THE MEASURE

OF A MAN

BY

AMELIA E. BARR

AUTHOR OF "THE BOW OF ORANGE RIBBON,"

"PLAYING WITH FIRE," "THE WINNING OF LUCIA," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

FRANK T. MERRILL

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK AND LONDON

1915

WITH SINCERE ESTEEM

I DEDICATE THIS BOOK

TO

MRS. ARTHUR ROBERTS

OF

EVANSTON, ILLINOIS

PREFACE

My Friends:

I had a purpose in writing this novel. It was to honor and magnify the sweetness and dignity of the condition of Motherhood, and of those womanly virtues and graces, which make the Home the cornerstone of the Nation. For it is not with modern Americans, as it was with the old Greek and Roman world. They put the family below the State, and the citizen absorbed the man. On the contrary, we know, that just as the Family principle is strong the heart of the Nation is sound. "Give me one domestic grace," said a famous leader of men, "and I will turn it into a hundred public virtues."

A Home, however splendidly appointed, is ill furnished without the sound of children's voices; and the patter of children's feet. It may be strictly orderly, but it is silent and forlorn; and has an air of solitude. Solitude is a great affliction, and Domestic Solitude is one of its hardest forms. No number of balls and dinner parties, no visits from friends, can make up for the absence of sons and daughters round the family table and the family hearth.

Yet there certainly is a restless feminine minority, who declare, both by precept and example, Family Life to be a servitude. Alas! They have not given themselves opportunity to discover that self-sacrifice is the meat and drink of all true affection.

But women have learned within the last two decades to listen to every side of an argument. Their Club life, with its variety of "views," has led them to decide that every phase of a question ought to be attentively considered. So I do not doubt that my story will receive justice, and I hope approval, from all the women—and men—that read it.

Affectionately to all,

AMELIA E. BARR.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE |

|---|---|

| I. THE GREAT SEA WATERS | 1 |

| II. THE PEOPLE OF THE STORY | 18 |

| III. LOVE VENTURES IN | 39 |

| IV. BROTHERS | 56 |

| V. THE HEARTH FIRE | 78 |

| VI. LOVE'S YOUNG DREAM | 99 |

| VII. SHOCK AND SORROW | 125 |

| VIII. THE GODDESS OF THE TENDER FEET | 146 |

| IX. JOHN INTERFERES IN HARRY'S AFFAIRS | 182 |

| X. AT HER GATES | 204 |

| XI. JANE RECEIVES A LESSON | 235 |

| XII. PROFIT AND LOSS | 262 |

| XIII. THE LOVE THAT NEVER FAILS | 286 |

| SEQUENCES | 312 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

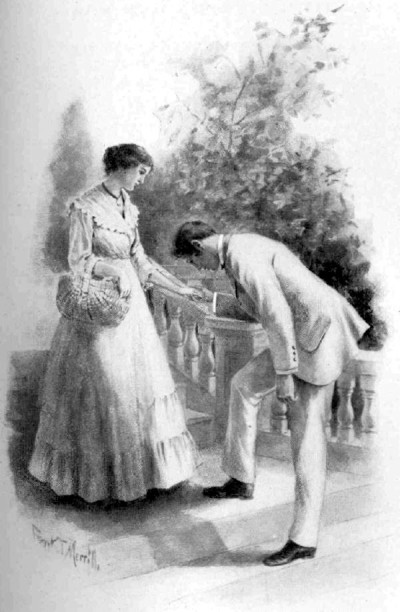

"Holding Bendigo's bridle, he had walked with her to the Harlow residence"...Frontispiece

"He knew her for his own ... as she stood with her father at the gate of their little garden"...72

"He ran down the steps to meet her, and she put her hand in his"...168

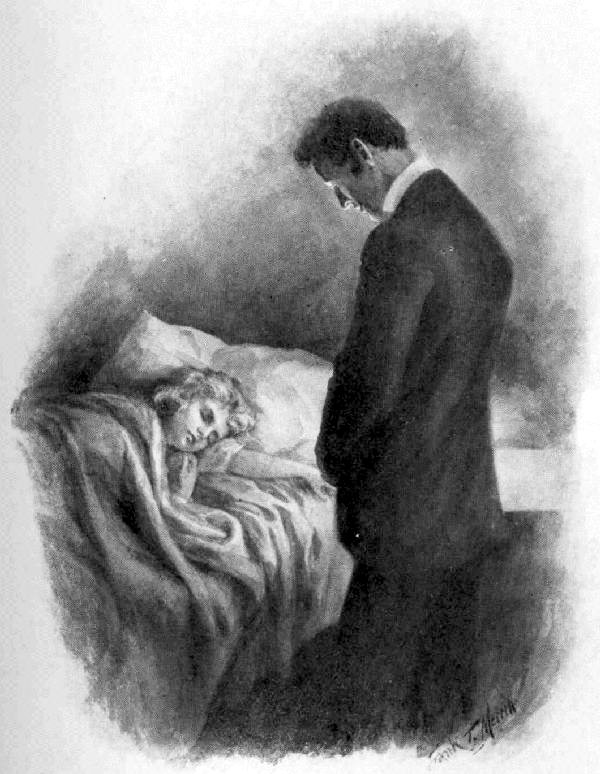

"Noiselessly he stepped to her side and ...stood in silent prayer"...232

THE MEASURE OF A MAN

CHAPTER I

THE GREAT SEA WATERS

My heart flits forth to these;

Back to the winter rose of Northern skies,

Back to the Northern seas.

I saw a man of God coming over the narrow zigzag path that led across a Shetland peat moss. Swiftly and surely he stepped. Bottomless bogs of black peat-water were on each side of him, but he had neither fear nor hesitation. He walked like one who knew his way was ordered, and when the moss was passed, he pursued his journey over the rocky moor with the same untiring speed. Now and then he sang a few lines, and now and then he lifted his cap, and stood still to listen to the larks. For the larks sing at midnight in the Shetland summer, and to the music of their heaven-soaring songs he set one sweet name, and in the magical radiance over land and sea had that momentary vision of a beloved face which the second-sight of Memory sometimes grants to a pure, unselfish love. Then with a joyful song nestling in his heart, he went rapidly forward. And the night was as the day, for the moon was full and the rosy spears of the Aurora were charging the zenith from every point of the horizon.

Very early he came to a little town. It was asleep and there was no sound of life in it; but a large yacht was lying at the silent pier with steam visible, and he went directly to her. During the full tide she had drifted a few feet from land, but he took the open space like a longer step, walked straight to the wheel, and softly whistled.

Then the Captain came quickly up the companion-way, and there was light and liking on his face, as he said,

"Welcome, sir! I was expecting thee."

"To be sure. I sent you word I should be here before sunrising. Are you ready to sail?"

"Quite ready, sir."

"Then cast off at once," and immediately there was movement all through the boat—the sound of setting sail, the lifting of the anchor, the rush of steam, and the hoarse melancholy voices of the sailors. Then the man laid his hand on the wheel, and with wind and tide in her favor, the yacht was soon racing down the great North Sea.

"It is Yoden's time at the wheel, sir," said the Captain. "If so be he is wanted."

"He is not wanted yet. I am going to take her as far as the Hoy—if it suits you, Captain."

"Take your will, sir. I am always well suited with it."

Now John Hatton was a cotton-spinner, but he knew the ways of a boat, and the winds and tides that would serve her, and the road southward she must take; and at his will she went, as if she was a solan flying for the rocks. When they first started, the sea-birds were dozing on their perches, waiting for the dawn, and their unwonted silence lent a stronger sense of loneliness to the gray, misty waters. But as they approached the pillars of Hoy, the wind rose and the waves swelled refulgent in the crimsoning east.

Then the man at the wheel was seen in all his great beauty—a man of lofty stature perfectly formed and full of power and grace in every movement. His head had an antique massiveness and was crowned with bright brown hair thrown backward. His forehead was wide and contemplative, his eyes large and gray and thickly fringed, lustrous but not piercing. His loving and vehement soul was not always at their windows, but when there, it drew or commanded all who met its gaze. His nose was long and straight, showing great refinement, and his chin unblunted by animal passions. A wonderful face, because the soul and the mind always found their way at once and in full force to it, as well as to the gestures, the speech, and every action of the body. And this was the quality which gave to the whole man that air of distinction with which Nature autographs her noblest work.

