THE CHARM OF GARDENS

| AMERICA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY |

| 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, NEW YORK | |

| AUSTRALASIA | THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS |

| 205 Flinders Lane, MELBOURNE | |

| CANADA | THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA LTD. |

| St. Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, TORONTO | |

| INDIA | MACMILLAN & COMPANY LTD. |

| Macmillan Building, BOMBAY | |

| 309 Bow Bazaar Street, CALCUTTA |

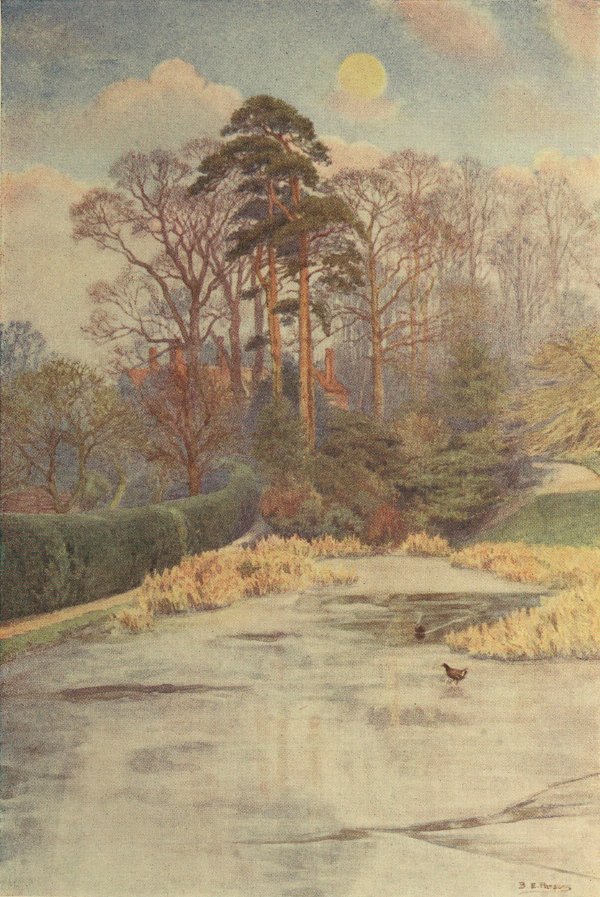

THE LAKE GARDEN AYSCOUGH FEE HALL, SPALDING.

| PUBLISHED BY . | 4 SOHO SQUARE |

| ADAM & CHARLES | LONDON . . W. |

| BLACK . . . . | MCMXI . . . . |

CONTENTS

| PART I | ||

| A VIEW OF ENGLAND | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Spirit of Gardens | 3 |

| II. | The Garden of England: The Patchwork Quilt | 10 |

| III. | A Country Lane: A Memory from Abroad | 18 |

| IV. | Fields | 23 |

| V. | Episode of the Contented Tailor | 27 |

| VI. | The Bluebell Wood and the Calm Stone Dog | 35 |

| VII. | The Tailor’s Sister’s Tombstone | 42 |

| VIII. | The Cottage Garden | 54 |

| IX. | A Feast of Wild Strawberries | 64 |

| X. | The Praises of a Country Life | 71 |

| PART II | ||

| GARDENS AND HISTORY | ||

| I. | The Roman Garden in England | 75 |

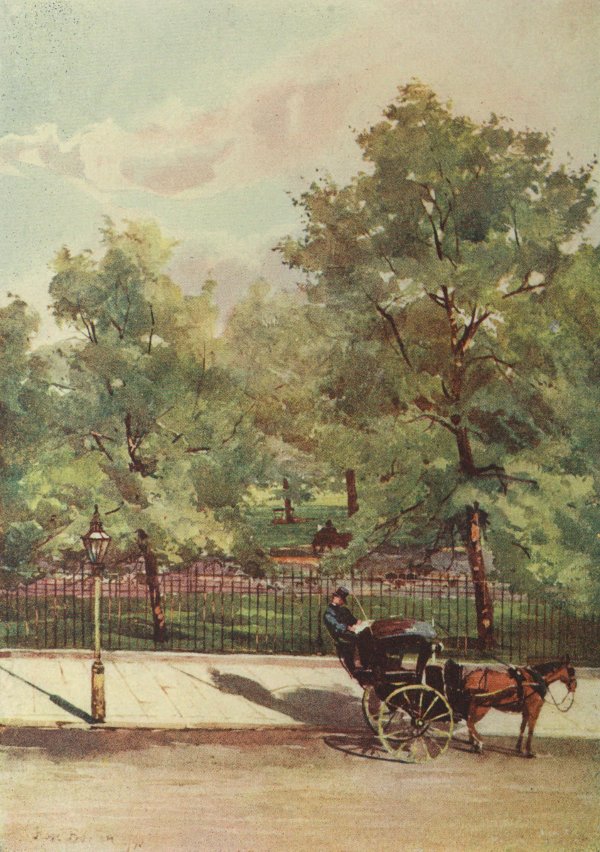

| II. | St. Fiacre, Patron Saint of Gardeners and Cab-Drivers | 88 |

| III. | Evelyn’s “Sylva” | 96 |

| xPART III | ||

| KALENDARIUM HORTENSE | 108 | |

| PART IV | ||

| GARDEN MOODS | ||

| I. | Town Gardens | 151 |

| II. | The Effect of Trees | 163 |

| III. | A Lover of Gardens | 182 |

| IV. | Of the Crown of Thorns | 185 |

| V. | Of Apples | 187 |

| VI. | Of the First Gardener | 189 |

| VII. | Of the First Roses | 191 |

| VIII. | Of the Abbey Garden | 193 |

| IX. | The Olympian Aspect | 195 |

| X. | Evening Red and Morning Grey | 204 |

| XI. | Garden Promises | 213 |

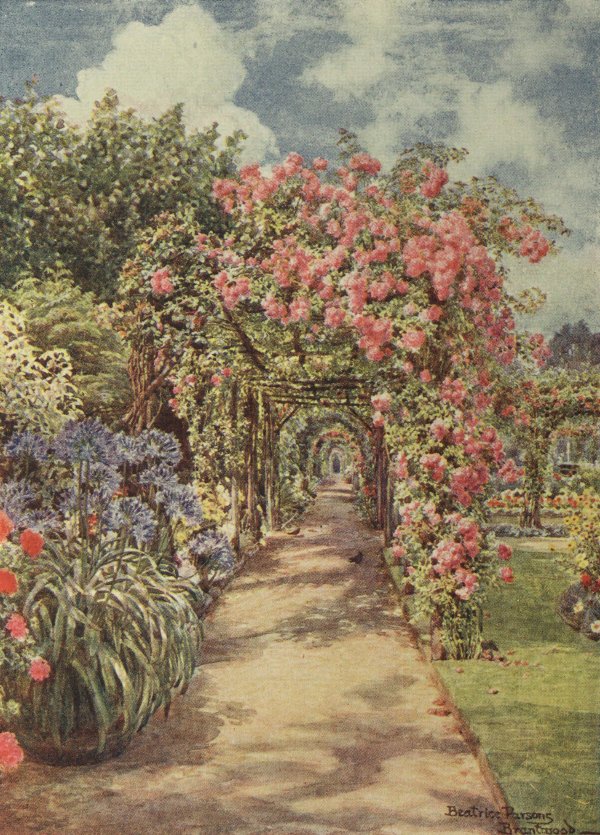

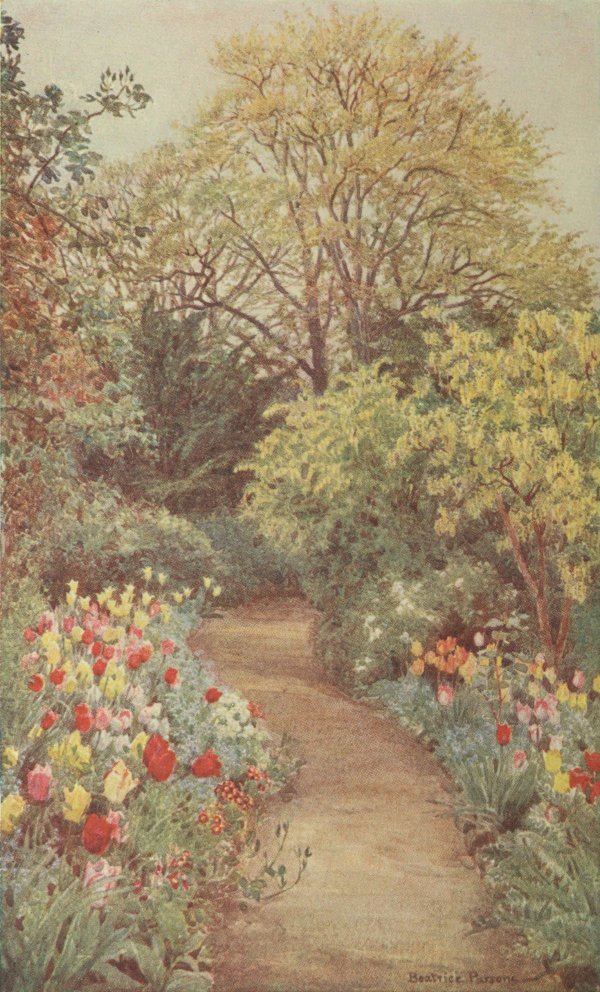

| XII. | Garden Paths | 220 |

| XIII. | The Gardens of the Dead | 233 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| 1. | The Lake Garden, Ayscough Fee Hall, Spalding | Frontispiece |

| Facing page | ||

| 2. | A Primrose Bank near Dorking | vi |

| 3. | Sir Walter’s Sundial, Abbotsford | 9 |

| 4. | The Weald of Kent, showing the Country like a Patchwork Quilt | 16 |

| 5. | Poppies in Surrey | 25 |

| 6. | Porches grown over with Honeysuckle and Roses at Broadway in the Cotswolds | 32 |

