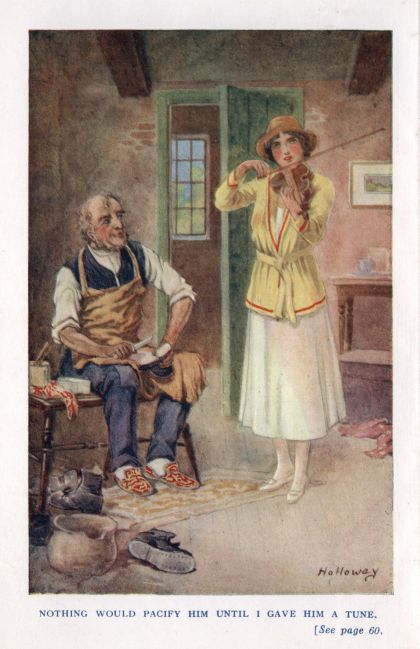

NOTHING WOULD PACIFY HIM

UNTIL I GAVE HIM A TUNE.

DWELL DEEP

OR

HILDA THORN'S LIFE STORY

BY

AMY LE FEUVRE

AUTHOR OF "PROBABLE SONS," "TEDDY'S BUTTON,"

"ERIC'S GOOD NEWS," "ODD," ETC.

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

MANCHESTER, MADRID, LISBON, BUDAPEST

1896

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | |

| I | A NEW HOME |

| II | TAKING A STAND |

| III | THE REASON WHY |

| IV | AN OPENING FOR WORK |

| V | OPPORTUNITIES |

| VI | ONLY A FRIEND |

| VII | A FRESH ACQUAINTANCE |

| VIII | DRAWN TOGETHER |

| IX | QUIET DAYS |

| X | LONG AGO |

| XI | A DIFFERENT ATMOSPHERE |

| XII | A TEST |

| XIII | TAKE HOME |

| XIV | WOOED AND WON |

| XV | A GATHERING CLOUD |

| XVI | DARK DAYS |

| XVII | DAWN |

| XVIII | WEDDED |

| XIX | OLD FRIENDS |

DWELL DEEP

CHAPTER I

A NEW HOME

'Meet is it changes should control

Our being, lest we rust in ease.'—Tennyson.

A golden cornfield in the still sunshine of a warm August afternoon. In one corner of it, bordering a green lane, a group of shady elms, and under their shadow a figure of a young girl, who, gazing dreamily before her, sat leaning her head against an old gnarled trunk in quiet content. A small-shaped head, with dark curly hair, and a pair of blue-grey eyes with black curved lashes, these were perhaps her chief characteristics; more I cannot say, for it is difficult to describe oneself, and it was I, Hilda Thorn, who was seated there.

It was a beautiful scene before me. Beyond the corn stretched a green valley, and far in the distance were blue misty hills and moorland. My soul seemed rested by the sweet stillness around, but from the beauties of nature my eyes kept reverting to the Bible on my knee, and two words on the open page were occupying my thoughts—'Dwell deep.'

I had been left an orphan at the age of ten, both parents dying in India whilst I was at an English boarding-school. There I stayed till I was nineteen, when I went to an old cousin in London, and for three years I lived a quiet uneventful life in a dull London square, seeing very little society but that of elderly ladies and a few clergymen.

Suddenly my whole life was changed. My guardian, who had been living abroad with his wife and family, returned to England, and wished me to make my home with him. And my cousin was quite willing that it should be so.

'You are young, my dear,' she said to me, 'and it is only right for you to mix with young people and see the world. I am getting to prefer being alone, so I shall not miss you.'

It did not take long to settle matters, and I soon left London for my guardian's lovely place in Hertfordshire, feeling both shy and curious at the strange future before me.

But during my stay in London there had been another and perhaps a greater change in my life than this. I had been brought up religiously, had said my prayers night and morning, and had read my Bible regularly once a day, but with these outward forms my religion ceased.

I suppose all my thoughts were in the world and of the world. I had been a favourite with my school-fellows, who assured me I had more than my fair share of beauty, and with all the ignorance and inexperience of girlhood had planned out glowing descriptions of the brilliant offers of marriage I would have, and the delightful times before me. I listened and laughed at them, yet had chafed at the quiet monotony of my cousin's home, and had longed for a break to come in the dull routine of our daily life.

Then one night I had attended some mission services that were held in our church, and for the first time beheld life and death as they are in reality. For several days I was in great distress of mind, and turned with real earnestness to my Bible for guidance and comfort. The light came at last, and I saw how completely Christ had taken my place as a sinner, and how as a little child I must come and claim the pardon that He had died to procure, and was now holding out to me as a free gift.

This brought a wonderful joy into my life, and as each day seemed to draw me nearer to my Saviour, I felt that no life could be monotonous with all the boundless opportunities of speaking and working for Him. My craving for a gay, worldly life passed away, and a deep, restful peace crept into my heart and remained there.

When I told my cousin of my experience she looked puzzled, and shook her head.

'Young people nowadays always go to such extremes; but you look happy, child, and I shall not interfere with your serious views.'

And then my guardian arrived on the scene—a tall, stern-looking man, with iron-grey hair. He had just retired from an Indian cavalry regiment, and still bore upon him the stamp of an officer accustomed to command.

He only stayed with us a few days, and then carried me off to his country home. It all seemed very strange to me, and, though Mrs. Forsyth gave me a warm welcome, I could see I was an object of curiosity and criticism on the part of her three daughters, who were all lively, talkative girls. Two grown-up sons completed the home circle, both of whom seemed to be at home doing nothing. I learnt afterwards that Hugh, the eldest, wrote a great deal for some scientific magazines, and was up in London very constantly engaged in literary pursuits.

My thoughts were perplexed and anxious as I laid my head down on my pillow the first night. Little as I had as yet seen of them, I knew from the conversation around me that there was no one who would sympathise with me in religious matters. How should I, a mere beginner in the Christian life, be able to take a stand amongst this happy, careless family circle, who already were including me in dances and theatricals that were shortly coming off in the neighbourhood? And then the next afternoon, pleading fatigue from my journey, I saw the girls go off to a tennis party with their mother and, taking my Bible in hand, crept out of the house and grounds, and found my way, as I have already mentioned, into that quiet, sunshiny cornfield.

Was it by chance that my eyes alighted on those two little words in Jeremiah? I think not. I had heard a sermon upon them, and now I seized hold of them with a fresh realization of their strength and beauty.

'Dwell deep!' Oh, how I silently prayed, as I sat there looking up into the bright blue above me, that I might do so day by day and hour by hour! Silently could I feast and refresh my soul, even amidst the gay laughter and talk around me, for had I not an unseen Friend always with me, upon whom I could lean for support and guidance through every detail in my daily life?

And so I sat on, drinking in the sweet, fresh country air, and feeling so thankful for the quiet time I was having.

Suddenly the barking of a dog and men's voices roused me from my meditations, and in another moment Kenneth Forsyth sprang over a stile near, and approached me, in company with another young fellow about the same age.

'Halloo!' was his exclamation as he perceived me; 'is it you, Miss Thorn? And all by yourself, too? What a shame of the girls! Let me introduce my friend, Captain Gates. You certainly have selected a cool spot. May we share your retreat? We were just lamenting the heat, and longing for a piece of shade.'

And, without waiting for my answer, he flung himself down on the grass beside me, whilst Captain Gates lounged against a tree close by.

I was a little vexed at the interruption, and did not feel inclined to stay there with them. Kenneth was at present almost a stranger to me. He had a mischievous, quizzical intonation in his voice when he spoke to me, and Violet, his youngest sister, a bright, merry schoolgirl of fourteen, had confided in me the previous night that 'Kenneth was never so happy as when he was teasing people, and that he took stock of every one, and mimicked them—very often to their faces.'

I closed my little Bible quietly. My first impulse had been to hide it, but I conquered that as being unworthy of a Christian, and then I said brightly,—

'I have enjoyed this so much. You don't know what a pleasure it is, after the grime and smoke and roar of London, to come to a place like this. Your sisters wanted me to go with them this afternoon, but I was a little tired, so came out here instead.'

'And are you fond of solitude?' inquired Captain Gates. 'Most girls are not, I fancy.'

'I like it—sometimes,' I replied slowly.