When they reached the Hoy he left the wheel and stood in wonder and awe gazing at the sea around him. For some time it had been cloudy and unquiet, but among these great basaltic pillars and into their black measureless caves it flung itself with the rush and roar of a ten-knot tide gone mad. Yet the thundering bellow of its waves was not able to drown the aërial clamor of the millions of sea-birds that made these lonely pillars and cliffs their home. Eagles screamed from their summits. Great masses of marrots and guillemots rocked on the foam. Kittiwakes of every kind in incalculable numbers and black and brown-backed gulls by the thousands filled the air as thickly as snowflakes in a winter's storm; while from shelves and pinnacles of the cliffs, incredible numbers of gannots were diving with prodigious force and straight as an arrow, after their prey—all plunging, rising, screaming and shrieking, like some maddened human mob, the more terrible because of the ear-piercing metallic ring of their unceasing clamor.

After a long silence John Hatton turned to his Captain and said,

"Is it always like this, Captain?"

"It is often much livelier, sir. I have seen swarms of sea-birds miles long, darkening the air with their wings. Our Great Father has many sea children, sir. Next summer—God willing!—we might sail to the Faroe Islands, and you would be among His whales, and His whale men."

"Then you have been to the Faroes?"

"More than once or twice. I used to take them on my road to Iceland. It is a wayless way there, but I know it. And the people are a happy, comfortable, pious lot; they are that! Most of them whale-hunters and whale-eaters."

"Eaters?"

"To be sure, sir. When it is fresh, a roast of whale isn't half bad. I once tried it myself."

"Once?"

"Well, then, I didn't want it twice. You know, I'm beef-bred. That makes a difference, sir. I like to go to lonely islands, and as a general thing I favor the kind of people that live on them."

"What is the difference between these lonely islanders and Yorkshire men like you and me?"

"There is a good bit of difference, in more ways than one, sir. For instance, they aren't fashionable. The women mostly dress the same, and there are no stylish shapes in the men's 'oils' and guernseys. Then, they call no man 'master.' God is their employer, and from His hand they take their daily bread. And they don't set themselves up against Him, and grumble about their small wages and their long hours. And if the weather is bad, and they are kept off a sea that no boat could live in, they don't grumble like Yorkshire men do, when warehouses are overstocked and trade nowhere, and employers hev to make shorter hours and less pay."

"What then?"

"The men smoke a few more pipes, and the women spin a few more hanks of wool. And in the long evenings there's a good bit of violin-playing and reciting, but there's no murmuring against their Great Master. And there's no drinking, or dance halls. And when the storm is over, the men untie their boats with a shout and the women gladly clean up the stour of the idle time."

"Did you ever see a Yorkshire strike?"

"To be sure I hev; I had my say at the Hatton strike, I hed that! You were at college then, and your father was managing it, so we could not take the yacht out as expected, and I run down to Hatton to hev a talk with Stephen Hatton. There was a big strike meeting that afternoon, and I went and listened to the men stating 'their grievances.' They talked a lot of nonsense, and I told them so. 'Get all you can rightly,' I said, 'but don't expect Stephen Hatton or any other cotton lord to run factories for fun. They won't do it, and you wouldn't do it yersens!'"

"Did they talk sensibly?"

"They talked foolishness and believed it, too. It was fair capping to listen to them. There was some women present, slatterns all, and I told them to go home and red up their houses and comb up their hair, and try to look like decent cotton-spinners' wives. And when this advice was cheered, the women began to get excited, and I thought I would be safer in Hatton Hall. Women are queer creatures."

"Were you ever married, Captain?"

"Not to any woman. My ship is my wife. She's father and mother and brother and sister to me. I have no kin, and when I see how much trouble kin can give you, I don't feel lonely. The ship I sail—whatever her name—is to me 'My Lady,' and I guard and guide and cherish her all the days of her life with me."

"Why do you say 'her life,' Captain?"

"Because ships are like women—contrary and unreasonable. Like women they must be made to answer the rudder, or they go on the rocks. There are, of course, men-of-war, and they get men's names, and we give them fire and steel to protect themselves, but when your yacht with sails set, goes curtsying over the waves like a duchess, you know she's feminine, and you wouldn't call her after your father or yourself, but your sweetheart's name would be just suitable, I'm sure."

John smiled pleasantly, and his silence encouraged the Captain to continue. "Why, sir, the very insurance offices speak of a ship as she, and what's more they talk naturally of the 'life and death of a ship,' and I can tell you, sir, if you had ever seen a ship fight for her life and go down to her death, you would say they were right. Mr. Hatton, there is no sadder sight than a ship giving up the fight, because further fight is useless. Once I was present at the death of a ship. I pray God that I may never see the like again. Her captain and her men had left her alone, and from the boats standing abaft, they silently watched her sinking. Sir, many a man dies in his bed with all his kin around, and does not carry as much love with him as she did. Why-a! The thought of that hour brings a pain to my heart yet—and it is thirty years ago."

"You are a true sailor, Captain."

"To be sure I am. As the Fife men say, 'I was born with the sea in my mouth.' I thank God for it! Often I have met Him on the great deep, for 'His path is on the waters.' I don't believe I would have found Him as easy and as often, in a cotton-spinning factory—no, I don't!"

"A good man like you, Captain, ought to have a wife and a home."

"I'm not sure of that, Mr. Hatton. On my ship at sea I am lord and master, and my word is law as long as I stop at sea. If any man does not like my word and way, he can leave my ship at the first land we touch, and I see that he does so. But it is different with a wife. She is in your house to stay, whether you like it or not. All you have is hers if you stick to the marriage vow. Yes, sir, she even takes your name for her own, and if she does not behave well with it, you have to take the blame and the shame, whether you deserve it or not. It is a one-sided bargain, sir."

"Not always as bad as that, Captain."

"Why, sir, your honored father, who lorded it over every man he met and contradicted everything he didn't like, said, 'Yes, my dear,' to whatever Mrs. Hatton desired or declared. I hed to do the same thing in my way, and Mrs. Hatton on board this yacht was really her captain. I'm not saying but what she was a satisfactory substitute, for she hed the sense to always ask my advice."

"Then she acted under orders, Captain."

"To be sure. But I am Captain Lance Cook, of Whitby, a master navigator, a fourth in direct line from Captain James Cook, who sailed three times round the world, when that was a most uncommon thing to do. And every time he went, he made England a present of a few islands. Captain James Cook made his name famous among Englishmen of the sea, and I hevn't come across the woman yet I considered worthy to share it."

"You may meet her soon now, Captain. There is a 'new woman' very much the fashion these days. Perhaps you have not seen her yet."

"I have seen her, sir. I have seen all I want to see of her. She appears to hev got the idea into her head that she ought to hev been a man, and some of them have got so far in that direction that you are forced to say that in their dress and looks there isn't much difference. However, I hev heard very knowing men declare they always found the old woman in all her glory under the new one, and I wouldn't wonder if that was the case. What do you think, Mr. Hatton?"

"It may be, Captain, that it is the 'new man' that is wanted, and not the 'new woman.' I think most men are satisfied with the old woman. I am sure I am," and his eyes filled with light, and he silently blessed the fair woman who came into his memory ere he added, "but then, I have not a great ancestor's name to consider. The Hattons never gave anything in the way of land to England."

"They hev done a deal for Yorkshire, sir."

"That was their duty, and their pleasure and profit. Yorkshire men are kinsmen everywhere. If I met one in Singapore, or Timbuctoo, I would say 'Yorkshire?' and hold out my hand to him."

"Well, sir, I've seen Yorkshire men I wouldn't offer my hand to; I hev that, and sorry I am to say it! I never was in Singapore harbor, and I must acknowledge I never saw or heard tell of Timbuctoo harbor."

John laughed pleasantly. "Timbuctoo is in Central Africa. It was just an illustration."

"Illustration! You might have illustrated with a true harbor, sir—for instance, New York."

"You are right. I ought to have done so."

"Well, sir, it's hard to illustrate and stick to truth. There is the boatswain's whistle! I must go and see what's up. Pentland Firth is ever restless and nobody minds that, but she gets into sudden passions which need close watching, and I wouldn't wonder if there was not now signs of a Pentland tantrum."

The Captain's supposition was correct. In a few minutes the ship was enveloped in a livid creeping mist, and he heard the Captain shout, "All hands stand by to reef!" Reef they did, but Pentland's temper was rapidly rising, and in a few minutes there was an impetuous shout for the storm jib, "Quick," and down came a blast from the north, and with a rip and a roar the yacht leaped her full length. If her canvas had been spread, she would have gone to the bottom; but under bare masts she came quickly and beautifully to her bearings, shook herself like a gull, and sped southward.

