SOME EXPERIENCES OF A NEW

GUINEA RESIDENT MAGISTRATE

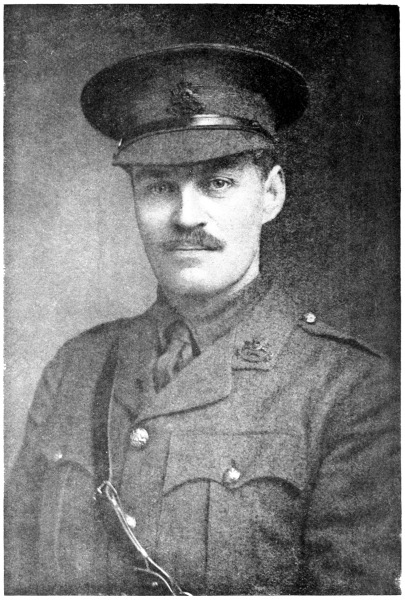

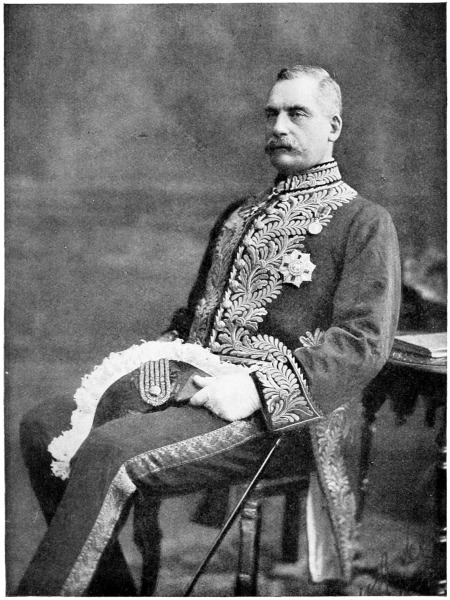

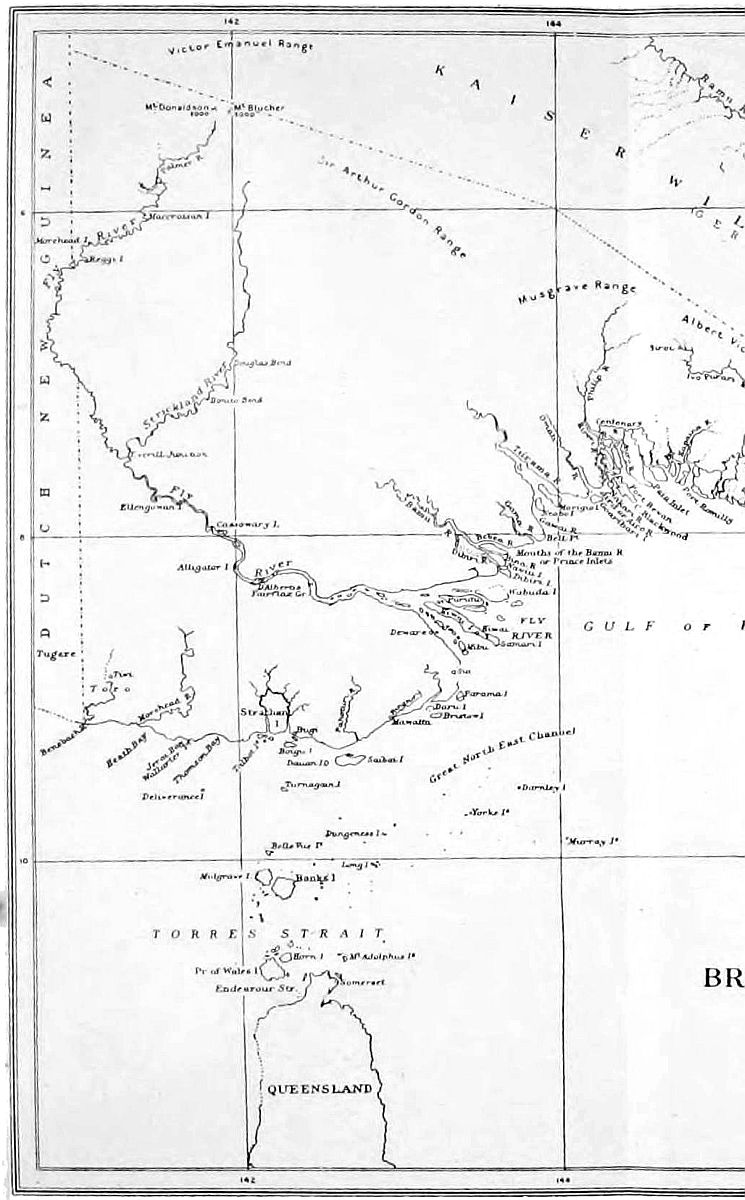

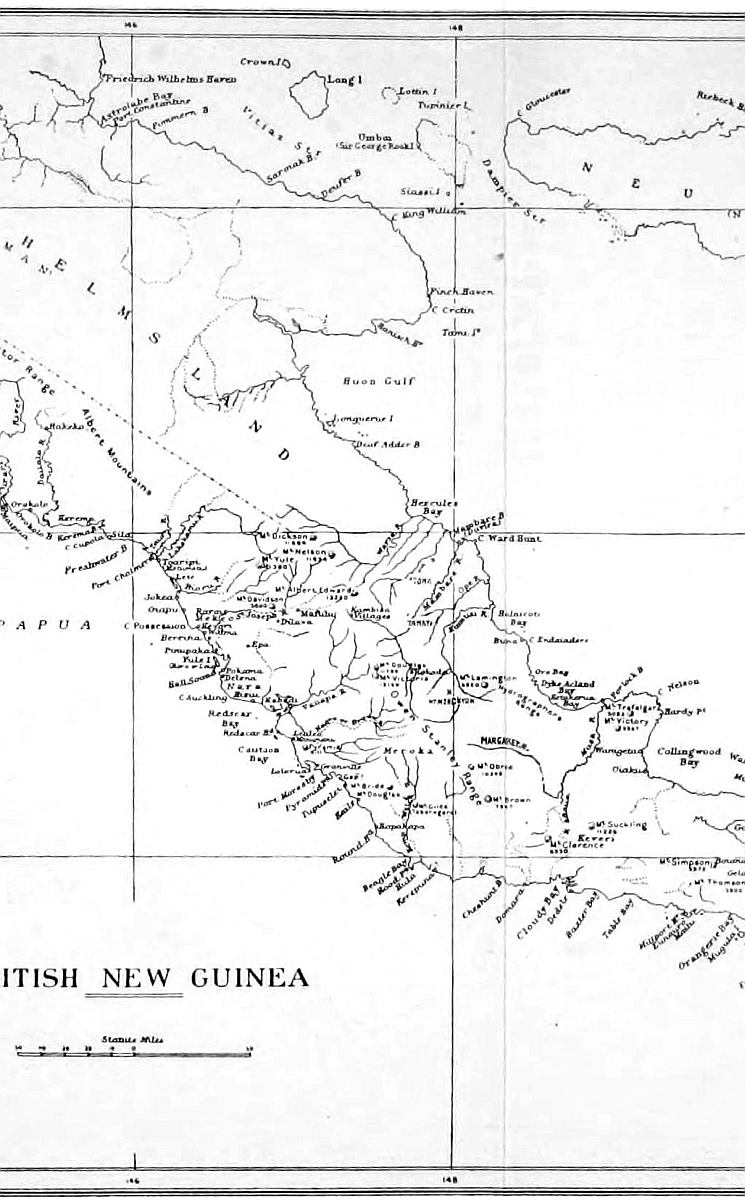

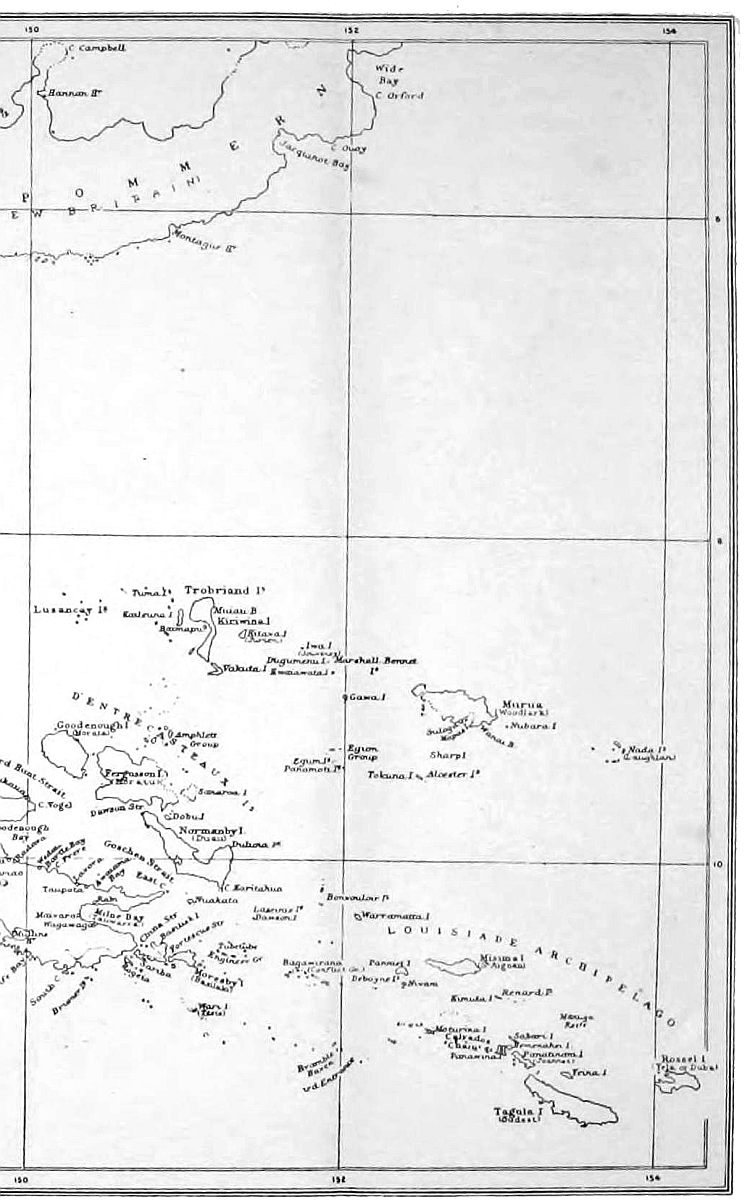

SOME EXPERIENCES OF A NEW GUINEA RESIDENT MAGISTRATE BY CAPTAIN C. A. W. MONCKTON, F.R.G.S., F.Z.S., F.R.A.I., SOMETIME OFFICIAL MEMBER OF EXECUTIVE AND LEGISLATIVE COUNCILS, RESIDENT MAGISTRATE AND WARDEN FOR GOLDFIELDS, HIGH SHERIFF AND HIGH BAILIFF, AND SENIOR OFFICER OF ARMED CONSTABULARY FOR H.M.’s POSSESSION OF NEW GUINEA WITH 37 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD, VIGO ST.

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY

![]() MCMXXI

MCMXXI

THIRD EDITION

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED, LONDON AND BECCLES, ENGLAND

TO MY

WIFE

PREFACE

It appears to be the custom, for writers of books of this description, to begin with apologies as to their style, or excuses for their production. I pretend to no style; but have simply written at the request of my wife, for her information and that of my personal friends, an account of my life and work in New Guinea. To the few “men that know” who still survive, in one or two places gaps or omissions may appear to occur; these omissions are intentional, as I have no wish to cause pain to broken men who are still living, nor to distress the relations of those who are dead. Much history is better written fifty years after all concerned in the making are dead. Governor or ruffian, Bishop or cannibal, I have written of all as I found them; I freely confess that I think when the last muster comes, the Great Architect will find—as I trust my readers will—some good points in the ruffians and the cannibals, as well, possibly, as some vulnerable places in the armour of Governors and Bishops.

I do not pretend that this book possesses any scientific value; such geographical, zoological, and scientific work as I have done is dealt with in various journals; but it does picture correctly the life of a colonial officer in the one-time furthest outpost of the Empire—men of whose lives and work the average Briton knows nothing.

Conditions in New Guinea have altered; where one of Sir William MacGregor’s officers stood alone, there now rest a number of Australian officials and clerks. Much credit is now annually given to this host; some little, I think, might be fairly allotted to the dead Moreton, Armit, Green, Kowold, De Lange, and the rest of the gallant gentlemen who gave their lives to win one more country for the flag and to secure the Pax Britannica to yet another people.

I have abstained from putting into the mouths of natives the ridiculous jargon or “pidgin English” in which they are popularly supposed to converse. The old style of New Guinea officer spoke Motuan to his men, and I have, where required, merely given a free translation from that language into English. Inviii recent books about New Guinea, written by men of whom I never heard whilst there, I have noticed sentences in pidgin English, supposed to have been spoken by natives, which I would defy any European or native in New Guinea, in my time, either to make sense of or interpret.

