Little Cousin Series

Each volume illustrated with six or more full page plates in

tint. Cloth, 12mo, with decorative cover

per volume, $1.00

LIST OF TITLES

By Col. F. A. Postnikov, Isaac Taylor

Headland, Edward C. Butler,

and Others

| Our Little African Cousin |

| Our Little Alaskan Cousin |

| Our Little Arabian Cousin |

| Our Little Argentine Cousin |

| Our Little Armenian Cousin |

| Our Little Australian Cousin |

| Our Little Austrian Cousin |

| Our Little Belgian Cousin |

| Our Little Bohemian Cousin |

| Our Little Brazilian Cousin |

| Our Little Bulgarian Cousin |

| Our Little Canadian Cousin of the Great Northwest |

| Our Little Canadian Cousin of the Maritime Provinces |

| Our Little Chinese Cousin |

| Our Little Cossack Cousin |

| Our Little Cuban Cousin |

| Our Little Czecho-Slovac Cousin |

| Our Little Danish Cousin |

| Our Little Dutch Cousin |

| Our Little Egyptian Cousin |

| Our Little English Cousin |

| Our Little Eskimo Cousin |

| Our Little Finnish Cousin |

| Our Little French Cousin |

| Our Little German Cousin |

| Our Little Grecian Cousin |

| Our Little Hawaiian Cousin |

| Our Little Hindu Cousin |

| Our Little Hungarian Cousin |

| Our Little Indian Cousin |

| Our Little Irish Cousin |

| Our Little Italian Cousin |

| Our Little Japanese Cousin |

| Our Little Jewish Cousin |

| Our Little Jugoslav Cousin |

| Our Little Korean Cousin |

| Our Little Malayan (Brown) Cousin |

| Our Little Mexican Cousin |

| Our Little Norwegian Cousin |

| Our Little Panama Cousin |

| Our Little Persian Cousin |

| Our Little Philippine Cousin |

| Our Little Polish Cousin |

| Our Little Porto Rican Cousin |

| Our Little Portuguese Cousin |

| Our Little Quebec Cousin |

| Our Little Roumanian Cousin |

| Our Little Russian Cousin |

| Our Little Scotch Cousin |

| Our Little Servian Cousin |

| Our Little Siamese Cousin |

| Our Little South African (Boer) Cousin |

| Our Little Spanish Cousin |

| Our Little Swedish Cousin |

| Our Little Swiss Cousin |

| Our Little Turkish Cousin |

| Our Little Ukrainian Cousin |

| Our Little Welsh Cousin |

| Our Little West Indian Cousin |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY (Inc.)

53 Beacon Street Boston, Mass.

Our Little

|

||

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

Made in U. S. A.

| Published May, 1905 |

| Fourth Impression, May, 1908 |

| Fifth Impression, October, 1909 |

| Sixth Impression, June, 1911 |

| Seventh Impression, February, 1913 |

| Eighth Impression, October, 1915 |

| Ninth Impression, March, 1918 |

| Tenth Impression, May, 1919 |

| Eleventh Impression, February, 1922 |

| Twelfth Impression, March, 1926 |

PRINTED BY C. H. SIMONDS COMPANY

BOSTON, MASS., U. S. A.

INTRODUCTION

If a little girl or boy helps another who is in trouble, they are sure to be the best of friends. In the early days, before this country became a great nation, when the Colonies were at war with England, fighting for the independence and freedom which we now celebrate each year on the Fourth of July, a French nobleman by the name of Lafayette came across the sea to help us. We needed his help, and when the brave Colonial soldiers at last won a great victory, and the Colonies became one nation, we were very grateful to Lafayette for the help he had given, and because he was a Frenchman, the people of France and the people of the United States became fast friends.

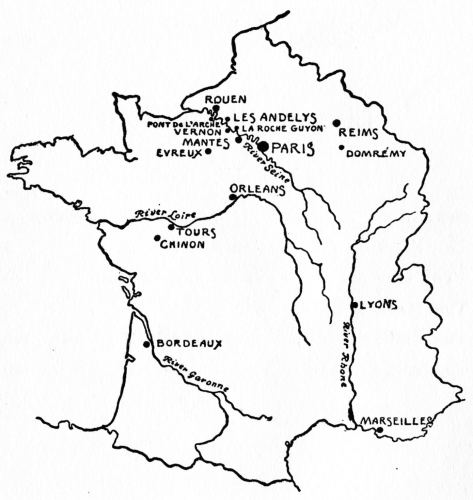

This story was written to help us learn more about our wonderful French cousins. Germaine,[vi] "Our Little French Cousin," happened to live in Normandy, but her every-day life, her parents and her friends were just like those of other French children. True, she travelled more than most children, but if she had not, the story would not tell so much about other parts of her native land.

It was in the early days of August, 1914, that the French people learned that Germany, her conqueror in the Franco-Prussian war, had again declared war, and was even then hammering at the forts of Belgium so she could march her armies right into their beloved France.

The news stirred the French people, but while the brave little army of Belgians halted the German troops, an army was gathered quickly under the leadership of Joseph-Jacques-Cesaire Joffre, a man of humble birth whom every one loved. We all know how the Prussian army defeated the Belgians and how the French were forced to retreat until they reached the River Marne,[vii] and then how they made a stand which resulted in such a glorious victory for France.

During these bitter days Germaine, and thousands of other French children, learned how to suffer and yet smile. She learned that her beloved France could produce heroes as great as Bayard, Du Guesclin, Ney, Henry of Navarre, Lafayette and Rochambeau. She never tired of hearing stories of the great General Petain, a quiet, reserved man who filled his troops with a new spirit which urged them on to another great victory at Verdun.

When, in 1917, the American soldiers went to France to help the French, the English, the Canadians, the Australians, the Belgians and all the other Allies drive the Germans out of France and Belgium, General Pershing, commander of the American Army, visited the tomb of Lafayette. He placed a wreath upon the tomb and made the greatest speech that was ever made in so few words. He said, "Lafayette,[viii] we're here." So we repaid our debt to France.

Then General Ferdinand Foch was made Commander-in-chief of all the armies that France and all the other nations had raised to show the Germans that right is greater than might. Then Germaine became even more proud of her native land when she was told of Georges Clemenceau, the "Tiger" premier, who was so brave and so sure, always, of success, and who played such a great part in making peace again throughout the world.

As a reward for her many sacrifices during the four years of the most cruel war the world has ever known, France regained her two lost provinces, Alsace and Lorraine. In another volume, "Our Little Alsatian Cousin," is told the story of the home life, the work and the play of the little folks who live in these provinces which were long a part of Germany, not because the people wanted it, but because Germany had won the Franco-Prussian war.

Preface

"Our Little French Cousin" is an attempt to tell, in plain, simple language, something of the daily life of a little French girl, living in a Norman village, in one of the most progressive and opulent sections of France.

The old divisions, or ancient provinces, of France each had its special characteristics and manners and customs, which to this day have endured to a remarkable extent.

To American children, no less than to our English cousins, the memories of the great names of history which have come down to us from ancient Norman times are very numerous.

Besides the great Norman William who conquered England, and Richard the Lion-hearted,[x] there are the lesser lights, such as Champlain, La Salle, and Jean Denys,—the discoverer of Newfoundland; and before them was the Northman ancestor of Rollo, Lief, the son of Eric, who was perhaps the real discoverer of America. All these link Normandy with the New World in a manner that is perhaps not at first remembered.

"Our Little French Cousin" lives in Normandy, simply because she must live somewhere, and not because any attempt has been made to specialize or localize the every-day life of Germaine, her parents, and her friends. Indeed, for a little French girl, it may be thought that she had remarkable opportunities for acquaintanceship with the outside world.

But to-day even little French girls live in a progressive world, and what with tourists and automobilists, to say nothing of a reasonably large colony of English-speaking folk who had actually settled near her home, it was but natural[xi] that her outlook was somewhat different from what it might have been had she lived a hundred years ago.

So far as France in general goes, the great world of Paris, and much that lay beyond, were also brought to her notice in, it is believed, a perfectly rational and plausible fashion; and thus within the restricted limits of this little book will be found many references to the life and history of Old France which, in one way or another, has linked itself with the early days in the history of America, in a manner of which little American cousins are in no way ignorant.

