CATCHER CRAIG

CATCHER CRAIG

By

AUTHOR OF “PITCHING IN A PINCH,” “PITCHER POLLOCK,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

CHARLES M. RELYEA

NEW YORK

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1915, by

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | SAM MAKES A PURCHASE | 3 |

| II | OFF FOR CAMP | 15 |

| III | “THE WIGWAM” | 26 |

| IV | THE BLANKET THAT RAN AWAY | 45 |

| V | A SLIDE TO THE PLATE | 61 |

| VI | THE TILTING MATCH | 72 |

| VII | SAM OFFERS A SUGGESTION | 85 |

| VIII | THE “BLUES” WIN! | 96 |

| IX | DOUGHNUTS IN THE RAIN | 109 |

| X | SIDNEY SINGS A DITTY | 118 |

| XI | MAKING THE NINE | 138 |

| XII | ON CONQUEST BENT | 150 |

| XIII | OUT AT THIRD! | 163 |

| XIV | TIED IN THE EIGHTH | 175 |

| XV | STEVE SCORES | 188 |

| XVI | KIDNAPPED | 200 |

| XVII | “GREYSIDES” | 211 |

| XVIII | MR. YORK MAKES A PROPOSITION | 229 |

| XIX | HOME AGAIN | 238 |

| XX | THE MAN IN THE PANAMA | 249 |

| XXI | MR. HALL TALKS BASEBALL | 263 |

| XXII | BASES FULL! | 276 |

| XXIII | A THROW TO SECOND | 295 |

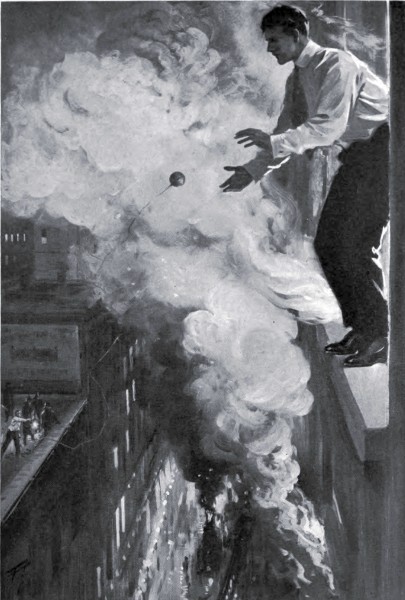

| XXIV | FIRE! | 311 |

| XXV | SAM SIGNALS FOR A FAST ONE | 327 |

| XXVI | CATCHER CRAIG | 339 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

CATCHER CRAIG

CHAPTER I

SAM MAKES A PURCHASE

It was a window to gladden any boy’s heart. Behind the big plate-glass pane were baseball bats of all sorts and prices, masks and protectors, gloves and mitts, balls peeking temptingly forth from their tin-foil wrappers, golf clubs and bags, running shoes and apparel, and many, many other things to send a chap’s hand diving into his pocket.

Sam Craig’s hand was already there, jingling the few coins he had with him, while his gaze wandered raptly over the enticing array. Always, though, it returned to the display of catcher’s mitts.

He was seventeen, a sturdy, brown-haired youth with a well-tanned face from which dark grey eyes looked untroubledly forth. As he stood there in front of Cummings and Wright’s window his feet were planted apart, his attitude seeming to say: “Here I am and here I stay!” And the resolute[4] expression of his face backed up the assertion of his body, so that, had you for any reason wished to move Sam from in front of that window, it would never have occurred to you to try force. If persuasion failed you’d have let him stay there!

You wouldn’t have called Sam handsome, although, judged separately, his features were all good. His nose was straight and short, his eyes thoughtful, his mouth fairly wide and firm, and his chin purposeful. What you might have mistaken for a dimple in the cleft of the chin was in reality only a tiny scar, the result of collision with the point of a newly sharpened pencil caused by a fall on an icy sidewalk many years before. When accounting for that scar Sam was wont to indulge in one of his infrequent jokes. There was, he would tell you, a queer coincidence about it; it had happened in Faber-ary. If, through ignorance of the brand of pencils affected in Amesville, you missed the point of the joke, Sam didn’t explain it. He had evolved that pun all himself, and, not being addicted to airy persiflage, thought rather well of it. Consequently, if you didn’t catch it, Sam thought poorly of your sense of[5] humour and wasted no effort on you. He appreciated jokes when he heard them, but seldom perpetrated one himself. And his appreciation was seldom demonstrative. When others laughed Sam confined himself to a slight lifting of one corner of his mouth and a quizzical expression in his calm grey eyes. When others doubled themselves over and frankly shouted their amusement, Sam merely chuckled.

He was captain of the Amesville High School Baseball Team. When, two days after the final contest with Petersburg, a contest which had resulted in a victory for Amesville and given the Brown-and-Blue the season’s championship, the players had met to choose a leader for the next year, the honour had gone to Sam. Probably had Tom Pollock, whose heady pitching had done more than anything else to win the Petersburg series, been in his final year at high school, the captaincy would have gone to him by acclamation. But Tom was still a junior and it was the custom to elect a senior, and, with Tom out of it, the choice fell naturally on Sam. The school at large was well satisfied. Sam Craig was well liked. It would be stretching a point to say that he was[6] popular, for he was quiet, unassuming, and kept pretty much to himself, and in consequence made friends slowly. Certainly he was not socially popular as was Sidney Morris, nor was he hailed as a hero as was Tom Pollock. But he was liked and respected, and, if he wasn’t called a hero, few failed to realise that his steady, always cool-headed and sometimes brilliant work behind the bat had had more than a little to do with the successful outcome of the season just finished. Sam’s election had been made unanimous, Sam had faltered a much embarrassed speech of acceptance, and the team had disbanded for the summer.

To-day, a bright, warm morning in the latter part of June and just over a week after the election, Sam was seriously debating a momentous question, which was whether to deplete his slender hoard of spending-money for one of the brand-new mitts lying so temptingly beyond the glass, or to save his money and make his old one, a thing of many honourable scars, do him until next spring. If, he told himself, he had a lot of money, there were many things in that window he would buy: a new ball—his own had been several times restitched—a new mask and—yes, by jingo, if he could afford[7] it!—one of those dandy black-tipped bats bearing the facsimile signature of a noted Big Leaguer. More than once his hand came out of his pocket and more than once he half turned away, but each time his fingers went back to the coins again, and, at last, he entered the wide, hospitably open door of the big hardware and sporting-goods store. If he had not done so this story would have been far different, for more than the purchase of a catcher’s mitt resulted from his visit that morning to Cummings and Wright’s.

The front of the store, to the left as you entered, was devoted to the sporting goods. The department was only about two years old, but already it had thrice outgrown its limit, until now it occupied fully a third of the store’s space. There were racks of golf clubs, shelves filled with enticing boxes, handsome show-cases over which a red-blooded boy could hang entranced for a long time, polished counters holding things cunningly displayed, and, between window and cases, an oak-topped desk, at which a boy of about Sam’s age was busily writing. He was a capable-looking fellow, with much red-brown hair and a pair of frank and honest blue eyes and a nice smile. And[8] the smile appeared the minute he glanced up from the letter he was writing and glimpsed Sam over the top of the desk.

“Hello!” he said, jumping up. “Haven’t seen you since they made you captain, Sam. How are you?”

“All right,” said Sam, viewing him, with his quizzical smile, across the bat-rack. “Say, Tom, I want to buy a mitt. How much do I have to pay?”

“Oh, we never tell you that till we’ve shown you the goods,” laughed Tom Pollock. “What you want is one of these, Sam. It’s just like your old one, I think, and you can’t beat it at any price. We’ve got them for more money, but——”

“This is all right, thanks.” Sam thrust a hand into the black leather mitt and thumped it experimentally with his right fist. “How much, Tom?”

“Well, you get the team discount, Sam.” Tom tore a piece of paper from a pad and figured on it. Then he pushed it toward Sam, and Sam read the result, hesitated momentarily, and then nodded.

“All right,” he said, “I’ll take it. You needn’t do it up.”

“Going to wear it home?” asked Tom, with a laugh. “By the way, Morris was talking the other day about getting the Blues together again this summer. You’ll play if we do, won’t you?”

“I guess so. I don’t know yet. I’m looking for a job, Tom. Know anyone who wants to hire a strong, willing chap like me?”

Tom smiled and shook his head. “I’m afraid I don’t, Sam.”

“I went over to see Harper at the mills yesterday and got a sort of half promise of a job in the packing-room later. I’m not crazy about that, though. Maybe I’m lazy, but they sure do work you hard over there. I worked in the stock-room one summer and nearly passed out! And hot!”

“Must be,” Tom agreed. “Wish I did know of something, Sam, but——” He paused and glanced toward his desk. Then, “By Jove!” he muttered. “I wonder—Look here, Sam, mind going away from home?”

“How far? Where to?”

“Indian Lake.”

