Transcriber's Note:

A group of asterisks represents an ellipsis.

A complete list of typographical corrections follows the text.

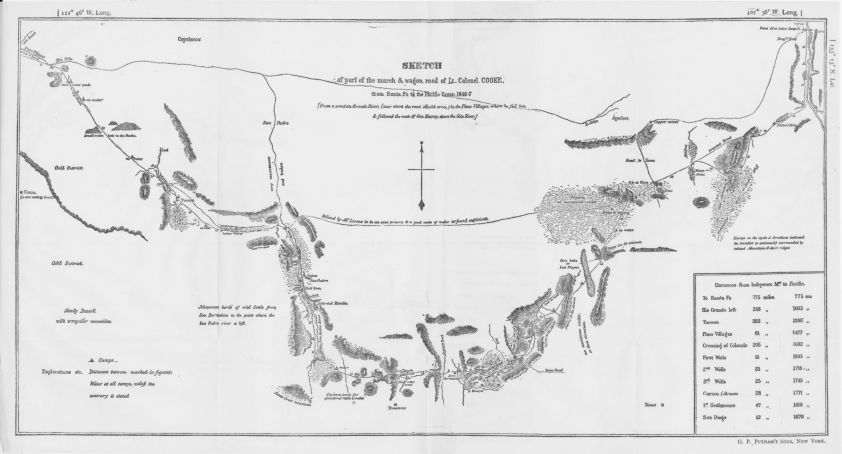

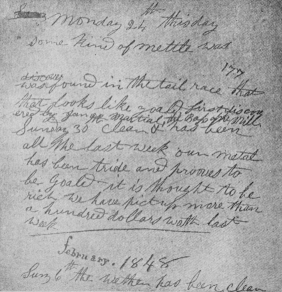

Click on the map and on the diary page to see a larger image.

The Mormon Battalion

ITS HISTORY AND

ACHIEVEMENTS

By

B. H. ROBERTS

THE DESERET NEWS

Salt Lake City, Utah

1919

[ii] Copyright, 1919.

BY B. H. ROBERTS.

Table of Contents

| I. | |

| The March of the Battalion Compared With Other Historical Marches. | |

| Retreat of the Ten Thousand | 1 |

| Doniphan's Expedition into Mexico | 3 |

| The World's Record for a March of Infantry | 4 |

| II. | |

| The Call of the Battalion. | |

| The Mormon Appeal to the United States Government for Help | 5 |

| Little's Consultations with the President | 7 |

| The Order to Enlist Mormon Volunteers | 11 |

| Terms of Enlistment | 12 |

| Captain Allen in the Mormon Camps | 13 |

| Brigham Young's Activities in Raising the Battalion | 16 |

| Muster of the Battalion | 18 |

| Farewell Scenes | 19 |

| III. | |

| Advantages and Disadvantages in the Call of the Battalion. | |

| A Sacrifice Nevertheless | 21 |

| Advantages of the Enlistment | 22 |

| Money Value of the Enlistment | 24 |

| The Equipment of the Battalion to be Retained | 25 |

| Appreciation of the Mormon Leaders | 26 |

| IV. | |

| The March of the Battalion From Fort Leavenworth to Santa Fe. | |

| Death of Colonel Allen. Question of a Successor | 27 |

| Complaints of the Volunteers | 28 |

| The Line of March | 29 |

| Arrival at Santa Fe. Condition of the Command | 30 |

| Invalided Detachment Sent to Pueblo | 32 |

| [iv]V. | |

| The March of the Battalion From Santa Fe to the Mouth of the Gila. | |

| More Invaliding | 34 |

| Hardship of Excessive Toil | 35 |

| Irrigation in New Mexico | 36 |

| March Down the Rio Grande | 36 |

| "Blow the Right." The Westward Turn | 37 |

| The Fight with Wild Bulls | 38 |

| Mexican Opposition at Tucson | 39 |

| Junction with Kearny's Trail | 42 |

| March Down the Gila | 42 |

| At the Mouth of the Gila | 43 |

| VI. | |

| The March of the Battalion From the Colorado to the Pacific Ocean. | |

| Destitution and Suffering of the Men en March | 45 |

| From Carriso Creek to San Phillipe | 47 |

| At Warner's Rancho | 49 |

| The March Directed to San Diego | 49 |

| In Sight of the Pacific | 50 |

| San Diego Mission | 51 |

| Col. Cooke's Bulletin on the Battalion's March | 51 |

| VII. | |

| The Battalion in California. | |

| At San Luis Rey Mission | 54 |

| Clean up and Drill | 54 |

| Company B at San Diego | 55 |

| The Conquest of California | 56 |

| The Kearny-Fremont Controversy | 56 |

| VIII. | |

| Record of the Battalion in California. | |

| Efforts to Re-enlist the Battalion | 58 |

| Homeward Bound | 60 |

| The Discharge and Payment of the Pueblo Detachments | 61 |

| The Purchase of Ogden Site with Battalion Money | 61 |

| The Battalion's Contribution of Seeds to Utah Colonies | 63 |

| The Battalion's Part in the Discovery of Gold | 63 |

| [v]The Date of the Discovery of Gold | 65 |

| The Tide of Western Civilization Started | 67 |

| The Mormon Battalion's "Diggings" on the American River | 68 |

| The Call of Duty | 69 |

| Ascent of the Sierras from the Western Side | 72 |

| Wagon Trail from Los Angeles to Salt Lake | 72 |

| Evidence of Appreciation of the Battalion's Services | 73 |

| Efforts to Raise a Second Mormon Battalion | 74 |

| IX. | |

| The Battalion in the Perspective of Seventy-Three Years. | |

| The Battalion as Utah Pioneers | 76 |

| Achievements of the Battalion | 77 |

| Territory Added to the United States | 77 |

| The Gadsden Purchase and the Battalion Route | 78 |

| Connection with Irrigation | 80 |

| X. | |

| The Subsequent Distinction Achieved by the Battalion's Commanding Officers. | |

| Colonel Cooke | 83 |

| Lieut. A. J. Smith | 84 |

| Lieut. George Stoneman | 84 |

| XI. | |

| Anecdotes. | |

| Character of Col. Cooke | 85 |

| Col. Cooke and Christoper Layton | 85 |

| Col. Cooke and Lot Smith | 86 |

| The Colonel, the Mule, and Bigler | 87 |

| "Wire, Wire, Wire D——n You Sir!" | 88 |

| Col. Cooke's Respect for the Battalion | 88 |

| ADDENDA. | |

| The Battalion's Monument. | |

| The State of Utah's Mormon Battalion Monument Commission | 89 |

| Description of the Monument | 91 |

| The Duty of the People of Utah | 95 |

The Mormon Battalion

I.

THE MARCH OF THE BATTALION COMPARED WITH OTHER HISTORICAL MARCHES.

"The Lieutenant-Colonel commanding congratulates the Battalion on their safe arrival on the shores of the Pacific ocean, and the conclusion of their march of over two thousand miles. History will be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry."

So wrote Lieutenant-Colonel P. St. George Cooke in "Order No. I," from "Head Quarters Mormon Battalion, Mission of San Diego", under date of January 30th, 1847. If Col. Cooke is accurate in his statement—and one has a right to assume that he is, since he was a graduate of the United States Military academy of West Point, and hence versed in the history of such military incidents—then the march of this Battalion is a very wonderful performance. For if history might be searched in vain for an equal march of infantry when Col. Cooke wrote his "Order No. I," then certainly no march of infantry since that time has equaled it.

The only other historical marches that are comparable with the Mormon Battalions' march are Xenophon's and Doniphan's, the former in ancient, the latter in modern times.

"Retreat of the Ten Thousand."—Xenophon's march is commonly known as the "Retreat of the Ten [2]Thousand," 401 B. C. The account of the "Retreat" is given in Xenophon's Anabasis. About fourteen thousand Greek soldiers under a Spartan leader named Clearchus entered the service of a Persian prince, Cyrus, surnamed the younger, brother of the then reigning King of Persia, Artaxerxes II. The purpose of Cyrus was to deprive his brother of the throne of Persia, and reign in his stead. The expedition marched through Asia Minor to Cunaxa, near old Babylon, where an army of 900,000 Persians engaged the army of Cyrus, which, with his Greek auxiliaries number but 300,000. The smaller army was really successful in the battle, but a rash attempt on the part of Cyrus to slay his brother during the engagement—in which he himself was killed—changed the fortunes of the day, the expedition ended in failure and hence the retreat of the Greek ten thousand up the valley of the Tigris, through Armenia to Trebizond, a Greek city on the Euxine—our modern Black Sea.

