RAMBLES BY LAND & WATER.

RAMBLES

BY

LAND AND WATER,

OR

NOTES OF TRAVEL

IN

CUBA AND MEXICO;

INCLUDING A CANOE VOYAGE UP THE RIVER PANUCO, AND RESEARCHES AMONG THE RUINS OF TAMAULIPAS, &c.

"He turns his craft to small advantage, Who knows not what to light it brings."

By B. M. NORMAN,

AUTHOR OF RAMBLES IN YUCATAN, ETC

NEW-YORK:

PUBLISHED BY PAINE & BURGESS.

NEW ORLEANS:

B. M. NORMAN.

1845.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1845, by

PAINE & BURGESS,

in the Clerk's office of the District Court of the United States, for

the Southern District of New York.

Stereotyped by Vincent L. Dill,

128 Fulton st. Sun Building, N. Y.

C. A. Alvord, Printer; Cor. of John and Dutch sts.

PREFACE.

The present work claims no higher rank than that of a humble offering to the Ethnological studies of our country. Some portions of the field which it surveys, have been traversed often by others, and the objects of interest which they present, have been observed and treated of, it may be, with as much fidelity to truth, and in a more attractive form. Of that the reading public will judge for itself. But there are other matters in this work, which are now, for the first time, brought to light. And it is the interest, deep and growing, which hangs about every thing relating to those mysterious relics of a mysterious race, which alone emboldens the author to venture once more upon the troubled sea of literary enterprise. Had circumstances permitted, he would have extended his researches among the sepulchres of the past, with the hope of securing a more ample, and a more worthy[Pg vi] contribution to the museum of American Antiquities. He has done what he could, under the circumstances in which he was placed. From what he has been enabled to accomplish, alone and unaided, he hopes that others, more capable, and better furnished with "the sinews" of travel, will be induced to make a thorough exploration of these regions of ruined cities and empires, and bring to light their almost boundless treasures of curious and interesting lore. The field is immense. It is, as yet, scarcely entered upon. No one of its boundaries is accurately ascertained. The researches made, and the materials gathered, are yet insufficient to enable us to solve satisfactorily the great problem of the origin of the races, that once filled this vast region with the arts and luxuries of civilization, and reared those mighty and magnificent structures, and fashioned those wonderful specimens of sculptured art, which now remain, in ruins, to perpetuate the memory of their greatness, though not of their names.

The exploration and illustration of these marvels of antiquity, belong appropriately to American literature. They should be accomplished by American enterprise. If not soon attempted, the honor, the pleasure, and the profit, will assuredly fall into other hands. Enough has already been done, to awaken a general interest and curiosity among the wonder-seeking and world-exploring adventurers of Europe; and, if we do not speedily follow up our small beginnings, with an[Pg vii] efficient and thorough survey, the Belzonis, and the Champollions of the Old World, will have anticipated our purpose, and borne away forever the palm and the prize.

But who shall undertake the arduous achievement? Who shall be responsible for its faithful execution? If the difficulties are too great for individual enterprise, could it not be accomplished by a concert of action between the numerous respectable Historical and Antiquarian Societies of our country? What more interesting field for their united labors? Which of them will take the hint, and set the ball in motion?

It is only required, that when it is done, it should be well done—not a mere experiment in book-making, a catch-penny picture book, without plan, or argument, or conclusion, leaving all the questions it proposed to discuss and solve, more deeply involved in the mist than before—but a substantial standard work, complete, thorough and conclusive, such as all our libraries would be proud to possess, and posterity would be satisfied to rely upon. There are men among us of the right kind, with the taste, the courage, the zeal, and the skill both literary and artistic, to do the work as it should be done. But they have not the means to go on their own account. They must be sent duly commissioned and provided, prepared and resolved to abide in the field, till they have traversed it in all its length and breadth and investigated and decyphered[Pg viii] so far as it can now be done, every trace that remains of its ancient occupants and rulers—and the country, and the world, will reap the advantage of their labors.

The author does not presume to flatter himself, that he has done any thing, in his present or any other humble offering, towards the accomplishment of such a work as the above suggestion proposes. He is fully conscious of his incompetence to such an undertaking. His main desire, and his highest aim, has been to present the matter in such a light, as to awaken the attention, and stimulate the interest of those who have the means, the influence, and the capacity to do it ample justice. And yet, he would not be true to himself, if he did not declare, that, in the effort to secure this end, he has used his utmost endeavor to afford, to the reader of his notes, a just equivalent for that favorable regard, which is found in that wholesome impulse which ought invariably and naturally to precede the perusal of any book.

New Orleans, October, 1845.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I.

PAGE

Voyage from new orleans to havana.—description of the capital of cuba, 21

Introductory remarks, 21

Departure from New Orleans, 23

Compagnons de Voyage, 24

Grumblers and grumbling, 24

Arrival at Havana, 25

Passports.—Harbor of Havana, 26

Fortifications.—Moro Castle, 27

The city, its houses, &c., 28

An American Sailor, 29

Society in Havana, 30

Barriers to social intercourse, 31

Individual hospitality, 32

Love of show, 33

[Pg x]Neatness of the Habañeros, 34

CHAPTER II.

Public buildings of havana.—the tomb of columbus, 35

The Tacon Theatre, 35

The Fish Market, 36

The Cathedral 36

Its architecture—paintings—shrines, 37

Decline of Romanism, 38

The Tomb of Columbus, 39

The Inscription, 40

Reflections, 40

Burial, and removal of his remains, 41

Ceremonies of his last burial, 41

Reception of remains at Havana, 42

The funeral procession, 43

The Pantheon, 43

Mr. Irving's reflections, 44

Plaza de Armas, 44

A misplaced monument, 45

Statue of Ferdinand VII., 45

Regla—business done there, 46

Going to decay, 47

Material for novelists, 48

CHAPTER III.

The suburbs of havana, and the interior of the island, 49

Gardens.—Paseo de Tacon, 49

Guiness, an inviting resort for invalids, 50

Scenery on the route.—Farms—hedges—orange groves, 51

Luxuriance of the soil, 52

Sugar and Coffee plantations, 52

[Pg xi]Forests and birds, 53

Arrival at Guiness.—The town, 53

Valley of Guiness, 54

Buena Esperanza, 54

Limonar—Madruga—Cardenas—Villa Clara, 55

Hints to invalids, 55

Dr. Barton, 56

Splendors of a tropical sky, 57

The Southern Cross, 58

CHAPTER IV.

General view of the island of cuba, its cities, towns, resources, government, &c. 59

Political importance of Cuba, 59

Coveted by the nations, 60

Climate and forests, 61

Productions and Population, 62

Extent—principal cities, 63

Matanzas.—Cardenas, 64

Principe.—Santiago 65

Bayamo—Trinidad.—Espiritu Santo, 66

Government of Cuba, 66

Don Leopold O'Donnell.—Count Villa Nueva, 67

General Tacon, his services, 67

State of Cuba when appointed governor, 68

Change affected by his administration, 69

His retirement, 70

Commerce of Cuba with the United States, 70

Our causes of complaint, 71

The true interests of Cuba, 71

State of education, 72

Low condition of the people, 73

Discovery of Cuba, 73

Early History.—Velasquez.—Narvaez, 74

[Pg xii]Story of the Cacique Hatuey, 75

The island depopulated, 76

Rapidly colonized by Spaniards, 77

Seven cities founded in four years, 77

Havana removed.—The Gibraltar of America, 77

Possibility of a successful attack, 78

CHAPTER V.

Departure from havana.—the gulf of mexico.—arrival at vera cruz, 79

The British mail steamer Dee, 79

Running down the coast, 80

Beautiful scenery—associations, 81

Discoveries of Columbus.—The island groups, 82

The shores of the continent, 83

The Columbian sea, 84

The common lot of genius, 85

Sufferings of the great.—Cervantes,—Hylander, &c., 86

Associations, historical and romantic, 87

Shores of the Columbian sea, 88

Wonderful changes wrought by time, 89

Peculiar characteristics of this sea, 90

Arrival at Vera Cruz.—Peak of Orizaba 90

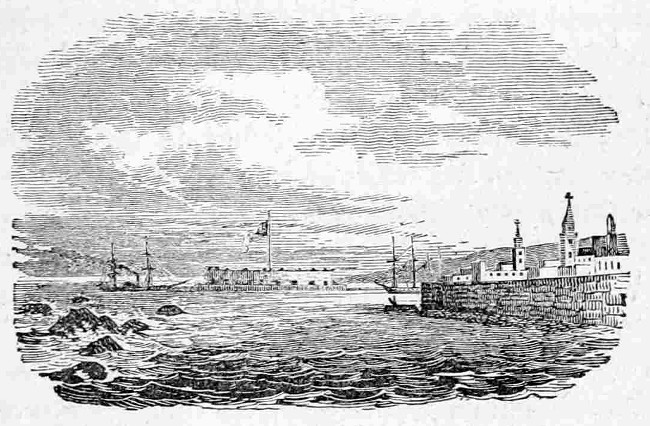

Castle of St. Juan de Ulloa, 91

The harbor and the city 92

Best view from the water—houses—churches, 93

Suburbs—population, 94

Health—early history, 95

The old and new towns of Vera Cruz, 96

CHAPTER VI.

