All the Days of My Life: An Autobiography

The Red Leaves of a Human Heart

By Amelia E. Barr

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK AND LONDON

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

MCMXIII

Copyright, 1913, by

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

TO MY FRIENDS

DR. CARLOS H. STONE

AND

MRS. STONE

I INSCRIBE

WITH AFFECTIONATE ESTEEM

THIS STORY OF MY LIFE

Cherry Croft

A.D. 1913

This is to be a book about myself but, even before I begin it, I am painfully aware of the egotistical atmosphere which the unavoidable use of the personal pronouns creates. I have hitherto declared that I would not write an autobiography, but a consideration of circumstances convinces me that an autobiography is the only form any personal relation can now take. For the press has so widely and so frequently exploited certain events of my life—impossible to omit—that disguise is far out of the question. Fiction could not hide me, nor an assumed name, nor even no name at all.

Why, then, write the book? First, because serious errors have constantly been published, and these I wish to correct; second, there has been a long-continued request for it, and third, there are business considerations not to be neglected. Yet none, nor all of these three reasons, would have been sufficient to induce me to truck my most sacred memories through the market-place for a little money, had I not been conscious of a motive that would amply justify the book. The book itself must reveal that reason, or it will never be known. I am sure, however, that many will find it out, and to these souls I shall speak, and they will keep my memory green, and listen to my words of strength and comfort long after the woman called Amelia Huddleston Barr has disappeared forever.

Again, if I am to write of things so close and intimate as my feelings and experiences, I must claim a large liberty. Many topics usually dilated on, I shall pass by silently, or with slight notice; and, if I write fully and truly, as I intend to do, I must viii show many changes of opinion on a variety of subjects. This is only the natural growth of the mental and spiritual faculties. For the woman within, if she be of noble strain, is never content with what she has attained; she unceasingly presses forward, in lively hope of some better way, or some more tangible truth. If any woman at eighty years of age was the same woman, spiritually and mentally, she was at twenty, or even fifty, she would be little worthy of our respect.

Also, there are supreme tragedies and calamities in my life that it would be impossible for me to write down. It would be treason against both the living and the dead. But such calamities always came from the hand of man. I never had a sorrow from the hand of God that I could not tell to any good man or woman; for the end of God-sent sorrow is some spiritual gain or happiness. We hurt each other terribly in this world, but it is in ways that only the power which tormented the perfect man of Uz would incite.

I write mainly for the kindly race of women. I am their sister, and in no way exempt from their sorrowful lot. I have drank the cup of their limitations to the dregs, and if my experience can help any sad or doubtful woman to outleap her own shadow, and to stand bravely out in the sunshine to meet her destiny, whatever it may be, I shall have done well; I shall not have written this book in vain. It will be its own excuse, and justify its appeal.

AMELIA BARR

| PAGE | ||

| I. | The Border Land of Life | 1 |

| II. | At Shipley, Yorkshire | 11 |

| III. | Where Druids and Giants Dwelt | 25 |

| IV. | At Ripon and the Isle of Man | 47 |

| V. | Sorrow and Change | 60 |

| VI. | In Norfolk | 69 |

| VII. | Over the Border | 81 |

| VIII. | Love Is Destiny | 91 |

| IX. | The Home Made Desolate | 106 |

| X. | Passengers for New York | 126 |

| XI. | From Chicago to Texas | 146 |

| XII. | A Pleasant Journey | 177 |

| XIII. | In Arcadia | 195 |

| XIV. | The Beginning of Strife | 214 |

| XV. | The Break-up of the Confederacy | 235 |

| XVI. | The Terror by Night and by Day | 259 |

| XVII. | The Never-Coming-Back Called Death | 278 |

| XVIII. | I Go to New York | 300 |

| XIX. | The Beginnings of a New Life | 319 |

| XX. | The Family Life | 335 |

| XXI. | Thus Runs the World Away | 354 |

| XXII. | The Latest Gospel: Know Thy Work and Do It | 374 |

| XXIII. | The Gods Sell Us All Good Things for Labor | 405 |

| XXIV. | Busy, Happy Days | 426 |

| XXV. | Dreaming and Working | 446 |

| XXVI. | The Verdict of Life | 466 |

| Appendix I. | Huddleston Lords of Millom | 481 |

| Appendix II. | Books Published by Dodd, Mead and Company | 488 |

| Appendix III. | Books Published by Other Publishers | 490 |

| Appendix IV. | Poems | 492 |

| Appendix V. | Letters | 499 |

| Index | 513 |

| PAGE | |

| Mrs. Barr at 80 | Frontispiece |

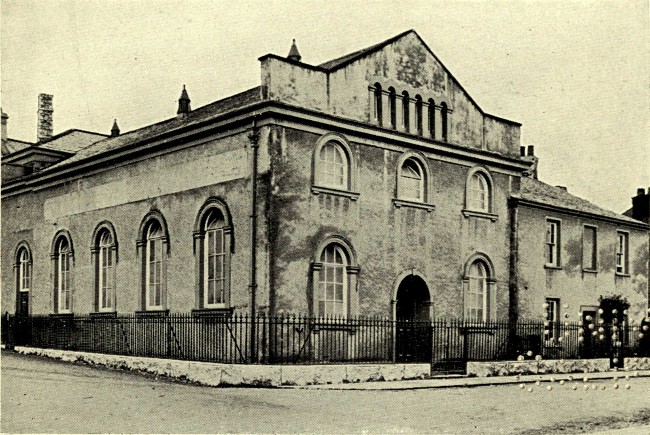

| Mrs. Barr’s Birthplace | 8 |

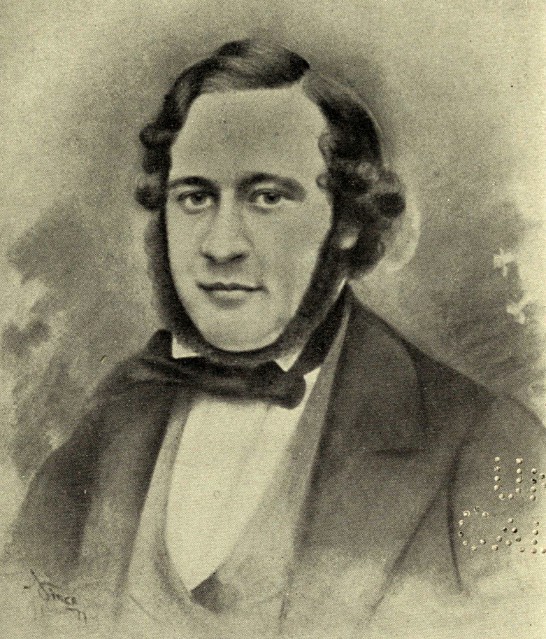

| Rev. William Henry Huddleston | 52 |

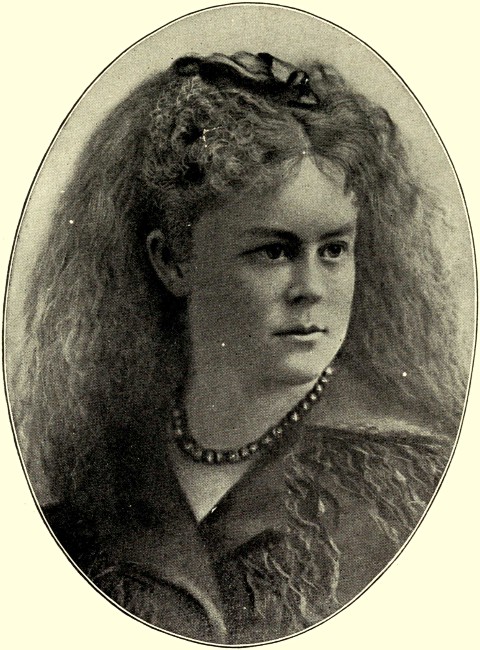

| Mrs. Barr at 18 | 98 |

| Mr. Robert Barr | 204 |

| Miss Lilly Barr | 288 |

| Mrs. Barr November, 1880 | 364 |

| Miss Mary Barr (Mrs. Kirk Munroe) | 378 |

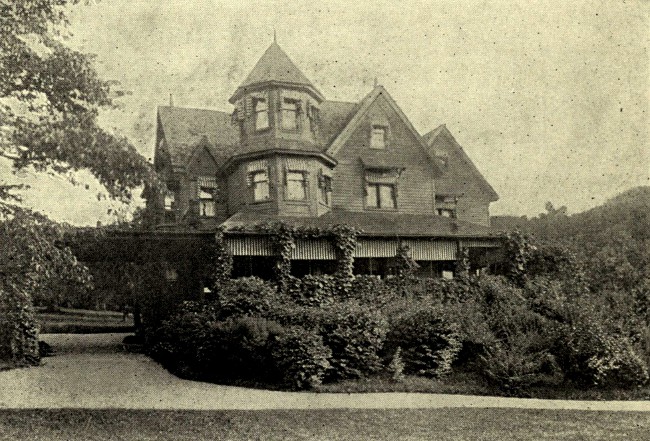

| “Cherry Croft,” Cornwall-on-Hudson | 428 |

| Miss Alice Barr | 456 |

“Date not God’s mercy from thy nativity, look beyond to the Everlasting

Love.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“Ask me not, for I may not speak of it—I saw it.”—Tennyson.