This march of Greek infantry though attended with almost incredible hardships from cold, hunger, and the assaults of enemies, was not equal to the march of the Mormon Battalion for the reason that it covered but fifteen hundred miles, as against the two thousand miles covered by the Battalion. While the Greek infantry in their retreat numbered more men than the Battalion, and fought many battles, their march was, for the most part, through settled lands and along well defined roads, while the greater part of the Battalion's march was through desert lands; and four hundred and seventy-four miles of it through trackless deserts where nothing but savages and wild beasts were found, "or deserts where, for want of water, there was no living creature."[2:a]

[3]Doniphan's Expedition into Mexico.—Doniphan's march occurred in the same year, and in the same war in which the Battalion served—the war with Mexico, 1846. The march is known as Doniphan's Expedition into Mexico. The expedition started from Santa Fe and marched to Matamoras, near where the Rio Grande empties into the Gulf of Mexico—a distance of about thirteen or fourteen hundred miles.[3:b] The march was via El Paso, Chihuahua, Parras, Saltillo and Monterey, thence to Matamoras. Here the expedition embarked for New Orleans, where the men were mustered out of service. The important battles of Brazito and Sacramento were fought enroute, the former placing El Paso, and the latter the city of Chihuahua—capital of the state of the same name—in the hands of the Americans. The expedition numbered about nine hundred men, mostly from Missouri, and under the command of Col. Alexander W. Doniphan of that state, and returned to Missouri via the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi.

The march overland it will be observed was less than that of the Battalion's. For the most part, moreover, Doniphan's march was through a settled country, and over roads long used between Santa Fe and points in northern and central Mexico. Besides, the Expedition was not exclusively made up of infantry, being mixed cavalry and infantry, and therefore would not strictly come in competition with the Battalion which was [4]entirely of infantry, with accompanying baggage wagons. Doniphan's Expedition is so wonderful a performance, however, and has been so generously acclaimed, that if unmentioned in connection with the performance of the Battalion, and the contrast made as above, it might be thought by some to rival the march of the latter. This, however, is not the case.

The World's Record for a March of Infantry.—Not even in the World's Great War, now happily ended, has the Mormon Battalion's march been equaled, though in all other things that war has surpassed the previous war experiences of mankind. And since the Battalion's march has not been equaled by any march of infantry in the World's Great War, nor in ancient times, it is not likely now, owing to the new methods for the transportation of troops that have been developed, that the Mormon Battalion's march across more than half of the North American continent will ever be equaled. It will stand as the world's record for a march of infantry.

FOOTNOTES:

[2:a] See Cooke's Wagon Road Map for this part of the route.

[3:b] I am aware that the historian of "Doniphan's Expedition"—William E. Connelley, credits the expedition with a grand circuit of 5,500 miles, 2,500 miles of which he states was by water, leaving a distance of 3,500 miles by land; but he accounts the expedition as starting from Independence, Mo., and returning to it. Whereas the expedition was organized and began its great march at Santa Fe, and ended at Matamoras, where it embarked for home.

II.

THE CALL OF THE BATTALION.

The Mormon Battalion owes its existence to the exodus of the Mormon people from the state of Illinois to the then (1846) little known region of the Rocky Mountain west. The leaders of that people had decided that there was little prospect of their being able to live in peace with their neighbors in Illinois, or in any of the surrounding states, owing to the existence of strong prejudices against their religion, and therefore they resolved upon seeking a new home in the west—"within the Basin of the Great Salt Lake, or Bear River Valley * * * believing that to be a point where a good living will require hard labor, and consequently will be coveted by no other people, while it is surrounded by so unpopulous but fertile a country."[5:a]

The Mormon Appeal to the United States Government for Help.—Before the exodus from Illinois began, as early as the 20th of January (1846), the high council at Nauvoo made public announcement of the intention of the Mormon people to move to "some good valley of the Rocky Mountains;" and in the event of President Polk's "recommendation to build block houses and stockade forts on the route to Oregon, becoming a law, we have encouragement," they said "of having that work to do, and under our peculiar circumstances, we can do it with less expense to the government than any other people."[5:b]

[6]Six days later Jesse C. Little was appointed by the Mormon Church authorities president of the Eastern States Mission, and in his letter of appointment was instructed as follows:

"If our government shall offer any facilities for emigrating to the western coast, embrace those facilities, if possible. As a wise and faithful man, take every honorable advantage of the times you can."[6:c]

"In consonance with my instructions," says Mr. Little, in his report to Brigham Young, which is recorded in the latter's manuscript history, "I * * * resolved upon visiting James K. Polk, President of the United States, to lay the situation of my brethren before him, and ask him, as the representative of our country, to stretch forth the federal arm in their behalf."

In pursuance of this design Mr. Little obtained a letter of introduction from John H. Steel, governor of New Hampshire, in which state Mr. Little had been reared. The governor in his letter declared that he had known Mr. Little from childhood, and believed him honest in his views and intentions, and added:

"Mr. Little visits Washington, if I understand him correctly, for the purpose of procuring, or endeavoring to procure, the freight of any provisions or naval stores which the government may be desirous of sending to Oregon, or to any portion of the Pacific. He is thus desirous of obtaining freight for the purpose of lessening the expense of chartering vessels to convey him and his followers to California, where they intend going and making a permanent settlement the present summer."[6:d]

[7]From Luke Milber, also of Petersboro, N. H., Mr. Little secured a letter to Hon. Mace Moulton in Washington, which in addition to vouching for the high character of Mr. Little, based upon personal knowledge of him for twelve years, announced that he was "soliciting some aid from the general government, to assist himself and brethren throughout the United States in emigrating to California."

In May of the same year, at a church conference held in Philadelphia, Mr. Little made the acquaintance of the Kanes. They were an old and honorable Pennsylvania family. The father, Judge John K. Kane, had been attorney general of the state of Pennsylvania; and at the time of Mr. Little's visit at his home he was United States judge for the district of Pennsylvania, also President of the American Philosophical Society. Dr. Elisha Kent Kane, the famous arctic explorer and scientist, was his son; as was also Thomas L. Kane, who afterward served with distinction as Colonel and Brigadier General in the Union Army in the war between the states. From the latter Mr. Little received a letter of introduction to Hon. Geo. M. Dallas, Vice-President of the United States. "He visits Washington," said Kane's letter to Mr. Dallas, "with no other object than the laudable one of desiring aid of the government for his people."

Little's Consultation with the President.—The arrival of Mr. Little at Washington on the 21st of May was most opportune for the business he had in hand. He called upon President Polk that same evening in company with a Mr. Dame of Massachusetts, and Mr. King, a representative of the same state. Sam Houston of Texas and other distinguished gentlemen were present. News of the capture of an American reconnoitering troop [8]of dragoons under command of Captain Thornton, on the east side of the Rio Grande, sixteen of whom were killed, had reached Washington early in May, and enabled the President in his message to Congress, on the 11th of that month, to say that "Mexico had invaded our territory, and shed the blood of our citizens on our own soil;" which led Congress two days later to declare war and vote the funds necessary to its vigorous prosecution. By the time Mr. Little called upon the President the news had reached Washington of the victory of the American forces under General Taylor at the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, fought on the 8th and 9th of May respectively. News of these victories aroused the war spirit throughout the land,[8:e] and hastened all the government schemes for prosecuting the war, including the plan of gathering the "Army of the West" at Fort Leavenworth, under Col. Stephen W. Kearny, to invade New Mexico, and ultimately co-operate with the Pacific fleet which it was designed should sweep round Cape Horn and attack on the Pacific coast of Mexico.[8:f] It was with this "Army of the West" that the Mormon Battalion was destined to be connected.

