HOW TO PRODUCE AMATEUR PLAYS

Copyright, 1917, 1922,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

PREFACE TO THE REVISED EDITION

This book aims to supply the demand for a simple guide to the production of plays by amateurs. During the past decade a number of books dealing with the subject have been published, but these are concerned either with theoretical and educational, or else with limited and, from the practical viewpoint, unessential aspects of the question. In the present manual the author has attempted an altogether practical work, which may be used by those who have little or no knowledge of producing plays.

The book is not altogether limited in its appeal merely to producers; actors themselves and others having to do with amateur producing will find it helpful. The author has added a number of suggestions on a matter which is rapidly becoming of prime importance: the construction of stages and setting, and the manipulation of lighting.

It is always well to bear in mind that no art can be taught by means of books. The chief purpose [pg vi] of this volume is to lay down the elements and outline the technique of amateur producing.

A careful study of it will enable the amateur stage manager to do much for himself which has heretofore been either impossible or attended with dire difficulty.

The plan of the book is simple: each question and problem is treated in its natural order, from the moment an organization decides to "give a play", until the curtain drops on the last performance of it.

This new edition of "How to Produce Amateur Plays" has been revised throughout, and the list of plays in Chapter X completely re-written and brought up to date.

The author acknowledges his indebtedness for suggestions and help, as well as for permission to reproduce diagrams, photographs, and passages from plays, to Mr. T. R. Edwards, Mr. Hiram Kelly Moderwell, Mr. L. R. Lewis, Mr. Clayton Hamilton, Miss Grace Griswold, Miss Edith Wynne Matthison, Mr. Maurice Browne, Miss Ida Treat, Mr. Sam Hume, John Lane Company, Samuel French, Brentano's, and Henry Holt and Company.

March, 1922

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

Preface v

I. Choosing the Play 1

II. Organization 8

III. Choosing the Cast 18

IV. Rehearsing I 22

V. Rehearsing II 48

VI. Rehearsing III 73

VII. The Stage 76

VIII. Lighting 86

IX. Scenery and Costumes 91

X. Selective Lists of Amateur Plays 110

APPENDICES

I. Copyright and Royalty 127

II. A Note on Make-up 130

INDEX 139

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

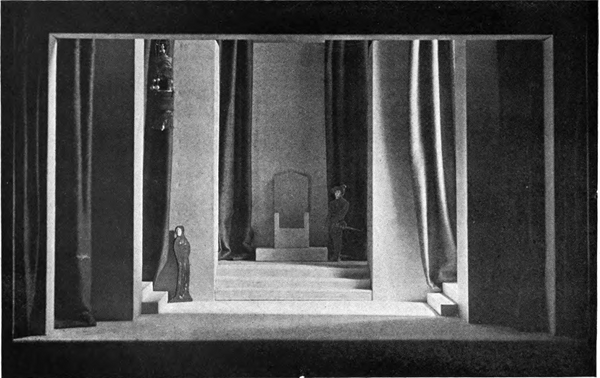

Setting for a Poetic Drama, by Sam Hume Frontispiece

PAGE

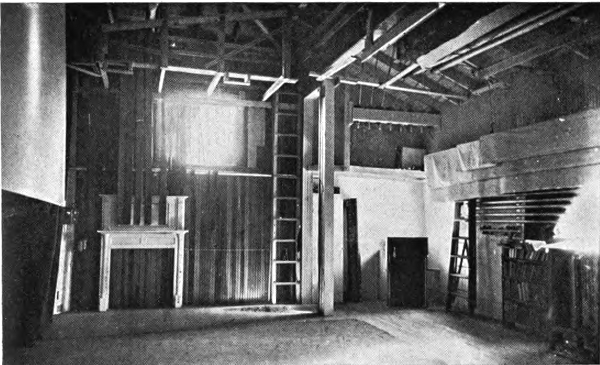

"The Grotesques", by Cloyd Head. Produced at the Little Theater, Chicago 8

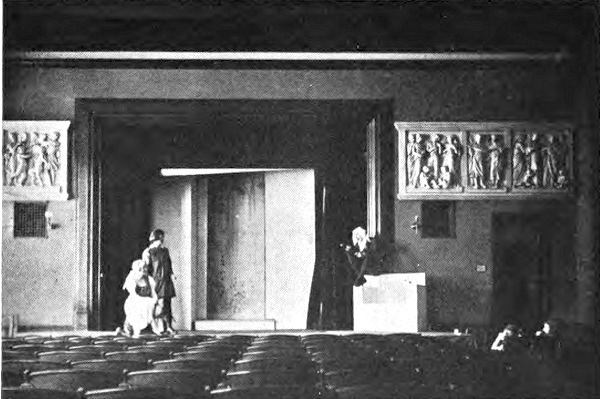

"The Trojan Women" of Euripides. Produced at the Little Theater, Chicago 18

"Captain Brassbound's Conversion", by Shaw. Set of Act I, as Produced by the Neighborhood Playhouse, New York 22

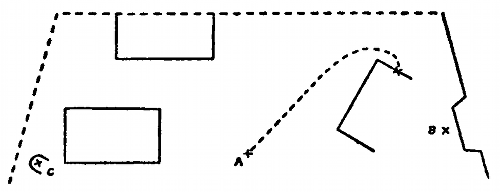

Set for Musset's "Whims." Produced by the Washington Square Players 48

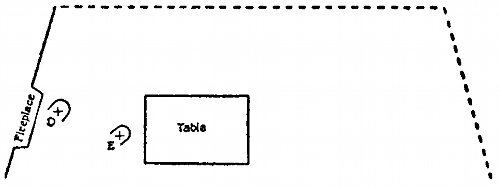

"Sister Beatrice" of Maeterlinck. Produced at the Western Reserve College for Women 74

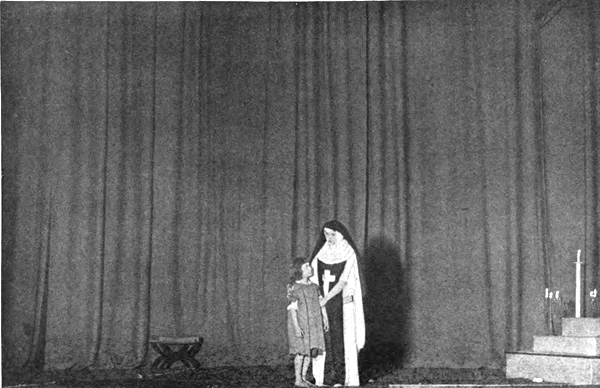

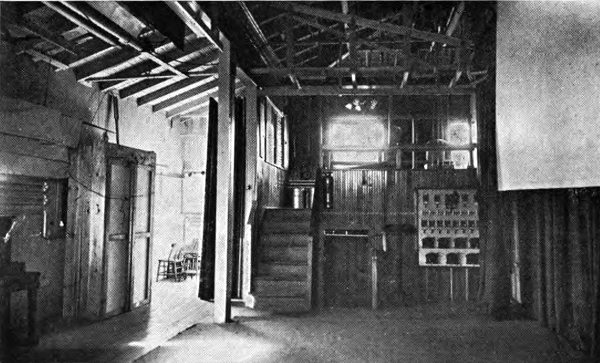

Two Views of the Stage at Tufts College, Showing Plenty of Open Space for the Storing and Shifting of Scenery 76

An Ordinary Box-set. From Dumas fils' "The Money Question." Produced at Tufts College 80

Scenes From Euripides' "Electra." Produced at Illinois State College 90

Two Views of the Stage at the University of North Dakota 106

HOW TO PRODUCE AMATEUR

PLAYS

CHAPTER I

CHOOSING THE PLAY

The first important question arising after the decision to give a play, is "What play?" Only too often is this question answered in a haphazard way. Of recent years a large number of guides to selecting plays have made their appearance, most of which are incomplete and otherwise unsatisfactory. The large lists issued by play publishers are bewildering. Toward the end of the present volume is a selective list of plays, all of which are, in one way or another, "worth while"; but as conditions differ so widely, it is practically impossible to do otherwise than merely indicate in a general way what sort of play is suggested.

[pg 2] Each play considered by any organization should be read by the director or even the whole club or cast, after the requisite conditions have been considered. These conditions usually are:

1. Size of the Cast. This is obviously a simple matter: a cast of ten cannot play Shakespeare.

2. Ability of the Cast. This is a little more difficult. While it is a laudable ambition to produce Ibsen, let us say, no high-school students are sufficiently mature or skilled to produce "A Doll's House." As a rule, the well-known classics—Shakespeare, Molière, Goldoni, Sheridan, Goldsmith—suffer much less from inadequate acting and production than do modern dramatists. The opinion of an expert, or at least of some one who has had experience in coaching amateur plays, should be sought and acted upon. If, for example, "As You Like It" is under consideration, it must be borne in mind that the rôle of Rosalind requires delicate and subtle acting, and if no suitable woman can be found for that part, a simpler play, like "The Comedy of Errors", had much better be substituted. Modern plays are on the whole more difficult: [pg 3] the portrayal of a modern character calls for greater variety, maturity, and skill than the average amateur possesses. The characters in Molière's "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme" ("The Merchant Gentleman"), Shakespeare's "The Comedy of Errors", Sheridan's "The Rivals", are more or less well-known types, and acting of a conventional and imitative kind is better suited to them. On the other hand, only the best-trained amateurs are able to impart the needful appearance of life and actuality to a play like Henry Arthur Jones's "The Liars." Still, there are many modern plays—among them, Shaw's "You Never Can Tell" and Wilde's "The Importance of Being Earnest"—in which no great subtlety of characterization is called for. These can be produced as easily by amateurs as can Shakespeare and Sheridan.

3. The Kind of Play to be presented usually raises many questions which are entirely without the scope of purely dramatic considerations. In this country especially, there is a studied avoidance among schools and often among colleges and universities, of so-called "unpleasant plays." Without entering into the reasons for this aversion, it is rather fortunate, [pg 4] because as a general rule, "thesis", "sex", and "problem" plays are full of pitfalls for amateur actors and producers.

While it is a splendid thing to believe no play too good for amateurs, some moderation is necessary where a play under consideration is obviously beyond the ability of a cast: "Hamlet" ought never to be attempted by amateurs, nor such subtle and otherwise difficult plays as "Man and Superman." Plays of the highest merit can be found which are not so taxing as these. There is no reason why Sophocles' "Electra", Euripides' "Alcestis", or the comedies of Lope de Vega, Goldoni, Molière, Kotzebue, Lessing, not to mention the better-known English classics, should not be performed by amateurs.

