CHRISTINE

By AMELIA E. BARR

Christine

Joan

Profit and Loss

Three Score and Ten

The Measure of a Man

The Winning of Lucia

Playing with Fire

All the Days of My Life

D. Appleton & Company

Publishers New York

CHRISTINE

A FIFE FISHER GIRL

BY

AMELIA E. BARR

AUTHOR OF “JOAN”, “PROFIT AND LOSS”, “THE MEASURE OF A MAN”, “ALL THE DAYS OF MY LIFE”, ETC.

FRONTISPIECE BY

STOCKTON MULFORD

“The sea is His, and He made it”

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

NEW YORK LONDON

1917

Copyright, 1917, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

I Inscribe This Book To

Rutger Bleecker Jewett

Because He is my Friend, And

Expresses All That Jewel of a

Monosyllable Requires And

Because, Though a Landsman,

He Loves the Sea And

In His Dreams, He is a Sailor.

Amelia E. Barr.

January 7th, 1917.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Fishers of Culraine | 1 |

| II. | Christine and the Domine | 23 |

| III. | Angus Ballister | 38 |

| IV. | The Fisherman’s Fair | 61 |

| V. | Christine and Angus | 86 |

| VI. | A Child, Two Lovers, and a Wedding | 115 |

| VII. | Neil and a Little Child | 152 |

| VIII. | An Unexpected Marriage | 183 |

| IX. | A Happy Bit of Writing | 212 |

| X. | Roberta Interferes | 247 |

| XI. | Christine Mistress of Ruleson Cottage | 280 |

| XII. | Neil’s Return Home | 306 |

| XIII. | The Right Mate and the Right Time | 339 |

| XIV. | After Many Years | 362 |

The hollow oak our palace is

Our heritage the sea.

Howe’er it be it seems to me

’Tis only noble to be good.

Kind hearts are more than coronets

And simple faith than Norman blood.

Friends, who have wandered with me through England, and Scotland, and old New York, come now to Fife, and I will tell you the story of Christina Ruleson, who lived in the little fishing village of Culraine, seventy years ago. You will not find Culraine on the map, though it is one of that chain of wonderful little towns and villages which crown, as with a diadem, the forefront and the sea-front of the ancient kingdom of Fife. Most of these towns have some song or story, with which they glorify themselves, but Culraine—hidden in the clefts of her sea-girt rocks—was 2 in the world, but not of the world. Her people lived between the sea and the sky, between their hard lives on the sea, and their glorious hopes of a land where there would be “no more sea.”

Seventy years ago every man in Culraine was a fisherman, a mighty, modest, blue-eyed Goliath, with a serious, inscrutable face; naturally a silent man, and instinctively a very courteous one. He was exactly like his great-grandfathers, he had the same fishing ground, the same phenomena of tides and winds, the same boat of rude construction, and the same implements for its management. His modes of thought were just as stationary. It took the majesty of the Free Kirk Movement, and its host of self-sacrificing clergy, to rouse again that passion of religious faith, which made him the most thorough and determined of the followers of John Knox.

The women of these fishermen were in many respects totally unlike the men. They had a character of their own, and they occupied a far more prominent position in the village than the men did. They were the agents through whom all sales were effected, and all the money passed through their hands. They were talkative, assertive, bustling, and a marked contrast to their gravely silent husbands.

The Fife fisherman dresses very much like a sailor—though he never looks like one—but the Fife fisher-wife had then a distinctly foreign look. She 3 delighted in the widest stripes, and the brightest colors. Flaunting calicoes and many-colored kerchiefs were her steady fashion. Her petticoats were very short, her feet trigly shod, and while unmarried she wore a most picturesque headdress of white muslin or linen, set a little backward over her always luxuriant hair. Even in her girlhood she was the epitome of power and self-reliance, and the husband who could prevent her in womanhood from making the bargains and handling the money, must have been an extraordinarily clever man.

I find that in representing a certain class of humanity, I have accurately described, mentally and physically, the father and mother of my heroine; and it is only necessary to say further that James Ruleson was a sternly devout man. He trusted God heartily at all hazards, and submitted himself and all he loved to the Will of God, with that complete self-abnegation which is perhaps one of the best fruits of a passionate Calvinism.

For a fisherman he was doubtless well-provided, but no one but his wife, Margot Ruleson, knew the exact sum of money lying to his credit in the Bank of Scotland; and Margot kept such knowledge strictly private. Ruleson owned his boat, and his cottage, and both were a little better and larger than the ordinary boat and cottage; while Margot was a woman who could turn a penny ten times over better than any other woman in the cottages of Culraine. Ruleson also had been blessed with 4 six sons and one daughter, and with the exception of the youngest, all the lads had served their time in their father’s boat, and even the one daughter was not excused a single duty that a fisher-girl ought to do.

Culraine was not a pretty village, though its cottages were all alike whitewashed outside, and roofed with heather. They had but two rooms generally—a but and a ben, with no passage between. The majority were among the sand hills, but many were built on the lofty, sea-lashed rocks. James Ruleson’s stood on a wide shelf, too high up for the highest waves, though they often washed away the wall of the garden, where it touched the sandy shore.

The house stood by itself. It had its own sea, and its own sky, and its own garden, the latter sloping in narrow, giddy paths to the very beach. Sure feet were needed among its vegetables, and its thickets of gooseberry and currant bushes, and its straying tangles of blackberry vines. Round the whole plot there was a low stone wall, covered with wall-flowers, wild thyme, rosemary, and house-leek.

A few beds around the house held roses and lilies, and other floral treasures, but these were so exclusively Margot’s property, and Margot’s adoration, that I do not think she would like me even to write about them. Sometimes she put a rosebud in the buttonhole of her husband’s Sunday coat, and sometimes 5 Christina had a similar favor, but Margot was intimate with her flowers. She knew every one by a special name, and she counted them every morning. It really hurt her to cut short their beautiful lives, and her eldest son Norman, after long experience said: “If Mither cuts a flower, she’ll ill to live wi’. I wouldna tine her good temper for a bit rosebud. It’s a poor bargain.”

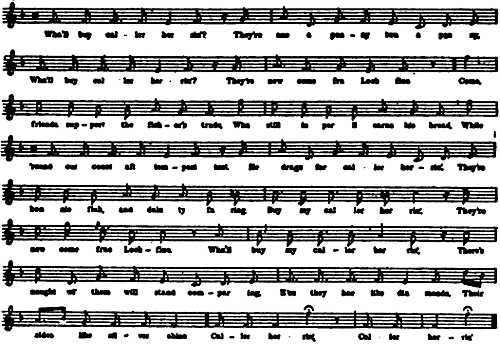

One afternoon, early in the June of 1849, Christine Ruleson walked slowly up the narrow, flowery path of this mountain garden. She was heard before she was seen, for she was singing an east coast ballad, telling all the world around her, that she

—Cast her line in Largo bay,

And fishes she caught nine;

Three to boil, and three to fry,

And three to bait the line.

So much she sang, and then she turned to the sea. The boat of a solitary fisherman, and a lustrously white bird, were lying quietly on the bay, close together, and a large ship with all her sails set was dropping lazily along to the south. For a few moments she watched them, and then continued her song.

She was tall and lovely, and browned and bloomed in the fresh salt winds. Her hair had been loosened by the breeze, and had partially escaped from her cap. She had a broad, white brow, and the dark blue eyes that dwelt beneath it were full of soul—not 6 a cloud in them, only a soft, radiant light, shaded by eyelids deeply fringed, and almost transparent—eyelids that were eloquent—full of secrets. Her mouth was beautiful, her lips made for loving words—even little children wanted to kiss her. And she lived the very life of the sea. Like it she was subject to ebb and flow. Her love for it was perhaps prenatal, it might even have driven her into her present incarnation.

When she came to the top of the cliff, she turned and gazed again at the sea. The sunshine then fell all over her, and her dress came into notice. It was simple enough, yet very effective—a white fluted cap, lying well back on her bright, rippling hair, long gold rings in her ears, and a vivid scarlet kerchief over her shoulders. Her skirt was of wide blue and gray stripes, but it was hardly noticeable, for whoever looked in Christine’s face cared little about her dress. He could never tell what she wore.

As she stood in the sunshine, a young man ran out of the house to meet her—a passing handsome youth, with his heart in his eager face and outstretched hands.

“Christine! Christine!” he cried. “Where at a’ have you keepit yourself? I hae been watching and waiting for you, these three hours past.”

“Cluny! You are crushing the bonnie flowers i’ my hands, and I’m no thanking you for that.”

