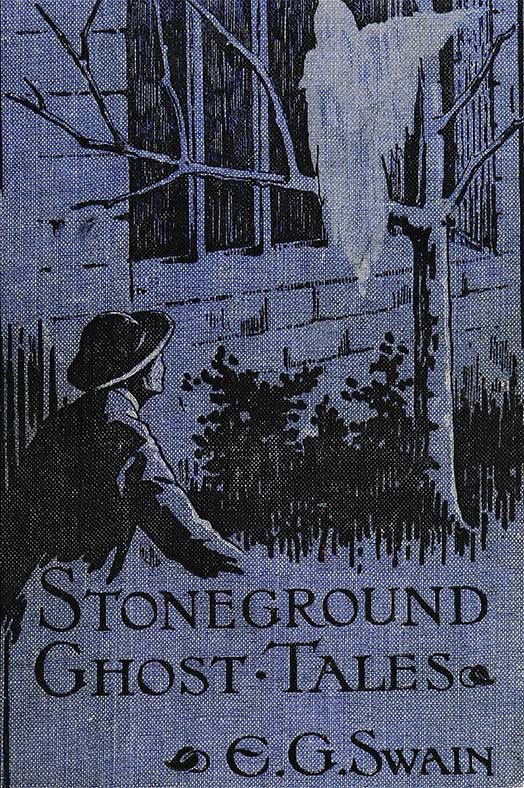

London:

Simpkin, Marshall and Co., Ltd.

THE STONEGROUND

GHOST TALES

COMPILED FROM THE RECOLLECTIONS OF

THE REVEREND ROLAND BATCHEL,

VICAR OF THE PARISH.

BY

E. G. SWAIN

Cambridge:

W. HEFFER & SONS Ltd.

1912

TO

MONTAGUE RHODES JAMES

(LITT.D., HON. LITT.D. DUBLIN,

HON. LL.D. ST. ANDR., F.B.A., F.S.A., ETC.)

PROVOST OF KING’S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE,

FOR TWENTY PLEASANT YEARS MR. BATCHEL’S FRIEND,

AND THE INDULGENT PARENT OF SUCH TASTES

AS THESE PAGES INDICATE.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| I.—The Man With the Roller | 1 |

| II.—Bone to His Bone | 19 |

| III.—The Richpins | 35 |

| IV.—The Eastern Window | 63 |

| V.—Lubrietta | 83 |

| VI.—The Rockery | 103 |

| VII.—The Indian Lamp Shade | 123 |

| VIII.—The Place of Safety | 147 |

| IX.—The Kirk Spook | 175 |

I.

THE MAN WITH THE ROLLER.

On the edge of that vast tract of East Anglia, which retains its ancient name of the Fens, there may be found, by those who know where to seek it, a certain village called Stoneground. It was once a picturesque village. To-day it is not to be called either a village, or picturesque. Man dwells not in one “house of clay,” but in two, and the material of the second is drawn from the earth upon which this and the neighbouring villages stood. The unlovely signs of the industry have changed the place alike in aspect and in population. Many who have seen the fossil skeletons of great saurians brought out of the clay in which they have lain from pre-historic times, have thought that the inhabitants of the place have not since changed for the better. The chief habitations, however, have their foundations not upon clay, but upon a bed of gravel which anciently gave to the place its name, and upon the highest part of this gravel stands, and has stood for many centuries, the Parish Church, dominating the landscape for miles around.

Stoneground, however, is no longer the inaccessible village, which in the middle ages stood out above a waste of waters. Occasional floods serve to indicate what was once its ordinary outlook, but in more recent times the construction of roads and railways, and the drainage of the Fens, have given it freedom of communication with the world from which it was formerly isolated.

The Vicarage of Stoneground stands hard by the Church, and is renowned for its spacious garden, part of which, and that (as might be expected) the part nearest the house, is of ancient date. To the original plot successive Vicars have added adjacent lands, so that the garden has gradually acquired the state in which it now appears.

The Vicars have been many in number. Since Henry de Greville was instituted in the year 1140 there have been 30, all of whom have lived, and most of whom have died, in successive vicarage houses upon the present site.

The present incumbent, Mr. Batchel, is a solitary man of somewhat studious habits, but is not too much enamoured of his solitude to receive visits, from time to time, from schoolboys and such. In the summer of the year 1906 he entertained two, who are the occasion of this narrative, though still unconscious of[3] their part in it, for one of the two, celebrating his 15th birthday during his visit to Stoneground, was presented by Mr. Batchel with a new camera, with which he proceeded to photograph, with considerable skill, the surroundings of the house.

One of these photographs Mr. Batchel thought particularly pleasing. It was a view of the house with the lawn in the foreground. A few small copies, such as the boy’s camera was capable of producing, were sent to him by his young friend, some weeks after the visit, and again Mr. Batchel was so much pleased with the picture, that he begged for the negative, with the intention of having the view enlarged.

The boy met the request with what seemed a needlessly modest plea. There were two negatives, he replied, but each of them had, in the same part of the picture, a small blur for which there was no accounting otherwise than by carelessness. His desire, therefore, was to discard these films, and to produce something more worthy of enlargement, upon a subsequent visit.

Mr. Batchel, however, persisted in his request, and upon receipt of the negative, examined it with a lens. He was just able to detect the blur alluded to; an examination[4] under a powerful glass, in fact revealed something more than he had at first detected. The blur was like the nucleus of a comet as one sees it represented in pictures, and seemed to be connected with a faint streak which extended across the negative. It was, however, so inconsiderable a defect that Mr. Batchel resolved to disregard it. He had a neighbour whose favourite pastime was photography, one who was notably skilled in everything that pertained to the art, and to him he sent the negative, with the request for an enlargement, reminding him of a long-standing promise to do any such service, when as had now happened, his friend might see fit to ask it.

This neighbour who had acquired such skill in photography was one Mr. Groves, a young clergyman, residing in the Precincts of the Minster near at hand, which was visible from Mr. Batchel’s garden. He lodged with a Mrs. Rumney, a superannuated servant of the Palace, and a strong-minded vigorous woman still, exactly such a one as Mr. Groves needed to have about him. For he was a constant trial to Mrs. Rumney, and but for the wholesome fear she begot in him, would have converted his rooms into a mere den. Her carpets and tablecloths were continually bespattered with chemicals; her chimney-piece ornaments had[5] been unceremoniously stowed away and replaced by labelled bottles; even the bed of Mr. Groves was, by day, strewn with drying films and mounts, and her old and favourite cat had a bald patch on his flank, the result of a mishap with the pyrogallic acid.

Mrs. Rumney’s lodger, however, was a great favourite with her, as such helpless men are apt to be with motherly women, and she took no small pride in his work. A life-size portrait of herself, originally a peace-offering, hung in her parlour, and had long excited the envy of every friend who took tea with her.

“Mr. Groves,” she was wont to say, “is a nice gentleman, AND a gentleman; and chemical though he may be, I’d rather wait on him for nothing than what I would on anyone else for twice the money.”

Every new piece of photographic work was of interest to Mrs. Rumney, and she expected to be allowed both to admire and to criticise. The view of Stoneground Vicarage, therefore, was shown to her upon its arrival. “Well may it want enlarging,” she remarked, “and it no bigger than a postage stamp; it looks more like a doll’s house than a vicarage,” and with this she went about her work, whilst Mr. Groves retired to his dark room with the film, to see what he could make of the task assigned to him.

Two days later, after repeated visits to his dark room, he had made something considerable; and when Mrs. Rumney brought him his chop for luncheon, she was lost in admiration. A large but unfinished print stood upon his easel, and such a picture of Stoneground Vicarage was in the making as was calculated to delight both the young photographer and the Vicar.

Mr. Groves spent only his mornings, as a rule, in photography. His afternoons he gave to pastoral work, and the work upon this enlargement was over for the day. It required little more than “touching up,” but it was this “touching up” which made the difference between the enlargements of Mr. Groves and those of other men. The print, therefore, was to be left upon the easel until the morrow, when it was to be finished. Mrs. Rumney and he, together, gave it an admiring inspection as she was carrying away the tray, and what they agreed in admiring most particularly was the smooth and open stretch of lawn, which made so excellent a foreground for the picture. “It looks,” said Mrs. Rumney, who had once been young, “as if it was waiting for someone to come and dance on it.”

