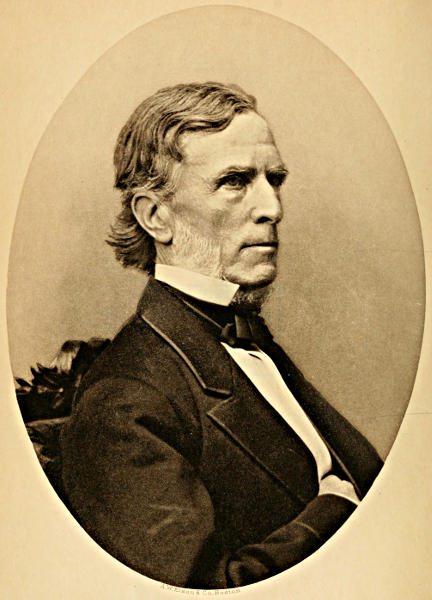

A. W. Elson & Co. Boston

WILLIAM PITT FESSENDEN

Charles Sumner; his complete works, volume 15 (of 20)

Copyright, 1875 and 1877,

BY

FRANCIS V. BALCH, Executor.

Copyright, 1900,

BY

LEE AND SHEPARD.

Statesman Edition.

Limited to One Thousand Copies.

Of which this is

Norwood Press:

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

CONTENTS OF VOLUME XV.

THE CESSION OF RUSSIAN AMERICA TO THE UNITED STATES.

Speech in the Senate, on the Ratification of the Treaty between the United States and Russia, April 9, 1867.

Thirteen governments founded on the natural authority of the people alone, without a pretence of miracle or mystery, and which are destined to spread over the northern part of that whole quarter of the globe, are a great point gained in favor of the rights of mankind.—John Adams, Preface to his Defence of the American Constitutions, dated Grosvenor Square, London, January 1, 1787: Works, Vol. IV. p. 293.

Barbarous and stupid Xerxes, how vain was all thy toil to cover the Hellespont with a floating bridge! Thus rather wise and prudent princes join Asia to Europe; they join and fasten nations together, not with boards or planks or surging brigandines, not with inanimate and insensible bonds, but by the ties of legitimate love, chaste nuptials, and the infallible gage of progeny.—Plutarch, Morals, ed. Goodwin, Vol. I. p. 482.

Late in the evening of Friday, March 29, 1867, Mr. Sumner, on reaching home, found this note from Mr. Seward awaiting him: “Can you come to my house this evening? I have a matter of public business in regard to which it is desirable that I should confer with you at once.” Without delay he hurried to the house of the Secretary of State, only to find that the latter had left for the Department. His son, the Assistant Secretary, was at home, and he was soon joined by Mr. de Stoeckl, the Russian Minister. From the two Mr. Sumner learned for the first time that a treaty was about to be signed for the cession of Russian America to the United States. With a map in his hand, the Minister, who had just returned from St. Petersburg, explained the proposed boundary, according to verbal instructions from the Archduke Constantine. After a brief conversation, when Mr. Sumner inquired and listened without expressing any opinion, they left together, the Minister on his way to the Department, where the treaty was copying. The clock was striking midnight as they parted, the Minister saying with interest, “You will not fail us.” The treaty was signed about four o’clock in the morning of March 30th, being the last day of the current session of Congress, and on the same day transmitted to the Senate, and referred to the Committee on Foreign Relations.

April 1st, the Senate was convened in Executive session by the proclamation of the President of the United States, and the Committee proceeded to the consideration of the treaty. The Committee at the time was Messrs. Sumner (Chairman), Fessenden, of Maine, Cameron, of Pennsylvania, Harlan, of Iowa, Morton, of Indiana, Patterson, of New Hampshire, and Reverdy Johnson, of Maryland. Carefully and anxiously they considered the question, and meanwhile it was discussed outside. Among friendly influences was a strong pressure from Hon. Thaddeus Stevens, the acknowledged leader of the other House, who, though without constitutional voice on the ratification of a treaty, could not restrain his earnest testimony. Mr. Sumner was controlled less by desire for more territory than by a sense of the amity of Russia, manifested especially during our recent troubles, and by an unwillingness to miss the opportunity of dismissing another European sovereign from our continent, predestined, as he believed, to become the broad, undivided home of the American people; and these he developed in his remarks before the Senate.

April 8th, the treaty was reported by Mr. Sumner without amendment, and with the recommendation that the Senate advise and consent thereto. The next day it was considered, when Mr. Sumner spoke on the negotiation, its origin, and the character of the ceded possessions. A motion by Mr. Fessenden to postpone its further consideration was voted down,—Yeas 12, Nays 29. After further debate, the final question of ratification was put and carried on the same day by a vote of Yeas 37, Nays 2,—the Nays being Mr. Fessenden, and Mr. Morrill, of Vermont. The ratifications were exchanged June 20th, and the same day the treaty was proclaimed.

The debate was in Executive session, and no reporters were present. Senators interested in the question invited Mr. Sumner to write out his remarks and give them to the public. For some time he hesitated, but, taking advantage of the vacation, he applied himself to the work, following precisely in order and subdivision the notes of a single page from which he spoke.

The speech was noticed at home and abroad. At home, the Boston Journal, which published it at length, remarked:—

“This speech, it will be remembered, coming from the Chairman of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, and abounding in a mass of pertinent information not otherwise accessible to Senators, exerted a most marked, if not decisive, effect in favor of the ratification of the treaty. Since then, the rumors of Mr. Sumner’s exhaustive treatment of the subject, together with the increasing popular interest in our new territory, have stimulated a general desire for the publication of the speech, which we are now enabled to supply. As might be expected, the speech is a monument of comprehensive research, and of skill in the collection and arrangement of facts. It probably comprises about all the information that is extant concerning our new Pacific possessions, and will prove equally interesting to the student of history, the politician, and the man of business.”

A Russian translation, by Mr. Buynitzky, appeared at St. Petersburg, with an introduction, whose complimentary character is manifest in its opening:—

“Senator Charles Sumner, of Massachusetts, appears, since the election of Lincoln, as one of the most eloquent and conspicuous representatives of the Republican party. His name stands in the first rank of the zealous propagators of Abolitionism, and all his political activity is directed toward one object,—the completion of the glorious act of enfranchisement of five millions of citizens by a series of laws calculated to secure to freedmen the actual possession of civil and political rights. As Chairman of the Senate Committee upon Foreign Relations, Mr. Sumner [Pg 5]attentively watches the march of affairs in Europe generally; but, in the course of the present decade, his particular attention was attracted by the reforms which took place in Russia. The emancipation of the peasants in our country was viewed with the liveliest sympathy by the American statesman, and this sympathy expressed itself eloquently in his speeches, delivered on various occasions, as well in Congress as in the State conventions of Massachusetts.”

A French writer, M. Cochin, whose work on Slavery is an important contribution to the literature of Emancipation, in a later work thus characterizes this speech:—

“All that is known on Russian America has just been presented in a speech, abundant, erudite, eloquent, poetic, pronounced before the Congress of the United States by the great orator, Charles Sumner.”[1]

On the appearance of the speech, May 24th, Professor Baird, the accomplished naturalist of the Smithsonian Institution, wrote, expressing the hope that some Boston or New York publisher would reprint what he called the “Essay” in a “book-form,” adding: “It deserves some more permanent dress than that of a speech from the Globe office.” This is done for the first time in the present publication.

These few notices, taken from many, are enough to show the contemporary reception of the speech.

SPEECH.

MR. PRESIDENT,—You have just listened to the reading of the treaty by which Russia cedes to the United States all her possessions on the North American continent and the adjacent islands in consideration of $7,200,000 to be paid by the United States. On the one side is the cession of a vast country, with its jurisdiction and resources of all kinds; on the other side is the purchase-money. Such is the transaction on its face.

BOUNDARIES AND CONFIGURATION.

