] plush of its head. Then this bird has a pale blue beak and pale pink legs, and I am sure if he thinks himself very handsome, you can hardly call him conceited. For he would be handsome only with this that I have told you about; that would be quite enough to make him a beautiful bird without anything else.

But has he anything else—any other kind of beauty besides what I have told you about? Listen. The emerald throat and the yellow velvet-plush head and the blue beak and the pink legs are as nothing, nothing whatever, compared to the glorious plumes which this Bird of Paradise has on each side of his body. Oh, you never saw such plumes, and you cannot think how lovely they are. There are two of them—one on each side—and each one is made up of a number of very long, soft, delicate silky feathers, which are of an orange-gold or golden-orange colour, and so bright and glossy that they shine in the sun like floss-silk. Just where they spring from the body each one of them has a stripe of deep crimson-red, and, towards the top, they soften into a pretty pale, mauvy brown. Even one feather like that on each side would be beautiful—or one all by itself in the middle—but fancy a plume of them on each side, a thick plume too, though each feather is so slender and delicate—there are so many of them. They look lovely enough when they stream out[Pg 38] behind as the bird flies, for they are twice as long as its whole body, so, of course, the two plumes come together and make one lovely large one that lies as softly on the air as the feather of a swan does on the water. The body, then, is almost covered up in all these soft feathers, so that it is just like looking at a flying plume with wings and a head to it.

Yes, they look lovely enough then, these glorious plumes; but sometimes they look lovelier still, and that is when the Great Bird of Paradise raises them both up above its back so that they shoot into the air like two golden feather-fountains that mingle together and bend over and fall in spray all around, only it is a spray of feathers—not a real spray—and, instead of falling, they only wave and dance. Such a glorious, plumy cascade! The bird himself is almost hidden in his own shower-bath, but the emerald throat and the yellow-plush head look out of it and gleam like jewels as he peeps and peers about from side to side to see if any one is looking at him. For, of course, the Great Bird of Paradise does not make himself so very beautiful just for nothing. When he shoots up his feather-fountains and sits in a soft, silky shower-bath, he does it to be looked at, and the person he wants to look at him most is the hen Great Bird of Paradise, for—do you know and can you believe it?—the poor hen Great Bird of Paradise is not beautiful.[Pg 39] She has no wonderful plumes—she has no plumes at all—and out of all those splendid colours I have told you about—orangy-gold and emerald green and all the rest of them—she has only one, which is the coffee-brown. Now, of course, a nice rich coffee-brown is a very good colour, but still, by itself it is not enough to make a bird one of the most beautiful birds in the world. So when a bird is only coffee-brown, then, compared to a bird who has all those other colours and the most wonderful plumes as well, it is quite a plain bird. So a poor hen Great Bird of Paradise is quite a plain bird compared to her handsome husband, with his emerald throat and yellow-plush head and his wonderful orangy-gold plumes.

But, then, if the poor hen bird has no glorious plumes of her own, she is always looking at them, always having them spread out on purpose for her to look at, and that must be very pleasant indeed. When the male Great Birds of Paradise wish to show their poor plain hens how handsome they are—just to comfort them and make them not mind being plain themselves—they come to a particular kind of tree in the forest, a tree that has a great many wide-spreading branches at the top, with not so very many leaves upon them, so that it is easy for them to be seen by the hens, who are sitting in other trees near, all ready to watch them. Then they raise up their[Pg 40] wings above their backs, stretch out their emerald necks, bow their yellow heads politely to each other, and shoot up their golden feather-fountains, making each of the long, plumy tufts tremble and vibrate and quiver, as they droop all over them and almost cover them up. The plumes begin from under the wings—that is why they lift their wings up first so that they can shoot straight up and so that the hen birds may see the little stripes of red, which I told you about, and which look like little crimson clouds floating in a little golden sunset. How beautiful they must look! Perhaps there may be a dozen Great Birds of Paradise, all bowing their heads and quivering their plumes, on a dozen branches of the tree, whilst a dozen more will be flying about from one branch to another, so that the tree and the air are full of beauty. The air never had anything to float upon her softer or lovelier than those golden floating plumes, and no tree ever bore blossoms quite so beautiful as those wonderful golden Paradise-flowers. And both the air and the trees are happy. Both of them whisper, “Oh thank you, thank you, Birds of Paradise.” Of course the Birds of Paradise are happy too. They are happy to have such beauty and to be able to show it to the hens, who sit hidden in the trees and bushes around, and they perhaps—the hens for whom it is all done—are happiest of all. Then it is all[Pg 41] happiness—and beauty. Beauty and happiness, those are the two things it is made up of.

