Early Western Travels

1748-1846

Volume XXVI

Early Western Travels

1748-1846

A Series of Annotated Reprints of some of the best

and rarest contemporary volumes of travel,

descriptive of the Aborigines and Social

and Economic Conditions in the Middle

and Far West, during the Period

of Early American Settlement

Edited with Notes, Introductions, Index, etc., by

Reuben Gold Thwaites, LL.D.

Editor of "The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents," "Original

Journals of the Lewis and Clark Expedition," "Hennepin's

New Discovery," etc.

Volume XXVI

Part I of Flagg's The Far West, 1836-1837

Cleveland, Ohio

The Arthur H. Clark Company

1906

Copyright 1906, by

THE ARTHUR H. CLARK COMPANY

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

The Lakeside Press

R. R. DONNELLEY & SONS COMPANY

CHICAGO

CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXVI

| Preface to Volumes XXVI and XXVII. The Editor | 9 |

| The Far West: or, A Tour beyond the Mountains. Embracing Outlines of Western Life and Scenery; Sketches of the Prairies, Rivers, Ancient Mounds, Early Settlements of the French, etc. etc. (The first thirty-two chapters, being all of Vol. I of original, and pp. 1-126 of Vol. II.) Edmund Flagg. | |

| Copyright Notice | 26 |

| Author's Dedication | 27 |

| Author's Preface | 29 |

| Author's Table of Contents | 33 |

| Text (chapters i-xxxii; the remainder appearing in our volume xxvii) | 43 |

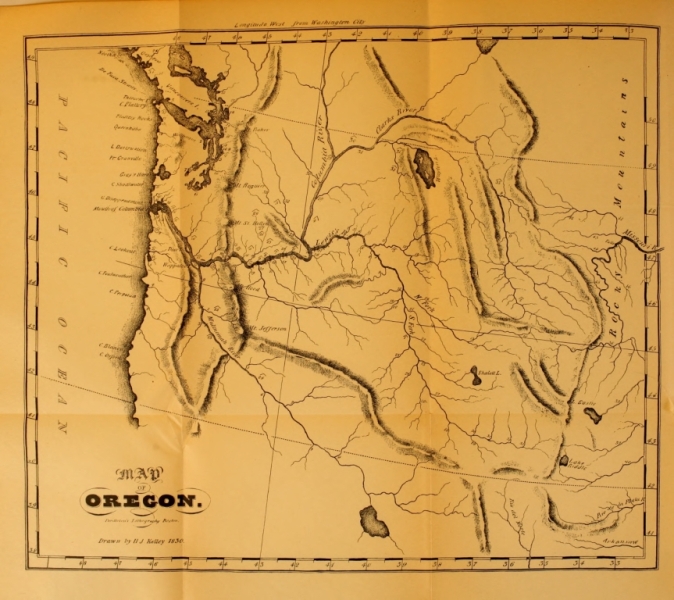

ILLUSTRATIONS TO VOLUME XXVI

| Map of Oregon; drawn by H. J. Kelley, 1830 | 24 |

| Facsimile of title-page to Vol. I of Flagg's The Far West | 25 |

PREFACE TO VOLUMES XXVI-XXVII

These two volumes are devoted to reprints of Edmund Flagg's The Far West (New York, 1838), and Father Pierre Jean de Smet's Letters and Sketches, with a Narrative of a Year's Residence among the Indian Tribes of the Rocky Mountains (Philadelphia, 1843). Flagg's two-volume work occupies all of our volume xxvi and the first part of volume xxvii, the remaining portion of the latter being given to De Smet's book.

Edmund Flagg was prominent among early American prose writers, and also ranked high among our minor poets. A descendant of the Thomas Flagg who came to Boston from England, in 1637, Edmund was born November 24, 1815, at Wescasset, Maine. Being graduated with distinction from Bowdoin College in 1835, in the same year he went with his mother and sister Lucy to Louisville, Kentucky. Here, in a private school, he taught the classics to a group of boys, and contributed articles to the Louisville Journal, a paper with which he was intermittently connected, either as editorial writer or correspondent, until 1861.

The summer and autumn of 1836 found Flagg travelling in Missouri and Illinois, and writing for the Journal the letters which were later revised and enlarged to form The Far West, herein reprinted. Tarrying at St. Louis in the autumn of 1836, our author began the study of law, and the following year was admitted to the bar; but in 1838 he returned to newspaper life, taking charge for a time of the St. Louis Commercial Bulletin. During the winter of 1838-39 he assisted George D. Prentice, founder of the[Pg 10] Louisville Journal, in the work of editing the Louisville Literary News Letter. Finding, however, that newspaper work overtaxed his health, Flagg next accepted an invitation to enter the law office of Sergeant S. Prentiss at Vicksburg, Mississippi, where in addition to his legal duties he found time to edit the Vicksburg Whig. Having been wounded in a duel with James Hagan of the Sentinel in that city, Flagg returned to the less excitable North and undertook editorial duties upon the Gazette at Marietta, Ohio (1842-43), and later (1844-45) upon the St. Louis Evening Gazette. He also served as official reporter of the Missouri state constitutional convention the following year, and published a volume of its debates; subsequently (until 1849) acting as a court reporter in St. Louis.

The three succeeding years were spent abroad; first as secretary to Edward A. Hannegan, United States minister to Berlin, and later as consul at Venice. In February, 1852, he returned to America, and during the presidential campaign of that year edited a Democratic journal at St. Louis, known as the Daily Times. Later, as a reward for political service, he was made superintendent of statistics in the department of state, at Washington—a bureau having special charge of commercial relations. Here he was especially concerned with the compilation of reports on immigration and the cotton and tobacco trade, and published a Report on Commercial Relations of the United States with all Foreign Nations (4 vols., Washington, 1858). Through these reports, particularly the last named, Flagg's name became familiar to merchants in both the United States and Europe. From 1857 to 1860 he was Washington correspondent for several Western newspapers, and from 1861 to 1870 served as librarian of copyrights in the department of the interior. Having in 1862 married Kate Adeline, daughter of Sidney S. Gallaher, of Virginia, he moved to[Pg 11] Highland View in that state (1870), and died there November 1, 1890.

In addition to his labors in the public service and as a newspaper man, Flagg found time for higher literary work, and won considerable distinction in that field. His first book, The Far West, although somewhat stilted in style, possesses considerable literary merit. Encouraged by the success of his initial endeavor, he wrote the following year (1839) the Duchess of Ferrara and Beatrice of Padua, two novels, each of which passed through at least two editions. The Howard Queen (1848) and Blanche of Artois (1850) were prize productions. De Molai (1888), says the New York Sun of the period, is "a powerful, dramatic tale which seems to catch the very spirit of the age of Philip of France. It is rare to find a story in which fact and invention are so evenly and adroitly balanced." Our author also wrote several dramas, which were staged in Louisville, Cincinnati, St. Louis, and New York; he also composed numerous poems for newspapers and magazines. His masterpiece, however, was a history dedicated to his lifelong friend and colleague, George D. Prentice, entitled The City of the Sea (2 vols., New York, 1853). This work was declared by the Knickerbocker to be "a carefully compiled, poetically-written digest of the history of the glorious old Venice—a passionate, thrilling, yet accurate and sympathetic account of the last struggle for independence." At the time of his death Flagg had in preparation a volume of reminiscences, developed from a diary kept during forty years, but this has never been published.1

"In hope of renovating the energies of a shattered constitution," we are told, Flagg started in the early part of[Pg 12] June, 1836, on a journey to what was then known as the Far West. Taking a steamboat at Louisville, he went to St. Louis by way of the Ohio and the Mississippi, and after a brief delay ascended the latter to the mouth of the Illinois, and thence on to Peoria. Prevented by low water from proceeding farther, he returned by the same route to St. Louis, whence after three weeks' stay, spent either in the sick chamber or in making short trips about the city and its environs, the traveller crossed the Mississippi and struck out on horseback across the Illinois prairies, visiting Edwardsville, Alton, Carlinsville, Hillsborough, Carlisle, Lebanon, Belleville, and the American Bottoms. In July, after recrossing the Mississippi, he visited in like manner St. Charles, Missouri, by way of Bellefontaine and Florissant; crossed the Mississippi near Portage des Sioux, and passed through the Illinois towns of Grafton, Carrollton, Manchester, Jacksonville, Springfield, across Grand Prairie to Shelbyville, Mount Vernon, Pinkneyville, and Chester, and returned to St. Louis by way of the old French settlements of Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, and Cahokia.

During this journey Flagg wrote for the Louisville Journal, as already stated, a series of letters describing the country through which he travelled. Hastily thrown together from the pages of his note book, this correspondence appeared anonymously under the title, "Sketches of a Traveller." They were, however, soon attributed to Flagg, and two years later were collected by the author and published in two small volumes by Harper and Brothers (New York, 1838), as The Far West. These volumes are in many respects the best description of the Middle West that had appeared up to the time they were written. Roughly following the journals of Michaux, Harris, and Cuming by forty, thirty, and twenty years respectively, Flagg skillfully shows the remarkable growth and development of the Western coun[Pg 13]try. His descriptions of the Ohio, Mississippi, and Illinois rivers are still among the best in print, particularly from the artistic standpoint. His account of the steamboat traffic is valuable for the history of navigation on the Western rivers, and shows vividly the obstacles which still confronted merchants of that time. Chapters xi, xii, and xiii, dealing with St. Louis and its immediate vicinity, are the most detailed in our series, while the descriptions of St. Charles and the Illinois towns through which Flagg passed, are excellent.

