THE COURIER OF THE OZARKS

THE YOUNG MISSOURIANS SERIES

BY BYRON A. DUNN

AUTHOR OF "THE YOUNG KENTUCKIANS" SERIES

WITH EIGHT ILLUSTRATIONS

BY H. S. DeLAY

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1912

Copyright

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1912

Published September, 1912

W. F. HALL PRINTING COMPANY, CHICAGO

To the Loyal Men of Missouri, who as members of the militia did so much to save the State to the Union, this book is dedicated. History gives them scant notice, and the Federal government has failed to reward them as they deserve.

"Follow the colors," he shouted.

PREFACE

During the year 1862, after the capture of Island No. 10 and New Madrid, no large armies operated in Missouri; but the State was the theater of a desperate guerrilla warfare, in which nearly or quite a hundred thousand men took part. It was a warfare the magnitude of which, at the present time, is very little known; and its cruelty and barbarity make a bloody page in the history of those times.

This book is a story of this warfare. It is a story of adventure, of hair-breadth escapes, and of daring deeds. In it the same characters figure as those in With Lyon in Missouri and The Scout of Pea Ridge. It tells how our young heroes were instrumental in thwarting the great conspiracy by which the Confederate government, by sending officers into the State, and organizing the different guerrilla bands into companies and regiments, was in hopes of wresting the State from Federal control.

As in former books, history is closely followed.

Waukegan, Illinois.

August, 1912.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER I. Bruno Carries a Message

CHAPTER II. An Internecine War

CHAPTER III. A Mysterious Communication

CHAPTER IV. Moore's Mill

CHAPTER V. A Fight in the Night

CHAPTER VI. Kirksville

CHAPTER VII. Poindexter Captured

CHAPTER VIII. Lone Jack

CHAPTER IX. Captured by Guerrillas

CHAPTER X. The Guerrilla's Bride

CHAPTER XI. The Story of Carl Meyer

CHAPTER XII. The News from Corinth

CHAPTER XIII. Porter Captures Palmyra

CHAPTER XIV. Ten Lives for One

CHAPTER XV. A Girl of the Ozarks

CHAPTER XVI. A Wounded Confederate

CHAPTER XVII. Trailing Red Jersey

CHAPTER XVIII. Live—I Cannot Shoot You

CHAPTER XIX. Mark Has a Rival

CHAPTER XX. Capturing a Train

CHAPTER XXI. The Old Man of the Mountains

CHAPTER XXII. Mark Confesses His Love

CHAPTER XXIII. Into the Lion's Mouth

CHAPTER XXIV. Prairie Grove

CHAPTER XXV. Called to Other Fields

OTHERS IN SERIES

ILLUSTRATIONS

"Follow the colors," he shouted.

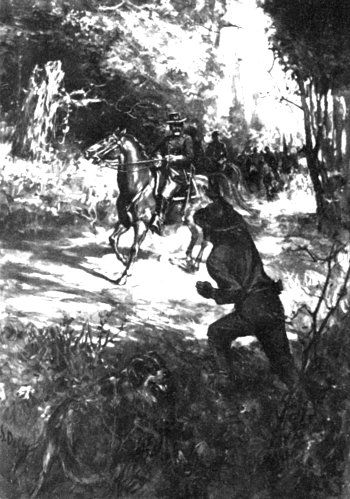

"Halt the advance. Ambuscade!" gasped Harry.

Down the street they rode at full speed.

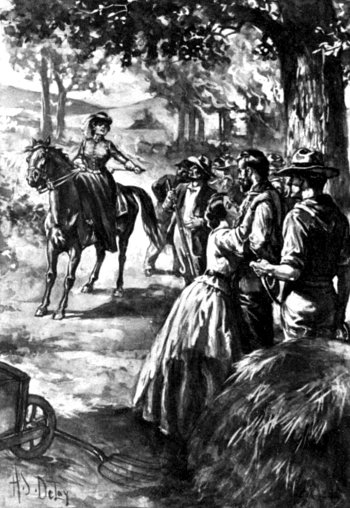

"You pretend to be men and call this war?"

To catch the rider as he reeled from the saddle.

He was looking into the muzzle of a revolver.

Her revolver was pointed at his breast.

An old man leaning on a staff.

THE COURIER OF THE OZARKS

CHAPTER I

BRUNO CARRIES A MESSAGE

"Down! Bruno, down!"

These words were uttered in a guarded whisper by a boy about seventeen years of age, to a great dog that stood by his side.

At the word of command, the dog crouched down, his whole body quivering with excitement. His master gently patted him on the head, and whispered, "There, there, old fellow, don't get nervous. Our lives would not be worth much, if we were discovered."

The boy was lying full length on the ground, concealed in a dense thicket, but from his point of vantage he had a full view of the road which ran a few yards in front of him. This road ran north and south, and nearly in front of where he lay another road entered it, coming in from the west.

The cause of the dog's excitement was apparent, for coming up the road from the west was a large body of horsemen, and a motley troop they were. They were mostly dressed in homespun, and armed with all sorts of weapons, from cavalry sabers to heavy knives fashioned out of files by some rude blacksmith; the army musket, the squirrel rifle, and the shotgun were much in evidence.

As the head of the column reached the north and south road the leader called a halt, and looked up and down the road, as if expecting some one. He did not have long to wait. The sound of the swift beating of horse-hoofs was heard from the south, and soon three men came riding up. One, a man of distinguished looks and military bearing, was a little in advance of the other two. As he came up, the leader of the little army saluted him awkwardly and exclaimed, "Glad to see you, Colonel. What news?"

"Glad to see you, Captain Poindexter," replied the Colonel. "I see you are on time. As for the news, all goes well. Within a week all Missouri will be ablaze, and the hottest place for Yankees in all Christendom. How many men have you, Captain?"

"About five hundred, and more coming in all the time."

"So that is Jim Poindexter, the bloody villain," muttered the boy between his set teeth, and nervously fingering his revolver. "How I would like to take a shot at him! But it would not do. It would be madness."

The next question asked by the Colonel, whose name was Clay, and who had been in the State for the past two months promoting the partisan uprising, was, "Where is Porter?"

"At Brown's Springs. I am to join him there tonight. But he was to meet me here with a few followers, knowing you were to be here."

"Good! I will be more than pleased to see him," answered Colonel Clay. "But I thought he was farther north."

"Most of his force is," answered Poindexter. "But he promised to meet me at Brown's Springs with five hundred followers. We have our eye on Fulton. My spies report it is garrisoned by less than a hundred men. Fulton captured, I can supply my men with both clothes and arms, and then Jefferson City next."

"Jefferson City?" asked Colonel Clay in surprise. "Do you look that far?"

"Yes. Thanks to the Yankee Government, there are not over five hundred soldiers in Jefferson City. Fulton once taken, the boys will flock to our standard by thousands, and Jefferson City will become an easy prey."

"Accomplish this, Poindexter," cried Colonel Clay, "and Missouri will be redeemed. All over southwestern Missouri the boys are rallying and sweeping northward. The object is to capture Independence, and then Lexington. This done, we will once more control the Missouri River, and the State will be anchored firmly in the Southern Confederacy. Then with your victorious legions you can march south and help drive the Yankee invaders from the land. Poindexter, Missouri can, and should, put fifty thousand Confederate soldiers in the field."

Poindexter shrugged his shoulders. "Colonel, not so fast," he exclaimed. "I could not drag my men into the regular Confederate service with a two-inch cable. Neither do I have any hankering that way myself. The free and easy life of a partisan ranger for me."

Colonel Clay looked disgusted. "Captain," he asked, "don't you get tired of skulking in the brush, and waging a warfare which is really contrary to the rules of war of civilized nations? There is little honor in such a warfare; but think of the honor and glory that would await you if you could free Missouri, and then help free the entire South. Why, it is not too much to say that the star of a general might glisten on your shoulder."

A look of rage came over the face of Poindexter. "If you don't like the way we fight," he growled, "why are you here, urging us to rise? If we can free this State of Yankees, we will accomplish more than your armies down south have. We prefer to fight our own way. Here, I am a bigger man than Jeff Davis. I fight when it suits me, and take to the brush when I want to. If you have any thoughts of influencing me or my men to join the regular Confederate army, you may as well give up the idea. As for the rules of civilized warfare, I don't care that," and he snapped his fingers contemptuously.