In endeavoring to estimate its character, I am glad to begin with what is clear and beyond question. I refer to the boundaries fixed by the treaty. Commencing at the parallel of 54° 40´ north latitude, so famous in our history, the line ascends Portland Canal to the mountains, which it follows on their summits to the point of intersection with the meridian of 141° west longitude, which it ascends to the Frozen Ocean, or, if you please, to the north pole. This is the eastern boundary, separating the region from the British possessions, and it is borrowed from the treaty between Russia and Great Britain in 1825, establishing the relations between these two powers on this continent. It is seen that this boundary is old; the rest is new. Starting from the Frozen Ocean, the western boundary descends Behring[Pg 7] Strait, midway between the two islands of Krusenstern and Ratmanoff, to the parallel of 65° 30´, just below where the continents of America and Asia approach each other the nearest; and from this point it proceeds in a course nearly southwest through Behring Strait, midway between the island of St. Lawrence and Cape Chukotski, to the meridian of 172° west longitude, and thence, in a southwesterly direction, traversing Behring Sea, midway between the island of Attoo on the east and Copper Island on the west, to the meridian of 193° west longitude, leaving the prolonged group of the Aleutian Islands in the possessions transferred to the United States, and making the western boundary of our country the dividing line which separates Asia from America.

Look at the map and observe the configuration of this extensive region, whose estimated area is more than five hundred and seventy thousand square miles. I speak by authority of our own Coast Survey. Including the Sitkan Archipelago at the south, it takes a margin of the main-land fronting on the ocean thirty miles broad and five hundred miles long to Mount St. Elias, the highest peak of the continent, when it turns with an elbow to the west, and along Behring Strait northerly, then rounding to the east along the Frozen Ocean. Here are upwards of four thousand statute miles of coast, indented by capacious bays and commodious harbors without number, embracing the peninsula of Alaska, one of the most remarkable in the world, twenty-five miles in breadth and three hundred miles in length; piled with mountains, many volcanic and some still smoking; penetrated by navigable rivers, one of which is among the largest of the world; studded[Pg 8] with islands standing like sentinels on the coast, and flanked by that narrow Aleutian range which, starting from Alaska, stretches far away to Kamtchatka, as if America were extending a friendly hand to Asia. This is the most general aspect. There are details specially disclosing maritime advantages and approaches to the sea which properly belong to this preliminary sketch. According to accurate estimate, the coast line, including bays and islands, is not less than eleven thousand two hundred and seventy miles. In the Aleutian range, besides innumerable islets and rocks, there are not less than fifty-five islands exceeding three miles in length; there are seven exceeding forty miles, with Oonimak, which is the largest, exceeding seventy-three miles. In our part of Behring Sea there are five considerable islands, the largest of which is St. Lawrence, being more than ninety-six miles long. Add to all these the group south of the peninsula of Alaska, including the Shumagins and the magnificent island of Kadiak, and then the Sitkan group, being archipelago added to archipelago, and the whole together constituting the geographical complement to the West Indies, so that the northwest of the continent answers to the southeast, archipelago for archipelago.

DISCOVERY OF RUSSIAN AMERICA BY BEHRING, UNDER INSTRUCTIONS FROM PETER THE GREAT.

The title of Russia to all these possessions is derived from prior discovery, being the admitted title by which all European powers have held in North and South America, unless we except what England acquired by conquest from France; but here the title[Pg 9] of France was derived from prior discovery. Russia, shut up in a distant interior and struggling with barbarism, was scarcely known to the other powers at the time they were lifting their flags in the western hemisphere. At a later day the same powerful genius which made her known as an empire set in motion the enterprise by which these possessions were opened to her dominion. Peter, called the Great, himself ship-builder and reformer, who had worked in the ship-yards of England and Holland, was curious to know if Asia and America were separated by the sea, or if they constituted one undivided body with different names, like Europe and Asia. To obtain this information, he wrote with his own hand the following instructions, and ordered his chief admiral to see them carried into execution:—

“One or two boats with decks to be built at Kamtchatka, or at any other convenient place, with which inquiry should be made in relation to the northerly coasts, to see whether they were not contiguous with America, since their end was not known. And this done, they should see whether they could not somewhere find an harbor belonging to Europeans or an European ship. They should likewise set apart some men who were to inquire after the name and situation of the coasts discovered. Of all this an exact journal should be kept, with which they should return to Petersburg.”[2]

The Czar died in the winter of 1725; but the Empress Catharine, faithful to the desires of her husband, did not allow this work to be neglected. Vitus Behring, Dane by birth, and navigator of experience, was made commander. The place of embarkation was on[Pg 10] the other side of the Asiatic continent. Taking with him officers and ship-builders, the navigator left St. Petersburg by land, 5th February, 1725, and commenced the preliminary journey across Siberia, Northern Asia, and the Sea of Okhotsk, to the coast of Kamtchatka, which they reached only after infinite hardships and delays, sometimes with dogs for horses, and sometimes supporting life by eating leather bags, straps, and shoes. More than three years were consumed in this toilsome and perilous journey. At last, on the 20th of July, 1728, the party was able to set sail in a small vessel, called the Gabriel, and described as “like the packet-boats used in the Baltic.” Steering in a northeasterly direction, Behring passed a large island, which he called St. Lawrence, from the saint on whose day it was seen. This island, which is included in the present cession, may be considered as the first point in Russian discovery, as it is also the first outpost of the North American continent. Continuing northward, and hugging the Asiatic coast, Behring turned back only when he thought he had reached the northeastern extremity of Asia, and was satisfied that the two continents were separated from each other. He did not penetrate further north than 67° 30´.

In his voyage Behring was struck by the absence of such great and high waves as in other places are common to the open sea, and he observed fir-trees swimming in the water, although they were unknown on the Asiatic coast. Relations of inhabitants, in harmony with these indications, pointed to “a country at no great distance towards the east.” His work was still incomplete, and the navigator, before returning home, put forth again for this discovery, but without[Pg 11] success. By another dreary land journey he made his way back to St. Petersburg in March, 1730, after an absence of five years. Something was accomplished for Russian discovery, and his own fame was engraved on the maps of the world. The strait through which he sailed now bears his name, as also does the expanse of sea he traversed on his way to the strait.

The spirit of discovery continued at St. Petersburg. A Cossack chief, undertaking to conquer the obstinate natives on the northeastern coast, proposed also “to discover the pretended country in the Frozen Sea.” He was killed by an arrow before his enterprise was completed. Little is known of the result; but it is stated that the navigator whom he had selected, by name Gwosdeff, in 1730 succeeded in reaching “a strange coast” between sixty-five and sixty-six degrees of north latitude, where he saw people, but could not speak with them for want of an interpreter. This must have been the coast of North America, and not far from the group of islands in Behring Strait, through which the present boundary passes, separating the United States from Russia, and America from Asia.

The Russian desire to get behind the curtain increased. Behring volunteered to undertake the discoveries yet remaining. He was created Commodore, and his old lieutenants were created captains. The Senate, the Admiralty, and the Academy of Sciences at St. Petersburg, all united in the enterprise. Several academicians were appointed to report on the natural history of the coasts visited, among whom was Steller, the naturalist, said to be “immortal” from this association. All of these, with a numerous body of officers, journeyed across Siberia, Northern Asia, and the Sea[Pg 12] of Okhotsk, to Kamtchatka, as Behring had journeyed before. Though ordered in 1732, the expedition was not able to leave the eastern coast until 4th June, 1741, when two well-appointed ships set sail in company “to discover the continent of America.” One of these, called the St. Peter, was under Commodore Behring; the other, called the St. Paul, was under Captain Tschirikoff. For some time the two kept together, but in a violent storm and fog they were separated, when each continued the expedition alone.

