THE COMPLETE WORKS OF

ARTEMUS WARD

By Charles Farrar Browne

(AKA Artemus Ward)

___________________________________

TABLE OF CONTENTS

___________________________________

BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH by Melville D. Landon

PART I.ESSAYS, SKETCHES, AND LETTERS.

Mr. Ward's first Business Letter

Atlantic Cable Celebration at Baldinsville

The Show Business and Popular Lectures

Boston. (A. Ward to his Wife.)

How "Old Abe" received the News of his Nomination

Interview with President Lincoln

Interview with Prince Napoleon

Affairs around the Village Green

PART II.WAR.

The War Fever in Baldinsville.

Artemus Ward to the Prince of Wales.

PART III.STORIES AND ROMANCES.

Moses the Sassy; or, The Disguised Duke.

Marion: A Romance of the French School.

William Barker, the Young Patriot

Roberto the Rover; A Tale of Sea and Shore.

Pyrotechny: A Romance after the French.

A Mormon Romance—Reginald Gloverson.

PART IV.TO CALIFORNIA AND RETURN.

Horace Greeley's Ride to Placerville.

PART V.THE LONDON PUNCH LETTERS.

The Green Lion and Oliver Cromwell.

A Visit to the British Museum.

PART VI.ARTEMUS WARD'S PANORAMA.

Program of the Egyptian Hall Lecture.

Program of the Dodworth Hall Lecture.

PART VII.MISCELLANEOUS.

Artemus Ward among the Fenians.

Scenes Outside the Fair Grounds.

____________________

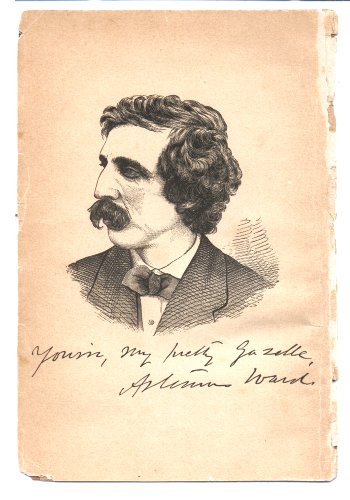

CHAS. FARRAR BROWNE

"ARTEMUS WARD"

____________________

A BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH BY MELVILLE D. LANDON.

Charles Farrar Browne, better known to the world as "Artemus Ward," was born at Waterford, Oxford County, Maine, on the twenty-sixth of April, 1834, and died of consumption at Southampton, England, on Wednesday, the sixth of March, 1867.

His father, Levi Browne, was a land surveyor, and Justice of the Peace. His mother, Caroline E. Brown, is still living, and is a descendant from Puritan stock.

Mr. Browne's business manager, Mr. Hingston, once asked him about his Puritanic origin, when he replied: "I think we came from Jerusalem, for my father's name was Levi and we had a Moses and a Nathan in the family, but my poor brother's name was Cyrus; so, perhaps, that makes us Persians."

Charles was partially educated at the Waterford school, when family circumstances induced his parents to apprentice him to learn the rudiments of printing in the office of the "Skowhegan Clarion," published some miles to the north of his native village. Here he passed through the dreadful ordeal to which a printer's "devil" is generally subjected. He always kept his temper; and his eccentric boy jokes are even now told by the residents of Skowhegan.

In the spring, after his fifteenth birthday, Charles Browne bade farewell to the "Skowhegan Clarion;" and we next hear of him in the office of the "Carpet-Bag," edited by B.P. Shillaber ("Mrs. Partington"). Lean, lank, but strangely appreciative, young Browne used to "set up" articles from the pens of Charles G. Halpine ("Miles O'Reilly") and John G. Saxe, the poet. Here he wrote his first contribution in a disguised hand, slyly put it into the editorial box, and the next day disguised his pleasure while setting it up himself. The article was a description of a Fourth of July celebration in Skowhegan. The spectacle of the day was a representation of the battle of Yorktown, with G. Washington and General Horace Cornwallis in character. The article pleased Mr. Shillaber, and Mr. Browne, afterwards speaking of it, said: "I went to the theatre that evening, had a good time of it, and thought I was the greatest man in Boston."

While engaged on the "Carpet-Bag," the subject of our sketch closely studied the theatre and courted the society of actors and actresses. It was in this way that he gained that correct and valuable knowledge of the texts and characters of the drama, which enabled him in after years to burlesque them so successfully. The humorous writings of Seba Smith were his models, and the oddities of "John Phoenix" were his especial admiration.

Being of a roving temper Charles Browne soon left Boston, and, after traveling as a journeyman printer over much of New York and Massachusetts, he turned up in the town of Tiffin, Seneca County, Ohio, where he became reporter and compositor at four dollars per week. After making many friends among the good citizens of Tiffin, by whom he is remembered as a patron of side shows and traveling circuses, our hero suddenly set out for Toledo, on the lake, where he immediately made a reputation as a writer of sarcastic paragraphs in the columns of the Toledo "Commercial." He waged a vigorous newspaper war with the reporters of the Toledo "Blade," but while the "Blade" indulged in violent vituperation, "Artemus" was good-natured and full of humor. His column soon gained a local fame and everybody read it. His fame even traveled away to Cleveland, where, in 1858, when Mr. Browne was twenty-four years of age, Mr. J.W. Gray of the Cleveland "Plaindealer" secured him as local reporter, at a salary of twelve-dollars per week. Here his reputation first began to assume a national character and it was here that they called him a "fool" when he mentioned the idea of taking the field as a lecturer. Speaking of this circumstance while traveling down the Mississippi with the writer, in 1865, Mr. Browne musingly repeated this colloquy:

WISE MAN:—"Ah! you poor foolish little girl—here is a dollar for you."

FOOLISH LITTLE GIRL:—"Thank you, sir; but I have a sister at home as foolish as I am; can't you give me a dollar for her?"

Charles Browne was not successful as a NEWS reporter, lacking enterprise and energy, but his success lay in writing up in a burlesque manner well-known public affairs like prize-fights, races, spiritual meetings, and political gatherings. His department became wonderfully humorous, and was always a favorite with readers, whether there was any news in it or not. Sometimes he would have a whole column of letters from young ladies in reply to a fancied matrimonial advertisement, and then he would have a column of answers to general correspondents like this:—

VERITAS:—Many make the same error. Mr. Key, who wrote the "Star Spangled Banner," is not the author of Hamlet, a tragedy. He wrote the banner business, and assisted in "The Female Pirate," BUT DID NOT WRITE HAMLET. Hamlet was written by a talented but unscrupulous man named Macbeth, afterwards tried and executed for "murdering sleep."

YOUNG CLERGYMAN:—Two pints of rum, two quarts of hot water, tea-cup of sugar, and a lemon; grate in nutmeg, stir thoroughly and drink while hot.

It was during his engagement on the "Plaindealer" that he wrote, dating from Indiana, his first communication,—the first published letter following this sketch, signed "Artemus Ward" a sobriquet purely incidental, but borne with the "u" changed to an "a" by an American revolutionary general. It was here that Mr. Browne first became, IN WORDS, the possessor of a moral show "consisting of three moral bares, the a kangaroo (a amoozing little rascal; 'twould make you larf yourself to death to see the little kuss jump and squeal), wax figures of G. Washington, &c. &c." Hundreds of newspapers copied this letter, and Charles Browne awoke one morning to find himself famous.

In the "Plaindealer" office, his companion, George Hoyt, writes: "His desk was a rickety table which had been whittled and gashed until it looked as if it had been the victim of lightning. His chair was a fit companion thereto,—a wabbling, unsteady affair, sometimes with four and sometimes with three legs. But Browne saw neither the table, nor the chair, nor any person who might be near, nothing, in fact, but the funny pictures which were tumbling out of his brain. When writing, his gaunt form looked ridiculous enough. One leg hung over the arm of his chair like a great hook, while he would write away, sometimes laughing to himself, and then slapping the table in the excess of his mirth."

While in the office of the "Plaindealer," Mr. Browne first conceived the idea of becoming a lecturer. In attending the various minstrel shows and circuses which came to the city, he would frequently hear repeated some story of his own which the audience would receive with hilarity. His best witticisms came back to him from the lips of another who made a living by quoting a stolen jest. Then the thought came to him to enter the lecture field himself, and become the utterer of his own witticisms—the mouthpiece of his own jests.

On the 10th of November, 1860, Charles Browne, whose fame, traveling in his letters from Boston to San Francisco, had now become national, grasped the hands of his hundreds of New York admirers. Cleveland had throned him the monarch of mirth, and a thousand hearts paid him tributes of adulation as he closed his connection with the Cleveland Press.

Arriving in the Empire City, Mr. Browne soon opened an engagement with "Vanity Fair," a humorous paper after the manner of London "Punch," and ere long he succeeded Mr. Charles G. Leland as editor. Mr. Charles Dawson Shanly says: "After Artemus Ward became sole editor, a position which he held for a brief period, many of his best contributions were given to the public; and, whatever there was of merit in the columns of "Vanity Fair" from the time he assumed the editorial charge, emanated from his pen." Mr. Browne himself wrote to a friend: "Comic copy is what they wanted for "Vanity Fair." I wrote some and it killed it. The poor paper got to be a conundrum, and so I gave it up."

