THE PORTSMOUTH ROAD

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

ENGLISH PEN ARTISTS OF TO-DAY: Examples of their work, with some Criticisms and Appreciations. Super royal 4to, £3 3s. net.

THE BRIGHTON ROAD: Old Times and New on a Classic Highway. With 95 Illustrations by the Author and from old prints. Demy 8vo, 16s.

FROM PADDINGTON TO PENZANCE: The Record of a Summer Tramp. With 105 Illustrations by the Author. Demy 8vo, 16s.

A PRACTICAL HANDBOOK OF DRAWING FOR MODERN METHODS OF REPRODUCTION. Illustrated by the Author and others. Demy 8vo, 7s. 6d.

THE MARCHES OF WALES: Notes and Impressions on the Welsh Borders, from the Severn Sea to the Sands o’ Dee. With 115 Illustrations by the Author and from old-time portraits. Demy 8vo, 16s.

REVOLTED WOMAN: Past, Present, and to Come. Illustrated by the Author and from old-time portraits. Demy 8vo, 5s. net.

THE DOVER ROAD: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike. With 100 Illustrations by the Author and from other sources. Demy 8vo. [In the Press.

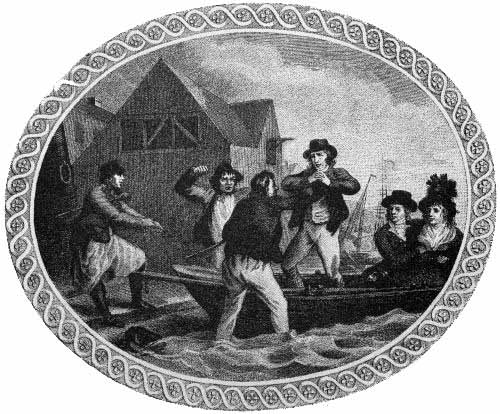

From a painting by George Morland.

| “Till, woe is me, so lubberly, The vermin came and pressed me.” |

THE PORTSMOUTH

ROAD AND ITS TRIBUTARIES:

TO-DAY AND IN DAYS OF OLD.

By CHARLES G. HARPER,

AUTHOR OF

The Brighton Road,

Marches of Wales,

Drawing for Reproduction,

&c., &c., &c.

Illustrated by the Author, and from Old-time Prints and

Pictures.

London: CHAPMAN & HALL Limited

1895

(All Rights Reserved.)

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

To HENRY REICHARDT, Esq.

My dear Reichardt,

Here is the result of two years’ hard work for your perusal; the outcome of delving amid musty, dusty files of by-gone newspapers; of research among forgotten books, and pamphlets curious and controversial; of country jaunts along this old road both for pleasures sake and for taking the notes and sketches that go towards making up the story of this old highway.

You will appreciate, more than most, the difficulties of contriving a well-ordered narrative of times so clean forgotten as those of old-road travel, and better still will you perceive the largeness of the task of transmuting the notes and sketches of this undertaking into paper and print. Hence this dedication.

Yours, &c.,

CHARLES G. HARPER.

There has been of late years a remarkable and widespread revival of interest in the old coach-roads of England; a revival chiefly owing to the modern amateur’s enthusiasm for coaching; partly due to the healthy sport and pastime of cycling, that brings so many afield from populous cities who would otherwise grow stunted in body and dull of brain; and in degree owing to the contemplative spirit that takes delight in scenes of by-gone commerce and activity, prosaic enough, to the most of them that lived in the Coaching Age, but now become hallowed by mere lapse of years and the supersession of horse-flesh by steam-power.

The Story of the Roads belongs now to History, and History is, to your thoughtful man, quite as interesting as the best of novels. Sixty years ago the Story of the Roads was brought to an end, and at that time (so unheeded is the romance of every-day life) it seemed a story of the most commonplace type, not worthy the telling. But we have gained what was of necessity denied our fathers and grandfathers in this matter—the charm of Historical Perspective, that lends a saving grace to experiences of the most ordinary description, and to happenings the most untoward. Our forebears travelled the[Pg x] roads from necessity, and saw nothing save unromantic discomforts in their journeyings to and fro. We who read the records of their times are apt to lament their passing, and to wish the leisured life and not a few of the usages of our grandfathers back again. The wish is vain, but natural, for it is a characteristic of every succeeding generation to look back lovingly on times past, and in the retrospect to see in roseate colours what was dull and, neutral-tinted to folk who lived their lives in those by-gone days.

If we only could pierce to the thought of æons past, perhaps we should find the men of the Stone Age regretting the times of the Arboreal Ancestor, and should discover that distant relative, while swinging by his prehensile tail from the branches of some forest tree, lamenting the careless, irresponsible life of his remote forebear, the Primitive Pre-atomic Globule.

However that may be, certain it is that when our day is done, when Steam shall have been dethroned and natural forces of which we know nothing have revolutionized the lives of our descendants, those heirs of all the ages will look back regretfully upon this Era of ours, and wistfully meditate upon the romantic life we led towards the end of the nineteenth century!

The glamour of old-time travel has appealed to me equally with others of my time, and has led me to explore the old coach-roads and their records. Work of this kind is a pleasure, and the programme I have mapped out of treating all the classic roads of England in this wise, is, though long and difficult, not (to quote a horsey phrase suitable to this subject) all “collar work.”

CHARLES G. HARPER.

35, Connaught Street, Hyde Park,

London, April 1895.

