TROOP ONE OF THE LABRADOR

The Talbot Baines Series

With fine attractive new wrappers

The Fifth Form At St. Dominic's. By Talbot Baines Reed

The Adventures Of A Three-guinea Watch. By Talbot Baines Reed

The Cock-house At Fellsgarth. By Talbot Baines Reed

A Dog With A Bad Name. By Talbot Baines Reed

The Master Of The Shell. By Talbot Baines Reed

The School Ghost, And Boycotted. By Talbot Baines Reed

The Silver Shoe. By Major Charles Gilson

The Treasure Of Tregudda. By Argyll Saxby

The Two Captains Of Tuxford. By Frank Elias

The Riders From The Sea. By G. Godfray Sellick

A Son Of The Dogger. By Walter Wood

A Fifth Form Mystery. By Harold Avery

A Scout Of The '45. By E. Charles Vivian

From Slum To Quarter-deck. By Gordon Stables

Comrades Under Canvas. By F.P. Gibbon

(For Complete List see Catalogue)

OF All BOOKSELLERS

IT WAS DR. JOE BEYOND A DOUBT!

IT WAS DR. JOE BEYOND A DOUBT!

TROOP ONE OF THE

LABRADOR

BY

DILLON WALLACE

AUTHOR OF "GRIT-A-PLENTY," "THE RAGGED

INLET GUARDS," ETC., ETC.

THE "BOY'S OWN PAPER" OFFICE

4 Bouverie Street And 65 St. Paul's Churchyard, E.c.4

MADE IN GREAT BRITAIN

Printed by

UNWIN BROTHERS, LIMITED

LONDON AND WOKING

CONTENTS

- Page

- I. DOCTOR JOE, SCOUTMASTER9

- II. PLANS37

- III. "'TIS THE GHOST OF LONG JOHN"51

- IV. SHOT FROM BEHIND63

- V. LEM HORN'S SILVER FOX71

- VI. THE TRACKS IN THE SAND94

- VII. THE MYSTERY OF THE BOAT109

- VIII. TRAILING THE HALF-BREED120

- IX. ELI SURPRISES INDIAN JAKE126

- X. THE END OF ELI'S HUNT135

- XI. THE LETTER IN THE CAIRN147

- XII. THE HIDDEN CACHE165

- XIII. SURPRISED AND CAPTURED179

- XIV. THE TWO DESPERADOS192

- XV. MISSING!198

- XVI. BOUND AND HELPLESS206

- XVII. LOST IN A BLIZZARD220

- XVIII. A PLACE TO "BIDE"232

- XIX. SEARCHING THE WHITE WILDERNESS240

- XX. "WOLVES!" YELLED ANDY251

- XXI. THE ALARM IN THE NIGHT259

- XXII. THE IMMUTABLE LAW OF GOD268

ILLUSTRATIONS

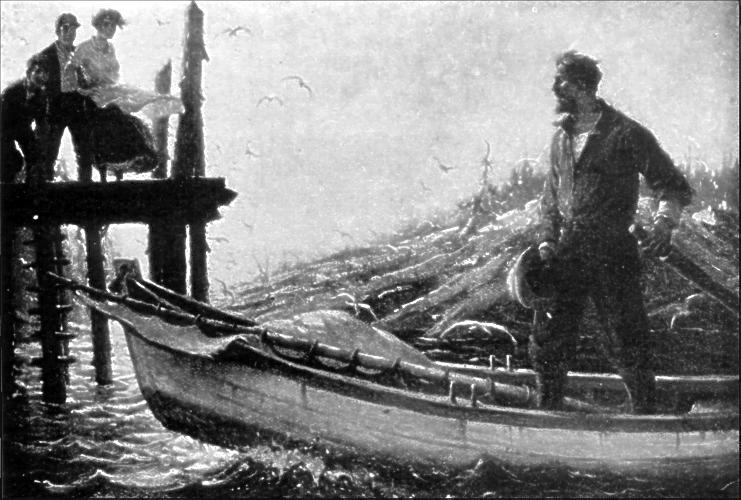

- IT WAS DR. JOE BEYOND A DOUBT!Frontispiece

- Facing Page

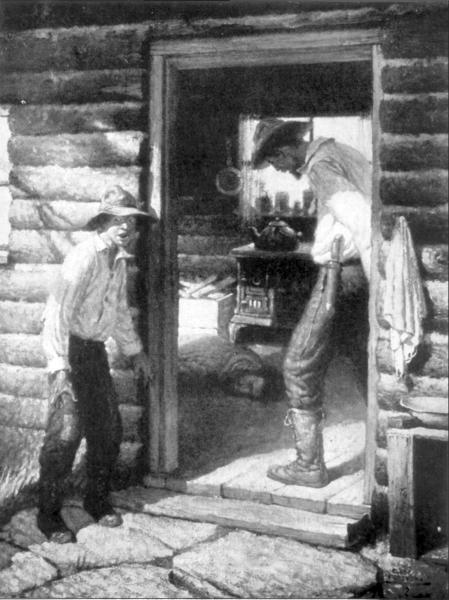

- STRETCHED UPON THE FLOOR LAY LEM HORN70

- ON THE RIGHT SEETHED THE DEVIL'S TEA KETTLE104

- "YOU STAND WHERE YOU IS AND DROP YOUR GUN!"132

- IT WAS A FIGHT TO THE DEATH260

Troop One of the Labrador

CHAPTER I

DOCTOR JOE, SCOUTMASTER

"Doctor Joe! Doctor Joe's comin'! He just turned the p'int!"

Jamie Angus burst into the cabin at The Jug breathlessly shouting this joyful news, and then rushed out again with David and Andy at his heels.

"Oh, Doctor Joe! It can't be Doctor Joe, now! Can it, Pop? It must be some one else Jamie sees! It can't be Doctor Joe, whatever!" exclaimed Margaret in a great flutter of excitement.

"Jamie's keen at seein'! He'd know anybody as far as he can see un!" assured Thomas, no less excited at the news than was Margaret. "But 'tis strange that he's comin' back so soon!"

Of course Margaret, who was laying the table for supper, must needs follow the boys; and Thomas, who was leaning over the wash basin removing the grime of the day's toil, snatched the towel from its peg behind the door and, drying his hands as he ran, sacrificing dignity to haste, followed Margaret, who had joined the three boys at the end of the jetty which served as a boat landing.

A skiff had just entered the narrow channel which connected The Jug, as the bight where the Anguses lived was called, with the wider waters of Eskimo Bay. There could be no doubt, even at that distance, that the tall man standing aft and manipulating the long sculling oar, was Doctor Joe. As the little group gathered on the jetty he took off his hat and waved it high above his head. It was Doctor Joe beyond a doubt! The boys waved their caps and shouted at the top of their lusty young lungs, Margaret, undoing her apron, waved it and added her voice to the chorus, and Thomas, quite carried away by the excitement, waved the towel and in a great bellowing voice shouted a louder welcome than any of them.

There was no happier or better contented family on all The Labrador than the family of Thomas Angus, though they had their trials and ups and downs and worries like any other family in or out of Labrador.

"Everybody must expect a bit o' trouble and worry now and again," Thomas would say when things did not go as they should. "If we never had un, and livin' were always fine and clear, we'd forget to be thankful for our blessin's. We has t' have a share o' trouble in our lives, and here and there a hard knock whatever, t' know how fine the good things are and rightly enjoy un when they come. And in the end troubles never turn out as bad as we're expectin', by half. First and last there's a wonderful sight more good times than bad uns for all of us."

Thomas had reason to be proud and thankful. Jamie could see as well as ever he could, and it was all because of Doctor Joe and his wonderful operation on Jamie's eyes when it seemed certain the lad was to become blind. Through the skill of Doctor Joe, Jamie's eyes were every whit as keen as David's and Andy's, and there were no keener eyes in the Bay than theirs.

David was now nearly seventeen and Andy was fifteen—brawny, broad-shouldered lads who had already faced more hardships and had more adventures to their credit than fall to many a man in a whole lifetime. In that brave land adventures are to be found at every turn. They bob up unexpectedly, and the man or boy who meets them successfully must know the ways of the wilderness and must be self-reliant and resourceful, must have grit a-plenty and a stout heart.

Margaret kept house for the little family, a responsibility that had been thrust upon her, and which she cheerfully accepted, when her mother was laid to rest and she was a wee lass of twelve. Now she was eighteen and as tidy and cheerful a little housekeeper as could be found on the coast, and pretty too, in manner as well as in feature. "'Tis the manner that counts," said Thomas, and he declared that there was no prettier lass to be found on the whole Labrador.

