Barlow Cumberland

Barlow Cumberland

A Century of Sail and Steam on the Niagara River

By Barlow Cumberland

TORONTO:

The Musson Book Company

Limited

COPYRIGHTED

IN CANADA

1913

PUBLISHERS' NOTE.

Although the book is published about two months after the author's death, it will be gratifying to many readers to know that all the final proofs were passed by Mr. Cumberland himself. Therefore the volume in detail has the author's complete sanction. We have added to the illustrations a portrait of the author.[Pg v]

FOREWORD.

This narrative is not, nor does it purport to be one of general navigation upon Lake Ontario, but solely of the vessels and steamers which plyed during its century to the ports of the Niagara River, and particularly of the rise of the Niagara Navigation Co., to which it is largely devoted.

Considerable detail has, however been given to the history of the steamers "Frontenac" and "Ontario" because the latter has hitherto been reported to have been the first to be launched, and the credit of being the first to introduce steam navigation upon Lake Ontario has erroneously been given to the American shipping.

Successive eras of trading on the River tell of strenuous competitions. Sail is overpassed by steam. The new method of propulsion wins for this water route the supremacy of passenger travel, rising to a splendid climax when the application of steam to transportation on land and the introduction of railways brought such decadence to the River that all its steamers but one had disappeared.

The transfer of the second "City of Toronto" and of steamboating investment from the Niagara River to the undeveloped routes of the Upper Lakes leads to a diversion of the narration as bringing the initiation of another era on the Niagara River and explaining how the steamer, which formed its centre, came to be brought to the River service.

The closing 35 years of the century form the era of the Niagara Navigation Co., in which the period of decadence was converted into one of intense activity and splendid success.[Pg vi]

Our steam boating coterie had been promised by Mr. Chas. Gildersleeve, General Manager of the Richelieu & Ontario Navigation Co., that he would write up the navigation history of the Lake Ontario and St. Lawrence River sections upon which he and his forbears had been foremost leaders. Unfortunately he passed away somewhat suddenly, before being able to do this, and they pressed upon me to produce the Niagara section which had been alloted to myself.

The narration has been completed during the intervals between serious illness and is sent out in fulfilment of a promise, but yet in hope that it may be found acceptable to transportation men and with its local historical notes interesting to the travelling public.

Thanks are given to Mr. J. Ross Robertson, for the reproduction of some cuts of early steamers, and particularly to Mr. Frederick J. Shepard, of the Buffalo Public Library, who has been invaluable in tracing up and confirming data in the United States.

Dr. A. G. Dougaty, C.M.G., Archivist of Canada, Mr. Frank Severance, of the Buffalo Historical Society, and Mr. Locke, Public Librarian, Toronto, have been good enough to give much assistance which is warmly acknowledged.

Barlow Cumberland.

Dunain, Port Hope.

A CENTURY OF SAIL AND STEAM ON THE NIAGARA RIVER.

Chap. I.—The First Eras of Canoe and Sail 9

Chap. II.—The First Steamboats on the River and Lake Ontario 17

Chap. III.—More Steamboats and Early Water Routes.

The River the Centre of Through Travel East and

West. 25

Chap. IV.—Expansion and Decline of Traffic on the

River. A Final Flash, and a Move to the North 36

Chap. V.—On the Upper Lakes With the Wolseley

Expedition and Lord Dufferin 47

Chap. VI.—A Novel Idea and a New Venture. Buffalo

in Sailing Ship Days. A Risky Passage 58

Chap. VII.—Down Through the Welland. The

Miseries of Horse-towing Times. Port Dalhousie

and a Lake Veteran. The Problem Solved.

Toronto at Last 68

Chap. VIII.—The Niagara Portal. Old Times and Old

Names at Newark and Niagara. A Winter of

Changes. A New Rivalry Begun 80

Chap. IX.—The First Season of The Niagara Navigation

Company. A Hot Competition. Steamboat

Manoeuvres 94

Chap. X.—Change Partners Rate-cutting and Racing.

Hanlan and Toronto Waterside. Passenger Limitation

Introduced 109

Chap. XI.—Niagara Camps Formed. More Changes

and Competition. Beginnings of Railroads in

New York State. Early Passenger Men and

Ways 119

Chap. XII.—First Railways to Lewiston. Expansion

Required. The Renown of the Let-Her-B. A

Critic of Plimsoll 134

Chap. XIII.—Winter and Whisky in Scotland. Rail

Arrives at Lewiston Dock. How Cibola got Her

Name. On the U. E. Loyalist Route. Ongiara

Added 143

Chap. XIV.—Running the Blockade on the Let-Her-B.

as Told by Her Captain-owner 156

Chap. XV.—The Canadian Electric Railway to Queenston.

An Old Portage Route Revived. The Trek

to the Western States. Chippewa Arrives. Railway

Chief 165

Chap. XVI.—Cibola Goes, Corona Comes. The Gorge

Electric Railway Opens to Lewiston. How the

Falls Cut Their Way Back Through the Rocks.

Royal Visitors. The Decisiveness of Israel Tarte. 178

Chap. XVII.—Cayuga Adds Her Name. Niagara and

Hamilton Rejoined. Ice Jams on the River. The

Niagara Ferry Completed. Once More the United

Management From "Niagara to the Sea" 189

INDEX.

A.

Accommodation, Steamer 17

Advertising, N. Y. C. 175

Alaska, S.S. 145

Alberta, Steamer 121

Albany Northern Railroad 42

Alciope, Steamer 29

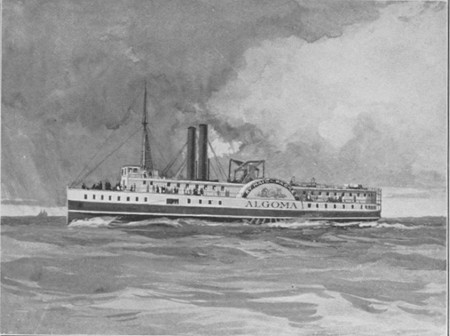

Algoma, Steamer 35, 44, 121

Algoma, qualifications of electors 46

American Civil War 43

American Colonists under James II 81

American Constitution Compared 47

American Express Line 37

American Prisoners from Queenston Heights 14

Arabian, Steamer 37

Armenia, Steamer 126

Asia, Steamer 78

Assiniboia, Steamer 121

B.

Barre, Chevalier de la 81

Barrie, R. N., Commodore 29, 30

Baldwin, Dr. 15

Bankruptcy of Steamers on River 43

Bay State, Steamer 37, 105

Baxter, Alderman John 152

Beatty, Jas, Jr., Mayor 114

Bell, Mr. David 64

Benson, Judge 33

Benson, Capt 33

Blockade-Running 160

Bolton, Col. R. E. 48

Book Tickets Introduced 132

Boswell, A. R 114

Bouchette, Commodore 13

Bowes, Mayor J. G. 38

Boynton, Capt. George B. 156

Brampton, Mills 42

Britannia, Steamer 33

Brock, General 15, 33, 169

Brock's Monument, Imitation of 33

Brooklyn, Steamer 48

Bruce Mines 44

Buffalo & Niagara Falls Railroad 31

Buffalo Dry Dock Co. 63

Buffalo in Sailing Days 64

Buffalo & Niagara Falls Burlington, Steamer 32

Butler, Col. 84

Butlersberg Begun 84

C.

