BY PROF. CHARLES FOSTER KENT

THE SHORTER BIBLE—THE NEW TESTAMENT.

THE SHORTER BIBLE—THE OLD TESTAMENT.

THE SOCIAL TEACHINGS OF THE PROPHETS AND JESUS.

BIBLICAL GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY.

THE ORIGIN AND PERMANENT VALUE OF THE OLD TESTAMENT.

HISTORY OF THE HEBREW PEOPLE. From the Settlement in Canaan to the Fall of Jerusalem in 586 B.C. 2 vols.

HISTORY OF THE JEWISH PEOPLE. The Babylonian, Persian and Greek Periods.

THE HISTORICAL BIBLE. With Maps. 6 vols.

STUDENT'S OLD TESTAMENT. Logically and Chronologically Arranged and Translated. With Maps. 6 vols.

THE MESSAGES OF ISRAEL'S LAW-GIVERS.

THE MESSAGES OF THE EARLIER PROPHETS.

THE MESSAGES OF THE LATER PROPHETS.

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

BIBLICAL

GEOGRAPHY AND HISTORY

BY

CHARLES FOSTER KENT, Ph.D.

WOOLSEY PROFESSOR OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE IN YALE UNIVERSITY

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1926

Copyright, 1911, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Printed in the United States of America

Published April, 1911

PREFACE

Geography has within the past few years won a new place among the sciences. It is no longer regarded as simply a description of the earth's surface, but as the foundation of all historical study. Only in the light of their physical setting can the great characters, movements, and events of human history be rightly understood and appreciated. Moreover, geography is now defined as a description not only of the earth and of its influence upon man's development, but also of the solar, atmospheric, and geological forces which throughout millions of years have given the earth its present form. Hence, in its deeper meaning, geography is a description of the divine character and purpose expressing itself through natural forces, in the physical contour of the earth, in the animate world, and, above all, in the life and activities of man. Biblical geography, therefore, is the first and in many ways the most important chapter in that divine revelation which was perfected through the Hebrew race and recorded in the Bible. Thus interpreted it has a profound religious meaning, for through the plains and mountains, the rivers and seas, the climate and flora of the biblical world the Almighty spoke to men as plainly and unmistakably as he did through the voices of his inspired seers and sages.

No other commentary upon the literature of the Bible is so practical and luminous as biblical geography. Throughout their long history the Hebrews were keenly attentive to the voice of the Eternal speaking to them through nature. Their writings abound in references and figures taken from the picturesque[vi] scenes and peculiar life of Palestine. The grim encircling desert, the strange water-courses, losing themselves at times in their rocky beds, fertile Carmel and snow-clad Hermon, the resounding sea and the storm-lashed waters of Galilee are but a few of the many physical characteristics of Palestine that have left their indelible marks upon the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. The same is true of Israel's unique faith and institutions. Biblical geography, therefore, is not a study by itself, but the natural introduction to all other biblical studies.

In his Historical Geography of the Holy Land and in the two volumes on Jerusalem, Principal George Adam Smith, of Aberdeen, has given a brilliant and luminous sketch of the geographical divisions and cities of Palestine, tracing their history from the earliest times to the present. Every writer on Palestine owes him a great debt. The keenness and accuracy of his observations, are confirmed at every point by the traveller. At the present time, the need of a more compact manual, to present first the physical geography of the biblical lands and then to trace in broad outlines the history of Israel and of early Christianity in close conjunction with their geographical background, has long been recognized. In the present work unimportant details have been omitted that the vital facts may stand out clearly and in their true significance. The aim has been to furnish the information that every Bible teacher should possess in order to do the most effective work, and the geographical data with which every student of the Bible should be familiar, in order intelligently to interpret and fully appreciate the ancient Scriptures.

This volume embodies the results of many delightful months spent in the lands of the eastern Mediterranean, and especially in Palestine, during the years 1892 and 1910. Owing to improved conditions in the Turkish Empire it is now possible, with the proper camp equipment, to travel safely through the remotest[vii] places east of the Jordan and to visit Petra, that most fascinating of Eastern cities. By securing his equipment at Beirut the traveller may cross northern Galilee and then, with comfort, go southward in the early spring through ancient Bashan, Gilead, Moab, and Edom. Thence, with great economy of time and effort, he may return through central Palestine, making frequent détours to points of interest. In this way he will find the quaint, fascinating old Palestine that has escaped the invasions of the railroads and western tourists, and he will bear away exact and vivid impressions of the land as it really was and still is.

The difficulties and expense of Palestine travel, however, render such a journey impossible for the majority of Bible students. Fortunately, the marvellous development of that most valuable aid to modern education, the stereoscope and the stereograph, make it possible for every one at a comparatively small expense to visit Palestine and to gain under expert guidance in many ways a clearer and more exact knowledge of the background of biblical history and literature than he would through months of travel. Through the courtesy of my publishers and the co-operation of the well-known firm of Underwood & Underwood, of New York and London, I have been able to realize an ideal that I have long cherished, and to place at the disposal of the readers of this volume one hundred and forty stereographs (or, if preferred for class and lecture use, stereopticon slides) that illustrate the most important events of biblical geography and history. They have been selected from over five hundred views taken especially for this purpose, and enable the student to gain, as he alone can through the stereoscope, the distinct state of consciousness of being in scores of historic places rarely visited even by the most venturesome travellers. Numbers referring to these stereographs (or stereopticon slides) have been inserted in the body of the text. In Appendix II the titles corresponding to each number are given.

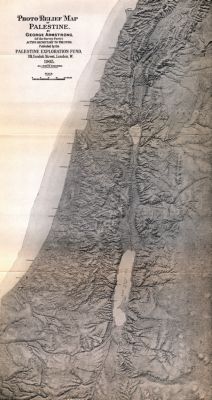

[viii]The large debt that I owe to the valiant army of pioneers and explorers who have penetrated every part of the biblical world and given us the results of their observations and study is suggested by the selected bibliography in Appendix I. I am under especial obligations to the officers of the Palestine Exploration Fund, who kindly placed their library and maps in London at my service and have also permitted me to use in reduced form their Photo-Relief Map of Palestine.

C. F. K.

Yale University,

January, 1911.

CONTENTS

PART I—PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY

PAGE

I. The General Characteristics of the Biblical World 3

Extent of the Biblical World.—Conditions Favorable to Early Civilizations.—Egypt's Climate and Resources.—Its Isolation and Limitations.—Conditions in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley.—Forces Developing Its Civilization.—Civilization of Arabia.—Physical Characteristics of Syria and Palestine.—Their Central Position and Lack of Unity.—Asia Minor.—Mycenæ.—Greece.—Italy.—Situation of Rome.—Reason Why Rome Went Forth to Conquer.—Résumé.

II. The General Characteristics of Palestine 13

History of the Terms Palestine and Canaan.—Bounds of Palestine.—Geological History.—Alluvial and Sand Deposits.—General Divisions.—Variety in Physical Contour.—Effects of This Variety.—Openness to the Arabian Desert.—Absence of Navigable Rivers and Good Harbors.—Incentives to Industry.—Incentives to Faith and Moral Culture.—Central and Exposed to Attack on Every Side.—Significance of Palestine's Characteristics.

III. The Coast Plains21

Extent and Character.—Fertility.—Divisions.—Plain of Tyre.—The Plain of Acre.—Carmel.—Plain of Sharon.—The Philistine Plain.—The Shephelah or Lowland.

IV. The Plateau of Galilee and the Plain Of Esdraelon 27

Physical and Political Significance of the Central Plateau.—Natural and Political Bounds.—Its Extent and Natural Divisions.—Physical Characteristics of Upper Galilee.—Its Fertility.—Characteristics of Lower Galilee.—Situation and Bounds of the Plain of Esdraelon.—Plain of Jezreel.—Water Supply and Fertility of Plain of Esdraelon.—Central and Commanding Position.—Importance of the Plain in Palestinian History.

V. [x] The Hills of Samaria and Judah 34

Character of the Hills of Samaria.—Northeastern Samaria.—Northwestern Samaria.—The View from Mount Ebal.—Bounds and General Characteristics of Southern Samaria.—Southwestern Samaria.—The Central Heights of Judah.—Lack of Water Supply.—Wilderness of Judea.—Western Judah.—Valley of Ajalon.—Wady Ali.—Valley of Sorek.—Valley of Elah.—Valley of Zephathah.—Wady el-Jizâir.—Significance of These Valleys.—The South Country.—Its Northern and Western Divisions.—Its Central and Eastern Divisions.—The Striking Contrasts between Judah and Samaria.—Effect upon Their Inhabitants.

VI. The Jordan and Dead Sea Valley 45

Geological History.—Evidences of Volcanic Action.—Natural Divisions.—Mount Hermon.—Source of the Jordan at Banias.—At Tell el-Kadi.—The Two Western Confluents.—The Upper Jordan Valley.—The Rapid Descent to the Sea of Galilee.—The Sea of Galilee.—Its Shores.—From the Sea of Galilee to the Dead Sea.—Character of the Valley.—The Jordan Itself.—Fords of the Lower Jordan.—Ancient Names of the Dead Sea.—Its Unique Characteristics.—Its Eastern Bank.—The Southern End.—The Western Shores.—Grim Associations of the Dead Sea.