The modern reader cannot but wish that Flagg had devoted less space to his youthful philosophizing, but the atmosphere is at least wholesome. Unlike Harris, whose criticism of Western society was keen and acrid, Flagg was a man of broad sympathies, possessing an insight into human nature remarkable for so youthful a writer—for he was but twenty years of age at the time of his travels, and twenty-two when the book was published. Although mildly reproving the old French settlers for their lack of enterprise, he fully appreciates their domestic virtues, and gives a faithful picture of these pleasure-loving, contented, unprogressive people. His description of the once thriving villages of Kaskaskia, Prairie du Rocher, and Cahokia, are valuable historically, as showing the decay settling upon the French civilization after a few years of American occupation. Our author's interview with the Mormon convert, his conversations with early French and American settlers, his accounts of political meetings, his anecdotes illustrating Western curiosity, and particularly his carefully-recounted local traditions, throw much light on the beliefs, manners, and customs of the Western people of his time. The Far West is thus not only a graphic and often forceful description of the interesting region through which the author travelled, but a sympathetic synopsis of its local annals, affording much varied[Pg 14] information not otherwise obtainable. The present reprint, with annotations that seek to correct its errors, will, we think, prove welcome in our series.

In the Letters and Sketches of Father de Smet, we reprint another Western classic, related to the volumes of Flagg by their common terminus of travel at St. Louis.

No more interesting or picturesque episode has occurred in the history of Christian missions in the New World, than the famous visit made in the autumn of 1831 to General William Clark at St. Louis by the Flathead chiefs seeking religious instruction for their people. Vigorously exploited in the denominational papers of the East, this delegation aroused a sentiment that led to the founding of Protestant missions in Oregon and western Idaho, and incidentally to the solution of the Oregon question. But in point of fact, the Flathead deputation was sent to secure a Catholic missionary; and not merely one but four such embassies embarked for St. Louis before the great desideratum, a "black robe" priest, could be secured for ministration to this far-distant tribe. Employed in the Columbian fur-trade were a number of Christian Iroquois from Canada, who had been carefully trained at St. Regis and Caughnawaga in all the observances of the Roman Catholic church. Upon the Pacific waterways and in the fastnesses of the Rockies, these Iroquois taught their fellow Indians the ordinances of the church and the commands of the white man's Great Spirit. John Wyeth (see our volume xxi) testifies to the honesty and humanity of the Flathead tribe: "they do not lie, steal, nor rob any one, unless when driven too near to starvation." He also testifies that they "appear to keep the Sabbath;" and that their word is "as good as the Bible." These were the neophytes who craved instruction, and to whom was assigned that remarkable Jesuit missionary, Father Jean Pierre de Smet.[Pg 15]

Born in Belgium in 1801, young De Smet was educated in a religious school at Malines. When twenty years of age he responded to an appeal to cross the Atlantic and carry the gospel to the red men of the Western continent. Arrived in Philadelphia (1821), the young Belgian was astonished to see a well-built town, travelled roads, cultivated farms, and other appurtenances of civilization; he had expected only a wilderness and savages. Two years were spent in the Jesuit novitiate in Maryland, before the zealous youth saw any traces of frontier life. Then the youthful novice was removed to Florissant, Missouri, not far from St. Louis, where the making of a log-cabin and the breaking of fresh soil furnished a mild foretaste of his future career. Still more years elapsed before the cherished project of missionary labor could be realized. In 1829 St. Louis University was founded, and herein the young priest, who had been ordained in 1827, was employed upon the instructional force. Later years (1833-37) were spent in Europe, while recruiting his health and securing supplies for the infant university. It was not until 1838 that the first missionary enterprise was undertaken by Father de Smet, when a chapel for the Potawatomi was built on the site of the modern Council Bluffs. There, in 1839, the fourth Flathead deputation rested after the long journey from their Rocky Mountain home; and at the earnest solicitation of the young missioner, he was in the spring of 1840, detailed by his superior to ascertain and report upon the prospects of a mission to the mountain Indians.

Of the two tribesmen who had come down to St. Louis, Pierre the Left-handed (Gaucher) was sent back to his people with news of the success of the embassy, while his colleague Ignace was detained to serve as guide to the adventurous Jesuit who in April, 1840, set forth for the Flathead country with the annual fur-trade caravan. The[Pg 16] route traversed was the well-known Oregon Trail as far as the Green River rendezvous; there the father was rejoiced to meet a deputation of ten Flatheads, sent to escort him to their habitat, and at Prairie de la Messe was celebrated for them the first mass in the Western mountains. The trail led them on through Jackson's and Pierre's Holes; and in the latter valley the waiting tribesmen to the number of sixteen hundred had collected, and received the "black robe" as a messenger from Heaven. Chants and prayers were heard on every side; "in a fortnight," reports the delighted missionary, "all knew their prayers." After two months spent among his "dear Flatheads," wandering with them across the divide, and encamping for some time at the Three Forks of the Missouri—where nearly forty years before Lewis and Clark first encountered the Western Indians—De Smet took leave of his neophytes. Protected by a strong guard through the hostile Blackfeet country, he arrived at last at the fur-trade post of Fort Union at the junction of the Missouri and the Yellowstone. Descending thence to St. Louis he arrived there on the last day of December, 1840.

The remainder of the winter was occupied in preparations for a new journey, and in securing men and supplies for the equipment of the far-away mission begun under such favorable auspices. Once more the father departed from Westport—this time in May, 1841. The little company consisted, besides himself, of two other priests and three lay brothers, all of the latter being skilled mechanics. Among the members of the caravan were a number of California pioneers, one of whom has thus related his impressions of the young missionary: "He was genial, of fine presence, and one of the saintliest men I have ever known, and I cannot wonder that the Indians were made to believe him divinely protected. He was a man of great kindness and[Pg 17] great affability under all circumstances; nothing seemed to disturb his temper."2

Father de Smet's letters describe in detail the scenery and incidents of the route from the eastern border of Kansas to Fort Hall, in Idaho, where the British factor received the travellers with abounding hospitality. Here some of the Flatheads were in waiting to convey the missionaries to the tribe, the chiefs of which met them in Beaver Head Valley, Montana, and testified their welcome with dignified simplicity. Passing over to the waters of the Columbia, they founded the mission of St. Mary upon the first Sunday in October, in the beautiful Bitter Root valley at the site of the later Fort Owen. Thence Father de Smet made a rapid journey in search of provisions to Fort Colville, on the upper Columbia, but was again at his mission stockade before the close of the year. In April a longer journey was projected, as far as Fort Vancouver, on the lower Columbia, where Dr. McLoughlin, the British factor, received the good priest with that cordial greeting for which he was already famous. During this journey the father narrowly escaped drowning in the turbulent rapids of the Columbia, where five of his boatmen perished. Returned to St. Mary's, the prospects for a harvest of souls both among the Flatheads and the neighboring tribes appeared so promising that the missionary determined to seek re-enforcement and further aid in Europe. Thereupon he left his companions in charge of the "new Paraguay" of his hopes, and once more undertook the long and adventurous journey to the settlements, this time by way of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, arriving at St. Louis the last of October, 1842. At this point the journeys detailed in the volume here reprinted come to an end. The later career of Father de Smet and his subsequent[Pg 18] journeyings will be detailed in the preface to volumes xxviii and xxix, in the latter of which will appear his Oregon Missions.

Father de Smet's writings on missionary subjects ended only with his death, and were increasingly voluminous and detailed. The Letters and Sketches were his first published work, with the exception of a portion of a compilation that appeared in 1841, on the Jesuit missions of Missouri. We find therefore, in the present reprint, the vitality and enthusiasm of the young traveller relating new scenes, and the abounding joy of the successful missionary uplifting a barbaric race. The book was written with the avowed purpose of creating interest in his newly-organized work, and securing contributions therefor. The freshness of description, the wholesome simplicity of the narrative, the frank presentation of wilderness life, charm the reader, and make this book a classic of early Western exploration. Cast in the form of letters, wherein there is more or less repetition of statement, it is nevertheless evident that these have been subjected to a certain editorial revision, and that literary quality has been considered. Aside from the interest evoked by the personality of the writer, and the events of his narrative, the work throws much light upon wilderness travel, the topography and scenery of the Rocky Mountain region, and above all upon the habits and customs, modes of thought, social standards, and religious conceptions of the important tribes of the interior.

After the present series of reprints had been planned for, and announced in a detailed prospectus, there was issued from the press of Francis P. Harper of New York the important volumes edited by Major H. M. Chittenden and Alfred Talbot Richardson, entitled Life, Letters, and Travels of Father Pierre Jean de Smet, S. J., 1801-73. This publication contains much new material, derived from manu[Pg 19]script sources, which has been interwoven in chronological order with the missionary's several books; and to it all have been added an adequate biography and bibliography of De Smet. This scholarly work has been of great service to us in preparing for accurate reprint the original editions of the only two of Father de Smet's publications that fall within the chronological field of our series.