Colonel Clay concealed the indignation and disgust which he felt towards the fellow, and said: "While we may not think alike, we are both working for the same cause—the liberation of our beloved Southland from the ruthless invasion of the Yankee hordes. If you can accomplish what you think, surely the South will call you one of her most gallant sons. Neither should we be too squeamish over the means used to rid ourselves of the thieves and murderers that have overrun our fair State."

"Now you are talking," exclaimed Poindexter, with an oath. "If Porter comes—and he should be here by now—we will discuss the situation more thoroughly; but the first thing for us to do is to capture Fulton."

"Are you sure," asked Clay, "that your plans will not miscarry? Mr. Daniels, one of the gentlemen here with me, informs me that that regiment of devils, the Merrill Horse, is only a few miles to the west. May they not interfere with your plans?"

At the mention of the Merrill Horse, Poindexter's countenance took on a demoniac expression. Striking the pommel of his saddle with his clenched hand, he hissed: "I will never rest until I shoot or hang every one of that cursed regiment. But you are mistaken in thinking the force west consists of the entire Merrill Horse. Only part of the regiment is there; the rest is up north. The force west is about five hundred strong. I have given out the impression that I am making for the woods which skirt Grand River, to join Cobb. Every citizen they meet will tell them so. Little does Colonel Shaffer, who is in command, think I have slipped past him, McNeil believes Porter is up around Paris—the most of his force is—but he is to join me here with a goodly number. Ah! here he comes now."

Down the road from the north a party of horsemen were coming at a swift gallop. They rode up, and salutations were spoken and hands shaken.

A look of passion came into the face of the watching boy, and again he fingered his revolver. Even the dog partook of the boy's excitement, for his whole body was quivering.

"Quiet, old boy, quiet," whispered the boy. "No doubt you would like to tear the bloody monster to pieces, and I would give ten years of my life for a shot, but it will not do."

The boy was now listening intently, trying to catch every word that was said.

"Mighty glad to see you, Jo," Poindexter was saying. "How many men have you at Brown's Springs?"

"About four hundred when I left; but squads were coming in continually. I count on six hundred by night."

"Good! Then we will swoop down on Fulton tonight."

"Don't know about that," answered Porter. "Many of the boys have ridden, or will ride, fifty miles to join us. Their horses will be tired. Tomorrow will be all right. How is everything?"

"Splendid," answered Poindexter, rubbing his hands. "Not over a hundred soldiers in Fulton. The only drawback is that there is a Yankee force of about five hundred a few miles to the west, part of them the Merrill Horse."

"The Merrill Horse! The Merrill Horse!" cried Porter with a dreadful oath. "I thought they were north. They are surely giving me enough trouble up there."

"About four companies are down here, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Shaffer," answered Poindexter. "They have been trying to find me for the past week. But they haven't found me yet," and he chuckled. "The fact is," he continued, "I have fooled them. Shaffer thinks I am making for the woods along the Grand River, to join Cobb. I skipped past him last night. By this time he is making for the Grand River as fast as he can go. No trouble from him in our little business with Fulton."

"Don't be too sure," exclaimed Porter. "Shaffer is about as sharp as the devil; but I trust you are right."

The conversation now took a general turn, Colonel Clay going over the ground, telling them what was being done, and what he hoped would be accomplished. "As for me," he said, "I must be across the river by tomorrow. Everything depends on the movement to capture Independence and Lexington. Then, if you gentlemen are successful here, and capture Fulton and Jefferson City, our brightest hopes will be fulfilled. I must now bid you good-bye. May success attend you."

The Colonel and his two friends rode back towards the south, from whence they came. Poindexter watched them until they were out of sight, and then, turning to Porter, said: "What do you think, Jo? The Colonel wanted me and my men to join the regular Confederate army."

"Humph!" sniffed Porter, "I reckon you jumped at the chance."

"Not much; but he did more. He mentioned that I was not conducting this blood-letting business strictly on the rules of genteel, scientific murder."

"I reckon, before we indulged in a necktie party, he would want us to say, 'Beg pardon, sir, but I am under the painful necessity of hanging you,'" replied Porter, indulging in a coarse laugh.

"I told him," continued Poindexter, "we fought as we pleased, and asked no favors of General Price, Jeff Davis, or any other man. As for the Confederate service, none of it for me."

"They have offered me a colonelcy, if I take my men down into Arkansas," answered Porter. "If it gets too hot for me here I may go. You know there is a price on my head. But I must go, or my boys will be getting uneasy. Join me at the Springs as soon as possible." Thus saying, he and his party rode away.

Poindexter ordered his men to fall in, and they followed Porter, but at a more leisurely gait.

When the last one had disappeared, the boy arose and shook himself. "What do you think of that, Bruno?" he asked, patting the dog's head. The dog stood with hanging head and tail, as if ashamed he had let so many of his enemies get away unharmed. He looked up in his master's face and whined at the question, as much as to say, "I don't like it."

"Well, my boy, there is the Old Nick to pay. Both Porter and Poindexter on the warpath. Fulton to be attacked, and not a hundred men to defend it. Shaffer with the boys miles away. How are both to be warned? We must see, old fellow, we must see. There is no time to lose."

Thus saying, the boy hurriedly made his way back through the woods where in a hollow in the midst of a dense thicket a horse stood concealed. Those who have read "The Scout of Pea Ridge" will readily recognize the boy as Harry Semans, and Bruno as his celebrated trained dog. After the battle of Pea Ridge and upon the dissolution of the company of scouts under the command of Captain Lawrence Middleton, Harry had returned to Missouri, and become a scout for the Merrill Horse. The Merrill Horse, officially known as the Second Missouri Cavalry, was a regiment composed of companies from Missouri, Illinois, and Michigan.

It can safely be said that no other regiment in the Federal army ever saw more service in fighting guerrillas than did the Merrill Horse. From the very first of the war their work was to help exterminate the guerrilla bands which infested the State. The name "Merrill Horse" became a terror to every bushwhacker and guerrilla in Missouri. No trail was so obtuse, no thicket so dense that members of that regiment would not track them to their lair. A true history of the Merrill Horse, and the adventures of its different members, would read like the most exciting fiction.

When Harry reached his horse he stood for a moment in deep thought, and then speaking to Bruno, said: "Yes, old boy, you must do it. I know you can, can't you?"

Bruno gave a bark and wagged his tail as if to say, "Try me."

Tearing a leaf from a blank book, Harry wrote a brief note to Colonel Shaffer, telling him what had happened, and begging him to march with all speed to Fulton. This note he securely fastened to Bruno's collar and said, "Bruno, go find Colonel Shaffer and the boys. You know where we left them. Go."

For a moment Bruno stood and looked up in his master's face, as if undecided.

"Go and find Colonel Shaffer. Go," Harry repeated, sternly.

The dog turned and was away like a shot. Harry gazed after him until he was out of sight, then patting the glossy neck of his horse, said, "Now, Bess, it's you and I for Fulton; the machinations of those two archfiends, Poindexter and Porter, must be brought to naught."

Harry believed he would have no trouble in reaching Fulton, as the guerrillas were generally quiet near a place garrisoned by Federal troops, therefore he took the main road, as he was desirous of reaching Fulton as soon as he possibly could. He had not gone more than two miles when he met two men, rough-looking fellows, whom Harry had no desire to meet, but there was no way to avoid it, except flight, so he rode boldly forward.

Harry was dressed in the homespun of the country, and had all the appearance of a country bumpkin. As to arms, none were visible, but stowed away beneath his rough jacket was a huge navy revolver, and Harry was an adept in the use of it.

"Hello, youn' feller," cried one of the men. "Whar be yo' goin' in sich a hurry? Halt, and give an account of yo'self."

"Goin' to Fulton, if the Yanks will let me," drawled Harry. "Whar be yo 'uns goin'?"

"That 's nun yo' business. Air yo 'un Union or Confed?"

"Which be yo'uns?"

"Look heah, young feller, nun of yo' foolin'. I reckon yo' air a Yank in disguise. That 's a mighty fine hoss yo 'un air ridin'. 'Spose we 'uns trade."

"'Spose we 'uns don't."

During this conversation Harry's right hand was resting beneath his jacket, grasping the butt of his revolver.

"I reckon we 'uns will," jeered the fellow, reaching for his pistol.