| 7. | Bluebells in Surrey | 41 |

| 8. | A Cottage Garden | 48 |

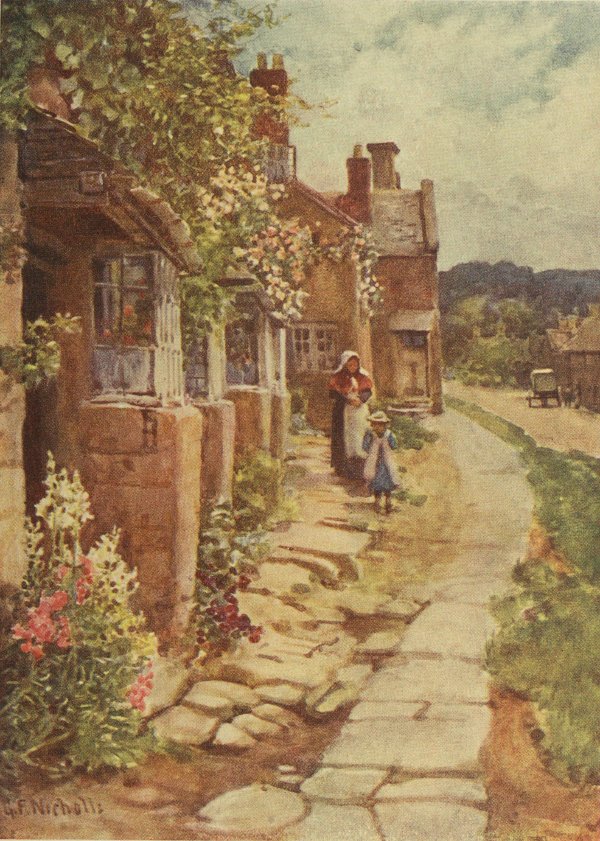

| 9. | A Surrey Cottage | 57 |

| 10. | Patches of Heather | 64 |

| 11. | A Pergola in an English Garden | 73 |

| 12. | Entrance to the Gardens, Ayscough Fee Hall, Spalding | 80 |

| 13. | A Cab-Driver in Piccadilly | 89 |

| 14. | A Wood at Wotton, the Home of John Evelyn | 96 |

| 15. | Tulips in the “Garden of Peace” | 105 |

| 16. | Apple Trees | 112 |

| xii17. | Daffodils in a Middlesex Garden | 121 |

| 18. | A Poet’s Orchard in Kent | 128 |

| 19. | A Kentish Garden in Autumn | 137 |

| 20. | A Hampstead Garden in Winter | 144 |

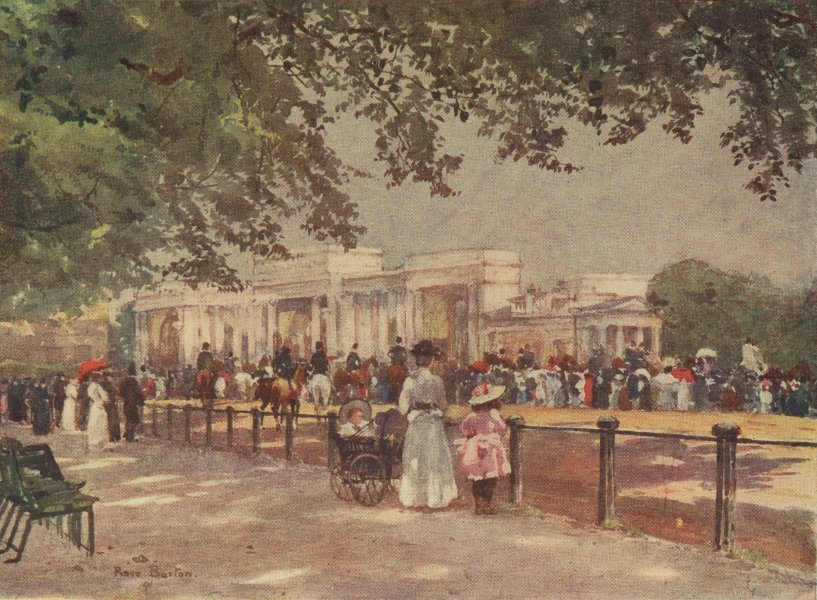

| 21. | Azaleas in Bloom, Rotten Row | 153 |

| 22. | In Hyde Park | 160 |

| 23. | The Seat beneath the Oak in the Poet Laureate’s Garden | 169 |

| 24. | In the Botanic Garden, Oxford | 176 |

| 25. | The Pride of Spring, Surrey | 185 |

| 26. | A Rose Garden in Berkshire | 192 |

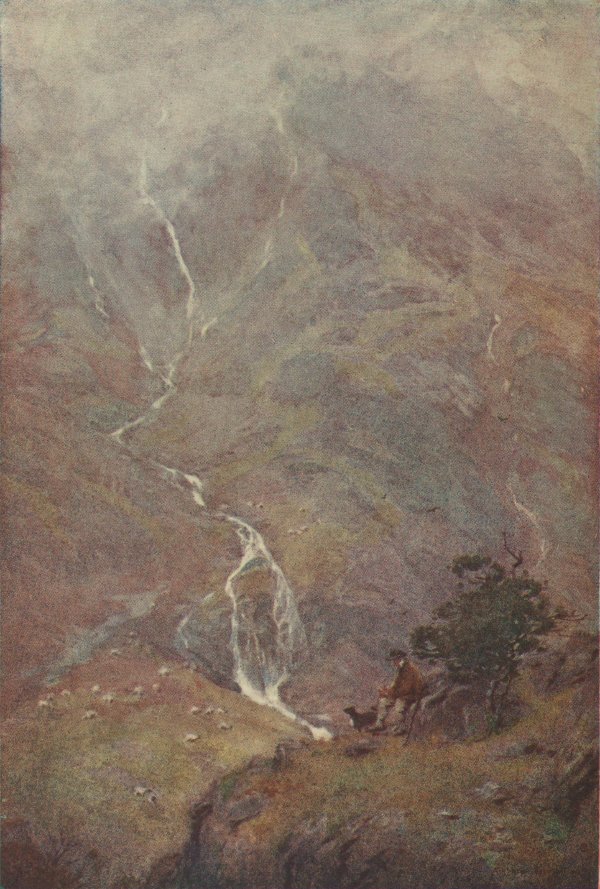

| 27. | A Shepherd of Coniston | 201 |

| 28. | A Dovecote in a Sussex Garden | 208 |

| 29. | A Northamptonshire Garden | 217 |

| 30. | A Path in a Rose Garden | 224 |

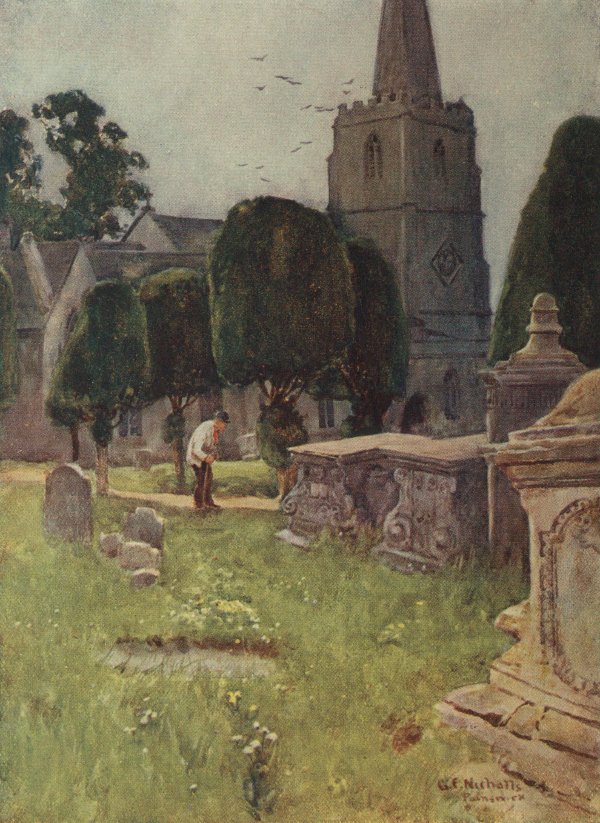

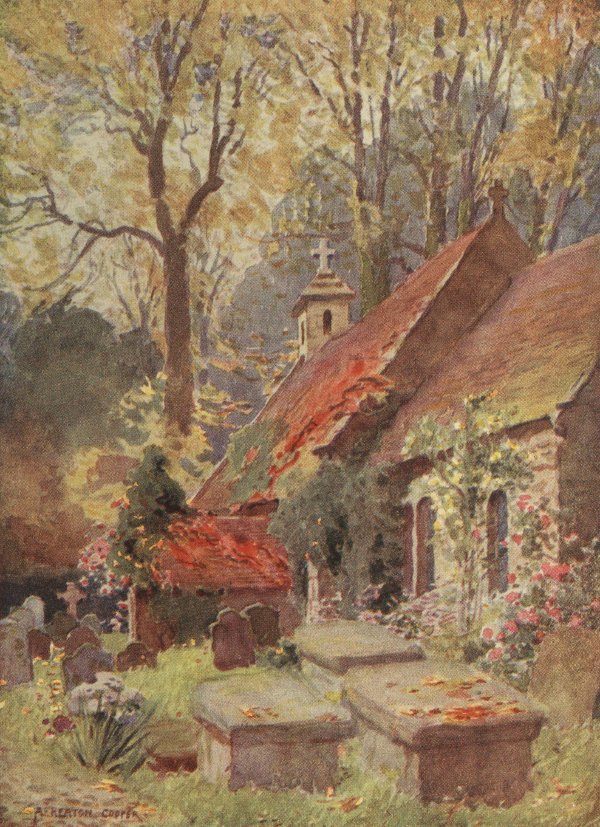

| 31. | A Churchyard in the Cotswolds | 235 |

| 32. | Autumn Colour at Bonchurch Old Church near Ventnor | 238 |

PART I

A VIEW OF ENGLAND

I

THE SPIRIT OF GARDENS

Once, I remember well, when I was hungering for a breath of country air, a woman, brown with the caresses of the wind and sun, brought the Spring to my door and sold it to me for a penny. The husky rough scent of those Primroses gave me news of England that I longed to hear. When I had placed my flowers in a bowl and put them on the table where I worked, they told me stories of the lanes and woods, how thrushes sang, and the wild Cherry Blossom flared delicately across the purpling trees.

A flower often will reclaim a mood when nothing else will bring it back.