Santa anna de tamaulipas and its vicinity, 97

[Pg xiii]The old and new towns of Tampico, 97

The French Hotel, 98

Early history of Tampico.—Grijalva, 98

Situation of the new town—health, 99

Commerce of the place—smuggling, 100

Foreign letters—mails, 101

Buildings—wages—rents—tone of morals, 102

Gambling almost universal, 103

The army.—The Cargadores, 104

The Market Place—monument to Santa Anna, 105

A national dilemma, 106

"The Bluff"—Pueblo Viejo, 107

Visit to Pueblo Viejo, 108

Its desolate appearance.—"La Fuente," 109

Return at sunset.—Beautiful scenery, 110

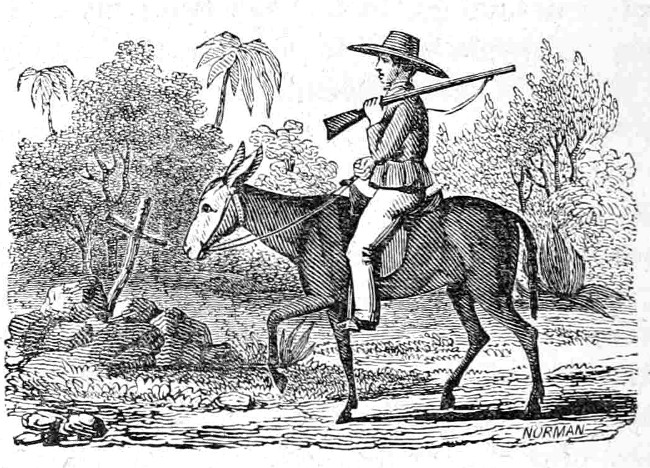

The Rancheros of Mexico, 110

The Arrieros, 111

A home comparison, 111

CHAPTER VII.

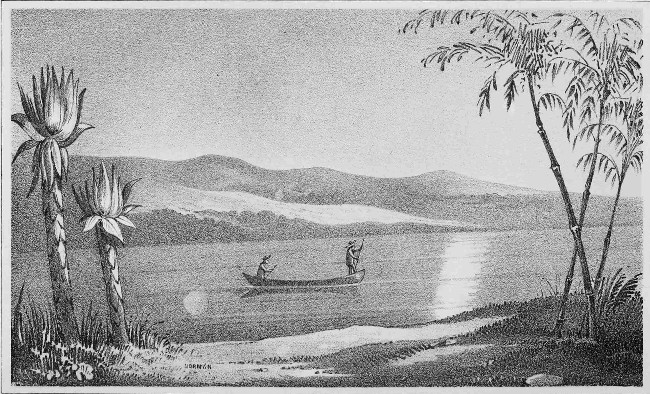

Canoe voyage up the river panuco.—rambles among the ruins of ancient cities, 113

An independent mode of travelling, 113

The river Panuco—its luxuriant banks, 114

A Yankee Brick Yard, 115

Indians—their position in society, 116

An Indian man and woman, 117

Topila Creek.—"The Lady's Room," 118

Fellow lodgers, 119

An aged Indian, 120

Ancient ruins—site of an aboriginal town, 121

Rancho de las Piedras 122

The Topila hills—mounds, 122

[Pg xiv]An ancient well, 123

A wild fig tree—mounds, 124

An incident—civil bandoleros, 125

CHAPTER VIII.

Further explorations or the ruins in the vicinity of the rancho de las piedras, 127

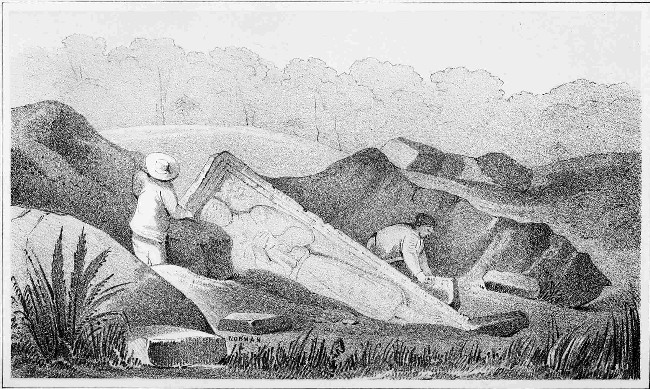

Situation of the ruins, 127

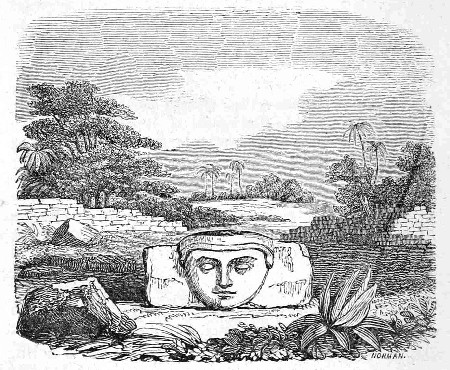

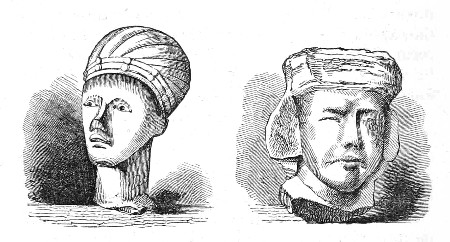

Discoveries—a female head 128

Description—transportation to New York, 129

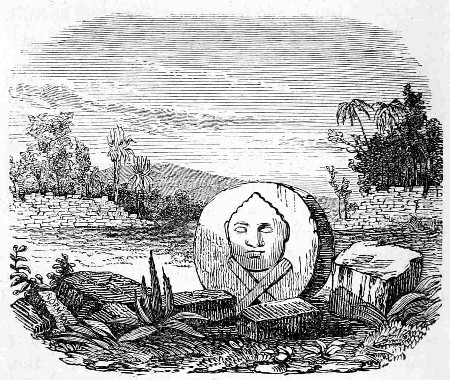

Colossal head, 130

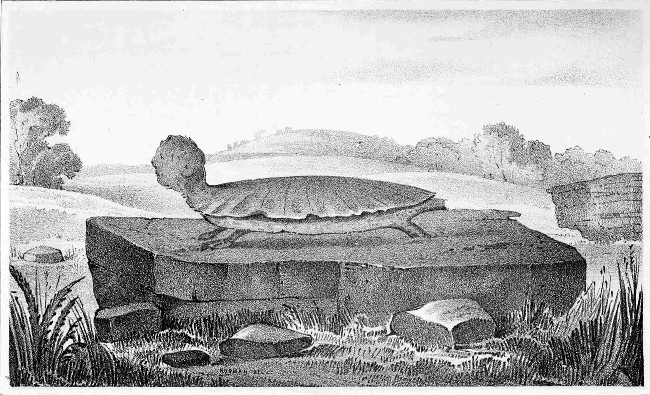

The American Sphinx, 132

Conjectures, 134

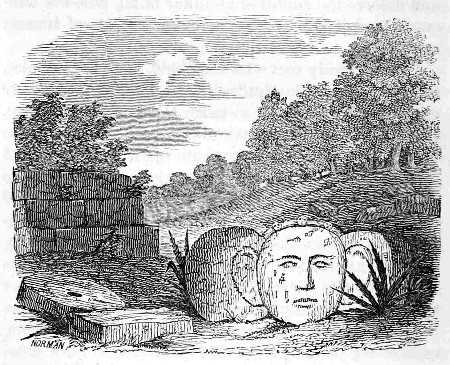

Curiously ornamented head, 136

A mythological suggestion, 137

Deserted by my Indian allies, 138

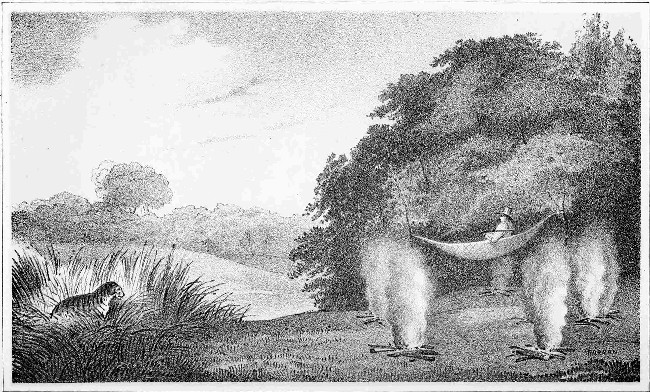

A thrilling adventure, 139

The escape, 140

A road side view, 140

CHAPTER IX.

Visit to the ancient town of panuco.—ruins, curious relics found there, 141

Route along the banks of the river, 141

Scenery—rare and curious trees, 142

Panuco and its inhabitants, 143

Language—antiquarian researches—Mr. Gallatin, 144

Extensive ruins in the vicinity of Panuco, 145

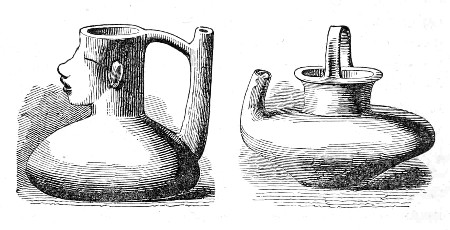

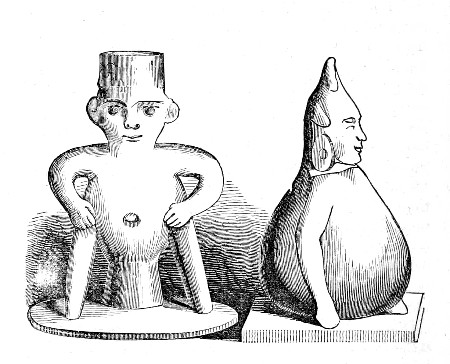

Sepulchral effigy, 145

Custom of the ancient Americans.—A conjecture, 147

An inference, and a conclusion, 148

Ruins on every side—Cerro Chacuaco, &c. 149

[Pg xv]A pair of vases, 150

CHAPTER X.

