Georgina of the Rainbows

by

Annie Fellows Johnston

Author of Two Little Knights of Kentucky, The Giant Scissors, The Desert of Waiting, Etc.

“... _Still bear up and steer;

right onward._” Milton

To

My Little God-daughter

“Anne Elizabeth”

Contents

- Her Earlier Memories

- Georgina’s Playmate Mother

- The Towncrier Has His Say

- New Friends and the Green Stairs

- In the Footsteps of Pirates

- Spend-the-Day Guests

- “The Tishbite”

- The Telegram that Took Barby Away

- The Birthday Prism

- Moving Pictures

- The Old Rifle Gives Up Its Secret

- A Hard Promise

- Lost and Found at the Liniment Wagon

- Buried Treasure

- A Narrow Escape

- What the Storm Did

- In the Keeping of the Dunes

- Found Out

- Tracing the Liniment Wagon

- Dance of the Rainbow Fairies

- On the Trail of the Wild-Cat Woman

- The Rainbow Game

- Light Dawns for Uncle Darcy

- A Contrast in Fathers

- A Letter to Hong-Kong

- Peggy Joins the Rainbow-Makers

- A Modern “St. George and the Dragon”

- The Doctor’s Discovery

- While They Waited

- Nearing the End

- Comings and Goings

“As Long as a Man Keeps Hope at the Prow He Keeps Afloat.”

“Put a Rainbow ’Round Your Troubles.”--Georgina.

Chapter I

Her Earlier Memories

If old Jeremy Clapp had not sneezed his teeth into the fire that winter day this story might have had a more seemly beginning; but, being a true record, it must start with that sneeze, because it was the first happening in Georgina Huntingdon’s life which she could remember distinctly.

She was in her high-chair by a window overlooking a gray sea, and with a bib under her chin, was being fed dripping spoonfuls of bread and milk from the silver porringer which rested on the sill. The bowl was almost on a level with her little blue shoes which she kept kicking up and down on the step of her high-chair, wherefore the restraining hand which seized her ankles at intervals. It was Mrs. Triplett’s firm hand which clutched her, and Mrs. Triplett’s firm hand which fed her, so there was not the usual dilly-dallying over Georgina’s breakfast as when her mother held the spoon. She always made a game of it, chanting nursery rhymes in a gay, silver-bell-cockle-shell sort of way, as if she were one of the “pretty maids all in a row,” just stepped out of a picture book.

Mrs. Triplett was an elderly widow, a distant relative of the family, who lived with them. “Tippy” the child called her before she could speak plainly--a foolish name for such a severe and dignified person, but Mrs. Triplett rather seemed to like it. Being the working housekeeper, companion and everything else which occasion required, she had no time to make a game of Georgina’s breakfast, even if she had known how. Not once did she stop to say, “Curly-locks, Curly-locks, wilt thou be mine?” or to press her face suddenly against Georgina’s dimpled rose-leaf cheek as if it were somthing too temptingly dear and sweet to be resisted. She merely said, “Here!” each time she thrust the spoon towards her.

Mrs. Triplett was in an especial hurry this morning, and did not even look up when old Jeremy came into the room to put more wood on the fire. In winter, when there was no garden work, Jeremy did everything about the house which required a man’s hand. Although he must have been nearly eighty years old, he came in, tall and unbending, with a big log across his shoulder. He walked stiffly, but his back was as straight as the long poker with which he mended the fire.

Georgina had seen him coming and going about the place every day since she had been brought to live in this old gray house beside the sea, but this was the first time he had made any lasting impression upon her memory. Henceforth, she was to carry with her as long as she should live the picture of a hale, red-faced old man with a woolen muffler wound around his lean throat. His knitted “wrist-warmers” slipped down over his mottled, deeply-veined bands when he stooped to roll the log into the fire. He let go with a grunt. The next instant a mighty sneeze seized him, and Georgina, who had been gazing in fascination at the shower of sparks he was making, saw all of his teeth go flying into the fire. If his eyes had suddenly dropped from their sockets upon the hearth, or his ears floated off from the sides of his head, she could not have been more terrified, for she had not yet learned that one’s teeth may be a separate part of one’s anatomy. It was such a terrible thing to see a man go to pieces in this undreamed-of fashion, that she began to scream and writhe around in her high-chair until it nearly turned over.

She did upset the silver porringer, and what was left of the bread and milk splashed out on the floor, barely missing the rug. Mrs. Triplett sprang to snatch her from the toppling chair, thinking the child was having a spasm. She did not connect it with old Jeremy’s sneeze until she heard his wrathful gibbering, and turned to see him holding up the teeth, which he had fished out of the fire with the tongs.

They were an old-fashioned set such as one never sees now. They had been made in England. They were hinged together like jaws, and Georgina yelled again as she saw them all blackened and gaping, dangling from the tongs. It was not the grinning teeth themselves, however, which frightened her. It was the awful knowledge, vague though it was to her infant mind, that a human body could fly apart in that way. And Tippy, not understanding the cause of her terror, never thought to explain that they were false and had been made by a man in some out-of-the-way corner of Yorkshire, instead of by the Almighty, and that their removal was painless.

It was several years before Georgina learned the truth, and the impression made by the accident grew into a lurking fear which often haunted her as time wore on. She never knew at what moment she might fly apart herself. That it was a distressing experience she knew from the look on old Jeremy’s face and the desperate pace at which he set off to have himself mended.

She held her breath long enough to hear the door bang shut after him and his hob-nailed shoes go scrunch, scrunch, through the gravel of the path around the house, then she broke out crying again so violently that Tippy had hard work quieting her. She picked up the silver porringer from the floor and told her to look at the pretty bowl. The fall had put a dent into its side. And what would Georgina’s great-great aunt have said could she have known what was going to happen to her handsome dish, poor lady! Surely she never would have left it to such a naughty namesake! Then, to stop her sobbing, Mrs. Triplett took one tiny finger-tip in her large ones, and traced the name which was engraved around the rim in tall, slim-looped letters: the name which had passed down through many christenings to its present owner, “Georgina Huntingdon.”

Failing thus to pacify the frightened child, Mrs. Triplett held her up to the window overlooking the harbor, and dramatically bade her “hark!” Standing with her blue shoes on the window-sill, and a tear on each pink cheek, Georgina flattened her nose against the glass and obediently listened.

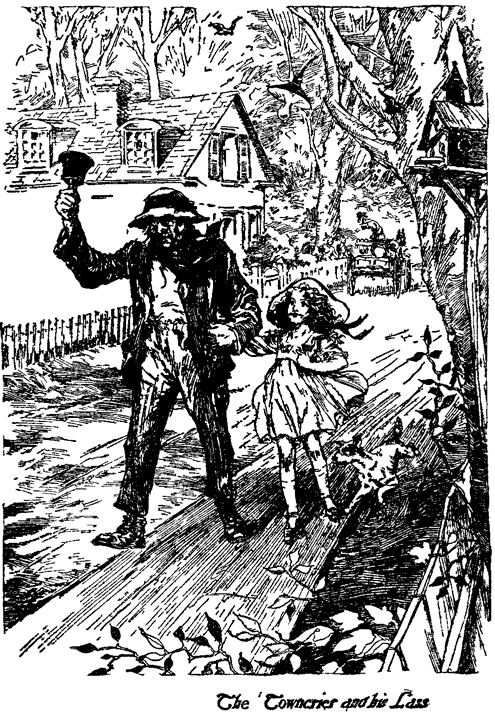

The main street of the ancient seaport town, upon which she gazed expectantly, curved three miles around the harbor, and the narrow board-walk which ran along one side of it all the way, ended abruptly just in front of the house in a waste of sand. So there was nothing to be seen but a fishing boat at anchor, and the waves crawling up the beach, and nothing to be heard but the jangle of a bell somewhere down the street. The sobs broke out again. “Hush!” commanded Mrs. Triplett, giving her an impatient shake. “Hark to what’s coming up along. Can’t you stop a minute and give the Towncrier a chance? Or is it you’re trying to outdo him?”

The word “Towncrier” was meaningless to Georgina. There was nothing by that name in her linen book which held the pictures of all the animals from Ape to Zebra, and there was nothing by that name down in Kentucky where she had lived all of her short life until these last few weeks. She did not even know whether what Mrs. Triplett said was coming along would be wearing a hat or horns. The cow that lowed at the pasture bars every night back in Kentucky jangled a bell. Georgina had no distinct recollection of the cow, but because of it the sound of a bell was associated in her mind with horns. So horns were what she halfway expected to see, as she watched breathlessly, with her face against the glass.