Joliet, Champlain, La Salle, Père Marquette, and many others first pointed the way and mapped out the civilization of America, when it was but the home of the red man, now so nearly disappeared.

Later came Lafayette and Rochambeau, who were indeed good friends to the then new[xii] nation, and lastly, if it is permissible to think of it in that light, the great Statue of Liberty, in New York Harbour, is another witness of the friendliness of the French nation for the people of the United States. A reciprocal echo of this is found in the recent erection, in Paris, of a statue of Washington.

To her cousins across the sea little Germaine, "Our Little French Cousin," holds out a cordial hand of greeting.

Les Andelys, Eure, January, 1905.

Contents

|

List of Illustrations

| PAGE | |

| Germaine | Frontispiece |

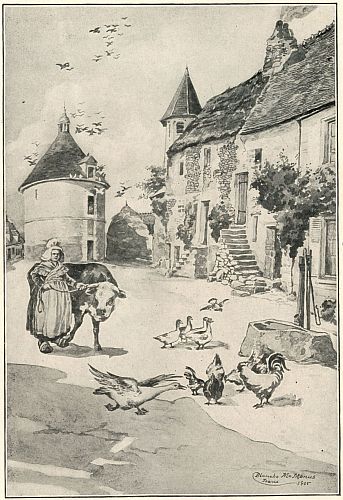

| The Farm of La Chaumière | 8 |

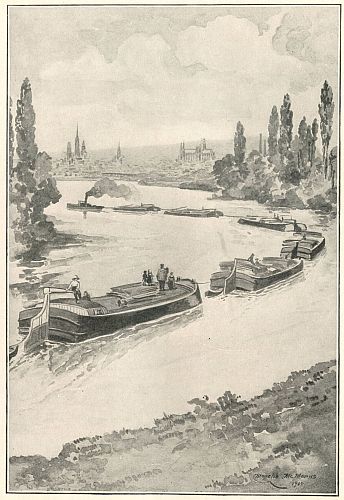

| "The city began to unfold before them" | 40 |

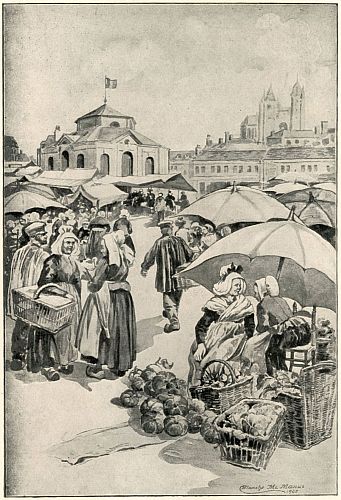

| The Market-square | 75 |

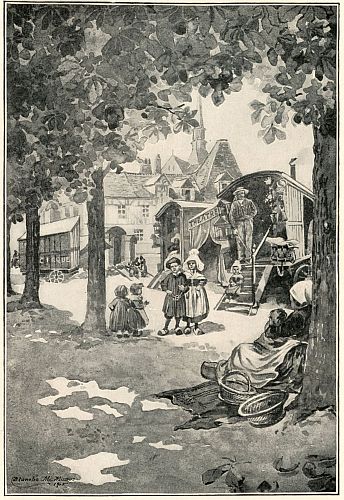

| The Circus | 100 |

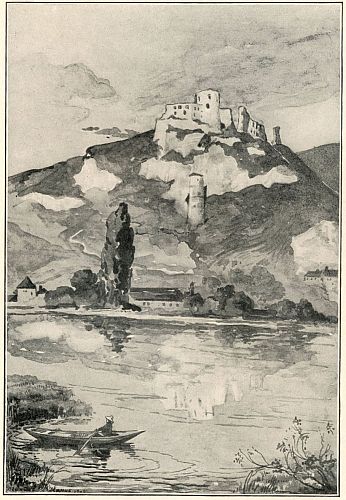

| Château Gaillard | 106 |

CHAPTER I.

AT THE FARM OF LA CHAUMIÈRE

"Oh, mamma!" cried little Germaine, as she jumped out of bed and ran to the window, "how glad I am it is such a beautiful day."

Germaine was up bright and early on this sunshiny day, for many pleasant things were going to happen. However, this was not her only reason for early rising. French people always do so, and little French children are not allowed to lie in bed and to be lazy.

At the first peep of daylight Germaine's papa and mamma were up, and soon the "little breakfast," as it is called, was ready in[2] the big kitchen of the farmhouse. Even the well-to-do farmers, like Germaine's papa, eat their meals in their kitchens, which are also used as a general sitting-room.

Everything about a French house is very neat, but especially so is the kitchen, whose bare wooden or stone floor is waxed and polished every day until it shines like polished mahogany. On the mantelpiece of the kitchen of Germaine's home, which was more than twice as tall as Germaine herself, was a long row of brass candlesticks, a vase or two, and a little statue of the Madonna with flowers before it.

The fireplace took up nearly all of one side of the room, and was so large that it held a bench in either side where one could sit and keep nice and warm in winter. Hanging in the centre, over the fire, was a big crane,—a chain with a hook on the end of it on which to hang pots and kettles to boil. There[3] were beautiful blue tiles all around the fireplace, and a ruffle of cloth along the edge of the mantel-shelf.

Not far from the fireplace was a good cooking-stove, for the better class farmers do not cook much on the open fire, as do the peasants.

All about the walls were hung row after row of copper cooking utensils of all kinds and shapes, all highly polished with "eau de cuivre." Madame Lafond, Germaine's mamma, prided herself on having all her pots and pans shine like mirrors.

"Be quick, my little one," said Madame Lafond, as Germaine seated herself at the table in the centre of the room. "You have much to do, for, as you know, we are to see M. Auguste before we go to meet Marie; and we must finish our work here, so as to be off at an early hour."

Germaine's breakfast was a great bowl of[4] hot milk, with coffee and a slice from the big loaf lying on the bare table. The French have many nice kinds of bread, and what they call household bread, made partly of flour and partly of rye, is the kind generally eaten by the country people. It is a little dark in colour, but very good.

It was to-day that Germaine was to go with Madame Lafond to the station at Petit Andelys to meet her sister Marie, who had been away at a convent school at Evreux, and who was coming home for the summer holidays. On their way they were to stop at the Hôtel Belle Étoile, for it was the birthday—the fête-day, as the French call it—of their good friend the proprietor, M. Auguste, and Madame Lafond was taking him a little present of some fine white strawberries which are quite a delicacy, and which are grown only round about. M. Lafond was to meet them at the station, and all were to take dinner with her[5] Uncle Daboll at his house in the village, to celebrate Marie's home-coming.

So, as may be imagined, Germaine did not linger over her breakfast, but set to work at her morning tasks with a will.

"Blanche, you want your breakfast, too," she said, as she stroked her pet white turtledove, who had been walking over the table trying to attract her attention with soft, deep "coos," "and you shall have it here in the sunshine," and, putting her pet on the deep window-ledge, she sprinkled before it a bountiful supply of crumbs. "That, now, must last until I get back."

"Now, come, Raton," she called to their big dog. "We must feed the rabbits," and, taking a basket of green stuff, she ran across the courtyard into the garden.

In France the farm buildings are often built around an open square, which is entered by a large gate. This is called a closed farm. In[6] olden times there were also the fortified farms, which were built strongly enough to withstand the assaults of marauders, and some of these can still be seen in various parts of the country.

The gateway was rather a grand affair, with big stone pillars, on top of which was a stone vase, and in the gate was a smaller one, which could be used when there was no need to open the large one to allow a carriage or wagon to enter.

On one side of the yard was the laiterie, where the cows were kept and milked. There were a number of cows, for M. Lafond sold milk and butter, carrying it into the market at Grand Andelys.

On another side was the stable, where were kept the big farm-horses,—Norman horses as we know them, one of the three celebrated breeds of horses in France. Near by were the wire-enclosed houses for the chickens and[7] geese and the ducks, which ran about the yard at will and paddled in the little pond in one corner.

In the centre was the pigeon-house, a large, round, stone building, such as will be seen on all the old farms like this of M. Lafond's. It was an imposing structure, and looked as if it could shelter hundreds of pigeon families. Under a low shed stood the farm-wagons and the farming tools and implements.

La Chaumière, as the farm was known, took its name from the thatch-covered cottage. Many of the houses in this part of the country have roofs thatched with straw, as had the other buildings on the farm. Germaine's home, however, had a red tile roof, though it was thatched in the olden days, for it had been in M. Lafond's family for many generations.

