Spinifex and Sand

by David W. Carnegie

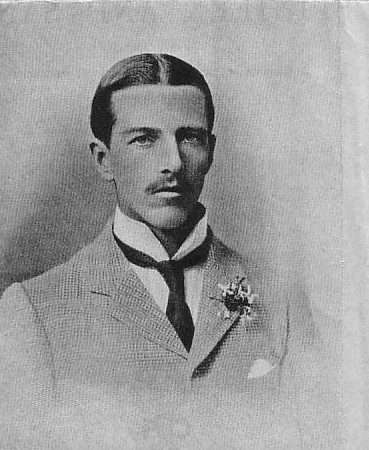

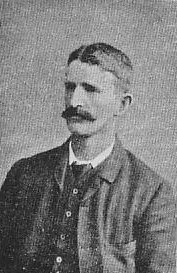

In 1896-1897, the Hon. David Wynford Carnegie, born in 1871, youngest son of the Earl of Southesk, led one of the last great expeditions in the exploration of Australia. His route from Lake Darlôt to Halls Creek and return, took thirteen months and covered over three thousand miles. Carnegie financed his expedition from the results of a successful gold strike at Lake Darlôt.

David Carnegie returned to England in 1898, was awarded a medal by the Royal Geographic Society and in 1899 was appointed Assistant Resident and Magistrate in Northern Nigeria. On November 27, 1900 while on an expedition to capture a brigand he was shot in the thigh with a poisoned arrow and died minutes later. He is buried at Lokaja, Nigeria and a memorial to his memory is in St. George's Cathedral, Perth.

SPINIFEX AND SAND

A Narrative of Five Years' Pioneering and Exploration in Western Ausralia

By The

HON. DAVID W CARNEGIE (1871-1900)

Illustration 1: David W. Carnegie.

To MY MOTHER

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

PART I - EARLY DAYS IN COOLGARDIE

PART II - FIRST PROSPECTING EXPEDITION

- The Rush To Kurnalpi—We Reach Queen Victoria Spring

- In Unknown Country

- From Mount Shenton To Mount Margaret

PART III - SECOND PROSPECTING EXPEDITION

- The Joys Of Portable Condensers

- Granite Rocks, “Namma Holes,” And “Soaks”

- A Fresh Start

- A Camel Fight

- Gold At Lake Darlôt

- Alone In The Bush

- Sale Of Mine

PART IV - MINING

PART V - THE OUTWARD JOURNEY

- Previous Explorers In The Interior Of Western Australia

- Members And Equipment Of Expedition

- The Journey Begins

- We Enter The Desert

- Water At Last

- Woodhouse Lagoon

- The Great Undulating Desert Of Gravel

- A Desert Tribe

- Dr. Leichardt's Lost Expedition

- The Desert Of Parallel Sand-Ridges

- From Family Well To Helena Spring

- Helena Spring

- From Helena Spring To The Southesk Tablelands

- Death Of Stansmore

- Wells Exploring Expedition

- Kimberley

- Aboriginals At Hall's Creek

- Preparations For The Return Journey

Appendix To Part V

PART VI - THE JOURNEY HOME

- Return Journey Begins

- Sturt Creek And “Gregory's Salt Sea”

- Our Camp On The “Salt Sea”

- Desert Once More

- Stansmore Range To Lake MacDonald

- Lake MacDonald To The Deep Rock-Holes

- The Last Of The Ridges Of Drift Sand

- Woodhouse Lagoon Revisited

- Across Lake Wells To Lake Darlôt

- The End Of The Expedition

APPENDIX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

(47 illustrations appeared in the original text, published in 1898. A number have not been reproduced in the html version of the etext.)

- Hon. D. W. Carnegie

- Jarrah Forest, West Australia

- General store And Post-office, Coolgardie, 1892

- The first hotel at Coolgardie

- The “Gold Escort”

- Grass trees, near Perth

- Death of “Tommy”

