WHEN A COBBLER

RULED THE KING

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK * BOSTON * CHICAGO * DALLAS

ATLANTA * SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON * BOMBAY * CALCUTTA

MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

When a Cobbler Ruled the King

by

Augusta Husiell Seaman

with

Decoration and Drawings by

George Wharton Edwards

New York The Macmillan Co. 1919

Copyright, 1911,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

TO MY HUSBAND

FOREWORD

About the tradition of the "Lost Dauphin" there hovers a romance and charm perennially new, and history contains perhaps no more appealing little figure than that of Louis XVII of France.

At the time when the tempest of the French Revolution submerged the throne of the Bourbon monarchy, Louis Charles, royal Dauphin, was but a child of seven. On his sunny head, for the space of three years, the Terror wreaked its vengeance; and at the age of ten, it would have been difficult to recognize in the forlorn little captive of the Temple Tower, aged by imprisonment and abuse, and experienced in many forms of suffering, the once light-hearted and lovely child of Versailles and the Tuileries.

History in its most accepted form has chosen to close this regrettable chapter with the death of the little prince at the age of ten, and while still in his unjust captivity. With the receding years, however, there has arisen a not unreasonable doubt of this premature ending. Evidences strangely convincing have come to light, revealing a possibility of his having been rescued, spirited away from his native land, and allowed to live out the alloted number of his days in peaceful obscurity.

There are few of us who do not welcome this possibility, who do not relish the thought that his watchful and heartless tormentors may have been cleverly hoodwinked. And added to our pleasure in a happier fate for this much-wronged child of monarchy, is the delightful romance and mystery with which a possible escape and an existence thenceforth incognito has surrounded the history of the "Lost Dauphin." In the field of fiction the subject affords an all but endless variety of solution, and numerous are the romances woven about the person of "Little Capet." Curiously enough, few if any of these novels are quite suitable for younger readers, though the subject is one that should have a special appeal for the hearts of youth, since the chief personality is a child of peculiarly winning characteristics, and one who endured diversified and exciting vicissitudes.

Such a story I have striven to relate in When a Cobbler Ruled the King, endeavoring to present a picture, faithful as far as it goes, of the historical and political situation. It may add to the interest of the story to know that except for the persons of "Jean," "La Souris" and "Prevôt," who are pure fiction, there is not one character in the book but has a counterpart in history. These characters are in the main obscure enough to admit of much latitude in fictitious presentation. The Citizeness Clouet, of number 670 rue de Lille, was actually the laundress for the Temple Tower, and her little daughter was occasionally introduced into the prison by Commissary Barelle to play with the captive prince. Had there been schemes of escape concocted by the few friends remaining to royalty, as doubtless there were, it would be scarcely strange if the laundress had been involved in them.

Be these things as they may, it is to be hoped that the history of the throneless, crownless, ill-used child-king, Louis XVII of France, will make its own appeal to the hearts of all childhood.

A. H. S.

Richmond Hill, L. I.

February, 1911.

CONTENTS

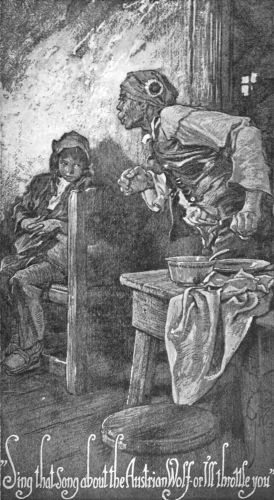

ILLUSTRATIONS

From drawings by George Wharton Edwards

| The King and his Family driven through the pitiless crowd |

| Sing that song about the Austrian wolf or I'll throttle you |

| He stood before the former child of the Tower—Louis XVII |

IN THE DAUPHIN'S GARDEN

CHAPTER I

IN THE DAUPHIN'S GARDEN

"Hurry along, Yvonne! Why do you lag behind so!"

"Oh, Jean! I am doing my best, but your legs are so long, and you take such great strides that I can scarcely keep up!"

Two children, a well-grown, long-limbed boy of twelve, and a little girl of scarcely more than seven, were hurrying hand-in-hand along the Rue St. Honoré, on a brilliant May morning in the year 1792. Paris on that day resembled, more than anything else, a great bee-hive whose swarming population buzzed hither and thither under the influence of angry excitement and general unrest.[Pg 4] The two youngsters were bubbling over with the same eager restlessness that agitated their elders. They pushed their way through throngs of men in red liberty-caps, soldiers in uniforms of the National Guard, and women in tri-coloured skirts and bodices. Poor little Yvonne, panting and tired, struggled to keep up with the striding gait of her larger companion.

"If you don't hurry," said Jean, "we shall not see the little 'Wolf-Cub' out for his walk, and I want a look at him!"

"Is he very dreadful to look at?" queried Yvonne, innocently.

"I don't know,—I've never seen him," answered Jean, "but he must be pretty ugly if he's the son of a monster,—and that's what they call our Citizen King!"

They turned into a narrow lane with but few houses on either side. At one end stood the church of St. Roch, and at the other lay the park of the Tuileries, in the centre of which rose the royal palace.[Pg 5]

"This is called the Rue du Dauphin because the little monster comes through it when he goes to church," remarked Jean.

"Well, I think he can't be so very dreadful if he goes to church," protested Yvonne.

"Oh, he only pretends to be good to deceive us!" answered Jean, carelessly.

When they reached the park, they turned and ran along the edge till they came to the side flanked by the river Seine. Here they were stopped by a low wooden fence decorated with festoons of tri-coloured ribbons and bunting. In a small plot of ground behind this fence, a little boy could be seen digging up the ground about some flower-beds. He was a really beautiful child and his age evidently did not much exceed seven years. Great blue eyes looked out of a face whose expression was one of charming attractiveness. His silky golden-brown hair fell in curls about his shoulders, and he was dressed in the uniform of a tiny National Guard, with a small jewelled sword hanging at his side.[Pg 6] About his feet a handsome, coal-black spaniel romped, shaking his long ears that almost trailed on the ground, barking and biting at the spade in his master's hand.

Jean stopped and looked over the fence. His snapping black eyes grew soft at the sight of the group within. What boyish heart does not yearn toward a dog!

"That's a fine little spaniel you have there, Citizen Boy!" he remarked. "What do you call him?" The child inside the fence looked up with a pleased smile.

"His name is Moufflet. Isn't he a beauty? Don't you want to pet him?" The little boy lifted the wriggling animal to the fence while Jean put out his hand and stroked the long, curly ears.

"Jean! Jean! lift me up! I want to see him too!" begged Yvonne who was so short that her head barely came to the top of the fence. Jean reached down, and with his strong arms swung her to a seat on his shoulder.[Pg 7]

"Oh, you beautiful thing!" she exclaimed. "And what a pretty little boy, too! I like you, boy!" The little fellow laughed with pleasure.

"And I like you also!" he declared. "Don't you want some flowers? I gathered some for my mother this morning, but I think there are enough left to make you a nice bouquet." Dropping the dog, he ran hither and thither gathering from one bush and another, till he had collected quite a large mass of blossoms. These he handed to the little girl, saying:

"And won't you tell me your name?"

"I am Yvonne Marie Clouet," she answered, burying her face in the fragrant bunch, "and I thank you!"

Jean, however, was growing restless. This was all very pleasant, but it was not that for which he had stolen a holiday from the services of the Citizeness Clouet, risking thereby the prospect of certain punishment, and had hurried through two miles of hot streets to[Pg 8] see. He leaned across the fence toward the boy, and spoke in a half-whisper:

"I say, Citizen Boy, do you happen to know whereabouts we can get a sight of the little 'Wolf-Cub'?" The child looked startled.

"I don't know what you mean!" he replied.

"Why, you must know!—the son of that monster, the Citizen King!" The little fellow drew back proudly. His blue eyes grew dark with anger, and he laid his hand on the hilt of his sword.

"I am the Dauphin of France! And my father the King is not a monster! He is a good man!" Jean was so astonished that he let go his hold of Yvonne, who all but toppled from her perch on his shoulder.

"But—but—" he stammered, "you are not a bit like what they said! What does all this mean? I—I like you! I don't care if you are the Dauphin! Say, will you forgive me, little Citizen Prince?" The generous heart of the royal child was as quick to forgive[Pg 9] as it was to take offence, and he held out his hand with a charming smile. Jean took it, glanced furtively around, and shook it heartily.

"I hope no one sees me doing this!" he muttered. The Dauphin, now all restored to good humour, seated himself on an upturned box and nursed his knees with his clasped hands.