Mr. Little a few days later was informed by his friends in Washington that the plan for the Mormon participation in this movement to the west, discussed by the [9]President and his cabinet, was for Mr. Little to go directly to the camps of the Mormon people in the west and have one thousand men fitted out and plunge into California, officered by their own men, the commanding officer to be appointed by President Polk; and to send one thousand more by way of Cape Horn, who will take cannon and everything needed in preparing defense; those by land to receive pay from the time Little should see them, and those going by water, from September first.[9:g]

At this point Mr. Little seems to have taken up the matter personally and directly with the President, and under date of June 1st addressed an "Appeal" to him. In it Mr. Little expresses confidence in the President, else he would not have left his home "to ask favors" of him for his people (i. e., the Mormons). He gave an account of himself and his forefathers, who fought "in the battles of the Revolution;" of his own character, vouched for by his letters of introduction from men of high standing; and then avers that the people he represents are of as high character as himself. "I come to you," he said, "fully believing that you will not suffer me to depart without rendering me some pecuniary assistance. * * * Our brethren in the west are compelled to go [west]; and we in the eastern country are determined to go and live, and, if necessary, to suffer and die with them. Our determinations are fixed and cannot be changed. From twelve to fifteen thousand have already left Nauvoo for California, and many others are making ready to go. Some have gone around Cape Horn, and I trust before this time have landed at the Bay of San Francisco.

"We have about forty thousand (members) in the [10]British Isles, and hundreds upon the Sandwich Islands, all determined to gather to this place, and thousands will sail this fall. There are yet many thousands scattered through the states, besides the great number in and around Nauvoo, who are determined to go as soon as possible, but many of them are poor (but noble men and women), and are destitute of means to pay their passage either by sea or land.

"If you assist us at this crisis," said the "Appeal," "I hereby pledge my honor, my life, my property and all I possess as the representative of this (the Mormon) people to stand ready at your call, and that the whole body of the people will act as one man in the land to which we are going, and should our territory be invaded we hold ourselves ready to enter the field of battle, and then like our patriot fathers * * * make the battlefield our grave or gain our liberty." Mr. Little signs himself "Agent of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the Eastern States."[10:h]

Interviews followed with President Polk on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th of June. Of the visit to the President on the 5th Mr. Little writes in his Report:

"I visited President Polk; he informed me that we should be protected in California, and that five hundred or one thousand of our people should be taken into the service, officered by our own men; said that I should have letters from him, and from the secretary of the navy to the squadron. I waived the President's proposal until evening, when I wrote a letter of acceptance."[10:i]

There followed another and final interview with President Polk on the 8th of June:

[11]"I called on the President, he was busy but sent me word to call on the secretary of war. I went to the war department, but as the secretary was busy, I did not see him; the President wished me to call at two p. m., which I did, and had an interview with him; he expressed his good feelings to our people—regarded us as good citizens, said he had received our suffrages, and we should be remembered; he had instructed the secretary of war to make out our papers, and that I could get away tomorrow."[11:j]

The Orders to Enlist Mormon Volunteers.—Colonel Thomas L. Kane was entrusted with the orders to Colonel, afterwards General, Stephen W. Kearny, and accompanied Mr. Little as far as St. Louis. Here they separated, Kane to go with his orders to Kearny, then at Fort Leavenworth, and Little to the camps of his people; then moving through southern Iowa.

It is not known just what considerations led President Polk to cut down the number of Mormons to be sent to occupy California from two thousand to five hundred. But in the orders sent to Col. Kearny, that officer was directed not to take into the service a greater number of Mormons than one-third of his command, which was limited to about fifteen hundred men. "It is known," said Kearny's order, to enlist Mormon volunteers, "that a large body of Mormon emigrants are en route to California, for the purpose of settling in that country. You are desired to use all proper means to have a good understanding with them, to the end that the United States may have their co-operation in taking possession of, and holding, that country. It has been suggested here that many of these Mormons would willingly enter into the [12]service of the United States, and aid us in our expedition against California. You are hereby authorized to muster into service such as can be induced to volunteer; not, however, to a number exceeding one-third of your entire force. Should they enter the service they will be paid as other volunteers, and you can allow them to designate, so far as it can be properly done, the persons to act as officers."[12:k]

Terms of Enlistment.—Under this order Kearny issued instructions to Captain James Allen, of the First Regular Dragoons, to proceed to the camps of the Mormons and endeavor to raise from among them four or five companies of volunteers to join him in his expedition to California. The character of the Battalion, terms of enlistment, pledges of the government are clearly set forth in Allen's instructions:

"Each company to consist of any number between 73 and 109; the officers of each company will be a captain, first lieutenant and second lieutenant, who will be elected by the privates, and subject to your approval; and the captains then to appoint the non-commissioned officers, also subject to your approval. The companies, upon being thus organized, will be mustered by you into the service of the United States, and from that day will commence to receive the pay, rations and other allowances given to the other infantry volunteers, each according to his rank. You will, upon mustering into service the fourth company, be considered as having the rank, pay and emoluments of a lieutenant-colonel of infantry, and are authorized to appoint an adjutant, sergeant-major, and quartermaster-sergeant for the battalion.

[13]"The companies, after being organized, will be marched to this post [i. e., Fort Leavenworth, whence the order was issued] where they will be armed and prepared for the field, after which they will, under your command, follow on my trail in the direction of Santa Fe, and where you will receive further orders from me.

"You will, upon organizing the companies, require provisions, wagons, horses, mules, etc. You must purchase everything that is necessary and give the necessary drafts upon the quartermaster and commissary departments at this post, which drafts will be paid upon presentation.

"You will have the Mormons distinctly to understand that I wish to have them as volunteers for twelve months; that they will be marched to California, receiving pay and allowances during the above time, and at its expiration they will be discharged, and allowed to retain, as their private property, the guns and accoutrements furnished to them at this post.

"Each company will be allowed four women as laundresses, who will travel with the company, receiving rations and other allowances given to the laundresses of our army.

"With the foregoing conditions, which are hereby pledged to the Mormons, and which will be faithfully kept by me and other officers in behalf of the government of the United States, I cannot doubt but that you will in a few days be able to raise five hundred young and efficient men for this expedition."

Captain Allen in the Mormon Camps.—Captain Allen arrived at Mount Pisgah on the 26th of June, accompanied by three dragoons and presented to the leading men of that place "A Circular to the Mormons" in [14]harmony with his instructions. The presiding brethren at Mount Pisgah did not feel authorized to take any steps in the matter of Captain Allen's communication on the enlistment of a Battalion, but gave him a letter of introduction to President Young at Council Bluffs, for which place the Captain started immediately and arrived on the 30th of June. The following day he met with President Young and others in council and presented the whole question of raising a Battalion from the Mormon camps.

The question arose in the minds of the Mormon leaders as to the disposition of the camps which would be materially crippled by the withdrawal of so many young, strong, and able-bodied men. Already the question of wintering the camps and caring for so large an amount of stock possessed by them, loomed large among their difficulties. About one hundred and fifty miles to the west, in La Platte river, was "Grand Island," fifty-two miles long, with an average width of a mile and three-quarters, and well timbered; in the neighborhood of which also were immense areas of grass that might be cut for hay, and the rank growth of rushes here and there along the extensive river bottoms would enable much of the stock to winter on this range, could government permission be obtained for a large contingent of the camp to be stationed there. This country, as well as the one the camps were then occupying, was within the Louisiana Purchase, and largely divided into Indian reservations, hence could only be occupied by the whites by permission of the government.

The question of government permission therefore, in the event of the Battalion being raised, was submitted to Captain Allen, and he assumed the responsibility of saying that the camps might locate on Grand Island [15]until they could prosecute their journey. In his speech made to the camp the same day, the captain promised to write President Polk to give leave to the Mormon camps to stay on their route wherever it was necessary. At a council meeting held later in the day, on Brigham Young asking Captain Allen "if an officer enlisting men in an 'Indian country' had not a right to say to their families, You can stay till your husbands return," the Captain replied "that he was the representative of President Polk and could act till he notified the President, who might ratify his engagements, or indemnify for damages. The President might give permission to travel through the Indian country and stop whenever and wherever circumstances required."[15:l]

After the first council meeting between Captain Allen and the Mormon leaders a public meeting was held at noon on the same day. Brigham Young introduced Captain Allen who addressed the people: "He said he was sent by Col. Stephen W. Kearny through the benevolence of Jas. K. Polk, President of the United States, to enlist five hundred of our men; that there were hundreds of thousands of volunteers ready [to enlist] in the states. He read his order from Col. Kearny and the circular which he himself had issued from Mount Pisgah and explained."[15:m]

The statement of Captain Allen that there were hundreds of thousands of volunteers ready to enlist in the states was quite true. The declaration of war upon Mexico by the congress "authorized the President to accept the service of fifty thousand volunteers, and placed ten millions of dollars at his disposal. * * * The call for [16]volunteers was answered by the prompt tender of the service of more than 300,000 men."[16:n] "Four regiments were called for from Illinois, nine answered the call, numbering 8,370; only four of them, numbering 3,720 men, could be taken."[16:o]

Brigham Young's Activities in Raising the Battalion. Brigham Young followed Captain Allen in an address, at the aforesaid meeting. His own account of his remarks stand in his Ms. history as follows:

"I addressed the assembly; wished them to make a distinction between this action of the general government and our former oppressions in Missouri and Illinois. I said, the question might be asked, is it prudent for us to enlist to defend our country? If we answer in the affirmative, all are ready to go.