“And my puir heart! It is atween your twa 7 hands, and it’s crushing it you are, day after day. Christine, it is most broke wi’ the cruel grip o’ longing and loving—and not a word o’ hope or love to help it haud together.”

“You should learn seasonable times, Cluny. It’s few lasses that can be bothered wi’ lovers that come sae early. Women folk hae their hands full o’ wark o’ some kind, then.”

“Ay, full o’ flowers. They canna even find time to gie the grip o’ their hand to the lad that loves them, maist to the death throe.”

“I’m not wanting any lad to love me to the death throe, and I’m not believing them, when they talk such-like nonsense. No indeed! The lad I love must be full o’ life and forthput. He must be able to guide his boat, and throw and draw his nets single-handed—if needs be.”

“I love you so! I love you so! I can do nothing else, Christine!”

“Havers! Love sweetens life, but it’s a long way from being life itsel’. Many a man, and many a woman, loses their love, but they dinna fling their life awa’ because o’ that misfortune—unless they have no kindred to love, and no God to fear.”

“You can’t tell how it is, Christine. You never were i’ love, I’m thinking.”

“I’m thankfu’ to say I never was; and from all I see, and hear, I am led to believe that being in love isna a superior state o’ life. I’m just hoping that what you ca’ love isna of a catching quality.”

“I wish it was! Maybe then, you might catch love from me. Oh Christine, give me a hope, dear lass. I canna face life without it. ‘Deed I can not.”

“I might do such a thing. Whiles women-folk are left to themsel’s, and then it goes ill wi’ them;” and she sighed and shook her head, as if she feared such a possibility was within her own fate.

“What is it you mean? I’m seeking one word o’ kindness from you, Christine.”

Then she looked at him, and she did not require speech. Cluny dared to draw closer to her—to put his arm round her waist—to whisper such alluring words of love and promise, that she smiled and gave him a flower, and finally thought she might—perhaps—sometime—learn the lesson he would teach her, for, “This warld is fu’ o’ maybe’s, Cluny,” she said, “and what’s the good o’ being young, if we dinna expect miracles?”

“I’m looking for no miracle, Christine. I’m asking for what a man may win by a woman’s favor. I hae loved you, Christine, since I was a bit laddie o’ seven years auld. I’ll love you till men carry me to the kirk yard. I’d die for your love. I’d live, and suffer a’ things for it. Lassie! Dear, dear lassie, dinna fling love like mine awa’. There’s every gude in it.”

She felt his heart throbbing in his words, but ere she could answer them, her brother Neil called her three times, in a voice that admitted of no delay. “Good-by, Cluny!” she said hurriedly. “You 9 ken Neil isna to be put off.” Then she was gone, and Cluny, full of bewildered loving and anxious feelings, rushed at headlong speed down the steep and narrow garden path, to his grandmother’s cottage on the sands.

Neil stood by a little pine table covered with books and papers. He was nearly twenty-one years old, and compared with his family was small in stature, lightly built, and dark in complexion. His hair was black, his eyes somberly gray, and full of calculation. His nose, lean and sharp, indicated selfish adherence to the realities of life, and the narrow nostrils positively accused him of timidity and caution. His mouth was firm and discreet. Taken as a whole, his face was handsome, though lean and thoughtful; but his manner was less pleasant. It was that of a serious snob, who thinks there is a destiny before him. He had been petted and spoiled all his life long, and his speech and conduct were full of the unpleasant survivals of this treatment. It spoiled him, and grated on Christine’s temperament, like grit in a fine salad.

He had never made a shilling in his life, he was the gentleman of the family, elected by the family to that position. In his boyhood he had been delicate, and quite unfit for the rough labor of the boats, but as he had developed an extraordinary love for books and learning, the minister had advised his dedication to the service of either the Law or the Gospel. To this proposal the whole household 10 cheerfully, even proudly, agreed. To have an educated man among the Rulesons pleased everyone. They spoke together of the great Scotch chancellors, and the great Scotch clergy, and looked upon Neil Ruleson, by special choice and election, as destined in the future to stand high among Scotland’s clergy or Scotland’s lawyers.

For this end, during eleven years, all had given their share without stint or holdback. That Neil had finally chosen to become a Lord of the Law, and to sit on the Bench, rather than stand in the Pulpit, was a great disappointment to his father, who had stubbornly hoped his son would get the call no man can innocently refuse to answer. His mother and brothers were satisfied. Norman Ruleson had once seen the Lords ride in civic pomp and splendid attire to Edinburgh Parliament House, and he was never weary of describing the majesty of the judges in their wigs and gowns, and the ceremonials that attended every step of the administration of justice.

“And the big salary coming to the judges!” Normany always added—“the salary, and the visible honors arena to be lightlied, or made little o’. Compared wi’ a minister’s stipend, a judge’s salary is stin-pen-dous! And they go wi’ the best i’ the land, and it isna anything o’ a wonder, when a judge is made a lord. There was Lord Chancellor Campbell, born in Fife itsel’, in the vera county town o’ Cupar. I have seen the house next the Bell Inn 11 where he was born, and his feyther was the minister o’ Cupar. About the year 18——”

“You needna fash either us, or yoursel’, Norman, wi’ names and dates; it will be time in plenty, when you can add our lad to the list.”

Margot at this hour was inclined to side with her husband. Margot believed in realities. She saw continually the honorable condition of the Scotch clergy; Norman’s story about the royal state and power of the judges was like something read out of a book. However, now that Neil was in his last year of study, and looking forward to the certificate which would place him among men in such a desirable condition, she would not darken his hopes, nor damp his ardor.

Neil’s classes in the Maraschal college at Aberdeen were just closed, but he was very busy preparing papers for their opening in September. This was to be his final term, and he expected to deliver a valedictory speech. The table in the best room, which he was permitted to occupy as a study, was covered with notes, which he wished copied—with books from which he was anxious to recite—with work of many kinds, which was waiting for Christine’s clear brain and fine penmanship.

It had been waiting an hour and Neil was distinctly angry.

“Mother! Where at all is Christine?” he asked.

“She went to your brither Norman’s cottage. His little lad isna as weel as he should be.”

“And my wark has to wait on a sick bairn. I’m not liking it. And I have no doubt she is wasting my time with Cluny McPherson—no doubt at all.”

“Weel! That circumstance isna likely to be far out o’ the way.”

“It is very far out of my way. I can tell you that, Mother.”

“Weel, lad, there’s no way always straight. It’s right and left, and up and down, wi’ every way o’ life.”

“That is so, Mother, but my work is waiting, and it puts me out of the right way, entirely!”

“Tut! tut! What are you complaining aboot? The lassie has been at your beck and call the best pairt o’ her life. And it’s vera seldom she can please you. If she gave you the whites o’ her e’en, you would still hae a grumble. It’s Saturday afternoon. What’s your will sae late i’ the week’s wark?”

“Ought I not to be at my studies, late and early?”

“That stands to reason.”

“Well then, I want Christine’s help, and I am going to call her.”

“You hae had her help ever sin’ you learned your A B C’s. She’s twa years younger than you are, but she’s twa years ahead o’ you in the ordinary essentials. Do you think I didna tak’ notice that when she was hearing your tasks, she learned them the while you were stumbling all the way through 13 them. Dod! The lassie knew things if she only looked in the face o’ them twice o’er, and it took you mair than an hour to get up to her—what you ca’ history, and ge-o-graph-y she learned as if they were just a bairn’s bit rhyming, and she was as quick wi’ the slate and figures as you were slow. Are you forgetting things like these?”

“It is not kind in you to be reminding me of them, Mother. It is not like you.”

“One o’ my duties to a’ my men-folk, is to keep them in mind o’ the little bits o’ kindness they are apt to forget. Your feyther isna to mind, he ne’er misses the least o’ them. Your brother Norman is like him, the rest o’ you arena to lippen to—at a’ times.”

“I think I have helped Christine as much as she has helped me. She knows that, she has often said so.”

“I’ll warrant! It was womanlike! She said it to mak’ ye feel comfortable, when you o’erworked her. Did ye ever say the like to her?”

“I am going to call her. She is better with me than with Cluny Macpherson—that I am sure of.”

“You and her for it. Settle the matter as it suits ye, but I can tell ye, I hae been parfectly annoyed, on several occasions, wi’ your clear selfishness—and that is the vera outcome o’ all my thoughts on this subject.”

Then Neil went to the door, and called Christine thrice, and the power of long habit was ill to restrain, 14 so she left her lover hurriedly and went to him.

“I have been watching and waiting—waiting for you, Christine, the last three hours.”

“Tak’ tent o’ what you say, Neil. It isna twa hours yet, since we had dinner.”

