FALCON BOOKS

The Mercer Boys at Woodcrest

BY CAPWELL WYCKOFF

The mystery of Clanhammer Hall, at Woodcrest Military Academy, interested Don and Jim Mercer and their friend Terry Mackson from the moment of their arrival at Woodcrest. But their curiosity about the old, empty building faded into the back of their minds as they became involved in the mysterious disappearance of their headmaster, Colonel Morrell, whom they had never seen. With initiative and ingenuity the Mercer boys, aided by Cadet Vench, did a little detective work and uncovered a fantastic story of crime. An exciting story of adventure for modern boys.

Other titles in The Mercer Boys Series:

THE MERCER BOYS’ CRUISE IN THE LASSIE

THE MERCER BOYS AT WOODCREST

THE MERCER BOYS ON A TREASURE HUNT

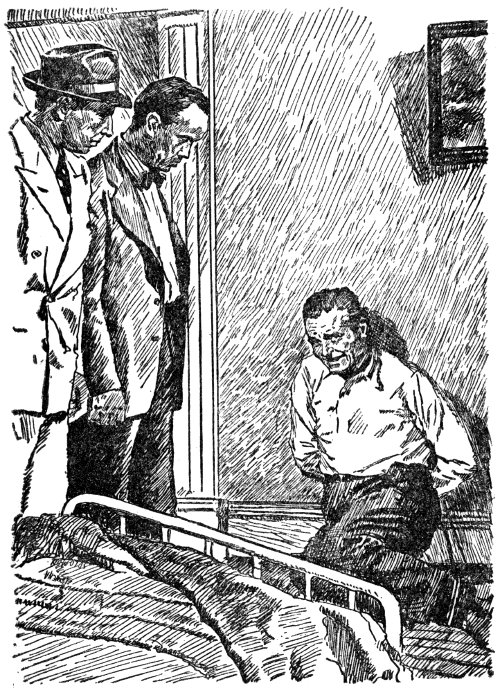

Dennings made Colonel Morrell a prisoner.

The Mercer Boys

AT WOODCREST

by CAPWELL WYCKOFF

THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

CLEVELAND AND NEW YORK

Falcon Books

are published by THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

2231 West 110th Street · Cleveland 2 · Ohio

W 3

COPYRIGHT 1948, BY THE WORLD PUBLISHING COMPANY

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

CONTENTS

- 1. Terry Makes a Mistake 7

- 2. Life at Woodcrest 17

- 3. Disturbing News 26

- 4. The Sunlight Message 34

- 5. The Man with the Key 42

- 6. Rapid Developments 54

- 7. Jim Makes an Enemy 66

- 8. The Fall Offensive 75

- 9. Under Fire 83

- 10. Rebellion 90

- 11. Vench Breaks Silence 99

- 12. The Paper Chase 108

- 13. Vench Is Astonished 118

- 14. The Postscript 126

- 15. The Journey in the Night 134

- 16. Vench Learns Something 143

- 17. In Clanhammer Hall 152

- 18. Don Meets the Colonel 161

- 19. Vench Is Mysterious 171

- 20. The Major Makes a Move 182

- 21. The Surprise Attack 191

- 22. The Man on the Ice 199

- 23. The End of the Mystery 205

1. Terry Makes a Mistake

“Pardon me,” said the red-headed boy with a grin, “but what is that old jalopy over there?”

The tall young man on the station platform turned and looked with a slight frown at the battered station wagon across the street. He was dressed in a gray uniform and wore a tall military hat. The letters W. M. I. in gold showed plainly on the hat. It meant Woodcrest Military Institute, and Lieutenant Sommers was an important part of that institution.

Two boys who had just stepped from a train at Portville station grinned and nudged each other. They were nice-looking young boys, with sandy hair, freckles, and lean faces browned by exposure to the wind and sun. Don Mercer whispered to his brother:

“Terry’s at it again. He’s forever fooling around and playing jokes on someone.”

Jim Mercer laughed. “Looks like he’s trying to get a rise out of that cadet officer. Golly, Don, is it possible we’ll be wearing uniforms like that soon!”

Lieutenant Sommers turned to look coldly at the genial-looking boy with the mop of red hair. “That,” said he with precision, “is the school station wagon.”

“I see,” murmured Terry. “And those things in the front are headlights, aren’t they?”

“That’s what I’ve always called them,” retorted the Lieutenant, growing still colder.

“Thanks. Is the school far away? I mean, could I walk it?” Terry pressed.

“Not very well. Why should you want to walk it?”

“That station wagon looks like it’s ready to fall apart and I don’t care for the wild tilt of that chassis. Look at the way it leans to one side! I was just thinking——”

“Don’t,” cut in the lieutenant, a faint spot of red showing in his cheek. “Judging by appearances, thinking would make a wreck of you physically and mentally!” He turned to the six or seven boys, all in civilian clothes, who had listened with ill-concealed delight to the conversation. “All those who are bound for Woodcrest please follow me.” Turning on his heel he walked toward the station wagon.

Terry chuckled and started off. But at that moment two pairs of strong hands clutched him.

“Hold on there, Chucklehead!” commanded Don Mercer.

“Where are you off to in such a rush, kid?” called Jim.

The three boys shook hands heartily. They were the best of friends and had spent the previous summer on a cruise down the coast of Maine. During that time they helped capture a gang of marine bandits who had been pilfering the coast for some time. Don and Jim were sons of a wealthy lumberman of Bridgewater, Maine, and Terry, who had only a mother and sister, lived in a town near them. They had been school friends and Terry had won a scholarship to Woodcrest Military Institute during the previous spring. Both Jim and Don had no future plans, and wishing to be with their cheerful comrade, whose bobbing red head had earned him the name of Chucklehead, they had enrolled in the same school. Now, after an exciting summer, details of which were related in the first volume of this series, The Mercer Boys’ Cruise in the Lassie, they had met on the platform of the Portville station in New York State, ready to begin school again.

“It’s swell to see you guys,” greeted Terry. “Were you on the train I came in on?”

“No, we just arrived on the later one,” offered Jim. “What were you up to with that lieutenant?”

“Oh, nothing,” confessed Terry. “He was so dignified looking that I couldn’t help leading him on a little, that’s all. Hey, let’s go. If we don’t get a move on he’ll court-martial us as soon as we get to the school. He had me with that last crack, didn’t he?”

The boys picked up their suitcases and climbed into the station wagon, the three friends sitting in the first seat back of the driver. The driver was a little man with scant gray hair who took no particular notice of them, but drooped unemotionally in the forward seat. After seeing that all of the new members were safely in, the correct-looking lieutenant climbed up beside the driver.

“Let’s go, Ashley,” he directed.

The driver stepped on the starter but the car stalled before lurching down the road toward the distant hills and woods. The three friends had plenty to talk about, but the rest of the boys were silent. Most of them were making their first trip away from home and all were strangers, so they sat in silence and watched the scenery. The boys on the first seat gradually grew quiet too and enjoyed the magnificent view unfolded in the sweeping hills and rolling woods from which the academy had derived its name.

The seats of the station wagon were plain board planks and the legs of the boys dangled in plain view beneath them. Right in front of Terry were the gray-clad legs of the lieutenant, and the boy’s eyes wandered more than once to them. A thoughtful look came into his gray eyes and he began to feel in the lapel of his coat. From it he drew two pins and then leaned over to Don.

“Got a piece of string with you?” he whispered.

Don shook his head and Terry repeated his question to Jim. The younger Mercer unwound one which had been twisted around the handle of his suitcase and handed it to Terry.

“What do you want with it?” he asked.

Terry winked but did not reply. He looked once searchingly at the back of the lieutenant and then bent the pins, much like primitive fish hooks. Then, taking the string, he tied it from one pin to the other. The boys watched him intently.

The two pins having been joined together by an eighth-inch length of string, the red-headed boy leaned down and passed one hook carefully through the sharply creased trousers of the cadet in front of him. It dangled there, and Terry sat back to look for danger. Nothing happened, and he once more bent down, this time to lift the cuff of the trousers and slip the second pin into it. The operation was accomplished without accident, and the lieutenant had one leg of his trousers drawn up for a space of four or five inches.

The boys in the station wagon grinned broadly when they saw what Terry was driving at, but the red-headed boy looked calmly away to the hills. Totally unconscious of the fact that he was the object of their mirth the important young officer stared straight ahead of him. Out of the side of his mouth Terry spoke to Don.

