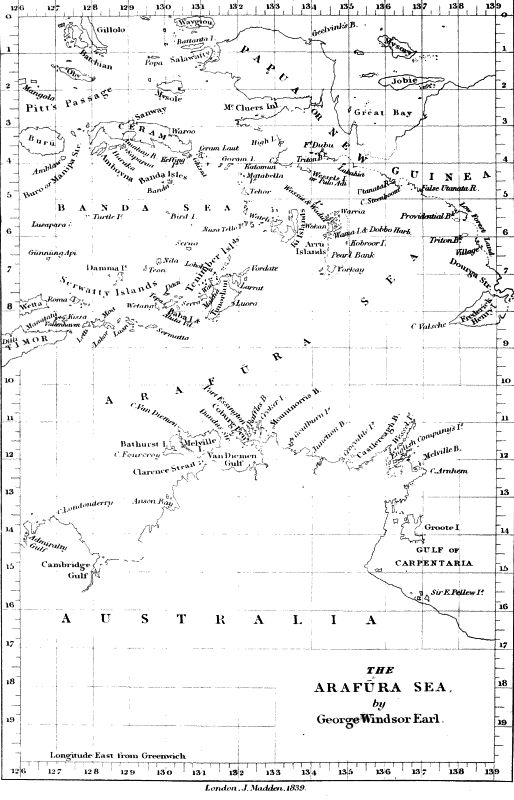

THE

ARAFŪRA SEA,

by

George Windsor Earl.

VOYAGES

OF THE

DUTCH BRIG OF WAR

DOURGA,

THROUGH THE

SOUTHERN AND LITTLE-KNOWN PARTS

OF THE

MOLUCCAN ARCHIPELAGO,

AND ALONG THE

PREVIOUSLY UNKNOWN SOUTHERN COAST

OF

NEW GUINEA,

PERFORMED

DURING THE YEARS 1825 & 1826.

BY

D.H. KOLFF, Jun.

LUITENANT TER ZEE, 1e KLASSE, EN RIDDER VAN DE MILITAIRE WILLEMS ORDE.

TRANSLATED FROM THE DUTCH

By GEORGE WINDSOR EARL,

AUTHOR OF THE "EASTERN SEAS."

LONDON:

JAMES MADDEN & CO., LEADENHALL STREET,

LATE PARBURY & Co.

1840.

LONDON:

EDWARD BREWSTER, PRINTER,

HAND COURT, DOWGATE.

AUTHOR'S PREFACE.

A plain preface will be best adapted for a simple narrative of events that occurred and observations made during Voyages through important countries, with a portion of which we were previously unacquainted, while the remainder have been but rarely visited. I was repeatedly requested by relatives and friends, both in India and in the Mother Country, to communicate these to the Public, as being information that would be deemed useful and important, not only by Government and Naval officers, but by every inquiring Netherlander. This encouragement induced me, who, being a seaman, cannot aspire to literary renown, to employ my leisure hours in compiling the following unadorned narrative of my voyages through the Southern parts of the Archipelago of the Moluccas, and along the South-west coast of New Guinea.

If the hopes I have cherished as to the importance of the information here given be not without ground, I trust that I shall not demand in vain the indulgence of my honoured Readers, which I am sure will be readily granted when it is taken into consideration, that the continued fatigues I endured, not only while engaged in performing the voyages here described, but also while employed in the expedition against Celebes in 1824, have undermined and broken my constitution. The confidence with which the Government honoured me by entrusting to me the execution of these voyages of examination, was certainly a spur which incited me to overcome all difficulties, and to make myself as useful as possible to my country.

With the assistance of my officers and of intelligent natives, I was fortunately enabled to collect accurate details concerning numerous islands and coasts, which I subsequently laid down in a chart, and forwarded it to the Government, a correct copy of which, on a smaller scale, I offer to my reader, as an illustration to the narrative.

If I have succeeded in effecting the object for which this volume is offered to the Public, I shall consider the time and trouble bestowed upon its compilation as being richly rewarded.

D.H. KOLFF, Jun.

November, 1838.

TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE.

The numerous islands lying between the Moluccas and the northern coasts of Australia, have hitherto been very little known to the world; indeed, we cannot discover that any account of them has yet been made public, with the exception of some observations in Valentyn's "Oude en Nieuw Oost Indien," a work published in Holland more than a century ago:—we are, therefore, induced to offer a few particulars concerning their early history, as an introduction to M. Kolff's narrative.

We cannot discover that these islands were ever visited by Europeans previous to 1636, in which year Pieter Pieterson, a Dutch navigator, touched at the Arru Islands during his voyage to examine the northern coasts of Australia, which had been discovered thirty years previously by a small Dutch vessel, called the Duyfken. Six years subsequently the Arru group was again visited by F. Corsten, when several of the native chiefs were induced to acknowledge the supremacy of the Dutch East India Company, binding themselves to trade with no other Europeans, and investing them with the monopoly of the pearl banks, the produce of which the Dutch conveyed to Japan, and there found a ready market and a lucrative return. Transactions, with similar views, subsequently took place at the adjacent islands, on which small bodies of troops were placed, to whose control the simple natives willingly submitted, and viewed with indifference the destruction of the spice trees, which were vigorously sought for and up-rooted by the new comers.

As it was the object of the Dutch to restrict the trade in spices within narrow limits, in order to enhance the value of this commodity, of which they enjoyed the monopoly, the East India Company did not permit even their own countrymen to carry on a commercial intercourse with these islands; indeed, the only advantages the Company derived from their possession, consisted in their affording slaves to cultivate the clove and nutmeg plantations of Banda and Amboyna, the only settlements in which they allowed spices to be grown. Notwithstanding these restrictions, an extensive contraband trade was carried on with the islands; for the Europeans who were, from time to time, encouraged by the Company to settle in the Moluccas as planters, although receiving bounties in the shape of free grants of land, with advances of slaves and provisions on credit and at original cost, under the sole condition that they should supply the Company with the produce at a fixed price, soon abandoned their plantations, and embarked in the more exciting and lucrative trade with the islands to the southward, sending confidential slaves in charge of their prahus.[1] It is[Pg a010] recorded, that many individuals collected enormous fortunes by this traffic, which, indeed, was nearly all profit, as the goods sent there were of very small value. The trepang fishery, now the principal source of wealth to these islands, then scarcely existed, and the return cargoes of the prahus consisted chiefly of less bulky articles, such as amber, pearls, tortoise-shell and birds-of-paradise.

Towards the close of the last century, when the rigorous monopoly of the Dutch had induced other natives to produce spices, which were cultivated with success by the French in the Isle of Bourbon, and by the English on the west coast of Sumatra, the Moluccas began to decline in importance, and with a view to reduce government expenditure, the Dutch withdrew their military establishments from the islands to the southward. The Bughis, an enterprising people from the southern part of the island of Celebes, and Chinese merchants from Java and Macassar, immediately engrossed the trade with the islands:—the wars which broke out in Europe about this time affording them great encouragement, since the Dutch, sufficiently occupied in maintaining their more important possession, could offer little interruption. The British, during their short occupation of the Moluccas, were so exclusively occupied by the immediate affairs of newly-acquired settlements, that the countries beyond their limits were, in a great measure, neglected; indeed, the inhabitants of some of the more remote islands were not aware that the Moluccas had changed masters; the Dutch flags left among them many years previously, being still hoisted on festive occasions.

When Java and its dependencies were restored to Dutch dominion after the peace of 1814, their East India Company had ceased to exist; the Government, however, continued to monopolize the traffic with the Moluccas. The Chinese merchants of Java and Macassar had, by this time, embarked largely in the trade with the Arru and Serwatty Islands; several brigs and large prahus, manned with Javanese, but having Chinese supercargoes, annually resorting to them from Sourabaya, and the other commercial ports to the westward.

Christianity, the seeds of which had been sown by the Dutch during their occupation of the islands, also began to spread among the inhabitants, and the native Amboynese teachers, who established themselves in some of the chief villages, were encouraged rather than molested by the Bughis and Chinese traders, these perceiving that their interests would be promoted by any advance the natives might make in civilization. The Bughis, unlike the Malayan and Ceramese Mohammedans, care little about making proselytes; neither do the Chinese feel much inclination to obtain converts to their half atheistical creed, which they themselves seem disposed to ridicule.

The founding of Singapore by Sir Stamford Raffles, in the year 1819, forms an important era in the history of the Indian Archipelago. The liberality of the institutions adopted there gave an impulse to commerce and civilization throughout the Eastern Seas, and even the most distant and barbarous tribes have not been excluded from participation in the general improvement. Among the first to avail themselves of this new state of affairs, were the enterprising Bughis tribes of Celebes, who flocked to Singapore by thousands, delighted at the favourable opportunity offered them for disposing of their produce to Europeans and Chinese merchants, without being subjected to extortionate imposts, or the annoyances of custom-house officers, which had hitherto checked their enterprize.