The idea of entering the field as a lecturer now seized Mr. Browne stronger than ever. Tired of the pen, he resolved on trying the platform. His Bohemian friends agreed that his fame and fortune would be made before intelligent audiences. He resolved to try it. What should be the subject of my lecture? How shall I treat the subject? These questions caused Mr. Browne grave speculations. Among other schemes, he thought of a string of jests combined with a stream of satire, the whole being unconnected—a burlesque upon a lecture. The subject,—that was a hard question. First he thought of calling it "My Seven Grandmothers," but he finally adopted the name of "Babes in the Woods," and with this subject Charles Browne was introduced to a metropolitan audience, on the evening of December 23d, 1861. The place was Clinton Hall, which stood on the site of the old Astor Place Opera House, where years ago occurred the Macready riot, and where now is the Mercantile Library. Previous to this introduction, Mr. Frank Wood accompanied him to the suburban town of Norwich, Connecticut, where he first delivered his lecture, and watched the result. The audience was delighted, and Mr. Browne received an ovation. Previous to his Clinton Hall appearance the city was flooded with funny placards reading—

Owing to a great storm, only a small audience braved the elements, and the Clinton Hall lecture was not a financial success. It consisted of a wandering batch of comicalities, touching upon everything except "The Babes." Indeed it was better described by the lecturer in London, when he said, "One of the features of my entertainment is, that it contains so many things that don't have anything to do with it."

In the middle of his lecture, the speaker would hesitate, stop, and say: "Owing to a slight indisposition we will now have an intermission of fifteen minutes." The audience looked in utter dismay at the idea of staring at vacancy for a quarter of an hour, when, rubbing his hands, the lecturer would continue: "but, ah—during the intermission I will go on with my lecture!"

Mr. Browne's first volume, entitled "Artemus Ward; His Book," was published in New York, May 17th, 1862. The volume was everywhere hailed with enthusiasm, and over forty thousand copies were sold. Great success also attended the sale of his three other volumes published in '65, '67, and '69.

Mr. Browne's next lecture was entitled "Sixty Minutes in Africa," and was delivered in Musical Fund Hall, Philadelphia. Behind him hung a large map of Africa, "which region," said Artemus, "abounds in various natural productions, such as reptiles and flowers. It produces the red rose, the white rose, and the neg-roes. In the middle of the continent is what is called a 'howling wilderness,' but, for my part, I have never heard it howl, nor met with any one who has."

After Mr. Browne had created immense enthusiasm for his lectures and books in the Eastern States, which filled his pockets with a handsome exchequer, he started, October 3d, 1863, for California, a faithful account of which trip is given by himself in this book. Previous to starting, he received a telegram from Thomas Maguire, of the San Francisco Opera House, inquiring "what he would take for forty nights in Californis." Mr. Brown immediately telegraphed back,—

| "Brandy and water. | |

| A. Ward." |

And, though Maguire was sorely puzzled at the contents of the dispatch, the Press got hold of it, and it went through California as a capital joke.

Mr. Browne first lectured in San Francisco on "The Babes in the Woods," November 13th, 1863, at Pratt's Hall. T. Starr King took a deep interest in him, occupying the rostrum, and his general reception in San Francisco was warm.

Returning overland, through Salt Lake to the States, in the fall of 1864, Mr. Browne lectured again in New York, this time on the "Mormons," to immense audiences, and in the spring of 1865 he commenced his tour through the country, everywhere drawing enthusiastic audiences both North and South.

It was while on this tour that the writer of this sketch again spent some time with him. We met at Memphis and traveled down the Mississippi together. At Lake Providence the "Indiana" rounded up to our landing, and Mr. Browne accompanied the writer to his plantation, where he spent several days, mingling in seeming infinite delight with the negroes. For them he showed great fondness, and they used to stand around him in crowds listening to his seemingly serious advice. We could not prevail upon him to hunt or to join in any of the equestrian amusements with the neighboring planters, but a quiet fascination drew him to the negroes. Strolling through the "quarters," his grave words, too deep with humor for darkey comprehension, gained their entire confidence. One day he called up Uncle Jeff., an Uncle-Tom-like patriarch, and commenced in his usual vein: "Now, Uncle Jefferson," he said, "why do you thus pursue the habits of industry? This course of life is wrong—all wrong—all a base habit, Uncle Jefferson. Now try to break it off. Look at me,—look at Mr. Landon, the chivalric young Southern plantist from New York, he toils not, neither does he spin; he pursues a career of contented idleness. If you only thought so, Jefferson, you could live for months without performing any kund of labor, and at the expiration of that time feel fresh and vigorous enough to commence it again. Idleness refreshes the physical organization—it is a sweet boon! Strike at the roots of the destroying habit to-day, Jefferson. It tires you out; resolve to be idle; no one should labor; he should hire others to do it for him;" and then he would fix his mournful eyes on Jeff. and hand him a dollar, while the eyes of the wonder-struck darkey would gaze in mute admiration upon the good and wise originator of the only theory which the darkey mind could appreciate. As Jeff. went away to tell the wonderful story to his companions, and backed it with the dollar as material proof, Artemus would cover his eyes, and bend forward on his elbows in a chuckling laugh.

"Among the Mormons" was delivered through the States, everywhere drawing immense crowds. His manner of delivering his discourse was grotesque and comical beyond description. His quaint and sad style contributed more than anything else to render his entertainment exquisitely funny. The programme was exceedingly droll, and the tickets of admission presented the most ludicrous of ideas. The writer presents a fac-simile of an admission ticket which was presented to him in Natchez by Mr. Browne:—

In the spring of 1866, Charles Browne first timidly thought of going to Europe. Turning to Mr. Hingston one day he asked: "What sort of a man is Albert Smith? Do you think the Mormons would be as good a subject to the Londoners as Mont Blanc was?" Then he said: "I should like to go to London and give my lecture in the same place. Can't it be done?"

Mr. Browne sailed for England soon after, taking with him his Panorama. The success that awaited him could scarcely have been anticipated by his most intimate friends. Scholars, wits, poets, and novelists came to him with extended hands, and his stay in London was one ovation to the genius of American wit. Charles Reade, the novelist, was his warm friend and enthusiastic admirer; and Mr. Andrew Haliday introduced him to the "Literary Club," where he became a great favorite. Mark Lemon came to him and asked him to become a contributor to "Punch," which he did. His "Punch" letters were more remarked in literary circles than any other current matter. There was hardly a club-meeting or a dinner at which they were not discussed. "There was something so grotesque in the idea," said a correspondent, "of this ruthless Yankee poking among the revered antiquities of Britain, that the beef-eating British themselves could not restrain their laughter." The story of his Uncle William who "followed commercial pursuits, glorious commerce—and sold soap," and his letters on the Tower and "Chowser," were palpable hits, and it was admitted that "Punch" had contained nothing better since the days of "Yellowplush." This opinion was shared by the "Times," the literary reviews, and the gayest leaders of society. The publishers of "Punch" posted up his name in large letters over their shop in Fleet Street, and Artemus delighted to point it out to his friends. About this time Mr. Browne wrote to his friend Jack Rider, of Cleveland:

"This is the proudest moment of my life. To have been as well appreciated here as at home; to have written for the oldest comic Journal in the English language, received mention with Hood, with Jerrold and Hook, and to have my picture and my pseudonym as common in London as in New York, is enough for

| "Yours truly, | |

| "A. Ward." |

England was thoroughly aroused to the merits of Artemus Ward, before he commenced his lectures at Egyptian Hall, and when, in November, he finally appeared, immense crowds were compelled to turn away. At every lecture his fame increased, and when sickness brought his brilliant success to an end, a nation mourned his retirement.

On the evening of Friday, the seventh week of his engagement at Egyptian Hall, Artemus became seriously ill, an apology was made to a disappointed audience, and from that time the light of one of the greatest wits of the centuries commenced fading into darkness. The Press mourned his retirement, and a funeral pall fell over London. The laughing, applauding crowds were soon to see his consumptive form moving towards its narrow resting-place in the cemetery at Kensal Green.

By medical advice Charles Browne went for a short time to the Island of Jersey—but the breezes of Jersey were powerless. He wrote to London to his nearest and dearest friends—the members of a literary club of which he was a member—to complain that his "loneliness weighed on him." He was brought back, but could not sustain the journey farther than Southampton. There the members of the club traveled from London to see him—two at a time—that he might be less lonely.