"Let us talk awhile!" he begged. "I do not see any children now, except my sister, and I'm often very lonely. Please tell me your name."

"I am called Jean Dominique Mettot," answered his new friend. "That is the name they gave me in the Foundling Hospital from which the Citizeness Clouet took me."

"Oh, did you come from the Foundling Hospital?" eagerly replied the Dauphin. "Why, I used to go there often with the Queen, my mother. We brought food and money for the sick children. I loved to go there! I never wanted to come away!"[Pg 10]

"Did the Citizeness Queen really go there?" marvelled Jean. "Why, she can't be such a bad one, after all!" The Dauphin's face grew sad.

"Do you know," he said, "I believe that people say a great many false things about my father and mother because they do not know the truth,—they do not know how really good they are!"

"Oh, they say bad enough things!" remarked Jean, cheerfully. "You ought to hear a man they call Citizen Marat! He gets up on a bench in our street and tells the people that the king and queen are starving them just for the pastime of hearing them howl for bread,—that they like that kind of music!"

"It is not true! It is not true!" repeated the Dauphin with tears in his eyes. "Oh, if you could only see my father, you would not think so!" Then, glancing over his shoulder he exclaimed gladly, "Why, here he is now!" Jean made a movement to put[Pg 11] down Yvonne and take to his heels, but the Dauphin begged him to stay. They all stood silent, watching the approach of a large, stout man who walked slowly with his hands clasped behind him. His face was gentle, thoughtful and kindly. Across his coat were stretched the ribbons of several royal orders.

"Father!" called the Dauphin when the King drew near enough. "These are my little new friends, Yvonne and Jean. Won't you speak to them?" The King smiled at his son and came over to the fence.

"Good-morning, my children!" he said kindly, laying a hand on Jean's shoulder. "I am glad to know and greet the friends of my son." Jean looked up into the fatherly eyes, and noticed the sad lines about the gentle mouth. He was sorely puzzled in his boyish heart. Certainly this was not the horrible monster such as he had heard the King described in the Faubourg St. Antoine. The boy was thoroughly in sympathy with the downtrodden people who were rising at last[Pg 12] to claim their liberty and a few other inalienable human rights. But there was something wrong somewhere! At any rate, this royal gentleman had that about him which compelled his reverence and trust. Snatching off his red liberty-cap, Jean bent his knee and kissed the hand of Louis XVI of France!

"Yvonne," remarked Jean, as they strolled homeward, "we—at least I will have to pay for this little holiday!"

"Oh, Jean, I'm sorry! I ought to take part of the punishment, for I made you take me," sympathised Yvonne.

"Mother Clouet won't beat you, you can warrant, but this is the day when I should have carried the wash to the Rue du Bac," explained her companion. "Oh, well! I have had my dance, now I must pay the fiddler!" It was evident that this was not Jean's first attempt at playing truant. Then a new thought struck him and he stopped short.[Pg 13]

"Yvonne, what do you think of the poor little Citizen Dauphin?"

"I love him!" she answered simply.

"Well, I do too, and yet I suppose I ought not, if I am to be a good citizen of the Nation. Kings are wrong! We've had enough kings, and they've trodden us under foot and robbed us of our rights for centuries. And yet this little fellow might make a good one. Who knows! And there's his father, too—the Citizen King. How did you like him?"

"He seemed very, very kind," answered Yvonne, "and very sad. I felt sorry for him. And I don't believe all the things they say about him, either. Why did you kiss his hand, Jean?"

"I don't know! Something made me. Perhaps it's because he is so different from what we thought. But, see here, Yvonne! Let me tell you that if anyone finds out how we feel, or that I kissed his hand, our heads won't be safe on our shoulders! Do you[Pg 14] know that?" The child made a frightened gesture of assent.

"Then keep it to yourself!" said Jean, shortly. They walked on in silence, and with dragging steps. It was plain that they were in no hurry to get home.

"Shall we go to see the little prince again?" inquired Yvonne.

"I'd certainly like to. We will try to go soon,—as soon as I can make up my mind to another beating!" answered Jean, whimsically. Then in a more sober manner:

"He's lonesome, poor little fellow! It's a shame for the people to take away his liberty and keep him cooped up in that palace without any little friends, I say!"

They turned at length into the Rue de Lille, a narrow, dirty street, rather deserted at the time, since most of the inhabitants were off at the Place de la Révolution, singing the "Marseillaise," shouting for Danton, or dancing the Carmagnole. At the door of the house numbered "670," stood a woman in a[Pg 15] short cotton dress and wooden shoes. She was shading her eyes and looking far up the street, in the direction opposite to that from which the children were approaching.

"There's Mère Clouet now!" whispered Jean. Suddenly the woman turned, caught sight of the pair, and made a dash at Jean who ducked, slid aside and came out unharmed quite behind the enraged laundress. But Mère Clouet was agile, and moreover well acquainted with Jean's system of manœuvres!

"Ah, you rascal!" she shouted, catching him deftly by the collar. "You will run away for the whole day, and leave me to carry home the wash myself! You will entrap my little Yvonne and force her to accompany you, scaring her good mother almost beyond her wits lest the child come to harm! To bed you go this night with never a bite or a sup, and lucky you'll be if there's a whole bone in your lazy, idle body!"

With her great, muscular arms she shook[Pg 16] Jean till his teeth clicked together, dropping him only when sheer exhaustion compelled her. Poor Yvonne stood by, trembling, wide-eyed and frightened. Citizeness Clouet having temporarily disposed of Jean, turned her attention to her daughter.

"And as for thee, naughty little mouse!—" Then her eyes fell for the first time on the flowers.

"But by all the saints, where did you get that magnificent bouquet, child? Never since I was a girl in Normandy have I seen such blossoms, except on the altars in the churches at Eastertide!"

"Why, Mother, the dear little Citizen Dauphin gave them to me!" exclaimed Yvonne. Then she cast a frightened glance at Jean, remembering too late his warning on the way home. Jean himself trembled, and expected that Mère Clouet would break into a torrent of abuse and invective against the little prince. But to their astonishment she replied:[Pg 17]

"The poor little fellow! Well do I remember how his mother brought him to the great church of Notre Dame when he was but a tiny baby. You, Yvonne, were also but a few months old, and I carried you out with me to see the sight. The Queen in her carriage held him up that all the people might see him, and how the crowds sang and shouted for joy! Who would have thought that in seven years they would be keeping him a prisoner in his own palace and calling him names! These are marvellous times! But tell me how you came to see him. 'Tis quite a jaunt from here to the Tuileries."

Encouraged by her mother's relenting mood, Yvonne told the story of their morning, described the Dauphin, the King and even Moufflet. Jean too forgot that he was in disgrace, and added his say to the tale at frequent intervals. Then Yvonne cast all caution to the winds.

"Mother," she ended, "I love the little Citizen Dauphin, and I'm sorry for his father[Pg 18] the Citizen King, and I don't care if you do know it! So does Jean!"

"Hush, hush, precious one!" exclaimed her mother in alarm. "The walls may have ears! Never say that thought aloud if you do not wish us all to be made acquainted with the sharp edge of La Guillotine! But tell me, what else said the little lad?"

"He said, Citizeness Clouet," broke in Jean, "just when we were coming away, that if we were ever in need or trouble, his good parents the King and Queen would help us out if they could. Do you know, I believe that if you were to ask them, they would give you the money to pay the taxes that you said would be due next month, and that you could never pay. Then we would not be turned out of the house. Why don't you ask it?" But Mère Clouet was incredulous.

"The little Prince is all very well," she remarked scornfully, "but his father and mother are a different matter. They have ground the poor under their heel for many[Pg 19] years, and they only do an act of charity when there may be a crowd around to see and applaud it. Trust me, Jean and Yvonne, the King and Queen would set the soldiery upon us were we to come and demand money!" But Jean was far from convinced.

"If you would only try!" he begged. "They seemed so kind to-day. Come[Pg 20] with us to-morrow, and see the little fellow! At least it can do no harm!"

"Well, we shall see!" she conceded. "But tell no one about this, or,—" and she made a sign indicative of the instability of their heads. "And[Pg 21] now, sit you down to your supper, Yvonne. And you, idle good-for-nothing, sit you down also, since you have paid with your chattering tongue for your day's wickedness!"

And so Jean sat down![Pg 22]

JEAN MEETS WITH A THIN YOUNG MAN

CHAPTER II

JEAN MEETS WITH A THIN YOUNG MAN

When the Dauphin came to dig in his garden next morning, he found his new friends again at the fence, accompanied by a woman.

