PLAYING WITH FIRE

BY AMELIA E. BARR

AUTHOR OF "ALL THE DAYS OF MY LIFE," "THE BOW OF ORANGE RIBBON," ETC.

stagnates; creeds are merely stagnant truth."

ILLUSTRATED BY

HOWARD HEATH

WILLIAM BRIGGS

TORONTO

1914

Copyright, 1914, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

WITH SINCERE RESPECT AND EVERY GOOD WISH

I INSCRIBE THIS NOVEL

TO

WILLIAM JOHN MATHESON, ESQ.

OF HUNTINGTON, LONG ISLAND

"'Good-bye, Richard!' she cried. 'Good-bye, dearest of all!'"]

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I. The Minister's Family

CHAPTER II. Lord Richard Cramer

CHAPTER III. Donald Pleases His Father

CHAPTER IV. The Great Temptation

CHAPTER V. The Minister in Love

CHAPTER VI. Donald Takes His Own Way

CHAPTER VII. Marion Decides

CHAPTER VIII. Macrae Learns a Hard Lesson

CHAPTER IX. When Will the Night Be Past?

CHAPTER X. A Dream

CHAPTER XI. Love Is the Fulfilling of the Law

CHAPTER XII. Afterward

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

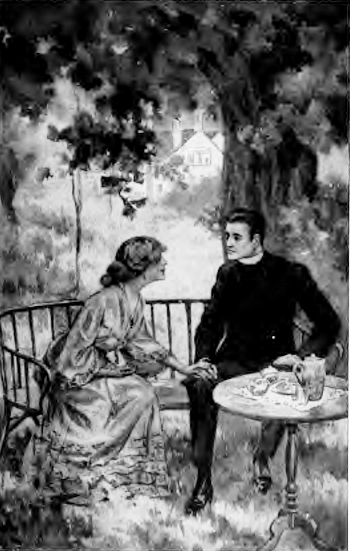

"'Good-bye, Richard!' she cried. 'Good-bye, dearest of all!'"

"There came again to her that singular sense of a past familiarity"

"She smiled and laid her jeweled white hand confidingly on his"

"The descent seemed steep and dark"

PLAYING WITH FIRE

CHAPTER I

THE MINISTER'S FAMILY

An high priest clothed with doctrine and with truth.—Esdras I: 5:40.

Glasgow is the city of Human Power. It is not a beautiful city, but the gray granite of which it is built gives it a natural nobility. There is nothing romantic about its situation, and its streets are too often steeped in wet, gray mist, or wrapped in yellowish vapor. But there are no loungers in them. The crowd is a busy, hard-working crowd, whose civic motto is Enterprise and Perseverance. They made the river that made the city, and then established on its banks those immense shipbuilding yards, whose fleets take the river to the ocean, and the ocean to every known port of the world.

It is also a very religious city. Its inhabitants do not forget that they are mortals, though no doubt mortals of a superior order, and the number of churches they have built is amazing. It is impossible to walk far in any direction without coming face to face with one. I am writing of the midway years of the nineteenth century, when there was one church among the many that all strangers were advised to visit. It was not the Cathedral, nor the old Ram's Horn Kirk; it was a large, plain building, called the Church of the Disciples. No one could find it to-day, for it stood upon a corner that became necessary to the trade of a certain great street. Then the Church of the Disciples disappeared, and handsome shops devoted to business of many kinds rose in its place.

This church derived its fame from its minister, a very handsome man, of great scholarly attainments and a preponderance of that quality we call "presence." Even when at twenty-three years of age he stepped from the halls of St. Andrew's into the pulpit of the Church of the Disciples, elders, deacons, and the whole congregation succumbed to his influence. And when, after twenty-one years of service, he made his dramatic exit from that pulpit he still held his congregation in the hollow of his hand.

He was a Highlander of the once powerful house of Macrae; tall among his brethren as was Saul among his people. His face was darkly handsome, and made doubly attractive by a shadowy Celtic pathos. His eyes were piercing but sad, his voice grand and resonant, suiting well the wrathful, impassioned Calvinism of his sermons. For he was a Pharisee of Pharisees touching every tittle of the law laid down by that troubler of mankind called John Calvin.

One evening in the beginning of June he went to his home after a rather unimportant session with his elders. He had taken his own way as usual, and was not in the least moved by the slight opposition he had been compelled to silence. With a slow, stately step he walked up the wide spaces of Bath Street until he came to the handsome residence in which he dwelt. He had no time to open the door; it was gently set wide by a girl who stood just within its shelter. A tinge of pleasure came into the minister's face, and when she said in a low, sweet voice:

"Father!" he answered her in one word full of tenderness:

"Marion!"

They went into the parlor together. It was the ordinary parlor of its day, inartistic and comfortably ugly, but withal suitable and pleasant to the generation, who found in it their ideal of "home." A Brussels carpet covered the floor, the furniture was of mahogany upholstered in black horse-hair cloth. There were crimson damask curtains at the windows, a crimson cloth on the large center table, and a soft large rug before the bright steel grate, which held a handful of fire, though it was a fine day in the early part of June. The chimneypiece was of dark marble; on it there were two bronze figures and a handsome clock, above it a very large picture of Queen Victoria's coronation. It was a parlor duplicated in every respectable residence. Such rooms were comfortable and serviceable and very suitable to the big men who occupied them.

The minister felt its pleasant "use and wont," and with a sigh of relief took the easy-chair his daughter drew to the fireside. Then she brought him a glass of water and his slippers, went for the mail which had come during his absence, lit the gas, and in many other ways fluttered so lovingly about him that it was amazing he hardly seemed to notice her affectionate service. An American father would have drawn the girl to his side, given her sweet words and tender kisses, and doubtless Dr. Macrae felt all the affection necessary for this result, but he had never seen fathers pet their daughters, never been told to do so, had no precedents to go by, and, on the contrary, had been constantly instructed both by precept and example that women were not "to be put too much forward, or given too much praise." Service was the duty of the women in any household, and men were born with the expectation of it in their blood. So Dr. Macrae watched and felt and admired and loved, but made no attempt to express his feelings, and Marion did not expect it.

Dr. Macrae had lifted a paper, but he soon laid it down, and asked impatiently: "Marion, where is Aunt Jessy?"

"She will be here anon, Father—here she comes!" and at the words a little woman wearing a gray dress, a white lace tippet, and a small white lace cap, set with pink bows, entered. She was rather pretty, and sweet and homely as honey. A maid carrying the simple supper of the family accompanied her. Dr. Macrae looked at her pleasantly, and she said:

"Well, Ian!"

That was all, until the boiled oatmeal and milk, and the toasted cakes and cheese were spread upon the table. But as soon as the minister had his plate of boiled oatmeal and his glass of milk before him, she continued:

"You are a bit late home to-night, Ian. I was wondering about it."

"There was a useless kind of session—much talking about nothing."

"Men must talk, especially when they are in session for that purpose. What were they talking about?"

"Many usual things, rather unusually, about the Bible."

"What for were they meddling with the Book? They were hearing it, or reading it, all day yesterday."

"They were discussing the buying of a new Bible for the Church. Deacon Laird proposed it. He said he had been noticing for a long time that the pulpit Bible was frizzled and worn, and the cushion much faded; both of them looking as they should not look in the Church of the Disciples."

"And what words did you give them?"

"I let them talk among themselves, until Elder Black said he knew a place where a large Bible could be got at a very cheap figure, likewise the cushion, and he would take time to ask the selling price of the same this week."

"Well?"

"I said then: 'Elder, you will keep your silence concerning a cheap Bible. I'll have no cheap Bible in my pulpit. You are grudging nothing of the best for all your private necessities, and you will buy the House of God what is fitting for it.'"

"You spoke well. Now they will be looking for the best Bible in Scotland. But what for did Deacon Laird raise that question, when the congregation, in its most respectable part, is going down the water for the summer months?"

"He is young, and only just elected, and he was trying to do something that none of the other deacons had thought of. That is my surmise. If I wrong the man, I ask pardon."

"He will have to pay for his bit of forwardness. The others will see to it that he backs his proposal with his money."