VII. The East-Jordan Land 55

Form and Climate of the East-Jordan Land.—Well-Watered and Fertile.—The Four Great Natural Divisions.—Characteristics of the Northern and Western Jaulan.—Southern and Eastern Jaulan.—Character of the Hauran.—Borderland of the Hauran.—Gilead.—The Jabbok and Jebel Ôsha.—Southern Gilead.—Character of the Plateau of Moab.—Its Fertility and Water Supply.—Its Mountains.—Its Views.—The Arnon.—Southern Moab and Edom.—Significance of the East-Jordan Land.

VIII. The Two Capitals: Jerusalem and Samaria64

Importance of Jerusalem and Samaria.—Site of Jerusalem.—The Kidron Valley.—The Tyropœon Valley.—The Original City.—Its Extent.—The Western Hill.—The Northern Extension of the City.—Josephus's Description of Jerusalem.—The Geological Formation.—The Water Supply.—Jerusalem's Military Strength.—Strength of Its Position.—Samaria's Name.—Its Situation.—Its Military Strength.—Its Beauty and Prosperity.

IX. [xi] The Great Highways of the Biblical World73

Importance of the Highways.—Lack of the Road-building Instincts among the Semites.—Evidence that Modern Roads Follow the Old Ways.—Ordinary Palestinian Roads.—Evidence that the Hebrews Built Roads.—The Four Roads from Egypt.—Trails into Palestine from the South.—Highway Through Moab.—The Great Desert Highway.—Character of the Southern Approaches to Palestine.—The Coast Road.—The "Way of the Sea."—Its Commercial and Strategic Importance.—The Central Road and Its Cross-roads in the South.—In the North.—The Road Along the Jordan.—Roads Eastward from Damascus.—The Highway from Antioch to Ephesus.—The Road from Asia Minor to Rome.—From Ephesus to Rome.—From Syria to Rome by Sea.—From Alexandria to Rome by Sea.—Significance of the Great Highways.

PART II—HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY

X. Early Palestine87

The Aim and Value of Historical Geography.—Sources of Information Regarding Ancient Palestine.—Evidence of the Excavations.—The Oldest Inhabitants of Palestine.—The Semitic Invasions from the Desert.—Influence of the Early Amorite Civilization Upon Babylonia.—Probable Site of the Oldest Semitic Civilization.—Remains of the Old Amorite Civilization.—Babylonian Influence in Palestine.—Egyptian Influence in the Cities of the Plain.—Different Types of Civilization in Palestine.—Conditions Leading to the Hyksos Invasion of Egypt.—Fortunes of the Invaders.—The One Natural Site in Syria for a Great Empire.—Influences of the Land Upon the Early Forms of Worship.—Upon the Beliefs of Its Inhabitants.

XI. Palestine Under the Rule of Egypt97

Reasons why Egypt Conquered Palestine.—Commanding Position of Megiddo.—Its Military Strength.—Thotmose III's Advance Against Megiddo.—The Decisive Battle.—Capture of Megiddo.—The Cities of Palestine.—Disastrous Effects of Egyptian Rule.—Lack of Union in Palestine.—Exposure to Invasions from the Desert.—Advance of the Habiri.—Rise of the Hittite Power.—Palestine between 1270 and 1170 B.C.—The Epoch-making Twelfth Century.

XII. [xii]The Nomadic and Egyptian Period of Hebrew History106

The Entrance of the Forefathers of the Hebrews Into Canaan.—References to Israelites During the Egyptian Period.—The Habiri in Eastern and Central Palestine.—The Trend Toward Egypt.—The Land of Goshen.—The Wady Tumilat.—Ramses II's Policy.—Building the Store Cities of Ramses and Pithom.—Condition of the Hebrew Serfs.—Training of Moses.—The Historical Facts Underlying the Plague Stories.—Method of Travel in the Desert.—Moses' Equipment as a Leader.—The Scene of the Exodus.—Probability that the Passage was at Lake Timsah.

XIII. The Hebrews in the Wilderness and East of the Jordan115

Identification of Mount Sinai.—Lateness of the Traditional Identification.—Probable Route of the Hebrews.—Kadesh-barnea.—Effect of the Wilderness upon the Life of the Hebrews.—Evidence that the Hebrews Aimed to Enter Canaan from the South.—Reasons Why They Did Not Succeed.—Tribes that Probably Entered Canaan from the South.—The Journey to the East of the Jordan.—Stations on the Way.—Conquests East of the Dead Sea.—Situation of Heshbon.—Sojourn of the Hebrews East of the Jordan.—Its Significance.

XIV. The Settlement in Canaan124

The Approach to the Jordan.—Crossing the Jordan.—Strategic Importance of Jericho.—Results of Recent Excavations.—Capture of Jericho.—Evidence that the Hebrews Were Still Nomads.—Roads Leading Westward from Jericho.—Conquests In the South.—Conquest of Ai and Bethel.—Incompleteness of the Initial Conquest.—Migration of the Danites.—The Moabite Invasion.—The Rally of the Hebrews Against the Canaanites.—The Battle-field.—Effect of a Storm Upon the Plain.—Results of the Victory.—The East-Jordan Tribes.—The Tribes in Southern Canaan.—The Tribes in the North.—Effects of the Settlement Upon the Hebrews.

XV. The Forces that Led to the Establishment of the Hebrew Kingdom136

The Lack of Unity Among the Hebrew Tribes.—The Scenes of Gideon's Exploits.—Gideon's Kingdom.—Reasons for the Superiority of the Philistines.—Scenes of the Samson Stories.—The Decisive Battle-field.—Fortunes of the Ark.—The Sanctuary at Shiloh.—Samuel's Home at Ramah.—The Site of Gibeah.—Situation of Jabesh-Gilead.—The Sanctuary at Gilgal.—The Philistine Advance.—The Pass of Michmash.—The Great Victory Over the Philistines.—Saul's Wars.

XVI. [xiii]The Scenes of David's Exploits147

David's Home at Bethlehem.—The Contest in the Valley of Elah.—Situation of Nob.—The Stronghold of Adullam.—Keilah.—Scenes of David's Outlaw Life In Southeastern Judah.—David at Gath.—At Ziklag.—Reasons Why the Philistines Invaded Israel in the North.—Saul's Journey to Endor.—The Battle on Gilboa.—The Remnant of Saul's Kingdom.—Hebron, David's First Capital.—Fortunes of the Two Hebrew Kingdoms.—The Final Struggle with the Philistines.—David's Victories.

XVII. Palestine Under the Rule of David And Solomon157

Establishment of Jerusalem as Israel's Capital.—Israel's Natural Boundaries.—Campaigns Against the Moabites and Ammonites.—Situation of Rabbath-Ammon.—The Water City.—Extent of David's Empire.—Absalom's Rebellion.—David East of the Jordan.—Rebellion of the Northern Tribes.—Scenes of Adonijah's Conspiracy and Solomon's Accession.—Capture of Gezer.—Solomon's Fortresses.—Solomon's Strategic and Commercial Policy.—Site of Solomon's Temple.—Significance of the Reigns of David and Solomon.—Influences of the United Kingdom Upon Israel's Faith.—Solomon's Fatal Mistakes.—Forces that Made for Disunion.—Situation of Shechem.—Significance of the Division.

XVIII. The Northern Kingdom168

The Varied Elements in the North.—Capitals of Northern Israel.—The Aramean Kingdom.—The Philistine Stronghold of Gibbethon.—Omri's Strong Rule.—Ahab's Aramean Wars.—Strength and Fatal Weakness of Ahab's Policy.—Elijah's Home.—The Scene on Mount Carmel.—Ancient Jezreel.—Situation of Ramoth-Gilead.—Elisha's Home.—Jehu's Revolution.—Rule of the House of Jehu.—The Advance of Assyria.—Amos's Home at Tekoa.—Influence of His Environment Upon the Prophet.—Evidence Regarding Hosea's Home.—View from Jebel Ôsha.—Conquest of Galilee and Gilead.—The Exiled Northern Israelites.—The Fate of Northern Israel.

XIX. The Southern Kingdom182

Effect of Environment Upon Judah's History.—Shishak's Invasion.—War Between the Two Kingdoms.—Amaziah's Wars.—Uzziah's Strong Reign.—Isaiah of Jerusalem.—His Advice to Ahaz in the Crisis of 734 B.C.—The Great Rebellion of 703 B.C.—Home of the Prophet Micah.—Judah's Fate in 701 B.C.—Isaiah's Counsel in a Later Crisis.—The Reactionary Reign of Manasseh.—Two Prophetic Reformers.—Situation of Anathoth.—Josiah's Reign.—The Brief Rule of Egypt.—Jehoiakim's Reign.—The First Captivity.—The Second Captivity.—The End of the Southern Kingdom.