All night they were beating about in a fierce wind and heavy sea; and Hatton, lying awake, listened to the mysterious hungering voice of the waves, till he was strangely sad and lonely. And there was no Captain to talk with, though he could hear his hoarse, strong voice above the roar of wind and waters. For the sea was rising like the gable of a house, but the yacht was in no trouble; she had held her own in far worse seas. In the morning the sky was of snaky tints of yellow and gray, but the wind had settled and the waves were flatting; but John saw bits of trailing wreckage floating about their black depths, making the Firth look savagely haggard.

On the second evening the Captain came to eat his dinner with John. "The storm is over, Mr. Hatton," he said. "The sea has been out of her wits, like an angry woman; but," he added with a smile, "we got the better of her, and the wind has gone down. There is not breeze enough now to make the yacht lie over."

"I could hear your voice, strong and cheerful, above all the uproar, Captain, so I had no fear."

"We had plenty of sea room, sir, a good boat, and—"

"A good captain."

"Yes, sir, you may say that. The Pentland roared and raged a bit, but the sea has her Master. She hears a voice we cannot hear. It says only three words, Mr. Hatton, three words we cannot hear, but a great calm follows them."

"And the three words are—?"

"Peace! Be still!"

Then John Hatton looked with a quick understanding into his Captain's face, and answered with a confident smile,

The Sailor of the Lake of Galilee."

"I hope, and I believe so, sir. I have been in big storms, and felt it."

"I got a glimpse of you in a flash of lightning that I shall never forget, Captain Cook. You were standing by the wheel, tightening your hat on your head; your feet were firm on the rolling deck, and you were searching the thickest of the storm with a cheerful, confident face. Do you like a storm?"

"Well, sir, smooth sea-sailing is no great pleasure. I would rather see clouds of spray driving past swelling sails, than feel my way through a nasty fog. Give me a sea as high as a masthead, compact as a wall, and charging with the level swiftness of a horse regiment, and I would rather take a ship through it, than make her cut her way through a thick, black fog, as if she was a knife. In a storm you see what you are doing, and where you are going, but you hev to steal and creep and sneak through a fog, and never know what trap or hole may be ahead of you. I know the sea in all her ways and moods, sir. Some of them are rather trying. But my home and my business is on her, and in her worst temper she suits me better than any four-walled room, where I would feel like a stormy petrel shut up in a cage. The sea and I are kin. I often feel as if I had tides in my blood that flow and ebb with her tides."

"I would not gainsay you, Captain. Every man's blood runs as he feels. You were a different man and a grander man when you were guiding the yacht through the storm than you are sitting here beside me eating and drinking. My blood begins to flow quick when I go into big rooms filled with a thousand power looms. Their noise and clatter is in my ears a song of praise, and very often the men and women who work at them are singing grandly to this accompaniment. Sometimes I join in their song, as I walk among them, for the Great Master hears as well as sees, and though these looms are almost alive in their marvelous skill, it may be that He is pleased to hear the little human note mingling with the voices of the clattering, humming, burring looms."

"To be sure He is. The song of labor is His, and I hev no doubt it is quite as sweet in His ear as the song of praise. Your song is among the looms, and mine is among the winds and waves, but they are both the same, sir. It is all right. I'm sure I'm satisfied."

"How you do love the sea, Captain!"

"To be sure, I was born on it and, please God, I hope my death may be from it and my grave in it, nearby some coast where the fisher-folk live happily around me."

There was a few moments' silence, then John Hatton asked, "Are we likely to have fine weather now?"

"Yes, sir, middling fine, until we pass Peterhead. At Aberdeen and southward it may be still finer, and you might have a grand sail along the east coast of Scotland and take a look at some of its famous towns."

This pleasant prospect was amply verified. It was soon blue seas and white sea-birds and sunny skies, with a nice little whole-sail breeze in the right direction. But John was not lured by any of the storied towns of the east coast. "What time I can now spare I will give to Edinburgh," he said, in answer to the Captain's suggestion concerning St. Andrews, Aberdeen, Anstruther and Largo. "I am straight for Edinburgh now. I feel as if my holiday was over. I heard the clack of the looms this morning. They need me, I dare say. I suppose we can be in Leith harbor by Saturday night, Captain?"

"It may be Sunday, sir, if this wind holds. It is an east-windy west-windy coast, and between here and Edinburgh the wind doesn't know its own mind an hour at a time."

"Well, then, say Sunday. I will stay a few days in Edinburgh, and then it must be Whitby and home."

It was Sunday afternoon when the yacht was snug in Leith harbor, and the streets of Edinburgh were full of congregations returning home from the different churches. He went to an hotel on Prince Street and ordered a good dinner spread in his sitting-room. It was a large outlooking apartment, showing him in the glorious sunset the Old Town piled as by a dreamer, story over story, and at the top of this dream-like hill, the gray ancient castle with bugles and the roll of drums sounding behind its ramparts. Bridges leaped across a valley edged with gardens connecting the Old Town with the New Town. Wherever his eyes fell, all was romance and memories of romance, a magically

Waited upon by hills,

River, and wide-spread ocean; tinged

By April light, or draped and fringed

As April vapor wills.

Hanging like some vast Cyclops' dream

High in the shifting weather gleam.

After dinner he sat at the open window, thinking of many things, until he finally fell asleep to dream of that illuminated vault in the castle, in which glitters mysteriously the crown and scepter of the ancient kings and queens of Scotland.

Into the glamour of this vision there came suddenly a dream of his mother, and his home, and he awakened from it with an intense conviction that his mother needed his presence, and that he must make all haste to reach his home. In half an hour he had paid his bill and taken a carriage for Leith harbor, and the yacht was speeding down the Firth ere the wan, misty daylight brightened the colorless sea. The stillness of sea and sky was magical and they were a little delayed by the calm, but in due time the wind sprang up suddenly and the yacht danced into Whitby harbor.

Then John parted from Captain Cook, saying as he did so, "Good-bye, Captain. We have had a happy holiday together. Get the yacht in order and revictualed, for in two weeks my brother Henry may join you. I believe he is for the south."

"Good-bye, sir. It has been a good time for me. You have been my teacher more than my master, and you are a rich man and I am a poor one."

"A man's a man for all that, Captain."

"Well, sir, not always. Many are not men in spite of all that. God be with you, sir."

"And with you, Captain." Then they clasped hands and turned away, each man where Duty called him.

CHAPTER II

THE PEOPLE OF THE STORY

Swings our life in its weary way;

Now at its ebb, and now at its flow,

And the evening and morning make up the day.

Fear and rejoicing its moments know;

Yet from the discords of such a life,

The clearest music of heaven may flow.

Duty led John Hatton to take the quickest road to Hatton-in-Elmete, a small manufacturing town in a lovely district in Yorkshire. In Saxon times it was covered with immense elm forests from which it was originally called Elmete, but nearly a century ago the great family of Hatton (being much reduced by the passage of the Reform Bill and their private misfortunes) commenced cotton-spinning here, and their mills, constantly increasing in size and importance, gave to the Saxon Elmete the name of Hatton-in-Elmete.

The little village had become a town of some importance, but nearly every household in it was connected in some way or other with the cotton mills, either as cotton masters or cotton operatives. There were necessarily a few professional men and shopkeepers, but there was street after street full of cotton mills, and the ancient manor of the lords of Hatton had become thoroughly a manufacturing locality.

But Hatton-in-Elmete was in a beautiful locality, lying on a ridge of hills rising precipitously from the river, and these hills surrounded the town as with walls and appeared to block up the way into the world beyond. The principal street lay along their base, and John Hatton rode up it at the close of the long summer day, when the mills were shut and the operatives gathered in groups about its places of interest. Every woman smiled at him, every man touched his cap, but a stranger would have noticed that not one man bared his head. Yorkshire men do not offer that courtesy to any man, for its neglect (originally the expression of strong individuality and self-respect) had become a habit as natural and spontaneous as their manner or their speech.

About a mile beyond the town, on the summit of a hill, stood Hatton Hall, and John felt a hurrying sense of home as soon as he caught a glimpse of its early sixteenth-century towers and chimneys. The road to it was all uphill, but it was flagged with immense blocks of stone and shaded by great elm-trees; at the summit a high, old-fashioned iron gate admitted him into a delightful garden. And in this sweet place there stood one of the most ancient and picturesque homes of England.