There are not so many things that are made up of just those two. Try and think of some. A party, perhaps you may say (only it must be a juvenile one), or a pantomime. Well, of course, there is an enormous amount of beauty and happiness at things of that kind; but is it all beauty and happiness? Not quite all, I think. Still I am sure you would think it a very unkind thing if somebody were to break up a party before it were over, or to stop a pantomime before the last act had been performed. You would think that cruel, I am sure. And now if you were looking at those beautiful, happy Birds of Paradise at their party or pantomime (I think it is as pretty as a transformation scene), and all at once, when they were just in the middle of it, first one and then another of them were to fall down dead to the ground, till at last half of them lay there underneath the tree and the rest had flown away, would you not think that a most cruel and dreadful thing? Where would be the beauty and the happiness now? It would all be gone. Joy would have been changed into sorrow, and beauty almost into ugliness—for a dead bird is almost ugly compared to a beautiful, living one. And life would have been changed into death—yes, and such life, the life of happy, lovely birds, of[Pg 42] Birds of Paradise. And I think that if you were there and saw that happen—saw those beautiful birds fall down dead—murdered—all of a sudden—you would be sorry and angry too, and you would say that only a demon could have done so wicked a thing.

You would be right if you were to say so. It could only be a demon—that same little demon that I told you about who sang a charm to send the Goddess of Pity to sleep and then froze the hearts of the women with his bad, wicked powder. That wretched little demon who wears the magic suit of clothes, which makes him seem all that he ought to be, is always killing the poor Birds of Paradise, just when they are feeling so happy and looking so beautiful. He does not do it himself (any more than the women), for, as he could not be in more than one place at a time, he would not be able to kill a sufficient number to satisfy him, and besides he has a great many other things of the same kind, but more important, to do. So he makes his servants do it. That has always been his plan. He has servants all over the world, and you must not think that they are as bad as himself, for that is not the case at all. They are not bad, but enchanted, so that they do all sorts of bad things without having any idea that they are bad. In fact they generally think that they are the finest things in the world. The demon has all sorts of[Pg 43] little bottles with different kinds of powders in them, one for every kind of servant that he wants. In his little private workshop they all stand in rows upon a shelf and every one has a different label on it, so that he knows which to take up in a minute. One is labelled “Glory,” and has a powder in it of all sorts of different colours, scarlet, blue, green, white, and a little of it dirty yellow. The man on whom a grain of this powder falls will always be wanting to kill people, and the more he kills the better man he will think himself, and so, too, will other people think him. You may imagine what a lot of work the demon can get out of a servant like that. Another one is labelled “Justice,” and whoever the powder in that falls on will go through life always saying what he doesn't believe, and trying to make other people believe it. Others are labelled “Patriotism,” “Duty,” “Culture,” “Refinement,” “Taste,” “Sensibility,” and so on (all which words your mother will explain to you). The demon chooses them according to the kind of thing he wants done, and all on whom any of the powders inside the bottles fall become his servants in different ways—very grand ways, too, they are often thought—and go on serving him and thinking well of themselves, and being held always in great honour and respect, all their lives.