"Little Citizen Prince, this is my mother," said Yvonne, "and we have persuaded her to come with us and beg you to fulfil the promise that you gave for your good father and mother yesterday. She is indeed in sore need of help." The Dauphin came to the fence and gave Mother Clouet his hand with his own peculiarly winning smile.

"Good Madame Clouet, my mother will be walking here in a little while. Will you not wait and speak to her yourself? I know she will be glad to help you." Now Mère Clouet bore no animosity toward this little prince,—on[Pg 24] the contrary, she admired and almost loved him,—but she was plainly reluctant to meet the Queen who appealed in no way to her sympathies. But there seemed nothing else to be done, so she drew aside while the children chatted together and romped with Moufflet. Presently, hearing voices, the Dauphin left his friends, ran along one of the walks, and came back leading a lady and a young girl of thirteen.

"This is my Mother-Queen, and this is my sister, Marie-Thérèse," he announced. "Mother, these are the new friends that I told you of yesterday, and this is Yvonne's mother. She wishes to ask something of you."

"Good Mistress Clouet," said the Queen gently, "whatever I can do for you I will, if you will but make known your request." Her voice was soft and penetratingly sweet, and her face, framed in waving hair whitened by sorrow, was full of a strange beauty veiled by overwhelming sadness. Here was something[Pg 25] entirely different from the haughty sovereign that Mère Clouet had expected to meet, and she was overcome by surprise and bashfulness, but she managed to stammer out her request.

"Your Majesty," she faltered, "my good man when he died, left me the house I live in, but though I work hard,—I am a laundress,—I have been unable to do more than provide our three mouths with bread. Jean here I adopted from the Foundling Hospital to help me with my work. But his mouth is wide!—he eats quantities unknown, and hardly does he pay for his keep! For three years past I have been unable to pay the taxes, so great is their amount, and now they threaten to turn me out and keep the house, if I do not pay up every sou next month. For myself, I would go uncomplainingly, but how can I rob the little Yvonne of a roof to shelter her!" Tears came into the woman's eyes as she clasped tighter her little daughter's hand. "So I must beg for my daughter's[Pg 26] sake, but Madame I trust that some day I may repay it, for I would not be under obligations, even to a queen!" The Queen was sincerely touched by this revelation of mingled pride and mother-love.

"I know how you feel, Mistress Clouet. I should not be ashamed to do the same for my own children. How much is the amount?" The laundress shuddered, as with bated breath she named the sum,—a fortune in her eyes.

"A thousand francs, your Majesty!" The Queen seemed not a whit appalled.

"I have not the money with me to-day, but come to-morrow and the Dauphin shall give it to you. I do not walk out every day. God bless you and the little Yvonne, and Jean also!" She held out her little white hand, and Mère Clouet, moved by a gratitude and respect the like of which she would not yesterday have believed she could experience, took it in both her rough, work-worn ones. And so they stood a moment gazing at each[Pg 27] other, the proud, beautiful Marie Antoinette, and Citizeness Clouet, the woman of the people, hand locked in hand across the tri-coloured fence.

"Some day I will repay you!" declared Mère Clouet. "It may not be in money, but it shall be in service. We are of the people, and our hearts and sympathies are with the people. But this is a debt of gratitude which we three shall never forget. We will repay you!"

The Citizeness Clouet spoke more truly than she knew!

After this event, Jean was sorely perplexed. He talked his trouble over with Mère Clouet who seemed more kindly disposed toward him since the load of debt had been lifted from her shoulders, and her mind had been set at rest about a home for her beloved Yvonne.

"I do not now know how to act," he told her. "My heart is still all for the people[Pg 28] and the cause of our Liberty, yet I do truly love the little prince, and even the King and Queen. And I fear from the things I have heard, that the people will sometime do them harm."

"Let your sympathies still be with the people," counselled Mère Clouet wisely. "We are not royalists, and our heads will not be safe should we appear so! But that need not prevent your loyal friendship for these royal ones, only you must keep it very secret. Heaven help us should it be discovered! I pray God that the royalty may be left in peace, or at least be allowed to depart from the country unharmed when the time comes. We may not desire their sway, but we should not menace their personal safety."

"Well, at least," answered Jean, "it will do no harm for me to keep posted as to what the popular intention toward them may be. And for this, I could learn best what I wish at one of the political clubs,—the Cordeliers[Pg 29] or the Jacobins. But none except the initiated are allowed to enter. However, I'm going to watch my chance and try!" True to this resolve, he informed Mère Clouet one evening:

"I shall go to the Rue St. Honoré to-night and linger near the Jacobin Club. We shall see what we shall see!" And he was off before she could even protest at the lateness of the hour.

The way from the Rue de Lille to the Rue St. Honoré was not long, but it was varied by sights and sounds only to be witnessed in Paris during one of her revolutions. More than once Jean caught the infection from some shouting group, and snatching outstretched hands, joined in the wild dance of the Carmagnole. Then again he would pause before a gesticulating orator madly haranguing his audience from a bench or improvised platform. The air was filled with shouts of "Vive la Nation!" "Vive Danton!" "A bas le Roi!" Jean drank it all in, his[Pg 30] boyish bosom filled with pride at the thought of this strange, new liberty. Yet at the cry, "Down with the King!" his heart would grow sick with the menace that it carried for his benefactors.

At last he reached the Rue St. Honoré and stood before the great stone building, so long the peaceful retreat of the Dominican Monks, now given over to the strongest political society of the day,—the Jacobin Club. Men were passing through its well-guarded doorway, each separately interviewed for a moment by a crabbed, ill-disposed doorkeeper. Each as he passed this watchful sentinel, exhibited a card or murmured some magic password. Jean possessed neither a card nor the knowledge of the proper watchword, but he was not to be daunted by either lack. Boldly he marched up the steps, and would have walked straight into the hall, had not the doorkeeper seized him wrathfully by the collar. No one else was passing in at that moment.[Pg 31]

"Impudent! What is your business here?" he shouted.

"I am a good citizen who loves liberty, and I demand to be admitted to this meeting!" replied Jean, hopefully.

"Well, of all outrages!" gasped the astounded doorkeeper. "Begone, you young scamp! The Nation has little use for such as you!" He released the boy's collar, and pursued him down the steps with a thick cane he had snatched up. Jean, deeming flight his wisest course, took to his heels and was speedily beyond the premises. But so rapid was his retreat that before he was aware of it, he had butted plumply into someone who was coming in the opposite direction, and the concussion knocked the stranger flat on his back!

"Oh, I beg your pardon!" entreated Jean, breathlessly, assisting his victim to rise.

"You would make a splendid catapult on a field of artillery!" answered the stranger who proved to be a short and exceedingly[Pg 32] thin young man. He was wrapped in an old grey great-coat, though the weather was May, and warm. A round, shabby black hat was pulled over his eyes. His hair was arranged in a slovenly manner, and hung about his ears. In the lamplight his face was sallow, with high cheek-bones and a very prominent chin. But he had, so Jean thought, the most extraordinary eyes in the world. They were deepset, grey and piercing, and fixed one with a look as sharp as a sword. Jean felt that, had the man's lips commanded him to throw himself into the fire, those eyes would have compelled him to obey!

"Perhaps you will explain the cause for this unwarrantable attack on a peaceful citizen!" said the stranger as he brushed his coat.

"Indeed I meant no harm, nor even knew what I was about, since I was occupied in being forcibly put out of the Jacobin Club!" laughed the boy.[Pg 33]

"And why should you want to be in the Jacobin Club!" demanded the stranger. Jean was on his guard at once.

"All good citizens must wish to be present at meetings so important," he replied airily. "I merely had a curiosity to know what was going on!" The young man fixed him with his brilliant eyes, and Jean felt the blood mount guiltily to his cheeks.

"There's something deeper than that!" he remarked coolly. "I can see it! What are your real reasons? Are you a royalist?"

"Indeed, I'm not!" asserted Jean vehemently.

"Well, it doesn't make a sou's difference to me!" his new companion declared. "I'm neither a royalist, nor am I a republican, nor, for that matter, even a Frenchman. But I happen to have a ticket for the Jacobins myself to-night, and since you're so interested, and have even graciously condescended to knock me down, I'll take you in with me!" Here was a stroke of luck indeed! Jean was[Pg 34] instant in expressing his delight, and the two climbed together the steps down which he had so lately fled in ignominy. The gatekeeper scolded and muttered, but there was nothing to do but let him pass, since a man with a card vouched for him.