Mr. Groves left his lodgings—we must now be particular about the hours—at half-past two,[7] with the intention of returning, as usual, at five. “As reg’lar as a clock,” Mrs. Rumney was wont to say, “and a sight more reg’lar than some clocks I knows of.”

Upon this day he was, nevertheless, somewhat late, some visit had detained him unexpectedly, and it was a quarter-past five when he inserted his latch-key in Mrs. Rumney’s door.

Hardly had he entered, when his landlady, obviously awaiting him, appeared in the passage: her face, usually florid, was of the colour of parchment, and, breathing hurriedly and shortly, she pointed at the door of Mr. Groves’ room.

In some alarm at her condition, Mr. Groves hastily questioned her; all she could say was: “The photograph! the photograph!” Mr. Groves could only suppose that his enlargement had met with some mishap for which Mrs. Rumney was responsible. Perhaps she had allowed it to flutter into the fire. He turned towards his room in order to discover the worst, but at this Mrs. Rumney laid a trembling hand upon his arm, and held him back. “Don’t go in,” she said, “have your tea in the parlour.”

“Nonsense,” said Mr. Groves, “if that is gone we can easily do another.”

“Gone,” said his landlady, “I wish to Heaven it was.”

The ensuing conversation shall not detain us. It will suffice to say that after a considerable time Mr. Groves succeeded in quieting his landlady, so much so that she consented, still trembling violently, to enter the room with him. To speak truth, she was as much concerned for him as for herself, and she was not by nature a timid woman.

The room, so far from disclosing to Mr. Groves any cause for excitement, appeared wholly unchanged. In its usual place stood every article of his stained and ill-used furniture, on the easel stood the photograph, precisely where he had left it; and except that his tea was not upon the table, everything was in its usual state and place.

But Mrs. Rumney again became excited and tremulous, “It’s there,” she cried. “Look at the lawn.”

Mr. Groves stepped quickly forward and looked at the photograph. Then he turned as pale as Mrs. Rumney herself.

There was a man, a man with an indescribably horrible suffering face, rolling the lawn with a large roller.

Mr. Groves retreated in amazement to where Mrs. Rumney had remained standing. “Has anyone been in here?” he asked.

“Not a soul,” was the reply, “I came in to[9] make up the fire, and turned to have another look at the picture, when I saw that dead-alive face at the edge. It gave me the creeps,” she said, “particularly from not having noticed it before. If that’s anyone in Stoneground, I said to myself, I wonder the Vicar has him in the garden with that awful face. It took that hold of me I thought I must come and look at it again, and at five o’clock I brought your tea in. And then I saw him moved along right in front, with a roller dragging behind him, like you see.”

Mr. Groves was greatly puzzled. Mrs. Rumney’s story, of course, was incredible, but this strange evil-faced man had appeared in the photograph somehow. That he had not been there when the print was made was quite certain.

The problem soon ceased to alarm Mr. Groves; in his mind it was investing itself with a scientific interest. He began to think of suspended chemical action, and other possible avenues of investigation. At Mrs. Rumney’s urgent entreaty, however, he turned the photograph upon the easel, and with only its white back presented to the room, he sat down and ordered tea to be brought in.

He did not look again at the picture. The face of the man had about it something[10] unnaturally painful: he could remember, and still see, as it were, the drawn features, and the look of the man had unaccountably distressed him.

He finished his slight meal, and having lit a pipe, began to brood over the scientific possibilities of the problem. Had any other photograph upon the original film become involved in the one he had enlarged? Had the image of any other face, distorted by the enlarging lens, become a part of this picture? For the space of two hours he debated this possibility, and that, only to reject them all. His optical knowledge told him that no conceivable accident could have brought into his picture a man with a roller. No negative of his had ever contained such a man; if it had, no natural causes would suffice to leave him, as it were, hovering about the apparatus.

His repugnance to the actual thing had by this time lost its freshness, and he determined to end his scientific musings with another inspection of the object. So he approached the easel and turned the photograph round again. His horror returned, and with good cause. The man with the roller had now advanced to the middle of the lawn. The face was stricken still with the same indescribable look of suffering. The man seemed to be appealing to the[11] spectator for some kind of help. Almost, he spoke.

Mr. Groves was naturally reduced to a condition of extreme nervous excitement. Although not by nature what is called a nervous man, he trembled from head to foot. With a sudden effort, he turned away his head, took hold of the picture with his outstretched hand, and opening a drawer in his sideboard thrust the thing underneath a folded tablecloth which was lying there. Then he closed the drawer and took up an entertaining book to distract his thoughts from the whole matter.

In this he succeeded very ill. Yet somehow the rest of the evening passed, and as it wore away, he lost something of his alarm. At ten o’clock, Mrs. Rumney, knocking and receiving answer twice, lest by any chance she should find herself alone in the room, brought in the cocoa usually taken by her lodger at that hour. A hasty glance at the easel showed her that it stood empty, and her face betrayed her relief. She made no comment, and Mr. Groves invited none.

The latter, however, could not make up his mind to go to bed. The face he had seen was taking firm hold upon his imagination, and seemed to fascinate him and repel him at the same time. Before long, he found himself[12] wholly unable to resist the impulse to look at it once more. He took it again, with some indecision, from the drawer and laid it under the lamp.

The man with the roller had now passed completely over the lawn, and was near the left of the picture.

The shock to Mr. Groves was again considerable. He stood facing the fire, trembling with excitement which refused to be suppressed. In this state his eye lighted upon the calendar hanging before him, and it furnished him with some distraction. The next day was his mother’s birthday. Never did he omit to write a letter which should lie upon her breakfast-table, and the pre-occupation of this evening had made him wholly forgetful of the matter. There was a collection of letters, however, from the pillar-box near at hand, at a quarter before midnight, so he turned to his desk, wrote a letter which would at least serve to convey his affectionate greetings, and having written it, went out into the night and posted it.

The clocks were striking midnight as he returned to his room. We may be sure that he did not resist the desire to glance at the photograph he had left on his table. But the results of that glance, he, at any rate, had not anticipated. The man with the roller had disappeared.[13] The lawn lay as smooth and clear as at first, “looking,” as Mrs. Rumney had said, “as if it was waiting for someone to come and dance on it.”

The photograph, after this, remained a photograph and nothing more. Mr. Groves would have liked to persuade himself that it had never undergone these changes which he had witnessed, and which we have endeavoured to describe, but his sense of their reality was too insistent. He kept the print lying for a week upon his easel. Mrs. Rumney, although she had ceased to dread it, was obviously relieved at its disappearance, when it was carried to Stoneground to be delivered to Mr. Batchel. Mr. Groves said nothing of the man with the roller, but gave the enlargement, without comment, into his friend’s hands. The work of enlargement had been skilfully done, and was deservedly praised.

Mr. Groves, making some modest disclaimer, observed that the view, with its spacious foreground of lawn, was such as could not have failed to enlarge well. And this lawn, he added, as they sat looking out of the Vicar’s study, looks as well from within your house as from without. It must give you a sense of responsibility, he added, reflectively, to be sitting where your predecessors have sat for[14] so many centuries and to be continuing their peaceful work. The mere presence before your window, of the turf upon which good men have walked, is an inspiration.

The Vicar made no reply to these somewhat sententious remarks. For a moment he seemed as if he would speak some words of conventional assent. Then he abruptly left the room, to return in a few minutes with a parchment book.

“Your remark, Groves,” he said as he seated himself again, “recalled to me a curious bit of history: I went up to the old library to get the book. This is the journal of William Longue who was Vicar here up to the year 1602. What you said about the lawn will give you an interest in a certain portion of the journal. I will read it.”

Aug. 1, 1600.—I am now returned in haste from a journey to Brightelmstone whither I had gone with full intention to remain about the space of two months. Master Josiah Wilburton, of my dear College of Emmanuel, having consented to assume the charge of my parish of Stoneground in the meantime. But I had intelligence, after 12 days’ absence, by a messenger from the Churchwardens, that Master Wilburton had disappeared last Monday sennight, and had been no more seen. So here I am again in my study to the entire[15] frustration of my plans, and can do nothing in my perplexity but sit and look out from my window, before which Andrew Birch rolleth the grass with much persistence. Andrew passeth so many times over the same place with his roller that I have just now stepped without to demand why he so wasteth his labour, and upon this he hath pointed out a place which is not levelled, and hath continued his rolling.

