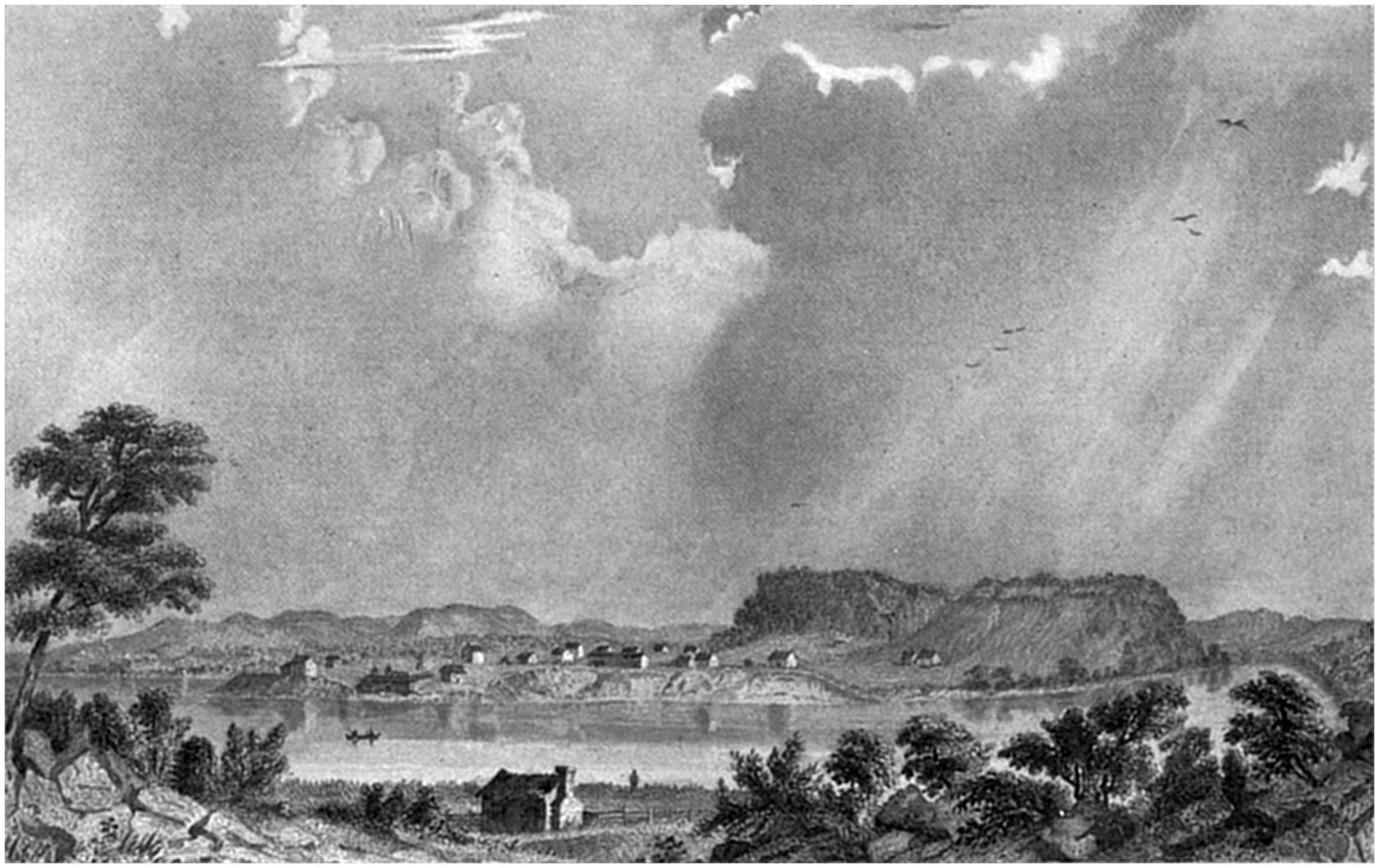

PITTSBURGH IN 1790

As sketched by Lewis Brantz

From Schoolcraft’s Indian Antiquities

PITTSBURGH

A SKETCH OF ITS EARLY

SOCIAL LIFE

BY

CHARLES W. DAHLINGER

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

1916

Copyright, 1916

BY

CHARLES W. DAHLINGER

The Knickerbocker Press, New York

v

To

B. McC. D.

PREFACE

The purpose of these pages is to describe the early social life of Pittsburgh. The civilization of Pittsburgh was crude and vigorous, withal prescient of future culture and refinement.

The place sprang into prominence after the conclusion of the French and Indian War, and upon the improvement of the military roads laid out over the Alleghany Mountains during that struggle. Pittsburgh was located on the main highway leading to the Mississippi Valley, and was the principal stopping place in the journey from the East to the Louisiana country. The story of its early social existence, interwoven as it is with contemporaneous national events, is of more than local interest.

C. W. D.

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania,

November, 1915.

vii

vi

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I.— | The Formative Period | 1 |

| II.— | A New County and a New Borough | 22 |

| III.— | The Melting Pot | 38 |

| IV.— | Life at the Beginning of the Nineteenth Century | 62 |

| V.— | The Seat of Power | 90 |

| VI.— | Public and Private Affairs | 114 |

| VII.— | A Duel and Other Matters | 138 |

| VIII.— | Zadok Cramer | 161 |

| IX.— | The Broadening of Culture | 184 |

| Index | 209 |

viii

1

Pittsburgh

CHAPTER I

THE FORMATIVE PERIOD

Until all fear of Indian troubles had ceased, there was practically no social life in American pioneer communities. As long as marauding bands of Indians appeared on the outskirts of the settlements, the laws were but a loose net with large meshes, thrown out from the longer-settled country whence they emanated. In the numerous interstices the laws were ineffective. In this Pittsburgh was no exception. The nominal reign of the law had been inaugurated among the settlers in Western Pennsylvania as far back as 1750, when the Western country was no man’s land, and the rival claims set up by France and England were being subjected to the arbitrament2 of the sword. In that year Cumberland County was formed. It was the sixth county in the province, and comprised all the territory west of the Susquehanna River, and north and west of York County—limitless in its westerly extent—between the province of New York on one side, and the colony of Virginia and the province of Maryland on the other. The first county seat was at Shippinsburg, but the next year, when Carlisle was laid out, that place became the seat of justice.

After the conclusion of the French and Indian War, and the establishment of English supremacy, a further attempt was made to govern Western Pennsylvania by lawful methods, and in 1771 Bedford County was formed out of Cumberland County. It included nearly all of the western half of the province. With Bedford, the new county seat, almost a hundred miles away, the law had little force in and about Pittsburgh. To bring the law nearer home, Westmoreland County was formed in 1773, from Bedford County, and embraced all of the province west of “Laurel Hill.” The county seat was at Hannastown, three miles northeast of the present borough of Greensburg.3 But with Virginia and Pennsylvania each claiming jurisdiction over the territory an uncertainty prevailed which caused more disregard for the law. The Revolutionary War came on, with its attendant Indian troubles; and in 1794 the western counties revolted against the national government on account of the imposition of an excise on whisky. It was only after the last uprising had been suppressed that the laws became effective and society entered upon the formative stage.

Culture is the leading element in the formation and progress of society, and is the result of mental activity. The most potent agency in the production of culture is education. While Pittsburgh was a frontier village, suffering from the turbulence of the French and Indian War, the uncertainty of the Revolution, and the chaos of the Whisky Insurrection, education remained at a standstill. The men who had blazed trails through the trackless forests, and buried themselves in the woods or along the uncharted rivers, could usually read and write, but there were no means of transmitting these boons to their children. The laws of the province made no provision for schools4 on its frontiers. In December, 1761, the inhabitants of Pittsburgh subscribed sixty pounds and engaged a schoolmaster for the term of a year to instruct their children. Similar attempts followed, but, like the first effort, ended in failure. There was not a newspaper in all the Western country; the only books were the Bible and the almanac. The almanac was the one form of secular literature with which frontier families were ordinarily familiar.

In 1764, while Pittsburgh was a trading post, the military authorities caused a plan of the village to be made by Colonel John Campbell. It consisted of four blocks, and was bounded by Water Street, Second Street, now Second Avenue, Market and Ferry Streets, and was intersected by Chancery Lane. The lots faced in the direction of Water Street. In this plan most of the houses were built.