Now you must not, of course, think that these[Pg 44] bottles really contain the things that are written on their labels. No, indeed, they are false labels, for, you see, these bottles stand in the window where people can see them, the demon does not keep them in his pocket like those other two I told you of. So when people see them they think that they have good powders instead of bad ones inside them, and when the stoppers are taken out the powders fly into their eyes, and they are blinded and never know the difference. Almost every one is blinded, for the demon just stands at the window of his workshop and blows his powders through the world. It is not necessary for him to walk up and down in it sprinkling them about. That would be a long, tedious way of doing things. He just blows them, and he need never be afraid of blowing too much away, for his bottles are magic bottles and always full. Outside his window there is always a great crowd looking at the bottles and admiring them, whilst the demon stands there in his magic suit of clothes, and seems to every one to be just what he ought to be.

They say that somewhere else in the world there is a very beautiful house with a radiant angel inside it, and that there, in vases of crystal and diamond—or something like crystal and diamond, but very much more beautiful—are the real things which the demon only pretends to have in his ugly little bottles. Any[Pg 45] one has only to step in and ask for them, and the angel will open the vase and shed the essence that is inside it into his very heart. But—is it not funny?—hardly anybody ever goes into that house, and the few who do cannot persuade others to follow them. I will tell you why this is. The beautiful house does not look like a beautiful house at all to most people, and the angel of light who sits in the open doorway seems to them to be only a shabbily dressed, unfashionable sort of person. Nobody sees his wings, or, if they do, they think wings are vulgar and out of date. It is the demon who is to blame for this. He has had time to blow his magic powders all about the world, and they have blinded people's eyes and made what is really beautiful seem mean and ugly to them—for the demon's powders can blind the eyes as well as freeze the heart. But the little workshop of the demon, which is really as mean and wretched a place as you could find, that people think glorious and beautiful, and his ugly bottles are to them as vases of crystal and diamond. So they crowd about the demon's workshop, thinking it to be the angel's house, and into the angel's house they never go, for they think a demon—or at least an unfashionably dressed person with wings—which are out of date—lives there.

Now, it is one of those bottles with the false labels which the demon takes when he wants one of his[Pg 46] servants in that part of the world to kill the Great Bird of Paradise; for I don't think the men in those countries would much mind what the women said to them. I cannot tell you which bottle it is, but it is none of those that I have told you about. The label upon it is not nearly such a grand one, and the powder is of a much coarser grain, for the man that the demon is going to blow it at is only a poor savage, who is black and nearly naked, and who is not able to serve him in such important ways as are people of a lighter colour and less scantily dressed. He is only fit to do little odd jobs now and again, and his wages are very low in consequence. Even what he gets he is often not allowed to keep, for the demon's upper servants take them away from him, and he is not strong enough to resist. One of his odd jobs is killing the poor Great Birds of Paradise, and now I will tell you how he does it. Only you must not be angry with him, or even with the other people whose servant he thinks he is, though they are all of them really the servants of one master, that wretched little demon in the magic suit of clothes, which makes him seem nice to everybody, although he is so nasty. It is he you must be angry with, for it is he who does all the mischief, in the way I have told you. He gets people into his power; but, if you do as I tell you, perhaps you will be able to save them from him,[Pg 47] and to save the poor, beautiful Birds of Paradise, as well as other beautiful birds, from being killed and killed until they are all dead. Think what a lot of good you will have done, then, to have kept such beauty safe in the world, when it might have been lost out of it for ever. Yes, and you will have done more good than that even, for you will have helped to wake up the Goddess of Pity, and when once she is awake there will be so much for her to do—for, ah! she has been asleep so long.