“It will be tough, if one of those pins sticks his leg.”

Nothing of the sort happened. The attention of the boys was now drawn to the view that suddenly unfolded as they topped a final rise of ground. Before them, at the top of the ridge, against the dark background of the surrounding woods, was Woodcrest Military Academy itself, with its ivy-covered central hall, its two dormitories and its gymnasium and boathouse. Back of the school a single large sheet of beautiful silver water showed, the Lake Blair so often spoken of in the catalogue which the boys had. On all sides trees and hills spread out until they were lost in the distance.

“That’s beautiful,” breathed Jim, enthusiastically.

“I’ll say it is,” agreed Don, and Terry nodded. Don went on, “That center hall must be Locke Hall, and the one to the right of it either Inslee or Clinton. We got our rooms in Locke, on the second floor. Where will you be located, Terry?”

“For the present I’m in Inslee,” returned Terry. “I didn’t know where you fellows would go, so I didn’t say anything. After a day or so I’ll try to see if I can’t be transferred.”

Nothing more was said until they drove up to the lawn before Locke Hall and then the station wagon came to a stop. The lieutenant jumped out and faced the new boys.

“Step down out of there!” he commanded. “On the double, now!” They obeyed and faced him, casting furtive glances at his hiked-up trouser leg. The lieutenant looked them over slowly and then once more addressed them. “You are now to become students at this institution, and I would like to say that from now on you’ll have to give up some of the soft things that you have been used to. Among them, some of your pet foolishness.” Here he looked straight at Terry, who returned the look with bland interest. “You will acquire a measure of dignity and poise that will make new men out of you. I am representative of the efficiency and discipline of this school, and I hope we may expect as much from each one of you. What are you laughing at?”

The question was addressed to the entire number of boys, so no one took the responsibility of answering. The lieutenant turned away.

“Report at Locke Hall and register,” he snapped, and strode off, the one leg ridiculous in the extreme. The newcomers watched him with interest. A brother lieutenant came out of Locke Hall and they saluted, and once past him the other turned to look at the upraised trouser. Then he grinned until, seeing the new boys looking, he composed his face and passed them. Still unheeding the lieutenant went on until he met an instructor, also in uniform, whom he saluted and would have passed, except that the instructor stopped him.

“What has happened to your trousers, Sommers?” the boys heard the instructor ask.

Sommers looked down at his right leg and then stooped and savagely tore the pins and string out. With a savage glance he looked back at the interested group of boys and his eyes blazed. Hastily saluting his superior he hurried on, and the teacher, with a faint smile on his face, resumed his walk.

“Well,” sighed Terry. “That’s over. Worked better than I thought it would.”

“You’re lucky,” laughed Don, as they made their way to the office. “I wouldn’t be surprised if he took it out on you later on.”

Don and Jim registered first and then went off to their rooms, which were on the floor above. Terry registered and awaited his orders.

“Inslee Hall,” nodded the clerk, with an engaging smile. “Room 17, second floor.” He pointed out of the door. “Go to your left along the path and you can’t miss it. Supper at six o’clock. Next!”

Terry picked up his suitcase and went out of the screen door and out onto the well-kept driveway. A wide expanse of lawn spread out before him and off in the distance he saw the hall which was to be his dormitory. Just beyond it he could see the roof of another building that they had not been able to see from the main road. Terry was not sure which of them was Inslee Hall, especially as the path ran, after a split, to both of them.

“Must be the one in the rear,” he thought, and started toward it. After skirting a clump of high bushes and a fringe of fine trees he saw the hall before him, an old wooden building with three chimneys and broad windows. The path which ran to it was not as well kept and Terry wondered at that. Drawing nearer to the place he was amazed at the neglected appearance of the place. Close to the building weeds grew in careless profusion, and the steps were covered with brushwood and dirt. Terry was frankly puzzled.

“I’ll want to get a transfer from this place in a hurry,” he murmured. “Funny, there doesn’t seem to be anyone around.”

He stepped up on the stone steps and looked in the narrow windows that flanked the main door. At once he saw his mistake.

“This isn’t the place,” he decided. “This place is deserted. Wonder what kind of a place it is?”

He pressed his face close to the glass and looked in. The main hall of the old building was before him, and a desk, two chairs and a bookcase stood there. Thick layers of dust covered everything. In the back of the hall a curving flight of stairs ran up to the second floor.

“This place hasn’t been used for years,” thought Terry, about to turn away. Just at that moment a white door at the far end of the downstairs hall opened slowly and an old man appeared. In his hand he had a tin tray, upon which were two plates of meat and potatoes. Steam rose from the tray, and as the old man shuffled slowly forward Terry noticed that he held a lighted candle in his hand.

“Somebody does live in the place,” he thought. “Wonder they wouldn’t clean up a bit.”

At that moment the old man looked up and saw him. With an expression of terror he blew out his candle, at the same time stepping into a doorway and out of sight. Terry stared in amazement.

“Well, what do you know about that!” he gasped. “Poor old guy must have thought I was a ghost or something. Well, I’m in the wrong place, I can see that.” He stepped back and looked up at the front of the building. On a board sign, its letters almost rubbed out by the elements, was a name painted in white. It said “Clanhammer Hall.”

“Clanhammer Hall,” mused Terry, turning away. “According to my catalogue, that was the original building of Woodcrest School. Well, it isn’t much of a place now, I can tell you. I wonder why that old man ducked out of sight when he saw me?”

2. Life at Woodcrest

He had no further trouble finding Inslee Hall and once there room 17 was easy to find. Two newcomers were already there, young fellows by the name of Harlow and Murray, and Terry got acquainted with them before he left to go to Locke Hall. He stowed his belongings away and then went over to the main hall to look up his friends. He found them in room 21, a large pleasant room in the front of the main building. They were arranging things around the room when he entered and he sat on the extra bed and watched them.

“Just saw something awfully queer,” he informed them, when they had finished.

In answer to their inquiries he told them of his experience at Clanhammer Hall. Both of the boys were interested but treated the matter lightly.

“They must use the place for something special,” Don suggested.

“That’s all well and good, but that doesn’t explain why that old guy ducked into the doorway the way he did. No, I feel that there is something more in it than that. However, perhaps we had better keep it to ourselves, at least until we are a little better acquainted around here.”

The Mercer brothers agreed that this plan was best. Just at that moment a knock sounded on the door. Jim called, “Come in.”

The door opened to admit a fine-looking fellow in full uniform with stripes of a cadet captain. He had a nice smile and the newcomers felt a friendliness toward him at once.

“How do you do, boys?” greeted the cadet. “I am Captain Rhodes of the senior class, and I’ve come to look in on you. One of the traditions of the seniors here is to make fourth class men feel at home, and so I’ve come to introduce myself. I’m not intruding, I hope?”

“Not at all, Captain Rhodes,” replied Don. “Very glad to have you, and we appreciate your tradition. I am Don Mercer, and this is my brother Jim. This is Terry Mackson.”

“Glad to know you all,” nodded the captain, shaking hands with them. “Is this the fellow who pinned up Sommers’ trousers?”

“My fame has run before me!” murmured Terry, smiling.

“Yes, Terry’s the culprit,” laughed Don. “A bad boy all around, always into something, but he means well, Mr. Rhodes.”

“I don’t doubt it,” returned the cadet. “You may drop the mister, Mercer. Speaking of Terry’s well-meaning attempt on Mr. Sommers, I can safely say that no harm was done except a temporary bruising of the lieutenant’s feelings. He is our prize dignitary, but underneath a very nice fellow. Nothing mean about him, but simply filled with a spirit of military efficiency. Well, how do you think you are going to like Woodcrest?”

The boys assured him that they thought they would like it very much. Rhodes went on to tell them a few things about the school and to praise their colonel.

“Colonel Morrell is a fine man,” he said. “We all look up to our headmaster. He isn’t here yet, but will be in a day or so. At present we are in the charge of his assistant, Major Tireson. The colonel is a little short, fat fellow, full of good humor and every inch a man. Have you seen the grounds yet?”

“We’ve been busy unpacking,” replied Jim. “But Terry saw some of them. He’s rooming over at Inslee.”

“I didn’t see much,” put in Terry. “I did see that old dormitory in the back, Clanhammer Hall. Isn’t the place used any more?”

