All these sketches, except "The Sikh" and "The Drabi," were written in Mesopotamia. My aim has been, without going too deeply into origins and antecedents, to give as accurate a picture as possible of the different classes of sepoy. In Mesopotamia I met all the sixteen types included in this volume, some for the first time. My acquaintance with them was at first hand. But neither sympathy nor observation can initiate the outsider into the psychology of the Indian soldier; or at least he cannot be certain of his ground. One must be a regimental officer to understand the sepoy, and then as a rule one only knows the particular type one commands.

Therefore, to avoid mistakes and misconceptions, everything that I have set down has been submitted to authority, and embodies the opinion of officers best qualified to judge--that is to say, of officers who have passed the best part of their lives with the men concerned. Even so I have no doubt that passages will be found that are open to dispute. Authorities disagree; estimates must vary, especially with regard to the relative worth of different classes; and one must always bear in mind that every company officer who is worth his salt is persuaded that there are no men like his own. It is a pleasing trait and an essential one. For it is the sworn confraternity between the British and Indian officer, and the strong tie that binds the sepoy to his Sahib which have given the Indian Army its traditions and prestige.

All references and statistics concerning the Indian Army will be found to relate to the pre-war establishment; and no class of sepoy is included which has been enlisted for the first time since 1914. At the outbreak of war the strength of the Army in India was 76,953 British and 239,561 Indian. During the war 1,161,789 Indians were recruited. The grand total of all ranks sent overseas from India was 1,215,338. The casualties sustained by the force were 101,439. Races which never enlisted before enlisted freely, and the Indian Army List when published on the conclusion of Peace will be changed beyond recognition.

One or two classes I have omitted. The introduction of the Gujar, Meo, Baluchi and Brahui, for instance, as separate types, would be an error of perspective in a volume this size. It is hardly necessary to differentiate the Gujar from the Jat; the origin of the two races is much the same, and in appearance they are not always distinguishable. The Meo, too, approximates to the Merat. The Baluchi proper has practically ceased to enlist, and the sepoy who calls himself a Baluch is generally the descendant of immigrants. There is also a scattering of Brahuis in the Indian Army. They and the Baluchis are of the same stock, and are supposed to have come from Aleppo way, though in some extraordinary manner which nobody can understand the Brahuis have picked up a Dravidian accent.

It is difficult, too, to write of the Madrasi--Hindu, Mussalman, or Christian--as an entity apart. All I know of him is that in the Indian Sappers and Miners and Pioneer regiments, when he is measured with other classes, his British officer speaks of him as equal to the best.

The names of the officers to whom I am indebted would make a long list. I met them in camps, messes, trenches, dugouts, and in the open field. Some are old friends; others are unknown to me by name; many are unaware that they have contributed material for these sketches; and I can only thank them collectively for their help. For verification I have consulted the official handbooks of the Indian Army; and for certain of my references to the achievements of the Indian Army in France I am indebted to the semi-official history ("The Indian Corps in France," by Lieut.-Col. J. W. B. Merewether, C.I.E., and Sir Frederick Smith) published under the authority of the Secretary of State for India. One chapter, "The Drabi," I have taken almost bodily from my "Year of Chivalry," which also included the story of Wariam Singh; my thanks are due to the publishers, Messrs. Simpkin Marshall, for their permission to reprint it. For the account of the Jharwas I am indebted to an officer in a Gurkha regiment who wishes to remain anonymous. For illustrations my thanks are due to General Holland Pryor, M.V.O., Major G. W. Thompson, and Lieut.-Cols. Alban Wilson, D.S.O., R. C. Wilson, D.S.O., M.C., F. L. Nicholson, D.S.O., M.C., H. M. W. Souter, W. H. Carter, E. R. P. Berryman, and Mr. T. W. H. Biddulph, C.I.E.

Two Indian words occur frequently in these pages. They are izzat and jiwan, words that are constantly in the mouths of officers and sepoys. "Izzat" is best rendered by "honour" or "prestige"; "jiwan" means a "youngster," and is applied to the rank and file of the Indian Army without reference to age. I have kept the vernacular forms, as it is difficult to find exact English equivalents, and much that is homely and familiar in the words is lost in translation.