When the history of New Guinea comes to be written, I think it will be found that the names of several people stand out from the others in brilliant prominence; amongst its Governors, Sir William MacGregor; its Judges, that of Sir Francis Winter; its Missions, that of the Right Rev. John Montagu Stone-Wigg, first Anglican Bishop; and in the development of its natural resources, that of the pioneer commercial firm of Burns, Philp and Company.

ix

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | 9 |

| CHAPTER III | 16 |

| CHAPTER IV | 27 |

| CHAPTER V | 32 |

| CHAPTER VI | 41 |

| CHAPTER VII | 47 |

| CHAPTER VIII | 60 |

| CHAPTER IX | 72 |

| CHAPTER X | 83 |

| CHAPTER XI | 94 |

| CHAPTER XII | 109 |

| CHAPTER XIII | 124 |

| CHAPTER XIV | 139 |

| CHAPTER XV | 149 |

| CHAPTER XVI | 163 |

| CHAPTER XVII | 177 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | 191 |

| CHAPTER XIX | 204 |

| CHAPTER XX | 222 |

| CHAPTER XXI | 233 |

| CHAPTER XXII | 250 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | 268 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXV | 294 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | 304 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | 324 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| TO FACE PAGE | |

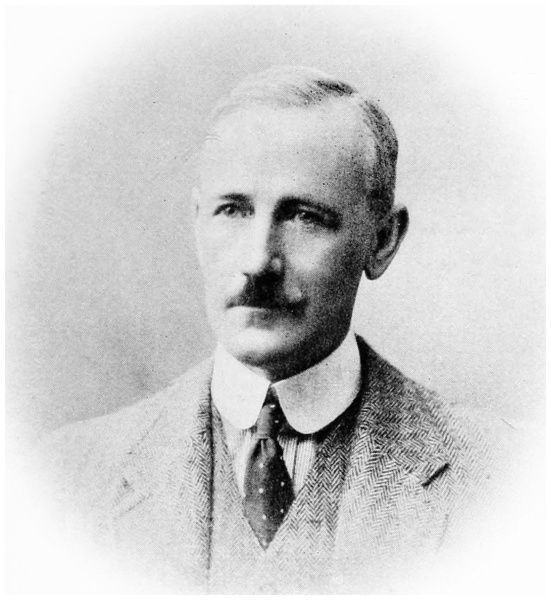

| The Author Frontispiece | |

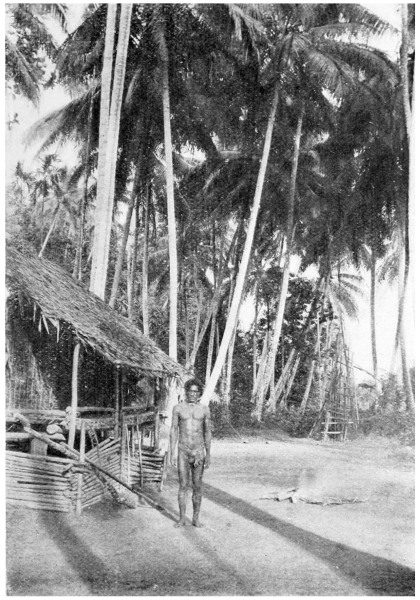

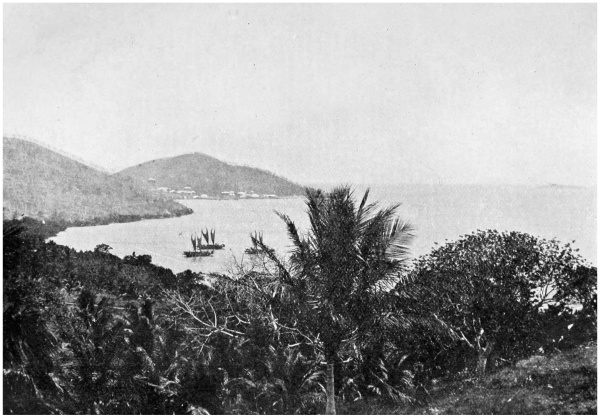

| Cocoanut Grove, near Samarai | 6 |

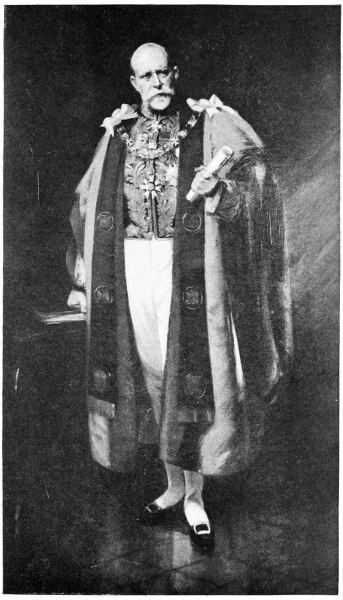

| The Rt. Hon. Sir William MacGregor, P.C., G.C.M.G., C.B., etc. | 10 |

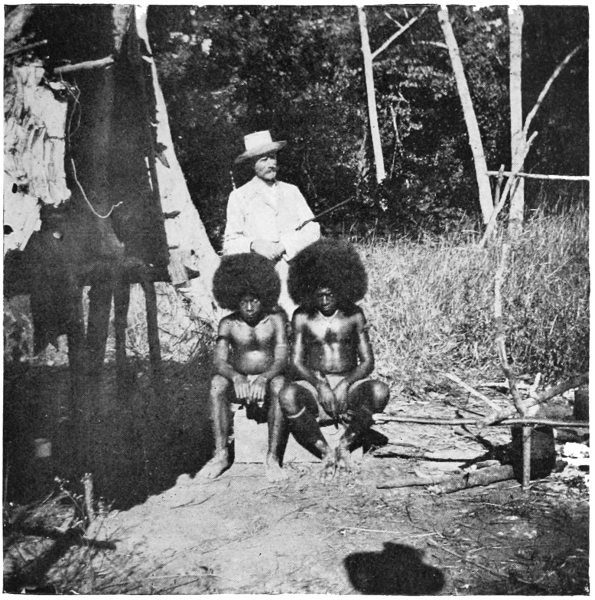

| R. F. L. Burton, Esq., and his Motuan boys | 62 |

| Port Moresby from Government House, showing the Government Offices | 70 |

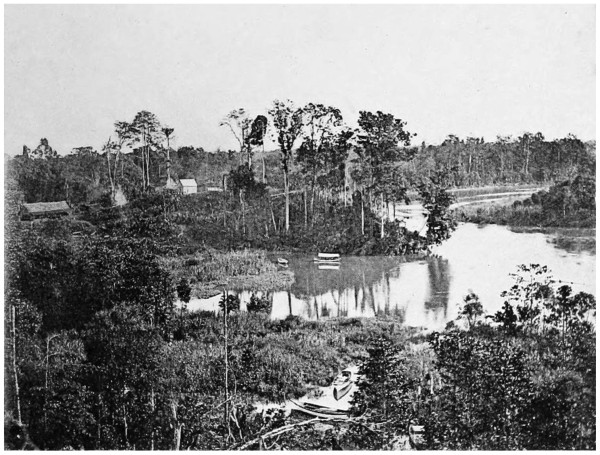

| Tamata Creek | 78 |

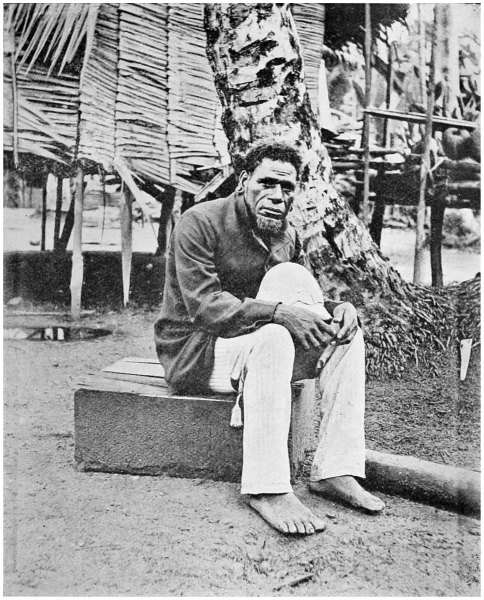

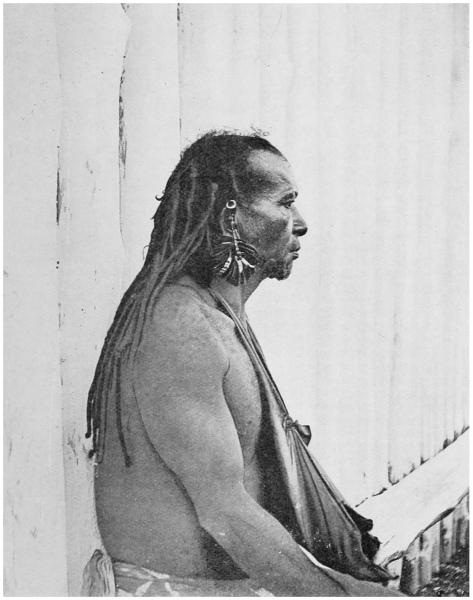

| Bushimai, chief of the Binandere people | 80 |

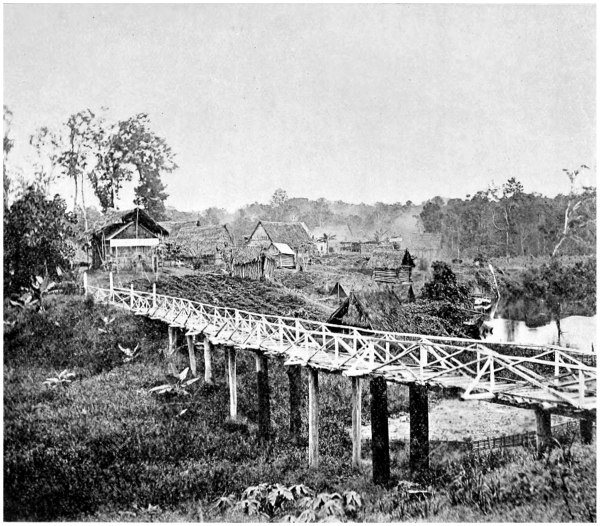

| Tamata Station | 82 |

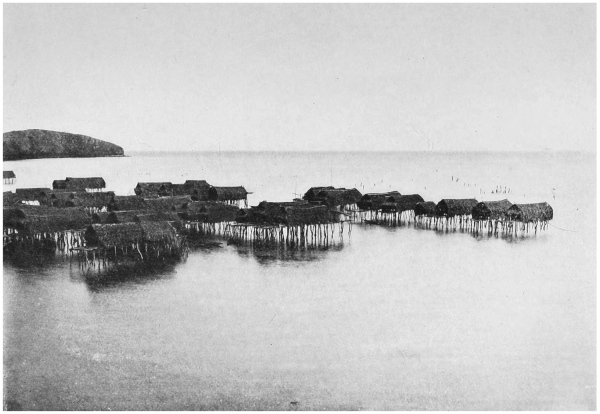

| Village in the Trobriand Islands | 86 |

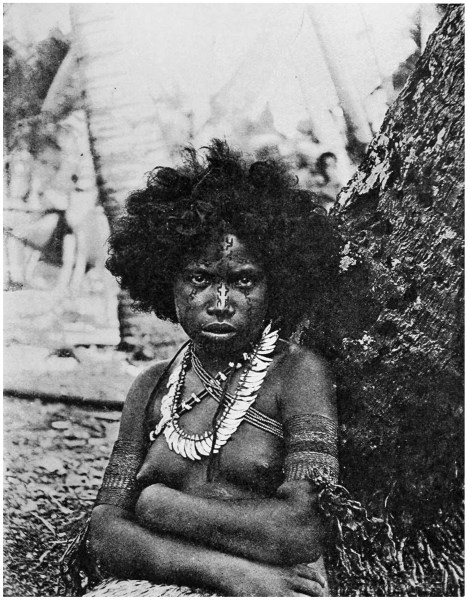

| A Motuan girl | 112 |

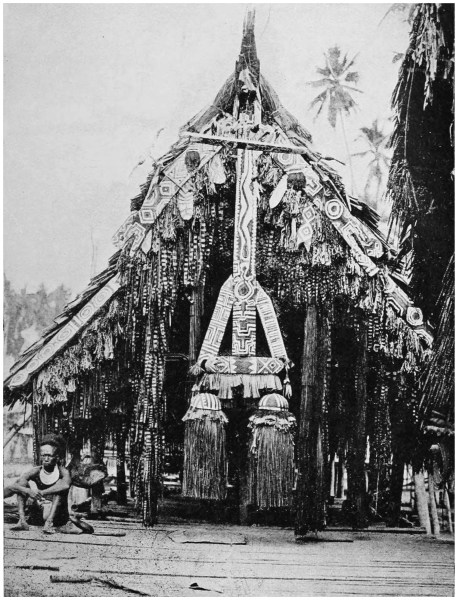

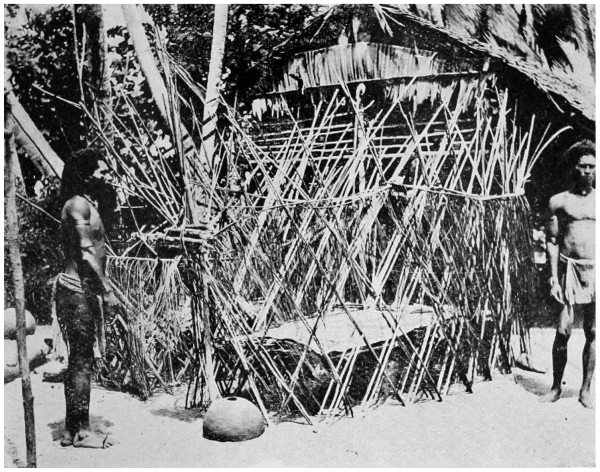

| Dobu house, Mekeo | 114 |

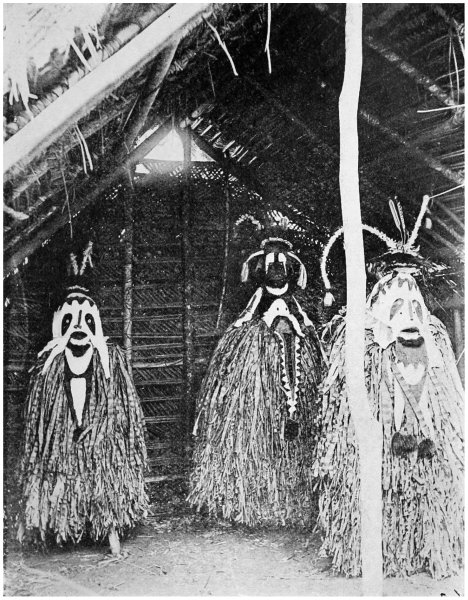

| Masks of the Kaiva Kuku Society, Mekeo | 118 |

| House at Apiana, Mekeo | 120 |

| Village near Port Moresby | 136 |

| Sir George Le Hunte, K.C.M.G. | 148 |

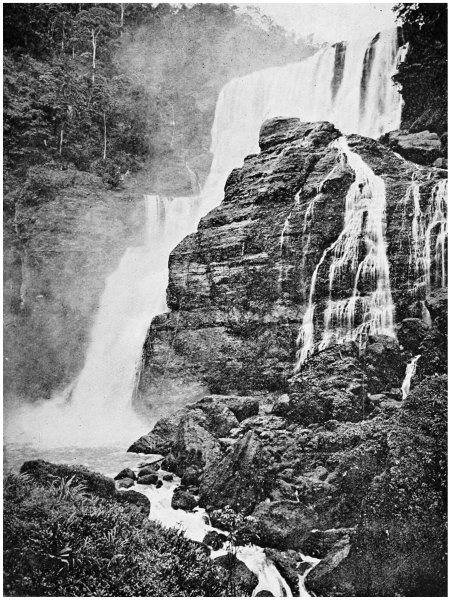

| The Laloki Falls | 156 |

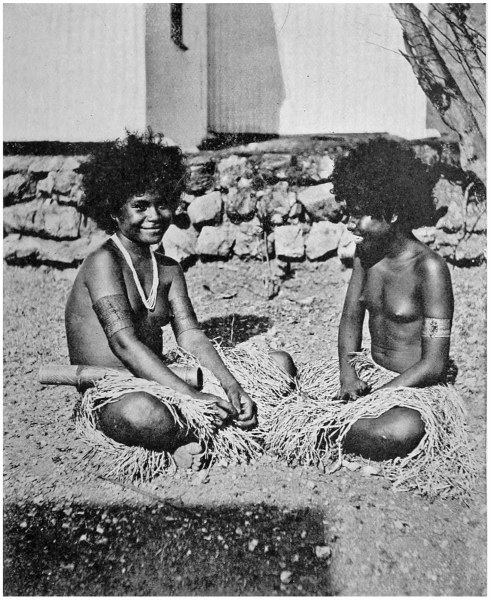

| Two Motuan girls | 162 |

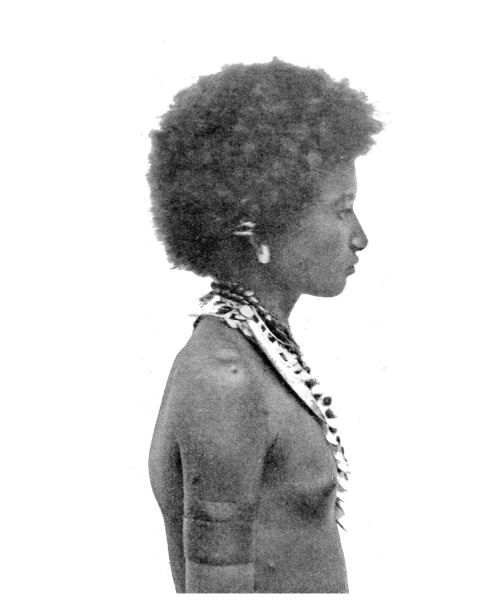

| Motuan girl | 164 |

| Sir G. Le Hunte presenting medals to Sergeant Sefa and Corporal Kimai | 166 |

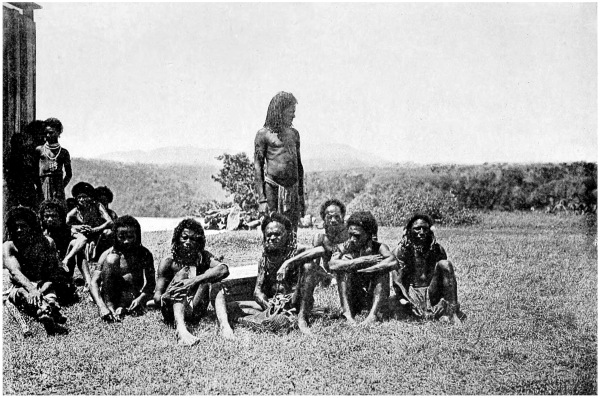

| Kaili Kaili natives | 166 |

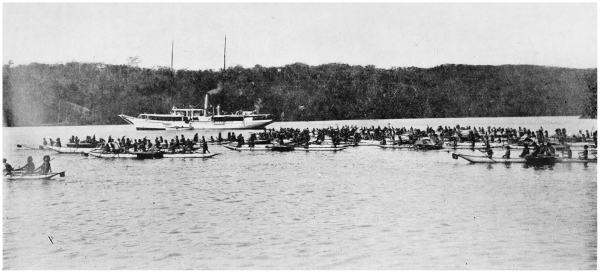

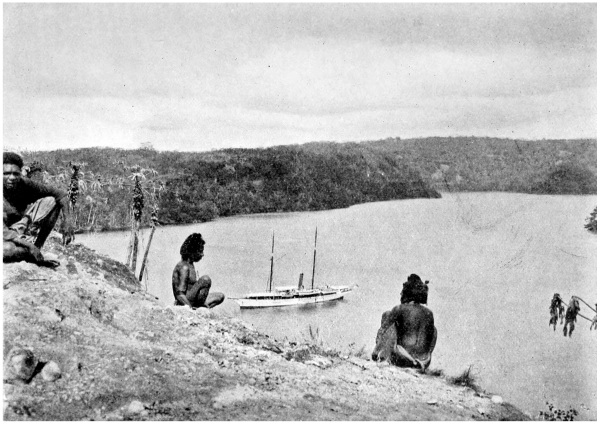

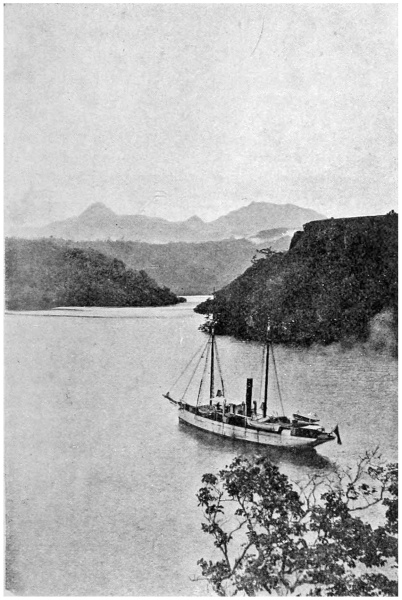

| The Merrie England at Cape Nelson and Giwi’s canoes | 168 |

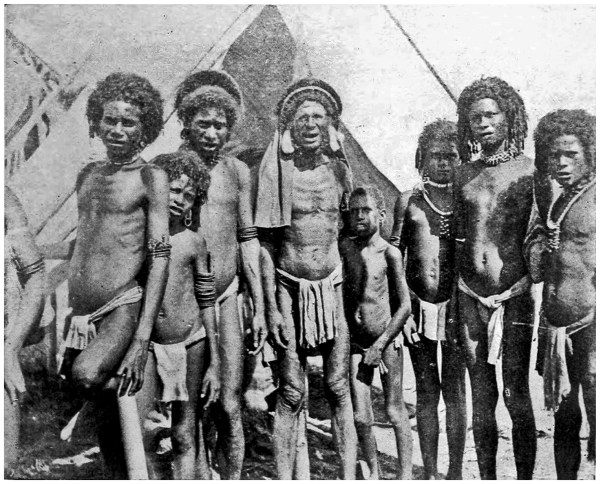

| Giwi and his sons | 174 |

| View from the Residency, Cape Nelson | 178 |

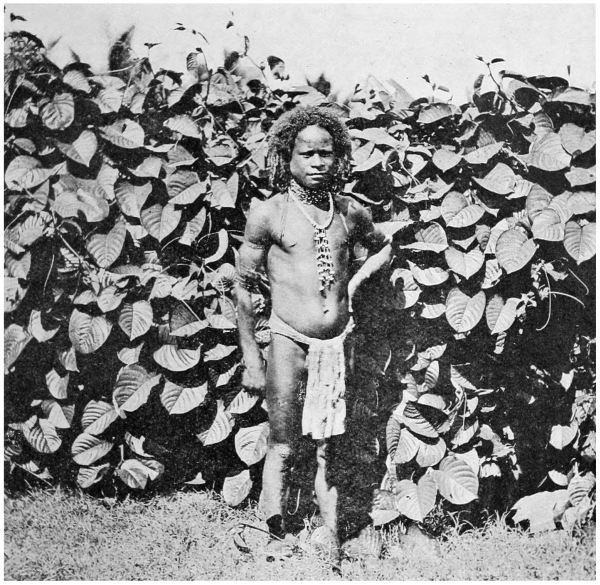

| Toku, son of Giwi | 184 |

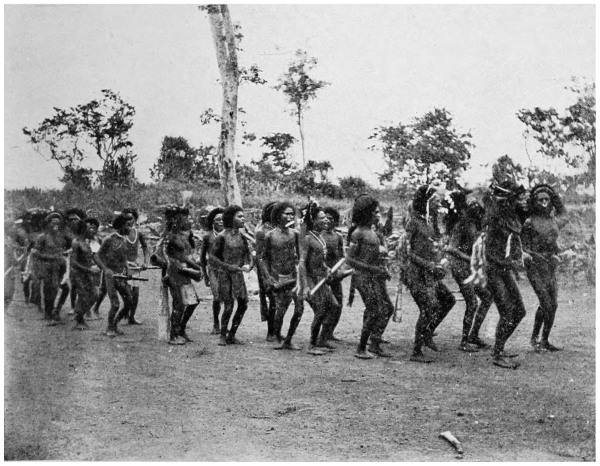

| Kaili Kaili | 192 |

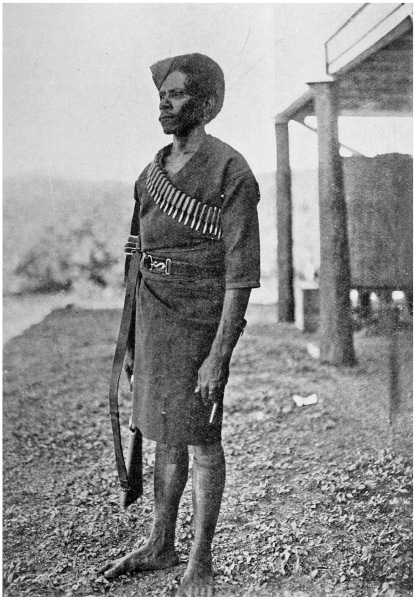

| Sergeant Barigi | 200x |

| Grave of Wanigela, sub-chief of the Maisina tribe | 208 |

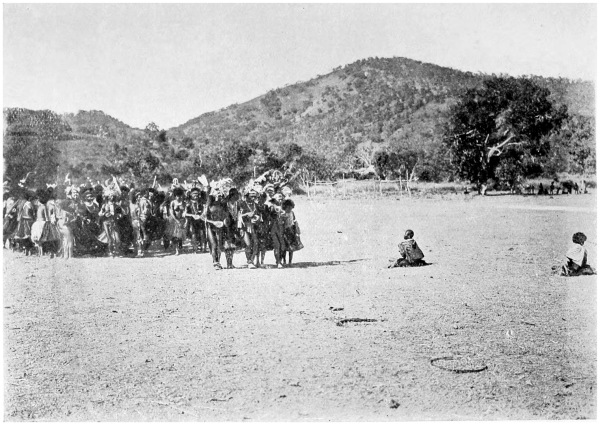

| Kaili Kaili dancing | 208 |

| Captain F. R. Barton, C.M.G. | 212 |

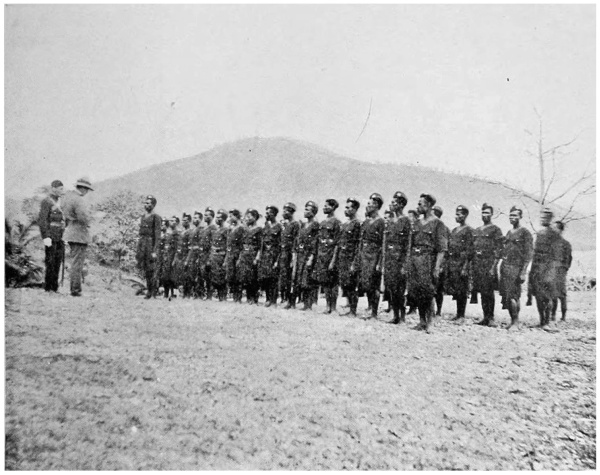

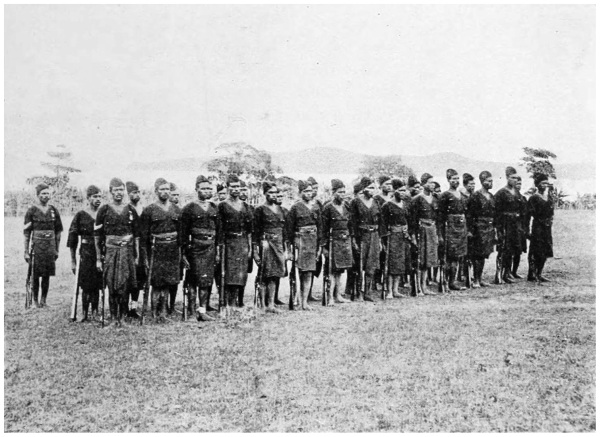

| Armed Constabulary, Cape Nelson detachment | 216 |

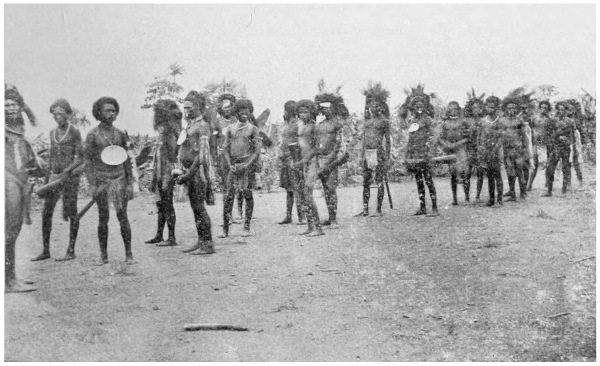

| Kaili Kaili carriers with the Doriri Expedition | 218 |

| The Merrie England at Cape Nelson | 234 |

| Group, including Sir G. Le Hunte, K.C.B., Sir Francis Winter, C.J., etc. | 264 |

| Oiogoba Sara, chief of the Baruga tribe | 270 |

| Agaiambu village | 274 |

