EDMUND DULAC'S

PICTURE-BOOK

FOR THE FRENCH RED CROSS

BY HODDER AND STOUGHTON

LONDON · NEW YORK · TORONTO

| PAGE | |

THE STORY OF THE BIRD FENG a Fairy Tale from China |

1 |

YOUNG ROUSSELLE: a French Song of the Olden Time |

5 |

LAYLÁ AND MAJNÚN: a Persian Love Story |

9 |

THE NIGHTINGALE: after a Fairy Tale by Hans Andersen |

29 |

THREE KINGS OF ORIENT: a Carol |

41 |

SINDBAD THE SAILOR: a Tale from the Thousand and One Nights |

43 |

THE LITTLE SEAMSTRESS: a French Song of the Olden Time |

55 |

THE REAL PRINCESS: after a Fairy Tale by Hans Andersen |

57 |

MY LISETTE: an Old French Song |

61 |

CINDERELLA: a Fairy Tale from the French |

65 |

THE CHILLY LOVER: a Song from the French |

79 |

THE STORY OF AUCASSIN AND NICOLETTE: an Old World Idyll |

81 |

BLUE BEARD: an Old Tale from the French |

85 |

CERBERUS, THE BLACK DOG OF HADES |

99 |

THE LADY BADOURA: a Tale from the Thousand and One Nights |

102 |

THE SLEEPER AWAKENED: a Tale from the Thousand and One Nights |

110 |

JUSEF AND ASENATH: a Love Story of Egypt |

124 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

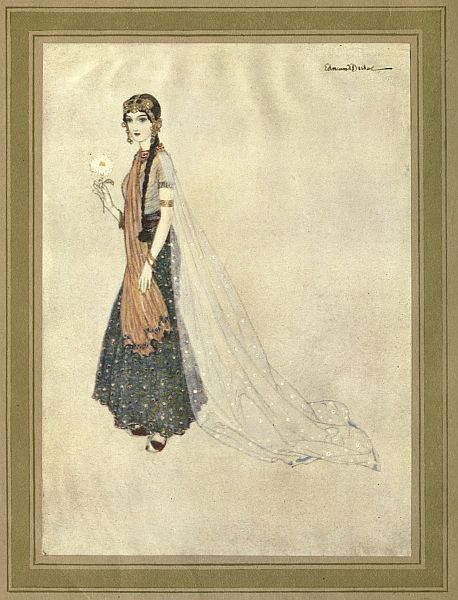

JUSEF AND ASENATH | |

| Asenath | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

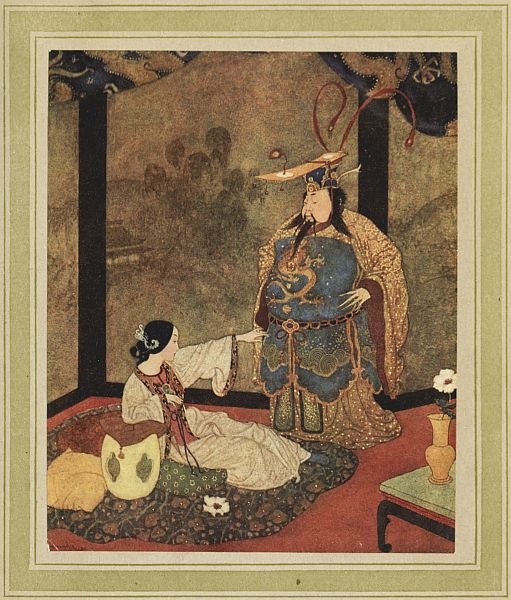

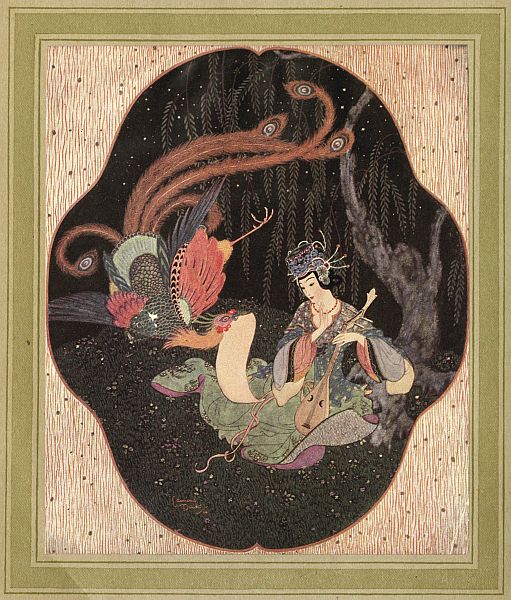

THE STORY OF THE BIRD FENG | |

The wonderful bird, like a fire of many colours come down from heaven, alighted before the princess, dropping at her feet the portrait |

1 |

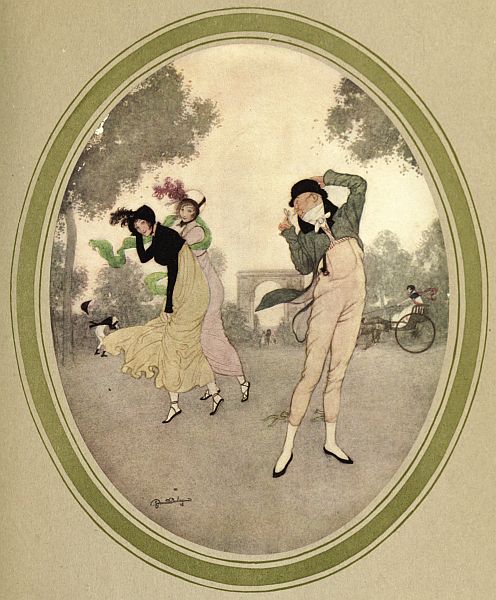

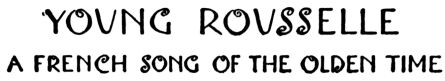

YOUNG ROUSSELLE | |

What do you think of Young Rousselle? |

8 |

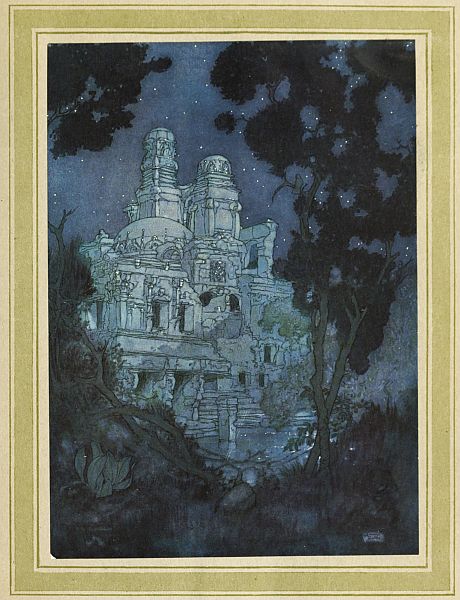

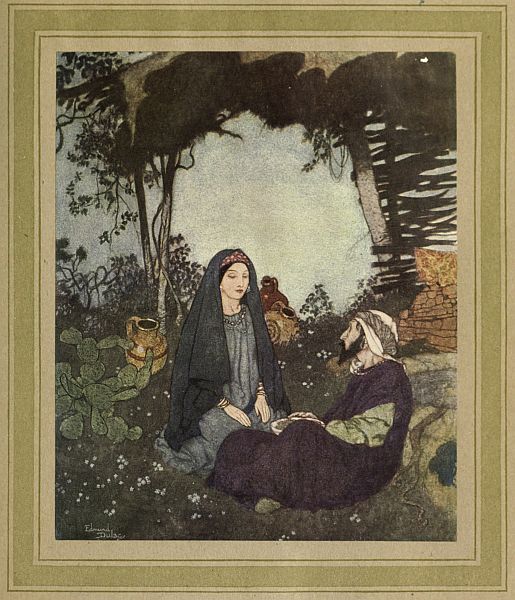

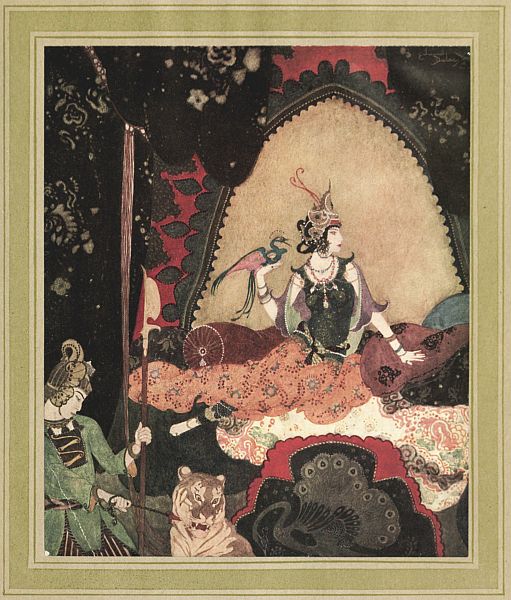

LAYLÁ AND MAJNÚN | |

In a high chamber of the palace—it was as wondrous as that of a Sultan |

16 |

If the desert were my home—then would I let the world go by |

18 |

She would sit for hours, with the bird perched on the back of her hand, listening to its soft intonation of that one word 'Majnún' |

