Transcriber’s Note

Text on cover added by Transcriber and placed in the Public Domain.

THE NORTH DEVON COAST

WORKS BY CHARLES G. HARPER

The Portsmouth Road, and its Tributaries: To-day and in Days of Old.

The Dover Road: Annals of an Ancient Turnpike.

The Bath Road: History, Fashion, and Frivolity on an Old Highway.

The Exeter Road: The Story of the West of England Highway.

The Great North Road: The Old Mail Road to Scotland. Two Vols.

The Norwich Road: An East Anglian Highway.

The Holyhead Road: The Mail-Coach Road to Dublin. Two Vols.

The Cambridge, Ely, and King’s Lynn Road: The Great Fenland Highway.

The Newmarket, Bury, Thetford, and Cromer Road: Sport and History on an East Anglian Turnpike.

The Oxford, Gloucester, and Milford Haven Road: The Ready Way to South Wales. Two Vols.

The Brighton Road: Speed, Sport, and History on the Classic Highway.

The Hastings Road and the “Happy Springs of Tunbridge.”

Cycle Rides Round London.

A Practical Handbook of Drawing for Modern Methods of Reproduction.

Stage-Coach and Mail in Days of Yore. Two Vols.

The Ingoldsby Country: Literary Landmarks of “The Ingoldsby Legends.”

The Hardy Country: Literary Landmarks of the Wessex Novels.

The Dorset Coast.

The South Devon Coast.

The Old Inns of Old England. Two Vols.

Love in the Harbour: a Longshore Comedy.

Rural Nooks Round London (Middlesex and Surrey).

The Manchester and Glasgow Road; This way to Gretna Green. Two Vols.

Haunted Houses; Tales of the Supernatural.

The Somerset Coast. [In the Press.

E. D. Percival

[Ilfracombe.

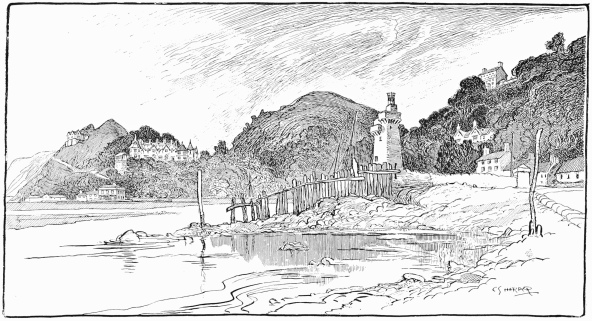

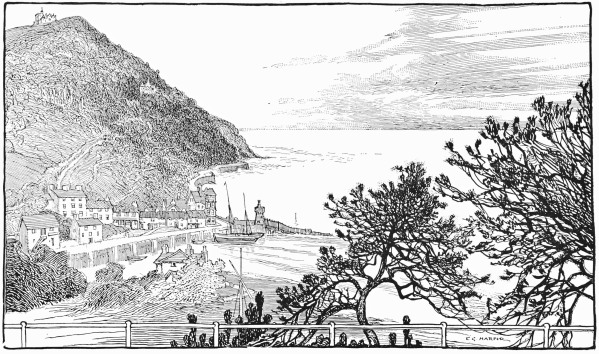

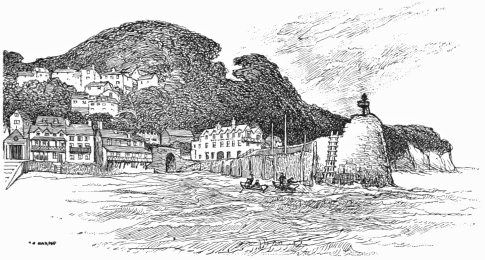

LYNMOUTH, FROM THE BEACH.

THE NORTH DEVON

COAST

BY

CHARLES G. HARPER

“Let us, in God’s name, adventure one voyage more, always with this caution, that you be pleased to tolerate my vulgar phrase, and to pardon me if, in keeping the plain highway, I use a plain low phrase; and in rough, rugged and barren places, rude, rustic, and homely terms.”—Thomas Westcote, 1620.

London: CHAPMAN & HALL, Ltd.

1908

PRINTED AND BOUND BY

HAZELL, WATSON AND VINEY, LD.,

LONDON AND AYLESBURY.

vii

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| LYNMOUTH | 9 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| LYNTON—THE WICHEHALSE FAMILY, IN FICTION AND IN FACT | 21 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE COAST, TO COUNTISBURY AND GLENTHORNE | 35 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE NORTH WALK—THE VALLEY OF ROCKS—LEE “ABBEY”—WOODA BAY—HEDDON’S MOUTH—TRENTISHOE—THE HANGMAN HILLS | 44 |

| CHAPTER VIviii | |

| COMBEMARTIN, AND ITS OLD SILVER MINES—THE CHURCH—WATERMOUTH CASTLE—HELE | 71 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| “’COMBE” IN HISTORY—MODERN ’COMBE—THE OLD CHURCH | 84 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

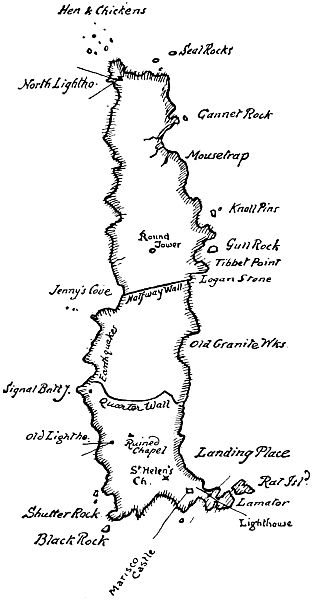

| LUNDY—HISTORY OF THE ISLAND—WRECK OF THE “MONTAGU”—LUNDY OFFERED AT AUCTION—DESCRIPTION | 106 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| CHAMBERCOMBE AND ITS “HAUNTED HOUSE”—BERRYNARBOR | 123 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| LEE—MORTE POINT—MORTHOE AND THE TRACY LEGEND—WOOLACOMBE—GEORGEHAM—CROYDE—SAUNTON SANDS—BRAUNTON, BRAUNTON BURROWS, AND LIGHTHOUSE | 131 |

| CHAPTER XIix | |

| PILTON—BARNSTAPLE BRIDGE—OLD COUNTRY WAYS—BARUM—HISTORY AND COMMERCIAL IMPORTANCE—OLD HOUSES—“SEVEN BRETHREN BANK”—FREMINGTON—INSTOW AND THE LOVELY TORRIDGE | 155 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| KINGSLEY AND “WESTWARD HO!”—BIDEFORD BRIDGE—THE GRENVILLES—SIR RICHARD GRENVILLE AND THE “REVENGE”—THE ARMADA GUNS—BIDEFORD CHURCH—THE POSTMAN POET | 177 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

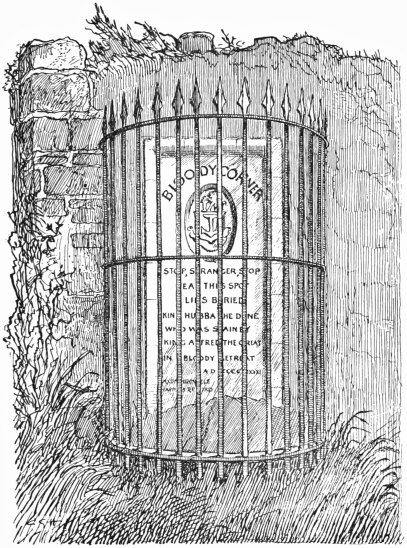

| THE KINGSLEY STATUE—NORTHAM—“BLOODY CORNER”—APPLEDORE—WESTWARD HO! AND THE PEBBLE RIDGE | 197 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| ABBOTSHAM—“WOOLSERY”—BUCK’S MILL | 205 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| CLOVELLY—“UP ALONG” AND “DOWN ALONG”—THE “NEW INN”—APPRECIATIVE AMERICANS—THE QUAY POOL—THE HERRING FISHERY | 208 |

| CHAPTER XVIx | |

| MOUTH MILL AND BLACK CHURCH ROCK—THE COAST TO HARTLAND—HARTLAND POINT—HARTLAND ABBEY—HARTLAND QUAY | 224 |

| INDEX | 245 |

xi

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

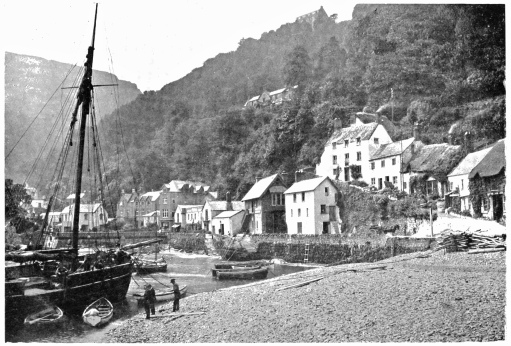

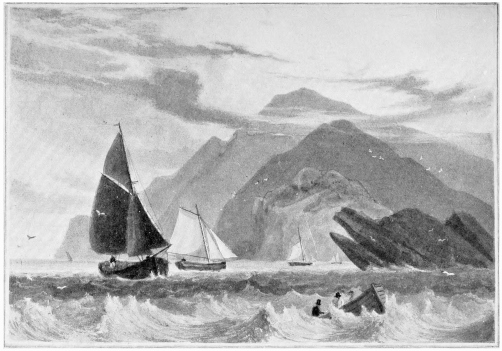

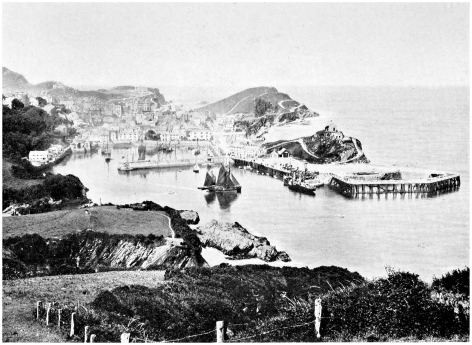

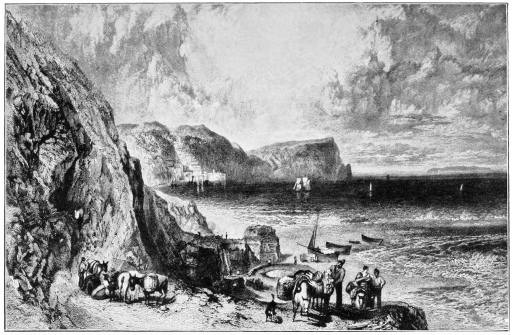

| Lynmouth, from the Beach | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