| SEPARATE PLATES | ||

| PAGE | ||

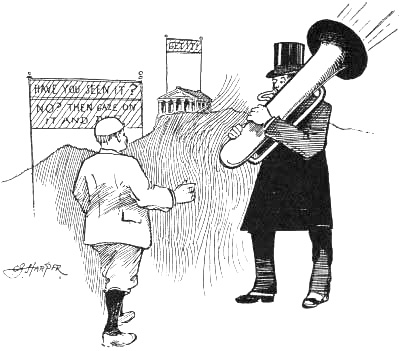

| 1. | The Press Gang. By George Morland. | Frontispiece. |

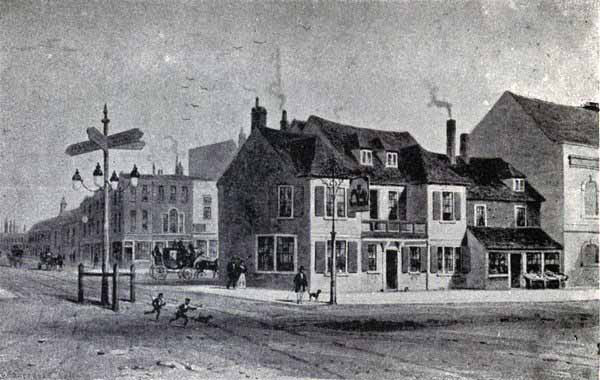

| 2. | Old “Elephant and Castle,” 1824 | 22 |

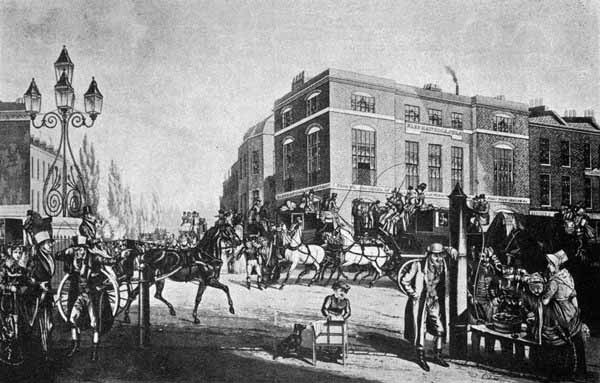

| 3. | “Elephant and Castle,” 1826 | 30 |

| 4. | Admiral Byng | 48 |

| 5. | A Strange Sight Some Time Hence | 52 |

| 6. | The Shooting of Admiral Byng | 56 |

| 7. | William Pitt | 74 |

| 8. | The Recruiting Sergeant | 90 |

| 9. | Road and Rail: Ditton Marsh, Night | 94 |

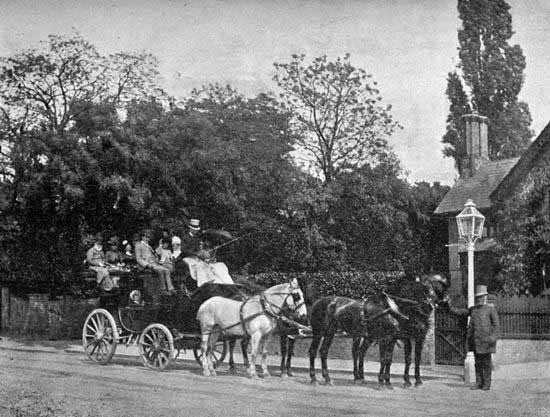

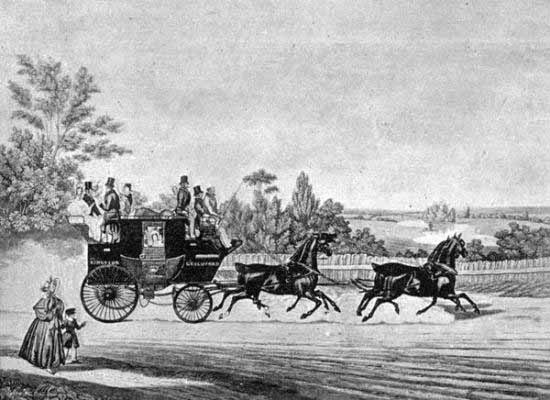

| 10. | The “New Times” Guildford Coach | 98 |

| 11. | The “Tally-ho” Hampton Court and Dorking Coach | 104 |

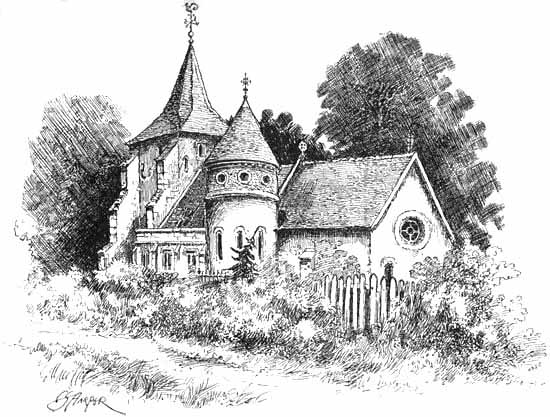

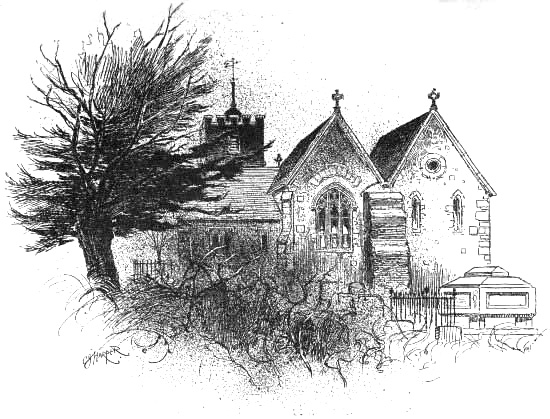

| 12. | Mickleham Church | 108 |

| 13. | Brockham Bridge | 114 |

| 14. | Esher Place | 120 |

| 15. | Lord Clive | 124 |

| 16. | Princess Charlotte of Wales | 128 |

| 17. | The “Anchor,” Ripley | 142 |

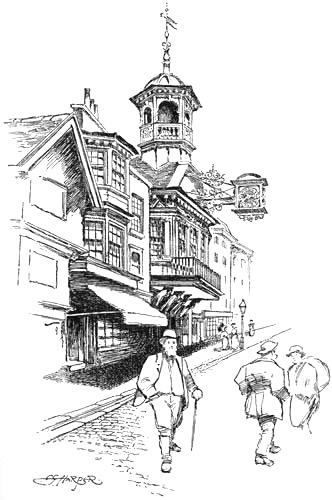

| 18. | Guildhall, Guildford | 148 |

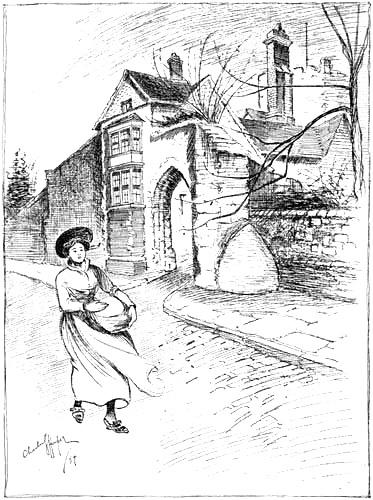

| 19. | Castle Arch | 152 |

| 20. | An Inn Yard, 1747. After Hogarth | 162 |

| 21. | The “Red Rover” Guildford and Southampton Coach | 166 |

| [Pg xii]22. | St. Catherine’s Chapel. After J. M. W. Turner | 170 |

| 23. | Mary Tofts | 178 |

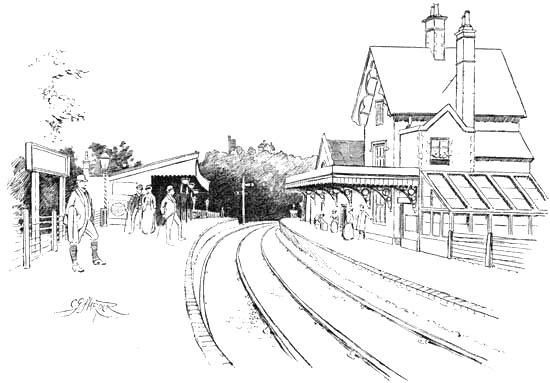

| 24. | New Godalming Station | 184 |

| 25. | The Devil’s Punch Bowl | 194 |

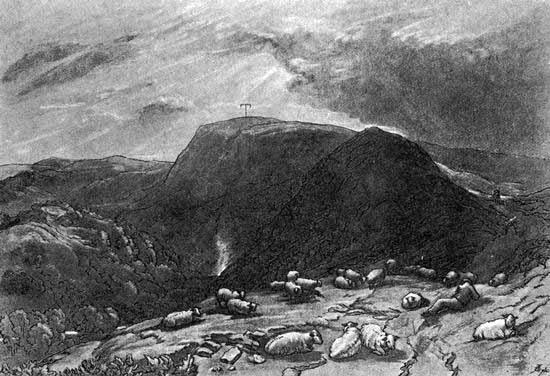

| 26. | Hindhead. After J. M. W. Turner | 198 |

| 27. | Tyndall’s House | 208 |

| 28. | Samuel Pepys | 236 |

| 29. | John Wilkes | 240 |

| 30. | Sailors Carousing. From a Sketch by Rowlandson | 252 |

| 31. | The “Flying Bull” Inn | 268 |

| 32. | Petersfield Market-Place | 278 |

| 33. | The “Coach and Horses” Inn | 298 |

| 34. | Catherington Church | 320 |

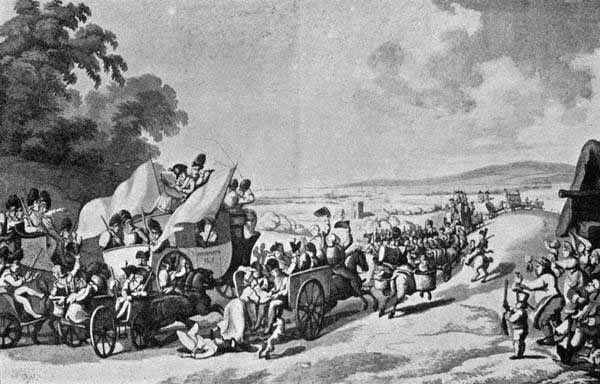

| 35. | An Extraordinary Scene on the Portsmouth Road. By Rowlandson | 330 |

| 36. | The Sailor’s Return | 334 |

| 37. | True Blue; or Britain’s Jolly Tars Paid Off at Portsmouth, 1797. By Isaac Cruikshank |

