Transcriber's Note:

1. Minor print errors corrected. Details at the end of this

text.

2. All dialect spelling has been retained.

The Crow's Nest

Cover

Cover

This Simian World

By Clarence Day, Jr.

"One of the best pieces of satire from the pen of an American. As a recruiting pamphlet for the human race. 'This Simian World' cannot be surpassed."

—New York Tribune.

"The most amusing little essay of the year. We like best his picture of the cat civilization. It is even finer than Swift's immortal description of a country governed by the super-horse."

—The Independent.

$1.50 net at all bookshops

New York: Alfred A. Knopf

The Crow's Nest

by Clarence Day, Jr.

With Illustrations by the Author

New York | Alfred · A · Knopf | Mcmxxi |

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY

CLARENCE DAY, Jr.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

With Acknowledgments to the Editors of

the Metropolitan Magazine, Harpers Magazine,

Harpers Weekly, The New Republic,

and The Boston Transcript.

Contents

| PAGE | ||

| The Three Tigers | 3 | |

| As They Go Riding By | 7 | |

| A Man Gets Up in the Morning | 15 | |

| Odd Countries | 18 | |

| On Cows | 26 | |

| Stroom and Graith | 28 | |

| Legs vs. Architects | 44 | |

| To Phoebe | 49 | |

| Sex, Religion and Business | 51 | |

| An Ode to Trade | 63 | |

| Objections to Reading | 65 |

ON AUTHORS

| The Enjoyment of Gloom | 77 | |

| Buffoon Fate | 84 | |

| The Wrong Lampman | 89 | |

| The Seamy Side of Fabre | 93 | |

| In His Baby Blue Ship | 101 |

PROBLEMS

| The Man Who Knew Gods | 109 | |

| Improving the Lives of the Rich | 118 | |

| From Noah to Now | 128 | |

| Sic Semper Dissenters | 135 | |

| Humpty Dumpty and Adam | 137 | |

| How It Looks to a Fish | 142 | |

| A Hopeful Old Bigamist | 147 | |

| The Revolt of Capital | 154 | |

| Still Reading Away | 161 |

PORTRAITS

| A Wild Polish Hero | 165 | |

| Mrs. P.'s Side of It | 173 | |

| The Death of Logan | 183 | |

| Portrait of a Lady | 190 | |

| Grandfather's Three Lives | 198 | |

| Story of a Farmer | 217 |

The Crow's Nest

The Three Tigers

As to Tiger Number One, what he likes best is prowling and hunting. He snuffs at all the interesting and exciting smells there are on the breeze; that dark breeze that tells him the secrets the jungle has hid: every nerve in his body is alert, every hair in his whiskers; his eyes gleam; he's ready for anything. He and Life are at grips.

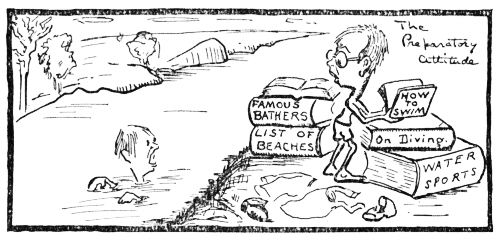

Number Two is a higher-browed tiger, in a nice cozy cave. He has spectacles; he sits in a rocking-chair reading a book. And the book describes all the exciting smells there are on the breeze, and tells him what happens in the jungle, where nerves are alert; where adventure, death, hunting and passion are found every night. He spends his life reading about them, in a nice cozy cave.

It's a curious practice. You'd think if he were interested in jungle life he'd go out and live it. There it is, waiting for him, and that's what he really is here for. But he makes a[4] cave and shuts himself off from it—and then reads about it!

Once upon a time some victims of the book-habit got into heaven; and what do you think, they behaved there exactly as here. That was to be expected, however: habits get so ingrained. They never took the trouble to explore their new celestial surroundings; they sat in the harp store-room all eternity, and read about heaven.

Book-lovers in Heaven

Book-lovers in Heaven

They said they could really learn more about heaven, that way.

And in fact, so they could. They could get more information, and faster. But information's pretty thin stuff, unless mixed with experience.

But that's not the worst. It is Tiger Number Three who's the worst. He not only reads all the time, but he wants what he reads sweetened up. He objects to any sad or uncomfortable account of outdoors; he says it's sad enough in his cave; he wants something uplifting So authors obediently prepare uplifting accounts of the jungle, or they try to make the jungle look pretty, or funny, or something; and Number Three reads every such tale with great satisfaction. And since he's indoors all the time[5] and never sees the real jungle, he soon gets to think that these nice books he reads may be true; and if new books describe the jungle the way it is, he says they're unhealthy. "There are aspects of life in the jungle," he says, getting hot, "that no[6] decent tiger should ever be aware of, or notice."

Tiger Number Two speaks with contempt of these feelings of Three's. Tigers should have more courage. They should bravely read about the real jungle.

The realist and the romantic tiger are agreed upon one point, however. They both look down on tigers that don't read but merely go out and live.[7]

As They Go Riding By

What kind of men do we think the mediæval knights really were? I have always seen them in a romantic light, finer than human. Tennyson gave me that apple, and I confess I did eat, and I have lived on the wrong diet ever since. Malory was almost as misleading. My net impression was that there were a few wicked, villainous knights, who committed crimes such as not trusting other knights or saying mean things, but that even they were subject to shame when found out and rebuked, and that all the rest were a fine, earnest Y. M. C. A. crowd, with the noblest ideals.

But only the poets hold this view of knights, not the scholars. Here, for example, is a cold-hearted scholar, Monsieur Albert Guerard. He has been digging into the old mediæval records with an unromantic eye, hang him; and he has emerged with his hands full of facts which prove the knights were quite different. They did have some good qualities. When invaders came around the knights fought them off as nobly as possible; and they often went away and fought Saracens or ogres or such, and when thus engaged they gave little trouble to the good folk at home. But in[8] between wars, not being educated, they couldn't sit still and be quiet. It was dull in the house. They liked action. So they rode around the streets in a pugnacious, wild-western manner, despising anyone who could read and often knocking him down; and making free with the personal property of merchants and peasants, who they thought had no special right to property or even to life. Knights who felt rough behaved as such, and the injuries they inflicted were often fatal.

They must have been terrors. Think of being a merchant or cleric without any armor, and meeting a gang of ironclads, with the nearest police court centuries off! Why, they might do anything, and whatever they did to a merchant, they thought was a joke. Whenever they weren't beating you up they fought with one another like demons—I don't mean just in tournaments, which were for practice, but in small, private wars. And to every war, public or private, citizens had to contribute; and instead of being thanked for it, they were treated with the utmost contempt.

Suppose a handsome young citizen, seeing this and feeling ambitious, tried to join the gang and become a knight himself. Would they let him? No! At first, if he were a powerful fighter, he did have a small chance, but as time went on and the knights got to feeling more noble than ever,[9] being not only knights but the sons of knights, they wouldn't let in a new man. The mere idea made them so indignant they wanted to lynch him. "Their loathing for the people seemed almost akin in its intensity to color prejudice."

They were also extravagant and improvident and never made money, so the more they spent the more they had to demand from the people. When every one had been squeezed dry for miles around, and had been thumped to make sure, the knights cursed horribly and borrowed from the Church, whether the Church would or no, or got hold of some money-lender and pulled his beard and never paid interest.

The Church tried to make them religious and partly succeeded; there were some Christian knights who were soldierly and courtly, of course. But, allowing for this (and for my exaggerating[10] their bad side, for the moment), they certainly were not the kind of men Tennyson led me to think.

I do not blame Tennyson. He had a perfect right to romanticize. He may have known what toughs the knights were as well as anybody, but loved their noble side, too, and dreamed about it until he had made it for the moment seem real to him, and then hurried up and written his idyls before the dream cracked. He may never have intended me or any of us to swallow it whole. "It's not a dashed bible; it's a book of verse," I can imagine him saying, "so don't be an idiot; don't forget to read your encyclopedia, too."

