Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

On page 431, 1854 should possibly be 1845.

On page 533, the page number referenced is missing on the first Chapter XXXV citation.

On page 544, the pages listed as pp 226-223 are possibly a typo.

On page 487, \B and \F represent VB and VF ligatures.

POMPEII

ITS LIFE AND ART

POMPEII

ITS LIFE AND ART

BY

AUGUST MAU

GERMAN ARCHAEOLOGICAL INSTITUTE IN ROME

Translated into English

BY FRANCIS W. KELSEY

UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM ORIGINAL

DRAWINGS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

NEW EDITION, REVISED AND CORRECTED

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

LONDON: MACMILLAN & CO., Ltd.

1902

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1899, 1902,

By FRANCIS W. KELSEY.

First Edition, October, 1899.

New Revised Edition, with additions, November, 1902.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing & Co.—Berwick & Smith

Norwood Mass. U.S.A.

PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION

For twenty-five years Professor Mau has devoted himself to the study of Pompeii, spending his summers among the ruins and his winters in Rome, working up the new material. He holds a unique place among the scholars who have given attention to Pompeian antiquities, and his contributions to the literature of the subject have been numerous in both German and Italian. The present volume, however, is not a translation of one previously issued, but a new work first published in English, the liberality of the publishers having made it possible to secure assistance for the preparation of certain restorations and other drawings which Professor Mau desired to have made as illustrating his interpretation of the ruins.

In one respect there is an essential difference between the remains of Pompeii and those of the large and famous cities of antiquity, as Rome or Athens, which have associated with them the familiar names of historical characters. Mars' Hill is clothed with human interest, if for no other reason, because of its relation to the work of the Apostle Paul; while the Roman Forum and the Palatine, barren as they seem to-day, teem with life as there rise before the mind's eye the scenes presented in the pages of classical writers. But the Campanian city played an unimportant part in contemporary history; the name of not a single great Pompeian is recorded. The ruins, deprived of the interest arising from historical associations, must be interpreted with little help from literary sources, and repeopled with aggregate rather than individual life.

A few Pompeians, whose features have survived in herms or statues and whose names are known from the inscriptions, seem vi near to us,—such are Caecilius Jucundus and the generous priestess Eumachia; but the characters most commonly associated with the city are those of fiction. Here, in a greater degree than in most places, the work of reconstruction involves the handling of countless bits of evidence, which, when viewed by themselves, often seem too minute to be of importance; the blending of these into a complete and faithful picture is a task of infinite painstaking, the difficulty of which will best be appreciated by one who has worked in this field.

It was at first proposed to place at the end of the book a series of bibliographical notes on the different chapters, giving references to the more important treatises and articles dealing with the matters presented. But on fuller consideration it seemed unnecessary thus to add to the bulk of the volume; those who are interested in the study of a particular building or aspect of Pompeian culture will naturally turn to the Pompeianarum antiquitatum historia, the reports in the Notizie degli Scavi, the reports and articles by Professor Mau in the Roman Mittheilungen of the German Archaeological Institute, the Overbeck-Mau Pompeji, the Studies by Mau and by Nissen, the commemorative volume issued in 1879 under the title Pompei e la regione sotterrata dal Vesuvio, the catalogues of the paintings by Helbig and Sogliano, together with Mau's Geschichte der decorativen Wandmalerei in Pompeji, H. von Rohden's Terracotten von Pompeji, and the older illustrated works, as well as the beautiful volume, Pompeji vor der Zerstoerung, published in 1897 by Weichardt.

The titles of more than five hundred books and pamphlets relating to Pompeii are given in Furchheim's Bibliografia di Pompei (second edition, Naples, 1891). To this list should be added an elaborate work on the temple of Isis, Aedis Isidis Pompeiana, which is soon to appear. The copperplates for the engravings were prepared at the expense of the old Accademia ercolanese, but only the first section of the work was published; the plates, fortunately, have been preserved without vii injury, and the publication has at last been undertaken by Professor Sogliano.

Professor Mau wishes to make grateful acknowledgment of obligation to Messrs. C. Bazzani, R. Koldewey, G. Randanini, and G. Tognetti for kind assistance in making ready for the engraver the drawings presenting restorations of buildings; to the authorities of the German Archaeological Institute for freely granting the use of a number of drawings in its collection; and to the photographer, Giacomo Brogi of Florence, for placing his collection of photographs at the author's disposal and making special prints for the use of the engraver. In addition to the photographs obtained from Brogi, a small number were furnished for the volume by the translator, and a few were derived from other sources.

The restorations are not fanciful. They were made with the help of careful measurements and of computations based upon the existing remains; occasionally also evidence derived from reliefs and wall paintings was utilized. Uncertain details are generally omitted.

It is due to Professor Mau to say that in preparing his manuscript for English readers I have, with his permission, made some changes. The order of presentation has occasionally been altered. In several chapters the German manuscript has been abridged, while in others, containing points in regard to which English readers might desire a somewhat fuller statement, I have made slight additions. The preparation of the English form of the volume, undertaken for reasons of friendship, has been less a task than a pleasure.

FRANCIS W. KELSEY.

Ann Arbor, Michigan,

October 25, 1899.

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

The author and the translator unite in expressing their deep appreciation of the kind reception accorded to the first edition of this book.

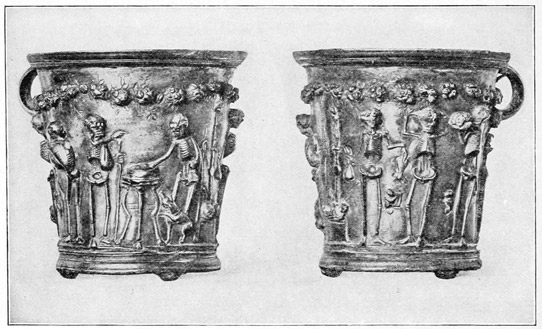

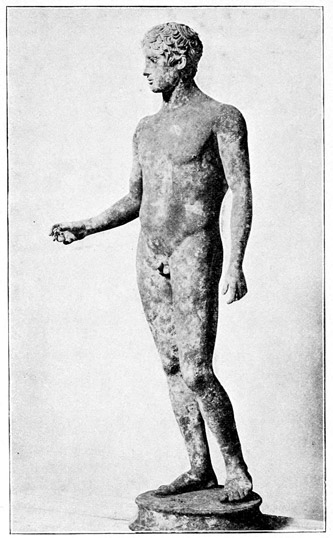

The second edition has been revised on the spot. Besides minor additions, it has been enlarged by a chapter on the recently discovered temple of Venus Pompeiana, and a Bibliographical Appendix; prepared in response to requests from various quarters. Among the new illustrations in the text are a restoration of the temple of Vespasian and a reproduction of the bronze youth found in 1900, besides the Alexandria patera and one of the skeleton cups from the Boscoreale treasure; in Plate VIII are presented two additional paintings from the house of the Vettii.

The translator is alone responsible for Chapter LIX, which was prepared for the first edition at Professor Mau's request, at a time when he was pressed with other work; for the paragraphs in regard to the treasure of Boscoreale, and for one-half of the references in the Bibliographical Appendix.

AUGUST MAU

FRANCIS W. KELSEY

Albergo del Sole, Pompei

August 2, 1901

CONTENTS

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

| I. | The Situation of Pompeii | 1 | |

| II. | Before 79 | 8 | |

| III. | The City Overwhelmed | 19 | |

| IV. | The Unearthing of the City | 25 | |

| V. | A Bird's-eye View | 31 | |

| VI. | Building Materials, Construction, and Architectural Periods | 35 | |

| PART I | |||

| PUBLIC PLACES AND BUILDINGS | |||

| VII. | The Forum | 45 | |

| VIII. | General View of the Buildings about the Forum.—The Temple of Jupiter | 61 | |

| IX. | The Basilica | 70 | |

| X. | The Temple of Apollo | 80 | |

| XI. | The Buildings at the Northwest Corner of the Forum, and the Table of Standard Measures | 91 | |

| XII. | The Macellum | 94 | |

| XIII. | The Sanctuary of the City Lares | 102 | |

| XIV. | The Temple of Vespasian | 106 | |

| XV. | The Building of Eumachia | 110 | |

| XVI. | The Comitium | 119 | |

| XVII. | The Municipal Buildings | 121 x | |

| XVIII. | The Temple of Venus Pompeiana | 124 | |

| XIX. | The Temple of Fortuna Augusta | 130 | |

| XX. | General View of the Public Buildings near the Stabian Gate.—The Forum Triangulare and the Doric Temple | 133 | |

| XXI. | The Large Theatre | 141 | |

| XXII. | The Small Theatre | 153 | |

| XXIII. | The Theatre Colonnade used as Barracks for Gladiators | 157 | |

| XXIV. | The Palaestra | 165 | |

| XXV. | The Temple of Isis | 168 | |

| XXVI. | The Temple of Zeus Milichius | 183 | |

| XXVII. | The Baths at Pompeii.—The Stabian Baths | 186 | |

| XXVIII. | The Baths near the Forum | 202 | |

| XXIX. | The Central Baths | 208 | |

| XXX. | The Amphitheatre | 212 | |

| XXXI. | Streets, Water System, and Wayside Shrines | 227 | |

| XXXII. | The Defences of the City | 237 | |

| PART II | |||

| THE HOUSES | |||

| XXXIII. | The Pompeian House | 245 | |

| I. | Vestibule, Fauces, and Front Door | 248 | |

| II. | The Atrium | 250 | |

| III. | The Tablinum | 255 | |

| IV. | The Alae | 258 | |

| V. | The Rooms about the Atrium. The Andron | 259 | |

| VI. | Garden, Peristyle, and Rooms about the Peristyle | 260 | |

| VII. | Sleeping Rooms | 261 | |

| VIII. | Dining Rooms | 262 | |

| IX. | The Kitchen, the Bath, and the Storerooms | 266 xi | |

| X. | The Shrine of the Household Gods | 268 | |

| XI. | Second Story Rooms | 273 | |

| XII. | The Shops | 276 | |

| XIII. | Walls, Floors, and Windows | 278 | |

| XXXIV. | The House of the Surgeon | 280 | |

| XXXV. | The House of Sallust | 283 | |

| XXXVI. | The House of the Faun | 288 | |

| XXXVII. | A House near the Porta Marina | 298 | |

| XXXVIII. | The House of the Silver Wedding | 301 | |

| XXXIX. | The House of Epidius Rufus | 309 | |

| XL. | The House of the Tragic Poet | 313 | |

| XLI. | The House of the Vettii | 321 | |

| XLII. | Three Houses of Unusual Plan | 341 | |

| I. | The House of Acceptus and Euhodia | 341 | |

| II. | A House without a Compluvium | 343 | |

| III. | The House of the Emperor Joseph II | 344 | |

| XLIII. | Other Noteworthy Houses | 348 | |

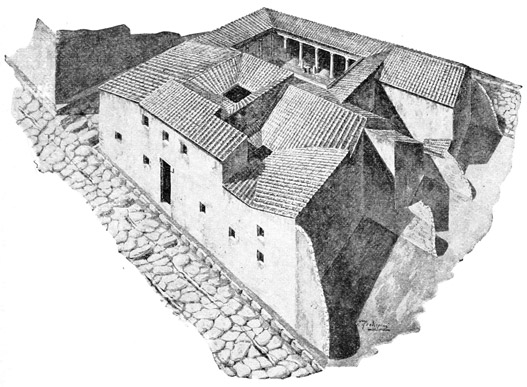

| XLIV. | Roman Villas.—The Villa of Diomedes | 355 | |

| XLV. | The Villa Rustica at Boscoreale | 361 | |

| XLVI. | Household Furniture | 367 | |

| PART III | |||

| TRADES AND OCCUPATIONS | |||

| XLVII. | The Trades at Pompeii.—The Bakers | 383 | |

| XLVIII. | The Fullers and the Tanners | 393 | |

| XLIX. | Inns and Wineshops | 400 | |

| PART IV | |||

| THE TOMBS | |||

| L. | Pompeian Burial Places.—The Street of Tombs | 405 | |

| LI. | Burial Places near the Nola, Stabian, and Nocera Gates | 429 xii | |

| PART V | |||

| POMPEIAN ART | |||

| LII. | Architecture | 437 | |

| LIII. | Sculpture | 445 | |

| LIV. | Painting.—Wall Decoration | 456 | |

| LV. | The Paintings | 471 | |

| PART VI | |||

| THE INSCRIPTIONS OF POMPEII | |||

| LVI. | Importance of the Inscriptions.—Monumental Inscriptions and Public Notices | 485 | |

| LVII. | The Graffiti | 491 | |

| LVIII. | Inscriptions relating to Business Affairs | 499 | |

| CONCLUSION | |||

| LIX. | The Significance of the Pompeian Culture | 509 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHICAL APPENDIX | 512 | ||

| INDEX | 551 | ||

| KEY TO THE PLAN OF POMPEII | 559 | ||

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PLATES | |||

| PLATE | |||

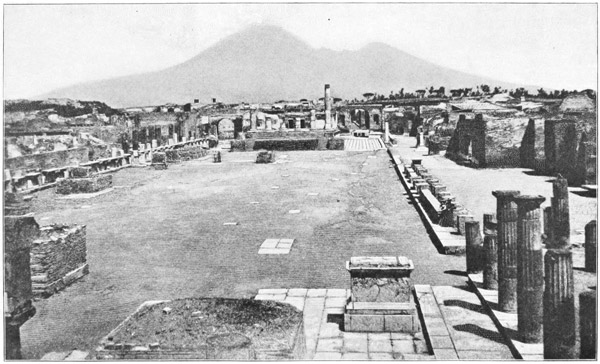

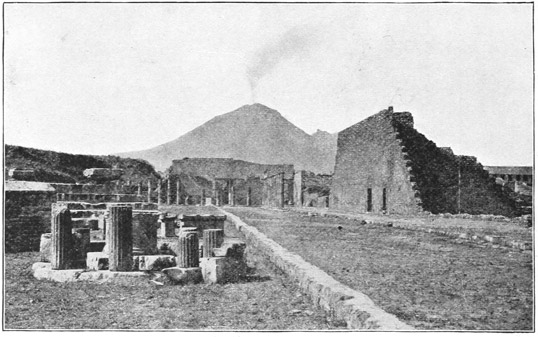

| I. | View of the Forum, looking toward Vesuvius. From a photograph | Frontispiece | |

| FACING PAGE | |||

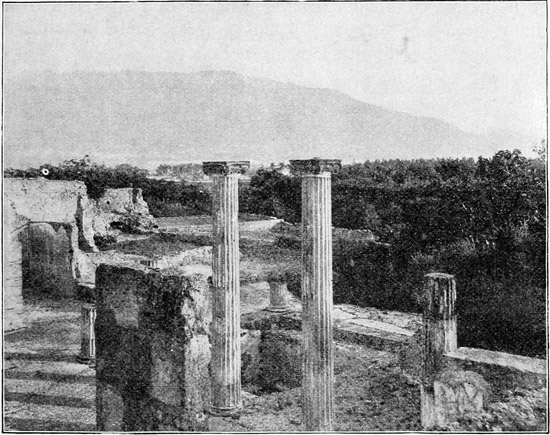

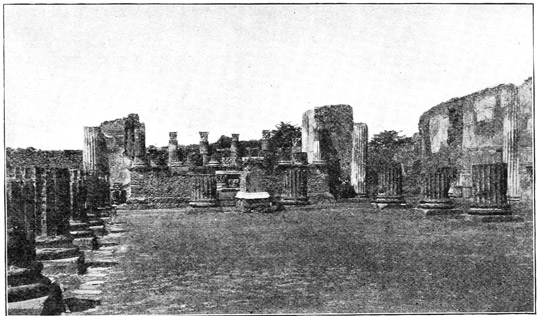

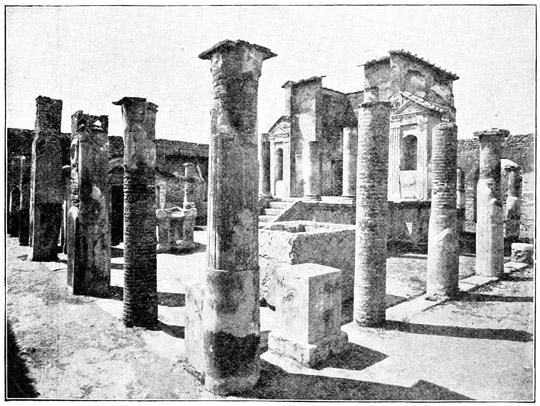

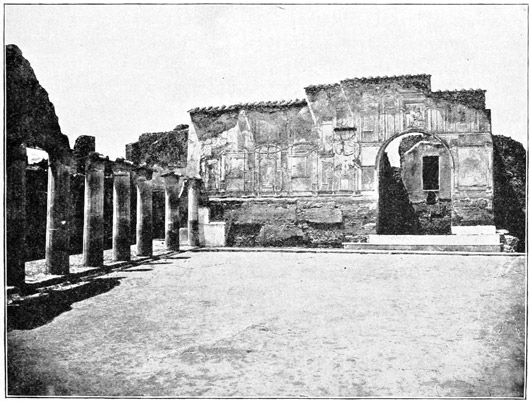

| II. | Court of the Temple of Apollo. From a photograph | 88 | |

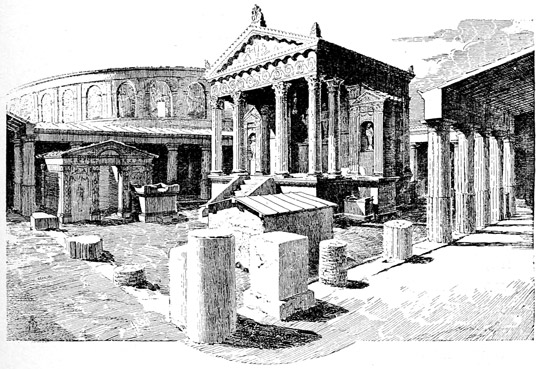

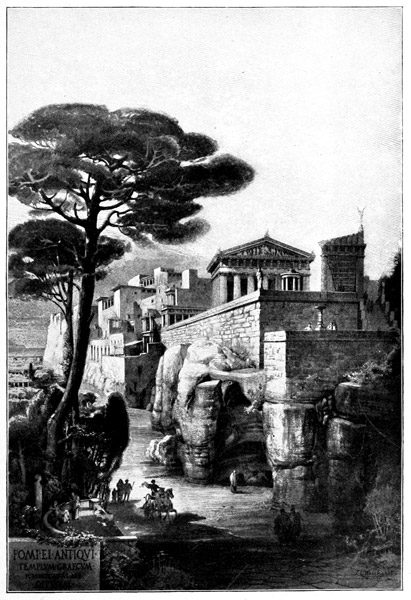

| III. | The Greek Temple and the Forum Triangulare, seen from the South. Restoration (Weichardt, Pompeji vor der Zerstörung, Tafel II) | 134 | |

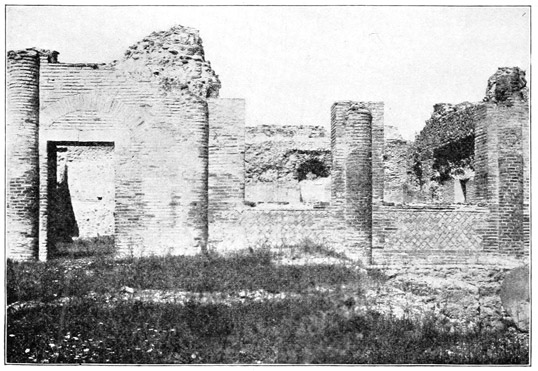

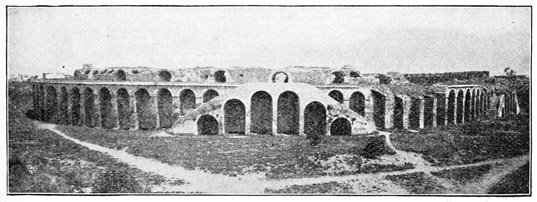

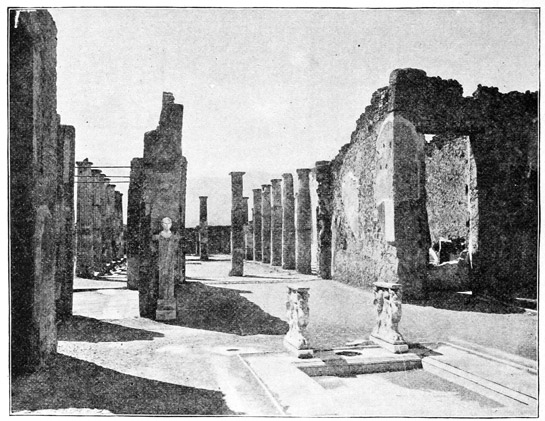

| IV. | The Barracks of the Gladiators. From a photograph | 160 | |

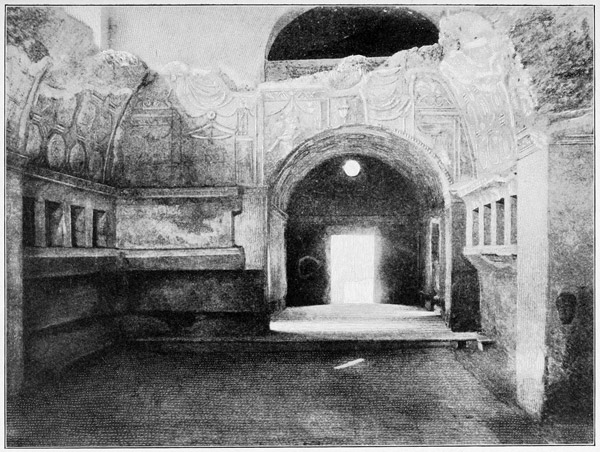

| V. | Stabian Baths: Men's Apodyterium, with the Anteroom leading from the Palaestra. From a photograph | 188 | |

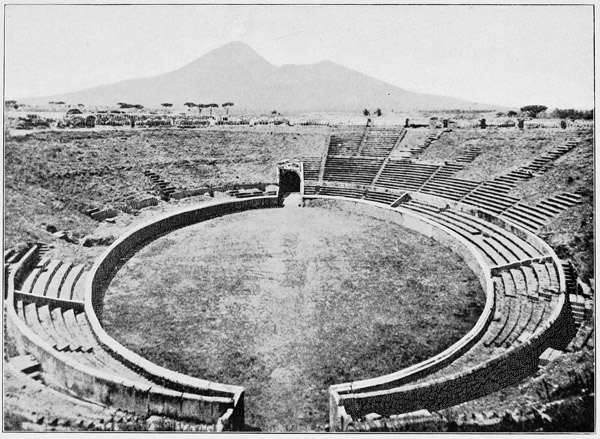

| VI. | Interior of the Amphitheatre, looking Northwest. From a photograph | 216 | |

| VII. | Interior of a House (IX. v. 11), looking from the Middle of the Atrium into the Peristyle. From a photograph | 260 | |

| VIII. | Two Wall Paintings in the House of the Vettii—Apollo after the Slaying of the Dragon, and Agamemnon in the Sanctuary of Artemis. From photographs | 328 | |

