The Glamour of the Arctic

It is a strange thing to think that there is a body of men in Great Britain, the majority of whom have never, since their boyhood, seen the corn in the fields. It is the case with the whale-fishers of Peterhead. They begin their hard life very early as boys or ordinary seamen, and from that time onward they leave home at the end of February, before the first shoots are above the ground, and return in September, when only the stubble remains to show where the harvest has been. I have seen and spoken with many an old whaling-man to whom a bearded ear of corn was a thing to be wondered over and preserved.

The trade which these men follow is old and honorable. There was a time when the Greenland seas were harried by the ships of many nations, when the Basques and the Biscayens were the great fishers of whales, and when Dutchmen, men of the Hansa towns, Spaniards, and Britons, all joined in the great blubber hunt. Then one by one, as national energy or industrial capital decreased, the various countries tailed off, until, in the earlier part of this century, Hull, Poole, and Liverpool were three leading whaling-ports. But again the trade shifted its centre. Scoresby was the last of the great English captains, and from his time the industry has gone more and more north, until the whaling of Greenland waters came to be monopolized by Peterhead, which shares the sealing, however, with Dundee and with a fleet from Norway. But now, alas! the whaling appears to be upon its last legs; the Peterhead ships are seeking new outlets in the Antarctic seas, and a historical training-school of brave and hardy seamen will soon be a thing of the past.

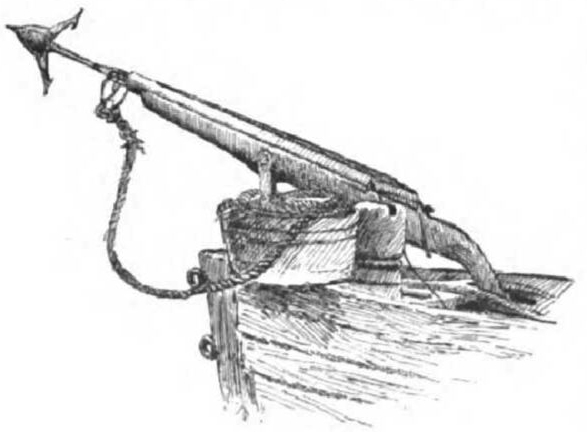

THE SWIVEL GUN.

It is not that the present generation is less persistent and skilful than its predecessors, nor is it that the Greenland whale is in danger of becoming extinct; but the true reason appears to be, that Nature, while depriving this unwieldy mass of blubber of any weapons, has given it in compensation a highly intelligent brain. That the whale entirely understands the mechanism of his own capture is beyond dispute. To swim backward and forward beneath a floe, in the hope of cutting the rope against the sharp edge of the ice, is a common device of the creature after being struck. By degrees, however, it was realized the fact that there are limits to the powers of its adversaries, and that by keeping far in among the icefields it may shake off the most intrepid of pursuers. Gradually the creature has deserted the open sea, and bored deeper and deeper among the ice barriers, until now, at last, it really appears to have reached inaccessible feeding grounds; and it is seldom, indeed, that the watcher in the crow’s nest sees the high plume of spray and the broad black tail in the air which sets his heart a-thumping.

A PETERHEAD HARPOONER.

But if a man have the good fortune to be present at a “fall,” and, above all, if he be, as I have been, in the harpooning and in the lancing boat, he has a taste of sport which it would be ill to match. To play a salmon is a royal game, but when your fish weighs more than a suburban villa, and is worth a clear two thousand pounds; when, too, your line is a thumb’s thickness of manilla rope with fifty strands, every strand tested for thirty-six pounds, it dwarfs all other experiences. And the lancing, too, when the creature is spent, and your boat pulls in to give it the coup de grâce with cold steel, that is also exciting! A hundred tons of despair are churning the waters up into a red foam; two great black fins are rising and falling like the sails of a windmill, casting the boat into a shadow as they droop over it; but still the harpooner clings to the head, where no harm can come, and, with the wooden butt of the twelve-foot lance against his stomach, he presses it home until the long struggle is finished, and the black back rolls over to expose the livid, whitish surface beneath. Yet amid all the excitement—and no one who has not held an oar in such a scene can tell how exciting it is—one’s sympathies lie with the poor hunted creature. The whale has a small eye, little larger than that of a bullock; but I cannot easily forget the mute expostulation which I read in one, as it dimmed over in death within hand’s touch of me. What could it guess, poor creature, of laws of supply and demand; or how could it imagine that when Nature placed an elastic filter inside its mouth, and when man discovered that the plates of which it was composed were the most pliable and yet durable things in creation, its death-warrant was signed?