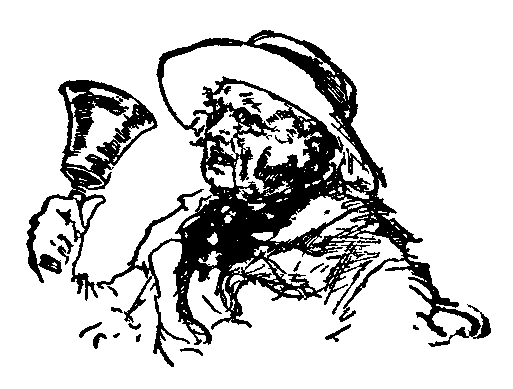

“Hark to what he’s calling!” urged Mrs. Triplett. “A fish auction. There’s a big boat in this morning with a load of fish, and the Towncrier is telling everybody about it.”

So a Towncrier was a man! The next instant Georgina saw him. He was an old man, with bent shoulders and a fringe of gray hair showing under the fur cap pulled down to meet his ears. But there was such a happy twinkle in his faded blue eyes, such goodness of heart in every wrinkle of the weather-beaten old face, that even the grumpiest people smiled a little when they met him, and everybody he spoke to stepped along a bit more cheerful, just because the hearty way he said “_Good_ morning!” made the day seem really good.

“He’s cold,” said Tippy. “Let’s tap on the window and beckon him to come in and warm himself before he starts back to town.”

She caught up Georgina’s hand to make it do the tapping, thinking it would please her to give her a share in the invitation, but in her touchy frame of mind it was only an added grievance to have her knuckles knocked against the pane, and her wails began afresh as the old man, answering the signal, shook his bell at her playfully, and turned towards the house.

As to what happened after that, Georgina’s memory is a blank, save for a confused recollection of being galloped to Banbury Cross on somebody’s knee, while a big hand helped her to clang the clapper of a bell far too heavy for her to swing alone. But some dim picture of the kindly face puckered into smiles for her comforting, stayed on in her mind as an object seen through a fog, and thereafter she never saw the Towncrier go kling-klanging along the street without feeling a return of that same sense of safety which his song gave her that morning. Somehow, it restored her confidence in all Creation which Jeremy’s teeth had shattered in their fall.

Taking advantage of Georgina’s contentment at being settled on the visitor’s knee, Mrs. Triplett hurried for a cloth to wipe up the bread and milk. Kneeling on the floor beside it she sopped it up so energetically that what she was saying came in jerks.

“It’s a mercy you happened along, Mr. Darcy, or she might have been screaming yet. I never saw a child go into such a sudden tantrum.”

The answer came in jerks also, for it took a vigorous trotting of the knees to keep such a heavy child as Georgina on the bounce. And in order that his words might not interfere with the game he sang them to the tune of “Ride a Cock Horse.”

“There must have been--some--very good----

Reason for such--a hulla-ba-loo!”

“I’ll tell you when I come back,” said Mrs. Triplett, on her feet again by this time and halfway to the kitchen with the dripping floor cloth. But when she reappeared in the doorway her own concerns had crowded out the thought of old Jeremy’s misfortune.

“My yeast is running all over the top of the crock, Mr. Darcy, and if I don’t get it mixed right away the whole baking will be spoiled.”

“That’s all right, ma’am,” was the answer. “Go ahead with your dough. I’ll keep the little lass out of mischief. Many’s the time I have sat by this fire with her father on my knee, as you know. But it’s been years since I was in this room last.”

There was a long pause in the Banbury Cross ride. The Crier was looking around the room from one familiar object to another with the gentle wistfulness which creeps into old eyes when they peer into the past for something that has ceased to be. Georgina grew impatient.

“More ride!” she commanded, waving her hands and clucking her tongue as he had just taught her to do.

“Don’t let her worry you, Mr. Darcy,” called Mrs. Triplett from the kitchen. “Her mother will be back from the post-office most any minute now. Just send her out here to me if she gets too bothersome.”

Instantly Georgina cuddled her head down against his shoulder. She had no mind to be separated from this new-found playfellow. When he produced a battered silver watch from the pocket of his velveteen waistcoat, holding it over her ear, she was charmed into a prolonged silence. The clack of Tippy’s spoon against the crock came in from the kitchen, and now and then the fire snapped or the green fore-log made a sing-song hissing.

More than thirty years had passed by since the old Towncrier first visited the Huntingdon home. He was not the Towncrier then, but a seafaring man who had sailed many times around the globe, and had his fill of adventure. Tired at last of such a roving life, he had found anchorage to his liking in this quaint old fishing town at the tip end of Cape Cod. Georgina’s grandfather, George Justin Huntingdon, a judge and a writer of dry law books, had been one of the first to open his home to him. They had been great friends, and little Justin, now Georgina’s father, had been a still closer friend. Many a day they had spent together, these two, fishing or blueberrying or tramping across the dunes. The boy called him “Uncle Darcy,” tagging after him like a shadow, and feeling a kinship in their mutual love of adventure which drew as strongly as family ties. The Judge always said that it was the old sailor’s yarns of sea life which sent Justin into the navy “instead of the law office where he belonged.”

As the old man looked down at Georgina’s soft, brown curls pressed against his shoulder, and felt her little dimpled hand lying warm on his neck, he could almost believe it was the same child who had crept into his heart thirty years ago. It was hard to think of the little lad as grown, or as filling the responsible position of a naval surgeon. Yet when he counted back he realized that the Judge had been dead several years, and the house had been standing empty all that time. Justin had never been back since it was boarded up. He had written occasionally during the first of his absence, but only boyish scrawls which told little about himself.

The only real news which the old man had of him was in the three clippings from the Provincetown _Beacon_, which he carried about in his wallet. The first was a mention of Justin’s excellent record in fighting a fever epidemic in some naval station in the tropics. The next was the notice of his marriage to a Kentucky girl by the name of Barbara Shirley, and the last was a paragraph clipped from a newspaper dated only a few weeks back. It said that Mrs. Justin Huntingdon and little daughter, Georgina, would arrive soon to take possession of the old Huntingdon homestead which had been closed for many years. During the absence of her husband, serving in foreign parts, she would have with her Mrs. Maria Triplett.

The Towncrier had known Mrs. Triplett as long as he had known the town. She had been kind to him when he and his wife were in great trouble. He was thinking about that time now, because it had something to do with his last visit to the Judge in this very room. She had happened to be present, too. And the green fore-log had made that same sing-song hissing. The sound carried his thoughts back so far that for a few moments he ceased to hear the clack of the spoon.

Chapter II

Georgina’s Playmate Mother

As the Towncrier’s revery brought him around to Mrs. Triplett’s part in the painful scene which he was recalling, he heard her voice, and looking up, saw that she had come back into the room, and was standing by the window.

“There’s Justin’s wife now, Mr. Darcy, coming up the beach. Poor child, she didn’t get her letter. I can tell she’s disappointed from the way she walks along as if she could hardly push against the wind.”

The old man, leaning sideways over the arm of his chair, craned his neck toward the window to peer out, but he did it without dislodging Georgina, who was repeating the “tick-tick” of the watch in a whisper, as she lay contentedly against the Towncrier’s shoulder.

“She’s naught but a slip of a girl,” he commented, referring to Georgina’s mother, slowly drawing into closer view. “She must be years younger than Justin. She came up to me in the post-office last week and told me who she was, and I’ve been intending ever since to get up this far to talk with her about him.”

As they watched her she reached the end of the board-walk, and plunging ankle-deep into the sand, trudged slowly along as if pushed back by the wind. It whipped her skirts about her and blew the ends of her fringed scarf back over her shoulder. She made a bright flash of color against the desolate background. Scarf, cap and thick knitted reefer were all of a warm rose shade. Once she stopped, and with hands thrust into her reefer pockets, stood looking off towards the lighthouse on Long Point. Mrs. Triplett spoke again, still watching her.