"Suppose we were admitted into the union as a state, and the government did not call on us, we would feel ourselves neglected. Let the Mormons be the first to set their feet on the soil of California. Captain Allen has assumed the responsibility of saying that we may locate on Grand Island, until we can prosecute our journey. This is the first offer we have ever had from the government to benefit us.

"I proposed that the five hundred volunteers be mustered and I would do my best to see all their families brought forward, as far as my influence extended, and feed them when I had anything to eat myself."[16:p]

At the close of the public meeting another council meeting was held, with Captain Allen present, when the question of the people having a right to remain on [17]Indian lands during the absence of the soldiers, and indeed along their whole route of travel, was further considered. Captain Allen withdrew from the council "and the Twelve," says Brigham Young, "continued to converse on the favorable prospect before us."[17:q]

It was arranged that Brigham Young should go to Mount Pisgah to raise volunteers for the Battalion; and that other leaders should prosecute the work of raising volunteers in the camps about Council Bluffs.

There was apparently some reluctance among the people to respond to this unexpected call, and it required some considerable persuasion to dispel it.

On the 11th of July, Col. Thomas L. Kane reached the Mormon camps at Council Bluffs, and gave assurance that the general government had taken the Mormon case into consideration, inferentially with benevolent intentions.[17:r]

When within eleven miles of Mount Pisgah, Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball met Jesse C. Little, president of the Eastern States Mission, who reported his labors at Washington. His written report was incorporated in Brigham Young's Ms. History for that year.

While at Pisgah Brigham Young wrote the camp at Garden Grove, and sent his letter by special messenger. After describing the terms of enlistment and the conditions under which the volunteers would be mustered out of service in California, etc., he said:

"They may stay (i. e. in California), look out the best locations for themselves and their friends, and defend the country. This is no hoax. Mr. Little, President of the [18]New England churches, is here direct from Washington, who has been to see the President on the subject of emigrating the saints to the western coast, and confirms all that Captain Allen has stated to us. The United States want our friendship, the President wants to do us good and secure our confidence. The outfit of this five hundred men costs us nothing, and their pay will be sufficient to take their families over the mountains. There is war between Mexico and the United States, to whom California must fall a prey, and if we are the first settlers, the old citizens cannot have a Hancock [county] or Missouri pretext to mob the saints. The thing is from above, for our good."

A letter of like spirit was sent by Brigham Young to the trustees at Nauvoo. In that letter the following passage occurs: "This is the first time the government has stretched forth its arm to our assistance, and we receive their proffers with joy and thankfulness. We feel confident they [the Battalion] will have little or no fighting. The pay of the five hundred men will take their families to them. The Mormons will then be the old settlers and have a chance to choose the best locations."[18:s]

Muster of the Battalion.—When Brigham Young returned from Mount Pisgah, a public meeting was held on the 13th of July, and the final work of enrollment of the Battalion began. At the opening meeting Brigham Young said:

"If we want the privilege of going where we can worship God according to the dictates of our conscience, we must raise the Battalion. I say it is right, and who cares for sacrificing our comfort for a few years. I [19]would rather have undertaken to raise 2,000 a year ago in 24 hours, than 100 in one week now."[19:t]

Later he said to the mustering companies, "You could not ask for anything more acceptable than this mission."[19:u] An American flag—flag of the United States—"brought out from the store-house of things rescued"—in the Mormon exodus from Illinois—"was hoisted to a tree mast, and under it the enrollment took place."[19:v] The enrollment of the Battalion was completed on the 16th of July, and that day Captain Allen took the organization under his command.

Farewell Scenes.—"There was no sentimental affectation at their leave-taking," remarks Col. Kane in his account of the departure of the Battalion from the camps. The afternoon before their departure a "ball" was given in their honor. Of this "ball," Col. Kane says:

"A more merry dancing rout I have never seen, though the company went without refreshments and their ball room was of the most primitive kind. [Under a bowery where the ground had been trodden firm and hard by frequent use.] To the canto of debonair violins, the cheer of horns, the jingle of sleigh bells, and the jovial snoring of the tambourine, they did dance! None of your minuets or other mortuary processions of gentles in etiquette, tight shoes, and pinching gloves, but the spirited and scientific displays of our venerated and merry grandparents, who were not above following the fiddle to the Foxchase Inn, or Gardens of Gray's Ferry. French fours, Copenhagen jigs, Virginia reels, and the like forgotten figures executed with the spirit of people too [20]happy to be slow, or bashful, or constrained. Light hearts, lithe figures, and light feet, had it their own way from an early hour till after the sun had dipped behind the sharp sky line of the Omaha hills."[20:w]

On the 20th of July the Battalion took up its march for Fort Leavenworth, where it arrived on the 1st of August, and began preparations for the great western march.

FOOTNOTES:

[5:a] From a letter of Brigham Young to President James K. Polk, date of August 9, 1846. History of Brigham Young, MS. Bk. 2 p. 137.

[5:b] Times and Seasons, Vol. V, p. 1096.

[6:c] Little's Report, Hist. of Brigham Young, MS. Bk. 2, pp. 11-12.

[6:d] Little's Report to Brigham Young.

[8:e] Mr. Little notes this excitement in his Report, to Brigham Young, by saying in recording his movements of the 23rd of May: "There was considerable excitement in consequence of the news that Gen. Taylor had fought two battles with the Mexicans" (Little's Report, Hist. of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, p. 16). And Lossing says that when "news of the two brilliant victories reached the states a thrill of joy went throughout the land, and bonfires, illuminations, orations, the thunder of cannons, were seen and heard in all the great cities". (Hist. U. S., p. 483).

[8:f] Lossing's History U. S., 1872 Edition, p. 483.

[9:g] Little's Report, p. 16.

[10:h] Little's Report, p. 20-22.

[10:i] Ibid, p. 23.

[11:j] Little's Report, p. 23.

[12:k] Executive Document No. 60, Letter of Secretary of War to Gen. Kearny, marked "Confidential", 1846.

[15:l] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, pp. 4, 5.

[15:m] Ibid, pp. 3, 4.

[16:n] History of the United States, Marcus Wilson, appendix p. 682; same Lossing, p. 482; Stephens, p. 488.

[16:o] Gregg's History of Hancock Co. Ill., p. 118.

[16:p] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, pp. 4, 5.

[17:q] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, pp. 4, 5.

[17:r] Taylor's Journal, entry of July 11th, 1846.

[18:s] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, pp. 30-34.

[19:t] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, p. 44.

[19:u] History of Brigham Young, Ms. Bk. 2, p. 48.

[19:v] Kane's Lecture "The Mormons", p. 80.

[20:w] Kane's Lecture "The Mormons", pp. 80, 81.

III.

ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES TO THE MORMONS ARISING FROM THE ENLISTMENT

OF THE BATTALION.

The "call" for the Mormon Battalion was not an unfriendly act on the part of the United States' government towards the Mormon people. A representative of the Church, as we have seen, had appealed most earnestly to the executive of the nation for aid in the western emigrations of that people; and when it was decided by the administration to "accept" the services of such a force of volunteers, the Mormon leaders received the decision as an answer to their appeal for aid.