338 |

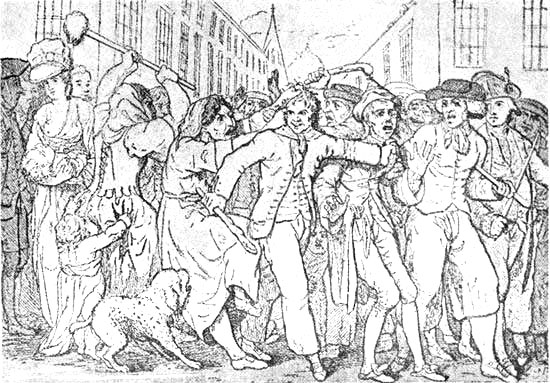

| 38. | The Liberty of the Subject, 1782. By James Gillray | 346 |

| [Pg xiii] | ||

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN TEXT | ||

| PAGE | ||

| The Revellers | 12 | |

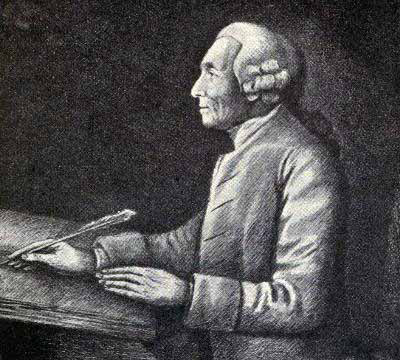

| Edward Gibbon | 19 | |

| “Dog and Duck” Tavern | 28 | |

| Sign of the “Dog and Duck” | 29 | |

| Jonas Hanway | 43 | |

| “If the shades of those antagonists foregather” | 44 | |

| The First Umbrella | 46 | |

| The “Green Man,” Putney Heath | 70 | |

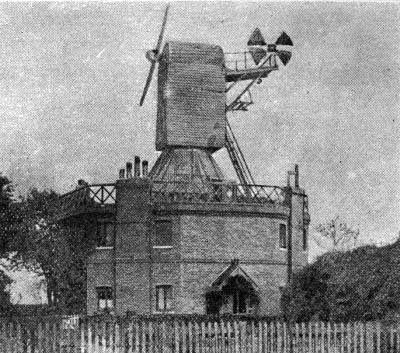

| The Windmill, Wimbledon Common | 74 | |

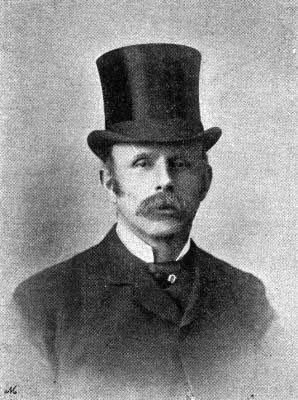

| Mr. Walter Shoolbred | 97 | |

| Boots at the “Bear” | 102 | |

| The “Bear,” Esher | 103 | |

| Burford Bridge | 111 | |

| The “White Horse,” Dorking | 112 | |

| The Road to Dorking | 113 | |

| Castle Mill | 117 | |

| Cobham Churchyard | 137 | |

| Pain’s Hill | 139 | |

| Fame up-to-Date | 142 | |

| Herbert Liddell Cortis | 146 | |

| Market-House, Godalming | 176 | |

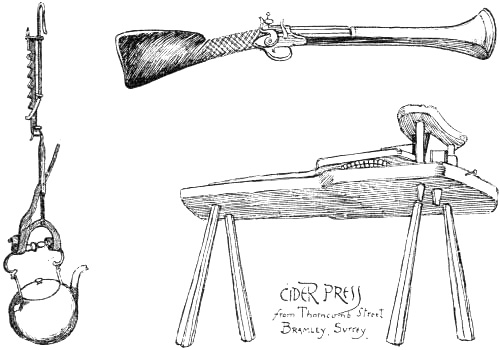

| Charterhouse Relics | 189 | |

| Gowser Jug | 190 | |

| Wesley | 191 | |

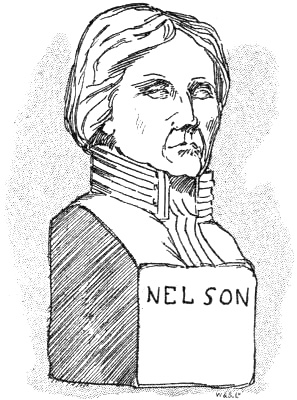

| Bust of Nelson | 192 | |

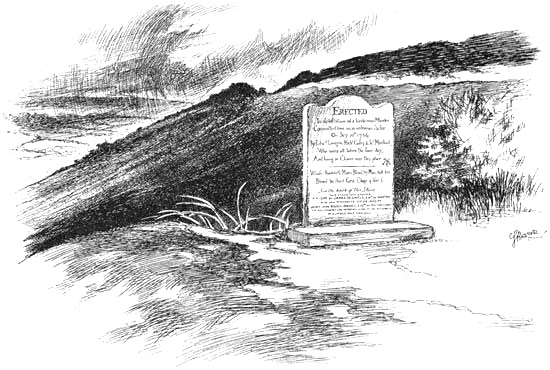

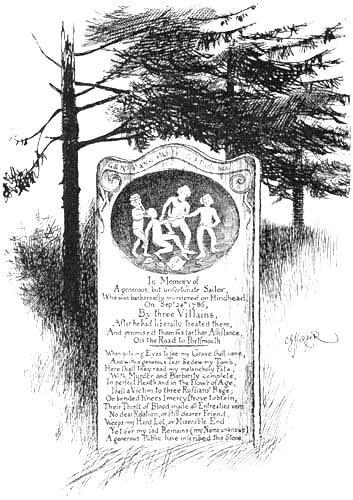

| Tombstone, Thursley | 204 | |

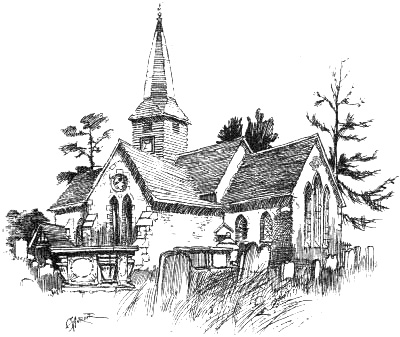

| Thursley Church | 205 | |

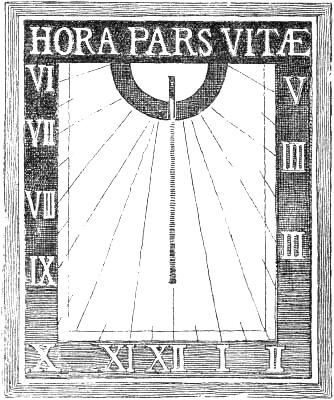

| [Pg xiv] | Sun-dial, Thursley | 206 |

| “Considering Cap” | 223 | |

| Milland Chapel | 260 | |

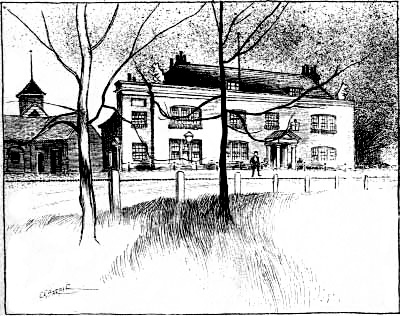

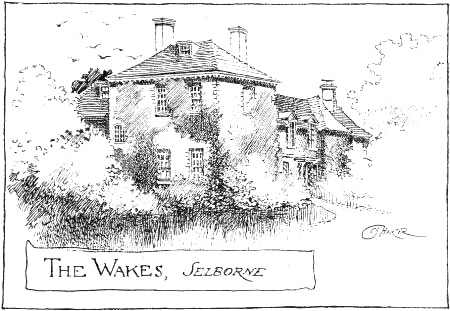

| “The Wakes,” Selborne | 261 | |

| Badge of the Selborne Society | 267 | |

| The “Flying Bull” Sign | 271 | |

| The “Jolly Drovers” | 272 | |

| “Shaved with Trouble and Cold Water” | 284 | |

| Edward Gibbon | 288 | |

| Windy Weather | 304 | |

| Benighted | 319 | |

| Dancing Sailor | 361 | |

THE ROAD TO PORTSMOUTH

| Miles | |

| Stone’s End, Borough, to— | |

| Newington | ¼ |

| Vauxhall | 1½ |

| Battersea Rise | 4 |

| Wandsworth (cross River Wandle) | 5½ |

| Tibbet’s Corner, Putney Heath | 7¾ |

| “Robin Hood,” Kingston Vale | 9 |

| Norbiton Church | 11¼ |

| Kingston Market-place | 12 |

| Thames Ditton | 13¾ |

| Esher | 16 |

| Cobham Street (cross River Mole) | 19½ |

| Wisley Common | 20¼ |

| Ripley | 23½ |

| Guildford (cross River Wey) | 29½ |

| St. Catherine’s Hill | 30½ |

| Peasmarsh Common (cross River Wey) | 31¼ |

| Godalming | 34 |

| Milford | 35¾ |

| Moushill and Witley Commons | 36¼ |

| Hammer Ponds | 38½ |

| Hindhead (Gibbet Hill) | 41¼ |

| Cold Ash Hill and “Seven Thorns” Inn | 44¼ |

| Liphook (“Royal Anchor”) | 46¾ |

| Milland Common | 47½ |

| [Pg xvi]Rake | 50¼ |

| Sheet Bridge (cross River Rother) | 53¾ |

| Petersfield | 55 |

| “Coach and Horses” | 59 |

| Horndean | 62½ |

| Waterlooville and White Lane End | 65½ |

| Purbrook (cross Purbrook stream) | 66½ |

| Cosham | 68¼ |

| Hilsea | 69½ |

| North End | 70¾ |

| Landport | 71½ |

| Portsmouth Town | 72 |

| Portsmouth, Victoria Pier | 73 |

I

The Portsmouth Road is measured (or was measured when road-travel was the only way of travelling on terra firma, and coaches the chiefest machines of progression) from the Stone’s End, Borough. It went by Vauxhall to Wandsworth, Putney Heath, Kingston-on-Thames, Guildford, and Petersfield; and thence came presently into Portsmouth through the Forest of Bere and past the frowning battlements of Porchester. The distance was, according to Cary,—that invaluable guide, philosopher, and friend of our grandfathers,—seventy-one miles, seven furlongs; and[Pg 2] our forebears who prayerfully entrusted their bodies to the dangers of the roads and resigned their souls to Providence, were hurried along this route at the break-neck speed of something under eight miles an hour, with their hearts in their mouths and their money in their boots for fear of the highwaymen who infested the roads, from London suburbs to the gates of Portsmouth Citadel.

“Cary’s Itinerary” for 1821 gives nine hours as the speediest journey performed in that year by what was then considered the meteoric and previously unheard-of swiftness of the “Rocket,” which, in that new and most fashionable era of mail and stage-coach travelling, had deserted the grimy and decidedly unfashionable precincts of the Borough and the “Elephant and Castle,” for modish Piccadilly. So imagine the “Rocket” (do you not perceive the subtle allusion to speed in that title?) starting from the “White Bear,” Piccadilly, which stood where the “Criterion” now soars into the clouds—any morning at nine o’clock, to the flourishes of the guard’s “yard of tin,” and to the admiration of a motley crowd of ’prentice-boys; Corinthians, still hazy in their ideas and unsteady on their legs from debauches and card-playing in the night-houses of the Haymarket round the corner; and of a frowzy, importunate knot of Jew pedlars, and hawkers of all manner of useful and useless things which might, to a vivid imagination, seem useful on a journey by coach. Away, with crack of whip, tinful, rather than tuneful, fanfare, performed by scarlet-coated, purple-faced guard, and with merry rattle of harness, to Putney, where, upon the Heath, the coach joined the

[Pg 3]

“... old road, the high-road,

The road that’s always new,”

thus to paraphrase the poet.

They were jolly coach-loads that fared along the roads in coaching days, and, truly, all their jollity was needed, for unearthly hours, insufficient protection from inclement weather, and the tolerable certainty of falling in with thieves on their way, were experiences and contingencies that, one might imagine, could scarce fail of depressing the most buoyant spirits. But our forebears were composed of less delicate nerves and tougher thews and sinews than ourselves. Possibly they had not our veneer of refinement; they certainly possessed a most happy ignorance of science and art; of microbes, and all the recondite ailments that perplex us moderns, they knew nothing; they did all their work by that glorious rule, the rule of thumb; and for their food, they lived on roast beef and home-brewed ale, and damned kickshaws, new-fangled notions, gentility, and a hundred other innovations whole-heartedly, like so many Cobbetts. And Cobbett, in very truth, is the pattern and exemplar of the old-time Englishman, who cursed tea, paper money, “gentlemen” farmers, and innumerable things that, innovations then, have long since been cast aside as old-fashioned and out of date.

The Englishman of the days of road-travel was a much more robust person than the Englishman of railway times. He had to be! The weaklings were all killed off by the rigours of the undeniably harder winters than we experience to-day, and by the rough-and-ready conditions of existence that made for the[Pg 4] survival of the strongest constitutions. Luxurious times and easier conditions of life breed their own peculiar ills, and the Englishman of a hundred years ago was a very fine animal indeed, who knew little of nerves, and, altogether, compared greatly to his own advantage with his neuralgia-stricken descendants of to-day.

Still, our ancestors saw nothing of the romance of their times. That has been left for us to discover, and that glamour in which we see their age is one afforded only by the lapse of time.

No: coaching days had their romance, more obvious perhaps to ourselves than to those who lived in the times of road-travel; but most certainly they had their own peculiar discomforts which we who are hurled at express speed in luxurious Pullman cars, or in the more exclusive and less sociable “first,” to our destination would never endure were railways abolished and the coaching era come again. I should imagine that three-fourths of us would remain at home.

Here are some of the coaching miseries experienced by one who travelled before steam had taken the place of good horseflesh, and, sooth to say, there is not much in the nature of romantic glamour attaching to them:—

Misery number one. Although your place has been contingently secured some days before, and although you have risen with the lark, yet you see the ponderous vehicle arrive full. And this, not unlikely, more than once.

2. At the end of a stage, beholding the four panting, reeking, foaming animals which have dragged you [Pg 5]twelve miles, and the stiff, galled, scraggy relay, crawling and limping out of the yard.

3. Being politely requested, at the foot of a tremendous hill, to ease the horses. Mackintoshes, vulcanized india-rubber, gutta-percha, and gossamer dust-coats unknown then.

4. An outside passenger, resolving to endure no longer “the pelting of the pitiless storm,” takes refuge, to your consternation, inside; together with his dripping hat, saturated cloak, and soaked umbrella.

5. Set down with a promiscuous party to a meal bearing no resemblance to that of a good hotel, excepting in the charge; and no time allowed in which to enjoy it.

6. Closely packed in a box, “cabin’d, cribb’d, confin’d, bound in,” with five companions morally or physically obnoxious, for two or three comfortless days and nights.

7. During a halt overhearing the coarse language of the ostlers and the tipplers of the roadside pot-house: and besieged with beggars exposing their horrible mutilations.

8. Roused from your fitful nocturnal slumber by the horn or bugle; the lashing and cracking of whips; the noisy arrivals at turnpike gates, or by a search for parcels (which, after all, are not there) under your seat: to say nothing of solicitous drivers who pester you with their entirely uncalled-for attentions.

9. Discovering, at a diverging-point in your journey, that the “Tally-ho” coach runs only every other day or so, or that it has been finally stopped.

