THE LITTLE COLONEL'S KNIGHT

COMES RIDING

ANNIE FELLOWS JOHNSTON

| The Little Colonel Series | |

| (Trade Mark, Reg. U. S. Pat. Of.) | |

| Each one vol., large 12mo, cloth, illustrated | |

The Little Colonel Stories | $1.50 |

| (Containing in one volume the three stories, "The Little Colonel," "The Giant Scissors," and "Two Little Knights of Kentucky.") | |

| The Little Colonel's House Party | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel's Holidays | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel's Hero | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel at Boarding-School | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel in Arizona | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel's Christmas Vacation | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel: Maid of Honor | 1.50 |

| The Little Colonel's Knight Comes Riding | 1.50 |

| Mary Ware: The Little Colonel's Chum | 1.50 |

| The above 10 vols., boxed | 15.00 |

| The Little Colonel Good Times Book | 1.50 |

Illustrated Holiday Editions | |

| Each one vol., small quarto, cloth, illustrated, and printed in colour | |

| The Little Colonel | $1.25 |

| The Giant Scissors | 1.25 |

| Two Little Knights of Kentucky | 1.25 |

| Big Brother | 1.25 |

Cosy Corner Series | |

| Each one vol., thin 12mo, cloth, illustrated | |

| The Little Colonel | $.50 |

| The Giant Scissors | .50 |

| Two Little Knights of Kentucky | .50 |

| Big Brother | .50 |

| Ole Mammy's Torment | .50 |

| The Story of Dago | .50 |

| Cicely | .50 |

| Aunt 'Liza's Hero | .50 |

| The Quilt that Jack Built | .50 |

| Flip's "Islands of Providence" | .50 |

| Mildred's Inheritance | .50 |

Other Books | |

| Joel: A Boy of Galilee | $1.50 |

| In the Desert of Waiting | .50 |

| The Three Weavers | .50 |

| Keeping Tryst | .50 |

| The Legend of the Bleeding Heart | .50 |

| The Rescue of the Princess Winsome | .50 |

| Asa Holmes | 1.00 |

| Songs Ysame (Poems, with Albion Fellows Bacon) | 1.00 |

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

200 Summer Street Boston, Mass.

"WITH THE DONNING OF THE ANCIENT DRESS SHE SEEMED TO HAVE PUT ON THE SWEET SHY MANNER THAT HAD BEEN THE CHARM OF ITS FIRST WEARER."

"WITH THE DONNING OF THE ANCIENT DRESS SHE SEEMED TO HAVE PUT ON THE SWEET SHY MANNER THAT HAD BEEN THE CHARM OF ITS FIRST WEARER."(See page 142)

THE LITTLE COLONEL'S

KNIGHT COMES RIDING

AUTHOR OF

"THE LITTLE COLONEL SERIES," "BIG BROTHER,"

"OLE MAMMY'S TORMENT," "JOEL: A BOY

OF GALILEE," "ASA HOLMES," ETC.

Illustrated by

ETHELDRED B. BARRY

The knights come riding, two by two."

The Lady of Shalott.

BOSTON

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

By L. C. Page & Company

———m——

(INCORPORATED)

———m——

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All rights reserved

First impression, October, 1907

Second impression, April, 1909

COLONIAL PRESS

Electrotyped and Printed by C. H. Simonds & Co.

Boston, U. S. A.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Hanging of the Mirror | 1 |

| II. | Bed-time Confidences | 27 |

| III. | A Knight Comes Riding | 46 |

| IV. | Betty's Novel | 68 |

| V. | A Camera Helps | 97 |

| VI. | "Garden Fancies" | 116 |

| VII. | Spanish Lessons | 134 |

| VIII. | "Shadows of the World Appear" | 161 |

| IX. | More Shadows | 181 |

| X. | By the Silver Yard-stick | 199 |

| XI. | The End of Several Things | 221 |

| XII. | Six Months Later | 242 |

| XIII. | The Miracle of Blossoming | 266 |

| XIV. | The Royal Mantle | 285 |

| XV. | "As It Was written in the Stars" and Betty's Diary | 308 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

"With the donning of the ancient dress she seemed to have put on the sweet shy manner that had been the charm of its first wearer" (See page 142) | Frontispiece |

| "The other grasped some dark object that seemed to be a picture frame" | 6 |

| "Drew rein a moment at the gate, to look down the stately avenue" | 47 |

| "He was bending anxiously over a bubbling saucepan" | 87 |

| "Making a cup of her white hands" | 126 |

| "For once the red and green bird was on its good behaviour" | 180 |

| "She poured the corn into the popper and began to shake it over the red coals" | 261 |

| "'She looked to me just like one of her own lilies'" | 315 |

THE

LITTLE COLONEL'S KNIGHT

COMES RIDING

CHAPTER I

It was a June morning in Kentucky. The doctor's nephew coming at a gallop down the pike into Lloydsboro Valley, reined his horse to a walk as he reached the railroad crossing, and leaning forward in his saddle, hesitated a moment between the two roads.

The one along the railroad embankment was sweet with a tangle of wild honeysuckle, and led straight to the little post-office where his morning mail awaited him. The other would take him a mile out of his way, but it was through a thick beech woods, and the cool leafage of its green aisles tempted him. A red-bird darting on ahead[2] suddenly decided his course, for following some quick impulse, as if the cardinal wings had beckoned him, he turned off the highway into the woods.

"I might as well go around and have a look at that Lindsey Cabin," he said to himself, as an excuse for turning aside. "If it's in as good shape as I think it is, maybe I can persuade the Van Allens to rent it for the summer. It's a pity to have a picturesque place like that standing empty when it has such possibilities for hospitality, and the Van Allen girls a positive genius for giving jolly house-parties. To get that family out to Lloydsboro for the summer would be paving the way to no end of good times."

The farther he rode into the cool woods the better the idea pleased him, and where the bridle-path crossed a narrow creek he paused a moment before plunging down the bank. Somewhere up the ravine a spring was trickling out in a ceaseless flow. He could not see it, but he could hear the gurgle of the water, as cold and crystal clear it splashed down into its rocky basin.

"They could picnic here to their hearts' content," he said aloud, glancing up and down the ravine at the rank growth of fern and maidenhair which festooned the rocks.

Alex Shelby had spent only part of two summers in Lloydsboro Valley, but the woodsy smell of mint and pennyroyal, mingling with the fern, brought back the recollection of at least a dozen picnics he had enjoyed near this spot, most of them moonlight affairs, and all of them so pleasant that he was determined to bring about their repetition if possible. Of course this summer he would not have as much time for outings as he had had then. Now that he had finished his medical course he intended to shoulder as much as possible of his uncle's work. The old doctor's practice had grown far too heavy for him. But at the same time there need be no limit to the pleasant things that the summer could bring forth, especially if the Van Allen family could be installed in the Lindsey Cabin.

A quarter of a mile more brought him almost to the edge of the woods and to the beginning of the Lindsey place. The spacious, two-story log cabin standing back among the great forest trees, might have been a relic of Daniel Boone's day, so carefully had his pioneer pattern been copied by skilful architects. But the resemblance was only outward. Inside it was luxuriously equipped with every modern convenience. For a year it had stood tenant-less, and Alex Shelby never passed it without regretting[4] that such a charming old place should be abandoned to dust and spiders. The last time he had gone by it, he had noticed that it was beginning to show the effect of its long neglect. Some of the windows were completely overgrown by ragged rose-vines and Virginia Creeper, and a tin waterspout that had blown loose from its fastenings, dangled from the eaves.

Now as he came near he saw in surprise that the place seemed to have an alert, live air, as if just awakened from sleep. The windows were all thrown open, the vines were trimmed, and were a mass of bloom, the dead leaves were raked neatly in piles and the cobwebs no longer hung from the cornices in dusty festoons.

A long ladder leaning against the front of the house, rested on the sill of an upper window, and Alex wondered if the agents had painters at work. He hoped so. The more thorough the renovation, the more attractive it would be to the Van Allens.

Suddenly his pleased expression changed to one of surprise and dismay, as he saw that the place was already inhabited. Empty packing-boxes, excelsior and wrapping paper littered the front porch. A new hammock hung between the posts. Somebody's garden-hat lay on the steps. Moreover, a[5] slender girl in a white dress stood at the foot of the ladder, evidently about to ascend, for she shook it to test its balance, and then cautiously stepped up on the first round.