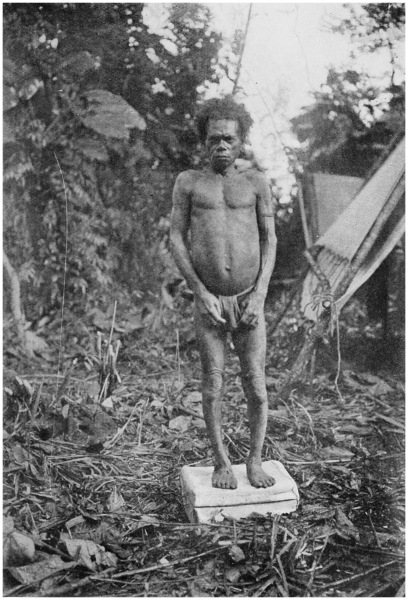

| Agaiambu man | 278 |

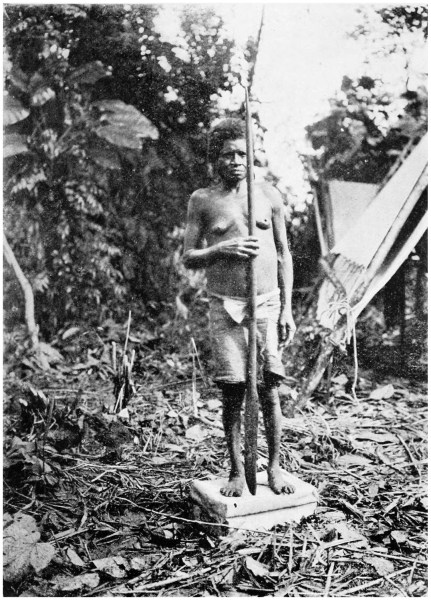

| Agaiambu woman | 280 |

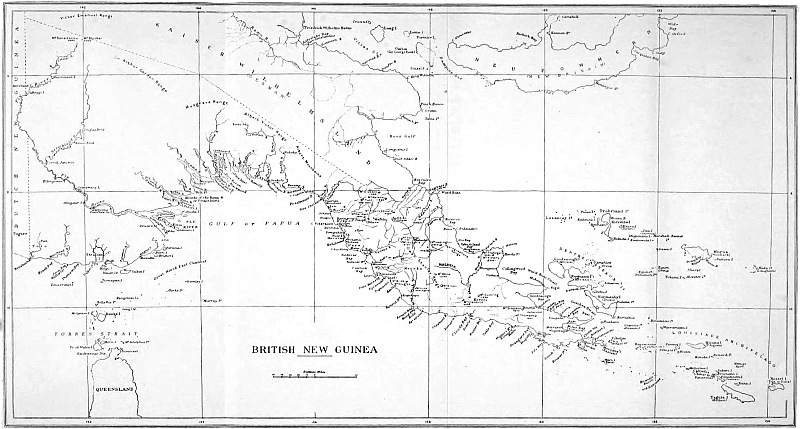

| Map | 324 |

SOME EXPERIENCES OF A NEW

GUINEA RESIDENT MAGISTRATE

1

CHAPTER I

In the year 1895 I found myself at Cooktown in Queensland, aged 23, accompanied by a fellow adventurer, F. H. Sylvester, and armed with £100, an outfit particularly unsuited to the tropics, and a letter of introduction from the then Governor of New Zealand, the Earl of Glasgow, to the Lieutenant-Governor of British New Guinea, Sir William MacGregor.

After two or three weeks of waiting, we took passage by the mail schooner Myrtle, 150 tons, one of two schooners owned by Messrs. Burns, Philp and Co., of Sydney, and subsidized by the British New Guinea Government to carry monthly mails to that possession; in fact they were then the only means of communication between New Guinea and the rest of the world. These two vessels, after a chequered career in the South Seas, as slavers—then euphoniously termed in Australia “labour” vessels—had, by the lapse of time and purchase by a firm of high repute and keen commercial ambition, now been promoted to the dignity of carrying H.M. Mails, Government stores for the Administration of New Guinea, and supplies to the branches of the firm at Samarai and Port Moresby; and were, under the energetic superintendence of their respective masters, Steel and Inman, extending the commercial interests of their owners throughout both the British and German territories bordering on the Coral Sea.

Good old ships long since done with, the bones of one lie scattered on a reef, the other when last I saw her was a coal hulk in a Queensland port. And good old Scotch firm of trade grabbers that owned them, sending their ships, in spite of any risk, wherever a possible bawbee was to be made, and taking their hundred per2 cent. of profit with the same dour front they took their frequently trebled loss. Mopping up the German trade until the day came when the heavily subsidized ships of the Nord Deutscher Lloyd drove them out; as well they might, for in one scale hung the efforts of a small company of British merchants, unassisted as ever by its country or Government, the other, a practically Imperial Company backed by the resources of a vast Empire.

But to return to the Myrtle, then lying in the bay off the mouth of the Endeavour River, to which we were ferried in one of her own boats, perched on the top of hen coops filled with screeching poultry, several protesting pigs, and two goats; all mixed up with a belated mail bag, parcels sent by local residents to friends in New Guinea, and three hot and particularly cross seamen. The goats we learnt later were destined to serve as mutton for the Government House table; the pigs and hens were a little private venture of the ship’s cook, these being intended for barter with natives.

On our arrival at the ship’s side, we were promptly boosted up a most elusive rope ladder by the seamen who had ferried us across, the schooner meanwhile rolling in a nasty cross sea and raising the devil’s own din with her flapping sails. Tumbled over the bulwarks on to the deck, we were seized upon by a violent little man in a frantic state of excitement, perspiration, and bad language, and ten seconds later found ourselves helping him to haul on the tackles of the boat that brought us, which was then being hoisted in, pigs, goats, luggage, etc., holus bolus; this operation completed, our violent little man introduced himself as Mr. Wisdell, the ship’s cook, and volunteered to show us to our berths, after which, as soon as the bustle of getting under way was over, he stated his intention of formerly introducing us to the captain.