Discovery of talismanic penates.—return by night to tampico, 151

Two curious ugly looking images, 151

Speculations, 152

Humbugs, 153

The blending of idolatries, 154

Far-fetched theories, 155

Similarity in forms of worship evidence of a common origin, 156

Ugliness deified—Ugnee—Gan—Miroku, 157

The problem settled, 158

The Chinese—Tartars—Japanese, 159

Return to the "Lady's Room," 160

Travelling by night—arrival at Tampico, 161

Rumor of war—attitude of the French, 161

Mexicans check-mated, 162

Backing out, 163

Dii Penates, 164

CHAPTER XI.

Excursion on the tamissee river.—chapoté, its appearance in the lakes and the gulf of mexico, 165

Once more in a canoe, 165

The Tamissee—its fertile banks, 166

Wages of labor—a promising speculation, 167

The Banyan.—The Royal Palm, 168

Extensive ruins.—Mounds on Carmelote creek, 169

A Yankee house.—The native Mexicans, 170

The chapoté in the lakes of Mexico, 171

The chapoté in the gulf of Mexico, 172

New Theory of the Gulf Stream, 172

[Pg xvi]Comparative temperature of the Gulf Stream and the Ocean, 174

Objections to this new Theory, 175

Another Theory, not a new one, 177

Tampico in mourning, 178

CHAPTER XII.

General view of mexico, past and present.—sketch of the career of santa anna. 179

Ancient Mexico—its extent—its capital, 180

Its imperial government—its sovereigns, 181

Its ancient glory.—The last of a series of monarchies, 182

Extent and antiquity of its ruins, 183

Present condition of Mexico, 184

Population—government—transfer of power, 185

The Revolution—Iturbide, 186

Internal commotions—Factions, 187

Santa Anna, his origin and success 188

Victoria.—Santa Anna in retirement, 189

Pedraza,—Santa Anna in arms again, 189

Guerrero—Barradas defeated by Santa Anna, 190

Bustamente President.—Pedraza again, 190

Santa Anna President.—Taken prisoner at San Jacinto, 191

Returns to Mexico, and goes into retirement, 191

In favor again.—Dictator—President, 192

Paredes—Herrera—Santa Anna banished, 193

Literature in Mexico—Veytia—Clavigero, 194

Antonio Gama,—The inflated character of the Press, 195

Preparing to depart—annoyances, 196

Detained by illness,—Kindness of the American Consul, 197

Departure—at home, 198

CHAPTER XIII.

The two american riddles, 199

[Pg xvii]Baron Humboldt's caution, 199

Enigmas of the Old World but recently solved, 200

The two extremes of theorists, 201

A medium course, 202

Previous opinions of the author confirmed, 203

Absence of tradition respecting American buildings, 203

Nature and importance of tradition, 204

The Aztecs an imaginative people, 205

Supposed effect of the conquest upon them, 206

The Aztecs not the only builders,—The Toltecs 207

Extensive remains of Toltec architecture,—A dilemma, 208

Character and condition of these ruins, 208

Evidently erected in different ages, 209

Origin of the builders—sceptical philosophies, 210

The solitary tradition, 211

Imaginary difficulties—tropical animals, 212

A new Giant's Causeway, 212

The Aborigines were not one, but many races, 213

No head of the American type found among their sculptural remains, 213

Art an imitation of nature—copies only from life, 214

Inference from the absence of the Indian type, 214

American ruins of Asiatic origin, 215

Migratory habits of the early races of men, 215

Overflowings of the populous north, 215

Conclusion, 216

[Pg xix]

LIST OF EMBELLISHMENTS.

PAGE.

Vignette title page.

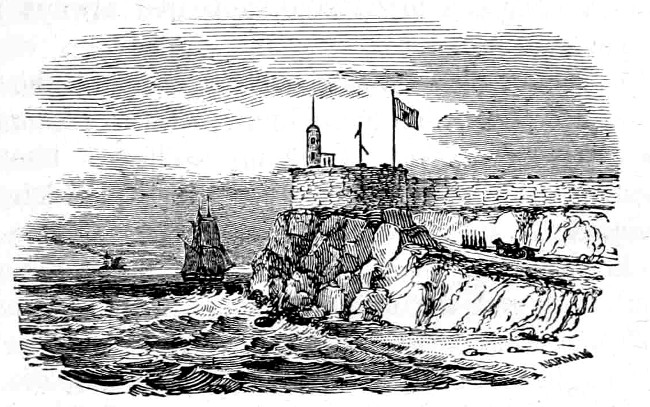

Moro castle, havana. 27

Peak of orizaba. 90

Castle of san juan de ulloa, vera cruz. 91

Indian man and woman. 117

Female head. 128

Colossal head. 130

The american sphinx. 132

Curiously ornamented head. 136

A situation. 139

A road side. 140

Sepulchral effigy. 145

A pair of vases. 150

Travelling by night. 161

Talismanic penates. 164

Fragments of idols. 178

RAMBLES BY LAND AND WATER.

CHAPTER I.

VOYAGE FROM NEW ORLEANS TO HAVANA. DESCRIPTION OF THE CAPITAL OF CUBA.

Introductory remarks.—Departure from New Orleans.—Compagnons de voyage.—Their different objects.—Grumblers and grumbling.—Arrival at Havana.—Passports.—The Harbor.—The Fortifications.—The City.—Its streets and houses.—Anecdote of a sailor.—Society in Cuba.—The nobility.—"Sugar noblemen."—Different grades of Society.—Effects upon the stranger.—Charitable judgment invoked.—Hospitality of individuals.—General love of titles and show.—Festival celebration.—Neatness of the Habañeros.

Who, in these days of easy adventure, does not make a voyage, encounter the perils of the boisterous ocean, gaze with rapture upon its illimitable expanse, make verses upon its deep, unfathomable blue—if perchance the Muse condescends to bear him company—plant his foot on a foreign shore, scrutinize the various objects which are there presented to his view, moralize upon them all, contemplate nations in their past, present[Pg 22] and future existence, swell with wonder at the largeness of his comprehension—and return, if haply he may, to his native land, to pour into the listening ears of friends and countrymen, the tale of his ups and downs, his philosophic gatherings, with undisguised complacency? Whose history does not present a chapter analogous to this? We might almost write one universal epitaph, and apply it to every individual who has flourished in the present century.—"He lived, travelled, wrote a book, and died."

And, seeing that in this auspicious age, when the public mind is alive

That genius condescends to undergo—"

when it seems disposed to appreciate the toil of intellectual effort, by the deference which it pays, the obedience it yields, and the signal support which it gives, to the meritorious productions of the historian, the statesman and the scholar; when we behold the power of discrimination so strikingly developed in the fact, that men are infinitely more regaled with the simple, truthful narrative, than with the ponderous tome of fictitious events, however pleasing the fabrication is made to appear;—who, it may be asked, I care not whether he has washed his hands in the clouds, while tossed upon the summit of a troubled wave, or looked out upon the world, from Alps highest peak, or whether he has leaned over the side of an humble canoe, to disturb the tranquil waters of some placid stream, above the bosom of which, his modest aspirations will never suffer him to rise,—who that has travelled, it matters not how,[Pg 23] can do otherwise than exclaim, "Oh that my words were now written—Oh that they were printed in a book!"

Though not disposed to allow that no higher sentiment than this prevalent cacoethes scribendi has influenced me in the present attempt, I am, nevertheless, so thoroughly convinced of its epidemic prevalence at the present time, that I am resolved neither to wonder nor complain, if friends as well as foes, "gentle readers" as well as carping critics, should set it down as only and unquestionably a symptom. I shall retain my own opinion, however, albeit I do not express it; and, contenting, nay congratulating myself with being in good company, shall complacently set out upon another "ramble," and sit down to another book, whenever

or health, or business, drives me away from my quiet pursuits at home.

It is no slight gratification, it must be allowed, to be enabled, by so feeble an effort, to make all one's friends, as well as a portion of the great world unknown, compagnons de voyage in all our rambles—to bring them into such a magnetic communication with our souls, that they shall at once see with our eyes, and hear with our ears, and enjoy, without the toil and weariness of travel, all that is worthy of remembrance and record, in our various adventures by sea and land.

On the 20th of January, 1844, in company with sixty fellow passengers, I turned my back upon the crescent city, and embarked on board the Steam Ship Alabama, Captain Windle, bound from Now Orleans to Havana. Many of our number, like myself, were in[Pg 24] pursuit of health and pleasure, some were braving the dangers and enduring the privations of the passage, for the purpose of amassing wealth in the sugar and coffee trade; and others were seeking, what they probably will never find this side the grave, a happier home than the one they were leaving behind them.

