THE BARBER’S CHAIR,

AND

THE HEDGEHOG LETTERS.

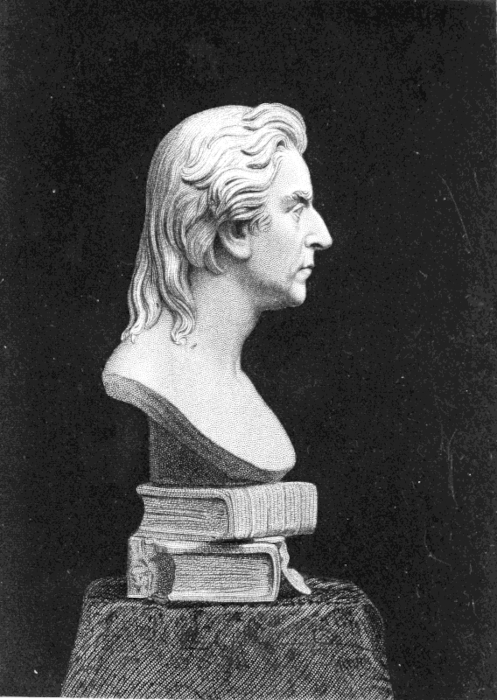

DOUGLAS JERROLD.

Taken from the Marble Bust by E. H. Bailey, R.A.F.R.S.

The Barber’s Chair,

AND

The Hedgehog Letters.

BY

DOUGLAS JERROLD.

EDITED, WITH AN INTRODUCTION, BY HIS SON,

BLANCHARD JERROLD.

London:

CHATTO AND WINDUS, PICCADILLY.

1874.

Contents.

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction, | vii | |

| The Barber’s Chair, | 1 | |

| The Hedgehog Letters— | ||

| 1. | To Peter Hedgehog, at Sydney, | 211 |

| 2. | To Mrs Hedgehog of New York, | 216 |

| 3. | To Mrs Hedgehog of New York, | 222 |

| 4. | To Michael Hedgehog, at Hong-Kong, | 228 |

| 5. | To Mrs Barbara Wilcox, at Philadelphia, | 231 |

| 6. | To Mr Jonas Wilcox, Philadelphia, | 234 |

| 7. | To John Squalid, Weaver, Stockton, | 239 |

| 8. | To —— ——, Naples, | 244 |

| 9. | To Mrs Hedgehog of New York, | 247 |

| 10. | To Samuel Hedgehog, Galantee Showman, Ratcliffe Highway, | 252 |

| 11. | To Chickweed, Widow, Penzance, | 257 |

| 12. | To Isaac Moss, Slop-seller, Portsmouth, | 260 |

| 13. | To Mrs Hedgehog of New York, | 263 |

| 14. | To Mrs Hedgehog of New York, | 272 |

| 15. | To Miss Kitty Hedgehog, Milliner, Philadelphia, | 279 |

| 16. | To Mrs Hedgehog, New York, | 285 |

| 17. | To Michael Hedgehog, Hong-Kong, | 290 |

| 18. | To Richard Monckton Milnes, Esq., M.P., | 293 |

| 19. | To Isaac Moss, Slop-seller, Portsmouth, | 297 |

| 20. | To Mrs Hedgehog, New York, | 300 |

| 21. | To Sir J. B. Tyrell, Bart., M.P. for North Essex, | 308 |

| 22. | To Mrs Hedgehog, New York, | 312 |

| 23. | To Mrs Hedgehog, New York, | 319 |

[Pg vii]

Introduction.

These dialogues on passing events appeared in Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper, a journal started by my father in 1846. They became at once very popular. The idea was a fresh and happy one that, like “Caudle’s Lectures,” went home to all classes of readers. Indeed, in Mrs Nutts we have indications of Mrs Caudle’s vein: Mrs Nutts might have been a poor relation of the Caudle family. Nutts is such a barber as the Gossip was, who for many years occupied a little shop against Temple Bar—with one door in the City and the other in Middlesex. He was the most talkative, the most knowing, the most confident of barbers. His mind had possibly been sharpened by the distinguished men from the Temple, and from the Fleet Street newspaper offices, whom he had shaved. He had more than[Pg viii] a smattering of literary and forensic gossip: he was something of a humourist, and, like Mr Nutts, it took very much in the way of news to surprise him. Mr Nutts observes that he has had so much news in his time, that he has lost the flavour of it. He could relish nothing weaker than a battle of Waterloo. To this state of satiety had the Temple Bar barber shaved and talked himself.

Indeed it is my firm belief that the “Barber’s Chair,” which in 1847 was set up in the offices of Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper, next door to the Strand Theatre, was the chair taken from Temple Bar; and that the most loquacious and original of barbers sat for Mr Nutts.

These weekly humorous commentaries on passing events, made by Mr Nutts and his customers, carry me back to the bright time when they were written. It was about the happiest epoch of my father’s life. He had won his place; he had troops of friends; he could gather Dickens, Leigh Hunt, Maclise, Macready, Mark Lemon, Lord Nugent, and other merry companions, to dine under his great tent by the mulberry-tree at West Lodge; he was in good health—a rare enjoyment in his case; and his own newspaper and magazine were[Pg ix] prospering. On the stage, in the volumes of Punch, and in his own organs, he was addressing the public. All his intellectual forces were at their brightest. With Dickens, Mr Forster, Leech, and Lemon he had recently delighted picked audiences as Master Stephen in “Every Man in his Humour.” He wrote about this time to Dickens that his newspaper was a substantial success; and that henceforth he was beyond the reach of stern Fortune, who had treated him roughly for many a weary year. Dickens, in reply, said, “Two numbers of the ‘Barber’s Chair’ have reached me. It is a capital idea, and capable of the best and readiest adaptation to things as they arise.”

Suddenly the glowing lights of the picture faded. A daughter who was living in Guernsey fell dangerously ill; and he was called away from the editorial chair, and from the “Barber’s Chair.” He was so affected by the danger in which he found my sister that he could not write a line. Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper began to appear without Mr Nutts and his customers; and each week the newsboys would ask, “Any Barber?”

Answered in the negative, they would take a[Pg x] less number of copies. Week after week, while my father remained away, the circulation of the paper fell. Not only was his pen absent, but he had weighted it with heavy contributors, who were possibly sound, but unquestionably dull. He could not say nay to a friend; and directly he had installed himself as editor of a weekly journal, he was besieged. He would take a series, thinking rather of the pleasure he was giving the writer than of the way in which the public would receive it. Thus he became entangled in a currency series of interminable length, that tried the patience of readers to the utmost. In Angus Reach he had a lively and spirited colleague, and Frederick Guest Tomlins was a fair manager; but these could not make way, in his absence, against the dull men, and the decline of circulation continued. My father returned to London to find a newspaper which he had left a handsome property, dwindled to a concern that hardly paid its expenses.

The “Barber’s Chair” was resumed, and with it the flagging paper revived. Messrs Nutts, Nosebag, Tickle, Bleak, Slowgoe, and the rest of the authorities of the barber’s shop, talked about the events[Pg xi] of the week in the old sprightly manner. Nutts and his wife cross to France, and the lady is rudely treated at the Customhouse. They were searched, said Nutts, as though they had brought a cutler’s shop and a cotton-mill in every one of their pockets. Slowgoe reproaches the barber as the advocate of universal peace, “and all that sort of stuff;” and defends war on the ground that “there’s nothing so little as doesn’t eat up something as is smaller than itself.”

One week, a poor babe is picked up in a basket, on a doorstep: the same week the papers have an account of the betrothal of the young Queen of Spain to a man whom she loathed. She sobbed as she was forced to plight her troth to him. The two cases are contrasted in the barber’s shop. On the one hand we have Betsy of Bermondsey, and on the other Isabella of Spain. Betsy gets on in life “as a football gets on by all sorts o’ kicks and knocks.” Betsy has the humblest fortune, but she gives her heart away, and is all the lighter and rosier for the gift. And “she marries the baker, and in as quick a time as possible she’s in a little shop, with three precious babbies, selling penny rolls, and almost making ’em twopennies by the good nature[Pg xii] she throws about ’em.” Then comes the case of the Queen of Spain—a “poor little merino lamb!” Next week Mr Bleak reads glorious news—the Duke of Marlborough intends shortly to take up his permanent residence at Blenheim Palace. Whereupon Nosebag observes, “Well, that’s somethin’ to comfort us for the ’tato blight;” and he wonders why the papers that tell the people when dukes and lords change their houses, don’t also tell them when they change their coats. Nutts supplies an instance: “We are delighted to inform our enlightened public that the Marquis of Londonderry appeared yesterday in a bran-new patent paletot. He will wear it for the next fortnight, and then return to his usual blue for the season.” Gilbert à Beckett had ridiculed the Court newsman and the Jenkinses of the period, years before. One bit was especially good: “Her Royal Highness the Princess Victoria walked yesterday morning in Kensington Gardens. We are given to understand that her Royal Highness used both legs.”