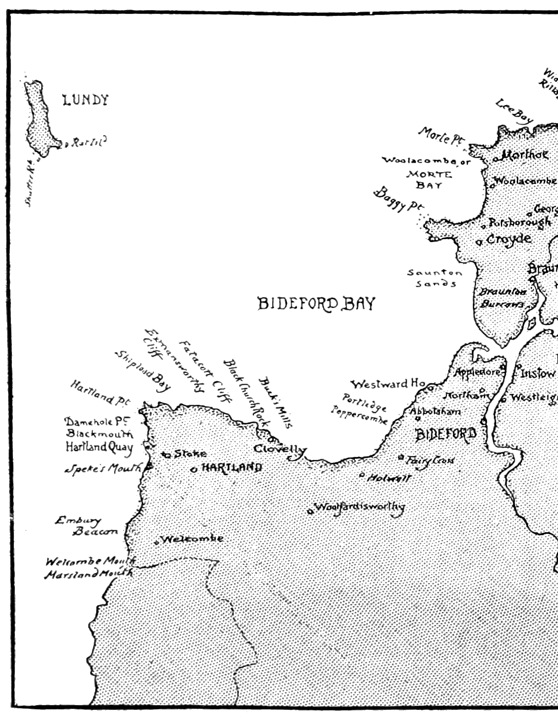

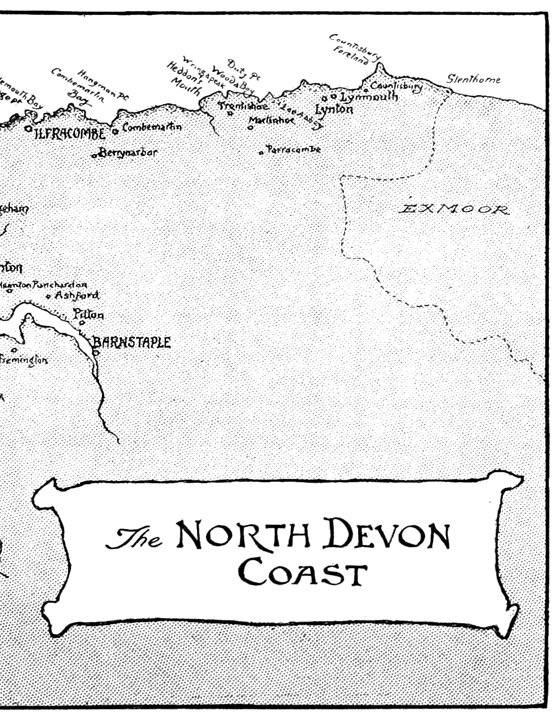

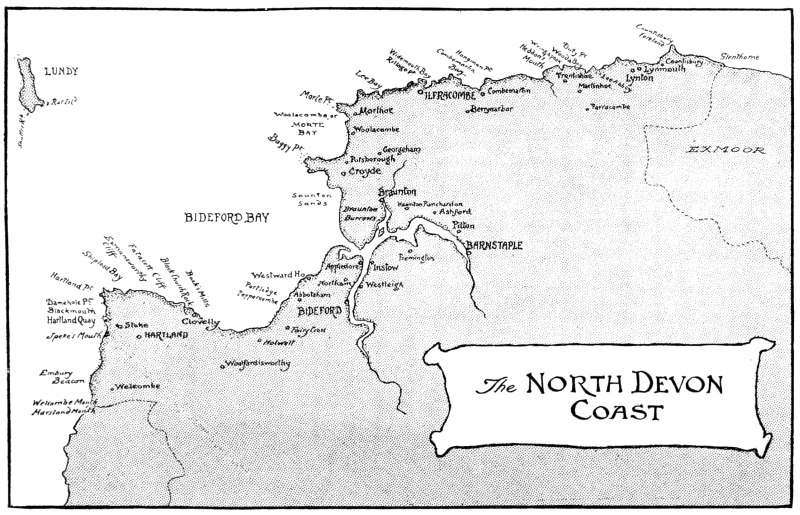

| Map of North Devon Coast | 1 |

| Headpiece | 1 |

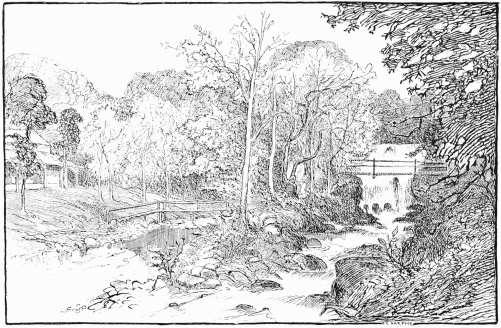

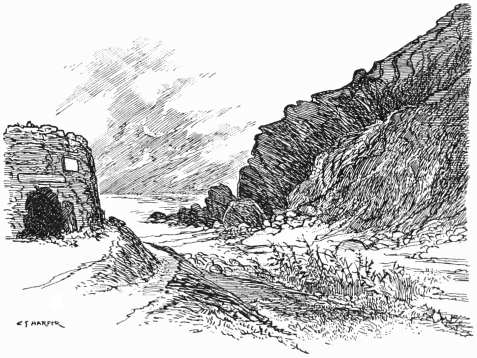

| Watersmeet | 6 |

| Lynmouth and the Tors, from the Beach | 12 |

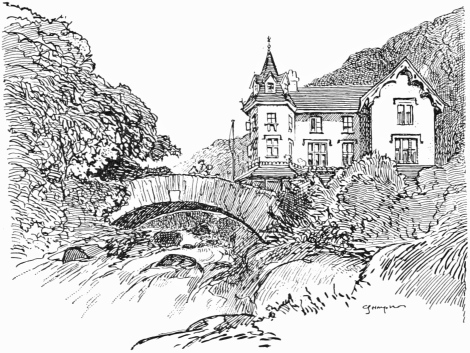

| Lyndale Bridge | 17 |

| Lynmouth, from the Tors Hotel | 18 |

| Lynton | 24 |

| The “Blue Ball” | 37 |

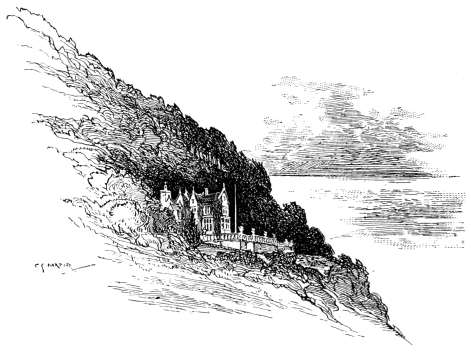

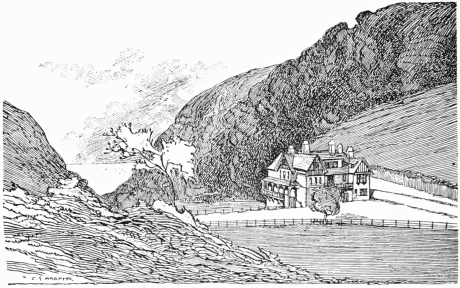

| Glenthorne | 42 |

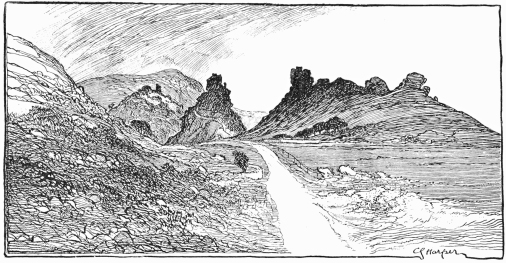

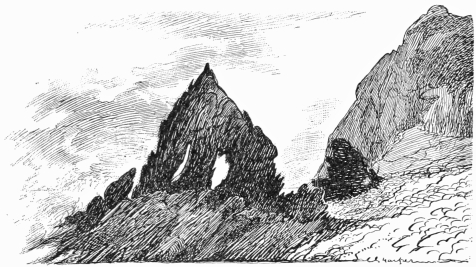

| The Valley of Rocks | 47 |

| Lee “Abbey” | 53 |

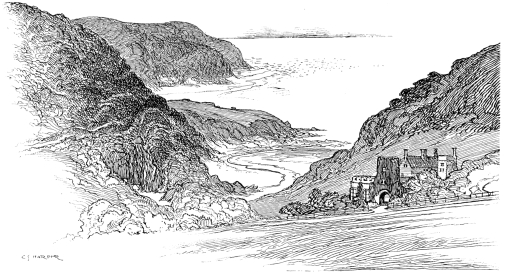

| Wooda Bay | 59 |

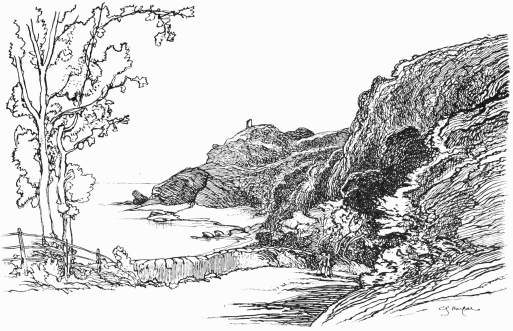

| Heddon’s Mouth | 62 |

| “Hunter’s Inn” | 64 |

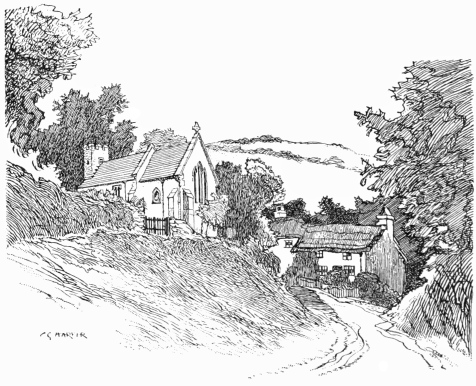

| Trentishoe Church | 66 |

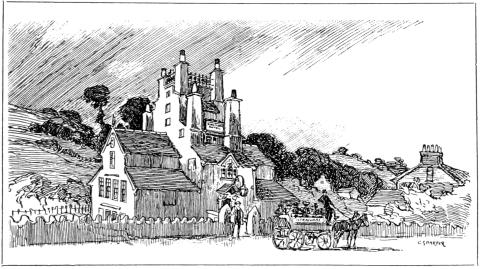

| The “Pack of Cards,” Combemartin | 73 |

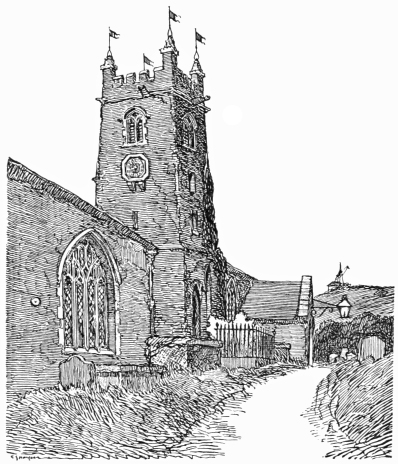

| Combemartin Church | 77 |

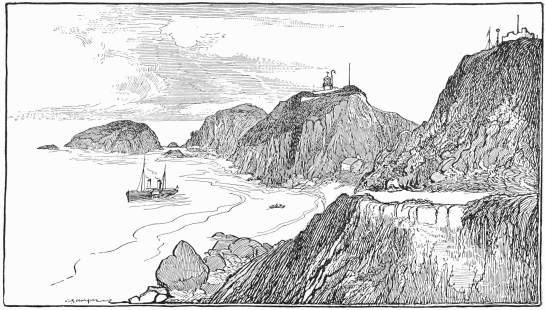

| Great Hangman Hill, and Entrance to Combemartin Harbour | 80 |

| Widemouth Bay | 81xii |

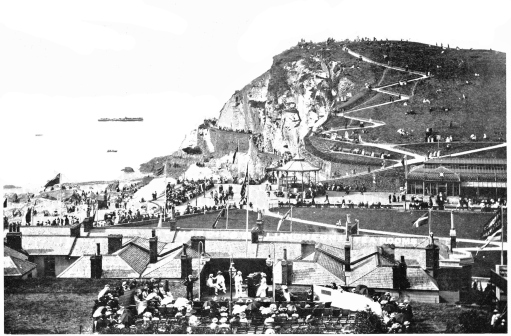

| Capstone Hill and the Concert Parties | 84 |

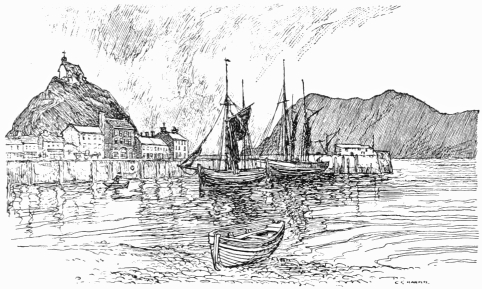

| In the Harbour, Ilfracombe | 89 |

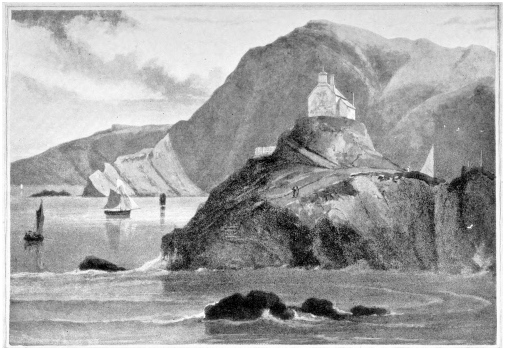

| Lantern Hill, Ilfracombe | 90 |

| Ilfracombe | 100 |

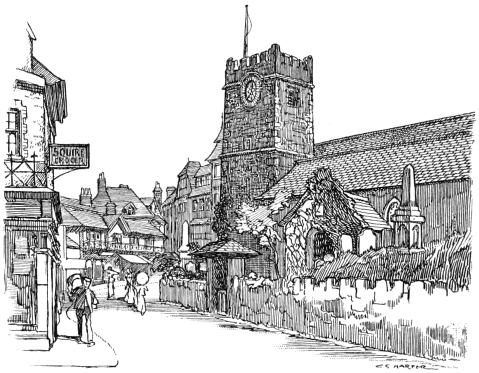

| Ilfracombe Church-tower | 103 |

| Lundy | 107 |

| The Landing-place, Lundy | 111 |

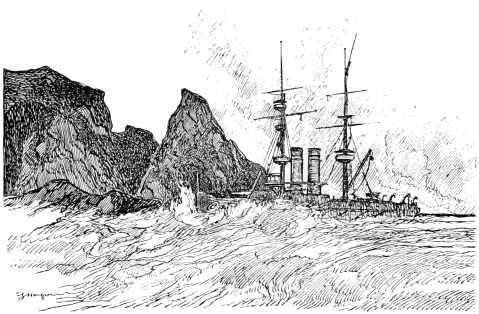

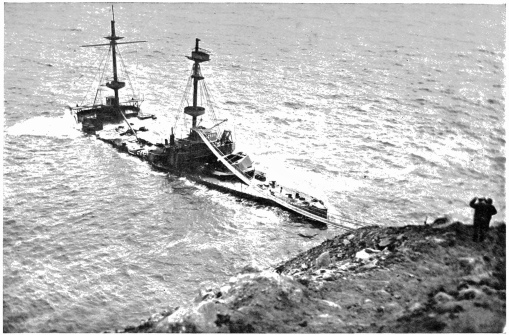

| The Montagu, on the Shutter Rock | 117 |

| The last of the Montagu, August, 1907 | 118 |

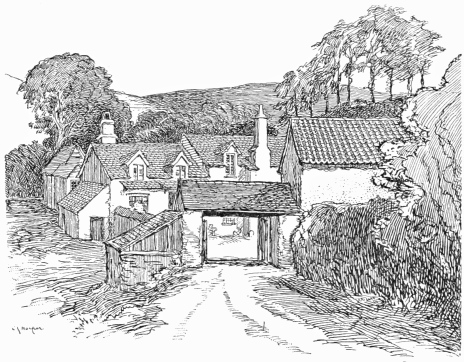

| Chambercombe | 125 |

| The “Haunted House” of Chambercombe | 127 |

| Morthoe | 135 |

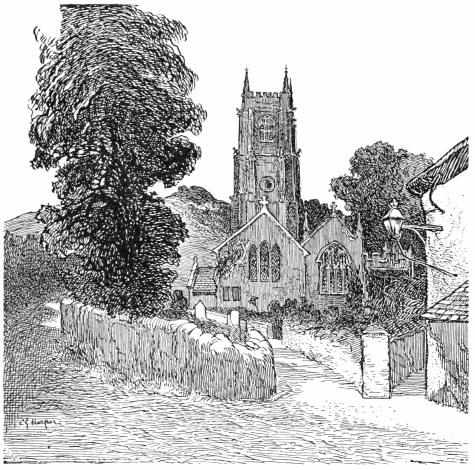

| Braunton Church | 147 |

| Sir John Schorne and his Devil | 148 |

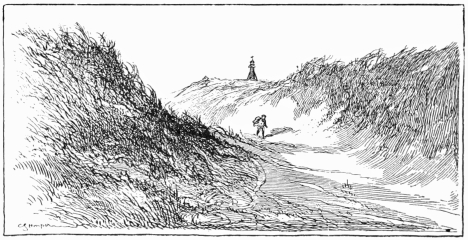

| Braunton Burrows | 150 |

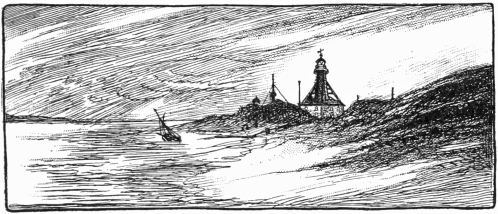

| Braunton Lighthouse | 153 |

| The Jester’s Head | 156 |

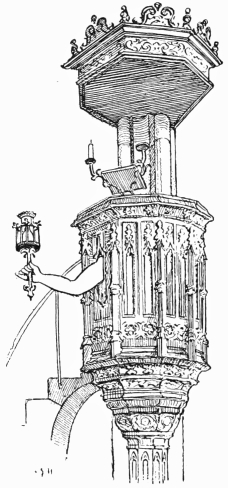

| Pulpit and Hour-glass, Pilton | 157 |

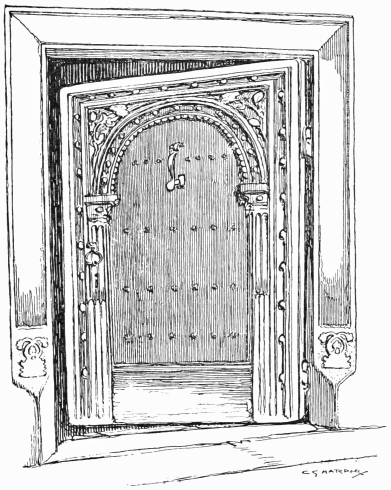

| An Old Door, Barnstaple | 165 |

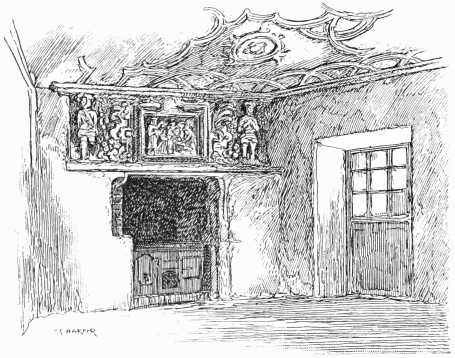

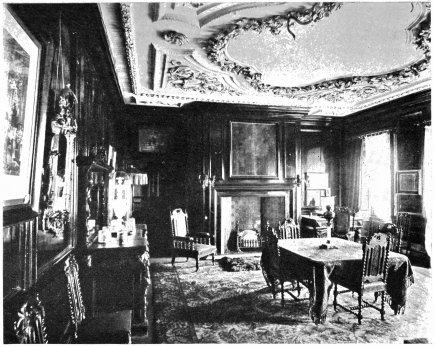

| Old Room in the “Trevelyan Arms” | 167 |

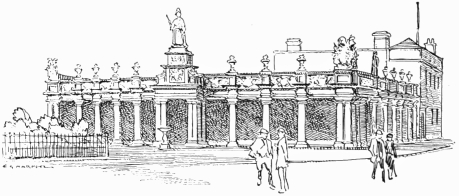

| “Queen Anne’s Walk” | 168 |

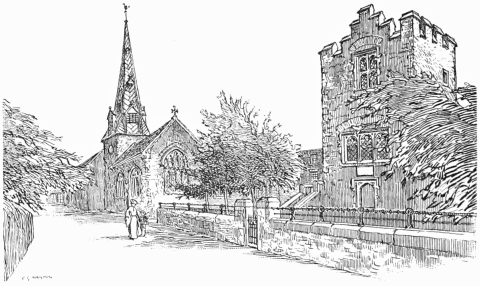

| Barnstaple Church and Grammar School | 170 |

| The “Kingsley Room,” Royal Hotel, Bideford | 178 |