With a variety of humors, but for the most part with light hearts, we committed ourselves to the mercy of a kind Providence, a capricious element, and a competent and gentlemanly captain; and, setting aside such regrets as the sensitive mind cannot but indulge, in bidding adieu to the land of its birth, the companions of youth, and the faithful friends of after years, to visit distant and dangerous regions, to invite disease and brave death in many forms, we were probably as happy and merry a company as ever pursued their trackless path over the bounding deep. Our ship and its regulations were unexceptionable, our table was sumptuously spread, and the weather, all that the most fastidious invalid could desire.

To the above description of our company, I ought, perhaps, to make an exception in favor of a few professional grumblers from our fatherland. "Those John Bulls" of our company, ceased not their murmurings and repinings, until the recollection of imaginary wrongs, was swallowed up in the experience of real and substantial suffering, in the land of their glorious anticipations. But we must not marvel at, or find fault with, the redeeming trait of British character. It has long been universally admitted that John Bull is a grumbler. Whether it is a "streak in the blood," a universal family characteristic, or a matter of national[Pg 25] education, I know not; but it certainly belongs to the species, as truly and distinctively as a light heart and a gay deportment do, to their neighbors on the other side of the channel. It matters not whether you speak of the King or the Queen, the Royal Patronage or the doings of Parliament, of England, or France, or the moon, he is always ready with a loud and argumentative complaint, drawn from his own experience. If you sympathize with him, well; if not, his indifference to your regard will certainly match your stoicism. Talk to him about Church affairs; and, in all probability, he will find a "true bill" against every Ecclesiastical officer, from his Grace down to the humblest subordinate. Still, if it be a redeeming trait, why should we not respect it as such? True, it does not sound well, to hear one speak in terms of approbation respecting a grumbler. But surely, it must be simply because we are not accustomed to view this character in its proper light. A popular English writer observes, that "it is probably this harsh and stubborn but honest propensity, which forms the bulwark of British grandeur abroad, and of British freedom at home. In short, it is this, more than any thing else, which has contributed to make, and still contributes to keep England what it is." No—it will never answer to make war upon a character like that of Bull. We may occasionally introduce him to the reader, but it shall be with a just appreciation of his imprint, and a profound regard for his material substance.

After sixty hours delightful sail, we passed the celebrated castle of the Moro, and entered the harbor of Havana. Contrary to our expectations, we were permitted[Pg 26] to land with but little delay or inconvenience, except that which arose from "Elnorte," or a dry norther, which was blowing when we arrived, and rendered our landing a little uncomfortable. The thermometer stood at 70°, and the "natives" were shivering under the severity of the cold!

The traveller, visiting this Island, should furnish himself with a passport, issued or verified by the Spanish Consul, at the port from which he embarks. When furnished with this ihdispensable credential, if he pay a strict regard to the laws of the island, little difficulty is to be apprehended; but, neglecting this, he will be subject to fines and the most vexatious delays; and, probably, he will be prevented from landing. Strangers proceeding into the interior, for a period not exceeding four months, must also be prepared with a license from the Governor to that effect, countersigned by the Consul of the nation to which he belongs. This requisition is undoubtedly made upon the unsuspecting traveller, in consequence of impositions practiced by foreigners, during the recent difficulties which have taken place in Cuba. Thus will undisguising honesty ever suffer in the faults of a common humanity.

The harbor of Havana is one of the best in the world. The entrance into it is by a narrow channel, admitting only one vessel at a time, while its capacious basin within, is capable of containing more than a thousand ships. The view of the harbor, as you approach it from without, with its forest of masts, and the antique looking buildings and towers of the city, contrasting powerfully with the luxuriant verdure of the hills in the back-ground, is scarcely second to any[Pg 27] in the world, in panoramic beauty and effect; while the view sea-ward, after you enter the sheltered bay, the waters of the Gulf Stream lashing the very posts of the narrow gateway by which you came in, presents one of those bold and striking contrasts, which the eye can take in, and the mind appreciate, but which no pencil can pourtray, no pen describe.

MORO CASTLE.

MORO CASTLE.

The celebrated Moro, resting upon its craggy eminence, frowns over the narrow inlet. The Cabañas crowning every summit of the hills opposite the city, is a continuous range of fortifications of great extent, from whose outer parapet, elevated at least a hundred and fifty feet above the level of the sea, a most commanding view of the city and its beautiful environs is obtained. These fortifications are said to have cost forty millions of dollars. Within a mile on the opposite shore from the Moro, is still another fortress, so situated upon a considerable height, that its batteries could easily[Pg 28] sweep the whole space between. Looking down from these frowning battlements upon the busy scene below, I was struck with the variety of flags, from almost every nation under heaven, blending their various hues and curious devices, amid the thick forest of masts that lay at my feet. But of all the gay and flaunting streamers that waved proudly in the morning breeze, the stripes and stars, the ensign of freedom, the pride of my own green forest land, appeared always most conspicuous.

The city of Havana stands on a plain, on the west side of the harbor, but is gradually, with its continually increasing population, stretching itself up into the bosom of the beautifully verdant hills by which it is surrounded. Its general appearance is that of a provincial capital of Spain. There is an air of antiquity about this, and the cities of Mexico, which has no similitude in the United States. The streets, which are straight and at right angles to each other, are McAdamized, and, in good weather, are remarkably clean; but, during the rainy season, they become almost impassable. They are also very narrow, and without any side walks for the foot passenger. The houses, many of which are one story high, with flat roofs, have a general air of neatness, and comfort. They are usually either white or yellow washed. Many of them are of the old Moorish style of architecture, dark and sombre, as the ages to which it traces back its origin. The doors and windows reach from the ceiling to the floor, and would give an airy and agreeable aspect to the buildings, were it not for their massive walls, and the iron gratings to the windows, which remind one too[Pg 29] strongly of the prison's gloom. It is here, however, that the females enjoy the luxury of the air, and display their charms. They are never seen walking in the streets. Those who cannot afford the expense of a volante, arraying themselves with the same care as they would for a promenade, or a party, may be seen daily peering through their grated windows upon the passers by, and holding familiar conversation with their friends and acquaintances in the streets. Many a bright lustrous eye, and fairy-like foot, have I thus seen through the wires of her cheerful cage, which were scarcely ever seen beyond it.

A characteristic anecdote is related of an American sailor, who saw several ladies looking out upon the street, through their grated parlor windows. Supposing them to be prisoners, and sympathizing with their forlorn condition, he told them to keep up a good heart,—and then, after observing that he had been in limbo himself, he threw them a dollar, to the great amusement of the spectators, who understood the position of the inmates.

But notwithstanding the gloomy appearance of the windows, the houses are well ventilated by interior courts, which permit a free circulation of air,—a commodity which is very desirable in these latitudes. The floors are of flat stone or brick, the walls stuccoed or painted,—and the traveller, judging from the external appearance, is led to imagine that within, every desirable accommodation may be obtained. In this, however, he is disappointed, and must content himself with some privations. Huge door-ways and windows, a spacious saloon, together with solidity of construction, are the[Pg 30] chief objects to which the architect in this country seems to direct his attention. The main entrance answers the purpose of a coach-house; and it is no uncommon thing to see the volantes occupying a very considerable portion of the parlor. The amount demanded for rent, in proportion to similar accommodations in other cities, is exorbitant. The present population of the city and its suburbs, is about 185,000.

Society in Havana,—and it is the same throughout the island—is a singular anomaly to the stranger. It is neither that of the city, nor that of the country alone—neither national, oecumenical, nor provincial, nor a mixture of all. There are three distinct classes of what may be termed respectable society—the Spanish, the creole, and the foreigner. Among the former, with here and there an individual of the second grade, there are some who have purchased titles of nobility, at prices varying from thirty to fifty thousand dollars. They are often distinguished by the ludicrous sobriquet of "sugar noblemen," most of them having acquired their titles from the proceeds of their sugar plantations. Besides these, there are some few who have obtained the coveted distinction, as a reward for military services. Though more honorably obtained, the title is of less value to such, as they rarely have the means to support the style, which usually accompanies the rank. There are some sixty or seventy persons in the island, thus distinguished, who cannot, as a matter of course, condescend to associate in common, with the untitled grades below them. Neither do they maintain any social relations among themselves. The proud Spaniard despises the creole, and, titled or plebeian, will have[Pg 31] nothing to do with him, beyond the necessary courtesies of business. Then the "nobleman," who has worn his dearly bought honors twenty years, esteems it quite beneath his dignity to exchange civilities with those novi homines, who are but ten years removed from the vulgar atmosphere of common life;—while he, in his turn, is quite too green to stand on a par with those, whose ancestors, for two or three generations back, have been known to fame.

The same impassable distinctions exist among the plebeian grades of society. The Spaniard hates the foreign resident, and will have no intercourse with him, except so far as his interest, in the ordinary transactions of business, requires. He despises the creole, who, in his turn, hates the Spaniard, and is jealous of the foreigner. The result of this position of these antagonist elements of society is, that there is no such thing as general social intercourse among the inhabitants of Cuba, and scarcely any chance at all for the stranger, to be introduced to any society but that of the foreign residents. As these are from almost all nations, the range, for any particular one, is necessarily small.