“I didn’t want to take Justin’s offer when he first wrote to me, although the salary he named was a good one, and I knew the work wouldn’t be more than I’ve always been used to. But I had planned to stay in Wellfleet this winter, and it always goes against the grain with me to have to change a plan once made. I only promised to stay until she was comfortably settled. A Portugese woman on one of the back streets would have come and cooked for her. But land! When I saw how strange and lonesome she seemed and how she turned to me for everything, I didn’t have the heart to say go. I only named it once to her, and she sort of choked up and winked back the tears and said in that soft-spoken Southern way of hers, ‘Oh, don’t leave me, Tippy!’ She’s taken to calling me Tippy, just as Georgina does. ’When you talk about it I feel like a kitten shipwrecked on a desert island. It’s all so strange and dreadful here with just sea on one side and sand dunes on the other.’”

At the sound of her name, Georgina suddenly sat up straight and began fumbling the watch back into the velveteen pocket. She felt that it was time for her to come into the foreground again.

“More ride!” she demanded. The galloping began again, gently at first, then faster and faster in obedience to her wishes, until she seemed only a swirl of white dress and blue ribbon and flying brown curls. But this time the giddy going up and down was in tame silence. There was no accompanying song to make the game lively. Mrs. Triplett had more to say, and Mr. Darcy was too deeply interested to sing.

“Look at her now, stopping to read that sign set up on the spot where the Pilgrims landed. She does that every time she passes it. Says it cheers her up something wonderful, no matter how downhearted she is, to think that she wasn’t one of the Mayflower passengers, and that she’s nearly three hundred years away from their hardships and that dreadful first wash-day of theirs. Does seem to me though, that’s a poor way to make yourself cheerful, just thinking of all the hard times you might have had but didn’t.”

“_Thing_ it!” lisped Georgina, wanting undivided attention, and laying an imperious little hand on his cheek to force it. “_Thing_!”

He shook his head reprovingly, with a finger across his lips to remind her that Mrs. Triplett was still talking; but she was not to be silenced in such a way. Leaning over until her mischievous brown eyes compelled him to look at her, she smiled like a dimpled cherub. Georgina’s smile was something irresistible when she wanted her own way.

“_Pleathe!_” she lisped, her face so radiantly sure that no one could be hardhearted enough to resist the magic appeal of that word, that he could not disappoint her.

“The little witch!” he exclaimed. “She could wheedle the fish out of the sea if she’d say please to ’em that way. But how that honey-sweet tone and the yells she was letting loose awhile back could come out of that same little rose of a mouth, passes my understanding.”

Mrs. Triplett had left them again and he was singing at the top of his quavering voice, “Rings on her fingers and bells on her toes,” when the front door opened and Georgina’s mother came in. The salt wind had blown color into her cheeks as bright as her rose-pink reefer. Her disappointment about the letter had left a wistful shadow in her big gray eyes, but it changed to a light of pleasure when she saw who was romping with Georgina. They were so busy with their game that neither of them noticed her entrance.

She closed the door softly behind her and stood with her back against it watching them a moment. Then Georgina spied her, and with a rapturous cry of “_Barby!_” scrambled down and ran to throw herself into her mother’s arms. Barby was her way of saying Barbara. It was the first word she had ever spoken and her proud young mother encouraged her to repeat it, even when her Grandmother Shirley insisted that it wasn’t respectful for a child to call its mother by her first name.

“But I don’t care whether it is or not,” Barbara had answered. “All I want is for her to feel that we’re the best chums in the world. And I’m _not_ going to spoil her even if I am young and inexperienced. There are a few things that I expect to be very strict about, but making her respectful to me isn’t one of them.”

Now one of the things which Barbara had decided to be very strict about in Georgina’s training was making her respectful to guests. She was not to thrust herself upon their notice, she was not to interrupt their conversation, or make a nuisance of herself. So, young as she was, Georgina had already learned what was expected of her, when her mother having greeted Mr. Darcy and laid aside her wraps, drew up to the fire to talk to him. But instead of doing the expected thing, Georgina did the forbidden. Since the old man’s knees were crossed so that she could no longer climb upon them, she attempted to seat herself on his foot, clamoring, “Do it again!”

“No, dear,” Barbara said firmly. “Uncle Darcy’s tired.” She had noticed the long-drawn sigh of relief with which he ended the last gallop. “He’s going to tell us about father when he was a little boy no bigger than you. So come here to Barby and listen or else go off to your own corner and play with your whirligig.”

Usually, at the mention of some particularly pleasing toy Georgina would trot off happily to find it; but to-day she stood with her face drawn into a rebellious pucker and scowled at her mother savagely. Then throwing herself down on the rug she began kicking her blue shoes up and down on the hearth, roaring, _"No! No!"_ at the top of her voice. Barbara paid no attention at first, but finding it impossible to talk with such a noise going on, dragged her up from the floor and looked around helplessly, considering what to do with her. Then she remembered the huge wicker clothes hamper, standing empty in the kitchen, and carrying her out, gently lowered her into it.

It was so deep that even on tiptoe Georgina could not look over the rim. All she could see was the ceiling directly overhead. The surprise of such a novel punishment made her hold her breath to find what was going to happen next, and in the stillness she heard her mother say calmly as she walked out of the room: “If she roars any more, Tippy, just put the lid on; but as soon as she is ready to act like a little lady, lift her out, please.”

The strangeness of her surroundings kept her quiet a moment longer, and in that moment she discovered that by putting one eye to a loosely-woven spot in the hamper she could see what Mrs. Triplett was doing. She was polishing the silver porringer, trying to rub out the dent which the fall had made in its side. It was such an interesting kitchen, seen through this peep-hole that Georgina became absorbed in rolling her eye around for wider views. Then she found another outlook on the other side of the hamper, and was quiet so long that Mrs. Triplett came over and peered down at her to see what was the matter. Georgina looked up at her with a roguish smile. One never knew how she was going to take a punishment or what she would do next.

“Are you ready to be a little lady now? Want me to lift you out?” Both little arms were stretched joyously up to her, and a voice of angelic sweetness said coaxingly: “_Pleathe_, Tippy.”

The porringer was in Mrs. Triplett’s hand when she leaned over the hamper to ask the question. The gleam of its freshly-polished sides caught Georgina’s attention an instant before she was lifted out, and it was impressed on her memory still more deeply by being put into her own hands afterwards as she sat in Mrs. Triplett’s lap. Once more her tiny finger’s tip was made to trace the letters engraved around the rim, as she was told about her great-great aunt and what was expected of her. The solemn tone clutched her attention as firmly as the hand which held her, and somehow, before she was set free, she was made to feel that because of that old porringer she was obliged to be a little lady.

Tippy was not one who could sit calmly by and see a child suffer for lack of proper instruction, and while Georgina never knew just how it was done, the fact was impressed upon her as years went by that there were many things which she could not do, simply because she was a Huntingdon and because her name had been graven for so many generations around that shining silver rim.

Although to older eyes the happenings of that morning were trivial, they were far-reaching in their importance to Georgina, for they gave her three memories--Jeremy’s teeth, the Towncrier’s bell, and her own name on the porringer--to make a deep impression on all her after-life.

Chapter III

The Towncrier Has His Say

The old Huntingdon house with its gray gables and stone chimneys, stood on the beach near the breakwater, just beyond the place where everything seemed to come to an end. The house itself marked the end of the town. Back of it the dreary dunes stretched away toward the Atlantic, and in front the Cape ran out in a long, thin tongue of sand between the bay and the harbor, with a lighthouse on its farthest point. It gave one the feeling of being at the very tip end of the world to look across and see the water closing in on both sides. Even the road ended in front of the house in a broad loop in which machines could turn around.

In summer there was always a string of sightseers coming up to this end of the beach. They came to read the tablet erected on the spot known to Georgina as “holy ground,” because it marked the first landing of the Pilgrims. Long before she could read, Mrs. Triplett taught her to lisp part of a poem which said:

“Aye, call it holy ground,

The thoil where firth they trod.”

She taught it to Georgina because she thought it was only fair to Justin that his child should grow up to be as proud of her New England home as she was of her Southern one. Barbara was always singing to her about “My Old Kentucky Home,” and “Going Back to Dixie,” and when they played together on the beach their favorite game was building Grandfather Shirley’s house in the sand.

Day after day they built it up with shells and wet sand and pebbles, even to the stately gate posts topped by lanterns. Twigs of bayberry and wild beach plum made trees with which to border its avenues, and every dear delight of swing and arbor and garden pool beloved in Barbara’s play-days, was reproduced in miniature until Georgina loved them, too. She knew just where the bee-hives ought to be put, and the sun-dial, and the hole in the fence where the little pigs squeezed through. There was a story for everything. By the time she had outgrown her lisp she could make the whole fair structure by herself, without even a suggestion from Barbara.