I entered this incarnation on March the twenty-ninth, A.D. 1831, at the ancient town of Ulverston, Lancashire, England. My soul came with me. This is not always the case. Every observing mother of a large family knows that the period of spiritual possession varies. For days, even weeks, the child may be entirely of the flesh, and then suddenly, in the twinkling of an eye, the mystery of the indwelling spirit is accomplished. This miracle comes not by observation; no mother ever saw it take place. She only knows that at one moment her child was ignorant of her; that at the next moment it was consciously smiling into her face, and that then, with an instinctive gladness, she called to the whole household, “the baby has begun to notice.”

I brought my soul with me—an eager soul, impatient for the loves and joys, the struggles and triumphs of the dear, unforgotten world. No doubt it had been aware of the earthly tabernacle which was being prepared for its home, and its helper in the new onward effort; and was waiting for the moment which would make them companions. The beautifully fashioned little body was already dear, and the wise soul would not suffer it to run the risks of a house left empty and unguarded. Some accident might mar its beauty, or cripple its powers, or still more 2 baneful, some alien soul might usurp the tenement, and therefore never be able effectually to control, or righteously use it.

I was a very fortunate child, for I was “possessed by a good spirit, yea rather being good, my spirit came into a body undefiled and perfect” (Wisdom of Solomon, 8:20). Also, my environments were fair and favorable; for my parents, though not rich, were in the possession of an income sufficient for the modest comforts and refinements they desired. My father was the son of Captain John Henry Huddleston, who was lost on some unknown sea, with all who sailed in his company. His brother, Captain Thomas Henry Huddleston, had a similar fate. His ship, The Great Harry, carrying home troops from America, was dashed to pieces on the Scarlet Rocks, just outside Castletown, the capital of the Isle of Man. When the storm had subsided the bodies of the Captain and his son Henry were found clasped in each other’s arms, and they were buried together in Kirk Malew churchyard. During the years 1843 and 1844 I was living in Castletown, and frequently visited the large grave with its upright stone, on which was carved the story of the tragedy. Fifteen years ago my sister Alethia went purposely to Castletown to have the lettering on this stone cleared, and made readable; and I suppose that it stands there today, near the wall of the inclosure, on the left-hand side, not far from the main entrance.

When my grandmother, Amelia Huddleston, was left a widow she had two sons, John Henry and William Henry, both under twelve years of age. But she seems to have had sufficient money to care well for them, to attend to their education, and to go with them during the summer months to St. Ann’s-by-the-Sea for a holiday; a luxury then by no means common. She inspired her sons with a great affection; my father always kept the anniversary of her death in solitude. Yet, he never spoke of her to me but once. It was on my eleventh birthday. Then he took my face between his hands, and said: “Amelia, you have the name of a good woman, loved of God and man; see that you honor it.”

After the death of their mother, I believe both boys went to their uncle, Thomas Henry Huddleston, collector of the port of Dublin. He had one son, the late Sir John Walter Huddleston, 3 Q. C., a celebrated jurist, who died in 1891 at London, England. I was living then at East Orange, New Jersey. Yet, suddenly, the sunny room in which I was standing was thrilled through and through by an indubitable boding token, the presage of his death—a presage unquestionable, and not to be misunderstood by any of his family.

Sir John Walter was the only Millom Huddleston I ever knew who had not “Henry” included in his name. This fact was so fixed in my mind that, when I was introduced to the one Huddleston in the city of New York, a well-known surgeon and physician, I was not the least astonished to see on his card “Dr. John Henry Huddleston.” Again, one day not two years ago, I lifted a newspaper, and my eyes fell on the words “Henry Huddleston.” I saw that it was the baptismal name of a well-known New Yorker, and that he was seriously ill. Every morning until his death I watched anxiously for the report of his condition; for something in me responded to that singular repetition, and, though I never heard any tradition concerning it, undoubtedly there is one.

Millom Castle and lands passed from the Huddleston family to the Earls of Lonsdale, who hold them with the promise that they are not to be sold except to some one bearing the name of Huddleston. Not more than ten years ago, the present Earl admitted and reiterated the old agreement. One part of the castle is a ruin covered with ivy, the rest is inhabited by a tenant of the Earl. My sister stayed with this family a few days about twelve years ago. Soon afterwards Dr. John Henry Huddleston, accompanied by his wife, visited Millom and brought me back some interesting photos of the church and the Huddleston monuments.

The Millom Huddlestons have always been great ecclesiastics. There lies upon my table, as I write, a beautifully preserved Bible of the date A.D. 1626. It has been used by their preachers constantly, and bears many annotations on the margins of its pages. It is the most precious relic of the family, and was given to me by my father on my wedding-day. Their spiritual influence has been remarkable. One tradition asserts that an Abbot Huddleston carried the Host before King Edward 4 the Confessor, and it is an historical fact that Priest Huddleston, a Benedictine monk, found his way up the back stairs of Windsor Castle to King Charles the Second’s bedroom, and gave the dying monarch the last comforting rites of his church.

When they were not priests they were daring seamen and explorers. In the seventeenth century India was governed by its native princes, and was a land of romance, a land of obscure peril and malignant spells. An enchanted veil hung like a mist over its sacred towns on the upper Ganges, and the whole country, with its barbaric splendors and amazing wealth, had a luring charm, remote and unsubstantial as an ancient fable. In that century, there was likely always to be some Captain Huddleston rounding the Cape, in a big, unwieldy Indiaman. That the voyage occupied a year or two was no deterrent. Their real home was the sea, their Millom home only a resting-place. By such men the empire of England was builded. They gave their lives cheerfully to make wide her boundaries, and to strengthen her power.

My father and his brother both chose theology, and they were suitably educated for the profession. John Henry, on receiving orders, sailed for Sierra Leone as one of the first, if not the first missionary of the English Church to the rescued slaves of that colony. My father finally allied himself with the Methodist Church, a decision for which I never heard any reason assigned. But the reason must have been evident to any one who considered the character and movements of William Henry Huddleston. In that day the English Church, whatever she may do now, did not permit her service to be read, in any place not sanctified by a bishop with the proper ceremonies. My father found in half a dozen shepherds on the bare fells a congregation and a church he willingly served. To a few fishers mending their nets on the shingly seashore, he preached as fine a sermon as he would have preached in a cathedral. It was his way to stroll down among the tired sailormen, smoking and resting on the quiet pier in the gloaming, and, standing among them, to tell again the irresistible story of Christ and Him Crucified.

He was indeed a born Evangelist, and if he had been a contemporary of General Booth would certainly have enrolled himself 5 among the earliest recruits of his evangelizing army. In the Methodist Church this tendency was rather encouraged than hindered, and that circumstance alone would be reason most sufficient and convincing to a man, who believed himself in season and out of season in charge of souls. In this decision I am sure there was no financial question; he had money enough then to give his conscience all the elbow-room it wanted.

Soon after this change my father married Mary Singleton—

“A perfect woman, nobly planned,

To trust, to comfort, and command.”

Physically she was small and delicately formed, but she possessed a great spirit, a heart tender and loving as a child’s, and the most joyous temper I ever met. Every fret of life was conquered by her cheerfulness. Song was always in her heart, and very often on her lips. She brooded over her children like a bird over its nest, and was exceedingly proud of her clever husband, serving and obeying him, with that touching patience and fidelity which was the distinguishing quality of English wives of that period.

And it was to this happy couple, living in the little stone house by the old chapel in Ulverston, I came that blessed morning in March, A.D. 1831. Yes, I will positively let the adjective stand. It was a “blessed” morning. Though I have drunk the dregs of every cup of sorrow,

“My days still keep the dew of morn,

And what I have I give;

Being right glad that I was born,

And thankful that I live.”

