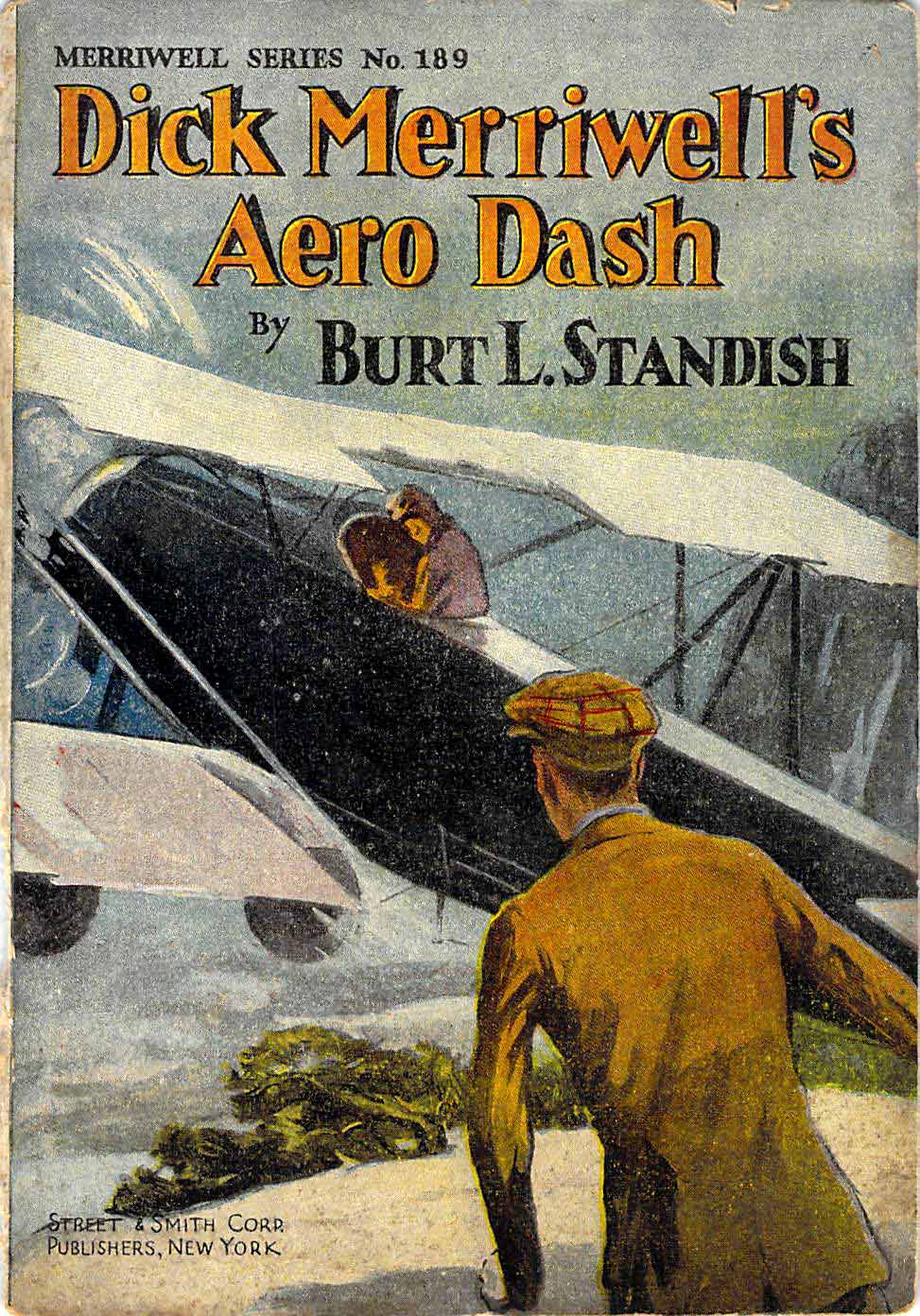

Dick Merriwell’s Aëro Dash

CONTENTS

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Catastrophe | 5 |

| II. | The Coward | 12 |

| III. | A Scrap of Paper | 25 |

| IV. | Stovebridge Finds an Ally | 35 |

| V. | The Struggle in the Dark | 54 |

| VI. | Dick Merriwell Wins | 66 |

| VII. | The Brand of Fear | 75 |

| VIII. | The Young Man in Trouble | 83 |

| IX. | A Disgruntled Pitcher | 89 |

| X. | In Dolan’s Café | 106 |

| XI. | The Explosion | 121 |

| XII. | The Game Begins | 135 |

| XIII. | Against Heavy Odds | 147 |

| XIV. | Three Men of Millions | 159 |

| XV. | The Mysterious Mr. Randolph | 173 |

| XVI. | The Mysterious House | 183 |

| XVII. | In the Shadow of the Cliffs | 195 |

| XVIII. | Bert Holton, Special Officer | 209 |

| XIX. | The Race in the Clouds | 222 |

| XX. | The Outlaws | 235 |

| XXI. | Dick Merriwell’s Fist | 247 |

| XXII. | All Arranged | 254 |

| XXIII. | Chester Arlington’s Mother | 260 |

| XXIV. | Two Indian Friends | 267 |

| XXV. | The Man in the Next Room | 277 |

| XXVI. | When Greek Meets Greek | 282 |

| XXVII. | Shangowah’s Backers | 290 |

| XXVIII. | Batted Out | 295 |

| XXIX. | The Finish | 303 |

Dick Merriwell’s Aëro Dash

OR

WINNING ABOVE THE CLOUDS

By

BURT L. STANDISH

Author of the famous Merriwell stories.

STREET & SMITH CORPORATION

PUBLISHERS

79–89 Seventh Avenue, New York

Copyright, 1910

By STREET & SMITH

Dick Merriwell’s Aëro Dash

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian.

Printed in the U. S. A.

CHAPTER I.

THE CATASTROPHE.

A glorious midsummer morning, clear, balmy and bracing. An ideal stretch of macadam, level as a floor and straight as a die for close onto two miles, with interminable fields of waving wheat on either side. A new, high-power car in perfect running order.

It was a temptation for speeding which few could resist, certainly not Brose Stovebridge, who was little given to thinking of the consequences when his own pleasure was concerned, and who had a reputation for reckless driving which was exceeded by none.

With a shout of joy, he snatched off his cap and flung it on the seat beside him. The next instant he had opened the throttle wide and advanced the spark to the last notch. The racing roadster leaped forward like a thing alive and shot down the stretch—cut-out wide open and pistons throbbing in perfect unison—a blurred streak of red amidst a swirling cloud of dust.

Stovebridge bent over the wheel, his eyes shining with excitement and his curly, blond hair tossed by the cutting wind into a disordered mass above his rather handsome face. The speedometer hand was close to the fifty mark.

“You’ll do, you beauty,” he muttered exultingly. “I could squeeze another ten out of you, if I had the chance.”

6 The horn shrieked a warning as he pulled her down to take the curve ahead, but her momentum was so great that she shot around the wide swerve almost on two wheels, with scarcely any perceptible slackening.

The next instant Stovebridge gave a gasping cry of horror.

Directly in the middle of the road stood a little girl. Her eyes were wide and staring, and she seemed absolutely petrified with fright.

The car swerved suddenly to one side, there was a grinding jar of the emergency and the white, stricken face vanished. With a sickening jolt, the roadster rolled on a short distance and stopped.

For a second or two Stovebridge sat absolutely still, his hands trembling, his face the color of chalk. Then he turned, as though with a great effort, and looked back.

The child lay silent, a crumpled, dust-covered heap. The white face was stained with blood, one tiny hand still clutched a bunch of wild flowers.

The man in the car gave a shuddering groan.

“I’ve killed her!” he gasped. “My God, I’ve killed her!”

He would be arrested—convicted—imprisoned. At the thought every bit of manhood left him and fear struck him to the soul. He knew that every law, human or divine, bound him to pick up the child and hurry her to a doctor, for there might still be a spark of life which could be fanned into flame. But he was lost to all sense of humanity, decency, or honor. Maddened by the fear of consequences, his one impulse was to fly—fly quickly before he was discovered.

In a panic he threw off the brakes, started the car and ran through his gears into direct drive with frantic haste. The car leaped forward, and, without a backward glance at the victim of his carelessness, Stovebridge7 opened her up wide and disappeared down the road in a cloud of dust.

The child lay still where she had fallen. Slowly the dust settled and a gentle breeze stirred the flaxen hair above her blood-stained face.

Then came the throbbing of another motor approaching, a deep-toned horn sounded, and a big, red touring car, containing four young fellows, rounded the bend at a fair speed.

Dick Merriwell, the famous Yale athlete, was at the wheel, and, catching sight of the little heap in the roadway, he stopped the car with a jerk and sprang out.

As he ran forward and gathered the limp form into his arms, he gave an exclamation of pity. Then his face darkened.

“By heavens!” he cried. “I’d like to get my hands on the man who did this. Poor little kid! Just look at her face, Brad.”