“You should have told me that you were intending to fritter and fool your afternoon away.”

“My mither bid me go and speir after Norman’s little laddie. He had a sair cold and fever, and——”

“Sit down. Are your hands clean? I want you to copy a very important paper.”

“What aboot?”

“Differences in the English and Scotch Law.”

“I don’t want to hae anything to do wi’ the Law. I canna understand it, and I’m no wanting to understand it.”

“It is not necessary that you should understand it, but you know what a peculiar writing comes from my pen. I can manage Latin or Greek, but I cannot write plainly the usual English. Now, you write a clear, firm hand, and I want you to copy my important papers. I believe I have lost honors at college, just through my singular writing.”

“I wouldn’t wonder. It is mair like the marks the robin’s wee feet make on the snow, than the writing o’ human hands. I wonder, too, if the robin kens his ain footmarks, and if they mean anything to him. Maybe they say, ‘It’s vera cold this morning—and the ground is covered wi’ snow—and 15 I’m vera hungry—hae ye anything for me this morning?’ The sma footmarks o’ the wee birds might mean all o’ this, and mair too, Neil.”

“What nonsense you are talking! Run away and wash your hands. They are stained and soiled with something.”

“Wi’ the wild thyme, and the rosemary, and the wall-flowers.”

“And the rough, tarry hand of Cluny Macpherson. Be quick! I am in a hurry.”

“It is Saturday afternoon, Neil. Feyther and Eneas will be up from the boats anon. I dinna care to write for you, the now. Mither said I was to please mysel’ what I did, and I’m in the mind to go and see Faith Balcarry, and hae a long crack wi’ her.”

Neil looked at her in astonishment. There was a stubborn set to her lovely mouth, he had never seen there before. It was a feminine variety of an expression he understood well when he saw it on his father’s lips. Immediately he changed his tactics.

“Your eyes look luck on anything you write, Christine, and you know how important these last papers are to me—and to all of us.”

“Wouldna Monday suit them, just as weel?”

“No. There will be others for Monday. I am trusting to you, Christine. You always have helped me. You are my Fail-Me-Never!”

She blushed and smiled with the pleasure this acknowledgment 16 gave her, but she did not relinquish her position. “I am vera sorry, Neil,” she answered, “but I dinna see how I can break my promise to Faith Balcarry. You ken weel what a friendless creature she is in this world. How could I disappoint a lass whose cup is running o’er wi’ sorrow?”

“I will make a bargain with you, Christine. I will wait until Monday, if you will promise me to keep Cluny Macpherson in his place. He has no business making love to you, and I will make trouble for him if he does so.”

“What ails you at Cluny? He is in feyther’s boat, and like to stay there. Feyther trusts him, and Eneas never has a word out o’ the way with him, and you ken that Eneas is often gey ill to wark wi’, and vera demanding.”

“Cluny Macpherson is all right in the boat, but he is much out of his place holding your two hands, and making love to you. I saw him doing it, not ten minutes ago.”

“Cluny has made love to me a’ his life lang. There is nae harm in his love.”

“There is no good in it. Just as soon as I am one of Her Majesty’s Councilors at Law, I shall take an office in the town, and rent a small floor, and then I shall require you to keep house for me.”

“You are running before you can creep, Neil. How are you going to pay rents, and buy furnishings? Forbye, I couldna leave Mither her lane. She hasna been hersel’ this year past, and whiles 17 she has sair attacks that gie us all a fearsome day or twa.”

“Mither has had those attacks for years.”

“All the more reason for us to be feared o’ them. Neil, I canna even think o’ my life, wanting Mither.”

“But you love me! I am bound to bring all kinds o’ good luck to our family.”

“Mither is good luck hersel’. There would be nae luck about the house, if Mither went awa’.”

“Well then, you will give Cluny up?”

“I canna say that I will do anything o’ that kind. Every lass wants a lover, and I have nane but Cluny.”

“I have a grand one in view for you.”

“Wha may the lad be?”

“My friend at the Maraschal. He is the young Master of Brewster and Ballister, and as fine a young fellow as walks in shoe leather. The old Ballister mansion you must have seen every Sabbath, as you went to the kirk.”

“Ay, I hae seen the roof and turrets o’ it, among the thick woods; but naebody has lived there, since I was born.”

“You are right, but Ballister is going to open the place, and spend gold in its plenishing and furnishing. It is a grand estate, and the young master is worthy of it. I am his friend, and I mean to bring you two together. You are bonnie, and he is rich; it would be a proper match. I owe you something, 18 Christine, and I’ll pay my debt with a husband worthy of you.”

“And how would I be worthy o’ him? I hae neither learning nor siller. You are talking foolishness, Neil.”

“You are not without learning. In my company you must have picked up much information. You could not hear my lessons and copy my exercises without acquiring a knowledge of many things.”

“Ay, a smattering o’ this and that. You wouldna call that an education, would you?”

“It is a better one than most girls get, that is, in the verities and the essentials. The overcome is only in the ornamentals, or accomplishments—piano-playing, singing, dancing, and maybe what you call a smattering of the French tongue. There is a piano in Ballister, and you would pick out a Scotch song in no time, for you sing like a mavis. As for dancing, you foot it like a fairy, and a mouthful of French words would be at your own desire or pleasure.”

“I hae that mouthfu’ already. Did you think I wrote book after book full o’ your French exercises, and heard you recite Ollendorf twice through, and learned naething while I was doing it? Neil, I am awa’ to Faith, I canna possibly break my word to a lass in trouble.”

“A moment, Christina——”

“I havna half a moment. I’ll do your writing Monday, Neil.”

“Christine! Christine!”

She was beyond his call, and before he got over his amazement, she was out of sight. Then his first impulse was to go to his mother, but he remembered that she had not been sympathetic when he had before spoken of Christine and Cluny Macpherson.

“I will be wise, and take my own counsel,” he thought, and he had no fear of wanting his own sympathy; yet when he reviewed his conversation with Christine, he was annoyed at its freedom.

“I ought not to have told her about Ballister,” he thought, “she will be watching for him at the kirk, and looking at the towers o’ Ballister House as if they were her own. And whatever made me say I thought of her as my housekeeper? She would be the most imprudent person. I would have the whole fishing-village at my house door, and very likely at my fireside; and that would be a constant set-down for me.”

This train of thought was capable of much discreet consideration, and he pursued it until he heard the stir of presence and conversation in the large living room. Then he knew that his father and brother were at home, to keep the preparation for the Sabbath. So he made himself look as lawyer-like as possible, and joined the family. Everyone, and everything, had a semi-Sabbath look. Ruleson was in a blue flannel suit, so was Eneas, and Margot had put on a clean cap, and thrown over her shoulders 20 a small tartan shawl. The hearth had been rid up, and the table was covered with a clean white cloth. In the oven the meat and pudding were cooking, and there was a not unpleasant sancta-serious air about the people, and the room. You might have fancied that even the fishing nets hanging against the wall knew it was Saturday night, and no fishing on hand.

Christine was not there. And as it was only on Saturday and Sunday nights that James Ruleson could be the priest of his family, these occasions were precious to him, and he was troubled if any of his family were absent. Half an hour before Christine returned home, he was worrying lest she forget the household rite, and when she came in he asked her, for the future, to bide at home on Saturday and Sabbath nights, saying he “didna feel all right,” unless she was present.

“I was doing your will, Feyther, anent Faith Balcarry.”

“Then you were doing right. How is the puir lassie?”

“There’s little to be done for her. She hasna a hope left, and when I spoke to her anent heaven, she said she knew nobody there, and the thought o’ the loneliness she would feel frightened her.”

“You see, James,” said Margot, “puir Faith never saw her father or mother, and if all accounts be true, no great loss, and I dinna believe the lassie ever knew anyone in this warld she would want to see in 21 heaven. Nae wonder she is sae sad and lonely.”

“There is the great multitude of saints there.”

“Gudeman, it is our ain folk we will be seeking, and speiring after, in heaven. Without them, we shall be as lonely as puir Faith, who knows no one either in this world, or the next, that she’s caring to see. I wouldn’t wonder, James, if heaven might not feel lonely to those who win there, but find no one they know to welcome them.”

“We are told we shall be satisfied, Margot.”

“I’m sure I hope sae! Come now, and we will hae a gude dinner and eat it cheerfully.”

After dinner there was a pleasant evening during which fishers and fishers’ wives came in, and chatted of the sea, and the boats, and the herring fishing just at hand; but at ten o’clock the big Bible, bound round with brass, covered with green baize, and undivested of the Books of the Apocrypha, was laid before the master. As he was trying to find the place he wanted, Margot stepped behind him, and looked over his shoulder:

“Gudeman,” she said softly, “you needna be harmering through thae chapters o’ proper names, in the Book o’ Chronicles. The trouble is overganging the profit. Read us one o’ King David’s psalms or canticles, then we’ll go to our sleep wi’ a song in our hearts.”

