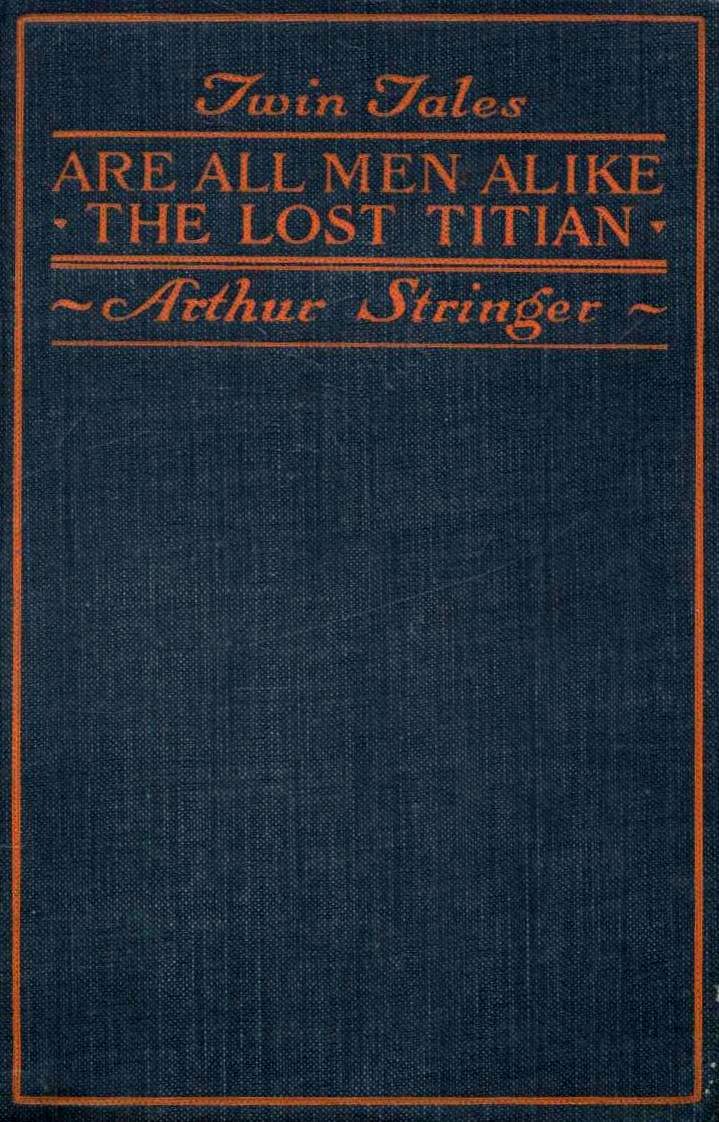

TWIN TALES

Are All Men Alike

and

The Lost Titian

By

ARTHUR STRINGER

McCLELLAND & STEWART

PUBLISHERS TORONTO

Copyright 1920

McClure’s Magazine, Inc.

Copyright 1920

The Curtis Publishing Company

Copyright 1921

The Bobbs-Merrill Publishing Company

Printed in the United States of America

TWIN TALES

| Contents |

| Are All Men Alike |

| The Lost Titian |

TWIN TALES

CHAPTER ONE

Her name was Theodora, which means, of course, “the gift of God,” as her sad-eyed Uncle Chandler was in the habit of reminding her. In full, it was Theodora Lydia Lorillard Hayden. But she was usually called Teddie.

She was the kind of girl you couldn’t quite keep from calling Teddie, if you chanced to know her. And even though her frustrated male parent had counted on her being a boy, and even though there were times when Teddie herself wished that she had been a boy, and even though her own Aunt Tryphena—who still reverentially referred to Ward McAllister and still sedulously locked up the manor gates at Piping Rock when that modern atrocity yclept the Horse Show was on—solemnly averred that no nice girl ever had a boy’s name attached to her without just cause, Teddie, you must remember, was not masculine. God bless her adorable little body, she was anything but that! She was merely a poor little rich girl who’d longed all her life for freedom and had only succeeded in bruising, if not exactly her wings, at least the anterior of a very slender tibia, on the bars of a very big and impressive cage.

What she really suffered from, even as a child, was the etiolating restraints of the over-millioned. She panted for an elbow-room which apparently could never be hers. And as she fought for breathing-space between the musty tapestries of deportment she was called intractable and incorrigible, when the only thing that was wrong with her was the subliminal call of the wild in her cloistered little bosom, the call that should have been respected by turning her loose in a summer-camp or giving her a few weeks in the Adirondacks, where she might have straightened out the tangled-up Robinson Crusoe complexes that made her a menace and a trial to constituted authority.

But constituted authority didn’t understand Teddie. It even went so far, in time, as to wash its hands of her. For those passionate but abortive attempts at liberation had begun very early in Teddie’s career.

At the tender age of seven, after incarceration for sprinkling the West Drive with roofing-nails on the occasion of a fête champêtre from which she had been excluded on the ground of youth, she had amputated her hair and purchased appropriate attire from her maturer neighbor and playmate, Gerald Rhindelander West, intent on running away to the Far West and becoming a cowboy.

But Major Chandler Kane, an uncle who stoutly maintained that obstreperous youth should not be faced as a virtue or a vice but as a fact, happened to be coming out for the week-end at about the same time, and intercepted Teddie at the railway station. So, after discreetly depriving her of the gardener’s knife and the brass-mounted Moorish pistol from the library mantel, with the assistance of three chocolate mousses and an incredibly complicated and sirup-drenched and maraschino-stippled and pineapple-flavored nut sundae not inappropriately designated on the menu-card as “The Hatchet-Burier,” he succeeded in wheedling out of her the secret of her disguise, telephoned for the car, and brought her home with a slight bilious attack and a momentarily tempered spirit.

A year later, after condign punishment for having tied sunbonnets on the heads of the Florentine marble lions in the Sunken Garden, she revolted against the tyranny of French verbs and the chinless Mademoiselle Desjarlais by escaping from the study window to the leads of the conservatory, from which she climbed to the top of the chauffeurs’ domicile above the garage, where she calmly mounted a chimney and ate salted pecans and refused to come down. It began to rain, later on, but this didn’t matter. What really mattered was the arrival of Ladder-Truck Number Three of the Tuxedo Fire Department. That was a great hour in the life of our over-ennuied Teddie, who, in fact, formed so substantial a friendship with those helmeted heroes that she was thereafter permitted to slide down the polished brass pole which led from the sleeping-quarters to the ground floor of the Fire Hall. So active was her interest in their burnished apparatus, and so dominating grew her hunger to hear the great red motors roar and see the Ladder-Truck wheels strike fire as they took the car-rails at the Avenue-crossing, that she turned in a quite unnecessary alarm. The resultant spectacle she regarded as almost as satisfying as the Chariot Race in Ben-Hur. For this offense, however, she was first severely reprimanded and later confined to the Lilac Room, where she locked herself in the old nursery bathroom and proceeded to flood the marble basin therein, reveling in the primitive joy of running water until the servants’ stairs became like unto a second Falls of Montmorency, and Wilson, the second footman, had to wriggle in over the transom to shut off the taps and save the house from inundation.

On the heels of this she was reported as having bitten the dentist’s fingers when he unexpectedly touched a nerve. She further embarrassed the family and the tranquillity of Tuxedo Park by prying open an express crate and liberating two Russian wolf-hounds awaiting delivery on one end of the neat little depot platform. She claimed, it is true, that the dogs had stood there for a whole day, and wanted to get out, and were starving to death—but that was not a potent factor when it came to final adjustment of damages.

She hated the thought of captivity, of course, just as she hated inertia, for two years earlier she had appropriated a niblick for the purpose of demolishing a new French doll, protesting, after the demolition, that she would be satisfied with nothing if she couldn’t carry about something “with real livings in it.” Her preoccupied parents, after the manner of their kind, maintained that she had a blind spot in her moral nature and talked vaguely but hopefully of what school would do to her when the time came.

She was, in fact, emerging into her tumultuous teens before she could be persuaded that waxed parquetry was not made for the purpose of sliding on and that a tea-wagon was not the correct thing to cascade down the terrace on. And when the golden key of the printed word might have opened a newer and wider world to her she was allotted a series of exceedingly namby-pamby “uplift” books (kindly suggested by the Bishop one day after he’d had a glance over the Ketley orchids in the greenhouse). These, however, she quietly consigned to the garage water-tank, and having entered into secret negotiations with Muggsie, the head chauffeur’s stepson, she bartered a wrist-watch with a broken hair-spring, a silver-studded dog-collar, and two Tournament racquets for a dog-eared copy of The Hidden Hand and a much-thumbed copy of The Toilers of the Sea with the last seven chapters missing. Then, urged on by that undecipherable ache for freedom, she padded a crotch in the upper regions of the biggest copper-beech on the East Drive, padded it with two plump sofa-pillows, and there ensconcing herself, let her spirit expand in direct ratio to the accruing cramp in her spindly young legs. But copper-beeches are not over-comfortable places to read in, and Teddie developed a settled limp which prompted her mother to shake her head and reiterate a conviction that the child should be looked over by an orthopedic specialist.