“No, and it hasn’t been for a number of years. It was the original hall of the school, in fact, the only building when the school was first started, but it was condemned some years ago as a fire trap and hasn’t been used since. Colonel Morrell is going to have it cleaned out this year and opened up as a sort of memorial of the original school. As far as I know no one has been in it for years.”

“No one in it now?” asked Terry, quickly.

“Oh, no. No one ever goes in it. I don’t know who has the key for it.” A bell sounded loudly in the hall and the senior got up. “That is warning bell for supper,” he explained. “You have ten minutes to wash and report at the dining hall, downstairs. I’ll see you after supper, perhaps.”

“You notice that Rhodes said no one had been in that hall for years,” reminded Terry a few minutes later, as they walked down the stairs.

“Yes,” said Don. “There seems to be some sort of a mystery there.”

The boys were assigned places at the table and enjoyed their first meal at the academy. After the meal the boys were free to roam, and they walked all over the place, visiting the gymnasium, the boathouse, and the other dormitories. They walked along the margin of the beautiful lake and on the way back they passed Clanhammer Hall, dimly seen in the dusk.

“It certainly looks deserted now,” commented Jim.

“Yes,” said Terry. “It did when I first saw it. Suppose we ought to look in the windows?”

“I wouldn’t,” declared Don. “We’re new here, and have no right to snoop. Perhaps we will later on.”

Before retiring they sat around their room and Rhodes paid them a brief visit, bringing with him two other senior class men, Merton and Chipps. Merton was a tall blond fellow; Chipps was small and energetic. They talked of sports and Rhodes asked them if they planned to come out for football.

“I hardy think so,” answered Don. “During this first year we want to pay particular attention to our studies, though we don’t expect to neglect athletics. But we have all been on track teams at home, and we expect to go out for that here.”

“That’s a good idea,” approved Chipps. “Most of our veterans of last year have returned this year and the best you fellows could probably do would be to get places on the scrub team. I think you’d do well to put in a year training on the track team or the crew, and take up football later on.”

A warning bell sent the seniors back to their rooms and Terry departed for Inslee. At ten o’clock the lights went out and the boys were in bed.

“Well, Don,” commented Jim, as he lay in bed. “Tomorrow we’ll get into harness.”

“Yes,” his brother returned. “I guess we’d better get in a good night’s sleep. Bet you a dollar that we’ll be ready for bed by this time tomorrow night.”

“I won’t take you up,” Jim retorted. “I have a sneaking idea you’ll win. ’Night.”

At seven o’clock in the morning a bugle pealed out and the Mercer brothers woke to find the sunlight streaming in their windows. They jumped out of bed, washed quickly and then went to chapel, meeting Terry in the hall. When all of the cadets had been seated a thin man in the uniform of a major came out on the platform and opened the session with a prayer. After it was over he addressed them briefly, in a rather sharp, precise voice.

“The second, senior and third classes will resume work as usual,” he announced. “The new members, those of the fourth class, will report for lesson instructions, medical examination, uniform measurements, and drill after dinner. Fourth class lessons will begin officially tomorrow morning at eight-fifteen. I may say briefly that Colonel Morrell will arrive either tomorrow or the day following, and until he does, you will refer all questions to me, Major Tireson. That will be all for this morning, boys. Report to the dining hall for breakfast.”

After the morning meal the new boys found plenty to keep them busy. They reported at five different classes and obtained books, went under a rigid medical examination, and were then measured for their uniforms. Before dinnertime the three friends walked out on the lawn, resplendent in neat gray uniforms and black hats.

“By thunder mighty, as old Captain Blow used to say,” commented Terry, looking proudly at his sleeves. “I feel like the last word in dressed-upness. Can’t one of you guys get a full length mirror and hold it up for me to see myself?”

“You saw yourself in the glass inside,” laughed Jim.

“That wasn’t enough,” said Terry. “I want to look at me forever!”

After the noon meal they assembled on the parade ground and were lined up in squads of eight. Under first, second and third class lieutenants they were drilled.

“Oh, boy, look who we got!” whispered Terry, who was flanked on either side by his two friends.

Lieutenant Sommers was their drill instructor and he was a thorough one. But when they were finished Terry could not find any fault with the man. He was not a bully nor even revengeful; he recognized Terry at once, but he did not press him any more than the others. He was every inch a young soldier and did his work with snap and precision, leaving completely personal feeling out of it. Terry agreed with Rhodes’ statement that Sommers was a good fellow beneath his dignity.

After drill the boys were at liberty to do whatever they chose until five-thirty and, with others whose acquaintance they had made by now, they elected to go swimming in Lake Blair while it was yet warm enough to do so. Terry went off to see about changing his dormitory.

“See if you can’t get somewhere in Locke,” Jim said, just before he left. “We have an extra bed in our room, but I think someone is coming to claim it in a day or so.”

Terry came back and joined them in the boathouse, where the boys changed into their trunks. Don and Jim, dripping wet, came out of the water as he was changing into his trunks.

“What luck?” yelled Don.

“I got a place in Locke,” said Terry, carelessly, pulling on his trunks.

“Whereabouts?” asked Jim.

“Room 21,” answered Terry, innocently.

“Why, that’s our room!” exclaimed Don.

“Sure it is! I found out that the boy who was to room with you isn’t going to turn up, so I got it. I’ll bring my stuff over later on.”

The boys were overjoyed at the prospect of being together and after an invigorating swim in Lake Blair they helped Terry fix up his corner of the dormitory room. After supper they had an hour to themselves and then they began to study. Just before warning and taps they were visited by a few friends.

“Well Jim, how do you feel about what I said last night?” asked Don, as he got into bed.

Jim yawned with enthusiasm. “Just as I told you, you win, hands down. I feel like a good sleep. That business of holding your little finger against the seam of your trouser and making your back as straight as a board is somewhat strenuous. But it certainly will straighten us up some, though I never could lay any claim to being the least bit round-shouldered. But I like the life here first rate. Let me have your pillow.”

Before Don could reply Jim took his pillow and hurled it at Terry who, clad in a pair of blue pajamas, was staring out into the blackness of the night. The red-headed boy turned and looked grimly at Jim. Then he stooped down and scooped up the pillow.

“Cut it out, you two,” ordered Don. “I hear that an Officer of the Day looks in on us every night at this time to see if everything is okay before the lights go out. I don’t want to get called down because I haven’t a pillow on my bed. Let’s have it, Terry.”

The pillow was delivered through the air, with considerable force. Jim grumbled.

“I just threw it at him to wake him up. What were you dreaming about then?”

“I was just wondering about that old hall, and what is going on in there,” Terry replied, getting into bed.

“Oh, to heck with that old hall!” snorted Jim. “Forget it!”

A third classman, Officer of the Day, looked in the door and around the room. “Okay, gentlemen,” he said quietly and withdrew. The lights went out suddenly. For a minute all was silent. Then, from Terry’s bed:

“Forget nothing! There is something wrong there, and I’d like to find out what it is!”

3. Disturbing News

A week passed and the boys settled without difficulty into the routine life of Woodcrest Military Institute. They began to enjoy their classes and the drill, which each day seemed to become less burdensome and rigorous. In the afternoons they reported for track work. The evening, while mostly devoted to study, gave them plenty of time for visiting friends and having some good wholesome fun, and at the week’s ending they found that they thoroughly enjoyed their life at the institute.

Colonel Morrell had not as yet appeared at the academy and the boys from Maine were anxious to see him. No one seemed to know precisely what the trouble was, and even Major Tireson seemed to have something on his mind. Not that the routine was at all broken by the colonel’s absence. Things went along as smoothly as they did when the headmaster was present, and aside from a few statements of wonder, expressed by the cadets, nothing was thought about the matter until one evening during their second week at school.

Don and Jim had gone to their room and had been studying for about fifteen minutes when Terry burst into the room.

“What’s the big rush?” asked Jim, looking up from his book with a slight frown.

“You guys heard the news?” Terry blurted out. “Of course you haven’t, or you wouldn’t be sitting there calmly studying.”

“We haven’t heard anything but your mad rush in the door,” said Don, laying down his book. “Suppose you tell us what’s up?”

“What do you think? Our colonel has disappeared!”

“What?” cried the Mercer boys, in a breath.

