TWENTY YEARS OF SPOOF & BLUFF

TWENTY YEARS

OF

SPOOF AND BLUFF

BY

“CARLTON”

ILLUSTRATED

HERBERT JENKINS LIMITED

YORK STREET, ST. JAMES’S

LONDON, S.W. 1 MCMXX

WILLIAM BRENDON AND SON, LTD., PRINTERS, PLYMOUTH, ENGLAND

It has been said that any man of mature age could write at least one interesting book, if he confined himself to relating his own experiences.

Well, that is what I have done. This is primarily the story of my life, interspersed with various anecdotes, “wheezes,” and “gags,” pertaining to a profession concerning the real inside of which the public is mostly ignorant.

Like Topsy, the book “growed.” An incident recalled here, a story remembered there, has been jotted down at haphazard as the mood seized me.

I may add that the incidents recorded in Chapters XIV. and XV., as also the human telescope story in Chapter XIII., first saw the light in the Strand Magazine, to the Editor of which periodical I am indebted for permission to reproduce them here.

| CHAPTER I | |

| EARLY EXPERIENCES | |

| PAGE | |

| Work as a telegraph messenger boy—First attempts at “public” entertainment—Small but appreciative audiences—I introduce the cycle to the post office—Christmas-boxing on my own—I am rewarded with the “Order of the Sack”—Hard times—A home-made conjuring outfit—On tramp to Southend—Busking on the sands—Wrathful “niggers”—“Stage” fright—“Best clear, kid”—I clear—On the road back to London—Hunger and thirst—Four shows for fourpence—A “welcome” home—No food in the house and the brokers in—“Covering the spot”—Jimmy Jennings—I win watches—Beat a game and gain a friend—“A quick way of making money”—Learning to be a street patterer—Tricks of the showman’s trade—Nearly a riot—Jimmy grows anxious—Good-bye to London once more—A new pitch—And the beginning of a new life | 3 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| I POSE AS A SHOWMAN | |

| Practising conjuring—Why I rarely play cards—The great Maskelyne and Cooke box trick—I make a trick box of my own—The “Flying Lady” who flew—away—In partnership with Gypsy Brown—My life with the show folk—I begin to make money—The kings of the fair grounds—Caravan life and cookery—The Romany people and their ways—Gypsy Brown cheats me—How the “bluers” work—Fights in the Fair Ground—The etiquette of the showmen—In a boxing booth—Taking on all comers—A rough life—“Do a slang to get a pitch”—The tricks of the travelling boxing-booth proprietors—A gypsy duel with cocoanut balls | 17 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| WITH THE GYPSIES | |

| I start a show of my own—Gypsy Brown plays me a dirty trick—The hunchback in the box—Bank Holiday at Cheriton Fair—I plan to circumvent Gypsy Brown—And succeed only too viiiwell—The crowd wrecks Brown’s booth—Pandemonium in the fair ground—The gypsies attack my show—The fate of a peace-maker—My fight with Gypsy Brown—£10 to £1 on my opponent and no takers—A knock-out blow—Gypsy Brown vows revenge—My life in danger—How I outwitted the gypsies—The last of my experiences as a fair-ground showman | 30 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE TRICK THAT FAILED | |

| Back in London—At the Westminster Aquarium—“The Pro.’s Casual Ward”—Zæo’s Maze—“Oriental beauties from the Far East-End of London”—“Fake” side-shows—A “fasting lady’s” prodigious appetite—A lively subject for a coffin—I sell conjuring tricks to visitors—“Uncle” Ritchie—An audience of one—Annie Luker, the champion lady high diver—I find myself barred from the Aquarium—The mysterious voice in the maze—Mr. Ritchie investigates—And Mr. Wieland scores—Penny-gaffing in London—Working the shops—Sham hypnotism—How to eat coal and candles—And drink paraffin oil—The box trick again—Venice in Newcastle—I offer a £1000 prize—The trick that failed—My first engagement in a regular “hall”—My absent-minded partner | 41 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| CLIMBING TO FAME AND FORTUNE | |

| I give an impromptu show at the Palace Theatre—“Chuck him out!”—I seek out Mr. Wieland again—At the Crystal Palace—I adopt my present make-up—“The Human Hairpin”—Charlie Coborn and “Two Lovely Black Eyes”—I do a trial turn at the Bedford Music-hall—Billed as a star turn at the Alhambra and Palace Theatres—And at the “Flea Pit,” Hoxton—My reception there—I work the Alhambra, Palace, Middlesex, Metropolitan, and Cambridge together—A record for those days—A Press “spoof”—Continental engagements—Paris, Milan—An overdose of Chianti—And its results—The night life of Milan—A blood-curdling adventure—Murder most foul—Callous passers-by | 54 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| PLAYING IN HUNLAND | |

| Vienna and the Viennese—Churls by nature and instinct—How I made “There’s a Girl in Havana” go down there—Chorus men and waiters—Some innocent tricks of the music-hall trade—In Berlin—Death of my giant—Official boorishness—German sharp practice—I engage a Hun giant—Uncomfortable railway travelling—At Buda-Pesth—More sharp practice—I throw up my engagement and return to ixEngland in disgust—Litigation and worry—My case is taken up by the Variety Artistes’ Federation—A new “Battle of Prague”—Which I lose—A story of a “misspelled” railway station—Back in Old England—A day’s rabbit shooting—The two “Arthur Carltons” | 72 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| AUSTRALIAN EXPERIENCES | |

| Eastward bound on the Ortona—Dinners and diners—Spoofing a chief steward—A brush with the master-at-arms—“Queering” a poker game—Trouble in the smoke-room—We plan revenge—And execute it—Potatoes as ammunition—The cold water cure—The Captain sends for me—I decline to go—Trouble brewing—I run my head into the lion’s mouth—And am frog-marched before the captain—A stormy interview—I am threatened to be put in irons—All’s well that ends well—A benefit performance at sea—Arrival in Melbourne—A tale of two champions—Rabbit shooting extraordinary—I bag a laughing jackass—And am hauled before the “beak”—Fined ten shillings and costs—I am glad at having “got the bird”—The “interfering parrot” | 90 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| MELBOURNE TO LONDON | |

| The “Under the Earth” bar in Melbourne—A swimming challenge spoof—The Australian Vaudeville Association—My connection therewith—They present me with an Address—At Adelaide—A cheery send-off—I bring to London with me Charlie Griffin, the feather-weight Australian champion—Fix up a match at the London National Sporting Club—I train him myself during a pantomime engagement—He is beaten by Jim Driscoll—But afterwards defeats Joe Bowker—My fight at the National Sporting Club with “Apollo”—All the “pro.’s” present—A great night—I am beaten by “Apollo”—Congratulations all round—Only Mrs. “Carlton” does not approve—Other boxing and sporting yarns | 107 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| SOME AMERICAN EXPERIENCES | |

| To New York on the Mauretania—Gambling on ocean liners—A “dear” old gentleman—Phenomenal luck—My suspicions are aroused—I play the part of a private detective—A puzzling proposition—The light that shone by night—My suspicions are confirmed—An artful dodge—A new use for smoke-coloured glasses—Doctored cards—The most beautiful American city—Los Angeles—Tuna fishing at Santa Catalina—Monsters of 400 lb. weight—The Tuna Club—A record catch—Fishing with kites—Wild goat stalking—Outwitting a gambler—Diamond cut diamond—A ride on an ostrich—American xpolice methods—An unpleasant experience | 121 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| MORE AMERICAN EXPERIENCES | |

| Through the Great American Desert—A land of desolation—An adventure at Santa Fé—“Hands up!”—Railway strike methods in the wild and woolly West—At Kansas City—The Magicians’ Club—“Welcome to our city”—A disappointing show—In the land of the Mormons—Salt Lake City—Brigham Young’s seraglio—The Mormon Temple and Tabernacle—Something like an angel—Brigham Young’s statue—My worst Press notice—A journalistic tragedy—In New York—I am served a scurvy trick—Hammerstein’s—A row with the management—Sharp Yankee practice—I perform in the New York Synagogue in the presence of the Chief Rabbi—A unique honour—Rubber-neck cars—The almighty dollar—The Statue of Liberty—A suggestive pose—New York hotels—A tip as to boots | 136 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| PANTOMIME SPOOFS AND JOKES | |

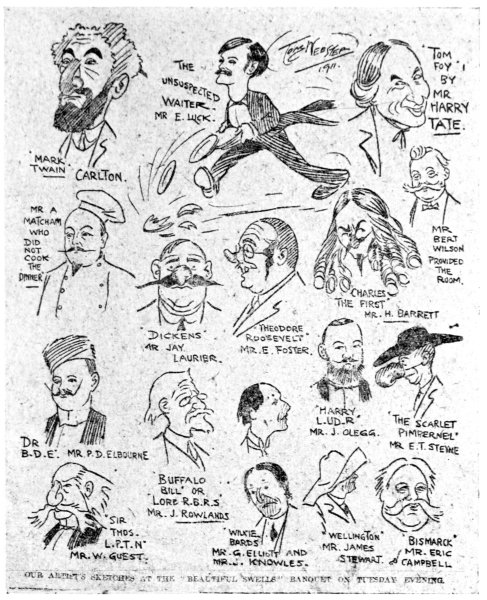

| Harry Tate and I—Together we found the order of “The Beautiful Swells”—The Birmingham spoof supper—A mouthwatering menu—The “Beautiful Swells” anthem—Cockroach soup—Property viands—A mysterious waiter—Ernie Lotinga’s little joke—The spoofers spoofed—A pigeon pie that flew—A surplus of farthings—Rehearsing for pantomime—My first rehearsal—I am “fired” out of the theatre—Pantomime in Hoxton—The gallery boy’s irony—A cutting retort—I get married—Courting under difficulties—The married chorus-girl and the lovesick manager—Supper for two in a private room—Hoaxing the police—A sham tragedy and its sequel—The fat policeman and the big lobster—Sold again | 149 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| AFRICA AND THE ORIENT | |