Aug. 2.—There is a change in Andrew Birch since my absence, who hath indeed the aspect of one in great depression, which is noteworthy of so chearful a man. He haply shares our common trouble in respect of Master Wilburton, of whom we remain without tidings. Having made part of a sermon upon the seventh Chapter of the former Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians and the 27th verse, I found Andrew again at his task, and bade him desist and saddle my horse, being minded to ride forth and take counsel with my good friend John Palmer at the Deanery, who bore Master Wilburton great affection.

Aug. 2 continued.—Dire news awaiteth me upon my return. The Sheriff’s men have disinterred the body of poor Master W. from beneath the grass Andrew was[16] rolling, and have arrested him on the charge of being his cause of death.

Aug. 10—Alas! Andrew Birch hath been hanged, the Justice having mercifully ordered that he should hang by the neck until he should be dead, and not sooner molested. May the Lord have mercy on his soul. He made full confession before me, that he had slain Master Wilburton in heat upon his threatening to make me privy to certain peculation of which I should not have suspected so old a servant. The poor man bemoaned his evil temper in great contrition, and beat his breast, saying that he knew himself doomed for ever to roll the grass in the place where he had tried to conceal his wicked fact.

“Thank you,” said Mr. Groves. “Has that little negative got the date upon it?” “Yes,” replied Mr. Batchel, as he examined it with his glass. The boy has marked it August 10. The Vicar seemed not to remark the coincidence with the date of Birch’s execution. Needless to say that it did not escape Mr. Groves. But he kept silence about the man with the roller, who has been no more seen to this day.

Doubtless there is more in our photography than we yet know of. The camera sees more than the eye, and chemicals in a freshly[17] prepared and active state, have a power which they afterwards lose. Our units of time, adopted for the convenience of persons dealing with the ordinary movements of material objects, are of course conventional. Those who turn the instruments of science upon nature will always be in danger of seeing more than they looked for. There is such a disaster as that of knowing too much, and at some time or another it may overtake each of us. May we then be as wise as Mr. Groves in our reticence, if our turn should come.

II.

BONE TO HIS BONE.

William Whitehead, Fellow of Emmanuel College, in the University of Cambridge, became Vicar of Stoneground in the year 1731. The annals of his incumbency were doubtless short and simple: they have not survived. In his day were no newspapers to collect gossip, no Parish Magazines to record the simple events of parochial life. One event, however, of greater moment then than now, is recorded in two places. Vicar Whitehead failed in health after 23 years of work, and journeyed to Bath in what his monument calls “the vain hope of being restored.” The duration of his visit is unknown; it is reasonable to suppose that he made his journey in the summer, it is certain that by the month of November his physician told him to lay aside all hope of recovery.

Then it was that the thoughts of the patient turned to the comfortable straggling vicarage he had left at Stoneground, in which he had hoped to end his days. He prayed that his successor might be as happy there as he had been himself. Setting his affairs in order, as became[20] one who had but a short time to live, he executed a will, bequeathing to the Vicars of Stoneground, for ever, the close of ground he had recently purchased because it lay next the vicarage garden. And by a codicil, he added to the bequest his library of books. Within a few days, William Whitehead was gathered to his fathers.

A mural tablet in the north aisle of the church, records, in Latin, his services and his bequests, his two marriages, and his fruitless journey to Bath. The house he loved, but never again saw, was taken down 40 years later, and re-built by Vicar James Devie. The garden, with Vicar Whitehead’s “close of ground” and other adjacent lands, was opened out and planted, somewhat before 1850, by Vicar Robert Towerson. The aspect of everything has changed. But in a convenient chamber on the first floor of the present vicarage the library of Vicar Whitehead stands very much as he used it and loved it, and as he bequeathed it to his successors “for ever.”

The books there are arranged as he arranged and ticketed them. Little slips of paper, sometimes bearing interesting fragments of writing, still mark his places. His marginal comments still give life to pages from which all other interest has faded, and he would have but a dull[21] imagination who could sit in the chamber amidst these books without ever being carried back 180 years into the past, to the time when the newest of them left the printer’s hands.

Of those into whose possession the books have come, some have doubtless loved them more, and some less; some, perhaps, have left them severely alone. But neither those who loved them, nor those who loved them not, have lost them, and they passed, some century and a half after William Whitehead’s death, into the hands of Mr. Batchel, who loved them as a father loves his children. He lived alone, and had few domestic cares to distract his mind. He was able, therefore, to enjoy to the full what Vicar Whitehead had enjoyed so long before him. During many a long summer evening would he sit poring over long-forgotten books; and since the chamber, otherwise called the library, faced the south, he could also spend sunny winter mornings there without discomfort. Writing at a small table, or reading as he stood at a tall desk, he would browse amongst the books like an ox in a pleasant pasture.

There were other times also, at which Mr. Batchel would use the books. Not being a sound sleeper (for book-loving men seldom are), he elected to use as a bedroom one of the two chambers which opened at either side into the[22] library. The arrangement enabled him to beguile many a sleepless hour amongst the books, and in view of these nocturnal visits he kept a candle standing in a sconce above the desk, and matches always ready to his hand.

There was one disadvantage in this close proximity of his bed to the library. Owing, apparently, to some defect in the fittings of the room, which, having no mechanical tastes, Mr. Batchel had never investigated, there could be heard, in the stillness of the night, exactly such sounds as might arise from a person moving about amongst the books. Visitors using the other adjacent room would often remark at breakfast, that they had heard their host in the library at one or two o’clock in the morning, when, in fact, he had not left his bed. Invariably Mr. Batchel allowed them to suppose that he had been where they thought him. He disliked idle controversy, and was unwilling to afford an opening for supernatural talk. Knowing well enough the sounds by which his guests had been deceived, he wanted no other explanation of them than his own, though it was of too vague a character to count as an explanation. He conjectured that the window-sashes, or the doors, or “something,” were defective, and was too phlegmatic and too unpractical to make any investigation. The matter gave him no concern.

Persons whose sleep is uncertain are apt to have their worst nights when they would like their best. The consciousness of a special need for rest seems to bring enough mental disturbance to forbid it. So on Christmas Eve, in the year 1907, Mr. Batchel, who would have liked to sleep well, in view of the labours of Christmas Day, lay hopelessly wide awake. He exhausted all the known devices for courting sleep, and, at the end, found himself wider awake than ever. A brilliant moon shone into his room, for he hated window-blinds. There was a light wind blowing, and the sounds in the library were more than usually suggestive of a person moving about. He almost determined to have the sashes “seen to,” although he could seldom be induced to have anything “seen to.” He disliked changes, even for the better, and would submit to great inconvenience rather than have things altered with which he had become familiar.

As he revolved these matters in his mind, he heard the clocks strike the hour of midnight, and having now lost all hope of falling asleep, he rose from his bed, got into a large dressing gown which hung in readiness for such occasions, and passed into the library, with the intention of reading himself sleepy, if he could.

The moon, by this time, had passed out of the south, and the library seemed all the darker[24] by contrast with the moonlit chamber he had left. He could see nothing but two blue-grey rectangles formed by the windows against the sky, the furniture of the room being altogether invisible. Groping along to where the table stood, Mr. Batchel felt over its surface for the matches which usually lay there; he found, however, that the table was cleared of everything. He raised his right hand, therefore, in order to feel his way to a shelf where the matches were sometimes mislaid, and at that moment, whilst his hand was in mid-air, the matchbox was gently put into it!

Such an incident could hardly fail to disturb even a phlegmatic person, and Mr. Batchel cried “Who’s this?” somewhat nervously. There was no answer. He struck a match, looked hastily round the room, and found it empty, as usual. There was everything, that is to say, that he was accustomed to see, but no other person than himself.