The boy never forgot that night. He reached home and the Rue de Lille long after midnight, encountering Mère Clouet at the door. She had been very uneasy, and was inclined to be somewhat wrathful at the lateness of the hour. But Jean was too excited to care.

"Don't scold, Mère Clouet!" he entreated. "I've gotten into the Jacobin Club at last!"

"You young rascal!" she exclaimed incredulously, "are you telling the truth?"

"Every bit!" he answered. "Give me a bite to eat, good mother, and I'll tell you all about it."

"Always hungry!" she muttered, but nevertheless she gave him a generous slice of bread and jam. Between great mouthfuls,[Pg 35] he told the story of his forcible encounter with the thin young man and its sequel,—his admission to the club.

"Ah, but it was a wonderful night for me!" he continued. "Such speeches did I hear from Citizen Marat who is its president, and from one, Robespierre, whose voice, they say, has greater weight than any, and also from Citizen Danton, the president of the Cordeliers, who came this evening with many more of his own club! Much of what they said was hard for me to understand, but one thing I learned that it is well to know.

"The citizens of the Faubourg St. Antoine are planning a fête for the twentieth of June (that's the day after to-morrow), in which they will form a procession and march to the palace to present a petition to the King. That, of course, is all very well, but let me tell you what I heard whispered about by Santerre, the brewer, who is to lead them. Each sans-culotte is to carry a pike, and he[Pg 36] thinks that when the King sees forty thousand pikes assembled about his door that he will become alarmed. Then will be the time to lead a general insurrection and demand that he resign his throne and crown or else force him to it. Is it not outrageous thus to take advantage of him unfairly?" Mère Clouet was alarmed and indignant.

"It is indeed!" she declared. "I believe the King means to do the right thing by his people, but the country is becoming mob-ruled. It is only the scum of Paris, of which that Santerre is a good sample, who would sanction such plans! But sadly do I fear that they will do the royal family harm!"

"And so do I," replied Jean, "and therefore I intend to march with the mob on the twentieth. Who knows but I may be in some way useful to the poor little Citizen Dauphin!"

"But," continued Mère Clouet, "it was kind of that strange young man to take you[Pg 37] into the club to-night! Did you learn who he may be?"

"Indeed I did!" answered the boy. "All through the meeting he sat with his arms folded and his strange eyes fixed on the speakers. Once, when[Pg 38] Santerre harangued us, I heard him mutter, 'Canaille!' and another time when Robespierre was speaking, he whispered to me, 'That is a man of power, but—one should beware!' When we left the club, we parted on[Pg 39] the Rue St. Honoré, and he said, 'Perhaps you will tell me your name, young sir. You seem a lad of spirit!' When I had informed him, he told me his own. 'Tis a strange one, and has a foreign sound,—Napoleon[Pg 40] Bonaparte!"

IN WHICH THE DAUPHIN WEARS THE RED CAP

CHAPTER III

IN WHICH THE DAUPHIN WEARS THE RED CAP

There is nothing in this world so fickle as a Parisian mob! A breath, a word, a gesture even, can often turn it aside from its most murderous purpose, and bring it worshipping to the very feet of those it sought but a moment before to destroy!

The great palace of the Tuileries was crowded to suffocation. Hordes of savage men, women, and even children from the poorest quarters of Paris, thronged, jostled and fought one another to get a sight of their hated sovereigns. A small company of soldiers strove in vain to clear the rooms and defend the royalty from the taunts and insults of the populace. Outside the palace, a still greater section of the mob, unable to force an entrance, shrieked for something[Pg 42] spectacular, even to demanding the heads of the royal family. It was a wild, turbulent scene!

Jean had kept his word. Throughout the four hours' march along the Rue St. Honoré, on that memorable twentieth of June, he had stayed closely by that great giant of a Santerre, who finally gave him his heavy pike to carry. At the palace gate the mob forced the doors with a rush, and Jean, by virtue of being in the van with the brewer, entered among the first. Up the Grand Staircase they hurried, pell-mell, dragging a piece of cannon with them, and using hatchets, commenced to force the door behind which it was rumoured that the King was hiding. Doubtless the mob expected to find him cowering in terror behind a few faithful soldiers. What then was their amazement when the panels of the door fell in, to behold him standing directly before them, calm and unmoved!

"Here I am!" announced Louis XVI.[Pg 43] "Had you waited but a moment, you might have entered the door without destroying it. What do you wish with me?" The rabble fell back a pace, in enforced respect. Jean crept behind some of the tallest, not wishing the King to perceive him and misinterpret his intentions.

"We have here a decree concerning the rights of the people!" announced one, Legendre, a butcher, who had constituted himself their spokesman. "We wish you to sanction it!"

"This," said the King quietly, "is neither the place nor the time for me to do that. You know that I will do all which your new Constitution requires of me!" His kingly dignity quite changed the attitude of the turbulent throng.

"Vive la nation!" suddenly shouted his assailants in response.

"Yes," answered the King, "shout for the nation! I am its best friend!"

"Well, prove it then!" demanded a bold[Pg 44] voice, and its owner handed the King a red cap on the point of a pike. Jean held his breath, wondering what the monarch would do now. But Louis XVI deemed this neither the time nor the place to resist what was after all but a symbol. He lifted the cap, and with a dignified gesture, placed it on his head. Further than that, he even poured some liquor from a bottle offered to him, and drank to the nation, though there were a thousand chances that he had been presented with poison. After that he was loudly applauded, and there was plainly no reason to fear an attack upon his person.

But now Jean became anxious for the safety of the little prince, and pushed his way from the room to ascertain what he could concerning the other members of the royal family. At the door of the council hall he heard it said that within could be seen the "Austrian Wolf," as they called the Queen. Truly enough, there she was at the end of the room. Jean's heart gave a bound at the[Pg 45] sight of the group. Fenced in by a long table stood Marie Antoinette, her head high, her great eyes flashing, her cheeks deathly pale. On one side of her stood young Marie-Thérèse, pale also, but brave and unflinching, her hand clasped in her mother's. And on the table, supported by his mother's arm, stood the Dauphin. In his face was mingled astonishment and fright, and he turned his eyes constantly toward his mother, as if to read in her countenance the meaning of this amazing invasion.

For a time nothing but confusion reigned. Cries of "Down with the Austrian Wolf!" mingled with shouts of "Vive Santerre!" "Vivent les Sans-culottes!" "Vive le Faubourg St. Antoine!" Then suddenly there was silence. A huge woman pushed her way through the crowd, threw her red woollen liberty-cap on the table and cried:

"If thou art so fond of the nation, thou Austrian Wolf, let thy son wear the red cap of liberty!"[Pg 46]

"Yes, yes!" shrieked the crowd. "Crown the little Wolf-Cub with the red cap, and give him some tri-coloured ribbons to wear!" Someone threw down the ribbons beside the cap. The Queen turned to one of the guards standing close by.

"Place the cap on his head!" she commanded, and the grenadier did so, setting it on the boy's brown curls; then he tied the ribbons in his button-hole. The little fellow, hardly comprehending whether this might be in sport or insult, smiled uncertainly. The multitude shouted and applauded, and more confusion ensued. Jean, taking advantage of the racket, slipped to the front, and placed himself directly before the Dauphin. The little prince at once recognised him, but before he should show that he did, Jean leaned across the table and shouted "Vive la nation!" and then in an undertone whispered: "I am only here to help you! What can I do?" The Dauphin's face lit up with a smile[Pg 47] of understanding, and without an instant's hesitation he murmured:

"Find Moufflet!" Comprehending well the boy's anxiety for his pet, Jean passed on, melted into the crowd and quickly scurried away, darting here and there, in and out of all the rooms to which he could find admittance. But it was like hunting for a needle in a haystack. Chance alone finally favoured him. As he passed a thickly-packed group in one of the corridors, he thought he distinguished a faint yelp. In another moment he knew that he was not mistaken. Hating anything that was royal property, a crowd of rough sans-culottes had surrounded the poor shivering animal, for lack of being able to get any nearer its master.

"Here, Jacques!" called one ruffian, "give me your pike and I'll finish him!" He was just about to spear the frightened, yelping ball of fluff, when Jean broke madly through the crowd.[Pg 48]

"Give him to me!" he commanded. "He's just the kind of a dog I want! I'll teach him to bark for Liberty, Equality and Fraternity!" The crowd laughed, patted Jean's head approvingly, and handing Moufflet over to his protection, hurried off to seek other prey. The dog whined his recognition of a former friend, and tried to hide under the boy's jacket.

