THE LITTLE BAREFOOT.

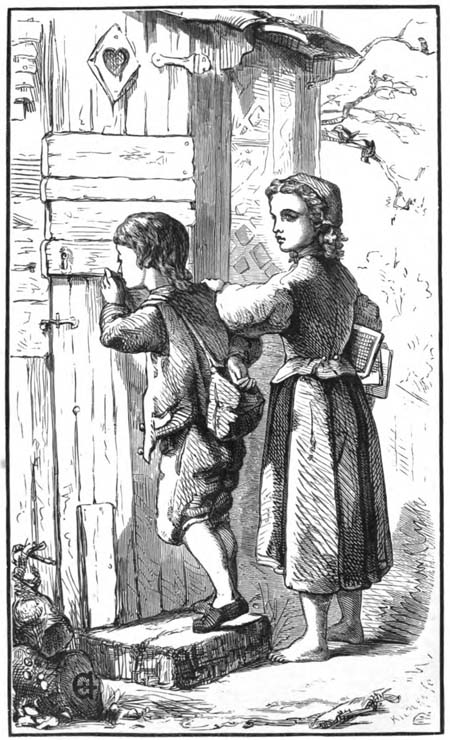

THE CHILDREN KNOCK—Page 8.

THE

Little Barefoot.

A TALE.

BY

BERTHOLD AUERBACH.

TRANSLATED BY ELIZA BUCKMINSTER LEE.

ILLUSTRATED.

BOSTON:

H. B. FULLER AND COMPANY,

(Successors to Walker, Fuller, & Co.,)

245 WASHINGTON STREET.

1867.

Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1867, by

H. B. FULLER,

In the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Stereotyped by C. J. Peters & Son, 13 Washington Street, Boston.

Printed by John Wilson & Son, Cambridge.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE CHILDREN KNOCK | 7 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| THE FAR-OFF SPIRIT | 16 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE TREE BY THE PARENTS’ HOUSE | 25 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| OPEN THE DOOR | 31 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| UPON THE HOLDER COMMON | 53 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| HER OWN COOK | 74 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE SISTER OF CHARITY | 92 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| SACK AND AXE | 112 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| AN UNBIDDEN GUEST | 123 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| ONLY ONE DANCE | 142 |

| CHAPTER XI.[6] | |

| AS IT IS IN THE SONG | 159 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| HE HAS COME | 168 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| OUT OF A MOTHER’S HEART | 183 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE HORSEMAN | 196 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| BANISHED AND SAVED | 205 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| SILVER TROT | 223 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| OVER MOUNTAIN AND VALLEY | 232 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE FIRST FIRE UPON THE HEARTH | 248 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| SECRET TREASURES | 260 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| FAMILY WAYS | 268 |

THE LITTLE BAREFOOT

CHAPTER I.

THE CHILDREN KNOCK.

EARLY in the morning of an autumnal day, when the morning mist lay upon the ground, two children, a boy and a girl of six and seven years old, went hand in hand through the back, or garden path, out of the village. The girl appeared the oldest, and carried slate, books, and a writing-book under her arm; the boy had the same in a gray linen satchel, which was slung over his shoulder. The girl wore a cap of white drill that reached only to the forehead, and made the full arch of her brow the more conspicuous. The boy was bareheaded. The footstep of the boy only could be heard, for he had strong shoes on his feet; but the girl was barefoot. Where the path permitted, the children went close together; but, when the hedges made it too narrow, the girl always went first.

[8]Upon the yellow leaves of the shrubbery lay a white frost, and the berries of the hawthorn, the tall stems of the wild brier, looked as though they were silvered over. The sparrows in the hedges twitter and fly in uneasy flocks close to the children, then light again not far from them, twittering and chirping, till at length they fly to a garden, where they light upon an apple-tree, so that the dry leaves rustle, and fall to the ground. A magpie flies quickly up from the path across the fields, and then rests upon the great pear-tree, where the ravens still cawed. This magpie must have told them a secret, for the ravens flew up and crossed over the tree, and an old one let himself down upon the topmost wavering branch, while the others found for themselves, upon the lower branches, good places, where they could rest and look out. They appeared to desire to know why the children, with their school-books, struck into the side street, and wandered out of the village. One of the ravens flew like a scout, or spy, and placed himself upon a stunted willow by the fish-pond. But the children went quietly on their way by the alders near the pond, till they came out again into the street; then crossed to the other side of the street where stood a small, low house. The house is entirely closed, and the children stand at the door and knock softly. Then the girl calls courageously, “Father! Mother!” and the boy timidly repeats, “Father! Mother!” At[9] length the girl seizes the door-latch, and presses it softly up; the boards rustle and she listens, but nothing comes. Now she ventures in quicker strokes to press the latch up and down, but only the sound echoes from the deserted house. No human voice answers. The boy places his lips upon a crack in the door and calls again, “Father! Mother!” Inquiringly he looks up to his sister; and when he looks down again his breath upon the door-latch has become hoar-frost.

From the mist-covered village sound the measured strokes of the thresher; now rapid and loud, falling confusedly, and now with slow and wearied strokes; then again clear and vivid; then stifled and hollow. The children stand as though bewildered. At length they cease to call and knock, and sit down upon scattered logs of wood. These lay piled around the stem of a mountain-ash, overshadowing the side of the house, and now ornamented with its red autumn berries. The children rivet their eyes upon the door of the house; but all remains silent and closed.

“Father brought this wood from Moosbrunnenwood,” said the girl, pointing to the log upon which she was sitting; then she added, with a wise look, “it gives good warmth, and there is a great deal of rosin in it that burns like a torch, but it costs a great deal to split it.”

“If I was grown up,” said the boy, “I would take father’s great axe and the two iron wedges[10] and split it into pieces as smooth as glass, and I would make a beautiful pile of it, like that of the coal-burner Mathew, in the forest; and then when father comes home he will be glad, and he will say, ‘Who did that?’ Don’t you dare to tell him,” and he pointed his finger threateningly at his sister.

The latter appeared to have a dawning perception that it would be of no use to wait for father and mother, and she cast a melancholy glance at the boy; and then, looking at his shoes, she said, “Then you must also put on father’s boots. But come, we will skip stones in the lake, and see if I can throw farther than you; and, as we go, I will give you a riddle to guess. What wood is that which warms without burning?”

“The master’s ruler when the palms catch it,” said the boy.

“No, I don’t mean that. The wood that they split makes one warm without burning it.” When standing by the hedge she asked, “It sits upon a little stem, hath a little red coat, and its belly is full of stones. What may that be?”

The boy knit his brows and cried out, “Hush! Don’t tell me what it is. It is a hip-berry.”

The girl nodded applause, and made a face as though she told him the riddle for the first time, whereas she had often told it before to divert him from sorrow.

The sun had now scattered the fog, and the[11] little valley came out in clear shining sunlight as the children turned towards the pond and began to make the flat stones dance through the water.

In passing, the girl lifted the latch again many times, but the door did not open, and nothing appeared at the window. They soon played, full of joy and laughter, at the pond, and the girl seemed especially glad that her brother was always the most skilful, and, beating her at the sport, he became wholly gay. She, indeed, made herself less skilful than she really was, for her stones plumped, at the first throw, deep into the water, at which the boy laughed loud. In the zeal of their sport, both children forgot where they were, and why they had come there, and yet to both it was melancholy and strange.

In that house, now so silent and closed, had dwelt for some time back Josenhans, with his wife and two children, Amrie (Anna Maria) and Dami (Damian). The father was a wood-cutter in the forest, but also handy at any work; for the house which he had purchased in a neglected condition, he had repaired himself, and wholly covered in the roof. In the autumn he intended to whiten the wall of the interior. The chalk for that purpose was lying in a pit covered with brushwood. His wife was one of the best workwomen in the village. Day and night, in sorrow and in joy, she was a helper to every one; always willing, always[12] ready, for she had early taught her children, especially Amrie, to take care of themselves. Industry, contentment, and domestic competency made the house one of the happiest in the village. An insidious illness prostrated the mother, and the next evening the father also, and after a few days two coffins were borne on the same evening from the humble house. The children were taken into one of the neighbor’s houses during the illness of their parents, and they learnt their death only on Monday, when they were dressed in their Sunday clothes, to follow in the funeral procession.

