IN BLUE CREEK CAÑON

BY ANNA CHAPIN RAY

AUTHOR OF "HALF A DOZEN BOYS," "HALF A DOZEN GIRLS," ETC.

NEW YORK: 46 East 14th Street

THOMAS Y. CROWELL & CO.

BOSTON: 100 Purchase Street

Copyright, 1892,

By Thomas Y. Crowell & Co.

Printed and Electrotyped by

Alfred Mudge & Son, Boston.

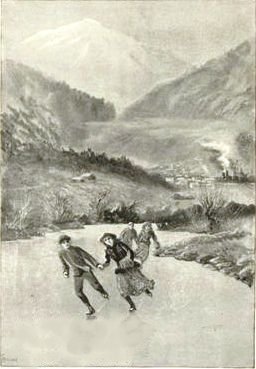

"A quartette of boys and girls were darting about on skates."

Say you're sorry and make it square;

If he's wronged you, wink so tight

None of you see what's plain in sight.

Lend a hand to help him along;

When his stockings have holes to darn,

Don't you grudge him your ball of yarn.

All the closer as age leaks in;

Squalls will blow, and clouds will frown,

But stay by your ship till you all go down!

Oliver Wendell Holmes.

CONTENTS.

CHAPTER I. A Council on Skates

CHAPTER II. To Welcome the Coming Guest

CHAPTER III. The Everett Household

CHAPTER IV. On the Cross-head

CHAPTER V. The Meeting in the Waters

CHAPTER VI. Marjorie's Party

CHAPTER VII. Janey's Prophecy

CHAPTER VIII. In the Dark

CHAPTER IX. Camping on the Beaverhead

CHAPTER X. Up the Gulch

CHAPTER XI. "Sweet Charity's Sake"

CHAPTER XII. Home without a Mother

CHAPTER XIII. At the Nine-hundred Level

CHAPTER XIV. The Beginning of the Old Story

CHAPTER XV. Mr. Atherden

CHAPTER XVI. The Completed Story

CHAPTER XVII. The Tragedy of the Unexpected

CHAPTER XVIII. Under Orders

L'ENVOI.

Other Books Published by T. Y. CROWELL & CO.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"A quartette of boys and girls were darting about on skates."

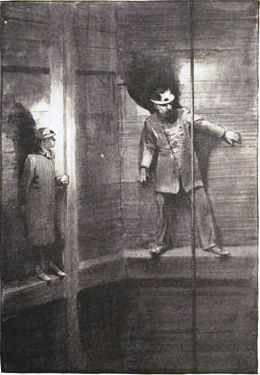

"He cautiously moved away a few inches along the beam."

IN BLUE CREEK CAÑON.

CHAPTER I.

A COUNCIL ON SKATES.

A strong southeast wind was blowing up the cañon and driving before it the dense yellow smoke which rolled up from the great red chimneys of the smelter. To the east and west of the town, the mountains rose abruptly, their steep sides bare or covered with patches of yellow pine. At the north, the cañon closed in to form a narrow gorge between the mountains; but towards the south it opened out into a broad valley, through which the swiftly rushing creek twisted and turned along its willow-bordered bed. A half mile below the town the creek suddenly broadened into a little lake that was now frozen over, forming a sheet of dazzling ice, upon which a quartette of boys and girls were darting about on skates.

"Ugh!" gasped one of the boys, as a sudden gust of wind, coming straight from the east, brought the stifling cloud in their direction; "I'm glad I'm not up in town this afternoon. It's getting ready for a storm, I think, from the way the smoke comes down; and they must be catching it all, up there."

"Oh, dear!" sighed the girl with whom he was skating; "if it storms 'twill be sure to be more snow, and spoil the ice. It's too bad, for we get so little skating out here, and it's almost time to go home now. Just see how low the sun is getting!"

"Never mind, Marjorie," said the boy, as he paused to breathe on his cold fingers; then held out his hand to her once more. "We'll have one more go across the pond, anyway, for there's no knowing when we'll have another chance. You take Allie, Ned, and we'll race you, two and two, over to that largest stump. Come on, and get into line. One! two! three!"

Away they flew, the bright blades of their skates flashing in the long slanting rays of the late afternoon sun, and their eyes and cheeks glowing with the cold air and rapid exercise. Marjorie and her attendant knight were the first to reach the goal, and turned, panting, to face the others as they came up to them.

"That was just fine!" exclaimed Allie's companion, as he dropped her hand and spun around in a narrow circle which sent the chips of ice flying from under his heel. "Don't let's go home just yet, 't won't be dark for an hour anyway, and we can go up in fifteen minutes. I'll race you over to the other side and back again, Howard, while the girls are getting their breath."

"You don't mind being left, Allie?" And the taller boy glanced at the girls.

"All right, just for once," said Allie; "then we really ought to go up, Howard; mamma wants us to be home in good season to-night, for dinner is going to be early, so papa can get the train down."

"Is your father going away again?" asked Marjorie, as the girls skated idly to and fro, waiting for the boys to join them. "I thought he came in from camp only this morning."

"So he did," answered her friend, burying her small nose in her muff for a moment, as she faced the cutting wind. "He's only going down to Pocatello to-night, and out on the main line a little ways, to meet Charlie MacGregor, our cousin that's coming."

"Yes," nodded Marjorie, in acquiescence; "I remember now; I'd forgotten he was coming so soon. What fun you'll have with him, Allie! I wish I had a brother, or cousin, or something."

"Perhaps I shall wish I didn't have both," said Allie, laughing. "I don't know how he and Howard will get on. I think Howard doesn't want him much; but I'd just as soon he'd be here."

"What's he like?" queried Marjorie curiously.

"I haven't much idea; I've never seen him," said Allie. "Papa saw him when he was east last summer, and we have a picture of him taken ever so long ago."

"Who's that—Charlie MacGregor?" asked Howard, skating up to them at that moment. "He's not much to look at, Marjorie, if his picture's any good. He has a pug nose and wears giglamps, and I've a suspicion that he's a fearful dude. He'll be a tenderfoot, of course, but he'll get over that; but if he's a dude, we boys will make it lively for him."

"Howard, you sha'n't!" remonstrated his sister, loyally coming to the defence of their unknown cousin. "It must be horrid for him to lose all his friends and have to be sent out here to relations he doesn't know nor care anything about, just like a barrel of flour." Allie's metaphors were becoming mixed; but she never heeded that, as she went on proudly: "And besides, we're MacGregors as much as he is, and mamma says that no MacGregor was ever rude to a cousin, or to anybody in trouble."

"Good for you, Allie!" shouted the younger boy, as he stopped in the middle of a figure eight to applaud her words. "You're in the right of it; but you needn't think you'll ever keep Howard in order. How old is this lad, anyhow?"

"Half way between Howard and me," replied Allie, as they started to skate slowly up the creek towards home, and Howard and Marjorie dropped a little in the rear. "He was thirteen last summer, and papa says he's a real, true musician. He'll bring his own piano with him; but I don't know where he'll find room to put it, for our house is full as can be, now. Then he sings, too,—at least, he used to,—in a boy choir. Haven't you seen his picture, Ned? It's homely, but it looks as if he might not be so bad."

"Where's he coming from?" asked Ned.

"New York. He's lived there always; but, you know, his father died two years ago, and his mother last month. He hasn't any relations but just us, so he is to live here for a while. You and Howard will stand by him, won't you, Ned?" she added persuasively, laying her mittened hand on his. "I'm afraid the other boys will run on him and make fun of him. Don't tell Howard I said so, but I don't expect to like him much myself, only I'm sort of sorry for him; and then he's our cousin, so I suppose we must make sure he has a good time."

"I won't be hard on him, Allie," her companion answered her, laughing a little at the unwonted seriousness of her tone; "as long as he doesn't put on airs and talk big about New York and 'the way we do East,' and all that poppycock, I'll stand by him. But if he's coming out here to show us how to do it, the sooner it's taken out of him the better."

"Wait till the train comes in, day after to-morrow morning, Ned," said Howard, as, with a few quick strokes, he and Marjorie overtook them once more. "We'll take a look at him and see what he's like, before we make too many promises. Now, then, ma'am," he added, as he and Marjorie paused at a great stone on the bank of the creek; "if you'll be good enough to sit down, I'll have your skates off instanter."