XX. [xiv]The Babylonian and Persian Periods194

Jewish Refugees in Egypt.—Situation of Tahpanhes.—Memphis.—The Colony at Elephantine.—Results of the Excavations.—Transformation of the Jews Into Traders.—Home of the Exiles in Babylonia.—Their Life in Babylonia.—Conditions of the Jews in Palestine.—Extent of the Jewish Territory.—Evidences that There Was No General Return of the Exiles in 537 B.C.—The Rebuilding of the Temple.—Discouragement and Hopes of the Jews.—Nehemiah's Response to the Call for Service.—Conditions in the Jewish Community.—Preparations for Rebuilding the Walls.—Character of the Data.—The Walls and Towers on the North.—On the West.—On the South.—On the East.—Significance of Nehemiah's Work.—Extension of Jewish Territory to the Northwest.—Development of Judaism During the Latter Part of the Persian Period.

XXI. The Scenes of the Maccabean Struggle207

Alexander's Conquests.—The Impression Upon Southwestern Asia.—The City of Alexandria.—Greek Influence in Palestine.—The Ptolemaic Rule.—Situation of Antioch.—Causes of the Maccabean Struggle.—The Town of Modein.—The First Flame of Revolt.—Character and Work of Judas.—The Pass of Beth-horon.—Scene of the Victory Over the Syrian Generals.—Victory at Bethsura.—Rededication of the Temple.—Campaigns South and East of the Dead Sea.—Victories in Northeastern Gilead.—Cities Captured North of the Yarmuk.—The Second Victory Over Timotheus.—Judas's Return.—Significance of Judas's Victories.—Battle of Beth-zacharias.—Fortunes of Judas's Party.—Victory over Nicanor.—Death of Judas.—Judas's Character and Work.

XXII. The Maccabean and Herodian Age222

Jonathan's Policy.—Basis of Agreement With the Syrians.—Concessions to Jonathan.—His Conquests.—Simon's Achievements.—His Strong and Prosperous Rule.—Growth of the Two Rival Parties.—Wars and Conquests of John Hyrcanus.—Reign of Aristobulus I.—The Cruel Rule of Alexander Janneus.—The Rivalry of Parties Under Alexandra.—The Influence of Antipater.—Advance of Rome.—The Appeal to Pompey.—His Capture of the Temple.—Palestine Under the Rule of Rome.—Rebellions Led by Aristobulus and His Sons.—Antipater's Services to Rome.—Rewards for His Services.—The Parthian Conquest.—Herod Made King of the Jews.—His Policy.—His Work as a City Builder.—Herod's Temple.—The Tragedies of His Family Life.—The Popular Hopes of the Jews.

XXIII. [xv]The Background of Jesus' Childhood and Young Manhood236

The Short Reign of Archelaus.—The Roman Province of Judea.—Territory and Character of Herod Antipas.—Philip's Territory.—The Decapolis.—Place of Jesus' Birth.—Situation of Nazareth.—Its Central Position.—View from the Heights above the City.—The Spring at Nazareth.—Roads to Jerusalem.—Jesus' Educational Opportunities.—Scene of John the Baptist's Early Life.—Field of His Activity.—The Baptism of Jesus.—Machærus, Where John the Baptist Was Beheaded.—Effect of John's Death Upon Jesus.—Jesus' Appearance.

XXIV. The Scenes of Jesus' Ministry247

Why Jesus Made Capernaum His Home.—Site of Capernaum.—Archælogical Evidence.—Ruins at Tell Hum.—Testimony of the Gospels and Josephus.—Statements of Early Pilgrims.—Site of Chorazin.—Bethsaida.—Probable Scene of the Feeding of the Multitudes.—The Night Voyage of the Disciples.—Places Where Jesus Taught His Disciples.—Northern End of the Sea of Galilee.—Contrast Between Its Northern and Southern Ends.—Jesus' Visit to the Gadarene Territory.—The Chief Field of Jesus' Ministry.—Journey to Phœnicia.—At Cæsarea Philippi.—The Journey Southward from Galilee.—At Jericho.—Situation of Bethany.—The Triumphal Entrance Into Jerusalem.—Jesus' Activity in the Temple.—The Last Supper and Agony.—Scenes of the Trials.—Traditional Place of the Crucifixion.—The More Probable Site.—The Place of Burial.

XXV. The Spread of Christianity Throughout the Roman Empire264

Original Centre at Jerusalem.—Spread of Christianity Outside Judea.—Philip's Work In the South and West.—Extension and Expansion of Christianity During the First Decade.—Situation and History of Tarsus.—Influence of His Early Home Upon Paul.—Work at Antioch.—Importance of the Pioneer Work of Paul.—Paul and Barnabas in Cyprus.—At Paphos.—Journey to Antioch in Galatia.—Conditions at Antioch.—At Iconium.—At Lystra and Derbe.—Decision of the Great Council at Jerusalem.—Work of Paul and Silas in Asia Minor.—Paul's Vision at Troas.—Paul and Silas at Philippi.—At Thessalonica.—Paul at Berœa.—At Athens.—Importance of Corinth.—Paul's Work at Corinth.—His Third Journey.—Situation and Importance of Ephesus.—Return to Palestine.—Journey to Rome.—The World-wide Conquests of Christianity.

APPENDIX I. [xvi]Selected Bibliography279

APPENDIX II. Stereographs and Stereopticon Slides Illustrating Biblical Geography and History283

INDEX OF NAMES AND PLACES 289

LIST OF MAPS

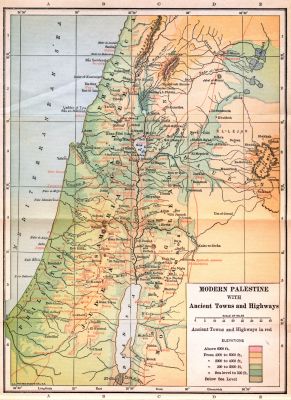

| I. | Modern Palestine, With Ancient Towns and Highways | Frontispiece | |

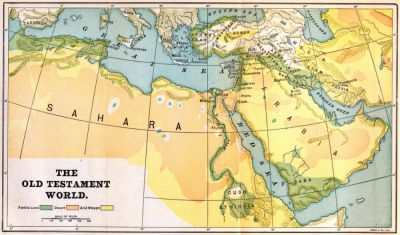

| II. | The Old Testament World | to face page | 3 |

| III. | Photo-relief Map of Palestine | to face page | 13 |

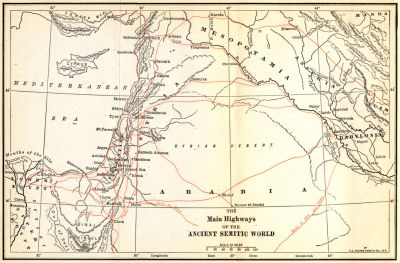

| IV. | The Main Highways of the Ancient Semitic World | to face page | 73 |

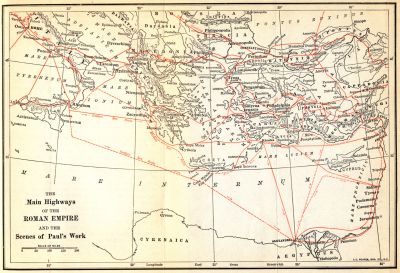

| V. | The Main Highways of the Roman Empire and the Scenes of Paul's Work | to face page | 82 |

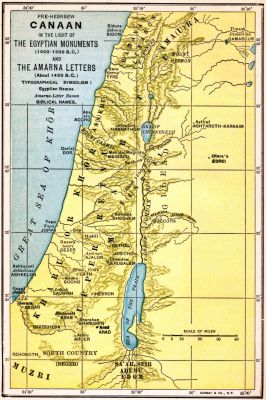

| VI. | Pre-Hebrew Canaan in the Light of the Egyptian Monuments and the Amarna Letters | to face page | 97 |

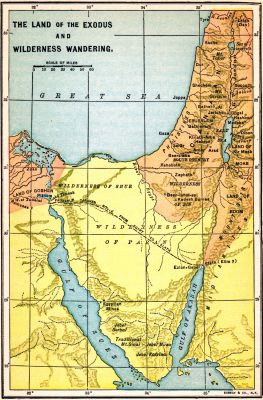

| VII. | The Land of the Exodus and Wilderness Wandering | to face page | 115 |

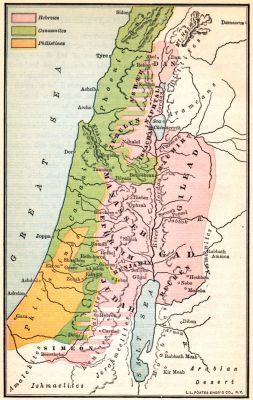

| VIII. | Territorial Division of Canaan After the Final Settlement of the Hebrew Tribes | to face page | 127 |