As Brad Buckhart, Dick’s Texas chum, caught sight of the great gash over the child’s temple, his eyes flashed and he clenched his fists.

“The coyote!” he exploded. “He certain ought to have a hemp necktie put around his neck with the other end over a limb. I’d sure like to have a hold of that other end. You hear me talk!”

Squeezing past the portly form of Bouncer Bigelow, Tommy Tucker leaned excitedly out of the tonneau.

“Is she dead, Dick?” he asked anxiously.

Merriwell took his fingers from the small wrist he had been feeling.

“Not quite,” he said shortly. “But it’s no thanks to the scoundrel who ran her down and left her here.”

His eyes, which had been looking keenly to right and left, lit up as they fell upon the roof of a farm house nestling among some trees a little way back from the road.

8 “There’s a house, Brad,” he said in a relieved tone. “Even if she doesn’t belong there, they’ll make her comfortable and send for a doctor.”

With infinite tenderness he carried the child down the road a little way to a gate, and thence up a narrow walk bordered with lilac bushes. The door of the farm house was open and, without hesitation, he walked into the kitchen, where a woman stood ironing.

“I found——” he began.

The woman turned swiftly, and as she saw his burden, her face grew ghastly white and her hands flew to her heart.

“Amy!” she gasped in a choking voice. “Is—she——”

“She’s not dead,” Dick reassured her, “but I’m afraid she’s badly hurt. I picked her up in the road outside. Some one in a car had run over her and left her there.”

For an instant he thought the woman was going to faint. Then she pulled herself together with a tremendous effort.

“Give her to me!” she cried fiercely, her arms outstretched. “Give her to me!”

Her eyes were blinded with a sudden rush of tears.

“Little Amy, that never did a bit o’ harm to nobody,” she sobbed. “Oh, it’s too much!”

“Careful, now,” Merriwell cautioned. “Take her gently. I’m afraid her arm is broken.”

“Would you teach a woman to be gentle to her child?” she cried wildly.

Without waiting for a reply, she gathered the little form tenderly into her arms and laid her down on a sofa which stood at one side of the room. Then running to the sink for some water, she wet her handkerchief and began to wipe off the child’s face.

9 “You mustn’t mind what I said,” she faltered the next moment. “I didn’t mean it. I’m just wild.”

“I know,” Dick returned gently. “A doctor should be called at——”

“Of course!”

She sprang to her feet and flew into another room, whence Dick heard the insistent ringing of a telephone bell, followed quickly by rapid, broken sentences. As the handkerchief fell from her hand he had picked it up and was sprinkling the child’s face with water.

Presently the girl gave a little moan and opened her eyes.

“Mamma,” she said faintly—“mamma!”

The woman ran into the room at the sound.

“Here I am, darling,” she said, as she knelt down by the couch. “Where do you feel bad, Amy dear?”

“My arm,” the child moaned, “and my head. A big red car runned right over me.”

“Red!” muttered Merriwell, his eyes brightening.

“My precious!” soothed the mother. “The doctor’ll be here right off. Does it hurt much?”

The child closed her eyes and slow tears welled from under the lashes.

“Yes,” she sobbed, “awful.”

Dick ground his teeth.

“It’s a crime for such men to be allowed on the road,” he said in a low, tense tone. “I’m going to do my level best to run down whoever was responsible for this, and if I do, they’ll suffer the maximum penalty.”

“I hope you do,” the woman declared fiercely. “Hanging’s too good for ’em! My husband, George Hanlon, ain’t the man to sit still an’ do nothing, neither.”

“They—wasn’t—men,” sobbed the child. “Only one.”

10 “One man in a red car of some sort,” Dick murmured thoughtfully. “He must belong around here; a fellow wouldn’t be touring alone.”

Then he turned to Mrs. Hanlon.

“I think I’ll be getting on,” he said quickly. “I can’t do anything here, and the longer I delay the less chance there’ll be of catching this fellow. I’ll call you up to-night and find out how the little girl is doing.”

“God bless you for what you’ve done,” the woman said brokenly.

“I wish it might have been more,” Dick answered as he walked quickly toward the door. “Good-by.”

As he hurried out he almost ran into a slim young fellow, who was running up the walk. He was bare-headed, and his long black hair straggled down over a pair of fierce black eyes that had a touch of wildness in them.

Catching sight of Dick he glared at the Yale man, and hesitated for an instant as if he meant to stop him. Then, with a curious motion of his hands, he brushed past Merriwell and disappeared into the house.

“I’ve found a clue, pard,” Buckhart announced triumphantly, as Dick reached the car.

“What is it?”

The Texan held up a cloth cap.

“Picked it up by the side of the road,” he explained. “Find the owner of that and you’ll sure have the onery varmit who did this trick. You hear me gently warble!”

Dick took it in his hand and turned it over. The stuff was a small black and white check and was lined with gray satin. Stamped in the middle of the lining was the name of the dealer who had sold it:

“Jennings, Haberdasher,

Wilton.”

11 Wilton was a good-sized town they had passed through about four miles back.

“I thought he belonged around here,” Merriwell said as he rolled up the cap and stuffed it into his pocket. “Look out for a fellow without a hat, alone, in a red car of some sort, Brad. That’s all we’ve got to go by at present, but I shouldn’t wonder if it would be enough.”

He stepped into the car and started the engine, Brad sprang up beside him and they were off.

They had not gone a hundred feet when the black haired youth rushed out of the gate to the middle of the road. His eyes flashed fire, and as he saw the car moving rapidly away from him his mouth moved and twisted convulsively as if he wanted to shout, but could not.

Then, as the touring car disappeared around a turn in the road, he clenched one fist and shook it fiercely in that direction. The next moment he was following it as hard as he could run.

CHAPTER II.

THE COWARD.

With pallid face and nervous, twitching fingers, which his desperate grip on the wheel scarcely served to hide, Brose Stovebridge flew along the high road between Wilton and the Clover Country Club.

Now and then he looked back fearfully; at every crossroad his eyes darted keenly to right and left, as he let out the car to the very highest speed he dared, hoping and praying that he might reach his goal without encountering any one.

All the time fear—deadly, unreasoning, ignoble fear—was tugging at his heart-strings.

He had gone through just such an experience as this little more than a year ago in Kansas City. How vividly it all came back to him! The unexpected meeting with two old school chums whom he had not seen in months; their hilarious progress of celebration from one café to another, which ended, long past midnight, in that wild joy ride through the silent, deserted streets.

He shuddered. He thought he had succeeded in thrusting from his mind the details of it all: The sudden skidding around a corner on two wheels; the man’s face that flashed before them in the electric light, dazed—white—terrified. The thud—the fall—the sickening jolt, as the wheels went over him. Then that wild, unreasoning, terror-stricken impulse to fly, to escape the consequences at any cost, which possessed him. He gave no thought to his unconscious victim. He only wanted to get away before any one came, and somehow he had done so.

A few days later, in the safe seclusion of his home13 near Wilton, when he read that the fellow had succumbed to his injuries in the Kansas City hospital, his first thought was one of self-congratulation at his own cleverness in eluding pursuit.

His two chums he had never seen since that morning. Only a few weeks ago one of them had declined an invitation to visit him. He wondered why.

Once in his prep school days, when the dormitory caught fire, he had stumbled blindly down the fire escape and left his roommate sleeping heavily. Luckily the boy was roused in time; but it was no thanks to Brose that he escaped with his life.

For Stovebridge was a coward. In spite of his handsome face and dashing manner; in spite of his popularity, his athletic prowess, his many friends—in spite of all, he was a moral coward.

Few suspected it and still fewer knew, for the fellow was constantly on his guard and clever at hiding this unpleasant trait. But it was there just the same, ready to leap forth in a twinkling, as it had done this morning, and stamp his face with the brand of fear.

As the great, granite gateposts of the club appeared in sight, Stovebridge breathed a sigh of relief. By some extraordinary luck he had encountered no one on his wild ride thither. He had passed several crossroads, any one of which he was prepared to swear he had come by, and for the present he was safe.

Slowing down, he turned into the drive, and as he did so he took out a handkerchief and passed it over his moist forehead. He must compose himself before encountering any of his fellow members.

He carefully smoothed his ruffled hair with slim, brown fingers, and reached over for his cap.

The seat was empty. The cap had disappeared.

14 The discovery was like a physical blow, and for an instant his heart stood still.

Where had he lost it?

The spot where he had run down the child was the only feasible one. The cap must have fallen out when he put on the emergency, and probably lay in plain sight, a clue for the first passerby to pick up.

For a moment he had a wild idea of going back for it, but he thrust this from him instantly. It was impossible.

Then the clubhouse came in sight. He must pull himself together at once; he would get something to steady his nerves before he met any one.

Instead of continuing on to the front of the clubhouse, where a crowd was congregated on the wide veranda, he turned sharply to the right and drove his car into one of the open sheds back of the kitchen. Then he dived through a side door into the buffet.

“Whisky, Joe,” he said nervously to the attendant.