Behring first saw the continent of North America 18th July, 1741, in latitude 58° 28´. Looking at it from a distance, “the country had terrible high mountains that were covered with snow.” Two days later, he anchored in a sheltered bay near a point, which he called, from the saint’s day on which he saw it, Cape St. Elias. He was in the shadow of Mount St. Elias. Landing, he found deserted huts, fireplaces, hewn wood, household furniture, arrows, “a whetstone on which it appeared that copper knives had been sharpened,” and “store of red salmon.” Here also birds unknown in Siberia were noticed by the faithful Steller, among which was the blue-jay, of a peculiar species, now called by his name. At this point, Behring found himself constrained by the elbow in the coast to turn westward, and then in a southerly direction. Hugging the shore, his voyage was constantly arrested by islands without number, among which he zigzagged to find his way. Several times he landed. Once he saw natives, who wore “upper garments of whales’ guts, breeches of seal-skins, and caps of the skins of sea-lions, adorned with various feathers, especially those of hawks.” These “Americans,” as they are called, were fishermen, without[Pg 13] bows and arrows. They regaled the Russians with “whale’s flesh,” but declined strong drink. One of them, on receiving a cup of brandy, “spit the brandy out again as soon as he had tasted it, and cried aloud, as if he was complaining to his countrymen how ill he had been used.” This was on one of the Shumagin Islands, near the southern coast of the peninsula of Alaska.

Meanwhile the other solitary ship, proceeding on its way, had sighted the same coast 15th July, 1741, in the latitude of 56°. Anchoring at some distance from the steep and rocky cliffs before him, Tschirikoff sent his mate with the long-boat and ten of his best men, provided with small-arms and a brass cannon, to inquire into the nature of the country and to obtain fresh water. The long-boat disappeared behind a headland, and was never seen again. Thinking it might have been damaged in landing, the captain sent his boatswain with the small boat and carpenters, well armed, to furnish necessary assistance. The small boat disappeared also, and was never seen again. At the same time a great smoke was observed continually ascending from the shore. Shortly afterwards, two boats filled with natives sallied forth and lay at some distance from the vessel, when, crying, “Agai, Agai,” they put back to the shore. Sorrowfully the Russian navigator turned away, not knowing the fate of his comrades, and unable to help them. This was not far from Sitka.

Such was the first discovery of these northwestern coasts, and such are the first recorded glimpses of the aboriginal inhabitants. The two navigators had different fortunes. Tschirikoff, deprived of his boats, and therefore unable to land, hurried home. Adverse winds[Pg 14] and storms interfered. He supplied himself with fresh water by distilling sea-water or pressing rain-water from the sails. But at last, on the 9th of October, he reached Kamtchatka, with his ship’s company of seventy diminished to forty-nine. During this time Behring was driven, like Ulysses, on the uncertain waves. A single tempest raged for seventeen days, so that Andrew Hasselberg, the ancient pilot, who had known the sea for fifty years, declared that he had seen nothing like it in his life. Scurvy came with disheartening horrors. The Commodore himself was a sufferer. Rigging broke; cables snapped; anchors were lost. At last the tempest-tossed vessel was cast upon a desert island, then without a name, where the Commodore, sheltered in a ditch, and half covered with sand as a protection against cold, died, 8th December, 1741. His body, after his decease, was “scraped out of the ground” and buried on this island, which is called by his name, and constitutes an outpost of the Asiatic continent. Thus the Russian navigator, after the discovery of America, died in Asia. Russia, by the recent demarcation, does not fail to retain his last resting-place among her possessions.

TITLE OF RUSSIA.

For some time after these expeditions, by which Russia achieved the palm of discovery, imperial enterprise in those seas slumbered. The knowledge already acquired was continued and confirmed only by private individuals, who were led there in quest of furs. In 1745 the Aleutian Islands were discovered by an adventurer in search of sea-otters. In successive voyages all these islands were visited for similar[Pg 15] purposes. Among these was Oonalaska, the principal of the group of Fox Islands, constituting a continuation of the Aleutian Islands, whose inhabitants and productions were minutely described. In 1768 private enterprise was superseded by an expedition ordered by the Empress Catharine, which, leaving Kamtchatka, explored this whole archipelago and the peninsula of Alaska, which to the islanders stood for the whole continent. Shortly afterwards, all these discoveries, beginning with those of Behring and Tschirikoff, were verified by the great English navigator, Captain Cook. In 1778 he sailed along the northwestern coast, “near where Tschirikoff anchored in 1741”; then again in sight of mountains “wholly covered with snow from the highest summit down to the sea-coast,” with “the summit of an elevated mountain above the horizon,” which he supposed to be the Mount St. Elias of Behring; then by the very anchorage of Behring; then among the islands through which Behring zigzagged, and along the coast by the island of St. Lawrence, until arrested by ice. If any doubt existed with regard to Russian discoveries, it was removed by the authentic report of this navigator, who shed such a flood of light upon the geography of the whole region.

Such from the beginning is the title of Russia, dating at least from 1741. I have not stopped to quote volume and page, but I beg to be understood as following approved authorities, and I refer especially to the Russian work of Müller, already cited, on the “Voyages from Asia to America,” the volume of Coxe on “Russian Discoveries,” with its supplement on the “Comparative View of the Russian Discoveries,” the volume of Sir John Barrow on “Voyages into the Arctic Regions,[Pg 16]” Burney’s “Northeastern Voyages,” and the third voyage of Captain Cook, unhappily interrupted by his tragical death from the natives of the Sandwich Islands, but not until after the exploration of this coast.

There were at least four other Russian expeditions, by which this title was confirmed, if it needed any confirmation. The first was ordered by the Empress Catharine, in 1785. It was under the command of Commodore Billings, an Englishman in the service of Russia, and was narrated from the original papers by Martin Sauer, secretary of the expedition. In the instructions from the Admiralty at St. Petersburg the Commodore was directed to take possession of “such coasts and islands as he shall first discover, whether inhabited or not, that cannot be disputed, and are not yet subject to any European power, with consent of the inhabitants, if any”; and this was to be accomplished by setting up “posts marked with the arms of Russia, with letters indicating the time of discovery, a short account of the people, their voluntary submission to the Russian sovereignty, and that this was done under the glorious reign of the great Catharine the Second.”[3] The next was in 1803-6, in the interest of the Russian American Company, with two ships, one under the command of Captain Krusenstern, and the other of Captain Lisiansky, of the Russian navy. It was the first Russian voyage round the world, and lasted three years. During its progress, Lisiansky visited the northwest coast of America, and especially Sitka and the island of Kadiak. Still another enterprise, organized by the celebrated minister Count Romanzoff, and at[Pg 17] his expense, left Russia in 1815, under the command of Lieutenant Kotzebue, an officer of the Russian navy, and son of the German dramatist, whose assassination darkened the return of the son from his long voyage. It is enough for the present to say of this expedition that it has left its honorable traces on the coast even as far as the Frozen Ocean. There remains the enterprise of Lütke, at the time captain, and afterward admiral in the Russian navy, which was a voyage of circumnavigation, embracing especially the Russian possessions, commenced in 1826, and described in French with instructive fulness. With him sailed the German naturalist Kittlitz, who has done so much to illustrate the natural history of this region.

A FRENCH ASPIRATION ON THIS COAST.

So little was the Russian title recognized for some time, that, when the unfortunate expedition of La Pérouse, with the frigates Boussole and Astrolabe, stopped on this coast in 1786, he did not hesitate to consider the friendly harbor, in latitude 58° 36´, where he was moored, as open to permanent occupation. Describing this harbor, which he named Port des Français, as sheltered behind a breakwater of rocks, with a calm sea and a mouth sufficiently large, he announces that Nature seemed to have created at the extremity of America a port like that of Toulon, but vaster in plan and accommodations; and then, considering that it had never been discovered before, that it was situated thirty-three leagues northwest of Los Remedios, the limit of Spanish navigation, about two hundred and twenty-four leagues from Nootka, and a hundred leagues[Pg 18] from Prince William Sound, the mariner records his judgment, that, “if the French Government had any project of a factory on this part of the coast of America, no nation could pretend to have the slightest right to oppose it.”[4] Thus quietly was Russia dislodged. The frigates sailed further on their voyage, and never returned to France. Their fate was unknown, until, after fruitless search and the lapse of a generation, some relics from them were accidentally found on an obscure island of the Southern Pacific. The unfinished journal of La Pérouse, recording his visit to this coast, had been sent overland, by way of Kamtchatka and Siberia, to France, where it was published by a decree of the National Assembly, thus making known his supposed discovery and his aspiration.