On the opposite side of the house was the garden, surrounded by a high wall finished off with a sort of roof of red tiles. The square[8] beds of fine vegetables were bordered by flowers, for in France the two are usually cultivated together in one garden. Against the wall were trained peach, pear, and plum trees, as if they were vines; this to ripen the fruit well. In a corner were piled up the glass globes,—shaped like a bell or a beehive,—which are used to put over the young and tender plants to protect them and hasten their growth.

Against one corner of the wall were the hutches for the rabbits, built in tiers, one above the other, and full of dozens of pretty "bunnies," white, black and white, and some quite black.

It was Germaine's duty to feed them night and morning, and she liked nothing better than to give them crisp lettuce and cabbage leaves and see them nibble them up, wriggling their funny little noses all the time. "Well, bunnies, you will have to eat your breakfast alone this morning; I cannot spare you much[9] time," Germaine told them, as she gave them the contents of her basket. Raton was leaping beside her and barking, for he was a great pet, and more of a companion than most dogs in French farms. They are usually kept strictly for watch purposes, the poor things being tied up in the yard all of the time; but Germaine's people were very kind to animals, and Raton did much as he pleased.

"I am ready, mamma," said Germaine, running into the kitchen.

"So am I, my dear," and Madame Lafond took from behind a copper saucepan hanging on the wall a bag of money, from which she took some coins and put the bag back again in this queer money-box. She then placed the basket of strawberries on their bed of green leaves on her arm, and she, Germaine, and Raton set off.

Madame Lafond had on a neat black dress, very short, and gathered full around the waist,[10] and a blue apron. Her hair was brushed back under her white cap, and on her feet she wore sabots, the wooden shoes all the working people in the country wear.

Germaine's dress was her mother's in miniature, and her little sabots clacked as she ran down the road, carrying in her hand a pot holding a flower, carefully wrapped about with white paper for M. Auguste. It was a beautiful walk through the fields and apple orchards, into the road, shaded by old trees that led to the top of the hill, and then down the hillside past the old Château Gaillard; that wonderful castle whose history Germaine never wearied of hearing.

It seemed to her like a fairy-tale that such things could have happened so near her papa's farm, though it all took place many hundreds of years ago, when there was nothing but wild woods where now stands their farm and those of their neighbours.

The château was built by the great Norman who became an English king. He was known as Richard the Lion-hearted, because he was so brave and fearless. Perhaps our little English cousins will remember him best by this romantic story. Once King Richard was imprisoned by his enemies, no one knew where; his friends had given him up for lost—all but his faithful court musician Blondel, who went from castle to castle, the length and breadth of Europe, singing the favourite songs that he and his royal master had sung together. One day his devotion was rewarded, for, while singing under the windows of a castle in Austria, he heard a voice join with his, and he knew he had found his master.

At that time France was not the big country it is now. Normandy belonged to the English Crown, and the Kings of France were always trying to conquer it for their own.

So Richard built this strong fortress on the[12] river Seine, at the most important point where the dominion of France joined that of Normandy. He planned it all himself, and, it is said, even helped to put up the stones with his own hands. It was begun and finished in one year, and when the last stone was placed in the big central tower, King Richard cried out: "Behold my beautiful daughter of a year." Then he named it Château Gaillard, which is the French for "Saucy Castle," and stood on its high walls and defied the French king, Philippe-Auguste, who was encamped across the river, to come and take it from him,—just as a naughty boy puts a chip on his shoulder and dares another boy to knock it off. Well, the French king took his dare, but he also took care to wait until the great, brave Richard had been killed by an arrow in warfare. Then for five months he and his army besieged the castle, and a desperate fight it was on both sides. At last the French[13] forced an entrance. After that, for several hundred years, its story was one of bloody deeds and fierce fights, until another French king, Henri IV., practically destroyed it, in order to show his power over the Norman barons whom he feared; and so it stands to-day only a big ruin—but one of the most splendid in France.

Germaine often wondered why it was called "Saucy," for it did not look so to her now. The big central tower with its broken windows seemed to her like an old face, with half-shut eyes and great yawning mouth, weary with its struggles, leaning with a tired air against the few jagged walls that still stood around it.

But it looked very grand for all that, and Germaine was fond of it, and she with her cousin Jean often played about its crumbling walls. Jean would stand in the great broken window and play he was one of the archers of King Richard's time, with a big bow six feet[14] long in his hand, and arrows at his belt, and that he was watching for the enemy who always travelled by the river, for in those days there were few roads, and journeying by boat on the river was the most convenient way to come and go.

There is no finer outlook in all France than from King Richard's castle at Petit Andelys, for one can look ten miles up the river on one side and ten miles down on the other. Thus no one could go from France into Normandy without being seen by the watchman on the tower of the Château Gaillard. Three hundred feet below is the tiny village of Petit Andelys, looking like a lot of toy houses.

As they entered the main street of the village, Madame Lafond stopped at the Octroi, to pay the tax on her strawberries. All towns in France put a tax on all produce brought into the town, and for this purpose there is a small building at each entrance to the town where[15] every one must stop and declare what they have, and pay the small tax accordingly.

"I hear the 'Appariteur,'" said Germaine, as they walked down the narrow cobble-paved street, "I wonder what he is calling out." The "Appariteur" is a sort of town-crier, who makes the announcements of interest to the neighbourhood by going along the streets beating a drum and crying out his news, while the people run to the windows and doors to listen. It takes the place of a daily newspaper to some extent, and costs nothing to the public.

They were soon at the Hôtel Belle Étoile, and found stout, good-natured M. Auguste at the entrance, seeing some of his guests off. He was delighted with the strawberries, and when Germaine gave him the bouquet of flowers, with a pretty little speech of congratulation for his birthday, he kissed her, French fashion, on both cheeks, and took them into[16] the café, where he gave them a sweet fruit-syrup to drink. It is always the custom among our French cousins to offer some kind of refreshment on every possible occasion, and especially on a visit of ceremony such as this. So when M. Auguste asked Madame Lafond what she would take, she and Germaine chose a "Sirop de Groseilles," which is made of the juice of gooseberries and sweetened. A few spoonfuls of this in a glass of soda-water makes a delightful cool drink in hot weather, and one of which French children are very fond. There are also syrups made in the same way from strawberries, raspberries, peaches, etc., but this is one of the best liked.

"There is Madeleine making signs to you outside the door. Run and see what she wants, my little one," said M. Auguste. "I can guess," he said, laughingly, as Germaine ran to greet the waitress of the hotel, who[17] always looked so neat and pretty in her white country cap, her coloured apron over a black dress, and a coloured handkerchief around her neck, with neat black slippers on her feet.

"Let me show you how we are going to celebrate the fête-day of M. Auguste," said she, smiling, and, opening a box, she showed Germaine the sticks of powder, which they would burn when night came, and make the beautiful red and green light such as all children and many grown folks like. The first of these sticks was to be burnt at the very entrance door, that all the village might know that it was M. Auguste's birthday. Madeleine and the cook and the housemaid and the washerwoman and the boy that blacked the guests' boots had each given a few centimes (or cents) to buy these, as well as other things that wriggled along the ground and went off with a bang, as a surprise for[18] M. Auguste. Also the American and English visitors at the hotel had bought "Roman candles" and some "catharine-wheels," which were to be let off in front of the Belle Étoile; so the hotel would be very gay that night.

M. Auguste's name-day had also been celebrated in another way some time before. On the fête of St. Auguste it was the custom to carry around a big anvil and stop with it in front of the house of every one who is named Auguste or Augustine. A cartridge was placed on the anvil and hit sharply with a hammer, when of course it made a frightful noise; and for some unknown reason this was supposed to please good St. Auguste as well as those who bore his name. Then the person who had this little attention paid him or her would come out and ask every one into their house to have a glass of calvados, which is a favourite drink in this part of France, and is made from apples.

The Belle Étoile, like most of the hotels of France, was built with a courtyard in the centre, and around this were galleries or verandas, on which the sleeping-rooms opened. Carriages passed through an archway into this courtyard, on the one side of which were stables, on another the kitchen and servants' quarters, and the entrance to the big cellar where were kept the great barrels of cider.