With Teddie the movies were still strictly taboo, but having secretly visited the Hippodrome with her Uncle Chandler, she became the victim of a brief but burning passion to go on the stage, preferably in tank-work, whereby she might startle the world through the grace of her aquatic feats. When she proceeded to perfect herself in this calling, however, by practising diving in the deeper end of the Lily Pond, she was given castor-oil and sent to bed to obviate a perhaps fatal cold which gave no slightest signs of putting in an appearance.

Her spirit was scotched, but not killed, for when, duly chaperoned, she was permitted to visit the Garden and see Barnum & Bailey’s in all its glory, she decided to run away with the circus and wear spangled tights and do trapeze-work under the Big Top. She even escaped from official guardianship long enough to offer a burly elephant-feeder two thoroughbred Shetland ponies and what was left of her spending-money for the privilege of being smuggled away in one of the band-wagons. The burly feeder took pains to explain that their next move was into winter quarters at Providence, but gravely assured the rapt-eyed girl that he’d fix the thing up for her, once they went out under canvas again in the spring. So for months poor deluded Teddie secretly and sedulously practised chinning the bar and skin-the-cat and the muscle-grind, together with divers other aerial contortions, only to learn, when the crocuses bloomed again, that elephant-feeders weren’t persons one could always depend upon.

About this time the era of indigestion and temperament came along, the era when Teddie began to betray an abnormal interest in what might repose on the buffet, and queen-olives fought with chocolate éclairs, and pickled walnuts combined with biscuit Tortoni to dispute the ventral supremacy of broiled mushrooms. It was the era when capon-wings and melon mangoes were apt to be found wrapped up in embroidered towels with insets of Venetian lace, and tucked in under the edges of the oppressively big colonial mahogany bed with the pineapple posts, and bonbon-boxes obtruded from the corners of a much becushioned bergère, and salted almonds mysteriously transferred themselves from below stairs to the lacquered jewel-box in a lilac-tinted boudoir. This occurred about the time that her mother so zealously took up the study of genealogy and had an entirely new crest made for the family stationery and even neglected her club work and her charity organizations to trace out the little-known intermarriages in the house of the Romanoffs. And it was about the same time that her dreamy-eyed father, who had been born to more millions than he cared to count, “gave up dining out to count electrons,” as Uncle Chandler expressed it. For Teddie’s father was an amateur mathematician and scientist who had made two highly important discoveries in light-deflection, highly important in only an abstract and theoretical way, as he was at pains to point out, since like the Einstein Theory they could never by any manner or means affect any object or any person on this terrestrial globe. It was sufficient, however, to convert him into what Uncle Chandler denominated as “an eclipse-hound,” which meant that he and his complicated photographic paraphernalia went dreamily and repeatedly off to Arizona or upper Brazil or Egypt or the Island of Principe.

And this brought about the divorce in the Hayden family, the old Major sturdily maintained, not an out-and-out Supreme Court one, but an astral one, with a twelve-inch telescope as a co-respondent. However that might have been, it left Trumbull Hayden a very faint and ghostly figure to his daughter Theodora Lydia Lorillard, who had her own natural and inherited love for solitude, but could never be alone, just as she could never be free. For always, when she moved about, she did so with a maid or a governess or a groom at her heels. And to add to her misery and her despair of final emancipation, the régime of the governess and the tutor and the dancing-master crept stealthily upon her. It was her second tutor, an Oxford importation with a hot-potato accent and a pale but penetrating eye, whom Teddie adroitly tied up in one of the big library fauteuils and refused to liberate until he had duly recounted the entire story of The Pit and the Pendulum, with The Fall of the House of Usher put in for good measure. And two days later, during tea on the terrace, she put smelling-salts in his cup, the same being not only punishment for an unfavorable conduct-report, but a timely intimation that tittle-tattlers would have short shrift with her.

Then came other tutors and teachers and governesses, each determined in character and each departing in time with a secret consolation check from Uncle Chandler and the conviction that Miss Theodora was anything but the gift of God. And then came boarding-school, boarding-school from which so much was surreptitiously expected. But from this first boarding-school, which had castellated eaves and overlooked the Hudson, Teddie was brought back by her Uncle Chandler in disgrace and a peacock-blue landaulet. A year later the attempt was renewed, it is true, this time in a Quaker establishment with a Welsh name and an imitation Norman arch over its main entrance. But this school, besides being ultra-fashionable in name was also ultra-frugal in all matters of menu, and Teddie proved so successful in playing cutthroat poker for “desserts” that seventeen extraneous sweets in one week did not and could not escape the attention of the quiet-eyed maiden-ladies in attendance. So this, added to the gumming up of one of the grand-pianos in the practise-room with five pounds of prohibited chocolate-creams, led to an interview with the lady-principal herself. And even that interview might not have been a valedictory one had Teddie not been detected perusing a copy of Daudet’s Jack during an ancient-history “period,” a Daudet’s Jack from which was unearthed an excellent caricature of the lady-principal herself. So Teddie awoke still again to the discovery that her dream of personal freedom was merely an ignis fatuus, and she journeyed homeward, a melancholy loss to the basket-ball team and an even more melancholy accession to the paternal acres at Tuxedo.

Nor was the spirit of the home circle very greatly brightened when Teddie attended her first holiday party in the white and gold ballroom of the St. Regis, where she danced very badly with very dignified young partners in Eton jackets. There she not only stumbled on to the bewildering consciousness that there was something vaguely but ineradicably different in boys and girls, but publicly punched one of the older youths in the eye for holding her in a manner which she regarded as objectionable. And later in the same evening, when the still older brother of the thumped one sought to make family amends by the seeming honesty of his apologies, and Teddie relentingly agreed to let bygones be bygones, and they shook hands over it, man to man, as it were, and while Teddie stood studying a hawthorn rose-jar on one of the tulip-wood consoles, that same persistent youth, seeking to translate a moment of impersonal softening into a movement of personal appropriation, cheerfully and clumsily tried to kiss her. Whereupon, let it be duly noted, Theodora Lydia first enunciated her significant, her perplexed, and her slightly exasperated query: “Are all boys like that?”

Yet by the time the governess-cart had been stowed away and Teddie had learned there was little use being a millionaire’s daughter, after all, since the third pound of Maillards never did taste as sweet as the first, her butternut-brown showed a tendency to fade into magnolia-pink with a background of gardenia-white, and certain earlier boy-like straightnesses of line took unto themselves mysterious contours, and the runway of freckles that spanned the bridge of her adorable little nose faded like a Milky Way in the morning sky.

And that meant still another era, the era of solemnly visited shops in the City, and muffled and many-mirrored salons where she was pinned up and snipped at and pressed down, and sleepy afternoon concerts that smelled of violets and warm furs and over-breathed air, and a carefully selected matinée or two, and even revived lessons in dancing, which, oddly enough, the resilient-spirited Teddie never greatly took to. And then came equally sedate and carefully timed migrations to Lakewood and Aiken and Florida, though Teddie openly acknowledged her dislike to traveling with a retinue and seventeen pieces of baggage, to say nothing of the genealogical books and the case of certified milk.

But there were quite a number of inexplicable wrinkles in Teddie’s mental make-up. Although to the manner born, she entertained a fixed indifference toward animals and a disturbingly bourgeois admiration for machinery. Horses bit at you as you passed them, and dogs were rather smelly, and Guernsey cows put their heads down and tried to horn you if you went near them in scarlet sports-clothes. But a machine was a machine, and did only and always what it was ordained to do. If you took the trouble to understand it and treat it right, it remained your meek and faithful servant. Restoring the viscera of disemboweled traveling-clocks, in fact, gave Teddie many repeated lessons in patience, and one of her pleasantest rainy-day occupations was to dissect and then reassemble one of her father’s larger and more expensive lucernal microscopes.

And this tends to explain why Teddie, even before her toes could quite reach the pedals, was able to run the Haydens’ big royal-blue limousine. On one glorious occasion, indeed, and quite unknown to her deluded family, she chauffed in secret all the morning of Election Day, chauffed for the Democratic party, with strange banners encircling that dignified vehicle and even stranger figures reposing therein, to say nothing of a tin box of champagne-wafers and a brocaded carton of candied fruit on the driving-seat beside her.