EARLY SPANISH CLAIM.

Spain also has been a claimant. In 1775, Bodega, a Spanish navigator, seeking new opportunities to plant the Spanish flag, reached the parallel of 58° on this coast, not far from Sitka; but this supposed discovery was not followed by any immediate assertion of dominion. The universal aspiration of Spain had embraced this whole region even at an early day, and shortly after the return of Bodega another enterprise was equipped to verify the larger claim, being nothing less than the original title as discoverer of the strait between America and Asia, and of the conterminous continent, under the name of Anian. This curious episode is not out of place in the present brief history. It has two branches: one concerning early maps, on[Pg 19] which straits are represented between America and Asia under the name of Anian; the other concerning a pretended attempt by a Spanish navigator at an early day to find these straits.

There can be no doubt that early maps exist with northwestern straits marked Anian. There are two in the Congressional Library, in atlases of the years 1680 and 1717; but these are of a date comparatively modern. Engel, in his “Mémoires Géographiques,” mentions several earlier, which he believes genuine. There is one purporting to be by Zaltieri, and bearing date 1566, an authentic pen-and-ink copy of which is now before me, from the collection of our own Coast Survey. On this very interesting map, which is without latitude or longitude, the western coast of the continent is delineated with a strait separating it from Asia not unlike Behring’s in outline, and with the name in Italian, Stretto di Anian. Southward the coast has a certain conformity with what is now known to exist. Below is an indentation corresponding to Bristol Bay; then a peninsula somewhat broader than that of Alaska; then the elbow of the coast; then, lower down, three islands, not unlike Sitka, Queen Charlotte, and Vancouver; and then, further south, is the peninsula of Lower California. Sometimes the story of Anian is explained by the voyage of the Portuguese navigator Gaspar de Cortereal, in 1500, when, on reaching Hudson Bay in quest of a passage round America, he imagined that he had found it, and proceeded to name his discovery “in honor of two brothers who accompanied him.” Very soon maps began to record the Strait of Anian; but this does not explain the substantial conformity of the early delineation with the reality, which seems truly remarkable.

The other branch of inquiry is more easily disposed of. This turns on a Spanish document entitled “A Relation of the Discovery of the Strait of Anian, made by me, Captain Lorenzo Ferrer Maldonado, in the Year 1588.”[5] If this early account of a northwest passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific were authentic, the whole question would be settled; but recent geographers indignantly discard it as a barefaced imposture. Clearly Spain once regarded it otherwise; for her Government in 1789 sent out an expedition “to discover the strait by which Laurent Ferrer Maldonado was supposed to have passed, in 1588, from the coast of Labrador to the Great Ocean.”[6] The expedition was unsuccessful, and nothing more has been heard of any claim from this pretended discovery. The story of Maldonado has taken its place in the same category with that of Munchausen.

REASONS FOR CESSION BY RUSSIA.

Turning from the question of title, which time and testimony have already settled, I meet the inquiry, Why does Russia part with possessions associated with the reign of her greatest ruler and filling an important chapter of geographical history? Here I am without information not open to others. But I do not forget that the first Napoleon, in parting with Louisiana, was controlled by three several considerations. First, he needed the purchase-money for his treasury; secondly, he was unwilling to leave this distant unguarded territory[Pg 21] a prey to Great Britain, in the event of hostilities, which seemed at hand; and, thirdly, he was glad, according to his own remarkable language, “to establish forever the power of the United States, and give to England a maritime rival that would sooner or later humble her pride.”[7] Such is the record of history. Perhaps a similar record may be made hereafter with regard to the present cession. There is reason to imagine that Russia, with all her great empire, is financially poor; so that these few millions may not be unimportant to her. It is by foreign loans that her railroads have been built and her wars aided. All, too, must see that in those “coming events” which now more than ever “cast their shadows before” it will be for her advantage not to hold outlying possessions from which thus far she has obtained no income commensurate with the possible expense for their protection. Perhaps, like a wrestler, she strips for the contest, which I trust sincerely may be averted. Besides, I cannot doubt that her enlightened Emperor, who has given pledges to civilization by an unsurpassed act of Emancipation, would join the first Napoleon in a desire to enhance the maritime power of the United States.

These general considerations are reinforced, when we call to mind the little influence which Russia has been able thus far to exercise in this region. Though possessing dominion for more than a century, the gigantic power has not been more genial or productive there than the soil itself. Her government is little more than a name or a shadow. It is not even a skeleton. It is hardly visible. Its only representative is a fur company, to which has been added latterly an ice company.[Pg 22] The immense country is without form and without light, without activity and without progress. Distant from the imperial capital, and separated from the huge bulk of Russian empire, it does not share the vitality of a common country. Its life is solitary and feeble. Its settlements are only encampments or lodges. Its fisheries are only a petty perquisite, belonging to local or personal adventurers rather than to the commerce of nations.

In these statements I follow the record. So little were these possessions regarded during the last century that they were scarcely recognized as a component part of the empire. I have now before me an authentic map, published by the Academy of Sciences at St. Petersburg in 1776, and reproduced at London in 1780, entitled “General Map of the Russian Empire,”[8] where you will look in vain for Russian America, unless we except the links of the Aleutian chain nearest to the two continents. Alexander Humboldt, whose geographical insight was unerring, in his great work on New Spain, published in 1811, after stating that he is able from an official document to give the position of the Russian factories on the American continent, says that they are “for the most part mere collections of sheds and cabins, but serving as store-houses for the fur-trade.” He remarks further that “the larger part of these small Russian colonies communicate with each other only by sea”; and then, putting us on our guard not to expect too much from a name, he proceeds to say that “the new denomination of ‘Russian America,’ or ‘Russian Possessions on the New Continent,’ must not lead us to think that the coasts of Behrin[Pg 23]g’s Basin, the peninsula of Alaska, or the country of the Tchuktchi have become Russian provinces in the sense given to this word in speaking of the Spanish provinces of Sonora or New Biscay.”[9] Here is a distinction between the foothold of Spain in California and the foothold of Russia in North America which will at least illustrate the slender power of the latter in this region.

In ceding possessions so little within the sphere of her empire, embracing more than one hundred nations or tribes, Russia gives up no part of herself; and even if she did, the considerable price paid, the alarm of war which begins to fill our ears, and the sentiments of friendship declared for the United States would explain the transaction.

THE NEGOTIATION, IN ITS ORIGIN AND COMPLETION.

I am not able to say when the idea of this cession first took shape. I have heard that it was as long ago as the Administration of Mr. Polk. It is within my knowledge that the Russian Government was sounded on the subject during the Administration of Mr. Buchanan. This was done through Mr. Gwin, at the time Senator of California, and Mr. Appleton, Assistant Secretary of State. For this purpose the former had more than one interview with the Russian minister at Washington, some time in December, 1859, in which, while professing to speak for the President unofficially, he represented that “Russia was too far off to make the most of these possessions, and that, as we were near, we could derive more from them.” In reply to an inquiry[Pg 24] of the Russian minister, Mr. Gwin said that “the United States could go as high as $5,000,000 for the purchase,” on which the former made no comment. Mr. Appleton, on another occasion, said to the minister that “the President thought the acquisition would be very profitable to the States on the Pacific; that he was ready to follow it up, but wished to know in advance if Russia was ready to cede; that, if she were, he would confer with his Cabinet and influential members of Congress.” All this was unofficial; but it was promptly communicated to the Russian Government, who seem to have taken it into careful consideration. Prince Gortchakoff, in a despatch which reached here early in the summer of 1860, said that “the offer was not what might have been expected, but that it merited mature reflection; that the Minister of Finance was about to inquire into the condition of these possessions, after which Russia would be in a condition to treat.” The Prince added for himself, that “he was by no means satisfied personally that it would be for the interest of Russia politically to alienate these possessions; that the only consideration which could make the scales incline that way would be the prospect of great financial advantages, but that the sum of $5,000,000 did not seem in any way to represent the real value of these possessions”; and he concluded by asking the minister to tell Mr. Appleton and Senator Gwin that the sum offered was not considered “an equitable equivalent.” The subject was submerged by the Presidential election which was approaching, and then by the Rebellion. It will be observed that this attempt was at a time when politicians who believed in the perpetuity of Slavery still had power. Mr. Buchanan was President,[Pg 25] and he employed as his intermediary a known sympathizer with Slavery, who shortly afterwards became a Rebel. Had Russia been willing, it is doubtful if this controlling interest would have sanctioned any acquisition too far north for Slavery.