Doctor Joe, whose real name was Joseph Carver, was their nearest neighbour at Break Cove, ten miles down Eskimo Bay. He had come to the coast nine years before, a mysterious stranger, nervous and broken in health. Thomas gave him shelter at The Jug, helped him build his cabin at Break Cove and taught him the ways of the land and how to set his traps. Doctor Joe became a trapper like his neighbours, and in time, with wholesome living in the out-of-doors, regained his health and came to love his adopted country and its rugged life.

No one knew then that Joseph Carver was indeed a doctor, but he was so handy with bandages and medicines that the folk of the Bay recognized his skill and soon fell, by common consent, to calling him "Doctor Joe."

It was a year before our story begins that Jamie had first complained of a mist in his eyes. With passing weeks the mist thickened, and one day Doctor Joe examined the eyes and announced that only a delicate and serious operation could save the lad's sight. This demanded that Jamie be taken to a hospital in New York where a specialist might operate. It was an expensive undertaking. Neither Thomas nor Doctor Joe had the necessary money, but Thomas hoped to realize enough from his winter's trapping in the interior and Doctor Joe was to add the proceeds of his own winter's work to the fund. Then Thomas broke his leg. Doctor Joe must needs remain at The Jug to care for him, and there seemed no hope for Jamie but a life of darkness.

But David was confident that he could take his father's place on the trails, and with some persuasion, for the need was desperate, Thomas consented that David and Andy should spend the winter in the great interior wilderness with no other companion than Indian Jake, a half-breed.

That was an experience needing the stoutest heart. Through long dreary months they faced the sub-arctic cold and fearful blizzards that swept the wilderness, following silent trails over wide white wastes or through the depths of dark forests, and falling upon many a wild adventure that tried their mettle a hundred times. It was a man's job, but they both made good, and that is something to be proud of—to make good at the job you tackle.

Jamie had pluck too, but pluck alone could not save his eyes. The mist thickened more rapidly than Doctor Joe had expected it would, and there came a time when Jamie could scarcely see at all. Then it was that Doctor Joe announced one day before the return of David and Andy from the trails, that the operation could be no longer delayed if Jamie's eyesight was to be saved, and that to attempt to delay it until the ice cleared from the coast and the mail boat came to bear him away to New York would be fatal.

After making this announcement, Doctor Joe revealed the fact that he had once been a great eye surgeon. With Thomas's consent he offered to perform the operation on Jamie's eyes. Thomas had unbounded faith in his friend. Doctor Joe operated and Jamie's sight was saved.

In curing Jamie, Doctor Joe discovered that he himself was cured, and that he was again in possession of all his former skill. It was quite natural, therefore, that he should wish to resume the practice of surgery. He was an indifferent trapper, and the living that he made following the trails amounted to a bare existence. He decided, therefore, that it was his duty to himself to return to the work for which, during long years of study, he had been trained.

Six weeks before Doctor Joe had sailed away on the mail boat from Fort Pelican, bound for New York, that far distant, mysterious, wonderful city of which he had told so many marvellous tales. Thomas had grave doubts that they would ever see him again, though he had said that he would some day return to visit his friends at The Jug and to see his own little deserted cabin at Break Cove, where he had spent so many lonely but profitable years, for it was here that he had rebuilt his broken health. He had good reason to love the place, and he was quite sure he had no better or truer friends in all the world than Thomas Angus and his family.

"Thomas," said he at parting, "if I had the means to support myself I would stay here on The Labrador and be doctor to the people that need me, for there are folk enough that need a doctor's help up and down the coast. But I'm a poor man, and if I stopped here I'd have to make my living as a trapper, and you know how poor a trapper I've been all these years. Back in New York I can do much good, and there I can live as I was reared to live. But I'll not forget you, Thomas, and some day I'll come to see you."

"I'm not doubtin' 'tis best you go and the Lord's will," said Thomas. "But we'll be missin' you sore, Doctor Joe. I scarce knows how we'll get on without you. 'Twill seem strange—almost like you were dead, I'm fearin'."

"Thomas," and Doctor Joe's voice trembled with emotion, "there's no one in the wide world nearer my affections than you and the boys and Margaret. It hurts me to go, but it's best I should. I might scratch along here for a few years, but I was not born to the work and the time would come when I'd be a burden on some one, and it would make me unhappy. I know that I'll wish often enough to be back here with you at The Jug."

"You'd never be a burden, whatever!" Thomas declared, quite shocked at the suggestion. "I feels beholden to you, Doctor Joe. There's nary a thing I could ever do to make up to you for savin' Jamie's eyes. You made un as good as new. He'd ha' been stone blind now if 'tweren't for you—and the mercy o' God."

"The mercy of God," Doctor Joe repeated reverently.

And here at the end of six weeks was Doctor Joe back again. What wonder that Thomas Angus and his family were quite beside themselves with joy, shouting themselves hoarse down there on the jetty.

And presently, when the skiff drew alongside, and Doctor Joe stepped out upon the jetty, he was quite overwhelmed with the welcome he received.

"Well, Thomas," he said as they walked up to the cabin with Jamie clinging to one of his hands and Andy to the other, "here I am back again, as you see. I couldn't stay away from you dear, good people. I may as well confess, I was homesick for you before I reached New York, and I'm back to stay. I found my fortune had been made while I was here, and now I can do as I please."

"Oh, that's fine now!" exclaimed Margaret. "'Tis fine if you're to stay!"

"We were missin' you sore," said Thomas. "'Tis like the Lord's blessin' to have you back at The Jug!"

"And there's good old Roaring Brook!" Doctor Joe stopped for a moment with half closed eyes, to listen to the rush of water over the rocks, where Roaring Brook tumbled down into The Jug. "It's the sweetest music I've heard since I left here! And the smell of the spruce trees! And such a scene! Thomas, my friend, it's a rugged land where we live, but it's God's own land, just as He made it, beautiful, and undefiled by man!"

Doctor Joe turned about and stretched his right arm toward the south. Before them lay the shimmering placid waters of The Jug, reaching away to join the wider, greater waters of Eskimo Bay. In the distance, beyond the Bay, the snow-capped peaks of the Mealy Mountains stood in silent majesty, now reflecting the last brilliant rays of the setting sun. As they tarried, watching them, the light faded and shafts of orange and red rose out of the west. The waters became a throbbing expanse of colour, and the woods on the Point, at the entrance to The Jug, sank into purple.

"'Tis a bit of the light of heaven that the Lord lets out of evenin's for us to see," said Jamie, and perhaps Jamie was right.

"You must be rare hungry, now," observed Thomas, as they entered the cabin. "Margaret were just puttin' supper on when Jamie sights you turnin' the P'int. 'Twill be ready in a jiffy."

"What have you got for us, Margaret?" asked Doctor Joe. "I believe I am hungry for the good things you cook."

"Fried trout, sir," said Margaret.

"Fried trout!" Doctor Joe rolled his eyes in mock ecstasy. "It couldn't have been better!"

"You always says that, whatever," laughed Margaret. "If 'twere just bread and tea I'm thinkin' you'd like un fine."

"But trout!" exclaimed Doctor Joe. "Why, fresh trout are worth five dollars a pound where I've been—and couldn't be had for that!"

"Well, now!" said Margaret in astonishment. "And we has un so plentiful!"

David lighted a lamp and Thomas renewed the fire, which crackled cheerily in the big box stove, while everybody talked excitedly and Margaret set on the table a big dish of smoking fried trout, a heaping plate of bread, and poured the tea.

"Set in! Set in, Doctor Joe!" Thomas invited.

And when they drew up to the table, with Thomas at one end and Margaret at the other, and Doctor Joe and Jamie at Thomas's right, and David and Andy at his left, Thomas devoutly gave thanks for the return of their friend and asked a blessing upon the bounty provided.

"Help yourself, now, and don't be afraid of un," Thomas admonished, passing the dish of trout to Doctor Joe.

"A real banquet," Doctor Joe declared, as he helped himself liberally. "I've eaten in some fine places since I've been away, but I've had no such feast as this! And there's no one in the whole world can fry trout like Margaret!"

"You always says that, sir," and Margaret's face glowed with pleasure at the compliment.

"'Tis true!" declared Doctor Joe. "'Tis true!"

"I'm wonderin' now about the trout," remarked David.

"What are you wondering?" asked Doctor Joe.

"How folks get along with no trout to eat off where you've been, sir."

"There are men who go far out from the city and fish in the streams for trout, just for the sport of catching them," explained Doctor Joe. "They will tramp all day along brooks, and feel lucky if they catch a dozen little fellows so small we'd not look at them here. But it is only the few who do it for sport that ever get any at all, and there are hundreds of people there who never even saw a trout, they catch so very few of them."

"'Twould seem like a waste o' time," remarked Thomas, "if they catches so few. I'd never walk all day for a dozen trout unless I was wonderful hard up for grub. If I were wantin' fish so bad I'd set a net for whitefish or salmon, or if there were cod grounds about I'd gig for cod, though salmon or cod or whitefish would never be takin' the place o' good fresh trout with me."

