A ROSE

OF A

HUNDRED LEAVES

A Love Story

BY

AMELIA E. BARR

AUTHOR OF “FRIEND OLIVIA,” “THE BOW OF ORANGE RIBBON,” “JAN VEDDER’S WIFE,” ETC.

NEW YORK

DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY

1891

Copyright, 1891,

By J. B. Lippincott Company.

Copyright, 1891,

By Dodd, Mead and Company.

All rights reserved.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Wild Rose is the Sweetest | 9 |

| II. | Forgive me, Christ! | 35 |

| III. | Only Brother Will | 77 |

| IV. | For Mother’s Sake | 113 |

| V. | But they were Young | 151 |

| VI. | “Love shall be Lord of Sandy-Side” | 180 |

| VII. | “A Rose of a Hundred Leaves” | 208 |

I tell again the oldest and the newest story of all the world,—the story of Invincible Love!

This tale divine—ancient as the beginning of things, fresh and young as the passing hour—has forms and names various as humanity. The story of Aspatria Anneys is but 10 one of these,—one leaf from all the roses in the world, one note of all its myriad of songs.

Aspatria was born at Seat-Ambar, an old house in Allerdale. It had Skiddaw to shelter it on the northwest; and it looked boldly out across the Solway, and into that sequestered valley in Furness known as “the Vale of the Deadly Nightshade.” The plant still grew there abundantly, and the villagers still kept the knowledge of its medical value taught them by the old monks of Furness. For these curious, patient herbalists had discovered the blessing hidden in the fair, poisonous amaryllis, long before modern physicians called it “belladonna.”

The plant, with all its lovely relations, had settled in the garden at Seat-Ambar. Aspatria’s mother had loved them all: the girl could still remember her thin white hands clasping the golden jonquils in her coffin. This memory was in her heart, as she hastened through the lonely place one evening in spring. It ought to 11 have been a pleasant spot, for it was full of snowdrops and daffodils, and many sweet old-fashioned shrubs and flowers; but it was a stormy night, and the blossoms were plashed and downcast, and all the birds in hiding from the fierce wind and driving rain.

She was glad to get out of the gray, wet, shivery atmosphere, and to come into the large hall, ruddy and glowing with fire and candle-light. Her brothers William and Brune sat at the table. Will was counting money; it stood in small gold and silver pillars before him. Brune was making fishing-flies. Both looked up at her entrance; they did not think words necessary for such a little maid. Yet both loved her; she was their only sister, and both gave her the respect to which she was entitled as co-heir with them of the Ambar estate.

She was just sixteen, and not yet beautiful. She was too young for beauty. Her form was not developed; she would probably gain two or three inches in height; 12 and her face, though exquisitely modelled, wanted the refining which comes either from a multitude of complex emotions or is given at once by some great heart-sorrow. Yet she had fascination for those capable of feeling her charm. Her large brown eyes had their childlike clearness; they looked every one in the face with its security of good-will. Her mouth was a tempting mouth; the lips had not lost their bow-shape; they were red and pouting, but withal ever ready to part. She might have been born with a smile. Her hair, soft and dark, had that rarest quality of soft hair,—a tendency to make itself into little curls and tendrils and stray down the white throat and over the white brow; yet it was carefully parted and confined in two long braids, tied at the ends with a black ribbon.

She wore a black dress. It was plainly made, and its broad ruffle around the open throat gave it an air of simplicity almost childlike in effect. Her arms below the elbows were uncovered, and her hands 13 were small and finely formed, as patrician hands should be. There was no ring upon them, and no bracelet above them. She wore neither brooch nor locket, nor ornament of any kind about her person; only a daffodil laid against the snowy skin of her bosom. Even this effect was not the result of coquetry; it was a holy and loving sentiment materialized.

Altogether, she was a girl quite in keeping with the antique, homelike air of the handsome room she entered; her look, her manner, and even her speech had the local stamp; she was evidently a daughter of the land. Her brothers resembled her after their masculine fashion. They were big men, whom nature had built for the spaces of the moors and mountains and the wide entrances of these old Cumberland homes. They would have been pushed to pass through narrow city doorways. A fine open-air colour was in their faces; they had that confident manner which great physical strength imparts, and that air of conscious pride which is born in lords of the soil.

Indeed, William and Brune Anneys made one understand how truthfully popular nomenclature has called an Englishman “John Bull.” For whoever has seen a bull in its native pastures—proud, obstinate, conscious of his strength, and withal a little surly—must understand that there is a taurine basis to the English character, finely expressed by the national appellation.

A great thing was to happen that hour, and all three were as unconscious of the approaching fate as if it was to be a part of another existence. Squire William finished his accounts, and played a game of chess with his brother. Aspatria walked up and down the hall, with her hands clasped behind her, or sat still in the Squire’s hearth-chair, with her dress lifted a little in front, to let the pleasant heat fall upon her ankles. She did not think of reading or of sewing, or of improving the time in any way. Perhaps she was not as dependent on books as the women of this generation. Aspatria’s mind was 15 sensitive and observing; it lived very well on its own ideas.

The storm increased in violence; the rain beat against the windows, and the wind howled at the nail-studded oak door, as if it intended to blow it down. A big ploughman entered the room, shyly pulled his front hair, and looked with stolid inquiry into his master’s face. The Squire pushed aside the chess-board, rose, and went to the hearth-stone; for he was young in his authority, and he felt himself on the hearth-stone to hold an impregnable position.

“Well, Steve Bell, what is it?”

“Be I to sow the high land next, sir?”

“If you can have a face or back wind, it will be best; if you have an elbow-wind, you must give the land an extra half-bushel.”

“Be I to sow mother-of-corn[1] on the east holme?”

“It is matterless. Is it going to be a flashy spring?”

“A right season, sir,—plenty of manger-meat.”

“How is the weather?”

“The rain is near past; it will take up at midnight.”

As he spoke, Aspatria, who had been sitting with folded hands and half-shut eyes, straightened herself suddenly, and threw up her head to listen. There was certainly the tramp of a horse’s feet, and in a moment the door was loudly and impatiently struck with the metal handle of a riding-whip.

Steve Bell went to 17 answer the summons; Brune trailed slowly after him. Aspatria and the Squire heard nothing on the hearth but a human voice blown about and away by the wind. But Steve’s reply was distinct enough,—

“You be wanting Redware Hall, sir? Cush! it’s unsensible to try for it. The hills are slape as ice; the becks are full; the moss will make a mouthful of you—horse and man—to-night.”

The Squire went forward, and Aspatria also. Aspatria lifted a candle, and carried it high in her hand. That was the first glimpse of her that Sir Ulfar Fenwick had.