'This afternoon, for instance,' Kenneth said, with a laugh. 'But too much solitude is bad for the young, so we are breaking in upon it for a good purpose. It makes them morbid and self-engrossed.'

I saw that his quick eyes had already noted my Bible, and was vexed to feel my cheeks flushing.

'Miss Thorn's appearance is certainly not morbid,' said Captain Gates good-naturedly; and as I looked up at him I met a frank, kindly glance from his dark eyes.

'No, I am not morbid,' I said; 'I am very happy.'

'Ah!' put in Kenneth with a mock sigh, 'you are looking out at life with inexperienced eyes at present, and everything has a roseate hue to you. Your experience has yet to come!'

For some little time longer they stayed there with me laughing and talking, and then we all went back to the house together, and my quiet time was over. I liked Kenneth better than his brother Hugh, who seemed to me to be too sarcastic and supercilious for any one to be comfortable in his presence; but there was a look of mischief in Kenneth's eyes which puzzled me, as again and again this afternoon his glance met mine.

At dinner I was enlightened. It was a merry home party that night. Captain Gates and another man, a Mr. Stroud by name, had come to stay for a few days' shooting, and they certainly proved lively additions to our gathering. In the midst of a buzz of conversation and laughter, there was, as so often happens, a sudden lull, and then Kenneth from the other side of the table suddenly broke the silence:

'Miss Thorn, Nell here wants to know the name of the book you were studying so deeply this afternoon in the corn-field?'

My cheeks flushed a little; for one moment I hesitated, and every one seemed to be waiting for my answer; then I said in a tolerably steady voice,

'It was my Bible.'

I felt, rather than saw, the astonishment depicted on the faces of those at the table.

Nelly, who was always overflowing with fun, burst out laughing:

'You don't mean to say that you are religious?' she said; but her mother hushed her rather sharply, and changed the subject at once.

I felt I had difficult times coming. Later on in the evening, when music was going on, Captain Gates came over to me as I sat looking out into the dusky garden by one of the long French windows, and said,

'I see you have no difficulty in showing your colours, Miss Thorn.'

I looked up at him gravely. 'I ought to have no difficulty,' I said; 'it is nothing to be ashamed of.'

He smiled, and leaning against the half-open window seemed to regard me with some amusement.

'Is it a rude question to ask with whom you have been living before you came here?'

I told him, and then he said reflectively,

'It's a strange thing why the Bible should be thought so out of place sometimes; but I wonder now if you read it out of pure pleasure, or only from a sense of duty?'

'Why, I love it!' I exclaimed; then a little impulsively I added,

'I don't mind telling you, Captain Gates, or any one else, for that matter, it is only just lately that I have felt so differently about it. I used to think it dull and tedious, but it has changed now, or rather, I have changed, and there is nothing I like better than getting away alone somewhere and having a nice read all by myself.'

'You will not find much quiet time in this house,' he rejoined. 'We are always on the go here; you have come into a different life. I fancy your Bible reading will soon be a thing of the past.'

'Never, I hope!' I said a little warmly. 'I don't mean to lead a gay life, Captain Gates; I don't care for those kind of things now!'

He laughed. 'Perhaps you have never tried it?'

'I never mean to.'

Our conversation was interrupted here, and for the rest of the evening I said very little to any one; but a short time after I had been in my bedroom that night Nelly, knocked at my door.

'I'm coming in for a talk,' she said; 'I'm very curious about you. Do you know that we have all been discussing you downstairs?'

'I dare say,' I said, laughing. Somehow, I felt very much drawn to Nelly; she seemed such a pleasant, outspoken girl. Constance, the eldest of them, though full of life and spirits, was rather cold and distant in manner towards me. In fact, she had given me the impression that my arrival had not been welcome to her.

Nelly seated herself in a low rocking-chair, and scanned me rather mischievously before she proceeded:

'You are such a pretty, bright little thing to look at, that Bible reading seems so incongruous! Of course, I read my Bible in the evening when I go to bed—at least, when I am not too tired—but that's a different matter. Mother said we mustn't take any notice of you, and you would soon shake off these notions; but Captain Gates said you told him you didn't intend to lead a gay life as we do—you have evidently taken him into your confidence—and he said he would back you against us for your determination of purpose. Now will you take my advice, Hilda? Don't look so hot and uncomfortable. You haven't come into a houseful of saints, you know, so you can't expect us to fall in with your views at once. Mother, of course, won't like it if you go against her plans for you; she will be very vexed, but she will eventually give in; but it's a different matter with father, and he is your guardian, remember. He hates "cant," as he calls it, and he has great ideas of your taking your position in society as you should. If you cross his will, I warn you you will bring the house down upon your ears; he never will stand any opposition. And what father will do by his authority, Kenneth will do out of sheer love of teasing. He will lead you a life of it, I can tell you; so I warn you beforehand.'

'But,' I said, flushing a little, though I tried to speak quietly, 'I have no intention of setting up my will in opposition to your father's—I wouldn't dream of it. What do you think me like, Nelly?'

Nelly laughed. 'I think you are a curiosity,' she said, 'and whether we shall crush your originality out of you in a few weeks' time, remains to be proved. I thought I would give you a friendly intimation of what to expect. And now good-night!'

She left me, and, perplexed and troubled by her words, I went to my window, and, opening the casement, leant out to cool my hot cheeks. Such a soft, still night it was! As I raised my eyes to the innumerable stars above, and felt the hush and solemnity of the darkness, again the words came to me: 'Dwell deep.' What did it matter if I found I should have a cross to take up, if I had to bear a little teasing from others who did not think as I did? When I realized in the depths of my heart the riches I had, and the stores of hidden wealth of which they knew nothing, I could rest down upon it with such comfort, feeling that my inner life would be sustained and strengthened by One who never left me. And so I went to sleep that night at perfect peace in my new surroundings.

CHAPTER II

TAKING A STAND

'Who is not afraid to say his say,

Though a whole town's against him.'—Longfellow.

I was soon at home with the Forsyths. Nelly and Violet treated me as a sister, and Constance was too much engrossed at present with her own concerns to take much notice of me. Kenneth was the only one who was continually bringing forward serious topics of conversation in my presence, and requesting me to give him my views on them. He never let me alone, and though I tried to keep out of his way, and say as little as possible, I found it increasingly difficult. Captain Gates more than once came to my rescue; but since I felt he had betrayed my confidence a few evenings before, I could not talk with the same freedom to him.

I saw very little of General Forsyth. He spent the greater part of his time out of doors, and it was only in the evening that he joined us all. His children, though fond of him, never seemed to feel at ease in his company, and I soon found that his will was law with all.

One afternoon soon after my arrival I went out for a stroll across the fields at the back of the house. I felt I wanted to be alone, and away from the constant chatter and laughter of the girls. So I wandered on farther than I had intended, and found myself at last on the edge of a wild moor. My thoughts were grave ones, but very happy ones; and as I gazed over the broad expanse of heather in front of me away into the blue distance, where the soft fleecy clouds seemed to stoop and kiss the outlines of purple hills as they swept gently by, I could not help thanking God with all my heart that He had brought me into my present surroundings.

Suddenly I was startled by hearing close to me a child's sobs, and after some minutes' search I came upon a tiny boy crouched amongst the heather, grasping a bunch of faded harebells in his chubby fist, and crying as if his heart would break.

As I bent over him, he looked up into my face and sobbed out pitifully,—

'Cally me home, lady; I wants my mother.'

'You poor little mite!' I said. 'What is your name? and where do you live?'

But as I lifted him up he uttered a sharp cry. 'My foots is hurted; I tumbled down, and I've losted my boot.'

I saw that this was indeed the case; his little foot was cut and bleeding, perhaps from coming in contact with some sharp stone, and I was for a moment at a loss what to do. He seemed about three or four years old, but a heavily built child, and my heart sank at the prospect of carrying him. Yet this was the only alternative, and as he seemed to have very little idea of where he lived, I decided to bring him back with me to our village, there being no other houses in sight.

He was quite willing to be carried, and wound his fat little arms so tightly round my neck that I thought he would throttle me. But my progress was painfully slow; the sun blazed down with fierceness, and there was no shade on the moor; even the fresh breeze which I had so enjoyed in coming seemed to have disappeared, and every now and then I had to stop and rest. The child himself soon dropped asleep in my arms, and I became so tired myself that I was strongly inclined to leave him lying on the heather, and send some one to fetch him when I got home. At last, to my great relief, as I was crossing a field I saw a figure approaching, and this proved to be Kenneth.