Farther on there is a conversation in the shop on the possibility of contemplating such a social revolution as the marriage of a princess with a commoner. “What!” cries Slowgoe, “marry a[Pg xiii] princess to a husband with no royal blood! do you know the consequence? What would you think if the eagle was to marry the dove?” Nutts replies, “Why, I certainly shouldn’t think much of the eggs.” They were, for the most part, “dreadful Radicals” in Mr Nutts’ shop. They said many good things, however. Mr Tickle remarks, “Married people grin the most at a wedding, ’cause other folks can get into a scrape as well as themselves.” Slowgoe opines that “the world isn’t worth fifty years’ purchase,” because the railway people are using up all the iron, which “we may look upon as the bones of the world.” Nutts says, “The real gun-cotton’s in petticoats.” Again, “Family pride, and national pride, to be worth anything, should be like a tree: taking root years ago, but having apples every year.” He describes Justice as keeping a chandler’s shop in the Old Bailey, to “serve out penn’orths to poor people.”

In due course the dialogues of Mr Nutts and his customers were brought to a close. The sage reflections of Mr Tickle were left unreported, albeit at the very last he was at his best. “How often,” he remarked to loyal Mr Slowgoe, “has Fortune crowned where she ought to have bonneted.”

[Pg xiv]

Other series were essayed in the newspaper. In 1848 my father went to Paris, well furnished with letters of introduction to Lamartine and the prominent men of the Republican Government, to write a number of papers on the aspects of the French capital. He would never speak about that journey afterwards. He was not at home by the banks of the Seine. He hated turmoil. He could never write in a hurry, nor under uncomfortable circumstances. He felt directly he had reached the hotel that he had made a mistake, and that descriptive reporting was no gift of his. His secretary was sent abroad to gather bits of information, and brought back a budget of peculiar and exclusive news in the evening—but it was left unused. Even the letters of introduction remained upon the writing-table; and they were never delivered. Only a few columns of writing ever reached the newspaper; and “Douglas Jerrold in Paris” had been advertised far and wide!

In brief, Douglas Jerrold had tired of his newspaper. He could not work up against the tide. The break in the “Barber’s Chair,” and the consequent loss of circulation, had never been recovered; whereas the Currency series, signed Aladdin, was[Pg xv] interminable, and its dulness provoked protests and wearied out subscribers. The papers were perhaps admirable. They were written by a very clever man. But they should have been in the Banker’s Magazine, or the Economist, and not in the columns of a popular newspaper. The end was a heavy loss, which might have been substantial fortune. It was a bitter result, brought about by the editor’s inability to sustain a continuous effort; and by his easy-going friendship, that led him to open his columns to incompetent writers. This latter editorial defect harmed the Illuminated Magazine, and hastened the death of the Shilling Magazine. Both were suffocated by importunate dullards, who would besiege the editor in his study, and never leave him till they had obtained his consent to print a score of articles from their fatally facile pens.

Of Douglas Jerrold’s Weekly Newspaper there remains only—“The Barber’s Chair.” It is a bright remnant, however; and this, I trust, the reader will fully admit.

Blanchard Jerrold.

Reform Club, June 1874.

[Pg 1]

THE BARBER’S CHAIR.

Chapter I.

SCENE.—A Barber’s Shop in Seven Dials. Nutts (the Barber) shaving Nosebag. Pucker, Bleak, Tickle, Slowgoe, Nightflit, Limpy, and other customers, come in and go out.

Nightflit. Any news, Mr Nutts? Nothin’ in the paper?

Nutts. Nothing.

Nightflit. Well, I’m blest if, according to you, there ever is. If an earthquake was to swallow up London to-morrow, you’d say, “There’s nothin’ in the paper: only the earthquake.”

Nutts. The fact is, Mr Nightflit, I’ve had so much news in my time, I’ve lost the flavour of it. ’Couldn’t relish anything weaker than a battle of Waterloo now. Even murders don’t move me. No; not even the pictures of ’em in the newspapers, with the murderer’s hair in full curl, and a dresscoat[Pg 2] on him: as if blood, like prime Twankay, was to be recommended to the use of families.

Tickle. There you go agin, Nutts: always biting at human nature. It’s only that we’re used to you, else I don’t know who’d trust you to shave him.

Slowgoe. Tell me—Is it true what I have heard? Are the Whigs really in?

Nutts. In! Been in so long that they’re half out by this time. As you’re always so long after everybody else, I wonder you ain’t in with ’em.

Bleak. Come now! I was born a Whig, and won’t stand it. In the battle of Constitution aren’t the Whigs always the foremost?

Nutts. Why, as in other battles, that sometimes depends upon how many are pushing ’em behind.

Tickle. There’s another bite! Why, Nutts, you don’t believe good of nobody. What a cannibal you are! It’s my belief you’d live on human arts.

Nutts. Why not? It’s what half the world lives upon. Whigs and Tories. Tell you what; you see them two cats. One of them I call Whig, and t’ other Tory; they are so like the two-legged ones. You see Whig there, a-wiping his whiskers. Well, if he in the night kills the smallest mouse that ever squeaked, what a clatter he does kick up! He keeps my wife and me awake for hours; and sometimes—now this is so like Whig—to catch a[Pg 3] mouse not worth a fardin’, he’ll bring down a row of plates or a teapot or a punch-bowl worth half-a-guinea. And in the morning when he shows us the measly little mouse, doesn’t he put up his back and purr as loud as a bagpipe, and walk in and out my legs, for all the world as if the mouse was a dead rhinoceros. Doesn’t he make the most of a mouse, that’s hardly worth lifting with a pair of tongs and throwing in the gutter? Well, that’s Whig all over. Now there’s Tory lying all along the hearth, and looking as innocent as though you might shut him up in a dairy with nothin’ but his word and honour. Well, when he kills a mouse, he makes hardly any noise about it. But this I will say, he’s a little greedier than Whig; he’ll eat the varmint up, tail and all. No conscience for the matter. Bless you, I’ve known him make away with rats that he must have lived in the same house with for years.

Bleak. Well, I hate a man that has no party. Every man that is a man ought to have a side.

Nutts. Then I’m not a man; for I’m all round like a ninepin. That will do, Mr Nosebag. Now, Mr Slowgoe, I believe you are next. (Slowgoe takes the chair.)

Slowgoe. Is it true what I have heard, that the Duke of Wellington (a great man the Duke; only Catholic ’Mancipation is a little spick upon him)—is[Pg 4] it true that the Duke’s to have a ’questrian statue on the Hyde Park arch?

Tickle. Why, it was true, only the cab and bus men have petitioned Parliament against it. They said it was such bad taste ’twould frighten their horses.

Slowgoe. Shouldn’t wonder. And what’s become of it?

Tickle. Why, it’s been at livery in the Harrow Road, eating its head off, these two months. Sent up the iron trade wonderful. Tenpenny nails are worth a shilling now.

Slowgoe. Dear me, how trade fluctuates! And what will Government do with it?

Tickle. Why, Mr Hume’s going to cut down the army estimates—going to reduce ’em—our Life Guardsmen; one of the two that always stands at the Horse Guards; and vote the statue of the Duke there instead. Next to being on the top of a arch, the best thing, they say, is to be under it. Besides, there’s economy. For Mr Hume has summed it up; and in two hundred years, five weeks, two days, and three hours, the statue—bought at cost price, for the horse is going to the dogs—will be cheaper by five and twopence than a Life-Guardsman’s pay for the same time.

Slowgoe. The Duke’s a great man, and it’s my opinion——

[Pg 5]

Nutts. Never have an opinion when you’re being shaved. If you whobble your tongue about in that way, I shall nick you. Sorry to do it; but can’t wait for your opinion. Have a family, and must go on with my business. Anything doing at the playhouses, Mr Nosebag?

Nosebag. Well, I don’t know; not much. I go on sticking their bills in course, as a matter of business; but I never goes. Fash’nable hours—for now I always teas at seven—won’t let me. As I say, I stick their posters, but I haven’t the pride in ’em I used to have.

Tickle. How’s that, Nosey?

Nosebag. Why, seriously, they have so much gammon. I’ve stuck “Overflowing Houses” so often, I wonder I haven’t been washed off my feet. And then the “Tremendous Hits” I’ve contin’ally had in my eye—Oh, for a lover of the real drama—you don’t know my feelings!

Nutts. The actors do certainly bang away in large type now.

Nosebag. And the worst of it is, Mr Nutts, there seems a fate in it; for the bigger the type the smaller the player. I could show you a playbill with Mr Garrick’s name in it not the eighth of an inch. And now, if you want to measure on the wall “Mr Snooks as Hamlet,” why, you must take a three-foot rule to do it. Don’t talk on it. The[Pg 6] players break my heart; but I go on sticking ’em of course.

Nutts. To be sure. Business before feelings. Have you seen Miss Rayshall, the French actress at the St James’s?

Nosebag. Not yet. I’m waiting till she goes to the ’Aymarket.

Tickle. But she isn’t a-going there.

Nosebag. Isn’t she? How can she help it? Being of the French stage, somebody’s safe to translate her.

Tickle. Ha, so I thought. But all the French players have been put on their guard; and there isn’t one of ’em will go near the Draymatic Authors’ Society without two policemen.

Pucker. Well, I’m not partic’lar; but really, gen’l’men, to talk in this way about plays and players, on a Sunday morning too, is a shocking waste of human life. I was about to say——

Nutts. Clean as a whistle, Mr Slowgoe. Mr Tickle, now for you. (Tickle takes the chair.)

Pucker. I was about to say, it’s nice encouragement to go a-soldiering—this flogging at Hounslow.

