PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE

PRISONERS OF

CONSCIENCE

By

AMELIA E. BARR

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1897

Copyright, 1896, 1897, by

The Century Co.

The De Vinne Press.

| CONTENTS | ||

| BOOK FIRST–LIOT BORSON | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Weaving of Doom | 3 |

| II. | Jealousy Cruel as the Grave | 23 |

| III. | A Sentence for Life | 44 |

| IV. | The Door Wide Open | 62 |

| BOOK SECOND–DAVID BORSON | ||

| V. | A New Life | 85 |

| VI. | Kindred–the Quick and the Dead | 107 |

| VII. | So Far and No Farther | 127 |

| VIII. | The Justification of Death | 144 |

| IX. | A Sacrifice Accepted | 169 |

| X. | In the Fourth Watch | 192 |

| XI. | The Lowest Hell | 210 |

| XII. | “At Last it is Peace” | 220 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| “He Repeated all the Blessed Words” | Frontispiece | |

| A Lerwick Man | 33 | |

| “The Waters of the Great Deep” | 55 | |

| “‘I Want to Find my Father’s People’” | 91 | |

| Nanna and Vala | 103 | |

| “But she Held her Peace” | 133 | |

| At the Kirk | 137 | |

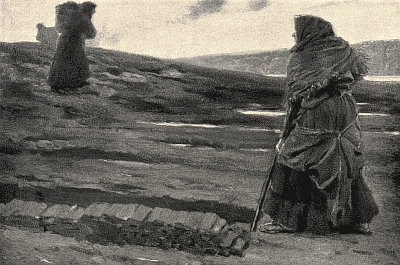

| Peat-gatherers | 161 | |

| Groat | 193 | |

| On the Way to Nanna’s Cottage | 223 | |

| “Went in and out among his Mates” | 237 | |

PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE

Book First

LIOT BORSON

| BOOK FIRST | ||

| CONTENTS | ||

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Weaving of Doom | 3 |

| II. | Jealousy Cruel as the Grave | 23 |

| III. | A Sentence for Life | 44 |

| IV. | The Door Wide Open | 62 |

PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE

3I

THE WEAVING OF DOOM

In the early part of this century there lived at Lerwick, in the Shetland Islands, a man called Liot Borson. He was no ignoble man; through sea-fishers and sea-fighters he counted his forefathers in an unbroken line back to the great Norwegian Bor, while his own life was full of perilous labor and he was off to sea every day that a boat could swim. Liot was the outcome of the most vivid and masterful form of paganism and the most vital and uncompromising form of Christianity. For nearly eight hundred years the Borsons had been christened, but who can deliver a man from his ancestors? Bor still spoke to his son through the stirring stories of the sagas, and Liot knew the lives of Thord and Odd, of Gisli and the banded men, and the tremendous drama of Nial and his sons, just as well as he knew the histories of the prophets and heroes of his Old Testament. It is true 4 that he held the former with a kind of reservation, and that he gave to the latter a devout and passionate faith, but this faith was not always potential. There were hours in Liot’s life when he was still a pagan, when he approved the swift, personal vengeance which Odin enjoined and Christ forbade–hours in which he felt himself to be the son of the man who had carried his gods and his home to uninhabited Iceland rather than take cross-marking for the meek and lowly Jesus.

In his youth–before his great sorrow came to him–he had but little trouble from this subcharacter. Of all the men in Lerwick, he knew best the king stories and the tellings-up of the ancients; and when the boats with bare spars rocked idly on the summer seas waiting for the shoal, or the men and women were gathered together to pass the long winter nights, Liot was eagerly sought after. Then, as the women knit and the men sat with their hands clasped upon their heads, Liot stood in their midst and told of the wayfarings and doings of the Borsons, who had been in the Varangian Guard, and sometimes of the sad doom of his fore-elder Gisli, who had been cursed even before he was born.

He did not often speak of Gisli; for the man ruled him across the gulf of centuries, and he was always unhappy when he gave way to the temptation to do so; for he could not get rid of the sense of kinship with him, nor of the memory of that withering spaedom with which the first Gisli had been cursed by the wronged thrall who slew him–“This is but the beginning of the ill luck which I will bring on thy kith and kin after thee.”

5Never had he felt the brooding gloom of this wretched heirship so vividly as on the night when he first met Karen Sabiston. Karen lived with her aunt Matilda Sabiston, the richest woman in Lerwick and the chief pillar of the kirk and its societies. On that night the best knitters in Lerwick were gathered at her house, knitting the fine, lace-like shawls which were to be sold at the next foy for some good cause which the minister should approve. They were weary of their own talk, and longing for Liot to come and tell them a story. And some of the young girls whispered to Karen, “When Liot Borson opens the door, then you will see the handsomest man in the islands.”

“I have seen fine men in Yell and Unst,” answered Karen; “I think I shall see no handsomer ones in Lerwick. Is he fair or dark?”

“He is a straight-faced, bright-faced man, tall and strong, who can tell a story so that you will be carried off your feet and away wherever he chooses to take you.”

“I have done always as Karen Sabiston was minded to do; and now I will not be moved this way or that way as some one else minds.”

“As to that we shall see.” And as Thora Glumm spoke Liot came into the room.

“The wind is blowing dead on shore, and the sea is like a man gone out of his wits,” he said.

And Matilda answered, “Well, then, Liot, come to the fire.” And as they went toward the fire she stopped before a lovely girl and said, “Look, now, this is my niece Karen; she has just come from Yell, and she can tell a story also; so it will be, which can better the other.”

6Then Liot looked at Karen, and the girl looked up at him; in that instant their souls remembered each other. They put their hands together like old lovers, and if Liot had drawn her to his heart and kissed her Karen would not have been much astonished. This sweet reciprocity was, however, so personal that onlookers did not see it, and so swift that Liot appeared to answer promptly enough:

“It would be a good thing for us all if we should hear a new story. As for me, the game is up. I can think of nothing to-night but my poor kinsman Gisli, and he was not a lucky man, nor is it lucky to speak of him.”

“Is it Gisli you are talking about?” asked Wolf Skegg. “Let us bring the man among us; I like him best of all.”

“He had much sorrow,” said Andrew Grimm.

“He had a good wife,” answered Gust Havard; “and not many men are so lucky.”

“’Twas his fate,” stammered a very old man, crouching over the fire, “and in everything fate rules.”

“Well, then, Snorro, fate is justice,” said Matilda; “and as well begin, Liot, for it will be the tale of Gisli and no other–I see that.”

Then Liot stood up, and Karen, busy with her knitting, watched him. She saw that he had brown hair and gray eyes and the fearless carriage of one who is at home on the North Sea. His voice at first was frank and full of brave inflections, as he told of the noble, faithful, helpful Gisli, pursued by evil fortune even in his dreams. Gradually its tones became sad as the complaining of the sea, and a brooding melancholy 7 touched every heart as Gisli, doing all he might do to ward off misfortune, found it of no avail. “For what must be must be; there is no help for it,” sighed Liot. “So, then, love of wife and friends, and all that good-will dared, could not help Gisli, for the man was doomed even before his birth.”

Then he paused, and there was a dead silence and an unmistakable sense of expectation; and Liot’s face changed, and he looked as Gisli might have looked when he knew that he had come to his last fight for life. Also for a moment his eyes rested on old Snorro, who was no longer crouching over the hearth, but straight up and full of fire and interest; and Snorro answered the look with a nod, that meant something which all approved and understood; after which Liot continued in a voice full of a somber passion:

“It was the very last night of the summer, and neither Gisli nor his true wife, Auda, could sleep. Gisli had bad dreams full of fate if he shut his eyes, and he knew that his life-days were nearly over. So they left their house and went to a hiding-place among the crags, and no sooner were they there than they heard the voice of their enemy Eyjolf, and there were fourteen men with him. ‘Come on like men,’ shouted Gisli, ‘for I am not going to fare farther away.’”

Then old Snorro raised himself and answered Liot in the very words of Eyjolf:

“‘Lay down the good arms thou bearest, and give up also Auda, thy wife.’”

“‘Come and take them like a man, for neither the arms I bear nor the wife I love are fit for any one else!’” cried Liot, in reply. And this challenge and 8 valiant answer, though fully expected, charged the crowded room with enthusiasm. The women let their knitting fall and sat with parted lips and shining eyes, and the men looked at Liot as men look whose hands are on their weapons.