Dr. Macrae made no further remark on the subject. He took from his pocket a letter and said: "I had a few lines from Lady Cramer, and she tells me that the Little House will be unoccupied this summer. Some unforeseen circumstances preventing Lady Kitty Baird's family visiting her, she offers it to me for four or five months. If you could pack your clothes to-morrow, you might remove there on Wednesday or Thursday, and, by taking the train from Edinburgh, you would reach Cramer early in the afternoon."

"Do you mean that Marion and I are to go there?"

"I do."

"O Father, how very delightful! I am so happy!"

"It is a pretty place. I saw it when I was last at Cramer. Also, it is near the sea. You will like that, Marion."

"We will both of us like it, Ian. I shall be glad to be near the hills and the sea, and Marion is needing a change. But, Ian, you will have to consider that, if we are going—in a manner—as Lady Cramer's friends or guests, Marion will be asked—at odd times—to the Hall, and she must have one or two frocks, and other things in accordance."

"Marion can go to Stuart and McDonald's and get whatever she wants."

Then Marion lifted her eyes and met her father's eyes, and she smiled and nodded; and, though no word was spoken, both were well satisfied.

"Now," continued Dr. Macrae, "I am going to my study to read. You will have plenty to talk about. I should only be in your way."

"Bide a minute, Ian; what about the servant lasses? You cannot shut up this house. Donald—poor lad—must have some place to lay his head, and eat his bread."

"I suppose there are servants in the Little House. Lady Cramer said you would require to bring nothing but your clothing. All else was provided."

"I will have my own servant girls, or none at all."

"Will you be requiring more than one? You might take Aileen, and leave Janet here to look after myself and Donald."

"If that pleases you, I'll make it suit me."

"Think, and talk over the matter. You will know your wish better in the morning. Good night."

The salutation was general, but he looked at Marion, and she answered the look in a way he understood and approved. Then Mistress Caird disappeared for half an hour, and when she returned to the parlor Marion had completed her shopping list.

"Aunt," she said, as she fluttered the bit of paper, "I have made out my list. I want so many things, I fear the bill will be very large."

"You need take no thought about the bill, dear. It will be a means of grace for your father to pay it. It is very seldom he has a fit of the liberalities. Teach him to open his hand now and then. A shut hand is a shut heart."

"But he was so prompt and kind about it. He never curtailed me in any way. It is mean to take advantage of his trust and generosity."

"You have to be mean to make men generous. You must keep your father's hand open. Let me see your list."

She read it with a smile, and then, laughing gaily, said: "Well, Marion, if this is your idea of fine dressing, it is a very primitive one. You must have at least one silk dress, and what about gloves and satin slippers and silk stockings to wear with them? And you will require a spangled fan, and satin sashes, and bits of lace, and there's no mention of hats or parasols. It is a fragmentary document, Marion, and I am sure you had better begin it over again, with Jessy Caird to help you."

When this revision had been made, Marion was still more disturbed. "It does seem too much, Aunt," she said. "I cannot treat Father in this way. It is mean."

"Now I will tell you something. I maybe ought to have told you before. Listen! You are spending your own money, not his. Your mother left you all she had, and got your father's promise to give you the interest of it for your private spending, as soon as your school days were over. She knew you would then be wanting this and that, and perhaps not be liking to ask for it. Your father is just giving you your own. Spend it wisely, and I have no doubt he will continue to give it to you at regular periods."

"That makes things different. My mother! Did I ever see her?"

"She died when you were two days old. She saw you. From her breast I took you to my heart, and I have loved you, Marion, as my own child."

"I am your own child, Aunt. I love you with all my heart. Why did you never talk to me of my mother before?"

"Because it is always wise to let the Past alone. Give all your heart and sense to the Priceless Present. You have nothing to do with the unborn To-morrow or the dead Yesterday."

"But my mother——"

"Some day I'll tell you all about her. Did you notice how unconcerned your father was regarding the house, and the servant girls—and your brother, also?"

"He advised us to take one girl and leave the other here. You said 'Yes' to that proposal, Aunt."

"He took me unawares. I shall say 'No' to it to-morrow. Men have an idea that a house takes care of itself, that servants work naturally, and that dinners are bought ready cooked. He knew enough, however, to choose the best of the two girls to stay here. I am going to take both of them with me. I will not be beholden to my Lady for servants, not I! I shall send for old Maggie in the morning; she can look after the house and the two men in it—fine!"

"I wish Donald could go with us."

"If he could, your father would not let him. He is very angry with Donald, these six months past."

"Why?"

"He wanted him to go to St. Andrews to prepare for the ministry, and the lad, who usually keeps his own good sense to the fore, forgot himself and told his father—his father, mind you!—that he would 'not preach Calvinism' if he got 'the city of Glasgow for doing it.' And the minister was angry, and Donald got dour and then said a few words he should not have said to anybody in a Calvinist minister's presence."

"What did he say?"

"He said he did not believe in Election. He said every soul was elect; that even in hell Dives held fast to the fatherhood of God, and God called Dives 'son.' He said Religion was not a creed, it was a Life, and moreover, he said, Calvinism was a wall between the soul and God, and what use was there in hewing out roads to a wall?"

"Poor Father! Donald should not have said such things in his presence. No, he should not! I am angry at Donald for doing so."

"Well, the Macrae was aboon the Reverend that day. He was white angry. He could not, he did not dare to, open his mouth. He just set the door wide, and ordered Donald out with a wave of his hand."

"Poor Donald! That was hard, too."

"Yes, the Macraes are always

And worse to their foes.'

Donald just came to my room, and I left him alone to cry his young heart out. But my heart was, and is, with Donald. He is man grown, and he has a right to have his own opinions."

"Maybe so, Aunt. But he should not throw his opinions like a stone in Father's face."

"Perhaps you'll do the same some day."

"Me! Never! Never!"

"I'm glad to hear that."

"How came Donald to go to Reed and McBryne's shipping office?"

"He spent the next few days miserably. He did not see his father save at meal times, and the two of them never opened their mouths. So I said one morning, 'A new housekeeper will be necessary here, for I will not eat my bread like a dumb beast a day longer.' Then the mail brought the news of the break-up in your school, and your father said to me as soon as we were by ourselves, 'Jessy, you must see that Marion's room is made pretty. She is a young lady now, and, if anything is needing, get it.'"

"That was like Father's thoughtfulness."

"The thought was not all for you. There were other serious considerations, and he was keeping them in mind. I looked straight in his face and asked, 'What are you going to do about Donald's future?' He said, 'I do not know'; and I answered, 'You must find out, for, if I stay here, something must be done for Donald this day, and I will not require to tell you this again, Ian.'"

"O Aunt! how could you speak, or even think, of leaving us? What would I do here, wanting you?"

"You did not have to want me, child, and I knew that. At the dinner hour your father laid down his knife and fork in the middle of the dessert, and said, 'Donald, you will go in the morning to Reed and McBryne's shipping office. I have got you a clerkship there. The salary is small, but your home will be here, and you will have few and trifling expenses.'"

"What answer did Donald make?"

"He was red with passion when his father finished speaking, and he answered quickly, 'I will not be a shipping clerk. No, sir! I will take the Queen's shilling and go to the army. Macraes have ever been fighters. I want no pen. I will have a sword. How can you ask me to be a clerk, Father? It is cruel! Too cruel!'"

"Poor Donald!"

"I think his father felt as much as he did. He could not speak until he saw the lad move his chair from the table. Then, in a very moderate voice, he said, 'Stay, Donald, and listen to me. Honor as well as prudence forbids you the army. You are the last male of our family, except your aged uncle and myself. Its continuation rests with you. It is a duty you would be a kind of traitor to ignore. After me, you are the Macrae. I know the world thinks little of the dead Highland clans, but we think none the less of ourselves because of the world's indifference. You will be the Macrae; you must marry, and raise up sons to keep the name alive. You cannot go to the army. You cannot put your life constantly in jeopardy. Until something more to your liking turns up, go to Reed and McBryne's. It is better than moping idly about the house.'"

"I think Father was right, Aunt."