It is not quite accurate, however, to say that everything was in its usual state. Upon the tall desk lay a quarto volume that he had certainly not placed there. It was his quite invariable practice to replace his books upon the shelves after using them, and what we may call his library habits were precise and methodical. A book out of place like this,[25] was not only an offence against good order, but a sign that his privacy had been intruded upon. With some surprise, therefore, he lit the candle standing ready in the sconce, and proceeded to examine the book, not sorry, in the disturbed condition in which he was, to have an occupation found for him.

The book proved to be one with which he was unfamiliar, and this made it certain that some other hand than his had removed it from its place. Its title was “The Compleat Gard’ner” of M. de la Quintinye made English by John Evelyn Esquire. It was not a work in which Mr. Batchel felt any great interest. It consisted of divers reflections on various parts of husbandry, doubtless entertaining enough, but too deliberate and discursive for practical purposes. He had certainly never used the book, and growing restless now in mind, said to himself that some boy having the freedom of the house, had taken it down from its place in the hope of finding pictures.

But even whilst he made this explanation he felt its weakness. To begin with, the desk was too high for a boy. The improbability that any boy would place a book there was equalled by the improbability that he would leave it there. To discover its uninviting character[26] would be the work only of a moment, and no boy would have brought it so far from its shelf.

Mr. Batchel had, however, come to read, and habit was too strong with him to be wholly set aside. Leaving “The Compleat Gard’ner” on the desk, he turned round to the shelves to find some more congenial reading.

Hardly had he done this when he was startled by a sharp rap upon the desk behind him, followed by a rustling of paper. He turned quickly about and saw the quarto lying open. In obedience to the instinct of the moment, he at once sought a natural cause for what he saw. Only a wind, and that of the strongest, could have opened the book, and laid back its heavy cover; and though he accepted, for a brief moment, that explanation, he was too candid to retain it longer. The wind out of doors was very light. The window sash was closed and latched, and, to decide the matter finally, the book had its back, and not its edges, turned towards the only quarter from which a wind could strike.

Mr. Batchel approached the desk again and stood over the book. With increasing perturbation of mind (for he still thought of the matchbox) he looked upon the open page. Without much reason beyond that he felt constrained to do something, he read the words[27] of the half completed sentence at the turn of the page—

“at dead of night he left the house and passed into the solitude of the garden.”

But he read no more, nor did he give himself the trouble of discovering whose midnight wandering was being described, although the habit was singularly like one of his own. He was in no condition for reading, and turning his back upon the volume he slowly paced the length of the chamber, “wondering at that which had come to pass.”

He reached the opposite end of the chamber and was in the act of turning, when again he heard the rustling of paper, and by the time he had faced round, saw the leaves of the book again turning over. In a moment the volume lay at rest, open in another place, and there was no further movement as he approached it. To make sure that he had not been deceived, he read again the words as they entered the page. The author was following a not uncommon practise of the time, and throwing common speech into forms suggested by Holy Writ: “So dig,” it said, “that ye may obtain.”

This passage, which to Mr. Batchel seemed reprehensible in its levity, excited at once his interest and his disapproval. He was prepared to read more, but this time was not allowed.[28] Before his eye could pass beyond the passage already cited, the leaves of the book slowly turned again, and presented but a termination of five words and a colophon.

The words were, “to the North, an Ilex.” These three passages, in which he saw no meaning and no connection, began to entangle themselves together in Mr. Batchel’s mind. He found himself repeating them in different orders, now beginning with one, and now with another. Any further attempt at reading he felt to be impossible, and he was in no mind for any more experiences of the unaccountable. Sleep was, of course, further from him than ever, if that were conceivable. What he did, therefore, was to blow out the candle, to return to his moonlit bedroom, and put on more clothing, and then to pass downstairs with the object of going out of doors.

It was not unusual with Mr. Batchel to walk about his garden at night-time. This form of exercise had often, after a wakeful hour, sent him back to his bed refreshed and ready for sleep. The convenient access to the garden at such times lay through his study, whose French windows opened on to a short flight of steps, and upon these he now paused for a moment to admire the snow-like appearance of the lawns, bathed as they were in the moonlight. As he[29] paused, he heard the city clocks strike the half-hour after midnight, and he could not forbear repeating aloud

“At dead of night he left the house, and passed into the solitude of the garden.”

It was solitary enough. At intervals the screech of an owl, and now and then the noise of a train, seemed to emphasise the solitude by drawing attention to it and then leaving it in possession of the night. Mr. Batchel found himself wondering and conjecturing what Vicar Whitehead, who had acquired the close of land to secure quiet and privacy for garden, would have thought of the railways to the west and north. He turned his face northwards, whence a whistle had just sounded, and saw a tree beautifully outlined against the sky. His breath caught at the sight. Not because the tree was unfamiliar. Mr. Batchel knew all his trees. But what he had seen was “to the north, an Ilex.”

Mr. Batchel knew not what to make of it all. He had walked into the garden hundreds of times and as often seen the Ilex, but the words out of the “Compleat Gard’ner” seemed to be pursuing him in a way that made him almost afraid. His temperament, however, as has been said already, was phlegmatic. It was commonly said, and Mr. Batchel approved the verdict, whilst he condemned its inexactness,[30] that “his nerves were made of fiddle-string,” so he braced himself afresh and set upon his walk round the silent garden, which he was accustomed to begin in a northerly direction, and was now too proud to change. He usually passed the Ilex at the beginning of his perambulation, and so would pass it now.

He did not pass it. A small discovery, as he reached it, annoyed and disturbed him. His gardener, as careful and punctilious as himself, never failed to house all his tools at the end of a day’s work. Yet there, under the Ilex, standing upright in moonlight brilliant enough to cast a shadow of it, was a spade.

Mr. Batchel’s second thought was one of relief. After his extraordinary experiences in the library (he hardly knew now whether they had been real or not) something quite commonplace would act sedatively, and he determined to carry the spade to the tool-house.

The soil was quite dry, and the surface even a little frozen, so Mr. Batchel left the path, walked up to the spade, and would have drawn it towards him. But it was as if he had made the attempt upon the trunk of the Ilex itself. The spade would not be moved. Then, first with one hand, and then with both, he tried to raise it, and still it stood firm. Mr. Batchel, of course, attributed this to the frost, slight[31] as it was. Wondering at the spade’s being there, and annoyed at its being frozen, he was about to leave it and continue his walk, when the remaining words of the “Compleat Gard’ner” seemed rather to utter themselves, than to await his will—

“So dig, that ye may obtain.”

Mr. Batchel’s power of independent action now deserted him. He took the spade, which no longer resisted, and began to dig. “Five spadefuls and no more,” he said aloud. “This is all foolishness.”

Four spadefuls of earth he then raised and spread out before him in the moonlight. There was nothing unusual to be seen. Nor did Mr. Batchel decide what he would look for, whether coins, jewels, documents in canisters, or weapons. In point of fact, he dug against what he deemed his better judgment, and expected nothing. He spread before him the fifth and last spadeful of earth, not quite without result, but with no result that was at all sensational. The earth contained a bone. Mr. Batchel’s knowledge of anatomy was sufficient to show him that it was a human bone. He identified it, even by moonlight, as the radius, a bone of the forearm, as he removed the earth from it, with his thumb.

Such a discovery might be thought worthy[32] of more than the very ordinary interest Mr. Batchel showed. As a matter of fact, the presence of a human bone was easily to be accounted for. Recent excavations within the church had caused the upturning of numberless bones, which had been collected and reverently buried. But an earth-stained bone is also easily overlooked, and this radius had obviously found its way into the garden with some of the earth brought out of the church.

Mr. Batchel was glad, rather than regretful at this termination to his adventure. He was once more provided with something to do. The re-interment of such bones as this had been his constant care, and he decided at once to restore the bone to consecrated earth. The time seemed opportune. The eyes of the curious were closed in sleep, he himself was still alert and wakeful. The spade remained by his side and the bone in his hand. So he betook himself, there and then, to the churchyard. By the still generous light of the moon, he found a place where the earth yielded to his spade, and within a few minutes the bone was laid decently to earth, some 18 inches deep.