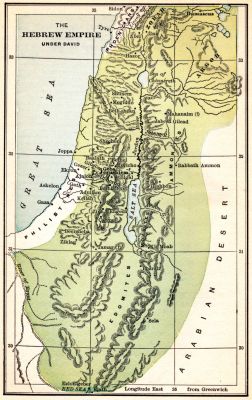

| IX. | The Hebrew Empire Under David | to face page | 147 |

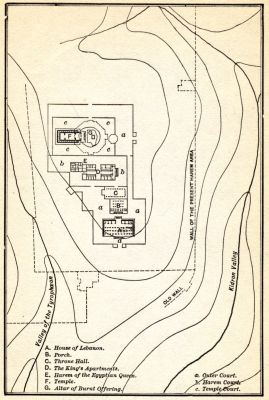

| X. | Plan of Solomon's Palace | to face page | 164 |

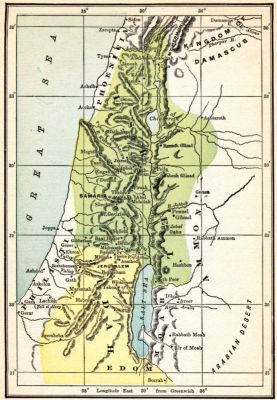

| XI. | Israel After the Division of the Hebrew Empire | to face page | 168 |

| [xviii] | |||

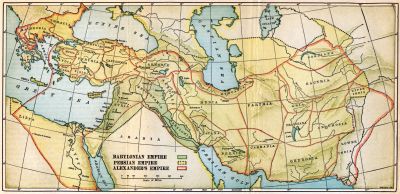

| XII. | Babylonian, Persian, and Greek Empires | to face page | 194 |

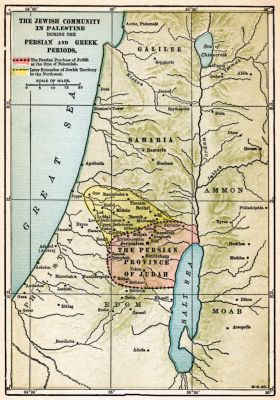

| XIII. | The Jewish Community in Palestine During The Persian and Greek Periods | to face page | 199 |

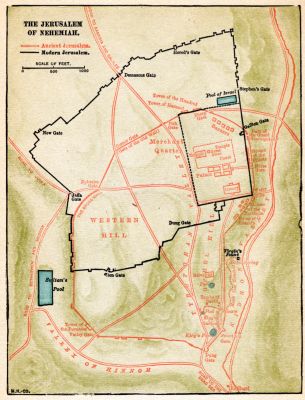

| XIV. | The Jerusalem of Nehemiah | to face page | 203 |

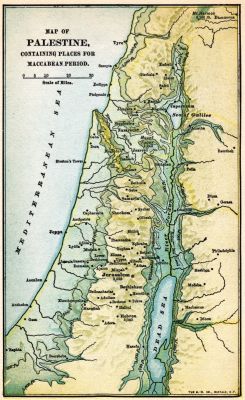

| XV. | Palestine in the Maccabean Period | to face page | 207 |

| XVI. | Palestine in the Time of Jesus | to face page | 236 |

PART I

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY

I

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BIBLICAL WORLD

Extent of the Biblical World. In its widest bounds, the biblical world included practically all the important centres of early human civilization. Its western outpost was the Phœnician city of Tarshish in southern Spain (about 5° west longitude) and its eastern outpost did not extend beyond the Caspian Sea and Persian Gulf (about 55° east longitude). Its southern horizon was bounded by the land of Ethiopia (about 5° south latitude) and its northern by the Black Sea (about 45° north altitude). Thus the Old and New Testament world extended fully sixty degrees from east to west, but at the most not more than fifty degrees from north to south. With the exception of Arabia, all of these lands gather about the Mediterranean, for although the waters of the Tigris and the Euphrates ultimately find their way into the Indian Ocean, the people living in these fertile valleys ever looked toward the Mediterranean and for the most part found their field for conquest and commerce in the west rather than in the east and south.

Conditions Favorable to Early Civilizations. The greater part of this ancient world consisted of wastes of water, of burning sands or of dry, rocky, pasture lands. Less than one-fifth was arable soil, and yet the tillable strips along the river valleys on the eastern and northern Mediterranean were extremely fertile. Here in four of five favored centres were supplied in varying measure the conditions requisite for a strong primitive civilization: (1) a warm, but not enervating climate; (2) a[4] fertile and easily cultivated territory which enabled the inhabitants to store up a surplus of the things necessary for life; (3) a geographical unity that made possible a homogeneous and closely knit political and social organization; (4) a pressure from without which spurred the people on to constant activity and effort; (5) an opportunity for expansion and for intercommunication with other strong nations. The result was that the lands about the eastern Mediterranean were the scenes of the world's earliest culture and history. From these centres emanated the great civic, political, intellectual, artistic, moral, and religious ideas and ideals that still strongly influence the life and faith of the nations that rule the world. The character of each of these early civilizations was in turn largely shaped by the natural environment amidst which it arose.

Egypt's Climate and Resources. The land of the Nile was peculiarly favorable for the development of an exceedingly early civilization. Lying near the equator and between extended areas of hot, dry desert, it possessed an almost perfect climate. While warm, it was never excessively hot, thanks to the fresh north winds which blew from the sea. The desert kept the atmosphere dry and cloudless through at least eleven months in the year. The narrow strip of alluvial soil which constituted the real land of Egypt was practically inexhaustible. The Nile, which rose during the hot summer months, furnished abundant water for irrigation. At the same tune the necessity for constant activity in order to develop the full resources of the land was a valuable incentive to industry. Finally, the uniformity of the Nile valley furnished an excellent basis for a unified social and political organization.

Its Isolation and Limitations. At first Egypt's isolation favored, but in the end fatally impeded the development of its civilization. On every side it was shut in, not only by miles of rocky desert on the east and west, but also on the north and south by almost impassable barriers. In the south the fertile territory narrows to a mere ribbon, with no natural highways by land, while several great cataracts cut off approach by water.[5] On the north the Nile broadens out into a great impassable marsh with only two narrow gateways. One of these is the main western arm of the Nile, which reaches the Mediterranean near Alexandria; the other is the Wady Tumilat, which runs from the Isthmus of Suez through the biblical land of Goshen to the Nile valley. In early centuries these few narrow and uninviting avenues of approach on the north and south were easily guarded. The result was that the Egyptians, at a very early date, attained a high stage of culture, but they lacked that stimulus from without which is essential to the highest development. Once or twice, as in the days of the Hyksos and Ethiopian invasions, foreigners pressed into the land, and as a result the centuries immediately following were the most glorious in Egypt's history. In general, however, the civilization of the Nile valley was deficient in depth and idealism. It was grossly material; it developed too easily and the people were too contented. Even on the artistic side the brilliant promise of the earlier centuries failed of fruition. Moreover, the protecting natural barriers proved constricting, so that there was little opportunity for expansion. Hence Egypt's civilization was always provincial and by 500 B.C. had ceased to develop. From this time on the people of the Nile tamely submitted to the succession of foreign conquerors who have ever since ruled over this garden land of the eastern world.

Conditions in the Tigris-Euphrates Valley. Physical conditions in the Tigris-Euphrates valley were in many ways similar to those along the Nile. A warm but invigorating climate, fertile, alluvial soil, deposited by the great rivers and renewed each year by the floods, and the protection of the desert on the west favored the development of a virile civilization, as early if not earlier than that of Egypt. Starting from the same northern mountains, the two great rivers find their way to the Persian Gulf by widely different courses. The Tigris flows southeast in a comparatively direct course of eleven hundred miles. Its name, "The Arrow," suggests the rapidity of its descent. The Euphrates, on the contrary, makes a long detour[6] westward toward the Mediterranean and then turns to the southeast, where for the greater part of the last half of its one thousand eight hundred miles it flows through the desert. The lands lying between the lower waters of these great rivers were by nature fitted to become the home of the earliest civilization. At a very early period these level plains attracted the nomadic tribes from the neighboring desert. Here they found soil that was exceedingly fertile, but covered to a great extent by the overflow of the great rivers. To be made productive it had to be drained in the flood and irrigated in the dry season by an extensive system of canals and reservoirs. Hence this region furnished powerful incentives to develop an energetic, enterprising civilization. The absence of natural barriers in the level plains of Babylonia and the uniformity of its physical contour meant that in time all the Tigris-Euphrates valley would inevitably be brought under one rule.

Forces Developing Its Civilization. Unlike Egypt, Babylonia was constantly subject to those thrusts from without which were essential to a great civilization. From the Arabian desert came nomadic invaders and from the mountains to the east and north and probably from northern Syria powerful, warlike peoples who either spurred the river dwellers on to strenuous activity in order to repel the hostile attacks or else as conquerors infused new blood and energy into the older races. On the other hand, the absence of constraining barriers gave ample opportunity for natural growth and expansion. The great rivers were the highways of commerce and conquest. The necessity of defence also suggested the advantages of conquest. The result was that at a very early period the armies of Babylonia had penetrated the mountains to the east and north and had carried their victorious rule as far as the shore of the Mediterranean on the west. Traders followed the armies, bearing the products of Babylonian art and in turn enriching the home-land with those of other nations. It was thus that Babylonia in time became not only the mistress of the ancient world, but also one of the chief centres from which emanated[7] political, legal, artistic, and religious ideas and institutions that influenced all the peoples living about the eastern Mediterranean.

Civilization of Arabia. Very different was the site of the third Semitic civilization. The eastern shores of the Red Sea are rocky and barren. No important streams or harbors are found along this cheerless coast. The eastern slope of the range of mountains that runs parallel to the Red Sea is, however, one of the garden lands of the East. The clouds, chilled by the mountains, deposit their rains here, while mountain streams make it possible by irrigation to transform this part of Arabia into a rich agricultural land. Here from an early period was found a high type of civilization. Climate, soil, and the spur of foreign invasion fostered its development. Its products were famous throughout the ancient world. But it was in the highest degree isolated from the stream of the world's progress. Its one means of communication with outside nations was by the caravans which crossed the deserts. Hence a certain halo of mystery always surrounded this distant civilization. Like that of Egypt, it lacked opportunity for expansion and communication and so failed to rise above a certain level or to make any deep or significant impression upon the other Semitic nations.