But, now, listen. I have told you that the man who kills the Great Bird of Paradise is black and naked and a savage. But he is not a negro, although he is rather like one. His hair is something like a negro's hair, but there is much more of it. In fact it is quite a mop, and he is very proud of it. He is a Papuan, and the islands that he lives in are called the Papuan Islands, and are a very long way from Africa, which is where the negroes live. He is a tall, fine-looking man, with a beautiful figure, and he looks very much better naked than he would do if he were dressed. And when I said that he was black, this was not quite true, because he is really brown, but it is such a very dark brown that it looks black, and when a man is such a very dark brown that he looks black, then people will call him a black man, so that is what we will call this Papuan. Now, this[Pg 48] black man is very quick and active—which is what most savages are—and he can climb trees almost as well as a monkey. When he finds one of those trees where the Great Birds of Paradise have their parties, their “Sacalelies” (that is what he calls them, it is a word that means a dancing-party), he climbs up into it early in the morning, before it is daylight, and waits for them to come. It does not matter how tall the tree is (and this kind of tree is very tall), or how dark it may be, this naked Papuan savage climbs up it quite easily and without slipping, just like a monkey. He takes up with him some leafy branches of another tree, and with these he makes a little screen to sit under, so that the Birds of Paradise shall not see him. Besides this, he takes his bow and arrows to shoot the poor birds with, for he does not use a gun, which would make too much noise, and, besides, the shot would hurt the beautiful plumage. The arrows do not hurt the plumage as the shot would, because at the end of each one there is a piece of wood, shaped something like an acorn, but as large as a teacup, and the large end of it makes what would be the point of an ordinary arrow. When the poor birds are hit with that great, smooth piece of wood they are killed, because it hits them so hard, but their plumage is not hurt at all, for nothing has gone into the skin, or torn the feathers.

So the naked black man waits behind his screen for the Great Birds of Paradise to come, and as soon as they come and begin to spread their plumes, he shoots first one and then another of them with his great wooden arrows, and they fall down dead underneath the tree. And, do you know, they are so occupied in showing off their beautiful plumes, and so happy and excited as they spread them out and look through them, or fly like little feathery cascades from branch to branch, that it is not till quite a number of them have been killed (for the black savage does not often miss his aim) that the others take fright and fly away. Then the black man climbs down from the tree and picks up the poor, beautiful, dead birds and takes them to another man who is yellow and not quite so naked as he is, who gives him something for them, but not so much as he ought to. The yellow man cheats the black man, and, when he has cheated him, he takes the skins to a white man, who is quite dressed and civilised, and sells them to him, and the white man cheats him a good deal more than he has cheated the black man—for, of course, the white man is the cleverest of the three. (You see there are yellow men in those countries—called Malays—as well as black men, and a good many white men go there as well.) Then the white man puts all the beautiful skins that he has bought[Pg 52] from the yellow man, as well as a great many others which have been brought to him from all the country and from all the islands round about, into one of those large kinds of boxes called “crates,” that I have told you about, and it is put on board a ship where there are a great many others of the same kind, all full of the skins and feathers of beautiful birds that have been killed. And the ship sails to England, and then up the Thames to London, where the crates are taken out and put into great vans and driven away to the great ugly warehouses to be unpacked and laid on the floor there in a heap, all as I have told you. You know what happens to them then.

And now I will tell you something funny that I daresay you would never have thought of, but which is quite true all the same. That great heap of brightly coloured feathers lying on the floor, to make which hundreds of thousands of the most beautiful birds in the world have been killed, and hundreds of hundreds of thousands of their young ones that would have grown up beautiful, too, have been starved to death in the nest—that great big heap of the loveliest plumage is not so lovely, not nearly so beautiful as one living thrush or one living blackbird or one living swallow or one living robin-redbreast. That is the difference between life and death. A live Bird of Paradise is hundreds[Pg 53] of times more beautiful than a live blackbird or thrush or swallow or robin-redbreast, but when it is dead it is not so beautiful as they are. Its feathers are more beautiful, still, of course, but where are the waving feathers, the floating plumes, the bright eyes, the quick, graceful movements, and the flight—the glorious flight—of a bird. They are gone, they are gone for ever, and, in their place, there is only stiffness and deadness and dustiness. Oh never, never wish to see a dead Bird of Paradise in a hat, when you can see a living thrush or blackbird on the lawn of your garden, or a living swallow flying over it. And even if you can never see a living Bird of Paradise—as I daresay you never will be able to—what then?—what then? You cannot see everything, but have you not got an imagination (your mother, who has got one, will tell you what it is), and is it not better to imagine a beautiful bird flying about in life and loveliness than to see it dead? And the people who have these hats with the Birds of Paradise, or with other beautiful birds, sewn into them, how much do you think they really care about them? Do they ever look at them after they have once bought them? Oh no, they never do. Sometimes they look in the glass with the hat on—yes—but then it is only to see themselves in the hat, not the hat.