| PAGE | |

| The Gurkha | 1 |

| The Sikh | 26 |

| The Punjabi Mussalman | 49 |

| The Pathan | 63 |

| The Dogra | 92 |

| The Mahratta | 104 |

| The Jat | 115 |

| The Rajput and Brahman | 125 |

| The Garhwali | 138 |

| The Khattak | 149 |

| The Hazara | 159 |

| The Mer and Merat | 170 |

| The Ranghar | 181 |

| The Meena | 188 |

| The Jharwas | 200 |

| The Drabi | 208 |

| The Santal Labour Corps | 217 |

| The Indian Follower | 227 |

| FACING PAGE | |

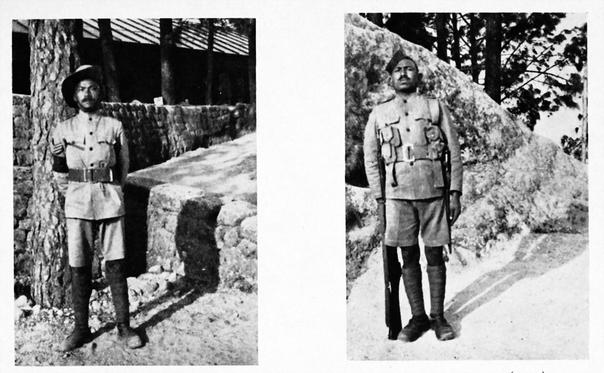

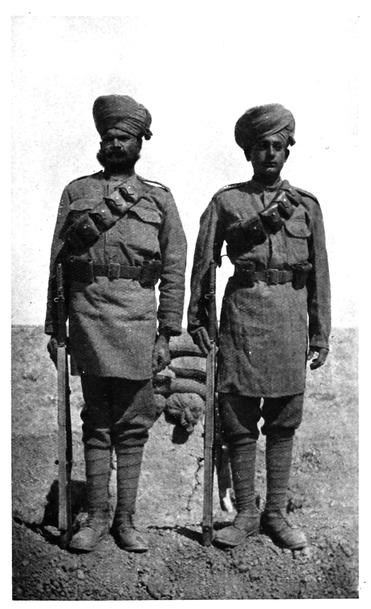

| Havildar Chandradhoj (Rai) | 6 |

| Tekbahadur Ghotam (Khas) | 6 |

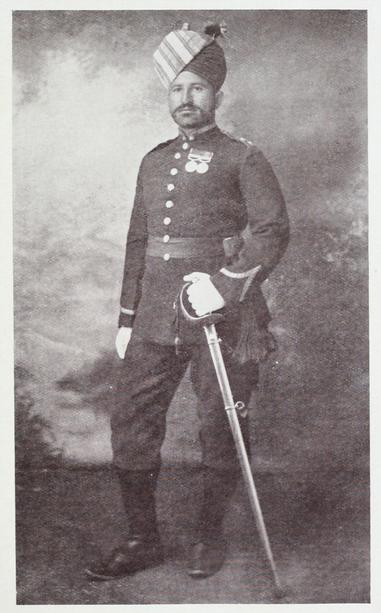

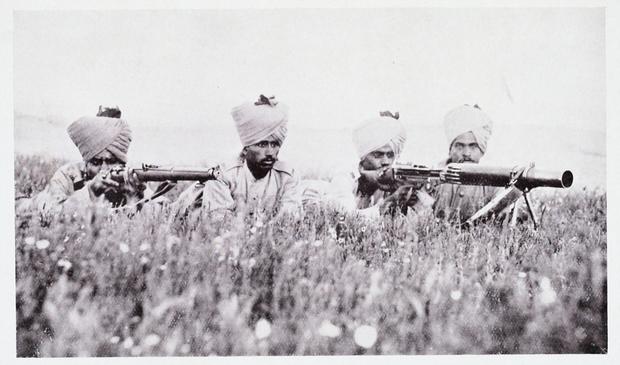

| The Sikh | 26 |

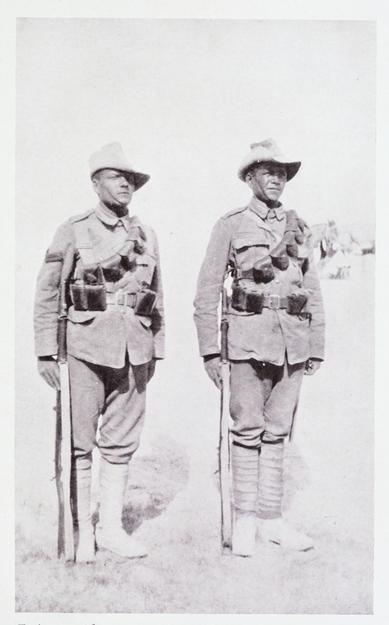

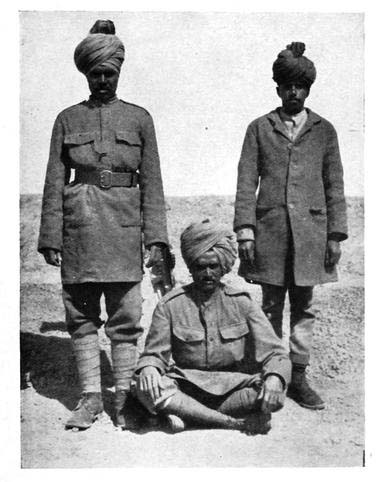

| The Punjabi Mussalman | 50 |

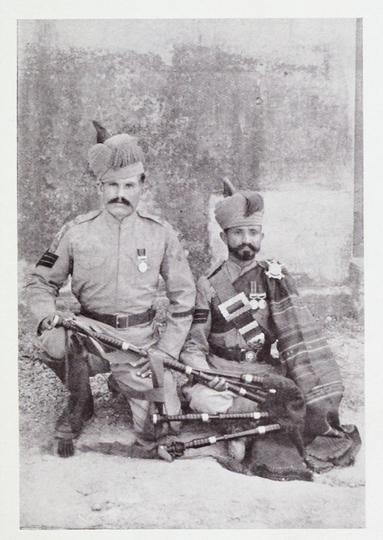

| The Pathan Pipers | 64 |

| The Dogra | 92 |

| The Konkani Mahratta | 104 |

| The Dekhani Mussalman | 112 |

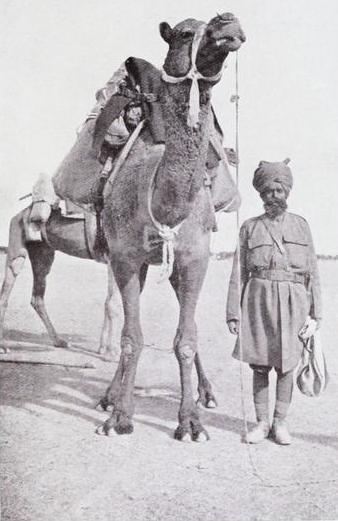

| A Jat Camel Sowar | 116 |

| The Rajput | 126 |

| The Garhwali | 138 |

| The Hazara | 160 |

| The Merat | 170 |

| The Ranghar | 182 |

| The Meena | 188 |

| The Jharwa | 200 |

| Bhil Followers | 230 |

THE GURKHA

So much has been written of the Gurkha and the Sikh that officers who pass their lives with other classes of the Indian Army are tired of listening to their praises. Their fame is deserved, but the exclusiveness of it was resented in days when one seldom heard of the Mahratta, Jat, Dogra, and Punjabi Mussalman. But it was not the Gurkha's or the Sikh's fault if the man in the street puts them on a pedestal apart. Both have a very distinctive appearance; with the Punjabi Mussalman they make up the bulk of the Indian Army; and their proud tradition has been won in every fight on our frontiers. Now other classes, whose qualities were hidden, live in the public eye. The war has proved that all men are brave, that the humblest follower is capable of sacrifice and devotion; that the Afridi, who is outwardly the nearest thing to an impersonation of Mars, yields nothing in courage to the Madrasi Christian of the Sappers and Miners. These revelations have meant a general levelling in the Indian Army and the uplift of classes hitherto undeservedly obscure. At the same time the reputation of the great fighting stocks has been splendidly maintained.

The hillmen of Nepal have stood the test as well as the best. Ask the Devons what they think of the 1/9th Gurkhas who fought on their flank on the Hai. Ask Kitchener's men and the Anzacs how the 5th and 6th bore themselves at Gallipoli, and read Ian Hamilton's report. Ask Townshend's immortals how the 7th fought at Ctesiphon; and the British regiments who were at Mahomed Abdul Hassan and Istabulat what the 1st and 8th did in these hard-fought fights. Ask the gallant Hants rowers against what odds the two Gurkha battalions[1] forced the passage of the Tigris at Shumran on February 23rd. And ask the commander of the Indian Corps what sort of a fight the six Gurkha battalions[2] put up in France.

Nothing could have been more strange to the Gurkha and more different from what his training for frontier warfare had taught him to expect than the conditions in Flanders. The first trenches the Gurkhas took over when they were pushed up to the front soon after their arrival in France were flooded and so deep that the little men could not stand up to the parapet. They were exposed to the most devastating fire of heavy artillery, trench-mortars, bombs, and machine guns. Parts of their trench were broken up and obliterated by the Hun Minnewerfers and became their graves. They hung on for the best part of a day and a night in this inferno, but in the end they were overwhelmed and driven out of the position, as happens sometimes with the best troops in the world. The surprising thing is that they became inured to this kind of warfare. Not only did they stand their ground, but in more than one assault they drove the Huns from their positions, and in September, 1915, the same battalion that had suffered so severely near Givenchy carried line after line of German trenches west of Martin du Pietre.

Those early months in France, when our troops, ill provided with bombs and trench-mortars and inadequately supported by artillery, were shattered by a machinery of destruction to which they could make little reply, were very much like hell. The soldier's dream of war had come, but in the form of a nightmare. Afterwards in Mesopotamia, the trench-fighting at El-Hannah and Sannaiyat was not much more inspiring. But the hour was to come when our troops had more than a sporting chance in a fight, and war became once more for the man at the end of the rifle something like his picture of the great game. The Gurkhas were severely tried in the ordeal by which this change was effected, and they played a stout part especially in the Tigris crossing, the honour of which they shared with the Norfolks; but, like the British Tommy in these trying times, they were always cheerful.

It is not the nature of any Sepoy to grouse. Patience and endurance is the heritage of all, but cheerfulness is most visible in the "Gurkh." He laughs like Atkins when the shells miss him, and he is never down on his luck. When the Turks were bombarding us on the Hai, I watched three delighted Gurkhas throwing bricks on the corrugated iron roof of a signaller's dug-out. A lot of stuff was coming over, shrapnel and high explosive, but the Gurkhas were so taken up with their little joke of scaring the signallers that the nearer the burst the better they were pleased. The signallers wisely lay "doggo" until one of the Gurkhas appeared at the door of the dug-out and gave the whole show away by a too expansive grin.

In France the element of shikar was eliminated. It would be affectation in the keenest soldier to pretend that he enjoyed the long-linked bitterness of Festubert, Givenchy, and Neuve Chapelle. But in Mesopotamia, especially after the crossing of the Tigris and the capture of Baghdad, there were many encounters in which one could think of war in the terms of sport. "There has been some shikar," is the Gurkha's way of describing indifferently a small scrap or a big battle. Neuve Chapelle was shikar. And it was shikar the other day when a Gurkha patrol by a simple stratagem surprised some mounted Turks. The stratagem succeeded. The Turks rode up unsuspectingly within easy range, but the Gurkhas did not empty a single saddle. Their British officer chaffed them on their bad shooting; but the havildar grinned and said, "At least a little shikar has taken place." That is the spirit. War is a kind of sublimated shikar. It is the mirror of the chase. The Gurkha is hunting when he is battle-mad, and sees red; and he is hunting when he glides alone through the grass or mud on a dark, silent night to stalk an enemy patrol. Following up a barrage on the Hai, the 1/9th were on the Turks like terriers. "Here, here, Sahib!" one of them called, and pointing to a bay where the enemy still cowered, pitched his bomb on a Turk's head with a grin of delight and looked round at a paternal officer for approval. Another was so excited that he followed his grenade into the trench before it had burst, and he and his Turk were blown up together.

The first time I saw Gurkhas in a civilized battle was at Beit Aieesa, where the little men were scurrying up and down the trenches they had just taken, with blood on their bayonets and clothes, bringing up ammunition and carrying baskets of bombs as happy and keen and busy as ferrets. They had gone in and scuppered the Turk before the barrage had lifted. They had put up a block and were just going to bomb down a communication trench. I saw one of them pull up the body of a British Tommy who had been attached to the regiment as a signaller and was bombed into a mess. The Gurkha patted him on the shoulder and disappeared behind the traverse without a word.

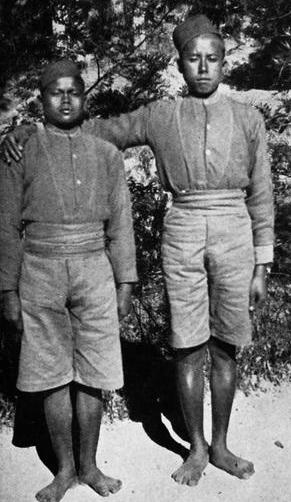

left. Havildar Chandrahoj (Raj).

right. Tekbahadur Ghotam (Khas).