| Bound for Cape Town—A pleasant voyage—Ships’ games—A contrast in voyages—“Cock-fighting” at sea—“Chalking the Pig’s Eye”—“Swinging the Monkey”—Marine cricket—A new kind of golf—Cycling at sea—Sweepstakes on the vessel’s run—Races on the ocean wave—Mock breach-of-promise trials—By bullock waggon to Kimberley—I perform before Cecil Rhodes—Get shot in a street row—Contrast on my second visit—The great strike riots in Johannesburg—Fire and dynamite—A night of horror—A gay but expensive city—Dear drinks—Performing in the back veldt—Eggs for throwing—At Pretoria—Kruger’s house—Where Winston Churchill swam the river—A disappointing stream—My prize giant—A Jo’burg sensation—Buying a forty-shilling suit to measure—A disgusted tailor—Special railway travelling—My giant proves his agility—In Colombo—Indian fakirs—Their xiconjuring skill overrated—The boy and rope trick—Two versions of a similar story—The whole thing a fake—The evidence of H.H. the Maharajah of Jodhpur—I offer £100 to any native who can do it—No takers—The mango seed trick—Outwitting a fakir—“Let me plant the seed”—The camera in action—The Tree of Life—Cobra and mongoose fight | 166 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| WHEEZES AND GAGS | |

| The social side of music-hall life—The Vaudeville Club—A telephone wheeze—The swanking “pro.” and his mythical salary—About “tops” and “bottoms”—Ring up “625 Chiswick”—“Big Fred” and Fred Lindrum—A queer billiard match—An unexpected dénouement—Roberts and the Australian billiard marker—I make of myself a human telescope—Growing to order—Willard the original “man who grew”—Puzzling a Scotland Yard “’tec”—My most wonderful fall—I make a “hit” in a double sense—A Wigan wheeze—The performer who got too much “bird”—A blood-thirsty barber—My worst insult | 183 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| THE BIGGEST NEWSPAPER SPOOF ON RECORD | |

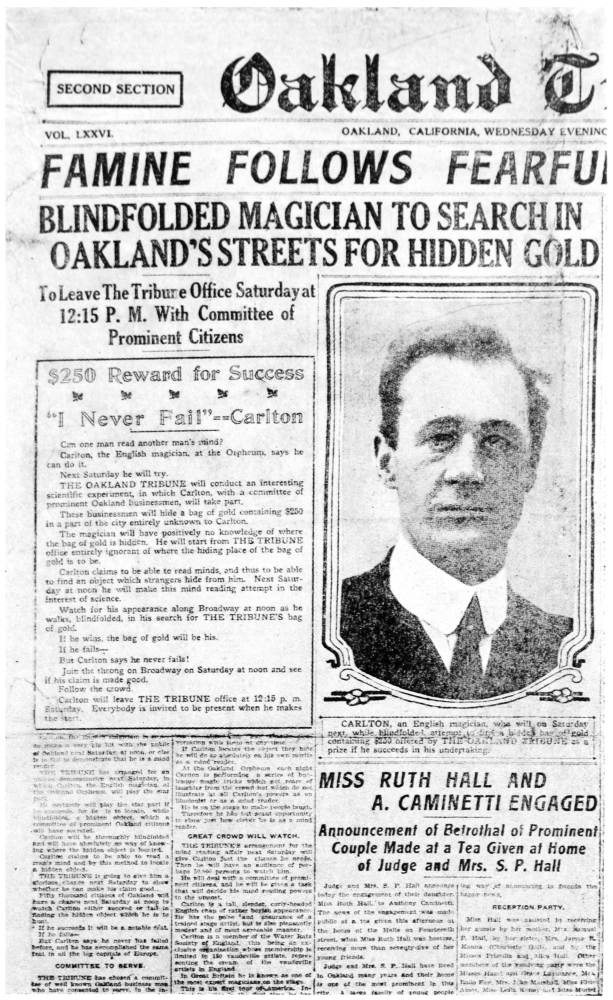

| How the great spoof first came into my mind—Hoaxing the newspaper Press of two continents—Telepathy and thought-transference—The incredulous reporter—I propose a drastic test—A representative of the Bristol Times and Mirror hides a stylograph pen in an unknown quarter of the city—I am blindfolded and find it—Amazement and enthusiasm of the people—A column report in the newspaper—An insoluble problem—Various theories as to how it was done—An indoors test imposed by the Editor of the Bath Chronicle—Blindfolded through the streets of Bath—Vast crowds—I am again successful—Press and public alike bewildered—Hoaxing the Yankees—The Oakland, California, Tribune’s test—Two hundred and fifty dollars in gold hidden—The Secretary of the Oakland Chamber of Commerce is chosen to secrete the treasure—Again I am successful—My best free Press “ad.”—Congratulations all round | 203 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| HOW THE BIG SPOOF WAS WORKED | |

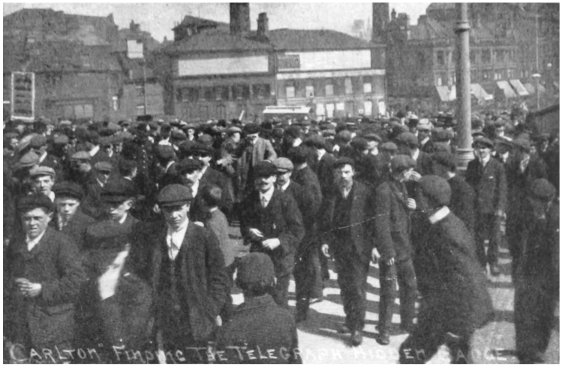

| Muscle training on novel lines—How not to be blindfolded—Artificially developed frontal muscles—The advantage of possessing a prominent proboscis—Following one’s nose—I study boots—A Sherlock Holmes of footwear—Acting blind—Not so easy as it sounds—Queer happenings at Halifax—A mishap at Leeds—Police stop the performance—A curious mischance at Bath—Ingenious explanations to account for the feat—Invisible wires—Guided by bugle calls—Following xiithe scent | 213 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| TELEPATHIC AND MESMERIC SPOOFS | |

| Real spiritualism and sham mesmerism—Spoof séances—I ring one off on my landlady—The self-playing piano—The spirit that walked upside-down—Some simple explanations—Manufacturing a telepathist to order—Thought-reading extraordinary—The colour test—Telepathy by wire—A brief dream of wealth—A sleepy wife and a hidden match-box—The dead-head who was spoofed—A disconcerting reception—Story of Houdini, the “Handcuff King”—More telepathy—Over the telephone this time—A puzzling link—And the explanation | 226 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| SHARPS AND FLATS | |

| Spoofing a mesmerist—The spoofer spoofed—Spoof card tricks—Racecourse sharps—The “dud” diamond wheeze—I am beautifully “had”—Three-card trick sharps—A Newcastle adventure—Bunny’s spoof—Spoofing a “new chum”—The performing elephant and the dude—Wheezes and gags | 242 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| FLOTSAM AND JETSAM | |

| Sharing terms—Some tricks of the trade—Spoof telegrams—A Bradford dispute—I engage to fight “The Terror of the Meat Market”—A packed house—I enter a lion’s den—And am glad to get out again—A trick the police foiled—Tricks of trick swimmers—I learn a secret or two—Pigeon shooting extraordinary—“Satan’s Dream”—Royalty at a side-show—My mother hears me over the electrophone—At Wentworth Woodhouse—A kind reception—My embarrassing mistake—An angler’s paradise | 263 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| IN EGYPT IN WAR-TIME | |

| My trip to the land of the Pharaohs—Giants and dwarfs on a P. & O. liner—We are ordered into Plymouth—Submarines—An exciting experience—Destroyers to the rescue—The dwarfs and the lifebelts—Sports at sea—My contortionist is taken ill—Anxious days—Kindness of the Maharajah of Jodhpur—Arrival at Port Said—Cairo—I engage another contortionist—Pelted with money—Pigs at Port Said—Captured Turkish pontoons at Cairo—Turkish prisoners playing tennis—Interned enemy ships at Alexandria—Wounded soldiers—At the Pyramids—Ammunition from India—On the way home—Across France in war-time—The Channel passage—Elaborate precautions—Submarine nets—Paris in war-time—Madrid in war-time | 280 |