| Seal of Bideford | 182 |

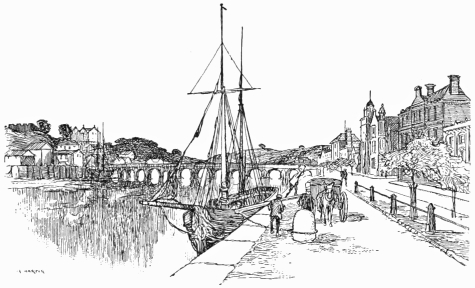

| Bideford Bridge | 183 |

| Bideford Quay | 191 |

| “Bloody Corner” | 199 |

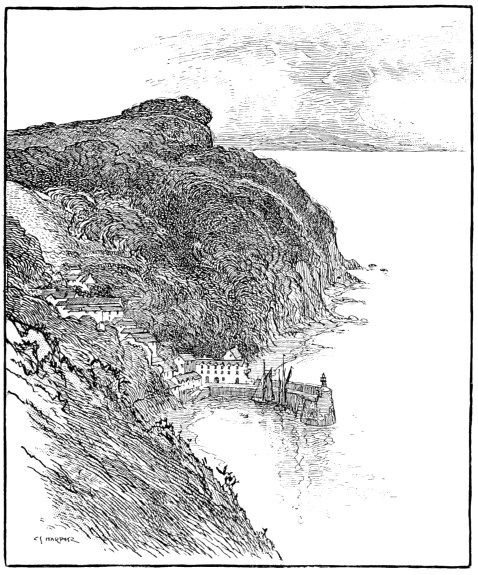

| Clovelly, from Buck’s Mill | 206xiii |

| Clovelly, from the Hobby Drive | 209 |

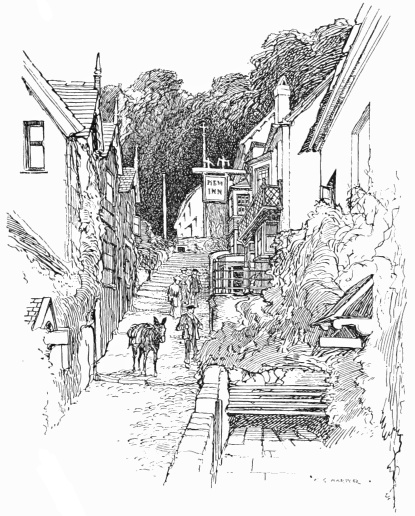

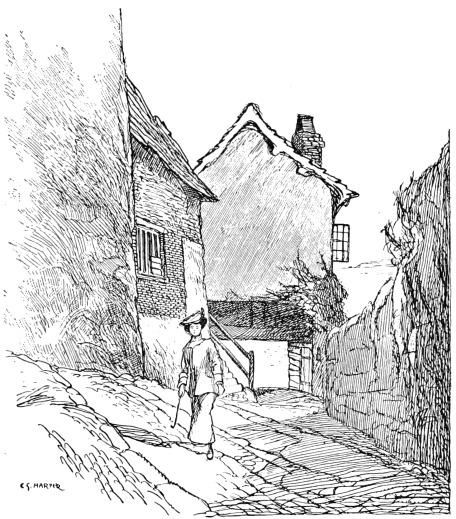

| “Up-along,” Clovelly | 213 |

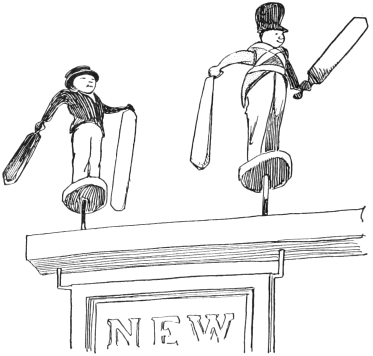

| Sign of the “New Inn,” Clovelly | 216 |

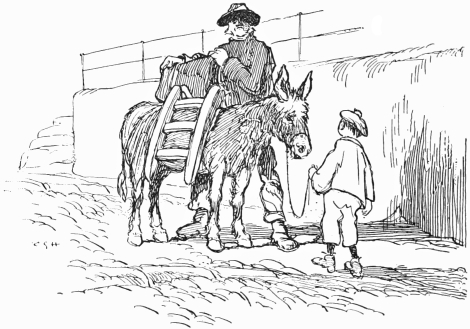

| A Clovelly Donkey | 218 |

| “Temple Bar” | 219 |

| The Quay, Clovelly | 220 |

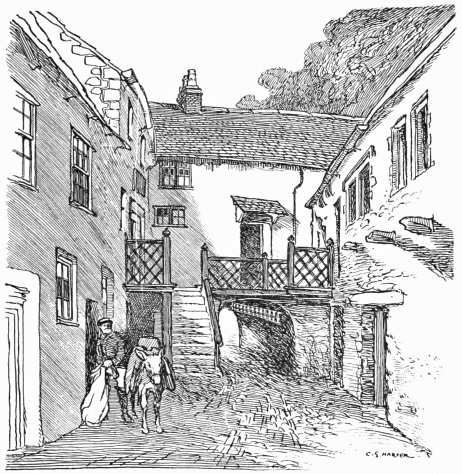

| Back of the “Red Lion,” Clovelly | 221 |

| Clovelly, from the Sea | 225 |

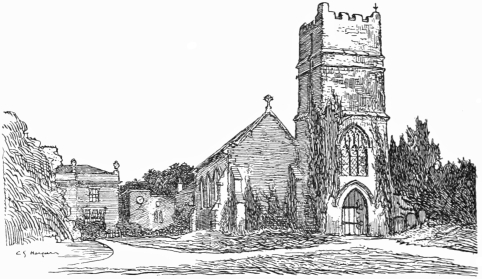

| Clovelly Church | 226 |

| Black Church Rock | 227 |

| Hartland Point | 229 |

| Hartland Quay | 237 |

| Speke’s Mouth | 238 |

| At Marsland Mouth | 243 |

1

THE

North Devon

Coast

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTORY

No one can, with advantage, explore the rugged coast of North Devon by progressing direct from the point where it begins and so continuing, without once harking back. The scenery is exceptionally bold and fine, and the tracing of the actual coast-line by consequence a matter of no little difficulty. Only the pedestrian can see this coast as a whole, and even he needs to be blessed with powers of endurance beyond the ordinary, if he would miss none of those rugged steeps, those rocky coves and “mouths” and leafy combes that for the most part make up the tale of the North Devon littoral. It is true that there are sands in places, but they are principally sands like those2 yielding wastes of Braunton Burrows, whereon you even wish yourself back again upon the hazardous, stone-strewn hillsides sloping down to the sea that make such painful walking in the region of Heddon’s Mouth; and there you wish yourself on the sands again. It is so difficult as to be almost impossible, to have at once the boldest scenery and the easiest means of progression. At any rate, the two are found to be utterly incompatible on the North Devon coast, and it consequently behoves those who would thoroughly see this line of country to take their exploration in small doses. As for the cyclist, he can do no more upon his wheel than (so to speak) bore try-holes into the scenery, and merely sample it at those rare points where practicable roads and tracks approach the shore. The ideal method is a combined cycling and walking expedition; establishing headquarters at convenient centres, becoming acquainted with the districts within easy reach of them, and then moving on to new.