When she grew older the shore was her schoolroom also. She learned to read from letters traced in the sand, and to make them herself with shells and pebbles. She did her sums that, way, too, after she had learned to count the sails in the harbor, the gulls feeding at ebb-tide, and the great granite blocks which formed the break-water.

Mrs. Triplett’s time for lessons was when Georgina was following her about the house. Such following taught her to move briskly, for Tippy, like time and tide, never waited, and it behooved one to be close at her heels if one would see what she put into a pan before she whisked it into the oven. Also it was necessary to keep up with her as she moved swiftly from the cellar to the pantry if one would hear her thrilling tales of Indians and early settlers and brave forefathers of colony times.

There was a powder horn hanging over the dining room mantel, which had been in the battle of Lexington, and Tippy expected Georgina to find the same inspiration in it which she did, because the forefather who carried it was an ancestor of each.

“The idea of a descendant of one of the Minutemen being afraid of _rats!_” she would say with a scornful rolling of her words which seemed to wither her listener with ridicule. “Or of an empty garret! _Tut!_”

When Georgina was no more than six, that disgusted “Tut!” would start her instantly down a dark cellar-way or up into the dreaded garret, even when she could feel the goose-flesh rising all over her. Between the porringer, which obliged her to be a little lady, and the powder horn, which obliged her to be brave, even while she shivered, some times Georgina felt that she had almost too much to live up to. There were times when she was sorry that she had ancestors. She was proud to think that one of them shared in the honors of the tall Pilgrim monument overlooking the town and harbor, but there were days when she would have traded him gladly far an hour’s play with two little Portugese boys and their sister, who often wandered up to the dunes back of the house.

She had watched them often enough to know that their names were Manuel and Joseph and Rosa. They were beautiful children, such as some of the old masters delighted to paint, but they fought and quarreled and--Tippy said--used “shocking language.” That is why Georgina was not allowed to play with them, but she often stood at the back gate watching them, envying their good times together and hoping to hear a sample of their shocking language.

One day when they strolled by dragging a young puppy in a rusty saucepan by a string tied to the handle, the temptation to join them overcame her. Inch by inch her hand moved up nearer the forbidden gate latch and she was just slipping through when old Jeremy, hidden behind a hedge where he was weeding the borders, rose up like an all-seeing dragon and roared at her, “Coom away, lass! Ye maun’t do that!”

She had not known that he was anywhere around, and the voice coming suddenly out of the unseen startled her so that her heart seemed to jump up into her throat. It made her angry, too. Only the moment before she had heard Rosa scream at Manuel, “You ain’t my boss; shut your big mouth!”

It was on the tip of her tongue to scream the same thing at old Jeremy and see what would happen. She felt, instinctively, that this was shocking language. But she had not yet outgrown the lurking fear which always seized her in his presence that either her teeth or his might fly out if she wasn’t careful, so she made no answer. But compelled to vent her inward rebellion in some way, she turned her back on the hedge that screened him and shook the gate till the latch rattled.

Looking up she saw the tall Pilgrim monument towering over the town like a watchful giant. She had a feeling that it, too, was spying on her. No matter where she went, even away out in the harbor in a motor boat, it was always stretching its long neck up to watch her. Shaking back her curls, she looked up at it defiantly and made a face at it, just the ugliest pucker of a face she could twist her little features into.

But it was only on rare occasions that Georgina felt the longing for playmates of her own age. Usually she was busy with her lessons or happily following her mother and Mrs. Triplett around the house, sharing all their occupations. In jelly-making time she had the scrapings of the kettle to fill her own little glass. When they sewed she sewed with them, even when she was so small that she had to have the thread tied in the needle’s eye, and could do no more than pucker up a piece of soft goods into big wallops. But by the time she was nine years old she had learned to make such neat stitches that Barbara sent specimens of her needlework back to Kentucky, and folded others away in a little trunk of keepsakes, to save for her until she should be grown.

Abo by the time she was nine she could play quite creditably a number of simple Etudes on the tinkly old piano which had lost some of its ivories. Her daily practicing was one of the few things about which Barbara was strict. So much attention had been given to her own education in music that she found joy in keeping up her interest in it, and wanted to make it one of Georgina’s chief sources of pleasure. To that end she mixed the stories of the great operas and composers with her fairy tales and folk lore, until the child knew them as intimately as she did her Hans Andersen and Uncle Remus.

They often acted stories together, too. Even Mrs. Triplett was dragged into these, albeit unwillingly, for minor but necessary parts. For instance, in “Lord Ullin’s Daughter,” she could keep on with her knitting and at the same time do “the horsemen hard behind us ride,” by clapping her heels on the hearth to sound like hoof-beats.

Acting came as naturally to Georgina as breathing. She could not repeat the simplest message without unconsciously imitating the tone and gesture of the one who sent it. This dramatic instinct made a good reader of her when she took her turn with Barbara in reading aloud. They used to take page about, sitting with their arms around each other on the old claw-foot sofa, backed up against the library table.

At such performances the old Towncrier was often an interested spectator. Barbara welcomed him when he first came because he seemed to want to talk about Justin as much as she desired to hear. Later she welcomed him for his own sake, and grew to depend upon him for counsel and encouragement. Most of all she appreciated his affectionate interest in Georgina. If he had been her own grandfather he could not have taken greater pride in her little accomplishments. More than once he had tied her thread in her needle for her when she was learning to sew, and it was his unfailing praise of her awkward attempts which encouraged her to I keep on until her stitches were really praiseworthy.

He applauded her piano playing from her first stumbling attempt at scales to the last simple waltz she had just learned. He attended many readings, beginning with words of one syllable, on up to such books as “The Leatherstocking Tales.” He came in one day, however, as they were finishing a chapter in one of the Judge’s favorite novels, and no sooner had Georgina skipped out of the room on an errand than he began to take her mother to task for allowing her to read anything of that sort.

“You’ll make the lass old before her time!” he scolded. “A little scrap like her ought to be playing with other children instead of reading books so far over her head that she can only sort of tip-toe up to them.”

“But it’s the stretching that makes her grow, Uncle Darcy,” Barbara answered in an indulgent tone. He went on heedless of her interruption.

“And she tells me that she sometimes sits as much as an hour at a time, listening to you play on the piano, especially if it’s ’sad music that makes you think of someone looking off to sea for a ship that never comes in, or of waves creeping up in a lonely place where the fog-bell tolls.’ Those were her very words, and she looked so mournful that it worried me. It isn’t natural for a child of her age to sit with a far-away look in her eyes, as if she were seeing things that ain’t there.”

Barbara laughed.

“Nonsense, Uncle Darcy. As long as she keeps her rosy cheeks and is full of life, a little dreaming can’t hurt her. You should have seen her doing the elfin dance this morning. She entered into the spirit of it like a little whirlwind. And, besides, there are no children anywhere near that I can allow her to play with. I have only a few acquaintances in the town, and they are too far from us to make visiting easy between the children. But look at the time _I_ give to her. I play with her so much that we’re more like two chums than mother and child.”

“Yes, but it would be better for both of you if you had more friends outside. Then Georgina wouldn’t feel the sadness of ’someone looking off to sea for a ship that never comes in.’ She feels your separation from Justin and your watching for his letters and your making your whole life just a waiting time between his furloughs, more than you have any idea of.”

“But, Uncle Darcy!” exclaimed Barbara, “it would be just the same no matter how many friends I had. They couldn’t make me forget his absence.”

“No, but they could get you interested in other things, and Georgina would feel the difference, and be happier because you would not seem to be waiting and anxious. There’s some rare, good people in this town, old friends of the family who tried to make you feel at home among them when you first came.”

“I know,” admitted Barbara, slowly, “but I was so young then, and so homesick that strangers didn’t interest me. Now Georgina is old enough to be thoroughly companionable, and our music and sewing and household duties fill our days.”

It was a subject they had discussed before, without either convincing the other, and the old man had always gone away at such times with a feeling of defeat. But this time as he took his leave, it was with the determination to take the matter in hand himself. He felt he owed it to the Judge to do that much for his grandchild. The usual crowds of summer people would be coming soon. He had heard that Gray Inn was to be re-opened this summer. That meant there would probably be children at this end of the beach. If Opportunity came that near to Georgina’s door he knew several ways of inducing it to knock. So he went off smiling to himself.