At the outbreak of the Revolution, the proprietors of the province were the cousins, John Penn, Jr., and John Penn, both grandsons of William Penn, the founder of Pennsylvania. Being royalists, they had been divested of the title to all their5 lands in Pennsylvania, except to a few tracts which had been surveyed, called manors, one of them being “Pittsburgh,” in which was included the village of that name. In 1784 the Penns conceived the design of selling land in the village of Pittsburgh. The first sale was made in January, when an agreement to sell was entered into with Major Isaac Craig and Colonel Stephen Bayard, for about three acres, located “between Fort Pitt and the Allegheny River.” The Penns determined to lay out a town according to a plan of their own, and on April 22, 1784, Tench Francis, their agent, employed George Woods, an engineer living at Bedford, to do the work. The plan was completed in a few months, and included within its boundaries all the land in the triangle between the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, extending to Grant Street and Washington, now Eleventh, Street. Campbell’s plan was adopted unchanged; Tench Francis approved the new plan and began to sell lots. Major Craig and Colonel Bayard accepted, in lieu of the acreage purchased by them, a deed for thirty-two lots in this plan.

Until this time, the title of the occupants of6 lands included in the plan had been by sufferance only. The earlier Penns were reputed to have treated the Indians, the original proprietors of Pennsylvania, with consideration. In the same manner John Penn, Jr., and John Penn dealt with the persons who made improvements on the lands to which they had no title. They permitted the settlement on the assumption that the settlers would afterwards buy the land; and they gave them a preference. Also when litigation arose, caused by the schemes of land speculators intent on securing the fruits of the enterprise and industry of squatters on the Penn lots, the courts generally intervened in favor of the occupants.1 The sale was advertised near and far, and immigrants and speculators flocked into the village. They came from Eastern Pennsylvania, from Virginia, from Maryland, from New York, and from distant New England. The pack trains carrying merchandise and household effects into Pittsburgh became ever longer and more numerous.

Once that the tide of emigration had set in toward the West, it grew constantly in volume. The roads over the Alleghany Mountains were7 improved, and wheeled conveyances no longer attracted the curious attention that greeted Dr. Johann David Schoepf when he arrived in Pittsburgh in 1783, in the cariole in which he had crossed the mountains, an achievement which until then had not been considered possible.2 The monotonous hoof-beats of the pack horses became less frequent, and great covered wagons, drawn by four horses, harnessed two abreast, came rumbling into the village. But not all the people or all the goods remained in Pittsburgh. There were still other and newer Eldorados, farther away to the west and the south, and these lands of milk and honey were the Meccas of many of the adventurers. Pittsburgh was the depository of the merchandise sent out from Philadelphia and Baltimore, intended for the western and southern country and for the numerous settlements that were springing up along the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers.3 From Pittsburgh trading boats laden with merchandise were floated down the Ohio River, stopping at the towns on its banks to vend the articles which they carried.4 Coal was cheap and emigrant and trading boats carried8 it as ballast.5 In Pittsburgh the immigrants lingered, purchasing supplies, and gathering information about the country beyond. Some proceeded overland. Others sold the vehicles in which they had come, and continued the journey down the Ohio River, in Kentucky flat or family boats, in keel boats, arks, and barges. The construction and equipping of boats became an industry of moment in Pittsburgh.

The last menace from the Indians who owned and occupied the country north of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers was removed on October 21, 1784, when the treaty with the Six Nations was concluded at Fort Stanwix, by which all the Indian lands in Pennsylvania except a tract bordering on Lake Erie were ceded to the State. This vast territory was now opened for settlement, and resulted in more immigrants passing through Pittsburgh. The northerly boundary of the village ceased to be the border line of civilization. The isolation of the place became less pronounced. The immigrants who remained in Pittsburgh were generally of a sturdy class, and were young and energetic. Among them were former Revolutionary9 officers and soldiers. They engaged in trade, and as an adjunct of this business speculated in lands in the county, or bought and sold town lots. A few took up tavern keeping. From the brief notes left by Lewis Brantz who stopped over in Pittsburgh in 1785, while on a journey from Baltimore to the Western country, it appears that at this time Fort Pitt was still garrisoned by a small force of soldiers; that the inhabitants lived chiefly by traffic, and by entertaining travellers; and that there were but few mechanics in the village.6 The extent of the population can be conjectured, when it is known that in 1786 there were in Pittsburgh only thirty-six log buildings, one of stone, and one of frame; and that there were six stores.7

Religion was long dormant on the frontier. In 1761 and 1762, when the first school was in operation in Pittsburgh, the schoolmaster conducted religious services on Sundays to a small congregation. Although under the direction of a Presbyterian, the services consisted in reading the Prayers and the Litany from the Book of Common Prayer.8 During the military occupation, a chaplain10 was occasionally stationed at Fort Pitt around which the houses clustered. From time to time missionaries came and tarried a few days or weeks, and went their way again. The long intervals between the religious services were periods of indifference. An awakening came at last, and the religious teachings of early life reasserted themselves, and the settlers sought means to re-establish a spiritual life in their midst. The Germans and Swiss-Germans of the Protestant Evangelical and Protestant Reformed faiths jointly organized a German church in 1782; and the Presbyterians formed a church organization two years later.

The first pastor of the German church was the Rev. Johann Wilhelm Weber, who was sent out by the German Reformed Synod at Reading.9 He had left his charge in Eastern Pennsylvania because the congregation which he served had not been as enthusiastic in its support of the Revolution as he deemed proper.10 The services were held in a log building situated at what is now the corner of Wood Street and Diamond Alley.11 Besides ministering to the wants of the Pittsburgh church, there were three other congregations on11 Weber’s circuit, which extended fifty miles east of Pittsburgh. When he came West in September, 1782, the Revolutionary War was still in progress; Hannastown had been burned by the British and Indians in the preceding July; hostile Indians and white outlaws continually beset his path. He was a soldier of the Cross, but he was also ready to fight worldly battles. He went about the country armed not only with the Bible, but with a loaded rifle,12 and was prepared to battle with physical enemies, as well as with the devil.

Hardly had the churches come into existence when another organization was formed whose origin is claimed to be shrouded in the mists of antiquity. In the American history of the order, the membership included many of the greatest and best known men in the country. On December 27, 1785, the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania, Free and Accepted Masons, granted a charter to certain freemasons resident in Pittsburgh, which was designated as “Lodge No. 45 of Ancient York Masons.” It was not only the first masonic lodge in Pittsburgh, but the first in the Western country.1312 Almost from the beginning, Lodge No. 45 was the most influential social organization in the village. Nearly all the leading citizens were members. Toward the close of the eighteenth century the place of meeting was in the tavern of William Morrow, at the “Sign of the Green Tree,” on Water Street, two doors above Market Street.14 Although not a strictly religious organization, the order carefully observed certain Church holidays. St. John the Baptist’s day and St. John the Evangelist’s day were never allowed to pass without a celebration. Every year in June, on St. John the Baptist’s day, Lodge No. 45 met at 10 o’clock in the morning and, after the services in the lodge were over, paraded the streets. The members walked two abreast. Dressed in their best clothes, with cocked hats, long coats, knee-breeches, and buckled shoes, wearing the aprons of the craft, they marched “in ancient order.” The sword bearer was in advance; the officers wore embroidered collars, from which depended their emblems of office; the wardens carried their truncheons; the deacons, their staves. The Bible, surmounted by a compass and a square,13 on a velvet cushion, was borne along. When the Rev. Robert Steele came to preach in the Presbyterian Meeting House, the march was from the lodge room to the church. Here Mr. Steele preached a sermon to the brethren, after which they dined together at Thomas Ferree’s tavern at the “Sign of the Black Bear,”15 or at the “Sign of the Green Tree.”16 St. John the Evangelist’s day was observed with no less circumstance. In the morning the officers of the lodge were installed. Addresses of a semi-religious or philosophic character, eulogistic of masonry, were delivered by competent members or visitors. This ceremony was followed in the afternoon by a dinner either at some tavern or at the home of a member. Dinners seemed to be a concomitant part of all masonic ceremonies.

By the time that the last quarter of the eighteenth century was well under way, the hunters and trappers had left for more prolific hunting grounds. The Indian traders with their lax morals17 had disappeared forever in the direction of the setting sun, along with the Indians with whom they bartered. If any traders remained,14 they conformed to the precepts of a higher civilization. Only a scattered few of the red men continued to dwell in the hills surrounding the village, or along the rivers, eking out a scant livelihood by selling game in the town.18

A different moral atmosphere appeared: schools of a permanent character were established; the German church conducted a school which was taught by the pastor. Secular books were now in the households of the more intelligent; a few of the wealthier families had small libraries, and books were sold in the town. On August 26, 1786, Wilson and Wallace advertised “testaments, Bibles, spelling books, and primers” for sale.19 Copies of the Philadelphia and Baltimore newspapers were brought by travellers, and received by private arrangement.