It goes without saying that the facile, trashy, "popular" comedies of the past two or three generations are to be avoided by amateurs who take their work seriously. This does not mean that all farces and comedies should be left out of the repertory: "The Magistrate" and "The Importance of Being Earnest" are among the finest farces in the language. The point to be impressed is that it is better to attempt a play which may be more difficult [pg 5] to perform than "Charley's Aunt", than to give a good performance of that oft-acted and decidedly hackneyed piece. It is much more meritorious to produce a good play poorly, if need be, than a poor play well.

If, after having consulted the list in this volume and similar other lists, the club is still unable to decide on a suitable modern play, the best course is to return to the classics. It is likely that the plays that have pleased audiences for centuries will please us. Aristophanes' "The Clouds" and "Lysistrata", with a few necessary "cuts"; Plautus' "The Twins" and Terence's "Phormio"; Goldoni's "The Fan"; Shakespeare's "Comedy of Errors" and half a dozen other comedies; Molière's "Merchant Gentleman" and "Doctor in Spite of Himself"; Sheridan's "The Rivals" and Goldsmith's "She Stoops to Conquer"; Lessing's "Minna von Barnhelm"—almost any one of these is "safe." A classic can never be seen too often and, since true amateurs are those who play for the joy of playing, they will receive ample recompense for their efforts in the thought that they have at least added their mite to the sum total of true enjoyment in the theater. Another argument [pg 6] in favor of the performance of the classics is that they are rarely produced by professionals. If an amateur club revives a classic, especially one which is not often seen nowadays, it may well be proud of its efforts.

If, however, the club insists on giving a modern play, it will have little difficulty in finding suitable material. It is well not to challenge comparison with professional productions by choosing plays which have had professional runs of late; try rather to select (1) good modern plays which by reason of their subject matter, form, etc., cannot under present conditions be commercially successful (like Granville Barker's "The Marrying of Ann Leete"); (2) translations of contemporary foreign plays which are not well known either to American readers or producers; and, finally (3) original plays. Here it is difficult to advise. It cannot be hoped that an amateur club will discover many masterpieces among original plays submitted to it, but if any of the works considered has even a touch of originality, some good characterization, any marked technical skill; in a word, if there is something interesting or promising, then it is worth producing. Doubtless many beginners are discouraged [pg 7] from writing plays for lack of experience gained by seeing their work staged; for such, the amateur club is the only resource.

Besides these particular considerations, there remain the minor but necessary points relating to rights and royalties. A full statement of the legal aspect of the case is to be found in the first appendix in this book.

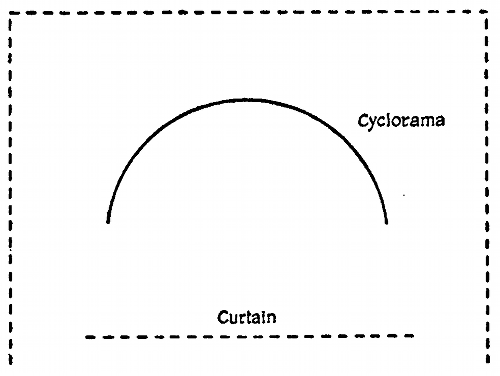

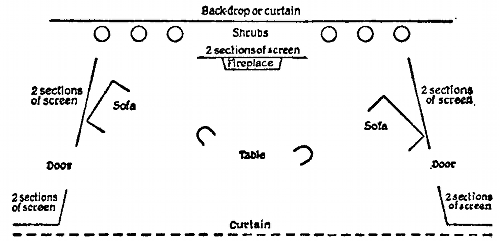

"The Grotesques", by Cloyd Head. Produced at the

Little Theater, Chicago

A shallow cyclorama. The simple design forms an effective background for the grouping of the figures.

(Courtesy of Maurice Browne).

CHAPTER II

ORGANIZATION

A great many more factors go into the making of a successful dramatic production than may at first be apparent. To organize a staff whose duty it is to furnish and equip a theater, hall, or schoolroom; to arrange and efficiently run rehearsals; to supply "props", costumes, and furniture; to manage the stage during the performance—all this is next in importance to the acting itself.

Of late years especially it has been made clear that the art of the theater, although it is a collaboration of the brains and hands of many persons, must be under the supervision of one dominating and far-seeing chief. That is to say, one person and one alone must be responsible for the entire production. Except in rare instances this head cannot know of and attend to each detail himself, but it is his [pg 9] business to see that the whole organization is formed and managed according to his wishes. The function of this ideal manager has been compared with that of the orchestral conductor: it is he who leads, and he should be the first to detect the slightest discord. While the foregoing remarks are more strictly applicable to acting and staging, it will readily be seen that if the same leader is not in touch with the more practical side of the production, there is likely to arise that working at cross-purposes which has ruined many an amateur as well as professional production. While a great deal of the actual work must be done by subordinates, it should be clearly understood that the director has the final word of authority.

Much in the matter of organization depends upon the number and ability and experience of those persons who are available, but the suggestions about to be made as to the organization of a staff are based upon the assumption that the director is a capable person, and his assistants at least willing to learn from him. As a rule, he will have plenty of material to work with.

The Director. The producer, the head under whose guidance the entire work of rehearsing [pg 10] and organization should lie, is called the director. However, since this position is often held by a hired coach or by some one else who cannot be expected to attend to much outside the actual rehearsing, there must be elected or appointed an officer who is directly responsible. This officer is:

The Stage Manager. As the director cannot always be present at every rehearsal, and as oftentimes two parts of the play are rehearsed simultaneously, it is evident that another director must be ready to act in place of the head. It is chiefly his duty to "hold" the prompt-book and keep a careful record of all stage business, "cuts", etc. At every rehearsal he must be ready to prompt, either lines or "business"—action, gestures, crosses, entrances, exits, and the like—and call the attention of the director to omissions or mistakes of every sort. In the event of the director's absence, he becomes the pro tem. director himself.

It is advisable—though not always possible—to delegate the duties of property man, lightman, curtain man, costume man (or wardrobe mistress) to different persons; but even when this is done, it is better for the stage [pg 11] manager to keep a record of all "property plots", "light plots", "furniture plots", etc.

It is also the stage manager's business to arrange the time and place of rehearsals, and hold each actor responsible for attendance.

On the occasion of the dress rehearsal and of the actual production, it is the stage manager, and not the director, who supervises everything. His position is that of commander-in-chief. He either holds the book, or is at least close by the person who actually follows the lines; sees that each actor is ready for his entrance; that the curtain rises and falls when it should; that his assistants are each in their respective places; and that the entire performance "goes" as it is intended to go.

The Business Manager. This person attends to such matters as renting the theater—or arranging some place for the performance—printing and distributing tickets; in short, everything connected with the receipt and expenditure of money. It is not of course imperative that he should have much to do with the director; the only point to be borne in mind being that every one connected with the production of a play should be in touch with those in authority. The business manager [pg 12] ought to have at least a preliminary conference with the director, and report to him every week until a few days before the performance, when he should be within instant call in case of emergency. The property, light, furniture, and costume people must naturally keep in close touch with him, although no purchases should be made without the permission of the director, who in this case must be at one with the club or organization.

The Property Man. The duties attaching to this position are definitely and necessarily limited, but of great importance. Working under the stage manager, he supplies all the objects—such as revolvers, swords, letters, etc.—in a word, everything actually used by the actors, and not falling under the categories of "scenery", "costumes", and "furniture."

It will be found necessary in some cases to add to the staff one person whose business it is to attend to the matter of furnishings: rugs, hangings, pictures, furniture, and so forth; but in case there is no such person, the property man attends to these details himself.

It cannot be too strongly urged that from the very first as many "props", as much furniture [pg 13] or as many set pieces as possible (depending on whether the set is an indoor or outdoor one), should be used by the actors. In this way they will be better able to associate their thoughts, words, and gestures with the material objects with which they will be surrounded on the fatal night. If this is impracticable, that is, if most of these objects cannot be secured from the first, then at least suitable substitutes should be used. The presence of such fundamentally important articles as the wall in Rostand's "The Romancers", and the dentist's chair in Shaw's "You Never Can Tell", when used from the first rehearsals, always minimizes the danger of confusion of lines or business at the last moment.

The property man must keep a list of everything required; this should be a duplicate of that in the possession of the stage manager.

The Lightman. Sometimes even nowadays called the "Gasman." He is not indispensable, because almost always the regular electrician attends to the switchboard. However, some one should be with the electrician at the dress rehearsal and on the evening of the performance to give him the necessary light [pg 14] cues. Usually, however, the stage manager who holds the prompt-book where all the light cues are indicated can fulfill this function.

The Costume Man (or Wardrobe Mistress, as the case may be). Again the duties are simple. If the play is a classic—Shakespeare, for instance,—the costumes, in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred, had better be rented from a regular costumer. The costume man, then, together with the business manager, attends to the details of renting, and sees that all costumes are ready for the dress rehearsal. If the costumes are made to order, the matter is supervised by the costume man. But, as with everything else connected with the best amateur efforts, there should be some expert adviser, not so much one versed in history and archeology as an artist with an eye for color and style. The director in any event must be consulted, so that lights, scenery, and costumes may harmonize. Details as to costumes are to be found in many books, and need not here be discussed. In spite of a good deal that has been written to the contrary, historical accuracy is not of vast importance: so long as there are no glaring anachronisms, Shakespeare may be presented with actors wearing [pg 15] pre- or post-Elizabethan costumes, provided they are beautiful, and harmonize.

Among the thousand and one minor details of producing, there are some which in large productions might be assigned to specially appointed individuals, but most of the duties to be briefly enumerated below may easily be given over to the stage manager, property man, or costume man, or even to the lightman.

Handling and Setting of Scenery and Furniture. This is usually taken care of by the property man and his assistants, under the direction of the stage manager. As in every other branch of the work, all details must be planned beforehand, and recorded.

Music. The music cues should be marked in the stage manager's prompt-book. Incidental music, whether it be on, behind, or off-stage in the orchestra pit, ought to be rehearsed at least two or three times. On the occasion of the performance, the stage manager gives directions from his prompt-book for all music cues.

Crowds or Large Groups. The management and rehearsing of crowds or large groups is considered under "Rehearsing" (p. 58). Here it will suffice to state that it is well to [pg 16] have an assistant whose duty it is to see that the "supes" [supernumeraries] are conducted on and off the stage at the right time.

Among the further details which must be looked after are the duties which are sometimes left to the stage manager: the ringing of bells, calling of actors at the regular performance, etc. A "call boy" may be delegated to do this.