Quick as a flash Harry had covered him with his revolver. Fortunately for him, the two men were close together. "Hands up," he ordered. "A move, a motion to draw a weapon, and one or both of you will die. It don't pay to fool with one of Porter's men."

The hands of both went up, but one exclaimed, "One of Porter's men? Be yo' one of Porter's men? We 'uns are on our way to join him. We 'uns heard he was at Brown's Springs."

"Yo 'uns will find him thar. I am taking a message from him to a friend in Fulton. Yo 'uns can lower your hands. I reckon we 'uns understand each other now."

"We 'uns certainly do," said one of the men, as they dropped their hands, looking foolish.

"Wall, good-bye; may see yo 'uns in Fulton tomorrow." And Harry rode off, leaving the men sitting on their horses watching him.

"Ought to have shot both of them," muttered Harry, "but I cannot afford to take any risks just now."

Harry had no further adventures in reaching Fulton, and at once reported to Captain Duffield, who was in command of the post.

Captain Duffield listened to Harry's report with a troubled countenance.

"A thousand of the devils, did you say?" he asked.

"Yes, and more coming in every hour."

"And I have only eighty men," replied Duffield, bitterly. "If they attack before I can get help, there is no hope for us."

"Colonel Shaffer is a few miles to the west with about five hundred men," replied Harry. "If they do not attack tonight, as I do not reckon they will from what Porter said, he may be here in time to help. I have sent him word."

"Sent him word? By whom?" asked Outfield, eagerly.

"By my dog," and Harry explained.

As Duffield listened, his countenance fell. "I see no hope from that," he said. "It is preposterous to think that a dog will carry a message for miles, and hunt up a man."

"If you knew Bruno, you would think differently," replied Harry, smiling.

"I can put no dependence on any such thing," said Duffield. "My only hope is getting word to Colonel Guitar, at Jefferson City. If I get any help, it must come from him. God grant that Porter may not attack tonight."

"I think there is little danger tonight, but they may be down in the morning," said Harry. "Do you think Guitar can reinforce you by morning?"

"He must; he must. I will send a message to him by courier mounted on one of my fleetest horses."

"Bess is about as fast as they make them," replied Harry. "I know the country. I will go if you wish."

Duffield looked at him a moment doubtfully, and then said, "You may go, as you can tell Colonel Guitar all you have told me. But I will send one of my own men with you."

Captain Duffield wrote two messages, giving one to Harry, and the other to the soldier who was to accompany him.

"If you have trouble," said Captain Duffield, "for the love of Heaven, one of you get through, if the other is killed. The safety of this post depends on Colonel Guitar receiving the message."

"It will go through, if I live," calmly replied Harry, as he carefully concealed the message in the lining of his coat.

To Harry's surprise, the soldier detailed to go with him proved to be a boy, not much older than himself. He was mounted on a spirited horse and his manner showed he was ready for any kind of an adventure, no matter where it might lead.

The shades of night were falling when Captain Duffield bade them good-bye, and they rode away and were soon lost to view in the dusk.

Captain Duffield stood looking after them, and then said to one of his lieutenants, "I don't know what to make of that boy. He told a straight story, but his thinking that dog of his would take a message to Shaffer is a little too much to believe."

But Captain Duffield soon had other things to think about. Reports began to come in from other sources of the gathering of the guerrillas at Brown's Springs, and their number was augmented to two thousand. He posted his little force in the best manner possible to resist an attack, and with an anxious heart, watched and waited through the long hours of the night; but to his immense relief, no attack came.

CHAPTER II

AN INTERNECINE WAR

After the battle of Pea Ridge, the Confederate Government had no regular organized troops in Missouri. General Sterling Price, with his Missouri regiments, which had enlisted in the Confederate service, was ordered east of the Mississippi. But there were thousands of State troops that had followed Price, and although they refused to enlist in the regular Confederate service, they were, at heart, as bitter towards the Union as ever. These men found their way back home, and although thousands of them took the oath of allegiance to the Federal Government, the majority of them were not only ready, but eager, to ally themselves with some of the guerrilla bands which were infesting the State.

The Federal authorities, knowing that Price, with his army, had been ordered east, thought that the Confederates had given up all hopes of holding the State, and that the fighting was over, except with small guerrilla bands, that could easily be kept in check. Therefore, the great majority of the Federal troops in Missouri were withdrawn to swell the armies of Buell and Grant.

The Confederates now thought they saw their opportunity. Numbers of the Confederate officers secretly made their way into the State and commenced to organize the disloyal forces, co-operating with the guerrilla bands. Among these officers was Colonel Clay, who appeared in the first chapter.

This movement was so successful that during the summer of 1862 it is estimated that there were from thirty to forty thousand of these men enrolled and officered. Places of rendezvous were designated, where all were to assemble at a given signal, and, by a coup-de-main, seize all the important points in the State which were feebly garrisoned. Then they were to co-operate with an army moving up from Arkansas, and the State would be redeemed.

It was a well laid plan, but fortunately it was early discovered by General J. M. Schofield, who was in command of the Department of Missouri. How General Schofield first received his information will be told hereafter.

General Schofield frantically appealed to Halleck for aid, and then to Washington, but he was answered that owing to the great military movements going on, not a regiment could be spared.

General Schofield, thus left to his own resources, rose grandly to the occasion. He would use the Confederates' own tactics. So he ordered the entire militia of the State to be enrolled. Thousands of Confederate sympathizers fled the State, or took to the bush. During the summer of 1862 between forty and fifty thousand loyal State militia were organized. Thus the whole State became one vast armed camp, nearly forty thousand men on a side, arrayed against each other.

It was father against son, brother against brother, neighbor against neighbor. The only wonder is that owing to the passions of the times there were not more excesses and murders committed than there were.

During the year 1862 there were at least one hundred and fifty engagements fought on the soil of Missouri, in which the numbers engaged varied from forty or fifty to five or six thousand. In these engagements General Schofield says the Union troops were successful in nine out of ten, and that at least three thousand guerrillas had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoners, and that ten thousand had fled the State.

This terrible warfare between neighbors receives scant mention in history, but in no great battles of the war was greater bravery shown, greater heroism displayed, than in many of the minor engagements fought in Missouri.

CHAPTER III

A MYSTERIOUS COMMUNICATION

In the month of May, 1862, a young Federal officer reported in St. Louis, and found himself without a command, and without a commission. This officer, Captain Lawrence Middleton, had greatly distinguished himself during the first year of the war on the staff of General Nathaniel Lyon. After the death of Lyon he was commissioned a captain by General Fremont, and authorized to raise an independent company of scouts. With this company he had rendered valiant service in the campaign which ended with the battle of Pea Ridge.

Many of the acts of Fremont, and a number of commissions which he had granted, had been repudiated by the Government, and thus Middleton had found himself free. But he had no intention of remaining inactive, his heart was too much in the cause. If no other field was open, he would enlist as a private soldier. But there was no need of that, he was too well known. Though young, scarcely more than eighteen, he had rendered services and performed deeds which made his name known throughout the State. He had thwarted the machinations of Frost, Price, Governor Jackson, and other disloyal leaders in their efforts to drag Missouri out of the Union.

While Lawrence was undecided just what to do he met Frank P. Blair, who was overjoyed to see him. He had been Blair's private secretary during the troublesome months before the opening of the war, and a lieutenant in one of his regiments of Home Guards.

Blair, who had been appointed a brigadier general in the Federal army, had been at home on business, and was about to return to his command.

"Never better pleased to see anyone in my life," said Blair, nearly shaking Lawrence's arm off. "Oh, I've kept track of you, you've been keeping up your reputation. But what are you doing in St. Louis? I thought you were with Curtis."

Lawrence told Blair of his predicament,—that he was now without a command or a commission.

"Good!" cried Blair, shaking Lawrence's hand again. "I was about to write to Curtis to see if I could not get you away from him. I will see that you are commissioned as captain, and I will detail you on my staff. I need just such fellows as you."

"I couldn't ask anything better," said Lawrence, "and, General, I thank you from the bottom of my heart. It is more than I could have possibly hoped, more than I deserve."

"Too modest, my boy. If you had your deserts, you would be wearing a star on your shoulder, as well as myself. I am a little selfish in asking you to go on my staff. I want you."