"Donald did not think so. He left the table without a word, but I could see his father had fathomed him, and found out one weak spot. For as soon as he said, 'You will be the Macrae,' I saw the light that flashed into Donald's eyes, and the way in which he straightened himself to his full height. Then, bowing, he left the room without a yea or nay in his mouth. Immediately afterward he left the house, but he did not stay long, and then I had a straight talk with him. I knew where he had been in the interval."

"Where could he go but to you?"

"He has a friend."

"Matthew Ballantyne."

"Just so. The lads love each other, and they are both daft about the same thing—a violin. He went to Matthew, and Matthew told him to humor his father and bide his time, and he would get his own way in the long run."

"Did that please you, Aunt?"

"Yes, it makes my work easy. And I am going to be good to the lads. I am going to tell Maggie to make them nice little suppers, and let them play till midnight, while we are at Cramer Brae. That night you were at the Lindseys' and your father at Stirling, I had them to supper. There was three of them, one being a violinist in Menzie's orchestra. He was a few years older than Donald and Matthew, but just as foolish as they were. And after their merry meal they played the heart out of me."

"O Aunt! Aunt! I shall have to stop at home and watch you. The idea of you standing for Donald behind Father's back in this way. I would not have believed it. You must love Donald."

"What for wouldn't I love him? He is most entirely lovable, and when I love I like to show it—to do foolish things to show it—ordinary things are not worth as much."

"I would not have thought it. You, so proper and respectable, making a feast for three young men, who played the heart out of you with their violins!"

"Poor Donald has not a violin of his own, yet he plays better than Matthew or the orchestra lad. How it comes I cannot tell, but he does, and there's no 'ifs' or 'ands' about it."

"Are violins dear things, Aunt?"

"Too dear for Donald to buy, and he dare not ask his father for money to buy a violin. Yes, Marion, violins cost a lot of money."

"You say I have some money of my own."

"What by that? You shall not ware it on a violin. Donald's violin will come its own road, and that will not be out of your purse. There's the clock striking twelve. Whatever are we doing here? I must have lost my senses to be keeping you."

"Don't mind an hour or two, Aunt. This has been the most wonderful night to me. You have spoken of my mother. I have had an invitation to Lady Cramer's. I have heard that I am, in a small way, an heiress. I have learned all about the trouble between Father and Donald. I have made out the list for a far finer wardrobe than I ever expected to own. I am sorry this wonderful day is over."

"But it is over, and it is now Tuesday. It will be Saturday before we can be ready for Cramer Brae. You must stay here until your new frocks are fitted, and that will make us Saturday. Now sleep well, for I shall have you called at seven sharp."

As Mrs. Caird anticipated, it was Saturday afternoon when they arrived at Cramer Brae. The Cramer carriage was waiting to take them to the Little House, which was more than a mile inland. It stood on the Brae at the foot of the hills, and was shielded on the east and west by large beech trees. The hills were behind, the sea in front of it, and when the wind was lulled, or from the south, the roar and the beat of its waves were distinctly heard.

It was a long, low house. The leaded, diamond-shaped windows opened like doors on their hinges, and flower boxes, drooping vines and blooms were on every sill. Gardens and lawns, with a little paddock for the ponies to run in, covered the six acres of land surrounding it. Marion was delighted. "Here we shall be so happy, Aunt," she cried in a voice full of sweet inflections, for she was thanking God in her heart for bringing her to such a beautiful spot.

Aileen and Kitty met them at the door and tea was waiting in the small dining-room. There was a low bowl of pansies in the center of the table, which was set with cream Wedgwood and silver of the date of Queen Anne. Every necessity and every luxury for the hour were there, and a wonderful peace brooded over all things.

Marion was enchanted. "This place must be like Heaven," she said; and Mrs. Caird answered, "I hope you are right. I cannot imagine any circumstances much pleasanter. We may thank God even for this cup of young Pekoe and thick cream, and delicate bread and fresh butter. They are just a part of the whole blessing. I have heard of a great English writer who thought that among many higher pleasures we should not miss the homely delicacies of our earthly table. I hope we shall not. I would like a little of earth in heaven; it might be as good to us as is a little of heaven on earth. Why not? All God's gifts are blessed, if we bless Him for them."

"I wonder if Father and Donald will have a good tea?"

"I'll warrant you. Maggie knows all your father's ways and likings—queer and otherwise. He would want a bit of broiled fish, or the like of it. I don't think you or I would care for hot meat now."

"What could be nicer than this cold, tender chicken?"

"Nothing, but men are keen for something hot. They don't feel as if they were fed, wanting the taste and smell of fresh-cooked flesh—of one kind or another."

"Donald promised me he would keep straight with Father, if possible."

"Whiles it is not possible to do that—but he made me the same promise, and he'll keep it, if his father will let him."

"Father is not at all quarrelsome, Aunt."

"Isn't he, dear? I'm very glad to hear it."

"You ought to know, Aunt; you have lived with him for——"

"Nearly eighteen years, and I am not settled in my mind yet on that subject."

"If people attack Father's creed, it is right for him to be angry. Donald ought to have kept his opinions to himself."

"That is the hardest kind of work, Marion. I know, for I've been trying to do it ever since you were born. Yes, Marion, I have, and it is hard work to-day."

"What makes you try it, Aunt?"

"The same reason as stirs Donald up."

"Calvinism?"

"Just Calvinism."

"But you are a Calvinist?"

"Not I! No, indeed! But when I came here to take care of Donald and yourself I promised Jessy Caird never to bring that subject to dispute. I knew, if I did, I would have to leave you, and I thought more of you two children than of any creed in Christendom."

"What creed do you like, Aunt?"

"I was christened and confirmed in the English Church and I love it with a great love; but I'm loving Donald and you far better—and her that's gone—and, if the Syrian was to be forgiven for worshiping out of his own temple for his Master's sake, I think Mother Church will forgive me for loving two motherless children more than her liturgy."

"Did Father never ask you if you would like to go to St. Mary's and hear your own prayers? They are very fine prayers. I have heard them, for when I was at school Miss Lamont took us sometimes on Sunday afternoons to the English Church."

"You are right, but I would not name Miss Lamont's freedom before your father. I never talk on this subject to him; if I did, we would be passing disagreeable words in ten minutes. For your sakes, I go cheerfully to the Calvinistic kirk every Sabbath, and nobody but your father and myself has known that my soul was Armenian, and hated a Calvinist even in its most charitable hours."

"What is an Armenian?"

"St. Paul was an Armenian, and St. Augustine, and Luther, and John Wesley, and all the millions that follow their teaching. I am not ashamed of my faith. I am going to heaven in the best of good company. But what for are we talking this happy hour of Calvinism? We ought to let weary dogs lie, and there are few wearier ones than Calvinism."

"I like to talk of it, Aunt. I want to know all about it."

"Then talk to the Minister. Here are mountains and trees and flowers of every kind. Here are birds singing as if they never would grow old, and winds streaming out of the hills cool as living waters, and wafting into us scents that tell the soul they come from heaven. Oh, my dear Marion, let us enjoy God's good gifts and be thankful."

"Are you going to unpack the trunks to-night, Aunt?"

"No. Aileen and Kitty would have a conscience ache if we did anything not necessary so near the Sabbath Day. We must respect their feelings. Aileen is very strict in her religion. I am tired, and am going to lie down for an hour, and you can wander about and please yourself. Go into the garden. I wouldn't wonder if you had a few pleasant surprises."

So Marion went into the garden, leaving the old house until she had a whole day to give it. She went among the rose trellises first. The roses were just budding—gold and pink and white. What a wonder of roses there would be in a week or two! The pansy beds were another marvel. Such pansies she had never before seen, for they represented all that the highest culture could do for size and coloring. Sweet old-fashioned flowers and flowering shrubs like lad's love were everywhere, and a little green carpet of camomile was spread in the center of the place for the fairies. Not far from it was a great bed of lavender and thyme, a special gift to the honeybees, who lived in the pretty antique straw skeps near it. Heavily laden with honey, hundreds of bees were flying slowly home to them, and the misty air was full of an odor from the hives that stirred something at the very roots of her being. She stood lost in thought before the skeps and the returning bees, and as she drew great breaths of the scented air she whispered to herself, "Where and when have I seen this very picture before?"