Her back was toward Alex, and he fervently hoped that she would turn around so that he might see her face, then more fervently hoped that she wouldn't, since it would be somewhat embarrassing to be caught staring as inquisitively as he was doing. Unconsciously at sight of her he had brought his horse to a standstill, and now sat wondering who she could be and what she was about to do. It was as if a curtain had gone up on the first scene of an intensely interesting play, and for the moment he forgot everything else in admiration of the stage setting, and the graceful little figure poised on the ladder.

"Probably going up for an armful of roses," he thought.

"Hold tight, Ca'line Allison! Don't let it slip!" she called in a high sweet voice, almost as if she were singing the words, and Alex noticed for the first time, a small coloured girl behind the ladder, bracing herself against it to hold it steady.

The ascent was a slow one. Twice she tripped on her skirts, and with a little shriek almost slipped[6] through between the rounds. Only one hand was free for climbing. The other grasped some dark object that seemed to be a picture frame, though why one should be carrying a picture frame up the outside of a house was more than the young man could imagine, and he concluded he must be mistaken.

"THE OTHER GRASPED SOME DARK OBJECT THAT SEEMED TO BE A PICTURE FRAME."

"THE OTHER GRASPED SOME DARK OBJECT THAT SEEMED TO BE A PICTURE FRAME."

The last step brought her head on a level with the second story window, and up where the sun struck through the trees in a broad shaft of light. Her hair had been beautiful in the shadow; a rare tint of auburn with bronze gold glints, but now in the sunshine it was an aureole. What was it it reminded him of? A fragment of a half-forgotten poem came to his mind, although he was not given to remembering such things:

Sandalphon the angel of prayer."

Then he almost laughed aloud at the comparison, for a dazzling flash of light, blinding him for an instant, was reflected into his eyes from the object she carried, and he saw that it was a looking-glass that she was taking up the ladder with such care.

"What a very human and very feminine angel[7] of glory it is," he thought. But the next instant, still with the amused smile on his face, he was spurring his horse down the road as fast as it could gallop. The girl on the ladder had caught sight of his reflection in the mirror as she reached up to lay it on the window sill, and had turned a startled face towards him. Not for worlds would he have had her know that he had been so discourteous as to sit staring at her. He had forgotten himself in the interest of the moment.

Eager to find out who the new tenants were at the Lindsey Cabin, he rode rapidly on, turning from the woodland road into a maple-lined avenue leading back to the post-office. Just as he made the turn another surprise confronted him. He almost collided with two girls who were hurrying along arm in arm, under a red parasol.

Both Lloyd Sherman and Kitty Walton were old friends of his, but he had to look twice to assure himself that he saw aright. They had been away at school all year, and he had not heard of their return.

"I thought you were still at Warwick Hall!" he exclaimed, dismounting and stepping forward with bared head, to shake hands in his most cordial way. "When did you get home?"

"Only this mawning," answered Lloyd. "All the Commencement exercises were ovah last Thursday, and we're school girls no longah. 'Beyond, the Alps lies Italy!' Kitty can tell you all about it, for she had the Valedictory."

Kitty met Alex's amused smile with a flash of her black eyes, but before she could deny having used the trite subject that had been so popular in the old Lloydsboro seminary as to have become a standing joke, Alex answered, "Well, you've certainly lost no time in starting out to explore the wide world that lies before you. I've always heard that there's nothing to equal the zeal of a sweet girl graduate about to scale her Alps. You've barely reached home, haven't been off the cars three hours, I'll bet, and yet here you are on the war-path again. What Italy are you climbing after now?"

Ordinarily his banter would have been promptly resented by both girls, but now it served only to recall the amazing news that had sent them hurrying away from the post-office on an excited quest. With a dramatic gesture, Kitty drew a letter from her belt and held it out to him.

"Think of it!" she exclaimed, her cheeks pink with excitement. "Gay Melville's here in the Valley![9] Right here in Lloydsboro! Settled in the Lindsey Cabin for the summer, and we didn't know anything about it till ten minutes ago."

"Gay Melville," repeated Alex, instantly alert at mention of the cabin.

"Oh he doesn't know her, Kitty," interposed Lloyd. "He wasn't out in the Valley the wintah she spent her Christmas vacation with you."

"Then you've something to live for!" declared Kitty with emphasis. "She's one of the old Warwick Hall girls. Was in last year's class with Allison and Betty, and she's just the sweetest, dearest—"

"Don't tell him any moah," interrupted Lloyd. "Let him find out for himself."

"What's she doing at the Lindsey Cabin?" he asked. He kept a straight face, although inwardly chuckling over the fact that he knew well enough what she was doing, at least what she had been doing three minutes ago.

"They've taken it for the summer, that is, her sister Lucy and husband have, Mr. and Mrs. Jameson Harcourt. They're from San Antonio, and you know the Lindseys spend their winters there. It seems they interested Mr. Harcourt in the Cabin, and of course Gay was wild to get back[10] to the Valley, and she persuaded them to come. She wrote to me just as soon as it was decided, but the letter never reached me till this morning. She thought I would get it before I started home; but it's just like Gay to mix up her address with mine. She was so excited when she wrote that she addressed it to Warwick Hall Station, Texas, instead of District of Columbia. It has been travelling all over the country, and it's a wonder that it ever reached me at all."

"And the worst of it is," added Lloyd, "of co'se she expected we'd all be heah to meet her. But we stayed ovah in Washington two days, and when they came in last night there wasn't a soul at the station to welcome them. The ticket agent told me about it just now as we came past. She seemed surprised, he said, and disappointed. She must have thought it queah that none of us were there."

"Won't she be funny when she's found what a mistake she's made!" exclaimed Kitty. "She's always making mistakes, and is always perfectly ridiculous over them when she finds it out. We're going to take you to call on her, Alex, just as soon as they're settled. She plays the violin divinely."

"I'll go right back with you now," he offered promptly.

"No you won't," they cried in the same breath, and Kitty explained, "No telling what sort of a mess they'll be in with their unpacking. But if they're ready to see company by night, I'll telephone to you, and we'll all go over."

"I shall live only for that moment," he declared, laughing, then added as he turned to mount his horse, "I'm mighty glad I met you, and I'm more than glad that you've both come home to stay."

A flourish of the red parasol answered the courtly sweep of his hat as they parted. He rode on rapidly towards the post-office, wondering if they would find the girlish, white-clad figure still perched on the ladder, up among the roses, with the sun making an aureole of her shining hair. He had never seen such hair. "Sandalphon, the angel of glory"—but the quotation broke off with a laugh. Her name was Gay, and it was a looking glass that she was carrying up the ladder. "Well, she's an original little thing," he mused, "and if she lives up to her name the Lindsey Cabin will be just as lively a social centre as if the Van Allen girls had possession."

The encounter with Alex had delayed the girls but a moment or two, still they walked on faster than ever to make up the lost time.

"What do you suppose we'll find her doing?" queried Lloyd.

"Something unexpected, I'll be bound," was the answer. "Will you ever forget that first time we saw her, when she came out to play the violin at the Freshman reception? Such a pretty white dress, and that rapt, uplifted look on her face that makes you think of St. Cecilias and seraphim, and with one foot in a white kid shoe, and the other in that awful old red felt bedroom slipper, edged in black fur!"

"Or the time she lost her belt in Washington," suggested Lloyd. "Probably we'll find her unpacking if the trunks came. But Gay's trunks nevah were known to arrive on time. We may have to be lending her shirtwaists and collahs for a month."

By this time they had reached the rustic footbridge leading over a ravine to the Cabin, and were in full view of the front windows. Gay was still on the ladder. She had made several trips up and down it since Alex passed. It was hard to decide at what angle to hang the mirror on the window casing, as she had seen them in old Dutch houses in Holland; and in marking the place with the point of the only nail that she had provided on which to hang the mirror, she dropped the nail.[13] Several minutes had been wasted in a fruitless search for it. Others were to be had for the pulling, if one could extract them from the empty packing-boxes, but no hammer could be found on the premises, and it was only after much twisting and struggling that the little coloured girl finally managed to pull one with her teeth.

Another five minutes had been wasted in searching for something with which to drive the nail. Then Gay gingerly ascended the ladder again, armed with a pair of heavy old tongs, taken from the porch fireplace. She had just reached the top of the ladder when the girls caught sight of her.

"Mercy!" exclaimed Kitty in a low tone. "It'll never do in the world to appear at this juncture. She's pretty sure to drop through the ladder anyhow, or upset herself, or have some exhibition of the usual Melville luck, even if she's left to herself. And if she should suddenly discover us there's no telling what dreadful thing might happen."