The Gurkha fights as he hunts. Parties of them go into the jungle to hunt the boar. They beat the beast up and attack him with kukris when he tries to break through their line. It is a desperate game, and the casualties are a good deal heavier than in pig-sticking. The Gurkha's attitude to the Turk or the Hun is his attitude to the boar. There is no hostility or hate in him, and he is a cheerful, if a grim, fighter. There was never a Gurkha fanatic. The Magar or Gurung does not wish to wash his footsteps in the blood of the ungodly. To the righteous or the unrighteous stranger he is alike indifferent. There is no race he would wish to extirpate, and he has few prejudices and no hereditary foes. When his honour or interest is touched he is capable of rapid primitive reprisals, but he does not as a rule brood or intrigue. His outlook is that of a healthy boy. There is no person so easy to get on with as the "Gurkh." The ties of affection that bind him to his regimental officers are very intimate indeed. When the Sahib goes on leave trekking, or shooting, or climbing, he generally takes three or four of the regiment with him. I have often met these happy hunting-parties in and beyond the Himalayas. I have a picture in my mind of a scene by the Woolar Lake in Kashmir. The Colonel of a Gurkha regiment is sitting in a boat waiting for a youth whom he has allowed to go to a village on some errand of his own. The Colonel has waited two hours. At last the youth appears, all smiles, embracing a pumpkin twice the size of his head. No rebuke is administered for the delay. The youth squats casually in the boat at his Colonel's feet, and as he cuts the pumpkin into sections, makes certain unquotable comments on the village folk of Kashmir. As the pair disappear across the lake over the lotus leaves I hear bursts of laughter.

The relations between officers and men are as close as between boys and masters on a jaunt together out of school, and the Gurkha no more thinks of taking advantage of this when he returns to the regiment than the English schoolboy does when he returns to school. It is part of his jolly, boyish, uncalculating nature that he is never on the make. In cantonments, when any fish are caught or any game is shot, the first-fruits find their way to the mess. No one knows how it comes. The orderly will simply tell you that the men brought it. Perhaps after a deal of questioning the shikari may betray himself by a fatuous, shy, bashful grin.

The Gurkha does not love his officer because he is a Sahib, but because he is his Sahib, and the officer has to prove that he is his Sahib first, and learn to speak his language and understand his ways. A strange officer coming into a Gurkha regiment is not adopted into the Pantheon at once. He has to qualify. There may be a period of suspicion; but once accepted, he is served with a fidelity and devotion that are human and dog-like at the same time. I do not emphasize the exclusive attachment of the Gurkha to his own Sahib as an exemplary virtue; it is a fault, though it is the defect of a virtue. And it is a peculiarly boyish fault. It is the old story of magnifying the house to the neglect of the school. Infinite prestige comes of it; and this is to the good. But prestige is often abused. Exclusiveness does not pay in a modern army. In the organism of the ideal fighting machine the parts are compact and interdependent; and it would be a point to the good if every Gurkha were made to learn Hindustani and encouraged to believe that there are other gods besides his own.

When one hears officers in other Indian regiments disparage the Gurkha, as one does sometimes, one may be sure that the root of the prejudice lies in this exclusiveness. I have heard it counted for vanity, indifference, disrespect. It is even associated, though very wrongly, with the eminence, or niche apart, which he shares in popular estimation with the Sikh. But the Gurkha probably knows nothing about this niche. He is a child of nature. His clannishness is very simple indeed. He frankly does not understand a strange Sahib. Directly he tumbles to it that anything is needed of him he will lend a hand, but having no very deeply-ingrained habit of reverence for caste in the abstract apart from his devotion to the proved individual, he may appear sometimes a little neglectful in ceremony. But no Sahib with a grain of imagination or understanding in him will let the casual habits of the little man weigh in the balance against his grit and gameness, his loyalty, and his splendid fighting spirit. I am always suspicious of the officer who depreciates the Gurkha. He is either sensitively vain, or dull in reading character, or jealous of the dues which he thinks have been diverted from some other class to which he is personally attached.

This last infirmity one can understand and forgive. It grows out of an officer's attachment to his men. It is present sometimes in the British officers who command Gurkhas. Indeed, a man who after a year's service with any class of Sepoy is so detached and impartial in mind as not to find peculiar and distinctive virtues in his own men, ought not to be serving in the Indian Army at all. I remember once hearing a subaltern in a very obscure regiment discussing his class company. The battalion had not seen service for at least three generations, and everyone took it for granted that they would "rat" the first time they heard a shot fired. But the boy was full of "bukh."

"By Jove!" he said, "our fellows are simply splendid, the best plucked crowd in the Indian Army, and so game.... Oh no! they've never been in action, but you should just see how they lay one another out at hockey."

Before the war one would have smiled inwardly at this "encomium," if one could have preserved one's outward countenance, but Armageddon, the corrective of exclusiveness and pride, has taught us that gallantry resides under the most unlikely exteriors. It has taught us to look for it there. Anyhow the boy had the right spirit even if his faith were founded in illusion; for it is through these ties of mutual loyalty that the spirit of the Indian Army is strong.

The devotion of the Sepoy to his officer is common to most, perhaps to all, classes of the Indian Army. In some of the Gurkha battalions it is usual for two of the men to mark their Sahib when he goes into action, to follow him closely, and if he falls, to look after him and bring him back whether wounded or dead. This is a tacitly understood and quite unofficial arrangement, and the officer knows no more about his self-appointed guard than the hero or villain of melodrama about the detective who dogs his footsteps in the street. In France a British officer in a Gurkha regiment knocked out by shell-shock opened his eyes to find his orderly kneeling over him fanning the flies off his face. He lost consciousness again. When he came to the Gurkha was still fanning him, and the tears were rolling down his cheeks.

"Why are you crying, 'Tegh Bahadur?'" he said; "I am not badly hit."

"I am crying, Sahib," he said, "because my arm is gone, and I am no more able to fight." And with a nod he indicated the wound. The shell that had stunned the Sahib had carried off the orderly's forearm at the elbow.

The Medical Officer will tell you that the Gurkha is the pluckiest little fellow alive. In hospital he will go on smoking and chatting to you when he is dying, fighting his battles over again. I remember a Gurkha in an ambulance at Sinn pointing his index finger, which was hanging by a tendon, as he described the attack. During a cholera outbreak in 1916 among the Nepalese troops garrisoning the Black Mountains frontier a Gurkha, who was evidently in extremis, was being carried by his Major and another officer to a bit of rising ground where there was some shade and a little breeze. When in an interval of consciousness he opened his eyes and saw two Sahibs carrying him, he tried to raise himself to the salute, but fell back in a half faint. "You must pardon me, Sahib," he said, "but owing to weakness I am unable to salute." The Major told him to lie still. "We are taking you to a cool place," he explained. "Now you must be quick and get well." The Gurkha answered with a faint smile, "Now that your honours have honoured me by carrying me, I shall quickly get well." In a few minutes he died.

The Gurkha is not given to the neatly turned speech, the apt phrase, and one might search one's memory a long time before one recalled a compliment similar to this one spoken in simple sincerity by a dying man. The arts of conciliation are not practised where he camps. There is a delightful absence of the courtier about him, and he could not make pretty speeches if he tried. The "Our Colonel Sahib shot remarkably well, but God was merciful to the birds" story is told of a very different race. If a colonel of Gurkhas shoots really badly, his orderly will probably be found doubled up with mirth. The few comments of the Gurkha that stick in the mind are memorable in most instances for some crudeness, or misconception, or for a primitive, and not infrequently a somewhat gruesome, sense of humour. One meets many types, but the average "Gurkh," though observant, is not as a rule quick at the uptake. I heard a characteristic story of one, Chandradhoj, a stalwart Limbu of Eastern Nepal. It was in November last year, in the days of trench warfare. His Colonel had sent him from the Sannaiyat trenches to Arab Village to have his boots mended, and when he was returning in the evening the Turks got it into their heads that a relief was taking place, and put in a stiff bombardment, paying special attention to the road. Chandradhoj got safely back through this. When the Colonel met him in the evening passing his dug-out he stopped him and asked him how he had fared.

"Well, you've got back all right," he said. "You wern't hit!"

"No, Sahib, I was not hit. I came back in artillery formation."

One could see him solemnly stepping aside a few paces from the road, the prescribed distance from the imaginary sections on the left or right. These were the Sahib's orders at such times, he would argue, and there must be salvation in the rite.

The Gurkha sees what he sees, and his visual range is his mental range. At Kantara he only saw the desert, and the desert was sand. Other conditions beyond the horizon, an oasis for instance, were inconceivable. He tried to get it out of his Sahib how and where the Bedouin lived who came into Kantara Post. He thought they lived in holes in the sand, but what they ate he could not imagine. When they came into the Post looking wretched and miserable he gave them chapattis. "But, Sahib," he asked, "what could they have eaten before we came other than sand?"

One is never quite sure what will move a Gurkha to laughter. He grins at things which tickle a child's fancy, and he grins at things which make the ordinary man feel very sick inside. When the Turk abandoned Sinn in May, 1916, we occupied the position. The advance lay over the month-old battlefield of Beit Aieesa, and the enemy's dead were lying everywhere in a very unpleasant stage of dissolution. Suddenly the grimness of the scene was disturbed by explosive bursts of laughter. It was the Gurkhas. "Well, what is the joke? What are you laughing at?" an officer asked them. "Look, Sahib!" one of them said. "The devils are melting." Only he used a much more impolite word than "devil," for which we have no translation.

The Gurkha has not a very high estimate of the value of life. A few years ago, when Rugby football was introduced in a certain battalion, there was an unfortunate casualty soon after the first kick-off. One of the men, collared by his Sahib, broke his neck on the hard ground, and was killed stone-dead. The incident sealed the fate of Association in the regiment, and Rugby became the vogue from that hour. "This is something like a game," they said, "when you kill a man every time you play."