Of course, it is only the one species, and the very rarest species, of whale which is the object of the fishery. The common rorqual or finner, largest of creatures upon this planet, whisks its eighty feet of worthless tallow round the whaler without fear of any missile more dangerous than a biscuit.

A PETERHEAD SEAMAN—BOAT-STEERER.

This, with its good-for-nothing cousin, the hunchback whale, abounds in the Arctic seas, and I have seen their sprays on a clear day shooting up along the horizon like the smoke from a busy factory. A stranger sight still is, when looking over the bulwarks into the clear water, to see, far down, where the green is turning to black, the huge, flickering figure of a whale gliding under the ship. And then the strange grunting, soughing noise which they make as they come up, with something of the contented pig in it, and something of the wind in the chimney! Contented they well may be, for the finner has no enemies, save an occasional sword-fish; and Nature, which in a humorous mood has in the case of the right whale affixed the smallest of gullets to the largest of creatures, has dilated the swallow of its less valuable brother, so that it can have a merry time among the herrings.

The gallant seaman, who in all the books stands in the prow of a boat, waving a harpoon over his head, with the line snaking out into the air behind him, is only to be found now in Paternoster Row. The Greenland seas have not known him for more than a hundred years, since first the obvious proposition was advanced that one could shoot both harder and more accurately than one could throw. Yet one clings to the ideals of one’s infancy, and I hope that another century may have elapsed before the brave fellow disappears from the frontispieces, in which he still throws his outrageous weapon an impossible distance. The swivel gun, like a huge horse-pistol, with its great oakum wad, and twenty-eight drams of powder, is a more reliable, but a far less picturesque object.

But to aim with such a gun is an art in itself, as will be seen when one considers that the rope is fastened to the neck of the harpoon, and that, as the missile flies, the downward drag of this rope must seriously deflect it. So difficult is it to make sure of one’s aim, that it is the etiquette of the trade to pull the boat right on to the creature, the prow shooting up its soft, gently-sloping side, and the harpooner firing straight down into its broad back, into which not only the four-foot harpoon, but ten feet of the rope behind it, will disappear. Then, should the whale cast its tail in the air, after the time-honored fashion of the pictures, that boat would be in evil case; but, fortunately, when frightened or hurt, it does no such thing, but curls its tail up underneath it, like a cowed dog, and sinks like a stone. Then the bows splash back into the water, the harpooner hugs his own soul, the crew light their pipes and keep their legs apart, while the line runs merrily down the middle of the boat and over the bows. There are two miles of it there, and a second boat will lie alongside to splice on if the first should run short, the end being always kept loose for that purpose. And now occurs the one serious danger of whaling. The line has usually been coiled when it was wet, and as it runs out it is very liable to come in loops which whizz down the boat between the men’s legs. A man lassoed in one of these nooses is gone, and fifty fathoms deep, before the harpooner has time to say, “Where’s Jock?” Or if it be the boat itself which is caught, then down it goes like a cork on a trout-line, and the man who can swim with a whaler’s high boots on is a swimmer indeed. Many a whale has had a Parthian revenge in this fashion. Some years ago a man was whisked over with a bight of rope round his thigh. “George, man, Alec’s gone!” shrieked the boat-steerer, heaving up his axe to cut the line. But the harpooner caught his wrist. “Na, na, mun,” he cried, “the oil money’ll be a good thing for the widdie.” And so it was arranged, while Alec shot on upon his terrible journey.