“Where’s that?”

“Up toward Mendon. About a hundred and twenty miles north of here.”

“What’s up there? Say, it isn’t peddling books, is it? I tried that one time and nearly starved to death. Sold four sets of Murray’s Compendium of Universal History and cleared just eleven dollars and eighty cents in a month!”

Tom smiled. “No, it’s—— Here’s—here’s the letter I got this morning. You can read it for yourself. I don’t know why they wrote to me unless this chap has bought goods from us. I haven’t looked him up yet.”

Sam took the brief typewritten letter and read it. It was addressed to “Manager Sporting Goods Department, Cummings and Wright, Amesville, Ohio,” and was as follows:

“Dear Sir:—Do you happen to know of a young man who will accept a position in a boys’ camp this summer, July 5 to September 13? We’ve only been running one year and can’t offer big pay, but we’ll provide comfortable sleeping quarters and plenty of good food and pay five a week. If you know of anyone, please drop me a line right away. Applicant must be moral, know something about handling boys—we take them from eleven to fifteen—and able to help instruct in athletics. References required. Thanking[11] you in advance for any trouble I am putting you to,

“Respectfully,

“Warren Langham, Director.”

The letter was typed on a sheet of paper bearing at the top the legend: “The Wigwam; a Summer Camp for Boys, Indian Lake, Ohio. Warren Bradley Langham, A.M., Director.”

Sam read it twice, the second time more thoughtfully. Then he looked questioningly at Tom.

“Interest you?” asked the latter. “If I could take it I’d do it in a minute, Sam.”

“Yes, but this man’s looking for someone a heap older than I am, I guess, Tom, although he doesn’t say anything about age. ‘A young man’; that’s all.”

“Well, aren’t you a young man?”

“I’m young,” agreed Sam, “but I’m no man yet. Anyway, I suppose I couldn’t go so far. There’s just my mother and Nell at home——”

“It would be only about nine weeks, though. The pay isn’t big, but——”

“The pay’s all right, Tom, because I’d be getting my board, you see. The only thing would[12] be leaving my folks alone so long. Still——” Sam thoughtfully fondled the catcher’s mitt.

“You could give him all the references he wanted,” urged Tom.

“Who from?” asked the other doubtfully. “What sort of references?”

“Why, from your minister and your school principal, of course.”

“Oh! Well, what about handling boys? I never handled any. And what about helping to instruct in athletics?”

“He doesn’t say that you must be used to handling them; only that you must know something about it. You do, don’t you?”

Sam looked blank. “Do I?” he asked.

“Of course you do! Any fellow does who has sense and has been a kid himself.” Tom laughed. “You’re too modest, Sam. Throw out your chest! Aren’t you captain of the Amesville High School Nine? As for instructing in athletics, why, all that means is that you’ll have to play ball with the kids and arrange running and jumping stunts and—— Say, you can swim, can’t you?”

“Yes.” Sam seemed quite decided about that.

“There you are, then! You take the letter and write to Mr. Whatshisname right off.”

“I’d like to,” mused Sam. “I’d like the job.”

“Take it then! I’ll drop the man a note and tell him I’ve got just the fellow for him; baseball captain, all-around athlete, fine swimmer, highly moral, and a wonder at handling boys! How’s that?”

“Pack of lies,” replied Sam, with a smile. “You let me take this letter and I’ll think it over to-night and talk to mother and Nell about it and see you in the morning. If they think it’s all right maybe I’ll try for it. Just the same, I know mighty well he’ll think I’m too young.”

“In years, maybe,” said Tom, “but in experience, Sam!” Tom shook his head knowingly. “It’s experience that counts, my boy.”

“You’re a chump,” said Sam. “Mind if I take this, though?”

“Not a bit. Let me know in the morning, Sam. Joking aside, I think it would be a first-rate thing. You’d come back in September simply full of health and able to lick your weight in bear-cats. We’ll miss you, though, if we get the ball team[14] together again. Who could we get to catch for us, Sam?”

“Buster Healey.”

“That’s so, he might do. Anything else I can sell you, Sam?”

“No, I guess not. Did I pay you for this?”

“Not yet. You needn’t if you don’t want to. Let me charge it to you.”

“No, thanks,” said Sam hurriedly, diving for his money. “If I get that place I’ll need this mitt, I guess. I’ve been trying to persuade myself all the morning that I really ought to have it.”

“Another reason for accepting the job, Sam,” said Tom cheerfully. “It’ll justify your extravagance.”

“That’s putting ’em over,” said Sam, with a chuckle. “‘Justify your extravagance!’ Gee, Tom, that’s real language, that is!”

“Yes, right in the groove, Sam. Say, I’d like to get out and pitch a few. What are you doing this evening? Let’s get a ball and see how it feels. Will you? Good stuff! Drop around here at five and get me.”

CHAPTER II

OFF FOR CAMP

Sam gave his new mitt a good try-out that evening. He and Tom and Tom’s particular chum, Sid Morris, took possession of the alley behind the hardware store and, admiringly regarded by a dozen or so small boys, pitched and caught until supper-time. Sidney, a slim, lithe, handsome chap of nearly eighteen, had been told about The Wigwam and, like Tom, sighed because he could not accept the position himself.

“I’ll tell you what, though, Sam,” he said, as he made an imaginary swing at the ball just before it thumped into Sam’s new glove, “if you go up there Tom and I will come and visit you for a day or two. I suppose they’d let us, wouldn’t they, Tom?”

“I don’t see how they could stop us visiting the place, but they might object to our staying overnight. Here goes for a knuckle-ball, Sam. Watch it.” But the attempt was not successful and Tom[16] shook his head as the ball came back to him. “I guess I’ll never make much out of that,” he said. “What’s that, Sam? Four fingers? I can’t see very well. All right, here she goes.” A slow ball sped across the imaginary plate and Sidney, making believe to swing and miss, uttered a disappointed grunt and angrily slanged a non-existent umpire, to the delight of the gallery. It was time to stop then, and, pocketing his ball, Tom accompanied Sam and Sidney to Main Street and, after Sidney had jumped a car to hurry home to dinner, detained Sam a minute on a corner.

“Made up your mind yet?” he asked.

Sam hesitated a moment. “Mother wants me to try for it,” he said, “and Nell, too, but I don’t know as I ought to leave them so long.”

“Well, you know best, Sam. Only, if you can do it you’d better. You know as well as I do that there’s mighty little chance of a fellow’s getting work in Amesville in summer, except at the mills; and they don’t pay anything over there.”

Sam nodded agreement. “I guess,” he answered thoughtfully, “I’ll write and see what Mr. Langham says. I suppose, though, he will tell me I’m too young.”

“How would it do,” asked Tom, “to say nothing about your age? He didn’t seem particular about that, you know. Just tell him you’re in your senior year at high school and are captain of the nine; and that you think you could hold down the place to the King’s taste, and so on!”

“I might, only—I’d feel pretty cheap if I got up there and he told me I wouldn’t do. Besides, it wouldn’t be quite honest, I guess.”

“I suppose not. No, you’d better tell him you’re nearly eighteen.”

“But I’m not,” objected Sam gravely. “I won’t be until December.”

“Then tell him you’re well over seventeen,” laughed Tom. “Anyway, make yourself out as old as you can, you fussy old chump! And don’t be too modest. I don’t know but that I ought to see that letter before you send it, Sam.”

Sam shook his head. “I’ll do it all right,” he said. “And you write to him, too, if you don’t mind.”

“I’ll do it this evening. So long. You ought to get an answer by Friday, I should think. I hope it comes out all right, Sam.”

“So do I,” said Sam soberly. “It would be a[18] dandy job if I could get it. Good night, Tom, and thank you for telling me about it.”

That wasn’t an easy letter to write, as Sam discovered later when, with the assistance of his mother and sister, he set about its composition. Nell, a pretty girl a year older than Sam, scored his first draft indignantly.

“Why, you haven’t said a thing about what you can do,” she exclaimed. “You’ve just told him what you can’t! The idea of saying that you’re a fair swimmer! You know very well, Sam, that you’re a perfect wonder in the water.”

“Pshaw, lots of fellows can swim better than I do.”

“No one around here, anyway. And you practically tell him that you don’t know a thing about looking after young boys.”

“I don’t!”

“But you don’t have to say so, do you? Now, you write that all over and—I tell you what, Sam! Write it just as if you were trying to get the place for someone else!”

Finally both Nell and Mrs. Craig approved, and Sam made a clean copy of the letter, slipped it into an envelope, stamped and addressed it, and[19] went out to the mail box with it so it would be gathered up at eleven-thirty and go off on the early morning train. Now that he had made up his mind to get the position if he could he was impatient to learn his fate.

But three days passed without any response and he had begun to think that nothing was to come of his application, when one afternoon a messenger boy brought a telegram. It was extremely brief.

“Mail references immediately. Langham.”