Most of the courtyard was given up to a beautiful garden, set about with shrubs and flowers. At little tables under big, gay, striped garden-umbrellas, the guests of the Belle Étoile ate their meals. In the country, every one who can dines in the garden during the summer months, which is another pleasant custom of this people.

M. Auguste was very fond of little Germaine, and often told her of his boyhood days in the gay little city of Tours, where the purest French is spoken, with its fine old cathedral[20] and the lovely country thereabouts all covered with grape-vines; and how in the bright autumn days the vineyards are full of workers filling the baskets on their backs with the green and purple grapes; how late in the evening the big wagons, full of men, women, and children, come rolling home, piled up with grapes, the pickers all singing and joyous, with great bunches of wild flowers tied on the front of each wagon. "A very happy, gay people, my dear," would remark M. Auguste, "not like these cold, stolid Normans." But to us foreigners all the French people seem as gay as these good folk of Touraine, the land of vineyards and beautiful white châteaux.

M. Auguste had also been a great traveller, for his father was well-to-do, and he thought that his boy should see something of his own country—though French people as a rule are not great travellers. They are the most home-loving people in the world, and their greatest[21] ambition is to have a little house and a garden in which to spend their days.

So M. Auguste had seen much. He had been to the bustling city of Lyons, where the finest silks and velvets in the world are made. He had journeyed along the beautiful coast of France where it borders on the blue Mediterranean, where palms and oranges and such lovely flowers grow, especially the sweet purple violets from which the perfumes are made. From here also come the candied rose-petals and violets, that the confectioners sell you as the latest thing in sweetmeats.

He had visited the great port of Marseilles, the most important in France, where are to be seen ships from all over the world, and there he learned to make their famous dish, the bouillabaisse, which is a luscious stew of all kinds of fish—for M. Auguste prides himself on the special dishes that he cooks for his guests, and Germaine is often asked to try[22] them. He had been also to the rich city of Bordeaux, where the fine wines come from. Oh, M. Auguste is a great traveller, thought Germaine, as they sat together in the kitchen of the Belle Étoile, while M. Auguste talked with Mimi, the white cat, sitting on his shoulder, while Fifine, the black one, was on his knee. They were great pets of M. Auguste, and as well known and liked as himself by the guests at the Belle Étoile.

CHAPTER II.

TO ROUEN ON A BARGE

Germaine and her parents, and her Uncle Daboll and his wife, and their little son Jean, just one year younger than Germaine, were all at the station long before the train was due. The two children were fairly prancing with glee, while Raton leaped about no less excited. They were very fond of Marie, as was every one who knew her, for she was a gentle, kind-hearted girl, and though several years older than Germaine, they were great companions. This was her first year away from home, and Germaine had missed her sadly.

"There she is," cried Germaine, as the train pulled slowly in, and a young girl appeared at the window of one of the third-class carriages,[24] waving her handkerchief, and throwing them kisses.

Her father lifted her down, and every one kissed her twice, on either cheek, and amid much laughing and talking they walked toward Uncle Daboll's house, while Raton danced in circles about them as if he had gone mad.

"Oh, Marie," cried Germaine and Jean in the same breath, "we have such a lovely surprise for you! You have heard, of course, of the grand 'Norman Fêtes,' which are to be held at Rouen next week! Well, just think, we are all going to see them, that is, you and Jean and me and uncle and aunt, and better still—how do you think we are going?" "Why, on the train, of course," laughed Marie, "and won't we have a good time." "No," spoke up Jean, quickly, "we are going a brand-new way. What do you say to going on a barge on the river?" "A barge," cried Marie, "but I thought no one was allowed to travel[25] on the barges, except the people who ran them and lived on them." "That is true," said Germaine, "but uncle has fixed all that; you know he sends lots of brick to Rouen by the barges—one is being loaded up now at the quay, and he has arranged that we go on it to Rouen and stay on the barge while it is being unloaded, and see the fêtes. Then we will come back by train. Won't it be glorious?" "And," chimed in Jean, "papa is going to tell us all about the history of these fêtes after dinner."

M. Daboll's home was a neat little cottage, with its upper part of black beams and white plaster, and a pretty red-tiled roof, the ground floor being of stone. M. Daboll owned a large brick-kiln, and was quite well-to-do.

They all gathered for dinner about a round table in an arbour that overlooked the river. The arbour was ingeniously formed by training the branches of two trees and interlacing them[26] as if they were vines, which gave complete shelter from the sun.

Every one was eager to listen to Marie's account of her school life at the convent. It was a very old convent, with beautiful gardens surrounding it, built as usual around a courtyard, in the centre of which was a statue of St. Antoine, who is a favourite patron saint of schools, and considered the special guardian of children. He also, according to tradition, helps one find lost articles, and as we all know how school-children are always losing their belongings, this may be another reason for having the kind St. Antoine as a protector of school-children. At six the girls are up, and study an hour before the "little breakfast" of a roll and butter and chocolate or coffee. Lessons take up the time until noon, when they have their dinner of soup, meat, vegetable, and cider, with a gâteau, as they call a cake, on Sundays. After dinner they are[27] taught plain sewing, and when the sewing hour is over they can play about the gardens until the study hour comes around again. A plain supper of bread and cheese, chocolate or milk, follows, and by nine o'clock every one is in bed. The children dress very simply,—plain cotton frocks, which indoors are always completely covered with a black apron or tablier. On Thursdays they have a half-holiday, and in the care of the Sisters go on little excursions or walks in the neighbourhood. A pleasant, simple life, and, as M. Lafond said, as he pinched Marie's cheek, "It seems to agree with you, my dear."

"Now, papa, you promised to tell us about these Norman Fêtes," said Jean, when the table had been cleared away, and the little coffee-cups brought out.

"So I will, Jean, and first you bring me that big roll which you will find on the side-table in the dining-room."

Jean was back with it directly, and Uncle Daboll unrolled a big poster, advertising the fêtes. It showed a fine, strong man in ancient armour, seated on a prancing horse, carrying on his arm a shield, emblazoned with two red lions, and holding aloft a spear. Below him on the river were to be seen three small boats, each with one sail, and also arranged so that it could be rowed by hand.

"This represents Rollo," went on M. Daboll, as the children clustered around him, "the leader of a great race of people whose home was in the cold, far-away North. Tall people they were, with golden hair, and great sailors, who sailed in tiny ships, like those you see in the picture, over the bleak, stormy sea which lies between their land and France, until they came to the river Seine, where it empties into the Atlantic Ocean.

"They rowed up the river and camped where the fine city of Rouen now stands,[29] and from these fair-haired Northmen are descended the present-day Normans. It has been many centuries since all this happened, so the good people of Rouen thought this a suitable time to celebrate the founding of their city, and of the great Norman race, at one time the most powerful in France."

"And at Rouen we shall also see the spot where poor Jeanne d'Arc was burned," said Marie. "We have just been reading her history at the school."

"Tell us her story again," said Jean.

"She will on the barge. You will have plenty of time then," said M. Lafond; "but we must be getting home now. It is quite a walk, and our little Marie must be tired after her long day."

It was about six o'clock in the morning of the next day when the gay little party found themselves on the barge bound for Rouen.

"Now here comes our tow that we must tie[30] up to," said the bargeman, as a tug with five barges in tow came puffing down the river; and taking a long pole with a hook in the end of it, he began pushing the barge away from the shore until it moved toward the middle of the river. Then the tugboat slowed down until the long line of barges was just creeping along; one could hardly see that they moved at all. Just as the last one passed that which carried our party, the man in the stern of it threw them a rope which was quickly caught and fastened to the forward end, and as it grew taut, the barge began to move and soon took its place at the tail-end of the long procession.

The children at once began to make themselves at home in their new surroundings. "Did you ever see anything nicer?" said Germaine, as she dragged Marie into the little house under the big tiller, where the bargeman and his wife lived.

"Does it not look like a doll's house?" said Marie, as they went down the ladder into the tiny living room. Everything was as neat as could be, and painted white, with lace curtains at each of the small windows.

It was wonderful how much could be stowed away inside, and yet leave plenty of room. A sewing-machine stood in one corner; a bird-cage was hanging in the window, and a little stove, a table to dine on, and a couple of chairs completed the arrangements, save the pictures on the walls, the china in a neat little cupboard, and the beds which were built like shelves, one above the other, to allow all the floor space possible. On deck, one side of the house was given up to a shelf full of gay flowers in pots, and vines were trained up against the side of the house. There was also on deck a chest to hold the meat and vegetables, so as to keep them cool and fresh, and a small cask was made into a house for[32] the dog. Every barge has its dog and cat, which usually get on together very well, considering their crowded quarters. Everything about the house end of the barge was painted white with green trimmings, and all was very clean and neat.