“So,” continued Liot, “the men made for the crags; but Gisli fought like a hero, and in that bout four men were slain. And when they were least aware Gisli leaped on a crag, that stands alone there and is called Oneman’s Crag, and there he turned at bay and called out to Eyjolf, ‘I wish to make those three hundred in silver, which thou hast taken as the price of my head, as dear bought as I can; and before we part thou wouldst give other three hundred in silver that we had never met; for thou wilt only take disgrace for loss of life.’ Then their onslaught was harder and hotter, and they gave Gisli many spear-thrusts; but he fought on wondrously, and there was not one of them without a wound who came nigh him. At last, full of great hurts, Gisli bade them wait awhile and they should have the end they wanted; for he would have time to sing this last song to his faithful Auda:

|

‘Wife, so fair, so never-failing, So truly loved, so sorely cross’d, Thou wilt often miss me, wailing; Thou wilt weep thy hero lost. But my heart is stout as ever; Swords may bite, I feel no smart; Father! better heirloom never Owned thy son than fearless heart.’ |

And with these words he rushed down from the crag and clove Thord–who was Eyjolf’s kinsman–to the 9 very belt. There Gisli lost his life with many great and sore wounds. He never turned his heel, and none of them saw that his strokes were lighter, the last than the first. They buried him by the sea, and at his grave the sixth man breathed his last; and on the same night the seventh man breathed his last; and an eighth lay bedridden for twelve months and died. And though the rest were healed, they got nothing but shame for their pains. Thus Gisli came to his grave; and it has always been said, by one and all, that there never was a more famous defense made by one man in any time, of which the truth is known; but he was not lucky in anything.”

“I will doubt that,” said Gust Havard. “He had Auda to wife, and never was there a woman more beautiful and loving and faithful. He had love-luck, if he had no other luck. God give us all such wives as Auda!”

“Well, then,” answered Matilda, “a man’s fate is his wife, and she is of his own choosing; and, what is more, a good husband makes a good wife.” Then, suddenly stopping, she listened a moment and added: “The minister is come, and we shall hear from him still better words. But sit down, Liot; you have passed the hour well, as you always do.”

The minister came in with a smile, and he was placed in the best chair and made many times welcome. It was evident in a moment that he had brought a different spirit with him; the old world vanished away, and the men and women that a few minutes before had been so close to it suffered a transformation. As the minister entered the room they became 10 in a moment members of the straitest Christian kirk–quiet, hard-working fishers, and douce, home-keeping women. He said the night was bad and black, and spoke of the boats and the fishers in them. And the men talked solemnly about the “takes” and the kirk meetings, while some of the women knitted and listened, and others helped Matilda and Karen to set the table with goose and fish, and barley and oaten cakes, and the hot, sweet tea which is the Shetlander’s favorite drink.

Many meals in a lifetime people eat, and few are remembered; but when they are “eventful,” how sweet or bitter is that bread-breaking! This night Liot’s cake and fish and cup of tea were as angels’ food. Karen broke her cake with him, and she sweetened his cup, and smiled at him and talked to him as he ate and drank with her. And when at last they stood up for the song and thanksgiving he held her hand in his, and their voices blended in the noble sea psalm, so dear to every seafarer’s heart:

|

“The floods, O Lord, have lifted up, They lifted up their voice! The floods have lifted up their waves And made a mighty noise.

“But yet the Lord, that is on high, Is more of might by far Than noise of many waters is, Or great sea-billows are.” |

Soft and loud the singing swelled, and the short thanksgiving followed it. To bend his head and hold Karen’s hand while the blessing fell on his ears was heaven on earth to Liot; such happiness he had never 11 known before–never even dreamed of. He walked home through the buffeting wind and the drenching rain, and felt neither; for he was saying over and over to himself, “I have found my wife! I have found my wife!”

Karen had the same prepossession. As she unbound her long, fair hair she thought of Liot. Slowly unplaiting strand from strand, she murmured to her heart as she did so:

“Such a man as Liot Borson I have never met before. It was easy to see that he loved me as soon as he looked at me; well, then, Liot Borson shall be my husband–Liot, and only Liot, will I marry.”

It was at the beginning of winter that this took place, and it was a kind of new birth to Liot. Hitherto he had been a silent man about his work; he now began to talk and to sing, and even to whistle; and, as every one knows, whistling is the most cheerful sound that comes from human lips. People wondered a little and said, “It is Karen Sabiston, and it is a good thing.” Also, the doubts and fears that usually trouble the beginnings of love were absent in this case. Wherever Liot and Karen had learned each other, the lesson had been perfected. At their third meeting he asked her to be his wife, and she answered with simple honesty, “That is my desire.”

This betrothal was, however, far from satisfactory to Karen’s aunt; she could bring up nothing against Liot, but she was ill pleased with Karen. “You have some beauty,” she said, “and you have one hundred pounds of your own; and it was to be expected that you would look to better yourself a little.”

12“Have I not done so? Liot is the best of men.”

“And the best of men are but men at best. It is not of Liot I think, but of Liot’s money; he is but poor, and you know little of him. Those before us have said wisely, ‘Ere you run in double harness, look well to the other horse.’”

“My heart tells me that I have done right, aunt.”

“Your heart cannot foretell, but you might have sense enough to forethink; and it is sure that I little dreamed of this when I brought you here from the naked gloom of Yell.”

“It is true your word brought me here, but I think it was Liot who called me by you.”

“It was not. When my tongue speaks for any Borson, I wish that it may speak no more! I like none of them. Liot is good at need on a winter’s night; but even so, all his stories are of dool and wrong-doing and bloody vengeance. From his own words it is seen that the Borsons have ever been well-hated men. Now, I have forty years more of this life than you have, and I tell you plainly I think little of your choice; whatever sorrow comes of it, mind this: I didn’t give you leave to make it.”

“Nor did I ask your leave, aunt; each heart knows its own; but you have a way to throw cold water upon every hope.”

“There are hopes I wish at the bottom of the sea. To be sure, when ill is fated some one must speak the words that bring it about; but I wish it had been any other but myself who wrote, ‘Come to Lerwick’; for I little thought I was writing, ‘Come to Liot Borson.’ As every one knows, he is the son of unlucky 13 folk; from father to son nothing goes well with them.”

“I will put my luck to his, and you will learn to think better of Liot for my sake, aunt.”

“Not while my life-days last! That is a naked say, and there’s no more to it.”

Matilda’s dislike, however, did not seriously interfere with Liot’s and Karen’s happiness. It was more passive than active; it was more virulent when he was absent than when he was present; and all winter she suffered him to visit at her house. These visits had various fortunes, but, good or bad, the season wore away with them; and as soon as April came Liot began to build his house. Matilda scoffed at his hurry. “Does he think,” she cried, “that he can marry Karen Sabiston when he lists to? Till you are twenty-one you are in my charge, and I will take care to prevent such folly as long as I can.”

“Well, then, aunt, I shall be of age and my own mistress next Christmas, and on Uphellya night[1] I will be married to Liot.”

“After that we shall have nothing to say to each other.”

“It will not be my fault.”

“It will be my will. However, if you are in love with ill luck and fated for Liot Borson, you must dree your destiny; and Liot does well to build his home, for he shall not wive himself out of my walls.”

“It will be more shame to you than to me, aunt, if I am not married from your house; also, people will speak evil of you.”

14“That is to be expected; but I will not be so ill to myself as to make a feast for a man I hate. However, there are eight months before Uphellya, and many chances and changes may come in eight months.”

The words were a prophecy. As Matilda uttered them Thora Fay entered the room, all aglow with excitement. “There is a new ship in the harbor!” she cried. “She is called the Frigate Bird, and she has silk and linen and gold ornaments for sale, besides tea and coffee and the finest of spirits. As for the captain, he is as handsome as can be, and my brother thinks him a man of some account.”

“You bring good news, Thora,” said Matilda. “I would gladly see the best of whatever is for sale, and I wish your brother to let so much come to the man’s ears.”

“I will look to that,” answered Thora. “Every one knows there is to be a wedding in your house very soon.” And with these words she nodded at Karen, and went smiling away with her message.