So it was all arranged, and Lawrence went to see his uncle and tell him of his new position on Blair's staff. This uncle, Alfred Middleton, was one of the wealthiest citizens of St. Louis, and an ardent secessionist. Now that Lawrence was out of the army, he was in hopes that he would stay out, and he showed his disappointment in his face. He had also been greatly worried of late. His only son was with Price, and it was a sore spot with him that the Missouri Confederate troops had been ordered east, and not been left to defend their native State.

In fact, the Confederates of the State felt that they had been deserted by the Richmond Government, and bore Jeff Davis and his cabinet no great love.

"I am sorry, Lawrence," said his uncle, sadly. "I was in hopes that as long as you were out of the army you would stay out. Why will you persist in fighting against those who were your friends? Your whole interest lies with the South."

"Uncle, please do not let us discuss that question again," replied Lawrence. "You and I are both firm in our belief, and no amount of discussion will change either."

Mr. Middleton sighed, but did not resume the subject. That Lawrence, whom he looked upon almost as a son, should take up arms against the South was to him a source of endless regret.

The next two or three days were busy ones with Lawrence. The new arrangement had one drawback, it would separate him from Dan Sherman, who had been a lieutenant in his company of scouts, and the two were inseparable. Dan would not hear of parting from Lawrence; he would go with him if he had to go as his servant.

"I can never consent to that, Dan," said Lawrence. "I had rather tell Blair I have reconsidered his proposition and cannot accept."

"You'll do no such thing," retorted Sherman. "I will try and behave myself, but I feel that something will happen, and we will not be separated."

Something did happen, much quicker than either one expected. Something which entirely changed the calculations of Lawrence. It was to be some months before he saw service with Blair.

Lawrence and Dan were passing a newspaper office, before which a large crowd had gathered, reading the war bulletins. They told that Halleck was tightening his lines around Corinth and that the place must soon fall; and that McClellan was well on his way towards Richmond.

It was curious to watch the faces of those who read. The countenances of those who were for the Union would brighten when anything was posted favorable to the Union cause, and now and then a cheer would be given.

The iron heel of the Yankees was on St. Louis, and the Confederate sympathizers dare not be so outspoken, but when anything favorable to the South was posted their eyes would flash, and their countenances beam with joy.

And thus the crowd stood and read, once friends and neighbors, but now ready to rend each other to pieces at the first opportunity.

Lawrence mingled with the crowd, and as he read he felt a bulky envelope thrust in his hand and caught a glimpse of a dusky arm. He glanced at the address and then turned to see who had given it to him, but could not. He glanced at the envelope again. Yes, it was for him. In bold letters was written, "For Captain Lawrence Middleton. Important."

The writing was strange to Lawrence, and making his way through the crowd he sought a private place where he could see what had so mysteriously come into his possession. As he read, a look of surprise came over his face, and then his countenance grew stern and grim. Carefully he read the document through from beginning to end. It was signed "By One Who Knows." There was not a mark to tell who was the writer. The writing was strong and bold, and possessed an originality of its own, as if the writer had put much of his own character in it. Lawrence sat and pondered long. He looked the manuscript over and over again to see if he could not discover some private mark, something that would identify the writer, but he found nothing.

"Strange," he muttered, "but if Guilford Craig was alive I would swear he was the writer of this. Who else would write me, and me alone, and give such important information? Who else could obtain the information contained in this letter? Yet Guilford is dead. Benton Shelly was seen to shoot him. There were those who saw him lying on the ground, still in death, his bosom drenched in blood. But his body was not found. Guilford, Guilford, are you still alive? But why do I indulge in such vain hope that he is alive? The proof of his death is too plain. This letter must have been written by another, but who? Who? And why send it to me?"

The letter was, in fact, a full and complete exposé of the plans of the Confederates. It told of the conception of the plot; who was carrying it out; of the hundreds who had taken the oath of allegiance in order that they might work more securely, and that many had even enlisted in the State militia, so that when the supreme time came they could desert: the time set for the uprising was the last of July or else the first of August, by which time they hoped to have at least forty thousand men enrolled.

"Blair and Schofield must see this, and no time lost," said Lawrence to himself as he placed the communication carefully in his pocket.

Blair was soon found. After carefully reading the letter he said, "I am not surprised. I warned the Government of the folly of removing so many troops from the State. But who could have written this?"

"If Guilford Craig was alive there would be but one answer," replied Lawrence. "As it is, it is a mystery."

"Let us see Schofield at once," said Blair. "There should be no time lost."

Repairing to the headquarters of General Schofield, they were readily admitted. General Schofield was the chief of staff to General Lyon at the time of the battle of Wilson Creek, and, of course, knew Lawrence well. "Glad to see you, Captain," said the General. "Curtis has written me of your good work. You are not with him now, are you?"

"No, you know the commission I held was granted by Fremont. The authorities at Washington declared it illegal."

"Ah, there was a large number of those commissions. I must see what I can do for you."

"I thank you, General, but General Blair has just done me the great honor of appointing me on his staff."

"General Blair, as well as yourself, is to be congratulated," answered the General.

Blair now spoke. "General, our business with you is very important. Captain Middleton, please show the General the communication you received."

Lawrence handed the General the mysterious message and Schofield read it with a darkened brow.

"Who wrote this?" he asked, abruptly.

"General, I do not know."

"Then it may be a fake, a joke. Someone may be trying to scare us."

"General, it is no joke, the proof is too positive," replied Lawrence, earnestly.

"That is so," answered the General. "It also confirms rumors I have been hearing. There has been unusual activity among Southern sympathizers, all over the State, yet outside of the guerrilla bands there have been no hostile demonstrations. This must have been written by someone deep in their counsels."

"General, do you remember Guilford Craig?"

"Remember him! Indeed, I do. Can I ever forget what he and you were to Lyon?"

"If Guilford Craig had not been killed at the battle of Pea Ridge I would be positive the communication came from him. But the handwriting bears no resemblance to his."

"Are you certain he was killed?"

"The proof seems positive, but his body was not found," answered Lawrence.

Schofield sat for a moment in silence, and then suddenly said to Blair, "General Blair, I have a great favor to ask of you."

"What is it, General? Any favor I can give you will be readily granted."

"That you relinquish your claim on Captain Middleton, at least, until this crisis is over, and let me have him."

Blair looked surprised, but no more so than Lawrence.

"You know," continued Schofield, "there is no one who can help me more just now than Captain Middleton. No one who understands the work before me better. This Guilford Craig, as you are aware, was a curious character. To no one would he report but to Captain Middleton. This exposé, coming to Middleton, instead of to me, leads me to believe that Craig was not killed, as supposed, but in some way got off the field, and for reasons, known only to himself, remains in hiding. Judging the future by the past, if he is alive, and has more information to impart, it would be given only through the same source. For these reasons I would like to attach Captain Middleton to my staff."

"General, your reasons are good," replied Blair, "and it shall be for Captain Middleton to decide."

"Where I can do my country the most good, there I am willing to go," answered Lawrence.

So it was decided that for the summer Lawrence should remain with General Schofield. The words of General Schofield had also given Lawrence hope that Guilford lived. But as weeks and months passed, and no other communication came to him, he again looked upon Guilford as dead.

Hopeless of getting relief from the Federal Government, General Schofield entered upon the gigantic task of organizing the militia of the State. In this Lawrence was of the greatest service, and through a system of spies and scouts he was enabled to keep General Schofield well informed as to what was going on in the State.

In helping organize the militia, Lawrence had many adventures and many hair-breadth escapes, and by his side always rode the faithful Dan Sherman, and together they shared every danger.

By the last of July, as has been stated, there were nearly one hundred thousand men arrayed against each other. It was a partisan warfare on a mighty scale, and the storm was about to burst.

CHAPTER IV

MOORE'S MILL

We left Harry Semans and his young companion just starting on their lonely ride to Jefferson City, a distance of twenty-seven miles. The soldier with Harry proved rather a garrulous youth. He said his name was David Harris; that he belonged to the Third Iowa Cavalry; was a farmer boy, and rather liked the service. "It's exciting, you know," he added.

"Very much so at times," dryly answered Harry.

"Say, what makes you dress like a blamed guerrilla?" suddenly asked Dave. "You are a soldier, aren't you?"

"I am a scout," replied Harry. "I dress like a guerrilla because I have to pretend to be one about half the time. Just before I reached Fulton today I passed myself off as one of Porter's men. It saved me a dangerous encounter, perhaps my life."