Neither Josenhans nor his wife had relations in the place, and yet loud weeping and praise of the dead were heard at the grave; and the Mayor of the village led both children by the hand, as all three followed in the procession. At the grave both children were still and quiet; they were even cheerful, although they often asked, “Where were their father and mother?” They ate at the table of the Mayor, and everybody was kind to them. When they left the table, they received little tarts wrapped in paper to take with them.

As the evening came on, the Mayor ordered a man of the name of Krappenzacher to take Dami home with him, and a woman, called Brown Mariann, to take care of Amrie; but now the children would not be separated. They wept aloud, and insisted upon being taken to their parents. Dami, at length, was coaxed by false pretences, but[13] Amrie could not be forced to leave her brother. At length the foreman of the Mayor took her in his arms and carried her, by main strength, to the house of Brown Mariann. There she found her own bed from the parents’ house; but she would not lie down upon it, and wept herself to sleep upon the floor, when they laid her all dressed as she was upon her bed. Dami was also heard weeping and screaming aloud, but soon he was still. The much defamed Brown Mariann showed this evening how considerate and tender she was for the orphan intrusted to her care. For many years she had been bereft of her children, and as she stood by the sleeping girl she said in a low voice, “Ah! happy sleep of childhood; it weeps and instantly falls asleep without the twilight of hope, without the anxiety of dreams.” She sighed deeply.

The next morning, early, Amrie went to dress her brother and to console him for what had happened. “As soon as father comes back,” she said, “he will take you home and pay the Krappenzacher.” Then both the children went out to the parental house, knocked on the door and wept aloud.

At length Mathew, the coal-burner, who lived near, came and carried them both to school. He asked the schoolmaster to make the children understand that their parents were dead, for Amrie especially appeared incapable of believing[14] it. The teacher did all that was possible, and they became more quiet and resigned. But from the school they went again to the parents’ house, and waited there, hungry and thirsty, till some compassionate person carried them away.

The person who had a mortgage upon the Josenhans house took it, and the payment which Josenhans had already made was lost; for, according to the custom of the village, whatever had been paid was forfeited. There were many houses in the village beside the Josenhans that remained untenanted. All the possessions of their parents were sold, and a small sum obtained for the children, but not sufficient to pay their board. Thus they became parish orphans, and were of course boarded with those who would take them at the lowest price.

Amrie informed her brother one day with delight, that she had found out where the cuckoo clock of their parents was. Mathew, the coal-burner, had bought it; in the evening they went and stood near the house and waited till the clock cried cuckoo,—then they looked at each other and laughed.

The children continued every morning to go to their parents’ house, knock at the door, call and wait. Then they played at the fish-pond, as we have seen them to-day. Afterwards they listened to a call which they used not to hear at this season of the year, for the cuckoo at Mathew’s called eight times.

[15]“We must to the school,” said Amrie, and hastened with her brother through the garden paths into the village. As they passed behind the barn of Farmer Rodel, Dami said, “Our guardian has had a great deal of threshing done to-day,” and he pointed to the straw that hung as a trophy over the half door of the barn. Amrie nodded silently.

CHAPTER II.

THE FAR-OFF SPIRIT.

FARMER RODEL, whose house, ornamented with red striped beams, and a pious sentence, enclosed in the form of a heart, stood not far from the Josenhans dwelling, had himself appointed by the Mayor, guardian of the orphan children. His guardianship consisted in nothing more than in preserving the unsold clothes of their father, and when he met or passed one of the children in the street he would ask, “Have you clothes enough?” and, without waiting to be answered, he would pass on. Yet the children felt a strange pride in having that great farmer called their guardian. They often stood by the great house and looked longingly at it, as though they expected something, they knew not what, and they sat often down by the ploughs and harrows at the corner of the shed and read over again and again the pious sentence on the house. The house spoke to them if all others were silent.

The Sunday before All Souls, the children played again before their parents’ deserted house.[17] They seemed, as it were, banished to this place. There came along the wife of Farmer Landfried from the Hochdorfer Road. She had a red silk umbrella under her arm and a dark hymn-book in her hand. She had come to make her last visit in the place of her birth. Yesterday, her servant in a four-horse wagon had taken all her furniture out of the village, and early this morning with her husband and three children she would move to their lately purchased estate in the far-off district of Allgäu. When at some distance she nodded to the children; but they saw nothing but the melancholy expression upon the face of the woman. As she now stood by them she said, “God bless you, children! what do you do here? to whom do you belong?”

“To the Josenhans,” answered Amrie, pointing towards the house.

“Oh! you poor children,” she cried, striking her hands together; “I should have known you, lass! exactly so did your mother look, when we went to school together. We were good comrades and friends, and your father worked with my cousin, Farmer Rodel. I know all about you—but tell me, Amrie, why have you no shoes on? You will take cold in this wet weather. Say to Mariann that Farmer Landfried’s wife, from Hochdorf, said it was not right to let you run about in this manner; no—you need say nothing. I will speak to her. But, Amrie, you must now be sensible[18] and prudent, and take care of yourself. Think of it—what if thy mother knew that in this time of the year you went about barefoot!”

The child looked earnestly at the woman as though she would say, “Does not my mother then know it?”

“Ah, that is the worst of it,” she said, answering the thought of the child, “that you can never know what good and honest people your parents were; that must elder people tell you. Think of it, Amrie, that it will make your parents happy in heaven when they hear people say, ‘There are the Josenhans children, they are a proof of all goodness. There they see plainly the blessing of good and honest parents.’”

At these last words big tears ran down the cheeks of the farmer’s wife. Painful emotions (that had, indeed, a wholly different source), at these thoughts and words, made them continue to flow. She laid her hand upon the head of the girl, who, at the sight of her tears, began to weep violently. She felt that a good soul had turned towards her, and a dawning belief that her parents were really lost became clearer to her.

The countenance of the women suddenly lighted. She raised her eyes filled with tears to heaven and said, “Thou, good God, has sent this thought to me!” Then she turned to the child and said, “Listen! I will take you with me! My Lisbeth was taken from me at your age. Speak! will you go with me to Allgäu, and always remain with me?”

[19]“Yes,” said Amrie, resolutely.

She felt herself seized from behind, and a slight blow upon her shoulder.

“You dare not,” said Dami, embracing her, and trembling from head to foot.

“Be quiet,” said Amrie, “the good lady will take you also. Is it not so?” she said, timidly. “My Dami may go with us?”

“No, child, that cannot be; I have boys enough at home.”

“Then I must remain here,” said Amrie, and took hold of her brother’s hand.

There is sometimes in the soul an emotion where fever and frost contend. It has been so with the stranger, and now she looked upon the child with a species of relief. Through strong emotion, and influenced by the purest benevolence, she would have undertaken a duty whose significance and difficulty she had not sufficiently considered; and especially as she did not know how her husband would take it. Now, as the child herself refused, there intervened a sufficient reason; all was clear again, and she turned quickly from the duty. She had satisfied her heart by proposing it, and now that the objection came not from herself, she had a kind of satisfaction in having offered, without herself taking back her word.

“As you please,” said the stranger; “I will not urge you. Who knows? perhaps it would be better that you should grow up first. It is well to[20] learn to suffer in youth; the good comes easier after we have learnt the evil. Be only honest and good, and never forget that, on account of your parents, as long as God spares my life you shall have a shelter with me. Remember, if it does not go well with you, that you are not left alone in the world. Think of the wife of Farmer Landfried, in Zusmarshofen, in Allgäu. A word more. Don’t say in the village that I would have taken you. It is the way with people—they would blame you because you did not go—but it is as well so. Wait, I will give you something to remember me by.” She sought in her pocket, then suddenly putting her hand to her neck she drew out a five stringed garnet necklace, to which there was fastened a Swedish ducat, and, throwing the ornament over the neck of the child, she kissed her. Amrie looked as one enchanted upon all these proceedings. “For thee, alas! I have nothing,” she said to Dami, who stood with a little switch in his hand which he continued to break into small pieces; “but I will send you a pair of leather trousers of my John’s—they are not entirely new, but you can wear them when you are taller. Now God protect you, dear children! If it is possible I will come to see you again, Amrie. In the mean time send Mariann to me in the church. Remember always to be good, pray constantly for your parents, and never forget that you have a protector in heaven and also upon earth.”