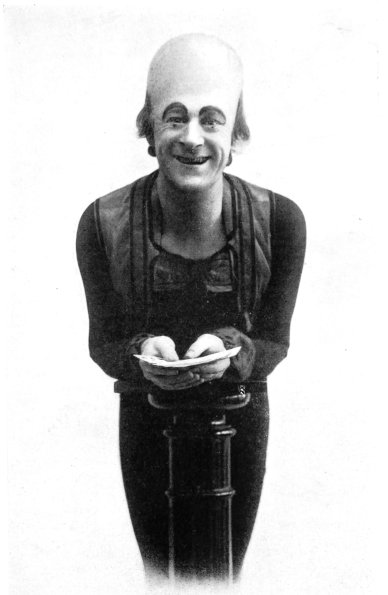

| Carlton—Off | Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

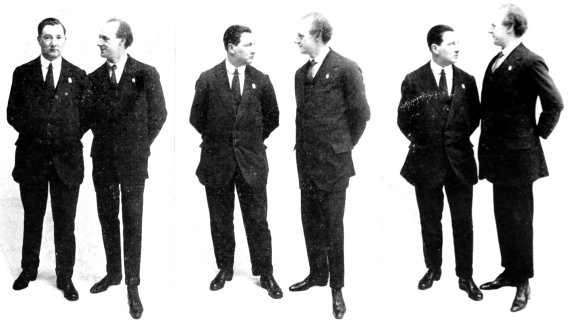

| Carlton—On | 20 |

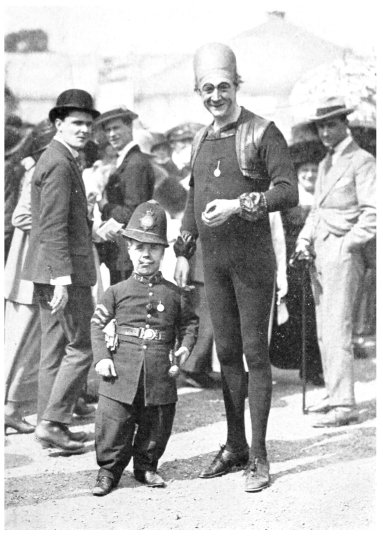

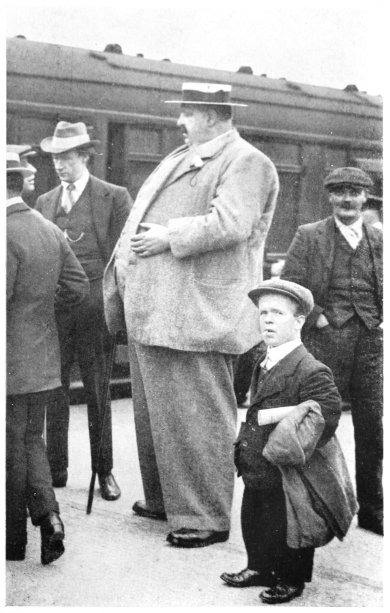

| Carlton and One of his Satellites at the Theatrical Garden Party, London, 1919 | 50 |

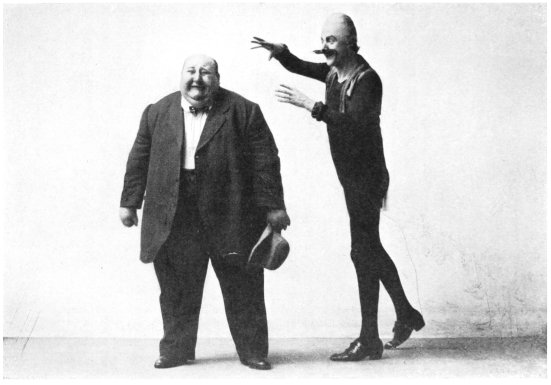

| Carlton Mesmerising Bobby Dunlop | 74 |

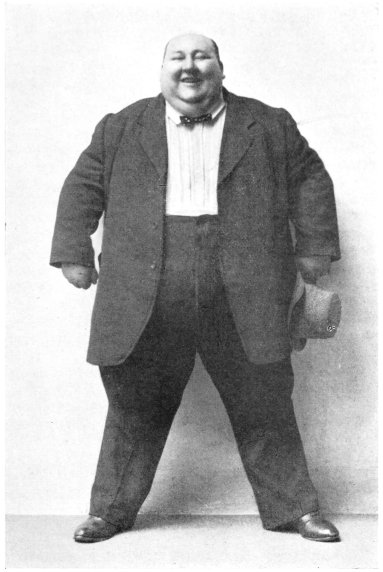

| Bobby Dunlop, Carlton’s American “Fat Man,” who dropped dead in Berlin | 78 |

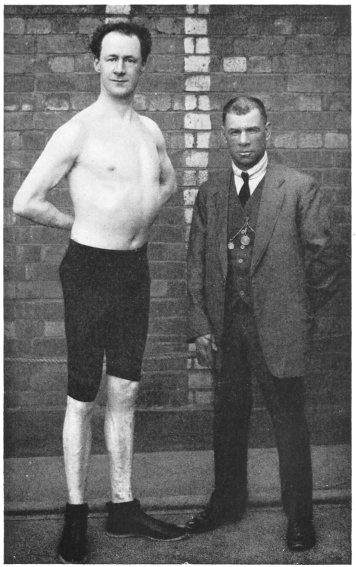

| Carlton and his Trainer, Dai Dollings, the Famous Welsh Athlete, stripped ready for his Fight with Apollo | 114 |

| Carlton and Jimmy Wilde at the National Sporting Club | 116 |

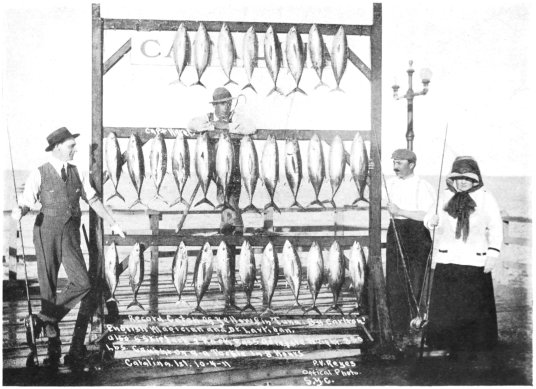

| Official Photograph of a Record Catch of Yellow Fin Tuna caught by Carlton and another Fisherman jointly at Santa Catalina | 130 |

| The “Beautiful Swells” Spoof Supper—a Page of Caricatures by Tom Webster | 152 |

| Arrival in Johannesburg of Carlton, his Giant, and his Dwarf | 174 |

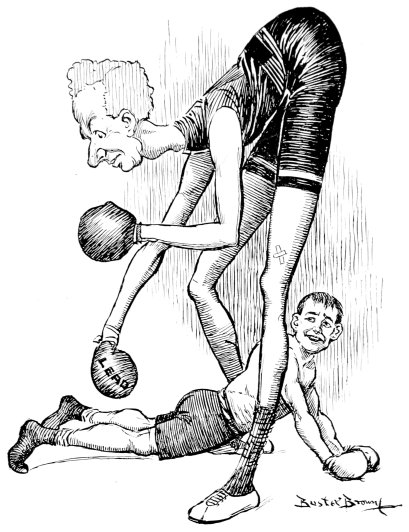

| Carlton as a “Human Telescope” | 192 |

| Portion of Front Page of the “Oakland Tribune” with Report of Carlton’s Treasure Hunt in that City | 206 |

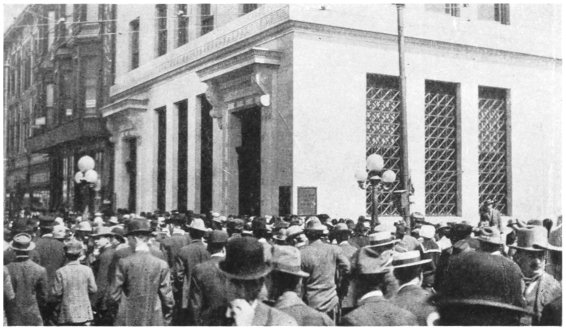

| Crowd in Bradford watching Carlton’s Search for the Hidden “Telegraph” Badge | 222 |

| Crowd at Oakland (California) watching Carlton’s Search for Hidden Treasure | 222 |

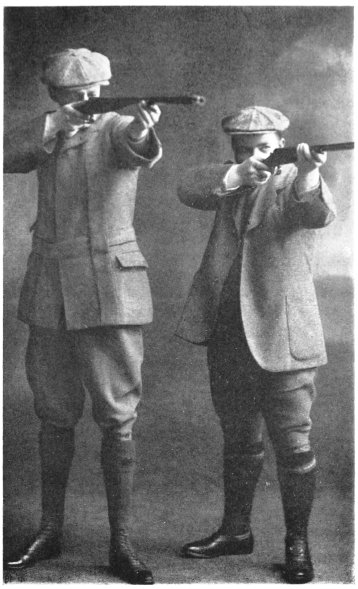

| Carlton and Billy Grant, the Open Champion Pigeon Shot of Scotland | 272 |

TWENTY YEARS OF SPOOF & BLUFF

Work as a telegraph messenger boy—First attempts at “public” entertainment—Small but appreciative audiences—I introduce the cycle to the Post Office—Christmas-boxing on my own—I am rewarded with the “Order of the Sack”—Hard times—A home-made conjuring outfit—On tramp to Southend—Busking on the sands—Wrathful “niggers”—“Stage” fright—“Best clear, kid”—I clear—On the road back to London—Hunger and thirst—Four shows for fourpence—A “welcome” home—No food in the house and the brokers in—“Covering the spot”—Jimmy Jennings—I win watches—Beat a game and gain a friend—“A quick way of making money”—Learning to be a street patterer—Tricks of the showman’s trade—Nearly a riot—Jimmy grows anxious—Good-bye to London once more—A new pitch—And the beginning of a new life.

My first experience as a public conjuror and card manipulator dates back somewhere about five-and-twenty years. Sheer necessity drove me to it. A slim, shy youth of sixteen, or thereabouts, I was out of a job at the time, with no prospect, so far as I could see, of getting into one.

This was awkward, because I was practically the sole support of my widowed mother, who was a cripple, and four young sisters. So, as a last resort, I determined to tramp down to some4 seaside town, and try and earn a little money busking on the sands.

As a boy I had worked for a while as a telegraph messenger, one of those blind-alley occupations that lead nowhere, and I had frequently watched peripatetic conjurors giving their shows at street corners and elsewhere. These exhibitions had always had a great fascination for me, and I presently started to try and copy their tricks.

It was difficult at first, for I had no one to teach or advise me, but I persevered, and was able in time to do quite a variety of simple stock tricks with cards, coins, etc. My audiences were small but appreciative, consisting as they did of my fellow telegraph messengers attached to the old Buckingham Gate Post Office in the Buckingham Palace Road—long since done away with—where I was then stationed. Afterwards I was sent to the Castelnau Post Office, Barnes, which was situated at a chemist’s shop.

Here I had plenty of spare time on my hands, telegrams being comparatively few and far between. The distances I had to travel to deliver them, however, were often considerable, and this gave me an idea. I was at the time the proud possessor of an ancient solid-tyred bicycle. This I requisitioned in order to cover the ground more quickly, a complete novelty in those days, when cycles for post-office work were not even thought of.