“Your will be it, Margot. Hae you any choice?”

“I was reading the seventy-first this afternoon, and I could gladly hear it o’er again.”

And O how blessed is that sleep into which we fall, hearing through the darkness and silence, the happy soul recalling itself—“In thee, O Lord, do I put my trust—Thou art my hope, O Lord God—my trust from my youth—I will hope continually—and praise Thee—more and more—my soul which Thou hast—redeemed! Which Thou hast redeemed!” With that wonderful thought falling off into deep, sweet sleep—it might be into that mysteriously conscious sleep, informed by prophesying dreams, which is the walking of God through sleep.

I remember the black wharves and the boats,

And the sea tides tossing free;

And the fishermen with bearded lips,

And the beauty and mystery of the ships,

And the magic of the sea.

The Domine is a good man. If you only meet him on the street, and he speaks to you, you go for the rest of the day with your head up.

One day leads to another, and even in the little, hidden-away village of Culraine, no two days were exactly alike. Everyone was indeed preparing for the great fishing season, and looking anxiously for its arrival, but if all were looking for the same event, it had for its outcome in every heart a different end, or desire. Thus, James Ruleson hoped its earnings would complete the sum required to build a cottage for his daughter’s marriage portion, and Margot wanted the money, though not for the same object. Norman had a big doctor’s bill to pay, and Eneas thought of a two weeks’ holiday, and a trip to Edinburgh and Glasgow; while Neil was anxious about an increase 24 in his allowance. He had his plea all ready—he wanted a new student’s gown of scarlet flannel, and some law books, which, he said, everyone knew were double the price of any other books. It was his last session, and he did hope that he would be let finish it creditably.

He talked to Christine constantly on the subject, and she promised to stand up for the increase. “Though you ken, Neil,” she added, “that you hae had full thirty pounds a session, and that is a lot for feyther to tak’ out o’ the sea; forbye Mither was aye sending you a box full o’ eggs and bacon, and fish and oatmeal, ne’er forgetting the cake that men-folk all seem sae extra fond o’. And you yoursel’ were often speaking o’ the lads who paid their fees and found their living out o’ thirty pounds a session. Isn’t that sae?”

“I do not deny the fact, but let me tell you how they manage it. They have a breakfast of porridge and milk, and then they are away for four hours’ Greek and Latin. Then they have two pennyworths of haddock and a few potatoes for dinner, and back to the college again, for more dead languages, and mathematics. They come back to their bit room in some poor, cold house, and if they can manage it, have a cup of tea and some oat cake, and they spend their evenings learning their lessons for the next day, by the light of a tallow candle.”

“They are brave, good lads, and I dinna wonder they win all, an’ mair, than what they worked for. 25 The lads o’ Maraschal College are fine scholars, and the vera pith o’ men. The hard wark and the frugality are good for them, and, Neil, we are expecting you to be head and front among them.”

“Then I must have the books to help me there.”

“That stands to reason; and if you’ll gie me your auld gown, I’ll buy some flannel, and mak’ you a new one, just like it.”

“The college has its own tailor, Christine. I believe the gowns are difficult to make. And what is more, I shall be obligated to have a new kirk suit. You see I go out with Ballister a good deal—very best families and all that—and I must have the clothes conforming to the company. Ballister might—nae doubt would—lend me the money—but——”

“What are you talking anent? Borrowing is sorrowing, aye and shaming, likewise. I’m fairly astonished at you naming such a thing! If you are put to a shift like that, Christine can let you hae the price o’ a suit o’ clothing.”

“O Christine, if you would do that, it would be a great favor, and a great help to me. I’ll pay you back, out of the first money I make. The price o’ the books I shall have to coax from Mother.”

“You’ll hae no obligation to trouble Mother. Ask your feyther for the books you want. He would be the vera last to grudge them to you. Speak to him straight, and bold, and you’ll get the siller wi’ a smile and a good word.”

“If you would ask him for me.”

“I will not!”

“Yes, you will, Christine. I have reasons for not doing so.”

“You hae just one reason—simple cowardice. O Man! If you are a coward anent asking a new suit o’ clothes for yoursel’, what kind o’ a lawyer will you mak’ for ither folk?”

“You know how Father is about giving money.”

“Ay, Feyther earns his money wi’ his life in his hands. He wants to be sure the thing sought is good and necessary. Feyther’s right. Now my money was maistly gi’en me, I can mair easily risk it.”

“There is no risk in my promise to pay.”

“You havna any sure contract wi’ Good Fortune, Neil, and it will be good and bad wi’ you, as it is wi’ ither folk.”

“I do not approve of your remarks, Christine. When people are talking of the fundamentals—and surely money is one of them—they ought to avoid irritating words.”

“You’ll mak’ an extraordinar lawyer, if you do that, but I’m no sure that you will win your case, wanting them. I thought they were sort o’ necessitated; but crooked and straight is the law, and it is well known that what it calls truth today, may be far from truth tomorrow.”

“What ails you today, Christine? Has the law injured you in any way?”

“Ay, it played us a’ a trick. When you took up the books, and went to the big school i’ the toun to prepare for Aberdeen, we all o’ us thought it was King’s College you were bound for, and then when you were ready for Aberdeen, you turned your back on King’s College, and went to the Maraschal.”

“King’s College is for the theology students. The Maraschal is the law school.”

“I knew that. We a’ know it. The Maraschal spelt a big disappointment to feyther and mysel’.”

“I have some work to finish, Christine, and I will be under an obligation if you will leave me now. You are in an upsetting temper, and I think you have fairly forgotten yourself.”

“Well I’m awa, but mind you! When the fishing is on, I canna be at your bidding. I’m telling you!”

“Just so.”

“I’ll hae no time for you, and your writing. I’ll be helping Mither wi’ the fish, from the dawn to the dark.”

“Would you do that?”

“Would I not?”

She was at the open door of the room as she spoke, and Neil said with provoking indifference: “If you are seeing Father, you might speak to him anent the books I am needing.”

“I’ll not do it! What are you feared for? You’re parfectly unreasonable, parfectly ridic-lus!” 28 And she emphasized her assertions by her decided manner of closing the door.

On going into the yard, she found her father standing there, and he was looking gravely over the sea. “Feyther!” she said, and he drew her close to his side, and looked into her lovely face with a smile.

“Are you watching for the fish, Feyther?”

“Ay, I am! They are long in coming this year.”

“Every year they are long in coming. Perhaps we are impatient.”

“Just sae. We are a’ ready for them—watching for them—Cluny went to Cupar Head to watch. He has a fine sea-sight. If they are within human ken, he will spot them, nae doubt. What hae you been doing a’ the day lang?”

“I hae been writing for Neil. He is uncommon anxious about this session, Feyther.”

“He ought to be.”

“He is requiring some expensive books, and he is feared to name them to you; he thinks you hae been sae liberal wi’ him already—if I was you, Feyther, I would be asking him—quietly when you were by your twa sel’s—if he was requiring anything i’ the way o’ books.”

“He has had a big sum for that purpose already, Christine.”

“I know it, Feyther, but I’m not needing to tell you that a man must hae the tools his wark is requiring, or he canna do it. If you set Neil to mak’ 29 a table, you’d hae to gie him the saw, and the hammer, and the full wherewithals, for the makin’ o’ a table; and when you are for putting him among the Edinbro’ Law Lords, you’ll hae to gie him the books that can teach him their secrets. Isn’t that fair, Feyther?”

“I’m not denying it.”

“Weel then, you’ll do the fatherly thing, and seeing the laddie is feared to ask you for the books, you’ll ask him, ‘Are you wanting any books for the finishing up, Neil?’ You see it is just here, Feyther, he could borrow the books——”

“Hang borrowing!”

“Just sae, you are quite right, Feyther. Neil says if he has to borrow, he’ll never get the book when he wants it, and that he would never get leave to keep it as long as he needed. Now Neil be to hae his ain books, Feyther, he will mak’ good use o’ them, and we must not fail him at the last hour.”

“Wha’s talking o’ failing him? Not his feyther, I’m sure! Do I expect to catch herrings without the nets and accessories? And I ken that I’ll not mak’ a lawyer o’ Neil, without the Maraschal and the books it calls for.”

“You are the wisest and lovingest o’ feythers. When you meet Neil, and you twa are by yoursel’s, put your hand on Neil’s shoulder, and ask Neil, ‘Are you needing any books for your last lessons?’”