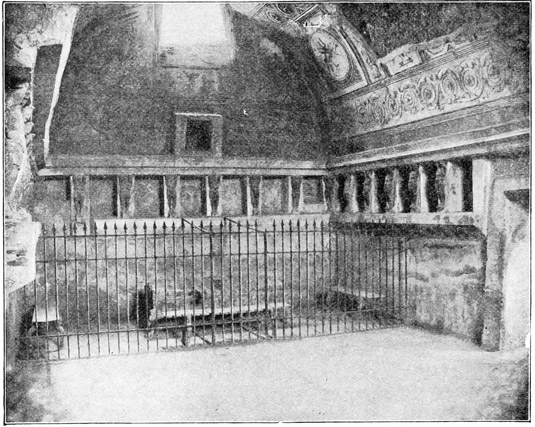

| IX. | A Dining Room in the House of the Vettii. From a photograph | 338 | |

| X. | The Street of Tombs, looking toward the Herculaneum Gate. From a photograph | 420 | |

| XI. | Artemis. Copy of an Archaic Work. From a photograph | 444 | |

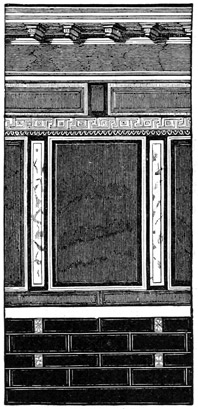

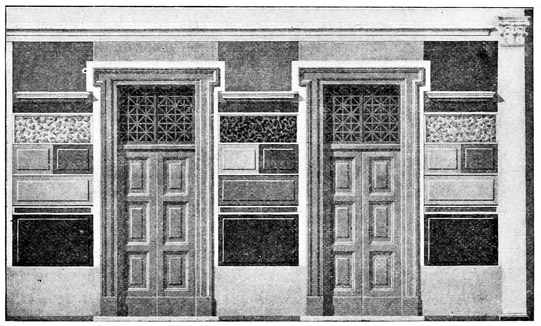

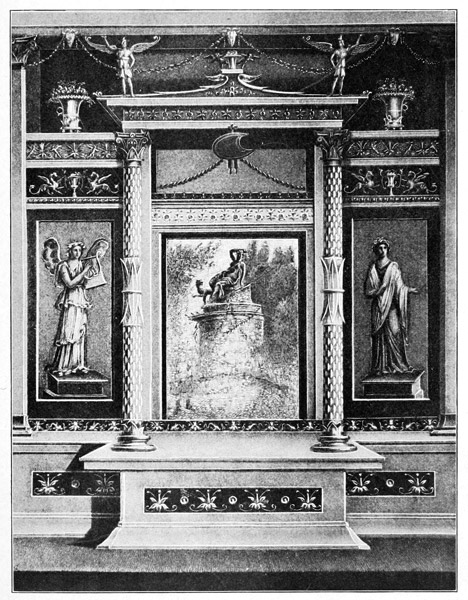

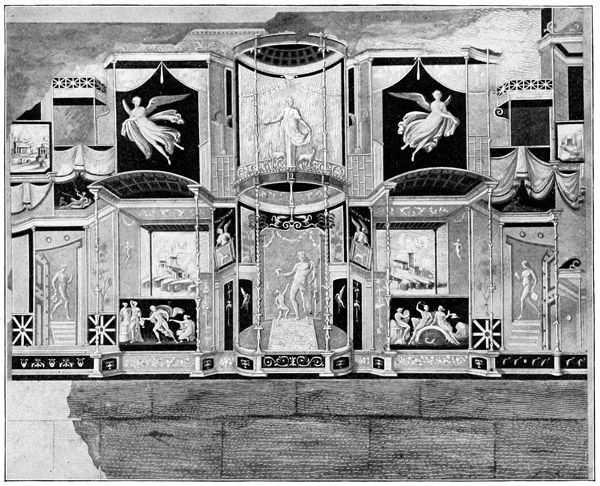

| XII. | Specimen of Wall Decoration. Second or Architectural Style (Mau, Geschichte der decorativen Wandmalerei in Pompeji, Tafel V) | 462 | |

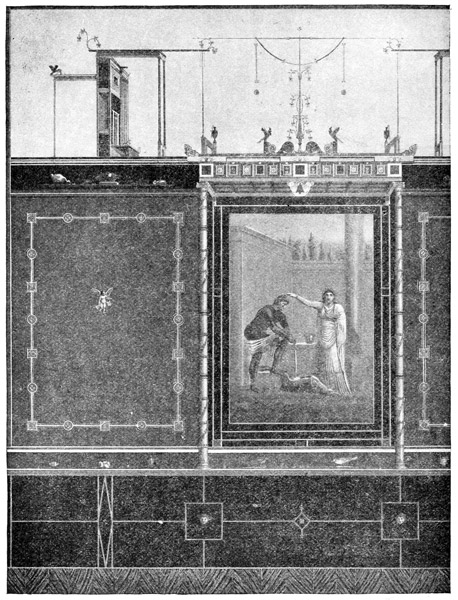

| XIII. | Specimen of Wall Decoration, in the Court of the Stabian Baths. Fourth or Intricate Style. From a drawing in the Naples Museum | 470 | |

| PLANS | |||

| PLAN | |||

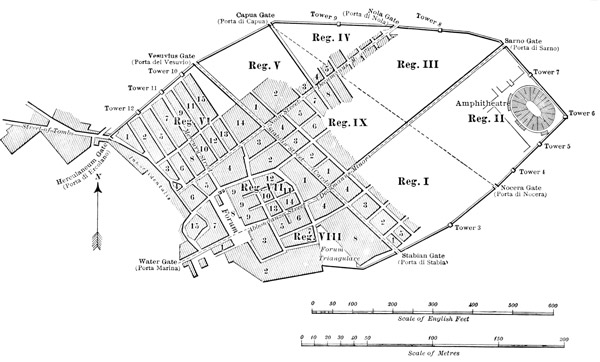

| I. | Outline Plan of Pompeii | preceding Chap. V | |

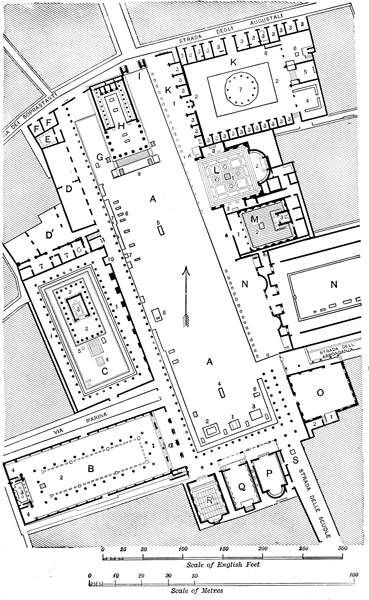

| II. | The Forum, with Adjoining Buildings | preceding Chap. VII xiv | |

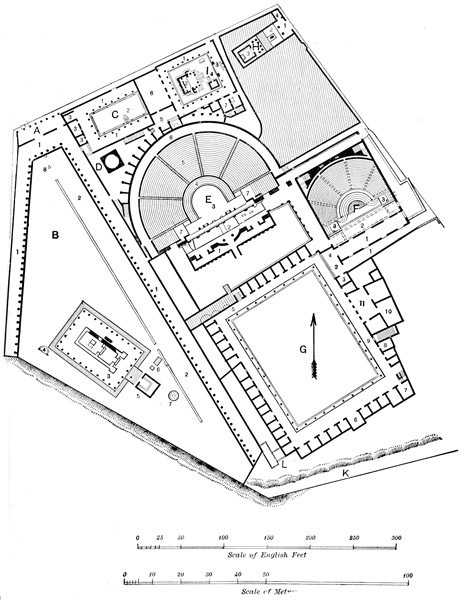

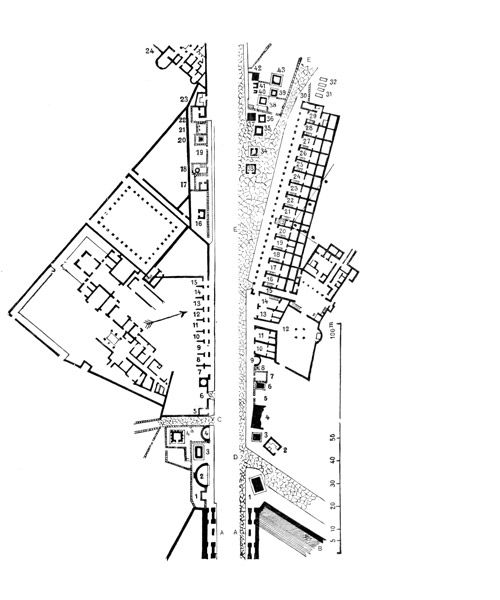

| III. | The Forum Triangulare, with Adjacent Buildings | preceding Chap. XX | |

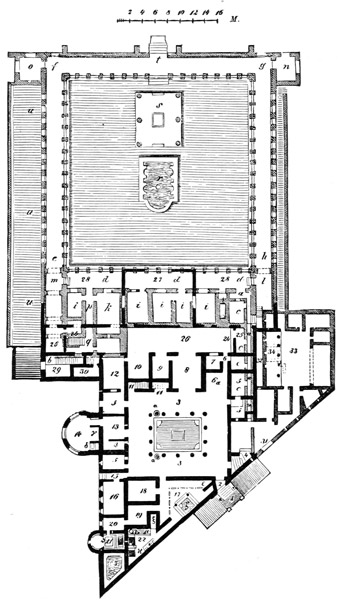

| IV. | The Villa Rustica near Boscoreale | preceding Chap. XLV | |

| V. | The Street of Tombs | preceding Chap. L | |

| VI. | The Excavated Portion of Pompeii | following the Index | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT | |||

| FIGURE | PAGE | ||

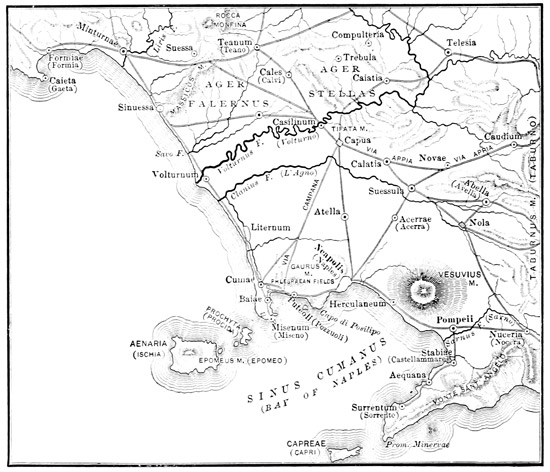

| 1. | Map of Ancient Campania | 2 | |

| 2. | Vesuvius as seen from Naples. From a photograph | 3 | |

| 3. | View from Pompeii, looking south. From a photograph (A. M.) | 5 | |

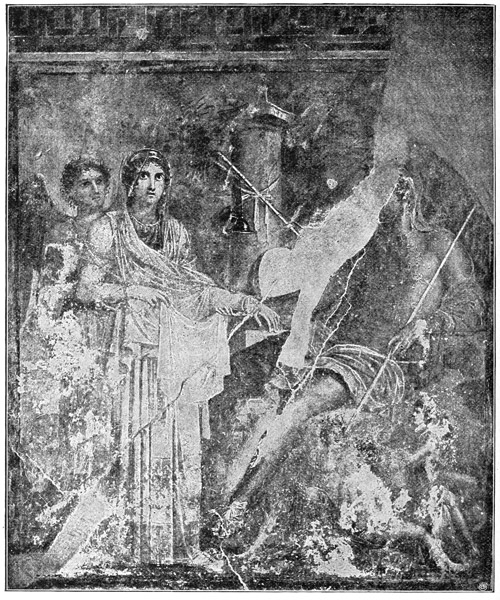

| 4. | Venus Pompeiana. Wall painting. House of Castor and Pollux. After Monumenti dell' Instituto, Vol. III, pl. vi. b | 12 | |

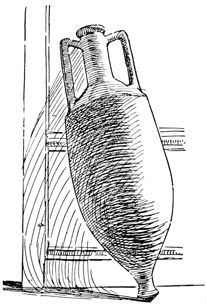

| 5. | An amphora from Boscoreale. Collection of Classical Antiquities, University of Michigan. From a drawing | 15 | |

| 6. | The Judgment of Solomon. Wall painting. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 17 | |

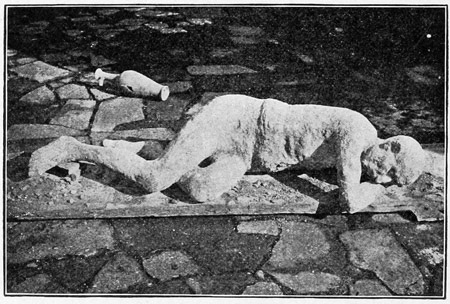

| 7. | Cast of a man. Museum at Pompeii. From a photograph | 22 | |

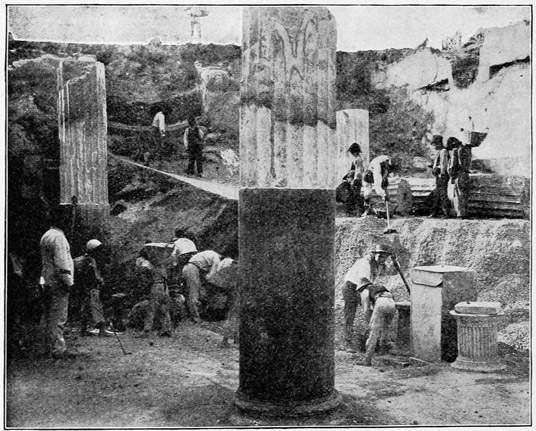

| 8. | An Excavation. Atrium of the house of the Silver Wedding. From a photograph | 28 | |

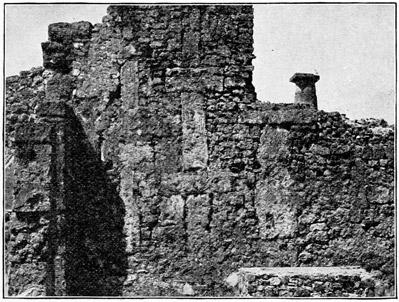

| 9. | Wall with limestone framework (Ins. VII. iii. 13). From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 37 | |

| 10. | Façade of Sarno limestone, house of the Surgeon. From a photograph | 39 | |

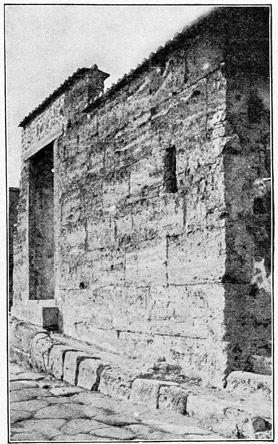

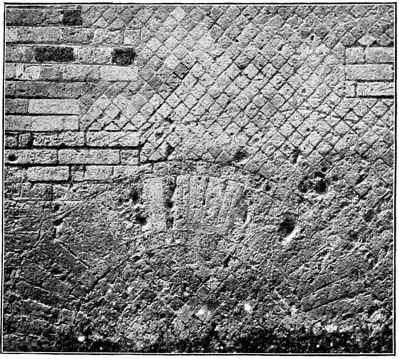

| 11. | Quasi-reticulate facing, with brick corner, at the entrance of the Small Theatre. From a photograph | 42 | |

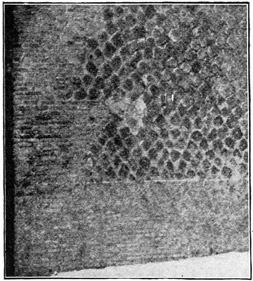

| 12. | Reticulate facing, with corners of brick-shaped stone (I. iii. 29). From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 43 | |

| 13. | North end of the Forum, with the temple of Jupiter, restored. From an original drawing[1] | 49 | |

| 14. | Remnant of the colonnade of Popidius, at the south end of the Forum. From a photograph (A. M.) | 51 | |

| 15. | Part of the new colonnade, near the southwest corner of the Forum. From a photograph (A. M.) | 53 | |

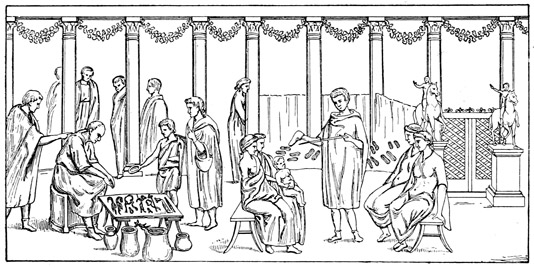

| 16. | Scene in the Forum—a dealer in utensils, and a shoemaker. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. III, pl. 42 | 55 | |

| 17. | Scene in the Forum—citizens reading a public notice. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. III, pl. 43 | 56 | |

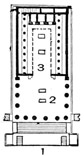

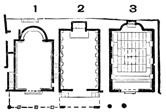

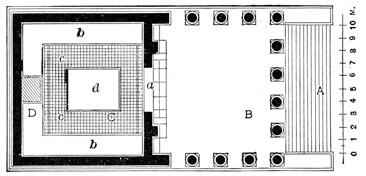

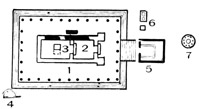

| 18. | Plan of the temple of Jupiter | 63 | |

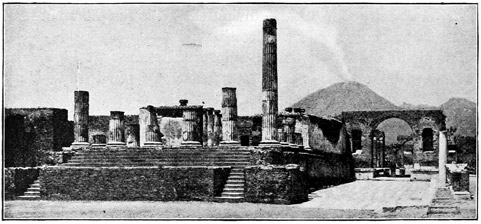

| 19. | Ruins of the temple of Jupiter. From a photograph | 64 xv | |

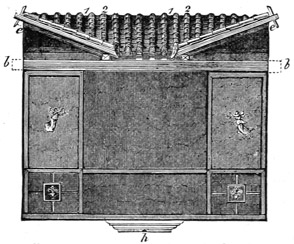

| 20. | Section of wall decoration in the cella of the temple of Jupiter. After Mazois, Les Ruines de Pompéi, Vol. III, pl. 36 (Overbeck-Mau, Pompeji, Fig. 46) | 65 | |

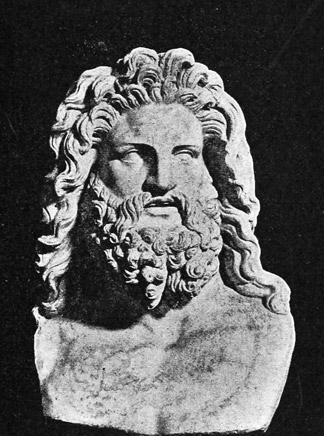

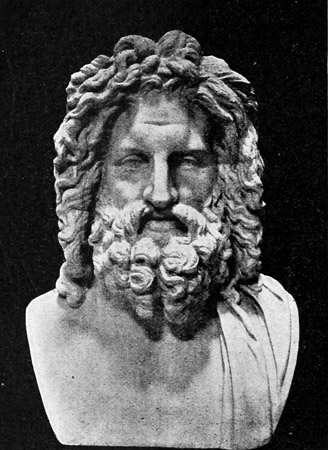

| 21. | Bust of Zeus found at Otricoli. Vatican Museum. After Tafel 130 of the Brunn-Bruckmann Denkmaeler | 68 | |

| 22. | Bust of Jupiter found at Pompeii. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 69 | |

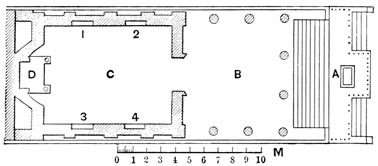

| 23. | Plan of the Basilica | 71 | |

| 24. | View of the Basilica, looking toward the tribunal. From a photograph | 73 | |

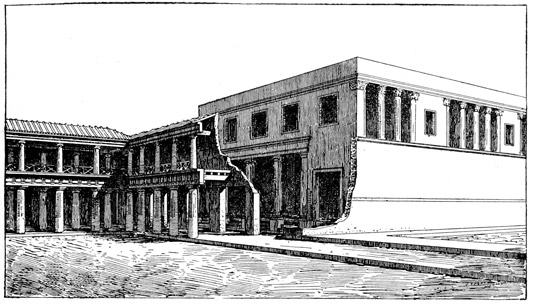

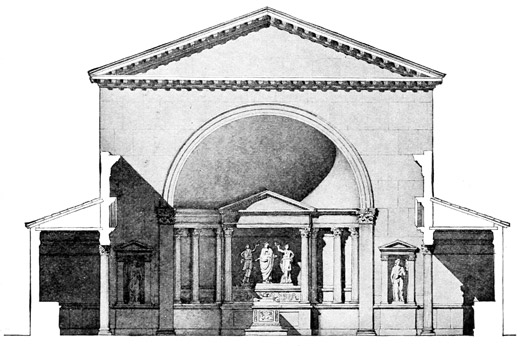

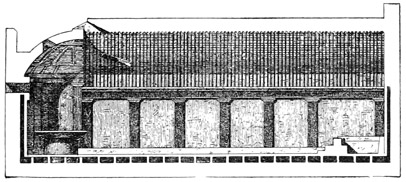

| 25. | Exterior of the Basilica, restored. From an original drawing | 75 | |

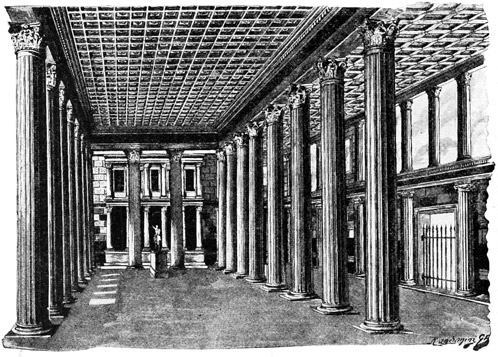

| 26. | Interior of the Basilica, looking toward the tribunal, restored. From an original drawing | 76 | |

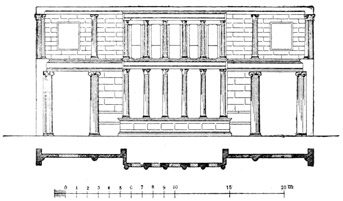

| 27. | Front of the tribunal of the Basilica. Plan and elevation. From an original drawing | 77 | |

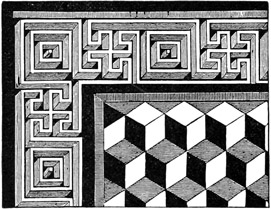

| 28. | Corner of mosaic floor, cella of the temple of Apollo. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 23 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 50) | 80 | |