10. Clambering from the wheel by various iron[Pg 6] projections to your elevated seat, fearful, all the while, of breaking your precious neck.

11. After threading the narrowest streets of an ancient town, entering the inn-yard by a low archway, at the imminent risk of decapitation.

12. Seeing the luggage piled “Olympus high,” so as to occasion an alarming oscillation.

13. Having the reins and whip placed in your unpractised hands while coachee indulges in a glass and chat.

14. To be, when dangling at the edge of a seat, overcome with drowsiness.

15. Exposed to piercing draughts, owing to a refractory glass; or, vice versâ, being in a minority, you are compelled, for the sake of ventilation, to thrust your umbrella accidentally through a pane.

16. At various seasons, suffocated with dust and broiled by a powerful sun; or crouching under an umbrella in a drenching rain—or petrified with cold—torn by fierce winds—struggling through snow—or wending your way through perilous floods.

17. Perceiving that a young squire is receiving an initiatory lesson into the art of driving; or that a jibbing horse, or a race with an opposition coach, is endangering your existence.

18. Losing the enjoyment, or employment, of much precious time, not only on the road, but also from subsequent fatigue.

19. Interrupted by your two rough-coated, big-buttoned, many-caped friends, the coachman and guard, who hope you will remember them before the termination of your hurried meal. Although[Pg 7] the gratuity has been frequently calculated in anticipation, you fail in making the mutual reminiscences agreeable.

Clearly this was no laudator temporis acti.

II

But there are two sides to every medal, and it would be quite as easy to draw up an equally long and convincing list of the joys of coaching. It was not always raining or snowing when you wished to go a journey. Highwaymen were always too many, but they did not lurk in every lane; and the coach was not overturned on every journey, nor, even when a coach did upset, were the spilled passengers killed and injured with the revolting circumstance and hideous complexity of a railway accident. On a trip by coach, it was possible to see something of the country and to fill one’s lungs with fresh air, instead of coal-smoke and sulphur—and so forth, ad infinitum!

The Augustan age of coaching,—by which I mean the period when George IV. was king,—was celebrated for the number of gentlemen-drivers who ran smart coaches upon the principal roads from London. Many of them mounted the box-seat for the sake of sport alone: others, who had run through their property and come to grief after the manner of the time, became drivers of necessity. They could fulfil no other useful occupation, for at that day professionalism was confined only to the Ring, and although professors[Pg 8] of the Noble Art of Self-Defence were admired and (in a sense) envied, they were not gentlemen, judge them by what standard you please. What was a poor Corinthian to do? To beg he would have been ashamed, to dig would have humiliated him no less; the only way to earn a living and yet retain the respect of his fellows, was to become a stage-coachman. He had practically no alternative. Not yet had the manly sports of cricket and football produced their professionals; lawn-tennis and cycling were not dreamed of, and the professional riders, the “makers’ amateurs,” subsidized heavily from Coventry, were a degraded class yet to be evolved by the young nineteenth century. So coachmen the young Randoms and Rake-hells of the times became, and let us do them the justice to admit that when they possessed handles to their names, they had the wit and right feeling to see that those accidents of their birth gave them no licence to assume “side” in the calling they had chosen for the love of sport or from the spur of necessity. If they were proud by nature, they pocketed their pride. They drove their best, took their fares, and pocketed their tips with the most ordinary members of the coaching fraternity, and they were a jolly band. Such were Sir St. Vincent Cotton; Stevenson of the “Brighton Age,” a graduate he of Trinity College, Cambridge; and Captain Tyrwhitt Jones.

St. Vincent Cotton, known familiarly to his contemporaries as “Vinny,” was one who drove a coach for a livelihood, and was not ashamed to own it. He became reduced, as a consequence of his own[Pg 9] folly, from an income of five thousand a year to nothing; but he took Fortune’s frowns with all the nonchalance of a true sportsman, and was to all appearance as light-hearted when he drove for a weekly wage as when he handled the reins upon his own drag.

“One day,” says one who knew him, “an old friend booked a place and got up on the box-seat beside him, and a jolly five hours they had behind one of the finest teams in England. When they came to their journey’s end, the friend was rather put to it as to what he ought to do; but he frankly put out his hand to shake hands, and offered him a sovereign. ‘No, no,’ said the coachman. ‘Put that in your pocket, and give me the half-crown you give to another coachman; and always come by me, and tell all your friends and my old friends to do the same. A sovereign might be all very well for once, but if you think that necessary for to-day you would not like to feel it necessary the many times in the year you run down this way. Half-a-crown is the trade price. Stick to that, and let us have many a merry meeting and talk of old times.’”

“What was right,” says our author, “he took as a matter of course in his business, as I can testify by what happened between him and two of my young brothers. They had to go to school at the town to which their old friend the new coachman drove. Of course they would go by him whom they had known all their little lives. They booked their places and paid their money, and were proud to sit behind their friend with such a splendid team.

[Pg 10]“The Baronet chaffed and had fun with the boys, as he was always hail-fellow-well-met with every one, old and young, all the way down; and at the end, when he shook hands and did not see them prepare to give him anything, he said, as they were turning away, ‘Now, you young chaps, hasn’t your father given you anything for the coachman?’

“‘Yes,’ they said, looking sheepish, ‘he gave us two shillings each, but we didn’t know what to do: we daren’t give it to you.’

“‘Oh,’ said he, ‘it’s all right. You hand it over to me and come back with me next holidays, and bring me a coach-full of your fellows. Good-bye.’”

“I drive for a livelihood,” said the Baronet to a friend. “Jones, Worcester, and Stevenson have their liveried servants behind, who pack the baggage and take all short fares and pocket all the fees. That’s all very well for them. I do all myself, and the more civil I am (particularly to the old ladies) the larger fees I get.” And with that he stowed away a trunk in the boot, and turning down the steps, handed into the coach, with the greatest care and civility, a fat old woman, saying as he remounted the box, “There, that will bring me something like a fee.”

The Baronet made three hundred a year out of this coach, and got his sport out of it for nothing.

III

The “Rocket,” and the other fashionable West-end coaches of the Regency and George IV.’s reign,[Pg 11] scorning the plebeian starting-point of the “Elephant and Castle,” whence the second and third-rate coaches, the “rumble-tumbles” and the stage-wagons set out, took their departure from the old City inns, and, calling at the Piccadilly hostelries on their way, crossed the Thames at Putney, even as Captain Hargreaves’ modern Portsmouth “Rocket” did in the notable coaching revival some years since, and as Mr. Shoolbred’s Guildford coach, the “New Times,” does now.

Here they paid their tolls at the old bridge—eighteenpence a time—and laboriously toiled up the long hill that leads to Putney Heath, not without some narrow escapes of the “outsiders” from having their heads brought into sudden and violent contact with the archway of the old toll-house that—though by no means picturesque in itself—was so strange and curious an object in its position, straddling across the roadway.

What Londoner worthy the name does not regret the old crazy, timbered bridge that connected Fulham with Putney? Granted that it was inconveniently narrow, and humped in unexpected places, like a dromedary; conceded that its many and mazy piers obstructed navigation and hindered the tides; allowing every objection against it, old Putney Bridge was infinitely more interesting than the present one of stone that sits so low in the water and offends the eye with its matter-of-fact regularity, proclaiming fat contracts and the unsympathetic baldness of outline characteristic of the engineer’s most admired efforts.

[Pg 12]Perhaps an artist sees beauty where less privileged people discover only ugliness; how else shall I account for the singular preference of the guide-book, in which I read that “the ugly wooden bridge was replaced in 1886 by an elegant granite structure”?

THE REVELLERS.

Old Putney Bridge could never have been anything else than picturesque, from the date of its opening, in 1729, to its final demolition twelve years ago: the new bridge will never be less than ugly and formal, and an eyesore in the broad reach that was spanned so finely by the old timber structure for over a hundred and fifty years. The toll for one person walking across the bridge was but a halfpenny, but it[Pg 13] frequently happened in the old days that people had not even that small coin to pay their passage, and in such cases it was the recognized custom for the tollman to take their hats for security. The old gatekeepers of Putney Bridge were provided with impressive-looking gowns and wore something the appearance of beadles. Also they were provided with stout staves, which frequently came in useful during the rows which were continually occurring upon the occasions when wayfarers had their hats snatched off. “Your halfpenny or your hat” was an offensive cry, and, together with the scuffles with strayed revellers, left little peace to the guardians of the bridge.

Everything is altered here since the old coaching-days; everything, that is to say, but the course of the river and the trim churches of Fulham and Putney, whose towers rise in rivalry from either shore. And Putney church-tower is altogether dwarfed by the huge public-house that stands opposite: a flaunting insult scarcely less flagrant than the shame put upon the House of God by Cromwell and his fellows who sate in council of war in the chancel, and discussed battles and schemed strife and bloodshed over the table sacred to the Lord’s Communion. Putney has suffered from its nearness to London. Where, until ten years ago, old mansions and equally old shops lined its steep High Street, there are now only rows of pretentious frontages occupied by up-to-date butchers and bakers and candlestick-makers; by drapers, milliners, and “stores” of the suburban, or five miles radius, variety. Gone is “Fairfax House,”[Pg 14] most impressive and dignified of suburban mansions, dating from the time of James I., and sometime the headquarters of the “Army of God and the Parliament”; gone, too, is Gibbon’s birthplace, and the very church is partly rebuilt—although that is a crime of which our forebears of 1836 are guilty. It is guilt, you will allow, who stand on the bridge and look down upon the mean exterior brick walls of the nave, worse still by comparison with the rough, weathered stones of the old tower. Every part of the church was rebuilt then, except that tower, and though the Perpendicular nave-arcade was set up again, it has been scraped and painted to a newness that seems quite of a piece with other “improvements.” All the monuments, too, were moved into fresh places when the general post of that sixty-years-old “restoration” was in progress. The dainty chantry of that notable native of Putney, Bishop West, who died in 1533, was removed from the south aisle to the chancel, and the ornate monument to Richard Lussher placed in the tower, as one enters the church from the street.

Richard Lussher was not a remarkable man, or if he was the memory of his extraordinary qualities has not been handed down to us. But if he was not remarkable, his epitaph is, as you shall judge:—

“Memoriae Sacrum.

“Here lyeth ye body of Ric: Lussher of Puttney in ye Cōnty of Surey, Esq: who married Mary, ye second daughter of George Scott of Staplefoord, tanner, in ye Cōnty of Essex, Esq: he departed ys lyfe ye 27th of September, Anoo 1618. Aetatis sue 30.