Physical Characteristics of Syria and Palestine. In marked contrast with Arabia was the strip of hill and mountain country lying on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, known in later tunes as Syria and Palestine. The dominant feature in this part of the Semitic world was the southern spurs of the Taurus mountains, which here run parallel with the coast in two ranges known as the Lebanons and the Anti-Lebanons. A warm, equable climate and fertile soil, especially in the broad valleys between the mountains, furnish the first necessities for a strong civilization. Frequent rain during the whiter and many perennial springs and brooks supply throughout most of this region the water needed for a prosperous, agricultural population. The desert on the east and the mountains in the north were the[8] homes of active, migrating peoples whose ever-recurring attacks gave the inhabitants of Syria and Palestine a constant stimulus.

Its Central Position and Lack of Unity. This region was also the isthmus lying between the sea and the desert that connected Asia with Africa, and the ancient empires of Egypt and Babylonia. The great caravan routes led across it from Arabia on the south and Babylonia on the east to Asia Minor and thence by sea to the ports of the northern Mediterranean. One fatal defect, however, prevented it from becoming the permanent home of one strong, conquering people: it lacked physical unity. Its two rivers, the Orontes and the Jordan, were comparatively unimportant and flowed in opposite directions. Mountain ranges running from north to south and in the north one running from east to west divided the territory into eight or ten distinct areas. Wide variations in climate, flora, and fauna separated these different zones, making a uniform civilization practically impossible. No region, except the fertile valley between the Lebanons and Anti-Lebanons, possessed sufficient natural advantages to rule the whole territory immediately east of the Mediterranean. As a result Syria and Palestine were only at rare and comparatively brief periods completely dominated by native conquerors. The physical characteristics of this territory also suggested from the first a mixed civilization, combining those of the desert, of Babylonia, of Egypt, and of the other lands lying along the Mediterranean. The infusion of foreign elements largely explains the remarkable culture and religious life that flourished within the narrow bounds of Syria and Palestine. This land was at the same time the strategic point that commanded the rest of the ancient world and was destined to send forth influences that were to extend to the uttermost parts of the earth.

Asia Minor. Asia Minor, like Syria, is lacking in physical unity. Its centre is a high, barren plateau. This is encircled on the south, west, and east by fertile coast plains. These coast plains, however, are broken up into independent areas[9] by lofty mountains. From the central plateau came the invaders, who spurred on the coast dwellers to put forth their strongest efforts. Communication by sea and along the great highways that run across the land from east to west brought to these maritime city states the culture of the East and the West. Under these conditions there naturally sprang up an exotic civilization, not unified, but gathered about different civic centres; not independent, but a brilliant fusion of native elements with Semitic and Hellenic culture.

Mycenæ. To the northwest, along the Dardanelles, the coastal plain broadens out into one of the most fertile regions in the ancient world. Frequent rains and perennial mountain streams water the gently rolling fields. Here, in a comparatively small area, were supplied in rich measure the five conditions essential to a strong, early civilization. Here was the seat of that ancient Mycenæan state, whose art and institutions for a brief period rivalled, and in many ways surpassed, those of Babylon and Egypt.

Greece. Of all the ancient centres of civilization Greece was in many ways the most unpromising. Its soil was for the greater part stony and unproductive. Less than one-third could be profitably tilled. The plains were not large and the mountain ranges dominated the land, dividing it into small, distinct areas. There were no navigable rivers and few perennial streams available for irrigation. Moreover, the streams brought down silt into the valleys, transforming them into malarious marshes. As a result, Greece is to-day and probably always has been the most malarial country in Europe. Its limited area gave no opportunity for a great and extensive civilization. Its great assets were a regular climate, a purifying north wind, and the protection of its insular position, which insured its security in its earlier days. While the land of Greece was insular it was also central and in close touch with the civilizations of Asia Minor and the eastern Mediterranean, for the islands of the Ægean Sea were like stepping-stones connecting Greece with the ancient East. The sea was also a great[10] highway which led to the most distant lands. Finally, Greece was in a position to feel the invigorating shock of foreign invasion from the north and east. Its division into small areas meant the development of petty city states, with constant rivalry of arms as well as of wit and art. This keen rivalry and the intense civic loyalty that it kindled were the chief forces in the development of the civilization of ancient Hellas. Its physical character favored the rapid rise of a noble culture, but one which would fall with equal rapidity because of the lack of an opportunity for local expansion. It meant inevitably a scattered people and a widely dispersed civilization. The result was that even in the period of its decline Greek culture permeated and ruled the entire civilized world.

Italy. Further to the west Italy juts out into the heart of the Mediterranean. On the north the lofty Alps protect it from cold winds and snows. On almost every side it is encircled by the warm waters of the Mediterranean and its tributary bays. Throughout most of this narrow peninsula run the high Apennines. On the east they are so close to the coast that the descent to the sea is steep, the rivers insignificant, and the harbors few. On the western side, however, the slope is much more gradual and the coastal plains are exceedingly fertile. They are traversed by rivers fed by the melting snows. The result is that this western coast, with its many good harbors, and its abounding fertility, furnished from earliest times a favorable home for strong and active peoples. Here grew, mingled in great profusion, the fruits and grains of both the temperate and tropical climes. At many points, with the aid of irrigation, the soil yields four or more crops a year. Throughout most of this garden land the climate is semi-tropical without being enervating. The brilliant sunshine is tempered by the cool breezes from the sea and mountains. It is pre-eminently a land of contrasts. On one side is the blue sea, on the other the snow-capped mountains. On this western slope the temperature varies from that of the chill snows and storms on the mountains to the warm, humid air of the river basins. From[11] the beautiful clear lakes on the heights the descent is sudden to the malarial marshes in the lowlands.

Situation of Rome. This western slope is cut midway from north to south by the Tiber, next to the Po the largest river in Italy. To the east the Apennines rise to their greatest height, insuring a heavy annual rainfall. The Tiber valley itself was one of the earliest highways from east to west and was in ancient times the natural division between the highly civilized Etruscans on the north and the Latins and the Greek colonies on the south. Here the varied life of ancient Italy met and mingled and the result was a virile race and a strong, aggressive civilization. Its centre was the Palatine hill, a low volcanic mound beside the Tiber, fourteen miles from its mouth. The uniformity of the Italian territory favored the union of its mixed population under the leadership of Rome its central city.

Reason Why Rome Went Forth to Conquer. Even more important in the development of its culture were the attacks from without to which it was constantly exposed. Even the lofty Alps did not prove impassable barriers to the barbarian hordes who were attracted by this fertile land. Ancient Italy, encircled by the sea and plentifully provided with open harbors on the east and south, was never free from the dread of foreign attack. Not until Rome had conquered the powerful nations living on even the most distant shores of the Mediterranean could she feel secure in her central position. It was this constant fear, as well as the influence of her commanding position, that made Rome in time the mistress of the Mediterranean. From the East she received a century or two later than Greece all that the old civilizations could give, both of good and evil. This inheritance she in turn gave to the western world toward which she faced and to which she belonged. Thus Rome was the great connecting link between the East and the West, between the ancient and the modern world.

Résumé. The biblical world was, both in extent and point of time, identical with the ancient civilized world. The outlook of the biblical writers was at first limited to the eastern Mediterranean,[12] but was gradually broadened until it included practically all the peoples living about the great inland sea. Similarly the life and faith of the Hebrews, at first local, became in time world-wide. Each of the ancient races followed the lines of development marked out by their geographical environment. Two civilizations—that of the Hebrews and that of the Greeks—lacking a suitable background for local growth and expansion, went forth to conquer and transform the life and thought and faith of all the world.

II

THE GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS OF PALESTINE

History of the Terms Palestine and Canaan. The term Palestine, originally applied to the home of Israel's foes, the Philistines, was used by the Greeks as a designation of southern Syria, exclusive of Phœnicia. The Greek historian Herodotus was the first to employ it in this extended sense. The Romans used the same term in the form Palestina and through them the term Palestine has become the prevailing name in the western world of the land once occupied by the Israelites and their immediate neighbors on the east and west. The history of the older name Canaan (Lowland) is similar. In the Tell el-Amarna Letters, written in the fourteenth century B.C., Canaan is limited to the coast plains; but as the Canaanites, the Lowlanders, began to occupy the inland plains the use of the term was extended until it became the designation of all the territory from the Mediterranean to the Jordan and Dead Sea valley. It does not appear, however, to have ever been applied to the east-Jordan land.

Bounds of Palestine. Palestine lies between the eastern shore of the Mediterranean Sea and the Arabian desert. Its northern boundary is the southern slope of Mount Hermon and the River Litany, as it turns abruptly to flow westward into the Mediterranean. Palestine begins where the Lebanons and Anti-Lebanons break into a series of elevated plateaus. Its southern boundary is the varying line drawn east from the southeastern end of the Mediterranean a little south of the Dead Sea at the point where the hills of Judah and the South[14] Country descend to the desert. Palestine therefore lies between 33° 30' and 31° north latitude and 34° and 37° east longitude. Its approximate width is about a hundred miles and its length from north to south only about a hundred and fifty miles. It is, therefore, about the size of the State of Vermont.