22 |

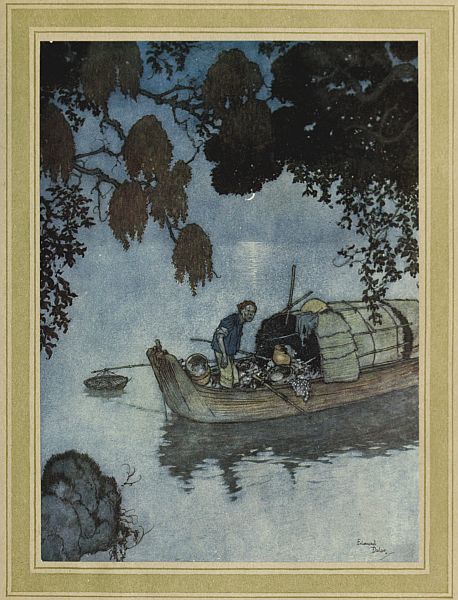

THE NIGHTINGALE | |

Even the poor fisherman would pause in his work to listen |

32 |

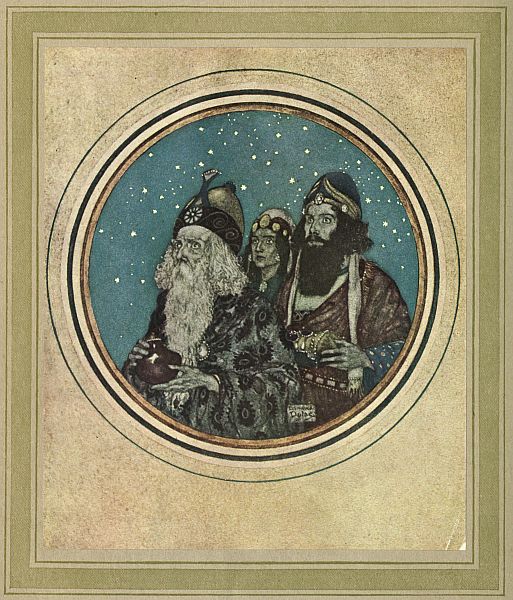

THREE KINGS OF ORIENT | |

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night |

41 |

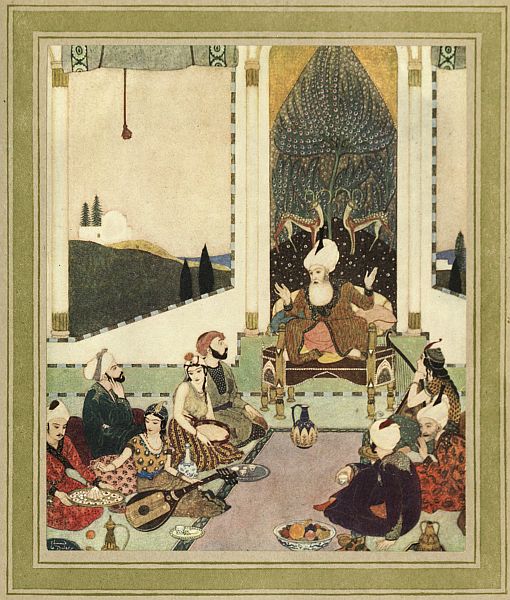

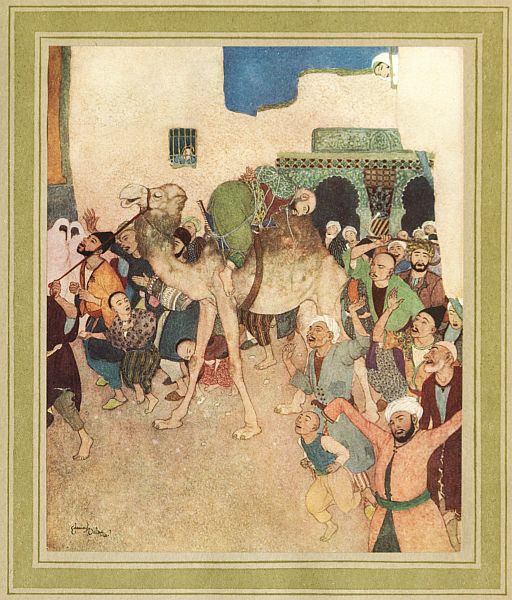

SINDBAD THE SAILOR | |

Knowest thou that my name is also Sindbad? |

50 |

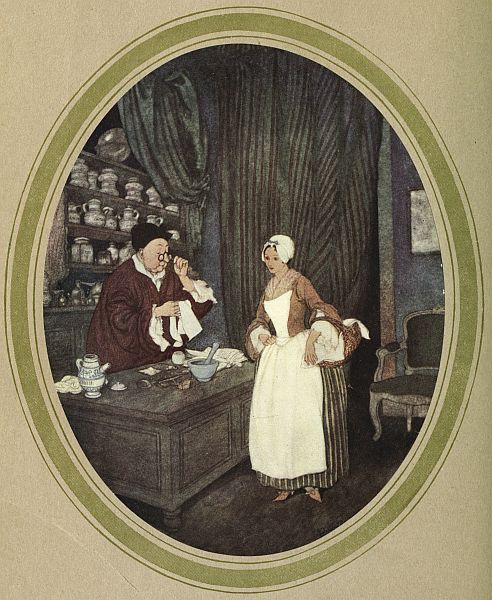

THE LITTLE SEAMSTRESS | |

I never at all Saw sewing so small! |

55 |

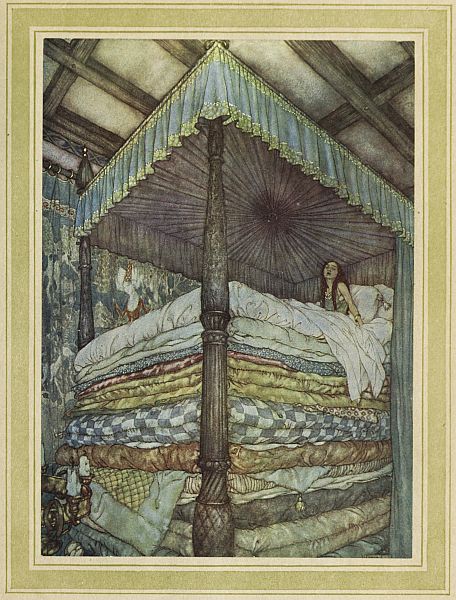

THE REAL PRINCESS | |

Not a wink the whole night long |

58 |

MY LISETTE | |

'Tis Lisette whom I adore, And with reason, more and more! |

62 |

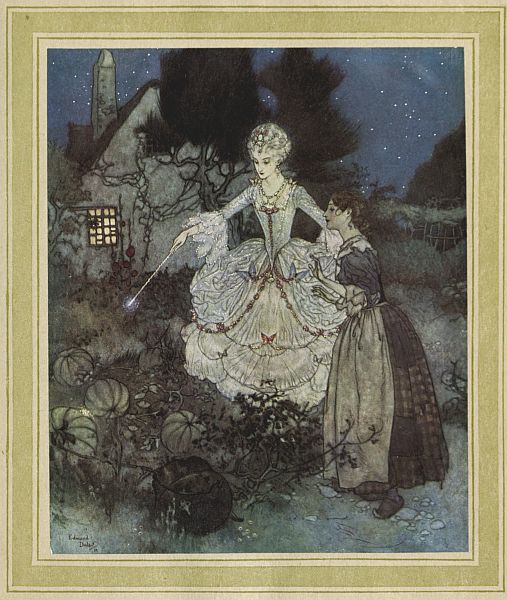

CINDERELLA | |

'There,' said her godmother, pointing with her wand, ... 'pick it and bring it along' |