The Gurkha would not be such a fine fighter if he had not a bit of the primitive in him. Several years ago two companies of a Gurkha battalion, who were holding a post in a frontier show, were bothered by snipers at night. The shots came from a clump of bushes on the edge of a blind nullah full of high brushwood, which for some reason it was inadvisable to picquet. Here was an excellent chance of shikar, and a havildar and four men asked if they might go out at night and stalk the Pathans. They were allowed to go, the conditions being that they were to go bare-footed, they were not to take rifles, and they were to do the work with the kukri. Also they were to stay out all night, as they would certainly be shot by the sentries of other regiments if they tried to come in. Only one sniper's bullet whizzed into camp that night. The next morning the havildar entered the mess while the officers were breakfasting. He came in with his left hand behind his back and saluted.

"Sahib," he said, "two of the snipers have been killed."

"That's good, havildar," the Colonel said. "But how do you know that you got them? Are they lying there, or have their brothers taken them away?"

The havildar, grinning broadly, produced a Pathan's head, and dumped it on the breakfast table. "The other is outside," he said. "Shall I bring it in?"

The Gurkha is good at this kind of night-work; he has the nerve of a Highlander and the stealth of a leopard. His great fault in a general attack is that he does not know when to stop. Without his Sahib he would not survive many battles. And that is why the casualties are so heavy in regiments when the British officers fall early in the fight. When the Gurkhas were advancing at Beit Aieesa, I heard an officer in a Sikh regiment say, "Little blighters. They're always scurrying on ahead, and if you don't look after them they will make a big salient and bite off more than they can chew." This is exactly what happened, though with the Turkish guns as a bait, guns which they took and lost afterwards by reason of the offending salient, they would not have been human if they had held back.

The Gurkha battalions, as everybody knows, have permanent cantonments in the hills, and do not move about like other regiments from station to station. Most of them have their wives and families in the lines, and in the leave season they get away for a time to their homes in Nepal. In peace the permanent cantonment with its continuity of home life is a privilege; but in the war the Gurkhas, like every other class of sepoy, have had to bear with a weariness of exile which it is difficult for any one but their own officers to understand. It is true of the Gurkha, as of the Indian of the plains, that he gives up more when he leaves his home to fight in a distant country than the European. The age-worn traditions and associations which make up homeliness for him, the peculiar and cherished routine, cannot be translated overseas. And it must be remembered that the sepoy has not the same stimulus as we have. It is true that he is a soldier, and that it is his business to fight, and that he is fighting his Sahib's enemy. That carries him a long way. But he does not see the Hun as his Sahib sees him, as an intolerable, blighting incubus which he must cast off or die. One appreciates his cheerfulness in exile all the more when one remembers this.

On a transport this summer in Basra, Asbahadur, a young Gurung from Western Nepal was pointed out to me. He had just come home from leave. He had six weeks in India, but there was the depôt to visit first. He had to pick up his kit and draw his pay, and by the time he had got to his village, Kaski Pokhri, on the Nepal frontier, sixteen days hard going from Gorakhpur in the U.P., he found that he had only four days at home before he must start off again to catch his steamer at Bombay. But he had seen his family, his house, his crops, the barn that had to be repaired, the familiar stretch of jungle and stream. He had dumped his money in the only place where money is any good; and he had seen that all was well.

He had learned, too, that it was well with his young brother, who had run away from home to join the army, as so many young Gurkhas did at the beginning of the war,--literally "running" for the best part of two nights and days, only a short neck ahead of his pursuing parents, who had now forgiven him.

There is conscription in Nepal now and there is no need for the young men to run away. Asbahadur told me that he had met very few young men of his age near his home. In his village the women were doing the work, as they were in France, and as he understood was the case in the Sahib's country. The garrisoning of India by the Nepalese troops had depleted the county of youth. You only met old men and cripples and boys. Early in the war the Nepal Durbar came forward with a splendid offer of troops, which we were quick to accept. Thousands of her best, including the Maharaja's Corps de garde, poured over the frontier into Hindustan, and released many regular battalions for service overseas. They have fought on the frontier, and taken their part in policing the border from the Black Mountains on the north to as far south as the territory of the Mahsuds.

There are three main divisions of Gurkhas: the Magar and Gurung of Central and Western Nepal, indistinguishable except for a slight accent; the Limbu and Rai of Eastern Nepal; and the Khattri and Thakur, who are half Aryan. The Magars and Gurungs are the most Tartar-like, short, with faces flat as scones. The Limbu and Rai physiognomy assimilates more with the Chinese. In the Khattri and Thakur, or Khas Gurkhas as they are called by others, though they do not accept the term, the Hindu strain is distinguishable, though the Mongol as a rule is predominant. They are the descendants of Brahmans or Rajputs and Gurkha women; hence the opprobrious "khas," or "fallen." But it is a blend of nobility--a proud birthright. It is only the implication of the "fall" they resent,--for these marriages were genuine but for the narrow legislation of orthodoxy and caste. Before the war it was taken as a matter of course by some that the streak of plainsman in the mountaineer must imply a softening of the national fibre, but the war has proved them as good as the best. In the crossing of the Tigris at Shumran, the miniature Mesopotamian Gallipoli, the Khas (9th Gurkhas) shared the honours in full with the Magars and Gurung (2nd Gurkhas); but long before that any suspicion of inferiority had been dissipated.

It is difficult to differentiate the different classes, but the Khas Gurkha is probably the most intelligent. In the Limbu and the Rai there are sleeping fires. They are as fastidious about their honour as the Pathan and the Malay, and when any sudden and grim poetic justice is exacted in blood in a Gurkha regiment the odds are that one or the other are at the bottom of it. The Magars and the Gurung are the basic type, the "everyman" among Gurkhas, the backbone in numbers of the twenty battalions. As regards pluck there is nothing to choose between any of them, and if one battalion goes further than another the extra stiffening is the work of the British officers.

One's impression of the Gurkha in war and peace is of an almost mechanical smartness, movements as quick and certain as the click of a rifle bolt. Soldiering is a ritual among them. You may mark it in the way they pitch camp, solemnly, methodically, driving in each peg as if it were an ordained rite. They have learnt it all by rote. They could do it as easily in their sleep. And the discipline has stood the shock of seismic disturbance. In the Dharmsala earthquake of 1905 the quarter guard of the 2/8th Gurkhas turned out and saluted their officer with the same clockwork precision, when their bungalow had fallen like a house of cards. They had escaped by a miracle, and half the regiment had been killed, or maimed, or buried alive.

But remove the Gurkha from the atmosphere of barracks and camps and the whole ritual is forgotten like a dream. Out on shikar, or engaged in any work away from the battalion, he becomes his casual self again. But the guest of a Gurkha regiment does not see this side of him. I have memories of the men called into the mess and standing round like graven images, the personality religiously suppressed, the smile tardily provoked if Generals or strange Sahibs are present. A boy, with a smooth, round, innocent face, as still and as expressionless as if he had been hypnotized. Next to him a man with the face of a bonze. Another with an expression of ferocity asleep and framed in benevolence. Passion has drawn those deep lines at right angles with the mouth. They are scars of the spirit--often enough now in the same setting as dints of lead and steel.

You get these faces in Gurung, Magar, Limbu, Khas, and Rai. But differentiation is profitless and often misleading, whether as regards the outward or inward man. I heard an almost heated discussion as to relative values by officers, who should know best, terminated by an outsider with the laconic comment, "They are all dam good at chivying chickens." As to this all were agreed. And the remark called up another picture--the Gurkha returning from a punitive raid against a cut-throat tribe, smothered in spoil and accoutrements, three carpets under one saddle, and the little man on top with chickens under each arm, and strung as thick as cartridges to his belt and bandolier.

It has often been said that the Indian Army has kept Sikhism alive. War is a conserver of the Khalsa, peace a dissolvent. When one understands how this is so, one has grasped what Sikhism has done for the followers of the faith, and why the Sikh is different in habit and thought from his Hindu and Muhammadan neighbour, though in most cases he derives from the same stock.

The Sikhs are a community, not a race. The son of a Sikh is not himself a Sikh until he has taken the pahul, the ceremony by which he is admitted into the Khalsa, the community of the faithful. It would take volumes to explain exactly what initiation means for him. But the important thing to understand is that the convert, in becoming a Sikh, is not charged with a religious crusade. There is no bigotry in the faith that has made a Singh of him. His baptism by steel and "the waters of life" only means that he has gained prestige by admission into a military and spiritual brotherhood of splendid traditions.

THE SIKH.

Guru Nanak (1469-1539), the founder of the sect, was a man of peace and a quietist. He only sought to remove the cobwebs that had overgrown sectarian conceptions of God. He could not in his most prophetic dreams have foreseen the bearded, martial Sikh whom we know to-day. This is the Govindi Sikh, the product of the tenth Guru, that inspired leader of men who welded his followers into the armed fraternity which supplanted the Moguls and became the dominant military class of the Punjab.