The islands in the eastern part of the Archipelago were, however, too distant from this emporium for the natives to partake of the benefits it offered, in an equal degree with those of the countries more adjacent. The greater portion of the produce afforded by the Arru and neighbouring islands, was collected and brought by the Bughis to Celebes, where it was re-shipped for Singapore; at least twelve months being required to send the goods to market and receive the returns.

It was chiefly to establish an intercourse with the natives of these parts, by presenting to them a more convenient mart for their produce, that a British settlement was formed on Melville Island, near the coast of Australia, in 1824, by Captain, now, Sir J.J. Gordon Bremer, and if this, and the settlement subsequently formed at Raffles Bay, proved unsuccessful, it is more to be attributed to our want of information concerning these islands than to any other cause. Two small vessels successively were sent among them by the authorities of Melville Island, neither of which returned. It will be seen by M. Kolff's narrative, that, unhappily, both these vessels directed their course to parts previously unvisited by foreigners, and that the natives, unable to resist the temptation of acquiring more valuable property than they had ever before contemplated, attacked and plundered them, killing the greater portion of their crews. Had they visited the parts of these islands which were frequented by the traders, they might have done so with comparative safety, as the natives there would have been too well aware of the value of commerce to risk the danger of putting a stop to it by an action likely to draw upon them the vengeance of a powerful people.

From M. Kolff's voyage having been undertaken so soon after our occupation of Melville Island, there is some reason to believe, that the formation of that settlement had considerable influence in inducing the Dutch Government suddenly to take a deep interest in the islands adjacent to it, which had been almost totally neglected for half a century previously. Whether this voyage was beneficial or otherwise to the British interest in that quarter the reader will be able to judge from the work itself, but, at all events, we have to thank M. Kolff for information which cannot but be valuable, now that we are about to found another settlement in that part of the world; H.M. ships Alligator and Britomart, again under the command of Sir Gordon Bremer, being on their voyage to the northern coast of Australia for the purpose. The arrangement of the work for publication has afforded the Translator occupation and amusement during a long voyage, and he trusts it may be the means of conveying useful information concerning a simple and industrious people, occupying a number of richly productive islands, in the immediate vicinity of a continent which may be considered a vast British colony, and with whom his countrymen may open an intercourse likely to prove advantageous to both parties.

H.M. Ship Alligator,

Sydney.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Si quelque habitans de Banda avaient acquis des richesses, ils ne les avaient nullement à l'industrie agricole, mais à la contrabande et au commerce avec les îles d'Arauw (Arru), ou ils envoyaeint des embarcations dirigées par les esclaves qu'on leur avait procurés pour l'entretien des pares (spice plantations). Quelques individus ont fait de cette manière une immense fortune.—Count de Hogendorp's "Coup-d'œil sur l'Isle de Java," p. 333.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| EXPEDITIONS IN THE MOLUCCA AND JAVA SEAS. | |

| PAGE | |

| Outward Voyage.—Tristan D'Acunha.—English Settlement.—Expedition in the Molucca Seas.—Voyage to Palembang and Banka.—Fidelity of Javanese Seamen.—Expedition to Macassar.—Particulars concerning the Macassar War. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| TIMOR. | |

| Object of the Voyage.—Sail for Timor.—Arrive at the Portuguese Settlement of Dilli.—Poverty of the Inhabitants.—Mean Reception.—Agriculture much neglected.—Slave Trade.—Symptoms of Distrust on the Part of the Portuguese.—Discontented state of their Native Subjects.—Departure for the Island of Wetta. | 29 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE SERWATTY ISLANDS. | |

| Arrival at the Island of Wetta.—Productions.—Trade.—Interview with the natives.—Destruction of the chief village.—Depart for Kissa.—The Christian inhabitants.—The fort Vallenhoven.—Friendly reception by the natives.—Beauty of the landscape.—State of agriculture.—Attachment of the people to the Dutch government.—General assemblage of the people.—Performance of divine service.—Native hospitalities.—Order, neatness and industry of the people of Kissa. | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| LETTE. | |

| Arrival at the Island of Lette.—Anchoring Place.—Series of Disasters.—Character of the Inhabitants.—The Mountaineers.—Differences among the Islanders.—Good Effects of our Mediation.—Respect entertained by the Natives towards the Dutch Government. | 57 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| MOA AND ROMA. | |

| Boat Expedition to the Island of Moa.—Good Inclination of the Inhabitants.—The Block-house.—The Duif Family.—Character of the People.—Respect entertained by the Heathen towards the Christian Inhabitants.—State of Civilization and Public Instruction.—Kind Hospitality of the Natives.—Their Feelings of Attachment and Confidence towards the Dutch Government.—Departure for the Island of Roma. | 70 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| DAMMA. | |

| Arrival at the Island of Damma.—Description of the Country and Inhabitants.—Warm Springs.—Retrograde Movements of the Natives in point of Civilization.—Their Attachment to the Religion and Manners of the Dutch.—Productions of the Soil.—Dangerous Channel along the Coast.—The Columba Globicera.—Wild Nutmeg Trees.—General Meeting of the Chiefs.—Transactions of M. Kam. | 91 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| LAKOR. | |

| Description of the Island Lakor.—Coral Banks.—Shyness of the Inhabitants.—Productions.—Singular Expedition.—Childish Litigiousness and obstinate Implacability.—Native Hospitality.—Customs and Dress of the People. | 107 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| LUAN. | |

| Arrival at the Island Luan.—Dangerous Passage.—Our Reception by the People.—Commerce and Fisheries.—The Christians of Luan.—Their Customs and Dispositions.—Hospitality and Good Nature of the Inhabitants.—Hazardous Situation on leaving the Island. | 117 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| BABA. | |

| Voyage towards Banda.—Remarks on the Islands Sermatta, Teon and Nila.—Arrival at Banda.—Humanity of an Orang-Kaya.—Description of the Island Baba.—Great Fear and Distrust of the Inhabitants.—Their Manners and Customs.—The Island Wetang.—Cause of the Distrust of the Natives.—Murderous and plundering Propensities of the People of Aluta.—Disturbances between the Inhabitants of Tepan and Aluta. | 129 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE ARRU ISLANDS. | |

| Daai Island.—Singular Change in the Colour of the Sea.—Festivities on Board.—The Arru Islands.—Description of these remarkable Regions.—Customs of the Arafuras.—Total Absence of Religion.—Proofs of the Mildness of their Form of Government.—Singular Treatment of their Dead. | 149 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE ARRU ISLANDS. | |

| Trade of the Arru Islands.—Chief Productions.—Trepang.—The Island Vorkay.—The Pearl Fishery.—The Arafuras of Kobroor and Kobiwatu.—Duryella, the capital of Wama.—The Schoolmaster.—Homage paid by the Natives to M. Kam. | 171 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE ARRU ISLANDS. | |

| Gathering of the People at Wokan.—Religious Exercises of the People.—Their singular Mode of Dress.—The Church.—The Fort.—State of Christianity on Wokan.—Dobbo, an important Trading Place.—Commercial Advantages that may be gained there.—Valuable Fishery.—The Pilandok.—Ludicrous alarm of the Arafuras. | 187 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE ARRU ISLANDS.—THE TENIMBER ISLANDS. | |

| Arrival at the Island Wadia.—Particulars concerning the Island and its Inhabitants.—Dispute between them and the Orang Tua of Fannabel.—Sad Result of their Contentions.—Departure from the Arru Islands.—Arrival at the Tenimber Group.—Vordate.—Ignorance and Perplexity of the Pilot.—Singular Customs.—Violent Conduct of the People of Timor-Laut.—The Inhabitants of Watidal and their Chiefs. | 206 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE TENIMBER ISLANDS. | |

| Visit to Watidal.—Respect shown to the Dutch Flag.—The English supposed by the Natives to be Orang-gunung, or Mountaineers.—The Prosperity of the People inseparable from the Rule of the Dutch over these Countries.—Traces of the Christian Religion having formerly obtained here.—Departure from Larrat to Vordate.—Allurements of the latter Island.—The Inhabitants of the Tenimber Islands.—Their Manners and Customs.—Mode of Warfare.—Striking Proofs of their Attachment to the Dutch Government. | 232 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE TENIMBER ISLANDS. | |