But her Uncle Chandler, who was a staunch Republican, beheld that alliance with the treacherous enemy and rescued the royal-blue limousine from ignominy while Teddie was regaling herself on three ice-cream sodas in a corner drug store. Being less expert at such things than he imagined, however, Uncle Chandler steered the big car into a box-pillar, and broke the lamps, and dolorously entered into a compact with his niece to the end that the doings of the day in question might remain a sealed book to the rest of the family. For Uncle Chandler resolutely maintained, when Teddie was not in hearing, that the girl was a brick and a bit of a wonder, and that he hoped to heaven life wouldn’t tame her down to a chow-chow in permanent-wave and petticoats.

“The fact is,” he was in the habit of saying to Lydia Hayden, “I can’t possibly conceive how two every-day old oysters like you and Trummie ever came into possession of a high-stepper like Theodora”—though, mercifully, he never imparted this bit of information to Teddie herself. For Teddie was quite hard enough to live with, even as things were. She rather hated the town house on the Avenue, which she openly called a mausoleum and agreed with her absent father that the one redeeming feature about brownstone fronts was the fact that the brownstone itself could never survive more than a century. She was, as her mother sorrowfully and repeatedly acknowledged, without a sense of the past, for she mocked at that town house’s crystal chandeliers and its white marble mantels and the faded splendor of its antique gold-and-ivory furniture, which looked as though it had come out of the Ark and made you think of Queen Victoria with a backache. When the spreading tides of commerce crept to and even encircled their staid party-walls and a velour-draped art-emporium opened up beside them, Teddie protested that she wasn’t greatly taken with the idea of living next to a paint shop. For it was about this time that she first threatened to become a trained nurse or a Deaconess if she had to have balsam-salts in her bath and a maid to chaperon the faucet-flow and poke her feet into rabbit-skin bags. She still hungered for freedom, and complained to her Uncle Chandler about “having to punch a time-clock,” as she put it, and more than once had been found enlarging on the Edwardian nature of her environment.

“Poor mother, you know, hasn’t a thought later than 1899,” this apostle of the New had quite pensively averred.

“There were some very respectable thoughts in 1899, as I remember them,” her Uncle Chandler had promptly responded, vaguely aware of little black clouds on the sky-line.

“Yes, that’s what’s the matter with them,” acknowledged Teddie. “They were too respectable. They were smug. And I despise smugness.”

The wrinkled-eyed old dandy contemplated her with a ruminative and abstracted stare.

“You’re right, Teddikins,” he finally agreed. “We all get smug as we get older. That’s what that chap—er—that chap called Wordsworth tried to tell us once. Life, my dear, is a waffle-iron that shuts down on us and squeezes us into nice little squares like all the other waffles in the world. It will come and take even the immortal You-ness out of you. It tames you, Teddie, and trims you down, and turns you out an altogether acceptable but an altogether commonplace member of society. It converts you from a gooey savage into a genteel and straight-edged type. So if you can’t quite jibe with the mater, don’t take it all too tragically. There’ll be a time when Little Teddie Number Two will feel exactly the same about you, and——”

“You’ll never see me idiotic enough to get married,” interrupted Teddie.

“Well, there’s lots of time to think about that. But in the meantime, my dear, don’t break the Fifth Commandment, even though you have to bend it a little. And on the way out I’m going to remind Lydia about that roadster I’ve been telling her you ought to have. It’s wonderful what a lot of steam you can let off in a roadster of your own!”

Teddie, in time, came into possession of her roadster, a small wine-colored racer upholstered in dove-gray and neatly disguised as a shopping-car. And it seemed, during the first few weeks of its ownership, that the wings of personal freedom had finally been bestowed upon the recalcitrant Teddie, who went hillward in her roadster with claret and caviar sandwiches packed under its seat and went cityward with fat and disorderly little rolls of bank-notes tucked under its cushion-ends. She loved that car, for a fortnight at least, with a devotion that was wonderful to behold, and talked to it fraternally as her narrow-toed brogan spurred it into slipping past dust-trailing joy-riders on the back roads, and wept openly when it blew a tire and buckled a radius-rod in the ditch, patting its side sympathetically and saying soothing little words to it as though it were an animal.

But time, alas, proved to Teddie that her Château en Espagne was not to be reached on rubber tires. For a car, after all, is only a merry-go-round with an elastic orbit, a humdrum old merry-go-round that isn’t so merry as it seems, since it must always cover the same old roads and the same old rounds and remain hampered and held in by the same old urban and suburban regulations. Teddie, it is true, soon found herself on nodding terms with the Park “canaries” and the traffic cops, and was able to weed out the ones who’d give her the wink when she forgot about the one-way streets and the parking signs and the speed-laws in general. Yet three times in one season she shocked Tuxedo Park by appearing in court and being twice fined for road violations and once publicly lectured for imperiling the peace and safety of the commonwealth.

So even with the machinery which she loved she began to see that she was still restricted and hampered and circumscribed and imprisoned. And the poor little rich girl who should have been quite happy, remained quite normally and satisfactorily and luxuriously miserable.

CHAPTER TWO

The Friday Junior Cotillions for the “Not-Outs,” in those older days when the Banquet-Room at Sherry’s was still a beehive of youth and beauty, had no particular appeal to a girl who preferred spanners and monkey-wrenches to dance-favors. And even the charity-façaded carnivals of the Junior League, which couldn’t be open to her before she “had gone down the skids” (as Teddie flippantly phrased her long-discussed début), stood without that glamour which consecrated them to the humbler-born social climber. For the Tuxedo and Meadow Brook colonies, Teddie had always mistily understood, were the salt of the earth and the elect of the Social Register. Many a time, indeed, with amused and indifferent eyes she had witnessed the gentle art of freezing-out exercised at even so romping a thing as the Toboggan Slide, and many a time, warm in her own security, she had beheld the tennis and squash courts translated into frigidities which left Dante’s Seventh Inferno sultry in comparison. Yet she heard diatribes on the new-rich with a rather disdainful indifference, for not a few of these Want-to-Be’s seems much handsomer to the eye than most of the Have-Beens, to say nothing of being brighter and brisker. Teddie, in fact, nursed a secret disdain for the hereditary millionaire, since it was the dullness of the brood, she maintained, which was embittering her blighted young life. For Teddie still chafed against the bars of her gilded cage and nursed the pardonably human illusion that the thing you can’t quite get is the thing you must have.

Now, most girls of Teddie’s set and inclination escape from their adolescent boredom by excursion into amorous adventure. But Teddie felt that she had exhausted love very early in life. For at the tender age of nine she had fallen in love with the Park policeman who’d so easily gathered her up in his arm after a fall on the Bridle Path just under the Seventy-Second Street bridge, where the deep shadow of the arch gave too abrupt a change from sunlight to gloom and caused her horse to swerve, buck, and then bolt riderless as far as the Sheep-fold. But it was Officer McGlinchy who picked up Teddie, with what he described as “a foine bump on the bean,” little dreaming that through his purely official and impersonal ministrations he was bruising Teddie’s heart almost as badly as the Bridle Path had bruised her head. Teddie’s passion remained a secret one, it is true, but the promised vision of the statuesque Patrick McGlinchy gave a new interest to her morning canter along the Bridle Path and a richer coloring to the sward and rocks of Central Park. It was not until she was on the eve of forlornly engineering still another fall in the neighborhood of that over-taciturn officer that Teddie learned McGlinchy was sedately married and the father of seven little McGlinchys down in the Ninth Ward.

Then she fell in love with Biquet, the second chauffeur, who had been a flying-man and had a slashing wound of honor across his well-tanned young cheek-bone. But her feeling for Biquet proved an odd confusion of issues, for she found that she liked him only when he permitted her to assist in eviscerating one of the car-engines or let her help overhaul and assemble the landaulet’s differential, with her ready little paws covered with oil and axle-grease and her white corduroy frock as black as a sweep’s. But she realized, on witnessing Biquet kissing the pantry-maid, one night when blockade-running for certain residuary oyster pâtés, that it was not really Biquet she loved, but the machinery over which he presided.