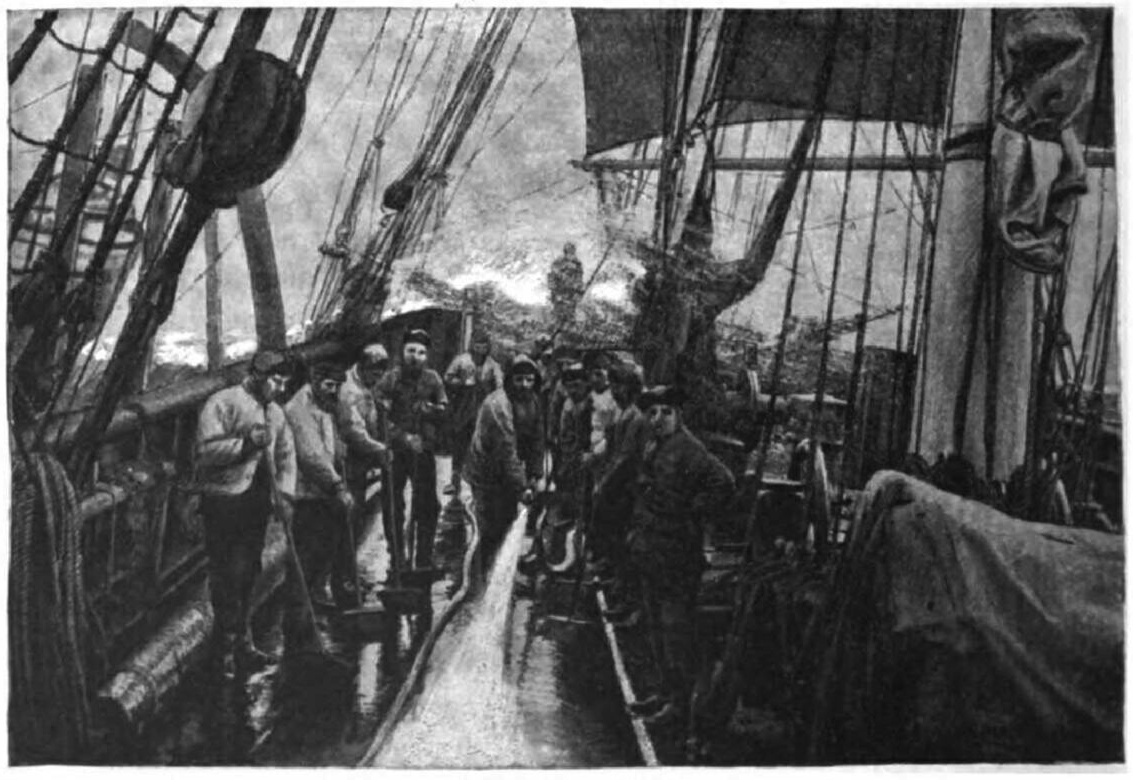

THE DECK OF A WHALER.

That oil money is the secret of the frantic industry of these seamen, who, when they do find themselves taking grease aboard, will work day and night, though night is but an expression up there, without a thought of fatigue. For the secure pay of officers and men is low indeed, and it is only by their share of the profits that they can hope to draw a good check when they return. Even the new-joined boy gets his shilling in the ton, and so draws an extra five pounds when a hundred tons of oil are brought back. It is practical socialism, and yet a less democratic community than a whaler’s crew could not be imagined. The captain rules the mates, the mates the harpooners, the harpooners the boat-steerers, the boat-steerers the line-coilers, and so on in a graduated scale which descends to the ordinary seaman, who, in his turn, bosses it over the boys. Every one of these has his share of oil money, and it may be imagined what a chill blast of unpopularity blows around the luckless harpooner who, by clumsiness or evil chance, has missed his whale. Public opinion has a terrorizing effect; even in those little floating communities of fifty souls. I have known a grizzled harpooner burst into tears when he saw by his slack line that he had missed his mark, and Aberdeenshire seamen are not a very soft race either.