[21]For convenience in walking she had turned up her outer garment; now, at the entrance of the village, she let it down and went on with quick steps without once turning back.

Amrie kept her face bent down in order to see the keepsake upon her neck, but the necklace was too short. Dami was chewing the last piece of his stick when his sister, observing tears in his eyes, said, “We shall see—you will have the most beautiful pair of trousers in the village.”

“I will not take them,” said Dami, and spit out the last piece of stick.

“And I will ask her to give you a knife. I will stay at home the whole day; perhaps she will come to us.”

“Yes! if she were there already,” said Dami, without knowing what he said. His anger, and the feeling of being rejected, had excited these suspicious reproaches.

At the first stroke of the bell they hastened back to the village. Amrie gave over, with few words, her new ornament into the hands of Mariann, who said, “Thou art fortune’s child! I will take good care of it. Now hasten to the church.”

During the service both children looked constantly at their new friend, and when it was over they waited for her at the door of the church; but the respectable matron was so surrounded by men and women, all claiming her notice, that she could only turn in the circle to answer, sometimes here,[22] sometimes there; thus for the waiting glances of the children she found no attention. She held Rose, the youngest daughter of Farmer Rodel, by the hand. She was a year older than Amrie, and thrust herself constantly before the latter, as though pressingly to take her place by the matron. Had, then, the respectable matron eyes only for Amrie by the last house in the solitude of the village, but in the midst of the people she did not know her? Amrie was frightened, when this thought just dawning in her mind was spoken aloud by Dami; but while she, with her brother, followed at a distance the great crowd that surrounded the matron, she gave utterance herself to the same thought. The matron vanished at last into the house of Farmer Rodel, and the children turned quietly back.

“When she comes,” said Dami, “tell her that she must go to Krappenzacher and tell him that he must treat me better.”

Amrie nodded, and the children separated, each to go to the house where they had found shelter.

The fog that had been so great in the morning now came down in pouring rain. The great red umbrella of Madam Landfried moved here and there in the village, and the form that was under it could scarcely be seen. Mariann had not met her, and at coming home she said, “She can come to me—I shall not seek her again.”

The two children wandered out again, and sat[23] down together upon the threshold of their parents’ house. They waited silently, and again the thought came to them, that their parents would never return to them. Dami would count how many drops fell from the roof. But they came all too quickly, and he shouted out at once, “A thousand million.”

“She must pass here as she goes home,” said Amrie, “and we will call to her. Only cry out at the same time with me, and then she will speak to us again.”

So said Amrie, for the children waited here only for the Landfried to pass.

A whip snapped in the village; they heard the quick step of a horse upon the road, and a carriage rolled by. Their friend sat within it.

“Our father and mother will come in a carriage to fetch us,” said Dami. Amrie cast a melancholy glance at her brother. “Do not chatter so,” she said. As she turned again, the wagon was close to them, and some one nodded from beneath the red umbrella. It rolled on, only Mathew’s dog barked after it, and made as though he would seize the spokes of the wheels with his teeth. At the fish-pond he turned back, barked once more, and then slipped into the house.

“Hurrah! she has gone,” cried Dami with triumph. “That was the Landfried. Did not you know Farmer Rodel’s black horse?”

“Don’t forget my leather trousers,” he shrieked[24] with all the strength of his lungs, although the wagon had already vanished in the valley, and was creeping up the little height of the Holder Meadow. The children turned back silently to the village.

Who can tell how this bitter experience struck a tiny root into the inner being of a child, and what may hereafter spring from it? Other feelings may immediately overpower the consciousness of this heavy disappointment, but the bitter root has struck into the soul.

CHAPTER III.

THE TREE BY THE PARENTS’ HOUSE.

THE day before “All Souls” Mariann said to the children, “Go and find the mountain-ash berries; to-morrow we shall want them for the churchyard.”

“I know where I can find them,” said Dami, with a truly avaricious joy, and ran out of the village with such haste that Amrie could scarcely overtake him. When she arrived at the parental house, he was already upon the tree, and signed proudly to her that she should also come up, because he knew that she could not. He plucked the red berries and threw them down into the apron of his sister. She prayed him to break off the stems with the berries, and she would weave a crown. “That I shall not,” he answered, and yet there came no berry down afterwards without a stem.

“Listen, how the sparrows scold,” cried Dami from the tree. “They are angry because I take their food from them.” When he had plucked them all, he said, “I will not go down again from[26] this tree, but will stay up here day and night, till I fall down dead. I will never go down to you, Amrie, unless you promise me something.”

“What then?”

“That you will never wear the present that the Landfried gave you—never, as long—as long as I can see it.”

“No!”

“Then I will never come down.”

“Not on my account?” said Amrie, and went and sat down at a little distance, behind a pile of wood, and began to weave a crown, peeping out, however, every moment, to see if Dami was coming. She placed the crown upon her head, but suddenly an inexpressible anxiety, on account of Dami, overcame her. She ran back. Dami sat upon a branch, his back against the trunk of the tree, and his arms crossed before him.

“Come down,” she said, “Oh! come down; I will promise every thing you wish.” In a second Dami was at her side, upon the ground.

They went home, and Mariann scolded the foolish children because they had made crowns from the berries which were needed at the graves of their parents. She tore the crowns apart—at the same time saying some mysterious words. Then she took both children by the hand, and led them out to the churchyard. Pointing to the two graves lying together, she said, “There are your parents!”

[27]The children looked amazed at each other. Mariann made, with a stick, a deep cross upon both the graves, and showed the children how to strew the berries therein. Dami was the more nimble, and triumphed because his red cross was ready before his sister’s. Amrie looked at him with tears, and when Dami said, “That will make father glad,” she gave him a little blow and said, “Be still!”

Dami wept, more perhaps because he had become serious. Then Amrie cried aloud, “for Heaven’s sake forgive me—oh! forgive me that I did that. Yesterday I promised, that for my whole life long I would do for you all I can, and give you all that I have. Say, Dami, that I have not hurt you. Can you not forget it? It shall never happen again as long as I live. Oh never! never again! Never! Oh, mother! Oh, father! I will be good! I promise you, Oh, mother! Oh, father!” She could say no more, but wept silently, and they say that one deep sob after another convulsed her. Then as Brown Mariann wept aloud, Amrie wept with her.

They went home, and as Dami said, “Good-night,” she whispered softly in his ear, “Now I know that we shall never see our parents again in this world!” Yet in this communication there mixed a certain childish joy, a child’s pride in knowing something, a consciousness that the parents’ lips are closed forever. When death closes the lips of one who must call thee child, a living[28] breath has vanished which can never again return.

As Mariann sat by the bed of Amrie, the child said to her, “I feel as though I were falling and falling forever! Let me have your hand.” She held her hand fast and began to slumber, but as often as Mariann withdrew her hand she caught it again. Mariann understood what that feeling of endless falling signified to the child. By the inward consciousness of the death of her parents, which she had gained to-day, they seemed to her to hover in an undefined distance,—she knew not whence, nor where. Not before midnight could Mariann leave the bed of the child, and after she had repeated her prayers, who knows how many times?

A stern scorn lay upon the countenance of the sleeping child. One hand was crossed upon her breast. Mariann took it softly away, and said, as though to herself, “If always an eye could watch over thee, and a hand help thee, as now, in thy sleep, and without thy knowledge could lift the weight from thy heart! But this can no mortal do—only He! Do thou to my child in a strange country as I do for this.”

Brown Mariann was a person whom people feared—she was so austere and crabbed in appearance. It was eighteen years since she lost her husband, who was shot as he made an attack with other companions upon the post-wagon. Mariann[29] bore child beneath her heart, when her husband’s corpse was brought into the village with his blackened face. But she suppressed her agony, and washed the black from the face of the dead, as though she could thereby wash the guilt from his soul. Her three daughters died in close succession, after the last child was born. He had become a smart little fellow, although with a strange dark face. He was now a journeyman mason, out upon his wanderings in some distant place; and his mother, who for her whole life had never been out of the village, and never had any desire to wander, often said, “That she was like a hen who had hatched one egg, but clucked always secretly at home.”

It would scarcely be believed that Mariann was one of the most cheerful persons in the village. She was never observed to be melancholy. She would not allow people to pity her, and therefore she was disliked and solitary. In winter she was the most industrious spinner in the village, and in summer the most diligent wood-gatherer, so that she was able to sell a good part of it.