Understudies. Trouble is always likely to arise, especially among amateurs, because there is no effective method of holding the actors to strict account. Often, one or more of the cast finds, or thinks he finds, good reason for leaving it, and a new actor must sometimes be found and trained to fill the vacancy on perilously short notice. Sickness or indisposition invariably give rise to the same problem. If possible, an entire second cast should be trained, so that any member of it could at a moment's notice be called upon to play in the first cast. While this second company should be letter-perfect and know the "business" in every detail, it is not necessary that their acting be so finished and detailed as that of the others. Understudy rehearsals are under the direction of the stage manager, although the director should witness at least two or three.

[pg 17] Since the performance depends almost wholly on the knowledge, sympathy, and taste of the director, the greatest care should be taken in choosing him. Needless to say, the ideal director does not exist; still, his attributes should be constantly borne in mind. If he lacks the artist's sense of color, rhythm, and proportion, then an art adviser must be called in to suggest color schemes as regards costumes, scenery, furniture, and lighting. Nowadays, great attention is being paid to these matters, and the subtle effect of background and detail is much greater than is commonly supposed. The play is of first importance—that must never be forgotten—but these other matters are too often neglected.

Similarly with costumes, music, scenery, it is never amiss to consult authorities. But once more be it repeated, the whole production should bear the imprint of the director's personality, because only in this way can we hope for that essential unity of effect which is a basic principle of all art.

Coöperation with, but, in the last analysis, subserviency to, the director, is the keynote of success.

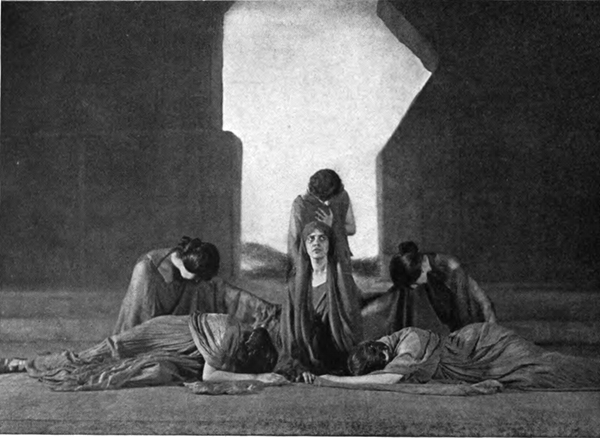

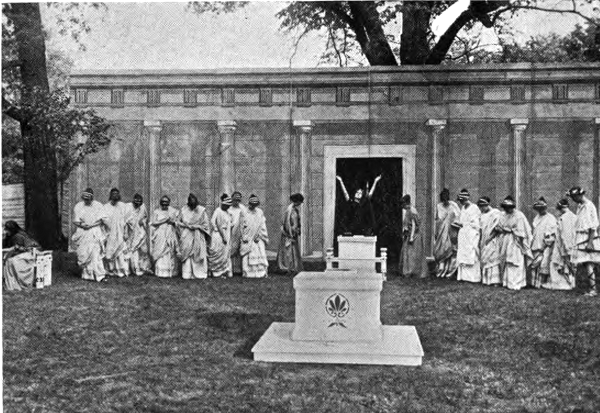

"The Trojan Women", of Euripides. Produced at the

Little Theater, Chicago.

Effective grouping against a simple background. (Courtesy of Maurice Browne).

CHAPTER III

CHOOSING THE CAST

Obviously, the choice of the cast should depend upon the ability of the actors, although in the case of an organization like a school or college dramatic club, this system is not always practicable or even advisable. Every member of such a club should be trained to work for a common end, and a system by which amateurs are made to understand the necessity of assuming first small and unimportant rôles and working up gradually to the greater and more important ones, makes for harmony and completeness of effect in performances. It should be one of the chief ends of amateur producing to get away from the curse of the professional stage: the star system. It has been stated here that the greatest emphasis must be laid on the play itself, and no actor, professional or amateur, should ever labor under the delusion [pg 19] that he is of greater or even as great importance as the play in which he strives to act his part. The average actor is inclined to judge a play's merit according to the sort of part it furnishes him; the amateur spirit has done much to do away with this attitude, and it is to be hoped that no coach will ever do otherwise than discourage it.

Competition as a means of selecting a cast is in most cases the best method. The play once selected, the people from among whom the cast is to be formed are assembled. It is a good plan to have every one read the play first, and make a study of at least one scene of it. Then, either alone or in company with one, two, or three others, he reads—or recites from memory—the scene in question, either before the entire club or before a committee of judges. Each actor is judged on appearance, ease, voice, and insight into the character he is portraying. The judges, seconded possibly by the members of the club (whose votes should, by the way, be of only secondary importance), then select those whom they consider best fitted for the parts. In every case the director should give final sanction to the selection.

In cases where members must at first assume [pg 20] only minor parts because of club rules, there may arise some difficulty: for example, a beginner may be better fitted to assume an important rôle than older club members. Such cases must of course be dealt with individually.

In organizations which are not run on so democratic a basis, the director selects the cast himself. On the whole, this is much the best system, as the director is left a free field in which to work out his own problems in his own way. If it is at all possible, an amateur club ought to put everything, including the responsibility, into the hands of a competent director. In this respect, the despotism of the professional stage is most beneficial. Whether the coach be an outsider hired for the occasion, or a regular member of the club, in nine cases out of ten he will establish and maintain harmony, allow no real talent to languish, and be at least in a position to produce definite artistic results. Amateur management has spoiled much good material. A director with full authority can work more easily and efficiently if left to his own devices than if trammeled with rules and regulations.

The theater, behind the scenes, is a despotic institution; it must be, but the greatest care [pg 21] must be taken in choosing the right despot. Should the coach be a professional manager or actor, or should he be an amateur? The question is a difficult one. There are, it goes without saying, many excellent directors who are or have been professionals; on the other hand, it cannot be denied that some of the best amateur work in this country has been done by directors whose experience on the professional stage has, to say the least, been limited. Some such training is beneficial, but to put a professional of many years' experience in charge of amateurs is likely to make of the amateurs a company of puppets imitating only some of the externals of professionaldom. The best director, therefore, seems to be a person who has some professional experience, but who has likewise dealt with amateurs; one who enters into the amateur spirit, and understands its difference from the professional world, and does not try to train his company to imitate stock actors or "stars."

Understudies may be chosen in the same manner as the first cast.

After the choosing of the casts, the next step is rehearsing. To this complicated process the next three chapters are devoted.

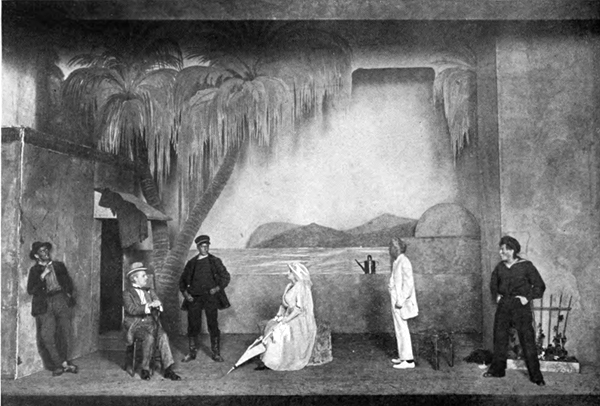

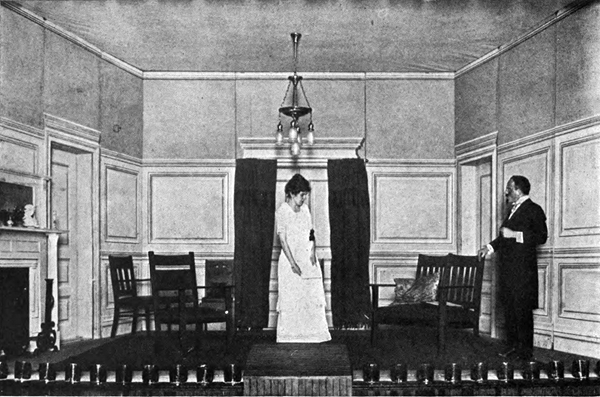

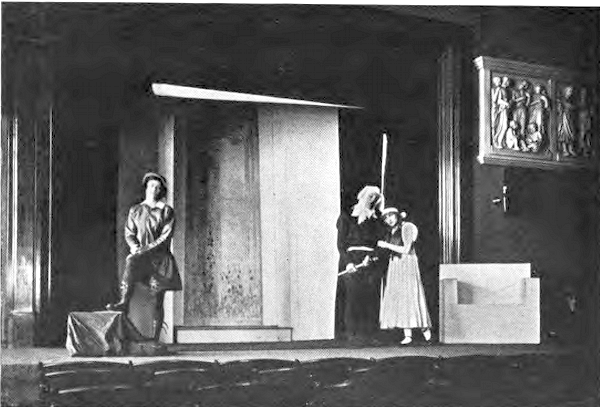

"Captain Brassbound's Conversion", by Shaw. Set of Act I, as produced by the Neighborhood Playhouse, New York.

(Photo by White. Courtesy of Neighborhood Playhouse).

CHAPTER IV

REHEARSING

I

The first rehearsal should be "called" as soon as possible after the cast has been selected and a place chosen in which to work. If the play is to be performed in a regular theater, it is wise to block out the general action and have at least the first two or three rehearsals on the stage. It would be still better if all the rehearsals could be conducted there, but as this is seldom possible, the stage manager should take its dimensions and secure some room as near the size of the stage as he can find. A room too large or too small, or not the requisite shape, is more than likely to confuse the actors. As many of the essential "props" and articles of furniture as possible should be used from the very first, in order to accustom the actors to work under approximately [pg 23] the same conditions as on the occasion of the performance.

If the play can be secured in printed form, each actor will have his copy, and a general reading to the cast by the director or stage manager be rendered unnecessary. However, a few remarks by him as to the nature and spirit of the play will not be amiss. It is not uncommon to hear of professionals who have never read or seen the entire play even after acting in it for many months. Unless each actor knows and feels what the play is about and enters into its spirit, there can be little chance for unity and harmony.

"Cutting", or other alteration, is often necessary. The director should read his alterations and allow each actor to make his text conform with the prompt-copy.

When the play is not obtainable in book form, each rôle is then copied from the manuscript, together with the "cues" and all the stage business. In this case, a general reading to the cast is imperative.

The preliminaries disposed of, the play is read, each actor taking his part. This is merely to familiarize the actors with the play and show them briefly their relation to each [pg 24] other and the work as a whole. At this first rehearsal, there should be no attempt at acting; that is reserved for the next meeting.

At the second rehearsal[1]—which should take place the day after the first—the director blocks out the action. If the play be a full-length one (approximately two hours) then one act of this general blocking out will be found to occupy all the time. If the play is in a single act, and provided it be not too long, then the entire play may be blocked out.