There was a time, too, during this period of potential romantic alliances, when she might possibly have entertained some tenderer feeling for Gerry Rhindelander West, her next-door neighbor whose grilled iron gateway in the midst of its manorial stone wall was quite as munificent as her own. But Gerry disappointed her. He primarily disappointed her by meanly resorting to the habit of addressing her as “Nero” (the soubriquet of a Great Dane of uncertain temper owned by her mother) after Teddie had bit him on the wrist when forcibly held down in a bitter struggle to recover from her possession a domesticated and one-eyed Russian rat which had been, indiscreet enough to invade the Hayden estate. And he finally disappointed her by abandoning his fixed intention of becoming an engine-driver and deciding to waste a once promising young life on due preparation for the study of law. Gerry, it is true, later on attempted to revive this blighted romance by bombarding her with purple-tinted boxes of English violets done up in glazed paper and surmounted by small and neatly addressed white envelopes, and sometimes with striped boxes so big they looked like baby-coffins, except for the thorny stalks which protruded from one cut-away end, until the matter-of-fact Teddie reminded him that he was wasting a tremendous amount of money, as her mother’s head-gardener grew those things in abundance. So before retiring into his professional shell Gerry was at pains to point out, in a somewhat stilted little note, that he had quite overlooked the etymology of “Tuxedo,” which he found to be an Algonquin word derived from “Tuxcito,” which in the original language meant “the meeting place of bears”—with the “bears” heavily underlined.

But the fact that Gerry essayed little more than a stiff bow as he passed by did not greatly trouble Teddie, for about this time she fell secretly in love with an Episcopalian curate of delicate health and indescribably melancholy eyes, a young man with a face like a Shelley and an audible and asthmatic manner of breathing. And at the same time that he sobered Teddie down a great deal his health improved perceptibly under Teddie’s arduous campaign of forced feeding. She even extended those ventral activities to the despatching of marrons and bar de luc to hospital wards, and spoke of giving up her life to prison reform, and argued on the beauties of the monastic life, and for a time considered taking the veil. But the Shelley with the melancholy eyes unfortunately developed a cough and for the sake of his health was transferred to a curacy in southern California. This deportation gave every promise of fanning the flame which it should have tempered, translating the exile into a figure ideally romantic—until Teddie learned that on his western migration he had inconsiderately married a certain ex-contralto of the First Presbyterian Church who had graduated into the Chautauqua Circuit.

Teddie thereupon threw herself into golf and spent whole days on the Tuxedo links, and the gardenia-white once more darkened down to the beechnut brown. She became as hard as nails, both in body and spirit, and did her best to forget to remember her asthmatic young curate’s pet story of the Bishop who said “Assouan” every time he fuzzled the turf, because Assouan, of course, was acknowledged to be the biggest “dam” in the world.

But the time came when Teddie was tired of golf, just as tired of making the rounds of her eighteen holes as she was of making the rounds of the circular ballroom of the Tuxedo Club with fox-trotting youngsters and sedately waltzing oldsters. She was tired of dinners at Table Rock, and tired of seeing the “No-One-Admitted-Without-Permit” signs, and tired of the Meadow Brook steeplechase, and tired of the stately and stupid dinners in town. She was tired of life and tired of even herself. But most of all she was tired of that complicated machinery of existence in which she found herself so inextricably enmeshed. She still dreamed of liberating herself from that ponderously engineered intricacy of protectional pulleys and powers. But even while she felt that she was encaged, encaged as a pulsing hair-spring is encaged in a watch-case of smothering gold, she scarcely knew which way to look for escape. She caught a momentary breath or two of freedom, it is true, by boldly introducing motor-polo within the “No-Admittance-Without-Permit” precincts, a brand of sublimated polo played with a football from a runabout with a stripped chassis. But the gardeners and the board of governors united in objecting to the havoc wrought to the Club turf, and Monty Tilford broke an arm in one of the collisions, so a ban was put on what might have proved a belated safety-valve for Teddie’s spiritual steam-chest.

Still later, however, when her mother was undergoing hydropathic revision in Virginia, she made one last and listless effort to escape by taking up flying. This she did sub rosa and under an assumed name, and might have medicined her mysterious ailment with tail-spins and altitude-tests, but she suffered inordinately from nose-bleed and was unfortunately snapshotted for one of the Sunday papers the same week that she taxied into a signboard—which demanded appallingly expensive repairs to the machine and involved a cracked patella and a month or two with a crick in her knee, though it was a rather ridiculous three-hundred-word telegram from Virginia which really dissuaded the hangar authorities from continuing the services of their ruthlawing young novitiate.

And it was then that Teddie tipped over the apple-cart. It was then that she broke jail, and bolted, and took her life in her own hands.

She took her life in her own hands, as even humbler prisoners of circumstance had done before her, by allying herself with Art. She abjured the parental roof, leased a studio in the well-policed wilderness of Greenwich Village, and announced that she intended to express herself through the pure and impersonal medium of dry-point or modeling-clay. She wasn’t quite sure which it was to be, but that was a matter of secondary importance. She panted for freedom and she didn’t stop to worry over what particular hand was to bring about her liberation. She installed the wine-colored roadster in a down-town garage (to be taken out rarely and rather shamefacedly), and bought a Latin-Quarter paint-smock and bobbed her hair and learned how to make her own coffee and manipulate a kitchenette gas-range without smothering herself.

And her old Uncle Chandler, on becoming duly acquainted with this state of affairs, assented to everything but the bobbing of the hair, which he regarded as much too lovely hair to be snipped off anybody’s head. He even put the seal of his approval on her insurrection by sending down to her a hamper of potted truffles and brandied peaches.

Yet he stood aghast, the next day, when these were duly returned to him. That reversal of form, in fact, so disturbed him that he couldn’t get Teddie out of his mind, for a Teddie without an appetite was a Teddie who was no longer her old self. And the more he thought about it the more he realized that it was his plain and bounden duty to go down to Greenwich Village and investigate.

“The fact of the matter is,” he confidentially acknowledged to old Commodore Stillman before the hickory-logs of the Nasturtium Club, “that girl’s a demmed sight too good-looking to be left lying around loose!”

“Oh, the kid’ll take care of herself all right,” ventured the Commodore, with rather vivid memories of a freckled young Artemis making a polo-pony jump the tennis nets out at the Park. “And the learning how will help her. It will help her considerable!”

CHAPTER THREE

The old Major, a little out of breath from the stairs, was glad of the chance to sit down and recover himself. He was also glad that he had found the roughly scrawled “Back at Two” sign on the door and the studio still empty, for when Teddie was about there was always small chance of studying anything beyond Teddie herself.

So, having returned to a normal manner of respiration, he proceeded to a quiet but none the less critical examination of the premises. He was disturbed, on the whole, by the baldness of the dingy-walled old studio with its broken and paint-spattered floor and its big north window entirely out of alignment. There was a long cherrywood table pretty well littered with brushes and paint-tubes and boxes of pastels and a wooden manikin and various disjointed portions of the human figure reproduced in plaster-of-paris. And there was an easel, and an armchair draped in faded brown velvet, and a number of hammered brass things, and a castered model-platform, and a bedraggled blue canvas blouse over a chair-back, and many drawings of very lean ladies and very muscular young gentlemen thumb-tacked to the walls. And behind the studio, to the right, was a much more orderly kitchenette, and, to the left, a rather nun-like little sleeping-alcove with a couch-bed about as wide as a tombstone.

Uncle Chandler sighed with relief, for he had resolutely keyed himself up to expect what he’d called “a goulash of the Oriental stuff,” with ruby lanterns and draped divans and punk-sticks in jade bowls. But Uncle Chandler found himself in what looked more like a workshop than a palm-reader’s parlor, and the frown of trouble lightened a little on his wrinkled old forehead. He even took up an oblong of draughting-board and was studying a pea-green omnibus going under a café-au-lait Washington Arch which veered a trifle to the right when the door opened and Teddie herself came in with a big pigskin portfolio under her arm.

“Hello there, Teddie,” he said guardedly, as he watched her unspear a turban-thing of twisted velvet from her bobbed hair.

“Hello, Uncle Chandler,” she rather indifferently responded as she put the pigskin portfolio on the cherrywood table. “How’s the haute monde and your sciatica?”

“How’s l’art pour l’art?” almost tartly responded her uncle, noting, however, with undivulged satisfaction the clear crispness of her movements and that she was thinner than usual, with an adorable little Lina-Cavaliera hollow in the center of the cheek where the butternut-brown had once more blanched into a magnolia-white.

Teddie laughed, without deigning an answer.

“How about some tea?” she said instead. And without waiting for his reply she lifted out a battered old samovar and pushed the cigarettes toward his end of the table as she proceeded, somewhat more deftly than her visitor had anticipated, with the business in hand.