"Let's slip up behind the arbour and watch till she's safely down to earth," whispered Lloyd. "What do you suppose she's trying to do, and where do you suppose she managed to pick up Ca'line Allison?"

"Sh!" was the answer. "That's the Dutch[14] mirror she got in Amsterdam last summer. She wrote that it was the triumph of her life when she got home with it whole. She carried it all the way, instead of packing it in her trunk. Listen! What's that she's saying?"

The words floated down to them distinctly. "Ca'line Allison, you'll have to get me something besides these tongs to drive this nail with. I might as well try to do it with a pair of stilts. Besides it's making dents in them, and it's wicked to spoil such beautiful old brasses. Mercy! Don't get up yet!" she shrieked wildly, as the shifting of Ca'line Allison's small body made the ladder slip a trifle.

"Wait till I poke these tongs through the window and take hold with both hands. Now! Hunt around and find me a stone or a piece of brick."

The girls behind the arbour could not see her face, but the sight of the familiar little figure clinging to the ladder, and the sound of the beloved voice made them long to rush out and squeeze her.

"Isn't her hair a glory, up there in the sunshine?" whispered Kitty. "The idea of anybody calling it plain red—such a fluff of bronzy auburn with all those little crinkles of gold! And listen to that whistle! You'd think it was a real mocking bird."

Wholly unconscious of her audience, Gay teetered on the ladder, whistling and trilling like a happy bobolink, until the little black girl climbed up after her with a brick which she had dug out from the well curb. The girls waited until the nail was securely in place, the mirror hung and Gay had begun to crawl down the ladder backward, before they rushed out from their hiding-place.

They pounced upon her just as she reached the bottom round, and then ensued what Kitty called a pow-wow—an enthusiastic welcome known only to old school chums who have been separated so long a time as a whole twelvemonth. Questions, answers, explanations, a bubbling over of delight at once more being together, kept them talking all at once for nearly ten minutes. Then Gay, remembering her duty as hostess led the way into the house.

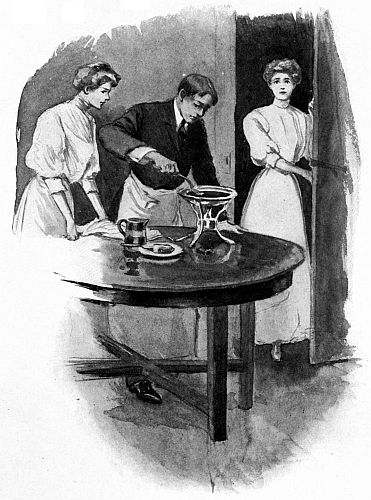

"Come in and see Lucy and her fond spouse," she exclaimed. "They're still at breakfast although it's ten o'clock. None of us could make a fire in the range. It simply wouldn't burn. But we had brought a chafing dish in one of the boxes, and we found another in the pantry, and they've been mussing around for the last two hours with them, having the time of their lives. Lucy made[16] fudge and omelette and tea for her breakfast, being the things she knows best how to make, and brother Jameson is trying flap-jacks and coffee."

"What did you have?" asked Lloyd.

"I? Oh I emulated the example of 'The old person of Crewd' who said

It's cheap by the ton

And it nourishes one,

And that's the main object of food.'

Throwing open the dining-room door she began a series of breezy introductions that set them all to laughing and swept away every vestige of formality.

Both Lloyd and Kitty protested against taking a single mouthful at that hour, but the young host poured out a cup of very muddy coffee with such a beaming smile, and the little bride offered a very bitter cup of tea in competition, with a merry insistence so like Gay's, that they could not refuse.

"It's going to be lovely," Kitty managed to[17] whisper under cover of the bustle of bringing in more hot water. "They're almost as harum-scarum and hap-hazard as Gay herself, and 'brother Jameson' looks as if he might be the 'Gibson man's' youngest brother."

"These 'babes in the wood' would have perished but for me," began Gay, who was rattling along as if she were wound up. "I was the robin who came to the rescue. I went over to Stumptown bright and early—you see I remembered the short cut through the woods—and as luck would have it, found some one willing to come, at the very first house where I inquired. (But she can't come till nearly noon, hence this disorderly feasting and rioting.) Ca'line Allison was swinging on the gate, with her finger in her mouth. I didn't know her, but she remembered me, and complimented me by asking if I'd done brought my fiddle along. I think I'll engage her for the summer for my little maid-in-waiting. She's as quick as a monkey and would look so cunning diked up in a cap and apron. What's that rhyme Betty made about her when she was flower-girl at her own mother's wedding? Oh by the way, where is Betty? Why didn't she come with you?"

"For the good reason that we didn't know we[18] were coming heah ourselves when we left home," answered Lloyd. "Betty went on to Commencement with all the rest of the family, but it was hard for her to tear herself away from her beloved writing. We hadn't been back at Locust half an houah this mawning till she was at it again."

"Betty is Mrs. Sherman's god-daughter," explained Gay in an aside to her brother-in-law. "The one who I told you is such a genius. She's writing a book." Then turning to Lloyd. "It isn't that same old one she was at work on at school, is it?"

"No, it's something she began last fall. Mothah wanted her to make her début in Louisville when she was through school, just as I am going to do next wintah, but Betty begged to be allowed to stay in the country. She said she'd nevah be a brilliant success socially, but that she'd do her best to be a credit to the family in some other way."

"She will, too," prophesied Gay. "Some day we'll all be proud of the little song-bird you rescued from the Cuckoo's Nest. Dear old Betty! I'd like to hug her this very minute."

The grandfather's clock in the hall was striking eleven when they rose from the table, but Gay would not listen when the girls attempted to take[19] their leave. "You haven't seen my room," she insisted, "nor my mirror. Come on up stairs and look into my mirror. It's the joy of my heart, and maybe we'll all see our fate in it. I like to pretend that it's a sort of magic glass—that some wizard of the wood has laid a spell on it, so that at certain times all the figures that have ever been reflected in it must march across it again. Wouldn't it be lovely if all the good times it is going to reflect this summer could be made to pass over it again whenever I wanted to recall them?"

"We'd lead the procession," announced Kitty, "for we were the first objects that crossed the path after you got it hung. If we were not 'a group of damsels glad' we were at least a couple of them."

"But you were not the first," confessed Gay. "Just as I held it up to adjust it, I had such a thrillingly romantic experience that I nearly fell off the ladder. It showed me the reflection of an awfully good looking young man on horse-back. But when I turned to look over my shoulder at the original he was galloping down the road like a blue streak."

"I wondah who it could have been," mused Lloyd. "We met Alex Shelby on hawseback just a few minutes befoah we got heah, but he nevah[20] said a word about having seen anybody, and he seemed surprised when we told him that the cabin had been rented."

They were up in Gay's room now, and running to the window, Kitty seated herself in the low chair beside it. "Oh how fine!" she called. "It's at exactly the right angle, for I can see everything along the path without looking out. It'll be a sort of Hildegarde's mirror, won't it! Like the Lady of Shalott's."

Half under her breath she began to recite the lines they had learned so long ago, and from force of habit Lloyd joined the sing-song chant:

That hangs before her all the year,

Shadows of the world appear."

Smiling to see how well they remembered it, they went on in unison down to the couplet:

The knights come riding two by two."

There Kitty broke off to say "I don't see how that can happen here this summer. It will be sheer luck if they come even in singles. There never were so few boys left in the Valley, and it's too bad to have it happen so the summer that you're here. Nearly everybody is going away. You can[21] count on the fingers of one hand the few who will stay."

"What about the two knights of Kentucky?" asked Gay. "You're a lucky girl, Kitty, to have two such splendid cousins as Keith and Malcolm MacIntyre."

"They are already gone. They sailed for England with Uncle Sydney and Aunt Elise last week. You know I wrote you they were going and that Allison was to be in the party too. And oh Gay! Didn't you get that letter? Then you haven't heard the most important thing of all! Allison is engaged! It didn't happen till a few days before they sailed, and it isn't announced yet, but of course she wanted you to know and I wrote to you right away."

Gay bounced out of her chair as if a bomb exploded in the room.

"Oh you don't mean it!" she cried tragically, clasping her hands. "Why she's only been out of school a year! The first of our class to go! Oh tell me all about it! Begin at the beginning and don't skip a thing!"