Marjorie laughed, as she dropped down on the stone and put one little foot on Howard's knee, while Ned performed a similar service for Allie.

"I'm crazy to see your cousin, Allie," she said. "I know he's going to be great fun, only I'm afraid he'll think we are hopeless tomboys. Probably he's been used to girls that sit in the parlor and sew embroidery, instead of skating and riding bronchos bareback, and playing hare and hounds with the boys."

"Don't care if he has!" And Allie made a little grimace of defiance as she scrambled to her feet. "I'm not going to give up all my good times and take to fancy work, when it's as much as I can do to sew on my own buttons. He can stay in the house, and sing songs and sew patchwork all day long, if he wants to, but I'm not going to give up all my frolics; need I, boys?" she concluded, in a mutinous outburst, quite at variance with her recent plea for their expected guest.

Howard laughed teasingly.

"Catch Allie turning the fine young lady! If you shut her up in a parlor, she'd jump over the chairs and play tag with herself around the table; and Marjorie is about as bad."

"Perhaps I am," she assented placidly; "but you boys could never get along without us. I've heard you say, over and over again, that we can catch a ball as well as half the boys in town, and I can outrun you any day. Want to try?"

"Not much," returned Howard, laughing, though there rankled in his mind the memory of recent races in which he had not been the winner. "You only beat me because you've been used to this air longer than I have. Besides, it would hurry us home too much, and I've an idea that this may be the last time that we four chums will be off together, for one while. I shall have to trot round with that fellow, for the next week, and show him the ways of the country, so he won't make too great a jay of himself. But, I say, if it doesn't storm to-morrow, we'll come down here again in the afternoon, and have an hour or two on the ice before it's spoiled."

With their skates strapped together and slung over their shoulders, their collars turned up around their ears, and their hands plunged deep into pockets and muffs, they turned northward along the bank of the creek for a short distance, and then struck off across the level, open ground till they came into one of the streets of the little town, which they followed until they reached the main business street. There they parted, Ned and Marjorie turning to the west, while Howard and Allie kept straight on towards the north, and finally stopped at a small brick house, a low, one-story affair, yet much more elaborate than the average dwelling of the town, where the architecture was largely of the log-house species, though often covered with a layer of boards to disguise the primitive nature of the materials.

The front door opened directly into the little parlor, and into this cosy room Howard and Allie plunged, laughing and breathless after their quick walk in the cold. A bright-faced little woman sat sewing by the front window, holding up her work to catch the last fading light, and a rosy boy, two years old, was tumbling about on the carpet, rolling over and over the great dog, who was dozing as peacefully as if such demonstrations were quite to his liking.

"Hullo, mammy! Hullo, Vic! Dinner ready?" exclaimed Howard, casting his skates into the nearest chair, and moving up to the stove to warm his chilled fingers.

"How was the skating?" asked his mother, looking up from her work to smile at Allie, as she pulled off her coat and hat, and then caught up the child from the floor.

"Fine; but we're 'most starved—at least, I am," returned Howard, as he wriggled himself out of his coat and handed it to Allie, who received it quite as a matter of course, and went away to hang it in its usual place.

"Well, dinner is all ready, and papa will be here in a minute; so you can go and tell Janey to take it up. Do you know," she added, with a laugh which took all the sting from the reproof; "I think it is time my boy learned to take his sister's coat for her, instead of expecting her to wait on him."

"All right," answered Howard, by no means abashed by the rebuke. "Here, sis, if you'll just bring back your coat and put it on again, I'll see what can be done about it." And he bent over to stroke his mother's hair with a boyish affection which filled her heart with gratitude for having such a son, even while it sent her off to her toilet table to repair the damages which his fingers had wrought. Then he marched out to the kitchen to tease Janey, until she threatened to pour the soup over his favorite pudding, unless he left her to take up the dinner in peace.

Mr. Burnam, Howard's father, was a successful civil engineer, who, in the line of his professional life, had been ordered up and down the West according to the demands of the great railroad corporation by whom he was employed. The life of a locating engineer is much like that of the soldier, in its need for strict obedience to orders, and for eighteen years Mr. Burnam had been stationed, now here, now there,—on the rolling prairies of Iowa, in the Dakota bad lands, in the alkali deserts of Wyoming, and among the cañons and passes of the Colorado Rockies. Six months before this time he had been ordered to western Montana, to lay out a possible railway across the mountains, which should give the Pacific-coast cities a more direct connection with their eastern neighbors. The survey for this line would occupy him for a year or more, and in order to have his family near him during this time, he had made his headquarters in the little mining camp, which the first prospectors along the cañon, some four years before, had christened "Blue Creek," from the clear, bright waters of the mountain stream. Here he established his family in the most comfortable house that the town afforded, and here he had his office, which served as headquarters for his corps of men, whenever they came in town for a few days. By virtue of his position as chief of the party, Mr. Burnam often spent weeks at a time at home, working up his estimates and maps, and only driving out to camp now and then, for a day or two, to see that all was well in his absence. Then, just as his family were settling down to the full enjoyment of his society, he would be sent for, to oversee some difficult bit of work, and Mrs. Burnam and Allie would be left to the protection of Howard, and of Ben, the great Siberian bloodhound, who was as gentle as a kitten until molested, when all his old savage instincts sprang into life.

One of the early graduates from Cornell, Mr. Burnam had gone West when a mere boy, fresh from college; and now, at forty, he had made himself a brilliant reputation in his profession. The chief, as they called him, was adored by all his men, who knew, from long experience, that however great the danger and hardship might be, he was always ready to share it with them, and that he made it a part of his creed never to ask a subordinate to take a risk which he himself would shun. Quick-tempered and outspoken in the presence of any suspicion of shirking or deceit, he was yet a just, honorable man in dealing with his "boys," who loved and respected him accordingly. At home, he was a different man; for he threw aside his professional dignity, to tease his wife, or romp with his children, lavishing upon them all the love of which his great, generous nature was capable.

For the sake of her husband, Mrs. Burnam had willingly cut herself adrift from her family and friends in New York, and for sixteen years she had patiently followed him here and there through the West; now living in camp for a summer, now boarding at tiny country hotels, in order to be within driving distance of his party; now left for months at a time in the busy solitude of a great city hotel, while Mr. Burnam was far away in unexplored forests, and often, as now, settled near him for a few months of housekeeping which should give her children at least a slight knowledge of home life and its charms.

Two years after her marriage, a little son had come to her, and, soon after that, a daughter had helped to fill out the family circle. It seemed to Mrs. Burnam but a few months since then; but Howard was fourteen now, and Allie twelve, while, two years before this time, a third child had come to brighten the home with his baby prattle and pranks. For weeks, his name had been a subject of almost constant discussion, until, one day, Howard had solved the problem in a most unexpected fashion.

"I'll tell you what," he said suddenly; "name him Victor, for my new bicycle." And the name was decided upon accordingly.

Howard, himself, was a worthy son of the handsome, brown-bearded man whom he called papa. Tall, slender, and yellow haired, he was as bonnie a laddie as ever filled a mother's heart with pride; a healthy, happy boy, affectionate and generous, and full of a rollicking fun which made him at once the delight and terror of his sister, who never knew in what direction his next outbreak would come. In spite of his merciless teasing, the brother and sister were close friends and constantly together. Girls were scarce in the town, and Allie and her one friend, Marjorie Fisher, would have been largely left to their own devices, had it not been for Howard and Ned Everett, through whose influence they were received on equal terms among the boys, and had a share in most of their good times. It was no uncommon thing to hear them speak of "Allie and Marjorie and the other boys," and neither Mrs. Burnam nor Mrs. Fisher felt any desire to have it otherwise. They were too sensible mothers to force their little daughters towards womanhood, and much preferred the tone of free-and-easy companionship to the childish flirtations so commonly indulged in. They could trust to their influence over their children to keep them gentle and womanly, and the boys were all gentlemen, largely sons of Eastern men whom business had brought to the town. So the girls walked and rode, skated and romped with the lads, unconsciously teaching them many a pretty lesson in chivalry, while in return the boys gave them a training which made them enduring and courageous, and hardy as a pair of little Indians. For six months, this had been their life, and by this time there had formed one well-recognized set whose members were constantly together, and, though they mingled more or less with the other young people, yet kept themselves distinct from their companions. Four of this number were the little group of skaters, the fifth was Ned's younger brother, Grant, who was usually the central figure in their frolics.