His remains were followed to the grave from the rooms of his friend Arthur Sketchley, by a large number of friends and admirers, the literati and press of London paying the last tribute of respect to their dead brother. The funeral services were conducted by the Rev. M.D. Conway, formerly of Cincinnati, and the coffin was temporarily placed in a vault, from which it was removed by his American friends, and his body now sleeps by the side of his father, Levi Browne, in the quiet cemetery at Waterford, Maine. Upon the coffin is the simple inscription:—

His English executors were T.W. Robertson, the playwright, and his friend and companion, E.P. Hingston. His literary executors were Horace Greeley and Richard H. Stoddard. In his will, he bequeathed among other things a large sum of money to his little valet, a bright little fellow; though subsequent denouments revealed the fact that he left only a six-thousand-dollar house in Yonkers. There is still some mystery about his finances, which may one day be revealed. It is known that he withdrew 10,000 dollars from the Pacific Bank to deposit it with a friend before going to England; besides this, his London "Punch" letters paid a handsome profit. Among his personal friends were George Hoyt, the late Daniel Setchell, Charles W. Coe, and Mr. Mullen, the artist, all of whom he used to style "my friends all the year round."

Personally Charles Farrar Browne was one of the kindest and most affectionate of men, and history does not name a man who was so universally beloved by all who knew him. It was remarked, and truly, that the death of no literary character since Washington Irving caused such general and widespread regret.

In stature he was tall and slender. His nose was prominent,—outlined like that of Sir Charles Napier, or Mr. Seward; his eyes brilliant, small, and close together; his mouth large, teeth white and pearly; fingers long and slender; hair soft, straight, and blonde; complexion florid; mustache large, and his voice soft and clear. In bearing, he moved like a natural-born gentleman. In his lectures he never smiled—not even while he was giving utterance to the most delicious absurdities; but all the while the jokes fell from his lips as if he was unconscious of their meaning. While writing his lectures, he would laugh and chuckle to himself continually.

There was one peculiarity about Charles Browne—He never made an enemy. Other wits in other times have been famous, but a satirical thrust now and then has killed a friend. Diogenes was the wit of Greece, but when, after holding up an old dried fish to draw away the eyes of Anaximenes' audience, he exclaimed "See how an old fish is more interesting than Anaximenes," he said a funny thing, but he stabbed a friend. When Charles Lamb, in answer to the doting mother's question as to how he liked babies, replied, "b-b-boiled, madam, boiled!" that mother loved him no more: and when John Randolph said "thank you!" to his constituent who kindly remarked that he had the pleasure of passing his house, it was wit at the expense of friendship. The whole English school of wits—with Douglas Jerrold, Hood, Sheridan, and Sidney Smith, indulged in repartee. They were parasitic wits. And so with the Irish, except that an Irishman is generally so ridiculously absurd in his replies as to only excite ridicule. "Artemus Ward" made you laugh and love him too.

The wit of "Artemus Ward" and "Josh Billings" is distinctively American. Lord Kames, in his "Elements of Criticism," makes no mention of this species of wit, a lack which the future rhetorician should look to. We look in vain for it in the English language of past ages, and in other languages of modern time. It is the genus American. When Artemus says in that serious manner, looking admiringly at his atrocious pictures,—"I love pictures—and I have many of them—beautiful photographs—of myself;" you smile; and when he continues, "These pictures were painted by the Old Masters; they painted these pictures and then they—they expired;" you hardly know what it is that makes you laugh outright; and when Josh Billings says in his Proverbs, wiser than Solomon's "You'd better not know so much, than know so many things that ain't so;"—the same vein is struck, but the text-books fail to explain scientifically the cause of our mirth.

The wit of Charles Browne is of the most exalted kind. It is only scholars and those thoroughly acquainted with the subtilty of our language who fully appreciate it. His wit is generally about historical personages like Cromwell, Garrick, or Shakspeare, or a burlesque on different styles of writing, like his French novel, when hifalutin phrases of tragedy come from the clodhopper who—"sells soap and thrice—refuses a ducal coronet."

Mr. Browne mingled the eccentric even in his business letters. Once he wrote to his Publisher, Mr. G.W. Carleton, who had made some alterations in his MSS.: "The next book I write I'm going to get you to write." Again he wrote in 1863:

"Dear Carl:—You and I will get out a book next spring, which will knock spots out of all comic books in ancient or modern history. And the fact that you are going to take hold of it convinces me that you have one of the most massive intellects of this or any other epoch.

| "Yours, my pretty gazelle |

| "A. Ward." |

When Charles F. Browne died, he did not belong to America, for, as with Irving and Dickens, the English language claimed him. Greece alone did not suffer when the current of Diogenes' wit flowed on to death. Spain alone did not mourn when Cervantes, dying, left Don Quixote, the "knight of la Mancha." When Charles Lamb ceased to tune the great heart of humanity to joy and gladness, his funeral was in every English and American household; and when Charles Browne took up his silent resting-place in the sombre shades of Kensal Green, jesting ceased, and one great Anglo-American heart,

Like a muffled drum went beating

MELVILLE D.

LANDON.

____________________

To the Editor of the——

Sir—I'm movin along—slowly along—down tords your place. I want you should rite me a letter, sayin how is the show bizniss in your place. My show at present consists of three moral Bares, a Kangaroo (a amoozin little Raskal—t'would make you larf yerself to deth to see the little cuss jump up and squeal) wax figgers of G. Washington Gen. Tayler John Bunyan Capt Kidd and Dr. Webster in the act of killin Dr. Parkman, besides several miscellanyus moral wax statoots of celebrated piruts & murderers, &c., ekalled by few & exceld by none. Now Mr. Editor, scratch orf a few lines sayin how is the show bizniss down to your place. I shall hav my hanbills dun at your offiss. Depend upon it. I want you should git my hanbills up in flamin stile. Also git up a tremenjus excitemunt in yr. paper 'bowt my onparaleld Show. We must fetch the public sumhow. We must wurk on their feelins. Cum the moral on 'em strong. If it's a temperance community tell 'em I sined the pledge fifteen minits arter Ise born, but on the contery ef your peple take their tods, say Mister Ward is as Jenial a feller as we ever met, full of conwiviality, &the life an sole of the Soshul Bored. Take, don't you? If you say anythin abowt my show say my snaiks is as harmliss as the new-born Babe. What a interestin study it is to see a zewological animil like a snaik under perfeck subjecshun! My kangaroo is the most larfable little cuss I ever saw. All for 15 cents. I am anxyus to skewer your infloounce. I repeet in regard to them hanbills that I shall git 'em struck orf up to your printin office. My perlitercal sentiments agree with yourn exackly. I know thay do, becawz I never saw a man whoos didn't.

Respectively yures,

A. Ward.

P.S.—You scratch my back &Ile scratch your back.

____________________

Every man has got a Fort. It's sum men's fort to do one thing, and some other men's fort to do another, while there is numeris shiftliss critters goin round loose whose fort is not to do nothin.

Shakspeer rote good plase, but he wouldn't hav succeeded as a Washington correspondent of a New York aily paper. He lackt the rekesit fancy and imagginashun.

That's so!

Old George Washington's Fort was not to hev eny public man of the present day resemble him to eny alarmin extent. Whare bowts can George's ekal be found? I ask, & boldly anser no whares, or eny whare else.

Old man Townsin's Fort was to maik Sassyperiller. "Goy to the world! anuther life saived!" (Cotashun from Townsin's advertisemunt.)

Cyrus Field's Fort is to lay a sub-machine tellegraf under the boundin billers of the Oshun, and then hev it Bust.

Spaldin's Fort is to maik Prepared Gloo, which mends everything. Wonder ef it will mend a sinner's wickid waze? Impromptoo goak.

Zoary's Fort is to be a femaile circus feller.

My Fort is the grate

moral show bizniss & ritin choice famerly literatoor for the

noospapers. That's what's the matter with ME.

My Fort is the grate

moral show bizniss & ritin choice famerly literatoor for the

noospapers. That's what's the matter with ME.

&c., &c., &c. So I mite go on to a indefnit extent.

Twict I've endeverd to do things which thay wasn't my Fort. The fust time was when I undertuk to lick a owdashus cuss who cut a hole in my tent & krawld threw. Sez I, "my jentle Sir go out or I shall fall onto you putty hevy." Sez he, "Wade in, Old wax figgers," whareupon I went for him, but he cawt me powerful on the hed & knockt me threw the tent into a cow pastur. He pursood the attack & flung me into a mud puddle. As I aroze & rung out my drencht garmints I koncluded fitin wasn't my Fort. Ile now rize the kurtin upon Seen 2nd: It is rarely seldum that I seek consolation in the Flowin Bole. But in a sertin town in Injianny in the Faul of 18—, my orgin grinder got sick with the fever & died. I never felt so ashamed in my life, & I thowt I'd hist in a few swallows of suthin strengthin. Konsequents was I histid in so much I dident zackly know whare bowts I was. I turnd my livin wild beests of Pray loose into the streets and spilt all my wax wurks. I then Bet I cood play hoss. So I hitched myself to a Kanawl bote, there bein two other hosses hitcht on also, one behind and anuther ahead of me. The driver hollerd for us to git up, and we did. But the hosses bein onused to sich a arrangemunt begun to kick & squeal and rair up. Konsequents was I was kickt vilently in the stummuck & back, and presuntly I fownd myself in the Kanawl with the other hosses, kickin & yellin like a tribe of Cusscaroorus savvijis. I was rescood, & as I was bein carrid to the tavern on a hemlock Bored I sed in a feeble voise, "Boys, playin hoss isn't my Fort."