“My John,”—so she called her son,—“My John,” was heard in every sentence from her lips. The little Amrie, she said, she had taken not out of compassion, but because she would have a living being near her. She was rough and cross outwardly, and to other people, and enjoyed secretly the pride of being kind, and doing right.

[30]Exactly the opposite of this was Krappenzacher, with whom Dami had found a shelter. Before the world he showed himself one of the most good-humored benefactors; in secret he ill treated his dependants and especially Dami, for whom he received but a very small compensation. His true name was Zacharia. He received his nickname because he once brought home to his wife what he called a daintily-prepared roast, of a pair of doves. They were but a pair of plucked ravens, here in the country named Krappen. Krappenzacher spent the most of his time knitting woollen stockings and jackets, and sat with his knitting-needles in any part of the village where tattling was to be had. This gossip in which he heard every thing, served him to meddle with the business of his neighbors. He was the so-called match-maker of the place. When any of his marriages were really brought about, he played the violin at the wedding. In this he was really a country amateur. He also played the clarionet and the horn, when his arm was weary with the fiddle. He was, indeed, a “Jack-of-all-trades.”

Thus were both scions, which had sprung from the same root, transplanted into very different soil. Position and culture, and the nature which they severally possessed, would lead them to very different fortunes.

CHAPTER IV.

OPEN THE DOOR.

ALL SOULS’ DAY, it was dark and foggy. The children were among the people collected in the churchyard. Krappenzacher had led little Dami by the hand, but Amrie had come alone without Brown Mariann. Many of the people scolded at the hard-hearted woman, and some touched upon the truth, when they said, “Mariann could gain nothing by a visit to the churchyard, for she knew not where her husband was buried.”

Amrie was quiet, and shed no tears; while Dami, through the pitying speeches of the people, wept freely, and especially because Krappenzacher secretly scolded and cuffed him.

Amrie stood a long time dreamily forgetting herself, looking fixedly at the lights at the head of the graves, how the flame consumed the wax, the wick burnt to coal, till at last the light was wholly burnt down.

Among the people, there moved around a man in a respectable city dress, with a ribbon in his button-hole. It was Severin, the Inspector of Buildings—upon[32] a journey, who had come to visit the graves of his father and mother. His sister and her family surrounded him continually with a certain reverence, and indeed the attention of every one was directed towards this respectable visitor.

Amrie observed him, and asked Krappenzacher, “If he were a bridegroom?”

“Why?”

“Because he has a ribbon in his button-hole.”

Instead of answering the child, Krappenzacher hastened towards a group to say what a stupid speech the child had made. And around among the graves echoed loud laughter at such silliness.

But the wife of Farmer Rodel said, “I find it not so very foolish. If Severin wears it as an honorable distinction, it is yet strange that he should wear it in the churchyard; here where all are equal, whether in life they have been dressed in silk or fustian. It had already displeased me that he wore it in the church. We must lay aside something before we go into the church; how much more in the churchyard!”

The question of little Amrie must at length have reached the ear of Severin, for he was seen hastily to button his overcoat, and nod towards the child. He asked who she was, and scarcely had he heard the answer, than he hastened towards the children at the fresh graves, and said to Amrie, “Come, child, open thy hand. Here, I give thee a ducat; buy thyself whatever you want.”

[33]The child stared at him, and did not answer. But when Severin had turned away, she said half aloud, “I take no presents,” and threw the ducat after him. Many of the people who saw this came up to Amrie and scolded her, and were on the point of ill treating her, had not Madame Rodel, who had already protected her with words, now saved her from their rough hands. She, also, desired that Amrie should at least hasten after Severin and thank him; but Amrie was silent, and remained obstinate, so that her protectress left her. After much search, the ducat was found. The Mayor took it immediately into his possession, to give it over to the guardian of the child.

These incidents brought the little Amrie a strange reputation in the village. They said she had been only a few days with Brown Mariann, and had already acquired her manners and her character. It was unheard of, they repeated, that a child of such poverty should have so much pride; and while they reproached her whole bearing on account of this pride, it was the more apparent that this principle of independence in the young childish soul was there to protect her. Brown Mariann did all she could to strengthen this disposition. She said, “No greater good fortune can happen to the poor than that they should be called proud. It is the only safeguard; for every one would trample upon them, and then expect that they should thank them for doing it.”

[34]In the winter, Amrie was often at the fireside with Krappenzacher, listening eagerly to his violin. Yes, Krappenzacher once gave her great praise. He said, “Child, you are not stupid;” for after listening a long time Amrie had said, “It is wonderful how a fiddle can hold its breath so long. I cannot do it.” And at home in the quiet winter nights when Brown Mariann related exciting or horrible tales, or magical histories, Amrie, drawing a long breath when they were ended, would say, “Oh, Mariann, I must now take breath, for as long as you are speaking I cannot breathe; I must hold my breath.”

Was not that a sign of deep devotion to what was present, and yet a remarkable free observation of the same, and of her own relation to it?

No one took much notice of Amrie, and she was left to dream of whatever came into her mind. The school-teacher once said, in the sitting of the Parish Council, “That he had never met with such a child; that she was proud, but gentle and submissive; dreamy, and yet wide-awake; and in fact she had already, with all her childish self-forgetfulness, a feeling of self-reliance; a certain self-defence in opposition to the world, its favor and its wickedness.” Dami, on the contrary, at every little occasion, came weeping and complaining to his sister. He always had great pity for himself; and when, in the rough play of his companions, he was thrown down, he would say, “Yes, because I[35] am an orphan, they hurt me. Oh, if only my father or my mother knew it!”

Dami would take presents of food from anybody who offered them, and was therefore always eating, while Amrie was satisfied with very little, and accustomed herself to be very moderate in every thing. Even the rudest and wildest boy feared Amrie without knowing why; while Dami ran from the youngest. In the school, Dami was always uneasy, moving his hands and his feet, and the corners of his book were dog’s-eared. Amrie, on the contrary, was always neat, active, and diligent. She wept often in the school, not because she was punished, for that was very rare, but because Dami often received correction.

Amrie could please her brother best when she told him riddles. Both children sat often near the house of their rich guardian; sometimes by the wagon, sometimes by the oven at the back of the house, where they warmed themselves, especially in the autumn. And Amrie asked, “What is the best thing about the oven?”

“You know that I can’t guess,” said Dami, complainingly.

“Then I will tell you. The best of the oven is, that it does not eat the bread that is put into its mouth;” and, pointing to the wagon before the house, she said, “What is nothing but holes, and yet holds fast?” Without waiting for the answer, she said, “That is a chain.”

[36]“Now you have given me two riddles?” said Dami. And Amrie answered, “Yes, but you give them up. See, there come the sheep; now, I know another.”

“No,” cried Dami. “No! I can’t hold three; I have enough with two.”

“No, you must hear this, else I take the others back;” and Dami repeated anxiously to himself, “chain,” “self-eating,” while Amrie asked, “Upon which side have the sheep the most wool?”

“Baa, baa! upon the outside,” she added, gayly singing, while Dami sprang away to tell the riddles to his comrades. When he reached them, he had forgotten all but the chain, and Rodel’s eldest boy, whom he did not ask, immediately cried out the solution. Then Dami came weeping back to his sister.

The little Amrie’s knowledge of riddles could not long remain concealed from the village; and even the rich, serious farmers, who scarcely spoke with any one, especially not with a poor child, often stopped from their work, and asked the little Amrie to give them a riddle. That she knew a great number which she might have heard from Mariann, was easy to believe, but that she could always answer new ones, excited universal wonder. She could not cross the street or the field without being stopped. She made it a rule that she would give no man the solution of her riddles, and they were ashamed at once to give them up. She knew how[37] to turn from them, so that they were banished, as it were. Yet never in a village was a poor child so much respected as the little Amrie. But as she grew to womanhood, she excited less attention; for men observe the blossom and the fruit with a sympathizing eye, but not the long ripening process from one stage to the other. Before Amrie left school, destiny gave her a riddle to guess whose solution was very difficult.