A few hours afterward Captain Bele Trenby of the Frigate Bird stepped across Matilda Sabiston’s threshold. It was the first step toward his death-place, though he knew it not; he took it with a laugh and a saucy compliment to the pretty servant who opened the door for him, and with the air of one accustomed to being welcome went into Matilda Sabiston’s presence. He delighted the proud, wilful old woman as soon as she saw him; his black eyes and curling black hair, the dare-devil look on his face, and the fearless dash of his manner reminded her of Paul Sabiston, the husband of her youth. She opened her 15 heart and her purse to the bold free-trader; she made him eat and drink, and with a singular imprudence told him of secret ways in and out of the voes, and of hiding-places in the coast caverns that had been known to her husband. And as she talked she grew handsome; so much so that Karen let her knitting fall to watch her aunt’s face as she described Paul Sabiston’s swift cutter–“a mass of snowy canvas, stealing in and out of the harbor like a cloud.”

The coming of this man was the beginning of sorrow. In a few days he understood the situation, and he resolved to marry Karen Sabiston. Her fair, stately beauty charmed him, and he had no doubt she would inherit her aunt’s wealth; that she was cold and shy only stimulated his love, and as for Liot, he held his pretensions in contempt. All summer he sailed between Holland and Shetland, and the Lerwick people gave him good trade and good welcome. With Matilda Sabiston he had his own way; she did whatever he wished her to do. Only at Karen her power stopped short; neither promises nor threats would induce the girl to accept Bele as her lover; and Matilda, accustomed to drive her will through the teeth of every one, was angry morning, noon, and night with her disobedient niece.

As the months wore on Liot’s position became more and more painful and humiliating, and he had hard work to keep his hands off Bele when they met on the pier or in the narrow streets of the town. His smile, his voice, his face, his showy dress and hectoring manner, all fed in Liot’s heart that bitter hatred which springs from a sense of being personally held in contempt; 16 he felt, also, that even among his fellow-townsmen he was belittled and injured by this plausible, handsome stranger. For Bele said very much what it pleased him to say, covering his insolences with a laugh and with a jovial, jocular air, that made resentment seem ridiculous. Bele was also a gift-giver, and for every woman, old or young, he had a compliment or a ribbon.

If Liot had been less human, if he had come from a more mixed race, if his feelings had been educated down and toned to the level of modern culture, he could possibly have looked forward to Uphellya night, and found in the joy and triumph that Karen would then give him a sufficient set-off to all Bele’s injuries and impertinences. But he was not made thus; his very blood came to him through the hearts of vikings and berserkers, and as long as one drop of this fierce stream remained in his veins, moments were sure to come in the which it would render all the tide of life insurgent.

It is true Liot was a Christian and a good man; but it must be noted, in order to do him full justice, that the form of Christianity which was finally and passionately accepted by his race was that of ultra-Calvinism; it spoke to their inherited tendencies as no other creed could have done. This uncompromising theology, with its God of vengeance and inflexible justice, was understood by men who considered a blood-feud of centuries a duty never to be neglected; and as for the doctrine of a special election, with all its tremendous possibilities of damnation, they were not disposed to object to it. Indeed, they were such good haters that Tophet and everlasting enmity were the bane and doom 17 they would have unhesitatingly chosen for their enemies. This grim theology Liot sucked in with his mother’s milk, and both by inheritance and by a strong personal faith he was a child of God after the order of John Calvin.

Therefore he constantly brought his enemy to the ultimate and immutable tribunal of his faith, and just as constantly condemned him there. Nothing was surer in Liot’s mind than that Bele Trenby was the child of the Evil One and an inheritor of the kingdom of wrath; for Bele did the works of his father every day, and every hour of the day, and Liot told himself that it was impossible there should be any fellowship between them. To Bele he said nothing of this spiritual superiority, and yet it was obvious in his constant air of disapproval and dissent, in his lofty silence, his way of not being conscious of Bele’s presence or of totally ignoring his remarks.

“Liot Borson mocks the very heart of me,” said Bele to Matilda one day, as he gloomily flung himself into the big chair she pushed toward him.

“What said he, Bele?”

“Not a word with his tongue, or I had struck him in the face; but as I was telling about my last cargo and the run for it, his eyes called me ‘Liar! liar! liar!’ like blow on blow. And when he turned and walked off the pier some were quiet, and some followed him; and I could have slain every man’s son of them, one on the heels of the other.”

“That is vain babble, Bele; and I would leave Liot alone. He has more shapes than one, and he is ill to anger in any of them.”

18Bele was not averse to be so counseled. In spite of his bravado and risky ventures, he was no more a brave man than a dishonorable or dishonest man ever is. He knew that if it came to fighting he would be like a child in Liot’s big hands, and he had already seen Liot’s scornful silence strip his boasting naked. So he contented himself with the revenge of the coward–the shrug and the innuendo, the straight up-and-down lie, when Liot was absent; the sulky nod or bantering remark, according to his humor, when Liot was present.

However, as the weeks went on Liot became accustomed to the struggle, and more able to take possession of such aids to mastery of himself as were his own. First, there was Karen; her loyalty never wavered. If Liot knew anything surely, it was that at Christmas she would become his wife. She met him whenever she could, she sent him constantly tokens of her love, and she begged him at every opportunity for her sake to let Bele Trenby alone. Every day, also, his cousin Paul Borson spoke to him and praised him for his forbearance; and every Sabbath the minister asked, “How goes it, Liot? Is His grace yet sufficient?” And at these questions Liot’s countenance would glow as he answered gladly, “So far He has helped me.”

From this catechism, and the clasp and look that gave it living sympathy, Liot always turned homeward full of such strength that he longed to meet his enemy on the road, just that he might show him that “noble not caring,” which was gall and wormwood to Bele’s touchy self-conceit. It was a great spiritual 19 weakness, and one which Liot was not likely to combat; for prayer was so vital a thing to him that it became imbued with all his personal characteristics. He made petition that God would keep him from hurting Bele Trenby, and yet in his heart he was afraid that God would hear and grant his prayer. The pagan in Liot was not dead; and the same fight between the old man and the new man that made Paul’s life a constant warfare found a fresh battle-ground in Liot’s soul.

He began his devotions in the spirit of Christ, but they ended always in a passionate arraignment of Bele Trenby through the psalms of David. These wondrously human measures got Liot’s heart in their grip; he wept them and prayed them and lived them until their words blended with all his thoughts and speech; through them he grew “familiar” with God, as Job and David and Jonah were familiar–a reverent familiarity. Liot ventured to tell Him all that he had to suffer from Bele–the lies that he could not refute, the insolences he could not return, his restricted intercourse with Karen, and the loss of that frank fellowship with such of his townsmen as had business reasons for not quarreling with Bele.

So matters went on, and the feeling grew no better, but worse, between the men. When the devil could not find a man to irritate Bele and Liot, then he found Matilda Sabiston always ready to speak for him. She twitted Bele with his prudences, and if she met Liot on the street she complimented him on his patience, and prophesied for Karen a “lowly mannered husband, whom she could put under her feet.”

20One day in October affairs all round were at their utmost strain. The summer was over, and Bele was not likely to make the Shetland coast often till after March. His talk was of the French and Dutch ports and their many attractions. And Matilda was cross at the prospect of losing her favorite’s society, and unjustly inclined to blame Bele for his want of success with her niece.

“Talk if you want to, Bele,” she said snappishly, “of the pretty women in France and Holland. You are, after all, a great dreamer, and you don’t dream true; the fisherman Liot can win where you lose.”

Then Bele said some words about Liot, and Matilda laughed. Bele thought the laugh full of scorn; so he got up and left the house in a passion, and Matilda immediately turned on Karen.

“Ill luck came with you, girl,” she cried, “and I wish that Christmas was here and that you were out of my house.”

“No need to wait till Christmas, aunt; I will go away now and never come back.”

“I shall be glad of that.”

“Paul Borson will give me shelter until I move into my own house.”

“Then we shall be far apart. I shall not be sorry, for our chimneys may smoke the better for it.”

“That is an unkind thing to say.”

“It is as you take it.”

“I wonder what people will think of you, aunt?”

“I wonder that, too–but I care nothing.”

“I see that talk will come to little, and that we had better part.”