'Halloo!' he said, when he caught sight of me and my burden, 'what on earth have you got here? You are certainly the most extraordinary young person that we have had in these parts for a long time! Where have you picked up this small fry? Are you taking a pilgrimage and doing penance for your sins with him? If you only could see your face! It makes me burn to look at you!'

'Don't tease,' I said wearily, as I tried in vain to disengage the little fellow's arms from round my neck. 'I found him crying amongst the heather, and he has hurt his foot and cannot walk. Do take him from me, will you?'

This was not such an easy matter. The child woke up cross, screamed when Kenneth took him, and with his little fist struck him full in the face with all his childish strength, crying out,—

'I won't be callied by you; I wants the lady.'

Kenneth tossed him across his shoulder with calm indifference to his cries.

'I shall have a reckoning with you by-and-by, young man, for this assault. He is the infant pickle of our village, Miss Thorn—commonly called Roddy Walters; his mother keeps the small general shop, and Roddy keeps her pretty lively with his pranks. His last mania has been running away whenever he gets a chance, and if you intend to carry him home from wherever you find him, you will have enough to do, I can tell you.'

I made no reply, for I felt quite exhausted, and was greatly relieved to find that Kenneth knew where to take him.

Presently I was asked,—

'Been having a Bible study on the moor this afternoon?'

'No,' I said quietly, 'I have not.'

'That's a pity, isn't it? You have been out all the afternoon; it's rather frivolous, isn't it, and a waste of precious time to be sauntering over the moor doing nothing? A time of meditation, perhaps?'

Yes,' I answered, smiling a little in spite of myself, 'I have been thinking, as I walked, what lovely country it is round here.'

'We are going to have some grand doings in our neighbourhood soon,' Kenneth pursued after a few moments' silence; 'the autumn manoeuvres are coming on, and every one round here keeps open house. We generally start the ball rolling by a dance. Are you fond of dancing?'

'I used to be fond of it at school,' I said, 'but I—I don't care about it now.'

I felt he was trying to draw me out, and resolved to say as little as possible.

'Ah! you wait till you're in the thick of it, and see the scarlet jackets flying round. All the girls here lose their heads, and their hearts, too, for the matter of that. I was telling that fellow Stroud to-day that if he means anything, he had better cut in at once and get it settled, for Constance will have nothing to say to him a few weeks later.'

I said nothing; I had noticed Mr. Stroud's attentions to Constance, and had drawn my own conclusions; but when Kenneth went on in the same strain declaring that Constance would keep him hanging on till she saw any she liked better, I turned upon him rather sharply,—

'I am very thankful you are not my brother. I think it is a shame of you to talk so, and I won't listen to any more of it!'

He laughed, and as we were now entering the village there was little more conversation between us till we had reached the small general shop. Mrs. Walters came out to us in a great state of excitement, and Roddy, who had nearly fallen asleep again, woke up and began to cry at the top of his voice.

'I'm sure I don't know what to do with him,' she complained; 'he runs away from school whenever he get a chance, and last Sunday he breaks into my neighbour's chicken-house, and smashes a whole set of eggs that was being 'atched! School do keep him a bit quiet in the week, but Sundays he's just rampageous!'

'Does he go to Sunday School?' I asked.

'There's no Sunday School in our village, miss; the bigger ones they goes to the next parish; but it's two good miles, and my Roddy he can't walk so fur. Now thank the leddy and gentleman, you scamp, for bringin' you home!'

Roddy turned his big blue eyes upon us, then suddenly held out his arms to me.

'I'll kiss her, for she callied me much nicer nor the gempleum!'

I gave the little fellow a hug. He looked such a baby in his mother's arms, and I felt quite drawn to him.

'I love little children so,' I said to Kenneth as we were walking home. 'I wish there was a Sunday School in this place. I should like Roddy in my class.'

'You might start a Sunday School,' suggested Kenneth gravely. 'Our old rector will let you do exactly as you like, I am sure.'

'I wonder if I could,' I said reflectively; 'just a class for the little ones, and those that can't walk as far as the bigger, stronger ones. I should be glad if I could do something on Sunday.'

Then remembering to whom I was speaking, I checked myself and said no more on the subject, though my thoughts were busy.

When we came up to the house we found that afternoon tea was going on under the old elms on the lawn. Mrs. Forsyth was in a low wicker-chair with her work, Constance was pouring out tea, and Nelly was swinging lazily in a hammock, whilst Captain Gates and Mr. Stroud were making themselves generally agreeable.

'Have you two been taking a walk together?' asked Nelly as we approached. 'I have been hunting for you everywhere, Hilda. Lady Walker has been calling, and wanted to see you; she used to know your mother.'

'How warm you look!' observed Constance, eyeing me, I felt, with disapproval. 'What have you been doing?'

I sat down on the garden seat, glad to rest, and Kenneth, leaning against the tree opposite, began:—

'Well now, I will give you a true account of her. She felt so disgusted with our frivolity at lunch, that she went out to get away from us; she wandered on dreaming her dreams and building her castles in the air, mourning over our depravity, and lamenting that she had no scope with us for all her benevolent projects, until she found herself out upon the moor, whereupon she looked round, and after a time found Roddy Walters asleep. It was an opportunity to act the Good Samaritan; she hoisted him up into her arms in spite of his howls, and insisted upon carrying him home. And I met her panting and struggling with him in old Drake's meadows.'

'But why didn't you let him walk, Hilda?' interrupted Nelly.

'He had hurt his foot, poor little fellow—it was impossible; even your brother saw that, for he carried him the rest of the way himself.'

'And now,' pursued Kenneth gravely, 'the upshot is that she is so aghast at the state of heathenism and wickedness that the village children are in, that she is going to start a Sunday School herself next Sunday, and I expect she hopes to enlist some of us as teachers. Will you go, Gates? I will back you up.'

'Oh, I will go as a scholar,' said Captain Gates readily.

'I think, Kenneth, you are letting your tongue run on too fast,' said Mrs. Forsyth gently; 'I am quite sure Hilda has no such intentions.'

I felt myself getting vexed under all this chaffing, but it has always been my way to speak out, and so, turning to Mrs. Forsyth, I said,—

'He is not representing it fairly, Mrs. Forsyth. Mrs. Walters was telling us she wished she could send Roddy to Sunday School, and I said how much I wished I could have him to teach. It was Mr. Kenneth who suggested my having a Sunday School. I certainly liked the idea, and meant to speak to you about it, but not now.'

Kenneth laughed. 'You meant to have a private confabulation with the mater and the parson, but we like everything above board here. We haven't much to amuse us, and so every one likes to know every one else's business. I can see you have an eye for reform, so think it just as well to warn others about you.'

'Hilda,' said Mrs. Forsyth, who evidently wished to change the subject, 'Lady Walker has invited you to go to some theatricals next Wednesday with the girls. I told her you had no engagement; you will enjoy it, I hope. They live a little distance off in a beautiful old abbey, and are very nice people.'

There was silence; I felt that difficulties were all round me this afternoon, and perhaps being so tired helped to make me less willing to assert my views. I sipped my cup of tea before replying, and then said quietly,—

'It was very kind of her to ask me.'

'It will be great fun, Hilda. The Walkers are awfully good at that kind of thing, and they are going to have the stage out of doors. I wish I was going to take part in it, but we shall finish up with a dance after, so I shall keep myself for that.'

Silently I put up a prayer for courage, and then replied,—

'I don't think I shall go, Nelly; I do not care about theatricals nor dancing.'

'I have accepted for you,' said Mrs. Forsyth quickly and decidedly, 'for General Forsyth wishes you to go. I am afraid you must keep your likes and dislikes in the background whilst with us about matters like this.' And taking up her work she left us and went towards the house, whilst I felt my cheeks burn, as I realized how displeased she was at my speech.

Nelly began laughing and talking with Captain Gates, Constance and Mr. Stroud soon strolled away, and I sat on, conscious that Kenneth's eyes were upon me, yet feeling so uncertain of myself that I dared not speak. I think I was very near tears. Presently Nelly turned to me: 'Have you finished your tea, Hilda? will you come and get some flowers for the dinner-table?'