The one other member of the Burnam household, who is as yet in the background, deserves at least a passing remark. This was Janey, the young negro maid who ruled their kitchen. What had ever brought her from the warm South into the midst of Rocky Mountain snows, it would be hard to tell; but, two months before, she had answered to Mrs. Burnam's advertisement for a servant, and was promptly installed in her kitchen, where she convulsed the family with her pranks, and averted many a well-merited lecture by some sudden, artless remark, which sent Mrs. Burnam hurrying out of the room, in search of a corner where she could laugh unseen. Surely, since the days of Topsy, the immortal, there was never such an imp as Janey. Mrs. Burnam declared that she was as good as a tonic, and Mr. Burnam made no secret of his enjoyment of her antics, which were always as original as they were unexpected.

"My name's Edmonia Jackson," she had said, in answer to Mrs. Burnam's question; "but dey mos'ly calls me Janey. But laws, Mis', ef you 'll on'y let me stay yere, you all can call me what you want. Names is nothin', but I don' want to work in one o' them log-cabins; they 's too much like what our po' w'ites lives in. Give me brick or nothin'!"

CHAPTER II.

TO WELCOME THE COMING GUEST.

"Only ten minutes more!" said Allie, excitedly prancing up and down the platform. "I do so hope the train won't be late."

"Allie's getting in a hurry to see the cousin," remarked Grant Everett teasingly. "You and Howard'll have to step out of the way when he comes, Ned. You needn't think you're going to stand any chance against this new attraction."

"Maybe so," said Howard scornfully, while he flattened his nose against the ticket-office window, in a vain endeavor to see the clock. "Girls always like a new face, and Allie's just like all the rest of them."

"No," said Allie judicially, as she pulled the collar of her fur jacket more closely about her ears. "Of course I like you boys best, but I'm sort of curious about Charlie, as long as he's going to live with us for a year or so. If he's nice, it will be like having another brother; but if he's horrid, it will spoil all our good times. It's a very dependable circumstance, as Janey says, that's all."

It was the second morning after their skating party, and Howard, Allie, and the two Everett boys were pacing up and down the platform, while they waited for the coming of the train which should bring them their new companion. They formed an attractive little group as they moved to and fro, talking and laughing, or pausing now and again to turn and gaze down the track, which stretched far away before them in two shining rows of steel. With the instinct of the true hostess, Allie had arrayed herself in her state and festival suit, and sallied forth to meet her father and cousin, and extend to their guest a prompt welcome to his new home. Half-way to the station she was surprised at being overtaken by the three boys, who came rushing after her, shouting her name as they ran.

"'Where are you going, my pretty maid?'" panted Ned, dropping into step at one side, while Howard took the other, and Grant capered along the sidewalk in front of them, now backwards, now sideways, and now forwards, as the conversation demanded his entire attention, or became uninteresting once more.

"'I'm going to meet Cousin Charlie, she said,'" answered Allie, laughing.

"So that's the why of all these fine feathers," commented Ned; while Howard added,—

"All right; we'll go with you."

"But I thought you just told mamma that you wouldn't go, anyway," responded Allie, astonished at this sudden change of plan.

"Well, I'm here," answered Howard calmly. "I'm not going to welcome him with open arms, though; and you needn't think I am. We fellows are just going to take a look at him on the sly, and then we can tell better how to treat him."

"But, Howard, you mustn't; he'll see you," remonstrated Allie, scandalized at the suggestion. "If papa knows it he won't like it a bit."

"Oh, that's all right, Allie," said Ned reassuringly. "All we 're going to do is to hide behind that pile of freight boxes over there, and get a good look at him without his knowing it. Then we'll light out for home, and Howard will be there ahead of you, see if he isn't; so, if you don't give it away, there'll be no harm done."

"Unless you tell of it yourselves," said Allie doubtfully. "I don't half like it; and if Howard won't help meet him, he ought to keep clear out of the way. But there's one thing about it, boys, you must, you really must, stop talking so much slang. It's bad enough with us girls, and I'm getting to use it as much as you do; but you'll scare Charlie to pieces if you talk so much of it."

"Does our right worshipful brother maintain himself in his usual health and spirits?—is that the style, Allie?" asked Howard, as he took off his cap with a flourish, and bowed low before some imaginary personage.

"I caught Allie studying the dictionary, yesterday morning," said Grant, turning to face them once more. "She had a piece of paper in her lap, with concatenation and peripatetic and nostalgia written on it, and I supposed she was studying her spelling lesson, but now I see,—she was just making up a sentence to say to him. Speak up loud, Allie, so we can hear."

"You'd better stay here and listen," said Allie. "But there's the train, see, just coming round the curve down the cañon. Off with you, if you really are going to be so silly!"

The boys whirled around hastily, to assure themselves that it was no false alarm; then they left her to wait alone, while they settled themselves behind a pile of great wooden boxes which half filled the upper end of the platform. Allie watched them arrange themselves at their ease; then, when they were quite hidden from view, she turned back to look at the train as it rushed up the valley towards her, sending along the rails before it a fierce throbbing which kept time to her own leaping pulse.

In spite of her light talk and laughter, Allie was conscious of a keen sense of excitement, as she stood waiting to receive her cousin. He was the only child of Mrs. Burnam's only brother; and now, at thirteen, he was left alone in the world, doubly orphaned, and with no near relatives save this one aunt, to whose care his dying mother had intrusted her boy. All that Allie knew had only served to interest her in the young stranger; his love for music and his unusual talent for it, his former life spent in a luxurious city home, even his present loneliness had touched her girlish heart with pity, and made her resolve to render his new life pleasant to him, in spite of the possible teasing he might have to undergo from the boys. And then, while she was determined to become his champion at any cost, there was always the delightful possibility that he might be a pleasant addition to their little circle, and contribute his share to the frolics which were continually taking place at either the Burnams' or the Everetts'. Far into the hours of the previous night she had lain awake, picturing her cousin as he would probably appear to them, and going over and over in her own mind the details of their first meeting. She was sorry that he had lost his mother; but she found herself fervently hoping that he would not be so very dismal, and even that he might laugh a little occasionally, when anything particularly amusing should occur.

"Well, daught, how goes it?" And Allie found herself in her father's arms, and then released, as Mr. Burnam added, "Here, Charlie, this is your Cousin Alice."

With a sudden shyness, Allie put her hand into the one before her, as she glanced up at the boyish face which was looking down into her own. Something she read there, in the half-anxious expression of the brown eyes, made her forget her more formal salutation, and say cordially,—

"Are you the new brother that's come to live at our house? It's going to be splendid to have you there." And with a little confiding, sisterly gesture, she pulled his hand through her arm, in an unspoken welcome which was inexpressibly grateful to the lad, tired with his three thousand miles of lonely journeying, and dreading to meet these strange cousins into whose home life he had been so abruptly forced. Now, as he looked at Allie's slight, girlish figure, and at her bright, happy face which not even her irregular features could render plain, he felt a sudden sense of relief, and secretly wished that all the family might be as attractive as his genial uncle and the pleasant cousin who had given him so sisterly a greeting.

"Come," she added, as her father beckoned to them; "we'll go over and get into that carriage, while papa hunts up your trunks." And she led the way across the platform with an apparent unconsciousness of the three heads which precipitately bobbed down out of sight at their approach, while the owners of the heads coiled themselves up in the narrowest of corners, with much scraping of shoes on the boards, in the process.

"This old station is just full of rats," she continued, in a tone of careless explanation, as they passed the hiding-place of her brother and his friends. "I heard the ticket-man say, just before your train came in, that he was coming out with his gun to shoot some of them, as soon as the engine had backed down out of the way."

A long-drawn squeak, as of an animal in pain, answered to her words, and they went on, while Allie threw one triumphant glance over her shoulder at the three heads which had promptly reappeared as soon as her back was turned.