But Jean could not carry the little thing around in his arms, and at the same time restore him to his master, that was plain. Where could he place him so that the little animal might remain in safety? He looked about him in despair. There was not a corner or the smallest cubby-hole where it would be secure. Suddenly he remembered that in one of the rooms now deserted, he had opened a door of what seemed to be a large closet. He hurried to the spot and found just the hiding-place he needed. Thrusting Moufflet into the darkness, he commanded:

"You be a good dog! Lie down and be[Pg 49] quiet!" As if comprehending the situation completely, the dog crawled into a far corner, curled up and lay shivering and silent. Jean closed the door, turned the key, and ran back to the council-hall. Meanwhile, what had taken place in his absence?

For many minutes the Dauphin stood crowned with the heavy woollen cap, while the crowd hooted, laughed and jeered. The day was very hot, and the perspiration streamed down his face and dampened his curls. His mother pressed him closer to her, whispering him to be brave a little longer. As she did so, a young woman in front called out:

"How proud and haughty that Austrian is! How she hates us!" The girl was pretty, and her expression mild and gentle. The Queen wondered at the contrast between her appearance and her words. For the first time that day, she opened her lips and answered:

"I do not hate you, my friend! Why[Pg 50] should I? But I am afraid that you hate me, though I have done you no wrong!" The young woman began to feel a little ashamed.

"No, no! I do not mean that you hate me," she replied, "but the nation. You love only Austria from whence you came!"

"You poor child!" answered the Queen. "They have told you that and you believe it, but it is not true! I came from Austria when I was a very young girl, to marry the King. But since then I have forgotten the land of my birth. I love only France! Why, see! am I not the mother of your future king?" and she pointed to the Dauphin. "I love all my French people, and I only wish them to be happy!" The girl was so touched by the Queen's gentle, reproachful manner, that the tears came into her eyes.

"Oh, pardon me, Madame! I did not know you!" she begged. "I see now that you are not as wicked as they said!" It was then that the humour of the mob changed. Women and men who had been the fiercest,[Pg 51] wept at the grief in the Queen's words and looks. They pressed about the table, admiring the bravery of Marie Antoinette and the beauty of her children. Cries of "Down with the Queen!" gave place to words of praise and admiration for her courage. Even the big, brutal Santerre was touched.

"Take off that cap from the little fellow's head!" he ordered. "Don't you see how hot he is?" And then to the Queen he whispered: "Have no fear, Madame! I will send away the people in peace!"

It was then that Jean returned to the room, amazed at the changed aspect of affairs. Under Santerre's direction the throng began to file out past the royal family, contenting themselves with kindly looks and words, or rough ones, as their changeable tempers dictated. Jean was among the last to leave, and he had only time to whisper in a very low voice as he passed the prince,

"It's all right! The closet in the next room!" But by the grateful smile of his little[Pg 52] Highness, Jean knew that the Dauphin had both heard and understood.

Outside, on the terrace of the Tuileries, other events of interest appeared to be happening, and Jean lingered to witness them. A man standing on an armchair at a window in the palace, was addressing the crowds below. It proved to be Pétion, the Mayor of Paris, and he was bidding the mob disperse peaceably now that the King had been interviewed. While Jean was looking up, he felt himself clapped on the shoulder, and a voice exclaimed:

"Well, if here is not my young friend the catapult!" and turning, he found himself face to face with the thin young man. "And what may you be doing here? Helping to mob the King?" Now Jean could scarcely have explained why, but something about this young man both invited and compelled his confidence, and he had the instinctive feeling that confidence in him would not be misplaced. So he boldly declared:[Pg 53]

"No, Citizen Bonaparte, indeed I have been far from mobbing the King. I am not a royalist, and I wish to be a true patriot, but I feel that the people are not dealing rightly with the King, and that they will yet allow the rabble to do him an ill turn!"

"Well said!" agreed the young man, heartily. "My opinion to a dot! My friend, I am a Corsican by birth, and I have aided in the unsuccessful fight for Corsica's liberty, but now I believe I will adopt a new country and become a French patriot. The situation in this land appeals to me. My heart thrills when I see an oppressed people rising to throw off the yoke of the oppressor! And you are right when you say that, groping in the twilight of their first new liberties, the people are not dealing justly with their king. But, look you, my friend! Their king means well, only he is making the biggest mistake a monarch ever made! He is yet their monarch! He should show it! The people bow to force, to power, and to that alone. See[Pg 54] him now!" and he pointed to a window where Louis XVI, still crowned with the red cap, was surveying the throng below.

"Never should he have allowed them to put on him that emblem!" continued Bonaparte vehemently. "Never should he have countenanced this invasion of his palace! It was madness! Had he turned a few cannon upon them, and blown a hundred or more of this rabble to pieces, the rest would have taken to their heels and fled with respect for him in their hearts! As it is now, they have none! Mark my words!—worse will come, and he will live to regret his forbearance!"

Jean marvelled at the fire that flashed from those grey eyes. Instinct told him that here was a man born to command, and he felt drawn to the stranger by a feeling of intense admiration.

"I came here to-day through curiosity," he continued, "but what did you in the palace, my young friend?" And Jean, in his new trust, told the whole story of his attachment[Pg 55] to the little Dauphin, and the debt of gratitude the Clouets owed to the Queen. When he had finished his auditor remarked:

"You are a faithful soul, my little friend, and I admire your spirit of[Pg 56] gratitude. I too am genuinely sorry for the royal family. But I fear you have set yourself a hard road to travel, between your patriotism and your friendship for royalty. Beware of the many pitfalls that beset you! I am staying at the Rue Cléry, number 548, over the tobacconist's. Come[Pg 57] and see me sometimes. Fortune is not dealing with me so very lavishly just at present, and I should be grateful for your bright companionship while I am far from my family and friends!"

And Jean gladly promised to come.[Pg 58]

ON TERRIBLE AUGUST TENTH

CHAPTER IV

ON TERRIBLE AUGUST TENTH

Jean speedily availed himself of the invitation from Bonaparte to visit him. A few evenings after June twentieth, he went to the Rue Cléry, ascended to a room over the tobacconist's shop, and found Bonaparte reading by the light of a single candle. The room was empty of all but the barest necessities, and it was evident that its occupant was having a hard struggle to make ends meet. But Bonaparte seemed pleased at the visit of his new friend, and the two were soon engaged in lively conversation.

That night Jean heard the story of this young man's life. He told the eager, sympathetic lad how he had been born of a fine family in Corsica; how his father had lost all in[Pg 60] the vain struggle for Corsican liberty; how he, Napoleon, a poor shy, proud boy had been sent to the military school at Brienne where he suffered agonies of wounded pride among his richer classmates; how at fifteen he had spent a year at the military school of Paris, suffering similar humiliation because of his poverty, and at sixteen was appointed second lieutenant of a regiment of artillery at Valence; how, soon after, his father died, leaving practically on his shoulders the responsibility of a mother, four brothers and three sisters! how he left the army and for a time devoted himself to straightening out his family affairs; how he had returned to the army, but encouraged by the breaking out of the Revolution in 1789, he had again attempted to aid in freeing Corsica, and for this reason had lost his place in the French army. Now he was hoping to regain it, but in the present disturbed condition of affairs, could obtain little attention from the authorities. In the meantime he was struggling[Pg 61] along, poor as a church mouse, making the barest kind of a living by doing a little writing. All this information was not imparted at once, but came out by degrees in the course of their conversation. Jean drank it in with intense interest.

"But the tide will turn!" ended Bonaparte. "Something tells me that I was born under a fortunate star. Things will be different some day!" And catching the proud flash from his wonderful eyes, Jean had no doubt of it!

As the days went on, Jean was drawn by an irresistible fascination more and more into the society of "the thin young man," as he often spoke of him to Mère Clouet and Yvonne. One evening, as he ran up the stairs of Rue Cléry, number 548, Napoleon's first greeting was:

"I've something to tell you that will interest you, Jean! I've been to the Jacobins again. There's a bloody insurrection planned for August tenth! They are going[Pg 62] to mob the palace, dethrone the King, seize the Dauphin, and make all the royal family prisoners. Santerre is at the head of it, and Danton, of course, at the bottom! You'd better look sharp for your royal friends!"

"Oh!" said Jean thankfully, "I'm so glad you warned me. I shall be there, at least, and see what I can do to help them! I can't of course do much, but—who knows!"