[1] The system here followed must of necessity be arbitrary, but the principle is easy to grasp. A great deal depends on the ability of the actors and the time they can afford.

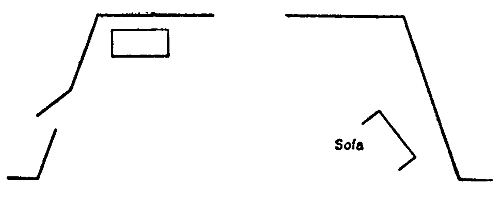

What is "blocking out"? Let us take an easy example and block out the first few minutes' of Wilde's "The Importance of Being Earnest."[2] Here follows the text of the first two and a half pages:

[2] Editions published by French, Putnam, Luce, Nichols, and Baker.

Scene—Morning-room in Algernon's flat in Half Moon Street. The room is luxuriously and artistically furnished. The sound of a piano is heard in the adjoining room.

[LANE is arranging afternoon tea on the table, and after the music has ceased, ALGERNON enters.]

[pg 25] ALGERNON. Did you hear what I was playing, Lane?

LANE. I didn't think it polite to listen, sir.

ALGERNON. I'm sorry for that, for your sake. I don't play accurately—any one can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life.

LANE. Yes, sir.

ALGERNON. And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

LANE. Yes, sir. [He hands them on a salver.]

ALGERNON. [Inspects them, takes two, and sits down on the sofa.] Oh! ... by the way, Lane, I see from your book that on Thursday night, when Lord Shoreman and Mr. Worthing were dining with me, eight bottles of champagne are entered as having been consumed.

LANE. Yes, sir, eight bottles and a pint.

ALGERNON. Why is it that at a bachelor's establishment the servants invariably drink the champagne? I ask merely for information.

LANE. I attribute it to the superior quality of the wine, sir. I have often observed that [pg 26] in married households the champagne is rarely of a first-rate brand.

ALGERNON. Good Heavens! Is marriage so demoralizing as that?

LANE. I believe it is a very pleasant state, sir. I have had very little experience of it myself up to the present. I have only been married once. That was in consequence of a misunderstanding between myself and a young person.

ALGERNON. [Languidly.] I don't know that I am much interested in your family life, Lane.

LANE. No, sir; it is not a very interesting subject. I never think of it myself.

ALGERNON. Very natural, I am sure. That will do, Lane, thank you.

LANE. Thank you, sir. [LANE goes out.]

ALGERNON. Lane's views on marriage seem somewhat lax. Really, if the lower orders don't set us a good example, what on earth is the use of them? They seem, as a class, to have absolutely no sense of moral responsibility. [Enter LANE.]

LANE. Mr. Ernest Worthing. [Enter JACK. LANE goes out.]

ALGERNON. How are you, my dear Ernest? What brings you up to town?

[pg 27] JACK. Oh, pleasure, pleasure! What else should bring me anywhere? Eating as usual, I see, Algy?

ALGERNON. [Stiffly.] I believe it is customary in good society to take some slight refreshment at five o'clock. Where have you been since last Thursday?

JACK. [Sitting down on the sofa.] In the country.

ALGERNON. What on earth do you do there?

JACK. [Pulling off his gloves.] When one is in town one amuses oneself. When one is in the country one amuses other people. It is excessively boring.

ALGERNON. And who are the people you amuse?

JACK. [Airily.] Oh, neighbors, neighbors.

ALGERNON. Got nice neighbors in your part of Shropshire?

JACK. Perfectly horrid! Never speak to one of them.

ALGERNON. How immensely you must amuse them! (Goes over and takes sandwich.) By the way, Shropshire is your county, is it not?

JACK. Eh? Shropshire? Yes, of course. Hallo! Why all these cups? Why such extravagance [pg 28] in one so young? Who is coming to tea?

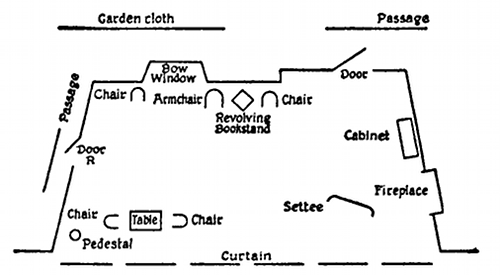

The first point to be noticed is that the stage directions are not sufficient. To begin with, the only information we have as to the morning-room is that it is in Algernon Moncrieff's flat in Half Moon Street, and that it is "luxuriously and artistically furnished." The next directions—"LANE is arranging tea on a table"—prove that there is a tea-table with tea things on it. We are therefore dependent on the ensuing dialogue and the implied or briefly described action to furnish clues as to the entrances, furniture, and "props" which will be required in the course of the act. It is, of course, the director's and the stage manager's business to go through the play beforehand, and have all these points well in mind. Let us now see how this is done, and proceed to block out the first part of the play.

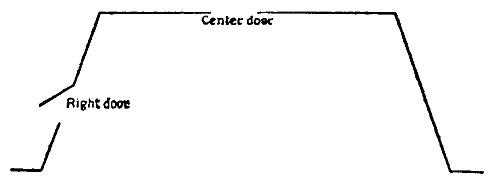

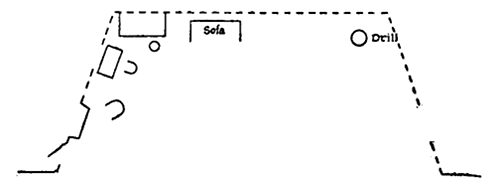

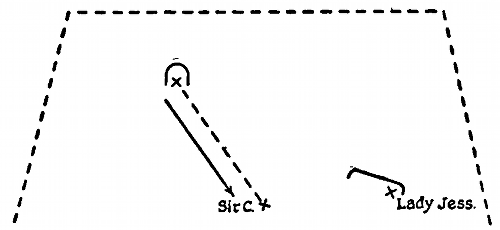

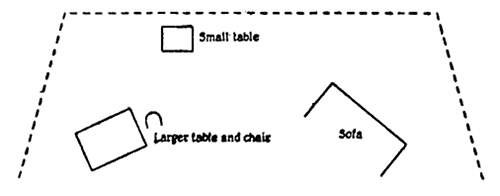

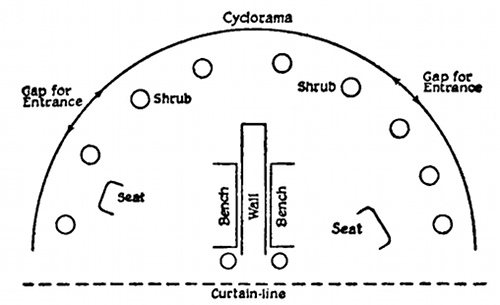

The room evidently at least has two doors: one leading into the hallway—up-stage Center—the other halfway down-stage Right,[3] let us say for the present, as in the diagram:

[3] Right and Left in stage directions mean from the actors' point of view. Up-stage and down-stage mean respectively away from and toward the footlights.

Before Algernon's entrance, Lane, the butler, is preparing tea. Where is the table? Some subsequent business may necessitate its being in a position different from the one first chosen, but let us assume that it is up-stage to the right:

There it is not likely to be in the way of the actors; furthermore, it is not on the same side of the stage as the sofa—which is the next article of furniture to be placed. If the table and the sofa and the door were all on the same side of the stage, it would be much too crowded, especially as the larger part of the subsequent action revolves about them.

[pg 30] Lane, then, is busied with the tea things for a moment, as and after the curtain rises. Then the music of a piano is heard off-stage to the right. It stops, and a moment later Algernon enters. As he evidently has nothing in particular to do at that moment, he may stand at the center of the stage, facing Lane, who stops his work and respectfully answers his master's questions. When Algernon says: "And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?", what more natural than that he should look in the direction of the table, and perhaps even make a step toward it? Lane then goes to the table, takes up the salver with the sandwiches on it, and hands it to Algernon. Here there are no other directions than "Hands them on salver." The other "business" is inferred from the dialogue. Algernon then "Inspects them, takes two, and sits down on the sofa."

This is the first reference to the sofa. The original prompt-copy must, of course, have made clear exactly where each article of furniture stood, but, for the reasons above enumerated, let us place the sofa as in the diagram:

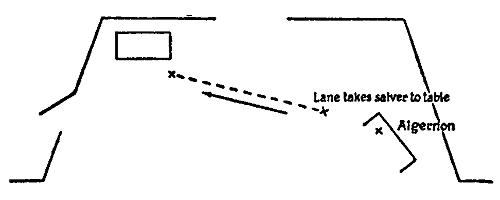

Notice now that nothing is said of the salver. But from the direction near the top of page 3—(Luce and Baker editions) "Goes over and takes sandwich"—we may assume that Lane takes the salver back to the table. Undoubtedly, he does this as Algernon sits on the sofa. This stage direction should be indicated in the prompt-copy, as well as in that of the actor playing Lane, as follows:

As soon as Lane has done this, or even before, Algernon resumes his conversation, while Lane turns and listens to him. Lane stands somewhere between the table and the sofa, [pg 32] at a respectful distance from Algernon. The next "business" occurs when Algernon says "That will do, Lane, thank you", and Lane replies "Thank you, sir", and goes out. This brings up another question which is not answered, as yet at least, in the text. Does Lane go out Right? Possibly; or is there another entrance Left, leading to the butler's room? So far as we are able to determine, there is no good reason why the room to the right, where Algernon was playing, should not lead to the butler's room, or to wherever he is supposed to go. And in this case, there is no reason why Lane cannot, during Algernon's soliloquy, have heard the doorbell ring, answered it, and been ready to reënter, announcing, as he does: "Mr. Ernest Worthing." Jack then enters, Right. Although again there is no stage direction, it is likely that Algernon rises to greet his friend and shake hands with him.

Once more, the stage directions, or rather the want of them, are apt to confuse. On the top of page 3, we read that Jack pulls "off his gloves." He wears a hat, of course, and probably a coat. He carries his hat in his hand, but presumably still wears his coat, [pg 33] and certainly his gloves. Lane, before he leaves, would undoubtedly take Jack's hat, help him off with his coat, and take them out with him. Then, before the two men shake hands—if they do—Jack pulls off his gloves. Jack's line, "Eating as usual, I see, Algy," is sufficient indication to prove that in one hand Algernon holds a sandwich. Algernon then sits down. The dramatist would surely have mentioned Jack's sitting down if that had been his intention; therefore Jack may stand. Now comes the direction about Jack's "Pulling off his gloves." What does he do with them? For the present, at least, let us allow him to go to the tea table, and lay them on it. A moment later, Algernon "Goes over and takes sandwich." He stands by the table, eating, and this attracts Jack's attention to the somewhat elaborate preparations for tea. Algernon then says: "By the way, Shropshire is your county, is it not?" But Jack, too engrossed in the preparations, scarcely hears the other, and answers: "Eh? Shropshire? Yes, of course," and so on. Then he evidently goes to the tea table.