72 |

THE CHILLY LOVER | |

| O Ursula, for thee My heart is burning,— But I'm so cold! | 80 |

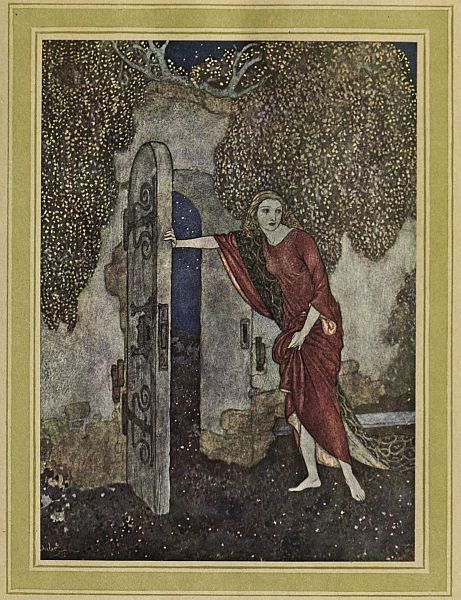

THE STORY OF AUCASSIN AND NICOLETTE | |

But Nicolette one night escaped |

82 |

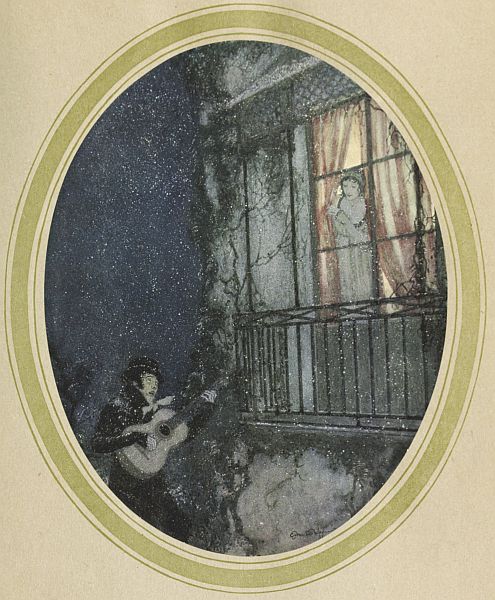

BLUE BEARD | |

Seven and one are eight, madam! |

86 |

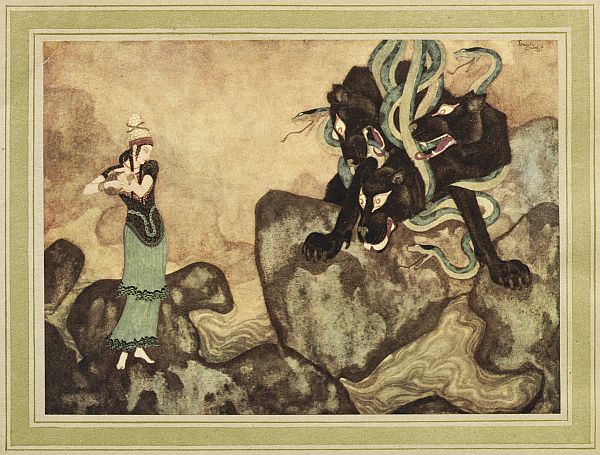

CERBERUS | |

Cerberus, the black dog of Hades |

99 |

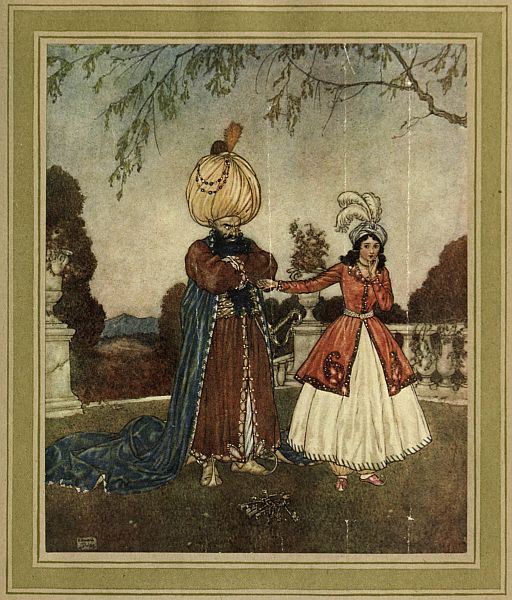

THE LADY BADOURA | |

Nay, nay; I will not marry him |

102 |

THE SLEEPER AWAKENED | |

Behold the reward of those who meddle in other people's affairs |

120 |

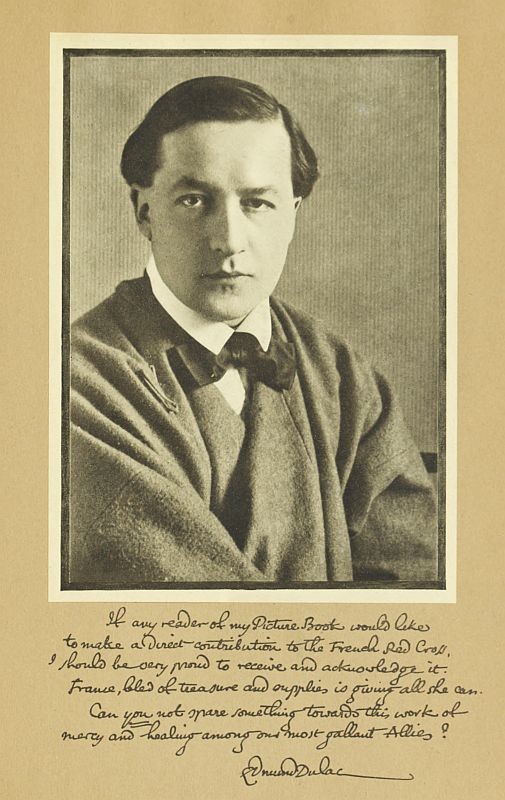

EDMUND DULAC |

128 |

PUBLISHED ON BEHALF OF THE

CROIX ROUGE FRANÇAISE

| COMITÉ DE LONDRES | |

| 9 KNIGHTSBRIDGE, LONDON, S.W. | |

| Président d'honneur | Présidente |

| S. E. Monsieur PAUL CAMBON | VICOMTESSE DE LA PANOUSE |

Under the Patronage of | |

| H.M. QUEEN ALEXANDRA | |

The work of the French Red Cross is done almost entirely by the willing sacrifice of patriotic people who give little or much out of their means. The Comité is pleased to give the fullest possible particulars of its methods and needs. It is sufficient here to say that every one who gives even a shilling gives a wounded French soldier more than a shilling's worth of ease or pleasure.

The actual work is enormous. The number of men doctored, nursed, housed, fed, kept from the worries of illness, is great, increasing, and will increase.

You must remember that everything to do with sick and wounded has to be kept up to a daily standard. It is you who give who provide the drugs, medicines, bandages, ambulances, coal, comfort for those who fight, get wounded, or die to keep you safe. Remember that besides fighting for France, they are fighting for the civilised world, and that you owe your security and civilisation to them as much as to your own men and the men of other Allied Countries.

There is not one penny that goes out of your pockets in this cause that does not bind France and Britain closer together. From the millionaire we need his thousands; from the poor man his store of pence. We do not beg, we insist, that these brave wounded men shall lack for nothing. We do not ask of you, we demand of you, the help that must be given.

There is nothing too small and nothing too large but we need it.

Day after day we send out great bales of goods to these our devoted soldiers, and we must go on.

Imagine yourself ill, wounded, sick, in an hospital, with the smash and shriek of the guns still dinning in your ears, and imagine the man or woman who would hold back their purse from helping you.

Times are not easy, we know, but being wounded is less easy, and being left alone because nothing is forthcoming is terrible. You have calls upon you everywhere, you say; well, these men have answered their call, and in the length and breadth of France they wait your reply.

What is it to be?

EDMUND DULAC, c/o "The Daily Telegraph," London, E.C.

THE

STORY OF THE BIRD FENG

A FAIRY TALE FROM CHINA

Ta-Khai, Prince of Tartary, dreamt one night that he saw in a place where he had never been before an enchantingly beautiful young maiden who could only be a princess. He fell desperately in love with her, but before he could either move or speak, she had vanished. When he awoke he called for his ink and brushes, and, in the most accomplished willow-leaf style, he drew her image on a piece of precious silk, and in one corner he wrote these lines:

Will they ever bloom?

A day without her

Is like a hundred years.

He then summoned his ministers, and, showing them the portrait, asked if any one could tell him the name of the beautiful maiden; but they all shook their heads and stroked their beards. They knew not who she was.

So displeased was the prince that he sent them away in disgrace to the most remote provinces of his kingdom. All the courtiers, the generals, the officers, and every man and woman, high and low, who lived in the palace came in turn to look at the picture. But they all had to confess their ignorance. Ta-Khai then called upon the[2] magicians of the kingdom to find out by their art the name of the princess of his dreams, but their answers were so widely different that the prince, suspecting their ability, condemned them all to have their noses cut off. The portrait was shown in the outer court of the palace from sunrise till sunset, and exalted travellers came in every day, gazed upon the beautiful face, and came out again. None could tell who she was.

Meanwhile the days were weighing heavily upon the shoulders of Ta-Khai, and his sufferings cannot be described; he ate no more, he drank no more, and ended by forgetting which was day and which was night, what was in and what was out, what was left and what was right. He spent his time roaming over the mountains and through the woods crying aloud to the gods to end his life and his sorrow.

It was thus, one day, that he came to the edge of a precipice. The valley below was strewn with rocks, and the thought came to his mind that he had been led to this place to put a term to his misery. He was about to throw himself into the depths below when suddenly the bird Feng flew across the valley and appeared before him, saying:

'Why is Ta-Khai, the mighty Prince of Tartary, standing in this place of desolation with a shadow on his brow?'

Ta-Khai replied: 'The pine tree finds its nourishment where it stands, the tiger can run after the deer in the forests, the eagle can fly over the mountains and the plains, but how can I find the one for whom my heart is thirsting?'

And he told the bird his story.

The Feng, which in reality was a Feng-Hwang, that is, a female Feng, rejoined:

'Without the help of Supreme Heaven it is not easy to acquire wisdom, but it is a sign of the benevolence of the spiritual beings that I should have come between you and destruction. I can make myself large enough to carry the largest town upon my back, or small enough to pass through the smallest keyhole, and I know all[3] the princesses in all the palaces of the earth. I have taught them the six intonations of my voice, and I am their friend. Therefore show me the picture, O Ta-Khai, and I will tell you the name of her whom you saw in your dream.'

They went to the palace, and, when the portrait was shown, the bird became as large as an elephant, and exclaimed, 'Sit on my back, O Ta-Khai, and I will carry you to the place of your dream. There you will find her of the transparent face with the drooping eyelids under the crown of dark hair such as you have depicted, for these are the features of Sai-Jen, the daughter of the King of China, and alone can be likened to the full moon rising under a black cloud.'

At nightfall they were flying over the palace of the king just above a magnificent garden. And in the garden sat Sai-Jen, singing and playing upon the lute. The Feng-Hwang deposited the prince outside the wall near a place where bamboos were growing and showed him how to cut twelve bamboos between the knots to make the flute which is called Pai-Siao and has a sound sweeter than the evening breeze on the forest stream.

And as he blew gently across the pipes, they echoed the sound of the princess's voice so harmoniously that she cried:

'I hear the distant notes of the song that comes from my own lips, and I can see nothing but the flowers and the trees; it is the melody the heart alone can sing that has suffered sorrow on sorrow, and to which alone the heart can listen that is full of longing.'

At that moment the wonderful bird, like a fire of many colours come down from heaven, alighted before the princess, dropping at her feet the portrait. She opened her eyes in utter astonishment at the sight of her own image. And when she had read the lines inscribed in the corner, she asked, trembling:

'Tell me, O Feng-Hwang, who is he, so near, but whom I cannot see, that knows the sound of my voice and has never heard me, and can remember my face and has never seen me?'

Then the bird spoke and told her the story of Ta-Khai's dream, adding:

'I come from him with this message; I brought him here on my wings. For many days he has longed for this hour, let him now behold the image of his dream and heal the wound in his heart.'

Swift and overpowering is the rush of the waves on the pebbles of the shore, and like a little pebble felt Sai-Jen when Ta-Khai stood before her....

The Feng-Hwang illuminated the garden sumptuously, and a breath of love was stirring the flowers under the stars.

It was in the palace of the King of China that were celebrated in the most ancient and magnificent style the nuptials of Sai-Jen and Ta-Khai, Prince of Tartary.

And this is one of the three hundred and thirty-three stories about the bird Feng as it is told in the Book of the Ten Thousand Wonders.

YOUNG ROUSSELLE A FRENCH SONG OF THE OLDEN TIME

Never a roof to all the lot,—

For swallows' nests they will serve quite well—

What do you think of Young Rousselle?

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three top-coats;

Two are of cloth as yellow as oats;

The third, which is made of paper brown,

He wears if it freezes or rain comes down.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three old hats;

Two are as round as butter-pats;

The third has two little horns, 'tis said,

Because it has taken the shape of his head.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three fine eyes;

Each is quite of a different size;

One looks east and one looks west,

The third, his eye-glass, is much the best.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

[6]A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three black shoes

Two on his feet he likes to use;

The third has neither sole nor side:

That will do when he weds his bride.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle three hairs can find:

Two in front and one behind;

And, when he goes to see his girl,

He puts all three of them in curl.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, three boys he has got:

Two are nothing but trick and plot;

The third can cheat and swindle well,—

He greatly resembles Young Rousselle.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three good tykes;

One hunts rabbits just as he likes,

One chivies hares,—and, as for the third,

He bolts whenever his name is heard.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has three big cats,

Who never attempt to catch the rats;

The third is blind, and without a light

He goes to the granary every night.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

[7]A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has daughters three,

Married as well as you'd wish to see;

Two, one could scarcely beauties call,

And the third, she has just no brains at all.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he has farthings three,—

To pay his creditors these must be;

And, when he has shown these riches vast,

He puts them back in his purse at last.

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

Young Rousselle, he will run his rig

A long while yet ere he hops the twig,

For, so they say, he must learn to spell

To write his own epitaph,—Young Rousselle!

Ah! ah! ah! truth to tell,

A jolly good chap is Young Rousselle.

LAYLA AND MAJNÚN A PERSIAN LOVE STORY

She was beautiful as the moon on the horizon, graceful as the cypress that sways in the night wind and glistens in the sheen of a myriad stars. Her hair was bright with depths of darkness; her eyes were dark with excess of light; her glance was shadowed by excess of light. Her smile and the parting of her lips were like the coming of the rosy dawn, and, when love came to her—as he did with a load of sorrow hidden in his sack—she was as a rose plucked from Paradise to be crushed against her lover's breast; a rose to wither, droop, and die as Ormazd snatched it from the hand of Ahriman.