But verse is mightier than any encyclopedia. At least it prevails. That's because the human race is emotional and goes by its feelings. Why haven't encyclopedists considered this? They are the men I should blame. What is the use of embodying the truth about everything in a precise condensed style which, even if we read it, we can't remember, since it does not stir our feelings? The encyclopedists should write their books over again, in passionate verse. What we need in an encyclopedia is lyrical fervor, not mere completeness—Idyls of Economic Jurisprudence, Songs of the Nitrates. Our present compendiums are meant for scholars rather than people.

Well, the knights are gone and only their armor[11] and weapons remain; and our rich merchants who no longer are under-dogs, collect these as curios. They present them with a magnificent gesture to local museums. The metal suit which old Sir Percy Mortimer wore, when riding down merchants, is now in the Briggsville Academy, which never heard of Sir Percy, and his armor is a memorial to Samuel Briggs of the Briggs Tailoring Company. In Europe a few ancient families, in financial decay, are guarding their ancestors' clothing as well as they can, but sooner or later they will be driven to sell it, to live. And they won't live much longer at that. The race will soon be extinct.

Last year I got a bulletin of the Metropolitan[12] Museum of Art about armor. It described how an American collector saw a fine set in Paris. "A single view was quite enough to enable him to decide that the armor was too important to remain in private hands." And that settled it. These collectors are determined fellows and must have their own way—like the knights.

But there were difficulties this time. They couldn't at first get this set. The knightly owner of the armor, "in whose family it was an heirloom, was, from our point of view, singularly unreasonable: he ... was unwilling to part with it; the psychological crisis when he would allow it to pass out of his hands must, therefore, be awaited." For there comes "a propitious moment in cases of this kind," adds the bulletin.

Yes, "in cases of this kind" collectors comfortably wait for that crisis when the silent old knightly owner finally has to give in. They leave agents to watch him while he struggles between want and pride, agents who will snap him up if a day comes when the old man is weak. These agents must be persistent and shrewd, and must present tactful arguments, and must shoo away other agents, if possible, so as to keep down the price. When the "propitious" time comes they must act quickly, lest the knight's weakness pass, or lest some other knight send him help and thus make them wait longer. And, having got the[13] armor, they hurry it off, give a dinner, and other merchants come to view it and measure it and count up the pieces.

This sort of thing has been happening over and over in Europe—the closing scenes of the order of knighthood, not foreseen at gay tournaments! They were lucky in those days not to be able to look into the future. Are we lucky to be blind, at Mount Vernon or on some old campus? The new times to come may be better—that always is possible—but they won't be the kind we are building, and they may scrap our shrines.

Some day when our modern types of capitalists are extinct, in their turn, will future poets sing of their fine deeds and make young readers dream? Our capitalists are not popular in these days, but the knights weren't in theirs, and whenever abuse grows extreme a reaction will follow. Our critics and reformers think they will be the heroes of song, but do we sing of critics who lived in the ages of chivalry? There must have been reformers then who pleaded the cause of down-trodden citizens, and denounced and exposed cruel knights, but we don't know their names. It is the knights we remember and idealize, even old Front-de-Bœuf. They were doers—and the men of the future will idealize ours. Our predatory interests will seem to them gallant and strong. When a new Tennyson appears, he will never look up the[14] things in our newspapers; he won't even read the encyclopedia—Tennysons don't. He will get his conception of capitalists out of his heart. Mighty men who built towers to work in, and fought with one another, and engaged in great capitalist wars, and stood high above labor. King Carnegie and his round directors' table of barons of steel. Armour, Hill and Stillman, Jay Gould—musical names, fit for poems.

The men of the future will read, and disparage their era, and wish they had lived in the wild clashing times we have now. They will try to enliven the commonplaceness of their tame daily lives by getting up memorial pageants where they can dress up as capitalists—some with high hats and umbrellas (borrowed from the museums), some as golfers or polo players, carrying the queer ancient implements. Beautiful girls will happily unbuckle their communist suits and dress up in old silken low-necks, hired from a costumer. Little boys will look on with awe as the procession goes by, and then hurry off to the back yard and play they are great financiers. And if some essay, like this, says the capitalists were not all noble, but a mixed human lot like the knights, many with selfish, harsh ways, the reader will turn from it restlessly. We need these illusions.

Ah, well, if we must romanticize something, it had best be the past.[15]

A man gets up in the morning and looks out at the weather, and dresses, and goes to his work, and says hello to his friends, and plays a little pool in the evening and gets into bed. But only a part of him has been active in doing all that. He has a something else in him—a wondering instinct—a "soul." Assuming he isn't religious, what does he do with that part of him?

He usually keeps that part of him asleep if he can. He doesn't like to let it wake up and look around at the world, because it asks awful questions—about death, or truth—and that makes him uncomfortable. He wants to be cheery and he hates to have his soul interfere. The soul is too serious and the best thing to do is to deaden it.

Humor is an opiate for the soul, says Francis Hackett. Laugh it off: that's one way of not facing a trouble. Sentimentality, too, drugs the soul; so does business. That's why humor and sentimentality and business are popular.

In Russia, it's different. Their souls are more awake, and less covered. The Russians are not businesslike, and they're not sentimental, or humorous. They are spiritually naked by contrast. An odd, moody people. We look[16] on, well wrapped-up, and wonder why they shiver at life.

"My first interest," the Russian explains, "is to know where I stand: I must look at the past, and the seas of space about me, and the intricate human drama on this little planet. Before I can attend to affairs, or be funny, or tender, I must know whether the world's any good. Life may all be a fraud."

The Englishman and American answer that this is not practical. They don't believe in anyone's sitting down to stare at the Sphinx. "That won't get you anywhere," they tell him. "You must be up and doing. Find something that interests you, then do it, and—"

"Well, and what?" says the Russian.

"Why—er—and you'll find out as much of the Riddle in that way as any."

"And how much is that?"

"Why, not so very damn much perhaps," we answer. "But at least you'll keep sane."

But why stay sane?

But why stay sane?

"Why keep sane?" says the Russian. "If there is any point to so doing I should naturally wish to. But if one can't find a meaning to anything, what is the difference?"

And the American and Englishman continue to recommend business.[18]

Odd Countries

When I go away for a vacation, which I don't any more, I am or was appalled at the ridiculous inconveniences of it. I have sometimes gone to the Great Mother, Nature; sometimes to hotels. Well, the Great Mother is kind, it is said, to the birds and the beasts, the small furry creatures, and even, of old, to the Indian. But I am no Indian; I am not even a small furry creature. I dislike the Great Mother. She's damp: and far too full of insects.

And as for hotels, the man in the next room always snores. And by the time you get used to this, and get in with some gang, your vacation is over and you have to turn around and go home.

The farmer who hates you on sight

The farmer who hates you on sight

I can get more for my money by far from a book. For example, the Oppenheim novels: there are fifty-three of them, and to read them is almost like going on fifty-three tours. A man and his whole family could[19] take six for the price of one pair of boots. Instead of trying to find some miserable mosquitoey hotel at the sea-shore, or an old farmer's farmhouse where the old farmer will hate you on sight, and instead of packing a trunk and running errands and catching a train I go to a book-shop and buy any Oppenheim novel. When I go on a tour with him, I start off so quickly and easily. I sit in my armchair, I turn to the first page, and it's like having a taxi at the door—"Here's your car, sir, all ready!" The minute I read that first page I am off like a shot, into a world where things never stop happening. Magnificent things! It's about as swift a change as you could ask from jog-trot daily life.

Is she an adventuress?

Is she an adventuress?

On page two, I suddenly discover that beautiful women surround me. Are they adventuresses? I cannot tell. I must beware every minute. Everybody is wary and suave, and they are all princes and diplomats. The atmosphere is heavy with the clashing of powerful wills. Paid murderers and spies are about. Hah! am I being watched? The excitement soon gets to a point where it goes to my head. I find myself muttering[20] thickly or biting my lips—two things I never do ordinarily and should not think of doing. I may even give a hoarse cry of rage as I sit in my armchair.

I wonder if I'm being watched?

I wonder if I'm being watched?