Just as we were somewhat dismally becoming quite assured that our imaginations were not deceiving us as to the number of beetles and cockroaches a berth of most attenuated size could contain; also beginning to find that the motions of a schooner of 150 tons were decidedly upsetting to our stomachs, after those of big vessels, Mr. Wisdell returned and, diving into a locker, produced a bottle of whisky, some sodawater, and four tumblers. Three of the latter he placed with the other materials in the fiddle of the cabin’s table, the remaining tumbler he held behind his back. Then politely bowing to us, Mr. Wisdell signed that we were to precede him up the companion way on to the poop, where a red-faced, cheery looking little man, clothed in immaculate white ducks, gazed fixedly at the sails or at the man at the wheel, a regard that the helmsman looked as if he would willingly have done without. To him Mr. Wisdell marched, and then “Mr.3 Sylvester—Captain Inman—Captain Inman—Mr. Monckton—etc.” Never did Clapham dancing master receive the bows of his class with greater dignity and grace, than did Captain Inman receive those which, modelling our deportment on that of Mr. Wisdell, we made him.

Then Mr. Wisdell, still carrying the tumbler behind his back, spake thus: “Perhaps, Captain Inman, you would like to offer the gentlemen a little something in the cabin?” Captain Inman unbent: “Billy, the mate has the blasted fever; send the bo’sun.” Upon the appearance of that potentate, and his having apparently taken over the command, by dint of fixing the man at the wheel with a basilisk glare, Captain Inman led the way to the cabin, where Mr. Wisdell, kindly placing a glass in each of our hands, drew attention to the bottle and, with deprecating little coughs directed towards his commander, modestly backed away. Captain Inman, however, was well versed in the etiquette the occasion demanded and rose to it. “What, Billy, only three glasses! We want another!” Out shot Mr. Wisdell’s glass from behind his back and the occasion was complete.

Two days of violent sea-sickness then intervened, the misery of which was broken only by the visits of Mr. Wisdell, or as better acquaintance now permitted us to call him, “Billy,” bearing “mutton” broth prepared from goat. These animals, by the way, appear to be indigenous to the streets of Cooktown and to frequent them in large herds; their sustenance seems to be gleaned from the rubbish heaps and back yards; for of grass, at the time I was there, there was none, and their camping places were for choice the doorsteps and verandahs of the hotels, from which vantage points, at frequent intervals, the slumbers of the lodgers were cheered by the sound of violent strife, and sweetened by the peculiar fragrance diffused by ancient goats.

Then came one fine and memorable morning when our cheerful little skipper called us to look at Samarai, at that time called by the hideous name of Dinner Island, towards the anchorage of which we were slowly moving, the while, from every direction, a swarm of canoes paddled furiously towards us, crowded with fuzzy-headed natives, all eager to earn a few sticks of tobacco, by assisting in the discharge of the cargo we carried. The canoes were warned off pending the arrival of a health officer to grant pratique, and that official soon appeared in the person of Mr. R. E. Armit, a well-set-up, soldierly looking man of about fifty years of age. Poor Armit, long since killed by the deadly malaria of the Northern Division.

Mr. Armit was Subcollector of Customs and goodness knows what else at Samarai, and was himself an extraordinary personality. An accomplished linguist, widely read and travelled, I never found4 a subject about which Armit did not know something and usually a very great deal. He, however, did not possess a faculty for making or retaining money, and did possess a particularly caustic tongue and pen, which, when the mood took him, he would exercise even upon his superior officers; hence he was frequently in hot water and never lacked enemies.

Samarai boasted neither wharf nor jetty; our cargo was therefore simply shot over the side into the multitude of canoes and thence ferried to the beach, with such assistance as the ship’s boats could afford.