“It doesn’t look as though he thought you too young,” said Tom when, later, Sam dropped in at Cummings and Wright’s to tell the news. “If he did he wouldn’t bother with your references. I guess you’ve got it, Sam.”

And Sam acknowledged that it looked so. The letters of reference went off that evening, one from the High School principal and one from the minister of the church Sam attended. Both were, he considered, undeservedly flattering. They bore immediate result. Just thirty-four hours later another telegram arrived, this time not quite so brief.

“Satisfactory. Join camp July fifth. Rail to East Mendon, stage to Indian Lake. Bring grey flannel trousers, blue sleeveless shirt, sweater, sneakers, mackintosh. Langham.”

They referred to that telegram at intervals all day. Sam was a bit troubled because it said nothing about socks or a hat, but Nell said she supposed Mr. Langham gave him credit for enough sense to bring such things without being told.

“He doesn’t say whether the sweater has to be any special colour, either,” mused Sam. “Mine’s grey.”

“That thing!” exclaimed Nell scathingly. “Why, mother’s darned that and darned it, Sam. It isn’t fit to be seen in. You must have a new one.”

“Gee, if I buy a new sweater besides all those other things I won’t have any money left! I asked Miller, at the station, what the fare to Indian Lake is and he said it’s four dollars and sixty cents.”

“I don’t care, Sam, you can’t take that old sweater. You can get a new one for three dollars, I guess.”

“Can’t afford it,” said Sam decisively.

“Then I’ll present it to you. I’ve got a lot of money.”

“I think,” said Mrs. Craig, “it would be nice if Nellie and I bought those things for you, dear. How much would they cost, do you think?”

Sam demurred, but in the end they had their way, and the next morning Sam set out to Cummings and Wright’s with his precious telegram in hand and laid the matter before Tom Pollock.

“So you got it!” exclaimed Tom. “Gee, but I’m awfully glad, Sam! Shake! Now let’s see what you need. What shade of blue do you suppose that means? Dark, I guess. Here you are, then. Eighty-five cents each. You’ll need two of them. Sneakers are ninety-five and a dollar and a quarter. Better pay the difference, Sam. The cheaper ones aren’t much. What about flannel trousers? I’m afraid—Oh, you’ve got a pair? All right. Then that leaves only the sweater. What colour?”

“It doesn’t say. What do you think?”

“Guess it doesn’t matter, Sam. Grey’s usually the best because it won’t fade and doesn’t show dirt, but you can have blue or red or white or——”

“Grey, I guess; and not very expensive.”

“Here’s one for two and a half and here’s a better one for three and here’s——”

“I guess this three-dollar one will do, Tom. Do I get anything off on this truck?”

“Certainly; fifteen off, Sam. That makes it—let me see—five dollars and six cents; call it five dollars even, Sam. What about the raincoat?”

“I’ve got an old one that will do, I guess. You see, I don’t want to spend very much, because the fare up there and back comes to over nine dollars, and that’s two weeks’ wages.”

“He didn’t say anything about paying your fare, then?”

Sam shook his head. “He wouldn’t, would he?”

“I don’t know. Seems to me he ought to pay it one way, at least, though, Sam. I’d mention it to him, anyway.”

“Maybe I will,” replied Sam doubtfully. “Well, I guess that’s all, then. I’ll take these things along with me. How many boys do you suppose there will be up there, Tom?”

“I don’t know. Maybe forty or fifty. And look here, Sam.” Tom walked around the counter when he had finished tying up the bundle and[23] seated himself on the edge, swinging his legs. “Don’t do this,” he explained, “when there’s customers around. Look here, Sam. About those kids, now. Take my advice and start ’em off right.”

“How do you mean, Tom?”

“I mean make ’em understand right away that you won’t take any nonsense from them. Of course, a summer camp’s different from a school, I suppose, and there’s a lot more—more give-and-take between the councillors and the boys, but it’s a good idea, I guess, to make the kids understand that while you love ’em all to death you aren’t going to tell ’em to do a thing more than once. Get the idea? Kind but firm, Sam.”

“Anyone would think you invented boys’ camps,” said Sam, with a twinkle. Tom laughed.

“Never you mind whether I did or not, Sam. You do as I tell you and you’ll find things going easier. You aren’t enough older than the boys to make ’em much scared of you, so you want to hold the reins pretty tight at first. No charge for the advice. When do you go?”

“Seven-ten on the fifth. That gets me to East Mendon at eleven-twenty. Then there’s a stage-coach[24] or something that goes over to the Lake at two.”

“I’ll go down and see you off, Sam, and wish you luck.”

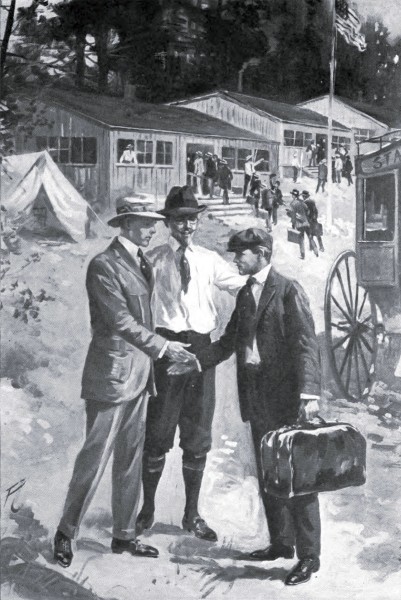

And a week later Tom kept his promise. He and Sidney escorted Sam to the train, Tom carrying the traveller’s old-fashioned yellow leather valise and Sid his raincoat, leaving Sam the free use of both hands with which to satisfy himself every two or three moments that his ticket was safe. There was one excruciating minute when they reached Locust Street, and were in sight of the station, when Sam couldn’t find the ticket in any of his pockets and blank dismay overspread his countenance. He was on the verge of retracing his steps when Sidney patiently reminded him that just one block back he had placed the precious pasteboard in the lining of his straw hat for safe-keeping. Sam said, “Oh!” and looked extremely foolish, and, amidst the laughter of his guard of honour, the journey began again.

News of Sam’s departure had spread through town and there was quite a gathering of friends to see him off. Buster Healey was there, with a bouquet consisting of two sprays of gladiolus,[25] mostly in bud, which Buster was suspected of having acquired by the simple expedient of reaching through someone’s garden fence; and Tommy Hughes was there, and Joe Kenny, and half a dozen more; and there was a good deal of noise and rough-house until the train pulled into the station and Sam climbed aboard. You might have thought that Sam was leaving for the Grand Tour or for a year in Darkest Africa. All kinds of advice was showered on him. He was instructed not to put his head out the window, not to speak to strangers, not to take any wooden money, and not to lose his ticket. Then the train moved and a cheer went up and a much embarrassed Sam waved good-bye from a window. And at that moment Buster discovered that Sam had left his flowers on a baggage truck, and rescued them and raced the length of the platform before he was finally able to hurl them in at the window. So began the journey.

CHAPTER III

“THE WIGWAM”

Sam had never done much travelling. He had been to Columbus twice and had journeyed around more or less within a fifty-mile radius of Amesville, but penetrating a hundred and twenty-odd miles into the wilds of northern Ohio was something new and not a little exciting. There had never, particularly since his father had died, been much money for railroad tickets and sight-seeing. Sam’s father had been a railroad engineer, and a good one. For many years when Sam was just a little chap Mr. Craig had held the throttle on the big Mogul engine that had pulled the Western Mail through Amesville. Sam didn’t see a great deal of his father in those days, for Mr. Craig “laid-over” in Amesville but twice a week, and the days when he did see him were red-letter days. He had been very fond of his dad, and very proud of him, too; and it had been Sam’s[27] earnest desire to grow up quick and be an engineer too. When, however, in Sam’s twelfth year, Mr. Craig returned home for the last time on a stretcher to live but a few hours, Sam lost that desire. For once the engineer had not been held to blame for an accident; a muddle-headed despatcher had sent the Western Mail crashing into a through freight between sidings; and so the railroad paid a pension to the widow. On this the family had lived until Sam, first, and then Nell, had begun to supplement the pension money with small earnings. Sam had delivered papers, worked in the mill as stock-boy, and tried his hand at several other things, while Nell, having finished school the spring before, was now a public stenographer with a tiny room of her own in Amesville’s new office building, and was a little more than making expenses.

The first thrill of excitement wore off after a half-hour or so, and Sam, tired of watching the view from the car window, picked up the magazine he had bought and settled back to read. The train was not a fast one, and it stopped at a good many stations and seemed disinclined at each to take up its journey again. Nevertheless, it eventually[28] did arrive at East Mendon, and Sam anxiously collected his belongings and alighted. Inquiries elicited the information that the stage started at two o’clock from the other side of the platform, shortly after the arrival of the through express. Consequently Sam had a full two hours and a half to wait. He checked his bag and coat at the station and started out in search of dinner. East Mendon was a small place, hardly more than a full-grown village, and his choice of eating-places was not large. The Commercial Hotel seemed to be the principal hostelry, but Sam knew that if he went there he would have to pay at least seventy-five cents for his meal, and seventy-five cents was about fifty cents more than he cared to spend. At last, on a side street, he came across a small and dingy restaurant which advertised the principal dishes of the day’s menu on a blackboard outside. Sam, his feet spread well apart and his hands in his trousers pockets, studied the list thoughtfully.