“You must stay at Seat-Ambar to-night,” said William Anneys. “You cannot go farther and be sure of your life. You are welcome here heartily, sir.”

The traveller dismounted, gave his horse to Steve, and with words of gratitude came out of the rain and darkness into the light and comfort of the home opened to him. “I am Ulfar Fenwick,” he said,—“Fenwick of Fenwick and Outerby; and 18 I think you must be William Anneys of Ambar-Side.”

“The same, sir. This is my brother Brune, and my sister Aspatria. You are dreeping wet, sir. Come to my room and change your clothing.”

Sir Ulfar bowed and smiled assent; and the bow and the smile were Aspatria’s. Her cheeks burned; a strange new life was in all her veins. She hurried the housekeeper and the servants, and she brought out the silver and the damask, and the famous crystal cup in its stand of gold, which was the lucky bowl of Ambar-Side. When Fenwick came back to the hall, there was a feast spread for him; and he ate and drank, and charmed every one with his fine manner and his witty conversation.

They sat until midnight,—an hour strange to Seat-Ambar. No one native in that house had ever seen it before, no one ever felt its mysterious influence. Sir Ulfar had been charming them with tales of the strange lands he had visited, and the 19 strange peoples who dwelt in them. He had not spoken much to Aspatria, but it was in her face he had found inspiration and sympathy. For her young eyes looked out with such eager interest, with glances so seeking, so without guile and misgiving, that their bright rays found a corner in his heart into which no woman had ever before penetrated. And she was equally subjugated by his more modern orbs,—orbs with that steely point of brilliant light, generated by large experience and varied emotion,—electric orbs, such as never shone in the elder world.

When the clock struck twelve, Squire Anneys rose with amazement. “Why, it is strike of midnight!” he said. “It is past all, how the hours have flown! But we mustn’t put off sleeping-time any longer. Good-night heartily to you, sir. It will be many a long day till I forget this night. What doings you have seen, sir!”

He was talking thus to his guest, as he led him to the guest-room. Aspatria still stood by the dying fire. Brune rose 20 silently, stretched his big arms, and said: “I’ll be going likewise. You had best remember the time of night, Aspatria.”

“What do you think of him, Brune?”

“Fenwick! I wouldn’t think too high of him. One might have to come down a peg or two. He sets a good deal of store by himself, I should say.”

“You and I are of two ways of judging, Brune.”

“Never mind; time will let light into all our ways of judging.”

He went yawning upstairs and Aspatria slowly followed. She was not a bit sleepy. She was wider awake than she had ever been before. Her hands quivered like a swallow’s wings; her face was rosy and luminous. She removed her clothing, and unbraided her hair and shook it loose over her slim 21 shoulders. There was a smile on her lips through all these preparations for sleep,—a smile innocent and glad. Suddenly she lifted the candle and carried it to the mirror. She desired to look at herself, and she blushed deeply as she gratified the wish. Was she fair enough to please this wonderful stranger?

It was the first time such a query had ever come to her heart. She was inclined to answer it honestly. Holding the light slightly above her head, she examined her claims to his regard. Her expressive face, her starry eyes, her crimson, pouting lips, her long dark hair, her slight, virginal figure in its gown of white muslin scantily trimmed with English thread-lace, her small, bare feet, her air of childlike, curious happiness,—all these things, taken together, pleased and satisfied her desires, though she knew not how or why.

Then she composed herself with intentional earnestness. She must “say her prayers.” As yet it was only saying prayers with Aspatria,—only a holy habit. A 22 large Book of Common Prayer stood open against an oaken rest on a table; a cushion of black velvet was beneath it. Ere she knelt, she reflected that it was very late, and that her Collect and Lord’s Prayer would be sufficient. Youth has such confidence in the sympathy of God. She dropped softly on her knees and said her portion. God would understand the rest. The little ceremony soothed her, as a mother’s kiss might have done; and with a happy sigh she put out the light. The old house was dark and still, but her guardian angel saw her small hands loose lying on the snowy linen, and heard her whisper, “Dear God! how happy I am!” And this joyous orison was the acceptable prayer that left the smile of peace upon her sleeping face.

In the guest-chamber Ulfar Fenwick was also holding a session with himself. He had come to his room very wide awake; midnight was an early hour to him. And the incidents he had been telling filled his mind with images of the past. 23 He could not at once put them aside. Women he had loved and left visited his memory,—light loves of a season, in which both had declared themselves broken-hearted at parting, and both had known that they would very soon forget. Neither was much to blame: the maid had long ceased to remember his vows and kisses; he, in some cases, had forgotten her name. Yet, sitting there by the glowing oak logs, he had visions of fair faces in all kinds of surroundings,—in lighted halls, in moon-lit groves under the great stars of the tropics, on the Shetland seas when the aurora made for lovers an enchanted atmosphere and a light in which beauty was glorified. Well, they had passed as April passes, and now,—

As a glimpse of a burnt-out ember

Recalls a regret of the sun,

He remembered, forgot, and remembered

What love saw done and undone.

Aspatria was different from all. He whispered her strange name on his lips, and he thought it must have wandered 24 from some sunny southern clime into these northern solitudes. His eyes shone; his heart beat. He said to it: “Make room for this innocent little one! What a darling she is! How clear, how candid, how beautiful! Oh, to be loved by such a woman! Oh, to kiss her!—to feel her kiss me!” He set his mouth tightly; the soft dreamy look in his face changed to one of purpose and pleasure.

“I shall win her, or die for it,” he said. “By Saint George! I would rather die than know that any other man had married her.”

Yet the thought of marriage somewhat sobered him. “I should have to give up my voyage to the Spanish Colonies,—and I am very much interested in their struggle. I could not take her to Mexico, I suppose,—there is nothing but fighting there; and I could not—no, I could not leave her. If she were mine, I should hate to have any one else breathe the same air with her. I could not endure that others should speak to her. I should want to strike any man who touched her hand. Perhaps I 25 had better go away in the morning, and ride this road no more. I have made my plans.”

And fate had made other plans. Who can fight against his destiny? When he saw Aspatria in the morning, every plan that did not include her seemed unworthy of his consideration. She was ten times lovelier in the daylight. She had that fresh invincible charm which women of culture and intellect seldom have: she was inspired by her heart. It taught her a thousand delightful subjugating ways. She served his breakfast with her own fair hands; she offered him the first sweet flowers in the garden; she fluttered around his necessities, his desires, his intentions, with a grace and a kindness nothing but love could have taught her.