This being the case, with the constitution of society in Cuba, it would be extremely difficult for a temporary sojourner correctly to delineate the character of its inhabitants, perhaps, even unfair to attempt it. He can never see them, as they see each other. He can rarely learn, from his personal observation, any thing of society, as a whole, though he may often have favorable opportunities of becoming favorably acquainted with individual families. And here, two remarks seem to me to be demanded, before leaving this subject.[Pg 32] First, that in all cases where such marked distinctions, and deeply rooted jealousies exist between the different sections of society, the open slanders and covert insinuations of the one against the other, should be received with the most liberal allowances for prejudice. Envy and contempt are, by their very natures, evil-eyed, uncharitable, and arrant liars. They see through a distorted medium. They judge with one ear always closed. And he who receives their decisions as law will generally abuse his own common sense and good nature, by condemning the innocent unheard. Secondly, if the society which Cuba might enjoy may be judged of by the known urbanity and hospitality of individuals, it might become, by the breaking down of these artificial barriers, the very paradise of patriarchal life. I know of nothing in the world to compare with the free, open-handed, whole-souled hospitality which the merchant, or planter, of whatever grade, lavishes upon those, who are commended to his regard by a respectable introduction from abroad. With such a passport, he is no longer a stranger, but a brother, and it is the fault of his own heart if he is not as much at home in the family, and on the estate of his friend, as if it were his own. There is nothing forced, nothing constrained in all this. It is evidently natural, hearty, and sincere, and you cannot partake of it, without feeling, however modest you may be, that you are conferring, rather than receiving a favor. This remark may be applied, with almost equal force, to many of the planters in our Southern states, and in the other West India Islands. Many and many are the invalid wanderers from home, who have known and felt it, like[Pg 33] gleams of sunshine in their weary pilgrimage, whose hearts will gratefully respond to all that I have said. What a pity then, that such noble elements should always remain in antagonism to each other, instead of amalgamating into one harmonious confraternity, mutually blessing and being blessed, in all the sweet humanizing interchanges of social life.

Much as the inferior grades of society envy and dislike those above them, they all display the same love of show, the same passion for titles, trappings, and badges of honor, whether civil or military, whenever they come within their reach. And when attained, either temporarily or permanently, their fortunate possessors do not fail to look down on those beneath them, with the same supercilious pride and self gratulation, which they so recently condemned in others. I saw some striking, and to me, exceedingly ludicrous developments of this trait of character, during the progress of a festival celebration, in honor of the day, when queen Isabel was declared of age, and all the military and civil powers swore allegiance to her Catholic Majesty. The ceremonies of this celebration were continued through three days. The Plaza, and the quarters of the military, were splendidly illuminated with variegated lamps, and the buildings, public and private, were hung with tapestry and paintings, interspersed with small brilliant lights. Business was entirely suspended, and the streets were thronged with gay excited multitudes, arrayed with every species of finery, and decked with every ornament of distinction, which their circumstances, or position in society, would allow. Reviews of troops, and sham fights on land and sea, in[Pg 34] which the Governor, and all the high dignitaries of the island, took part, occupied a portion of the time, the remainder being filled up with balls, masquerades, and a round of other amusements.

I do not know that it has been remarked by any other writer, but I observed it so often as to satisfy myself that it was a general characteristic of the better classes of the Habañeros, that they have a singular antipathy to water. After a shower of rain, they are seldom seen in the streets, except in their volantes, till they have had time to become perfectly dry. When necessity compels them to appear, they walk with the peculiar circumspection of a cat, picking their way with a care and timidity that often seems highly ludicrous. They are neat and cleanly in their persons, almost to a fault, and it is the fear of contracting the slightest soil upon their dress, that induces this scrupulous nicety in "taking heed to their steps."

CHAPTER II.

PUBLIC BUILDINGS OF HAVANA, AND THE TOMB OF COLUMBUS.

The Tacon Theatre.—The Fish Market.—Its Proprietor.—The Cathedral.—Its adornments.—View of Romanism.—Infidelity.—The Tomb of Columbus.—The Inscription.—Reflections suggested by it.—The Removal of his Remains.—Mr. Irving's eloquent reflections.—A misplaced Monument.—Plaza de Armas.

Among the public buildings in Havana, there are many worthy of a particular description. Passing over the Governor's House, the Intendencia, the Lunatic Asylum, Hospitals, etc., to which I had not time to give a personal inspection, I shall notice only the Tacon Theatre, the Fish Market, and the Cathedral.

The Tacon Theatre is a splendid edifice, and is said to be capable of containing four or five thousand spectators. It has even been stated, that, at the recent masquerade ball given there, no less than seven thousand were assembled within its walls. This building was erected by an individual, at an expense of two hundred thousand dollars. It contains three tiers of boxes, two galleries, and a pit, besides saloons, coffee-rooms, offices, etc., etc. A trellis of gilded iron, by which the boxes[Pg 36] are balustraded, imparts to the house an unusually gay and airy appearance. The pit is arranged with seats resembling arm-chairs, neatly covered, and comfortably cushioned. The Habañeros are a theatre-going people, and bestow a liberal patronage upon any company that is worthy of it.

The Fish Market is an object of no little interest in Havana, not only for the rich variety of beautiful fishes that usually decorate its long marble table, but for the place itself, and its history. It was built during the administration of Tacon, by a Mr. Marti, who, for a service rendered the government, in detecting a gang of smugglers, with whom it has been suspected he was too well acquainted, was permitted to monopolize the sale of fish in the city for twenty years. Having the prices at his own control, he has made an exceedingly profitable business of it, and is now one of the rich men of the island. He is the sole proprietor of the Tacon Theatre, which is one of the largest in the world, and which has also the privilege of a twenty years monopoly, without competition from any rival establishment.

The Fish Market is one hundred and fifty feet in length, with one marble table extending from end to end, the roof supported by a series of arches, resting upon plain pillars. It is open on one side to the street, and on the other to the harbor. It is consequently well ventilated and airy. It is the neatest and most inviting establishment of the kind that I have ever seen in any country; and no person should visit Havana, without paying his respects to it.

The Cathedral is a massive building, constructed in[Pg 37] the ecclesiastical style of the fifteenth century. It is situated in the oldest and least populous part of the city, near the Fish Market, and toward the entrance of the port. It is a gloomy, heavy looking pile, with little pretensions to architectural taste and beauty, in its exterior, though the interior is considered very beautiful. It is built of the common coral rock of that neighborhood, which is soft and easily worked, when first quarried, but becomes hard by exposure to the atmosphere. It is of a yellowish white color, and somewhat smooth when laid up, but assumes in time a dark, dingy hue, and undergoes a slight disintegration on its surface, which gives it the appearance of premature age and decay.

In the interior, two ranges of massive columns support the ceiling, which is high, and decorated with many colors in arabesque, with figures in fresco. The sides are filled, as is usual in Roman Catholic churches, with the shrines of various Saints, among which, that of St. Christoval, the patron of the city, is conspicuous. The paintings are numerous; and some of them, the works of no ungifted pencils, are well worthy of a second look.

The shrines display less of gilding and glitter than is usual in other places. They are all of one style of architecture, simple and unpretending; and the effect of the whole is decidedly pleasing, if not imposing. This effect is somewhat heightened by the dim, uncertain light which pervades the building. The windows are small and high up towards the ceiling, and cannot admit the broad glare of day, to disturb the solemn and gloomy grandeur of the place of prayer.[Pg 38]

It has been observed by residents as well as by strangers, that the attendance on the masses and other ceremonies of the Roman church, has greatly diminished within a few late years. I have often seen nearly as many officiating priests, as worshippers, at matins and vespers. They are attended, as in all other places, chiefly by women, and not, as the romances of the olden time would have us suppose it once was, by the young, the beautiful, the warm-hearted and enthusiastic, but by the old and ugly, so that a looker-on might be led to imagine that the holy place was only a dernier resort, and refuge for those, for whom the world had lost its charms. That there were some exceptions, however, to this remark, my memory and my heart must bear witness—some, whose graceful, voluptuous figures, bent down before their shrines, their beaming faces and keen black eyes scarce hidden by their mantillas, might have furnished a more stoical heart than mine with a very plausible excuse for paying homage to them, rather than to the saints, before whose shrines they were kneeling.

In the various religious orders of this church, there has been a corresponding diminution of numbers and zeal. The convents of friars, in Havana, have been much reduced, and but few young men are found, who are disposed to join them; so that, in another generation, they may become quite extinct, unless their numbers are replenished from the mother country. The Government has taken possession of their buildings, and converted them to other uses, and pensioned off their inmates, allowing a premium to those who would quit the monastic life, and engage in secular business.[Pg 39]

Among the people, infidelity seems to have taken the place of the old superstition. Their holy-days are still kept up, because they love the excitement and revelry, to which they have been accustomed. Their frequent recurrence is a great annoyance to those who have business at the Custom House, and other public offices, while they add nothing to the religious or moral aspect of the place. Sunday is distinguished from the other days of the week, only by the increase of revelry, cock-fighting, gambling, and every other species of unholy employment. These are certainly no improvement upon the customs of other days, for blind superstition is better than profaneness, and ignorance than open vice. But, in one respect, the protestant sojourner in Havana may feel and acknowledge that times have changed for the better, since he is not liable now, as formerly, to be knocked down in the street, or imprisoned, for refusing to kneel in the dirt, when "the host" was passing.