| The Village Chiefs of Sebeano.—Ludicrous Mistake.—War between Romian and Ewena.—The insignificant Cause which gave rise to it.—Successful Attempts at Reconciliation.—Contribution towards giving a Knowledge of their Character.—State of the Country.—Productions and Commerce.—The Author visits Larrat.—Uncivil Reception at Kalioba.—Departure for Watidal.—Meeting on the North-west Point of Timor Laut.—Departure for Serra. | 249 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| THE TENIMBER ISLANDS. | |

| Departure for the Island Maling.—Laboba Island.—Productive Fishery.—Heavy Dew on the Island Wau.—Arrival at the Village of Maktia.—Occurrences there.—One of the Crew severely wounded.—Return towards Vordate.—Return of the Envoys to Serra.—Want of Water.—Poisonous Beans.—Death of the wounded Man.—Return to the Brig.—Arrival of the Chiefs of Serra.—Transactions at Vordate.—Departure from the Tenimber Islands.—Arrival at Amboyna. | 268 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| THE CERAM-LAUT AND GORAM ISLANDS. | |

| Preparations for a Voyage to New Guinea.—Departure from Amboyna.—Banda.—Arrival at Kilwari.—Ghissa.—Character of the Inhabitants.—Visit from the Chiefs of Kilwari and Keffing.—Their Wars.—Force of the Islanders.—The Ceram Laut Islands.—Their Vessels.—Commerce.—Exclusive Right assumed by the Inhabitants over the Coast of New Guinea.—Smuggling Trade of the English.—Papuan Pirates devour their Prisoners.—Slaves.—Sale of Children by their Parents. | 284 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| GORAM AND THE ARRU ISLANDS. | |

| The Keffing Islands.—Dwellings of the Chiefs.—Pass the Goram Islands.—Description of the same.—Acquaintance of the Natives with the Coast of New Guinea.—The Products of these Islands of vital Importance to Banda.—Small Portion of the Trade enjoyed by our Settlements.—Coin.—Costume of the Inhabitants.—Equipment of Paduakan.—Snake-Eaters.—The Fishery.—Arrival of the Brig at Wadia.—Number of trading Prahus at Dobbo.—Adjustment of Disputes.—Christian Teachers on the Arru Islands.—Their Poverty.—Visit Wokan.—Appointment of an Upper Orang Kaya, and other Transactions on the Arru Islands. | 302 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| NEW GUINEA. | |

| Voyage towards the St. Bartholomeus River.—Encounter a Multitude of Whales.—Discover a Sand-bank.—Nautical Remarks.—Difficulty in approaching the Land.—Sharks.—Crocodiles.—Discover a River.—The Author ascends it.—Remarkable Behaviour of the Natives.—Their Wild State.—Unable to land.—Arrival at an uninhabited Bay on the Island of Lakahia.—Visit from some of the Chiefs. | 317 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| NEW GUINEA. | |

| Armed Boats sent on Shore.—Treacherous Attack of the Natives.—A Soldier killed.—Cowardly Conduct of the Officers in Charge of the Watering-Party.—The Author personally visits the Bay.—Causes of the Barbarism of the Natives of New Guinea.—Faithless and arbitrary Conduct of the Ceramese.—Profitable Nature of the Trade.—Departure from New Guinea. | 332 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE KI AND TENIMBER ISLANDS. | |

| The Ki Islands.—Character of the People.—Arrive at Vordate.—Improved Condition of the Natives.—Ceramese Pirates.—The English Captives at Luora.—The Author departs for Serra in the Boats.—Meet with a Prahu-tope.—Honesty of the Natives in their Dealings.—Arrival at Serra.—Native Warfare.—Ceremonies attending the Peace-making.—Return towards Vordate.—Turtles and their Eggs.—Wild Cattle.—Arrival on Board the Brig.—Singular Customs with regard to Trade.—Demand for Gold Coin.—Departure from the Tenimber Islands.—Arrival at Amboyna.—Approval of our Proceedings by the Government.—Conclusion. | 344 |

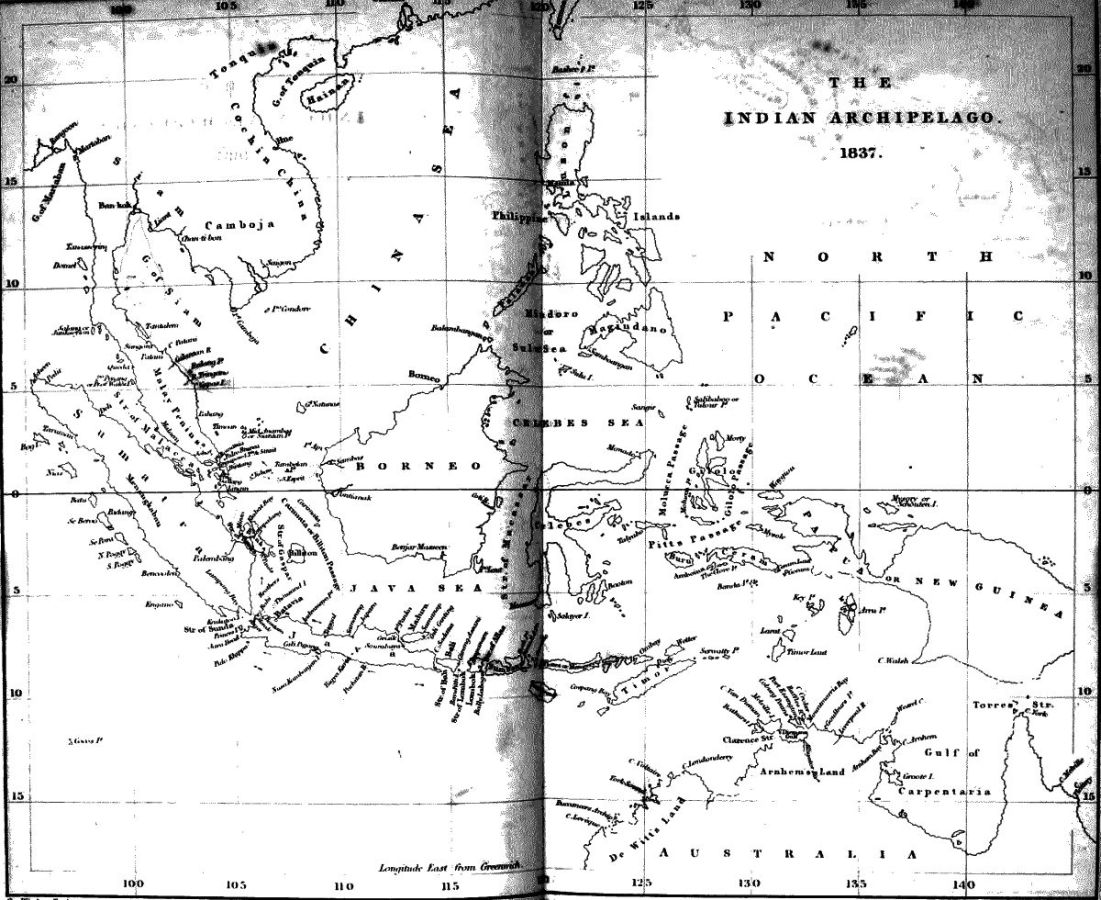

THE

INDIAN ARCHIPELAGO.

1837.

[Pg 1]

VOYAGES

OF THE

DUTCH BRIG DOURGA,

&c. &c.

CHAPTER I.

EXPEDITIONS IN THE MOLUCCA AND JAVA SEAS.

Outward Voyage.—Tristan D'Acunha.—English Settlement.—Expedition in the Molucca Seas.—Voyage to Palembang and Banka.—Fidelity of Javanese Seamen.—Expedition to Macassar.—Particulars concerning the Macassar War.

As an introduction to the narrative, I will communicate to the reader a short account of my outward voyage to India, and of the various expeditions in which I was engaged previous to undertaking the voyage to the eastern parts of the Indian Archipelago, which forms the subject of this volume.

[Pg 2]

In January 1817, I was appointed by the Minister of Marine to the corvette Venus, Commander B.W.A. Van Schuler, then lying in the Niewe Diep, ready for sea on a voyage to Batavia. On the 28th of the same month we sailed, under a salute of the guns, and having sent away the pilot with parting letters to our friends, we stood out to sea, the shores of our beloved country soon fading from view.

Remarkable events seldom occurring during the outward voyage, a few words will suffice to give an account of our proceedings. In the month of April we arrived off Tristan D'Acunha, and having espied a number of huts on the shores of a bay on the north side of the island, we stood towards them, and anchored in twenty-five fathoms, tolerably close to the land. When viewed from a distance the island has the appearance of a single high mountain, the sides rising abruptly out of the sea. The bay in which we anchored lies open to the sea, and therefore can afford no shelter to vessels. Its shores were steep and lined with alternate patches of sand and rock, against which the sea beat with great violence. The snow-white foam of the surf, glittering in the sun-beams, contrasted strikingly with the soft green of the uplands; the charming prospect this afforded[Pg 3] being embellished by a beautiful waterfall tumbling into the sea from the hills above.