[Pg 15]

“What tounge can speake ye Vertues of ys Creature?

Whose body fayre, whose soule of rarer feature;

He livd a Saynt, he dyed an holy wight,

In Heaven on earth a Joyfull heav̄y sight.

Body, Soule united, agreed in one.

Lyke strings well tuned in an unison,

No discord harsh ys navell could untye.

’Twas Heauen ye earth ys musick did envye;

Wherefore may well be sayd he lived well,

& being dead, ye World his vertues tell.”

Some scornful commentator has called this doggerel; but I would that all doggerel were as interesting.

We have already heard of one Cromwell at Putney, but another of the same name, Thomas Cromwell,—almost as great a figure in the history of England as “His Highness” the Protector,—was born here, a good deal over a hundred years before warty-faced Oliver came and set his men in array against the King’s forces from Oxford. Thomas was the son of a blacksmith whose forge stood somewhere in the neighbourhood of the Wandsworth Road, on a site now lost; but though of such humble origin he rose to be a successor of Wolsey, that romantic figure whom we shall meet lower down the road, at Esher, who himself was of equally lowly birth, being but the son of a butcher. But while Wolsey,—that “butcher’s dogge,” as some jealous contemporary called him,—rendered much service to the Church, Cromwell, like his namesake, had a genius for destruction, and became a veritable malleus ecclesia. He it was who, unscrupulous and servile in attendance upon the King’s freaks, unctuous in flatteries of that Royal paragon of vanity, sought and obtained the Chancellorship of England,[Pg 16] by suggesting that Henry should solve all his difficulties with Rome by establishing a national Church of which he should be head. No surer way of rising to the kingly favour could have been devised. Henry listened to his adviser and took his advice, and Thomas Cromwell rose immediately to the highest pinnacle of power, a lofty altitude which in those times often turned men giddy and lost them their heads, in no figurative sense. None so bitter and implacable towards an old faith than those who, having once held it, have from one reason or another embraced new views; and Cromwell was no exception from this rule. He was most zealous and industrious in the work of disestablishing the religious houses, and the most rapacious in securing a goodly share of the spoils. He was a terror to the homeless monks and religious brethren whom his untiring industry had sent to beg their bread upon the roads, and “fierce laws, fiercely executed—an unflinching resolution which neither danger could daunt nor saintly virtue move to mercy—a long list of solemn tragedies weigh upon his memory.”

But these topmost platforms were craggy places in Henry VIII.’s time, and the occupants of such dizzy heights fell frequently with a crash that was all the greater from the depth of their fall. Wolsey had been more than usually fortunate in his disgrace, for he was ill, and died from natural causes. When his immediate successor, Sir Thomas More, fell, his life was taken upon Tower Green. “Decollat,” says a contemporary document, with a grim succinctness, “in castrum Londin: vulgo turris appellatur.” Indeed,[Pg 17] this was the common end of all them that walked arm-in-arm with the King, and could have at one time boasted his friendship in the historic phrase, “Ego et Rex meus.” Why, the boast was a sure augury of disaster. Wolsey found it so, and so also did More; and now Cromwell was to follow More to the block. That his head fell amid protestations of his belief in the Catholic faith is a singular comment upon the conduct of his life, which was chiefly passed in violent persecutions of its ministers.

Another famous man was born at Putney: Edward Gibbon, the historian. Him also we shall meet at another part of the road, but we may halt awhile to hear some personal gossip at Putney, although it would be vain to seek his birthplace to-day.

He says, in his posthumously-published “Memoirs of My Life and Writings”: “I was born at Putney, the 27th of April, O.S., in the year one thousand seven hundred and twenty-seven; the first child of the marriage of Edward Gibbon, Esq., and of Judith Porten. My lot might have been that of a slave, a savage, or a peasant; nor can I reflect without pleasure on the bounty of Nature, which cast my birth in a free and civilized country, in an age of science and philosophy, in a family of honourable rank, and decently endowed with the gifts of fortune. From my birth I have enjoyed the rights of primogeniture; but I was succeeded by five brothers and one sister, all of whom were snatched away in their infancy. My five brothers, whose names may be found in the parish register of Putney, I shall not pretend to lament.... In my ninth year,” he continues, “in a lucid interval[Pg 18] of comparative health, my father adopted the convenient and customary mode of English education; and I was sent to Kingston-upon-Thames, to a school of about seventy boys, which was kept by a Doctor Wooddeson and his assistants. Every time I have since passed over Putney Common, I have always noticed the spot where my mother, as we drove along in the coach, admonished me that I was now going into the world, and must learn to think and act for myself.”

At that time of writing he had “not forgotten how often in the year ’46 I was reviled and buffetted for the sins of my Tory ancestors.” At length, “by the common methods of discipline, at the expence of many tears and some blood, I purchased the knowledge of the Latin syntax; and, not long since, I was possessed of the dirty volumes of Phædrus and Cornelius Nepos, which I painfully construed and darkly understood.”

Gibbon’s “Miscellaneous Works,” published after his death, are prefaced by a silhouette portrait, cut in 1794 by a Mrs. Brown, and reproduced here. Lord Sheffield, who edited the volume, remarks that “the extraordinary talents of this lady have furnished as complete a likeness of Mr. Gibbon, as to person, face, and manner, as can be conceived; yet it was done in his absence.” By this counterfeit presentment we see that the author of the “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” was possessed of a singular personality, curiously out of keeping with his stately and majestic periods.

EDWARD GIBBON.

This is how Gibbon’s personal appearance struck[Pg 19] one of his contemporaries—that brilliant Irishman, Malone:—

“Independent of his literary merit, as a companion Gibbon was uncommonly agreeable. He had an immense fund of anecdote and of erudition of various kinds, both ancient and modern, and had acquired such a facility and elegance of talk that I had always great pleasure in listening to him. The manner and voice, though they were peculiar, and I believe artificial at first, did not at all offend, for they had become so appropriated as to appear natural. His indolence and inattention and ignorance about his own state are scarce credible. He had for five-and-twenty years a hydrocele, and the swelling at length was so large that he quite straddled in his walk; yet he never sought for any advice or mentioned it to his most intimate friend, Lord Sheffield, and two or three days before he died very gravely asked Lord Spencer and him whether they had perceived his malady. The answer could only be, ‘Had we eyes?’ He thought, he said, when he was at Althorp last Christmas, the ladies looked a little oddly. The fact is that poor Gibbon, strange as it may seem, imagined himself[Pg 20] well-looking, and his first motion in a mixed company of ladies and gentlemen was to the fireplace, against which he planted his back, and then, taking out his snuff-box, began to hold forth. In his late unhappy situation it was not easy for the ladies to find out where they could direct their eyes with safety, for in addition to the hydrocele it appeared after his death that he had a rupture, and it was perfectly a miracle how he had lived for some time past, his stomach being entirely out of its natural position.”

For other memories of Gibbon we must wait until we reach his ancestral acres of Buriton, near Petersfield, and meanwhile, we have come to the hill-brow, where the new route and the old meet, and the Portsmouth Road definitely begins.

There are many other memories at Putney; too many, in fact, to linger over, if we wish to come betimes to the dockyard town that is our destination.

So no more than a mention of Theodore Hook, who lived in a little house on the Fulham side of Putney Bridge, which was visited by Barham (dear, genial Tom Ingoldsby!) while rowing up the Thames one fine day. Hook was absent, and Barham wrote some impromptu verses in the hall, beginning—

“Why, gadzooks! here’s Theodore Hook’s,

Who’s the author of so many humorous books!”

But the author of those books was the author also of many practical jokes, of which the Berners Street Hoax is still the undisputed classic. But that monumental piece of foolery is not more laughable than the jape he put upon the Putney inn-keeper[Pg 21] (I think he was the landlord of the old “White Lion”).

He called one day at that house and ordered an excellent dinner, with wine and all manner of delicacies for one, and having finished his meal and made himself particularly agreeable to the host (who by some singular chance did not know his guest), he suddenly asked him if he would like to know how to be able to draw both old and mild ale from the same barrel. Of course he would! “Then,” said Hook, “I’ll show you, if you will take me down to your cellar, and will promise never to divulge the secret.” The landlord promised. “Then,” said the guest, “bring a gimlet with you, and we’ll proceed to work.” When they had reached the cellar the landlord pointed out a barrel of mild ale, and the stranger bored a hole in one side with the gimlet. “Now, landlord,” said he, “put your finger over the hole while I bore the other side.” The second hole having been bored, it was stopped, in the same way, by the landlord’s finger. “And now,” said the stranger, “where’s a glass? Didn’t you bring one?” “No,” said mine host. “But you’ll find one up-stairs,” replied the guest. “Yes; but I can’t leave the barrel, or all the ale will run away,” rejoined the landlord. “No matter,” exclaimed the stranger, “I’ll go for you,” and ran up the cellar steps for one. Meanwhile, the landlord waited patiently, embracing the barrel, for five minutes—ten minutes—a quarter of an hour, and then began to shout for the other to make haste, as he was getting the cramp. His shouts at length brought—not the stranger—but his own wife. “Well,[Pg 22] where’s the glass? where’s the gentleman?” said he. “What, the gentleman who came down here with you?” “Yes.” “Oh, he went off a quarter of an hour ago. What a pleasant-spoken gent——” “What!” cried the landlord, aghast, “what did he say?” “Why,” said his spouse, after considering a moment, “he said you had been letting him into the mysteries of the cellar.” “Letting him in,” yelled the landlord, in a rage, “letting him in! Why, confound it, woman, he let me in—he’s never paid for the dinner, wine, or anything.”

When Hook subsequently called upon the landlord and settled his bill, it is said that he and his victim had a good laugh over the affair, but if that tale is true, that landlord must have been a very forgiving man.

IV

Let us now turn our attention to the original route to Portsmouth; the road between the Stone’s End, Borough, and Wandsworth. I warrant we shall find it much more interesting than going from the West-end coach-offices with the fashionables; for they were more varied crowds that assembled round the old “Elephant and Castle” than were any of the coach-loads from the “Cross Keys,” Cheapside, or from that other old inn of coaching memories, the “Golden Cross,” Charing Cross.

OLD “ELEPHANT AND CASTLE,” 1824.