"Gee! it must be exciting," said the boy. "I wish I was a scout."

"Couldn't be one," laughed Harry. "Your Yankee brogue would give you away. I notice you say 'keow' instead of 'cow' and 'guess' instead of 'reckon.' But please don't talk any more, we must keep both ears and eyes open."

After this they rode along in silence; that is, as much as Dave would allow, until Harry ordered him to ride in the rear, and if he must talk, talk to himself, and so low that no one else could hear.

For some ten miles they proceeded at a swift gallop without adventure, meeting two or three horsemen who seemed as little desirous of making acquaintance as they were themselves, and Dave began to think the ride rather tame.

As they were passing a place where the bushes grew thickly by the side of the road, they received a gruff command to halt. Instead of obeying, Harry, as quick as thought, drew his revolver and fired, at the same time putting spurs to his horse and shouting to Harris, "Ride for your life."

There was a rustling in the bushes, an angry exclamation as well as a groan. Harry's shot had gone true, and came as a surprise to the bushwhackers as well, for two or three seconds elapsed before three or four shots rang out, and they went wild.

"Well, how do you like it?" asked Harry, as he drew rein, considering the danger past.

"It was so sudden," said Dave. "I think I would have halted, and asked what was wanted."

"And got gobbled, and in all probability hanged afterwards. Dave, you have to learn something yet before you become a scout. Always be ready to fire at a moment's notice; and if you have to run don't tarry on your going. I took chances as to whether there was a large party or not, but concluded it was not, or some of them would have been in the road."

"Did you think of all that? Why, the word 'Halt' was hardly out of the fellow's mouth when you fired."

"Think quickly, act quickly; it has saved my bacon many a time. You ought to have been with me when I was with Captain Lawrence Middleton. There is the fellow to ride with. But this wouldn't have happened if Bruno had been with me."

"Bruno? Who is Bruno?" asked Dave.

"Bruno is my dog. He would have smelled those fellows out before we were within forty rods of them. I am never afraid of a surprise when Bruno is with me. But no more talking now."

Once more their horses took up a swinging gallop, and they met with no further adventures, and within less than three hours from the time they started they were halted by the Union pickets who guarded the approach to the river opposite Jefferson City.

Harry demanded of the Lieutenant in command of the picket that they be ferried across the river without loss of time, but the Lieutenant demurred, saying it was against orders to allow anyone to cross the river during the night.

"I have important dispatches from Captain Duffield to Colonel Guitar. Refuse to take me over, and I would not give much for your command," angrily answered Harry.

"Who are you?" demanded the Lieutenant. "From your dress you are certainly not a soldier."

"I am Harry Semans, scout for the Merrill Horse," answered Harry.

"At the name 'Merrill Horse' the Lieutenant became as meek as a lamb.

"Excuse me," he exclaimed. "I will see that you get over the river immediately. Anything new at Fulton?"

"Porter and Poindexter are within eleven miles of the place, and Duffield expects to be attacked by morning."

The Lieutenant gave a low whistle. "The devil," he ejaculated, and rushed to give the necessary orders.

It was eleven o'clock before the river was crossed and the headquarters of Colonel Guitar reached. He had just retired, but Harry and Dave were without ceremony admitted into his bedroom. The Colonel read the dispatch of Captain Duffield, sitting on his bed in his nightclothes.

At once all was excitement. There were but five hundred men guarding the important post of Jefferson City. Of this force, Colonel Guitar ordered one hundred to accompany him to Fulton. He dared not deplete the little garrison more.

While Harry and Dave were in the Colonel's bedroom, Harry noticed that Dave was regarding Guitar with a great deal of interest. When they passed out Dave said to Harry in a whisper, "That general don't amount to shucks. Think of him fighting Porter?"

"Why, what's the matter with Guitar?" asked Harry.

"Matter! He wears a nightgown just like a woman. Who ever heard of a man wearing a nightgown?"[1]

Harry exploded with laughter. "Many men wear nightgowns," he explained. "I have no doubt but what General Schofield does. I reckon you will find out that Guitar will fight."

During the day there had been two important arrivals in Jefferson City, that of Lawrence Middleton and Dan Sherman. They had told Colonel Guitar of the rapid concentration of the guerrilla bands all through the counties north of the river, and had warned him to be on the lookout for trouble. In fact, they had brought orders from General Schofield for him to send two of his companies to Columbia, as it was thought that was the place in greatest danger.

Lawrence and Dan were told of the danger that threatened Fulton, and they determined to accompany Guitar in his expedition.

It was not until they were on the ferryboat crossing the river that Harry was aware that Lawrence and Dan were of the number. He nearly went wild on seeing them.

"And how is Bruno?" asked Lawrence.

"Bruno is all right. I sent him with a dispatch to Colonel Shaffer."

Hurry as fast as they could, it was long past midnight before the force was across the river, and then there was a twenty-seven mile ride ahead of them.

On the march Harry had an opportunity to tell Lawrence much that had happened to him since they parted.

It was daylight when Fulton was reached, and, much to their relief, the place had not been attacked, but the excitement ran high. Rumor had increased Porter's force to two thousand. Colonel Guitar believed this estimate to be much too high. So, small as his force was, only one hundred and eighty, he determined to move out and attack Porter without delay.

When this became known to the few Union inhabitants of Fulton they implored Guitar not to do it. "Your force will be annihilated," they exclaimed, "and Fulton will be at the mercy of the foe."

Lawrence agreed with Colonel Guitar. "We came here in the night," said he. "Porter does not know how many men you brought. No doubt your force is magnified, the same as his. Assuming the offensive will disconcert him, and also prevent him receiving further reinforcements."

So it was decided, and the little force took up the march for Brown's Springs, eleven miles away. Couriers were dispatched to find Colonel Shaffer, for even if Bruno had succeeded in delivering Harry's message Shaffer would march for Fulton instead of Brown's Springs.

It was about eleven o'clock when the column reached the vicinity of Brown's Springs. Nothing as yet had been heard from Colonel Shaffer, but Guitar determined to attack. Lawrence had been asked by Guitar to act as his aid, to which he gladly assented.

Two or three small parties of guerrillas had been sighted, but they took to the brush at the sight of the Federals.

The command now moved cautiously forward, but there was to be no battle. Harry, who had been scouting in front, returned with the news that the guerrillas had fled. Their camp was soon occupied. Everything showed a rapid flight; even the would-be dinner of the guerrillas was found half cooked.

Along in the afternoon Porter's force was located near Moore's Mill, about four miles distant.

As Colonel Guitar's men had not slept a wink the night before, and as both men and horses were tired out, the Colonel decided to camp, rest his men and await the coming of Shaffer.

Why Porter fled from Brown's Springs and yet gave battle the next day, after Shaffer had come up, will never be known. If he had fought at Brown's Springs he would have had five men to Guitar's one. He may have thought Shaffer was miles away. What Poindexter had told him would lead him to believe this. And it would have been the case had it not been for Harry and the faithful Bruno.

Every precaution was taken by Colonel Guitar to guard against a night attack, but his little army was allowed to rest in peace.

During the night the couriers sent out to locate Shaffer reported. Bruno had done his work well, but Shaffer had been miles farther away than thought, and as had been requested by Harry in his report, had marched for Fulton. He was yet ten miles away, and it would be impossible for him to join Guitar before morning.

The morning came and with it Shaffer, and with him five hundred and fifty men, eager for the combat. How Guitar's men did cheer when they saw Shaffer coming.

Scouts reported that Porter still occupied his camp, and showed no sign of moving. It looked as if he had resolved to stay and fight. Colonel Guitar gave the order to move forward and attack. The advance had to be carefully made, for the country was rough, wooded, and covered with a dense undergrowth of bushes.

Harry now had Bruno with him, and leaving his horse, he, with the dog, made his way to the front, in order to discover, as far as possible, the plans and position of the enemy. So dense was the undergrowth he could not see thirty feet ahead of him, but Bruno, as stealthy as a tiger in the jungle, crept through the bushes ahead of him and more than once gave him warning to turn aside his steps and take another direction. At last he came to quite a hill, on the summit of which grew a tree with branches close to the ground. Leaving Bruno to guard, Harry climbed the tree, and to his satisfaction had a good view of the country. But what he saw filled him with consternation.