Until the twilight deepened and a gray mist from the sea blended with it she sat thinking of many things. Life had been so vivid to her during the past week. She felt as if she had never lived before, and it was not until all was shadowy and indistinct that she remembered her aunt had warned her to come into the house before the dew fell and the sea mist rolled inland.

Turning hurriedly, she was about to obey this order when she heard footsteps on the flagged sidewalk running along the front of the house. She stood still and listened. Perhaps it was Donald. No, the steps were not like Donald's, they were firmer and faster, and had a military ring in them. She was standing under a large silver-leafed birch tree, and not visible from the sidewalk, yet, by stepping a little further into its shadow, she thought she could satisfy her curiosity. However, she could see nothing but a tall figure, hastening through the gathering gloom and looking neither to the right nor to the left. But for the footsteps, the figure passed silently and swiftly as a bird through the gray mist. Its sudden appearance and disappearance impressed her powerfully, and then there came again to her that singular sense of a past familiarity. "I have stood in a garden watching that figure before. Where was it? Who is he?"

"There came again to her that singular sense of a past familiarity"

She was disturbed by the recurrence of the influence, and she went with rapid steps into the house. Mrs. Caird was coming to meet her. "Marion," she said, "I have slept past my intentions. Where have you been? It is too late for you to be outside. Come into the house and shut the door."

"I was walking in the garden. You told me to do so."

"Go now to the parlor and sit down. I will be with you directly."

But Marion knew that her aunt's "directly" had an elastic quality. It might be half an hour, it might be much more. So she took a book of poems from a bookcase hanging against the wall, saying to herself as she did so: "Miss Lamont told me to commit to memory as much good poetry as I could, because there came hours in every life when a verse learned, perhaps twenty years before, would have its message and come back to us. I suppose just as the bees and the man came back to me. I don't remember where from."

In less than an hour Mrs. Caird came into the parlor with a glass of milk in her hand. "Drink it, Marion," she said, "and then go to your sleep. You have surely worn the day threadbare by this time."

"I was learning a few lines until you came to me. I want to tell you something. When it was nearly dark, and I was coming to the house, a man passed here."

"I shouldn't wonder."

"I thought at first it might be Donald."

"You need not look for Donald. I have told you that before."

"He was very tall. He walked like a soldier, and passed through the mist like a darker shadow. He gave me a queer feeling."

"Which way did he go?"

"Straight past the house. When his feet touched the brae I lost his footsteps. I saw him but a moment or two. He passed so quickly. It was like a dream. I wonder who he was?"

"Most likely the young Lord. Your father told me he might be at Cramer Hall. He hoped not, but thought it more than possible. It will be the right thing for him to keep shadowy and dreamlike. From what I have heard of the young Lord, he is not proper company for any nice girl. The old Lord—God rest his soul—was a very saint in his religion and a wonderful scholar. Your father thought much of him, and he was never weary of your father's company, and he left him, also, a good testimony of his friendship in his will."

"Then Father should not infer ill of his son."

"Marion, men may be perfectly fit and proper for each other's company, and very unfit for a nice girl to talk with. The young man has been six or seven years in a regiment, but now that he has come to the estate and title I dare say he will resign. He has to look after his stepmother and the land, for I judge that she is but a young, canary-headed, thoughtless creature."

"Who said he wasn't good company for a nice girl?"

"The Minister himself said it, and to me he said it. So, Marion, if you should meet him, which I'm thinking is particularly likely, you must act according to my report. 'He isn't proper company for a good girl,' that is what the Minister said."

"Perhaps he is not a Calvinist," and Marion smiled, and Mrs. Caird tried not to smile.

"I don't want any complications," she continued, "so don't dream of him, don't think of him, and don't have any queer feelings about him. Your father will not have things go contrary to his plans, if he can help it, and Lord Richard Cramer is not in his plans."

"I know who is, Aunt, but he is not in my plans."

"What are you talking about?"

"About Allan Reid. Oh, I know Father's plan. Allan is making love to me whenever he can get a chance. And, if I go down town, I'm meeting him round every corner. I know how Donald came to get into Reid and McBryne's office."

"If you know so much, why were you keeping so quiet about things?"

"You were always telling me to keep my own counsel and share secrets with nobody."

"I was not including myself in that order."

"Father cannot bend either Donald's or my life to his wish."

"It is your life-long happiness and welfare he is planning for."

"God will order my life. That will content me. And God would not want me to marry Allan Reid, with his long neck and weak eyes, because I could never love him, and I suppose you ought to love the man you marry."

"I believe it is thought necessary by some people. Allan will have lots of money, and in good time walk to the head of the biggest shipping business in Glasgow. He is a religious young man, always in kirk when kirktime comes, and I hear that he is also the cleverest of men in a matter of business. He'll be the richest shipper in Glasgow some day."

"I shall never marry for money. Never! Never!"

"You'll never marry for money, won't you? Let me tell you, it is a far better way of marrying, in general, than comes of vows and kisses and all such gentle shepherding."

"For all that, 'I will marry my own true love.'"

"When he comes, young lady."

"When he comes! I think he will not be long in coming now."

"Go away to your sleep. You're just dreaming with your eyes open. Good night, dear."

"Good night; and 'I will marry my own true love,'" and, with the lilt on her lips, she went singing to her room.

Mrs. Caird sat down, completely perplexed. "Here's a nice state of affairs!" she mused. "I said but a few words about the young Lord, and, out of a woman's pure contradiction, she instantly made a graven image of him, and set him up in her mind to worship. She was ready, though she never saw him, to defend him against her father's judgment. I could see that plainly. What kind of a girl is this? Never a thought of love did I give Andrew Caird until he said in so many words, 'Jessy, will you be my wife?' Time enough then to begin the worshiping. Well, Ian is going to have his hands and heart full with these two children, and I'll be getting the blame of it. And, of course, I shall stand by both of them. I kissed that promise on my dying sister's lips, and I wouldn't break it for Lords, nor Commons, nor the General Assembly of the Kirk added to them. I shall stand by both! There's no harm in Donald's opinions. I hold the same myself, and, what's more, I always shall hold them. Fire couldn't burn them out of me. As for Marion, if she wants to build her a little romance, why should I hinder? The girl shall have her dream, if it pleases her." Then she slowly went upstairs to her room, and the Little House was still as a resting wheel.

CHAPTER II

LORD RICHARD CRAMER

"Souls see each other at a glance, as two drops of rain might look into each other, if they had life."

It is not in the face, but in the mind."

It was the Sabbath, and all its surroundings were steeped in that wonderful Sabbath stillness that not even great cities are without. The servants had put on with their kirk gowns the quiet movements they kept for this day, and, as they noiselessly prepared the breakfast, they talked softly to each other in monosyllables. Marion was used to this formality, and indeed was herself involuntarily affected by it. She stood hesitating on the doorsteps about a walk in the garden. Her feet longed for the soft lawns and the flowery paths, but she had not escaped the Sabbath thraldom of her house and native city.

"It might be wrong," she mused, "perhaps I ought to go to God's house and honor Him before all else. I must ask Aunt Jessy."

In a few minutes she heard her aunt coming downstairs. Evidently Mrs. Caird had forgotten that it was the Sabbath; she took the steps quickly, with some noise, too, and her face was happy; indeed, she looked ready to laugh.

"This is a heavenly place!" she said cheerfully, "and here comes Kitty with breakfast. There's no wonder you stand at the open door, Marion. Look at that little summerhouse. It is covered with jasmine stars. If you saw an angel resting in it, you would not be astonished."

"I was longing to walk in the garden."

"And why not?"

"It is the Sabbath."

"All days are Sabbath to the grateful heart."

"Yes, but this is the Kirk Day, and I was wondering how we were to get there. Aileen says it is near two miles away. I can walk two miles, but you——"

"I can walk as well as you can, but I'm not going to try it. I'm not going to the Kirk at all to-day—walking or riding."

"Not going to Kirk, Aunt!"

"No. I have made up my mind to have one long, sweet, quiet day, and to keep it with none present but God. As soon as I opened my eyes this morning I heard larks singing up to the very gate of heaven. I saw one rise from the brae just outside. I'll warrant you his nest was there. Marion, he was worshiping before any of our Glasgow burghers were out of their beds. I sent a prayer up with his song. God bless the bird!"