“Beef Stew with Dumplings, 15 cents.” “Corn Beef Hash with Bread and Butter, 15 cents.” “Baked White Fish and Fried Potatoes, 20 cents.” “Ribs of Beef with Browned Potatoes, 25 cents.”[29] “Vegatable Soup with Bread and Butter, 10 cents.”

Sam’s eyes twinkled. “Me for that, I guess,” he said to himself. “Vegetable soup with two A’s sounds good. And maybe a cup of good hot coffee and a piece of pie. I’m not awfully hungry, anyhow.”

The “vegatable” soup was good and there was plenty of it, and even if the bread proved so crumbly that he found himself breading the butter instead of buttering the bread, he made out very well. But the good coffee didn’t materialize. There was coffee, and it was hot, but Sam couldn’t pronounce it good. Nor was the pie much better. He suspected the little shock-haired proprietor of having held and cherished that pie for a long, long time!

Afterwards he wandered back to the principal street of the village and bought three very green apples for a nickel and munched them while he tried to find interest in the store windows. But the East Mendon stores were neither large nor flourishing, and their window displays were not at all enthralling. It was still only slightly after twelve-thirty as, having exhausted the entertainments[30] of the village, he went back to the station, got his magazine from his bag, and made himself as comfortable as he could in a corner of the small waiting-room. It was hot and close in there, and smelled of dust and train smoke, but he found a good story in the magazine and was soon lost to everything but the adventures of the hero. That first story was so interesting that, having finished it, he started another, after a cursory glance about the room which was now beginning to fill up. He was halfway through the second story when the express came thundering in with much screeching of brake-shoes. The event promised excitement and so he slipped his magazine in a pocket of his coat, took up his bag, and went out on the platform with the other occupants of the room.

It seemed at first glance that everyone was getting out of the express and Sam had to flatten himself against the station wall to keep from being trod on. To his momentary surprise, most of the arrivals appeared to be boys; there must, he thought, be a hundred of them! Then it dawned on him that he was getting his first look at his future charges. When, presently, the express went on again and the crowd on the platform had[31] sorted itself out, he saw that the hundred boys really numbered only about thirty or forty. In age they seemed between twelve and fifteen, and they were of all sorts; short boys and tall boys, fat boys and thin boys, quiet boys and noisy boys. Each had his bag beside him and most of them were pestering the baggage-man about their trunks. Suddenly into the mêlée about that exasperated official pushed a broad-shouldered, capable-looking man of twenty-two or three years. He had a sun-browned face and wore a straw hat with a yellow-and-blue band around it.

“Now then, fellows!” Sam heard him say briskly. “Every one across to the other platform, please. I’ll take charge of your checks.”

In a minute order grew out of chaos and the boys, yielding their trunk checks, went off around the station. Sam followed. Two stage-coaches and four three-seated carriages were backed up to the platform and the boys were scrambling for outside seats on the coaches. Suit-cases and bags were being piled on the roofs, and pandemonium again reigned until, as before, the man with the yellow-and-blue hat-band appeared and took charge. “That’s enough on top now! Pile inside,[32] you chaps. That’ll do. The rest of you get into the hacks. Room for one more here, though. You going to Indian Lake?”

This to Sam, who was waiting for a chance to find a seat. Sam assented and squeezed into a rear seat of one of the stages, aware of the other’s puzzled regard. Evidently the man with the coloured hat-band thought Sam a bit old to be going to The Wigwam, and Sam wondered what Mr. Langham would think! He was quite certain that this was not Mr. Langham. First, because the coloured hat-band chap was keeping a sharp eye on a huge suit-case marked “A. A. G.,” and, second, because it stood to reason that Mr. Langham was a much older man.

Possibly the boys, too, thought Sam rather too mature to be one of them, for they favoured him with many curious glances as he squeezed into his seat. He still retained his valise and, as there was no place on the floor for it, he had to take it in his lap and drape his raincoat over it. That battered, old-fashioned bag occasioned more than one amused look and whispered comment.

After they were all seated a long wait ensued. A big wagon was backed up to the platform and[33] the baggage-man and the drivers began the loading of the trunks. There were a lot of them, but fortunately many were of the small steamer variety. Sam, whose entire wardrobe was contained between the bulging sides of his valise, wondered at those trunks. Finally the last one was aboard, restless youths who had slipped from their places scuttled back to them, the man with the hat-band seated himself beside the driver of one of the carriages and, with a cheer, the procession of vehicles set out.

Sam had never ridden in an old-style stage-coach before and he found the experience more novel than comfortable. The body swayed amazingly on its leather springs, and when, presently, they were on the rough country road, bumped up and down most erratically. Sam held tight to his bag, braced his feet against the floor, and watched the landscape unfold. Most of the way the road was bordered with woods, although occasionally there was a clearing and, now and then, a small farm. The road wound and turned up hill and down and the horses kept at an even trot. The more adventurous spirits on top of the coaches cheered and shouted and sang, but Sam’s[34] companions inside were more subdued. He sat next a small boy of perhaps thirteen, who looked rather depressed and homesick. Sam tried conversation with him, but it was not a success. After a half-hour or so a louder cheer than usual came from outside, and Sam, looking ahead, saw a blue, sun-lit lake below them, lying in the green bowl of the wooded hills. Then it was lost to sight again and they began the descent, the brakes scraping hard against the big wheels as the coach swayed and bumped. Five minutes later they had arrived.

Sam descended before a large many-windowed wooden building, hardly more than a shed in appearance. A wide uncovered porch ran across the front of it. The building was so new that only the roof had weathered. Beyond it was a second of similar size and appearance, and beyond that, again, on slightly higher ground, was a smaller structure. The buildings faced the lake, the shore of which was some fifty yards distant. Behind the clearing the forest of birch and maples and oaks, with an occasional pine or hemlock, gave enticing glimpses of shadowed paths, but about the camp were few trees left standing, and of[35] these, one had been shorn of its branches and bore, floating lazily from its tip, a white flag with a blue pyramid, doubtless intended to represent an Indian wigwam. There was little breeze to-day and the sun beat down hotly, and Sam looked longingly into the dim recess seen beyond the wide, open door of the nearer building.

With the arrival of the foremost stage three men came down the steps. One was a short, stocky gentleman, brisk and alert, who wore knickerbockers and golf stockings and a soft white shirt, and whose round face seemed at first glance to be all brown Vandyke beard and rubber-rimmed Mandarin spectacles. He was followed by two younger men, one not much more than a boy and the other somewhere about thirty. Unlike the older man, they each wore camp costume; flannel trousers belted over a blue sleeveless shirt, and brown “sneakers.” It was the short man in knickerbockers who now took command. One by one, the arrivals were shaken by the hand and passed on to the older of the two councillors, who, in turn, directed them to one or the other of the larger buildings. The short man knew many of the boys by name and greeted them warmly, and these,[36] addressing him as “Chief,” seemed equally pleased at the meeting. If he did not know the name of a boy, he asked it and, on being told, said briskly, “Oh, yes! Well, Jones, I’m glad to know you. Mr. Haskins, this is Jones. Just look after him, please.” And so Jones or Smith, or whatever his name might be, shook hands again and was finally sent trudging on into one or the other of the dormitories.

Sam stood aside and waited until the boys had been distributed. Then, formulating a little speech of introduction, he moved toward where the short man and the man with the coloured hat-band were shaking hands. But his speech was not required. “Well, Craig, so you found us, eh?” asked the short man, with a smile and a firm clasp of the hand. “Very glad to see you. My name is Langham. Mr. Gifford I suppose you know.”

The man with the coloured hat-band explained, however, that they had not met. “I saw you at the station,” he said, “but I wasn’t sure that you were one of us. Very stupid of me. Well, let’s go and get into some comfortable togs. I suppose Craig is in The Tepee, Chief?”

“Yes. If Haskins is there, ask him to come out and show the men about the trunks, please. By the way, I thought we’d better get them into the water about four.”

Sam was surprised until he realized that “them” meant the boys and not the trunks. He followed Mr. Gifford to the further dormitory, climbed a flight of four steps, crossed the unroofed porch, and entered through a wide doorway. For a moment the sudden change from the sunlight to the dimmer light inside confused him. Presently, though, he was examining his new home with interest.