It was persecution that made the Sikh what he is--not theological conviction. Dogma was incidental. The rise of the Khalsa was a political movement. The thousands of Jat yeomen who joined the banner accepted the book with the sword. To make a strong and distinctive body of them, to lift them above the Hindu ranks, to convert a sect into a religion, to give them a cause and a crusade was Govind's work. It was he who consolidated the Sikhs by giving them prestige. He instituted the Khalsa, or the commonwealth of the chosen, into which his disciples were initiated by the ceremony of the pahul. He swept away ritual, abolished caste, and ordained that every Sikh should bear the old Rajput title of Singh, or Lion, as every Govindi Sikh does to this day. He also gave national and distinctive traits to the dress of his people, ordaining that they should carry a sword, dagger, and bracelet of steel, don breeches instead of a loincloth, and wear their hair long and secured in a knot by a comb. He it was who grafted the principles of valour, devotion, and chivalry on the humble gospel of Nanak, and introduced the national salutation of "Wah Guru ji ka Khalsa! Wa Guru ji ki Futteh!"--"Hail to the Khalsa! Victory to God"--a chant that has dismayed the garrison of many a doomed trench held by the Turk and the Hun.

It was odd that the Arabs in Mesopotamia should have called the Sikh "The Black Lion,"[4] bearing witness to the boast that every member of the Khalsa when he puts on the consecrated steel and adopts the title of Singh is lionised in the most literal sense of the word and becomes the part in fact as well as in name.

War is a necessary stimulus for Sikhism. In the reaction of peace the Sikh population dwindles. It was in the struggle with Islam, during the ascendency of Ranjit Singh, in the two wars against the British, and after in the Mutiny, when the Sikhs proved our loyal allies, that the Khalsa was strongest. Without the incentive to honour and the door open to military service the ineradicable instincts of the Hindu reassert themselves. Fewer jiwans come forward and take the pahul; not only is the community weakened by lack of disciples, but many who hold fast to the form let go the spirit; ritual, idolatry, superstition, exclusiveness, and caste, the old enemies to the reformed religion, creep in again; the aristocracy of honour lapses into the aristocracy of privilege. Then the Brahman enters in, and the simple faith is obscured by all manner of un-Sikh-like preoccupations. Sikhism might have fallen back into Hinduism and become an obscure sect if it had not been for the Indian Army. But here the insignia of Guru Govind have been maintained, and his laws and traditions. The class regiments and class-company regiments have preserved not merely the outward observances; they have kept alive the inward spirit of the Khalsa. Thus it is that the Sikh has more class feeling than any other sepoy, and more pride in himself and his community. Govind set the lion stamp on him as he intended. By his outward signs he cannot be mistaken--by his beard, the steel bracelet on his wrist, his long knotted hair, or if that is hidden, by the set of his turban, above all by his grave self-respect. The casual stranger can mark him by one or all of these signs, but there is a subtler physical distinction in expression and feature that you cannot miss when you know the Sikh well. This is quite independent of insignia. It is as marked in a boy without a hair to his chin as in an old campaigner. This also is Govind's mark, the sum of his influence inscribed on the face by the spirit. A great tribute this to the genius of the Khalsa, when one remembers that the Sikh is not a race apart, but comes of the same original stock as most of his Hindu and Muhammadan neighbours in the Punjab, and that Govind, his spiritual ancestor, only died two hundred years ago.

Amongst all the races and castes that have been caught up into the Khalsa, by far the most important in influence and numbers is the Jat. Porus was probably of the race. When Alexander, impressed by his gallantry, asked him what boon he might confer, he demanded "to be treated like a king"--a very Sikh-like speech. The Sikh soldier is the Jat sublimated, and the bulk of the Sikhs in the Indian Army are of Jat origin. Authorities differ as to the derivation of the Jats, but it is commonly believed that they and the Rajputs are of the same Scythian origin, and that they represent two separate waves of invasion; and this is borne out by their physical resemblance and by a general similarity in their communal habits of life. The Jat, so long as he remains a Hindu, is called Jāt (pronounced Jā-āt), while the Jat who has adopted Sikhism is generally referred to as Jăt (pronounced Jŭt). The spelling is the same, and to the uninitiated this is a constant source of confusion. The difference in pronunciation arose from a subtlety of dialect, it being customary in the part of the Punjab where Sikhs preponderate to shorten the long Ā of the Hindi.

The Jat is the backbone of the Punjab. From his Scythian ancestors is derived the same stubborn fibre that stiffens the Punjabi cultivator, whatever changes he may have suffered by influence of caste or creed, whether he be Hindu, Muhammadan, or Sikh. The admitted characteristics of the Jat are stubbornness, tenacity, patience, devotion, courage, discipline and independence of spirit fitly reconciled; add to these the prestige and traditions of the Khalsa and you have the ideal Sikh.

I say "the ideal Sikh," for without the contributory influences you may not get the type as Govind conceived it. The ideal Sikh is the happy Sikh, the Sikh who is content with the place he occupies in his cosmos, who respects and believes in his superior officers, who does not consider himself unjustly treated, and who has received no injury to his self-esteem. For the virtuous ingredients in his composition are subject to reaction. When he fancies he is wronged, he broods. The milk in him becomes gall. The "waters of life" stirred by steel, his baptismal draught, take on an acid potency. "I'd rather command Sikhs than any other class of sepoy," a brigadier told me, and he had commanded every imaginable class of sepoy for twenty years, "but they must be happy Sikhs," he added. The brooding or intriguing Sikh is a nuisance and a danger.

The pick of the Khalsa will be found in the class regiments and class company regiments to which the Sikhism of to-day owes its conservation, vigour, and life. The 14th Sikhs were raised at Ferozepore in 1846; the 15th at Ludhiana in the same year; the 45th Rattray's Sikhs in 1856 for service among the Sonthals; the 35th and 36th Sikhs in 1887, the 47th in 1901. The 15th, the oldest Sikh battalion, and the 47th, the latest raised, were the first to be given the opportunity of showing the mettle of the Khalsa in a European war. The 47th, who were not raised till 1901, earned as proud a record as any in France, distinguishing themselves from the day in October, 1914, when, with the 20th and 21st Sappers and Miners, they cleared the village of Neuve Chapelle after some Homeric hand-to-hand fighting in the houses and streets, to the desperately stubborn advance up the glacis to the German trenches on April 26, 1915, in the second battle of Ypres, when the regiment went in with eleven British and ten Indian officers and 423 other ranks, of whom but two British and two Indian officers and 92 rank and file mustered after the action. The 15th Sikhs, one of the two earliest-raised Sikh battalions, were the first to come into action in France, and they maintained a high-level reputation for gallantry all through the campaign. The story of Lieutenant Smyth and his ten Sikh bombers at Festubert is not likely to be forgotten. Smyth and two sepoys were the only two survivors of this gallant band who passed by a miracle, crawling over the dead bodies of their comrades, through a torrent of lead, and carried their bombs through to the first line. Smyth was awarded the V.C., Lance-Naik Mangal Singh the Indian Order of Merit, and every sepoy in the party the Indian Distinguished Service Medal. Two of these men belonged to the 45th Sikhs, four to the 19th Punjabis. And here it should be remembered that the Sikhs earned a composite part of the honour of nearly every mixed class-company regiment in France; of the Punjabi regiments, for instance, and of the Frontier Force Rifle battalions, in which the number of Sikh companies varies from one to four, not to mention the Sappers and Miners. It was in the very first days of the Indians' début in France that a Sikh company of the 57th Rifles earned fame when it was believed that the line must have given way, holding on all through the night against repeated counter-attacks, though the Germans were past them on both flanks. As for the Sappers, the story of Dalip Singh is pure Dumas. This fire-eater helped his fallen officer, Lieut. Rail-Kerr, to cover, stood over him and kept off several parties of Germans by his fire. On one occasion--a feat almost incredible, but well established--he was attacked by twenty of the enemy, but beat them all off and got his officer away.[5]

It is in "sticking it out" that the Sikh excels. No one will deny his élan; yet élan is not so remarkably and peculiarly his as the dogged spirit of resistance that never admits defeat, the spirit that carried his ancestors through the long ordeal by fire in their struggle with the Moguls. It is in defensive action that the Sikhs have won most renown, fighting it out against hopeless, or almost hopeless odds, as at Arrah and Lucknow in the Mutiny, and in the Tirah campaign at Saraghiri on the Samana ridge. The defence of the little house at Arrah by Rattray's (the 45th) Sikhs was one of the most glorious episodes of the Indian Mutiny, and the story of the Sikh picket at Saraghiri will live as long in history. The whole garrison of the post, twenty-one men of the 36th Sikhs, a battalion lately raised and then in action for the first time, fell to a man in its defence. The Afridis admitted the loss of two hundred dead in the attack. As they pressed in on all sides in overwhelming numbers the Sikhs kept up their steady fire for six hours, until the walls of the post fell. The last of the little band perished in the flames as he defended the guard-room door, and shot down twenty of the assailants before he succumbed.