So now you know what kind of birds the Birds of[Pg 54] Paradise are, and how very beautiful they are, and you know how gloriously beautiful the Great Bird of Paradise is, and how it is killed and not allowed to live and be happy, just because it is so beautiful. But now these Great Birds of Paradise live only in some quite small islands and just in one part of one large one, and although there may be a good many of them where they do live, yet if they are always being killed in that way, very soon there will be no more of them left. Then there will be no more Great Birds of Paradise in the world—for they do not live outside those islands—and when they are once gone they can never, never come again.

But do you not think that it would be a dreadful thing if such a bird as this—this beautiful Great Bird of Paradise that I have told you about—were to be killed and killed until it was not in the world any more? Of course you think it would be a dreadful thing, and I am sure that you would prevent it if you could. And you can prevent it—now—yes, now—and in the easiest way possible. All you have to do—only you must do it directly—is to put your arms round your mother's neck and make her promise never, never to wear a hat with the feathers of a Great Bird of Paradise in it. Of course she will promise, if you ask her in that way, and keep on, and when she once has promised you must not let her[Pg 55] forget it. You must remind her of it from time to time (“Remember, mother, you promised”), and, especially, when you hear her talking about getting a new hat. And when you have made her promise about herself, then you must make her promise never to let you wear a hat of the sort (of course when you are grown-up and buy your own hats you never will), or your sisters either. And if you have a sister very much older than yourself who buys her own hats, then you can make her promise too. Perhaps that will be less easy, but she will do it in time if you tease her enough about it and want her to read the book. And then if you can get any other lady to promise, well, the more who do, the better chance there will be for the beautiful Great Bird of Paradise. Only you must make your mother promise first—that is the chief thing—and, to do it, you must tell her all about the wicked little demon, with his powders and his charm to send the Goddess of Pity to sleep. So now go to your mother, go at once, do not wait, or, if your mother is out anywhere, you must only wait till she comes home again.

CHAPTER IV

The Red Bird of Paradise

Then there is another very beautiful Bird of Paradise which is called the Red Bird of Paradise. It is no use trying to find out whether he or the one I have just been telling you about is the most beautiful, because if somebody were to think that one were, somebody else would be sure to have a different opinion. But now I will tell you what this Red Bird of Paradise is like, and then you will know how beautiful to think him. You know those lovely plumes that I told you about, that the Great Bird of Paradise has growing from both his sides, under the wings, and how he lifts up his wings and shoots them right up into the air, so that they fall all over him, like two most beautiful fountains that meet in the air and mingle their waters together. Now the Red Bird of Paradise has those plumes—those feather-fountains—too, and he can shoot them up into the air and let them fall all over him, and look out from amongst them as they bend and wave, and think[Pg 57] “How lovely I am!” just the same as the Great Bird of Paradise can. They are not so long, it is true, but then they are very thick, and of a most glorious crimson colour—such a colour as you see, sometimes, in the western sky, when the sun is flushing it, just before he sinks down for the night. People talk about a sky like that and call it a glorious sunset when they see it in Switzerland. One can see it here, too, if one likes, but it is not usual to talk about it or even to look at it, unless one is in Switzerland (your mother will tell you the reason of this). Fancy a bird that looks out of a crimson sunset of feathers—crimson, but with beautiful white tips to them! Crimson and white, that is almost more splendid than orange-gold and mauvy-brown; unless you like orange-gold and mauvy-brown better—it is all a matter of taste.

But there is another thing that the Red Bird of Paradise has, which the Great Bird of Paradise has not got at all. He has two little crests of feathers—beautiful metallic green feathers—on his forehead. Just fancy! Not one crest, merely, but two. One talks about a feather in one's cap (which, of course, a bird may have without its being wrong); but what is a feather in one's cap compared to two crests of feathers on one's forehead? And such crests! And, besides his crimson sunset plumes with their white tips and the two little lovely green crests on his forehead, this bird has two[Pg 58] wonderful feathers in his tail; they are not feathers at all, really, that is to say, the soft part of them on each side of the quill, which we call the web, is gone, and there is only the quill left, but it is such a funny sort of quill that you would never think it was one. It is flat and smooth and shiny, and quite a quarter of an inch wide. In fact it looks like a ribbon, a beautiful, black, glossy ribbon, twenty-two inches (which is almost two feet) long.