The children had an uncle who lived about seven hours’ journey from Holdenbrunn, a wood-hewer in Fluorn. They had seen him once, at the funeral of their parents; he walked behind the Mayor, who led the children by the hand. Since then the children had often dreamed of their uncle in Fluorn. They were often told that he looked like their father, and since they had given up the hope that father and mother would come back again, they were more curious to see their uncle. But as years passed, and they every year strewed the mountain-ash berries on their graves, and they had learned to read the names of their parents upon the same dark cross, they forgot the uncle in Fluorn. In all these years they had heard nothing of him. Both children were called one day into the house of their guardian. There sat a man large and tall, with a brown complexion.

“Come here, children,” cried the man, at their entrance. He had a rough, harsh voice. “Do you not know me?”

[38]The children looked at him with open eyes. Did there awake in them the recollection of their father’s voice? The man continued, “I am your father’s brother. Come here, Lisbeth! And you, also, Dami.”

“I am not Lisbeth; my name is Amrie,” said the young girl, and wept. She gave her uncle no hand; a feeling of estrangement made her tremble, because her uncle had called her by a false name. How could there be any true dependence on him, when he had forgotten her name?

“If you are my uncle, why did you not know my name?” she asked many times.

“Thou art a stupid child; go immediately and give him thy hand,” ordered Farmer Rodel; then he added half aloud to the stranger, “She is a strange child; Brown Mariann has put wonderful things into her head, and you know that all is not right with her.”

Amrie looked deeply wounded, and tremblingly gave the uncle her hand. Dami had already done it, and now asked, “Uncle, have you brought us any thing?”

“I had not much to bring. I bring myself—and you will go home with me. Do you know, Amrie, it is not right that you will not know your uncle. You have no one else in the whole world. Whom have you beside? Come, think better of it; sit near me—still nearer; do you see that Dami is much more sensible? He looks more like our family—but you belong to us also.”

[39]A maid came and brought in some garments. “These are thy brother’s clothes,” said Rodel to the stranger; and turning to Amrie he said,—“Do you see, these are thy father’s clothes; we will take them, and you also, will go first to Fluorn, and then over the brook.”

Amrie touched, tenderly and tremblingly, first the coat of her father, and then his blue striped waistcoat. The uncle held the clothes up, and pointing to the worn elbows, said to Farmer Rodel,—“They are not worth much; I don’t know whether I could wear them over there in America without being laughed at.”

Amrie seized convulsively the sleeve of the coat. That they should say the dress of her father was of little value; that, which she had thought of inestimable worth; and that this dress should be worn in America, and there laughed at, confused and confounded all her ideas, especially those about America.

It was soon made clear to her, for Madame Rodel came in, and with her Brown Mariann. Madame said,—

“Listen, for once, husband; this I think must not go on so quickly. The children must not be sent in such haste with this man to America.”

“He is their only living relation, the brother of Josenhans.”

“Yes indeed, but he has not till now shown that he is a relation, and I think they cannot do[40] this without leave of the Parish Council. The children have in the Parish a right of home, and they cannot take it away in their sleep; the children cannot say themselves what they will do, and that I call taking them in their sleep.”

“My Amrie is wide-awake enough. She is just thirteen, but as wise as another of thirty years,” said Mariann.

“You both should be counsellors,” said Rodel.

“But I also am of opinion that children should not be taken away like calves with a halter. Good! Let the man speak with them alone; afterwards, let them decide what they will do. He is their natural guardian, and has the right to take the father’s place. Listen; go with thy brother’s children a little out of the village while the women remain here—there speak to them alone.”

The wood-hewer took both children by the hand and left the house with them.

“Where shall we go?” he asked the children in the street.

“If thou wouldst be our father, go home with us. There is our house,” said Dami.

“Is it open?”

“No! but Mathew has the key. He has never let us go in. I will spring before and fetch the key;” and Dami withdrew his hand and sprang before. Amrie followed, as though fettered to the hand of the uncle, who now spoke with more confidence[41] and interest. He told her as an excuse that he had an expensive family; that he and his wife with difficulty supported five children. But now, he informed her, a man who possessed large forests in America had offered him a free passage, and after the forest was felled, a good number of acres from the best land as a free possession. In gratitude to God, who had thus provided for him and his children, he had immediately thought it would be a good deed to take his brother’s children with him. He would not constrain them, and would take them only with the condition that they could look upon him as their second father.

Amrie, after these words, looked earnestly at him. If she only could make out to love this man! But she feared him, and knew not what to do. That he had fallen, as it were, out of the clouds so suddenly, and desired her love, only excited her opposition to him.

“Where then is thy wife?” asked Amrie. She might well feel that a woman had been milder and more suitable for this business.

“I will tell thee, honestly,” answered the uncle, “that my wife will have nothing to do in this affair. She says, ‘she will say nothing for nor against it.’ She is a little harsh, but only at first; and if you are amiable towards her, you are so sensible that you can wind her round your finger. If any thing should occur that you do not like,[42] think that you are with your father’s brother, and tell me alone, and I will do all I can to help you. But you will see that now you begin first to live.”

Amrie stood with tears in her eyes, and yet she could say nothing. She felt this man was wholly strange to her. His voice, like her father’s, moved her; but when she looked at him, she would willingly have fled from him.

Dami came with the key. Amrie would have taken it from him, but he would not give it up. With the peculiar pedantic conscientiousness of a child, he said he had sacredly promised Mathew’s wife that he would give the key only to his uncle. He received it, and to Amrie it appeared as though a magical secret was to open when the key, for the first time, rattled and then turned in the lock. The bolt bent back and the door opened. A peculiar tomb-like coldness breathed from the dark room that had formerly served as a kitchen. Upon the hearth lay the cold heaped ashes, and upon the door were written the first letters of “Caspar Melchior Balthes.” Underneath, the date of the death of the parents written with chalk. Amrie read it aloud. “Father wrote it,” said Dami. “Look, the 8’s are made just as you make them; such as the teacher will not suffer. Look, from right to left.” Amrie winked at him to be quiet. To her it was fearful and sinful that Dami should talk so lightly here where it seemed[43] to her like a church; yes, as though they were in eternity; quite out of the world, and yet in it. She opened the door. The little room was dark and gloomy; for the shutters were closed, and only a trembling sunbeam pressed through a crack, and fell upon an angel’s head upon the door of the stove, so that the angel appeared to laugh. Amrie, frightened, could scarcely stand, but when she looked again, her uncle had opened one of the windows, and the warm air from without pressed into the room. There was no furniture in the apartment, except a bench nailed to the wall. There had the mother spun, and there had she pressed the little hands of Amrie together, and taught her to knit.

“So, children, now we will go,” said the uncle. “There is nothing good here. Come with me to the baker’s. I will buy for both a white loaf; or would you rather have a cracknel?”

“No, no, stay a little longer,” said Amrie, always stroking the place where her mother had sat. Then pointing to a white spot on the wall she said in a low voice, “There hung our cuckoo clock, and the soldier’s reward of our father; and there is the place where the skeins of yarn hung, that our mother spun. She could spin finer than Brown Mariann. Yes, Mariann said so herself; always quicker, and more out of a pound of wool than any other; and all so even, there was not a single knot in it; and see there is the ring there upon the wall.[44] That was beautiful when she had finished a skein. If I, at that time, had been old enough, I would never have consented that they should sell my mother’s distaff; it was my inheritance. But there was nobody to care for us. Oh, dear mother! oh, dear father! if you only knew how we are thrust about, it would make you sorry even in your blessedness!”

Amrie began to weep aloud, and Dami wept with her. Even the uncle dried a tear, and pressed them to go now. It seemed to him that this unnecessary heart-rending did neither himself nor the children any good. But Amrie said decidedly, “If you go now, I will not go with you.”

“How do you mean that? You will not go with me?”

Amrie was frightened. She now thought of what she had said. And indeed it might be taken as consenting; but she immediately answered,—

“No, of other things I know nothing now. I only meant that I would not go out of this house till I had seen every thing again. Come, Dami, thou art my brother. Come with me to the garret; you know where we used to play hide, behind the chimney. And then we will look out of the window where we dried the mushrooms. Don’t you remember the beautiful gold piece father received for them?”

Something shook and rolled over the ceiling. All three were frightened. But the uncle quickly[45] said, “Stay here, Dami; and you also, Amrie. Why would you go up there? Do you not hear how the mice rattle?”