[Pg 25]Every one journeyed from the “Elephant and Castle” in the old stage-coach days, before the mails were introduced, and this well-known house early became famous. It was about 1670 that the first inn bearing this sign was erected here, on a piece of waste ground that, although situated so near the borders of busy Southwark, had been, up to the time of Cromwell and the era of the Commonwealth, quite an unconsidered and worthless plot of ground, at one period the practising-ground for archers,—hence the neighbouring title of Newington Butts,—but then barren of everything but the potsherds and general refuse of neighbouring London. In 1658, some one, willing to be generous at inconsiderable cost, gave this Place of Desolation towards the maintenance of the poor of Newington; and it is to be hoped that the poor derived much benefit from the gift. I am, however, not very sure that they found their condition much improved by such generosity. Fifteen years later, things wore a different complexion, for when we hear of the gift being confirmed in 1673, and that the premises of the “Elephant and Castle” inn were but recently built, the prospects of the poor seem to be improving in some slight degree. Documents of this period put the rent of this piece of waste at £5 per annum! and this amount had only risen to £8 10s. in the space of a hundred years. But so rapidly did the value of land now rise, that in 1776 a lease was granted at the yearly rent of £100; and fourteen years later a renewal was effected for twenty-one years at £190.

The poor of Newington should have been in excellent case by this time, unless, indeed, their numbers increased with the times. And certainly the neighbourhood had now grown by prodigious[Pg 26] leaps and bounds, and Newington Butts had now become a busy coaching centre. How rapidly the value of land had increased about this time may be judged from the results of the auction held upon the expiration of the lease in 1811. The whole of the estate was put up for auction in four lots, and a certain Jane Fisher became tenant of “the house called the ‘Elephant and Castle,’ used as a public-house,” for a term of thirty-one years, at the enormously increased rent of £405, and an immediate outlay of £1200. The whole estate realized £623 a year. As shown by a return of charities, printed for the House of Commons in 1868, the “Elephant and Castle” Charity, including fourteen houses and an investment in Government stock, yielded at that time an annual income of £1453 10s. 0d.

The two old views of the “Elephant and Castle” reproduced here, show the relative importance of the place at different periods. The first was in existence until 1824, and the larger house was built two years later. A dreadful relic of the barbarous practice by which suicides were buried in the highways, at the crossing of the roads, was discovered, some few years since, under the roadway opposite the “Elephant and Castle,” during the progress of some alterations in the paving. The mutilated skeleton of a girl was found, which had apparently been in that place for considerably over a hundred years. Local gossips at once rushed to the conclusion that this had been some undiscovered murder, but the registers of St. George’s Church, Southwark, probably afford a clue to the mystery. The significant entry [Pg 27]occurs—“1666: Abigall Smith, poisoned herself: buried in the highway neere the Fishmongers’ Almshouses.”

No one has come forward to explain the reason of this particular sign being selected. “Yt is call’d ye Elephaunt and Castell,” says an old writer, “and this is ye cognizaunce of ye Cotelers, as appeareth likewise off ye Bell Savage by Lud Gate;” but this was never the property of the Cutlers’ Company, while the site of “Belle Sauvage” is still theirs, and is marked by an old carved stone, bearing the initials “J. A.,” with a jocular-looking elephant pawing the ground and carrying a castle.

When the first “Elephant and Castle” was built on this site, the land to the westward as far as Lambeth and Kennington was quite rustic, and remained almost entirely open until the end of last century. Lambeth and Kennington were both villages, difficult of access except by water, and this tract of ground, now covered with the crowded houses of an old suburb, was known as St. George’s Fields. It was low and flat, and was traversed by broad ditches, generally full of stagnant water. Roman and British remains have been found here, and it seems likely that some prehistoric fighting was performed on this site, but as all this took place a very long while before the Portsmouth Road was thought of, I shall not propose to go back to the days of Ostorius Scapula or of Boadicea to determine the facts. Instead, I will pass over the centuries until the times of King James I., when there stood in the midst of St. George’s Fields, and on the site of Bethlehem Hospital, a disreputable tavern[Pg 28] known as the “Dog and Duck,” at which no good young man of that period who held his reputation dear would have been seen for worlds.

“DOG AND DUCK” TAVERN.

There still remains, let into the boundary-wall of “Bedlam,” the old stone sign of the “Dog and Duck,” divided into two compartments; one showing a dog holding what is intended for a duck in his mouth, while the other bears the badge of the Bridge House Estate, pointing to the fact that the property belonged to that corporation. Duck-hunting was the chiefest amusement here, and was carried on before a company the very reverse of select in the grounds attached to the tavern, where a lake and rustic arbours preceded the establishment of Rosherville.

At later periods St. George’s Fields were the scene of “Wilkes and Liberty” riots, and of the lively proceedings of Lord George Gordon’s “No Popery” enthusiasts. It is by a singular irony that upon the very spot where forty thousand rabid[Pg 29] Protestants assembled in 1780 to wreak their vengeance upon the Catholics of London, there stands to-day the Roman Catholic cathedral of St. George.

SIGN OF THE “DOG AND DUCK.”

This event brings us to the threshold of the coaching era, for in 1784, four years after the Gordon Riots, mail-coaches were introduced, and the roads were set in order. Years before, when only the slow stages were running, a journey from London to Portsmouth occupied fourteen hours, if the roads were good! Nothing is said of the time consumed on the way in the other contingency; but we may pluck a phrase from a public announcement towards the end of the seventeenth century that seems to hint at dangers and problematical arrivals. “Ye ‘Portsmouth Machine’ sets out from ye Elephant and Castell, and arrives presently by the Grace of[Pg 30] God....” In those days men did well to trust to grace, considering the condition of the roads; but in more recent times coach-proprietors put their trust in their cattle and McAdam, and dropped the piety.

A fine crowd of coaches left town daily in the ’20’s. The “Portsmouth Regulator” left at eight a.m., and reached Portsmouth at five o’clock in the afternoon; the “Royal Mail” started from the “Angel,” by St. Clement’s, Strand, at a quarter-past seven every evening, calling at the “George and Gate,” Gracechurch Street, at eight, and arriving at the “George,” Portsmouth, at ten minutes past six the following morning; the “Rocket” left the “Belle Sauvage,” Ludgate Hill, every morning at half-past eight, calling at the “White Bear,” Piccadilly, at nine, and arriving (quite the speediest coach of this road) at the “Fountain,” Portsmouth, at half-past five, just in time for tea; while the “Light Post” coach took quite two hours longer on the journey, leaving London at eight in the morning, and only reaching its destination in time for a late dinner at seven p.m.

The “Night Post” coach, travelling all night, from seven o’clock to half-past seven the next morning, took an intolerable time; the “Hero,” which started from the “Spread Eagle,” Gracechurch Street, at eight a.m., did better, bringing weary passengers to their destination in ten hours; and the “Portsmouth Telegraph” flew between the “Golden Cross,” Charing Cross, and the “Blue Posts,” Portsmouth, in nine hours and a half.

“ELEPHANT AND CASTLE,” 1826.

V

Many were the travellers in olden times upon the Portsmouth Road, from Kings and Queens—who, indeed, did not “travel,” but “progressed”—to Ambassadors, nobles, Admirals of the Red, the White, the Blue, and sailor-men of every degree. The admirals went, of course, in their own coaches, the captains more frequently in public conveyances, and the common ruck of sailors went, I fear, either on foot, or in the rumble-tumble attached to the hinder part of the slower stages; or even in the stage-wagons, which took the best part of three days to do the distance between the “Elephant and Castle” and Portsmouth Hard. If they had been paid off at Portsmouth and came eventually to London, they would doubtless have walked, and with no very steady step at that, for the furies of Gosport and the red-visaged trolls of Portsea took excellent good care that Jack should be fooled to the top of his bent, and that having been done, there would be little left either for coach journeys or indeed anything else, save a few shillings for that indispensable sailor’s drink, rum. So, however Jack might go down to Portsmouth, it is tolerably certain that he in many cases either tramped to London on his return from a cruise, or else was carried in one of those lumbering stage-wagons that, drawn by eight horses, crawled over these seventy-three miles with all the airy grace and tripping step of the tortoise. He lay, with one or two companions, upon the noisome straw of the interior, alternately[Pg 34] swigging at the rum-bottle which when all else had failed him was his remaining stay, and singing, with husky and uncertain voice, seafaring chanties or patriotic songs, salty of the sea, of the type of the “Saucy Arethusa” or “Hearts of Oak.” He was a nauseous creature, full of animal and ardent spirits, redolent of rum, and radiant of strange and most objectionable oaths. He had, perhaps, been impressed into the Navy against his will; had seen, and felt, hard knocks, and expected—nay, hoped—to see and feel more yet, and, whatever might come to him, he did his very best to enjoy the fleeting hour, careless of the morrow. He was frankly Pagan, and fatalist to a degree, but he and his like won our battles by sea and made England mistress of the waves, and so we should contrive all our might to blink his many faults, and apply a telescope of the most powerful kind to a consideration of his sterling virtues of bull-dog courage and cheerfulness under the misfortunes which he brought upon himself.

Marryat gives us in “Peter Simple” a vivid and convincing picture of the sailor going to Portsmouth to rejoin his ship. He must have witnessed many such scenes on his journeys to and from the great naval station, and it is very likely that this incident of the novel was drawn from actual observation.

Peter is setting out for Portsmouth for the first time, and everything is new to him. He starts of course from the time-honoured starting-point of the Portsmouth coaches, the historic “Elephant and Castle”; now, alas! nothing but a huge ordinary “public,” where a grimy railway-station and tinkling [Pg 35]tram-cars have taken the place of the old stage-coaches.

“Before eight,” says Peter, “I had arrived at the ‘Elephant and Castle,’ where we stopped for a quarter of an hour. I was looking at the painting representing this animal with a castle on its back; and assuming that of Alnwick, which I had seen, as a fair estimate of the size and weight of that which he carried, was attempting to enlarge my ideas so as to comprehend the stupendous bulk of the elephant, when I observed a crowd assembled at the corner; and asking a gentleman who sat by me in a plaid cloak whether there was not something very uncommon to attract so many people, he replied, ‘Not very, for it is only a drunken sailor.’

“I rose from my seat, which was on the hinder part of the coach, that I might see him, for it was a new sight to me, and excited my curiosity; when, to my astonishment, he staggered from the crowd, and swore that he’d go to Portsmouth. He climbed up by the wheel of the coach and sat down by me. I believe that I stared at him very much, for he said to me—

“‘What are you gaping at, you young sculping? Do you want to catch flies? or did you never see a chap half-seas-over before?’

“I replied, ‘that I had never been to sea in my life, but that I was going.’

“‘Well then, you’re like a young bear, all your sorrows to come—that’s all, my hearty,’ replied he. ‘When you get on board, you’ll find monkey’s allowance—more kicks than halfpence. I say, you pewter-carrier, bring us another pint of ale.’