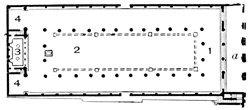

| 29. | Plan of the temple of Apollo | 81 | |

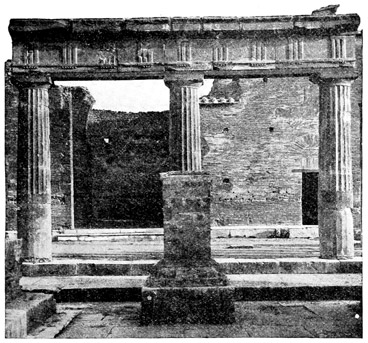

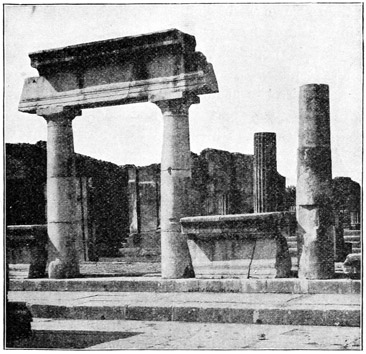

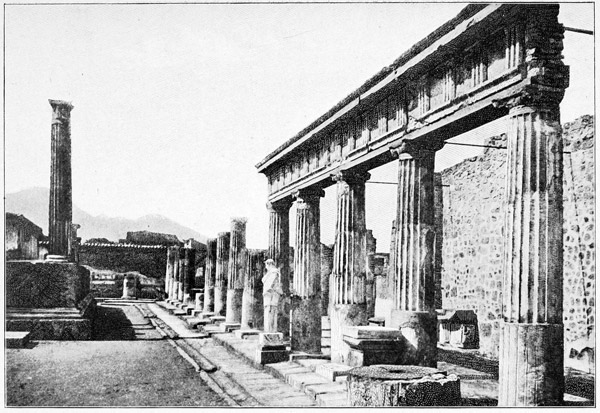

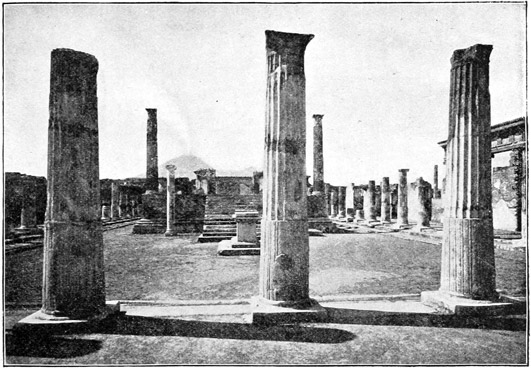

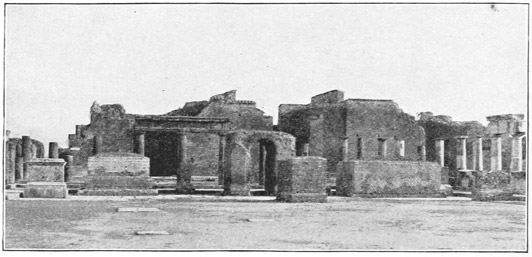

| 30. | View of the temple of Apollo, looking toward Vesuvius. From a photograph | 83 | |

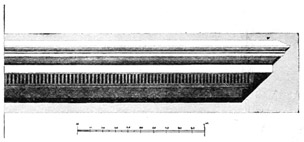

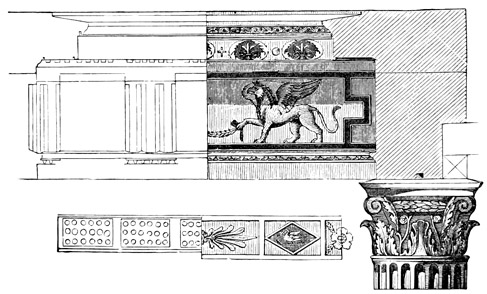

| 31. | Section of the entablature of the temple of Apollo, showing the original form and the restoration after the earthquake of 63. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 21 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 264) | 84 | |

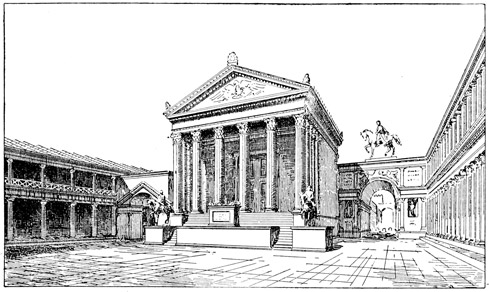

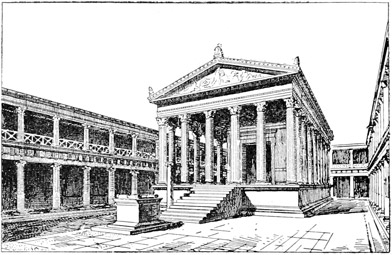

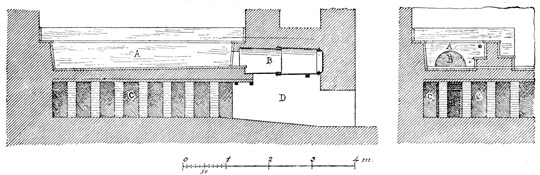

| 32. | Temple of Apollo, restored. From an original drawing | 86 | |

| 33. | Plan of the buildings at the northwest corner of the Forum | 91 | |

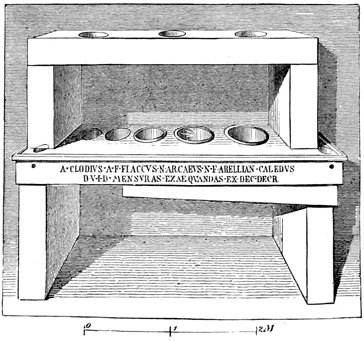

| 34. | Table of Standard Measures. After Mazois, Vol. III, pl. 40 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 23) | 93 | |

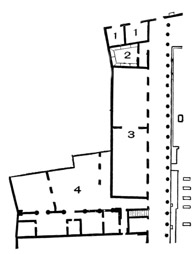

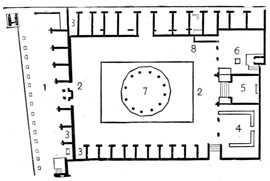

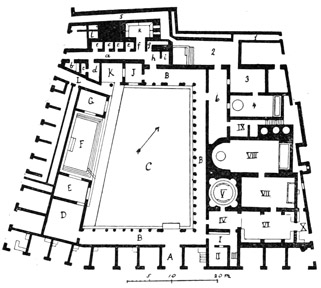

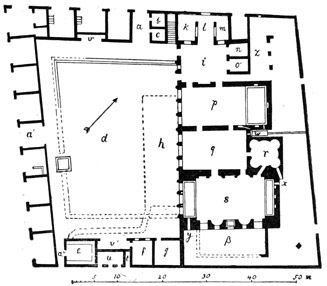

| 35. | Plan of the Macellum | 94 | |

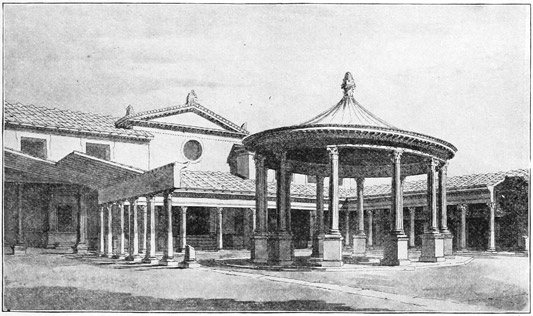

| 36. | View of the Macellum. From a photograph | 95 | |

| 37. | The Macellum, restored. From an original drawing | 97 | |

| 38. | Statue of Octavia, sister of Augustus, found in the chapel of the Macellum. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 98 | |

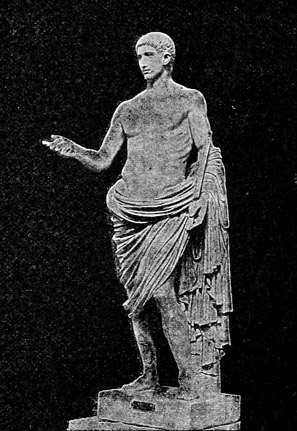

| 39. | Statue of Marcellus, son of Octavia, found in the chapel of the Macellum. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 101 | |

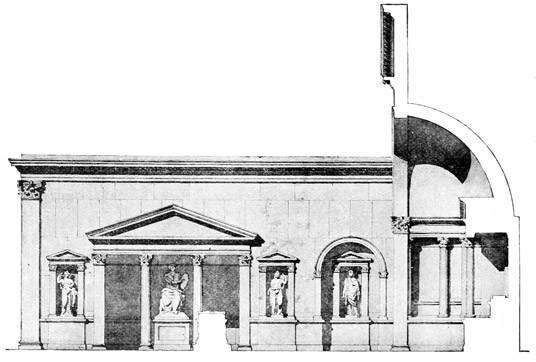

| 40. | Plan of the sanctuary of the City Lares | 102 | |

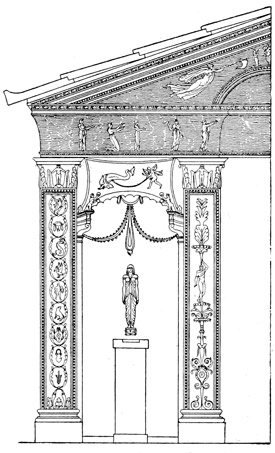

| 41. | Sanctuary of the City Lares, looking toward the rear, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 288) | 103 | |

| 42. | North side of the sanctuary of the City Lares, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 289) | 104 | |

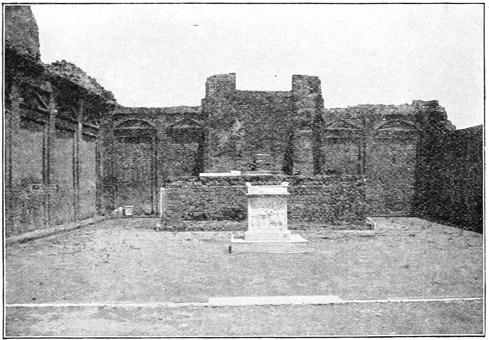

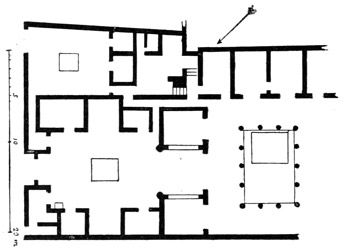

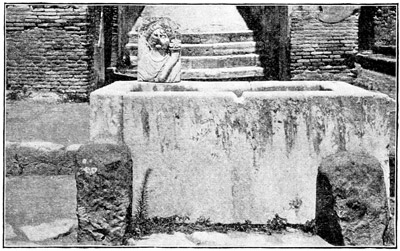

| 43. | Plan of the temple of Vespasian | 106 | |

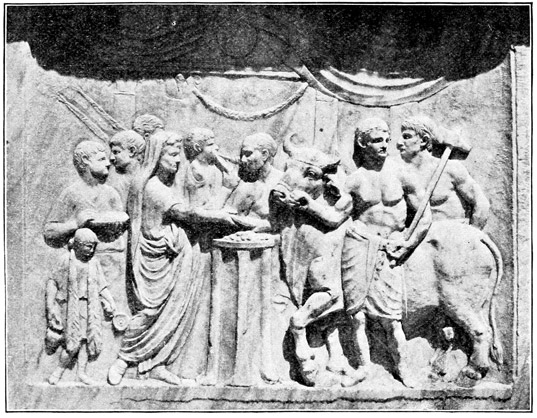

| 44. | Front of the altar in the court of the temple of Vespasian. From a photograph | 107 | |

| 45. | View of the temple of Vespasian. From a photograph | 108 | |

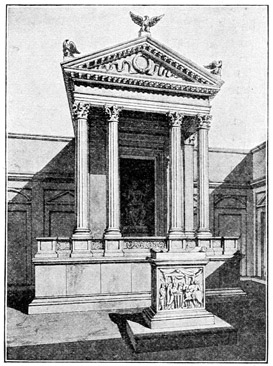

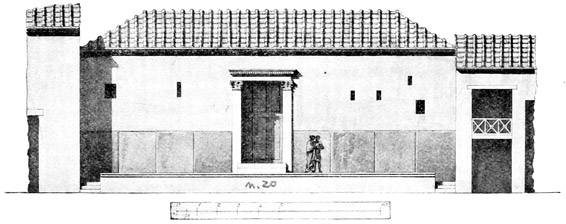

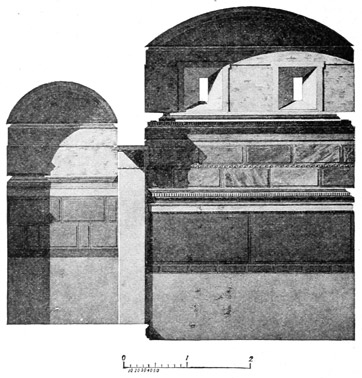

| 46. | The temple of Vespasian, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1900, p. 133) | 109 xvi | |

| 47. | Plan of the building of Eumachia | 110 | |

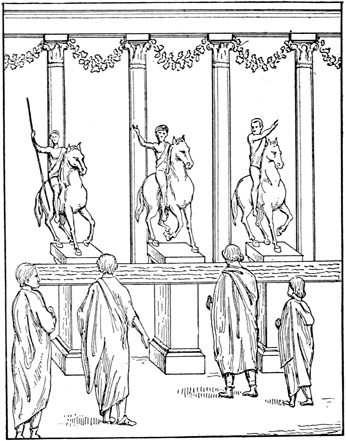

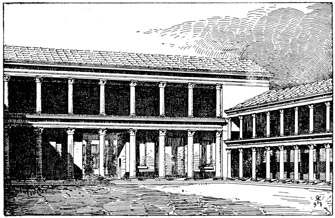

| 48. | Building of Eumachia—front of the court, restored. From an original drawing | 114 | |

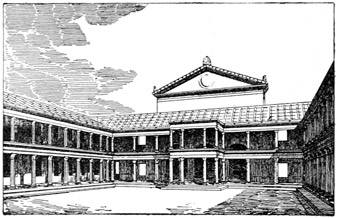

| 49. | Building of Eumachia—rear of the court, restored. From an original drawing | 116 | |

| 50. | Fountain of Concordia Augusta. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 117 | |

| 51. | Plan of the Comitium | 119 | |

| 52. | Plan of the Municipal Buildings | 121 | |

| 53. | View of the south end of the Forum. From a photograph (A. M.) | 122 | |

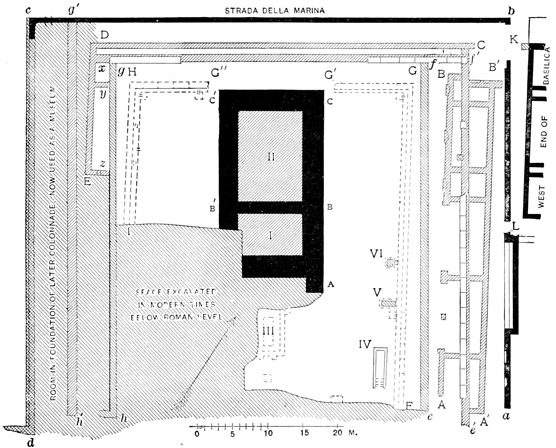

| 54. | Plan of the ruins of the temple of Venus Pompeiana* | 125 | |

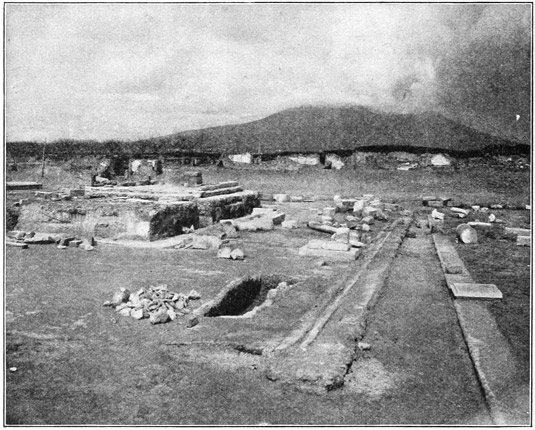

| 55. | View of the ruins of the temple of Venus Pompeiana. From a photograph | 126 | |

| 56. | Plan of the temple of Venus Pompeiana, restored* | 128 | |

| 57. | Plan of the temple of Fortuna Augusta* | 130 | |

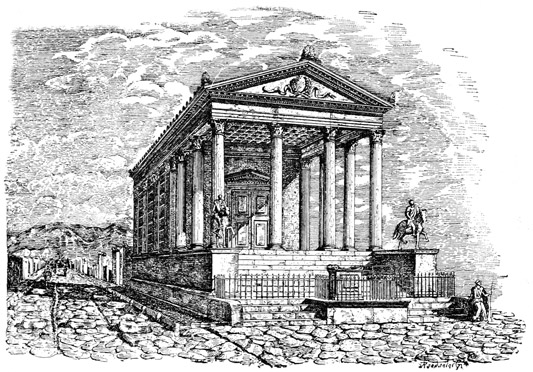

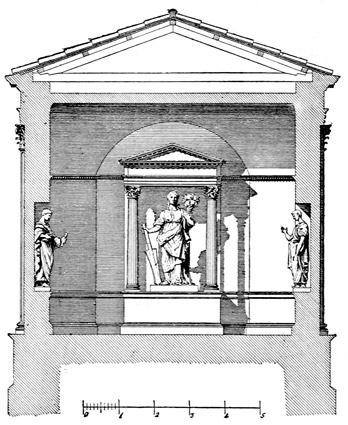

| 58. | Temple of Fortuna Augusta, restored. From an original drawing | 131 | |

| 59. | Temple of Fortuna Augusta—rear of the cella with the statue of the goddess, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 280) | 132 | |

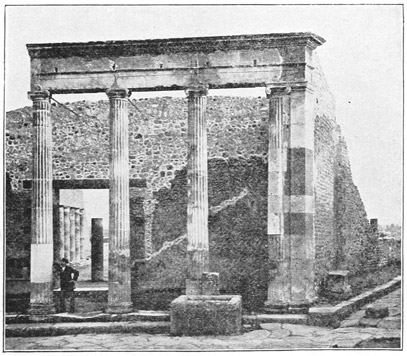

| 60. | Portico at the entrance of the Forum Triangulare. From a photograph | 135 | |

| 61. | View of the Forum Triangulare, looking toward Vesuvius. From a photograph | 136 | |

| 62. | Plan of the Doric temple in the Forum Triangulare | 137 | |

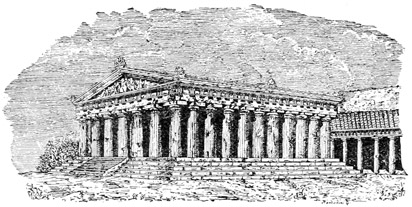

| 63. | The Doric temple, restored. From an original drawing | 138 | |

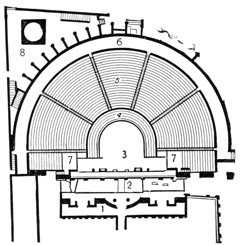

| 64. | Plan of the Large Theatre | 143 | |

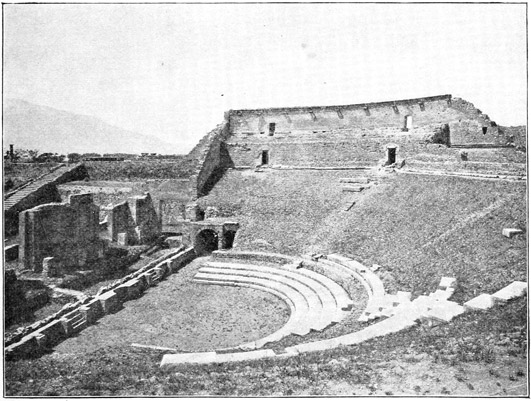

| 65. | View of the Large Theatre. From a photograph | 145 | |

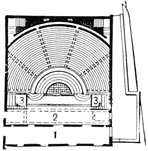

| 66. | Plan of the Small Theatre | 153 | |

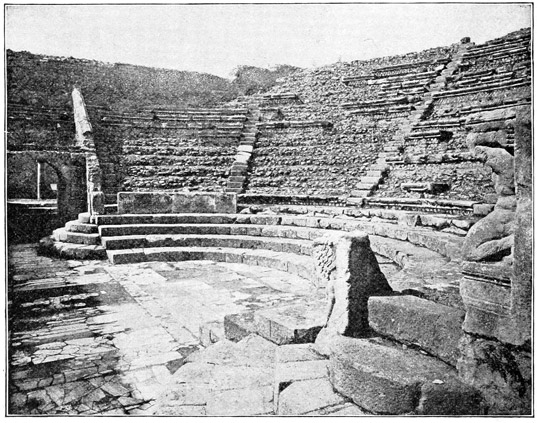

| 67. | View of the Small Theatre. From a photograph | 154 | |

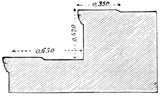

| 68. | Section of a seat in the Small Theatre. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 29 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 101) | 155 | |

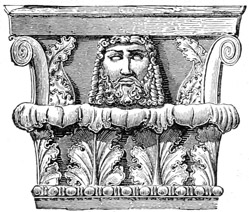

| 69. | A terminal Atlas from the Small Theatre. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 29 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 100) | 156 | |

| 70. | Ornament at the ends of the parapet in the Small Theatre—lion's foot. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 29 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 99) | 156 | |

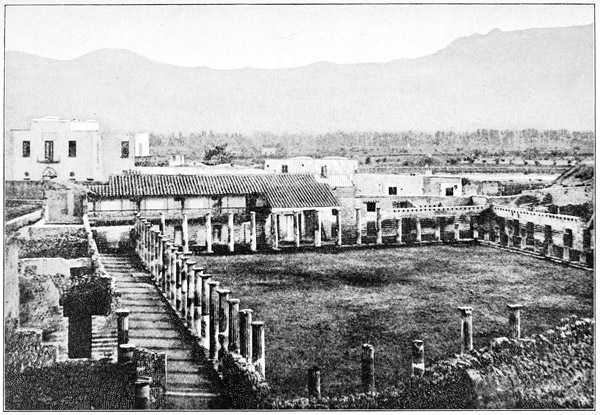

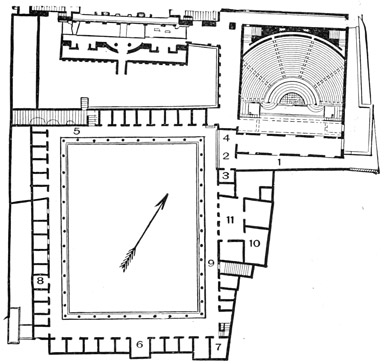

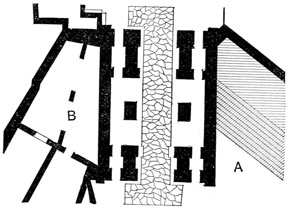

| 71. | Plan of the Theatre Colonnade, showing its relation to the two theatres | 157 | |

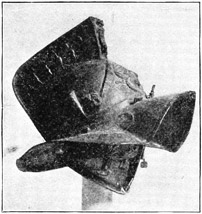

| 72. | A gladiator's greave. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 162 | |

| 73. | A gladiator's helmet. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 163 | |

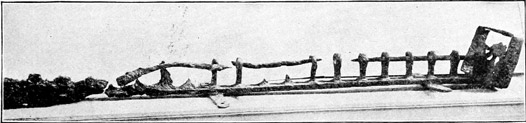

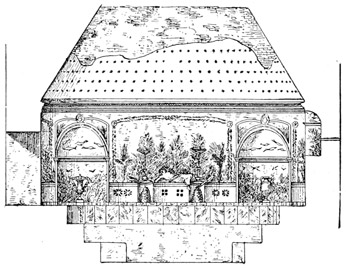

| 74. | Remains of stocks found in the guard-room of the barracks. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 163 | |

| 75. | Plan of the Palaestra | 165 | |

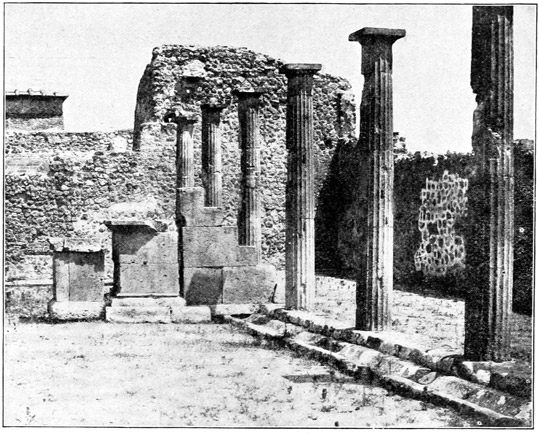

| 76. | View of the Palaestra, with the pedestal, table, and steps. From a photograph | 166 xvii | |