21“If you will marry Bele we need not part; then I will be good to you.”

“I will not marry Bele–no, not for the round world.”

“Then, what I have to say is this, and I say it out: go to the Borsons as soon as you can; there is doubtless soul-kin between you and them, and I want no Borson near me, in the body or out of the body.”

So that afternoon Karen went to live with Paul Borson, and there was great talk about it. No sooner had Liot put his foot ashore than he heard the story, and at once he set it bitterly down against Bele; for his sake Karen had been driven from her home. There were those that said it was Bele’s plan, since she would not marry him, to separate her from her aunt; he was at least determined not to lose what money and property Matilda Sabiston had to leave. These accusations were not without effect. Liot believed his rival capable of any meanness. But it was not the question of money that at this hour angered him; it was Karen’s tears; it was Karen’s sense of shame in being sent from the home of her only relative, and the certain knowledge that the story would be in every one’s mouth. These things roused in Liot’s soul hatred implacable and unmerciful and thirsty for the stream of life.

Yet he kept himself well in hand, saying little to Karen but those things usually whispered to beloved women who are weeping, and at the end of them this entreaty:

“Listen, dear heart of mine! I will see the minister, and he will call our names in the kirk next Sunday, 22 and the next day we shall be married, and then there will be an end to this trouble. I say nothing of Matilda Sabiston, but Bele Trenby stirs up bickerings all day long; he is a low, quarrelsome fellow, a very son of Satan, walking about the world tempting good men to sin.”

And Karen answered: “Life is full of waesomeness. I have always heard that when the heart learns to love it learns to sorrow; yet for all this, and more too, I will be your wife, Liot, on the day you wish, for then if sorrow comes we two together can well bear it.”

23II

JEALOUSY CRUEL AS THE GRAVE

After this event all Lerwick knew that Karen Sabiston was to be married to Liot Borson in less than three weeks. For the minister was unwilling to shorten the usual time for the kirk calling, and Karen, on reflection, had also come to the conclusion that it was best not to hurry too much. “Everything ought to bide its time, Liot,” she said, “and the minister wishes the three askings to be honored; also, as the days go by, my aunt may think better and do better than she is now minded to.”

“If I had my way, Karen–”

“But just now, Liot, it is my way.”

“Yours and the minister’s.”

“Then it is like to be good.”

“Well, let it stand at three weeks; but I wish that the time had not been put off; ill luck comes to a changed wedding-day.”

“Why do you forespeak misfortune, Liot? It is a bad thing to do. Far better if you went to the house-builder and told him to hire more help and get the 24 roof-tree on; then we need not ask shelter either from kin or kind.”

It was a prudent thought, and Liot acknowledged its wisdom and said he would “there and then go about it.” The day was nearly spent, but the moon was at its full, and the way across the moor was as well known to him as the space of his own boat. He kissed Karen fondly, and promised to return in two or three hours at the most; and she watched his tall form swing into the shadows and become part and parcel of the gray indistinctness which shut in the horizon.

There was really no road to the little hamlet where the builder lived. The people used the sea road, and thought it good enough; but the rising moon showed a foot-path, like a pale, narrow ribbon, winding through the peat-cuttings and skirting the still, black moss waters. But in this locality Liot had cut many a load of peat, and he knew the bottomless streams of the heath as well as he knew the “races” of the coast; so he strode rapidly forward on his pleasant errand.

The builder, who was also a fisherman, had just come from the sea; and as he ate his evening meal he talked with Liot about the new house, and promised him to get help enough to finish it within a month. This business occupied about an hour, and as soon as it was over Liot lit his pipe and took the way homeward. He had scarcely left the sea-shore when he saw a man before him, walking very slowly and irresolutely; and Liot said to himself, “He steps like one who is not sure of his way.” With the thought he called out, “Take care!” and hastened forward; and the man stood still and waited for him.

25In a few minutes Liot also wished to stand still; for the moon came from behind a cloud and showed him plainly that the wayfarer was Bele Trenby. The recognition was mutual, but for once Bele was disposed to be conciliating. He was afraid to turn back and equally afraid to go forward; twice already the moonlight had deceived him, and he had nearly stepped into the water; so he thought it worth his while to say:

“Good evening, Liot; I am glad you came this road; it is a bad one–a devilish bad one! I wish I had taken a boat. I shall miss the tide, and I was looking to sail with it. It is an hour since I passed Skegg’s Point–a full hour, for it has been a step at a time. Now you will let me step after you; I see you know the way.”

He spoke with a nervous rapidity, and Liot only answered:

“Step as you wish to.”

Bele fell a couple of feet behind, but continued to talk. “I have been round Skegg’s Point,” he said with a chuckling laugh. “I wanted to see Auda Brent before I went away for the winter. Lovely woman! Brent is a lucky fellow–”

“Brent is my friend,” answered Liot, angrily. But Bele did not notice the tone, and he continued:

“I would rather have Auda for a friend.” And then, in his usual insinuating, boastful way, he praised the woman’s beauty and graciousness in words which had an indefinable offense, and yet one quite capable of that laughing denial which commonly shielded Bele’s impertinence. “Brent gave me a piece of Saxony cloth and a gold brooch for her–Brent is in 26 Amsterdam. I have taken the cloth four times; there were also other gifts–but I will say nothing of them.”

“You are inventing lies, Bele Trenby. Touch your tongue, and your fingers will come out of your lips black as the pit. Say to Brent what you have said to me. You dare not, you infernal coward!”

“You have a pretty list of bad words, Liot, and I won’t try to change mine with them.”

Liot did not answer. He turned and looked at the man behind him, and the devil entered into his heart and whispered, “There is the venn before you.” The words were audible to him; they set his heart on fire and made his blood rush into his face, and beat on his ear-drums like thunder. He could scarcely stand. A fierce joy ran through his veins, and the fiery radiations of his life colored the air around him; he saw everything red. The venn, a narrow morass with only one safe crossing, was before them; in a few moments they were on its margin. Liot suddenly stopped; the leather strings of his rivlins[2] had come unfastened, and he dropped the stick he carried in order to retie them. At this point there was a slight elevation on the morass, and Bele looked at Liot as he put his foot upon it, asking sharply:

“Is this the crossing?”

Liot fumbled at his shoe-strings and said not a word; for he knew it was not the crossing.

“Is this the crossing, Liot?” Bele again asked. And again Liot answered neither yes nor no. Then Bele flew into a passion and cried out with an oath:

27“You are a cursed fellow, Liot Borson, and in the devil’s own temper; I will stay no longer with you.”

He stepped forward as he spoke, and instantly a cry, shrill with mortal terror, rang across the moor from sea to sea. Liot quickly raised himself, but he had barely time to distinguish the white horror of his enemy’s face and the despair of his upthrown arms. The next moment the moss had swallowed the man, and the thick, peaty water hardly stirred over his engulfing.

For a little while Liot fixed his eyes on the spot; then he lifted his stick and went forward, telling his soul in triumphant undertones: “He has gone down quick into hell; the Lord has brought him down into the pit of destruction; the bloody and deceitful man shall not live out half his days; he has gone to his own place.”

Over and over he reiterated these assurances, stepping securely himself to the ring of their doom. It was not until he saw the light in Paul Borson’s house that the chill of doubt and the sickness of fear assailed him. How could he smile into Karen’s face or clasp her to his breast again? A candle was glimmering in the window of a fisherman’s cottage; he stepped into its light and looked at his hands. There was no stain of blood on them, but he was angry at the involuntary act; he felt it to be an accusation.

Just yet he could not meet Karen. He walked to the pier, and talked to his conscience as he did so. “I never touched the man,” he urged. “I said nothing to lead him wrong. He was full of evil; his last words were such as slay a woman’s honor. I did right not to 28 answer him. A hundred times I have vowed I would not turn a finger to save his life, and God heard and knew my vow. He delivered him into my hand; he let me see the end of the wicked. I am not to blame! I am not to blame!” Then said an interior voice, that he had not silenced, “Go and tell the sheriff what has happened.”