"But, see here, my lad," answered Bonaparte, laying his hand on the boy's shoulder, "you must not go alone! You are hardly more than a child yet, and these are perilous times. I'd be anxious for your safety. Promise me that you will not go without me! Together, we may be a protection for each other." Jean gave his word, deeply touched that his new friend should exhibit such thoughtfulness for his welfare.

Meanwhile, gloomy days had ensued for Louis Charles, royal Dauphin of France.[Pg 63] His little garden where he longed to dig among the flower-beds and romp with Moufflet was forbidden him. Once only since the hateful day of June twentieth, he had gone there accompanied by his mother. But the shouts and threats of the crowd behind the fence, quickly drove them into the palace again for safety.

Distrust and suspicion were in the very air! For the people of Paris, like a sullen, angry dog that has obtained a bone only to have it snatched away again, felt that they had been defeated of their purpose on the day they besieged the Tuileries. They were laying dark plans to repeat the expedition, which this time, they vowed, should not fail. Just at present they were only lying in wait till the time should be fully ripe.

The Dauphin roamed from room to room in the castle, pressed his face to the windows and gazed with envy at the Park, brilliant with sunshine, and at the throngs of common people who were free to come and go as they[Pg 64] pleased. He wondered whether Jean and Yvonne ever came to the garden now. Once he thought he distinguished the boy among the strolling crowds but he could not be sure. The King and Queen were preoccupied and sad. His aunt, Madame Elizabeth, was much with them, and had little time to give to his amusement. Even his sister sometimes forgot to romp and frolic with him as had been her wont. To all it was a season of breathless suspense.

And then the fatal day arrived. On the night of August ninth, after his supper, the Queen went to the Dauphin's room where he was being put to bed, to kiss him good-night. Tears stood in her eyes as she clasped him more closely than usual.

"But, Mother, you are crying!" he exclaimed. "Is anything the matter?"

"There is some danger, we have heard, but perhaps not immediate. You would not understand if I explained it, little son!"

"But can you not stay with me this evening?"[Pg 65] he begged. "I am so lonesome, and everyone is so sad!"

"That I would love to do, but I must be with your father. He needs me most. Do not be afraid, for we shall be near you."

For a long time the boy lay sleepless, pondering his mother's words. What did it all mean, anyway! His childish mind strove in vain to comprehend why the French people should hate his parents so. There must certainly be something very wrong somewhere! Sleep refused to come to his tired little brain, and the hours passed slowly by.

Suddenly he was startled by the strokes of a bell sounding far across the city. It was the great tocsin of the Cordeliers Club, striking the general alarm. Immediately it was answered by bells from all sections, mingled with cannon-shots and the hoarse cries of an infuriated mob. Nearer and nearer came the racket, and then the tumult became general both within and without the palace. The Dauphin was hurriedly dressed,[Pg 66] and joined his parents, sister and aunt in another room. The King alone seemed calm.

"Come," said he, "we must all visit the soldiers who are defending the palace and encourage them! Are you afraid, my son?"

"Indeed no, Father!" answered the boy. "Let us go at once!" and he seized the King's hand in his own. Down the stairs and from room to room they passed, the King, calm and gentle as ever, speaking words of encouragement to the few defenders who remained with them. The grand gallery of the palace was filled with the troops of the Swiss Guard. As the royal family passed, the captain snatched up the Dauphin, lifted the child high above his head, and shouted:

"Long live the King and the King's son!" Wild huzzas broke from every throat, but their enthusiasm was short-lived. For without was approaching a sinister clamour. Horrible cries, chiefly "The Crown or the King's head!" "Deposition or Death!" resounded[Pg 67] on all sides. At that moment there burst into the room the procureur-general, who approached the king crying:

"Sire, the danger is beyond all expression! All Paris is in arms! Resistance is impossible! They demand that you resign the throne! It is death to you and yours if you refuse!" Louis XVI gave one last despairing look about him. He feared nothing for his own life, but he refused to risk those of his loved ones.

"It is done!" he said gravely. "I make the last sacrifice! Do with me what you will!" And so fell the ancient monarchy of France!

"Come!" commanded an officer. "You must leave the palace!"

It was quarter past six in the morning, when the sad procession wended its way from the abode of its ancestors forever. Louis XVI went first with Madame Elizabeth. Marie Antoinette followed, leading her two children by the hand. The Dauphin looked[Pg 68] back constantly, dragging at his mother's hand.

"What is it, son," she said at last, "that you are looking back for?"

"Oh, Mother, can I not wait and find Moufflet?" he pleaded. "I must not leave him behind! I know just where he is!"

"No, no!" she exclaimed. "You would be killed if you went back! Be a brave boy and make up your mind to part with Moufflet!" Tears stood in the little fellow's eyes, and he struggled hard to keep them from falling. A few trickled down, however, and he dashed them away, lest someone should think them caused by fear. "My poor Moufflet!" he thought, when he saw the mob forcing its entrance into the Tuileries. Could he have known that in the midst of the bloodthirsty rabble was his little friend Jean, he would have been both amazed and sorely troubled.

But how did Jean get there! All the evening of August ninth, he had been uneasy, and found it almost unendurable to stay quietly[Pg 69] at home with Mère Clouet and Yvonne. Excitement was in the air! A great event was about to occur, and when the tocsin of the Cordeliers sounded the first stroke, he was off like a rocket to the Rue Cléry.

"Citizen Bonaparte!" he clamoured, hammering on that young man's closed door. "Come! come! They are about to assault the Tuileries! Here I am as I promised!" Bonaparte came out dressed, after what seemed an age to Jean, and the two hurried into the street and were instantly carried almost off their feet in the swirling human current sweeping toward the Tuileries. Men, women and children, chiefly of the lowest scum of Paris, carried pikes, knives, hatchets, bludgeons,—anything that might serve as a weapon of offence. "Death to the King!" "Down with the Austrian Wolf!" "To the guillotine with Royalty!" were the predominating cries.

Into the Rue St. Honoré, through the Pont Neuf and the Pont Royal they poured, ever[Pg 70] increasing in numbers and ferocity. Almost without volition on their part, Bonaparte and Jean were carried along by the throng that swept through the Rue St. Honoré, and in the first faint dawn of morning, they, with the crowds, drove through the ill-guarded palace gates, and stood before the long windows. Pressed close to the wall of the palace, the two friends witnessed the departure of the royal family, and Jean even guessed at the meaning of the little Dauphin's despairing, backward looks.

"Citizen Bonaparte," he whispered, "I see plainly that we can do nothing now to help the royal ones, since they have placed themselves in the care of the National Assembly, and will probably be safe. But I would like to save that poor little fellow's pet, if it be possible. What do you think?"

Before Bonaparte could reply, there was an exchange of volleying shots between the outside mob, and the inner defenders. With a roar of exasperation, the rabble flung itself[Pg 71] at the doors and windows using the hatchets, and when these gave way, the throng poured into the palace. For a moment Jean and Bonaparte were hurried along in the rush, and then at some sudden obstruction were forcibly separated, and Jean found himself alone amid a scene of indescribable confusion and danger.

The mob, first inhumanly butchered the Swiss Guard who had remained to defend the palace, then turned its attention to pillaging and destroying, with ruthless indiscrimination, the carefully hoarded treasures of this kingly mansion, and when this grew wearisome, attempted to set fire to different parts of the building. In such a reign of confusion, members of the mob frequently failed to discriminate among their victims, and often turned their weapons upon their own numbers.

Now Jean saw no reason for uselessly exposing himself to murder, and he looked about for the safest and most convenient[Pg 72] place to hide. It occurred to him that the closet where he had placed Moufflet on that memorable twentieth of June, would afford the best shelter. Making his way through the crush with the greatest difficulty, he at last reached the room, and managed to slip unobserved into this retreat, closing the door and locking it on the inside. The space was small, and no sooner had he crouched down in the farthest corner, than he felt something warm and soft under his hand. For a moment it startled him, and then, with a stifled cry, he clasped the fluffy mass to his heart.

"Moufflet!" he breathed, and the dog licked his face in an ecstasy of delighted recognition. Then he realised that the Dauphin must have placed him once more in this retreat, when the first alarm was heard. He felt almost happy. Here was half his plan accomplished! Now if he could only find Bonaparte, and they could get away unharmed, all would be well. He was just about to emerge from his hiding-place with[Pg 73] Moufflet under his coat, when horrible shouts filled the room, and he quickly decided to remain where he was.