The city clocks struck one as he finished. The whole world seemed asleep, and Mr. Batchel slowly returned to the garden with his spade. As he hung it in its accustomed place he felt[33] stealing over him the welcome desire to sleep. He walked quietly on to the house and ascended to his room. It was now dark: the moon had passed on and left the room in shadow. He lit a candle, and before undressing passed into the library. He had an irresistible curiosity to see the passages in John Evelyn’s book which had so strangely adapted themselves to the events of the past hour.

In the library a last surprise awaited him. The desk upon which the book had lain was empty. “The Compleat Gard’ner” stood in its place on the shelf. And then Mr. Batchel knew that he had handled a bone of William Whitehead, and that in response to his own entreaty.

III.

THE RICHPINS.

Something of the general character of Stoneground and its people has been indicated by stray allusions in the preceding narratives. We must here add that of its present population only a small part is native, the remainder having been attracted during the recent prosperous days of brickmaking, from the nearer parts of East Anglia and the Midlands. The visitor to Stoneground now finds little more than the signs of an unlovely industry, and of the hasty and inadequate housing of the people it has drawn together. Nothing in the place pleases him more than the excellent train-service which makes it easy to get away. He seldom desires a long acquaintance either with Stoneground or its people.

The impression so made upon the average visitor is, however, unjust, as first impressions often are. The few who have made further acquaintance with Stoneground have soon learned to distinguish between the permanent and the accidental features of the place, and have been astonished by nothing so much as by[36] the unexpected evidence of French influence. Amongst the household treasures of the old inhabitants are invariably found French knick-knacks: there are pieces of French furniture in what is called “the room” of many houses. A certain ten-acre field is called the “Frenchman’s meadow.” Upon the voters’ lists hanging at the church door are to be found French names, often corrupted; and boys who run about the streets can be heard shrieking to each other such names as Bunnum, Dangibow, Planchey, and so on.

Mr. Batchel himself is possessed of many curious little articles of French handiwork—boxes deftly covered with split straws, arranged ingeniously in patterns; models of the guillotine, built of carved meat-bones, and various other pieces of handiwork, amongst them an accurate road-map of the country between Stoneground and Yarmouth, drawn upon a fly-leaf torn from some book, and bearing upon the other side the name of Jules Richepin. The latter had been picked up, according to a pencilled-note written across one corner, by a shepherd, in the year 1811.

The explanation of this French influence is simple enough. Within five miles of Stoneground a large barracks had been erected for the custody of French prisoners during the war[37] with Bonaparte. Many thousands were confined there during the years 1808-14. The prisoners were allowed to sell what articles they could make in the barracks; and many of them, upon their release, settled in the neighbourhood, where their descendants remain. There is little curiosity amongst these descendants about their origin. The events of a century ago seem to them as remote as the Deluge, and as immaterial. To Thomas Richpin, a weakly man who blew the organ in church, Mr. Batchel shewed the map. Richpin, with a broad, black-haired skull and a narrow chin which grew a little pointed beard, had always a foreign look about him: Mr. Batchel thought it more than possible that he might be descended from the owner of the book, and told him as much upon shewing him the fly-leaf. Thomas, however, was content to observe that “his name hadn’t got no E,” and shewed no further interest in the matter. His interest in it, before we have done with him, will have become very large.

For the growing boys of Stoneground, with whom he was on generally friendly terms, Mr. Batchel formed certain clubs to provide them with occupation on winter evenings; and in these clubs, in the interests of peace and good-order, he spent a great deal of time. Sitting one December evening, in a large circle of boys[38] who preferred the warmth of the fire to the more temperate atmosphere of the tables, he found Thomas Richpin the sole topic of conversation.

“We seen Mr. Richpin in Frenchman’s Meadow last night,” said one.

“What time?” said Mr. Batchel, whose function it was to act as a sort of fly-wheel, and to carry the conversation over dead points. He had received the information with some little surprise, because Frenchman’s Meadow was an unusual place for Richpin to have been in, but his question had no further object than to encourage talk.

“Half-past nine,” was the reply.

This made the question much more interesting. Mr. Batchel, on the preceding evening, had taken advantage of a warmed church to practise upon the organ. He had played it from nine o’clock until ten, and Richpin had been all that time at the bellows.

“Are you sure it was half-past nine?” he asked.

“Yes,” (we reproduce the answer exactly), “we come out o’ night-school at quarter-past, and we was all goin’ to the Wash to look if it was friz.”

“And you saw Mr. Richpin in Frenchman’s Meadow?” said Mr. Batchel.

“Yes. He was looking for something on the ground,” added another boy.

“And his trousers was tore,” said a third.

The story was clearly destined to stand in no need of corroboration.

“Did Mr. Richpin speak to you?” enquired Mr. Batchel.

“No, we run away afore he come to us,” was the answer.

“Why?”

“Because we was frit.”

“What frightened you?”

“Jim Lallement hauled a flint at him and hit him in the face, and he didn’t take no notice, so we run away.”

“Why?” repeated Mr. Batchel.

“Because he never hollered nor looked at us, and it made us feel so funny.”

“Did you go straight down to the Wash?”

They had all done so.

“What time was it when you reached home?”

They had all been at home by ten, before Richpin had left the church.

“Why do they call it Frenchman’s Meadow?” asked another boy, evidently anxious to change the subject.

Mr. Batchel replied that the meadow had probably belonged to a Frenchman whose name[40] was not easy to say, and the conversation after this was soon in another channel. But, furnished as he was with an unmistakeable alibi, the story about Richpin and the torn trousers, and the flint, greatly puzzled him.

“Go straight home,” he said, as the boys at last bade him good-night, “and let us have no more stone-throwing.” They were reckless boys, and Richpin, who used little discretion in reporting their misdemeanours about the church, seemed to Mr. Batchel to stand in real danger.

Frenchman’s Meadow provided ten acres of excellent pasture, and the owners of two or three hard-worked horses were glad to pay three shillings a week for the privilege of turning them into it. One of these men came to Mr. Batchel on the morning which followed the conversation at the club.

“I’m in a bit of a quandary about Tom Richpin,” he began.

This was an opening that did not fail to command Mr. Batchel’s attention. “What is it?” he said.

“I had my mare in Frenchman’s Meadow,” replied the man, “and Sam Bower come and told me last night as he heard her gallopin’ about when he was walking this side the hedge.”

“But what about Richpin?” said Mr. Batchel.

“Let me come to it,” said the other. “My mare hasn’t got no wind to gallop, so I up and went to see to her, and there she was sure enough, like a wild thing, and Tom Richpin walking across the meadow.”

“Was he chasing her?” asked Mr. Batchel, who felt the absurdity of the question as he put it.

“He was not,” said the man, “but what he could have been doin’ to put the mare into that state, I can’t think.”

“What was he doing when you saw him?” asked Mr. Batchel.

“He was walking along looking for something he’d dropped, with his trousers all tore to ribbons, and while I was catchin’ the mare, he made off.”

“He was easy enough to find, I suppose?” said Mr. Batchel.

“That’s the quandary I was put in,” said the man. “I took the mare home and gave her to my lad, and straight I went to Richpin’s, and found Tom havin’ his supper, with his trousers as good as new.”

“You’d made a mistake,” said Mr. Batchel.

“But how come the mare to make it too?” said the other.

“What did you say to Richpin?” asked Mr. Batchel.

“Tom,” I says, “when did you come in? ‘Six o’clock,’ he says, ‘I bin mendin’ my boots’; and there, sure enough, was the hobbin’ iron by his chair, and him in his stockin’-feet. I don’t know what to do.”

“Give the mare a rest,” said Mr. Batchel, “and say no more about it.”

“I don’t want to harm a pore creature like Richpin,” said the man, “but a mare’s a mare, especially where there’s a family to bring up.” The man consented, however, to abide by Mr. Batchel’s advice, and the interview ended. The evenings just then were light, and both the man and his mare had seen something for which Mr. Batchel could not, at present, account. The worst way, however, of arriving at an explanation is to guess it. He was far too wise to let himself wander into the pleasant fields of conjecture, and had determined, even before the story of the mare had finished, upon the more prosaic path of investigation.