[Pg 36]“The waiter of the inn, who was attending the coach, brought out the ale, half of which the sailor drank, and the other half threw into the waiter’s face, telling him ‘that was his allowance. And now,’ said he, ‘what’s to pay?’ The waiter, who looked very angry, but appeared too much afraid of the sailor to say anything, answered fourpence: and the sailor pulled out a handful of bank-notes, mixed up with gold, silver, and coppers, and was picking out the money to pay for his beer, when the coachman, who was impatient, drove off.

“‘There’s cut and run,’ cried the sailor, thrusting all the money into his breeches pocket. ‘That’s what you’ll learn to do, my joker, before you have been two cruises to sea.’

“In the meantime the gentleman in the plaid cloak, who was seated by me, smoked his cigar without saying a word. I commenced a conversation with him relative to my profession, and asked him whether it was not very difficult to learn.

“‘Larn,’ cried the sailor, interrupting us, ‘no; it may be difficult for such chaps as me before the mast to larn, but you, I presume, is a reefer, and they a’n’t got much to larn, ’cause why, they pipeclays their weekly accounts, and walks up and down with their hands in their pockets. You must larn to chaw baccy, drink grog, and call the cat a beggar, and then you knows all a midshipman’s expected to know now-a-days. Ar’n’t I right, sir?’ said the sailor, appealing to the gentleman in a plaid cloak. ‘I axes you, because I see you’re a sailor by the cut of your jib. Beg pardon, sir,’ continued he, touching his hat, ‘hope no offence.’

[Pg 37]“‘I am afraid that you have nearly hit the mark, my good fellow,’ replied the gentleman.

“The drunken fellow then entered into conversation with him, stating that he had been paid off from the ‘Audacious’ at Portsmouth, and had come up to London to spend his money with his messmates; but that yesterday he had discovered that a Jew at Portsmouth had sold him a seal as gold for fifteen shillings, which proved to be copper, and that he was going back to Portsmouth to give the Jew a couple of black eyes for his rascality, and that when he had done that he was to return to his messmates, who had promised to drink success to the expedition at the ‘Cock and Bottle,’ St. Martin’s Lane, until he should return.

“The gentleman in the plaid cloak commended him very much for his resolution: for he said, ‘that although the journey to and from Portsmouth would cost twice the value of a gold seal, yet that in the end it might be worth a Jew’s eye.’ What he meant I did not comprehend.

“Whenever the coach stopped, the sailor called for more ale, and always threw the remainder which he could not drink into the face of the man who brought it out for him, just as the coach was starting off, and then tossed the pewter pot on the ground for him to pick up. He became more tipsy every stage, and the last from Portsmouth, when he pulled out his money he could find no silver, so he handed down a note, and desired the waiter to change it. The waiter crumpled it up and put it into his pocket, and then returned the sailor the change for a one-pound note: but the gentleman in the plaid had observed[Pg 38] that it was a five-pound note which the sailor had given, and insisted upon the waiter producing it, and giving the proper change. The sailor took his money, which the waiter handed to him, begging pardon for the mistake, although he coloured up very much at being detected. ‘I really beg your pardon,’ said he again, ‘it was quite a mistake,’ whereupon the sailor threw the pewter pot at the waiter, saying, ‘I really beg your pardon too,’—and with such force, that it flattened upon the man’s head, who fell senseless on the road. The coachman drove off, and I never heard whether the man was killed or not.”

“Liberty” Wilkes was a frequent traveller on this road, as also was Samuel Pepys before him; but as I have a full and particular account of them both later on in these pages, at the “Anchor” at Liphook—a house which they frequently patronized,—we may pass on to others who were called this way on business or on pleasure bent. And the business of one very notorious character of the seventeenth century was a most serious affair: nothing, in short, less than murder, red-handed, sudden, and terrible.

John Felton’s is one of the most lurid and outstanding figures among the travellers upon the Portsmouth Road. For private and public reasons he conceived he had a right to rid the world of the gay and debonair “Steenie,” George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. Felton at this time was a man of thirty-two, poor and neglected. He was an officer in the army who had chanced, by his surly nature, to offend his superior, one Sir Henry Hungate, a friend of the Duke’s, and who effectually prevented his[Pg 39] obtaining a command. Felton retired from the service with the rank of lieutenant, disgusted and vindictive at having juniors promoted over his head. Arrears of pay, amounting, according to his own statement, to £80 were withheld from him, and no amount of entreaty could induce the authorities to make payment. Ideas of revenge took possession of him while in London, staying with his mother in an alley-way off Fleet Street. The famous Remonstrance of the Commons presented to the King convinced Felton that to deprive Buckingham of existence was to serve the best interests of the nation, and to this end he determined to set out for Portsmouth, where the Duke lay, directing the expedition for the relief of La Rochelle. He first desired the prayers of the clergy and congregation of St. Bride’s for himself, as one wretched and disturbed in mind, and, buying a tenpenny knife at a cutler’s upon Tower Hill, he set out, Tuesday, August 19, 1628, upon the road, first sewing the sheath of the knife in the lining of his right-hand pocket, so that with his right hand (the other was maimed) he could draw it without trouble. He also transcribed the opinion of a contemporary polemical writer, that “that man is cowardly and base, and deserveth not the name of a gentleman or soldier, who is not willing to sacrifice his life for his God, his King, and his country,” and pinned the paper, together with a statement of his own grievances, upon his hat. He did not arrive at Portsmouth until the next Saturday, having ridden upon horseback so far as his slender funds would carry him, and walking the rest of the way.

[Pg 40]Buckingham was staying at a Portsmouth inn—the “Spotted Dog,” in High Street—long since demolished. Access to him was easy, among the number who waited upon his favours, and so Felton experienced no difficulty in approaching within easy striking distance. The Duke had left his dressing-room to proceed to his carriage on a visit to the King at Porchester, when, in the hall of the inn, Colonel Friar, one of his intimates, whispered a word in his ear. He turned to listen, and was instantly stabbed by Felton, receiving a deep wound in the left breast; the knife sticking in his heart. Exclaiming “Villain!” he plucked it out, staggered backwards, and falling against a table, was caught in the arms of his attendants, dying almost immediately. No one saw the blow struck, and the cry was raised that it was the work of a Frenchman; but Felton, who had coolly walked from the room, returned, and with equal composure declared himself to be the man. Thus died the gay and profligate Buckingham, in the thirty-seventh year of his age. Surrounded by his friends, his Duchess in an upper room, he was struck down as surely as though his assailant had met him solitary and alone.

Within the space of a few minutes from his falling dead and the removal of his body into an adjoining room, the place was deserted. The very horror of the sudden deed left no room for curiosity. The house, awhile before filled with servants and sycophants, was left in silence.

Many were found to admire and extol Felton and his deed. “God bless thee, little David,” said the[Pg 41] country folk, crowding to shake his hand as he was conveyed back to London for his trial. “Excellent Felton!” said many decent people in London; and tried to prevent the only possible ending to his career. That end came at Tyburn, where, we are told, “he testified much repentance, and so took his death very stoutly and patiently. He was very long a-dying. His body is gone to Portsmouth, there to be hanged in chains.”

VI

Among the memorable passengers along the Portsmouth Road in other days who have left any record of their journeys is “that strenuous and painful preacher,” the Rev. John Wesley, D.D. On the fifth day of October, 1753, he left the “humane, loving people” of Cowes, “and crossed over to Portsmouth.” Here he “found another kind of people” from the complaisant inhabitants of the Isle of Wight. They had, unlike the Cowes people, none of the milk of human kindness in their breasts, or if they possessed any, it had all curdled, for they had “disputed themselves out of the power, and well-nigh the form of religion,” as Wesley remarks in his “Journals.” So, after the third day among these backsliders and curdled Christians, he shook the dust of Portsmouth (if there was any to shake in October) off his shoes, and departed, riding on horseback to “Godalmin.”

We do not meet with him on this road for another eighteen years, when he seems to have found the Portsmouth folk more receptive, for now “the people[Pg 42] in general here are more noble than most in the south of England.” Curiously enough, on another fifth of October (1771), he “set out at two” from Portsmouth. This was, apparently, two o’clock in the morning, for “about ten, some of our London friends met me at Cobham, with whom I took a walk in the neighbouring gardens”—he refers, doubtless, to the gardens of Pain’s Hill, and is speaking of ten o’clock in the morning of the same day; for no one, after a ride of fifty miles, would take walks in gardens at ten o’clock of an October night—“inexpressibly pleasant, through the variety of hills and dales and the admirable contrivance of the whole; and now, after spending all his life in bringing it to perfection, the grey-headed owner advertises it to be sold! Is there anything,” he asks, “under the sun that can satisfy a spirit made for God?” This query is no doubt a very correct and moral one, but it seems somewhat cryptic.

Another traveller of a very singular character was Jonas Hanway, who, coming up to town from Portsmouth in 1756, wrote a book purporting to be “A Journal of an Eight Days’ Journey from Portsmouth to Kingston-on-Thames.” This is a title which, on the first blush, rouses interest in the breast of the historian, for such a book must needs (he doubts not) contain much valuable information relating to this road and old-time travelling upon it. Judge then of his surprise and disgust when, upon a perusal of those ineffable pages, the inquirer into old times and other manners than our own discovers that the author of that book has simply enshrined his not particularly luminous remarks upon things in general in two[Pg 43] volumes of leaded type, and that in all the weary length of that work, cast in the form of letters addressed to “a Lady,” no word appears relating to roads or travel. Vague discourses upon uninteresting abstractions make up the tale of his pages, together with an incredibly stupid “Essay on Tea, considered as pernicious to Health, obstructing Industry, and Impoverishing the Nation.”

JONAS HANWAY.

The disappointed reader, baulked of his side-lights on manners and customs upon the road, reflects with pardonable satisfaction that this book was the occasion of an attack by Doctor Johnson upon Hanway[Pg 44] and his “Essay on Tea.” It was not to be supposed that the Doctor, that sturdy tea-drinker, could silently pass over such an onslaught upon his favourite beverage. No; he reviewed the work in the “Literary Magazine,” and certainly the author is made to cut a sorry figure. Johnson at the outset let it be understood that one who described tea as “that noxious herb” could expect but little consideration from a “hardened and shameless tea-drinker” like himself, who had “for twenty years diluted his meals with only the infusion of this fascinating plant; whose kettle has scarcely time to cool; who with tea amuses the evening, with tea solaces the midnight, and with tea welcomes the morning.”