To garden, to garner up the seasons in a little space, is part of every wise man’s philosophy. To sow the seeds, to watch the tender shoots come out and brave the light and rain, to see the buds lift up their heads, and then to catch one’s breath as the flowers open and display their precious colours, living, breathing jewels, is enough to live for. But there is more than that. A man may choose the feast to spread before his eyes, may sow old memories and see them grow, and feel the answering colours in his heart. This Rose he used to pass on his way to school; it nodded to him over the high red wall, while next to it a Purple Clematis clung, arching over, so that, by standing on his pile of school-books, he could reach the flowers. This patch of Golden 4Marigolds reminds him of a long border in the garden where he spent his boyhood (they used to grow behind the bee skeps, had a little place to themselves next to the Horseradish and the early Lettuces). There’s a hedge of Lavender full of association, he may remember how he was allowed (or was it set him for a task?) to cut great sheaves of it and take them to the Apple-room, and hang them up to dry over old newspapers. To look at Lavender brings back the curious musty smell of that store-room, where Apples wintered on long shelves; where the lawn-mower stood, and the brooms, and the scythe (to cut the orchard grass), and untidy bundles of bass hung with string and coils of wire. What a wonderful place that store-room was, with the broken door and the rusty lock that creaked as the big key turned to let him in: to reach the latch he had to stand on tip-toe, and to turn the key seemed quite a grown-up task. There was all a garden needs stored in that room. It had been a dining-room once, a hundred years ago, a room where the members of a bowling club convivially met and fought old games; bias, twist, jack, all the terms ring in his ears, even the click of the bowls, sharp on the summer air, comes back; and the plastered ornamental ceiling had sagged and dropped away here and there, showing the laths. There was a big dusty window, across which the twisted arms of a Wisteria stretched, and a broken window seat in it that opened like a box to hold the bowls. Just the hedge of Lavender brings back the picture of the boy whose cherished dreams hung about those four walls; who, having strung his bunches, neatly tied, on wooden pegs along the walls, and spread his papers underneath to catch the falling seeds, sat, book in hand, and travelled into foreign lands with Mungo Park. There, on his left, and facing him as well, shelves lined the walls, and Pears, 5Apples and Medlars were arranged in rows, while by his side, placed on the window ledge to catch the sun, were fallen Nectarines, Peaches and big yellow Plums set to ripen.

What curious things a garden store-room holds! The tins, slopped over, of weed-killer, of patent plant foods, of fine white sand. The twisted string, criss-crossed upon a peg of wood, covered with whitewash, the string that serves to guide the marker for the tennis-court. Then an array of nets to cover Currant bushes, and bid birds beware of Gooseberries, Cherries and ripe Strawberries. A barrow, full of odds and ends, baskets, queer little bags of seeds, a heap of Groundsel gathered for a bird and lying there forgotten. Like a Dutch picture, half in gloom with bright lights on the shears, and along the edge of the scythe, and on the curved wire mesh made to guard young seedlings. Empty seed packets on the floor, bright coloured pictures of the flowers on the outsides, a little soiled by the earth and the gardener’s thumb.

Plant memories, indeed! A man may plant a host of them and never then recapture all his joys. There’s his first love garnishing a rustic arch, a deep yellow Rose, beautiful in the bud—William Allen Richardson: she wore them in her sash. He can laugh now and see the long yellow hair floating in a cloud behind her as she ran, and the twinkling black legs, and the merry pretty face looking down on him from between the leaves of the Apple-tree she climbed. He grows that Apple in his orchard now, and toasts her memory when the first ripe fruit of it shines on the dish before him at dessert.

The Clove Carnation with its spice-like scent he bought from a barrow in a London slum, brought with care—wrapped in paper on the rack of the railway carriage—and planted it here. This Picotee he hailed with joy 6in the flower-market at Saint Malo and carried it across the sea, each bloom tied up to a friendly length of cane. His neighbours marvel at his pains, but it recalls many a happy day to him.

There, in a corner under a nut-tree, is a grass bank thick with Primrose plants—another memory. A picture comes to him from the Primroses very clear, very distinct, a picture of the world gone black, of a day when a boy thought heaven and earth purposeless, cruel; when he ran from a garden to the woods and threw himself on a bank, covered with Primroses, sobbing and weeping till the world was blotted out with his tears, because his dog had died. It had been the first thing he had learnt to love, the first thing he had had to care for, to look after. All his childish ideas were whispered into the big retriever’s silky coat. They had secret understandings, a different language, ideas in common, and the dog’s death was his first hint of death in the world. Years after, when he planted this garden, he gave a place to Don, and planted the Primroses himself. The earth was kindly and the flowers flourished. The earth is kindly, even your cynic knows that and marks the spot where he hopes to lie, and thinks, not sourly, of the Daisies over his head.

There is something more than memory in a garden. There is that urgent need man has to be part of growing life. He must have open spaces, he takes health from the sight of a tree in bud, from the sight of a newly ploughed field, from a plant or so in a window-box, a flower in his button-hole. Men, who by a thousand ties are held at desks in cities, look up and hear a caged thrush sing, and their thoughts fly out to fields and the common wayside flowers, and, for a moment, the offices are filled with the perfume—indescribable—of the open road.

A PRIMROSE BANK NEAR DORKING.

7There is that in the hum and business of a garden that makes for peace; the senses are softly stirred even as the heart finds wings. No greeting is as sweet as the drowsy murmur of bees, in garden, lane or open heath. No day so good as that which breaks to song of birds. No sight so happy as the elegant confusion of flower-border still wet and glistening with the morning dew.

I heard a man once deliver a learned lecture on the Persian character, full of history, romance and thoughtful ideas. Towards the end of his discourse I began to feel that he, indeed, knew the Persian inside out, but that I could catch but a fleeting and momentary glimpse of his knowledge. Then, by way of background to an anecdote, he mirrored, with loving care and wealth of detail, Oriental in its imagery and elaboration, the gardens in a palace. There was a stream of clear water running through the garden, and the owner had paved the bed of the stream with exquisite old tiles; white Irises bloomed along the banks, white Roses, growing thickly, dropped scented petals in the stream. I have as good as lived in that garden; I saw it so well, and what little I know of the Persian I know from that description. Omar is more than a dead poet to me now; I can smell the Roses blooming over his grave.

There should be a sundial in every garden to mark the true beginning and the end of day; some noise of water somewhere; bees; good trees to give shade to us and shelter to the birds; a garden-house with proper amount of flower-lore on shelves within; a walk for scent alone, flowers grown perfume-wise; a solitary place, if possible, where should be a nest of owls; a spread of lawn to rest the eyes, no cut beds in it to spoil the symmetry, and at least one border for herbaceous plants. If this is greedy of good things leave out the owls—that’s but a fanciful thought. Do you know 8what a small space this requires? Those who might be free and yet choose to live in towns might have it all for the price of the rent of the ground their kitchen covers.

SIR WALTER’S SUNDIAL, ABBOTSFORD.

There are those aching spirits to whom no land is home, whose feet go wandering over the world; gipsy-spirits searching one must suppose for peace of mind in constant new sights. For them the well-ordered garden with its high walls, its neat lawn, its fair carriage-drive, is but a dull prison-house, and even if in the course of their wanderings they stray into such a place their talk is all of other lands; of scarlet twisted flowers in Cashmere; of fields of Arum Lilies near Table Mountain; of the sad-grey Olives and the gorgeous Orange groves of Spain; the Poppy fields of China, or the brightly painted Tulips growing orderly in Holland. We with our ancestral rookery near by, our talk of last year’s nests, or overweening pride in the soft snows of Mrs. Simpkin’s Pinks, seem to these folk like prisoners, who having tamed a mouse proclaim it chief of all the animal world. But ask of the Garden of England and the flowers it affords and see their eyes take on a far-away look as the road calls to them, and hear them at their own lore of roadside flowers, praising and loving Traveller’s Joy, the gilt array of Buttercups, the dusty pink of Ragged Robin, and the like sweet joys the vagabond holds dear. This one can whistle like a blackbird; that one has boiled the roots of Dandelions (Dent de Lion, a charming name) and has been cured by their juices. He knows that if he sees the delicate parachutes of Dandelion, Coltsfoot, or of Thistle-fly when there is not a breath of wind, then there will be rain. They read the skies, hear voices in the wind, take courses from the stars, and know the time of day from flowers. These men, having none of the spirit that inspires your gardener, 9see the results of the work and smile pleasantly, ask, perhaps, the name of some flower, to please you, know something of soils, praise your Mulberries, and admire your collection of Violas, but soon they are off and away, breathing more freely for leaving the sheltered peace of your well-kept place, and vanish to Spitzbergen or the Chinese desert in search of what their souls crave. We are different; we sit in the cool of the evening, overlooking our sweet-scented borders, gaining joy from the gathering night that paints out the detail of our world, and hope quietly for a soft, gentle rain in the night to stiffen the flowers’ drooping heads. We English are gardeners by nature: perhaps the greyness of our skies accounts for our desire to make our gardens blaze with colours.

We have our memories, our desire for peace, our love of colour, and, at the back of all, something infinitely more grand.

II

THE GARDEN OF ENGLAND: THE

PATCHWORK QUILT

Even your most unadventurous fellow can hardly look on a fair prospect of fields and meadows, woods, villages with smoking chimneys, a river, and a road, without a certain feeling rising in him that he would like to tread the road that winds so dapperly through the country, and discover for himself where it leads.

To those who love their country the road is but a garden path running between borders of fair flowers whose names and virtues should be known to every child.

A poet can weave a story from the speck of mud on a fellow traveller’s boot—the red soil of a Devonshire lane calls up such pictures of fern-covered banks, such rushing streams, as make a poem in themselves.

It strikes one from the very first how neatly most of England is kept. The dip and rise of softly swelling hills across which the curling ribbon of the road winds leisurely between neat hedges, the fields in patches, coloured brown and green, golden with Corn, scarlet with Poppies, yellow with Buttercups; the circular bunches of trees under whose shade fat cattle stand lazily switching their tails at flies; the woods, hangers, shaws and coppices, glades, dells, dingles and combes, all set out so orderly and precise that, from a hill, the country has the appearance of a patchwork quilt set in 11a pleasant irregularity, studded with straggling farms, and little sleepy villages where the resonant note of the church clock checks off the drowsy hours. The road that runs through this quilt land seems like a thread on which villages and market towns are strung, beads of endless variety, some huddled in a bunch upon a hill, some long and straggling, some thatched and warm, red-bricked and creeper-covered, others white with roofs of purple slate, others of grey stone, others of warm yellow. All alive with birds and flowers and village children, butterflies and trees; fed by broad rivers, or hanging over singing streams or deep in the lush grass of water meadows gay with kingcups.

This garden is for us who care to know it. We can take the road, our garden path, and pluck, as we will, flowers of all kinds from our borders; sleep in our garden on beds of bracken pulled and piled high under trees; or on soft heaps of heather heaped under sheltering stones. If we know our garden well enough it will give us food—salads, fruits and nuts; it will cure us of our ills by its herbs; feed our imagination by the quaint names of flower and herb. Here’s a small list that will sing a man to sleep, dreaming of England.