Strangely enough, these two regiments, the 36th and 45th Sikhs, to whom we owe two of the most enduring examples in history of "sticking it out," fought side by side on the Hai in an action which called for as high qualities of discipline and endurance under reverse as any that was fought in Mesopotamia. The Sikhs lived up to their tradition. Both regiments went over the parapet in full strength and were practically annihilated. Only 190 effectives came out of the assault; only one British officer returned unwounded. The 45th on the right were exposed to a massed counter-attack. A British officer was seen to collect his men and close in on the Turks in the open; he and his gallant band were enveloped and overwhelmed. So, too, in Gallipoli the 14th Sikhs, who saved Allahabad in the Mutiny and immortalized themselves with Havelock in the march on Lucknow and the defence of the Residency, displayed their old spirit. When they had fought their way through the unbroken wire at Gully Ravine (June 4, 1915) and taken three lines of trenches, they hung on all day, though they had lost three-fourths of their effectives, and every British officer but two was killed.

But I must tell the story of Wariam Singh, a Jat Sikh of a Punjabi regiment; it was told me by one Zorowar Singh, his comrade, in France. "You heard of Wariam Singh, Sahib," he asked--"Wariam Singh, who would not surrender?"

Wariam Singh was on leave when the regiment was mobilized, and the news reached him in his village. It was a very hot night. They were sitting by the well, and when Wariam Singh heard that the ---- Punjabis were going to Wilayat to fight for the Sircar against a different kind of white man, he said that, come what might, he would never surrender. He made a vow then and there, and, contrary to all regimental discipline, held by it.

I can picture the scene--the stencilled shadows of the kikar in the moonlight, the smell of baked flour and dying embers, the almost motionless group in a ring like birds on the edge of a tank, and in the background the screen of tall sugar-cane behind the dry thorn hedge. The village kahne-wallah (recounter of tales) would be half chanting, half intoning, with little tremulous grace-notes, the ballad about "Wa-ar-button Sahib," or Jân Nikalsain, when the lumbardar from the next village would appear by the well and portentously deliver the message.

The scene may have flickered before the eyes of Wariam Singh, lying stricken beside his machine-gun, just as the cherry blossom of Kent is said to appear to the Kentish soldier. The two English officers in his trench had fallen; the Germans had taken the trenches to the left and the right, and they were enfiladed up to the moment when the final frontal wave broke in. The order came to retire, but Wariam Singh said, "I cannot retire, I have sworn"; and he stood by his machine-gun.

"If he had retired no doubt he would have been slain. Remaining he was slain, but he slew many," was Zorowar Singh's comment.

Afterwards the trench was taken back, and the body of Wariam Singh was found under the gun. The corpses of the Germans lay all round "like stones in a river bed."

The disciples of Govind comprise many classes other than the Jat, of whom there are some thirty main clans. There are Sikhs of Brahman and Rajput descent, and a number of tribes of humbler origin. The Jat stands first in respect to honour and numbers; apart from him, it is the humbler classes who have contributed most weight to the fighting arms of the community. The Brahman-, Rajput-, and Khatri-descended Sikhs do not enlist freely.

The 48th Pioneers are recruited almost entirely from Labanas, a tribe whose history goes back to the beginning of time. There are Labanas, of course, who are not Sikhs. The Raja of the community is a Hindu and lives at Philibit, and there are Labana hillmen about Simla, farmers in the Punjab, traders in the Deccan and Bombay, and owners of ships; but I have no doubt that the pick of them are those that have enlisted in the Khalsa. The Labanas were soldiers at least two thousand years before Govind, and according to tradition formed the armed transport of the Pandavas and brought in the fuel (labanke--a kind of brushwood, hence the tribal name) for the heroes of the Mahabharata. I heard this story from a Labana Sikh one night on the upper reaches of the Euphrates near Khan Baghdadi, when we were miles ahead of our transport and had rounded up a whole army of Turks. He told it me with such impressment that I felt it must be true, though no doubt there are spoilers of romance who would unweave the web.

Theoretically Sikhism acknowledges no caste; but in practice the Sikh of Jat or Rajput descent will not eat or drink with Sikhs drawn from the menial classes, though the lowest in the social scale have been tried and proved on the field, and shown themselves possessed of military qualities which, apart from caste prejudice, should admit them to an equal place in the brotherhood of the faithful. The Mazbhis are a case in point. The first of this despised sweeper class to attain distinction were the three whom Guru Govind admitted into the Khalsa as a reward for their fidelity and devotion when they rescued the body of Tegh Bahodur, the murdered ninth Guru, from the fanatical Moslem mob at Delhi. When Sikhism was fighting for its life, these outcasts were caught up in the wave of chivalry and "gentled their condition;" but as soon as the Khalsa were dominant in the Punjab the Mazbhis found that the equality their religion promised them existed in theory rather than fact. They occupied much the same position among the Jat- and Khattri-descended Sikhs as their ancestors, the sweepers, enjoyed amongst the Hindus. They were debarred from all privileges, and were at one time even excluded from the army. It fell to the British to restore the status of the Mazbhi, or rather to give him the opening by which he was able to re-establish his honour and self-esteem. The occasion was in the Mutiny of 1857, when we were in great need of trained sappers for the siege-work at Delhi. A number of Mazbhis who were employed at the time in the canal works at Madhopur were offered military service and enlisted readily. On the march to Delhi these raw recruits fought like veterans. They were attacked by the rebels, beat them off, and saved the whole of the ammunition and treasure. During the siege Neville Chamberlain wrote of them that "their courage amounted to utter recklessness of life." Eight of them carried the powder-bags to blow up the Kashmir Gate, under Home and Salkeld. Their names are inscribed on the arch to-day and have become historical. John Lawrence wrote of the deed as one of "deliberate and sustained courage, as noble as any that ever graced the annals of war."

The Mazbhis are recruited for the Sikh Pioneer regiments, the 23rd, 32nd, and 34th, sister regiments of whom one, or more, has been engaged in nearly every frontier campaign from Waziristan in 1860 to the Abor expedition in 1911. It was the 32nd who carried the guns over the Shandur Pass in the snow, in the march from Gilgit, and relieved the British garrison in Chitral. The 34th were among the earliest Indian regiments engaged in France, and the Mazbhis gained distinction in October, 1914, when they were pushed up to relieve the French cavalry, and the Sikh officers carried on the defence for a day and a night under repeated attacks when their British officers had fallen. Great, too, was the gallantry of the Indian officers of the regiment at Festubert (November, 1914), and the spirit of the ranks. Yet the Mazbhis are still excluded from most privileges by the Khalsa. They are not eligible for the other Sikh class regiments. Nor are they acceptable in the cavalry or in other arms, for the aristocratic Jat Sikh, as a rule, refuses to serve with them. Yet you will find a sprinkling of Jat Sikhs in the Mazbhi Pioneer regiments--quick-witted, ambitious men usually, who are ready to make some sacrifice in the way of social prestige for the sake of more rapid promotion. The solid old Mazbhis, with all their sterling virtues, are not quick at picking up ideas. It is sometimes difficult to find men among them with the initiative to make good officers. Thus in a Mazbhi regiment the more subtle-minded Jat does not find it such a stiff climb out of the ranks.

It would be a mistake to think that the Jat Sikh is necessarily a better man in a scrap than the Mazbhi, though this is no doubt assumed as a matter of course by officers whose acquaintance with the Sikh is confined to the Jat. I shall never forget introducing a young captain in a Mazbhi regiment to a very senior Colonel on the Staff. The colonel in his early days had been a subaltern in the --th Sikhs, but had put in most of his life's work in "Q" Branch up at Simla, and did not know a great deal about the Sikh or any other sepoy. He turned to the young leader of Mazbhis, who is quite the keenest regimental officer I know, and said--

"Your men are Mazbhis, aren't they? But I suppose you have a stiffening of Jats."

The youngster's eyes glinted rage and he breathed fire.

"Stiffening, sir? Stiffening of Jats! Our men are Mazbhis."

Stiffening was an unhappy word, and it stuck in the boy's gorge for weeks. To stiffen the Mazbhi;

all come in the same catalogue of ridiculous excess. Stiffening! Why the man is solid concrete. It would take a stream of molten lava to make him budge. Or, as Atkins would say--

"He wants a crump on his blamed cokernut before he knows things is beginning to get a bit 'ot, and then he ain't sure."

It was to stiffen his men a bit, as they were all jiwans and likely to get a little flustered, that old Khattak Singh, Subadar of the 34th Sikh Pioneers, called "Left, right; right, left," as the regiment tramped into action at Dujaila; but the Mazbhi did not want stiffening. It is rather his part to contribute the inflexible element when there is fear of a bent or broken line. In the action at Jebel Hamrin, on March 25, 1917, when we tried to drive the Turks from a strong position in the hills, where they outnumbered us, the Mazbhis showed us how stiff they could be. They were divisional troops and for months they had been employed in wiring our line at night,--a wearing business, standing about for hours in the dark, under a blind but hot fire, casualties every night and never a shot at the Turk. So tired were they of being fired at without returning the enemy's fire that, when they got the chance at Jebel Hamrin and were rolling over visible Turks, for a long time they could not be induced to retire. The Turks were bringing off an enveloping movement which threatened our right. The order had been given for the retirement. But the Mazbhis did not, or would not, hear it. Somebody, I forget whether it was a British officer, or if it was an Indian officer after the British officers had all fallen, said that he would not retire without a written order. Ninety of them out of one hundred and fifty fell. Old Khattak Singh got back in the night, walked six miles to the hospital with seven wounds, one in his shoulder and two in his thigh, and said, "I had ninety rounds. I fired them all at the Turks and killed a few. Now I am happy and may as well lie up for a bit."