In the preparation for the press of Flagg's The Far West, the Editor has had the assistance of Clarence Cory Crawford, A. M.; in editing Father de Smet's Letters and Sketches, his assistant has been Louise Phelps Kellogg, Ph.D.

R. G. T.

Madison, Wis., April, 1906.

1 For a list of Flagg's prose and poetical writings, contributions to periodicals, and editorial works, see "Annual Report of the Librarian of Bowdoin College for the year ending June 1, 1891," in Bowdoin College Library Bulletin (Brunswick, Maine, 1895).

2 John Bidwell, "First Emigrant Train to California," in Century Magazine, new series, xix, pp. 113, 114.

Part I of Flagg's The Far West, 1836-1837

Reprint of Volume I, and chapters xxiii-xxxii of Volume II, of

original edition: New York, 1838

THE FAR WEST:

OR,

A TOUR BEYOND THE MOUNTAINS.

EMBRACING

OUTLINES OF WESTERN LIFE AND SCENERY; SKETCHES OF

THE PRAIRIES, RIVERS, ANCIENT MOUNDS, EARLY

SETTLEMENTS OF THE FRENCH, ETC., ETC.

"If thou be a severe, sour-complexioned man, then I here disallow thee to be a competent judge."—Izaak Walton.

"I pity the man who can travel from Dan to Beersheba, and cry, ''Tis all barren.'"—Sterne.

"Chacun a son stile; le mien, comme vous voyez, n'est pas laconique."—Me. de Sevigne.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

NEW-YORK:

PUBLISHED BY HARPER & BROTHERS

NO. 82 CLIFF-STREET.

1838.

[Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1838, by

Harper & Brothers,

in the Clerk's Office of the Southern District of New-York.]

To One—

AT WHOSE SOLICITATION THESE VOLUMES WERE COMMENCED,

AND WITH WHOSE ENCOURAGEMENT

THEY HAVE BEEN COMPLETED—

TO MY SISTER LUCY

ARE THEY AFFECTIONATELY INSCRIBED.

TO THE READER

Or makes a feast, more certainly invites

His judges than his friends; there's not a guest

But will find something wanting or ill dress'd."

In laying before the majesty of the public a couple of volumes like the present, it has become customary for the author to disclaim in his preface all original design of perpetrating a book, as if there were even more than the admitted quantum of sinfulness in the act. Whether or not such disavowals now-a-day receive all the credence they merit, is not for the writer to say; and whether, were the prefatory asseveration, as in the present case, diametrically opposed to what it often is, the reception would be different, is even more difficult to predict. The articles imbodied in the following volumes were, a portion of them, in their original, hasty production, designed for the press; yet the author unites in the disavowal of his predecessors of all intention at that time of perpetrating a book.

In the early summer of '36, when about starting upon a ramble over the prairies of the "Far West," in hope of renovating the energies of a shattered constitution, a request was made of the writer, by the distinguished editor of the Louisville Journal, to contribute [vi] to the columns of that periodical whatever, in the course of his pilgrimage, might be deemed of sufficient interest.1 A series of articles soon after[Pg 30] made their appearance in that paper under the title, "Sketches of a Traveller." They were, as their name purports, mere sketches from a traveller's portfeuille, hastily thrown upon paper whenever time, place, or opportunity rendered convenient; in the steamboat saloon, the inn bar-room, the log-cabin of the wilderness, or upon the venerable mound of the Western prairie. With such favour were these hasty productions received, and so extensively were they circulated, that the writer, on returning from his pilgrimage to "the shrine of health," was induced, by the solicitations of partial friends, to enter at his leisure upon the preparation for the press of a mass of MSS. of a similar character, written at the time, which had never been published; a thorough revision and enlargement of that which had appeared, united with this, it was thought, would furnish a passable volume or two upon the "Far West." Two years of residence in the West have since passed away; and the arrangement for the press of the fugitive sheets of a wanderer's sketch-book would not yet, perhaps, have been deemed of sufficient importance to warrant the necessary labour, had he not been daily reminded that his productions, whatever their merit, were already public property so far as could be the case, and at the mercy of every one who thought proper to assume paternity. "Forbearance ceased to be longer a virtue," and the result is now before the [vii] reader. But, while alluding to that aid which his labours may have rendered to others,[Pg 31] the author would not fail fully to acknowledge his own indebtedness to those distinguished writers upon the West who have preceded him. To Peck, Hall, Flint, Wetmore, and to others, his acknowledgments are due and are respectfully tendered.2

In extenuation of the circumstance that some portions[Pg 32] of these volumes have already appeared, though in a crude state, before the public, the author has but to suggest that many works, with which the present will not presume to compare, have made their debut on the unimposing pages of a periodical. Not to dwell upon the writings of Addison and Johnson, and other classics of British literature, several of Bulwer's most polished productions, the elaborate Essays of Elia, Wirt's British Spy, Hazlitt's Philosophical Reviews, Coleridge's Friend, most of the novels of Captain Marryatt and Theodore Hook, and many of the most elegant works of the day, have been prepared for the pages of a magazine.

And now, with no slight misgiving, does the author commit his firstborn bantling to the tender mercies of an impartial public. Criticism he does not deprecate, still less does he brave it; and farther than either is he from soliciting undue favour. Yet to the reader, as he grasps him by the hand in parting, would he commit his book, with the quaint injunction of a distinguished but eccentric old English writer upon an occasion somewhat similar:

"I exhort all people, gentle and simple, men, [viii] women, and children, to buy, to read, to extol these labours of mine. Let them not fear to defend every article; for I will bear them harmless. I have arguments good store, and can easily confute, either logically, theologically, or metaphysically, all those who oppose me."

E. F.

New-York, Oct., 1838.

CONTENTS

I

The Western Steamboat-landing—Western Punctuality—An Accident—Human Suffering—Desolation of Bereavement—A Contrast—Sublimity—An Ohio Freshet—View of Louisville—Early History—The Ohio Falls—Corn Island—The Last Conflict 43

II

The Early Morn—"Sleep no more!"—The Ohio—"La Belle Rivière!"—Ohio Islands—A Cluster at Sunset—"Ohio Hills"—The Emigrant's Clearing—Moonlight on the Ohio—A Sunset-scene—The Peaceful Ohio—The Gigantic Forest-trees—The Bottom-lands—Obstructions to Navigation—Classification—Removal—Dimensions of Snags—Peculiar difficulties on the Ohio—Leaning Trees—Stone Dams—A Full Survey—The Result 52

III

An Arrest—Drift-wood—Ohio Scenery—Primitive River-craft—Early Scenes on the Western Waters—The Boatmen—Life and Character—Annus Mirabilis—The Steam-engine in the West—The Freshet—The Comet—The Earthquakes—The first Steamboat—The Pinelore—The Steam-engine—Prophecy of Darwin—Results—Sublimity—Villages—A new Geology—Rivers—Islands—Forests—The Wabash and its Banks—New Harmony—Site—Settlement—Edifices—Gardens—Owen and the "Social System"—Theory and Practice—Mental Independence—Dissension—Abandonment—Shawneetown—Early History—Settlement—Advancement—Site—United States' Salines—Ancient Pottery 59

IV

Geology of the Mississippi Valley—Ohio Cliffs—The Iron Coffin—"Battery Rock"—"Rock-Inn-Cave"—Origin of Name—[x] A Visit—Outlines and Dimensions—The Indian Manito—Island opposite—The Freebooters—"The Outlaw"—The Counterfeiters—Their Fate—Ford and his Gang—Retributive Justice—"Tower Rock"—The Tradition—The Cave of Hieroglyphics—Islands—Golconda—The Cumberland—Aaron Burr's Island—Paducah—Name[Pg 34]—Ruins of Fort Massac—The Legend—Wilkinsonville—The "Grand Chain"—Caledonia—A Storm—Sunset—"The Meeting of the Waters"—Characteristics of the Rivers—"Willow Point"—The place of Meeting—Disappointment—A Utopian City—America 70

V

Darkness Visible—The "Father of Waters"—The Power of Steam—The Current—"English Island"—The Sabbath—A Blessed Appointment—Its Quietude—The New-England Emigrant—His Privations—Sorrows—Loneliness—"The Light of Home"—Cape Girardeau—Site—Settlement—Effects of the Earthquakes—A severer Shock—Staples of Trade—The Spiral Water-wheels—Their Utility—"Tyowapity Bottom"—Potter's Clay—A Manufactory—Rivière au Vase—Salines—Coal-beds—"Fountain Bluff"—The "Grand Tower"—Parapet of Limestone—Ancient Cataract—The Cliffs—Divinity of the Boatmen—The "Devil's Oven"—The "Tea-table"—Volcanic and Diluvial Action—The Torrent overcome—A Race—Breathless Interest—The Engineer—The Fireman—Last of the "Horse and Alligator" species—"Charon"—A Triumph—A Defeat 82

VI

Navigation of the Mississippi—The First Appropriation—Improvements of Capt. Shreve—Mississippi and Ohio Scenery contrasted—Alluvial Deposites—Ste. Genevieve—Origin—Site—The Haunted Ruin—The old "Common Field"—Inundation of '85—Minerals—Quarries—Sand-caves—Fountains—Salines—Indians—Ancient Remains—View of Ste. Genevieve—Landing—Outrage of a Steamer—Indignation—The Remedy—A Snag and a Scene—An Interview with "Charon"—Fort Chartres 93