Terry bounced onto the bed. “Yes, sir. The news leaked out tonight. I didn’t get all of the details, but he was on his way down here and suddenly disappeared. Just vanished into thin air, if Colonel Morrell could do that. I’ve heard he is pretty husky, so maybe he didn’t just float away, but he’s gone!”

“Where did you hear this?” inquired Don, study forgotten.

“Down at the office. I went down there to get some supplies and a detective was talking to Major Tireson. The detective talked in a loud voice, and three or four of us heard every word he said. The colonel’s brother hired detectives and they are searching for him. Major Tireson was saying that he had received a telegram from Colonel Morrell just before he left for the school here, and that was all that he knew. From the expression on the major’s face I could see that he didn’t want us to know it and would like to have kept it quiet, but it’s out now.”

Before the boys could reply to this astonishing piece of news a knock sounded on the door and a moment later Rhodes, Merton and Chipps came in. The three upper classmen had become quite friendly with the fourth class men during their short period of time at the school and were in the habit of dropping in evenings to talk over school topics with them. It was evident that the same subject was on their minds.

“Well,” remarked Rhodes after one look at their faces. “I see you fellows have heard the news, too.”

Jim nodded. “Yes, we have, and we’re terribly sorry to hear it, too. Terry was down in the office and heard it there.”

“You’d be even sorrier if you knew the colonel as we do,” put in Cadet Merton, seating himself on Jim’s bed. “Charlie, here, has the latest. Tell them about it, Rhodes.”

“The major called in the cadet captains,” began Rhodes. “And he told us the news. I don’t think he would have allowed the cadet body to know what had happened if some of the boys hadn’t heard it in the office. He told us to keep things running in our respective classes much the same as usual, and he was confident that everything would turn out all right in the end. The details are these: Colonel Morrell started for the school here last Wednesday, on the afternoon train. He lives up in Rockwood, New York, and he should have arrived at Portville at about seven o’clock. He had previously wired the major that he would be here at that time, so he was expected. We fellows didn’t know it, and of course it wasn’t until the last couple of days that we began to notice that he wasn’t here and to wonder why. The major must have been looking for him all the while, but he kept it to himself, although he told us that he was very much worried. He felt that if the cadets didn’t know anything about it, it would be better.

“As I said, the colonel started for here on the afternoon train, and he was supposed to come straight through. But for some unexpected reason he did not. Instead, he got off at a way station about sixteen miles from here, a little village called Spotville Point, and from that time to the present he hasn’t been seen! At least, not by anyone who ever told of it. The conductor on the train remembers that he got off there and that he had either a letter or a telegram in his hand, and that was the last ever heard of him. His brother wrote to him once or twice and then learned from Major Tireson that he hadn’t arrived here, so he got the police and detectives into action at once, so far without any result. That’s the whole story, and it’s a very queer one.”

“A queer one, and a distressing one,” murmured Chipps. “I hope nothing happened to our colonel.”

“We’re all with you on that,” returned Rhodes.

“He had a letter or a telegram with him, you say?” inquired Don.

“That is what the conductor said. I suppose the colonel was pretty well known, for he travels the railroad a couple of times a year, and has for the last number of years. But his brother declares that he didn’t have any letter or telegram with him when he left the house, and they have learned that he didn’t get any at the station or postoffice on his way down. Apparently there was nothing on his mind when he left his brother, either, so it certainly does make a mysterious case.”

“It surely does,” agreed Jim. “And he stopped off at Spotville Point?”

“Yes, and that’s a mystery in itself. I’ve been to Spotville Point myself. In fact, we’ve all passed through it on our way to summer encampment. Nothing to it except a dozen houses, most of them mere shacks, with one or two good-sized estates and the one station. Not even a postoffice.”

“Then he couldn’t have received a letter there,” said Terry.

“No. Besides, he had it when he got off the train. He simply must have had some reasonable excuse for getting off at a place like that. After he did get off no one saw which way he went. The man in the little station doesn’t even remember having seen anyone on that afternoon.”

Don glanced at the calendar. “That was last Wednesday, you say. That was October third, wasn’t it? Well, we’ve never seen Colonel Morrell, but from what we hear, he must be a very fine man, and we sincerely hope they find him quickly.”

“My only regret,” drawled Chipps, “is that they don’t turn the whole cadet corps loose to hunt him up! I’ll venture to say that we’d find him if we had to scour the whole country to do it!”

“If wanting to find him would accomplish anything, we’d find him in short order,” said Merton.

“If he should not turn up we’d have Major Tireson for headmaster, I suppose,” ventured Jim.

Rhodes nodded, but not cheerfully. “Yes, and I’m sure the fellows wouldn’t like that. Not that Major Tireson is a tyrant or anything like it, but he simply isn’t in the same class with the colonel. You can’t get close to him, if you see what I mean. Why, any guy in the corps could walk up to the colonel and talk to him without fear of being frowned down on, but the major is pretty much aloof. I personally like a man you can feel respect for and yet know him in a friendly way, but you can’t do that with the major. So here’s hoping our beloved colonel turns up safely.”

“We won’t think of any other possibility,” maintained Merton, stoutly.

“If we don’t think of getting in some studying pretty soon,” reminded Chipps, who stood at the head of all of his classes, “we’ll all do growl duty tomorrow.”

The new boys knew that “growl duty” meant remaining in after hours to brush up on lessons. The three upper classmen departed for their rooms, leaving the Mercers and Terry alone.

On the following morning the school buzzed with subdued excitement and the cadets lost no time in assembling in the chapel. When Major Tireson appeared on the platform he looked rather tired and worried and he was a little sharp in his tone as he led the morning exercises. When they were over he addressed the eager boys.

“You have all heard the story of what happened to Colonel Morrell,” he began. “I am sorry to say that it is true, but hasten to assure you that there need be no cause for excitement or worry over it. There is always some good reason for even the most mysterious things, and I’m sure that some day we will know just why Colonel Morrell went away as he did. In conclusion I want to say that I feel the colonel would want things to go on as usual, so see to it that all matter of routine is carried out with the same efficiency as when the colonel is here. Until he is here I will be in complete charge. Remember that. Assembly is dismissed.”

“He didn’t have to lay so much stress on efficiency,” grumbled Lieutenant Sommers, as they made their way to the breakfast hall. “We have a spirit of the corps in this school, if he doesn’t know it!”

Classes lagged that day, for the boys all had their minds on the missing colonel and his possible fate. Drill was carried through with its accustomed snap, justifying the statement of Lieutenant Sommers. In the evening the boys talked a good deal and several frequented the vicinity of the office, to be on hand in case anything new turned up. But nothing did, and when taps sounded the cadets went reluctantly to bed.

4. The Sunlight Message

The week drifted on with no word of the colonel and the cadets ceased to talk about his disappearance. Each one of them thought constantly of the missing man but the subject had been talked out, especially since there were no additional details. On Saturday the cadets always enjoyed a half holiday, and on that day Don, Jim, Rhodes and Terry went rowing on Lake Blair.

Inspection took up most of Saturday morning, but there was no drill and no athletic training, although all of the football games and baseball games were played on Saturday afternoons. In between seasons the cadets spent Saturday afternoons amusing themselves as they saw fit, some of them going to town, or swimming when it was warm enough to swim, or finding other amusements. The four friends had been to the village and had bought some things, and now, upon their return to the school, Don proposed that they go rowing.

“Can’t keep you off the water, I see,” Terry grinned.

Don shrugged his shoulders. “I do love it, to tell you the truth. However, going rowing will be slightly different than sailing the Lassie, if that is what you are referring to.”

“That’s what,” nodded Terry. “I haven’t been on the water as much as you have, but I won’t be sorry to go out myself.”

They went down to the boathouse on the lake and dragged out a large flat-bottomed rowboat which the cadets used whenever they liked. After launching it Rhodes and Jim took the oars and the other two sat in the stern. The two at the oars sent the boat out from the shore.

“Where away?” inquired Rhodes, looking at the two in the stern.

“I don’t care,” returned Don, lazily. “You might as well row around the lake and back. We haven’t seen all of it yet.”

“Do you expect to sit back and see me do all the work?” demanded Jim.

“Hadn’t thought much about it!” grinned Don. “Aren’t you?”

“Like heck I am,” retorted Jim.