The building was of a width that accommodated two rows of cots, one at each side, and left a wide passage between. At the farther end of the passage a second door stood wide open, framing a picture of green leaves in shadow and sunlight. On each side of the long room were many square openings, which did duty as windows. They were not sashed, but were provided with wooden shutters which opened inward and hooked back against the walls. In all the time that Sam was there the shutters were closed but once, and then only on one side of the dormitory. There were[38] twelve cots in one row and eight in the other. Midway on the side holding the fewer cots was a big rough-stone fireplace, and in front of it a table and chairs. At the foot of each cot was a shallow closet with hooks for garments below and some shelves above. Three large kerosene lamps hung from the roof.

Sam’s cot was the first one inside the door on the left. Mr. Gifford’s was opposite. At the head of each was a small stand holding a hand-lamp, and Mr. Gifford explained that the councillors were permitted to keep these burning after the dormitory lights were out. Sam followed the example of Mr. Gifford and the boys and changed into camp uniform, stowing the rest of his belongings in the tiny closet. Many of the youngsters were already scampering about in their new costumes.

“The Chief tells me you’re going to help me with athletics,” said Mr. Gifford from across the passage as he dragged on a pair of faded grey flannel trousers. “What’s your line?”

“Line?” asked Sam.

“I mean what do you go in for principally?”

“Oh! Baseball principally.”

“That’s good. We play a good deal of it. The[39] fellows seem to get more fun out of it than anything else, except, maybe, swimming. You swim, of course?”

“Yes.”

“Well, we’ll have a talk this evening and map things out. Now, if you’re ready, we’ll go out and have a look around, and see what’s to be done. There’s usually a good deal to attend to the first day.”

Satisfying himself that their assistance was not needed in the distribution of trunks, Mr. Gifford took Sam about the camp. They looked in at the other dormitory, known as The Wigwam, which was not materially different from The Tepee; and then visited the third building.

“This,” said Mr. Gifford, “is the dining-hall. The fellows call it the Grubbery. There are four tables, you see. The Chief sits at the head of this one and the rest of us fellows take the others. That doesn’t leave one for you, though, does it? Guess the Chief will put you at the foot of his. The fellows take turns at setting the tables and clearing them. We have a splendid cook and plenty of good things to eat. You won’t go hungry, Craig. Speaking of that——”

Mr. Gifford led the way across the hall and through a swinging door into a kitchen. Sam followed and was introduced to the cook, one Cady Betts, a tall, fair-complexioned French-Canadian whom the boys, as Sam discovered later, called “Kitty-Bett.”

“Cady,” said Mr. Gifford, “we’re starved. Got anything to eat?”

The cook, who had been stocking the shelves with the supplies which had reached camp a little while before, smiled doubtfully.

“There is nothing cook,” he said in his careful English, “but there is crackers and cheeses. Maybe you like them?”

Mr. Gifford declared that he did and, assisted moderately by Sam, consumed a large quantity of each, sitting on the kitchen table and chatting the while with “Kitty-Bett.” The latter, Sam learned by listening, came from Michigan and in winter cooked for a big lumber company. He had a pair of the mildest, softest blue eyes Sam had ever seen in a man, and a pleasant smile, but one had only to watch him handle the cans and bags and jugs for a minute to see that he was as deft and quick as he was amiable. Presently Mr. Gifford[41] conducted Sam back through the dining-hall again, pointing out the mail box which hung just inside the doorway. All the doors at the camp were double and swung outward, and, as Sam found in the course of time, were seldom ever closed. Eating in the dining-hall was much like eating out of doors, for, besides the big doorway and a shuttered opening at the front, the two sides of the building from three feet above the floor to the eaves opened out and up, admitting light and air and, it must be confessed, not a few flies!

There was an ice-house behind the kitchen, with a storage space in front for meats and eggs and milk and vegetables, a place whose temperature was most grateful after the warmth outside. From there they walked down to the landing. Here lay quite a flotilla of row-boats and canoes, which a tow-headed youth named Jerry—if he had another name Sam never learned it—was engaged in painting and varnishing. Jerry was a sort of general factotum; carried the mail across the lake once a day in the little naphtha launch, which had not yet been slid out of the small boat-house nearby, washed dishes after meals,[42] pared potatoes, ran errands, and performed a dozen other duties. Mr. Gifford shook hands with Jerry and formally presented Sam. Jerry observed, with a shy smile, that he was “pleased to meet you, sir.”

On the float, which was quite large, there was a springboard and a slide; also a covered box which held oars and oar-locks and canoe paddles, and had a life-belt hung at one end. There was not much of a beach there, for shore and lake met sharply. There was, however, Mr. Gifford explained, a fairly good stretch of sand further along, near the ball-field, which the older boys were allowed to go in from occasionally.

“About the first thing a boy has to do when he gets here,” said Mr. Gifford, “is learn to swim. We put them all into the water twice a day, and those who want to may duck before breakfast. It generally takes only about a month to get the most backward youngsters to a point where they can keep afloat. They usually do their best to learn quickly because we don’t allow them in the boats until they have; and it seems to be every boy’s ambition to spend half his life in a canoe! I suppose you can manage a boat, Craig?”

“I can row a little; not very well, I guess. I’ve never been in a canoe, though.”

“We’ll have to remedy that. It won’t take you long to learn. Well, I guess we’ve seen about all there is. What do you think of the place?”

“It’s very—interesting,” replied Sam. “I never was at a camp before.”

“Really?” Mr. Gifford was silent for a minute or two while they walked back toward the dormitories. Then: “If you don’t mind my asking, Craig, how old are you?” he inquired.

Sam told him and he nodded. “You look older than that,” he said. “Better let the boys think you are older. They’ll mind you better, I guess. You haven’t met Haskins and Brown yet, have you? Let’s find them.”

They were with Mr. Langham in the little partitioned-off room at the front of The Wigwam, which the Director used both as office and bedroom. Mr. Haskins was, next to the Director, the oldest of the five who, with the arrival of Mr. Gifford and Sam, crowded the small office to its capacity. He was rather serious-looking, wore thick-lensed glasses and was slightly bald. He was an instructor at Burton College, which institution[44] was well represented at The Wigwam, since Mr. Langham, too, was a member of the Burton faculty and Mr. Gifford was a post-graduate student there. Young Brown, a merry-faced boy of twenty, and Sam were the only ones not connected with Burton. Steve Brown was a sophomore at Western Reserve, and, like Sam, was a newcomer at the camp. After introductions were over Mr. Langham went over the daily schedule with the others—Sam found that his official title was junior councillor—and explained their duties. It seemed to Sam that The Wigwam was to be a very busy place and that time was not at all likely to hang heavily on his hands!

CHAPTER IV

THE BLANKET THAT RAN AWAY

Two days later The Wigwam was running according to schedule. The rising bugle sounded at seven and breakfast was at half-past. From the time breakfast was over until nine there was work of some sort for all hands. Beds had to be made, dormitories swept and put in order, grounds “policed,” lamps filled, wood piled for the evening’s “camp-fire” and numerous other duties attended to. From nine to eleven the boys did as they liked. A few were being coached in studies by Mr. Haskins and Mr. Gifford, and such work came in the forenoon. Then, too, Steve Brown conducted a class in photography which was well patronised, and once a week Mr. Langham took those who wanted to go for a walk through the woods or along the lake for Nature Study. At eleven there was what the boys called “soak.” Wearing bathing trunks, the boys lined[46] up on the edge of the float and at the word from one of the councillors plunged into the water. Those who could not swim did their “plunging” from the sides of the float where the water was only a couple of feet deep. “Soak” lasted the better part of an hour and all the councillors were on hand in bathing suits to give instruction and prevent accidents. It was the duty of one to sit in a row-boat a little ways off shore and go to the assistance of any bather in difficulties. In fine weather that morning bath was the most enjoyable hour of the day. There were thirty-eight boys at the camp, and when they all got to splashing around and skylarking there was much fun and merriment. Woe to any of them who stood unguardedly near the edge of the float, for someone was certain to sneak up behind and then there’d be a howl and a splash and a chorus of laughter as the victim came thrashing to the surface. And, of course, there were always upsets on the springboard, and some boy was forever discovering a new and ridiculous manner of going down the slide. The councillors interfered very little, and, although real hazing was put down with a firm hand, the youngsters had to stand a good[47] deal of ungentle handling which did them no harm and speedily taught them confidence.

Sam quickly proved himself the best swimmer at camp and to him was delegated the education of the more advanced pupils, a task which he thoroughly enjoyed and went into heart and soul. There were some eight or ten older boys who showed real ability, and one, Tom Crossbush, a youth of nearly sixteen years, who, before the summer was over, learned to duplicate nearly every feat of Sam’s, whether of diving or swimming.