The only possible or thinkable place where to begin this exploration of these seventy-eight miles is Lynmouth, situated six miles from Glenthorne, where the coast-line of Somerset is left behind. The one reasonable criticism of this plan is that, arrived at Lynmouth, you have the culmination of all the beauties of this beautiful district, and that every other place (except Clovelly) is apt to suffer by comparison.

Hardy explorers from the neighbourhood of London (of whom I count myself one) will find3 their appreciation of this coast greatly enhanced by traversing the whole distance to it by cycle. You come by this means through a varied country; from the level lands of Middlesex and Berkshire, through the chalk districts of Wilts; and so, gradually entering the delightful West, to the steep hills and rugged rustic speech of Somerset. It is a better way than being conveyed by train, and being deposited at last—you do not quite know how—at Lynton station.

Of course, the ideal way to arrive at Lynmouth is by motor-car, and there, as you come down the salmon-coloured road from Minehead and Porlock, the garage of the Tors Hotel faces you, the very first outpost of the place, expectantly with open doors. But, good roads, or indeed any kind of roads, only rarely approaching the coast of North Devon, it is merely at the coast-towns and villages, and not in a continual panorama, that the motorist will here come in touch with the sea.

To give a detailed exposition of the route by which I came, per cycle, to Lynmouth might be of interest, but it would no doubt be a little beside the mark in these pages. Only let the approach across Exmoor be described.

I come to Lynmouth in the proper spirit for such scenery: not hurriedly, but determined to take things luxuriously, for to see Lynmouth in a fleeting, dusty manner is to do oneself and the place alike an injustice. But the best of intentions are apt to be set at nought by circumstances, and circumstances make sport with all explorers.4 Thus leaving Dulverton at noon of a blazing July day, and making for Exmoor, there is at once a long, long ascent above the valley of the infant Exe to be walked, at a time when but a few steps involve even the most lathy of tourists in perspiration. And then, at a fork of the roads in a lonely situation, where guidance is more than usually necessary, a hoary signpost, lichened with the weather of generations and totally illegible, mocks the stranger. It is, of course, inevitable in such a situation as this that, of the two roads, the one which looks the likeliest should be the wrong one; and the likely road in this instance leads presently into a farmyard—and nowhere else. This is where you perspire most copiously, and think things unutterable. Then come the treeless, furze-covered and bracken-grown expanses of Winsford common and surrounding wide-spreading heaths, where the Exmoor breed of ponies roam at large; and you think you are on Exmoor. To all intents, you are, but, technically, Exmoor is yet a long way ahead.

It is blazing hot in these parts in summer, and yet, if you be an explorer worthy the name, you must needs turn aside, left and right; first to see Torr Steps, a long, primitive bridge of Celtic origin, crossing the river Barle, generally spoken of by the country-folk as “Tarr” steps, just as they would call a hornet a “harnet,” as evidenced in the old rustic song beginning,

A proper spiteful twoad was he”;

5 for it must be recollected that, although on the way to the North Devon coast, and near it, we are yet in Zummerzet. Secondly, an invincible curiosity to see what the village of Exford is like takes you off to the right. Cycling, you descend that long steep hill in a flash, but on the way back, in the close heat, arrive at the conclusion that Exford was not worth the mile and a half walk uphill again.

And so to Simonsbath, a tiny village in the middle of the moor and in a deep hollow where the river Barle prattles by. Unlike the moor above and all around, Simonsbath is deeply wooded. Simon himself is a half-mythical personage, one Simund, or Sigismund, of Anglo-Saxon times, according to some accounts a species of Robin Hood outlaw, and to others the owner of the manor in those days. “Bath” does not necessarily indicate bathing, and in this case it merely means a pool.

The traveller coming to Simonsbath in July finds himself in an atmosphere of “Baa,” and presently discovers hundreds of Earl Fortescue’s sheep being sheared. Then rising out of Simonsbath by a weariful, sun-scorched road, come the rounded treeless hills and the heathery hollows, where Exe Head lies on the left hand, with Chapman Barrows and the source of the river Lyn near by, in a wilderness, where the purple hills look solemnly down upon bogs, prehistoric tumuli, and hut-circles. Here, in the words of Westcote, writing in 1620, “we will, with an easy pace,6 ascend the mount of Hore-oke-ridge, not far from whence we shall find the spring of the rivulet Lynne.” Hoar Oak Stone, on this ridge, is a prominent landmark.

Presently, at Brendon Two Gates (where there is but one gate), we pass out of Exmoor and Somerset and into Devon, at something under six miles from Lynmouth. Alongside the unfenced road across the wild common, as far as Brendon Rectory, the sheep lie in hundreds. Then suddenly the road drops down into the deep gorge of Farley Water, and comes, with many a twist, to Bridge Ball, a picturesque hamlet with a water-mill. One more little rise, and then the road descends all the way to Lynmouth, through the splendidly romantic scenery of the Lyn valley and Watersmeet, where the streams of East and West Lyn unite.

Circumstances have by this time made the traveller, who promised himself a luxurious and leisurely journey, a hot, dusty and wearied pilgrim. To such, the sudden change from miles of sun-burnt heights is irresistibly inviting. To sit beneath the shade of those overhanging alders, those graceful hazels, oaks, and silver birches, reclining on some mossy shelf of rock, and watch the Lyn awhile, foaming here in white cataracts over the boulders in its path, or smoothly gliding over the deep pools, whose tint is touched to a brown-sherry hue by the peat held in solution, is a delight. It is a delightful spot, to which the tall foxgloves, standing pink in the half-light under the7 mossy stems of the trees, lend a suggestion of fairyland.

The road winds away down the valley, its every turn revealing increasingly grand hillsides, clothed with dwarf woods, and here and there a grey crag: very like the Cheddar Gorge, with an unaccustomed mantle of greenery. Descending this fairest of introductions to the North Devon coast, past the confluence at Watersmeet, where slender trees incline their trunks together by the waterfall, like horses amiably nuzzling, one comes by degrees within the “region of influence”—as they phrase it in the world of international politics—of the holiday-maker at Lynmouth, who is commonly so lapped in luxury there, and rendered so indolent by the soft airs of Devon, that Watersmeet forms the utmost bounds to which he will penetrate in this direction, when on foot. And when those who undertake so much do at length arrive here, they want refreshment, which they appear to obtain down below the road, beside the stream, at a rustic cottage styling itself “Myrtleberry,” claiming, according to a modest notice on the rustic stone wall bordering the road, to have supplied in one year 8,000 teas and 1,700 luncheons. There thus appears to be an opening for a philosophic discussion of “Scenery as an Influence upon Appetite.” The place is so far below the road that, the observer is amused to see, tradesmen’s supplies are carried to it in a box conveyed by aerial wires.

And so at length into Lynmouth, seated at the point where the rushing Lyn tumbles, slips, and8 slides at last into the sea. One misses something in approaching the place, nor does one ever find it there. It is something that can readily be spared, being indeed nothing less than the usual squalid fringe that seems so inevitable an introduction to towns and villages, no matter how large or small. There are no introductory gasworks in the approaches to Lynmouth; no dustbins, advertisement-hoardings, or flagrant, dirty domestic details that usually herald civilisation. The customary accumulated refuse is astonishingly absent: mysteriously etherialised and abolished; but how is it done? In what manner do the local authorities magic it away? Do they pronounce some incantation, and then, with a mystic pass or two, abolish it?

9

CHAPTER II

LYNMOUTH

Lynmouth would have pleased Dr. Johnson, who held the opinion that the most beautiful landscape was capable of improvement by the addition of a good inn in the foreground. We have grown in these days beyond mere inns, which are places the more luxurious persons admire from the outside, for their picturesque qualities—and pass on. Dr. Johnson’s ideal has been transcended here, and hotels, in the foreground, in the middle distance, above, below, and on the sky-line, should serve to render it, from this standpoint, the most picturesque place in this country. One odd result of this complexion of affairs is that when a Lynmouth hotel proprietor issues booklets of tariffs, including photographic views of the place, he finds that all his choice pictures contain representations of other people’s hotels. This is sorrow’s crown of sorrow, the acme of agony, the ne plus ultra of disgust. Resting on the commanding terrace of the Tors Hotel, seated amidst its wooded grounds like some Highland shooting-box, I can see perhaps eight others; and down in the village a house that is not either a hotel, an inn, or a boarding-house,10 or that does not let apartments, is a shop. And I don’t think there is a shop that does not sell picture-postcards! There are some few very fine villas, situated in their own grounds, on the hillsides, but whenever any one of these comes into the market, it also becomes a hotel.

And yet, with it all, there is a holy calm at Lynmouth. Save for the murmur of the Lyn, the breaking of the waves upon the pebbly shore, or the occasional bell of the crier, nothing disturbs the quiet. As there are no advertisement-hoardings, so also there are no town or other bands, minstrels, piano-organs, or public entertainers. Rows of automatic penny-in-the-slot machines are conspicuously not here. There is not a railway station. Nor is there anything in the likeness of a conventional sea-front. The Age of Advertisement is, in short, discouraged, and I am not sure that the ruling powers of the place have not something in the way of stripes and dungeon-cells awaiting would-be public entertainers.

But, lest it might be supposed that the advantages of Lynmouth end with these negative qualities, let something now be said of its own positive charms. It is daintiness itself, to begin with, and so small and neat, yet so rugged and unexpected, that it is sometimes difficult to believe in the bona fides of its picturesqueness, which looks almost as if it had been created to order. Yet the evidence of old prints proves, if proof were wanting, that Lynmouth—what there was then of it—was as romantic a hundred years ago as it is to-day.11 Indeed, an inspection of old prints leads one to believe that, though there are more houses now, the enclosing hills are more abundantly and softly wooded than then. And, with the exception of the Rhenish tower built on the stone pier, everything has been added legitimately, without any idea of being picturesque.

That quaint tower, a deliberate copy of one on the Drachenfels, owes its being to General Rawdon, who resided here from about 1840, and, finding his æsthetic taste outraged by a naked iron water-tank erected on posts, built this pleasing feature to harmonise with the scenery. An iron basket, still remaining, was provided to serve for a beacon, and now that Lynmouth is lighted by an installation of electric glow-lamps, a light is shown from it every night.

But let us halt awhile to learn something of the rise of Lynmouth, as a seaside resort. At the close of the eighteenth century, the place was a little hamlet, dependent partly on a precarious fishing industry, and partly on the spinning of woollen yarn. But presently, fishing and spinning were at once and together in a bad way, and Mr. William Litson, the largest employer of the spinners, found himself and his people out of work. It chanced at this time that the new-born delight in picturesque scenery, that had already set the literary men of the age scribbling, had brought some few travellers even into the wilds of North Devon. They fell into raptures over Lynton and Lynmouth: raptures rather dashed by the discovery12 that there was no sufficient accommodation for them. Litson, pondering upon these things, and with wits sharpened by threatened adversity, took opportunity by the hand, and in 1800, opening what is now the “Globe” inn as a hotel of sorts, and furnishing the cottages on either side for the reception of visitors, became the pioneer of what is now the great hotel-keeping interest of the two towns. Litson prospered in an amazing degree. Early among his patrons were Robert Coutts, famous in those days as a banker, and the Marchioness of Bute; and the stream of visitors grew so rapidly that by 1807 he was able to open the original “Valley of Rocks” hotel, up at Lynton. The adjoining “Castle” hotel soon followed.

About the time when Lynmouth and Lynton were thus first rising into favour, the poet Southey came this way, and wrote a description that has ever since been most abundantly quoted. But it is impossible not to quote it again, even though the comparison with places in Portugal is uncalled for, absurd, and entirely beside the mark.