Throwing herself down on the floor at Kitty's feet, she propped her chin on her hands, and her elbows in Kitty's lap, prepared to listen.

"There isn't much to tell. You know the fortune that Mammy Easter predicted for her was nice, but it wasn't very exciting. She was to 'wed wid de quality and ride in her ca'iage.' Well, his family is certainly quality, the Claibornes of Virginia, and she'll live in Washington and have several kinds of carriages. Isn't it odd? We knew him when he was just a boy. He was on the same transport with us when we went to the Philippines, and we never imagined then that we'd ever see him again."

"But I thought that that young Lieutenant Logan," began Gay.

Kitty interrupted her with a laugh. "Why my dear, he is a mere child compared to Raleigh Claiborne. That little affair was the mere A. B. C. of romance. He's paying attention to our youngest now. He sends music and bon bons to Elise."

"Think of Elise being old enough to receive such attentions!" groaned Gay. "It makes me feel like a patriarch. But never mind my hoary sensations, go on and tell me some more. She's going to get her trousseau abroad I suppose."

"Only part of it, for the wedding isn't to take place for a year. Allison didn't care much about going—thought she'd rather wait and take the[23] trip with Raleigh. But he is so busy it may be several years before he can get off for a whole summer, and Aunt Elise persuaded her to go with them. She said it wouldn't be so easy for her to go when she once assumed the responsibility of a big establishment."

Gay clasped her hands around her knees and rocked herself back and forth on the floor.

"I'm glad she's sensible enough to wait a year," she declared. "I don't see why girls are in such a hurry to tie themselves up in a knot. I suppose it's perfectly fascinating to be engaged and to have the choosing of a lovely trousseau, and the opening of all the wedding presents. Everybody takes so much interest in a prospective bride. But the fun comes to an end so quickly. It's like Fourth of July fire works. There's a big blaze and excitement while it lasts. Then it's all over and they settle down to be just prosy common-place married people. I should think that the reaction would be deadly, and that if a girl could see past the time of the rocket's shooting up, and realize that it can't stay among the stars, but must fall to earth again with a dull thud, she'd profit by other people's experiences, and not give up all the good times of her girlhood before she'd half enjoyed them."

Gay spoke so feelingly that her two listeners exchanged glances of surprise. This was not the way Gay had been wont to talk a year ago, and each wondered to herself if Lucy's marriage had caused this radical change in her opinion.

Suddenly she changed the subject, with the unexpectedness of a grasshopper's leap. "Which one of you girls is going to stay all night with me?"

Kitty answered first. "Neither of us ought to, for we've only just returned to the bosom of our families. You could hardly call us entirely arrived yet, for our trunks haven't come."

Lloyd started up, and looked at her watch in alarm. "It's a good thing you reminded me that I have a home," she laughed. "I told mothah I'd just stroll down to the post-office and be right back, and when I met Kitty with yoah lettah it drove everything else out of my head. She'll be wondering what has happened to me. I'll come some night next week and be glad to."

"No, one of you has to come back and stay with me to-night," Gay insisted. "So settle it between yourselves. You may as well draw straws to decide which is to be my victim." Then, glancing around the room—"I don't happen to see any straws at[25] hand, but you might pull hairs for the honour. Here! My head is at your service, ladies."

Dropping to her knees she made a profound salaam, and waited for them to draw. "The one who pulls the shortest hair comes back."

Laughing over the absurd manner of deciding such a matter, each girl reached out and plucked a hair by its roots, so vigorously that the pull was followed by a long drawn "ouch!"

"Mine's the shortest," giggled Lloyd, comparing it with the one that Kitty held up. "But I'm suah my family will object if I propose leaving them the very first night of my arrival, aftah I've been away at school all yeah."

"Don't leave them then," said Gay. "Bring them all over here to spend the evening. I'm wild for Lucy and brother Jameson to meet them as soon as possible. Then when bedtime comes let them leave you. Tell them that Kitty is going to bring all her family, and that everybody in the valley who is anybody is coming to the Harcourt's Housewarming to-night at the 'Cabin in the Wood.'"

Kitty began unfurling her red parasol. "That certainly sounds alluring. You can count on all my family, especially Ranald, and I'll go straight home and telephone to Alex Shelby."

"Who may he be?" inquired Gay, scrambling up from the floor, to follow her guests down stairs.

Kitty began an enthusiastic description of him, which Lloyd cut short with the laughing remark, "Go look in your little Dutch mirror. I'm not positive, but I think he's yoah first 'Knight of the Looking-glass.'"

CHAPTER II

That night a series of interesting shadows trooped across the little Dutch mirror, in the moonlight, but nobody watched beside it to see how faithfully it reflected the procession of guests, straggling up the path below. After the first pleased glance Gay had flown down-stairs to throw open the front door and bid them welcome. It was almost more than she had dared to hope that the old Colonel would come, and "Papa Jack" and Kitty's Grandmother MacIntyre. But they had needed no urging. Gay was reaping the aftermath now, of her first visit to the Valley. They had not forgotten the obliging little guest who had entertained them with her violin playing, amused them with her quaint unexpected speeches, and charmed old and young alike with her enthusiastic interest in everything and everybody.

Ranald had more than that to remember, for he had carried on a vigorous correspondence with Gay[28] for the last six months, started by a "dare" from Allison. Alex Shelby's memory of her dated back only to that morning, but the picture of a sunny little head up among the roses, and that line "Sandalphon the angel of glory" had been in his thoughts all day.

Their effort to show the newcomers how cordial a Lloydsboro welcome could be, was met by a hospitality which held them in its spell till after midnight. Lucy was in her element. As the popular daughter of a popular army officer, she had played gracious hostess ever since she had learned to talk. As for Gay, so anxious was she that her friends should be pleased with her family and her family with her friends, that she threw herself with all her might into the task of making each show off to the other.

An outside fire-place on the broad front porch was one of the features of the Cabin. The June night was cool enough to make the blaze on its hearth acceptable, and Lucy turned the picturesque old kettle, bubbling on the crane, to practical use, making coffee to serve with the marsh-mallows, which Jameson handed around on long sticks, that each one might toast his own over the glowing coals.

The informality of it all, and the good cheer, made every one relax into his jolliest mood, and Gay, hearing the old Colonel's laugh, as stretched out on the settle by the fire, he told stories and toasted marsh-mallows with a zest, felt that they had struck the right key-note in this first evening's entertainment. It was the harbinger of many others that would follow during the summer.

It was her violin that held them longest. Standing just inside the door where Kitty could accompany her on the piano, she played one after another of the favourite tunes that were called for in turn, till the fire burned low on the porch hearth, and even the voices of the night were stilled in the dense beech woods around the Cabin.

It was later than any one had supposed when Mrs. Sherman made the discovery that the hall clock had stopped.

"She didn't know that I stopped it on purpose," confessed Gay, when the last carriage had driven away, and Lloyd was following her sleepily up-stairs. She paused to bolt the bed-room door behind them.

"This has been a lovely evening for me. It gives one such a comfortable I-told-you-so sort of feeling to have everything turn out as you prophesied[30] it would. Of course I knew that Lucy would feel the charm of the Valley, and like it a thousand times better than the mountains or seashore or anywhere else, but I wasn't so sure of Jameson. Now my mind is completely at rest for the summer. I stopped worrying when I saw him hobnobbing with the Colonel and your father about those Lexington horses he wants to buy. He was so tickled over those letters of introduction they gave him. And he was so charmed to air his knowledge of the Philippines to Mrs. Walton. He spent a month there you know. I fairly patted myself on the back all the time he was talking. Somehow I feel so responsible for this household. There! I forgot to remind them to bring that bothersome old silver pitcher upstairs!"

Hastily unbolting the door she called out in sepulchral tones that echoed through the dark house, "Remember the Maine!"

There was a laugh in the room across the hall, then her brother-in-law who had just come up-stairs, shuffled down again in his slippers.

"I suppose I'll have to remind them every night this summer," continued Gay. "I don't like to call out 'remember the silver pitcher that was our great-great-grandmother Melville's, and the soup[31] ladle that some old Spanish grandee gave to one of Jameson's Castilian ancestors,' for if a burglar were prowling around he would be all the more anxious to break in. So the month I visited them, before we came here, I adopted that slogan for my war-cry: '"Remember the main" thing in life to be saved from burglars!' It always sends one or the other of them skipping, for they feel the responsibility of preserving such heirlooms for posterity. I used to wish that I were the oldest daughter, so that that pitcher would be handed down to me on my wedding day. I didn't realize what a bore it would be to be tied for life to such a responsibility. I asked Jameson why he didn't put it and the ladle in a safety vault and be done with it, and he read me such a lecture on the sacredness of old associations and family ties that I somehow felt that his old soup-ladle expected me to send it a written apology."

