THE LAST OF THE HUGGERMUGGERS,

A GIANT STORY.

BY

CHRISTOPHER PEARSE CRANCH

A GIANT STORY.

BY

CHRISTOPHER PEARSE CRANCH

CHAP. I.--How Little Jacket would go to Sea.

CHAP. II.--His Good and his Bad Luck at Sea.

CHAP. III.--How he fared on Shore.

CHAP. IV.--How Huggermugger came along.

CHAP. V.--What happened to Little Jacket in the Giant's Boot.

CHAP. VI.--How Little Jacket escaped from Kobboltozo's Shop.

CHAP. VII.--How he made use of Huggermugger in Travelling.

CHAP. VIII.--How Little Jacket and his Friends left the Giant's Island.

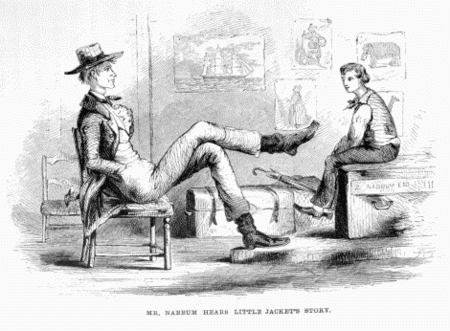

CHAP. IX.--Mr. Nabbum.

CHAP. X.--Zebedee and Jacky put their heads together.

CHAP. XI.--They sail for Huggermugger's Island.

CHAP. XII.--The Huggermuggers in a new light.

CHAP. XIII.--Huggermugger Hall.

CHAP. XIV.--Kobbletozo astonishes Mr. Scrawler.

CHAP. XV.--Mrs. Huggermugger grows thin and fades away.

CHAP. XVI.--The sorrows of Huggermugger.

CHAP. XVII.--Huggermugger leaves his island.

CHAP. XVIII.--The last of the Huggermuggers.

THE

LAST OF THE HUGGERMUGGERS.

HOW LITTLE JACKET WOULD GO TO SEA.

I dare say there are not many of my young readers who have heard about Jacky Cable, the sailor-boy, and of his wonderful adventures on Huggermugger's Island. Jacky was a smart Yankee lad, and was always remarkable for his dislike of staying at home, and a love of lounging upon the wharves, where the sailors used to tell him stories about sea-life. Jacky was always a little fellow. The country people, who did not much like the sea, or encourage Jacky's fondness for it, used to say, that he took so much salt air and tar smoke into his lungs that it stopped his growth. The boys used to call him Little Jacket. Jacky, however, though small in size, was big in wit, being an uncommonly smart lad, though he did play truant sometimes, and seldom knew well his school-lessons. But some boys learn faster out of school than in school, and this was the case with Little Jacket. Before he was ten years old, he knew every rope in a ship, and could manage a sail-boat or a row-boat with equal ease. In fine, salt water seemed to be his element; and he was never so happy or so wide awake as when he was lounging with the sailors in the docks. The neighbors thought he was a sort of good-for-nothing, idle boy, and his parents often grieved that he was not fonder of home and of school. But Little Jacket was not a bad boy, and was really learning a good deal in his way, though he did not learn it all out of books.

Well, it went on so, and Little Jacket grew fonder and fonder of the sea, and pined more and more to enlist as a sailor, and go off to the strange countries in one of the splendid big ships. He did not say much about it to his parents, but they saw what his longing was, and after thinking and talking the matter over together, they concluded that it was about as well to let the boy have his way.

So when Little Jacket was about fifteen years old, one bright summer's day, he kissed his father and mother, and brothers and sisters, and went off as a sailor in a ship bound to the East Indies.

HIS GOOD AND HIS BAD LUCK AT SEA

It was a long voyage, and there was plenty of hard work for Little Jacket, but he found several good fellows among the sailors, and was so quick, so bright, so ready to turn his hand to every thing, and withal of so kind and social a disposition, that he soon became a favorite with the Captain and mates, as with all the sailors. They had fine weather, only too fine, the Captain said, for it was summer time, and the sea was often as smooth as glass. There were lazy times then for the sailors, when there was little work to do, and many a story was told among them as they lay in the warm moonlight nights on the forecastle. But now and then there came a blow of wind, and all hands had to be stirring--running up the shrouds, taking in sails, pulling at ropes, plying the pump; and there was many a hearty laugh among them at the ducking some poor fellow would get, as now and then a wave broke over the deck.

Things went on, however, pretty smoothly with Little Jacket, on the whole, for some time. They doubled the Cape of Good Hope, and were making their way as fast as they could to the coast of Java, when the sky suddenly darkened, and there came on a terrible storm. They took in all the sails they could, after having several carried away by the wind. The vessel scudded, at last, almost under bare poles. The storm was so violent as to render her almost unmanageable, and they were carried a long way out of their course. Everybody had tremendous work to perform, and Little Jacket began to wish he were safe on dry land again. Day after day the poor vessel drifted and rolled. The sky was so dark, that the Captain could not take an observation to tell in what part of the ocean they were. At last, they saw that they were driving towards some enormous cliffs that loomed up in the darkness. Every one lost hope of the ship being saved. Still they neared the cliffs, and now they saw the white breakers ahead, close under them. The Captain got the boats out, to be in readiness for the worst. But the sea was too rough to use them. At last, with a mighty crash, the great ship struck upon the black rocks. All was confusion and wild rushing of the salt waves over them, and poor Jacky found himself in the foaming surge. Struggling to reach the shore, a great wave did what he could not have done himself. He was thrown dripping wet, and bruised, upon the rocks. When he came to himself, he discovered that several of his companions had also reached the shore, but nothing more was seen of the ship. She had gone down in the fearful tempest, and carried I know not how many poor fellows down with her.

HOW HE FARED ON SHORE.

All this was bad enough, as Little Jacket thought. But he was very thankful that he was alive and on shore, and able to use his limbs, and that he found some companions still left. He was not long either in using his wits, and in making the best use of the chances still left him. He found himself upon a rocky promontory. But on climbing a little higher up, he could see that there was beyond it, and joining on to it, a beautiful smooth beach. The rocks were enormous, and he and his comrades had hard work to clamber over them. It took them a good while to do so, exhausted as they were by fatigue, and dripping with wet. At length they reached the beach, the sands of which were of very large grain, and so loose that they had to wade nearly knee deep through them. The country back of the shore seemed very rocky and rough, and here and there were trees of an enormous magnitude. Every thing seemed on a gigantic scale, even to the weeds and grasses that grew on the edge of the beach, where it sloped up to join the main land. And they could see, by mounting on a stone, the same great gloomy cliffs which they saw before the ship struck, but some miles inland. But what most attracted their attention, was the enormous and beautiful great sea-shells, which lay far up on the shore. They were not only of the most lovely colors, but quite various in form, and so large that a man might creep into them. Little Jacket was not long in discovering the advantage of this fact, for they might be obliged, when night came on, to retire into these shells, as they saw no house anywhere within sight. Now, Little Jacket had read Robinson Crusoe, and Gulliver's Travels, and had half believed the wonderful stories of Brobdignag; but he never thought that he should ever be actually wrecked on a giant's island. There now seemed to be a probability that it might be so, after all. What meant these enormous weeds, and trees, and rocks, and grains of sand, and these huge shells? What meant these great cliffs in the distance? He began to feel a little afraid. But he thought about Gulliver, and how well he fared after all, and, on the whole, looked forward rather with pleasure at the prospect of some strange adventure. Now and then he thought he could make out something like huge footprints on the shore--but this might be fancy. At any rate, they would hide themselves if they saw the giant coming. And if they could only find some food to live upon, they might get on tolerably well for a time. And perhaps this was only a fancy about giants, and they might yet find civilized beings like themselves living here.