I came to them with hands full of gifts, and among them the faculty of recollection. To this hour I wear the key of memory, and can open every door in the house of my life, even to its first exquisite beginnings. The thrills of joy and wonder, of pleasure and terror I felt in those earliest years, I can still recapture; only that dim, mysterious memory of some previous existence, where the sandy shores were longer and the hills far higher, has 6 become fainter, and less frequent. I do not need it now. Faith has taken the place of memory, and faith is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”

Childhood is fed on dreams—dreams waking, and dreams sleeping. My first sharp, clear, positive recollection is a dream—a sacred, secret dream, which I have never been able to speak of. When it came to me, I had not the words necessary to translate the vision into speech, and, as the years went on, I found myself more and more reluctant to name it. It was a vision dim and great, that could not be fitted into clumsy words, but it was clearer and surer to me, than the ground on which I trod. It is nearly seventy-eight years since I awoke that morning, trembling and thrilling in every sense with the wonder and majesty of what I had seen, but the vision is not dim, nor any part of it forgotten. It is my first recollection. Beyond—is the abyss. That it has eluded speech is no evidence of incompleteness, for God’s communion with man does not require the faculties of our mortal nature. It rather dispenses with them.

When I was between three and four years old I went with my mother to visit a friend, who I think was my godmother. I have forgotten her name, but she gave me a silver cup, and my first doll—a finely gowned wax effigy—that I never cared for. I had no interest at all in dolls. I did not like them; their speechlessness irritated me, and I could not make-believe they were real babies. I have often been aware of the same perverse fretful kind of feeling at the baffling silence of infants. Why do they not talk? They have the use of their eyes and ears; they can feel and taste and touch, why can they not speak? Is there something they must not tell? Will they not learn to talk, until they have forgotten it? For I know

“Our birth is but a sleep and a forgetting

The soul that rises with us, our Life’s Star,

Hath had elsewhere its setting;

And cometh from afar.

Not in entire forgetfulness,

And not in utter darkness,

But trailing clouds of glory do we come

From God, who is our home.”

At this house, overlooking the valley of the Duddon, I needed nothing to play with. Every room in it was full of wonders, so also was the garden, with its dark walls shaded by yews, and pines, and glistening holly, the latter cut into all kinds of fantastic shapes. The house had a large entrance hall, and, rising sheer from it, was the steep, spiral stairway leading to the upper rooms. The stairs were highly polished and slippery, but they were the Alps of my baby ambition. Having surmounted them, there was in the corridor to which they led, queer, dark closets to be passed swiftly and warily, and closed guest rooms—obscure, indistinct, and shrouded in white linen. It gave me a singular pleasure to brave these unknown terrors, and after such adventures I returned to my mother with a proud sense of victory achieved; though I neither understood the feeling, nor asked any questions about it. Now I can accurately determine its why and its wherefore, but I am no happier for the knowledge. The joy, of having conquered a difficulty, and the elation of victory because of that conquest had then a tang and a savor beyond the power of later triumphs to give me. I know too much now. I calculate probabilities and attempt nothing that lacks strong likelihoods of success. Deservedly, then, I miss that exulting sense of accomplishment, which is the reward of those who never calculate, but who, when an attempt is to be made, dare and do, and most likely win.

There was also a closed room downstairs, and I spent much time there when the weather was wet, and I could not get into the garden. It had once been a handsome room, and the scene of much gaiety, but the passage of the Reform Bill had compelled English farmers to adopt a much more modest style of living; and the singing of lovers, and the feet of dancing youths and maidens was heard no more in its splendid space. But it was yet full of things strange and mysterious—things that ministered both to the heaven and hell of my imagination; beautiful images of girls carrying flowers and of children playing; empty shells of resplendent colors that had voices in them, mournful, despairing voices, that filled me with fear and pity; dreadful little heathen gods, monstrous, frightful! with more arms and hands and feet than they ought to have; a large white marble 8 clock that was dead, and could neither tick nor strike; butterflies and birds motionless, silent, and shut up in glass cases; and what I believed to be a golden harp, with strings slack or broken, yet crying out plaintively if I touched them.

One afternoon I went to sleep in this room, and, as my mother was out, I was not disturbed; indeed when I opened my eyes it was nearly dark. Then the occult world, which we all carry about with us, was suddenly wide awake, also; the place was full of whispers; I heard the passing of unseen feet, and phantom-like men and women slipped softly about in the mysterious light. My heart beat wildly to the visions I created, but who can tell from what eternity of experiences, the mind-stuff necessary for these visions floated to me? Who can tell?

It was, however, the long, long nights, far more than the wonderful days, which impregnated my future—the dark, still nights full of hints and fine transitions, shadowy terrors, fleeting visions and marvelous dreams. I shall remember as long as I live, nights that I would not wish to dream through again, neither would I wish to have been spared the dreams that came to me in them. The impression they made was perhaps only possible on the plastic nature of a child soul, but, though long years lay between the dream and the event typified, the dream was unforgotten, and the event dominated by its warning. All education has this provisional quality. In school, as well as in dreams, we learn in childhood a great deal that finds no immediate use or expression. For many years we may scarcely remember the lesson, then comes the occasion for it, and the information needed is suddenly restored.

There is then no wonder that, in the full ripeness of my mental growth, I look back with wondering gratitude to these first apparently uneventful years on the border land of being. In them I learned much anteceding any reasoning whatever. There is nothing incredible in this. Heaven yet lies around infancy, and we are eternally related to heavenly intelligences “a little lower” that is all. Thus, in an especial manner,

“Our simple childhood sits,

Our simple childhood sits upon a throne,

That hath more power than all the elements.”

For it is always the simple that produces the marvelous, and these fleeting shadowy visions and intimations of our earliest years, are far from being profitless; not only because they are kindred to our purest mind and intellect, but much rather because the soul

“Remembering how she felt, but what she felt

Remembering not; retains an obscure sense

Of possible sublimity.”

I have a kind of religious reluctance to inquire too closely into these almost sacred years. Yet when I consider the material education of the children of this period, I feel that I have not said enough. For a boy educated entirely on a material basis, is not prepared to achieve success, even financial success. The work of understanding must be enlightened by the emotions, or he will surely sink to the level of the hewers of wood and drawers of water. The very best material education will not save a child who has no imagination. Therefore do not deprive childhood of fairy tales, of tales of stirring adventure and courage, and of the wondrous stories of the old Hebrew world. On such food the imagination produces grand ideals and wide horizons. It is true we live in a very present and very real world, and many are only too ready to believe that the spiritual world is far-off and shadowy. On the contrary, the spiritual world is here and now and indisputably and preëminently real. It is the material world that is the realm of shadows.

I doubt if any child is born without some measure of that vision and faculty divine which apprehends the supernatural. This is “the light within which lighteth every man that cometh into the world.” If that light be neglected, and left to smoulder and die out, how great is the darkness it leaves behind! Precious beyond price are the shadowy recollections of a God-haunted childhood,

“Which be they what they may,

Are yet the fountain light of all our day;

Are yet the master light of all our seeing.”

A child is a deep mystery. It has a life of its own, which it reveals to no one unless it meets with sympathy. Snub its first halting confidences concerning the inner life, or laugh at them, or be cross or indifferent, and you close the door against yourself forever. Now there is no faculty given us that the soul can spare. If we destroy in childhood the faculty of apprehending the spiritual or supernatural, as detrimental to this life, if there be left

“... no Power Divine within us,

How can God’s divineness win us?”

“Sweet childish days that were as long

As twenty days are now.”

. . . . . . . . . .

“A child to whom was given

So much of earth, so much of heaven.”

Before I was three years old my father removed to Yorkshire, to Shipley, in the West Riding. I never can write or speak those two last words, “West Riding,” without a sensible rise of temperature, and an intense longing to be in England. For the West Riding is the heart of England, and, whatever is distinctively English, is also distinctively West Riding. Its men and women are so full of life, so spontaneously cheerful, so sure of themselves, so upright and downright in speech and action, that no one can for a moment misunderstand either their liking or disliking. Their opinions hold no element of change or dissent. They are as hearty and sincere in their religion, as their business, and if they form a friendship with a family, it will likely be one to the third and fourth generation. I correspond today with people whom I never saw, but whose friendship for my family dates back to a mutual rejoicing over the victory of Waterloo.

Of course I was not able to make any such observations on West Riding humanity when I first went there, but I felt the goodness of the people then, and in later years I both observed and experienced it. And it was well for me in my early childhood to live a while among such a strong, happy people. They impressed upon my plastic mind their confidant cheerfulness, and their sureness that life was a very good thing.