He thanked her with marvellous glances, with smiles, with single words dropped only for her ears, with all the potent eloquence which passion and experience teach. And he had to pay the price, as all men must do. The lesson he taught 26 he also learned. “Aspatria!” he said, in soft, penetrating accents; and when she answered his call and came to his side, her dress trailing across his feet bewitched him. They were in the garden, and he clasped her hand, and went down the budding alleys with her, speechless, but gazing into her face until she dropped her tremulous, transparent lids before her eyes; they were too full of light and love to show to any mortal.

The sky was white and blue, the air 27 fresh and sweet; the swallows had just come, and were chattering with the starlings; hundreds of daffodils “danced in the wind” and lighted the ground at their feet; troops of celandines starred the brook that babbled by the bee-skips; the southernwood, the wall-flower, the budding thyme and sweet-brier,—a thousand exhalations filled the air and intensified that intoxication of heart and senses which makes the first stage of love’s fever delirious.

Fenwick went away in the afternoon, and his adieus were mostly made to the Squire. He had done his best to win his favour, and he had been successful. He left Seat-Ambar under an engagement to return soon and try his skill in wrestling and pole-leaping with Brune. Aspatria knew he would return: a voice which Fenwick’s voice only echoed told her so. She watched him from her own window across the meadows, and up the mountain, until he was lost to her vision.

She was doubtless very much in love, 28 though as yet she had not admitted the fact to herself. The experience had come with a really shocking swiftness. Her heart was half angry and half abashed by its instantaneous surrender. Two circumstances had promoted this condition. First, the singular charm of the man. Ulfar Fenwick was unlike any one she had ever seen. The squires and gentlemen who came to Seat-Ambar were physically the finest fellows in England, but noble women look for something more than mere bulk in a man. Sir Ulfar Fenwick had this something more. Culture, travel, great experience with women, had added to his heroic form a charm flesh and sinew alone could never compass. And if he had lacked all other physical advantages, he possessed eyes which had been filled to the brim with experiences of every kind,—gray eyes with pure, full lids thickly fringed,—eyes always lustrous, sometimes piercingly bright. Secondly, Aspatria had no knowledge which helped her to ward off attack or protract surrender. In a 29 multitude of lovers there is safety; but Fenwick was Aspatria’s first lover.

He rode hard, as if he would ride from fate. Perhaps he hoped at this early stage of feeling to do as he had often done before,—

To love—and then ride away.

He had also a fresh, pressing anxiety to see his sister, who was Lady of Redware Manor. Seven years—and much besides 30 years—had passed since they met. She was his only sister, and ten years his senior. She loved him as mothers love, unquestioningly, with miraculous excuses for all his shortcomings. She had been watching for his arrival many hours before he appeared.

“Ulfar! how welcome you are!” she cried, with tears in her eyes and her voice. “Oh, my dear! how happy I am to see you once more!”

She might have been his only love, he kissed and embraced and kissed her again so fondly. Oh, wondrous tie of blood and kinship! At that moment there really seemed to Ulfar Fenwick no one in the whole world half so dear as his sister Elizabeth.

He told her he had lost his way in the storm and been detained by Squire Anneys; and she praised the Squire, and said that she would evermore love him for his kindness. “I met him once, at the Election Ball in Kendal. He danced with me; ‘we neighbour each other,’ you 31 see; and they are a grand old family, I can tell you.”

“There is a younger brother, called Brune.”

“I never saw him.”

“A sister also,—a child yet, but very handsome. You ought to see her.”

“Why?”

“You would like her. I do.”

“Ulfar, there is a ‘thus far’ in everything. In your wooing and pursuing, the line lies south of Seat-Ambar. To wrong a woman of that house would be wicked and dangerous.”

“Why should I wrong her? I have no intention to do so. I say she is a lovely lady, a great beauty, worthy of honest love and supreme devotion.”

“Such a rant about love and beauty! Nine tenths of the men who talk in this way do but blaspheme Love by taking his name in vain.”

“However, Elizabeth, it is marriage or the Spanish colonies for me. It is Miss Anneys, or Cuba, New Orleans, and 32 Mexico. Santa Anna is a supreme villain; I have a fancy to see such a specimen.”

“You are then between the devil and the deep sea; and I should say that the one-legged Spaniard was preferable to the deep sea of matrimony.”

“She is so fair! She has a virgin timidity that enchants me.”

“It will become matronly indecision, or mental weakness of will. In the future it will drive you frantic.”

“Her sweet sensibility—”

“Will crystallize into passionate irritation or callous opposition. These childlike, tender, clinging maidens are often capable of sudden and dangerous action. Better go to Cuba, or even to Mexico, Ulfar.”

“I suppose she has wealth. You will admit that excellence?”

“She is co-heir with her brothers. She may have two thousand pounds a year. You cannot afford to marry a girl so poor.”

“I have not yet come to regard a large 33 sum of money as a kind of virtue, or the want of it as a crime.”

“Your wife ought to represent you. How can this country-girl help you in the society to which you belong?”

“Society! What is society? In its elemental verity it means toil, weariness, loss of rest and health, useless expense, envy, disappointment, heart-burnings,—all for the sake of exchanging entertainments with A and B, C and D. It means chaff instead of wheat.”

“If you want to be happy, Ulfar, put this girl out of your mind. I am sure her brothers will oppose your suit. They will not let their sister leave Allerdale. No Anneys has ever done so.”

“You have strengthened my fancy, Elizabeth. There is a deal of happiness in the idea of prevailing, of getting the mastery, of putting hindrances out of the way.”

“Well, I have given you good advice.”

“There are many ‘counsels of perfection’ nobody dreams of following. To 34 advise a man in love not to love, is one of them.”

“Love!” she cried scornfully. “Before you make such a fuss about the Spanish Colonies and their new-found freedom, free yourself, Ulfar! You have been a slave to some woman all your life. You are one of those men who are naturally not their own property. A child can turn you hither and thither; a simple country girl can lead you.”

He laughed softly, and murmured,—

“There is a rose of a hundred leaves,

But the wild rose is the sweetest.”

The ultimatum reached by Fenwick in the consideration of any subject was, to please himself. In the case of Aspatria Anneys he was particularly determined to do so. It was in vain Lady Redware entreated him to be rational. How could he be rational? It was the preponderance of the emotional over the rational in his nature which imparted so strong a personality to him. He grasped all circumstances by feeling rather than by reason.

In a few days he was again at Seat-Ambar. Aspatria drew him, as the candle draws the moth which has once burned its wings at it. And among the simple Anneys folk he found a hearty welcome. With Squire William he travelled the hills, and counted the flocks, and speculated on the value of the iron-ore cropping out of 36 the ground. With Brune he went line-fishing, and in the wide barns tried his skill in wrestling or pole-leaping or single-stick. He tolerated the rusticity of the life, for the charming moments he found with Aspatria.