Now Little Jacket began to be very hungry, and so did his companions--there were six of them--and they all determined to look about as far inland as they dared to go, for some kind of fruit or vegetable which might satisfy their appetites. They were not long in discovering a kind of beach-plum, about as big as watermelons, which grew on a bush so tall, that they had to reach the fruit at arm's length, and on tiptoe. The stalks were covered with very sharp thorns, about a foot long. Some of these thorns they cut off, (they had their knives in their pockets still,) for Little Jacket thought they might be of service to them in defending themselves against any wild animal which might prowl around at night. It chanced that Little Jacket found good use for his in the end, as we shall see. When they had gathered enough of these great plums, they sat down and dined upon them.

They found them a rather coarse, but not unpalatable fruit. As they were still very wet, they took off their clothes, and dried them in the sun: for the storm had ceased, and the sun now came out very warm. The great waves, however, still dashed up on the beach. When their clothes were dry, they put them on, and feeling a good deal refreshed, spent the rest of the day in looking about to see what was to be done for the future. As night came on, they felt a good deal dispirited; but Little Jacket encouraged his companions, by telling stories of sailors who had been saved, or had been taken under the protection of the kings of the country, and had married the king's daughters, and all that. So they found a group of the great shells near each other, seven of them, lying high and dry out of the reach of the dashing waves, and, after bidding each other good night, they crept in. Little Jacket found his dry and clean, and having curled himself up, in spite of his anxiety about the future, was soon fast asleep.

HOW HUGGERMUGGER CAME ALONG.

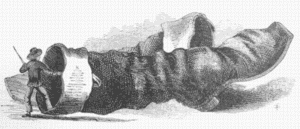

Now it happened that Little Jacket was not altogether wrong in his fancies about giants, for there was a giant living in this island where the poor sailors were wrecked. His name was Huggermugger, and he and his giantess wife lived at the foot of the great cliffs they had seen in the distance. Huggermugger was something of a farmer, something of a hunter, and something of a fisherman. Now, it being a warm, clear, moonlight night, and Huggermugger being disposed to roam about, thought he would take a walk down to the beach to see if the late storm had washed up any clams [Footnote: The "clam" is an American bivalve shell-fish, so called from hiding itself in the sand. A "clam chowder" is a very savory kind of thick soup, of which the clam is a chief ingredient. I put in this note for the benefit of little English boys and girls, if it should chance that this story should find its way to their country.] or oysters, or other shell-fish, of which he was very fond. Having gathered a good basket full, he was about returning, when his eye fell upon the group of great shells in which Little Jacket and his friends were reposing, all sound asleep.

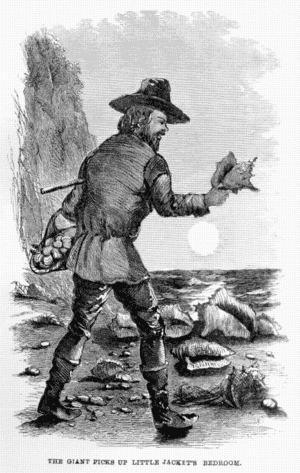

"Now," thought Huggermugger, "my wife has often asked me to fetch home one of these big shells. She thinks it would look pretty on her mantel-piece, with sunflowers sticking in it. Now I may as well gratify her, though I can't exactly see the use of a shell without a fish in it. Mrs. Huggermugger must see something in these shells that I don't."

So he didn't stop to choose, but picked up the first one that came to his hand, and put it in his basket. It was the very one in which Little Jacket was asleep. The little sailor slept too soundly to know that he was travelling, free of expense, across the country at a railroad speed, in a carriage made of a giant's fish-basket. Huggermugger reached his house, mounted his huge stairs, set down his basket, and placed the big shell on the mantel-piece.

"Wife," says he, "here's one of those good-for-nothing big shells you have often asked me to bring home."

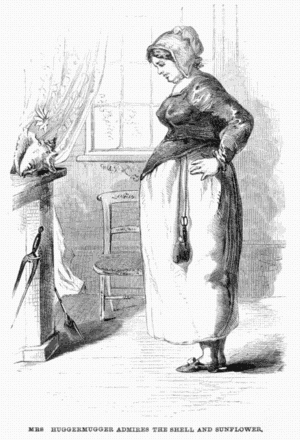

"Oh, what a beauty," says she, as she stuck a sunflower in it, and stood gazing at it in mute admiration. But, Huggermugger being hungry, would not allow her to stand idle.

"Come," says he, "let's have some of these beautiful clams cooked for supper--they are worth all your fine shells with nothing in them."

So they sat down, and cooked and ate their supper, and then went to bed.

Little Jacket, all this time, heard nothing of their great rumbling voices, being in as sound a sleep as he ever enjoyed in his life. He awoke early in the morning, and crept out of a shell--but he could hardly believe his eyes, and thought himself still dreaming, when he found himself and his shell on a very high, broad shelf, in a room bigger than any church he ever saw. He fairly shook and trembled in his shoes, when the truth came upon him that he had been trapped by a giant, and was here a prisoner in his castle. He had time enough, however, to become cool and collected, for there was not a sound to be heard, except now and then something resembling a thunder-like snoring, as from some distant room. "Aha," thought Little Jacket to himself, "it is yet very early, and the giant is asleep, and there may be time yet to get myself out of his clutches."

He was a brave little fellow, as well as a true Yankee in his smartness and ingenuity. So he took a careful observation of the room, and its contents. The first thing to be done was to let himself down from the mantel-piece. This was not an easy matter as it was very high. If he jumped, he would certainly break his legs. He was not long in discovering one of Huggermugger's fishing-lines tied up and lying not far from him. This he unrolled, and having fastened one end of it to a nail which he managed just to reach, he let the other end drop (it was as large as a small rope) and easily let himself down to the floor. He then made for the door, but that was fastened. Jacky, however, was determined to see what could be done, so he pulled out his jackknife, and commenced cutting into the corner of the door at the bottom, where it was a good deal worn, as if it had been gnawed by the rats. He thought that by cutting a little now and then, and hiding himself when the giant should make his appearance, in time he might make an opening large enough for him to squeeze himself through. Now Huggermugger was by this time awake, and heard the noise which Jacky made with his knife.

"Wife," says he, waking her up--she was dreaming about her beautiful shell--"wife, there are those eternal rats again, gnawing, gnawing at that door; we must set the trap for them to-night."