Shipley was then a pretty country town, though it is now a great manufacturing city, not far behind Bradford and Leeds. 12 I was three years there and during those years gradually dropped all remains of infancy, and became a child, a child eager for work and for play, and half-afraid the world might not last until I found out all about it. At first I went to a dame’s school. She did not take children over five years of age, and to these babies she taught only reading and needlework and knitting. We sat on very low benches in a room opening into a garden, and we spent a good deal of time in the garden. But she taught me to hem, and to seam, to fell and to gather, to stroke and to backstitch, and when I left her I could read any of the penny chap books I could buy. Most of them contained an abbreviated adventure from the “Arabian Nights” collection.

Soon after we removed to Shipley a woman came into our lives, called Ann Oddy, and my sister and I were told to be respectful to her and to obey her orders. She was a clever housekeeper, a superior cook, and had many domestic virtues; but she was authoritative, tyrannical, and quite determined to have things her own way. Fortunately I won her favor early, and for two simple reasons: first, my hair was easy to curl, and Sister Jane’s had to be carefully put in papers, and then did not “keep in.” Second, because she thought Jane was always ready to go “neighboring” with Mother, and then was so secret as to where she had been, and so “know nothing” of what was said; but I was better pleased to stay in the children’s room with a book and herself for company.

Indeed I liked Ann’s society. She had a grewsome assortment of stories, chiefly about bad fellows and their young women, but sometimes concerning bad children who had come to grief for disobeying their good parents, or for breaking the Sabbath Day. There was generally, however, an enthralling climax, relating to a handsome young man, whom she saw hanged at York Castle for murdering his sweetheart. At this narration I usually laid down my book, and listened with trembling interest to the awful fate of this faithless lover, and Ann’s warnings against men of all kinds who wanted helpless women to marry them. In those days I felt sure Ann Oddy had the true wisdom, and was quite resolved to look upon all handsome young men as probable murderers.

The three years I spent at Shipley were happy years. I enjoyed every hour of them, though the days were twenty times as long as days are now. There was a great deal of visiting, and visiting meant privileges of all kinds. We were frequently asked out to tea with our parents, especially if there were children in the house to which we were going, and there were children’s parties nearly every week at somebody’s house.

It was a good thing, then, that our usual fare was very plain, and not even the quantity left to our own desire or discretion. Breakfast was always a bowl of bread and milk boiled, and a rather thick slice of bread and butter after it. Fresh meat was sparingly given us at dinner, but we had plenty of broth, vegetables, and Yorkshire pudding. Our evening meal was bread and milk, rice or tapioca pudding, and a thick slice of sweet loaf—that is, bread made with currants, and caraway seeds, and a little sugar. But when we went out for dinner or tea, we had our share of the good things going; and, if the company was at our house, Ann Oddy usually put a couple of Christ Church tarts, or cheesecakes, among our plain bread. She always pretended to wonder where they came from; and, if I said pleadingly, “Don’t take them away, Ann,” she would answer in a kind of musing manner, “I’ll be bound the Missis put them there. Some people will meddle.” Then Jane would help herself, and I did the same, and we both knew that Ann had put the tarts there, and that she intended us to eat them. Yet this same little pretense of surprise was kept up for many years, and I grew to enjoy the making of it more perfect, and the changing of the words a little.

The house at which I liked best of all to visit was that of Jonathan Greenwood. He had a pretty place—with a fine strawberry bed—at Baildon Green. He was then a handsome bachelor of about forty years of age, and I considered him quite an old man. I knew also that he was Miss Crabtree’s sweetheart, and Ann’s look of disapproval, and the suspicious shake of her head made me anxious about both of them. What if Miss Crabtree should have another sweetheart! And what if Jonathan killed her because she had deceived him! Then there might be the York tragedy over again. These thoughts 14 troubled me so much that I ventured to suggest their probability to Ann. She laughed my fears to scorn.

“Martha Crabtree have another sweetheart! Nay, never my little lass! It will be the priest, not the hangman, that will tie Jonathan up.”

“Tie Jonathan up, Ann!” I ejaculated.

“To be sure,” she answered. “Stop talking.”

“But, Ann——”

“Do as I bid you.”

Then I resolved to ask Jonathan that afternoon. It was Thursday, and he would be sure to call for a cup of tea as he came from Leeds market. I did not do so, because he asked permission for me to go to Baildon Green with him, and stay until after the fair, and during the visit I knew I should find many better opportunities for the question. To go to Baildon Green, was the best holiday that came to me, unless it was to go to Mr. Samuel Wilson’s, at the village of Baildon. He had a much finer house, and a large shop in which there were raisins and Jordan almonds, and he had also a handsome little son of my own age, with whom I loved to play. But one visit generally included the other, and both were very agreeable to all my desires.

At Baildon Green I had many pleasures. I liked to be petted and praised and to hear the women say, “What a pretty child it is! God bless it!” and I liked to hang around them, and listen to their conversation as they made nice little dinners. I liked in the evening to look at the Penny Magazine, and to have Mr. Greenwood explain the pictures to me, and I certainly liked to go with him in his gig to Leeds on Leeds market day. Sometimes he took me with him into the Cloth Hall; sometimes also men would say, “Why, Jonathan, whose little lass is that?” And he would answer, “It is Mr. Huddleston’s little lass.” “Never!” would be the ejaculation, but I knew the word was not intended for dissent, but somehow for approval.

When I was at Baildon Green Saturday was the great day. Very early in the morning the weavers began to arrive with the web of cloth they had woven during the week. In those days there were no mills—all the cloth was made in the weavers’ 15 homes. Baildon Green was a weaving village. In every cottage there was a loom and a big spinning wheel. The men worked at the loom, the women and children at the wheel. At daybreak I could hear the shuttles flying, and the rattle of the unwieldy looms in every house. On Saturday they brought their webs to Jonathan Greenwood. He examined each web carefully, measured its length, and paid the weaver whatever was its value. Then, giving him the woolen yarn necessary for next week’s web, he was ready to call another weaver. There were perhaps twenty to thirty men present, and, during these examinations many little disputes arose. I enjoyed them. The men called the master “Jonathan,” and talked to him in language as plain, or plainer, than he gave them. Sometimes, after a deal of threaping, the master would lose his temper, then I noticed he always got the best of the argument. In the room where this business took place there was a big pair of scales, and I usually sat in them, swinging gently to and fro, and listening.

These weavers were all big men, the master bigger than any of them; and they all wore blue-checked linen pinafores covering them from neck to feet. Underneath this pinafore the master wore fine broadcloth and high shoes with silver latchets. I do not know what kind of cloth the men wore, but it was very probably corduroy, as that was then the usual material for workingmen’s clothes, and on their feet were heavy clogs clasped with brass, a footgear capable of giving a very ugly and even dangerous kick.

I have never seen a prouder or more independent class of men than these home weavers; and just at this time they had been made anxious and irritable by the constant reports of coming mills and weaving by machinery. But their religion kept them hopeful and confident, for they were all Methodists, made for Methodists, and Methodism made for them. And it was a great sight on a Sabbath morning to see them gathering in their chapel, full of that incompatible spiritual joy which no one understands but those who have it, and which I at that time, took for simple good temper. But I know now that if I was a preacher of the Word, I would not ask to be sent to an analyzing, argumentative, cold Scotch kirk; nor to a complacent, satisfied 16 English church; nor even to a meditative, tranquil Quaker meeting-house; I would say, “Send me to an inspiring, joyful, West Riding Methodist chapel.”

This visit to Baildon Green was the last of my Shipley experiences. During it Mr. Greenwood told me that he would have “a handsome wife” when I came again, and that she would take me about a bit. I was not much pleased at the prospect. Men were always kinder to me than women, and not so fussy about my hair being in curl, and my frock clean. So I did not speak, and he asked, “Are you not pleased, Milly?”

“No,” I answered bluntly.

“But why?” he continued.

“Because I like you—all to myself.” Then he laughed and was much pleased, and I learned that day that you may wisely speak the truth, if it is complimentary.

The event of this visit was Baildon Feast, a great public rejoicing on the anniversary of the summer solstice. It had been observed beyond the memory of man, beyond historical notice, beyond even the traditions of the locality. There was no particular reason for its observance that I could ever learn; it was just Baildon Feast, and that was all anybody knew about it.

I was awakened very early on the first day of the feast by the bands “playing the sun up,” and before we had finished breakfast the procession was forming. Now Baildon Green is flat and grassy as a meadow, and when I was six years old it had a pond in the center, while from the northwest there rose high hills. Only a narrow winding path led to the top of these hills, and about half way up, there was a cave which tradition averred had been one of Robin Hood’s retreats—a very probable circumstance, as this whole country-side was doubtless pretty well covered with oak forests.