A Sacrifice Nevertheless.—But notwithstanding the government service was asked for by the representative of the Mormon people, and the granting of it was regarded by the Mormon leaders at the time as a great advantage to their people, it brought to the volunteers and to the people generally much of sacrifice. For one thing the opportunity to avail themselves of their tendered service to the government came at an unexpected and a most inconvenient time. As explained afterwards by Col. Kane, "The young and those who could best have been spared, were then away from the main body, either with pioneer companies in the van, or, their faith unannounced, seeking work and food about the northwest settlements, to support them till the return of the season for commencing emigration. The force was therefore to be recruited from among the fathers of families, and others whose presence it was most desirable to retain."[21:a] Practically five hundred wagons were left without [22]teamsters, and as many families were left without their natural protectors and providers. The families of the Battalion, with the families of their friends, in whose care they must leave their loved ones, and upon whom they must depend for succor, were then scattered in a string of camps for some hundreds of miles between Nauvoo and Council Bluffs, with no certain abiding place designated, and no immediate prospect of being permanently settled. To volunteer for a "war-march" of two thousand miles, much of which was desert, under such circumstances, was doubly hard. Moreover the Mormon people, from their then point of view, had little to be grateful for to the government of the United States. Their appeals from what to them was the injustice of Missouri and Illinois had met with but cold reception at Washington. They did not and could not be expected to understand, much less sympathize with, the refinements employed by the national legislators in drawing nice distinctions about the division of sovereignty between the states and the general government. They were self-conscious of wrongs inflicted upon their community in the two states in which they had settled—Missouri and Illinois. They had appealed to the general government for a redress of those grievances without avail; and now they were asked by their leaders to go into the service of that government which might mean the sacrifice of life, and surely meant the abandonment of their families to the care of others under circumstances the most trying. To respond to the call made upon them—both as to the volunteers and the camped community whence they were mustered—was a manifestation of unselfishness not often paralleled in history.

Advantages of the Enlistment.—Notwithstanding all the sacrifices involved, Brigham Young and those associated [23]with him were too astute as leaders not to appreciate the advantages of having a considerable number of their people to enter the service of the United States. The charge of disloyalty to the American government had often been made against the Mormons, which not all their protests and denials could overcome. But to enter the service of the government in a time of war, involving such inconveniences as must be theirs, would be an evidence of loyalty that would stand forever, both unimpeached and unimpeachable. That such was the understanding of Brigham Young is specifically expressed by him about a month after the departure of the Battalion. "Let every one distinctly understand," said he, "that the Mormon Battalion was organized from our camp to allay the prejudices of the people, prove our loyalty to the government of the United States, and for the present and temporal salvation of Israel; that this act left near five hundred teams destitute of drivers and provisions for the winter, and nearly as many families without protection and help."[23:b]

The Right to Settle on Indian Lands Secured.—Another advantage appealed to the leaders: It had become evident before the call was made for the Battalion, that while it might be possible for a specially organized pioneer company to go over the mountains that season—preparations for which were being rapidly made—the very great majority of the camps would be under the necessity of spending a year or more in southern Iowa, principally on Indian lands. The prospects of remaining upon such lands in peace would be much enhanced if it could be pleaded that five hundred of their men were [24]in the service of the government of the United States; and subsequent events demonstrated the validity of such a plea; also it was the advantage sought to be secured by Brigham Young in his first conference with Captain Allen on the subject of the enlistment of the Battalion. Under these arrangements of occupancy, as the Indian titles in lands in Iowa expired, the Mormon occupants acquired valuable pre-emption rights up and down the Missouri river from Council Bluffs for a distance of between fifty and sixty miles, stretching back on the east side of said river some thirty or forty miles.[24:c]

Money Value of the Enlistment.—Another consideration of importance was the remuneration of these soldiers. A year's pay for their clothing in advance at the rate of $3.50 per man per month, would amount to $42.00 each; and to $21,000 for the Battalion. Deciding to make their march in the clothing they had when enlisting, part of their money for clothing was sent back from Fort Leavenworth to be used for the benefit of the families of the Battalion, and part of it to assist the Mormon leaders. Subsequently agents were secretly sent to Santa Fe to bring back to the camps the pay of the soldiers that had accrued by the time they had arrived there. This amounted to three months' pay at the following rates: captain, $50.00 per month—rations 20 cents per day; first lieutenant, $30.00 per month—rations 20 cents per day; second lieutenant, $25.00 per month—rations 20 cents per day; first sergeant, $16.00 per month; sergeants, $13.00 per month; corporals, $9.00 per month; musicians, $8.00 per month; and privates, $7.00 per month.

The payment at Santa Fe was made in government [25]checks—"not very available at Santa Fe"—i. e. not easily negotiable—writes Col. Cooke.[25:d] It has often been claimed that the Battalion was paid a bounty—$42.00 per man—on entering the service. This was not the case. The payment for clothing, one year in advance, at the rate of $3.50 per month has been mistaken for bounty.[25:e] It was only by foregoing the purchase of clothing that the Battalion could send the payment for it to their families and to the Mormon leaders. This source of revenue to the camps was accounted a very great blessing at the time. In official letters to the Battalion from the Mormon leaders, under date of August 16th and 21st, respectively, it was said, in the first, that the Battalion had been placed in circumstances which enabled them to control more means than all the rest of the Mormon people in the wilderness; in the second Brigham Young said: "We consider the money you have received, as compensation for your clothing, a peculiar manifestation of the kind providence of our Heavenly Father at this particular time, which is just the time for the purchasing of provisions and goods for the winter supply of the Camp."[25:f]

The Equipment of the Battalion to be Retained.—In addition to this payment for clothing, and the monthly pay, there was the five hundred stand of arms and camp equipment which were to become the personal property of the men when discharged in California. These several considerations led John Taylor—who became the [26]successor to Brigham Young in Mormon leadership—in an address to the Mormons in England—to say:

"The President of the United States is favorably disposed to us. He has sent out orders to have five hundred of our brethren employed for one year in an expedition that was fitting out against California, with orders for them to be employed for one year, and when to be discharged in California, and to have their arms and implements of war given to them at the expiration of the term, and as there is no prospect of any opposition, it amounts to the same as paying them for going to the place where they were destined to go without."[26:g]

Appreciation of Mormon Leaders.—In a letter to President Polk, under date of August 9th, 1846, after reminding the President of the disadvantages the Mormon camps experienced in raising the Battalion, Brigham Young said:

"But in the midst of this we were cheered with the presence of our friend, Mr. Little, of New Hampshire, who assures us of the personal friendship of the President in the act before us; and this assurance, though not doubted by us in the least, was soon made doubly sure by the testimony of Col. Kane, of Philadelphia."

FOOTNOTES:

[21:a] Transcriber's Note: Footnote missing in original.

[23:b] History of Brigham Young, August 14, 1846, Ms., Bk. 2, pp. 151-2.

[24:c] See Orson Pratt in Millennial Star, Vol. X, pp. 241-7.

[25:d] Conquest of New Mexico, p. 92.

[25:e] See History of the Mormon Church (Roberts), Americana, March, 1912, p. 308, for a letter from the United States War Department on this subject.

[25:f] History Mormon Church, Americana, March, 1912, p. 310.

[26:g] Mill. Star, Vol. VIII, p. 117.

IV.

THE MARCH OF THE BATTALION FROM FORT LEAVENWORTH.

At Fort Leavenworth the Battalion received its equipment of 100 tents, one for every 6 privates; also their arms and camp accoutrements. When drawing the checks for clothing, the paymaster expressed great surprise to find that every man was able to sign his own name to the pay roll.

Death of Col. Allen. Question of a Successor.—At Fort Leavenworth Col. Allen was taken ill; but on the 12th of August he ordered the Battalion to start on its western march, while he would remain a few days, recuperate and overtake them. He died on the 23rd, much lamented by the Battalion, which had become warmly attached to him. Commenting upon his demise the author of the "Doniphan Expedition," William E. Connelly, says:

"Thus died Lieutenant-Colonel Allen, of the first U. S. dragoons, in the midst of a career of usefulness under the favoring smiles of fortune, beloved while living, regretted after death by all who knew him, both among the volunteers and the troops."