Jean then came up to tell them that he had found out that every barge in the tow belonged to a different owner. This he had learned from the gaudy colours with which they were decorated. "You will see," said he, "that ours has a big white triangle with a smaller red triangle inside of that painted on the bow. The one next to us has a broad red band with two white circles, and there is another yellow with two big blue stars on either side. These are the distinguishing marks of the different companies to which they belong."

They were now leaving behind them the great high cliffs of white chalk that shine like snow, through which the river runs almost all[33] the way from Mantes to Rouen. Just here it wound through rich green meadows. Along the water's edge were clumps of willow-trees, whose long, pliable twigs are used by the country people to weave baskets. They trim off the branches, but leave the tree standing for more branches to grow, and so they never use up their basket material. The French take very good care of their trees, and when they cut one down, always plant another in its place.

Often the barge passed other long tows, whose barge-people would shout greetings across to them. For most bargees are acquainted, at least by sight, and the dogs would bark "How do you do's" as well. Great coal barges from Belgium passed, having come laden many hundreds of miles across France; and others with hogsheads of wine from the south, which have been brought by sea to Rouen.

A merry dinner was served on a table on deck under an awning. The wife of the bargeman had cooked a good meal on the little stove which stood on one of the hatches right out in the open. They had a favourite country soup first, beef and cabbage soup with a crust of bread in it. (French soups are usually called potage, though the real country soup is often known by the name we call it ourselves—soupe.) Then there was a crisp green salad, big jugs of Normandy cider, which is a beautiful golden colour, blanquette de veau, which is veal with a nice white egg sauce over it. Lapin garnne followed, which is nothing more than stewed rabbit, and a dish of which all French people are very fond, and have nearly every day when it is in season. Fresh Normandy cream cheese and cherries and little cakes finished the meal, with the usual coffee and calvados for the older people.

"We will soon see Pont de l'Arche," said[35] the bargeman, and they had barely finished dinner when the picturesque church of the town was seen rising above the trees.

"It has no spire nor towers; it looks like half of a church," said Jean.

"Which is true, but it is quite a famous church, nevertheless," said his father. "It is probably the only church in the world which is dedicated to 'Art and to the Artists.'"

"Our Lady of the Arts" it is called. Artists are beginning to visit it more from year to year, and it is a veritable place of pilgrimage now.

The barge soon passed under the old bridge at Pont de l'Arche, and left behind the church, standing high above the town, a landmark for miles along the river.

Marie had promised to tell the children the story of Jeanne d'Arc, as they wanted to have it fresh in their minds when they visited Rouen, for every part of this old city is full[36] of memories of this wonderful little peasant girl who saved her country, and, by so doing, made possible the existence of the great French nation of to-day.

Sitting under the awning, as the barge glided along, Marie told the story of the little peasant girl, only sixteen years old, who lived in the far-away village of Domremy. Believing that Heaven had chosen her to save her country from the hands of the English, she made her way to the court of Charles VII., then King of France. It was at Chinon in the valley of the Loire—that other great river of France—that she finally reached her king, and in one of the great castles, whose ruins still crown the heights above the city, eloquently pleaded her cause. Visitors there to-day can see the room with its great fireplace in which this famous meeting took place.

Her plea convinced the king, and she was made commander-in-chief of the army, which[37] she led on to Orleans, raised the siege of that city, and drove the English off. There is to-day no city in France as proud of the "Maid" as is Orleans; indeed she is known as the "Maid of Orleans." The house she is supposed to have stayed in is now preserved as a museum, and every May, on the anniversary of the day on which the siege was raised, a great celebration takes place in front of the cathedral, and a procession of priests and people carrying banners marches around the town chanting hymns in her praise. Jeanne d'Arc did break the power of the English in France, true to her promise, and finally brought King Charles to the magnificent cathedral at Reims, where the French kings were always crowned, and herself, amid great rejoicing, placed the crown upon his head. But the king forgot what the "Maid" had done for him and for his country, apparently, and finally she was betrayed into the hands of her enemies, who[38] took her to Rouen, and, after a mock trial, poor Jeanne was sentenced to death, and burnt in the market-place at Rouen.

In later years the French nation recognized the great good she had done, and the memory of the little peasant girl of Domremy is loved and venerated throughout the land. There is scarcely a city in France that has not honoured her in some way, either by erecting a statue to her, or naming a place or street in her honour.

The children were so much interested in the wonderful story of Jeanne d'Arc that they had not realized how time was flying. They were drawing near Rouen, for over the flat fields of the river valley on the left rose the tall chimneys of the cotton factories at Oissel and Elbeuf.

There is much cotton cloth made in the vicinity of Rouen, and shipped all over France. On the quays there may be seen the bales of cotton that is grown on the plantations in the[39] Southern States of America, and shipped from New Orleans direct to Rouen.

Just here the bargeman pointed out to them the tiny church of St. Adrien. The "Rock Church," as it is known, is cut out of the chalk cliff, hanging high above the river. It looks like a bird's house perched up so high, with its four small windows and tiny bell-tower.

Presently Uncle Daboll said, "Look way down the river, children, and tell me what you see."

"Oh," cried Jean, "I see three church spires."

"More than that," said Germaine. "I can count seven."

"Both of you are right," said Uncle Daboll. "The three spires are those of three of the most beautiful churches in France. That tall, needle-like one belongs to the Cathedral of Notre Dame."

"There is one which looks as if it has a crown on the top," said Germaine.

"It does look like a crown made of stone, and so it has been called the 'Crown of Normandy.' It is on the central tower of the church of St. Ouen."

The city began to unfold before them, with its long rows of quays lined with shops, hotels, and cafés on the one side, and ships from all parts of the world on the other.

Their barge soon deftly glided into what seemed a perfect tangle of barges of all kinds, and came to anchor next to a big Belgian coal-carrier, whose occupants, like themselves, were evidently bent on getting as much enjoyment out of their visit to Rouen as possible.

CHAPTER III.

THE FÊTES AT ROUEN

It was growing dark when our little party scrambled over the decks of several barges, and finally found themselves walking up the quay.

The lights were beginning to twinkle in all directions, and in a few minutes the river and city were ablaze. It seemed like fairyland to the children. The bridges were outlined with golden globes and festoons of tiny lamps of red, white, and blue. Wreaths of lights, in the shape of flowers of all colours, made innumerable arches of light across the streets. Everywhere were flags grouped about shields on which were the letters R. F., which stand for the words "Republic of France."

Walking in any direction was not easy. A mass of people swaying hither and thither blocked streets, bridges, and quays. Our little Les Andelys party did not attempt to stem the torrent. "We will just drift along," said Uncle Daboll, "and see what we can, and you children hold each other's hands and keep closely to us."

It was a motley and most good-natured crowd. Ladies in Parisian gowns mingled with country women in their fanciful white caps, kerchiefs, and short skirts. There were Breton fisherfolk and dark-skinned people from the far south; sailors and soldiers in their gay red and blue uniforms, and every now and then one would hear a clear English voice.

Vendors of toys for the little ones, and souvenirs for everybody, stood on every corner and did a flourishing trade, and high above the heads of every one floated masses of the small[43] red, white, and blue balloons, held captive on a long string, without which no French fête is complete. On the sidewalk in front of the cafés, people were sitting at small tables sipping their coffee and the numberless sweet drinks of which the French are so fond, while at each café a band was playing for the amusement of its guests, but was also enjoyed by the passing throngs. It took the combined efforts of many natty policemen—"gendarmes," they are called—to keep an open pathway through the crowd.

A gendarme looks more like a soldier than a policeman, in his dark blue uniform and soldier-cap, a short sword by his side, and a cape over his shoulders, all of which gives him quite a military air.

Presently, at a corner, they were stopped by an even denser throng who were watching a gaily dressed crowd of people entering a brilliantly decorated and illuminated building.

"What is this?" asked Uncle Daboll of a man near him.

"It is the grand costume ball at the theatre, where every one is expected to dress in old Norman costume," was the answer.