- Fresh meat at last

- Bayley Street, Coolgardie, 1894

- Condensing water on a salt lake

- Fever-stricken and alone

- Miner's Right

- Typical sandstone gorge

- Crossing a salt lake

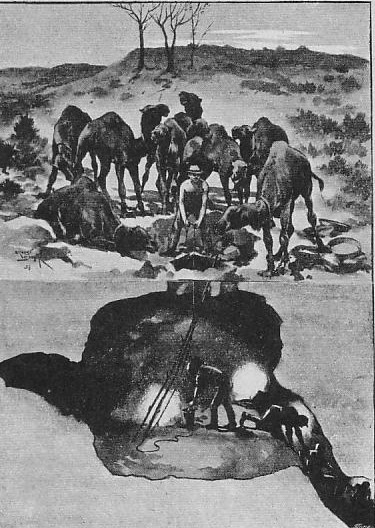

- Entrance to Empress Spring

- At work in the cave, Empress Spring

- Alexander Spring

- Woodhouse Lagoon

- A buck and his gins in camp at Family Well

- Cresting a sand-ridge

- Helena Spring

- The only specimen of desert architecture

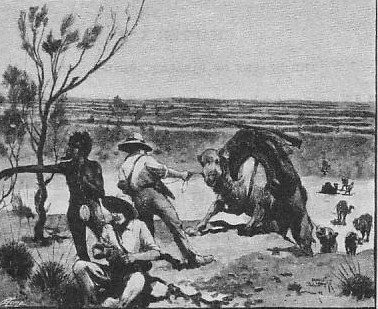

- The Mad Buck

- Southesk Tablelands

- A native hunting party

- Plan of sand-ridges

- Exaggerated section of the sand-ridges

- Charles W. Stansmore

- Native preparing for the emu dance

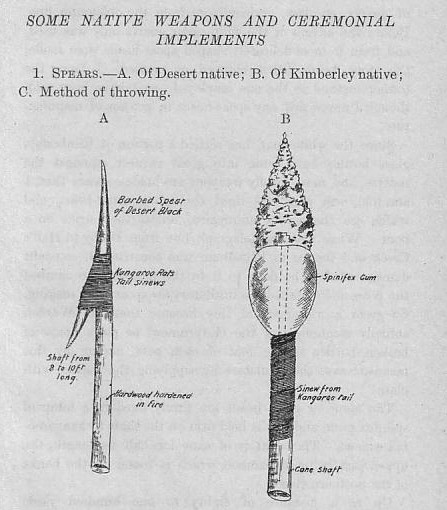

- Spears

- Woomera

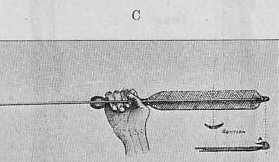

- Iron Tomahawks

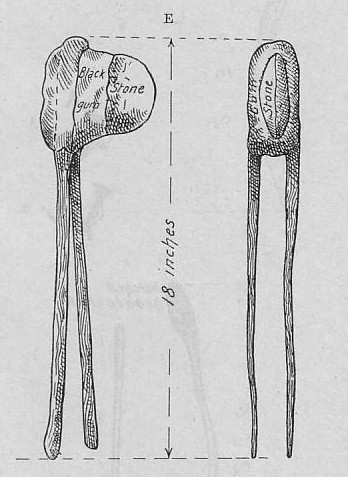

- Stone Tomahawks

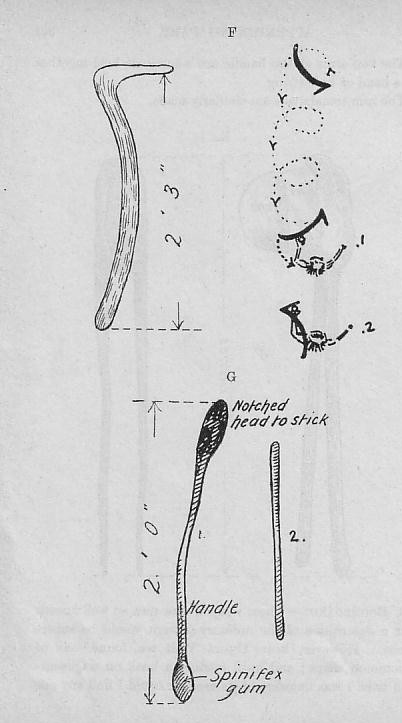

- Boomerangs

- Clubs and throwing-sticks

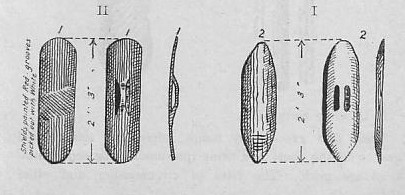

- Shields

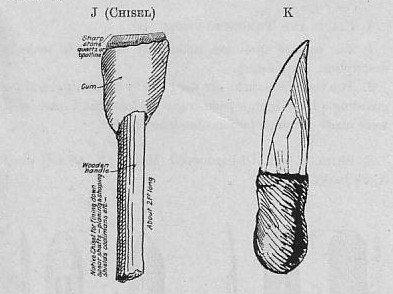

- Quartz knife

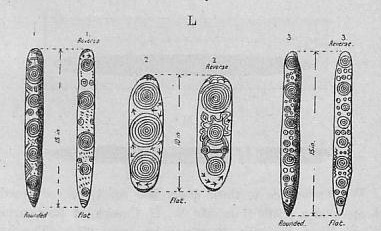

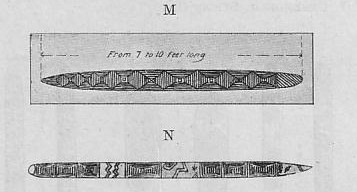

- Ceremonial sticks

- Rain-making boards

- Message sticks

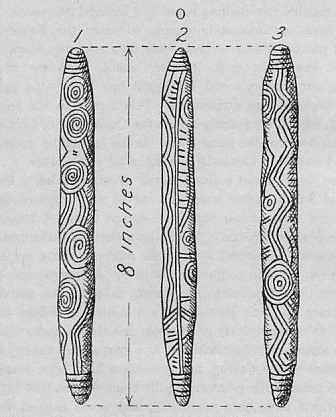

- Group Of Explorers

- Just in time

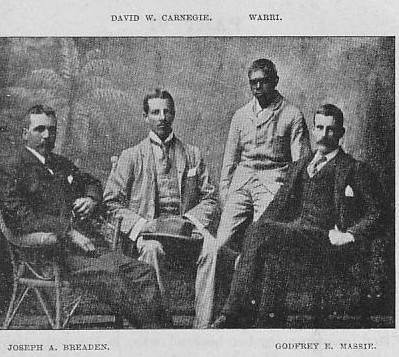

- A wild escort of nearly one hundred men

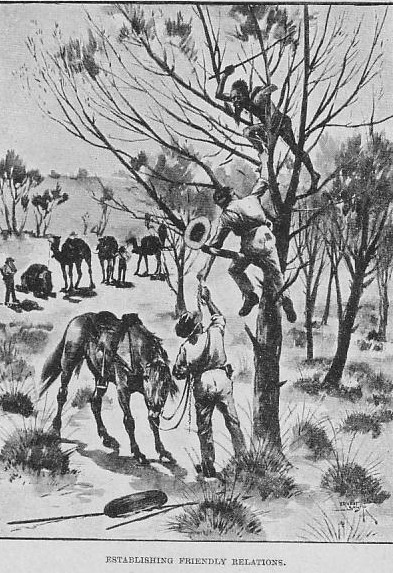

- Establishing friendly relations

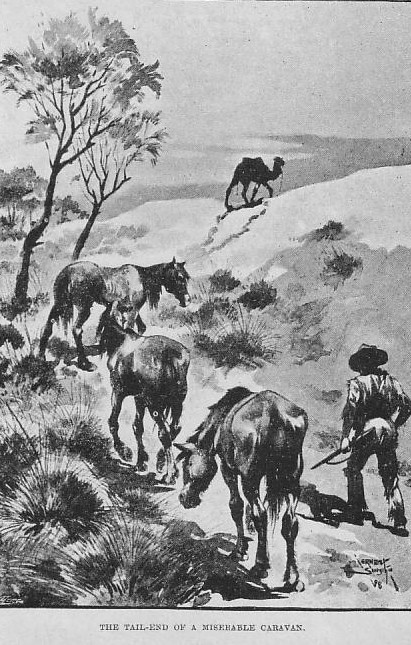

- The tail-end of a miserable caravan

- A karri timber train

- A pearl shell station, Broome, N.W. Australia

INTRODUCTION

“An honest tale speeds best, being plainly told.”

The following pages profess to be no more than a faithful narrative of five years spent on the goldfields and in the far interior of Western Australia. Any one looking for stirring adventures, hairbreadth escapes from wild animals and men, will be disappointed. In the Australian Bush the traveller has only Nature to war against—over him hangs always the chance of death from thirst, and sometimes from the attacks of hostile aboriginals; he has no spice of adventure, no record heads of rare game, no exciting escapades with dangerous beasts, to spur him on; no beautiful scenery, broad lakes, or winding rivers to make life pleasant for him. The unbroken monotony of an arid, uninteresting country has to be faced. Nature everywhere demands his toil. Unless he has within him impulses that give him courage to go on, he will soon return; for he will find nothing in his surroundings to act as an incentive to tempt him further.

I trust my readers will be able to glean a little knowledge of the hardships and dangers that beset the paths of Australian pioneers, and will learn something of the trials and difficulties encountered by a prospector, recognising that he is often inspired by some higher feeling than the mere “lust of gold.”

Wherever possible, I have endeavoured to add interest to my own experiences by recounting those of other travellers; and, by studying the few books that touch upon such matters to explain any points in connection with the aboriginals that from my own knowledge I am unable to do. I owe several interesting details to the Report on the Work of the Horn Scientific Expedition to Central Australia, and to Ethnological Studies among the North-West Central Queensland Aboriginals, by Walter E. Roth. For the identification of the few geological specimens brought in by me, I am indebted to the Government Geologist of the Mines Department, Perth, W.A., and to Mr. W. Botting Hemsley, through the courtesy of the Director of the Royal Gardens, Kew, for the identification of the plants.

I also owe many thanks to my friend Mr. J. F. Cornish, who has taken so much trouble in correcting the proofs of my MSS.

PART I

EARLY DAYS IN COOLGARDIE

CHAPTER I

Early Days In The Colony

In the month of September, 1892, Lord Percy Douglas (now Lord Douglas of Hawick) and I, found ourselves steaming into King George's Sound—that magnificent harbour on the south-west coast of Western Australia—building castles in the air, discussing our prospects, and making rapid and vast imaginary fortunes in the gold-mines of that newly-discovered land of Ophir. Coolgardie, a district then unnamed, had been discovered, and Arthur Bayley, a persevering and lucky prospector, had returned to civilised parts from the “bush,” his packhorses loaded with golden specimens from the famous mine which bears his name. I suppose the fortunate find of Bayley and his mate, Ford, has turned the course of events in the lives of many tens of thousands of people, and yet, as he jogged along the track from Gnarlbine Rock to Southern Cross, I daresay his thoughts reverted to his own life, and the good time before him, rather than to moralising on the probable effect of his discovery on others.

We spent as little time as possible at Albany, or, I should say, made our stay as short as was permitted, for in those days the convenience of the passenger was thought little of, in comparison with the encouragement of local industries, so that mails and travellers alike were forced to remain at least one night in Albany by the arrangement of the train service, greatly to the benefit of the hotel-keepers.

We were somewhat surprised to see the landlord's daughters waiting at table. They were such tremendously smart and icy young ladies that at first we were likely to mistake them for guests; and even when sure of their identity we were too nervous to ask for anything so vulgar as a pot of beer, or to expect them to change our plates.

Between Albany and Perth the country is not at all interesting being for the most part flat, scrubby, and sandy, though here and there are rich farming and agricultural districts. Arrived at Perth we found ourselves a source of great interest to the inhabitants, inasmuch as we announced our intention of making our way to the goldfields, while we had neither the means nor apparently the capability of getting there. Though treated with great hospitality, we found it almost impossible to get any information or assistance, all our inquiries being answered by some scoffing remark, such as, “Oh, you'll never get there!”

We attended a rather remarkable dinner—given in honour of the Boot, Shoe, Harness, and Leather trade, at the invitation of a fellow-countryman in the trade, and enjoyed ourselves immensely; speech-making and toast-drinking being carried out in the extensive style so customary in the West. Picture our surprise on receiving a bill for 10s. 6d. next morning! Our friend of the dinner, kindly put at our disposal a hansom cab which he owned, but this luxury we declined with thanks, fearing a repetition of his “bill-by-invitation.”

Illustration 2: Jarrah Forrest, West Australia

Owing to the extreme kindness of Mr. Robert Smith we were at last enabled to get under way for the scene of the “rush.” Disregarding the many offers of men willing to guide us along a self-evident track, we started with one riding and one packhorse each. These and the contents of the pack-bags represented all our worldly possessions, but in this we might count ourselves lucky, for many hundreds had to carry their belongings on their backs—“humping their bluey,” as the expression is.

Our road lay through Northam, and the several small farms and settlements which extend some distance eastward. Very few used this track, the more popular and direct route being through York, and thence along the telegraph line to Southern Cross; and indeed we did pass through York, which thriving little town we left at dusk, and, carrying out our directions, rode along the telegraph line. Unfortunately we had not been told that the line split up, one branch going to Northam and the other to Southern Cross; as often happens in such cases, we took the wrong branch and travelled well into the night before finding any habitation at which we could get food and water.

The owner of the house where we finally stopped did not look upon our visit with pleasure, as we had literally to break into the house before we could attract any attention. Finding we were not burglars, and having relieved himself by most vigorous and pictorial language (in the use of which the teamsters and small farmers are almost without rivals) the owner showed us his well, and did what he could to make us comfortable. I shall never forget the great hospitality here along this road, though no doubt as time went on the settlers could not afford to house hungry travellers free of cost, and probably made a fair amount of money by selling provisions and horse-feed to the hundreds of gold-fever patients who were continually passing.

Southern Cross, which came into existence about the year '90, was a pretty busy place, being the last outpost of civilisation at the time of our first acquaintance with it. The now familiar corrugated-iron-built town, with its streets inches deep in dust under a blazing sun, its incessant swarms of flies, the clashing of the “stamps” on the mines, and the general “never-never” appearance of the place, impressed us with feelings the reverse of pleasant. The building that struck me most was the bank—a small iron shanty with a hession partition dividing it into office and living room, the latter a hopeless chaos of cards, candle ends, whiskey bottles, blankets, safe keys, gold specimens, and cooking utensils. The bank manager had evidently been entertaining a little party of friends the previous night, and though its hours had passed, and a new day had dawned, the party still continued. Since that time it has been my lot to witness more than one such evening of festivity!