Little Jacket heard the giant's great voice, and was very much astonished that he spoke English. He thought that giants spoke nothing but "chow-chow-whangalorum-hallaballoo with a-ruffle-bull-bagger!" This made him hope that Huggermugger would not eat him. So he grew very hopeful, and determined to persevere. He kept at his work, but as softly as he could. But Huggermugger heard the noise again, or fancied he heard it, and this time came to see if he could not kill the rat that gnawed so steadily and so fearlessly. Little Jacket heard him coming, and rushed to hide himself. The nearest place of retreat was one of the giant's great boots, which lay on the floor, opening like a cave before him. Into this he rushed. He had hardly got into it before Huggermugger entered.

CHAPTER FIVE.

WHAT HAPPENED TO LITTLE JACKET IN THE GIANT'S BOOT.

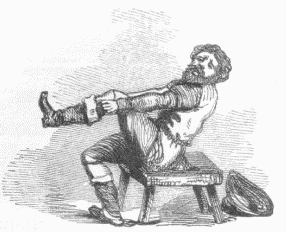

Huggermugger made a great noise in entering, and ran up immediately to the door at which Little Jacket had been cutting, and threshed about him with a great stick, right and left. He then went about the room, grumbling and swearing, and poking into all the corners and holes in search of the rat; for he saw that the hole under the door had been enlarged, and he was sure that the rats had done it. So he went peeping and poking about, making Little Jacket not a little troubled, for he expected every moment that he would pick up the boot in which he was concealed, and shake him out of his hiding-place. Singularly enough, however, the giant never thought of looking into his own boots, and very soon he went back to his chamber to dress himself. Little Jacket now ventured to peep out of the boot, and stood considering what was next to be done. He hardly dared to go again to the door, for Huggermugger was now dressed, and his wife too, for he heard their voices in the next room, where they seemed to be preparing their breakfast. Little Jacket now was puzzling his wits to think what he should do, if the giant should take a fancy to put his boots on before he could discover another hiding-place. He noticed, however, that there were other boots and shoes near by, and so there was a chance that Huggermugger might choose to put on some other pair. If this should be the case, he might lie concealed where he was during the day, and at night work away again at the hole in the door, which he hoped to enlarge enough soon, to enable him to escape. He had not much time, however, for thought; for the giant and his wife soon came in. By peeping out a little, he could just see their great feet shuffling over the wide floor.

"And now, wife." says Huggermugger, "bring me my boots." He was a lazy giant, and his wife spoiled him, by waiting on him too much.

"Which boots, my dear," says she.

"Why, the long ones," says he; "I am going a hunting to-day, and shall have to cross the marshes."

Little Jacket hoped the long boots were not those in one of which he was concealed, but unfortunately they were the very ones. So he felt a great hand clutch up the boots, and him with them, and put them down in another place. Huggermugger then took up one of the boots and drew it on, with a great grunt. He now proceeded to take up the other. Little Jacket's first impulse was to run out and throw himself on the giant's mercy, but he feared lest he should be taken for a rat. Besides he now thought of a way to defend himself, at least for a while. So he drew from his belt one of the long thorns he had cut from the bush by the seaside, and held it ready to thrust it into his adversary's foot, if he could. But he forgot that though it was as a sword in his hand, it was but a thorn to a giant. Huggermugger had drawn the boot nearly on, and Little Jacket's daylight was all gone, and the giant's great toes were pressing down on him, when he gave them as fierce a thrust as he could with his thorn.

"Ugh!" roared out the giant, in a voice like fifty mad bulls; "wife, wife, I say!"

"What's the matter, dear?" says wife.

"Here's one of your confounded needles in my boot. I wish to gracious you'd be more careful how you leave them about!"

"A needle in your boot?" said the giantess, "how can that be? I haven't been near your boots with my needles."

"Well, you feel there yourself, careless woman, and you'll see."

Whereupon the giantess took the boot, and put her great hand down into the toe of it, when Little jacket gave another thrust with his weapon.

"O-o-o-o!!" screams the wife. "There's something here, for it ran into my finger; we must try to get it out. She then put her hand in again, but very cautiously, and Little Jacket gave it another stab, which made her cry out more loudly than before. Then Huggermugger put his hand in, and again he roared out as he felt the sharp prick of the thorn.

"It's no use," says he, flinging down the boot in a passion, almost breaking Little Jacket's bones, as it fell. "Wife, take that boot to the cobbler, and tell him to take that sharp thing out, whatever it is, and send it back to me in an hour, for I must go a hunting today."

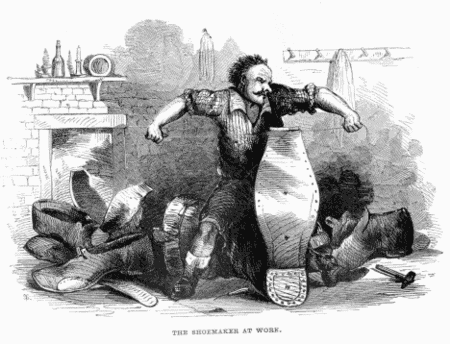

So off the obedient wife trotted to the shoemaker's, with the boot under her arm. Little Jacket was curious to see whether the shoemaker was a giant too. So when the boot was left in his workshop, he contrived to peep out a little, and saw, instead of another Huggermugger, only a crooked little dwarf, not more than two or three times bigger than himself. He went by the name of Kobboltozo.

"Tell your husband," says he, "that I will look into his boot presently--I am busy just at this moment--and will bring it myself to his house."

Little Jacket was quite relieved to feel that he was safe out of the giant's house, and that the giantess had gone. "Now," thought he, "I think I know what to do."

After a while, Kobboltozo took up the bout and put his hand down into it slowly and cautiously. But Little Jacket resolved to keep quiet this time. The dwarf were felt around so carefully, for fear of having his finger pricked, and his hand was so small in comparison with that of the giant's, that Little Jacket had time to dodge around his fingers and down into the toe of the boot, so that Kobboltozo could feel nothing there. He concluded, therefore, that whatever it was that hurt the giant and his wife, whether needle, or pin, or tack, or thorn, it must have dropped out on the way to his shop. So he laid the boot down, and went for his coat and hat. Little Jacket knew that now was his only chance of escape--he dreaded being carried back to Huggermugger--so he resolved to make a bold move. No sooner was the dwarf's back turned, as he went to reach down his coat, than Little Jacket rushed out of the boot, made a spring from the table on which it lay, reached the floor, and made his way as fast as he could to a great pile of old boots and shoes that lay in a corner of the room, where he was soon hidden safe from any present chance of detection.

HOW LITTLE JACKET ESCAPED FROM KOBBLETOZO'S SHOP.

Great was Huggermugger's astonishment, and his wife's, when they found that the shoemaker told them the truth, and that there was nothing in the boot which could in any way interfere with the entrance of Mr. Huggermugger's toes. For a whole month and a day, it puzzled him to know what it could have been that pricked him so sharply.