No one like Ulfar Fenwick had ever visited Ambar-Side. To the young men, who read nothing but the Gentleman’s Magazine and the Whitehaven Herald, and to Aspatria, who had but a volume of the Ladies’ Garden Manual, Notable Things, her Bible and Common Prayer, Fenwick was a book of travel, song, and story, of strange adventures, of odd bits of knowledge, and funny experiences. Things old and new fell from his handsome lips. Squire William and Brune heard them with grave attention, with delight and laughter; Aspatria with eyes full of wonder and admiration.

As the season advanced and they grew more familiar, Aspatria was thrown naturally into his society. The Squire was in the hay-field; Brune had his task there 37 also. Or they were down at the Long Pool, washing the sheep, or on the fells, shearing them. In the haymaking, Aspatria and Fenwick made some pretence of assistance; but they both very soon wearied of the real labour. Aspatria would toss a few furrows of the warm, sweet grass; but it was much sweeter to sit down under the oak-tree with Fenwick at her side, and watch the moving picture, and listen to the women singing in their high shrill voices, as they turned the 38 swaths, the Song of the Mower, and the men mournfully shouting out the chorus to it,—

“We be all like grass! We be all like grass!”

As for the oak, it liked them to sit under it; all its leaves talked to each other about them. The starlings, though they are always in a hurry, stopped to look at the lovers, and went off with a Q-q-q of satisfaction. The crows, who are a bad lot, croaked innuendoes, and said it was to be hoped that evil would not come of such folly. But Aspatria and Fenwick listened only to each other; they saw the whole round world in each other’s eyes.

Fenwick spoke very low; Aspatria had to droop her ear to his mouth to understand his words. And they were such delightful words, she could not bear to lose one of them. Then, as the sun grew warm, and the scent of the grass filled the soft air, and the haymakers were more and more subdued and quiet, heavenly languors stole over them. They sat hand in 39 hand,—Aspatria sometimes with shut eyes humming to herself, sometimes dreamily pulling the long grass at her side; Fenwick mostly silent, yet often whispering those words which are single because they are too sweet to be double,—“Darling! Dearest! Angel!” and the words drew her eyes to his eyes, drew her lips to his lips; ere she was aware, her heart had passed from her in long, loving, stolen kisses. On the fells, in the garden, in the empty, silent rooms of the old house, it was a repetition of the same divine song, with wondrously celestial variations. Goethe puts in Faust an Interlude in Heaven: Fenwick and Aspatria were in their Interlude.

One evening they stood among the wheat-sheaves. The round, yellow harvest-moon was just rising above the fells, and the stars trembling into vision. The reapers had gone away; their voices made faint, fitful echoes down the misty lane. The Squire was driving home one load of ripe wheat, and Brune another. Aspatria 40 said softly, “The day is over. We must go home. Come!”

She stood in the warm mystical light, with one hand upon the bound sheaf, the other stretched out to him. Her slim form in its white dress, her upturned face, her star-like eyes,—he saw all at a glance. He was subjugated to the innermost room of his heart. He answered, with inexpressible emotion,—

“Come! Come to me, my Dear One! My Love! My Joy! My Wife!” He held her close to his heart; he claimed her by no formal special yes, but by all the sweet reluctances and sweeter yieldings, the thousand nameless consents won day by day.

Oh, the glory of that homeward walk! The moon beamed upon them. The trees bent down to touch them. The heath and the honeysuckle made a posy for them. The nightingale sang them a canticle. They did not seem to walk; they trod on ether; they moved as people move in happy dreams of other stars, 42 where thought and wish are motion. It would have been heaven upon earth if those minutes could have lasted; but it was only an interlude.

That night Fenwick spoke to Squire William and asked him for his sister. The Squire was honestly confounded by the question. Aspatria was such a little lass! It was beyond everything to talk of marrying her. Still, in his heart he was proud and pleased at such high fortune for the little lass; and he said, as soon as Fenwick’s father and family came forward as they should do, he would never be the one to say nay.

Fenwick’s father lived at Fenwick Castle, on the shore of bleak Northumberland. He was an old man, but his natural feelings and wisdom were not abated. He consulted the History of Cumberland, and found that the family of Ambar-Anneys was as ancient and honourable as his own. But the girl was country-bred, and her fortune was small, and in a measure dependent upon her brother’s management 43 of the estate. A careless master of Ambar-Side would make Aspatria poor. While he was considering these things, Lady Redware arrived at the castle, and they talked over the matter together.

“I expected Ulfar to marry very differently, and I must say I am disappointed. But I suppose it will be useless to make any opposition, Elizabeth,” the old man said to his daughter.

“Quite useless, father. But absence works miracles. Try to secure twelve months. You ought to go to a warm climate this winter; ask Ulfar to take you to Italy. In a year time may re-shuffle the cards. And you must write to the 44 girl, and to her eldest brother, who is a fine fellow and as proud as Lucifer. I called upon them before I left Cumberland. She is very handsome.”

“Handsome! Old men know, Elizabeth, that six months after a man is married, it makes little difference to him whether his wife is handsome or not.”

“That may be, or it may not be, father. The thing to consider is, that young men unfortunately persist in marrying for that first six months.”

“Well, then, fortune pilots many a ship not steered. Suppose we leave things to circumstances?”

“No, no! Human affairs are for the most part arranged in such a way that those turn out best to which most care is devoted.”

So the letters were thoughtfully written; the one to Aspatria being of a paternal character, that to her brother polite and complimentary. To his son Ulfar the old baronet made a very clever appeal. He reminded him of his great age, and of the 45 few opportunities left for showing his affection and obedience. He regretted the necessity for a residence in Italy during the winter, but trusted to his son’s love to see him through the experience. He congratulated Ulfar on winning the love of a young girl so fresh and unspoiled by the world, but kindly insisted upon the wisdom of a little delay, and the great benefit this delay would be to himself.

It was altogether a very temperate, wise letter, appealing to the best side of Ulfar’s nature. Squire William read it also, and gave it his most emphatic approval. He was in no hurry to lose his little sister. She was but a child yet, and knew nothing of the world she was going into; and “surely to goodness,” he said, looking at the child, “she will have a lot of things to look after, before she can think of wedding.”

This last conjecture touched Aspatria on a very womanly point. Of course there were all her “things” to get ready. She had never possessed more than a few 46 frocks at a time, and those of the simplest character; but she was quite alive to the necessity of an elaborate wardrobe, and she had also an instinctive sense of what would be proper for her position.