Out of the night came Laylá, clothed with all its wondrous beauties: into the night she returned, and, while the wind told the tale of her love to the cypress above her grave, the stars, with an added lustre, looked down as if to say, 'Laylá is not lost: she was born of us; she hath returned to us. Look up! look up! there is brightness in the night where Laylá sits; there is splendour in the sphere where Laylá sits.

As the moon looks down on all rivers, though they reflect but one moon,—so the beauty of Laylá, which smote all hearts to love. Her father was a great chief, and even the wealthiest princes of other lands visited him, attracted by the fame of Laylá's loveliness. But none could win her heart. Wealth and royal splendour could not claim it, yet it was given to the young Qays, son of the mighty chief of Yemen. Freely was it given to Qays, son of the chief of Yemen.

Now Laylá's father was not friendly to the chief of Yemen. Indeed, the only path that led from the one to the other was a well-worn warpath; for long, long ago their ancestors had quarrelled, and, though there were rare occasions when the two peoples met at great festivals and waived their differences for a time, it may truly be said that there was always hate in their eyes when they saluted. Always? Not always: there was one exception. It was at one of these festivals that Qays first saw Laylá. Their eyes met, and, though no word was spoken, love thrilled along a single glance.

From that moment Qays was a changed youth. He avoided the delights of the chase; his tongue was silent at feast and in council; he sat apart with a strange light in his eyes; no youth of his tribe could entice him to sport, no maiden could comfort him. His heart was in another house, and that was not the house of his fathers.

And Laylá—she sat silent among her maidens with eyes downcast. Once, when a damsel, divining rightly, took her lute and sang a song of the fountain in the forest, where lovers met beneath the silver moon, she raised her head at the close of the song and bade the girl sing it again—and again. And, after this, in the evenings when the sun was setting, she would wander unattended in the gardens about her father's palace, roaming night by night in ever widening circles, until, on a night when the moon was brightest, she came to the confines of the gardens where they adjoined the deep forest beyond;—but ever and ever the moonlight beyond. And here, as she gazed adown the spaces between the tree trunks, she saw, in an open space where the moonbeams fell, a sparkling fountain, and knew it for that which had been immortalised in the sweet song sung by her damsel with the lute. There, from time immemorial, lovers had met and plighted their vows. A thrill shot through her at the thought that she had wandered hither in search of it. Her cheeks grew hot, and, with a wildly beating heart, she turned and ran back to her father's palace. Ran back, ashamed.

Now, in a high chamber of the palace,—it was as wondrous as that[11] of a Sultan,—where Laylá was wont to recline at the window looking out above the tree-tops, there were two beautiful white doves; these had long been her companions, perching on her shoulder and pecking gently at her cheek with 'Coo, coo, coo';—preeking and preening on her shoulder with 'Coo, coo, coo.' They would come at her call and feed from her hand; and, when she threw one from the window, retaining the other against her breast, the liberated one seemed to understand that it might fly to yonder tree; and there it would sit cooing for its mate until Laylá, having held her fluttering bird close for a time, would set it free. 'Ah!' she would sigh to herself, as the bird flew swiftly to its mate, 'when love hath wings it flies to the loved one, but alas! I have no wings.' And yet it was by the wings of a dove that her lover sent her a passionate message, which threw her into joy and fear, and finally led her footsteps to the place of lovers' meeting.

Qays, in the lonely musings which had beset him of late, recalled the story—well known among the people—of Laylá's two white doves. As he recalled it he raised himself upon his elbow on his couch and said to himself, 'If I went to her father, saying, "Give me thy daughter to wife!" how should I be met? If I sent a messenger, how would he be met? But the doves—if all tales be true, they fly in at her window and nestle to her bosom.'

With his thought suddenly intent upon the doves, he called his servant Zeyd, who came quickly, for he loved his master.

'Thou knowest, Zeyd,' said Qays, 'that in the palace of the chief of Basráh there are two white doves, one of which flies forth at its mistress's bidding, and cooes and cooes and cooes until its mate is permitted to fly to it.'

'I know it well, my master. They are tame birds, and they come to their mistress's hand.'

'Would they come, thinkest thou, to thy hand?'

Zeyd, who was in his master's confidence, and knew what troubled him, answered the question with another.

'Dost thou desire these doves, O my master? My father was[12] a woodman and I was brought up in the forests. Many a wilder bird than a dove have I snared in the trees. I even know the secret art of taking a bird with my hand.'

'Then bring me one of these doves, but be careful not to injure it—not even one feather of its plumage.'

Zeyd was as clever as his word. On the third evening thereafter he brought one of Laylá's white doves to Qays and placed it in his hand. Then Qays stroked the bird and calmed its fears, and, bidding Zeyd hold it, he carefully wrapt and tied round its leg a small soft parchment on which were written the following verses:—

And it hath come to me;

And it hath brought me all thy love,

Flying from yonder tree.

Thou shalt not have thy heart again,

For it shall stay with me;

Yet thou shalt hear my own heart's pain

Sobbing in yonder tree.

There is a fount where lovers meet:

To-night I wait for thee.

Fly to me, love, as flies the dove

To dove in yonder tree.

Now Laylá, who had sent her dove into the warm night, sat listening at her window to hear it coo to its mate held close in her bosom. But it cooed not from its accustomed bough on yonder tree. Holding the fluttering mate to her she leaned forth from the window, straining her ears to catch the well-known note, but, hearing nothing, she said to herself, 'What can have happened? Whither has it flown? Never was such a thing before. Perchance the bird is sleeping on the bough.'

Then, as the moon rose higher and higher above the tree-tops, shedding a glistening radiance over everything, she waited and waited, but there came no doling of the dove, no coo from yonder tree. At last, unable to account for it, she took the bird from her bosom and stroked it and spoke to it; then she threw it gently in the air as if to send it in search of its lost mate to bring it back.

The bird flew straight to the tree, and, perching there, cooed again and again, but there was no answering coo of its mate. Finally Laylá saw it rise from the tree and circle round the palace. Many times she saw it flash by and heard the beating of its wings, until at last it flew in at the window; and, when she took it and pressed it to her, she felt that it was trembling. For sure, it was distressed and trembling.

'Alas! poor bird!' she said, stroking it gently. 'It is hard to lose one's lover, but it is harder still never to have found him.'

But lo, as she was comforting the bird, the other dove suddenly fluttered in and perched upon her shoulder. She gave a cry of delight, and, taking it, held them both together in her arms. In fondling them her fingers felt something rough on the leg of the one that had just returned. Quickly she untied the fastenings, and, with beating heart, unfolded the parchment and read the writing thereon. It was the message from her lover. She knew not what to do. Should she go to the fountain where lovers meet beneath the moon? In her doubt she snatched first one dove and then the other, kissing each in turn. Then, setting them down, she rose and swiftly clothed herself in a long cloak, and stole quietly down the stairs and out of the palace by a side door. Love found the way to the path through the forest that led to the fountain where lovers meet. Like a shadow flitting across the bars of moonlight that fell among the trees she sped on, and at last arrived at the edge of the open space where the fountain played, its silvery, high-flung column sparkling like jewelled silver ere it fell in tinkling spray upon the shining moss.

Laylá paused irresolute in the shadows, telling herself that if her heart was beating so hard it was because she had been running.[14] Where was he who had stolen her dove and returned it with a message?

Wherever he was he had quick eyes, for he had discovered her in the shadows, and now came past the fountain, hastening towards her.

She darted into the light of the moon.

'Who art thou?'

Their eyes met. The moonlight fell on their faces. No other word was spoken, for they recognised each other in one glance.

'Laylá! thou hast come to me. I love thee.'

'And I thee!'

And none but the old moon, who has looked down on many such things before, saw their sudden embrace; and none but the spirit of the fountain, who had recorded the words of lovers ever since the first gush of the waters, heard what they said to one another.

And so Laylá and Qays met many times by the fountain and plighted their vows there in the depths of the forest. And once, as they lingered over their farewells, Qays said to Laylá, 'And oh! my beloved, if the desert were my home, and thou and I were free, even in the wilderness, eating the herbs that grow in the waste, or a loaf of thine own baking from the wild corn; drinking the water of the brook, and reposing beneath the bough,—then would I let the world go by, and, with no hate of thy people, live with thee and love thee for ever.'

'And I thee, beloved.'

'Then let us leave all, and fly to the wilderness—'

'Now?'

'No, not now. Thou must prepare. To-morrow, beloved, I will await thee here at this hour with two fleet steeds; and then, as they spurn the dust from their feet, so will we spurn the world—you and I.'

That night Laylá dreamed that she was in the wilderness with her lover, sitting beneath the bough, drinking from the waters of the brook, eating a loaf of her own making from the wild corn, and, in her lover's presence, happy to lose the luxury of palaces.

But alas! the dream was never to be realised. Some one at the palace—some one with more than two ears, and with eyes both back and front—some one, moreover, in the pay of Ibn Salám, a handsome young chief who greatly desired Laylá in marriage, breathed a word into the ear of Laylá's father. The following day the palace was deserted. The old chief, with Laylá and the whole of his retinue, had departed to his estate in the mountains, where it was hoped that the keen, pure air would be better for Laylá's health;—at least so her father said, though none could understand why, seeing that she had never looked better in her life.

Qays, knowing nothing of this sudden departure for several days, waited at the fountain at the appointed hour. At last one day, being already sad at heart, he learned—for Ibn Salám had not been idle in the matter—that Laylá had gone to the mountains of her own accord with her father's household, and that Ibn Salám, the favoured one, had gone with her also. Believing this to be true—for lovers are prone to credit what they fear—Qays ran forth from his abode like a man distraught. In the agony of his despair he thought of nothing but to search for, and find, Laylá. Setting his face towards the distant mountains, he plunged into the desert, calling 'Laylá! Laylá!' Every rock of the wilderness, every tree and thorny waste soon knew her name, for it echoed thereamong all that day and the following night, until at dawn he sank exhausted on a barren stretch of sand.

And here it was that his servant Zeyd and a party of his master's friends found him as the sun was rising. He was distracted. Worn out with fatigue and hunger and thirst, he wandered in his mind as he had wandered in the desert. They took him back to his father's abode and sought to restore him, but, when at last he was well, he still called continually for his lost love Laylá, so that they thought his reason was unhinged, and spoke of him as 'Majnún'—that is to say, 'mad with love'; and by this name he was called ever afterward.