Leaving the giant and his wife to their wonderment, let us return to Little Jacket. As soon as he found the dwarf was gone, and that all was quiet, he came out from under the pile of old shoes, and looked around to see how he should get out. The door was shut, and locked on the outside, for Kobboltozo had no wife to look after the shop while he was out. The window was shut too, the only window in the shop. This window, however, not being fastened on the outside, the little sailor thought he might be able to open it by perseverance. It was very high, so he pushed along a chair towards a table, on which he succeeded in mounting, and from the table, with a stick which he found in the room, he could turn the bolt which fastened the window inside. This, to his great joy, he succeeded in doing, and in pulling open the casement. He could now, with ease, step upon the window sill. The thing was now to let himself down on the other side. By good luck, he discovered a large piece of leather on the table. This he took the and cut into strips, and tying them together, fastened one end to a nail inside, and boldly swung himself down in sailor fashion, as he had done at the giant's, and reached the ground. Then looking around, and seeing nobody near, he ran off as fast as his legs could carry him. But alas! he knew not where he was. If he could but find a road which would lead him back to the seaside where his companions were, how happy would he had been! He saw nothing around him but huge rocks and trees, with here and there an enormous fence or stone wall. Under these fences, and through the openings in the stone walls he crept, but could find no road. He wandered on for some time, clambering over great rocks and wading through long grasses, and began to be very tired and very hungry; for he had not eaten any thing since the evening before, when he feasted on the huge beach plums. He soon found himself in a sort of blackberry pasture, where the berries were as big as apples; and having eaten some of these, he sat down to consider what was to be done. He felt that he was all alone in a great wilderness, and out of which he feared he never could free himself. Poor Jacky felt lonely and sad enough, and almost wished he had discovered himself to the dwarf, for whatever could have happened to him, it could not have been worse than to be left to perish in a wilderness alone.

HOW HE MADE USE OF HUGGERMUGGER IN TRAVELLING.

While Little Jacket sat pondering over his situation, he heard voices not far off, as of two persons talking. But they were great voices, as of trumpets and drums. He looked over the top of the rock against which he was seated, and saw for the first time the entire forms of Huggermugger and his wife, looming up like two great light-houses. He knew it must be they, for he recognized their voices. They were standing on the other side of a huge stone wall. It was the giant's garden.

"Wife," said Huggermugger, "I think now I've got my long boots on again, and my toe feels so much better, I shall go through the marsh yonder and kill a few frogs for your dinner; after that, perhaps I may go down again to the seashore, and get some more of those delicious clams I found last night."

"Well husband," says the wife, "you may go if you choose for your clams, but be sure you get me some frogs, for you know how fond I am of them."

So Huggermugger took his basket and his big stick, and strode off to the marsh. "Now," thought the little sailor, "is my time. I must watch which way he goes and if I can manage not to be seen, and can only keep up with him--for he goes at a tremendous pace--we shall see!"

So the giant went to the marsh, in the middle of which was a pond, while Little Jacket followed him as near as he dared to go. Pretty soon, he saw the huge fellow laying about him with his stick, and making a great splashing in the water. It was evident he was killing Mrs. Huggermugger's frogs, a few of which he put in his basket, and then strode away in another direction. Little Jacket now made the best use of his little legs that he ever made in his life. If he could only keep the giant in sight! He was much encouraged by perceiving that Huggermugger, who, as I said before, was a lazy giant, walked at a leisurely pace, and occasionally stopped to pick the berries that grew everywhere in the fields. Little Jacket could see his large figure towering up some miles ahead. Another fortunate circumstance, too, was, that the giant was smoking his pipe as he went, and even when Little Jacket almost lost sight of him, he could guess where he was from the clouds of smoke floating in the air, like the vapor from a high-pressure Mississippi steamboat. So the little sailor toiled along, scrambling over rocks, and through high weeds and grasses and bushes, till they came to a road. Then Jacky's spirits began to rise, and he kept along as cautiously, yet as fast as he could, stopping only when the giant stopped. At last, after miles and miles of walking, he caught a glimpse of the sea through the huge trees that skirted the road. How his heart bounded! "I shall at least see my messmates again," he said, "and if we are destined to remain long in this island, we will at least help each other, and bear our hard lot together."

It was not long before he saw the beach, and the huge Huggermugger groping in the wet sand for his shell-fish. "If I can but reach my companions without being seen, tell them my strange adventures, and all hide ourselves till the giant is out of reach, I shall be only too happy." Very soon he saw the group of beautiful great shells, just as they were when he left them, except that his shell, of course, was not there, as it graced Mrs. Huggermugger's domestic fireside. When he came near enough, he called some of his comrades by name, not too loud, for fear of being heard by the shell-fish-loving giant. They knew his voice, and one after another looked out of his shell. They had already seen the giant, as they were out looking for their lost companion, and had fled to hide themselves in their shells.

"For heaven's sake," cried the little sailor. "Tom, Charley, all of you! don't stay here; the giant will come and carry you all off to his house under the cliffs; his wife has a particular liking for those beautiful houses of yours. I have just escaped, almost by miracle. Come, come with me--here--under the rocks--in this cave--quick, before he sees us!"

So Little Jacket hurried his friends into a hole in the rocks, where the giant would never think of prying. Huggermugger did not see them. They were safe. As soon as he had filled his basket, he went off, and left nothing but his footprints and the smoke of his pipe behind him.

After all, I don't think the giant would have hurt them, had he seen them. For he would have known the difference between a sailor and a shell-fish at once, and was no doubt too good-natured to injure them, if they made it clear to his mind that they were not by any means fish: but, on the contrary, might disagree dreadfully with his digestion, should he attempt to swallow them.

HOW LITTLE JACKET AND HIS FRIENDS LEFT THE GIANT'S ISLAND.

They lived in this way for several weeks, always hoping some good luck would happen. At last, one day, they saw a ship a few miles from the shore. They all ran to the top of a rock, and shouted and waved their hats. Soon, to their indescribable joy, they saw a boat approaching the shore. They did not wait for it to reach the land, but being all good swimmers, with one accord plunged into the sea and swam to the boat. The sailors in the boat proved to be all Americans, and the ship was the Nancy Johnson, from Portsmouth, N. H., bound to the East Indies, but being out of water had made for land to obtain a supply.

The poor fellows were glad enough to get on board ship again. As they sailed off. they fancied they saw in the twilight, the huge forms of the great Mr. and Mrs. Huggermugger on the rocks, gazing after them with open eyes and mouths.

They pointed them out to the people of the ship, as Little Jacket related his wonderful adventures: but the sailors only laughed at them, and saw nothing but huge rocks and trees; and they whispered among themselves, that the poor fellows had lived too long on tough clams and sour berries, and cold water, and that a little jolly life on board ship would soon cure their disordered imaginations.

MR. NABBUM.

Little Jacket and his friends were treated very kindly by the Captain and crew of the Nancy Johnson, and as a few more sailors were wanted on board, their services were gladly accepted. They all arrived safely at Java, where the ship took in a cargo of coffee. Little Jacket often related his adventures in the giant's island, but the sailors, though many of them were inclined to believe in marvellous stories, evidently did not give much credit to Jacky's strange tale, but thought he must have dreamed it all.

There was, however, one man who came frequently on board the ship while at Java, who seemed not altogether incredulous. He was a tall, powerful Yankee, who went by the name of Zebedee Nabbum.

He had been employed as an agent of Barnum, to sail to the Indies and other countries in search of elephants, rhinoceroses, lions, tigers, baboons, and any wild animals he might chance to ensnare. He had been fitted out with a large ship and crew, and all the men and implements necessary for this exciting and dangerous task, and had been successful in entrapping two young elephants, a giraffe, a lion, sixteen monkeys, and a great number of parrots. He was now at Java superintending the manufacture of a very powerful net of grass-ropes, an invention of his own, with which he hoped to catch a good many more wild animals, and return to America, and make his fortune by exhibiting them for Mr. Barnum.