So the suggestions of Ulfar’s father were accepted in their entirety, and the old gentleman was put into a very good temper by the fact. And what was a year? “It will pass like a dream,” said Ulfar. “And I shall write constantly to you, and you will write to me; and when we meet again it will be to part no more.” Oh, the poverty of words in such straits as these! Men say the same things in the same extremities now that have been said millions of times before them. And Aspatria felt as if there ought to have been entirely new words, to express the joy of their betrothal and the sorrow of their parting.

The short delay of a last week together was perhaps a mistake. A very young girl, to whom great joy and great sorrow are alike fresh experiences, may afford a 47 prolonged luxury of the emotions of parting. Love, more worldly-wise, deprecates its demonstrativeness, and would avert it altogether. The farewell walks, the sentimental souvenirs, the pretty and petty devices of love’s first dream, are tiresome to more practised lovers; and Ulfar had often proved what very cobwebs they were to bind a straying fancy.

“Absence makes the heart grow fonder.” Perhaps so, if the last memory be an altogether charming one. It was, unfortunately, not so in Aspatria’s case. It should have been a closely personal farewell with Ulfar alone; but Squire Anneys, in his hospitable ignorance, gave it a public character. Several neighbouring squires and dames came to breakfast. There was cup-drinking, and toasting, and speech-making; and Ulfar’s last glimpse of his betrothed was of her standing in the wide porch, surrounded by a waving, jubilant crowd of strangers, whose intermeddling in his joy he deeply resented. Anneys had invited them in accord with the traditions of his 48 house and order. Fenwick thought it was a device to make stronger his engagement to Aspatria.

“As if it needed such contrivances!” he muttered angrily. “When it does, it is a broken thread, and no Anneys can knot it again.”

The weeks that followed were full of new interests to Aspatria. Mistress Frostham, the wife of a near shepherd-lord, had been the friend of Aspatria’s mother; she was fairly conversant with the world outside the fells and dales, and she took the girl under her care, accompanied her to Whitehaven, and directed her in the purchase of all considered necessary for the wife of Ulfar Fenwick.

Then the deep snows shut in Seat-Ambar, and the great white hills stood round about it like fortifications. But as often as it was possible the Dalton postman fought his way up there, with his packet of accumulated mail; for he knew that a warm welcome and a large reward awaited him. In the main, the long same 49 days went happily by. William and Brune had a score of resources for the season; the farm-servants worked in the barn; they were making and mending sacks for the wheat, and caps for the sheeps’ heads in fly-time, sharpening scythes and tools, doing the indoor work of a great farm, and mostly singing as they did it.

As Aspatria sat in her room, surrounded by fine cambric and linen and that exquisite English thread-lace now gone out of fashion, she 50 could hear their laughter and their song, and she unconsciously set her stitches to its march and melody. The days were not long to her. So many dozens of garments to make with her own slight fingers! She had not a moment to waste, but the necessity was one of the sweetest delight. The solitude and secrecy of her labour added to its charm. She never took her sewing into the parlour. And yet she might have done so: William and Brune had a delicacy of affection for her which would have made them blind to her occupation and densely stupid as to its design.

So, although the days were mostly alike, they were not unhappily so; and at intervals destiny sent her the surprises she loved. One morning in the beginning of February, Aspatria felt that the postman ought to come; her heart presaged him. The day was clear and warm,—so much so, that the men working in the barn had all the windows open. They were singing in rousing tones the famous North Country 51 song to the barley-mow, and drinking it through all its verses, out of the jolly brown bowl, the nipperkin, the quarter-pint, the quart and the pottle,—the gallon and the anker,—the hogshead and the pipe,—the well, and the river, and the ocean,—and then rolling back the chorus, from ocean to the jolly brown bowl. Suddenly, while a dozen men were shouting in unison,—

“Here’s a health to the barley mow!”

the verse was broken by the cry of “Here comes Ringham the postman!” Then Aspatria ran to the window and saw him climbing the fell. She did not like to go downstairs until Will called her; but she could not sew another stitch. And when at last the aching silence in her ears was filled by Will’s joyful “Come here, Aspatria! Here is such a parcel as never was,—from foreign parts too!” she hardly knew how her feet twinkled down the long corridor and stairs.

The parcel was from Rome. Ulfar had 52 sent it to his London banker, and the banker had sent a special messenger to Dalton with it. Over the fells at that season no one but Ringham could have found a safe way; and Ringham was made so welcome that he was quite imperious. He ordered himself a rasher of bacon, and a bowl of the famous barley broth, and spread himself comfortably before the great hearth-place. At the table stood Aspatria, William, and Brune. Aspatria was nervously trying to undo the seals and cords that bound love’s message to her. Will finally took his pocket-knife and cut them. There was a long letter, and a box containing exquisite ornaments of Roman cameos,—precious onyx, made more precious by work of rare artistic beauty, a comb for her dark hair, a necklace for her white throat, bracelets for her slender wrists, a girdle of stones linked with gold for her waist. Oh, how full of simple delight she was! She was too happy to speak. Then Will discovered a smaller package. It was for himself and Brune. 53 Will’s present was a cameo ring, on which were engraved the Anneys and Fenwick arms. Brune had a scarf-pin, representing a lovely Hebe. It was a great day at Seat-Ambar. Aspatria could work no more; Will and Brune felt it impossible to finish the game they had begun.

There is a tide in everything: this was the spring-tide of Aspatria’s love. In its overflowing she was happy for many a day after her brothers had begun to speculate and wonder why Ringham did not come. Suddenly it struck her that the snow was gone, and the road open, and that there was no letter. She began to worry, and Will quietly rode over to Dalton, to ask if any letter was lying there. He came back empty-handed, silent, and a little surly. The anniversary of their meeting was at hand: surely Ulfar would remember it, so Aspatria thought, and she watched from dawn to dark, but no token of remembrance came. The flowers began to bloom, the birds to sing, the May sunshine flooded the earth with glory, but 54 fear and doubt and dismay and daily disappointment made deepest, darkest winter in the low, long room where Aspatria watched and waited. Her sewing had been thrown aside. The half-finished garments, neatly folded, lay under a cover she had no strength to remove.

In June she wrote a pitiful little note to her lover. She said that he ought to tell her, if he was tired of their engagement. She told Will what she had said, and asked him to post the letter. He answered angrily, “Don’t you write a word to him, good or bad!” And he tore the letter into twenty pieces before her eyes.

“Oh, Will, I cannot bear it!”