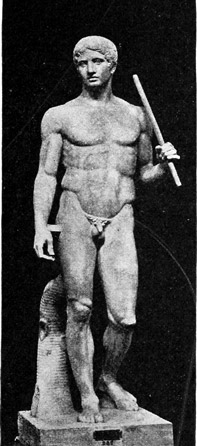

| 77. | Doryphorus. Statue found in the Palaestra. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 167 | |

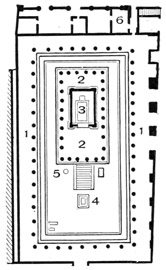

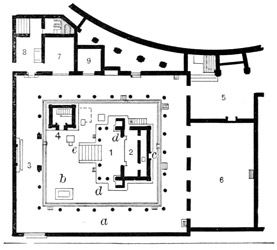

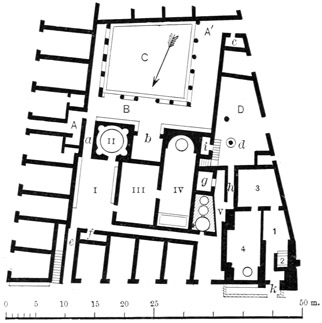

| 78. | Plan of the temple of Isis | 170 | |

| 79. | View of the temple of Isis. From a photograph | 172 | |

| 80. | The temple of Isis, restored. From an original drawing | 173 | |

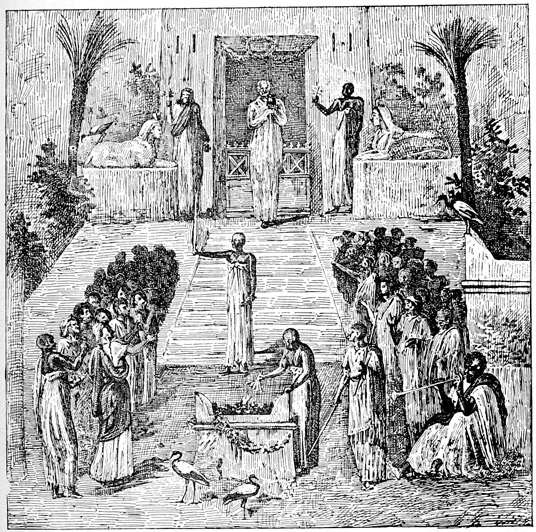

| 81. | Scene from the worship of Isis—the adoration of the holy water. Wall painting from Herculaneum. Naples Museum. Drawing, after a photograph | 177 | |

| 82. | Temple of Isis. Part of the façade of the Purgatorium. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 11, and Piranesi, Antiquités de Pompéi Vol. II, pl. 65 | 179 | |

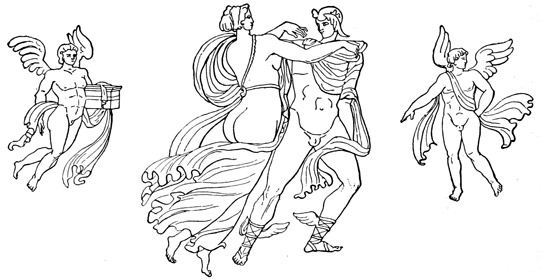

| 83. | Decoration of the east side of the Purgatorium—Perseus and Andromeda, floating Cupids. Stucco reliefs. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 10 | 180 | |

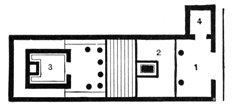

| 84. | Plan of the temple of Zeus Milichius | 183 | |

| 85. | Capital of a pilaster of the temple, with the face of Zeus Milichius. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 6 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 62) | 184 | |

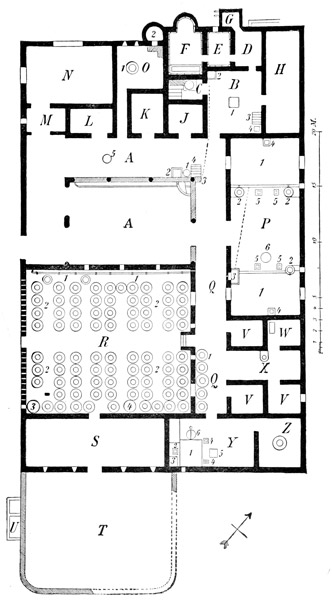

| 86. | Plan of the Stabian Baths | 190 | |

| 87. | Stabian Baths—interior of Frigidarium. Drawing, with indebtedness to Niccolini, Le Case ed i Monumenti di Pompei, Vol. I, Terme presso la porta stabiana, pl. 7 | 191 | |

| 88. | Bath basin in the women's caldarium—longitudinal and transverse sections, showing arrangements for heating. Drawing, with indebtedness to von Duhn und Jacobi, Der griechische Tempel in Pompeji, pl. IX | 194 | |

| 89. | Colonnade of the Stabian Baths—capital with section of entablature. Drawing | 198 | |

| 90. | Southwest corner of the palaestra of the Stabian Baths, showing part of the colonnade and wall decorated with stucco reliefs. From a photograph | 199 | |

| 91. | Plan of the Baths near the Forum | 202 | |

| 92. | Baths near the Forum—Interior of men's tepidarium. From a photograph | 204 | |

| 93. | Baths near the Forum—Longitudinal section of the men's caldarium. Drawing, after Gell, Pompeiana, edit. of 1837, Vol. II, pl. 33, facing p. 91 | 205 | |

| 94. | Plan of the Central Baths | 209 | |

| 95. | View of the Central Baths, looking from the Palaestra into the tepidarium. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 210 | |

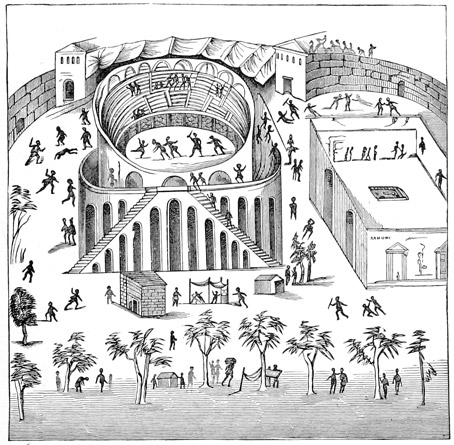

| 96. | The Amphitheatre, seen from the west side. From a photograph | 213 | |

| 97. | Preparations for the combat. Wall painting (no longer visible) in the Amphitheatre. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 48 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 107) | 214 | |

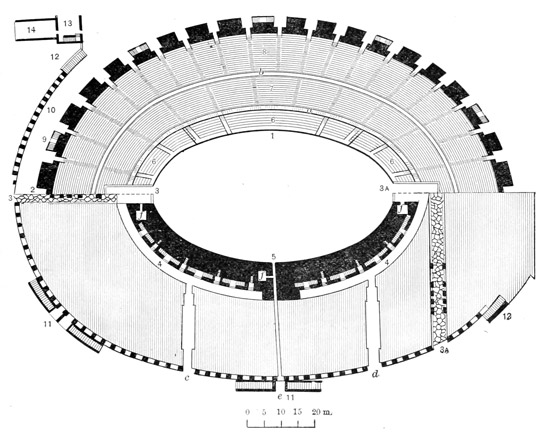

| 98. | Plan of the Amphitheatre | 215 xviii | |

| 99. | Transverse section of the Amphitheatre. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 46 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 104) | 217 | |

| 100. | Plan of the gallery of the Amphitheatre | 218 | |

| 101. | Conflict between the Pompeians and the Nucerians. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 3 | 221 | |

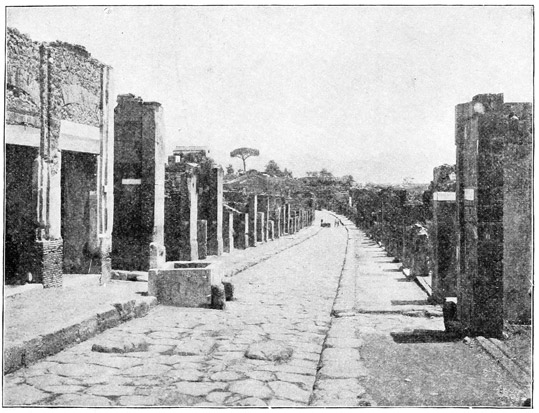

| 102. | View of Abbondanza Street, looking east. From a photograph | 227 | |

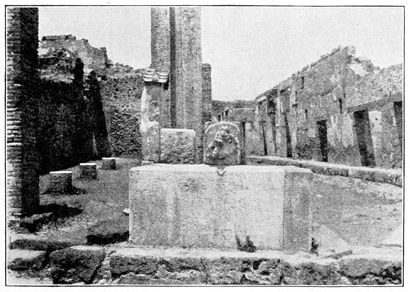

| 103. | Fountain, water tower, and street shrine, corner of Stabian and Nola streets. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 231 | |

| 104. | Plan of the reservoir west of the Baths near the Forum | 232 | |

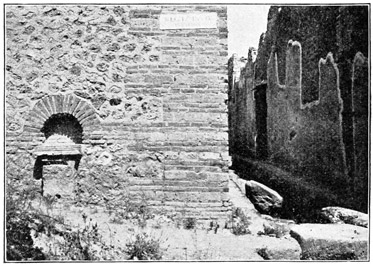

| 105. | Ancient altar in new wall—southeast corner of the Central Baths. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 234 | |

| 106. | Plan of a chapel of the Lares Compitales (VIII. iv. 24) | 235 | |

| 107. | Large street altar (VIII. ii. 25). From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 236 | |

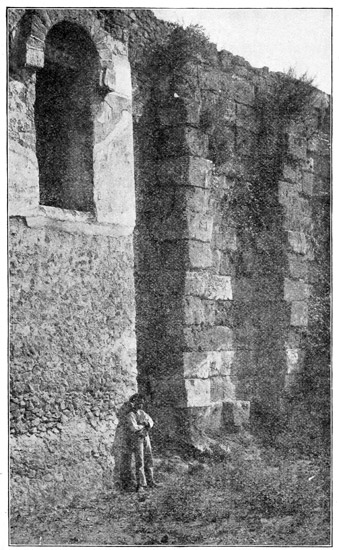

| 108. | Plan of a section of the city wall, with a tower and with stairs leading to the top. After Mazois, Vol. I. pl. 12 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 7) | 238 | |

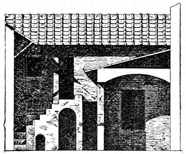

| 109. | View of the city wall, inside. From a photograph | 239 | |

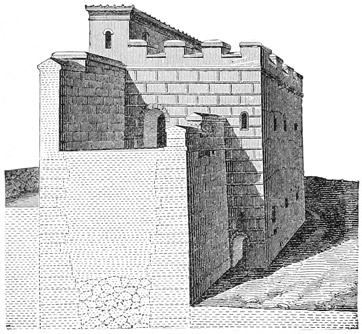

| 110. | Tower of the city wall, restored. After Mazois, Vol. I, pl. 13 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 8) | 241 | |

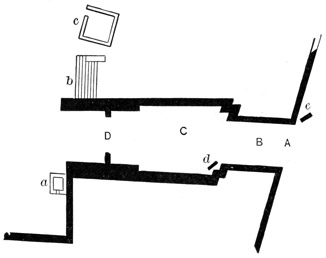

| 111. | Plan of the Stabian Gate | 242 | |

| 112. | Plan of the Herculaneum Gate | 243 | |

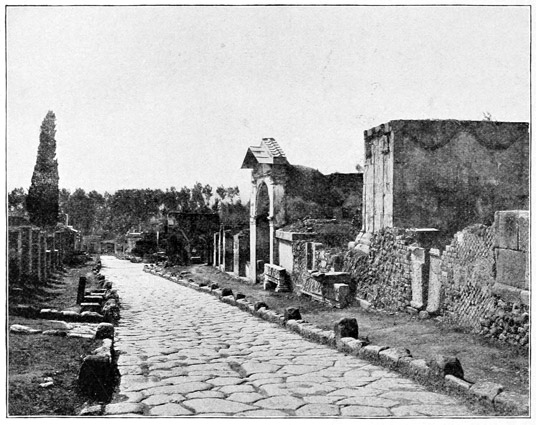

| 113. | View of the Herculaneum Gate, looking down the Street of Tombs. From a photograph | 244 | |

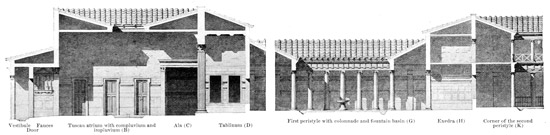

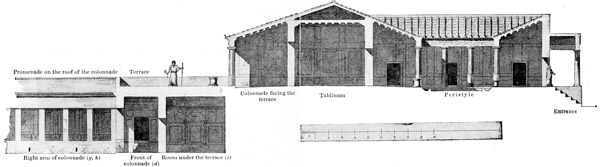

| 114. | Early Pompeian house, restored. From an original drawing | 246 | |

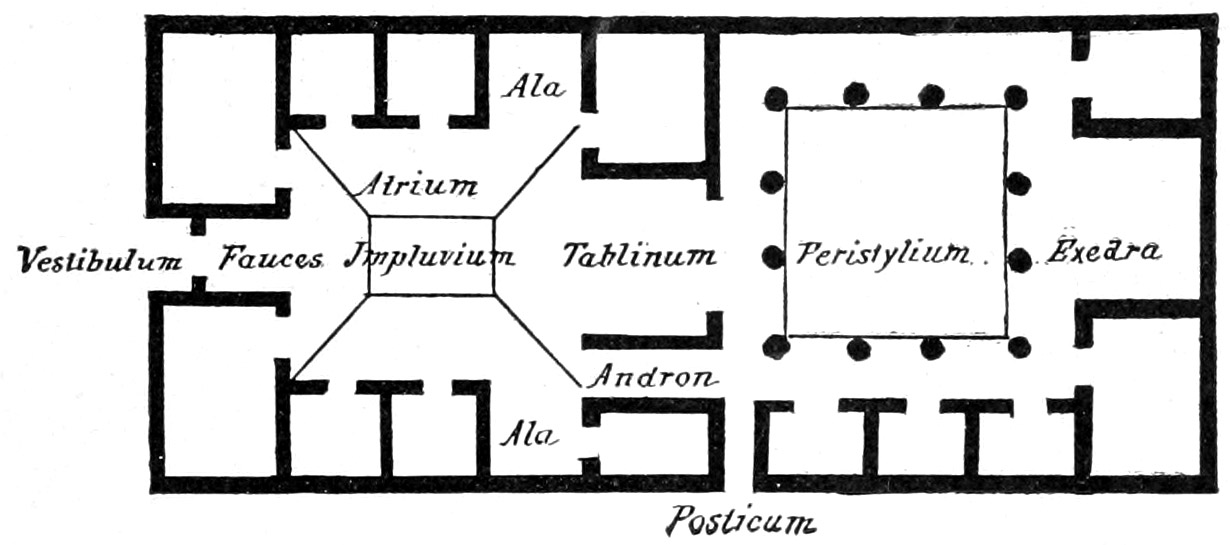

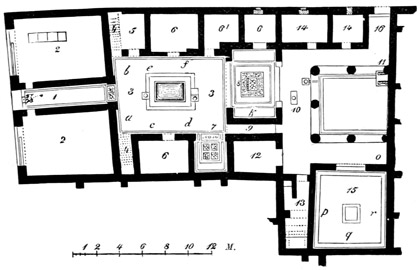

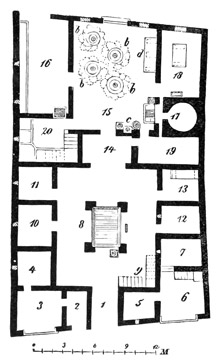

| 115. | Plan of a Pompeian house | 247 | |

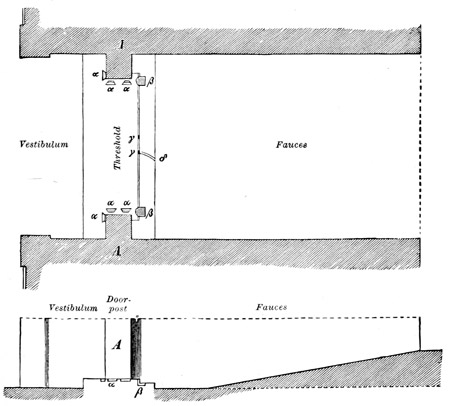

| 116. | Plan and section of the vestibule, threshold, and fauces of the house of Pansa. After Ivanoff, Mon. dell' Inst., Vol. VI, pl. 28, 3 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 136) | 249 | |

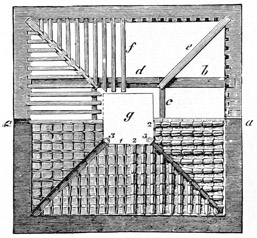

| 117. | A Tuscan atrium—plan of the roof. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 3 (Overbeck Mau, Fig. 139) | 251 | |

| 118. | A Tuscan atrium—section. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 3 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 140) | 252 | |

| 119. | Corner of a compluvium with waterspouts and antefixes, reconstructed. (Reconstruction, Ins. VII. iv. 16.) After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 143 | 253 | |

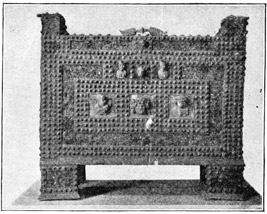

| 120. | A Pompeian's strong box, arca. Naples Museum. From photograph | 255 | |

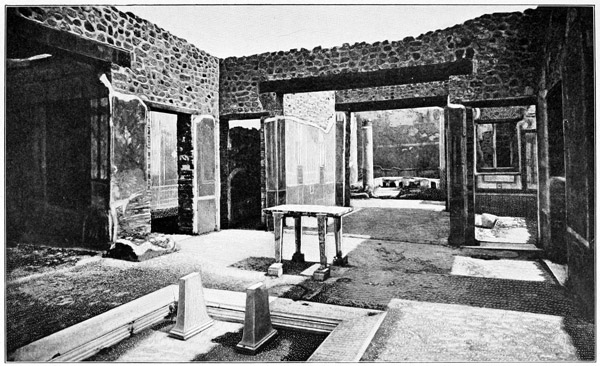

| 121. | Atrium of the house of Cornelius Rufus, looking through the tablinum and andron into the peristyle. From a photograph | 256 | |

| 122. | End of a bedroom in the house of the Centaur, decorated in the first style. From an original drawing | 262 | |

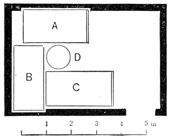

| 123. | Plan of a dining room with three couches | 263 | |

| 124. | Plan of a dining room with an anteroom containing an altar for libations (VIII. v.-vi. 16) | 264 xix | |

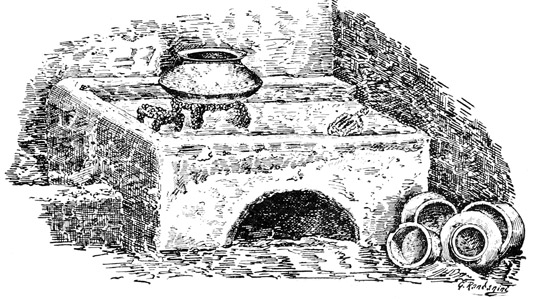

| 125. | Hearth of the kitchen in the house of the Vettii. From a drawing | 267 | |

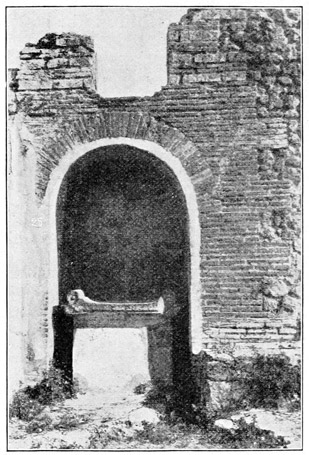

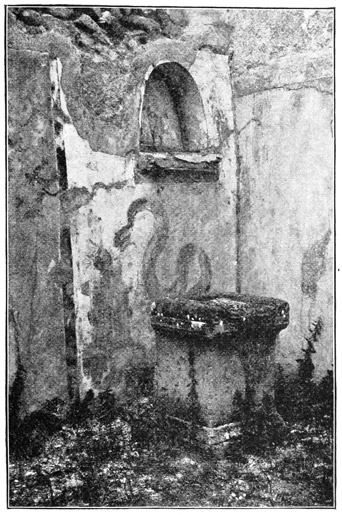

| 126. | Niche for the images of the household gods, in a corner of the kitchen in the house of Apollo. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 269 | |

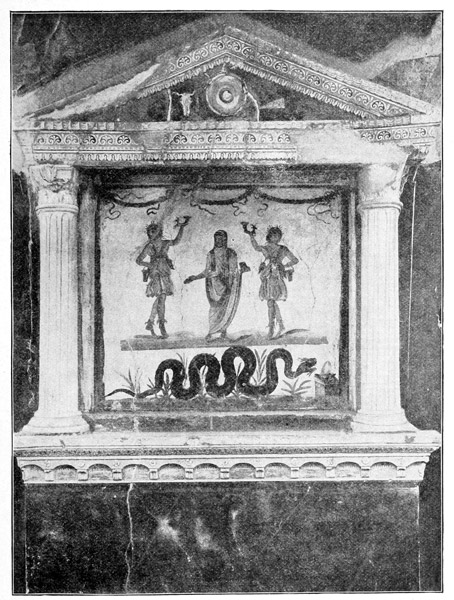

| 127. | Shrine in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 271 | |

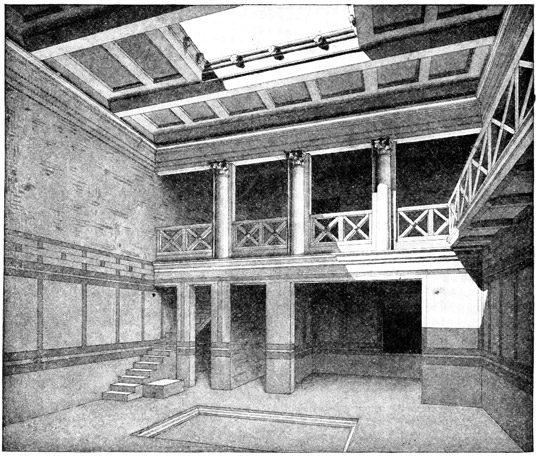

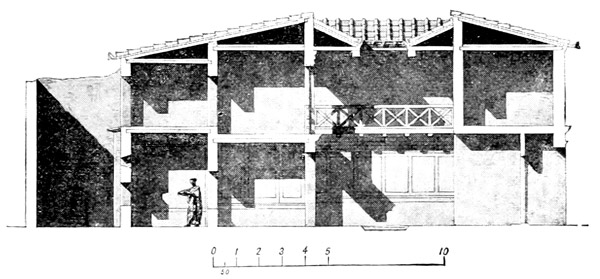

| 128. | Interior of a house (VII. xv. 8) with a second story dining room opening on the atrium, restored. From an original drawing | 274 | |

| 129. | Longitudinal section of the house with a second story dining room (VII. xv. 8) restored. From an original drawing | 275 | |

| 130. | Plan of a Pompeian shop. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 8 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 182) | 276 | |