On leaving Southern Cross we travelled with another company of adventurers, one of whom, Mr. Davies, an old Queensland squatter, was our partner in several subsequent undertakings.

The monotony of the flat timber-clad country was occasionally relieved by the occurrence of large isolated hills of bare granite. But for these the road, except for camels, could never have been kept open; for they represented our sources of water supply. On the surface of the rocks numerous holes and indentations are found, which after rain, hold water, and besides these, around the foot of the outcrops, “soaks,” or shallow wells, are to be found.

What scenes of bitter quarrels these watering-places have witnessed! The selfish striving, each to help himself, the awful sufferings of man and beast, horses and camels mad with thirst, and men cursing the country and themselves, for wasting their lives and strength in it; but they have witnessed many an act of kindness and self-denial too.

Where the now prosperous and busy town of Coolgardie stands, with its stone and brick buildings, banks, hotels, and streets of shops, offices, and dwelling-houses, with a population of some 15,000, at the time of which I write there stood an open forest of eucalyptus dotted here and there with the white tents and camps of diggers. A part of the timber had already been cleared to admit of “dry-blowing” operations—a process adopted for the separation of gold from alluvial soil in the waterless parts of Australia.

Desperate hard work this, with the thermometer at 100°F in the shade, with the “dishes” so hot that they had often to be put aside to cool, with clouds of choking dust, a burning throat, and water at a shilling to half a crown a gallon! Right enough for the lucky ones “on gold,” and for them not a life of ease! The poor devil with neither money nor luck, who looked into each dishful of dirt for the wherewithal to live, and found it not, was indeed scarcely to be envied.

Water at this time was carted by horse-teams in waggons with large tanks on board, or by camel caravans, from a distance of thirty-six miles, drawn from a well near a large granite rock. The supply was daily failing, and washing was out of the question; enough to drink was all one thought of; two lines of eager men on either side of the track could daily be seen waiting for these water-carts. What a wild rush ensued when they were sighted! In a moment they were surrounded and taken by storm, men swarming on to them like an army of ants. As a rule, eager as we were for water, a sort of order prevailed, and every man got his gallon water-bag filled until the supply was exhausted. And generally the owner of the water received due payment.

About Christmas-time the water-famine was at its height. Notices were posted by order of the Warden, proclaiming that the road to or from Coolgardie would soon be closed, as all wells were failing, and advising men to go down in small parties, and not to rush the waters in a great crowd. This advice was not taken, and daily scores of men left the “field,” and many were hard put to it to reach Southern Cross. It was a cruel sight in those thirsty days to see the poor horses wandering about, mere walking skeletons, deserted by their owners, for strangers were both unable to give them water, and afraid to put them out of their misery lest damages should be claimed against them. How long our own supplies would last was eagerly discussed, as we gathered round the butcher's shop, the great meeting-place, to which, in the evenings, most of the camp would come to talk over the affairs of the day.

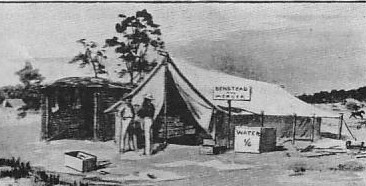

Postmaster, as well as butcher and storekeeper, was Mr. Benstead, a kind-hearted, hard-working man, and a good friend to us in our early struggles. What a wonderful post-office it was too! A proper match for the so-called coach that brought the mails. A very dilapidated buckboard-buggy drawn by equally dilapidated horses, used to do the journey from the Southern Cross to the new fields very nearly as quickly as a loaded waggon with eight or ten horses! The mail-coach used to carry not only letters, papers, and gold on the return journey, but passengers, who served the useful purposes of dragging the carriage through the sand and dust when the horses collapsed, of hunting up the team in the mornings, and of lightening the load by walking. For this exceedingly comfortable journey they had the pleasure of paying at least £five. It was no uncommon sight at some tank or rock on the road, to see the mail-coach standing alone in its glory, deserted by driver and passengers alike. Of these some would be horse-hunting, and the rest tramping ahead in hope of being caught up by the coach. There would often be on board many hundred pounds' worth of gold, sent down by the diggers to be banked, or forwarded to their families; yet no instance of robbing the mail occurred. The sort of gentry from whom bushrangers and thieves are made, had not yet found their way to the rush.

Illustration 3: General store and Post-office, Coolgardie, 1892

Many banks were failing at that time, and men anxiously awaited the arrival of news. The teamsters, with their heavy drays, would be eagerly questioned as to where they had passed Her Majesty's mail, and as to the probability of its arrival within the next week or so! The distribution of letters did not follow this happy event with great rapidity. Volunteers had to be called in to sort the delivery, the papers were thrown into a heap in the road, and all anxious for news were politely requested to help themselves. Several illustrated periodicals were regularly sent me from home, as I learnt afterwards, but I never had the luck to drop across my own paper!

On mail day, the date of which was most uncertain as the coach journeys soon overlapped, there was always a lengthy, well-attended “roll-up” at the Store. Here we first made acquaintance with Messrs. Browne and Lyon, then negotiating for the purchase of Bayley's fabulous mine of gold. No account of the richness of this claim at that time could be too extravagant to be true; for surely such a solid mass of gold was never seen before, as met the eye in the surface workings.

Messrs. Browne and Lyon had at their camp a small black-boy whom they tried in vain to tame. He stood a good deal of misplaced kindness, and even wore clothes without complaint; but he could not bear having his hair cut, and so ran away to the bush. He belonged to the wandering tribe that daily visited the camp—a tribe of wretched famine-stricken “blacks,” whose natural hideousness and filthy appearance were intensified by the dirty rags with which they made shift to cover their bodies. I should never have conceived it possible that such living skeletons could exist. Without begging from the diggers I fail to see how they could have lived, for not a living thing was to be found in the bush, save an occasional iguana and “bardies,” and, as I have said, all known waters within available distance of Coolgardie were dry, or nearly so.

“Bardies” are large white grubs—three or four inches long—which the natives dig out from the roots of a certain shrub. When baked on wood-ashes they are said to be excellent eating. The natives, however, prefer them raw, and, having twisted off the heads, eat them with evident relish.

Benstead had managed to bring up a few sheep from the coast, which the “gins,” or women, used to tend. The native camp was near the slaughter-yard, and it used to be an interesting and charming sight to see these wild children of the wilderness, fighting with their mongrel dogs for the possession of the offal thrown away by the butcher. If successful in gaining this prize they were not long in disposing of it, cooking evidently being considered a waste of time. A famished “black-fellow” after a heavy meal used to remind me of pictures of the boa-constrictor who has swallowed an ox, and is resting in satisfied peace to gorge.

The appeal of “Gib it damper” or “Gib it gabbi” (water), was seldom made in vain, and hardly a day passed but what one was visited by these silent, starving shadows. In appreciation no doubt of the kindness shown them, some of the tribe volunteered to find “gabbi” for the white-fellow in the roots of a certain gum-tree. Their offer was accepted, and soon a band of unhappy-looking miners was seen returning. In their hands they carried short pieces of the root, which they sucked vigorously; some got a little moisture, and some did not, but however unequal their success in this respect they were all alike in another, for every man vomited freely. This means of obtaining a water supply never became popular. No doubt a little moisture can be coaxed from the roots of certain gums, but it would seem that it needs the stomach of a black-fellow to derive any benefit from it.

Though I cannot say that I studied the manners and customs of the aboriginals at that time, the description, none the worse for being old, given to savages of another land would fit them admirably—“Manners none, customs beastly.”

CHAPTER II

“Hard Up”

During that drought-stricken Christmas-time my mate was down at the “Cross,” trying to carry through some business by which our coffers might be replenished; for work how we would on alluvial or quartz reefs, no gold could we find. That we worked with a will, the remark made to me by an old fossicker will go to show. After watching me “belting away” at a solid mass of quartz for some time without speaking, “Which,” said he, “is the hammer-headed end of your pick?” Then shaking his head, “Ah! I could guess you were a Scotchman—brute force and blind ignorance!” He then proceeded to show me how to do twice the amount of work at half the expenditure of labour. I never remember a real digger who was not ready to help one, both with advice and in practice, and I never experienced that “greening” of new chums which is a prominent feature of most novels that deal with Australian life.

In the absence of Lord Douglas, an old horse-artilleryman, Richardson by name, was my usual comrade. A splendid fellow he was too, and one of the few to be rewarded for his dogged perseverance and work. In a pitiable state the poor man was when first we met, half dead from dysentery, camped all alone under a sheet of coarse calico. Emaciated from sickness, he was unable to follow his horses, which had wandered in search of food and water, though they constituted his only earthly possession. How he, and many another I could mention, survived, I cannot think. But if a man declines to die, and fights for life, he is hard to kill!