"What will Father say?"

"Just what he wants to say. I'll not hinder him. When you have eaten your breakfast go into the garden and say a prayer among the flowers. You'll be in one of God's own kirks. Open all your heart to Him."

"And you?"

"I'll be mostly in my room. It is long, long years since I had a Sunday that rested me. I have made up my soul and my heart to have one this day."

"And Aileen and Kitty?"

"They can walk to the Kirk. It will do them good. A mile or two is nothing."

"I heard Aileen say there was a Victoria and a light wagon in the carriage house, and she supposed the wagon would be for the servants."

"It may be so and it may not. I heard nothing about vehicles, and I am not going to discuss them in any kind or manner. The girls can walk to Kirk if they want to go; if not, they can bide in their place here. And I'll tell them that plainly, as soon as I have finished my breakfast."

It is likely Mrs. Caird kept her word; for Sunday's dinner, always prepared on Saturday, was laid on the table immediately after breakfast and then the girls disappeared, and were not seen until it was time to prepare supper. They looked dissatisfied and disappointed, and Aileen admitted they were so.

"Cramer Kirk is a poor little place," she said, "and the Minister no better than the Kirk. Master always makes a great gulf between the good and the wicked, and his sermons hae some pith in them—the good get encouragement, and the wicked are plainly told what kind o' a future they are earning for themselves. But, with this man, it was just 'Love God! Love God!' as if there was any use in loving God if you didna serve Him. It was a poor sermon, Ma'am. Master would not like such doctrine, and I came hungry away from it. So did Kitty. Kitty was saying you were not in the Kirk. Were you sick, Ma'am?"

"Oh, no, Aileen! I was just loving God at home."

Aileen was amazed at the avowal. She looked at her mistress with wondering eyes, and, though she did not venture to blame, there was distinct disapproval in her attitude.

Mrs. Caird had spent the day in her room and in the summerhouse in the garden, and this day the wonderful garden paid for its making; for in the evening, as she was walking there with Marion she pointed to an inscription above the entrance to the jasmine-shaded bower, and said, "Read it to me, Marion." And Marion read slowly, as if she was tasting the sweet flavor of the words:

And made a garden there, for those

Who want herbs for their wounds."

The two women looked at each other. Their eyes were shining, but they did not speak. There was no need. That day Jessy Caird had found herbs in the sweet shadowy place for all her unsatisfied longings, her fears and anxieties, and received full payment for her long, unselfish love and service.

The next afternoon the Minister joined his daughter and sister-in-law. He was very cheerful and happy as he sat drinking a cup of tea. His daughter was at his side, and Mrs. Caird's presence added that sense of oversight and of "all things in order" which was so essential to his satisfaction. However, Mrs. Caird had a way of asking questions which he would rather not answer, and he felt this touch of earth when she said:

"How is Donald? And how is he faring altogether, Ian?"

The question was unanswered for a moment or two, then he said with distinct anger, "I did not see Donald. The Minister's pew was empty yesterday."

"Did you ask Maggie where he was?"

"Why should I do that? Donald ought to have told me where he was going on the Sabbath. It will be a black day when I have to go to servants for information about my son."

"Poor Donald! he cannot do right whatever he does. I dare say he only went with Matthew Ballantyne to his father's place near Rothesay. You will be getting a letter from him in the morning."

"I would rather have seen him where he ought to have been."

"In the Church of the Disciples?"

"Even so."

"You are all wrong. The boys would be on the water or climbing the mountains. They were in God's holiest temple. I hope you don't even the Church of the Disciples with it!"

"This, or that, Jessy, Donald ought to have been in the Kirk."

"Maybe he was at Matthew's Kirk. Dr. Ward is preaching there now, and both Matthew and Donald think a deal of him."

"I dare say. Donald's father is always last. He would rather hear any one preach than his father."

"There's a reason for that. He does not see the others in their daily life. They don't thwart his wishes and scorn his hopes and set him to work that he hates. He sees them only in the pulpit, where they have pulpit grace and pulpit manners."

"I have always treated Donald with loving kindness."

"To be sure, when Donald walked the narrow chalk line you made for him. You had your own will. You wanted to be a minister and no one hindered you."

"How do you know, Jessy, that I wanted to be a minister?"

"Because you could not be happy unless you had power, and spiritual power was all you could lay your hands on. Donald was willing to go either to the sea or the army. What for wouldn't you give him his desire?"

"I have told you his life is all the Macraes have to build upon."

"You yourself were in the same position before Donald was born."

"Yes, and so I chose the salvation of the ministry."

"You had the 'call' thereto. You liked the salvation of the ministry. Donald could not take it, so you tied him to a counting desk. It was like harnessing a stag to a plough. But you'll take your own way, no matter where it leads you. So I'll say no more."

"Thank you, Jessy. If you would consider the subject closed, I——"

"I will do no such thing. I shall speak for Donald whenever I can, in season or out of season. There is a letter for you from Lady Cramer. It came this morning."

Dr. Macrae took it with a touch of respect, and read it twice over before he spoke of its contents, though Mrs. Caird and Marion had their part in its message. Finally, he laid it down and, handing his cup to be refilled, he said:

"Jessy, at six o'clock this evening, Lady Cramer will send a carriage for me. She wishes me to stay until Wednesday afternoon, then she intends coming to pay her call of welcome to you and Marion, and I will return with her."

"So she is wanting you for the most part of two days. What for? She has her lawyers, and councillors, and her stepson."

"The business she wants me to talk over with her is beyond lawyers and councillors. It is of a literary and religious nature."

"Oh! You may keep it to yourself, Ian."

"I do not suppose you would understand it. The late Lord left some papers on scientific and theological subjects. Lady Cramer wishes me to prepare them for publication."

"Lord Angus Cramer was not a very competent man, if all is true I have heard about him. I think Marion and myself could understand anything he could write."

"Jessy, we all know that the mental qualities of men differ from those of women. The inequalities of sex——"

"Have nothing whatever to do with mental qualities. Inequalities of sex, indeed! They do not exist! They are a fiction that no sane man can argue about."

"Jessy, I say——"

"Look at your own fireside, Minister. Donald is well fitted to go to the army, take orders, and carry them out. Marion would be giving the orders. Donald has an average quantity of brains. Marion can double yours, and, if given fitting education and opportunity, would preach and write you out of all remembrance. And where would you be, I wonder, without Jessy Caird to guide and look after all your outgoings and incomings? Who criticizes your sermons and tells you where they are right, and where wrong, and who gives you 'the look' when you have said enough, and are going to pass your climax?"

"My dear sister, you are my right hand in everything. I do nothing without your advice. I admit that I should be a lost man physically without you."

"Mentally, likewise. Give me all the credit I ought to have."

"Yes, my sermons owe a great deal to you. And you have kept me socially right, also. I would have had many enemies, wanting your counseling."

"That's enough. I have been your faithful friend; and a faithful friend likes, now and then, to have the fact acknowledged. You had better go to your room now and put on the handsomest suit in your keeping. You'll find linen there white as snow, and pack a fresh wearing of it for to-morrow. By the grace of God you are a handsome man and you ought to show forth God's physical gifts, as well as His spiritual ones."

Doubtless the compliment was balm to the little pricks and pinches of her previous remarks; for Dr. Macrae went with cheerful, rapid steps to his toilet, and Mrs. Caird looked after him smiling and rubbing her lips complacently, as if she was complimenting them on their courage and moderation.

Tall, stately, aristocratic in appearance, Dr. Macrae stepped into the Cramer carriage with an air and manner that elicited the utmost respect, almost the servility, of the coachman and footman. Marion looked at her aunt with a face glowing with pride, and Mrs. Caird answered the look.

"You are right, Marion. In some ways there is none like him. If he would be patient and considerate with your brother, I would stand by Ian Macrae if the whole world was against him."

"Suppose I should displease him—suppose he told me I must marry Allan Reid, and I would not—would you stand by me as you stand by Donald, Aunt Jessy?"

"Through thick and thin to the very end of the controversy, no matter what it was."