Callaway, W. R. 123

Caldwell, Warships 13

Caledonia, Schooner 15

Caledonian Society 97

Caledonian S. S. Co. 140

Canada, Steamer 26, 28

Canadian Through Line 37

Canadian Constitution Compared 47

Canada Coasting Law Suspended 49

Canada Railway News Co. 93

Canadian Pacific Railway Terminals 51

Campana, Steamer 120

Campbell, Capt. Alexander, Selects Queenston portage 170

Captain Conn's Coffin, Schooner 14

Captain, position of, high importance 27

[Pg x]Cannochan, Miss Janet 119

Cataract, Steamer 37, 105

Cayuga Creek 10

Cayuga, 112 ways of spelling 189

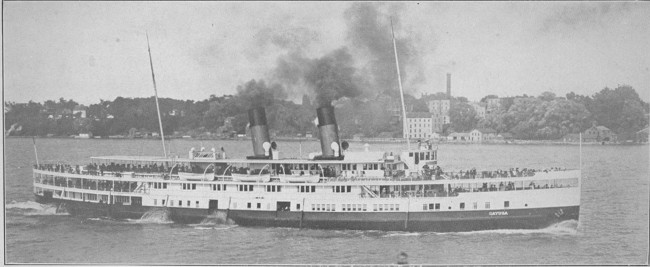

Cayuga, Steamer, launched, speed trials 190

Century, the close of a 198

Campion, Steamer 37

Charleston, S. C. 159

Charles II. Adventurers 45

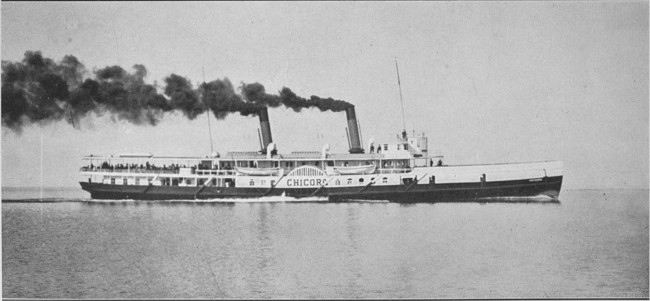

Chicora, Steamer—

With Woolesly 47

History name 148

Renown 138

Chicora, Steamer, decision to build partner 136

Chief Justice Robinson, Steamer 34, 39, 41

Chief Deseronto 152

Chief Brant 152

Chippawa River 9

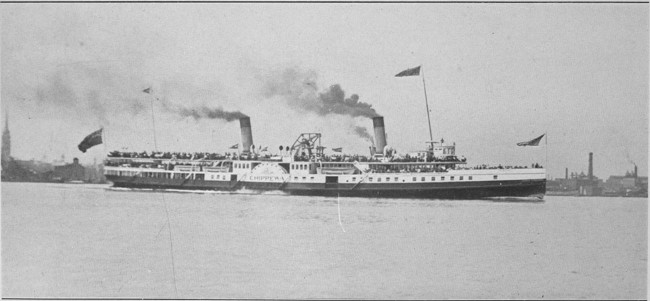

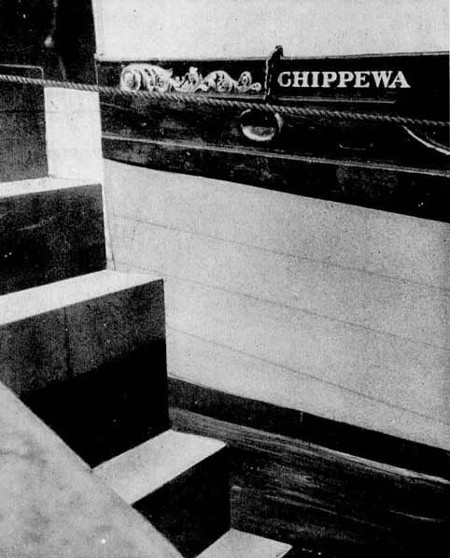

Chippewa, Steamer—

Name 173

Launched 174

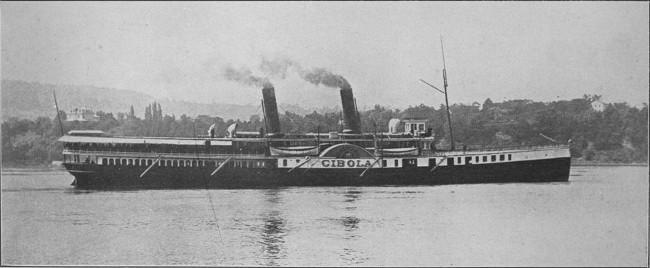

Cibola, Steamer—

Burned 17

Built 145

History of Name 148

City of Toronto, 1st Steamer 25

City of Toronto, 2nd Steamer 35

Rebuilt as Algoma 44

Transferred to Upper Lakes 45

City of Toronto, 3rd Steamer 35

Goes ashore 123

Burned 125

Clermont, Steamer 17

Collingwood-Lake Superior Line 109

Columba, Steamer 141

Commodore Barrie, Steamer 30

Connaught, H.R.H. Duke of 51

Conn, Capt. 14

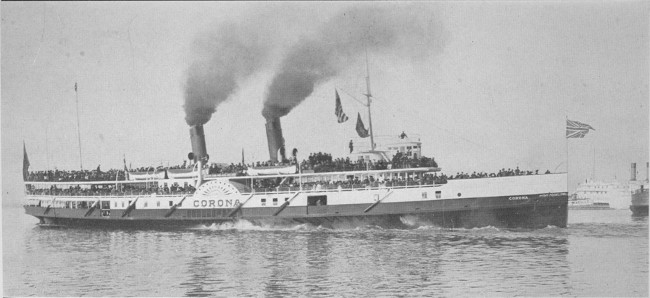

Corona, Steamer—

Named 179

Launched 179

Cornell, Mr. George 89, 102

Cross raised at Fort Niagara 81

Cross raised at Quebec by Cartier 81

Cumberland, Col. F. W., M.P. 48, 49, 53, 62, 78, 121

Cumberland, Barlow— 61, 109, 120, 172, 198

Cumberland, Mrs. Seraphina 122

Cumberland, Miss Mildred— 174, 179

Cumberland, Miss Constance 150

Cumberland, Steamer 63

Currie, James C. Neil 36

D.

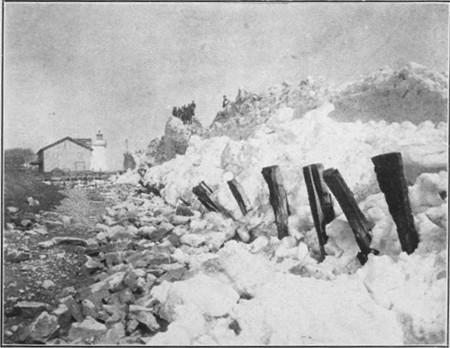

Daniels, Geo. H. 176

Dawson Road 44, 48

Dennis, Joseph 14, 26

Denison, Lt.-Col. Robert 154

Denonville, Marquis de 82

Demary, J. G. 73

Dick, Capt. Thomas 30, 44

Dick, Capt. Jas. 44

Doctors prescribe Niagara Line 132

Docks purchased—

Queenston 91

Youngstown 166

Niagara-on-Lake 181

Lewiston 191

Toronto 195

Dongan, Col. Thomas 81

Donaldson, Capt. William 110

Don Francesco de Chicora 149

Dorchester, Lord 13

Dorchester, Lady 13

Dove, Schooner 14

Dragon, H. M. S. 30

Dufferin, Lord 52

Tour through Upper Lakes 53

Dufferin, Countess of 54

Duke of Richmond, Packet 15

Duke and Duchess of York 183

Dunbarton, Scotland 38

E.

Early Steamer Routes and Rates 23, 24, 29, 31, 32, 134

Early Passenger Schedules—

[Pg xi]Albany and Bugalo 128

Early Passenger Agents 131

Early Closing Movement 185

Eckford, David 18

Electrical Traction, Infancy of 167

Emerald, Steamer 32

Empress of India, Steamer— 114, 126

Engineer Corps of U. S. A. 193

Erie Canal 36, 40

Erie & Ontario Railway 38

Ernestown 18

Esquesing, Mills 42

Estes, Capt. Andrew 28

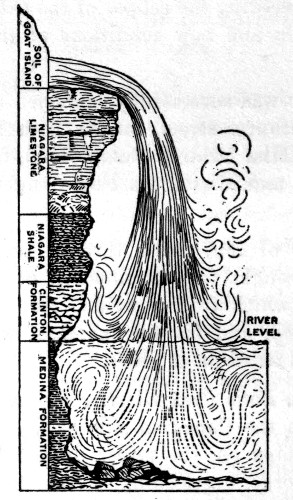

Evolution of the Niagara Gorge 180

Exclusive Rights for Navigation by Steam 18

Excursion, Queen's Birthday 94

Expansion of Niagara Navigation Co. 194

Exposition, Buffalo 182

F.

Fast Time to Niagara 26-31

Filgate, Steamer 114

Finkle's Point 18, 19, 25

First Vessel on Lake Erie 10

First Navies On Lake Ontario 17

First Company to Build Steamer for Lake Ontario 17

First Steamer on Lake U & First Steamer on Hudson River 17

First Steamer on St. Lawrence 17

First Steamer on Lake Ontario 19

First Steamers on Lake Ontario, dimensions of 22

First Board of Directors N. N. Co. 197

First Steamer to Run the Rapids 121

First Niagara Camp 119

First Twin-screw Steamer on Upper Lakes 121

First Canoe Route to Upper Lakes 9, 45

First Name of Niagara 155

First Iron Steamers 36

First Railroads in New York State 127

First Sleeping Cars 129

First Electric Railway to Niagara River 167

First U. E. Loyalists 153

First Suspension Bridge over Niagara 171

Flour Rates (1855) to New York 41

Flour via Lewiston to Montreal 42

Folger, Mr. B. W. 186

Fort William 45

Fort Garry 44

Fort George 83, 120

Fort York—Toronto 154

Fort Missasauga 80

Fort Niagara, contests for possession of 12

Fort Niagara—

Established by French 81

Evacuated 83

Captured by British 83

Never captured 83

Americans 83

Formalities on Early Steamers 26

Four Track Series 176

Foy, Hon. J. J. 184, 198

Foy, John 62, 109, 132, 188

Foy, Mr. A. 150

Foy, Miss Clara 179

French River 9, 45

French Pioneers, Trail of 11

French Encompass British 12

Friendly Hand Excursions 100

Frontenac, Count 10

Frontenac, Steamer, commenced 23, 24, 28

Frontenac Lake 12

Frontier House, Lewiston 146

Fulton, Robert 17

G.

Gallinee, Pere 81

[Pg xii]Gibraltar, Point 14

Gilbert, Abner 84

Gildersleeve Family Record 15

Gildersleeve, H. 25

Gildersleeve, Steamer 33

Gilkison, Robert 30, 31

Glasgow, Winter in 143

Gordon, L. B., Purser Peerless 41, 136

Gore, Steamer 30

Gorge Electric Railway 179

Governor Simcoe, Schooner 13

Grand Trunk Railway, opened 42

Great Britain, Steamer 29

Great Western Railway 42, 60

Great Trek to Western States 171

Griffon, Sloop 10, 81

Grimsby 32

Gunn, J. W. 37

Gzowski, Mr. Casimir 64

H.

Hall, Capt. 76

Hamilton, Hon. Robert 25, 29, 170

Hamilton, Hon. John 29, 36

Hamilton Steamboat Co. purchased 114

Hanlan, Edward, reception of 114

Harbottle, Capt. Thomas 36, 92

Harbour Regulations, Toronto, 1851 37-38

Hastings, Steamer 150

Hayter, Mr. Ross 152

Head of Navigation Portages 170

Hendrie, Geo. H. 173

Hendrie, Hon. J. S. 197

Hendrie, William 173

Hennepin, Father 10

Heron, Capt. 34

Highlander, Steamer 37

Historical Society, Buffalo 20

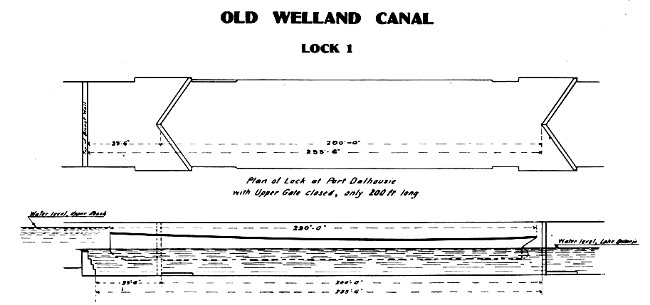

Horse Canalling through Welland 68

Hudson River Railroad 41

Hudson's Bay Fort 50

I.

Ice Jams on River 191-194

Irea, A Novel 59

Immigrants by Chippawa River 171

Indiana Excursions 99

Interest, Points of 101

Iroquois Cap 11

Irwin, C. W. 88

Isle Royale 11, 63

Israel Tarte's Decisiveness 184

J.

J. T. Robb, Tug 62

Jean Baptiste, Steamer 114

Johnson, Sir William 12, 83

Jonquiere 83

K.