“About those peaches and truffles, Uncle Chandler,” she said as she stooped to adjust the flickering blue flame. “I sent them back because I’m out of the flapper class now. It was kind of you, of course. But I’m no longer a schoolgirl. I’ve cut out that boarding-school stuff. I intend to be something more than a Strasbourg goose, and if I’m suffering from any sort of hunger, it’s more a hunger of the soul than of the body.”

This was a new note from Teddie, and not unlike most newnesses, it came with a slight sense of shock.

“My dear girl, I was only trying to get even with you for that—that delightful little water-color of the Palisades above Fort Lee. It was clever, my dear, and I always did like our Hudson River scenery.”

Teddie stood up straight. She stood inspecting him with a cold and slightly combative eye.

“That was the Flatiron Building in a snow-storm,” she somewhat frigidly explained.

“Ah!” said the astute old Major, settling into the brown velvet armchair. “That’s what I said, all along. That’s precisely what I told Higginson. And Higginson, who is always a bit bullheaded, y’ understand, insisted that it was Palisades, saying he’d lived on ’em all his life and ought to know. But I didn’t come here to talk about Higginson. I came here to find out how you’re getting along.”

This was a question which Teddie found necessary to sit back and consider carefully.

“You see, Uncle Chandler, I’ve so much to unlearn! You can’t keep a girl under glass most of her life and then expect her to horn in where the dairy-lunchers learned the game in their infancy.”

The Major winced a little. Here was still another newness to disturb him, a newness not so much of phraseology as of outlook.

“This is a new life,” Teddie gravely continued, “and I’ve got to get in step with it or get walked over. There are people down here who have the gift of making poverty romantic, people who can turn an empty pocketbook into a sort of adventure. They can eat onion soup and spaghetti au gratin and wash cold-storage capon down with that eau-de-quinine stuff they drink and be happy on it because they know they are free, free to express themselves as they want to express themselves, free to work and live and think, and come and go as they like. And that’s wonderful, Uncle Chandler, when you come to think of it.”

Uncle Chandler sat thinking this over, with no ponderable amount of enthusiasm on his face.

“And just how do you intend expressing yourself?” he asked as the samovar began to bubble.

“I think it will be in color,” said Teddie with the utmost solemnity. “I began with modeling, but it was rather messy, and I didn’t make much headway. I’m beginning to feel that pastel or dry-point is more my penchant. Raoul Uhlan is giving me three lessons a week.”

“That big stiff!” ejaculated the philistine old Major.

“He’s one of the cleverest painters in New York,” Teddie calmly explained.

“And a professional tame-robin who gets portrait commissions, I understand, because he can dance like a stage acrobat!”

“I know nothing about his dancing,” remarked Teddie, with her eyebrows up. “But I do know it’s sinful the way the children of our idle rich are kept cooped up and shut away from real life. They’re hemmed in with a lot of silly old taboos. They’re laced up in a straight-jacket of social laws until they’re too flabby to face a personal dilemma that an East Side shop-girl could decide before she’d finished powdering her nose.”

Uncle Chandler took up his teacup and then put it down again.

“I rather fail to see what the personal predicaments of shop-girls have got to do with the matter,” he said with some acerbity. “You’re a Hayden, the third wealthiest woman in Orange County, and a girl who’s had every comfort that money and machinery can give her. Yet you leave a home that cost about two-thirds of a million—without counting those cross-eyed marble lions your mother brought over from Florence for the Sunken Gardens!—and come down here into this moth-eaten backyard of the Eighth Ward and live on macaroni and red ink and dream that raw life is being dished up to you on the half-shell. You talk about liberty and expressing yourself, and all you’re doing is slumming, just slumming!”

Teddie smiled. It was a languid smile and a superior one.

“Uncle Chandler,” she remarked, “you really don’t know what you’re talking about. In the first place, I’ve decided that in one day you can see more life, real life, out of that crooked old window there than you could discern in Tuxedo Park in a century.” She ushered him toward the casement in question. “Look at that Italian woman with the bundle of clothes on her head. And those kids crowding about the hokey-pokey man. And that gray-headed old candy-seller with the feather-duster in his hand. And that white hearse with the white angel kneeling on the top and that line of bareheaded Dago mourners marching along just as you’d see them in Naples or Ancona. And look at that wagon-load of crated geese that have just come from the Gansevoort Market, with their necks craned out between the slats. Why, those poor things are fighting for liberty just about the same as I’ve been fighting for it!”

“And about as effectively,” remarked Uncle Chandler.

“Well, whose funeral is it, anyway?” demanded Teddie, with her first touch of impatience. “This happens to be my show, and I happen to be running it in my own way. I know what’s ahead of me, and I’m going straight for it.”

Teddie’s uncle was able to smile at the uncompromising ardor of youth. But there was a touch of impatience in his movements as he crossed over to what he hoped might prove a more comfortable chair. He had no intention of letting a snip of a girl Cook’s-guide him about his own city, the city he’d lived in for some sixty-odd years. And he wasn’t such a stranger to Greenwich Village as she imagined, for through the mists of time he could still remember Ned Harrigan and Perry Street, and Sim Sharp and certain Tough Club chowders of the olden and golden days.

“So you’re going straight, are you?” he snapped out, with only the light in his kindly old eyes to contradict the bruskness of his speech. “Well, all I have to say is that you’re a wonder if you can go straight in a district like this. Good gad, ma’am, even the streets don’t go straight down here. They’re as deluded as the benzine-daubers who tramp them. And it may be none of my business, but I’ve an itch to know what’s going to happen to a high-spirited girl who’s veering dead south when she dreams she’s heading due west.”

“And that means,” suggested Teddie, “that you propose to hang around to see what’s going to happen?”

“On the contrary, young lady, I’m going down to Hot Springs to-morrow morning to get some of the acid steamed out of my knee-joints. You’re old enough to do as you like. I’ve always admitted that. And I’ve talked to Trummie about it, before he got away. I’ve talked to your dad. And he remarked that it wasn’t a matter of such tremendous importance, after all, since he has just figured out that the planet on which we at present subsist will be completely obliterated in some six million years. And he seems to be more interested in Betelgeuse, at the moment, than he is in Greenwich Village. But I repeat that you’ve come into a crooked part of this old Island for any straight-cuts to freedom. You’ll do just what the streets do down here: you’ll get all twisted up. Just look at ’em! Look at ’em, I say. You’ve got Tenth Street doubling round and running into Fourth Street, and Waverley Place going in four directions at once—the same as the folks who live in it! They don’t know where they’re at, none of ’em. And even the upper side of your Square here is not only Washington Square North, but also Sixth Street, and at the same time also Waverley Place again. And the east side of your same old Square is University Place down as far as Fourth Street, and then without rhyme or reason it calls itself Wooster Street. And your south side is really Fourth Street, but on Fourth Street proper the numbers increase from east to west, but on what is really the same street called Washington Square South your numbers increase from west to east. And your Square isn’t even a square, but a rectangle. And if you can straighten all that out in your beautiful little bean you know your old New York a trifle better than I do—and that, I acknowledge, would be going some.”

“But I’m not interested in the streets and the mail-directory numbers,” Teddie patiently explained. “What I’ve been talking about is the spirit of the place, its aura.”

“Yes, I got a sniff of it as I came through that Italian settlement,” acknowledged Uncle Chandler. “And it was quite a penetrating aura.”

“But you’re only croaking out of a swamp of prejudices,” contended Teddie. “You don’t understand our ways of living or looking at life. You try to gauge Greenwich Village, which was once good enough for Poe and Masefield, by Fifth Avenue standards, and you get your numbers mixed.” She looked up at him with a more commiserative light in her earnest young eyes. “But if you want to see us as we are, why not take chow with me at the Blue Pigeon to-night?”

“Not muchee!” averred Uncle Chandler, with great alacrity. “I’ve altogether too much respect for my Fifth-Avenuey Little Mary. I’ve seen ’em before, those futuristic smoke-boxes with a tinned sardine rolled up in a pimento-skin and Mimis from Waterbury and up-State Villons who muss their hair and get mixed up on the garlic and free-verse. So, much as I love you, Teddie, I’ll toddle along to my benighted old Nasturtium Club and deaden my soul on Green Turtle clear and Terrapin, Philadelphia style, and breast of Chicken Fincise with sweet potatoes Dixie, and new peas Saute, and an ice and coffee to end up with.”

Teddie tried to look indifferent. But it took a struggle. For her Uncle Chandler had rather disdainfully picked up an oblong of cardboard and sat inspecting it with a none too approving eye.

What he inspected was a crayon sketch of an extremely muscular right arm and shoulder, a right arm and shoulder which at least demanded some qualified respect. But his grizzled old eyebrows were closer together as he looked up at Teddie again.