A numerous deputation from the village of Baildon, situated on the top of the hill, joined the procession which started from Baildon Green at an early hour. The sun was shining brightly, and I had on a clean white frock, pretty white sandals, a new blue sash, and a gypsy hat trimmed with blue ribbons. When the music approached it put a spirit into my feet and my heart 17 kept time to the exciting melody. I had never walked to music before, and it was an enchanting experience.

The procession appeared to my childish apprehension a very great one. I think now it may have consisted of five hundred people, perhaps less, but the great point of interest was two fine young heifers garlanded with flowers, and ornamented with streaming ribbons of every color. Up the winding path they went, the cattle lowing, the bands playing, the people singing and shouting up to the high places on which the village of Baildon stood. There at a particular spot, hallowed by tradition, the cattle garlanded for sacrifice were slain. I do not know whether any particular method or forms were used. I was not permitted to see the ceremony attending their death, and I confess I was much disappointed.

“It isn’t fit for a little lass to see,” said my friend Jonathan, “and I promised thy father and mother I wouldn’t let thee see it, so there now! Nay, nay, I wouldn’t whimper about such a thing as that. Never!”

I said I wasn’t whimpering, and that I didn’t care at all about seeing the animals killed, but I did care, and Baildon Fair without its tragedy no longer interested me, yet I stayed to see the flesh distributed among all who asked for it. There was an understanding, however, that those who received a festival roast should entertain any stranger claiming their hospitality. This ancient rite over, the people gave themselves up to sports of all kinds.

But their Methodism kept them within the bounds of decency, for there were favorite preachers invited from all the towns around, and if the men and boys were busy in the cricket fields all day, they were sure to be in the chapel at night. There was also a chapel tea party the last afternoon of the feast, and after it a great missionary meeting at which Bishop Heber’s hymn, “From Greenland’s Icy Mountains,” was sung with such mighty fervor as made me thrill and tremble with an emotion I can yet recall. That night I solemnly determined to be a missionary. I would go to the darkest of all heathen lands, and be the first to tell the story of Jesus. I went home in a state of beatific surrender, and whenever I think of that night, 18 I am aware of a Presence, and the face I wore when I was a little child turns to me. And I am troubled and silent before that little ghost with its eager eyes and loving enthusiasms, for I have done none of the things I promised to do, and an intangible clutch of memory gives me a spell of sadness keen and regretful.

This Baildon experience was one of those instances of learning in childhood things of no immediate use. I was hardly six years old then; I was seventy-six when it struck me, that I had perhaps taken part in a non-intentional sacrifice to the God Baal. For four years ago I was much interested in discovering that the Shetlanders, even to the close of the nineteenth century, kept the same feast at the summer solstice, and also made their children in some of the lonely islands pass through the Beltane fires, in fact paying the old God Bel or Baal the same services as the Hebrew prophets so often reproached the Israelites with performing. But I believe that wherever Druidical remains are found, relics of this worship may be traced either in names, superstitions, signs or traditions. In a letter I received from a Bradford lady dated September twenty-seventh, A.D. 1911, she says, “It was rather strange but we had a man at our house from Thornton the other day, and he was telling us how they paraded the cattle they were going to kill at the feast through the streets, and I thought of you, and what you remembered of it in Baildon.”

These details may seem to the reader trivial and futile; on the contrary, they were the very material from which life was building character. For all that surrounds a child, all that it sees, hears, feels or touches, helps to create its moral and intellectual nature. See then how fortunate were my first six years. My physical being was well cared for by loving parents in a sweet orderly home, and my mental life well fed by books stimulating the imagination. Through the “Arabian Nights” tales I touched the domestic life of the wonderful East, China, India, Persia and Arabia; and at the missionary meetings, and at my home, I met men who had been to these far away places, and brought back with them curious and beautiful things, even the very gods they worshipped. There had been hitherto in 19 other respects a good deal of judicious neglect in my education. Books had never been anything but a source of wonder and delight to me. I had never heard of a grammar and an arithmetic, and had never been deprived of a visit or a holiday because if I did not go to school, I would miss a mark, or lose my place in a class.

Fortunately this desultory education was marbled all through with keen spiritual incidents and issues. For the spiritual sight of children turns more sharply upon the world within the breast, than they show, or that anyone imagines. They hold in their memories imperishable days which all others have forgotten, visions beautiful and fearful, dreams without name or meaning, and they have an undefined impression of the awful oldness of things. They see the world through doors very little ajar, and they know the walking of God through their dreaming sleep.

The happy and prosperous children are those, who had before all else the education that comes by reverence. This education is beyond all doubt the highest, the deepest, the widest and the most perfect of all the forms of education ever given to man. A child that has not been taught to reverence God, and all that represents God to man—honor, honesty, justice, mercy, truth, love, courage, self-sacrifice, is sent into the world like a boat sent out to sea, without rudder, ballast, compass or captain.

But the education by reverence must begin early. Children of very tender years may be taught to wander through those early ages of faith, when God took Enoch, and no one was astonished; when Abraham talked with God as friend with friend; when the marvelous ladder was let down by Jacob’s pillow; when Hagar carrying her dying child in the desert saw without surprise the angel of the Lord coming to help her. Nor is there any danger in permitting them to enter that dimmer world lying about childhood, to which Robinson Crusoe and Scheherazade hold the keys. The multiplication table can wait, until the child has been taught to reverence all that is holy, wise and good, and the imagination received its first impulse. So I do not call such events as I have chronicled 20 trifling; indeed, I know that in the formation of my character, they had a wide and lasting influence.

A few days after the fair, Jonathan Greenwood was going to Bradford so he left me at my home as he passed there, and as soon as I came in sight of our house, I saw my sister running to the gate to meet me.

“I have a little brother!” she cried. “I have a little brother, Amelia.”

“Mine, too,” I asserted; and she answered, “Yes, I dare say.”

“Is he nice?” I asked.

“Middling nice. You should see how everyone goes on about him.”

“My word!” cried Jonathan, “you girls will be nobodies now. But, I shall stick by you, Milly.”

“Yes,” I answered dubiously, for I had learned already that little girls were of much less importance than little boys. So I shook my head, and gave Jonathan’s promise a doubtful “yes.”

“Tell Ann Oddy,” he said, “that I will be in for a cup of tea at five o’clock.” Then he drove away, and Jane and I walked slowly up the garden path together.

“Father called him John Henry, first thing,” said Jane, “and Mother is proud of him, as never was.”

“I want to see him,” I answered. “Let us go to the children’s room.”

“He is in Mother’s room, and Mother is sick in bed, and Ann is so busy with the boy, she forgot my breakfast, so I had breakfast with Father.”

“Breakfast with Father! Never!”

“Yes, indeed, and dinner, too, for three days now. Perhaps as you have come home, Ann will remember that girls need something for breakfast. Father wasn’t pleased at her forgetting me.”

“What did she say?”

She said, “Mr. Huddleston, I cannot remember everything, and the Mistress and the little lad do come first, I should say.”

“Was Father angry?” I asked.

“He said something about Mrs. Peacock.”

“What is Mrs. Peacock doing here?”

“She is hired to help, but I think she never leaves her chair. Ann sniffed, and told Father, Mrs. Peacock had all she could do to take care of Mrs. Peacock. Then Father walked away, and Ann talked to herself, as she always does, when she is angry.”

This conversation and much that followed I remember well, not all of it, perhaps, but its spirit and the very words used. It occurred in the garden which was in gorgeous August bloom, full of splendid dahlias and holly-hocks, and August lilies. I have never seen such holly-hocks since. We called them rose-mallows then which is I think a prettier name. The house door stood open, and the rooms were all so still and empty. There was a bee buzzing outside, and the girl Agnes singing a Methodist hymn in the kitchen, but the sounds seemed far away, and our little shoes sounded very noisy on the stairway.

I soon had my head on my mother’s breast, and felt her kisses on my cheek. She asked me if I had a happy visit, but she did not take as much interest in my relations as I expected; she was so anxious to show me the new baby, and to tell me it was a boy, and called after his father’s brother. I was jealous and unhappy, but Mother looked so proud and pleased I did not like to say anything disagreeable, so I kissed Mother and the boy again, and then went to the children’s room and had a good cry in Ann Oddy’s arms.

“Ann,” I said, “girls are of no account;” and she answered, “No, honey, and women don’t signify much either. It is a pity for us both. I have been fit to drop with work ever since you went away, Amelia, and who cares? If any man had done what I have done, there would be two men holding him up by this time.”