The road on which the Federals were marching was narrow and on each side lined with dense underbrush. Ahead of the Federal advance, the road itself was clear, not a guerrilla in sight, but Porter had left his camp and all his forces were stealthily creeping through the woods, and concealing themselves in the bushes which lined the road.

Harry knew that that meant an ambuscade, and the Federal advance was almost into it. In his eagerness he hardly knew whether he fell, jumped, or swung himself down by the branches, but he was out of the tree and tearing through the brush like a mad man to give warning.

He came to the road just as Colonel Guitar came along, riding at the head of his column, the advance, consisting of twenty-five men of Company E, Third Iowa Cavalry, being a short distance ahead.

"Halt the advance. Ambuscade," gasped Harry. He could say no more, as he fell from exhaustion.

"Halt the advance. Ambuscade," gasped Harry.

Guitar understood. "Halt," he cried, and to an aid, "Warn the advance."

The aid put spurs to his horse, but he was too late. Before he could give warning there came a crashing volley from the jungle on the east side of the road, the thicket burst into flame and smoke. It was an awful, a murderous volley. Out of the twenty-five men who composed the advance, hardly a man or horse escaped unscathed; all were killed or wounded.

Swift and terrible as this blow was, it created no panic in Guitar's little army. The road was narrow, thickets on each side. Nothing could be done with cavalry. Quickly the order was given to dismount and send the horses back in charge of every fourth man. Guitar then formed his slender line in the edge of the thicket on the west side of the road, with orders to hold until Shaffer came up, for Shaffer was still behind.

Hearing the sound of the conflict, Shaffer rushed forward, sent back his horses, and along the road and through the tangled undergrowth the line was formed and the battle became general.

The guerrillas displayed a bravery they seldom showed when engaged with regular troops, and fought with determination and ferocity. They had the advantage in position and numbers, but Guitar had the advantage in having a couple of pieces of artillery. One of these pieces was brought up by hand and planted in the road where it could sweep the woods in which the guerrillas were concealed.

Hidden from view, the guerrillas crept up near, poured in a murderous volley, and then raising a blood-curdling yell, dashed for the gun. Four of the gunners had fallen before the volley, and for the time the gun was silent. But behind the piece lay a line of sturdy cavalrymen. They waited until the guerrillas had burst from the thicket and were within forty feet of the gun, then sprang to their feet and poured a terrific volley almost into the faces of the foe.

Staggering and bleeding, the guerrillas shrank back into the woods, but only to rally and with fearful yells dash for the gun again. This time they were not met by the cavalrymen alone, but the cannon belched forth its deadly charge of canister in their faces.

When the four gunners fell at the first charge, Dan Sherman, seeing that the piece was not manned, rushed forward and snatched the primer from the dead hand of the man who was about to insert it when he fell. Dan inserted the primer, pulled the lanyard and sent the contents of the gun into the ranks of the enemy. Two of the artillerymen who had not been injured came to his assistance, and again the gun was thundering forth its defiance.

Through the chaparral Shaffer's men now pushed their way foot by foot. It was a strange conflict. So dense was the undergrowth the line could not be followed by the eye for thirty feet. No foe could be seen, but the thickets blazed and smoked, and the leaden hail swept through the bushes, tearing and mangling them as if enraged at their resistance.

The duty of Lawrence was a dangerous one. He had to break his way through the thickets, see that some kind of a line was kept, and that orders were being executed. While the men were sheltered by trees, logs and rocks, he had to be exposed, but as if possessed of a charmed life, he passed through unscathed.

Foot by foot the Federals dragged themselves forward, slowly pressing the guerrillas back. At last, tired of fighting an unseen foe, the men arose to their feet, and with a wild cheer sprang forward. Surprised, the foe wavered, then broke. The flight became a panic, and they fled terror-stricken from the field. The battle of Moore's Mill had been fought and won.

There was no pursuit that night. The day had been intensely hot, and the battle had raged from twelve noon until four. The soldiers, with blackened, swollen faces and tongues, were fainting with thirst. Colonel Guitar ordered his men to occupy the camp deserted by the foe. The dead were to be buried, the wounded cared for.

So precipitously had the guerrillas fled that except the severely wounded, few prisoners were taken. Porter had impressed upon his men that to be captured by the Yankees meant certain death.

While searching the field Lawrence noticed some white object crawling along like a large reptile. Upon investigation he found to his surprise that it was a man, and entirely nude.

"Why are you without clothes?" asked Lawrence.

The man looked tip into Lawrence's face with a scared expression and whined, "The guerrillas captured me, and they stripped me of my clothing."

"Then you are a Federal soldier?" inquired Lawrence.

"Y-e-s," came the halting answer.

"You lie," exclaimed Lawrence. "You are one of the guerrillas."

The fellow then broke down, and, piteously begging for his life, said he was one of Porter's men, and that he looked for nothing but death if captured, so he had divested himself of his clothing, hoping to pass himself off as a Federal.[2]

Lawrence ordered him to be tenderly cared for, and tears of gratitude ran down the fellow's face when he realised he was not to be murdered.

The battle of Moore's Mill, insignificant as it was compared to the great battles of the war, was important in this: It frustrated the plans of the conspirators, and was the beginning of a series of conflicts which forever ended the hopes of the Confederates to recapture the State by an uprising.

Colonel Guitar reported his loss in the battle as thirteen killed and fifty-five wounded. The guerrilla loss he reported at fifty-two left dead on the field and one hundred and twenty-five wounded.

In all the partisan battles in Missouri the guerrillas never reported their losses, and only the reports of the Federal commanders are accessible. In many cases no doubt these reports are exaggerated.

CHAPTER V

A FIGHT IN THE NIGHT

Early the next morning Colonel Guitar started in pursuit of the enemy. Lawrence took the advance with a party of six men. As a matter of course, Harry and Bruno made a part of this force.

"This seems like old times, Harry," said Lawrence, as they started off.

"It does that, Captain," replied Harry. "You, Dan, Bruno and myself make four of the old gang. Now if only Guilford was with us—" He stopped and sighed. His mind had gone back to the time when he and Guilford had so nearly faced death in among the Boston mountains. "You have heard nothing of him, have you, Captain?"

"Nothing. I did receive a communication about two months ago that I thought might be from him; but I have received nothing since and I have given up all hopes."

The trail left by the guerrillas was very plain. It followed the Auxvasse for some two miles, and then turned off into the hills. The country was very rough, the places for an ambuscade numerous, but with Bruno scouting, Lawrence had no fears of being surprised.

Soon they came to a place where the road forked. On the road that led to the left up the Auxvasse the trail was plainly marked; but the road that led on into the more open country had little appearance of being traveled; but it was rocky, and by being careful a large force could have passed over it and left but few traces behind.

Harry dismounted and carefully examined the ground. As for Bruno, he seemed to have no doubt; he was taking the blind trail.

"A blind," said Harry. "Not more than fifty took to the left, and they left as broad a trail as possible. The main force passed up the other road. If Guitar follows the broad trail it will lead him away among the hills and then disappear, for the party will separate."

Just then the advance of Guitar's force appeared, led by a young lieutenant.

"What are you waiting for?" he asked Lawrence. "Have you discovered the enemy?"

"No, but Porter evidently divided his forces here, and we were discussing which road the main body took."

The Lieutenant dismounted, and after looking over the ground, said, "Why, it's as plain as the nose on a man's face; they went to the left."

"Harry and Bruno both think differently," answered Lawrence.

The Lieutenant sniffed. "Much they know about it," he exclaimed. "I have trailed too many guerrillas to be mistaken."

Just then Colonel Guitar, at the head of his column, appeared. He was appealed to, and after examining the road, decided to take the left hand road, but told Lawrence he might keep on the other road with his scouts, and see what he could discover. As a matter of precaution he increased Lawrence's force to ten men.

The Lieutenant rode off highly elated over the fact that Colonel Guitar agreed with his views.

"Let them go," sputtered Harry. "They will be disgusted before night."

And so it proved. The trail led Guitar over hills, through ravines and rocky dells, through tangled forests, and twisted and turned, until it disappeared entirely; and, much to his disgust, Guitar found himself along in the afternoon within two miles from where he had started. The wily guerrilla chieftain had fooled him completely. Guitar led his mad, weary and swearing force back to the old camp grounds, and there awaited the return of Lawrence and his scouting party.