But I'm not in my armchair. I am on a terrace, alone, in the moonlight. A beautiful woman (a reliable one) comes swiftly toward me. Either she is enormously rich or else I am, but we don't think of that. We embrace each other. Hark! There is the duke, busily muttering thickly. How am I to reply to him? I decide to give him a hoarse cry of rage. He bites his lips at me. Some one else shoots us both. All is over.

If any one is too restless to take his vacation in books, the quaintest and queerest of countries is just around the corner. An immigrant is only[21] allowed to stay from 8.15 to 11 P. M., but an hour in this country does more for you than a week in the mountains. No canned fish and vegetables, no babies—

Babies seem so dissatisfied

Babies seem so dissatisfied

I wonder, by the way, why most babies find existence so miserable? Convicts working on roadways, stout ladies in tight shoes and corsets, teachers of the French language—none of these suffering souls wail in public; they don't go around with puckered-up faces, distorted and screaming, and beating the air with clenched fists. Then why babies? You may say it's the nurse; but look at the patients in hospitals. They put up not only with illness, but nurses besides. No, babies are unreasonable; they expect far too much of existence. Each new generation that comes takes one look at the world, thinks wildly, "Is this all they've[22] done to it?" and bursts into tears. "You might have got the place ready for us," they would say, only they can't speak the language. "What have you been doing all these thousands of years on this planet? It's messy, it's badly policed, badly laid out and built—"

Yes, Baby. It's dreadful. I don't know why we haven't done better. I said just now that you were unreasonable, but I take it all back. Statesmen complain if their servants fail to keep rooms and kitchens in order, but are statesmen themselves any good at getting the world tidied up? No, we none of us are. We all find it a wearisome business.

Let us go to that country I spoke of, the one round the corner. We stroll through its entrance, and we're in Theatrical-Land.

A remarkable country. May God bless the man who invented it. I always am struck by its ways, it's so odd and delightful—

"But," some one objects (it is possible), "it isn't real."

Ah, my dear sir, what world, then, is real, as a matter of fact? You won't deny that it's not only children who live in a world of their own, but débutantes, college boys, business men—certainly business men, so absorbed in their game that they lose sight of other realities. In fact, there is no one who doesn't lose sight of some, is[23] there? Well, that's all that the average play does. It drops just a few out. To be sure, when it does that, it shows us an incomplete world, and hence not the real one; but that is characteristic of humans. We spend our lives moving from one incomplete world to another, from our homes to our clubs or our offices, laughing or grumbling, talking rapidly, reading the paper, and not doing much thinking outside of our grooves. Daily life is more comfortable, somehow, if you narrow your vision. When you try to take in all the realities, all the far-away high ones, you must first become quite still and lonely. And then in your loneliness a fire begins to creep through your veins. It's—well—I don't know much about it. Shall we return to the theater?

The oddest of all entertainments is a musical comedy. I remember that during the war we had one about Belgium. When the curtain went up, soldiers were talking by the light of a lantern, and clapping each other on the shoulder when their feelings grew deep. They exchanged many well-worded thoughts on their deep feelings, too, and they spoke these thoughts briskly and readily, for it was the eve of a battle. One of the soldiers blinked his eye now and then. He was taking it hard. He said briskly he probably would never see his mother again.

His comrade, being affected by this, clapped[24] his friend on the shoulder, and said, Oh yes he would, and cheer up.

The other looked at him, stepped forward (with his chest well expanded), and said ringingly: "I was not thinking of myself, Jean. I was thinking of Bel-jum."

It was a trifle confusing, but we applauded him roundly for this. The light from the balcony shown full on the young hero's face. You could see he was ready for the enemy—his dark-rouged cheeks, his penciled eyebrows proved it. He offered to sing us a song, on the subject of home. His comrade hurried forward and clapped him some more on the shoulder.

Songs of home

Songs of home

The orchestra started.

"Muth-aw,

"Muth-aw," roared the hero, standing stiffly at attention,

"Let your arms en-fo-o-ho-old me."

All was silent on the firing-line—except of course, for this singing. The enemy waited politely. The orchestra played on. Then the song ended, and promptly the banging of guns was heard in the distance—and a rather mild bang hit the shed and the lantern went out.[25]

The audience was left there to shudder alone, in the darkness, not knowing whether the hero was dead—though, of course, we had hopes.... Then up went the curtain, and there he stood by a château, where a plump Belgian maid, dressed in white silk, was pouring high tea.

In Belgium?

In Belgium?

An American war-correspondent appeared on the scene. He was the humorous character of the performance. He was always in trouble over his passports. He had with him a Red Cross nurse who capered about, singing songs, as did also eight Belgian girls, from the neighboring farms. Belgian girls are all young and tuneful, the audience learned, and they spend their time during wars dancing with war-correspondents. They wear fresh, pretty clothes. So do soldiers who come home on leave. Sky-blue uniforms, gilt, shiny boots. All was smiling in Bel-jum.

Then the clock struck eleven. The curtain went down, like a wall. We were turned out, like poor Cinderella, into the cold, noisy streets. Dense pushing crowds. Newsboys shouting, "Great Slaughter in Flanders." The wails of some baby attempting to get used to existence.[26]

On Cows

If cows had time—

If cows had time—

I was thinking the other evening of cows. You say Why? I can't tell you. But it came to me, all of a sudden, that cows lead hard lives. It takes such a lot of grass, apparently, to keep a cow going that she has to spend all her time eating, day in and day out. Dogs bounce around and bark, horses caper, birds fly, also sing, while the cow looks on, enviously, maybe, unable to join them. Cows may long for conversation or prancing, for all that we know, but they can't spare the time. The problem of nourishment takes every hour: a pause might be fatal. So they go through life drearily eating, resentful and dumb. Their food is most uninteresting, and is frequently covered with bugs; and their thoughts, if they dwell on their hopeless careers, must be bitter.

In the old days, when huge and strange animals roamed through the world, there was an era[27] when great size was necessary, as a protection. All creatures that could do so grew large. It was only thus they felt safe. But as soon as they became large, the grass-eating creatures began to have trouble, because of the fact that grass has a low nutritive value. You take a dinosaur, for instance, who was sixty or seventy feet long. Imagine what a hard task it must have been for him, every day, to get enough grass down his throat to supply his vast body. Do you wonder that, as scientists tell us, they died of exhaustion? Some starved to death even while feverishly chewing their cud—the remoter parts of their bodies fainting from famine while their fore-parts got fed.

This exasperating fate is what darkens the mind of the cow.[28]

Stroom and Graith

When Graith was young

When Graith was young

From conquering the Northern Stars;

And showed to her the road he'd burned

Across the sky, to make his wars;

And smiled at Fear, and hid his scars—

He little dreamed his fate could hold

The doom of dwarfish avatars

That Vega sent, when Stroom was old.

When you are talking things over with any one, you have to take some precautions. If you have just come from a cathedral, and try to discuss its stained glass, with the janitor of your[29] apartment house, say,—why, it won't be much use, because stained glass means to him bathroom windows, and that's all his mind will run on. I am in exactly that position at this moment. I don't mean bathroom windows, I mean what is the use of my saying a word about Stroom and Graith, to any one who may think they are a firm of provision dealers in Yonkers. Any woman who began this essay thinking that Graith was a new perfume,—any man who said to himself "Stroom? Oh, yes: that Bulgarian ferment,"—are readers who would really do better to go and read something else.

Having settled that, I must now admit that until yesterday I knew nothing about them myself. Yet, centuries ago, Stroom and Graith were on every one's tongues. Then, I don't know what happened, but a strange silence about them began. One by one, those who had spoken of them freely in some way were hushed. The chronicles of the times became silent, and named them no more.

We think when we open our histories, we open the past. We open only such a small part of it! Great tracts disappear. Forgetfulness or secret taboos draw the dim curtains down, and hide from our sight awful thoughts, monstrous deeds, monstrous dooms....

Even now, in the bright lights and courage of the era we live in, there has been only one[30] writer who has ventured to name Stroom and Graith.

His name was Dixon; he was at Oxford, in the fifties, with that undergraduate group which included Burne-Jones, William Morris, and on the outside, Rossetti. Where he found what so long had been hidden, even he does not say. But he wrote certain poems, in which Stroom and Graith, and the Agraffe appear.