MORUL—Never don't do nothin which isn't your Fort, for ef you do you'll find yourself splashin round in the Kanawl, figgeratively speakin.

____________________

The Shakers is the strangest religious sex I ever met. I'd hearn tell of 'em and I'd seen 'em, with their broad brim'd hats and long wastid coats; but I'd never cum into immejit contack with 'em, and I'd sot 'em down as lackin intelleck, as I'd never seen 'em to my Show—leastways, if they cum they was disgised in white peple's close, so I didn't know 'em.

But in the Spring of 18—, I got swampt in the exterior of New York State, one dark and stormy night, when the winds Blue pityusly, and I was forced to tie up with the Shakers.

I was toilin threw the mud, when in the dim vister of the futer I obsarved the gleams of a taller candle. Tiein a hornet's nest to my off hoss's tail to kinder encourage him, I soon reached the place. I knockt at the door, which it was opened unto me by a tall, slick-faced, solum lookin individooal, who turn'd out to be a Elder.

"Mr. Shaker," sed I, "you see before you a Babe in the woods, so to speak, and he axes shelter of you."

"Yay," sed the Shaker, and he led the way into the house, another Shaker bein sent to put my hosses and waggin under kiver.

A solum female, lookin sumwhat like a last year's beanpole stuck into a long meal bag, cum in axed me was I athurst and did I hunger? to which I urbanely anserd "a few." She went orf and I endeverd to open a conversashun with the old man.

"Elder, I spect?" sed I.

"Yay," he said.

"Helth's good, I reckon?"

"Yay."

"What's the wages of a Elder, when he understans his bizness—or do you devote your sarvices gratooitus?"

"Yay."

"Stormy night, sir."

"Yay."

"If the storm continners there'll be a mess underfoot, hay?"

"Yay."

"It's onpleasant when there's a mess underfoot?"

"Yay."

"If I may be so bold, kind sir, what's the price of that pecooler kind of weskit you wear, incloodin trimmins?"

"Yay!"

I pawsd a minit, and then, thinkin I'd be faseshus with him and see how that would go, I slapt him on the shoulder, bust into a harty larf, and told him that as a yayer he had no livin ekal.

He jumpt up as if Bilin water had bin squirted into his ears, groaned, rolled his eyes up tords the sealin and sed: "You're a man of sin!" He then walkt out of the room.

Jest then the female in the meal bag stuck her hed into the room and statid that refreshments awaited the weary travler, and I sed if it was vittles she ment the weary travler was agreeable, and I follored her into the next room.

I sot down to the table and the female in the meal bag pored out sum tea. She sed nothin, and for five minutes the only live thing in that room was a old wooden clock, which tickt in a subdood and bashful manner in the corner. This dethly stillness made me oneasy, and I determined to talk to the female or bust. So sez I, "marrige is agin your rules, I bleeve, marm?"

"Yay."

"The sexes liv strickly apart, I spect?"

"Yay."

"It's kinder singler," sez I, puttin on my most sweetest look and speakin in a winnin voice, "that so fair a made as thow never got hitched to some likely feller." [N.B.—She was upards of 40 and homely as a stump fence, but I thawt I'd tickil her.]

"I don't like men!" she sed, very short.

"Wall, I dunno," sez I, "they're a rayther important part of the populashun. I don't scacely see how we could git along without 'em."

"Us poor wimin folks would git along a grate deal better if there was no men!"

"You'll excoos me, marm, but I don't think that air would work. It wouldn't be regler."

"I'm fraid of men!" she sed.

"That's onnecessary, marm. YOU ain't in no danger. Don't fret yourself on that pint."

"Here we're shot out from the sinful world. Here all is peas. Here we air brothers and sisters. We don't marry and consekently we hav no domestic difficulties. Husbans don't abooze their wives—wives don't worrit their husbans. There's no children here to worrit us. Nothin to worrit us here. No wicked matrimony here. Would thow like to be a Shaker?"

"No," sez I, "it ain't my stile."

I had now histed in as big a load of pervishuns as I could carry comfortable, and, leanin back in my cheer, commenst pickin my teeth with a fork. The female went out, leavin me all alone with the clock. I hadn't sot thar long before the Elder poked his hed in at the door. "You're a man of sin!" he sed, and groaned and went away.

Direckly thar cum in two young Shakeresses, as putty and slick lookin gals as I ever met. It is troo they was drest in meal bags like the old one I'd met previsly, and their shiny, silky har was hid from sight by long white caps, sich as I spose female Josts wear; but their eyes sparkled like diminds, their cheeks was like roses, and they was charmin enuff to make a man throw stuns at his granmother if they axed him to. They comenst clearin away the dishes, castin shy glances at me all the time. I got excited. I forgot Betsy Jane in my rapter, and sez I, "my pretty dears, how air you?"

"We air well," they solumly sed.

"Whar's the old man?" sed I, in a soft voice.

"Of whom dost thow speak—Brother Uriah?"

"I mean the gay and festiv cuss who calls me a man of sin. Shouldn't wonder if his name was Uriah."

"He has retired."

"Wall, my pretty dears," sez I, "let's have sum fun. Let's play puss in the corner. What say?"

"Air you a Shaker, sir?" they axed.

"Wall my pretty dears, I haven't arrayed my proud form in a long weskit yit, but if they was all like you perhaps I'd jine 'em. As it is, I'm a Shaker pro-temporary."

They was full of fun. I seed that at fust, only they was a leetle skeery. I tawt 'em Puss in the corner and sich like plase, and we had a nice time, keepin quiet of course so the old man shouldn't hear. When we broke up, sez I, "my pretty dears, ear I go you hav no objections, hav you, to a innersent kiss at partin?"

"Yay," they said, and I YAY'D.

I went up stairs to bed. I spose I'd bin snoozin half an hour when I was woke up by a noise at the door. I sot up in bed, leanin on my elbers and rubbin my eyes, and I saw the follerin picter: The Elder stood in the doorway, with a taller candle in his hand. He hadn't no wearin appeerel on except his night close, which flutterd in the breeze like a Seseshun flag. He sed, "You're a man of sin!" then groaned and went away.

I went to sleep agin, and drempt of runnin orf with the pretty little Shakeresses mounted on my Californy Bar. I thawt the Bar insisted on steerin strate for my dooryard in Baldinsville and that Betsy Jane cum out and giv us a warm recepshun with a panfull of Bilin water. I was woke up arly by the Elder. He said efreshments was reddy for me down stairs. Then sayin I was a man of sin, he went groanin away.

As I was goin threw the entry to the room where the vittles was, I cum across the Elder and the old female I'd met the night before, and what d'ye spose they was up to? Huggin and kissin like young lovers in their gushingist state. Sez I, "my Shaker friends, I reckon you'd better suspend the rules and git married."

"You must excoos Brother Uriah," sed the female; "he's subjeck to fits and hain't got no command over hisself when he's into 'em."

"Sartinly," sez I, "I've bin took that way myself frequent."

"You're a man of sin!" sed the Elder.

Arter breakfust my little Shaker frends cum in agin to clear away the dishes.

"My pretty dears," sez I, "shall we YAY agin?"

"Nay," they sed, and I NAY'D.

The Shakers axed me to go to their meetin, as they was to hav sarvices that mornin, so I put on a clean biled rag and went. The meetin house was as neat as a pin. The floor was white as chalk and smooth as glass. The Shakers was all on hand, in clean weskits and meal bags, ranged on the floor like milingtery companies, the mails on one side of the room and the females on tother. They commenst clappin their hands and singin and dancin. They danced kinder slow at fust, but as they got warmed up they shaved it down very brisk, I tell you. Elder Uriah, in particler, exhiberted a right smart chance of spryness in his legs, considerin his time of life, and as he cum a dubble shuffle near where I sot, I rewarded him with a approvin smile and sed: "Hunky boy! Go it, my gay and festiv cuss!"

"You're a man of sin!" he sed, continnerin his shuffle.

The Sperret, as they called it, then moved a short fat Shaker to say a few remarks. He sed they was Shakers and all was ekal. They was the purest and Seleckest peple on the yearth. Other peple was sinful as they could be, but Shakers was all right. Shakers was all goin kerslap to the Promist Land, and nobody want goin to stand at the gate to bar 'em out, if they did they'd git run over.

The Shakers then danced and sung agin, and arter they was threw, one of 'em axed me what I thawt of it.

Sez I, "What duz it siggerfy?"

"What?" sez he.