Amongst the prospectors it was customary for one mate to look after the horses, and pack water to the others who worked. These men, of course, knew several sources unknown to the general public. It was from one of them that we learnt of the existence of a small soak some thirteen miles from Coolgardie. Seeing no hope of rain, and no prospect of being able to stop longer at Coolgardie, Mr. Davies, who camped near us, and I, decided to make our way to this soak, and wait for better or worse times. Taking the only horse which remained to us, and what few provisions we had, we changed our residence from the dust-swept flats of Coolgardie to the silent bush, where we set up a little hut of boughs, and awaited the course of events. Sheltered from the sun's burning rays by our house, so low that it could only be entered on hands and knees, for we had neither time nor strength to build a spacious structure, and buoyed up by the entrancement of reading The Adventures of a Lady's Maid, kindly lent by a fellow-digger, we did our best to spend a “Happy Christmas.”

Somehow, the climate and surroundings seemed singularly inappropriate; dust could not be transformed, even in imagination, into snow, nor heat into frost, any more easily than we could turn dried apples into roast beef and plum-pudding. Excellent food as dried fruit is, yet it is apt to become monotonous when it must do duty for breakfast, dinner, and tea! Such was our scanty fare; nevertheless we managed to keen up the appearance of being quite festive and happy.

Having spread the table—that is, swept the floor clear of ants and other homely insects—and laid out the feast, I rose to my knees and proposed the health of my old friend and comrade Mr. Davies, wished him the compliments of the season, and expressed a hope that we should never spend a worse Christmas. The toast was received with cheers and honoured in weak tea, brewed from the re-dried leaves of our last night's meal. He suitably replied, and cordially endorsed my last sentiment. After duly honouring the toasts of “The Ladies,” “Absent Friends,” and others befitting the occasion, we fell to on the frugal feast.

For the benefit of thrifty housewives, as well as those whom poverty has stricken, I respectfully recommend the following recipe. For dried apples: Take a handful, chew slightly, swallow, fill up with warm water and wait. Before long a feeling both grateful and comforting, as having dined not wisely but too heavily, will steal over you. Repeat the dose for luncheon and tea.

One or two other men were camped near us, and I have no doubt would have willingly added to our slender store had they known to what short commons we were reduced. Our discomforts were soon over, however, for Lord Douglas hearing that I was in a starving condition, hastened from the “Cross,” not heeding the terrible accounts of the track, bringing with him a supply of the staple food of the country, “Tinned Dog”—as canned provisions are designated.

Wandering on from our little rock of refuge, we landed at the Twenty-five Mile, where lately a rich reef had been found. We pegged out a claim on which we worked, camped under the shade of a “Kurrajong” tree, close above a large granite rock on which we depended for our water; and here we spent several months busy on our reef, during which time Lord Douglas went home to England, with financial schemes in his head, leaving Mr. Davies and myself to hold the property and work as well as we could manage and I fancy that for a couple of amateurs we did a considerable amount of development.

Here we lived almost alone, with the exception of another small party working the adjoining mine, occasionally visited by a prospector with horses to water. Though glad of their company, it was not with unmixed feelings that we viewed their arrival, for it took us all our time to get sufficient water for ourselves. I well remember one occasion on which, after a slight shower of rain, we, having no tank, scooped up the water we could from the shallow holes, even using a sponge, such was our eagerness not to waste a single drop; the water thus collected was emptied into a large rock-hole, which we covered with flat stones. We then went to our daily work on the reef, congratulating ourselves on the nice little “plant” of water. Imagine our disgust, on returning in the evening, at finding a mob of thirsty packhorses being watered from our precious supply! There was nothing to be done but to pretend we liked it. The water being on the rock was of course free to all.

How I used to envy those horsemen, and longed for the time when I could afford horses or camels of my own, to go away back into the bush and just see what was there. Many a day I spent poring over the map of the Colony, longing and longing to push out into the vast blank spaces of the unknown. Even at that time I planned out the expedition which at last I was enabled to undertake, though all was very visionary, and I could hardly conceive how I should ever manage to find the necessary ways and means.

Nearly every week I would ride into Coolgardie for stores, and walk out again leading the loaded packhorse, our faithful little chestnut “brumby,” i.e., half-wild pony, of which there are large herds running in the bush near the settled parts of the coast. A splendid little fellow this, a true type of his breed, fit for any amount of work and hardship. As often as not he would do his journey into Coolgardie (twenty-five miles), be tied up all night without a feed or drink—or as long as I had to spend there on business—and return again loaded next morning. Chaff and oats were then almost unprocurable, and however kind-hearted he might be, a poor man could hardly afford a shilling a gallon to water his horse. On these occasions I made my quarters at Bayley's mine, where a good solid meal and the pleasant company of Messrs. Browne and Lyon always awaited me. Several times in their generosity these good fellows spared a gallon or two of precious water for the old pony.

They have a funny custom in the West of naming horses after their owners—thus the chestnut is known to this day as “Little Carnegie.” Sometimes they are named after the men from whom they are bought. This practice, when coach-horses are concerned, has its laughable side, and passengers unacquainted with the custom may be astonished to hear all sorts of oaths and curses, or words of entreaty and encouragement, addressed to some well-known name—and they might be excused for thinking the driver's mind was a little unhinged, or that in his troubles and vexations he was calling on some prominent citizen, in the same way that knights of old invoked their saints.

Thus, our peaceful life at the “Twenty-five” passed on, relieved sometimes by the arrival of horsemen and others in search of water. Amongst our occasional visitors was a well-known gentleman, bearing the proud title of “The biggest liar in Australia.” How far he deserved the distinction I should hesitate to say, for men prone to exaggerate are not uncommon in the bush. Sometimes, however, they must have the melancholy satisfaction of knowing that they are disbelieved, when they really do happen to tell the truth. A story of my friend's, which was received with incredulous laughter, will exemplify this.

This was one of his experiences in Central Australia. He was perishing from thirst, and, at the last gasp, he came to a clay-pan which, to his despair, was quite dry and baked hard by the sun. He gave up all hope; not so his black-boy, who, after examining the surface of the hard clay, started to dig vigorously, shouting, “No more tumble down, plenty water here!” Struggling to the side of his boy, he found that he had unearthed a large frog blown out with water, with which they relieved their thirst. Subsequent digging disclosed more frogs, from all of which so great a supply of water was squeezed that not only he and his boy, but the horses also were saved from a terrible death!

This story was received with laughter and jeers, and cries of “Next please!” But to show that it had foundations of truth I may quote an extract from The Horn Scientific Expedition to Central Australia (part i. p. 21), in which we read the following:—

…The most interesting animal is the Burrowing or Waterholding Frog, (Chiroleptes platycephalus). As the pools dry up it fills itself out with water, which in some way passes through the walls of the alimentary canal, filling up the body cavity, and swelling the animal out until it looks like a small orange. In this condition it occupies a cavity just big enough for the body, and simply goes to sleep. When, with the aid of a native, we cut it out of its hiding-place, the animal at first remained perfectly still, with its lower eyelids completely drawn over the eyes, giving it the appearance of being blind, which indeed the black assured us that it was…

Most travellers cannot fail to have noticed how clay-pans recently filled by rain, even after a prolonged drought, swarm with tadpoles and full-grown frogs and numberless water insects, the presence of which must only be explained by the ability of the frog to store his supply in his own body, and the fact that the eggs of the insects require moisture before they can hatch out.

Many a laugh we had round the camp-fire at night, and many are the yarns that were spun. Few, however, were of sufficient interest to live in my memory, and I fear that most of them would lose their points in becoming fit for publication. “Gold,” naturally, was the chief topic of conversation, especially amongst the older diggers, who love to tell one in detail how many ounces they got in one place and how many in another, until one feels that surely they must be either millionaires or liars. New rushes, and supposed new rushes, were eagerly discussed; men were often passing and repassing our rock, looking for somebody who was “on gold”—for the majority of prospectors seldom push out for themselves, but prefer following up some man or party supposed to have “struck it rich.”

The rumours of a new find so long bandied about at length came true. Billy Frost had found a thousand! two thousand!! three thousand ounces!!!—who knew or cared?—on the margin of a large salt lake some ninety miles north of Coolgardie. Frost has since told me that about twelve ounces of gold was all he found, And, after all, there is not much difference between twelve and three thousand—that is on a mining field. Before long the solitude of our camp was disturbed by the constant passing of travellers to and from this newly discovered “Ninety Mile”—so named from its distance from Coolgardie.

As a fact, this mining camp (now known as the town of Goongarr) is only sixty odd miles from the capital, measured by survey, but in early days, distances were reckoned by rate of travel, and roads and tracks twisted and turned in a most distressing manner, sometimes deviating for water, but more often because the first maker of the track had been riding along carelessly, every now and then turning sharp back to his proper course. Subsequent horse or camel men, having only a vague knowledge of the direction of their destination, would be bound to follow the first tracks; after these would come light buggies, spring-carts, drays, and heavy waggons, until finally a deeply rutted and well-worn serpentine road through the forest or scrub was formed, to be straightened in course of time, as observant travellers cut off corners, and later by Government surveyors and road-makers.

Prospectors were gradually “poking out,” gold being found in all directions in greater or less degree; but it was not until June, 1893, that any find was made of more than passing interest. Curiously, this great goldfield of Hannan's (now called Kalgoorlie) was found by the veriest chance. Patrick Hannan, like many others, had joined in a wild-goose chase to locate a supposed rush at Mount Yule—a mountain the height and importance of which may be judged from the fact that no one was able to find it! On going out one morning to hunt up his horses, he chanced on a nugget of gold. In the course of five years this little nugget has transformed the silent bush into a populous town of 2,000 inhabitants, with its churches, clubs, hotels, and streets of offices and shops, surrounded by rich mines, and reminded of the cause of its existence by the ceaseless crashing of mills and stamps, grinding out gold at the rate of nearly 80,000 oz. per mouth.