The English establishment, which had been fixed here a short time previous to our visit, consisted of seventy-four men, with their wives, under the command of Major Kloete, the settlement being a dependance of the Cape of Good Hope. It had already made great progress, agriculture being carefully attended to; and among other vegetables we were delighted to find an abundance of excellent potatoes. The industrious and orderly habits of these settlers, coupled with their civility towards strangers, of which we had evidence in the friendly reception we met with, entitled them to every praise. This settlement, however, now no longer exists.

After our departure from Tristan D'Acunha we encountered a severe gale, in which we lost two topmasts, the foremast and bowsprit. Lieutenant Vendoren with seven seamen also fell overboard, and the former only was saved. On the 29th of June we arrived at Batavia, and after a short stay there, departed for the populous town of Sourabaya to refit our damaged vessel.

The first expedition in which we were engaged was directed against Ceram and Sapanua, where some serious disturbances had taken place. On[Pg 4] the 22nd of February 1818 we obtained a decided victory over the Sultan Muda of Batjoli in the Moluccas, for which I believe, our commander, M. Van Schuler, was made Knight of the third class of the Military Order of William.

During the whole of the year 1818, we were employed in cruizing among the Molucca Islands, for the prevention of piracy and the contraband trade, especially the illegal sale of gunpowder to the natives in a state of insurrection. The pirates sometimes behave with great boldness, deriving confidence from the rapidity with which their light vessels can escape into the numerous creeks; the oars which they use when the wind is contrary giving them great advantages in point of swiftness over our cruizers. A couple of steam-boats, which would be able to follow them into their lurking places, would be very efficacious in ridding us of these plagues.

On the 12th of January 1819, the then Governor of the Moluccas, General De Kock, with his family, embarked on board the Venus for the purpose of being conveyed to Java. We sailed on the following day, and did not reach Batavia until the 4th of May following. During this tedious passage, a beautiful collection of the birds of the Moluccas,[Pg 5] the property of the General, died from want of food. Salt meat and biscuit formed our sole diet during the greater part of the voyage, and it is surprising that with such provisions, we did not have considerable sickness on board.

We now proceeded to Sourabaya, being accompanied by Captain Stout, of the Colonial Marine, with several light vessels. When off the Taggal Mountain we encountered some piratical vessels, and having been several times employed with native seamen, speaking their language with tolerable fluency, I was placed in charge of a Korra-korra, and sent in chase. Captain Stout met with a sad accident on this occasion. A gun that had been fired by the Captain himself, perhaps from its being overloaded, recoiled so much that it burst through the bulwarks on the opposite side of the vessel and fell overboard, striking the Captain violently on the breast during its passage, and causing the almost immediate death of this brave seaman.

In the latter part of the year 1819, the Venus was placed in readiness to return to the mother country. Our joyful expectations, however, were soon disappointed, for the disturbances which had broken out at Palembang, rendered it necessary that the corvette should proceed there, to be in[Pg 6] readiness to act against the Sultan Mohammed Badr-el-Din; and on the 4th of December we arrived in the roads of Minto, on the island of Banka, to await the time when our services would be required.

All prospects of a speedy return home were thus destroyed, but I consoled myself with the consideration that duty required the sacrifice, and that I could serve my country in these remote regions as well as in the Netherlands. Our foreign possessions, indeed, though far distant, are still provinces of the fatherland.

Actuated by these considerations, I willingly accepted the offer made to our junior officers to enter the Colonial Navy, and receive the command of a gun-boat armed with an 18-pounder, two 8-pounders, some swivels, and manned with thirty men, chiefly Javanese, the same rank being given me with that I held in the Royal Navy. I was now sent to the east coast of Banka, for the purpose of keeping the pirates in check, and of keeping open the communication with the tin mines. At first I was accompanied by the schooner Zeemeeuw, Lieutenant Alewyn, but this vessel was soon ordered on another station, and I remained here eight months, in daily contact with the pirates, without the assistance of[Pg 7] other Europeans; this period forming by no means the most agreeable portion of my stay in India. I had often serious engagements with the famed Radin Allin, who, however, never was courageous enough to board the gun-boat. Had he done so, our only resource would have been to blow up our vessel, to prevent her falling into the hands of the pirates, as the great superiority of their force would have rendered it impossible to withstand them. This Radin Allin displayed great intrepidity on several occasions. Once, while I was conveying some vessels to Kaba, he took advantage of my absence to attack and carry the fort of Batu-Rusa, on the Marawang river. On my return I found him still in the river with a large number of prahus, where I blockaded him until the month of September 1820, when I at length received assistance from Minto, at a period when such relief had become of the greatest necessity, as I had often thought that my last hour had arrived. Of my crew, only a few natives remained, the others having either been killed or sent to the hospital.

During these hazardous expeditions I had frequent opportunities of witnessing the fidelity of the Javanese seamen in the hour of danger. Their behaviour and disposition prepossessed me very[Pg 8] much in favour of the nation to which they belonged, and during my subsequent voyaging in India, where I considerably increased my acquaintance with them, I never had occasion to alter the favourable opinion I had formed. When a Javanese is treated with consideration, and is not subjected to tyrannical treatment, he is as much to be trusted as an European, and submits far more readily to control.

The force which came to my relief consisted of several vessels under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Keer, destined to act against the chiefs of the rebels, Radin Allin and Radin Kling, and I now obtained permission to return to Minto. In the beginning of 1821, I departed thence for Sourabaya, with the view of having the gun-boat repaired, as it was ordered to take part in the expedition which during that year re-established our authority at Palembang. The particulars of that renowned expedition being still fresh in the memory of my readers, I will give no circumstantial account of our proceedings, but I will relate a few occurrences in which I was personally engaged. After the first attack, when our fleet had retired to its former position, it was my good fortune to rescue Lieutenant Boerhave and his[Pg 9] men, together with the crew of another gun-boat, both of which had fallen into the hands of the enemy; and on the following 24th of June, during the second assault, the gun-boat under my command opened the way through the strong barricade erected across the river to the attack of the great floating battery, on which I was the first to plant the Netherlands flag. As a token of particular approbation on the part of the Government for this deed, three of my small crew received the decoration of the military order of William.

After the termination of this renowned expedition, which ended in the entire conquest of the kingdom of Palembang, I received orders to accompany General De Kock to Batavia. In the month of August I was appointed to the schooner Calypso, which circumstance I only mention for the purpose of rendering a just tribute to the meritorious character of Lieutenant Sondervan her commander. In this vessel I passed the entire year 1822, making several voyages in her, circumnavigating Java, and visiting the mines of Sambas and Pontiana, in Borneo. M. Tobias, the commissioner for our establishments in Borneo, was on board the schooner the greater portion of the time. The agreeable society of this gentleman, coupled with[Pg 10] the unbroken harmony that prevailed among us, rendered these voyages extremely pleasant, notwithstanding the hardships and fatigues we underwent. We made several journeys into the interior of Borneo, and inspected the mines of the Chinese, which are here very numerous. I will not particularise the voyages I subsequently undertook to Banka, Sumatra, and many other of our possessions, which I performed with pleasure, as they gave me many opportunities of gathering information concerning these countries and their native inhabitants.

Having thus passed a considerable time in India, without experiencing the lassitude of which Europeans in that part of the world so generally complain, I was appointed adjutant to my former chief, Captain Van Schuler, who had now become Commandant and Director of the Colonial Marine. Although I was much pleased by the honourable notice with which my brave chief favoured me, I soon became tired of an idle life at Batavia. I had been so long accustomed to the navigation of these seas, that I could not refrain from soliciting the Governor General, Van Der Capellen, to place me again in active service.

While performing a journey overland from Batavia to Sourabaya in company with Captain Van[Pg 11] Schuler, I took the opportunity of visiting Bantjar, in the district of Rembang, where I saw the beautiful frigate Javaan, with several brigs and schooners, then in the course of construction for the Colonial Navy.[2] The command of one of these was promised to me on this occasion. I will pass over the description of this part of Java, as being unconnected with the object of the work. We met with few occurrences worthy of remark, for I do not consider our adventure in crossing the Sumadang Mountains, where our carriage was overturned, of sufficient importance to detain me in my narrative.