Geological History. The geological history of Palestine is somewhat complex, but exceedingly illuminating. The underlying rock is granite. This is now almost completely concealed by later layers of sandstone (which appears in Edom and the east-Jordan), dolomitic and nummulitic limestone and marl. During the earlier geological periods the land was entirely covered by the waters of the sea. Probably at the close of the Pliocene period came the great volcanic upheaval which gave to Syria and Palestine their distinctive character. It left a huge rift running from north to south throughout Syria. This rift is represented to-day by the valley between the Lebanons and its continuation, the valley of the Jordan and Dead Sea. Further south it may be traced through the Wady Arabah and the Gulf of Akaba. This vast depression is the deepest to be found anywhere on the earth's surface. The same great volcanic upheaval gave to the mountains along the western coast their decided northern and southern trend and the peculiar cliff-like structure which characterizes their descent to the western shore. Through the centuries frequent and severe earthquakes have been felt along the borders of this ancient rift, and they are still the terror of the inhabitants, even as in the days of the Hebrew prophets.

Alluvial and Sand Deposits. Until a comparatively late geological period the sea came to the foot of the mountains. The coast rose gradually and has later been built up by the process of erosion that has cut down the mountains, especially on the western side, where the rainfall was heaviest. The plains along the shore have thus been enriched by vast alluvial deposits. Very different was the deposit of Nile sediment, which was blown in from the sea by the western winds, leaving a wide border of yellow sand along the coast of Palestine.

[15]General Divisions. Palestine is sharply divided by nature into four divisions or zones, which extend in parallel lines from north to south.(1)[1] Along the Great Sea lie the narrow coast plains which broaden in the south into the plains of Sharon and Philistia. The second zone is the central plateau, with hills three to four thousand feet in height in the north, which sink by stages to the large Plain of Esdraelon. South of this great plain lie the fertile hills of Samaria which in turn merge into the stern hills of Judah. These again descend into the low, rocky, rolling hills of the South Country. The third zone is the Jordan and Dead Sea valley which begins at the foot of Mount Hermon and rapidly sinks, until at the Dead Sea it is one thousand two hundred and ninety-two feet below the surface of the ocean. The fourth zone includes the elevated plateaus which extend east of the Jordan and Dead Sea out into the rocky Arabian desert.

Variety in Physical Contour. The first striking characteristic of Palestine is the great variety in physical contour, climate, flora, and fauna to be found within its narrow compass of less than fifteen thousand square miles. Coast plains, inland valleys, elevated plateaus, deep, hot gorges, and glimpses of snow-clad mountains are all included within the closest possible bounds. In a journey of from two to three days the traveller from west to east passes from the equable, balmy climate of the Mediterranean coast to the comparatively cold highlands of the central plateau and then down into the moist, tropical climate of the hot Jordan and Dead Sea valley. Thence he mounts the highlands of Gilead or Moab, where the sun beats down hot at noonday, while the temperature falls low at night and deep snows cover the hilltops in winter. The hills of the central plateaus, covered with the trees of the temperate zone, overhang the palms and tropical fruit trees of the coast plains and Jordan valley.

[16]Effects of this Variety. The different zones touch each other closely, and yet their wide differences in physical contour, climate, flora and fauna constitute invisible but insuperable barriers and produce fundamentally diverse types of life and civilization. To-day, as in the past, inhabitants of cities, tent dwellers, merchants, and peasants live in this narrow land within a few miles, yet separated from each other by the widest possible difference in culture and manner of life. The character of the land made impossible a closely knit civilization. It could never become the centre of a great world-power. It was rather destined to be the abode of many small tribes or nations, with widely differing institutions and degrees of culture. The great variety of scenery, climate, and life, however, made Palestine an epitome of all the world. It was pre-eminently fitted to be the home of a people called to speak a vital message in universal terms to all the races of the earth. Its striking contrasts and its marvellous beauty and picturesqueness also arrested the attention of primitive men and explain the prominence of nature worship among the early inhabitants of Palestine and the large place that its rocks, brooks, hills and meadows occupy in Israel's literature.

Openness to the Arabian Desert. The second marked peculiarity of Palestine is its openness to the desert. As Principal Smith has aptly said, Palestine "lay, so to speak, broadside on to the desert." With its comparatively fertile fields, it has proved a loadstone that for thousands of years has attracted the wandering Arabian tribes. These came in, however, not as a rule in great waves, but as families, or small tribes. Up through the South Country they penetrated the hills of Judah. There in time they learned to cultivate the vine, although they still retained their flocks. East of Moab and Gilead the arable land merges gradually into the rocky desert and the Arabs to-day, as in the past, claim as their own all the land to the Jordan and Dead Sea valley, except where the settled population successfully contests their claim by arms. Palestine, therefore, has always been powerfully influenced by the peculiar life and[17] centralized government and fierce rivalry between tribes and petty peoples—these are but a few of the characteristics of Palestine's history that are primarily due to its openness to Arabia.

Absence of Navigable Rivers and Good Harbors. Palestine, on the other hand, is shut off from close commercial contact with other peoples. No great waterway invited the trader and warrior to go out and conquer the rest of the world. Instead, in the early periods when men depended chiefly upon communication by river or sea, Palestine shut in its inhabitants and tended to develop an intensive rather than an extensive civilization. Its one large river, the Jordan, flows, not into the ocean, but into a low inland sea, whose only outlet is by evaporation. The coast line of Palestine is also characterized by the lack of a single good harbor. At Joppa, at the northwestern end of Carmel, and at Tyre the otherwise straight shore line curves slightly inland; but at each of these points there is no natural protection from the severe western gales. The Phœnicians, shut in by the eastern mountains, dared the perils of the deep; but to the early peoples of Palestine the Great Sea was, on the whole, a barrier rather than an invitation to commerce and conquest.

Incentives to Industry. The physical characteristics of Palestine were well fitted to develop active, industrious inhabitants. The constant pressure on their borders by Arabs, who could be held back only by a strong, organized civilization, was a powerful spur. The natural division of the land among independent and usually hostile races made eternal activity and watchfulness the price that must be paid for life and freedom. Popular tradition, based on a fact that pre-eminently impresses every traveller in the land to-day, states that the fabled Titan, who was sent to scatter stones over the face of the earth, distributed them equally over Europe and Africa, but that when he came to Asia and was passing through Syria, his bag broke, depositing its contents on Palestine. Throughout most[18] of its territory the rich soil can be cultivated only as the stones are gathered either in huge heaps or fences. The fertility of the plains can be utilized only as the waters of the mountain brooks are used for irrigation. It is, therefore, a land that bred hardy men, strong of muscle, resourceful, alert, and, active in mind and body.

Incentives to Faith and Moral Culture. Another still more significant characteristic of Palestine was the powerful incentive which it gave to the development of the faith of its inhabitants. The constant presence of Arab invaders powerfully emphasized their dependence upon their God or gods. The changing climate of Palestine deepened that sense of dependence. No great river like the Nile or the Euphrates brought its unfailing supply of water, and water was essential to life. The waters came down from heaven, or else burst like a miracle from the rocky earth. If the latter rains failed to fill the cisterns and enrich the springs and rivers, drought, with all its train of woes, was inevitable. Little wonder that the ancient Canaanites revered nature deities, and that they, like the Greeks, worshipped the spirits of the springs, and especially those from which came their dashing rivers. Locusts, earthquakes, and pestilence in the lowland frequently brought disaster. In all of these mysterious calamities primitive peoples saw the direct manifestation of the Deity. In the fourth chapter of his prophecy, Amos clearly voiced this wide-spread popular belief:

And I sent rain upon one city,

While upon another I did not let it rain,

Yet ye did not return to me," is the oracle of Jehovah.

I laid waste your gardens and vineyards,

Your fig and your olive trees the young locust devoured;

Yet you did not return to me," is the oracle of Jehovah.

I slew your youths by the sword, taking captive your horses,

And I caused the stench of your camps to rise in your nostrils,

Yet ye did not return to me," is the oracle of Jehovah (Am. 4:7-10).

Hence in a land like Palestine it was natural and almost inevitable that men should eagerly seek to know the will of the Deity and should strive to live in accord with it. It was a fitting school in which to nurture the race that attained the deepest sense of the divine presence, the most intense spirit of worship and devotion, and the most exalted moral consciousness.

Central and Exposed to Attack on Every Side. Palestine, in common with the rest of Syria, held a central position in relation to the other ancient civilizations. Through it ran the great highways from Babylon and Assyria to Egypt. Along its eastern border passed the great road from Damascus and Mesopotamia to Arabia. It was the gateway and key to three continents—Africa, Asia, and Europe. From each of these in turn came conquerors—Egyptians and Ethiopians, Babylonians and Assyrians, Greeks and Romans—against whom the divided peoples of Palestine were practically helpless. Palestine, because of its physical characteristics and central position was destined to be ruled by rather than to rule over its powerful neighbors. And yet this close contact with the powerful nations of the earth inevitably enriched the civilization and faith of the peoples living within this much contested land. It produced the great political, social, and religious crises that called forth the Hebrew prophets. It made the Israelites the transmuters and transmitters of the rich heritage received from their cultured neighbors and from their inspired teachers. In turn it gave them their great opportunity, for repeated foreign conquests and exile enabled them in time to go forth and conquer, not with the sword of steel, but of divine truth, and to build up an empire that knew no bounds of time or space.