This is the general method of attack to be pursued. It may be that later in the same [pg 34] scene it will be necessary to go back and undo some of the "business", because the only available text of this play—and this is almost always true of printed plays—is not in prompt-copy form. The making, therefore, of a prompt-copy is a slow process. First, the director goes through the play and plans in a general way what the action is to be, but only by rehearsing his cast on a particular stage and under specific conditions, is he able to know every detail of the action. By the time the actors are letter-perfect, the prompt-copy ought likewise to be fairly perfect. It is always dangerous to change "business" after the actors have memorized their parts.

During this preliminary blocking-out process, little or no attention need be paid to details: the mere outlining of the action, together with the reading of the lines by the actors, is sufficient.

Sometimes printed plays suffer from too many stage directions, and occasionally even the careful Bernard Shaw, as the following extract will prove, is far from clear. Here are the opening pages of "You Never Can Tell":[4]

[4] Published separately by Brentano's.

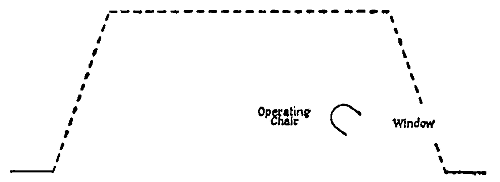

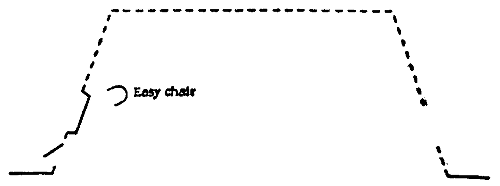

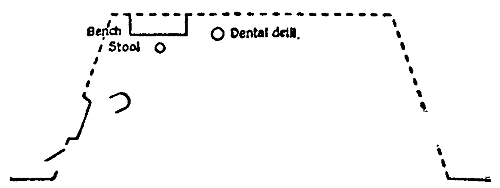

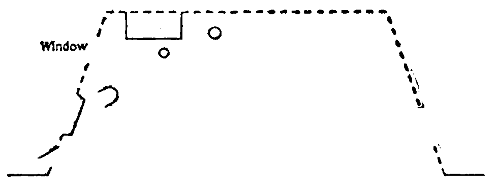

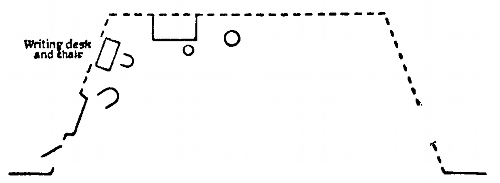

In a dentist's operating room on a fine August morning in 1896. Not the usual tiny London den, but the best sitting-room of a furnished lodging in a terrace on the sea front at a fashionable watering place. The operating chair, with a gas pump and cylinder beside it, is half way between the center of the room and one of the corners. If you look into the room through the window which lights it, you will see the fireplace in the middle of the wall opposite you, with the door beside it to your left; an M.R.C.S. diploma in a frame hung on the chimneypiece; an easy chair covered in black leather on the hearth; a neat stool and bench, with vice, tools, and a mortar and pestle in the corner to the right. Near this bench stands a slender machine like a whip provided with a stand, a pedal, and an exaggerated winch. Recognizing this as a dental drill, you shudder and look away to your left, where you can see another window, underneath which stands a writing table, with a blotter and a diary on it, and a chair. Next the writing table, towards the door, is a leather covered sofa. The opposite wall, close on your right, is occupied mostly by a bookcase. The operating chair is under your nose, facing you, with the cabinet of instruments handy to it on your left. [pg 36] You observe that the professional furniture and apparatus are new, and that the wall paper, designed, with the taste of an undertaker, in festoons and urns, the carpet with its symmetrical plans of rich, cabbagy nosegays, the glass gasalier with lustres, the ornamental, gilt-rimmed blue candlesticks on the ends of the mantelshelf, also glass-draped with lustres, and the ormolu clock under a glass cover in the middle between them, its uselessness emphasized by a cheap American clock disrespectfully placed beside it and now indicating 12 o'clock noon, all combine with the black marble which gives the fireplace the air of a miniature family vault, to suggest early Victorian commercial respectability, belief in money, Bible fetichism, fear of hell always at war with fear of poverty, instinctive horror of the passionate character of art, love and the Roman Catholic religion, and all the first fruits of plutocracy in the early generations of the industrial revolution.

There is no shadow of this on the two persons who are occupying the room just now. One of them, a very pretty woman in miniature, her tiny figure dressed with the daintiest gaiety, is of a later generation, being hardly eighteen yet. This darling little creature clearly does not belong [pg 37] to the room, or even to the country; for her complexion, though very delicate, has been burnt biscuit color by some warmer sun than England's; and yet there is, for a very subtle observer, a link between them. For she has a glass of water in her hand, and a rapidly clearing cloud of spartan obstinacy on her tiny firm mouth and quaintly squared eyebrows. If the least line of conscience could be traced between those eyebrows, an Evangelical might cherish some faint hope of finding her a sheep in wolf's clothing—for her frock is recklessly pretty—but as the cloud vanishes it leaves her frontal sinus as smoothly free from conviction of sin as a kitten's.

The dentist, contemplating her with the self-satisfaction of a successful operator, is a young man of thirty or thereabouts. He does not give the impression of being much of a workman: his professional manner evidently strikes him as being a joke; and it is underlain by a thoughtless pleasantry which betrays the young gentleman still unsettled and in search of amusing adventures, behind the newly set-up dentist in search of patients. He is not without gravity of demeanor; but the strained nostrils stamp it as the gravity of the humorist. His eyes are clear, [pg 38] alert, of sceptically moderate size, and yet a little rash; his forehead is an excellent one, with plenty of room behind it; his nose and chin cavalierly handsome. On the whole, an attractive, noticeable beginner, of whose prospects a man of business might form a tolerably favorable estimate.

THE YOUNG LADY (handing him the glass). Thank you. (In spite of the biscuit complexion she has not the slightest foreign accent.)

THE DENTIST (putting it down on the ledge of his cabinet of instruments). That was my first tooth.

THE YOUNG LADY (aghast). Your first! Do you mean to say that you began practising on me?

THE DENTIST. Every dentist has to begin on somebody.

THE YOUNG LADY. Yes: somebody in a hospital, not people who pay.

THE DENTIST (laughing). Oh, the hospital doesn't count. I only meant my first tooth in private practice. Why didn't you let me give you gas?

THE YOUNG LADY. Because you said it would be five shillings extra.

THE DENTIST (shocked). Oh, don't say that. It makes me feel as if I had hurt you for the sake of five shillings.

[pg 39] THE YOUNG LADY (with cool insolence). Well, so you have! (She gets up.) Why shouldn't you? it's your business to hurt people. (It amuses him to be treated in this fashion; he chuckles secretly as he proceeds to clean and replace his instruments. She shakes her dress into order, looks inquisitively about her; and goes to the window.) You have a good view of the sea from these rooms! Are they expensive?

THE DENTIST. Yes.

THE YOUNG LADY. You don't own the whole house, do you?

THE DENTIST. No.

THE YOUNG LADY (taking the chair which stands at the writing table and looking critically at it as she spins it round on one leg). Your furniture isn't quite the latest thing, is it?

THE DENTIST. It's my landlord's.

THE YOUNG LADY. Does he own that nice comfortable Bath chair? (pointing to the operating chair).

THE DENTIST. No: I have that on the hire-purchase system.

THE YOUNG LADY (disparagingly). I thought so. (Looking about her again in search of further conclusion.) I suppose you haven't been here long?

[pg 40] THE DENTIST. Six weeks. Is there anything else you would like to know?

THE YOUNG LADY (the hint quite lost on her). Any family?

Shaw's stage directions here are more than sufficient: they are intended not only for the director, stage manager, property man, scene painter, and actor, but for the reader as well. His directions are always stimulating and suggestive, and should be studied by the actors; but, from the point of view of the director and stage manager, they are bewilderingly diffuse and sometimes confusing. The fact, for instance, that the action takes place precisely in 1896, can be of little interest to the manager. Nor can a clock indicate twelve o'clock "noon." In such stage directions as these the director will therefore have to separate the purely mechanical elements from the literary and atmospheric. Let us now apply ourselves to the rather difficult task of making a diagram of the stage and its settings.

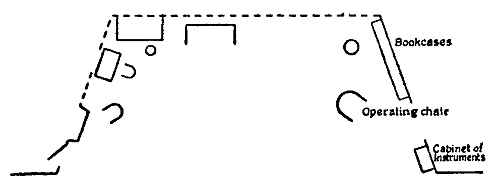

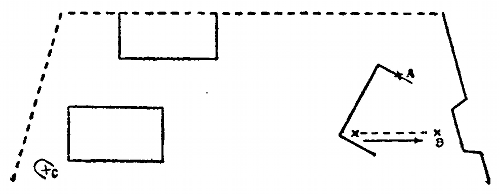

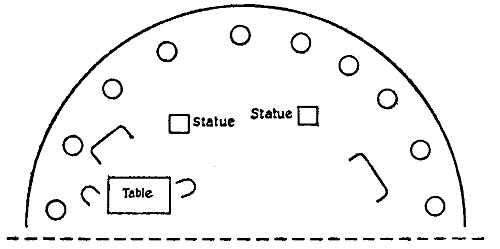

It is a "fine August morning." The sun is shining out-of-doors and, as the room looks out over the sea, the stage must be lighted through one of the windows. The dramatist [pg 41] goes on to say that the room is "Not the usual tiny London den, but the best sitting room of a furnished lodging." By inference, it is a large room. The operating chair is "half way between the center of the room and one of the corners." Which corner is not designated. Let us try to plot out the stage on the assumption that we are looking at it through a window halfway down-stage on the left (the actor's left, of course). The window which lights the room is placed thus:

Looking through this window, "you will see the fireplace in the middle of the wall opposite you, with the door beside it to your left":

[pg 42] The next article of furniture mentioned is the easy chair "on the hearth":

Then come "a neat stool and bench" and, near them, a dental drill:

"Near it" is not definite, but for the time being, let us allow it to stand up-stage near the stool and bench, but a little toward Center. Next, you "look away to your left, where you can see another window." The direction here is not practicable, but the window may well go above the fireplace, instead of below, thus:

Underneath this window stands a writing table and a chair:

"Next the writing table, towards the door, is a leather covered sofa." To add another article of furniture to this already crowded side of the stage would not only make the room appear unnatural to the audience, but would render it impossible for the actors to move about with ease. The director will therefore have to use his ingenuity and judgment as to where to put the sofa. Some subsequent "business" may necessitate a change of the disposition of more than one chair or sofa or stool, but the process here outlined is the first [pg 44] step. To proceed: the sofa, then, must be placed somewhere else. But where? By moving the drill to the left, in the corner, the sofa can be placed next to the table, as follows:

"The opposite wall, close on your right, is occupied mostly by a bookcase. The operating chair is under your nose, facing you, with the cabinet of instruments handy to it on your left."