In this Cathedral, on the right side of the great altar, is "The Tomb of Columbus." A small recess made in the wall to receive the bones, is covered with a marble tablet about three feet in length. Upon the face of this is sculptured, in bold relief, the portrait of the great discoverer, with his right hand resting upon a globe. Under the portrait, various naval implements are represented, with the following inscription in Spanish.

Mil siglos durad guardados en la Orna,

Y en la remembranza de nuestra Nacion.

[Pg 40]

On the left side of the high Altar, opposite the tomb, hangs a small painting, representing a number of priests performing some religious ceremony. It is very indifferent as a work of art, but possesses a peculiar value and interest, as having been the constant cabin companion of Columbus, in all his eventful voyages, a fact which is recorded in an inscription on a brass plate, attached to the picture.

The Lines on the tablet may be thus translated into English.

A thousand ages may you endure, guarded in this Urn;

And in the remembrance of our Nation.

Such is the sentiment inscribed on the last resting place of the ashes of the discoverer of a world. An inscription worthy of its place, bating the arrogance and selfishness of the last line, which would claim for a single nation, that which belongs as a common inheritance to the world. It is a pardonable assumption however; for, where is the nation, under the face of heaven, that would not, if it could, monopolize the glory of such a name?

The glory of a name! Alas! that those who win, are so seldom allowed to wear it! Through toil and struggle, through poverty and want, through crushing care and heart-rending disappointments, through seas of fire and blood, and perhaps through unrelenting persecution, contumely and reproach, they climb to some proud pinnacle, from which even the ingratitude and injustice of a heartless world cannot bring them down; and there, alone, deserted and pointed at, like an eagle[Pg 41] entangled in his mountain eyrie, amid the screams and hootings of inferior birds, they die,—bequeathing their greatness to the world, leaving upon the generation around them a debt of unacknowledged obligation, which after ages and distant and unborn nations, shall contend for the honor of assuming forever. The glory of a name! What a miserable requital for the cruel neglect and iron injustice, which repaid the years of suffering and self-sacrifice, by which it was earned!

Columbus died at Valladolid, on the 20th of May, 1506, aged 70 years. His body was deposited in the convent of St. Francisco, and his funeral obsequies were celebrated with great pomp, in the parochial church of Santa Maria de la Antigua. In 1513, his remains were removed to Seville, and deposited, with those of his son, and successor, Don Diego, in the chapel of Santo Christo, belonging to the Carthusian Monastery of Las Cuevas. In 1536, the bodies of Columbus and his son were both removed to the island of Hispaniola, which had been the centre and seat of his vice-royal government in this western world, and interred in the principal chapel of the Cathedral of the city of San Domingo. But even here, they did not rest in quiet. By the treaty of peace in 1795, Hispaniola, with other Spanish possessions in these waters, passed into the hands of France. With a feeling highly honorable to the nation, and to those who conducted the negotiations, the Spanish officers requested and obtained leave to translate the ashes of the illustrious hero to Cuba.

The ceremonies of this last burial were exceedingly magnificent and imposing, such as have rarely been rendered to the dust of the proudest monarchs on earth,[Pg 42] immediately after their decease, and much less after a lapse of almost three centuries. On the arrival of the San Lorenzo in the harbor of Havana, on the 15th of January, 1796, the whole population assembled to do honor to the occasion, the ecclesiastical, civil, and military bodies vying with each other in showing respect to the sacred relics. On the 19th, every thing being in readiness for their reception, a procession of boats and barges, three abreast, all habited in mourning, with muffled oars, moved solemnly and silently from the ship to the mole. The barge occupying the centre of these lines, bore a coffin, covered with a pall of black velvet, ornamented with fringes and tassels of gold, and guarded by a company of marines in mourning. It was brought on shore by the captains of the vessels, and delivered to the authorities. Conveyed to the Plaza de Armas, in solemn procession, it was placed in an ebony sarcophagus, made in the form of a throne, elaborately carved and gilded. This was supported on a high bier, richly covered with black velvet, forty-two wax candles burning around it.

In this position, the coffin was opened in the presence of the Governor, the Captain General, and the Commander of the royal marines. A leaden chest, a foot and a half square, by one foot in height, was found within. On opening this chest, a small piece of bone and a quantity of dust were seen, which was all that remained of the great Columbus. These were formally, and with great solemnity pronounced to be the remains of the "incomparable Almirante Christoval Colon." All was then carefully closed up, and replaced in the ebony sarcophagus.[Pg 43]

A procession was then formed to the Cathedral, in which all the pomp and circumstance of a military parade, and the solemn and imposing grandeur of the ecclesiastical ceremonial, were beautifully and harmoniously blended with the more simple, but not less heartfelt demonstrations of the civic multitude—the air waving and glittering with banners of every device, and trembling with vollies of musketry, and the ever returning minute guns from the forts, and the armed vessels in the harbor. The pall bearers were all the chief men of the island, who, by turns, for a few moments at a time, held the golden tassels of the sarcophagus.

Arrived at the Cathedral, which was hung in black, and carpeted throughout, while the massive columns were decorated with banners infolded with black, the sarcophagus was placed on a stand, under a splendid Ionic pantheon, forty feet high by fourteen square, erected under the dome of the church, for the temporary reception of these remains. The architecture and decorations of this miniature temple, were rich and beautiful in the extreme. Sixteen white columns, four on each side, supported a splendidly friezed architrave and cornice, above which, on each side, was a frontispiece, with passages in the life of Columbus figured in bas-relief. Above this, rising out of the dome of the pantheon, was a beautiful obelisk. The pedestal was ornamented with a crown of laurels, and two olive branches. On the lower part of the obelisk were emblazoned the arms of Columbus, accompanied by Time, with his hands tied behind him—Death, prostrate—and Fame, proclaiming the hero immortal in defiance of[Pg 44] Death and Time. Other emblematic figures occupied the arches of the dome.

The pantheon, and the whole Cathedral, was literally a-blaze with the light of wax tapers, several hundred of which were so disposed as to give the best effect to the imposing spectacle. The solemn service of the dead was chanted, mass was celebrated, and a funeral oration pronounced. Then, as the last responses, and the pealing anthem, resounded through the lofty arches of the Cathedral, the coffin was removed from the Pantheon, and borne by the Field Marshal, the Intendente, and other distinguished functionaries, to its destined resting place in the wall, and the cavity closed by the marble slab, which I have already described.

"When we read," says the eloquent Mr. Irving, "of the remains of Columbus, thus conveyed from the port of St. Domingo, after an interval of nearly three hundred years, as sacred national reliques, with civic and military pomp, and high religious ceremonial; the most dignified and illustrious men striving who should most pay them reverence; we cannot but reflect, that it was from this very port he was carried off, loaded with ignominious chains, blasted apparently in fame and fortune, and followed by the revilings of the rabble. Such honors, it is true, are nothing to the dead, nor can they atone to the heart, now dust and ashes, for all the wrongs and sorrows it may have suffered: but they speak volumes of comfort to the illustrious, yet slandered and persecuted living, showing them how true merit outlives all calumny, and receives it glorious reward in the admiration of after ages."

Near the Quay, in front of the Plaza de Armas, is a[Pg 45] plain ecclesiastical structure, in which the imposing ceremony of the mass is occasionally celebrated. It is intended to commemorate the landing of the great discoverer, and the inscription upon a tablet in the front of the building, conveys the impression that it was erected on the very spot where he first set foot upon the soil of Cuba. This, however, is an error. Columbus touched the shore of Cuba, at a point which he named Santa Catalina, a few miles west of Neuvitas del Principe, and some three hundred miles east of Havana. He proceeded along the coast, westward, about a hundred miles, to the Laguna de Moron, and then returned. He subsequently explored all the southern coast of the island, from its eastern extremity to the Bay of Cortes, within fifty miles of Cape Antonio, its western terminus. Had he continued his voyage a day or two longer, he would doubtless have reached Havana, compassed the island, and discovered the northern continent.

The Plaza de Armas is beautifully ornamented with trees and fountains. It is also adorned with a colossal statue of Ferdinand VII.; and during the evenings, when the scene is much enlivened by the fine music of the military bands stationed in the vicinity, it is the general resort of citizens and strangers;—the former of whom come hither to enjoy the cheering melody of the music and the freshness of the breeze,—the latter, for the purpose of doing homage to the memory of him whose footsteps are supposed to have sanctified the ground. Here, and around the sepulchre of the departed, a holy reverence seems to linger, which attracts the visitor as to "pilgrim shrines," before which he bends with respect and admiration.[Pg 46]

The village of Regla, one of the suburbs of Havana, is situated on the eastern side of the harbor, about a mile from the city, and having constant communication with it, by means of a ferry. It is a place of about six thousand inhabitants, and is the great depot of the molasses trade. Immense tanks are provided to receive the molasses, as it comes in from the neighboring estates. I say the neighboring estates, for the article is of so little value, that it will not pay the expense of transportation from any considerable distance; and very large quantities of it are annually thrown away. In some places you may see the ditches by the road side filled with it. In others, the liquid is given to any who will take it away, though in doing so, they are expected to pay something more than its real value for the hogshead.