“Come with me,” urged Amrie; “they will not eat us.” But Dami declared he would not go, and though Amrie was secretly afraid, she took heart and went up alone to the garret. She soon came back as pale as death, and had nothing in her hand but a basket of straw.

“Dami will go with me to America,” said the uncle, as she entered again. She was breaking up the straw in her hand. “I have nothing against it. I do not know what I shall do; but he can go alone,” she said.

“No!” cried Dami, “that I will not. Thou didst not go with Madame Landfried, when she would have thee; and so I will not go alone; but with thee!”

“Now, then, think of it; you are sensible enough to do so,” concluded the uncle, bolting again the window-shutters, so that they stood in the darkness. He pressed the children to the door, and then out of the house; locked the house door, and went to Mathew’s with the key, and then with Dami alone, into the village. He called out from a distance to Amrie, “You can have till the morning, early, to decide. Then I shall go, whether you go with me or not.”

Amrie was alone. She looked after him as he went on, and it seemed strange to her that one man[46] could go away from another, if that other belonged to him. There he goes, she thought, yet he belongs to thee, and thou to him.

Strange! as it sometimes happens in dreams that come we know not how. So it now seemed to Amrie in her waking dream. Wholly accidentally, had Dami spoken of her meeting with Madame Landfried.

The meeting had almost faded out of her recollection, and now it awoke clear and distinct as a picture from out of her past dreamed life. Amrie said, indeed, aloud to herself, “Who knows whether she also does not suddenly, she cannot say why, think of me; and perhaps now, just at this minute, for there in that spot, she promised that she would be my protector whenever I went to her. There by the willow-trees she promised. Why do the trees remain standing so that we may always see them, and why not also a word, like a tree, that stands firm so that we can hold by it, and why not by a word? Yes, it comes only from this, that they WILL; a word would be as good as a tree, and what an honorable woman said must be as firm and as true. She also wept, because she had left her home. But it was long before, that she was married from this village, and now has children. One is called John.”

Amrie stood by the mountain-ash tree, and laid her hand upon its stem and said,—

“Thou! why then dost thou not go forth? Why[47] do not men call upon thee to wander away? Perhaps it would be better for thee in another place? But thou didst not place thyself here. Who knows whether thou didst not come from another place. Stupid stuff! Yes, if he were my father I must go with him. He would not ask me. He who asks much, goes often wrong. Nobody can advise me—not even Mariann, and with our uncle it will be thus. If he does thee good, thou must pay him again. If he should be severe to me, and against Dami (because Dami is not sensible), after we have gone with him—where should we turn in that wild strange world? Here every man knows us. Every hedge, every tree, has a well-known face. Ah, ha! thou knowest me,” she said again looking up at the tree. “Oh, if thou couldst only speak! Thou wert created by God! Oh, why canst thou not speak? Thou hast known my father and my mother so well—why canst thou not tell me what they would advise? Oh, dear father! Oh, dear mother! to me it is so sad that I should go away—yet I have nothing here, and no one to care for me, and yet it would be as though I must get out of a warm bed, into the cold snow. Is that, which makes me so sorry to go, a sign that I should not go? Is it a right conscience, or is it only a foolish anxiety? Oh, dear Heaven! I know not. Oh, if only a voice from Heaven would come and tell me.”

The child trembled like a leaf, from the deepest[48] anxiety; and from this conflict of life, which now made its voice heard within her. Again she half spoke, half thought—but now more resolved.

“If I were alone I know certainly that I would not go. I would remain here. It is too hard to go; and I could, if alone, take care of myself. Ah, let me remember that! With myself I am perfectly agreed. I am one! Yes, but what a foolish thought. How can I think I am one—alone—without Dami! I am not alone. Dami belongs to me and I to him. For Dami were it better,—better for him if he were under a father who would tell him, and teach him what is right. But canst thou not care for him thyself, when it is necessary? I see plainly that if he were once at home there, he would remain there his life long, and be nothing but a servant, a dog for strange people to kick. Who knows how the children of the uncle would treat us? As they are poor people themselves, would they not play the master towards us? No, no, they are certainly good, and it would be beautiful if they would say, ‘Good-morning cousin,’ or ‘good-day, aunt.’ If our uncle had only brought one of the children with him, then I could have understood it all much better, and spoken much easier. Oh, dear! How is it all at once so difficult?”

Amrie sat down at the foot of the tree. A chaffinch came tripping about, picked up a little[49] seed here and there, looked around, and then flew away. She felt something creeping over her face. She swept it off with her hand. It was a little winged beetle. She suffered it to creep around upon her hand, between the mountains and valleys of her fingers, till it came upon the point of her finger, and flew away. “Perhaps he would tell thee where he has been,” thought Amrie. “Ah, it is well with such a little animal, wherever he flies, he is at home. And, listen! how the larks sing. It is well with them also; they need not think what they must say, and what they have to do. There drives the butcher, with his dog, a calf, out of the village. The butcher’s dog has a very different voice from the lark, but, indeed, they could not drive a calf with the song of the lark.”

“Where are you going with the foal?” cried Mathew, out of his window, to a young fellow who had a beautiful foal by a halter. “Farmer Rodel has sold it,” sounded the answer, and soon they heard the foal neigh in the valley beneath.

Amrie, as she heard this, must again think. “Yes, an animal is sold away from its mother, and the mother scarcely knows it, or who has taken it away. But they cannot sell a man; for him there is no halter. There comes Farmer Rodel with his horses, and the great foal springs after his mother. A man is not sold; he belongs to himself alone. An animal receives for his work no other reward than eating and drinking, and needs, indeed, nothing[50] else; but a man gains money as a reward for his work. Ah, yes! I can be a servant, and from my wages I can have Dami taught, and he can be a mason. But if we were with our uncle, Dami would be no longer mine as he is now. Listen! the starlings are flying home—there, above, in the house father set up for them, and they sing gayly. Father made the house out of old boards. I know now what he said, ‘that a starling would not fly into a house made of new boards.’ So it is with me!—Thou, tree, now I know! If thou shouldst rustle while I am sitting here by thee, I will remain here.”

Amrie listened breathless. Soon it seemed as though the tree rustled. She looked up at the branches, but they were motionless. She could not tell what she heard. A noisy cackling was heard on all sides; it came nearer, preceded by a cloud of dust. It was the flocks of geese driven home from the Holden Meadows. While the noise lasted, Amrie looked after them.

Her eyes closed. She was slumbering. A whole spring of flowers opened within this soul, with the blossoming trees in the valley that absorbed the cooling night dew, sending their perfume over to the child, who was sleeping upon the hearth of the home she could not leave.

It had long been night when she awoke as a voice cried, “Amrie, where art thou?” She rose up, but did not answer. She looked round astonished,[51] and then at the stars, and it seemed to her that the voice came from Heaven. As it was repeated, she knew it was the voice of Mariann, and answered, “Here I am.” Now came Brown Mariann nearer and said, “Oh, it is well that I have found thee. The whole village is, as it were, gone mad! One said, ‘I have seen her in the woods;’ another, ‘I met her in the field;’ and to me it seemed as though thou hadst thrown thyself into the fish-pond. Thou needst not fear, dear child! thou needst not fly! No one can force thee to go with thy uncle!”

“Who has said that I will not go?” Suddenly a quick wind breathed through the tree, so that the branches rustled powerfully. “But certainly I will not,” said Amrie, and laid her hand upon the tree.

“Come home! a severe shower is rising, and we shall have a high wind immediately; come home,” urged Brown Mariann.

Giddily Amrie went with Mariann into the village. The night was pitch dark, and only by the sudden flashes of lightning could they see the houses which shone as in clear daylight, so that their eyes were blinded, and they stood still in the darkness when the lightning vanished. In their own village home they seemed bewildered as in a strange place, and stepped uncertain, and confusedly forwards. Bathed in perspiration they toiled forwards, and came at last under heavy[52] drops of rain to their own door-stone. A gust of wind tore open the door, as Amrie cried, “Open!” She might have thought of a fairy tale where, at an enigmatical word, an enchanted castle opened.

CHAPTER V.

UPON THE HOLDER COMMON.

THE next morning when her uncle came, Amrie declared that she should remain at home. There was a strange mixture of bitterness and benevolence when her uncle said, “Indeed, thou tak’st after thy mother, who would never have any thing to do with us. But I cannot take Dami alone, even if he would go. For a long time he would do nothing but eat bread. Thou couldst have earned it.”