"Search this room! Search this room!" shrieked hoarse voices. "There may be aristocrats hiding here!" Then someone pulled at the door of his retreat. "Here's a locked door!" called a rough fellow. "A hatchet,—quick!" The splintered wood fell in with a crash, and shrieking with delight, they dragged Jean out of the closet. Thirsting for blood, the ruffians cared not, by this time, whether he was an aristocrat or one of their own number. He was hiding!—that was enough! A bloody hand grasped his collar, and another with a meat-axe was raised over his head. Jean was too paralysed with terror to do anything but wonder just how long it would take that axe to descend, when suddenly he saw it dashed from his assailant's hand, and a well-known voice shouted:

"Fool! Don't you know a good sans-culotte[Pg 74] when you see one? I believe you'd murder your own brother!" The ruffian backed away, apologised sheepishly, and darted off into the crowd. And with a glad cry of recognition, Jean found himself in the arms of Bonaparte!

"A close one for you, lad!" was all his rescuer had time to say. To the end of his days, Jean could never tell just how they two struggled out of that palace of horrors, nor how he managed to keep his grip on the frightened, shivering, squirming Moufflet. But at last they found themselves beyond the walls, and near the bank of the Seine. In sheer exhaustion they dropped to the ground and lay there in the sultry morning sun for over an hour, happy merely to be alive and whole, after the experiences of that dreadful day.

And elsewhere the hours of this memorable day wore on, filled with a series of confused events through which the Dauphin and his family moved, as through some horrible[Pg 75] nightmare. The child knew not their meaning, and could only occasionally grasp at the import of the drama. Three long, terribly uncomfortable days were passed in the great hall of the Assembly filled with representatives of the people. During all this time the royal family was crowded into a tiny hot room at the side where they were nearly stifled by the intense heat and discomfort, their hearts constantly trembling at the horrible sounds made by the mob raging without the building. Three weary nights were passed in the tiny cells in another building where they were taken to sleep.

The Assembly seemed to have great difficulty in deciding what to do with their superfluous ex-monarch! Some,—they were the fiercest,—wanted him killed immediately, as that would save them all further trouble and expense. Some thought that he and his family should be sent out of the country into exile. This was opposed because they said he might raise an army, march back and regain[Pg 76] his throne. Others were in favour of allowing him to live in retirement at the Luxembourg, a smaller palace than the Tuileries. This too was frowned down, because they thought it too luxurious and comfortable, and besides had underground passages to other parts of the city, through which he might escape. Finally they grew weary of the discussion.

"Oh, let us send him to the old Temple Tower, and keep him there! That is good enough for him!" And so it was decided. Two large carriages were procured, and the King, his family, and a few faithful servants were driven across the city, through the pitiless, mocking crowds, to the gloomy prison where they were to pass so many weary months and even years. The Dauphin, seated on his father's knee, looked out at the mob, shouting its frenzy of joy at their monarch's abasement.

"Are they not very wicked, Father?" he asked.[Pg 77]

"No, dear son," answered the forgiving Louis XVI. "They are not[Pg 78] wicked,—only mistaken!"

When at last the courtyard of the Temple was reached, the carriages halted and the occupants stepped out. The yard was filled with soldiers[Pg 79] commanded by Santerre (but yesterday made a general!) yet no one helped them to alight. As they walked to the entrance, no man removed his hat, and when Santerre addressed the King, he forgot to say "Your Majesty," or "Sire." At the doorway they paused a second, but they did not look[Pg 80] back. The crowd shouted "Vive la Nation!" They passed inside, and the door was shut on the humiliation of the dethroned monarch!

A DOMICILIARY VISIT

CHAPTER V

A DOMICILIARY VISIT

"This country is going to the dogs!" It was Bonaparte who spoke, striding up and down thoughtfully, his head bent, his hands clasped behind him. The two friends were taking an evening stroll in the Jardin des Plantes, and discussing, of course, the affairs of the nation, which were the only matters that interested anyone in those stirring days.

"Yes, the country, and especially this city is going to the dogs, and I think I'll leave it!" Jean was thoroughly startled.

"Leave it!" he echoed. "Oh, Citizen Bonaparte, where would you go?"

"I believe I'll go home to Corsica," replied Bonaparte. "I love my home, and I've always been happy there, poor though it is.[Pg 82] And besides, my sister Elisa has been a student at the royal school of St. Cyr. I have just received word that this school was closed and suppressed by the Assembly on August sixteenth. So I must go there and take Elisa home. I don't want to return. Paris is a horrible place!"

"But what shall I do without you?" wailed Jean. "You are my best friend! I have almost no others in these dreadful days."

"Come with me, then!" generously responded Bonaparte. "Have you never thought of becoming a soldier? I have received news of my reinstatement in the army, and I would gladly take you with me."

"Ah, but would I not love to do so!" answered the boy sadly. "It has ever been my secret wish to serve my country in the army, and in these days when we are struggling for liberty, I desire it beyond everything. But how can I leave Mère Clouet and Yvonne? The good mother has cared for me ever since she took me, a homeless waif from[Pg 83] the Foundling Hospital, and it would be wrong to leave her and the little Yvonne unprotected in this mad city. It is true I am young, but I am all they have! And besides, I have set my heart on being of service to the poor little Citizen Dauphin in prison, if I can. We owe that debt to him and to his parents, who helped us in our hour of need."

"You speak truly!" said Bonaparte. "Your family is your first concern, and nothing appeals to me more than the desire to pay a debt, whether of money or gratitude. But should the opportunity ever come, I'll take you with me in the army, lad, for I like your spirit. Would that Paris had in her many more such!

"But Paris is insane, blood-intoxicated!" he went on thoughtfully. "It is amazing how blind she has become to the real peril! She seems to think that the whole danger to her new liberty comes from within her midst, in the persons of suspected royalists. Whereas, look you! France is really[Pg 84] menaced from without by the foreign powers Austria and Prussia, whose armies are threatening our borders everywhere. These powers think that the conquest of this nation will be a mere summer picnic, because she is internally torn by a great Revolution. What the country needs is a head! Oh, for someone who could mass all her squabbling factions in one united whole, and lead her to a glorious victory!"

So declaimed Bonaparte on this dusky, starlit night in the Jardin des Plantes. What if the curtain of the future could have rolled back for an instant and revealed to Jean's astonished gaze this same shabby young man, eight years later! He is the hero of a hundred, victorious battles! He has raised the perishing land of France and set her on the highest pinnacle of power in the world! He is the emperor of his country and the king of Italy! He has made his impoverished brothers and sisters kings and queens. He is at once feared, obeyed and[Pg 85] adored! He has truly fulfilled his destiny! But the stars twinkled down on the Jardin des Plantes. Out of Paris rose the subdued murmur of an ever restless populace. The two friends walked together in silence for a space, and the future still darkly guarded the wonderful secret!

Suddenly the stillness of the night was broken by a roll of drums from the Rue Saint Victor. In an instant everyone was hurrying in that direction, realising that it was a signal of importance. Jean and Bonaparte lost no time in joining the ranks of the curious. What they learned that night served to add in no way to their peace of mind.

It seemed that the brain of Danton, ever fertile in inventing outrageous and unbearable measures, had hatched a new scheme. This was no less than to apprehend all aristocrats who had been concealing themselves since August tenth, all who had belonged to the late Court or were in any way connected[Pg 86] with it, and all who were suspected of royalistic sympathies. This was to be effected by a series of domiciliary visits. At the roll of the drums, all citizens were to repair at once to their homes and remain there two days, during which time they would be personally visited by a committee of surveillance. Suspicious evidences found in any house, would subject all its inmates to immediate imprisonment.

"You are to disperse at once!" ended the soldier who delivered this message. "By ten o'clock not a soul must be abroad! Citizens, retire at once to your homes!"

"Outrage! Unwarrantable outrage! This is worse than the Bourbon tyranny!" muttered Bonaparte, as the two separated, for it lacked but half an hour of the required time. "But go cautiously, Jean, when the inspectors visit your house! Remember, you've something incriminating there!"

When the following morning dawned, Paris was a singular sight! Streets that had been[Pg 87] populous with passing throngs and carriages, or swarming with the crowded masses of the poor, were silent and deserted. Everyone sought the vain protection of his own roof, which was soon to prove no protection at all, and waited in fearful expectation for the threatened visit. No one, were he never so innocent, could be certain of immunity. Valuable property was hurriedly concealed, and persons who had the slightest reason to think themselves objects of suspicion were carefully hidden, some even going so far as to have themselves nailed up within the walls of their houses!