My “boss,” the sub-postmaster, was particularly struck with the innovation, and he wrote to the Postmaster-General about it, with the unexpected, and to me very gratifying result, that I received from the Department an extra allowance of three shillings and sixpence a week for the upkeep, etc., of my machine. Afterwards5 the practice received general official sanction, and in time became well-nigh universal. But I can, I believe, truthfully lay claim to having been its originator, and I was certainly the first telegraph messenger-boy to ride a cycle for the Post Office in an official capacity.

From Barnes I was sent to Battersea, where our family had also gone to live, and it was here that my too-enterprising spirit led to the severance of my connection with the Post Office Service. It came about in this way. When Christmas came round I was given a temporary job as auxiliary postman. We boys used to hear the regular postmen talk a lot about their Christmas-boxes and the fine harvest of tips they expected to reap, and I did not see why, as I was doing my share of the work, I should not share in the pickings.

So, very early on Boxing Day morning, before the regular postman had started out to “box his walk,” I went round and collected the gratuities, or at all events a considerable portion of them. I didn’t say I was the postman, but simply knocked and asked for a Christmas box, and being a tall youth the money was mostly handed over to me without demur. Later on, of course, when the regular postman called round, there was an awful row, and I was called upon to resign; a polite way of investing me with the “order of the sack.” In this dilemma, as narrated above, I purposed turning to account my knowledge of conjuring in order to earn a livelihood, or try to.

As a preliminary I went and begged the lid of a cheese-box from a near-by shop. This I covered with a bit of old cloth my mother gave me, and trimmed it round with a yard or so of penny-threefarthing ball fringe. Next I set my transmogrified cheese-box lid on top of three thin6 bamboo canes, arranged tripod-wise, and behold I was in possession of quite a pretty little table, such as street conjurors affect.

Next I procured a rabbit—all conjurors had to have a rabbit in those days—and some balls and tins for what is called the cup-and-ball trick, together with a pack of cards, and a few other simple paraphernalia, not forgetting half-a-dozen pennies—in conjuring parlance “a pile of megs”—for palming and working disappearing coin tricks. Thus equipped, I set out. I had been told that Southend was the best place to go to, and as I had no money to pay my fare I had to walk there, carrying my poor little “props” with me.

It was weary work. The long dusty road seemed endless. Several times I was tempted to go into a public-house and try and do a show. But directly I set up my little table, my nerve forsook me, and out I came again. When night fell I chopped some wood for a farmer’s wife, who gave me in return a glass of milk and a crust of bread and cheese and permission to sleep in the barn.

Eventually I reached Southend, hungry, thirsty, and footsore. Also I was penniless, having been forced to part with my six coppers in order to keep myself in food on the road, thereby spoiling my best tricks. All day long I prowled about, watching the buskers at work on the beach, but never being able to pluck up sufficient courage to make a start myself.

I had managed to get a room by promising to pay at the end of the week, but after the first morning, when I ate a breakfast that I am afraid astonished and frightened my landlady, I was denied further board unless I paid something on7 account, which, of course, I was unable to do. For three days I prowled around, living as best I could, watching with hungry eyes the picnic parties on the beach, and greedily devouring the scraps they left after they took their departure. I never felt so famished in all my life before.

On the morning of the fourth day, a Bank Holiday, a letter came from my mother. She wrote that she had got the brokers in, that my little sisters were crying for bread, and would I please send her some money? That did it. I felt that it was now or never. And, marching down to the beach, I set up my little table, and soon had quite a respectable audience—respectable in point of size that is to say—gathered round me.

Then again the fatal shyness came over me; stage fright in its first, worst, and most terrible form—only there was no stage. My legs shook under me, my knees knocked together, my tongue felt as if glued to the roof of my mouth. I almost think I would have made a bolt for it once more, but for the fact that the crowd hemmed me in on every side.

Ten minutes passed by. My audience began to show unmistakable signs of impatience. “Get a move on, kid!” they cried; “start your bloomin’ show.” Thus adjured I began. But just as I was in the middle of my first trick, there was a commotion on the outskirts of the crowd, people jostling and shoving, pushing and being pushed, and a moment or two later four burly nigger minstrels burst through to where I was. I got a punch on the back of my neck that sent me sprawling, and when I scrambled to my feet I was just in time to see my poor little cheese-box table go flying seaward, propelled by a vigorous kick from the biggest and burliest of the niggers.

8 I was too weak from hunger to even try to retaliate, too flabbergasted at the unexpected, and as it seemed to me unprovoked and unwarrantable, attack to attempt to expostulate even. I just stood stock-still, open-mouthed and trembling, while the leader of the buskers asked me, in language the reverse of polite, what in thunder I meant by taking their pitch, for which they paid, and which nobody else therefore had the right to occupy?

There was some further talk, and then I learnt for the first time that the sands at Southend belonged to the corporation, and that buskers were not allowed to perform there without permission, and without paying for the privilege. Naturally I was terribly downhearted at this, and I suppose I showed it, for after the niggers had given their show they clubbed round amongst themselves, and handed me two shillings. “Best clear out, youngster,” they told me, not unkindly. “You can’t do anything here without capital.”

Their advice seemed good advice. So that very day I started to tramp back to London. I had retrieved my table, and although I had been compelled to sell my rabbit in order to buy food during my stay in Southend, I still had with me my pack of cards, and one or two other trifles. With these, on the way back, I gave four shows at as many separate “pubs.” One of these shows netted me fourpence, the other three yielded nothing. I reached home after a week’s absence, weak, weary, and ill, to find a welcome of words waiting for me, and that was all. There was not a morsel of food in the house, not even the proverbial crust, and the broker’s man had cleared out most of the furniture.

For these reasons I am not likely ever to forget9 my first “provincial tour.” That night I cried myself to sleep, the hunger gnawed at my vitals, and I don’t believe there was an unhappier lad in England than I was just then.

Next morning I felt a little better; but not much. However, it was, I reflected, no good sitting down and repining, and I started out to look for work. After a while I got a job as potman and under-barman at seven shillings a week in a public-house in the Battersea Park Road.

One day a travelling conjuror came into the saloon bar, and did a few tricks with coins. The proprietor was greatly interested in the show, and the next day, when he and I were having dinner together in a little recess behind the bar, he remarked:

“Clever chap that conjuror who was here yesterday. Those coin tricks of his were wonderful.”

“Oh!” I replied, “I didn’t think very much of them. Why I could do better than that myself. Look here!” And I took a penny from my pocket, and palming it from one hand to the other I made it disappear before his eyes.

To my unbounded surprise my employer promptly jumped up, his face crimson with rage. “You young rascal!” he cried. “That’s quite enough for me. I’ve been missing money from the till for quite a long while now. Out you go!” And, suiting the action to his words, he seized me by the scruff of the neck and the seat of my trousers, and threw me out of the house on to the pavement.

When I got home and told my story, my mother was naturally very much upset, and she went round and expostulated with the landlord; but all to no purpose. He insisted that money had10 been missed, and that I must be the thief, as there was nobody else who could have taken it except the head barman, and he had been with them a long while and was quite above suspicion.

This individual, who slept in the same room as myself, was, I may add, a very great pet of the landlady, who was firmly convinced that he could do nothing wrong.

Yet he was the thief all the while, as it turned out; for some little time afterwards, and while I was away in the country, he was convicted and sentenced to three months’ imprisonment, the stolen money having been found in his box. My mother sent me a copy of the local paper with the account of the police-court proceedings.

Some few years later I had succeeded in making a name for myself. I was at the Palace Theatre in Shaftesbury Avenue, and my name was blazoned in letters a foot long on the buses, and on all the hoardings in London. It was a hot day, and I felt thirsty. I turned into a little “pub” in Wellington Street, Strand. There behind the bar was my old “boss.”

I had grown a lot in the intervening years, and he didn’t know me; but I knew him directly.

Over a whisky-and-soda we got into conversation, and presently he asked me who I was.

“My name is Carlton,” I said, “I’m at the Palace Theatre this week.”

“Oh yes,” he replied, “of course. I saw you the other evening. Wonderful good show, yours.”

“Glad you like it,” I said. “But say—do you remember the day when you took me by the scruff of my neck and threw me out of your old place in the Battersea Park Road, after accusing me of stealing money from the till; money that your wife’s favourite boy afterwards got three11 months for stealing? Do you remember that—eh?”

The landlord looked surprised. So did his wife, who was behind the bar with him at the time. But they would neither of them admit that they remembered anything about the affair.

Of course they did, though; only they would not acknowledge it. Possibly they thought I might bring an action against them, even after the lapse of all that time, for wrongful dismissal and defamation of character.

But to resume the thread of my story. At the time I was thrown out of the “pub,” and out of work at the same time, we used to live in the neighbourhood of Clapham Junction, in a turning off the Falcon Road.

There was a man at a pitch near here who earned his living at a game called “covering the spot.” On a table covered with white oil-cloth he had painted several round red spots, each about as big as a plate. The player was given five tin discs, for which he paid a penny, and his aim was to drop these on one of the spots so as to completely cover it, leaving not even a peep of the red showing. If he succeeded in doing this he got a watch, which the proprietor of the game, if the winner so willed it, would buy back again for three shillings and sixpence.

It was rather a fascinating game to watch, and having nothing else in particular to do I stood and watched it for a long while. He was a splendid patterer, was the proprietor, and he was simply raking in the pennies like dirt all the while. The game was new then.

“Money for nothing!” was one of his stock phrases he kept shouting out. So it was “money for nothing,” but he was the man who got the12 money, I noticed. “If you don’t speculate, you can’t accumulate,” was another of his gags. “This, gentlemen, is a scientific game of skill. Span your tins and drop them on. Try it! Try it! Try it! Cover the red, and carry off a watch. Hide the red you win; show the red you lose. Come along, gents! Come along! Come along! Faint heart never won fair lady!” And so on, and so on. And in between his patter, at intervals, he would himself “cover the red” with the five discs to demonstrate how easily it could be done.