Thus, Southey: “My walk to Ilfracombe led me through Lynmouth, the finest spot, except Cintra and Arrabida, which I have ever seen. Two rivers join at Lynmouth; each of these flows down a combe, rolling over huge stones, like a long waterfall. Immediately at their junction they enter the sea, and the rivers and the sea make but one uproar. Of these combes, the one is richly wooded, the other runs between two high, bare, stony hills, wooded at the base. From the13 Summerhouse Hill between the two is a prospect most magnificent—on either hand combes and the river; before, the beautiful little village, which, I am assured by one who is familiar with Switzerland, resembles a Swiss village.”

And so with a host of others, to whom the hills “beetle,” the rocks “frown savagely,” the sea “roars like a devouring monster.” And all the while, you know, they don’t do anything of the kind. Instead, the hills slant away beautifully up skyward, the rocks, draped with ivy and moss and studded with ferns, look benignant, and the sea and the Lyn together still the senses with their combined drowsy murmur, as you sit looking alternately down upon the harbour or up at the wooded heights from that finest of vantage points, the “Tors” terrace, after dinner, when the lights in the village and those of the hillside villas twinkle in the twilight, like jewels. The poetry of the scene appeals to all, except perhaps Miss Marie Corelli, who, in the “Mighty Atom,” does not appear to approve of it. This, of course, is very discouraging, but the inhabitants are endeavouring to bear up; apparently with a considerable measure of success.

“How soothing the sound of rushing water,” observed a charming young lady, impressed with the scene. I agreed, but could not help remarking that there were exceptions. “My dear young lady,” said I, noticing the incredulous lift of her eyebrow’s, “you do not know the feelings of a householder whose water-pipes have burst in a14 rapid thaw. Rushing water, as it pours out of the bath-room, down the front stairs, does not soothe him.”

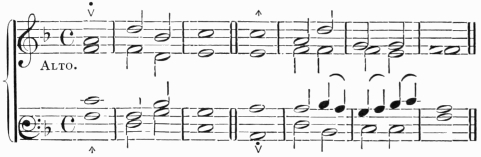

The voice of the Lyn has, however, suggested less prosaic thoughts, and has set many a minor poet, and many minimus poets, scribbling in the hotel “visitors’” books. Nay, no less a person than the Reverend William Henry Havergal, staying at the Lyndale Hotel, in September 1849, waking in the night and listening to that voice, harmonised it in the following chant which he inscribed in the book then kept at that establishment:—

It is a beautiful anthem-like fragment, “like the sound of a great ‘Amen,’” and brings thoughts of cathedral choirs and deep-toned organs. Havergal, of course, as a writer of devotional music, had a mind by long use attuned to finding such a motive; but I am not sure that another composer, with a bent towards secular music of a sprightly, light-opera kind, might not, lying wakeful here, find a suggestion for his own art in these untutored sharps and trebles.

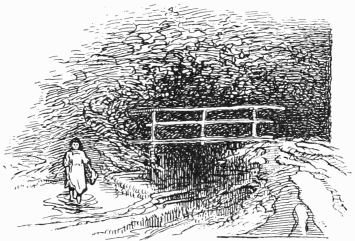

The Lyn in its final series of falls in the semi-private15 grounds of Glen Lyn, at the rear of the Lyndale Hotel, sounds a deeper note, and comes splashing down with a roar by fern-clad rocky walls and between a scatter of great boulders. A rustic bridge looks down upon the foaming water, flecked with sunlight coming in patches of gold through the overarching foliage.

No description of Lynmouth that has ever been penned gives even a remote idea of what the place is really like. I care nothing for Southey and his comparison with Cintra and Arrabida, for I have not been to those places, and don’t want to go: resembling, I suspect, in that disability, and in the disinclination to remedy it, most other visitors, to whom that parallel has no meaning. Lynmouth is really comparable with no other place. It is essentially individual and like nothing but itself; or, at any rate, like nothing else in nature. What it does really resemble is some romantic theatrical set scene, preferably in comic opera: the extraordinary picturesqueness of it seeming too impossible to be a part of real life. There is the quaint tower at the end of the tiny stone jetty, there are the bold, scrub-covered hills, with rocks jutting out from them, as they rarely do except in the imagination of a scene-painter, and here are the grouped little houses and cottages, mostly with the roses, the jessamine, and the clematis that are indispensable to rural cottages—on the stage. Even the very fishermen seem unreal. I don’t believe—or at least find some difficulty in believing—that they, really and truly, are fishermen,16 and almost imagine they must be paid to lounge out from the wings on to the stage—I mean the sea-front—in order to give an air of verisimilitude. They ask you, occasionally, it is true, if you want a boat, but with the air of playing a part that does not particularly interest them, and every moment you expect them to break into song, after the manner of the chorus in comic-opera, expressive of the delights of a life on the ocean wave, and the joys of sea-fishing.

Or, to adopt the conventions of melodrama, as formerly practised at the Adelphi, and still at Drury Lane; here you expect almost to see the villain smoking his inevitable villainous cigarette (an infallible stage symbol of viciousness), and, possibly in evening dress, that ultimate stage symbol of depravity, shooting his cuffs by the bridge that spans the Lyn; and on summer evenings the lighted hotels down in the huddled little street look for all the world like stage-hotels—abodes of splendour and gilded vice, whence presently there should issue some splendid creature of infamy, to plot with another villain, already waiting in his trysting-place, the destruction of hero and heroine. But, lest I be misunderstood, I hasten to add that all these expectations are vain things, and that villains really require a much faster place than Lynmouth.

I have spoken already about the “fishermen” of Lynmouth, but, truth to tell, that is but a conventional term, for sea-fishing here is not the industry it is on most coasts, and the jerseyed17 persons who loll about the harbour are more used to taking out and landing steamboat excursionists, or accompanying amateur fishermen with lines on pleasant days, than to enduring the rigours the trawler knows. Rock Whiting, Bass, and Grey Mullet give the chief sport in the sea, and in the Lyn are salmon, salmon-peel, and trout, as you may readily believe by examining the trophies of sport with rod and line treasured by Mr. Cecil Bevan, of the Lyn Valley Hotel.

There was formerly, indeed, a herring fishery at Lynmouth. Westcote speaks of it as existing in the time of Queen Elizabeth. “God,” says he, “hath plentifully stored with herrings, the king of fishes, which shunning their ancient places of repair in Ireland, come hither abundantly in shoals,18 offering themselves, as I may say, to the fishers’ nets, who soon resorted hither with divers merchants, and so for five or six years continued, to the great benefit and good of the country, until the parson vexed the poor fishermen for extraordinary unusual tithes, and then, as the inhabitants report, the fish suddenly clean left the coast.” They were not friends of the Establishment. But after a while some returned, and from 1787 to 1797 there was such an extraordinary abundance that the greater part of the catch could not be disposed of, and vast quantities were put upon the land for manure. Then they totally deserted the channel for a number of years; a fact at that time regarded by many as a Divine judgment for thus wasting the food sent. On Christmas Day 1811 a remarkable shoal appeared and choked the harbour, and in 1823 another shoal paid a visit; but since then, the herrings have given Lynmouth a wide berth.

I have visited Lynmouth in haste and at leisure. To arrive hurriedly and dustily, and to make a quick survey, and so hasten off, is unsatisfactory. Under such circumstances you feel a pariah among a leisured community who are cool and not dusty; and you do not assimilate the spirit of the place. The utmost satisfaction in the way of lazy enjoyment (it has been conceded by philosophers) is to watch other people at work. That is why, to some minds, Bank Holidays, when the entire population makes merry, are so unsatisfactory; there is no toil to form the shadow in your bright picture of dolce far niente. Now there is a rustic gallery,19 with a pavilion, where you can take tea and be consummately idle, built out from the sloping wooded grounds of the Tors Hotel, and thence you may, if so minded, spend the livelong day watching the people immediately below, in the central pool of Lynmouth’s life. Overhanging the road, you watch the holiday folk who are taking it easy, and those others who are making such hard work of it, rushing from place to place. And I, even I, looking down upon perspiring dust-covered cyclists arriving, thank Providence that I am not such as them: conveniently forgetting for the while that I have been and shall be once more!

The “North” in North Devon raises ideas, if not of a cold climate, at least of bracing air; but really, with the always up and always down of the scenery, the rather more bracing atmosphere than that of South Devon is forgotten, in the heated exertions of getting about.

Why do people so largely select torrid July and August for holidays? For the most part it is a matter of convention, but in part because by the end of July the schools have broken up. There remain, however, large numbers of holiday-makers who are unaffected by school-terms and would resent being thought slaves to convention. They can go a-pleasuring when they please, yet they wait until the dog-days. Now Lynmouth, in particular, and the North Devon coast, in general, are exceptionally delightful in May and June. The early dews of morning, the cool, fragrant thymy airs, that in July and August are dispelled20 long before midday and give place to brilliant sunshine and a great heat, which are in themselves enjoyable enough, but forbid much joy in considerable exercise, remain more or less throughout the day in those earlier months. September, too, when the fervency of summer mellows into an autumnal glow, has its own particular charm.

21

CHAPTER III

LYNTON—THE WICHEHALSE FAMILY, IN FICTION AND IN FACT

There is more difference between Lynmouth and Lynton than is found in the mere geographical fact that the one is situated over four hundred and twenty feet below the other; a certain jealousy on the one side and a little-veiled contempt on the other exist. Lynmouth people do not speak in terms of affection of Lynton. “Suburban,” they say, and certainly Lynton is overbuilt. Moreover, at Lynton, although it is on a height, you stew in the sun. It is cooler down below, at Lynmouth, rejoicing in the refreshing breezes blowing off the sea.

And there is no doubt that Lynmouth prides itself on being exclusive. As already shown, it does not cater for the crowd. Up at Lynton you are in the world and of the world, and find something of all sorts. Lynmouth’s idea of Lynton is instructive. It is that of a place where the gnomes work, who labour for the convenience and enjoyment of the village down by the sea: only here you have the paradox that the underworld of these labouring sprites is above, and that the socially superior place is the, geographically, nether world.22 It is only fair to remark that Lynton does by no means agree with these estimates of itself, and is indeed, a bright, clean, pretty little town, with its own individuality, and an amazing number of hotels, boarding-houses, and lodgings, the houses mostly built in excellent taste; and I assure you I have seen no such thing as a gnome there. You do not, generally, on the North Devon coast, as so often in South Devon, find the scenery outraged by a terrible lack of taste, displayed in a plenitude of plaster.

When Mr. Louis Jennings passed this way, about 1890, the Cliff Railway, or lift, was newly opened, but the Lynton and Barnstaple Railway was not yet in being. Lynton, nevertheless, was in the throes of expansion, and he found “the hand of man doing its usual fatal work on one of the loveliest spots our country has to boast of. Flaring notices everywhere proclaim the fact that building sites are procurable through the usual channels; this estate and the other has been ‘laid out’; the lady reduced in circumstances, and with spare rooms on her hands, watches you from behind the window-blinds; red cards are stuck in windows denoting that anything and everything is to be sold or let. A long and grievous gash has been torn in the side of the beautiful hill opposite Lynmouth—a gash which must leave behind it a broad scar never to be healed.

“‘Who has done this?’ I sorrowfully asked the waiter at the hotel.

23 “‘Tit-Bits, sir.’

“‘Who?’ said I, thinking the waiter was out of his mind.

“‘Tit-Bits,’ the man replied.

“‘Well, then,’ said I, ‘what has Tit-Bits done it for?’

“‘To make a lift, sir. Some people complain of the hill, and so this lift will shoot ’em up and down it, like it does at Scarborough. They say it will be a very good spec. You see, sir, he came along here and bought the land; and I have heard say that Rare-Bits is coming too, and means to make a railroad.’”

However, as this horrified traveller was fain to acknowledge, even although these things had come to pass and though the once old-fashioned hotel had been changed into “a huge, staring structure, assailing the eye at every turn”—he meant the Valley of Rocks Hotel—“it will take a long time to spoil Lynton utterly.”

Very much more has been done to Lynton since then, and building has gone on uninterruptedly. The narrow-gauge Lynton and Barnstaple Railway—the “Toy Railway,” as it is often called, from its rather less than two-foot gauge—opened in 1898, has been a disappointing enterprise for its shareholders, but has brought much expansion. Probably it would have been a better speculation had its Lynton terminus been in the town, rather than hidden on the almost inaccessible heights of “Mount Sinai,” another climb of about two hundred feet. The service is24 so infrequent and the pace so slow that, coupled with the initial difficulty of finding it at all, the traveller can perform a good deal of his journey by road to any place along the route, before the train starts. And an energetic cyclist can, any day, make a very creditable race with it.