[xi] VII

The Hills! the Hills!—Trosachs of Loch Katrine—Alluvial Action—Bluffs of Selma and Herculaneum—Shot-towers—Natural Curiosities—The "Cornice Cliffs"—The Merrimac—Its Riches—Ancient Lilliputian Graves—Mammoth Remains—Jefferson Barracks—Carondelet—Cahokia—U. S. Arsenal—St. Louis in the Distance—Fine View—Uproar of the Landing—The Eternal River—Character—Features—Sublimity—Statistics—The Lower Mississippi—"Bends"—"Cut-offs"—Land-slips—The Pioneer Cabin 102

VIII

"Once more upon the Waters!"—"Uncle Sam's Tooth-pullers"—Mode of eradicating a Snag—River Suburbs of North St. Louis—Spanish Fortifications—The Waterworks—The Ancient Mounds—Country Seats—The Confluence—Charlevoix's Description—A Variance—A View—The Upper Mississippi—Alton in distant View—The Penitentiary and Churches—"Pomp and Circumstance"—The City of Alton—Advantages—Objections—Improvements—Prospects—Liberality—Railroads—Alton Bluffs—"Departing Day"—The Piasa Cliffs—Moonlight Scene 113

IX

The Coleur de Rose—The Piasa—The Indian Legend—Caverns—Human Remains—The Illinois—Characteristic Features—The Canal—The Banks and Bottoms—Poisonous Exhalations—Scenes on the Illinois—The "Military Bounty Tract"—Cape au Gris—Old French Village—River Villages—Pekin—"An Unco Sight"—Genius of the Bacchanal—A "Monkey Show"—Nomenclature of Towns—The Indian Names 122

X

An Emigrant Farmer—An Enthusiast—Peoria—The Old Village and the New—Early History—Exile of the French—Fort Clarke—Indian Hostilities—The Modern Village—Site—Advantages—Prospects—Lake Pinatahwee—Fish—The Bluffs and Prairie—A Military Spectacle—The "Helen Mar"—Horrors of Steam!—A Bivouac—The Dragoon Corps—Military [xii] Courtesy—"Starved Rock"—The Legend—Remains—Shells—Intrenchments—Music—The Moonlight Serenade—A Reminiscence 132

XI

Delay—"A Horse!"—Early French Immigration in the West—The Villages of the Wilderness—St. Louis—Venerable Aspect—Site of the City—A French Village City—South St. Louis—The Old Chateaux—The Founding of the City—The Footprints in the Rock—The First House—Name of City—Decease of the Founders—Early Annals—Administration of St. Ange—The Common Field—Cession and Recession—"L'Annee du Grand Coup"—"L'Annee des Grandes Eaux"—Keel-boat Commerce—The Robbers Culbert and Magilbray—"L'Annee des Bateaux"—The First Steamboat at St. Louis—Wonder of the Indians—Opposition to Improvement—Plan of St. Louis—A View—Spanish Fortifications—The Ancient Mounds—Position—Number—Magnitude[Pg 36]—Outlines—Arrangement—Character—Neglect—Moral Interest—Origin—The Argument of Analogy 142

XII

View from the "Big Mound" at St. Louis—The Sand-bar—The Remedy—The "Floating Dry-dock"—The Western Suburbs—Country Seats—Game—Lakes—Public Edifices—Catholic Religion—"Cathedral of St. Luke"—Site—Dimensions—Peal of Bells—Porch—The Interior—Columns—Window Transparencies—The Effect—The Sanctuary—Galleries—Altar-piece—Altar and Tabernacle—Chapels—Paintings—Lower Chapel—St. Louis University—Medical School—The Chapel—Paintings—Library—Ponderous Volumes—Philosophical Apparatus—The Pupils 160

XIII

An Excursion of Pleasure—A fine Afternoon—Our Party—The Bridal Pair—South St. Louis—Advantages for Manufactures—Quarries—Farmhouses—The "Eagle Powder-works"—Explosion—The Bride—A Steeple-chase—A Descent—The Arsenal—Grounds—Structures—Esplanade—Ordnance—Warlike Aspect—Carondelet—Sleepy-Hollow—River-reach [xiii]—Time Departed—Inhabitants—Structures—Gardens—Orchards—Cabarets—The Catholic Church—Altar-piece—Paintings—Missal—Crucifix—Evergreens—Deaf and Dumb Asylum—Distrust of Villagers—Jefferson Barracks—Site—Extent—Buildings—View from the Terrace—The Burial Grounds—The Cholera—Design of the Barracks—Corps de Reserve—A remarkable Cavern—Our Guide—Situation of Cave—Entrance—Exploration—Grotesque Shapes—A Foot—Boat—Coffin in Stone—The Bats—Rivière des Pères—An Ancient Cemetery—Antiquities—The Jesuit Settlers—Sulphur Spring—A Cavern—A Ruin 170

XIV

City and Country at Midsummer—Cosmorama of St. Louis—The American Bottom—Cahokia Creek—A Pecan Grove—The Ancient Mounds—First Group—Number—Resemblance—Magnitude—Outline—Railroad to the Bluffs—Pittsburg—The Prairie—Landscape—The "Cantine Mounds"—"Monk Hill"—First Impressions—Origin—The Argument—Workmanship of Man—Reflections suggested—Our Memory—The Craving of the Heart—The Pyramid-builders—The Mound-builders—A hopeless Aspiration—"Keep the Soul embalmed" 180

XV

The Antiquity of Monk Mound—Primitive Magnitude—Fortifications of the Revolution—The Ancient Population—Two Cities—Design of the Mounds—The "Cantine Mounds"—Number—Size—Position—Outline—Features of Monk Mound—View from the Summit—Prairie—Lakes—Groves—Bluffs—Cantine Creek—St. Louis in distance—Neighbouring Earth-heaps—The Well—Interior of the Mound—The Monastery of La Trappe—Abbé Armand Rance—The Vows—A Quotation—Reign of Terror—Immigration of the Trappists—Their Buildings—Their Discipline—Diet—Health—Skill—Asylum Seminary—Worldly Charity—Palliation—A strange Spectacle 187

[xiv] XVI

Edwardsville—Site and Buildings—Land Mania—A "Down-east" Incident—Human Nature—The first Land Speculator—Castor-oil Manufacture—Outlines of Edwardsville—Collinsville—Route to Alton—Sultriness—The Alton Bluffs—A Panorama—Earth-heaps—Indian Graves—Upper Alton—Shurtliff College—Baptized Intelligence—Knowledge not Conservative—Greece—Rome—France—England—The Remedy 197

XVII

The Traveller's Whereabout—The Prairie in a Mist—Sense of Loneliness—The Backwoods Farmhouse—Structure—Outline—Western Roads—A New-England Emigrant—The "Barrens"—Origin of Name—Soil—The "Sink-holes"—The Springs—Similar in Missouri and Florida—"Fount of Rejuvenescence"—Ponce de Leon—"Sappho's Fount"—The Prairies—First View—The Grass—Flowers—Island-groves—A Contrast—Prairie-farms—A Buck and Doe—A Kentucky Pioneer—Events of Fifty Years—The "Order Tramontane"—Expedition of Gov. Spotswood—The Change—A Thunderstorm on the Prairies—"A Sharer in the Tempest"—Discretionary Valour 207

XVIII

Morning after the Storm—The Landscape—The sprinkled Groves—Nature in unison with the Heart—The Impress of Design—Contemplation of grand Objects elevates—Nature and the Savage—Nature and Nature's God—Earth praises God—Indifference and Ingratitude of Man—"All is very Good"—Influence of Scenery upon Character—The Swiss Mountaineer—Bold Scenery most Impressive—Freedom among the Alps—Caucasus—Himmalaya—Something to [Pg 38]Love—Carlinville—"Grand Menagerie"—A Scene—The Soil—The Inn—Macoupin Creek—Origin of Name—A Vegetable—An Indian Luxury—Carlinville—Its Advantages and Prospects—A "Fourth-of-July" Oration—The thronging Multitudes—The huge Cart—A Thunder-storm—A Log-cabin—Women and Children—Outlines of the Cabin—The Roof and Floor—The Furniture and Dinner-pot—A Choice of Evils—The Pathless Prairie 219

[xv] XIX

Ponce de Leon—The Fount of Youth—The "Land of Flowers"—Ferdinand de Soto—"El Padre de los Aguas"—The Canadian Voyageurs—"La Belle Rivière"—Sieur La Salle—"A Terrestrial Paradise"—Daniel Boone—"Old Kentucke"—"The Pilgrim from the North"—Sabbath Morning—The Landscape—The Grass and Prairie-flower—Nature at Rest—Sabbath on the Prairie—Alluvial Aspect of the Prairies—The Soil—Lakes—Fish—The Annual Fires—Origin—A Mode of Hunting—Captain Smith—Mungo Park—Hillsborough—Major-domo of the Hostelrie—His Garb and Proportions—The Presbyterian Church—Picturesqueness—The "Luteran Church"—Practical Utility—The Dark Minister—A Mistake—The Patriotic Dutchman—A Veritable Publican—Prospects of Hillsborough—A Theological Seminary—Route to Vandalia—The Political Sabbath 230