I kept watching him closely, and I saw there was a knack in it. A man who had tried twenty or thirty times, but without success, was turning away. On the impulse of the moment I spoke to him. “I can do it,” I said. “Lend me a penny and let me try; we’ll go halves if I win.”

The man looked at me rather dubiously. “Why don’t you risk your own money?” he asked. “Because I haven’t got any,” I replied. “Oh well, in that case here you are,” he said; and he handed me a penny.

I dropped the discs one by one, carefully, methodically, slowly, and—I covered the red. A great shout went up from the crowd. Everybody was delighted, including the proprietor. He wanted somebody to win occasionally, but not too often, and he made a tremendous fuss.

“Hi! Hi! Hi!” he cried. “The boy’s won a watch. Come along, you sports, now. Come and do likewise. Don’t let a lad like this beat you.”

He handed me the watch, and I gave it back to him, receiving in return three-and-sixpence. This, he explained, was because the law would not allow him to give a money prize direct. It was my first experience of how simple a thing it is to get round13 an inconvenient legal enactment, though not my last one by any means.

After sharing the cash with the “capitalist” who had financed my venture, I still had of course one shilling and ninepence left, and I invested a penny of this on my own account in another five discs.

Again I won. Things were getting lively. The crowd cheered louder than ever. I was more than cheerful. The proprietor tried his best to look cheerful also, but there was a glint of anxiety in his eyes.

For the third time I tried my luck, but this time I just failed. Or so, at least, the proprietor asserted. Producing a pin, he inserted the point between two of the discs without moving either of them, thereby proving to his satisfaction, if not quite to mine, that the red was not completely covered. Here was a new trick of the trade, I reflected; no smallest patch of red was visible, but the pin’s point showed apparently that it existed, therefore I had lost.

“Try! Try! Try again!” shouted the showman. “Faint heart never won fair lady.”

I took his advice, and this time I succeeded once more. This made three wins in four tries. “Clever lad!” cried the crowd. But the proprietor looked glum. He leaned over the table and implored me in a stage whisper to go away.

I went, taking with me my eight shillings and sixpence winnings. That night the family sat down to a real, slap-up hot supper of tripe and onions, the first square meal that any of us had eaten for many a long day.

As for me, I was in high glee. I had, I considered, hit on a quick and easy way of making money. Next evening I sauntered down to where14 the showman had his pitch, and directly he had got his table set up I marched in, and soon won another watch.

This was too much for the proprietor. He called me on one side.

“Look here,” he said, “you’re too hot for me. Come and have a drink.”

We adjourned to the “Queen Victoria” public-house, and he called for a large rum for himself. I had a “small lemon.”

Over our drinks we discussed business, or rather he did. His name, he informed me, was Jimmy Jennings.

“I have been in the business for years,” he went on, “but I’ve never run up against a smarter lad than you are at the game. You’re hot stuff, and no mistake. Tell you what now. There’s room for a couple of stalls at my pitch. Will you work for me if I put another one up for you to take charge of? I’ll pay you five shillings a night, and ten per cent. on the takings. What do you say?”

Naturally, I was quite agreeable, and the following day, true to his promise, Jimmy had a table fixed up all ready for me to start. Being pretty well known in the neighbourhood I soon had plenty of customers, and raked in a good lot of money. Here, too, I first learnt to do the showman’s patter, for Jimmy, as I have already intimated, was a splendid patterer, and I, being all the time at the next stall to him, naturally picked up the art from him, almost without effort on my part.

Also I learnt many tricks of the showman’s trade, more especially as regards the particular stunt we were working. I was shown, for instance, that although the five red spots on the tables15 looked to be all exactly of one size, they were not so in reality. As regards four of them, although they could just be covered by the discs, the task was so exceedingly difficult a one as to be almost impossible of achievement. The fifth spot, however, was slightly smaller than the others, and the feat of covering it, therefore, was comparatively easy.

But as it was impossible to detect the smaller spot without actually measuring it, the chances were five to one against any player, picking his spot at haphazard, as of course he invariably did, choosing the easiest one. When either of us performed the feat for the benefit of the onlookers, however, we naturally always used the small spot. It was due to my sharpness in detecting this fact—though not until after long watching—coupled with a natural dexterity and quickness of hand, that had enabled me to win the watches in the first instance.

I might also mention that the flares which we used to illuminate our stalls—we did not usually start performing until after dark—were so arranged as to throw the light slantwise to our side of the table where the smaller spot was. This enabled us, if we performed the trick quickly—and this we invariably did—to leave a little bit of red showing without the audience being able to detect the fact. This was both handy and necessary, for even when working on the smaller spot, and notwithstanding all our acquired dexterity, we were neither of us so clever at it as to be able to bring off the trick with certainty every time.

And one had to be very careful, and exercise plenty of tact. The main thing was to keep the crowd in a good humour. That is where the art of the patterer comes in. We should have stood16 but a poor chance without it. Even as it was there were rows. One of the worst was on my account. A man in the audience asserted that I was standing on a box, and that that was why I was able to perform the trick. “Let me come round your side of the table and mount your box,” he cried, “and I’ll do it as easily as you can.”

In vain I assured him that I was not standing on a box, that it was only my unusual height—6 ft. 2½ ins.—that made it appear to him as if I were. He protested, began to get obstreperous, tried to force his way round. The crowd took sides, for and against: mostly against. There was something approaching a free fight, and we were afraid the stalls would be mobbed and wrecked. However, a policeman appeared on the scene, and things quieted down after a bit.

But Jimmy looked thoughtful that night after we had closed down.

“Look here, laddie,” he said presently, “this pitch is getting a bit too hot. Tonbridge Fair opens next week. We’ll pack up and open there.”

Which we did.

So closed one chapter of my life. The next one was to open amongst far different surroundings.

Practising conjuring—Why I rarely play cards—The great Maskelyne and Cooke box trick—I make a trick box of my own—The “Flying Lady” who flew—away—In partnership with Gypsy Brown—My life with the show folk—I begin to make money—The kings of the fair grounds—Caravan life and cookery—The Romany people and their ways—Gypsy Brown cheats me—How the “bluers” work—Fights in the Fair Ground—The etiquette of the showmen—In a boxing booth—Taking on all comers—A rough life—“Do a slang to get a pitch”—The tricks of the travelling boxing-booth proprietors—A gypsy duel with cocoanut balls.

During the period when I was working for Jimmy Jennings at his “covering the spot” stall I had lots of spare time on my hands, for of course we only occupied our pitches for comparatively short intervals of an evening, and then only on certain days of the week, Saturday being always one.

This leisure I utilised mostly in practising conjuring tricks, and in card manipulation. In the beginning I used to use old tram and omnibus tickets for the latter purpose, and found them very useful, for being much smaller than ordinary playing cards they were of course more easily palmed or otherwise manipulated, while at the same time they afforded excellent practice to a comparative tyro, as I then was.

I may mention that at that time I rarely handled the cards themselves, and still more rarely played a card game. Nor do I now, at least not for money; and the same rule holds18 good, I have observed, with most professional conjurors and card-manipulators.

The reason of this self-denying ordinance is, of course, not very far to seek. Take my own case for example! If I should play cards for money, and win, although I have as much right to win as any other player taking part in the game, there is always the risk that the others—even one’s own friends—may think I have utilised my professional skill in order to take an unfair advantage of them; in other words that I have cheated them. While should I lose, people are apt to say: “Well, Carlton is not so smart with the pasteboards as we thought him to be, after all; the man’s a bit of a mug.” So that’s why I very rarely play.

It was, too, during my term of “apprenticeship” with Jimmy, if I may so term it, that I first became interested in the great Maskelyne and Cooke box trick. These two gentlemen were showing, at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, a trick which consisted in a man being corded up in a locked box, and from which he freed himself in a few seconds.

At each performance they offered £500 to anyone who could make a similar box, and successfully duplicate the trick. Two young men, clever mechanics they were, set to work, and eventually succeeded in making a box and performing the trick. I, being at the time a lithe and supple youth, was placed inside the box at the trial exhibition, and I released myself and appeared outside in three seconds.

I should add that after I was placed in the box, it was locked, and then enveloped completely in a canvas cover, which was sealed and corded, as Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke had stipulated. Notwithstanding this they declined to pay the19 promised £500, and the case came into the Queen’s Bench, and was eventually carried through the Court of Appeal right up to the House of Lords.

Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke lost, and the two young men who had made the box got their £500, but of course I received none of the money. Nevertheless, I have mentioned the incident because it was indirectly the cause of my getting my first real boost up in my present profession. But of this more anon.

Suffice it for the present to say that I had learnt all there was to know about that particular box trick. And not only that. I had set to work on my own initiative, without saying a word to anyone, and had made a similar trick box of my own, and in regard to which, moreover, being a youth of an experimental and inventive turn of mind, I had introduced one or two notable improvements; or at least so I regarded them, and so, as a matter of fact, they eventually turned out. The reason for my mentioning this here will appear presently.

On arriving at Tonbridge Fair Ground I became acquainted with a big gypsy named Brown, a typical Romany lad, or diddyki, as these people call themselves in their own dialect. He had a booth in which he was giving a show with a so-called “Flying Lady.” She had been working at other fairs with him on the basis of half the takings, but at Tonbridge, greatly to Brown’s disgust and disappointment, she failed to put in an appearance. The flying lady had in fact flown—away.

In this dilemma Brown suggested that I should take her place for a week, which I did, and this resulted eventually in my performing my box trick at his booth. I had, I should state, rehearsed20 the trick many times with a performer who called himself “Lieutenant Doctor Lynn, Junior,” and who was a son of the one-time famous conjuror, Dr. Lynn. He it was who presented the trick for the two young men mentioned above who successfully sued Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke. I was, therefore, absolutely part perfect in the act, and with the improvements I had made in my box I felt confident that I could hold my own with anybody in the business.