"I saw Father stop and look at the book I laid down."

"What book was it?"

"'David Copperfield,' and Father told me not to read Dickens. He said he was common, and would take me only into vulgar and improper company. He told me to read Scott, if I wanted fiction."

"Scott will take you into worse company. Romance does not make robbers and villains good company. Dickens's common people are real and human, and have generally some domestic virtues. Yes, indeed, some of his common people are most uncommonly good and lovable. For myself, I cannot be bothered with Scott's long pedigrees and descriptions. If there's a crack in a castle wall, he has to describe how far it runs east or west. It is the old, bad world Scott writes about, full of war and bloodshed, cruel customs and hatreds. And his characters are not the men and women we know, but if you go to England you will see the characters of Dickens in the omnibuses and on the streets."

"I would like us to have everything in beautiful order on Wednesday, Aunt."

"Everything is in beautiful order now and will be at any hour Lady Cramer chooses to call, as long as I am head of this house."

Still, on Wednesday afternoon Marion looked at the chairs and tables and all the pretty paraphernalia of the parlor critically. There was nothing in it she could wish different. The furniture was of rosewood upholstered in pale blue damask. The walls were covered with a delicate paper, and hung on them were pastels of lovely faces and green landscapes. The latticed windows were open, and a little wind gently moved the white lace curtains. The vases were full of flowers, and a small crystal one held the first rose of the season. There was nothing she could do but open the piano, and place a piece of music on its rack, that would give a sense of life and song to the room.

This done she looked around and, being satisfied, took a book and sat down. The book was "David Copperfield," and she had just arrived at that pleasant period when David finds out that Dora puts her hair in curl papers, and even watches her do it, when Mrs. Caird entered the room.

"Marion," she said, "I see the Cramer carriage coming, stand up and let me look at you."

Then Marion rose and she seemed to shine where she stood. From her throat to her sandals she was clothed in white organdie. A white satin belt was round her waist, and a necklace of polished white coral round her neck. There were white coral combs in her abundant black hair, and beautiful white laces at her elbows.

"You are a bonnie lassie," said her aunt proudly, "and see you hold up your own side. You are Ian Macrae's daughter and as good as any lady in the land. And beware of flattering my Lady in any form or shape. It is the worst of bad manners, as well as clean against your interests, to flatter a benefactor. Let them say nice words to you."

Then the carriage was at the door, and Mrs. Caird was there also, and Marion could hear the usual formalities, and the rustle of clothing and all the pleasant stir of arriving guests. She sat still until Lady Cramer entered, then rose to greet her. For a moment there was a slight hesitation, the next moment Lady Cramer cried, "You are Marion! I know you, child! I thought you were an angel!"

"Not yet, Lady Cramer."

The right key had been set. Lady Cramer fell at once into a charming, simple conversation and Dr. Macrae, who feared his daughter would be shy and uninteresting, was amazed at the cleverness of her conversation and the self-possession of her manner.

When tea was served, Marion waited upon Lady Cramer. She had given her father one look of invitation to take her place, but the Minister knew better than to answer it. The Apostles had refused to serve tables, he respected his office equally. Spiritually, he sat in the place of honor, how could he serve anyone with tea and muffins? There was a maid in cap and apron to perform that duty. The Macraes were a proud family, but it was not temporal pride that actuated the Minister. In all cases and at all hours he followed St. Paul's example and "magnified his office." He had always retired from anything like service, either at home or abroad, and it would be idle and false not to admit that he was admired and respected for it. It was honor enough that he condescended to be present, for in those days the Calvinistic ministry were a grave and rather haughty religious oligarchy. But they were not to blame; for the honor of God and their own satisfaction the people made them oligarchs.

After tea Lady Cramer asked Marion to sing for her. "There is a song," she said, "that I hear everywhere I go, and never too often. I dare say you can sing it, Marion. May I call you Marion?"

"I should like you to do so, Lady Cramer. And what is the name of the song?"

"I cannot tell you; it is about rowing in a boat; it is the music that charms. My dear, it beats like a human heart."

"I know it," answered Marion and, with a pleased acquiescence, she played a few chords embodying a wonderful melody, and anon her voice went with it, as if it was its very own:

Into the crypt of the night we float;

Fair, faint moonbeams wash and wander,

Wash and wander about the boat.

Not a fetter is here to bind us,

Love and memory lose their spell,

Friends of the home we have left behind us,

Prisoners of content! Farewell!"

At the last four lines the charm was doubled by someone—not in the room—singing them with her. It was a man's voice, a fine baritone, and was used with taste and skill. Every line raised Marion's enthusiasm, no one had ever heard her sing with such power and sweetness before, and during the little outburst of delight that thanked her Lord Richard Cramer entered the room.

"The praise is partly mine," he cried in a joyous voice, "and I know the musician will give me it." As he spoke he took the Minister's hand, and Dr. Macrae rose at the young man's request, and introduced his daughter to him. They looked, and they loved. The feeling was instantaneous and indisputable. Richard was on the point of calling her "Marion" a dozen times that happy hour; and "Richard" came as naturally and sweetly to Marion's lips. They sang the song over again, and before Lady Cramer left she had noticed the impression made upon her son, and resolved to have the young people under her supervision.

"I must have Marion for a week," she said to Mrs. Caird, and Lord Richard added that he had promised to teach Miss Macrae to ride, and that the lessons would require "a week at the very least." And Mrs. Caird was pleased to give such a ready consent to the proposal that Dr. Macrae could find no possible reason for refusing it.

Then the party broke up in a happy little tumult that defied the cold proprieties of the best society; for Lord Cramer had set the chatter and laughter going, and to Mrs. Caird the relaxation was like a glass of cold water to a thirsty woman.

"I am worldly enough to like the Cramers' way," she answered, when the Minister regretted the innocent merriment. "There was not a wrong word; no, nor a wrong thought, Ian; and I was fairly wearying for the sound of happy singing, and the voices of young folks chattering and laughing. This afternoon has been a great pleasure to me. And I'm hoping there will be plenty more like it. A man from the Hall has just brought a box. It appears to be a heavy one."

"It is full of books and papers."

"What kind of books, Ian?"

"Books that many are reading with an amazing interest, Jessy; and which I have long thought of examining. Huxley and Darwin's works, poor Hugh Miller's 'Investigations,' Bishop Colenso's 'Misconceptions,' Schopenhauer and others——"

"Ian, do not open one of them. There is your Bible. Don't you read a word against it. In a spiritual sense, it is the sun that warms, and the bread that feeds you."

"The intellectual feeling of the critical school of Bible readers ought to be familiar to me, or how can I preach against it, Jessy?"

"You have all the sins mentioned in the Commandments to preach against. The critical school can bear or mend its own sins."

"Let me explain, Jessy. The late Lord Cramer during his long illness read all these questioning, doubting books, and he wrote many refutations of their errors, or at least he believed them to be refutations. I have promised Lady Cramer to examine the papers, and prepare them for publication."

"Ian, do not do it. I entreat you to decline the whole business."

"You are unreasonable, Jessy."

"These men of the Critical School are intellectual giants. Are you strong enough to wrestle with them and not be overcome?"

"Not unless I comprehend them. Therefore, I must read what they say."

"What matters comprehension if you have Faith?"

"I have Faith, and I can trust my Faith. I know what I preach. My creed is reasonable and I believe it. I am no flounderer in unknown seas."

Nor was he. Ian Macrae was surely at this period of his life an upright soul. All his beliefs were fixed, and he was sure that he understood God perfectly. So he looked kindly into the pleasant, anxious face before him, and continued:

"I have not a doubt. I never had a doubt. I wish I was sure of everything concerning my life as I am of my creed. In my Bible, the blessed book from which I studied at St. Andrews, I have written these lines of an old poet, called Crawshaw:

Is a dead creed, a map correct of heaven,

Far less a feeling fond and fugitive—

It is an affirmation, and an act,

That bids eternal truth be present fact.'"

"We do not know ourselves, Ian; however, we do know that the Christ who carries our sins can carry our doubts. And no one is sure of what will happen in their life. What is troubling you in particular?"

"Donald—and Marion."