Once seated opposite her cousin in the carriage, while they waited for Mr. Burnam to join them, Allie could study his face at her ease, as she chattered away to him, in the hope of making him feel at home. He had attracted her at the first glance; and the more she looked at him the stronger became her impression that here was a cousin worth having. He was large of his age, finely formed, and taller than Howard, and had a frank, boyish face, which just now looked a little tired after his long journey, and a little troubled and nervous at coming among new friends. For the rest, he had a mass of soft, reddish-brown hair, a freckled face, firm red lips which parted, now and then, to show two rows of small, even teeth, and two deep dimples that came and went in his cheeks, and a pair of near-sighted brown eyes that looked very steadily into Allie's, as if trying to read his new kinswoman, and find out from her into what hands he was likely to fall.

And, indeed, he would have looked far that day without finding a more attractive cousin, for Allie, in her desire to play the hostess well, had dropped her usual rollicking manner, and assumed a sweet, childish dignity which became her as well as her more wonted gayety. Charlie's face cleared a little, as he looked into her great blue eyes and watched the changing expressions of her fresh young face, so pretty and bright in its soft, warm setting of fur.

"Why didn't Howard come down with you, daught?" asked Mr. Burnam, as he took his place beside them, and the carriage, turning from the station, drove away up the street towards the house.

For an instant, Allie's gaze was fixed on a distant opening between the buildings, where three boyish figures were scurrying along as fast as their feet could carry them. Then she roused herself, and turned to the lad before her, as if she had not heard her father's question.

"Didn't you have a good time on the way out here, Cousin Charlie?" she inquired hastily. "Howard and I have been envying you your journey."

"Can't say I enjoyed it," Charlie answered. "I'd never even travelled all night before, and it was no end lonesome, riding along, day in and day out, without a soul to speak to. An old friend of mother's met me in Chicago, and put me on the train for Council Bluffs, and 'twas easy enough changing there, so I didn't have any trouble; but you'd better believe I was glad to see Uncle Ralph when he walked into the sleeper yesterday afternoon."

"I believe I'd be willing to go round the world alone, if I could only go," said Allie. "I'm a real railroad man's daughter, and like to travel; don't I, poppy?" And she nestled closer to her father's side, while with amused eyes she watched their guest's expression change, first to astonishment, then to disgust, as he looked at the main street, with its low buildings, some few of brick, little one-story structures, whose fronts were run up in a thin, flat wall, with sham window blinds at a second-story level, to present the appearance of more pretentious buildings.

Fresh as he was from the closely-packed streets of the great city, with their unbroken rows of towering business blocks and apartment houses, Charlie was conscious of vague wonder at the rough little mining camp before him. Then he turned and looked up at the mountain, and, boy that he was, he forgot all else, all the crudeness of the buildings and all the roughness of the surroundings, as he saw the full grandeur of the snow-clad Rockies shining and glistening in the morning sunshine, which lay caressingly over their giants slopes. He bent forward to look at them once more, while his face grew very thoughtful and intent; then he dropped back into his old corner, saying, in an awed, hushed tone, as if to himself,—

"Jove! It's worth it all, to have a chance to look at those."

"I'm glad you like them," said Allie heartily, though she smiled at his "Jove," when she recalled her recent charge to Howard to avoid all slang. "The town must seem queer to you; but the mountains make up for it. Now lean 'way forward, and look out this side. That little brick house is ours; and there's mamma in the door, and Howard just back of her, waiting to give you greeting."

"Now, honestly, Allie, how did you like him?" Howard asked, as soon as his mother had taken Charlie to his room and the door closed behind them.

"I think I do like him," said Allie slowly. "He didn't talk much coming up; but I don't know as I wonder, when we're all strangers to him. He has sort of a good face; of course he isn't handsome, like Ned and Grant, but he looks as if he'd have some fun in him."

"I shouldn't think he did look like Ned," returned Howard disdainfully; "you don't often see anybody that does. This fellow has red hair, too, and I don't like that kind. He's dressed himself up regardless, in his derby hat and long-tailed ulster. Does he wear knickerbockers, Allie, or does he think he's too old for them?"

"How should I know?" answered Allie. "He's pretty long, and I began at the top, so I didn't get down so far; but when we are used to his freckles and his glasses, I don't think he'll seem so bad to us."

"You almost gave us away, with your rat speech," said Howard, laughing at the recollection. "Grant giggled till I was afraid Charlie'd hear him, so I squeaked to cover up the noise. You had us cornered there; and I didn't want to get caught, for I knew mammy wouldn't like it. She's been so anxious to have Charlie get here and have a good time with us, that I didn't want to spoil it all."

"How long have you been home?" asked his sister, as she turned away to go to her room and take off her jacket and hat.

"I had just time to drop off my coat, as I came in through the kitchen, and get to the front door, when you turned the corner. I believe mammy has spent the last hour between the door and window. I wonder what they're doing in there; I wish they'd hurry up, for I want some lunch. Charlie ought to be hungry, too, for he had breakfast at Argenta. Remember those elk steaks we had there last fall, sis?"

Allie made a wry face at the memory.

"Poor Charlie! He will think he's come into the wilderness. You should have seen his face, Howard, when we were driving up Main Street. It was too funny; he looked as if he didn't know whether to laugh or cry. He stood it very well till he came to the office; then that green sham front was too much for him, and he fairly groaned."

"I'll tell you what," Howard counselled her; "can't you get hold of him, and tell him about some of the ways we have out here, and get him used to it, so he won't show just what he thinks of us? Girls can do that sort of thing better than boys, and he'll need some coaching, of course. Just pussy-cat him a little; and then he looks as if he'd take any amount of advice. I don't care, for you and me; but the Everetts won't stand anything of that kind. They've been here ever since the town started, and they think it's the only place in the world."

"'Tis one of the best," said Allie decisively. "Of course, 'tisn't pretty, nor very fine; but I've had the best times since I came here I ever had, and I'm not going to have anybody run it down when I'm round. I'll give him a talking-to this very night. Now, let's just come out and take one race to the corner and back; I've been proper as long as I can, and I must do something to let off steam. He's all out of the way and won't see me. Come on!" And away they went, racing down the street in the warm noon sun.

After his quiet talk with his aunt, who had gone with him to lead the way to his room, Charlie no longer felt any doubt of his welcome. Mrs. Burnam was so like his father in her manner, so bright and brisk, yet so gentle, that her nephew felt at ease with her at once. There had been something indescribably motherly in her face, as she sat down on the edge of the bed, and, taking his hand, drew him down at her side, while she questioned him about his journey, and the friends he had left behind him. Then she spoke of his mother so tenderly that the boy's lips quivered, and two great tears rolled down his cheeks. That was more than Mrs. Burnam's warm heart could bear. For a moment she let his fresh sorrow have its way; then she bent forward and put her arm around him, just as she might have done with Howard.

"I know, Charlie," she said gently, "nobody else can take her place; but, while you are with us, remember that you are our own boy, and are as much at home with us as Howard himself. And now come, if you're ready, and get acquainted with your cousins, while I see about the lunch."

As Charlie went back to the parlor once more, he was surprised to find the room deserted and the front door slightly open. With a little shiver of cold and loneliness, he stepped across the room to close the door, and stood still, to gaze in astonishment at the sight before him. Up the middle of the road came two figures, evidently engaged in some mad race. The boy he recognized at once as being his Cousin Howard; but who was the small Amazon who rushed along at his side, bareheaded and with her short, thick hair flying in the wind, as she easily kept pace with the longer strides of her brother? Surely, this could not be Allie, the demure little maid who had met him with such easy, quiet grace! Charlie knew little of girls and their ways; but he had always looked upon them with a certain distrust, as being all-absorbed in their fine clothes and their prim deportment. The few he had known in New York had done nothing to alter his opinion, and it had never before occurred to him as a possibility that a young girl could romp and run, and enjoy the free, out-of-door life which is the rightful privilege of every healthy child. This new revelation was quite to his liking, and his astonishment gave place to interest and then to delight, as Allie gradually outstripped her brother, and came flying up the steps far in advance of him, with a triumphant shout of laughter, just as her cousin appeared in the open doorway, loudly applauding her victory.