“I’ll do as you say, dear lass. It is right I should.”

“Nay, but he should ask you to do it. If it was mysel’, I could ask you for anything I ought to have, but Neil is vera shy, and he kens weel how hard you wark for your money. He canna bear to speak o’ his necessities, sae I’m speaking the word for him.”

“Thy word goes wi’ me—always. I’ll ne’er say nay to thy yea,” and he clasped her hand, and looked with a splendid smile of affection into her beautiful face. An English father would have certainly kissed her, but Scotch fathers rarely give this token of affection. Christine did not expect it, unless it was her birthday, or New Year’s morning.

It was near the middle of July, when the herring arrived. Then early one day, Ruleson, watching the sea, smote his hands triumphantly, and lifting his cap with a shout of welcome, cried—

“There’s our boat! Cluny is sailing her! He’s bringing the news! They hae found the fish! Come awa’ to the pier to meet them, Christine.”

With hurrying steps they took the easier landward side of descent, but when they reached the pier there was already a crowd of men and women there, and the Sea Gull, James Ruleson’s boat, was making for it. She came in close-hauled to the wind, with a double reef in her sail. She came rushing across the bay, with the water splashing her gunwale. Christine kept her eyes upon the lad at the tiller, a handsome lad, tanned to the temples. His cheeks were flushed, and the wind was in his hair, 31 and the sunlight in his eyes, and he was steering the big herring boat into the harbor.

The men were soon staggering down to the boats with the nets, coiling them up in apparently endless fashion, and as they were loaded they were very hard to get into the boats, and harder still to get out. Just as the sun began to set, the oars were dipped, and the boats swept out of the harbor into the bay, and there they set their red-barked sails, and stood out for the open sea.

Ruleson’s boat led the way, because it was Ruleson’s boat that had found the fish, and Christine stood at the pier-edge cheering her strong, brave father, and not forgetting a smile and a wave of her hand for the handsome Cluny at the tiller. To her these two represented the very topmost types of brave and honorable humanity. The herring they were seeking were easily found, for it was the Grand Shoal, and it altered the very look of the ocean, as it drove the water before it in a kind of flushing ripple. Once, as the boats approached them, the shoal sank for at least ten minutes, and then rose in a body again, reflecting in the splendid sunset marvelous colors and silvery sheen.

With a sweet happiness in her heart, Christine went slowly home. She did not go into the village, she walked along the shore, over the wet sands to the little gate, which opened upon their garden. On her way she passed the life-boat. It was in full readiness for launching at a moment’s notice, 32 and she went close to it, and patted it on the bow, just as a farmer’s daughter would pat the neck of a favorite horse.

“Ye hae saved the lives of men,” she said. “God bless ye, boatie!” and she said it again, and then stooped and looked at a little brass plate screwed to the stern locker, on which were engraved these words:

Put your trust in God,

And do your best.

And as she climbed the garden, she thought of the lad who had left Culraine thirty years ago, and gone to Glasgow to learn ship building, and who had given this boat to his native village out of his first savings. “And it has been a lucky boat,” she said softly, “every year it has saved lives,” and then she remembered the well-known melody, and sang joyously—

“Weel may the keel row,

And better may she speed,

Weel may the keel row,

That wins the bairnies’ bread.

“Weel may the keel row,

Amid the stormy strife,

Weel may the keel row

That saves the sailor’s life.

“Weel may her keel row—”

Then with a merry, inward laugh she stopped, and said with pretended displeasure: “Be quiet, Christine! You’re makin’ poetry again, and you shouldna do the like o’ that foolishness. Neil thinks it isna becoming for women to mak’ poetry—he says men lose their good sense when they do it, and women! He hadna the words for their shortcomings in the matter. He could only glower and shake his head, and look up at the ceiling, which he remarked needed a coat o’ clean lime and water. Weel, I suppose Neil is right! There’s many a thing not becomin’ to women, and nae doubt makin’ poetry up is among them.”

When she entered the cottage, she found the Domine, Dr. Magnus Trenabie, drinking a cup of tea at the fireside. He had been to the pier to see the boats sail, for all the men of his parish were near and dear to him. He was an extraordinary man—a scholar who had taken many degrees and honors, and not exhausted his mental powers in getting them—a calm, sabbatic mystic, usually so quiet that his simple presence had a sacramental efficacy—a man who never reasoned, being full of 34 faith; a man enlightened by his heart, not by his brain.

Being spiritually of celestial race, he was lodged in a suitable body. Its frame was Norse, its blood Celtic. He appeared to be a small man, when he stood among the gigantic fishermen who obeyed him like little children, but he was really of average height, graceful and slender. His head was remarkably long and deep, his light hair straight and fine. The expression of his face was usually calm and still, perhaps a little cold, but there was every now and then a look of flame. Spiritually, he had a great, tender soul quite happy to dwell in a little house. Men and women loved him, he was the angel on the hearth of every home in Culraine.

When Christine entered the cottage, the atmosphere of the sea was around and about her. The salt air was in her clothing, the fresh wind in her loosened hair, and she had a touch of its impetuosity in the hurry of her feet, the toss of her manner, the ring of her voice.

“O Mither!” she cried, then seeing the Domine, she made a little curtsey, and spoke to him first. “I was noticing you, Sir, among the men on the pier. I thought you were going with them this night.”

“They have hard work this night, Christine, and my heart tells me they will be wanting to say little words they would not like me to hear.”

“You could hae corrected them, Sir.”

“I am not caring to correct them, tonight. Words 35 often help work, and tired fishers, casting their heavy nets overboard, don’t do that work without a few words that help them. The words are not sinful, but they might not say them if I was present.”

“I know, Sir,” answered Margot. “I hae a few o’ such words always handy. When I’m hurried and flurried, I canna help them gettin’ outside my lips—but there’s nae ill in them—they just keep me going. I wad gie up, wanting them.”

“When soldiers, Margot, are sent on a forlorn hope of capturing a strong fort, they go up to it cheering. When our men launch the big life-boat, how do they do it, Christine?”

“Cheering, Sir!”

“To be sure, and when weary men cast the big, heavy nets, they find words to help them. I know a lad who always gets his nets overboard with shouting the name of the girl he loves. He has a name for her that nobody but himself can know, or he just shouts ‘Dearie,’ and with one great heave, the nets are overboard.” And as he said these words he glanced at Christine, and her heart throbbed, and her eyes beamed, for she knew that the lad was Cluny.

“I was seeing our life-boat, as I came home,” she said, “and I was feeling as if the boat could feel, and if she hadna been sae big, I would hae put my arms round about her. I hope that wasna any kind o’ idolatry, Sir?”

“No, no, Christine. It is a feeling of our humanity, 36 that is wide as the world. Whatever appears to struggle and suffer, appears to have life. See how a boat bares her breast to the storm, and in spite of winds and waves, wins her way home, not losing a life that has been committed to her. And nothing on earth can look more broken-hearted than a stranded boat, that has lost all her men. Once I spent a few weeks among the Hovellers—that is, among the sailors who man the life-boats stationed along Godwin Sands; and they used to call their boats ‘darlings’ and ‘beauties’ and praise them for behaving well.”

“Why did they call the men Hovellers?” asked Margot. “That word seems to pull down a sailor. I don’t like it. No, I don’t.”

“I have been told, Margot, that it is from the Danish word, overlever, which means a deliverer.”

“I kent it wasna a decent Scotch word,” she answered, a little triumphantly; “no, nor even from the English. Hoveller! You couldna find an uglier word for a life-saver, and if folk canna be satisfied wi’ their ain natural tongue, and must hae a foreign name, they might choose a bonnie one. Hoveller! Hoveller indeed! It’s downright wicked, to ca’ a sailor a hoveller.”

The Domine smiled, and continued—“Every man and woman and child has loved something inanimate. Your mother, Christine, loves her wedding ring, your father loves his boat, you love your Bible, I love the silver cup that holds the sacramental 37 wine we drink ‘in remembrance of Him’;” and he closed his eyes a moment, and was silent. Then he gave his cup to Christine. “No more,” he said, “it was a good drink. Thanks be! Now our talk must come to an end. I leave blessing with you.”

They stood and watched him walk into the dusk in silence, and then Margot said, “Where’s Neil?”

“Feyther asked him to go wi’ them for this night, and Neil didna like to refuse. Feyther has been vera kind to him, anent his books an’ the like. He went to pleasure Feyther. It was as little as he could do.”

“And he’ll come hame sea-sick, and his clothes will be wet and uncomfortable as himsel’.”