Meanwhile the Rebellion was brought to an end, and peaceful enterprise was renewed, which on the Pacific coast was directed toward the Russian possessions. Our people there, wishing new facilities to obtain fish, fur, and ice, sought the intervention of the National Government. The Legislature of Washington Territory, in the winter of 1866, adopted the following memorial to the President of the United States, entitled “In reference to the cod and other fisheries.”

“To his Excellency Andrew Johnson,

“President of the United States.

“Your memorialists, the Legislative Assembly of Washington Territory, beg leave to show that abundance of codfish, halibut, and salmon, of excellent quality, have been found along the shores of the Russian possessions. Your memorialists respectfully request your Excellency to obtain such rights and privileges of the Government of Russia as will enable our fishing vessels to visit the ports and harbors of its possessions, to the end that fuel, water, and provisions may be easily obtained, that our sick and disabled fishermen may obtain sanitary assistance, together with the privilege of curing fish and repairing vessels in need of repairs. Your memorialists further request that the Treasury Department be instructed to forward to the collector of customs of this Puget Sound district such fishing licenses, abstract journals, and log-books as will enable our hardy fishermen to obtain the bounties now provided and paid to the fishermen in the Atlantic States. Your memorialists finally pray your Excellency to employ such ships as may be spared from the[Pg 26] Pacific naval fleet in exploring and surveying the fishing banks known to navigators to exist along the Pacific coast from the Cortés Bank to Behring Straits. And, as in duty bound, your memorialists will ever pray.

“Passed the House of Representatives January 10, 1866.

“Edward Eldridge,

“Speaker, House of Representatives.

“Passed the Council January 13, 1866.

“Harvey K. Hines,

“President of the Council.”

This memorial, on presentation to the President, in February, 1866, was referred to the Secretary of State, by whom it was communicated to Mr. de Stoeckl, the Russian minister, with remarks on the importance of some early and comprehensive arrangement between the two powers to prevent the growth of difficulties, especially from the fisheries in that region. At the same time reports began to prevail of extraordinary wealth in fisheries, especially the whale and cod, promising to become an important commerce on the Pacific coast.

Shortly afterwards another influence was felt. Mr. Cole, who had been recently elected to the Senate from California, acting in behalf of certain persons in that State, sought from the Russian Government a license or franchise to gather furs in a portion of its American possessions. The charter of the Russian American Company was about to expire. This company had already underlet to the Hudson’s Bay Company all its franchise on the main-land between 54° 40´ and Cape Spencer; and now it was proposed that an American company, holding directly from the Russian Government, should be substituted for the latter. The mighty Hudson’s Bay Company, with headquarters in London,[Pg 27] was to give way to an American company, with headquarters in California. Among letters on this subject addressed to Mr. Cole, and now before me, is one dated San Francisco, April 10, 1866, in which the scheme is developed:—

“There is at the present time a good chance to organize a fur-trading company, to trade between the United States and the Russian possessions in America; and as the charter formerly granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company has expired, this would be the opportune moment to start in.… I should think that by a little management this charter could be obtained from the Russian Government for ourselves, as I do not think they are very willing to renew the charter of the Hudson’s Bay Company, and I think they would give the preference to an American company, especially if the company should pay to the Russian Government five per cent. on the gross proceeds of their transactions, and also aid in civilizing and ameliorating the condition of the Indians by employing missionaries, if required by the Russian Government. For the faithful performance of the above we ask a charter for the term of twenty-five years, to be renewed for the same length of time, if the Russian Government finds the company deserving,—the charter to invest us with the right of trading in all the country between the British American line and the Russian Archipelago.… Remember, we wish for the same charter as was formerly granted to the Hudson’s Bay Company, and we offer in return more than they did.”

Another correspondent of Mr. Cole, under date of San Francisco, September 17, 1866, wrote:—

“I have talked with a man who has been on the coast and in the trade for ten years past, and he says it is much more valuable than I have supposed, and I think it very important to obtain it, if possible.”

The Russian minister at Washington, whom Mr. Cole saw repeatedly upon the subject, was not authorized to act, and the latter, after conference with the Department of State, was induced to address Mr. Clay, minister of the United States at St. Petersburg, who laid the application before the Russian Government. This was an important step. A letter from Mr. Clay, dated at St. Petersburg as late as February 1, 1867, makes the following revelation.

“The Russian Government has already ceded away its rights in Russian America for a term of years, and the Russo-American Company has also ceded the same to the Hudson’s Bay Company. This lease expires in June next, and the president of the Russo-American Company tells me that they have been in correspondence with the Hudson’s Bay Company about a renewal of the lease for another term of twenty-five or thirty years. Until he receives a definite answer, he cannot enter into negotiations with us or your California company. My opinion is, that, if he can get off with the Hudson’s Bay Company, he will do so, when we can make some arrangements with the Russo-American Company.”

Some time had elapsed since the original attempt of Mr. Gwin, also a Senator from California, and it is probable that the Russian Government had obtained information which enabled it to see its way more clearly. It will be remembered that Prince Gortchakoff had promised an inquiry, and it is known that in 1861 Captain-Lieutenant Golowin, of the Russian navy, made a detailed report on these possessions. Mr. Cole had the advantage of his predecessor. There is reason to believe, also, that the administration of the fur company had not been entirely satisfactory, so that there[Pg 29] were well-founded hesitations with regard to the renewal of its franchise. Meanwhile, in October, 1866, Mr. de Stoeckl, who had long been the Russian minister at Washington, and enjoyed in a high degree the confidence of our Government, returned home on leave of absence, promising his best exertions to promote good relations between the two countries. While he was at St. Petersburg, the applications from the United States were under consideration; but the Russian Government was disinclined to any minor arrangement of the character proposed. Obviously something like a crisis was at hand with regard to these possessions. The existing government was not adequate. The franchises granted there were about to terminate. Something must be done. As Mr. de Stoeckl was leaving for his post, in February, the Archduke Constantine, brother and chief adviser of the Emperor, handed him a map with the lines in our treaty marked upon it, and told him he might treat for cession with those boundaries. The minister arrived in Washington early in March. A negotiation was opened at once. Final instructions were received by the Atlantic cable, from St. Petersburg, on the 29th of March, and at four o’clock on the morning of the 30th of March this important treaty was signed by Mr. Seward on the part of the United States and by Mr. de Stoeckl on the part of Russia.

Few treaties have been conceived, initiated, prosecuted, and completed in so simple a manner, without protocol or despatch. The whole negotiation is seen in its result, unless we except two brief notes, which constitute all that passed between the negotiators. These have an interest general and special, and I conclude the history of this transaction by reading them.

“Department of State, Washington, March 23, 1867.

“Sir,—With reference to the proposed convention between our respective Governments for a cession by Russia of her American territory to the United States, I have the honor to acquaint you that I must insist upon that clause in the sixth article of the draft which declares the cession to be free and unincumbered by any reservations, privileges, franchises, grants, or possessions by any associated companies, whether corporate or incorporate, Russian or any other, &c., and must regard it as an ultimatum. With the President’s approval, however, I will add $200,000 to the consideration money on that account.