A bottle, glass and siphon were placed before him, and even the taciturn Joe was somewhat astonished at the size of the drink which Stovebridge poured with shaking hand and drained at a swallow.

He followed it with a little seltzer and, pouring out another three fingers, sat back in his chair and took out a gold cigarette case.

As he selected a cigarette with some care, and held it to the cigar lighter on the table, he noticed with satisfaction that his fingers scarcely trembled at all.

“That’s the stuff to steady a fellow’s nerves,” he muttered, blowing out a cloud of blue smoke. “There’s nothing like it.”

He took a swallow and then drained the glass for the second time.

Presently his view of life became slightly more optimistic.

15 “It was a new cap,” he remembered with a sudden feeling of relief.

“I’ve never worn it here, and there’s an old one in my locker. All I’ve got to do is to swear I never saw it before if I’m asked about it—which isn’t likely.”

When the cigarette was finished he went into the dressing room and took a thorough wash. There was no one there but the valet, who gave his clothes a good brushing, so he had no trouble in getting the old cap out of his locker and placing it at a becoming angle on his freshly brushed hair. Then he strolled out onto the veranda.

Three or four fellows, lounging near the door, greeted him jovially as he appeared.

“Rather late, aren’t you, Brose?” one of them remarked, as he joined them.

“A little,” Stovebridge returned nonchalantly. “It was such a bully morning I took a spin along the river road.”

“Alone?” the other asked slyly.

Stovebridge laughed.

“Well, I happened to be—this time,” he answered, a little self-consciously.

Being very much of a lady’s man, it was rare for him to be unaccompanied.

“How I do love a hog!” drawled one of the fellows who had not spoken. “Why the deuce didn’t you ’phone me? I’ve been sitting here bored to death for two solid hours.”

Stovebridge was looking curiously at a big, red touring car which had just driven up to the entrance.

“Er—I beg pardon, Marston,” he stammered. “What did you say?”

“Really not worth repeating,” returned the other languidly. “You seem to have something on your mind, Brose.”

16 Stovebridge gave a slight start as he turned back to his friends.

“I was wondering who those fellows are that just drove up,” he said carelessly. “They’re talking to old Clingwood.”

Fred Marston turned with an effort and surveyed the newcomers.

“Don’t know, I’m sure,” he drawled sinking back in his chair. “Never saw them before.”

For some reason the strangers seemed to interest Stovebridge extremely, and he continued to watch them furtively. There were four of them. The one who had driven the car, and with whom Roger Clingwood was doing the most talking, was tall and handsome, with dark hair and eyes, and the figure of an athlete. The fellow who stood near him was good-looking, too, and much more heavily built. Behind them, a short, wiry youth was talking to a tremendously stout fellow with a fat, good-humored face.

Presently Stovebridge left his friends and wandered along the veranda, pausing now and then to exchange a remark with some acquaintance, and before long he had reached the vicinity of the strangers, where he leaned carelessly against a pillar and looked out across the golf links.

“Very glad you could get here this morning, Merriwell,” Roger Clingwood, an old Yale graduate was saying. “You’ll be able to look around a bit before the race this afternoon.”

“Merriwell!” exclaimed Stovebridge under his breath. “I wonder if that can be Dick Merriwell, of Yale.”

Suddenly a hand struck him on the shoulder and a voice exclaimed heartily:

“Hello, Brose, old boy! Wearing your old brown17 cap, I see. What’s the matter with the one you got at the governor’s shop yesterday?”

Stovebridge wheeled around with a sudden tightening of his throat and saw the grinning face of Bob Jennings, son of the haberdasher at Wilton, who had been in the store when he bought that wretched cap the day before. Here was the first complication.

Stovebridge forced himself to smile.

“Left it at home, Bob,” he returned carelessly. “This was the first one I picked up as I came out this morning.”

In the pause which followed Roger Clingwood stepped forward.

“I didn’t notice you were here, Stovebridge,” he said pleasantly. “I’d like you to meet my friend Merriwell, who has come up with some of his classmates to spend a day or two at the club.”

“Delighted, I’m sure,” Stovebridge said with an air of good fellowship. “I know Mr. Merriwell very well by reputation, but have never had the pleasure of meeting him.”

“Dick, this is Brose Stovebridge,” Clingwood went on. “We claim for him—and I think justly—the title of champion sprinter of the middle West.”

Merriwell smiled as he held out his hand.

“Very glad indeed to meet you, Mr. Stovebridge,” he said heartily.

Stovebridge gave a sudden gasp and faltered; then he took the proffered hand limply.

“Glad to meet you,” he said hoarsely.

Instead of meeting Merriwell’s glance, his eyes were fixed intently on the corner of a checked cap which protruded from the Yale man’s pocket.

It was the cap he had lost out of the car that morning, or one exactly like it. Apparently it did not belong to Merriwell, who held his own in his left hand.18 Where had he picked it up? Where could he have found it but in that fatal spot? Stovebridge’s brain reeled and he felt a little faint. Then he realized that Clingwood was speaking to him—introducing the other Yale men—and with a tremendous effort he forced himself to turn and greet them with apparent calmness.

For a time there was a confused medley of talk and laughter as some of the other members strolled up and were presented to the strangers. Stovebridge was very thankful for the chance it gave him to pull himself together and hide his emotion.

Presently there was a momentary lull and Dick pulled the cap out of his pocket.

“Does this belong to any of your fellows?” he asked carelessly. “We picked it up in the road this morning.”

Bob Jennings pounced on it.

“Why, that looks like yours, Brose,” he said as he turned it over.

Stovebridge glanced at it indifferently. He had himself well in hand now.

“Rather like,” he drawled; “but mine is a little larger check; besides, I didn’t wear it this morning, you know.”

“I could have sworn that you bought one exactly like this,” Jennings said in a puzzled tone.

Stovebridge laughed.

“I wouldn’t advise you to put any money on it, Bob, because you’d lose,” he said lightly. “I’ll wear mine to-morrow, and you’ll see the difference.”

“Where did you find it, Dick?” Roger Clingwood asked.

Merriwell paused and glanced quietly around the circle of men. Most of them looked indifferent, as though they had very little interest in the cap or its unknown owner.

“It was picked up in the road about four miles this19 side of Wilton,” he said in a low, clear voice. “It lay near the body of a little girl who had been run over by some car and left there to die.”

There was a sudden, surprised hush, and then a perfect volley of questions were flung at the Yale man.

“Where was it?”

“Who was she?”

“Didn’t any one see it done?”

“Is she dead?”

The expression of languid indifference vanished from their faces with the rapidity and completeness of chalk under a wet sponge. Their eyes were full of eager interest, and, as soon as the clamor was quelled, Dick told the story with a brief eloquence which made more than one man curse fiercely and blink his eyes.

Once or twice the Yale man darted a keen glance at Stovebridge, but the latter had turned away so that only a small portion of his face was visible. He seemed to be one of the few to remain unmoved by the recital.

Another was his friend Fred Marston, a man of about thirty, with thin, dark hair plastered over a low forehead, sensuous lips, and that unwholesome flabbiness of figure which is always a sign of a life devoted wholly to ease.

As Dick finished the story, he shrugged his shoulders.

“Very likely she ran out in front of the car, and was bowled over before the fellow had time to stop,” he drawled. “Children are always doing things like that. Sometimes I believe they do it on purpose.”

Merriwell looked at him fixedly.

“That’s quite possible,” he said quietly, but with a certain challenging note in his voice. “But no one but a coward—a contemptible coward—would have run off and left her there.”

20 Marston flushed a little and started to reply, but before he could utter a word, a number of the club members began to voice their opinions, and for a time the talk ran fast and furious.

Merriwell noticed that Stovebridge took no part in it. He stood leaning against a pillar, his hands in his pockets, apparently absorbed in watching a putting match which was going on at a green just across the drive.

Presently the Yale man strolled over to his side.

“Nice links you have here,” he commented.

Stovebridge nodded silently without taking his eyes from the players.

“You have a car, haven’t you,” Dick went on casually.

The other’s shoulders moved a little.

“Yes,” he answered. “Racing roadster—sixty horse-power.”

There was a curious glitter in Dick Merriwell’s dark eyes.

“Dark red, isn’t she?” he queried.

Stovebridge hesitated for an instant.

“Ye-s.”

The players had finished their game and were coming slowly toward the clubhouse, but Stovebridge’s eyes never left the vivid patch of close-cropped turf.

He was afraid to look up, afraid to meet the glance of the man beside him. He dreaded the sound of the other’s low, clear voice. Why was he asking these questions? Why, indeed, unless he suspected?

“You didn’t happen to run over the main road from Wilton this morning, I suppose?”

The guilty man could not suppress a slight start. It had come, then. Merriwell did suspect him. His tongue clove to the roof of his mouth and for a moment he was speechless. He moistened his dry lips.

21 “No,” he said hoarsely. “I came—by the river road.”

What was the matter with him? That did not sound like his voice. It was not the way an innocent man would have answered an unmistakable innuendo. If he did not pull himself together instantly he would be lost.