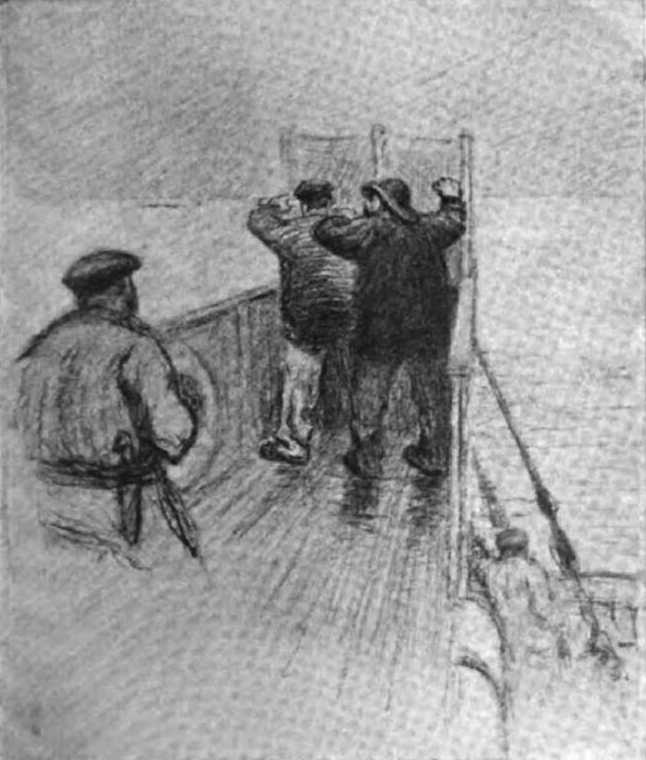

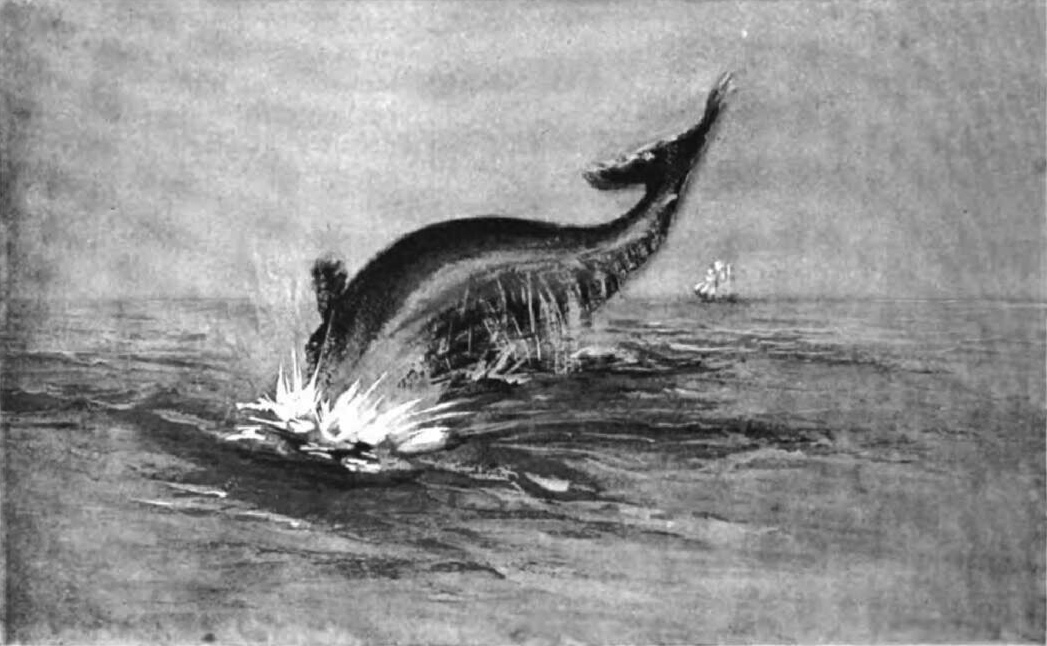

THE FIRST SIGHT OF THE WHALE.