On the death of Col. Allen the question of succession in command was considered. It appears that this subject was mooted at the time the companies of the Battalion were enlisted; and "Col. Allen repeatedly stated to us," says Brigham Young, "that there would be no officer in the Battalion, except himself, only from among our people; that if he fell in battle, or was sick, or disabled by any means, the command would devolve on the [28]ranking officer, which would be the Captain of Company 'A' and 'B', and so on according to letter." The Battalion appears to have had the same understanding, for at a council meeting of the officers it was agreed by them that Captain Jefferson Hunt, of Company "A", should assume command, which decision was afterwards sustained by the unanimous vote of the men. Meantime, however, Major Horton, in command at Fort Leavenworth, sent Lieutenant A. J. Smith, of the regular army, to take command of the Battalion. This led to a threatened complication; for an appeal to such written military authorities as were available to the officers of the Battalion, left them hopelessly divided in their conclusions. On the arrival of Lieutenant Smith a council of officers was held in which the Battalion officers demanded to know what reasons existed for their acceptance of him as commander rather than Captain Hunt. To which it was answered that the government property in possession of the Battalion was not yet receipted for, but that Lieutenant Smith could receipt for it, and being a commissioned officer of the regular army, he would be known at Washington, and his actions and orders recognized; whereas the officers of the Battalion had not yet received their commissions, and it would be doubtful if their selection of a commander would be approved. After this discussion Captain Hunt submitted the matter to the officers, and all but three voted in favor of accepting Lieutenant Smith as the commander of the Battalion.

Complaints of the Volunteers.—With Lieutenant Smith had come Dr. George B. Sanderson, whom Col. Allen, at Leavenworth, had appointed a surgeon in the U. S. army, to serve with the Mormon Battalion. [29]According to the historian of the Battalion,[29:a] the volunteers suffered much because of the "arrogance, inefficiency and petty oppressions" of these two officers. This view of these officers, however, is to be accounted for by the Volunteers being suddenly brought under the enforced discipline of the U. S. army regulations. The heat of the season was excessive, the men had been already much exhausted by the strenuous labor and exposure during the journey through Iowa with their people earlier in the season, and as a result many of them fell a prey to the malaria prevalent in the country and at this season of the year. For this Dr. Sanderson prescribed calomel and arsenic, and as the men were averse to taking medicine, pleading even religious scruples against the drugs, the matter gave rise to much unpleasantness between the Battalion physician and the command, involving therein Lieutenant Smith, who, in the interest of what he no doubt regarded as discipline, sided with the physician.

The Line of March.—The Battalion's line of march, from Fort Leavenworth, after crossing the Kaw or Kansas river, followed that of the first Missouri Dragoons, led over the route that same year by Col. Doniphan, via Council Grove, thence some distance up the Arkansas River to a little beyond Fort Mann, where they crossed that river in order to take what was known as the "Cimmeron Route"—because it crossed Cimmeron river and followed some distance up the south branch of the stream, called Cimmeron Creek. The last crossing of the Arkansas they reached on the 16th of September, and here the commanding officer insisted that most of the [30]families—about twelve or fifteen in number, which had so far accompanied the Battalion—should be detached and sent under a guard of ten men up the Arkansas to Pueblo, which nestles at the east base of the Rocky mountain range. There were stout protests against this "division of the Battalion;" as it was held to be a violation of the promise that the Battalion would not be divided, also that these families should be permitted to travel with the Battalion to California. Unquestionably, however, the arrangement was in the best interests both of the families and of the Battalion, and accordingly the detachment was made up as proposed, and marched to Pueblo under command of Captain Nelson Higgins.

Arrival at Santa Fe; Condition of the Command.—The main body of the command continued its march south-westward to San Miguel, thence turning the point of a mountain range marched north westward to Santa Fe, where they arrived in two detachments on the 9th and 12th of October, respectively. Upon the arrival of the first detachment the Battalion was received by a salute of one hundred guns by order of Col. Doniphan,[30:b] then in command both as civil and military head of the department of New Mexico; but making ready for what was to be his great and historic march upon Chihuahua.

On the arrival of the Battalion at Santa Fe it was learned that General Kearny, previous to his departure [31]for the west, had designated Col. P. St. George Cooke[31:c] to take command of the Battalion and to follow on his trail with wagons to California.

Speaking of the condition of the Battalion, on its arrival in Santa Fe, and remarking on its physical unfitness to undertake the march to California, Col. Cooke, in his "Conquest of New Mexico," says:

"Everything conspired to discourage the extraordinary undertaking of marching this Battalion eleven hundred miles, for the much greater part through an unknown wilderness, without road or trail, and with a wagon train.

"It was enlisted too much by families; some were too old and feeble, and some too young; it was embarrassed by many women; it was undisciplined; it was much worn by traveling on foot, and marching from Nauvoo, Illinois; their clothing was very scant; there was no money to pay them, or clothing to issue; their mules were utterly broken down; the quartermaster department was without funds, and its credit bad; and animals were scarce. Those procured were very inferior, and were deteriorating every hour for lack of forage or grazing."[31:d] "So every preparation must be pushed—hurried. A small [32]party with families had been sent from Arkansas crossing up the river, to winter at a small settlement close to the mountains, called Pueblo. The Battalion was now inspected, and eighty-six men found inefficient were ordered, under two officers, with nearly all the women, to go to the same point; five wives of officers were reluctantly allowed to accompany the march, but furnished their own transportation. By special arrangement and consent, the Battalion was paid in checks—not very available at Santa Fe (i. e. negotiable).

"With every effort, the quartermaster could only undertake to furnish rations for sixty days; and, in fact, full rations, of only flour, sugar, coffee and salt; salt pork only for thirty days, and soap for twenty. To venture without pack-saddles would be grossly imprudent, and so that burden was added."[32:e]

Invalided Detachment Sent to Pueblo.—It was understood that the men invalided and their escort, together with the women and children belonging to the Battalion, would have the privilege in the spring of intercepting the main body of their people moving to the west, and going with them "at government expense."[32:f] The above [33]arrangement was the result of a council of the officers of the Battalion with Colonel Doniphan of Missouri, then in charge of military and civil affairs at Santa Fe, and with Col. Cooke who had been designated by Gen. Kearny to take command of the Battalion in its march to the Pacific, on his own departure from Santa Fe to California. Captain James Brown, of Company C., and St. Elam Luddington, of Company B, were the two officers above referred to as being placed in charge of the detachment. This company arrived at Pueblo on the 17th of November, and went into winter quarters near the encampment of Captain Higgins, who had preceded them to that point; and the next spring, according to the above arrangement, joined in the westward movement of their people, following so closely the pioneer company led by Brigham Young, that they entered Salt Lake Valley on the 29th of July, five days after the arrival of the first pioneer company. To the wife of one of the members of the Battalion, Mrs. Catherine Campbell Steele, wife of John Steele, Company D, was born the first white child in "Utah," August 9th, 1847.

FOOTNOTES:

[29:a] This is Sergeant Daniel Tyler, author of "A Concise History of the Mormon Battalion in the Mexican War." The work was published in 1881. H. H. Bancroft speaks very highly of this work in his History of California, Vol. V, p. 477, note.

[30:b] Col. Doniphan had come to Santa Fe with Kearny, commanding the first Missouri regiment; and after the departure of the General for California, he was left in command at Santa Fe until the arrival of Col. Sterling Price, who when he arrived, was to take command at Santa Fe (Doniphan's expedition, Connelley, 1907, pp. 250-1-3). The historian of the Mormon Battalion notes that the command of Col. Price, numbering about 1,200 men, received no such marked honor on their arrival in Santa Fe as was accorded to the Battalion. (Tyler's Battalion, p. 164.)

[31:c] The Colonel was born in Virginia in 1809. Graduated from West Point in 1827; was in the Black Hawk war in Illinois—1832, and at the Battle of Bad Ax, fought in July of that year. In 1833 he was made a Lieutenant; saw service on the plains, principally in what is now Kansas, before the Mexican war; in this war he took a prominent part in the affairs at Santa Fe and marched the Mormon Battalion to California. "During the fifties, in the border troubles in Kansas he saw much service; in the Civil War he was for the Union. He was retired in 1873, having served in the army continuously for forty-six years. He died March 20, 1895." "Doniphan's Expedition," p. 264.

[31:d] Later, Col. Cooke again complains of his teams, in the following passage: "I have brought road tools and have determined to take through my wagons; but the experiment is not a fair one, as the mules are broken down at the outset. The only good ones, about twenty, which I bought near Albuquerque, were taken for the express for Fremont's mail—the General's order requiring the twenty-one best in Santa Fe." (Cooke's Conquest, p. 93). To this Sergeant Tyler adds: "It is but justice to the Colonel to state here that with few exceptions, the mule and ox teams used from Santa Fe to California were the same worn out and broken down animals that we had driven all the way from Council Bluffs and Fort Leavenworth; indeed, some of them had been driven all the way from Nauvoo, the same season." (Tyler's Battalion, p. 175).