The next moment he turned on the Yale man.

“Why do you ask that?” he said almost fiercely. “What do you mean by such a question?”

His face was calm, though a little pale. His long lashes drooped purposely over the blue eyes to hide the fear which filled them.

Merriwell looked at him keenly.

“I thought perhaps we could fix the time of the accident, if you had gone over the road before me,” he said quietly. “But I see we cannot.”

He turned away, with a slight shrug of his shoulders, and joined the others.

Brose Stovebridge gave a shiver as he saw him go. He had the desperate feeling of going to pieces; unless he could steady his nerves he felt that in a very few minutes he would give himself away.

Without a word to any one, he slipped through the big reception hall of the clubhouse and thence to the buffet. Here he tossed off another drink and then hurried out the side door.

The attendant looked after him with a shake of his head.

“He’s got something on his mind, he has,” he muttered. “Never knew him to take so much of a morning—and the very day he’s going to run, too.”

Stovebridge walked over to the automobile sheds. He was not likely to be disturbed there, and if some one did come around he could pretend to be fussing with his car.

22 He scarcely noticed Merriwell’s touring car, which had been put into the shed next to his own. At another time he would have examined it with interest, for he was a regular motor fiend. But now he passed it with a glance, and going up to his own car, lifted up the hood and leaned over the cylinders.

He had not been there more than a minute or two when he felt a hand grasp his shoulder firmly.

With a snarl of terror, he straightened up and whirled around.

He had expected to find Merriwell, come to accuse him. Instead, he saw before him Jim Hanlon, a deaf mute, who occasionally did odd jobs around the club. The fellow’s face was distorted with rage, his eyes flashed fire, his slight frame fairly quivered with emotion.

Stovebridge stepped back instinctively.

“What’s the matter with you?” he asked harshly. “What are you doing here?”

As the clubman spoke the deaf mute’s eyes were fixed upon his lips. Evidently he understood what the other said, for his own mouth writhed and twisted in his desperate, futile efforts to give voice to his emotion.

The next instant he snatched a scrap of soiled brown paper from his pocket and produced the stub of a pencil.

Stovebridge watched him with a vague uneasiness as he scrawled a few words and then thrust the paper into the clubman’s hand.

“Somebudy run over Amy an kill her.”

As he deciphered the illiterate sentence, Stovebridge shivered. Until that moment he had forgotten that this fellow was the child’s brother. What was he about to do? He looked as though he were capable of anything. Above all, how much did he know?

23 Looking up, Brose met the fellow’s eyes fixed fiercely on his own. He shivered again.

“Yes,” he said, with an effort at calmness. “I heard about it. It’s too bad.”

As the words left his lips he realized their utter inadequacy.

With a scowl, Hanlon snatched the paper from his hands and wrote again.

“I’ll kill the man that did it—kill him!”

The word kill was heavily underlined in a pitiful attempt at emphasis.

As Stovebridge read the short line he felt a cold chill going down his back. He had not the slightest doubt that the fellow meant what he had written. But how had he found out? Who had told him? Was it possible that he could have witnessed the accident from some place out of sight?

He shot another glance at Hanlon and met the same malignant glare of hate. The fellow looked positively murderous.

The next moment the deaf mute had pulled a long, keen knife out of his pocket, which he held up before Stovebridge’s terror-stricken eyes and shook it significantly. At the same time he nodded his head fiercely.

Brose gave a low gasp as he gazed at the wicked blade with fascinated horror. Why had he ever come out here alone and given the fellow this chance? Why hadn’t he stayed with the others? No matter what else might have happened, he would have been safe. Arrest, conviction, disgrace—anything would have been better than this.

Overcome by a momentary faintness, he closed his eyes.

Suddenly the paper was twitched from his fingers, and, with a frightened gasp, he looked up.

24 The knife had disappeared and Hanlon was writing, again.

Desperately, as a drowning man clutches a straw, Stovebridge snatched at the paper.

“What’s the name of the feller that came with three others in that car.”

Puzzled, the clubman looked at Hanlon and found him pointing at Dick Merriwell’s touring car. What did he mean? What could he want with Merriwell? Was it possible that he did not really know—that he wanted to get proof from the Yale man before proceeding with his murderous attack?

“Why do you want to know?” he faltered.

The other seized the paper from the man’s trembling fingers, wrote three words and thrust it back.

“He killed Amy.”

As Stovebridge read the short sentence, he could have shouted with joy. Hanlon did not know the truth, after all. For some unaccountable reason he suspected Merriwell. Perhaps it was because the Yale man had carried the child into the house; anyhow it did not matter, so long as he himself was safe.

Then another thought flashed into his mind. The fellow suspected Merriwell—not only suspected, but was convinced. He would try to kill the Yale man, and perhaps succeed. Well, what of that? With Merriwell out of the way Stovebridge would be safe—quite safe. No one else had the slightest suspicion.

He took the pencil out of the deaf mute’s hand, and, after a moment’s hesitation wrote, on the bottom of the paper:

“His name is Dick Merriwell.”

Somehow, as he handed the paper to the wild-eyed youth, he had the odd feeling that he had signed a death warrant.

CHAPTER III.

A SCRAP OF PAPER.

The Clover Country Club had acquired a wider reputation than is usual with an organization of that description.

Intended originally as a simple athletic club, with out-of-door sports and games the special features, it had one of the finest golf links in the Middle West. Its tennis courts were unsurpassed, its running track unrivaled. There was a well-laid-out diamond which had been the scene of many a hot game of baseball, and which was used in the fall for football. Indoors were bowling alleys, billiard, and pool tables, a beautiful swimming tank in a well-equipped gymnasium.

But in the course of time other and less desirable features had been added. The younger set had developed into a rather fast, sporting crowd, and, slowly increasing in numbers and in power, they gradually crowded the old conservatives to the wall, until finally they controlled the management.

To-day the club was better known for the completeness of its buffet, than for the gymnasium; and it was a well-known fact that frequently more money changed hands in the so-called private card room in a single night than in the old days had been won or lost on sporting bets in the course of an entire season.

In spite of all this, however, out-of-door sports were still a feature, and now and then, when some especially well-known athletes were at the club, matches and contests of various kinds were arranged.

That very afternoon a mile race had been planned between Stovebridge and Charlie Layton—a Columbia26 graduate reported to have beaten everything in his class from Chicago to Omaha—who was coming on from the latter city especially for the occasion.

Fred Marston and others of his ilk usually did a great deal of sneering at such affairs, calling them farcical relics of barbarism, and made it plain that they only attended for the excitement of betting on the result; but this made little difference in the general enthusiasm.

For a time after the departure of Stovebridge the discussion of Merriwell’s story continued with some warmth, and many were the speculations as to the identity of the brute who had run over the child and left her there. But even that topic could not hold the interest of such a crowd of men for very long, and presently they began to disperse, some seeking the card room, others the buffet, while the remainder found comfortable seats on the veranda to put in the hour before luncheon in indolent lounging and small talk.

Roger Clingwood hesitated an instant before the wide doors of the reception hall.

“It’s too late for golf or tennis,” he said regretfully. “Is there anything else you would like to do before lunch? Er—cards, perhaps, or——”

He was one of the older members who had fought vigorously, but in vain, against the introduction of gambling in the club; but his innate sense of hospitality made him suggest the only form of amusement possible in the short time.

Dick smiled.

“Not for me, thank you,” he said quickly. “It always seems a waste of time to sit around a table in a stuffy room when you might be doing something interesting outside.”

Clingwood’s face brightened.

27 “I’m glad of that,” he said warmly. “I enjoy a good rubber as well as the next man, but I don’t like the kind of play that goes on here. How do your friends feel about it?”

He looked inquiringly at the others.

“Nix,” Buckhart said decidedly. “Not for me.”

Tucker and Bigelow both shook their heads.

“I used to flip the pasteboards in my younger days,” the former grinned; “but I’ve reformed.”

“Why not just sit here and do nothing?” Merriwell asked. “I feel that I’d enjoy an hour’s loaf.”

Bigelow evidently agreed with him, for he sank instantly into one of the wicker chairs, with a sigh of thankfulness.

The others followed his example, and their host took out a well-filled cigar case and passed it around. Tucker accepted one; the others declined.

“Layton ought to show up soon,” Clingwood remarked, settling back in his chair and blowing out a cloud of smoke. “I believe he’s due in Wilton at eleven forty-seven.”

“Layton?” Dick exclaimed interestedly. “Not Charlie Layton, the Columbia man?”

“That’s the boy. Know him?”

“I’ve met him. He’s one of the best milers in the country. Stovebridge must be pretty good to run against him.”

“He is,” returned the older man. “He trains with a crowd that I’m not at all in sympathy with, but, for all that, he’s not a bad fellow; crackerjack tennis player, and has a splendid record for long distance running. He keeps himself in fair training and doesn’t lush as much as most of his friends do.”

“I see,” Dick said thoughtfully.