Mr. Batchel, either from strength or indolence of mind, as the reader may be pleased to determine, did not allow matters even of this exciting kind, to disturb his daily round of duty. He was beginning to fear, after what he had heard of the Frenchman’s Meadow, that he[43] might find it necessary to preach a plain sermon upon the Witch of Endor, for he foresaw that there would soon be some ghostly talk in circulation. In small communities, like that of Stoneground, such talk arises upon very slight provocation, and here was nothing at all to check it. Richpin was a weak and timid man, whom no one would suspect, whilst an alternative remained open, of wandering about in the dark; and Mr. Batchel knew that the alternative of an apparition, if once suggested, would meet with general acceptance, and this he wished, at all costs, to avoid. His own view of the matter he held in reserve, for the reasons already stated, but he could not help suspecting that there might be a better explanation of the name “Frenchman’s Meadow” than he had given to the boys at their club.

Afternoons, with Mr. Batchel, were always spent in making pastoral visits, and upon the day our story has reached he determined to include amongst them a call upon Richpin, and to submit him to a cautious cross-examination. It was evident that at least four persons, all perfectly familiar with his appearance, were under the impression that they had seen him in the meadow, and his own statement upon the matter would be at least worth hearing.

Richpin’s home, however, was not the first[44] one visited by Mr. Batchel on that afternoon. His friendly relations with the boys has already been mentioned, and it may now be added that this friendship was but part of a generally keen sympathy with young people of all ages, and of both sexes. Parents knew much less than he did of the love affairs of their young people; and if he was not actually guilty of match-making, he was at least a very sympathetic observer of the process. When lovers had their little differences, or even their greater ones, it was Mr. Batchel, in most cases, who adjusted them, and who suffered, if he failed, hardly less than the lovers themselves.

It was a negotiation of this kind which, on this particular day, had given precedence to another visit, and left Richpin until the later part of the afternoon. But the matter of the Frenchman’s Meadow had, after all, not to wait for Richpin. Mr. Batchel was calculating how long he should be in reaching it, when he found himself unexpectedly there. Selina Broughton had been a favourite of his from her childhood; she had been sufficiently good to please him, and naughty enough to attract and challenge him; and when at length she began to walk out with Bob Rockfort, who was another favourite, Mr. Batchel rubbed his hands in satisfaction. Their present difference, which now brought him to[45] the Broughtons’ cottage, gave him but little anxiety. He had brought Bob half-way towards reconciliation, and had no doubt of his ability to lead Selina to the same place. They would finish the journey, happily enough, together.

But what has this to do with the Frenchman’s Meadow? Much every way. The meadow was apt to be the rendezvous of such young people as desired a higher degree of privacy than that afforded by the public paths; and these two had gone there separately the night before, each to nurse a grievance against the other. They had been at opposite ends, as it chanced, of the field; and Bob, who believed himself to be alone there, had been awakened from his reverie by a sudden scream. He had at once run across the field, and found Selina sorely in need of him. Mr. Batchel’s work of reconciliation had been there and then anticipated, and Bob had taken the girl home in a condition of great excitement to her mother. All this was explained, in breathless sentences, by Mrs. Broughton, by way of accounting for the fact that Selina was then lying down in “the room.”

There was no reason why Mr. Batchel should not see her, of course, and he went in. His original errand had lapsed, but it was now replaced by one of greater interest. Evidently there was Selina’s testimony to add to that of[46] the other four; she was not a girl who would scream without good cause, and Mr. Batchel felt that he knew how his question about the cause would be answered, when he came to the point of asking it.

He was not quite prepared for the form of her answer, which she gave without any hesitation. She had seen Mr. Richpin “looking for his eyes.” Mr. Batchel saved for another occasion the amusement to be derived from the curiously illogical answer. He saw at once what had suggested it. Richpin had until recently had an atrocious squint, which an operation in London had completely cured. This operation, of which, of course, he knew nothing, he had described, in his own way, to anyone who would listen, and it was commonly believed that his eyes had ceased to be fixtures. It was plain, however, that Selina had seen very much what had been seen by the other four. Her information was precise, and her story perfectly coherent. She preserved a maidenly reticence about his trousers, if she had noticed them; but added a new fact, and a terrible one, in her description of the eyeless sockets. No wonder she had screamed. It will be observed that Mr. Richpin was still searching, if not looking, for something upon the ground.

Mr. Batchel now proceeded to make his remaining visit. Richpin lived in a little cottage by the church, of which cottage the Vicar was the indulgent landlord. Richpin’s creditors were obliged to shew some indulgence, because his income was never regular and seldom sufficient. He got on in life by what is called “rubbing along,” and appeared to do it with surprisingly little friction. The small duties about the church, assigned to him out of charity, were overpaid. He succeeded in attracting to himself all the available gifts of masculine clothing, of which he probably received enough and to sell, and he had somehow wooed and won a capable, if not very comely, wife, who supplemented his income by her own labour, and managed her house and husband to admiration.

Richpin, however, was not by any means a mere dependent upon charity. He was, in his way, a man of parts. All plants, for instance, were his friends, and he had inherited, or acquired, great skill with fruit-trees, which never failed to reward his treatment with abundant crops. The two or three vines, too, of the neighbourhood, he kept in fine order by methods of his own, whose merit was proved by their success. He had other skill, though of a less remunerative kind, in fashioning toys out of wood, cardboard, or paper; and every correctly-behaving[48] child in the parish had some such product of his handiwork. And besides all this, Richpin had a remarkable aptitude for making music. He could do something upon every musical instrument that came in his way, and, but for his voice, which was like that of the peahen, would have been a singer. It was his voice that had secured him the situation of organ-blower, as one remote from all incitement to join in the singing in church.

Like all men who have not wit enough to defend themselves by argument, Richpin had a plaintive manner. His way of resenting injury was to complain of it to the next person he met, and such complaints as he found no other means of discharging, he carried home to his wife, who treated his conversation just as she treated the singing of the canary, and other domestic sounds, being hardly conscious of it until it ceased.

The entrance of Mr. Batchel, soon after his interview with Selina, found Richpin engaged in a loud and fluent oration. The fluency was achieved mainly by repetition, for the man had but small command of words, but it served none the less to shew the depth of his indignation.

“I aren’t bin in Frenchman’s Meadow, am I?” he was saying in appeal to his wife—this is[49] the Stoneground way with auxiliary verbs—“What am I got to go there for?” He acknowledged Mr. Batchel’s entrance in no other way than by changing to the third person in his discourse, and he continued without pause—“if she’d let me out o’ nights, I’m got better places to go to than Frenchman’s Meadow. Let policeman stick to where I am bin, or else keep his mouth shut. What call is he got to say I’m bin where I aren’t bin?”

From this, and much more to the same effect, it was clear that the matter of the meadow was being noised abroad, and even receiving official attention. Mr. Batchel was well aware that no question he could put to Richpin, in his present state, would change the flow of his eloquence, and that he had already learned as much as he was likely to learn. He was content, therefore, to ascertain from Mrs. Richpin that her husband had indeed spent all his evenings at home, with the single exception of the one hour during which Mr. Batchel had employed him at the organ. Having ascertained this, he retired, and left Richpin to talk himself out.

No further doubt about the story was now possible. It was not twenty-four hours since Mr. Batchel had heard it from the boys at the club, and it had already been confirmed by at[50] least two unimpeachable witnesses. He thought the matter over, as he took his tea, and was chiefly concerned in Richpin’s curious connexion with it. On his account, more than on any other, it had become necessary to make whatever investigation might be feasible, and Mr. Batchel determined, of course, to make the next stage of it in the meadow itself.

The situation of “Frenchman’s Meadow” made it more conspicuous than any other enclosure in the neighbourhood. It was upon the edge of what is locally known as “high land”; and though its elevation was not great, one could stand in the meadow and look sea-wards over many miles of flat country, once a waste of brackish water, now a great chess-board of fertile fields bounded by straight dykes of glistening water. The point of view derived another interest from looking down upon a long straight bank which disappeared into the horizon many miles away, and might have been taken for a great railway embankment of which no use had been made. It was, in fact, one of the great works of the Dutch Engineers in the time of Charles I., and it separated the river basin from a large drained area called the “Middle Level,” some six feet below it. In this embankment, not two hundred yards below “Frenchman’s Meadow,” was one of the huge[51] water gates which admitted traffic through a sluice, into the lower level, and the picturesque thatched cottage of the sluice-keeper formed a pleasing addition to the landscape. It was a view with which Mr. Batchel was naturally very familiar. Few of his surroundings were pleasant to the eye, and this was about the only place to which he could take a visitor whom he desired to impress favourably. The way to the meadow lay through a short lane, and he could reach it in five minutes: he was frequently there.