“I avail myself of this occasion to offer to you a renewed assurance of my most distinguished consideration.

“William H. Seward.

“Mr. Edward de Stoeckl, &c., &c., &c.”

[TRANSLATION.]

“Washington, March 17 [29], 1867.

“Mr. Secretary of State,—I have the honor to inform you, that, by a telegram, dated 16th [28th] of this month, from St. Petersburg, Prince Gortchakoff informs me that his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias gives his consent to the cession of the Russian possessions on the American continent to the United States, for the stipulated sum of $7,200,000 in gold, and that his Majesty the Emperor invests me with full powers to negotiate and sign the treaty.

“Please accept, Mr. Secretary of State, the assurance of my very high consideration.

“Stoeckl.

“To Hon. William H. Seward,

“Secretary of State of the United States.”

THE TREATY.

The treaty begins with the declaration, that “the United States of America and his Majesty the Emperor[Pg 31] of all the Russias, being desirous of strengthening, if possible, the good understanding which exists between them,” have appointed plenipotentiaries, who have proceeded to sign articles, wherein it is stipulated on behalf of Russia that “his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias agrees to cede to the United States by this convention, immediately upon the exchange of the ratifications thereof, all the territory and dominion now possessed by his said Majesty on the continent of America and in the adjacent islands, the same being contained within the geographical limits herein set forth”; and it is stipulated on behalf of the United States, that, “in consideration of the cession aforesaid, the United States agree to pay at the Treasury in Washington, within ten months after the exchange of the ratifications of this convention, to the diplomatic representative or other agent of his Majesty the Emperor of all the Russias duly authorized to receive the same, $7,200,000 in gold.” The ratifications are to be exchanged within three months from the date of the treaty, or sooner, if possible.[10]

Beyond the consideration founded on the desire of “strengthening the good understanding” between the two countries, there is the pecuniary consideration already mentioned, which underwent a change in the progress of the negotiation. The sum of seven millions was originally agreed upon; but when it appeared that there was a fur company and also an ice company enjoying monopolies under the existing government, it was thought best that these should be extinguished, in consideration of which our Government added two hundred thousand to the purchase-money, and the Russian[Pg 32] Government in formal terms declared “the cession of territory and dominion to be free and unincumbered by any reservations, privileges, franchises, grants, or possessions, by any associated companies, whether corporate or incorporate, Russian or any other, or by any parties, except merely private individual property-holders.” Thus the United States receive the cession free of all incumbrances, so far at least as Russia is in a condition to make it. The treaty proceeds to say: “The cession hereby made conveys all the rights, franchises, and privileges now belonging to Russia in the said territory or dominion and appurtenances thereto.”[11] In other words, Russia conveys all she has to convey.

QUESTIONS ARISING UNDER THE TREATY.

There are questions, not unworthy of attention, which arise under the treaty between Russia and Great Britain, fixing the eastern limits of these possessions, and conceding certain privileges to the latter power. By this treaty, signed at St. Petersburg, 28th February, 1825, after fixing the boundaries between the Russian and British possessions, it is provided that “for the space of ten years from the signature of the present convention, the vessels of the two powers, or those belonging to their respective subjects, shall mutually be at liberty to frequent, without any hindrance whatever, all the inland seas, the gulfs, havens, and creeks on the coast, for the purposes of fishing and of trading with the natives”; and also that “the port of Sitka, or Novo Archangelsk, shall be open to the commerce and vessels of British subjects for the space of ten years from[Pg 33] the date of the exchange of the ratifications of the present convention.”[12] In the same treaty it is also provided that “the subjects of his Britannic Majesty, from whatever quarter they may arrive, whether from the ocean or from the interior of the continent, shall forever enjoy the right of navigating freely and without any hindrance whatever all the rivers and streams which in their course towards the Pacific Ocean may cross the line of demarcation.”[13] Afterwards a treaty of commerce and navigation between Russia and Great Britain was signed at St. Petersburg, 11th January, 1843, subject to be terminated on notice from either party at the expiration of ten years, in which it is provided, that, “in regard to commerce and navigation in the Russian possessions on the northwest coast of America, the convention concluded at St. Petersburg on the 16/28th February, 1825, continues in force.”[14] Then ensued the Crimean War between Russia and Great Britain, effacing or suspending treaties. Afterwards another treaty of commerce and navigation was signed at St. Petersburg, 12th January, 1859, subject to be terminated on notice from either party at the expiration of ten years, which repeats the last provision.[15]

Thus we have three different stipulations on the part of Russia: one opening seas, gulfs, and havens on the Russian coast to British subjects for fishing and trading with the natives; the second making Sitka a free port to British subjects; and the third making British rivers which flow through the Russian possessions forever free to British navigation. Do the United States succeed to these stipulations?

Among these I make a distinction in favor of the last, which by its language is declared to be “forever,” and may have been in the nature of an equivalent at the settlement of boundaries between the two powers. But whatever its terms or its origin, it is obvious that it is nothing but a declaration of public law, as always expounded by the United States, and now recognized on the continent of Europe. While pleading with Great Britain, in 1826, for the free navigation of the St. Lawrence, Mr. Clay, then Secretary of State, said that “the American Government did not mean to contend for any principle the benefit of which in analogous circumstances it would deny to Great Britain.”[16] During the same year, Mr. Gallatin, our minister in London, when negotiating with Great Britain for the adjustment of boundaries on the Pacific, proposed, that, “if the line should cross any of the branches of the Columbia at points from which they are navigable by boats to the main stream, the navigation of such branches and of the main stream should be perpetually free and common to the people of both nations.”[17] At an earlier day the United States made the same claim with regard to the Mississippi, and asserted, as a general principle, that, “if the right of the upper inhabitants to descend the stream was in any case obstructed, it was an act of force by a stronger society against a weaker, condemned by the judgment of mankind.”[18] By these admissions our country is estopped, even if the public law of the European continent, first declared at Vienna with regard[Pg 35] to the Rhine, did not offer an example which we cannot afford to reject. I rejoice to believe that on this occasion we apply to Great Britain the generous rule which from the beginning we have claimed for ourselves.

The two other stipulations are different in character. They are not declared to be “forever,” and do not stand on any principle of public law. Even if subsisting now, they cannot be onerous. I doubt much if they are subsisting now. In succeeding to the Russian possessions, it does not follow that the United States succeed to ancient obligations assumed by Russia, as if, according to a phrase of the Common Law, they were “covenants running with the land.” If these stipulations are in the nature of servitudes, they depend for their duration on the sovereignty of Russia, and are personal or national rather than territorial. So, at least, I am inclined to believe. But it is hardly profitable to speculate on a point of so little practical value. Even if “running with the land,” these servitudes can be terminated at the expiration of ten years from the last treaty by notice, which equitably the United States may give, so as to take effect on the 12th of January, 1869. Meanwhile, during this brief period, it will be easy by Act of Congress in advance to limit importations at Sitka, so that this “free port” shall not be made the channel or doorway by which British goods are introduced into the United States free of duty.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS ON THE TREATY.

From this survey of the treaty, as seen in its origin and the questions under it, I might pass at once to a survey of the possessions which have been conveyed;[Pg 36] but there are other matters of a more general character which present themselves at this stage and challenge judgment. These concern nothing less than the unity, power, and grandeur of the Republic, with the extension of its dominion and its institutions. Such considerations, where not entirely inapplicable, are apt to be controlling. I do not doubt that they will in a great measure determine the fate of this treaty with the American people. They are patent, and do not depend on research or statistics. To state them is enough.

1. Advantages to the Pacific Coast.—Foremost in order, if not in importance, I put the desires of our fellow-citizens on the Pacific coast, and the special advantages they will derive from this enlargement of boundary. They were the first to ask for it, and will be the first to profit by it. While others knew the Russian possessions only on the map, they knew them practically in their resources. While others were indifferent, they were planning how to appropriate Russian peltries and fisheries. This is attested by the resolutions of the Legislature of Washington Territory; also by the exertions at different times of two Senators from California, who, differing in political sentiments and in party relations, took the initial steps which ended in this treaty.