"Marion! The dear child! She has never given you a heartache in all her life."

"She gave me one this afternoon."

"Because she was happy. Ian, you are most unreasonable."

"I am afraid of Lord Cramer. He would have made love to her this afternoon——"

"I will suppose you are right and then ask, what wrong there would have been in it?"

"More than I can explain. For seven years he was in a fast cavalry regiment, and he kept its pace even to the embarrassing of the Cramer estate. He had reached the limit of his father's indulgence three years ago. His stepmother has been loaning him money ever since, and he is in honor bound to repay her as soon as possible. That duty comes before his marriage, unless he marries a rich woman. My daughter would be a most unwelcome daughter to Lady Cramer, and I will not have Marion put in such a position. Dislike spreads quickly, and from the mother to the son might well be an easy road. There is something else also——"

"Pray let me hear the whole list of the young man's sins."

"He is deeply influenced by the 'isms' of the day, and, though brought up strictly in the true church, Lady Cramer fears he never goes there; for she cannot get him to spend a Sabbath at home."

"All this, Ian, is hearsay and speculation. We have no right to judge him out of the mouth of others. Speak to him yourself."

"I cannot speak yet. But at once I wish you to speak to Marion. Tell her to hold her heart in her own keeping. The late Lord Cramer was my friend. He told me whom he wished his son to marry, and it would be a kind of treachery to the dead if I sanctioned the putting of my own daughter in her place. I would not only be humiliated in my own sight, but in the sight of the church, and of all who know me."

"No girl can hold her heart in her own keeping if the right man asks for it. There was my little sister——"

"We will not bring her name into the subject, Jessy. It is painful to me. I saw plainly this afternoon that Marion was pleased with Lord Cramer's attention."

"Any girl would have been so. He is a handsome, good-natured man, full of innocent mirth, and Marion loves, as I do, the happy side of life—and is hungry—as I am—for its uplifting."

"Marion has never seen the unhappy side of life. Her lines have fallen to her in pleasant places. A short time ago Allan Reid told me he loved her and asked my permission to win her love, if he could. I gave him it. She could not have a more suitable husband."

"Girls like handsome, well-made men, Ian, men like yourself. Allan Reid is not handsome; indeed, he is very unhandsome. Marion spoke to me of his long neck and weak eyes, and——"

"Girls are perfectly silly on that subject. A good man, and a rich man, is as much as a girl ought to expect."

"Men are perfectly silly on the same subject. A good woman with a heart full of love is as much, and more than, any man ought to expect. But, before he thinks of these things, he is particularly anxious that she should be beautiful, and graceful, and money in her purse makes her still more desirable."

"A man naturally wants a handsome mother for his children."

"Girls are just as foolish. They want a handsome father for their children. I think, Ian, you might as well give up all hopes of Marion's marrying Allan Reid. She believes him to be as mean-hearted as he is physically unhandsome. She will never accept him."

"I shall insist on this marriage. Say all you can in young Reid's favor."

"Preach for your own saint, Ian. I have nothing to say in Allan Reid's favor."

"Then say nothing in favor of Lord Cramer."

"What I have seen of Lord Cramer I like. Do you want me to speak ill of him?"

"I have told you what he has been."

"His father's death has put him in a responsible position. That of itself often sobers and changes young men. Ian Macrae, leave your daughter's affairs alone. She will manage them better than you can. And what are you going to do about Donald?"

"Donald is doing well enough."

"He is not. I am afraid every mail that comes will tell us that he has taken the Queen's shilling, or gone before the mast."

"What do you want me to do?"

"Ask Donald what he wants, and give him his desire—whatever it is."

"There is not a good father in Scotland that would do the like of that, Jessy."

"Then be a bad father and do it. I am sure you may risk the consequences."

"These children are a great anxiety to me. Something is wrong if they will not listen to their father. I am very much worried, Jessy. I will go and unpack those books and then read awhile."

"Listen to me, Ian. You say that now you have perfect Faith. When you have gone through those books, your Faith will be in rags and tatters."

"I do not fear. There is no danger but in our own cowardice. We are ourselves the rocks of our own doubt. The danger lies in fearing danger. I made a promise to the dead. I cannot break it, Jessy. Such a promise is a finality."

"You made that promise by the special instigation of the devil, Ian."

"Jessy, you never read these books. The men who wrote them were morally good men, seekers after truth and righteousness. I believe so much of them."

"You are partly right. I have never read the books, but I have read long, elaborate, wearisome reviews of them. That was enough, and more than enough, for me."

"Why did you read such reviews?"

"Because I wanted to know whether Donald and Marion should be warned against them. I think they ought to be warned."

"You can leave that duty to me. If I think it necessary, they will receive the proper instruction."

"I wonder the government allows such books to be published. They will ruin the coming generations. The Romans had not much of a religion, but when they began to doubt it they went madly into vice and atheism and national ruin. If men have such wicked thoughts as are in the books you are going to read, they ought to keep them in their own hearts. If they could not do that, I would put them in prison, and take pen and ink from them."

"Do be more charitable, Jessy. The Bible teaches——"

"It teaches us to let such destructive books alone. God himself specially warned the Israelites not even 'to make inquiry' about the religion of the Canaanites; they did it, of course, and you know the result as well as I do. And men these days are so set up with their long dominion and the varieties of strange knowledge they have accepted that they do not require any Eve to pull this apple of disobedience and doubt of God. They manage it themselves."

"Jessy Caird, you have no right to impute evil to either men or books that are only known to you through some critic's opinion." Then he rose and, standing with uplifted eyes, said with singular emotion:

Or judge less harshly where they cannot see.

O God, that men would draw a little nearer

To one another! They'd be nearer Thee!'"

With these words he left Jessy and went to the room where the fateful books were waiting for him.

And Jessy could say no more. But she threw her knitting out of her hands and let them drop hopelessly into her lap.

"When men stop reasoning, they quote poetry," she mused angrily. "I never heard Ian quote a whole verse before, unless he was in the pulpit; well, I have warned him, and now I can only hope he will feel that sense of utter desolation in his soul that I always felt after a few sentences of Schopenhauer or Darwin. There! I hear him opening the box. Now begin the to-and-fro paths of Doubt and Persuasion, days full of anxious brooding, nights full of shadowy chasms, that nothing but Faith can bridge. But Ian has Faith—at least in his creed—and there are spiritual influences that no one can predict or resist, for the way of the Spirit is the way of the wind." Motionless she sat for a few minutes, and then rose hastily, saying softly as she did so, "Wherever is Marion? I wonder she was not seeking me ere this."

She found Marion in her own room. She was kneeling at the open window with her elbows on the broad stone sill, and her cheeks were almost touching the sweet little mignonettes. A tender smile brooded over her face, a tender light was in her eyes, she was lost in a new, ineffable sense of something full of delight—some pleasure strangely personal that was hers and hers alone.

"I am lonely without you, Marion. Why did you run away from me?"

"I thought Father was with you and, perhaps, saying something I would not like—about our visitors."

"What could he say that was not pleasant? I am sure they were everything that any reasonable person could expect."

"You know what Father told you about Lord Cramer. I have now seen him. I would not believe any wrong of him. I shall not listen to any wrong of him without protesting it; so I thought it best not to go into temptation."

"You did right."

"He is a beautiful young man—and how exquisite are his manners! How did he learn them?"

"He has always lived among people of the highest distinction, and they practice them naturally—or ought to do so."

"To you, to his stepmother, to Father, and to me he was equally polite. He did not treat me indifferently because I have only the shy, half-formed manners of a school-girl. He paid you as much respect as he paid Lady Cramer, though you are old and beneath her in social rank, nor was he in the least subservient to Father because he is a famous minister. He was equally attentive and courteous to all."

"I will take leave to differ with you, Marion Macrae. I am not old. I am in the midway of my life, young in soul, mind and body, and I am nothing beneath Lady Cramer in rank. Keep that in your mind. And you are not a shy, untrained school-girl; you are a young, lovely woman, with the naturally fine manners that come from a good heart and proper education. As for subservience to your father, I saw nothing of it from Lord Cramer, but Lady Cramer deferred to him in everything, and I wonder she has not turned his head round, and his heart inside out with her humility, and homage, and her downcast eyes."