"Why this jumpin up and

singin? This long weskit bizniss, and this anty-matrimony

idee? My frends, you air neat and tidy. Your lands is

flowin with milk and honey. Your brooms is fine, and your

apple sass is honest. When a man buys a keg of apple sass of

you he don't find a grate many shavins under a few layers of

sass—a little Game I'm sorry to say sum of my New Englan

ancesters used to practiss. Your garding seeds is fine, and

if I should sow 'em on the rock of Gibralter probly I should raise

a good mess of garding sass. You air honest in your

dealins. You air quiet and don't distarb nobody. For

all this I givs you credit. But your religion is small

pertaters, I must say. You mope away your lives here in

single retchidness, and as you air all by yourselves nothing ever

conflicks with your pecooler idees, except when Human Nater busts

out among you, as I understan she sumtimes do. [I giv Uriah a

sly wink here, which made the old feller squirm like a speared

Eel.] You wear long weskits and long faces, and lead a gloomy

life indeed. No children's prattle is ever hearn around your

harthstuns—you air in a dreary fog all the time, and you

treat the jolly sunshine of life as tho' it was a thief, drivin it

from your doors by them weskits, and meal bags, and pecooler

noshuns of yourn. The gals among you, sum of which air as

slick pieces of caliker as I ever sot eyes on, air syin to place

their heds agin weskits which kiver honest, manly harts, while you

old heds fool yerselves with the idee that they air fulfillin their

mishun here, and air contented. Here you air all pend up by

yerselves, talkin about the sins of a world you don't know nothin

of. Meanwhile said world continners to resolve round on her

own axletree onct in every 24 hours, subjeck to the Constitution of

the United States, and is a very plesant place of residence.

It's a unnatral, onreasonable and dismal life you're leadin

here. So it strikes me. My Shaker frends, I now bid you

a welcome adoo. You hav treated me exceedin well. Thank

you kindly, one and all.

"Why this jumpin up and

singin? This long weskit bizniss, and this anty-matrimony

idee? My frends, you air neat and tidy. Your lands is

flowin with milk and honey. Your brooms is fine, and your

apple sass is honest. When a man buys a keg of apple sass of

you he don't find a grate many shavins under a few layers of

sass—a little Game I'm sorry to say sum of my New Englan

ancesters used to practiss. Your garding seeds is fine, and

if I should sow 'em on the rock of Gibralter probly I should raise

a good mess of garding sass. You air honest in your

dealins. You air quiet and don't distarb nobody. For

all this I givs you credit. But your religion is small

pertaters, I must say. You mope away your lives here in

single retchidness, and as you air all by yourselves nothing ever

conflicks with your pecooler idees, except when Human Nater busts

out among you, as I understan she sumtimes do. [I giv Uriah a

sly wink here, which made the old feller squirm like a speared

Eel.] You wear long weskits and long faces, and lead a gloomy

life indeed. No children's prattle is ever hearn around your

harthstuns—you air in a dreary fog all the time, and you

treat the jolly sunshine of life as tho' it was a thief, drivin it

from your doors by them weskits, and meal bags, and pecooler

noshuns of yourn. The gals among you, sum of which air as

slick pieces of caliker as I ever sot eyes on, air syin to place

their heds agin weskits which kiver honest, manly harts, while you

old heds fool yerselves with the idee that they air fulfillin their

mishun here, and air contented. Here you air all pend up by

yerselves, talkin about the sins of a world you don't know nothin

of. Meanwhile said world continners to resolve round on her

own axletree onct in every 24 hours, subjeck to the Constitution of

the United States, and is a very plesant place of residence.

It's a unnatral, onreasonable and dismal life you're leadin

here. So it strikes me. My Shaker frends, I now bid you

a welcome adoo. You hav treated me exceedin well. Thank

you kindly, one and all.

"A base exhibiter of depraved monkeys and onprincipled wax works!" sed Uriah.

"Hello, Uriah," sez I, "I'd most forgot you. Wall, look out for them fits of yourn, and don't catch cold and die in the flour of your youth and beauty."

And I resoomed my jerney.

____________________

In the Faul of 1856, I showed my show in Uticky, a trooly grate sitty in the State of New York.

The people gave me a cordyal recepshun. The press was loud in her prases.

1 day as I was givin a descripshun of my Beests and Snaiks in my usual flowry stile what was my skorn disgust to see a big burly feller walk up to the cage containin my wax figgers of the Lord's Last Supper, and cease Judas Iscarrot by the feet and drag him out on the ground. He then commenced fur to pound him as hard as he cood.

"What under the son are you abowt?" cried I.

Sez he, "What did you bring this pussylanermus cuss here fur?" and he hit the wax figger another tremenjis blow on the hed.

Sez I, "You egrejus ass, that air's a wax figger—a representashun of the false 'Postle."

Sez he, "That's all very well fur you to say, but I tell you, old man, that Judas Iscarrot can't show hisself in Utiky with impunerty by a darn site!" with which observashun he kaved in Judassis hed. The young man belonged to 1 of the first famerlies in Utiky. I sood him, and the Joory brawt in a verdick of Arson in the 3d degree.

____________________

Baldinsville, Injianny, Sep. the onct, 18&58.—I was summund home from Cinsinnaty quite suddin by a lettur from the Supervizers of Baldinsville, sayin as how grate things was on the Tappis in that air town in refferunse to sellebratin the compleshun of the Sub-Mershine Tellergraph & axkin me to be Pressunt. Lockin up my Kangeroo and wax wurks in a sekure stile I took my departer for Baldinsville—"my own, my nativ lan," which I gut intwo at early kandle litin on the follerin night & just as the sellerbrashun and illumernashun ware commensin.

Baldinsville was trooly in a blaze of glory. Near can I forgit the surblime speckticul which met my gase as I alited from the Staige with my umbreller and verlis. The Tarvern was lit up with taller kandles all over & a grate bon fire was burnin in frunt thareof. A Traspirancy was tied onto the sine post with the follerin wurds—"Giv us Liberty or Deth." Old Tompkinsis grosery was illumernated with 5 tin lantuns and the follerin Transpirancy was in the winder—"The Sub-Mershine Tellergraph & the Baldinsville and Stonefield Plank Road—the 2 grate eventz of the 19th centerry—may intestines strife never mar their grandjure." Simpkinsis shoe shop was all ablase with kandles and lantuns. A American Eagle was painted onto a flag in a winder—also these wurds, viz.—"The Constitooshun must be Presarved." The Skool house was lited up in grate stile and the winders was filld with mottoes amung which I notised the follerin—"Trooth smashed to erth shall rize agin—YOU CAN'T STOP HER." "The Boy stood on the Burnin Deck whense awl but him had Fled." "Prokrastinashun is the theaf of Time." "Be virtoous & you will be Happy." "Intemperunse has cawsed a heap of trubble—shun the Bole," an the follerin sentimunt written by the skool master, who graduated at Hudson Kollige: "Baldinsville sends greetin to Her Magisty the Queen, & hopes all hard feelins which has heretofore previs bin felt between the Supervizers of Baldinsville and the British Parlimunt, if such there has been, may now be forever wiped frum our Escutchuns. Baldinsville this night rejoises over the gerlorious event which sementz 2 grate nashuns onto one anuther by means of a elecktric wire under the roarin billers of the Nasty Deep. QUOSQUE TANTRUM, A BUTTER, CATERLINY, PATENT NOSTRUM!" Squire Smith's house was lited up regardlis of expense. His little sun William Henry stood upon the roof firin orf crackers. The old 'Squire hisself was dressed up in soljer clothes and stood on his door-step, pintin his sword sollumly to a American flag which was suspendid on top of a pole in frunt of his house. Frequiently he wood take orf his cocked hat & wave it round in a impressive stile. His oldest darter Mis Isabeller Smith, who has just cum home from the Perkinsville Female Instertoot, appeared at the frunt winder in the West room as the goddis of liberty, & sung "I see them on their windin way." Booteus I, sed I to myself, "you air a angil & nothin shorter. N. Boneparte Smith, the 'Squire's oldest sun, drest hisself up as Venus the God of Wars and red the Decleration of Inderpendunse from the left chambir winder. The 'Squire's wife didn't jine in the festiverties. She sed it was the tarnulest nonsense she ever seed. Sez she to the 'Squire, "Cum into the house and go to bed you old fool, you. Tomorrer you'll be goin round half-ded with the rumertism & won't gin us a minit's peace till you get well." Sez the 'Squire, "Betsy, you little appresiate the importance of the event which I this night commererate." Sez she, "Commemerate a cat's tail—cum into the house this instant, you pesky old critter." "Betsy," sez the 'Squire, wavin his sword, "retire." This made her just as mad as she could stick. She retired, but cum out agin putty quick with a panfull of Bilin hot water which she throwed all over the Squire, & Surs, you wood have split your sides larfin to see the old man jump up and holler & run into the house. Except this unpropishus circumstance all went as merry as a carriage bell, as Lord Byrun sez. Doctor Hutchinsis offiss was likewise lited up and a Transpirancy, on which was painted the Queen in the act of drinkin sum of "Hutchinsis invigorater," was stuck into one of the winders. The aldinsville Bugle of Liberty noospaper offiss was also illumernated, & the follerin mottoes stuck out—"The Press is the Arkermejian leaver which moves the world." "Vote Early." "Buckle on your Armer." "Now is the time to Subscribe." "Franklin, Morse & Field." "Terms 1.50 dollars a year—liberal reducshuns to clubs." In short the villige of Baldinsville was in a perfect fewroar. I never seed so many peple thar befour in my born days. Ile not attemp to describe the seens of that grate night. Wurds wood fale me ef I shood try to do it. I shall stop here a few periods and enjoy my "Oatem cum dig the tates," as our skool master observes, in the buzzum of my famerly, & shall then resume the show biznis, which Ive bin into twenty-two (22) yeres and six (6) months."