Chapter IV

New Friends and the Green Stairs

The town filled up with artists earlier than usual that summer. Stable lofts and old boathouses along the shore blossomed into studios. Sketching classes met in the rooms of the big summer art schools which made the Cape end famous, or set up their models down by the wharfs. One ran into easels pitched in the most public places: on busy street corners, on the steps of the souvenir shops and even in front of the town hall. People in paint-besmeared smocks, loaded with canvases, sketching stools and palettes, filled the board-walk and overflowed into the middle of the street.

The _Dorothy Bradford_ steamed up to the wharf from Boston with her daily load of excursionists, and the “accommodation” busses began to ply up and down the three miles of narrow street with its restless tide of summer visitors.

Up along, through the thick of it one June morning, came the Towncrier, a picturesque figure in his short blue jacket and wide seaman’s trousers, a red bandanna knotted around his throat and a wide-rimmed straw hat on the back of his head.

“Notice!” he cried, after each vigorous ringing of his big brass bell. “Lost, between Mayflower Heights and the Gray Inn, a black leather bill-case with important papers.”

He made slow progress, for someone stopped him at almost every rod with a word of greeting, and he stopped to pat every dog which thrust a friendly nose into his hand in passing. Several times strangers stepped up to him to inquire into his affairs as if he were some ancient historical personage come to life. Once he heard a man say:

“Quick with your kodak, Ethel. Catch the Towncrier as he comes along. They say there’s only one other place in the whole United States that has one. You can’t afford to miss anything _this_ quaint.”

It was nearly noon when he came towards the end of the beach. He walked still more slowly here, for many cottages had been opened for summer residents since the last time he passed along, and he knew some of the owners. He noticed that the loft above a boat-house which had once been the studio of a famous painter of marine scenes was again in use. He wondered who had taken it. Almost across from it was the “Green Stairs” where Georgina always came to meet him if she were outdoors and heard his bell.

The “Green Stairs” was the name she had given to a long flight of wooden steps with a railing on each side, leading from the sidewalk up a steep embankment to the bungalow on top. It was a wide-spreading bungalow with as many windows looking out to sea as a lighthouse, and had had an especial interest for Georgina, since she heard someone say that its owner, Mr. Milford, was an old bachelor who lived by himself. She used to wonder when she was younger if “all the bread and cheese he got he kept upon a shelf.” Once she asked Barbara why he didn’t “go to London to get him a wife,” and was told probably because he had so many guests that there wasn’t time. Interesting people were always coming and going about the house; men famous for things they had done or written or painted.

Now as the Towncrier came nearer, he saw Georgina skipping along toward him with her jumping rope. She was bare-headed, her pink dress fluttering in the salt breeze, her curls blowing back from her glowing little face. He would have hastened his steps to meet her, but his honest soul always demanded a certain amount of service from himself for the dollar paid him for each trip of this kind. So he went on at his customary gait, stopping at the usual intervals to ring his bell and call his news.

At the Green Stairs Georgina paused, her attention attracted by a foreign-looking battleship just steaming into the harbor. She was familiar with nearly every kind of sea-going craft that ever anchored here, but she could not classify this one. With her hands behind her, clasping her jumping rope ready for another throw, she stood looking out to sea. Presently a slight scratching sound behind her made her turn suddenly. Then she drew back startled, for she was face to face with a dog which was sitting on the step just on a level with her eyes. He was a ragged-looking tramp of a dog, an Irish terrier, but he looked at her in such a knowing, human way that she spoke to him as if he had been a person.

“For goodness’ sake, how you made me jump! I didn’t know anybody was sitting there behind me.” It was almost uncanny the way his eyes twinkled through his hair, as if he were laughing with her over some good joke they had together. It gave her such a feeling of comradeship that she stood and smiled back at him. Suddenly he raised his right paw and thrust it towards her. She drew back another step. She was not used to dogs, and she hesitated about touching anything with such claws in it as the paw he gravely presented.

But as he continued to hold it out she felt it would be impolite not to respond in some way, so reaching out very cautiously she gave it a limp shake. Then as he still kept looking at her with questioning eyes she asked quite as if she expected him to speak, “What’s your name, Dog?”

A voice from the top of the steps answered, “It’s Captain Kidd.” Even more startled than when the dog had claimed her attention, she glanced up to see a small boy on the highest step. He was sucking an orange, but he took his mouth away from it long enough to add, “His name’s on his collar that he got yesterday, and so’s mine. You can look at ’em if you want to.”

Georgina leaned forward to peer at the engraving on the front of the collar, but the hair on the shaggy throat hid it, and she was timid about touching a spot just below such a wide open mouth with a red tongue lolling out of it. She put her hands behind her instead.

“Is--is he--a pirate dog?” she ventured.

The boy considered a minute, not wanting to say yes if pirates were not respectable in her eyes, and not wanting to lose the chance of glorifying him if she held them in as high esteem as he did. After a long meditative suck at his orange he announced, “Well, he’s just as good as one. He buries all his treasures. That’s why we call him Captain Kidd.”

Georgina shot a long, appraising glance at the boy from under her dark lashes. His eyes were dark, too. There was something about him that attracted her, even if his face was smeary with orange juice and streaked with dirty finger marks. She wanted to ask more about Captain Kidd, but her acquaintance with boys was as slight as with dogs. Overcome by a sudden shyness she threw her rope over her head and went skipping on down the boardwalk to meet the Towncrier.

The boy stood up and looked after her. He wished she hadn’t been in such a hurry. It had been the longest morning he ever lived through. Having arrived only the day before with his father to visit at the bungalow he hadn’t yet discovered what there was for a boy to do in this strange place. Everybody had gone off and left him with the servants, and told him to play around till they got back. It wouldn’t be long, they said, but he had waited and waited until he felt he had been looking out to sea from the top of those green steps all the days of his life. Of course, he wouldn’t want to play with just a girl, but----

He watched the pink dress go fluttering on, and then he saw Georgina take the bell away from the old man as if it were her right to do so. She turned and walked along beside him, tinkling it faintly as she talked. He wished he had a chance at it. He’d show her how loud he could make it sound.

“Notice,” called the old man, seeing faces appear at some of the windows they were passing. “Lost, a black leather bill-case----”

The boy, listening curiously, slid down the steps until he reached the one on which the dog was sitting, and put his arm around its neck. The banister posts hid him from the approaching couple. He could hear Georgina’s eager voice piping up flute-like:

“It’s a pirate dog, Uncle Darcy. He’s named Captain Kidd because he buries his treasures.”

In answer the old man’s quavering voice rose in a song which he had roared lustily many a time in his younger days, aboard many a gallant vessel:

“Oh, my name is Captain Kidd,

And many wick-ud things I did,

And heaps of gold I hid,

As I sailed.”

The way his voice slid down on the word wick-_ud_ made a queer thrilly feeling run down the boy’s back, and all of a sudden the day grew wonderfully interesting, and this old seaport town one of the nicest places he had ever been in. The singer stopped at the steps and Georgina, disconcerted at finding the boy at such close range when she expected to see him far above her, got no further in her introduction to Captain Kidd than “Here he------”

But the old man needed no introduction. He had only to speak to the dog to set every inch of him quivering in affectionate response. “Here’s a friend worth having,” the raggedy tail seemed to signal in a wig-wag code of its own.

Then the wrinkled hand went from the dog’s head to the boy’s shoulder with the same kind of an affectionate pat. “What’s _your_ name, son?”

“Richard Morland.”

“What?” was the surprised question. “Are you a son of the artist Morland, who is visiting up here at the Milford bungalow?”

“Yes, that’s us.”

“Well, bless my stars, it’s _his_ bill-case I have been crying all morning. If I’d known there was a fine lad like you sitting about doing nothing, I’d had you with me, ringing the bell.”

The little fellow’s face glowed. He was as quick to recognize a friend worth having as Captain Kidd had been.

“Say,” he began, “if it was Daddy’s bill-case you were shouting about, you needn’t do it any longer. It’s found. Captain Kidd came in with it in his mouth just after Daddy went away. He was starting to dig a hole in the sand down by the garage to bury it in, like he does everything. He’s hardly done being a puppy yet, you know. I took it away from him and reckanized it, and I’ve been waiting here all morning for Dad to come home.”