This did not sound at all like a fellow who would run down a child and never stop to see how badly she28 was hurt. As a rule, good athletes are not cowards, though he had known exceptions.

At the same time, Stovebridge’s actions had been suspicious. Dick had not failed to notice his consternation at the sight of the cap, though he had quickly recovered himself and his explanation had been plausible enough.

Later, during Merriwell’s conversation with him, the fellow’s agitation had been palpable. That he was laboring under a tremendous mental strain, the Yale man was certain. Of course, the cause of it might have been something quite different, but to Dick it looked very much as though Brose Stovebridge knew a good deal more about the accident than would appear.

And he had come to the club that morning alone in a red car!

All at once Dick became conscious that some one had paused on the drive quite close to the veranda and was looking at him.

As he raised his head quickly, he saw that it was the same dark-haired, sullen youth he had passed as he came out of the farmhouse that morning.

To Dick’s astonishment the fellow’s eyes were fixed on him with a look of fierce, malignant hatred which was unmistakable. His fingers twitched convulsively and his whole attitude was one of consuming rage.

As Merriwell looked up, the other seemed to control himself with an effort, and, turning his head away, slouched on along the drive.

“What’s the matter with him I wonder?” the Yale man mused. “He looks as if he could eat me up with the greatest pleasure in life. I wonder who he is?”

He turned to Roger Clingwood, who was talking with Buckhart and Tucker.

29 “Who is that fellow that just passed, Mr. Clingwood?” he asked, when there was a lull in the conversation. “Did you notice him?”

“Yes, I saw him. That’s Jim Hanlon; he occasionally does odd jobs about the grounds.”

“Hanlon!” Dick exclaimed. “Any relation to the little girl?”

“Yes, her brother.”

“Oh, I see.”

Dick hesitated.

“Is he—all there?” he asked after a moment’s pause.

Roger Clingwood looked rather surprised.

“Yes, so far as I know. He’s deaf and dumb, you see, and has the reputation of being rather hot tempered at times; but I never heard that he didn’t have all his faculties. Poor fellow! It’s enough to drive any one dotty to have to do all one’s talking with pencil and paper. I’m not surprised that he loses his temper now and then.”

“I should say not,” Tucker put in. “Just imagine getting into an argument and having to write it all out. I’d lay down and cough up the ghost.”

“I opine you’d blow up and bust, Tommy,” Buckhart grinned. “Or else the hot air would strike in and smother you.”

“You’re envious of my wit and persiflage,” declared Tucker. “I’d be ashamed to show such a disposition as that, if I were you.”

“When you’re talking with Hanlon, do you also have to take to pencil and paper?” Dick asked interestedly.

“Oh, no,” Clingwood answered. “He knows what you’re saying by watching your lips. He’s amazingly good at it, too; I’ve never seen him stumped.”

At that moment Stovebridge strolled out of the clubhouse and stopped beside Clingwood’s chair.

30 “Any signs of Layton yet?” he drawled.

“Haven’t seen him,” the other man answered. “He’s had hardly time to get here from Wilton, has he?”

“Plenty, if he came on the eleven forty-seven. Sartoris went over with his car to meet him. I hope he’s not going to disappoint us.”

He turned away and walked slowly down the veranda toward Marston lounging in a corner.

As Dick followed him with his eyes, there was a slightly puzzled look in them.

Stovebridge was so cool and self-possessed, so utterly different from the man who had shown such agitation barely half an hour before, that for an instant Merriwell was staggered.

“Either I’m wrong and he’s innocent,” he thought to himself, “or he has the most amazing self-control. There isn’t a hint in his manner that the fellow has a trouble in the world.”

Then the Yale man’s intuitive good sense reasserted itself.

“He’s bluffing,” he muttered under his breath. “I’ll stake my reputation that, for all his pretended indifference, Brose Stovebridge is either the guilty man, or he knows who is. And I rather think he’s the one himself.”

Roger Clingwood pulled out his watch.

“Well, boys, it’s about time for lunch,” he remarked. “Suppose I take you up to your rooms and, after you’ve brushed up a bit, we’ll go in and have a bite to eat.”

“I’ll get the bags out of the car and be with you in a minute,” Dick said as they stood up.

“Wait, I’ll ring for a man to take them up,” proposed Clingwood.

“Don’t bother,” Dick said quickly. “They’re very light, and Brad and I can easily carry them. Besides,31 I’d like to see just where they’ve put the car so that I’ll know where to go if I want to take her out.”

“Well, have your own way,” smiled the other. “The garage is around at the back. Follow the drive and you can’t miss it.”

Leaving Tucker and Bigelow with their host, the two chums followed the latter’s directions and had no difficulty in locating the automobile sheds.

Merriwell was glad of the opportunity, for he wanted very much to have a look at Stovebridge’s car. In fact, that was his principal reason for coming out instead of having the bags sent for.

There were a dozen machines in the sheds, of all sizes and makes, but only two runabouts. One was a small electric, and the other—standing in the compartment next to Dick’s car, the Wizard—was a new, high-power roadster, painted a dark red.

“That’s the one, I reckon,” he said aloud, as they surveyed it.

The Texan’s eyes crinkled.

“I opine it is, pard, if you say so,” he grinned. “Might a thick, onery cow-puncher ask, what one?”

“Stovebridge’s car,” Merriwell explained briefly.

The Westerner gave a low whistle.

“Oh, ho! A red runabout,” he murmured. “So you think he’s the gent we’re after?”

As Dick stepped in to examine the car more closely, his eyes fell upon a scrap of paper which lay on the ground close by one of the forward wheels. Picking it up, he saw that it was a torn piece of common brown wrapping paper, very much mussed and dirty. He was about to toss it aside when he happened to turn it over. The next instant his eyes widened with surprise.

“What the mischief is this, I wonder?” he said in a low tone.

32 Buckhart stepped forward and looked at it over the other’s shoulder.

“‘His name is Dick Merriwell’,” he read slowly. “Who’s been taking your name in vain, partner?”

Dick made no reply. He was busy trying to decipher the illiterate scrawl which preceded the one legible sentence the Texan had read. Slowly, word by word, he made it out.

“Somebody—run over—Amy—and—kill her,” he read at last.

“Amy—who is Amy?” he mused. “Why, that’s the little girl we picked up this morning—Amy Hanlon.”

He looked at the paper again, and then, like a ray of light, the solution flashed into his brain.

“Why, that dumb fellow—her brother—must have written this!” he exclaimed. “Clingwood said he had to do his talking on paper. But what on earth is my name here for? Wait a minute.”

His eyes went back to the scrap of paper, and for a few minutes there was silence. When he looked up at Buckhart, his face was set and his eyes stern.

“Listen, Brad,” he said rapidly. “On this paper there are four questions and one answer. The questions were written by an illiterate person; the answer—was not. It is evidently part of a conversation between this dumb fellow and some one else. Hanlon first informs this person that his sister had been run over and killed. How he got the idea I don’t know, unless she had fainted when he went into the room, and he did not wait long enough to find out the truth. Then he proceeds to inform whoever he is talking with that he will kill the man who ran the child down. Then he writes: ‘What’s the name of the fellow that came, with three others, in that car?’ Do you make any sense out of that, Brad?”

“I sure don’t,” he said decidedly.

“Well, I don’t know as I blame you,” Merriwell returned. “The next sentence is apparently the answer to a question by the other man. It is: ‘He killed Amy.’ Meaning that the man in a car with three others ran over his sister, which, of course, we know isn’t so. There was only one, according to her statement. Then follows the line in another hand which you read: ‘His name is Dick Merriwell.’ Don’t you see now, Brad?”

“Afraid I’m awful thick——”

“Why, it’s clear as day,” Merriwell interrupted. “This Hanlon has somehow got the idea that I ran over the little girl. He doesn’t know my name and proceeds to ask this unknown person what it is, giving at the same time the reason why he wants to know. He gets the answer without a word of denial or explanation, and goes away with the firm belief that I am a murderer. That accounts for the look he gave me when he passed the veranda a little while ago.”

“The miserable snake!” exploded the irate Westerner. “Wait till I put my blinkers on him!”

“He isn’t to blame,” Dick asserted quickly. “He thinks he’s right. It’s the other man I’d like to get my hands on—the fellow that let him go on believing a lie.”

He paused and looked significantly at Buckhart.

“Who is the man most interested in shifting the blame to my shoulders?” he asked in a hard voice. “Whom have we suspected? Under whose car did I pick up this paper?”

“Stovebridge!”

The word came in a smothered roar from the lips of the irate Texan, and, turning swiftly, he started toward34 the clubhouse, his face flushed with rage and his eyes flashing.

“Stop! Come back, Brad,” Dick called. “You must not do anything now. We have no real proof; he would deny everything.”

Buckhart hesitated and then came slowly back to the shed. Dick went over to his own car and pulled out a couple of bags from the tonneau.

“Don’t worry, you untamed Maverick of the Pecos,” he said with a half smile. “We’ll get him right before very long.”

He folded the paper and put it carefully away in his breast pocket.