The greater part of the molasses that comes to Regla from the interior, to supply the export trade of Havana, is brought in five gallon kegs, on the backs of the mules, one on each side, after the manner of saddle-bags, or panniers. A common mule load is four or six kegs, equal to half, or two-thirds of a barrel. Large quantities are also transported in lighters from all the smaller towns on the coast, much of it coming in that way from a distance of more than a hundred miles. A large proportion of the article shipped from this port hitherto, having been unfit for ordinary domestic uses, and suitable only for the distillery, the trade in it has been greatly diminished by the operation of the mighty Temperance reform, which has blessed so large a portion of our favored land. I have not the means at hand to show the precise results; but will venture to assert,[Pg 47] from personal observation and knowledge of the matter, that the exports of this article from Cuba to this country, for distilling purposes, have fallen off more than one half in the last ten years.

The concentration of this once active and lucrative traffic at Regla, gave it, in former times, the aspect of a busy, thriving place. Now, it looks deserted and poor. It was formerly one of the many resorts of the pirates, robbers, and smugglers, who infested all the avenues to the capital, and carried on their business as a regular branch of trade, under the very walls of the city, and in full view of the custom-house and the castle. Thanks to the energetic administration of Tacon, they have no authorized rendezvous in Cuba now. Regla is consequently deserted. Its streets are as quiet as the green lanes of the country. Its houses are many of them going to decay. Its theatre is in ruins, and the spacious octagonal amphitheatre, once the arena for bull-fighting, the favorite spectacle of the Spaniards, both in Spain and in the provinces, and much resorted to from all quarters in the palmy days of piracy and intemperance, is now in a miserably dilapidated condition; affording the clearest proof of the immoral nature and tendency of the sport, by revealing the character of those who alone can sustain it. Tacon and temperance have ruined Regla.

The only amusement one can now find in Regla, is in listening to the wild and frightful stories of the robbers and robberies of other days. It is scarcely possible to conceive that scenes such as are there described, as of daily, or rather nightly occurrence, could have taken place in a spot now so quiet and secure, and without[Pg 48] any of those dark, mysterious lurking places, which the imagination so easily conjures up, as essential to the successful prosecution of the profession of an organized band of outlaws. The system set in operation by Tacon, is still maintained; and mounted guards are nightly seen scouring the deserted and comparatively quiet avenues, offering an arm of defence to the solitary and timid traveller, and a caution to the evil-disposed, that the stern eye of the law is upon them. Volumes of entertaining history, for those who have the taste to be entertained by the marvellous and horrible, might be written on this spot. And I respectfully recommend a pilgrimage to it, and a careful study of its scenery and topography, to those young novelists and magazine writers, who delight to revel in carnage, and blood, and treachery.

CHAPTER III.

THE SUBURBS OF HAVANA, AND THE INTERIOR OF THE ISLAND.

The Gardens.—The Paseo de Tacon.—Guiness an inviting resort.—Scenery on the route.—Farms.—Hedges of Lime and Aloe.—Orange Groves.—Pines.—Luxuriance of the Soil.—Coffee and Sugar Plantations.—Forests.—Flowers and Birds.—The end of the Road.—Description of Guiness.—The Hotel.—The Church.—The Valley of Guiness.—Beautiful Scenery.—Other Resorts for Invalids.—Buena Esperanza.—The route to it.—Limonar.—Madruga.—Cardenas, etc.—Cuba the winter resort of Invalids.—Remarks of an intelligent Physician.—Pulmonary Cases.—Tribute to Dr. Barton.—The clearness of the Moon.—The beauties of a Southern Sky.—The Southern Cross.

The neighborhood of Havana abounds with pleasant rides, and delightful resorts, in which the invalid may find the sweetest and most delicious repose, as well as invigorating recreation; while the man of cultivated taste, and the devout worshipper of nature, may revel in a paradise of delights. Among the many attractive localities, in the immediate vicinity of the city, the gardens of the Governor and the Bishop are pre-eminent.

Outside the city wall is the "Paseo de Tacon," which is a general resort, not only for equestrians and pedestrians,[Pg 50] but also for visitors in their cumbrous volantes. The stranger will find himself richly rewarded on a visit to this frequented resort. It consists of three ways: the central, and widest, for carriages; and the two lateral, which are shaded by rows of trees and provided with stone seats, for foot passengers. It presents a lively and picturesque scene, crowded as it is with people of all classes, neatly, if not elegantly dressed.

A delightful excursion to Guiness occupies but four or five hours by rail-road. It is much frequented by invalids, as an escape from the monotonous routine of city life, and presents many advantages for the restoration of health, and the gratification of rural tastes and pursuits. Surrounded by luxurious groves of orange and other fruit trees,—by coffee and sugar plantations,—in full view of the table lands, proximating towards the mountains, and enjoying from November till May, a climate unequalled perhaps by any other on the face of the globe; the fortunate visitor cannot but feel that, if earth produces happiness in any of its charmed haunts, "the heart that is humble might hope for it here;" and the invalid, forgetting the object of his pursuit, might linger forever around its rich groves and shady walks. During three months of the year, the thermometer ranges about 80° at sunrise, seldom varying more than from 70° to 88°. Nearer the coast, there is more liability to fever.

In the trip to Guiness, we did not fly over the ground as we often do on some of the rail-roads of our own country, the rate seldom exceeding fifteen miles an hour. And it would be more loss than gain to the passengers to go faster. The country is too beautiful, too[Pg 51] rich in verdure, too luxuriant in fruits and flowers, and too picturesque in landscape scenery, to be hurried over at a breath. Passing the suburbs of the city, and the splendid gardens of Tacon, the road breaks out into the beautiful open country, threading its arrowy way through the rich plantations and thriving farms, whose vegetable treasures of every description can scarcely be paralleled on the face of the earth. The farms which supply the markets of the city with their daily abundance of necessaries and luxuries, occupy the foreground of this lovely picture. They are separated from each other, sometimes by hedges of the fragrant white flowering lime, or the stiff prim-looking aloe, (agave americana,) armed on every side with pointed lances, and lifting their tall flowering stems, like grenadier sentinels with their bristling bayonets, in close array, full twenty feet into the air. Those who have not visited the tropics, can scarcely conceive the luxuriant and gigantic growth of their vegetable productions. These hedges, once planted, form as impenetrable a barrier as a wall of adamant, or a Macedonian phalanx; and wo to the unmailed adventurer, who should attempt to scale or storm those self-armed and impregnable defences.

Within these natural walls, clustered in the golden profusion of that favored clime, are often seen extensive groves of orange and pine apple, whose perennial verdure is ever relieved and blended with the fragrant blossom—loading the air with its perfume, till the sense almost aches with its sweetness—and the luscious fruit, chasing each other in unfading beauty and inexhaustible fecundity, through an unbroken round of summers, that know neither spring time, nor decay. There is[Pg 52] nothing in nature more enchantingly wonderful to the eye than this perpetual blending of flower and fruit, of summer and harvest, of budding brilliant youth, full of hope and promise and gaiety, and mature ripe manhood, laden with the golden treasures of hopes realized, and promises fulfilled. How rich must be the resources of the soil, that can sustain, without exhaustion, this lavish and unceasing expenditure of its nutritious elements! How vigorous and thrifty the vegetation, that never falters nor grows old, under this incessant and prodigal demand upon its vital energies!

It is so with all the varied products of those ardent climes. Crop follows crop, and harvest succeeds harvest, in uninterrupted cycles of prolific beauty and abundance. The craving wants, the grasping avarice of man alone exceeds the unbounded liberality of nature's free gifts.

The coffee and sugar plantations, chequering the beautiful valleys, and stretching far up into the bosom of the verdant hills, are equally picturesque and beautiful with the farms we have just passed. They are, indeed, farms on a more extended scale, limited to one species of lucrative culture. The geometrical regularity of the fields, laid out in uniform squares, though not in itself beautiful to the eye, is not disagreeable as a variety, set off as it is by the luxuriant growth and verdure of the cane, and diversified with clumps of pines and oranges, or colonnades of towering palms. The low and evenly trimmed coffee plants, set in close and regular columns, with avenues of mangoes, palms, oranges, or pines, leading back to the cool and shady mansion of the proprietor, surrounded with its village of thatched[Pg 53] huts laid out in a perfect square, and buried in overshadowing trees, form a complete picture of oriental wealth and luxury, with its painful but inseparable contrast of slavery and wretchedness.

The gorgeous tints of many of the forest flowers, and the yet more gorgeous plumage of the birds, that fill the groves sometimes with melody delightful to the ear, and sometimes with notes of harshest discord, fill the eye with a continual sense of wonder and delight. Here the glaring scarlet flamingo, drawn up as in battle array on the plain, and there the gaudy parrot, glittering in every variety of brilliant hue, like a gay bouquet of clustered flowers amid the trees, or the delicate, irised, spirit-like humming birds, flitting, like animated flowerets from blossom to blossom, and coqueting with the fairest and sweetest, as if rose-hearts were only made to furnish honey-dew for their dainty taste—what can exceed the fairy splendor of such a scene!

But roads will have an end, especially when every rod of the way is replete with all that can gratify the eye, and regale the sense, of the traveller. The forty-five miles of travel that take you to Guiness, traversing about four-fifths of the breadth of the island, appear, to one unaccustomed to a ride through such garden-like scenery, quite too short and too easily accomplished; and you arrive at the terminus, while you are yet dreaming of the midway station, looking back, rather than forward, and lingering in unsatisfied delight among the fields and groves that have skirted the way.