XX

The Race of Vagabonds—"Yankee Enterprise"—The Virginia Emigrant—The Western Creeks and Bridges—An Adventure in Botany—Unnatural Rebellion—Christian Retaliation—Vandalia—"First Impressions"—The Patriotic Bacchanal—The High-priest—A Distinction Unmerited—The Cause—Vandalia—Situation—Public Edifices—Square—Church—Bank—Land-office—"Illinois Magazine"—Tardy Growth—Removal of Government—Adventures of the First Legislators—The Northern Frontier—Magic of Sixteen Years—Route to Carlisle—A Buck and Doe—An old Hunter—"Hurricane Bottom"—Night on the Prairies—The Emigrant's Bivouac—The Prairie-grass—Carlisle—Site—Advantages—Growth—"Mound Farm" 238

XXI

The Love of Nature—Its Delights—The Wanderer's Reflections—The Magic Hour—A Sunset on the Prairies—"The Sunny Italy"—The Prairie Sunset—Route to Lebanon—Silver Creek—Origin of Name—The "Looking-glass Prairie"—The Methodist Village—Farms—Country Seats—Maize-[Pg 39]fields—Herds—M'Kendreean College—"The Seminary!"—Route to Belleville—The Force of Circumstance—A Contrast—Public [xvi] Buildings—A lingering Look—Route to St. Louis—The French Village—The Coal Bluffs—Discovery of Coal—St. Clair County—Home of Clouds—Realm of Thunder—San Louis 248

XXII

Single Blessedness—Text and Comment—En Route—North St. Louis—A Delightful Drive—A Delightful Farm-cottage—The Catholic University—A Stately Villa—Belle Fontaine—A Town plat—A View of the Confluence—The Human Tooth—The Hamlet of Florissant—Former Name—Site—Buildings—Church—Seminary—Tonish—Owen's Station—Scenery upon the Route—La Charbonnière—The Missouri Bottom—The Forest-Colonnade—The Missouri—Its Sublimity—Indian Names—Its Turbid Character—Cause—An Inexplicable Phenomenon—Theories—Navigation Dangerous—Floods of the Missouri—Alluvions—Sources of the Missouri and Columbia—Their Destinies—Human Life—The Ocean of Eternity—Gates of the Rocky Mountains—Sublimity—A Cataract—The Main Stream—Claims stated 257

[iii] XXIII

View of St. Charles and the Missouri—The Bluffs—"A stern round Tower"—Its Origin—The Windmill—A sunset Stroll—Rural Sights and Sounds—The River and Forest—The Duellist's Grave—The Hour and Scene—Requiescat—Reflections—Duelling—A sad Event—Young B——.—His Request—His Monument—"Blood Island"—Its Scenes and Annals—A visit to "Les Mamelles"—The Forest-path—Its Obscurity—Outlines of the Bluffs—Derivation of Name—Position—Resemblance—The Missouri Bluffs—View from The Mamelle—The Missouri Bottom—The Mamelle Prairie—The distant Cliffs and Confluences—Extent of Plain—Alluvial Origin—Lakes—Bed of the Rivers—An ancient Deposite 268

XXIV

St. Charles—Its Origin—Peculiarities—Early Name—Spanish Rule—Heterogeneous Population—Germans—The Wizard Spell—American Enterprise—Site of the Village—Prospects—The Baltimore Settlement—Catholic Religion and Institutions—"St. Charles College"—The Race of Hunters—A Specimen—The Buffalo—Indian Atrocities—The "Rangers"—Daniel Boone—"Too Crowded!"—The "Regulators"—Boone's Lick—His Decease—His Memory—The Missouri Indians—The Stoccade Fort—Ad[Pg 40]venture of a Naturalist—Route from St. Charles—A Prairie without a Path—Enormous Vegetation—The Cliffs—The Column of Smoke—Perplexity—A delightful Scene—A rare Flower—The Prairie Flora in Spring—In Summer—In Autumn—The Traveller loiters 276

[iv] XXV

Novel Feature of the Mamelle Prairie—A Footpath—An old French Village—Bewilderment—Mystery—A Guide—Portage des Sioux—Secluded Site—Advantages—"Common Field"—Garden-plats—A brick Edifice—A courteous Welcome—An amiable Personage—History of the Village—Origin—Earthquakes—Name—An Indian Legend—Teatable Talk—Patois of the French Villages—An Incident!—A Scene!—A civil Hint—A Night of Beauty—The Flush of Dawn—The weltering Prairie—The Forest—The river Scene—The Ferry-horn—Delay—Locale of Grafton—Advantages and Prospects 288

XXVI

Cave in the Grafton Cliffs—Outlines—Human Remains—Desecration of the Coopers—View from the Cave's Mouth—The Bluffs—Inclined Planes—The Railroad—A Stone-heap—A beautiful Custom—Veneration for the Dead—The Widow of Florida—The Canadian Mother—The Orientals—An extensive View—The River—The Prairie—The Emigrant Farm—The Illinois—A tortuous Route—Macoupin Settlement—Carrolton—Outlines of a Western Village—Religious Diversity—An agricultural Village—Whitehall—The Emigrant Family en route—A Western Village—Its rapid Growth—Fit Parallels—Manchester—The Scarcity of Timber not an insurmountable Obstacle—Substitutes—Morgan County—Prospects—Soil of the Prairies—Adaptation to coarse Grains—Rapid Population—New-England Immigrants—The Changes of a few Years—Environs of Jacksonville—Buildings of "Illinois College"—The Public Square 295

XXVII

Remark of Horace Walpole—A Word from the Author—Jacksonville—Its rapid Advancement—Its Site—Suburbs—Public Square—Radiating Streets—The Congregational Church—The Pulpit—A pleasant Incident—The "New-England of the West"—Immigrant Colonies—"Illinois College"—The Site—Buildings—"Manual Labour System"—The Founders—Their Success—Their Fame—Jacksonville—Attractions for the Northern Emigrant—New England Character—A faithful [v] Transcript—"The Pil[Pg 41]grim Fathers"—The "Stump"—Mr. W. and his Speech—Curious Surmisings—Internal Improvements—Route to Springfield—A "Baptist Circuit-rider"—An Evening Prairie-rider 305

XXVIII

The Nature of Man—Facilities for its Study—A Pilgrimage of Observation—Dissection of Character, Physical and Moral—The young Student—The brighter Features of Humanity—An unwitting Episode—Our World a Ruin—Sunrise on the Prairies—Springfield—Its Location—Advantages—Structures—Society—Prospects—The Sangamon River—Its Navigation—Bottom-lands—Aged Forests—Cathedral Pomp—A splendid Phenomenon—Civic Honours—"Sic itur ad astra!"—A Morning Ride—"Demands of Appetite"—"Old Jim"—A tipsy Host—A revolting Exhibition—Jacob's Cattle and the Prairie-wolves—An Illinois Table—The Staples—A Tea Story—Poultry and Bacon—Chicken Fixens and Common Doins—An Object of Commiseration 315

XXIX

The Burial-ground—A holy Spot—Our culpable Indifference—Cemeteries in our Land—A sad Reflection—The last Petition—Reverence for the Departed—Civilized and Savage Nations—The last Resting-place—Worthy of Thought—A touching Expression of the Heart—Franklin—The Object of Admiration and Love—The Burial-ground of Decatur—The dying Emigrant—The Spirit's Sympathy—A soothing Reflection to Friends—The "Grand Prairie"—The "Lost Rocks"—Decatur—Site and Prospects—A sunset Scene—The Prairie by Moonlight—The Log-cabin—The Exotic of the Prairie—The Heart—The Thank-offering—The Pre-emption Right—The Mormonites—Their Customs—Millennial Anticipations—The Angelic Visitant—The dénouément—The Miracle!—The System of "New Light"—Its Rise and Fall—Aberrations of the Mind—A melancholy Reflection—Absurdity of Mormonism 325

XXX

A wild Night—An Illusion—Sleeplessness—Loneliness—A Storm-wind on the Prairies—A magnificent Scene—Beauty of [vi] the lesser Prairies—Nature's chef d'œuvre—Loveliness lost in Grandeur—Waves of the Prairie—Ravines—Light and Shade—"Alone, alone, all, all alone!"—Origin of the Prairie—Argument for Natural Origin—Similar Plains—Derivation of "Prairie"—Absence of Trees [Pg 42]accounted for—The Diluvial Origin—Prairie Phenomena explained—The Autumnal Fires—An Exception—The Prairie sui generis—No Identity with other Plains—A Bed of the Ocean—A new Hypothesis—Extent of Prairie-surface—Characteristic Carelessness—Hunger and Thirst—A tedious Jaunt—Horrible Suggestions!—Land ho!—A Log-cabin—Hog and Honey 338