It is here to be noticed that in the early centuries of the English nation the homes of the nobles distinctly represented local feeling and physical conditions. In the North they generally stood on hillsides apart where the winds rattled the boughs of the surrounding pines or elms and the murmur of a river could be heard from below. The hill and the trees, the wind and the river, were their usual background, with the garden and park and the great plantations of trees belting the estate around; the house itself standing on the highest land within the circle.

Such was the location and adjuncts of the ancient home of the Hattons, and John Hatton looked up at the old face of it with a conscious love and pride. The house was built of dark millstone grit in large blocks, many of them now green and mossy. The roof was of sandstone in thin slabs, and in its angles grass had taken root. In front there was a tower and tall gables, with balls and pinnacles. The principal entrance was a doorway with a Tudor arch, and a large porch resting on stone pillars. Within this porch there were seats and a table, pots of flowers, and a silver Jacobean bell. And all round the house were gables and doorways and windows, showing carvings and inscriptions wherever the ivy had not hid them.

The door stood wide open and in the porch his mother was sitting. She had a piece of old English lace in her hand, which she was carefully darning. Suddenly she heard John's footsteps and she lifted her head and listened intently. Then with a radiant face she stood upright just as John came from behind the laurel hedge into the golden rays of the setting sun, and her face was transfigured as she called in a strong, joyful voice,

"O John! John! I've been longing for you days and days. Come inside, my dear lad. Come in! I'll be bound you are hungry. What will you take? Have a cup of tea, now, John; it will be four hours before suppertime, you know."

"Very well, mother. I haven't had my tea today, and I am a bit hungry."

"Poor lad! You shall have your tea and a mouthful in a few minutes."

"I'll go to my room, mother, and wash my face and hands. I am not fit company for a dame so sweet as you are," and he lifted his right hand courteously as he passed her.

In less than half an hour there was tea and milk, cold meat and fruit before John, and his mother watched him eating with a beaming satisfaction. And when John looked into her happy face he wondered at his dream in Edinburgh, and said gratefully to himself,

"All is right with mother. Thank God for that!"

She did not talk while John was eating, but as he sat smoking in the porch afterwards, she said,

"I want to ask you where you have been all these weeks, John, but Harry isn't here, and you won't want to tell your story twice over, will you, now?"

"I would rather not, mother."

"Your father wouldn't have done it, whether he liked to or not. I don't expect you are any different to father. I didn't look for you, John, till next week."

"But you needed me and wanted me?"

"Whatever makes you say that?"

"I dreamed that you wanted me, and I came home to see."

"Was it last Sunday night?"

"Yes."

"About eleven o'clock?"

"I did not notice the time."

"Well, for sure, I was in trouble Sunday. All day long I was in trouble, and I am in a lot of trouble yet. I wanted you badly, John, and I did call you, but not aloud. It was just to myself. I wished you were here."

"Then yourself called to myself, and here I am. Whatever troubles you, mother, troubles me."

"To be sure, I know that, John. Well, then, it is your brother Harry."

A look of anxiety came into John's face and he asked in an anxious voice, "What is the matter with Harry? Is he well?"

"Then what has he been doing?"

"Nay, it's something he wants to do."

"He wants to get married, I suppose?"

"Nay, I haven't heard of any foolishness of that make. I'll tell you what he wants to do—he wants to rent his share in the mill to Naylor's sons."

Then John leaped to his feet and said angrily, "Never! Never! It cannot be true, mother! I cannot believe it! Who told you?"

"Your overseer, Jonathan Greenwood, and Harry asked Greenwood to stand by him in the matter, but Jonathan wouldn't have anything to do with such business, and he advised me to send for you. He says the lad is needing looking after—in more ways than one."

"Where is Harry?"

"He went to Manchester last Saturday."

"What for, mother?"

"I don't know for certain. He said on business. You had better talk with Jonathan. I didn't like the way he spoke of Harry. He ought to remember his young master is a bit above him."

"That is the last thing Jonathan would remember, but he is a good-hearted, straight-standing man."

"Very, if you can believe in his words and ways. He came here Saturday to insinuate all kinds of 'shouldn't-be's' against Harry, and then on Sunday he was dropping his 'Amens' about the chapel so generously I felt perfectly sure they were worth nothing."

"Well, mother, you may trust me to look after all that is wrong. Let not your heart be troubled. I will talk with Jonathan in the morning."

"Nay, I'll warrant he will be here tonight. He will have heard thou art home, and he will be sure he is wanted before anybody else."

"If he comes tonight, tell him I cannot see him until half-past nine in the morning."

"That is right—but what for?"

"Because I am much troubled and a little angry. I wish to get myself in harness before I see anyone."

"Well, you know, John, that Harry never liked the mill, but while father lived he did not dare to say so. Poor lad! He hated mill life."

"He ought at least to remember what his grandfather and father thought of Hatton Mill. Why, mother, on his twenty-first birthday, father solemnly told him the story of the mill and how it was the seal and witness between our God and our family—yet he would bring strangers into our work! I'll have no partner in it—not the best man in England! Yet Harry would share it with the Naylors, a horse-racing, betting, irreligious crowd, who have made their money in byways all their generations. Power of God! Only to think of it! Only to think of it! Harry ought to be ashamed of himself—he ought that."

"Now, John, my dear lad, I will not hear Harry blamed when he is not here to speak for himself—no, I will not! Wait till he is, and it will be fair enough then to say what you want to. I am Harry's mother, and I will see he gets fair play. I will that. It is my bounden duty to do so, and I'll do it."

"You are right, mother, we must all have fair judgment, and I will see that the brother I love so dearly gets it."

"God love thee, John."

"And, mother, keep a brave and cheerful heart. I will do all that is possible to satisfy Harry."

"I can leave him safely with God and his brother. And tomorrow I can now look after the apricot-preserving. Barker told me the fruit was all ready today, but I could not frame myself to see it properly done, but tomorrow it will be different." Then because she wanted to reward John for his patience, and knowing well what subject was close to his heart, she remarked in a casual manner,

"Mrs. Harlow was here yesterday, and she said her apricots were safely put away."

"Was Miss Harlow with her?"

"No. There was a tennis game at Lady Thirsk's. I suppose she was there."

"Have you seen her lately?"

"She took tea with me last Wednesday. What a beauty she is! Such color in her cheeks! It was like the apricots when the sun was on them. Such shining black hair so wonderfully braided and coiled! Such sparkling, flashing black eyes! Such a tall, splendid figure! Such a rosy mouth! It seemed as if it was made for smiles and kisses."

"And she walks like a queen, mother!"

"She does that."

"And she is so bright and independent!"

"Well, John, she is. There's no denying it."

"She is finely educated and also related to the best Yorkshire families. Could I marry any better woman, mother?"

"Well, John, as a rule men don't approve of poor wives, but Miss Jane Harlow is a fortune in herself."

"Two months ago I heard that Lord Thirsk was very much in love with her. I saw him with her very often. I was very unhappy, but I could not interfere, you know, could I?"

"So you went off to sea, and left mother and Harry and your business to anybody's care. It wasn't like you, John."

"No, it was not. I wanted you, mother, a dozen times a day, and I was half-afraid to come back to you, lest I should find Miss Jane married or at least engaged."

"She is neither one nor the other, or I am much mistaken. Whatever are you afraid of? Jane Harlow is only a woman beautiful and up to date, she is not a 'goddess excellently fair' like the woman you are always singing about, not she! I'm sure I often wonder where she got her beauty and high spirit. Her father was just a proud hanger-on to his rich relations; he lived and died fighting his wants and his debts. Her mother is very near as badly off—a poor, wuttering, little creature, always fearing and trembling for the day she never saw."

"Perhaps this poverty and dependence may make her marry Lord Thirsk. He is rich enough to get the girl he wants."

"His money would not buy Jane, if she did not like him; and she doesn't like him."

"How do you know that, mother?"

"I asked her. While we were drinking our tea, I asked her if she were going to make herself Lady Thirsk. She made fun of him. She mocked the very idea. She said he had no chin worth speaking of and no back to his head and so not a grain of forthput in him of any kind. 'Why, he can't play a game of tennis,' she said, 'and when he loses it he nearly cries, and what do you think, Mrs. Hatton, of a lover like that?' Those were her words, John."

"And you believe she was in earnest?"

"Yes, I do. Jane is too proud and too brave a girl to lie—unless——"

"Unless what, mother?"

"It was to her interest."

"Tell me all she said. Her words are life or death to me."

"They are nothing of the kind. Be ashamed of yourself, John Hatton."

"You are right, mother. My life and death are by the will of God, but I can say that my happiness or wretchedness is in Jane Harlow's power."