This fact is recorded in only one book that I know of, and that is in the fifth volume of Mr. T. Humphry Ward's English Poets. When I opened this book, I read for the first time about Dixon. I also read one of his poems, which was wildish and weird:

Far ruined: the grey shingly floor

To thy crashing step answers, the doteril cries,

And on dipping wing flies:

'Tis their silence!"

Not knowing what a doteril was, I looked to see if the editor had explained: but no, all he said was that Dixon was fond of such words.

He added that others such as Stroom, Graith, and Agraffe appeared in his poems.

But he didn't print those poems in this collection, or explain those strange names.

Where the doteril cries

Where the doteril cries

The sound of them fascinated me. I sat there and dreamed for a while; and it was out of[31] these dreamings that I wrote that verse at the head of this essay. Some stern and vast mystery seemed to me about to enfold. What part the Agraffe played in it (a mediæval beast I imagined) I could not know, could not guess. But I pictured a strong-hearted Stroom to myself as some hero, waging far, lonely fights, against foes on the edge of the skies; and I dreamed of how Vega stood waiting, until Stroom married Graith, and of how at the height of his majesty she inflicted her doom—a succession of abhorrent rebirths as a grotesque little dwarf.

Still, these were only my imaginings, and I[32] wanted the records. I sent to the public library, and got out all of Dixon they had. Great red and gold volumes. But the one that I wanted—not there.... I sent to several famous universities.... It was not to be found.

I turned my search over to an obliging old friend, a librarian, and sat down feeling thwarted, to console myself with some other poet. There were many in Volume V of the English Poets, but not a one of them calmed me. I read restlessly every day, waiting to hear about Stroom. Then at last, one rainy evening, a telegram came! It was from that old friend. "Have found all those words Dixon used, in a dialect dictionary. It gives: 'Stroom: rightly strom: a malt strainer, a wicker-work basket or bottle, placed under the bunghole of a mash-tub to strain off the hops.' Mr. Dixon used it because he loved its sound, I suppose. As to Graith, it means 'furniture, equipment, apparatus for traveling.' And agraffes are the ornamented hooks used to fasten Knights' armor. They are mentioned in Ivanhoe."

Well, poets are always disappointing me.

I don't know why I read them.

However, having bought Volume V to read, I tried to keep on with it.

I read what it said about Browning's father being a banker. Poor old man, I felt sorry for[33] him. Imagine the long years when he and his son faced each other, the old father telling himself hopefully, "Ah, well, he's a child, he'll get over these queer poetical ways,"—and then his not getting over them, but proposing to give his life to poetry! Make a career of it!

If there are any kind of men who want sons like themselves, it's our bankers: they have their banks to hand on, and they long to have nice banker babies. But it seems they are constantly begetting impossible infants. Cardinal Newman for instance: his bewildered father too was a[34] banker. Fate takes a special pleasure in tripping these worthy men up.

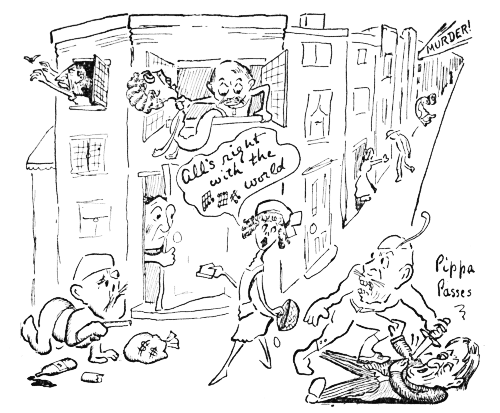

MURDER!—All's right with the world.—Pippa Passes.

MURDER!—All's right with the world.—Pippa Passes.

Imagine Browning senior reading "Pippa Passes," with pursed lips, at his desk. What mental pictures of his son's heroine did the old gentleman form, as he followed her on her now famous walk through that disreputable neighborhood?

I hope he enjoyed more "How They Brought the Good News from Ghent." For example, where the man says, while galloping fast down the road:

Then shortened each stirrup, and set the pique right,

Rebuckled the check-strap, chained slacker the bit—"

He made the girths tight

He made the girths tight

The banker must have been pleased that Robert could harness a horse in rhyme anyhow. I dare say he knew as we all do that it was poor enough[35] poetry, but at least it was practical. It was something he could tell his friends at the club.

Putting Browning aside with poor Stroom, I next tried Matthew Arnold.

The Arnolds: a great family, afflicted with an unfortunate strain. Unusually good qualities,—but they feel conscientious about them.

If Matthew Arnold had only been born into some other family! If he had only been the son of C. S. Calverley or Charles II, for instance.

He had a fine mind, and he and it matured early. Both were Arnold characteristics. But so was his conscientiously setting himself to enrich his fine mind "by the persistent study of 'the best that is known and thought in the world.'" This was deadening. Gentlemen who teach themselves just how and what to appreciate, take half the vitality out of their appreciation thereafter. They go out and collect all "the best" and bring it carefully home, and faithfully pour it down their throats—and get drunk on it? No! It loses its lift and intoxication, taken like that.

An aspiring concern with good art is supposed to be meritorious. People "ought" to go to museums and concerts, and they "ought" to read poetry. It is a mark of superiority to have a full supply of the most correct judgments.

This doctrine is supposed to be beyond discussion,[36] Leo Stein says. "I do not think it is beyond discussion," he adds. "It is more nearly beneath it.... To teach or formally to encourage the appreciation of art does more harm than good.... It tries to make people see things that they do not feel.... People are stuffed with appreciation in our art galleries, instead of looking at pictures for the fun of it."

Those who take in art for the fun of it, and don't fake their sensations, acquire an appetite that it is a great treat to satisfy. And by and by, art becomes as necessary to them as breathing fresh air.

To the rest of us, art is only a luxury: a dessert, not a food.

Some poets have to struggle with a harsh world for leave to be poets, like unlucky peaches trying to ripen north of Latitude 50. Coventry Patmore by contrast was bred in a hot-house. He was the son of a man named Peter G. Patmore, who, unlike most fathers, was willing to have a poet in the family. In fact he was eager. He was also, unfortunately, helpful, and did all he could to develop in his son "an ardor for poetry." But ardor is born, not cooked. A watched pot never boils. Nor did Patmore. He had many of the other good qualities that all poets need, but the quality Peter G. planned to[37] develop in the boy never grew. Young Patmore studied the best Parnassian systems, he obeyed the best rules, he practiced the right spiritual calisthenics, took his dumb-bells out daily: but he merely proved that poetry is not the automatic result of going through even the properest motions correctly.

Still he kept on, year by year, and the results were impressive. Many respected them highly. Including their author.

He grew old in this remarkable harness. Perhaps he also grew tired. At any rate, at sixty-three he "solemnly recorded" the fact that he had finally finished "his task as a poet." He lived for about ten years more, but the remainder was silence. "He had been a practicing poet for forty-seven years," Edmund Gosse says. Odd way for Gosse to talk: as though he were describing a dentist.

One of this worthy Mr. Patmore's most worthy ideas was that the actual writing of verse was but a part of his job. Not even professional poets, he felt, should make it their chief occupation. No; one ought to spend months, maybe years, meditating on everything, in order to supply his soul with plenty of suitable thoughts—like a tailor importing fine woolens to accumulate stock. And even with the shelves full, one ought not to work till just the right hour.[38]

His theories called for a conscientious inspection of each inspiration. They also obliged this good gentleman to exercise self-control. Many a time when he wanted to work he held back. Although "the intention to write was never out of his mind" (Mr. Gosse says), Mr. Patmore had "the power of will to refuse himself the satisfaction of writing, except on those rare occasions when he felt capable of doing his best."

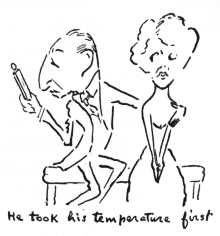

There once was a man I knew, who wooed his fiancée on those terms. He used to sit thinking away in his library, evenings, debating whether he had better go see her, and whether he was at his best. And after fiddling about in a worried way between yes and no, he would sometimes go around only to find that she would not see him. I think that she loved the man, too, or was ready to love him. "His honesty has a horrible fascination for me," I remember her saying, "but when he has an impulse to kiss me—and I see him stop—and look as though he were taking his temperature with a thermometer first, trying to see if his blood is up—I want to hit him and scream!"