Arriving one Sunday morning from our camp at the “Twenty-five,” I was astonished to find Coolgardie almost deserted, not even the usual “Sunday School” going on. Now I am sorry to disappoint my readers who are not conversant with miners' slang, but they must not picture rows of good little children sitting in the shade of the gum-trees, to whom some kind-hearted digger is expounding the Scriptures. No indeed! The miners' school is neither more nor less than a largely attended game of pitch-and-toss, at which sometimes hundreds of pounds in gold or notes change hands. I remember one old man who had only one shilling between him and the grave, so he told me. He could not decide whether to invest his last coin in a gallon of water or in the “heading-school.” He chose the latter and lost… subsequently I saw him lying peacefully drunk under a tree! I doubt if his intention had been suicide, but had it been he could hardly have chosen a more deadly weapon than the whiskey of those days.

The “rush to Hannan's” had depopulated Coolgardie and the next day saw Davies and myself amongst an eager train of travellers bound for the new site of fortune. “Little Carnegie” was harnessed to a small cart, which carried our provisions and tools. The commissariat department was easily attended to, as nothing was obtainable but biscuits and tinned soup. It was now mid-winter, and nights were often bitterly cold. Without tent or fly, and with hardly a blanket between us, we used to lie shivering at night.

A slight rain had fallen, insufficient to leave much water about, and yet enough to so moisten the soil as to make dry-blowing impossible in the ordinary way. Fires had to be built and kept going all night, piled up on heaps of alluvial soil dug out during the day. In the morning these heaps would be dry enough to treat, and ashes and earth were dry-blown together—the pleasures of the ordinary process being intensified by the addition of clouds of ashes.

A strange appearance these fires had, dotted through the brush, lighting up now a tent, now a water-cart, now a camp of fortunate ones lying cosily under their canvas roof, now a set of poor devils with hardly a rag to their backs. Oh glorious uncertainty of mining! One of these very poor devils that I have in my mind has now a considerable fortune, with rooms in a fashionable quarter of London, and in frock-coat and tall hat “swells” it with the best!

How quickly men change to be sure! A man who at one time would “steal the shirt off a dead black-fellow,” in a few short months is complaining of the taste of his wine or the fit of his patent-leather boots. Dame Fortune was good to some, but to us, like many others, she turned a deaf ear, and after many weeks' toil we had to give up the battle, for neither food, money, nor gold had we. All I possessed was the pony, and from that old friend I could not part. The fruits of our labours, or I should say my share in them, I sent home in a letter, and the few pin's-heads of gold so sent did not necessitate any extra postage. Weary and toil-worn we returned to Coolgardie, and the partners of some rather remarkable experiences split company, and went each his own way.

It is several years since I have seen Mr. Davies; but I believe Fortune's wheel turned round for him at length, and that now he enjoys the rest that his years and toils entitle him to. I have many kindly recollections of our camping days together, and of the numerous yarns my mate used to spin of his palmy days as a Queensland squatter.

CHAPTER III

A Miner On Bayley's

Returned from the rush, I made my way to Bayley's to seek employment for my pony and his master. Nor did I seek in vain, for I was duly entered on the pay-sheet as “surface hand” at £3 10 shillings per week, with water at the rate of one gallon per day. Here I first made the acquaintance of Godfrey Massie, a cousin of the Brownes, who, like me, had been forced by want of luck to work for wages, and who, by the way, had carried his “swag” on his back from York to the goldfields, a distance of nearly 300 miles. He and I were the first amateurs to get a job on the great Reward Claim, though subsequently it became a regular harbour of refuge for young men crowded out from the banks and offices of Sydney and Melbourne. Nothing but a fabulously rich mine could have stood the tinkering of so many unprofessional miners. It speaks well for the kindness of heart of those at the head of the management of the mine that they were willing to trust the unearthing of so much treasure to the hands of boys unused to manual work, or to work of any kind in a great many cases.

How rich the mine was, may be judged from the fact that for the first few months the enormous production of gold from it was due to the labours of three of the shareholders, assisted by only two other men. The following letter from Mr. Everard Browne to Lord Douglas gives some idea of what the yield was at the time that I went there to work:—

I am just taking 4,200 oz, over to Melbourne from our reef (Bayley's). This makes 10,000 oz. we have brought down from our reef without a battery, or machinery equal to treating 200 lbs. of stone per day; that is a bit of a record for you! We have got water in our shaft at 137 feet, enough to run a battery, and we shall have one on the ground in three months' time or under, Egan dollied out 1,000 oz, in a little over two months, before I came down, from his reef; and Cashman dollied 700 oz. out of his in about three weeks and had one stone 10 lbs. weight with 9 lbs. of gold in it, so we are not the only successful reefers since you left. I hope you will soon be with us again.If you are speaking about this 10,000 oz. we have taken out of our reef in six months, remember that Bayley and Ford dollied out 2,500 oz. for themselves before they handed it over to us on February 27th last, so that actually 12,500 oz. have been taken out of the claim, without a battery, in under nine months. The shoot of gold is now proved over 100 feet long on the course of the reef, and we were down 52 feet in our shaft on the reef, with as good gold as ever at the bottom. The other shaft, which we have got water in, is in the country (a downright shaft). We expect to meet the reef in it at 170 feet.

Besides Massie, myself, and Tom Cue, there were not then many employed, and really we used to have rather an enjoyable time than otherwise. Working regular hours, eight hours on and sixteen off, sometimes on the surface, sometimes below, with hammer and drill, or pick and shovel, always amongst glittering gold, was by no means unpleasant. It would certainly have been better still had we been able to keep what we found, but the next best thing to being successful is to see those one is fond of, pile up their banking account; and I have had few better friends than the resident shareholders on Bayley's Reward.

What good fellows, too, were the professional miners, always ready to help one and make the time pass pleasantly. Big Jim Breen was my mate for some time, and many a pleasant talk and smoke (Smoke, O! is a recognised rest from work at intervals during a miner's shift) we have had at the bottom of a shaft, thirty to fifty feet from the surface! I really think that having to get out of a nice warm bed or tent for night shift, viz., from midnight to 8 a.m., was the most unpleasant part of my life as a miner.

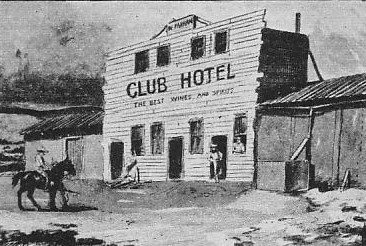

Illustration 4: The first hotel at Coolgardie

As recreation we used to play occasional games of cricket on a very hard and uneven pitch, and for social entertainments had frequent sing-songs and “buck dances”—that is, dances in which there were no ladies to take part—at Faahan's Club Hotel in the town, some one and a half miles distant. “Hotel” was rather too high-class a name, for it was by no means an imposing structure, hessian and corrugated iron taking the place of the bricks and slates of a more civilised building. The addition of a weather-board front, which was subsequently erected, greatly enhanced its attractions. Mr. Faahan can boast of having had the first two-storeyed house in the town; though the too critical might hold that the upper one, being merely a sham, could not be counted as dwelling-room. There was no sham, however, about the festive character of those evening entertainments.

Thus time went on, the only change in my circumstances resulting from my promotion to engine-driver—for now the Reward Claim boasted a small crushing plant—and Spring came, and with it in November the disastrous rush to “Siberia.” This name, like most others on the goldfields, may be traced to the wit of some disappointed digger.

The rush was a failure or “frost,” and so great a one that “Siberia” was the only word adequately to express the chagrin of the men who hoped so much from its discovery. Being one of these myself, I can cordially endorse the appropriateness of the name. What a motley crowd of eager faces throngs the streets and camp on the first news of a new rush—every one anxious to be off and be the first to make his fortune—every man questioning his neighbour, who knows no more than himself, about distances and direction, where the nearest water may be, and all manner of similar queries.

Once clear of the town, what a strange collection of baggage animals, horses, camels, and donkeys! What a mass of carts, drays, buggies, wheelbarrows, handbarrows, and many queer makeshifts for carrying goods—the strangest of all a large barrel set on an axle, and dragged or shoved by means of two long handles, the proud possessor's belongings turning round and round inside until they must surely be churned into a most confusing jumble. Then we see the “Swagman” with his load on his back, perhaps fifty pounds of provisions rolled up in his blankets, with a pick and shovel strapped on them, and in either hand a gallon bag of water. No light work this with the thermometer standing at 100°F in the shade, and the track inches deep in fine, powdery dust; and yet men start off with a light heart, with perhaps, a two hundred mile journey before them, replenishing their bundles as they pass through camps on their road.

“Siberia” was said to be seventy miles of a dry stage, and yet off we all started, as happy as kings at the chance of mending our fortunes.

Poor Crossman (since dead), McCulloch, and I were mates, and we were well off, for we had not only “Little Carnegie,” and who, like his master, had been earning his living at Bayley's, but a camel, “Bungo” by name, kindly lent by Gordon Lyon. Thus we were able to carry water as well as provisions, and helped to relieve the sufferings of many a poor wretch who had only his feet to serve him.