“IF THE SHADES OF THOSE ANTAGONISTS FOREGATHER.”

No; Hanway was not successful in his crusade against tea. As a merchant whose business had called him from England into Persia and Russia, he[Pg 45] had attracted much attention; for in those days Persia was almost an unknown country to Englishmen, and Russia itself unfamiliar. His first printed work—an historical account of British trade in those regions—was therefore the means of gaining him a certain literary success, which attended none of the seventy other works of which he was the author. Boswell, indeed, goes so far as to say that “he acquired some reputation by travelling abroad, and lost it all by travelling at home;” and Johnson, to whom Hanway addressed an indignant letter, complaining of that unkind review, regarded with contempt one who spoke so ill of the drink upon which he produced so much solid work.

Johnson’s defence of tea is vindicated by results; and if the shades of those antagonists foregather somewhere up beyond the clouds, then Ursa Major, over a ghostly dish of his most admired beverage, may point to the astonishing and lasting vogue of the tea-leaf as the best argument in favour of his preference.

Hanway was more successful as Champion of the Umbrella. He was, with a singular courage, the first person to carry an umbrella in the streets of London at a time when the unfurling of what is now become an indispensable article of every-day use was regarded as effeminate, and was greeted with ironical cheers or the savage shouts of hackmen, “Frenchman, Frenchman, why don’t you take a coach!” Those drivers of public conveyances saw their livelihood slipping away when folk walked about in the rain, sheltered by the immense structure[Pg 46] the umbrella was upon its first introduction: a heavy affair of cane ribs and oiled cloth, with a handle like a broomstick. In fact, the ordinary umbrella of that time no more resembled the dainty silk affair of modern use than an omnibus resembles a stage-coach of last century. Hanway defended his use of the umbrella by saying he was in delicate[Pg 47] health after his return from Persia. Imagine the parallel case of an invalid carrying a heavy modern carriage umbrella, and then you have some sort of an idea of the tax Hanway’s parapluie must have been upon his strength.

THE FIRST UMBRELLA.

For the rest, Jonas Hanway was a philanthropist who did good in the sight of all men, and was rejoiced beyond measure to find his benevolence famous. He was, in short, one of the earliest among professional philanthropists, and to such good works as the founding of the Marine Society, and a share in the establishment of the Foundling Hospital, he added agitations against the custom of giving vails to servants, schemes for the protection of youthful chimney-sweeps, and campaigns against midnight routs and evening assemblies. Carlyle calls him a dull, worthy man; and he seems to have been, more than aught else, a County Councillor of the Puritan variety, spawned out of all due time. He died, in fact, in 1786, rather more than a hundred years before County Councils were established, and was buried in Westminster Abbey. He was a meddlesome man, without humour, who dealt with a provoking seriousness with trivial things, and was the forerunner and beau ideal of all earnest “Progressives.”

The year after Jonas Hanway travelled on this road, noting down an infinite deal of nothing with great unction and a portentous gravity, there went down from London to Portsmouth a melancholy cavalcade, bearing a brave man to a cruel, shameful, and unjust death on the quarter-deck of the man-o’-war “Monarque,” in Portsmouth Harbour.

[Pg 48]Admiral Byng was sent to Portsmouth to be tried by court-martial; and at every stage of his progress there came and clamoured round his guards noisy crowds of people of every rank, who reviled him for a traitor and a coward, and thirsted for his blood in a practical way that only furious and prejudiced crowds could show. Their feeling was intense, and had been wrought to this pitch by the emissaries of a weak but vindictive Government, which sought to cloak its disastrous parsimony and the ill fortunes of war by erecting Byng into a sort of lightning-conductor which should effectually divert the bolts of a popular storm from incapable ministers. And these efforts of Government were, for a time, completely successful. The nation was brought to believe Byng a poltroon of a particularly despicable kind; and the crowds that assembled in the streets of the country towns through which the discredited Admiral was led to his fate were with difficulty prevented from anticipating the duty of the firing-party that on March 14, 1757, woke the echoes of Gosport and Portsmouth with their murderous volley.

Admiral Byng was himself the son of an admiral, who was created Viscount Torrington for his distinguished services. Some of the innumerable caricaturists who earned a blackguardly living by attacking a man who had few friends and powerful enemies, fixed upon his honourable birth as an additional means of wounding him; and thus there exists a rare print entitled “B-ng in Horrors; or T-rr-ngt-n’s Ghost,” which shows the shade of the father as he

“Darts through the Caverns of the Ship

Where Britain’s Coward rides,”

appearing to his son as he lies captive on board the “Monarque,” and reproaching him in a set of verses from which the above lines are an elegant extract.

ADMIRAL BYNG.

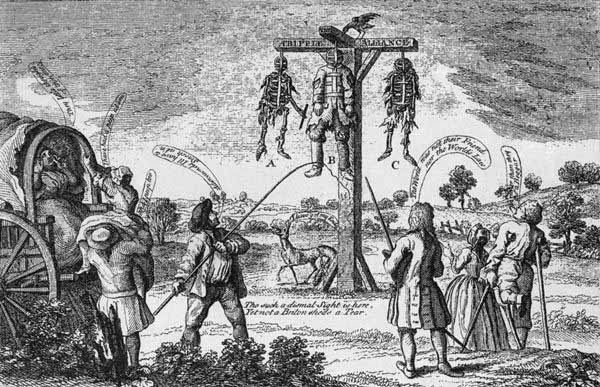

[Pg 51]Other caricatures of the period more justly include ministers in their satire. One is reproduced here, chiefly with the object of showing the pleasing roadside humour of hanging criminals in chains. By this illustration the native ferocity of the eighteenth-century caricaturists is glaringly exemplified. The figure marked A is intended for Admiral Lord Anson, B is meant for Byng, and C represents the Duke of Newcastle, the Prime Minister of the Administration that detached an insufficient force for service in the Mediterranean. The fox who looks up with satisfaction at the dangling bodies is of course intended for Charles James Fox, whose resignation produced the fall of the ministry. The other figures explain themselves by the aid of the labels issuing from their mouths.

And what was Byng’s crime, that his countrymen should have hated him with this ferocious ardour? The worst that can be said of him is that he probably felt disgusted with a Government which sent him on an important mission with an utterly inadequate force. His previous career had not been without distinction, and that he was an incapable commander had never before been hinted. He doubtless on this occasion felt aggrieved at the inadequacy of a squadron of ten ships, poorly manned, and altogether ill-found, which[Pg 52] he was given to oppose the formidable French armament then fitting at Toulon for the reduction of Minorca, and possibly for a descent upon our own coasts in the event of its first object being attained.

When Byng reached Gibraltar with his wallowing ships and wretched crews, he received intelligence of the French having already landed on the island, and laying siege to Port St. Philip. His duty was to set sail and oppose the enemy’s fleet, and thus, if possible, cut off the retreat of their forces already engaged on the island. He had been promised a force from the garrison of Gibraltar, but upon his asking for the men the Governor refused to obey his instructions, alleging that the position of affairs would not allow of his sparing a single man from the Rock. So Byng sailed without his expected reinforcement, and arrived off Minorca too late for any communication to be made with the English Governor, who was still holding the enemy at bay. For as he came in sight of land the French squadron appeared, and the battle that became imminent was fought on the following day.

Byng attacked the enemy’s ships vigorously: the French remained upon the defensive, and the superior weight of their guns told so heavily against the English ships that they were thrown into confusion, and several narrowly escaped capture. The Admiral sheered off and held a council of war, whose deliberations resulted four days later in a retreat to Gibraltar, leaving Minorca to its fate. Deprived of outside aid the English garrison capitulated, and Byng’s errand had thus failed. He was sent home under arrest, and confined in a room of Greenwich Hospital until the court-martial that was now demanded could be formed.

A STRANGE SIGHT SOME TIME HENCE.

[Pg 55]The action at sea had taken place on May 20, 1756, but the court-martial only assembled at Portsmouth on December 28, and it took a whole month’s constant attendance to hear the matter out. The court found Byng guilty of negligence in not having done his utmost in the endeavour to relieve Minorca. It expressly acquitted him of cowardice and disaffection, but condemned him to death under the provisions of the Articles of War, at the same time recommending him to mercy.

But no mercy was to be expected of King, Government, or country, inflamed with rage at a French success, and all efforts, whether at Court or in Parliament, were fruitless. The execution was fixed for March 14, and Byng’s demeanour thenceforward was equally unaffected and undaunted. He met his death with a calmness of demeanour and a fortitude of spirit that proved him to be no coward of that ignoble type which fears pain or dissolution as the greatest and most awful of evils. His personal friends were solicitous to avoid anything that might give him unnecessary pain, and one of them, a few days before the end, inventing a pitiful ruse, said to him, “Which of us is tallest?” “Why this ceremony?” asked the Admiral. “I know well what it means; let the man come and measure me for my coffin.”

At the appointed hour of noon he walked forth of his cabin with a firm step, and gazed calmly upon the waters of Portsmouth Harbour, alive with boats full of people who had come to see a fellow-creature die.[Pg 56] He refused at first to allow his face to be covered, lest he might be suspected of fear, but upon some officers around him representing that his looks might confuse the soldiers of the firing-party and distract their aim, he agreed to be blindfolded; and thus, kneeling upon the deck, and holding a handkerchief in his hand, he awaited the final disposition of the firing-party that was to send him out of the world by the aid of powder and ball, discharged at the range of half-a-dozen paces. At the pre-arranged signal of his dropping the handkerchief, the soldiers fired, and the scapegoat fell dead, his breast riddled with a dozen bullets.

The execution of Byng was (to adopt Fouché’s comment upon the murder of the Duc d’Enghien) worse than a crime; it was a blunder. The ministry fell, and the populace, who had before his death regarded Byng with a consuming hatred, now looked upon him as a martyr. The cynical Voltaire, who had unavailingly exerted himself to save the condemned man (and had thereby demonstrated that your cynic is at most but superficially currish), resumed his cynicism in that mordant passage of “Candide” which will never die so long as the history of the British Fleet is read: “Dans ce pays-ci,” he wrote, “il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un Amiral pour encourager les autres!”

THE SHOOTING OF ADMIRAL BYNG.

VII

One of the earliest records we have of Portsmouth Road travellers is that which relates to three sixteenth-century inspectors of ordnance:

“July 20th, 1532—Paid to X pofer Morys, gonner, Cornelys Johnson, the Maister Smythe, and Henry Johnson for their costs in ryding to Portismouthe to viewe the King’s ordenaunce there, by the space of X dayes at Xs’ the daye—V li.”