On my return to Batavia I was promoted to a Lieutenancy of the first class in the Colonial Marine, and at my urgent request was suffered to throw up my appointment as Adjutant, when I was invested with the command of H.M. Brig Dourga,[Pg 12][3] with orders to ship a crew, and fit her out in readiness to accompany the Governor General on his expedition to the Moluccas in 1824. So recently promoted, invested with a new command, and about to become a fellow-voyager with his Excellency, it will readily be conceived that my zeal was of the strongest, and that I exerted myself to the utmost to show myself worthy of the favours that had been conferred upon me.

After remaining a considerable time at Amboyna, a settlement distinguished by the courtesy and hospitality of its European inhabitants, we sailed for Banda in the train of the Governor General, (who was embarked in the frigate Eurydice), where we arrived on the 18th of April. The Gunung Api volcano was in a state of violent action at the time, filling the atmosphere with fire and smoke, the volumes of the latter being ejected with such force, that their collision caused constant vivid flashes of lightning, accompanied by a rumbling noise like that of thunder. This outbreak of nature was indescribably fine and majestic, and is memorable for having formed a new crater in the north-west side of the mountain. The town of Banda, remained, however, uninjured.

From Banda we sailed for Sapanua, an island[Pg 13] well known from the war which took place there in 1817, and I subsequently proceeded to Menado and Macassar, where I took part in the expedition called forth by the war that had broken out in Celebes.

The mode of warfare which obtains among the Macassars, differs considerably from that adopted by the other natives of the Archipelago, than whom they are more wealthy and better armed, while at the same time they take the lead in cleverness and ferocity. When under their own chiefs, they are not remarkable for shewing that courage which is commonly ascribed to them, especially to the Bughis, this being displayed rather upon the sea than on land. They will rarely stand firm against the attacks of regular troops in the field, but fight well from ambuscades or from behind entrenchments. Their arms consist of very good guns, manufactured by themselves, with spears, krisses, klewangs and lelahs.[4] The chiefs and head warriors wear armour, made of plaited iron or copper wire, which they call baju-ranti or chain shirt: it will resist a thrust from the klewang or[Pg 14] kriss, but affords no protection against a musket ball.

In the southern parts of Celebes, horses of a very good description are to be met with, which the natives manage with considerable skill. A cushion stuffed with cotton, and laid upon the animal's back, forms their saddle, on which they sit cross-legged, and with this simple contrivance their seat is so firm that they take bold leaps, and scour across the country in a manner truly surprising. When a chief is killed, his relatives and slaves do not care to survive, but a case of this sort rarely takes place, as the former usually remain on spots free from danger. The Bughis will carry their slain off the field of battle at every risk, and will submit to great loss rather than fail in this object. It is difficult, however, to draw them into making an assault en masse.

We anchored off the town of Macassar on the 5th of July, 1824, the king of the northern part of the state of which this is the capital, having by this time followed the example of the Bughis of Boni in rising against our government. On the 14th of the same month we sailed for Tannette, (a town on the west coast of Celebes,) with troops and munitions of war, our vessel forming part of a flotilla consisting[Pg 15] of the brigs Sirene, Nautilus, Jacoba-Elizabeth, and Dourga, with the corvette Courier, two gun-boats, and some prahus with native auxiliaries; the naval force being under the orders of Commander Buys, while the troops were led by Lieutenant Colonel De Steurs. Having assembled before Tannette, we formed into line and cannonaded the enemy's fortification, while at the same time the troops were landed and some gained possession of the forts and villages, together with some strongholds farther up the country. The loss on our side was small, but the enemy suffered greatly in killed and wounded. After sustaining this defeat, the king retired into the interior, and refused to submit. On the 22nd, Colonel De Steurs departed with the troops towards Macassar, with the intention of chastising the treacherous inhabitants of Labakang and Pankalina, those towns lying in the route. The squadron followed their march along the coast, with the view of affording assistance should it be required. The number of reefs and banks render the navigation of the coast hazardous and difficult; but the fishermen of the islands piloted us through them with safety. During the passage our armed boats were constantly employed on the coasts, more for the purpose of checking[Pg 16] the plundering propensities displayed by our native allies from Goa, than for the annoyance of the enemy. Plunder, indeed, seemed to be the chief object of these auxiliaries, for when they were required to fight, they either remained idle or took to their heels.

On the 24th we reached Macassar, the inhabitants of the intermediate coast having speedily been brought under subjection. The expedition had been fortunate and successful in every respect, and inspired us with so much confidence that we eagerly desired to be again led against the enemy.

An expedition consisting of 200 troops, under the command of Lieutenant-colonel Reder, was now set on foot to attack the Raja of Supa, the squadron being again employed in conveying them to their destination. On the 4th of August we anchored in the bay of Supa, and as the enemy obstinately refused to negociate, no other course remained for us than to land the troops, and prepare to carry into effect the orders of our Government. It immediately became apparent that the resources of the enemy had been incorrectly reported to us, and that more difficulty would be experienced in reducing the place than we had been led to believe would have been the case.

[Pg 17]

Supa, the capital, is extended near the shore on the north-east side of the bay, and is difficult of approach from seaward. The town, which lies low, is bounded on the south side by extensive rice fields, while to the south-west, in which direction the squadron lay, it is separated from the sea by a ridge of hills.

On the morning after our arrival, the troops, with detachments of seamen from the ships, were landed in good order under cover of the guns of the squadron. Our attack upon the well-fortified town of Supa was unsuccessful, the troops being driven back to the hills, of which, however, they maintained possession; the enemy returning into the town, with the exception of a number of horsemen, who remained at the foot of the hills, and some detachments which took up positions to the southward. Towards evening some mortars and brass six-pounders were landed, and placed in battery against the town. The firing was at first attended with little loss on either side, but the war-cries of the Bughis convinced us that they were assembled in great force.

Repeated attempts were now made to set fire to the strongholds of the enemy, but they were unsuccessful, and attended with considerable loss. The[Pg 18] vessels employed in keeping up the communication with Macassar had by this time brought a number of native auxiliaries furnished by the king of Sidenreng, but these took up a position to the southward, and never emerged from their hiding places.

Information which was now received of our garrisons at Pankalina and Labakang, consisting of sixty men each, having been overpowered and massacred to a man, spread dismay and dejection among the troops, while, through the weak indulgence of our commandant, military discipline was often disregarded, and our operations consequently, were deficient in point of combination. A second general assault was not determined on until the men had been wearied by useless skirmishing. All the men that could be spared from the ships were now ordered on shore, and on this as on the previous occasion I served with them; the command of the left wing of the battery being entrusted to me, while the right was under the direction of Commander Buys.

At daylight on the 14th, after our batteries had for some time played with vigour on the town, Lieutenant-colonel Reder advanced to the attack with one hundred and fifty soldiers, one hundred seamen, and forty marines, whom the enemy allowed[Pg 19] to approach close under the wall without firing a shot. Their cavalry had in the meantime been posted out of sight on the south side of the town, and when our troops had reached the walls, and commenced a sharp combat with those within, the cavalry fell upon them in flank, penetrated right through them, and even close up to our breast-works. The confusion created by this movement was so great, that notwithstanding the efforts of the officers the flight soon became general, and the disorder communicating itself to the reserve, the enemy were enabled to cause us considerable loss. The superior courage of Europeans soon, however, restored matters to order, for the fire of case-shot from our batteries checked the career of the enemy, and our troops having by this time rallied became the assailants in their turn, and drove the Bughis back to their batteries. Our advantage over the enemy was limited to this, so that our attack was attended with much bloodshed without being successful. We had to lament the loss of two brave officers, Lieutenants Van Pelt and Bannhoff, together with nearly one-third of the men engaged, six of my own crew being killed on this fatal occasion. During the engagement our auxiliaries[Pg 20] remained in the positions they had taken up, and did not stir a foot to assist us.

On the evening after this occurrence we were joined by Mr. Tobias, the commissioner, Colonel De Steurs, and the Raja of Sidenreng, the latter bringing with him a number of native auxiliaries. The arrival of Colonel De Steurs gave great joy to our troops, this officer being universally beloved and esteemed, but of what avail was his presence now that the pith of our force had been expended in ill-directed attacks? The enemy occasionally made night attacks on our position, but were always driven back, our auxiliaries showing on these occasions more courage than usual, repeatedly pursuing their adversaries close up to their forts.

On the 22nd, the frigate Eurydice joined the squadron, when a portion of her crew, with two long eighteen-pounders and some Congreve rockets were landed; the latter, however, did not answer our expectations upon trial. Our endeavours to gain an advantage over the enemy were still unattended by success, and our leader, seeing our force daily diminished by useless skirmishes, determined on making another general attack. Every body that could be spared from the ships, natives as well as Europeans, were landed to join in[Pg 21] the assault, the attacking force now amounting to three hundred men, exclusive of the auxiliaries, who could not be brought into motion. Our batteries had made several breaches in the enemy's breast-works, but these had always been repaired during the following night.