Amrie urged, “that for the present they would remain here in their village, and later, if her uncle remained of the same mind, she, with her brother, could go to him.”

The resolution of Amrie was somewhat shaken by the manner in which her uncle expressed his sympathy for the children, but she did not venture to say so, and only answered, “Greet your children and say to them, that it is very hard for me never to have seen my nearest relations, and as they are going over the sea, I shall probably never see them in my whole life.”

[54]Their uncle only said, “Greet Dami from me; I have no time to bid him farewell,” and he was gone.

As soon as Dami came in, and learned that he was gone, he would have run after him, as indeed Amrie was almost inclined to do, but she constrained herself again to remain. She spoke and acted as though some one had ordered every word and every motion, and yet her thoughts flew on the way that her uncle had taken. She went with her brother, hand in hand, through the village, and nodded to every one she met. She had now returned to them all. She was on the point of being torn away, and she thought they must all be as glad as herself that she did not go. But, alas! she soon remarked that they not only would have willingly parted with her, but they were angry that she did not go. Krappenzacher opened his eyes and said, “Yes, child, you have a proud spirit, and the whole village is angry with you for thrusting your fortune away with your foot. Every one says, ‘Who knows but it might have been a fortune for thee,’ and then they calculate how soon you will come upon the Parish. Do something, therefore, that you may not come upon the public alms.”

“Yes, ah! what shall I do?”

“Madame Rodel would have willingly taken you into service, but her husband would not consent.”

[55]Amrie felt, that from henceforth she must be doubly brave, that she might meet no reproach from herself or from others, and she asked again, “Do you then know of nothing that I can do?”

“Indeed you must be afraid of nothing but of begging. Have you not heard that the foolish little Fridolin yesterday killed two of the Sacristan’s geese? The goose-herd’s service is now open, and I advise you to take it.”[A]

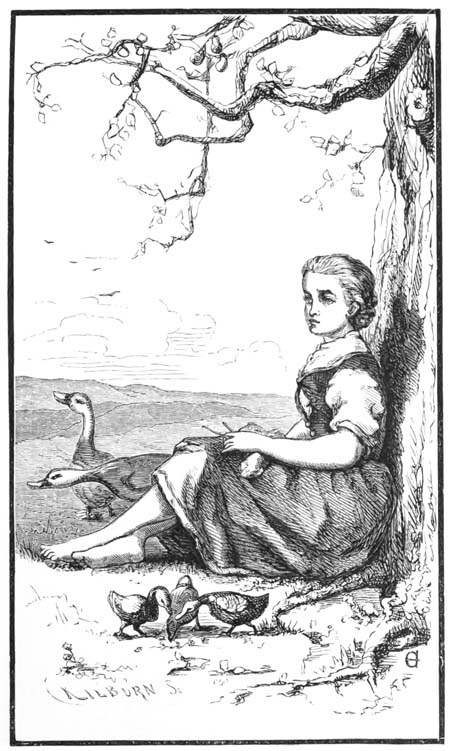

This soon happened, and by noon of that day Amrie was driving the geese upon the Holder Green, as they called the pasture-ground upon the little height by Hungerbrook. Dami helped his sister faithfully in this work.

Brown Mariann was very much dissatisfied with this new servitude, and asserted, not without some truth, “that the odium followed a person their life long, who once held such an office. People never forget it. If you attempt any thing else they say, ‘Ah, that is the goose-herd;’ and if, even out of pity, they should take you, you will receive a poor reward, and bad treatment. They will say, ‘Ah, it is good enough for a goose-herd.’”

“That will not be so very bad,” answered Amrie; “and you have related many hundred histories where goose-herds have become queens.”

“That was in the olden time. But who knows,[56] thou art of the old world; many times it appears to me that thou art not a child. Who knows then, thou ancient soul! perhaps some miracle will happen to thee!”

This opinion, that she was not on the lowest step of the ladder of honor, but that there was something upon which she could step down, made Amrie suddenly pause. For herself she could gain nothing more at present, but she would no longer suffer Dami to herd the geese with her. He was a man, and he should be one. It might injure him if it could afterwards be said that he had formerly kept the geese. But with all her zeal she could not make it clear to him. He was angry with her. It is always so. At the point where the understanding ceases, there begins an inward obstinacy; inward imbecility passes into outward injustice, and sometimes into injurious action.

Amrie rejoiced, that Dami could be for so many days angry with her; she hoped he would learn to stand up against others and assert his own will.

Dami also received an office. He was apprenticed by his guardian as Scarecrow. He turned the rattle the whole day in the quiet garden of Rodel’s farm to scare the sparrows from the early cherries, and from the salad-beds. But this, which in the beginning was only play, he soon gave up.

[57]It was a pleasant, but also a troublesome office, that Amrie had undertaken. It was especially often painful that she could do nothing to attach the animals to her. Indeed, they were scarcely to be distinguished, one from another; and was it not true what Brown Mariann had once said to her as she came out of the Moosbrunnenwood?

“Animals that live in herds, are all, each for himself, stupid.”

“I think,” added Amrie, “that geese on this account are stupid; that they can do too much. They can swim, and run, and fly, but they are neither in the water, nor on the ground, nor in the air, expert, or at home, and that makes them stupid.”

“I will stand by this,” said Mariann, “in thee is concealed an old hermit.”

In fact there formed itself in Amrie a disposition to solitary dreaminess, which was rarely interrupted by the occurrences of life. But, as through all the dreaming and observation of nature she continued industriously to knit, and to let no stitch drop; and as on the corner by the service-tree, the deepening night shadows and the refreshing strawberries were so near each other, that they appeared to sprout from the same root:—thus were the distinct representations of nature and the dreamy twilight of life near each other in the heart of the child.

Holder Green was no solitary, secluded place,[58] filled with fairy tales that the curious world only would willingly seek. In the midst, through the Holder Pasture, led a field-path, to Endringen, and not far from it stood the different colored boundary pillars, with the armorial bearings of the two gentlemen proprietors whose lands joined each other. Peasants passed through with every species of agricultural implements; men, women and girls went by with hatchets, sickles and scythes. The bailiffs of both estates often came through, and the reflection of their rifles glittered long before and long after they passed. Amrie was always greeted by the several bailiffs when she sat by the way, and was often asked whether this one or that one had passed by, but she never betrayed any one. Perhaps this concealment was from that inward dislike that the people, and especially the village children, have for the bailiff, who is always represented as the armed enemy of the peasantry, going about to seek whom he can insnare.

Old Manz, who was employed to break stones on the road, never spoke a word to Amrie. He went sadly from one heap of stones to another, and the sound of his pick was incessant as the tapping of the woodpecker, or the shrill chirp of the grasshoppers in the meadows and clover-field.

Notwithstanding all these human influences, Amrie was often borne into the kingdom of dreams. Freely soared her childish soul upwards and cradled itself in unlimited ether. As the[59] larks in the air sang and rejoiced without knowing the limits of their field, so would she soar away beyond the boundaries of the whole country. The soul of the child knew nothing of the limits placed upon the narrow life of reality. Whoever is accustomed to wonder, will find a miracle in every day.

“Listen,” she would say; “the cuckoo calls! This is the living echo of the woods which calls and answers itself. The bird sits over there in the service-tree. If you look up, he will fly away. How loud he calls, and how unceasingly! That little bird has a stronger voice than a man! Place thyself upon the tree and imitate him,—thou wilt not be heard as far as this bird, who is no larger than my hand. Listen! Perhaps he is an enchanted prince, and suddenly he may begin to speak to thee. Yes,” she said, “only tell me thy riddle, and let me think a little, and I will soon find the meaning of it; and then I will disenchant thee, and we will go into thy golden castle and take Mariann and Dami with us, and Dami shall marry the princess, thy sister, and we will then seek Mariann’s John through the whole world, and whoever finds him shall conquer thy kingdom. Ah! were it then all true? And why could I think it all out if it were not true?”