These well-known desires were founded, of course, on supposed advantages; and here experience and neighborhood were prompters. Since 1854 the people of California have received their ice from the fresh-water lakes in the island of Kadiak, not far westward from Mount St. Elias. Later still, their fishermen have[Pg 37] searched the waters about the Aleutians and the Shumagins, commencing a promising fishery. Others have proposed to substitute themselves for the Hudson’s Bay Company in their franchise on the coast. But all are looking to the Orient, as in the time of Columbus, although like him they sail to the west. To them China and Japan, those ancient realms of fabulous wealth, are the Indies. To draw this commerce to the Pacific coast is no new idea. It haunted the early navigators. Meares, the Englishman, whose voyage in the intervening seas was in 1788, recounts a meeting with Gray, the Boston navigator, whom he found “very sanguine in the superior advantages which his countrymen from New England might reap from this track of trade, and big with many mighty projects.”[19] He closes his volumes with an essay entitled “Some Account of the Trade between the Northwest Coast of America and China, &c.,” in the course of which[20] he dwells on the “great and very valuable source of commerce” offered by China as “forming a chain of trade between Hudson’s Bay, Canada, and the Northwest Coast”; and then he exhibits on the American side the costly furs of the sea-otter, still so much prized in China,—“mines which are known to lie between the latitudes of 40° and 60° north,”—and also ginseng “in inexhaustible plenty,” for which there is still such demand in China, that even Minnesota, at the head-waters of the Mississippi, supplies her contribution. His catalogue might be extended now.

As a practical illustration of this idea, it may be mentioned, that, for a long time, most, if not all, the sea-otter skins of this coast found their way to China.[Pg 38] China was the best customer, and therefore Englishmen and Americans followed the Russian Company in carrying these furs to her market, so that Pennant, the English naturalist, impressed by the peculiar advantages of the coast, exclaimed, “What a profitable trade [with China] might not a colony carry on, was it possible to penetrate to these parts of North America by means of the rivers and lakes!”[21] Under the present treaty this coast is ours.

The absence of harbors belonging to the United States on the Pacific limits the outlets of the country. On that whole extent, from Panama to Puget Sound, the only harbor of any considerable value is San Francisco. Further north the harbors are abundant, and they are all nearer to the great marts of Japan and China. But San Francisco itself will be nearer by the way of the Aleutians than by Honolulu. The projection of maps is not always calculated to present an accurate idea of distances. From measurement on a globe it appears that a voyage from San Francisco to Hong Kong by the common way of the Sandwich Islands is 7,140 miles, but by way of the Aleutian Islands it is only 6,060 miles, being a saving of more than one thousand miles, with the enormous additional advantage of being obliged to carry much less coal. Of course a voyage from Sitka, or from Puget Sound, the terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad, would be shorter still.

The advantages to the Pacific coast have two aspects,—one domestic, and the other foreign. Not only does the treaty extend the coasting trade of California, Oregon, and Washington Territory northward, but it also extends the base of commerce with China and Japan.

To unite the East of Asia with the West of America is the aspiration of commerce now as when the English navigator recorded his voyage. Of course, whatever helps this result is an advantage. The Pacific Railroad is such an advantage; for, though running westward, it will be, when completed, a new highway to the East. This treaty is another advantage; for nothing can be clearer than that the western coast must exercise an attraction which will be felt in China and Japan just in proportion as it is occupied by a commercial people communicating readily with the Atlantic and with Europe. This cannot be without consequences not less important politically than commercially. Owing so much to the Union, the people there will be bound to it anew, and the national unity will receive another confirmation. Thus the whole country will be a gainer. So are we knit together that the advantages to the Pacific coast will contribute to the general welfare.

2. Extension of Dominion.—The extension of dominion is another consideration calculated to captivate the public mind. Few are so cold or philosophical as to regard with insensibility a widening of the bounds of country. Wars have been regarded as successful, when they have given a new territory. The discoverer who had planted the flag of his sovereign on a distant coast has been received as a conqueror. The ingratitude exhibited to Columbus during his later days was compensated by the epitaph, that he had “found a new world for Castile and Leon.”[22] His discoveries were[Pg 40] continued by other navigators, and Spain girdled the earth with her possessions. Portugal, France, Holland, England, each followed the example of Spain, and rejoiced in extended empire.

Territorial acquisitions are among the landmarks of our history. In 1803, Louisiana, embracing the valley of the Mississippi, was acquired from France for fifteen million dollars. In 1819, Florida was acquired from Spain for about three million dollars. In 1845, Texas was annexed without purchase, but subsequently, under the compromises of 1850, an allowance of twelve and three fourth million dollars was made to her. In 1848, California, New Mexico, and Utah were acquired from Mexico after war, and on payment of fifteen million dollars. In 1854, Arizona was acquired from Mexico for ten million dollars. And now it is proposed to acquire Russian America.

The passion for acquisition, so strong in the individual, is not less strong in the community. A nation seeks an outlying territory, as an individual seeks an outlying farm. The passion shows itself constantly. France, passing into Africa, has annexed Algeria. Spain set her face in the same direction, but without the same success. There are two great powers with which annexion has become a habit. One is Russia, which from the time of Peter has been moving her flag forward in every direction, so that on every side her limits have been extended. Even now the report comes that she is lifting her southern landmarks in Asia, so as to carry her boundary to India. The other annexionist is Great Britain, which from time to time adds another province to her Indian empire. If the United States have from time to time added to their dominion, they have only[Pg 41] yielded to the universal passion, although I do not forget that the late Theodore Parker was accustomed to speak of Anglo-Saxons as among all people remarkable for “greed of land.” It was land, not gold, that aroused the Anglo-Saxon phlegm. I doubt, however, if this passion be stronger with us than with others, except, perhaps, that in a community where all participate in government the national sentiments are more active. It is common to the human family. There are few anywhere who could hear of a considerable accession of territory, obtained peacefully and honestly, without a pride of country, even if at certain moments the judgment hesitated. With increased size on the map there is increased consciousness of strength, and the heart of the citizen throbs anew as he traces the extending line.

3. Extension of Republican Institutions.—More than the extension of dominion is the extension of republican institutions, which is a traditional aspiration. It was in this spirit that Independence was achieved. In the name of Human Rights our fathers overthrew the kingly power, whose representative was George the Third. They set themselves openly against this form of government. They were against it for themselves, and offered their example to mankind. They were Roman in character, and turned to Roman lessons. With cynical austerity the early Cato said that kings were “carnivorous animals,” and probably at his instance it was decreed by the Roman Senate that no king should be allowed within the gates of the city. A kindred sentiment, with less austerity of form, has been received from our fathers; but our city can be nothing less than the[Pg 42] North American continent, with its gates on all the surrounding seas.

John Adams, in the preface to his Defence of the American Constitutions, written in London, where he resided at the time as minister, and dated January 1, 1787, at Grosvenor Square, the central seat of aristocratic fashion, after exposing the fabulous origin of the kingly power in contrast with the simple origin of our republican constitutions, thus for a moment lifts the curtain: “Thirteen governments,” he says plainly, “thus founded on the natural authority of the people alone, without a pretence of miracle or mystery, and which are destined to spread over the northern part of that whole quarter of the globe, are a great point gained in favor of the rights of mankind.”[23] Thus, according to the prophetic minister, even at that early day was the destiny of the Republic manifest. It was to spread over the northern part of the American quarter of the globe, and it was to help the rights of mankind.