"Oh," said Germaine, "that is why the ladies are wearing those funny tall head-dresses; look, Marie, there is one quite near us."

The costume was both pretty and odd. The lady had on a white head-dress made of embroidered muslin, very like a sunbonnet in shape, with a high crown, around which was tied a big bow of ribbon. A bright-coloured kerchief was about her neck, and she wore a square-necked cloth bodice neatly laced in front, with sleeves to the elbow; underneath this was a white chemisette, as it is called. Around the neck and sleeves of the bodice were bands of velvet. A very short skirt, gathered as full as possible about the waist, a dainty little apron of coloured silk with lace[45] insertion, wooden sabots, prettily carved, and lace mitts on her hands, completed her unusual costume.

The gentleman with her was also in Norman dress. He had big baggy trousers, a high velvet waistcoat embroidered in bright colours, a short round jacket with gold buttons, a high white collar with a big red silk handkerchief tied in a bow around the neck, enormous sabots, and all topped off with a high silk hat, with a straight brim.

While the children were busy looking at the details of the costumes, a carriage halted so near Germaine that she could have put out her hand and touched its occupant, who was a young girl about her own age. Germaine was at once attracted to her. She had a sweet pretty face, bright rosy cheeks, and soft blue eyes; her waving, brown hair fell loosely about her shoulders, and across her white dress was draped a small silk flag which Germaine recognized[46] as the British flag, known as the "Union Jack." She wore a wreath of red roses and carried in her hand a bunch of the same flowers in which were stuck two small silk flags—one French and the other British. Beside her sat a portly gentleman in a gorgeous robe of black and red trimmed with fur, while around his neck was a massive golden chain.

As Germaine was watching her, the little girl leaned eagerly out of the carriage window, and in so doing dropped her bouquet at Germaine's feet. "Oh, papa, I have lost my flowers," she cried. Meanwhile Germaine quickly picked them up, and handed them back to her; and not a moment too soon, for the carriage was moving on again and the bouquet would have been crushed under its wheels.

"Thank you so much," cried the little girl, looking back and waving her hand. Germaine did not understand the words, but knew she had been thanked in English.

Germaine had been so taken up with this little incident that she had not noticed that the crowd had separated her from her companions. Her heart gave a bound, and with a startled cry she realized that only strange faces were about her, and she stood motionless with fright. Her terror was fortunately short-lived, for through the crowd she saw Uncle Daboll making his way toward her, and rushing up to him thankfully clasped his hand, which he made her promise not to loose again until they were safe back on the barge.

It was not until later, when they were sitting on the deck of the barge watching the fireworks on the heights around the city leave fiery streaks and showers of shining stars on the blackness of the summer sky, that Germaine had the opportunity of telling the family of her adventure with the "little girl of the roses," as she called her.

Aunt Daboll thought that probably she[48] belonged to one of the parties of English visitors who had come to Rouen to take part in the Fêtes.

Very early the following morning they finished their coffee and rolls and began their round of sightseeing, all of which had to be crowded into the morning, as the afternoon was to be given over to the Water Tournament, to which the children were looking forward with great excitement.

Jean, especially, had been impressed with the posters which showed in brilliant colours men in unfamiliar dress, tumbling into the water and being fished out again, with, apparently, great unconcern as to the consequences.

"Well, what shall we see first?" asked Uncle Daboll.

"Oh, the big clock," said Jean, "and then let's climb the iron spire of the cathedral."

Germaine wanted to see where poor Jeanne[49] d'Arc had been put to death; the others were ready for anything.

"Everywhere one sees the name of Jeanne d'Arc," said Marie. "This street is named after her, and last night we were in the Boulevard Jeanne d'Arc."

"And just at the top of this same street," said Uncle Daboll, "we shall see the Tower of Jeanne d'Arc, where the poor girl was imprisoned during her mock trial in the great castle, of which only this one tower is left standing."

They soon turned into a narrow street, and there was the great clock, built in a tower, under which runs the roadway itself.

Another turning brought them to the Palais de Justice, with its big dormer windows elaborately carved in stone.

A few steps more, and they were in the old market-place, and little Germaine with bated breath looked at the stone let into the pavement[50] at her feet, which marks the spot where poor Jeanne bravely met her terrible death by fire. All about the place the market people were peddling their wares, bargaining and calling out the merits of their various vegetables and fruits and poultry, the scene not unlike what it may have been in those olden days when the Normans ruled.

Our party could not, however, linger very long over memories of the "Maid," for Uncle Daboll hurried them away to see the great church of St. Ouen, with such large windows that it seems to have walls of glass, and its curious Portal of the Marmosets, all over which are carved little animals which look like ferrets. They passed the little church of St. Maclou, set like a gem in a tangle of streets that were little more than alleys. As Jean said, the tall, old houses seemed to be leaning over toward one another as if they were trying to knock their heads together.

At one street corner there had been erected a triumphal arch which was surmounted by a facsimile of the statue of William the Conqueror, the original of which stands in the little Norman town of Falaise, where he was born.

All French children know the history of this great Norman, who was an unknown boy in an obscure little village, but who in time sailed across what is now known as the English Channel, conquered England, and made himself King of England as well as Duke of Normandy.

When they came to the cathedral, our party were glad to enter and rest awhile within the cool, lofty aisles and say a short prayer.

Marie remembered her favourite St. Antoine and dropped two sous in the box at the foot of his statue, for the poor.

While Uncle Daboll and Jean climbed up the iron spire, the rest of the party were taken[52] by the "suisse" to see the chapels with their tombs and tapestries.

The suisse is an imposing person in gorgeous dress of black velvet and gold lace, a big three-cornered hat covered with gold braid, white silk stockings, shoes with big buckles, and he carries a tall gold-headed stock.

It is his duty to guard the church and, for a small fee, to show visitors the chapels and other parts of the church not generally open.

Marie and Germaine felt quite in awe of him at first. They had never seen anything so magnificent before, but seeing their great interest in all that he pointed out to them, he unbent, and when he showed Germaine the spot where was buried the heart of King Richard, and she told him that she lived near the great castle the king had built, at Les Andelys, he smiled in a most friendly way, and patted her on the head.

It was quite a change when, after Uncle[53] Daboll and Jean joined them, they went out from the dark church into the square blazing with sunlight, and full of booths with all sorts of things to sell, toys, souvenirs, and picture post-cards galore.

Jean was full of his experiences in the tower: how they went up a little winding stairway to the very top, and they could see for miles around the city, and how the people looked like tiny black dots far below; and how, when coming down, he got a bit dizzy, and his father made him shut his eyes and sit still for a minute or two; but that was doing better than a grown man who was just behind them, and who had to go back just after they had started.

When Jean had finished telling his experiences, everybody found out that they were very hungry. Uncle Daboll laughed, and said he had never known them to be so much of one mind before.

"Well, follow me, little ones, and we shall find something," he said, and led the way down the street, gay with flags, wreaths, and flowers.

"Just one moment, uncle," cried Marie, "let us stop and buy some post-cards to send home."

"It will be better," said Uncle Daboll, "to get them after dinner, and while we are having our coffee at a café we can write them and send them off. If we stop now, we shall be late for dinner, for it is past noon."

"Here is our place for dinner," he continued, as they entered a small square surrounded by old-time houses near the river. On one side was a modest little hotel called the "Three Merchants." Going up an outside stairway, they entered a small room with a low ceiling and a stone floor, with a long table down the centre.

It was a typical place for the farmers to come for their dinners when they brought[55] their produce into the markets. Some of these farmers were now sitting at the table with blue or black blouses over their broadcloth suits, with their wives in black dresses and white caps, all talking and gesticulating away over their dinner.

There were two pleasant-faced curés in their long, tight black gowns closely buttoned up the front, the brims of their flat black hats caught up on either side with a cord, who had evidently come in from some country parish to see the fêtes. There was also a solitary bicyclist whose costume betrayed the fact that he was a Frenchman, for no other bicyclists in the world get themselves up in so juvenile a manner as do the French. A loose black alpaca coat, a broad waistband in which was sewed his purse, baggy knickerbockers of gray plaid, and socks with low shoes, leaving the leg bare to the knee, completed his marvellous costume.

You would think this a little boy's dress in America, would you not?

These were the guests to whom our party nodded, which is a polite and universal French custom when entering and leaving a room where others are, even though they may be unknown to you.