He began tugging at the pocket into which he had stowed the bill-case for safe-keeping, and Captain Kidd, feeling that it was his by right of discovery, stood up, wagging himself all over, and poking his nose in between them, with an air of excited interest. The Towncrier shook his finger at him.

“You rascal! I suppose you’ll be claiming the reward next thing, you old pirate! How old is he, Richard?”

“About a year. He was given to me when he was just a little puppy.”

“And how old are you, son?”

“Ten my last birthday, but I’m so big for my age I wear ’leven-year-old suits.”

Now the Towncrier hadn’t intended to stop, but the dog began burrowing its head ecstatically against him, and there was something in the boy’s lonesome, dirty little face which appealed to him, and the next thing he knew he was sitting on the bottom step of the Green Stairs with Georgina beside him, telling the most thrilling pirate story he knew. And he told it more thrillingly than he had ever told it before. The reason for this was he had never had such a spellbound listener before. Not even Justin had hung on each word with the rapt interest this boy showed. His dark eyes seemed to grow bigger and more luminous with each sentence, more intense in their piercing gaze. His sensitive mouth changed expression with every phase of the adventure--danger, suspense, triumph. He scarcely breathed, he was listening so hard.

Suddenly the whistle at the cold-storage plant began to blow for noon, and the old man rose stiffly, saying:

“I’m a long way from home, I should have started back sooner.”

“Oh, but you haven’t finished the story!” cried the boy, in distress at this sudden ending. “It _couldn’t_ stop there.”

Georgina caught him by the sleeve of the old blue jacket to pull him back to the seat beside her.

“Please, Uncle Darcy!”

It was the first time in all her coaxing that that magic word failed to bend him to her wishes.

“No,” he answered firmly, “I can’t finish it now, but I’ll tell you what I’ll do. This afternoon I’ll row up to this end of the beach in my dory and take you two children out to the weirs to see the net hauled in. There’s apt to be a big catch of squid worth going to see, and I’ll finish the story on the way. Will that suit you?”

Richard stood up, as eager and excited as Captain Kidd always was when anybody said “Rats!” But the next instant the light died out of his eyes and he plumped himself gloomily down on the step, as if life were no longer worth living.

“Oh, bother!” he exclaimed. “I forgot. I can’t go anywhere. Dad’s painting my portrait, and I have to stick around so’s he can work on it any old time he feels like it. That’s why he brought me on this visit with him, so’s he can finish it up here.”

“Maybe you can beg off, just for to-day,” suggested Mr. Darcy.

“No, it’s very important,” he explained gravely. “It’s the best one Daddy’s done yet, and the last thing before we left home Aunt Letty said, ’Whatever you do, boys, don’t let anything interfere with getting that picture done in time to hang in the exhibition,’ and we both promised.”

There was gloomy silence for a moment, broken by the old man’s cheerful voice.

“Well, don’t you worry till you see what we can do. I want to see your father anyhow about this bill-case business, so I’ll come around this afternoon, and if he doesn’t let you off to-day maybe he will to-morrow. Just trust your Uncle Darcy for getting where he starts out to go. Skip along home, Georgina, and tell your mother I want to borrow you for the afternoon.”

An excited little pink whirlwind with a jumping rope going over and over its head, went flying up the street toward the end of the beach. A smiling old man with age looking out of his faded blue eyes but with the spirit of boyhood undimmed in his heart, walked slowly down towards the town. And on the bottom step of the Green Stairs, his arm around Captain Kidd, the boy sat watching them, looking from one to the other as long as they were in sight. The heart of him was pounding deliciously to the music of such phrases as, _"Fathoms deep, lonely beach, spade and pickaxe, skull and crossbones, bags of golden doubloons and chests of ducats and pearls!"_

Chapter V

In the Footsteps of Pirates

The weirs, to which they took their way that afternoon in the Towncrier’s dory, _The Betsey_, was “the biggest fish-trap in any waters thereabouts,” the old man told them. And it happened that the net held an unusually large catch that day. Barrels and barrels of flapping squid and mackerel were emptied into the big motor boat anchored alongside of it.

At a word from Uncle Darcy, an obliging fisherman in oilskins held out his hand to help the children scramble over the side of _The Betsey_ to a seat on top of the cabin where they could have a better view. All the crew were Portuguese. The man who helped them climb over was Joe Fayal, father of Manuel and Joseph and Rosa. He stood like a young brown Neptune, his white teeth flashing when he laughed, a pitchfork in his hands with which to spear the goosefish as they turned up in the net, and throw them back into the sea. If nothing else had happened that sight alone was enough to mark it as a memorable afternoon.

Nothing else did happen, really, except that on the way out, Uncle Darcy finished the story begun on the Green Stairs and on the way back told them another. But what Richard remembered ever after as seeming to have happened, was that _The Betsey_ suddenly turned into a Brigantine. Perched up on one of the masts, an unseen spectator, he watched a mutiny flare up among the sailors, and saw that “strutting, swaggering villain, John Quelch, throw the captain overboard and take command himself.” He saw them hoist a flag they called “Old Roger,” “having in the middle of it an Anatomy (skeleton) with an hour-glass in one hand and a dart in the heart with three drops of blood proceeding from it.”

He heard the roar that went up from all those bearded throats--(wonderful how Uncle Darcy’s thin, quavering voice could sound that whole chorus)----

“Of all the lives, I ever say,

A Pirate’s be for I.

Hap what hap may, he’s allus gay

An’ drinks an’ bungs his eye.

For his work he’s never loth,

An’ a-pleasurin’ he’ll go

Tho’ certain sure to be popt of.

Yo ho, with the rum below."</i>

And then they made after the Portuguese vessels, nine of them, and took them all (What a bloody fight it was!), and sailed away with a dazzling store of treasure, “enough to make an honest sailorman rub his eyes and stagger in his tracks.”

Richard had not been brought up on stories as Georgina had. He had had few of this kind, and none so breathlessly realistic. It carried him out of himself so completely that as they rowed slowly back to town he did not see a single house in it, although every western window-pane flashed back the out-going sun like a golden mirror. His serious, brown eyes were following the adventures of these bold sea-robbers, “marooned three times and wounded nine and blowed up in the air.”

When all of a sudden the brigantine changed back into _The Betsey_, and he had to climb out at the boat-landing, he had somewhat of the dazed feeling of that honest sailor-man. He had heard enough to make him “rub his eyes and stagger in his tracks.”

Uncle Darcy, having put them ashore, rowed off with the parting injunction to skip along home. Georgina did skip, so light of foot and quick of movement that she was in the lead all the way to the Green Stairs. There she paused and waited for Richard to join her. As he came up he spoke for the first time since leaving the weirs.

“Wish I knew the boys in this town. Wish I knew which one would be the best to get to go digging with me.”

Georgina did not need to ask, “digging for what?” She, too, had been thinking of buried treasure.

“_I’ll_ go with you,” she volunteered sweetly.

He turned on her an inquiring look, as if he were taking her measure, then glanced away indifferently.

“You couldn’t. You’re a girl.”

It was a matter-of-fact statement with no suspicion of a taunt in it, but it stung Georgina’s pride. Her eyes blazed defiantly and she tossed back her curls with a proud little uplift of the chin. It must be acknowledged that her nose, too, took on the trifle of a tilt. Her challenge was unspoken but so evident that he answered it.

“Well, you know you couldn’t creep out into the night and go along a lonely shore into dark caves and everything.”

“_Pity_ I couldn’t!” she answered with withering scorn. “I could go anywhere _you_ could, anybody descended from heroes like _I_ am. I don’t want to be braggity, but I’d have you to know they put up that big monument over there for one of them, and another was a Minute-man. With all that, for you to think I’d be afraid! _Tut!_”

Not Tippy herself had ever spoken that word with finer scorn. With a flirt of her short skirts Georgina turned and started disdainfully up the street.

“Wait,” called Richard. He liked the sudden flare-up of her manner. There was something convincing about it. Besides, he didn’t want her to go off in that independent way as if she meant never to come back. It was she who had brought the Towncrier, that matchless Teller of Tales, across his path.

“I didn’t say you wasn’t brave,”

he called after her.

“I didn’t say you wasn’t brave,”

he called after her.