Early that evening Allie and her cousin were alone in the parlor, for Mrs. Burnam was putting Victor to bed, Mr. Burnam had gone down to his office for an hour, and Howard had gone out on an errand with the Everett boys. The afternoon had been devoted to helping Charlie to unpack and settle himself in his new quarters; and over this informal occupation their acquaintance had made rapid strides, so it was with a sense of duty well-performed that Allie curled herself up in the great easy-chair before the pine knots blazing on the andirons, and turned to look at the boy, pacing up and down the room. Divested of his long ulster, which had called forth Howard's criticism, her cousin stood before her, dressed, like many another boy, in the light brown suit of the period, but with a grace of position and pride of carriage which had made him a noticeable lad, even in the great city school, where he had only been one of scores of well-dressed, well-trained boys. Allie studied him for a moment in silence; then she gave a little contented nod to herself, as she said interrogatively,—

"Well, Charlie?"

"Well?" he responded, as he came to a halt at her chair, and, folding his arms on the back, stood looking down at her while she raised her face to his.

"What were you thinking about?" she demanded. "Were you homesick or tired, that made you look so sober?"

"I was thinking about New York," he answered candidly; "wondering about some of the fellows in our school. They were a jolly set, and I'd like to see them; but I'm not homesick a bit. I think I'm going to like it here, when I get used to it."

"I suppose it does seem very strange to you," mused Allie, as if to herself, while she watched the face above her, looking so thoughtful in the flickering light. Then she added abruptly, "Come round where I can talk to you, Charlie; I've something very important to say to you."

"Yes, ma'am," he answered, but without stirring from his place.

"Come," she insisted, patting the broad arm of her chair with an inviting gesture. "I want to give you your first lesson in Western life; and I can't talk to you half so well, when you're just back of me. If I can't watch you, I sha'n't know when you're getting vexed and wishing I'd stop."

"All right; fire ahead." And Charlie moved around to her side, where he clasped his hands and brought his spectacles to bear upon her with an owlish solemnity.

"That's a very good boy," said his cousin approvingly. Then she continued, in a tone of elderly counsel, "Now, my dear child, I am about to say a few words to you which shall be for your own good."

"Oh, I say," remonstrated Charlie, his dignity breaking down all at once; "how old are you, Allie,—sixty, or seventy-five?"

"You shouldn't laugh," returned Allie, shaking her head at him reproachfully. "That's just the way Mrs. Pennypoker talks to Ned and Grant; I've heard her, lots of times. But now, truly, I wish you'd be good and listen to me, for I do want to tell you something that will be a help to you. The people out here are different from those you've seen, and the ways aren't like those farther east. I don't know why 'tis, but they hate to be reminded of it, and, when we came here, papa told us never to say anything bad about the town, as if we didn't like it, for we'd get everybody down on us. We did like it, though, so we didn't have to fib. But now you're here you'd better just keep still about anything that strikes you funny, when you're off with the boys. Then you can come back and talk it over with me, when they aren't round, if you want to; I don't mind; only don't let Howard hear you, for he'd tell the Everetts. See? That's all; but I thought I'd warn you."

"You're a trump, Allie; and I'll try not to disgrace you," said Charlie gratefully. "Of course, it seems awfully queer to me; but I won't give it away, if I can help it. What's the matter now?" he demanded, as Allie leaned back in her chair and burst into a peal of laughter.

"I was just thinking how funny 'twas," she answered; "only this morning I was telling the boys that their slang would shock you, and they must drop it; but here you are, every bit as bad as they. I don't believe there's so much difference between Montana and New York, after all."

"'Tisn't the place, it's boys," responded Charlie sagely. "They're pretty much the same, wherever you take them. I think the difference is in the girls, and, if you please, I believe I prefer the Western ones."

Allie flushed rosy red at the unexpected compliment, but before she had time to enjoy it, or to reply, there came a sudden knock at the dining-room door, and Janey's black face peered in at the crack.

"Miss Allie, honey," she said in a wheedling tone, as she rolled up her great eyes at her little mistress, "cyarn you get time to write a letter for me, bymeby?"

"I'll come out as soon as Mr. Howard gets home, Janey," she answered; then, as the head vanished and the door closed, she added to her cousin, "Janey can't read nor write, so I have to do all her letters for her. She's engaged to marry a man in Washington, and she says he's 'in de guv'ment.' His name is Hamilton Lincoln Cornwallis; but he lives at number seven and a half Goat Alley, so I don't believe he's President yet. You've no idea how funny his letters are. Maybe she'll get you to read one, some day."

CHAPTER III.

THE EVERETT HOUSEHOLD.

Mrs. Euphemia Pennypoker belonged to that unpleasant type of individuals whose members, for lack of specific excellence, are commonly spoken of by their friends as "thoroughly estimable women." She possessed all the virtues, but none of the graces which make virtue attractive to the youthful mind; and she regulated her daily life by a cast-iron code that was as unvarying and heartless as the smile which sixty years of habit had stamped upon her thin, bloodless lips. Mrs. Pennypoker was said to have been handsome in her day, handsome with an austere, cold beauty; but her day was long past, and the only remaining trace of her good looks lay in her piercing gray eyes, and her long, straight Greek nose. The eyes were undimmed by time; but the crow's-feet had gathered thick about them, and the Greek nose was surmounted by a pair of large, round eye-glasses, which only served to intensify the sternness of the eyes behind them. To the children around her, there was something awe-inspiring in those eye-glasses, and in the broad black ribbon which held them suspended about her neck. In times of peace, they had the appearance of being on the watch for some hidden sin; but when occasion for punishment arose, there was something positively terrifying in their glare, and the culprit longed for his last hour to come, that he might escape from their power.

Dame Nature had been in a generous mood when she had endowed Mrs. Pennypoker, for she had given her a massive frame and constitution of bronze, which made her thoroughly intolerant of those unfortunates who were not similarly blessed. But, impressive as Mrs. Pennypoker was in most respects, there was yet one undignified peculiarity which marred the otherwise perfect majesty of her appearance. Like Samson, her vulnerable point lay in her hair; or, more properly speaking, in her lack of it. The ravages of time had removed a part of her dark brown locks, and left an oval bald spot, closely resembling the tonsure of a Romish priest. This defect was usually covered with an elaborate pile of braids and puffs; but occasionally the slippery surface of her bald crown and the power of gravitation proved too much for her hair-pins, and the whole structure slipped backward, to reveal a shining expanse of milk-white skin, gleaming forth from the dark tresses surrounding it. Moreover, rumor had been known to whisper that there was something peculiar about the rich brown hue of Mrs. Pennypoker's hair; that it was remarkable for a person of her age to be so free from the silver threads common among far younger women; and that, strangest of all, she was subject to periodical variations of color, her hair turning gray at the ends and then resuming its original tint, while, incredible as it might seem, the change always appeared at the ends nearest her scalp, though the tips of her hairs retained all their wonted lustre.

Coming from far-away New England, Mrs. Pennypoker was true to the blood of her Puritan ancestry. She had in her composition much of the stuff of which martyrs are made. She could have gone to the stake for her opinions; but she could just as cheerfully have turned the tables, and piled the fagots high about the misguided heretics who ventured to disagree with her own peculiar doctrines. Ever on the alert to find out the path of duty and to walk in it, she had promptly accepted the proposition of her distant cousin, Mr. Everett, to become his housekeeper, after the death of his wife; and, forsaking all her old associations, she had girded herself and her trunks, and, with her parrot as her sole companion, she had retired to the wilderness to subdue the dragons of anarchy and chaos which had probably entered into the Everett household.

Her first dragon proved to be a very long-tailed one; and though he was promptly met, he was by no means so promptly subdued. An hour after her arrival, she had penetrated to the kitchen, where she was suddenly confronted by Wang Kum, the shoe-button-eyed Chinaman who had been in the service of Mrs. Everett for months before her death. In their first interview, Mrs. Pennypoker was ignominiously routed and driven from the field, for Wang Kum ignored her stony gaze, and cheerfully and volubly chattered to her in a torrent of Pidgin-English which left her no opportunity for reply; so she withdrew, resolving that her first reform should be the removal of Wang from office. However, on this question Mr. Everett was determined; Wang Kum had been their faithful servant, and knew the ways of their household; moreover, he had been devoted to Mrs. Everett during her last illness, and in that kitchen Wang Kum should stay. Defeated in this main object, Mrs. Pennypoker next devoted herself to the task of civilization, and waged daily warfare with the Chinaman, in her endeavors to convert him to American ways and dress, and Calvinistic theology.