"It's not altogether for the trout the sportsmen tramp the streams all day," laughed Doctor Joe. "They prize the trout they get as a great delicacy, to be sure, but it's the joy of getting out into the open that pays them for the effort. I've done it myself. They get plenty of sea fish, they buy them at the shops."

"I never were thinkin' o' that," said Thomas. "I'm thinkin', now, that's where all the salmon we salts down and sells to the Post goes."

The boys were vastly interested, and asked many questions, which Doctor Joe answered with infinite patience, concerning the various kinds of fish people bought in the shops, and how the fish were caught and shipped to the shops to be sold fresh.

"And you'll stay now? You'll not be leavin' The Labrador again?" asked Thomas, after supper.

"Aye," said Doctor Joe, "I've elected to be a Labradorman." Then, turning to the boys, he suggested:

"Lads, there are a lot of things in that skiff of mine. I wish you'd bring them in. Will you do it while your father and I visit?"

The boys were not only glad but eager to do it, for there were doubtless many surprises for themselves in the skiff, and with one accord the three hurried out.

"Years ago, Thomas," said Doctor Joe, when the boys were gone, "in my days in New York, I invested a little money in a mining property. Shortly after I made the investment it was said the ore had run out, and I believed my money was lost. When I returned to New York this summer I found that more ore had been found later, and the mine had earned me a lot of money. I invested what was due to me in such a way that it will bring me an income each year sufficient to provide me with all I shall ever need."

"Oh, but that's fine now!" said Thomas.

"Thomas," Doctor Joe continued "I should not have been able to enjoy this had it not been for your kindness to me years ago, when I came first to The Labrador a man of broken health. If you had not offered me your friendship then I should have died an invalid in poverty.

"I've thought of this a thousand times. I believe God sent me here. I only knew then that I came because I sought a secluded spot on the earth where I could find relief from turmoil. Now, I believe He guided me to The Labrador and to The Jug to you. He had something for me to do in the world, and this was His way of saving me.

"When Jamie needed me I was here, and because you had befriended me I was prepared with God's help and with my skill and training to restore Jamie's eyesight. There are others on the coast who need a doctor's skill just as Jamie needed it, and they have no one to help them. I have decided that I shall be doctor to the people. If I can help the folk, as I am sure I can, I'll be happy in the knowledge that I'm making some little return for the great deal that you have done for me."

"I were never doin' much for you, Doctor Joe—just what one man would always do for another," Thomas protested. "But 'twill be a blessin' to the folk of The Labrador to have you doctor un! We all need doctors often enough when there's none to be had, and folks die for the need of un."

"Yes, folks die here for the need of a doctor," Doctor Joe agreed, "and I hope I may be the means of saving lives and giving relief."

The three boys broke in upon them with their arms full of packages.

"There's a lot more!" exclaimed Jamie depositing his load upon the floor.

"Perhaps we had better help them, Thomas," suggested Doctor Joe, rising.

"Oh, no, sir," Jamie protested. "Let us bring un up!"

And so said David and Andy also. They quickly had the contents of the skiff transferred to the cabin, and the exciting process of opening the packages began.

The first to be opened was for Margaret, and it contained many pretty and useful things, including two neat, substantial warm dresses, finer than any Margaret had ever before possessed or seen. Her eyes sparkled as she held them up for inspection, and she exclaimed over and over again:

"Oh, how wonderful pretty they is!"

For the boys there were innumerable gifts dear to boys' hearts, including a compass and a watch for each. For Thomas there was a fine pair of field-glasses, a compass and a very fine watch indeed, and he was as pleased and happy as the others.

"The glasses'll be a wonderful help t' me in huntin'," he declared. "When I climbs hills for a look around I can see deer that I'd sure to be missin' with no glasses. I'm not doubtin' the compass'll come in handy now and again in thick weather."

Then there was a big box of goodies. There were such candies as they had never dreamed of—oranges and big red-cheeked apples. Even Thomas had never before in his life tasted an orange or an apple, and they all declared that they had never imagined that anything could be so good. It was quite astonishing to learn that in the great world from which Doctor Joe had come there were people who ate oranges and apples every day of their lives if they wished them.

"'Tis strange the way the Lord fixes things," observed Thomas. "Here now we never saw the like of oranges and apples before in all our lives, but we has plenty of trout, and there are folks out there that has no trout but they all has oranges and apples. We has so many trout we forgets how fine they is, and what a blessin' 'tis we has un. And I'm thinkin' 'tis the same with them folks about the oranges and apples."

"Yes," agreed Doctor Joe, "it's only when things are taken away from us that we really appreciate them. Jamie, no doubt, appreciates his eyes much more than he would have done had the mist never clouded them."

"Aye, 'tis so," said Thomas.

"I dare say," Doctor Joe suggested, "that you've never eaten potatoes or onions?"

"No," said Thomas, "I've heard of un, but I never eats un. I never had any to eat."

"Well," announced Doctor Joe, "I've had several sacks of potatoes and a sack of onions and two barrels of apples shipped to Fort Pelican with a quantity of other goods. We'll have to go with the big boat for them."

The boys and Margaret were quite beside themselves with the wonder of it all, and Thomas was little less excited.

"We'll go for un to-morrow or the next day whatever," said Thomas.

There was one box still unopened, and the three boys were eyeing it expectantly, when Doctor Joe exclaimed:

"Here we've left till the last the most important thing of all. Get an axe, David, and we'll knock the cover off this box."

David had the axe in a jiffy, and when Doctor Joe removed the cover the box was found to be filled with books.

"O-h-h!" breathed the boys in unison.

"'Tis fine! Oh, I've been wishin' and wishin' for books t' look at and read!" exclaimed Margaret.

Doctor Joe had taught them all to read and write in the years he had been with them, an accomplishment that not every boy and girl on The Labrador possessed, for there were no schools there.

"There are some books to study and some to read. There are story books and books about birds and flowers and animals. And here is something that I know will please the boys," said Doctor Joe, drawing from the box six paper-bound volumes. "There's an interesting story attached to these books that I must tell you before you look at them, and then we'll go through them together.

"One day I was walking in a park in New York.

"Suddenly I heard a crashing noise, and I hurried in the direction in which I heard the noise, and turning a corner saw a motor-car lying on its side. Some boys wearing khaki-coloured uniforms, very much like soldiers' uniforms, had already reached the wreck, and before I came up with them had rescued two injured men. I never saw more efficient or prompt service than those boys were giving the poor men, who were both badly hurt. They had the men stretched out upon the grass. One had a severed artery in his arm, where the arm had been cut upon the broken glass wind shield. The man's blood was pouring in great spurts through the wound, but the boys were already adjusting the tourniquet, for which they used a handkerchief, and in a minute they had the bleeding stopped, as well as I could have done it. I've no doubt they saved the man's life, for without prompt help he'd have bled to death in a short time.

"The other man was cut and bruised, and the boys were making him as comfortable as possible until an ambulance came to take him to a hospital. There was really nothing I could do that the boys had not already done promptly and remarkably well.

"The instant they had discovered the accident two boys had run away to summon an ambulance and to notify the police, and in a little while an ambulance with a surgeon and two policemen came and took the men away.

"The boys were only about Andy's age, and I wondered at their training and efficiency. When the ambulance had gone with the injured men I walked a little way with the boys, and learned that they belonged to a wonderful organization called 'Boy Scouts.' I had heard of Boy Scouts, but I supposed it was one of the ordinary clubs where boys got together just for play.

"I was so much interested that I looked up the head office of the Boy Scouts, and asked questions about them. Then I bought these copies of the Boy Scout's Handbook. They tell about the things the scouts do, and how a boy may become a scout. I knew you chaps would be so interested you would each want a book, so I bought a half-dozen copies. The extra books we can give to other boys up the Bay."

"Could we be scouts?" asked Andy breathlessly.

"Yes, to be sure!" Doctor Joe smiled.

"'Twould be rare fun, now!" exclaimed David.

"All of us scouts, just like the boys in New York?" Jamie asked, his face aglow.

"Yes," answered Doctor Joe. "I knew you chaps would like to be scouts. We'll organize a troop, and we'll call it Troop One of The Labrador. There are Boy Scouts of America, and Boy Scouts of England, and Boy Scouts of nearly every country in the world except The Labrador. We'll be the Boy Scouts of The Labrador, and become a part of the great army of scouts. It'll be something to be proud of."

"How'll we do it?" asked David.

"I'll be leader, or scoutmaster as they call the leader," explained Doctor Joe. "These books explain all about the things we're to do.

"Before you become tenderfoot scouts you'll have to learn some things," Doctor Joe continued, after looking through one of the handbooks, until he found the proper page. "You can tie all the knots already. You do that every day. But there are plenty of boys, and men too, where I came from that can't even tie the ordinary square knot.