They rowed down the lake to the point where it narrowed into a mere creek and then started up the opposite side, across from the school. Lake Blair was a body of blue water about three miles long and a half mile wide, deep only in the center, and it made a fitting setting for the old school. Thick trees ran down to the shore, and now that autumn was at hand the leaves on the trees had turned a multitude of brilliant colors.

“This is certainly one swell place,” commented Terry enthusiastically.

“Yes,” nodded Rhodes. “I love it. I don’t think there is any place I’d rather be.”

“Then you’ll be sorry to graduate,” observed Don.

Rhodes smiled. “No, I won’t. I’ll let you fellows in on a little secret of mine. After I have graduated Colonel Morrell, provided everything is all right, is going to make me permanent drill commander. So I will stay here for some years to come.”

“That’s great,” said Jim, heartily. “I hope, for your sake, that the colonel turns up all right.”

“I hope he turns up all right for his own sake. You fellows like this lake? Well, so do I, but even as beautiful as it is now, there is a time when I like it better. I like it in the winter, when it is a sheet of ice, and we have the best skating in the world. At night we build big bonfires along the shore and have a heck of a good time. That’s when you will like it.”

When they had rowed to the other end of the lake, which was little more than a brook, the boys changed places and Don and Terry took the oars. They rowed back toward the boathouse, keeping over near the further shore, away from the school. On the bank directly opposite the boathouse a fine tree bent over the water, and the boat drifted under this. The boys pulled in the oars and sat there talking.

The sun was going down in the west and the back of Woodcrest was bathed in a reddish-yellow light. All three of the main halls and old Clanhammer shared the light of the declining sun, and a pretty picture was created. After they had admired it for a time and had talked of many things, Rhodes looked at his watch.

“It isn’t exactly what you would call late, but maybe we had better be getting back. We can take our time about it and maybe get in a little fun in the gymnasium before suppertime. Shall we go?”

“All right,” agreed Jim, picking up an oar.

But Don held up his hand. “Wait a minute, you guys. Don’t pull out from under these trees, yet.”

“Why not?” inquired Rhodes. “What’s up?”

“Look toward Clanhammer Hall,” returned Don, who had been looking in that direction. “Look at that upstairs window, over to the right.”

The boys looked in the direction indicated by their chum. For a second they did not see anything, then suddenly a flash of light came from the window which Don had mentioned. It disappeared immediately and a second came, which was steadier than the first, then other flashes followed.

“Wonder what that is?” asked Terry.

“Don’t ask me,” shrugged Rhodes. “I thought there was no one in that place.”

Don turned to Jim. “Doesn’t that look to you like the Morse code?” he asked.

Jim nodded. “I think it is. Let’s see if we can catch anything.”

The four boys in the boat sat silently and watched the flashes from the house across the water. They knew that the signals were being made with a mirror, into which the descending sun was pouring its last rays. Flash followed flash, some of them long and some of them short. To Rhodes and Terry they meant nothing, but to the Mercer brothers, who had once been very familiar with the telegraph code, it was plain that two words were being repeated. When the flashes had ceased they looked at each other, startled.

“What did you make out of it?” asked Don.

“Why—why, it seemed to me, if I was reading correctly,” stammered Jim, “that whoever it was was signalling the words ‘No progress.’ Is that what you got?”

“Yes,” his brother nodded. “That is just what I got. ‘No progress’ is right.”

“But what in the world can ‘no progress’ mean?” asked Terry.

“I don’t know,” answered Don. “But it means that something is going on in that old hall.”

“But there is no one in the place,” objected Rhodes.

“Tell Charlie what you saw the day you got here, Terry,” suggested Jim.

Terry told his story and Rhodes was very interested. “That certainly is queer,” he commented, when Terry had finished. “It has always been understood here that no one was in the place. What an old man with a plate of food and candle could be doing in there is more than I can see.”

“I wonder where that signal was going?” mused Don, who had been watching the building intently. “It must have been directed to some point in the woods directly back of us. The message was in reality going right over our heads. Is there any kind of a building in the woods near here, Charlie?”

“As I remember it, there is an old farmhouse just back of us in the woods,” said Rhodes, after a moment of thought. “I recall seeing it on one or two hikes we took. That signal might easily have been directed to the farmhouse, at least to the upper windows of it. That is the only building anywhere within a radius of five miles.”

“Then that was the place where the message was received,” declared Jim, with conviction. “Can’t we hike over there now and take a look at the place? Is it very far?”

Rhodes shook his head. “Not very far. We can get there in fifteen minutes, and we can land from the boat here without being seen, thanks to the overhanging trees. Want to go?”

The others agreed at once and the boat was pushed to shore, where they got out and tied it firmly. Then, under the leadership of the upper classman, they took their way through the thick trees that grew back of the lake front.

They walked on for fifteen minutes through the dusk of woods, until, coming to a slight rise in the ground, they came in sight of the farmhouse. It was an old clapboard house, but kept in order nevertheless. The doors were in place and the windows were unbroken. A few unpainted boards of lighter color showed some attempt at repairs had been made. Weeds grew about the back yard in profusion. Standing in the rough yard near the back door was an expensive looking car. The boys halted in the shelter of some large trees to consider, well out of sight of anyone in the house.

“Look at the upper back windows,” directed Rhodes. “They are above the level of the tree tops, and from them anyone could plainly catch a signal from Clanhammer Hall. What shall we do, now that we are here?”

“I don’t see that there is anything to do,” returned Don. “We can’t go up to the place, and we know that it isn’t deserted. Perhaps——”

Jim grabbed his arm. “Pipe down,” he whispered. “Someone is coming!”

The back door of the house opened and a man came out. He was tall and thin and was clothed in a dark suit, long light overcoat. He wore a hat pulled down over his eyes. He looked all around as he stepped out of the door and then closed it behind him with a resounding slam. Reaching into his pocket he took out a key and placed it in the lock, turning it and trying the knob. This done he walked to the car, started his engine and rolled out of the yard.

The boys waited until he was well out of sight and then discussed further plans. Jim was cautious about going to the house but was overruled.

“It will be all right to go up and look in the windows,” Terry argued. “The man locked the door, and that’s a sure sign that no one is in the place.”

They approached the house carefully and looked in the back windows. The place was almost bare of furniture, but they did see a table and two old chairs in the kitchen. The rest of the house, at least downstairs, was totally empty. When they had made a tour of the place they gave it up.

“I doubt if there is anything upstairs,” said Don. “I imagine this man, whoever he is, simply comes here to receive messages from the hall. Perhaps at night they send them by flashlight. It certainly is a puzzler.”

Rhodes looked at his watch. “Boys, we’ll have to get going. We’ve got just time to make it for supper. I suppose we won’t accomplish anything by standing here wondering, so we may as well beat it.”

They retraced their steps hastily and rowed across the lake, where they put the boat away and went inside to wash up for supper. After the evening meal the four of them spent some time talking things over. Just before leaving them the senior said:

“Well, we’ll keep this to ourselves. Whatever is going on may be all right, but I have my doubts. I think there is a mystery right here under our own noses, and let’s hope we can run it down. Suppose we all keep our eyes peeled and see what we can do.”

5. The Man with the Key

Although the four cadets took care to keep their eyes wide open they saw nothing in the succeeding days to help them solve the mystery which they had run across. At times they discussed the subject and made guesses, but these generally ended in nothing, and there were times when they half believed that they might be making a mountain out of a mole hill. No news had been received as to the whereabouts of their missing colonel, and life at Woodcrest drifted on in the same efficient manner.

The arrival of a new cadet gave them something else to think about. One rainy day when the cadets were loitering about the halls waiting for the dinner call, a young fellow in his late teens arrived at the front door of Locke Hall. He was very dark, exceedingly well dressed, and carried himself with a swaggering air. He carried a suitcase plastered with foreign labels, and a cigarette drooped carelessly from one corner of his mouth. Gaining the center of the main hall he looked carelessly around. The cadets were standing in groups laughing and talking, and finally he addressed a third-class man.

“Say, sonny,” called the newcomer. “Where do I find the sign-on-the-dotted-line room?”

Considering the fact that Bertram, the third class cadet, was at least a year older than the newcomer, the term “sonny” was something out of the way. Talk ceased instantly among the cadets and they turned to look. Mr. Bertram answered with easy courtesy.

“That is the door down there,” he said.

The new man nodded easily. “Thanks, kid. Information is appreciated, I assure you. Is the agony man inside?”

“I beg your pardon?” asked Bertram.