Nutts. Yes, it’s glory turned a little inside out. For my part, I shall never see the ribbands in the hat of a recruiting soldier again—the bright blue and red—that I shan’t think of the weals and cuts in poor White’s back.

[Pg 7]

Pucker. Or his broken heart-strings.

Nutts. What a very fine thing a soldier is, isn’t he? See him in all his feathers, and with his sword at his side, a sword to cut laurels with—and in my ’pinion, all the laurels in the world was never worth a bunch of wholesome watercresses. See him, I say, dressed and pipeclayed and polished, and turned out as if a soldier was far above a working man, as a working man’s above his dog—see him in all his parade furbelows, and what a splendid cretur he is, isn’t he? How stupid ’prentices gape at him, and feel their foolish hearts thump at the drum parchment, as if it was played upon by an angel out of heaven! And how their blood—if it was as poor as London milk before—burns in their bodies, and they feel for the time—and all for glory—as if they could kill their own brothers! And how the women——

Female voice. (From the back.) What are you talking about the women, Mr Nutts? Better go on with your shaving, like a husband and a father of a family, and leave the women to themselves.

Nutts. Yes, my dear. (Confidentially.) You know my wife? Strong-minded cretur.

Pucker. For my part, to say nothin’ against Mrs Nutts, I hate women of strong minds. To me they always seem as if they wanted to be men, and[Pg 8] couldn’t. I love women as women love babies, all the better for their weakness.

Nosebag. Go on about the sojer.

Nutts. (In a low voice.) As for women, isn’t it dreadful to think how they do run after the pipeclay? See ’em in the Park—if they don’t stare at rank and file, and fall in love with hollow squares by the heap. It is so nice, they think, to walk arm-in-arm with a bayonet. Poor gals! I do pity ’em. I never see a nice young woman courtin’ a soldier—or the soldier courtin’ her—as it may be, that I don’t say to myself, “Ha! it’s very well, my dear. You think him a sweet cretur, no doubt; and you walk along with him as if you thought the world ought to shake with the sound of his spurs and the rattling of his sword, and you hold on to his arm as if he was a giant that was born to take the wall of everybody as wasn’t sweetened with pipeclay. Poor gal! You little think that that fine fellow—that tremendous giant—that noble cretur with mustarshis to frighten a dragon, may to-morrow morning be stript to his skin, and tied up, and lashed till his blood—his blood, dearer to you than the blood in your own good-natured heart—till his blood runs, and the skin’s cut from him;—and his officer, who has been, so he says, ‘devilishly’ well-whipt at schools perhaps, and therefore thinks flogging very gentlemanly—and his officer looks on[Pg 9] with his arms crossed, as if he was looking at the twisting of an opera-dancer, and not at the struggling and shivering of one of God’s mangled creturs—and the doctor never feels the poor soul’s pulse (because there is no pulse among privates), and the man’s taken to the hospital to live or to die, according to the farriers that lashed him. You don’t think, poor gal, when you look upon your sweetheart, or your husband, as it may be, that your sweetheart, or the father of your children, may be tied and cut up this way to-morrow morning, and only for saying ‘Hollo’ in the dark, without putting a ‘sir’ at the tail of it. No: you never think of this, young woman; or a red coat, though with ever so much gold-lace upon it, would look like so much raw flesh to you.”

Nosebag. I wonder the women don’t get up a Anti-Bayonet ’Sociation—take a sort of pledge not to have a sweetheart that lives in fear of a cat.

Slowgoe. Doesn’t the song say, “None but the brave deserve the fair”?

Nosebag. Well, can’t the brave deserve the fair without deserving the cat-o’-nine-tails?

Nutts. It’s sartinly a pity they should go together. I only know they shouldn’t have the chance in my case, if I was a woman.

Mrs Nutts. (From within.) I think, Mr Nutts, you’d better leave the women alone, and——

[Pg 10]

Nutts. Certainly, my dear. (Again confidentially.) She’s not at all jealous; but she can’t bear to hear me say anything about the women. She has such a strong mind! Well, I was going to say, if I was a sojer, and was flogged——

Nosebag. Don’t talk any more about it, or I shan’t eat no dinner. Talk o’ somethin’ else.

Slowgoe. Tell me—Is it true what I have heard? Have they christened the last little Princess? And what’s the poppet’s name?

Nosebag. Her name? Why, Hél-ena Augusta Victoria.

Slowgoe. Bless me! Helleena——

Nosebag. Nonsense! You must sound it Hél—there’s a-goin’ to be a Act of Parliament about it. Hél—with a haccent on the first synnable.

Slowgoe. What’s a accent?

Nosebag. Why, like as if you stamped upon it. Here’s a good deal about this christening in this here newspaper; printed, they do say, by the ’thority of the Palace. The man that writes it wears the royal livery; scarlet run up and down with gold. He says (reads), “The particulars of this interesting event are subjoined; and they will be perused by the readers with all the attention which the holy rite as well as the lofty ranks of the parties present must command.”

Nutts. Humph! “Holy rite” and “lofty[Pg 11] rank,” as if a little Christian was any more a Christian for being baptized by a archbishop! Go on.

Nosebag. Moreover, he says (reads), “The ceremony was of the loftiest and most magnificent character, befitting in that respect at once the service of that all-powerful God who commanded His creatures to worship Him in pomp and glory under the old law.”

Nutts. Hallo! Stop there. What have we to do with the “old law” in christening? I thought the “old law” was only for the Jews. Isn’t the “old law” repealed for Christians?

Nosebag. Be quiet. (Reads.) “The vase which contained the water was brought from the river of Jordan”——

Nutts. Well, when folks was christened then, I think there was no talk about magnificence; not a word about the pomp of the “old law.” Don’t read it through. Give us the little nice bits here and there.

Nosebag. Well, here’s a procession with field-marshals in it, and major-generals, and generals.

Nutts. There wasn’t so much as a full private on the banks of the Jordan.

Nosebag. And “the whole of the costumes of both ladies and gentlemen were very elegant and magnificent; those of the former were uniformly[Pg 12] white, of valuable lace, and the richest satins or silks. The gentlemen were either in uniform or full Court dress.”

Nutts. Very handsome indeed; much handsomer than any coat of camel’s hair.

Nosebag. The Master of the Royal Buckhounds was present——

Nutts. With his dogs?

Nosebag. Don’t be wicked,—and “the infant Princess was dressed in a rich robe of Honiton lace over white satin.”

Nutts. Stop. What does the parson say? “Dost thou in the name of this child renounce the devil and all his works, the vain pomp and glory of this world?”

Nosebag. (Reads.) “The Duke of Norfolk appeared in his uniform as Master of the Horse. The Duke of Cambridge wore the Orders of the Garter, the Bath, St Michael, and St George. Earl Granville appeared”——

Nutts. That will do. There was no “vain pomp,” and not a bit of “glory.”

[Pg 13]

Chapter II.

Nutts. Now, Mr Slowgoe, when you’ve gone through the alphabet of that paper, I’m ready.

Slowgoe. Just one minute.

Nutts. Minutes, Mr Slowgoe, are the small-change of life. Can’t wait for nobody. I’ll take you then, Mr Limpy. (Limpy takes the chair.) It makes my flesh crawl to see some folks with a newspaper. They go through it for all the world like a caterpillar through a cabbage leaf.

Slowgoe. Well, for my part, I like to chew my news. I think a newspaper’s like a dinner; doesn’t do you half the good if it’s bolted. Haven’t come to it yet; but tell me—Is it true that the Duke of Wellington’s going to repeal flogging?

Tickle. Why, yes; they do say so; but the Duke does nothin’ in a hurry. Always likes to take his time. You know at Waterloo he would wait for the Prussians; and only because if he’d[Pg 14] licked the French afore, he didn’t know how else to spend the evening.

Slowgoe. I never heard that; but it’s very like the Duke. And there’s to be no flogging.

Tickle. No; it’s to be repealed by degrees, like the corn-laws. In nine years’ time there won’t be a single cat in the British army.

Nosebag. Why should they wait nine years?

Nutts. Nothin’ but reg’lar. You see the cat-o’-nine-tails is one of the institutions of the country, and therefore must be handled very delicate.

That’s been the old notion. And folks—that is, the folks with gold-lace that’s never flogged—think to ’bolish the cat at once would bring a blight upon laurels. They think sojers like eels—none the worse for fire for being well skinned.

Tickle. There you are; biting the ’thorities of your country agin. But since you’ve taken the story out of my mouth, go on, though every word you speak’s a bitter almond.

Nutts. Well, it isn’t a thing to talk sugar-plums about, is it? I’m not a young lady, am I?

Mrs Nutts. (From back parlour.) I wish you’d remember you’ve a wife and children, Mr Nutts, and never mind young ladies. You can’t shave and talk of young ladies too, I’m sure.

[Pg 15]

Nutts. (In a low voice.) It’s very odd; she’s one of the strongest-minded women, and yet she can never hear me speak of one of the sex without fizzing like a squib.

Nosebag. (Solemnly.) Same with ’em all. I suppose it’s love.

Nutts. Why, it is; that is, it’s jealousy, which is only love with its claws out.

Tickle. Well, claws brings you to the cat again; so go on.