These two wonderful ribbons—I told you there were two—hang down in graceful curves as the bird sits on the branch of a tree, first a curve out and then in and then out again, just at the tips, so that the two together make quite a pretty figure. Of course, when there is any wind at all, they float gracefully about and look very pretty indeed, and when the Red Bird of Paradise flies, his two wonderful ribbons float in the air behind him, just as if he had been into a linen-draper's shop and bought something, and flown out again with it, in his tail. And yet, to make these two pretty ribbons—which are feathers, really, though they do not look like them—the soft part of the feather, which is usually the pretty part, has been taken away, and only the quill, which is usually almost ugly by comparison, has been left. And yet they are so handsome. That is because Dame Nature is such a wonderful workwoman. She can[Pg 59] make almost anything she tries to, out of any kind of material.

Now, I must tell you that the Great Bird of Paradise has two funny feathers like this in his tail too—feathers, I mean, without webs to them—only his ones have just a little web at the beginning and, again, at the very tips; all the part in between has none at all. These funny feathers of the Great Bird of Paradise are even longer than those of the red one, for they are from twenty-four to thirty-four inches long, and thirty-four inches, you know, is almost three feet. But then they are thin, not broad like ribbons, and the plumes of the Great Bird of Paradise are so long that they are a good deal hidden by them, and, sometimes, hardly noticed amongst such a lot of finery. I think that must be why, when I was describing the Great Bird of Paradise to you, I forgot all about them, which, of course, I ought not to have done. But we all of us make mistakes sometimes, people who write books just as much as people who only read them, although, of course, people who write books ought to be more careful.

In fact, a great many of the Birds of Paradise have these funny feathers, and some of them have more than two. If you look for page 77 you will see a picture of the King Bird of Paradise, who has two beauties. He is not one of the birds that I talk[Pg 60] about in this book—there was no room for him—but that does not matter. He sent me his picture, and it will show you what these “funny feathers” are like. There is a Bird of Paradise that has twelve of them, but now I must finish talking about the Red Bird of Paradise. I have told you about the glorious crimson plumes that he has on his sides, and the two funny feathers, like ribbons, in his tail, and the double crest of beautiful emerald-green feathers on his forehead, but, of course, there are other parts of him besides these, and I must tell you what they are like too. His head and his back and his shoulders are yellow, as they are in the Great Bird of Paradise, but it is a deeper and richer yellow, not the light, straw-coloured yellow which he has and which is very pretty too (I am sure we should never agree as to which is the prettier of these two birds). His throat, too, is of a deep metallic green colour—you know what metallic means now—but those lovely green feathers go farther up, in fact right over the front part of the head—which is his forehead—so as to make those two sweet little crests which he has, and which help to make him such a very handsome bird. The rest of his wings and body, and his tail, except the two ribbons in it, are brown—a nice, handsome, rich, coffee-brown—his legs are blue, and his beak is a fine[Pg 61] gamboge-yellow. Ah, there is a beautiful bird indeed! What would you say if you were to see a bird that was yellow and green with crimson-sunset plumes, and with two long glossy ribbons in his tail, and two beautiful crests on his forehead, with blue legs and a gamboge bill, flying from tree to tree in your garden?

Ah, yes, if you were to see him like that he would be more beautiful than any bird that has ever been in your garden or that has ever flown about in the woods or fields all over England—for he would be alive then—alive and happy. But if you were to see him dead he would not be so beautiful as any of the birds in your garden—no, not even as the sparrows (which is saying a good deal), for the beauty of life would be gone out of him, and that is the greatest beauty of all. And even if he were in a cage—unless it were a very large one with a great many trees in it—he would hardly look as beautiful as a lark does when he sails and sings in the sky.