At Faversham Fair Ground, to which we went from Tonbridge, I arranged with Brown to share his booth, he paying the rent for the ground, or the “tobee” as the fair folk call it, each to have half the takings. I was also to help him by pattering outside the show, and performing card tricks, in order to attract the people, and by interesting them induce them to come inside: in showman’s parlance “doing a slang to get a pitch.” This arrangement was certainly a by no means unfavourable one for him, but he was not satisfied, as I shall have occasion to show hereafter.

Prior to our opening at Faversham I had cut some paper letters, and stuck them on a big, bright ultramarine blue banner, advertising my show as follows:

CARLTON PHILPS

in a facsimile of the famous

Box Trick

that won £500 in the House of Lords.

This act went with a rush from first to last, and this was where I began to make money. It was a novel experience to me, and need I say it was as21 pleasant as it was novel. I was now able to send home a substantial sum each week to my mother and sisters, put by a little against a rainy day, and still have enough left over for my personal needs, which, however, I may add, were at that time of quite modest dimensions.

To go back a little, I should explain that the roundabout people are the kings, so to speak, of the fair grounds; and it is these usually who arrange for the pitches in advance, and pay the “dinari for the tobee” (i.e. money for the ground) in a lump sum to whoever owns the land, afterwards sub-letting it to the smaller showmen, the amount of the rent paid by these latter varying with the size and position of their individual pitches. The name of the roundabout firm who rented the fair grounds at Tonbridge and Faversham was Messrs. Hastings and Wayman, now well-known travelling showmen in Wales.

I got very friendly both with Mr. Hastings and Mr. Wayman. Though wealthy men as show folk go, and very smart at a deal, they were poor scholars, and I used to assist them in making up their accounts. I also, at their request, acted as their advance agent in so far as I used to go on ahead and arrange for the renting of the tobee.

In this way I got my first insight into the life of the road as led by the Romany folk. It was, I have no hesitation in saying, the happiest time of my life. When on the move I lived in one of their waggons—caravans ordinary people call them, but to the gypsies they are always waggons—and to travel slowly along through the beautiful English country lanes behind the sleek, well-fed horses, was a revelation in restfulness to a bred and born Cockney lad like myself.

We almost lived on the country. Our dogs22 brought us in rabbits and to spare. Even pheasants for the pot were not lacking. For this I make neither apology nor excuse. The true gypsy regards all fur and feather that runs or flies as his by divine right, and the word “poaching” has for him literally no significance whatever. When we pulled up at set of sun by some wayside brook the odour of cooking was always quickly wafted on the breeze—and such cooking!

It was on one of these journeys that I first tasted that famous Romany dainty, a hedgehog rolled whole in clay, and baked in the hot ashes. Believe me it is a dish fit for a king; tasty, succulent, juicy, and possessing a delicious flavour—gamy but not too gamy—that is all its own. We also used to cook birds, and even rump steaks, after the same fashion, and very toothsome I found them. Of course care must be taken to select the right kind of clay for an envelope, and it is also advisable to pick out the worms from it before using it.

Heaven knows how long I might have continued leading this kind of life had it not been for an untoward incident that happened later on, and to which I shall refer presently. I might have even continued the vagrant gypsy existence that fitted in so well with my tastes and inclinations, and become in time almost one of themselves. As it was, after only a comparatively short spell of it, I was becoming half a Romany, using their dialect, and falling by degrees, and almost unconsciously, into their ways of thought and methods of expression.

However, as I have already said, my career as an amateur gypsy was destined to be cut short sooner than I had bargained for. I was, of course, never really one of themselves. All the23 gypsy show folk are related to one another more or less, either by marriage or descent, and although they will show friendship to an outsider on occasion, they never fully trust any such, or admit them to a real, close intimacy. My trouble with them began, as so many other troubles begin, over money matters.

My show, as I have said, was unusually successful, and for some time it had been borne in upon me that I was not getting my fair share of the takings. I mentioned my suspicions—they were in fact much more than mere suspicions—to Mr. Wayman, and he was very much upset and annoyed about it. At the same time he warned me that it would be as well to avoid if possible having any open quarrel with Brown, who had the reputation of being a violent man, and who would be certain, if trouble arose between us, to have all the other gypsies on his side irrespective of the rights or wrongs of the matter in dispute.

This of course was all very well in its way, and I quite recognised how excellent was his advice, and how kind and well-meaning was the man himself in giving it. But then, on the other hand, I did not see why I should go on being cheated, nor did I intend to, if I could help it. So one day between the shows I quietly slipped off up to London, without saying a word to anybody, and bought an automatic pocket register; one of those tiny affairs, not much bigger than a watch, which you can hold behind you, or keep hidden in your pocket if need be, and tick off with one hand the number of people passing in or out of the building.

That night when we came to settle up, I found, as I had surmised, that Brown was cheating me. His count of the number of patrons visiting my24 show was somewhere about fifty below that registered by my machine; and which, by the way, he did not know I possessed. Nor did I enlighten him even now on this latter point, merely remarking that I thought he must be mistaken as to the number, for I had kept count, and I made it fifty more than he did, which, at a penny each for admission, and reckoning half the takings as mine, made my share 2s. 1d. more than he was going to pay me.

“Oh, that can’t be,” objected Brown. “I’m sure my figure is the correct one. Perhaps you counted the ‘bluers.’”

In order that the reader may be able to appreciate the full significance of this remark, and also understand how little Brown thought, or affected to think, of my intelligence, I ought here to explain the meaning of the word “bluer”; a term perfectly familiar to all the great host of peripatetic showmen, roundabout proprietors, owners of cocoanut shies, and the like, but unknown probably to the generality of people outside these professions.

Literally, then, to “blue,” in the Romany dialect, means to push or shove, and a bluer, therefore, means a pushful, forceful individual, one who shoves and elbows his way to the front.

Bluers work on fair grounds in gangs of from four to six or eight. They hang about the outskirts of the crowd that gathers round the show where, we will say, the fat lady is on exhibition, or the tattooed man; and at the proper moment, that is to say when the showman has finished his harangue and is inviting all and sundry to “walk up—walk up—walk up,” the bluers start to elbow their way to the front from the rear, pay their pennies with assumed eagerness, and enter25 the show. The crowd, once the lead is set, follows like a flock of sheep, and the trick is done.

Afterwards the bluers spread themselves amongst the crowd outside again and discuss, of course in highly eulogistic terms, the wonders of the particular show they have just visited, before proceeding to another part of the fair ground, there to repeat their performance for the benefit of some other showman. Or they will give a lead at the cocoanut shies, where, being excellent throwers owing to long practice at the game, they invariably down the nuts, thereby encouraging others to try and do likewise.

Bluers are paid a shilling a day by each of the showmen having stands at a fair, and manage to make a very decent living, following the shows round from place to place all over the country, and from year’s end to year’s end.

Of course each bluer is furnished beforehand with a sufficient stock of pennies each day to pay for admission for himself to the various shows; and, equally of course, these pennies have to be deducted from the gross total of the takings at the close of the day, and allowed for.

The reader will be able to understand now, therefore, how exceedingly nettled and angry I was when Brown accused me of counting in the bluers; because it was obvious that I knew by sight every one of these men, and that I was not going to count them in as ordinary members of the paying public, unless indeed I was trying to cheat him, a course which, needless to say, I neither intended nor desired.

All this I explained to him, but he still persisted in saying that I was mistaken in my count; so, bearing in mind the advice given me by my friend Mr. Wayman, I decided to let the matter26 drop just then, hoping that he would take the hint, and treat me fairly for the future. Instead, however, matters kept going from bad to worse. Every night he docked me in sums running in the aggregate into quite a lot of money, and I felt very sore about it. Besides, it was very unpleasant in other ways, for the matter was a continual bone of contention between us, leading to constant bickerings and quarrels.

And I wanted no quarrels just then, either with Brown, or with any of the other gypsies. I had had quite enough to go on with already, if the truth must be told. Indeed, before I had been following the fairs a week I had fought no fewer than five pitched battles with the show folk, and their hangers-on the bluers, and others. This, however, was in a sense partly my own fault, and it was also partly due to my ignorance of the unwritten law that govern the working of the fair grounds.

For example, it is the custom for everybody to help in the setting up and taking down of the various shows, roundabouts, cocoanut shies, and so on. The bluers, too, gave a hand in this work without extra remuneration, except that when a fair is finished they are given a lift on the waggons as far as the next town to which the shows are going. Now I, being ignorant of this custom, used to go off on my own somewhere as soon as I had finished putting up or taking down Brown’s booth, thereby, of course, giving offence. The others thought I was trying to shirk my obligations to them, whereas nothing was further from my thoughts. I simply did not know.

However, I had been used to taking my own part. Trust a Cockney lad for that! So I was usually able to give a pretty good account of27 myself. Besides, I got plenty of practice in the fair grounds. When business was slack at our show, I used to go over to a boxing booth in another part of the ground that was kept by one Alf Ball, an ex-champion pugilist, and he put me up to many a pretty wrinkle.

In return I used to help him get an audience by “doing a slang” for him, and would also, on occasion, put on the gloves outside his booth. This meant taking on all comers, and I fought many a hard bout on his account, for being tall and thin, in fact a typical light-weight, people used to pick on me. “I’ll have ’em (the gloves) on wi’ yon long fellow,” a burly rustic would say, and smile confidently to himself in anticipation of an easy victory.

As a matter of fact, however, I always won, although not exactly on my merits. What happened usually was this. Alf would keep a watchful eye on our performance, and if my opponent turned out to be a bit of a bruiser, and “out for a scrap” as we used to say, then the rounds, instead of lasting the regulation three minutes, would be cut down to one minute, or even less. On the other hand, if I was getting the best of a round, then it would be made to last out to perhaps as long as five minutes, or until the chap was finally knocked out.