I jumped up, tired though I was, and when we were out of hearing of the others, Nelly put her hand caressingly on my arm:—

'You poor little thing, you have been having a hot time of it since you came back from your walk. I feel awfully sorry for you. Mother is vexed, of course, but she will have forgotten all about it by the time she next sees you. She is never angry for long. Captain Gates said to me just now that you were not wanting in courage or straightforwardness; you spoke up well, Hilda; but I have warned you beforehand, you had much better, as mother says, keep your likes and dislikes to yourself. As Captain Gates was saying, if a person feels in a foreign element, the only cure is to adapt themselves to it. He is taking quite an interest in you, Hilda; he told me you had a true ring about you. But it is awfully funny to me, your standing out against all innocent pleasure.'

'I will talk to you about it another day, Nelly,' I said, trying to speak gently; 'don't think me disobliging if I leave you now. I am so tired that I feel I cannot walk another step. You don't mind getting the flowers by yourself, do you?'

'Of course I don't. Go up to your room and have a nap; you will have a quiet time till dinner.'

I left her, for I felt I must be alone; and when I reached my room I took my Bible, and sitting down in the low window seat turned over its leaves for comfort and guidance. My thoughts were perplexed ones. How I longed to live at peace with every one! How easy it would be to slip along in this pleasant family life, doing as others did around me; how increasingly difficult I should find it, if I was continually setting myself up in opposition to all their plans and wishes for me! And yet in my heart I knew that unless I took a stand from the first, I should be drawn into a whirl of gaiety, such as I felt would not be the right position for a true Christian to be found in. Then I wondered what claims my guardian had upon me, how far it would be right to obey him, and where I must draw the line. 'If only I had some one to advise me!' I murmured, and the next minute felt ashamed of the thought as these words met my eye,—

'But the Comforter, which is the Holy Ghost, whom the Father will send in My name, He shall teach you all things.'

I bowed my head in prayer, and when a little later I turned again to my Bible I was not long left in doubt. 'Be not conformed to this world,' I read in Romans. I turned up the references: 'Not fashioning yourselves according to the former lusts in your ignorance.' 'Love not the world, neither the things that are in the world.' 'Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate, saith the Lord.' As I sat there drinking in these messages, and dwelling upon them each in turn, all doubt and hesitation left me. I was quieted and refreshed, and when the thought of my guardian's possible anger flitted across my mind, I was able to put it aside—'He shall teach you all things.'

And that took me to another verse, 'Take ye no thought how or what thing ye shall answer, or what ye shall say; for the Holy Ghost shall teach you in the same hour what ye ought to say.'

With this I was quite content.

CHAPTER III

THE REASON WHY

Let us, then, be what we are, and speak what we think, and

in all things

Keep ourselves loyal to truth.'—Longfellow.

'General Forsyth, may I speak to you for a few minutes?'

It was after breakfast the next morning that I made this request. I was determined to have the matter settled as soon as possible.

'Certainly,' my guardian said, looking at me in some surprise. 'Come into the library, for we shall be undisturbed there.'

He led the way, politely handed me a chair, and then stood leaning his back against the mantel-piece and stroking his moustache, giving me at the same time a keen glance from under his shaggy eyebrows.

'Well,' he said, 'what is it? Do you want any money?'

'No,' I said a little nervously; 'it is quite another matter;' then gathering courage, I looked him straight in the face and said, 'General Forsyth, I think you expect me to go to those theatricals at the Walkers' next week. I cannot do it.'

'Indeed!' he said lightly, 'is it a question of dress? What is the difficulty?'

'No, it is not that. I want to tell you now, for I think it may save difficulties afterwards. I do not wish to lead a gay life: I cannot go to dances or theatres with an easy conscience. Don't think it a mere whim or passing fancy; it is a matter of principle with me. I have given myself to God for His service, and I look at everything in that light, and from that standpoint.'

General Forsyth looked amused.

'Don't put so much tragedy in your tone, child! Since when have you taken up these peculiar notions?'

'About two or three months ago,' I replied. 'It has made a great difference in my life. I thought if I explained my reason to you, you would not press me to go to things which are thoroughly distasteful to me.'

'If it is only a couple of months since you formed these views, I think you will find that time will alter them, Hilda. I should like to state to you that, according to your father's will, I am to have full control of your money until you marry, or if that does not occur soon, until you are thirty years of age. After that you are your own mistress. Are you aware of this?'

'I did not quite understand it so,' I said, wondering at the turn our conversation was taking.

'I tell you this because it explains our position towards each other. So much for the terms of the will. Now for what will touch you closer: I was with your father when he died in India; he was one of my dearest friends, as you know, and on his dying bed he made me promise that when your education was finished I should look after you as one of my own daughters, see that you were given every advantage due to the position in society that he meant you to occupy, and in fact be to you what he would have been had he lived. I know what his views were for you, and those views I shall conscientiously try to further whilst you are with me. I shall not countenance for a moment your hiding away from friends of your parents, and others with whom I wish you to associate. A time will come when you will thank me for my firmness now, and for refusing to allow you to sacrifice all your prospects in life to some morbid fancies that you must have picked up in some Dissenting chapel.'

I was silent for a moment, then I said,—

'I think my father would have wished me to be happy, General Forsyth; I cannot go against my conscience in this matter, it would make me wretched. I do feel very grateful to you for giving me a home; but indeed I would rather go away and earn my own living than lead the life you have planned out for me.'

'We will not discuss the matter further,' said General Forsyth icily; 'I have told you my wishes on the subject. If I am to treat you as one of my own daughters, you will accompany them wherever they go. I am accustomed to be obeyed in my own house, and I do not think you will deliberately oppose my wishes for you.'

'I am sorry to displease you,' I said in a low voice, 'but in this one respect I feel I am right in acting so'; and then I left the room with a heavy heart. I went out into the garden a little later, and made my way to a quiet spot in a plantation near the house, where I had found a delightful little nook to sit in, and there I took my Bible and had a quiet read and prayer. General Forsyth was not in to luncheon, but I saw from Mrs. Forsyth's face that he had told her of our interview. She said very little to me, and when the theatricals were mentioned at the table she changed the subject at once.

In the afternoon I joined Violet and her governess in an expedition to a wood a little distance off. We took tea with us, and I thoroughly enjoyed it. Miss Graham was a quiet woman, but very clever, and she and her pupil were the best of friends.

'I wish you were in the schoolroom with me,' said Violet, as we sat chatting together in the cool shade under the trees. 'I think we should have great fun together, and do you know, I heard mother say to Constance this morning that she wished you were too, for then the difficulty would be solved. What did she mean?'

I gave an involuntary sigh, and Miss Graham looked at me a little curiously; then, as Violet started to her feet in pursuit of a squirrel, she laid her hand gently on my arm.

'You look troubled, Miss Thorn; I am afraid you are one of those who try to go through life too seriously, isn't it so?'

'I don't think so,' I said with a smile; 'I am a little troubled to-day because I am vexing both General and Mrs. Forsyth very much, I am afraid, but I cannot help it.'

'Ah! don't do it, my dear. Take their advice, and trust them about your life here. They are old, and you are young. I have heard from Nelly a little about your difficulty, and I am sorry for you, for I admire your sincerity. Still, we see things differently when we get older, and you will find that it is always best to give way to others, and keep your own opinions in the background, especially when you are young.'

'It isn't my opinions that I want to bring forward,' I said, 'but I am old enough to be responsible for my actions.'

'There was a time when I had such thoughts,' said Miss Graham; 'when I was quite a young girl I used to long to join a Sisterhood, and devote myself to good works for the rest of my life; but I was shown how visionary and unpractical such ideas were, and after a time I ceased to entertain them.'

'Why did you want to give yourself up to good works, Miss Graham?' I asked a little curiously.

She laughed. 'Well, if you really want to know, it was partly because I had met with a disappointment. Some one I was very fond of—in fact, to whom I was engaged, left me to marry a girl with money, and I was for the time disgusted with life. Then I think I did desire to live a useful life; but now I have realized there are many different ways of doing that.'

'I don't wonder you changed your mind, if those were your motives for leaving the world,' I said slowly.