The Staff Colonel had a certain spice of humour, if little tact, and I think he rather liked the boy for his outburst in defence of his dear Mazbhis. To the outsider these little passages afford continual amusement. One has to mix with different regiments a long time before one can follow all the nuances, but it does not take long to realize to what extent the British officer is a partisan. Insensibly he suffers through his affections a kind of conversion. He comes to see many things as his men see them, even to adopt their own estimate of themselves in relation to other sepoys. And one would not have it otherwise. It speaks well for the qualities of the Indian soldier, for the courage, kindliness, loyalty, and faith with which he binds his British officer to his own community. It may be very narrow and wrong, but an Indian regiment is the better fighting unit for it. Better an enthusiasm that is sometimes ridiculous than a lukewarm attachment. The officer who does not think much of his jiwans will not go far with them. There are cases, of course, where pride runs riot and verges on snobbishness. I remember a subaltern who was shocked at the idea of his men playing hockey with a regiment recruited from a lower caste. And I once knew a field officer in a class regiment of Jat Sikhs who, I am sure, would have felt very uncomfortable if he had been asked to sit down at table with an officer who commanded Mazbhis. Yet, I am told, he was a fine soldier.

Fanatics of his kidney were happily rare. I use the past tense for they have gone with the best, and I am speaking generally of a school that has vanished. It may be resuscitated, but it will hardly be in our time. Too many of the old campaigners, transmitters of tradition, splendid fellows who lived for the regiment and swore by it, are dead or crippled, and the pick of the Indian Army Reserve has been reaped by the same scythe. The gaps have had to be filled so fast and from a material so unready that one meets officers now who know nothing about their sepoys, who do not understand their language and who are not even interested in them, youngsters intended for other walks of life who will never be impressed by the Indian soldier until they have first learnt to impress him.

The "P. M.", or Punjabi Mussalman, is a difficult type to describe. Next to the Sikh, he makes up the greater part of the Indian Army. Yet, outside camps and messes, one hears little of him. The reason is that in appearance there is nothing very distinctive about him; in character he combines the traits of the various stocks from which he is sprung, and these are legion; also, as there are no P. M. class regiments, he is never collectively in the public eye.

Yet the P. M. has played a conspicuous part in nearly every action the Indian Army has fought in the war, and in every frontier campaign for generations; in gallantry, coolness, endurance, dependability, he is every bit as good as the best.

"Why don't you write about the P. M.?" a friend in the Nth asked me once. He was a major in a Punjabi regiment, and had grown grey in service with them.

We were standing on the platform of a flanking trench screened by sandbags from Turkish snipers, looking out over the marsh at Sannaiyat. Nothing had happened to write home about for six months, not since we delivered our third and bloodiest attack on the position on the 22nd April. The water had receded nearly a thousand yards since then. Our wire fences stood out high and dry on the alkaline soil. The blue lake seemed to stretch away into the interstices of the hills which in the haze looked a bare dozen miles away.

Two days before our last attack in April the water was clean across our front six inches deep, with another six inches of mud; on the 21st it was subsiding; on the 22nd the flooded ground was heavy, but it was decided that there was just a chance. So the assault was delivered. The Turkish front line was flooded; there was no one in it, and it was not until we had passed it that we were really in difficulties. The second line of trenches was neck deep in water; behind it there was a network of dug-outs and pits into which we floundered blindly. Beyond this, between the Turkish second and third lines, the mud was knee deep. The Highlanders, a composite battalion of the Black Watch and Seaforths, and the 92nd Punjabis, as they struggled grimly through, came under a terrific fire. It was here that their splendid gallantry was mocked by one of those circumstances which make one look darkly for the hand of God in war.

THE PUNJABI MUSSALMAN.

The breeches of their rifles had become choked and jammed with mud. The Jocks were tearing at them with their teeth, panting and sobbing, and choking for breath. They were almost at grips with the Turk, but could not return his fire.

The last action we fought for Kut was unsuccessful, but the gallantry of the men who poured into that narrow front through the marsh will become historic. The Highlanders hardly need praise. The constancy of these battalions has come to be regarded as a natural law. "The Jocks were magnificent," my friend said, "as they always are. So were the Indians."

And amongst the Indians were the P. Ms. There were other classes of sepoy who may have done as well, but the remnants of the three Indian battalions in this fight were mostly Punjabi Mussalmans. And here, as at Nasiriyeh, Ctesiphon and Kut-el-Amara, in Egypt and France, at Ypres, Festubert and Serapeum, the P. M. covered himself with glory. The Jock, that sparing critic of men, had nothing but good words for him.

"Yes! Why don't you write about the P. M.?" the Major asked. One of the reasons why I had not written about the P. M. is that he is a very difficult person to write about. There is nothing very salient or characteristic about him; or rather, he has the characteristics of most other sepoys. To write about the P. M. is to write about the Indian Army. And that is why, to my friend's intense annoyance, the man in the street, who speaks glibly of Gurkha, Sikh, and Pathan, has never heard of him.

"Here's the old P. M. sweating blood," he said, "all through the show, slogging away, sticking it out like a good 'un, and as modest as you make 'em. Never bukhs; never comes up after a show and tells you what he has done. You don't know unless you see him. Old Shere Khan, our bomb havildar, was hit through both jaws on the 22nd. He got two bullets in the arm. Then he was shot in the lungs. But it was only when he got his fifth wound in the leg that he ceased to lead his men and limped back to the first-aid post. All our B. O.'s were down, but a doctor man with the Highlanders happened to see the whole thing. So Shere Khan was promoted."

The Major was bound to his P. Ms. with hoops of steel. It was the rifles with fixed bayonets slung from pegs between the sandbags that recalled Polonius' metaphor. It seemed more apt at Sannaiyat.

He introduced me to the Jemadar, Ghulam Ali, a man with a mouth like a rat-trap and remarkable for a kind of dour smartness. The end of his pagri was drawn out into a jaunty little tuft by the side of his kula. His long hair, oiled, but uncurled, fell down to the nape of his neck. Ghulam Ali, though shot through the forearm himself, had built up a screen of earth round his Sahib when he was severely wounded at the Wadi, stayed with him till dusk, helped him back to better cover, and then returned to the firing line to bring in a lance-naik on his shoulders.

There were very few of the old crowd left in the trenches. "These youngsters are mostly recruits," the Major explained, "but they are a good lot. I wish you could have seen Subadar ----," and he mentioned a man who had practically run a district in East Africa all on his own when there was no white man by. A tremendous character. "And Subadar-Major Farman Ali Bahadar. He got the D.S.M. when he was with us in Egypt, led a handful of his men across the open at Touffoum, and turned the Turkish flank very neatly. He got an I.O.M. at Sheikh Saad. And he led the regiment back at Sannaiyat when all the British officers were down. He was a Khoreshi, by the way."

A Khoreshi is a member of the tribe of the Prophet. A good Khoreshi is a man to be sought for and honoured, for his influence is great; but a bad Khoreshi among the P. Ms. is as big a nuisance as a Mir among Pathans.

"A kind of ecclesiastical dignitary," the Major explained, "a sort of Rural Dean. You will find men who funk him for reasons which have nothing to do with discipline; and if he pulls the wrong way it is the very devil."

The P. Ms. in the trenches were varied in type. There was nothing distinctive or showy about them, only they all looked workman-like; Sikh, Jat, and Punjabi Mussalman are mostly of common stock, and they assimilate so much in feature that it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between them. The P. Ms. ancestry may be Rajput, Jat, Gujar, Arab or Mogul. There are more than 400 tribes which he can derive from, and these are broken up into innumerable sects and sub-divisions. He does not pride himself on his class, but on his clan. The generic "izzat" of the P. M. is merged in the specific "izzat" of the Gakkar, Tiwana, Awan, or whatever he may be. "Punjabi Mussalman" is a purely official designation. And that is why the general public hears so little of him.

As a class he is a kind of Indian Everyman and comprises all. You will find among the P. Ms. every variety of type, from the big-boned Awan, stalwart of the Salt Range, to the thin-bearded little hillman of Poonch; from the Tiwanas, bloods of the Thai country who give us the pick of our cavalry and will not serve on foot, to the wiry Baluchi, who has forgotten the language and observances of his kinsmen over the border. You will find descendants of all the Muhammadan invaders of India, from the time of Mahmud of Ghazni in A.D. 1001, and of pre-Islamic invaders centuries before that, and of the converts of every considerable Moslem freebooter since. The recruiting officer encourages pride of race, which is generally accompanied with a soldierly bearing and pride in arms, though the oldest stock is not always the best. You will find among the P. Ms. Khoreshis and Sayads of the tribes of the Prophet and of Ali, Gakkars who will only give their daughters to Sayads, Ketwals who descended from Alexander the Great. The Bhatti are Pliny's Baternae. The Awans claim descent from the iconoclast Mahmud. At Sannaiyat I saw a Jungua of the Jhelum district who might have stood for a portrait of Disraeli. The true, or spurious, seed of the Moguls are scattered all over the Punjab, and there are scions of ancient Rajput stock like the Ghorewahas, who preserve their bards and are still half Hindus, and the Manj, who are too blue-blooded to follow the plough. But as a rule the P. M. has less frills than the Hindu of the same stock; he will lend a hand at any honest work, and falls easily into disciplinary ways.