Now Zebedee Nabbum listened with profound attention to Little Jacket's story, and pondered and pondered over it.

"And after all," he said to himself, "why shouldn't it be true? Don't we read in Scripter that there war giants once? Then why hadn't there ought to be some on 'em left--in some of them remote islands whar nobody never was? Grimminy! If it should be true--if we should find Jacky's island--if we should see the big critter alive, or his wife--if we could slip a noose under his legs and throw him down--or carry along the great net and trap him while he war down on the beach arter his clams, and manage to tie him and carry him off in my ship! He'd kick, I know. He'd a kind o' roar and struggle, and maybe swamp the biggest raft we could make to fetch him. But couldn't we starve him into submission? Or, if we gave him plenty of clams, couldn't we keep him quiet? Or couldn't we give the critter Rum?--I guess he don't know nothin' of ardent sperets--and obfusticate his wits--and get him reglar boozy--couldn't we do any thing we chose to, then? An't it worth tryin', any how? If we could catch him, and get him to Ameriky alive, or only his skeleton, my fortune's made, I cal'late. I kind o' can't think that young fellow's been a gullin' me. He talks as though he'd seen the awful big critters with his own eyes. So do the other six fellows--they couldn't all of 'em have been dreamin'."

So Zebedee had a conversation one day with the Captain of the Nancy Johnson, and found out from him that he had taken the latitude and longitude of the coast where they took away the shipwrecked sailors. The Captain also described to Zebedee the appearance of the coast; and, in short, Zebedee contrived to get all the information about the place the Captain could give him, without letting it appear that he had any other motive in asking questions than mere curiosity.

ZEBEDEE AND JACKY PUT THEIR HEADS TOGETHER.

Zebedee now communicated to Little Jacket his plans about sailing for the giant's coast, and entrapping Huggermugger and carrying him to America. Little Jacket was rather astonished at the bold scheme of the Yankee, and tried to dissuade him from attempting it. But Zebedee had got his head so full of the notion now, that he was determined to carry out his project, if he could. He even tried to persuade Little Jacket to go with him, and his six companions, and finally succeeded. The six other sailors, however, swore that nothing would tempt them to expose themselves again on shore to the danger of being taken by the giant. Little Jacket agreed to land with Zebedee and share all danger with him, on condition that Zebedee would give him half the profits Barnum should allow them from the exhibition of the giant in America. But Little Jacket made Zebedee promise that he would be guided by his advice, in their endeavors to ensnare the giant. Indeed, a new idea had entered Jacky's head as to the best way of getting Huggermugger into their power, and that was to try persuasion rather than stratagem or force. I will tell you the reasons he had for so thinking.

1. The Huggermuggers were not Ogres or Cannibals. They lived on fish, frogs, fruit, vegetables, grains, &c.

2. The Huggermuggers wore clothes, lived in houses, and were surrounded with various indications of civilization. They were not savages.

3. The Huggermuggers spoke English, with a strange accent, to be sure. They seemed sometimes to prefer it to their own language. They must, then, have been on friendly terms with English or Americans, at some period of their lives.

4. The Huggermuggers were not wicked and blood-thirsty. How different from the monsters one reads about in children's books! On the contrary, though they had little quarrels together now and then, they did not bite nor scratch, but seemed to live together as peaceably and lovingly, on the whole, as most married couples. And the only time he had a full view of their faces, Little Jacket saw in them an expression which was really good and benevolent.

All these facts came much more forcibly to Jacky's mind, now that the first terror was over, and calm, sober reason had taken the place of vague fear.

He, therefore, told Mr. Nabbum, at length, his reasons for proposing, and even urging, that unless Huggermugger should exhibit a very different side to his character from that which he had seen, nothing like force or stratagem should be resorted to.

"For," said Little Jacket, "even if you succeeded, Mr. Nabbum, in throwing your net over his head, or your noose round his leg, as you would round an elephant's, you should consider how powerful and intelligent and, if incensed, how furious an adversary you have to deal with. None but a man out of his wits would think of carrying him off to your ship by main force. And as to your idea of making him drunk, and taking him aboard in that condition, there is no knowing whether drink would not render him quite furious, and ten times more unmanageable than ever. No, take my word for it, Mr. Nabbum, that I know Huggermugger too well to attempt any of your tricks with him. You cannot catch him as you would an elephant or a hippopotamus. Be guided by me, and see if my plan don't succeed better than yours."

"Well," answered Zebedee, "I guess, arter all, Jackie, you may be right. You've seen the big varmint, and feel a kind of o' acquainted with him, so you see I won't insist on my plan, if you've any better. Now, what I want to know is, what's your idee of comin' it over the critter?"

"You leave that to me," said Little Jacket; "if talking and making friends with him can do any thing, I think I can do it. We may coax him away; tell him stories about our country, and what fun he'd have among the people so much smaller than himself, and how they'd all look up to him as the greatest man they ever had, which will be true, you know: and that perhaps the Americans will make him General Huggermugger, or His Excellency President Huggermugger; and you add a word about our nice oysters, and clam-chowders.

"I think there'd be room for him in your big ship. It's warm weather, and he could lie on deck, you know; and we could cover him up at night with matting and old sails; and he'd be so tickled at the idea of going to sea, and seeing strange countries, and we'd show him such whales and porpoises, and tell him such good stories, that I think he'd keep pretty quiet till we reached America. To be sure, it's a long voyage, and we'd have to lay in an awful sight of provisions, for he's a great feeder; but we can touch at different ports as we go along, and replenish our stock.

"One difficulty will be, how to persuade him to leave his wife--for there wouldn't be room for two of them. We must think the matter over, and it will be time enough to decide what to do when we get there. Even if we find it impossible to get him to go with us, we'll get somebody to write his history, and an account of our adventures, and make a book that will sell."

THEY SAIL FOR HUGGERMUGGER'S ISLAND.

So Little Jacket sailed with Mr. Zebedee Nabbum, in search of the giant's island. They took along a good crew, several bold elephant-hunters, an author to write their adventures, an artist to sketch the Huggermuggers, Little Jacket's six comrades, grappling-irons, nets, ropes, harpoons, cutlasses, pistols, guns, the two young elephants, the lion, the giraffe, the monkeys, and the parrots.

They had some difficulty in finding the island, but by taking repeated observations, they at last discovered land that they thought must be it. They came near, and were satisfied that they were not deceived. There were the huge black cliffs--there were the rocky promontory--the beach. It was growing dusk, however, and they determined to cast anchor, and wait till morning before they sent ashore a boat.

Was it fancy or not, that Little Jacket thought he could see in the gathering darkness, a dim, towering shape, moving along like a pillar of cloud, now and then stooping to pick up something on the shore--till it stopped, and seemed looking in the direction of the ship, and then suddenly darted off towards the cliffs, and disappeared in the dark woods.

THE HUGGERMUGGERS IN A NEW LIGHT.