It is at once observed how necessary it was to move the drill from the other side of the room to this: over by the table, it would be out of convenient reach of the dentist.

[pg 45] The difficulty of arranging the stage in this case will at once prove the imperative need of going through the play with the utmost attention to stage directions and lines, in order to make an accurate series of stage diagrams, property, light, and furniture plots.

Notice that in the preliminary stage directions the center entrance is not designated. It soon becomes evident, however, that a center door (or one, at least, at the back of the stage) is taken for granted.

This elementary diagram will serve as a working basis. A very little rehearsing will soon make it necessary to arrange the furniture, and so on, in a manner more pleasing to the eye and more convenient to the actor.

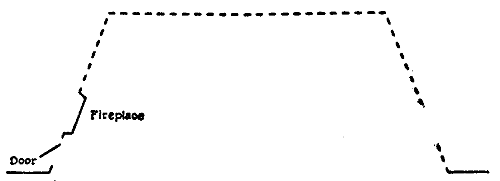

There is one more kind of text with which amateurs have to do: it is the reprint of [pg 46] actual prompt-copies, and is usually accurate in material details. The following extract is from the opening pages of the fourth act of Henry Arthur Jones's "The Liars" (in the special edition published by Samuel French):

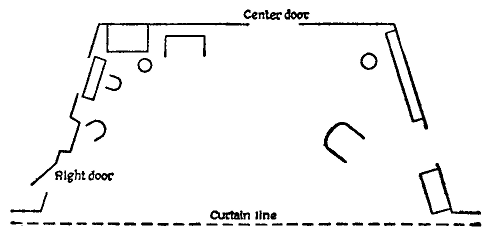

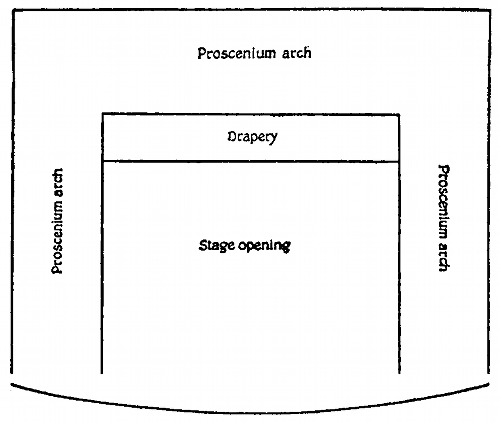

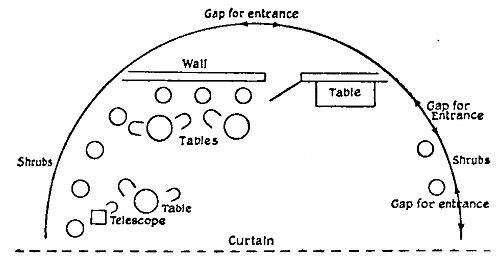

Scene: Drawing-room in Sir Christopher's flat in Victoria Street. L. at back is a large recess, taking up half the stage. The right half is taken up by an inner room furnished as library and smoking-room. Curtains dividing library from drawing-room. Door up-stage, L. A table down-stage, R. The room is in great confusion, with portmanteau open, clothes, etc., scattered over the floor; articles which an officer going to Central Africa might want are lying about.

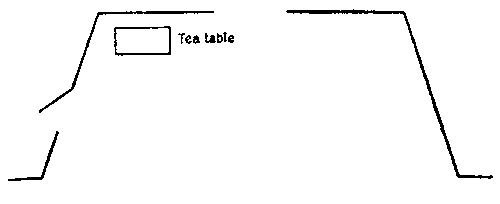

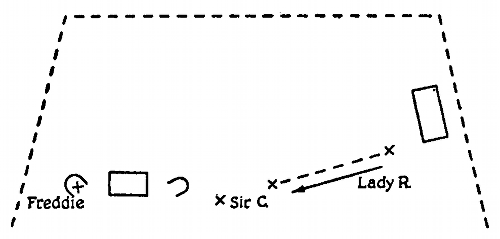

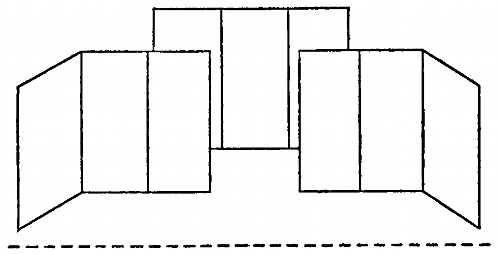

The diagram, as given in the text, is this:

[pg 47] This is merely a skeleton, as it were, of a diagram, but first, the preliminary stage directions—quoted above—and the detailed and full marginal and other stage directions in the text, make clear every crossing, entrance, and exit, and designate at least the important articles of furniture and "props." For example, it is learned from the text on the first and second pages of the act, that there is a uniform case "up-Center"—up-stage, that is, in the center of it; a folding stool by the table; a trunk to the left of Center; and a sofa on the extreme left. Unlike the quotations from the Wilde and Shaw plays, those of Jones supply all necessary information to the stage manager and the actors. Of course, as always, modifications must be made to meet the exigencies of certain stages and certain actors, but these are minor matters.

The fundamental principles of this preliminary blocking-out having been laid down, we shall now proceed to a consideration of the infinitely varied problems of grouping and detailed stage business.

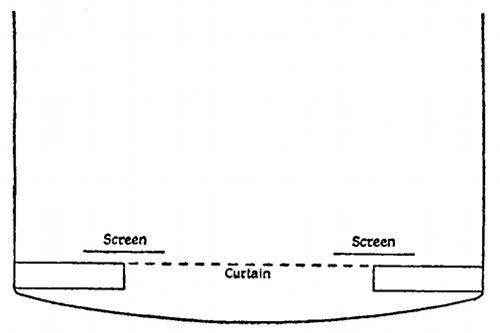

Set for Musset's "Whims", produced by The Washington Square Players.

(Courtesy of The Washington Square Players).

CHAPTER V

REHEARSING

II

While it is true that the possibilities of variation in the matter of grouping, crossing, and so on, are infinite, still there are some definite principles to be followed.

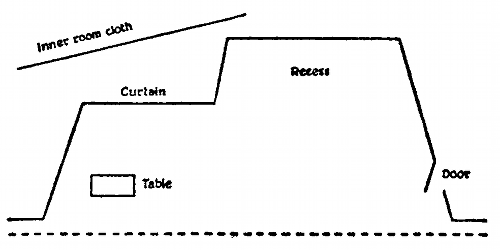

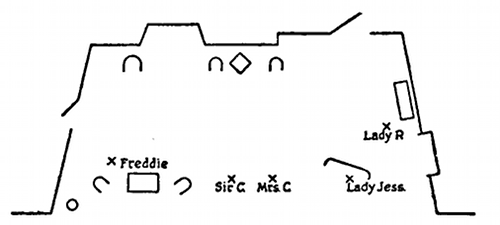

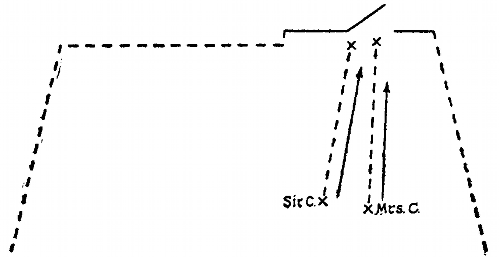

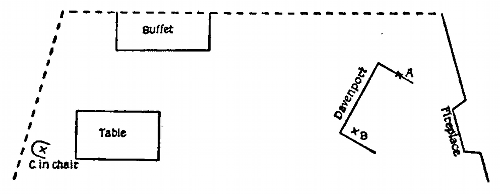

Suppose that the blocking-out process is over with, and the actors have a fair idea of their entrances, positions, business, and exits. The two following extracts (the first from the third act of Jones's "The Liars", the second from Edouard Pailleron's "The Art of Being Bored") serve to illustrate two ways of going about the problem of grouping actors on the stage. The first contains specific directions, the second only the merest suggestions. Below is the diagram of the stage in the third act of "The Liars":

Up to page 107, which is reproduced on page 50, the characters are grouped as indicated:

Following carefully the stage directions in the text and on the margin, the action is traced as follows:

Mrs. Crespin shakes hands with Sir Christopher. Then (marginal note) "Sir C. opens door L. for Mrs. Crespin":

(Exit Mrs. Crespin.[5] They all stand looking at each other, nonplussed. Sir Christopher slightly touching his head with perplexed gesture.)

[5] Sir C. opens door L. for Mrs. Crespin; after her exit, closes door. They all turn and look at Sir C. He sinks into a chair up C., and shakes his head at them.

Sir C.

Our fib won't do.

Lady R.

Freddie, you incomparable nincompoop!

Freddie.

I like that! If I hadn't asked her, what would have happened? George Nepean would have come in, you'd have plumped down on him with your lie, and what then? Don't you think it's jolly lucky I said what I did?[6]

[6] Lady Jess. sits L.C. Sir Chris. puts hat on bookcase C., and comes down C.

Sir C.

It's lucky in this instance. But if I am to embark any further in these imaginative enterprises, I must ask you, Freddie, to keep a silent tongue.

Freddie.

What for?

Sir C.

Well, old fellow, it may be an unpalatable truth to you, but you'll never make a good liar.[7]

[7] Lady R. and Lady Jess. agree with Sir C.

Freddie.

Very likely not. But if this sort of thing is going on in my house, I think I ought to.

Lady R.[8]

[8] Crosses to him C. Freddie sits R.C. annoyed.

Oh, do subside, Freddie, do subside!

Lady J.[9]

[9] 5th call. George.

Yes, George—and perhaps Gilbert—will be here directly. Oh, will somebody tell me what to do?