Dinner Island, or as I shall from now on term it, Samarai, is an island of about fifty acres. The hill, which forms the centre of the island, rises from what was then a malodorous swamp, surrounded by a strip of coral beach. The whole island was a gazetted penal district, and the town consisted of the Residency, a fine roomy bungalow built by the Imperial Government for the then Commissioner, General Sir Peter Scratchley—the first of New Guinea officials to be claimed by malaria—and now the headquarters of the Resident Magistrate for the Eastern Division; a small three-roomed building of native grass and round poles dubbed the Subcollector’s house; a gaol of native material, the roof of which served as a bond store for dutiable goods, and a cemetery: the three latter appeared to be well filled. There was also a small single-roomed galvanized iron building which served as a Custom’s house; in it was employed a clerk, unpaid; he was an affable gentleman of mixed French and Greek parentage, and was at the time awaiting his trial for murder. Two small stores, the one owned by Burns, Philp and Co., of Sydney, and the other by Mr. William Whitten, now the Honble. William Whitten, M.L.C., completed the main buildings.

Mr. Whitten was the son of a Queen’s Messenger, since dead of malaria, and possessed an adventurous disposition which had taken him off to sea as a boy. His first appearance in New Guinea was as one of the personal guard of Sir Peter Scratchley, a body which Sir William MacGregor replaced with his fine native constabulary. Whitten had saved money enough to purchase a small cutter, with which he had begun trading for bêche-de-mer in the Trobriand Islands. While dealing with the natives for that commodity, he had discovered that pearls of a fair quality existed in a small oyster forming one of the staple foods of the natives. Whitten purchased large quantities of the pearls from the natives for almost nothing, and had he only been able to keep his discovery to himself, would have had fortune in his grasp. Unfortunately for him, the sale of his prize in Australia brought down upon him a host of other competitors, and the natives, having discovered that the white man was keenly desirous of obtaining what were to5 them worthless stones, raised their prices higher and higher until there was little to be gained in the trade.

Whitten, however, had made enough to bring a young brother from England, purchase a bigger and better vessel, also a large quantity of merchandise. At the date of writing, Whitten Brothers own numerous plantations, several steamers and sailing vessels, conduct a banking business, have branches in the gold-fields, and are the largest employers of labour in the country; in 1895, however, this greatness was as yet undreamt of by them.

Other than the Residency and the glorified sardine box doing duty as the Custom House, the only other building in Samarai formed of European materials—by which I mean sawn timber and fastened with nails—was the bungalow occupied by Burns, Philp’s manager, and situated on perhaps the best site there. Gangs of prisoners—native—were engaged quarrying in the hill of Samarai and filling up the swamp, a palpably necessary work. Curiously enough in a pleasantly written little book by Colonel Kenneth Mackay, C.B., entitled “Across Papua,” I noticed a reference to this work, which was ultimately the means of stamping malaria out of the place. The author attributed it, amongst others, to Doctor Jones, a health officer who came to New Guinea in recent years. This statement is quite incorrect; the credit of banishing malaria from Samarai belongs to Sir William MacGregor, and to him alone.

A few sheds, occupied by boat-builders and carpenters, scattered along the beach, complete the buildings of Samarai. Of hotels and accommodation houses there were none, but then there was no travelling public to accommodate; gold-diggers to and from the islands of Sudest and St. Aignan camped in their tents, which as a rule consisted of a single sheet of calico stretched over a pole; traders lived in their vessels. Alcoholic refreshment was dispensed at the stores; Burns, Philp’s manager, for instance, or one of the Whittens, ceasing from their book-keeping labours to serve thirsty customers with lager beer or more potent fluids over the store counter. Whitten Brothers had a large roofed balcony with no sides, situated at the back of the store, and here at night, as to a general club-house, foregathered all the Europeans of the island. Under a centre table was placed a supply of varied drinks, and as men came in and bottles were emptied, they were hurled over the edge on to the soft coral sand. In the morning one of the Whittens caused the bottles to be collected by a native boy, counted them, and avoided the trouble of book-keeping by the simple method of dividing the sum total of bottles by the number of men he knew, or that his boy told him, had visited the “house”; each man therefore, whether a thirsty person or not, was charged exactly the same as his neighbour.

All Samarai was planted with cocoanut palms, the dodging of6 falling nuts from which, in windy weather, served to keep the inhabitants spry. Pyjamas were the almost universal wear, varied in the case of some traders by a strip of turkey-red twill, worn petticoat fashion, and a cotton vest.

Among the traders were two picturesque ruffians, alike in nothing, save the ability with which they conducted their business and dodged hanging. Each had spent his life trading in the South Seas and had amassed a fair fortune. Of them and their exploits I have heard endless yarns. Of one of these men, who was known far and wide through the South Seas as “Nicholas the Greek”—Heaven knows why, for his real name sounded English, and his reckless courage was certainly not typical of the modern Greek—the following stories are told.

A vessel had been cut out in one of the New Guinea or Louisade Islands—which it was I have forgotten—and the crew massacred. When this became known, a man-of-war or Government ship was sent to punish the murderers, and in especial to secure a native chief, who was primarily responsible. The punitive ship came across Nicholas and engaged him as pilot and interpreter, he being offered one hundred pounds when the man wanted was secured. Nicholas safely piloted his charge to some remote island where the inhabitants, doubtless having guilty consciences, promptly fled for the hills, where it was impossible for ordinary Europeans to follow them. He then offered to go alone to try and locate them, and, armed with a ship’s cutlass and revolver, disappeared on his quest. Some days elapsed, then in the night a small canoe appeared alongside the ship, from which emerged Nicholas, bearing in his hand a bundle. Marching up to the officer commanding, he undid it, and rolled at the officer’s feet a gory human head, remarking, “Here is your man, I couldn’t bring the lot of him. I’ll thank you for that hundred.”

Another story was that Nicholas on one occasion was attacked and frightfully slashed about by his native crew and then thrown overboard, he shamming dead. Sinking in the water he managed to get under the keel, along which he crawled like a crawfish until he came to the rudder, upon which he roosted under the counter until night fell and his crew slept. Then he climbed on board, secured a tomahawk, and either killed or drove overboard the whole crew, they thinking he was an avenging ghost. This done, badly wounded and unassisted, he worked his vessel to a neighbouring island, where, being sickened and disgusted with men, he shipped and trained a crew of native women, with whom he sailed for many years, in fact, I think, until the day came when Sir W. MacGregor appeared upon the scene and passed the Native Labour Ordinance, which, amongst other things, prohibited the carrying of women on vessels.

7 Of Nicholas also is told the story that once, in the bad old pre-protectorate days, so many charges were brought against him by missionaries and merchantmen that a man-of-war was sent to arrest him, wherever found, and bring him to trial. He, through a friendly trader, got wind of the fact that he was being sought for, and accordingly laid his plans for the bamboozlement of his would-be captors. Summoning his crew, he informed them that his father was dead, and that as he had his father’s name of Nicholas, his name must now be “Peter,” as the custom of his tribe was, even as that of some New Guinea peoples, viz. not to mention the name of the dead lest harm befall. Then he sailed in search of the pursuing warship and, eventually finding her, went on board and volunteered his services as pilot, which were gladly accepted. To all of his haunts he then guided that ship, but in all the reply of the native was the same, when questioned as to his whereabouts, “We know not Nicholas, he is gone. Peter your pilot comes in his place. Nicholas is dead, and ’tis wrong to mention the name of the dead.” It was said of him that on no part of his body could a man’s hand be placed without touching the scar of some old wound—a story I can fully believe.

The second of this interesting couple was known as “German Harry,” a man of insignificant appearance and little physical strength, but the most venomous little scorpion, when thoroughly roused, it has ever been my lot to meet; at the same time he was the most generous-hearted little man towards the hard up and unfortunate. He had also spent a considerable portion of his time in dodging arrest or explaining certain alleged manslaughters of his before various tribunals. I remember one little specimen I witnessed of Harry’s fighting methods, and from that understood why the biggest of bullies and “hard cases” treated him with respect.

A vessel, owned and commanded by a hulking brute of a Dane, had come over from Queensland bringing, amongst other things, some recent papers, one of which contained an account of a disgraceful wife-beating case, in which the Dane figured and in which he had escaped—as such brutes generally do in civilized countries—by the payment of a miserable fine.

As Harry, the Dane and I, were sitting in a gold-field store, Harry read the account, and then gazing at the Dane, said something in German, of which “Schweinhund” was the only word I understood. A glass of rum promptly smashed on Harry’s teeth, followed by a bellow of rage and the thrower’s rush. Harry in a single instant became a lunatic, and flying like a wild cat at the other’s face, kicking, biting, and clawing, bore the big man to the ground, from where, in a few seconds, agonized yells of, “He is eating me,” told us the Dane was in dire trouble. Harry was8 dragged away by main force, and we found half his victim’s nose bitten off, while a bloodshot and protruding eye showed how nearly his thumb had got its work in. The wife-beater went off a mass of funk and misery, while Harry proceeded calmly to attend to the glass cuts on his face. “You are a nice cheerful sort of little hyena,” I remarked to Harry afterwards. “What sort of fighting do you call that?” “That? Oh, that’s nothing. I only wanted to frighten him or I would have had his eye out as well. He won’t throw a glass at German Harry again in a hurry.”

Some years later I met German Harry in a Sydney street, and though I had long since thought I was beyond being surprised at anything he did, he yet gave me a further shock when he told me he had purchased a “Matrimonial Agency.”

9

CHAPTER II

The day following our arrival in Samarai, loud yells of “Sail Ho!” from every native in the island announced that the Merrie England was returning from the Mambare River, where the Lieut.-Governor had been occupied in punishing the native murderers of a man named Clarke, the leader of a prospecting party in search of gold; and in establishing at that point, for the protection of future prospectors, a police post under the gallant but ill-fated John Green. Clarke’s murder was destined, though no one realized it at the time, to be the beginning of a long period of bloodshed and anarchy in the Northern Division—then still a portion of the Eastern Division. These events, however, belong to a later date and chapter.

On her voyage south from the Mambare, the Merrie England had waited at the mouth of the Musa River, while Sir William MacGregor traversed and mapped that stream. Whilst so engaged, accompanied by but one officer and a single boat’s crew of native police, His Excellency discovered a war party of north-east coast natives returning from a cannibal feast, with their canoes loaded with dismembered human bodies. Descending the river, Sir William collected his native police and, attacking the raiders, dealt out condign and summary justice, which resulted in the tribes of the lower Musa dwelling for many a year in a security to which several generations had been strangers.

Some little time after the ship had cast anchor, my friend and myself received a message that Sir William was disengaged; whereupon we went on board to meet, for the first time, the strongest man it has ever been my fate to look upon. Short, square, slightly bald, speaking with a strong Scotch accent, showing signs of overwork and the ravages of malaria, there was nothing in the first appearance of the man to stamp him as being out of the ordinary, but I had not been three minutes in his cabin before I realized that I was in the presence of a master of men—a Cromwell, a Drake, a Cæsar or Napoleon—his keen grey eyes looking clean through me, and knew that I was being summed and weighed. Once, and only once in my life, have I felt that a man was my master in every way, a person to be blindly obeyed and one who must be10 right and infallible, and that was when I met Sir William MacGregor.

Years afterwards, in conversation with a man who had held high command, who had distinguished himself and been much decorated for services in Britain’s little wars, I described the impression that MacGregor had made upon me, the sort of overwhelming sense of inferiority he, unconsciously to himself, made one feel, and was told that my friend had experienced a like impression when meeting Cecil Rhodes.

The story of how Sir William MacGregor came to be appointed to New Guinea was to me rather an interesting one, as showing the result, in the history of a country, of a fortunate accident. It was related to me by Bishop Stone-Wigg, to whom it had been told by the man responsible for the appointment, either Sir Samuel Griffiths, Sir Hugh Nelson, or Sir Thomas McIlwraith, which of the three I have now forgotten. Sir William, at the time Doctor MacGregor, was attending, as the representative of Fiji, one of the earlier conferences regarding the proposed Federation of Australasia; he had already made his mark by work performed in connection with the suppression of the revolt among the hill tribes of that Crown Colony. At the conference, amongst other questions, New Guinea came up for discussion, whereupon MacGregor remarked: “There is the last country remaining, in which the Englishman can show what can be done by just native policy.” The remark struck the attention of one of the delegates, by whom the mental note was made, “If Queensland ever has a say in the affairs of New Guinea, and I have a say in the affairs of Queensland, you shall be the man for New Guinea.” When later, New Guinea was declared a British Possession, Queensland had a very large say in the matter, and the man who had made the mental note happening to be Premier, he caused the appointment of Administrator to be offered to MacGregor, by whom it was accepted.

Of Sir William, a story told me by himself will illustrate his determination of character, even at an early age, though not related with that intention.