“I’ve got this, for one thing,” he went on, “and I also have an idea in my head which I think will come to something.”

CHAPTER IV.

STOVEBRIDGE FINDS AN ALLY.

Brose Stovebridge dropped down in a chair beside his friend Marston and pulled out his cigarette case.

“Have one?” he invited, extending it to the other.

Marston selected a cigarette languidly.

“How did this fellow Merriwell happen to honor the club with his presence to-day?” he inquired sarcastically.

Stovebridge struck a match and held it to the other’s cigarette; then, lighting his own, he sank back in the chair.

“He’s Clingwood’s friend, I believe,” he answered with apparent indifference. “You speak as though you didn’t like him.”

“I don’t,” snapped Marston. “I hate him—hate the whole brood.”

The blond fellow raised his eyebrows.

“I didn’t know you’d ever met him,” he commented. “You certainly didn’t greet him as though you had ever laid eyes on him before.”

“I haven’t,” the other said bitterly. “I know his brother—that’s enough.”

“His brother?” queried Stovebridge.

“Yes, Frank Merriwell. I ran up against him at Yale, and of all the straight-laced freaks he took the cake—wouldn’t drink, wouldn’t smoke; wouldn’t play poker, wouldn’t do anything but bone, and go in for athletics.”

“Humph!” remarked Stovebridge cynically. “I don’t wonder you didn’t like him. He wasn’t in your class at all. But if he was as good an athlete as his brother,36 he must have been some pumpkins. I don’t just see, though, how that accounts for your violent antipathy. Why didn’t you let him go on his benighted way and have nothing to do with him?”

Marston’s heavy brows contracted in a scowl.

“You don’t suppose I cared a hang what he did, do you?” he snarled. “That didn’t worry me any, but he had to get meddlesome and butt into my affairs. Got my best friend so crazy about him that he went and gave up cards and all that, and trained with Merriwell’s crowd. Of course, he was no use to me after that. Do you wonder that I dislike Frank Merriwell, and his brother as well?”

Stovebridge hesitated.

“Don’t know as I do?” he said in a preoccupied manner.

He had been thinking of something else.

They smoked for a few minutes in silence. Once or twice Marston glanced curiously at his friend, who was scowling at the floor.

“What’s the matter with you to-day, Brose?” he asked presently. “You act like you had something on your mind.”

The other looked up with a sudden start.

“Why, no; I——”

Marston shrugged his shoulders indifferently.

“Don’t tell me, if you don’t want to,” he drawled. “But if it’s something you want to keep to yourself, for goodness sake, wipe that scowl off your face and brace up.”

Stovebridge eyed the other with a speculative glance. Why not confide in Marston? He hated Merriwell and would certainly never peach. Besides, he might suggest something helpful.

“I’ll tell you about it, Fred,” he said in a low tone, as he drew his chair closer to his friend. “I’m in a37 deuce of a scrape. I—I—was the one—who ran over that kid this morning.”

His face flushed a little; his eyes were averted. He did not find it easy to tell, even to Fred Marston.

The latter gave a low whistle.

“By Jove!” he exclaimed. “You don’t say! How did it happen?”

“It was at the bend by the Hanlon farm,” Stovebridge explained. “I was hitting up a pretty good clip, and when I came round the bend she was standing in the middle of the road. There was plenty of time for her to get away, but she never moved. I tried to run to one side, but there wasn’t room, and—the kid went under.”

“I always said they didn’t have sense enough to get out of the way,” Marston remarked in a vexed tone.

Then he looked curiously at his friend.

“What made you beat it?” he asked. “Why didn’t you stop and pick her up? It wasn’t your fault—no one could have blamed you, if you only hadn’t run away.”

“I couldn’t, Fred—I simply couldn’t,” Stovebridge confessed, without lifting his eyes. “My one idea was to get away before any one saw me. You know the beastly things they do to a fellow sometimes. Why, I might have been jugged for a year or more.”

“Yes, I know,” agreed the other. “Still——”

He stopped abruptly and looked out over the golf course in a meditative way.

“You managed pretty well, though,” he said presently as he turned back to Stovebridge. “No one saw you on your way here, I suppose?”

The other shook his head.

“No; if it wasn’t for that beastly cap I should feel quite safe. But Merriwell suspects me on that account.”

38 Marston’s beady eyes glittered.

“Let him suspect!” he snapped angrily. “We’ll fix that all right. It wouldn’t be safe for you to buy another, but there’s nothing to prevent my doing so.”

“Of course there isn’t!” Stovebridge exclaimed in a tone of relief. “And you’ll do it?”

Marston’s teeth snapped together.

“I certainly will,” he declared. “I’d do more than that to spite a Merriwell. Lend me your car and I’ll go to Wilton right after lunch.”

Stovebridge breathed a sigh of relief. How fortunate he had confided in Marston. With the question of the cap settled and Jim Hanlon sidetracked, he would have nothing to fear. Dick Merriwell might do his worst, but he could prove nothing.

Marston arose to his feet, yawning.

“Well, let’s toddle in and get something sustaining,” he suggested. “I feel the need of a little bracer.”

“Don’t forget to pick out a medium check,” Stovebridge reminded, as they strolled through the reception hall to the dining room beyond. “I said mine was a little larger than the one he picked up, but if you get it too pronounced, Bob Jennings will smell a rat. He’s a bit doubtful now.”

“Trust me,” Marston returned confidently.

They settled themselves comfortably at a small table near one of the windows, and a waiter hurried up.

“Two Martinis—dry,” Marston said, unfolding his napkin. “Bring them right away.”

“Not any for me,” Stovebridge put in hastily. “I’ve got to run this afternoon.”

“Oh, shucks! What’s one cocktail?” expostulated the other. “Just put a little ginger into you.”

But Stovebridge persisted in his refusal; already he39 had taken considerably more stimulant than he felt was wise. So when the cocktails came Marston drank them both.

While his friend was writing out the order, Stovebridge glanced idly about the well-filled room. He gave a slight start as his eyes met those of Dick Merriwell, who was seated with his party three or four tables away. The Yale man was looking at him with a certain steady scrutiny that was a little disconcerting. There was no gleam of friendliness in his dark eyes, but rather a cold, steely glitter. His fine mouth was set in a hard line, curving disdainfully at the corners, as though he were regarding something beneath his contempt. It was not a pleasant expression, and, despite his belief that the other could really prove nothing, Stovebridge could not help feeling a little uneasy.

“Who are you staring at?”

Marston’s drawling voice roused Stovebridge, and, turning quickly, he looked at his friend.

“Merriwell,” he breathed softly.

“Bah!” snapped the other. “He can’t do anything. We’ll put a spoke in his wheel. For goodness’ sake, Brose, do brace up and forget it!”

Stovebridge made an effort to do so, but all the time he was eating lunch he had an uneasy feeling that those cold eyes were still fixed upon him, and it was only by the most determined exertion of will power that he kept himself from looking again toward the table where Roger Clingwood and his guests seemed to be enjoying themselves so thoroughly.

As they came out to the veranda after lunch, Roger Clingwood pulled out his watch impatiently.

“Almost two!” he exclaimed. “What in the world is the matter with Layton?”

He turned to a short, pleasant-faced, youngish-looking40 fellow who, also watch in hand, was looking anxiously down the drive.

“Heard anything of Charlie Layton, Niles?” he asked.

“Not a thing,” the other answered petulantly. “I can’t understand what’s delayed him. He promised to be here soon after twelve, and the race was to be pulled off at three. People are beginning to come already.”

“Sartoris is there to meet him, I believe,” Clingwood remarked.

“Yes, and I tried just now to get him on the phone, but couldn’t.”

Jack Niles shut his watch with a snap and shoved it back in his pocket irritably. He was extremely homely. Every feature seemed to be either too large or too small, or not placed right on his face; but for all that there was something very attractive in his expression, and in the straightforward, honest directness of his brown eyes. His clothes were loud almost to eccentricity, and it was quite evident that he was a thorough-going, out-and-out sport.

As he started to walk away, Roger Clingwood caught his arm.

“Oh, by the way, Jack,” he said suddenly, “I want you to meet my friend Merriwell. Dick, this is Jack Niles, to whose efforts is due the fact that we still occasionally have athletic events at the club.”

As Niles turned quickly, his hand outstretched, the worried look on his face gave place to one of surprised interest.

“Not Dick Merriwell, of Yale?” he asked eagerly.

Dick smiled as he took the other’s hand.

“I happen to be,” he said quietly.

41 He felt a sudden liking for this homely young fellow with the honest eyes, who looked as though he was square down to the very bone.

“Well, say!” Niles exclaimed, as he gripped Dick’s hand and worked it up and down like a pump handle. “If this isn’t a little bit of all right. I’ve seen you play ball, and I’ve seen you run, but I never had a chance of shaking hands before. What are you doing away out here?”

“Touring with some friends of mine,” Dick answered smiling. “I’d like you to meet them.”

He introduced Buckhart, Tucker and Bigelow, and for a few minutes they stood talking together.