"You'll have to learn the oath and law. You live pretty close to the requirements of the law now, but it'll be necessary to learn it, and I'll explain then what each law means. You'll have to learn what the scout badge stands for and how it's made up, and other things."

Doctor Joe carefully marked the necessary pages and references.

"Now about the flag," said Doctor Joe. "You'll have to learn about the formation of the flag and what it stands for. This book is for the Boy Scouts of America, and the flag it refers to is the United States flag. I'm an American, but you chaps are living in British territory and you're British subjects, so you'll have to learn about the British flag or Union Jack, as it's called, for that's your flag.

"The Union Jack is the national flag of the whole British Empire. The English flag was originally a red cross on a white field. This is called the flag of St. George. Three hundred years ago King James the First added to it the banner of Scotland, which was a blue flag with a white cross, called St. Andrew's Cross, lying upon the blue from corner to corner—that is diagonally."

Doctor Joe opened his travelling bag and drew forth two small flags, one the Stars and Stripes and the other the British Union Jack.

"I nearly forgot about these," said he, spreading the flags upon the table. "This is the flag of my country," and he caressed the United States flag affectionately. "I love it as you should love your flag. The Union Jack is the emblem of the great British Empire, of which you are a part. It is one of the greatest and best countries in the world to live in. To be a British subject is something to be proud of indeed."

"Aye," broke in Thomas, "'tis that, now."

"Yes," continued Doctor Joe, "I want you to be as proud of it as I am that I'm a citizen of the United States, and I'm so proud of it I wouldn't change for any other country in the world. When I reached St. John's and saw the American flag flying over the office of the United States Consulate, my eyes filled with tears. I hadn't seen that old flag for years, and I stood in the street for an hour doing nothing but look at it and think of all it represents. It makes my blood tingle just to touch it. You chaps must feel the same toward the British flag, for that's your flag.

"Now let me show you how the flag is made up," and Doctor Joe proceeded to trace St. George's Cross and St. Andrew's Cross, explaining them again as he did so. "In the year 1801 another banner was added. This was the Banner of St. Patrick of Ireland. St. Patrick's Cross was a red diagonal cross on a white field, and here you see it."

Doctor Joe traced it on the flag.

"There," he went on, "you have the British flag complete. No one knows exactly why it is called the 'Jack,' but it may have been because in the old days, the English knights, when they went out to fight their battles, wore a jacket over their armour with the St. George's Cross upon it, so it would be known to what nation they belonged. This jacket was sometimes called a 'jack' for short.

"The Union Jack did not become a complete flag as we have it to-day until the year 1801, when St. Patrick's Cross was added to it. The Stars and Stripes, the flag of my country, was first made in 1776, and on June 14, 1777, it was adopted by the United States Congress as the national emblem, so you see it is even older than the British flag. The flags of all nations in the world have changed since 1777 excepting only the United States flag, and every American is proud of the fact that his flag is older than the flag of any other Christian nation in the world."

The boys, and Thomas and Margaret also, were fascinated with Doctor Joe's brief story of the flags. They were quite excited with the thought that they were to be a part of the great army of Boy Scouts, and to do the same things that other boys in far-away lands were doing, and the other boys that they had never seen seemed suddenly very much nearer to them and more like themselves than they had ever seemed before.

The three buried their noses in the handbook, now and again asking Doctor Joe questions. They were so excited and so interested, indeed, that they could scarcely lay the books aside when Thomas announced that it was time to "turn in," and Andy declared he could hardly wait for morning when they could be at them again.

And so it came about that Troop I, Boy Scouts of The Labrador, was organized, and in the nature of things the troop was destined to meet many adventures and unusual experiences.

CHAPTER II

PLANS

The cabin at The Jug had three rooms. There was a square living-room, entered through an enclosed porch on its western grade. At the end of the living-room opposite the entrance were two doors, one leading to Margaret's room, the other to the room occupied by the boys. Thomas himself slept in a bunk, resembling a ship's bunk, built against the north wall.

The furnishings of the living-room consisted of a home-made table, a big box stove, three home-made chairs and some chests, which served the double purpose of storage places for clothing and seats. A cupboard was built against the wall at the left of the entrance, and between two windows on the south side of the room, which looked out upon The Jug, was a shelf upon which Thomas kept his Bible and Margaret her sewing basket—a little basket which she had woven herself from native grasses. Behind the stove was a bench, upon which stood a bucket of water and the family wash basin, and over the basin hung a towel for general family use.

Pasted upon the walls were pictures from old newspapers and magazines. There were no other decorations but these and snowy muslin curtains at the windows, but the floor, table, chairs—all the woodwork, indeed—were scoured to immaculate whiteness with sand and soap, and everything was spotlessly clean and tidy. Despite the austere simplicity of the room and its furnishings, it possessed an indescribable atmosphere of cosy comfort.

Doctor Joe's bed was spread upon the floor. It was still candle-light when he was awakened by Thomas building a fire in the stove, for in this land of stern living there is no lolling in bed of mornings.

"Good-morning, Thomas," said Doctor Joe, with a yawn and a stretch as he sat up.

"Marnin'," said Thomas.

"How's the morning, Thomas, fair for our trip to Fort Pelican?"

"Aye, 'tis a fine marnin'," announced Thomas, "but I were thinkin' 'twould be better to wait over till to-morrow for the trip. After your long voyage 'twould be a bit trying for you to turn back to-day to Fort Pelican without restin' up, and I'm not doubtin' a day whatever'll do no harm to the potaters and things."

"I believe you're right, Thomas," and Doctor Joe spoke with evident relief. "I thought you'd be getting ready for the trapping and would like to get the Fort Pelican trip out of the way. We'll put the trip off till to-morrow."

Doctor Joe dressed hurriedly, and went out to enjoy the cool, crisp morning. Everything was white with hoarfrost. The air was charged with the perfume of balsam and spruce and other sweet odours of the forest. Doctor Joe took long, deep, delicious breaths as he looked about him at the familiar scene.

The last stars were fading in the growing light. A low mist hung over The Jug, and beyond the haze lay the dark, heaving waters of Eskimo Bay. In the distance beyond the Bay the high peaks of the Mealy Mountains rose out of the gloom, white with snow and looming above the dark forest at their base in cold and silent majesty. Behind the cabin stretched the vast, mysterious, unbounded wilderness which held, hidden in its unmeasured depths, rivers and lakes and mountains that no man, save the wandering Indian, had ever looked upon—great solitudes whose silence had remained unbroken through the ages.

"If some of those Boy Scouts could only see this!" exclaimed Doctor Joe.

"'Twere fashioned by the Almighty for comfortable livin'," said Thomas, who had called Margaret and the boys and come out unobserved by Doctor Joe. "There's no better shelter on the coast, and no better place for seals and salmon, with neighbours handy when we wants to see un, and plenty o' room to stretch. 'Tis the finest I ever saw, whatever."

"Yes, 'tis all of that," agreed Doctor Joe. "But I wasn't thinking now of The Jug alone. I was thinking of the majestic grandeur of the whole scene. I was enjoying the freedom from the noise and scramble, the dirt and smoke and smudge of the city, with its piles upon piles of ugly buildings, and never a breath of such pure air as this to be breathed. I was thinking of these fine young chaps, the Boy Scouts I saw there, who are trying to study God's big out-of-doors and must content themselves with stingy little parks. It's the love of Nature that takes them to the parks, and compared with this they have a poor substitute. This is the world as God made it, with all its primordial beauty. We're fortunate that circumstances placed us here, Thomas, and we should be for ever thankful."

"I'm wonderin' now," observed Thomas, as he and Doctor Joe paced up and down the gravelly beach, "why folks ever lives in such places as you tells about. There's plenty o' room down here on The Labrador, and plenty o' other places, I'm not doubtin', where they'd be free from the crowds and dirt, and have plenty o' room to stretch, and live fine like we lives."

"We're a thousand miles from a railway," said Doctor Joe. "Most of the people in the cities wouldn't live a thousand paces from a railway if they could help themselves. They take a car and ride if they've only half a mile to go. They ride so much they've almost forgotten how to walk. They like crowds. They'd be lonesome if they were away from them."

"'Tis strange, wonderful strange, how some folks lives," remarked Thomas, quite astonished that any could prefer the city to his own big, free Labrador. "When folks has enough to keep un busy they never gets lonesome, and bein' idle is like wastin' a part of life. A man could never be lonesome where there's plenty o' water and woods about. I always finds jobs a-plenty to turn my hand to, and I has no time to feel lonesome. And I never could live where I didn't have room enough to stretch, whatever."

"That's it!" Doctor Joe spoke decisively. "Room enough to stretch mind as well as body. Why, Thomas, I've often heard men say that they had to 'kill time', and didn't know what to do with themselves for hours together!"