The story of Siberia may be soon told. Hundreds “rushed” over this dry stage, at the end of which a small and doubtful water supply was obtainable. When this supply gave out fresh arrivals had to do their best without it, the rush perforce had to set back again, privations, disaster, and suffering being the only result. Much was said and written at the time about the scores of dead and dying men and horses who lined the roads—roads because there were two routes to the new field. There may have been deaths on the other track, but I know that we saw none on ours. Men in sore straits, with swollen tongues and bleeding feet, we saw, and, happily, were able to relieve; and I am sure that many would have died but for the prompt aid rendered by the Government Water Supply Department, which despatched drays loaded with tanks of water to succour the suffering miners. So the fortunes, to be made at Siberia, had again to be postponed.

Illustration 5: The “Gold Escort”

Shortly after our return to Coolgardie a “gold escort” left Bayley's for the coast, and as a guardian of the precious freight I travelled down to Perth. There was no Government escort at that time, and any lucky possessor of gold had to carry it to the capital as best he could.

With four spanking horses, Gordon Lyon as driver, three men with him on the express-waggon, an outrider behind and in front, all armed with repeating rifles, we rattled down the road, perhaps secretly wishing that someone would be venturesome enough to attempt to “stick us up.” No such stirring event occurred, however, and we reached the head of the then partially constructed line, and there took train for Perth, where I eagerly awaited the arrival of my old friend and companion, Percy Douglas. He meanwhile had had his battles to fight in the financial world, and had come out to all appearances on top, having been instrumental in forming an important mining company from which we expected great things.

PART II

FIRST PROSPECTING EXPEDITION

CHAPTER I

The Rush To Kurnalpi—We Reach Queen Victoria Spring

Shortly after Lord Douglas's return, I took the train to York, where “Little Carnegie,” who had formed one of the team to draw the gold-laden express waggon from Bayley's to the head of the railway line, was running in one of Mr. Monger's paddocks. The Mongers are the kings of York, an agricultural town, and own much property thereabouts. York and its surroundings in the winter-time might, except for the corrugated-iron roofs, easily be in England. Many of the houses are built of stone, and enclosed in vineyards and fruit gardens. The Mongers' house was quite after the English style, so also was their hospitality. From York I rode along the old track to Southern Cross, and a lonely ride I had, for the train had superseded the old methods of travel, much to the disgust of some of the “cockies,” or small farmers, who expressed the opinion that the country was going to the dogs, “them blooming railways were spoiling everything”; the reason for their complaint being, that formerly, all the carrying had been in the teamsters' hands, as well as a considerable amount of passenger traffic.

I had one or two “sells” on the road, for former stopping-places were now deserted, and wells had been neglected, making it impossible, from their depth, for me to get any water. I was fortunate in falling in with a teamster and his waggon—a typical one of his class; on first sight they are the most uncouth and foul-tongued men that it is possible to imagine. But on further acquaintance one finds that the language is as superficial as the dirt with which they cannot fail to be covered, since they are always walking in a cloud of dust. My friend on this occasion was apostrophising his horses with oaths that made my flesh creep, to help them up a steep hill. The top reached, he petted and soothed his team in most quaint language. At the bottom of the slope he was a demon of cruelty, at its summit a kind-hearted human being! I lunched with him, sitting under his waggon for shade, and found him most entertaining—nor was the old pony neglected, for he was given a fine feed of chaff and oats.

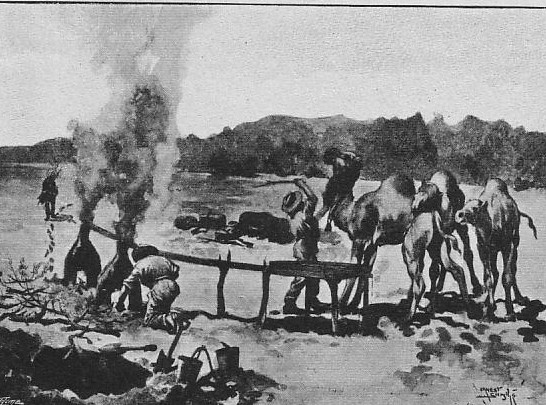

In due time I reached Coolgardie, where Lord Douglas and our new partner, Mr. Driffield (since drowned in a boating accident on the Swan River), joined me. They had engaged the services of one Luck and his camels, and had ridden up from the Cross. The rush to Kurnalpi had just broken out, so Driffield, Luck, and I joined the crowd of fortune-hunters; and a queer-looking crowd they were too, for every third or fourth swagman carried on his shoulder a small portable condenser, the boiler hanging behind him and the cooler in front; every party, whether with horses, carts, or camels, carried condensers of one shape or another; for the month was January, no surface water existed on the track, and only salt water could be obtained, by digging in the salt lakes which the road passed. The nearest water to the scene of the rush was a salt lake seven miles distant, and this at night presented a strange appearance. Condensers of every size and capacity fringed the two shores of a narrow channel; under each was a fire, and round each all night long could be seen figures, stoking the burning wood or drawing water, and in the distance the sound of the axe could be heard, for at whatever time a party arrived they had forthwith to set about “cooking water.” The clattering and hammering the incessant talking, and the figures flitting about in the glare, reminded one of a crowded open-air market with flaring lamps and frequent coffee stalls. Kurnalpi was known at first as “Billy-Billy,” or as “The Tinker's Rush”—the first name was supposed by some to be of native origin, by others to indicate the amount of tin used in the condensing plants—“Billy,” translated for those to whom the bush is unfamiliar, meaning a tin pot for boiling tea in, and other such uses.

Certainly there was plenty of tin at Kurnalpi, and plenty of alluvial gold as well for the lucky ones—amongst which we were not numbered. Poor Driffield was much disgusted; he had looked upon gold-finding as the simplest thing in the world—and so it is if you happen to look in the right place! and when you do so it's a hundred to one that you think your own cleverness and knowledge guided you to it! Chance? Oh dear, no! From that time forth your reputation is made as “a shrewd fellow who knows a thing or two”; and if your find was made in a mine, you are an “expert” at once, and can command a price for your report on other mines commensurate with the richness of your own!

As the gold would not come to us, and my partner disliked the labour of seeking it, we returned to Coolgardie, and set about looking after the mines we already had. Financial schemes or business never had any charms for me; when therefore I heard that the Company had cabled out that a prospecting party should be despatched at once, I eagerly availed myself of the chance of work so much to my taste. As speed was an object, and neither camels nor men procurable owing to the rush, we did not waste any time in trying to form a large expedition, such as the soul of the London director loveth, but contented ourselves with the camels already to hand.

On March 24, 1894, we started; Luck, myself, and three camels—Omerod, Shimsha, and Jenny by name—with rations for three months, and instructions to prospect the Hampton Plains as far as the supply of surface water permitted; failing a long stay in that region I could go where I thought best.

To the east and north-east of Coolgardie lie what are known as the Hampton Plains—so named by Captain Hunt, who in 1864 led an expedition past York, eastward, into the interior. Beyond the Hampton Plains he was forced back by the Desert, and returned to York with but a sorry tale of the country he had seen. “An endless sea of scrub,” was his apt description of the greater part of the country. Compared to the rest, the Hampton Plains were splendid pastoral lands. Curiously enough, Hunt passed and repassed close to what is now Coolgardie, and, though reporting quartz and ironstone, failed to hit upon any gold. Nor was he the only one; Coolgardie had several narrow squeaks of being found out.

Giles and Forrest both traversed districts since found to be gold-bearing, and though, like Hunt, reporting, and even bringing back specimens of quartz and ironstone, had the bad luck to miss finding even a “colour.”

Alexander Forrest, Goddard, and Lindsay all passed within appreciable distance of Coolgardie without unearthing its treasures, though in Lindsay's journal the geologist to the expedition pronounced the country auriferous. When we come to consider how many prospectors pass over gold, it is not so wonderful that explorers, whose business is to see as much country as they can, in as short a time as possible, should have failed to drop on the hidden wealth.

Bayley and Ford, its first discoverers, were by no means the first prospectors to camp at Coolgardie. In 1888 Anstey and party actually found colours of gold, and pegged out a claim, whose corner posts were standing at the time of the first rush; but nobody heeded them, for the quartz was not rich enough.

In after years George Withers sunk a hole and “dry blew” the wash not very far from Bayley's, yet he discovered no gold. Macpherson, too, poked out beyond Coolgardie, and nearly lost his life in returning, and, indeed, was saved by his black-boy, who held him on the only remaining horse.

Other instances could be given, all of which show that Nature will not be bustled, and will only divulge her secrets when the ordained time has arrived. It has been argued that since Giles, for example, passed the Coolgardie district without finding gold, therefore there is every probability of the rest of the country through which he passed being auriferous. It fails to occur to those holding this view, that a man may recognise possible gold-bearing country without finding gold, or to read the journals of these early travellers, in which they would see that the Desert is plainly demarcated, and the change in the nature of the country, the occurrence of quartz, and so forth, always recorded. These folk who so narrowly missed the gold were not the only unfortunate ones; those responsible for the choosing for their company of the blocks of land on the Hampton Mains were remarkably near securing all the plums.