'Why, what other motives would you have? What is yours? Isn't it a desire to be good and fit yourself for heaven one day?'

'No,' I replied softly; 'it isn't to earn my salvation that I want to keep clear of the world; it is because I have had that given to me already, and I want to show my love to the Saviour by my life. I do love Him, and I am so afraid of a whirl of gaiety spoiling the communion I have with Him day by day.'

Miss Graham looked at me in astonishment, and was about to speak, when Violet came back, and we changed the conversation. I do not know how it was that I spoke so openly to Miss Graham, for I generally found it very difficult to express my thoughts to any one; but I seemed to have been led into it, and as we walked back in the cool of the evening I just put up a prayer that she might be made to see things differently.

I was rather relieved to hear that General and Mrs. Forsyth were dining out that night. Perhaps their absence accounted for the extra gaiety of our party; I had never seen Constance and Nelly so full of spirits, and Kenneth and Captain Gates seemed bent upon having 'a real good time of it,' as they expressed it. Hugh kept them a little in check at dinner; but when they joined us in the drawing-room afterwards, I saw they meant to be as good as their word.

Constance sat down to the piano and began playing some waltzes, and then Captain Gates sprang up. 'Here, Kenneth, give me a hand; we will move some of these obstacles, and have a dance.'

In a few minutes, chairs had been piled up one on top of the other in a corner, tables and couches pushed to the side, and a clear space left in the middle of the room.

Hugh made his exit in disgust, saying, 'I think it is a romp, not a dance, that you are wanting!'

And Mr. Stroud, a quiet little man, said protestingly, 'I think you will find it very warm work in here; would you not rather take a stroll by the river, Miss Forsyth?'

Constance shook her head, and continued playing, and then, before I knew where I was, Nelly seized hold of me and, whirling me round, waltzed away. I could not help enjoying it; I had always loved dancing at school, so without a thought I gave myself up to it; and when Captain Gates stopped us, declaring that he would not waltz with Kenneth, and we must make a speedy exchange, I made no objection. I danced with him and with Kenneth afterwards, and then took Constance's place at the piano, to let her have a turn.

When we were all tired out and were resting Kenneth said,—

'I think we are in good form for the Walkers' wind-up now. What do you think, Miss Thorn? You have changed your mind about going, haven't you?'

'No,' I said decidedly, 'I am not going.'

'Nonsense!' Nelly exclaimed, 'you are. Mother said this morning that it was settled, and why on earth do you want to keep away? you dance like——'

'Like a midsummer elf,' put in Captain Gates; 'I thought you did not care about dancing. Why, you love it, you know you do!'

I felt my cheeks flush, as I realized how foolish I had been, and then I said, resolving to be truthful at all events,—

'Well, I thought I did not care for it. I did not know till Nelly started me off how enjoyable it is still to me. But that does not alter my decision at all about going to the theatricals next Wednesday.'

'It is those, then, that you dislike, not the dancing?'

I did not answer. Kenneth now spoke from the depth of a large couch upon which he had thrown himself.

'Now look here, Goody Two-Shoes, just stand up and give us a discourse on the iniquities of dancing and such like. Here is your opportunity; five worldlings before you! Shall I ring the bell for Tomkins to fetch your Bible? I would go myself, only I'm just about done up. You will want a text. Give us your views; it will be most interesting and edifying. Who knows? You may so convince us of the awful sin of going to the Walkers', that we shall all send in an apology for our absence, and from henceforth do our dancing at home!'

'Joking apart, we should really like to know your reasons for abstaining from evening parties,' said Captain Gates.

Still I was silent, feeling the difficulty of my position; and then, after a swift prayer for guidance, I said slowly: 'I don't think any of you will understand me, and I am very sorry I have been carried away to-night by the music. It isn't dancing itself that's a sin, and I am not judging any of you; but I know in my heart that dancing and theatricals are wrong for me; they are the essentials of worldliness, those and horse-racing, and card-playing, and other things of the same sort. I want to keep clear of them all, as I know if I go in for any I shall be gradually more and more engrossed in them. And the very proof I have had to-night of how my taste for dancing has not gone, will make me keep right away from it for the future.'

'But why is it such a sin for you?' asked Nelly wonderingly.

'Because,' I said, feeling the colour rise to my cheeks with the effort of speaking out,—'because I have given myself, body and soul, to God, and I want to live only for Him. You asked me for a text—here is the one that has helped me: "He died for all, that they which live should not henceforth live unto themselves, but unto Him which died for them and rose again."'

There was silence, then Constance said with a light laugh: 'To be consistent, Hilda, you ought to go into a Sisterhood; are you thinking of doing it?'

'No; why should I? I only tell you this to show you how inconsistent I should be if I threw myself into the midst of a gay life and thought of nothing but enjoying myself.'

'Like the rest of us? Give me one of your sort for parading their own virtues at the expense of their neighbours!' said Kenneth, with a yawn.

'Oh, please don't say that! You made me give my reasons.'

'And so you have drawn out this hard-and-fast line of life for yourself, and think you will be happy in stifling all your natural instincts?' asked Captain Gates.

'I am happy—I don't want these things I have something much better!' Then, warming with my subject, I added impulsively, 'I don't believe any of you know what it is to realize that religion is not an outward form, something we hear and read about, but is a reality in one's soul. It is living instead of merely existing, it is being in touch with everything beautiful and ennobling, and with a living personal Friend, whose love is such an utterly different thing from anything else on earth!'

'I think we have had enough,' Kenneth interrupted in a drawling tone. 'Spare us any more rhapsodies. Can't we have a little music? You might give us a song, Stroud.'

Mr. Stroud complied with this request at once; he seemed never so happy as when Constance was playing his accompaniments, and for the next twenty minutes she and he were singing together. Then Captain Gates asked me a little hesitatingly if I would play on my violin. I had not often used it since I had been with the Forsyths, but I had always been very fond of it, and had played for hours to my old cousin in London.

'I think a violin is rather worldly,' objected Kenneth in his mocking tone; 'I am sure it is not a fit conclusion to the sermon we have just been hearing.'

'I don't think it is at all worldly,' I said determinedly, as I moved across to one of the long French windows and took my violin from the case; then leaning against the side of the window I looked out into the soft summer night, and dreamily began to play.

Perhaps it was the absence of General and Mrs. Forsyth that made me feel more at ease, but instead of playing any of my classical pieces I drifted into improvising as I went along, and then, as my thoughts took me far away, I gave myself up to them entirely. 'Dwell deep' was ringing softly but clearly in my ears. Storms could come and storms could go, but in all and through all were those two little words of peace and quiet. And my violin was with me, and understood my mood. I don't know how long I played, but when I came to myself and surroundings, soothed and comforted in spirit, I found them all staring at me in astonishment. I let my bow fall in perfect silence, and Captain Gates asked with a long-drawn breath, 'What is the name of that?'

'Dwell deep!' I replied with a full heart; and then putting my violin by, without another word I left them, and went up to my room. I did not go down again that night.

CHAPTER IV

AN OPENING FOR WORK

'Whoever fears God, fears to sit at ease.'—E. B. Browning.

'Hilda, mother wants to speak to you in her boudoir. We have just been having a grand discussion about our dresses for the Walkers' affair, and she wants to find out from you whether you are really going or not.'

I sighed as Nelly finished speaking.

I was picking some roses on the lawn, and Captain Gates had just sauntered out of the smoking-room, cigar in mouth.

It was such a lovely morning that I was meditating spending it in my favourite nook in the plantation, and for the time I had forgotten everything unpleasant.

'You poor little creature!' said Nelly sympathetically, 'aren't you tired of it? You have discussed the subject with father, given us a long preach last night, and now there still remains mother! Let me advise you, don't be too outspoken with her. Constance told her about our dance last night, and mother seems to think that it must be pure wilfulness on your part if you still refuse to go with us.'

'I wish I could be left alone,' I said a little wistfully; 'I shall only make your mother angry.'

'Are you tired of showing your colours?' questioned Captain Gates.

'I hope not,' I said in a brighter tone, and then I went into the house.

Mrs. Forsyth was kind at first, but when she saw that I was really determined she became vexed.

'It is placing me in a very awkward position, Hilda. What excuse can I make for you? You have not even delicacy of health to account for your absence. I am anxious to take you about with my own daughters, and people will think I am purposely keeping you in the background. I do wish you had given us some intimation of these strange views before you came to live with us. It will be a continual annoyance to us.'