“I don’t know what we’ll do if Layton throws us down,” Niles said anxiously. “We’ve made so much talk about the race, and there’ll be an awful mob here to see it. Oh, there’s Sartoris! Now we’ll find out something. Excuse me, will you?”

Without waiting for a reply, he dashed down the steps toward a car that had just driven up. Its occupant, a tall, bare-headed fellow in tennis flannels, sprang out, waving a yellow envelope in his hand.

“He can’t get here until to-morrow,” he explained. “Held up by a wreck on the road.”

Niles took the telegram in silence, and, as he read it, his face shadowed.

“Well, what do you think of that?” he muttered, as he crumpled it in his hand. “To-morrow! And look at the bunch that’s here to-day, expecting to see something good. Coming thicker every minute, too.”

He glanced down the drive where several cars were in sight, heading toward the clubhouse.

“Wouldn’t that drive you to the batty house!” he went on. “I suppose it’s up to yours truly to get busy and announce that there ‘won’t be no race.’”

His eyes, full of an expression of whimsical chagrin,42 roved slowly over the crowd which had hastily gathered at the approach of Sartoris, until they rested on Dick Merriwell’s face.

The next moment a gleam of hope had leaped into them, and Niles sprang up the steps to the Yale man’s side.

“Say, what’s the matter with your taking Layton’s place, old fellow, and saving my rap?” he asked eagerly.

Merriwell smiled a little.

“It would be rather difficult to take his place,” he said slowly. “Layton is one of the best milers in the country, and it’s a long time since I’ve done any running.”

“Oh, that be hanged!” exploded Niles. “You’re too blamed modest. You can do it if you want to. Come ahead, old fellow, and save me from making an ass of myself by disappointing this crowd.”

“When you put it that way, Niles, I can scarcely refuse,” Dick smiled. “I’ll be very glad to do what you want, only you mustn’t expect too much of me.”

Jack Niles was overjoyed.

“That’s bully!” he exclaimed. “You’ve helped me out of a deuce of a hole and saved the day. It’s just my luck to find a substitute as good or better than the original.”

Brose Stovebridge stood near, a slight sneer on his face.

“It’s lucky I’m not the one who didn’t show up,” he drawled. “Merriwell seems to think such a lot of this fellow Layton that I don’t suppose he could possibly have been induced to run against him, if our positions were reversed.”

Apparently his words were intended for the man next to him, but they were quite loud enough for the Yale man to hear.

43 The latter turned and surveyed Stovebridge with a cool, disconcerting glance.

“I happen to have run against Layton several times, Mr. Stovebridge,” he said quietly. “If he were here to-day, I should be very glad to do so again. I hesitated just now—for another reason.”

To the guilty man, his meaning was obvious; and though Stovebridge shrugged his shoulders with affected indifference, his face flushed, and he made no reply.

“Come ahead, fellows, and get ready,” Niles broke in briskly. “We’ve got just ten minutes to start on time.”

He took Dick’s arm and hustled him through to the dressing room, where he hunted up running trunks, shoes, and shirt; and in less than the allotted time, the Yale man was ready for the contest.

As they came out of the clubhouse and walked over to the track, Merriwell felt a thrill of the old enthusiasm. The well-kept track and the crowd of spectators thronging both sides made his blood course more swiftly and caused his eyes to sparkle.

They went directly to the starting point, where Stovebridge presently joined them. Niles, mounted on a stand, megaphone in hand, waved his arm for silence. When the hub-bub of talk and laughter had ceased he put the instrument to his lips.

“Gentlemen,” he declaimed, “I have to announce that Mr. Layton has been detained by a wreck and cannot reach the club this afternoon.”

A murmur of disappointment arose from the crowd, which was quickly stilled by another motion from Niles.

“I have, however,” he went on, “secured an efficient substitute in the person of Dick Merriwell, of Yale,44 who has kindly consented to run in order that we shall not be disappointed.”

As he jumped to the ground, the quick round of hearty applause, mingled with cheers, showed that Merriwell’s name was not unknown. Then the buzz of talk started up again with renewed vigor, as the judges and timekeepers consulted with Niles and arranged the details of the race.

Dick stood a little to one side of the mark, talking to Buckhart, whose face was aglow with enthusiasm.

“Lick the stuffing out of the coyote, pard,” urged Brad, in a low tone. “You can sure do it if you try.”

“No question of my trying, old fellow,” Merriwell smiled. “There’s no use in going into a thing unless you do your best! But they seem to think this fellow is pretty good, and you know I’m out of practice.”

“That don’t worry me a whole lot,” the Texan grinned.

“Say, Merriwell, come over here, will you?” Niles called, standing near Stovebridge.

“We’ll have to toss for positions,” he explained, as Dick walked over to him. “The track is just a mile in circumference, so that you’ll have to make one complete circuit, and of course, the fellow on the inside has a little the advantage.”

He took a coin out of his pocket and sent it spinning in the air.

“Heads, or tails?”

“Tails,” Dick said quickly.

The other caught the coin deftly.

“Heads it is,” he grinned. “You lose. Take your places, gentlemen—Stovebridge, inside; Merriwell, out.”

Dick toed the mark, and his eyes wandered for an45 instant down the long line of eagerly watching men. As he did so, he caught sight of the dark, sullen face of Jim Hanlon glaring at him from behind two of the clubmen.

“Still thinks I’m it, by the looks of him,” the Yale man said to himself. “I must have a talk with him when this is over.”

Then he thrust the fellow out of his mind and crouched for the start. Stovebridge was beside him, vibrant and ready. The two timekeepers stood by the mark, stop watches in hand. Niles stepped back a pace and drew a small revolver from his pocket.

“Are you ready?” he called in a clear voice.

He raised the revolver above his head.

“Set!”

Both runners quivered slightly, as they waited with every muscle tense the moment when they could shoot forward down the track.

The sharp crack of the pistol split the silence, and like a flash both men leaped forward, to the accompaniment of a bellow from the watching crowd, and flew down the stretch of hard, dry cinders.

Merriwell had made the better start and was slightly ahead of the other man. Presently it was seen that this lead was slowly increasing, and the spectators cheered wildly as they observed it, for as a rule they were an impartial lot and believed in shouting for the best man. Besides they were grateful to the stranger for having made the race possible.

Almost imperceptibly this lead increased. In spite of his lack of practice, the Yale man was wonderfully speedy and ran in almost perfect form, and with amazing ease. His body was bent forward but slightly, with his head held up naturally. He threw his legs out well in front with a full easy stride, and brought his feet down squarely, his thighs and knees thrown a46 little forward. There was absolutely no lost motion. His arms swung easily beside his body, and, with every stride, seemed to help him along.

Stovebridge ran well, but he had a bad trick of swinging his arms back and forth across his body, which retarded him slightly, and moreover, in his haste to finish the stride, he bent his knee somewhat, thus losing a fraction of an inch each time, which would mount up considerably in the course of the mile.

The first quarter of a mile was made by Merriwell in a fraction over a minute—almost sprinting time. Stovebridge was barely two seconds longer. Then both men seemed to settle down to a slightly easier gait, for such speed could not be kept up for the entire distance, and the second quarter took several seconds longer.

The excitement was intense. Men shoved and jostled each other in their eagerness to get a good view; some even ran out onto the track behind the runners. There was no more talking and laughing. A tense silence had fallen upon the crowd as they watched breathlessly.

Suddenly the Yale man was seen to stumble and almost lose his footing. As he recovered his balance with a tremendous effort, Stovebridge shot by him, and a great sigh went up from the crowd.

“He’s twisted his ankle!” gasped Jack Niles, his fingers closing on Buckhart’s arm with unconscious strength.

The Texan made no reply. His face was set and a little pale.

The next instant Merriwell had recovered himself and flashed on down the track with almost his former speed. To most of the spectators there did not seem to be anything the matter with him, but those who were47 near enough to see his face, noticed the lines of pain in it, and the great beads of perspiration which stood out on his forehead.

“By Jove, that’s plucky!” Niles muttered. “It’s the nerviest thing I ever saw.”

His keen eye had instantly taken in the situation. In some way the Yale man had strained his ankle, but, instead of giving up the race he was going to fight it out to the finish.

As Merriwell flashed over the three-quarter mile mark, Stovebridge had a good twelve feet lead, but was showing signs of exhaustion. His breath came in gasps, the sweat poured down his face, and his stride was perceptibly shorter.

The Yale man, on the contrary, was in much better condition, except for his left leg, which he seemed trying to favor at each step. It was apparent to everyone, by this time, that he was suffering tortures with every stride, but he showed no signs of giving up. Instead, to the amazement of all, he took a fresh spurt and actually began to gain on his opponent.

Slowly he crept up. Foot by foot the distance between the two was lessened, until at length it was reduced to a yard. But there was not enough time. Already the finish was in sight, and the eager watchers waited in strained silence the end of this amazing race. Could the gamey fellow from Yale possibly make up those three feet in the few seconds which remained? They feared not, for almost without exception, their sympathies were with the man who was now showing such extraordinary pluck.