Mr. Patmore, however, was very firm about this being necessary. He had many a severe inner struggle because of his creed. He would repulse the most enticing inspiration, if his thermometer wasn't at just the right figure. Neither[39] he nor his inspirations were robust, but they were evenly matched, and they must have wrestled obstinately and often in the course of his life, and pushed each other about and exchanged slaps and tense bloodless pinches. But whenever Mr. Patmore felt it his duty to wrestle, he won.

He took his temperature first

He took his temperature first

Consequently, looking backward he felt able to say when he was old: "I have written little, but it is all my best; I have never spoken when I had nothing to say, nor spared time nor labor to make my words true. I have respected posterity, and should there be a posterity which cares for letters, I dare to hope that it will respect me."

That last phrase has a manly ring. Imagine him, alone late at night, trying to sum up his life, and placing before us what bits he had managed to do before dying. We may live through some evening of that sort ourselves, by and by. We may turn to look back at the new faces of the young men and women who will some day be inheriting our world as we go out its gate. Will they laugh at us and think us pompous, as some of us regard Mr. Patmore? He doesn't seem[40] very hopeful, by the way, about our caring for letters, but he does seem to think, if we do, that we will not make fun of him.

I don't think he ought to mind that, though, if we are friendly about it. We certainly respect him compared with many men of his time—the shifty politicians, the vicious or weak leaders of thought, who went through life as softies, without rigid standards of conduct. He shines out by contrast, this incorruptible, solemn old Roman.

Only—he was so solemn! "From childhood to the grave" he thought he had "a mission to perform," with his poems. And what was this mission that he was so determined to fill? "He believed himself to be called upon to celebrate Nuptial Love."

Again it is his solemnity one smiles at, but not his idea. Nuptial Love? Very good. The possibilities of episodic love have been hotly explored, its rights have been defended, its spiritual joys have been sung. But Nuptial Love, our queer breed of humans, inconstant at heart, believes to be a tame thing by contrast: nearly all anti-climax. There are delights at the beginning, and a gentle glow (perhaps) at the end: for the rest it is a long dusty journey of which the less said the better. Exceptional couples who do somewhat better than this, and not only get along without storms but live contentedly too, are apt to congratulate[41] themselves and call their lives a success. Contentedly! Pah! Content with mere absence of friction! No conception, apparently, of the depths beyond depths two should find, who devote themselves deeply to each other for all of their lives. I don't say this often is possible: I think people try: but one or the other comes up against a hard place and stops. Only, sometimes it's not that which prevents going further; it's a waywardness that will not stick to any one mine to get gold. A man slips away and runs about, picking up stray outcroppings, but loses the rich veins of metal, far down in the earth.

Why is it that so few of us contentedly stick to one mate, and say to ourselves, "Here is my treasure; I will seek all in her."

Well, this is a subject on which I should enjoy speculating—but Nuptial Love happens to be a field in which I have had no experience, and furthermore it is not my theme anyhow, but my friend Mr. Patmore's, whose spirit has been standing indignantly by, as I wrote, as though it were ordering me away, with a No Trespassing look. I will therefore withdraw, merely adding that he himself didn't do any too well with it.

However, no poet can avoid an occasional slump. For all Mr. Patmore's efforts, he needs to be edited as much as the rest of them. Some of his little chance sayings were taking and odd:[42]

To animals that do not love."

But he always fell back into being humdrum and jog-trot. Take this stanza, from his poetical flight entitled Tamerton Church Tower:

And scaled the easy steep;

And soon beheld the quiet flag

On Lanson's solemn Keep.

But he was writing jokes for Punch;

So I, who knew him well,

Deciding not to stay for lunch,

Returned to my hotel."

May I ask why such verses should be enshrined in a standard collection of poetry? The last four lines are good, they have a touch of humor or lightness, perhaps; but what can be said for the first four? And they, only, are Patmore's. The last four I added myself, in an effort to help.

"A man may mix poetry with prose as much as he pleases, and it will only elevate and enliven," as Landor observed; "but the moment he mixes a particle of prose with his poetry, it precipitates the whole."

All but the vulgar like poetry. This is using vulgarity in the sense in which Iva Jewel Geary defines it, as being "in its essence the acceptance of life as low comedy, and the willingness to be entertained by it always, as such. Whereas poetry," she says, "is the interpretation of life as serious drama: a play, in the main dignified and beautiful, or tragic."

Some readers take to poetry as to music, because it enraptures the ear. Others of us feel a need for its wisdom and insight—and wings. It deepens our everyday moods. It reminds us of Wonder. Here we are, with our great hearts and brains, descended from blind bits of slime, erecting a busy civilization on a beautiful earth; and that earth is whirling through space, amid great golden worlds: and yet, being grandsons of slime, we forget to look around us.

As Patmore expressed it:

Looks round him; but, for all the rest,

The world, unfathomably fair,

Is duller than a witling's jest.

Love wakes men, once a lifetime each;

They lift their heavy lids, and look;

And, lo, what one sweet page can teach,

They read with joy, then shut the book."

[44]

Legs vs. Architects

I don't know how many persons who hate climbing there are in the world; there must be, by and large, a great number. I'm one, I know that. But whenever a building is erected for the use of the public, the convenience of a non-climbing person is wholly ignored.

I refer, of course, to the debonair habit which architects have of never designing an entrance that is easy to enter. Instead of leaving the entrance on the street level so that a man can walk in, they perch it on a flight of steps, so that no one can get in without climbing.

The architect's defense is, it looks better. Looks better to whom? To architects, and possibly to tourists who never go in the building. It doesn't look better to the old or the lame, I can tell you; nor to people who are tired and have enough to do without climbing steps.

There are eminent scholars in universities, whose strength is taxed daily, because they must daily climb a parapet to get to their studies.

Everywhere there are thousands of men and women who must work for a living where some nonchalant architect has needlessly made their work harder.[45]

I admit there is a dignity and beauty in a long flight of steps. Let them be used, then, around statues and monuments, where we don't have to mount them. But why put them where they add, every day, to the exertions of every one, and bar out some of the public completely? That's a hard-hearted beauty.

Suppose that, in the eye of an architect, it made buildings more beautiful to erect them on poles, as the lake dwellers did, ages back. (It would be only a little more obsolete than putting them on top of high steps.) Would the public meekly submit to this standard and shinny up poles all their lives?

Let us take the situation of a citizen who is not a mountaineering enthusiast. He can command every modern convenience in most of his ways. But if he happens to need a book in the Public Library what does he find? He finds that some architect has built the thing like a Greek temple. It is mounted on a long flight of steps, because the Greeks were all athletes. He tries the nearest university library. It has a flight that's still longer. He says to himself (at least I do), "Very well, then, I'll buy the damn book." He goes to the book-stores They haven't it. It is out of stock, out of print. The only available copies are those in the libraries, where they are supposed to be ready for every[46] one's use; and would be, too, but for the architects and their effete barricades.

This very thing happened to me last winter. I needed a book. As I was unable to climb into the Public Library, I asked one of my friends to go. He was a young man whose legs had not yet been worn out and ruined by architects. He reported that the book I wanted was on the reference shelves, and could not be taken out. If I could get in, I could read it all I wanted to, but not even the angels could bring it outside to me.

We went down there and took a look at the rampart which would have to be mounted. That high wall of steps! I tried with his assistance to climb them, but had to give up.

He said there was a side entrance. We went there, but there, too, we found steps.

"After you once get inside, there is an elevator," the doorkeeper said.

Isn't that just like an architect! To make everything inside as perfect as possible, and then keep you out!

There's a legend that a lame man once tried to get in the back way. There are no steps there, hence pedestrians are not admitted. It's a delivery entrance for trucks. So this man had himself delivered there in a packing case, disguised as the Memoirs of Josephine, and let them haul him all the way upstairs before he revealed he was not. But it seems they turn those cases upside[47] down and every which way in handling them, and he had to be taken to the hospital. He said it was like going over Niagara.