His father came and pleaded with him to put away his infatuation for the daughter of a chief no friend of his; but, finding him[16] reasonable in all things save his mad love, the chief said within himself: 'If he can be healed of this one thing he will be whole.' Then, being willing further to cement enmity or establish a bond with the chief of Basráh, he decided to set the matter to the test. Collecting a splendid retinue, he journeyed to the mountains on a mission to the chief, his enemy, leaving Majnún in the care of the faithful Zeyd.

When, after many days' journey, he at last arrived at the estate of Laylá's father, he stood before that chief and haughtily demanded the hand of his daughter in marriage with his son, setting forth the clear meaning of consent on the one hand and refusal on the other. His proposal was rejected as haughtily as it had been made. 'News travels far,' said the chief of Basráh. 'Thy son is mad: cure him of his madness first, and then seek my consent.'

Cyd, the chief of Yemen, was a proud man and fierce. He could not brook this answer. He had proposed a bond of friendship, and it had been turned into a barbed shaft of war. He withdrew from Basráh's presence with the cloud of battle lowering on his brows. He returned to his own place to come again in war, vowing vengeance on Basráh.

But Yemen's chief delayed his plans, for, on his return, he discovered that his son, accompanied by the faithful Zeyd, had set out on the yearly pilgrimage to Mecca, there to kneel before the holy shrine and drink of the sacred well in the Kaába.

'Surely,' said he, 'that sacred well of water which sprang from the parched desert to save Hagar and her son will restore my own son to his health of mind. I will follow him and pray with him at the holy shrine; I will drink also at the sacred well, and so, perchance, he will be restored to me.'

But it so chanced that, when the chief, followed by a splendid retinue, was but two days on his journey towards Mecca, he was met by a lordly chief of the desert named Noufal, who, with a small band of warriors, rode in advance of a cloud of dust to greet him in friendly fashion.

'I know thee,' said Noufal, reining in his magnificent horse so[17] suddenly that the sand and gravel scattered wide; 'thou art the chief of Yemen and the father of Majnún, whom I have met in the desert. Greetings to thee! I have succoured thy son, whom I found in sore straits and nigh unto death. I have heard his story, and I will aid him and thee against the chief of Basráh, if it be thy will, O chief of Yemen.'

'Greetings to thee, O Noufal! I know thy name; thou art a wanderer of the desert, but I have heard many brave tales of thy prowess and thy generosity. Thou hast my son in thy keeping? But how comes it that he failed of his pilgrimage to Mecca, whither I was following to join him at the holy shrine?'

'Alas! he fell by the wayside in sight of my warriors; and, when they came to him, his only cry was, "Laylá! Laylá!" They brought him to me, and from his broken story and this oft-repeated cry of "Laylá" I knew him for Majnún, thy son; for the tale of beauty and love, O chief of Yemen, travels far in the silent desert.'

'What wouldst thou, then, Noufal?'

'I would that thou and I, for the sake of thy son, go up against the chief of Basráh and demand his daughter. If he consent not, and we conquer, I will extend thine interests and protect them through the desert and beyond. If he consent, thou and I and he will be for ever at peace, and will combine our territories on just terms of thine own choosing.'

'Thou hast spoken well, O Noufal, and I trust thee. Go thou up against the chief of Basráh and demand Laylá in my name. I will follow thy path, and, if thou returnest to meet me with Laylá in thy protection, all is well; but, if not, then we will proceed against Basráh together, and thy terms shall be my terms. For the rest, thou hast swift messengers, as have I.'

At the word Noufal wheeled his horse and gave commands to some of his warriors, and presently six fleet-footed chargers were speeding towards the horizon in six different directions to call the warriors of the desert to converge on a point at the foot of the mountains. Meanwhile similar messengers were hastening back to[18] Yemen with orders from their chief. Noufal and his band of warriors set out for the rendezvous, but the chief of Yemen waited for the return of his messengers.

Meanwhile Laylá, on her father's estate among the mountains, lived in the depths of misery. The young chief Ibn Salám, well favoured of her father, was continually pleading for her hand in marriage, but Laylá's protestations and tears so moved her father that he was fain to say to the handsome and wealthy suitor, 'She is not yet of age; wait a little while and all will be well.' For Basráh looked with a calculating eye on this young chief, who had splendid possessions and many thousands of warriors. As for Laylá, she immured herself from the light of day, communing only with the stars by night, and saying within her heart, 'I will die a maiden rather than marry any but Majnún, who is now, alas! distracted, even as I.'

Now Laylá, well knowing that her doves were nesting in 'yonder tree,' had left them to the care of the attendants at the palace. They had always been a solace to her, especially since one had been Love's messenger, and she missed that solace now. A young tiger, obedient only to an Ethiopian slave, could not speak to her of love as the doves had done! But one day a slave-girl brought her a bird of paradise, saying, 'My boy lover caught this in the forests of the hills and bade me offer it to thee for thy kindness to me.'

Laylá treasured the bird in her solitude, and soon discovered that it could imitate the sounds of her voice. On this she straightway taught it one word, and one word only. Then she would sit for hours, with the bird perched on the back of her hand, listening to its soft intonation of that one word: 'Majnún.' Again and again and again the bird would speak softly in her ear that sweetest name in all the world: 'Majnún, Majnún, Majnún,' and her heart would leave her bosom and range through the desolation of the desert, seeking always Majnún.

The affair of her heart stood in such case when, one day at dawn, Noufal, with a large band of warriors, smote with his sword upon the gates and demanded to see the chief of Basráh.

It was a short and pointed exchange of few words between Noufal and Basráh as the broadening band of sunlight crept slowly down the background of mountains; and, when it smote upon the gates as the sun burst up, the talk was finished and Noufal and his band were galloping towards the desert to meet the oncoming hosts of Yemen. The chief of Basráh gazed upon the cloud of dust that rose between him and the sun, and in it read the signs of sudden war.

Now Basráh's mountain estate adjoined the territory of Ibn Salám, and, as soon as the latter learned that the chief had flouted Noufal in favour of his own suit, and that the thunder-cloud of battle was arising against the wind, he offered the aid of a thousand of his warriors—an offer which was eagerly accepted. But the thousand he offered were not a third part of the warriors at his call.

The way of war was paved. Before noon a host of Ibn Salám's warriors came riding in. Laylá, from her window, noted their brave array. Then, looking far out on to the desert, she saw the dust-cloud rising from the hoofs of an advancing host. 'Alas!' she cried, 'the heart that beats in my bosom is the cause of this. I love my father; I love Majnún: Destiny must choose between them.'

Destiny hath strange reversals. The shock and clash of battle dinned on her ears till near nightfall, when, with a heart divided between hope and fear, she saw clearly that Ibn's hosts could not hold their ground. The onslaughts of her father's foe were forcing them back. They scattered, and rallied, and scattered again. Those that were left retreated within the gates. The gates were battered down, and all was lost—or won. A herald advanced, offering terms of surrender. Laylá leaned from her window, listening. No word could she hear until her father, still defiant in the face of defeat, spoke in ringing tones.

'And, if I deliver not up my daughter, you will take her. Yea, but you will not take her alive. I have but to raise my hand and[20] she will be slain. I have lost all, but my servants will still obey me: if I give the word, her dead body is yours for the asking.'

At this the chief of Yemen bade him hold his hand from committing this terrible deed.

'O chief of Basráh,' he said, 'I give thee one day to think about this matter. There are two sides to it: the one is that thou deliver up thy daughter to be given to my son to wife, so that there may be a bond of friendship between us; the other is that thou keep thy daughter and surrender thy sovereignty, retaining thy territories only in vassalage to me.'

With that the chief of Yemen and his ally, Noufal, withdrew, leaving Basráh to decide before dawn the following day.

Now, among Ibn Salám's messengers that he had sent out was one whose orders were to ride back, as if from Yemen, bringing word that he had discovered Majnún, who, having fled from his attendants in the night, was lying dead in the desert. This was not truth, but Ibn had reason to believe that it soon would be, for he had sent out others to find him and kill him. It was to his purpose that the false news should arrive quickly, for, on that, and the offer of a further host of warriors at his command, he hoped to gain Laylá's promise and strengthen her father's hand in the matter.

The victors had scarcely withdrawn when the messenger rode in, shouting the news to victors and vanquished alike. The chief of Yemen heard it and wept for his son. Noufal heard it and said, 'Laylá is nothing to us now; at dawn we shall dictate our own terms.' Ibn Salám and Laylá's father heard the news without grief, and Ibn said, 'Now there can be no obstacle to thy daughter's consent, for she is a woman, and must know that the living is more desirable than the dead. I have already helped thee, O Chief, and we have failed. But thy daughter has only to speak the word and a further host of my warriors—more than treble the number that fought to-day—will come out of the desert at my call. Half will come to aid our defence, and half will attack the hosts of Yemen from the desert. Thus your foes will be scattered like chaff in the[21] wind. Go to thy daughter and show her now how a word from her will save thee from destruction and make thee great.'

The chief of Basráh went to his daughter, and, when Ibn heard sounds of a woman wailing, he knew that the false news of Majnún's death was believed. Long time the chief pleaded with Laylá, urging the uselessness of weeping for Majnún when, by accepting Ibn in marriage, she could save Basráh and make it a great kingdom. Then he spoke of her duty to him, her father, in this terrible plight, from which her word alone could save him; and Laylá saw, through her tears, that for her father's sake the sacrifice must be made; and through duty, not love, she mournfully pledged herself to Ibn Salám.

As soon as Ibn knew this he called some of his warriors and questioned them on the matter of his hosts in reserve.

'Four thousand,' he said, when he had heard their replies. 'The foe is but three thousand, and we are little more than one thousand.'

Then he gave orders to some chosen messengers and bade them steal forth secretly and deliver them to his generals. Half the four thousand was to arrive by night under cover of the mountains and be ready for battle at sunrise. The other half was to make a circuit of the desert and fall upon the foe from behind when the battle was at its hottest. On this sudden stroke he relied for complete victory.

And he was not wrong. When dawn broke over the desert, and the mountain peaks were flushed with sunrise fire, the dark shadows at the base were two thousand strong. There they waited hidden from the foe, while, as the sun rose, a herald came to the gates. In the name of Yemen, he dictated the terms of surrender without any condition in regard to Laylá.

The chief of Basráh laughed him to scorn. 'Go tell the chief of Yemen and his robber friend of the desert,' he said, 'that if they desire my domains they must take them by force of arms. Tell them that Basráh never surrenders: he prefers to live free, or to die fighting.'