"'Tis wicked and against the Lord's will," and Thomas shook his head. "The Lord never wants folks to be idle or kill time. He fixes it so there's a-plenty of useful things for everybody to do all the time, and they wants to do un."

"'Tis the measure of a man's worth," remarked Doctor Joe. "The worth-while man never has an hour to kill. The day hasn't hours enough for him. It's the other kind that kill time—the sort that are not, and never will be, of much account in the world."

They walked a little in silence, each busy with his own thoughts, when Thomas remarked:

"The Lord has been wonderful good to me, Doctor Joe, givin' me three as fine lads and as fine a lass as He ever gave a man. Then He saves the little lad's eyes, when they were goin' blind, by sendin' you to cure un. And when I were breakin' my leg and couldn't work He sends along Indian Jake to go to the trails to hunt with David and Andy, and they makes a fine hunt and keeps us out o' debt. And this summer we has as fine a catch of salmon as ever we has, and we're through with un a fortnight ahead of ever before, with all the barrels filled and the gear stowed, and the salt salmon traded in at the Post, and plenty o' flour and pork and molasses and tea t' see us through the winter, whatever."

"Last year at this time things looked pretty blue for us," said Doctor Joe, "but everything worked out well in the end, Thomas."

"Aye," agreed Thomas, "wonderful well. I'm thinkin' that if we does our best t' help ourselves when troubles come the Lord is like t' step in and give us a hand. He wants us to do the best we can t' help ourselves and when He sees we're doin' it He lifts the troubles."

"That's true," agreed Doctor Joe, "and if a man takes advantage of every opportunity that comes to him, and don't waste his time, he's pretty sure to succeed."

"Aye, that he is," said Thomas. "Now I were thinkin' that the lads worked so wonderful hard at the salmon th' summer, I'd let un go with you to Fort Pelican t' manage the boat, and I'll be staying home to make ready for the trail. There's a-plenty to be done yet to make ready without hurry, and a trip to Fort Pelican will be a rare treat for the lads. But I'll go if you wants. I were just askin' if 'twould be suitin' you if I stays home and lets they go?"

"Why, of course! That's great! Simply great!" exclaimed Doctor Joe. "The boys will make a fine crew! Will Jamie go too?"

"Aye, Jamie's been workin' like a man, and he'll be keen for the trip," said Thomas. "And last night I were thinkin' after I goes to bed how fine 'tis that you're to be doctor to the coast. Indian Jake's to be my trappin' pardner th' winter, and the lads'll 'bide home. You'll be needin' dogs and komatik (sledge) to take you about. There'll be little enough for the dogs to do, and you'll be welcome to un. The lads can do the drivin' for you and whatever you wants un to do. Use un all you needs. I wants to do my share to help you do the doctorin'."

"Thank you! Thank you, Thomas!" Doctor Joe accepted gratefully. "This will make it possible for me to see a good many people that I otherwise would not be able to see, and make it easier for me also."

"Aye," said Thomas, "I were thinkin' that too, and the lads will be glad enough to lend you a hand when you needs un."

It was broad daylight. While Thomas and Doctor Joe talked on the beach, the boys had been busily engaged in carrying the day's supply of water from Roaring Brook to a water barrel in the porch. Now Jamie appeared to announce breakfast. While they ate the boys were able to talk of little else than the scout books, and the fact they were to do as boys did in other parts of the world. And they were delighted beyond measure when they learned that they were to make the voyage to Fort Pelican with Doctor Joe. It was an event of vast importance.

"There'll be plenty o' time in the boat to study the scout book things," Andy suggested. "Maybe now we could learn to be scouts before we gets back home."

"I've no doubt you can pass all the tenderfoot tests while we're away," said Doctor Joe. "And since you're to take me about with dogs and komatik this winter when I go to visit sick people, there'll be no end of chances to show what good scouts you are."

"To take you about?" asked Andy excitedly.

Then Thomas must needs explain that they must do their share in looking after the sick folk, and that David and Andy were to be Doctor Joe's dog drivers when winter came.

"'Twill be fine to manage the dogs for you, sir!" exclaimed David, turning to Doctor Joe.

"Wonderful fine!" echoed Andy.

"And will you be goin' outside the Bay?" asked David.

"Aye, outside the Bay and in it, wherever there's need to go," said Doctor Joe.

"'Twill be tryin' and hard work sometimes," suggested Thomas, "travellin' when the weather's nasty, but I'm not doubtin' the lads'll be able t' manage un."

"We'll manage un!" David declared with pride in the confidence placed in him and Andy.

To drive dogs on these sub-arctic trails in fair weather and foul calls for courage and grit, and the lads felt justly proud of the responsibility that had been laid upon them. There would be many a shift to make on the ice, they knew. There would be blinding blizzards and withering arctic winds to face, and no end of hard work. But these lads of The Labrador loved to stand upon their feet like men and face and conquer the elements like hardy men of courage. This is the way of boys the world over—eager for the time when they may assume the responsibility of manhood. Such a time comes earlier to the lads of The Labrador than with us. In that stern land there is no idling and there are no holidays, and every one, the lad as well as his father, must always do his part, which is his best.

Fort Pelican, the nearest port at which the mail boat called, was seventy miles eastward from The Jug. With the uncertainty of wind and tide the boat journey to Fort Pelican usually consumed three days, and with equal time required for return, the voyage could seldom be accomplished in less than six days. Lem Horn and his family lived at Horn's Bight, thirty miles from The Jug, and fifteen miles beyond, at Caribou Arm, was Jerry Snook's cabin. Save an Eskimo settlement of half a dozen huts near Fort Pelican and the families of Lem Horn and Jerry Snook, the country lying between The Jug and Fort Pelican was uninhabited. It was unlikely that evening would find the travellers in the vicinity of either Horn's or Snook's cabins, and therefore it was to be a camping trip, which was quite to the liking of the boys.

The boys washed the old fishing boat and packed the equipment and provisions for the voyage. Margaret baked three big loaves of white bread, and as a special treat a loaf of plum bread. The remaining provisions consisted of tea, a bottle of molasses for sweetening, flour, baking-powder, fat salt pork, lard, margarine, salt and pepper. The equipment included a frying-pan, a basin for mixing dough, a tin kettle for tea, a larger kettle to be used in cooking, one large cooking spoon, four teaspoons and some tin plates. Each of the boys as well as Doctor Joe was provided with a sheath knife carried on the belt. The sheath knife serves the professional hunter as a cooking knife, as well as for eating and general purposes.

For camping use there was a cotton wedge tent, a small sheet-iron tent stove, three camp axes, some candles and matches, a file for sharpening the axes and a sleeping-bag for each. Men in that land do not travel without arms, and it was decided that David should take a carbine and Andy and Doctor Joe each a double-barrel shotgun, for there might be an opportunity to shoot a fat goose or duck.

Thomas's big boat had two light masts rigged with leg-o'-mutton sails. Just forward of the foremast David and Andy placed some flat stones, and covering them with two or three inches of gravel set the tent stove upon the gravel. Here they could cook their meals at midday, and the gravel would protect the bottom of the boat from heat. A sufficient quantity of fire-wood was taken aboard, and the provisions and other equipment stowed under a short deck forward where the things would be protected from storm and all would be in readiness for an early start in the morning.

CHAPTER III

"'TIS THE GHOST OF LONG JOHN"

The morning was clear and crisp. Breakfast was eaten by candle-light, and before sunrise Doctor Joe and the boys, with the tide to help them, worked the big boat down through The Jug and past the Point into Eskimo Bay. In the shelter of The Jug, which lay in the lee of the hills, the sails flapped idly and it was necessary to bring the long oars into service. But beyond the sheltered harbour a light north-west breeze caught and filled the sails, the oars were stowed, the rudder shipped, and with David at the tiller Doctor Joe lighted his pipe and settled himself for a quiet smoke while Andy and Jamie turned their attention to their scout handbooks.

It was an inspiring morning. The sky was cloudless. The air was charged with scent of spruce and balsam fir, wafted down by the breeze from the forest, lying in dark and solemn silence and spreading away from the near-by shore until it melted into the blue haze of rolling hills far to the northward. The huge black back of a grampus rose a hundred feet from the boat and with a noise like the loud exhaust of steam sank again beneath the surface of the Bay. Now and again a seal raised its head and looked curiously at the travellers and then hastily dived. Gulls and terns soared and circled overhead, occasionally dipping to the water to capture a choice morsel of food. A flock of wild geese, honking in flight, turned into a bight and alighted where a brook coursed down through a marsh to join the sea.

"There's some geese," remarked David, breaking the silence. "They're comin' up south now. We'll have a hunt when we gets home. They always feeds in that mesh when they're bidin' about the Bay."

Presently Andy exclaimed:

"I can tie un all! I can tie every knot in the book!"

"I can tie un too!" said Jamie.

"Yes! Yes! There are the scout tests!" broke in Doctor Joe. "Suppose we all tie the knots and pass the tests."