If there must be a test imposed on every one who enters a library, have a brain test, and keep out all readers who are weak in the head. No matter how good their legs are, if their brains aren't first-rate, keep 'em out. But, instead, we impose a leg test, every day of the year, on all comers. We let in the brainless without any examination at all, and shut out the most scholarly persons unless they have legs like an antelope's.

If an explorer told us of some tribe that did this, we'd smile at their ways, and think they had something to learn before they could call themselves civilized.

There are especially lofty steps built around the Metropolitan Museum, which either repel or tire out visitors before they get in. Of those who do finally arrive at the doors, up on top, many never have enough strength left to view the exhibits. They just rest in the vestibule awhile, and go home, and collapse.

It is the same way with most of our churches, and half of our clubs. Why, they are even beginning to build steps in front of our great railway stations. Yes, that is what happens when railway men trust a "good" architect. He designs something that will make it more difficult for people to[48] travel, and will discourage them and turn them back if possible at the start of their journey. And all this is done in the name of art. Why can't art be more practical?

There's one possible remedy:

No architect who had trouble with his own legs would be so inconsiderate. His trouble is, unfortunately, at the other end. Very well, break his legs. Whenever we citizens engage a new architect to put up a building, let it be stipulated in the contract that the Board of Aldermen shall break his legs first. The only objection I can think of is that his legs would soon get well. In that case, elect some more aldermen and break them again.[49]

To Phoebe

It has recently been discovered that one of the satellites of Saturn, known as Phoebe, is revolving in a direction the exact contrary of that which all known astronomical laws would have led us to expect. English astronomers admit that this may necessitate a fundamental revision of the nebular hypothesis.—Weekly Paper.

In our neatly-plotted sky,

Listen, Phoebe, to my lay:

Won't you whirl the other way?

And revolve the way they should.

You alone, of that bright throng,

Will persist in going wrong.

We have made a Law instead.

Have you never heard of this

Neb-u-lar Hy-poth-e-sis?

Just how every star should act.

Tells each little satellite

Where to go and whirl at night.

[50] Disobedience incurs

Anger of astronomers,

Who—you mustn't think it odd—

Are more finicky than God.

Really, we can't rearrange

Every chart from Mars to Hebe

Just to fit a chit like Phoebe.

[51]

Sex, Religion and Business

A young Russian once, in the old nineteenth century days, revisited the town he was born in, and took a look at the people. They seemed stupid—especially the better classes. They had narrow-minded ideas of what was proper and what wasn't. They thought it wasn't proper to love, except in one prescribed way. They worried about money, and social position and customs. The young Russian was sorry for them; he felt they were wasting their lives. His own way of regarding the earth was as a storehouse of treasures—sun, air, great thoughts, great experiences, work, friendship and love. And life was our one priceless chance to delight in all this. I don't say he didn't see much more to life than enjoyment, but he did believe in living richly, and not starving oneself.

The people he met, though, were starving themselves all the time. Certain joys that their natures desired they would not let themselves have, because they had got in the habit of thinking them wrong.

Well, of course this situation is universal; it's everywhere. Most men and women have social and moral ideas which result in their starving their[52] natures. If they should, well and good. But if not, it is a serious and ridiculous matter. It's especially hard upon those who don't see what they are doing.

I know in my own case that I have been starved, more than once. I'm not starved at the moment; but I'm not getting all I want either. So far as the great joys of life go, I live on a diet. And when something reminds me what splendors there may be, round the corner, I take a look out of the door and begin to feel restless. I dream I see life passing by, and I reach for my hat.

But a man like myself doesn't usually go at all far. His code is too strong—or his habits. Something keeps the door locked. Most of us are that way; we aren't half as free as we seem. When a man has put himself into prison it is hard to get out.

To go back to this Russian, he was in a novel of Artzibashef's, called Sanine. I thought at first that he might release me from my little jail. But it is an odd thing: we victims get particular about being freed. We're unwilling to be released by just any one: it must be the right man. It's too bad to look a savior in the mouth, but it is highly important. This man Sanine, for instance, was for letting me out the wrong door.

I didn't see this at the start. In fact I felt drawn to him. I liked his being silent and caustic[53] and strong in his views. The only thing was, he kept getting a little off-key. There was a mixture of wrongness in his rightness that made me distrust him.

Sanine was in his twenties, and in order to get all the richness that his nature desired, he had to attend to his urgent sexual needs. He wasn't in love, but his sexual needs had to be gratified. In arranging for this he recognized few or no moral restrictions. His idea was that people were apt to make an awful mistake when they tried to build permanent relations out of these fleeting pleasures. Even if there were babies.

These views didn't commend themselves to some of Sanine's neighbors and friends, or to that narrow village. They believed in family-life, and in marrying, and all that kind of thing, and they got no fun at all out of having illegitimate children. They had a lot of prejudices, those people. Sanine gave them a chill. Among them was a young man named Yourii; he's the villain of this book. He was not wicked, but stupid, poor fellow. He was pure and proud of it. I hardly need state that he came to a very bad end. And when they urged Sanine, who was standing there at Yourii's burial, to make some little speech, he replied: "What is there to say? One fool less in the world." This made several people indignant, and the funeral broke up.[54]

A friend of Sanine's named Ivanoff, went with him to the country one day, and they passed some girls bathing in a stream there, without any bathing suits.

He was pure and

proud of it

He was pure and

proud of it

"Let's go and look at them," suggested Sanine.

"They would see us."

"No they wouldn't. We could land there, and go through the reeds."

"Leave them alone," said Ivanoff, blushing slightly.... "They're girls ... young ladies.... I don't think it's quite proper."

"You're a silly fool," laughed Sanine. "Do you mean to say that you wouldn't like to see them? What man wouldn't do the same if he had the chance?"

"Yes, but if you reason like that, you ought to watch them openly. Why hide yourself?"

"Because it's much more exciting."

"I dare say, but I advise you not to—"

"For chastity's sake, I suppose?"

"If you like."

"But chastity is the very thing that we don't possess."

Ivanoff smiled, and shrugged his shoulders.

"Look here, my boy," said Sanine, steering toward the bank, "if the sight of girls bathing[55] were to rouse in you no carnal desire, then you would have the right to be called chaste. Indeed though I should be the last to imitate it, such chastity on your part would win my admiration. But, having these natural desires, if you attempt to suppress them, then I say that your so-called chastity is all humbug."

This was one of the incidents that made me dislike Mr. Sanine. I liked his being honest, and I liked his being down on prudery and humbug. But I thought his theory of life was a good deal too simple. "Don't repress your instincts," he said. That's all very well, but suppose a man has more than one kind? If a cheap peeping instinct says "Look," and another instinct says "Oh, you bounder," which will you suppress? It comes down to a question of values. Life holds moments for most of us which the having been a bounder will spoil.

The harmonizing of body and spirit and all the instincts into one, so we'll have no conflicting desires, is an excellent thing—when we do it; and we can all do it some of the time, with the will and the brains to. But no one can, all the time. And when you are not fully harmonized, and hence feel a conflict—different parts of your nature desiring to go different ways—why, what can you do? You must just take your choice of repressions.[56]

As to Sanine, his life is worth reading, and—in spots—imitating. But I thought he was rather a cabbage. A cabbage is a strong, healthy vegetable, honest and vigorous. It's closely in touch with nature, and it doesn't pretend to be what it isn't. You might do well to study a cabbage: but not follow its program. A cabbage has too much to learn. How our downright young moderns will learn things, I'm sure I don't know. Sanine scornfully says "not by repression." Well, I don't think highly of repressions; they're not the best method. Yet it's possible that they might be just the thing—for a cabbage.

Long before Sanine was born—in the year 1440 in fact—there was a man in India who used to write religious little songs. Name of Kabir. I tried to read his books once, but couldn't, not liking extremes. He was pretty ecstatic. I could no more keep up with him than with Sanine.