These alone of hundreds give a lift to the day: there’s a story to each of them.

Take our England as a garden and let the eye roam over the land. Here’s the flat country of the Fens, 12long, long vistas of fields, with spires and towers sticking up against the sky. Plenty of rare flowers there for your gardener, marsh flowers, water plants galore. That’s the place to see the sky, to watch a summer storm across the plain, to see the Poplars bending in an angry wind, and the white windmills glare against purple rain clouds. Few hedges here but plenty of banks and dykes, and canals they call drains. Here you may find Marsh Valerian, Water Crowsfoot, Frogbit, pink Cuckoo-flowers, Bog Bean, Sundews, Sea Lavender, and Bladder-worts. The Sundews alone will give you an hour’s pleasure with their glistening red glands tricked out to catch unwary flies and midges.

Then there’s a wild garden waiting you by stone walls in the dales of Derbyshire, or in the Yorkshire wolds, or the Lancashire fells. On the open heaths, where the grey roads wind through warm carpets of ling and heather, you can fill your nostrils with the sweet scent of Gorse and Thyme.

I was sitting one hot afternoon, drawing the twisted bole of a Beech tree. All the wood in which I sat was stirring with life; the dingle below me a mist of flowers, Primroses, Wind-flowers, Hyacinths whose bells made the air softly fragrant. Above me the sky showed through a trellis-work of young leaves, the distance of the wood was purple with opening buds, and the floor was a swaying sea of Bluebells dancing in a gentle breeze. Squirrels chattered in the trees; now and then a wood pigeon flopped out of a tree, and a blackbird whistled in some hidden place.

All absorbed in my work, following the grotesquely beautiful curves of the beech roots, I heard no sound of approaching footsteps. A voice behind me said “Good,” and I started, dropping my pencil in my confusion.

13“Sorry. Didn’t mean to startle you,” said the voice.

I turned round and saw a man standing behind me, a man without a cap, with curly brown hair, and a face coloured deep brown by the sun. He was dressed in a faded suit of greenish tweed, wore a blue flannel shirt, carried a thick stick in his hand, and had a worn-looking box slung over his shoulders by a stained leather strap.

I suppose my surprise showed in my face in some comic way, for he laughed heartily, showing a set of strong white teeth.

“No, I’m not Pan,” he said laughing, “or a keeper, or a vision. I’m a gardener.”

His admirable assurance and pleasant address were very captivating.

I asked him what he did there, and he immediately sat down by me, pulled out a black clay pipe, and lit up before replying. He extended the honours of his match to my cigarette and I noticed that his hands were well formed, and that he wore a silver ring on the little finger of his right hand.

When he had arranged himself to his comfort, propping his back against a tree and crossing his legs, he told me he was a gardener on a very large scale.

I wished him joy of his garden, at which he smiled broadly, and informed me in the most matter-of-fact way that he gardened the whole of Great Britain.

For a moment I wondered if I had fallen in with an amiable lunatic, but a closer inspection of his face showed me he was sane, uncommonly healthy, and, I judged, a clever man.

“A vast garden?” I said.

Without exactly replying to my remark, which was put half in the manner of a question, he said, partly to 14himself, “The slight fingers of April. Do you notice how delicate everything is?”

I had noticed. The air was full of suggestion, the flowers were very fairylike, the green of the trees very tender.

“Pied April,” said I.

Instead of answering me again he unstrapped the box that now lay beside him on the grass, opened it and took from it a beautiful Fritillaria.

“There’s one of the April Princesses, if you like,” he said. “There are not many about here, just an odd one or two; plenty near Oxford though.”

“You know Oxford?” said I.

“Guess again,” he said, smiling. “I’m no Oxford man, but I know the woods about there well. Please go on working; I’ll talk.”

I was about to look at my watch when he stopped me.

“It’s half-past two,” he said. “The slant of the sun on the leaves ought to tell you that.”

I was amused, interested in the man; he was so odd and quaint. “I’ve not eaten my lunch yet,” I said. “Perhaps you’ll share it with me.”

“I was wondering if you’d invite me,” he replied. “I’m rather hungry.”

I had, luckily, enough for two. Slices of ham, some cheese, a loaf of new bread, and a full flask. Very soon we were eating together like old friends.

In an inconsequent way he asked me what I thought of the name of Noakes.

I said it was as good as any other.

“Let’s have it Noakes, then,” he said, laughing again. A very merry man.

“About this garden of yours, Mr. Noakes?” I asked.

He tapped his wooden box and said, “If you want to 15know, I’m a herbalist. You can scarcely call me a civilised being, except on occasions when I do go among my fellow men to winter.” He pulled a cap and a pair of gloves out of his pocket. “My titles to respectability,” he said.

“And in the Spring?”

“I take to the road with the Coltsfoot and the Butterburrs. I come out with the first Violet, and the Pussy-cat Willow. I wander, all through the year, up and down the length and breadth of England, with my box of herbs. I get my bread and cheese that way—while you draw for pleasure.”

“Partly.”

“It must be for pleasure, or you wouldn’t take so much pains. I suppose you think I’m a very disgraceful person, a bad citizen, a worse patriot. But I know the news of the world better than those who read newspapers. Although I trade on superstitions, I do no harm.”

“Do you sell your herbs?”

“Colchicum for gout—Autumn Crocus, you know it,” he replied. “Willow-bark quinine; Violet distilled, for coughs. Not a bad trade—besides, it keeps me free.”

I hazarded a question. “Tell me—you must observe these things—do swifts drink as they fly? It has often puzzled me.”

“I don’t know,” said he. “Ask Mother Nature. Some of these things are the province of professors. I’m not a learned man; just a herbalist.”

At that moment a thrush began to sing in a tree overhead. My friend cocked his head, just like an animal.

“There’s the wise thrush,” he quoted softly, “he sings his song twice over.”

16“So you read Browning,” I said.

“I have a garret and a library,” he said. “Winter quarters. We shall meet one day, and you’ll be surprised. I actually possess two dress suits. It’s a mad world.” He stopped abruptly to listen to the thrush. “This is better than the Carlton or Delmonico’s, anyhow!”

“What do you do?” I asked. “Go from village to village selling herbs?”

“That’s about it. Lord! Listen to that bird. I heard and saw a nightingale sing once in a shaw near Ewelme. I think a thrush is the better musician, though. Yes, I sell my herbs, all sorts and kinds. Drugs and ointments, very simple I assure you—Hemlock and Poppy to cure the toothache. Wood Sorrel—full of oxalic acid, you know, like Rhubarb—for fevers. Aconite for rheumatics—very popular medicine I make of that, sells like hot cakes in water meadow land, so does Agrimony for Fen ague. Tansy and Camomile for liver—excellent. Hellebore for blisters, and Cowslip pips for measles—I’m a regular quack, you see.”

“And it’s worth doing, is it?”

He leaned back, his pipe between his lips, a very contented man. “Worth doing!” he said. “Worth owning England, with all the wonderful mornings, and the clean air; worth waking up to the scent of Violets; worth lying on your back near a Bean field on a summer day; worth seeing the Bracken fronds uncurl; watching kingfishers; worth having the fields and hedgerows for a garden, full of flowers always—I should think so. I earn my bread, and I’m happy, far happier than most men. I can lend a hand at haymaking, at the harvest; at sheep-shearing, at the cider press, at hoeing, when I’m tired of my own company. I’ve worked the seines in the mackerel season on the South coast—do you know the bend of shore by Lyme and Charmouth? 17I’ve ploughed in the Lowlands, and found lost sheep in the Lake Country; caught moles for a living in Norfolk, and cut Hop-poles in Kent, and Heather in the Highlands.—And I’m not forty, and I’m never ill.”

THE WEALD OF KENT SHOWING THE COUNTRY LIKE A PATCHWORK QUILT.

“It sounds delightful.”

He rose to his feet and gave me his hand.

“We shall meet again,” he said laughing. “Perhaps in the conventional armour of starched shirts and inky black. For the present—to my work,” he pointed over his shoulder. “I’m building hen-coops for a widow. Hasta luego.”

With that he vanished as quietly as he came. Almost as soon as the trees had hidden him from my sight, a blackbird began to whistle, then stopped, and a laugh came out of the woods.

Altogether a very strange man.

I found, when he had gone, that he had written something on a piece of paper and had pinned it to the tree with a long thorn. It was this:

“I think, very likely, you may not know Ben Jonson’s ‘Gipsy Benediction.’ If you don’t, accept the offering as a return for my excellent lunch.

He signed, at the foot, “Noakes, Under the Greenwood Tree.” And he seemed to have written some of his clear laughter into it.

III

A COUNTRY LANE: A MEMORY

FROM ABROAD

I was looking at a vision of the world upside down, mirrored in the deep blue of a still sea. Where the inverted picture of my boat gleamed white, and the rope that moored her to a tree showed grey, I saw the dark fir trees growing upside down, the bank of emerald grass looking more brilliant because of the grey-green lichened rocks; a black rock, glistening, hung with brown seaweed, made the vision clear, and, over all, clouds chased each other in the sky, seemingly below me. They were those round fleecy clouds, like sheep, and they reminded me of something I could not quite arrest.

A fish swam—dash—across my mirror, another and another, rippling the sky, the trees, the bank, distorting everything. Then I looked up and saw a fishing-boat come sailing by with its great orange and tawny sails all set out to catch the land breeze; and bright blue nets hung out ready, floating and billowing in the slight wind. There was a creaking of ropes and a hum of Breton as the sailors talked. From my moorings by the island I watched her sail—Saint Nicholas she was called, and had a little figure of the Madonna on her stern. Out of the land-locked harbour she slipped, tacking to make the neck that led to the outer harbour, and there she was going to meet other gaily 19coloured ships and sail with them to the sardine grounds off the coast of Spain.

After she had passed, leaving her wide white wake in the still waters, I followed her in my mind, seeing the nets cast and the shimmering silver fish drawn up, and the long loaves of bread eaten, with wine and onions, until the waters round me were quiet again, and I could look once more into my mirror and wonder what it was the flocks of clouds said to my brain.