The herald took back this proud answer of defiance. On hearing it Yemen wondered and questioned, but Noufal, who was a man of the desert, sudden in temper and quick to act, counselled an immediate attack.

The battle was joined. At the first shock came Ibn's two thousand warriors from their concealment, and the invaders fell back in astonishment. Yet they rallied again, and fiercely raged the fight between the opposing hosts, now equally matched in numbers. Laylá looked from her window in horror. She noted how the battle swayed this way, then that. And now it seemed that the foe was steadily gaining the mastery. But what was that in the distance of the desert? What was that, thrust forward from the desert? A great cloud of dust, quickly approaching. It drew near, its cause quickly outstripping it. A mighty host of warriors now shook the earth with the thunder of their horses' feet. They drew nearer. Now like a whirlwind they hurled themselves upon the invaders and bore them down like trodden wheat—sweeping the flying remainder of them like chaff to the four winds.

Yemen was slain. Noufal, flying from numbers on swifter steeds than his, laughed back at his pursuers, then slew himself, dying, as he had lived, at full gallop.

Basráh was victorious. That night Laylá was given by her father to Ibn Salám. That night, too, the chief of Basráh, having been previously wounded in the battle, died. Ibn ruled now over three vast territories welded into one. And, where he was king, Laylá was queen.

Years passed by, and Ibn and Laylá reigned in peace. The palace of her fathers was their abode, and the bird of paradise and the two white doves were often her companions, recalling to her heart a lost, but never-to-be-forgotten, love. The faithful Zeyd, who had wandered long in the desert searching in vain for his master, was now her servant.

One day news came secretly to Zeyd that Majnún, long mourned[23] as dead, had returned disguised as a merchant from distant parts, and would be waiting for him at a certain spot on the outskirts of the desert at sunset. Zeyd said nothing of this to his mistress, but, unknown to her, he caught one of the doves and took it away with him to the meeting-place, for he reasoned that what had happened once would happen again with like result. Full of joy was the meeting between Majnún and Zeyd on the edge of the desert as the sun went down.

Now Laylá, when she repaired to her high chamber that evening, was astonished to find one of her doves missing. She sent the other forth to the great tree, thinking the two might return together, but presently it returned alone. Then, wondering greatly, she sat by the window, musing on the past: how, three years ago, the dove had returned after an absence, bearing a love-message from Majnún, and how she had met him again and again at the lovers' fountain in the forest. Alas! all was changed: Majnún was dead, and she was the wife of another. Her eyes filled with tears, and, bowing her head on her arms upon the window-sill, she wept silently.

For a long time she remained like this. Then, suddenly, she was aroused from her weeping by a sound. It was the 'coo, coo, coo' of the missing dove, and it came from the great tree. Immediately the other dove fanned her hair as it sped past her to its mate. It made her long for wings that she too might fly away and away to her lover.

Presently the two birds fluttered in at the window and came to her. What strange thing was this? There, wrapped round the leg of one was a small strip of soft parchment as on that night long ago. With trembling fingers she unfastened and read what was written thereon. It was from Majnún! He was alive and well! As before, the writing begged her to come that very night to the lovers' fountain at moonrise.

In her sudden joy at learning that her lover was alive and near at hand, Laylá forgot all, and, as the gibbous moon was already brightening the horizon, she arose and cloaked herself and stole[24] down the stairway of the palace. She reached the side door unobserved. She passed out and closed it behind her. Her heart flew before her to Majnún, but suddenly, as she hastened, it rebounded swiftly and almost stopped beating. Her footsteps faltered and she clutched at a bough of a tree for support. Her husband! Her duty! Once she had given all for duty's sake: should she take it back now, and in this way? What would it mean? With Majnún's arms around her she would forget all—husband, duty, her people: all, all would be forgotten, and the step once taken could not be retraced. Alas! this was not the act of a wife! It was not the act of a queen! She groaned as she grasped the bough, and her body swayed with her spirit's woe as she then and there rejected her purpose and accepted her sorrow.

Slowly Laylá strengthened herself; then, like one in a dream, she turned and retraced her steps to the palace, no sigh, no sob escaping her. All that night she refused sleep or comfort, dry-eyed; and it was only when the dawn came that tears came too, to save her reason on its throne.

Majnún waited long by the lovers' fountain, and, at last, learning from Zeyd that his mistress had ventured forth and had returned, he went away, treasuring to his heart a love that could not give one glance without giving all; for, from Zeyd's story he knew this to be so. As Laylá had gone back to the palace, silent and strong, so Majnún set his face towards distant cities, praying ever that the years might bring surcease of woe, if not the rapture of the love of Laylá.

Two years passed by, and Fate stepped in. Ibn Salám fell stricken with a fever and died. The news spread far, and one day Majnún, in a distant city, looked up and heard that Laylá, the queen of Yemen and Basráh, was free. Swift, then, were the steeds that bore him to Yemen. But, remembering how she had twice sacrificed herself for duty, he forbore to approach her until the expiration of the prescribed term of widowhood—four moons and half a moon. This period he spent, alone and unknown, in an abode[25] from which he could see the lights of Laylá's palace. His longing ate into his heart, and it was harder to bear than his former distraction, by which he had earned his name of Majnún ('mad with love'). But as, in the first instance, his reason had borne the strain, so now it bore the stress of all this weary waiting at the gates of Paradise.

Zeyd bore tidings of Laylá to Majnún, but from Majnún to Laylá no message passed until, on a day when the prescribed term had passed, Zeyd took word to her that Majnún would come to her at the palace at noon, or, according to her choice, wait for her at the lovers' fountain at two hours after sunset.

Zeyd brought back the delayed message: 'Noon has passed, but noon will come again—after this eventide.' Which was not unlike the answer Majnún had expected.

The saddest part of the history of these ill-destined lovers is yet to be told. Two hours after sunset Majnún kept the tryst. Two hours after sunset Laylá, her eyes smouldering with a pent-up fire, cloaked herself as of old and went out by the side door of the palace. There was no moon, but the stars shed a soft light upon the gardens. She passed among the trees; her heart beat fast and her breath came quick. The whole of her life seemed wrapped up in her two feet, which ran a hot race with each other. She reached the edge of the forest and paused, clasping her hands over her bosom. She must regain her breath to show Majnún how little she had hastened. Then, before she had regained it, she ran on, losing it the more. There was the fountain—the fountain where lovers had always met—she saw it sparkling in the starlight through the trees. Now she stood on the edge of the open space, the folds of her cloak parted, her masses of raven hair fallen loose, her breast heaving.

A figure darted from the fountain's side. She faltered forward, swaying. A moaning cry escaped her as Majnún caught her in a wild embrace.

Who knows if it was but a moment or a thousand years? Love has no dial. But that time-moment two hours after sunset was their swift undoing. At the touch of her lips upon his, Majnún's reason[26] was wrenched away. At the touch of his lips upon hers, she swooned in his arms. He let her fall, and ran, shrieking, out of the forest and into the desert; shrieking her name, far into the desert.

'Laylá! Laylá! Laylá!'—his maniac cries echoed on and on until, in the hopeless waste of wilderness, he fell exhausted. But Zeyd, who had followed his voice, at last found him. Many a day and night he tended his master, but to no purpose. Joy had done what grief had failed to do: he was mad!

Laylá awoke from her swoon, and, hearing her own name repeated again and again,—that wild cry coming from farther and farther in the desert,—divined the truth and returned, slowly and wringing her hands, to the palace.

From time to time Zeyd sent news of Majnún and his undying love, which even his madness had failed to touch.

Day by day, and week by week, Laylá's eyes grew brighter and her cheeks paler. Slowly she pined away, and then she died of a broken heart. Her last words were a message to Majnún—a message of love that could not die, though it must quit the beautiful, unhappy house of clay in which it had suffered so much.

'And tell him,' she said, 'that my body shall be buried by the side of the fountain where he first clasped me in his arms. And tell him, too, these very words: 'Majnún, lift thine eyes! See, yonder are the Fields of Light, and a fountain springing in the sunshine—yonder—a fountain of eternal waters, where lovers meet, never to part again;—thou shalt find me there!' And with that she died, and her spirit sped on her parting thought to that place of lovers' meeting;—the immortal font of lovers' meeting.

Dawn was breaking on the desert when two figures came running. Each held the other by the hand, and on the face of one was that look which told how he had been driven mad by love. Majnún, outstripping Zeyd, left him to follow, and plunged into the forest. Soon he came to the open space in which the fountain played. Well he knew the spot where he had first clasped Laylá[27] in his arms. There was now a newly made grave. Exhausted, not with running, but with love, madness, and grief, he flung himself upon it.

'Laylá! Laylá!' he moaned, with a heart-bursting pang. 'I will come soon—ah, soon! Hold thy shroud of night about thee! Hide thy beauty in the Fields of Light—until I find thee there!'

And, as the sun rose, Zeyd came and stood by the grave, gazing down upon his master through tears of grief;—gazing down upon the dead through bitter tears of grief.

THE NIGHTINGALE AFTER A FAIRY TALE BY HANS ANDERSEN

From every land travellers came to see the emperor's palace and walk in the wonderful garden, but those who heard the Nightingale sing said, 'There is nothing here so entrancing as that song.' And these went away carrying the music in their hearts and the tale of it on their lips to tell in their own lands. Thus the wonder of the Nightingale was known afar, and learned men wrote books about it, describing at length the beauty of the emperor's palace and garden only as a fit setting for the crowning wonder of all—the bird whose entrancing song lifted all this earthly splendour to heaven. Many were the poems written and sung about the far-off Nightingale which filled and thrilled the woods with music by the deep-blue sea. The books and the poems went through the whole world, and of course many of them reached the emperor.

Sitting in his golden chair reading, he nodded his head with a smile of pleasure at the splendid descriptions of palace and garden and all they contained; but, when he read that all this splendour was of minor account compared to the glorious singing of a Nightingale in the woods by the sea, he sat up straight and said, 'A Nightingale? What is this? A wonder in my own home, my own garden—a wonder that travels afar and yet I have never heard of it till now! What strange things we read about in books, to be sure. But I'll soon settle the matter.'

With this he summoned his gentleman-in-waiting—a very important personage; so important, indeed, that when one of less importance dared to address him on even a matter more important than either of them, he would simply answer, 'Ph!'—which, as you know, means nothing at all.

'They say,' said the emperor, 'ahem! they say there is a wonderful bird here called a Nightingale, compared with whose delicious song my palace and garden are of small account. Why have I not been informed of this marvel?'

The gentleman-in-waiting protested that he knew nothing whatever of such a thing as a Nightingale—at least, he was certain it had never been presented at court.