It was, of course, his intention to be there again that evening: to spend the night there, if need be, rather than let anything escape him. He only hoped he should not find half the parish there also. His best hope of privacy lay in the inclemency of the weather; the day was growing colder, and there was a north-east wind, of which Frenchman’s Meadow would receive the fine edge.

Mr. Batchel spent the next three hours in dealing with some arrears of correspondence, and at nine o’clock put on his thickest coat and boots, and made his way to the meadow. It became evident, as he walked up the lane, that he was to have company. He heard many voices, and soon recognised the loudest amongst them. Jim Lallement was boasting of the[52] accuracy of his aim: the others were not disputing it, but were asserting their own merits in discordant chorus. This was a nuisance, and to make matters worse, Mr. Batchel heard steps behind him.

A voice soon bade him “Good evening.” To Mr. Batchel’s great relief it proved to be the policeman, who soon overtook him. The conversation began on his side.

“Curious tricks, sir, these of Richpin’s.”

“What tricks?” asked Mr. Batchel, with an air of innocence.

“Why, he’s been walking about Frenchman’s Meadow these three nights, frightening folk and what all.”

“Richpin has been at home every night, and all night long,” said Mr. Batchel.

“I’m talking about where he was, not where he says he was,” said the policeman. “You can’t go behind the evidence.”

“But Richpin has evidence too. I asked his wife.”

“You know, sir, and none better, that wives have got to obey. Richpin wants to be took for a ghost, and we know that sort of ghost. Whenever we hear there’s a ghost, we always know there’s going to be turkeys missing.”

“But there are real ghosts sometimes, surely?” said Mr. Batchel.

“No,” said the policeman, “me and my wife have both looked, and there’s no such thing.”

“Looked where?” enquired Mr. Batchel.

“In the ‘Police Duty’ Catechism. There’s lunatics, and deserters, and dead bodies, but no ghosts.”

Mr. Batchel accepted this as final. He had devised a way of ridding himself of all his company, and proceeded at once to carry it into effect. The two had by this time reached the group of boys.

“These are all stone-throwers,” said he, loudly.

There was a clatter of stones as they dropped from the hands of the boys.

“These boys ought all to be in the club instead of roaming about here damaging property. Will you take them there, and see them safely in? If Richpin comes here, I will bring him to the station.”

The policeman seemed well pleased with the suggestion. No doubt he had overstated his confidence in the definition of the “Police Duty.” Mr. Batchel, on his part, knew the boys well enough to be assured that they would keep the policeman occupied for the next half-hour, and as the party moved slowly away, felt proud of his diplomacy.

There was no sign of any other person about the field gate, which he climbed readily enough, and he was soon standing in the highest part of the meadow and peering into the darkness on every side.

It was possible to see a distance of about thirty yards; beyond that it was too dark to distinguish anything. Mr. Batchel designed a zig-zag course about the meadow, which would allow of his examining it systematically and as rapidly as possible, and along this course he began to walk briskly, looking straight before him as he went, and pausing to look well about him when he came to a turn. There were no beasts in the meadow—their owners had taken the precaution of removing them; their absence was, of course, of great advantage to Mr. Batchel.

In about ten minutes he had finished his zig-zag path and arrived at the other corner of the meadow; he had seen nothing resembling a man. He then retraced his steps, and examined the field again, but arrived at his starting point, knowing no more than when he had left it. He began to fear the return of the policeman as he faced the wind and set upon a third journey.

The third journey, however, rewarded him. He had reached the end of his second traverse,[55] and was looking about him at the angle between that and the next, when he distinctly saw what looked like Richpin crossing his circle of vision, and making straight for the sluice. There was no gate on that side of the field; the hedge, which seemed to present no obstacle to the other, delayed Mr. Batchel considerably, and still retains some of his clothing, but he was not long through before he had again marked his man. It had every appearance of being Richpin. It went down the slope, crossed the plank that bridged the lock, and disappeared round the corner of the cottage, where the entrance lay.

Mr. Batchel had had no opportunity of confirming the gruesome observation of Selina Broughton, but had seen enough to prove that the others had not been romancing. He was not a half-minute behind the figure as it crossed the plank over the lock—it was slow going in the darkness—and he followed it immediately round the corner of the house. As he expected, it had then disappeared.

Mr. Batchel knocked at the door, and admitted himself, as his custom was. The sluice-keeper was in his kitchen, charring a gate post. He was surprised to see Mr. Batchel at that hour, and his greeting took the form of a remark to that effect.

“I have been taking an evening walk,” said Mr. Batchel. “Have you seen Richpin lately?”

“I see him last Saturday week,” replied the sluice-keeper, “not since.”

“Do you feel lonely here at night?”

“No,” replied the sluice-keeper, “people drop in at times. There was a man in on Monday, and another yesterday.”

“Have you had no one to-day?” said Mr. Batchel, coming to the point.

The answer showed that Mr. Batchel had been the first to enter the door that day, and after a little general conversation he brought his visit to an end.

It was now ten o’clock. He looked in at Richpin’s cottage, where he saw a light burning, as he passed. Richpin had tired himself early, and had been in bed since half-past eight. His wife was visibly annoyed at the rumours which had upset him, and Mr. Batchel said such soothing words as he could command, before he left for home.

He congratulated himself, prematurely, as he sat before the fire in his study, that the day was at an end. It had been cold out of doors, and it was pleasant to think things over in the warmth of the cheerful fire his housekeeper never failed to leave for him. The reader will have no more difficulty than Mr. Batchel[57] had in accounting for the resemblance between Richpin and the man in the meadow. It was a mere question of family likeness. That the ancestor had been seen in the meadow at some former time might perhaps be inferred from its traditional name. The reason for his return, then and now, was a matter of mere conjecture, and Mr. Batchel let it alone.

The next incident has, to some, appeared incredible, which only means, after all, that it has made demands upon their powers of imagination and found them bankrupt.

Critics of story-telling have used severe language about authors who avail themselves of the short-cut of coincidence. “That must be reserved, I suppose,” said Mr. Batchel, when he came to tell of Richpin, “for what really happens; and that fiction is a game which must be played according to the rules.”

“I know,” he went on to say, “that the chances were some millions to one against what happened that night, but if that makes it incredible, what is there left to believe?”

It was thereupon remarked by someone in the company, that the credible material would not be exhausted.

“I doubt whether anything happens,” replied Mr. Batchel in his dogmatic way, “without the chances being a million to one[58] against it. Why did they choose such a word? What does ‘happen’ mean?”

There was no reply: it was clearly a rhetorical question.

“Is it incredible,” he went on, “that I put into the plate last Sunday the very half-crown my uncle tipped me with in 1881, and that I spent next day?”

“Was that the one you put in?” was asked by several.

“How do I know?” replied Mr. Batchel, “but if I knew the history of the half-crown I did put in, I know it would furnish still more remarkable coincidences.”

All this talk arose out of the fact that at midnight on the eventful day, whilst Mr. Batchel was still sitting by his study fire, he had news that the cottage at the sluice had been burnt down. The thatch had been dry; there was, as we know, a stiff east-wind, and an hour had sufficed to destroy all that was inflammable. The fire is still spoken of in Stoneground with great regret. There remains only one building in the place of sufficient merit to find its way on to a postcard.

It was just at midnight that the sluice-keeper rung at Mr. Batchel’s door. His errand required no apology. The man had found a night-fisherman to help him as soon as the fire[59] began, and with two long sprits from a lighter they had made haste to tear down the thatch, and upon this had brought down, from under the ridge at the South end, the bones and some of the clothing of a man. Would Mr. Batchel come down and see?

Mr. Batchel put on his coat and returned to the place. The people whom the fire had collected had been kept on the further side of the water, and the space about the cottage was vacant. Near to the smouldering heap of ruin were the remains found under the thatch. The fingers of the right hand still firmly clutched a sheep bone which had been gnawed as a dog would gnaw it.