It came in a flash. Big Claus said to Little Claus, “After I threw you into the river in the sack, where did you get all those sheep and cattle?” And Little Claus said, “Out of the river, brother, for there I came upon a man in beautiful meadows, and he was tending the sheep and cattle. There were so many that he gave me a flock of sheep and a herd of cattle for myself, and I drove them out of the river and up here to graze.” Now they were looking over the bridge at the time, and the description Little Claus gave of the meadows and the sheep below in the river made the mouth of Big Claus begin to water with greed. As they looked, Little Claus pointed excitedly at the water, and said, “Look, brother, there go a flock of sheep under your very nose.” It was, really, nothing but the reflection of the clouds in the water, but Big Claus was too interested to think of this, and he implored his brother to tie him in a sack and push him into the water, that he, too, might get some of these wonderful herds. This Little Claus did, and that was the end of Big Claus.

How well I remember now—so well that when I looked into the water and saw the fleecy clouds go floating by, the picture changed for me and I saw an English country lane, and a small boy sitting under a hedge out of a summer shower, and he was deep in 20dreams over an old brown volume of “Grimm’s Fairy Tales.”

How wonderful the lane smelt after the rain! The Honeysuckle filled the air and mingled with the smell of warm wet earth. It was a deep lane, with the high hedges grown so rank and wild that they nearly crossed overhead, and the curved arms of the Dog Roses criss-crossed against the patch of turquoise sky. The thin new thread of a single wire crossed high overhead, shining like gold in the sun. It went, I knew, to the Coast Guard Station below me, and I remember clearly how I used to wonder what flashed across the wire to those fortunate men: news of thrilling wrecks, of smugglers creeping round the point, of battle-ships put out to sea, and other tales the sailors told me.

The lane was deep and twisted, and so narrow that when a flock of sheep was driven down it, the dogs ran across the backs of the sheep to head off stragglers. What a cloud of white dust they made, and how thick it lay on the leaves and flowers until the rain washed them clean again.

On the day of which I was dreaming, there had been one of those sharp angry storms, very short and fierce, with growling thunder in the distance, and purple and deep grey clouds flying along with torn, rust-coloured edges. I had sheltered under a quick-set hedge (set, that is, while the thorn was alive—quick, and bent into a kind of wattle pattern by men with sheepskin gloves) and where I sat, under a wayfaring tree (the Guelder Rose), the lane had a double turn, fore and aft, so that a space of it was quite shut off, like an island. I had my garden here and knew all the flowers and the butterflies.

On this day the rain washed the Foxgloves and made them gay and bright, each bell with a sparkling 21drop of water on its lips. The Brambles had long rows of drops on them, all shining like jewels, until a yellow-hammer perched on one of the arched sprays and shook all the raindrops off in a fluster of bright light.

Behind me, and in front, trailing Black Bryony twisted its arms round Traveller’s Joy, Honeysuckle and Wild Roses. Here and there, pink and white Bindweed hung, clinging to the hedge. By me, on the bank, Monkshood, Our Lady’s Cushion, and Butterfly Orchis grew, all shining with the rain, and the Silverweed shone better than them all.

Presently came two great cart horses, their trappings jingling, down my lane, and on the back of one, riding sideways, a small boy, swaying as he rode. His face was a perfect country poem, blue eyes, shaded by a battered hat of felt, into the band of which a Dog Rose was stuck. His hair, like Corn, shone in the sun, and his face, red and freckled, a blue shirt, faded by many washings and sun-bleached to a fine colour, thick boots, a hard horny young fist, and in his mouth a long stem of feathery grass. He looked as much part of Nature as the flowers themselves. There was some sort of greeting as he passed. I can see the group now; the slow patient horses, the boy, the yellow canvas coat slung to dry across the horse’s neck, a straw basket, from which a bottle neck protruded, hitched on the horse’s collar. They passed the bend in the lane and the boy began to whistle an aimless tune, but very good to hear. And it was England, every bit of it, the kind of thing one hungers for when a southern sun is beating pitilessly on one’s head, or when the rains in the tropics bring out overpowering scents, heavy and stifling.

So I might have dreamed on about this garden lane 22I carried in my mind, had not the tide turned and little waves begun to lop the sides of my boat.

I slipped my moorings, shipped the oars, and sailed home quietly on the tide under a clear blue sky from which all the clouds had vanished like my dream.

IV

FIELDS

A man will tell you how he has walked to such and such a place “across the fields,” with an air of saying, “You, I suppose, not knowing the country, painfully pursue the highroad.” He has the look of one who has made the discovery that it is good and wise to leave the beaten track, the cart rut, and the plain and obvious road, and has adventured in a daring spirit from stile to stile, from gate to ditch, where only the knowing ones may go. He is generally so occupied in the pride of reaching his destination by these means, that he has had little time to look about him and enjoy the expanse of country. For all that, he is a man after my own heart for, in a sense, he becomes part owner of England with me as soon as he puts his leg across a stile and begins to cast an eye across country.

There is an extraordinary satisfaction in following a footpath, that is made doubly sweet if one sucks in the joy of the day, and the blitheness of that through which we pass. To be knee-high in a bean field in flower is as good a thing as I know, more especially if it be on a hillside overlooking the sea.

I sat once on the polished rail of a stile (very well made with cross arms to hold by, like two short step-ladders, each with one long arm) and looked at a path I had taken that lay through a field of whispering oats. They seemed to hold a thousand secrets that they passed 24from ear to ear all down the field, and when the breeze came, and blew birds across the hedge, the whole field swayed, showing a rustling, silken surface, as if it enjoyed a great joke. The Poppies and Cornflowers and the White Convolvulus had no part in the conversation of the Oats, but field mice had, and ran across the path hurrying like urgent messengers, and once a mole nosed its way from the earth by my stile and vanished grumbling—like some gruff old gentleman—along the hedgerow. I never saw a field laugh as much as that field, or be so frivolous, or so feminine. The field at my back was more like a great lady in a green velvet gown, embroidered with Daisies. There, at the bottom of the field, was a pond like a bright blue eye in the green, and lazy cattle, red and white, stood in it, while others lay under a chestnut tree near by.

Down in the valley, a long undulating spread before me, fields of different hues, some green, some brown, some golden with ripe Corn, lay baked in the heat, quivering under a calm blue sky. In one field a man was sharpening a scythe with a whetstone—the rasp came floating up to me clearly, and presently he began to open a field of wheat for the reaping machine I could see, with men round her, under a clump of trees. Next to this field was a narrow strip of coarse grass all aglow with Buttercups, then a wide triangular field, with a pit in the corner of it, snowed over with Daisies, and then a farm looking like a toy place, neat with white painted railings, and a dovecote, and a long barn covered over with yellow Stone Crop. I could see—all in miniature—the farmer come out of his house door, beckon to a dog, and walk past a row of Hollyhocks and a flush of pink Sweet Williams, open the gate and cross a road to the Corn-field. The dog leapt ahead of him, barking joyously.

POPPIES IN SURREY.

25A little further down, and cut off partly from view by the May tree that sheltered me, was a village, white and grey, sheltered by Elm trees. In the midst of the handful of cottages the square-towered flint church stood with Ivy on the tower and dark Yews in the churchyard. The graves in the churchyard looked like the Daisies in the distant field, as if they grew there. At the back of the church, and facing the high road, was a line of trees from whence came an incessant noise of rooks.

Very few things moved on the high road, a lumbering waggon, the doctor’s trap, a bicycle, and then the carrier’s cart with a man I knew driving it, a very pleasant man who preached in the Sion Chapel on Sundays and chalked up texts in the tilt of his waggon—but with a shrewd eye to business: a man who never forgave a debt.

As I sat on my stile I felt this was all mine: no person there knew the beauty of it as I did, or cared to capture its sweetness as I did. No one but I saw the field of Oats laugh, or cared to note the business of the dragon fly, or the flashing patterns of the butterflies. I had seen these fields turned up, rich and brown, under the plough, and tender green when the seeds came up, and waving green, and gold when they bore their harvest of Corn, or silver and green with roots and red with Beets. I had counted the sheep on the hillsides, and watched the cattle stray in a long line to be milked at milking time, and though I did not farm an acre of it, I owned it with my heart, and gathered its harvest with my eyes.

Every field footpath had its story, the road was rich in old romance, and hidden by the trees at the head of the valley was the big house where my hostess lived and with a loving hand directed all 26this little world—but I doubt if she owned it more than I.

To end all this, comes a little maid through the Oats, almost hidden by them, her face quivering with tears because of a misplaced trust in a bunch of Nettles. So we apply Dock leaves and a penny, and a farthing’s worth of country wisdom, and part friends—I to the head of the valley, she to her father’s farm on the other side of the hill.

V

EPISODE OF THE CONTENTED TAILOR

Not a hundred yards out of a certain village I came across a little man dressed in grey. We were alone on the road, we were going in the same direction, and I came to learn that he travelled with as little purpose as I.

As soon as I saw his face, his jaunty walk, his knapsack and his stick, I knew him for a friend.

I hailed him. He stopped, smiled pleasantly, and fell in with my stride. We soon found a mutual bond of esteem. It appeared we were out in search of adventures.

He explained to me, quite simply, that he was not going anywhere, and that he proposed to be some four months about it.

“Just walking about looking at things,” he volunteered.

“That is my case,” I replied.

“I’m a tailor, sir,” said he.

“Having a look at the cut of the country?”

He gave a little friendly nod.

“And do you tailor as you go along?” I asked, for I had never met a travelling tailor before: tinkers galore; haberdashers aplenty; patent medicine men a few; sailors; old soldiers (the worst); apothecaries I have mentioned; gentlemen, many; ploughboys, purse thieves, one or two, and ugly customers—they 28were in a dark lane—but a tailor, never. It seemed all the world could tread the high road but a tailor. Then I remembered my fairy tales—“Seven at a Blow”—and laughed aloud.

“I’ve given up my trade,” he explained, as we began to mount the hill. “No more sitting on a bench for me in the spring or summer. I do a bit in the winter, but I’m a free man on two pounds ten a week.”

And he was young—forty at the most.

“Put by?” said I.

He smiled again. “Not quite, sir. I had a little bit put by, but a brother of mine went to Australia, and made a fortune—he died, poor Tom, and left his money to me and my sister. Two pound ten a week for each of us.”

“And it has brought you—this,” I explained, pointing with my stick at the expanse of country. “It’s like a romance.”

“Isn’t it?”

“Then you read romances?” I asked quickly.

“I read all I can lay hands on,” he replied. “I’m living just as my sister and I dreamed we’d live if ever something wonderful happened.”

“And it has happened?”