[32:e] Conquest of New Mexico and California. An Historical and Personal Narrative by P. St. George Cooke, G. P. Putnam and Sons, N. Y. 1878: pp. 91-2.

[32:f] See History of the Mormon Church, Americana, (Roberts), April No. p. 3776—note.

V.

THE MARCH OF THE BATTALION FROM SANTA FE TO THE MOUTH OF THE GILA.

The Battalion began its march from Santa Fe on the 19th of October, Colonel Cooke in command, Lieutenant A. J. Smith, who had led the Battalion to Santa Fe, became the acting commissary of subsistence; and Lieutenant George Stoneman, acting quartermaster, instead of Lieutenant Samuel E. Gully, who had resigned. Both Smith and Stoneman were of the regular army. Dr. Sanderson was continued as Physician-surgeon to the command. The guides to the expedition—appointed by Gen. Kearny—were Weaver, Charbonneau, and Leroux; and Stephen C. Foster, called "Doctor," in all the narratives, was employed as interpreter.

More Invaliding.—The course of the march for some time was southward down the valley of the Rio Grande. On the 10th of November, fifty-five more men were declared physically unable through sickness to continue the march, and accordingly were detached, and under Lieutenant W. W. Willis were ordered back to Pueblo to join the other detachments that had been sent there. After much suffering from the hardships of the journey—weak teams, scant supplies of food, illy clad, general sickness among the men, the fall of December snows in the mountain ranges north of Santa Fe, excessive cold, and several deaths occurring, this detachment finally arrived at Pueblo between the 20th and 24th of December, in a most pitiable condition; but they were warmly received [35]by members of the Battalion already quartered there,[35:a] numbering, now, all told, about one hundred and fifty.

Hardship of Excessive Toil.—One cause of so many men breaking down in health was the excessive toil at the wagons through the sand stretches of the road, began early in the march from Santa Fe—while yet in the valley of the Rio del Norte, in fact, and continuing along the whole route to and through the California desert lying between the Colorado and the coast range of mountains. "Our course now lay down the Rio del Norte [The Rio Grande]," says Sergeant Tyler. "We found the roads extremely sandy in many places, and the men while carrying blankets, knapsacks, cartridge boxes (each containing thirty-six rounds of ammunition), and muskets on their backs, and living on short rations, had to pull at long ropes to aid the teams. The deep sand alone, without any load was enough to wear out both man and beast." Later he remarks: "We had to leave the river for a time, and have twenty men to each wagon with long ropes to help the teams pull the wagons over the sand hills. The commander perched himself on one of the hills, like a hawk on a fence post, sending down his orders with the sharpness of—well, to the Battalion, it is enough to say—Colonel Cooke."

One of the Battalion celebrates this incident of the march in doggerel verse of which two stanzas follow:

In the trackless part of the Battalion's march through the sand stretches, in addition to pulling at the wagons, companies marched in double-single file, in each other's footsteps, to make tracks for the wagon wheels.

Irrigation in New Mexico.—It was while at Santa Fe, and while passing down the Rio del Norte, that the Battalion saw, for the first time, irrigation in operation. Tyler thus describes it: "Canals for irrigation purposes were found all along the banks of the river. Some of them several miles in length. They conveyed water to the farms, or as they were called in that country, ranchos. There being little or no rain during the growing season, the water was made to flow over the ground until it was sufficiently saturated, and then shut off until needed again for the same purpose."

March Down the Rio Grande.—As the command in its southward movement down the Rio Grande reached the point where General Kearny left the valley for a direct march westward—228 miles south of Santa Fe—and where, too, Kearny had abandoned his wagons; the guides declared it impossible to follow the Gila route proper with the wagons; and hence a circuit to the south through Sonora via Janos and Fronteras was proposed and determined upon at a council of officers.

In the first stages of this changed course, however, the road bore to the southeast, and this was not to the [37]liking of Col. Cooke, because it would carry his command within hailing distance of General Wool, who might incorporate it in the "Army of the Centre,"—as the General's division of the invading forces against Mexico was called—to operate against Chihuahua. In that event, as the Colonel himself expressed it, he would lose his trip to California. To bear to the southeast was not to the liking of the Battalion, as that was not in the direction of California, but one which might lead them within the sphere of the "Army of the Centre," and they would find themselves discharged in Old Mexico instead of California, at the end of their term of enlistment. The entire command was thrown into gloom by this change in the line of march: "All of our hopes, conversations and songs," says the historian of the Battalion—Tyler—"were centered on California. Somewhere on that broad domain we expected to join our families and friends."

"Blow the Right!" The Westward Turn.—"On the morning of the 21st," says Tyler, "the command resumed its journey, marching in a southern direction for about two miles, when it was found that the road began to bear southeast instead of southwest, as stated by the guides. The Colonel looked in the direction of the road, then to the southwest, then to the west, saying, 'I don't want to get under General Wool, and lose my trip to California.' He arose in his saddle and ordered a halt. He then said with firmness: 'This is not my course. I was ordered to California,' 'and,' he added with an oath, 'I will go there or die in the attempt.' Then turning to the bugler, he said, 'Blow the right!'

"Turning westward at this point, 32° 41´ north latitude, and but a short distance—some thirty miles—north of the present city of El Paso—the course of march was [38]westward to San Bernardino rancho, thence to Yanos and so to the San Pedro river where the command arrived on the 9th of December.

"The Fight with Wild Bulls.—Here occurred the only fighting the Battalion engaged in on its expedition, a battle with wild bulls. This section of the country seemed to abound with herds of wild cattle, and the males among them were much more bold and ferocious than among the buffalos. Attracted by curiosity these herds gathered along the line of march, alternately scampering away and approaching; and some of the bolder ones, as if in resentment of the Battalion's invasion, attacked the column. Several mules were gored to death by them, both in the teams and among the pack animals; and Colonel Cooke records how some of the wagons were thrown about by the mad charge of these furious beasts. The troops had been ordered to march with guns unloaded, but in the presence of such a danger the men loaded their muskets without waiting for an order to that effect, and when attacked would fire upon the charging beasts, so that the rattle of musketry was for once heard all along the line. The bulls were very tenacious of life, however, and more desperate and dangerous when wounded than before."

Tyler speaks of one fight between Dr. William Spencer and a bull which was shot five times, twice through the lungs, twice through the heart, and once through the head, and yet would alternately rise and fall and rush upon the doctor until a sixth ball between the eyes, and near the curl of the pate, proved fatal.[38:c] Colonel Cooke confirms Tyler's narrative about the bull continuing to [39]rush on after being twice shot through the heart, and adds: "I have seen the heart." Cooke also relates the feat of Corporal Frost in bringing down one of these ferocious animals: "I was very near Corporal Frost, when an immense coal-black bull came charging upon us, a hundred yards distant. Frost aimed his musket, a flintlock, very deliberately and only fired when the beast was within six paces; it fell headlong, almost at our feet."[39:d] Tyler adds: "The Corporal was on foot while, of course, the Colonel and staff were mounted. On the first appearance of the bull, the Colonel, with his usual firm manner of speech, ordered the corporal to load his gun, supposing, of course, that he had observed the previous order of prohibition. To this command he (the corporal) paid no attention. Thinking him either stupified or, dumbfounded, with much warmth and a foul epithet he next ordered him to run, but this mandate was as little heeded as the other. Doubtless Cooke thought one man's 'ignorance with some stubborness' was about to receive a terrible retribution, but when he saw the monster lifeless at his feet, through the well-directed aim of the brave and fearless corporal, how changed must have been his feelings!"[39:e] The number of the wild bovine enemy killed in the engagement is variously reported as from twenty to sixty, and by one writer as high as eighty-one.

Mexican Opposition at Tucson.—Leaving the San Pedro the command marched northeasterly to Tucson, a Mexican town of between four and five hundred inhabitants. It was garrisoned at the time by a Mexican force two hundred strong, according to Cooke, commanded by Captain Comaduran, who was under order from the [40]Governor of Sonora, Don Manuel Gandara, not to allow an armed force to pass through the town without resistance. The guides furnished the Battalion by General Kearny, however, declared it was for the command either to march through Tucson, or make a detour which would mean a hundred miles out of the way over a trackless wilderness and mountains. Cooke determined to march through Tucson. Foster, the interpreter, went into the town in advance and was put under guard; a corporal, son of the Mexican commander, with three Mexican soldiers was met by the command and questioned about Foster, and on admitting that he was under guard, the corporal and his escort were immediately placed under arrest by Cooke, to be held as hostages for the safety of the interpreter. One Mexican, however, was released, who, with two of the Battalion guides, carried a note demanding Foster's release. This was complied with, and about midnight Foster was brought to camp, attended by two officers authorized "to make a special armistice." Cooke proposed that the Mexican command deliver up a few arms as a guarantee of surrender, and a token that the inhabitants of Tucson would not fight against the United States unless they were exchanged as prisoners of war; the Mexican prisoners were also released.[40:f] These events occurred while the Battalion was about sixteen miles from Tucson.