Andy and Jamie tied them easily enough, and then Doctor Joe tied them himself to keep pace with the boys, and Andy relieved David at the tiller that he might try his hand at them; David not only tied all the knots illustrated in the handbook, but for good measure added a bowline on a bight, a double carrick bend, a marlin hitch and a halliard hitch.

"That's wonderful easy to do," David declared as he laid the rope down. "'Tis strange they calls that a test, 'tis so easy done."

"Easy for us," admitted Doctor Joe, "but for boys who have never had much to do with boats or ropes it's a hard test, and an important one. You chaps knew how to tie them, so in doing it you haven't learned anything new. Let us make up our minds as scouts to learn something new every day—something we never knew before, no matter how small or unimportant it may seem. Think what a lot we'll know next year that we do not know now; everything we learn, too, is sure to be of use to us sometime in our lives.

"As we go along we'll find there is a great deal to learn in this handbook, and all of it is worth knowing. We don't look far ahead. Suppose we begin with the scout law. With your good memories you'll learn it before we go ashore to-night. I want you to learn the twelve points of the law in order as they appear in the book, so that you can repeat them and tell me in your own words what each point means."

Doctor Joe turned to the scout law and explained each point in detail. When he told them that "A Scout is kind" meant that they must not only be kind to people, but that they must protect and not kill harmless birds and animals, David protested:

"If we promises that, sir, 'twould stop us huntin' seals and deer and pa'tridges and plenty o' things."

"Oh, no!" explained Doctor Joe. "It does not mean that. It means that you must kill nothing needlessly. Here in Labrador we must kill seals and deer and partridges and other game for food and for their skins. That is the way we make our living. In the same way they have to kill cows and sheep and goats and pigs for food in the country I came from and to get skins for boots and gloves. In the same way we are permitted to kill game when necessary. But we're not to kill anything that's harmless unless we need it for some purpose. The Indians and other people about here shoot at loons for sport. I've seen them chase the loons in canoes and keep shooting at them every time they came up after a dive, until the loons were too tired to dive quickly enough to get out of the way of the shot, and then the poor things were killed. The flesh isn't fit to eat and they're always thrown away. That is cruel."

"I never thought of un that way. I've killed loons too," David confessed, "but I'll never shoot at a loon again. 'Tis the same with gulls and other things we never uses when we kills, and just shoot at for fun."

"That's the idea," said Doctor Joe enthusiastically. "Now what do you think about killing hen partridges in summer?"

"We can kill pa'tridges, can't we?" asked David. "We always eats un, and you said we could kill un."

"But we've got to use our heads about it," Doctor Joe explained. "I'm talking now about hen partridges in summer. They always have broods of little partridges then. If you kill the mother all the little ones die, for they're too small to take care of themselves. Do you think that's right?"

"I never thought of un before," said David. "'Tis wicked to kill un! I'll never kill a hen pa'tridge in summer again! Not me!"

"We'll have to be tellin' everybody in the Bay about that!" declared Andy. "Nobody has ever thought about the poor little uns starvin' and dyin'!"

"That'll be doing good scout work," Doctor Joe commended. "That's one way you'll be useful as scouts here in Labrador. Not only will you be showing kindness to the mother and little partridges, but if the mother is permitted to live and raise her brood, all the little birds will be full grown by winter, and it will make that many more partridges that can be used for food when food is needed."

When presently Jamie announced that it was "'most noon" and he was "fair starvin'," and the others suddenly discovered that they were hungry too, a fire was lighted in the stove and a cosy lunch of fried pork and bread, and hot tea sweetened with molasses, was eaten with an appetite and relish such as only those can enjoy who live in the open. Then, with growing interest the lads returned to their scout books, and camping time came almost before they were aware.

The sun was drooping low in the west when David, indicating a low, wooded point, said:

"That's Flat P'int. There's good water there and 'tis a fine camping place."

"Then we'll camp there," Doctor Joe agreed.

"Look! Look!" exclaimed Andy, as the boat approached the shore. "There's a porcupine!"

Following the direction in which Andy pointed, a fat porcupine was discovered high up in a spruce tree feeding upon the tender branches and bark.

"Shall we have un for supper?" Andy asked excitedly.

"Aye," said David, "let's have un for supper. Fresh meat'll go fine."

A shot from the rifle, when they had landed, brought the unfortunate porcupine tumbling to the ground, and Andy proceeded at once to skin and dress his game for supper.

"I'll be cook and Andy cookee," Doctor Joe announced. "We'll get wood for the fire, David, and you and Jamie pitch the tent and get it ready."

Flat Point was well wooded, and the floor of the forest thickly carpeted with grey caribou moss. David selected a level spot between two trees on a little rise near the shore. The ridge rope was quickly stretched between the trees and the tent securely pegged down. Then David and Jamie broke a quantity of low-hanging spruce boughs, which they snapped from the trees with a dexterous upward bend of the wrist. When a liberal pile of these had been accumulated at the entrance of the tent, David proceeded to lay the bed.

The rear of the tent was to be the head. Here he laid a row of the boughs, three deep, with the convex side uppermost, then he began "shingling" the boughs in rows toward the foot. This was done by placing the butt end of the bough firmly against the ground with half the bough, the convex side uppermost, overlapping the bough above it, as shingles are lapped on a roof. Thus continuing until the floor of the tent was covered he had a soft, fragrant springy bed, quite as soft and comfortable as a mattress, and upon this he and Jamie spread the sleeping-bags.

In the meantime Doctor Joe and Andy had collected an ample supply of dry wood for the evening, and when, presently, David and Jamie joined them, a cheerful fire was blazing and already an appetizing odour was rising from the stew kettle.

When the stew and some tender dumplings were done Doctor Joe lifted the kettle from the fire, and while he filled each plate with a liberal portion, and Andy poured tea, David put fresh wood upon the fire, for the evening had grown cold and frosty with the setting sun. The blazing fire was cheerful indeed as they settled themselves upon the seat of boughs and proceeded to enjoy their supper.

"Um-m-m!" exclaimed Andy. "You knows how to cook wonderful fine, Doctor!"

"'Tis wonderful fine stew!" seconded David.

"Not half bad," admitted Doctor Joe, "but Andy had as much to do with it as I, and the porcupine had a good deal to do with it. It was young and fat, and it's tender."

There is no pleasanter hour for the camper or voyageur than the evening hour by a blazing camp fire. There is no sweeter odour than that of the damp forest mingled with the smell of burning wood. Beyond the narrow circle of light a black wall rises, and behind the wall lies the wilderness with its unfathomed mysteries. Out in the darkness wild creatures move, silent, stealthy and unseen, behind a veil that human eyes cannot penetrate. But we know they are there going about the strange business of their life, and our imagination is awakened and our sensibilities quickened.

The camp fire is a shrine of comradeship and friendship. Here it was that the primordial ancestors of every living man and woman and child gathered at night with their families, in those far-off dark ages before history was written. The fire was their home. Here they found rest and comfort and protection from the savage wild beasts that roamed the forests. It was a place of veneration. The primitive instinct, perchance inherited from those far-off ancestors of ours, slumbering in our souls, is sometimes awakened, and then we are called to the woods and the wild places that God made beautiful for us, and at night we gather around our camp fire as our ancient ancestors gathered around theirs, and we love it just as they loved it.

And so it was with the little camp fire on Flat Point and with Doctor Joe and the boys. With darkness the uncanny light of the Aurora Borealis flashed up in the north, its long, weird fingers of changing colours moving restlessly across the heavens. The forest and the wide, dark waters of Eskimo Bay sank behind a black wall.

There was absolute silence, save for the ripple of waves upon the shore, each busy with his own thoughts, until presently Jamie asked:

"Did you ever see a ghost, Doctor?"

"A ghost? No, lad, and I fancy no one else ever saw one except in imagination. What made you think of ghosts?"

"'Tis so—still—and dark out there," said Jamie, pointing toward the darkness beyond the fire-glow. "And—I were thinkin' I heard something."

"But there is ghosts, sir, plenty of un," broke in Andy. "Pop's seen ghosts and so has Zeke Hodge and Uncle Billy and plenty of folks. They says the ghost of Long John, the old Injun that used to be at the Post and was drowned, goes paddlin' and paddlin' about in a canoe o' nights."

"Yes," said David, "I'm thinkin' I saw Long John's ghost myself one evenin'. I weren't certain of un, but it must have been he."

"Nonsense!" Doctor Joe had no patience with the belief popular among Labradormen that ghosts of men who have been drowned or killed return to haunt the scene of their death. "There's no such thing as a ghost."

"What's that now?" Jamie held up his hand for silence, and spoke in a subdued voice.