Nutts. To be sure. Well, as I was saying——(To Limpy.) What’s the matter? I’m sure this razor would shave a new-born baby; but for a poor man I don’t know where you got such a delicate skin. I will say this, Mr Limpy, for one of the swinish multitude, you are the tenderest pork I ever shaved.

Slowgoe. But the Duke of Wellington——

Nutts. Don’t hurry me; I’m going to his Grace. Well, they do say that he’s going to get rid of the cat by little and little. He knows the worth of knotted cords to the British soldier, and, like a dowager with false curls, can’t give ’em all up at once. So there’s to be a law that the cat is still to be used upon the British Lion in regimentals, only that the cat is to lose a tail every year.1

[Pg 16]

Slowgoe. Is it true?

Nutts. Certain. So you see, with the loss of one tail per annum, in only nine years’ time, or in anno Domino 1855, every tail will be ’bolished; that is, the cat with its nine tails will have lost its nine lives, and be defunct and dead.

Slowgoe. I don’t like to give an opinion, but that seems a very slow reform.

Nutts. Why, yes: when folks have a tooth that pains ’em, they don’t get cured in that fashion. But then, again, it’s wonderful with what patience we can bear the toothache of other people.

Nosebag. What horrid things there’s been all the week in the papers. Officers of all sorts writing what they’ve seen done with the cat. Well, if I was a sojer, my red coat would burn like red-hot iron in me; I should think all the world looked at me, as if they was asking themselves, “I wonder how often you’ve been flayed.”

Slowgoe. Bless your heart! and here’s a dreadful matter. James Sayer, a marine on board the Queen, sentenced to be hanged for assaulting two sergeants—to be hanged by the neck. And the President says, “James Sayer, I am sorry indeed that I cannot offer you hope that the sentence of this court will not be fully carried out, and I recommend you to prepare yourself to meet your doom.”

Bleak. What a difference is made by salt water![Pg 17] Frederick White, private soldier, is sentenced to be flogged for giving a blow to his sergeant. James Sayer, marine, is to be hanged for the same offence. So a blow afloat and a blow ashore isn’t the same thing.

Nutts. But there’ll be no hanging in the case; they say as much in Parliament, don’t they?

Slowgoe. But it says here the President was “much affected.” Why pass sentence, why give no hope?

Nutts. Why now, I suppose that’s what they’d call a fiction of the law; and when we think what a dry matter all law is, can we wonder that the ’torneys and such folks spice it up with a few lies? Bless you, if all law was all true, nobody would go on swallowing it. It’s the precious fibs that’s in it that gives it a flavour, and makes men live, and grow fat upon it.

Slowgoe. It can’t be.

Nutts. Tell you ’tis. Was you never on a jury? La! bless you, when one of the gen’lemen of the long robe, as they call ’em—one of the conjurors in horse-hair—get hold of a fib, or a flaw, or a something to bring a blush into the face of Common-sense, and so put her out of court at once—doesn’t he enjoy it? Doesn’t he relish the fiction, as it’s called, as if it was his first “Goody Two Shoes”? He relishes it; all the bar—’xcept, perhaps,[Pg 18] the conjuror against him—relishes it, and the judge himself. Oh! haven’t I seen him with the wrinkles about his eyes like the map of England; haven’t I seen him relish it too, for all the world like an old sporting dog that had given up hunting himself, but still did so love the smell of the game!

Tickle. I tell you what it is, Nutts, I feel my blood a-gettin’ vinegar all the while I hear you. I feel a-changing from a man to a cruet; and I won’t have it. You are so sour, you’d pickle salmon to look at it. Nosebag, tell us something pleasant. What have they done at the playhouse this week?

Nosebag. Why, there’s been Miss Faucit at the Hayma’ket, but only for one night. Your very great players now, they’re like the new aloe at the Colossyum; they only blossom once in a hundred years, or somethin’ of that sort. London’s gettin’ low for ’em, I s’pose. I have heard—though I know nothin’ about what you call the currency—I have heard that there isn’t, for any long time, ready gold enough in the country to pay ’em.

Tickle. Couldn’t they take ’Chequer bills?

Nosebag. Why, I believe they was offered to a singer last week; but he wouldn’t have ’em, ’cause he’d no faith in the Government.

Tickle. Well, and how did the young lady go off?

Nosebag. Never go to a benefit, for fear I should[Pg 19] be taken for a private friend of the actors. But I’m told the—the—what is it?—the fibula was another tremendous hit.

Limpy. (Rising.) That will do, Mr Nutts. What’s the fibular?

Nosebag. Why, a emerald buckle that the Irish House of Commons give to Miss Faucit last year for playing in Antigony. It was very well to put it in the playbill, ’cause of course it drew so many folks who’d never seen a buckle. Nevertheless, if Mr Webster—and I don’t mean to say anything against Mr Webster, not by no means—nevertheless, if he’d known his own interest he would have had five hundred posters with a bold woodcut of that fibula. And I should have stuck ’em.

Limpy. And you didn’t go to see it?

Nosebag. No; but I shall go next week, if I never go agin. For they do say that Mrs Humby—dear cretur!—is goin’ to appear in a thimble presented to her by the ladies’-maids of London. And if anybody ever deserved a bit of plate, Mrs Humby deserves that thimble.

Nutts. Now, Mr Slowgoe. (Slowgoe takes the chair.) There’s quite enough discourse of the playhouses, let’s talk of serious matters. Have you heard? They’ve been proposin’ in Parliament to make nineteen more bishops, and one of ’em a Bishop of Melton Mowbray.

[Pg 20]

Tickle. Ha! a sportin’ bishop; for the morals of the neighbourhood. And I shouldn’t wonder if we’ve a Bishop of Epsom, and a Bishop of Newmarket, and a Bishop of Ascot, and a Bishop of Doncaster. And very proper. Black aprons may reform blacklegs. Seein’ the bishops do so much good, in course they’re most wanted in the worst places. They’re to be sent in holes and corners of wickedness; jist as my wife hangs bags of camphor about the necks of the little ones when she hears of fevers. Now a bishop—the Bishop of Exeter, for instance (by the way, he’s been havin’ another row in the House of Lords—he’s always at it)—the Bishop of Exeter, what is he, I should like to know, but a big lump of camphor in a bag of black silk hung about the whole neck of the West of England? Why, the good he does nobody knows.

Bleak. (With newspaper.) ’Pon my word, when I read these things I do feel ashamed that I’m a man.

Nutts. Daresay; but ’tisn’t your fault. What is it?

Bleak. That a good quiet gen’lewoman can’t go by herself in a railway carriage without having to scream out for the police! Insulted by a coward with a good coat on him. Thinks himself, I daresay, one of the lords of the creation. Lords!—I call ’em apes.

[Pg 21]

Nutts. My wife—and I’d advise every lady to do the like—my wife never travels by rail without a pair of scissors. But then she’s a woman of sich strong mind!

Slowgoe. So, I see they’ve been givin’ a dinner at Lynn to Lord George Bentinck. He’s a great man, Lord George; and they’ve had him all the way from London to tell him. Made a beautiful speech, I see. Here’s a touch after my own heart. He’s a-talkin’ about the corn-laws, and he says, “When some foreign ship, some Swede or Norwegian or Dane, with an outlandish name for herself and her captain, which neither you nor I could pronounce (cheers and laughter), comes into port (cheers), I ask you how much this foreigner pays out of his wages to support the trade of your town?” Well, I say, that’s what I call talking like a true Briton.

Nutts. To be sure it is; no argument like that. The argument is—the argument that the Norfolk farmers cheer at is, that the Swede and the Norwegian and the Dane have outlandish names; that in fact they aren’t called, like the boys in the spelling-book, Jones, Brown, and Robinson. That’s the way t’ appeal to British bosoms, and Lord George knows it. Bless you! shouldn’t wonder, when the farmers went home, if they didn’t kill their wives’ and daughters’ canary-birds[Pg 22] ’cause they were all outlandish, and not true-born British linnets. Nothin’ like calling names; every fool can understand mud.

Slowgoe. Still Lord George is a wonderful man. Here he says, in this very speech, “he was eighteen years silent in the House of Commons.”

Nosebag. That reminds me of a pantomine I once saw, where there was a wild man that said nothin’ all through the piece, and then at last somebody came for’ard, and held up a scroll in gold letters, that said, “Orson is endowed with reason!”

Nutts. The worst of them members of Parliament is that, like children when they’re backward in their speech, they more than make up for it when they do begin. Like the Thames froze up, when once they’ve a quick thaw, they threaten to wash the speaker off his legs, and overflow the whole House of Parliament. Great pity some of these members aren’t like the Paddington Canal—with locks.

Tickle. There you are agin, ’busin’ of the ’thorities. I’ve read the whole of it, and it was a very pretty bit of speechifying at Lynn. Didn’t the Duke of Richmond, too, talk of the battle of Waterloo? I’ve no doubt——

Nutts. In course he did. He talks of it when he’s asleep. The battle of Waterloo to the Duke[Pg 23] of Richmond is like a wax doll to a little gal. He always will be showing it to company—opening and shutting its eyes, pointing out its red morocco shoes, and white frock, and cherry-coloured sash. I wish the Duke of Wellington would take the battle of Waterloo from him, and lock it up, and only let him bring it in at Apsley House once a year with the dessert.