____________________

My naburs is mourn harf crazy on the new-fangled ideas about Sperrets. Sperretooul Sircles is held nitely & 4 or 5 long hared fellers has settled here and gone into the Sperret biznis excloosively. A atemt was made to git Mrs. A. Ward to embark into the Sperret biznis but the atemt faled. 1 of the long hared fellers told her she was a ethereal creeter & wood make a sweet mejium, whareupon she attact him with a mop handle & drove him out of the house. I will hear obsarve that Mrs. Ward is a invalerble womum—the partner of my goys & the shairer of my sorrers. In my absunse she watchis my interests & things with a Eagle Eye & when I return she welcums me in afectionate stile. Trooly it is with us as it was with Mr. & Mrs. INGOMER in the Play, to whit,—

2 soles with but a single thawt 2 harts which beet as 1.

My naburs injooced me to attend a Sperretooul Sircle at Squire Smith's. When I arrove I found the east room chock full includin all the old maids in the villige & the long hared fellers a4sed. When I went in I was salootid with "hear cums the benited man"— "hear cums the hory-heded unbeleever"— "hear cums the skoffer at trooth, " etsettery, etsettery.

Sez I, "my frens, it's troo I'm hear, & now bring on your Sperrets."

1 of the long hared fellers riz up and sed he would state a few remarks. He sed man was a critter of intelleck & was movin on to a Gole. Sum men had bigger intellecks than other men had and thay wood git to the Gole the soonerest. Sum men was beests & wood never git into the Gole at all. He sed the Erth was materiel but man was immaterial, and hens man was different from the Erth. The Erth, continnered the speaker, resolves round on its own axeltree onct in 24 hours, but as man haint gut no axeltree he cant resolve. He sed the ethereal essunce of the koordinate branchis of super-human natur becum mettymorfussed as man progrest in harmonial coexistunce & eventooally anty humanized theirselves & turned into reglar sperretuellers. (This was versifferusly applauded by the cumpany, and as I make it a pint to get along as pleasant as possible, I sung out "bully for you, old boy.")

The cumpany then drew round the table and the Sircle kommenst to go it. Thay axed me if thare was an body in the Sperret land which I wood like to convarse with. I sed if Bill Tompkins, who was onct my partner in the show biznis, was sober, I should like to convarse with him a few periods.

"Is the Sperret of William Tompkins present?" sed 1 of the long hared chaps, and there was three knox on the table.

Sez I, "William, how goze it, Old Sweetness?"

"Pretty ruff, old hoss," he replide.

That was a pleasant way we had of addressin each other when he was in the flesh.

"Air you in the show bizniz, William?" sed I.

He sed he was. He sed he & John Bunyan was travelin with a side show in connection with Shakspere, Jonson & Co.'s Circus. He sed old Bun (meanin Mr. Bunyan,) stired up the animils & ground the organ while he tended door. Occashunally Mr. Bunyan sung a comic song. The Circus was doin middlin well. Bill Shakspeer had made a grate hit with old Bob Ridley, and Ben Jonson was delitin the peple with his trooly grate ax of hossmanship without saddul or bridal. Thay was rehersin Dixey's Land & expected it would knock the peple.

Sez I, "William, my luvly friend, can you pay me that 13 dollars you owe me?" He sed no with one of the most tremenjis knox I ever experiunsed.

The Sircle sed he had gone. "Air you gone, William?" I axed. "Rayther," he replide, and I knowd it as no use to pursoo the subjeck furder.

I then called fur my farther.

"How's things, daddy?"

"Middlin, my son, middlin."

"Ain't you proud of your orfurn boy?"

"Scacely."

"Why not, my parient?"

"Becawz you hav gone to writin for the noospapers, my son. Bimeby you'll lose all your character for trooth and verrasserty. When I helpt you into the show biznis I told you to dignerfy that there profeshun. Litteratoor is low."

He also statid that he was doin middlin well in the peanut biznis & liked it putty well, tho' the climit was rather warm.

When the Sircle stopt thay axed me what I thawt of it.

Sez I, "My frends I've bin into the show biznis now goin on 23 years. Theres a artikil in the Constitooshun of the United States which sez in effeck that everybody may think just as he darn pleazes, & them is my sentiments to a hare. You dowtlis beleeve this Sperret doctrin while I think it is a little mixt. Just so soon as a man becums a reglar out & out Sperret rapper he leeves orf workin, lets his hare grow all over his fase & commensis spungin his livin out of other peple. He eats all the dickshunaries he can find & goze round chock full of big words, scarein the wimmin folks & little children & destroyin the piece of mind of evry famerlee he enters. He don't do nobody no good & is a cuss to society & a pirit on honest peple's corn beef barrils. Admittin all you say abowt the doctrin to be troo, I must say the reglar perfessional Sperrit rappers—them as makes a biznis on it—air abowt the most ornery set of cusses I ever enkountered in my life. So sayin I put on my surtoot and went home.

| Respectably | Yures, |

| Artemus Ward. |

____________________

Gents of the Editorial Corpse.—

Since I last rit you I've met with immense success a showin my show in varis places, particly at Detroit. I put up at Mr. Russel's tavern, a very good tavern too, but I am sorry to inform you that the clerks tried to cum a Gouge Game on me. I brandished my new sixteen dollar huntin-cased watch round considerable, & as I was drest in my store clothes & had a lot of sweet-scented wagon-grease on my hair, I am free to confess that I thought I lookt putty gay. It never once struck me that I lookt green. But up steps a clerk & axes me hadn't I better put my watch in the Safe. "Sir," sez I, "that watch cost sixteen dollars! Yes, Sir, every dollar of it! You can't cum it over me, my boy! Not at all, Sir." I know'd what the clerk wanted. He wanted that watch himself. He wanted to make believe as tho he lockt it up in the safe, then he would set the house a fire and pretend as tho the watch was destroyed with the other property! But he caught a Tomarter when he got hold of me. From Detroit I go West'ard hoe. On the cars was a he-lookin female, with a green-cotton umbreller in one hand and a handful of Reform tracks in the other. She sed every woman should have a Spear. Them as didn't demand their Spears, didn't know what was good for them. "What is my Spear?" she axed, addressing the people in the cars. "Is it to stay at home & darn stockins & be the ser-LAVE of a domineerin man? Or is it my Spear to vote & speak & show myself the ekal of a man? Is there a sister in these keers that has her proper Spear?" Sayin which the eccentric female whirled her umbreller round several times, & finally jabbed me in the weskit with it.

"I hav no objecshuns to your goin into the Spear bizness," sez I, "but you'll please remember I ain't a pickeril. Don't Spear me agin, if you please." She sot down.

At Ann Arbor, bein seized with a sudden faintness, I called for a drop of suthin to drink. As I was stirrin the beverage up, a pale-faced man in gold spectacles laid his hand upon my shoulder, & sed, "Look not upon the wine when it is red!"

Sez I, "This ain't wine. This is Old Rye."

"'It stingeth like a Adder and biteth like a Sarpent!'" sed the man.

"I guess not," sed I, "when you put sugar into it. That's the way I allers take mine."

"Have you sons grown up, sir?" the man axed.

"Wall," I replide, as I put myself outside my beverage, "my son Artemus junior is goin on 18."

"Ain't you afraid if you set this example be4 him he'll cum to a bad end?"

"He's cum to a waxed end already. He's learnin the shoe makin bizness," I replide. "I guess we can both on us git along without your assistance, Sir," I obsarved, as he was about to open his mouth agin.

"This is a cold world!" sed the man.

"That's so. But you'll get into a warmer one by and by if you don't mind your own bizness better." I was a little riled at the feller, because I never take anythin only when I'm onwell. I arterwards learned he was a temperance lecturer, and if he can injuce men to stop settin their inards on fire with the frightful licker which is retailed round the country, I shall hartily rejoice. Better give men Prusick Assid to onct, than to pizen 'em to deth by degrees.

At Albion I met with overwhelmin success. The celebrated Albion Female Semenary is located here, & there air over 300 young ladies in the Institushun, pretty enough to eat without seasonin or sass. The young ladies was very kind to me, volunteerin to pin my handbills onto the backs of their dresses. It was a surblime site to see over 300 young ladies goin round with a advertisement of A. Ward's onparaleld show, conspickusly posted onto their dresses.