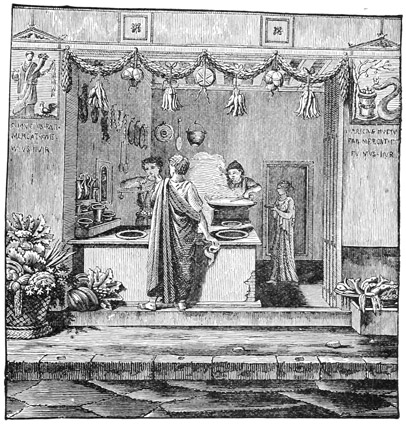

| 131. | A shop for the sale of edibles, restored. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 8 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 183) | 277 | |

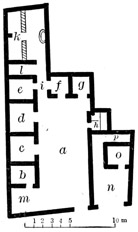

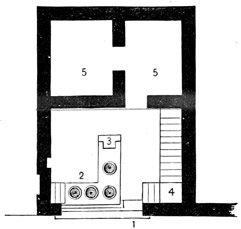

| 132. | Plan of the house of the Surgeon | 280 | |

| 133. | A young woman painting a herm. Wall painting from the house of the Surgeon. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. V, pl. 1 | 282 | |

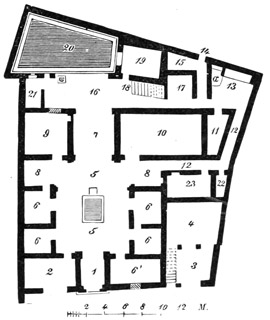

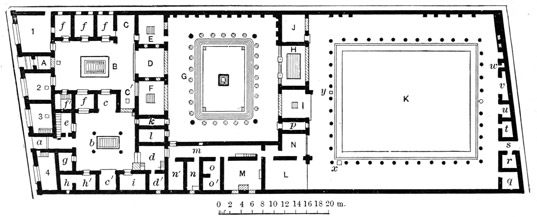

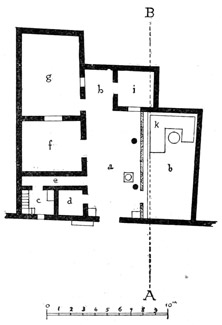

| 134. | Plan of the house of Sallust. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 35 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 165) | 284 | |

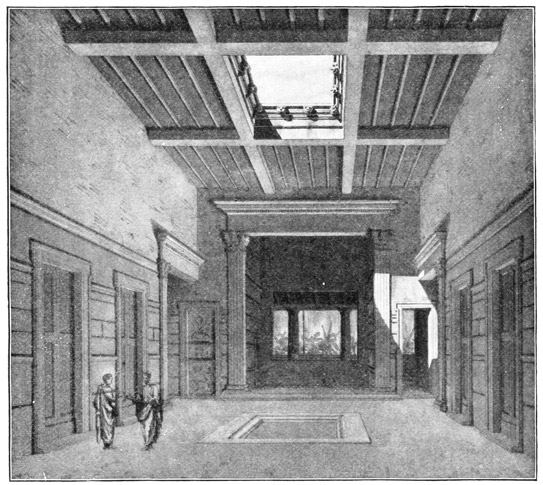

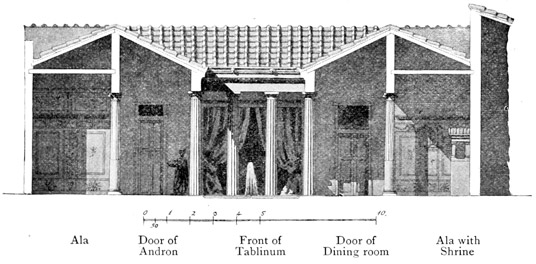

| 135. | Atrium of the house of Sallust, looking through the tablinum and colonnade at the rear into the garden, restored. From an original drawing | 286 | |

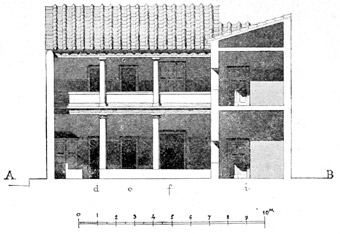

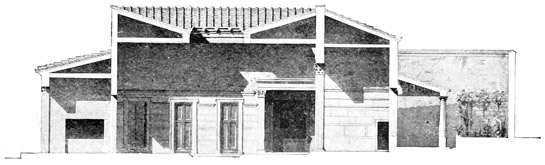

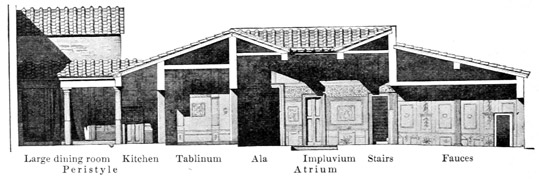

| 136. | Longitudinal section of the house of Sallust, restored. From an original drawing | 287 | |

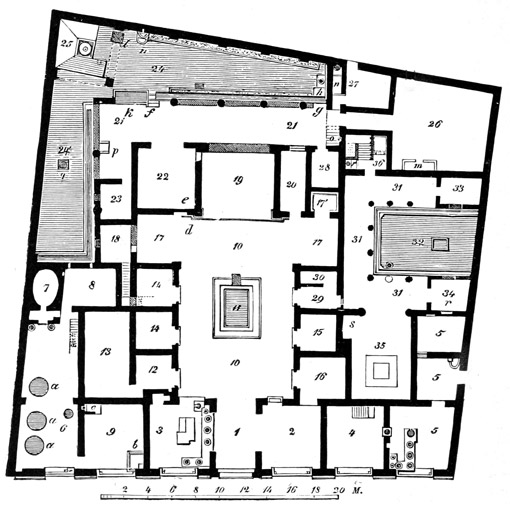

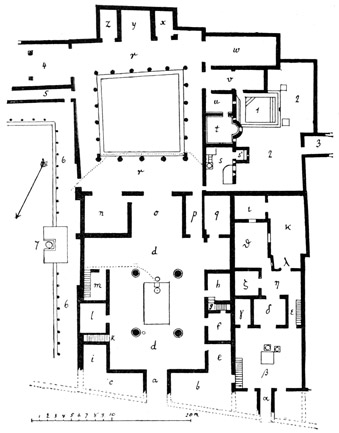

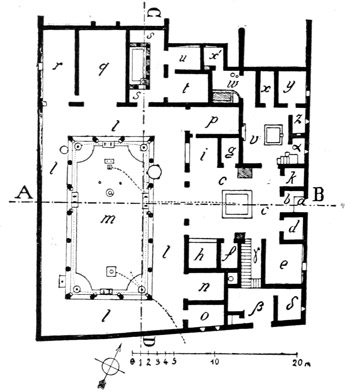

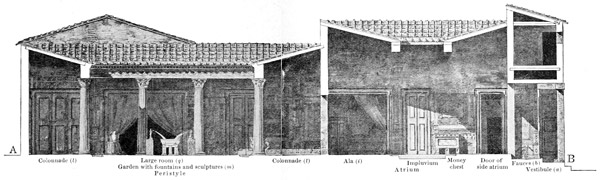

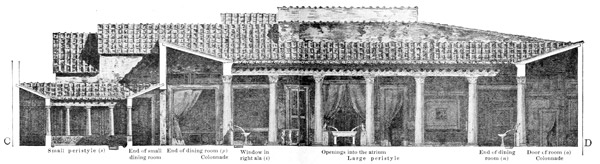

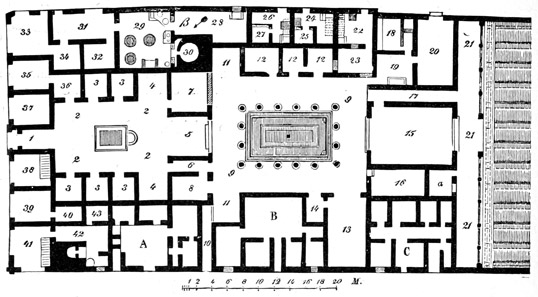

| 137. | Plan of the house of the Faun | 288 | |

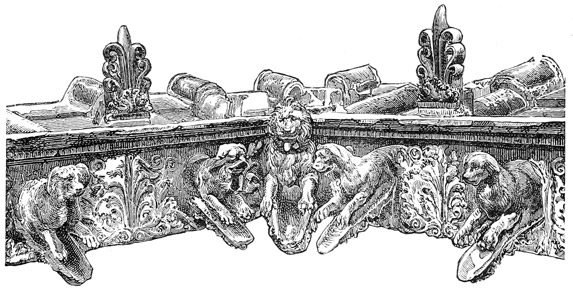

| 138. | Part of the cornice over the large front door of the house of the Faun. From an original drawing | 289 | |

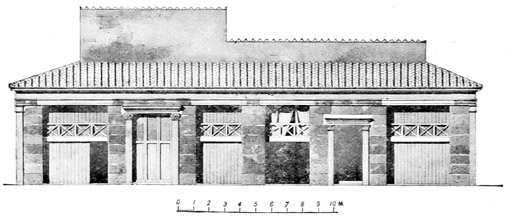

| 139. | Façade of the house of the Faun, restored. From an original drawing | 290 | |

| 140. | Border of mosaic with tragic masks, fruits, flowers, and garlands, at the inner end of the fauces, house of the Faun. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 14 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 315) | 290 | |

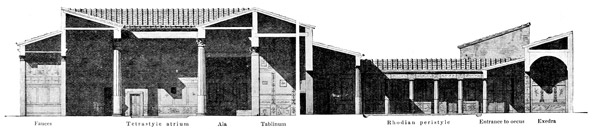

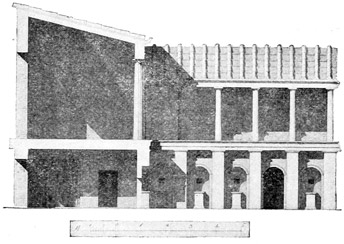

| 141. | Longitudinal section of the house of the Faun, showing the large atrium, the first peristyle, and a corner of the second peristyle, restored. From an original drawing | 292 | |

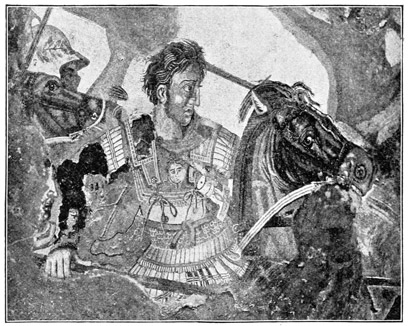

| 142. | Detail from the mosaic representing the battle between Alexander and Darius. From a photograph | 294 | |

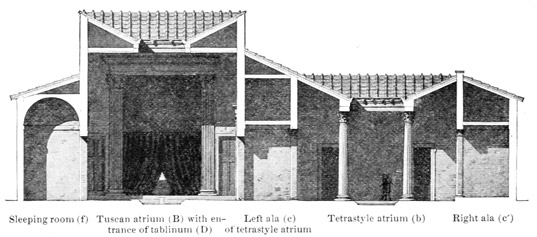

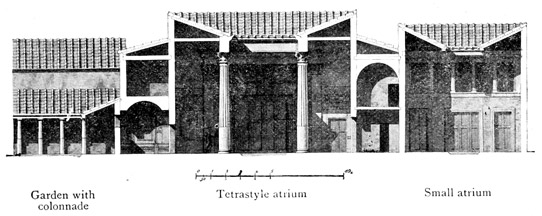

| 143. | Transverse section of the house of the Faun, showing the two atriums with adjoining rooms, restored. From an original drawing | 296 | |

| 144. | Plan of a house near the Porta Marina (VI. Ins. Occid. 13) | 298 | |

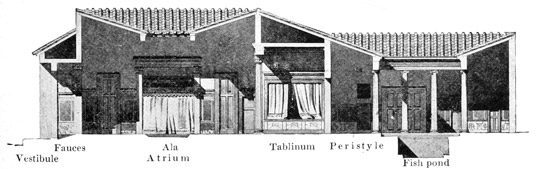

| 145. | Longitudinal section of the house near the Porta Marina, restored. From an original drawing | 299 xx | |

| 146. | Plan of the house of the Silver Wedding | 302 | |

| 147. | Longitudinal section of the house of the Silver Wedding, restored. From an original drawing | 304 | |

| 148. | Transverse section of the house of the Silver Wedding, as it was before 63. From an original drawing | 307 | |

| 149. | Plan of the house of Epidius Rufus | 310 | |

| 150. | Façade of the house of Epidius Rufus, restored. From an original drawing | 311 | |

| 151. | Transverse section of the house of Epidius Rufus. From an original drawing | 312 | |

| 152. | Plan of the house of the Tragic Poet | 313 | |

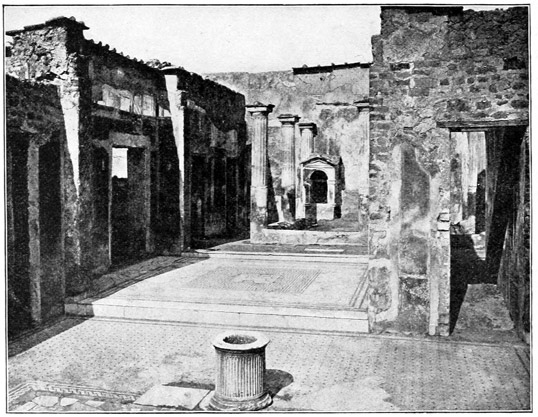

| 153. | View of the house of the Tragic Poet, looking from the middle of the atrium toward the rear. From a photograph | 314 | |

| 154. | Longitudinal section of the house of the Tragic Poet, restored. From an original drawing | 316 | |

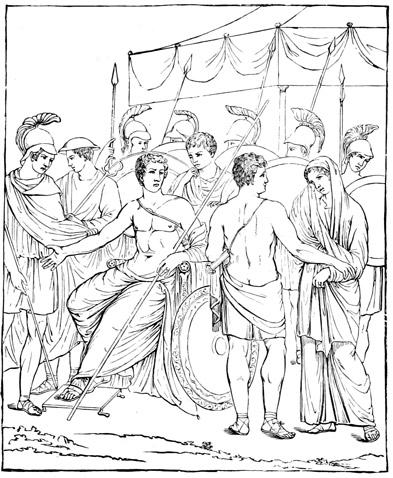

| 155. | The delivery of Briseis to the messenger of Agamemnon. Wall painting from the house of the Tragic Poet. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. II, pl. 58 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 311) | 317 | |

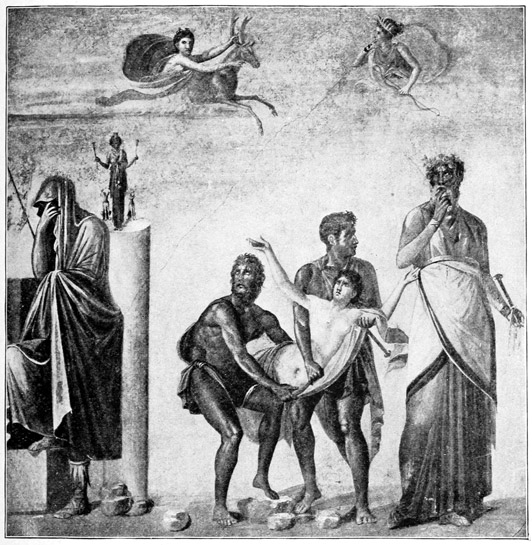

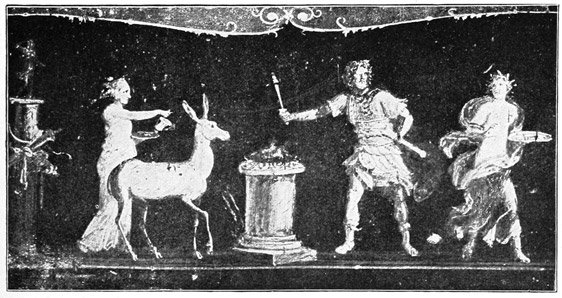

| 156. | The sacrifice of Iphigenia. Wall painting from the house of the Tragic Poet. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 319 | |

| 157. | Exterior of the house of the Vettii, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 4) | 321 | |

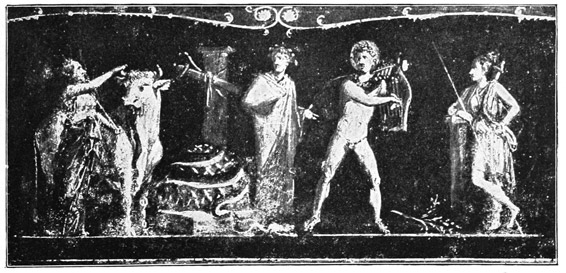

| 158. | Plan of the house of the Vettii* | 322 | |

| 159. | Longitudinal section of the house of the Vettii, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, pl. 1) | 324 | |

| 160. | Transverse section of the house of Vettii, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, pl. 2) | 324 | |

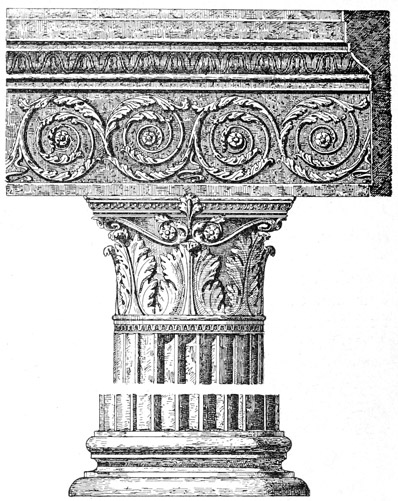

| 161. | Base, capital, and section of entablature from the colonnade of the peristyle in the house of the Vettii. From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 31) | 326 | |

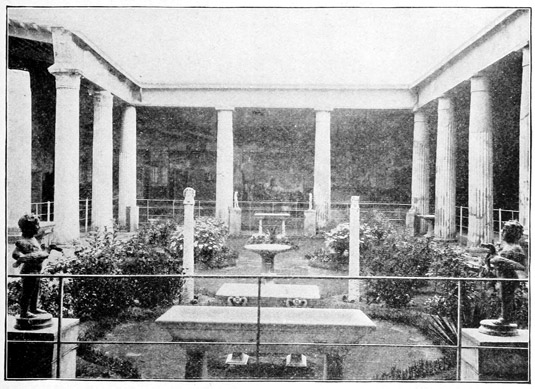

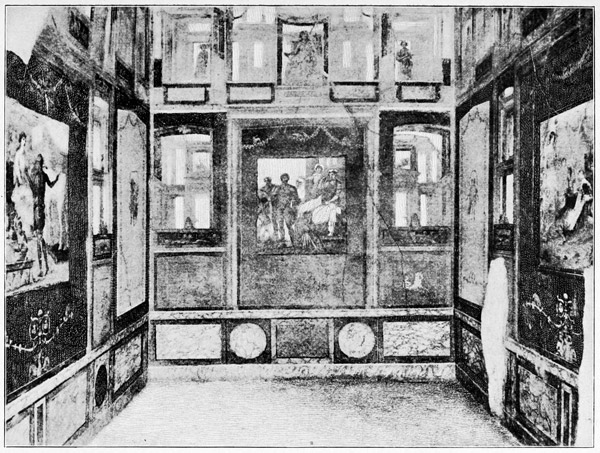

| 162. | View of the peristyle of the house of the Vettii, looking toward the south end. From a photograph | 327 | |

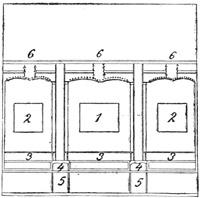

| 163. | System of wall division in the large room opening on the peristyle of the house of the Vettii | 329 | |

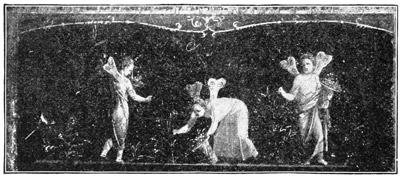

| 164. | Psyches gathering flowers. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 330 | |

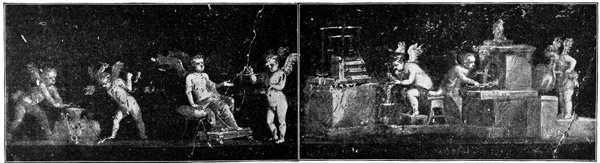

| 165. | Cupids as makers and sellers of oil. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 332 | |

| 166. | Press for olives. From a wall painting found at Herculaneum. Naples Museum. Drawing after Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. I, pl. 35 | 333 | |

| 167. | Cupids as goldsmiths. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 334 xxi | |

| 168. | Cupids gathering and pressing grapes. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 81) | 336 | |

| 169. | Cupids as wine dealers. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 337 | |

| 170. | Cupids celebrating the festival of Vesta. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1896, p. 80) | 338 | |

| 171. | The punishment of Ixion. Wall painting in the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 340 | |

| 172. | Plan of the house of Acceptus and Euhodia (VIII. v.-vi. 39) | 341 | |

| 173. | Longitudinal section of the house of Acceptus and Euhodia, restored. From an original drawing | 342 | |

| 174. | Plan of a house without a compluvium* (V. v. 2) | 343 | |

| 175. | Transverse section of the house without a compluvium, restored. From an original drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1895, p. 148) | 344 | |

| 176. | Plan of the house of the Emperor Joseph II (VIII. ii. 39) | 345 | |

| 177. | Bake room of the house of the Emperor Joseph II, at the time of excavation. After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 34 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 4) | 346 | |

| 178. | Capital of a pilaster at the entrance of the house of the Sculptured Capitals (VII. iv. 57). From a photograph | 349 | |

| 179. | Plan of the house of Pansa (VI. vi. 1) | 350 | |

| 180. | Section showing a part of the peristyle of the house of the Anchor (VI. x. 7), restored. From an original drawing | 351 | |

| 181. | Plan of the house of the Citharist (I. iv. 5) | 352 | |

| 182. | Orestes and Pylades before Thoas. Wall painting from the house of the Citharist. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 353 | |