Kaministiqua River 45

Kathleen, Steamer 150

Kendrick, Mr. D. M. 175

Kent, H. R. H. Duke of 13

Kerr, Capt. Robert 32, 87

Kingston Gazette 19

Kingston Dockyard 29

Kirby, Mr. Frank 173

L.

La Salle 10

Lady Dorchester, Schooner 13

Lady Washington, Schooner 13

Lahn, S.S. 138

Lake Superior 44

Lake Ontario Steamboat Co. 20

Lake Nipissing 81

Leach, Capt. Thomas 43, 62, 125

Leach, Alexander 62, 103

Legislature, Provincial 46

Lewiston 12, 20, 89

Lewiston, Railway Development 134

Liancourt, Duke de 85

Ligneris 12

[Pg xiii]Limitation of Passengers 116-118

Limnale, Warship 13

Livingston 18

Long Point Bay 14

Lord of the Isles, Steamer 141

Lunt, Mr. R. C. 88, 110, 111, 118

Lusher 19

M.

Mackinac 57

Macdonald, Bruce 198

Macklem, Oliver T. 38

Magnet, Steamer 37

Maid of the Mist, Steamer 121

Maitland, Lady 26

Maitland, Sir Peregrine 26

Mallahy, U. S. N. Capt. Francis 22

Manchester 31

Manitoulin Island 44

Manson, Capt. William 62, 70, 78

Maple Leaf, Steamer 37

Marine Dept., United States 63

Marine Insurance Anomalies 66

Mariner, An Ancient 73

Marks, Thomas 51

Martha Ogden, Steamer 20, 28, 29

Matthews, W. D. 198

Maude, John 85

Maxwell, Steamer 114

Mayflower, Steamer 37

McBride, R. H. 62, 78, 198

McCorquodale, Capt. 130, 152, 187

McGiffin, Capt. 152, 180

McKenzie, R.N. Capt. James 23, 29

McLean, Capt. 48

McLure, General, Retreats from Newark 86

McNab, Capt. 56

Meeker, Mr. C. B. 127

Mellish, John 85

Milloy, Capt. Duncan 38, 43

Milloy, N. & Co. 47

Milloy Estate, Arrangements with 87

Milloy, Donald 88, 110, 122

Milloy, Capt. Wm. Assumes Control 122

Minerva, Packet 15

Missassag River 45

Mississippi River 11

Mohawk, Sloop 13

Moira, Warship 15

Molson, Hon. John 17

Monett, Mr. Henry 175

Moore, George, Chief Engineer 93

Morton, Mr. Robert 142

Mowats Dock 124

Murdock, William 51

Muir's Dry Dock 59

Muir, Mr. W. K. 60

Muir, Capt. D. 72

Mull, Y. Cantire 144

Murney, Captain 15

Murphy, Steve 130

Myers, Capt. 14

N.

Names for Steamers, why chosen 147, 155, 173, 179, 188

Navigation, Upper Lakes, Permitive 52

Navy Hall 13, 120

Nepigon River 45

Newark 84

Seat of Government, burned by Americans, rises from ashes 85, 86

New Orleans 11

New Era, Steamer 37

New York Central Railway 40, 127, 128, 172

New York to Buffalo in 1847 172

Niagara River, Gateway of West 11-12

Niagara River Steamers in 1826 28

Niagara, Steamer 28, 29

Niagara Navigation Co.—

Formed 61

First Directors 61-62

[Pg xiv]Niagara Dock Co. 30

Niagara Falls & Ontario Railway 40

Niagara Escarpment, View from 70, 168

Niagara-on-the-Lake 80

Niagara Portal 80

Niagara-on-Lake, Changes in Name 86

Niagara River Line 95

Niagara Dock 104

Niagara Historical Society 119

Niagara Line, Final Supremacy 126

Niagara Falls & Ontario R. K. 135

Niagara River Navigation Co., U. S. A. 166

Niagara Falls Park and River Railway 167

Niagara to the Sea 196-197

Niles Weekly Register 20, 21

North-West Company 13

Northerner, Steamer 37

Notable Day (1840) on River 33

Notable Passages to Niagara 187

O.

Oakville, Mills 42

Oakville Church 95

Oates, Commander Edward 16

Observation Cars 151

Ogdensburgh 29

Ohio River 11

Onandaga Salt Wells 35

Ongiara, Steamer 155

Ontario, Steamer—

Commenced 14

Launched 21, 22, 24

Ontario Steamboat Co. 19, 20

Orion, Schooner 49

Orr, Capt. James C. 55

Osler, Mr. E. B. 173, 188, 198

Osler, F. Gordon 198

Osler, Miss Niary 174

Oskwego Lake 9

Ottawa, Steamer 30

Ottawa River 9

Ozone, Steamer 141

P.

Pandora, Schooner 49

Parry Sound 53, 56

Parry, W. H. 177

Passport, Steamer 36

Peerless, Steamer 38

Pellatt, C.V.O., Sir Henry 198

Penobscot, Maine 30

Phelan, T. P. 93

Pioneers of France 11

Plimsoll's Legislation 139

Point Aux Pins 48

Point Ahina 67

Pollard, Capt. & Adjt. 119

Port Dalhousie 32, 72

Port Colborne 62, 63

Port Credit, Mills 42

Port Arthur 51

Pouchot 12

Powhatan, Warship, U. S. 158

Prince Edward, Sloop 13

Prince Arthur's Landing 50

Origin of Name 51

Prince Arthur of Connaught 51

Presquile 11, 14

Puchot, Capt. 83

Q.

Quebec 12

Quebec Gazette 20

Queenston Heights 10

Queenston Heights, Battle of 169

Queenston, Steamer 25, 28, 29

Queen Victoria, Steamer 30, 32

Queen Anne, Communion Service 152

Queen Victoria Niagara Park 151

Queen Charlotte, Steamer 25

Queen City, Steamer 42

Quinte, Bay of 18

R.

Racing, Protest Against 111

[Pg xv]Rainy River 11

Rankin, Blackmore & Co. 142

Rathbun, E. W. 145, 151

Red Jacket, Steamer 31

Red River 45

Reindeer, Schooner 14

Richards, Mr. E. J. 129

Richardson, Capt. James 14

Richardson, Capt. Hugh 26, 37

Richardson, Capt. Hugh, Jr. 34

Riel Rebellion 47

Rochester, Steamer 35

Rothsay Castle, Steamer 43

Rothesay, Steamer 88, 92, 118

Rouge River 26

Route Hudson Bay & North-West Co. 45

Royal Mail Line 37,196

Ruggles, A. W. 177

Running the Blockade on the "Let Her B" 156

Rupert, Steamer 125

Russell, Governor 85

S.

Sackett's Harbour 18

Sailing Era Closed 16

Salter, Rev. G. 172

Sault Canal 48

Scott, General Winfield 15

Second Canoe Route to Upper Lakes 11

Seneca, Warship 13

Shickluna, Steamer 49

Shipbuilding at Niagara 30-38

Simcoe, Sloop 14

Simcoe, Lieut.-Gov. 84, 85

Sinclair, Capt. James 30

Six Nation Indians 152

Smith, Hon. Frank, afterward Sir 61, 78, 92, 109, 183

Smyth, Charles 18, 20

Solmes, W. H., Capt. 67

Sorel 78

Southern Belle, Steamer 43, 59

Speedy, Schooner 14

St. Clair Lake 10, 11

St. Louis 11

St. Nicholas, Steamer 42

St. Catharines 32, 60, 71

St. Catharines & Toronto Line 126

Stages to Lewiston 25, 171

Steamboating Era Begins 17

Stoney Point 29

Sutherland, Capt. J. 37

Sullivan, J. M. 197

Sydenham, Lord, Gov.-Genl. 33

T.

Teabout & Chapman 18, 25

Tea in Canada 144

The Old Portage 168

Through the Last Lock 74, 76

Thunder Bay 47

Tillingharst, Mr. 92

Tinning's Wharf 43

Toronto, Schooner 14

Toronto citizens given to water sports 114

Toronto Field Battery 119

Tour, Lord Dufferin 53

Towed Across Lake Erie 66, 77

Transfer Coaches at Lewiston 146

Transit, Steamer 30, 34

Traveller, Steamer 30

Trickett, Edward 114

Troyes, Pierre de 82

Turbinia, Steamer Competes 190

Twohey, Capt. H. 36

U.

Underwood, Mr. 177

United Kingdom, Steamer 29

United States, Steamer 30

V.

Van Cleve, Capt. 20, 21, 28, 29, 146

Vancouver 30

Vanderbilt, Commodore 127

Victoria, Steamer 31

Vrooman's Bay 105

W.

Wabash District 99

[Pg xvi]Washago, Laying Corner Stone 53-54

Wauhuno Channel 56

Waubuno, Steamer 56, 57

Weather Bureau, United States 65

Weekes, E. J. 176

Welland Canal 58, 60, 68

Western Railroad 41

West Niagara 84

Whalen, J., Foreman 145

Where the Falls Once Were 181

Whiskey in Scotland 144

White, W. 136

Whitehead, M. F. 15

Whitney, Capt. Joseph 29

William IV., Steamer 30, 31

Wilson, Joseph 49

Winter Mail Services 34, 39, 40, 42

Wolseley Expedition 47

American Obstacles to 50

Wolseley, Col. Garnet 50

Names Prince Arthur's Landing 51

Woodward, M. D. 60

Wyatt, Capt. Thomas 88

Y.

York, Schooner 13

York 37, 85

Youngstown 28, 29, 135

Z.