Out of the darkness came the rhythmic dipping of a paddle. They all heard it now. Doctor Joe arose, and closely followed by the boys, stepped down beyond the fire glow. In dim outline they could see the silhouette of a canoe containing the lone figure of a man paddling with the short, quick stroke of the Indian.

"'Tis the ghost of Long John!" breathed Jamie. "'Tis sure he!"

CHAPTER IV

SHOT FROM BEHIND

The canoe was coming directly toward them. In a moment it touched the shore, and as its occupant stepped lightly out the boys with one accord exclaimed:

"Injun Jake! 'Tis Injun Jake!"

And so it proved. The greeting he received was hearty enough to leave no doubt in his mind that he was a welcome visitor. Perhaps it was the heartier because of the relief the boys experienced in the discovery that the lone canoeman was not, after all, the wraith of Long John, but was their friend Indian Jake in flesh and blood.

When his packs had been removed, Indian Jake lifted his canoe from the water, turned it upon its side and followed the boys to the fire, where Doctor Joe awaited him.

"Just in time!" welcomed Doctor Joe, as he shook Indian Jake's hand. "We've finished eating, but there's plenty of stew in the kettle. Andy, pour Jake some tea."

Indian Jake, grunting his thanks, silently picked up David's empty plate and heaped it with stew and dumpling from the kettle without the ceremony of waiting to be served.

He was a tall, lithe, muscular half-breed, with small, restless, hawk-like eyes and a beaked nose that was not unlike the beak of a hawk. He had the copper-hued skin and straight black hair of the Indian, but otherwise his features might have been those of a white man. Indian Jake had been the trapping companion of David and Andy the previous winter, and, as previously stated, was this year to be Thomas Angus's trapping partner on the fur trails.

The boys were vastly fond of Indian Jake, and Thomas and Doctor Joe shared their confidence, but the Bay folk generally looked upon him with distrust and suspicion. Several years before, he had come to the Bay a penniless stranger. He soon earned the reputation of being one of the best trappers in the region. Then, suddenly, he disappeared owing the Hudson's Bay Company a considerable sum for equipment and provisions sold him on credit. It was well known that in the winter preceding his disappearance Indian Jake had had a most successful hunting season and was in possession of ample means to pay his debts. His failure to apply his means to this purpose was looked upon as highly dishonest—akin, indeed, to theft.

Two years later he reappeared, again penniless. The Company refused him further credit, and he had no means of purchasing the supplies necessary for his support during the trapping season in the interior. It was at this time that Thomas Angus broke his leg, and it became necessary for David and Andy to take his place on the trails. They were too young to endure the long months of isolation without an older and more experienced companion. There was none but Indian Jake to go with them, and he was engaged to hunt on shares a trail adjacent to theirs.

With his share of the furs captured by the end of the trapping season, Indian Jake discharged his old debt with the Company. This was not sufficient, however, to re-establish confidence in him. There was a lurking suspicion among them, fostered by Uncle Ben Rudder of Tuggle Bight, the wiseacre and oracle of the Bay, that Indian Jake's payment of the debt was not prompted by honesty but by some ulterior motive.

Indian Jake emptied his plate. He refilled it with the last of the stew and again emptied it, in the interim swallowing several cups of hot tea.

"Good stew," he remarked in appreciation and praise when his meal was finished. "When were you gettin' back?"

"I reached The Jug day before yesterday," said Doctor Joe.

"Huh!" Indian Jake grunted approval, as he puffed industriously at his pipe. "Where you goin' now? To see Lem Horn?"

"No," Doctor Joe answered, "we're going to Fort Pelican to get some things I brought in on the mail boat."

"I been goose huntin'," Indian Jake explained. "Not much goose yet. Too early. Got four. Goin' to The Jug now to give Thomas a hand. Want to start for Seal Lake soon. Don't want to be late."

"Pop's thinkin' to start in a fortnight," said David.

"Good!" acknowledged Indian Jake. "Maybe we start sooner. Start when we're ready. I want to go quick. Have plenty time get there before freeze-up."

Indian Jake had apparently finished talking. Doctor Joe and the boys made several attempts to continue the conversation, but only receiving responsive grunts, turned to a discussion of the flag and other scout problems, while Indian Jake was absorbed in his own thoughts. Presently he rose and proceeded to unroll his bed.

"Plenty of room in the tent," Doctor Joe invited. "Better come in with us, Jake."

"Goin' early. Sleep here," he declined, as he spread a caribou skin upon the ground to protect himself from the damp earth. Then he produced a Hudson's Bay Company blanket, once white but now of uncertain shade, and rolling himself in the blanket, with his feet toward the fire, was soon snoring peacefully.

"We won't trouble to douse the fire," Doctor Joe suggested presently. "He wants to sleep by it, and he'll look after it. Let's turn in."

And with the front of the tent open that they might enjoy the air and profit by the firelight, they were soon snug in their sleeping-bags and as sound asleep as Indian Jake.

The three boys sat up. It was broad daylight, and Doctor Joe, on his hands and knees, was looking out of the tent.

"Our visitor has gone, and there's little wonder, for we've been sleeping like bears and it's broad daylight. Hurry, lads, or the sun'll be well up before we get away."

The boys sprang up and were soon dressed. The fire had burned low, indicating that Indian Jake had been gone for a considerable time. A fat goose was hanging from the limb of a tree. Fastened to it was a piece of birch bark, and scribbled upon the birch bark with a piece of charcoal from the fire, these words:

"cerprize fur the lads bekos they likes Goos."

Another surprise awaited them. When they lifted the lid of the large cooking kettle they found it nearly full of boiled goose.

"That's the way o' Indian Jake!" Andy exclaimed. "He's always plannin' fine surprises for folks."

"It's surely a fine surprise," said Doctor Joe. "Breakfast all ready but the tea, and a goose for to-night."

Every one hurried, but the sun was well up when they put out the fire and hoisted sail. There was little wind, however, and the light breeze soon dropped to a dead calm. Doctor Joe unshipped the rudder and began sculling, while the boys laboured at the long oars. At length the tide began running in, and progress was so slow that it was decided to go ashore and await a turn of the tide or a breeze.

"Lem Horn lives just back o' that island," said David, indicating a small wooded island. "We might stop and bide there till a breeze comes, and see un."

In accordance with the suggestion Doctor Joe turned the boat inside the island, and there, on the mainland in the edge of a little clearing and not a hundred yards distant, stood Lem Horn's cabin. It was a secluded and peculiarly lonely spot, hidden by the island from the few boats that plied the Bay. Here lived Lem Horn and his wife and two sons, Eli, a young man of twenty-one years, and Mark, nineteen years of age.

"There's no smoke," observed Jamie.

"Maybe they're all down to Fort Pelican getting their winter outfit," suggested David.

"There seems to be no one about but the dogs," said Doctor Joe, as he stepped ashore with the painter and made it fast, while Lem's big sledge dogs, lolling in the sun, watched them curiously.

Visitors do not knock in Labrador. The cabins are always open to travellers whether or not the host is at home. Andy was in advance, and opening the door he stopped on the threshold with an exclamation of horror.

Stretched upon the floor lay Lem Horn, his face and hair smeared with blood, and on the floor near him was a small pool of blood. A chair was overturned, and Lem's legs were tangled in a fish-net.

Doctor Joe leaned over the prostrate figure.

"Shot," said he, "and from behind!"

"Does you mean somebody shot he?" asked David, quite horrified.

"Yes, and it must have happened yesterday," said Doctor Joe.

STRETCHED UPON THE FLOOR LAY LEM HORN

STRETCHED UPON THE FLOOR LAY LEM HORN

CHAPTER V

LEM HORN'S SILVER FOX

"He's alive, and this doesn't look like a bad wound," said Doctor Joe after a brief examination. "David, put a fire in the stove and heat some water! Andy, find some clean cloths! Jamie, bring up my medicine kit from the boat!"

The boys hurried to carry out the directions, while Doctor Joe made a more careful examination and discovered a second wound in Lem's back, just below the right shoulder.

"Both shots from the back," he mused. "This wound explains his condition. The one in the head only scraped the skull, and couldn't have more than stunned him for a short time. The other has caused a good deal of bleeding and may be serious."

With David's help Doctor Joe carried Lem to his bunk and removed his outer clothing.

The water in the kettle on the stove was now warm enough for Doctor Joe's purpose. He poured some of it into a dish, and after dissolving in it some antiseptic tablets, cleansed and temporarily dressed the wounds.

Restoratives were now applied. Lem responded promptly. His breathing became perceptible, and at length he opened his eyes and stared at Doctor Joe. There was no recognition in the stare and in a moment the eyes closed. Presently they again opened, and this time Lem's lips moved.

"Where's Jane?" he asked feebly.

"Your wife seems to be away and the boys, too," said Doctor Joe. "We found you alone."

"Gone to Fort Pelican," Lem murmured after a moment's thought. He stared at Doctor Joe for several minutes, now with the look of one trying to recall something, and at length asked:

"What's—been—happenin' to me?"