'These books cannot all be wrong,' said the emperor; 'especially as they all agree in their accounts of it. It appears that the whole world knows what I am possessed of, and yet I have never known it myself till now. I command you to bring this rare bird here this evening to sing to me.'

The gentleman-in-waiting went off, well knowing what would happen if he failed to produce the bird in the time appointed. But how was it to be found? He ran up and down stairs and through all the corridors asking rapid questions of every one he could find, but not one knew anything about the Nightingale. 'Ha!' thought he, 'this thing is a myth, invented by writers to make their books more interesting.' And he ran back and told the emperor so.

'Nonsense!' cried the emperor. 'This book here was sent me by his powerful majesty the emperor of Japan, so it must be true—every word of it. I will give this bird my most gracious protection, but, as for those who fail to find it and bring it here to-night—well, if it is not forthcoming, I will have the whole court trampled upon after supper!'

'Tsing-pe!' said the gentleman-in-waiting, and hurried off. Up and down all the stairs, in and out all the corridors he ran again, and this time half the court ran with him, for the thought of being trampled upon got into their heels and there was no time to be wasted. Still, no one in court knew anything about the Nightingale with which all the outside world was so familiar. But at last they came to a poor little maid in the scullery. She knew all about it. 'Oh yes; the delightful Nightingale!' she cried. 'Of course I know it. Every evening I hear it sing in the wood by the seashore on my way home. Ah me! its music brings tears into my eyes and makes me feel as if my mother is kissing me.'

'Listen, little kitchen-maid!' said the gentleman-in-waiting, 'if you will lead us to the Nightingale I will give you permission to see the emperor dining to-night.'

She clapped her hands with glee at this, and very soon they were all following her on the way to the wood. As they ran a[32] cow began to bellow loudly, and they stopped. 'That's it!' cried a young courtier. 'What a magnificent voice for so small a creature!'

'Nay, nay; that's a cow. We have not reached the place yet.' And the little maid hurried them on.

Presently the frogs of a neighbouring marsh raised a chorus of 'Koax! koax!'

'How beautiful!' cried the palace chaplain; 'more beautiful than the sound of church bells. This bird——'

'Nay, nay; those are frogs; but we are coming to the Nightingale soon.' And the little maid ran on. Then, suddenly, they all paused, breathless, beneath the trees, for the Nightingale had begun to sing.

'There it is! there it is!' cried the little kitchen-maid, pointing to the little gray bird among the branches. 'Listen!'

'Ph!' said the gentleman-in-waiting; 'what a common little object! I suppose meeting so many grand people from other lands has driven all its colours away. But it can——'

'Nightingale!' called the little kitchen-maid; 'our most gracious emperor wants you to sing to him to-night!'

'With all the pleasure in the world,' replied the bird, trilling out the most delightful notes.

'Extraordinary!' said the gentleman-in-waiting, who had perceived that the Nightingale was thinking, very naturally, that he was the emperor; and all the courtiers took up the word; for if he said 'Extraordinary!' instead of 'Ph!' surely the whole world had a perfect right to go into hysterics over such singing.

'My dear little Nightingale,' he said at last, 'I have the honour to command your attendance at court to-night to sing before the emperor.'

'I think it sounds best among the trees,' replied the Nightingale, 'but I will do my best to please the emperor.' And it fluttered down and perched on the little kitchen-maid's shoulder. Then away they went to the palace.

That evening the splendid abode of the emperor was a sight to see. The china walls and floors shone with the radiance of a thousand golden lamps; the corridors were decked with the rarest flowers from the garden, each with its little silver bell attached, so that when the breeze swept their subtle perfumes along the ways of the palace they rang a peal of joy.

In the great reception-room sat the emperor, and near by his side was a golden rod on which was perched the Nightingale. Every one was there, and all were dressed in their very best, for it was a time of rejoicing; the wonderful bird had been found, and the whole court had escaped being trampled upon. Even the little kitchen-maid, who had now been raised to the position of cook, was allowed to stand behind the door, where she could feast her wide eyes on the mighty emperor.

There was silence. Then the little gray bird began to sing. The emperor nodded approvingly; then, as a burst of glorious song came in liquid notes from the Nightingale and welled out into the palace, the emperor's eyes slowly filled with tears, which soon rolled down over his cheeks. Seeing this the bird sang more divinely still, so that all hearts were touched. The emperor wrung his hands with delight; he was so charmed that he said he would decorate the Nightingale: it should have his gold slipper to wear round its neck. But this the Nightingale declined gracefully, with thanks.

'I have seen tears in the eyes of the emperor,' it said, 'and that is sufficient reward.' Then it burst again into its sweet, melodious song.

The Nightingale soon became the one absorbing fashion. The ladies, when any one spoke to them, took water in their mouths, raised their heads and gurgled, thinking to imitate its song. The lackeys and chamber-maids, who are always the most difficult people to please, freely admitted they had nothing whatever against the bird; while the people of the town could think of nothing else but this new wonder of the palace. So great was their feeling on the matter that when two met in the street one would say, 'Night,' to[34] which the other replied, 'Gale'; then they would sigh and pass on, perfectly understanding each other. Eleven different cheesemongers' children, who had the good luck to be born during this time, were named after the bird, but not one of these cheese-mites ever developed the semblance of a voice.

As for the Nightingale itself, it had indeed made a great sensation, and was accorded every honour. Living at court, it was assigned a special cage, with full liberty to walk out twice a day and once in the night. On these outings it was attended by twelve footmen, each holding a separate ribbon attached to its leg. You can imagine how the poor bird sang for joy when it got back to its cage again.

One day the emperor was sitting in his golden chair when a large parcel was brought to him bearing on the outside the word 'Nightingale.' Thinking it was another book on the subject he put it aside, but, when he came to open it later, he was astonished to find that it was no book, but an exquisite little work of art—an artificial Nightingale, just like the real one, but in place of gray feathers there were wonderful diamonds, and rubies, and sapphires. Round its neck was a ribbon on which was written, 'The emperor of Japan's Nightingale is a poor bird compared with the emperor of China's.'

On examination it was found that this splendid toy was meant to go. So it was wound up, and immediately it sang that extremely lovely thing which the real Nightingale had first sung to the emperor.

'How delightful!' cried everybody, and immediately the emperor summoned the messenger who had delivered the parcel, and there and then created him Imperial Nightingale-Carrier in Chief.

'Now,' said the emperor, as the I.N.-C.C. withdrew, 'the two birds must sing together. What a duet we shall have!'

But the duet was not a great success, for the real Nightingale sang with its soul in its throat, while the other merely sang with the machinery it was stuffed with. They did not get on at all well together. But the music master explained all this quite easily,[35] saying that their voices, though of equal merit, were of widely different quality, and each could be heard to best advantage alone. As to time and tune and dramatic attack, he said, there was nothing to choose between them.

So the toy bird had to sing alone, and everybody said the music master was right; there was nothing to choose between the two, unless it was that the toy bird's coat was a blaze of dazzling jewels, while that of the other was a gray drab—common in the extreme. The toy bird sang just as well, and, besides, it was much prettier to look at.

When the new Nightingale had sung the same tune thirty-three times and the courtiers wanted still to hear the tune again, the emperor said, 'No; the real bird must have its turn now.' But the real bird was nowhere to be found: it had flown out at the open window, back to its own woods by the side of the deep-blue sea.

'What does this mean?' cried the emperor.

The gentleman-in-waiting stepped forward.

'It means, your Majesty,' he said, 'it means, I'm afraid, that it was an ungrateful bird, but still clever enough to give place to its betters.'

And then, when all were agreed that they had got the better bird, the toy Nightingale sang the same tune again, for the thirty-fourth time, because, though they had heard it so often, they did not know it thoroughly even yet: it was so very difficult.

The music master was loud in his praises of the bird. He extolled it inside as well as out, saying that it was not only beautiful and valuable, but that its works were perfect. The real bird sang what it liked, but here one could choose a given tune and hear it sung. The whole thing was far more perfect than the real. The court agreed with him, and the emperor was prevailed upon to let the people hear the toy bird sing on the following Sunday.

When Sunday came the whole town assembled before the palace, and, when they heard the bird sing, they were as excited as if they had drunk themselves merry on tea, which is a way they have in[36] China. All except the poor fisherman, who had so often paused from his toil to listen to the real Nightingale. 'It is a very good imitation,' said he; 'but it lacks something, I can't say what.' And the little kitchen-maid, who was now a real cook, said nothing, but stole away in sadness to the wood, where she knew that she would hear the real music that she loved.

Following the opinion of the people the emperor banished the real Nightingale from the kingdom, and placed the toy bird on a silken cushion close to his bed, with the gifts of gold and jewels it had received arranged around it. And he promoted it to the rank of 'Chief Imperial Singer of the Bed-Chamber,' class one, on the left side; that is to say, nearest the heart, for even an emperor's heart is on the left side. And he gave the music master royal permission to write a work of five-and-twenty volumes about the bird, which no one has ever read to this day, because it is so tremendously difficult; but you would not find any one in China who would not claim to have mastered it thoroughly, since they one and all object to be thought stupid and to have their bodies trampled upon.

For a whole year the artificial bird ground out its mechanical tunes. They were even set to music by the skilled men of the time, and the people sang them in their homes. On great public festivals, when the bird sang before delighted multitudes, they would raise their voices and join in the chorus. It was a great success. But one night, when the bird was singing its best by the emperor's bedside, something inside the toy went 'whizz.' Then, with a grating catch and a snap, the main crank broke: 'whirr' went all the wheels, and the music stopped.

The emperor immediately summoned the Chief Winder of the Imperial Singer of the Bed-Chamber, and he, with the assistance of the skilled workmen of his department, managed, in less than seven days and nights of talk and toil, to put the works right again; but, he said, the inside of the bird was not what it used to be, and, unless it was used very sparingly, say once a year, he hesitated to say what might happen in the end.

This was a terrible blow to China! The bird could only sing once a year, but, on that great annual occasion, it was listened to with long-pent-up enthusiasm; and, at the end of the concert, the music master made a speech, in which he used none but the most difficult words, to prove that the bird was still as good as ever, in fact even better, and that his saying so made it so.

Five years passed away, during which time the bird sang five times; and then a great grief fell upon the nation. The emperor lay dying. The physicians came and went, shaking their heads: they gave no hope. The gentleman-in-waiting, when questioned by the people as to the state of their emperor, merely answered 'Ph!' So bad was the outlook that already a new emperor had been chosen, and the whole court hurried to congratulate him.