“Did you say you drew from models?” he casually inquired.

“Of course,” acknowledged Teddie, pausing long enough to answer her telephone and explain that she and not the landlord had ordered the new glass for the skylight.

“You don’t mean to say you have men come up here and—and expose their muscles for this sort of thing?” demanded Uncle Chandler, with a gesture toward the ample biceps in crayon.

Teddie laughed.

“Oh, no, that wasn’t a professional model. That’s the arm of Gunboat Dorgan, the prize-fighter. I sketched that the other afternoon when he was up here with Ruby Reamer, one of my regular models. He’s Ruby’s steady, as she calls it. She’s very proud of him, and had him showing me some of his stunts. So I thought it would be a good chance to get a study of an arm like that. And Gunnie—that’s what Ruby calls him—isn’t a bit like what I thought a prize-fighter would be. He’s rather a bright-minded boy, and a little shy, and if he wins the lightweight bout from Slim Britton, the English boxer, he’s going to marry Ruby and take a flat down on Second Avenue.”

“But you say he’s a fighter, a ring-fighter?”

“Yes, that’s how he makes his living. He’s quite serious about it all, and trains hard, and plans about working his way up, just as a man in any other profession would.”

Uncle Chandler sat thinking this over. He would have done considerably more thinking if he’d been in possession of the information that his niece had already allowed this same prize-fighter to pilot her and Ruby and the wine-colored roadster out to a sea-food dinner at a Sound road-house. But even as it was, Uncle Chandler seemed sufficiently upset.

“Say, Teddikins,” he somewhat grimly remarked out of the silence that had fallen over the darkening studio, “what d’you suppose your mother would think about all this?”

“I’m not in the least interested in what mother thinks about it,” was Teddie’s altogether irresponsible and wilful rejoinder.

The old Major, who had already risen to go, turned this speech over, turned it over with great deliberation. Then he sat down again.

“It’s not so much Lydia, my dear,” he said. “It’s what poor old Lydia embodies, the organized entrenchments that surround young girls, the machinery of service that may shut you in, but at the same time does things for you and gives you something to fall back on when the pinch comes!”

“But I don’t understand what you mean by the pinch,” Teddie told him, straightening the gardenia that stood so stiff and straight in his coat-lapel. For she liked her Uncle Chandler, and she liked him a lot. And she was a little disturbed by the look of anxiety that had come into his worldly-wise old face.

He stared at her for a moment, shrugged his shoulders, and took up his hat and stick.

“You’re all right, Teddie,” he announced with decision as he solemnly kissed her on the cheek-bone. “But—but I wish somebody was looking after you when I’m down there being boiled out.”

This made Teddie laugh. She not only laughed, but she extended her arms, like a traffic-officer stopping a jay-driver, or a young eagle trying its wings.

“But I don’t need any one to look after me, thank heaven! I’m free!”

The old Major stopped at the door.

“And you feel that you can manage it all right? That you can——”

For reasons entirely his own he did not finish the sentence.

“I am managing it,” the girl quietly asserted.

And Uncle Chandler, in finally taking his departure, experienced at least a qualified relief. The girl was wrong, all wrong. And what was worse, she was much too lovely to the eye to remain unmolested by predaceous man. But she had a will of her own, had Teddie. And, what was more, she might have gone to Paris to “express herself,” as she called it. Or she might have tried to find her soul by going on the stage. And the Major knew well enough what that would have meant. After all, the girl would learn to scratch for herself. She would have to. And as old Stillman had intimated, it might do her a world of good!

CHAPTER FOUR

Teddie, as a matter-of-fact girl, had scant patience with the undue attribution of the romantic to the commonplace. Yet the manner in which she had first met Raoul Uhlan, it must be admitted, was not without its touch of the picturesque.

Teddie, still a little intoxicated with her new-found liberty, and further elated by the sparkling morning sunshine of Fifth Avenue, was swinging smartly up that slope which an over-busy world no longer remembers as Murray Hill. She was in a slightly shortened blue serge skirt that whipped against her slim young knees suggestively akin to the drapery of the Nike of Samothrace, and was just approaching the uplands of the Public Library Square when she caught sight of a violet-peddler.

A glimpse of the seven earthy-smelling clumps of bloom, buskined in tin-foil and neatly arranged on their little wooden tray, promptly intrigued the girl into stopping, fumbling in her none too orderly hand-bag, and passing over to the sloe-eyed Greek a bank-note with double-X’s imprinted on its silk-threaded surface. And having adjusted the sword-knotted clump to her belt by means of one of the peddler’s glass-headed pins, she looked up to see this same peddler contemplating the bank-note with a frown of perplexity. He was explaining, in broken English, that his exchequer stood much too limited to make change for a hill so big. Then, with a smile of inspiration, he placed the tray of violets in the girl’s hands, pointed toward a near-by store on the side-street, and plainly implied that he would break the twenty and return with more negotiable currency.

So Teddie stood patiently holding the tray of violets, in the clear white light of the sunny Avenue, happy in the flowery perfumes which were being wafted up to her delicately distended nostril.

But something else was at the same time being wafted in Teddie’s direction. It was a tall and handsome stranger in tight-fitting tweeds, carrying a cane and an air of preoccupation. There was lightness in his step, notwithstanding his size, and any unseemly amplitude of ventral contour was fittingly corrected by a tightly laced obesity-belt, just as the somewhat heavy line of the lips was lightened by a short-trimmed and airily-pointed mustache. For the stranger was Raoul Uhlan, and Raoul Uhlan was an artist, though any thoughtless motion-picture director who had dared to flash him on the screen as a type of his profession would have been held up to ridicule and reproof. But this particular artist, who was neither dreamy-eyed nor addicted to velveteen jackets, found the quest of beauty both a professional and a personal necessity. So when he beheld a young lady of most unmistakable charm standing beside a gray-stone retaining wall with a street-peddler’s violet-tray in her hands, he momentarily forgot about the prospective sitter from Pittsburgh with whom he was to breakfast. He hove-to in the offing, in fact, for the seemingly innocent purpose of buying a boutonnière. It would be gracious, he also decided as he soberly inquired the price of violets that morning, to give the little thing a thrill. For Raoul often wondered what it was about him that made him so attractive to women.

“One dollar a bunch,” soberly responded the little thing, in answer to his question, giving scant evidence of being thrilled. She was uncertain about prices, and her thoughts, in fact, were fixed on the matter of not cheating the humble and honest tradesman whose wares had been delegated to her hands. She noticed the strange man’s momentary wince, but never dreamed it arose from a confrontation with profiteering. She nonchalantly took his dollar, however, tucked it into one corner of the tray, and handed him the violets and the essential pin.

She was quite prepared to repeat the operation with a dandified old gentleman in pearl spats, who was hovering near, when an officer in uniform sauntered up and, being out of sorts with the world that morning, confronted her with a lowering and saturnine brow.

“Yuh gotta license t’ peddle them flowers?” he demanded.

Teddie, in no wise disturbed, explained the situation and further announced that the gentleman who owned the tray would return immediately.

Her urbanity, however, was wasted on the Avenue air.

“Yuh just made a sale to this guy here, didn’t yuh?” persisted the officer of the law, with a none too respectful thumb-jerk toward the immaculately tweeded figure with the over-sized bouquet in his button-hole.

“Yes, this is the dollar he paid me,” Teddie sweetly acknowledged.

“That’s enough,” averred her persecutor. “Yuh’re street peddlin’ without a license. So yuh’ll have to come along wit’ me.”

“But, odd as it may seem, I rather want my nineteen dollars,” maintained Teddie, with an intent gaze down the side-street.

“Your nineteen dollars and seventy-five cents,” corrected the man in tweeds, not forgetful of a recent extortion.

“Yuh’re likely to clap eyes on that Dago again, ain’t yuh!” The open scorn of the officer was monumental. “He’ll be spendin’ what’s left of his days tryin’ to ferret yuh out, I s’pose, wastin’ his young life away battlin’ to get that easy coin back to yuh! What he’s breakin’ now isn’t a twenty-dollar bill, my gerrl, but a travelin’ record down to the Third Ward. And I guess the sooner yuh come along wit’ me, and the quieter yuh come, the better.”

“But you really can’t do this sort of thing, you know, Officer,” the man in tweeds interposed. “This girl——”

“Yuh shut your trap,” announced the upholder of law and order, with an indifferent side-glance at the interloper, “or I’ll gather yuh in wit’ the dame here.”

“That’s an eventuality which I’d rather welcome,” averred the other, with his blood up.