“Is the clerk or headmaster or whoever officiates in there?”

“I think you will find someone in there who will take care of you,” returned the upper classman.

“I hope so. Somebody had better. I usually get what I want, you know.”

Mr. Bertram didn’t know anything about it and he looked fixedly at the boy. Totally unabashed at the looks cast in his direction the newcomer walked into the office, where an instructor was sitting behind the information desk.

The instructor looked up as the boy placed his suitcase on the floor. “How do you do?” he said, smiling pleasantly at the visitor. “What can I do for you?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said the boy. “Not an awful lot, I guess. My name is Vench, Raoul Vench.” He paused and waited, but Captain Chalmers said nothing.

“My name is Vench,” repeated the newcomer.

“Yes, Mr. Vench. Well, what can I do to help you?”

“Do you mean to say that you didn’t know I was coming?” demanded the new student.

Chalmers shook his head, his glance keen. “I didn’t know it. Perhaps Major Tireson did. Are you going to register with us?”

“I certainly am,” answered the boy. “My father sent your headmaster a letter and told him that I was coming. I should have thought he would tell you, so you could be on the lookout for me. Yes, I’m going to be a member of your cadet corps and I’m here to sign up. Pass over the articles and a pen, already dipped in ink, if you don’t mind.”

Captain Chalmers looked steadily at the boy for an instant and then his gaze wandered to the groups of cadets outside of the door. Suddenly he bit his lips to keep back a smile, a rather grim one, and then reached in the drawer of the desk, to take out some sheets of paper and a pen. With intense seriousness he dipped the pen into the ink and then looked at Vench.

“Not cold, are you?” he asked.

“No,” answered the boy with a stare. “Why?”

“I thought maybe you were,” returned the instructor. “You still have your hat on. And that cigarette, which will be your last for something like four years, is already burned out. As there isn’t anything in that wastebasket you might throw it in there.”

Vench looked closely at the teacher and seemed on the point of saying something, but evidently he changed his mind, for he took off his hat, threw away the cigarette and turned once more to the captain.

“What is your name, please?” asked the instructor.

“Raoul Mulroy Vench, of Murray Bay, Florida, lately from Quebec and points all over the world,” glibly answered the youth. “Age, 18, unmarried, nationality American citizen, though French-Canadian. How is that for a start, general?”

“That is a very good start,” gravely replied the captain. “I’m glad you recognized my rank, Mr. Vench.” He continued to write for a few minutes and then looked up. “Have you any money on you at present?”

Mr. Vench looked knowing. “I’m surprised at you, sir. I only arrive here and you want to borrow from me already! Yes, I have a few odd pennies on me. About two hundred dollars, I think.”

“Hand it over, please, Mr. Vench. At the end of the year it will be returned to you. While you are here you will be allowed just two dollars a week of it, with which you can pay your expenses.”

Vench threw back his head and laughed. “Two dollars!” he exclaimed. “My dear man, I was counting on that two hundred lasting me just for two months, and that would be stretching it. Is it a joke?”

“Not at all, Mr. Vench. Have you read over the rules of the institution? Surely you must have. You didn’t come here without knowing the rules and regulations. The cadets are busy with their studies and athletics and have almost no use for ready money except for cokes and sodas. Transportation to games is furnished free and money is not strictly needed. You see how it is.”

“Yes, I see,” grumbled Vench, handing over the money. “I expected to have a good time in this place, but I see I am quite mistaken.”

Again Chalmers glanced at the groups in the hall. “I think you will have at least an interesting time here, Mr. Vench. Now the next thing for you to do is report at the medical department for examination.”

“The second nuisance, eh?” sighed Vench. “That’ll be a waste of time, officer. I’m in tip-top shape.”

“For the sake of our teams, I am very glad to hear it, Mr. Vench. However, the rules require that you go through with an examination.” Chalmers beckoned to a cadet in the hallway. “Will you step here a moment, Mr. Sears?”

Mr. Sears stepped up and saluted the instructor, who returned it. “Take Mr. Vench to the medical department,” the teacher directed.

“Very good, sir.” Sears turned to Vench. “Right this way, sir.”

Vench grinned and picked up his bag. “Right with you, usher. Thanks a lot, officer.” He followed Cadet Sears down the hall, passing carelessly through the waiting throng. Captain Chalmers looked thoughtfully after him, and then, shaking his head, resumed his work.

The cadets in the hall had remained quiet during the conversation, every word of which they had heard plainly, but now that Vench was out of earshot they began to talk.

“Hey, how do you like that!” chuckled Terry to the group around him.

“Well,” drawled Chipps, rubbing his chin. “I don’t just know what to think. You’ve got to give me time. This is the first time I’ve ever seen anything like that.”

“I’m afraid he’ll have a whole lot to learn,” smiled Don.

“If he lasts long enough to learn anything,” said Jim.

“All in the line of duty,” added Rhodes. “We’ll have to help him lose some of his flipness and importance. What do you say, Lieutenant Sommers?”

“I’d say that the spirit of the corps will have a hard time sinking into him,” said Sommers, as the bell sounded.

Mr. Vench was fitted out with a uniform that afternoon and little more was seen of him. But on the following day he began his career at Woodcrest, and that career furnished amusement and some annoyance to the cadet body. The boy was thoroughly spoiled and almost unbearable. Two of the seniors and Terry tried to do the right thing by calling on him that evening, in an effort to make him feel at home. Terry returned to his room and reported in high disgust to Don and Jim.

“My gosh, what a sample of misdirected energy!” he exclaimed with a snort. “We tried to be decent to him in spite of what we saw this noon, but it was time wasted. Not that he was rude, but absolutely unbearable! Talks continually of his travels, his girl friends, who seem to swoon with grief if he doesn’t write daily, and his ability to do all of everything on the face of the earth. I’m through. I’m willing to try to be nice to any fellow who will be halfway human, but I draw the line on one who spends all of his time praising his own virtues.”

“Likes himself, eh?” inquired Jim.

“No,” snapped Terry. “Bows down and worships himself. I’m afraid that boy will run aground on trouble hard.”

“And yet,” said Don, slowly. “I imagine he could be a very nice guy if he wanted to be. Maybe he’ll come out of his shell sometime.”

“I’m glad you imagine it,” retorted Terry. “That’s as far as it is likely to go.”

“All right, Terry,” Jim grinned. “Hadn’t you better study your history? Any man that will try and tell his teacher, as you did today, that Blucher wasn’t at the battle of Waterloo, should brush up a bit, I think.”

“Okay, kid, I will. The only thing that surprises me is the fact that Vench wasn’t there, or related to Napoleon or something else. Maybe he was, I don’t know. That fellow is thoroughly spoiled.”

“A little too much money, no doubt,” said Don. “If we give him a chance he’ll get over it.”

“Optimist!” said Terry, beginning to study.

Few if any of the cadets were inclined to take Don’s view of Cadet Vench. During the following days he made himself objectionable in every way. Even in the drill he tried to show his superiority, but Lieutenant Sommers promptly checked him and after due and fair consideration reported his short-comings. Major Tireson rebuked the unruly cadet and he had no more use for the precise lieutenant. But Sommers took great pride in the squads that it was his duty to drill, and the cadets, always inclined to laugh at the dignity of the fussy lieutenant, upheld him in his act.

Vench had few friends, and they were recruited from the weaker element of the fourth class, with whom he was very liberal. It was evident that he had more money than his allowance and it was thought that he had lied to Captain Chalmers or that he was getting it from some outside source. A small group went often to the town and ate plentifully between meals, but as it was not particularly the business of the cadets they commented on it among themselves and let it go at that.

One boast that Vench made was listened to with interest by the entire body of cadets. He was standing with the group of fourth classmen just before the study hall bell rang, and Don and Terry heard it. That morning Major Tireson had made a statement that most of the cadets thought unnecessary. He had told them that with the colonel not there, he didn’t think it was wise to plan on having their mid-term dance that year.

Several times during the year, mid-term, Christmas, and in the spring, the school held a dance. Each class usually sponsored one of these events and kept whatever profit they made. The competition was high among the four classes, each one trying to outdo the next in originality and cleverness. It took a good deal of ingenuity to plan decorations that could disguise the gym for an evening. The year before, the second-class men, who had sponsored the spring prom, had transformed the gym into a carnival. They had even devised a revolving stage resembling a carrousel from which the band played.