Though twenty or thirty whales have been taken in a single year in the Greenland seas, it is probable that the great slaughter of last century has diminished their number until there are not more than a few hundreds in existence. I mean, of course, of the right whale; for the others, as I have said, abound. It is difficult to compute the numbers of a species which comes and goes over great tracts of water and among huge icefields; but the fact that the same whale is often pursued by the same whaler upon successive trips shows how limited their number must be. There was one, I remember, which was conspicuous through having a huge wart, the size and shape of a beehive, upon one of the flukes of its tail. “I’ve been after that fellow three times,” said the captain, as we dropped our boats. “He got away in ’61. In ’67 we had him fast, but the harpoon drew. In ’76 a fog saved him. It’s odds that we have him now!” I fancied that the betting lay rather the other way myself, and so it proved; for that warty tail is still thrashing the Arctic seas for all that I know to the contrary.

I shall never forget my own first sight of a right whale. It had been seen by the lookout on the other side of a small icefield, but had sunk as we all rushed on deck. For ten minutes we awaited its reappearance, and I had taken my eyes from the place, when a general gasp of astonishment made me glance up, and there was the whale in the air. Its tail was curved just as a trout’s is in jumping, and every bit of its glistening lead-colored body was clear of the water. It was little wonder that I should be astonished, for the captain, after thirty voyages, had never seen such a sight. On catching it, we discovered that it was very thickly covered with a red, crablike parasite, about the size of a shilling, and we conjectured that it was the irritation of these creatures which had driven it wild. If a man had short, nailless flippers, and a prosperous family of fleas upon his back, he would appreciate the situation.

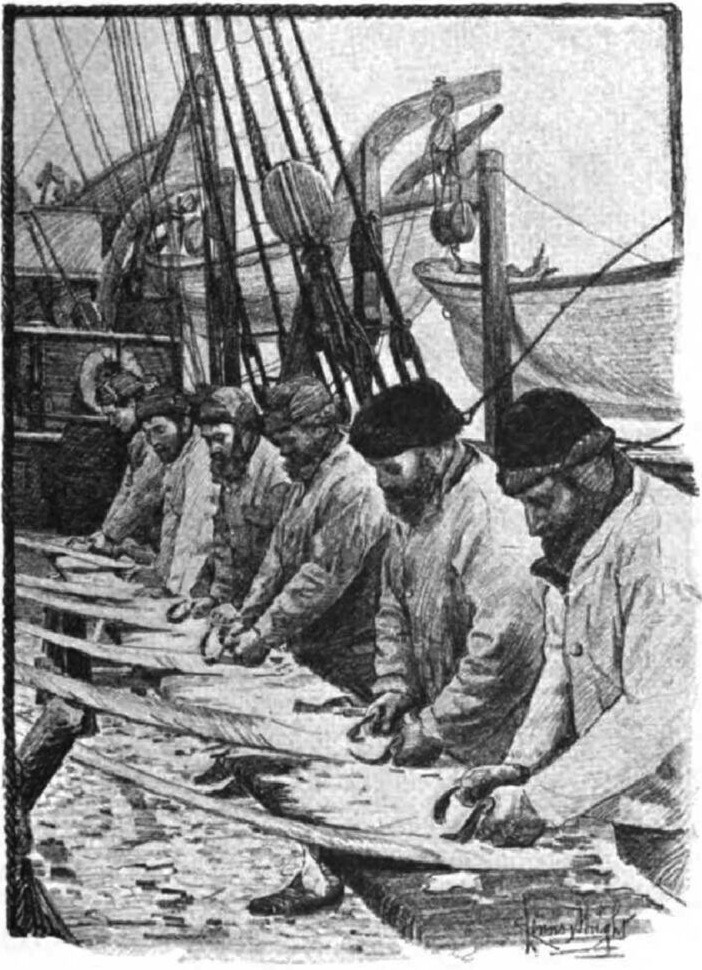

When a fish, as the whalers will forever call it, is taken, the ship gets alongside, and the creature is fixed head and tail in a curious and ancient fashion, so that by slacking or tightening the ropes, each part of the vast body can be brought uppermost. A whole boat may be seen inside the giant mouth, the men hacking with axes, to slice away the ten-foot screens of bone, while others with sharp spades upon the back are cutting off the deep great-coat of fat in which kindly Nature has wrapped up this most overgrown of her children. In a few hours all is stowed away in the tanks, and a red islet, with white projecting bones, lies alongside, and sinks like a stone when the ropes are loosed. Some years ago, a man, still lingering upon the back, had the misfortune to have his foot caught between the creature’s ribs, at the instant when the tackles were undone. Some aeons hence those two skeletons, the one hanging by the foot from the other, may grace the museum of a subtropical Greenland, or astonish the students of the Spitzbergen Institute of Anatomy.