"Your happiness is in your own power. Her 'no' might be a disappointment in hours you weren't busy among your looms and cotton bales, or talking of discounts and the money market, but its echo would grow fainter every hour of your life, and then you would meet the other girl, whose 'yes' would put the 'no' forever out of your memory."

"Well, mother, you have given me hope, and I have been comforted by you 'as one whom his mother comforteth.' If the dear girl is not to be won by Thirsk's title and money, I will see what love can do."

"I'll tell you, John, what love can do"—and she went to a handsome set of hanging book shelves containing the favorite volumes of Dissent belonging to John's great-grandfather, Burnet, Taylor, Doddridge, Wesley, Milton, Watts, quaint biographies, and books of travel. From them she took a well-used copy of Taylor's "Holy Living and Dying," and opening it as one familiar with every page, said,

"Listen, John, learn what Love can do.

"Love solves where learning perplexes. Love attracts the best in every one, for it gives the best, Love redeemeth, Love lifts up, Love enlightens, Love hath everlasting remembrance, Love advances the Soul, Love is a ransom, and the tears thereof are a prayer. Love is life. So much Love, so much Life. Oh, little Soul, if rich in Love, thou art mighty."

"My dear mother, thank you. You are best of all mothers. God bless you."

"Your father, John, was a man of few words, as you know. He copied that passage out of this very book, and he wrote after it, 'Martha Booth, I love you. If you can love me, I will be at the chapel door after tonight's service, then put your hand in mine, and I will hope to give you hand and heart and home as long as I live.' And for years he kept his word, John—he did that!"

"Father always kept his word. If he but once said a thing, no power on earth could make him unsay it. He was a handsome, well-built man."

"Well, then, what are you thinking of?"

"I was thinking that Lord Thirsk is, by the majority of women, considered handsome."

"What kind of women have that idea?"

"Why, mother, I don't exactly know. If I go into my tailor's, I am told about his elegant figure, if into my shoemaker's, I hear of his small feet, if to Baylor's glove counter, some girl fitting my number seven will smilingly inform me that Lord Thirsk wears number four. And if you see him walking or driving, he always has some pretty woman at his side."

"What by all that? His feet are fit for nothing but dancing. He could not take thy long swinging steps for a twenty-mile walk; he couldn't take them for a dozen yards. His hands may be small enough, and white enough, and ringed enough for a lady, but he can't make a penny's worth with them. I've heard it said that if he goes to stay all night with a friend he has to take his valet with him—can't dress himself, I suppose."

"He is always dressed with the utmost nicety and in the tip-top of the fashion."

"I'll warrant him. Jane told me he wore a lace cravat at the Priestly ball, and I have no doubt that his pocket handkerchief was edged with lace. And yet she said, 'No woman there laughed at him.'"

"At any rate he has fine eyes and hair and a pleasant face."

"I wouldn't bother myself to deny it. If anyone fancies curly hair and big brown eyes and white cheeks and no chin to speak of and no feet fit to walk with and no hands to work with, it isn't Martha Hatton and it isn't Jane Harlow, I can take my affidavit on that," and the confident smile which accompanied these words was better than any sworn oath to John Hatton.

"You see, John," she continued, "I talked the man up and down with Jane, from his number four gloves to his number four shoes, and I know what she said—what she said in her own way, mind you. For Jane's way is to pretend to like what she does not like, just to let people feel the road to her real opinions."

"I do not quite understand you, mother."

"I don't know whether I quite understand myself, and it isn't my way to explain my words—people usually know what I mean—but I will do it for once, as John Hatton is wanting it. For instance, I was talking to Jane about her lovers—I did not put you among them—and she said, 'Mrs. Hatton, there are no lovers in these days. The men that are men are no longer knights-errant. They don't fight in the tournament lists for their lady-love, nor even sing serenades under her window in the moonlight. We must look for them,' she said, 'in Manchester warehouses, or Yorkshire spinning-mills. The knights-errant are all on the stock exchange, and the poets write for Punch.' And I could not help laughing, and she laughed too, and her laugh was so infectious I could not get clear of it, and so poured my next cup of tea on the tea board."

"I wish I had been present."

"So do I, John. Perhaps then you would have understood the contradictious girl, as well as I did. You see, she wanted me to know that she preferred the Manchester warehouse men, and the Yorkshire spinners, and the share-tumblers of the stock exchange to knights and poets and that make of men. Now, some women would have said the words straightforward, but not Jane. She prefers to state her likings and dislikings in riddles and leave you to find out their meaning."

"That is an uncomfortable, uncertain way."

"To be sure it is, but if you want to marry Jane Harlow, you had better take it into account. I never said she was perfect."

"If ever she is my wife, I shall teach her very gently to speak straightforward words."

"Then you have your work set, John. Whether you can do it or not, is a different thing. I don't want you to marry Jane Harlow, but as you have set your heart on her, I have resolved to make the most of her strong points and the least of her weak ones. You had better do the same."

There was silence for a few moments, then John asked, "Was that all, mother?"

"We had more to say, but it was of a personal nature—I don't think it concerns you at present."

"Nay, but it does, mother. Everything connected with Jane concerns me."

Mrs. Hatton appeared reluctant to speak, but John's anxiety was so evident, she answered, "Well, then, it was about my children."

"What about them?"

"She said she had heard her mother speak of my 'large family' and yet she had never seen any of them but Henry and yourself. She wondered if her mother had been mistaken. And I said, 'Nay, your mother told the truth, thank God!'

"'You see,' she continued, 'I was at school until a year ago, and our families were not at all intimate.' I said, 'Not at all. Your father was a proud man, Miss Harlow, and he would not notice a cotton-spinner on terms of social equality. And Stephen Hatton thought himself as good as the best man near him. So he was. And no worse for the mill. It kept up the Hall, so it did.' She said I was right, and would I tell her about my children."

"I hope you did, mother. I do hope you did."

"Why not? I am proud of them all, living or dead—here or there. So I said, 'Well, Miss Harlow, John is not my firstborn. There was a lovely little girl, who went back to God before she was quite a year old. People said I ought to think it a great honor to give my first child to God, but it was a great grief to me. Soon after her death John was born, and after John came Clara Ann. She married before she was eighteen, a captain of artillery in the army, and she has ever since been with him in India, Africa, or elsewhere. Then I had Stephen, who is now a well-known Manchester warehouse man and seldom gets away from his business. Then Paul was given to me. He is a good boy, and a fine sailor. His ship is the Ajax, a first-class line of battleship. I see him now and then and get a letter from every port he touches. Then came Harry, who served an apprenticeship with his father, but never liked the mill; and at last, the sweetest gift of all God's gifts, twin daughters, called Dora and Edith. They lived with us nearly eight years, and died just before their father. They were born in the same hour and died within five minutes of each other. The Lord gave them, and the Lord took them away, and blessed be the name of the Lord!' This is about what I said, John."

The conversation was interrupted here, by the entrance of a parlor-maid. She said, "Sir, Jonathan Greenwood is here to ask if you can see him this evening."

"Tell him I cannot. I will see him at the mill about half-past nine in the morning."

The girl went away, but returned immediately. "Jonathan says, sir, that will do. He wants to go to a meeting tonight, sir." Then Mrs. Hatton looked at her son, and exclaimed, "How very kind of your overseer to make your time do! Is that his usual way?"

"About it. He is a very independent fellow, and he knows no other way of talking. But father found it worth his while to put up with his free speech. Jonathan has a knowledge of manufactures and markets which enables him to protect our interests, and entitles him to speak his mind in his own way."

"I'm glad the same rule does not go in my kitchen. I have a first-class cook, but if she asked me for a holiday and I gave her two days and she said nothing but, 'That will do,' I would tell her to her face I was giving her something out of my comfort and my pocket, and not something that would only 'do' in the place of what she wanted. I would show her my side of the question. I would that."

"For what reason?"

"I would be doing my duty."

"Well, mother, you could not match her and the bits of radicalism she would give you. Keep the peace, mother; you have not her weapons in your armory."

"I am just talking to relieve myself, John. I know better than to fratch with anyone—at least I think I do."

"Just before I went away, mother, Jonathan came to me and said, 'Sir, I hev confidence in human nature, generally speaking, but there's tricks and there's turns, and if I was you I would run no risks with them Manchester Sulbys'. Then he put the Sulby case before me, and if I had not taken his advice, I would have lost three hundred pounds. It is Jonathan's way to love God and suspect his neighbor."

"He will find it hard to do the two things at the same time, John."