What is it then that differentiates the Punjabi Mussalman? I put the case to my friend.

"Your P. M. comes from all stocks, has the same ancestor as the Jat, the Sikh, the Rajput, or the Pathan. Can you tell me exactly what being a P. M. does for him?"

The Major was unable to enlighten me fully. He told me what I had heard officers say of other classes of sepoy; only he left out all their faults.

"Personally, I think the P. M. is more human," he said. "He is not so proud as the ----, or so ambitious as the ----, or so mean as the ----, or so stupid as the ----. He is a cheery soul, and when he gets money he doesn't mind spending it. He is the most natural and direct of men, and there is no damned humbug about him. I remember old Fazal Khan pulling up a jiwan (youth) we had up, and who was being cross-examined in an inquiry about some lost ammunition. The youngster hedged, corrected himself, modified his statements, and generally betrayed his reluctance to come to the point. Fazal Khan's rebuke was characteristic. 'Judging distance ka mafik gawahi mut do!' he said ('Don't give your evidence as if you were judging distance at the range!'). He had a wholesome contempt for civilian ways. The regiment was giving a tamasha in the lines--an anniversary show--and one of our subalterns suggested putting up a row of flags all the way from the gate to the marquee. But Fazal Khan was not for it. 'No, sahib!' he said gravely, 'too civil ka mafik,' 'the sort of thing a civilian would do.' The old fellow is a soldier all through."

The Major's story gave me a glimmering of what it was that being a P. M. did for Fazal Khan and his brood. "There is no damned humbug about them,"--which was his way of saying that his friends neglect the arts of insinuation.

"There is something downright about the P. M. Even when he is mishandled, he is not mulish, only dispirited. And he'll do anything for the right kind of Sahib. Besides, look how he rolls up, recruiting is now better than ever--he is the backbone of the Indian Army."

A good "certifkit" and I think in the main true, though necessarily partial. But the Major was not literally accurate in saying that the P. M. is the backbone of the Indian Army. The Sikhs would have something to say to that, for 214 companies of infantry, including the class regiments, and forty squadrons of cavalry, are recruited entirely from the Khalsa, besides a large proportion of sappers and miners, and half the mountain batteries. The Gurkhas contribute twenty battalions of foot, but they serve only in the infantry. Taking infantry, cavalry, artillery and sappers, the P. M. in point of numbers is an easy second to the Sikh.[6]

There are, of course, Mussalman sepoys and sowars recruited from other provinces than the Punjab. Those from the United Provinces fall under the official designation of "Hindustani Mussalman," and need not be differentiated from the Muhammadans east of the Jumna. The same qualities may be discovered in any clan; the difference is only in degree; it is among the Punjabi Mussalmans that you will find the pick of Islam in the Indian Army.

Of quality it is difficult to speak. He is a bold man who would generalise upon the Indian Army, more especially upon the Punjab fighting stocks. The truth is that, if you pick the best of them and give them the same officers, there is nothing to choose between Sikh, Jat, and Punjabi Mussalman. Only you must be careful to choose your men from districts where they inherit the land and are not alien and browbeaten, but carry their heads high.

Why, then, if the P. M. is as good as the best, has he not been discovered by the man in the street? One reason I have suggested. You can shut your eyes in the Haymarket and conjure up an image of Gurkha, Sikh, or Pathan, but you cannot thus airily summon the P. M.--because he is Everyman, the type of all. Another source of his obscurity is the illogical nomenclature of the Indian Army. A class designation does not mean a class regiment. How many Baluchis proper are there in the so-called Baluchi regiments? Who gives a thought to the Dogras, P. Ms. and Pathans in the 51st, 52nd, 53rd, and 54th Sikhs, the Dekkani Mussalman in the Maharatta regiments, or the Dogras and P. Ms. in the 40th Pathans? Now the P. M. only exists in the composite battalions. He has no class regiment of his own. You may look in vain in the Army List for the 49th Gakkars, 50th Awans, or the 69th Punjabi Mussalmans. Hence it is that the P. M. swells the honour of others, while his own name is not increased.

Every boy in the street heard of the 40th Pathans at Ypres, but few knew that there were two companies of P. Ms. in the crowd--"as good as any of them," the Major said, "men who would stiffen any regiment in the Indian Army."

And when it is generally known that the ---- Sikhs were first into the Turkish trenches on the right bank at Sheikh Saad and captured the two mountain guns, nobody is likely to hear anything of the P. M. company who was with them, a composite part of the battalion.

The Major's men had been complimented for every action they had been in, and this was the scene of their most desperate struggle. But there was little to recall the Sannaiyat of April--only an occasional bullet whistling overhead, or cracking against the sandbags. Instead of mud a thin dust was flying and the peaceful birds stood by the edge of the lake.

I wished the P. M. could have his Homer. Happily he is not concerned with the newspaper paragraph. Were the Press to discover him it is doubtful if he would hear of it. He enlists freely. He is such an obvious fact, stands out so saliently wherever the Indian Army is doing anything, looms so large everywhere, that it has probably never entered his head that his light could be obscured. But his British officer takes the indifference of the profane crowd to heart. When he hears the Sikh, Gurkha, and Pathan spoken of collectively as synonymous with the Indian Army he is displeased; and his displeasure is natural, if not philosophic. If he were philosophic he would find consolation in the same sheets which annoy him, for it is better to be ignored than to be advertised in a foolish way. It is with a joy that has no roots in pride that the Indian Army officer reads of the Gurkha hurling his kukri at the foe, or blooding his virgin blade on the forearms of the self-devoting ladies of Marseilles, or of the grave, bearded Sikhs handing round the hubble-bubble with the blood still wet on their swords; or of the Bengali lancer dismounting and charging the serried ranks of the Hun with his spear. Hearing of these wonders, the Sahib who commands the Punjabi Mussalman, and loves his men, will discover comfort in obscurity.

One often hears British officers in the Indian Army say that the Pathan has more in common with the Englishman than other sepoys. This is because he is an individualist. Personality has more play on the border, and the tribesman is not bound by the complicated ritual that lays so many restrictions on the Indian soldier. His life is more free. He is more direct and outspoken, not so suspicious or self-conscious. He is a gambler and a sportsman, and a bit of an adventurer, restless by nature, and always ready to take on a new thing. He has a good deal of joie de vivre. His sense of humour approximates to that of Thomas Atkins, and is much more subtle than the Gurkha's, though he laughs at the same things. He will smoke a pipe with the Dublin Fusiliers and share his biscuits with the man of Cardiff or Kent. He is a Highlander, and so, like the Gurkhas, naturally attracted by the Scot. Yet behind all these superficial points of resemblance he has a code which in ultimate things cuts him off from the British soldier with as clean a line of demarcation as an unbridged crevasse.

The Pathan's code is very simple and distinct in primal and essential things. The laws of hospitality, retaliation, and the sanctuary of his hearth to the guest or fugitive are seldom violated. But acting within the code the Pathan can indulge his bloodthirstiness, treachery, and vindictiveness to an extent unsanctioned by the tables of the law prescribed by other races and creeds. It is a savage code, and the only saving grace about the business is that the Pathan is true to it, such as it is, and expects to be dealt with by others as he deals by them. The main fact in life across the border is the badi, or blood-feud. Few families or tribes are without their vendettas. Everything that matters hinges on them, and if an old feud is settled by mediation through the Jirgah, there are seeds of a new one ready to spring up in every contact of life. The favour of women, insults, injuries, murder, debt, inheritance, boundaries, water-rights,--all these disputes are taken up by the kin of the men concerned, and it is a point of honour to assassinate, openly or by stealth, any one connected by blood with the other side, however innocent he may be of the original provocation. Truces are arranged at times by mutual convenience for ploughing, sowing, or harvest; but as a rule it is very difficult for a man involved in a badi to leave his watch-tower, and still more difficult for him to return to it. It will be understood that the Pathan is an artist in taking cover. He probably has a communication trench of his own from his stronghold to his field, and no one better understands the uses of dead ground.

THE PATHAN PIPERS.

What makes these blood-feuds so endless and uncompromising is that quarrels begun in passion are continued in cold blood for good form. The Malik Din and Kambur Khil have been at war for nearly a century and nobody remembers how it all began. It is a point of honour to retaliate, however inconvenient the state of siege may be. The most ordinary routine of life may become impossible. The young Pathan may be itching to stroll out and lie on a bank and bask or fall asleep in the sun. But this would be to deliver himself into the hands of his enemy. There is no dishonour in creeping up and stabbing a man in the back when he is sleeping; but there is very great dishonour in failing to take an advantage of an adversary or neglecting to prosecute a blood feud to its finish. Such softness is a kind of moral leprosy in the eyes of the Pathan.