MacGregor, when completing his training at a Scotch University, found his money becoming exhausted; no time could he spare from his studies in which to earn any, even were the opportunity there. Something had to be done, so MacGregor called his old Scotch landlady into consultation as to ways and means. “Well, Mr. MacGregor, how much a week can you find?” “Half a crown.” “Well, I can do it for that.” And this is how she did it. MacGregor had a bowl of porridge for breakfast, nothing else; two fresh herrings or one red one, the cost of the fresh ones being identical with the cured one, for dinner; and a bowl of porridge11 again for supper. Thus he completed his course and took the gold medal of his year.

THE RIGHT HONBLE. SIR WILLIAM MACGREGOR, P.C., G.C.M.G., C.B., ETC., ETC., ETC.

From the portrait by James Quinn, R. A., exhibited at the Royal Academy, 1915

This thoroughness and grim determination MacGregor still carried into his work; for instance, it was necessary for him, unless he was prepared to have a trained surveyor always with him on his expeditions, to have a knowledge of astronomy and surveying. This he took up with his usual vigour, and I once witnessed a little incident which showed, not only how perfect Sir William had made himself in the subject, but also his unbounded confidence in himself. We were lying off a small island about which a doubt existed as to whether it was within the waters of Queensland or New Guinea. The commander of the Merrie England, together with the navigating officer, took a set of stellar observations; the chief Government surveyor, together with an assistant surveyor, took a second set; and Sir William took a third. The ship’s party and the surveyors arrived at one result, Sir William at a slightly different one; an ordinary man would have decided that four highly competent professional men must be right and he wrong; not so, however, MacGregor. “Ye are both wrong,” was his remark, when their results were handed to him by the commander and surveyor. They demurred, pointing out that their observations tallied. “Do it again, ye don’t agree with mine;” and sure enough Sir William proved right and they wrong.

My part in this had been to hold a bull’s-eye lantern for Sir William to the arc of his theodolite, and to endeavour to attain the immobility of a bronze statue while being devoured by gnats and mosquitoes. Therefore later I sought Stuart Russell, the chief surveyor, with the intention of working off a little of the irritation of the bites by japing at him. “What sort of surveyors do you and Commander Curtis think yourselves? Got to have a bally amateur to help you, eh?” “Shut up, Monckton,” said Stuart Russell, “we are surveyors of ordinary ability, Sir William is of more than that.”

The same sort of thing occurred with Sir William in languages; he spoke Italian to Giulianetti, poor Giulianetti later murdered at Mekeo; German to Kowold, poor Kowold, too, later killed by a dynamite explosion on the Musa River; and French to the members of the Sacred Heart Mission. I believe if a Russian or a Japanese had turned up, Sir William would have addressed him in his own language. Ross-Johnston, at one time private secretary to Sir William, once wailed to me about the standard of erudition Sir William expected in a man’s knowledge of a foreign language. Ross-Johnston had been educated in Germany and knew German, as he thought, as well as his own mother tongue. Sir William while reading some abstruse German book, struck a passage the12 meaning of which was to him somewhat obscure; he referred to Ross-Johnston, who, far from being able to explain the passage, could not make sense of the chapter. Whereupon Sir William remarked that he thought Ross-Johnston professed to know German. Ross-Johnston, feeling somewhat injured, took the book to Kowold, who was a German. Kowold gave one look at it, then exclaimed, “Phew! I can’t understand that, it’s written by a scientist for scientists!”

One little story about MacGregor, a story I have always loved, was that on one occasion while sitting in Legislative Council some member, bolder than usual, asked, “What happens, your Excellency, should Council differ with your views?” “Man,” replied Sir William, “the result would be the same.” But I digress, as Bullen remarks, and shall return from stories about MacGregor to his cabin and my own affairs.

Sir William told my friend and myself, that for two reasons he could not offer either of us employment in his service. Firstly, that the amount of money at his disposal, £12,000 per annum, did not permit of fresh appointments until vacancies occurred; secondly, that his officers must be conversant with native customs and ways of thought, which experience we were entirely lacking. His Excellency, however, told us that he had just received word of the discovery of gold upon Woodlark Island, to which place the ship would at once proceed, and that we might go in her; an offer we gladly accepted.

Then for the first time I met Mr. F. P. Winter, afterwards Sir Francis Winter, Chief Magistrate of the Possession; the Hon. M. H. Moreton, Resident Magistrate of the Eastern Division; Cameron, Chief Government Surveyor; Mervyn Jones, Commander of the Merrie England; and Meredith, head gaoler.

Winter had been a law officer in the service of Fiji, and upon the appointment of Sir William MacGregor to New Guinea, had been chosen by him as his Chief Justice and general right-hand man; the wisdom of which choice later years amply showed. Widely read, a profound thinker, possessed of a singular charm of manner, simple and unaffected to a degree, Winter was a man that fascinated every one with whom he came in contact. I don’t think he ever said an unkind word or did a mean action in his life. Every officer in the Service, then and later, took his troubles to him, and every unfortunate out of the Service appealed to his purse.

Moreton, a younger brother of the present Earl of Ducie, had begun life in the Seaforth Highlanders; plucky, hard working, and the best of good fellows, he was fated to work on in New Guinea till, with his constitution shattered, an Australian Government chucked him out to make room for a younger man; shortly after which he died.

13 Cameron, the surveyor, was another good man, and wholly wrapped up in his work. Of Cameron it was said, that he imagined that surveyors were not for the purpose of surveying the earth, but that the earth was created solely for them to survey. He, good chap, was luckier than Moreton, for his fate was to die in harness; he being found sitting dead in his chair, pen in hand, with a half-written dispatch in front of him.

Mervyn Jones was a particularly smart seaman and navigator; educated at Eton for other things, the sea had, however, exercised an irresistible fascination for him; being too old for the Navy, he had worked up into the Naval Reserve through the Merchant Service, and thus had come out to command the Merrie England. The charts of the Coral Sea owe much to his labour, and to that also of his two officers, Rothwell and Taylor. All these officers were destined later to share a more or less common fate: Jones died of a combination of lungs and malaria, Taylor of malaria at sea, whilst Rothwell was invalided out of the service. Meredith was taking a gang of native convicts down to Sudest Island; they had been lent by the New Guinea Government to assist in making a road to a gold reef discovered there which was now being opened by an Australian company. It was here that he and many of his charges left their bones.

Not far from Sudest lies Rossel Island, a wooded hilly land, inhabited by a small dark-skinned people differing in language and customs from all other Papuans. Personally I do not believe they have any affinity with Papuans, either by descent or in other ways, whatever views ethnologists may hold. The Rossel Islanders have among their songs several Chinese chants, the origin of which is explained in this way. In September, 1858, the ship St. Paul, bound from China to the Australian gold-fields, and carrying some three hundred Chinese coolies, was wrecked on an outlying sand-bank of Rossel. The European officers and crew took to the boats and made their way to Queensland, the Chinamen being left to shift for themselves. Thus abandoned to their fate, the Chinamen were discovered by the islanders, and were by them liberally supplied with food and water; when well fattened they were removed in canoes to the main island, in lots of five and ten, and there killed and eaten. The Chinamen, when removed, were under the impression that they were merely taken in small numbers as the native canoes could only carry a few passengers at a time, being ignorant of the distance of the sea journey. As they left their awful sand-bank in the canoes, they sang pæans and chants of joy, which the quick-eared natives picked up and incorporated in their songs. In 1859 but one solitary Chinaman remained of the three hundred, and he, fortunate man, was taken off Rossel by a passing French steamer and landed in Australia,14 where history or scandal says he later pursued the occupation of sly grog seller at a Victorian gold rush, and being convicted thereof, was later pardoned in consideration of his sufferings and being the sole survivor of three hundred.

From Sudest the Merrie England went on to Woodlark Island, from whence the discovery of gold had been reported by a couple of traders, Lobb and Ede. These two men were a very good example of the old gold-field’s practice of “dividing mates.” Lobb was professional gold or other mineral prospector, who had sought for gold in any land where it was likely to occur; when successful, his gains, however great, soon slipped away; when unsuccessful, he depended on a “mate” to finance and feed him, in diggers’ language, “grub stake” him, until such time as his unerring instinct should again locate a fresh find. Ede was a New Guinea trader owning a cocoanut plantation on the Laughlan Isles, together with a small vessel. Ede landed Lobb on Woodlark with a number of reliable natives, and, keeping him going with tools, provisions, etc., at last had his reward by word from Lobb of the discovery of payable gold. Thereupon they had reported their discovery and applied for a reward claim to the Administration, together with the request that the island should be proclaimed a gold-field; and at the same time had informed their trader friends, some twenty in all, of what was to be gained at the island.

Lobb and Ede, with their twenty friends, formed the European population of the island when the Merrie England arrived there; with the exception of Lobb, there was not an experienced miner in the lot. The twenty were a curious collection of men: an ex-Captain in Les Chasseurs D’Afrique, whom later on I got to know very well, but who, poor chap, was always most unjustly suspected by the diggers of being an escapee from the French convict establishment at New Caledonia, merely because he was a Frenchman; an unfrocked priest, who by the way was a most plausible and finished scoundrel; and the son of the Premier of one of the Australian colonies; these now, with Ede and myself, constitute the sole survivors of the men who heard Sir William declare the island a gold-field. Here it was that an ex-British resident, and the son of a famous Irish Churchman, jostled shoulders with men whose real names were only known to the police in the various countries from which they hailed. “Jimmy from Heaven,” an angelic person, who was once sentenced to be hanged for murder and, the rope breaking, gained a reprieve and pardon, hence his sobriquet; “Greasy Bill”; “Bill the Boozer”; “French Pete”; and “The Dove,” a most truculent scoundrel; the names they answered to sufficiently explain the men.

15 All nationalities and all shades of character, from good to damned bad, they however all held two virtues in common: a dauntless courage and a large charity to the unfortunate; traits which will perhaps stand them in better stead in the bourne to which they have gone than they did in New Guinea.

16

CHAPTER III

Some six months I put in at Woodlark Island, acquiring during that time a fine strong brand of malaria, a crop of boils, which had spread like wildfire among the mining camps, catching Europeans and natives alike, a little gold, and a large amount of experience; all of which were most painfully acquired.

Sylvester, after having suffered some particularly malignant bouts of malaria and having developed some corroding and fast-spreading mangrove ulcers, parted company with me and went to New Zealand. The mangrove ulcer, commonly called New Guinea sore, is, I think, quite the most beastly thing one has to contend with on those islands; it is mainly caused, in the first instance, by leech or mosquito bites setting up an irritation which causes the victim to scratch; then the poisonous mud of either mangrove or pandanus swamps gets into the abrasion, and an indolent ulcer is set up, which slowly but perceptibly spreads, as well as eating inward to the bone, for which I know no remedy other than a change to a temperate climate. Painful when touched during the day, it is agony itself when the legs stiffen at night.

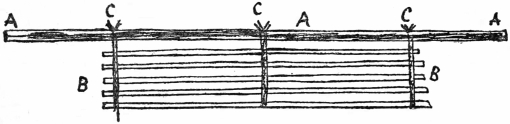

The method of obtaining gold, at the time I was at Woodlark Island, was primitive and simple in the extreme, and was performed in this way. Having located a stream, gully or ravine, in which a “prospect” could be found to the “dish,” the “prospect” consisting of one or more grains of gold, the “dish” holding approximately thirty pounds weight of wash dirt, i.e. gold-bearing gravel, the miner—or digger, as he is more generally called—pegged out a claim of some fifty feet square. When he had done this he put in a small dam, to the overflow of which he attached a wooden box some six feet long by twelve inches wide, having a fall of one inch to the foot, and paved with either flat stones or plaited vines. Into the head of this box was then thrown the wash dirt, from which the action of the water washed away the stones, sand, etc., leaving the gold precipitated at the bottom. The larger the flow of water, the more dirt could be put through, and the more dirt the more gold.

The title to a claim consisted of a document called a “Miner’s17 Right,” which permitted the holder to peg out and keep the above area, or as many more of similar dimensions as he chose to occupy or man. A miner’s right cost ten shillings per annum and ipso facto constituted the holder a miner—sex, infancy, or nationality notwithstanding, the only ineligibles being Chinese. “Manning ground” consisted of placing a person holding a miner’s right in occupation thereof, the wages that person received being immaterial. Thus a man employing ten or a dozen Papuans, at wages ranging from five to ten shillings a month, could, by merely paying ten shillings per annum per head for miner’s rights, monopolize ten or a dozen claims. The wages of the European miner ranged from twenty shillings a day and upwards, this, of course, being the man contemplated by the Queensland Mining Act, and adopted by New Guinea, as the person likely to man and work ground held by the miner holding ground in excess of that to which his own “right” entitled him.

In theory, it is of course manifestly unfair, that the native of a country should be classed as an alien, and debarred from any privilege conferred by law upon Europeans; but in practice, the granting of miner’s rights to them merely means that the European able to employ a number of natives can monopolize claims, to the exclusion of other Europeans. The native gets no more wages for his privilege of holding ground, and were the privilege withdrawn would still obtain exactly the employment he gets now, as his labour in working the claims is necessary and profitable to his employer, and the supply of native labour for the miner is never equal to the demand.