Gay had bolted the door again, and as she talked, drew the curtains across the casement windows. Now she sat on the edge of the bed, shaking out her wealth of sunny hair, to brush and braid it for the night. It was a cosy room, with low ceiling and old-fashioned wall paper. With the curtains drawn and the candles in the quaint pewter sticks[32] lighting up the claw-footed mahogany furniture, it was an ideal place for the exchanging of bedtime confidences. Gay was the first to break the silence.

"What was the matter with Betty tonight? She was as quiet as a mouse. Hardly had a word to say, and all the time I was playing, she sat looking out into the night as if she were ready to cry."

"No wondah! They were so beautiful, some of those nocturnes and things, that we all had lumps in our throats. Nothing's the mattah with Betty. It's just the last chaptah she can't get to suit her. She's gone around in a sawt of dream all day."

"Who's playing the devoted to her now?"

"Nobody as far as I know. All the boys love Betty. They've been perfectly devoted to her ever since she came to Locust to live; but not—not in the sentimental way you mean; for instance the way that Alex Shelby cares for Kitty."

"Oh don't tell me there is anything in that," wailed Gay, "at least on Kitty's part, for I've set my heart on her marrying a friend of mine in San Antonio, so she'll always be near me. You know when Mammy Easter told her fortune, it was that her fate would come through running water when the weather vane points West. I'm wild to have her visit me at Fort Sam Houston next year, and[33] this Frank Percival is the very one of all others for her. He's a banker and as good as gold and—oh well, there's no use wasting time singing his praises to you when I want him for Kitty! But about this Alex Shelby, Kitty told me this very afternoon that it is you he admires so much. She told me all about that Bernice Howe affair, and said that ever since Katie Mallard up and told him how honourably you acted in the matter, he has put you on a pedestal and given you a halo. She said you could have him crazy about you if you'd so much as lift an eyelash in encouragement."

"Don't you believe it!" cried Lloyd. "That's just Kitty's way of throwing you off the track. We've been unusually good friends evah since he found out why I broke my engagement to go riding with him, but he is at The Beeches every bit as much as he is at The Locusts, and it's you he'll be in love with befoah the summah is ovah. He was the first one reflected in yoah looking glass, for he confessed this evening how he sat and watched you on the laddah, and how he'd thought of you all day; and he even quoted poetry about it, and that's a very serious symptom for Alex to show. He nevah was known to do such things befoah! Then tonight he was simply carried away by yoah playing.[34] He adores a violin and you played all his favourites. Oh I see yoah finish!"

There was a pause in which Gay kicked off her slippers and sat absently gazing at them, while Lloyd tied the ribbons which fastened the lace in the collar of her dainty gown. Again it was Gay who spoke first.

"Doesn't it seem queer to think of Allison's being engaged? It is such a little while since we were all school girls together. Nobody knows whose turn will come next. It makes me feel like a soldier on a battle field—comrades being shot down all around you right and left and you never knowing how soon it'll be your turn to fall. It's awful! Lloyd, what's become of that boy out in Arizona, the one who sent you those orange-blossoms in Joyce's letter when I was here before? He was best man at Eugenia Forbes' wedding."

"Oh, you mean Phil Tremont!" answered Lloyd placidly, without the conscious blush that Gay had expected to see. "He is out West again, doing splendidly, Eugenia writes."

"I thought you wrote to him yourself."

Lloyd, stooping to pick up her dress and hang it over a chair, did not see with what keen interest Gay watched her as she questioned.

"Oh, we still keep up a sawt of hit and miss correspondence. He writes every few weeks and I manage to reply once in two months or so. It's dreadfully uphill work for me to write to people whom I nevah see. It's been two yeahs since he was heah, and I nevah know what he'll be interested in."

"I suppose it's easier writing to some one you've known all your life, like Malcolm MacIntyre for instance. I'm so sorry he and Keith are abroad this summer."

Lloyd's face dimpled mischievously as she began to see the drift of Gay's questioning. "I can't tell you how easy it is to write to Malcolm, because I've nevah done it. Now it's my turn to ask questions. Where did you get this new photograph of Ranald Walton on yoah dressing table? Beg it from Kitty as you did that one at Warwick Hall, when he was a little cadet, or get it from headquartahs?"

"Direct from headquarters," confessed Gay with a laugh. "He isn't so afraid of girls as he used to be. Wasn't he charming tonight?"

So the questioning and answering went on for quarter of an hour longer, each anxious to find how far the other had drifted into the unexplored country[36] of their dreams. Then Gay blew out the candles and climbed into the high four-posted bed beside Lloyd, where they lay looking out through the open window into the starlight. The moon had been down for some time. It was so still here in the heart of the beech woods that the silence could almost be felt. The girls spoke in whispers.

"It settles down on one like a pall," said Gay. "Are you sleepy?"

"Not very," answered Lloyd, stifling a yawn.

"Then there's one more person in the valley I want to ask about. I believe I've heard an account of every one else. Where's Rob Moore and what is he doing? I thought he would come over with you all tonight."

"Poah old Rob," answered Lloyd, swallowing another yawn. "His fathah died a little ovah a yeah ago, and he's nevah been like himself since. He seemed to grow into a man in just a few hours. It was awfully sudden—Mistah Moore's death. The shock neahly killed Rob's mothah, and the deah old judge, his grandfathah, you know, was simply heartbroken. Rob just gave up his entire time to them aftah that. He was such a comfort. Nevah left the place, and took charge of all the business mattahs, to spare them every worry.[37] When things were settled up they found there wasn't as much left as they had thought there would be, and Rob wouldn't touch a cent to finish his law course. He was afraid his mothah would have to deny herself some luxury she had always been used to, and he didn't want her to miss a single one she had had in his fathah's lifetime. So he took a position in Louisville, and has been working like a dawg evah since. He reads law at night with the old Judge, so I scarcely evah see him. We've just drifted apart, till it seems as if the little old Bobby I grew up with is dead and gone. I missed him dreadfully at first, all last summah, for he'd almost lived at our house, and was just like a brothah. I haven't seen him at all this vacation, though to be suah I've only been home this one day."

In the dim starlight Lloyd could not see the complacent smile on Gay's face, but her voice showed that she was well pleased with the answers to her string of questions.

"Now I'll tell you why I put you through such a catechism," she began. "I wanted to make sure that the coast is clear, so that you can undertake a mission that is to be laid at your door this summer. Jameson's brother Leland will be here to-morrow afternoon. If he takes a fancy to the place[38] he will probably stay as long as we do, and we are all very anxious for him to stay. He's only three years younger than Jameson, but the two were left alone in the world when they were just little tots, and Jameson has been like a father to him. He feels so responsible for him and so does Lucy. I do too, now, although he's only my brother-in-law's brother, because I persuaded them to come here for the summer, and Jameson wanted to go somewhere where Leland would be satisfied to stay."

"What's the mattah with him, that he needs so much looking aftah? If he's twenty-three yeahs old it seems to me that he might take the responsibility of himself on his own shouldahs. Is he wild?"

"No. Jameson says he's always been too high-minded to do the things men mean when they talk about sowing their wild oats; but he is as utterly irresponsible as a will-o-the-wisp. He won't stay tied down to anything—just drifts around, here and there, having a good time. It's a pity that he isn't as poor as a church mouse. Then he'd have to do something. He's so bright he easily could make something splendid of himself. Now Jameson has good sensible ideas about not squandering his money, and although he doesn't have to work[39] any more than Leland does, he looks after the details of his own business as a man should.

"He knows all about the mines he has stock in down in Mexico, and he studies mineralogy and labour problems and investments, and has an office that he goes to regularly every morning. He takes after his father's side of the house, practical English people. But Leland is like his mother's family (they were proud old Spaniards just a generation or so back). He is adventurous and roving and romantic, and has the dolce far niente in the blood. Jameson says that all that Leland needs is to be kept keyed up to the right pitch, for he is so impetuous and headstrong that he always gets what he starts after, no matter what stands in the way; and that if he could just fall heels over head in love with some girl with great force of character, who wouldn't look at him till he'd measured up to her standards, it would be the making of him."