I think the giant must have seen the ship, and ran home at full speed to tell his wife about it. For in the morning early, as Little Jacket and Nabbum and several others of the boldest of the crew had just landed their boat, and were walking on the beach, whom should they see but Huggermugger and his wife hastening towards them with rapid strides. Their first impulse was to rush and hide themselves, but the Huggermuggers came too fast towards them to allow them to do so. There was nothing else to do but face the danger, if danger there was. What was their surprise to find that the giant and giantess wore the most beaming smiles on their broad faces. They stooped down and patted their heads with their huge hands, and called them, in broken English, "pretty little dolls and dears, and where did they come from, and how long it was since they had seen any little men like them--and wouldn't they go home and see them in their big house under the cliffs?" Mrs. Huggermugger, especially, was charmed with them, and would have taken them home in her arms--"she had no children of her own, and they should live with her and be her little babies." The sailors did not exactly like the idea of being treated like babies, but they were so astonished and delighted to find the giants in such good humor, that they were ready to submit to all the good woman's caresses.

Little Jacket then told them where they came from, and related his whole story of having been shipwrecked there, and all his other adventures. As he told them how Huggermugger had carried home the big shell with him in it, sound asleep; how he had let himself down from the mantel-piece, and had tried to escape by cutting at the door; and how, when he heard Huggermugger coming, he had rushed into the boot, and how he had pricked the giant's toe when he attempted to draw his boot on, and how the boot and he were taken to the cobbler's--then Huggermugger and his wife could contain themselves no longer, but burst into such peals of laughter, that the people in the ship, who were watching their movements on shore through their spy-glasses, and expected every moment to see their companions all eaten alive or carried off to be killed, knew not what to make of it. Huggermugger and his wife laughed till the tears ran down their faces, and made such a noise in their merriment, that the sailors wished they were further off. They, however, were in as great glee as the giant and giantess, and began to entertain such a good opinion of them, that they were ready to assent to anything the Huggermuggers proposed. In fact, except in matter of size, they could see very little difference between the giants and themselves. All Zebedee Nabbum's warlike and elephant-trapping schemes melted away entirely, and he even began to have a sort of conscientious scruple against enticing away the big fellow who proved to be such a jolly good-humored giant. He was prepared for resistance. He would have even liked the fun of throwing a noose over his head, and pulling him down and harpooning him, but this good-humored, merry laughter, this motherly caressing, was too much for Zebedee. He was overcome. Even Little Jacket was astonished. The once dreaded giant was in all respects like them--only O, so much bigger!

So, after a good deal of friendly talk, Huggermugger invited the whole boat's crew to go home with him to dinner, and even to spend some days with him, if they would. Little Jacket liked the proposal, but Zebedee said they must first send back a message to the ship, to say where they were going. Huggermugger send his card by the boat, to the rest of the ship's company--it was a huge piece of pasteboard, as big as a dining-table--saying, that he and Mrs. H. would be happy, some other day, to see all who would do him the honor of a visit. He would come himself and fetch them in his fish-basket, as the road was rough, and difficult for such little folks to travel.

HUGGERMUGGER HALL.

The next morning Huggermugger appeared on the beach with his big basket, and took away about half a dozen of the sailors. Zebedee and Little Jacket went with them. It was a curious journey, jogging along in his basket, and hanging at such a height from the ground. Zebedee could not help thinking what a capital thing it would be in America to have a few big men like him to lift heavy stones for building, or to carry the mail bags from city to city, at a railroad speed. But, as to travelling in his fish-basket, he certainly preferred our old-fashioned railroad cars.

They were all entertained very hospitably at Huggermugger Hall. They had a good dinner of fish, frogs, fruit, and vegetables, and drank a kind of beer, made of berries, out of Mrs. Huggermugger's thimble, much to the amusement of all. Mrs. Huggermugger showed them her beautiful shell, and made Little Jacket tell how he had crept out of it, and let himself down by the fishing-line. And Huggermugger made him act over again the scene of hiding in the boot. At which all laughed again. The little people declined their hosts' pressing invitation to stay all night, so Huggermugger took them all back to their boat. They had enough to tell on board ship about their visit. The next day, and the day after, others of the crew were entertained in the same way at Huggermugger Hall, till all had satisfied their curiosity. The giant and his wife being alone in the island, they felt that it was pleasant to have their solitude broken by the arrival of the little men. There were several dwarfs living here and there in the island, who worked for the giants, of whom Kobboltozo was one; but there were no other giants. The Huggermuggers were the last of their race. Their history, however, was a secret they kept to themselves. Whether they or their ancestors came from Brobdignag, or whether they were descended from Gog and Magog, or Goliath of Gath, they never would declare.

Mr. Scrawler, the author, who accompanied the ship, was very curious to know something of their history and origin. He ascertained that they learned English of a party of adventurers who once landed on their shore, many years before, and that the Huggermugger race had long inhabited the island. But he could learn nothing of their origin. They looked very serious whenever this subject was mentioned. There was evidently a mystery about them, which they had particular reasons never to unfold. On all other subjects they were free and communicative. On this, they kept the strictest and most guarded silence.

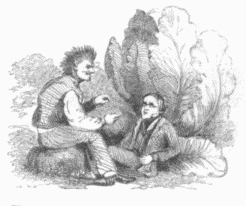

KOBBLETOZO ASTONISHES MR. SCRAWLER.

Now it chanced that some of the dwarfs I have spoken of, were not on the best of terms with the Huggermuggers. Kobboltozo was one of these. And the only reason why he disliked them, as far as could be discovered, was that they were giants, and he (though a good deal larger than an ordinary sized man) was but a dwarf. He could never be as big as they were. He was like the frog that envied the ox, and his envy and hatred sometimes swelled him almost to bursting. All the favors that the Huggermuggers heaped upon him, had no effect in softening him. He would have been glad at almost any misfortune that could happen to them.

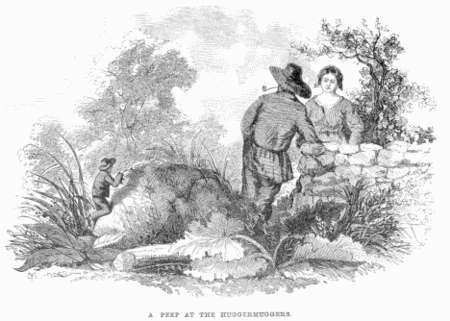

Now Kobboltozo was at the giant's house one day when Mr. Scrawler was asking questions of Huggermugger about his origin, and observed his disappointment at not being furnished with all the information he was so eager to obtain; for Mr. Scrawler calculated to make a book about the Huggermuggers and all their ancestors, which would sell. So while Mr. Scrawler was taking a stroll in the garden, Kobboltozo came up to him and told him he had something important to communicate to him. They then retired behind some shrubbery, where Kobboltozo, taking a seat under the shade of a cabbage, and requesting Mr. Scrawler to do the same, looked around cautiously, and spoke as follows:--

"I perceive that you all are very eager to know something about the Huggermugger's origin and history. I think that I am almost the only one in this island besides them, who can gratify your curiosity in this matter. But you must solemnly promise to tell no one, least of all the giants, in what way you came to know what I am going to tell you, unless it be after you have left the island, for I dread Huggermugger's vengeance if he knows the story came from me."

"I promise," said Scrawler.