Dinner was at half-past twelve, and, following it, came thirty minutes of siesta when every occupant of the camp, barring Kitty-Bett and Jerry, the chore-boy, was required to lie on his bed and keep absolutely quiet. The boys corrupted the word to “sister” and, most of them, thoroughly disliked that period. At two o’clock came recreation until four-thirty. There were two fairly good tennis courts and a ball-field about a quarter of a mile from camp. There, too, were set up standards for jumping and vaulting, and there was a ring for shot-putting and a stretch of fairly smooth turf used for sprinting. The boys were[48] all required to take up some form of athletic endeavour and those two hours and a half from two to four-thirty constituted the busiest period of the day for Mr. Gifford, Steve Brown, and Sam. Steve instructed in tennis—he was a good player—and helped at anything else he could. Mr. Gifford presided over track and field athletics and Sam was given entire charge of baseball. With very few exceptions all the boys played ball or tried to. Three nines were formed, the members drawn by lot by Mr. Gifford, Steve, and Sam, each of whom acted as manager for his aggregation. Captains were then chosen and practice began. Regular games were played twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays, and by the end of a fortnight the keenest rivalry had developed and they were having some exciting, if not very scientific contests.

The afternoon bathe, or “plunge,” as it was called, came at half-past four and was over at five. Supper was at five-thirty. The camp-fire was lighted at eight and boys and councillors gathered about it to talk over together the day’s happenings, make plans for the morrow and tell stories, sing songs and, finally, say prayers, and retire to the dormitories at nine. At ten o’clock[49] the big lights were put out and after that quiet was supposed to prevail. Sometimes it didn’t, however, for all sorts of jokes were played in the darkness and quite frequently the councillors, at the end of the hall, would hear stealthy footsteps, muffled laughter, the sound of struggles and, sometimes, the crash of a cot whose wooden legs had been surreptitiously reversed beforehand and now deftly folded up underneath by the aid of a cord pulled, perhaps, from far down the hall. Sam was surprised to find that these larks were seldom interfered with by Mr. Gifford. If too much “rough-house” resulted the latter sent a cautioning, “That will do, fellows! Cut it out now!” travelling through the darkness and the usual result was instant quiet. “All the fun you like so long as it’s harmless” was the rule at The Wigwam.

Being a newcomer, Sam had to undergo some initiating. The second night he was there, after he had settled himself comfortably on his straw mattress and was drowsily watching the stars through the window at the foot of his cot, something at once startling and mysterious occurred. If Sam had been more experienced with boys he[50] would have become suspicious at the almost instant silence which prevailed that night after “lights.” Almost before the boys had exchanged “good night” with the councillors, unmistakable evidences of healthy slumber came from various quarters. Something else that might have warned Sam was the prompt dousing of his reading-light by Mr. Gifford. The previous night that gentleman had burned his lamp until almost midnight, as Sam, the unaccustomed surroundings and the strange bed keeping him wakeful, well knew. But to-night Mr. Gifford had blown out his lamp only a minute or so after ten.

Sam was just on the verge of sinking off into slumber when the blanket—there were no sheets at The Wigwam—suddenly slid off to the floor. Sleepily, he reached down and felt for it, but failed to get hold of it. Wider awake now, he groped again but with no success. There was enough light from the open doorway and the windows to show him the blanket lying under the next cot. Blinking, he put his legs out of bed and reached for it. It wasn’t there! He stared in amazement. He stooped and peered under the cot. The blanket was now between it and the next[51] one. Still too bemused by sleep to suspect a trick, he got up and walked around to the next aisle. The snoring had quite ceased, but Sam failed to notice the fact. Again he leaned down to pick up the blanket and again it wasn’t there!

He realised then he was the victim of a practical joke, but the mechanism still puzzled him. Up and down the dormitory not a figure moved. Intense silence prevailed. With the breeze playing about his bare legs, Sam stood in the passage and deliberated. Finally a slow smile spread over his face and the next instant he had whisked the blanket from the nearest cot and was walking sedately back to his bed! And at that moment shouts went up from all over the dormitory and every boy was sitting up in his cot, wide awake and swaying with laughter. And, as Sam lay down again and drew his stolen blanket over him, he was surprised to hear Mr. Gifford’s laughter mingling heartily with the rest!

The boy whose bed-clothing Sam had taken in reprisal was now dodging from one aisle to the next in wild pursuit of the elusive blanket which, pulled at the end of a cord from the farther end of the hall, led him a merry chase. Meanwhile[52] the boys were calling demurely to Sam: “Cold night, Mr. Craig!” “Anything I can do, sir?” “That was a mean trick, Mr. Craig!” And then Mr. Gifford’s voice from across the passage: “We all have to take it, Craig! All right now?”

“Yes, thanks,” replied Sam. “Anyone who gets this will have to fight for it!”

At which there was more laughter and some applause and at last the dormitory really settled down to slumber and the snores that Sam heard were not feigned. Sam chuckled once or twice before he too dropped off to sleep.

A day or so later he was given an involuntary bath. He was standing on the end of the landing watching Horace Chase try to do the Australian crawl-stroke, when there was a sudden push from behind and in he went, heels over head, and for a moment he and young Chase were inextricably mixed up, for he had landed squarely on that youth. When he came to the surface, sputtering and blinking, he supposed that it had been an accident, but the grinning faces of the boys on the landing told a different tale, as did the smile that played over the countenance of Mr. Haskins, who was on duty in the row-boat. Then Sam[53] grinned too, pulled himself quickly to the landing, and charged the miscreants. Over they went, with shouts and squeals, striking the water every which way and for the next few minutes giving Sam a wide berth. His good-natured acceptance of their jokes won their approval, and, although some few boys at first rather resented being under the authority of a fellow who was only a year or two older than they were, Sam soon found that he had won his place.

Every forenoon at ten o’clock the councillors met in Mr. Langham’s little office and made their reports and talked over with the Chief all matters concerning the conduct of the camp. Now and then, at first very infrequently, it was necessary to discipline some too-spirited youth. But on the whole the boys were well-behaved and little punishment had to be meted out. Usually the council ended in a jovial give-and-take in which even the Chief had to accept his share of joking. Sam found himself a bit too slow at repartee to take much part in these exchanges of banter, but he enjoyed them in his quiet way and was perhaps better liked because he bore himself modestly.

He had plenty to keep him busy, but all the[54] tasks were more like play than work, and the fact that he was out of doors practically every moment of each day, and might as well have been outdoors at night as far as fresh air was concerned, made his duties easy, kept him fit and gave him a most voracious appetite of which he was inclined to be ashamed until he saw that it was no more remarkable than Steve Brown’s or Mr. Gifford’s, or, for that matter, some of the boys themselves! Things certainly tasted good, too. The food was plain but plentiful, and well-cooked. Kitty-Bett disdained coal, and the meats had a wonderful wood-fire flavour that appealed to appetites grown out-o’-doors. Blueberries were in season and wild raspberries were to be had for the picking. Fresh vegetables were brought every day from a neighbouring farm. There was hot meat at noon—steak or roasts—and cold meat for supper. The eggs were freshly-laid, and, whether boiled or made into one of Kitty-Bett’s inimitable omelets, were delicious. And as for Kitty-Bett’s pies and doughnuts and griddle-cakes! Well, words would have quite failed Sam there! The doughnuts—Kitty-Bett called them “fried-cakes”—were in such demand that he had[55] to fry a batch almost every day. Between meals there was always a bowl of them on one of the tables in dining-hall, and there was no one to see whether you took one or a half-dozen.

Fortunately, for a whole two weeks the weather was fair; pretty hot in the middle of the day, but cool enough at night to make at least one thickness of blanket acceptable. Life at The Wigwam was very pleasant, and to this effect Sam wrote home to his mother and sister, and, later, to Tom Pollock. Sam felt very grateful to Tom for having told him of the situation, and said so in the letter which he penned one Sunday afternoon, seated under the trees by the shore of the lake. Among other things, Sam wrote: “You were right about the railway fare. Mr. Langham asked me how much it was and he is going to pay it back to me at the end of the month. I told him he needn’t, but he said it was the custom and everybody got his travelling expenses, even Kitty-Bett, who is the cook and a wonder. I just wish, Tom, you could taste some of his blueberry pie. The shirts you sold me are fine, but I haven’t worn the sweater yet. The weather has been very warm and no rain yet. Have you started the[56] nine again? Please write and tell me the news.”

Tom replied very promptly and told all the happenings. The Blues were getting together again and Buster Healey was to catch for them. Sid was to play first base. They hadn’t arranged for many games yet, but Lynton had promised to play them a week from next Saturday. Tom was glad Sam liked the camp, and he and Sid meant to run up some time in August and see it.