There were other “tricks of the trade” too, all designed to make sure that the booth’s champion won. For instance, all the boxing-gloves looked alike; but that was all. My pair, weighing perhaps fourteen ounces, were of solid leather. The pair lent to my opponent for the bout were padded with horsehair, and as soft as a couple of sofa cushions. With these “dud” gloves he could make little impression on me, while if I got28 one home with mine it was all over with the other fellow. “By gum, but that thin consumptive-looking chap can punch,” my discomfited opponent would remark, as he quitted the ring, a sadder and sorer man than when he entered it.

I may add, however, that the gypsies, when fighting between themselves, seldom “fight fair,” as the term is understood amongst boxers. They “go for” one another with sticks, feet, hands, stones, anything. One favourite way of settling their differences is by what may be called a duel with cocoanut balls.

Everybody nearly is familiar, of course, with these round, hard wooden balls, and the gypsy keepers of the cocoanut shies are naturally adepts at throwing them. When two of them fall out, and agree to fight after this fashion, two heaps of six or eight balls are placed about twenty yards apart. The “duellists” then stand back to back midway between the two heaps, and at the word “go” from their seconds each makes a quick dash for the heap facing him, gathers up the balls, and then, turning about, he races towards his opponent, throwing one or more balls as he advances.

They do not, however, as a rule advance directly towards one another, but zigzag and circle about, wary as two panthers, and every now and again one or the other of them will let fly a ball with unerring aim, which the other has to dodge, or run the risk of being put out of action, for a blow from one of these missiles, when thrown by a gypsy, is extremely apt to be a knock-out one.

I once indeed saw a man’s arm broken in one such encounter, and another gypsy had his skull fractured. The interest of the spectators of these curious duels increases as ball after ball is disposed29 of, and reaches fever-heat when each combatant has thrown all his balls but one, without any decisive result being attained; for obviously the holder of the last ball, if he is not disabled, has his opponent practically at his mercy. The other can only run, circle, and dodge, in order to try and evade for as long as possible the blow he knows must come sooner or later.

I start a show of my own—Gypsy Brown plays me a dirty trick—The hunchback in the box—Bank Holiday at Cheriton Fair—I plan to circumvent Gypsy Brown—And succeed only too well—The crowd wrecks Brown’s booth—Pandemonium in the fair ground—The gypsies attack my show—The fate of a peace-maker—My fight with Gypsy Brown—£10 to £1 on my opponent and no takers—A knock-out blow—Gypsy Brown vows revenge—My life in danger—How I outwitted the gypsies—The last of my experiences as a fair-ground showman.

Meanwhile all this time Brown was steadily robbing me. Again I confided in my friend Mr. Wayman, telling him that I had by this time saved enough money to buy a tent (but not a proper showman’s booth) and asking his advice as to starting on my own. He thought it would be a good idea, but again took occasion to warn me against incurring the enmity of Brown, and his many friends and relations.

At this time we were performing at Sheerness on an open space in front of the beach, and having made up my mind to act on Mr. Wayman’s advice and chance it, I went to Messrs. Gasson & Sons of Rye, the big military tent-makers, and bought from them a fairly large second-hand army marquee, that I considered would about answer my purpose, at all events for the time being. Then, after our last show at Sheerness, having quite decided to sever all connection with Brown for the future, I made shift to get my box away31 from his keeping; but unfortunately he was able to retain possession of my banner, and my other “outside props.”

Our next destination after Sheerness was Cheriton, outside Folkestone, where there was a big volunteer camp. We arrived here on an August Bank Holiday, which, I should explain, is the showman’s day of days. All was bustle and animation. I could not, I reflected, have chosen a more auspicious occasion for my first venture as an independent showman.

Helped by the bluers, and a few others, I soon ran up my marquee, and Mr. Wayman very kindly lent me a lorry for an outside platform. I had previously engaged a big ex-army man named Sam Cliff as doorman, and to take the money, etc. He was a fine-built chap, weighing over fourteen stone, and by his own account a bit of a bruiser. I had also provided myself with another banner, a duplicate of the first one I had made, and which was now in Brown’s possession.

“Let him keep it,” I kept saying to myself. “Much good may it do him! He’ll never dare to use it.”

But to my disgust and disappointment this is precisely what he did do. Our two shows, situated almost directly opposite one another, each flaunted an almost identical banner proclaiming to all and sundry that Carlton Philps would give a performance of the famous box trick that won £500 in the House of Lords.

This was, of course, intolerable, and I promptly went over to Mr. Wayman and lodged a complaint. Whilst I was talking to him a little hunchback chap came over to where we were, and asked:

32 “Are you Mr. Carlton Philps?”

“Yes,” I said, “that’s me. What do you want?”

“Well, sir,” he answered, “I hope you won’t be offended, but Mr. Brown has engaged me to do a box trick. He fetched me down from London to do it, and now I find that he is using your banner for my trick.”

“Oh,” I said, affecting an indifference I was far from feeling, “that’s all right. Of course there are box tricks and box tricks. Now what sort of a one is yours, may I ask?”

The hunchback gave me a description of it, from which I gathered that his was a very ordinary show indeed, and far inferior to mine; his box being about four times as big as mine was, and minus the canvas cover. Also his trick was worked by means of a trap-door, whereas mine was independent of any such adjunct. So, after turning the matter over in my mind for a little while, I told him it was all right, and he was to get on with his trick.

Well, by the time the fair ground opened, there were I should think between fifteen and twenty thousand people present. The weather was lovely, the crowd was in excellent spirits, and it looked as if we had a record day in front of us.

Brown was ready before me, and he gave a first show under my banner. “This will never do,” I thought. “I’ve got to queer him right here now, or else he’ll queer me.”

So, after thinking hard for a second or two, I called to Cliff, and told him to come up outside on the lorry with me, and to bring my box, together with the canvas cover and the rope.

33 “Now,” I said, addressing the crowd, “I want some of you gentlemen to step up here on the platform, put me inside this box after you have examined it, lock it and keep the key, and then put on the canvas cover and cord it up as tightly and securely as you can. Then, when you have done all this, I want you to carry the box, with me in it, inside the tent, and I will escape from it inside of ten seconds. Finally I will guarantee that, as regards this my first performance here, everybody shall get their money back which they have paid for admittance.”

“Hurrah!” cried the crowd, and before you could say “Jack Robinson” half a dozen sailors had scrambled up on the lorry, and proceeded to carry out my instructions as to locking me in the box, and roping it up. Afterwards they carried me inside, followed by the rest of the crowd, and I escaped from it, as I had said I would, within the time stipulated.

Then I made them another speech, explaining to them that I was the one and only original Carlton Philps, and showing them my photograph and papers to prove it. “Now,” I concluded, “I promised that you should all have your money back, and so you shall—but on one condition. I want each one of you to take the penny my doorkeeper will give you, and go over to the opposition show and see fair play. I ask you to rope the other man up in the same way as you roped me, using the same precautions. Then see whether he will be able to get out as I have done.”

“Hurrah!” shouted the crowd once more. And off they went, sailors and all, their pennies clutched tight in their hands, making a bee-line for Brown’s booth. Then I began to get frightened.34 Cliff, too, looked serious. But, as I pointed out to him, it was no good worrying ourselves. What had to be, must be. Our business now was with our own show.

By this time the fair was in full swing. The roundabouts were going merrily, the steam organs were at full blast, and I had just begun to gather another crowd round me when I suddenly noticed the central pole of Brown’s booth began to wobble to and fro in a most alarming manner. I could plainly hear, too, angry shouts, and cries of derision, coming from the interior, and almost immediately the entire canvas edifice collapsed with a crash.

“Good Lord! That’s done it!” cried Cliff. “Now we’re in for it. The gypsies will never forget or forgive us for this day’s work.”

I began to think the same, for I quite realised what had happened. The sailors had roped the hunchback in the box, and he had been unable to get out. In revenge the crowd, led by the sailors, had wrecked the show.

However, I reflected, this was primarily Brown’s concern, not mine, and I went on with my preparations for my own show. My marquee was about half full of people, and more swarming in every minute, when the expected happened. Brown, his huge face crimson with anger, and bellowing like a bull, came charging across from the ruins of his booth, followed by a score or so members of his tribe, all of them obviously bent on mischief.

Nor did they come unarmed. Some carried iron tent pegs, others long cudgels, and one big, brawny ruffian swung aloft a heavy iron-shod oak capstan bar, used in the roundabout business. I also noticed, and this caused me most misgiving,35 that several had round wooden balls taken from the cocoanut-shy boxes. These are very dangerous missiles indeed in the hand of the gypsies, for they can throw them, owing to long practice, as straight as a rifle-shot. Many a time had I seen men stretched senseless by a well-directed shot from one of them, as narrated in the previous chapter, and I had no wish to repeat the experiment in my own person.

However, there was neither time nor opportunity to do much thinking. Calling to Cliff to follow me, I scrambled on the lorry, and with a loaded revolver in one hand, which was ordinarily used in my show business, and a heavy stake hammer in the other, I awaited the onset of the gypsies. These surged round my lorry, a veritable sea of savage humanity, shouting curses and execrations, and swearing that they would have my life.

Sticking my revolver in my belt, I swung the heavy hammer aloft, and threatened to dash out the brains of the first man who tried to climb up on the lorry. This made them pause. Not that they were not plucky. There was, I doubt not, many a brave lad amongst them. But none was so brave or so foolhardy as to wish to court certain death.

By this time pandemonium reigned in the fair ground. All the shows emptied, the roundabouts stopped, the cocoanut shies were deserted, and everybody, showmen and public alike, came surging round my tent. At this moment Sam Cliff, first throwing away a wooden stake he had armed himself with, very pluckily leapt down amongst the gypsies, and tried to parley with their leader. But hardly had he uttered two words, when Brown, mad with rage, rushed at him and36 knocked him senseless with a terrific blow in the face.