Lawrence did not think for a moment but that Harry was right, and that fact soon became evident. They were now in a more open country, and the signs that a large body of troops had passed became numerous. Not only this, but in the houses along the road they found a number of severely wounded that the guerrillas had been forced to leave.

After some miles they came to a road that crossed the one they were on, and which led to the west. Here the ground had been much trampled, and that but a short time before.

Again Harry dismounted and examined the ground carefully. "We are close onto them," he said. "I do not believe they have been gone half an hour."

"Harry, you are a regular Kit Carson for trails," laughed Lawrence. "Are you sure you are right?"

"Perfectly, and what is more, their force divided here, but the larger force kept on. The explanation is plain. Porter operates to the north and east, so he has kept on with the larger force; Poindexter and Cobb have their chief haunts along the Chariton and Grand, so with their forces they have gone to the west."

"We had better hurry back to Guitar and tell him this," exclaimed Lawrence.

"No," snapped Harry. "I don't propose to be snubbed again. You only have my word now. Let's keep on until you and everyone present have proof that cannot be doubted."

"I believe you are right, Harry," said Lawrence, and he gave the command to continue on.

They had proceeded a mile when Bruno came running back, showing by his manner he had news to impart.

Halting his squad, Lawrence dismounted, and taking Harry, they carefully made their way to the brow of a hill which lay in front. Cautiously peering over, they saw about a quarter of a mile ahead a commodious house, around which a number of horses were hitched.

It was evident that they had come on the rear guard of the retreating guerrillas, and that they had halted to rest, and were being well entertained, for a number of black women were passing back and forth from the house to a rude outdoor kitchen, all bearing dishes, and it looked very tempting to Lawrence and Harry.

"Feel like eating myself," whispered Harry. "I didn't know I was so hungry."

"How many do you reckon there are?" asked Lawrence.

Harry carefully counted the horses and then said, "Not over fifteen or twenty. I can count only fifteen horses, but there may be some out of sight."

"Feel like appropriating that dinner myself," said Lawrence.

"The boys would never forgive us if we didn't," answered Harry.

Hurrying back they explained the situation, and by unanimous vote it was decided to make a charge on that dinner without loss of time.

"Harry and I will ride a little ahead," said Lawrence. "Harry is dressed in homespun and my uniform is so dusty they won't be able to distinguish its color until we are close to them. Dan, when I give the signal, come on in a rush."

So Lawrence find Harry rode ahead, the squad some fifteen or twenty paces in the rear, leisurely following. Scarcely had they rode over the brow of the hill when two sentinels they had not seen before suddenly showed themselves on the road. The sentinels seemed much alarmed, and drew up their carbines as if to shoot.

Harry waved his hat and signaled they were friends. Seeing the squad coming so leisurely and the two in advance, the sentinels lowered their guns and waited, thinking it must be some of their own men. But when Lawrence and Harry were a few yards from them one of the sentinels caught the color of Lawrence's uniform.

Giving a terrific whoop, he raised his gun and fired, the ball just missing Lawrence's head. The other sentinel fired, but his shot went wild. Both wheeled their horses and dashed back, yelling, "Yanks! Yanks! Yanks!"

There was no need of Lawrence signaling Dan to come on, for the squad were urging their horses to the limit.

The guerrillas at dinner heard the firing and came pouring out of the house. Close on the heels of the flying sentinels thundered the Federals. The guerrillas took one look, and with cries of terror sprang for their horses, and cutting the halter straps were up and away. By this time the balls were falling among them thick and fast, killing two, and the horse of a third one fell and the rider was taken prisoner.

The fight was over and Lawrence rode up to the house, and was met on the porch by a white haired, fine looking old gentleman.

"Sorry to trouble you," said Lawrence, urbanely, "but with your permission I will have my men finish that dinner that your friends have so ungraciously and suddenly declined."

"Step right in, suh, the dinner is waiting," the old gentleman replied with a wan smile, "but my guests are not accustomed to invite themselves."

"Sorry, sir, but when you consider the improvement in the character of your guests, you should rejoice," rejoined Lawrence. "Entertaining such guests as have run away is dangerous."

"I shall feed no Yankees," cried a shrill voice, and a young lady flounced out of the door, her face red with anger.

Lawrence saw that she was good to look at, tall, willowy and fair of face. Taking off his hat and bowing politely, he said, "My dear lady, I humbly beg your pardon, but my men must certainly finish that dinner you so kindly prepared for those who were so impolite and cowardly as to run away and leave it. It would take more than Rebel bullets to make me decline a meal prepared by your fair hands."

The compliment was lost. "Cowardly?" cried the girl. "Is it cowardly for twenty to flee before a regiment of Yankee cut-throats?"

"There are only a dozen of us," said Lawrence, "and a dozen finer gentlemen you never entertained, every one a prince and as brave as a lion. If it were not so, twenty of your friends would not have fled from them."

The young lady flashed a look of scorn at him and cried, "Yankee cut-throats and robbers—gentlemen and brave! You amaze me." She abruptly turned and went into the house, and much to Lawrence's regret he did not see her again.

"You must excuse my daughter," said the old man, nervously.

"That's all right, so we get the dinner," answered Lawrence. "Don't you see my men are getting impatient?"

"Come right in. I feed you, not because I want to, but because I must." Thus speaking, he led them into the house, where they found a sumptuous repast but partly eaten; and not a man in the squad but did full justice to it.

Lawrence found the prisoner they had taken shaking with terror, for some of the men had coolly informed him that after dinner he was to be hanged.

Lawrence was about to reprimand the men for their cruel joke, when it occurred to him he might use the fellow's fears to some advantage. So he told him if he would tell all he knew, not only would his life be spared, but that he would be paroled, but he would have to be careful and tell nothing but the truth.

The prisoner eagerly embraced the opportunity, and confirmed what Harry had said. He moreover stated that before Porter and Poindexter parted they had agreed to gather up all the men they could, and join forces again somewhere along the line of the Hannibal and St. Joseph Railroad.

"I guess that is straight enough for Guitar to believe, instead of that upstart lieutenant," said Harry.

Back to find Guitar the scouts rode; but it was night when they found him and then nearly where they had left him. All day his men had marched beneath a broiling sun, and when they found out how they had been led astray, against the protests of Harry, they wanted to lynch the smart lieutenant; and it was a long time before the poor fellow heard the last of it.

Colonel Guitar concluded to rest his men until morning, and then continue the pursuit. "I will chase Porter clear to the Iowa line, if necessary, to catch him," he said.

While it was arranged that Colonel Guitar should march straight for Mexico, Lawrence, with a detail of ten men dressed as guerrillas, was to follow directly on the trail of Porter, thus keeping track of his movements. Lawrence chose ten of the Merrill Horse to go with him.

One of the men in looking over the squad and noticing that with Lawrence, Dan, and Harry there were thirteen of them, demurred, saying that another man should be added, as thirteen was an unlucky number. "No thirteen for me," he said.

"Step aside," ordered Lawrence. "I want no thirteen cranks. I, for one, am not troubled over the old superstition of thirteen. Who will volunteer to take this fellow's place?"

A dozen were eager to go, and Lawrence chose a manly looking fellow. "Our timid friend here counted wrong," he said. "He forgot Bruno, and he is equal to a dozen men."

This raised a laugh, and the party started in the highest spirits. After going a short distance, Lawrence halted and made his men a short speech.

"Boys," he said, "dressed as we are, it will be certain death if we are captured. If circumstances arise where we must fight, fight to the death—never surrender. We are strong enough to beat off any small party, and large ones we must avoid. But remember, our object is to get information, not to fight. To all appearances we must be simon-pure guerrillas. If we meet with guerrillas, as no doubt we will, keep cool, and let Harry or me do the talking."

"All right, Captain," they shouted, and they rode merrily forward, careless of what dangers they might meet. So often had they faced death, they considered him an old acquaintance.

They found little trouble in following the trail of Porter. Taken for guerrillas, every Southern sympathizer was eager to give them all the information possible.

For two days they traveled, frequently meeting with small parties of guerrillas, and to these Lawrence always represented they belonged south of the river, and had been obliged to cross to avoid a large party of Federals, and that they had concluded to keep on and join Porter.

By questioning, Lawrence found all of these parties had orders to join Porter at or near Paris. Some of these parties gave Lawrence a good deal of trouble by wanting to join forces with him, but he put them off by saying it would be safer to travel in small parties, as they would not then be so liable to attract the attention of the Federals.