Meanwhile Sam learned to handle a pair of oars with skill and a canoe paddle less dexterously. There were fish in the lake and Sam was a devoted disciple of Walton. His usual companion on his fishing trips was Tom Crossbush. Tom pretended to be enthusiastic about the sport, but I think his liking for Sam was the real reason for his participation in the excursions down the lake. At all events, his enthusiasm soon wore off after his line was dropped and most of the fish that were caught came up on Sam’s hook. Once or twice Steve Brown went along, but Steve didn’t pretend to know much about the gentle art and as often as not sat for long stretches with, as he said, “nothing on his hook but water.” Nevertheless,[57] it was Steve who, later on in August, by some miracle hauled in the biggest black bass in the history of the camp. It weighed just four pounds and six ounces and Steve was so delighted that he sent it away to be mounted. Mr. Langham, who, could he have done so, would have been on the lake every day holding a bass rod, threw up his hands in disgust when he saw Steve’s capture. “Beginner’s luck!” he grumbled. “I’ve fished in that lake twenty times and never got better than a two-pounder! What bait did you have?”

“Just a worm, sir,” answered Steve innocently.

“A worm! You mean an angle-worm?” sputtered the Chief.

Steve assented, and Sam, laughing, said: “He won’t use hellgamites, Chief. He says they’re too ugly!”

“A garden worm!” exclaimed Mr. Langham. “Great jumping Jupiter! Don’t you know you don’t catch bass with angle-worms, you ignoramus?”

“Sorry,” replied Steve, grinning. “I caught this one that way, though.”

“I wouldn’t boast of it, then,” grunted the Chief. “You insulted the fish’s intelligence![58] Four pounds and six ounces!” Mr. Langham subsided, shaking his head and viewing the fish enviously.

Bass didn’t always bite, however, and perch were the usual catch. But four or five fair-sized perch make a palatable addition to the supper or breakfast menu, and the Chief’s table, at the lower end of which Sam had his place, was not infrequently graced with it.

Once every week there was a picnic, and on those occasions Sam’s prowess with hook and line was in demand. Sad to relate, however, it was at such times that his luck failed him, and very seldom did the picnickers’ vision of crisply fried perch materialise. That fact never spoiled the fun, though, and the weekly picnic was a favourite event. The boys piled into row-boats and canoes, after the small launch had been filled, and, at the end of tow-lines, were taken up or down or across Indian Lake to one of the numerous sites. Fellows who could be thoroughly trusted in canoes were allowed to paddle, but most of them floated along in the wake of the little launch which, with half a dozen boats holding her back, barely managed to make six miles an hour. Sam suspected that one[59] reason picnics were so popular was because there was no “sister” on such days. To be sure, after luncheon was eaten, a luncheon skilfully prepared by Kitty-Bett, the boys were supposed to lie down and keep quiet for the usual half-hour, but the rule was not rigidly enforced and the boys found many ways of amusing themselves without actually moving around. By half-past two they were generally back at the playing-field, for even a picnic doesn’t take the place of a ball game!

Sam’s team was called the Mascots, Mr. Gifford’s the Indians, and Steve Brown’s the Brownies. The councillors sometimes played, but more often confined themselves to coaching. If they did take a hand in a game they went into the outfield so that the boys might play in the coveted infield positions. Mr. Gifford’s team was showing up best at the end of the first fortnight and had won two games. Sam’s charges had won one and lost one and the Brownies had lost both of their contests. In fairness to the last named nines, though, it should be explained that the Indians were fortunate in the possession of the only first-class pitcher in camp, one George Porter, a slight, wiry chap of fifteen who had a[60] good curve and a fast straight ball and could mix them up cunningly. Even Sam, who was considered a very dependable batsman back in Amesville, had more than once failed to hit young Porter safely. Aside from pitchers, however, the three teams were evenly matched and when, the Saturday following the receipt of Tom Pollock’s letter, the Mascots and the Indians met for their third game, the entire camp was moved to a high pitch of excitement.

CHAPTER V

A SLIDE TO THE PLATE

The minute “sister” was over the boys were hurrying toward the playing-field, followed more leisurely by Sam and Mr. Gifford and Steve Brown, who was to umpire the contest. The way led through the woods for nearly a quarter of a mile, over a well-worn path that now skirted the lake, and now turned inland to cross a brook by a log bridge. Then it climbed up-hill through a plantation of young maples, hugged the face of a limestone boulder and dipped again to the edge of the field. The whole camp turned out, if we omit Mr. Langham, Kitty-Bett, and Jerry; and Mr. Langham arrived later. Sam and Mr. Gifford set their teams to warming up and the fellows who were to play the parts of spectators arranged themselves along the base-lines. It was fairly hot this afternoon and scarcely a ripple stirred the surface of the lake. The Indians won the toss and[62] went into the field and Steve Brown called: “Play ball!”

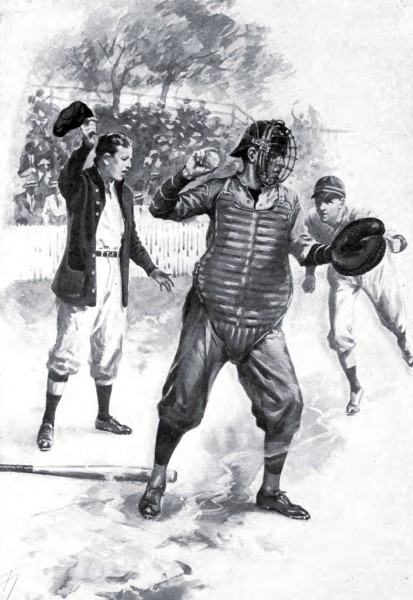

George Porter disposed of the first three Mascots handily. Tom Crossbush, who led the batting list, was the only one of the trio to connect with the ball and his effort only resulted in an easy out at first. Dick Barry, who pitched for Sam’s nine, was a chunky, stub-nosed youth of fourteen with very little science but a whole big lot of assurance. Ned Welch caught him, and Ned, a year older, was a steady chap behind the plate and handled Dick cleverly. But to-day, as usual, Dick was touched up pretty frequently. Ed Thursby began the fun for Mr. Gifford’s tribe with a fly that Dan Peterson, in left field, misjudged miserably. Ed got to second and the Indians’ third baseman bunted him to third and reached first himself when Dick Barry threw low to Crossbush, who played the initial sack. The next man fanned and Dick’s friends in the audience shouted approval. But Sawyer, the Indian first baseman, found something he liked and slammed a hit between second and short and Thursby came home with the first tally. Another hit a minute later scored a second run and then a pop fly descended into Dick’s glove[63] and made the second out and before the runner on third could score a second strike-out was secured by Dick.

The game ran along at two to nothing until the first of the third. Then the Mascots managed to get a run across by a combination of a hit, a sacrifice fly, and an error by the Indians’ third baseman. But the Indians came back in their half with a slugging fest and put two more tallies across. Neither team was able to do anything in the fourth or fifth. George Porter ran his strike-out total up to seven and Dick Barry, while he only fooled one more Indian, somehow managed to escape punishment. Steve Brown made a decision at first that dissatisfied the Mascots, when Dick suddenly shot the ball across to Tom Crossbush and apparently nailed Ned Welch a foot off the bag. But the umpire didn’t see it that way and, anyhow, the decision made no difference in the outcome.

In the first of the sixth inning Sam’s team started off with a rush. Young Fairchild dribbled a weak bunt along third-base line and the throw to first went wild. The runner scurried to second and then, coached frantically to go on, made an[64] apparently hopeless attempt to reach third. But another wild heave saved him. Third baseman blocked the ball, but not in time to make the out, and Terry Fairchild, immensely proud of his feat, sat on the bag and tried to recover his breath and made derisive remarks to the baseman. Sam instructed the next batter, Pete Simpson, to try to bunt, hoping that the ball would be played to the plate and that Pete would get his base. Naturally, the runner on third was not supposed to go home unless the way was clear, for there were no outs.

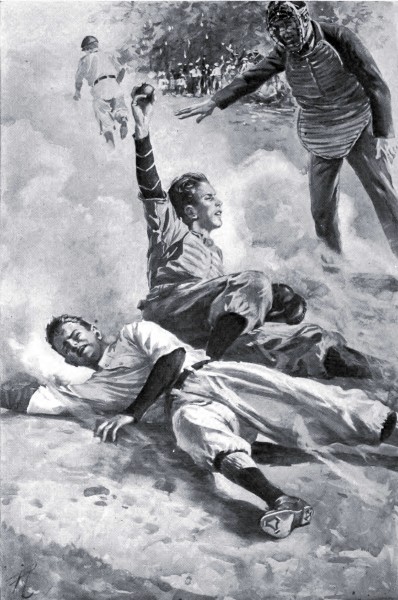

Pete had a strike and two balls called on him before he found anything he thought he could use to advantage. Then he struck loosely against a high ball and by good luck sent it rolling along the first-base path. Pete raced for first and Pitcher Porter raced for the ball. And, contrary to instructions from the third-base coach, young Fairchild, doubtless desiring to still further glorify himself, sprinted for home. He had about one chance in twenty of reaching it safely, for Porter scooped up the ball on the run, turned swiftly, and threw to the plate. And Jimmy Benson, astride the platter, caught it waist-high, and[65] everything should have been lovely for the Indians. But Terry Fairchild, sprawling on his back, with both legs kicking in the air, arrived a fraction of a second after the ball and, since Benson was in the way, Terry just naturally collided with him, knocked his feet from under him, and went by. Unfortunately, the shock was so disturbing to the catcher that he inadvertently loosed his hold on the ball and the ball followed Terry into the dust. And Steve Brown, who had already motioned the runner out, reversed his decision, and Peter Simpson slid to second.