In July, 1786, John Scull and Joseph Hall, two young men of more than ordinary daring, came from Philadelphia and established a weekly newspaper called the Pittsburgh Gazette, which was the first newspaper published in the country west of the Alleghany Mountains. The partnership lasted only a few months, Hall dying on November 10, 1786,15 at the early age of twenty-two years;20 and in the following month, John Boyd, also of Philadelphia, purchased Hall’s interest and became the partner of Scull.21 For many years money was scarcely seen in Pittsburgh in commercial transactions, everything being consummated in trade. A few months after its establishment, the Pittsburgh Gazette gave notice to all persons residing in the country that it would receive country produce in payment of subscriptions to the paper.22

The next year there were printed, and kept for sale at the office of the Pittsburgh Gazette, spelling books, and The A.B.C. with the Shorter Catechism, to which are Added Some Short and Easy Questions for Children; secular instruction was combined with religious.23 The Pittsburgh Gazette also conducted an emporium where other reading matter might be purchased. In the issue for June 16, 1787, an illuminating notice appeared: “At the printing office, Pittsburgh, may be had the laws of this State, passed between the thirtieth of September, 1775, and the Revolution; New Testaments; Dilworth’s Spelling Books; New England Primers, with Catechism; Westminster Shorter Catechism;16 Journey from Philadelphia to New York by Way of Burlington and South Amboy, by Robert Slenner, Stocking Weaver; ... also a few books for the learner of the French language.”

In November, 1787, there was announced as being in press at the office of the Pittsburgh Gazette the Pittsburgh Almanac or Western Ephemeris for 1788.24 The same year that the almanac appeared, John Boyd attempted the establishment of a circulating library. In his announcement on July 26th,25 he declared that the library would be opened as soon as a hundred subscribers were secured; and that it would consist of five hundred well chosen books. Subscriptions were to be received at the office of the Pittsburgh Gazette. Boyd committed suicide in the early part of August by hanging himself to a tree on the hill in the town, which has ever since borne his name, and Scull became the sole owner of the Pittsburgh Gazette. This act of self-destruction, and the fact that Boyd’s name as owner appeared in the Pittsburgh Gazette for the last time on August 2d, would indicate that the library was never established. Perhaps it was the anticipated failure of17 the enterprise that prompted Boyd to commit suicide.

The door to higher education was opened on February 28, 1787, when the Pittsburgh Academy was incorporated by an Act of the General Assembly. This was the germ which has since developed into the University of Pittsburgh. Another step which tended to the material and mental advancement of the place, was the inauguration of a movement for communicating regularly with the outside world. On September 30, 1786, a post route was established with Philadelphia,26 and the next year the general government entered into a contract for carrying the mails between Pittsburgh and that city.27 Almost immediately afterward a post office was established in Pittsburgh with Scull as postmaster, and a regular post between the village and Philadelphia and the East was opened on July 19, 1788.28 These events constituted another milestone in the progress of Pittsburgh.

Another instrument in the advancement of the infant community was the Mechanical Society which came into existence in 1788. On the twenty-second18 of March, the following unique advertisement appeared in the Pittsburgh Gazette: “Society was the primeval desire of our first and great ancestor Adam; the same order for that blessing seems to inhabit more or less the whole race. To encourage this it seems to be the earnest wish of a few of the mechanics in Pittsburgh, to have a general meeting on Monday the 24th inst., at six P.M., at the house of Andrew Watson, tavern keeper, to settle on a plan for a well regulated society for the purpose. This public method is taken to invite the reputable tradesmen of this place to be punctual to their assignation.”

Andrew Watson’s tavern was in the log building, at the northeast corner of Market and Front Streets. Front Street was afterward called First Street, and is now First Avenue. At that time all the highways running parallel with the Monongahela River were designated as streets, as they are now called avenues. The object of the Mechanical Society was the improvement of the condition of the workpeople, to induce workpeople to settle in the town, and to procure manufactories to be established there.

19

The society was more than local in character, similar societies being in existence in New York, Philadelphia, and in the neighboring village of Washington. At a later day the Mechanical Society of Pittsburgh produced plays, some of which were given in the grand-jury room in the upper story of the new court house. The society also had connected with it a circulating library, a cabinet of curiosities, and a chemical laboratory.

20

REFERENCES

Chapter I

1 James Fearnly v. Patrick Murphy, Addison’s Reports, Washington, 1800, p. 22; John Marie v. Samuel Semple, ibid., p. 215.

2 Johann David Schoepf. Reise durch einige der mittlern und südlichen vereinigten nordamerikanischen Staaten, Erlangen, 1788, vol. i., p. 370.

3 F. A. Michaux. Travels to the Westward of the Alleghany Mountains, London, 1805, p. 37.

4 Thaddeus Mason Harris. The Journal of a Tour, Boston, 1805, p. 42.

5 “A Sketch of Pittsburgh.” The Literary Magazine, Philadelphia, 1806, p. 253.

6 Lewis Brantz. “Memoranda of a Journey in the Westerly Parts of the United States of America in 1785.” In Henry R. Schoolcraft’s Indian Antiquities, Philadelphia, Part III., pp. 335–351.

7 Niles’ Weekly Register, Baltimore, August 19, 1826, vol. xxx., p. 436.

8 James Kenney. The Historical Magazine, New York, 1858, vol. ii., pp. 273–274.

9 Rev. Cyrus Cort, D.D. Historical Sermon in the First Reformed Church of Greensburgh, Pennsylvania, October 13, 1907, pp. 11–12.

10 Johann David Schoepf. Reise durch einige der mittlern und südlichen vereinigten nordamerikanischen Staaten, Erlangen, 1788, vol. i., p. 247.

11 Carl August Voss. Gedenkschrift zur Einhundertfuenfundzwanzig-jaehrigen Jubel-Feier, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1907, p. 14.

21

12 Rev. Cyrus Cort, D.D. Historical Sermon in the First Reformed Church of Greensburgh, Pennsylvania, October 13, 1907, p. 20.

13 Samuel Harper. “Seniority of Lodge No. 45,” History of Lodge No. 45, Free and Accepted Masons, 1785–1910, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, pp. 97–109.

14 Pittsburgh Gazette, June 15, 1799.

15 Tree of Liberty, June 6, 1801.

16 Tree of Liberty, June 12, 1802.

17 Diary of David McClure, New York, 1899, p. 53.

18 Perrin DuLac. Voyage dans les Deux Louisianes, Lyon, An xiii-(1805), p. 132.

19 Pittsburgh Gazette, August 26, 1786.

20 Pittsburgh Gazette, November 18, 1786.

21 Pittsburgh Gazette, January 6, 1787.

22 Pittsburgh Gazette, December 2, 1786.

23 Pittsburgh Gazette, May 5, 1787.

24 Pittsburgh Gazette, November 17, 1787.

25 Pittsburgh Gazette, July 26, 1788.

26 Pittsburgh Gazette, September 30, 1786.

27 Pittsburgh Gazette, March 24, 1787.

28 Pittsburgh Gazette, July 19, 1788.

22

CHAPTER II

A NEW COUNTY AND A NEW BOROUGH

The constantly rising tide of immigration required more territorial subdivisions in the western part of the State. Westmoreland County had been reduced in size on March 28, 1781, by the creation of Washington County, but was still inordinately large. The clamor of the inhabitants of Pittsburgh for a separate county was heeded at last, and on September 24, 1788, Allegheny County was formed out of Westmoreland and Washington Counties. To the new county was added on September 17, 1789, other territory taken from Washington County. In March, 1792, the State purchased from the United States the tract of land adjoining Lake Erie, consisting of two hundred and two thousand acres, which the national government had recently acquired23 from the Indians. This was added to Allegheny County on April 3, 1792. The county then extended northerly to the line of the State of New York, and the border of Lake Erie, and westerly to the present State of Ohio.29 On March 12, 1800, the county was reduced by the creation of Beaver, Butler, Mercer, Crawford, Erie, Warren, Venango, and Armstrong Counties, the area of these counties being practically all taken from Allegheny County. By Act of the General Assembly of March 12, 1803, a small part of Allegheny County was added to Indiana County, and Allegheny County was reduced to its present form and dimensions.30

On the formation of Allegheny County, Pittsburgh became the county seat. The county was divided into townships, Pittsburgh being located in Pitt Township. Embraced in Pitt Township was all the territory between the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, as far east as Turtle Creek on the Monongahela River, and Plum Creek on the Allegheny River, and all of the county north of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers. With the growth of prosperity in the county, petty offenses24 became more numerous, and a movement was begun for the erection of a jail in Pittsburgh.31

Next to the establishment of the Pittsburgh Gazette, the publication and sale of books, and the opening of the post route to the eastern country, the most important event in the early social advancement of Pittsburgh was the passage of an Act by the General Assembly, on April 22, 1794, incorporating the place into a borough. The township laws under which Pittsburgh had been administered were crude and intended only for agricultural and wild lands, and were inapplicable to the development of a town. Under the code of laws which it now obtained, it possessed functions suitable to the character which it assumed, and could perform acts leading to its material and social progress. It was given the power to open streets, to regulate and keep streets in order, to conduct markets, to abate nuisances, and to levy taxes.32