They've got a Panick up this way and refooze to take Western money. It never was worth much, and when western men, who knows what it is, refooze to take their own money it is about time other folks stopt handlin it. Banks are bustin every day, goin up higher nor any balloon of which we hav any record. These western bankers air a sweet & luvly set of men. I wish I owned as good a house as some of 'em would break into!

Virtoo is its own reward.

A. Ward.

____________________

It is with no ordernary feelins of Shagrin & indignashun that I rite you these here lines. Sum of the hiest and most purest feelins whitch actoate the humin hart has bin trampt onto. The Amerycan flag has bin outrajed. Ive bin nussin a Adder in my Boozum. The fax in the kase is these here:

A few weeks ago I left Baldinsville to go to N.Y.fur to git out my flamin yeller hanbills fur the Summer kampane, & as I was peroosin a noospaper on the kars a middel aged man in speckterkuls kum & sot down beside onto me. He was drest in black close & was appeerently as fine a man as ever was.

"A fine day, Sir," he did unto me strateway say.

"Middlin," sez I, not wishin to kommit myself, tho he peered to be as fine a man as there was in the wurld—"It is a middlin fine day, Square," I obsarved.

Sez he, "How fares the Ship of State in yure regine of country?"

Sez I, "We don't hav no ships in our State—the kanawl is our best holt."

He pawsed a minit and then sed, "Air yu aware, Sir, that the krisis is with us?"

"No," sez I, getting up and lookin under the seet, "whare is she?"

"It's hear—it's everywhares," he sed.

Sez I, "Why how you tawk!" and I gut up agin & lookt all round. "I must say, my fren," I continnered, as I resoomed my seet, "that I kan't see nothin of no krisis myself." I felt sumwhat alarmed, & arose & in a stentoewrian voice obsarved that if any lady or gentleman in that there kar had a krisis consealed abowt their persons they'd better projuce it to onct or suffer the konsequences. Several individoouls snickered rite out, while a putty little damsell rite behind me in a pinc gown made the observashun, "He, he."

"Sit down, my fren," sed the man in black close, "yu miskomprehend me. I meen that the perlittercal ellermunts are orecast with black klouds, 4boden a friteful storm."

"Wall," replide I, "in regard to perlittercal ellerfunts I don't know as how but what they is as good as enny other kind of ellerfunts. But I maik bold to say thay is all a ornery set & unpleasant to hav around. they air powerful hevy eaters & take up a right smart chans of room, & besides thay air as ugly and revenjeful, as a Cusscaroarus Injun, with 13 inches of corn whisky in his stummick." The man in black close seemed to be as fine a man as ever was in the wurld. He smilt & sed praps I was rite, tho it was ellermunts instid of ellerfunts that he was alludin to, & axed me what was my prinserpuls?

"I haint gut enny," sed I—"not a prinserpul. Ime in the show biznis." The man in black close, I will hear obsarve, seemed to be as fine a man as ever was in the wurld.

"But," sez he, "you hav feelins into you? You cimpathize with the misfortunit, the loly & the hart-sick, don't you?" He bust into teers and axed me ef I saw that yung lady in the seet out yender, pintin to as slick a lookin gal as I ever seed.

Sed I, "2 be shure I see her—is she mutch sick?" The man in black close was appeerently as fine a man as ever was in the wurld ennywhares.

"Draw closter to me," sed the man in black close. "Let me git my mowth fernenst yure ear. Hush—SHESE A OCTOROON!"

"No!" sez I, gittin up in a exsited manner, "yu don't say so! How long has she bin in that way?"

"Frum her arliest infuncy," sed he.

"Wall, whot upon arth duz she doo it fur?" I inquired.

"She kan't help it," sed the man in black close. "It's the brand of Kane."

"Wall, she'd better stop drinkin Kane's brandy," I replide.

"I sed the brand of Kane was upon her—not brandy, my fren. Yure very obtoose."

I was konsiderbul riled at this. Sez I, "My gentle Sir, Ime a nonresistanter as a ginral thing, & don't want to git up no rows with nobuddy, but I kin nevertheles kave in enny man's hed that calls me a obtoos," with whitch remarks I kommenst fur to pull orf my extry garmints. "Cum on," sez I—"Time! hear's the Beniki Boy fur ye!" & I darnced round like a poppit. He riz up in his seet & axed my pardin—sed it was all a mistake—that I was a good man, etsettery, & sow 4th, & we fixt it all up pleasant. I must say the man in black close seamed to be as fine a man as ever lived in the wurld. He sed a Octoroon was the 8th of a negrow. He likewise statid that the female he was travlin with was formurly a slave in Mississippy; that she'd purchist her freedim & now wantid to purchiss the freedim of her poor old muther, who (the man in black close obsarved) was between 87 years of age & had to do all the cookin & washin for 25 hired men, whitch it was rapidly breakin down her konstitushun. He sed he knowed the minit he gazed onto my klassic & beneverlunt fase that I'd donate librully & axed me to go over & see her, which I accordingly did. I sot down beside her and sed, "yure Sarvant, Marm! How do yer git along?"

She bust in 2 teers & sed, "O Sur, I'm so retchid—I'm a poor unfortunit Octoroon."

"So I larn. Yure rather more Roon than Octo, I take it," sed I, fur I never seed a puttier gal in the hull endoorin time of my life. She had on a More Antic Barsk & a Poplin Nubier with Berage trimmins onto it, while her ise & kurls was enuff to make a man jump into a mill pond without biddin his relashuns good-by. I pittid the Octoroon from the inmost recusses of my hart & hawled out 50 dollars kerslap, & told her to buy her old muther as soon as posserbul. Sez she "kine sir mutch thanks." She then lade her hed over onto my showlder & sed I was "old rats." I was astonished to heer this obsarvation, which I knowd was never used in refined society & I perlitely but emfattercly shovd her hed away.

Sez I "Marm, I'm trooly sirprized."

Sez she, "git out. Yure the nicist old man Ive seen yit. Give us anuther 50!" Had a seleck assortment of the most tremenjious thunderbolts descended down onto me I couldn't hav bin more takin aback. I jumpt up, but she ceased my coat tales & in a wild voise cride, "No, Ile never desart you—let us fli together to a furrin shoor!"

Sez I, "not mutch we wont," and I made a powerful effort to get awa from her. "This is plade out," I sed, whereupon she jerkt me back into the seet. "Leggo my coat, you scandaluss female," I roared, when she set up the most unarthly yellin and hollerin you ever heerd. The passinjers & the gentlemunly konducter rusht to the spot, & I don't think I ever experiunsed sich a rumpus in the hull coarse of my natral dase. The man in black close rusht up to me & sed "How dair yu insult my neece, you horey heded vagabone. You base exhibbiter of low wax figgers—yu woolf in sheep's close," & sow 4th.

I was konfoozed. I was a loonytick fur the time bein, and offered 5 dollars reward to enny gentleman of good morrul carracter who wood tell me whot my name was & what town I livd into. The konducter kum to me & sed the insultid parties wood settle for 50 dollars, which I immejitly hawled out, & agane implored sumbuddy to state whare I was prinsipully, & if I shood be thare a grate while my self ef things went on as they'd bin goin fur sum time back. I then axed if there was enny more Octoroons present, "becawz," sez I, "ef there is, let um cum along, fur Ime in the Octoroon bizniss." I then threw my specterculs out of the winder, smasht my hat wildly down over my Ise, larfed highsterically & fell under a seet. I lay there sum time & fell asleep. I dreamt Mrs. Ward & the twins had bin carried orf by Ryenosserhosses & that Baldinsville had bin captered by a army of Octoroons. When I awoked the lamps was a burnin dimly. Sum of the passinjers was a snorein like pawpusses & the little damsell in the pinc gown was a singin "Oft in the Silly nite." The onprinsipuld Octoroon & the miserbul man in black close was gone, & all of a suddent it flasht ore my brane that I'de bin swindild.

____________________

About two years ago I arrove in Oberlin, Ohio. Oberlin is whare the celebrated college is. In fack, Oberlin IS the college, everything else in that air vicinity resolvin around excloosivly for the benefit of that institution. It is a very good college, too, & a grate many wurthy yung men go there annooally to git intelleck into 'em. But its my onbiassed 'pinion that they go it rather too strong on Ethiopians at Oberlin. But that's nun of my bisniss. I'm into the Show bizness. Yit as a faithful historan I must menshun the fack that on rainy dase white peple can't find their way threw the streets without the gas is lit, there bein such a numerosity of cullerd pussons in the town.

As I was sayin, I arroved at Oberlin, and called on Perfesser Peck for the purpuss of skewerin Kolonial Hall to exhibit my wax works and beests of Pray into. Kolonial Hall is in the college and is used by the stujents to speak peaces and read essays into.

Sez Perfesser Peck, "Mister Ward, I don't know 'bout this bizniss. What are your sentiments?"

Sez I, "I hain't got any."

"Good God!" cried the Perfesser, "did I understan you to say you hav no sentiments!"