“Thou art a woman: bear what other women have tholed before thee.” Then he went angrily from her presence. Brune was thrumming on the window-pane. She thought he looked sorry for her; she touched his arm and said, “Brune, will you take a letter to Dalton post for me?”

“For sure I will. Go thy ways and 55 write it, and I’ll be gone before Will is back.”

It was an unfortunate letter, as letters written in a hurry always are. Absolute silence would have piqued and worried Ulfar. He would have fancied her ill, dying perhaps; and the uncertainty, vague and portentous, would have prompted him to action, if only to satisfy his own mind. Sometimes he feared that a girl so sensitive would fade away in neglect; and he expected a letter from William Anneys saying so. But a hurried, halting, not very correct epistle, whose whole tenour was, “What is the matter? What have I done? Do you remember last year at this time?” irritated him beyond reply.

He was still in Italy when it reached him. Sir Thomas Fenwick was not likely ever to return to England. He was slowly dying, and he had been removed to a villa in the Italian hills. And Elizabeth Redware had a friend with her, a young widow just come from Athens, who affected at times its splendid picturesque national 56 costume. She was a very bright, handsome woman, whose fine education had been supplemented by travel, society, and a rather unhappy matrimonial experience. She knew how to pique and provoke, how to flirt to the very edge of danger and then sheer off, how to manipulate men before the fire of passion, as witches used to manipulate their waxen images before the blazing coals.

She had easily won Ulfar’s confidence; she had even assisted in the selection of the cameos; and she declared to Elizabeth that she would not for a whole world interfere between Ulfar and his pretty innocent! A natural woman was such a phenomenon! She was glad Ulfar was going to marry a phenomenon.

Elizabeth knew her better. She gave the couple opportunity, and they needed nothing more. There were already between them a good understanding, transparent secrets, little jokes, a confessed confidence. They quickly became affectionate. The lovely Sarah, relict of Herbert Sandys, 57 Esq., not only reminded Ulfar of his vows to Aspatria, but in the very reminder she tempted him to break them. When Aspatria’s letter was put into his hand, she was with him, marvellously arrayed in tissue of silver and brilliant colours. A head-dress of gold coins glittered in her fair braided hair; her long white arms were shining with bracelets; she was at 58 once languid and impulsive, provoking Elizabeth and Ulfar to conversation, and then amazing them by the audacity and contradiction of her opinions.

“It is so fortunate,” she said, “that Ulfar has found a little out-of-the-way girl to appreciate his great beauty. The world at present does not think much of masculine beauty. A handsome fellow who starts for any of its prizes is judged to be frivolous and poetical, perhaps immoral: you see Byron’s beauty made him unfit for a legislator, he could do nothing but write poetry. I should say it was Ulfar’s best card to marry this innocent with the queer name: with his face and figure, he will never get into Parliament. No one would trust him with taxes. He is born to make love, and he and his country Phyllis can go simpering and kissing through life together. If I were interested in Ulfar——”

“You are interested in Ulfar, Sarah,” interrupted Elizabeth. “You said so to me last night.”

“Did I? Nevertheless, life does not 59 give us time really to question ourselves, and it is the infirmity of my nature to mistake feeling for evidence.”

“You must not change your opinions so quickly, Sarah.”

“It is often an element of success to change your opinions. It is hesitating among a variety of views that is fatal. The man who does not know what he wants is the man who is held cheap.”

“I am sure I know what I want, Sarah.” And as he spoke, Ulfar looked with intelligence at the fair widow, and in answer she shot from her bright blue eyes a bolt of summer lightning that set aflame at once the emotional side of Ulfar’s nature.

“You say strange things, Sarah. I wish it was possible to understand you.”

“‘Who shall read the interpretation thereof?’ is written on everything we see, especially on women.”

“I believe,” said Elizabeth, “that Ulfar has quarrelled with his country maid. Is there a quarrel, Ulfar, really?”

“No,” he answered, with some temper.

Sarah nodded at Ulfar, and said softly: “The absent must be satisfied with the second place. However, if you have quarrelled with her, Ulfar, turn over a new leaf. I found that out when poor Sandys was alive. People who have to live together must blot a leaf now and then with their little tempers. The only thing is to turn over a new one.”

“If anything unpleasant happens to me,” said Ulfar, “I try to bury it.”

“You cannot do it. The past is a ghost not to be laid; and a past which is buried alive, it is terrible.” It was Sarah who spoke, and with a sombre earnestness not in keeping with her usual character. There was a minute’s pregnant silence, and it was broken by the entrance of a servant with a letter. He gave it to Ulfar.

It was Aspatria’s sorrowful, questioning note. Written while Brune waited, it was badly written, incorrectly constructed and spelled, and generally untidy. It had the same effect upon Ulfar that a badly dressed, untidy woman would have had. 61 He was ashamed of the irregular, childish scrawl. He did not take the trouble to put himself in the atmosphere in which the anxious, sorrowful words had been written. He crushed the paper in his hand with much the same contemptuous temper with which Elizabeth had seen him treat a dunning letter. She knew, however, that this letter was from Aspatria, and, saying something about her father, she went into an adjoining room, and left Ulfar and Sarah together. She thought Sarah would be the proper alterative.

The first words Sir Thomas Fenwick uttered regarded Aspatria. Turning his head feebly, he asked: “Has Ulfar quarrelled with Miss Anneys? I hear nothing of her lately.”

“I think he is tired of his fancy for her. There is no quarrel.”

“She was a good girl,—eh? Kindhearted, beautiful,—eh, Elizabeth?”

“She certainly was.”

He said no more then; but at midnight, when Ulfar was sitting beside him, he 62 called his son, and spoke to him on the subject. “I am going—almost gone—the way of all flesh, Ulfar. Take heed of my last words. You promised to make Miss Anneys your wife,—eh?”

“I did, father.”

“Do not break your promise. If she gives it back to you, that might be well; but you cannot escape from your own word and deed. Honour keeps the door of the house of life. To break your word is to set the door wide open,—open for sorrow and evil of all kinds. Take care, Ulfar.”

The next day he died, and one of Ulfar’s first thoughts was that the death set him free from his promise for one year at the least. A year contained a multitude of chances. He could afford to write to Aspatria under such circumstances. So he answered her letter at once, and it seemed proper to be affectionate, preparatory to reminding her that their marriage was impossible until the mourning for Sir Thomas was over. Also death had softened 63 his heart, and his father’s last words had made him indeterminate and a little superstitious. A clever woman of the world would not have believed in this letter; its aura—subtle but persistent, as the perfume of the paper—would have made her doubt its fondest lines. But Aspatria had no idea other than that certain words represented absolutely certain feelings.