Before the incorporation of the borough, various steps had been taken in anticipation of that event. The Pittsburgh Fire Company was organized in 1793, with an engine house33 and a hand engine25 brought from Philadelphia. A new era in transportation was inaugurated on Monday, October 21, 1793, by the establishment of a packet line on the Ohio River, between Pittsburgh and Cincinnati, with boats “sailing” bi-weekly. The safety of the passengers from attacks by hostile Indians infesting the Ohio Valley, was assured. The boats were bullet-proof, and were armed with small cannon carrying pound balls; muskets and ammunition were provided, and from convenient portholes, passengers and crew could fire on the enemy.34

One of the first measures enacted after Pittsburgh was incorporated, was that to prohibit hogs running at large.35 The dissatisfaction occasioned by the imposition of the excise on whisky, had caused a spirit of lawlessness to spring up in the country about Pittsburgh. When this element appeared in the town, they were disposed, particularly when inflamed with whisky, to show their resentment toward the inhabitants, whom they regarded as being unfriendly to the Insurgent cause, by galloping armed through the streets, firing their pieces as they sped by, to the terror of26 the townspeople. This was now made an offense punishable by a fine of five shillings.36

Literary culture was hardly to be expected on the frontier, yet a gentleman resided in Pittsburgh who made some pretension in that direction. Hugh Henry Brackenridge was the leading lawyer of the town, and in addition to his other activities, was an author of note. Before coming to Pittsburgh he had, jointly with Philip Freneau, written a volume of poetry entitled, The Rising Glory of America, and had himself written a play called The Battle of Bunker Hill. While a resident in Pittsburgh he contributed many articles to the Pittsburgh Gazette. His title to literary fame, however, results mainly from the political satire that he wrote, which in its day created a sensation. It was called Modern Chivalry, and as originally published was a small affair. Only one of the four volumes into which it was divided was printed in Pittsburgh, the first, second, and fourth being published in Philadelphia. The third volume came out in Pittsburgh, in 1793, and was printed by Scull, and was the first book published west of the Alleghany Mountains. The27 work, as afterward rewritten and enlarged, ran through more than half a dozen editions.

The interest in books increased. In 1793, William Semple began selling “quarto pocket and school Bibles, spelling books, primers, dictionaries, English and Dutch almanacs, with an assortment of religious, historical, and novel books.”37 “Novel books” was no doubt meant to indicate novels. In 1798 the town became possessed of a store devoted exclusively to literature. It was conducted in a wing of the house owned and partially occupied by Brackenridge on Market Street.

John C. Gilkison had been a law student in Brackenridge’s office, and had tutored his son. Abandoning the idea of becoming a lawyer, he began with the aid of Brackenridge, to sell books as a business.38 In his announcement to the public his plans were outlined:39 “John C. Gilkison has just opened a small book and stationery store.... He has a variety of books for sale, school books especially, an assortment of which he means to increase, and keep up as encouragement may enable him; he has also some books of28 general instruction and amusement, which he will sell or lend out for a reasonable time, at a reasonable price.”

Changes were made in the lines of the townships at an early day. When the new century dawned, Pitt Township adjoined Pittsburgh on the east. East of Pitt Township and between the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers were the Townships of Plum, Versailles, and Elizabeth. On the south side of the Monongahela River, extending from the westerly line of the county to Chartiers Creek, was Moon Township. East of Chartiers Creek, and between that stream and Streets Run was St. Clair Township, and east of Streets Run, extending along the Monongahela River, was Mifflin Township, which ran to the county line. Back of Moon Township was Fayette Township. North of the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers were the Townships of Pine and Deer. They were almost equal in area, Pine being in the west, and Deer in the east, the dividing line being near the mouth of Pine Creek in the present borough of Etna.

The merchants and manufacturers of Pittsburgh had been accumulating money for a decade. In29 the East money was the medium of exchange, and it was brought to the village by immigrants and travelers, and began to circulate more freely than before. In addition to the money put into circulation by the immigrants, the United States Government had expended nearly eight hundred thousand dollars on the expedition which was sent out to suppress the Whisky Insurrection. At least half of this sum was spent in Pittsburgh and its immediate vicinity, partly for supplies and partly by the men composing the army. The expedition was also the means of advertising the Western country in the East, and created a new interest in the town. A considerable influx of new immigrants resulted. With the growth in population, the number of the mercantile establishments increased. Pittsburgh became more than ever the metropolis of the surrounding country.

Ferries made intercourse with the districts across the rivers from Pittsburgh easy, except perhaps in winter when ice was in the streams. Three ferries were in operation on the Monongahela River. That of Ephraim Jones at the30 foot of Liberty Street40 was called the Lower Ferry. A short distance above the mouth of Wood Street was Robert Henderson’s Ferry, formerly conducted by Jacob Bausman. This was known as the Middle Ferry. Isaac Gregg’s Ferry, at this time operated by Samuel Emmett,41 also called the Upper Ferry, was located a quarter of a mile above the town, at the head of the Sand Bar. Over the Allegheny River, connecting St. Clair Street with the Franklin Road, now Federal Street, was James Robinson’s Ferry. As an inducement to settle on the north side of the Allegheny River, Robinson advertised that “All persons going to and returning from sermon, and all funerals, ferriage free.”42

The aspect of the town was changing. It was no longer the village which Lewis Brantz saw on his visit in 1790, when he painted the sketch which is the first pictorial representation of the place extant.43 In the old Military Plan the ground was compactly built upon. Outside of this plan the houses were sparse and few in number, and cultivated grounds intervened. Thomas Chapman who visited Pittsburgh in31 1795, reported that out of the two hundred houses in the village, one hundred and fifty were built of logs.44 They were mainly of rough-hewn logs, only an occasional house being of sawed logs. The construction of log houses was discontinued, the new houses being generally frame. Houses of brick began to be erected, the brick sold at the dismantling of Fort Pitt supplying the first material for the purpose. The houses built of brick taken from Fort Pitt were characterized by the whiteness of the brick of which they were constructed.45 Brickyards were established. When Chapman was in Pittsburgh, there were two brickyards in operation in the vicinity of the town.46 With their advent brick houses increased rapidly.

With the evolution in the construction of the houses, came another advance conducive to both the health and comfort of the occupants. While window glass was being brought from the East, and was subject to the hazard of the long and rough haul over the Alleghany Mountains, the windows in the houses were few, and the panes of small dimensions; six inches in width by eight inches in length was an ordinary size. The32 interior of the houses was dark, cheerless, and damp. In the spring of 1797, Albert Gallatin, in conjunction with his brother-in-law, James W. Nicholson, and two Germans, Christian Kramer and Baltzer Kramer, who were experienced glass-blowers, began making window glass at a manufactory which they had established on the Monongahela River at New Geneva in Fayette County.47 The same year that window glass was first produced at New Geneva, Colonel James O’Hara and Major Isaac Craig commenced the construction of a glass manufactory on the south side of the Monongahela River, opposite Pittsburgh, and made their first window glass in 1800. Both manufactories produced window glass larger in size than that brought from the East, O’Hara and Craig’s glass measuring as high as eighteen by twenty-four inches.48 The price of the Western glass was lower than that brought across the mountains. With cheaper glass, windows became larger and more numerous, and a more cheerful atmosphere prevailed in the houses.

All that remained of Pittsburgh’s former military importance were the dry ditch and old ramparts33 of Fort Pitt,49 in the westerly extremity of the town, together with some of the barracks and the stone powder magazine, and Fort Fayette near the northeasterly limits, now used solely as a military storehouse.50 Not a trace of architectural beauty was evident in the houses. They were built without regularity and were low and plain. In one block were one- and two-story log and frame houses, some with their sides, others with their gable ends, facing the street. In the next square there was a brick building of two or possibly three stories in height; the rest of the area was covered with wooden buildings of every size and description. The Lombardy poplars and weeping willows which grew along the streets51 softened the aspect of the houses before which they were planted. The scattered houses on the sides of the hills which commanded the town on the east52 were more attractive.