The general attack, which took place early in the morning, was conducted with much bravery. The road to the town was studded with sharp stakes, by which many of our people suffered severely. The enemy in the meantime remained within their entrenchments, protecting themselves from our shot by sitting in holes dug in the ground; and on our advancing up to them they fought with desperation, surrounding their wives and children, and determining to die to the last man rather than surrender. Our troops were sometimes engaged hand to hand with the enemy, who opposed our bayonets and swords with their krisses and klewangs. At length Colonel De Steurs, finding that many of our men, with a captain and a first lieutenant, had fallen, determined to draw off our small body of heroes, with the intention of renewing the attack with the reserve; but this was found impracticable, as the latter, which consisted only of a small number of seamen from the frigate, had already sustained considerable loss. The[Pg 22] retreat was therefore sounded, and thus, for the fourth time, had our efforts proved unavailing. On this occasion, also, one-third of the attacking force was placed hors de combat. We were, nevertheless, convinced that had a correct report been given to the government of the force of the enemy, and had our proceedings been conducted with order and regularity, the victory must infallibly have been on our side. It is a consolation, however, to know, that although the enemy maintained their position, they experienced, in a forcible manner, the superiority of our courage; for notwithstanding the relaxation of discipline which at first prevailed, no one can deny that our men displayed much personal bravery. The expedition, although unsuccessful, had therefore the effect of inspiring the people of Supa with a dread of the Dutch arms. According to the account of trustworthy natives, their loss had been very great; indeed, their successes never gave them sufficient confidence to emerge from behind their entrenchments. We now endeavoured to reduce them by a close blockade, but in this we were also unsuccessful; and this object was not effected until six months afterwards, when General Geer appeared before the place with a force much greater than that employed on the previous occasion.

[Pg 23]

On the 6th of October, the squadron left Supa for Macassar, carrying away the troops, with the exception of one hundred men, who were left under the command of Captain Van Doornum. The brig under my command, together with a gun-boat, also remained, and we were soon joined by the corvette Courier. On the 20th, I sailed for Macassar, and two days afterwards, when off Tannette, a number of prahus were seen standing in towards the fort there, in which we had a garrison of fifty men. On perceiving the brig the prahus altered their course and stood out to sea, a proceeding which aroused my suspicion, and as the sea breeze prevented me from following them, I ran in, and brought up off the mouth of the river. A small prahu soon came alongside, bringing the information that the fort was beset on the land side by the enemy, who threatened an attack with so large a force that our small garrison could not possibly resist. The commandant wished to embark his men in the brig and desert the fort; but as I could not receive them without having received orders to that effect from the governor, I sent one of the small vessels that attended the brig to Macassar, to make known to the authorities there the hazardous position we were in. It appeared that the enemy intended to have attacked the fort both[Pg 24] by sea and land, in which case not one of the garrison would have escaped. My accidental arrival had fortunately prevented this double attack, which would not have been the case had I come a day later, or had I missed the prahus, the appearance of which caused me to anchor off the fort. I therefore thanked Providence for leading me to adopt the route which brought me near the besieged place, the garrison of which, but for this opportune visit, must have experienced the same fate with that which had already befallen those of Labakang and Pankalina. On the following day the brig Nautilus arrived to relieve us.

In the mean time the people of Boni had risen, all the tribes to the northward of Macassar being now in arms against us. The town of Macassar was often threatened by the enemy, but they never ventured an attack, being deterred by the force our ally, the king of Goa, had brought into the field, and by the reinforcements that arrived from Java. Preparations were now made for a grand expedition, the troops that had been left at Supa and Tannette being withdrawn from their uncomfortable posts to join the main force at Macassar.

On the 1st of December I sailed for Sourabaya, the brig being in want of repairs; and on the 19th[Pg 25] of January, 1825, returned to Bonthian Bay, on the south coast of Celebes. On the 10th of March, General Van Geen arrived there with the frigate Javaan, and a number of vessels large and small. The general was accompanied by the Panambahan,[5] of Samanap, on the island of Madura, who brought with him a number of native auxiliaries, paid and equipped at his own expense; the Raja of Goa also furnishing a large number of men for the expedition, who were armed by our government. The ships of war were attended by a number of transports; so that the fleet presented a very imposing appearance.

On the 16th of March the fleet sailed from Bonthian Bay, and passing through the straits of Salayer, entered the Bay of Boni, without incurring injury from the numerous coral reefs that were scattered along our route. A melancholy accident occurred soon after our departure from Bonthian. A detachment of three officers and ninety-three light infantry men, had been embarked on board a prahu, totally unfitted for a transport. Some vessels having been perceived by the people on deck, they called out[Pg 26] that some pirates had hove in sight, on which those who were below rushed up, and climbing on one side of the vessel, capsized her, only the three officers and thirty-three of the men being saved.

Our operations commenced at Sengey, where the troops were landed, and the enemy not only driven helter-skelter out of their intrenchments, but forced also to evacuate the neighbouring country. The portion of our force which marched overland having joined us, we pushed forward to Batjua, the capital of the kingdom of Boni, taking and destroying the stockades of the enemy as we advanced. Batjua consists of a chain of beautiful villages, defended by stockades erected in the water and well provided with guns. It is considered as the seat of the court of Boni, although the king resides about an hour and a half's journey in the interior. Being the chief commercial depôt of the kingdom, the trade is considerable. We found a large number of prahus here, the greater number of which had been hauled up on the beach to prevent our destroying them.

General Van Geen determined to effect a landing here, and the enemy having been drawn away from the beach by a clever ruse, the troops were put on shore without difficulty. The Boniers fled before the advance of our courageous soldiers, sustaining[Pg 27] great loss in their retreat. The town was found to have been evacuated by the enemy, although two-hundred pieces of cannon of small calibre were mounted on the walls. The troops brought to the field by the Panambahan of Samanap behaved very well in the attack. Notwithstanding their defeat, the enemy obstinately refused to enter into negotiations with us.

The armed boats of the squadron were constantly employed in landing the troops, and in attacking the batteries of the enemy. On one of these occasions we had the misfortune to lose Lieutenant Alewyn, the commander of the brig Siwa, an officer universally esteemed.

I will pass over in silence many other particulars of minor importance, connected with this expedition. As the westerly monsoon was now drawing to a close, and the number of our sick had become very great, we found it impossible to pursue the enemy into the interior. Macassar had been freed from danger, Supa had been taken, and the island of Celebes placed in a state of more tranquillity; but not a single native chief had been brought under the subjection of our government, so that the expedition had produced no other useful effect than that of affording a new proof of the total inability of the[Pg 28] natives to withstand the courage and military skill of Europeans.

On the departure of the fleet from the Bay of Boni, my brig, together with the Nautilus and the Daphne, sailed for Amboyna, touching at Buton on the way, to obtain refreshments. Every ship that had been employed had a large number of their men sick, one fifth only of the crew of my brig being fit for duty. My officers and myself also suffered much; indeed, on our arrival at Amboyna there was not a healthy man on board. This prevalence of sickness is to be attributed to the fatigues we had endured, and it should act as a warning to our government to deter them from undertaking expeditions like these except in cases of urgent necessity, or when they have very important objects in view.

I will now proceed to give an account of the more agreeable duties entrusted to my charge, which I was fortunate enough to carry into execution to the satisfaction of the government, and within a tolerably short period of time.

FOOTNOTES:

[2] The yard in which these vessels were built, was subsequently burned by the rebels; Mr. Waller, the shipwright, losing all the property he had collected by his diligence.

[3] This name, unfamiliar to European ears, is derived from a fable of the Bramins, whose religion once obtained in Java. Dourga was the consort of the god Siva, in fact the Juno of the Jupiter of the Hindoos. Many images of this deity are to be met with among the ruins of the temples scattered over the island.

[4] The kriss is a short dagger of a serpentine form; the klewang, a sort of hanger or short sword; and the lelah, a cannon of small calibre, usually composed of brass.

[5] Panambahan is a Javanese title, the possessor of which takes precedence of a Pangeran or Prince, but ranks below a Raja or Sultan.

[Pg 29]

CHAPTER II.

TIMOR.

Object of the Voyage.—Sail for Timor.—Arrive at the Portuguese Settlement of Dilli.—Poverty of the Inhabitants.—Mean Reception.—Agriculture much neglected.—Slave Trade.—Symptoms of Distrust on the Part of the Portuguese.—Discontented state of their Native Subjects.—Departure for the Island of Wetta.