"Nary a sentiment!" sez I.

"Mister Ward, don't your blud bile at the thawt that three million and a half of your culled brethren air a clankin their chains in the South?"

Sez I, "Not a bile! Let 'em clank!"

He was about to continner his flowry speech when I put a stopper on him. Sez I, "Perfesser Peck, A. Ward is my name & Americky is my nashun; I'm allers the same, tho' humble is my station, and I've bin in the show bizniss goin on 22 years. The pint is, can I hav your Hall by payin a fair price? You air full of sentiments. That's your lay, while I'm a exhibiter of startlin curiosities. What d'ye say?"

"Mister Ward, you air endowed with a hily practical mind, and while I deeply regret that you air devoid of sentiments I'll let you hav the hall provided your exhibition is of a moral & elevatin nater."

Sez I, "Tain't nothin shorter."

So I opened in Kolonial Hall, which was crowded every nite with stujents, &c. Perfesser Finny gazed for hours at my Kangaroo, but when that sagashus but onprincipled little cuss set up one of his onarthly yellins and I proceeded to hosswhip him, the Perfesser objected. "Suffer not your angry pashums to rise up at the poor annimil's little excentrissities," said the Perfesser.

"Do you call such conduck as THOSE a little excentrissity?" I axed.

"I do," sed he; sayin which he walked up to the cage and se zhe, "let's try moral swashun upon the poor creeter." So he put his hand upon the Kangeroo's hed and sed, "poor little fellow—poor little fellow—your master is very crooil, isn't he, my untootered frend," when the Kangaroo, with a terrific yell, grabd the Perfesser by the hand and cum very near chawin it orf. It was amoozin to see the Perfesser jump up and scream with pane. Sez I, "that's one of the poor little fellow's excentrissities!"

Sez he, "Mister Ward, that's a dangerous quadruped. He's totally depraved. I will retire and do my lasserated hand up in a rag, and meanwhile I request you to meat out summery and severe punishment to the vishus beest," I hosswhipt the little cuss for upwards of 15 minutes. Guess I licked sum of his excentrissity out of him.

Oberlin is a grate plase. The College opens with a prayer and then the New York Tribune is read. A kolleckshun is then taken up to buy overkoats with red horn buttons onto them for the indignant cullured people of Kanady. I have to contribit librally two the glowrius work, as they kawl it hear. I'm kompelled by the Fackulty to reserve front seets in my show for the cullered peple. At the Boardin House the cullered peple sit at the first table. What they leeve is maid into hash for the white peple. As I don't like the idee of eatin my vittles with Ethiopians, I sit at the seckind table, and the konsequence is I've devowered so much hash that my inards is in a hily mixt up condishun. Fish bones hav maid their appearance all over my boddy and pertater peelins air a springin up through my hair. Howsever I don't mind it. I'm gittin along well in a pecunery pint of view. The College has konfired upon me the honery title of T.K., of which I'm suffishuntly prowd.

____________________

Thare was many affectin ties which made me hanker arter Betsy Jane. Her father's farm jined our'n; their cows and our'n squencht their thurst at the same spring; our old mares both had stars in their forreds; the measles broke out in both famerlies at nearly the same period; our parients (Betsy's and mine) slept reglarly every Sunday in the same meetin house, and the nabers used to obsarve, "How thick the Wards and Peasleys air!" It was a surblime site, in the Spring of the year, to see our sevral mothers (Betsy's and mine) with their gowns pin'd up so thay couldn't sile 'em, affecshuntly Bilin sope together & aboozin the nabers.

Altho I hankerd intensly arter the objeck of my affecshuns, I darsunt tell her of the fires which was rajin in my manly Buzzum. I'd try to do it but my tung would kerwollup up agin the roof of my mowth & stick thar, like deth to a deseast Afrikan or a country postmaster to his offiss, while my hart whanged agin my ribs like a old fashioned wheat Flale agin a barn floor.

'Twas a carm still nite in Joon. All nater was husht and nary a zeffer disturbed the sereen silens. I sot with Betsy Jane on the fense of her farther's pastur. We'd bin rompin threw the woods, kullin flours & drivin the woodchuck from his Nativ Lair (so to speak) with long sticks. Wall, we sot thar on the fense, a swingin our feet two and fro, blushin as red as the Baldinsville skool house when it was fust painted, and lookin very simple, I make no doubt. My left arm was ockepied in ballunsin myself on the fense, while my rite was woundid luvinly round her waste.

I cleared my throat and tremblin sed, "Betsy, you're a Gazelle."

I thought that air was putty fine. I waitid to see what effeck it would hav upon her. It evidently didn't fetch her, for she up and sed,

"You're a sheep!"

Sez I, "Betsy, I think very muchly of you."

"I don't b'leeve a word you say—so there now cum!" with which obsarvashun she hitched away from me.

"I wish thar was winders to my Sole," sed I, "so that you could see some of my feelins. There's fire enuff in here," sed I, strikin my buzzum with my fist, "to bile all the corn beef and turnips in the naberhood. Versoovius and the Critter ain't a circumstans!"

She bowd her hed down and commenst chawin the strings to her sun bonnet.

"Ar could you know the sleeplis nites I worry threw with on your account, how vittles has seized to be attractiv to me & how my lims has shrunk up, you wouldn't dowt me. Gase on this wastin form and these 'ere sunken cheeks"—

I should have continnered on in this strane probly for sum time, but unfortnitly I lost my ballunse and fell over into the pastur ker smash, tearin my close and seveerly damagin myself ginerally.

Betsy Jane sprung to my assistance in dubble quick time and dragged me 4th. Then drawin herself up to her full hite she sed:

"I won't listen to your noncents no longer. Jes say rite strate out what you're drivin at. If you mean gettin hitched, I'M IN!"

I considered that air enuff for all practicul purpusses, and we proceeded immejitely to the parson's, & was made 1 that very nite.

(Notiss to the Printer: Put some stars here.)

| * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * |

I've parst threw many tryin ordeels sins then, but Betsy Jane has bin troo as steel. By attendin strickly to bizniss I've amarsed a handsum Pittance. No man on this footstool can rise & git up & say I ever knowinly injered no man or wimmin folks, while all agree that my Show is ekalled by few and exceld by none, embracin as it does a wonderful colleckshun of livin wild Beests of Pray, snaix in grate profushun, a endliss variety of life-size wax figgers, & the only traned kangaroo in Ameriky—the most amoozin little cuss ever introjuced to a discriminatin public.

____________________

[This Oration was delivered before the commencement of the war.]

On returnin to my humsted in Baldinsville, Injianny, resuntly, my feller sitterzens extended a invite for me to norate to 'em on the Krysis. I excepted & on larst Toosday nite I peared be4 a C of upturned faces in the Red Skool House. I spoke nearly as follers:

Baldinsvillins: Hearto4, as I hav numerously obsarved, I have abstrained from having any sentimunts or principles, my pollertics, like my religion, bein of a exceedin accommodatin character. But the fack can't be no longer disgised that a Krysis is onto us, & I feel it's my dooty to accept your invite for one consecutive nite only. I spose the inflammertory individooals who assisted in projucing this Krysis know what good she will do, but I ain't 'shamed to state that I don't scacely. But the Krysis is hear. She's bin hear for sevral weeks, & Goodness nose how long she'll stay. But I venter to assert that she's rippin things. She's knockt trade into a cockt up hat and chaned Bizness of all kinds tighter nor I ever chaned any of my livin wild Beests. Alow me to hear dygress & stait that my Beests at presnt is as harmless as the newborn Babe. Ladys & gentlemen needn't hav no fears on that pint. To resoom—Altho I can't exactly see what good this Krysis can do, I can very quick say what the origernal cawz of her is. The origernal cawz is Our Afrikan Brother. I was into BARNIM'S Moozeum down to New York the other day & saw that exsentric Etheopian, the What Is It. Sez I, "Mister What Is It, you folks air raisin thunder with this grate country. You're gettin to be ruther more numeris than interestin. It is a pity you coodent go orf sumwhares by yourselves, & be a nation of What Is Its, tho' if you'll excoose me, I shooden't care about marryin among you. No dowt you're exceedin charmin to hum, but your stile of luvliness isn't adapted to this cold climit. He larfed into my face, which rather Riled me, as I had been perfeckly virtoous and respectable in my observashuns. So sez I, turnin a leetle red in the face, I spect, "Do you hav the unblushin impoodents to say you folks haven't raised a big mess of thunder in this brite land, Mister What Is It?" He larfed agin, wusser nor be4, whareupon I up and sez, "Go home, Sir, to Afriky's burnin shores & taik all the other What Is Its along with you. Don't think we can spair your interestin picters. You What Is Its air on the pint of smashin up the gratest Guv'ment ever erected by man, & you actooally hav the owdassity to larf about it. Go home, you low cuss!"

I was workt up to a high pitch, & I proceeded to a Restorator & cooled orf with some little fishes biled in ile—I b'leeve thay call 'em sardeens.