'Do you think I had better go back to my cousin's in London?' I asked. 'I really do not want to be such a trouble. If you would only let me be happy in my own way, and stay quietly at home, I should be so grateful, because you have all been so kind to me that I love to be here.'

'I really don't know what we shall do with you,' Mrs. Forsyth replied, in a milder tone. 'I believe General Forsyth has his own plans for you, and if you will not fall in with them, it would be better for us all that you should be away from us. However, of course, we cannot force you to go with us next Wednesday, so I must try and explain it as best I can to Lady Walker. I need hardly say that General Forsyth will not be at all pleased about it.'

I left her feeling rather downhearted. Looking at it from their point of view, I must be somewhat of a trial to them, and yet I knew I could not act otherwise.

As I was stepping out into the garden again, deep in thought, I was startled by the sudden appearance of little Roddy Walters from behind a large tree close to the house. His hands were full of yellow marsh marigolds and blue forget-me-nots.

'Roddy has brought them for you,' were his first words, as he caught sight of me.

I had seen the little fellow several times since our first meeting, but this was the first time that he had ventured to come up to the house to see me, though whenever I passed through the village he would run after me, and I had great difficulty in getting away from him.

'How lovely!' I exclaimed, as I took the bunch from his hot little hands; 'but, Roddy, you ought to be at school. Have you run away?'

He laughed and nodded: 'Bess Brown did take me to school, but she slapped me, and I runned away, and Jim tooked me down to the water, and we picked these booful flowers, and I loves you, and Jim said I might give 'em to you.'

'And who is Jim?'

'Jim is waiting for me, Jim is, he's sittin' on the gate; you come and I'll show you him.'

He led me down the avenue as fast as his little legs could carry him, and there on a side gate that led into some fields was a lad about fifteen. He got down directly he saw me, and I noticed that he was a cripple and had a crutch by his side.

'Are you Jim?' I asked.

'Yes, mum!'

'Don't you know that Roddy ought to be at school? It isn't right of you to encourage him to play truant.'

Jim laughed. 'He's such a little 'un, he is.'

And then we drifted into talk. Jim told me he lived with his uncle, who was a cobbler, but he himself had no occupation except that of gathering wild flowers, and taking them into the market town near, twice a week. I found to my surprise that he could not read.

'I was on my back for years when I might 'a had my schoolin', and when I was able to get about with my crutch I was that 'shamed to go, being such a big 'un, and such a dunce. Uncle Sam, he has a tried to teach me, but he has a awful temper, and says I'm that slow I aggrewate him into fits.'

'How I wish I could teach you!' I exclaimed; 'wouldn't you like to learn?'

'Ay, shouldn't I! but I'm an awful dullard.'

We talked a little longer. I took a great fancy to this thin lanky lad, with his great dark questioning eyes—he seemed lonely—and his affection for little Roddy was very touching. That afternoon the old rector happened to call while we were at tea, and I took the opportunity of asking him about the boy; he seemed quite pleased at my interest in him, and then of his own accord he broached the subject of Sunday School.

'I should like to get one of you young ladies to have a class of the little ones on Sunday. I am an old man myself, and don't feel up to it. I sometimes wish I had a wife or daughter to help me about these things. Mrs. Forsyth, what do you think about it?'

'I have no doubt Miss Thorn would be delighted to do what you wish. She has already expressed a desire, I believe, to do something of the sort.'

Mrs. Forsyth's tone was a little stiff, but I was so glad that she made no objection to the suggestion that I felt quite grateful to her. And before the rector left us he had settled that I should start a class the following Sunday afternoon from three to four in the vestry of the little church.

'I will go round to my parishioners and let them know. Of course you will be prepared for very little ones, as the bigger ones attend a school a little distance off. And as for Jim Carter, if you can give him a reading lesson now and then in the week, I shall be delighted.'

When the rector had gone, I ran up to my room, and just knelt down and thanked God for the work He had already given me. Only that morning I had been praying for something to do, and had anticipated great difficulties in the way.

Yet the opening had come, and everything seemed made easy for me. And for the rest of the day this fresh interest made me forget my troubles, until I was reminded of them in the drawing-room that evening.

We were all there, General Forsyth reading the evening paper, Mrs. Forsyth with her work, and the girls round the piano, when suddenly Kenneth said, turning to me,—

'What kind of a mood are you in to-night? A musical one? Because if so, please favour us with a repetition of last night's performance.'

'What? Another dance?' said Nelly laughing. 'She is never going to dance again, she says!'

'Wait and see,' and Kenneth's tone was a little scornful; 'but it was the violin I was alluding to.'

Then General Forsyth looked up.

'I hope you have thought better about going to Lady Walker's, Hilda. I hear you were nothing loth to turn this room into chaos last night in order to enjoy a dance, so I conclude you have overcome your foolish scruples about it.'

'I am sorry, General Forsyth,' I said, trying to speak bravely, 'but I told Mrs. Forsyth this morning that I cannot go.'

'You have your father's obstinacy, I see;' and throwing down his paper angrily, General Forsyth got up and left the room.

'Never saw the general lose his temper before,' murmured Mr. Stroud to Constance; and she replied, in tones loud enough for me to hear, 'She is a provoking little thing; I believe it is nothing but cant with her. I hate those kind of people.'

Captain Gates was sitting close to me, and his eyes met mine as we caught the sneering words. He did not say anything, but got up from his seat and fetched my violin, which he put into my hands saying,—

'Give us another treat, for you make it speak!'

I shook my head, then, as he begged me so hard, I felt I ought not to refuse, but I could not play as I had done the night before, and when I had finished he said,—

'Thank you, but that is rather different to last night.'

'It is rather too classical, perhaps. I will try a little lullaby. It's German, and I think you may like it.'

'Hilda,' said Mrs. Forsyth when I had finished, 'you ought to cultivate your gift for music, for you have got a good touch. I am anxious for Violet to play well, but her violin lessons with Miss Graham are a source of constant trouble to me. I wish you could give her a few hints about it. Miss Graham is a good musician, but she certainly does not handle the instrument as you do.'

'I shall be very glad to practise with Violet a little,' I said, 'if Miss Graham does not object.'

Then Nelly called to me from the balcony outside the windows, and I joined her with a sense of relief at getting out into the still, cool evening air.

Captain Gates joined us, and leant against one of the stone pillars enjoying a cigar.

We talked and laughed for some time, then as Nelly moved off a little farther to speak to Hugh, who had also come out, Captain Gates turned to me and said, 'You are having rather a hot time of it just now, Miss Thorn, I feel afraid. Why are you so determined in your views? I feel sorry for you, because you have every one against you.'

His tone was sympathetic.

'I shall get accustomed to that, I suppose,' I said; but as I looked away to the still hills in the distance, my eyes suddenly filled with tears, and I realized how lonely my position was.

'I can't think why you hold out; you are planning a dreary life for yourself, don't you think so?'

'No,' I said, hastily brushing away my tears, and smiling at his gloomy tone; 'I shall not be a bit dreary; how could I be!'

'I wish you would explain a few things to me, and then perhaps I should understand better. Do you consider us all dreadful sinners here?'

'I judge no one, Captain Gates. It seems to me you must have something to fill your life and interest and occupy you, and if you haven't got what I have, you must have worldly amusements.'

'And what have you got that we have not?'

I was silent for a moment, then I said,—

'Do you ever read your Bible, Captain Gates?'

'Not often.'

'You will find a great deal about the Christian's portion there, if you look; but I suppose the summing up of it all is just Christ Himself. If we have Him we want nothing more.'

There was another silence.

At length he said meditatively, 'I should like to be enlightened. Will you come for a row on the river to-morrow, and let us thrash the subject out?'

'I don't know,' I said hesitatingly; 'I will see what plans the others have.' And then I stepped back into the drawing-room, leaving him alone there, and wondering if he was really in earnest, or only drawing me out for his amusement.

When I went forward to wish General Forsyth 'good-night' that evening, he refused to take my hand, saying coldly, 'I shall have nothing to say to you for the present; your conduct is highly displeasing to me.'

I felt the blood rush to my cheeks, as he did not lower his voice, and all in the room heard his words; then I left the room slowly, like a naughty child being sent off to bed in disgrace. Nelly came rushing upstairs after me, and linked her arm in mine.