"Know then," said Kobboltozo, "that the ancestors of the Huggermuggers--the Huggers on the male side, and the Muggers on the female--were men smaller than me, the poor dwarf. Hundred of years ago they came to this island, directed hither by an old woman, a sort of witch, who told them that if they and their children, and their children's children, ate constantly of a particular kind of shell-fish, which was found in great abundance here, they would continue to increase in size, with each successive generation, until they became proportioned to all other growth on the island--till they became giants--such giants as the Huggermuggers. But that the last survivors of the race would meet with some great misfortune, if this secret should ever be told to more than one person out of the Huggermugger family. I have reasons for believing that Huggermugger and his wife are the last of their race; for all their ancestors and relations are dead, and they have no children, and are likely to have none. Now there are two persons who have been told the secret. It was told to me, and I tell it to you!"

As Kobboltozo ended, his face wore an almost fiendish expression of savage triumph, as if he had now settled the giants' fate forever.

"But," said Scrawler, "how came you into possession of this tremendous secret; and, if true, why do you wish any harm to happen to the good Huggermuggers?"

"I hate them!" said the dwarf. "They are rich--I am poor. They are big and well-formed--I am little and crooked. Why should not my race grow to be as shapely and as large as they; for my ancestors were as good as theirs, and I have heard that they possessed the island before the Huggermuggers came into it? No! I am weary of the Huggermuggers. I have more right to the island than they. But they have grown by enchantment, while my race only grew to a certain size, and then we stopped and grew crooked. But the Huggermuggers, if there should be any more of them, will grow till they are like the trees of the forest.

"Then as to the way I discovered their mystery. I was taking home a pair of shoes for the giantess, and was just about to knock at the door, when I heard the giant and his wife talking. I crept softly up and listened. They have great voices--not difficult to hear them. They were talking about a secret door in the wall, and of something precious which was locked up within a little closet. As soon as their voices ceased, I knocked, and was let in. I assumed an appearance as if I had heard nothing, and they did not suspect me. I went and told Hammawhaxo, the carpenter--a friend of mine, and a dwarf like me. I knew he didn't like Huggermugger much. Hammawhaxo was employed at the time to repair the bottom of a door in the giant's house, where the rats had been gnawing. So he went one morning before the giants were up, and tapped all around the wainscoting of the walls with his hammer, till he found a hollow place, and a sliding panel, and inside the wall he discovered an old manuscript in the ancient Hugger language, in which was written the secret I have told you. And now we will see if the old fortune-teller's prophecy is to come true or not."

MRS. HUGGERMUGGER GROWS THIN AND FADES AWAY.

Scrawler, though delighted to get hold of such a story to put into his book, could not help feeling a superstitious fear that the prediction might be verified, and some misfortune before the good Huggermuggers. It could not come from him or any of his friends, he was sure; for Zebedee Nabbum's first idea of entrapping the giant was long since abandoned. If he was ever to be taken away from the island, it could only be by the force of persuasion, and he was sure that Huggermugger would not voluntarily leave his wife.

Scrawler only hinted then to Huggermugger, that he feared Kobboltozo was his enemy. But Huggermugger laughed, and said he knew the dwarf was crabbed and spiteful, but that he did not fear him. Huggermugger was not suspicious by nature, and it never came into his thoughts that Kobboltozo, or any other dwarf could have the least idea of his great secret.

Little Jacket came now frequently to the giant's house, where he became a great favorite. He had observed, for some days, that Mrs. Huggermugger's spirits were not so buoyant as usual. She seldom laughed--she sometimes sat alone and sighed, and even wept. She ate very little of shell-fish--even her favorite frog had lost its relish. She was growing thin--the once large, plump woman. Her husband, who really loved her, though his manner towards her was sometimes rough, was much concerned. He could not enjoy his lonely supper--he scarcely cared for his pipe. To divert his mind, he would sometimes linger on the shore, talking to the little men, as he called them. He would strip off this long boots and his clothes, and wade out into the sea to get a nearer view of the ship. He could get near enough to talk to them on board. "How should you like to go with us," said the little men, one day, "and sail away to see new countries? We can show you a great deal that you haven't seen. If you went to America with us, you would be the greatest man there."

Huggermugger laughed, but not one of his hearty laughs--his mind was ill at ease about his wife. But the idea was a new one, of going away from giant-land to a country of pygmies. Could he ever go? Not certainly without his wife--and she would never leave the island. Why should he wish to go away? "To be sure." he said, "it is rather lonely here--all our kindred dead--nobody to be seen but little ugly dwarfs. And I really like these little sailors, and shall be sorry to part with them. No, here I shall remain, wife and I, and here we shall end our days. We are the last of the giants--let us not desert our native soil."

Mrs. Huggermugger grew worse and worse. It seemed to be a rapid consumption. No cause could be discovered for her sickness. A dwarf doctor was called in, but he shook his head--he feared he could do nothing. Little Jacket came with the ship's doctor, and brought some medicines. She took them, but they had no effect. She could not now rise from her bed. Her husband sat by her side all the time. The good-hearted sailors did all they could for her, which was not much. Even Zebedee Nabbum's feelings were touched. He told her Yankee stories, and tales of wild beasts--of elephants, not bigger than one of her pigs--of lions and bears as small as lapdogs--of birds not larger than one of their flies. All did what they could to lessen her sufferings. "To think," said Zebedee, "aint it curious--who'd a thought that great powerful critter could ever get sick and waste away like this!"

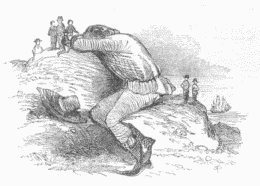

THE SORROWS OF HUGGERMUGGER.

At last, one morning while the sailors were lounging about on the beach, they saw the great Huggermugger coming along, his head bent low, and the great tears streaming down his face. They all ran up to him. He sat, or rather threw himself down on the ground. "My dear little friends," said he, "it's all over. I never shall see my poor wife again--never again--never again--I am the last of the Huggermuggers. She is gone. And as for me--I care not now whither I go. I can never stay here--not here--it will be too lonely. Let me go and bury my poor wife, and then farewell to giant-land! I will go with you, if you will take me!"

They were all much grieved. They took Huggermugger's great hands, as he sat there, like a great wrecked and stranded ship, swayed to and fro by the waves and surges of his grief, and their tears mingled with his. He took them into his arms, the great Huggermugger, and kissed them. "You are the only friends left me now," he said, "take me with you from this lonely place. She who was so dear to me is gone to the great Unknown, as on a boundless ocean; and this great sea which lies before us is to me like it. Whether I live or die, it is all one--take me with you. I am helpless now as a child!"

HUGGERMUGGER LEAVES HIS ISLAND

Zebedee Nabbum could not help thinking how easily he had obtained permission of his giant. There was nothing to do but to make room for him in the ship, and lay in a stock of those articles of foods which the giant was accustomed to eat, sufficient for a long voyage.

Huggermugger laid his wife in a grave by the sea-shore, and covered it over with the beautiful large shells which she so loved. He then went home, opened the secret door in the wall, took out the ancient manuscript, tied a heavy stone to it, and sunk it in a deep well under the rocks, into which he also threw the key of his house, after having taken everything he needed for his voyage, and locked the doors.