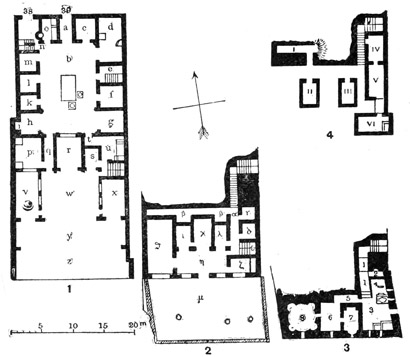

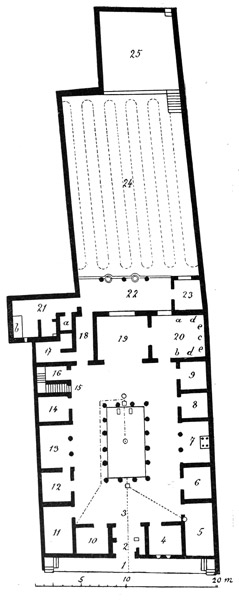

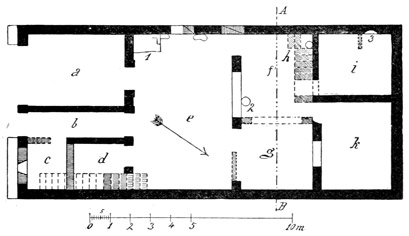

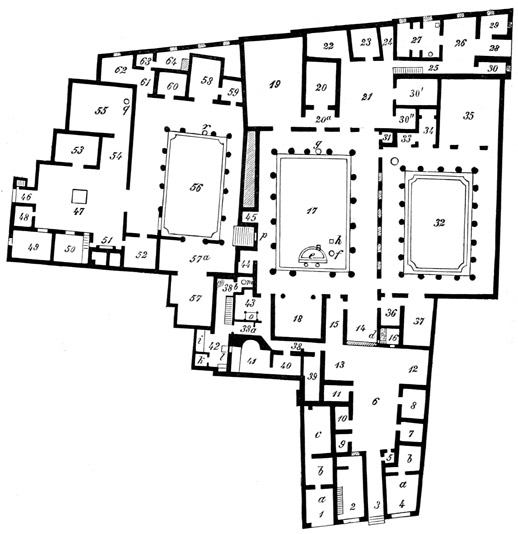

| 183. | Plan of the villa of Diomedes | 356 | |

| 184. | Longitudinal section of the villa of Diomedes, restored. From an original drawing, in part based on Ivanoff, Architektonische Studien, Vol. II, pl. 5, 6 | 358 | |

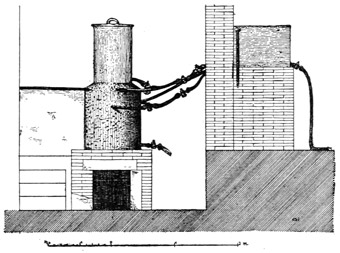

| 185. | Hot-water tank and reservoir for supplying the bath in the Villa Rustica at Boscoreale. Museo de Prisco, Pompeii. From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1894, p. 353) | 362 | |

| 186. | Olive crusher found in the Villa Rustica at Boscoreale. Museo de Prisco. From a photograph | 365 | |

| 187. | Silver patera, with a representation of the city of Alexandria. Boscoreale treasure, Louvre. After H. de Villefosse. Le trésor de Boscoreale, pl. 1 | 366 | |

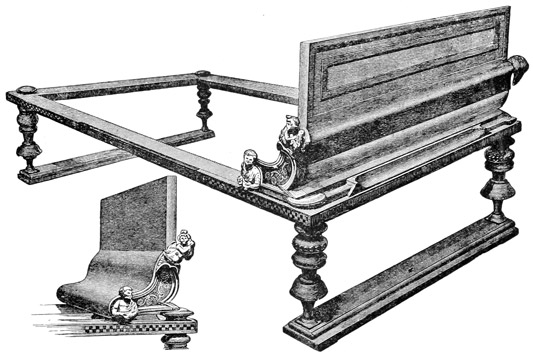

| 188. | Dining couch with bronze mountings, the wooden frame being restored. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 228 | 367 | |

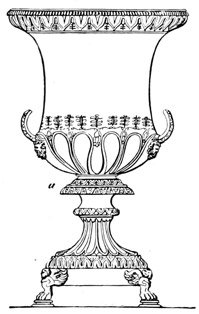

| 189. | Round marble table. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 56 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 229) | 368 xxii | |

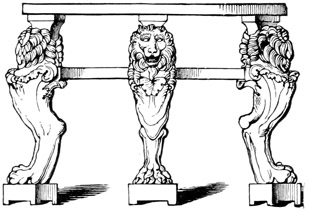

| 190. | Carved table leg, found in the second peristyle of the house of the Faun. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pl. 43 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 229) | 368 | |

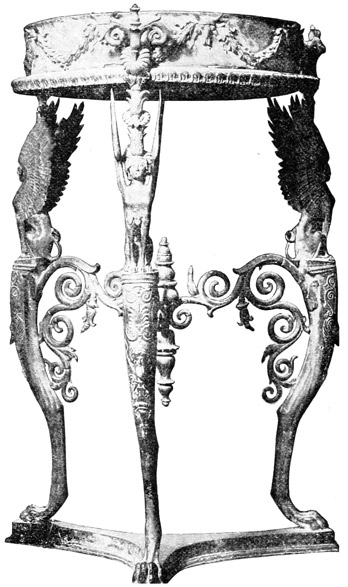

| 191. | Bronze stand with an ornamental rim around the top. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 369 | |

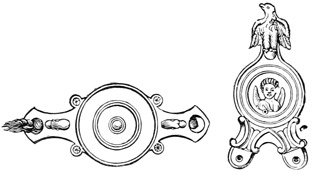

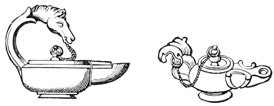

| 192. | Lamps of the simplest form, with one nozzle. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 370 | |

| 193. | Lamps with two nozzles. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 370 | |

| 194. | Lamps with more than two nozzles. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 370 | |

| 195. | Bronze lamps with ornamental covers attached to a chain. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 371 | |

| 196. | Bronze lamps with covers ornamented with figures. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 371 | |

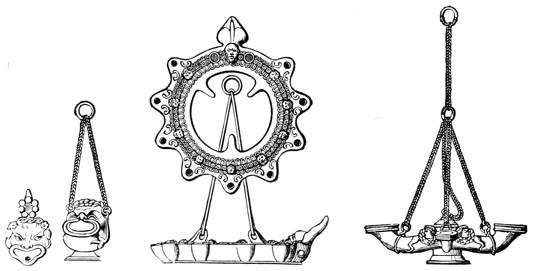

| 197. | Three hanging lamps. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 372 | |

| 198. | A nursing-bottle, biberon. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 231 | 372 | |

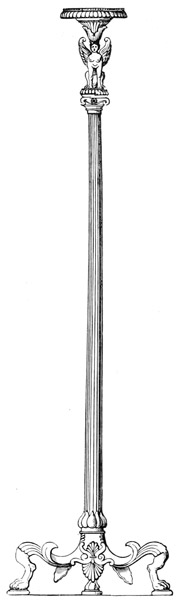

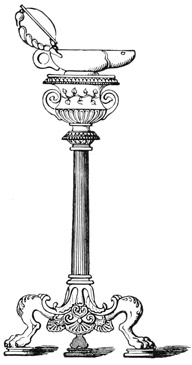

| 199. | Lamp standard of bronze. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 57 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 234) | 373 | |

| 200. | Lamp holder for a hand lamp. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 233 | 374 | |

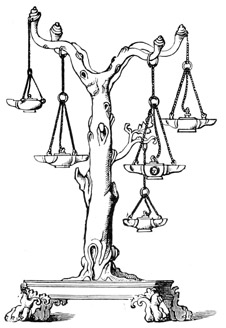

| 201. | Lamp holder for hanging lamps. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. II, pl. 13 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 233) | 374 | |

| 202. | Lamp holder in the form of a tree trunk. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 233 | 374 | |

| 203. | Lamp stand. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 374 | |

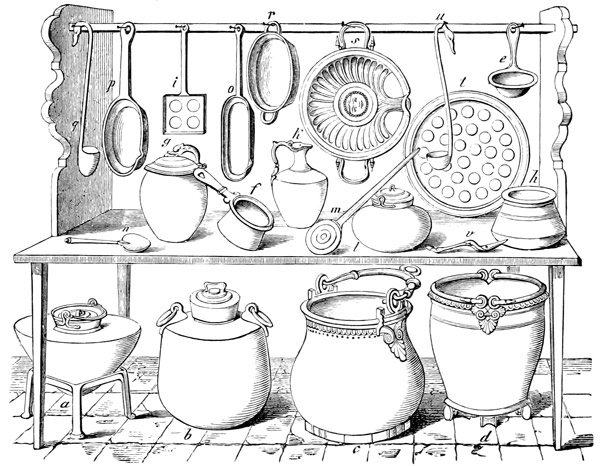

| 204. | Bronze utensils. Naples Museum. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 241, and Museo Borb. | 375 | |

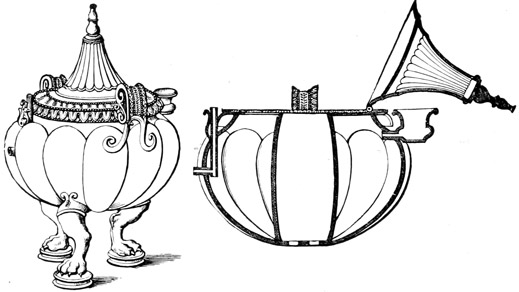

| 205. | Mixing bowl, of bronze, in part inlaid with silver. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. II, pl. 32 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 248) | 376 | |

| 206. | Water heater for the table, view and section. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. III, pl. 63 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 240) | 376 | |

| 207. | Water heater in the form of a brazier. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. II, pl. 46 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 238) | 377 | |

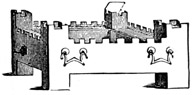

| 208. | Water heater in the form of a brazier, representing a diminutive fortress. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. II, pl. 46 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 238) | 377 | |

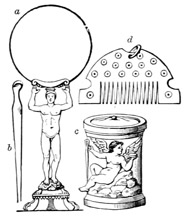

| 209. | Appliances for the bath. After Museo Borb., Vol. VII, pl. 16 (Overbeck Mau, Fig. 251) | 377 | |

| 210. | Combs. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pl. 15 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 252) | 377 xxiii | |

| 211. | Hairpins, with two small ivory toilet boxes. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pls. 14, 15 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 252) | 378 | |

| 212. | Glass box for cosmetics. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pl. 15 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 252) | 378 | |

| 213. | Hand mirrors. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pl. 14 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 252) | 378 | |

| 214. | Group of toilet articles. After Museo Borb., Vol. IX, pl. 15 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 252) | 378 | |

| 215. | Gold arm band. After Museo Borb., Vol. VII, pl. 46 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 318) | 379 | |

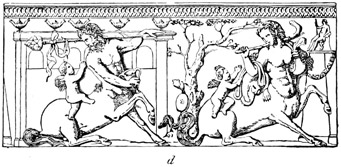

| 216 a-d. | Silver cups. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. XI, pl. 45; Vol. XIII, pl. 49; Overbeck-Mau, pl. facing p. 624 | 379 | |

| 216 e. | Detail of cup with centaurs | 380 | |

| 217. | Silver cup. Boscoreale treasure, Louvre. After H. de Villefosse, Le trésor de Boscoreale, pl. 8 | 382 | |

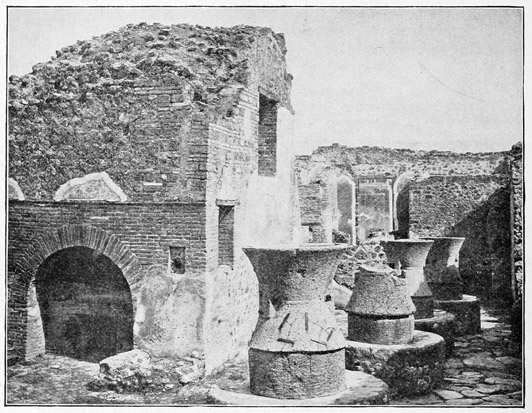

| 218. | Ruins of a bakery, with millstones (VII. ii. 22). From a photograph | 386 | |

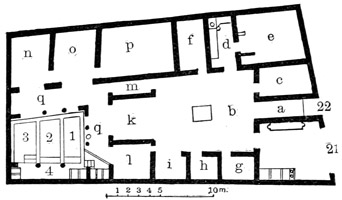

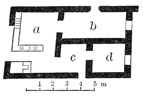

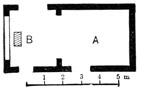

| 219. | Plan of a bakery (VI. iii. 3) | 388 | |

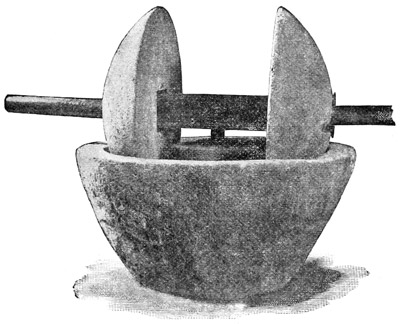

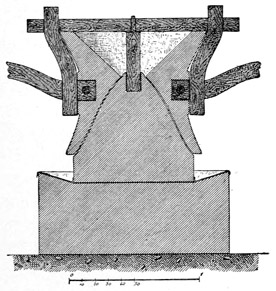

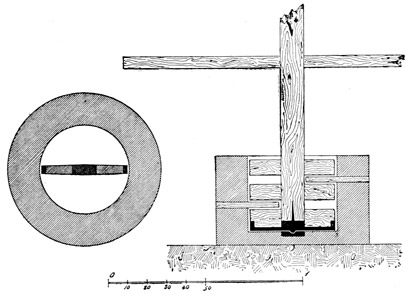

| 220. | A Pompeian mill, without the framework | 389 | |

| 221. | Section of a mill, restored. From an original drawing | 389 | |

| 222. | A mill in operation. Relief in the Vatican Museum. After Ber. der Sächs. Gesellschaft, 1861, pl. xii. 2 | 390 | |

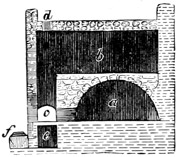

| 223. | Section of a bake oven (VI. iii. 3). After Mazois, Vol. II, pl. 18 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 192) | 391 | |

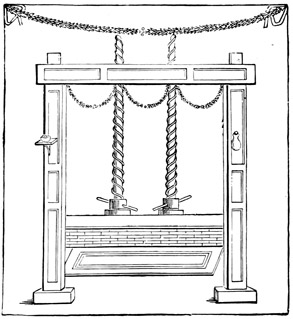

| 224. | Kneading machine, restored (VI. xiv. 35). From an original drawing | 391 | |

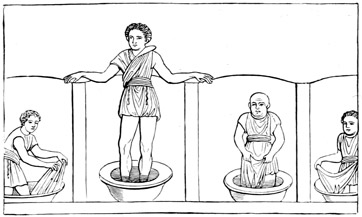

| 225. | Scene in a fullery—treading vats. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 49 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 195) | 394 | |

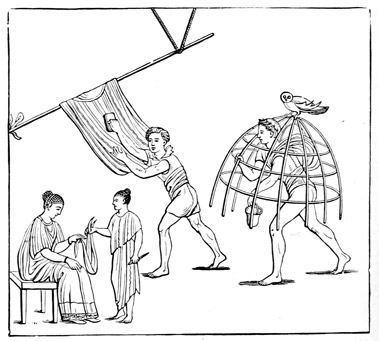

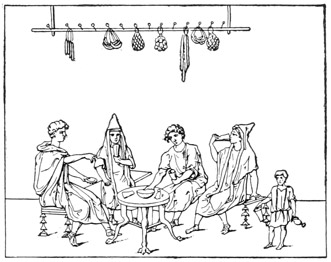

| 226. | Scene in a fullery—inspection of cloth, carding, bleaching frame. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 49 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 194) | 394 | |

| 227. | A fuller's press. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. 50 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 196) | 395 | |

| 228. | Plan of a fullery (VI. xiv. 22) | 396 | |

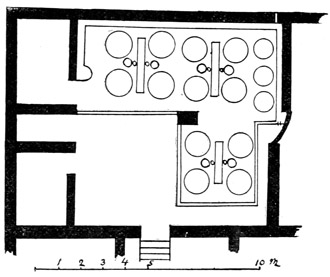

| 229. | Plan of the vat room of the tannery (I. v. 2) | 398 | |

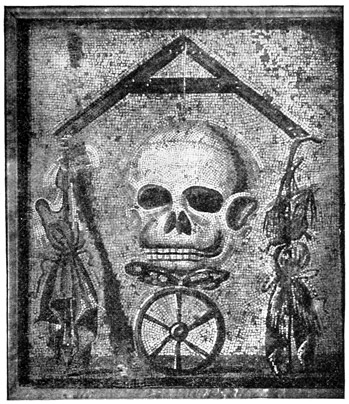

| 230. | Mosaic top of the table in the garden of the tannery. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 399 | |

| 231. | Plan of an inn (VII. xii. 35) | 401 | |

| 232. | Plan of the inn of Hermes (I. i. 8) | 402 | |

| 233. | Plan of a wineshop (VI. x. 1) | 402 | |

| 234. | Scene in a wineshop. Wall painting (VI. x. 1). After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. A | 403 | |

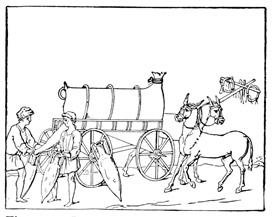

| 235. | Delivery of wine. Wall painting (VI. x. 1). After Museo Borb., Vol. IV, pl. A | 403 xxiv | |

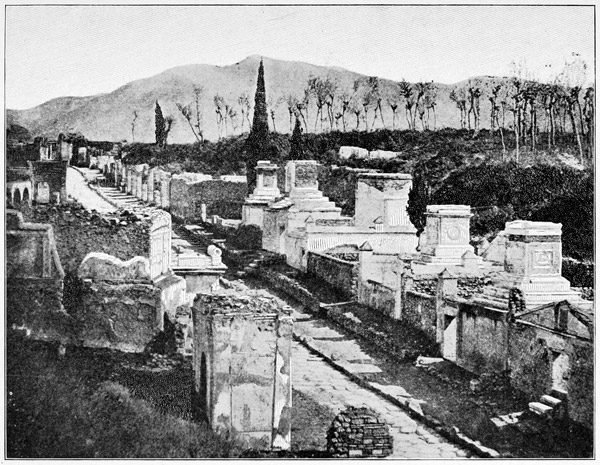

| 236. | Sepulchral benches of Veius and Mamia; tombs of Porcius and the Istacidii. From a photograph (A. M.) | 409 | |

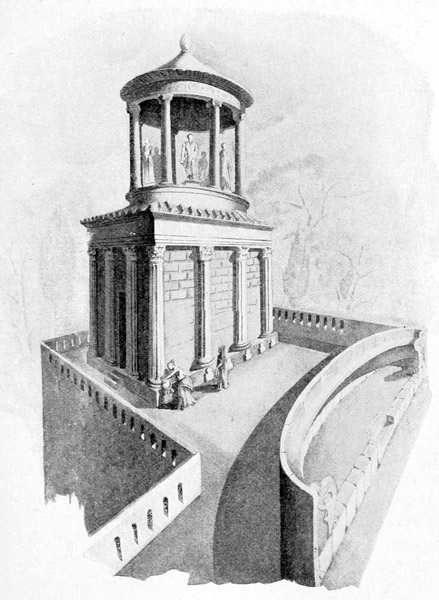

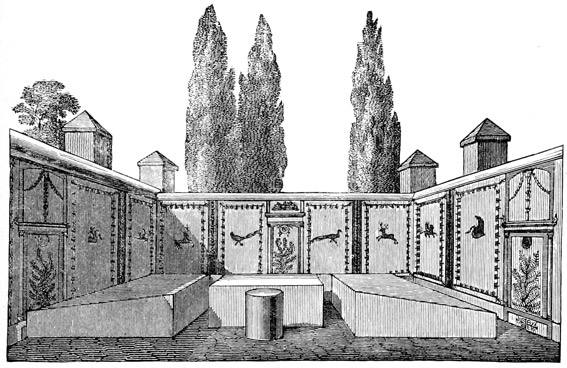

| 237. | The tomb of the Istacidii, restored. From an original drawing | 411 | |

| 238. | View of the Street of Tombs. From a photograph | 414 | |

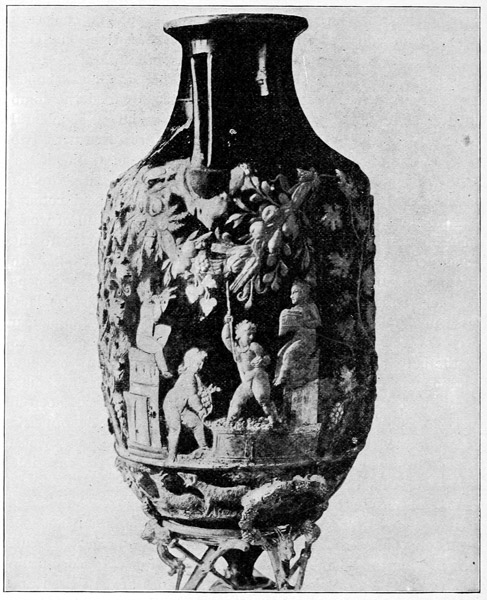

| 239. | Glass vase, with vintage scene, found in the tomb of the Blue Glass Vase. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 416 | |

| 240. | Bust stone of Tyche, slave of Julia Augusta. After Mazois, Vol. I, p. 31 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 223), with the correction in the spelling of the name TYCHE | 418 | |

| 241. | Relief, symbolic of grief for the dead. After Mazois, Vol. I, pl. 29 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 221) | 421 | |

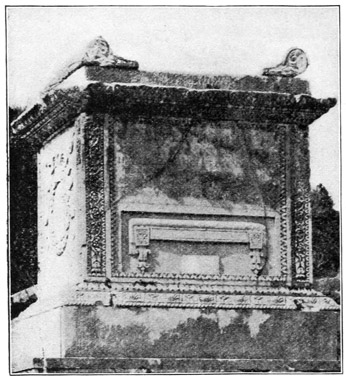

| 242. | Front of the tomb of Calventius Quietus, with bisellium. From a photograph | 422 | |

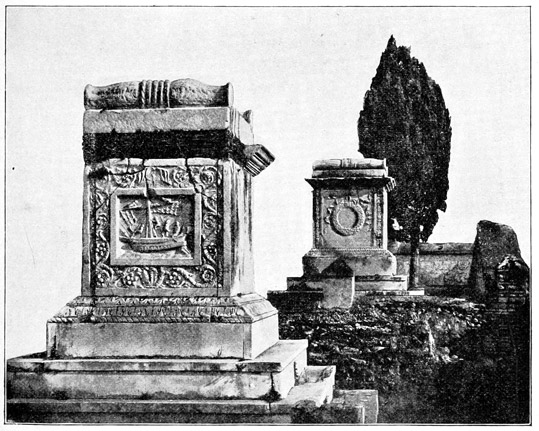

| 243. | End of the tomb of Naevoleia Tyche, with relief representing a ship entering port. From a photograph | 423 | |

| 244. | Cinerary urn in a lead case. After Mazois, Vol. I. pl. 22 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 213) | 424 | |

| 245. | Sepulchral enclosure, with triclinium funebre. After Mazois, Vol. I, pl. 20 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 210) | 425 | |