“Weel, that’s his way, Mither. I wish the night was o’er.”

“Tak’ patience. By God’s leave the day will come.”

If Love comes, it comes; but no reasoning can put it there.

Love gives a new meaning to Life.

Her young heart blows

Leaf by leaf, coming out like a rose.

The next morning the women of the village were early at the pier to watch the boats come in. They were already in the offing, their gunwales deep in the water, and rising heavily on the ascending waves; so they knew that there had been good fishing. Margot was prominent among them, but Christine had gone to the town to take orders from the fish dealers; for Margot Ruleson’s kippered herring were famous, and eagerly sought for, as far as Edinburgh, and even Glasgow.

It was a business Christine liked, and in spite of her youth, she did it well, having all her mother’s bargaining ability, and a readiness in computing values, that had been sharpened by her knowledge of figures and profits. This morning she was unusually fortunate in all her transactions, and brought home such large orders that they staggered Margot.

“I’ll ne’er be able to handle sae many fish,” she said, with a happy purposeful face, “but there’s naething beats a trial, and I be to do my best.”

“And I’ll help you, Mither. It must ne’er be said that we twa turned good siller awa’.”

“I’m feared you canna do that today, Christine. Neil hasna been to speak wi’, since he heard ye had gone to the toun; he wouldna’ even hear me when I ca’ed breakfast.”

“Neil be to wait at this time. It willna hurt him. If Neil happens to hae a wish, he instantly feels it to be a necessity, and then he thinks the hale house should stop till his wish is gi’en him. I’m going to the herring shed wi’ yoursel’.”

“Then there will be trouble, and no one so sorry for it as Christine! I’m telling you!”

At this moment Neil opened the door, and looked at the two women. “Mother,” he said in a tone of injury and suffering, “can I have any breakfast this morning?”

“Pray, wha’s hindering you? Your feyther had his, an hour syne. Your porridge is yet boiling in the pot, the kettle is simmering on the hob, and the cheena still standing on the table. Why didna you lift your ain porridge, and mak’ yoursel’ a cup o’ tea? Christine and mysel’ had our breakfasts before it chappit six o’clock. You cam’ hame wi’ your feyther, you should hae ta’en your breakfast with him.”

“I was wet through, and covered with herring 40 scales. I was in no condition to take a meal, or to sit with my books and Christine all morning, writing.”

“I canna spare Christine this morning, Neil. That’s a fact.” His provoking neatness and deliberation were irritating to Margot’s sense of work and hurry, and she added, “Get your breakfast as quick as you can. I’m wanting the dishes out o’ the way.”

“I suppose I can get a mouthful for myself.”

“Get a’ you want,” answered Margot; but Christine served him with his plate of porridge and basin of new milk, and as he ate it, she toasted a scone, and made him a cup of tea.

“Mother is cross this morning, Christine. It is annoying to me.”

“It needna. There’s a big take o’ fish in, and every man and woman, and every lad and lass, are in the herring sheds. Mither just run awa’ from them, to see what orders for kippers I had brought—and I hae brought nine hundred mair than usual. I must rin awa’ and help her now.”

“No, Christine! I want you most particularly, this morning.”

“I’ll be wi’ you by three in the afternoon.”

“Stay with me now. I’ll be ready for you in half an hour.”

“I can hae fifty fish ready for Mither in half an hour, and I be to go to her at once. I’ll be back, laddie, by three o’clock.”

“I’m just distracted with the delay,” but he 41 stopped speaking, for he saw that he was alone. So he took time thoroughly to enjoy his scone and tea, and then, not being quite insensible to Christine’s kindness, he washed the dishes and put them away.

He had just finished this little duty, when there was a knock at the outside door. He hesitated about opening it. He knew no villager would knock at his father’s door, so it must be a stranger, and as he was not looking as professional and proper as he always desired to appear, he was going softly away, when the door was opened, and a bare-footed lad came forward, and gave him a letter.

He opened it, and looked at the signature—“Angus Ballister.” A sudden flush of pleasure made him appear almost handsome, and when he had read the epistle he was still more delighted, for it ran thus:

Dear Neil,

I am going to spend the rest of vacation at Ballister Mansion, and I want you with me. I require your help in a particular business investigation. I will pay you for your time and knowledge, and your company will be a great pleasure to me. This afternoon I will call and see you, and if you are busy with the nets, I shall enjoy helping you.

Your friend,

Angus Ballister.

Neil was really much pleased with the message, and glad to hear of an opportunity to make money, 42 for though the young man was selfish, he was not idle; and he instantly perceived that much lucrative business could follow this early initiation into the Ballister affairs. He quickly finished his arrangement of the dishes and the kitchen, and then, putting on an old academic suit, made his room as scholarly and characteristic as possible. And it is amazing what an air books and papers give to the most commonplace abode. Even the old inkhorn and quill pens seemed to say to all who entered—“Tread with respect. This is classic ground.”

His predominating thought during this interval was, however, not of himself, but of Christine. She had promised to come to him at three o’clock. How would she come? He was anxious about her first appearance. If he could in any way have reached her, he would have sent his positive command to wear her best kirk clothes, but at this great season neither chick nor child was to be seen or heard tell of, and he concluded finally to leave what he could not change or direct to those household influences which usually manage things fairly well.

As the day went on, and Ballister did not arrive, he grew irritably nervous. He could not study, and he found himself scolding both Ballister and Christine for their delay. “Christine was so ta’en up wi’ the feesh, naething else was of any import to her. Here was a Scottish gentleman coming, who might be the makin’ o’ him, and a barrel o’ herrin’ stood in his way.” He had actually fretted himself into 43 his Scotch form of speech, a thing no Gael ever entirely forgets when really worried to the proper point.

When he had said his heart’s say of Christine, he turned his impatience on Ballister—his behavior was that o’ the ordinary rich young man, who has naething but himsel’ to think o’. He, Neil Ruleson, had lost a hale morning’s wark, waiting on his lairdship. Weel, he’d have to pay for it, in the long run. Neil Ruleson had no waste hours in his life. Nae doubt Ballister had heard o’ a fast horse, or a fast——

Then Ballister knocked at the door, and Neil stepped into his scholarly manner and speech, and answered Ballister’s hearty greeting in the best English style.

“I am glad to see you, Neil. I only came to Ballister two days ago, and I have been thinking of you all the time.” With these words the youth threw his Glengary on the table, into the very center and front of Neil’s important papers. Then he lifted his chair, and placed it before the open door, saying emphatically as he did so—

Lands may be fair ayont the sea,

But Scotland’s hills and lochs for me!

O Neil! Love of your ain country is a wonderful thing. It makes a man of you.”

“Without it you would not be a man.”

Ballister did not answer at once, but stood a moment with his hand on the back of the deal, rush-bottomed chair, and his gaze fixed on the sea and the crowd of fishing boats waiting in the harbor.

Without being strictly handsome, Ballister was very attractive. He had the tall, Gaelic stature, and its reddish brown hair, also brown eyes, boyish and yet earnest. His face was bright and well formed, his conversation animated, his personality, in full effect, striking in its young alertness.

“Listen to me, Neil,” he said, as he sat down. “I came to my majority last March, when my uncle and I were in Venice.”

“Your uncle on your mother’s side?”

“No, on the sword side, Uncle Ballister. He told me I was now my own master, and that he would render into my hands the Brewster and Ballister estates. I am sure that he has done well by them, but he made me promise I would carefully go over all the papers relating to his trusteeship, and especially those concerning the item of interests. It seems that my father had a good deal of money out on interest—I know nothing about interest. Do you, Neil?”

“I know everything that is to be known. In my profession it is a question of importance.”

“Just so. Now, I want to put all these papers, rents, leases, improvements, interest accounts, and so forth, in your hands, Neil. Come with me to Ballister, and give the mornings to my affairs. Find 45 out what is the usual claim for such service, and I will gladly pay it.”

“I know the amount professionally charged, but——”

“I will pay the professional amount. If we give the mornings to this work, in the afternoons we will ride, and sail, fish or swim, or pay visits—in the evenings there will be dinner, billiards, and conversation. Are you willing?”

“I am delighted at the prospect. Let the arrangement stand, just so.”

“You will be ready tomorrow?”

“The day after tomorrow.”

“Good. I will——”

Then there was a tap at the door, and before Neil could answer it, Christine did so. As she entered, Ballister stood up and looked at her, and his eyes grew round with delighted amazement. She was in full fisher costume—fluted cap on the back of her curly head, scarlet kerchief on her neck, long gold rings in her ears, gold beads round her throat, and a petticoat in broad blue and yellow stripes.