Apart from sport, there is a glamour about those circumpolar regions which must affect everyone who has penetrated to them. My heart goes out to that old, gray-headed whaling-captain who, having been left for an instant when at death’s door, staggered off in his night gear, and was found by his nurses far from his house, and still, as he mumbled, “pushing to the norrard.” So an Arctic fox, which a friend of mine endeavored to tame, escaped, and was caught many months afterwards in a gamekeeper’s trap in Caithness. It also was pushing “norrard,” though who can say by what strange compass it took its bearings? It is a region of purity, of white ice, and of blue water, with no human dwelling within a thousand miles to sully the freshness of the breeze which blows across the icefields. And then it is a region of romance also. You stand on the very brink of the unknown, and every duck that you shoot bears pebbles in its gizzard which come from a land which the maps know not.

GEORGE, MAN, ALEC’S GONE.

These whaling-captains profess to see no great difficulty in reaching the Pole. Some little margin must be allowed, no doubt, for expansive talk over a pipe and a glass, but still there is a striking unanimity in their ideas. Briefly they are these: What bars the passage of the explorer as he ascends between Greenland and Spitzbergen is that huge floating ice-reef which scientific explorers have called “the palæocrystic sea,” and the whalers, with more expressive Anglo-Saxon, “the barrier.” The ship which has picked its way among the great ice-floes finds itself, somewhere about the eighty-first degree, confronted by a single mighty wall, extending right across from side to side, with no chink or creek up which she can push her bows. It is old ice, gnarled and rugged, and of an exceeding thickness, impossible to pass, and nearly impossible to travel over, so cut and jagged is its surface. Over this it was that the gallant Parry struggled with his sledges in 1827, reaching a latitude (about 82° 30’, if my remembrance is correct) which for a long time was the record. As far as he could see, this old ice extended right away to the Pole.

Such is the obstacle. Now for the whaler’s view of how it may be surmounted.

This ice, they say, solid as it looks, is really a floating body, and at the mercy of the water upon which it rests. There is in those seas a perpetual southerly drift, which weakens the cohesion of the huge mass; and when, in addition to this, the prevailing winds happen to be from the north, the barrier is all shredded out, and great bays and gulfs appear in its surface. A brisk northerly wind, long continued, might at any time clear a road, and has, according to their testimony, frequently cleared a road, by which a ship might slip through to the Pole. Whalers fishing as far north as the eighty-second degree have in an open season seen no ice, and, more important still, no reflection of ice in the sky to the north of them. But they are in the service of a company; they are there to catch whales, and there is no adequate inducement to make them risk themselves, their vessels, and their cargoes, in a dash for the north.

SPLITTING WHALEBONE

The matter might be put to the test without trouble or expense. Take a stout wooden gunboat, short and strong, with engines as antiquated as you like, if they be but a hundred horse-power. Man her with a sprinkling of Scotch and Shetland seamen from the Royal Navy, and let the rest of the crew be lads who must have a training-cruise in any case. For the first few voyages carry a couple of experienced ice-masters, in addition to the usual naval officers. Put a man like Markham in command. Then send this ship every June or July to inspect the barrier, with strict orders to keep out of the heavy ice unless there were a very clear water-way. For six years she might go in vain. On the seventh you might have an open season, hard, northerly winds, and a clear sea. In any case no expense or danger is incurred, and there could be no better training for young seamen. They will find the Greenland seas in summer much more healthy and pleasant than the Azores or Madeira, to which they are usually despatched. The whole expedition should be done in less than a month.