“You’re right, sir. My sister lives in the little cottage I bought with my savings. She’s got all she wants—all anybody might want, you might say. A cottage, six-roomed, all white, with a Pink Rose growing over the porch, and a canary in a cage in the parlour. Then there’s a garden, and a bit of orchard, and bees and a river at the bottom of the little meadow, and a Catholic Church within a stone’s throw—so it’s all right. She’s a rare good gardener, is my sister.”

“I envy you both,” I said.

He looked me up and down for a moment before 29speaking. “No cause for you to do that, I expect, sir.”

“Well, you know what you want, and you’ve got it.”

We had reached the crest of the hill now after a longish climb. It was a hot day and I proposed a rest. Besides, it was one o’clock and I was hungry.

I had four hard boiled eggs, and he had bread and cheese—we divided our goods evenly, and ate comfortably under a hedge in a field.

“I’ve often sat on my bench,” he said, “and looked out at the sun in the dusty street and wondered if I should ever be able to sit out in it on the grass and have nothing to do. We used to go for a day in the country, I and my sister, whenever I could spare the money, and it was a holiday. You wouldn’t believe what the sight of green fields and trees meant to me and my sister: you see the hedgerows were the only garden we could afford, and we could ill-afford that. My sister used to talk about the Roses she’d have, and the Carnations, and the Sunflowers and Asters, when our ship came home. It came home—think of that.” He stretched his limbs luxuriously. “And here we are with everything, and more.”

“And more?” I asked.

“Well, you see, it is more, somehow. I’m ‘me’ now—do you follow the idea? I never knew what it was to be on my own: just ‘me.’ I can lie abed now as long as I want to, I can wear what I like, do what I like. And I’ve a garden of my own.”

“But you don’t stop there,” I said.

“Well,” he said, “I wonder if you’d know what I meant if I said that a garden and sitting about is a bit too much for me for the present. I want to walk and walk in the open air, and see things, and stretch my legs a bit to get rid of twenty odd years of the bench. 30I want to run up the top of hills and shout because—well, because I feel as if I had a right to shout when the sun is shining.”

“I quite understand that,” I said.

“And then,” he went on, and his face showed the joy he felt, “everything is so wonderful. Look at that village we came through: those people there feel the same as you and me. They’ve got to express themselves somehow, so they grow flowers right out into the road, just as a gift to you and me. A sort of something comes to them that they must have flowers at the front door. Whenever I see a good garden, full of Pinks and Roses and Larkspur, I get a bed at that cottage, if I can. I’ve slept all over the place, all over England, you might say; and cheap, too.”

“That was a beautiful village, below there,” I said.

He nodded wisely. “Seems as if they’d decorated the street on purpose to make the cottages look as if they grew like the flowers. All the porches covered with Honeysuckle and Roses, and everlasting Peas, and flowers up against the windows. I’ve a perfect craze for flowers—can’t think where I get it from.”

“You are the real gardener,” said I.

“I believe I am,” he said. “And why I took to tailoring beats me, now. My father was a butcher.”

I pointed over my shoulder towards the village. “Do you live in a place like that?” I asked.

“Better than that,” he answered proudly. “It took me nearly two years to find the place my sister and I had dreamed of. We wanted a cottage in a county as much like a garden as possible. I found it—in Devonshire; my eye, it’s a wonderful place, all orchards. In the blossom time it looks like—well, as if it was expecting somebody, it’s so beautiful.”

31“I know,” I said. “Sometimes the country dresses itself as if a lover were coming.”

“Do you ever read Browning?” he asked. “Because he answers a lot of questions for me.”

“For me too.”

“Well,” he said, and reddened shyly as he said it; “do you remember the poem that ends

I understood perfectly. He was a man of soul, my tailor.

“I expect you are surprised to find I read a lot,” he went on in his artless way. “But when I was a boy I was in a book shop, before my father lost all his money, and put me out to be a tailor. My mother was a lady’s maid, and she encouraged me to read. There was a priest, Father Brown, who helped me too; it was from him I first learned to love flowers.”

“Then, as you are a Catholic, you know what to-day is,” said I.

“The twenty-ninth of August. No, sir, I’m afraid I don’t.”

“It is dedicated to one of our patron Saints—there are two for gardeners—Saint Phocas, a Greek, and Saint Fiacre, an Irishman. To-day is the day of Saint Phocas.”

The tailor crossed himself reverently.

“I’ll tell you the story if you like.” And, as he lay on his back, I told him the little legend of

“At the end of the third century there lived a certain good man called Phocas, who had a little dwelling outside the gates of the city of Sinope, in Pontus. He had a small garden in which he grew flowers and 32vegetables for the poor and for his own needs. Prayer, love of his labour, and care for the things he grew filled his life.”

My tailor interrupted here to ask, apologetically, what manner of garden Saint Phocas would have.

“Neat beds,” said I—for I had gone into the matter myself—“edged with box. The flowers and vegetables growing together. Violets, Leeks, Onions, with Crocuses, Narcissus, and Lilies. Then, in their season, Gladiolus, Hyacinths, Iris, Poppies, and plenty of Roses. Melons, also, and Gherkins, Peaches, Plums, Apples and Pomegranates, Olives, Almonds, Medlars, Cherries, and Pears, of which quite thirty kinds were known. In his house, on the window ledge, if he had one, he may have grown Violets and Lilies in window pots, for they did that in those days.”

“Now, isn’t that interesting?” said the tailor. “My sister will care to know that. I shouldn’t be a bit surprised to find her putting a statue of Saint Phocas over the door. She’s all for figures.”

“I’m afraid,” said I, “there will be some trouble over that. There is a statue of him in Saint Mark’s in Venice, a great old man with a fine beard, dressed like a gardener, and holding a spade in his hand. There’s one of him, too, in the Cathedral at Palermo, but I have never seen them copied. Now I must tell you the rest of the story.

“There were days, you know, when Christians were hunted out and killed. One evening there came to the house of the Saint, two strangers. It was the habit of this good man to give of what he had to all travellers, food, rest, water to bathe their feet, and a kindly welcome. On this occasion the Saint performed his hospitable offices as usual—set the strangers at his board, prepared a meal for them, and led them afterwards to a 33place where they might sleep. Before going to rest they told him their errand; they were searching for a certain man of the name of Phocas, a Christian, and, having found him, they were to slay him. When they were asleep, the Saint, after offering up his prayers, went into his garden and dug a grave in the middle of the flower beds.

“The morning came, and the strangers prepared to depart, but the Saint, standing before them, told them he was the very man whom they sought. A horror seized them that they should have eaten with the man they had set out to kill, but Saint Phocas, leading them to the grave among the flowers, bid them do their work. They cut off his head, and buried him in his own garden, in the grave he had dug.”

PORCHES GROWN OVER WITH HONEYSUCKLE AND ROSES AT BROADWAY IN THE COTSWOLDS.

The little tailor was silent. I lit my pipe, and began to put my traps together.

Then he spoke. “I couldn’t do that, you know. Those martyrs—by gum!”

“Death,” said I, “was life to them. Their life was only a preparation for death.”

The tailor sat up. “My sister’s like that,” he said. “She’s bought a tombstone—think of that. Said she’d like to have it by her. She’s a one for a bargain, if you like; saw this tombstone marked ‘Cheap,’ in a stonemason’s yard down our way, and went in at once to ask the price. She’d price anything, my sister would. You’ve only got to mark a thing down ‘Cheap’ and she’s after the price in a minute.”

“How did the tombstone come to be marked ‘cheap’?” I asked, laughing with him.

“It was this way,” said the tailor. Then he turned, in his inconsequent way to me. “I wonder,” he said, “if, as you’re so kind as to take an interest, you’d care to see our cottage. We’d be proud, my sister and 34I, if you would come. If you are just walking about for pleasure, perhaps you’d come down as far as that one day and—and, well, sir, it’s very humble, but we’d do our best.”

“When shall you be there?” I said. “Because I want to come very much.”

“I’m going back; I’m on my way now,” he said; “I always go back two or three times in the summer just to tell her the news. I tell her what’s happened, and what flowers they grow where I’ve been. If you would really come, sir, perhaps you’d come in three weeks from now, if you have nothing better to do. I’d let her know.”

“Then she could tell me the story of the tombstone herself?” I said.

It ended at that. He wrote the address for me in my sketch-book, and took his leave of me in characteristic fashion.

“I hope I’m not taking a liberty,” he said, as he jerked his knapsack into a comfortable place between his shoulders.

“There’s nothing I should like better,” said I.

“You’ll like the garden,” he said as an inducement.

And this was how I came to hear the story of the “Tailor’s Sister’s Tombstone.”

VI

THE BLUEBELL WOOD AND THE CALM

STONE DOG

Man is an autobiographical animal, he speaks only from his thimbleful of human experience, and the I, I, I, of his talk drops out like an insistent drip of water. Even the knowledge we gain from books has to be grafted on to the knowledge we have of life before it bears fruit in our minds. Like patient clerks we are always adding up the columns of facts, fancies, and ideas, and arriving at the very tiny total at the end of the day.

In order to give themselves scope when they wish to soliloquise, many authors address their conversation to a cat, a grandfather clock, a dog, a picture on the wall, or what-not. Cats, I think, have the preference. I have often wondered what Crome, the painter, said to his cat when he pulled hairs out of her to make paint-brushes; or what Doctor Johnson said to his cat Hodge, about Boswell. Having explained this much, I may easily be forgiven for repeating the conversation I had with a Stone Dog who sat on his haunches outside the door of a woodman’s cottage.

The cottage stood on the edge of a wood, and was, as I shall point out, a remnant of departed glory, of which the dog was the most pertinent reminder.

A cottage on the borders of a wood is in itself one of the most valuable pictures for a romance. A woodcutter 36may be in league with goodness knows how many fairies, elves, and witches. It is a place where heroes meet heroines; where kings in disguise eat humble pie; where dukes, lost in hunting a white stag, meet enchanted princesses.

The wood, of which I speak, was once, years ago—about three hundred years—part of the park of Tanglewood Court, an extensive property, an old house, a great family possession.

Gone, like last winter’s snow, were the family of Bois; gone the pack; gone the glories of the great family; gone the portraits, the armour, the very windows of Tanglewood Court, of which but a fine ruin remained. And the lane, a mere cart track, was all that was left of the fine sweep of drive to the house; and a tangled undergrowth under ancient trees all that stood for the grand avenue down which my Lord Bois had once ridden so madly. They call the lane Purgatory Lane, and they tell a story of wild doings and of a beautiful avenue, that cannot have its place here.