Liot turned home at this advice. Why should he speak now? Bele was dead and buried; let his memory perish with him. He summoned from every nook of his being all the strength of the past, the present, and the future, and with a resolute hand lifted the latch of the door. Karen threw down her knitting and ran to meet him; and when he had kissed her once he felt that the worst was over. Paul asked him about the house, and talked over his plans and probabilities, and after an interval he said:

“I saw Bele Trenby’s ship was ready for sea at the noon hour; she will be miles away by this time. It is a good thing, for Mistress Sabiston may now come to reason.”

“It will make no odds to us; we shall not be the better for Bele’s absence.”

“I think differently. He is one of the worst of men, and he makes everything grow in Matilda’s eyes as he wishes to. Lerwick can well spare him; a bad man, as every one knows.”

“A man that joys the devil. Let us not speak of him.”

“But he speaks of you.”

“His words will not slay me. Kinsman, let us go to sleep now; I am promised to the fishing with the early tide.”

29But Liot could not sleep. In vain he closed his eyes; they saw more than he could tell. There were invisible feet in his room; the air was heavy with presence, and full of vague, miserable visions; for “Wickedness, condemned by her own witness, is very timorous, and, being pressed with Conscience, always forecasteth grievous things.”

When Bele stepped into his grave there had been a bright moonlight blending with the green, opalish light of the aurora charging to the zenith; and in this mysterious mingled glow Liot had seen for a moment the white, upturned face that the next moment went down with open eyes into the bottomless water. Now, though the night had become dark and stormy, he could not dismiss the sight, and anon the Awful One who dwelleth in the thick darkness drew near, and for the first time in his life Liot Borson was afraid. Then it was that his deep and real religious life came to his help. He rose, and stood with clasped hands in the middle of the room, and began to plead his cause, even as Job did in the night of his terror. In his strong, simple speech he told everything to God–told him the wrongs that had been done him, the provocations he had endured. His solemnly low implorations were drenched with agonizing tears, and they only ceased when the dayspring came and drove the somber terrors of the night before it.

Then he took his boat and went off to sea, though the waves were black and the wind whistling loud and shrill. He wanted the loneliness that only the sea could give him. He felt that he must “cry aloud” for deliverance from the great strait into which he 30 had fallen. No man could help him, no human sympathy come between him and his God. Into such communions not even the angels enter.

At sundown he came home, his boat loaded with fish, and his soul quiet as the sea was quiet after the storm had spent itself. Karen said he “looked as if he had seen Death”; and Paul answered: “No wonder at that; a man in an open boat in such weather came near to him.” Others spoke of his pallor and his weariness; but no one saw on his face that mystical self-signature of submission which comes only through the pang of soul-travail.

He had scarcely changed his clothing and sat down to his tea before Paul said: “A strange thing has happened. Trenby’s ship is still in harbor. He cannot be found; no one has seen him since he left the ship yesterday. He bade Matilda Sabiston good-by in the morning, and in the afternoon he told his men to be ready to lift anchor when the tide turned. The tide turned, but he came not; and they wondered at it, but were not anxious; now, however, there is a great fear about him.”

“What fear is there?” asked Liot.

“Men know not; but it is uppermost in all minds that in some way his life-days are ended.”

“Well, then, long or short, it is God who numbers our days.”

“What do you think of the matter?” asked Paul.

“As you know, kinsman,” answered Liot, “I have ever hated Bele, and that with reason. Often I have said it were well if he were hurt, and better if he were dead; but at this time I will say no word, good or 31 bad. If the man lives, I have nothing good to say of him; if he is dead, I have nothing bad to say.”

“That is wise. Our fathers believed in and feared the fetches of dead men; they thought them to be not far away from the living, and able to be either good friends or bitter enemies to them.”

“I have heard that often. No saying is older than ‘Bare is a man’s back without the kin behind him.’”

“Then you are well clad, Liot, for behind you are generations of brave and good men.”

“The Lord is at my right hand; I shall not be moved,” said Liot, solemnly. “He is sufficient. I am as one of the covenanted, for the promise is ‘to you and your children.’”

Paul nodded gravely. He was a Calvinistic pagan, learned in the Scriptures, inflexible in faith, yet by no means forgetful of the potent influences of his heroic dead. Truly he trusted in the Lord, but he was never unwilling to remember that Bor and Bor’s mighty sons stood at his back. Even though they were in the “valley of shadows,” they were near enough in a strait to divine his trouble and be ready to help him.

The tenor of this conversation suited both men. They pursued it in a fitful manner and with long, thoughtful pauses until the night was far spent; then they said, “Good sleep,” with a look into each other’s eyes which held not only promise of present good-will, but a positive “looking forward” neither cared to speak more definitely of.

The next day there was an organized search for Bele Trenby through the island hamlets and along the coast; but the man was not found far or near; he 32 had disappeared as absolutely as a stone dropped into mid-ocean. Not until the fourth day was there any probable clue found; then a fishing-smack came in, bringing a little rowboat usually tied to Howard Hallgrim’s rock. Hallgrim was a very old man and had not been out of his house for a week, so that it was only when the boat was found at sea that it was missed from its place. It was then plain to every one that Bele had taken the boat for some visit and met with an accident.

So far the inference was correct. Bele’s own boat being shipped ready for the voyage, he took Hallgrim’s boat when he went to see Auda Brent; but he either tied it carelessly or he did not know the power of the tide at that point, for when he wished to return the boat was not there. For a few minutes he hesitated; he was well aware that the foot-path across the moor was a dangerous one, but he was anxious to leave Lerwick with that tide, and he risked it.

These facts flashed across Liot’s mind with the force of truth, and he never doubted them. All, then, hung upon Auda Brent’s reticence; if she admitted that Bele had called on her that afternoon, some one would divine the loss of the boat and the subsequent tragedy. For several wretched days he waited to hear the words that would point suspicion to him. They were not spoken. Auda came to Lerwick, as usual, with her basket of eggs for sale; she talked with Paul Borson about Bele’s disappearance; and though Liot watched her closely, he noticed neither tremor nor hesitation in her face or voice. He thought, indeed, that she showed very little feeling of any kind in the matter. It took him some time to reach the conclusion that Auda was playing a part–one she thought best for her honor and peace.

35In the mean time the preparations for his marriage with Karen Sabiston went rapidly forward. He strove to keep his mind and heart in tune with them, but it was often hard work. Sometimes Karen questioned him concerning his obvious depression; sometimes she herself caught the infection of his sadness; and there were little shadows upon their love that she could not understand. On the day before her marriage she went to visit her aunt Matilda Sabiston. Matilda did not deny herself, but afterward Karen wished she had done so. Almost her first words were of Bele Trenby, for whom she was mourning with the love of a mother for an only son.

“What brings you into my sight?” she asked the girl. “Bele is dead and gone, and you are living! and Liot Borson knows all about it!”

“How dare you say such a thing, aunt?”

“I can dare the truth, though the devil listened to it. As for ‘aunt,’ I am no aunt of yours.”

“I am content to be denied by you; and I will see that Liot makes you pay dearly for the words that you have said.”

“No fear! he will not dare to challenge them! I know that.”

“You have called him a murderer!”

“He did the deed, or he has knowledge of it. One who never yet deceived me tells me so much. Oh, if I could only bring that one into the court I would hang Liot higher than his masthead! I wish to die 36 only that I may follow Liot, and give him misery on misery every one of his life-days. I would also poison his sleep and make his dreams torture him. If there is yet one kinsman behind my back, I will force him to dog Liot into the grave.”

“Liot is in the shelter of God’s hand; he need not fear what you can do to him. He can prove you liar far easier than you can prove him murderer. On the last day of Bele’s life Liot was at sea all day, and there were three men with him. He spent the evening with John Twatt and myself, and then sat until the midnight with Paul Borson.”

“For all that, he was with Bele Trenby! I know it! My heart tells me so.”

“Your heart has often lied to you before this. I see, however, that our talk had better come to an end once for all. I will never come here again.”

“I shall be the happier for that. Why did you come at this time?”

“I thought that you were in trouble about Bele. I was sorry for you. I wished to be friends with every one before I married.”

“I want no pity; I want vengeance; and from here or there I will compass it. While my head is above the mold there is no friendship possible between us–no, nor after it. Do you think that Bele is out of your way because he is out of the body? He is now nearer to you than your hands or feet. And let Liot Borson look to himself. The old thrall’s curse was evil enough, but Bele Trenby will make it measureless.”