In his private life Kabir was a married man and had several children. By trade he was a weaver. Weaving's like knitting: it allows you to make a living and think of something else at the same time. It was the very thing for Kabir, of course. Gave him practically the whole day to make songs in, and think of religion. He seems to have been a happy fellow—far more so than Sanine.[57]

Sanine's comment would have been that Kabir was living in an imaginary world, not a real one, and that he was autointoxicating himself with his dreamings.

I couldn't keep up with Kabir

I couldn't keep up with Kabir

Kabir's answer would have been that Sanine ought to try that world before judging it, and had better begin by just loving people a little. More love, and more willingness to deal with his poor fellow-creatures, instead of flinging them off in impatience—that would have been Kabir's prescription. And, as a fact, it might really have been an eye-opener for Sanine.

Of the two, however, I preferred Sanine to Kabir. The trouble with Kabir was, he wouldn't let you alone. He wanted everybody to be as religious as he was: it would make them so happy, he thought. This made him rather screechy.

He sang some songs, however, that moved me. Like many a modern, I'm not religious; that is, I've no creed; but I don't feel quite positive that this army of planets just happened, and that man's[58] evolution from blindness to thought was an accident and that nowhere is any Intelligence vaster than mine.

Therefore, I'm always hoping to win some real spiritual insight. It has come to other men without dogma (I can't accept dogmas) and so, I keep thinking, it may some day come to me, too. I never really expect it next week, though. It's always far off. It might come, for instance, I think, in the hour of death. And here is the song Kabir sang to all men who think that:

live, know whilst you live, understand

whilst you live; for in life deliverance

abides.

living, what hope of deliverance in death?

shall have union with Him because it has

passed from the body:

City of Death.

it hereafter."

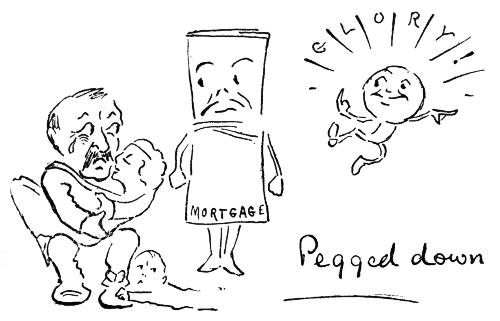

Both Sanine and Kabir should have read Tarkington's novel, The Turmoil, which is all about the rush and hustle-bustle of life in America.[59] It would have made them see what great contrasts exist in this world. Kabir thought too much about religion. Sanine, of sex. Nobody in The Turmoil was especially troubled with either. Some went to church, maybe, and sprinkled a little religion here and there on their lives; but none deeply felt it, or woke up in the morning thinking about it, or allowed it to have much say when they made their decisions. And as to sex, though there were lovers among them, it was only incidentally that they cared about that. They satisfied nature in a routine way, outside office hours. No special excitement about it. Nothing hectic—or magical.

Now, sex is a fundamental state and concern of existence: it's a primary matter. If it's pushed to one side, we at least should be careful what does it. And religion, too, God or no God, is a primary matter, if we stretch the word to cover all the spiritual gropings of man. Yet what is it that pushes these two great things aside in America? What makes them subordinate? Business. We put business first.

And what is this business? What is the charm of this giant who engrosses us so? In Tarkington's novel you find yourself in a town of neighborly people, in the middle west somewhere; a leisurely and kindly place—home-like, it used to be called. But in the hearts of these[60] people was implanted a longing for size. They wished that town to grow. So it did. (We can all have our wishes.) And with its new bigness came an era of machinery and rush. "The streets began to roar and rattle, the houses to tremble, the pavements were worn under the tread of hurrying multitudes. The old, leisurely, quizzical look of the faces was lost in something harder and warier."

"You don't know what it means, keepin' property together these days," says one of them. "I tell you when a man dies the wolves come out of the woods, pack after pack ... and if that dead man's children ain't on the job, night and day, everything he built'll get carried off.... My Lord! when I think of such things coming to me! It don't seem like I deserved it—no man ever tried harder to raise his boys right than I have. I planned and planned and planned how to bring 'em up to be guards to drive the wolves off, and how to be builders to build, and build bigger.... What's the use of my havin' worked my life and soul into my business, if it's all goin' to be dispersed and scattered, soon as I'm in the ground?"

Poor old business! It does look pretty sordid. Yet there is a soul in this giant. Consider its power to call forth the keenness in men and to[61] give endless zest to their toil and sharp trials to their courage. It is grimy, shortsighted, this master—but it has greatness, too.

Only, as we all know, it does push so much else to one side! Love, spiritual gropings, the arts, our old closeness to nature, the independent outlook and disinterested friendships of men—all these must be checked and diminished, lest they interfere. Yet those things are life; and big business is just a great game. Why play any game so intently we forget about life?

Well, looking around at mankind, we see some races don't. The yellow and black—and some Latins. But Normans and Saxons and most Teutons play their games hard. Knight-errantry was once the game. See how hard they played that. The Crusades, too,—all gentlemen were supposed to take in the Crusades. Old, burly, beef-crunching wine-bibbers climbed up on their chargers and went through incredible troubles and dangers—for what? Why, to rescue a shrine, off in Palestine, from the people who lived there. Those people, the Saracens, weren't doing anything very much to it; but still it was thought that no gentleman ought to stay home, or live his life normally, until that bit of land had been rescued, and put in the hands of stout prelates instead of those Saracans.

Then came the great game of exploring new[62] lands and new worlds. Cortez, Frobisher, Drake. Imagine a dialogue in those days between father and son, a sea-going father who thought exploration was life, and a son who was weakly and didn't want to be forced into business. "I don't like exploration much, Father. I'm seasick the whole time, you know; and I can't bear this going ashore and oppressing the blacks." "Nonsense, boy! This work's got to be done. Can't you see, my dear fellow, those new countries must be explored? It'll make a man of you."

So it goes, so it goes. And playing some game well is needful, to make a man of you. But once in a while you get thinking it's not quite enough.[63]

An Ode to Trade

"Recent changes in these thoroughfares show that trade is rapidly crowding out vice."—Real Estate Item.

All drink, and at whose feet all bow

May I inquire what you are up

To now?

And ravenous of old your shrine;

But still, O Trade, you ought to draw

The line.

Of leisure—do not these suffice?

Ah, tell me not you're also death

On vice.

That has from boyhood soothed my grief

Must fall into the sere and yellow

leaf;

Must also share this cruel lot:

That every haunt of sin must go

To pot.

Engulf our aristocracy,

Our poets, all who love the arts

But me:

[64]

Seduce, I say, the world's elect—

I, in my clear and ringing verse,

Object.

You see us of all else bereft;

You know quite well that vice alone

Is left.

Nor do we grudge the sacrifice.

But worms will turn! You've got to spare

Us vice

[65]

Objections to Reading

When I was a child of tender years—about five tender years, I think—I felt I couldn't wait any longer: I wanted to read. My parents had gone along supposing that there was no hurry; and they were quite right; there wasn't. But I was impatient. I couldn't wait for people to read to me—they so often were busy, or they insisted on reading the wrong thing, or stopping too soon. I had an immense curiosity to explore the book-universe, and the only way to do it satisfactorily was to do it myself.

Consequently I got hold of a reader, which said, "See the Dog Run!" It added, "The Dog Can Run and Leap," and stated other curious[66] facts. "The Apple is Red," was one of them, I remember, and "The Round Ball Can Roll."

There was certainly nothing thrilling about the exclamation, "See the Dog Run!" Dogs run all the time. The performance was too common to speak of. Nevertheless, it did thrill me to spell it out for myself in a book. "The Round Ball Can Roll," said my book. Well, I knew that already. But it was wonderful to have a book say it. It was having books talk to me.

Years went on, and I read more and more. Sometimes, deep in Scott, before dinner, I did not hear the bell, and had to be hunted up by some one and roused from my trance. I hardly knew where I was, when they called me. I got up from my chair not knowing whether it was for dinner or breakfast or for school in the morning. Sometimes, late at night, even after a long day of play—those violent and never-pausing exertions that we call play, in boyhood—I would still try to read, hiding the light, until my eyes closed in spite of me. So far as I knew, there were not many books in the world; but nevertheless I was in a hurry to read all there were.