Lloyd yawned. "Excuse me for saying it," she began teasingly, "but I don't see how you can get up so much interest in anybody like that, even if he is yoah brothah-in-law's brothah. It sounds to me as if he is just plain lazy and I nevah did have any use for a man that had to be nagged all[40] the time to keep his ambition up to high-watah mark."

Gay sat up in bed in her earnestness. "Oh Lloyd, don't say that!" she protested. "Don't judge him till you've seen him. He's perfectly dear in lots of ways, in spite of his faults. You'll find him fascinating. Everybody does. And I'm going to be entirely honest with you—I've fairly prayed that you'd like him. You are so strong yourself, the strongest character of any girl I know, and you influence people so forcibly in spite of themselves, that I've felt from the start it would be the making of Leland if you'd take him in hand this summer."

Lloyd smothered a laugh in the pillow. "'Why don't you speak for yourself, John,'" she said mischievously. "Why don't you take him in hand? You are already interested so much that you'd only be combining pleasuah with duty."

Gay was too much in earnest to tolerate any levity, and went on in her intense eager way. "Oh I've already worn myself out trying to influence him, but it's of no use. He knows me too well. He's called me 'Pug' and 'Red-bird' ever since we went to kindergarten together. I'm just one of the family. But I've showed him your picture[41] and told him what an unapproachable, unattainable creature you are, and whetted his curiosity till it's as keen as a razor. Oh I've played my little game like an expert, and he doesn't suspect in the faintest degree what I want. He thinks I'm trying to interest him in Kitty Walton. I told him she's the darlingest, jolliest, prettiest thing in ten states, and that I'd guarantee he wouldn't feel bored once this entire summer if he'd make her acquaintance.

"But you—I've painted as so indifferent and entirely above his reach, that just to prove to me I'm mistaken, he'll nearly break his neck to put himself on good terms with you. It's just as Jameson says, he'll ride rough-shod over everything that stands in his way, to get what he wants."

Lloyd raised herself on her elbow and turned a protesting face towards her eloquent bed-fellow.

"Well of all cool things," she began, half inclined to be indignant, yet so amused at Gay's masterly management that the exclamation ended in a giggle. "Where do I come in, pray? You say he always gets what he goes aftah. Did it evah occur to you that I might not want to be taken possession of in that high-handed way? That I might have something to say in the mattah? Haven't[42] you as much interest in my welfare as in yoah sistah's husband's brothah?"

"Of course! you blessed little goose!" exclaimed Gay, giving the arm next hers an impetuous squeeze. "Don't I know the haughty Princess well enough to be sure that all the king's horses and all the king's men couldn't budge her against her will? I'm not looking ahead any farther than this summer. But if you could just shake him up and put him on his mettle that long, that's all I ask of you. And seriously, dear, you might go the world over and not find one who measures up to your ideals in more ways. He's well born and talented and rich and fairly good-looking. He's so entertaining one never tires of his company, good-hearted and generous to a fault, and—Oh Lloyd, please say you'll take enough interest to keep him keyed up to the right pitch for awhile. It's all he lacks to make a splendid man."

"Do you know, I think that's a mighty big lack," said Lloyd, honestly. "I've had strings on my harp that wouldn't stay strung. It's the most exasperating thing in the world. You know how it is, with a violin. Right in the midst of the loveliest passages one will begin to slip back—just a trifle, maybe, not more than a hair's breadth, but[43] enough to make it flat and spoil the harmony. Then you stop and tune it up again, and go on for awhile, but back it will slip just when you've gotten to depending on it. You know I couldn't have any respect for a man who had to be kept up to the notch that way. It would spoil the whole thing to have him flat on a single note when I'd depended on him to ring clear and true."

Gay had no reply ready for this unexpected argument, and her experience with stringed instruments made it very forcible. It was several minutes before she answered, then she spoke triumphantly.

"But you know what a master can do where a novice would fail. He can fit the keys to hold any position he gives them. Leland has never felt the touch of a master-hand. No one has ever controlled him. He has always been petted and spoiled. He has never known a girl like you. I'm sure that if you were only willing to make the attempt to arouse his pride and ambition, you could do wonders for him."

It was the most potent appeal Gay could have made. To feel that her influence may sway a man to higher, better things, will make even the most frivolous girl draw quicker breath with a sense of power, and to a conscientious girl like Lloyd this[44] seemed an opportunity and a responsibility that could not be lightly thrust aside.

"Well," she said finally, after a moment of hesitation, "I'll try."

Gay reached over with an impulsive kiss. "Oh you dear! I knew you would. Now I can let you go to sleep in peace. 'Something accomplished, something done, has earned a night's repose.' It must be awfully late. Goodnight dear."

Long after Gay had fallen asleep, Lloyd lay thinking of the mission thus thrust upon her. If this Leland Harcourt had needed reforming, she told herself, she wouldn't have had anything to do with him. Her poor Violet's experience with Ned Bannon had taught her one lesson—how mistaken any girl is who thinks she can accomplish that. But to be the master-hand that could put in tune some really splendid instrument (ah, Gay's appeal was subtle and strong) any girl would be glad and proud to be that: the inspiration, the power for good, the beckoning hand that would lead a man to the noblest heights of attainment.

There was something exhilarating, uplifting in the thought, that banished sleep. Night often brings exalted moods that seem absurd next day. Lying there, looking out at the stars, the pleasing[45] fancy came to her that each one was a sacred altar-flame, given into the keeping of some unseen vestal virgin. Now she too had joined this star-world Sisterhood, and had lighted a vestal fire on the altar of a promise. In its constant watch, she would keep tryst with all that Life demanded of her.

CHAPTER III

Next morning Lloyd found that her exalted mood had faded away with the stars. Any fire must pale before the broad light of day, and her vestal-maiden fervour had given place to a very lively but mundane interest in the brother-in-law's brother.

She was glad to hear at breakfast that he liked tennis, was a good horseman, that private theatricals were always a success when he had a hand in them. She stored away in her memory for future use, the information that he had lived several years in Spain and Mexico, and spoke Spanish like a native, that unlike Jameson he was prouder of his Castilian ancestors than his English ones, and that two of his fads were collecting pipes and rare old ivory carvings.

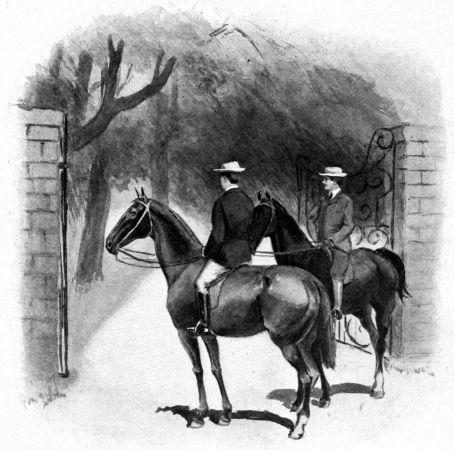

"DREW REIN A MOMENT AT THE GATE, TO LOOK DOWN THE STATELY AVENUE."

"DREW REIN A MOMENT AT THE GATE, TO LOOK DOWN THE STATELY AVENUE."

The more she heard about him the less sure she felt of being able to keep her promise to Gay. It began to seem presumptuous to her that a mere school-girl should imagine that she could exert any[47] influence over such an accomplished man of the world as he evidently was. All that day she pictured to herself at intervals how she should meet him and what she should say. It was a new experience for the haughty Princess who had always been so indifferent to the opinions of her boy friends. Gay's request had made her self-conscious. Fortunately she had a glimpse of him before he saw her, which helped her to adjust herself to the rôle she wanted to assume.

The morning after his arrival in the Valley, he and Ranald rode past the Locusts, and drew rein a moment at the gate, to look down the stately avenue which was always pointed out to strangers. Lloyd watched their approach from behind a leafy screen of lilac bushes. The gleam of a wild strawberry had lured her over there from the path, a few minutes before. Then the discovery of a patch of four-leaf clovers near by had tempted her to a seat on the grass. She was arranging the long stems of the clovers in a cluster when the sound of hoof-beats made her look up.

So thickset were the lilacs between her and the road that not a glimpse of her white dress or the flutter of a ribbon betrayed her presence, and they paused to admire the avenue, unknowing that a far[48] prettier picture was hidden away a few yards from them, in full sound of their voices—a girl half lying in the grass, with June's own fresh charm in her glowing face, and the sunshine throwing dappled leaf shadows over her soft fair hair. The mischievous light in her hazel eyes deepened as she watched them.