Significance of Palestine's Characteristics. Thus the more important characteristics of Palestine are richly suggestive[20] of the unfolding of Israel's life and of the rôle that Judaism and Christianity were destined to play in the world's history. Palestine is the scene of the earlier stages of God's supreme revelation of himself and his purpose to man and through man. The more carefully that revelation is studied the clearer it appears that the means whereby it was perfected were natural and not contra-natural. The stony hills and valleys of Palestine, the unique combination of sea and plain, of mountain and desert, placed in the centre of the ancient world, were all silent but effective agents in realizing God's eternal purpose in the life of man.

III

THE COAST PLAINS

Extent and Character. The eastern shore of the Mediterranean is skirted by a series of low-lying coast plains, from one to five miles wide in the north to twenty-five miles wide in the south. At two points in Palestine the mountains come down to the sea; the one is at the so-called Ladder of Tyre, about fifteen miles south of the city from which it is named. Here the precipitous cliffs break directly over the sea. The other point is at Carmel, which, however, does not touch the sea directly, but is bounded on its western end by a strip of plain about two hundred yards wide. The soil of these coast plains consists of alluvial deposits, largely clay and red quartz sand washed down in the later geological periods from the mountains of the central plateau and constantly renewed by the annual freshets.

Fertility. Because of the nature of the soil and their position, these plains are among the most fertile spots in all Palestine. Numerous brooks and rivers rush down from the eastern headlands. Some of these are perennial; others furnish a supply of water, which, if stored during the winter in reservoirs on the heights above, is amply sufficient to irrigate the plains below. The average temperature of these coast plains is sixty-eight degrees. The cool sea-winds equalize the climate so that the temperature changes little throughout the year and there is but slight variation between the north and the south. Under these favorable conditions the soil produces in rich abundance a great variety of tropical fruits. Here grow side by side oranges, lemons, apricots, figs, plums, bananas, grapes, olives, pomegranates,[22] almonds, citrons, and a great variety of vegetables, as well as the cereals of the higher altitudes.

Divisions. The coast plains of Palestine fall naturally into four great divisions, broken by two mountain barriers. The northern is the Plain of Tyre, which is the southern continuation of the rich plains about Sidon. The second division is the Plain of Acre, which lies directly south of the Ladder of Tyre and extends to Carmel. The third is the Plain of Sharon, which begins at the south of Carmel and merges opposite Joppa into the ever widening Plain of Philistia.

Plain of Tyre. Throughout the Plain of Tyre the low foot-hills come down within a mile of the sea; but for five or six miles back from the coast they must be reckoned as a part of the same division, for their natural and political associations are all with the coast rather than with the uplands. The city of Tyre was originally built on an island (2) and was supplied with water from the Spring of Tyre, near the shore about five miles to the south. The four great perennial rivers of Phœnicia were the Litany (the present Nahr el-Kasimiyeh, a few miles north of Tyre), the Zaherâni, south of Sidon, the Nahr el-Auwali, which was the ancient Bostrenus that watered the plain to the north of Sidon, and the Nahr ed-Damur which was the Tamyras of the ancients. Many springs in the plain and on the hillsides contribute to the fertility of this land, which was the home of the Phœnicians. At the best the narrowness of the territory, which supported only a very limited population, made it necessary for this enterprising race to find an outlet elsewhere. Long before the days of the Hebrews their colonies had extended down the coast plains to Joppa and northward to the Eleutherus (the present Nahr el-Kebir, north of Tripoli). The nineteenth chapter of Judges refers to the Sidonian colony at Laish (later the Hebrew Dan) at the foot of Mount Hermon; but, with this exception, there is no evidence that they ever attempted to plant colonies inland. Instead they found their great outlet in the sea to the west. Launching their small craft from the smooth sands that extend crescent-shaped to the[23] north and to the south of their chief cities, Tyre and Sidon, they skirted the Mediterranean, colonizing its islands and shores until a line of Phœnician settlements extended from one end of the Great Sea to the other. Thus they were the first to open that great door to the western world through which passed not only the products of Semitic art and industry, but also in time the immortal messages of Israel's inspired prophets, priests, and sages, and of him who spoke as never man spoke before.

The Plain of Acre. For ten miles to the south of the Plain of Tyre the coast plain is almost completely cut off by the mountains, which at Ras el-Abjad, the White Promontory of the Roman writers, and at Ras en-Nakurah push out into the sea. The great coast road runs along the cliffs high above the waters in the rock-cut road made by Egyptian, Assyrian, and Roman conquerors. The Plain of Acre, less than five miles wide in the north, widens to ten miles in the south. Four perennial streams water its fertile fields. On the west the sand from the sea has swept in at places for a mile or more, blocking up the streams in the south and transforming large areas into wet morasses. In ancient times, however, most of the southern part of the plain (like the northern end at present) was probably in a high state of cultivation. Many large tells or ruined mounds testify that it once supported a dense population. During most of its history this plain was held by the Phœnicians or their Greek and Roman conquerors, but at certain times the Hebrews appear to have here reached the sea.

Carmel. The most striking object on the western side of central Palestine is the bold elevated plateau of Carmel. Except for the little strip of lowland on its seaward side, it completely interrupts the succession of coast plains. Its formation is the same as that of the central plateaus. Viewing Palestine as a whole, it would seem that Carmel had slipped out of its natural position, leaving the open Plain of Esdraelon and destroying the otherwise regular symmetry of the land. Its long, slightly waving sky-line, as it rises abruptly above the plains of Acre and Esdraelon, commands the landscape for miles to the[24] north(3) and adds greatly to the picturesqueness of Palestine. It is about eighteen hundred feet in height and slopes gradually downward to the southeast and northwest. The ascent on the north is more abrupt than on the south, where it descends slowly to the Plain of Sharon. As its name Carmel, The Garden, suggests, it is by no means a barren, rocky mountain. Instead, where the thickets and wild flowers have not taken possession of the soil, it is still cultivated, as was most of its broad surface in earlier times. The ruins of wine and olive presses and of ancient villages testify to its rich productivity. On its top the western showers first deposit their waters, so that in the Old Testament Carmel is a synonym for superlative fertility. Like the uplands of central Palestine, it was held by the Hebrews, who from its heights gained their clearest view of the Great Sea.

Plain of Sharon. South of Carmel, beginning with an acute angled triangle between the mountains and sea, rolls the undulating Plain of Sharon. Opposite the southern end of Carmel it is six or seven miles wide. Thence the plain broadens irregularly until, at its southern end, opposite Joppa, it is twelve miles in width. From north to south it is nearly fifty miles long. Groups of hills from two to three hundred feet high dot this undulating expanse of field and pasture. Five perennial streams flow across it to the sea. Of these the most important are the Crocodile River (the modern Nahr el-Zerka) a little north of Cæsarea, and the Iskanderuneh in the south. Here again a wide fringe of yellow sand bounds the sea and at several points holds back the waters of the streams, making large marshes. In the north there are a few groves of oaks, sole survivors of the great forest, mentioned by Josephus and Strabo, which once covered the Plain of Sharon. To-day the southern part of the plain is a series of cultivated, fruitful fields and gardens,(4) but the northern end is covered in spring by a wealth of wild flowers, among which are found anemones, brilliant red poppies, the narcissus, which is probably the rose of Sharon, and the blue iris, which may be the lily of the valley. Rich soil and abundant waters[25] are found on this plain; but its resources were never fully developed, for it was the highway of the nations. Across it ran the great coast road from Egypt to Phœnicia in the north and to Damascus and Babylonia in the northwest. Phœnician, Philistine, and Israelite held this plain in turn, but only in part and temporarily, for having no natural defences, it was open to all the world.

The Philistine Plain. The only natural barrier that separates the plains of Sharon and Philistia is the river which comes down in two branches from the eastern hills, one branch leading westward past the Beth-horons and the other through the Valley of Ajalon. After much twisting and turning, and under many local names, this, the largest river south of Carmel, finds the sea a little north of Joppa. Southward the Plain of Philistia, about forty miles in length, broadens until it is twenty miles wide. The low hills of the Plain of Sharon change first into long, rolling swells and then throughout much of the distance settle into an almost absolutely level plain. In the southwest the sands of the sea have come in many miles. Ashkelon now lies between a sea of water and a sea of sand. At many other points the yellow waves are steadily engulfing the cultivated fields. Three perennial streams, with sprawling confluents, cut their muddy course across this rich alluvial plain. It is one of the important grain fields of Palestine, for the subsoil is constantly saturated with the moisture which falls in abundance in the winter and spring. No barns are necessary, for the grain is thrashed and stored out under the rainless summer skies. It is a land well fitted to support a rich and powerful agricultural civilization. Like all the coast plains, it is wide open to the trader and to the invader. Its possessors were obliged to be ever ready and able to defend their homes from all foes. Its inhabitants necessarily dwelt in a few strongly guarded cities. Here in ancient times, especially on the eastern side, were found the city-dwelling Canaanites. Later the valiant, energetic Philistines established their title to these fruitful plains and maintained it for centuries by sheer enterprise and force of[26] arms. The chief Philistine cities were Ekron and Ashdod in the north, Askelon by the shore, quite close to the Judean foot-hills and Gaza(5) in the southwest. Except during the heroic Maccabean age, the Israelites never succeeded and apparently never seriously attempted to dispute this title. Lying on the highway that ran straight on along the coast to Egypt, this part of Palestine was most exposed to the powerful influences that came from the land of the Nile. The oldest Egyptian inscriptions, as well as the results of recent excavations, all reveal the wide extent of this influence.