The ship was now all ready to sail. The sailors had made a large raft, on which the giant sat and paddled himself to the ship, and climbed on board. The ship was large enough to allow him to stand, when the sea was still, and even walk about a little; but Huggermugger preferred the reclining posture, for he was weary and needed repose.

During the first week or two of the voyage, his spirits seemed to revive. The open sea, without any horizon, the sails spreading calmly above him, the invigorating salt breeze, the little sailors clambering up the shrouds and on the yards, all served to divert his mind from his great grief. The sailors came to around him and told him stories, and described the country to which they were bound; and sometimes Mr. Nabbum brought out his elephants, which Huggermugger patted and fondled like dogs. But poor Huggermugger was often sea-sick, and could not sit up. The sailors made him as comfortable as they could. By night they covered him up and kept him warm, and by day they stretched an awning above him to protect him from the sun. He was so accustomed to the open air, that he was never too cold nor too warm. But poor Huggermugger, after a few weeks more, began to show the symptoms of a more serious illness then sea-sickness. A nameless melancholy took possession of him. He refused to eat--he spoke little, and only lay and gazed up at the white sails and the blue sky. By degrees, he began to waste away, very much as his wife did. Little Jacket felt a real sorrow and sympathy, and so did they all. Zebedee Nabbum, however, it must be confessed "though he felt a kind o' sorry for the poor critter," thought more of the loss it would be to him, as a money speculation, to have him die before they reached America. "It would be too bad," he said, "after all the trouble and expense I've had, and when the critter was so willin', too, to come aboard, to go and have him die. We must feed him well, and try hard to save him; for we can't afford to lose him. Why, he'd be worth at least 50,000 dollars--yes, 100,000 dollars, in the United States." So Zebedee would bring him dishes of his favorite clams, nicely cooked and seasoned, but the giant only sighed and shook his head. "No," he said, "my little friends, I feel that I shall never see your country. Your coming to my island has been in some way fatal for me. My secret must have been told. The prophecy, ages ago, has come true!"

THE LAST OF HUGGERMUGGER.

Mr. Scrawler now thought it was time for him to speak. He had only refrained from communicating to Huggermugger what the dwarf had told him, from the fear of making the poor giant more unhappy and ill than ever. But he saw that he could be silent no longer, for there seemed to be a suspicion in Huggermugger's mind, that it might be these very people, in whose ship he had consented to go, who had found out and revealed his secret.

Mr. Scrawler then related to the giant what the dwarf had told him in the garden, and about the concealed MS., and the prophecy it contained.

Huggermugger sunk his head in his hands, and said: "Ah, the dwarf--the dwarf! Fool that I was; I might have known it. His race always hated mine. Ah, wretch! that I had punished thee as thou deservest!

"But, after all, what matters it?" he added, "I am the last of my race. What matters it, if I die a little sooner than I thought? I have little wish to live, for I should have been very lonely in my island. Better it is it that I go to other lands--better, perhaps, that I die here ere reaching land.

"Friends, I feel that I shall never see your country--and why should I wish it? How could such a huge being as I live among you? For a little while I should be amused with you, and you astonished at me. I might find friends here and there, like you; but your people could never understand my nature, nor I theirs. I should be carried about as a spectacle; I should not belong to myself, but to those who exhibited me. There could be little sympathy between your people and mine. I might, too, be feared, be hated. Your climate, your food, your houses, your laws, your customs--every thing would be unlike what mine has been. I am too old, to weary of life, to begin it again in a new world."

So, my young readers, not to weary you with any more accounts of Huggermugger's sickness, I must end the matter, and tell you plainly that he died long before they reached America, much to Mr. Nabbum's vexation. Little Jacket and his friends grieved very much, but they could not help it, and thought that, on the whole, it was best it should be so. Zebedee Nabbum wished they could, at least, preserve the giant's body, and exhibit it in New York. But it was impossible. All they could take home with them was his huge skeleton; and even this, by some mischance, was said to be incomplete.

Some time after the giant's death, Mr. Scrawler, one day when the ship was becalmed, and the sailors wished to be amused, fell into a poetic frenzy, and produced the following song, which all hands sung, (rather slowly) when Mr. Nabbum was not present, to the tune of Yankee Doodle:--

Yankee Nabbum

went to sea

A huntin' after lions;

He came upon an island where

There was a pair of giants.

He brought his nets and big harpoon,

And thought he'd try to catch 'em;

But Nabbum found out very soon

There was no need to fetch 'em.

Yankee Nabbum went ashore,

With Jacky and some others;

But Huggermugger treated them

Just like his little brothers.

He took 'em up and put 'em in

His thunderin' big fish basket;--

He took 'em home and gave them all

they wanted, ere they asked it.

The giants were as sweet to them

As two great lumps of sugar,--

A very Queen of Candy was

Good Mrs. Huggermugger.

But, Ah! The good fat woman died,

The giant too departed,

And came himself on Nabbum's ship,

Quite sad and broken hearted.

He came aboard and sailed with us,

A sadder man and wiser--

But pretty soon, just like his wife,

He sickened and did die, Sir.

But Nabbum kept his mighty bones--

How they will stare to see 'em,

When Nabbum has them all set up

in Barnum's great Museum!

A huntin' after lions;

He came upon an island where

There was a pair of giants.

He brought his nets and big harpoon,

And thought he'd try to catch 'em;

But Nabbum found out very soon

There was no need to fetch 'em.

Yankee Nabbum went ashore,

With Jacky and some others;

But Huggermugger treated them

Just like his little brothers.

He took 'em up and put 'em in

His thunderin' big fish basket;--

He took 'em home and gave them all

they wanted, ere they asked it.

The giants were as sweet to them

As two great lumps of sugar,--

A very Queen of Candy was

Good Mrs. Huggermugger.

But, Ah! The good fat woman died,

The giant too departed,

And came himself on Nabbum's ship,

Quite sad and broken hearted.

He came aboard and sailed with us,

A sadder man and wiser--

But pretty soon, just like his wife,

He sickened and did die, Sir.

But Nabbum kept his mighty bones--

How they will stare to see 'em,

When Nabbum has them all set up

in Barnum's great Museum!

Nothing is dearly known, strange to say, as to what became of this skeleton. In the Museum, at Philadelphia, there are some great bones, which are usually supposed to be those of the Great Mastodon. It is the opinion, however, of others, that they are none other than those of the great Huggermugger--all that remains of the last of the giants.

NOTE:--I was told, several years hence, that Mr. Scrawler's narrative of his adventures in Huggermugger's Island, was nearly completed, and that he was only waiting for a publisher. As, however, nothing has as yet been heard of his long expected book, I have taken the liberty to print what I have written, from the story, as I heard it from Little Jacket himself, who is now grown to be a man. I have been told that Little Jacket, who is now called Mr. John Cable, has left the sea, and is now somewhere out in the Western States, settled down as a farmer, and has grown so large and fat, that he fears he must have eaten some of those strange shell-fish, by which the Huggermugger race grew to be so great. Other accounts, however, say that he is as fond of the sea as ever, and has got to be the captain of a great ship; and that he and Mr. Nabbum are still voyaging round the world, in hopes of finding other Huggermuggers.