“Ann, why do men get so much more praise than women, and why are they so much more thought of?”

“God only knows child,” she answered. “Men have made out, that only they can run the world. It’s in about as bad a state as it well can be, but they are proud of their work. What I say is, that a race of good women would have done 22 something with the old concern by this time. Men are a poor lot. I should think thou would want something to eat.”

I told her I was “as hungry as could be,” but that Jonathan was coming to tea at five o’clock.

“Then he’ll make it for himsel’,” she said. “Mr. Huddleston has gone to Windhill to some sort of meeting. Mrs. Huddleston can’t get out of bed. I have the baby on my hands, and Mrs. Peacock makes her own tea at five o’clock—precisely.”

“Then Ann let me make Jonathan’s tea. I am sure I can do it, Ann. Will you let me?”

“I’ll warrant thee.” Then she told me exactly what to do, and when Jonathan Greenwood came, he found a good pot of tea and hot muffins ready, and he had given Agnes some Bradford sausage, with their fine flavoring of herbs, to fry, and Agnes remembered a couple of Kendal wigs[1] that were in the house and she brought them in for a finishing dish. I sat in my mother’s chair, and poured out tea; but I sent for Jane when all was ready, and she gave me a look, still unforgotten, though she made no remark to disturb a meal so much to her liking. Later, however, when we were undressing for bed, and had said our prayers, she reminded me that she was the eldest, and that I had taken her place in making tea for Mr. Greenwood. Many a time I had been forced to receive this reproof silently, but now I was able to say:

“You are not the oldest any longer, Jane. John is the oldest now. Girls don’t count.”

In my childhood this eldest business was a sore subject, and indeed to this day the younger children in English families express themselves very decidedly about the usurpation of primogenital privileges, and the undue consideration given to boys.

A few weeks after the advent of my brother, John Henry, we removed to Penrith in Cumberland, and the night before leaving, a circumstance happened which made a great impression on me. There was a circle of shrubs in the garden, and a chair 23 among them on which I frequently sat to read. This night I went to meet Mother at the garden gate, and as we came up the flagged walk, I saw a man sitting on the chair. “Let us go quickly to the house,” said Mother; but a faint cry of “Mary!” made her hesitate, and when the cry was repeated, and the man rose to his feet, my mother walked rapidly towards him crying out, “O Will! Will! O my brother! Have you come home at last?”

“I have come home to die, Mary,” he said.

“Lean on me, Will,” she replied. “Come into the house. We leave for Penrith to-morrow, and you can travel with us. Then we shall see you safely home.”

“What will your husband say?” the man asked.

“Only kind words to a dying man. Are you really so ill, Will?” And the man answered, “I may live three months. I may go much sooner. It depends——”

Then my mother said, “This is your uncle, Dr. Singleton, Milly;” and I was very sorry for a man so near death, and I went and took his hand, but he did not seem to care about me. He only glanced in my face, and then remarked to Mother, “She seems a nice child.” I felt slighted, but I could not be angry at a man so sick.

When I went upstairs I told Ann that my uncle had come, and that he said he was going home to Kendal to die. “He will travel with us to-morrow as far as Kendal; Mother asked him to do so,” I added.

“I dare say. It was just like her.”

“Don’t you like my uncle, Ann? I thought he was a very fine gentleman.”

“Maybe he is. Be off to your bed now. You must be up by strike-of-day to-morrow;” and there was something in Ann’s look and voice, I did not care to disobey.

Indeed Ann had every one up long before it was necessary. We had breakfast an hour before the proper time; but after all, it was well, for the house and garden was soon full of people come to bid us “good-bye.” Some had brought lunches, and some flowers and fruits, and there was a wonderful hour of excitement, before the coach came driving furiously up to 24 the gate. It had four fine horses, and the driver and the guard were in splendid livery, and the sound of the horn, and the clatter of the horses’ feet, and the cries of the crowd stirred my heart and my imagination, and I believe I was the happiest girl in the world that hour. I enjoyed also the drive through the town, and the sight of the people waving their handkerchiefs to Father and Mother from open doors and windows. I do not think I have ever since had such a sense of elation and importance; for Father and I had relinquished our seats inside the coach to Uncle Will Singleton, and I was seated between the driver and Father, seeing well and also being well seen.

Never since that morning have I been more keenly alive in every sense and more ready for every event that might come; the first of which was the meeting and passing of three great wains loaded high with wheat, and going to a squire’s manor, whose name I have forgotten. There were some very piquant words passed between the drivers about the coach going a bit to the wrong side. On the top of the three wagons about a dozen men were lying at their ease singing the prettiest harvest song I ever heard, but I only caught three lines of it. They went to a joyful melody thus:

“Blest be the day Christ was born!

We’ve gotten in the Squire’s corn,

Well bound, and better shorn.

Hip! Hip! Hurrah!”

But as they sang the dispute between the drivers was growing less and less friendly, and the driver of the coach whipped up his horses, and took all the road he wanted, and went onward at such a rattling pace as soon left Shipley forever behind me.

“... upon the silent shore

Of memory, we find images and precious thoughts,

That shall not die, and cannot be destroyed.”

I was greatly delighted with Penrith. It was such a complete change from Shipley, and youth is always sure that change must mean something better. In the first place the town was beautiful, and generally built of the new red sandstone on which it stands; but our house was white, being I think of a rough stucco, and it stood on one of the pleasantest streets in the town, the one leading up to the Beacon. Its rooms appeared very large to me then; perhaps I might not think so highly of them now. Its door opened directly into the living-room, and it was always such a joy to open it, and step out of the snow or rain into a room full of love and comfort. Since those days I have liked well the old English houses where the front door opens directly into the living-room. Ten or twelve years ago a lady built in Cornwall-on-Hudson a handsome house having this peculiarity, and I often went to see her, enjoying every time that one step from all out doors, into the sweet home influence beyond it.

The sound of the loom and the shuttle were never heard in the broad still streets of Penrith. Business was a thing rather pushed into a corner, for Penrith was aristocratic, and always had been. The great earls of Lonsdale lent it their prestige, and circling it were some of the castles and seats of the most famous nobility. It had been often sacked, and had many royal associations. Richard the Third had dwelt in its castle when the Duke of Gloucester, and Henry the Eighth’s last wife, Catherine Parr, came from Kendal. The castle itself had been 26 built by Edward the Third, and destroyed by Cromwell. All these and many more such incidents I heard the first day of my residence in the town from a young girl we had hired for the kitchen, and she mingled with these facts the Fairy Cup of Eden Hall, and the great Lord Brougham, Long Meg and her daughters, and the giant’s grave in Penrith churchyard; and I felt as if I had stepped into some enchanted city.

Up to this time I had never been to what I called a proper school. The dame’s school at Shipley I had far outstepped, and I was so eager to learn, that I wished to begin every study at once. There were two good schools in Penrith, one kept by a Miss Pearson, and the other by a man whose name I have forgotten. I wanted to go to Miss Pearson. She had the most select and expensive school. The man’s school was said to be more strict and thorough, and much less expensive; but there was a positive prejudice against boys and girls being taught together. I could tell from the chatter of the girl in the kitchen, that it was looked down upon, and considered vulgar by the best people. I was anxious about the result. Jane and I whispered our fears to each other, but we did not dare to express any opinion to our parents. At last I talked feelingly to Ann Oddy about the situation, and was glad to find her most decidedly on our side.

“I am for the woman,” she said straight out, “and I shall tell the Master so plainly. What does that man know about trembling shy little girls?” she asked indignantly, “and I’ve heard,” she continued, “that he uses the leather strap on their little hands—even when they are trying to do the best they know how. His own children look as if they got plenty of ‘strap.’ I’ve told your mother what I think of him.”

“What did Mother say, Ann?” we eagerly asked.

“She said such a man as that would never do. So I went on—‘Mrs. Huddleston, our society wouldn’t like it. He teaches girls to write a big, round man’s hand. You may see it yourself, Mrs. Huddleston, if you’ll lift his letter to you—good enough for keeping count of what money is owing you, but for young ladies, I say it isn’t right—and his manners! if he has any, won’t be fit to be seen, and you know, Mrs. Huddleston, how 27 men talk, he won’t be fit to be heard at times; at any rate that is the case with most men—except Mr. Huddleston.’”