There was a final spurt on the part of both men, and then, almost in the last stride, Stovebridge flung himself forward with uplifted arms, and breasted the tape a fraction in advance of Dick.

The Clover Club champion had won, but the resulting48 applause was strangely feeble. There was scarcely a man present who did not realize that Merriwell was the better of the two.

As Dick reeled across the line, he staggered and a spasm of pain flashed into his face.

Jack Niles caught him by the shoulder.

“Quick, Buckhart!” he ripped out in his sharp, decisive tones. “We must get him into the house and look after that ankle. Good nerve, my boy—good nerve!”

Merriwell smiled faintly.

“Well, I lost the race for you, Niles!” he said.

“Lost be hanged!” snapped the other. “You’re the gamest piece of work that ever came down the pike. Why the deuce didn’t you stop when you twisted your ankle that way?”

“I don’t generally give up when I can still go ahead,” Dick said quietly.

“Well, you’ve got that foot of yours into a beautiful condition,” Niles went on. “It’s beginning to swell already. Here, sit down, while we take you into the house.”

He and Buckhart clasped hands and, lifting Merriwell up between them, started slowly back toward the clubhouse, the spectators straggling behind, discussing the result with much interest.

The two fellows carried Dick into the dressing room, where he rested on a chair while they bathed his ankle in cold water and then bandaged it as tightly as they could to keep down the swelling.

“How the mischief did you do it, pard?” Buckhart asked, while this was being done.

“I think I stepped on a small stone,” Dick answered “At least it felt like that.”

“A stone!” he exclaimed. “That’s impossible. I walked over the track an hour before the race and it was in perfect condition. It couldn’t have been a stone.”

“Well, it felt like one,” Dick smiled. “I can’t swear to it.”

Niles turned to one of the men who had acted as timekeepers, and who was helping them with the bandage.

“Say, Johnson, just take a run out to the track and see if you can see anything of a stone, will you?” he asked. “I want to find out about this.”

Johnson was back in a few minutes and reported that he could not find even a pebble on the track. He had questioned the dumb fellow, Hanlon, who was raking up near the clubhouse, and found that he had not yet touched anything on the track.

“I must have been mistaken, then,” Dick said lightly. “It was just pure carelessness.”

He took a shower and then dressed and limped into the reception hall with Buckhart and Niles, who had waited for him.

A group of men were talking in the centre of the room, and Niles stepped aside for a moment to speak to one of them, leaving Merriwell and the Texan standing close beside one of the big windows which opened on the veranda.

Brose Stovebridge was lounging in a wicker chair just outside, and as Dick noticed him he saw a look of eager interest flash into the fellow’s eyes, which were turned toward the drive.

A moment later Fred Marston came in sight, walking rapidly along the veranda, and presently stopped beside his friend’s chair.

50 “Well, did you get it?” the latter asked eagerly.

“Sure, I did,” returned Marston with a smile.

He pulled a small parcel wrapped in brown paper out of his pocket and handed it to Stovebridge, who almost snatched it out of his hand.

“Ah,” he breathed in a tone of relief. “I guess that will settle his hash. He can suspect all he wants——”

He broke off abruptly as he turned his head and looked into Dick Merriwell’s cool, slightly smiling eyes. A sudden rush of color flamed into his face, and, with a quick drawn breath, he half rose from his chair.

“What’s the matter?” asked Marston.

Then, following the direction of the other’s fascinated gaze, he too, saw the Yale man, and scowled fiercely.

“Come in and let’s get a drink,” he said abruptly. “I need a bracer.”

Stovebridge got up a little unsteadily, and the two vanished in the direction of the buffet.

Dick looked significantly at the Texan.

“What do you think of that, Brad?” he asked quietly.

“Huh!” grunted Buckhart contemptuously. “The onery varmit’s sure a whole lot shy of you, pard. If he isn’t the coyote you’re looking for, I’ll eat my hat. You hear me gently warble!”

Merriwell gazed thoughtfully out of the window.

“I wonder what was in that package,” he mused. “And I wonder too, where this Marston comes in.”

“I reckon he’s in the same class as Stovebridge,” the Texan said emphatically. “I wouldn’t trust him as far as I could throw a yearling by the tail.”

Jack Niles came up briskly at that moment.

51 “Well, fellows, let’s make ourselves comfortable outdoors,” he said. “You don’t want to stand on that leg of yours more than you can help for a while, old chap.”

“It’s feeling pretty comfortable just now,” Dick returned, with a smile. “Your bandages are all to the good.”

At the same time he was not sorry to sit down in one of the big wicker chairs, soon becoming the centre of a laughing, joking crowd of men, all bent on showing their admiration for the Yale athlete who had given such an exhibition of nerve and pluck as few of them had ever seen.

Merriwell thoroughly enjoyed himself, and was so taken up with the discussion and talk that he had no time to give to the problem which he had set himself to solve. At length, as the afternoon wore on, the fellows began to drop away. One by one, or in parties of two or three, they left the club in motor cars, runabouts, or on horseback, and by six o’clock there were only about a dozen left on the veranda, who were either stopping at the club or taking dinner there.

Then Dick remembered Jim Hanlon, and turned to Buckhart who sat beside him.

“Say, Brad,” he said in a low tone. “Do you think you could find that dumb fellow and bring him into the clubhouse? You know I wanted to straighten him out about who ran over the little girl. He seems to have an idea that I did it.”

The Texan got up readily.

“Sure thing. He ought to be around somewheres—maybe in the kitchen.”

It was ten minutes before he came back with the announcement that Hanlon was not to be found. They had told him in the kitchen that the fellow usually went home at six o’clock.

52 “Well, it doesn’t matter much,” Dick said. “I’ll probably see him to-morrow.”

Very soon afterward they went in to dinner. Niles and two other men joined them, and they made a jolly party around a big table in the middle of the room, which was not so empty after all, quite a number of people having driven out to the club especially to take dinner there. Stovebridge and Marston sat at the same table they had occupied at lunch, and Dick noticed that both seemed to be hitting it up pretty freely.

The evening being a little chilly, they did not return to the veranda after dinner, but made themselves comfortable in the reception hall, where a fire had been lit in the great stone fireplace.

Presently Merriwell remembered that he wanted to call up the Hanlon farm to find out about the little girl, and, on inquiring, found that the telephone was in a small room opening out of the hall.

He had no trouble in getting the number, and Mrs. Hanlon herself came to the telephone. She seemed very much worried and nervous, and told that the doctor had been there almost all the afternoon. The child’s arm had been broken and her head badly cut, and, from the symptoms, the physician was afraid that there was some internal trouble.

“Poor little kid!” Dick muttered as he hung up the receiver. “I certainly shall do my best to show up the brute who is responsible for that. He ought to get the maximum penalty, and if she doesn’t pull through I shouldn’t like to be in his shoes.”

He opened a door which led directly outside, and stepped out on the deserted veranda. It was a perfect night, still and rather cool for that time of year, and, as he looked up at the glittering stars, he drew a long breath of pure oxygen.

All at once he heard a stealthy footfall behind him,53 and, half turning, he caught a glimpse of a crouching figure close upon him.

As he leaped instinctively to one side he felt the impact of a spent blow on his back. Something sharp pricked his skin.

He whirled around swiftly, only to see a shadowy figure leap from the end of the veranda and disappear into the darkness.

CHAPTER V.

THE STRUGGLE IN THE DARK.

Like a flash Dick was after him, but as he reached the edge of the veranda, he realized the futility of pursuing the would-be assailant. The fellow, whoever he was, evidently knew the ground thoroughly, and, handicapped as the Yale man was with his bandaged ankle, it would be a waste of time to try and catch him.

He walked slowly back into the light that streamed out through one of the windows, and slipped off his coat.

Just between the shoulders was a clean cut about twelve or fourteen inches long, evidently made by an extremely sharp instrument.

The Yale man gave a low whistle.

“That fellow was out for blood,” he murmured. “That’s about as close a call as I’ve ever had. I wonder——”

Putting his hand up to his back, he found that both shirt and undershirt had been cut through, though not so badly, and that there was a tiny cut in the skin just between the shoulder blades.

Thoughtfully he slipped into his coat again.

“That couldn’t have been Stovebridge,” he mused. “Much as the fellow hates me, I don’t believe he would deliberately attempt murder.”

He glanced through the window into the reception-hall. Neither the tall athlete nor his friend Marston were in the room.

Dick shook his head slowly.

“Just the same, it wasn’t him. It must have been55 that dumb fellow. He’s been looking at me all day as though he would like to knife me, and now he’s tried it. I wish I could get hold of him to convince him that he’s on the wrong track.”

Just now, however, the Yale man was more troubled as to how he could get up to his room and slip into his spare coat without attracting attention by passing through the reception hall. He saw nothing to be gained by letting the clubmen know what had happened. They could do no good now, and Roger Clingwood would be worried to death and tremendously mortified at the thought of such a thing happening to his guest.