It was forty years before houses, even on the leading streets, were numbered.53 The taverns and many of the stores, instead of being known by the number of their location on the street, or by the name of the owner, were recognized by their34 signs, which contained characteristic pictures or emblems. The signs were selected because associated with them was some well-known sentiment; or the picture represented a popular hero. In the latter category was the “Sign of General Washington,” conducted by Robert Campbell, at the northeast corner of Wood Street and Diamond Alley. Sometimes the signs were of a humorous character, as the “Whale and the Monkey” with the added doggerel:

displayed by D. McLane54 when he conducted the tavern on Water Street, afterward known as the “Sign of the Green Tree.” The sign was hung either on the front of the house, or on a board attached to a wooden or iron arm projecting from the building, or from a post standing before it. The last was the manner in which most of the tavern signs were displayed. This continued until 1816, when all projecting or hanging signs were prohibited, except to taverns where stabling and other35 accommodations for travelers could be obtained. Only taverns located at street corners were thereafter permitted to have signposts.55

Not a street was paved, not even the footwalks, except for such irregular slabs of stone, or brick, or planks as had been laid down by the owners of adjoining houses. Major Thomas S. Forman who passed through Pittsburgh in December, 1789, related that the town was the muddiest place he was ever in.56 In 1800, there was little improvement. Samuel Jones was the first Register and Recorder of Allegheny County, and held those offices almost continuously well into the nineteenth century. He resided in Pittsburgh during the entire period, and his opportunities for observation were unexcelled. His picture of the borough in 1800 is far from attractive. “The streets,” he wrote, were “filled with hogs, dogs, drays, and noisy children.”57 At night the streets were unlighted. “A solitary lamp twinkled here and there, over the door of a tavern, or on a signpost, whenever the moon was in its first or last quarter. The rest of the town was involved in primeval darkness.”

36

REFERENCES

Chapter II

29 Laura G. Sanford. The History of Erie County, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1862, p. 60.

30 Judge J. W. F. White. Allegheny County, its Early History and Subsequent Development, Pittsburgh, Pa., 1888, pp. 70–71.

31 Pittsburgh Gazette, December 14, 1793.

32 Act of April, 22, 1794; Act of September 12, 1782.

33 Pittsburgh Gazette, November 2, 1793.

34 Pittsburgh Gazette, November 23, 1793.

35 Pittsburgh Gazette, May 31, 1794.

36 Pittsburgh Gazette, June 21, 1794.

37 Pittsburgh Gazette, November 2, 1793; Ibid., June 28, 1794.

38 H. M. Brackenridge. Recollections of Persons and Places in the West, Philadelphia, 1868, pp. 44, 68.

39 Pittsburgh Gazette, December 29, 1798.

40 Neville B. Craig. The History of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, 1851, p. 295.

41 Pittsburgh Gazette, April 30, 1802; Ibid., April 16, 1802.

42 Pittsburgh Gazette, May 13, 1803.

43 Lewis Brantz. “Memoranda of a Journey in the Westerly Parts of the United States of America in 1785.” In Henry R. Schoolcraft’s Indian Antiquities, Philadelphia, Part III., pp. 335–351.

44 Thomas Chapman. “Journal of a Journey through the United States,” The Historical Magazine, Morrisania, N. Y., 1869, vol. v., p. 359.

45 The Navigator for 1808, Pittsburgh, 1808, p. 33.

46 Thomas Chapman. “Journal of a Journey through the United States,” The Historical Magazine, Morrisania, N. Y., 1869, vol. v., p. 359.

37

47 Sherman Day. Historical Collections of the State of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, p. 345; Rev. William Hanna: History of Green County, Pa., 1882, pp. 247, 248.

48 Pittsburgh Gazette, February 1, 1800.

49 F. Cuming. Sketches of a Tour to the Western Country, in 1807–1809, Pittsburgh, 1810, p. 225.

50 The Navigator for 1808, Pittsburgh, 1808, p. 33.

51 F. Cuming. Sketches of a Tour to the Western Country, in 1807–1809, Pittsburgh, 1810, p. 226.

52 F. A. Michaux. Travels to the Westward of the Alleghany Mountains, London, 1805, p. 30.

53 Harris’s Pittsburgh and Allegheny Directory, for 1839, p. 3; ibid., for 1841.

54 Pittsburgh Gazette, May 3, 1794.

55 Ordinance City of Pittsburgh, September 7, 1816, Pittsburgh Digest, 1849, p. 238.

56 Major Samuel S. Forman. “Autobiography,” The Historical Magazine, Morrisania, N. Y., 1869, vol. vi., PP. 324–325.

57 S. Jones. Pittsburgh in the Year 1826, Pittsburgh, 1826, pp. 39–41.

38

CHAPTER III

THE MELTING POT

The population of Pittsburgh was composed of various nationalities; those speaking the English language predominated. In addition to the Germans and Swiss-Germans, there were French and a few Italians. The majority of the English-speaking inhabitants were of Irish or Scotch birth, or immediate extraction. Of those born in Ireland or Scotland, some were old residents—so considered if they had lived in Pittsburgh for ten years or more—while others were recent immigrants. The Germans and French had come as early as the Irish and Scotch. The Italians were later arrivals. There was also a sprinkling of Welsh. The place contained a number of negroes, nearly all of whom were slaves, there being in 1800 sixty-four negro slaves in39 Allegheny County,58 most of whom were in Pittsburgh and the immediate vicinity. A majority of the negroes had been brought into the village in the early days by emigrants from Virginia and Maryland. Their number was gradually decreasing. By Act of the General Assembly of March 1, 1780, all negroes and mulattoes born after that date, of slave mothers, became free upon arriving at the age of twenty-eight years. Then on March 29, 1788, it was enacted that any slaves brought into the State by persons resident thereof, or intending to become such, should immediately be free.59 Also public sentiment was growing hostile to the institution of negro slavery. The few free negroes in Pittsburgh were engaged in menial occupations, and the name of only one, whose vocation was somewhat higher, has been handed down to the present time. This was Charles Richards, commonly called “Black Charley,” who conducted an inn in the log house, at the northwest corner of Second and Ferry Streets.

Among themselves the Germans and the French spoke the language of their fathers, but in their intercourse with their English-speaking neighbors40 they used English. The language of the street varied from the English of New England and Virginia, to the brogue of the Irish and Scotch, or the broken enunciation of the newer Germans and French. Being in a majority the English-speaking population controlled to a considerable extent the destinies of the community. Their manufactories were the most extensive, the merchandise in their stores was in greater variety, and the stocks larger than those carried in other establishments.

Next in numbers to those whose native language was English, were the German-speaking inhabitants. They constituted the skilled mechanics; some were merchants, and many were engaged in farming in the neighboring townships. They were all more or less closely connected with the German church. Only the names of their leading men have survived the obliterating ravages of time. Among the mechanics of the higher class were Jacob Haymaker, William Eichbaum, and John Hamsher. The first was a boatbuilder, whose boatyard was located on the south side of the Monongahela River at the Middle Ferry;41 Eichbaum was employed by O’Hara and Craig in the construction and operation of their glass works. John Hamsher was a coppersmith and tin-worker, whose diversion was to serve in the militia, in which he was captain.60

Conrad Winebiddle, Jonas Roup, Alexander Negley, and his son, Jacob Negley, were well-to-do farmers in Pitt Township. Winebiddle was a large holder of real estate, who died in 1795, and enjoyed the unique distinction of being the only German who ever owned negro slaves in Allegheny County. Nicholas Bausman and Melchoir Beltzhoover were farmers in St. Clair Township; and Casper Reel was a farmer and trapper in Pine Township, where he was also tax collector. Samuel Ewalt kept a tavern in Pittsburgh in 1775, and was afterward a merchant. He was Sheriff of Allegheny County during the dark days of the Whisky Insurrection, and later was inspector of the Allegheny County brigade of militia. He was several times a member of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives. William Wusthoff was Sheriff of Allegheny County in 1801. Jacob Bausman had a varied career. He was a resident of Pittsburgh42 as far back as 1771, and was perhaps the most prominent German in the place. As a young man he was an ensign in the Virginia militia, during the Virginia contention. He established the first ferry on the Monongahela River, which ran to his house on the south side of the stream, where the southern terminus of the Smithfield Street bridge is now located. The right to operate the ferry was granted to him by the Virginia Court on February 23, 1775, and was confirmed by the General Assembly of Pennsylvania ten years later. At his ferry house he also conducted a tavern. His energies were not confined to his private affairs. Under the Act of the General Assembly incorporating Allegheny County, he was named as one of the trustees to select land for a court house in the tract reserved by the State, in Pine Township, and was again, under the Act of April 13, 1791, made a trustee to purchase land in Pittsburgh for the same purpose. He was treasurer of the German church and, jointly with Jacob Haymaker, was trustee, on the part of the church, of the land deeded by the Penns to that congregation for church purposes at the northeast43 corner of Smithfield and Sixth Streets, where the congregation’s second and all subsequent churches were built. Michael Hufnagle was a member of the Allegheny County Bar, being one of the first ten men to be admitted to practice, upon the organization of the county. He was the only lawyer of German nationality in the county. He had been a captain in the Revolution, and prothonotary of Westmoreland County. On July 13, 1782, when the Indians and Tories attacked Hannastown, he occupied a farm situated a mile and a half north of that place, which has ever since been known in frontier history as the place where the townsfolk were harvesting when the attack began.61

By their English-speaking neighbors the Germans were generally designated as “Dutch.” In the references to them in the Pittsburgh Gazette and other early publications, they were likewise called “Dutch.” Books printed in the German language were advertised as “Dutch” books. The custom of speaking of the Germans as “Dutch” was however not confined to Pittsburgh, but was universal in America. The Dutch inhabitants44 of New York and elsewhere, were the first settlers in the colonies, whose language was other than English. The bulk of the English-speaking population, wholly ignorant of any language except their own, were easily led into the error of confusing the newer German immigrants with the Dutch, the only persons speaking a foreign tongue with whom they had come in contact. Nor were the uneducated classes the only transgressors in this respect. The Rev. Dr. William Smith, the scholarly Provost of the College of Philadelphia, writing during the French and Indian War, spoke of the Germans as “the Dutch or Germans.”62 Also “Dutch” bears a close resemblance to “Deutsch,” the German name for people of the German race, which may account, to some extent, for the misuse of the word.