“Christine,” said Neil, who, suddenly relieved of his great anxiety, was unusually good-tempered. “Christine, this is my friend, Mr. Angus Ballister. You must have heard me speak of him?”

“That’s a fact. The man was your constant talk”—then turning to Ballister—“I am weel pleased to see you, Sir;” and she made him a little curtsey so full of independence that Ballister knew well she 46 was making it to herself—“and I’m wondering at you twa lads,” she said, “sitting here in the house, when you might be sitting i’ the garden, or on the rocks, and hae the scent o’ the sea, or the flowers about ye.”

“Miss Ruleson is right,” said Ballister, in his most enthusiastic mood. “Let us go into the garden. Have you really a garden among these rocks? How wonderful!”

How it came that Ballister and Christine took the lead, and that Neil was in a manner left out, Neil could not tell; but it struck him as very remarkable. He saw Christine and his friend walking together, and he was walking behind them. Christine, also, was perfectly unembarrassed, and apparently as much at home with Ballister as if he had been some fisher-lad from the village.

Yet there was nothing strange in her easy manner and affable intimacy. It was absolutely natural. She had never realized the conditions of riches and poverty, as entailing a difference in courtesy or good comradeship; for in the village of Culraine, there was no question of an equality founded on money. A man or woman was rated by moral, and perhaps a little by physical qualities—piety, honesty, courage, industry, and strength, and knowledge of the sea and of the fisherman’s craft. Christine would have treated the great Duke of Fife, or Her Majesty, Victoria, with exactly the same pleasant familiarity.

She showed Ballister her mother’s flower garden, that was something beyond the usual, and she was delighted at Ballister’s honest admiration and praise of the lovely, rose-sweet plot. Both seemed to have forgotten Neil’s presence, and Neil was silent, blundering about in his mind, looking for some subject which would give him predominance.

Happily strolling in and out the narrow walks, and eating ripe gooseberries from the bushes, they came to a little half-circle of laburnum trees, drooping with the profusion of their golden blossoms. There was a wooden bench under them, and as Christine sat down a few petals fell into her lap.

“See!” she cried, “the trees are glad o’ our company,” and she laid the petals in her palm, and added—“now we hae shaken hands.”

“What nonsense you are talking, Christine,” said Neil.

“Weel then, Professor, gie us a bit o’ gude sense. Folks must talk in some fashion.”

And Neil could think of nothing but a skit against women, and in apologetic mood and manner answered:

“I believe it is allowable, to talk foolishness, in reply to women’s foolishness.”

“O Neil, that is cheap! Women hae as much gude sense as men hae, and whiles they better them”—and then she sang, freely and clearly as a bird, two lines of Robert Burns’ opinion—

“He tried His prentice hand on man,

And then He made the lasses O!”

She still held the golden blossoms in her hand, and Ballister said:

“Give them to me. Do!”

“You are vera welcome to them, Sir. I dinna wonder you fancy them. Laburnum trees are money-bringers, but they arena lucky for lovers. If I hed a sweetheart, I wouldna sit under a laburnum tree wi’ him, but Feyther is sure o’ his sweetheart, and he likes to come here, and smoke his pipe. And Mither and I like the place for our bit secret cracks. We dinna heed if the trees do hear us. They may tell the birds, and the birds may tell ither birds, but what o’ that? There’s few mortals wise enough to understand birds. Now, Neil, come awa wi’ your gude sense, I’ll trouble you nae langer wi’ my foolishness. And good day to you, Sir!” she said. “I’m real glad you are my brother’s friend. I dinna think he will go out o’ the way far, if you are wi’ him.”

Ballister entreated her to remain, but with a smile she vanished among the thick shrubbery. Ballister was disappointed, and somehow Neil was not equal to the occasion. It was hard to find a subject Ballister felt any interest in, and after a short interval he bade Neil good-bye and said he would see him on the following day.

“No, on the day after tomorrow,” corrected Neil. “That was the time fixed, Angus. Tomorrow I will 49 finish up my work for the university, and I will be at your service, very happily and gratefully, on Friday morning.” Then Neil led him down the garden path to the sandy shore, so he did not return to the cottage, but went away hungry for another sight of Christine.

Neil was pleased, and displeased. He felt that it would have been better for him if Christine had not interfered, but there was the delayed writing to be finished, and he hurried up the steep pathway to the cottage. Some straying vines caught his careless footsteps, and threw him down, and though he was not hurt, the circumstance annoyed him. As soon as he entered the cottage, he was met by Christine, and her first remark added to his discomfort:

“Whate’er hae you been doing to yoursel’, Neil Ruleson? Your coat is torn, and your face scratched. Surely you werna fighting wi’ your friend.”

“You know better, Christine. I was thrown by those nasty blackberry vines. I intend to cut them all down. They catch everyone that passes them, and they are in everyone’s way. They ought to be cleared out, and I will attend to them tomorrow morning, if I have to get up at four o’clock to do it.”

“You willna touch the vines. Feyther likes their fruit, and Mither is planning to preserve part o’ it. And I, mysel’, am vera fond o’ vines. The wee wrens, and the robin redbreasts, look to the vines 50 for food and shelter, and you’ll not dare to hurt their feelings, for

“The Robin, wi’ the red breast,

The Robin, and the wren,

If you do them any wrong,

You’ll never thrive again.”

“Stop, Christine, I have a great deal to think of, and to ask your help in.”

“Weel, Neil, I was ready for you at three o’clock, and then you werna ready for me.”

“Tell me why you dressed yourself up so much? Did you know Ballister was coming?”

“Not I! Did you think I dressed mysel’ up for Angus Ballister?”

“I was wondering. It is very seldom you wear your gold necklace, and other things, for just home folk.”

“Weel, I wasn’t wearing them for just hame folk. Jennie Tweedie is to be married tonight, and Mither had promised her I should come and help them lay the table for the supper, and the like o’ that. Sae I was dressed for Jennie Tweedie’s bridal. I wasna thinking of either you, or your fine friend.”

“I thought perhaps you had heard he was coming. Your fisher dress is very suitable to you. No doubt you look handsome in it. You likely thought its novelty would—would—make him fall in love with you.”

“I thought naething o’ that sort. Novelty! Where would the novelty be? The lad is Fife. If he was sae unnoticing as never to get acquaint wi’ a Culraine fisher-wife, he lived maist o’ his boyhood in Edinburgh. Weel, he couldna escape seeing the Newhaven fisherwomen there, nor escape hearing their wonderful cry o’ ‘Caller herrin’!’ And if he had ony feeling in his heart, if he once heard that cry, sae sweet, sae heartachy, and sae winning, he couldna help looking for the woman who was crying it; and then he couldna help seeing a fisher-wife, or lassie. I warn you not to think o’ me, Christine Ruleson, planning and dressing mysel’ for any man. You could spane my love awa’ wi’ a very few o’ such remarks.”

“I meant nothing to wrong you, Christine. All girls dress to please the men.”

“Men think sae. They are vera mich mista’en. Girls dress to outdress each ither. If you hae any writing to do, I want to gie you an hour’s wark. I’ll hae to leave the rest until morning.”

Then Neil told her the whole of the proposal Angus had made him. He pointed out its benefits, both for the present and the future, and Christine listened thoughtfully to all he said. She saw even further than Neil did, the benefits, and she was the first to name the subject nearest to Neil’s anxieties.

“You see, Neil,” she said, “if you go to Ballister, you be to hae the proper dress for every occasion. 52 The best suit ye hae now will be nane too good for you to wark, and to play in. You must hae a new suit for ordinary wear, forbye a full dress suit. I’ll tell you what to do—David Finlay, wha dresses a’ the men gentry round about here, is an old, old friend o’ Feyther’s. They herded together, and went to school and kirk togither, and Feyther and him have helped each ither across hard places, a’ their life long.”

“I don’t want any favors from David Finlay.”

“Hae a little patience, lad. I’m not asking you to tak’ favors from anyone. I, mysel’, will find the money for you; but I canna tell you how men ought to dress, nor what they require in thae little odds and ends, which are so important.”

“Odds and ends! What do you mean?”

“Neckties, gloves, handkerchiefs, hats, and a proper pocket book for your money. I saw Ballister take his from his pocket, to put the laburnum leaves in, and I had a glint o’ the bank bills in it, and I ken weel it is more genteel-like than a purse. I call things like these ‘odds and ends.’”

“Such things cost a deal of money, Christine.”