“Such words are like the rest of your lying; I will 37 not fear them, since God is himself, and he shall rule the life Liot and I will lead together. When a girl is near her bridal every one but you will give her a blessing. I think you have no heart; surely you never loved any one.”

“I have loved–yes!” Then she stood up and cried passionately: “Begone! I will speak no more to you–only this: ask Liot Borson what was the ending of Bele Trenby.”

She was the incarnation of rage and accusation, and Karen almost fled from her presence. Her first impulse was to go to Liot with the story of the interview, but her second was a positive withdrawal of it. It was the eve of her bridal day, and the house was already full of strangers. Paul Borson was spending his money freely for the wedding-feast. In the morning she was to become Liot’s wife. How could she bring contention where there should be only peace and good-will?

Besides, Liot had told her it was useless to visit Matilda; he had even urged her not to do so, for all Lerwick knew how bitterly she was lamenting the loss of her adopted son Bele; and Liot had said plainly to Karen: “As for her good-will, there is more hope of the dead; let her alone.” As she remembered these words a cold fear invaded Karen’s heart; it turned her sick even to dismiss it. What if Liot did know the ending of Bele! She recalled with a reluctant shiver his altered behavior, his long silences, his gloomy restlessness, the frequent breath of some icy separation between them. If Matilda was right in any measure–if Liot knew! Merciful God, if Liot had 38 had any share in the matter! She could not face him with such a thought in her heart. She ran down to the sea-shore, and hid herself in a rocky shelter, and tried to think the position down to the bottom.

It was all a chaos of miserable suspicion, and at last she concluded that her fear and doubt came entirely from Matilda’s wicked assertions. She would not admit that they had found in her heart a condition ready to receive them. She said: “I will not again think of the evil words; it is a wrong to Liot. I will not tell them to him; he would go to Matilda, and there would be more trouble, and the why and the wherefore spread abroad; and God knows how the wicked thought grows.”

Then she stooped and bathed her eyes and face in the cold salt water, and afterward walked slowly back to Paul Borson’s. The house was full of company and merry-making, and she was forced to fall into the mood expected from her. Women do such things by supreme efforts beyond the power of men. And Karen’s smiles showed nothing of the shadow behind them, even when Liot questioned her about her visit.

“She is a bad woman, Liot,” answered Karen, “and she said many temper-trying words.”

“That is what I looked for, Karen. It is her way about all things to scold and storm her utmost. Does she trouble you, dear one?”

“I will not be word-sick for her. There is, as you said, no love lost between us, and I shall not care a rap for her anger. Thanks to the Best, we can live without her.” And in this great trust she laid her hand in Liot’s, and all shadows fled away.

39It was then a lovely night, bright with rosy auroras; but before morning there was a storm. The bridal march to the kirk had to be given up, and, hooded and cloaked, the company went to the ceremony as they best could. There was no note of music to step to; it was hard enough to breast the gusty, rattling showers, and the whole landscape was a little tragedy of wind and rain, of black, tossing seas and black, driving clouds. Many who were not at the bridal shook their heads at the storm-drenched wedding-guests, and predicted an unhappy marriage; and a few ventured to assert that Matilda Sabiston had been seen going to the spaewife Asta. “And what for,” they asked, “but to buy charms for evil weather?”

All such dark predictions, however, appeared to be negatived by actual facts. No man in Lerwick was so happy as Liot Borson. The home he had built Karen made a marvel of neatness and even beauty; it was always spotless and tidy, and full of bits of bright color–gay patchwork and crockery, and a snow-white hearth with its glow of fiery peat. Always she was ready to welcome him home with a loving kiss and all the material comforts his toil required. And they loved each other! When that has been said, what remains unsaid? It covers the whole ground of earthly happiness.

How the first shadow crossed the threshold of this happy home neither Liot nor Karen could tell; it came without observation. It was in the air, and entered as subtly and as silently. Liot noticed it first. It began with the return of Brent. When he gave Bele the piece of cloth and the gold brooch for his wife, he was 40 on the point of leaving Amsterdam for Java. Fever and various other things delayed his return, but in the end he came back to Lerwick and began to talk about Bele. For Auda, reticent until her husband’s return, then told him of Bele’s visit; and one speculation grew on the top of another until something like the truth was in all men’s minds, even though it was not spoken. Liot saw the thought forming in eyes that looked at him; he felt it in little reluctances of his mates, and heard it, or thought he heard it, in their voices. He took home with him the unhappy hesitation or misgiving, and watched to see if it would touch the consciousness of Karen. The loving wife, just approaching the perilous happiness of maternity, kept asking herself, “What is it? What is it?” And the answer was ever the same–the accusing words that Matilda Sabiston had said, and the quick, sick terror of heart they had awakened.

On Christmas day Karen had a son, a child of extraordinary beauty, that brought his soul into the world with him. The women said that his eyes instantly followed the light, and that his birth-cry passed into a smile. Liot was solemnly and silently happy. He sat for hours holding his wife’s hand and watching the little lad sleeping so sweetly after his first hard travail; for the birth of this child meant to Liot far more than any mortal comprehended. He knew himself to be of religiously royal ancestry, and the covenant of God to such ran distinctly, “To you and your children.” So, then, if God had refused him children, he would certainly have believed that for his sin in regard to Bele Trenby the covenant between God and 41 the Borsons was broken. This fair babe was a renewal of it. He took him in his arms with a prayer of inexpressible thanksgiving. He kissed the child, and called him David with the kiss, and said to his soul, “The Lord hath accepted my contrition.”

For some weeks this still and perfect happiness continued. The days were dark and stormy, and the nights long; but in Liot’s home there was the sunlight of a woman’s face and the music of a baby’s voice. The early spring brought the first anxiety, for it brought with it no renewal of Karen’s health and strength. She had the look of a leaf that is just beginning to droop upon its stem, and Liot watched her from day to day with a sick anxiety. He made her go to sea with him, and laughed with joy when the keen winds brought back the bright color to her cheeks. But it was only a momentary flush, bought at far too great a price of vitality. In a few weeks she could not pay the price, and the heat of the summer prostrated her. She had drooped in the spring; in the autumn she faded away. When Christmas came again there was no longer any hope left in Liot’s broken heart; he knew she was dying. Night and day he was at her side, there was so much to say to each other; for only God knew how long they were to be parted, or in what place of his great universe they should meet again.

At the end of February it had come to this acknowledgment between them. Sometimes Liot sat with dry eyes, listening to Karen’s sweet hopes of their reunion; sometimes he laid his head upon her pillow and wept such tears as leave life ever afterward dry at its source. And the root of this bitterness was Bele Trenby. If 42 it had not been for this man Liot could have shared his wife’s hopes and said farewell to her with the thought of heaven in his heart; but the very memory of Bele sank him below the tide of hope. God was even then “entering into judgment with him,” and what if he should not be able to endure unto the end, and so win, though hardly, a painful acceptance? In every phase and form such thoughts haunted the wretched man continually. And surely Karen divined it, for all her sweet efforts were to fill his heart with a loving “looking forward” to their meeting, and a confident trust in God’s everlasting mercy.

One stormy night in March she woke from a deep slumber and called Liot. Her voice had that penetrating intelligence of the dying which never deceives, and Liot knew instantly that the hour for parting had come. He took her hands and murmured in tones of anguish, “O Karen, Karen! wife of my soul!”

She drew him closer, and said with the eagerness of one in great haste, “Oh, my dear one, I shall soon be nearer to God than you. At his feet I will pray. Tell me–tell me quick, what shall I ask for you? Liot, dear one, tell me!”

“Ask that I may be forgiven all my sins.”

“Is there one great sin, dear one? Oh, tell me now–one about Bele Trenby? Speak quickly, Liot. Did you see him die?”

“I did, but I hurt him not.”

“He went into the moss?”

“Yes.”

“You could have saved him and did not?”

“If I had spoken in time; there was but a single 43 moment–I know not what prevented me. O Karen, I have suffered! I have suffered a thousand deaths!”

“My dear one, I have known it. Now we will pray together–I in heaven, thou on earth. Fear not, dear, dear Liot; he spareth all; they are his. The Lord is the lover of souls.”