XXXI

Cis-atlantic Character—Avarice—Curiosity—A grand Propellant—A Concomitant and Element of Mental Vigour—An Anglo-American Characteristic—Inspection and Supervision—"Uncle Bill"—The Quintessence of Inquisitiveness—A Fault "on Virtue's Side"—The People of Illinois—A Hunting Ramble—A Shot—Tempis fugit—Shelbyville—Dame Justice in Terrorem—A Sulphur Spring—The Inn Register—Chill Atmosphere of the Forest—Contrast on the Prairie—The "Green-head" Prairie-fly—Effect upon a Horse—Numerous in '35—The "Horse-guard"—The Modus Bellandi—Cold Spring—A presuming Host—Musty Politics—The Robin Redbreast—Ornithology of the West—The Turtle-dove—Pathos of her Note—Paley's Remark—Eloquence of the Forest-bird—A Mormonite, Zionward—A forensic Confabulation—Mormonism Developed—The seduced Pedagogue—Mount Zion Stock—The Grand Tabernacle—Smith and Rigdom—The Bank—The Temple—The School—Appearance of Smith—Of Rigdom—Their Disciples—The National Road—Its Progress—Structure—Terminus—Its enormous Character—A Contrast—"Shooting a Beeve"—The Regulations—Salem—A New-England Seaport—The Location—The Village Singing-school—The Major 348

XXXII

Rest after Exertion—A Purpose—"Mine Ease in mine Inn"—The "Thread of Discourse"—A Thunder-gust—Its Approach and Departure—A Bolt—A rifted Elm—An impressive [vii] Scene—Gray's Bard—Mount Vernon—Courthouse—Site—Medicinal Water—A misty Morning—A blind Route—"Muddy Prairie"—Wild Turkeys—Something Diabolical!—The direct Route—A vexatious Incident—The unerring Guide—A Tug for a Fixen—An evening Ride—Pinkneyville—Outlines and Requisites—The blood-red Jail—The Traveller's Inn—"'Tis true, and Pity 'tis"—A "Soul in Purgatory"—An unutterable Ill—Incomparable—An unpitied and unenviable Situation—A laughable Bewilderment—Host and Hostess—The Mischief of a Smile—A Retaliation 362

THE FAR WEST

[PART I]

I

When I was wandering—"

Manfred.

It was a bright morning in the early days of "leafy June." Many a month had seen me a wanderer from distant New-England; and now I found myself "once more upon the waters," embarked for a pilgrimage over the broad prairie-plains of the sunset West. A drizzly, miserable rain had for some days been hovering, with proverbial pertinacity, over the devoted "City of the Falls," and still, at intervals, came lazily pattering down from the sunlighted clouds, reminding one of a hoiden girl smiling through a shower of April tear-drops, while the quay continued to exhibit all that wild uproar and tumult, "confusion worse confounded," which characterizes the steamboat commerce of the Western Valley. The landing at the time was thronged with steamers, and yet the incessant "boom, boom, boom," of the high-pressure engines, the shrill hiss of scalding steam, and the fitful port-song of the negro firemen rising ever and anon upon the breeze, gave notice of a constant [14] augmentation to the number. Some, too, were getting under way, and their lower guards were thronged by emigrants with their household and agricultural utensils. Drays were rattling hither and thither over the rough pavement; Irish porters were cracking their whips and roaring forth alternate staves of blasphemy and song; clerks hurrying to and fro, with fluttering note-books, in all the fancied dignity of "brief authority;"[Pg 44] hackney-coaches dashing down to the water's edge, apparently with no motive to the nervous man but noise; while at intervals, as if to fill up the pauses of the Babel, some incontinent steamer would hurl forth from the valves of her overcharged boilers one of those deafening, terrible blasts, echoing and re-echoing along the river-banks, and streets, and among the lofty buildings, till the very welkin rang again.

To one who has never visited the public wharves of the great cities of the West, it is no trivial task to convey an adequate idea of the spectacle they present. The commerce of the Eastern seaports and that of the Western Valley are utterly dissimilar; not more in the staples of intercourse than in the mode in which it is conducted; and, were one desirous of exhibiting to a friend from the Atlantic shore a picture of the prominent features which characterize commercial proceedings upon the Western waters, or, indeed, of Western character in its general outline, at a coup d'œil, he could do no better than to place him in the wild uproar of the steamboat quay. Amid the "crowd, the hum, [15] the shock" of such a scene stands out Western peculiarity in all its stern proportion.

Steamers on the great waters of the West are well known to indulge no violently conscientious scruples upon the subject of punctuality, and a solitary exception at our behest, or in our humble behalf, was, to be sure, not an event to be counted on. "There's dignity in being waited for;" hour after hour, therefore, still found us and left us amid the untold scenes and sounds of the public landing. It is true, and to the unending honour of all concerned be it recorded, very true it is our doughty steamer ever and anon would puff and blow like a porpoise or a narwhal; and then would she swelter from every pore and quiver in every limb with the ponderous labouring of her huge enginery, and the steam would shrilly whistle and shriek like a spirit in its[Pg 45] confinement, till at length she united her whirlwind voice to the general roar around; and all this indicated, indubitably, an intention to be off and away; but a knowing one was he who could determine the when.

Among the causes of our wearisome detention was one of a nature too melancholy, too painfully interesting lightly to be alluded to. Endeavouring to while away the tedium of delay, I was pacing leisurely back and forth upon the guard, surveying the lovely scenery of the opposite shore, and the neat little houses of the village sprinkled upon the plain beyond, when a wild, piercing shriek struck upon my ear. I was hurrying immediately forward to the spot whence it seemed to proceed, [16] when I was intercepted by some of our boat's crew bearing a mangled body. It was that of our second engineer, a fine, laughing young fellow, who had been terribly injured by becoming entangled with the flywheel of the machinery while in motion. He was laid upon the passage floor. I stood at his head; and never, I think, shall I forget those convulsed and agonized features. His countenance was ghastly and livid; beaded globules of cold sweat started out incessantly upon his pale brow; and, in the paroxysms of pain, his dark eye would flash, his nostril dilate, and his lips quiver so as to expose the teeth gnashing in a fearful manner; while a muttered execration, dying away from exhaustion, caused us all to shudder. And then that wild despairing roll of the eyeball in its socket as the miserable man would glance hurriedly around upon the countenances of the bystanders, imploring them, in utter helplessness, to lend him relief. Ah! it is a fearful thing to look upon these strivings of humanity in the iron grasp of a power it may in vain resist! From the quantity of blood thrown off, the oppressive fulness of the chest, and the difficult respiration, some serious pulmonary injury had evidently been sustained; while a splintered clavicle and[Pg 46] limbs shockingly shattered racked the poor sufferer with anguish inexpressible. It was evident he believed himself seriously injured, for at times he would fling out his arms, beseeching those around him to "hold him back," as if even then he perceived the icy grasp of the death angel creeping over his frame.

[17] Perhaps I have devoted more words to the detail of this melancholy incident than would otherwise have been the case, on account of the interest which some circumstances in the sufferer's history, subsequently received from the captain of our steamer, inspired.

"Frank, poor fellow," said the captain, "was a native of Ohio, the son of a lone woman, a widow. He was all her hope, and to his exertions she was indebted for a humble support."

Here, then, were circumstances to touch the sympathies of any heart possessed of but a tithe of the nobleness of our nature; and I could not but reflect, as they were recounted, how like the breath of desolation the first intelligence of her son's fearful end must sweep over the spirit of this lonely widow; for, like the wretched Constance, she can "never, never behold him more."3

Her widow-comfort, and her sorrow's cure!"

While indulging in these sad reflections a gay burst of music arrested my attention; and, looking up, I perceived the packet-boat "Lady Marshall" dropping from her mooring at the quay, her decks swarming with passengers, and under high press of steam, holding her bold course against the current, while the merry dashing of the wheels, mingling with the wild clang of martial music, imparted an air almost of romance to the scene. How strangely did this contrast with that misery from which my eye had just turned![Pg 47]

There are few objects more truly grand—I had [18] almost said sublime—than a powerful steamer struggling triumphantly with the rapids of the Western waters. The scene has in it a something of that power which we feel upon us in viewing a ship under full sail; and, in some respects, there is more of the sublime in the humbler triumph of man over the elements than in that more vast. Sublimity is a result, not merely of massive, extended, unmeasured greatness, but oftener, and far more impressively, does the sentiment arise from a combination of vast and powerful objects. The mighty stream rolling its volumed floods through half a continent, and hurrying onward to mingle its full tide with the "Father of Waters," is truly sublime; its resistless power is sublime; the memory of its by-gone scenes, and the venerable moss-grown forests on its banks, are sublime; and, lastly, the noble fabric of man's workmanship struggling and groaning in convulsed, triumphant effort to overcome the resistance offered, completes a picture which demands not the heaving ocean-waste and the "oak leviathan" to embellish.

It was not until the afternoon was far advanced that we found ourselves fairly embarked. A rapid freshet had within a few hours swollen the tranquil Ohio far beyond its ordinary volume and velocity, and its turbid waters were rolling onward between the green banks, bearing on their bosom all the varied spoils of their mountain-home, and of the rich region through which they had been flowing. The finest site from which to view the city we found to be the channel of the Falls upon the Indiana side of the stream, called the Indian [19] chute, to distinguish it from two others, called the Middle chute and the Kentucky chute. The prospect from this point is noble, though the uniformity of the structures, the fewness of the spires, the unimposing character of the public edifices, and the depression of the site upon[Pg 48] which the city stands, give to it a monotonous, perhaps a lifeless aspect to the stranger.