She hesitated, then stopped, turning half-way around.

“I just said you was a girl. Most of them _are_ ’fraid cats, but if you ain’t I don’t know as I’d mind taking you along. That is,” he added cautiously, “if I could be dead sure that you’re game.”

At that Georgina turned all the way around and came back a few steps.

“You can try me,” she answered, anxious to prove herself worthy to be taken on such a quest, and as eager as he to begin it.

“You think of the thing you’re most afraid of yourself, and tell me to do it, and then just watch me.”

Richard declined to admit any fear of anything. Georgina named several terrors at which he stoutly shook his head, but presently with uncanny insight she touched upon his weakest point.

“Would you be afraid of coffins and spooks or to go to a graveyard in the dead of the night the way Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn did?”

Not having read Tom Sawyer, Richard evaded the question by asking, “How did they do?”

“Oh, don’t you know? They had the dead cat and they saw old Injun Joe come with the lantern and kill the man that was with Muff Potter.”

By the time Georgina had given the bare outline of the story in her dramatic way, Richard was quite sure that no power under heaven could entice him into a graveyard at midnight, though nothing could have induced him to admit this to Georgina. As far back as he could remember he had had an unreasoning dread of coffins. Even now, big as he was, big enough to wear “’leven-year-old suits,” nothing could tempt him into a furniture shop for fear of seeing a coffin.

One of his earliest recollections was of his nurse taking him into a little shop, at some village where they were spending the summer, and his cold terror when he found himself directly beside a long brown one, smelling of varnish, and with silver handles. His nurse’s tales had much to do with creating this repulsion, also her threat of shutting him up in a coffin if he wasn’t a good boy. When she found that she could exact obedience by keeping that dread hanging over him, she used the threat daily.

“I’ll tell you what I’ll do,” he said finally. “I’ll let you go digging with me if you’re game enough to go to the graveyard and walk clear across it all by yourself and”--dropping his voice to a hollow whisper-- “_touch--ten--tombstones!_”

Now, if Richard hadn’t dropped his voice in that scary way when he said, “and touch ten tombstones,” it would have been no test at all of Georgina’s courage. Strange, how just his way of saying those four words suddenly made the act such a fearsome one.

“Do it right now,” he suggested.

“But it isn’t night yet,” she answered, “let alone being mid-night.”

“No, but it’s clouding up, and the sun’s down. By the time we’d get to a graveyard it would be dark enough for me to tell if you’re game.”

Up to this time Georgina had never gone anywhere without permission. But this was something one couldn’t explain very well at home. It seemed better to do it first and explain afterward.

Fifteen minutes later, two children and a dog arrived hot and panting at the entrance to the old burying ground. On a high sand dune, covered with thin patches of beach and poverty grass, and a sparse growth of scraggly pines, it was a desolate spot at any time, and now doubly so in the gathering twilight. The lichen-covered slabs that marked the graves of the early settlers leaned this way and that along the hill.

The gate was locked, but Georgina found a place where the palings were loose, and squeezed through, leaving Richard and the dog outside. They watched her through the fence as she toiled up the steep hill. The sand was so deep that she plunged in over her shoe-tops at every step. Once on top it was easier going. The matted beach grass made a firm turf. She stopped and read the names on some of the slabs before she plucked up courage to touch one. She would not have hesitated an instant if only Richard had not dared her in that scary way.

Some little, wild creature started up out of the grass ahead of her and scurried away. Her heart beat so fast she could hear the blood pounding against her ear-drums. She looked back. Richard was watching, and she was to wave her hand each time she touched a stone so that he could keep count with her. She stooped and peered at one, trying to read the inscription. The clouds had hurried the coming of twilight. It was hard to decipher the words.

“None knew him but to love him,” she read slowly. Instantly her dread of the place vanished. She laid her hand on the stone and then waved to Richard. Then she ran on and read and touched another. “Lost at sea,” that one said, and under the next slabs slept “Deliverance” and “Experience,” “Mercy,” and “Thankful.” What queer names people had in those early days! And what strange pictures they etched in the stone of those old gray slabs--urns and angels and weeping willows!

She signaled the tenth and last. Richard wondered why she did not turn and come back. At the highest point of the hill she stood as if transfixed, a slim little silhouette against the darkening sky, her hands clasped in amazement. Suddenly she turned and came tearing down the hill, floundering through sand, falling and picking herself up, only to flounder and fall again, finally rolling down the last few yards of the embankment.

“What scared you?” asked Richard, his eyes big with excitement as he watched what seemed to be her terrified exit. “What did you see?” But she would not speak until she had squeezed between the palings and stood beside him. Then she told him in an impressive whisper, glancing furtively over her shoulder:

“There’s a whole row of tombstones up there with _skulls and cross-bones on them! They must be pirate graves!"_

Her mysterious air was so contagious that he answered in a whisper, and in a moment each was convinced by the other’s mere manner that their suspicion was true. Presently Georgina spoke in her natural voice.

“You go up and look at them.”

“Naw, I’ll take your word for it,” he answered in a patronizing tone. “Besides, there isn’t time now. It’s getting too dark. They’ll be expecting me home to supper.”

Georgina glanced about her. The clouds settling heavily made it seem later than it really was. She had a guilty feeling that Barby was worrying about her long absence, maybe imagining that something had happened to _The Betsey_. She startad homeward, half running, but her pace slackened as Richard, hurrying along beside her, began to plan what they would do with their treasure when they found it.

“There’s sure to be piles of buried gold around here,” he said. “Those pirate graves prove that a lot of ’em lived here once. Let’s buy a moving picture show first.”

Georgina’s face grew radiant at this tacit admission of herself into partnership.

“Oh, yes,” she assented joyfully. “And then we can have moving pictures made of _us_ doing all sorts of things. Won’t it be fun to sit back and watch ourselves and see how we look doing ’em?”

“Say! that’s great,” he exclaimed. “All the kids in town will want to be in the pictures, too, but we’ll have the say-so, and only those who do exactly to suit us can have a chance of getting in.”

“But the more we let in the more money we’d make in the show,” was Georgina’s shrewd answer. “Everybody will want to see what their child looks like in the movies, so, of course, that’ll make people come to our show instead of the other ones.”

“Say,” was the admiring reply. “You’re a partner worth having. You’ve got a _head_.”

Such praise was the sweetest incense to Georgina. She burned to call forth more.

“Oh, I can think of lots of things when once I get started,” she assured him with a grand air.

As they ran along Richard glanced several times at the head from which had come such valuable suggestions. There was a gleam of gold in the brown curls which bobbed over her shoulders. He liked it. He hadn’t noticed before that her hair was pretty.

There was a gleam of gold, also, in the thoughts of each. They could fairly see the nuggets they were soon to unearth, and their imaginations, each fired by the other, shoveled out the coin which the picture show was to yield them, in the same way that the fisherman had shoveled the shining mackerel into the boat. They had not attempted to count them, simply measured them by the barrelful.

“Don’t tell anybody,” Richard counseled her as they parted at the Green Stairs. “Cross your heart and body you won’t tell a soul. We want to surprise ’em.”

Georgina gave the required sign and promise, as gravely as if it were an oath.

From the front porch Richard’s father and cousin, James Milford, watched him climb slowly up the Green Stairs.

“Dicky looks as if the affairs of the nation were on his shoulders,” observed Cousin James. “Pity he doesn’t realize these are his care-free days.”

“They’re not,” answered the elder Richard. “They’re the most deadly serious ones he’ll ever have. I don’t know what he’s got on his mind now, but whatever it is I’ll wager it is more important business than that deal you’re trying to pull off with the Cold Storage people.”

Chapter VI

Spend-the-Day Guests

There was a storm that night and next day a heavy fog dropped down like a thick white veil over town and sea. It was so cold that Jeremy lighted a fire, not only in the living room but in the guest chamber across the hall.

A week earlier Tippy had announced, “It’ll never do to let Cousin Mehitable Huntingdon go back to Hyannis without having broken bread with us. She’d talk about it to the end of her days, if we were the only relations in town who failed to ask her in to a meal, during her fortnight’s visit. And, of course, if we ask her, all the family she’s staying with ought to be invited, and we’ve never had the new minister and his wife here to eat. Might as well do it all up at once while we’re about it.”