These were her last words. With clasped hands and wide-open eyes she lay still, watching and listening, ready to follow when beckoned, and looking with fixed vision, as if seeing things invisible, into the darkness she was about to penetrate. Steeped to his lips in anguish, Liot stood motionless until a dying breath fluttered through the room; and he knew by his sudden sense of loss and loneliness that she was gone, and that for this life he was alone forevermore.

44III

A SENTENCE FOR LIFE

All Lerwick had been anticipating the death of Karen, but when it came there was a shock. She was so young and so well loved, besides which her affectionate heart hid a great spirit; and there was a general hope that for her husband’s and child’s sake she would hold on to life. For, in spite of all reasoning, there remains deep in the heart of man a sense of mastery over his own destiny–a conviction that we do not die until we are willing to die. We “resign” our spirits; we “commit” them to our Creator; we “give up the ghost”; and it did not seem possible to the wives and mothers of Lerwick that Karen would “give up” living. Her mortality was so finely blended with her immortality, it was hard to believe in such early dissolution. Alas! the finer the nature, the more readily it is fretted to decay by underlying wrong or doubt. When Matilda Sabiston drove Karen down to the sea-shore on the day before her bridal she really gave her the death-blow.

For Karen needed more than the bread and love of 45 mortal life to sustain her. She belonged to that high order of human beings who require a sure approval of conscience even for their physical health, and whose house of life, wanting this fine cement, easily falls to dissolution. Did she, then, doubt her husband? Did she believe Matilda’s accusations to be true? Karen asked herself these questions very often, and always answered them with strong assurances of Liot’s innocence; but nevertheless they became part of her existence. No mental decisions, nor even actual words, could drive them from the citadel they had entered. Though she never mentioned the subject to Liot, though she watched herself continually lest any such doubts should darken her smiles or chill her love, yet they insensibly impregnated the house in which they dwelt with her. Liot could not say he felt them here or there, but they were all-pervading.

Karen withered in their presence, and Liot’s denser soul would eventually have become sick with the same influence. It was, therefore, no calamity that spared their love such a tragic trial, and if Liot had been a man of clearer perceptions he would have understood that it was not in anger, but in mercy to both of them, that Karen had been removed to paradise. Her last words, however, had partially opened his spiritual vision. He saw what poison had defiled the springs of her life, and he knew instinctively that Matilda Sabiston was the enemy that had done the deed.

It was, therefore, little wonder that he sent her no notice of her niece’s death. And, indeed, Matilda heard of it first through the bellman calling the funeral hour through the town. The day was of the stormiest, 46 and many remembered how steadily storm and gust had attended all the great events of Karen’s short life. She had been born in the tempest which sent her father to the bottom of the sea, and she herself, in coming from Yell to Lerwick, had barely escaped shipwreck. Her bridal garments had been drenched with rain, and on the day set for her baby’s christening there was one of the worst of snow-storms. Indeed, many said that it was the wetting she received on that occasion which had developed the “wasting” that killed her. The same turmoil of the elements marked her burial day. A cold northeast wind drove through the wet streets, and the dreary monotony of the outside world was unspeakable.

But Matilda Sabiston looked through her dim windows without any sense of the weather’s depressing influence–the storm of anger in her heart was so much more imperative. She waited impatiently for the hour appointed for the funeral, and then threw over her head and shoulders a large hood and cloak of blue flannel. She did not realize that the wind blew them backward, that her gray hairs were dripping and disarranged, and her clothing storm-draggled and unsuitable for the occasion; her one thought was to reach Liot’s house about the time when the funeral guests were all assembled. She lifted the latch and entered the crowded room like a bad fate. Every one ceased whispering and looked at her.

She stepped swiftly to the side of the coffin, which was resting on two chairs in the middle of the room. Liot leaned on the one at the head; the minister stood by the one at the foot, and he was just opening the 47 book in his hands. He looked steadily at Matilda, and there was a warning in the look, which the angry woman totally disdained. Liot never lifted his eyes; they were fixed on Karen’s dead face; but his hands held mechanically a Bible, open at its proper place. But though he did not see Matilda, he knew when she entered; he felt the horror of her approach, and when she laid her hand on his arm he shook it violently off and forced himself to look into her evilly gleaming eyes.

She laughed outright. “So the curse begins,” she said, “and this is but the first of it.”

“This is no hour to talk of curses, Mistress Sabiston,” said the minister, sternly. “If you cannot bring pity and pardon to the dead, then fear to come into their presence.”

“I have nothing to fear from the dead. It is Liot Borson who is ‘followed,’ not me; I did not murder Bele Trenby.”

“Now, then,” answered the minister, “it is time there was a stop put to this talk. Speak here, before the living and the dead, the evil words you have said in the ears of so many. What have you to say against Liot Borson?”

“Look at him!” she cried. “He dares to hold in his hands the Holy Word, and I vow those hands of his are red with the blood of the man he murdered–I mean of Bele Trenby.”

Liot kept his eyes fixed on her until she ceased speaking; then he turned them on the minister and said, “Speak for me.”

“Speak for thyself once and for all, Liot. Speak here before God and thy dead wife and thy mates and 48 thy townsmen. Did thy hands slay Bele Trenby? Are they indeed red with his blood?”

“I never lifted one finger against Bele Trenby. My hands are clear and clean from all blood-guiltiness.” And he dropped the Word upon Karen’s breast, and held up his hands in the sight of heaven and men.

“You lie!” screamed Matilda.

“God is my judge, not you,” answered Liot.

“It is the word of Liot Borson. Who believes it?” asked the minister. “Let those who do so take the hands he declares guiltless of blood.” And the minister clasped Liot’s hands as he spoke the words, and then stepped aside to allow others to follow him. And there was not one man or woman present who did not thus openly testify to their belief in Liot’s innocence. Matilda mocked them as they did so with output tongue and scornful laughs; but no one interfered until the minister said:

“Mistress Sabiston, you must now hold your peace forever.”

“I will not. I will–”

“It is your word against Liot’s, and your word is not believed.”

Then the angry woman fell into a great rage, and railed on every one so passionately that for a few moments she carried all before her. Some of the company stood up round the coffin, as if to defend the dead; and the minister looked at Grimm and Twatt, two big fishermen, and said, “Mistress Sabiston is beside herself; take her civilly to her home.” And they drew her arms within their own, and so led her storming out into the storm.

49Liot had the better of his enemy, but he felt no sense of victory. He did not even see the manner of her noisy exit, for he stood in angry despair, looking down at the calm face of his dead wife. Then the door shut out the turmoil, and the solemn voice of the minister called peace into the disquieted, woeful room. Liot was insensible to the change. His whole soul was insurgent; he was ready to accuse heaven and earth of unutterable cruelty to him. Strong as his physical nature was, at this hour it was almost impotent. His feet felt too heavy to move; he saw, and he saw not; and the words that were spoken were only a chaos of sounds.

Andrew Vedder and Hal Skager took his right arm and his left, and led him to his place in the funeral procession. It was only a small one. Those not closely connected with the Borsons went to their homes after the service; for, besides the storm, the hour was late and the night closing in. It seemed as if nature showed her antagonism to poor Karen even to the last scene of her mortal drama; for the tide flowed late, and a Shetlander can only be buried with the flowing tide. The failing light, however, was but a part of the great tragedy of Liot’s soul; it seemed the proper environment.

He bared his head as he took his place, and when urged to put on his hat flung it from him. The storm beat on Karen’s coffin; why not on his head also? People looked at him pitifully as he passed, and an old woman, as she came out of her cottage to cast the customary three clods of earth behind the coffin, called out as she did so, “The comforts of the Father, Son, 50 and Holy Ghost be with you, Liot.” It was Margaret Borson, and she was a century old. She tottered into the storm, and a little child handed her the turf clods, which she cast with the prayer. It came from kindred lips, and so entered Liot’s ears. He lifted his eyes a moment, looked at the eldrich, shadowy woman trembling in the gray light, and bowing his head said softly, “Thank you, mother.”

There was not a word spoken at the open grave. Liot stood in a breathing stupor until all was over, and then got back somehow to his desolate home. Paul Borson’s wife had taken the child away with her, and other women had tidied the room and left a pot of tea on the hob and a little bread and meat on the table. He was alone at last. He slipped the wooden bolt across the door, and then sat down to think and to suffer.