An interesting feature in connection with gold-mining on Woodlark Island was that frequently the gold-bearing gravel ran under old coral reefs, thus showing plainly that the whole gold-field had once been submerged under the sea. A warm spring running into one of the streams was, however, the only indication of past volcanic action. In the pearling ground off the island of Sudest, there occurs again under the sea, at a depth of fifteen fathoms, a big quartz reef running through the live coral and sand bottom—whether gold-bearing or not I cannot say—and dipping underground as it nears the shore.

Some time after my arrival at Woodlark the schooner Ivanhoe came in bringing provisions, tools, etc., for the gold-diggers, together with a number of fresh arrivals, among whom was a Russian Finn, the meanest and, in his personal habits, the dirtiest beast I have ever met. This fellow proved most successful in his mining; but eventually, while prospecting near his claim, lost himself in the forest. Upon his being missed, a search party was organized by the diggers to look for him, but after some weeks the quest was abandoned as hopeless and the man given up for18 lost; a considerable amount was, however, subscribed and offered by the diggers as a reward to any one finding or bringing him in. The Finn, in the long run, was discovered in a starving condition by some natives who, after feeding him and nursing him back to life, brought him to the mining camp, where he learnt of the reward offered for his recovery. He then had the ineffable impudence to object to its being paid over to the natives, on the ground that it was subscribed for his benefit, and that therefore he should receive it, magnanimously saying, however, that the natives should be given a few pounds of tobacco. Needless to remark, his views were disregarded, and the natives received the full amount; the man, however, as he was yet in a weak state of health and professed to have lost all his gold, was given sufficient to pay his passage to Samarai and maintain himself for a month from a fresh “hat” collection. At Samarai he resided for some time cadging, loafing, and pleading poverty, until one day the repose of the inhabitants was disturbed by wails of bitter grief proceeding from the interior of a small building, which was built over a bottomless hole descending through the coral rock, and was used by the islanders as a receptacle for refuse. Inquiry disclosed the fact that, during all the time he was lost and later, the Finn had worn a belt next his skin containing over two hundred ounces of gold, which he had kept carefully concealed. Having cadged a little more gold, he had gone to the small building, as being the most secluded place, to add it to his store when, being suddenly startled, he had inadvertently knocked the belt into the hole, where it lies to this day.

This was an instance of a man losing his gold, and well he deserved it; but I knew of another instance in which a large amount of gold was lost and recovered in a manner so miraculous, that but for the fact that many men are yet living in New Guinea, fully acquainted with all the circumstances, I should hesitate to tell the story.

A party of successful miners was returning to Samarai in a small cutter chartered for the occasion, the gold belonging to the individual men in their separate parcels or “shammys” as they are called—the name is derived from a corruption of chamois, the skin of which animal is fondly supposed by diggers to furnish the only material for bullion bags—being sown up together in a large hoop of canvas, and placed on the hatch in open view of all hands. The weather was fine and clear, no danger being anticipated, when as the vessel entered China Straits she was struck by a sudden squall, and heeling over shot the diggers’ shammys into the scuppers, through one of which they disappeared. So soon as the startled skipper could collect his wits and get his vessel in hand, he took soundings and bearings, and running hastily into Samarai, collected such pearlers as were there working, and offered19 half the gold to any of them recovering it. Several pearlers at once sailed for the spot, accompanied by the cutter of the bereaved diggers, which dropped her anchor at the scene of the accident and proceeded to watch operations. Diver after diver descended and toiled, diver after diver ascended and reported a soft mud bottom and a hopeless quest; pearler after pearler lifted his anchor and went back to Samarai, until at last the cutter hoisted her anchor also, preparatory to taking the diggers back to the gold-fields. A disconsolate lot of men watched that anchor coming up, but I leave to the imagination the change in their expressions when, clinging in the mud to the fluke of the anchor, they saw their canvas belt of gold.

After the departure of Sylvester I went into partnership with one Karl Wilsen, a Swede; he furnishing towards the assets of the partnership a poor claim and local mining experience, I, a well-filled chest of drugs and some knowledge of medicine. A couple of weeks after our partnership had been arranged, Lobb, the original prospector of the island, appeared at our claim with the news of a new gold find, at which he advised us to peg out a claim. At the same time he told me he was sailing for Samarai in a lugger owned by his partner Ede, in order to buy fresh stores, and asked me for company’s sake to go with him, holding out, as an inducement, that by doing so I could obtain some natives to assist in the heavy manual labour of the claim. Wilsen hastily left for the new find to peg out a joint claim for the pair of us, and I departed with Lobb for Samarai.

Lobb’s vessel, on which I now found myself, was an old P. and O. lifeboat, built up until of about seven tons burthen, lug-rigged on two masts, and carrying a crew of six Teste Island (“Wari”) boys. Lobb, I soon found to be absolutely ignorant of the most elementary knowledge of either seamanship or navigation; the seamanship necessary for our safe journey being furnished by the Wari boys, who had for generations been the makers and sailors of the large Wari sailing canoes trading between the islands. This kind of navigation consisted of sailing from island to island, being entirely dependent on the local knowledge of individual members of the crew to identify each island when sighted.

Shortly after leaving Woodlark we fell into a dead calm which lasted until nightfall—after which Lobb improved the occasion by getting drunk—then came on heavy variable rain squalls, during which the native crew appealed to me as to how they were to steer; being unable to see, they did not know where they were going, and Lobb was not by any means in a state to direct them. Fortunately I had noticed the compass bearing when we had left the passage from Woodlark and headed for Iwa, this being the20 line laid down by the crew in daylight; upon my asking them whether we should be safe if we followed that, and their replying “we should be,” I pasted a slip of white paper on the compass card and told them to keep it in a line with the jib-boom. When dawn broke, we had Iwa in front of us a few miles ahead, and running slowly up to it, hove-to in deep water, there being no anchorage off its shores.

Iwa is a somewhat remarkable island, and inhabited by a somewhat remarkable people. Rising sheer from the sea with precipitous faces, the only means of access to the summit is by the inhabitants’ ladders, made of vines and poles lashed together. The summit consists of shelving tablelands and terraces, all under a system of intense cultivation; yams, taro, the root of a sort of Arum, sweet potatoes, paw paws, pumpkins, etc., being grown in enormous quantities. The island of Iwa is quite impregnable so far as any attack by an enemy unarmed with cannon is concerned, and the natives have succeeded well as pirates in years gone by. From the top of Iwa, a clear view of many miles of surrounding sea could be had, and the husbandman, toiling in his garden, usually owned a share in a large paddle canoe, one of many hauled up in the crevices and rocks at the foot of the precipices of his island home. Sooner or later he would sight a sailing canoe, belonging to one of the other islands, becalmed or brought by the drift of currents to within sight of Iwa. At once, in response to his yell, a dozen paddle canoes, crowded with men, would take the water, and unless a breeze in the meantime sprang up, the traders usually fell easy victims. Reprisals there could be none, for no war party dispatched by one of the outraged tribes had a hope of scaling the cliffs of Iwa. The people there possessed an unusual skill in wood carving, their paddles, shaped like a water-lily leaf, being frequently marvels of workmanship.

Lobb remained hove-to for a couple of days at Iwa, purchasing copra (dried cocoanut kernel), used for making oilcake for cattle and the better quality of soap, together with the before-mentioned beautiful carved paddles of the people. Sometimes the lugger lay within a couple of hundred yards of the shore, sometimes she drifted out a couple of miles, whereupon half a dozen canoes, manned by a dozen sturdy natives, would drag us back to within the shorter distance. On the second day of our stay I witnessed a particularly callous and brutal murder. A woman swam out and sold a paddle to Lobb, for which she received payment in tobacco. Swimming ashore she met a man, apparently her husband, to whom she handed the tobacco. He, seeming not to be at all pleased with the price, struck the woman, and she fled into the sea, where he pursued and clubbed her, the body of the murdered woman drifting out and past our vessel. Lobb, to my amazement,21 took absolutely no notice of this little incident, and upon my drawing his attention to it and suggesting we should seize the murderer and take him to Samarai for trial, merely remarked, that I should do better to mind my own business.

Upon leaving the island, four days’ sail put us into Samarai, where, amongst other things in the course of casual conversation, I told Moreton of the murder I had seen at Iwa. Moreton questioned Lobb, who professed to know nothing about it. Lobb then tackled me, asking whether I was desirous of hanging about Samarai for three or four months, at my own expense, waiting for a sitting of the Central Court—the only court in New Guinea for capital offences—and upon my replying, that in that case I should starve as I had little money and there was no opportunity in Samarai of making any, Lobb said, “Exactly; well you had better forget all about that murder at Iwa, or you will be kept here.” I then went again to Moreton, who asked me whether I could swear to the man who did the murder, and I replied that I could not, as he was some hundred yards distant from me at the time and one native looked very like another. Moreton remarked, “I think Lobb’s advice to you is rather good, better follow it.”

Lobb remained about a week in Samarai recruiting a number of “boys” for work in his claim, and among them a couple, Sione and Gisavia, for me. We then sailed again for Woodlark. Upon our arrival back at the gold-field, I heard that the claim pegged out by Wilsen for the pair of us was a very rich one, but that he had taken Bill the Boozer into partnership instead of me. This story I found to be true; Wilsen had been tempted by a solid bribe when he found how good the ground was, and had drawn the pegs in my portion, which were at once replaced by Bill the Boozer, Wilsen declaring that I had gone for good. Wilsen and I then had a fight, in which I succeeded in giving him the father of a licking; this being followed by a law suit which I lost, mainly owing to the magnificent powers of lying displayed by Wilsen and the Boozer. I only met Wilsen twice after this, once, when he was witness in a court in which I was presiding as magistrate, and where he was so glib and fluent that I gave judgment for the opposing side, feeling quite convinced that any people Wilsen was connected with must be in the wrong; and again, when I held an inquest on his corpse, his death having been caused by his getting his life line and air pipe entangled while diving for pearl shell, and being paralysed by the long-sustained pressure. These events, however, were to occur at a later time.

In the meantime I had no claim, and it behoved me to find one; whereupon, accompanied by Sione and Gisavia, I wandered off into the jungle of Woodlark in search of a gold-bearing gully.22 Creek after creek and gully after gully we sunk holes in and tried, sometimes getting for our pains a few pennyweights of gold, but more often nothing. For food we depended on a small mat of rice of about fifty pounds weight carried by one boy, and as many sweet potatoes, yams or taro we could pick up from wandering natives. The other boy carried a pick and shovel, tin dish, crowbar, axe and knife, and three plain deal boards with a few nails, comprising our simple mining equipment, together with a sheet of calico, used as a “fly” or tent, to keep the rain from us at night. My pack consisted of a spare shirt, trousers and boots, rifle, revolver, ammunition, two billy cans for making tea and boiling rice, compass and matches, and last but not least a small roll case of the excellent tabloid drugs of Messrs. Burroughs and Wellcome.

In our wanderings we struck a valley—now known as Bushai—where at intervals of three hundred yards we put down pot holes without a “colour” to the dish. (A colour is a speck of gold, however minute.) This was an instance of bad luck sometimes dogging a prospector, for, some months later, a man named Mackenzie found the valley, and in the first hole he sunk found rich gold, while the claims pegged out on each side of his holding proved very payable “shows.” I came there again when it was a proved field and, recognizing the valley, asked Mackenzie whether on his first arrival he had noticed any pot holes. “Yes,” he said, “three of them. I don’t know who made them, but they were the only spots in the valley where I could not find a payable prospect.” There was then no ground left for me, so I went away, cursing the fates that had made me select the only barren parts of a rich valley in which to sink my holes.

This incident, however, belongs to a later day, and having “duffered” the valley as I thought, my boys and I prowled on through the forest over the place where the Kulamadau mine now stands, at which point we finished our “tucker” and obtained a few ounces of gold, enough to buy supplies for a few more weeks, when we should get to some place where such could be obtained. Living mainly on roots and a few birds, we fell into a mangrove swamp, where the three of us obtained such a crop of mangrove ulcers that we were hardly able to walk, and were obliged to strike straight for the sea. My boys of course wore no boots, and their swollen legs, painful as they might be, were not so inconvenient to them as mine were to me; for in my case I did not dare to take off my boots, for fear of not being able to get my enlarged feet into them again.

After a day with nothing to eat, we found the sea and an alligator. The alligator I shot, and we were eating him when we saw the sails of a schooner coming round a point close in shore.23 By dint of firing my revolver, and my boys howling vigorously, we attracted the attention of those on board; and a boat was lowered and sent to us, in which we went off to her, and then I discovered it was German Harry’s craft, the Galatea. German Harry had a cargo of stores for Woodlark, and was accompanied by a European wife—not his own, but some one else’s with whom he had bolted. He received me with sympathy and hospitality, and, telling his cook to boil quantities of hot water for the treatment of my own and my boys’ mangrove ulcers, set to work looking for bandages and soothing unguents, leaving me to be entertained by the other man’s wife.