The Germans were in Pittsburgh to stay. Their efforts were directed largely toward private ends. When men of other blood made records in public life, the Germans made theirs in the limited sphere of their own employment or enterprises. Owing to their inability to speak the English language, their position was more isolated45 than that of the greenest English-speaking immigrant in the village. That they were clannish was a natural consequence. This disposition was accentuated when a newspaper printed in the German language was established on November 22, 1800, in the neighboring borough of Greensburgh, entitled The German Farmers’ Register, being the first German paper published in the Western country. Subscriptions were received in Pittsburgh at the office of the Tree of Liberty,63 then recently established, and the effort to acquire a knowledge of English in order to be able to read the news of the day in the Pittsburgh newspapers, was for the time being largely abandoned. As the Germans learned to speak and read English, their social intercourse was no longer restricted to persons of their own nationality. With the next generation, intermarriages with persons of other descent took place. The German language ceased to be cultivated; they forsook the German church for one where English was the prevailing language. It is doubtful if a single descendant of the old Germans is now able to speak the language of his forbears unless it was learned at school, or that46 he is a member of or attends the services of the German church.

The French element was an almost negligible quantity, yet it exerted an influence far beyond what might be expected when its numbers are considered. So strong was the tide of public opinion in favor of all things French, occasioned by the events of the French Revolution, that Albert Gallatin, a French-Swiss, who had just been naturalized, and still spoke English with a decided foreign accent, attained high political honors. To the people he was essentially a Frenchman, and in 1794, he was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, from Fayette County where he lived. At the same time he was elected to Congress from the district consisting of Allegheny and Washington Counties; and was twice re-elected from the same district, which included Greene County after the separation from Washington County in 1796, and its erection into a separate county. It was while serving this constituency that Gallatin developed those powers in finance and statesmanship which caused his appointment as Secretary of the Treasury by President Jefferson,47 and by Jefferson’s successor, President Madison. From the politicians of this Congressional District, Gallatin learned those lessons in diplomacy which enabled him, while joint commissioner of the United States, to secure the signature of England to the Treaty of Ghent, by which the War of 1812 was brought to a close, and which led to his becoming United States Minister to France and to England. The training of those early days finally made him the most famous of all Americans of European birth, and brought about his nomination for Vice-President by the Congressional caucus of the Republican party, an honor which he first accepted, but later declined.64

Another prominent Frenchman was John B. C. Lucus. In 1796, he lived on a farm on Coal Hill on the south side of the Monongahela River, in St. Clair Township, five miles above Pittsburgh. It was said of him that he was an atheist and that his wife plowed on Sundays, in spite of which he was several times elected to the General Assembly.65 In 1800, he was appointed an associate judge for the county. He quarrelled with Alexander Addison, the president judge of the judicial district to48 which Allegheny County was attached, yet he had sufficient standing in the State to cause Judge Addison’s impeachment and removal from the Bench. In 1802, Lucus was elected to Congress and was re-elected in 1804. In 1805, he was appointed United States District Judge for the new Territory of Louisiana, now the State of Missouri.

Dr. Felix Brunot arrived in Pittsburgh in 1797. He came from France with Lafayette and was a surgeon in the Revolutionary War and fought in many of its battles. His office was located on Liberty Street, although he owned and lived on Brunot Island. An émigré, the Chevalier Dubac, was a merchant.66 Dr. F. A. Michaux, the French naturalist and traveler, related of Dubac:67 “I frequently saw M. Le Chevalier Dubac, an old French officer who, compelled by the events of the Revolution to quit France, settled in Pittsburgh where he engaged in commerce. He possesses very correct knowledge of the Western country, and is perfectly acquainted with the navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, having made several voyages to New Orleans.” Morgan Neville a son of Colonel Presley Neville, and a writer49 of acknowledged ability, drew a charming picture of Dubac’s life in Pittsburgh.68

Perhaps the best known Frenchman in Pittsburgh was John Marie, the proprietor of the tavern on Grant’s Hill. Grant’s Hill was the eminence which adjoined the town on the east, the ascent to the hill beginning a short distance west of Grant Street. The tavern was located just outside of the borough limits, at the northeast corner of Grant Street and the Braddocksfield Road, where it connected with Fourth Street. The inclosure contained more than six acres, and was called after the place of its location, “Grant’s Hill.” It overlooked Pittsburgh, and its graveled walks and cultivated grounds were the resort of the townspeople. For many years it was the leading tavern. Gallatin, who was in Pittsburgh, in 1787, while on the way from New Geneva to Maine, noted in his diary that he passed Christmas Day at Marie’s house, in company with Brackenridge and Peter Audrian,69 a well-known French merchant on Water Street. Marie’s French nationality naturally led him to become a Republican when the party was formed, and his tavern was50 long the headquarters of that party. Numerous Republican plans for defeating their opponents originated in Marie’s house, and many Republican victories were celebrated in his rooms. Also in this tavern the general meetings of the militia officers were held.70 Michaux has testified that Marie kept a good inn.71 The present court house, the combination court house and city hall now being erected, and a small part of the South School, the first public school in Pittsburgh, occupy the larger portion of the site of “Grant’s Hill.”

Marie’s name became well known over the State, several years after he retired to private life. He was seventy-five years of age in 1802, when he discontinued tavern-keeping and sold “Grant’s Hill” to James Ross, United States Senator from Pennsylvania, who was a resident of Pittsburgh. Marie had been estranged from his wife for a number of years and by some means she obtained possession of “Grant’s Hill,” of which Ross had difficulty in dispossessing her. In 1808, Ross was a candidate for governor against Simon Snyder. Ross’s difference with Mrs. Marie, whose husband had by this time divorced her, came to the51 knowledge of William Duane in Philadelphia, the brilliant but unscrupulous editor of the Aurora since the discontinuance of the National Gazette, in 1793, the leading radical Republican newspaper in the country. The report was enlarged into a scandal of great proportions both in the Aurora and in a pamphlet prepared by Duane and circulated principally in Philadelphia. The title of the pamphlet was harrowing. It was called “The Case of Jane Marie, Exhibiting the Cruelty and Barbarous Conduct of James Ross to a Defenceless Woman, Written and Published by the Object of his Cruelty and Vengeance.” Although Marie was opposed to Ross politically, he defended his conduct toward Mrs. Marie as being perfectly honorable. Nevertheless, the pamphlet played an important part in obtaining for Snyder the majority of twenty-four thousand by which he defeated Ross.

Notwithstanding the high positions which some of the Frenchmen attained, they left no permanent impression in Pittsburgh. After prospering there for a few years, they went away and no descendants of theirs reside in the city unless it be some of the descendants of Dr. Brunot.52 Some went south to the Louisiana country, and others returned to France. Gallatin, himself, long after he had shaken the dust of Western Pennsylvania from his feet, writing about his grandson, the son of his son James, said: “He is the only young male of my name, and I have hesitated whether, with a view to his happiness, I had not better take him to live and die quietly at Geneva, rather than to leave him to struggle in this most energetic country, where the strong in mind and character overset everybody else, and where consideration and respectability are not at all in proportion to virtue and modest merit.”72 And the grandson went to Geneva to live, and his children were born there and he died there.73

The United States Government was still in the formative stage. Until this time the men who had fought the Revolutionary War to a successful conclusion, held a tight rein on the governmental machinery. Now a new element was growing up, and, becoming dissatisfied with existing conditions, organized for a conflict with the men in power. The rise of the opposition to the Federal party was also the outcome of existing social conditions. Like53 the modern cry against consolidated wealth, the movement was a contest by the discontented elements in the population, of the men who had little against those who had more. Abuses committed by individuals and conditions common to new countries were magnified into errors of government. Also the people were influenced by the radicalism superinduced by the French Revolution and the subsequent happenings in France. “Liberty, fraternity, and equality” were enticing catchwords in the United States.