"I do not understand how John works the problem, mother, but he does it at least to his own satisfaction. He has told us often in the men's weekly meeting that he is 'safe religiously, and that all his eternal interests are settled,' but I notice that he trusts no man until he has proved him honest."

"I don't believe in such Christians, John, and I hope there are not very many of the same make."

"Indeed, mother, this union of a religious profession with a sharp worldly spirit is the common character among our spinners. Jonathan has four sons, and he has brought every one of them up in the same way."

"One of the four got married last week—married a girl who will have a factory and four hundred looms for her fortune—old Aker's granddaughter, you know."

"Yes, I know. Jonathan told me about it. He looked on the girl as a good investment for his family, and discussed her prospects just as he would have discussed discounts or the money market."

Then John went to look after the condition of the cattle and horses on the home farm. He found all in good order, told the farmer he had done well, and made him happy with a few words of praise and appreciation. But he said little to Mrs. Hatton on the subject, for his thoughts were all close to the woman he loved. As they sat at supper he continually wondered about her—where she was, what she was doing, what company she was with, and even how she was dressed.

Mrs. Hatton did not always answer these queries satisfactorily. In fact, she was a little weary of "dear Jane," and had already praised her beyond her own judgment. So she was not always as sympathetic to this second appeal for information as she might have been.

"I'll warrant, John," she answered a little judicially, "that Jane is at some of the quality houses tonight; and she'll be singing or dancing or playing bridge with one or other of that pale, rakish lot I see when I drive through the town."

"Mother!"

"Yes, John, a bad, idle, lounging lot, that don't do a day's work to pay for their living."

"They are likely gentlemen, mother, who have no work to do."

"Gentlemen! No, indeed! I will give them the first four letters of the word—no more. They are not gentlemen, but they may be gents. We don't expect much from gents, and how the women of today stand them beats me."

John laughed a little, but he said he was weary and would go to his room. And as he stood at Mrs. Hatton's side, telling her that he was glad to be with her again, she found herself in the mood that enabled her to say,

"John, my dear lad, you will soon marry, either Jane or some other woman. You must do it, you know, for you must have sons and daughters, that you may inherit the promise of God's blessing which is for you and your children. Then your family must have a home, but not in Hatton Hall—not just yet. There cannot be two mistresses in one house, can there?"

"No, but by my father's will and his oft-repeated desire, this house is your home, mother, as long as you live. I am going to build my own house on the hill, facing the east, in front of the Ash plantation."

"You are wise. Our chimneys will smoke all the better for being a little apart."

"And you, my mother, are lady and mistress of Hatton Hall as long as you live. I will suffer no one to infringe on your rights." Then he stooped his handsome head to her lifted face and kissed it with great tenderness; and she turned away with tears in her eyes, but a happy smile on her lips. And John was glad that this question had been raised and settled, so quickly, and so lovingly.

CHAPTER III

LOVE VENTURES IN

Our fortunes meet us.

John had been thinking about building his own home for some time and he resolved to begin it at once. Yet this ancient Hatton Hall, with its large, low rooms, its latticed windows and beautifully carved and polished oak panelings, was very dear to him. Every room was full of stories of Cavaliers and Puritans. The early followers of George Fox had there found secret shelter and hospitality. John Wesley had preached in its great dining-room, and Charles Wesley filled all its spaces and corridors with the lyrical cry of his wonderful hymns. There were harmless ghosts in its silent chambers, or walking in the pale moonlight up the stairs or about the flower garden. No one was afraid of them; they only gave a tender and romantic character to the surroundings. If Mrs. Hatton felt them in a room, she curtsied and softly withdrew, and John, on more than one occasion, had asked, "Why depart, dear ghosts? There is room enough for us all in the old house."

But for all this, and all that, it did not answer the spirit of John's nature and daily life. He was essentially a man of his century. He loved large proportions and abundance of light and fresh air, and he dreamed of a home of palatial dimensions with white Ionic pillars and wide balconies and large rooms made sunny by windows tall enough for men of his stature to use as doors if they so desired. It was to be white as snow, with the Ash plantation behind it and gardens all around and the river washing their outskirts and telling him as he sat in the evenings—with Jane at his side—where it had come from and what it had seen and heard during the day.

He went to sleep in this visionary house and did not awaken until the sun was high up and hurrying men and women to work. So he rose quickly, for he counted himself among this working-class, felt his responsibilities, and began to reckon with the difficulties he had to meet and the appointments he could not decline. He had promised to see his overseer at half-past nine, and he knew Jonathan would have a few disagreeable words ready, if he broke his promise—words it was better to avoid than to notice or discount.

At half-past eight he was ready to ride to the mill. His gig was waiting, but he chose his saddle horse, because the creature so lovingly neighed and neighed to the sound of his approaching footsteps, evidently rejoicing to see him, and pawing the ground with his impatience to feel him in the saddle. John could not resist the invitation. He sent the uncaring gig away, laid his arm across Bendigo's neck, and his cheek against Bendigo's cheek. Then he whispered a few words in his ear and leaped into the saddle as only a Yorkshireman or a gypsy can leap, and Bendigo, thrilling with delight, carried his master swiftly away from the gig and its driver, neighing with triumph as he passed them.

When about halfway to the mill he met Miss Harlow returning home from her early morning walk. She was dressed with extreme simplicity in a short frock of pink corduroy, and a sailor hat of coarse Dunstable straw, with a pink ribbon round it. Long, soft, white leather gauntlets covered her hands, and she carried in them a little basket of straw, full of bluebells and ferns. John saw her approaching and he noticed the lift of her head and the lift of her foot and said to himself, "Proud! Proud!" but in his heart he thought no harm of her stately, graceful carriage. To him she was a most beautiful girl, fresh and fair and,

That sniffs the forest air,

Bringing the smell of the heather bell,

In the tresses of her hair.

They met, they clasped hands, they looked into each other's eyes, and something sweet and subtle passed between them. "I am so glad, so glad to see you," said John, and Miss Harlow said the same words, and then added, "Where have you been? I have missed you so much."

"And, Oh, how happy I am to hear that you have missed me! I have been away to the North—on the road to Iceland. May I call on you this evening, and tell you about my journey?"

"Yes, indeed! If you will pleasure me so far, I will send an excuse to Lady Thirsk, and stay at home to listen to you."

"That would be a miraculous favor. May I come early?"

"We dine early. Come and take your dinner with us. Mother will be glad to see you and to hear your adventures, and mother's pleasure is my greatest happiness."

"Then I will come."

As he spoke, he took out his watch and looked at it. "I have an engagement in ten minutes," he said. "Will you excuse me now?"

"I will. I wish I had an engagement. Poor women! They have bare lives. I would like to go to business. I would like to make money. There are days in which I feel that I could run a thousand spindles or manage a department store very well and very happily."

"Why do you talk of things impossible? Good-bye!"

"Until seven o'clock?"

He had dismounted to speak to her and, holding Bendigo's bridle, had walked with her to the Harlow residence. He now said, "Good-bye," and the light of a true, passionate lover was on his face, as he leaped into the saddle. She watched him out of sight and then went into her home, and with an inscrutable smile, began to arrange the ferns and bluebells in a vase of cream-colored wedgewood.

In the meantime John had reached the Hatton mill, and after his long absence he looked up at it with conscious pride. It was built of brick; it was ten stories high; every story was full of windows, every story airy as a bird-cage. Certainly it was not a thing of architectural beauty, but it was a grandly organized machine where brains and hands, iron and steel worked together for a common end. As John entered its big iron gates, he saw bales of cotton going into the mill by one door, and he knew the other door at which they would come out in the form of woven calico. In rapid thought he followed them to the upper floors, and then traveled down with them to the great weaving-rooms in the order their processes advanced them. He knew that on the highest floor a devil would tear the fiber asunder, that it would then go to the scutcher, and have the dust and dirt blown away, then that carding machines would lay all the fibers parallel, that drawing machines would group them into slender ribbons, and a roving machine twist them into a soft cord, and then that a mule or a throstle would spin the roving into yarn, and the yarn would go to the weaving-rooms, where a thousand wonderful machines would turn them into miles and miles of calico; the machines doing all the hard work, while women and girls adjusted and supplied them with the material.

It was to the great weaving-room John went first. As soon as he stood in the open door he was seen and in a moment, as if by magic, the looms were silenced, and the women and girls were on their feet, looking at him with eager, pleasant faces. John lifted his hat and said good morning and a shout of welcome greeted him. Then at some signal the looms resumed their noisy work and the women lifted the chorus from some opera which they had been singing at John's entrance, and "t' master's visit" was over.