"Old lady heap talkee; Wang Kum no care," he used to confide to Louise Everett, after an unusually long and tedious fray. "Wang min' Miss Lou; old lady too flesh."

Four years before this time, when the Blue Creek copper mine was opened and the building of the great smelter had brought to the creek the first settlers of the mining camp, Mr. Everett had been made superintendent of the mine, and had brought his family out to be with him. Of his three children, Louise was now in the first flush of young womanhood, a pretty, graceful blonde of twenty, who had been educated in an Eastern school until the sudden death of her mother had called her home to take charge of the housekeeping, before Mrs. Pennypoker appeared upon the scene, to relieve her of the care, and act as matron to watch over her young cousin with an eagle eye. For the past few years, Louise had been away from home so much of the time that the loss of her mother fell less heavily upon her than on her young brothers, who had been the constant companions of the bright, pretty little woman who had devoted her life to theirs.

Mrs. Pennypoker was scarcely the person to make good their loss; and Ned and Grant would have had a lonely life, had it not been for motherly Mrs. Burnam, whose heart was large enough to take in all the children with whom she came in contact. The Everetts were likable boys, too, just the companions she would have chosen for Howard and Allie: gay and mischievous, as every healthy boy should be, but with the high sense of honor and firm principle which can only come from a good mother and careful home training. Ned, the older one, at thirteen was the image of his father, with a rich, dark beauty which made him a striking contrast to Grant's light yellow hair and pink and white cheeks. Grant was his mother's own boy, in all but his eyes, which were like his father's, large and brown; and he had received his mother's maiden name, just as he had received the features and complexion of her family.

Of all the members of the Everett household, Grant was the only one who felt no fear of Mrs. Pennypoker. Even his father was far more in subjection to her rule than was his little son. Grant had been the first to discover her bald spot—which he promptly christened her storm centre—and to call Ned's attention to it; and therein lay much of his power over her. Now, whenever Mrs. Euphemia threatened to get the better of him, he had only to fix his eyes steadily on the top of her head, or abstractedly rub his hand over his own yellow pate, to cause her to abandon her lecture and escape to her mirror, in order to assure herself that all was as it should be.

The Everetts lived a little to the west of the Burnam's, in what was usually spoken of as "one of the old houses," to distinguish it from the more modern structures of brick and boards. This particular old house was, in fact, the oldest one in the camp, for it had been built by the superintendent for his family, when the other inhabitants of the place were still living in tents pitched along the edge of the creek. Like most of the other houses of the town, it was a one-story building, low and rambling, with odd wings and projections, which had been added to the original square structure as the needs of the family demanded. It was built of rough-hewn logs, but the front was coated with clapboards, in deference to the prevailing style of architecture, which literally put its best foot forward.

Within, the walls were guiltless of lath or plaster, but were covered with strips of cotton cloth, to which the wall-paper was pasted. At certain seasons, this imparted a peculiar effect to the rooms, for, in the fierce winter gales, occasional breezes would work their way through the crannies of the wall and cause the paper and its cloth background to sway backwards and forwards, to the horror of the stranger unused to such modes of finish, since the sight of the walls swaying and wriggling before his eyes could only be satisfactorily explained as the result of intoxication, or of temporary insanity. The same stranger would have stopped short in surprise, on entering the Everetts' clumsy log-house. In spite of its unattractive exterior, it was a cosy, luxurious dwelling, with furniture, draperies and pictures which would do credit to any Eastern city house; for Mrs. Everett had loved pretty things, and had gathered them about her in the hope of making home the spot most enjoyable for her children.

The Everetts were gathered around the table for their late dinner, one night in February, soon after Charlie's arrival in Blue Creek. At the head of the table sat Mrs. Pennypoker, who never appeared so majestic as when she was presiding over the bountifully spread board, for Mrs. Pennypoker was what is known as a liberal provider, and had a lingering fondness, herself, for the good things of this earth. To-night, she was unusually benign, for Wang Kum had outdone himself, and the soup was the perfection of flavoring, the roast done to a turn; so she could relax her anxious scrutiny of the appointments of the table, and lend an ear to what Mr. Everett was saying to his daughter.

"Yes, Mr. Nelson came down to the office to see me to-day. It seems he's been talking up the matter of a boy choir, and he wants Ned and Grant, here, to sing in it. He's going to have Howard, and he's heard that Charlie sings; then there are about a dozen little German fellows, and some men. I told him I'd no objection, and I'd ask the boys what they thought."

"He said something about it to me, after service last night," answered Louise, who acted as organist at the little Episcopal chapel. "He said he wanted to get his plans all made as soon as he could, so we could go to work on the vestments and begin training, to have the choir ready to sing at Easter. I told him that both the boys sang, but I didn't know what you'd say to it."

"I'm willing," Mr. Everett was beginning, when Mrs. Pennypoker interrupted him.

"Do you mean," she asked with icy distinctness, as she leaned forward over the table to add emphasis to her words, "that you are going to let your sons sing in one of those choirs that march into church with their night-gowns on, and singsong the answers to what the priest says?"

"Why, yes," said Mr. Everett, smiling at his cousin, in the hope of calming her disgust. "Yes; that is, if that's what you call it. The boys both have good voices, and it certainly won't hurt them any, for Mr. Nelson knows how to train them well."

"Humph!" returned Mrs. Pennypoker uncompromisingly. "It's my belief that they'd much better go to hear good old Dr. Hornblower, and let this flummery alone. Your Nelson man is no better than a papist, with his colored windows and his chants and all; and, now he's succeeded in getting his new chapel, there'll be no stopping him."

"Just watch the storm centre," whispered Grant to his brother, as Mrs. Pennypoker ended her remark with an expressive, but ill-advised shake of her head. "It's coming into action fast."

"I am glad you feel satisfied with the doctor," answered Mr. Everett, looking squarely into the face of his irate relative. "He is doubtless a good man; but my wife was a member of Mr. Nelson's church, and her children have always been accustomed to going there, so I think they would better continue. Another thing I started to tell you, Lou," he went on, as he turned to his daughter again, "I hear that, at last, Blue Creek is to have a new doctor. There's a young fellow from one of the Eastern colleges on his way out here to settle. The Fullertons know him, and say he's a brilliant man. It's about time we had somebody, for since old Dr. Meacham died, nobody's dared be ill, for fear they'd die before a doctor could get over from Butte."

"And when this one comes, we're all going to celebrate by being ill; is that what you mean, papa?" Louise asked playfully, as she shook her head at Grant, who was stretching up, to peer curiously at the top of Mrs. Pennypoker's head, where a pale crescent was gradually appearing and waxing wider. "When's he coming?"

"Not for five or six weeks," her father answered; "so you'll have to keep well for a while longer. He's on his way; but he's going to visit some friends in Omaha and Denver, before he gets here."

"Hullo!" exclaimed Ned suddenly.

"What's struck you?" asked Grant.

"Nothing; only I was wondering if this could be the same man Charlie Mac was telling about. He met a young man on the train, papa, who came from Chicago to the Bluffs with him. He had next section, so they talked some, and he told Charlie he was from way back East, and was coming to Blue Creek, too. He said he'd never been here, and asked Charlie all manner of questions about the place and all."

"I don't believe he found out much," said Grant with a giggle. "Charlie hadn't any more idea than a dead man what 'twas going to be like out here."

"No; but he's done pretty well since he came, though," said Ned admiringly. "He's acted as if 'twere just what he'd always been used to. It's my belief that Allie's been coaching him; he'd never get on so well by himself, I know."

"He came pretty near finishing himself, the second day he was here, all the same," added Grant. "Did you hear about it, papa? Nobody'd told him to look out a little, till he was used to this air. He started out to run, and it used him up in no time, so he turned blue-white, and nearly dropped. He's taking it slowly, now; and is getting into it by little and little."

"By the way," asked Louise suddenly; "what has become of Marjorie? I haven't seen her for a week."

"She's under punishment," replied Ned lugubriously; "and we haven't any of us seen her since the afternoon we were out skating, just before Charlie came. I don't know exactly what 'tis; but it must be something pretty bad, for her mother to keep her away so long."