The next day, when on the march, Cooke received a message from Captain Comaduran declining the proposition to surrender. The Battalion were ordered to load their guns with ball. Before reaching the town, however, another message was received saying that the garrison had retreated taking two brass cannons and forcing [41]most of the inhabitants to accompany them. About a dozen armed Mexicans met the American force to escort them into the town. Before passing through the gates, the commander of the Battalion addressed the soldiers saying, in effect, that the garrison and citizens had fled leaving their property behind; but they had not come to make war upon Sonora, and there must be no interference with the private property of the citizens.[41:g] The Battalion marched through Tucson and went into camp about half a mile beyond on a small stream.

Before leaving the vicinity Cooke with a party of fifty reconnoitered the country above the town towards a village and church, where, it was supposed, the garrison and main body of the people had taken refuge. As the nature of the country, however, afforded excellent opportunities for ambush, if the Mexicans should choose to make resistance, the company of fifty returned. However the movement was not without its value since, according [42]to Col. Cooke, and as was afterwards ascertained, it caused the Mexicans who had fled to the aforesaid village to still further retreat, and the reinforcements which had come from the presidios of Fronteras, Santa Cruz and Tubac, to return to their posts.[42:h]

Junction With Kearny's Trail.—Renewing its journey the command in the course of three days, by hard marching, reached the Gila river and intersected the route followed by General Kearny, four hundred and seventy-four miles from the point at which they left it in the valley of the Rio Grande.

The Southern Pacific Railroad traverses practically the route of the Battalion between these two points. Colonel Cooke made a map of this part of the Battalion's journey—published in his book, (see map fold) and referring to it, in connection with the Southern Pacific Railroad, he says: "A new administration, in which Southern interests prevailed, with the great problem of the practicability and best location of a Pacific Railroad under investigation, had the map of this wagon route before them with its continuance to the west, and perceived that it gave exactly the solution of its unknown element, that a southern route would avoid both the Rocky Mountains and Sierra Nevada, with their snows, and would meet no obstacle in this great interval. The new 'Gadsden Treaty' was the result; it was signed, December 30, 1853."[42:i]

The March Down the Gila.—Following more or less the windings of the Gila, the way made difficult from alternating stretches of deep sand and miry clay, the [43]command arrived at the junction of the Gila with the Colorado on the 8th of January.

An attempt at the shipment of part of the command's provisions down the river on a flat boat proved a sad failure, and ended in considerable loss. The scheme was Col. Cooke's. The "boat" was constructed by placing two wagon beds end to end and lashing them to two dry cottonwood logs. On this improvised boat two thousand five hundred pounds of provision and corn were placed. At places the river spread out over sand bars with but three or four inches of water covering them; the boat was repeatedly lodged on these, and the precious stores of food had to be landed in several places. The most of it was never recovered, though repeated efforts were made to regain it.

At the Mouth of the Gila.—Speaking of the Gila at its junction with the Colorado, and of the conditions obtaining in the command at that stage of the march, Col. Cooke writes: "A vast bottom; the country about the two rivers is a picture of desolation; nothing like vegetation beyond the alluvium of the two rivers; bleak mountains, wild looking peaks, stony hills and plains, fill the view. We are encamped in the midst of wild hemp. The mules are in mezquit thickets, with a little bunch grass, a half a mile off. The mules are weak, and their failing, or flagging to-day in ten miles, is very unpromising for the hundred mile stretch, dry and barren, before them. There is no grass, and only scanty cottonwood boughs for them to-night, but I sent out forty men to gather the fruit, called tornia, a variety of the mezquit. They have gathered twelve or fifteen bushels, which has been spread out to be eaten on a hard part of the sand-bar.

"Francisco was sent across the river to fire the thickets [44]beyond—this to clear the way for the pioneer party in the morning. He says the river is deeper than usual; it is wider than the Missouri, and of the same muddy color. * * * It is said to be sixty miles to the mouth of the river."—the Colorado.[44:j]

FOOTNOTES:

[35:a] See Tyler's Battalion Ch. XX. Lieutenant Willis gives the date of arrival 24th of December. Captains Brown and Higgins, stationed at Pueblo, give the 20th. The latter kept a daily journal.

[36:b] Tyler's History of The Mormon Battalion, pp. 180-183.

[38:c] Tyler's Battalion, pp. 219, 220.

[39:d] Cooke's Conquest, pp. 145, 6.

[39:e] Tyler's Battalion, p. 219.

[40:f] Cooke's Conquest, p. 149.

[41:g] Previous to this the Colonel had issued the following order:

"Head Quarters Mormon Battalion,

"Camp on the San Pedro,

"December 13th, 1846.

"Thus far on our course we have followed the guides furnished us by the General [Kearny]. These guides now point to Tucson, a garrison town, as our road, and assert that any other course is a hundred miles out of the way and over a trackless wilderness of mountains, rivers and hills. We will march, then, to Tucson. We came not to make war on Sonora, and less still to destroy an important outpost of defense against Indians: but we will take the straight road before us, and overcome all resistance. But shall I remind you that the American soldier ever shows justice and kindness to the unarmed and unresisting? The property of individuals you will hold sacred. The people of Sonora are not our enemies.

"By order of

[42:h] See Cooke's Conquest, p. 151; also Tyler's Battalion, pp. 228-230.

[42:i] Cooke's Conquest, p. 159.

[44:j] Conquest, pp. 170-1.

VI.

THE MARCH OF THE BATTALION FROM THE COLORADO TO THE PACIFIC OCEAN.

This part of the march led through what is now marked on the maps of southern California as the "Colorado Desert," "nature's exhausted region lying between the Colorado river and the eastern base of the coast range"—some of it being below the sea level. Much of the dreary way lay through stretches of sand, and the men were compelled to aid the teams by pulling on ropes, fifteen to twenty men to a wagon. No water was to be had but by the digging of deep wells in the desert sands. These often yielded but little, and at that a poor quality, of water. The suffering of both men and beasts was terrible. "The march of the last five days"—the time it took to cross the desert to the little running stream called "Carriso Creek,"—was "the most trying of any we had made on both men and animals," writes Col. Cooke.

Destitution and Suffering of the Men en March.—"We here found the heaviest sand, hottest days, and coldest nights," says Tyler, "with no water and but little food." "At this time," he continues, "the men were nearly bare-footed; some used, instead of shoes, rawhide wrapped around their feet, while others improvised a novel style of boots by stripping the skin from the leg of an ox. To do this, a ring was cut around the hide above and below the gambrel joint, and then the skin taken off without cutting it lengthwise. After this, the lower end was sewed up with sinews, when it was ready for the [46]wearer, the natural crook of the hide adapting it somewhat to the shape of the foot. Others wrapped cast-off clothing around their feet, to shield them from the burning sand during the day and the cold at night.

"Before we arrived at the Carriso many of the men were so nearly used up from thirst, hunger and fatigue, that they were unable to speak until they reached the water or had it brought to them. Those who were strongest reported, when they arrived, that they had passed many lying exhausted by the way-side."[46:a]

Col. Cooke refers to these conditions in his "Conquest of New Mexico:"[46:b] "A great many of my men are wholly without shoes, and used every expedient, such as rawhide moccasins and sandals, and even wrapping their feet in pieces of woolen and cotton cloth." Of the march on the 16th of January the Colonel remarks: "Near eleven, [A. M.] I reached, with the foremost wagon, the first water of the Carriso [Cooke's spelling is 'Cariza']; a clear running stream gladdened the eyes, after the anxious dependence on muddy wells for five or six days. I found the march [i. e. of the day] to be nineteen miles; thus without water for near three days, (for the working animals) and camping two nights in succession, without water, the battalion made in forty-eight hours, four marches, of eighteen, eight, eleven and nineteen miles, suffering from frost, and from summer heat."[46:c]