Poor Cliff was not expecting this. In fact he was purposely holding his hands down by his sides at the time to show that his intentions were peaceful. But Brown seemed to think he had done a very clever and plucky thing in “outing” him for the time being, and elated by his success, he came straight for my lorry, and made as if to climb up on it. I raised my hammer aloft, and in my temper I should most certainly have used it. But the crowd, fearing a tragedy, pulled him back.

Meanwhile Messrs. Hastings and Wayman, the managers, were talking to the other gypsies, and trying to pacify them, pointing out to them that they were wasting the best hours of the best day of the year; that while they were quarrelling, money was being turned away, and that people were even now commencing to leave the fair ground, fearing a riot. “Yes, and as for the others,” put in Mr. Hastings, addressing Brown and me, “they’re mostly climbing on the roundabouts and tents, and damaging my property. Let’s to business, before it is too late.”

By this time I began to see that there was only one way out of it. “I’ll fight Brown now,” I cried, “if the crowd will make a ring, and see to it that I get fair play.”

“We’ll see to that, never fear,” yelled the crowd; and in a few seconds a big ring was formed, and Brown, taking his place in the centre of it, stripped himself to the waist. His huge hairy chest heaved with excitement, and I noted, not without inward misgiving, his powerful biceps, his brawny bull-like neck, and the closely37 cropped, bullet-like head of the fighter by instinct and profession.

When I came to strip in my turn, a great roar of laughter went up from the multitude, and no wonder. I was lean and lanky, and my skin, by contrast with his, appeared soft as velvet, and in colour and sheen not unlike to old ivory. “The lad’s beat before he begins,” said one man in the forefront of the crowd, and who looked like a professional pugilist; “I’ll lay £10 to £1 on the big ’un,” and he looked round inquiringly. But alas! in all that crowd there were no takers. I don’t blame them.

Directly I stepped into the ring Brown made a rush at me, his great arms whirling aloft like the sails of a windmill. I stopped him with a straight left on the nose, and down he went. He scrambled to his feet, and came for me again, bellowing with rage. This time I caught him in the eye with my right, more by luck than by judgment, and he tripped and fell over a tuft of grass.

Now in a rough-and-tumble fight such as this was the strict rules of the prize ring are, it is well understood, not exactly enforced. You may not kick of course, and you may not hit a man when he is completely down, and that is about all. Everything else almost is considered fair, or at all events legitimate. So when Brown, having partially recovered himself, raised himself on one knee, I considered that my turn had come, and making a dive at him, and stooping down myself, I upper-cut him under the chin, and down he went again flat on his back.

Moreover, greatly to my relief, this time he elected to stay down. He wasn’t knocked out by any means, but he had had enough. The other38 gypsies picked him up, and took him away. The crowd dispersed. The roundabouts were restarted, the shows reopened, and all the fun of the fair was soon in full swing once more. Only Brown’s one-time beautiful booth remained lying where it had fallen, a tangled heap of rent canvas and broken cordage. Brown himself spent the rest of the day presiding at a cocoanut-shy, and nursing a bad black eye.

Every now and again he would turn and shoot a malevolent look in my direction, nor did it need this to tell me that my trouble with him was only now beginning. All day long, too, the other gypsies kept coming up to my show in order to tell me of what was in store for me later. “Brown,” they said, “swears he’ll kill you to-night, and he’s a man of his word.” “Tell Brown,” I retorted, showing them my revolver loaded in all six chambers with ball cartridge, “that I’ll certainly shoot dead any man I catch prowling round my marquee after the fair closes down.”

This, I may add, was a bit of sheer bluff, designed to throw them off the scent. I used to sleep in my marquee, there was nowhere else to sleep in fact, and I knew full well that I could not keep awake all the night long, and that once asleep it would be easy for one of them to creep under the canvas and brain me with a stake hammer. True, Cliff and I might have taken it in turns to keep awake and on guard, one watching while the other slept; but even this, I reflected, would only be postponing the evil day, or rather night. I knew too well the fierce, vindictive nature of the gypsies, to imagine for one moment that Brown and his tribe were going to forgo their revenge altogether.

39 No! I had another plan worked out in my mind, and soon after it was dark I proceeded to put it into execution, with the help of Mr. Wayman in whom I had confided.

He had slipped off to the station at my request, and had ascertained that a fast train left for London at 10.20 p.m. The fair ground closed at 11 p.m. Shortly before ten o’clock struck a man with a barrow, whom I had engaged beforehand, took his position, silently and without being observed, in a lane at the back of my tent.

Then I started the usual patter on the lorry outside in order to collect an audience. I could see that the gypsies were watching me. Possibly they had some suspicion of my intentions. But anyhow I outwitted them.

We got the crowd inside all right, but these people did not get their money back, nor did they see the show; for, instead of giving it, Cliff and I made some excuse to the audience for a brief delay, as we put it, and quietly slipped away out under the tent at the back, bearing with us my box, which I had already packed with our joint personal belongings. To hoist it on to the barrow was the work of a moment. Then we trundled it off to the station. We had, of course, to leave the marquee behind us, but as Mr. Wayman had promised me to look after it, and sell it for me as soon as he got a fair offer for it, this did not trouble me much.

As luck would have it, the train was on time. And as it steamed out of the station, bearing our two selves with it, I was just in time to wave my hand derisively at Brown and a lot of the other gypsies, who, having found out too late the trick I had served them, came charging pell-mell up the40 lane, cursing and shouting, with the object of trying to cut off our retreat.

So ended my first, last, and only experience as a fair-ground showman. I never went back to the business again; nor, if the truth be told, had I ever the least desire to do so.

Back in London—At the Westminster Aquarium—“The Pro.’s Casual Ward”—Zæo’s Maze—“Oriental beauties from the Far East-End of London”—“Fake” side-shows—A “fasting lady’s” prodigious appetite—A lively subject for a coffin—I sell conjuring tricks to visitors—“Uncle” Ritchie—An audience of one—Annie Luker, the champion lady high diver—I find myself barred from the Aquarium—The mysterious voice in the maze—Mr. Ritchie investigates—And Mr. Wieland scores—Penny-gaffing in London—Working the shops—Sham hypnotism—How to eat coal and candles—And drink paraffin oil—The box trick again—Venice in Newcastle—I offer a £1000 prize—The trick that failed—My first engagement in a regular “hall”—My absent-minded partner.

Returning to London after my exciting experiences at Cheriton Fair Ground, I got into rather low water financially, and was glad to accept an engagement at thirty shillings a week at the Royal Aquarium, Westminster.

This famous place of amusement used to be known irreverently in the profession as the “Pro.’s Casual Ward,” on account of the very meagre salaries ruling there. At the time I went there it was the custom of the management to pay in cash those artistes who were in receipt of anything under £2 a week. Those drawing over that amount were paid by cheque, which they had to cross the road to the bank to cash. Very few crossed the road.

My engagement, however, was not with the Aquarium people direct, but with Mr. Harry42 Wieland, the husband of Zæo, a once famous gymnast. She was the lady who used to be shot out of a catapult, and perform other sensational feats in mid-air, and concerning whose performance, or rather, to be strictly accurate, the poster advertising it, which was the first poster to appear on the hoardings of a lady in tights, so tremendous a controversy raged in the public Press and elsewhere during the spring and summer of 1890.

At the time I went to the Aquarium, however, Zæo had ceased to perform as a gymnast, and was engaged in running a profitable side-show known as “Zæo’s Maze,” and which consisted mainly of a lot of mirrors arranged at different angles. There was also run in conjunction with the maze what we called a Turkish Harem, the forerunner of the similar type of exhibition afterwards made popular by the proprietors of “Constantinople in London” at Olympia.

My job was to act as doorman and attendant at this exhibition, and by my patter, etc., to induce the public to enter. “Pass in, ladies and gentlemen!” I would cry. “Pass in and see the wondrous hall of mirrors, and the bevy of dark-eyed Oriental beauties from the Far, Far East-End of London.”

This sort of thing served to put the crowd in a good humour, and in they would troop. The maze was a sufficiently puzzling place to be in, owing to the arrangement of the mirrors, fifty-two in number. But by swinging a certain double one round I was able, when I deemed it expedient to do so, to close the exit altogether, so that it was impossible for anybody inside to get out until I chose to let them. Many a sixpence and shilling used I to receive for showing bewildered wanderers43 round and round, how to escape from the trap I myself had set for them.

Also, visitors were not permitted to take sticks or umbrellas inside the maze, for fear they might poke the mirrors. I took charge of these for them, and the fees I received from this source still further swelled my income. It needed some swelling, I may add, to transform it into a living wage, for I only got thirty shillings a week from Mr. Wieland, and in return for this sum, in addition to all my other work, I had to clean the mirrors, so it will be readily apparent that my job was no sinecure.

Most of the Aquarium side-shows at this time were more or less of the “fake” variety. I remember, for instance, a “fasting lady” who came there. She was of quite Amazonian proportions when she first put in an appearance, but when she left she was as thin as a lath. Afterwards, however, I helped to clear out the room she had occupied during her forty days’—I think it was—“fast.”

Then the mystery, such as it was, was solved. We found sufficient horsehair padding to stuff a good-sized sofa, and then leave enough over for a couple of armchairs. There were also a lot of thin pieces of old iron, weighing in the aggregate pretty nearly half a hundredweight, and these she had evidently used for the purpose of concealing about her person under her clothes, when she was weighed prior to beginning her “fast.” Furthermore, in a certain dark corner was a huge pile of empty tins, that had once contained “bully” beef, salmon, sardines, chicken, vegetables of almost all sorts, baked beans, and various other toothsome comestibles. I came to the conclusion there and then that I would not have44 minded “fasting” for forty days on the same diet as did that lady.