It was in the year 1778 that a settlement was first commenced upon the spot on which the fair city of Louisville now stands.4 In the early spring of that year, General George Rodgers Clarke, under authority of the State of Virginia, descended the Ohio with several hundred men, with the design of reducing the military posts of Kaskaskia, Cahokia, and Fort Vincent, then held by British troops. Disembarking upon Corn Island at the Falls of the Ohio, opposite the present city, land sufficient for the support of six families, which were left, was cleared and planted with corn. From this circumstance the island received a name which it yet retains. General Clarke proceeded upon his expedition, and, in the autumn returning successful, the emigrants were removed to the main land, and a settlement was commenced where Louisville now stands. During the few succeeding years, other families from Virginia settled upon the spot, and in the spring of 1780 seven stations were formed upon Beargrass Creek,5 which here empties into the Mississippi, and Louisville commenced its march to its present importance.

The view of the city from the Falls, as I have remarked, is not at all imposing; the view of the [20] Falls from the city, on the contrary, is one of beauty and romance. They are occasioned by a parapet of limestone extending quite across the stream, which is here about one mile in width; and when the water is low the whole chain sparkles with bubbling foam-bells. When the stream is full the descent[Pg 49] is hardly perceptible but for the increased rapidity of the current, which varies from ten to fourteen miles an hour.6 Owing to the height of the freshet, this was the case at the time when we descended them, and there was a wild air of romance about the dark rushing waters: and the green woodlands upon either shore, overshadowed as they were by the shifting light and shade of the flitting clouds, cast[Pg 50] over the scene a bewitching fascination. "Corn Island," with its legendary associations, rearing its dense clump of foliage as from the depths of the stream, was not the least beautiful object of the panorama; while the receding city, with its smoky roofs, its bustling quay, and the glitter and animation of an extended line of steamers, was alone neces[Pg 51]sary to fill up a scene for a limner.7 And our steamer swept onward [21] over the rapids, and threaded their maze of beautiful islands, and passed along the little villages at their foot and the splendid steamers along their shore, till twilight had faded, and the dusky mantle of departed day was flung over forest and stream.

Ohio River.

II

How glorious in its action and itself!"

Manfred.

Of the great Western World when day declines,

And louder sounds the roll of distant floods."

Hemans.

Long before the dawn on the morning succeeding our departure we were roused from our rest by the hissing of steam and the rattling of machinery as our boat moved slowly out from beneath the high banks and lofty sycamores of the river-side, where she had in safety been moored for the night, to resume her course. Withdrawing the curtain from the little rectangular window of my stateroom, the dark shadow of the forest was slumbering in calm magnificence upon the waters; and glancing upward my eye, the stars were beaming out in silvery brightness; while all along the eastern horizon, where

Beat up the light with their bright silver hoofs

And drive it through the sky,"

[22] rested a broad, low zone of clear heaven, proclaiming the coming of a glorious dawn. The hated clang of the bell-boy was soon after heard resounding far and wide in querulous and deafening clamour throughout the cabins, vexing the dull ear of every drowsy man in the terrible language of Macbeth's evil conscience, "sleep no more!" In a very desperation of self-defence I arose. The mists of night had not yet wholly dispersed, and the rack and fog floated quietly upon the placid bosom of the stream, or ascended in ragged masses from the dense foliage upon its banks. All this melted gently away like "the baseless[Pg 53] fabric of a vision," and "the beauteous eye of day" burst forth in splendour, lighting up a scene of unrivalled loveliness.

Much, very much has been written of "the beautiful Ohio;" the pens of an hundred tourists have sketched its quiet waters and its venerable groves; but there is in its noble scenery an ever salient freshness, which no description, however varied, can exhaust; new beauties leap forth to the eye of the man of sensibility, and even an humble pen may not fail to array them in the drapery of their own loveliness. There are in this beautiful stream features peculiar to itself, which distinguish it from every other that we have seen or of which we have read; features which render it truly and emphatically sui generis. It is not "the blue-rushing of the arrowy Rhone," with castled crags and frowning battlements; it is not the dark-rolling Danube, shadowy with the legend of departed time, upon whose banks armies have met and battled; it is not [23] the lordly Hudson, roaming in beauty through the ever-varying romance of the Catskill Highlands; nor is it the gentle wave of the soft-flowing Connecticut, seeming almost to sleep as it glides through the calm, "happy valley" of New-England: but it is that noble stream, bounding forth, like a young warrior of the wilderness, in all the joyance of early vigour, from the wild twin-torrents of the hills; rolling onward through a section of country the glory of a new world, and over the wooded heights of whose banks has rushed full many a crimson tide of Indian massacre. Ohio,8 "The River of Blood," was its fearfully significant name from the aboriginal native; La Belle Rivière was its euphonious distinction from the simple Canadian voyageur, whose light pirogue first glided on its blue bosom. "The Beautiful River!"—it is no misnomer—from its earliest commence[Pg 54]ment to the broad embouchure into the turbid floods of the Mississippi, it unites every combination of scenic loveliness which even the poet's sublimated fancy could demand.9 Now it sweeps along beneath its lofty bluffs in the conscious grandeur of resistless might; and then its clear, transparent waters glide in undulating ripples over the shelly bottoms and among the pebbly heaps of the white-drifted sand-bars, or in the calm magnificence of their eternal wandering,

Sing they a sleepy tune."

From either shore streams of singular beauty and euphonious names come pouring in their tribute [24] through the deep foliage of the fertile bottoms; while the swelling, volumed outlines of the banks, piled up with ponderous verdure rolling and heaving in the river-breeze like life, recur in such grandeur and softness, and such ever-varying combinations of beauty, as to destroy every approach to monotonous effect. From the source of the Ohio to its outlet its waters imbosom more than an hundred islands, some of such matchless loveliness that it is worthy of remark that such slight allusion has been made to them in the numerous pencillings of Ohio scenery. In the fresh, early summertime, when the deep green of vegetation is in its luxuriance, they surely constitute the most striking feature of the river. Most of them are densely wooded to the water's edge; and the wild vines and underbrush suspended lightly over the waters are mirrored in their bosom or swept by the current into attitudes most graceful and picturesque. In some of those stretched-out, endless reaches which are constantly recurring, they seem bursting up like beautiful bouquets of[Pg 55] sprinkled evergreens from the placid stream; rounded and swelling, as if by the teachings of art, on the blue bosom of the waters. A cluster of these "isles of light" I well remember, which opened upon us the eve of the second day of our passage. Two of the group were exceedingly small, mere points of a deeper shade in the reflecting azure; while the third, lying between the former, stretched itself far away in a narrow, well-defined strip of foliage, like a curving gash in the surface, parallel to the [25] shore; and over the lengthened vista of the waters gliding between, the giant branches bowed themselves, and wove their mingled verdure into an immense Gothic arch, seemingly of interminable extent, but closed at last by a single speck of crimson skylight beyond. Throughout its whole course the Ohio is fringed with wooded bluffs; now towering in sublime majesty hundreds of feet from the bed of the rolling stream, and anon sweeping inland for miles, and rearing up those eminences so singularly beautiful, appropriately termed "Ohio hills," while their broad alluvial plains in the interval betray, by their enormous vegetation, a fertility exhaustless and unrivalled. Here and there along the green bluffs is caught a glimpse of the emigrant's low log cabin peeping out to the eye from the dark foliage, sometimes when miles in the distance; while the rich maize-fields of the bottoms, the girdled forest-trees and the lowing kine betray the advance of civilized existence. But if the scenes of the Ohio are beautiful beneath the broad glare of the morning sunlight, what shall sketch their lineaments when the coarser etchings of the picture are mellowed down by the balmy effulgence of the midnight moon of summer! When her floods of light are streaming far and wide along the magnificent forest-tops! When all is still—still! and sky, and earth, and wood, and stream are hushed as a spirit's breathing! When thought is almost audible, and memory is busy with the past! When the distant bluffs,[Pg 56] bathed in molten silver, gleam like beacon-lights, and the far-off vistas of the [26] meandering waters are flashing with the sheen of their ripples! When you glide through the endless maze, and the bright islets shift, and vary, and pass away in succession like pictures of the kaleidoscope before your eye! When imagination is awake and flinging forth her airy fictions, bodies things unseen, and clothes reality in loveliness not of earth! When a scene like this is developed, what shall adequately depict it? Not the pen.

Such, such is the beautiful Ohio in the soft days of early summer; and though hackneyed may be the theme of its loveliness, yet, as the dying glories of a Western sunset flung over the landscape the mellow tenderness of its parting smile, "fading, still fading, as the day was declining," till night's dusky mantle had wrapped the "woods on shore" and the quiet stream from the eye, I could not, even at the hazard of triteness, resist an inclination to fling upon the sheet a few hurried lineaments of Nature's beautiful creations.