I was permitted by the Government to remain a considerable time at Amboyna, as the greater part of the brig's crew were forced to enter the hospital, while the vessel herself was in want of considerable repair. The fine climate of this agreeable island, coupled with the attendance of a skilful physician (M. Zengacker), soon restored my brave crew to their former health and vigour, and the fresh air of Batu Gadja, the residence of the much-respected governor, M.P. Merkus, with the kind hospitality of its owner, soon caused me to forget the fatigues and hardships I had undergone. When my health was sufficiently[Pg 30] restored to permit me to resume active duties, I made preparations for a voyage to the Arru, Tenimber, and the other islands lying between Great Timor and New Guinea, the conduct of which had been entrusted to me by an order of the Government. These islands were formerly possessions of our old East India Company, who had created small forts on many of them, the better to secure to themselves the entire trade in spices. Well known events connected with the state, which undermined the monopoly of the East India Company, caused these islands to decrease in importance, until at length the communication with them ceased, and had continued so for a long series of years. During the period in which the English had possession of the Moluccas these islands were disregarded, so that their inhabitants were scarcely aware that they had changed masters, and still continued to view themselves as subjects of the Dutch, hoisting their flag on all festive occasions. It is also a well-known fact, that at our factory in Japan (thanks to the firm conduct of the chief, H. Doeff), our flag was never hauled down; while the Dutch, therefore, ceased to exist as a nation, our colours continued flying, and our authority acknowledged in several of the remote possessions acquired by the courage and enterprize[Pg 31] of our forefathers. I trust we may again be actuated by the desire, not to conquer new countries, but to maintain and increase our power in those bequeathed to us by our ancestors.

With reference to the above-mentioned islands, the fifth article of my instructions contained the following passage:—"And further, you will inquire as to what remains exist of the forts erected by the East India Company on the islands, especially on those of Arru, Tenimber, and Kessa, noting down with correctness the particulars you may obtain concerning them, subjoining your own observations on their positions, and other points." A second object of my expedition was: "to kindle and renew friendly relations with the natives, and to invite them to visit Banda for the purpose of trading, this being an object of importance to the islanders themselves, since they would there obtain the goods they might require in exchange for their produce, on more advantageous terms than from the traders who have hitherto supplied them." By my instructions I was also requested, not only to note down answers to the points of inquiry contained in them, but also to embody in a report any observations I might make on subjects of importance to the Government, that the information concerning these possessions might be as full as possible.

[Pg 32]

M. Dielwaart, a gentleman in the employ of the Government, accompanied me for the purpose of assisting in the examination; and M. Kam, a clergyman, was also attached to the expedition, his object being to promote the interests of Christianity, and to arrange all matters connected with church affairs and public instruction. An interpreter for the Malayan language, and another acquainted with the dialect spoken by the mountaineers, were furnished to me, together with a guard of seven soldiers.

On the 26th of May we sailed from Amboyna, and soon cleared the bay—this being sometimes attended with much difficulty—when we steered to the southward towards the town of Dilli, on the north-west coast of Timor. Having to contend against squalls and contrary winds, we did not reach the roads of Dilli until the 2nd of June. On arriving outside the reefs which shelter the roads, we hove-to, and were boarded by a Portuguese naval officer, who acted as harbour-master, and conducted us into the inner roads by a narrow channel to the westward of the town, which forms the only entrance. A ship may come to an anchor outside the reefs, but the water is very deep, and she would be quite unsheltered.

We found a large ship from Macao at anchor in[Pg 33] the roads, but no other vessel, not even a native prahu, was to be seen. After having anchored we saluted the fort with thirteen guns, which the latter returned with only eleven. On my demanding the reason of this deficiency, it was attributed to the carelessness of the officer of artillery, for which it appeared he was to be punished. Soon after entering the roads, I sent Lieutenant Bruining on shore to inform the Governor of our arrival. This gentleman having just retired to take his siesta, his people had the incivility to allow M. Bruining to walk in front of the house from noon until three o'clock, before being admitted into his presence. The Governor expressed himself much gratified at our arrival, and wished me to call upon him in the evening, when I went to his house in company with several of the gentlemen who were embarked with me, and experienced a more hospitable reception than could have been expected from the poverty-stricken appearance of the place.

The Governor of the Portuguese possessions in the north coast of Timor usually resides at Dilli, and pays himself and the other officials out of the revenue derived from the trade. They are all engaged in mercantile pursuits. Their pay, indeed, is extremely small, the officers receiving only eleven[Pg 34] guilders,[6] and the soldiers three guilders per month. Their dwellings are miserable, dirty, and poor.

The Governor resides in a small wooden house situated at the back of the fort, which contains no other furniture than a few tables, benches, and old chairs. When dining at his house the following day, we plainly perceived that the chairs, dishes, plates, and even the table-linen, had been lent for the occasion by various individuals, all being of different make and fashion; and our opinion on this point was afterwards confirmed.

The Governor appeared to be much pleased on finding that I was in want of some cattle and various articles, with which he offered to supply me. He charged me seven dollars a head for the buffaloes, and eighty-six guilders for half a picul (sixty-six pounds and a half) of wax candles, that I purchased from him, in addition to which I paid six per cent. export duty at the custom-house. Slaves were frequently offered to me on sale, the Commandant, among others, wishing me to purchase two children of seven or eight years of age, who were loaded with heavy irons. The usual price of an adult male slave is forty guilders, that of a woman or a child being from twenty-five to thirty. These unfortunate people[Pg 35] are kidnapped in the interior, and brought to Dilli for sale, the Governor readily providing the vender with certificates under his hand and seal, authorizing him to dispose of the captives as he may think fit.[7]

In addition to the slave trade, from which the government officers appeared to derive the greater part of their income, a commerce is also earned on in wax and sandal-wood, which the natives are forced to deliver up at a small, and almost nominal price. The trade is entirely engrossed by the governor and officials, no other individual being permitted to embark in commerce. This, with other abuses, caused so much discontent, that many of the inhabitants of Dilli, both natives and Chinese, expressed to me their strong desire to be freed from the hateful yoke[Pg 36] of the Portuguese. Scarcely had we anchored in the roads, when several came on board the brig and gave vent to their joy, supposing that we had come to take possession of the place.

The fort, a square inclosure, without bastions, containing within it a house and a magazine, is constructed of stone and clay. Several pieces of cannon are mounted on the walls, but the greater number are unprovided with carriages. Some of our officers wished to inspect the interior, but orders had been issued to the sentry not to allow us to enter; at all events, our officers were refused admission on the plea, that our visiting the fort would be viewed with displeasure by the Governor. We did not think it worth while to make a formal request for permission to visit this pitiful fortress, as the appearance of the exterior gave us a good idea of what we might expect to meet with inside.

Excepting the wife of the master of a merchant ship, we did not meet with a single European woman here. Even those of the mixed breed were scarce, two or three only being encountered by us during our stay.

When the Portuguese go abroad to pay a visit or to take the air, they are carried by two or three slaves in a canvass hammock, suspended from a[Pg 37] bamboo pole, over which an awning is extended to protect the rider from the sun and rain. There are excellent horses in the place, but very little use is made of them, neither carts nor carriages being employed by the inhabitants. The Portuguese, indeed, betray no activity, and appear to have given themselves up to an indolent mode of life, all their actions being redolent of laziness and apathy.

The population appeared to be numerous, but no signs of prosperity were visible. The dwelling-houses, small, dirty and ruinous, and built without order or symmetry, were scattered irregularly over the town. On each side of the quarter inhabited by the Portuguese two redoubts have been erected, on which some old iron guns of small calibre were mounted. The sentinels were half naked, and their muskets were for the most part without locks, so that they could only be carried for show. In addition to their muskets they carried long poniards or daggers.

A large plain extended to the eastward of the town, on which appeared an exceedingly high gallows. A short distance inland to the south-west the chief of the native inhabitants resided, to whom I would willingly have paid a visit, had it not been so much against the inclination of the governor, who[Pg 38] pretended that the chief was seriously indisposed. A feeling of distrust on the part of the Portuguese was apparent throughout our intercourse with them, and they evidently wished us to hold no intercourse with the natives.

The land around the settlement is highly fertile, and fruit, which here as in other parts of India, is produced without the assistance of human industry, was plentiful; but culinary vegetables were very scarce. The land would produce abundantly were the indolent Portuguese to turn their attention to agriculture, or to encourage the natives to do so; but they prefer seeing the innocent natives carried off from their peaceful homes in the hills, that they may profit by their sale, to allowing them to better their condition by their labour and agricultural skill.