San Julian de los Guiness is a village of about twenty-five hundred inhabitants, and one of the pleasantest in the interior of the Island. It is a place of considerable[Pg 54] resort for invalids, and has many advantages over the more exposed places near the northern shore. The houses in the village are neat and comfortable. The hotel is one of the best in the island. The church is large, built in the form of a cross, with a square tower painted blue. Its architecture is rude, and as unattractive as the fanciful color of its tower.

The valley, or rather the plain of Guiness, is a rich and well watered bottom, shut in on three sides by mountain walls, and extending between them quite down to the sea, a distance of nearly twenty miles. It is, perhaps, the richest district in the island, and in the highest state of cultivation. It is sprinkled all over with cattle and vegetable farms, and coffee and sugar estates, of immense value, whose otherwise monotonous surface is beautifully relieved by clusters, groves, and avenues of stately palms, and flowering oranges, mangoes and pines, giving to the whole the aspect of a highly cultivated garden.

I have dwelt longer upon the description of Guiness, and the route to it, because it will serve, as it respects the scenery, and the general face of the country, as a pattern for several other routes; the choice of which is open to the stranger, in quest of health, or a temporary refuge from the business and bustle of the city.

One of these is Buena Esperanza, the coffee estate of Dr. Finlay, near Alquizar, and about forty miles from Havana. One half of this distance is reached in about two hours, in the cars. The remainder is performed in volantes, passing through the pleasant villages of Bejucal, San Antonio, and Alquizar, and embracing a view of some of the most beautiful portions of Cuba. Limonar,[Pg 55] a small village, embosomed in a lovely valley, a few miles from Matanzas—Madruga, with its sulphur springs, four leagues from Guiness—Cardenas—Villa Clara—San Diego—and many other equally beautiful and interesting places, will claim the attention, and divide the choice of the traveller.

An intelligent writer remarks that, "with the constantly increasing facilities for moving from one part of this island to the other, the extension and improvement of the houses of entertainment in the vicinity of Havana, and the gaiety and bustle of the city itself during the winter months, great inducements are held out to visit this 'queen of the Antilles;' and perhaps the time is not far distant, when Havana may become the winter Saratoga of the numerous travellers from the United States, in search either of health or recreation." He then proceeds to suggest, what must be obvious to any reflecting and observing mind, that those whose cases are really critical and doubtful, should always remain at home, where attendance and comforts can be procured, which money cannot purchase. To leave home and friends in the last stages of a lingering consumption, for example, and hope to renew, in a foreign clime and among strangers, the exhausted energies of a system, whose foundations have been sapped, and its vital functions destroyed, is but little better than madness. In such cases, the change of climate rarely does the patient any good, and particularly if accompanied with the usual advice—to "use the fruits freely." Those, however, who are but slightly affected, who require no extra attention and nursing, but simply the benefit a favorable climate, co-operating with their own prudence in[Pg 56] diet and exercise, and who are willing to abide by the advice of an intelligent physician on the spot, may visit Cuba with confidence, nay, with positive assurance, that a complete cure will be effected. This is the easiest, and, in most cases, the cheapest course that can be pursued, in the earlier stages of bronchial affections.

As a lover of my species, and particularly of my countrymen, so many of whom have occasion to resort to blander climates, to guard against the insidious inroads of consumption, I cannot leave this subject, without making use of my privilege, as a writer, to say a word of an eminent physician, residing in Havana, who enjoys an exalted and deserved reputation in the treatment of pulmonary diseases. I refer to Dr. Barton, a gentleman whose name is dear, not only to the many patients, whom, under providence, he has restored from the verge of the grave, but to as numerous a circle of devoted friends, as the most ambitious affection could desire. His skill as a physician is not the only quality, that renders him peculiarly fitted to occupy the station, where providence has placed him. His kindness of heart, his urbanity of manners, his soothing attentions, his quick perception of those thousand nameless delicacies, which, in the relation of physician and patient, more than any other on earth, are continually occuring, give him a pre-eminent claim to the confidence and regard of all who are brought within the sphere of his professional influence. To the stranger, visiting a foreign clime in quest of health, far from home and friends, this is peculiarly important. And to all such, I can say with the fullest confidence, they will find in him all[Pg 57] that they could desire in the most affectionate father, or the most devoted brother.

In the interior of the island, I observed that the moon displays a far greater radiance than in higher latitudes. To such a degree is this true, that reading by its light was discovered to be quite practicable; and, in its absence, the brilliancy of the Milky Way, and the planet Venus, which glitters with so effulgent a beam as to cast a shade from surrounding objects, supply, to a considerable extent, the want of it. These effects are undoubtedly produced by the clearness of the atmosphere, and, perhaps, somewhat increased by the altitude. The same peculiarities have been observed, in an inferior degree, upon the higher ranges of the Alleghany mountains, and in many other elevated situations, where, far above the dust and mists of the lower world, celestial objects are seen with a clearer eye, as well as through a more transparent medium.

In this region, the traveller from the north is also at liberty to gaze, as it were, upon an unknown firmament, contemplating stars that he has never before been permitted to see. The scattered Nebulæ in the vast expanse above—the grouping of stars of the first magnitude, and the opening of new constellations to the view, invest with a peculiar interest the first view of the southern sky. The great Humboldt observed it with deep emotion, and described it, as one appropriately affected by its novel beauty. Other voyagers have done the same, till the impression has become almost universal, among those who have not "crossed the line," that the southern constellations are, in themselves, more brilliant, and more beautifully grouped, than those of the northern[Pg 58] hemisphere. In prose and poetry alike, this illusion has been often sanctioned by the testimony of great names. But it is an illusion still, to be accounted for only by the natural effect of novelty upon a sensitive mind, and an ardent imagination. The denizen of the south is equally affected by the superior wonders of the northern sky, and expatiates with poetic rapture upon the glories which, having become familiar to our eyes, are less admired than they should be.

If any exception should be made to the above remarks, it should be only with reference to the Southern Cross, which, regarded with a somewhat superstitious veneration by the inhabitants of these beautiful regions, as an emblem of their faith, is seen in all its glory, shedding its soft, rich light upon the rolling spheres, elevating the thoughts and affections of the heart, and leading the soul far beyond those brilliant orbs of the material heavens, to the contemplation of that "Hope, which we have as an anchor of the soul, both sure and steadfast."

It would be an easy task to enlarge upon the wonders of the sky, but how shall man describe the works of Him "who maketh Arcturus, Orion, Pleiades, and the Chambers of the South?"

CHAPTER IV.

GENERAL VIEW OF THE ISLAND OF CUBA, ITS CITIES, TOWNS, RESOURCES, GOVERNMENT, ETC.

Its political importance.—Coveted by the Nations.—National Robbery and Injustice.—Climate of Cuba.—Its Forests and Fruits.—Its great staples, Sugar and Coffee.—Copper mines.—Population.—Extent and surface.—Principal cities.—Matanzas.—Cardenas.—Puerto del Principe.—Santiago de Cuba.—Bayamo.—Trinidad de Cuba.—Espiritu Santo.—Government of the Island.—Count Villa Nueva.—Character and Services of Tacon.—Commerce of Cuba.—Relations to the United States.—Our causes of complaint.—The true interests of Cuba.—State of Education.—Discovery and early history of the Island.

Cuba is the largest, richest, most flourishing, and most important of the West India Islands. In a political point of view, its importance cannot be rated too high. Its geographical position, its immense resources, the peculiar situation, impregnable strength, and capacious harbor of its capital, give to it the complete command of the whole Gulf of Mexico, to which it is the key. It is certainly an anomaly in the political history of the world, that so weak a power as that of Spain, should be allowed to hold so important a post, by the all-grasping,[Pg 60] ambitious thrones of Europe—to say nothing of the United States, where decided symptoms of relationship to old England begin to appear. It has often been found easy, where no just cause of quarrel exists, to make one; and it is a matter of marvel that the same profound wisdom and far-reaching benevolence, that found means to justify an aggressive war upon China, because, in the simplicity of her semi-barbarism, she would not consent to have the untold millions of her children drugged to death with English opium—cannot now make slavery, or the slave trade, or piracy, or something else of the kind, a divinely sanctioned apology for pouncing upon Cuba. That she has long coveted it, and often laid plots to secure it, there is no doubt. That it would be the richest jewel in her crown, and help greatly to lessen the enormous burdens under which her tax-ridden population is groaning, there can be no question. But, the science of politics is deep and full of mysteries. It has many problems which even time cannot solve.

And then, as to these United States—how conveniently might Cuba be annexed! How nicely it would hook on to the spoon-bill of Florida, and protect the passage to our southern metropolis, and the trade of the Gulf. We can claim it by an excellent logic, on the ground that it was once bound closely to Florida, the celebrated de Soto being governor of both; and Spain had no more right to separate them, in the sale and cession of Florida, than she or her provinces had, afterwards, to separate Texas from Louisiana. It is a good principle in national politics, to take an ell where an inch is given, especially when the giver is too weak to resist[Pg 61] the encroachment—and it has been so often practised upon, that there is scarcely a nation on earth that can consistently gainsay it. The annexation fever is up now, and I suggest the propriety of taking all we intend to, or all we want, at a sweep—lest the people should grow conscientious, and conclude to respect the rights of their weaker neighbors.

But, to be serious, let us take warning from the past, and learn to be just, and moderate, in order that we may be prosperous and happy. The epitaph of more than one of the republics of antiquity, might be written thus—ruit sua mole.