Slowgoe. Ha! Nutts, you haven’t a good word for nobody. I’m sure it’s quite cutting to read what Lord Bentinck and Mr Disraeli say of themselves: each of ’em trying to be smaller than the other one.

Nosebag. Jist like boys at leap-frog. Each in his turn “tucks in his twopenny,” that the other may go clean over his head. But then, you see, Mr Slowgoe, like leap-frog, it’s only make-game after all.

Slowgoe. I won’t have it. The member for S’rewsbury’s a great man. What a tongue he has!

Nutts. Very great; measure tongue and all, and he’s very great, to be sure. He reminds me of a—a—dear me!—that thing that lives on wind, that I once saw at Mr Tyler’s Zologicul Gardens—a—a——

Tickle. Lives on wind! It can’t be nothing but a bagpipe or a chameleon.

Nutts. That’s it: a chameleon. Well, that has[Pg 24] a tongue as long as his body; but for all that, he can only catch flies with it. And that’s the case, I take it, with the member for S’rewsbury. I know it’s said he talked for loaves and fishes. And acause Sir Robert wouldn’t give him so much as a penny roll, not so much as the smallest sprat that swims in the Treasury, why then——

Slowgoe. Sir Robert! Hear what he does to Sir Robert, accordin’ to Sir John Tyrrel, who was at Lynn. He says the member for S’rewsbury “tears off Sir Robert Peel’s flesh, then polishes his bones, and sends ’em to the British Museum.”

Nutts. Well, that’s a nice compliment for a gen’l’man—bone-polisher to Sir Robert Peel! But certainly Sir John Tyrrel is a good one at a compliment. Didn’t he once say that the Duke of Wellington was the greatest man since our blessed Saviour? He did, as I’m a sinner. And if Sir John is very red in the face, which he ought to be, it is because he hasn’t done blushing ever since.

[Pg 25]

Chapter III.

Nutts lathering a customer; others waiting. Enter Little Girl.

Nutts. Now, my little dear, what’s for you?

Girl. Please, Mr Nutts, my mother says you’ve sent the wrong front. This is a red un, and mother’s is a light brown.

Nutts. Oh! if she says it’s red, I know it isn’t hers. Now the lady as that belongs to calls it auburn. Not that I should like to walk with her into a powder-magazine with her wearing it.

Girl. And please, my mother says she hopes the curls are a little tighter than——

Nutts. Tighter! You tell that blessed widow, your mother, that they’re just what she wants—tight enough to hold a second husband. I know the man; and though I’ve no grudge agin him, I curled ’em a-purpose.

Limpy. Why, isn’t that Mrs Trodsam’s little[Pg 26] girl? And the woman going to be married agin?

Nutts. In course. When her husband died she vowed she’d go into weeds and her own grey hairs for life. That’s barely a twelvemonth ago; and now the weeds are gone, and she wears marigolds in her cap, to catch the milkman. I don’t know who’d have a widder! Seven times have I curled that front in three weeks.

Slowgoe. (With newspaper.) Well, this is a pretty bus’ness, this Religious ’Pinions Bill. Going to make friends with the Pope! Going to let him send his bulls into the country, as many as he likes. Well, I don’t know; but I should think the British Lion—if he’s got a war life in him—won’t stand that.

Tickle. That’s nothin’. They say we’re goin’ to send a ’bassador to Rome, and Sir Randrews Agnew’s to be ’pinted to the post. Oh, isn’t the Pope a—a-gammin’ us! He’s a-goin’ to buy down railroads right and left. Now what do you think the rails are for?

Slowgoe. Why, for steam-ingines.

Tickle. Not a bit on it. I know somebody as knows Colonel Sibthorpe’s footman as knows all about it. The Pope intends to get up a fancy fair in Rome for the conversion of the Jews. Well, this will fill Rome with English dowagers, taking[Pg 27] all their pincushions ready-made with them. And when they get there, the rails (they’re made o’ purpose) will be taken up and turned into gridirons; and won’t the Papishes roast us agin, as they did in Smithfield?

Slowgoe. No doubt on it. This comes of giving up good old names. I always thought what would come of it when we left off calling the Pope the Scarlet——

Nutts. Mr Slowgoe, allow me to say that my wife—Mrs Nutts—is only in the next room.

Slowgoe. When we left off calling the Pope an improper person in a scarlet garment. It’s the growin’ evil of the times, Mr Tickle, that we don’t respect old names.

Tickle. We don’t. And yet Colonel Sibthorpe says the Pope—that is, his Scarletness—is as scarlet as ever he was.

Slowgoe. It’s a great comfort to see that the Colonel spoke against the bill; but it passed the second reading for all that.

Tickle. That’s the worst of it, and just reminds me of what I saw last Sunday. There was a nice old animal eating his thistle upon a common—as nice a cretur as ever drew a cart. Well, the Kingston train came smoking, whizzing, rumbling along; when, suddenly, the animal left his thistle, and, stretching his legs to take firmer[Pg 28] hold of the ground, brayed and brayed at the train, as if he would bring the sky right down upon it; but, as you say of the bill, it passed for all that.

Tickle. You’ve heard of the Pertection Peers o’ course? Heard what they’ve come to a resolution to do?

Slowgoe. No—what?

Tickle. Why, they’ve all met in the first-pair front of the Morning Post; and feelin’ that the country is ruined, they’ve resolved like patryots, as they are, to do nothin’.

Nosebag. Shouldn’t wonder if they succeed. It’s a dreadful thing, though, for peers and lords, when they know a country’s done up for ever, to be obliged to live in the ruins. I wonder they don’t move.

Nutts. Bless you! they can’t. The more rickety the country gets, the more they like it. Just as a woman loves her bandiest baby all the best. In their hearts they never was so fond of the British Lion as now, though Mr Tyler of the Zologicul Gardens wouldn’t give no price for him unless the Unicorn was thrown in with the bargain. Providence is very good to dukes and lords, for they do say this season grouse is perdigious plentiful.

Slowgoe. I’m glad on it. For it’s my ’pinion that grouse and pheasants, and in fact all[Pg 29] sorts of game, was only sent into the world for superior people.

Nutts. Shouldn’t wonder; only it’s a pity they warn’t somehow ticketed. ’Twould have hindered much squabblin’. Agin; when Adam give their names to all the birds and beasts, he might have ’lotted ’em out into partic’lar folks that was to eat ’em—ven’son for lords, mutton for commons.

Tickle. Might ha’ gone further than that, and have marked the very joints—sirlines for them as is respectable, and stickings for the poor.

Slowgoe. I tell you what, Mr Nutts, if you talk of Adam in that way, you don’t shave me. I’ll not trust my throat to an infidel.

Mrs Nutts. And that’s the way, Mr Nutts, you’ll drive everybody from the shop. At this time of day, what’s Adam to you? Look after your own family—Adam did, I’ve no doubt.

Slowgoe. Talkin’ o’ the Pertectionists—I see they’ve had another dinner.

Nutts. Yes. The country’s done for; but it’s a comfort to think that, though their hearts are broke, they can dine still. If an earthquake were to gulp England to-morrow, they’d manage to meet and dine somehow among the rubbish, just to celebrate the event.

Slowgoe. Dinner to the Marquis of Granby.

[Pg 30]

Nosebag. Ha! seen him at a good many public-houses in my time.

Slowgoe. Dinner at Walsham. Chairman something like a chairman; drank the Queen; and this is what I call real speaking (reads): “They must have observed what benignant smiles were upon her countenance and how she appreciated their loyalty. Her Consort, too, was in the fields of sport, and he rode with courage and brilliancy with the hounds till night closed the chase.”

Nutts. I’m not intimate with his Royal Highness, but the paper always says he goes home to the castle to luncheon. And then to praise a gen’lewoman for smilin’! I s’pose they think that a compliment, as if it warn’t at all easy for a queen to look pleasant. Again, if it’s sich a recommendation to state affairs to be in the “fields of sport,” I wonder they don’t make a foxhound a prime minister!

Slowgoe. The Duke of Richmond says (reads), “I never had a fancy to ride upon the whirlwind and direct the storm.”

Nutts. So far a very sensible old gentleman. A whirlwind isn’t made for every man’s hobby.

Slowgoe. And doesn’t Mr Disreally give it to Manchester a little? Makes it a nothin’. Puts, as I may say, his crush hat over all the tall chimneys, and kivers ’em quite. He says, “Magna[Pg 31] Charta was not procured by Manchester; Manchester was not known then!”

Nutts. And is that really Benjamin? Well! And if only two years ago, at a Manchester sworry, if he didn’t stand up in the ’Theneum, and butter the youths of Manchester as if they was so many muffins! And he talked to ’em too—I recollect it well—as familiarly about Jacob’s ladder as if it had been placed in the Minories, and he’d been used to run right up it and slide down it from a boy.

Nightflit. Well, this is good news, isn’t it? Here’s Mr Jones has brought up a report to the Common Council of London; and we are to have a house, as he says—“the heart of St Giles’”—built for poor people.

Nutts. The heart of St Giles’! Well, it’s the way to put a heart into it, anyhow.

Slowgoe. What, goin’ to do away with all the cellars? Well, all I hope is this, I hope they’re not goin’ too fast.