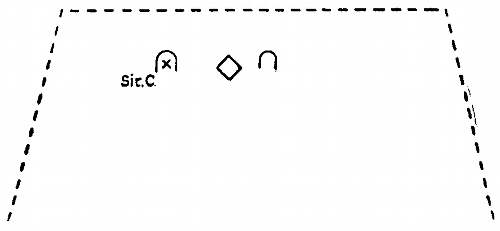

[pg 51] Then, "after her exit, closes door. They all turn and look at Sir C. He sinks into a chair and shakes his head at them." Into which chair does he sink? Since in a moment he must put his hat on the bookcase, Center, he had better sit on the chair to the right of it:

Then, at the end of Freddie's speech, "Lady Jess. sits L.C. [left of Center]. Sir Chris. puts hat on bookcase C., and comes down C."

The last speech of Lady Rosamund on this page is accompanied by the following stage [pg 52] direction: "Crosses to him [Sir Christopher] C. Freddie sits R.C. annoyed."

This is very simple, but only in the rarest instances are stage directions so carefully worked out and indicated. The director will usually be confronted by long pages where there are few or no definite or dependable directions. The original text of Shakespeare affords us only the most elementary explanations of stage "business", so that when Shakespeare is produced it is wisest to use one of the many stage editions, in which the traditional directions, or others equally good, are given at some length. Usually, however, the director will be aided by directions which are fairly full and fairly accurate, but never quite dependable. The following excerpt—from "The Art of Being Bored"—contains the [pg 53] ordinary sort of directions, the kind that are found in good plays and bad. The set is described in the first act as being:

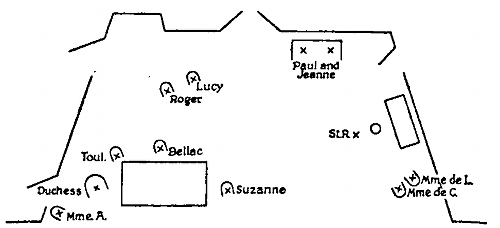

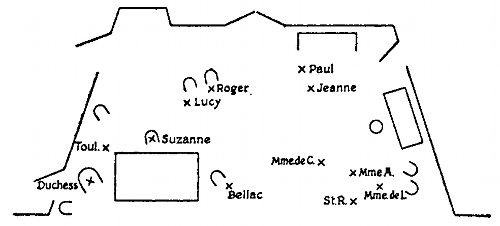

"A drawing-room, with a large entrance at the back, opening upon another room. Entrances up- and down-stage. To the left, between the two doors, a piano. Right, an entrance down-stage; farther up, a large alcove with a glazed door leading into the garden; a table, on either side of which is a chair; to the right, a small table and a sofa; arm-chairs, etc."

This may be plotted in the following manner:

There are no specific directions as to the position of the sofa and chairs, but as a large number of characters are on the stage at one time, a great many will be necessary. The exact number of chairs, as well as the positions they will have to occupy, depend largely on [pg 54] the size and shape of the stage. The above diagram will serve at first as a working basis. Turning to the opening of the second act, we find the following directions:

(Same as Act 1.

(Bellac, Toulonnier, Roger, Paul Raymond, Madame de Céran, Madame de Loudan, Madame Arriégo, the Duchess, Suzanne, Lucy, Jeanne seated in a semi-circle, listening to Saint-Réault, who is finishing his lecture).

SAINT-RÃAULT. And, make no mistake about it! Profound as these legends may appear because of their baffling exoticism, they are merely—my illustrious father wrote in 1834—elemental, primitive imaginings in comparison with the transcendental conceptions of Brahmin lore, gathered together in the Upanishads, or indeed in the eighteen Paranas of Vyasa, the compiler of the Vedda.

JEANNE (aside to Paul). Are you asleep?

PAUL. No, no—I hear some kind of gibberish.

SAINT-RÃAULT. Such, in simple terminology, is the concretum of the doctrine of Buddha.—And at this point I shall close my remarks.

(Murmurs. Some of the audience rise).

Here two or three—Bellac and Roger, and one of the ladies, let us say—rise, and chat in undertones in a small group among themselves.

SEVERAL VOICES (weakly). Very good! Good!

SAINT-RÃAULT. And now—(He coughs).

MADAME DE CÃRAN (eagerly). You must be tired, Saint-Réault?

At this, Madame de Céran might well rise, as if to put an end to Saint-Réault's speech. The others are impatient, and perhaps one or two start to rise. The others whisper, or appear to do so. Then Saint-Réault continues:

SAINT-RÃAULT. Not at all, Countess!

MADAME ARRIÃGO. Oh, yes, you must be; rest yourself. We can wait.

It is likely that here Madame Arriégo would [pg 56] rise and go to Saint-Réault. Two or three others would follow her.

SEVERAL VOICES. You must rest!

MADAME DE LOUDAN. You can't always remain in the clouds. Come down to earth, Baron.

SAINT-RÃAULT. Thank you, but—well, you see, I had already finished.

(Everybody rises).

Saint-Réault's audience may then form into small groups, somewhat as follows:

Care must be taken not to give the stage a crowded appearance, nor yet an air of too well-ordered symmetry. To continue:

SEVERAL VOICES. So interesting!—A little obscure!—Excellent!—Too long!

BELLAC (to the ladies). Too materialistic!

[pg 57] PAUL (to Jeanne). He's bungled it.

SUSANNE (calling). Monsieur Bellac!

BELLAC. Mademoiselle?

SUSANNE. Come here, near me.

(Bellac goes to her).

ROGER (aside to the Duchess). Aunt!

The direction "aside to the Duchess" shows that (1) Roger, after the company rose, either went to the Duchess; or that, (2) meantime he goes to her. This may be done either way, so long as the two are within reasonable whispering distance.

DUCHESS (aside to Roger). She's doing it on purpose!

SAINT-RÃAULT (coming to table). One word more! (General surprise. The audience sit down in silence and consternation).

Bearing in mind the change of position of Bellac, Roger, and Saint-Réault, we may reseat the characters as follows:

[pg 58] While, as has been said, grouping depends to a great extent on the size and shape of the stage, it should always be borne in mind that the stage should in most cases be made to resemble a picture as regards balance and composition. This means that the director must avoid crowding; that the actors must learn to take their places as part of that picture, and not attempt either to usurp the center of the stage or to disappear behind other actors. No grouping should ever be left to chance or the inspiration of the moment; every actor must have marked down in his own script every movement he makes. Groups and crowds require a great deal of rehearsing, in order that they may always assume the right position at the right moment.

When an impression of vast numbers of people is desired—as in "Julius Cæsar"—large numbers of "supes" are not needed. Eight or ten or twelve people, well managed, are sufficient to create an effect of this sort on a small stage, and perhaps twenty on a large. The basic principle of the art of the theater is suggestion, not reproduction.

In the "forum scene" of Shakespeare's "Julius Cæsar" there are practically no stage [pg 59] directions. The management of the mob, therefore, is left entirely to the director. When the Third Citizen says: "The noble Brutus is ascended. Silence!" we are of course given to understand—by the word "Silence!"—that there has been some noise and confusion. The text affords the most important indications.

Plot out, for practice, the position of the various members of the mob throughout this scene.

As a rule, the best impression of a crowd is made by massing and manipulating groups of from three to six individuals. If movement is demanded, it must be precise and measured out carefully during rehearsals. Therefore, since it is nearly always impossible to get trained actors to compose mobs, it is well to intersperse two or three "leaders" in any crowd, who will give the cue for concerted action.

The foregoing discussion, both in the present and preceding chapter, has been made largely from the director's and the stage manager's viewpoint. Let us now go back to the actor, and suggest a few methods which will help him.

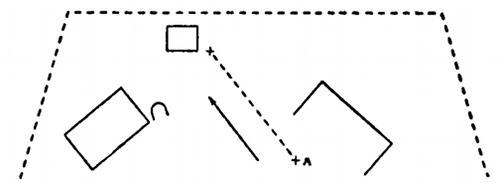

[pg 60] An easy and vivid way of remembering "business" at first is to make a very simple diagram, thus:

Supposing A, who stands down-stage before the sofa, crosses up-stage to the small table, as he says: "I'll not stand it any longer!" Just after this line, the actor places a mark referring him to the margin of his "script", and makes another diagram:

This represents A crossing to up-stage, left of the small table. In this way, when the actor is studying his lines, he cannot help [pg 61] studying the "business", and vice versa; and since lines and "business" almost always go hand in hand, he will run no danger of having first learned the one without the other.

Considerable confusion is likely to arise when an overzealous director insists that his actors be "letter perfect" before the "business" is well formulated and worked out and thoroughly learned.

In the first chapter on Rehearsing, the blocking-out process was discussed, but the order in which each act was to be rehearsed, the time to be spent on it, etc.—these matters were deferred, and will now be taken up.

At the next rehearsal—that is, after the blocking-out of the first act—the second is treated in the same way. And after the last act has been blocked out, the first should be rehearsed with greater care. Details of "business", grouping, the delivery of lines—especially the correction of errors in interpretation—must be carefully considered. Probably some of the "business" blocked out in the first rehearsal will have to be changed, or at least amplified. Entrances and exits must be repeatedly rehearsed until they go smoothly. The crossings and recrossing of one, two, or [pg 62] more characters, can scarcely be rehearsed too often.

Let us take a few examples of this sort of detail work. A man comes home late, tired and hungry. Outside the sitting room through an open door, is seen the hatrack. How can this simple incident be made to appear true and interesting? Here is at least one manner of accomplishing it: a door is heard closing off-stage; footsteps resound in the hall. A, the man, appears, wearing a hat, overcoat, and gloves, at the Center door, looks into the room to see whether any one is present, seems surprised, utters a short exclamation, and then turns to the hatrack. His back to the audience, he takes off his hat, hangs it carelessly on a hook, then slowly draws off his gloves, allows his coat to fall from his shoulders, looks at himself in the glass for an instant, and then, with a sigh, comes into the room again.

The incident, of course, is capable of a hundred variations, depending upon the character of the man, the circumstances under which he comes home, and so forth.

Or, a little more complicated instance: A, B, and C, three men, are seated, talking after dinner. They are stationed as follows:

A sits on the arm of the davenport, B on the davenport itself, and C in a chair at the lower right-hand side of the table.

Notice first that the davenport is not placed at right angles to the audience; this is done so that two people, sitting side by side, may be better seen by the "house." Notice, too, that A is at the extreme left-hand corner of the davenport. Visualize this for an instant: here is proportion, line, and balance, but without the appearance of stiffness or symmetry, which should always be avoided. B rises and stands before the fireplace: again notice the grouping:

[pg 64] A then rises and goes to the center of the stage, standing near the left of the table:

This simple moving about the room should never be obtrusive; that is to say, the audience must never be conscious of the director's hand. First, every bit of "business", every move, every gesture, must be justified, otherwise it calls attention to itself. This is a distinct problem with amateurs, who naturally find it difficult not to move about when they have nothing else to do. They feel self-conscious unless they are "acting." The best rule for any amateur—although it is again the director who is responsible and should look after this—is, never to do anything unless he knows precisely why he does it, and unless he feels it.