With such words Ann reasoned, and if I remembered the very words used it would be only natural, for I heard them morning, noon and night, until Mother went to see Miss Pearson, and came home charmed with her fine manners and method of teaching. Then our dress had to be prepared, and I shall never forget it; for girls did not get so many dresses then as they do now, and I was delighted with the blue Saxony cloth that was my first school dress. Dresses were all of one piece then, and were made low with short baby sleeves, but a pelerine was made with the dress, which was really an over-waist with two little capes over the shoulders. My shoes were low and black, and had very pretty steel buckles; my bonnet, a cottage one of coarse Dunstable straw. It had a dark blue ribbon crossed over it, and a blue silk curtain behind, and some blue silk ribbon plaited just within the brim, a Red Riding Hood cloak and French pattens for wet weather completed my school costume, and I was very proud of it. Yet it is a miracle to me at this day, how the children of that time lived through the desperate weather, deep snows and bitter cold, in such insufficient clothing. I suppose it was the survival of the fittest.

My first school day was one of the greatest importance to me. I have not forgotten one incident in all its happy hours. I fell in love with Miss Pearson as soon as I saw her; yes, I really loved the woman, and I love her yet. She was tall and handsome, and had her abundant black hair dressed in a real bow knot on the top of her head; and falling in thick soft curls on her temples, and partly down her cheeks. An exceedingly large shell comb kept it in place. Her dress was dark, and she wore a large falling collar finely embroidered and trimmed with deep lace, and round her neck a long gold chain. She came smiling to meet us, and as soon as the whole school was gathered in front of the large table at which she sat, she rose and said,

“Young ladies, you have two new companions. I ask for them your kindness—Jane and Amelia Huddleston. Rise.”

Then the whole school rose and curtsied to us, and as well as we were able, we returned the compliment. As soon as we were seated again, Miss Pearson produced a large book, and as she unclasped it, said,

“Miss Huddleston will come here.”

Every eye was turned on Jane, who, however, rose at once and went to Miss Pearson’s table. Then Miss Pearson read aloud something like the following words, for I have forgotten the exact form, though the promises contained in it have never been forgotten.

“I promise to be kind and helpful to all my schoolmates.

“I promise to speak the truth always.

“I promise to be honorable about the learning and repeating of my lessons.

“I promise to tell no malicious tales of any one.

“I promise to be ladylike in my speech and manners.

“I promise to treat all my teachers with respect and obedience.”

These obligations were read aloud to Jane and she was asked if she agreed to keep them. Jane said she would keep them all, and she was then required to sign her name to the formula in the book, which she did very badly. When my turn came, I asked Miss Pearson to sign it for me. She did so, and then called up two girls as witnesses. This formality made a great impression on me, the more so, as Miss Pearson in a steady positive voice said, as she emphatically closed the book, “The first breaking of any of these promises may perhaps be forgiven, for the second fault there is no excuse—the girl will be dismissed from the school.”

I was in this school three years and never saw one dismissed. The promise with the little formalities attending it had a powerful effect on my mind, and doubtless it influenced every girl in the same way.

After my examination it was decided that writing was the study to be first attended to. I was glad of this decision, for I longed to write, but I was a little dashed when I was taken to a long table running across the whole width of the room. This table was covered with the finest sea sand, there was a 29 roller at one end, and the teacher ran it down the whole length of the table. It left behind it beautifully straight lines, between which were straight strokes, pothooks, and the letter o. Then a brass stylus was given me, and I was told to copy what I saw, and it was on this table of sand, with a pencil of brass, I took my first lessons in writing. When I could make all my letters, simple and capital, and knew how to join, dot, and cross them properly, I was promoted to a slate and slate pencil. In about half a year I was permitted to use paper and a wad pencil, but as wad, or lead, was then scarce and dear, we were taught at once how to sharpen and use them in the most economical manner. While I was using a wad pencil I was practicing the art of making a pen out of a goose quill. Some children learned the lesson easily. I found it difficult, and spoiled many a bunch of quills in acquiring it.

I remember a clumsy pen in my father’s desk almost as early as I remember anything. It was a metal tube, fastened to an ivory handle, and originated just before I was born. I never saw my father use it; he wrote with a quill all his life. In 1832, the year after my birth, thirty-three million, one hundred thousand quills were imported into England, and I am sure that at the present date, not all the geese in all the world would meet the demand for pens in the United States alone. Penny postage produced the steel pen. It belonged to an age of machinery, and could have belonged to no other age; for the great problem to be solved in the steel pen, was to convert iron into a substance as thin as the quill of a dove’s wing, yet as strong as the strongest quill of an eagle’s wing. When I was a girl not much over seven years old, children made their own pens; the steam engine now makes them.

A short time before Christmas my mother received the letter from Uncle Will Singleton she had been expecting. It came one Saturday morning when the snow lay deep, and the cold was intense. Jane and I were in the living-room with Mother. She had just cut a sheet down the middle, where it was turning thin, and I had to seam the two selvedge edges together, thus turning the strong parts of the sheet into the center. This seam required to be very neatly made, and the sides were to 30 be hemmed just as neatly. I disliked this piece of work with all my heart, but with the help of pins I divided it into different places, for the pins represented the cities, and I made up the adventures to them as I sewed. Jane, who was a better needlewoman than I, had some cambric to hem for ruffling, but the hem was not laid, it had to be rolled as it was sewn between the thumb and first finger of the left hand. Jane was always conceited about her skill in this kind of hemming, and as I write I can see her fair, still face with its smile of self-satisfaction, as her small fingers deftly and rapidly made the tiny roll, she was to sew with almost invisible needle and thread. Mother was singing a song by Felicia Hemans, and Father was in the little parlor across the hall reading a book called “Elijah, the Tishbite;” for he had just been in the room to point out to Mother how grandly it opened. “Now Elijah the Tishbite,” without any weakening explanations of who or what Elijah was, and Mother had said in a disconcerting voice, “Isn’t that the way it opens in the Bible, William?” There was a blazing fire above the snow-white hearth, and shining brass fender, and a pleasant smell of turpentine and beeswax, for Ann Oddy was giving the furniture a little rubbing. Suddenly there was a knock at the door, and Ann rose from her knees and went to open it. The next moment there was evident disputing, and Ann Oddy called sharply, “Mr. Huddleston, please to come here, sir.”

When Father appeared, Mother also went to the door, and Jane and I stopped sewing in order to watch and to listen. It was the postman and he had charged a shilling for a letter, that only ought to be eight pence and while Ann was pointing out this mistake, my mother took the letter from her hand and looked at it.

“William,” she said, “it is a death message, do not dispute about that toll.” So Father gave the postman the shilling, and the door was shut, and Mother went to the fireside and stood there. Father quickly joined her. “Well, Mary,” he said, “is it from your brother? What does he say?”

“Only eight words, William,” Mother answered; and she read them aloud, “Come to me, Mary. The end is near.”

Father was almost angry. He said she could not go over Shap Fells in such weather, and that snow was lying deep all the way to Kendal. He talked as though he was preaching. I thought Mother would not dare to speak any more about going to Kendal. But when Father stopped talking, Mother said in a strange, strong way,

“I shall certainly go to my brother. I shall try to get a seat in the coach that passes through here at ten o’clock to-night.” I had never seen Mother look and talk as she did then, and I was astonished. So was Father. He watched her leave the room in silence, and for a few minutes seemed irresolute. Then Ann came in and lifted the beeswax, and was going away when Father said,

“Where is your mistress, Ann?”

“In her room, Mr. Huddleston.”

“What is she doing?”

“Packing her little trunk. She says she is going to Kendal.”

“She ought not to go to Kendal. She must not go.”

“She’s right enough in going, Mr. Huddleston, and she is sure to go.”

“I never heard anything like this!” cried Father. He really was amazed. It was household rebellion. “Ann,” he continued, “go upstairs and remind your mistress that John Henry has been sickly for two weeks. I have myself noticed the child looking far from well.”

“Yes, sir, the child is sickly, but her brother is dying.”

“Do you think the child should be left?”

“It would be worse if the brother died alone. I will look after John, Mr. Huddleston.”

Then Father went upstairs, and Mother went by the night mail, and we did not see her again for nearly three weeks.

I do not apologize for relating a scene so common, for these simple intimacies and daily events, these meetings and partings, these sorrows and joys of the hearth and the family, are really the great events of our life. They are our personal sacred history. When we have forgotten all our labors, and even all our successes, we shall remember them.

Mother was the heart and hinge of all our home and happiness, 32 and while she was away, I used to lie awake at nights in my dark, cold room and think of death entering our family. In his strange language he whispered many things to my soul that I have forgotten, but one thing I am sure of—I had no fear of death. My earliest consciousness had been a strong and sure persuasion of God’s goodness to men. And I had no enmity towards God; though a dozen catechisms told me so, I would not admit the statement. I loved God with all my child heart. He was truly to me “my Father who art in heaven.” Well then, death whom He sent to every one, even to little babies, must be something good and not evil. Also, I thought, if the dead are unhappy, their faces would show it, and I had never seen a dead face without being struck by its strange quiet. The easiest way to my school lay through the graveyard, and though it was in the midst of the town, I knew no quiet like the quiet of the dead men in that churchyard. I have felt it like an actual pressure on my ear drum.