"'The knights come riding two by two,'" she quoted in a whisper, closely scrutinizing the stranger.

"He rides well, anyhow," was her first thought. The next was that he looked much older than Gay's description had led her to imagine. Probably it was because he wore a moustache, while Rob and Malcolm and Alex and Ranald were all smooth-shaven. Maybe it was that same black moustache, with the gleam of white teeth and the flashing glance of his black eyes that gave him that dashing cavalier sort of look. How wonderfully his dark face lighted up when he smiled, and how distinctly one recalled it when he had passed on. And yet it wasn't a handsome face. She wondered wherein lay its charm.

Gay's words recurred to her: "So fiery and impetuous he would ride rough-shod over anything that stood in his way to get what he wants."

"He looks it," she thought, raising her head a trifle to watch them out of sight. "I'm afraid I can't do as much for him as Gay expects for I'll simply not stand his putting on any of his lordly ways with me." Gathering up her clovers, she started back to the house, her head held high unconsciously, in her most Princess-like pose.

Some one else had watched the passing of the two young men on horseback. From his arm chair on the white pillared porch, old Colonel Lloyd reached out to the wicker table beside him for his field-glass, to focus it on the distant entrance gate.

"I don't seem to place them," he said aloud. "It looks like young Walton on the roan, but the other one is a stranger in these parts."

Then as he saw they were not coming in, he shifted the glass to other objects. Slowly his gaze swept the landscape from side to side, till it rested on Lloyd, sitting on the grass by the lilac thicket, sorting her lapful of clovers.

Something in her childish occupation and the sunny gleam of the proud little head bowed intently over her task, recalled another scene to the old Colonel; that morning when through this same glass he had watched her first entrance into Locust. Was it fourteen or fifteen years ago? It seemed[50] only yesterday that he had found her near that same spot coolly feeding his choicest strawberries to an elfish looking dog. Time had gone so fast since his imperious little grand-daughter had come into his life to fill it with new interests and deeper meaning. Yes, it certainly seemed no longer ago than yesterday that she was tyrannizing over him in her adorable baby fashion, making an abject slave of him, whom every one else feared. And now here she was coming towards him across the lawn, a tall, fair girl in the last summer of her teens. Why Amanthis was no older than she when he had brought her home to Locust, a bride. And no doubt some one would be coming soon, wanting to carry away Lloyd, the light of his eyes and the life of the place.

It made him angry to think of it, and when she stopped beside his chair to give him a soft pat on the cheek her first remark sent a jealous twinge through him.

"So that's who the stranger was with young Walton," he responded. "Humph! I don't think much of him."

"But grandfathah, how could you tell at such a distance?" laughed Lloyd. "It isn't fair to form an opinion at such long range. You'd bettah come[51] with us tonight again ovah to the Cabin, and make his acquaintance. There's to be anothah housewahming, especially for him. Kitty and Ranald are engineering it. They've invited all the young people in the neighbourhood—sawt of a surprise you know. At least they call it that, although Gay and Lucy are expecting us. Even Rob is going, for Kitty waylaid him as he got off the train yestahday evening, and talked him into consenting."

"I'm glad of that," answered the old Colonel heartily. "'All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.' This last year has been hard on the lad. The Judge tells me he's never left the place a single night since his Daddy died. He just grinds along in that hardware store all day, and is into his law books as soon as he gets home. He's getting to be an old man before his time. I'm glad your little friend Gay is here this summer, on his account, if for no other reason. She'll draw him out of his shell if anybody can. I remember how much he seemed to be taken with her that Christmas Vacation she spent in the Valley."

Lloyd gaped at him in astonishment. "Why grandfathah! I nevah dreamed that you noticed things like that!"

"I certainly do, my dear," he answered playfully.[52] "I was young myself once upon a time. It's easy to recognize familiar landmarks on a road you've travelled. But why," he said suddenly in a changed tone, "if I may be so bold as to ask, why is this young Texan to be ushered into the valley with this blare of trumpets and torchlight effect? Is he anything out of the ordinary?"

"No, but it will make him feel that he hasn't dropped down into a poky inland village with nothing doing, but into a lovely social whirl instead. They want him to be so pleased with the place that he'll be satisfied to stay all summah."

It was almost on the tip of her tongue to tell why his family were so desirous of keeping him with them, but another scornful "humph!" checked her. For some unaccountable reason the old Colonel seemed to have taken a dislike to this stranger, and she knew that this information would deepen it to such an extent, that he would not want her to have anything to do with him.

"He'd be furious if he knew what I promised Gay," she thought, "for he takes such violent prejudices that the least thing 'adds fuel to the flame.' He might not want me to let him call heah or anything."

"What do you keep saying 'humph!' to me[53] foh?" she asked saucily, "when I'm trying to tell you the news and am so kind and polite as to ask you to go to the pahty with us. It's dreadful to have such an old ogah of a grandfathah, who makes you shake in yoah shoes every time he opens his mouth."

Her arm was round his neck as she spoke, and her cheek pressed against his. The caress drove away every other thought save that it was good to have his little Colonel home again, and he gave a pleased chuckle as she went on scolding him in a playful manner that no one else in the world ever dared assume with him. But all the while that she was twisting his white moustache, and braiding his Napoleon-like goatee into a funny little tail, she was thinking about the evening, and the indifferent air with which she intended to meet Leland Harcourt. She would have to be indifferent, and oblivious of his existence as far as she could politely, because Gay had told him that she was unapproachable and unattainable. She would talk to Rob most of the evening, she decided. She was glad that she would have the opportunity, for she had not seen him since coming home. He had called at The Locusts the night after her return from school,[54] but that was the night she had stayed at the Cabin with Gay, and she had missed him.

"Did you know that your trunks came while you were at the post-office?" asked the Colonel presently. Owing to some mistake in checking their baggage in Washington, Lloyd's trunks had been delayed, and she had been wearing some of Betty's clothes the two days she had been at home.

"Why didn't you tell me soonah?" she asked, springing up from her seat on the arm of his chair. "I've been puzzling my brains all mawning ovah what I could weah tonight." Hastily gathering up the handful of clovers that she had dropped on the wicker table, she ran upstairs. Everything in her pink bower of a room was in confusion. Her Commencement gown lay on the bed like an armful of thistledown, with her gloves and lace fan beside it. On the mantel stood the little white slippers in which she had tripped across the rostrum at Warwick Hall to receive her diploma from Madam Chartley's hands. Now the diploma with its imposing red seals and big blue satin bow, was reposing on top of the clock on the same mantel with the slippers, and from the open trunks which Mom Beck was unpacking, a motley collection of books,[55] clothing, sorority banners and school-girl souvenirs flowed out all over the floor.

The old coloured woman was garrulous this morning. Her trip to Washington "with all her white folks, to her baby's Finishment" (she couldn't understand why it should be called Commencement), had been the event of her life; and when she could get no one else to listen, she talked to herself, recounting each incident of her journey with unctuous enjoyment.

She was on her knees now before one of the trunks, talking so earnestly into its depths, that Lloyd, entering the room, looked around to see who her audience could be. At the sound of Lloyd's step the monologue came to a sudden stop, and the wrinkled old face turned with a smile.

"What you want me to do with all these yeah school books, honey, now you done with 'em fo' evah?"

"Mercy, Mom Beck! don't talk as if I had come to the end of every thing, and am too old to study any moah! I expect to keep up my French and German all next wintah, even if I am a débutante. Don't you remembah what Madam Chartley said in her lovely farewell speech to the graduating[56] class? What's the good of taking you to Commencement, if that's all the impression it made?"

A pleased cackle of a laugh answered her. "Law, honey, I couldn't listen to speeches! I was too busy thinkin' of Becky Potah in her black silk dress that ole Cun'l give me for the grand occasion, an' the purple pansies in my bonnet. The queen o' Sheby couldn't held a can'le to me that day."

She was off on another chapter of reminiscences now, but Lloyd paid no attention. As she picked up the books and found places for them on the low shelves that filled one side of the room, she felt as if she were assisting at the last sad rites of something very dear; for each page was eloquent with happy memories of her last year at school. Every scribbled margin recalled some pleasant recitation hour, and most of the fly-leaves were decorated by Kitty's ridiculous caricatures. She and Kitty had been room-mates this last year.