'Never mind, Hilda. You see father is never accustomed to have any one oppose him, and he cannot understand you. You are a bold little thing, to say what you do to him. Now tell me what conspiracy was going on between you and Captain Gates this evening? He is asking mother if we can have a picnic on the river to-morrow. Constance and Mr. Stroud are delighted, and mother has given her consent. Mother says she won't start with us, but may join us later in the day. He said we had better have three boats; but I wonder how we are going to pair off. I am not always going to be coupled with Kenneth, he and I are sure to fight. And I know Captain Gates will have you with him if he can manage it; he follows you about everywhere. Constance and Mr. Stroud are inseparable, and no one takes any notice of me!'

'Oh, Nelly, how you run on!' I exclaimed, half laughing, half vexed. 'I dare say I shall not go with you.'

'But you must; it will be great fun. Well, good night; I must be going.'

CHAPTER V

OPPORTUNITIES

'Draw through all failure to the perfect flower;

Draw through all darkness to the perfect light.

Yea, let the rapture of Thy spring-tide thrill

Through me, beyond me, till its ardour fill

The ungrowing souls that know not Thee aright,

That Thy great love may make of me, e'en me,

One added link to bind the world to Thee.'—E. S. A.

We had a very enjoyable day up the river, Violet begged a holiday, and came with us. We had only two boats—Constance, Violet, and Mr. Stroud in one, and Nelly, Kenneth, Captain Gates, and I in the other. We took our lunch with us, and landed in a wood that came down to the water's edge. And after our meal was over Captain Gates asked me to come for a stroll through the woods with him. I did not feel inclined to do this at first, yet hardly liked to refuse, and it was not long before he turned our conversation towards serious subjects.

'I looked into a Bible which was in my room last night, Miss Thorn, but I couldn't see anything in it to make me wish to alter my life. It seems to me that as long as we slip along, and live decent, respectable lives, that is all that is required. God is merciful, isn't He? He won't require too much of us.'

'"What doth the Lord thy God require of thee, but to fear the Lord thy God, to walk in all His ways and to love Him, and to serve the Lord thy God with all thy heart and with all thy soul?"'

I repeated this verse rather slowly, adding,—

'I don't think many of us can say we come up to God's requirements, Captain Gates. "God will put up with a great many things in the human heart, but there is one thing He will not put up with in it—a second place." He who offers God a second place offers Him no place. I think that has been very truly said; don't you think so?'

'Well, I must plead guilty, of course, when you bring up a verse like that,' he responded lightly; 'but that is an impossible standard to set up for us poor human mortals.'

'Yes,' I said, after a minute's silence, 'judging us from that standard, we have all failed. We are "condemned already." I don't believe, Captain Gates, that we can ever be in real earnest about having our souls saved till we realize our condemnation. The verse that made me miserable was this one: "He that believeth not the Son shall not see life, but the wrath of God abideth on him."'

'Were you ever an unbeliever, then?' and Captain Gates looked at me curiously as he spoke.

'Of course I believed about Jesus Christ,' I replied in a low voice, 'but I didn't believe in Him. I hadn't come to Him and accepted my pardon at His hands. I didn't understand that, however good I might try to be, I could never expect to enter heaven unless I was washed and cleansed by Him.'

There was silence, and I was afraid I had been too outspoken. Then, as we were passing a bush, with the most lovely honeysuckle at the top of it, I stopped and asked him if he would get me some.

This he willingly did, and as he handed me some beautiful sprays of it said,—

'There is no uncertain sound about your preaching, Miss Thorn. I believe you could do something with me if you were to try, but your doctrines are strange to me, and it will take me some time to get reconciled to them. You must take me in hand; will you?'

I looked up, and our eyes met. Again I wondered if he were sincere.

'I think you will find all you need in the Bible,' I said; and then I changed the conversation.

A few minutes after we met some of the others, and when we came down to the river's side Violet seized hold of my arm.

'Hilda, you come in our boat. I had an awfully dull time of it coming here. I think I was put in to act gooseberry, and I'm not going to do it again. Do come!'

'I will, of course, if Constance likes.'

And that was the order in which we came home, for Mrs. Forsyth never appeared at all. I was not surprised when Nelly came to me the last thing at night, as she was so fond of doing, and announced,—

'Well, it is all settled. Constance and Mr. Stroud are engaged, and I wish her joy of him. Mother is pleased, because he has a nice little property; but I wouldn't have him for all the properties in creation. He is a regular stick, and hasn't a spark of fun in him. I only hope he won't stay on here after next week. Both he and Captain Gates said they must go when the Walkers' theatricals are over.'

'Is Constance very happy about it?' I asked.

'She seems to be, in her way. Of course, everything is rose colour to-night. Hilda, do you like Captain Gates?'

'Yes, I like him pretty well,' I said.

Nelly came up and put both hands on my shoulders.

'Now, look me straight in the face, and say that again.'

'I don't know what you mean,' I said, confronting her steadily.

'Sometimes I wonder if you are as innocent as you appear,' Nelly continued, laughing. 'But let me warn you of this: he is a great flirt, and tries it on with every girl he comes across. Kenneth asked him to-night downstairs if he thought a saint would make any man a good wife, and I never saw him so put out. He went off in a huff, and Kenneth said he thought he was hit at last. What did you talk about, Hilda, when you and he went off for your solitary ramble?'

I have always been told that I have an easy temper, but Nelly was never nearer making me really angry than she was that night.

'I wish you would not speak so, Nelly,' I said, flushing a little as I turned away from her; 'I cannot bear that kind of talk; as if you cannot be friendly to any one without having such motives ascribed to you. Captain Gates talks to me like any one else; he is a little more polite to me than your brothers are, that is the only difference.'

'My dear, how your eyes are flashing! I shall begin to be quite frightened of you. I didn't ascribe any motives to you, but I only warned you to beware of Captain Gates. He told Kenneth you were a bewitching little thing two days after he had first seen you, and I think the fact of your being so different to the usual run of girls he sees fascinates him for the time. I was going to advise you how to deal with him, but really I hardly dare now.'

'I don't mean to be cross, Nelly; but I am tired, and I want to be left alone.'

She laughed, gave me a kiss, and departed. I sat down to my Bible with my thoughts in a tumult. I should have been stupid indeed if I had not seen that Captain Gates liked to pay me little attentions, and his look as he handed me the honeysuckle that afternoon in the woods had made me shrink into myself, for I realized that he was not only interested in the subject of our conversation, but in me myself. I had honestly felt glad that he wished to talk on serious subjects, and I had been praying for him a great deal that day. Now Nelly's chaffing words had left their sting, and I felt humiliated by being discussed downstairs so freely before them all. My desires for Captain Gates' welfare were at an end. I felt I could never talk to him again.

But when I went down on my knees, and just spread the whole matter out in prayer, and then waited in silence till the quiet and peace came back into my heart, the case looked very different. And, turning over the leaves of my Bible, I was guided to this verse, 'As every man hath received the gift, even so minister the same one to another, as good stewards of the manifold grace of God.' Yes; I resolved that when opportunities were given to me of speaking a word for my Master, I would take them gladly, yet at the same time I would not seek to make them for myself, especially in connection with Captain Gates.

'Dwell deep!' I said to myself. 'I can let these little vexations and misunderstandings pass unnoticed; they are like the breezes on the surface of a lake. If I dwell below, I shall enjoy the calm.'

The next day was Sunday, and at three o'clock in the afternoon I found myself waiting in the vestry for my scholars. They were not long after me. First Roddy, with a shining face and a large bunch of asters from his mother's garden, which he presented to me with great pride; then two little girls in huge sun-bonnets, and very brown arms and legs, named Hetty and Polly Tyke; a very heavy, sleepy-looking boy about four years old, sucking a large piece of sugar-candy; and lastly Jim Carter and a big girl about his own age, whom he held by the hand.

'We thought you'd like if Kitty was to come; she's blind, you see, and has never been to no Sunday School, because no one will take charge of her; they runs off after a time, and then she comes to grief, she do!'