Nightflit. How can they go too fast? when the report says (reads), “They propose to build a house, giving clean and wholesome lodging to one hundred single labourers, at a rent not greater than they are now forced to pay for accommodation in houses filled with dirt, vermin, unwholesome air, bad society, and many other evil circumstances.”[Pg 32] Can’t get rid of dirt and varmint too soon, can we?

Slowgoe. I won’t be sure of that; when people have been born and reared among ’em, dirt and varmin are as second nature.

Nutts. And aren’t comfort and cleanliness?

Slowgoe. It’s all very well, but I’m the friend of order, I am. I only hope the Government won’t find it out. Make poor people clean and spruce, and you don’t know what they’ll want next. All too fast, too fast.

Nutts. Well, I wonder you ever use your legs. I wonder you don’t go upon all fours by choice, acause it’s slower.

Slowgoe. Look here; keep people in dirt accordin’ to their station, and you’ll keep ’em quiet. A man as lives in a cellar, or in a house, for the matter of that, with ten or twelve in a room, without any talk of water, and air, and gas, and such stuff as was never talked of in St Giles’ afore—why, he never thinks o’ nothin’ but his drop o’ wholesome gin. All he wants is, like a wild beast, some place to hide his head in for the night, that he may go to the public-house the next mornin’. Well, he goes; and he gets his glass, and his glass; and every glass seems to put new clothes on his back, and drop new shillings into his pocket, and all about him looks gold and purple—a sort of glory.[Pg 33] And though his wife is bone and skin, and kivered with rags; when he’s comfortable drunk, she looks like any queen in a silver petticoat. And if his children with their thin chalk faces do make a hullabaloo for bread, why, when he’s as drunk as he ought to be, they seem to him nothin’ more than crying cherrybims.

Nutts. Well, but where’s the man’s heart all the while?

Slowgoe. Heart! Nonsense: doesn’t feel no heart. If he takes gin enough, it’s all gone; burnt up like a bit o’ sponge in the burning spirits o’ wine. Water, and gas, and air, and wholesome lodging! Why, isn’t gin cheapest, when it makes a man do without ’em?

Nosebag. Not a bit on it. Gin never made a man respectable; now, water, air, and all that does.

Slowgoe. I’ve said I’m a friend to order——

Nutts. Order! Well, if ever they make a Order of the Pigsty—and there is, I believe, a Order of the Sheep-pen, or Fleece, or something of the sort—you ought to have it.

Slowgoe. Nonsense. ’Thusyism is puttin’ the poor out o’ their proper places. I’ll just take the other tack. A poor man gets out of dirt and foul air, and all that. Gets raised in the scale, as the story of it goes. Why, there must be always somebody at the bottom of the steps, mustn’t there?

[Pg 34]

Nutts. Why, yes. But then the steps themselves needn’t be in muck, need they? Why shouldn’t the lowest of us have plenty of sweet water, and God’s sweet air, and all be raised together?

Slowgoe. ’Thusyism, as I say, is very well; but you know nothin’ of political economy. Look here. A man gets used to all the Common Council talks about; to wholesome lodging, and all that. Well, he doesn’t go to the gin-shop. Then, how, I ask you, is the revenoo to be kept up? Where’s taxes to come from? I was only readin’ it yesterday. It seems that the publican alone pays money enough to build all the ships, pay all the sailors, fit out all the sojers with their cannons and bayonets, and what not. Well, the man who’s a good stiff drinker ought to feel pride in this. Every sojer he sees, every musket that’s made, every ball-cartridge that goes into the warm bowels of an enemy, he helps with every blessed drop of gin he swallows, to pay for. Isn’t it, or oughtn’t it to be, a comfort to a man, if he hasn’t a bit of liver left, to know that it’s gone to help to load bullets, and sharpen swords, and pipeclay cross-belts? I say it: a man with no liver, his tongue like shoe-leather, his nose no better than a stale strawberry, and every limb on him shaking like leaves upon the aspling-tree, sich a man, thinkin’ what the[Pg 35] publican pays through him, may still go into the Parks, and seeing the sojers on parade, take a pride in ’em.

Nutts. Well, and suppose the man is taken out of the muck that’s helped to make him drink? What then?

Slowgoe. What then? Why, then comes the danger to Government. The man doesn’t go to the public-house. No: he gets used to a clean place and a clean shirt; and has light about him, and doesn’t live like a two-legged bat, and has water enough to swim in. Well, he begins to read and to think, and to trouble his head about his vote, and all such stuff, that with the gin-glass at his mouth, he never dreamt on. Well, the end on it is, such will be the presumption of the poorer sort, when you take ’em from dirt and darkness, which, in my ’pinion, is their nat’ral elyment—such is their conceit, that I’m blest if they soon won’t talk of having a stake in the country!

Nosebag. Well, and every man as has muscles and bones, and is willing to work with ’em, has a stake, hasn’t he?

Slowgoe. Where is it? You can’t see it!

Nutts. Why, suppose his muscles and his bones helps to build a house for a man?

Slowgoe. Well, it’s the man’s stake it’s built for, and not his’n that builds it. And that’s perlitical[Pg 36] economy. But I was goin’ to say when you put me out, that the Government doesn’t know what it’s after encouragin’ cleanliness, and temperance, and such new-fangled stuff. It’s all revolution in disguise. We’ve had gunpowder revolution, and moral revolutions; but they’re nothing to what’s coming, for they’ll be the revolutions of water and soap. No government upon the ’versal earth can stand with everybody clean and sober. Do away with the swinish multitude, and I ask you, what becomes of the guinea-pigs o’ society? Tell me that.

Nosebag. Why, we shall all be guinea-pigs together.

Slowgoe. Impossible! The likes o’ you a guinea-pig! ’Tisn’t in nature. All I ask is, where will you get your taxes? Last week at the great meetin’ o’ the waters, as I call it, at Common Garden Theatre—last week, I stood in Bow Street, and watched mobs o’ people goin’ in, all on ’em conspiring against the revenoo of the country. There wasn’t one there, man or ’oman—and very pretty women some on ’em was, bloomin’ like fresh flowers in fresh water—that wasn’t a conspirator aginst the taxes that pays the sojers and the sailors, and the salaries in Woolwich Dockyard, and the Government never sent the p’lice to take ’em, but let ’em all sport away like the fountain in[Pg 37] Temple Gardens. Temperance and cleanliness! I’ve lived to see somethin’! I’ve heard of the age of iron, the age of gold, and the age of silver, and I should like to know what age we are to call this?

Nutts. Why, by your own account, the best of all on ’em—the Age of Soap and Water.

Slowgoe. (With newspaper.) This must have been a beautiful sight, gen’lemen, a beautiful sight, at Portsmouth. Quite makes a man’s heart beat to read about it.

Nightflit. What’s the perdicament?

Slowgoe. Quite a solemn thing. Field-Marshal Prince Albert has given a spick-and-span new set of flags to the 13th Foot, or what is called his own Light Infantry. The old ones had been so singed by fire, and torn to bits by bullets in Afghanistan, wheresomever that may be.

Nutts. Doesn’t say who ’broidered the colours, does it?

Slowgoe. Not as I see.

Nutts. That’s a pity. But I s’pose it was some o’ the women. Fine ladies, as wouldn’t so much as take up a stitch in a silk stocking acause they’d think it low and beneath ’em—fine ladies work at flags, and, I really do believe, like the work better than if it was their own baby-linen.

Limpy. How d’ ye account for that, Mr Nutts?

[Pg 38]

Nutts. Why, you see, it’s a part of the finery of sojering; and that always takes the women. And so they’ll stitch and stitch away at colours, and, for what I know, work their own precious locks of hair in ’em, acause they’re to be carried by smart young gen’lemen covered with red and daubed with gold, and the drums and the fifes and the trumpets will play about ’em; and they think that’s glory, poor souls! Silly creturs! if they only thought of the blood, and groans, and mashed limbs, and burning houses, and trodden-down babies, and screeching women, suffering worse than death—if they only thought that their needlework was to be waved and fluttered above such horrors as these, it’s my ’pinion they’d as soon do sewing and stitching for Beelzebub.

Slowgoe. Don’t be profane, Mr Nutts.

Nutts. Never was, Mr Slowgoe. But I will say it, I do think there’s a devil sleeping in every trumpet; and he wakes up and bellows out every time the brass is blown.

Nightflit. And the account goes on to say (reads), “The colours were consecrated by the Chaplain of the Forces.”

Nutts. Never heard of one of the apostles with such a post—did you? Consecrated! I s’pose dipped in blood, and then fumigated with gunpowder.

[Pg 39]

Limpy. Is that the way, Mr Nutts?

Nutts. Can’t tell for certain, as I never read the recipe in the New Testament.

Tickle. I once heard how it was done. The beadle o’ St Giles’ told me all about it. The colours are taken into the church, and the parson or the bishop, as it may be, who’s to bless ’em, stays in the church, fasting all night with ’em, praying that every bullet as is fired off under ’em shall be directed by an angel; that every sword drawn beneath ’em, and cutting through the skull of a man, shall have the edge of it sharpened by Christian love; and that every bayonet thrust into the bowels of a man shall be pushed home with a blessing. And he prays that wherever them colours may wave, all the gunpowder may be kept dry under the wings of angels; and the firelocks be continually oiled by the tears of Christian spirits. After all, it must be a great comfort to a man—shot down, mangled, and mashed like a crushed frog—to turn his dying eyes to them colours and remember there’s a parson’s blessing on ’em. It must give him some pleasure to think of it when he’s screeching for water, it may be, all night, and the moon with her cold, white, unpitying face looking down upon him. Consecrated colours! Well, if the flags are consecrated, in course they fire with sacred gunpowder and holy[Pg 40] bullets. And then the bombshells! They can’t be s’posed to carry death and destruction when they drop; but, being blessed, must fall like manna in the streets and on the roofs of houses.