The Shephelah or Lowland. Along the eastern side of the Philistine plain, from the valley of Ajalon southward, runs a series of low-lying foot-hills, which are separated from the central plateau of Palestine by broad, shallow valleys running north and south.(6) This territory was called by the biblical writers, the Shephelah or Lowland. These low chalk and limestone hills, with their narrow glens, their numerous caves and broken rocks, was the debatable ground between plain and hill country. Sometimes it was held by the inhabitants of the plain, sometimes by those of the hill country; always it was the battle-field between the two. Even to-day it is sparsely inhabited, the haunt of the Bedouin tribes, whose presence is clearest evidence of the difficulties that the local government experiences in controlling this wild border land. Like the Scottish lowlands, this region is redolent with the memories of ancient border warfare. It is also richly suggestive of one phase of that severe training which through the long centuries produced a race with a mission and a message to all the world.

IV

THE PLATEAU OF GALILEE AND THE PLAIN OF ESDRAELON

Physical and Political Significance of the Central Plateau. The backbone of Palestine is the great central plateau. It was in this important zone that the drama of Israel's history was chiefly enacted. Here was the true home of the Hebrews. By virtue of its position this central zone naturally commanded those to the east and west. For one brief period the Philistines from the western coast plain nearly succeeded in conquering and ruling all Palestine; but otherwise, until the world powers outside began to invade the land, the centre of power lay among the hills. This significant feature of Palestinian history is due to two facts: (1) that in war the great advantage lies with the people who hold the higher eminences and so can fight from above; and (2) that the rugged uplands usually produce more virile, energetic, liberty-loving people. At the same time it may be noted that, while the centre of power lay among the hills, the hill-dwellers never succeeded in conquering completely or in holding permanently the zones to the east and west. So firmly were the invisible bounds of each zone established that the dwellers in one were never able wholly to overleap these real though intangible lines and to weld together the diverse types of civilization that sprang up in these different regions, so near in point of distance, yet really so far removed from each* other.

Natural and Political Bounds. A part of the northern plateau bore even in early Hebrew days the name of Galilee, the Circle or the Region (I Kings, 9:11, II Kings, 15:29, Josh. 20:7). At first this region appears to have been confined to a[28] small area about Kedesh, where the Hebrew and older Gentile population met and mingled. Gradually the name was extended, until in the Maccabean and Roman period Galilee included all of the central plateau north of the Plain of Esdraelon as far as the Litany itself. Its western boundary lay where the central plateau descends to the foot-hills and coast plains of Tyre and Acre, and its eastern was the abrupt cliffs of the Jordan valley. These were its natural boundaries; but Josephus, whose knowledge of Galilee was peculiarly personal, includes in it the towns about the Lake of Gennesaret (commonly designated in the New Testament as the Sea of Galilee), the Plain of Esdraelon and even Mount Carmel (cf. Jewish Wars, II, 3:4, 8:1, III, 3:1).

Its Extent and Natural Divisions. Defined by its narrower natural bounds, Galilee is about thirty miles wide from east to west, and nearly fifty miles long from north to south. It comprises an area, therefore, of a little less than fifteen hundred square miles. It falls into two clearly marked divisions: (1) Upper Galilee with its rolling elevated plateaus, bounded on the east and west by hills which rise rapidly to the height of between two thousand and four thousand feet; and (2) Lower Galilee, lying to the south of an irregular line drawn westward from the northern end of the Lake of Gennesaret to Acre on the shore of the Mediterranean. This division line is marked by the Wady Amud and the Wady et-Tuffah, which flow into the northwestern end of the Lake of Gennesaret, and the series of plains which cut from east to west through Galilee to a point opposite Acre. This second division includes the lower hills, which extend southward from the high plateaus of northern Galilee, making an irregular terrace, never over nineteen hundred feet high and gradually sloping to the Plain of Esdraelon, which sends out several low valleys to meet and intersect the descending hills. This clear-cut line of division was recognized both by Josephus and the Talmudic writers.

Physical Characteristics of Upper Galilee. The elevated hills of upper Galilee constitute, therefore, the first terrace that flanks the southern part of the Lebanons. The deep clefts between[29] the higher Lebanons and Anti-Lebanons to the north here disappear. Even the Litany turns abruptly westward on the northern border of Galilee, leaving a broad mass of rounded limestone hills, greatly weathered by frost and rain. At a distance this mass looks like a mountain range, but it consists in reality of a high rolling plateau, cut by irregular valleys. This plateau of upper Galilee reaches its highest elevation in a line drawn northwest from Safed, which was probably "the city set on a hill" of the Gospel record.(7) The mountain on which Safed stands is two thousand seven hundred and fifty feet above the sea, while to the northwest Jebel Jermak, the highest mountain of Galilee, rises to the height of three thousand nine hundred and thirty-four feet. From this point many fertile upland valleys radiate to the northwest, the north, the northeast, and the east, but none to the south. Thus upper Galilee presents its boldest front to the south, towering high above lower Galilee and sloping to the north until it meets the mountains of the southern Lebanons. On the southeast it slopes gradually down to the Jordan and Lake Huleh, where two brooks come down from the plain of Hazor. Farther north the hills rise very abruptly from the Jordan and present a front unbroken by any important streams. At many points on this eastern slope lava streams have left their bold deposit of trap-rock. On the northwest the descent to the coast plains is very gradual and regular, but farther south the hills jut out abruptly to the sea. Upper Galilee is an open region with splendid vistas of the blue coastline of the Mediterranean on the west, of Carmel and the Samaria hills on the south, of the lofty almost unbroken line of the plateau of the Hauran and Gilead on the east; while the Lebanons tower on the north, and above them all rises the massive peak of Hermon, long into the springtime clad in cold, dazzling whiteness. Galilee, as a whole, was a land well fitted to breed enthusiasts and men of vision, intolerant alike of the inflexible rule of Rome and of the constricting priestcraft of Jerusalem. The Talmud states that the Galileans were ever more anxious for honor than for money.

[30]Its Fertility. Upper Galilee was also a land of great fertility. The one limitation was the profusion of rocks strewn especially over the northern part. But if the Lebanons have poured their stones over northern Galilee, they have compensated with the wealth of waters which run through the valleys and break out in springs or else are scattered in dashing showers and deposited in heavy dews upon its rich soil. Where wars and conquest have not denuded the land, trees grow to the summits of the hills and grass and flowers flourish everywhere in greatest profusion. It is a land of plenty, sunshine, beauty, and contentment. Significant is the fact that it figures so little in Israel's troubled history, for happy is the land that has no history. Josephus's statement that in his day Galilee had a population of nearly three millions is undoubtedly an exaggeration. Even though, as in some parts of the land, to-day, the villages almost touched each other and no part of the land lay idle, Galilee could not have supported more than four or five hundred thousand inhabitants (cf. Masterman, Studies in Galilee, 131-134).

Characteristics of Lower Galilee. Lower Galilee possesses the fertility of upper Galilee in even greater measure. With a lower elevation and slightly warmer climate it bears a large variety of trees and fruits. Its valleys are also broader and lower and enriched with the soil washed down from the hills. The broad, low plain of Asochis (the present Sahel el-Buttauf) lies a little north of the heart of lower Galilee and from it valleys radiate to the northeast, southwest, and southeast. Another broad plain runs northeast from the Plain of Esdraelon to the neighborhood of Nazareth and Mount Tabor, and east of Tabor still another extends down to the Jordan River. The rounded top of Mount Tabor commands a marvellous view of lower Galilee. Across the fertile fields to the northeast lies the Sea of Galilee, shut in by its steep banks, and beyond it the mountain plateau of the Jaulan.(8) Across the valley to the south is the Hill of Moreh and the Samaritan hills beyond.(9) Two perennial brooks, the Wady Fejjas and the Wady el-Bireh,[31] flow down through southeastern Galilee into the Jordan. The result is that lower Galilee is made up of a series of irregular hills (of which the Nazareth group, a little south of the centre, is the chief) separated by a network of broad, rich, intersecting plains. It combines the vistas and large horizons of the north with the fruitfulness of the plains. Here many different types of civilization meet and mingle. Instead of being remote and provincial, as is sometimes mistakenly supposed, lower Galilee is close to the heart of Palestine and open to all the varied influences which radiate from that little world. It is also intersected by a network of little wadys running in every direction from its open valleys and through its low-lying hills. Thus it was bound closely not only to the rest of Palestine, but also to the greater world that lay beyond.