The old emperor lay pale and still in his gorgeous bed, but he was not dead. While the courtiers were jostling each other in their efforts to catch the eye of the emperor-elect; while the lackeys were running hither and thither exchanging the news, and the chamber-maids giving a grand coffee-party, the old emperor's spark of life flickered and flickered. Through a high open window the moon shone in upon the bed with its velvet hangings and heavy golden tassels; upon the pale face of the emperor; upon the jewelled bird by his side. Now he gasped for breath: there was something heavy on his chest. With a great effort he opened his eyes, and there, sitting upon him, he saw Death, wearing his own golden crown, with his own golden sword in one hand, and in the other his own imperial banner. Death grinned as he settled himself more heavily. Then, as the emperor still struggled for breath, he saw, peering at him round the folds of the bed-hangings, the faces of all the deeds he had ever committed. Some were hideous as they hissed, 'Do you remember?' Others were sweet and loving as they murmured, 'Do you remember?' And then, while they told him in one breath all that he had ever done, good and bad, Death sat heavier and heavier upon him, nodding his head at all they had to say.

The perspiration streamed down the emperor's face. At last he[38] shrieked aloud, 'This is unbearable! Sound the drums! Give me music to drown their voices!' Then he said to the bird by his side, 'You precious little bird—golden bird with your coat of jewels—sing, sing! I have given you everything; I have even hung my golden slipper round your neck,—now sing, I command you, sing!'

But there was no response. The bird stood there, a dumb thing: you see, it could not sing because there was nobody there to wind it up. Then, as Death fastened his empty sockets upon him, a terrible silence fell. Deeper and deeper it grew, and the emperor could hear nothing but the beating of Death's heart—his own would soon be silent.

Suddenly through the open window came a lovely burst of song. Radiant, sparkling as a shower of pearls, the living notes of rarest melody fell within the silent chamber. It was the Nightingale, perched on a branch outside—the Nightingale as God had made it, singing the song that God had taught it. It had heard the emperor's call, and had come to bring him comfort.

Slowly, slowly, as it sang divinely, the faces that peered round the velvet folds grew wan. Pale Death himself started, and turned still paler with wonder and amazement. 'How beautiful!' he said; 'sing on, little bird, thrilling with life!'

'Lay down the imperial banner,' answered the Nightingale; 'lay down the golden sword; lay down the emperor's crown.'

'Agreed!' And the mighty snatcher, Death, laid down these treasures for the price of a song. The Nightingale went on singing. And it sang as it flitted from bough to bough, until it reached the quiet churchyard where the grass grows green upon the graves, where the roses bloom living on the breast of death, and the cypress points to the immortal skies. There on the cypress' topmost twig it perched and sang a song so rich and rare, so far-reaching, that it touched the heart of Death sitting on the chest of the emperor,—for, after all, Death has a tender heart. Filled with a longing for his own garden, melted by the Nightingale's song, he vanished in a cold, grey mist,—out at the window.

Soon came the Nightingale fluttering with delight above the emperor's bed. Then it perched by the side of the toy bird, and the emperor looked, and knew at last the difference between the natural and the artificial. He knew, too, that he ought to have known it before.

'You heavenly little bird!' he said. 'Welcome back to my heart! I banished you from my kingdom, but you heard my call and returned to charm away those evil visions, and even Death himself. Thanks! A world of thanks! How can I ever repay you?' Tears shone in the emperor's eyes.

'I am already repaid,' said the Nightingale. 'When first I sang to you I saw tears in your eyes, and now I see them again. Those are the jewels that I wear in my heart, not upon my coat. But sleep now; you must get well. Sleep—I will sing you to sleep!'

So the little bird sang, and the emperor fell into a healing sleep. In the morning, when the sun shone in at the window, he awoke refreshed and well. Where were his attendants? None was there: they were all busy running after the emperor-elect. But the Nightingale was there, perched on the window-sill, singing divinely.

'Little Nightingale,' said the emperor tenderly, 'you must come and stay with me always. You shall sing only when you like; and, as to this toy bird here, I will smash it in a thousand bits.'

'Oh! you mustn't do that,' replied the real bird, 'it did its best, and, after all, it is a pretty thing. Keep it always by you. I can't come to live in the palace, but let me come whenever I like and sit in the tree outside your window and sing to you in the evening. I will sing you songs to make you happy, to cheer and comfort you. And sometimes I will sing of those who suffer, to make you sad, and then you will long to help them. I will sing of many things unknown to you in your great wide kingdom, for the little gray bird flies far and wide, from the roof-tree of the humblest peasant to the bed of the mighty emperor. Yes, I will come very often—but—but will you promise me one thing?'

'I will promise you anything, little bird.' The emperor had[40] risen from his bed; he now stood by the window in his imperial robes, and the jewels in the golden crown upon his head flashed and sparkled in the moonlight. Taking his heavy sword he pressed the golden hilt against his heart as he repeated, 'anything—anything!'

'It is just one little thing,' said the Nightingale. 'Never let any one know that you have a little gray bird who tells you everything. It is far better.'

With that the Nightingale skipped to a branch of the tree, trilled a long trill, and then, in the grey light of dawn, flew off to her nest.

When the courtiers and attendants came in to view the body of their late master, he was still standing by the window in his imperial robes. They gasped in horror at missing their grief.

'Good morning!' said the emperor.

THREE KINGS OF ORIENT A CAROL

GASPAR, MELCHIOR, BALTHAZAR:

Bearing gifts we traverse afar

Field and fountain,

Moor and mountain,

Following yonder star.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night,

Star with Royal Beauty bright,

Westward leading,

Still proceeding,

Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

GASPAR.

Gold I bring to crown Him again,

King for ever,

Ceasing never

Over us all to reign.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night,

Star with Royal Beauty bright,

Westward leading,

Still proceeding,

Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

MELCHIOR:

Incense owns a Deity nigh.

All men, raising

Prayer and praising,

Worship Him, God on High.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night,

Star with Royal Beauty bright,

Westward leading,

Still proceeding,

Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

BALTHAZAR:

Breathes a life of gathering gloom;—

Sorrowing, sighing,

Bleeding, dying,

Sealed in the stone cold tomb.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night,

Star with Royal Beauty bright,

Westward leading,

Still proceeding,

Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

GASPAR, MELCHIOR, BALTHAZAR:

King and God and Sacrifice;

Heav'n sings Hallelujah,

Hallelujah the earth replies.

O Star of Wonder, Star of Night,

Star with Royal Beauty bright,

Westward leading,

Still proceeding,

Guide us to Thy perfect Light.

SINDBAD THE SAILOR A TALE FROM THE THOUSAND AND ONE NIGHTS

But first let me call to thy recollection how Sindbad the Sailor came to tell his story to Sindbad the Landsman, for herein lies much meaning, O King.

In the time of the Caliph Harun-er-Rashid, in the palmy days of Baghdad, there lived and slaved a poor, discontented porter, whose moments of rest and leisure were most pleasantly occupied in grumbling at his hard lot. Others lived in luxury and splendour while he bore heavy burdens for a pittance. There was no justice in the world, said he, when some were born in the lap of wealth, and others toiled a lifetime for the price of a decent burial.

This discontented porter would run apace with his burden to gain time for a rest upon the doorstep of some mansion of the rich, where, a master in contrasts, he would draw comparisons between his own lot and that of the rich man dwelling within. Loudly would he call on Destiny to mark the disparity, the incongruity, the injustice of the thing; and not until he had drunk deep at the fountain of discontent would he take up his burden and trudge on, greatly refreshed.

One day, in pursuance of this strange mode of recreation, he chanced to select the doorstep of a wealthy merchant named Sindbad the Sailor, and there, through the open window, he heard as it were[44] the chink of endless gold. The song, the music, the dance, the laughter of the guests—all seemed to shine with the light of jewels and the lustre of golden bars. Immediately he began to revel in his favourite woe. He wrung his hands and cried aloud: 'Allah! Can such things be? Look on me, toiling all day for a piece of barley bread; and then look on him who knows no toil, yet eateth peacocks' tongues from golden dishes, and drinketh the wine of Paradise from a jewelled cup. What hath he done to obtain from thee a lot so agreeable? And what have I done to deserve a life so wretched?'

As one who flings back a difficult question, and then bangs the door behind him, so the porter rose and shouldered his burden to continue his way, when a servant came running from within, saying that his master had sharp ears and had invited the porter into his presence for a fuller hearing of his woes.

As soon as the porter came before the wealthy owner of the house, seated among his guests and surrounded by the utmost luxury and magnificence, he was greeted with the question: 'What is thy name?' 'My name is Sindbad,' replied the porter, greatly abashed. At this the host clapped his hands and laughed loudly. 'Knowest thou that my name is also Sindbad?' he cried. 'But I am Sindbad the Sailor, and I have a mind to call thee Sindbad the Landsman, for, as thou lovest a contrast, so do I.'

'True,' said the porter, 'I have never been upon the sea.'

'Then, Sindbad the Landsman,' was the quick rejoinder, 'thou hast no right to complain of thy hard lot. Come, be seated, and, when thou hast refreshed thyself with food and wine, I will relate to thee what at present I have told no man—the tale of my perils and hardships on the seas and in other lands—in order to show you that the great wealth I possess was not acquired without excessive toil and terrible danger. I have made seven voyages: the first thou shalt hear presently—nay, if thou wilt accept my hospitality for seven days, I will tell thee the history of one each day.'

Thus it was, O King, that Sindbad the Sailor, surrounded by a[45] multitude of listeners, came to tell the story of his voyages to Sindbad the Landsman. Now on the fifth day he spoke as follows:

Having sworn that my fourth voyage should be my last, I dwelt in the bosom of my family for many months in the utmost joy and happiness. But soon my heart grew restless in my bosom, and I longed again for the perils of the sea, and the adventures found only in other lands. Moreover, I had become inspired of a new ambition to possess a ship of my own in which to sail afar, and even to greater profit than on my former voyages.

I arose, therefore, and gathered together in Baghdad many bales of rich merchandise, and departed for the city of El-Basrah, where, in the river's mouth, I soon selected a splendid vessel. I purchased this and secured a master and a crew, over whom I set my own trusty servants. Then, together with a goodly company of merchants as passengers, their bales and mine being placed in the hold, I set sail.

Fair weather favoured us as we passed from island to island, bartering everywhere for gain, as merchants do, until at length we came to an island which seemed never to have known the fretful heel of man. Here we landed, and, almost immediately, on sweeping our gaze over the interior, we espied a strange thing, on which all our attention and wonder soon became centred.