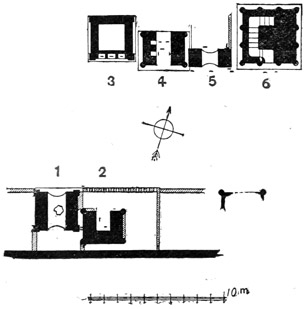

| 246. | Plan of the tombs east of the Amphitheatre* | 431 | |

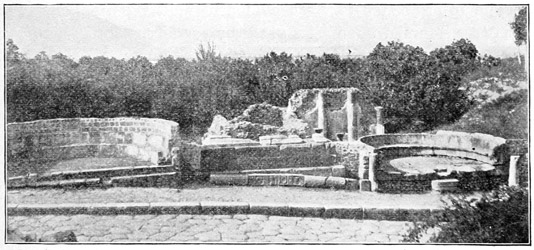

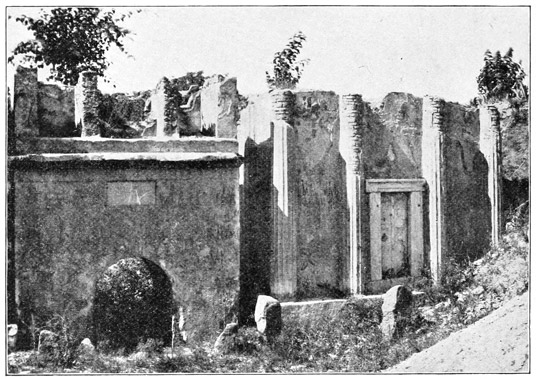

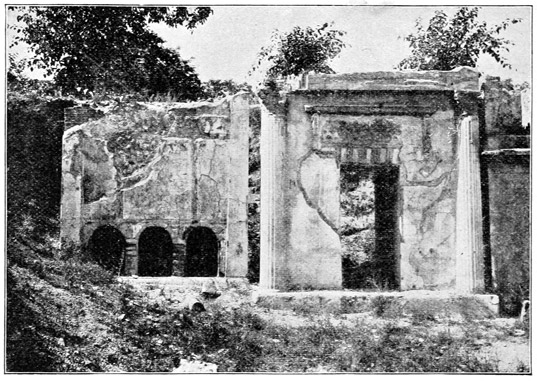

| 247. | View of two tombs east of the Amphitheatre. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 432 | |

| 248. | View of other tombs east of the Amphitheatre. From a photograph (F. W. K.) | 434 | |

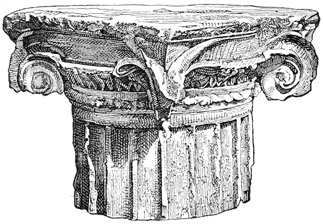

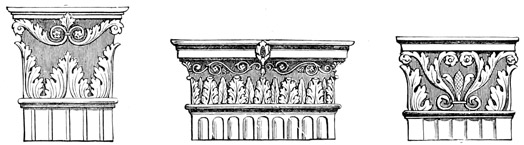

| 249. | Four-faced Ionic capital. Portico of the Forum Triangulare. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 272 | 439 | |

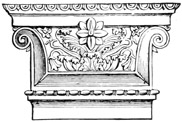

| 250. | Capital of pilaster. Casa del duca d'Aumale. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 274 | 439 | |

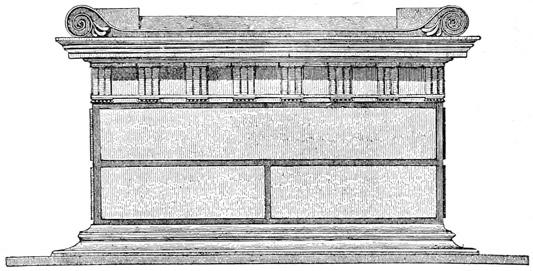

| 251. | Altar in the court of the temple of Zeus Milichius. After Mazois, Vol. IV, pl. 6 (Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 63) | 440 | |

| 252. | Capitals of columns, showing variations from typical forms. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 274 | 442 | |

| 253. | Capital of pilaster, modified Corinthian type. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 274 | 443 | |

| 254. | Capitals of pilasters, showing free adaptation of the Corinthian type. After Overbeck-Mau, Fig. 274 | 443 | |

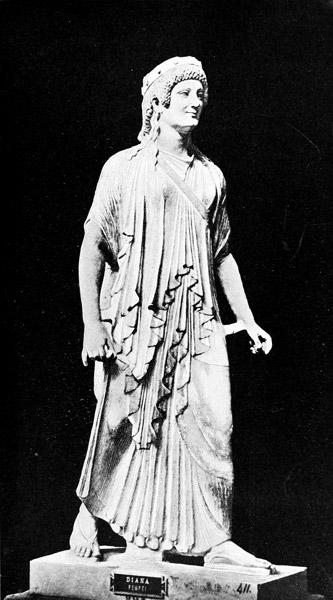

| 255. | Statue of the priestess Eumachia. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 446 | |

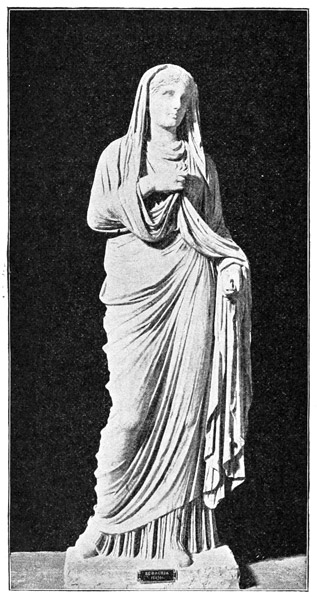

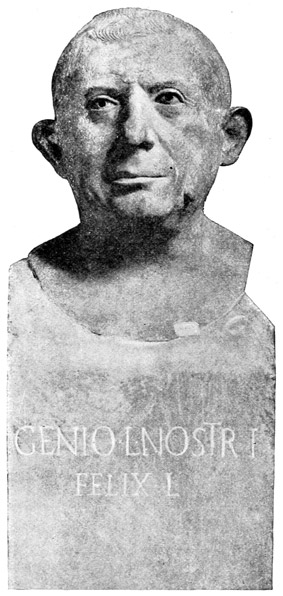

| 256. | Portrait herm of Caecilius Jucundus. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 447 | |

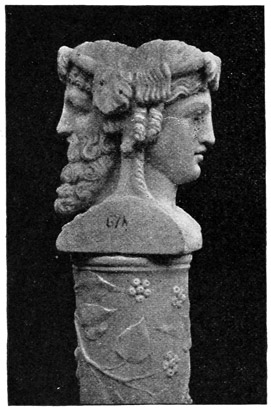

| 257. | Double bust, Bacchus and a bacchante. Garden of the house of the Vettii. From a photograph | 448 | |

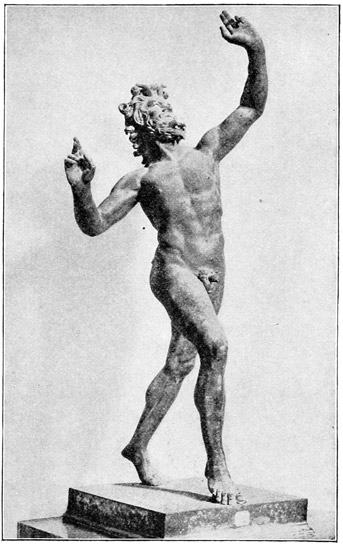

| 258. | Dancing Satyr. Bronze statuette found in the house of the Faun. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 451 xxv | |

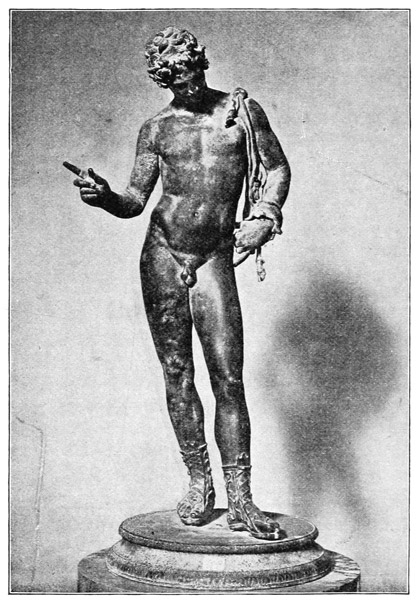

| 259. | Listening Dionysus, wrongly identified as Narcissus. Bronze statuette in the Naples Museum. From a photograph | 452 | |

| 260. | Bronze youth, found in November, 1900. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 454 | |

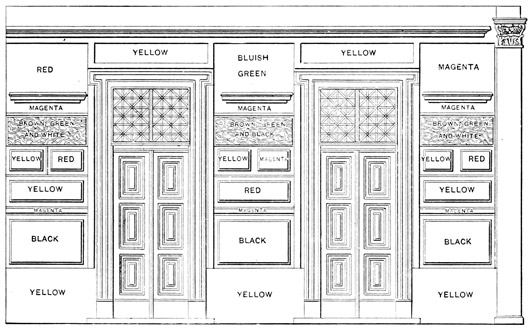

| 261. | Wall decoration in the atrium of the house of Sallust. First or Incrustation Style. After Tafel II of Mau's Geschichte der decorativen Wandmalerei in Pompeji | 460 | |

| 262. | Distribution of colors in the section of wall represented in Fig. 261 | 461 | |

| 263. | Specimen of wall decoration in the house of Spurius Mesor (VII. iii. 29). Third or Ornate style. After Tafel XII of Mau's Wandmalerei | 466 | |

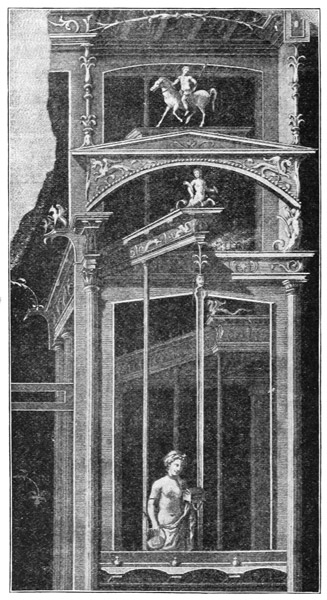

| 264. | Detail of wall decoration. Fourth style. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. IV. pl. 57 | 468 | |

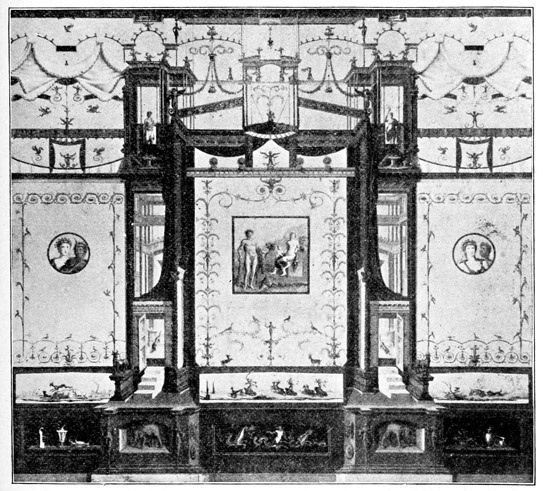

| 265. | Specimen of wall decoration. Fourth style. From a copy in the Naples Museum (showing decoration that has disappeared) | 469 | |

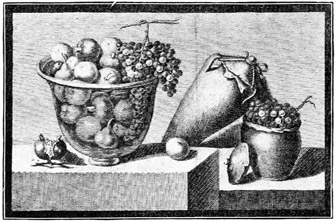

| 266. | A fruit piece, Xenion. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. II, pl. 58 | 474 | |

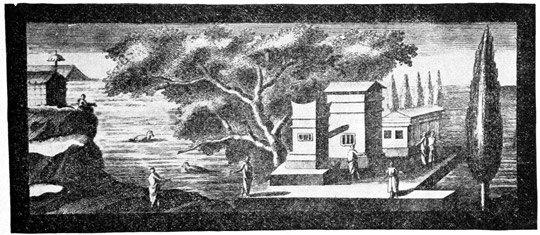

| 267. | A landscape. Wall painting. Naples Museum. After Pitture di Ercolano, Vol. V, p. 149 | 475 | |

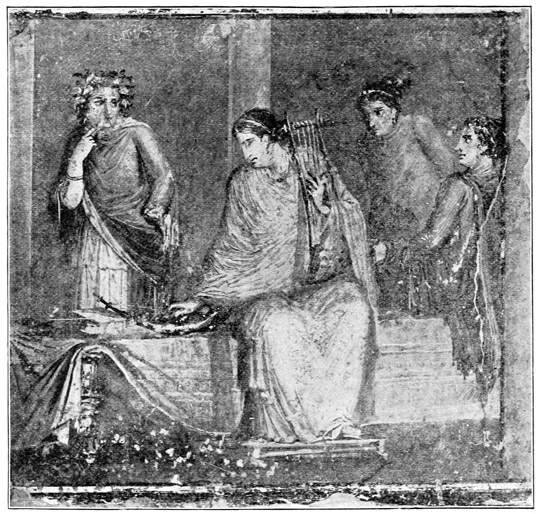

| 268. | A group of women, one of whom is sounding two-stringed instruments. Wall painting. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 476 | |

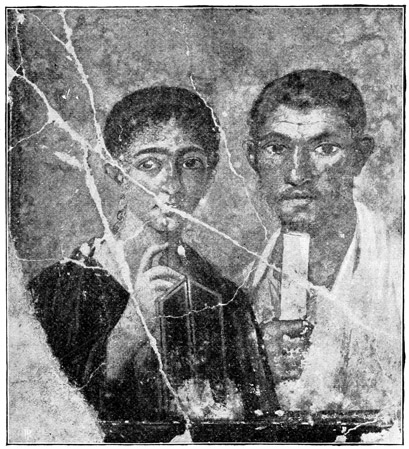

| 269. | Paquius Proculus and his wife. Wall painting. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 477 | |

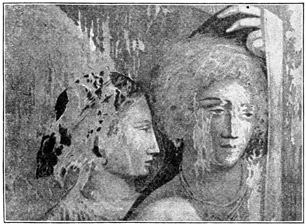

| 270. | The grief of Hecuba. Fragment of a wall painting. House of Caecilius Jucundus. After Ann. dell' Inst., 1877, Tafel P | 479 | |

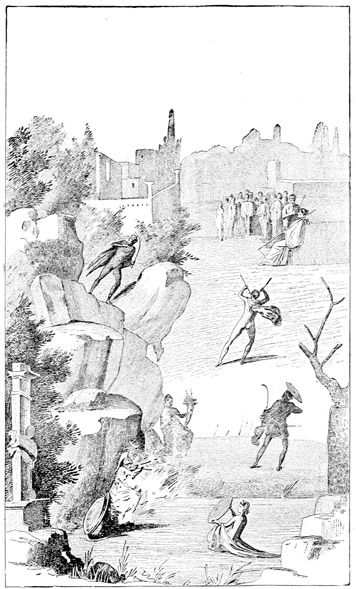

| 271. | Athena's pipes and the fate of Marsyas. Wall painting (V. ii. 10). Naples Museum. From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1890, p. 267) | 482 | |

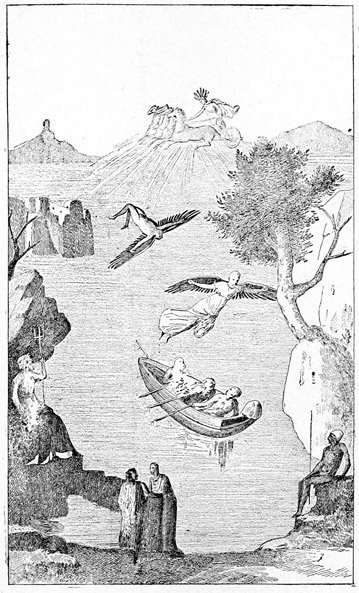

| 272. | The fall of Icarus. Wall painting (V. ii. 10). From a drawing.* (Cf. Röm. Mitth., 1890, p. 264) | 483 | |

| 273. | Zeus and Hera on Mt. Ida. Wall painting from the house of the Tragic Poet. Naples Museum. From a photograph | 484 | |

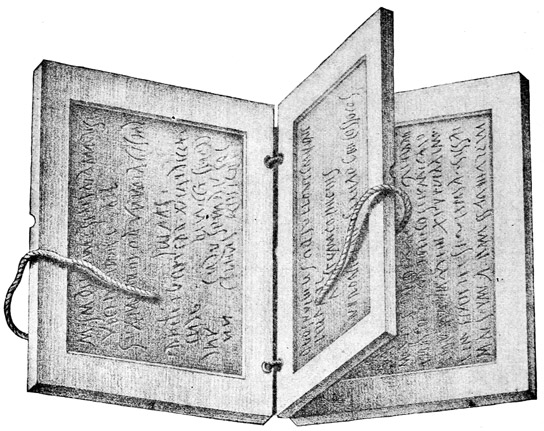

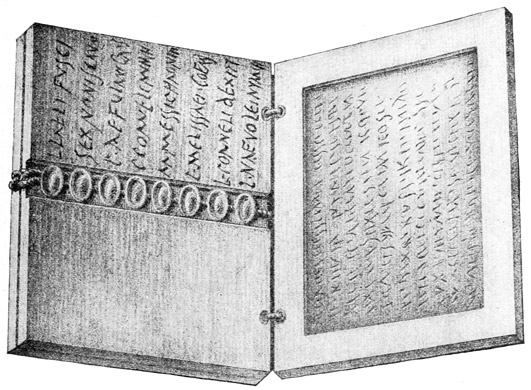

| 274. | Tablet with three leaves, opened so as to show the receipt and part of the memorandum, restored. After Overbeck-Mau, pl. facing p. 489 | 500 | |

| 275. | Tablet restored, with the two leaves containing the receipt tied and sealed. After Overbeck-Mau, pl. facing p. 489 | 501 | |

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I

THE SITUATION OF POMPEII

From Gaeta, where the south end of the Volscian range borders abruptly upon the sea, to the peninsula of Sorrento, a broad gulf stretched in remote ages, cutting its way far into the land. Its waves dashed upon the base of the mountains which now, rising with steep slope, mark the eastern boundary of the Campanian Plain—Mt. Tifata above Capua, Mt. Taburno back of Nola, and lying across the southeast corner, the huge mass of Monte Sant' Angelo, whose sharply defined line of elevation is continued in the heights of Sorrento.

This gulf was transformed by volcanic agencies into a fertile plain. Here two fissures in the earth's crust cross each other, each marked by a series of extinct or active volcanoes. One fissure runs in the direction of the Italian Peninsula; along it lie Monti Berici near Vicenza, Mt. Amiata below Chiusi, the lakes of Bolsena and Bracciano filling extinct craters, the Alban Mountains, and finally Stromboli and Aetna. The other runs from east to west; its direction is indicated by Mt. Vulture near Venosa, Mt. Epomeo on the island of Ischia, and the Ponza Islands.

At three places in the old sea basin the subterranean fires burst forth. Near the north shore rose the great volcano of Rocca Monfina, which added itself to the Volscian Mountains, and heaping the products of its eruptions upon Mons Massicus,—once an island,—formed with this the northern boundary of the plain. Toward the middle the numerous small vents of the Phlegraean Fields threw up the low heights, to which the north 2 shore of the Bay of Naples—Posilipo, Baiae, Misenum—is indebted for its incomparable beauty of landscape. Finally, near the south shore, at the intersection of the fissures, the massive cone of Vesuvius rose, in complete isolation—the only volcano on the continent of Europe still remaining active. Its base on the southwest is washed by the sea, while on the other sides a stretch of level country separates it from the mountains that hem in the plain. On the side opposite from the sea, however, Vesuvius comes so near to the mountains that we may well say that it divides the Campanian plain into two parts, of which the larger, on the northwest side, is drained by the Volturno; the small southeast section is the plain of the Sarno.

The Sarno, like the Umbrian Clitumnus, has no upper course. At the foot of Mt. Taburno, bounding the plain on the northeast, 3 are five copious springs that soon unite to form a stream. Since 1843 the river has been drawn off for purposes of irrigation into three channels, which are graded at different levels; the distribution of water thus assured makes this part of Campania one of the most fertile districts in Italy. In antiquity the Sarno must have been confined to a single channel; according to Strabo it was navigable for ships.

In Roman times three cities shared in the possession of the Sarno plain. Furthest inland, facing the pass in the mountains that opens toward the Gulf of Salerno, lay Nuceria, now Nocera. On the seashore, where the coast road to Sorrento branches off toward the southwest, was Stabiae, now Castellammare. North of Stabiae, at the foot of Vesuvius, Pompeii stood, on an elevation overlooking the Sarno, formed by the end of a stream of lava that in some past age had flowed from Vesuvius down toward the sea. Pompeii thus united the advantages of an easily fortified hill town with those of a maritime city. "It lies," says Strabo, "on the Sarnus, which accommodates a traffic in both imports and exports; it is the seaport of Nola, Nuceria, and Acerrae."

A glance at the map will show how conveniently situated Pompeii was to serve as a seaport for Nola and Nuceria; but it seems hardly credible that the inhabitants of Acerrae, which lay much nearer Naples, should have preferred for their 4 marine traffic the circuitous route around Vesuvius to the Sarno. However that may have been, Pompeii was beyond doubt the most important town in the Sarno plain.

Pompeii formerly lay nearer the sea and nearer the river than at present. In the course of the centuries alluvial deposits have pushed the shore line further and further away. It is now about a mile and a quarter from the nearest point of the city to the sea; in antiquity it was less than a third of a mile. The line of the ancient coast can still be traced by means of a clearly marked depression, beyond which the stratification of the volcanic deposits thrown out in 79 does not reach. The Sarno, too, now flows nearly two thirds of a mile from Pompeii; in antiquity, according to all indications, it was not more than half so far away.

In point of climate and outlook, a fairer site for a city could scarcely have been chosen. The Pompeian, living in clear air, could look down upon the fogs which in the wet season frequently rose from the river and spread over the plain. And while in winter Stabiae, lying on the northwest side of Monte Sant' Angelo, enjoyed the sun for only a few hours, the elevation on which Pompeii stood, sloping gently toward the east and south, more sharply toward the west, was bathed in sunlight during the entire day.

Winter at Pompeii is mild and short; spring and autumn are long. The heat of summer, moreover, is not extreme. In the early morning, it is true, the heat is at times oppressive. No breath of air stirs; and we look longingly off upon the expanse of sea where, far away on the horizon, in the direction of Capri, a dark line of rippling waves becomes visible. Nearer it comes, and nearer. About ten o'clock it reaches the shore. The leaves begin to rustle, and in a few moments the sea breeze sweeps over the city, strong, cool, and invigorating. The wind blows till just before sunset. The early hours of the evening are still; the pavements and the walls of the houses give out the heat which they have absorbed during the day. But soon—perhaps by nine o'clock—the tree tops again begin to murmur, and all night long, from the mountains of the interior, a gentle, refreshing stream of air 5 flows down through the gardens, the roomy atriums and colonnades of the houses, the silent streets, and the buildings about the Forum, with an effect indescribably soothing.

How shall I undertake to convey to the reader who has not visited Pompeii, an impression of the beauty of its situation? Words are weak when confronted with the reality. Sea, mountains, and plain,—strong and pleasing background,—great masses and brilliant yet harmonious colors, splendid foreground effects and hazy vistas, undisturbed nature and the handiwork of man, all are blended into a landscape of the grand style, the like of which I should not know where else to look for.