“All right, then, come along, the both o’ yuh,” was the prompt and easy response. “And come quick or I’ll make it a double pinch for blockin’ traffic.”

But Raoul Uhlan, clinging to what was left of his dignity, insisted on calling a taxi-cab (which Teddie paid for when they arrived at the Forty-Seventh Street station-house) and in transit managed to say many soothing and valorous things, so that by the time Teddie stood before a somewhat grim-looking desk in the neighboring receiving depot for miscreants, her courage had come back to her and she didn’t even resort to home addresses and influences for a short-cut out of her difficulty. She soon had the satisfaction, indeed, of seeing her moody patrolman picturesquely berated by his higher official behind the desk, who apologized for retaining the dollar bill and the tray of violets and announced that as there was no case and no charge against her—which any one but a pin-headed flatty with a double-barreled grouch could have seen!—she was quite free to enjoy the morning air once more.

So Teddie sallied forth with a great load off her mind and with Raoul Uhlan at her side. And the latter, instead of breakfasting with the plutocrat from Pittsburgh who wished to perpetuate his obesity in oils, sent a polite fib of explanation over the wires which were more or less inured to such things, and carried Teddie off to luncheon at the Brevoort, where he learned that she was one of the Haydens of Tuxedo and had a studio on the fringe of Greenwich Village and wanted to paint. And before she quite knew how it had all been arranged it was agreed that Uhlan was to come three times a week and give her lessons in Art, for the sake of Art.

CHAPTER FIVE

It wasn’t until the third lesson that Teddie, even through her self-immuring hunger for knowledge, began to doubt the wisdom of her arrangement with Raoul Uhlan. She began to dislike the perfume with which this master of the brush apparently anointed his person, just as she detected a growing tendency to emigrate from the realms of pure Art to the airier outlands of more personal issues. She was as clean of heart as she was clear of head, and she resented what began to dawn on her as the rather unnecessary physical nearness of the man as he corrected her drawing or pointed out her deficiencies in composition. But his knowledge was undeniable, and his criticisms were true. She was learning something. She was unquestionably getting somewhere. So she refused to see what she had no wish to see. She endured the uliginous oyster of self-esteem for the white pearl of knowledge that it harbored.

But on the day after the talk with her Uncle Chandler, when the next lesson was under way, a new disquiet crept through her. The man seemed to be forgetting himself. Instead of studying her over-scrambled color-effects he seemed intent on studying the much more bewitching lines of her forward-thrust chin and throat. Once, when he leaned closer, apparently by accident, she moved away, apparently without thought. It both puzzled and disturbed her, for she had not remained as oblivious as she pretended to his stare of open hunger. Yet the intentness of his gaze, as he attempted to lock glances with her, turned out to be a bullet destined forever to fall short of its target. He was, in fact, wasting his time on a Morse-code of the soul which had no distinct meaning to her. He was lavishing on her a slowly-perfected technique for which she had no fit and proper appreciation. Teddie, in fact, didn’t quite know what he was driving at.

It wasn’t until she realized, beyond all measure of doubt, that the repeated contact of his shoulder against hers was not accidental that a faint glow of revulsion, shot through with anger, awakened in her. But her inner citadels of fear remained uninvaded. She had nipped more than one amatory advance in the bud, in her time. With one brief look, long before that, she had blighted more than one incipient romance. Her scorn was like a saber, slender and steel-cold, and she could wield it with the impersonal young brutality of youth. And it had always been sufficient.

When he stood close behind her, as she still sat confronting her sketch, and, as he talked, placed his left hand on the shoulder of her blue canvas blouse, and then, leaning closer, caught in his big bony hand her small hand that held the pencil, to guide it along the line it seemed unable to follow, she told herself that he was merely intent on correcting her drawing. But a trouble, vague and small as the worry of a mouse behind midnight wainscotting, began to nibble at her heart. For that enclosing big hand was holding her own longer than need be, that small horripilating disturbance of her hair was something more than accidental. The small nibble of trouble grew into something disturbing, something almost momentous, something to be stopped without loss of time.

She got up sidewise from her chair, with a half-twist of the torso that was an inheritance from her basket-ball days. It freed her without obvious effort from all contact with the over-intimate leaning figure. She even retained possession of the crayon-pencil, which she put down beside her Nile-green brush-bowl after crossing the room to the blackwooded console between the two windows.

“I guess that will about do us for to-day, won’t it?” she said in her quiet and slightly reedy voice as she proceeded, with deluding grave impersonality, to open one of the windows.

But he crossed the room after her and stood close beside her at the window. He towered above her in his bigness like something taurine, alert and yet ponderously calm.

“Why are you afraid of me?” he asked, with his eyes on the gardenia-white oval of her cheek.

“I’m not,” she replied with a crisp small laugh like the stirring of chopped ice in a wine-cooler. “I’m not in the least afraid of you.”

A less obtuse man would have been chilled by the scorn in her voice. But Uhlan was too sure of his ground, his all too familiar ground, to heed side-issues.

“It’s you who makes me afraid of myself,” he murmured, stooping closer to her. He spoke quite collectedly, though his face was a shade paler than before.

“You said to-morrow at three, I believe,” she observed in an icily abstracted voice. That tone, she remembered, had always served its purpose. It was conclusive, coolly dismissive. For she still refused to dignify that approach with opposition. She declined to recognize it, much less to combat it.

“Did I?” he said in a genuinely abstracted whisper, for his mind was not on what he said or heard. His mind, indeed, was fixed on only one thing. And that was her utterly defenseless loveliness. The blackness of his pupils and the aquiline cruelty about the corner of his eyes frightened her even more than his pallor.

But she did not give way to panic, for to do so was not the custom of her kind. She fought down her sudden weak impulse to cry out, her equally absurd propulsion to flight, her even more ridiculous temptation to break the window-panes in front of her with her clenched fist and scream for help.

For she realized, even before he made a move, that he was impervious to the weapons that had always served her. He stood beyond the frontiers of those impulses and reactions in which she moved and had her being. The very laws of her world meant nothing to him. It was like waking up and finding a burglar in the house, a burglar who knew no law but force.

So she wheeled slowly about, with her head up, watching him. There was a blaze like something perilously close to hate in her slightly widened eyes, for she knew, now, what lay ahead of her. Instinct, in one flash, told her what lurked beside her path. And her inability to escape it, to confront it with what it ought to be confronted with, was maddening.

“You Hun!” she said in a passionate small moan of misery which he mistook for terror. “Oh, you Hun!”

He could afford to smile down at her, fortified by her loss of fortitude, warm with the winy ichors of mastery.

“You adorable kid!” he cried out, catching the hand which she reached out to the window-frame to steady herself with.

“Don’t touch me!” she called out in a choking squeak of anger. And this time, as he swung her about, he laughed openly.

“You wonderful little wildcat!” he murmured, as he pinned her elbows close to her sides and drew her, smothered and helpless, in under the wing of his shoulder.

For a moment or two she fought with all that was left of her strength, writhing and twisting and panting, struggling to free her pinioned arms. Then she ceased, abruptly, devastated, not so much by her helplessness as by the ignominy of her efforts. She went limp in his arms as he forced back her head, and with his arm encircling her shoulders, kissed her on the mouth.

He stopped suddenly, perplexed by her passiveness, even suspecting for a moment that she might have fainted. But he found himself being surveyed with a tight-lipped and narrow-eyed intentness which shot a vague trouble through his triumph. He even let his arms drop, in bewilderment, though the drunkenness had not altogether gone out of his eyes.

She was wiping her mouth with her handkerchief, with a white look of loathing on her face. She was still mopping her lips as she crossed to the studio-door and swung it open.

“But I didn’t say I was going,” he demurred, frowning above his smile. He was sure of himself, sure of his mastery, sure of his technique.

“You are going,” she said, slowly and distinctly.

He stood there, as she repeated those three flat-toned words of hers, reviewing his technique, going back over it, for some undivulged imperfection. For it was plain that she piqued him. She more than piqued him; she disturbed him. But he refused to sacrifice his dignity for any such momentary timidity. It was familiar ground to him; each endearing move and maneuver was instinctive with him. Only the type was new. And novelty was not to be scoffed at.

He was smiling absently as he picked up his hat and gloves from the cherrywood table. And he stopped in front of her, still smiling, on his way out.

“Remember, wild-bird, that I am coming back to-morrow,” he said, arrested in spite of himself by the beauty of the white face with the luminous eyes. “To-morrow, at three!”

She did not look at him. She didn’t even bother to attempt to look through him.

“You are not coming back,” she quietly explained.