While the thoughts of Amrie thus soared beyond all limits, the geese also felt themselves at liberty to stray and enjoy the good things of the neighboring[60] clover or barley field. Awaking out of her dreams, she had heavy trouble to bring the geese back; and, when these freebooters came in regiments, they had much to tell of the promised land where they had fed so well. To their gossiping and chattering there seemed no end. Here and there was heard an old goose holding on, after all the others had ceased, with a drowsy or significant word, while others stuck their bills beneath their wings, and continued to dream of the goodly land.

Again Amrie soared, “Look! there fly the birds. No bird in the air goes astray; even the swallows, in their continually crossing flight, are always safe, always free! Oh! could we only fly! How must the world look above where the larks soar. Hurrah! always higher and higher, farther and farther! Oh, could I fly! I would fly into the wide world and to the Landfried, and see what she does, and ask her whether she ever thinks of me.

‘Thinkest thou of me in distant lands?’”

Thus she sang herself suddenly away from all the noise and from all her thoughts. Her breath, which by the thought of flight had become deeper and quicker, as though she really hovered in the higher ether, became again calm and measured.

But not always glowed her cheek in waking dreams; not always did the sun shine clear in the open flowers and in the bending grain. In the spring came those cold, wet days, in which the[61] blossoming trees stood like trembling foreigners, and all day long the sun scarcely beamed upon them. A sterile frost pierced through the natural world, interrupted only by gusts of wind that tore and scattered the blossoms from the trees. The larks alone kept jubilee, high in the air, above the clouds; and the finches’ little complaining note was heard from the wild pear-tree, against which Amrie leant. Now, in white stripes, rattled down the hail, and the geese pointed their beaks upwards, that the tender brain might not be hurt. There above, behind Endringen, it is already clear, and the sun will soon break through the clouds and the hills; the woods and the fields will look like the human countenance, which has been bathed in the tears of grief, but now shines out with beams of joy. The geese, which through the shower had pressed close together, and turned their bills upward, now venture to spread themselves apart and graze, and gaggle of the passing storm to the young, tender, downy brood, who have never before lived through such an experience.

Immediately after Amrie had been overtaken by the hail-storm, she endeavored to provide for the future. She took with her, out upon the green pasture, an empty corn-sack, which she had inherited from her father. Two axes, crossed with the name of her father, were painted upon it. When the showers came down, she covered and folded herself within it, and looked out from a protecting[62] roof upon the wild conflict in the sky. A cold shower of snow would end in melancholy, which would sometimes overpower her. Then she would weep over the destiny which left her so alone—deprived of father and mother—thrust out, as it were, from her fellows. But she early gained a power that trial and difficulty teaches one to exert, to swallow down her tears. This makes the eyes sparkle, and to be doubly clear in the midst of all trouble.

Amrie could conquer her melancholy, especially when she recollected a proverb of Brown Mariann’s. “Who will not have his hands frozen in the cold, must double his fist.” Amrie did so, both spiritually and physically. She looked proudly into the world, and soon cheerfulness came over her face. She rejoiced at the beautiful lightning, and held her breath till the thunder followed after. The geese pressed close together, and looked strangely at the lightning.

“They,” said Amrie, “experience only good. All the clothing they need grows upon their bodies; and for that which is pulled out in the spring, other is already provided. When the shower is over, there is joy in the air and in the trees, and the geese rejoice in the rare luxuries it has left, pressing upon each other, greedily consume the snails and the young frogs that venture forth after it is over.”

Of the thousand-fold meanings that lived in Amrie’s[63] soul, Brown Mariann received only, at times, the intimation. Once, when she came from the forest with her load of wood, and imprisoned in her sack May-bugs and worms for Amrie’s geese, the latter said to her,—

“Aunt, do you know why the wind blows?”

“No! do you know?”

“Yes; I have remarked every thing that grows must move about. The bird flies, the beetle creeps; the hare, the stag, the horse, and all animals, must run. The fish swim, and frogs also. But there stand the trees, the corn, and the grass; they cannot go forth, and yet they must grow. Then comes the wind and says, ‘Only remain standing, and I will do for you what others can do for themselves. See, how I turn, and shake, and bend you. Be glad that I come; I do thee good, even if I make thee weary.’”

Brown Mariann said nothing, except her usual speech:

“I maintain it; in thee is concealed the soul of an old hermit.”

Once only Mariann led the quiet observation of Amrie upon another trace.

The quail began already to be heard in the high rye-fields; near Amrie, the field-larks sang the whole day incessantly. They wandered here and there, and sang so tenderly, so into the deepest heart, it seemed as though they drew their inspiration from the source of life—from the soul itself.[64] The tone was more beautiful than that of the skylark, which soars high in the air. Often one of the birds came so near to Amrie, that she said, “Why cannot I tell thee that I will not hurt thee? Only stay!” But the bird was timid, and removed farther off. Then Amrie considered quickly, and said, “It is well that the birds are timid, else we could not drive away the thievish starlings.”

At noon, when Mariann came to her, she said, “Could I only know what a bird, all through the live-long day, has to say; and, even then, he has not sung it all out.”

Mariann answered, “Look, an animal can keep nothing back to reflect upon and resolve it in himself. But in man something is always speaking; it does not cease, although it is never loud. There are thoughts that sing, weep, and speak, but quietly; we scarcely hear them ourselves. Not so the bird—when he ceases singing, he is ready to eat or sleep.”

As Mariann turned and went forth with her bundle of wood, Amrie looked smiling after her. “There goes a great singing bird,” she thought. None but the sun saw how long the child continued to smile and to think.

AMRIE.—Page 64.

[65]Thus, day after day, Amrie lived. Long she sat dreaming, as the wind moved the shadows of the branches around her. Then she gazed at the motionless banks of clouds on the horizon, or upon the flying clouds that chased each other through the sky. As without, in the wide space, so in the soul of the child the cloud-pictures arose and melted away, receiving, for the moment only, existence and form. Who can tell how the soul of the child interpreted and gave life to the cloud, within or without?

When spring breaks over the earth, thou canst not comprehend the thousand-fold seeds and sprouts spread over the ground—the singing and jubilee upon the branches and in the air. A single lark seizes upon eye and ear. It soars aloft. For a time thou canst follow it as it spreads its wings; for a time thou canst not determine whether that dark point is thy vanishing lark. Now it is gone from thy eye, and soon from thy ear; for thou canst not tell if the singing thou hearest comes from thy vanished lark. Couldst thou listen for a whole day to a single lark in the whole wide heaven, thou wouldst hear that the morning, the mid-day, and the evening song, are wholly different; and couldst thou trace it from its first trembling pipe, through the whole year, thou wouldst find what various tones mingle in its spring, its summer, and its harvest song. Over the first stubble-field sing a new brood of larks.

When the spring breaks in a human soul,—when the whole world opens before it and within it,—thou canst not understand the thousand voices that make themselves heard. Thou canst[66] not seize nor hold the thousand buds and blossoms that perpetually unfold and extend themselves; thou only knowest that there it sings, and that it expands.

How quietly spring appeared again in the firmly rooted plant. There, by the meadow-hedge and the pear-tree, the sloe blossomed early, and was only rarely ripe. What a beautiful bloom has the whortleberry, and what a powerful perfume it has! The little pears are quite formed, and glow with a faint red; and the poisonous night-shade already looks dark. Soon will come those clear, sharp-cut, harvest days, when the atmosphere is of so clear and cloudless a blue, that during the whole day the half-moon can be seen in the sky; then we mark how it fills itself, and how it wanes, till only a finely-cut side, like a little cloud, stands in the horizon. In nature, and in the human soul, there is a pause before the goal is reached.

There was soon life upon the road that led through the Holder Green. Quickly rattling went the empty peasants’ wagons, where sat women and children, and laughed,—shaken by laughing as well as by the rolling of the wagons. Then they came, sheaf-laden, slowly back, creaking homewards. Reapers, both men and women, passed very near Amrie.

She gained of the rich harvest only what her geese, who boldly followed the laden wagons, robbed from their hanging sheaves.

[67]There often comes into men’s souls, with all their joy over the harvested fields and the harvest blessing, a certain timidity. Expectation has become certainty; and where all was so moving and transitory, it is now quiet. The season has changed. Summer has turned to frost.

The brooks upon Holder Green, in whose flood the geese contentedly struggled, had the best water in the place. The passer-by often paused at the broad channel to drink, while their animals ran before. Then, rinsing their mouths, they ran, shrieking after them. Others, returning from the fields, watered their beasts here.