"You've been shot," said Doctor Joe. "We found you on the floor. Some one has shot you."

"The silver! The silver fox skin!" Lem displayed excitement. "Be it on the table? I had un there!"

"There was no fur on the table when we came," said Doctor Joe.

Lem made a feeble attempt to rise, but Doctor Joe pressed him gently back upon the pillow, saying as he did so:

"You must lie quiet, Lem. Don't try to move. You're not strong enough."

Lem, like a weary child, closed his eyes in compliance. Several minutes elapsed before he opened them again, and then he looked steadfastly at Doctor Joe.

"Do you know who I am?" Doctor Joe asked.

"Yes," answered Lem in a feeble voice; "you're Doctor Joe. I knows you. I'm—glad you—came—Doctor Joe."

"Lem, you've been shot, but we'll pull you through. It isn't so bad, but you've lost some blood, and that's left you weak for a little while. Don't talk now. Rest, and you'll soon be on your feet again."

While Lem lay with closed eyes, Doctor Joe turned to consideration of the crime. If it were true that a silver fox skin had been taken, robbery was undoubtedly the motive for the shooting. But who could have known of the existence of the skin? And who could have come to this out-of-the-way place unobserved by the old trapper and shot him without warning?

Instinctively Indian Jake rose before his eyes. The half-breed's unsavoury reputation forced itself forward. And there was the circumstance of Indian Jake's visit to Flat Point camp the previous evening, his hurried departure in the morning, and his evident desire to hurry into the interior wilderness where he would be swallowed up for several months, and from which there would be innumerable opportunities to escape. Suddenly Doctor Joe was startled by Lem's voice, quite strong and natural now:

"I'm thinkin' 'twere that thief Injun Jake that shoots me."

"What makes you think so?" asked Doctor Joe.

"He were huntin' geese just below here, and he comes in and sits for a bit. I had a silver fox skin I were holdin' for a better price than they offers at Fort Pelican. 'Twere worth five hundred dollars whatever, and they only offers three hundred. I were busy mendin' my fishin' gear before I stows un away when Injun Jake comes. We talks about fur and I brings the silver out t' show he. Then I lays un on the table and keeps on mendin' the gear after he goes, thinkin' to put the fur up after I gets through mendin'."

"What time did Indian Jake come?" asked Doctor Joe.

"A bit after noon. Handy to one o'clock 'twere, for I were just boilin' the kettle. He eats a snack with me."

"How long did he stay? What time did he go?"

"I'm not knowin' just the time. I were a bit late boilin' the kettle. I boiled un around one o'clock. We sets down to the table about ten after and 'twere handy to half-past when we clears the table. Then Injun Jake has a smoke, and I shows he the silver, and I'm thinkin' 'twere a bit after two when he goes. He said he were goin' to stop on Flat P'int last night and get to Tom Angus's to-night whatever."

"A little after two o'clock when he left?"

"Maybe 'twere half-past. He had a down wind to paddle agin', and he were sayin' 'twould be slow travellin', and 'twould take three or four hours whatever to make Flat P'int."

"I were settin' mendin' the gear thinkin' to finish un and stow un away, and I keeps at un till just sundown. I were just gettin' up to put the kettle on for supper. That's all I remembers, exceptin' I wakes up two or three times and tries to move, but when I tries there's a wonderful hurt in my shoulder, and my head feels like she's bustin', and everything goes black in front of my eyes. If the fur's gone, Injun Jake took un."

"It's strange," said Doctor Joe, "very strange. There's a bullet in your shoulder. After you rest a while we'll probe for it and see if we can get it out. Don't talk any more. Just lie quietly and sleep if you can."

The boys were out-of-doors. Doctor Joe was glad they had not heard Lem's accusation against Indian Jake. The half-breed had been good to them, and they held vast faith in his integrity. There was some hope that Lem's suspicions were not well founded; nevertheless Doctor Joe was forced to admit to himself that circumstances pointed to Indian Jake as the culprit. It was highly improbable that any one else should have been in the vicinity without Lem's knowledge. It was quite possible that Lem's statement of the hour when he was shot was incorrect, for his mind could hardly yet be clear enough to be certain, without doubt, of details.

Lem quickly dropped into a refreshing sleep, and Doctor Joe left him for a little while to join the boys out-of-doors. He found them behind the house picking the goose Indian Jake had left in the tree at the Flat Point camp.

"How's Lem, sir? Is he hurt bad?" David asked as Doctor Joe seated himself upon a stump.

"He's sleeping now. After he rests a little we'll see how badly he's hurt," said Doctor Joe. "I fancy you chaps are thinking about dinner. Hungry already, I'll be bound!"

"Aye," grinned David, "wonderful hungry. 'Tis most noon, sir."

Doctor Joe consulted his watch.

"I declare it is. It must have been nearly eleven o'clock when we reached here. I didn't realize it was so late."

"'Twere ten minutes to eleven, sir," said Andy. "I were lookin' to see how long it takes us to come from Flat P'int."

"What time did we leave Flat Point?" asked Doctor Joe.

"'Twere twenty minutes before seven, sir." Andy drew his new watch proudly from his pocket to refer to it again, as he did upon every possible occasion.

"No," corrected David, "'twere only twenty-five minutes before eleven when we leaves Flat P'int, and fifteen minutes before eleven when we gets here. I looks to see."

"Perhaps your watches aren't set alike," suggested Doctor Joe. "Suppose we compare them."

The comparison disclosed a difference, as Doctor Joe predicted, of five minutes. Then each must needs set his watch with Doctor Joe's, which was a little slower than Andy's and a little faster than David's.

Doctor Joe made some mental calculations. Both David and Andy had observed their watches, and there could be no doubt of the length of time it had required them to come from Flat Point to Lem's cabin. They had consumed four hours, but their progress had been exceedingly slow. Indian Jake had doubtless travelled much faster in his light canoe, but, at best, with the wind against him, he could hardly have paddled from Lem's cabin to Flat Point in less than two hours. He had arrived one hour after sunset. If Lem were correct as to the time when the shooting took place, Indian Jake could not be guilty.

But still there was, with but one hour or possibly a little more in excess of the time between sunset and Indian Jake's arrival at camp, an uncertain alibi for Indian Jake. Lem may have been shot much earlier in the afternoon than he supposed. When Lem grew stronger it would be necessary to question him closely that the hour might be fixed with certainty. Whoever had shot and robbed Lem must have known of the existence of the silver fox skin, and been familiar with the surroundings. The shots had doubtless been fired through a broken pane in a window directly behind the chair in which Lem was sitting at the time.

"Why not cook dinner out here over an open fire?" Doctor Joe presently suggested. "You chaps are pretty noisy, and if you come into the house to cook it on the stove, I'm afraid you'll wake Lem up, and I want him to sleep."

"We'll cook un out here, sir," David agreed.

"'Tis more fun to cook here," Jamie suggested.

"Very well. When it's ready you may bring it in and we'll eat on the table. Lem will probably be awake by that time and he'll want something too. Stew the goose so that there'll be broth, and we'll give some of it to Lem to drink. You'll have to go to Fort Pelican without me. I'll have to stay here and take care of Lem. If the wind comes up, and I think it will, you may get a start after dinner," and Doctor Joe returned to the cabin to watch over his patient.

The goose was plucked. David split a stick of wood, and with his jack-knife whittled shavings for the fire. The knife had a keen edge, for David was a born woodsman and every woodsman keeps his tools always in good condition, and the shavings he cut were long and thin. He did not cut each shaving separately, but stopped his knife just short of the end of the stick, and when several shavings were cut, with a twist of the blade he broke them from the main stick in a bunch. Thus they were held together by the butt to which they were attached. He whittled four or five of these bunches of shavings, and then cut some fine splints with his axe.

David was now ready to light his fire. He placed two sticks of wood upon the ground, end to end, in the form of a right angle, with the opening between the sticks in the direction from which the wind came. Taking the butt of one of the bunches of shavings in his left hand, he scratched a match with his right hand and lighted the thin end of the shavings. When they were blazing freely he carefully placed the thick end upon the two sticks where they came together, on the inside of the angle, with the burning end resting upon the ground. Thus the thick end of the shavings was elevated. Fire always climbs upward, and in an instant the whole bunch of shavings was ablaze. Upon this he placed the other shavings, the thin ends on the fire, the butts resting upon the two sticks at the angle. With the splints which he had previously prepared arranged upon this they quickly ignited, and upon them larger sticks were laid, and in less than five minutes an excellent cooking fire was ready for the pot.

Before disjointing the goose, David held it over the blaze until it was thoroughly singed and the surface of the skin clear. Then he proceeded to draw and cut the goose into pieces of suitable size for stewing, placed them in the kettle, and covered them with water from Lem's spring.