I was a little nonplussed, as I had only expected quite an infant class; but I made the best of it, and after singing a hymn that they all seemed to know I had a short prayer, and then settled down to a Bible story. I took Samuel's first call, made them each learn a little verse about it, and then began to talk to them. They were very quiet and listened almost breathlessly, but we had a few interruptions: Roddy suddenly nodded his head very violently towards me, and burst forth in the middle of my talk,—'I'll bring you a robin's egg to-morrer, a booful little egg for your breakfus! I'll go in at the big gates all by myself, and I'll knock at the big door with my stick, and then won't you be very 'stonished!'

I hushed him, and a few minutes after little Tommy Evans dropped his piece of sugar-candy, and in bending down to pick it up, overbalanced himself and fell with a crash to the ground; of course he howled, and I had to take him on my knee to pacify him. But these little incidents did not lessen their interest in the Bible story, and when I gave them each a little reward ticket at the close their delighted faces showed their appreciation of it all. The hour over, I dismissed them, and after promising to come again the next Sunday with several fresh scholars, the little ones scampered off. Jim politely offered to put the room tidy again, and whilst he was doing it I drew the blind girl out into the church porch and had a little talk with her. She told me her mother took in washing, and she helped her as much as she could. 'For father's been dead this five years, and grandfather's an old man, and has rheumatics so bad in his knee he can't do no work, so mother she keeps him; I wasn't always blind, I had scarlet fever when I was just on three years old, but oh, I does wish for my sight in the summer!'

'You poor child!' I said pityingly, 'you must long to see the flowers, I feel sure.'

'Teacher,' she said earnestly, 'I like that about Samuel; I shall try and say softly sometimes, "Speak, Lord, for Thy servant heareth." He will speak, won't He? I should like to hear His voice.'

'You will, Kitty, I know you will. God wants to have you for His servant. You give yourself to Him, and ask for His Holy Spirit to teach you day by day.'

This short conversation sent me home with a happy heart. I felt thankful that I had found some work, and I resolved to visit the parents of each child during the week.

It was a very different atmosphere I came into a short time later. Tea on Sunday afternoon was a time for visitors to drop in, and the conversation seemed to me always on the most frivolous subjects.

Constance and Mr. Stroud had escaped and gone away into the garden by themselves, and of course their engagement was being discussed as well as the gaieties of the coming week.

I got into a quiet corner and took my tea in silence, hoping I might be left unmolested, but this was not to be. A Miss Gordon, with a magnificent voice, was singing as I entered, and when she had finished Kenneth turned to me: 'Now, Goody Two-Shoes, give us something from your violin.'

He invariably addressed me by that name now, and I knew how vain it would be to protest against it.

'Oh yes, Miss Thorn,' said Miss Gordon, 'we have heard wonderful things of your playing; you are quite a genius, aren't you?'

'No,' I said, colouring a little, 'I am certainly not that, though I am very fond of it; I must ask you, I am afraid, to excuse my playing this afternoon.'

'Oh, please play; why won't you oblige us?'

'I never use my violin on Sunday.'

There was dead silence; then a Mrs. Parker, a young widow who had come with Miss Gordon, said, 'But, my dear Miss Thorn, play us something sacred, of course. I always consider the violin quite a Sunday instrument. In our village the chapel people have two going at every service they hold. You surely cannot think it wicked to play it on Sunday?'

No,' I said, 'I don't think it is wicked, but I would rather not do it. I am sure you will not press me.'

'She has just come back from Sunday School,' said Kenneth, looking across at me with a twinkle in his eye, 'and so she is doubly shocked with our levity. I assure you, Mrs. Parker, her religious scruples are such that I don't think she would pick a flower in the garden if you were to ask her to on the Sabbath!

I rose from my seat, for I had finished my tea, and pointing to a crimson rose in my waist-belt I said half laughing; 'I picked this as I came in this afternoon,' and then I left the room and went upstairs, where I had a nice quiet hour by myself. I felt quiet times alone were quite essential to me now, otherwise I seemed to almost lose touch with the unseen things that were so dear to me.

CHAPTER VI

ONLY A FRIEND

'Surely a woman's affection

Is not a thing to be asked for, and had for only the asking?—Longfellow.

Wednesday evening came, and all went off to Lady Walker's except Hugh and myself. He seemed very rarely to go out with the others, and was generally up in London several nights a week. I had helped the girls to dress, and had done all I could for them before they went, but it had been a trying time. General Forsyth had hardly spoken to me since he knew my decision was final, and Mrs. Forsyth was continually referring to my foolishness. So I was relieved when they were out of the house, and quite enjoyed the quiet dinner with Hugh. He certainly exerted himself to be agreeable, and asked me if I would come upstairs and sit in his study after dinner.

'Bring your violin,' he said, 'and if you will play nicely to me I will treat you to a glimpse of the heavens through my telescope. It is a beautiful starry night.'

His study was a very comfortable-looking room, with a large bay window overlooking the open country, and I took up my position in front of it as I played to him. I did not know he was so fond of music; but as I laid my violin down I noticed how he was leaning back in his chair with a dreamy smile upon his face, and drawing in a long breath, he said,—

'Thank you. I think that's a better class of entertainment than what is going on at the Walkers' at present. A low-level life there, I consider, and one only marvels at men and women spending their whole existence in such trifles: time and talents utterly wasted, and powers of intellect used and abused in the foolish chit-chat of society!'

He spoke so contemptuously that I looked up in surprise.

'I think,' I said, 'every one must have something to fill their life. They are as much occupied in their gay sphere as you are in your literary one.'

'Or as you in your pious one! Quite true; and I suppose we each think our own sphere immeasurably superior to any other. I tell you honestly, I have a contempt for the frivolous one, and a pity for the religious. I look at both from a higher platform.'

'You place all your faith in man's intellect,' I said slowly; 'but "religious" people, as you call them, place their faith in the Creator of man's intellect. I don't think you are on a higher platform than they; you haven't got quite high enough.'

He made a movement of impatience in his chair, then relapsed into his natural supercilious manner.

'It is amusing to hear you air your views so dogmatically; if you were versed in some of the literature of the present day, and knew how many old-time notions and superstitions are disappearing under the full clear light of reason and science, you would not speak so positively. You must let me lend you a few books that may enlarge your thoughts and enlighten you on these subjects.'

'No, thank you,' I said quietly; 'you mustn't be vexed if I say again, you don't rise high enough; you read and study the works and production of men's brains, but I go by God's own Book, and that is beyond and above them all.'

Hugh laughed. 'I never argue with women, or I would show you how faulty your statements are. But never mind. I would rather see a girl take serious views of life than fritter it away as most do. You mean well, and live up to your light. Now would you like to have a look through my telescope?'

I assented; but I could not help wondering how much or how little Hugh really did believe. Nothing could be kinder than his explanations of the different planets and stars that we looked out upon, and for a full hour I was engrossed in gazing at various constellations above. I had always been interested in astronomy, and Hugh was very lucid as well as patient in giving me a great deal of fresh information. I listened and gazed breathlessly, and at last came away from the telescope with a deep-drawn breath of regret.

'It is so lovely; it seems to carry one quite away from earth altogether: the infinite space stretching away and away. Oh, Mr. Forsyth, you do not doubt the existence of God, do you?'

'No; I believe in a Supreme Being. I am not such an utter unbeliever as that.'

'I should hardly think any one who studied astronomy could believe that the universe was made by chance. Isn't there some spot in the Pleiades which is the centre of the whole solar system? I remember seeing some article about it once, and I like to think of heaven there.'

He smiled, but changed the conversation, and we did not touch on serious subjects again. When I prayed that night, I especially remembered Hugh; it seemed so sad to me that he was only using his intellect to try and discover flaws in the Bible, and prove to himself and others that some of the most important truths in Christianity were only popular superstitions.

Nelly had told me much about him; for though he kept himself aloof a great deal from the girls, every now and then he would unbend, and, as he had done this night, would take them into his study and interest them with his telescope and conversation.

But I resolved not to read any of his books. I felt I dared not wilfully go into such temptation; and when, as I was leaving him, he asked me if I would like the loan of a few, I answered, 'No, thank you, I would rather not. I am not a dissatisfied, restless soul that is seeking for the truth. I have found it, and am happy in it.'

'You are a very self-satisfied soul, at all events,' he said.

I coloured up, for I had been feeling a little self-righteous as I mentally condemned him for his free-thinking opinions.