One further example: imagine a five-minute conversation, in the text of which there are no stage directions. It is between two women: [pg 65] D and E. They are seated, one in an arm-chair by the fire, the other in an ordinary chair to the right of a library table:

There are not many plays in which two characters merely converse for so long a period without well-motivated reasons, but it is well to take an extreme example. Let us assume that D is telling E the story of her life, and that for two minutes her speech contains little more than straight narrative. Suddenly she tells a sad incident, and E, who has a sympathetic nature, wipes her eyes with her handkerchief. D continues, and E, no longer able to restrain her tears but not wishing to show her emotion to D, rises and goes to the left of the stage for a moment or two. The long conversation scene is now broken up by a natural bit of action. While in life such a conversation might consume hours, on the stage it must be made more attractive and [pg 66] emotionally stimulating; in the theater, the appeal is through the eye and ear, to the emotions.

Such a scene as the one just outlined must be repeatedly rehearsed, until every detail of the "business" is worked out perfectly.

After approximately ten days' work on the first act—during which period each of the other acts should be run through at least three times—the actors should be letter perfect and able to give a fairly smooth performance.

Then the other acts are rehearsed in like manner. Each act, after it is finished in this way, must be rehearsed at least every three or four days. When all the acts have been worked out, then each rehearsal is devoted to going through the whole play. Minor points in acting, minor "business", rendering of the lines, voice, gesture, etc., must naturally be insisted upon. Special cases must be dealt with outside the regular rehearsals, for the play should be interrupted as seldom as possible, because it is wise to let the actors become accustomed to going through the entire piece. It will be found expeditious, too, for small groups of characters who have scenes together to rehearse by themselves. The full rehearsals [pg 67] of the play are valuable both to actors and the director, for the latter is given a general view of his stage pictures which could in no other way be afforded him, and he is in a position to judge of his general and massed effects. At the same time the actors will more readily enter into the spirit of the work if they are permitted to play without interruption. Where the actors forget their lines, they should be prompted without other delay, but if they do anything actually wrong, or if the director wishes to make an important change, the performance must, of course, be stopped for a moment.

The number of rehearsals necessary for the production of a play by amateurs depends largely on the attitude of the amateurs themselves, and the amount of time at their disposal. It is safe to say that ninety-nine out of a hundred such performances suffer noticeably from need of rehearsing. Nor is this to be wondered at, for the average professional play usually requires four or five weeks' rehearsing—seven to eight hours daily—for six and sometimes seven days in the week! Of course, an amateur is an amateur because he is not a professional, and he cannot afford very much [pg 68] time for work which is after all only a pastime. One other point should be well borne in mind: the average amateur has not the patience of the professional. If he is rehearsed too long or too steadily, he will grow "stale", and lose interest in his work.

Still, no full-length play can safely be produced with less than four weeks' work, on an average of five rehearsals of three hours each, per week. (This does not include special and individual outside rehearsals.) Four weeks is the shortest time that can be allowed, while six or seven should be devoted to it. So much time is not necessary in order that the company may attempt to become professionals; that would be impossible and not at all advisable. The amateur, if rightly trained, should be able to impart a certain natural, naïve, unprofessional tone to the part he is impersonating, but this can only be done by constant rehearsing. The director usually finds that the amateur's first instinct is to imitate the tricks of the professional actor, and not allow himself to feel the character of the rôle. The professional quickly assimilates mannerisms which are only too likely to become mechanical, but which the amateur, because he is an amateur, [pg 69] is not likely to learn, if at first he is trained to avoid them.

There is no particular excuse for presenting plays which can be seen acted anywhere and any time by professionals; amateurs should strive to produce classics, or modern plays which for one reason or another are not often seen, and impart to them that peculiar flavor which charms as well as interests and attracts. Nor is there much use in the amateur actor's striving to become professional in manner: he cannot hope, in the short time he can spare for his work, to become a good professional; or, if he gives signs of becoming such, then he no longer belongs in amateur dramatics. Allow the amateur plenty of leeway in the matter of interpretation, if he has any original ideas of his own; but of course these must never be at variance with the general idea of the play. Let him work out his own salvation: here lies the value of amateur production, both to the actor and to the audience.

Often amateurs are called upon to portray feelings, actions, passions, of which they have no knowledge or experience. Love scenes, for instance, are invariably difficult. In this case, the actors must be taught a few conventional [pg 70] gestures, attitudes, and tricks, but they should not be permitted—except in rare cases—to lay much stress on the acting. This also applies to such purely conventional matters as kissing, dying, fighting, etc., for which a set of recognized technical tricks has been evolved. Any competent director can train actors to do this.

One more point before this part of rehearsing is dispensed with: amateur productions suffer largely from a lack of continuous tension and variety. Often the action is slow, jerky, and consequently tedious. Constant rehearsing, with a view to inspiring greater confidence and sureness in the actors, under a good director, is the best means to overcome these great drawbacks. The last eight or ten rehearsals, after the cast are familiar with their lines and "business", are the most important in the matter of tempo. Details of shading, well-developed and modulated action, and a well-defined climax, are what must be worked for. When the actors are no longer thinking of when they must cross or sit down or rise, they are ready to enter whole-heartedly into the spirit of the play as an artistic unit.

As an example, on a small scale, of how a scene may be modulated and shaded, two pages [pg 71] from Meilhac and Halévy's "Indian Summer" (published by Samuel French) are here reprinted with marginal notes explaining how these effects are obtained.

|

Slowly |

ADR. Just a moment ago I forgot that such a thing was out of the question— BRI. Why out of the question—? ADR. Why, because— |

|

Slight increase |

BRI. Because what? How much did that American family pay you? I'll give you twice as much—three times as much. Whatever you want! ADR. Only to read to you? BRI. Why, yes. |

|

Slowly |

ADR. That wouldn't be so bad—there's just one thing against it—it might be just a wee bit compromising! BRI. Oh! ADR. Really, don't you think so? Just a bit? BRI. At my age? ADR. (gaily). Oh, it's all very well—a young person like me—alone with you. (Seriously.) Oh, if you only didn't live alone—! BRI. If I—? If I weren't alone? |

|

Staccato. |

ADR. If you only had some relatives—married relatives—your nephew, for instance, with his wife—then I might— |

|

Emphasis |

BRI. Once more, don't speak to me of—! He's the one that brought all this trouble on us—that letter that forces you to—that letter came from him. (ADRIENNE makes a quick movement of protest.) 'Tisn't his fault, I know, but I hold a grudge against him as if it were— |

|

Momentary |

ADR. And yet, if I told you— BRI. (stopping her). Shh! If you please. (Pause.) |

|

Diminuendo. |

ADR. (moved). Then I must go. That was the only way; and you don't want to do that. I'm sure I don't know what will happen afterward. I still hope—But for the moment, I must (Mild access of crying). Oh I'm sorry—so sorry—(Falls into chair at side of table). |

|

Slight increase |

BRI. (excitedly). Adrienne! ADR. (recovering mastery over herself). I beg your pardon—there! There! (Brushing away her tears). See, it's all over! |

|

Quickly Quickly. |

BRI. Adrienne! ADR. (rising). Monsieur! BRI. It's true, then, if there were some way, you would—? Not the way I mentioned just now—but another—you wouldn't leave, would you? You'd stay here—near me—always—and be happy? ADR. (lightly). Oh yes, it's too—I say it from the bottom of my heart! BRI. Very well, you shan't go. ADR. I—? BRI. No, you shan't go. ADR. But—how?—Why? |

|

Moment |

BRI. I have found a way! ADR. And it is? |

|

Climax. |

BRI. To make you my wife! ADR. (Sits down again, overcome). |

|

High tension |

BRI. I'll do it!—Go and speak to your Aunt—Here! Come here! (Enter NOEL, right, carrying a bundle of papers). Come here! Don't be afraid! You may go and get your wife. Bring her here! I'll forgive her as I forgive you! (Shakes hands warmly with NOEL). NOEL. Uncle! BRI. You were right—now I know it! What do I care if she is a watchmaker's daughter? Go and get your wife—bring her here—and we'll live together, the four of us us— NOEL. All four of us? BRI. Yes, all four! (To ADRIENNE). I am going to speak to your Aunt—I'll be back at once. (Exit Center). |

"Sister Beatrice" of Maeterlinck, produced at the Western Reserve College for Women.

The simple hangings produce a good cyclorama effect. (Courtesy of Miss Ida Treat).

CHAPTER VI

REHEARSING

III

The dress rehearsal usually takes place on the night before the regular performance.

Every effort must be made on this occasion to have conditions, on the stage and behind it, as nearly as possible like those under which the play is to be given. Scenery, lighting, costumes, must all be ready, and the performance carried through with as few interruptions as the director can afford to make. The director should be in the back of the "house", and stop the players only when they do something absolutely wrong. It is very unwise to change lines or "business" at this eleventh hour. The stage manager and his assistants must be in their assigned places, the lights manipulated, actors "called", the curtain rung up and down on schedule. The director watches the general effects, sees that the stage is not [pg 74] crowded, that the lights are in order, and above all, watches the tempo of the performance.

The actors must be informed that on the occasion of the performance the audience is likely to distract them by applause, laughter, etc., and that they, the actors, must pause for a moment when there is any such interruption. A little advice as to resting, not worrying about lines, etc., will not be out of place.

Besides the acting dress rehearsal, there should be a scene and light rehearsal. This is merely for the assistants behind the stage. The different scenes (if there is more than one) should be set and "struck" (taken down), furniture and "props" stationed, lights worked, exactly as they are to be on the following night. Everything should go according to clockwork, the stage manager "holding the book" on all his assistants.

The performance should begin on time. Every one knows the irksome delay usually incident to amateur performances, and it ought to be the object of every director to remedy a defect which is inherent in our usual slipshod method of reproducing plays. Promptness is the prime requisite of efficiency, and the production of plays is successful only when the component [pg 75] elements are organized on a sort of military basis. The actors must be in the theater on time, and "made-up" in costume, at least half an hour before the curtain rises. It is well for each actor to see the property man and make sure that all the "props" necessary to his part are in readiness. The property man himself must also check up his list for the last time, in order to avoid confusion during the performance.

When everything is in order, there is little more to be done. The director might make a few general remarks to the cast, endeavor to inspire them with confidence and impress upon them the necessity of playing together harmoniously, and so on, but if his work has been well done during rehearsals, this will not be necessary.