Major Tireson, however, was firmly against holding a dance in the colonel’s absence.

“He needn’t worry,” Rhodes had said, briefly. “Until the colonel gets back we aren’t likely to do any of the things we generally do, or have much fun.”

Vench was defiant about it. “Half the fun of going to school is having dances and picnics,” he said, in study hall. “At all the other schools I’ve been to, they have lots of them. But this stuffy old major vetoes it before we even have a chance to suggest it. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’m going to organize the best dance this school’s ever seen. Something that will go down in the unwritten history of this academy.”

“Better wait until the colonel gets back before you do, Vench,” advised Don.

“I will not! I’ll do as I please!”

“Suit yourself,” said Don, turning away.

“I generally do. Want to be in on it, Redhead?”

“Why, I think not,” drawled Terry. “I don’t want to be dismissed from here in my very first year. And referring to the highly disrespectful way in which you speak of my blond locks, don’t you think they might shine out in the darkness and give you and your party away?”

“You guys make me sick!” growled Vench.

“Sorry,” said Terry. “Can I show you the way to the doctor’s office?”

Late in the afternoon Jim and Rhodes got special permission from the Officer of the Day and went to the town to buy some things. Special permission was necessary except on Saturday afternoons, and they lingered in town until the sun had set. The days were growing much shorter and it was dark when they arrived at the gate and walked up the path. None of the cadets were around and they started to cross the lawn when Rhodes pulled Jim suddenly into a clump of high bushes that lined the path.

“What’s up?” asked Jim, quickly.

“Somebody just came around Locke Hall and is going toward Clanhammer!” whispered the senior.

Jim looked in the direction indicated and saw that Rhodes was speaking the truth. A man, his form somewhat indistinct in the twilight, was walking rapidly down the path in the direction of the silent old hall. By peering through the bushes the two cadets could watch him, and they could hear his footsteps on the gravel. The man did not pause or look behind, but walked straight up the stone steps, inserted a key in the lock and opened the door. With a bold and confident step he went inside.

“Wonder who in the world that is?” breathed Jim.

“I couldn’t make out,” replied Rhodes. “But who ever it is, he has the key to Clanhammer Hall. There is no light in the place, so he must know his way around.”

They waited for some time, but no one appeared and the hall remained in total darkness. Rhodes looked at his watch.

“We’ll have to go,” he announced, regretfully. “We have to be in at six, you know, and it is ten of now. We have to wash for supper, so we haven’t any time to spare. I’d surely like to stay here and see who comes out.”

“So would I,” agreed Jim. “But we’ll have to go. If we could only see who it was!”

The two cadets returned to the building, checked in, and went to their rooms. While Jim washed he told the other two of their discovery. Terry went to the window and watched the lawn, but without discovering anything.

“We’ll see if anyone is missing from the dining hall,” Don suggested. But although they took great care to check up they could learn nothing at the evening meal. Every cadet and officer was in his place at the tables.

“That leaves us one theory,” decided Rhodes, a little later, as they talked it over in the boys’ room. “Either the man got back before supper or one of the cooks or the janitor went in there. The question is: who, besides the colonel, has a key to Clanhammer Hall?”

6. Rapid Developments

For the next few days nothing worthy of note happened. It was early one morning the following week that things began to move. The boys had studied until bedtime and had turned in when the lights were put out. Life at the school flowed on as it did when the colonel had been there. Mr. Vench seemed busier than usual and made several trips to town. Clanhammer Hall revealed nothing new.

How long the boys had been asleep on that particular night they did not know, but they were aroused by a sound that was entirely new to them. A furious clanging of gongs sounded throughout the school on every hall and stairs, and the cadets started up in bed with rapidly beating hearts. They had often seen the huge gongs out in the halls but had never heard them in action. Now they were being rung violently.

Terry was the first to bounce out of his bed. “Come on, you guys,” he called. “The school is on fire!”

Don and Jim lost no time in springing from their beds and reaching for their clothes. “Too bad they don’t turn on the lights,” he grumbled.

As though in answer to his complaint the overhead lights were turned on and the boys could see what they were doing. The sound of the gongs then died down abruptly, but a rushing, scattering sound told them that the cadets were all up and hurrying into their clothes.

“Wonder where it is?” speculated Jim, as he pulled on his shirt. “I don’t see any blaze or smell any smoke.”

“It may only be a very small one,” said Terry, who was now fully dressed. “I suppose we report in assembly, don’t we? Or maybe we march out on the campus. One thing they have neglected to do around here is to give us any fire regulations.”

Terry was right in his statement and the Mercers wondered if the oversight was due to the fact that the colonel was missing. They opened their door and hurried out into the hall. Almost every door was open and cadets were talking and walking toward the stairs.

The cadet captain of the third class hurried down the hall and saw to it that each boy was out of his room. With the rest of the cadets in Locke Hall the three chums went down the stairs and found the biggest gathering in the hall. There was no smoke or fire to be seen anywhere.

“Well, there may be a fire somewhere,” observed Terry. “But it certainly ran away in a hurry.”

“Whatever it was, it was in the library,” a cadet said. “I just saw the Officer of the Day and Major Tireson go in there in a hurry.”

With one accord the cadets trooped down the lower hall and congregated at the door of the library. They noticed that the door was flung far back and that the lock was still sprung. It was evident that the door had been violently broken open, and as none of the cadets had ever known the library door to be locked, they were surprised.

A number of books had been thrown out of a bookcase near the panelled wall, and the major and Rollins, the appointed Officer of the Day, were looking closely at an old portrait on the wall. Impelled by their growing curiosity the cadets of Locke Hall crowded into the room and around the two officers. Then they saw that the bottom of the picture, along the frame, had been slashed for at least five inches, close to the wood. The picture, an inexpensive one portraying the celebrated “Thin Red Line” in action, was a familiar article to the young men, and they were at a loss to know why it should have been slashed.

“Very singular,” Major Tireson was saying. “Let me have a full account of what happened, Rollins.”

“I had finished my duties as Officer of the Day,” said Rollins. “And I had returned to my room, unfortunately forgetting to return my report book to the office. I noticed the omission and was going back with the book when I saw the library door closed and a light coming out from beneath. I knew that there should be no light there at this time of night—or morning, and I quietly opened the door. Two men were in the room, one of whom was engaged in slitting the picture, while the other stood near the door in which I was looking. He must have heard me step to the door, for before I could grapple with him he had thrown his weight against the door and pushed me out into the hall. I heard the lock snapped into place and then I rang the gongs to attract attention and get help. As you know, when you and I finally broke in, the men were gone, probably through the window.”

“Did you get any kind of a glance at the faces of the men?” asked the major.

“Only a brief glimpse, sir. The man at the portrait had his face turned away and I didn’t see it at all, but the man here at the door gave me just time to see him. He was tall and quite dark, but as he had a slouch hat pulled down over his eyes I could not altogether make him out. That is all I have to report, sir.”

The major’s eyes wandered back to the slashed picture and a puzzled look spread over his face. “I can’t see what object any outsider could have in our picture,” he observed. “It certainly isn’t a masterpiece or anything of the kind.” He turned and frowned slightly at the cadets who had listened with great attention. “You wouldn’t say it was one of the men of the corps, up to any prank, would you, Rollins?”

“Oh, no, sir,” promptly reported the cadet. “These were men dressed in business suits and civilian hats.”

“Well,” decided the major, “I suppose the men have gotten away; in fact I heard the motor of an automobile as I came downstairs. This is most puzzling. In the future you had better quietly call me instead of ringing the fire alarm. I see that the cadets from Inslee and Clinton Hall are here, too.”

The major soon after ordered them to their rooms, and the cadets from the other halls, who had turned out when they had heard the clashing gongs in Locke, went back to their dormitories, a confused idea of the whole thing in their minds. The students from Locke Hall went rather reluctantly up to their rooms, but many of them did not attempt to go to sleep at once. Each room held its own conference, and that occupied by the Mercers and Terry was no exception.

“Suppose it all had something to do with what goes on at Clanhammer Hall?” whispered Jim, as they sat on Don’s bed in the darkness.

“I don’t know what to think,” his brother answered. “This happening beats them all, to my way of thinking. You can imagine some sort of an excuse for most actions, but who in the world could explain why two men should start to cut out a cheap picture in our library?”