Zimmerman, Steamer 38

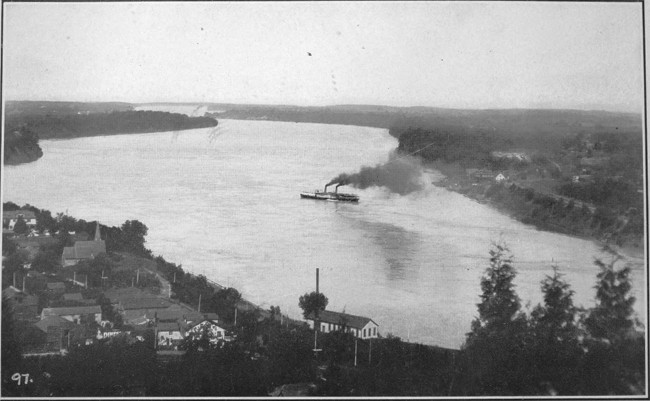

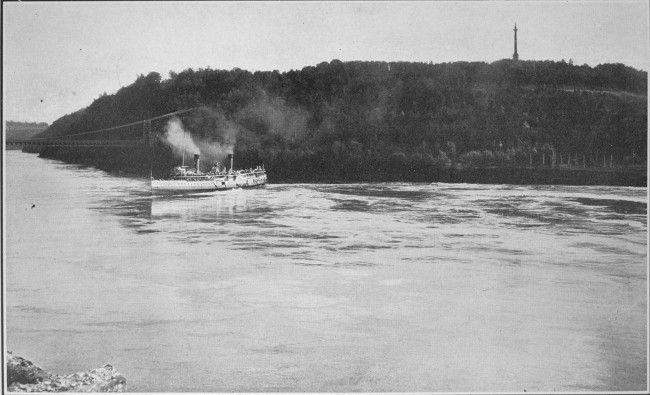

Queenstown. The NIAGARA RIVER from Queenston Heights. (page

169) Lewiston.

Queenstown. The NIAGARA RIVER from Queenston Heights. (page

169) Lewiston.

A CENTURY OF SAIL AND STEAM ON THE NIAGARA RIVER

CHAPTER I.

The First Eras of Canoe and Sail.

Since ever the changes of season have come, when grasses grow green, and open waters flow, the courses of the Niagara River, above and below the great Falls, have been the central route, for voyaging between the far inland countries on this continent, and the waters of the Atlantic shores.

Here the Indian of prehistoric days, unmolested by the intruding white, roamed at will in migration from one of his hunting-grounds to another, making his portage and passing in his canoe between Lake Erie and Lake Oskwego (Ontario). In later days, when the French had established themselves at Quebec and Montreal, access to Lake Huron and the upper lakes was at first sought by their voyageurs along the nearer route of the Ottawa and French Rivers, a route involving many difficulties in surmounting rapids, heavy labour on numberless portages, and exceeding delay. Information had filtered down gradually through Indian sources of the existence of this Niagara River Route, on which there was but one portage of but fourteen miles to be passed from lake to lake, and only nine miles if the canoes entered the water again at the little river (Chippawa) above the Falls.

On learning the fact the French turned their attention to this new waterway, but for many a weary decade were[Pg 10] unable to establish themselves upon it. In 1678 Father Hennepin, with an expedition sent out by Sieur La Salle sailed from Cataraqui (Kingston) to the Niagara River, the name "Hennepin Rock" having come down in tradition as a reminiscence of their first landing below what is now Queenston Heights. Passing over the "Carrying Place," they reached Lake Erie. Here, at the outlet of the Cayuga Creek, on the south shore, they built a small two-masted vessel rigged with equipment which they brought up for the purpose from Cataraqui, in the following year.

This vessel, launched in 1679, and named the "Griffon" in recognition of the crest on the coat of arms of Count Frontenac, the Governor of Canada, was the first vessel built by Europeans to sail upon the upper waters. In size she so much exceeded that of any of their own craft, with her white sails billowing like an apparition, and of novel and unusual appearance, that intensest excitement was created among the Indian tribes as she passed along their shores.

Her life was brief, and the history of her movements scanty; the report being that after sailing through Lake St. Clair she reached Michilimakinac and Green Bay, on Lake Michigan, but passed out of sight on Lake Huron on the return journey, and was never heard of afterwards.

Tiny though this vessel was and sailing slow upon the Upper Lakes, yet a great epoch had been opened up, for she was the progenitor of all the myriad ships which ply upon these waters at the present day. It was the entrance of the white man, with his consuming trade energy, into the red man's realm, the death knell of the Indian race.

With greatly increased frequency of travelling and the more bulky requirements of freightage this "one portage" route was more increasingly sought, and as the[Pg 11] result of their voyagings these early French pioneers have marked their names along the waterways as ever remaining records of their prowess—such as Presquile (almost an island); Detroit (the narrow place); Lac Sainte Clair; Sault Ste Marie (Rapids of St. Mary River); Cap Iroquois; Isle Royale; Rainy River (after René de Varennes); Duluth (after Sieur du Luth, of Montreal); Fond du Lac (Head of Lake Superior).

From here mounting up the St. Croix River, seeking the expansion of that New France to whose glory they so ungrudgingly devoted their lives, these intrepid adventurers reached over to the Mississippi, and sweeping down its waters still further marked their way at St. Louis (after their King) and New Orleans (after his capital), annexing all the adjacent territories to their Sovereign's domains.

The Niagara River Route then became the motive centre of a mighty circum-vallation by which the early French encompassed within its circle the English Colonies then skirting along the Atlantic.

What a magnificent conception it was of these intrepid French to envelope the British settlements and strengthened by alliances with the Indian tribes and fortified by a line of outposts established along the routes of the Ohio and the Mississippi, to hem their competitors in from expansion to the great interior country of the centre and the west. Standing astride the continent with one foot on the Gulf of St. Lawrence, at Quebec, and the other at New Orleans, on the Gulf of Mexico, the interior lines of commerce and of trade were in their hands. They hoped that Canada, their New France, on this side of the ocean, was to absorb all the continent excepting the colonies along the shores of the sea. So matters remained for a century.[Pg 12]

Meanwhile the English colonies had expanded to the south shores of the Lakes Oswego and Frontenac, and in 1758 we read of an English Navy of eight schooners and three brigs sailing on Lake Ontario under the red cross of St. George and manned by sailors of the colonies.

In 1759, came the great struggle for the possession of the St. Lawrence and connecting lines of the waterways. Fort Niagara, whose large central stone "castle," built in 1726, still remains, passed from the French under Pouchot, to the British under Sir William Johnson; a great flotilla of canoes conveying the Indian warriors under Ligneris to the aid of the Fort, had come down from the Upper Lakes, to the Niagara River, but upon it being proved to them that they were too late, for the Fort had fallen, they re-entered their canoes and re-traced their way up the rivers back to their Western homes.

Next followed the fall of Quebec, and with the cession of Montreal in 1760 the "New France" of old from the St. Lawrence to the Mexican Gulf became merged in the "New England" of British Canada.

The control of the great central waterway, of which this Niagara River was the gateway, had passed into other hands.

For another fifty years only sailing vessels navigated the lakes to Niagara, and these, and batteaux, pushed along the shores and up the river by poles, made their way to the foot of the rapids at Lewiston with difficulty. These vessels were mainly small schooners with some cabin accommodation.

After the cession of Canada, by the French, the British Government began the establishment of a small navy on Lake Ontario. An official return called for[Pg 13] by Lord Dorchester, Governor-General of Canada, gives the Government vessels as being in 1787, Limnale, 220 tons, 10 guns. Seneca, 130 tons, 18 guns. Caldwell, 37 tons, 2 guns, and two schooners of 100 tons each being built. As there was at that time but one merchant vessel, the schooner Lady Dorchester, 80 tons, sailing on the lake, and a few smaller craft the property of settlers, transport for passengers between the principal ports was mainly afforded by the Government vessels. As an instance of their voyaging may be given that of H.M.S. Caldwell, which in 1793, carrying Lady Dorchester, the wife of the Governor-General, is reported to have made "an agreeable passage of thirty-six hours from Kingston to Niagara."

In this same year H.R.H. the Duke of Kent [afterwards father of Her Majesty Queen Victoria] is reported as having proceeded from Kingston up Lake Ontario to Navy Hall on the Niagara River in the King's ship Mohawk commanded by Commodore Bouchette.

Further additions to the merchant schooners were the York, built on the Niagara River in 1792, and the Governor Simcoe, in 1797, for the North-West Company's use in their trading services on Lake Ontario. Another reported in 1797—the Washington—built at Erie, Pa., was bought by Canadians, portaged around the Falls and run on the British register from Queenston to Kingston as the Lady Washington.

The forests of those days existed in all their primeval condition, so that the choicest woods were used in the construction of the vessels. We read in 1798 of the Prince Edward, built of red cedar, under Captain Murney of Belleville, and capable of carrying seven hundred barrels of flour, and of another "good sloop" upon the stocks at Long Point Bay, near Kingston, being built of black walnut. A schooner, "The Toronto," built in 1799, a little[Pg 14] way up the Humber, by Mr. Joseph Dennis, is described as "one of the handsomest vessels, and bids fair to be the swiftest sailing vessel on the lake, and is admirably calculated for the reception of passengers." This vessel, often mentioned as "The Toronto Yacht," was evidently a great favorite, being patronized by the Lieutenant-Governor and the Archbishop, and after a successful and appreciated career, finished her course abruptly by going ashore on Gibraltar Point in 1811. The loss of the Government schooner Speedy was one of the tragic events of the times. The Judge of the District Court, the Solicitor General and several lawyers who were proceeding from York to hold the Assizes in the Newcastle District, together with the High Constable of York, and an Indian prisoner whom they were to try for murder, were all lost when the vessel foundered off Presquile in an exceptional gale on 7th October, 1804.

Two sailing vessels, the schooners Dove and the Reindeer, (Capt. Myers) are reported in 1809 as plying between York and Niagara. A third, commanded by Capt. Conn, is mentioned by Caniff, but no name has come down of this vessel, but only her nickname of "Captain Conn's Coffin." This j'eu d'esprit may have been due to some peculiarity in her shape, but as no disaster is reported as having occurred to her she may have been more seaworthy than the nickname would have indicated.

Of other events of sailing vessels was the memorable trip from Queenston to York in October, 1812, of the sloop Simcoe, owned and commended by Capt. James Richardson.

After the battle of Queenston Heights, on October 13th, she had been laden with American prisoners, among them General Winfield Scott, afterwards the conqueror in Mexico, to be forwarded at once to Kingston. The Moira[Pg 15] of the royal navy was then lying off the port of York and on her Mr. Richardson, a son of the Captain, was serving as sailing master.

As the Simcoe approached she was recognized by young Richardson, who, putting off in a small boat, met her out in the lake and was much surprised at seeing the crowded state of her decks and at the equipment of his father, who, somewhat unusually for him, was wearing a sword.

The first words from the ship brought great joy—a great battle had been fought on Queenston Heights—the enemy had been beaten. The Simcoe was full of prisoners of war to be transported at once to the Moira for conveyance to Kingston. Then came the mournful statement, "General Brock has been killed." The rapture of victory was overwhelmed by the sense of irreparable loss. In such way was the sad news carried in those sailing days to York.