"She is very pretty, Aunt."

"She is fairly beautiful. She has the witching ways of those golden-haired women, and all their flattering submissions. She can drop her blue eyes, and then lift them with a flash that would trouble any man's heart that had love or life left in it. And see how wisely and warily she dresses herself—the long, black, satin gown, with its white crape collar and cuffs, and the black and white satin ribbons so fresh and uncreased!"

"And the wave and curl of her lovely hair, under the small white lace bonnet! I thought, Aunt, she——"

"She ought not to have worn a white bonnet. It is too soon after her husband's death to wear a bit of white lace and a few white flowers on her head. She should have worn her widow's bonnet for two years, and it is wanting half a year at least of that term. But, this or that, she is a butterfly of beauty and vanity, and I would not be astonished if she fell in love with your father. To most women he would be an extraordinarily attractive man."

"O Aunt Jessy, what an idea! That would be the most unlikely of things."

"For that very reason it is likely."

"Father never notices women except in a religious way—when they are in trouble, or want his advice about their souls."

"You can no more judge your father by his outside than you can judge a cocoanut. He has a volcanic soul—ordinarily the fire is low and quiet, but if it should become active it would be a dangerous thing to meddle with."

"Father may have an austere face, but he has a tender mouth; and, O Aunt, I have seen love leap into his shadowy eyes when I have met him at the door, or drawn my chair close to his side in the evening."

"Your father is a good man. He has a genius for divine things—but women are not reckoned in that class."

"And I think Lord Cramer is a good man, though his genius may be for military things. He had the light of battle on his face this afternoon when he told us of that fight with the Afghans; and how sad was his expression when he described the burying of his company's colonel after it—the open grave in a cleft of hills dark with pines, the solemn dead march, the noble words spoken as they left their leader forever, and turned back to camp to the tender, homely strains of Annie Laurie. Oh, I could see and hear all. I have felt ever since as if I had been present."

"He appears to be a fine young fellow, though we must remember that men judge men better than women can; and it may be possible your father's opinion of Lord Richard Cramer has at least some truth in it."

"I do not believe it has. I think, also, that Lord Cramer is the handsomest man I ever saw. Just compare him with Allan Reid."

"Why are you speaking of Allan Reid?"

"Because Father thinks I will marry the creature."

"Will you do as your father wishes?"

"Once, I might have done so—perhaps. Not now. My eyes have been opened. I have seen a man like Lord Richard Cramer, and I will marry no man of a meaner kind. How tall and straight and slender is his figure! How bold and manly his face! His gray eyes are full of quick, undaunted spirit, he is all nerve and fire, and I believe he could love as well as I am sure he can fight."

"You need not take love into the question. Richard Cramer will be compelled to marry a rich woman. Your father says he is bound both by honor and necessity to do so."

Marion buried her face in the mignonette, and did not answer; and Mrs. Caird, after a few moments' silence, said:

"Be glad that your heart is your own, and do not give it away until it is asked for."

"As if I would be so foolish, Aunt! I stand by Lord Cramer because people tell lies about him. I always stand by anyone wronged. I would even stand by Allan Reid, if I knew he was slandered without just cause."

"That is very good of you. If Allan heard tell of your opinion, he would get someone to lie him into your favor."

"He could not, because I would believe anything bad of Allan."

Then Mrs. Caird laughed, and Marion wondered why. She had forgotten the exception just made in his favor. Her thoughts were not with Allan Reid.

CHAPTER III

DONALD PLEASES HIS FATHER

When harps were in the hall;

And each proud note made lance and spear

Thrill on the banner'd wall.

With songs of sadness and of mirth.

That they might touch the hearts of men

And bring them back to heaven again."

The Minister had said he would go and read awhile, and Mrs. Caird had heard him unpacking the box of books that had arrived. But at that hour he went no further than to arrange them conveniently on a table at his side. He was too utterly amazed at Mrs. Caird's admitting that she had read criticisms and reviews of books she considered objectionable for himself. He remembered then, what he had only casually observed during all the years she had dwelt with him, that Jessy Caird was never without a book in her work-basket. But he had noticed on all of them the cover and the mark of the public library, and had felt certain they were novels. And, as the children were at schools and she much alone, he had been considerate in the matter and not asked any questions. How could he suspect that such objectionable literature was lying openly among her knitting and mending?

As he made this reflection, his eyes sought the volumes lying on the table, and he noticed that his Bible was close to them. Its familiar aspect brought a warm, comfortable sense to his heart. It was surely the Word of His Father in heaven. He leaned forward and laid his head affectionately upon it. What a Friend it had been to him! What a Counselor! In every way he had such a tremendous prepossession in its truth and blessing that he could smile defiantly at any man, or any man's book, being able to make him doubt a tittle of its law or its promises.

"The heavens and the earth may pass away," he said, "but not one word of God shall perish!" And, though he spoke softly, as to his own heart, the affirmation was hot with the love and fervor that thrilled the words through and through. In a few moments he rose, lifted the Book with tender homage, and laid it on a small table holding nothing but one white moss rose in a slender crystal vase. He did it without intention, actuated by a sudden spiritual reverence for holy things.

But as soon as the transfer was accomplished he began to reason about it. "Why did I remove the Bible?" he asked himself. He was not sure why, but he was sure that the impulse to do so had been a good and proper one.

"There is no book that looks like it in all the world," he thought. "It belongs to the Sanctuary. It is the Sanctuary in itself. How could I leave it among books that doubt and perhaps revile it?" Then his glance fell upon the books to which he had attributed a crime so likely and so heinous, and he continued his reflections.

"How commonplace and similar they look! They might be text-books, or novels, or even poetry. But God has set his mark upon the Bible. We cannot mistake it. Printed in any size or shape, bound in any color or any material, we know the moment our eyes fall upon it that it is the Word of God."

However, it is easy for the mind to find a ready road from spiritual to personal things, and it was not long before Lord Cramer had possession of the Minister's meditations. There appears to be no relevancy between the Bible and Lord Cramer, but Thought has swift and secret passages, and perhaps the way had been through the discredited books; for he was thinking of the young nobleman with much the same feelings as he had given the doubtful and objectionable volumes. He had felt them to be unworthy to lie on the same table with the Bible. He was equally certain that Lord Richard Cramer was unworthy to lift his eyes to Marion Macrae, and quite as positive that he intended to do so.

"Marion must marry Allan Reid," he decided. "It is for her happiness every way. What profit is there in a title, if its holder is too poor to honor it? Young Reid is rich, and will be rich enough to buy a title if he wants one. Moreover, Lord Richard is not like his father in a religious sense. Lord Angus Cramer—my friend—was present at divine service as long as he was able to be so. Lord Richard does not observe the Sabbath. His stepmother is troubled at his attitude toward the Church. Such a man is not fit to be my son-in-law—a man who does not keep the Sabbath! The idea is an impossible one! Allan Reid fills his place every Sabbath in the Church of the Disciples. To be honorable, and rich, and to keep the Sabbath! These are the three cardinal points of a respectable and religious life, and Marion must be made to accept them." Yet he felt quite sure that, at that very moment, Lord Richard Cramer was thinking of his daughter, and almost equally sure that Marion was thinking of Richard Cramer.

In a measure Macrae was correct. Lord Cramer was thinking of Marion, but he was telling himself it was only in a philosophical way. Sitting smoking on the lawn in the late twilight, he was curiously asking his heart the question so many ask, "Why is it that, out of the thousands of persons we meet, only one can rouse in us the tremendous passion of a first true love?" Yet, in whatever manner Richard Cramer tried to reason with himself, he was quite aware that something had happened that afternoon that could never be satisfied by any reasoning.

He would not believe it was love. Yet he had an extraordinary elation, his heart beat rapidly, and he was in a fever of longing and wonderment about the girl he had just met. He thought he knew all about women, but Marion was quite different, and she had called into life something deeper down than he had ever felt before. He was dreamy and yet restless, he was strangely happy, and yet strangely unhappy. Ah, though he would not admit it, the poignant thirst and exquisite hunger of a great love were beginning to trouble him.