But the mercy of God found him out, and he fell into a deep sleep; and in that sleep he dreamed a dream, and was a little comforted. “I have sinned,” he said when he awoke; “but I am His child, and I cannot slip beyond His mercy. My life shall be atonement, and I will not fear to fall into His hands.”

And, thank God, no grief lasts forever. As the days and weeks wore away Liot’s sorrow for his wife grew more reasonable; then the spring came and the fishing was to attend to; and anon little David began to interest his heart and make him plan for the future. He resolved to save money and send the lad to St. Andrew’s, and give him to the service of the Lord. All that he longed for David should have; all that he had failed to accomplish David should do. He would give his 51 own life freely if by this sacrifice he could make David’s life worthy to be an offering at His altar.

The dream, though it never came true, comforted and strengthened him; it was something to live for. He was sure that, wherever in God’s universe Karen now dwelt, she would be glad of such a destiny for her boy. He worked cheerfully night and day for his purpose, and the work in itself rewarded him. The little home in which he had been so happy and so miserable was sold, and the money put in the bank for “David’s education.” All Liot’s life now turned upon this one object, and, happily, it was sufficient to restore to him that hope–that something to look forward to–which is the salt of life.

Matilda gave him no further trouble. She sent him a bill for Karen’s board, and he paid it without a word; and this was the last stone she could throw; besides which, she found herself compelled by public opinion to make some atonement for her outrageous behavior, since in those days it would have been as easy to live in St. Petersburg and quarrel with the czar as to live in Shetland and not have the minister’s approval. So Mistress Sabiston had a special interview with the Rev. Magnus Ridlon, and she also sent a sum of money to the kirk as a “mortification,” and eventually was restored to all sacred privileges, except the great one of the holy table. This depended inexorably on her public exoneration of Liot and her cultivation of good-will toward him. She utterly refused Liot, and preferred to want the sacred bread and wine rather than eat and drink them with Liot Borson. And though Liot declared his willingness to forgive Matilda fully, 52 in his heart he was not sorry to be spared the spiritual obligation.

So the seasons wore away, and summer and winter brought work and rest, until David was nearly six years old. By this time the women of Lerwick thought Liot should look for another wife. “There is Halla Odd,” said Jean Borson; “she is a widow of thine own age and she is full-handed. It is proper for thee now to make a home for thyself and David. When a wife has been dead four years there has been mourning enough.”

Impatient of such talk at first, Liot finally took it into some consideration; but it always ended in one way: he cast his eyes to that lonely croft where Karen slept, and remembered words she had once spoken:

“In a little while I shall go away, Liot, and people will say, ‘She is in her grave’; but I shall not be there.”

That was exactly Liot’s feeling–Karen was not there. She had loved God and believed in heaven, and he was sure that she had gone to heaven. And from every spot on the open sea or the streeted town or the solitary moors he had only to look up to the place where his beloved dwelt. He did, however, as Jean Borson desired: he thought about Halla Odd; he watched her ways, and speculated about her money and her house skill and the likelihood of her making a good stepmother to David.

Probably, if events had taken their usual course, he would have married Halla; but at the beginning of the summer this thing happened: a fine private yacht was brought into harbor with her sails torn to rags and her mainmast injured. Coming down from the north, 53 she had been followed and caught by a storm, and was in considerable distress when she was found by some Lerwick fisher-smacks. Then, as Liot Borson was the best sailmaker in the town, he was hired to put the yacht’s canvas in good condition; and while doing so the captain of the yacht, who was also her owner, talked often with him about the different countries he had visited. He showed him paintings of famous places and many illustrated volumes of travel, and so fired Liot’s heart that his imagination, like a bird, flew off in all directions.

In a short time the damaged wayfarer, with all her new sails set, went southward, and people generally forgot her visit. But Liot was no more the same man after it. He lived between the leaves of a splendid book of voyages which had been left with him. Halla went out of his thoughts and plans, and all his desires were set to one distinct purpose–to see the world, and the whole world. David was the one obstacle. He did not wish to leave him in Shetland, for his intention was to bid farewell forever to the island. It had suddenly become a prison to him; he longed to escape from it. So, then, David must be taken away or the boy would draw him back; but the question was, where should he carry the child?

He thought instantly of his sister, who was married to a man in comfortable circumstances living at Stornoway, in the Outer Hebrides, and he resolved to take David to her. He could now afford to pay well for his board and schooling, and he was such a firm believer in the tie of blood-kinship that the possibility of the child not being kindly treated never entered 54 his mind. And as he was thinking over the matter a man came from Stornoway to the Shetland fishing, and spoke well of his sister Lizzie and her husband. He said also that their only child was in the Greenland whaling-fleet, and that David would be a godsend of love to their solitary hearts.

This report satisfied Liot, and the rest was easily managed. Paul Borson urged him to stay until the summer fishing was over; but Liot was possessed by the sole idea of getting away, and he would listen to nothing that interfered with this determination. He owned half the boat in which he fished, and as it was just at the beginning of the season he was obliged to buy the other half at an exorbitant price. But the usually prudent man would make no delays; he paid the price asked, and then quickly prepared the boat for the voyage he contemplated.

One night after David was asleep he carried him on board of her; and Paul divined his purpose, though it was unspoken. He walked with him to the boat, and they smoked their last pipe together in the moonlight on her deck, and were both very silent. Paul had told himself that he had a great deal to say to his cousin, yet when it came to the last hour they found themselves unable to talk. At midnight both men stood up.

“The tide serves,” said Liot, softly, holding out his hand.

And Paul clasped it and answered: “God be with thee, Liot.”

“We shall meet no more in this life, Paul.”

“Then I tryst thee for the next life; that will be a good meeting. Fare thee well. God keep thee!”

“Then we shall be well kept, both of us.”

That was the last of Shetland for Liot Borson. He watched his kinsman out of sight, and then lifted his anchor, and in the silence and moonlight went out to sea. When the Lerwick people awoke in the morning Liot was miles and miles away. He was soon forgotten. It was understood that he would never come back, and there was no more interest in him than there is in the dead. Like them, he had had his time of sojourn, and his place knew him no more.

As for Liot, he was happy. He set his sails, and covered David more warmly, and then lay down under the midnight stars. The wind was at his back, and the lonely land of his birth passed from his eyes as a dream passes. In the morning the islands were not to be seen; they were hidden by belts of phantom foam, wreathed and vexed with spray and spindrift. There was, fortunately, no wrath in the morning tide, only a steady, irresistible set to the westward; and this was just what Liot desired. For many days these favorable circumstances continued, and Liot and David were very happy together; but as they neared the vexed seas which lash Cape Wrath and pour down into the North Minch, Liot had enough to do to keep his boat afloat.

He was driven against his will and way almost to the Butt of Lewis; and as his meal and water were very low, he looked for death in more ways than one. Then the north wind came, and he hoped to reach the broad Bay of Stornoway with it; but it was soon so strong and savage that nothing could be done but make all snug as possible for the gale and then run 58 before it. It proved to be worse than Liot anticipated, and, hungry and thirsty and utterly worn out, the helpless boat and her two dying occupants were picked up by some Celtic coasters from Uig, and taken to the little hamlet to which they were going.

There Liot stayed all summer, fishing with the men of the place; but he was not happy, for, though they were Calvinists as to faith, they were very different from the fair, generous, romantic men of his own islands. For the fishers of Uig were heavy-faced Celts, with the impatient look of men selfish and greedy of gain. They made Liot pay well for such privileges as they gave him; and he looked forward to the close of the fishing season, for then he was determined to go to Stornoway and get David a more comfortable and civilized home, after which he would sell his boat and nets. And then? Then he would take the first passage he could get to Glasgow, for at Glasgow there were ships bound for every port in the world.

It was on the 5th of September that he again set sail for Stornoway, and on the 11th he was once more brought back to Uig. A great storm had stripped him of everything he possessed but his disabled boat. David was in a helpless, senseless condition, and Liot had a broken arm, and fainted from suffering and exhaustion while he was being carried on shore. In some way he lost his purse, and it contained all his money. He looked at the sea and he looked at the men, and he knew not which had it. So there was nothing possible for another winter but poverty and hard toil, and perchance a little hope, now and then, of a better voyage in the spring.