Spend-the-day guests were rare in Georgina’s experience. The grand preparations for their entertainment which went on that morning put the new partnership and the treasure-quest far into the back-ground. She forgot it entirely while the dining-room table, stretched to its limit, was being set with the best china and silver as if for a Thanksgiving feast. Mrs. Fayal, the mother of Manuel and Joseph and Rosa, came over to help in the kitchen, and Tippy whisked around so fast that Georgina, tagging after, was continually meeting her coming back.

Georgina was following to ask questions about the expected guests. She liked the gruesome sound of that term “blood relations” as Tippy used it, and wanted to know all about this recently discovered “in-law,” the widow of her grandfather’s cousin, Thomas Huntingdon. Barby could not tell her and Mrs. Triplett, too busy to be bothered, set her down to turn the leaves of the family album. But the photograph of Cousin Mehitable had been taken when she was a boarding-school miss in a disfiguring hat and basque, and bore little resemblance to the imposing personage who headed the procession of visitors, arriving promptly at eleven o’clock.

When Cousin Mehitable came into the room in her widow’s bonnet with the long black veil hanging down behind, she seemed to fill the place as the massive black walnut wardrobe upstairs filled the alcove. She lifted her eyeglasses from the hook on her dress to her hooked nose to look at Georgina before she kissed her. Under that gaze the child felt as awed as if the big wardrobe had bent over and put a wooden kiss on her forehead and said in a deep, whispery sort of voice, “So this is the Judge’s grand-daughter. How do you do, my dear?”

All the guests were middle aged and most of them portly. There were so many that they filled all the chairs and the long claw-foot sofa besides. Georgina sat on a foot-stool, her hands folded in her lap until the others took out their knitting and embroidery. Then she ran to get the napkin she was hemming. The husbands who had been invited did not arrive until time to sit down to dinner and they left immediately after the feast.

Georgina wished that everybody would keep still and let one guest at a time do the talking. After the first few minutes of general conversation the circle broke into little groups, and it wasn’t possible to follow the thread of the story in more than one. Each group kept bringing to light some bit of family history that she wanted to hear or some old family joke which they laughed over as if it were the funniest thing that ever happened. It was tantalizing not to be able to hear them all. It made her think of times when she rummaged through the chests in the attic, pulling out fascinating old garments and holding them up for Tippy to supply their history. But this was as bad as opening all the chests at once. While she was busy with one she was missing all that was being hauled out to the light of day from the others.

Several times she moved her foot-stool from one group to another, drawn by some sentence such as, “Well, she certainly was the prettiest bride I ever laid my two eyes on, but not many of us would want to stand in her shoes now.” Or from across the room, “They do say it was what happened the night of the wreck that unbalanced his mind, but I’ve always thought it was having things go at sixes and sevens at home as they did.”

Georgina would have settled herself permanently near Cousin Mehitable, she being the most dramatic and voluble of them all, but she had a tantalizing way of lowering her voice at the most interesting part, and whispering the last sentence behind her hand. Georgina was nearly consumed with curiosity each time that happened, and fairly ached to know these whispered revelations.

It was an entrancing day--the dinner so good, the ancient jokes passing around the table all so new and witty to Georgina, hearing them now for the first time. She wished that a storm would come up to keep everybody at the house overnight and thus prolong the festal feeling. She liked this “Company” atmosphere in which everyone seemed to grow expansive of soul and gracious of speech. She loved every relative she had to the remotest “in-law.”

Her heart swelled with a great thankfulness to think that she was not an orphan. Had she been one there would have been no one to remark that her eyes were exactly like Justin’s and she carried herself like a Huntingdon, but that she must have inherited her smile from the other side of the house. Barbara had that same smile and winning way with her. It was pleasant to be discussed when only pleasant things were said, and to have her neat stitches exclaimed over and praised as they were passed around.

She thought about it again after dinner, and felt so sorry for children who were orphans, that she decided to spend a large part of her share of the buried treasure in making them happy. She was sure that Richard would give part of his share, too, when he found it, and when the picture show which they were going to buy was in good running order, they would make it a rule that orphans should always be let in free.

She came back from this pleasant day-dream to hear Cousin Mehitable saying, “Speaking of thieves, does anyone know what ever became of poor Dan Darcy?”

Nobody knew, and they all shook their heads and said that it was a pity that he had turned out so badly. It was hard to believe it of him when he had always been such a kind, pleasant-spoken boy, just like his father; and if ever there was an honest soul in the whole round world it was the old Town-crier.

At that Georgina gave such a start that she ran, her needle into her thumb, and a tiny drop of blood spurted out. She did not know that Uncle Darcy had a son. She had never heard his name mentioned before. She had been at his house many a time, and there never was anyone there besides himself except his wife, “Aunt Elspeth” (who was so old and feeble that she stayed in bed most of the time), and the three cats, “John Darcy and Mary Darcy and old Yellownose.” That’s the way the old man always spoke of them. He called them his family.

Georgina was glad that the minister’s wife was a newcomer in the town and asked to have it explained. Everybody contributed a scrap of the story, for all side conversations stopped at the mention of Dan Darcy’s name, and the interest of the whole room centered on him.

It was years ago, when he was not more than eighteen that it happened. He was a happy-go-lucky sort of fellow who couldn’t be kept down to steady work such as a job in the bank or a store. He was always off a-fishing or on the water, but everybody liked him and said he’d settle down when he was a bit older. He had a friend much like himself, only a little older. Emmett Potter was his name. There was a regular David and Jonathan friendship between those two. They were hand-in-glove in everything till Dan went wrong. Both even liked the same girl, Belle Triplett.

Here Georgina’s needle gave her another jab. She laid down her hemming to listen. This was bringing the story close home, for Belle Triplett was Tippy’s niece, or rather her husband’s niece. While that did not make Belle one of the Huntingdon family, Georgina had always looked upon her as such. She visited at the house oftener than anyone else.

Nobody in the room came right out and said what it was that Dan had done, but by putting the scraps together Georgina discovered presently that the trouble was about some stolen money. Lots of people wouldn’t believe that he was guilty at first, but so many things pointed his way that finally they had to. The case was about to be brought to trial when one night Dan suddenly disappeared as if the sea had swallowed him, and nothing had ever been heard from him since. Judge Huntingdon said it was a pity, for even if he was guilty he thought he could have got him off, there being nothing but circumstantial evidence.

Well, it nearly killed his father and mother and Emmett Potter, too.

It came out then that Emmett was engaged to Belle. For nearly a year he grieved about Dan’s disappearance. Seems he took it to heart so that he couldn’t bear to do any of the things they’d always done together or go to the old places. Belle had her wedding dress made and thought if she could once get him down to Truro to live, he’d brace up and get over it.

They had settled on the day, when one wild, stormy night word came that a vessel was pounding itself to pieces off Peaked Hill Bar, and the life-saving crew was starting to the rescue. Emmett lit out to see it, and when something happened to the breeches buoy so they couldn’t use it, he was the first to answer when the call came for volunteers to man a boat to put out to them. He would have had a medal if he’d lived to wear it, for he saved five lives that night. But he lost his own the last time he climbed up on the vessel. Nobody knew whether it was a rope gave way or whether his fingers were so nearly frozen he couldn’t hold on, but he dropped into that raging sea, and his body was washed up on the beach next day.

Georgina listened, horrified.

“And Belle with her wedding dress all ready,” said Cousin Mehitable with a husky sigh.

“What became of her?” asked the minister’s wife.

“Oh, she’s still living here in town, but it blighted her whole life in a way, although she was just in her teens when it happened. It helped her to bear up, knowing he’d died such a hero. Some of the town people put up a tombstone to his memory, with a beautiful inscription on it that the summer people go to see, almost as much as the landing place of the Pilgrims. She’ll be true to his memory always, and it’s something beautiful to see her devotion to Emmett’s father. She calls him ‘Father’ Potter, and is always doing things for him. He’s that old net-mender who lives alone out on the edge of town near the cranberry bogs.”

Cousin Mehitable took up the tale:

“I’ll never forget if I live to be a hundred, what I saw on my way home the night after Emmett was drowned. I was living here then, you know. I was passing through Fishburn Court, and I thought I’d go in and speak a word to Mr. Darcy, knowing how fond he’d always been of Emmett on account of Dan and him being such friends. I went across that sandy place they call the Court, to the row of cottages at the end. But I didn’t see anything until I had opened the Darcy’s gate and stepped into the yard. The house sits sideways to the Court, you know.