The letter made her joyful. It brought back the roses to her cheeks, the spring of motion to her steps. She began to work in her room once more. Now and then her brothers heard her singing the old song she had sung so constantly with Ulfar,—

“A shepherd in a shade his plaining made,

Of love, and lovers’ wrong,

Unto the fairest lass that trod on grass,

And thus began his song:

‘Restore, restore my heart again,

Which thy sweet looks have slain,

Lest that, enforced by your disdain, I sing,

Fye! fye on love! It is a foolish thing!

But the lifting of the sorrow was only that it might press more heavily. No more letters came; no message of any kind; none of the pretty love-gages he delighted in giving during the first months of their acquaintance. A gloom more wretched than that of death or sickness settled in the old rooms of Seat-Ambar. William and Brune carried its shadow on their broad, rosy faces into the hay-fields and the wheat-fields. It darkened all the summer days, and dulled all the usual mirth-making of the ingathering feasts. William was cross and taciturn. He loved his sister with all his heart, but he did not know how to sympathize with her. Even mother-love, when in great anxiety, sometimes wraps itself in this unreasonable irritability. Brune understood better. He had suffered from a love-change himself; 65 he knew its ache and longing, its black despairs and still more cruel hopes. He was always on the lookout for Aspatria; and one day he heard news which he thought would interest her. Lady Redware was at the Hall. William had heard it a week before, but he had not considered it prudent to name the fact. Brune had a kinder intelligence.

“Aspatria,” he said, “Redware Hall is open again. I saw Lady Redware in the village.”

“Brune! Oh, Brune, is he there too?”

“No, he isn’t. I made sure of that.”

“Brune, I want to go to Redware. Perhaps his sister may tell me the truth. Go with me. Oh, Brune, go with me! I am dying of suspense and uncertainty.”

“Ay, they’re fit to kill anybody, let alone a little lass like you. It will put William about, and it may make bad bread between us; but I’ll go with you, even if we do have a falling out. I’m not flayed for William’s rages.”

The next market-day Brune kept his word. As soon as Squire Anneys had climbed the fell breast and passed over the brow of the hill, Brune was at the door with horses for Aspatria and himself. She was a good rider, and they made the distance, in spite of hills and hollows, in two hours. Lady Redware was troubled at the visit, but she came to the door to welcome Aspatria, and she asked Brune with particular warmth to come into the house with his sister. Brune knew better; he was sure in such a case that it would prove a mere formal call, and that Aspatria would 67 never have the courage to ask the questions she wished to.

But Aspatria had come to that point of mental suffering when she wanted to know the truth, even though the truth was the worst. Lady Redware saw the determination on her face, and resolved to gratify it. She was shocked at the change in Aspatria’s appearance. Her beauty was, in a measure, gone. Her eyes were hollow, and the lids dark and swollen with weeping. Her figure was more angular. The dew of youth, the joy of youth, was over. She drooped like a fading flower. If Ulfar saw her in such condition he might pity, but assuredly he would not admire her.

Lady Redware kissed the poor girl. “Come in, my dear,” she said kindly. “How ill you look! Here is wine: take a drink.”

“I am ill. I even hope I am dying. Life is so hard to bear. Ulfar has forgotten me. I have vexed him, and cannot find out in what way. If you would only tell me!”

“You have not vexed him at all.”

“What then?”

“He is tired, or he has seen a fresher face. That is Ulfar’s great fault. He loves too well, because he does not love very long. Can you not forget him?”

“No.”

“You must have other lovers?”

“No. I never had a lover until Ulfar wooed me. I will have none after him. I shall love him until I die.”

“What folly!”

“Perhaps. I am only a foolish child. If I had been wise and clever, he would not have left me. It is my fault. Do you believe he will ever come to Seat-Ambar again?”

“I do not think he will. It is best to tell you the truth. My dear, I am truly sorry for you! Indeed I am, Aspatria!”

The girl had covered her face with her thin white hands. Her attitude was so hopeless that it brought the tears to Lady Redware’s eyes. Hoping to divert her attention, she said,—

“Who called you Aspatria?”

“It was my mother’s name. She was born in Aspatria, and she loved the place very much.”

“Where is it, child? I never heard of it.”

“Not far away, on the sea-coast,—a little town that brother Will says has been asleep for centuries. Such a pretty place, straggling up the hillside, and looking over the sea. Mother was born there, and she is buried there, in the churchyard. It is such an old church, one thousand years old! Mother said it was built by Saint Kentigern. I went there to pray last week, by mother’s grave. I thought she might hear me, and help me to bear the suffering.”

“You poor child! It is shameful of Ulfar!”

“He is not to blame. Will told me that it was a poor woman who couldn’t keep what she had won.”

“It was very brutal in Will to say such a thing.”

“He did not mean it unkindly. We are plain-spoken people, Lady Redware. Tell me, as plainly as Will would tell me, if there is any hope for me. Does Ulfar love me at all now?”

“I fear not.”

“Are you sure?”

“I am sure.”

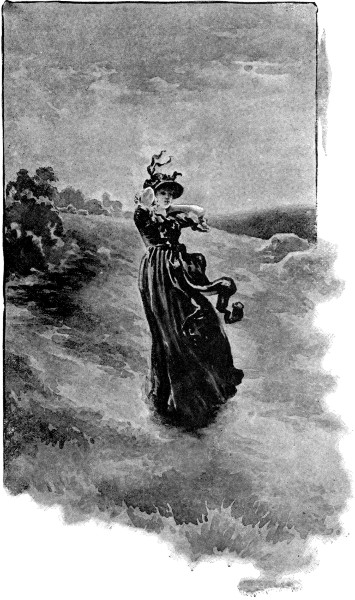

“Thank you. Now I will go.” She put out her hands before her, as if she was blind and had to feel her way; and in answer to all Lady Redware’s entreaties to remain, to rest, to eat something, she only shook her head, and stumbled forward. Brune saw her coming. He was standing by the horses, but he left them, and went to meet his sister. Her misery was so visible that he put her in the saddle with fear. But she gathered the reins silently, and motioned him to proceed; and Aspatria’s last sad smile haunted Lady Redware for many a day. Long afterward she recalled it with a sharp gasp of pity and annoyance. It was such a proud, sorrowful farewell.

She reached home, but it took the last 71 remnant of her strength. She was carried to her bed, and she remained there many weeks. The hills were white with snow, and the winter winds were sounding among them like the chant of a high mass, when she came down once more to the parlor. Even then Will carried her like a baby in his arms. He had carried her mother in the same way, when she began to die; and his heart trembled and smote him. He was very tender with his little sister, but tempests of rage tossed him to and fro when he thought of Ulfar Fenwick.