The Minerva, "Packet," owner and built by Henry Gildersleeve, at Finkle's Point in 1817, held high repute. Richard Gildersleeve emigrated from Hertfordshire, England, in 1635, and settled in Connecticut. His great-great-grandson, Obadiah, established a successful shipbuilding yard at "Gildersleeve," Conn. Henry Gildersleeve, his grandson, here learned his business and coming to Finkle's Point in 1816 assisted on the Frontenac, and continuing in shipbuilding, married Mrs. Finkle. When Minerva arrived at Kingston she was declared by Capt. Murray, R.N., to be in her construction and lines the best yet turned out, as she proved when plying as a "Packet" between Toronto and Niagara.

Many sailing vessels meeting with varying success, were plying between all the ports on the lake. The voyages were not always of the speediest. "The Caledonia,"[Pg 16] schooner, is reported to have taken six days from Prescott to York. Mr. M. F. Whitehead, of Port Hope, crossed from Niagara to York in 1818, the passage occupying two and a half days. In a letter of his describing the trip he enters:—"Fortunately, Dr. Baldwin had thoughtfully provided a leg of lamb, a loaf of bread, and a bottle of porter; all our fare for the two days and a half."

These vessels seem to have sailed somewhat intermittently, but regular connection on every other day with the Niagara River was established by "The Duke of Richmond" packet, a sloop of one hundred tons built at York in 1820, under Commander Edward Oates.

His advertisements announced her to "leave York Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 9 a.m. Leave Niagara on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday at 10 a.m., between July and September," after that "according to notice." The rates of passage were:—"After Cabin ten shillings; Fore Cabin 6s. 6.; sixty lbs. of baggage allowed for each passenger, but over that 9d. per cwt. or 2s. per barrel bulk."

The standard of measurement was a homely one, but no doubt well understood at that time, and easily ascertained. In the expansion of the size of ladies' trunks in these present days it is not beyond possibility that a measurement system such as used in the early part of the last century might not be inadvisable.

The reports of the "packet" describe her as being comfortable and weatherly, and very regular in keeping up her time-table. She performed her services successfully on the route until 1823, when she succumbed to the competition of the steamboats which had shortly before been introduced. With the introduction upon the lakes of this new method of propulsion the carrying of passengers on sailing vessels quickly ceased.

CHAPTER II.

The First Steamboats on Lake Ontario and the Niagara River.

The era of steamboating had now arrived. The Clermont, built by Robert Fulton, and furnished with English engines by Boulton & Watts, of Birmingham, had made her first trip on the Hudson from New York to Albany in August, 1807, and was afterwards continuing to run on the river.

In 1809 the Accommodation, built by the Hon. John Molson at Montreal, and fitted with engines made in that city, was running successfully between Montreal and Quebec, being the first steamer on the St. Lawrence and in Canada.

The experience of both of these vessels had shown that the new system of propulsion of vessels by steam power was commercially profitable, and as it had been proved successful upon the river water, it was but reasonable that its application to the more open waters of the lakes should next obtain consideration.

The war of 1812 between Great Britain and the United States, accompanied by its constant invasions of Canada, had interrupted any immediate expansion in steamboating enterprises.

Peace having been declared in February, 1815, the projects were immediately revived and in the spring of that year a British company was formed with shareholders in Kingston, Niagara, York, and Prescott, to build a steamboat[Pg 18] to ply on Lake Ontario. A site suitable for its construction was selected on the beaches on Finkle's Point, at Ernestown, 18 miles up the lake from Kingston, on one of the reaches of the Bay of Quinte.

A contract was let to Henry Teabout and James Chapman, two young men who had been foremen under David Eckford, the master shipbuilder of New York, who during the war had constructed the warships for the United States Government at its dockyard at Sackett's Harbor. Construction was commenced at Finkle's Point in October, 1815, and with considerable delays caused in selection of the timbers, was continued during the winter. (Canniff—Settlement of Upper Canada). The steamer was launched with great eclat on 7th September, 1816, and named the Frontenac, after the County of Frontenac in which she had been built.

A similar wave of enterprise had arisen also on the United States side and it becomes of much interest to search up the annals of over a hundred years ago and ascertain to which side of the lake is to be accorded the palm for placing the first steamboat on Lake Ontario. Especially as opinions have varied on the subject, and owing to a statement made, as we shall find, erroneously, in a distant press the precedence has usually been given to an American steamer.

The first record of the steamboat on the American side is an agreement dated January 2, 1816, executed between the Robert Fulton heirs and Livingston, of Clermont, granting to Charles Smyth and others an exclusive right to navigate boats and vessels by steam on Lake Ontario.

These exclusive rights for the navigation on American waters "by steam or fire" had previously been granted to[Pg 19] the Fulton partnership by the Legislature of the State of New York.

The terms of the agreement set out that the grantees were to pay annually to the grantors one-half of all the net profits in excess of a dividend of 12 per cent. upon the investment. On the 16th of the next month a bill was passed in the Legislature of New York incorporating the "Ontario Steamboat Co.," but in consequence of the too early adjournment of the Legislature did not become law.

At this time, (February, 1816) the construction of the Canadian boat at Ernestown was well under way.

By an assignment dated August 16th, 1816, Lusher and others became partners with Smyth, and as a result it is stated (Hough—History of Jefferson County, N.Y.) "a boat was commenced at Sackett's Harbor the same summer."

Three weeks after the date of this commencing of the boat on the American side, or Sackett's Harbour, the Frontenac, on the Canadian side, was launched on the 7th September, 1816, at Finkle's Point.

In the description of this launch of the Frontenac given in the September issue of the Kingston Gazette, the details of her size are stated. "Length, 170 feet; beam, 32 feet; two paddle wheels with circumference about 40 feet. Registered tonnage, 700 tons." Further statements made are, "Good judges have pronounced this to be the best piece of naval architecture of the kind yet produced in America." "The machinery for this valuable boat was imported from England and is said to be an excellent structure. It is expected that she will be finished and ready for use in a few weeks."

Having been launched with engines on board in early September the Frontenac then sailed down the lake from Ernestown to Kingston to lay up in the port.[Pg 20]

In another part of this same September issue of the Kingston Gazette an item is given: "A steamboat was lately launched at Sackett's Harbor."

No name is given of the steamer, nor the date of the launch, but this item has been considered to have referred to the steamer named Ontario, built at Sackett's Harbor and in consequence of its having apparently been launched first, precedence has been claimed for the United States vessel.

This item, "A steamboat was lately launched at Sackett's Harbor," develops, on further search, to have first appeared as a paragraph under the reading chronicles in "Niles Weekly Register," published far south in the United States at Baltimore, Maryland. From here it was copied verbatim as above by the Kingston Gazette, and afterwards by the Quebec Gazette of 26th Sept., 1816.

Further enquiry, however, nearer the scene of construction indicates that an error had been made in the wording of the item, which had apparently been copied into the other papers without verification.

In the library of the Historical Society at Buffalo is deposited the manuscript diary of Capt. Van Cleve, who sailed as clerk and as captain on the Martha Ogden, the next steamboat to be built at Sackett's Harbor six years after the Ontario. In this he writes, "the construction of the Ontario was begun at Sackett's Harbor in August, 1816." He also gives a drawing, from which all subsequent illustrations of the Ontario have been taken. Further information of the American steamer is given in an application for incorporation of the "Lake Ontario Steam Boat Co." made in December, 1816, by Charles Smyth and others, of Sackett's Harbor, who stated in their petition that they had "lately constructed a steam boat at[Pg 21] Sackett's Harbor"—"the Navy Department of the United States have generously delivered a sufficiency of timber for the construction of the vessel for a reasonable sum of money"—"the boat is now built"—"the cost so far exceeds the means which mercantile men can generally command that they are unable to build any further"—"the English in the Province of Upper Canada have constructed a steam boat of seven hundred tons burthen avowedly for the purpose of engrossing the business on both sides of the lake."

All this indicates that the American boat had not been launched and in December was still under construction.

It is more reasonable to accept the statements of Capt. Van Cleve and others close to the scene of operations rather than to base conclusions upon the single item in the publication issued at so far a distance and without definite details.

It is quite evident that the item in Niles Register should have read "was lately commenced," instead of "was lately launched." The change of this one word would bring it into complete agreement with all the other evidences of the period and into accord with the facts.

No absolute date for the launching of the Ontario or of the giving of her name has been ascertainable, but as she was not commenced until August it certainly could not have been until after that of the Frontenac on Sept. 7th, 1816. The first boat launched was, therefore, on the Canadian side.

The movements of the steamers in the spring of 1817 are more easily traced. Niles Register, 29th March, 1817, notes, "The steamboat Ontario is prepared for the lake," and Capt. Van Cleve says, "The first enrollment of the[Pg 22] Ontario in the customs office was made on 11th April," and "She made her first trip in April."

The data of the dimensions of the Ontario are recorded, being only about one-third the capacity of the Frontenac, which would account for the shorter time in which she was constructed. The relative sizes were:

| Length. | Beam. | Capacity, tons. | |

| Frontenac | 170 | 32 | 700 |

| Ontario | 110 | 24 | 240 |

No drawing of the Frontenac is extant, but she has been described as having guards only at the paddle wheels, the hull painted black, and as having three masts, but no yards. The Ontario had two masts, as shown in the drawing by Van Cleve.

No distinctive date is given for the first trip in April of the Ontario, on which it is reported (Beers History of the Great Lakes) "The waves lifted the paddle wheels off their bearings, tearing away the wooden coverings. After making the repairs the shaft was securely held in place."

Afterwards under the command of Capt. Francis Mallaby, U. S. N., weekly trips between Ogdensburgh and Lewiston were attempted, but after this interruption by advertisement of 1st July, 1817, the time had to be extended to once in ten days. The speed of the steamer was found to seldom exceed five miles per hour. (History of Jefferson County. Hough).

The Ontario ran for some years, but does not seem to have met with much success and, having gone out of commission, was broken up at Oswego in 1832.

In the spring of 1817 the first mention of the Frontenac is in Kingston of her having moved over on 23rd[Pg 23] May to the Government dock at Point Frederick, "for putting in a suction pipe," the Kingston Gazette further describing that "she moved with majestic grandeur against a strong wind." On 30th May the Gazette reports her as "leaving this port for the purpose of taking in wood at the Bay Quinte. A fresh breeze was blowing into the harbor against which she proceeded swiftly and steadily to the admiration of a great number of spectators. We congratulate the managers and proprietors of this elegant boat, upon the prospect she affords of facilitating the navigation of Lake Ontario in furnishing an expeditious and certain mode of conveyance to its various ports."