Slowgoe. None o’ your sedition, Mr Tickle, none o’ your sedition. Noble regiment the 13th Foot, and nobly rewarded! Why, it seems as long ago as 1776, when they were commanded by the Duke of Cumberland——

Nutts. What! Billy the Butcher, as they called him?

Slowgoe. As long ago as 1776 (reads), “as a mark of distinction for their gallant conduct, the sashes of the officers and sergeants were ordered to be tied on the right side instead of the left.”

Nutts. The officers and sergeants only! Then the privates did nothing in the way of fighting? And what a mark of distinction, to be sure! Why didn’t they at the same time order ’em to change the gaiters of the regiment, wearing the right on the left leg, and the left on the right; or to turn their hats the hind part afore, or their shirts inside out?

Slowgoe. And now the brave 13th, for fighting in India like any dragons, come in for more luck. For “her Majesty has been pleased to order the facings of the regiment from yellow to blue, and the regiment to be called Prince Albert’s Regiment”!

[Pg 41]

Nutts. What a comfort—what a consolation for a man in a hailstorm of bullets—what a pleasure after marching and counter-marching, and living through the pains of fifty deaths,—to think that the yellow serge of his cuffs and collars shall be turned to blue! What a blessing to leave his children! Well, there’s glory in colours, isn’t there? Shouldn’t wonder that when some regiment some day does some wonderful thing never heard of afore, if her Majesty isn’t pleased to order that the same be dressed all over with harlequin patches. From yellow to blue! Well, that’s a great change in life, isn’t it?

Nightflit. Talking of soldiers, I see they haven’t got Field-Marshal Duke of Wellington on the top of his arch yet.

Bleak. Why, no. They say in Parliament—I’ve jest been readin’ on it—that they’re goin’ to wait till the people return to town, till they come back from raffling at the watering-places, and suchlike; and then when the statu’s up they’re to give their ’pinions.

Slowgoe. Ha! So I see. But won’t it be a little difficult to get to the feelin’ o’ the public?

Tickle. Not at all. Yon Colonel Trench, who says the arch was made for the statue, and the statue for the arch, just as they say of two people afore they marry——

[Pg 42]

Nutts. Go on. Say what you like about marriage. My wife’s out.

Tickle. Just as they say of folks afore they marry; who, when married, turn the worst match as can be. Colonel Trench is going to manage the whole matter. When all London comes back to town, and is gathered together under the arch, the Colonel will go round and toss for the Duke—the best two out of three—with every man, woman, and child upon the ground. The Colonel’s taken odds that he’ll win, and the Duke keep the arch.

Slowgoe. But I see they’re going to try the effect with a sort of dummy, a Wooden Duke for the Iron one.

Nutts. Very disrespectful. Now I’ve a notion they might try it much better and cheaper. Why not hire one of the folks and a horse from Ashley’s Amphitheatre? They might hoist the animal a-top of the arch, and there he might be mounted by the player as is used to him.

Nightflit. But the horse and the rider would only be the size of life. How could folks judge then?

Tickle. Why, very well. Let all the House of Commons go into the Park with telescopes magnifying four-horse power, and spying through them; why, in course they would see the ’fect, and no mistake.

[Pg 43]

Slowgoe. I see Lord John Russell’s withdrawn the Irish Arms Bill.

Nutts. I said he would. That’s the first Whig blunderbuss as is missed fire.

Tickle. Or rayther, the blunderbuss was so high charged, Lord John didn’t like to pull the trigger. ’Fraid it would kick a little too strong, and crack the Cabinet like chaney.

Nutts. Talking about model dukes and dummy horses, isn’t it a pity there isn’t a sort o’ model Parliament afore which the Whigs might try their bills? They find so many split when they come to prove ’em afore the real house. One night Lord John holds fast to his Arms Bill, like a child to a new drum; and the next he gives it up as if it was of no use, somebody having knocked a hole in it.

Tickle. Tell you it’s the old Whig cowardice. They’re so often afraid o’ their own blunderbuss. Howsumever, this is a fault of the right sort, only hope they’ll do no worse.

Nightflit. Any news about Young Ireland? What’s he done with the “sword” that he took from ’Ciliation Hall?

Tickle. Why, they do say he’s swallowed it, like the Injun juggler; only—not like him—they do say he’ll never be allowed to bring it up agin. Old Daniel offers to take O’Brien back to his[Pg 44] busum if he’ll promise never more to smell of gunpowder.

Nosebag. I’ve heard that O’Connell’s going to write up in ’Ciliation Hall somethin’ like what they print in the playbills.

Slowgoe. What’s that?

Nosebag. Why, “Young Ireland in arms not admitted.”

Nutts. And he might add, “No money returned.”

Bleak. So I see Mr Hume’s lost his motion for opening skittle-grounds on Sundays.

Slowgoe. Skittle-grounds—I thought ’twas to open the British Museum, the National Gallery, and suchlike.

Bleak. Well, it seems to be all the same, for Lord John Russell won’t have it nohow. He says (reading), “As to the admission on Sundays to the British Museum and National Gallery, he thought it was better not to lay down any positive rule, or for that House to interfere by a resolution. There were some places where a single porter at the door would be sufficient as a protection. Such places he thought it was quite right to have open on the Sundays; but if they went further, he did not see why they might not ask to have the theatres open on a Sunday. Listening to a play of Shakespeare, it might be said, would divert[Pg 45] people from habits of drunkenness. Then as to opening such places as the Museum and National Gallery on Sundays, it would tend to deprive a great many persons of their only day of rest; and they could not well supply their places with others who were not in the daily habit of taking care of rooms.” Well, for my part, it does seem to me that what holds good with “many persons” ought to hold good with a “single porter.”

Nutts. Agin. Why don’t they ’bolish steamboats on the river; Sunday rail-travelling; Sunday coach and cab stands; Sunday tea-gardens? These things and places—all of ’em—deprive a great many persons of their only day of rest! So do Sunday public-houses. And then, as if taking care of the pictures at the National Gallery, that folks don’t run their walking-sticks through ’em—and keeping a sharp eye upon the mummies at the Museum, for fear they should be run away with—was such delicate work that people must serve a ’prenticeship to learn it.

Tickle. And ’specially, too, when Mr Wakby said there was so many Jews who’d be delighted to take the post o’ Sundays, and be ’specially delighted to take the money for it.

[Pg 46]

Chapter IV.

Enter Peabody (Policeman).

Nutts. Well, I’m glad somebody’s come. Thought all the beards had gone out of town. Just as you come, was thinking of shuttin’ up shop and goin’ myself. Never saw the Dials so dull, Mr Peabody. There isn’t a back pair that isn’t at a watering-place.

Slowgoe. (With newspaper.) Watering-place! Pretty goings on there, I think. Here’s a letter taken from the Times, when the gentleman as writes says, “Ramsgate’s shocking. Ladies bathing with no more thought than if they was mermaids; and chairs let out at a penny a piece, for an enlightened public to sit—as if they was in the opera stalls—to look at ’em.”

Nutts. Bless my soul! Where did you say?

Slowgoe. At Ramsgate.

Nutts. You may go on. Mrs Nutts is at Margate.

[Pg 47]

Slowgoe. And the gen’leman says in his letter that the young ladies dance polkas and waltzes in their bathing-gowns; and dance and scream the more for the people looking at ’em.

Peabody. Where’s the police?

Slowgoe. That’s what the gen’leman asks. Where’s the police to put ’em down? Where’s the police to warn ’em back to the machines?

Tickle. Why not have a coast-guard with indy-rubber uniforms, to run into the water, and take the ladies up, and make an example of the ring-leaders?

Nutts. I don’t know how it is, I’ve often thought of it; but somehow—I’ve observed the circumstance to Mrs Nutts—somehow the female mind seems to gain courage at watering-places. A young thing that won’t raise a eyelid in London, will meet you like the full moon at the seaside.

Tickle. Well, I’ve often thought of that too. Somehow or other the sea air does harden ’em. Now, Mr Peabody, you who was a schoolmaster afore you was a policeman, can you, who knows everything—can you explain it?

Peabody. Why, the female mind is naturally susceptible——

Nutts. That’s what Mrs Nutts said, when on one occasion she would have a pint of peas at five shillings.

[Pg 48]

Peabody. And sympathises with external nature. The female mind, too, often confined to the limits of a slop-basin, feels itself grow and expand in presence of the universal deep. A woman who may be no better than a doll in London, shall be a first-rate philosopher at Broadstairs.

Nutts. Humph! Like young ducks; don’t know all their strength till they take to the water.

Peabody. But it all goes off with the season.

Nutts. I’m glad of that. Mrs Nutts, as you know, is a woman of strong mind; nevertheless, she must come back to the slop-basin.