If we turn toward the south, we have at our feet the level plain of the Sarno, in antiquity as now—we may suppose—not checkered with villages but dotted here and there with groups of farm buildings, surrounded with stately trees. Beyond the plain rises the lofty barrier of Monte Sant' Angelo, thickly wooded 6 in places, its summit standing out against the sky in a long, beautiful profile, which, toward the right, breaks up into bold, rugged notches; the side of the mountain below is richly diversified with deep valleys, projecting ridges, and terraces that in the distance seem like steps, where among vineyards and olive orchards stand two villages fair to look on, Gragnano and Lettere, so near that individual houses can be clearly distinguished. Further west the plain before us opens out upon the sea, while the mountains are continued in the precipitous coast of the peninsula of Sorrento. Height crowds upon height, with villages wreathed in olive orchards lying between. Here the hills descend in terraces to the sea, covered with vegetation to the water's edge; there the covering of soil has been cast off from the steep slopes, exposing the naked rock, which shines in the afternoon sun with a reddish hue that wonderfully accords with the dark shades of the foliage and the brilliant blue of the sea. Further on the tints become duller, and the sight is blurred; only with effort can we distinguish Sorrento, resting on cliffs that rise almost perpendicularly from the line of the shore. Further still the outline of the peninsula sinks into the sea and gives place to Capri, island of fantastic shape, whose crags rising sheer from the water stand out sharply in the bright sunlight.

But we look toward the north, and the splendid variety of form and color vanishes; there stands only the vast, sombre mass of the great destroyer, Vesuvius, towering above the city and the plain. The sun as it nears the horizon veils the bare ashen cone with a mantle of deep violet, while the cloud of smoke that rises from the summit shines with a golden glow. Far above the base the sides are covered with vineyards, among which small groups of white houses can here and there be seen. West of us the outline of the mountain descends in a strong, simple curve to the sea. Just before it blends with the shore there rise behind it distant heights wrapped in blue haze, the first of moderate elevation, then others more prominent and further to the left. They are the heights along the north shore of the Bay of Naples—Gaurus crowned with the monastery of Camaldoli, famous for its magnificent view; 7 the cliffs of Baiae, the promontory of Misenum, and the lofty cone of Epomeo on the island of Ischia. So the eye traverses the whole expanse of the Bay; Naples itself, hidden from our view, lies between those distant heights and the base of Vesuvius.

But meanwhile the sun has set behind Misenum; its last rays are lighting up the cloud of smoke above Vesuvius and the summit of Monte Sant' Angelo. The brilliancy of coloring has faded; the weary eye finds rest in the soft afterglow. We also may take leave of these beautiful surroundings, and inquire into the beginnings of the city which was founded here. 8

CHAPTER II

BEFORE 79

When Pompeii was founded we do not know. It is more than likely that a site so well adapted for a city was occupied at an early date. The oldest building, the Doric temple in the Forum Triangulare, is of the style of the sixth century B.C.; we are safe in assuming that the city was then already in existence.[2] The founders were Oscans. They belonged to a widely scattered branch of the Italic stock, whose language, closely related with the Latin, has been imperfectly recovered from a considerable number of inscriptions, so imperfectly that in each of the longer inscriptions there still remain words the meaning of which is obscure or doubtful. From this language the name of the city came; for pompe in Oscan meant 'five.' The word does not, however, appear in its simple form; we have only the adjective derived from it, pompaiians, 'Pompeian.' If we are right in assuming that the name appeared in Oscan, as it does in Latin, in the plural form, it was probably applied first to a gens, or clan, and thence to the city; the Latin equivalent of Pompeii would be Quintii. Pompeii was thus the city of the clan of the Pompeys, as Tarquinii was the city of the Tarquins, and Veii the city of the Veian clan. The name Pompeius was common in Pompeii down to the destruction of the city, and in other Campanian towns, notably Puteoli, to much later times.

In order to follow the course of events at Pompeii, it will be necessary to pass briefly in review the main points in the history of Campania. The Campanian Oscans, sprung from a 9 rude and hardy race, became civilized from contact with the Greeks, who at an early period had settled in Cumae, in Dicaearchia, afterward Puteoli, and in Parthenope, later Naples; and the coast climate had an enervating effect upon them. When toward the end of the fifth century B.C. the Samnites, kinsmen of the Oscans, left their rugged mountain homes in the interior and pressed down toward the coast, the Oscans were unable to cope with them. In 424 B.C. the Samnites stormed and took Capua, in 420, Cumae; and Pompeii likewise fell into their hands. But they were no more successful than the Oscans had been in resisting the influence of Greek culture. How strong this influence was may be seen in the remains at Pompeii. The architecture of the period was Greek; Greek divinities were honored, as Apollo and Zeus Milichius; and the standard measures of the mensa ponderaria were inscribed with Greek names.

In less than a hundred years new strifes arose between the more cultured Samnites of the plain and their rough and warlike kinsmen in the mountains. But Rome took a part in the struggle, and in the Samnite Wars (343-290 B.C.) brought both the men of the mountains and the men of the plain under her dominion. Although the sovereignty of Rome took the form of a perpetual alliance, the cities in reality lost their independence. The complete subjugation and Romanizing of Campania, however, did not come till the time of the Social War (90-88 B.C.) and the supremacy of Sulla; the Samnites staked all on the success of the popular party, and lost.

In the narrative of these events Pompeii is not often mentioned. At the time of the Second Samnite War, in the year 310 B.C., we read that a Roman fleet under Publius Cornelius landed at the mouth of the Sarno, and that a pillaging expedition followed the course of the river as far as Nuceria; but the country folk fell on the marauders as they were returning, and forced them to give up their booty. We have no definite information regarding the attitude of the Pompeians after the battle of Cannae (216 B.C.); probably they joined the side of Hannibal, who, however, was defeated by Marcus Marcellus near Nola in the following year, and was obliged to leave Campania to the Romans. 10

In the Social War, when, in the summer of 90 B.C., the Samnite army marched into Campania, Pompeii allied itself with the insurgents; as a consequence, in 89, it was besieged by Sulla, but without success. Two years later, Sulla went to Asia to conduct the war against Mithridates. Returning victorious in the spring of 83 B.C., he led his army into Campania, where he spent the winter of 83-82; his soldiers, grown brutal in the Asiatic war and accustomed to every kind of license, may have proved unwelcome guests for the Pompeians.

The sequel came in the year 80, when a colony of Roman veterans was settled in Pompeii under the leadership of Publius Sulla, a nephew of the Dictator. Cicero later made a speech in behalf of this Sulla, defending him against the charge that he had taken part in the conspiracy of Catiline and had tried to induce the old residents of Pompeii to join in the plot. From this speech we learn that Sulla's reorganization of the city was accomplished with so great regard for the interests of the Pompeians, that they ever after held him in grateful remembrance. We learn, also, that soon after the founding of the colony disputes arose between the old residents and the colonists, about the public walks (ambulationes) and matters connected with the voting; the arrangements for voting had probably been so made as to throw the decision always into the hands of the colonists. The controversy was referred to the patrons of the colony, and settled by them. From this time on, the life of Pompeii seems not to have differed from that of the other small cities of Italy.

As the harbor of Pompeii was on the Sarno, which flowed at some distance from the city, there must have been a small settlement at the landing place. To this probably belonged a group of buildings, partly excavated in 1880-81, lying just across the Sarno canal (canale del Bottaro), about a third of a mile from the Stabian Gate. Here were found many skeletons, and with them a quantity of gold jewellery, which was afterward placed in the Museum at Naples. The most reasonable explanation of the discovery is, that the harbor was here, and that these persons, gathering up their valuables, fled from Pompeii at the time of the eruption either in order to escape by 11 sea or to take refuge in Stabiae. Flight in either case was cut off. If ships were in the harbor, they must soon have been filled with the volcanic deposits; if there was a bridge across the river it was probably thrown down by the earthquake.

A second suburb sprang up near the sea, in connection with the salt works (salinae) of the city. Our knowledge of the inhabitants, the Salinenses, is derived from several inscriptions painted upon walls, in which they recommend candidates for the municipal offices, and from an inscription scratched upon the plaster of a column in which a fuller by the name of Crescens sends them a greeting: Cresce[n]s fullo Saline[n]sibus salute[m]. From another inscription we learn that they had an assembly, conventus, possibly judicial in its functions; for in connection with a date, it speaks of a fine of twenty sesterces, which would amount to about 3½ shillings, or 85 cents: VII K. dec. Salinis in conventu multa HS XX, 'Fine of twenty sesterces; assembly at Salinae, November 25.' Still another inscription speaks of attending such a meeting on November 19: XIII K. dec. in conventu veni.

The suburb most frequently mentioned was at first called Pagus Felix Suburbanus, but after the time of Augustus, Pagus Augustus Felix Suburbanus. Its location is unknown. As it evidently took the name of Felix from the Dictator Sulla, who used this epithet as a surname, we may assume that its origin dates from the establishment of the Roman colony; it may have been founded to provide a place for those inhabitants of Pompeii who had been forced to leave their homes in order to make room for the colonists. The existence of a fourth suburb is inferred from two painted inscriptions in which candidates for office are recommended by the Campanienses; this name would naturally be applied to the inhabitants of a Pagus Campanus, who, perhaps, had originally come from Capua.

Of the government of Pompeii in the earliest times, before the Samnite conquest, nothing is known. The names of various magistrates in the Samnite period, however, particularly the period of alliance with Rome (290-90 B.C.), are learned from inscriptions. Mention is made of a chief administrative officer 12 (mediss, mediss tovtiks); of quaestors, who, probably, like the quaestors in Rome, were charged with the financial administration and let the contracts for public buildings; and of aediles, to whom, no doubt, was intrusted the care of streets and buildings, together with the policing of the markets. The Latin names of the last two officials suggest that their offices were introduced after 290. There was also an assembly called kombenniom, with which we may compare the Latin conventus; but whether it was an assembly of the people or a city council cannot now be determined.

After the establishment of the Roman colony, Pompeii was named Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum, from the gentile name of the Dictator Sulla (Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix) and from the goddess to whom he paid special honor, who now, as Venus Pompeiana, became the tutelary divinity of the city. This goddess is represented in wall paintings. In that from which our illustration is taken (Fig. 4), she appears in a blue mantle studded with golden stars, and wears a crown set with green stones. Her left hand, which holds a sceptre, rests upon a rudder; in her right is a twig of olive. A Cupid stands upon a pedestal beside her, holding up a mirror.

From this time the highest official body, as in Roman colonies everywhere, was the city council, composed of decurions. The administration was placed in the hands of two pairs of officials, the duumvirs with judiciary authority, duumviri iuri dicundo, and two aediles, who were responsible for the care of buildings and streets and the oversight of the markets. When the duumvirs and the aediles joined in official acts they were known as the Board of Four, quattuorviri. Down to the time of the Empire it appears that the aediles were not designated 13 officially by that name, but by a title known to us only in an abbreviated form, duumviri v. a. sacr. p. proc. This probably stands for duumviri viis, aedibus, sacris publicis procurandis, 'duumvirs in charge of the streets, the temples, and the public religious festivals.' The title of aedile seems to have been avoided because it had been in use in the days of autonomy, and the authorities thought it prudent to suppress everything that would suggest the former state of independence. Nevertheless, the word retained its place in ordinary speech, as is shown by its use in the inscriptions painted on walls recommending candidates for office; thence it finally forced its way back into the official language. The duumvirs of every fifth year were called quinquennial duumvirs, duumviri quinquennales, and assumed functions corresponding with those of the censors at Rome; they gave attention to matters of finance, and revised the lists of decurions and of citizens.

All these officials were elected annually by popular vote. The candidates offered themselves beforehand. If none came forward, or there were too few,—for the city officials not only received no salary, but were under obligation to make generous contributions for public purposes, as theatrical representations, games, and buildings,—the magistrate who presided at the election named candidates for the vacancies; but each candidate so named had the right to nominate a second for the same vacancy, the second in turn a third. The voting was by ballot; each voter threw his voting tablet into the urn of his precinct. No information has come down to us regarding the precincts (curiae) into which the city must have been divided for electoral purposes.

The election of a candidate was valid only in case he received the vote of an absolute majority of the precincts. If the result was indecisive for all or a part of the offices, the city council chose an extraordinary official who bore the title of prefect with judiciary authority, praefectus iuri dicundo. This prefect took the place of the duumvirs, not only when an election was indecisive, but also when vacancies arose in some other way, or when peculiar conditions seemed to make it desirable to have an officer of unusual powers, a kind of dictator; or finally, when 14 the emperor had received the vote; in the last two cases, the prefect was undoubtedly appointed by the emperor. Thus, in the years 34 and 40 A.D., the Emperor Caligula was duumvir of Pompeii; but the duties of the office were discharged by a prefect. A law passed in Rome toward the end of the Republic on the motion of a certain Petronius contained provisions regarding the appointment of prefects; one chosen in accordance with them was called praefectus ex lege Petronia, 'prefect according to the law of Petronius.'

There were also in Pompeii priests supported by the city, but only a few of them are mentioned in the inscriptions. References are found to augurs and pontifices, to a priest of Mars, and to priests (flamen, sacerdos) of Augustus while he was still living; Nero had a priest even before he ascended the throne. Mention is made of priestesses, too, a priestess of Ceres and Venus, priestesses of Ceres, and others, the divinities of whom are not named.

The suburbs could scarcely have had a separate administration; they remained within the jurisdiction of the magistrates of the city. In the case of the Pagus Augustus Felix mention is made of a magister, 'director,' ministri, 'attendants,' and pagani, 'pagus officials'; but apparently these were all appointed for religious functions only, in connection with the worship of the emperor. The magister and the pagani, in part at least, were freedmen; the four ministri, first appointed in 7 B.C., were slaves.

Apart from commerce, an important source of income for the Pompeians lay in the fertility of the soil. In antiquity, as now, grapes were cultivated extensively on the ridge projecting from the foot of Vesuvius toward the south. The evidence afforded by the great number of wine jars, amphorae (Fig. 5), that have been brought to light would warrant this conclusion; and lately wine presses also have been discovered near Boscoreale, above Pompeii. Pliny makes mention of the Pompeian wine, but remarks that indulgence in it brings a headache that will last till noon of the following day. The olive too was cultivated, but only to a limited extent; this we infer from the small capacity of the press and other appliances for making oil found in the 15 same villa in which the wine presses were discovered. At the present time the making of oil is not carried on about Pompeii. In the plain below the city vegetables were raised, as at the present day; the cabbage and onions of Pompeii were highly prized.

The working up of the products of the fisheries formed an important industry. The fish sauces which so tickled the palate of ancient epicures, garum, liquamen, and muria, were produced here of the finest quality. The making of them seems to have been practically a monopoly in the hands of a certain Umbricius Scaurus; a great number of earthen jars have been found with the mark of his ownership (p. 506).

The Pompeians turned to account, also, the volcanic products of Vesuvius. Pumice stone was an article of export. From the lava millstones were made for both grain mills and oil mills, which were apparently already in extensive use in the time of Cato the Elder; he twice mentions the oil mills of Pompeii. In Pompeii itself the millstones of the oldest period are of lava from Vesuvius; later it was found that the lava of Rocca Monfina was better adapted for the purpose, and millstones of that material were preferred. Small hand-mills of the lava from Vesuvius were in use at Pompeii down to 79; but the larger millstones of this material found in the bakeries had been put one side. In shape and finish the mills of local make were superior to the more carelessly worked stones from Rocca Monfina; the preference for the latter was due to the fact that they contained numerous crystals of leucite, which broke off as the mill wore away, and so kept the grinding surfaces always rough. Millstones from Rocca Monfina may be seen at different places in Rome, as in the Museum of the Baths of Diocletian. 16

To the sources of revenue which contributed to the prosperity of Pompeii we may add the presence of wealthy Romans, who, attracted by the delightful climate, built country seats in the vicinity. Among them was Cicero, who often speaks of his Pompeian villa (Pompeianum). That the imperial family also had a villa here is inferred from a curious accident. We read that Drusus, the young son of the Emperor Claudius, a few days after his betrothal to the daughter of Sejanus, was choked to death at Pompeii by a pear which he had thrown up into the air and caught in his mouth. These country seats, no doubt, lay on the high ground back of Pompeii, toward Vesuvius; they probably faced the sea. But the identification of a villa excavated in the last century, and then filled up again, as the villa of Cicero, is wholly without foundation.

Salve lucrum, 'Welcome, Gain!' Such is the inscription which a Pompeian placed in the mosaic floor of his house. Lucrum gaudium, 'Gain is pure joy,' we read on the threshold of another house. A thrifty Pompeian certainly did not lack opportunity to acquire wealth.

How large a population Pompeii possessed at the time of the destruction of the city it is impossible to determine. A painstaking examination of all the houses excavated would afford data for an approximate estimate; but the results thus far obtained by those who have given attention to the subject are unsatisfactory. Fiorelli assigned to Pompeii twelve thousand inhabitants, Nissen twenty thousand. Undoubtedly the second estimate is nearer the truth than the first; according to all indication the population may very likely have exceeded twenty thousand.

This population was by no means homogeneous. The original Oscan stock had not yet lost its identity; inscriptions in the Oscan dialect are found scratched on the plaster of walls decorated in the style prevalent after the earthquake of the year 63. From the time when the Roman colony was founded no doubt additions continued to be made to the population from various parts of Italy. The Greek element was particularly strong. This is proved by the number of Greek names in the accounts of Caecilius Jucundus, for example, and by the Greek inscriptions 17 that have been found on walls and on amphorae. The Greeks may have come from the neighboring towns; most of them were probably freedmen. In a seaport we should expect to find also Greeks from trans-marine cities; and, in fact, an Alexandrian appears in one of the receipts of Jucundus. There were Orientals, too, as we shall see when we come to the temple of Isis.

Thus far there has come to hand no trustworthy evidence for the presence of Christians at Pompeii; but traces of Jewish influence are not lacking. The words Sodoma, Gomora, are scratched in large letters on the wall of a house in Region IX (IX. i. 26). They must have been written by a Jew, or possibly a Christian; they seem like a prophecy of the fate of the city.

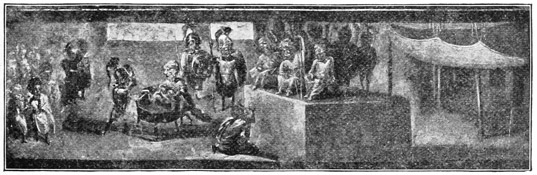

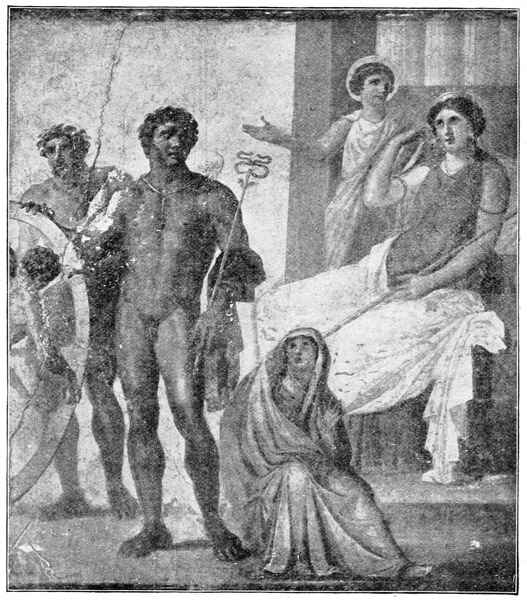

Another interesting bit of evidence is a wall painting, which appears to have as its subject the Judgment of Solomon (Fig. 6). On a tribunal at the right sits the king with two advisers; the pavilion is well guarded with soldiers. In front of the tribunal a soldier is about to cut a child in two with a cleaver. Two women are represented, one of whom stands at the block and is already taking hold of the half of the child assigned to her, while the other casts herself on her knees as a suppliant before the judges. It is not certain that the reference here is to Solomon; such tales pass from one country to another, and a somewhat similar story is told of the Egyptian king Bocchoris. The balance of probability is in favor of the view that we have here the Jewish version of the story, because this is consistent with other facts that point to the existence of a Jewish colony at Pompeii. 18

The names Maria and Martha appear in wall inscriptions. The assertion that Maria here is not the Hebrew name, but the feminine form of the Roman name Marius, is far astray. It appears in a list of female slaves who were working in a weaver's establishment, Vitalis, Florentina, Amaryllis, Januaria, Heracla, Maria, Lalage, Damalis, Doris. The Marian family was represented at Pompeii, but the Roman name Maria could not have been given to a slave. That we have here a Jewish name seems certain since the discovery of the name Martha.

In inscriptions upon wine jars we find mention of a certain M. Valerius Abinnerichus, a name which is certainly Jewish or Syrian; but whether Abinnerich was a dealer, or the owner of the estate on which the wine was produced, cannot be determined. In this connection it is worth while to note that vessels have been found with the inscribed labels, gar[um] cast[um] or cast[imoniale], and mur[ia] cast[a]. As we learn from Pliny (N. H. XXXI. viii. 95), these fish sauces, prepared for fast days, were used especially by the Jews.

Some have thought that the word Christianos can be read in an inscription written with charcoal, and have fancied that they found a reference to the persecution of the Christians under Nero. But charcoal inscriptions, which will last for centuries when covered with earth, soon become illegible if exposed to the air; such an inscription, traced on a wall at the time of the persecutions under Nero, must have disappeared long before the destruction of the city. The inscription in question was indistinct when discovered, and has since entirely faded; the reading is quite uncertain. If it were proved that the word "Christians" appeared in it, we should be warranted only in the inference that Christians were known at Pompeii, not that they lived and worshipped there. According to Tertullian (Apol. 40) there were no Christians in Campania before 79. 19

CHAPTER III

THE CITY OVERWHELMED

Previous to the terrible eruption of 79, Vesuvius was considered an extinct volcano. "Above these places," says Strabo, writing in the time of Augustus, "lies Vesuvius, the sides of which are well cultivated, even to the summit. This is level, but quite unproductive. It has a cindery appearance; for the rock is porous and of a sooty color, the appearance suggesting that the whole summit may once have been on fire and have contained craters, the fires of which died out when there was no longer anything left to burn."

Earthquakes, however, were of common occurrence in Campania. An especially violent shock on the fifth of February, 63 A.D., gave warning of the reawakening of Vesuvius. Great damage was done throughout the region lying between Naples and Nuceria, but the shock was most severe at Pompeii, a large part of the buildings of the city being thrown down. The prosperous and enterprising inhabitants at once set about rebuilding. When the final catastrophe came, on the twenty-fourth of August, 79 A.D., most of the houses were in a good state of repair, and the rebuilding of at least two temples, those of Apollo and of Isis, had been completed. This renewing of the city, caused by the earthquake, may be looked upon as a fortunate circumstance for our studies.

Our chief source of information for the events of August 24-26, 79, is a couple of letters of the Younger Pliny to Tacitus, who purposed to make use of them in writing his history. Pliny was staying at Misenum with his uncle, the Elder Pliny, who was in command of the Roman fleet. In the first letter he tells of his uncle's fate. On the afternoon of the twenty-fourth, the admiral Pliny set out with ships to rescue from impending danger the people at the foot of Vesuvius, particularly in the vicinity 20 of Herculaneum. He came too late; it was no longer possible to effect a landing. So he directed his course to Stabiae, where he spent the night; and there on the following morning he died, suffocated by the fumes that were exhaled from the earth. The second letter gives an account of the writer's own experiences at Misenum.

To this testimony little is added by the narrative of Dion Cassius, which was written a century and a half later and is known to us only in abstract; Dion dwells at greater length on the powerful impression which the terrible convulsion of nature left upon those who were living at that time. With the help of the letters of Pliny, in connection with the facts established by the excavations, it is possible to picture to ourselves the progress of the eruption with a fair degree of clearness.