SCRAPING WHALEBONE

Singular incidents occur in those northern waters, and there are few old whalers who have not their queer yarn, which is sometimes of personal and sometimes of general interest. There is one which always appeared to me to deserve more attention than has ever been given to it. Some years ago, Captain David Gray of the “Eclipse,” the doyen of the trade, and the representative, with his brothers John and Alec, of a famous family of whalers, was cruising far to the north, when he saw a large bird flapping over the ice. A boat was dropped, the bird shot, and brought aboard, but no man there could say what manner of fowl it was. Brought home, it was at once identified as being a half-grown albatross, and now stands in the Peterhead Museum, with a neat little label to that effect between its webbed feet.

Now the albatross is an Antarctic bird, and it is quite unthinkable that this solitary specimen flapped its way from the other end of the earth. It was young, and possibly giddy, but quite incapable of a wild outburst of that sort. What is the alternative? It must have been a southern straggler from some breed of albatrosses farther north. But if there is a different fauna farther north, then there must be a climatic change there. Perhaps Kane was not so far wrong after all in his surmise of an open Polar sea. It may be that that flattening at the poles of the earth, which always seemed to my childhood’s imagination to have been caused by the finger and thumb of the Creator, when he held up this little planet before he set it spinning, has a greater influence on climate than we have yet ascribed to it. But if so, how simple would the task of our exploring ship become when a wind from the north had made a rift in the barrier!

There is little land to be seen during the seven months of a whaling-cruise. The strange solitary island of Jan Meyen may possibly be sighted, with its great snow-capped ex-volcano jutting up among the clouds. In the palmy days of the whale-fishing the Dutch had a boiling-station there, and now great stones with iron rings let into them and rusted anchors lie littered about in this absolute wilderness as a token of their former presence. Spitzbergen, too, with its black crags and its white glaciers, a dreadful looking place, may possibly be seen. I saw it myself, for the first and last time, in a sudden rift in the drifting wrack of a furious gale, and for me it stands as the very emblem of stern grandeur. And then towards the end of the season the whalers come south to the seventy-second degree, and try to bore in towards the coast of Greenland, in the south-eastern corner; and if you then, at the distance of eighty miles, catch the least glimpse of the loom of the cliffs, then, if you are anything of a dreamer, you will have plenty of food for dreams, for this is the very spot where one of the most interesting questions in the world is awaiting a solution.

Of course, it is a commonplace that when Iceland was one of the centres of civilization in Europe, the Icelanders budded off a colony upon Greenland, which throve and flourished, and produced sagas of its own, and waged war upon the Skraelings or Esquimaux, and generally sang and fought and drank in the bad old, full-blooded fashion. So prosperous did they become, that they built them a cathedral, and sent to Denmark for a bishop, there being no protection for local industries at that time. The bishop, however, was prevented from reaching his see by some sudden climatic change which brought the ice down between Iceland and Greenland, and from that day (it was in the fourteenth century) to this no one has penetrated that ice, nor has it ever been ascertained what became of that ancient city, or of its inhabitants. Have they preserved some singular civilization of their own, and are they still singing and drinking and fighting, and waiting for the bishop from over the seas? Or have they been destroyed by the hated Skraelings? Or have they, as is more likely, amalgamated with them, and produced a race of tow-headed, large-limbed Esquimaux? We must wait until some Nansen turns his steps in that direction before we can tell. At present it is one of those interesting historical questions, like the fate of those Vandals who were driven by Belisarius into the interior of Africa, which are better unsolved. When we know everything about this earth, the romance and the poetry will all have been wiped away from it. There is nothing so artistic as a haze.

There is a good deal which I had meant to say about bears, and about seals, and about sea-unicorns, and sword-fish, and all the interesting things which combine to throw that glamour over the Arctic; but, as the genial critic is fond of remarking, it has all been said very much better already. There is one side of the Arctic regions, however, which has never had due attention paid to it, and that is the medical and curative side. Davos Platz has shown what cold can do in consumption, but in the life-giving air of the Arctic Circle no noxious germ can live. The only illness of any consequence which ever attacks a whaler is an explosive bullet. It is a safe prophecy, that before many years are past, steam yachts will turn to the north every summer, with a cargo of the weak-chested, and people will understand that Nature’s ice-house is a more healthy place than her vapor-bath.

Transcriber’s Note: This story appeared in the March 1894 issue of McClure’s Magazine.