"Marjorie is always getting herself into trouble, it seems to me," said Mr. Everett, laughing indulgently as he spoke, for he had a genuine liking for this active, flyaway young girl, whose heart was as true and kind as her impulses were hasty and rash.

"So she is," returned Ned defensively; "but she flies into everything head first, and without thinking much about it; and then she goes into the depths of gunny-sacks and cinders afterwards, when it's too late to do any good."

"That isn't a very helpful kind of penitence," remarked Mrs. Pennypoker, looking up from her plate.

"It's a very natural one, I am afraid," said Mr. Everett charitably. "Then Marjorie hasn't seen this new friend of yours?"

"No, not yet," Grant answered. "It's a shame, too, for she was in a hurry to get a look at him. He is a first-rate fellow, really, papa; and doesn't seem a bad tenderfoot, even to old-timers like Ned and me. What do you want, Wang?" he added, as Wang Kum's head appeared at the door.

"Mas' How'd, he here," announced Wang briefly. "He no come in; wan' you." And he vanished, followed by the boys, who hurried out in search of their friend.

In the mean time, at the Burnam's a short conversation was taking place, which would have enlightened the boys on the subject of Charlie's easy adaptability to his new surroundings. It was his habit to practise for an hour after dinner each night, and Allie was usually beside him. She loved music as well as did her cousin, and was content to settle herself on a wide sofa drawn up beside the piano, sometimes with a book, but more often idly leaning back against the cushions, with her eyes fixed on her cousin's face, as he gradually lost all consciousness of her presence in his enjoyment of the music. Young boy as he was, and a normal, healthy boy, too, Charlie had undoubted genius in this one direction, and added to a rare talent for music the skill gained by five years of study under the best master that the city could afford, until, both in subject and method, his playing was far beyond what one would naturally expect in a lad of his years. It had been a great delight to him to find that Allie cared for his music, and could understand the varying moods which he tried to express in his hours of practice. The two cousins really had their best times in these nightly visits, for when his regular time of practice was over, Charlie would still linger at the piano, playing in a soft, fitful undertone, while they discussed the events of the day, or planned for the morrow's program. The week they had been together had quickly ripened their first liking for each other into a close friendship; and after a day of out-of-door frolics with the other boys, Charlie had learned to look forward to the time of talking it over with Allie, and listening to her merry, whimsical comments on what they had done and seen. But, on this particular night, Charlie was bound on gaining information.

"If you please, ma'am," he began, as he let his hands fall from the keys, and turned to face his cousin.

"Oh—yes—what?" responded Allie, gradually rousing herself from her story.

"If you please, I'd like to ask a question," he said meekly. "I'm in want of a few pointers."

"Well?" and Allie was all attention, as she smiled up at her cousin's perplexed face.

"In the first place, how much is a bit?" demanded Charlie.

"Twelve and a half cents," she answered promptly. "Why?"

"I don't know as I dare tell," Charlie replied, with a shamefaced laugh.

"Go on," urged Allie curiously. "I'm sure it's something funny, and you know I never tell tales."

"Well, if you'll promise, true blue. You see, I wanted some new rubbers, for mine were all full of holes, and I was tired of going round with wet feet; so I went down town this morning and tried to buy some. The clerk said they were six bits, but I didn't know how much that was, and didn't want to say so, so I told him that I didn't quite like the kind, and went off."

"You've a great mind, Charlie," said Allie approvingly. "Everybody here counts by bits; two make a quarter; and then, you know, we don't have any pennies here, nothing smaller than a five-cent piece. Remember that, and don't offer anybody a penny, even if it's a beggar. Go on; what next?"

"That's about all, for this time," he answered. "Oh, no; there's one thing more. What's that queer place down south of here, all fenced in, and with little bits of log cabins scattered around as if they'd just been dropped out of a pepper-box?"

"That's Chinatown," said Allie, laughing at the accuracy of the description. "We must get papa to take us there, some day. But now I want to tell you something. You know Marjorie Fisher?"

"Can't say I do," returned Charlie flippantly.

"Yes, I know what you mean," interrupted Allie; "but you know who she is, and you want to know her, herself, for she's great fun. She's been—busy, this last week; but I had a note from her to-night, and she wants us all to come down there to-morrow afternoon for a candy-pull. I told her we'd go, so she's going to stop here after school and wait for you and Howard, and we'll all go on together. The Everetts will be there, too, and we shall be sure to have a good time; we always do at Marjorie's."

CHAPTER IV.

ON THE CROSS-HEAD.

The old queen bee, with fiendish glee,

Was pulling a hornet's hair.

The monkey thought 'twas rough;

He took a pinch of snuff,

And then the bees began to sneeze,

And left,"—

sang a clear, boyish voice outside, and the next moment steps were heard on the piazza.

"Who's that?" asked Marjorie, glancing up from the skating cap, which, with infinite pains, she was crocheting, in thoughtful anticipation of Howard's birthday, the following summer.

"Charlie; don't you know his voice?" responded Allie, who was sitting with one foot tucked under her, while she sewed the buttons on her shoe.

"How should I? I've never heard him sing," answered Marjorie.

"You will soon, for he and Ned are to lead the new choir at Easter. Charlie seems to be feeling unusually comf'y to-day," said his cousin, as the boy came in at the side door opening into the dining-room, and walked over to the corner where they were sitting, curled up by the stove. "Where'd you get that pretty song?" she added.

"Made it up, of course; didn't you know I was a poet?" inquired Charlie blandly, while he nodded to Marjorie, and then pulled off his glasses to wipe away the steam condensed on them by the sudden change from the cold outer air to the heat within the house.

"I never should have supposed so," Marjorie answered, laughing. "You look altogether too plump and well-fed."

"Can't help it; you can't tell by looking at a toad how far he'll hop. I wrote it 'all my lone,' as Vic says," responded Charlie. "I'm very proud of it, too."

"Sit down and amuse us," said Allie, hospitably drawing a chair nearer the fire.

"No, thank you; I'm engaged, and must be going," returned Charlie, with a lofty air of importance which was not without its effect upon his cousin.

"What's going on?" she asked curiously. "I told Marjorie that you acted unusually set up over something."

"I met Mr. Everett just now, and he told me that, if I'd get over to the smelter at three, he'd let me go down the mine this afternoon."

"O Charlie, take us with you," begged his cousin, starting up, forgetful of the fact that she was still without one shoe. "I've never been, and I do want to go, so much."

"Can't; girls aren't invited," said Charlie heartlessly. "He did say that he'll take us all at once, though, as soon as they put the cage in, next month; but he doesn't like to take but one at a time, on this thing they're running now. I wish you could go, for 'twould be lots more fun."

"'Tisn't much to go down," said Marjorie, with an air of superior wisdom. "It's dark and slippery, and not any too clean; and you have to get out of the way of something or other, most every minute."

"Yes, I know," said Allie; "it's all very well to say that, when you've been; but I never had a chance to go. I was ill the time Howard went; and now I shall be the only one left that hasn't been down. I hope you'll have an awfully good time, though, Charlie, and not get lost, or smashed, or anything else that's bad, while you're underground. Isn't it growing colder?" she added, as Charlie turned up the collar of his ulster and scientifically pinched the edges of his ears, preparatory to starting out once more.

"'T isn't exactly balmy," he answered. "Want anything, before I go?" And a moment later the door closed behind him.

"You're a lucky girl, Allie," said Marjorie, while she watched the figure striding along down the road. "Even Ned says he's the jolliest fellow in town, all but Howard."

"Yes, 't is good to have him here," said Allie contentedly, as she slipped on her shoe and stooped to button it up. "He's just as good-natured and nice as he can be; and I think I like him better than any boy I ever saw, except Howard, even if he hasn't been here quite a month."

"Not better than Ned?" Marjorie exclaimed incredulously.

"Well—no—I don't know," said Allie, wavering a little. "Ned's just about as near right as he can be; but I believe, after all, I'd rather live in the house with Charlie. Ned might be a little too peppery for a steady diet."