After a bountiful middle-class dinner, our party passed out into the crowded streets again, when the energetic Jean exclaimed: "Now for our post-cards!"

"Now for a place to rest a little while," cried uncle and aunt in the same breath.

"Here is a pleasant, cool-looking little café across the street; the one with the green shrubs in boxes before it. We will have our coffee there while you select your post-cards. You will find them in that corner shop."

In a few minutes the children were back with the cards. Jean had selected a view of[57] the cathedral, because he wanted to show his uncle and aunt the great spire up which he had climbed; Marie sent several showing the decorations in the streets to various of her school friends, and Germaine did not forget her friend, M. Auguste, after sending one each to her father and mother.

Before two o'clock everybody was hurrying toward the river to see the water sports.

"Oh, aunty," cried Germaine, pulling her aunt by the sleeve, "look, there is my 'little girl of the roses,' see, walking this way with those ladies and gentlemen!"

Germaine was quite trembling with excitement as she saw the little girl recognized her, and came quickly toward them.

"Oh, I am so glad to see you," she cried. "I have wanted to see you again to thank you. Oh, but isn't it stupid of me?" she went on, with a sign of vexation. "Of course you don't know English, and I can't speak French,[58] except to say merci and bon jour and bon soir, so how can we talk to each other?" Then she stopped and laughed, and Germaine laughed, too, and the two little girls stood smiling at one another, when the portly gentleman, whom Germaine had seen in the carriage, hurried up. "Ethel, my dear, why did you run off like this?"

"Oh, papa, this is the little girl who handed me back my roses, when they fell from the carriage last night. You know my special programme was tied with the flowers, and I would not have lost it for anything."

Just then some French people came up who also spoke English, and the little girl explained the situation. Germaine then learned that Ethel was the daughter of the mayor of the English town of Hastings, and he had been invited to represent England at the fêtes, for it was at Hastings that William the Conqueror had landed, and near there that the[59] great battle of Hastings was fought, which gave England to the Normans.

That was so very long ago that everybody in England is now very proud of it, and the English cousins from Hastings were taking as much interest in the fêtes as the French themselves.

Germaine blushed while the gentleman was telling her all this, and Ethel took a little English flag that she had pinned on her dress and gave it to Germaine. When Ethel's papa heard where Germaine lived, he said he had been to Les Andelys, he had stayed at the Belle Étoile, and knew M. Auguste, and perhaps next year he would come there again and bring Ethel and her mother, and then they should all meet again.

After the French gentleman kindly made all this known to Germaine, the little girls shook hands and parted, for the Tournament had begun.

Two queer-looking craft, much like gondolas, took up their positions, one at either end of the course. The crew of one had a white costume with red sashes and red caps—the other was in similar dress, except that their caps and sashes were blue. These respective crews were known as the "Blues" and the "Reds."

On a raised platform at the end of his boat stood a "Red," with a long lance at rest; opposite was a "Blue" in the same position. At a given signal, the boats came toward one another, and one lance-man attempted to push the other off into the water.

Great was the excitement among their partisans on the banks, and cries of encouragement came from friends on either side. Jean had picked out the "Blue" as his choice, while Marie and Germaine hoped the "Red" would win. By this time the children were standing on their chairs, Jean waving his cap with[61] great enthusiasm. Suddenly "Red" gave a stronger push, and down went poor "Blue," head foremost in the water. However, he did not seem to mind it, as he sat dripping in the rescue boat. Jean felt rather badly over the fall of his hero, but another man took his place, and this time Jean's man won, to his intense delight. So the fun went on until late in the afternoon. Another evening's walk through the illuminated city, and the children were quite ready for their beds on the barge,—for the men of the party slept on deck while the rest had the little house to themselves.

CHAPTER IV.

GOING HOME BY TRAIN

It was with real regret that our little friends parted from the good barge people and their floating home, as well as from the beautiful city of Rouen, where they had seen so much, and had such a good time.

Germaine, who had not been before in a big railway station, was somewhat bewildered at the confusion about her, while Jean, who had been once to Mantes, was proud to be able to explain things to her. The tall man in a blue uniform was the station-master, and one could always tell him from the other blue-uniformed officials, because he wore a white cap. It was his duty to send off the trains, which he does[63] by blowing a small whistle, after which some one rings a hand-bell that sounds like a dinner-bell, and off goes the train.

The men who were pushing luggage around on small hand-trucks were the porters, in blue blouses like any French working man, except they were belted in at the waist by a broad band of red and black stripes.

Presently the station-master whistled off their train. "Keep a sharp lookout," said Uncle Daboll, "and, as soon as we leave this tunnel we are now going through, look out on the right side and you will have a fine view of the city."

Sure enough, in a few minutes they were on the bridge, crossing the river, and before them stretched out a panorama of Rouen, with a jumble of factory chimneys and church spires, and rising above all the grand three-towered cathedral.

Perhaps American children might like to[64] know what French trains are like; they are so different from theirs in every way. To begin with, there are first, second and third class cars,—carriages, they are called,—and each carriage is divided into compartments, each compartment holding six persons in the first class, three on each side, and eight persons in the second, and in the third class, five on a side—ten in all. There is a door and two small windows in each end of a compartment.

The first and second classes have cushioned seats, but there are only wooden benches in the third. In many of the third class the divisions between the compartments are not carried up to the roof, and one can look over and see who his neighbours may be. The people who travel third class on French railways are a very sociable lot, and every one soon gets to talking. A French third class carriage under these conditions is the liveliest place you were ever in, especially when the train stops at a town on[65] market-day and many people are about, as they were on this occasion.

Well! Such a hubbub, and such a time as they had getting all their various baskets and belongings in with them.

The big ruddy-faced women pulled themselves in with great difficulty, for these trains are high from the ground and hard to get into, especially when one has huge baskets on one's arm, and innumerable boxes and bundles are being pushed in after one by friends.

The men come with farming tools, bags of potatoes, and their big sabots, all taking up a lot of room.

One tall stout woman, with a basket in either hand, got stuck in the doorway until Uncle Daboll gave her a helping hand and her friends pushed her from the outside. She finally plumped down on a seat quite out of breath, when from under the cover of one basket two ducks' heads appeared with a loud[66] "quack, quack, quack." "Ah, my beauties, get back," and she tapped them playfully and shut the lid down, but out popped their heads again with another series of "quacks," just like a double jack-in-the-box. How the children laughed, and that made them all friends at once.

Germaine offered to hold one of her baskets, for there was not a bit of room in the overhead racks, or anywhere else. When she took it on her knee, she thought she saw a gleam of bright eyes through the cracks, and sure enough it was full of little white rabbits. The old woman, seeing her interest, let her stroke their sensitive little ears, while she told how she had bought them at a bon marché, a good bargain, and was taking them home to her grandchild, just Germaine's age.

Next to her were two women who were evidently carrying on some dispute that had begun early in the day, and each was bent on[67] having the last word. So their talk went on, an endless stream, while the fat woman sat by and laughed at them both. Perhaps no wonder one of them was cross. She looked every little while at a big basket of eggs she carried, some of which were broken, and with small wonder, it would seem to inexperienced eyes, for they were packed in the basket without anything between them. When she found one badly broken, she swallowed it, as much as to say, "That is safe anyway," and then she would talk faster than ever.

Uncle Daboll talked to the man next him about market prices, and the cider crop, and what a fine fruit year it was. One had only to look out at the orchards they were passing to see the truth of this, for the apple-trees were so full of fruit that branches had to be propped up with poles to keep them from breaking down.

In the next compartment a party of four[68] were playing dominoes, one of the women who was with them having spread out her apron for a table.

Another party was evidently making up for a meal they had lost, while doing business. The mother took from a basket a part of a big loaf, from which she cut slices and distributed them, with a bit of cheese, to her party, at the same time passing around a jug of cider.

There was an exciting time when one of the chickens escaped from a market-basket and had to be chased all over the carriage. Such a clattering of tongues, flapping of wings, and distressful clucks from the poor fowl, which was at last caught just as she was about to fly out of a window, were never heard before.

The chattering was increased by elaborate good-byes, as one by one the passengers dropped off at the small stations. No one grumbled at having to help sort out the luggage each time, but cheerfully and politely[69] helped disentangle the belongings of the departing ones, and carefully helped to lift the baskets on to the platform, amid profuse thanks, where more friends and relations met them, and there was as much kissing on both cheeks as if they had been on a long journey instead of merely to market.