It can well be imagined with what wonder the movements of this first steam-driven vessel were witnessed.

In the Kingston Gazette of June 7, 1817, entry is made, "The Frontenac left this port on Thursday, 5th, on her first trip for the head of the lake."

The opening route of the Frontenac, commanded by Capt. James McKenzie, a retired officer of the royal navy, was between Kingston and Queenston, calling at York and Niagara and other intermediate ports. The venture of a steamer plying on the open lakes, where the paddle wheels would be subjected to wave action, was a new one, so for the opening trips her captain announced, with the proverbial caution of a Scotchman, that the calls at the ports would be made "with as much punctuality as the nature of lake navigation will admit of." Later, the steamer, having proved her capacity by two round trips, the advertisements of June, 1817, state the time-table of the steamer as "leaving Kingston for York on the 1st, 11th, and 23rd days," and "York for Queenston on 3rd, 13th, and 25th days of each month, calling at all intermediate ports." "Passenger fares, Kingston to Ernestown,[Pg 24] 5s; Prescott, £1.10.0; Newcastle, £1.15.0; York and Niagara, £2.0.0; Burlington, £3.15.0; York to Niagara, £1.0.0." Further excerpts are: "A book is kept for the entering of the names of the passengers and the berths which they choose, at which time the passage money must be paid." "Gentlemen's servants cannot eat or sleep in the cabin." "Deck passengers will pay fifteen shillings, and may either bring their own provisions or be furnished by the steward." "For each dog brought on board, five shillings." "All applications for passage to be made to Capt. McKenzie on board." After having run regularly each season on Lake Ontario and the Niagara River her career was closed in 1827 when, while on the Niagara River, she was set on fire, it was said, by incendiaries, for whose discovery her owners, the Messrs. Hamilton, offered a reward of £100, but without result. Being seriously damaged, she was shortly afterwards broken up.

Such were the careers of the first two steamers which sailed upon Lake Ontario and the Niagara River, and from the data it is apparent that the Frontenac on the British side was the first steamboat placed on Lake Ontario, and that the Ontario, on the United States side, had been the first to make a trip up lake, having priority in this over her rival by perhaps a week or two, but not preceding her in the entering into and performance of a regular service.

With them began the new method for travel, far exceeding in speed and facilities any previously existing, so that the stage lines and sailing vessels were quickly eliminated.

This practical monopoly the steamers enjoyed for a period of fifty years, when their Nemesis in turn arrived and the era of rail competition began.

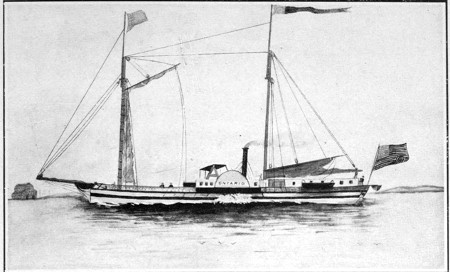

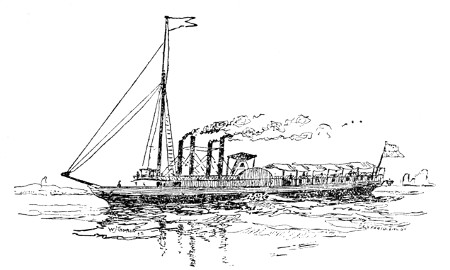

The ONTARIO. 1817. The second Steamer on Lake Ontario.

The ONTARIO. 1817. The second Steamer on Lake Ontario.From the original drawing by Capt. Van Cleve page 21

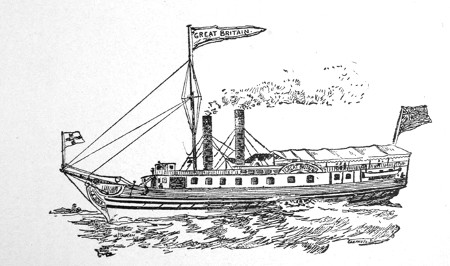

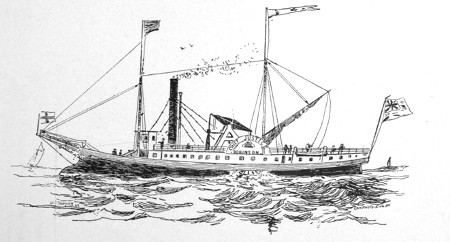

The GREAT BRITAIN. 1830.

The GREAT BRITAIN. 1830.By courtesy of Mr. John Ross Robertson reproduced from his "Landmarks of Toronto." page 29

CHAPTER III.

More Steamboats and Early Water Routes.

The River the Centre of Through Travel.

The Frontenac was followed by the Queen Charlotte, built in the same yards at Finkle's Point, by Teabout and Chapman, and launched on 22nd April, 1818, for H. Gildersleeve, the progenitor of that family which has ever since been foremost in the ranks of steamboating in Canada. He sailed her for twenty years as captain and purser, her first route being a round trip every ten days between Kingston, York and Queenston. The passage rates at this time were from Kingston to York and Niagara £3 ($12.00), from York to Niagara £1 ($4.00).

In 1824 appeared the first "City of Toronto," of 350 tons, built in the harbor of York at the foot of Church Street. Her life was neither long nor successful, she being sold by auction "with all her furniture" in December, 1830, and broken up.

Passenger traffic was now so much increasing that steamers began to follow more quickly. The Lewiston "Sentinel" in 1824, in a paragraph eulogizing their then rising town, says:—"Travel is rapidly increasing, regular lines of stages excelled by none, run daily by the Ridge Road to Lockport, and on Fridays weekly to Buffalo. The steamboats are increasing in business and affording every facility to the traveller." The Hon. Robert Hamilton, who for so many years afterwards was dominantly interested in steamboating, launched the "Queenston" in 1825[Pg 26] at Queenston. His fine residence, from which he could watch the movements of his own and other steamers, still stands on the edge of the high bank overlooking the Queenston dock.

In 1826 there was added the "Canada," built at the mouth of the Rouge River by Mr. Joseph Dennis and brought to York to have the engines installed, which had been constructed by Hess and Wards, of Montreal. Under the charge of Captain Hugh Richardson, her captain and managing owner, she had a long and notable career. The contemporary annals describe her as "a fast boat," and as making the trip from York to Niagara "in four hours and some minutes."

Her Captain was a seaman of the old school, dominant, and watchful of the proprieties on the quarter deck.

On one occasion in 1828, when Sir Peregrine Maitland, the Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada, and Lady Maitland, had taken passage with him from York to Queenston en route to Stamford, a newspaper item had accused him of undue exclusiveness on the "Canada" to the annoyance of other passengers.

To this the doughty "Captain and Managing Owner" replied by a letter in which he denied the accusation and added: "As long as I command the "Canada" and have a rag of colour to hoist, my proudest day will be when it floats at the masthead indicative of the presence and commands of the representative of my King."

The departure of his steamer from port was announced in an exceptional manner, as stated in the concluding words of his advertisement to the public: "N.B. A gun will be fired and colours hoisted twenty-five minutes before starting."[Pg 27]

In another controversy, which arose from the contract for carrying the mails on the Niagara route having been withdrawn from the steamer "Canada," it was developed that while the pay to the steamer was only 1s. 3d. per trip, the Government postage between York and Niagara was 7d. on each letter. This charge the captain considered excessive, but as the postmaster at Niagara now refused to receive any letters from his steamer he regretted he had to make public announcement that he was obliged (in future) to decline to accept any more letters to be taken across the lake.

The captain-commander of a lake steamboat in those days was a person of importance and repute. Unquestioned ruler on his "ship," he represented the honour of his Flag and obedience to his Country's laws.

Most of them had been officers of the Royal Navy and had served during the 1812 War, having been trained in the discipline and conventions of His Majesty's service, and similarly on the American boats had served in the United States Navy.

At the present day on our Muskoka and inland lakes, the advent of the daily steamer is a crowning event, bringing all the neighbourhood down to the waterside dock, in curiosity or in welcome. Still more so it was in those early times when the mode of steam progression was novel and a source of wonder, and the days of call so much more infrequent.

The captain was no doubt the bearer of letters to be delivered into the hands of friends, certainly the medium of the latest news (and gossip) from the other ports on the lake, and was sought for tidings from the outside, as well as in welcome to himself. In particular evidence of the confidence reposed in him and in his gallantry, he was[Pg 28] the honored Guardian of ladies and children, travelling alone, who were with much empressment confided to his care. Being usually a part owner his attentions were gracious hospitalities, so that a seat at the commander's table was not only a privilege, but an appreciated acknowledgement of social position.

These were the halcyon days of Officers on the lakes, when the increased speed of the new method was enjoyed and appreciated, but the congenialities of a pleasant passage, were not lost in impatient haste for its earlier termination.

There were in 1826 five steamers running on the Niagara River Route. The "Niagara" and "Queenston" from Prescott; "Frontenac" from Kingston; "Martha Ogden," an American steamer from the south shore ports and Ogdensburg, and the "Canada" to York and "head of the lake," presumably near Burlington, and return.

On this "Martha Ogden," built at Sackett's Harbour, in 1824, Captain Van Cleve, of Lewiston, served for many years as clerk, and afterwards as captain. In a manuscript left by him many interesting events in her history are narrated. In 1826 she ran under the command of Captain Andrew Estes between Youngstown and York. Youngstown was then a port of much importance. It was the shipping place of a very considerable hardwood timbering business the trees being brought in from the surrounding country. Its docks, situated close to the lake on an eddy separated from the rapid flow of the river, formed an easily accessible centre for the batteaux and sailing craft which communicated with the Eastern ports on Lake Ontario.

A considerable quantity of grain was also at that time raised in the district, providing material for the stone[Pg 29] flour mill built in 1840. This mill, grinding two hundred barrels per day, was in those days considered a marvel of enterprise. Though many years ago disused for such purpose it is still to be seen just a little above the Niagara Navigation Company's Youngstown dock.