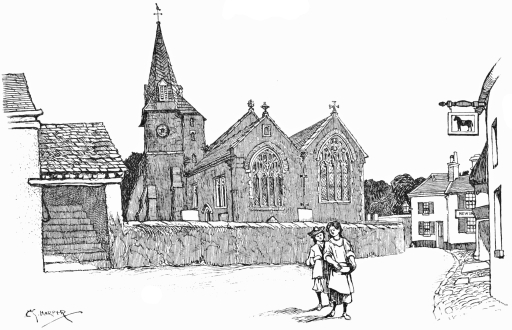

Lynton has now become no inconsiderable town, very bustling and cheerful in summer: its narrow street quite built in with the tall “Valley of Rocks Hotel” aforesaid, and a large number of shops and business premises not in the least rural. Between them, they contrive to make the old parish church look singularly out of place. That is just the irony of it! The interloping, hulking buildings themselves are alien from the25 spirit of the neighbourhood, but they have contrived to impress most people the other way. “How odd,” unthinking strangers exclaim, as they see a rustic church and grassy, tree-shaded churchyard amid the bricks and mortar; not pausing to consider that the church has been here hundreds of years, and few of the buildings around more than twenty. But there is little really ancient remaining of the church, for it was rebuilt, with the exception of the tower, in 1741, and has been added to and altered at different times since then. Quite recently it has again, to all intents, been rebuilt, and fitted and furnished most artistically, in the newer school of ecclesiastical decoration. Those who are sick at heart with the stereotyped patterns of the usual ecclesiastical furnisher, with his stock designs in lecterns and anæmic stained-glass saints, his encaustic tiles with an eternity of repetitive geometrical patterns, and indeed everything that is his, will welcome the something individual that here, and in some few other favoured places, may be found to redress the dreary monotony.

Everything within Lynton church has been smartened up and clean-swept; even the old wall-tablet in memory of Hugh Wichehalse has been gilded and tended until it glows like a modern antique, unlike the genuinely old relic it is. And since much of the ancient history of Lynton and its neighbourhood is inseparable from the story of the Wichehalse family, let that story be told here.

In the many old guide-books that treat of26 Lynton, it is stated, with much show of circumstantial evidence, that the Wichehalses were of Dutch origin, and fled from Holland about 1567, to escape the persecution of the Protestants. We are even told how “Hughe de Wichehalse” was “head of a noble and opulent family,” and learn how he had fought in the Low Countries against the persecuting Spaniards. Harrowing accounts are even given of his narrow escape, with wife and family, to England.

But the supremest effort is the legend, narrated in a score of guide-books, of Jennifrid Wichehalse and the false “Lord Auberley,” who loved and who rode away, in the days of Charles the First. It is a tale, narrated with harrowing details, of a daughter’s despair, of a tragic leap from the heights of “Duty Point” at Lee, and of a father’s revenge upon the recreant lover at the Battle of Lansdowne; where, with his red right hand (you know the sort of thing), he struck down the forsworn lord in death. Follows then the sequel: how the father, a Royalist, was persecuted, and forced, with kith and kin, to put off in a boat from Lee. “The surf dashed high over the rocky shore, as a boat manned by ten persons, the faithful retainers of this branch of the house of de Wichehalse, pushed desperately into the raging waters. It was never more heard of.”

But that is all fudge and nonsense. There was never a Jennifrid Wichehalse; still less, if that be possible, was there ever a Lord Auberley, and the Wichehalse family did not end in the way described.27 All those things are doubtless creditable to the imagination of their compilers, but they do not redound either to their sincerity, or to the tepid interest taken in the neighbourhood by past generations of visitors. Any cock-and-a-bull story sufficed until recently, but now that local history is acknowledged to be not unworthy of research, it has been proved to demonstration by painstaking local antiquaries that the Wichehalses were not Dutch, but of an ancient Devon stock, and that they consequently could not have been the heroes of those hair’s-breadth ’scapes ascribed to them.

But their own true story is sufficiently interesting. They are traced back to about 1300, to the hamlet of Wych, near Chudleigh, in South Devon, a hamlet itself deriving its name from a large wych-elm that grew there. From the hamlet the family drew their own name, spelled at various times and by many people in some twenty different ways; commonly, besides the generally-received style, “Wichelse,” and “Wichalls.”

It was in 1530 that the Wichehalses first came to North Devon; Nicholas, the third son of Nicholas Wichehalse, of Chudleigh, having settled at Barnstaple in that year. Like most younger sons in those days, even though they might be sons of considerable people, he went into trade, and became partner of one Robert Salisbury, wool merchant, and prospered. Robert Salisbury died, and Nicholas Wichehalse married his widow in 1551; prospered still more, became28 Mayor of Barnstaple in 1561, and lived in considerable state in his house in what is now Cross (formerly Crock) Street. The great wealth he accumulated may best be judged by mentioning merely some of the manors he purchased: those of Watermouth, Fremington, Countisbury, and Lynton. To this eminently successful kinsman, the nine children of his brother John, who had died in 1558, were sent, as wards. His own family numbered but two, Joan and Nicholas, who came of age in 1588.

Nicholas, succeeding his father, retired from trade, and is described in local records as “gentleman,” and appears incidentally in them as wounding another gentleman with a knife, in a quarrel. Something of a young blood, without a doubt, this young Nick. He never lived to be an old one, at any rate, dying in 1603, aged thirty-eight, leaving five sons and three daughters.

Large families appear to have been a rule not often broken among the Elizabethan Wichehalses. It was indeed in every way a spacious era, and one of the most continuously astonishing things to any one who travels greatly in England, and notices the late sixteenth and early seventeenth century monuments in the churches, is the inevitable repetition of family groups, with the reverend seniors facing one another, in prayer, above, and the Quakers’ meeting of children below, boys on one side and girls on the other, gradually receding from grown-up men and women, down to babies in swaddling clothes. Early and29 late the Elizabethans laboured to replenish the earth and people the waste places.

Hugh, the eldest son of Nicholas, the buck, or blood as I shall call him, was seventeen years of age when his father died. He also had nine children, and resided at the family mansion in Crock Street, until 1628, when that terrible scourge, the plague, frightened away for a time the trade of the town and such of the inhabitants as could by any means remove. It was a sorry time for Barnstaple, for the political and religious wrangles that were presently to break out in Civil War were already troubling it. For many reasons, therefore, Hugh Wichehalse, who appears to have been an amiable person, and above all, a lover of the quiet life, resolved to leave Barnstaple and reside at Lee, or Ley, in the old thatched manor-farm that then stood where Lee “Abbey” does now. Here he died twenty-five years later, as his monument in Lynton church duly informs us. The epitaph, characteristic of its period, is worth printing, not only as an example of filial piety, but as an instance of extravagant praise. From what we know of him, he certainly seems to have been the flower of his race; but, even so, he probably was not quite everything we are bidden believe.

HUGH WICHEHALSE OF LEY,

WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE

Christide Eve, 1653,

æt. 66.

30

That hide such worth, should in spight vocal grow;

We’ll rather sob it out, our grateful teares

Congeal’d to Marble shall vy threnes with theirs.

This weeping Marble then Drops this releife

To draw fresh lines to fame, and Fame to griefe:

Whose name was Wichehalse—’twas a cedar’s fall.

For search this Urn of Learned dust, you’le find

Treasures of Virtue and Piety enshrin’d,

Rare Paterns of blest Peace and Amity,

Models of grace, emblems of Charity,

Rich Talents not in niggard napkin Layd,

But Piously dispenced, justly payd,

Chast Spousal Love t’his Consort; to Children nine,

Surviving th’ other fowre his care did shine

In Pious Education; to Neighbours, friends,

Love seal’d with Constancy, which knowes no end.

Death would have stolne this Treasure, but in vaine

It stung, but could not kill; all wrought his gaine,

His life was hid with Christ; Death only made this story,

Christ call’d him hence his Eve, to feast with Him in glory.

The play upon words, “’twas a Cedar’s fall,” should be noticed above: it is by way of contrast to the “Wiche”—i.e., wych-elm, in the Wichehalse name.

Four years before the death of Hugh Wichehalse, his eldest surviving son, John, had married one Elizabeth Venner. He distinguished himself as one of the most bitter and relentless among the Puritans of Barnstaple, and especially as a persecutor of the loyal clergy. He found it prudent in after years to retire to Lee, and endeavour to efface himself when the Royalists returned to power. Whether it was for love he married again, a woman of Royalist sympathies, after the death of his first wife, who had been as bitterly Puritan as himself, or whether it was policy, does not31 appear; but, at any rate, when he died in 1676, aged fifty-six, he left the family estates much shrunken. The enriched Wichehalse family was already on the decline.

His eldest son, John, was an ineffectual and extravagant person, with a bent, that almost amounted to perverse genius, to muddling away his property; and a wife who in every respect aided and abetted him. After a while, they removed to Chard, in Somerset; then, returning, he sold the manor of Countisbury, to pay his debts. He raised repeated mortgages on his other properties, borrowed right and left from his own relatives and his wife’s; and finally, at his death in London, after the foreclosure of mortgages and many actions at law, practically all his lands had been dispersed.

His misfortunes were largely caused, according to popular superstition at the time, by the part he took in the capture of Major Wade, one of the fugitives after the Battle of Sedgemoor, on July 6th, 1685. Wade and some companions had fled across country after the battle, and, coming to Ilfracombe, seized a vessel there, intending to make off by sea. But being forced ashore by ships cruising in the Channel, they were obliged to separate and skulk along the coast. At Farley farm, above Bridgeball and Lynmouth, Wade was so fortunate as to excite the compassion of the wife of a small farmer named How. She brought food to him, hidden among the rocks, and induced a farmer named Birch to hide him in his still more32 secluded farm on the verge of Exmoor. Information leaked out that a fugitive was concealed in one of the few houses at Farley, and on the night of July 22nd, John Wichehalse, Mr. Powell, the parson of Brendon, Robert Parris, and John Babb, one of Wichehalse’s men, searched the place. Three houses were entered unsuccessfully, but in the fourth—which happened to be Birch’s—Major Wade was hiding behind the front door, as the search-party, armed, came in. Grace How admitted the party. Wade, who was disguised in Philip How’s rough country farmer’s clothes, ran off through the back door, with two other men, and John Babb, raising his gun, fired and hit him in the side. Wade was made prisoner. His wound was healed, and himself afterwards pardoned. It is a pleasing thing to record that he afterwards pensioned Grace How, who had succoured him in time of need.

The only tragedy of the affair was the suicide of Birch, who, afraid of his part, hanged himself some few days after the capture.

This affair deeply impressed the country-folk. Wichehalse was thought never after to have prospered, and it was told how John Babb was thenceforward a man accurst. He left his master’s service and went into the herring-fishery; whereupon the herrings deserted Lynmouth. He died unhonoured, and his granddaughter, Ursula Babb, was afflicted with the evil eye. She married and had one son, who was drowned at sea; and thenceforward lived lonely at Lynmouth, half-crazed;33 telling old stories of the departed grandeur of the Wichehalses which grew more and more marvellous and confused with every repetition. It was she who told the Reverend Matthew Mundy the legends, which he took down and first printed—with many embellishments of his own—of Jennifrid’s Leap.

There was never (let it be repeated) a Jennifrid Wichehalse. The feckless John Wichehalse, who ruined the family, had three sons and one daughter. The sons died without issue; the last vestiges of the family wealth being dissipated in their time by the effectual means of a Chancery suit. Mary, the daughter, married at Caerleon one Henry Tompkins, and had one son, Chichester Tompkins. She returned, in a half-demented condition, to Lynmouth, and was used to wander along the cliffs, the scene of her ancestors’ former prosperity, accompanied by one old retainer, Mary Ellis. At last Mary Tompkins fell over a steep rock into the sea, her body never being recovered; and so ended the last Wichehalse. To-day, in spite of those large families of the various Wichehalse branches, you shall not find one of that name remaining in Devonshire.

To-day the Newnes’ interest dominates Lynton. I shall draw no satirical picture of what has been made possible by the Elementary Education Act of 1869 and Tit-Bits. Such an alliance carries a man into unexpected horizons, but with so many Richmonds now crowding the field, the thing will not be so easily repeated. On the crest of Holiday34 Hill stands the residence of Sir George Newnes, Bart., and in the town the Town Hall he gave is a prominent object: picturesqueness itself, in its combined Gothic and Jacobean architectural styles, and contrasted masonry and magpie timber and plaster.