On two occasions some of the gentlemen of the settlement came off to pay us a visit, appearing to be much surprised by the interior arrangements of the brig. I had also invited the Governor, but he made some trifling excuses for remaining on shore. Having thus doubly requited the attention I experienced from these gentlemen, I made preparations for my departure, and sent the Governor a present of a thousand Manilla cigars, with a quantity of fishhooks,[Pg 39] in return for which he sent me off some sheep, and a number of shaddocks. We therefore parted on the best terms.

Having now fulfilled the orders of the Governor of the Moluccas, we weighed anchor on the 6th of June, and were piloted out by the same lieutenant who had taken us into the roads. No fees being demanded, I presented him with some provisions and trifles, which were received with thanks. The day previous to our departure having been the birthday of their king, a general promotion had taken place, by which this gentleman had received the rank of first lieutenant, with a monthly increase of pay of three guilders, his salary now amounting to fourteen guilders per month.

The Portuguese possessions lie on the north side of Timor, and consist of several small posts or factories, the principal of which are Batu-Gede to the west, and Manatatu to the east of Dilli, the capital. On the west and south-west sides of the island the Dutch settlements are situated, the town of Coepang being the seat of the Residency. As this part of Timor was beyond the limits of my intended voyage, I steered a direct course from Dilli towards the Island of Wetta.

FOOTNOTES:

[6] A guilder is 1s. 8d. sterling.—Trans.

[7] When Captain King first visited Melville Island, on the north coast of Australia, the natives appeared on the beach and called out to our voyager, "Ven aca," the Portuguese term for "Come here." From this, coupled with many circumstances that came under his observation during his stay at Melville Island, Major Campbell, in an excellent account of that island inserted in the journal of the Royal Geographical Society, states it to be his opinion, that the Portuguese sometimes touch here and carry off the natives as slaves. When this part of the world is better known, similar scandalous transactions will, probably, be brought to light.—Trans.

[Pg 40]

CHAPTER III.

THE SERWATTY ISLANDS.

Arrival at the island of Wetta.—Productions.—Trade.—Interview with the natives.—Destruction of the chief village.—Depart for Kissa.—The Christian inhabitants.—The fort Vallenhoven.—Friendly reception by the natives.—Beauty of the landscape.—State of agriculture.—Attachment of the people to the Dutch government.—General assemblage of the people.—Performance of divine service.—Native hospitalities.—Order, neatness and industry of the people of Kissa.

During the existence of the Dutch East India Company, a garrison of their troops occupied the village of Sau, on the south coast of Wetta, an island situated opposite the north coast of Timor. We directed our course thither, and stood close along shore to search for the village in question. The shores of the island were steep and hilly, but luxuriantly clothed with trees, among which appeared at intervals the huts of the inhabitants, the whole presenting a most picturesque view. The natives appeared to be extremely shy, none of them[Pg 41] making their appearance on the beach, nor indeed seeming to wish to look at us.

On the 10th of June we arrived off Sau, and came to an anchor in fifty fathoms water, about a cable's length from the shore, in a small bay, where we lay tolerably well sheltered from the south-east winds by a point of land. Having fired a gun, and hoisted the Dutch flag, two natives made their appearance on the beach, to whom I sent one of the interpreters, who soon brought them on board. They proved to be Christian native chiefs, Hura, the Orang Kaya, and Dirk-Cobus, the Orang Tua of the village.[8] Their appearance betokened great poverty, and they complained bitterly of the miserable state into which they had fallen since they had lost the protection of the Dutch. They informed me that four years previously their village had been plundered and burned to the ground, and several of their people killed, by the inhabitants of Lette, since which occurrence they had deserted the sea-coast,[Pg 42] and had taken up their residence in the hills.

With the view of inspiring them with confidence, I went on shore entirely alone, and landed near the remains of what had been a fine walled village, containing a church and a guard-house. The number of the fruit trees, and the luxuriant growth of the various plants, gave evidence that the ground over which I walked possessed exceeding fertility. A crowd of unconverted natives, who recognized the above-mentioned Christian chiefs as their rulers, now joined us. They were all armed with spears, bows, arrows, and parangs or chopping knives; but they soon laid these aside, and gave many tokens of friendship and confidence. A small quantity of arrack and tobacco which I distributed among them, put them in high spirits. With the exception of the two chiefs, none of the natives spoke the Malayan language, nor were my interpreters acquainted with their dialect.

On the beach I met with two sheds belonging to the people of Kissa, who had been in the habit of coming here to barter cloth, iron and gold, for sandal-wood, rice and Indian corn or maize. Coin is not in use as a currency among the natives. Buffaloes, hogs, sheep and fowls may be obtained here at[Pg 43] a very cheap rate in exchange for cloth, but not in very large numbers.

Having wandered for some time over this very beautiful country, we approached the eastern extremity of the village, and sat down on the banks of a river, which there emptied itself into the sea. They appeared much pleased by this, and with much energy of manner expressed their ardent desire to live once more in peace and quietude under the rule of the Dutch, at the same time offering up thanks to heaven on finding that the Company, (as they always styled our government) after having so long abandoned them, had now again appeared. Although both the chiefs spoke the Malayan language, I could not correctly understand the answers to all the questions I put, but they clearly expressed their desire to take up their residence again on the sea shore, and requested that one or two European soldiers, with a teacher to instruct them in the tenets of Christianity, might be left among them. For the latter in particular they appeared to be extremely anxious. They also made several other requests; on which I promised that the Netherlands' government should watch over their interests, but that their prosperity must depend chiefly on their own exertions.

[Pg 44]

From the account of the natives themselves, the sea coast population of the island is far from being numerous, many of the inhabitants having retired to the other islands after the destruction of Sau. On the other hand, the mountaineers, who are called Arafuras, are in great numbers, these simple people considering themselves as the subjects of the inhabitants of the coast. The natives of the north and east coasts of Wetta have a bad character, having plundered and murdered the crews of two prahus a short time previous to my visit to the island.

The Arafuras of the interior had been in a very unsettled state some time past, all regularity of government having been put an end to by the death of the Raja, Johannes Pitta, whose heir had retired with his mother to the island of Kissa. The natives besought me in the most earnest manner to summon this young man back to his native island, and install him as their chief.

The two chiefs and several of the people, returned with me to the brig, where I presented them with some cloth and a Dutch flag, promising to promote their interests to the best of my power at Kissa, towards which island, having nothing more to detain me here, I now steered.

Kissa possesses only two anchoring places, one on[Pg 45] the west, and the other on the south-east side of the island. When seen from a distance the land does not appear to be much elevated above the level of the sea, but on a nearer approach it will be perceived that the shores rise abruptly from the water, and are of a very rocky nature. Small creeks and inlets are to be seen here and there, but these will only admit prahus of a small draught of water. In former times Kissa was the seat of the Dutch Residency of the south-west islands,[9] and it is still the most populous of the group, the people being also farther advanced in civilization than their neighbours.

In standing westward towards the roads, we ran close along the south-west side of the island, where the violent breaking of the sea against the steep shore, presented a very picturesque appearance; but to us, who were at a very small distance from the land, the sight was combined with something of the terrific. On the 13th of June we anchored in a bight to the northward of the south-west point, on a strip[Pg 46] of sand and rocks, with very irregular soundings on it, and moored the brig with a hawser made fast to the steep shore. The beach was here flat and sandy, but was fronted by a reef, steep to on the outer side, over which small prahus can go at the time of high water. The inhabitants haul up their jonkos (trading prahus of about twenty tons burthen) on the beach.

The natives hoisted a Dutch flag on our arrival, and several of the chiefs came off to welcome us to their shores shortly after we had come to an anchor. I soon went on shore, accompanied by M. Kam and several of the gentlemen, when we found a multitude of natives assembled on the beach to receive us, provided with litters to carry us up into the country. The proofs of joy at our arrival, evinced by the assembled crowd, were indeed striking in the extreme.

My attention was first directed to the fort Vollenhoven, which was situated a little to the northward of our anchorage, in the middle of an extensive level plain. The fort consisted of an inclosure about ninety feet square, formed by stone walls ten feet high and three feet in thickness, with a gate on the east side, and a bastion with four embrasures on the[Pg 47] south-west and north-east corners. This portion of the fort was still in a good and serviceable state, but the interior works and the building had all fallen to the ground, the greater portion of the materials having been destroyed by the white ant.[10] We found five dismounted cannon lying on the sea bastion, one a one-pounder, and the others four-pounders, which were still in good condition. The fort, with all its contents, were considered by the natives as the property of the old East India Company, and for this reason had been preserved untouched by the natives, who viewed them as relics. They eagerly offered to put these, together with the Residency House, which was much decayed, into repair, if a Dutch garrison were again placed among them.