For two days Mère Clouet, Yvonne and Jean remained within doors in nerve-racking uncertainty, trembling at the slightest sound, or the faintest cry in the streets. For they had in their midst, as Bonaparte had said, "something most incriminating,"—the pretty, coal-black spaniel of Louis Charles, so lately imprisoned and deprived of his title.

"What shall we do with Moufflet, when the[Pg 88] committee of surveillance comes?" whispered Yvonne, who with all the others, instinctively lowered her voice in this time of peril, lest the very walls betray her.

"Leave that to me!" commanded Jean. "I've decided what I shall do and say, only be sure you do not contradict me, either by word or action!"

"I wish we could have hidden the little animal," sighed Mère Clouet, "but of course it would have been useless to try. He would surely betray both himself and us by some bark or whine!" So the hours wore away. The two days of suspense drew to an end, and the Clouet family were beginning to hope they had escaped the ordeal, when at dusk that night, a thundering knock was heard at the door.

"Open, or we break in!" growled a voice, and Jean hastened to comply.

"Coming, coming!" he called cheerfully. "You are welcome, citizens all!"

"That's a gayer greeting than we get at[Pg 89] most places!" answered a high nasal voice as the door was opened. And without further ceremony there tramped in six huge pikemen, headed by one of the committee of surveillance,—the owner of the nasal voice. He was a singularly unprepossessing specimen of humanity, thin, wiry, short of stature, evil-faced, with little, claw-like hands. He had a curious habit of slinking about with soft, noiseless steps and a watchful look in his beady eyes that reminded one irresistibly of a mouse. The pikemen addressed him as Citizen Coudert.

"Pikemen, do your duty," he commanded, "while I question these people!" And while the pikemen tramped through the house, emptying drawers, boxes and barrels, thumping the walls and floors, tearing up clothing and destroying china on the pretence of a more thorough search, Citizen Coudert proceeded to put the inmates upon a rack of torturing questions. He had just touched upon the ticklish subject of sympathy for the[Pg 90] ex-king and the royal family, when a shout from one of the pikemen announced the discovery of Moufflet, curled up in a distant corner.

"That's a dog I'll swear I saw at the Tuileries garden many a day this past year, with the little Wolf-Cub! I know dogs well, and am never mistaken in one!" Jean's heart was in his throat, but he maintained an indifferent air.

"Aha! is it so!" snarled Coudert, rubbing his claw-like hands, and with a gleam very like satisfaction in his beady eyes. "Answer me in regard to this dog, if you please, young sir! Is he the property of that Wolf-Cub brat?" Then Jean played his boldest card.

"He was, I suppose, Citizen Coudert, but he's mine now! And when you hear how I got him, you will say I did well, and acted worthily as a good republican citizen. I went with the throng to the palace on June twentieth, to see the sights. There I found[Pg 91] this little dog, and I said to myself,—'Won't it be a fine joke on royalty to take this animal and train him in good republican ways!' So I caught him and carried him home." Citizen Coudert looked incredulous.

"You do not believe me, Citizen," continued Jean eagerly, "but hark! I will prove it! Here, Moufflet! Bark for Liberty!" The little animal ran to him, crouched, and barked once. "Now for Equality!" Moufflet barked twice. "Now for Fraternity!" The dog gave three short, sharp barks, then sat up and lifted its paws to beg. And Mère Clouet and Yvonne realised now why Jean had been diligently training the intelligent animal in this new accomplishment during the past two days of seclusion.

"Bravo!" applauded the pikeman. "That's a rare trick for a royalist dog! You've done well, my boy! I imagine we've no fault to find with you!"

"Be silent, Citizen Prevôt!" growled Coudert. "Pay attention to your own duties,[Pg 92] and leave these things to me! Now, young sir, this is all very well, but what business had you to appropriate to yourself any property that belongs to the people at large? This dog should have been delivered to the Assembly. He is valuable, and might have been sold and the money turned to helping our starving poor. Hand him over to me! I will do what is right with him, but I'm going to keep a strict watch over you, do you understand? You have given me cause to be suspicious of you! Here, Prevôt, carry this dog! To the next house, pikemen!"

It was all Jean could do to be silent and submissive under this act of injustice and outrage, but imploring glances from Mère Clouet and Yvonne helped him to hold his tongue. The committee of surveillance left the house, accompanied by yelps of protest from Moufflet, struggling in the grip of Prevôt. When they were gone, Jean tramped up and down the room in a fury of rage and disappointment.[Pg 93]

"That sneak of a Coudert!" he exploded. "Has he any more right to that dog than we have? He'll never give it to the Assembly, that I know! He wants it for himself, or else he just took it for the sake of robbing us! And now I cannot restore Moufflet to his little master, as I had hoped some day to do!"

"Hush! hush!" begged Mère Clouet. "We were lucky to have gotten off without being dragged to prison! Had it not been for that dog's trick, which you were clever enough to teach him, I doubt not but we would have all been in La Conciergerie within an hour!" But Jean was not to be passified by such reasoning, and he went to bed in wrath and tears, and Yvonne followed his example.

Events, however, shortly came to pass that made him sincerely thankful they were all yet alive and going about with heads still secure on their shoulders. The domiciliary visits of the last of August had so filled to overflowing every prison in the city with victims (sad to say, for the most part[Pg 94] absolutely innocent of the crimes imputed to them!) that a still more horrible plan was determined upon by those two arch fiends of the Revolution, Marat and Danton,—one which should at once clear the prisons for more victims, and strike such terror to the hearts of any remaining royalists as to suppress absolutely all further tendencies in this direction. This was nothing more nor less than a general massacre of all the prisoners without trial, justice or mercy.

At two o'clock on Sunday, September 2, 1792, this wholesale slaughter commenced, and for five days the prisons of Paris were scenes of unspeakable and indescribable carnage till at last they were empty. Never was there in history so revolting a sacrifice of innocent lives. Twelve thousand victims perished, and with this fearful prelude, the Reign of Terror began!

Three days later, Jean went to make his farewell visit to his friend Bonaparte, now no longer a resident of the Rue Cléry, for[Pg 95] he had in the meantime brought his sister to the city from St. Cyr, and was staying at the little hotel De Metz in the Rue du Mail. Bonaparte introduced the boy to his sister, a slender, rather pretty girl of fifteen in the tight-fitting black taffeta cap of the St. Cyr school. As she had little to say for herself, Bonaparte suggested that she remain in her room, while he and Jean repaired for a walk to their favourite spot, the Jardin des Plantes. Once there, Jean reported to him the outrages of their domiciliary visit and discussed with him the horrors of the past few days.

"Oh, Citizen Bonaparte," he ended, "I am sorely tempted to go away with you and join the army! I want to fight for better things for France. This is not liberty, here in Paris! It is oppression and butchery! But I dare not leave yet! I feel that I have a sacred trust to fulfil! Yet all has gone wrong! Moufflet is stolen and I shall never see him again. We are constantly in danger from[Pg 96] that spying Coudert; it was only yesterday that I saw him again sneaking about our street! To help the royal family seems utterly impossible. And now you are going to leave me too,—you who once saved my life, and to whom I can never be grateful enough!"

"I am sorry, little Jean! I truly am!" answered his friend. "Many things call me away, but cheer up! The tide will turn, and there is no telling[Pg 97] what you may yet do—or what I may yet be! I tell you I believe in my fortunate star! But one thing I will say to you, my lad. You have a brave loyal spirit, than which I admire nothing more heartily. I like[Pg 98] you, and I will surely come back some day,—and who knows what we may yet do together! Au revoir now! Be true to your trust, and don't forget the friend you once made by butting him flat on his back!" Jean could not even answer. He seized the young man's hands, kissed them[Pg 99] passionately, and with a sob fled down one of the long, green alleys of the Jardin. Could he have guessed how long it would be before he and this thin young man with the marvellous eyes should meet again, his despair would have been deeper yet. But that also was guarded with the secret of the future![Pg 100]

ENTER THE COBBLER,—EXIT THE KING

CHAPTER VI

ENTER THE COBBLER,—EXIT THE KING

The warm September sun shone dazzlingly on the pavement before the buvette or tavern of Père Lefèvre. This shop was situated in the outer courtyard of the Temple Tower, and enjoyed the trade of all the soldiers, guards and commissaries employed in guarding the imprisoned king and his family. Père Lefèvre sat in a chair outside the door, nodding in the sunshine, for it was mid-afternoon and trade was dull.