There is always, in the summer, a cheerful stir in Lynton, and the railway has by no means abolished the four-horsed coach that plies between Ilfracombe and this point, and even on to Minehead. But when the close of the season has come and the holiday world has gone home, what then? The hotel-keepers and all the ministrants to the crowds of visitors must surely, to protect themselves from sheer ennui, institute a kind of desperate “general post,” and go and stay with each other, on excessive terms, to keep their hands in, so to say.

35

CHAPTER IV

THE COAST, TO COUNTISBURY AND GLENTHORNE

The six miles or so of the North Devon coast between Lynmouth and Glenthorne, where it joins Somerset, may best be explored from Lynton by taking the coast-line on the way out, and returning by the uninteresting, but at any rate not difficult, main road. The outward scramble is quite sufficiently arduous. The road sets out at first, artlessly enough, full in view of the sea. It rises from about the sea-level at Lynmouth, steeply up to a height of some four hundred feet at Countisbury, passing beneath a rawly red, new villa built on the naked hillside by a wealthy person whose hobby it is said to be to visit a fresh place almost every summer, to build a house, and then to move away. The name of the house I forget; suffice it to say that the Lynmouth people, gazing with seared eyes upon it, know it as “The Blot.” Below, on the left, is the strand known as “Sillery Sands,” which sounds like champagne. Some style them “Silvery” sands, others even “celery”; but they are not “silvery”; and no celery, and still less any champagne, is to be found there.

At the summit of this steep road are the few36 scattered cottages of Countisbury, or “Cunsbear,” as the old writers have it. Few would suspect that the names of Countisbury and Canterbury have an origin nearly akin; yet it is so, “Kaint-ys-burig”—the “headland camp,” being closely allied to the original Kaintware-burig, the “camp of the men of Kent.” But to the writers of a generation ago, who wrote in a blissful age when there were no students of the science of place-names to call them to account, the name was set down as a contraction of “county’s boundary.” Distinctly good as this may possibly be as an effort of the imagination, it is not borne out by facts; for the county boundary did not exist at the time when the name came into being, county divisions having been settled at a much later date. Moreover, the boundary is a good three miles distant. Old Risdon, writing in 1630, is even more delightful. He takes what the scientific world styles the “line of least resistance,” and gaily dismisses it with “probably the land of some Countess.”

But there is not much of this Countisbury, about whose name there has been so much said. Just a bleached-looking, weather-beaten church, the “Blue Ball” inn, typical rural hostelry of these parts, and the school-house. For the life of me, I do not know which drone the loudest on a hot, drowsy summer afternoon; the bees or the school-children at their lessons—the bees, I believe. And that is all there is to Countisbury, you think. This, indeed, is the sum-total of the village, but37 the parish itself ranges down to the Lyn, which forms the boundary, as the curious may duly discover, set forth on the keystone of the bridge that spans the stream, just outside the grounds of the Tors Hotel, which itself is, therefore, in the parish of Countisbury.

There is little within the old church, with the exception of some fine old characteristic West Country bench-ends, one of them bearing, boldly carved, the heraldic swan of the Bohuns and the bezants of the Courtenays.

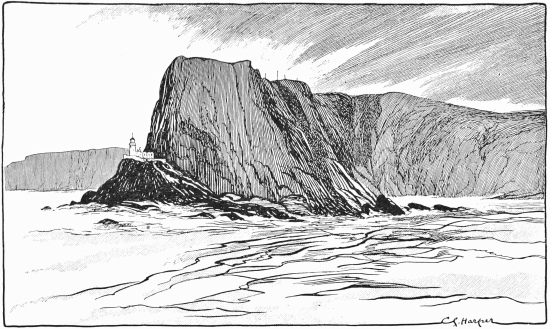

We here come to that great projection, Countisbury Foreland, past the school-house and by footpaths. A lighthouse, very new, very glaring, with white paint and whitewashed enclosure-walls, near the head of the point, sears the eye on brilliant sunshiny days. It was built so recently as 1899, and equipped with the latest things in scientific38 apparatus. It casts a warning ray on clear nights, it moans weirdly in foggy weather, like the spirits of the damned; and, in addition, it has machinery for exploding charges of gun-cotton at regular intervals. It is wound up once in four hours, and then proceeds to automatically produce thirteen explosions in the hour. So, in one way and another it will be allowed the shipping of the Bristol Channel is well looked after. From this point, the coast of South Wales is distinctly seen, or is supposed to be. Visitors to Lynmouth have no desire to see it, for the sight is a prelude to rainy weather. The Mumbles is twenty-three miles distant, and yet the hoarse bellowing (or mumbling, if you like it better) of the lighthouse siren there in thick weather is distinctly heard, like the voice of a cow calling her calf.

Like all approaches to modern lighthouses, the cart or carriage-road made to this at the Foreland is a stark, blinding affair of glaring rock and loose stones, very trying to wheels, hoofs, or feet; and the hillsides are covered with an amazing litter of loose stones that have resided there ever since the very beginning of things. The place looks like Nature’s rubbish-heap. The way to Glenthorne by the coast-path, therefore, looks more enticing. Something was wrong with the explosive-signal machinery, the day when this explorer chanced by; something that refused to be speedily set right, and the lighthouse man who was attending to it was not averse from ceasing work to give directions and, incidentally,39 to get a rest. So, quitting awhile his labours with refractory cogs, winches, and springs, he gave elaborate guidance by which one might keep the path along the rugged cliffs to Glenthorne. Not often does he find a stranger to hold converse with, and his directions were so long and full of parentheses that one quite forgot the beginning by the time the end was reached. But the burden of it was, “You go through those woods—they don’t look like more’n bracken from here, but they’re fair-sized trees, really—or else you can get to the road at the top.”

“I’ll take the woods,” said I, having had enough of the glaring sunshine; “they’ll be shady.”

“Yes—and full of flies,” returned the lighthouse man, “the place fairly ’ums with ’em.”

How true that was: how entirely true! They are charming woods of scrub-oak, hanging on the side of the scrambly cliff; and one would fain rest there awhile in the shade, on a moss-covered rock, beside the springs that trickle down the side of the cliff. But the celebrated “hoss-stingurrs”—the large grey horse-flies—that inhabit the place in force, and bite you through the thickest stockings, forbid any idea of resting in that tormented spot, and the beautiful thoughts that might have found expression in scenery so provocative of literary celebration, are lost in the defensive operations that accompany an undignified retreat. It is in places a very clamberous path to Glenthorne, and at some points more than a little40 difficult and dangerous. So few, evidently, and far between are those who come this way, that the track kept open by the occasional explorer who brushes aside the brambles and the branches that bar his path, is almost overgrown by the time the next stalwart forces a passage. Here and there a steep little gorge requires careful manœuvring; in some places, where the track emerges upon the open, bracken-grown hillside, descending alarmingly, and without a break, to the sea far below, it traverses broken, rock-strewn slanting ground, where a slip would send the incautious hopelessly rolling into the water; and at other places all signs of a track are lost. It is here, as the stranger goes chamoising up and down amid the tussocky bracken, that he feels sorry for himself. The excursion steamboats passing up and down Channel, half a mile out, command a fine uninterrupted view of these cliffs, and the adventurer, questing perspiringly up and down for any sign of a track, is fully aware that some fifty field-glasses are probably turned upon his efforts. He, therefore, unostentatiously drops down amid the bracken until those steamboats pass out of sight, beyond the Foreland.

One of the cruellest dilemmas is that which Fate is capable of presenting the stranger in these perilous ways. He slips on a mossy ledge under the shadow of lichened branches, and, to save himself, grips in the half-light what he thinks to be a foxglove, but is really a thistle. “Hold fast to that which is good,” say the Scriptures; and41 although in other circumstances a thistle is scarcely a desirable grip, yet, between the prospect of rolling down some hundreds of feet and the certainty even of excoriated hands, there is but one possible choice.

In the middle of July, when the bracken is come to full growth, the air is filled with the exquisite odour of it; a peculiar scent, heavy and sweet, like that of a huge making of strawberry jam. And presently, after much toil, you come to a broad green ride, where you may rest awhile and luxuriously inhale that fragrance.

Point Desolation is the name given to one of the headlands on the way, and “Rodney” the name of a cottage, now deserted, in a dark cleft, overhung with trees. Finally, the green drive conducts to a very welcome granite seat overlooking a wide expanse of sea, and thence through a gateway marked “private.” This is the entrance to the Glenthorne grounds, which are not so strictly private as the stranger might suppose. Through the gateway, the path continues, bordered here with laurels and fir-trees, and so dips down toward the mansion, built in 1830, in the domestic Gothic style, on a partly natural terrace, three parts of the way down the wooded cliffs and hillsides that go soaring up to a height of five hundred feet. The house is situated exactly on the borderline of Devon and Somerset, and is in the loneliest situation imaginable; having, indeed, been in the old days a favourite spot with the smugglers of these coasts. It was built, and the grounds42 enclosed, by the Reverend W. S. Halliday, a person whose eccentricities may yet be heard of at Lynmouth. One of his peculiar amusements was the sardonic fancy for burying genuine Roman coins in places where it is thought no Romans ever penetrated, with the expressed idea of puzzling future antiquaries. It seems—since he cannot be there to chuckle over the jest—a strange kind of humour.

The long ascent from Glenthorne, through the woods, is extraordinarily tiring, beautiful though those woods be, and aromatic with piny odours. The carriage-drive, zigzagging up, is steep, and a halt by the way, every now and then, more grateful and comforting than even a famous cocoa is advertised to be. But that ascent in the shade43 is a mere nothing to the further treeless ascent to the coach-road, under the July sun. Bare grassy combes, and white roads that wind round the mighty shoulders of the hills exhaust the wayfarer, who at last, taking on trust the prehistoric camp of Old Barrow, perched on a steep height, gains the dull highway with a sigh of relief. I daresay a good many of the sardonic Mr. Halliday’s Roman coins are buried in Old Barrow, awaiting antiquarian discovery.

The way back to Lynmouth, crossing Countisbury Common, has some beautiful glimpses away on the left, over the wooded valley of the East Lyn.

44

CHAPTER V

THE NORTH WALK—THE VALLEY OF ROCKS—LEE

“ABBEY”—WOODA BAY—HEDDON’S MOUTH—TRENTISHOE—THE

HANGMAN HILLS

And so at last to leave Lynmouth.

It is by no means necessary to take Lynton on the way to the Valley of Rocks and the coast-walk to Wooda Bay and Heddon’s Mouth. The cliff-path known as the North Walk avoids Lynton, and, climbing up midway along the hillside, forms a secluded route of the greatest beauty. It was cut in 1817 by a public-spirited Mr. Sanford. Until that time, there was no path, and only the most hardy climbers, at the risk of falling headlong into the sea, ever attempted to make their way by this route. It is merely a footpath, and so not in any way injurious to the wild, romantic nature of the scenery. Were some injudicious person, or local authority, to conceive the idea of forming it into a broad road, not Nature herself could, short of a convulsion, remedy the scar that would be made for all the neighbourhood to see. Trees cannot grow on this stony hillside, to hide such things; the great gash made for the Lift, or Cliff Railway, which here runs at right-angles up hill, being only by good fortune screened45 through ascending by a route affording foothold for shrubs and undergrowth. It is now, indeed, hidden in a degree those who saw the raw wound in 1890 dared not hope for. Kindly Nature, dear, forgiving, long-suffering, immortal mother, to whom we all come, weary, for rest at last, to your ample bosom, how great soever be our enormities, you bear with them all and, smiling, resume your way.

This rocky walk, winding past one grey crag after another, is rich in towered and spired masses and jutting pinnacles. Sometimes they rise up for all the world like pedestals rudely shaped to receive statues; but they would need to be statues of heroic size and pose to fit these surroundings. The eye ranges along the coast, past Castle Rock and Duty Point, to the softly rounded masses of woods covering the hillsides enclosing Wooda Bay; and only the restless, resistless spirit of exploration forbids long lingering here and there, on those occasional seats provided by the thoughtful Urban District Council that rules the twin places, Lynmouth and Lynton, and perseveringly tries to reconcile their jealousies. But one must needs rest awhile at that point where the North Walk, bending to the left, enters the Valley of Rocks. Here a convenient seat is placed, commanding a view backwards to Lynmouth and the Foreland, and looking down from a sheer height on to great emptinesses of blue, sunlit sea. Seagulls wheel and cry, or poise suddenly, on idle extended pinions, whimsically like a cyclist46 “free-wheeling”; excursion steamers, to and from Ilfracombe and other resorts, go by, and in the still August sea leave more than mile-long creamy wakes of foam traced in the blue, until they become indistinct in distance.