At one of the stops Germaine noticed a woman, holding a horn and a small red flag, standing by the sliding gates, where the road crossed the railway. She had seen these women before along the line, and her uncle explained that the railway is fenced in on either side by hedges or wire fencing, and wherever a road or street crossed, there are gates, which must be kept closed while trains are passing. Not only must the gatekeeper, who is generally a woman, have the gates tight shut, but she must also stand beside them like a soldier at his post, with her brass horn in one hand and a red flag, rolled up, in the[70] other, showing that she is prepared for any emergency. If she were not there, the engineer of the passing train would report it to headquarters, and she would doubtless be dismissed. The gatekeeper lives in a neat cottage adjoining, and some minutes before each train is due she takes the horn and flag from where they hang on the wall, and is at her post.

At the station were M. and Madame Lafond to welcome them home, and you can imagine how everybody talked at once, and how much there was to tell. The fête at Rouen was the topic of conversation until its glories paled before Petit Andelys' own special fête, which was held some weeks after, and which our little friends, with true French patriotism, thought the finest in the world, not excepting the more elaborate affair at Rouen.

CHAPTER V.

THE MARKET AT GRAND ANDELYS

There was always much noise and activity in the farmyard of La Chaumière on Mondays, for that was market-day at Grand Andelys,—the important event in a country neighbourhood in France.

For miles about, from the farms and small villages, every one meets in the market-place in the centre of the old town; not only to buy and sell, but to talk and be sociable, to hear news and tell it.

The French folk are very industrious, and they do not take much time for idle gossip unless there is some profit connected with it; but on market-day they combine business with[72] pleasure, and make good bargains and hear all the happenings of the countryside at the same time.

"Come, Germaine," called out Marie, after dinner on this particular Monday, "let us see them put the little calves in the cart. Papa is going to take four of them to market."

"I know it, but I felt so sorry I did not want to see them go," said Germaine, for she was very tender-hearted. Rather reluctantly she followed Marie into the farmyard. Marie was also very fond of the farm animals, but, having been away at school, had naturally not made such pets of them as had Germaine, who petted everything, from the big plough-horses to the tiny chickens just out of the shell. They were to her like friends, and it was really a grief to her when any of them were taken away to the market. But she tried to conquer the feeling, for it was part of her papa's business to sell cattle in the market, and he did so[73] to provide for his two little daughters. All French parents, of whatever position, will stint and save in order to accumulate a "dot," as it is called, for their children, and will make any reasonable sacrifice to start them well in life.

The four little calves had been tied in the cart with many bleatings, and much protesting on the part of their mothers. "Papa is going to take them to market, and mamma is to drive you and me," said Marie.

Madame Lafond and the two girls climbed into the cart hung high above its two great wheels. All three sat together on the one seat, which was quite wide. These country carts are almost square and also rather pretty. They are built of small panels of wood arranged in more or less ornamental patterns, and are usually painted in bright colours, and have, also, a big hood which can be put up as a protection from the rain.

The back of the cart was filled with baskets[74] of eggs, from a specially famous variety of fowl, for which the farm was noted.

The road to Les Andelys was crowded with their neighbours and friends bound in the same direction, and all in the same style of high carts, drawn by a single horse.

They drove beside the river that flows through the two villages, along which the washerwomen gathered when they washed their clothes. They knelt by a long plank and gossiped as they beat out the dirt with a paddle, rinsing the clothes afterward in the running water of the stream itself.

At the town they drove into the courtyard of the hotel of the "Bon Laboureur," where there were dozens of country carts like their own, from which the horses had already been taken. They left the stableman to take charge of theirs, and walked across to the market-square.

Booths, with awnings, held everything that[75] could be imagined, from old cast-off pieces of iron, locks, keys and the like, to the newest kinds of clothing; for everything under the sun is sold at these markets, and it is here that the people do most of their shopping rather than in the shops. Laces, crockery, imitation jewelry and furniture, and most things useful to man or beast are sold here.

Big umbrellas were stuck up for protection against sun and rain. Some of them were of brilliant colours, reds, blues, and greens, some were faded to neutral tints by the weathers of many market-days—looking like a field of big mushrooms.

On one side of the square was the vegetable and fruit market, where the women in their neat cotton dresses and white caps sat under their umbrellas, with heaped up baskets of peas, beans, cauliflower, melons, and crisp green stuff for salads around them. These vegetable and fruit sellers are known as the "Merchants[76] of the four seasons," because they sell, at various times, the products of the four seasons of the year.

Near by were the geese, ducks, and chickens packed in big basket-crates, piled one on top of the other, and all clucking and restless. Quantities of little rabbits were also there, and when a buyer wished to know if the rabbit were in prime condition, he would lift it up by the back of its neck just as one does a kitten, and feel its backbone. One does not know whether the poor rabbits like it or not, but they look very frightened, and seem glad when it is over.

Madame Lafond made her way toward the egg-market, where the eggs are displayed piled up in great baskets, stopping to speak to a friend or an acquaintance by the way. She was soon in her accustomed place, and had opened up her eggs for her customers, for eggs from La Chaumière never went begging.

The two little children of the wagon-maker joined Marie and Germaine, and the four amused themselves looking at the booths, and planning what they would buy if they had the money, or amused themselves watching the crowd that quite filled the big market-place. "There are the English," some one said, and, turning, Germaine saw her friend Mr. Carter, and his wife, the Americans who were spending the summer at the Belle Étoile, standing at one of the booths, buying a baton Normand, a rough stick of native wood, with a head of plaited leather, and a leather loop to hold it on the arm, for they are used by the peasants in driving cattle, and they frequently want to have their hands otherwise quite free. "This will make me a good walking-stick," said Mr. Carter, coming up to the little girls and shaking hands with them. "This is your sister back from school, eh? Well, when are you two going to take that ride with me?"

It had been a promise of long standing that when Marie was at home, they were to go for a day's trip in Mr. Carter's big automobile. "Well, I must fix on a day, and let M. Auguste send word to your mamma so that you and Marie can come to the Belle Étoile, and we can start from there."

"Won't it be lovely?" said Marie; "we shall feel as fine as M. Lecoq, the rich farmer who comes to market in his great auto, wearing his fur coat over his blouse, with his sabots on just as if he was in the farm wagon, riding behind his four white oxen."

All French working men wear the blouse. It is almost like a uniform, and by the colour of his blouse one can generally guess a man's trade. Painters, masons, grocers, and bakers wear the white blouse; mechanics and the better class of farmers seem to prefer black, and the ordinary peasants and labourers wear blue.

The blouse is made like a big full shirt, and reaches nearly to the knees. You will see men well dressed in black broadcloth, white shirts and neat ties, and over all the blouse. It is really worn now to protect the clothes, but is a survival of the olden times when all trades wore a livery.

At the market at Grand Andelys one could but notice the neatly dressed hair of the women folk.

All Frenchwomen, of whatsoever class, always dress their hair neatly and prettily: and as the young girls seldom wear a hat or a bonnet, it shows off to so much better advantage. This is all very well in summer, but one wonders that they do not take cold in winter. The women wear felt slippers, and thrust their feet into their sabots, when they go out, which are not so clumsy as those of the men, dropping them at the door when they come into the house. You will always see several pairs[80] of sabots around the entrance to the home of a French working man.

The children by this time had got to where the calves stood in their little fenced-in enclosure. They were not put in the market by the church with the big cattle, and Germaine felt much happier when she heard that they had been sold for farm purposes, and not for veal to the big butcher in his long white apron, who stood by, jingling his long knives that hung at his side from a chain around his waist.

As they were near the bakers', Marie suggested they buy a brioche, and take it home to eat with their chocolate. Brioche is a very delicate bread made with eggs and milk, and is esteemed as a great delicacy. The bakery looked very tempting filled with bread of all kinds and shapes,—sticks of bread a yard long, loaves like a big ring with a hole in the middle, big flat loaves which would nearly[81] cover a small table, twisted loaves and square loaves.

When they had made their purchases and rejoined their mother, they found her with Madame Daboll, who told them that poor M. Masson, the wealthy mill-owner, who had been ill so long, was dead, and there was to be a grand funeral at the church of St. Sauveur the next day.

In France great respect is paid to the dead, and funerals are conducted with as much pomp as one's circumstances permit.