By the text of our Constitution, the United States are bound to guaranty “a republican form of government” to every State in the Union; but this obligation, which is applicable only at home, is an unquestionable indication of the national aspiration everywhere. The Republic is something more than a local policy; it is a general principle, not to be forgotten at any time, especially when the opportunity is presented of bringing an immense region within its influence. Elsewhere it has for the present failed; but on this account our example is more important. Who can forget the generous lament of Lord Byron, whose passion for Freedom was not mitigated by his rank as[Pg 43] an hereditary legislator of England, when he exclaims, in memorable verse,—

Who can forget the salutation which the poet sends to the “one great clime,” which, nursed in Freedom, enjoys what he calls the “proud distinction” of not being confounded with other lands,—

The present treaty is a visible step in the occupation of the whole North American continent. As such it will be recognized by the world and accepted by the American people. But the treaty involves something more. We dismiss one other monarch from the continent. One by one they have retired,—first France, then Spain, then France again, and now Russia,—all giving way to the absorbing Unity declared in the national motto, E pluribus unum.

4. Anticipation of Great Britain.—Another motive to this acquisition may be found in the desire to anticipate imagined schemes or necessities of Great Britain. With regard to all these I confess doubt; and yet, if we credit report, it would seem as if there were already a British movement in this direction. Sometimes it is said that Great Britain desires to buy, if Russia will sell. Sir George Simpson, Governor-in-chief of the Hudson’s Bay Company, declared, that, without the strip on the coast underlet to them by the Russian Company, the interior would be “comparatively useless to England.”[24] Here, then, is provocation[Pg 44] to buy. Sometimes report assumes a graver character. A German scientific journal, in an elaborate paper entitled “The Russian Colonies on the Northwest Coast of America,” after referring to the constant “pressure” upon Russia, proceeds to say that there are already crowds of adventurers from British Columbia and California now at the gold mines on the Stikine, which flows from British territory through the Russian possessions, who openly declare their purpose of driving the Russians out of this region. I refer to the “Archiv für Wissenschaftliche Kunde von Russland,”[25] edited at Berlin as late as 1863, by A. Erman, and undoubtedly the leading authority on Russian questions. At the same time it presents a curious passage bearing directly on British policy, purporting to be taken from the “British Colonist,” a newspaper of Victoria, on Vancouver’s Island. As this was regarded of sufficient importance to be translated into German for the instruction of scientific readers, I am justified in laying it before you, restored from German to English.

“The information which we daily publish from the Stikine River very naturally excites public attention in a high degree. Whether the territory through which the river flows be regarded from a political, commercial, or industrial point of view, it promises within a short time to awaken a still more general interest. Not only will the intervention of the royal jurisdiction be demanded in order to give it a complete form of government, but, if the land proves as rich as there is now reason to believe it to be, it is not improbable that it will result in negotiations between England and Russia for the cession of the sea-coast to the British Crown. It is not to be supposed that a stream like the Stikine, which[Pg 45] is navigable for steamers from one hundred and seventy to one hundred and ninety miles, which waters a territory so rich in gold that it will attract myriads of men,—that the commerce upon such a road can always pass through a Russian gateway of thirty miles from the sea-coast to the interior. The English population which occupies the interior cannot be so easily managed by the Russians as the Stikine Indians of the coast manage the Indians of the interior. Our business must be in British hands. Our resources, our energies, our spirit of enterprise cannot be employed in building up a Russian emporium at the mouth of the Stikine. We must have for our merchandise a depot over which the British flag waves. By the treaty of 1825 the navigation of the river is secured to us. The navigation of the Mississippi was also open to the United States before the Louisiana purchase; but the growing strength of the North made the acquisition of that territory, either by purchase or by force of arms, an inevitable necessity. We look upon the sea-coast of the Stikine region in the same light. The strip of land which stretches along from Portland Canal to Mount St. Elias, with a breadth of thirty miles, and which, according to the treaty of 1825, forms a part of Russian America, must eventually become the property of Great Britain, either as the direct result of the gold discoveries, or from causes as yet not fully developed, but whose operation is certain. For can we reasonably suppose that the strip, three hundred miles long and thirty miles wide, which is used by the Russians solely for the collection of furs and walrus-teeth, will forever control the entrance to our immense northern territory? It is a principle of England to acquire territory only for purposes of defence. Canada, Nova Scotia, Malta, the Cape of Good Hope, and the greater part of our Indian possessions were all acquired for purposes of defence. In Africa, India, and China the same rule is followed by the Government to-day. With a power like Russia it would perhaps be more[Pg 46] difficult to arrange matters; but if we need the sea-coast in order to protect and maintain our commerce with an interior rich in precious metals, then we must have it. The United States needed Florida and Louisiana, and took them. We need the coast of New Norfolk and New Cornwall.

“It is just as much the destiny of our Anglo-Norman race to possess the whole of Russian America, however desolate and inhospitable it may be, as it has been that of the Russian Northmen to possess themselves of Northern Europe and Asia. As the Wandering Jew and his phantom, so will the Anglo-Norman and the Russian yet gaze at each other from the opposite sides of Behring Strait. Between the two races the northern halves of the Old and New World must be divided. America must be ours.

“The recent discovery of the precious metals in our hyperborean Eldorado will most probably hasten the annexation of the territory in question. It can hardly be doubted that the gold region of the Stikine extends away to the western affluents of the Mackenzie. In this case the increase of the business and of the population will exceed our most sanguine expectations. Who shall reap the profit of this? The mouths of rivers, both before and since the time of railroads, have controlled the business of the interior. To our national pride the thought, however, is intolerable, that the Russian griffin should possess a point which is indebted to the British lion for its importance. The mouth of the Stikine must be ours,—or at least a harbor of export must be established on British soil from which our steamers can pass the Russian belt. Fort Simpson, Dundas Island, Portland Canal, or some other convenient point, might be selected for this purpose. The necessity of speedy measures, in order to secure the control of the Stikine, is manifest. If we let slip the opportunity, we shall live to see a Russian city arise at the gates of a British colony.”

Thus, if we credit this colonial ejaculation, caught up[Pg 47] and preserved by German science, the Russian possessions were destined to round and complete the domain of Great Britain on this continent. The Russian “griffin” was to give way to the British “lion.” The Anglo-Norman was to be master as far as Behring Strait, across which he might survey his Russian neighbor. How this was to be accomplished is not precisely explained. The promises of gold on the Stikine failed, and it is not improbable that this colonial plan was as unsubstantial. Colonists become excited easily. This is not the first time that Russian America has been menaced in a similar way. During the Crimean War there seemed to be in Canada a spirit not unlike that of the Vancouver journalist, unless we are misled by the able pamphlet[26] of Mr. A. K. Roche, of Quebec, where, after describing Russian America as “richer in resources and capabilities than it has hitherto been allowed to be, either by the English, who shamefully gave it up, or by the Russians, who cunningly obtained it,” the author urges an expedition for its conquest and annexion. His proposition fell on the happy termination of the war, but it exists as a warning, with notice also of a former English title, “shamefully” abandoned.

This region is distant enough from Great Britain; but there is an incident of past history which shows that distance from the metropolitan government has not excluded the idea of war. Great Britain could hardly be more jealous of Russia on these coasts than was Spain in a former day, if we listen to the report of Humboldt. I refer again to his authoritative work, “Essai Politique sur la Nouvelle-Espagne,”[27] where it is recorded, that, as early as 1788, even while peace was still unbroken, the[Pg 48] Spaniards could not bear the idea of Russians in this region, and when, in 1799, the Emperor Paul declared war on Spain, the hardy project was formed of an expedition from the Mexican ports of Monterey and San Blas against the Russian colonies; on which the philosophic traveller remarks, in words which are recalled by the Vancouver manifesto, that, “if this project had been executed, the world would have witnessed two nations in conflict, which, occupying the opposite extremities of Europe, found themselves neighbors in the other hemisphere on the eastern and western boundaries of their vast empires.” Thus, notwithstanding an intervening circuit of half the globe, two great powers were about to encounter each other on these coasts. But I hesitate to believe that the British of our day, in any considerable numbers, have adopted the early Spanish disquietude at the presence of Russia on this continent.