Slowgoe. So I see that Cobden has been in France. Wanting to stir up a free trade in frogs, I s’pose. But they’re not such fools; they won’t give up pertecting their native produce like us. He says in his speech to the Frenchmen, “I am not a propagandist.” Now what does he mean by that?

Peabody. Why, that he doesn’t want to preach free trade to the French.

Tickle. But the best on it is, he can’t help it. Mr Nutts and I was talking about that afore, warn’t we, Nutts.

Nutts. The very fact, says I, of Cobden being received as he is by Frenchmen, makes him a propagandist. There he is, with every syllable he says, preaching free trade for the wine-growers,[Pg 49] though he doesn’t say a word about it. There he is in the city of Paris ten thousand times bigger conq’ror than Marshal Blucher. Lor’ bless you! the soldiers, poor fellows! never thought of it; but Cobden will prove the worst English general for them. He’s opened the campaign that will knock up their trade. There wasn’t a French soldier, whilst Cobden was talking and the Frenchmen were cheering, that oughtn’t to have felt his musket crumbling away in his arms like dust, and his bayonet melting like in its scabbard. There wasn’t a single French cannon, if it had had any sense at all, that oughtn’t to have groaned as with the bellyache, knowing that, as condemned old iron, it would go to the melting-pot. Then for the Gallic cock—the cock of glory!—the cock that, unlike any decent barndoor fowl, is always for picking out the eyes of nations—the cock that only lives upon a morning feed of bullets—why, after Cobden had made his speech, the poor thing felt his appetite get weaker and weaker for the garbage of glory, and in the end, depend on’t, he’ll live upon corn, without a drop o’ blood mixed in it, like a decent respectable bird, and never think of cock-a-doodle-dooing above all his neighbours.

Nightflit. Shouldn’t wonder. Why, doesn’t the French paper itself—the Journal des—des——

[Pg 50]

Peabody. The Journal des Débats—the Government organ.

Nightflit. Doesn’t it, here, in what it says about Cobden, talk as if it was ashamed of the business of the customhouse officers rumpling and tousling everybody as steps into the country, for smuggled goods? Turning people upside down, and shaking ’em like so many pickpockets.

Nutts. Don’t talk of it. Shall I ever forget when Mrs Nutts and me crossed to Calais to see France? Shall I ever forget how fellows in blue uniforms, with swords by their sides, searched us over and over, as if we’d brought a cutler’s shop and a cotton-mill in every one of our pockets? Isn’t it dreadful to think that men should be such fools to themselves as to pay soldiers and customhouse officers to prevent one country bringing its blessings to another, as if heaven only intended the best iron for England, and the best claret wines for France? Well, isn’t it a comfortable thing to think of, that Mr Cobden has spoken the dying speech of all them customhouse officers? They mayn’t believe it just yet, but it’s sure to come. They’ve got consumption in ’em, and sooner or later they must go. Only I do hope that on both sides they’ll save one or two specimens for their museums, just to show the children that come arter us what fools their fathers was afore ’em.

[Pg 51]

Slowgoe. Well, there’s one comfort left for me, I shan’t live to see it. You’re for universal peace, and all that sort of stuff. Very well in story-books, but never was intended. War and all that was meant from the first. War runs through our nature. Everything wars upon everything. There’s nothing so little as doesn’t eat up something as is smaller than itself. Look here now; here’s a paragraph from an Injy paper, the Agra Chronicle, about the battle-field in the Sutlej. It says: “We came viâ Loodianah and Firozepore, and on our way encamped on the fields of Alrival and Ferozeshah. Alrival was a beautiful green plain, the only one I saw between Meerut and this, and seemed intended by nature for a battle-field. A few skeletons were strewed over it, and of the wells one was just drinkable, and the other was so impregnated with gunpowder as to be wholly unfit for use.”

Tickle. I can’t have that. “Intended by nature for a battle-field.” And do you think when nature made this beautiful world, and filled it with fruits and flowers, and sent down blessed light upon it—made it, as I may say, a paradise for folks to live in—do you for a moment think that nature made certain “beautiful green plains” for slaughterhouses? You might as well say that when nature made iron, she made it not for carpenters’ tools, but a-purpose for swords and bayonets; and that[Pg 52] the sea would have all been fresh water only that we wanted the salt for gunpowder. That’s the shabby part of man. Whenever he does wickedness upon a large scale, he always lays it upon nature. If Cain had been a general, he’d have put all his bloodshed upon nature.

Nosebag. Then never mind nature; let’s talk of the Court. So the Queen’s a-goin’ to have another palace. Isn’t it an odd thing that kings and queens in our country never do get properly suited with houses? All their palaces—like their clothes—seem misfits when they leave ’em to them who comes after ’m. There was George the Fourth, he could no more live in his old father’s palace than he could get into his coat; so he had Buckingham Palace built, with a fine archway that always looks jest whitewashed. And now that’s so little that the present Royal Family fill it all up, like a cucumber in a bottle. And so we’re to have another building.

Slowgoe. Never mind that. It won’t cost a farthing. For doesn’t Sir F. Trench say in his motion—here it is—“That while this House feels confident that Parliament would willingly supply any reasonable amount of expense for the attainment of so desirable an object, it has great pleasure in expressing its belief, that by proper management of the means at the disposal of her[Pg 53] Majesty and her Government (in aid of the £150,000 voted for alterations at Buckingham Palace), this great and desirable national object may be obtained without adding one shilling to the burthens of the people.” What do you think of that? Not one shilling, says Sir Frederick.

Nosebag. Bless you! in the matter of money, who’d trust to bricks and mortar? But we’ll say the palace is built without a shilling from the people—we’ll say it’s built. How about the furniture? Why, afore the thing’s well up, the Minister will come down to the House and ask for about half a million of money to buy rolling-pins and tinder-boxes.

Slowgoe. But he won’t get it.

Tickle. Won’t he? Every farden on it; while all the House, and the Speaker into the bargain, will weep with pleasure while they put their hands in their pockets.

Slowgoe. And what will Mr Hume be about?

Tickle. He’ll oppose it, o’ course; and so will Mr Wakley and Mr Williams. And what o’ that? Why, the Minister will draw himself up upon his toes, and, looking as tragic as if they’d killed his dearest relations, ask the honourable members if they know what they’re opposin’. Put it to ’em as men, whether her Majesty ever before asked a single farden for rolling-pins—whether above all[Pg 54] sovereigns that ever went afore her—or that’ll come after her—she hasn’t been most scrupulous, most ekonomick in the article of tinder-boxes? He will ask what surrounding nations will think of us—higgling about rolling-pins—disputing on royal tinder-boxes; and then the House will get up, and hurray—and, as I say, weeping tears of gratitude, vote the money, as though with all their hearts and our pockets they wished it twice as much.

Slowgoe. Ha! you’re a cuss-of-liberty man, you are, Mr Tickle, and don’t know what befits the royal prerogative. They won’t want a shilling, sir—not a shilling. There’s the Pavilion at Brighton. I understand that the loyal people of that loyal town, out of love, and affection, and veneration for their monarch as a king, a man, a husband, a father, and—let me see—yes, a practical moralist, intend to purchase the Pavilion, and let it off in shops for jewellers, wig-makers, and tailors, and all as a monument to the memory of that great and good man George the Fourth.

Tickle. Well, to make the monument complete, I hope they won’t forget a wine and brandy vaults.

Nutts. But how about the Duke’s statue? I thought it was to be put up upon the gate, that the Queen might see it when she drove out. Now, if the Queen has a new house on Buckbeen Hill——

Tickle. Why, all the houses ’tween that and[Pg 55] Rutland Gate will be pulled down, that the statue may be brought near to the new palace with a telescope.

Slowgoe. I’m very happy to see that her Majesty, and the Prince, and the children are taking such pleasure on the sea.

Tickle. Yes. Parson M’Neile—he isn’t yet a bishop, I hear——

Nutts. Why, no; but as they say there’s going to be a bishop made for Manchester, and as he’s at Liverpool, so very near the spot, he keeps himself prepared for the best. They do say he sleeps with his carpet-bag and shovel-hat by his bedside, all in readiness for an early train.

Tickle. A very provident parson. Well, they say he preached another sermon last Sunday about the Prince and his doings. In fact, it is reported that he intends to follow up his Royal Highness through the Court Circular. Last Sunday he compared him to Noah.

Nutts. As how?

Tickle. Why, because his Royal Highness was afloat in the royal yacht. Bless you! he showed how the Prince was Noah, and how the Victoria and Albert was nothing more than the ark, holding the hopes of the world; and how the precious children were Ham, Shem, and Japheth, and how the ark held two of every living thing.

[Pg 56]

Tickle. Well, I can’t say about that; but if Parson M’Neile told men all the beasts in the ark was, St Jude’s could answer for one of the “creeping things.”

[Pg 57]

Chapter V.

Tickle. (With newspaper.) Well, it’s a shocking thing, isn’t it, when we read of babbies, left by things as call themselves their mothers, on highways and door-steps, and in all sort of places, exposed, I b’lieve they call it, to the elements and the severity of the season. It’s a little bad o’ such parents, isn’t it, Mr Nutts?

Mr Nutts. Bad! that isn’t the word, Mr Tickle; and the worst of it is, we can’t make a word bad enough for it.