Thomas Jefferson, on his return from France, in 1789, after an absence of six years, where he had served as United States Minister, during the development of French radicalism, came home much strengthened in his ideas of liberty. They were in strong contrast with the more conservative notions of government entertained by Washington, Vice-President Adams, Hamilton, and the other members of the Cabinet. In March, 1790, Jefferson became Secretary of State in Washington’s first Cabinet, the appointment being held open for him since April 13th of the preceding year, when Washington entered on the duties of54 the Presidency. Jefferson’s views being made public, he immediately became the deity of the radical element. At the close of 1793, the dissensions in the Cabinet had become so acute that on December 31st Jefferson resigned in order to be better able to lead the new party which was being formed. By this element the Federalists were termed “aristocrats,” and “tories.” They were charged with being traitors to their country, and were accused of being in league with England, and to be plotting for the establishment of a monarchy, and an aristocracy. The opposition party assumed the title of “Republican.” Later the word “Democratic” was prefixed and the party was called “Democratic Republican,”74 although in Pittsburgh for many years the words “Republican,” “Democratic Republican,” and “Democratic” were used interchangeably.

Heretofore Pennsylvania had been staunchly Federal. On the organization of the Republican party, Governor Thomas Mifflin, and Chief Justice Thomas McKean of the Supreme Court, the two most popular men in the State, left the Federal party and became Republicans. There was also55 a cause peculiar to Pennsylvania, for the rapid growth of the Republican party in the State. The constant increase in the backwoods population consisted largely of emigrants from Europe, chiefly from Ireland, who brought with them a bitter hatred of England and an intense admiration for France. They went almost solidly into the Republican camp. The arguments of the Republicans had a French revolutionary coloring mingled with which were complaints caused by failure to realize expected conditions. An address published in the organ of the Republican party in Pittsburgh is a fair example of the reasoning employed in advocacy of the Republican candidates: “Albert Gallatin, the friend of the people, the enemy of tyrants, is to be supported on Tuesday, the 14th of October next, for the Congress of the United States. Fellow citizens, ye who are opposed to speculators, land jobbers, public plunderers, high taxes, eight per cent. loans, and standing armies, vote for Mr. Gallatin!”75

In Pittsburgh the leader of the Republicans was Hugh Henry Brackenridge, the lawyer and dilettante in literature. In the fierce invective of the56 time, he and all the members of his party were styled by their opponents “Jacobins,” after the revolutionary Jacobin Club of France, to which all the woes of the Terror were attributed. The Pittsburgh Gazette referred to Brackenridge as “Citizen Brackenridge,” and after the establishment of the Tree of Liberty, added “Jacobin printer of the Tree of Sedition, Blasphemy, and Slander.”76 But the Republicans gloried in titles borrowed from the French Revolution. The same year that Governor Mifflin and Chief Justice McKean went over to the Republicans, Brackenridge made a Fourth of July address in Pittsburgh, in which he advocated closer relations with France. This was republished in New York by the Republicans, in a pamphlet, along with a speech made by Maximilien Robespierre in the National Convention of France. In this pamphlet Brackenridge was styled “Citizen Brackenridge.”77 The Pittsburgh Gazette and the Tree of Liberty, contained numerous references to meetings and conferences held at the tavern of “Citizen” Marie. On March 4, 1802, the first anniversary of the inauguration of Jefferson as President, a dinner was given by the57 leading Republicans in the tavern of “Citizen” Jeremiah Sturgeon, at the “Sign of the Cross Keys,” at the northwest corner of Wood Street and Diamond Alley, at which toasts were drunk to “Citizen” Thomas Jefferson, “Citizen” Aaron Burr, “Citizen” James Madison, “Citizen” Albert Gallatin, and “Citizen” Thomas McKean.78

In 1799, the Republicans had as their candidate for governor Chief Justice McKean. Opposed to him was Senator James Ross. Ross was required to maintain a defensive campaign. The fact that he was a Federalist was alone sufficient to condemn him in the eyes of many of the electors. He was accused of being a follower of Thomas Paine, and was charged with “singing psalms over a card table.” It was said that he had “mimicked” the Rev. Dr. John McMillan, the pioneer preacher of Presbyterianism in Western Pennsylvania, and a politician of no mean influence; that he had “mocked” the Rev. Matthew Henderson, a prominent minister of the Associate Presbyterian Church.79 Although Allegheny County gave Ross a majority of over eleven hundred votes, he was defeated in the State by58 more than seventy-nine hundred.80 McKean took office on December 17, 1799,81 and the next day he appointed Brackenridge a justice of the Supreme Court. All but one or two of the county offices were filled by appointment of the governor, who could remove the holders at pleasure. The idea of public offices being public trusts had not been formulated. The doctrine afterward attributed to Andrew Jackson, that “to the victors belong the spoils of office,” was already a dearly cherished principle of the Republicans, and Judge Brackenridge was not an exception to his party. Hardly had he taken his seat on the Supreme Bench, when he induced Governor McKean to remove from office the Federalist prothonotary, James Brison, who had held the position since September 26, 1788, two days after the organization of the county.

Brison was very popular. As a young man, he had lived at Hannastown, and during the attack of the British and Indians on the place had been one of the men sent on the dangerous errand of reconnoitering the enemy.82 He was now captain of the Pittsburgh Troop of Light Dragoons, the crack company in the Allegheny County brigade59 of militia, and was Secretary of the Board of Trustees of the Academy. He was a society leader and generally managed the larger social functions of the town. General Henry Lee, the Governor of Virginia, famous in the annals of the Revolutionary War, as “Light-Horse Harry Lee,” commanded the expedition sent by President Washington to suppress the Whisky Insurrection, and was in Pittsburgh several weeks during that memorable campaign. On the eve of his departure a ball was given in his honor by the citizens. On that occasion Brison was master of ceremonies. A few months earlier Brackenridge had termed him “a puppy and a coxcomb.” Brackenridge credited Brison with retaliating for the epithet, by neglecting to provide his wife and himself with an invitation to the ball. This was an additional cause for his dismissal, and toward the close of January the office was given to John C. Gilkison. Gilkison who was a relative of Brackenridge, conducted the bookstore and library which he had opened the year before, and also followed the occupation of scrivener, preparing such legal papers as were demanded of him.83

60

REFERENCES

Chapter III

58 Pittsburgh Gazette, January 23, 1801.

59 Collinson Read. An Abridgment of the Laws of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, MDCCCI, pp. 264–269.

60 Pittsburgh Gazette, December 7, 1799.

61 Neville B. Craig. The Olden Time, Pittsburgh, 1848, vol. ii., pp. 354–355.

62 A Brief State of the Province of Pennsylvania, London, 1755, p. 12.

63 Tree of Liberty, December 27, 1800.

64 John Austin Stevens. Albert Gallatin, Boston, 1895, p. 370.

65 Major Ebenezer Denny. Military Journal, Philadelphia, 1859, p. 21.

66 Pittsburgh Gazette, October 23, 1801.

67 Dr. F. A. Michaux. Travels to the Westward of the Alleghany Mountains in the Year 1802, London, 1805, p. 36.

68 Morgan Neville. In John F. Watson’s Annals of Philadelphia and Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1891, vol. ii., pp. 132–135.

69 Henry Adams. The Life of Albert Gallatin, Philadelphia, 1880, p. 68.

70 Tree of Liberty, November 7, 1800; Pittsburgh Gazette, February 20, 1801.

71 Dr. F. A. Michaux. Travels to the Westward of the Alleghany Mountains in the Year 1802, London, 1805, p. 29.

72 Henry Adams. The Life of Albert Gallatin, Philadelphia, 1880, p. 650.

73 Count De Gallatin. “A Diary of James Gallatin in Europe”; Scribner’s Magazine, New York, vol. lvi., September, 1914, pp. 350–351.

61

74 Richard Hildreth. The History of the United States of America, New York, vol. iv., p. 425.

75 Tree of Liberty, September 27, 1800.

76 Pittsburgh Gazette, February 6, 1801.

77 Political Miscellany, New York, 1793, pp. 27–31.

78 Tree of Liberty, March 13, 1802.

79 Tree of Liberty, September 19, 1801.

80 Pittsburgh Gazette, October 26, 1799.

81 William C. Armor. Lives of the Governors of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, 1873, p. 289.

82 Neville B. Craig. The Olden Time, Pittsburgh, 1848, vol. ii., p. 355.

83 H. M. Brackenridge. Recollections of Persons and Places in the West, Philadelphia, 1868, p. 68; Pittsburgh Gazette, December 29, 1798.