An elderly gentleman, who had hobbled up the path on gouty feet, sat down beside me. Like two true Britons, we sat there a minute or two together, each ignoring the presence of the other. He glanced a greatly impressed eye upon the short, steep and slippery slope of grass that alone intervened between his side of the seat and a sheer drop of some two hundred feet into the sea. “It would not be difficult to commit suicide here,” he at length remarked.

Was he wearied to extinction with his gout, and so determined here and now, to make an end? Not at all: it was a purely speculative thought.

“The easiest thing in the world,” I replied; “and one person might readily push another over, and no one——”

“Yes, yes,” he rejoined with alacrity, and relapsed into thoughtful silence a moment. Then, suddenly consulting his watch: “Time I was moving off for lunch.”

Now I don’t by any means, you know, regard myself as a very desperate-looking person, yet obviously that unlucky remark moved that nervous old gentleman to go off in quest of his lunch at a very early hour. I suppose he imagined himself to have experienced a very narrow escape. “One49 does read such dreadful things in the papers,” I hear him, in imagination, saying at lunch; “you never know what lunatic you may meet in some lonely spot.” True.

And so, into the Valley of Rocks. There was a time when every writer who happened upon the Valley of Rocks felt himself obliged to adopt an attitude of awe, and to ransack the dictionary for adjectives to fitly represent the complicated state of mind into which he generally lashed himself. That time has naturally been succeeded by a revulsion of feeling; and there is not a guidebook at the present day which does not apologise for those old transports of feeling, and declare the Valley of Rocks to be really nothing remarkable. But that later attitude is just as absurd as the earlier. The valley is very fine indeed, and its wildness is only impaired by the broad white ribbon of road that runs through it, and will not let you forget that here, too, however craggy and precipitous the piled-up masses of granite on either side, and however remote the feeling, actually the most up-to-date civilisation is very near indeed.

This is what was written of the Valley of Rocks in 1803: “The heights on each side are of a mountainous magnitude, but composed, to all appearances, of loose, unequal masses, which form here and there rude natural columns, and are fantastically arranged along the summits, so as to resemble extensive ruins impending over the pass.”

50 So far, this is literally true, and the name of Castle Rock, given to one of these stony heights, grimly coroneted with masses of rock, is excellently descriptive. The rocks so closely resemble towers and battlements that the stranger is often deceived into thinking them to be real masonry. A companion rocky hill, isolated midway in the valley, and called “Ragged Jack,” from its notched outline, is almost equally castellated.

It is only when the account already quoted proceeds to dilate upon the “awful vestiges of convulsion and desolation presenting themselves, and inspiring the most sublime ideas,” that we do not quite follow, and we suspect this was the outcome of much competitive writing; each succeeding writer striving to pile phrase upon phrase, very much after the manner in which the rocks of the Valley of Rocks are heaped upon one another.

The “Devil’s Cheese-wring” is the name of one of these curious stony piles, now partly overgrown with ivy. The Valley and the cheese-wring are mentioned in “Lorna Doone,” a romance no one can escape in North Devon, strive though he may; although, really, the Doone Valley and almost every incident of that story, are in, and concerned with, Somerset.

A wind-swept little wood is almost the only sign of vegetation, except the coarse grass, in this wild valley of grey stones; but it is the appalling heat, rather than the wind, which troubles the tourist in his passage, and he is often fain to51 shelter awhile in the welcome shade of some huge crag; thinking, as he does so, of that eloquent passage in Isaiah, “The shadow of a great rock in a weary land.” And really, the Valley of Rocks is very like the parched, stony land of Palestine, which suggested the phrase.

It is at the close of some sultry summer day that the Valley of Rocks looks its very best. The irradiated sky, throwing into silhouette the great masses of rock, has the effect of magnifying and glorifying them. On such summer evenings, the more youthful among the holiday-makers set out from Lynton, and there, on the rugged hillside of the Castle Rock or Ragged Jack, you may see the white frocks of the girls, looking more than a little like the white-robed figures of those Druids, who, according to old Polwhele, used this place of desolation as a temple, and carved the roughly shaped rock-pillars and granite hollows into “rock idols” and “sacrificial basins.” On the summit of Castle Rock a “white lady” of a different kind may be seen; a curious figure, resembling a woman, formed by a huge slab of rock fallen between two upright masses. The resemblance is sufficiently close to startle strangers coming this way at night.

The road goes under the rugged hills, past the little inlet of Wringcliff Bay, overhung with ferny precipices, to a gate leading into the domain of Lee Abbey. All kinds of wheeled traffic may go through by lodge and gate, except motor vehicles—they are forbidden.

52 Lee Abbey, occupying the site of the old manor-house of the Wichehalse family, is an abbey only in name and venerable only in appearance, having been built in 1850. But although “Abbey” be merely a fanciful name, and although there yet remain people who have seen the building of the entire range of mansion and outworks, the ivied entrance-tower and enclosing walls have so truly mediæval an appearance, that many people are entirely deceived, and, not seeking to inform themselves, dream wonderfully romantic dreams of “the old monks” and their religious life in this secluded spot, and live ever afterwards in happy ignorance of the deception. Lee “Abbey” is, in fact, nothing more than a very charming country residence, designed to fit an exceptionally beautiful site.

High above it is the woody hill with look-out tower overhanging that spot on Duty Point called “Jennifrid’s Leap,” of which we have already heard, and down below is the loveliest little bay—Lee Bay—with Wooda Bay opening out beyond it, and the little tumbled headland of Crock Point and the swelling, scrub-covered hillside of Bonhill Top in between. To style the little promontory Crock Point is entirely correct, for it was the scene of a landslip somewhere about 1796, when, one Sunday morning, the hillside fields, with their standing crops of wheat, suddenly slid down to the sea in utter ruin. This was due partly to the percolation of landsprings acting upon the clay, and the clay-digging that had for some while been55 in progress, for shipment to Holland. The names, “Crock Point” and “Crock Meads,” probably allude to this old digging for pottery uses.

Lee Bay looks like the choicest site in some delectable Land of Heart’s Desire. Down goes the road, through another gate and past the most entirely picturesque and well-constructed lodge I have ever seen, and so out of this private domain. Here a shady valley welcomes the heated traveller; a valley where everything but the generous trees, and the cool shade they spread, is in miniature. A little stream comes running swiftly down from the hilltops, as though it, too, were eager to enter from sunburnt heights into this place, where mossy tree-trunks radiate a welcome coolness, and hart’s-tongue ferns grow in lichened walls and look refreshing. The little stream presently falls over a ledge of rock and becomes a little waterfall, whose purring voice fills the narrow space; and everything is delightful. And there are not any of those horse-stingers, which generally infest the most desirable spots and, instead of confining themselves strictly to horse-stinging, interfere with inoffensive explorers.

The tiny bay that opens out from this twilight lane is a quiet spot, where boulders are scattered about amid the sand and shingle, with that look of studied abandon customary in stage-carpenters’ versions of the seaside; and surely we can give no higher praise than that! It is a spot where one might fitly converse with some not too forward young mermaid (keep your eye off her tail, and56 such, by all accounts, should be presentable enough); to be auditor of strange, uncanny legends; a thousand fearful wrecks “full fathom five,” and dead-men’s bones and drowned treasure.

But for tales of drowned treasure, or “money sunk” and lost, which, after all, is much the same to the owner of it—one need not go far, nor seek the dangerous society of mermaids. Wooda Bay, yonder, across the intervening neck of land, has a modern story of some interest. It was somewhere about 1895 that Benjamin Greene Lake, of the London firm of solicitors, Lake and Lake, conceived the idea of “developing” this secluded and extremely lovely spot, and of making it, as it were, a newer Lynmouth. He purchased much land, caused many roads to be made to the bay, and built an elaborate timber landing-stage for steamers. A few houses were indeed built here and there: among them the “Glen” Hotel, but Wooda Bay has not developed to any extent, in the building-estate sense. How many thousands of pounds were lost here, seems uncertain; according to some accounts, £25,000, or by others, much more. Unfortunately, this was one of Benjamin Greene Lake’s many speculations financed with other people’s money—without their knowledge or consent. He was sentenced in January 1901 to twelve years’ imprisonment, for converting trust funds to his own use. He had in various projects made away with no less than £170,000 of his clients’ money.

So there was an end of this great development57 idea. Only a few scattered houses and the roads gashed in the hill-tops remain to tell of it, for the sea speedily washed away every fragment of the timber pier.

The name of Wooda Bay, therefore, falls ill on the ears of not a few defrauded persons. It is a pity, for it is one of the loveliest bays on an exceptionally lovely coast. The Post Office authorities have adopted the new-fangled spelling, “Woody,” instead of “Wooda,” as appears by the tree-shaded post-office here; and the Lynton and Barnstaple Railway, which has a station for it, set down in a far-off wilderness, appears to spell the name, with a fine air of impartiality, in both styles. But the old rustic Devonian way was “Wooda”; a form characteristic of innumerable place-names throughout the country, and exemplified near by, in “Parracombe,” “Challacombe,” “Fullaford,” “Buzzacott,” and innumerable others.

Delightful lanes lead round the shores of the bay, amid woods, with here and there a waterfall; notably at a point where a bridge carrying a lane over a little stream is inscribed Inkerman Bridge, 1857.

Near the shore is the unpretending manor house of Martinhoe: the church of that parish being situated high above, away among the wild commons of a little-visited hinterland. It was here and at Trentishoe, many years since, that the future Bishop Hannington, who met a martyr’s fate in 1885 in the wilds of his African diocese, was58 curate. He dressed the part unconventionally, in a manner fitting a neighbourhood where there were no Dorcas Societies, mothers’ meetings, or any of the quaint machinery of a modern parish. Only rough farmers and their men, and wild and unfrequented footpaths formed everyday experiences. The typical curate would have soon found his conventional dress very much out of place. Hannington wore Bedford cord knee-breeches of a yellow hue, yellow Sussex gaiters with brass buttons, and great nailed boots that would have suited a ploughboy. A short jerkin of black cloth and a clerical waistcoat that buttoned up the side gave just a professional hint. In this costume, covered with the surplice, of course, he would take the services as well; not from any eccentricity, but simply because the conditions of these rustic parishes demanded it. They demanded much walking, too. “I see you’ve got fine legs,” Dr. Temple, the rather grim Bishop of Exeter, said: “mind you run about your parish.”

Over the wooded hill called Wringapeak, the way now lies on to Heddon’s Mouth.

There is no hint of monotony in this grand stretch of coast scenery. Here nature is full of resources and surprises, and each cliff-profile, valley, wooded hillside, or little bay is strikingly different from the last. Leaving Wooda Bay behind, having already, as you think, tasted every variety of scenic splendour, yet another aspect of these boundless resources is revealed, in an61 exquisite wood of dwarf oaks. Through this delightful boscage, delightful in itself and in the shade it gives on fervent days, the way lies, as a grassy path. Great grey boulders, covered with lichen, show on either side, in the half light, and the foliage of the oaks grows in wonderfully large lustrous leaves, by favour of this wonderful climate. It is all so quiet. Few people are ever met here; but, here and there, at infrequent intervals one finds a retired villa, three-parts hidden behind the shrubs of its ample grounds. One such you pass, and see amid the woodland trees a little tombstone to a pet dog; “‘Bruiser,’ a good dog”: concise, yet all-comprising.

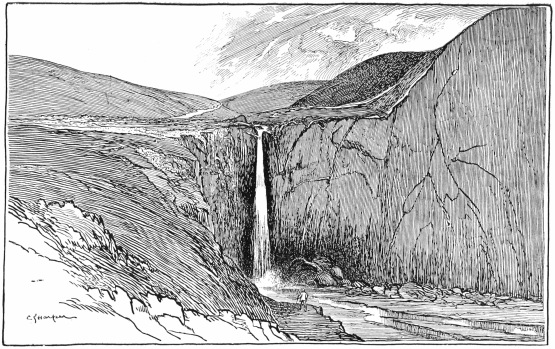

When rounding successive points, new and ever more beautiful views are disclosed, and sublime thoughts rise, but they do not find full expression in that form, because of the loose stones and fragments of rock that everywhere prodigally strew the cliff-paths. Midway between Wooda Bay and Heddon’s Mouth, a lovely waterfall comes spouting down the face of the cliff, in a little bight, the sides of it fringed with moss and ferns, and at the foot a tangle of trees and bushes that have found a precarious foothold. Here fragments of rock, like some prehistoric rubbish-heap, threaten unstable ankles.