“I was coming to that, Neil. I hae nearly ninety-six pounds in the bank. It hes been gathering there, ever since my grandfeyther put five pounds in for me at my baptisement—as a nest egg, ye ken—and all I hae earned, and all that Feyther or Mither hae gien me, has helped it gather; and on my last birthday, when Feyther gave me a pound, and Mither ten shillings, 53 I had ninety-six pounds. Now, Neil, dear lad, you can hae the use o’ it all, if so be you need it. Just let Dave Finlay tell you what to get, and get it, and pay him for it—you can pay me back, when money comes easy to you.”

“Thank you, Christine! You have always been my good angel. I will pay you out o’ my first earnings. I’ll give you good interest, and a regular I. O. U. which will be——”

“What are you saying, Neil? Interest! Interest! Interest on love? And do you dare to talk to me anent your I. O. U. If I canna trust your love, and your honor, I’ll hae neither interest nor paper from you. Tak my offer wi’ just the word between us, you are vera welcome to the use o’ the money. There’s nae sign o’ my marrying yet, and I’ll not be likely to want it until my plenishing and napery is to buy. You’ll go to Finlay, I hope?”

“I certainly will. He shall give me just what is right.”

“Now then, my time is up. I will be ready to do your copying at five o’clock in the morning. Then, after breakfast, you can go to the town, but you won’t win into the Bank before ten, and maist likely Finlay will be just as late. Leave out the best linen you hae, and I’ll attend to it, wi’ my ain hands.”

“Oh, Christine, how sweet and good you are! I’m afraid I am not worthy o’ your love!”

“Vera likely you are not. Few brothers love their 54 sisters as they ought to. It willna be lang before you’ll do like the lave o’ them, and put some strange lass before me.”

“There’s nae lass living that can ever be to me what you hae been, and are. You hae been mother and sister baith, to me.”

“Dear lad, I love thee with a’ my heart. All that is mine, is thine, for thy use and help, and between thee and me the word and the bond are the same thing.”

Christine was much pleased because Neil unconsciously had fallen into his Scotch dialect. She knew then that his words were spontaneous, not of consideration, but of feeling from his very heart.

In a week the change contemplated had been fully accomplished. Neil had become accustomed to the luxury of his new home, and was making notable progress in the work which had brought him there.

Twice during the week Margot had been made royally happy by large baskets of wonderful flowers and fruit, from the Ballister gardens. They were brought by the Ballister gardener, and came with Neil’s love and name, but Margot had some secret thoughts of her own. She suspected they were the result of a deeper and sweeter reason than a mere admiration for her wonderful little garden among the rocks; but she kept such thoughts silent in her heart. One thing she knew well, that if Christine were twitted on the subject, she would hate Angus 55 Ballister, and utterly refuse to see him. So she referred to the gifts as entirely from Neil, and affected a little anxiety about their influence on Ballister.

“I hope that young man isna thinking,” she said, “that his baskets o’ flowers and fruit is pay enough for Neil’s service.”

“Mither, he promised to pay Neil.”

“To be sure. But I didna hear o’ any fixed sum. Some rich people hae a way o’ giving sma’ favors, and forgetting standing siller.”

“He seemed a nice young man, Mither, and he did admire your garden. I am sure he has told Neil to send the flowers because you loved flowers. When folk love anything, they like others who love as they do. Mebbe they who love flowers hae the same kind and order o’ souls. You ken if a man loves dogs, he is friendly at once wi’ a stranger who loves dogs; and there’s the Domine, who is just silly anent auld coins—copper, siller or gold—he cares not, if they’re only auld enough. Nannie Grant, wha keeps his house, told Katie Tweedie that he took a beggar man into his parlor, and ate his dinner with him, just because he had a siller bit o’ Julius Cæsar in his pouch, and wouldna part wi’ it, even when he was wanting bread.”

“Weel then, the Domine doubtless wanted the penny.”

“Vera likely, but he wouldna tak it frae the puir soul, wha thought sae much o’ it; and Nannie was 56 saying that he went away wi’ a guid many Victoria pennies i’ his pouch.”

“The Domine is a queer man.”

“Ay, but a vera guid man.”

“If he had a wife, he would be a’ right.”

“And just as likely a’ wrang. Wha can tell?”

“Weel, that’s an open question. What about your ain marriage?”

“I’ll marry when I find a man who loves the things I love.”

“Weel, the change for Neil, and for the a’ of us has been—in a way—a gude thing. I’ll say that.”

Margot was right. Even if we take change in its widest sense, it is a great and healthy manifestation, and it is only through changes that the best lives are made perfect. For every phase of life requires its own environment, in order to fulfill perfectly its intention and if it does not get it, then the intent, or the issue, loses much of its efficiency. “Because they have no changes, therefore they fear not God,” is a truth relative to the greatest nations, as well as to the humblest individual.

Neil was benefited in every way by the social uplift of a residence in a gentleman’s home, and the active, curious temperament of Angus stimulated him. Angus was interested in every new thing, in every new idea, in every new book. The world was so large, and so busy, and he wanted to know all about its goings on. So when Neil’s business was over for the day, Angus was eagerly waiting to tell 57 him of something new or strange which he had just read, or heard tell of, and though Neil did not realize the fact, he was actually receiving, in these lively discussions with his friend, the very best training for his future forensic and oratorical efforts.

Indeed he was greatly pleased with himself. He had not dreamed of being the possessor of so much skill in managing an opposite opinion; nor yet of the ready wit, which appeared to flow naturally with his national dialect. But all this clever discussion and disputing was excellent practice, and Neil knew well that his visit to Ballister had been a change full of benefits to him.

One of the results of Neil’s investigations was the discovery that Dr. Magnus Trenabie had been presented to the church of Culraine by the father of Angus, and that his salary had never been more than fifty pounds a year, with the likelihood that it had often been much less. Angus was angry and annoyed.

“I give my gamekeeper a larger salary,” he said. “It is a shame! The doctor’s salary must be doubled at once. If there are any technicalities about it, look to them as quickly as possible. Did my father worship in that old church?”

“He did, and I have heard my father tell very frequently, how the old man stood by the church when the great Free Kirk secession happened. He says that at that burning time everyone left Dr. Trenabie’s church but Ballister and ten o’ his tenants, 58 and that the doctor took no notice of their desertion, but just preached to your father and the ten faithful. He was never heard to blame the lost flock, and he never went into the wilderness after them. Your father would not hear of his doing so.

“Magnus,” he would say, “tak’ time, and bide a wee. The puir wanderers will get hungry and weary in their Free Kirk conventicles, and as the night comes on, they’ll come hame. Nae fear o’ them!”

“Did they come home?”

“Every one of them but three stubborn old men. They died out of its communion, and the old Master pitied them, and told their friends he was feared that it would go a bit hard wi’ them. He said, they had leaped the fence, and he shook his head, and looked down and doubtful anent the outcome, since naebody could tell what ill weeds were in a strange pasture.”

After this discovery Angus went to the old church, where his father had worshiped, and there he saw Christine, and there he fell freshly in love with her every Sabbath day. It did not appear likely that love had much opportunity, in those few minutes in the kirk yard after the service, when Neil and Angus waited for Margot and Christine, to exchange the ordinary greetings and inquiries. James Ruleson, being leading elder, always remained a few minutes after the congregation had left, in order 59 to count the collection and give it to the Domine, and in those few minutes Love found his opportunity.

While Neil talked with his mother of their family affairs, Angus talked with Christine. His eyes rained Love’s influence, his voice was like a caress, the touch of his hand seemed to Christine to draw her in some invisible way closer to him. She never remembered the words he said, she only knew their inarticulate meaning was love, always love. When it was time for Ruleson to appear, Margot turned to Angus and thanked him for some special gift or kindness that had come to the cottage that week, and Angus always laughed, and pointing to Neil, said:

“Neil is the culprit, Mrs. Ruleson. It is Neil’s doing, I assure you.” And of course this statement might be, in several ways, the truth. At any rate, the old proverb which advises us “never to look a gift horse in the mouth,” is a good one. For the motive of the gift is more than the gift itself.

These gifts were all simple enough, but they were such as delighted Margot’s childlike heart—an armful of dahlias or carnations—a basket of nectarines or apricots—two or three dozen fresh eggs—a pot of butter—a pair of guinea fowls, then rare in poultry yards, or a brood of young turkeys to feed and fatten for the New Year’s festival. About these fowls, Neil wrote her elaborate directions. And Margot was more delighted with these 60 simple gifts than many have been with a great estate. And Christine knew, and Angus knew that she knew, and it was a subtle tie between them, made of meeting glances and clasping hands.

The winds go up and down upon the sea,

And some they lightly clasp, entreating kindly,

And waft them to the port where they would be:

And other ships they buffet long and blindly.

The cloud comes down on the great sinking deep,

And on the shore, the watchers stand and weep.