62

CHAPTER IV

LIFE AT THE BEGINNING OF THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The Pittsburgh Gazette was devoted to the interests of the Federal party, and Brackenridge and the other leading Republicans felt the need of a newspaper of their own. The result was the establishment on August 16, 1800, of the Tree of Liberty, by John Israel, who was already publishing a newspaper, called the Herald of Liberty, in Washington, Pennsylvania. The title of the new paper was intended to typify its high mission. The significance of the name was further indicated in the conspicuously displayed motto, “And the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.” The Federalists, and more especially their organ, the Pittsburgh Gazette,84 charged Brackenridge with being the owner of63 the new paper, and with being responsible for its utterances. Brackenridge, however, has left a letter in which he refuted this statement, and alleged that originally he intended to establish a newspaper, but on hearing of Israel’s intention gave up the idea.85

The extent of the comforts and luxuries enjoyed in Pittsburgh was surprising. The houses, whether built of logs, or frame, or brick, were comfortable, even in winter. In the kitchens were large open fire-places, where wood was burned. The best coal fuel was plentiful. Although stoves were invented barely half a century earlier, and were in general use only in the larger cities, the houses in Pittsburgh could already boast of many. There were cannon stoves, so called because of their upright cylindrical, cannon-like shape, and Franklin or open stoves, invented by Benjamin Franklin; the latter graced the parlor. Grates were giving out their cheerful blaze. They were also in use in some of the rooms of the new court house, and in the new jail.

The advertisements of the merchants told the story of what the people ate and drank, and of the64 materials of which their clothing was made. Articles of food were in great variety. In the stores were tea, coffee, red and sugar almonds, olives, chocolate, spices of all kinds, muscatel and keg raisins, dried peas, and a score of other luxuries, besides the ordinary articles of consumption. The gentry of England, as pictured in the pages of the old romances, did not have a greater variety of liquors to drink. There were Madeira, sherry, claret, Lisbon, port, and Teneriffe wines, French and Spanish brandies,86 Jamaica and antique spirits.87 Perrin DuLac, who visited Pittsburgh in 1802, said these liquors were the only articles sold in the town that were dear.88 But not all partook of the luxuries. Bread and meat, and such vegetables as were grown in the neighborhood, constituted the staple articles of food, and homemade whisky was the ordinary drink of the majority of the population. The native fruits were apples and pears, which had been successfully propagated since the early days of the English occupation.89

Materials for men’s and women’s clothing were endless in variety and design and consisted of65 cloths, serges, flannels, brocades, jeans, fustians, Irish linens, cambrics, lawns, nankeens, ginghams, muslins, calicos, and chintzes. Other articles were tamboured petticoats, tamboured cravats, silk and cotton shawls, wreaths and plumes, sunshades and parasols, black silk netting gloves, white and salmon-colored long and short gloves, kid and morocco shoes and slippers, men’s beaver, tanned, and silk gloves, men’s cotton and thread caps, and silk and cotton hose.

Men were changing their dress along with their political opinions. One of the consequences in the United States of the French Revolution was to cause the effeminate and luxurious dress in general use to give way to simpler and less extravagant attire. The rise of the Republican party and the class distinctions which it was responsible for engendering, more than any other reason, caused the men of affairs—the merchants, the manufacturers, the lawyers, the physicians, and the clergymen—to discard the old fashions and adopt new ones. Cocked hats gave way to soft or stiff hats, with low square crowns and straight brims. The fashionable hats were the beaver66 made of the fur of the beaver, the castor made of silk in imitation of the beaver, and the roram made of felt, with a facing of beaver fur felted in. Coats of blue, green, and buff, and waistcoats of crimson, white, or yellow, were superseded by garments of soberer colors. Coats continued to be as long as ever, but the tails were cut away in front. Knee-breeches were succeeded by tight-fitting trousers reaching to the ankles; low-buckled shoes, by high-laced leather shoes, or boots. Men discontinued wearing cues, and their hair was cut short, and evenly around the head. There were of course exceptions. Many men of conservative temperament still clung to the old fashions. A notable example in Pittsburgh was the Rev. Robert Steele, who always appeared in black satin knee-breeches, knee-buckles, silk stockings, and pumps.90

The farmers on the plantations surrounding Pittsburgh and the mechanics in the borough were likewise affected by the movement for dress reform. Their apparel had always been less picturesque than that of the business and professional men. Now the ordinary dress of the farmers and mechanics consisted of short tight-fitting round-abouts,67 or sailor’s jackets, made in winter of cloth or linsey, and in summer of nankeen, dimity, gingham, or linen. Sometimes the jacket was without sleeves, the shirt being heavy enough to afford protection against inclement weather. The trousers were loose-fitting and long, and extended to the ankles, and were made of nankeen, tow, or cloth. Some men wore blanket-coats. Overalls, of dimity, nankeen, and cotton, were the especial badge of mechanics. The shirt was of tow or coarse linen, the vest of dimity. On their feet, farmers and mechanics alike wore coarse high-laced shoes, half-boots, or boots made of neat’s leather. The hats were soft, of fur or wool, and were low and round-crowned, or the crowns were high and square.

The inhabitants of Pittsburgh were pleasure-loving, and the time not devoted to business was given over to the enjoyments of life. Men and women alike played cards. Whisk, as whist was called, and Boston were the ordinary games.91 All classes and nationalities danced, and dancing was cultivated as an art. Dancing masters came to Pittsburgh to give instructions, and adults and68 children alike took lessons. In winter public balls and private assemblies were given. The dances were more pleasing to the senses than any ever seen in Pittsburgh, except the dances of the recent revival of the art. The cotillion was executed by an indefinite number of couples, who performed evolutions or figures as in the modern german. Other dances were the minuet, the menuet à la cour, and jigs. The country dance, generally performed by eight persons, four men and four women, comprised a variety of steps, and a surprising number of evolutions, of which liveliness was the characteristic.

The taverns had rooms set apart for dances. The “Sign of the Green Tree,”92 had an “Assembly Room”; the “Sign of General Butler”93 and the “Sign of the Waggon”94 each had a “Ball Room.” The small affairs were given in the homes of the host or hostess, and the large ones in the taverns, or in the grand-jury room of the new court house.

The dancing masters gave “Practicing Balls” at which the cotillion began at seven o’clock, and the ball concluded with the country dance, which was continued until twelve o’clock.95 Dancing69 became so popular and to such an extent were dancing masters in the eyes of the public that William Irwin christened his race horse “Dancing Master.”96 The ball given to General Lee was talked about for years after the occurrence. Its beauties were pictured by many fair lips. The ladies recalled the soldierly bearing of the guest of honor, the tall robust form of General Daniel Morgan, Lee’s second in command, and the commander of the Virginia troops, famous as the hero of Quebec and Saratoga, who had received the thanks of Congress for his victory at Cowpens. They dwelt on the varicolored uniforms of the soldiers, the bright colors worn by the civilians, their powdered hair, the brocades, and silks, and velvets of the ladies.

In winter evenings there were concerts and theatrical performances which were generally given in the new court house. A unique concert was that promoted by Peter Declary. It was heralded as a musical event of importance. Kotzwara’s The Battle of Prague, was performed on the “forte piano” by one of Declary’s pupils, advertised as being only eight years of age; President70 Jefferson’s march was another conspicuous feature. The exhibition concluded with a ball.97

Comedy predominated in the theatrical performances. The players were “the young gentlemen of the town.” At one of the entertainments they gave John O’Keefe’s comic opera The Poor Soldier, and a farce by Arthur Murphy called The Apprentice.98 There were also performances of a more professional character. Bromley and Arnold, two professional actors, conducted a series of theatrical entertainments extending over a period of several weeks. The plays which they rendered are hardly known to-day. At a single performance99 they gave a comedy entitled Trick upon Trick, or The Vintner in the Suds; a farce called The Jealous Husband, or The Lawyer in the Sack; and a pantomime, The Sailor’s Landlady, or Jack in Distress. Another play in the series was Edward Moore’s tragedy, The Gamester.100

Much of Grant’s Hill was unenclosed. Clumps of trees grew on its irregular surface, and there were level open spaces; and in summer the place was green with grass, and bushes grew in profusion. Farther in the background were great71 forest trees. The hill was the pleasure ground of the village. Judge Henry M. Brackenridge, a son of Judge Hugh Henry Brackenridge dwelling on the past, declared that “it was pleasing to see the line of well-dressed ladies and gentlemen and children, ... repairing to the beautiful green eminence.”101 On this elevation “under a bower, on the margin of a wood, and near a delightful spring, with the town of Pittsburgh in prospect,” the Fourth of July celebrations were held.102 On August 2, 1794, the motley army of Insurgents from Braddocksfield rested there, after having marched through the town. Here they were refreshed with food and whisky, in order that they might keep in good humor, and to prevent their burning the town.103