A fortnight I put in with German Harry, acting for him as a sort of supercargo in tallying the sale of his cargo, listening to his tales of experiences in the islands, picking up the rudiments of navigation and the whole art of diving for pearls and mother of pearl by aid of the apparatus manufactured by either Siebe Gorman or Heinke, the only two firms of submarine engineers considered by the pearl fishers as at all worthy of patronage. Harry had on board the complete plants, from air pumps to dresses, of the rival manufacturers; and after exhaustive trials I came to the same conclusion as he, that both were equally excellent in still waters, and both beastly dangerous in currents or rough seas.

At the end of the two weeks the Galatea sailed for other parts, and I, refusing Harry’s invitation to accompany him again, plunged once more into the forest of Woodlark in search of gold and fortune. On this trip my sole discovery was some aged lime trees and old hard wood piles of European houses, which later inquiry among the natives showed me were the remains of an old French Jesuit Mission long since come and gone; these trees and piles and a few French words current among the natives, such as “couteaux,” being all that was left of their work.

Wandering back from the second and even more disastrous trip than the first (for in addition to an entire lack of gold and a second crop of ulcers, my boys and myself had now added intermittent and severe malaria to our stock-in-trade), I dropped into a gully in which a white miner was working by his lonesome self. Jim Brady was his name, and after feeding us and listening to our tales of adventure, or rather misadventure, he spake thus: “I have a damned poor show here, just about pays tucker, but if you like to chip in with your boys we will do a little better, and when we have fattened up a bit, one can keep the show going while t’other looks for something better.” Eagerly I accepted this offer, my boys and myself being only too thankful to find somewhere to rest out of the rain, with a fair prospect of three square meals a day. Brady and I then worked together for some months with24 varying fortune; the sole dissension arising between us being due to my stealing a piece of calico, in which he used to boil duff, with which to patch my only remaining pair of trousers.

Then one afternoon, whilst I and the two boys were digging out wash dirt and feeding the “sluice box,” he suddenly squealed, “What in the devil’s name are you sending me now? It’s a porphery leader and giving a weight to the dish,” i.e. a pennyweight of gold, worth about three shillings and fourpence. Brady then came and looked at the place where I was digging, and remarked, “Cover it up with mullock at once, it’s a good thing and we don’t want a crowd here.” I remonstrated, saying that we wanted all the gold we could get; but Brady said, “Yes, and we want all the ground we can get and enough money to clear from this blasted country; that leader wants capital, for which we shall have to arrange.” In obedience to Brady’s instructions I covered up the leader, and had hardly finished doing so, when an excited digger dropped into our claim exclaiming, “Have you heard the news? Mackenzie has struck a new gully with an ounce to the dish.” Brady and I at once bolted for a newly opened store to arrange a credit for tucker, to enable him to proceed to the new find. In the meanwhile, I was to remain and work our present claim to cover expenses. The store-keeper, one Thompson, was obdurate, refusing to give us any credit or even to sell us sufficient supplies for gold, to enable Brady to go to the new rush, he wishing to assist his own friends, or rather those men who could be depended on to spend all their earnings in grog at his store.

Brady and I were sitting most disconsolately outside the store when a cutter, the White Squall, came in loaded with diggers, but no supplies, when I suddenly overheard a remark of Thompson’s: “By God, I must buy or charter that cutter for Samarai for stores.” The cutter brought a mail, and amongst my letters I found a notice from Burns, Philp and Co., that £100 had been placed to my credit at Samarai; whereupon Thompson’s remark recurred to my memory. “Jim,” I said to Brady, “how much gold have we?” “Ten ounces,” he said. “Hand it over,” said I, “I have a ploy.” Brady handed it over, and I sought the owner of the cutter, saying I wanted to buy her. He said he was asking Thompson £100 for her, but Thompson was a ... Jew and only offered £60. I replied, “Well, here are ten ounces on deposit, and an order on Burns, Philp and Co., of Samarai, for the rest, and this letter of theirs will show it is all right.” In five minutes the deal was completed; and the White Squall papers being handed over to me, I returned to Brady. “Jim,” I said, “you need a sea trip and so do I; also we will set up as yacht owners and store-keepers. Let’s go up to25 Thompson and tell him the good news.” We found him and told him we had bought the White Squall, and intended to sail her to Samarai ourselves. I also pointed out that there was an absolute dearth of supplies at Woodlark, and we expected to make a good thing by store-keeping. Thompson’s language, as Bret Harte has it, was for a time “painful and free”; then he rushed off to the former owners of the cutter, to try and persuade them to cancel the deal as we were “dead broke,” and could not pay for the vessel. Unfortunately, however, for him the vendors chose to consider us as honest men, this apart from having completed the deal, and told Thompson to go to a warmer region. He then came again to me with an ad misericordiam appeal. “Look here, if I don’t get this boat I am a ruined man; how much do you want? I never thought that you two dead beats could buy a vessel, or I would have bid higher.” I gently pointed out that all Brady and I had wanted was fair treatment from him, which we had not got; also that we had no wish to become store-keepers or traders, but as he had forced us into the position, he could either buy us out or count on our opposition in his own business. I then remarked that I would leave the negotiations to Brady.

Brady’s terms were short and sweet: £100 for the vessel, £100 on top of that for ourselves, together with Thompson’s original offer of £60. Thompson squealed loudly, but as we were ready to go to sea, accepted the offer and took over the White Squall. In passing I might now remark that later knowledge showed me the White Squall was not worth £5; she was thoroughly rotten, the only good things about her being her pumps. She had sneaked out of a Queensland port without the cognizance of the authorities; but of these facts at the time I was ignorant; and Brady and I were much surprised to hear later that, after three or four highly profitable trips for Thompson, she had sunk. Her sinking was caused by an irate master leaping suddenly down into the forecastle to deal with a recalcitrant member of the crew, and in his energy sending his legs through her rotten planking.

After the completion of the White Squall deal, Brady went off to the new rush, where he pegged out a good claim, I remaining to shepherd our old one. A few days after his departure I received a note from him saying I had better abandon the claim I was holding, as our lode was safely buried, and come to the new rush. On my way thither I dropped into a gully and began prospecting it, just as another white man, accompanied as I was by two boys, started the same game. We both struck highly payable gold at about the same time, and each claimed the gully by right of discovery. For two or three minutes we—each with26 drawn revolvers, and each backed by our boys armed respectively with a rifle and fowling piece—argued the question; and in the end, as an alternative to murdering one another, decided to go into partnership and work it jointly, each to divide our share with our former mates.

My new partner was named John Graham; he had previously been an assistant Resident Magistrate in the service of the British New Guinea Government, and later the owner of some pearl-fishing vessels. We worked together very amicably for some months, when, receiving a good offer for our claim, we sold out and separated, he to buy the wreck of a vessel with the intention of refitting it and resuming trading. After about a week’s work again with Brady, some severe attacks of malaria gave me a distinct hint to go to sea for a short time, and at my suggestion we dissolved partnership, Brady remaining in the claim, and I, with my two boys, going to Suloga Bay with the intention of there finding a vessel bound for Samarai.

27

CHAPTER IV

At Suloga Bay I found Graham still waiting, in charge of a small cutter owned by a local resident, which he had undertaken to take to Samarai for repairs and a new crew, the original boys having deserted to the mines. Graham had a couple of natives as crew, but, as the cutter was leaking badly, had been afraid to put to sea weak-handed. My arrival with my two boys, however, relieved him of this difficulty, and away we went for Samarai.

Never since then have I known such a wholly beastly trip as that one was. We were all rotten with malaria, the cutter’s decks were warped and leaking everywhere from lying in the sun, consequently day and night we had to pump the wretched boat out, or she half filled. The North-West Monsoon was on; and the weather principally consisted of flat calms, during which we grilled under a burning sun, or fierce squalls accompanied by torrential rains, in which our rotten sails burst, and beneath decks was more like a combination of Turkish and shower baths than anything else. Pumping ship, patching sails, drying our clothes, and belting our sick boys into performing their necessary duties, formed our occupation; cursing freely, and betting on our temperatures taken with a clinical thermometer, our diversion; mouldy rice, stringy, oily, ever-warm tinned beef, pumpkin and stodgy taro, our diet. Vile tea and dirty-looking sugar we abandoned for a more healthful beverage, consisting of five grains of quinine and one drop of carbolic acid to a pannikin of water, always of course luke-warm. Dysentery beginning amongst the boys added to our woes; but fortunately for us, we crawled through the China Straits into Samarai on the day following their being taken ill, and gladly handed over our rotten tub to the boat-builders.

Here, Graham and I separated; he, after a week’s rest, going to see to his wreck, and I remaining to recuperate as the only guest in the “Golden Fleece Hotel,” which had recently been instituted by Tommy Rous upon a capital of ten pounds. The hotel consisted of one large room with a verandah all round it, a small room used as a cook-house detached from the other, and a28 bar-room next to Tommy’s bedroom. All the buildings were made of palms laced together and thatched with the leaf of the sago palm; with the exception of Tommy’s bedroom and the bar-room the whole place was innocent of doors and windows, other than square holes in the walls to admit light and air. The guests were expected to provide their own blankets, plates, knives, forks, and pannikins, and to sleep on the palm floor. A long wooden table ran down the verandah, at which meals were eaten. Meals never varied; Tommy’s cook, a New Guinea boy, had but two dishes: “situ,” which consisted of tinned meat, yams, sweet potatoes and pumpkins all stewed together; and “kari,” the same meat mixed with curry powder and served with rice. Anything else, fish or fresh game for instance, the guests were supposed to provide for themselves.

Tommy was the son of a New Zealand doctor and had gone to sea as a supercargo on one of Burns, Philp and Co.’s vessels. Falling down the hold at sea he had crushed in three ribs and otherwise hurt himself, and at his own request had been put ashore at Samarai, where Armit had patched him up as well as he could. Charles Arbouine, the manager for Burns, Philp and Co. at Samarai, suggested to Tommy that, as he was now incapacitated for any other work, he should start a hotel and relieve the firm of the retail liquor trade, he, Arbouine, being tired of traders and diggers clamouring to be served with drinks at all times. Tommy accordingly expended his capital in the building before mentioned, and with a staff of one native boy began business. Graham and I were his first regular guests. Nightly to the pub came Armit, Arbouine, one of the Whittens, or any wandering trader, to play whist or to gossip; if five or six were present we varied whist by loo or poker, in which quinine tabloids were used to represent counters of sixpence, and pistol cartridges shillings or half-crowns according to their calibre.

A fortnight or so after my return to Samarai, Moreton came back from a cruise in the Siai, and our monotony was further relieved by the arrival of a number of lucky diggers proceeding to that island. The result was that the “Golden Fleece” became most unpleasantly crowded, and I prepared to flit.

Tommy Rous, however, developed a nasty attack of malaria accompanied by hæmorrhage of the lungs due to his accident, and begged me to stay with him until his visitors had departed. He said, “It will be no trouble to you; just look after the pub until I am well again or this lot have cleared out. All you have to do, is to order the stores and collect the cash.” I protested that I knew nothing about running pubs and didn’t want to learn, also that I was certain that Tommy was going to be very ill and I should have to look after the show. Privately, Armit, Moreton29 and I were certain he was going to die. He cut short my protests by saying, “he knew nothing and I could not know less,” and followed it by becoming so ill that it would have been sheer cruelty to remove him from his room or trouble him with anything. The result was that I suddenly found myself in the position of unpaid hotel-keeper.

Tommy’s boy, the cook, began complications by striking cook’s duties to go and attend to him, and I had to turn on my own two boys as cooks. They were zealous and willing, but I feel convinced that their efforts in the culinary art seriously increased the flow of profanity in the hotel’s digger guests and impaired their faint hope of Heaven. I then made it a fixed rule that everything supplied was for cash, as I was not going to be bothered keeping accounts; this rule also caused a lot of profanity, as the supply of silver in the island was limited, and the diggers frequently had to wait for drinks until I had paid the takings into Burns, Philp and Co., and they again had bought it out for gold dust. At ten o’clock I closed the bar, in order that the row should not disturb Rous; whereupon some of our lodgers would go to bed on the floor of the big room, others would take bottles and visit various vessels or yarn on the beach, whilst another lot would adjourn to Whitten’s store. I then paid a visit to Tommy, fixed him up for the night, and told him the result of the day’s takings. After which my boys made me up a bed in the bar, and we turned in for the night.

About midnight, the first contingent of stray guests would return, more or less drunk, fall over those already occupying spaces on the floor and, after torrents of blasphemy and recriminations, turn in. After this, at intervals ranging until daylight, they returned in two’s and three’s, some singing, some arguing, some swearing, some quarrelling, but nearly all signalizing their arrival by also falling over the sleepers on the floor and again causing fresh floods of blasphemy and bad temper, which, in nine cases out of ten, ended in a free fight. Among our guests at the “Golden Fleece” were two who, when all else was peaceful, were almost certain to start a row, being just about as adaptable to one another as oil to water. The one was named Farquhar, a man as comfortable in the surroundings he was in, as a turtle would be on a tight rope; the other was O’Regan the Rager, a digger.