Already, she knew, all the doors of all the world were closed between them. The thing seemed so final, so irrefutably over and done with, that there was even a spurning touch of weariness in her tone. But he refused to be spurned.

“I am coming back,” he maintained, facing the eyes which refused to meet his, speaking more violently than he had at first intended to speak. “I am coming back again, as sure as that sun is shining on those housetops out there. I’m coming back, and I’m going to take you in my arms again. For I’m going to tame you, you crazy-hearted little stormy petrel, even though I have to break down that door of yours, and break down that pride of yours, to do it!”

She went whiter than ever as she stood there with her hand on the door-knob. She stood there for what seemed a very long time.

“To-morrow at three,” she repeated in her dead voice, with just the faintest trace of a shiver shaking her huddled figure. It was not altogether a question; it was not altogether an answer.

But it was enough for Uhlan, who passed with a dignity not untouched with triumph out through the open door. Yet Teddie’s shiver, as she stood staring after him, was the thoracic râle of her youth. And down on her protesting body, for the first time in her life, pressed a big flanged instrument with indented surfaces, like a pair of iron jaws from which she could not entirely free herself.

CHAPTER SIX

Theodora Lydia Lorillard Hayden, confronted by the first entirely sleepless night of her career, hugged her wounded pride to her breast and went pioneering. She lay on her narrow bed blazing new trails of thought. She turned and twisted and waited for morning, as torn in spirit as a Belgian villager over whom the iron hooves of war had trampled. For she found herself a victim of strange and violent reactions and her body a small but seething cauldron of bitterness.

The more she thought of Raoul Uhlan and his affront to her the more she hated him. The scene in her studio began to take on the distorted outlines of a nightmare, merging into something as disquieting as remembered dreams of being denuded. Even when the ordained reactions of nature demanded lassitude after tempest she found the incandescent coals of her hatred fanned by the thought of her helplessness. For it was for more than the mere indignities to her person that she hated the man. She hated him for crushing down with an over-brutal heel the egg-shell dream of her emancipation. She hated him for defiling her peace of mind, for undermining her faith in a care-free world which she had fought so hard to attain. He had done more than hurt her pride; he had shaken her temple of art down about her ears.

Teddie began to see, as she felt seismic undulations in what she had so foolishly accepted as bed-rock, that her home-life had perhaps stood for more than she imagined. It had meant not an accidental but an elaborately sustained dignity, a harboring seclusion, an achieved though cluttered-up spaciousness where the wheels of existence revolved on bearings so polished that one was apt to forget their power. And all this took her thoughts on to Ruby Reamer, the businesslike young girl of the studios from whom, without quite realizing it, she had learned so much. Beside the worldly-wise and sophisticated Ruby, Teddie remembered, she had more than once felt like a petted and pampered and slightly over-fed Pomeranian beside a quick-witted street-wanderer who’d only too early learned to forage for a living. And the question as to what Ruby might do in any such contingency led her to a calmer and colder assessment of her own resources.

But these, she found, were even more limited than she had imagined. There seemed no one to whom she could turn in her emergency, no one to whom she could look for any restoration of dignity without involving some still greater loss of dignity. And that one word of “dignity,” for all her untoward impulses of insurrection, was a very large word in the lexicon of Teddie’s life. She had been mauled and humiliated. She had been unthinkably misjudged and cheapened. And it was as much the insult to her intelligence as the hammer-blow to her pride which made her ache with the half-pagan hunger of rebellious youth for adequate atonement.

It wasn’t until daylight came that any possible plan of procedure presented itself. Then, as she paced her studio in the more lucid white light of morning, with the sheathed blade of her indignation still clanking at her heels, her eye fell on the crayon sketch of Gunboat Dorgan’s well muscled right arm.

She stopped short, arrested by a thought as new as though it had bloomed out of the cherrywood table beside her. Then she sat down in the velvet-draped armchair, letting this somewhat disturbing thought slip from her head to her heart, as it were, where it paced its silent parliaments of instinct until she had breakfasted. In leaving it thus to instinct she felt that she was leaving it to a conference of ancestral ghosts to argue over and fight out to a finish. But when that decision was once made she accepted it without questioning. Her only hope, she suddenly felt, lay in Gunboat Dorgan. Her only chance of balancing life’s ledger of violence rested with that East Side youth with the fore-shortened Celtic nose and the cauliflower ear. It was Gunboat Dorgan who could do for her what the situation demanded.

Her only way of getting in touch with young Dorgan, she remembered, was through Ruby Reamer. But Ruby’s telephone number had been left with her in case of need, and with impulse still making her movements crisp she went to the telephone and called up her model.

“Ruby,” she said in the most matter-of-fact tone of which she was capable, “can you tell me where I can find your friend, Mr. Dorgan?”

There was a ponderable space of silence.

“And what do you want with me friend Mr. Dorgan?” asked the voice over the wire, not without a slight saber-edge of suspicion.

Teddie entrenched herself behind a timely but guarding trill of laughter.

“It’s for something I can’t very well tell you,” she said, “something that I’ll be able to explain to you later on.”

And again a silence that was obviously meditative intervened.

“Of course I’ve never tried to butt in on Gunnie’s personal affairs,” announced a somewhat dignified Miss Reamer, remembering that the lady on the other end of the wire was much more attractive than anything she could fashion out of pastels. “But when Gunnie makes a date he’s never held himself above explainin’ it to me.”

Teddie fortified herself with a deep breath.

“Then suppose we leave the explaining to him, when he feels that the psychological moment has arrived,” she suggested. “So I’ll be obliged if you can tell me just where and how I might get in touch with Mr. Dorgan?”

“I guess maybe you’ll find him at the Aldine Athletic Club about this time any morning,” Ruby finally conceded, without any perceptible decrease of dignity. And with that the conference ended.

It took time, however, to get in touch with the gentleman in question. It was, in fact, three long hours before Gunboat had finished with his boxing-class at the Aldine Athletic Club, had taken his shower and his rub-down, and had apparelled himself in attire befitting a call on a rib, as he expressed it, who could bed her ponies down in bank-notes if she had a mind to. When he appeared before Teddie, accordingly, he did so in oxblood shoes and light tan gloves and a close-fitting “college” suit that translated him into anything but a knight of brawn.

“Mr. Dorgan,” promptly began Teddie, with a quietness which was merely a mask to her inner excitement, “I’m in a very great difficulty and I’ve been wondering if you’d be willing to help me out of it.”

“What’s the trouble, lady?” asked Gunboat, a little stiff and embarrassed in his Sunday best as he gazed at her out of an honest but guarded eye. For the knights of the ring, in their own world and in their own way, have many advances of the softer sex to withstand and many blandishments of the rose-sheathed enemy to be wary of.

But Teddie was direct enough, once she was under way.

“I’ve just been insulted in this studio by a brute who calls himself a man, intolerably and atrociously insulted.”

Gunboat Dorgan’s face lost a little of its barricaded look. This was a matter which brought him back to earth again. And Teddie saw that nothing was to be gained by beating about the bush.

“And this man threatens to come here to-day and repeat that insult,” she went on. “And, to speak quite plainly, I want some one to protect me.”

Gunboat’s face brightened. He moistened a hard young lip with the point of his tongue as he stood gazing into clouded eyes for which lances would surely have been shattered at Ashley.

“Who’s the guy what’s been gettin’ fresh?” he demanded.

Teddie, looking very lovely in a tailored black suit with an Ophelia rose pinned to its front, did her best to resist all undue surrender to the lethal tides of sympathy.

“It’s a beast called Raoul Uhlan,” she announced, disturbed for a moment by the slenderness of her would-be champion. But it was only for a moment, for she remembered the flexed right arm Ruby Reamer had tried to caliper with her admiring fingers on the afternoon that the crayon-drawing had been made.

“That puddin’!” cried Gunboat, with a touch of ecstasy. “Why, that guy tried to pull the soft stuff with Ruby last winter, but nothin’ put me wise until it was six months too late.” He fell to pacing the studio-rug, as though it were a roped ring, with significant undulatory movement of the shoulders. “Say, lady, what d’ yuh want me to do to that cuff-shooter? Blot ’im out?”

There was a hard light in the pagan young eyes of the girl in black.

“Yes,” she announced, without hesitation.

“Then he’ll get his!” affirmed the other, just as promptly.

“I want you to give him a lesson that he’ll never, never forget,” she explained, a little paler than usual. “I want you to show him it isn’t safe to insult defenseless girls.”

“Oh, I’ll show ’im!” announced Gunboat, with his chin out and his heels well apart. “He’ll know something when I get through wit’ him. And he’ll have a map like a fried egg!”

“But I don’t want you to——”