Bayley's is one and a half miles from their boundary, Kalgoorlie twelve miles, Kurnalpi seven miles, and a number of other places lie just on the wrong side of the survey line to please the shareholders, though had all these rich districts been found on their land, I fancy there would have been a pretty outcry from the general public.

At the time of which I am writing this land was considered likely to be as rich as Ophir. Luck and I were expected to trip up over nuggets, and come back simply impregnated with gold. Unfortunately we not only found no gold, but formed a very poor idea of that part of the property which we were able to traverse, though, given a good supply of water, it should prove valuable stock country. Before we had been very long started on our journey we met numerous parties returning from that region, though legally they had no right to prospect there; each told us the same story—every water was dry; and since every one we had been to was all but dry, we concluded that they were speaking the truth; so when we arrived at Yindi, a large granite rock with a cavity capable of holding some twenty thousand gallons of water, and found Yindi dry, we decided to leave the Hampton Plains and push out into new country.

Queen Victoria Spring, reported permanent by Giles, lay some seventy miles to the eastward, and attracted our attention; for Lindsay had reported quartz country near the Ponton, not far from the Spring, and the country directly between the Spring and Kurnalpi was unknown.

On April 15th we left Yindi, having seen the last water twenty-six miles back near Gundockerta, and passed Mount Quinn, entering a dense thicket of mulga, which lasted for the next twenty miles. It was most awkward country to steer through, and I often overheard Luck muttering to himself that I was going all wrong, for he was a first-rate bushman and I a novice. I had bought a little brumby from a man we met on the Plains, an excellent pony, and most handy in winding his way through the scrub. Luck rode Jenny and led the other two camels. Hereabouts we noticed a large number of old brush fences—curiously I have never once seen a new one—which the natives had set up for catching wallabies. The fences run out in long wings, which meet in a point where a hole is dug. Neither wallabies nor natives were to be seen, though occasionally we noticed where “bardies” had been dug out, and a little further on a native grave, a hole about three feet square by three feet deep, lined at the bottom with gum leaves and strips of bark, evidently ready to receive the deceased. Luck, who knew a good deal about native customs, told me that the grave, though apparently only large enough for a child, was really destined for a grown man. When a man dies his first finger is cut off, because he must not fight in the next world, nor need he throw a spear to slay animals, as game is supplied. The body is then bent double until the knees touch the chin—this to represent a baby before birth; and in this cramped position the late warrior is crammed into his grave, until, according to a semi-civilised boy that I knew, he is called to the happy hunting grounds, where he changes colour! “Black fella tumble down, jump up white fella.” A clear proof that this benighted people have some conception of a better state hereafter.

Once through the scrub, we came again into gum-timbered country, and when fifty miles east of Kurnalpi crossed a narrow belt of auriferous country, but, failing to find water, were unable to stop. In a few miles we were in desert country—undulations of sand and spinifex, with frequent clumps of dense mallee, a species of eucalyptus, with several straggling stems growing from one root, and little foliage except at the ends of the branches, an untidy and melancholy-looking tree. There was no change in the country till after noon on the 18th, when we noticed some grass-trees, or black-boys, smaller than those seen near the coast, and presently struck the outskirts of a little oasis, and immediately after an old camel pad (Lindsay's in 1892, formed by a caravan of over fifty animals), which we followed for a few minutes, until the welcome sight of Queen Victoria Spring met our eyes. A most remarkable spot, and one that cannot be better described than by quoting the words of its discoverer, Ernest Giles, in 1875, who, with a party of five companions, fifteen pack, and seven riding camels, happened on this spring just when they most needed water.

Giles says of it:—

It is the most singularly placed water I have ever seen, lying in a small hollow in the centre of a little grassy flat and surrounded by clumps of funereal pines… the water is no doubt permanent, for it is supplied by the drainage of the sandhills which surround it and it rests on a substratum of impervious clay. It lies exposed to view in a small, open basin, the water being about only one hundred and fifty yards in circumference and from two to three feet deep. Further up the slopes at much higher levels native wells had been sunk in all directions—in each and all of these there was water. Beyond the immediate precincts of this open space the scrubs abound… Before I leave this spot I had perhaps better remark that it might prove a very difficult, perhaps dangerous, place to any other traveller to attempt to find, because although there are many white sandhills in the neighbourhood, the open space on which the water lies is so small in area and so closely surrounded by scrubs, that it cannot be seen from any conspicuous one, nor can any conspicuous sandhill, distinguishable at any distance, be seen from it. On the top of the banks above the wells was a beaten corroboree path, where the denizens of the desert have often held their feasts and dances. Some grass-trees grew in the vicinity of this spring to a height of over twenty feet…

A charming spot indeed! but we found it to be hardly so cheerful as this description would lead one to expect. For at first sight the Spring was dry. The pool of water was now a dry clay-pan; the numerous native wells were there, but all were dry. The prospect was sufficiently gloomy, for our water was all but done, and poor Tommy, the pony, in spite of an allowance of a billy-full per night, was in a very bad way, for we had travelled nearly one hundred miles from the last water, and if this was dry we knew no other that we could reach. However, we were not going to cry before we were hurt and set to work to dig out the soak, and in a short time were rewarded by the sight of water trickling in on all sides, and, by roughly timbering the sides, soon had a most serviceable well—a state of affairs greatly appreciated by Tommy and the camels. This spring or soakage, whichever it may be, is in black sand, though the sand outside the little basin is yellowish white. From what I have heard and read of them it must be something of the nature of what are called “black soil springs.” Giles was right in his description of its remarkable surroundings—unless we had marched right into the oasis, we should perhaps have missed it altogether, for it was unlikely that Lindsay's camel tracks would be visible except where sheltered from the wind by the trees; and our only instruments for navigation were a prismatic and pocket compass, and a watch for rating our travel. I was greatly pleased at such successful steering for a first attempt of any distance, and Luck was as pleased as I was, for to him I owed many useful hints. Yet I was not blind to the fact that it was a wonderful piece of luck to strike exactly a small spot of no more than fifty acres in extent, hidden in the valleys of the sandhills, from whose summits nothing could be seen but similar mounds of white sand. Amongst the white gum trees we found one marked with Lindsay's initials with date. Under this I nailed on a piece of tin, on which I had stamped our names and date. Probably the blacks have long since taken this down and used it as an ornament. Another tree, a pine, was marked W. Blake; who he was I do not know, unless one of Lindsay's party. Not far off was a grave, more like that of a white man than of a native; about its history, too, I am ignorant.

Illustration 6: Grass trees, near Perth

Numerous old native camps surrounded the water, and many weapons, spears, waddies, and coolimans were lying about. The camps had not been occupied for some long time. In the scrub we came on a cleared space, some eighty yards long and ten to twelve feet wide. At each end were heaps of ashes, and down the middle ran a well-beaten path, and a similar one on either side not unlike an old dray track. Evidently a corroboree ground of some kind. From Luck I learnt that north of Eucla, where he had been with a survey party, the natives used such grounds in their initiation ceremonies. A youth on arriving at a certain age may become a warrior, and is then allowed to carry a shield and spear. Before he can attain this honour he must submit to some very horrible rites—which are best left undescribed. Seizing each an arm of the victim, two stalwart “bucks” (as the men are called) run him up and down the cleared space until they are out of breath; then two more take places, and up and down they go until at last the boy is exhausted. This is the aboriginal method of applying anaesthetics. During the operations that follow, the men dance and yell round the fires but the women may not be witnesses of the ceremony. Tribes from all neighbouring districts meet at such times and hold high revel. Evidently Queen Victoria Spring is a favourite meeting-place. I regret that I never had the chance of being present at such a gathering—few white men have. For except in thickly populated districts the ceremonies are rare; the natives are very ready to resent any prying into their mysteries, and Luck only managed it at some risk to himself. Whilst camped at the Spring we made one or two short excursions to the southward, but met with little encouragement. On turning our attention to the opposite direction we found that nearly two hundred miles due north a tract of auriferous country was marked on the map of the Elder Expedition. Between us and that point, the country was unmapped and untrodden except by black-fellows, and it seemed reasonable to suppose that since the belts of country run more or less north and south we had a fair chance of finding gold-bearing country extending southward. We should be getting a long way from Coolgardie, but if a rich company could not afford to open up the country, who could? To the east we knew that desert existed, to the south the country was known, and to return the way we had come would be only a waste of time. So we decided on the northern course, and chose Mount Shenton, near which a soakage was marked, as our objective point. We were not well equipped for a long march in new country, since we had few camels and scanty facilities for carrying water. By setting to work with the needle we soon had two canvas water-bags made; Luck, who had served in the French navy, like all sailors, was a very handy man in a camp, and could of course sew well, and gave me useful lessons in the handling of a sail-needle.

CHAPTER II

In Unknown Country

On April 22nd we left the spring, steering due north—carrying in all thirty-five gallons of water, though this supply was very perceptibly reduced by evening, owing to the canvas being new; loss by evaporation was lessened by covering the bags with a fly (a sheet of coarse calico). The class of country we encountered the first and second day can stand for the rest of the march. Spinifex plains, undulating sand-plains, rolling sandhills, steep sand-ridges, mallee scrubs, desert-gum forests, and dense thickets of mulga. The last were most unpleasant to travel through; for as we wound our way, one walking ahead to break down the branches, the other leading the camels, and Tommy following behind, every now and again the water-camel banged his precious load against a tree; and we walked with the constant risk of a dead branch ripping the canvas and letting out the water.