In the way of the nomenclature of steamers, that of the "Alciope," built at Niagara in 1828 for Mr. Robert Hamilton, and first commanded by Captain McKenzie, late of the "Frontenac," is unusual. This name in appearance would appear to be that of some ancient goddess, but is understood to be taken from a technical term in abstract zoology. Possibly it may at the time have attracted attention, but was evidently not considered satisfactory as it was changed in 1832 to the more suitable one of "United Kingdom."

More steamers come now in quick succession. The Hon. John Hamilton in 1830 brought out the "Great Britain" (Captain Joseph Whitney), of 700 tons, with two funnels, and spacious awning deck.

The route of the "Martha Ogden" had reverted back to the lake trip between Lewiston and Ogdensburgh. It was her ill luck to run ashore in 1830 and having sought repairs in the British Government naval establishment at Kingston, Captain Van Cleve mentions, with much satisfaction the cordial reception given to the American crew by Commodore Barrie, and the efficient work done for the ship in the Royal Dockyard. The "Martha Ogden" closed her days in 1832 by being lost off Stoney Point, Lake Ontario.

The sailing times of the through boats from the river at this time are given as "the steamer Great Britain leaves Niagara every five days, the Alciope, every Saturday evening, the Niagara every Monday evening at 6 o'clock, and[Pg 30] the Queenston every Tuesday morning at 9 o'clock for Kingston, Brockville and Prescott (board included) $8.00."

On the American side the United States and Oswego made a semi-weekly line between Lewiston and Ogdensburg, calling at all intermediate ports.

In 1832 added "William IV.," an unusual looking craft with four funnels; 1834 "Commodore Barrie," built at Kingston by the Gildersleeves, and sailed by Captain James Sinclair between (as the advertisement stated) "Prescott, Toronto (late York) and Niagara." Commodore Barrie, after whom the steamer was named, had a long and creditable naval career. As lieutenant he had been with Vancouver on the Pacific in 1792, served at Copenhagen in 1807, and as captain of "H.M.S. Dragon," 74 guns, had taken part in the successful expedition at Penobscot Maine in 1814. In 1830 he had been appointed to the command of the Royal Navy Yard at Kingston.

Ship building on the lake began now to take a more definite and established position. The "Niagara Dock Company" was formed in 1835. Robert Gilkison, a Canadian, of Queenston, who had been educated in shipbuilding at "Port Glasgow, Scotland," returned to Canada and was appointed designer and superintendent of the works at Niagara.

A number of ships were built under his charge. The first steamer was the "Traveller," 145 feet long, 23.6 beam, with speed of 11 to 12 miles followed by the "Transit," "Gore," and the "Queen Victoria," 130 feet long, 23.6 beam, with 50 horse power, a stated speed of 12 miles, and described as having been "fitted in elegant style." This steamer, launched in April, 1838, and commanded by Captain Thomas Dick, introduces a family which for many[Pg 31] years was connected with steamboating on the Niagara River Route.

In her first season Robert Gilkinson, her builder, noted in his diary, June 29th: "On the celebration of Her Majesty's coronation the Victoria, with a party of sixty ladies and gentlemen, made her first trip to Toronto, making the distance from Niagara to Toronto in 3 hours and 7 minutes, a rate scarcely met by any other boat."

"July 2. Commenced trips leaving Niagara 7 a.m., Toronto 11 a.m., and Hamilton 4 p.m., arrived here (Niagara) 8 p.m. Accomplished the 121 miles in ten and a half hours, a rate not exceeded by any boat on the lake."

The advertisements of the running times as then given in the press are interesting.

"The 'Queen Victoria' leaves Lewiston and Queenston 8 o'clock a.m. and Niagara 8.30 o'clock for Toronto. The boat will return each day, leaving Toronto for these places at 2 o'clock p.m."

A further enlargement of the running connections of this steamer on the route in 1839 stated:

"Passengers will on Monday and Thursday arrive at Toronto in time for the "William IV." steamer for Kingston and Prescott. Returning. On arrival at Lewiston, railroad cars will leave for the Falls. On arrival at Queenston stages will leave for the Falls, whence the passengers can leave next day by the steamer "Red Jacket" from Chippawa to Buffalo, or by the railroad cars for Manchester."

The "Railroad Cars" were those of the "Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad" opened in 1836, then running two trains a day each way between Buffalo and the Falls, leaving Buffalo at nine in the morning and five in the afternoon. Manchester was the name of the town laid out[Pg 32] in the neighborhood of the Falls, where, from the abundance of water power it was expected a great manufacturing centre would be established.

An advertisement in a later year (1844) mentions the steamer "Emerald" to "leave Buffalo at 9 a.m. for Chippawa, arrive by cars at Queenston for steamer for Toronto, Oswego, Rochester, Kingston and Montreal."

The "cars" at Queenston were those of a horse railroad which had been constructed along the main road from Chippewa to Queenston, of which some traces still remain. The rails were long wooden sleepers faced with strap iron.

During one season the "Queen Victoria" was chartered as a gunboat for Lake Ontario, being manned by officers and men from the Royal Navy. She presented a fine appearance and was received with great acceptance at the lake ports as she visited them.

A more direct route from this distributing point at the foot of the rapids on the Niagara River direct to the head of Lake Ontario and the country beyond, instead of crossing first to Toronto, was evidently sought. In 1840 the steamer "Burlington"—Captain Robert Kerr—is advertised to "Leave Lewiston 7 a.m., Niagara 7.30 a.m., landing (weather permitting) at Port Dalhousie (near St. Catherines, from which place a carriage will meet the boat regularly); Grimsby, and arrive at Hamilton about noon. Returning will leave at 3 p.m., and making the same calls, weather permitting, arrive at Lewiston in the evening."

The 30th July, 1841, was a memorable day in steamboating on the Niagara River. A great public meeting was held that day on Queenston Heights to arrange for the building of a new monument in memory of General[Pg 33] Brock to replace the one which had been blown up by some dastard on 17th April, 1840.

Deputations from the military and the patriotic associations in all parts of the province attended.

Four steamers left Toronto together about 7.30 in the morning. The "Traveller"—Captain Sandown, R.N., with His Excellency the Governor-General, Lord Sydenham, on board; "Transit"—Captain Hugh Richardson; "Queen Victoria"—Captain Richardson, Jr.; "Gore"—Captain Thomas Dick. At the mouth of the Niagara River these were joined by the "Burlington"—Captain Robert Kerr, and "Britannia" from Hamilton and the head of the lake, and by the "Gildersleeve" and "Cobourg" from the Eastern ports and Kingston.

Amidst utmost enthusiasm, and with all flags flying, the eight steamers assembled at Niagara and marshalled in the following order, proceeded up the river to Queenston:—

GILDERSLEEVE.

COBOURG.

BURLINGTON.

GORE.

BRITANNIA.

QUEEN.

TRANSIT.

The sight of this fleet of eight steamers must have been impressive as with flying colours they made up the stream.

Judge Benson, of Port Hope, says that his father, Capt. Benson, of the 3rd Incorporated Militia, was then occupying the "Lang House" in Niagara, overlooking the river, and that he and his brother were lifted up to the window to see the flotilla pass by, a reminiscence of loyal[Pg 34] fervor which has been vividly retained through a long life. Is it not a sufficient justification and an actual value resulting from special meetings and pageants that they not only serve to revivify the enthusiasm of the elders in annals of past days, but yet more to bring to the minds of youth actual and abiding touch with the historic events which are being celebrated?

The meeting was held upon the field of the battle, the memories of the struggle revived and honour done to the fallen.

The present monument was the result of the enterprise then begun.

Much rivalry existed between the steamers as to which would open the season first, as the boat which got into Niagara first before 1st March was free of port dues for the season. In this the "Transit" excelled and sometimes landed her passengers on the ice.

The Niagara Dock Company in 1842 turned out the "Chief Justice Robinson" commanded by Captain Hugh Richardson, Jr.

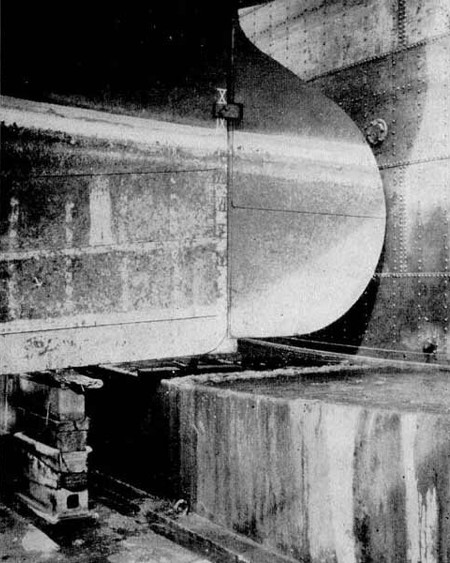

This steamer, largely owned by Captain Heron and the Richardsons, was specially designed to continue during the winter the daily connection by water to Toronto, and so avoid the long stage journey around the head of the lake. For this purpose her prow at and below the water line was projected forward like a double furrowed plough, to cut through the ice and throw it outwards on each side.

This winter service she maintained for ten seasons with commendable regularity between the outer end of the Queen's Wharf at Toronto (where she had sometimes to land passengers on the ice) and Niagara. On one occasion, in a snowstorm, she went ashore just outside the harbour[Pg 35] at Toronto, and was also occasionally frozen in at both ends of the route, but each time managed to extricate herself. After refitting in the spring she divided the daily Lewiston-Toronto Route after 1850 with the second City of Toronto, a steamer with two separate engines, with two walking beams built at Toronto in 1840, which had been running in the Royal Mail Line, but in 1850 passed into the complete ownership of Captain Thomas Dick.

The steamer "Rochester" is also recorded as running between Lewiston and Hamilton in 1843 to 1849.

CHAPTER IV.

Expansion of Steamboating on the Niagara—its Decline—a Final Flash and a Move To the North.

During this decade the Niagara River was more increasingly traversed by many steamers, and became the main line of travel between the Western and Centre States by steamer to Buffalo, and thence, via the Niagara River to Boston and New York via Ogdensburg and Albany, or by Montreal and Lake Champlain to the Hudson.

Lewiston had become a place of much importance, being the transhipping point for a great through freighting business. Until the opening of the Erie Canal all the salt used in the Western States and Canada was brought here by water from Oswego, in thousands of barrels, from the Onandaga Salt Wells. Business in the opposite direction was greatly active, report being made of the passing of a consignment of 900 barrels of "Mississippi sugar," and 200 hogsheads of molasses for Eastern points in the United States and Canada.