He went next to his office, and Jonathan brought his daybook and described, in particular detail, the commercial occurrences which had made the mills' history during his absence. Not all of them were satisfactory, and John passed nothing by as trivial. Where interferences had been made with his usual known methods, he rebuked and revoked them; and in one case where Jonathan had disobeyed his order he insisted on an apology to the person injured by the transaction.

"I told Clough," he said, "that he should have what credit would put him straight. You, Jonathan, have been discounting and cutting him down on yarns. You had no authority to do this. I don't like it. It cannot be."

"Well, sir, I was looking out for you. Clough will never straight himself. Yarns are yarns, and yarns are up in the market; we can use all we hev ourselves. Clough hes opinions not worth a shilling's credit. They are all wrong, sir."

"His opinions may be wrong, his life is right."

"Why, sir, he's nothing but a Radical or a Socialist."

"Jonathan, I don't bring politics into business."

"You're right, sir. When I see any of our customers bothering with politics, I begin to watch for their names in t' bankruptcy list. Your honorable father, sir, could talk with both Tories and Radicals and fall out with neither. Then he would pick up his order-book, and forget what side he'd taken or whether he hed been on any side or not."

"Write to Clough and tell him you were sorry not to fill his last order. Say that we have now plenty of yarns and will be glad to let him have whatever he wants."

"Very well, sir. If he fails—"

"It may be your fault, Jonathan. The yarns given him when needed, might have helped him. Tomorrow they may be too late."

"I don't look at things in that way, sir."

"Jonathan, how do you look at the Naylors' proposal?"

"As downright impudence. They hev the money to buy most things they want, but they hevn't the money among them all to buy a share in your grand old name and your well-known honorable business. I told Mr. Henry that."

"However did the Naylors get at Mr. Henry?"

"Through horses, sir. Mr. Henry loves horses, and he hes an idea that he knows all about them. I heard Fred Naylor had sold him two racers. He didn't sell them for nothing—you may be sure of that."

"Do you know what Mr. Henry paid for them, Jonathan?"

"Not I, sir. But I do know Fred Naylor; he never did a honest day's work. He is nothing but a betting book in breeches. He bets on everything, from his wife to the weather. I often heard your father say that betting is the argument of a fool—and Jonathan Greenwood is of the same opinion."

"Have you any particular dislike to the Naylors?"

"I dislike to see Mr. Henry evening himself with such a bad lot; every one of them is as worthless as a canceled postage stamp."

"They are rich, I hear."

"To be sure they are. I think no better of them for that. All they hev has come over the devil's back. I hev taken the measure of them three lads, and I know them to be three poor creatures. Mr. Henry Hatton ought not to be counted with such a crowd."

"You are right, Jonathan. In this case, I am obliged to you for your interference. I think this is all we need to discuss at this time."

"Nay, but it isn't. I'm sorry to say, there is that little lass o' Lugur's. You must interfere there, and you can't do it too soon."

"Lugur? Who is Lugur? I never heard of the man. He is not in the Hatton factory, that I know."

"He isn't in anybody's factory. He is head teacher in the Methodist school here."

"Well, what of that?"

"He has a daughter, a little lass about eighteen years old."

"And she is pretty, I suppose?"

"There's none to equal her in this part of England. She's as sweet as a flower."

"And her father is——"

"Hard as Pharaoh. She's the light o' his eyes, and the breath o' his nostrils. So she ought to be. Her mother died when she was two years old, and Ralph Lugur hes been mother and father both to her. He took her with him wherever he went except into the pulpit."

"The pulpit? What do you mean?"

"He was a Methodist preacher, but he left the pulpit and went into the schoolroom. The Conference was glad he did so, for he was little in the way of preaching but he's a great scholar, and I should say he hesn't his equal as a teacher in all England. He has the boys and girls of Hatton at a word. Sir, you'll allow that I am no coward, but I wouldn't touch the hem of Lucy Lugur's skirt, if it wasn't in respect and honor, for a goodish bit o' brass. No, I wouldn't!"

"What would you fear?"

"Why-a! I don't think he'd stop at anything decent. It is only ten days since he halted Lord Thirsk in t' High Street of Hatton, and then told him flat if he sent any more notes and flowers to Miss Lugur, 'Miss,' mind you, he would thrash him to within an inch of his life."

"What did Lord Thirsk say?"

"Why, the little man was frightened at first—and no wonder, for Lugur is big as Saul and as strong as Samson—but he kept his head and told Lugur he would 'take no orders from him.' Furthermore, he said he would show his 'admiration of Miss Lugur's beauty, whenever he felt disposed to do so.' It was the noon hour and a crowd was in the street, and they gathered round—for our lads smell a fight—and they cheered the little lord for his plucky words, and he rode away while they were cheering and left Lugur standing so black and surly that no one cared to pass an opinion he could hear. Indeed, my eldest daughter kept her little lad from school that afternoon. She said someone was bound to suffer for Lugur's setdown and it wasn't going to be her John Henry."

"He seems to be an ill-tempered man—this Lugur, and we don't want such men in Hatton."

"Well, sir, we breed our own tempers in Hatton, and we can frame to put up with them—but strangers!" and Jonathan appeared to have no words to express his suspicion of strangers.

"If Lugur is quarrelsome he must leave Hatton. I will not give him house room."

"You hev a good deal of influence, sir, but you can't move Lugur. No, you can't. Lugur hes been appointed by the Methodist Church, and there is the Conference behind the church, sir. I hev no doubt but what we shall hev to put up with the sulky beggar whether we want it or like it or not."

"It would be a queer thing, Jonathan Greenwood, if John Hatton did not have influence enough to put a troubler of Hatton town out of it. The Methodist Church is too sensible to oppose what is good for a community."

"Sir, you are reckoning your bill without your host. The church would likely stand by you, but all the women would stand by Lugur. And what is queerer still, all his scholars would fight anyone who said a word against him. He hes a way, sir, a way of his own with children, and I hev wondered often what is the secret of it."

"What do you mean?"

"I'll give you an example, sir. You know Silas Bolton hes a very bad lad, but the other day he went to Lugur and confessed he had stripped old Padget's apple-tree. Well, Lugur listened to him and talked to him and then lifted his leather strap and gave him a dozen good licks. The lad never whimpered, and t' master shook hands with him when the bit o' business was over and said, 'You are a brave boy, Will Bolton. I don't think you'll do a mean, cowardly act like that again, and if such is your determination, you can learn me double lessons for tomorrow; then all will be square between you and me'—and Bolton's bad boy did it."

"That was right enough."

"I hevn't quite finished, sir. In two days he went with the boy to tell old Padget he was sorry, and the man forgave him without one hard word; but I hev heard since, that t' master paid for the apples out of his own pocket, and I would not wonder if he did. What do you think of the man now?"

"I think a man like that is very much of a man. I shall make it my business to know him. But what has my brother to do with either Mister or Miss Lugur?"

"Mr. Henry hes been doing just what Lord Thirsk did; he has been sending Lucy Lugur flowers and for anything I know, letters. At any rate I saw them together in Mr. Henry's phaeton on the Lancashire road at ten o'clock in the morning. I was going to Shillingworth's factory, and I stayed there an hour, and as I came back to Hatton, Mr. Henry was just leaving her at Lugur's house door."

"In Byle's cottage at the top of the Brow."

"That was quite out of your way, Jonathan."

"I know it was. I took that road on purpose. I guessed the little woman was out with Mr. Henry, because she knew between ten and eleven o'clock her father was safe in t' schoolroom. Well, I saw Mr. Henry leave her at her own door, and though I doan't believe one-half that I hear, I can trust my own eyes even if I hevn't my spectacles on. And I doan't bother my head about other men's daughters and sweethearts, but Mr. Henry is a bit different. I loved and served his father. I love and serve his brother, and t' young man himself is very easy to love."

John was silent, and Jonathan continued, "I knew I was interfering, but—"

"You were doing your duty. I would thank you for it, but a man that serves Duty gets his wages in the service—and is satisfied."

Jonathan only nodded his head in assent, but there was the pleasant light of accepted favor on his face and he really felt much relieved when John added, "I will have a talk with my brother when he comes home about the Naylors and Miss Lugur. You can dismiss the subject from your mind. I'm sure you have plenty to worry you with the mill and its workers."

"I hev, sir, that I hev, and all the more because Lucius Yorke hes been here while you were away and he left a promise with the lads and lassies to come again and give you a bit of his mind when you bed finished your laking and larking and could at least frame yourself to watch the men and women working for you. Yorke is a sly one—you ought to watch him."