In order to find place for these books, which she had just brought home, she had to carry a row of old ones down to the library. They were juvenile tales, most of them, which she laid aside; girls' stories that had once been a never failing source of delight. She could remember the time (and not so very long ago, either) when it had seemed impossible[57] that she could out-grow them. And now as she trailed down stairs with an armful of her old favourites, she felt as if the shadowy figure of her childhood, the little Lloyd that used to be, followed her with reproachful glances for her disloyalty to these discarded friends.

On her way back to her room for a second armful, she stopped outside Betty's door for a moment, hoping to hear some noise within, which would indicate that Betty was not at her desk. There was so much that she wanted to talk to her about. One of the things she had looked forward to most eagerly in her home-coming was the long, sisterly talks they would have together. Now it was a disappointment to find her so absorbed in her writing that she was as inaccessible as if she had withdrawn into a cloister.

"I'll be glad when the old book is finished," thought Lloyd impatiently as she tip-toed away from the door. To her, Betty's ability to write was a mysterious and wonderful gift. Not for anything would she have interrupted her when "genius burned," but she resented the fact that it should rise between them as it had done lately. Even when Betty was not shut up in her room actually at work, her thoughts seemed to be on it. She was[58] living in a world of her own creating, more interested in the characters of her fancy than those who sat at table with her. Since beginning the last chapter she had been so preoccupied and absent-minded, that Lloyd hardly knew her. She was so unlike the old Betty, the sympathetic confidante and counsellor, who had been interested in even the smallest of her griefs and joys.

If Lloyd could have looked on the other side of the closed door just then, the expression on Betty's face would have banished every feeling of impatience or resentment, and sent her quietly away to wait and wonder, while Betty passed through one of the great hours of her life.

With a tense, earnest face bent over the manuscript, she reached the climax of her story—the last page, the last paragraph. Then with a throbbing heart, she halted a moment, pen in hand, before adding the words, The End. She wrote them slowly, reverently almost, and then realizing that the ambition of her life had been accomplished, looked up with an expression of child-like awe in her brown eyes. It was done at last, the work that she had pledged herself to do so long ago, back there in the little old wooden church at the Cuckoo's Nest.

For a time she forgot the luxurious room where she sat, and was back at the beginning of her ambition and high resolves, in that plain old meeting house in the grove of cedars. Again she tiptoed down the empty aisle, that was as still as a tomb, save for the buzzing of a wasp at the open window through which she had climbed. Again she opened the little red book-case above the back pew, that held the remnants of a scattered Sunday-school library. The queer musty smell of the time-yellowed volumes floated out to her as strong as ever, mingling with the warm spicy scent of pinks and cedar, from the graveyard just outside the open window.

Those tattered books, read in secret to Davy on sunny summer afternoons, had been the first voices to whisper to her that she too was destined to leave a record behind her. And now that she had done it, they seemed to call her back to that starting place. Sitting there in happy reverie, she wished that she could make a pilgrimage back to the little church. She would like to slip down its narrow aisle just when the afternoon sun was shining yellowest on its worn benches and old altar, and dropping on her knees as she had done years ago in a transport of gratitude, whisper a happy[60] "Thank you, God" from the depths of a glad little heart.

Presently the whisper did go up from her desk where she sat with her face in her hands. Then reaching out for the last volume of the white and gold series that chronicled her good times, she opened it to where a blotter kept the place at a half written page, and added this entry.

"June 20th. Truly a red-letter day, for hereon endeth my story of 'Aberdeen Hall.' The book is written at last. Two chapters are still to be copied on the typewriter, but the 'web' itself is woven, and ready to be cut from the loom. I am glad now that I waited; that I did not attempt to publish anything in my teens. The world looks very different to me now at twenty. I have outgrown my early opinions and ideals with my short dresses, just as Mrs. Walton said we would. Now the critics can say 'Thou waitedst till thy woman's fingers wrought the best that lay within thy woman's heart.' I can say honestly I have put the very best of me into it, and the feeling of satisfaction that I have accomplished the one great thing I started out to do so many years ago, gives me more happiness I am sure, than any 'diamond leaf' that any prince could bring."

Such elation as was Betty's that hour, seldom comes to one more than once in a life-time. Years afterward her busy pen produced far worthier books, which were beloved and bethumbed in thousands of libraries, but none of them ever brought again that keen inward thrill, that wave of intense happiness which surged through her warm and sweet, as she sat looking down on that first completed manuscript. She was loath to lay it aside, for the joy of the creator possessed her, and in the first flush of pleased surveyal of her handiwork, she humbly called it good.

She went down to lunch in such an uplifted frame of mind that she seemed to be walking on air. But Betty was always quiet, even in her most intense moments. Save for the brilliant colour in her cheeks and the unusual light in her eyes there was no sign of her inward excitement. She slipped into her seat at table with the careless announcement "Well, it's finished."

It was Lloyd who made all the demonstration amid the family congratulations. Waving her napkin with one hand and clicking two spoons together like castanets, she sprang from her chair and rushed around the table to give vent to her[62] pleasure by throwing her arms around Betty in a delighted embrace.

"Oh you little mouse!" she cried. "How can you sit there taking it so calmly? If I had done such an amazing thing as to write a book, I'd have slidden down the ban'istahs with a whoop, to announce it, and come walking in on my hands instead of my feet.

"Of co'se I'm just as proud of it as the rest of the family are," she added when she had expended her enthusiasm and gone back to her seat, "but now that it's done I'll confess that I've been jealous of that old book evah since I came home, and I'm mighty glad it's out of the way. Now you'll have time to take some interest in what the rest of us are doing, and you'll feel free to go in, full-swing, for the celebration at the Cabin tonight."

All the rest of that day seemed a fête day to Betty. Her inward glow lent a zest to the doing of even the most trivial things, and she prepared for the gaieties at the Cabin, as if it were her own entertainment, pleased that this red-letter occasion of her life should be marked by some kind of a celebration. It was to do honour to the day and not to the Harcourt's guest, that she arrayed herself in her most becoming gown.

Rob dropped in early, quite in the old way as if there had never been a cessation of his daily visits, announcing that he had come to escort the girls to the Cabin. Lloyd who was not quite ready, leaned over the banister in the upper hall for a glimpse of her old playmate, intending to call down some word of greeting; but he looked so grave and dignified as he came forward under the hall chandelier to shake hands with Betty, that she drew back in silence.

The next instant she resented this new feeling of reserve that seemed to rise up and wipe out all their years of early comradery. Why shouldn't she call down to him over the banister as she had always done? she asked herself defiantly. He was still the same old Rob, even if he had grown stern and grave looking. She leaned over again, but this time it was the sight of Betty that stopped her. She had never seen her so beaming, so positively radiant. In that filmy yellow dress, she might have posed as the Daffodil Maid. Her cheeks were still flushed, her velvety brown eyes luminous with the joy of the day's achievement.

Lloyd watched her a moment in fascinated admiration, as she stood laughing and talking under the hall light. Then she saw that Rob was just as[64] much impressed with Betty's attractiveness as she was, and was looking at her as if he had made a discovery.

His pleased glance and the frank compliment that followed sent a thought into Lloyd's mind that made her wonder why it had never occurred to her before. How well Betty would fit into the establishment over at Oaklea. What a dear daughter she would make to Mrs. Moore, and what a joy she would be to the old Judge! Rob seemed to be finding her immensely entertaining. Well, there was no need for her to hurry down now. She could take her time about changing her dress.

Lloyd could not have told what had made her decide so suddenly that her dress needed changing. She had put on a pale green dimity that she liked because it was simple and cool-looking, but now after a glance into the mirror she began to slip it off.

"It looks like a wilted lettuce leaf," she said petulantly to her reflection, realizing that nothing but white could hold its own when brought in contact with Betty's gown. That pale exquisite shade of glowing yellow would be the dominating colour in any place it might be worn.

"I must live up to Gay's expectations," she thought, "so white it shall be, Señor Harcourt!"

His dark face with its flashing smile rose before her, and stayed in the foreground of her thoughts, all the time she was arraying herself in her daintiest, fluffiest white organdy. Clasping the little necklace of Roman pearls around her throat, and catching up her lace fan, she swept up to the mirror for a last anxious survey. It was a thoroughly satisfactory one, and with a final smoothing of ribbons she smiled over her shoulder at the charming reflection.

"Now I'll go down and practise my airs and graces on Rob and Betty for awhile. But I'll leave them in peace after we get to the Cabin, for if there should be any possibility of their beginning to care for each othah, I wouldn't get in the way for worlds. Now this is the way I'll sail in to meet Mistah Harcourt!"