"I never thought you'd turn a cold shoulder to Ned," said Marjorie, shaking her head over Allie's defection. "Charlie's very nice and gentlemanly, and all that, but I don't believe he has half Ned's pluck. Do you remember the time he sprained his wrist falling off his pony, way up the gulch, and wouldn't tell of it till we were home again? I don't think Charlie Mac would stand that kind of thing long. There's no special reason he shouldn't be agreeable; we've all of us tried our best to make him have a good time."

"Charlie isn't a baby, though," returned Allie, valiantly rising to the defence of her cousin. "You think, just because he knows more about music than 'most anybody else in the camp, and looks and acts as if he came from a city, that he's more than half girl. But I'll tell you he isn't, Marjorie, and if anything came to try him, you'd find he'd come up to the mark every bit as well as Ned. I don't know as I care to have anything happen, though, just for the sake of proving it."

In the mean time, the subject of the conversation was walking rapidly in the direction of the smelter, whose pile of huge red buildings lay a little to the southeast of the town, across the creek and close to the foot of the mountain which towered above it sheer and straight. A few hundred feet down the cañon below it, and a little farther back from the creek, was the shaft leading down into the mine, and beside it the engine house with the machinery needful for raising the ore, and for carrying the miners to and from the cross-cuts, hundreds of feet below.

Though he had often been to the smelter with Ned and Grant, it was the first time that Charlie had visited the place alone. He felt very small and insignificant, as he stepped inside the enclosure, with its array of great buildings, mammoth chimneys whence rose the smoke from countless and undying fires, and its throng of busy workers. Then he entered the little building which served as superintendent's office, and in a moment the whir and clang of the outer life was left behind him, and he found himself in a quiet, pleasant room, with only a collection of maps and photographs and specimens of ores, to tell of the vast business centering there. As the boy shyly came in at the door, Mr. Everett rose to receive him.

"O Charlie, you're just on the minute, and I'm all ready for you," he said, glancing up at the clock.

"Somers, I'm going down the shaft with this young man; if anybody wants me, tell him I'll be here at five." And, putting on his overcoat, he went away, followed by Charlie, who was filled with an eager enthusiasm at the idea of going so far towards the center of the earth.

"I'm sorry," Mr. Everett said, as they followed a path winding in and out among the buildings, and then came out on the main road leading to the shaft; "I'm sorry that we haven't time to take in the smelter, too, to-day; but you can go there almost any time. Any of the men in the office can take you through it, as well as I can; but I don't let strangers go into the mine unless I'm with them. We're going to put in a new cage, next month," he added casually, as they drew near the shaft.

"What's that for?" asked Charlie, to whom cages and their construction were a mystery.

"Safer, and can carry more," answered his host concisely. "These cross-heads and buckets are slow work. A two-deck cage will do the same amount in much less time, and there's no fear of their catching, as these do sometimes."

As he spoke, they paused to look at the gearing of windlass and cable at the mouth of the shaft; then Charlie cautiously approached the opening. After all he had heard of mines and shafts, it was rather disappointing to him to see only a great, square hole leading down into the depths of the earth. What he had expected, it would be hard to say; but it is certain that his disappointment deepened when, after three strokes from the engineer's bell, the hoisting engine suddenly started into life, and, out from the darkness of the shaft, there slowly emerged into view an ungainly contrivance of four great timbers, arranged in a hollow square and hung on a cable, which passed freely through openings in the upper and lower timbers, to carry a huge bucket fastened to its end, while a black-faced miner stood in the bucket, much in the attitude of a jack-in-the-box after the spring is loosed.

"That's what we call the cross-head, above," explained Mr. Everett. "It slides free on the rope, and rests on the fastening of the bucket. Now you see how we bring up the ore."

"But do we have to go down in that thing?" inquired Charlie, drawing back in disgust, as he surveyed the grimy, dusty bucket before him.

"Not unless you prefer it," Mr. Everett answered, laughing. "It's against rules to ride in it; and anyway I usually go on the cross-head, myself, for the bucket reminds me too much of Simple Simon. Step on here," he added, as the crude elevator sank down until the upper beam was on a level with the surface of the ground. "Now, if you just hold on to the rope, you're all right. Let us go slowly, Joe," he went on, to the waiting engineer; "I want to take a look at the shaft, as we go down. We'll try the seven-hundred level to-day."

A moment later, they began to sink away from the light above them, while the opening at the mouth of the shaft grew smaller and smaller to their eyes, and their lamps only cast a sickly, uncertain light on the walls beside them. They went down slowly, so slowly, that, as soon as he had had time to accustom himself to the new sensation, Charlie had plenty of opportunity to examine the walls. For the most part, they were roughly cased with boards and surrounded at intervals by the massive collar-timbers, projecting ten or twelve inches inside the boards. At each side of the shaft were the heavy upright guides, running from top to bottom and serving to keep in place the cross-head, which was fitted to move easily between them. Down, down they went, for what seemed to the boy a limitless distance. They had passed a great square chamber, opening into along, lighted corridor which Mr. Everett had told him were the station and cross-cut at the four-hundred level, and still they were sinking. All at once they came to a sudden stop, and the next instant Charlie felt the rope he was holding slowly drawing down through his hands. Mr. Everett gave a quick exclamation.

"Let go the rope!" he commanded abruptly.

"I'm perfectly willing," answered Charlie, laughing, as he rubbed his tingling palms. "What's up, anyway? We don't seem to be anywhere in particular."

"We're caught a little," replied Mr. Everett quietly. "You needn't be frightened, for it's happened before. All is, the cross-head has caught, and the bucket is going down without us, and taking the rope with it. Have you a steady head?"

"I s'pose so," said Charlie lightly, for, in his ignorance of mines, he had no idea of the possible danger of his position.

"Very well; can you turn around and step down on the beam that's just below us?" returned Mr. Everett, still speaking in the same calm voice, though with the brevity of a captain giving his orders on a field of battle. "If you can, do it, and then put your arm around the back of the guide there. So; that's all right."

In another moment, he had followed Charlie, and taken his place beside him on the other side of the guide, where he showed the boy how to grasp the timber in such a way that the cross-head, coming up, should not touch his arm. That done, he breathed a sigh of relief.

"There!" he said; "now we're safe for the time being. The next question is: how are we going to get out of this trap?"

"Why couldn't we stay on the cross-head?" asked Charlie, as it began to move slowly away from the spot where it had lodged.

"Just that reason," returned Mr. Everett, with a motion of his head towards the clumsy frame which, once loosed, went sliding away down the rope after the bucket. "Though you may not have known it, young man, you were never in a much more dangerous place than you were five minutes ago; for, as soon as it could get free, the cross-head was going to crash down on top of the bucket, with force enough to kill anybody that happened to be on it. I knew 'twould go, sooner or later; but I didn't feel so sure that we could get off in time."

"Then it's done it before?" asked Charlie, in no wise moved by the knowledge of his past danger, but, boy-like, rather enjoying the novelty of his position, halfway down the shaft of the mine, and lodged like a fly on the wall, with only a narrow beam between himself and a fall of four or five hundred feet.

"Once," answered Mr. Everett, amused, in spite of his anxiety, by the boy's coolness. "It killed four men on the cross-head, and the one in the bucket; but they have such accidents in the other mines often enough, so we know about what the chances are. That's one reason we're going to put in a cage. Now," he went on, resuming his tone of authority, "don't you try to move, and, above all, don't look down. I'm going to get round to the other side, where I can reach the bell-rope, and signal the engineer to bring up the cross-head again."

"Not walk around on this beam!" exclaimed Charlie, as his interest changed to genuine alarm, for he realized that such an attempt was a very different matter from standing quiet and holding on by the upright timber between them.

"There's no other way," Mr. Everett answered, as he started on his perilous journey. "I can't reach to signal, from this side, and they never would find us without. We can't very well stay here, so that seems to be the only thing I can do. You needn't be alarmed, my boy," he added kindly, as he saw that the lad was now thoroughly frightened for his safety. "I am used to all these ins and outs, and know about what I can do, even if I never happened to get caught just here before. We miners get to be half monkeys, and can hang on where most men would fall."

He cautiously moved away a few inches along the beam; then he turned back to add one parting caution.

"He cautiously moved away a few inches along the beam."

"Remember," he said, "and don't try to look down, even if you think you hear the cross-head coming up again. If you do, you are likely to get dizzy and fall."