John smiled, dropped his eyes, and began to turn his paper-knife about. "Well, Jonathan," he answered, "when Yorke comes, tell him John Hatton will be pleased to know his mind. I do not think, Jonathan, that he knows it himself, for I have noticed that he has turned his back on his own words several times since he gave me his mind a year ago."

"Well, sir, a man's mind can grow, just as his body grows."

"I know that—but it can grow in a wrong direction as easily as in a right one. Now I must attend to my secretary; he sent me word that there was a large mail waiting."

"I'll warrant it. Mr. Henry hesn't been near the mill since Friday morning," and with these words the overseer lifted his books and records and left the room.

John sat very still with bent head; he shut his eyes and turned them on his heart, but it was not long before his thoughtful face was brightened by a smile as he whispered to himself, "I must hear what Harry has to say before I judge him. Jonathan has strong prejudices, and Harry must have what he considers 'reasonable cause' for what he wishes."

He waited anxiously all morning, going frequently to his brother's office, but it was mid-afternoon when he heard Harry's quick light step on the corridor. His heart beat to the sound, he quickly opened his door, and as he did so, Harry cried,

"John! I am so glad you are here!"

Then John drew the bright handsome lad to his side, and they entered his office together, and as soon as they were alone, John bent to his brother, drew him closer, and kissed him.

"I have been restless and longing to see you, Harry. Where have you been, dear lad?"

It was noticeable that John's tone and attitude was that of a father, more than a brother, for John was ten years older than Harry and through all his boyhood, his youth, and even his manhood he had fought for and watched over and loved him with a fatherly, as well as a brotherly, love. After their father's death, John, as eldest son, took the place and assumed the authority of their father and was by right of birth head of the household and master of the mill.

Hitherto John's authority had been so kind and so thoughtful that Harry had never dreamed of opposing it, yet the brothers were both conscious this afternoon that the old attitude towards each other had suffered a change. Harry showed it first in his dress, which was extravagant and very unlike the respectable tweed or broadcloth common to the manufacturers of the locality. Harry's garb was that of a finished horseman. It was mostly of leather of various colors and grades, from the highly dressed Spanish leather of his long, black boots to the soft, white, leather gauntlets, which nearly covered his arms. He had a leather jockey cap on his head, and a leather whip in his hand, and he gave John a long, loving look, which seemed to ask for his admiration and deprecate, if not dispute, his expected dislike.

For John's looks traveled down the handsome figure, whose hand he still clasped, with evident dismay and dissatisfaction, and Harry retaliated by striking his booted leg with his riding-whip. For an instant they stood thus looking at each other, both of them quite aware of the remarkable contrast they made. Harry's tall, slight form, black hair, and large brown eyes were a vivid antithesis to John's blond blue-eyed strength and comeliness. To her youngest son, Mrs. Hatton, who was a daughter of the Norman house of D'Artoe, had transmitted her quick temperament, her dark beauty, and her elastic grace of movement.

Harry's beauty had a certain local fame; when people spoke of him it was not of Henry Hatton they spoke, they called him "t' young master," or more likely, "that handsome lad o' Hattons." He was more popular and better loved than John, because his temper and his position permitted him a greater familiarity with the hands. They came to John for any solid favor or any necessary information, they came to Harry for help in their ball or cricket games or in any musical entertainment they wished to give. And Harry on such occasions was their fellow playmate, and took and gave with a pleasant familiarity that was never imposed on.

CHAPTER IV

BROTHERS

The pleasant habit of existence, the sweet fable of Life and Love.

With Life all other passions fly,

Love is indestructible.

This afternoon the brothers looked at each other with great love, but there was in it a sense of wariness; and Harry was inclined to bluff what he knew his brother would regard with inconvenient seriousness.

"Will you sit, Harry? Or are you going at once to mother? She is a bit anxious about you."

"I will sit with you half an hour, John. I want to talk with you. I am very unhappy."

"Nay, nay! You don't look unhappy, I'm sure; and you have no need to feel so."

"Indeed, I have. If a man hates his lifework, he is very likely to hate his life. You know, John, that I have always hated mills. The sight of their long chimneys and of the human beings groveling at the bottom of them for their daily bread gives me a heartache. And the smell of them! O John, the smell of a mill sickens me!"

"What do you mean, Harry Hatton?"

"I mean the smell of the vaporous rooms, and the boiling soapsuds, and the oil and cotton and the moisture from the hot flesh of a thousand men and women makes the best mill in England a sweating-house of this age of corruption."

"Harry, who did you hear speak of cotton mills in that foolish way? Some ranter at a street corner, I suppose. Hatton mill brings you in good, honest money. I think little of feelings that slander honest work and honest earnings."

"John, my dear brother, you must listen to me. I want to get out of this business, and Eli Naylor and Thomas Henry Naylor will rent my share of the mill."

"Will they? No! Not for all the gold in England! What are you asking me, Harry Hatton? Do you think I will shame the good name of Hatton by associating it with scoundrels and blacklegs? Your father kicked Hezekiah Naylor out of this mill twenty years ago. Do you think I will take in his sons, and let them share our father's good name, and the profits of the wonderful business he built up? I say no! A downright, upright no! Why, Harry, you must be off your head to think of such a thing as possible. It is enough to make father come back from the grave."

"You are talking nonsense, John. If father is in heaven, he wouldn't come back here about an old mill full of weariness and hatred and wretched lives; and if he isn't in heaven, he wouldn't be let come back. I am not afraid of father now."

"If you must sell or rent your share, I will make shift to buy or lease it. Then what do you mean to do?"

"Mr. Fred Naylor is going to coach me for horse-racing. You know I love horses, and Naylor says they will make me more money than I can count."

"Don't you tell me anything the Naylors say. I won't listen to it. Horse-racing is gambling. You don't come from gamblers. You will be a fool among them and every kind of odds will be against you."

"And I shall make money fast and pleasantly."

"Supposing you do make money fast, you will spend it still faster. That is the truth."

"Horse-racing is a manly amusement. No one can deny that, John."

"But, Harry, you did not come into this world to amuse yourself. You came to do the work God Almighty laid out for you to do. It wasn't horse-racing."

"I know what I am talking about, John."

"Not you. You are cheating and deceiving yourself, and any sin is easy, after that sin."

"I have told you already what I thought of mill work."

"You have not thought right of it. We have nearly eight hundred workers; half of them are yours. It is your duty to see that these men and women have work and wage in Hatton mill."

"I will not do it, John."

"You are not going to horse-racing. I want you to understand that, once and for all. Have no more to do with any of the Naylors. Drop them forever."

"I can not, John. I will not."

"Rule your speech, Henry Hatton. John Hatton is not saying today what he will unsay tomorrow. You are not going to horse-racing and horse-trading. Most men who do so go to the dogs next. People would wonder far and wide. You must choose a respectable life. I know that the love of horses runs through every Yorkshireman's heart. I love them myself. I love them too well to bet on them. My horse is my fellow-creature, and my friend. Would you bet on your friend, and run him blind for a hundred or two?"

"Naylor has made thousands of pounds."

"I don't care if he has made millions. All money made without labor or without equivalent is got over the devil's back to be squandered in some devil's pastime. Harry, bettors infer dupes. When you have to pay a jockey a small fortune to do his duty, he may be an honest man—but there are inferences. Can't you think of something better to do?"

"I wanted to be an artist and father would not let me. I wanted to have my voice trained and father laughed at me. I wanted to join the army and father was angry and asked me if I did not want to be a pugilist. He would not hear of anything but the mill. John, I won't go to the mill again. I won't be a cotton-spinner, and I'll be glad if you will buy me out at any price."

"I won't do that—not yet. I'll tell you what I will do. I will rent your share of the mill for a year if you will take Captain Cook and the yacht and go to the Mediterranean, and from the yacht visit the old cities and see all the fine picture galleries, and listen to the music of Paris and Milan or even Vienna. You must stay away a year. I want you to realize above all things that to live to amuse yourself is the hardest work the devil can set you to do."

"I promised Fred Naylor I would rent him my share."

"How dared you make such a promise? Did you think that I, standing as I do, for my father, Stephen Hatton, would ever lower the Hatton name to Hatton and Naylor? I am ashamed of you, Harry! I am that!"

"John, I am so unhappy in the mill. You don't understand—"

"Your duty is in the mill. If a man does his duty, he cannot be unhappy. No, he can not."