“Starved to death,” said the sluice-keeper, “I see a tramp like that ten years ago.”

They laid the bones decently in an outhouse, and turned the key, Mr. Batchel carried home in his hand a metal cross, threaded upon a cord. He found an engraved figure of Our Lord on the face of it, and the name of Pierre Richepin upon the back. He went next day to make the matter known to the nearest Priest of the Roman Faith, with whom he left the cross. The remains, after a brief inquest, were interred in the cemetery, with the rites of the Church to which the man had evidently belonged.

Mr. Batchel’s deductions from the whole circumstances were curious, and left a great deal to be explained. It seemed as if Pierre Richepin had been disturbed by some premonition of the fire, but had not foreseen that his mortal remains would escape; that he could not return to his own people without the aid of his map, but had no perception of the interval that had elapsed since he had lost it. This map Mr. Batchel put into his pocket-book next day when he went to Thomas Richpin for certain other information about his surviving relatives.

Richpin had a father, it appeared, living a few miles away in Jakesley Fen, and Mr. Batchel concluded that he was worth a visit. He mounted his bicycle, therefore, and made his way to Jakesley that same afternoon.

Mr. Richpin was working not far from home, and was soon brought in. He and his wife shewed great courtesy to their visitor, whom they knew well by repute. They had a well-ordered house, and with a natural and dignified hospitality, asked him to take tea with them. It was evident to Mr. Batchel that there was a great gulf between the elder Richpin and his son; the former was the last of an old race, and the latter the first of a new. In spite of the Board of Education, the latter was vastly the worse.

The cottage contained some French kickshaws which greatly facilitated the enquiries Mr. Batchel had come to make. They proved to be family relics.

“My grandfather,” said Mr. Richpin, as they sat at tea, “was a prisoner—he and his brother.”

“Your grandfather was Pierre Richepin?” asked Mr. Batchel.

“No! Jules,” was the reply. “Pierre got away.”

“Shew Mr. Batchel the book,” said his wife.

The book was produced. It was a Book of Meditations, with the name of Jules Richepin upon the title-page. The fly-leaf was missing. Mr. Batchel produced the map from his pocket-book. It fitted exactly. The slight indentures along the torn edge fell into their place, and Mr. Batchel left the leaf in the book, to the great delight of the old couple, to whom he told no more of the story than he thought fit.

IV.

THE EASTERN WINDOW.

It may well be that Vermuyden and the Dutchmen who drained the fens did good, and that it was interred with their bones. It is quite certain that they did evil and that it lives after them. The rivers, which these men robbed of their water, have at length silted up, and the drainage of one tract of country is proving to have been achieved by the undraining of another.

Places like Stoneground, which lie on the banks of these defrauded rivers, are now become helpless victims of Dutch engineering. The water which has lost its natural outlet, invades their lands. The thrifty cottager who once had the river at the bottom of his garden, has his garden more often in these days, at the bottom of the river, and a summer flood not infrequently destroys the whole produce of his ground.

Such a flood, during an early year in the 20th century, had been unusually disastrous to Stoneground, and Mr. Batchel, who, as a[64] gardener, was well able to estimate the losses of his poorer neighbours, was taking some steps towards repairing them.

Money, however, is never at rest in Stoneground, and it turned out upon this occasion that the funds placed at his command were wholly inadequate to the charitable purpose assigned to them. It seemed as if those who had lost a rood of potatoes could be compensated for no more than a yard.

It was at this time, when he was oppressed in mind by the failure of his charitable enterprise, that Mr. Batchel met with the happy adventure in which the Eastern window of the Church played so singular a part.

The narrative should be prefaced by a brief description of the window in question. It is a large painted window, of a somewhat unfortunate period of execution. The drawing and colouring leave everything to be desired. The scheme of the window, however, is based upon a wholesome tradition. The five large lights in the lower part are assigned to five scenes in the life of Our Lord, and the second of these, counting from the North, contains a bold erect figure of St. John Baptist, to whom the Church is dedicated. It is this figure alone, of all those contained in the window, that is concerned in what we have to relate.

It has already been mentioned that Mr. Batchel had some knowledge of music. He took an interest in the choir, from whose practices he was seldom absent; and was quite competent, in the occasional absence of the choirmaster, to act as his deputy. It is customary at Stoneground for the choirmaster, in order to save the sexton a journey, to extinguish the lights after a choir-practice and to lock up the Church. These duties, accordingly, were performed by Mr. Batchel when the need arose.

It will be of use to the reader to have the procedure in detail. The large gas-meter stood in an aisle of the Church, and it was Mr. Batchel’s practice to go round and extinguish all the lights save one, before turning off the gas at the meter. The one remaining light, which was reached by standing upon a choir seat, was always that nearest the door of the chancel, and experience proved that there was ample time to walk from the meter to that light before it died out. It was therefore an easy matter to turn off the last light, to find the door without its aid, and thence to pass out, and close the Church for the night.

Upon the evening of which we have to speak, the choir had hurried out as usual, as soon as the word had been given. Mr. Batchel had remained to gather together some of the books[66] they had left in disorder, and then turned out the lights in the manner already described. But as soon as he had extinguished the last light, his eye fell, as he descended carefully from the seat, upon the figure of the Baptist. There was just enough light outside to make the figures visible in the Eastern Window, and Mr. Batchel saw the figure of St. John raise the right arm to its full extent, and point northward, turning its head, at the same time, so as to look him full in the face. These movements were three times repeated, and, after that, the figure came to rest in its normal and familiar position.

The reader will not suppose, any more than Mr. Batchel supposed, that a figure painted upon glass had suddenly been endowed with the power of movement. But that there had been the appearance of movement admitted of no doubt, and Mr. Batchel was not so incurious as to let the matter pass without some attempt at investigation. It must be remembered, too, that an experience in the old library, which has been previously recorded, had pre-disposed him to give attention to signs which another man might have wished to explain away. He was not willing, therefore, to leave this matter where it stood. He was quite prepared to think that his eye had been deceived, but was none the less determined to find out what had[67] deceived it. One thing he had no difficulty in deciding. If the movement had not been actually within the Baptist’s figure, it had been immediately behind it. Without delay, therefore, he passed out of the church and locked the door after him, with the intention of examining the other side of the window.

Every inhabitant of Stoneground knows, and laments, the ruin of the old Manor House. Its loss by fire some fifteen years ago was a calamity from which the parish has never recovered. The estate was acquired, soon after the destruction of the house, by speculators who have been unable to turn it to any account, and it has for a decade or longer been “let alone,” except by the forces of Nature and the wantonness of trespassers. The charred remains of the house still project above the surrounding heaps of fallen masonry, which have long been overgrown by such vegetation as thrives on neglected ground; and what was once a stately house, with its garden and park in fine order, has given place to a scene of desolation and ruin.

Stoneground Church was built, some 600 years ago, within the enclosure of the Manor House, or, as it was anciently termed, the Burystead, and an excellent stratum of gravel such as no builder would wisely disregard,[68] brought the house and Church unusually near together. In more primitive days, the nearness probably caused no inconvenience; but when change and progress affected the popular idea of respectful distance, the Churchyard came to be separated by a substantial stone wall, of sufficient height to secure the privacy of the house.

The change was made with necessary regard to economy of space. The Eastern wall of the Church already projected far into the garden of the Manor, and lay but fifty yards from the south front of the house. On that side of the Churchyard, therefore, the new wall was set back. Running from the north to the nearest corner of the Church, it was there built up to the Church itself, and then continued from the southern corner, leaving the Eastern wall and window within the garden of the Squire. It was his ivy that clung to the wall of the Church, and his trees that shaded the window from the morning sun.

Whilst we have been recalling these facts, Mr. Batchel has made his way out of the Church and through the Churchyard, and has arrived at a small door in the boundary wall, close to the S.E. corner of the chancel. It was a door which some Squire of the previous century had made, to give convenient access to the Church for[69] himself and his household. It has no present use, and Mr. Batchel had some difficulty in getting it open. It was not long, however, before he stood on the inner side, and was examining the second light of the window. There was a tolerably bright moon, and the dark surface of the glass could be distinctly seen, as well as the wirework placed there for its protection.