In addition to the sailing craft five different steamers left the docks every day for other ports on the lake.

A new era was opened in 1847 by the introduction with great eclat and enterprise of the first iron steamers. The "Passport," commanded first by Captain H. Twohey and afterwards by Captain Thomas Harbottle, was constructed for the Hon. John Hamilton, the iron plates being moulded on the Clyde and put together at the Niagara shipyard by James and Neil Currie. The plates for[Pg 37] the "Magnet" were similarly brought out from England and put together for J. W. Gunn, of Hamilton, the principal stockholder, with Captain J. Sutherland her captain. Both these steamers in their long service proved the reliability of metal vessels in our fresh water. Both formed part of the Royal Mail Line leaving Toronto on the arrival of the river steamers.

In the early "fifties" the "American Express Line," running from Lewiston to Toronto, Rochester, Oswego and Ogdensburg, consisted of the fine upper cabin steamers "Cataract," "Bay State," "Ontario," and "Northerner."

The "New Through Line," a Canadian organization, was comprised of six steamers: the "Maple Leaf," "Arabian," "New Era," "Champion," "Highlander," "Mayflower." The route they followed was: "Leave Hamilton 7 a.m.; leave Lewiston and Queenston about half past 8 p.m., calling at all north shore Ontario ports between Darlington and Prescott to Ogdensburgh and Montreal without transhipment. Returning via the north shore to Toronto and Hamilton direct." The through time down to Montreal was stated in the advertisement to be "from Hamilton 33 hours, from the Niagara River 25 hours."

A good instance of the frequency of the entrances of the steamers into the harbours is afforded by an amusing suggestion which was in 1851, made by Captain Hugh Richardson, who had become Harbour Master at Toronto.

The steamers running into the port seem to have called sometimes at one dock first, sometimes at another, according, probably, to the freight which may have been on board to be delivered. Much trouble was thus caused to cabmen and citizens running up and down the water front from one dock to another.[Pg 38]

The captain, whose views with respect to the flying, and the distinctive meanings, of flags, we have already seen, proposed that all vessels when entering the harbour should designate the dock at which they intended to stop by the Following signals:—

For Browne's Wharf—Union Jack at Masthead.

For Maitland's Wharf—Union Jack at Staff aft.

For Tinnings Wharf—Union Jack in fore rigging.

For Helliwells Wharf—Union Jack over wheel-house.

It is to be remembered that in those days the "Western" was the only entrance to the harbour and Front Street without any buildings on its south side, followed the line of the high bank above the water so that the signals on the steamers could be easily seen by all. The proposal was publicly endorsed by the Mayor, Mr. J. G. Bowes, but there is no record of its having been adopted.

In 1853 there was built at Niagara for Mr. Oliver T. Macklem the steamer "Zimmerman," certainly the finest and reputed to be the fastest steamer which up to that time sailed the river. She was named after Mr. Samuel Zimmerman, the railway magnate, and ran in connection with the Erie and Ontario Railway from Fort Erie to Niagara, which he had promoted, and was sailed by Captain D. Milloy.

In this same year there was sailed regularly from Niagara another iron steamer, the "Peerless," owned by Captain Dick and Andrew Heron, of Niagara. This steamer was first put together at Dunbarton, Scotland, then taken apart, and the pieces (said to be five thousand in number) sent out to Canada, and put together again at the Niagara dockyard. These two steamers thereafter divided the services in competition on the Niagara Route to Toronto.[Pg 39]

These years were the zenith period for steamboating on Lake Ontario and the Niagara River, a constant succession of steamers passing to and fro between the ports. Progress in the Western States and in Upper Canada had been unexampled. Expansion in every line of business was active, population fast coming in, and the construction of railways, which was then being begun, creating large expenditures and distribution of money. The steamers on the water were then the only method for speedy travel, so their accommodation was in fullest use, and their earnings at the largest.

The stage routes around the shores of the lakes in those days were tedious and trying in summer, and in winter accompanied by privations. The services of the steamers in the winter were greatly appreciated and maintained with the utmost vigour every year, particularly for the carriage of mails between Toronto, Niagara, Queenston and Lewiston, for which the steamer received in winter £3 for each actual running day, and between Toronto and Hamilton, for which the recompense was £2 for service per day performed.

In 1851 the Chief Justice Robinson is recorded (Gordon's Letter Books) as having run on the Niagara River during 11 months of the year. The remaining portion, while she was refitting, was filled by the second City of Toronto.

It is mentioned that at one time she went to Oswego to be hauled out on the marine cradle there at a charge of 25 cents per ton.

In 1852-53 the services were performed by the same steamers. In 1854 the Peerless made two trips daily during ten months, the Chief Justice Robinson taking the balance of this service and also filling in during the other[Pg 40] months, with the second City of Toronto on the Hamilton Route.

The winter service to the Niagara River for 1855 was commenced by the Chief Justice Robinson on 1st January, the steamer crossing the lake on 22 days in that month. February was somewhat interrupted by ice, but the full service between the shores was performed on 23 days in the month of March.

So soon as the inner water in the harbour of Toronto was frozen up all these services were performed from the outer extremity of the Queen's Wharf, and in the mid-winter months mostly from the edges of the ice further out, the sleighs driving out alongside with their passengers and freight. It seems difficult for us, in these days of luxury in travel, to comprehend the difficulties under which the early travellers laboured and thrived.

There was a wonderful and final exploit in the winter business of the Niagara River Route.

The "Niagara Falls and Ontario Railway" was opened as far as Lewiston in 1854 and by its connection at the Falls with the New York Central Railway brought during its first winter of 1854-55 great activity to the Niagara steamers.

The Crimean War was in progress and food products for the armies in the field were being eagerly sought from all places of world-supply and from America. Shipments were accordingly sought from Upper Canada. In summer the route would be by the Erie Canal to Albany or by the St. Lawrence and Montreal, but both routes were closed in winter.

The New York Central had been connected as a complete rail route as far as Albany, where, as there was no bridge across the Hudson, transportation was made by a ferry to the Hudson River Railroad, on the opposite shore for New York, or to the Western Railroad for Boston.

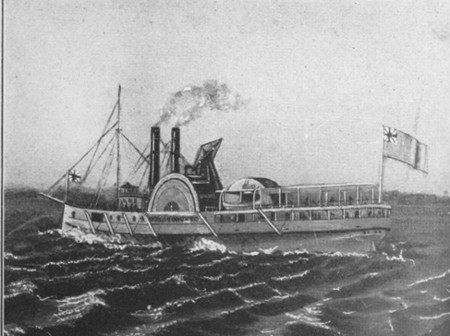

The WILLIAM IV. 1832.

The WILLIAM IV. 1832.From the "Landmarks of Toronto." page 30

The CHIEF JUSTICE ROBINSON. 1841.

The CHIEF JUSTICE ROBINSON. 1841.From the "Landmarks of Toronto." page 84

There was, at that time, no railroad around the head of Lake Ontario so a Freight Route by steamer across the lake was opened to Lewiston, from where rail connection could be made to the Atlantic.

In January, 1855, large shipments of flour made from Upper Canada mills along the north shore of Lake Ontario began to be collected. The enterprising agent of the Peerless (Mr. L. B. Gordon) wrote to the Central that he hoped to "make the consignment up to 10,000 barrels before the canal and river opens." This being a reference to the competing all-water route via the Erie Canal and Hudson River.

The first winter shipment of a consignment of 3,400 barrels was begun by the Chief Justice Robinson from the Queen's Wharf on 17th January.

The through rates of freight, as recorded in Mr. Gordon's books, are in these modern days of low rates, remarkable. Not the less interesting are the proportions accepted by each of the carriers concerned for their portion of the service, which were as follows:

Flour, per barrel, Toronto to New York—

| Steamer—Queen's Wharf to Lewiston | 12-1/2c |

| Wharfage and teaming (Cornell) | 6 |

| New York Central, Lewiston to Albany | 60 |

| Ferry at Albany | 3 |

| Hudson River Railroad to New York | 37-1/2 |

| —— | |

| Through to New York | $1.19 |

What would the Railway Commissioners and the public of the present think of such rates![Pg 42]

The shipments were largely from the products of the mills at the Credit, Oakville, Brampton, Esquesing, and Georgetown, being teamed to the docks at Oakville and Port Credit, from where they were brought by the steamers Queen City and Chief Justice Robinson at 5c per bbl. to the Queen's Wharf, Toronto, and from there taken across the lake by the Chief Justice Robinson and the Peerless.

The propeller St. Nicholas took a direct load of 3,000 barrels from Port Credit to Lewiston on Feb. 2nd. Shipments were also sent to Boston at $1,24-1/2 per bbl., on which the proportion of the "New York Central" was 68c, and the "Western Railroad" received 35c per bbl. as their share.

Nearly the whole consignment expected was obtained.

Another novel route was also opened. Consignments of flour for local use were sent to Montreal during this winter by the New York Central, Lewiston to Albany, and thence by the "Albany Northern Railroad" to the south side of the St. Lawrence River, whence they were most probably teamed across the ice to the main city.

Northbound shipments were also worked up and received at Lewiston for Toronto—principally teas and tobaccos—consignments of "English Bonded Goods" were rated at "second-class, same as domestic sheetings" and carried at 63c per 100 pounds from New York to Lewiston.

It was a winter of unexampled activity, but it was the closing effort of the steamers against the entrance of the railways into their all-the-year-round trade.

Immediately upon the opening of the Great Western Railway from Niagara Falls to Hamilton in 1855 and to Toronto in 1856, and of the Grand Trunk Railway from Montreal in 1856, the steamboating interests suffered still[Pg 43] further and great decay. In the financial crisis of 1857 many steamers were laid up. In 1858 all the American Line steamers were in bankruptcy, and in 1860 the Zimmerman abandoned the Niagara River to the Peerless, the one steamer being sufficient.

The opening of the American Civil War in 1860 opened a new career for the Lake Ontario steamers, as the Northern Government were short of steamers with which to blockade the Southern ports.

The "Peerless" was purchased by the American Government in 1861 and left for New York under command of Captain Robert Kerr, and by 1863 all the American Line steamers had been sold in the same direction and gone down the rapids to Montreal, and thence to the Atlantic. A general clearance had been affected.