Porter in his flight had crossed the North Missouri Railroad near Montgomery City, but in his haste did little damage.

It was after Lawrence had crossed this railroad that he had his first serious trouble. Here he came onto a company of at least fifty guerrillas under the command of Bill Duncan, a leader who often acted with Porter, and as noted for cruelty as he. The company was hastening to join Porter at Paris.

Lawrence thought it best to change his story. Duncan had roughly ordered him to join his company. This Lawrence firmly refused, saying they belonged to Poindexter's command; that after Poindexter and Porter had parted, Poindexter had found it impossible for him to join Porter, as he had promised, and that he had been sent post-haste by Poindexter to find Porter and inform him of the fact.

"But now," said Lawrence, "I need go no farther, as you can carry this information to Porter."

"Where are you going if I do this?" asked Duncan.

"Back to join Poindexter, as I promised," said Lawrence.

"I don't know but you are all right," said Duncan; "but I don't like the looks of your men. What did you say your name was?"

"I haven't told you, but it is Jack Hilton. Porter knows me well. Give him my respects. Be sure and tell him what I have told you, for it is very important. Good-day, Captain. Come on, boys," and Lawrence turned and rode back the way he had come.

Duncan watched them until they were out of sight; then, shaking his head, said: "I almost wish I hadn't let them go, but I reckon they're all right. That young chap in command told a mighty straight story."

About this time Lawrence was saying: "That was a mighty close shave, Dan. That fellow had a big notion to make trouble."

Bruno, who had been told to keep out of sight, joined them after they had gone some distance. He acted dejected and dispirited, and if he could have talked would have asked the meaning of it all. Time and time again he had given warning of the approach of guerrillas, only to have his master meet them as friends. He had given notice of the approach of Duncan's party, and to his surprise nothing had come of it. He was a thoroughly disgusted dog, and walked along with drooping head and tail; but it only took a word from Harry to set him all right again.

"We must turn north again at the first opportunity," said Lawrence. "This will put us back several miles."

They had not gone far before they met a solitary guerrilla. He was one of Duncan's party, and had gone out of his way to visit a friend. He was halted, and explained who he was.

"Ah, yes," said Lawrence; "your company is just ahead. We left it only a few moments ago."

"Whar be yo' goin'?" asked the fellow.

"Back to join Poindexter, where we belong. I was carrying a message to Porter from Poindexter, but on meeting Duncan I gave it to him, so we are on our way back."

The fellow had sharp eyes, and Lawrence noticed that he was scrutinizing his party closely, and when he saw Harry, who had been a little in the rear, and just now came up, he started perceptibly, but quickly recovered himself, and exclaimed, "I must be goin'." Putting spurs to his horse, he rode rapidly away.

Harry gazed on his retreating figure, his brow wrinkled in perplexity. Suddenly he cried: "Captain, I know that fellow, and I believe he recognized me. If he did, we are going to have trouble."

"Are you sure?" asked Lawrence, startled.

"Quite sure. I arrested him near Paris a couple of months ago, and he gave his parole. I had hard work to keep Bruno from throttling him. Where is Bruno?"

"There he comes now," said Lawrence, "and he seems to be greatly excited."

Bruno was indeed greatly excited, and he ran around Harry, growling, and then in the direction the fellow had taken, looking back to see if Harry was following.

"Bruno knows him, too," said Harry. "He never forgets. If that fellow saw Bruno, it is indeed all up. He will tell Duncan, and we will have a fight on our hands as sure as fate."

"By hard riding we can reach Mexico and avoid the fight," said Lawrence; "but I don't like the idea of running away."

"Nor I," said Harry. "Even if the fellow knew me, Duncan may not follow us."

"What do you think, Dan?" asked Lawrence.

Dan took a chew of tobacco, as he always did when about to decide anything weighty, and then slowly remarked: "Don't like to run until I see something to run from."

"That's it," cried Lawrence. "It is doubtful if Duncan follows us at all. If he does, it will be time enough to think of running."

It was therefore decided to take the first road they came to which led in the direction they wished to go. They soon came to the road, but before they turned into it, Lawrence took the precaution to make it appear that they had ridden straight on.

"Reckon Bruno and I will hang near this corner for a while," said Harry. "I want to make sure whether we are followed or not. I feel in my bones Duncan is after us."

Harry had good reasons for feeling as he did, for the guerrilla whose name was Josh Hicks, had not only recognized him, but he had also seen Bruno, and he bore the dog an undying hatred, for it was he who had captured him, and would have killed him had not Harry interfered.

No sooner was Hicks out of sight of the scouts than he put his horse to the utmost speed. "I have an account to settle with that dawg and his master," he muttered, "and it will be settled tonight or my name is not Josh Hicks."

He overtook Duncan's command, his horse covered with foam.

"Hello, Josh, what's up?" asked some of the men, as he dashed up. "Yo' un acts as if the Merrill Hoss was after yo'. What has skeered yo'?"

"Whar is Bill?" Hicks fairly shrieked.

"Up in front. What's the matter?" and the men began to look uneasy.

Seeing the excitement in the rear, Duncan came riding back. "What's the trouble?" he asked, gruffly.

"Don't know," answered one of the men, "but Josh Hicks has jest come up, his hoss covered with foam, and he seems mighty skeered about something."

Just then Hicks caught sight of Duncan, and yelled: "Bill, did yo' un meet a party of about a dozen men a few minutes ago?"

"Yes; what of it?"

"An' yo'un had them and let them go?" fairly screamed Hicks.

"Of course; they were Poindexter's men."

"Poindexter's men! Hell!" Hicks shouted. "They was Yanks in disguise, an' one of them was that damned boy scout of the Merrill Hoss. I know him, and I saw the dawg."

"Be you sure, Josh?" asked Duncan.

"Sure? Of course I'm sure. Don't I know the boy, and don't I know the dawg? Can I forgit the brute that had his teeth in my throat? Oh, yo' un be a nice one, yo' un be, Bill, to let them fellers slip through your fingers!"

Duncan flushed with anger and chagrin. "Look here, Josh," he roared, "none of your insinuations, or you settle with me. I never met that feller, and if you had been with us, as you ought to have been, instead of gallivanting around the country, you would have known them. Them fellers told a straight story, they did; but they'll never fool Bill Duncan but once. About face, boys."

In a moment more the guerrillas were thundering on the trail of the scouts. They had little difficulty until they came to the road where Lawrence had turned off. Here Duncan carefully examined the ground, and with the almost unerring instinct of his class, decided rightly as to the way the scouts had gone.

Harry had taken a position about half a mile from where the road turned, and where he had a good view without being seen. He saw the guerrillas stop and hesitate, and then take the right road.

"They are after us, sure," he muttered, and, spurring his horse, he did not pull rein until he had overtaken the scouts.

"They are close after us!" he exclaimed, pulling up his panting horse.

"It will soon be dark; we can elude them," said Lawrence.

"Let's fight them," said Dan, taking out his plug of tobacco and holding it until a decision was made.

"Yes, let's fight them," said the men. "This is the tamest scout we've ever been on—hobnobbing with the villains instead of fighting them."

"All right," replied Lawrence. "Let's ride rapidly ahead until dark. Dan, you and I must think up a bit of strategy in the meantime."

"All right," said Dan, biting off a big chew from the plug he was holding, and restoring the rest to his pocket. If the decision had been against a fight, Dan would have put the plug back without taking a chew. When Dan put his tobacco back unbitten, it was always an infallible sign that something had gone in a way that did not suit him.

That Lawrence and Dan had fixed up that bit of strategy was evident, for just as darkness was closing in, Lawrence ordered the scouts to stop long enough to gather a good feed of corn for their horses, from a near-by field. Then they rode on and camped in a wood, some little distance from the road.

"The guerrillas will not now attack us until some time in the night," he said, "thinking to surprise us."

He gave orders for the horses to be tethered a little distance in the rear of the camp, where they would be sheltered. "Hitch them so you can loose them in a twinkling, if it becomes necessary," he ordered.

Then he told the men they might build a fire, make some coffee, and roast some corn, if they wished.

"Had we not better dig a hole for the fire, and screen it with blankets?" suggested one of the men. "A light might give us away."

"Just what I want it to do," answered Lawrence, to the astonishment of all but Dan and Harry.