The great gates that once swung open to admit the carriage of Perpetua Bois (of the red hair, the full voluptuous figure, the smile Sir Peter Lely painted) were now two stone stumps at the feet of which two slots, green and worn, showed where the hinges had been. These fine gates once boasted, on the top of stone pillars, the greyhounds of Bois in stone. One of these dogs had been rescued from the undergrowth by the woodcutter, the other lies broken and bramble-covered in the wood. I wonder if they miss each other.

So you see I was addressing myself to a high-born Jacobean dog.

This dog, very calm and dignified, with a stone tail and a back worn smooth by wind and weather, sat 37with his back to the cottage which had been built out of the remains of the old stone lodge by a gentleman of the name of Bellington, who was afterwards found drowned in the lake. That lake held many secrets, indeed, some said (the woodcutter’s wife told me this) it held Lady Perpetua’s jewels. That did not concern me, for it held for me the finer jewels of Water Lilies that grew there in profusion, though I will not deny that the idea of Lady Perpetua gave an added touch of romance. How often had the clear water of the lake reflected her satin-clad figure and the forms of her little toy spaniels?

It so happening, I sat by the Stone Dog, on a wooden seat, to eat my lunch one day, and dropped into conversation with him, after a bite or two, in the most natural way in the world.

There was the wood in front of us, blue-purple with wild Hyacinths. There was the old cottage behind clothed with rambling Creepers; a carpet of smooth rabbit-worn grass at our feet; a profusion of Primroses, Wind Flowers, and budding trees before our eyes. There was also the enchanting hum of wild bees (like those wild bees Horace knew, that sought the mountain of Matinus in Calabria, and there “laboriously gathered the grateful thyme”) to soothe us in our solitude.

I addressed him then, “Stone Dog,” I said, “this is a very beautiful wood. Nature, laughing at the ghosts of the Bois family, steel-clad, periwigged, or patched, has reclaimed her own.”

The dog answered me never a word but kept his gaze fixed in front of him as if he saw visions in the wood.

“This was a Park once,” said I, “the pleasure-ground of great folk, where they might sport in playful dalliance”—I thought that sounded rather Jacobean.

38But, as I looked at him, it seemed, as though he listened for the sound of wheels, and turned his sightless eyes to look for the figure of Lady Perpetua.

“She was very fair,” I said, understanding him, knowing that he had seen many generations drive through the gates he sat to guard. “She would come down to the lodge-keeper’s house to take her breakfast draught of small ale. Poor Lady Perpetua, she was a good house wife, and saw to the pickling of Nasturtium buds, and Lime Tree buds, and Elder roots; and ordered the salting of the winter beef; and looked to it that plenty of Parsnips were stored to eat with it. What sights you must have seen!”

Even as I talked there emanated from the Stone Dog some atmosphere of the past, and we were once more in a fair English park, with its orangeries, and houses of exotic plants, and its maze, and leaden statues, and cut yew trees, and lordly peacocks. The great trees had been cut down, and the timber sold; acres of land, once grazing ground for herds of deer, were ploughed; here, in front of us, was the tangled wood, a corner of what was, once, a wild garden—a fancy of Lady Perpetua’s, no doubt, who loved solitudes, and sentimental poetry:

Perhaps it was here she met young Hervey; perhaps it was here Lord Bois found them, cutting initials on one of those very trees, G. H. and P. B. and two hearts with an arrow through them. Ah! then the smile Sir Peter Lely painted faded to a quiver of the lips. Lord Bois looked at the trembling mouth and his glance flew to the initials on the tree. “So this is why, madam,” I could hear him say, “you took to sylvan glades like a timid deer; so this is why you coaxed me up to 39London, leaving you alone—but, not unprotected.” I could see his sneering bow to young Hervey—a bow that was a blow.

And all the while I was only seeing with the Stone Dog’s eyes. There was just the rippling sea of wild Hyacinths, the pale gold of the Primroses, the innocent white of the wood Anemones—like fairies’ washing—and the purple haze of bursting buds.

Once the Stone Dog had looked along an avenue and had seen a vista of Tanglewood Court, and smooth terraces, and bright beds of flowers, with Lords and Ladies walking up and down, taking the air, discussing fruit trees, and Dutch gardening, and glass hives for bees. Now, he saw nothing but the woods all brimming with Spring flowers: a garden made by Nature.

And then I thought I saw one Bluebell detach itself from its fellows and come wafting to us with a fairy’s message, but it was a bright blue butterfly who sailed, rejoicing in the sun. Somehow the butterfly reminded me of the Lady Perpetua, soft and smiling, and fluttering in the sun: as if she had returned to her woods in that guise to hover near the tree, the trysting-place, on which the initials were cut.

I said as much to the Stone Dog, but received no answer.

“Stone Dog,” I said, “England is a very wonderful place: every park, every field, every little wood is full of stories. I cannot pass a park gate without thinking of the men and women who have been through it. What a Garden of History the whole place is! I’ll warrant a Roman has kissed a Saxon girl in this very place, for there’s a camp not far off—perhaps you have seen twinkling ghostly watch-fires gleaming in the night. Young Hervey’s dead, but you never saw him die; they fought in the garden on the smooth 40grass, and the story goes that he slipped, and Bois ran him through as he lay on the grass. What flowers grow over his head now? And Perpetua is dead. They say she ran out and saw her lover dead, and bared her breast to her husband’s sword. The grass was wet with her blood when you saw Lord Bois ride madly down the drive, through the gates, and out into the open country. The smile Sir Peter Lely painted is carved by the hand of Death. She was only a girl, after all. Who places flowers on her grave?”

Meanwhile the sun shone on the Bluebells, and struck odd leaves of the trees, picking them out with a fanciful finger till they shone like green fires.

Then the idea came to me that this wood held the spirit of Lady Perpetua fast for ever. The Bluebells were the satin sheen of her dress (blue like the Lely portrait), the red-brown autumn leaves and the dead Bracken were her hair; the Wind Flowers, like her body linen; the Violets, her eyes; the Primroses, her breath; the Cowslips, her golden ornaments; the Daisy petals like her pure white skin. A gentle breeze stirred all the flowers together, and—behold! there she was, alive. The wood was yielding up her secret, as woods and flowers will do to those who love them.

So the Stone Dog and I had a bond of sympathy between us, the bond of old memories, and the wood united us with its store of romance and beauty: and he who loves wild flowers and woods, as well as walled gardens and trees clipped in images, may gather store of pictures for his mind.

So the afternoon passed in this pleasant manner, and I took opportunity to speak once more to the Stone Dog before the woodcutter’s children came home from school to spoil our peace.

BLUEBELLS IN SURREY.

I said, “There is no man so poor but he can afford 41to take pleasure in Bluebells, and, even if he live in a town, there are wild flowers for sale in the streets, and a bunch of Spring to be bought for a penny. And there is no man so rich that he can wall up the treasures of heaven, or build his walls so high but a Rose will peep over the edge. Poor and rich are free of their thoughts, and there are thoughts and enough to spare, in a hedgerow or a wood. Uncaged birds sing best, and wild flowers yield the purest scents. You and I are fellow dreamers, and this wood is our garden, and these birds our orchestra, and this grass our carpet; and even when I am underneath the brown earth I love so well, you will sit here and listen for the sound of carriage wheels, and wonder if you will catch a glimpse of red hair and a satin dress through the long-silent avenue. There are mountains, Stone Dog, that still feel the pressure of the foot of Moses; and hills under which Roman soldiers lie; and there are woods growing where orchard gardens were; and gardens planted where the wild boar once ravaged.”

After I had said this came wild shouts, and the laughter of children, and a great clatter as the four children of the woodcutter came running from the village school.

As I left that place, and turned, before a bend of the road shut out the sight of the wood, I saw the sea of Bluebells, and the sky above, the Primroses and the Wind Flowers and last year’s leaves all melt into one. The figure they made was the figure of Lady Perpetua standing there smiling. Then I heard the wheels of a carriage on the road, and I could have sworn I saw the Stone Dog turn his head.

VII

THE TAILOR’S SISTER’S TOMBSTONE

I was on the hill over against the village where my friend the tailor lived, and was preparing to descend into the valley to inquire the whereabouts of his cottage, when one of those sharp summer storms came on, the sky being darkened as if a hand had drawn a curtain across it, and the entire village lit by a vivid, unnatural light, like limelight in its intensity.

Turning about, as the first great drops fell, to look for shelter, I spied a rough shed by the wayside, shut in on three sides with gorse, wattle and mud, and roofed over with heather thatch. Into this I scuttled and found a comfortable seat on a sack placed on a pile of hurdles.

It was evidently a place used by a shepherd for a store-house of the implements of his craft. At the back of a shed was one of those houses on wheels shepherds use in the lambing season; besides this were hurdles, sacks, several rusty tins, and a very rusty oil-stove. All very primitive, and possessed of a nice earthy smell. It gave me a sudden desire to be a shepherd.

Looking down into the valley I saw men running for shelter, hastily pulling their coats over their shoulders as they ran. In a field on the far side of the valley they were carting Wheat, and I saw two men quickly unhitch the cart horses, and lead them away to some place hidden from me by trees.

43The village was buried in orchards, and lay along the bank of a quickly running river that caught a glint of the weird light here and there between the trees like a path of shining silver. A squat church tower stuck up among the red roofs.

For a moment the scene shone in the fierce light, then the low growling thunder broke into a tremendous crash, and the light was gone in an instant. Then the rain blotted out everything.

The hiss of the rain on the dry heather thatch over my head was good enough company, and it was added to, soon, by the entrance of seven swallows that flew into my shelter and sat twittering on a beam just inside the opening. Then came an inky darkness, broken violently by a blare of lightning as if some hand had rent the dark curtain across in a rage. A great torn jagged edge of blue-white light streamed across the valley, showing everything in wet, glistening detail.

Only that morning I had been reading by the wayside an account of a storm in the Memoirs of Benvenuto Cellini. It came very pat for the day. It was at the time when Cellini rode from Paris carrying two precious vases on a mule of burden, lent him to go as far as Lyons, by the Bishop of Pavia. When they were a day’s journey from Lyons, it being almost ten o’clock at night, such a terrific storm burst upon them that Cellini thought it was the day of judgment. The hailstones were the size of Lemons; and the event caused him to sing psalms and wrap his clothes about his head. All the trees were broken down, all the cattle deprived of life, and a great many shepherds were killed.