In the day I talked to my sister of the changes Uncle’s death would make in our lives. When Christmas came, father would not permit us to go to any parties, and Jane was sure we would have to wear mourning, a kind of clothing I hated, I reminded her that the Pennants had not worn black when Mary Pennant died, and Jane reminded me that the Pennants were Quakers, and that when Frances and Eliza Pennant came back to school wearing their brown dresses, it was all the girls could manage, not to scorn them.

Of course we talked at school of our uncle, Dr. Singleton, and his expected death, and I do not understand how this circumstance imparted to us a kind of superiority, but it did. Jane put on airs, and was always on the point of crying, and I heard Laura Patterson correct the biggest pupil in the school for “speaking cross to a girl whose uncle was dying.” I dare say I had my own plan for collecting sympathy, for some of my classmates asked to walk home with me, others offered to help me with my grammer, and Adelaide Bond gave me the half of her weekly allowance of Everton toffy.

At last Mother returned home and, oh, how glad we were to see her! She came into the lighted room just as we were 33 sitting down to supper, and an angel from heaven would not have been as welcome. My father was somewhere in the Patterdale country, where he went for a week or two at regular intervals; and, oh, how good, how glorious a thing it was, to have Mother home again!

The first thing Mother did the following day was to send for black stuff and the dressmaker. I pleaded in vain, though Mother, being of Quaker descent, was as averse to mourning dresses as I was, but she was sure Father would insist on them, because of what the Society, and people in general would say. Jane made no objections. She was very fair, and had that soft pearly complexion which is rendered more lovely by black. As for Ann, she could only look at the wastefulness of putting new dresses away in camphor for a year. She said, “Girls will grow long and lanky, and in a year the skirts will be short and narrow, and the waists too small, and the armholes too tight, and the whole business out of fashion and likelihood.”

In a few days Father came home. The girl was pipeclaying the hearth and building up the fire for the evening, and Ann laying the table for Mother’s tea as he entered. He was so delighted to find Mother at home that he said to her, “Let the girls stay and have a cup of tea with us tonight.” Then when he had set down by the fire, Jane drew her stool close to him, and I slipped on to his knee, and whispered something in his ear I shall never tell to any one. Such a happy meal followed, but little was said about Uncle Singleton. Father asked if all was well with him? Mother answered almost joyfully, “All is well!”

“Poor fellow,” continued Father. “His life was defeat from its beginning to its end.”

“No, William,” cried Mother, “at the end it was victory!” and she lifted her radiant face, and her eyes rained gladness, as she said the word “victory” with that telling upward inflection on the last syllable, common in the North Country. I can never forget either the words or the look with which they were uttered. I thought to myself, “How beautiful she is!”

I waited after tea, hoping that Mother would tell us more about Uncle’s death, but she talked of our black dresses and 34 the bad weather, and then some neighbors came in, and I went upstairs to Ann. She had one of those high peaked sugar loaves before her, and was removing the thick dark purple paper in which they were always wrapped. The big sugar nippers were at her side, and I knew she was going to nip sugar for the next day’s use. It was, however, a kind of work it was pleasant to loiter over, and after talking awhile Ann said, “What did Mrs. Huddleston say about her brother?” Then I repeated what Mother said, and involuntarily tried to imitate her look and the tones of her voice. Ann asked if that was all, and I answered, “Yes.” Then I said, “Was he a bad man, Ann, or a good man, tell me;” and she said, “He was bad and good, like the rest of men. Don’t ask me any questions. Your mother will tell you all about him when the right time comes.”

And the right time did not come until eleven years afterwards.

In a week our dresses were ready, and we went back to school. We met with great sympathy. Jane looked beautiful, and received the attentions shown her with graceful resignation. I looked unlike myself, and felt as if I had somebody’s else frock on. But I had a happy heart, ready to make the best of any trouble, beside I knew I was unreasonable, since Ann, who was generally on my side, told me that I ought to be thankful I had any dress at all to wear, and so many nicer little girls than myself without one to put on their backs. And as for color, one color was just as good as another.

That was not true in my case, but I knew that it was no use telling Ann that story. Yet it is a fact, that I am, and have always been powerfully affected both by color and smell—the latter’s influence having a psychical or spiritual tendency. But how could I explain so complex a feeling to Ann, when I could not even understand it myself?

Queen Victoria ascended the throne of England a few weeks before I went to Penrith, but she was not crowned until a year afterwards. I remember the very June day so bright and exquisite it was! The royal and loyal town of Penrith was garlanded with roses, flags were waving from every vantage point, and the musical bells of the ancient church rang without 35 ceasing from dawn until the long summer gloaming was lost in the mid-summer night. Yet child as I was, I noticed and partly understood, the gloom and care on the faces of so many who had no heart to rejoice, and no reason to do so.

Without much explanation the story of ordinary English life at this period would be incredible to us, and I shall only revert to it at points where it touched my own life and character. Is it not all written in Knight’s and many other histories at every one’s hand? But I saw the slough of despair, of poverty and ignorance, in which the working class struggled for their morsel of bread. And the root of all their trouble was ignorance. For instance, the wealthy town of Penrith had not, when I first saw it, one National or Lancastrian school, nor yet one free school of any kind, but the little Sunday school held in the Methodist chapel two hours on Sunday afternoons. Fortunately it was the kind of Sunday school Raikes intended. There were no daintily dressed children, and fashionably attired teachers in it—not one. The pupils were semi-starved, semi-clothed, hopeless, joyless little creatures; their teachers were hard working men and women, who took from their Sabbath rest a few hours for Christ’s sake. For how could such little ones come unto Him, if there were none to show the way?

There was even at this date, 1838, villages in England without either church or school, though Methodism had swept through the land like a Pentecostal fire half a century before; and at this same time, the big cities of London, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham, Bristol had not one ragged school in them. A parliamentary investigation two years afterward found plenty of villages such as Dunkirk with one hundred and thirteen children, of whom only ten could read and write; and Boughton with one hundred and nineteen children, where only seven went to a school that taught writing, and thirty-two to a Sunday school. Learning and literature were not in fashion then, especially for women. Yes, indeed, it is true that I knew in my youth, many women of wealth, beautiful women who managed their large houses with splendid hospitality and were keenly alive to public affairs, who looked on books as something rather demoralizing, and likely to encroach in some way 36 upon works more in the way of their duty. I was very often reproved for “wasting my time over a book” so that my reading had a good deal of that charm which makes forbidden fruit “so good for food, so pleasant to the eyes, so much to be desired to make one wise.”

And in Penrith I began a new set of books which charmed me quite as much as “Robinson Crusoe” and the “Arabian Nights” had done. On my seventh birthday my father gave me Cook’s “Voyages Round the World,” and this volume was followed by Anson’s “Voyage,” by Mungo Park’s “Travels in Africa,” and Bruce’s “Travels in Abyssinia.” Twenty-two years ago I stood one afternoon at the grave of Bruce in a lonely kirk yard a few miles outside Glasgow. It was a neglected mound with the stone slanting down above it. I remembered then, as I do now, how severely his book had been criticized and even discredited. But later travellers substantiated all that Bruce had said and added to his recital still more unlikely stories.

There was also another book which at this time thrilled and charmed me beyond expression. I doubt if there is a single copy of it in America, and not many in England, such as remain I dare say being hid away in the old libraries of ancient farm or manor houses. It was called “News From the Invisible World,” by John Wesley. It was really a book of ghostly visitations and wonderful visions. My father took it out of my hands twice and then put it, as he supposed, out of my reach; but by putting a stool upon a chair, and climbing upon the chair and then upon the stool I managed to reach it. I can see myself today in a little gingham frock, and a white pinafore performing this rather dangerous feat. We were dressed very early in the morning, but never so early as not to find a good fire in the study; and the coal used in the north of England, is that blessed soft material, which gives in its bright manifold blazes, the light of half a dozen candles. Lying face downward upon the hearthrug, I could read with the greatest ease, and often spent an hour in “the invisible world” very much to my liking before the day really began.

One morning while thus engaged, Ann Oddy came in and 37 I asked her to put the book back in its place. She looked at me suspiciously, and said, “Who put it up there?”

“My father,” I answered.