They talked it all over and at length, but they arrived nowhere, so at last they went to sleep and slept soundly until morning. It was an excited and interested group of cadets who assembled in the chapel that morning, and they waited impatiently to see if the temporary headmaster would say anything about the events of the past morning. But to their disappointment he did not and they went away to classes, to speculate all day on the mystery.

But just before it was time to report for drill, and just as the last class was about to break up, certain cadets appeared in each classroom and gave instructions to the teacher. In the class where the fourth class men were studying Captain Chalmers rapped for attention.

“Immediately after leaving this classroom you will report to general assembly,” he announced.

There was a buzz and a stir among the cadets, and as soon as books had been put away they hurried to the assembly. An undercurrent of excitement was clearly visible, and they were eager for news of some sort. The major called for order and delivered his message briefly.

“It is not necessary for me to recount the details of what went on here last night,” he stated. “You all know it, I am sure. However, we have learned nothing new, and while I am not inclined to treat the matter as being of any importance, still I do think we may use it for a little military practice. My thought is that for the next few days we will detail certain cadets to do active guard duty around the school all night. That will give you each a touch of true military life. The captains of the classes will tell you when you are to serve, and also give you your position. Any negligence while on duty will not be tolerated. Assembly dismissed.”

Drill followed, but what followed drill was not part of the schedule, though human and natural. A general buzzing and discussion took place all over the campus and in rooms. Most of the boys welcomed the idea of patrolling the grounds because of the novelty of it, but they were divided as to the major’s reason. Could it be possible that he was really afraid? This question was more than the cadets could answer, and it furnished food for much speculation.

Don hurried into the room soon after supper with a grin on his face. “Well, I got it!” he announced.

“Got what?” asked Jim.

“I got my watch tonight,” Don explained. “From eleven ’til twelve I patrol from the end of the campus to the east gate, up the hill and down.”

“And while you are walking we’ll be blissfully sleeping,” smiled Terry.

“Oh, I don’t mind, tonight,” answered Don. “It looks as though it is going to be a peach of a night, with a big moon. I may be a whole lot luckier than you two, at that. You may get something like two or three in the morning, perhaps on a rainy morning, and I’ll be the one to sleep blissfully.”

“Say,” spoke up Jim. “Your patrol takes you right back of Clanhammer Hall, doesn’t it?”

There was silence for a minute and then Don nodded. “Yes, it does,” he said. “I pass right back of it. From the edge of the campus I walk back of the hall, down the slope near the lake and to the gate. Yes, I’ll pass the old place a good many times, I guess.”

“Perhaps you’ll see something that may help a bit,” Terry said. “Be careful not to get tangled up in anything, though.”

Don was compelled to go to bed until a quarter of eleven, when the Officer of the Day rapped on his door and in a low tone told him to report for guard duty. Both of the other boys were sound asleep when Don left the room and went to the office. A cadet by the name of Arthurs was due to be relieved, and Don received final instructions. Then, taking his rifle, which the cadets used in drill, Don went out of the side door of Locke Hall to the edge of the campus and waited for Arthurs.

The cadet came across the campus from the direction of the old hall and saluted Don briskly. He said that there was nothing to report.

“I’m a little sorry to have you relieve me,” he smiled. “Although I’m getting tired of tramping up and down. Nice night, isn’t it?”

Don said that it was, and after saying goodnight to Arthurs he commenced his patrol. His way led him across the grassy campus back of the school, back of the gloomy old hall and down the slope near the lake to the iron gate at the east end of the school grounds. He made his first trip and found that it took him a full five minutes from point to point.

Don rather liked the whole idea. It might be quite useless as far as definite results went, but it was fun and a touch of the life which interested him. All of the boys would have to take turns at it, and he knew as he paced up and down that other cadets were patrolling on the other three sides of the school. He had been very fortunate in the time, for a fine big moon rode overhead, lighting the country up in a yellow splendor. The night was cool, but not unpleasantly so, and he felt exhilarated as he moved along with a swift, snappy stride.

Each time he passed back of the old hall he looked searchingly at it, but it was deserted and black, seemingly wrapped up in its covering of ivy. Down by the east gate he lost sight of it, and it was a minute or more before he once more walked around back of it. Don had been patrolling for almost forty minutes, and was now down near the gate. Reaching it, he swung around and started on his backward patrol.

He once more came in sight of Clanhammer Hall and started to pass by it. His patrol had taken him some fifty feet back of the hall, close to some small trees, and he entered a patch of black shadows. From force of habit he looked at the old building and then came to a swift halt.

A file of seven men, bending low and obviously keeping in the shadows of the old place, was making its way around the corner of the building. Each of these cadets, whose uniforms Don could plainly make out, held something in his hand. Astonishment seized Don, and although he had a faint notion of what might be going on, he could hardly believe it.

But he knew his duty and he was quite determined to carry that out. It was evident to him that they thought he was still down by the gate. Lowering his rifle he stepped forward and then stopped.

He thought at first that they intended to gather in some corner outside the building, but he found he was mistaken. They had approached a cellar window and the leader raised it and thrust his leg through. Don hurried forward, challenging them sharply.

“Halt! Who goes there?”

The seven cadets, with the leader halfway through the window, started and turned. Don’s suspicions were confirmed. They were all fourth class men and each one of them had tools in his hand. They looked foolish and confused and glanced at each other.

“Hey!” cried Don, as no one spoke. “What’s going on here?”

“We were going in to fix up this old hall for a dance, Mercer,” said a cadet.

Don was bewildered. “On a night like this, when we have guard duty?” he cried. “And almost at twelve o’clock. You guys must be bats!” A sudden suspicion came over him. “Tell me, whose idea was this?”

There was an interval of silence and then the cadet who had answered him at first replied. “Vench’s idea.”

“I thought so,” nodded Don. “Why did he pick out tonight and why this place?”

“Well,” answered the spokesman. “He said he was going to put on a dance that would go down in history, and he wanted to do the decorating tonight, when there were guards out, and we’d have it in Clanhammer Hall, because nobody ever goes in there.”

“Where is Vench now?” asked Don.

“Inside.”

“Inside Clanhammer Hall!” cried Don sharply.

“Yes. He went in early to look the place over, and we were to join him in there.”

Don was taken aback at the news. If there was anything to be learned in that hall Vench might stumble on it, and he was disappointed to think that someone beside himself had been in Clanhammer first. Well, there was just one thing to do and that was to enter the old school himself. He turned to the waiting cadets.

“You fellows get back to your rooms at once, and do it without being seen by anyone. I won’t report you unless you disobey me. You’ve been a lot of silly fools to listen to Vench at all. Why, if you are caught you will probably be expelled! Have your dance when the colonel returns but not now. Now get back, before I am compelled to turn in a report of this.”

The seven cadets, glad of the chance to escape from an adventure which had begun to worry them, slipped away without a word toward the main hall. Don turned once more to the cellar window, prepared to enter the dark and forbidding place. But he drew back with a slight start.

The cellar window went up and was secured and a head appeared in the half light. Cadet Vench scrambled up and out of the window, his uniform covered with cobwebs and dirt. He looked briefly at Don and would have walked off, but Don grasped him by the arm.

“Here, Vench,” Don called. “Wait a minute. Let me look at your face. What is the matter?”

He swung the cadet toward him and for a brief instant the other looked at him with wide eyes. Don almost gasped. The ordinarily brown face of Cadet Vench was white, his eyes were big and his hands shook. Don released his hold.

“What did you see in there, Vench?” he asked.

“Nothing,” returned the other, dropping his eyes.

“Yes, you did,” retorted Don. “Out with it. Let’s have it.”

“I didn’t see anything!” snapped Vench, stepping away from him. “You let me go, Mercer. I—I want to get away from this place. You keep your mouth closed about it, too.”

He strode away, and Don was strongly tempted to recall him and make him tell or suffer the consequences. But he was undecided as to what course to follow and he watched the cadet disappear in the direction of Locke Hall. Once more Don looked at the hall so near at hand. There was no sound and he wondered if he should go in or not.

But he did not feel like going in. Vench had seen something in there that had made him turn white. And for another thing, his patrol time was up, a thing for which he was not altogether sorry. So with this new angle to puzzle over Don went back to report his patrol over with and sought his bed, to wonder and speculate until he fell asleep.

7. Jim Makes an Enemy

“The thing to do,” said Rhodes, “is to make Vench talk.”