Jimmy Benson was disgruntled, even angry, and said unkind things to Terry. But Terry, picking himself up with a swagger and patting the dust from his scant costume, only grinned exasperatingly and walked to the bench, there to be hilariously patted and hugged by his team-mates. When, however, he glanced toward Sam, expecting praise, he got a surprise.

“Don’t do that again, Fairchild,” said the junior councillor severely. “Mind what the coach tells you. You made it, but you had no business making it, and if Benson hadn’t dropped the ball you’d have looked pretty cheap. You take[66] your orders from the coach, Fairchild, after this.”

Terry, chastened in spirit, subsided amidst the smiles of the others as Jones faced the Indian pitcher. Porter was in the air now, and, although Mr. Gifford called encouragement and Benson counselled him to take his time and “put them over,” he slammed the ball in vindictively and Jones drew a pass. Porter steadied down then, but the team, especially the infield, was unsettled, and, after Welch, with two strikes against him, hit squarely to first baseman and made the first out, Simpson and Jones tried a double steal and got away with it, the Indian shortstop dropping the throw from the plate. Cheers and jeers rewarded this event. Benson tried to steady the team as Dick Barry went to bat.

“Never mind that, fellows!” called Jimmy. “Here’s an easy one! Strike him out, George! Three will do it! Put ’em right over the middle, he couldn’t hit a basket-ball!”

Possibly Dick couldn’t have hit a basket-ball, but he did manage to connect with one of Porter’s curves and send it just over second baseman’s head. When the ball was back in the pitcher’s[67] hands two more runs had crossed the plate, Dick was safe at first, and the score was a tie at four runs each. But the Mascots were not through even then. Sam, realising that now was the time to win, if ever, urged his fellows to their best endeavours. Tom Crossbush, however, over-anxious for a hit, struck at everything and, after fouling off two good ones, bit at a wide curve, and retired morosely to the bench.

“Two gone!” announced the coaches. “Run on anything, Dick!”

So Dick took a chance and scuttled for second and beat the ball by several feet. Peterson waited while Porter worked a strike and two balls on him. Then he met the next offering fairly and squarely for the longest hit of the game, and sent it far into centre field, at least a yard over Meldrum’s head, and while that youth scampered back for it, raced desperately around the bases in an attempt to stretch a three-bagger into a home run. Fortunately, though, he was held up at third, to score the sixth tally a minute later when Groom’s easy infield hit got by Thursby at second. Peterson reached the plate on his stomach, the merest fraction of an instant ahead of the ball. Then[68] White hit a swift one to Thursby, and that youth, retrieving his previous error, made a flying one-hand catch for the third out.

But six to four looked good to the Mascots and they trotted into the field with the determination to hold their advantage. And they did, for the rest of the sixth at least. For Dick Barry, summoning all the craft he knew, and ably seconded by Ned Welch, disposed of the next two Indians without trouble. The third banged out a two-bagger into right, and subsequently stole third when Welch let a delivery get past him, but he got no further that inning, for the next batsman was an easy out, second baseman to first.

There was no scoring in either half of the seventh, although the Indians had two men on bases at one time, with only one out. What luck there was broke for the Mascots; and the first double-play of the game, participated in by Groom and Crossbush, put an end to the inning. In the eighth the Mascots came near to scoring when Peterson reached third on a base hit and a wild throw to second and tried to score on White’s grounder to shortstop. At that the decision at the plate was close and might have gone either way.

In their half the Indians set to work with vim and lighted on Dick Barry hard. Codman hit safely, Benson got his base on balls, Porter struck out, Thursby sacrificed, and Nettleton, with only one gone, filled the bases by a pop fly to Dick, which that overeager youth dropped. Things looked desperate then for Sam’s charges, but a minute later Sawyer had fouled out to third baseman and the Mascots and their allies breathed freer. They were not to emerge unscathed, however, for Meldrum hit a bounder that just tipped Dick’s upstretched fingers and was finally fielded by Groom too late to throw to the plate or to first, and the Indians scored their fifth run. Then, after missing the plate three times out of four, and putting himself in a hole, Dick made a sudden throw to second and, after a wildly exciting moment, the runner was caught between bases.

Simpson opened the ninth for the Mascots with a bunt that trickled down the first-base line and threatened every instant to roll out, but never did, much to the disgust of Porter and Benson, who hovered anxiously over it. Had Porter fielded it at once he could have made the assist, but he left the decision with the ball and the ball fooled[70] him. Then Jones sacrificed Peterson to second, Welch struck out, Barry lifted a fly to left field that was an easy catch and, with two down and a runner on second, the inning looked about over. But Tom Crossbush drew a pass and stole second on the first pitch, while Simpson went to third, and then Dan Peterson scored Simpson, with a hit over second base.

The Mascots leaped and shrieked with delight, and while the Indians were still wondering what had happened, and while George Porter was winding up to send his first offering to Billy White, Crossbush, who was dancing back and forth a dozen feet from third, suddenly broke for the plate. Shouts of warning, shrieks of excitement! Porter momentarily faltering as he pitched! Crossbush sliding feet foremost for the platter! Benson leaping far to the right in a despairing effort to get the ball! Peterson rounding second like a runaway colt! And then, while the brown dust billowed, Steve Brown announcing, “Safe!”

Eight to five then, and nothing to it but the Mascots! Shouting and dancing and pandemonium along the lines! And, finally, White striking[71] out and a deep breath of relief from the Indians and their supporters.

And there practically ended the game, for the Indians failed to put over a single tally in their half of the final inning, and ten minutes later the camp was thronging homeward, the Mascots very cocky and talkative, and the Indians confiding to their friends what they would do the next time!

CHAPTER VI

THE TILTING MATCH

The afternoon’s game was talked over by all hands that evening at camp-fire. Once or twice the argument grew warm, but it never passed the bounds of good-nature. Mr. Gifford criticised the playing, as did Sam and Steve Brown, pointing out mistakes and making helpful suggestions. Mr. Gifford had played baseball all during his college course and knew the game well. Sam, with less experience, was chary of criticism until urged to it by the others. When he did give his opinion, however, it was worth hearing, for he spoke of several things which had seemingly evaded Mr. Gifford’s eyes.

“I noticed,” said Sam, “that neither of the outfields to-day studied the batsman as they should. They played in the same positions for a right-handed batter as for a left. Of course, it’s up to the captain or the pitcher to see the outfield as well as the infield is where it should be, but every[73] outfielder ought to realise that a right-handed batter is going to hit more to the left than a left-handed batter, and he ought to move over accordingly. The infield the same way, only, of course, the infield needn’t change position so much. On the Mascots, White stood too far back for most batsmen. He was all right for a long hit to centre, but he would have lost two out of three hits into short centre. The—the ideal position for any fielder is where he can run in quickly for short flies and grounders and run out easily for long ones. Of course no outfielder can station himself where he is going to be able to reach every ball. If he gets so far back that he can handle three-baggers and homers he is going to miss short hits. But you want to remember that it is a heap easier to run in for a ball than it is to run out, because when you’re running in you can judge the ball as you go, and when you’re running out you have got to make up your mind about where the ball is coming down and then turn your back and scoot. The only way to judge the ball is to look over your shoulder, and that isn’t easy. So the best thing for an outfielder to do is to play his position about two-thirds back. That is, leave two-thirds of his[74] territory in front of him and one-third behind him. And an outfielder’s territory begins at a point where it’s impossible for an infielder to reach a fly and extends to the farthest limits of a home run. If your infielders are smart at running back and getting flies, your territory is—is shortened just so much, and you can play further out than you can if your basemen and shortstop are weak on hits outside the diamond. I don’t know that I’ve explained this very clearly.”

“I think you have,” said Mr. Langham. “Don’t you, fellows?”

There was a chorus of assent, and Sam continued.

“Another thing was that Peterson played too far to the right in left field. That fly of Thursby’s would have been an out if Peterson had been in position for it. Thursby bats right-handed and Peterson was playing as though for a left-hander. Peterson made a fine try for it, but he had to cover too much ground. So, you see, an outfielder has got to divide his territory in two ways, lengthwise and crosswise. Of course, on the big teams it’s customary for the catcher, or sometimes the pitcher, to signal to the infield what the delivery[75] is to be and the infielders, usually second baseman or shortstop, let the outfielders know. Because a certain kind of a ball, if it is hit, is pretty sure to go to a certain part of the field, as you all know.”

“That’s something I didn’t know,” laughed the Chief. “Suppose you explain for my benefit, Craig.”