In this way, I ignorantly fastened a habit upon me. I got like an alcoholic, I could let no day go by without reading. As I grew older, I couldn't pass a book-shop without going in. And in libraries, where reading was free, I always read[67] to excess. The people around me glorified the habit (just as old songs praise drinking). I never had the slightest suspicion that it might be a vice. I was as complacent over my book totals as six bottle men over theirs.

Ak and the striped Wumpit—

Ak and the striped Wumpit—

Can there ever have been a race of beings on some other star, so fascinated as we are by reading? It is a remarkable appetite. It seems to me that it must be peculiar to simians. Would you find the old folks of any other species, with tired old brains, feeling vexed if they didn't get a whole newspaper fresh every morning? Back in primitive times, when men had nothing to read but knots in a string, or painful little pictures on birch[68] bark—was it the same even then? Probably Mrs. Flint-Arrow, 'way back in the Stone Age pored over letters from her son, as intensely as any one. "Only two knots in it this time," you can almost hear her say to her husband. "Really I think Ak might be a little more frank with his mother. Does it mean he has killed that striped Wumpit in Double Rock Valley, or that the Gouly family where you told him to visit has twins?"

maiden in

distress

maiden in

distress

There are one or two primitive ideas we still have about reading. I remember in a boarding-house in Tucson, I once met a young clergyman, who exemplified the belief many have in the power of books. "Here are you," he would say to me,[69] "and here is your brain. What are you going to put into it? That is the question." I could make myself almost as good as a bishop, he intimated, by choosing the noblest and best books, instead of mere novels. One had only to choose the right sort of reading to be the right sort of man.

Scenes of Horror

Scenes of Horror

He seemed to think I had only to read Socrates to make myself wise, or G. Bernard Shaw to be witty.

Cannibals eat the hearts of dead enemy chieftains, to acquire their courage; and this clergyman entered a library with the same simple notion.

But though books are weak implements for implanting good qualities in us, they do color our minds, fill them with pictures and sometimes ideas. There are scenes of horror in my mind to-day[70] that were put there by Poe, or Ambrose Bierce or somebody, years ago, which I cannot put out. No maiden in distress would bother me nowadays, I have read of too many, but some of those first ones I read of still make me feel cold. Yes, a book can leave indelible pictures .... And it can introduce wild ideas. Take a nice old lady for instance, at ease on her porch, and set the ballads of Villon to grinning at her over the hedge, or a deep-growling Veblen to creeping on her, right down the rail,—it's no wonder they frighten her. She doesn't want books to show her the underworld and blacken her life.

Dastardly attack by Veblen's latest.

Dastardly attack by Veblen's latest.

It's not surprising that some books are censored and forbidden to circulate. The surprising thing is that in this illiberal world they travel so freely. But they usually aren't taken seriously; I suppose that's the answer. It's odd. Many[71] countries that won't admit even the quietest living man without passports will let in the most active, dangerous thoughts in book form.

The habit of reading increases. How far can it go? The innate capacity of our species for it is plainly enormous. Are we building a race of men who will read several books every day, not counting a dozen newspapers at breakfast, and magazines in between? It sounds like a lot, but our own record would have astonished our ancestors. Our descendants are likely to read more and faster than we.

The Underworld

The Underworld

People used to read chiefly for knowledge or to pursue lines of thought. There wasn't so much fiction as now. These proportions have changed. We read some books to feed our curiosity but[72] more to feed our emotions. In other words, we moderns are substituting reading for living.

When our ancestors felt restless they burst out of their poor bookless homes, and roamed around looking for adventure. We read some one else's. The only adventures they could find were often unsatisfactory, and the people they met in the course of them were hard to put up with. We can choose just the people and adventures we like in our books. But our ancestors got real emotions, where we live on canned.

Volume of morbid Geography

attempting to enter Lone Gulch

Volume of morbid Geography

attempting to enter Lone Gulch

Of course canned emotions are thrilling at times, in their way, and wonderful genius has gone into putting them up. But a man going home from a library where he has read of some battle, has not the sensations of a soldier returning from war.[73]

This book tells you all about how fighting feels

This book tells you all about how fighting feels

Still—for us—reading is natural. If we

were more robust, as a race, or if earth-ways

were kinder, we should not turn so often to books

when we wanted more life. But a fragile yet

aspiring species on a stormy old star—why, a

substitute for living is the very thing such beings

need.[74]

[75]

On Authors

The Enjoyment of Gloom

There used to be a poem—I wish I could find it again—about a man in a wild, lonely place who had a child and a dog. One day he had to go somewhere So he left the dog home to protect the child until he came back. The dog was a strong, faithful animal, with large, loving eyes.

Something terrible happened soon after the man had gone off. I find I'm rather hazy about it, but I think it was wolves. The faithful dog had an awful time of it. He fought and he fought. He was pitifully cut up and bitten. In the end, though, he won.

The man came back when it was night. The dog was lying on the bed with the child he had saved. There was blood on the bed. The man's heart stood still. "This blood is my child's," he thought hastily, "and this dog, which I trusted,[78] has killed it." The dog feebly wagged his tail. The man sprang upon him and slew him.

He saw his mistake immediately afterward, but—it was too late.

When I first read this I was a boy of perhaps ten or twelve. It darn near made me cry. There was one line especially—the poor dog's dying howl of reproach. I think it did make me cry.

I at once took the book—a large, blue one—and hunted up my younger brothers. I made them sit one on each side of the nursery fire. "I'm going to read you something," I said.

"Keep all the wolves out now."

"Keep all the wolves out now."

They looked up at me trustfully. I remember their soft, chubby faces.

I began the poem, very much moved; and they too, soon grew agitated. They had a complete confidence, however, that it would come out all right. When it didn't, when the dog's dying howl came, they burst into tears. We all sobbed together.

Reading about the poor dog.

Reading about the poor dog.

This session was such a success that I read it to them several times afterward. I didn't get quite so much poignancy out of these encores myself but my little brothers cried every time, and that, somehow, gave me pleasure. It gave no pleasure to them. They earnestly begged me not to keep reading it. I was the eldest, however, and paid little attention, of course, to their wishes. They'd be playing some game, perhaps.[80] I would stalk into the room, book in hand, and sit them down by the fire. "You're going to read us about the dog again?" they would wail. "Well, not right away," I'd say. "I'll read something funny to start with." This didn't much cheer them. "Oh, please don't read us about the dog, please don't," they'd beg, "we're playing run-around." When I opened the book they'd begin crying 'way in advance, long before that stanza came describing his last dying howl.

It was kind of mean of me.

There's a famous old author, though, who's been doing just that all his life. He's eighty years old, and still at it. I mean Thomas Hardy. Dying howls, of all kinds, are his specialty.

His critics have assumed that from this they can infer his philosophy. They say he believes that "sorrow is the rule and joy the exception," and that "good-will and courage and honesty are brittle weapons" for us to use in our defense as we pass through such a world.

I'm not sure that I agree that that's Hardy's philosophy. It's fair enough to say that Hardy's stories, and still more his poems, paint chiefly the gloomy and hopeless situations in life, just as Mark Twain and Aristophanes painted the comic ones. But Mark Twain was very far from thinking the world was a joke, and I doubt[81] whether Hardy regards it at heart as so black.

He has written—how many books? twenty odd?—novels and poems. They make quite an edifice. They represent long years of work. Could he have been so industrious if he had found the world a chamber of horrors? He might have done one or two novels or poems about it, but how could he have kept on if he had truly felt the whole thing was hopeless? He kept on, because although sorrows move him he does not feel their weight. He found he could have a good time painting the world's tragic aspects. He is somehow or other so constituted that that's been his pleasure. And he has wanted his own kind of pleasure, just as you and I want our kinds. That's fair.

I like to think that the good old soul has had a lot of fun all his life, describing all the gloomiest episodes a person could think of. If a good, gloomy episode comes into his mind while he's shaving, it brightens the whole day, and he bustles off to set it down, whistling.