I was still engaged in picturing this when the sky above me grew lighter, the rain fell less heavily, and, in a very short time, all that was left of the storm was 44a distant sound as of a giant murmuring, a dark blot of rain cloud on the distant hills, and the ceaseless patter of dripping trees. The sun shone out and showed the village and landscape all fresh and shining. Then, as I looked, against the dark bank of distant clouds, a rainbow arched in glorious colours, one step of the arch on the hills tailing into mist, and one in the corn field below. The sight of the rainbow with its wonderful beauty, and its great message of hope thrilled me, as it always does. I do not care what the scientist tells me of its formation: he has not added one atom to my feeling, with all his knowledge. It remains for me the sign of God’s compact with man.

“And God said, This is the token of the covenant which I make between me and you, and every living creature that is with you, for perpetual generations.

“I set my bow in a cloud, and it shall be for a token of a covenant between me and the earth.

“And it shall come to pass, when I bring a cloud over the earth, that the bow shall be seen in the cloud.

“And I will remember my covenant which is between me and you, and every living creature of all flesh; and the waters shall no more become a flood to destroy all flesh.

“And the bow shall be in the cloud; and I will look upon it, that I may remember the everlasting covenant between God and every living creature of all flesh that is upon the earth.”

I learnt to love that when I was a child, and being still, in many ways, the same child, I look upon a rainbow and think of God remembering his covenant: and it makes me very happy.

Now as the storm was over, and I had no further excuse for stopping in my shelter, I took my knapsack again on to my shoulder and walked down, across two fields of grass, round the high hedges of two orchards, and came out into the road in the valley, about two 45hundred yards distant from the village church. It was about four of the afternoon.

I was about to turn towards the village to ask my best way to the tailor’s cottage, when who should turn the bend of the road but the tailor himself with all the air of looking for some one.

I grasped him warmly by the hand, and he held mine in a good grip like the good fellow he was, saying, “I was looking about for you, sir, thinking you might have forgotten my direction” (as indeed, I had), “and knowing you would most likely go to the village to inquire, I was on my way there.”

As we turned to walk down the road away from the church, the tailor informed me his sister was all agog to see me, but very nervous that I might think theirs too poor a place to put up with, and she had, at the last moment, implored him to take me to the inn instead.

The affection I had gained for the little man in my few hours’ talk with him made me certain I should be happy in his company, and I laughed at his fears.

“Why, man,” said I, “I have walked a good hundred miles to see you, do you think it likely I shall turn away at the last minute?”

“There,” cried the tailor, “I told her so. She’s a small body, you’ll understand, sir, and gets worried at times.”

We turned a corner and I saw before me one of the prettiest cottages I have ever seen. A low, sloping roof of thatch, golden brown where it had been mended, rich brown and green in the older part. The body of the cottage was white, with a fine tree of Cluster Roses, the Seven Sisters, I think it is called, growing over the porch and on the walls. The garden was one mass of bloom, a wonderful garden—as artists say, 46“juicy” with colour. Standard Roses, Sweet Williams, Hollyhocks, patches of Violas, Red Hot Pokers, Japanese Anemones, a hedge of Sweet Peas “all tip-toe for a flight” as Keats has it, clumps of Dahlias just coming out, with red pots on sticks to catch the earwigs; an old Lavender hedge, grey-green. A rain butt painted green; round a corner, three blue-coloured beehives; and all about, such flowers—I could not mention half of them. Bushes of Phlox, for instance; and great brown-eyed Sunflowers cracked across with wealth of seed; and tall spikes of Larkspur like the summer skies: and Carnations couched in their grey grass or tied to sticks. A worn brick pathway leading through it all.

The tailor watched the effect on me anxiously.

I stood with one hand on the gate and drank in the beauty of it. Set, as the place was, in a bower of orchards, it looked like a jewelled nest, a place out of a fairy tale, everything complete. The diamond panes of the windows with neat muslin curtains behind them, with fine Geraniums in very red pots on the window-sill, were like friendly eyes beaming pleasantly at the passing world. To a tired traveller making his way upon that road, such a sight would bring delight to his eyes, and cause him, most certainly, to pause before the glad garden. If he were a romantic man he would take off his hat, as men do abroad to a wayside Calvary, in honour of the peace that dwelt over all.

Like a rich illuminated page the garden glowed among the trees—like a jewel of many colours it shone in its velvet nest.

The tailor could restrain himself no longer. He said, “As neat as anything you’ve seen, sir?”

“Perfect,” said I. “As much as a man could want.”

He walked before me down the garden path and called, “Rose,” through the open door.

47In another minute I was shaking hands with the tailor’s sister.

In appearance she was as spotlessly clean as her muslin curtains. She was a tiny woman of about forty-five, very quick in her movements, with a little round red face and very bright blue eyes. She wore, in my honour, a black silk dress, and a black silk apron and a large cornelian brooch at her neck.

“Pray step inside, sir,” she said throwing open the door of the parlour.

When I was seated at tea with these people I kept wondering where they had learnt the refinement and taste everywhere exhibited. For one thing the few family possessions were good, and there was no tawdry rubbish. A grandfather clock, its case shining with polishing, ticked comfortably in one corner of the room. An old-fashioned sofa filled the window space. We sat upon Windsor chairs with our feet on a rag carpet. Most of the household gods were over or upon the mantelpiece, most prominent among which was a really fine landscape, hung in the centre. I inquired whose work this might be.

One had only to look in the direction of any object to get its history from the tailor.

“I bought that, sir,” he said, when I was looking at the picture, “of a man near Norwich. It cost me half a crown.”

“Three shillings,” said the sister. Then to me, “He takes a sixpence off, now and again, sir, because he’s jealous of my bargains; aren’t you, Tom?”

Tom smiled at her and winked at me. “She will have her bit of fun,” he said.

“But it’s a fine picture,” said I.

“Proud to have you say so,” he answered; “I like it, and the man didn’t seem to care about it. He was 48going to the Colonies and parting with a lot of odds and ends. I bought the brass candlesticks off him at the same time—a shilling.”

I could see why the little man liked the picture, for the same reason I liked it myself. It was of the Norwich School, a broad open landscape painted with care and finish of detail, and with much of the charming falsity of light common among certain pictures of that time. On the left was a cottage whose garden gave on to the road, a cottage almost buried under two great trees. The road wound past, out of the shadows of the trees, and vanished over a hill. The middle distance showed a great expanse of country dotted with trees with the continuation of the road running through the vale until it was lost in a wood. A sky of banked up clouds hung over all. Right across the middle of the picture was a wonderfully painted gleam of sunlight, flicking trees, meadows, and the road into bright colours; the rest of the picture being subdued to give this effect. Up the road, coming towards the cottage, was a small man in a three-cornered hat, knee breeches, and long skirted coat. This figure dated the picture a little earlier than I had at first thought it.

“That’s me,” said the tailor, pointing to the figure. “That’s what Rose said as soon as I brought it home, ‘Why that’s you, Tom.’”

“I did, sir, that’s just what I said. ‘Why Tom, that’s you,’ I said.”

“And so it is,” said the tailor.

Half a crown! Few of us are rich enough in taste to have bought it.

After tea I begged leave to see the garden. “And, Miss Rose,” I said, “to hear about the tombstone, please.”

She put her small fat hands to her face and laughed 49and laughed. “He’s been and told you that, sir? Well, I never did!”

A COTTAGE GARDEN.

We went out of the back door and into a second flower garden rivalling the one in front for a display of colour. There, sure enough, stood the tombstone, grey and upright, planted in a bed of flowers. They seemed to hurl themselves at the grim object, wave upon wave of coloured joy washing the feet of the emblem of Death.

“There she is,” said the tailor’s sister proudly.

“Please tell me about it,” said I, wondering at her cheerfulness.

“You see, sir,” she began, “before Tom and I came into our fortune, and got rich——”

Multi-millionaires, I thought, could you but hear that! But they were rich—as rich as any one could be. The flowers in the garden were worth a kingdom.

“—We used to wonder what we’d do if we ever had a bit of money. Of course, we never dreamed of anything like this.” Her eyes wandered proudly over her possessions.

“Yes,” said the tailor, joining in. “Our best dreams never came near this. I’d seen such places, but never thought to live in one, much less own one.”

“Well, you see, sir,” said his sister taking up the thread of her story, “there was one thing I’d always set my mind on—a nice place to lie in when I was dead. I had a horror of cemeteries, great ugly places, as you might say, with the tombstones sticking up like almonds in a tipsy cake pudding, and a lot of dirty children playing about. I lived for ten years in London, in a room that overlooked one, a most dingy place I called it. I couldn’t bear to think I’d be popped in with a crowd, anyhow. Now, a churchyard in the country—that’s quite different.”

50“I’d a great fancy for a spot I knew in Kent,” said the tailor. “Dark Yew trees all round one side, and Daisies over everything, and a seat near by for people to rest on, coming early to church.”

“Go on, Tom,” said his sister lovingly. “Ar’n’t you satisfied with what you’ve got?”

He turned to me after putting his arm through his sister’s. “We’ve got our piece of ground,” he said cheerfully. “I’m going to be planted next to her, on the left of the church door—well, it’s as good a place as you’d find anywhere, and people coming out of church will notice us easily. I’d like to be thought of, after I’m gone.”

Death held no terrors for these people, it seemed, they talked so happily of it, made such delightful plans to welcome it; robbed it of all its gloom and horror, its false trappings, its dingy grandeur.

There was a flaunting Red Admiral sunning its wings on the tombstone.

“I never thought,” said the sister, “I should find just what I wanted by accident. Isn’t it lovely?”

It certainly had a beauty of its own. It was a copy of an early eighteenth century tombstone, the top in three arches, the centre arch large, and round, ending in carved scroll work. In the centre of the arch a cherub was carved, very fat and smiling, with wings on either side of his head. Then, in good deep-cut lettering, were the words:

Both these curious people looked at me as I read the lettering. Arm in arm they looked nice, cheerful, loving friends, a good deal like one another in the face, 51very gay and homely, and with a certain sparkling brightness, like the flowers they loved. To see them standing there proudly, smiling at the grey tombstone, smiling at me, under the sun, in the garden so full of life and of growing healthy things, gave me a sensation that Death was present in friendly guise, a constant welcome companion to my new friends, and a pleasant image even to myself.

“Second-hand,” said the tailor’s sister, “all except the name, and he put that in for me at a penny the letter: that came to elevenpence, so I gave him a shilling to make an even sum.”

“A guinea, as it stands,” said the tailor.

“You like it, sir?” asked his sister anxiously.

“On the contrary,” said I, “I admire it enormously.”