There is not a stream upon the continent which, for the same distance, rolls onward so calmly, and smoothly, and peacefully as the Ohio. Danger rarely visits its tranquil bosom, except from the storms of heaven or the reckless folly of man, and hardly a river in the world can vie with it in safety, utility, or beauty. Though subject to rapid and great elevations and depressions, its current is generally uniform, never furious. The forest-trees which skirt its banks are the largest in North America, while the variety is endless; several sycamores were pointed out to us upon the shores from thirty to fifty feet in circumference. Its alluvial [27] bottoms are broad, deep, and exhaustlessly fertile; its bluffs are often from three to four hundred feet in height; its breadth varies from one mile to three, and its navigation,[Pg 57] since the improvements commenced, under the authority of Congress, by the enterprising Shreve, has become safe and easy.10 The classification of obstructions is the following: snags, trees anchored by their roots; fragments of trees of various forms and magnitude; wreck-heaps, consisting of several of these stumps, and logs, and branches of trees lodged in one place; rocks, which have rolled from the cliffs, and varying from ten to one hundred cubic feet in size; and sunken boats, principally flat-boats laden with coal. The last remains one of the most serious obstacles to the navigation of the Ohio. Many steamers have been damaged by striking the wrecks of the Baltimore, the Roanoke, the William Hulburt,11 and other craft, which were themselves snagged; while[Pg 58] keel and flat-boats without number have been lost from the same cause.12 Several thousands of the obstacles mentioned have been removed since improvements were commenced, and accidents from this cause are now less frequent. Some of the snags torn up from the bed of the stream, where they have probably for ages been buried, are said to have exceeded a diameter of six feet at the root, and were upward of an hundred feet in length. The removal of these obstructions on the Ohio presents a difficulty and expense not encountered upon the Mississippi. In the latter stream, the root of the snag, when eradicated, is deposited in some deep [28] pool or bayou along the banks, and immediately imbeds itself in alluvial deposite; but on the Ohio, owing to the nature of its banks in most of its course, there is no opportunity for such a disposal, and the boatmen are forced to blast the logs with gunpowder to prevent them from again forming obstructions. The cutting down and clearing away of all leaning and falling trees from the banks constitutes an essential feature in the scheme of improvement; since the facts are well ascertained that trees seldom plant themselves far from the spot where they fall; and that, when once under the power of the current, they seldom anchor themselves and form snags. The policy of removing the leaning and fallen trees is, therefore, palpable, since, when this is once thoroughly accomplished, no material for subsequent formation can exist. The construction of stone dams, by which to concentrate into a single channel all the waters of the river, where they are divided by islands, or from other causes are spread over a broad extent, is another operation now in[Pg 59] execution. The dams at "Brown's Island,"13 the shoalest point on the Ohio, have been so eminently successful as fully to establish the efficiency of the plan. Several other works of a similar character are proposed; a full survey of the stream, hydrographical and topographical, is recommended; and, when all improvements are completed, it is believed that the navigation of the "beautiful Ohio" will answer every purpose of commerce and the traveller, from its source to its mouth, at the lowest stages of the water.

Ohio River.

III

Though he alight sometimes, still goeth on."

Herbert.

Now like autumnal leaves before the blast

Wide scattered."

Sprague.

Thump, thump, crash! One hour longer, and I was at length completely roused from a troublous slumber by our boat coming to a dead stop. Casting a glance from the window, the bright flashing of moonlight showed the whole surface of the stream covered with drift-wood, and, on inquiry, I learned that the branches of an enormous oak, some sixty feet in length, had become entangled with one of the paddle-wheels of our steamer, and forbade all advance.

We were soon once more in motion; the morning mists were dispersing, the sun rose up behind the forests, and his bright beams danced lightly over the gliding waters. We passed many pleasant little villages along the banks, and it[Pg 60] was delightful to remove from the noise, and heat, and confusion below to the lofty hurricane deck, and lounge away hour after hour in gazing upon the varied and beautiful scenes which presented themselves in constant succession to the eye. Now we were gliding quietly on through the long island [30] chutes, where the daylight was dim, and the enormous forest-trees bowed themselves over us, and echoed from their still recesses the roar of our steam-pipe; then we were sweeping rapidly over the broad reaches of the stream, miles in extent; again we were winding through the mazy labyrinth of islets which fleckered the placid surface of the stream, and from time to time we passed the lonely cabin of the emigrant beneath the venerable and aged sycamores. Here and there, as we glided on, we met some relic of those ancient and primitive species of river-craft which once assumed ascendency over the waters of the West, but which are now superseded by steam, and are of too infrequent occurrence not to be objects of peculiar interest. In the early era of the navigation of the Ohio, the species of craft in use were numberless, and many of them of a most whimsical and amusing description. The first was the barge, sometimes of an hundred tons' burden, which required twenty men to force it up against the current a distance of six or seven miles a day; next the keel-boat, of smaller size and lighter structure, yet in use for the purposes of inland commerce; then the Kentucky flat, or broad-horn of the emigrant; the enormous ark, in magnitude and proportion approximating to that of the patriarch; the fairy pirogue of the French voyageur; the birch caïque of the Indian, and log skiffs, gondolas, and dug-outs of the pioneer without name or number.14 But[Pg 61] since the introduction of steam upon the Western waters, most of these unique and primitive contrivances [31] have disappeared; and with them, too, has gone that singular race of men who were their navigators. Most of the younger of the settlers, at this early period of the country, devoted themselves to this profession. Nor is there any wonder that the mode of life pursued by these boatmen should have presented irresistible seductions to the young people along the banks. Fancy one of these huge boats dropping lazily along with the current past their cabins on a balmy morning in June. Picture to your imagination the gorgeous foliage; the soft, delicious temperature of the atmosphere; the deep azure of the sky; the fertile alluvion, with its stupendous forests and rivers; the romantic bluffs sleeping mistily in blue distance; the clear waters rolling calmly adown, with the woodlands outlined in shadow on the surface; the boat floating leisurely onward, its heterogeneous crew of all ages dancing to the violin upon the deck, flinging out their merry salutations among the settlers, who come down to the water's edge to see the pageant pass,[Pg 62] until, at length, it disappears behind a point of wood, and the boatman's bugle strikes up its note, dying in distance over the waters; fancy a scene like this, and the wild bugle-notes echoing and re-echoing along the bluffs and forest shades of the beautiful Ohio, and decide whether it must not have possessed a charm of fascination resistless to the youthful mind in these lonely solitudes. No wonder that the severe toils of agricultural life, in view of such scenes, should have become tasteless and irksome.15 The lives of these [32] boatmen were lawless and dissolute to a proverb. They frequently stopped at the villages along their course, and passed the night in scenes of wild revelry and merriment. Their occupation, more than any other, subjected them to toil, and exposure, and privation; and, more than any other, it indulged them, for days in succession, with leisure, and ease, and indolent gratification. Descending the stream, they floated quietly along without an effort, but in ascending against the powerful current their life was an uninterrupted series of toil. The boat, we are told, was propelled by poles, against which the shoulder was placed and the whole strength applied; their bodies were naked to the waist, for enjoying the river-breeze and for moving with facility; and, after the labour of the day, they swallowed their whiskey and supper, and throwing themselves upon the deck of the boat, with no other canopy than the heavens, slumbered soundly on till the morning. Their slang was peculiar to the race, their humour and power of retort was remarkable, and in their frequent battles with the squatters or with their fellows, their nerve and courage were unflinching.

It was in the year 1811 that the steam-engine commenced its giant labours in the Valley of the West, and the first vessel propelled by its agency glided along the soft-flowing[Pg 63] wave of the beautiful river.16 Many events, we are told, united to render this year a most remarkable era in the annals of Western history.17 The spring-freshet of the rivers buried the whole valley from Pittsburgh to New-Orleans [33] in a flood; and when the waters subsided unparalleled sickness and mortality ensued. A mysterious spirit of restlessness possessed the denizens of the Northern forests, and in myriads they migrated towards the South and West. The magnificent comet of the year, seeming, indeed, to verify the terrors of superstition, and to "shake from its horrid hair pestilence and war," all that summer was beheld blazing along the midnight sky, and shedding its lurid twilight over forest and stream; and when the leaves of autumn began to rustle to the ground, the whole vast Valley of the Mississippi rocked and vibrated in earthquake-convulsion! forests bowed their heads; islands disappeared from their sites, and new one's rose; immense lakes and hills were formed; the graveyard gave up its sheeted and ghastly tenants; huge relics of the mastodon and megalonyx, which for ages had slumbered in the bosom of earth, were heaved up to the sunlight; the blue lightning streamed and the thunder muttered along the leaden sky, and, amid all the elemental war, the mighty current of the "Father of Waters" for hours rolled back its heaped-up floods towards its source! All this was the prologue to that mighty drama of Change which, from that period to the present, has been sweeping over the Western Valley; it was the fearful welcome-home to that all-powerful agent which has revolutionized the character of[Pg 64] half a continent; for at that epoch of wonders, and amid them all, the first steamboat was seen descending the great rivers, and the awe-struck Indian [34] on the banks beheld the Pinelore flying through the troubled waters.18 The rise and progress of the steam-engine is without a parallel in the history of modern improvement. Fifty years ago, and the prophetic declaration of Darwin was pardoned only as the enthusiasm of poetry; it is now little more than the detail of reality:

Drag the slow barge or drive the rapid car;

Or on wide-waving wings expanded bear

The flying chariot through the fields of air;

Fair crews triumphant, leaning from above,

Shall wave their fluttering kerchiefs as they move,

Or warrior bands alarm the gaping crowd,

And armies shrink beneath the shadowy cloud."19

The steam-engine, second only to the press in power, has in a few years anticipated results throughout the New World which centuries, in the ordinary course of cause and event, would have failed to produce. The dullest forester, even the cold, phlegmatic native of the wilderness, gazes upon its display of beautiful mechanism, its majestic march upon its element, and its sublimity of power, with astonishment and admiration.