On the second evening, in passing through a mallee scrub, we came on a small tract of “kopi country” (powdered gypsum). Here were numerous old native tracks, and we could see where the mallee roots had been dragged up, broken into short pieces, presumably sucked or allowed to drain into some vessel, and stacked in little heaps. Though we knew that the blacks do get water from the mallee roots, and though we were in a spot where it was clear they had done so perhaps a month before, yet our attempts at water-finding were futile. This kopi is peculiar soil to walk over; on the surface there is a hard crust—once through this, one sinks nearly to the knee; the camels of course, from their weight, go much lower.

On the night of the 23rd, we gave Tommy two gallons of water—not much of a drink, but enough to make him tackle the mulga, and spinifex-tops, the only available feed; none but West Australian brumbies could live on such fare, and they will eat anything, like donkeys or goats. On the 24th there was no change, a few quondongs affording a meal for the camels.

The next day we crossed more old native tracks and followed them for some time without any sign of water being near. More tracks the following day, fresher this time; but though doubtless there was water at the end of them, for several reasons we did not follow them far: first, they were leading south-west and we wished to go north; second, the quantity of mallee root heaps, suggested the possibility that the natives could obtain from them sufficient moisture to live upon. I think now that this is most unlikely, and that roots are only resorted to when travelling or in time of great need. However, at that time we were inclined to think it probable, and though we might have sucked roots in place of a drink of tea or water, such a source of supply was absolutely valueless to the camels and pony.

On the 27th we sighted a hill dead ahead, which I named Mount Luck, and on the southern side a nice little plain of saltbush and grass—a pleasant and welcome change. Mount Luck is sheer on its south and east sides and slopes gradually to the north-west; it is of desert sandstone, and from its summit, nearly due east, can be seen an imposing flat-topped hill, which I named Mount Douglas, after my old friend and companion, to the north of this hill two quaint little pinnacles stand up above the scrub to a considerable height.

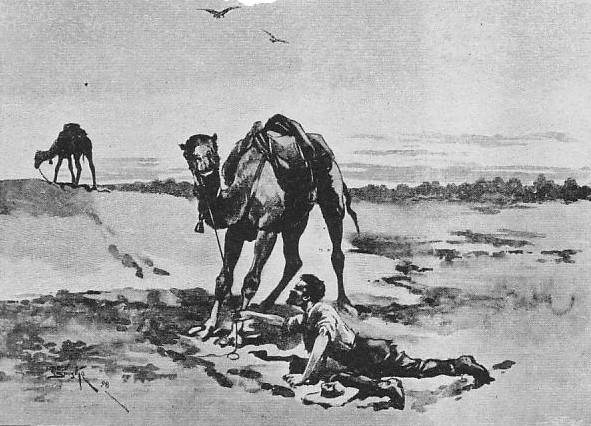

Poor Tommy was now getting very weak and had to be dragged by the last camel. I had not ridden him since the second day from the Spring; he was famished and worn to a skeleton. His allowance of two gallons a night had continued, which made a considerable hole in our supply, further diminished by the necessity of giving him damper to eat. Poor little pony! It was a cruel sight to see him wandering from pack to pack in camp, poking his nose into every possible opening, and even butting us with his head as if to call attention to his dreadful state, which was only too apparent. “While there's life there's hope,” and every day took us nearer to water—that is if we were to get any at all! So long as we could do so, we must take Tommy with us, who might yet be saved. This, however, was not to be, for on the 28th we again encountered sand-ridges, running at right angles to our course, and these proved too hard for the poor brave brumby. About midday he at last gave in, and with glazed eyes and stiff limbs he fell to the ground. Taking off the saddle he carried, I knelt by his head for a few minutes and could see there was no hope. Poor, faithful friend! I felt like a murderer in doing it, but I knew it was the kindest thing—and finished his sufferings with a bullet. There on the ridge, his bones will lie for many a long day. Brave Tommy, whose rough and unkempt exterior covered a heart that any warhorse might have envied, had covered 135 miles, without feed worth mentioning, and with only eleven gallons of water during that distance, a stage of nearly seven days' duration of very hard travelling indeed, with the weather pretty sultry, though the nights were cool. His death, however, was in favour of our water supply, which was not too abundant. So much had been lost by the bags knocking about on the saddle, by their own pressure against the side of the saddle, and by evaporation, that we had to content ourselves with a quart-potful between us morning and evening—by no means a handsome allowance.

Illustration 7: Death Of “Tommy”

On the 29th, after travelling eight hours through scrubs, we were just about to camp when the shrill “coo-oo” of a black-fellow met our ears; and on looking round we were startled to see some half-dozen natives gazing at us. Jenny chose at that moment to give forth the howl that only cow-camels can produce; this was too great a shock for the blacks, who stampeded pell-mell, leaving their spears and throwing-sticks behind them. We gave chase, and, after a spirited run, Luck managed to stop a man. A stark-naked savage this, and devoid of all adornment excepting a waist-belt of plaited grass and a “sporran” of similar material. He was in great dread of the camels and not too sure of us. I gave him something to eat, and, by eating some of it myself, put him more at ease. After various futile attempts at conversation, in which Luck displayed great knowledge of the black's tongue, as spoken a few hundred miles away near Eucla, but which unfortunately was quite lost on this native, we at last succeeded in making our wants understood. “Ingup,” “Ingup,” he kept repeating, pointing with his chin to the North and again to the West. Evidently “Ingup” stood for water; for he presently took us to a small granite rock and pointed out a soak or rock-hole, we could not say which. Whilst we stooped to examine the water-hole, our guide escaped into the scrub and was soon lost to view. Near the rock we found his camp. A few branches leaning against a bush formed his house. In front a fire was burning, and near it a plucked bird lay ready for cooking. Darkness overtook us before we could get to work on the rock-hole, so we turned into the blankets with a more satisfied feeling than we had done for some days past. During the night the blacks came round us. The camels, very tired, had lain down close by, and, quietly creeping to Jenny, I slapped her nose, which awoke her with the desired result, viz., a loud roar. The sound of rapidly retreating feet was heard, and their owners troubled us no more.

So sure were we of the supply in the granite that we gave the camels the few gallons that were left in our bags, and were much disgusted to find the next day that, far from being a soakage, the water was merely contained in a rock-hole, which had been filled in with sand and sticks.

April 30th and May 1st were occupied in digging out the sand and collecting what water we could, a matter of five or six gallons. So bad was this water that the camels would not touch it; however, it made excellent bread, and passable tea. Man, recognising Necessity, is less fastidious than animals who look to their masters to supply them with the best, and cannot realise that in such cases “Whatever is, is best.”

From a broken granite rock North-West of the rock-hole, we sighted numerous peaks to the North, and knew that Mount Shenton could not now be far away. To the East of the rock-hole is a very prominent bluff some fifteen miles distant; this I named Mount Fleming, after Colonel Fleming, then Commandant of the West Australian forces.

May 2nd we reached the hills and rejoiced to find ourselves once more in decent country. Numerous small, dry watercourses ran down from the hills, fringed with grass and bushes. In the open mulga, kangaroos' tracks were numerous, and in the hills we saw several small red kangaroos, dingoes, and emus. At first we found great difficulty in identifying any of the hills; but after much consultation and reference to the map we at last picked out Mount Shenton, and on reaching the hill knew that we were right, for we found Wells' cairn of stones and the marks of his camp and camels. The next difficulty was in finding the soakage, as from a bad reproduction of Wells' map it was impossible to determine whether the soak was at the foot of Mount Shenton or near another hill three miles away. It only remained to search both localities. Our trouble was rewarded by the finding of an excellent little soakage, near the foot of a granite rock, visible due East, from the top of Mount Shenton, some two miles distant. Here we had an abundant supply, and not before it was wanted. The camels had had no water with the exception of a mouthful apiece from the night of April 21st until the night of May 3rd, a period of twelve days, during which we had travelled nearly two hundred miles over very trying ground. The cool nights were greatly in their favour, and yet it was a good performance, more especially that at the end of it they were in pretty fair fettle.

What a joy that water was to us! what a luxury a wash was! and clean clothes! Really it's worth while being half famished and wholly filthy for a few days, that one may so thoroughly enjoy such delights afterwards! I know few feelings of satisfaction that approach those which one experiences on such occasions. Our cup of joy was not yet full, for as we sat mending our torn clothes, two over-inquisitive emus approached. Luckily a Winchester was close to hand, and as they were starting to run I managed to bowl one over. Wounded in the thigh he could yet go a great pace, but before long we caught up with him and despatched him with a blow on the head. What a feed we had! I suppose there is hardly a part of that bird, barring bones, feathers, and beak that did not find its way into our mouths during the next day or two! Tinned meat is good, sometimes excellent; but when you find that a cunning storekeeper has palmed off all his minced mutton on you, you are apt to fancy tinned fare monotonous! Such was our case; and no matter what the label, the contents were always the same—though we tried to differentiate in imagination, as we used to call it venison, beef, veal, or salmon, for variety's sake! “Well, old chap, what shall we have for tea—Calf's head? Grouse? Pheasant?” “Hum! what about a little er—minced mutton— we've not had any for some time, I think.” In this way we added relish to our meal.