And he was compelled lately to think of him very often. All over the fell-side, all through Allerdale, it had begun to be whispered, “Aspatria Anneys has been deserted by her lover.” How the fact had become known it was difficult to discover: it was as if it had flown from roof to roof with the sparrows. Will could see it in the faces of his neighbours, could hear it in the tones of their speech, could feel it in the clasp of their hands. And he thought of these things, until he could not eat a 72 meal or sleep an hour in peace. His heart was on fire with suppressed rage. He told Brune that all he wanted was to lay Fenwick across his knees and break his neck. And then he spread out his mighty hands, and clasped and unclasped them with a silent force that had terrible anticipation in it. And he noticed that after her illness his sister no longer wore the circlet of diamonds which had been her betrothal-ring. She had evidently lost all hope. Then it was time for him to interfere.

Aspatria feared it when he came to her room one morning and kissed her and bade her good-by. He said he was going a bit off, and might be a week away,—happen more. But she did not dare to question him. Will at times had masterful ways, which no one dared to question.

Brune knew where his brother was going. The night before he had taken Brune to the little room which was called the Squire’s room. In it there was a large oak chest, black with age and heavy 73 with iron bars. It contained the title-deeds, and many other valuable papers. Will explained these and the other business of the farm to Brune; and Brune did not need to ask him why. He was well aware what business William Anneys was bent on, before Will said,—“I am going to Fenwick Castle, Brune. I am going to make that measureless villain marry Aspatria.”

“Is it worth while, Will?”

“It is worth while. He shall keep his promise. If he does not, I will kill him, or he must kill me.”

“If he kills you, Will, he must then fight me.” And Brune’s face grew red and hot, and his eyes flashed angry fire.

“That is as it should be; only keep your anger at interest until you have lads to take your place. We mustn’t leave Ambar-Side without an Anneys to heir it. I fancy your wrath won’t get cold while it is waiting.”

“It will get hotter and hotter.”

“And whatever happens, don’t you be saving of kind words to Aspatria. The little lass has suffered more than a bit; and she is that like mother! I couldn’t bide, even if I was in my grave, to think of her wanting kindness.”

The next morning Will went away. Brune would not talk to Aspatria about the journey. This course was a mistake; it would have done her good to talk continually of it. As it was, she was left to chew over and over the cud of her mournful anticipations. She had no womanly friend near her. Mrs. Frostham had drawn back a little when people began to talk of 75 “poor Miss Anneys.” She had daughters, and she did not feel that her friendship for the dead included the living, when the living were unfortunate and had questionable things said about them.

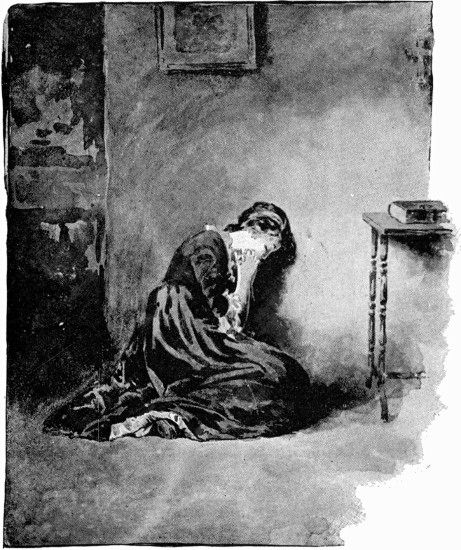

And the last bitter drop in Aspatria’s cup full of sorrow was the hardness of her heart toward Heaven. She could not care about God; she thought God did not care for her. She had tried to make herself pray, even by going to her mother’s grave, but she felt no spark of that hidden fire which is the only acceptable prayer. There was a Christ cut out of ivory, nailed to a large ebony cross, in her room. It had been taken from the grave of an old abbot in Aspatria Church, and had been in her mother’s family three hundred years. It was a Christ that had been in the grave and had come back to earth. Her mother’s eyes had closed forever while fixed upon it, and to Aspatria it had always been an object of supreme reverence and love. She was shocked to find herself unmoved by its white pathos. Even at her best 76 hours she could only stand with clasped hands and streaming eyes before it, and with sad imploration cry,—

“I cannot pray! I cannot pray! Forgive me, Christ!”

It was a dull raw day in late autumn, especially dull and raw near the sea, where there was an evil-looking sky to the eastward. Ulfar Fenwick stood at a window in Castle Fenwick which commanded the black, white-frilled surges. He was watching anxiously the point at which the pale gray wall of fog was thickest, a wall of inconceivable height, resting on the sea, reaching to the clouds, when suddenly there emerged from it a beautifully built schooner-yacht. 78 She cut her way through the mysterious barrier as if she had been a knife, and came forward with short, stubborn plunges.

All over the North Sea there are desolate places full of the cries of parting souls, but nowhere more desolate spaces than around Fenwick Castle; and as the winter was approaching, Ulfar was anxious to escape its loneliness. His yacht had been taking in supplies; she was making for the pier at the foot of Fenwick Cliff, and he was dressed for the voyage and about to start upon it. He was going to the Mediterranean, to Civita Vecchia, and his purpose was the filial one of bringing home the remains of the late baronet. He had promised faithfully to see them laid with those of his fore-elders on the windy Northumberland coast; and he felt that this duty must be done, ere he could comfortably travel the westward route he had so long desired.

He was slowly buttoning his pilot-coat, when he heard a heavy step upon the flagged passage. Many such steps had 79 been up and down it that hour, but none with the same fateful sound. He turned his face anxiously to the door, and as he did so, it was flung open, as if by an angry man, and William Anneys walked in, frowning and handling his big walking-stick with a subdued passion that filled the room as if it had been suddenly charged with electricity. The two men looked steadily at each other, neither of them flinching, neither of them betraying by the movement of an eyelash the emotion that sent the blood to their faces and the wrath to their eyes.

“William Anneys! What do you want?”

“I want you to set your wedding-day. It must not be later than the fifteenth of this month.”

“Suppose I refuse to do so? I am going to Italy for my father’s body.”

“You shall not leave England until you marry my sister.”

“Suppose I refuse to do so?”

“Then you will have to take your 80 chances of life or death. You will give me satisfaction first; and if you escape the fate you well deserve, Brune may have better fortune.”

“Duelling is now murder, sir, unless we pass over to France.”

“I will not go to France. Wrestling is not murder, and we both know there is a ‘throw’ to kill; and I will ‘throw’ until I do kill,—or am killed. There’s Brune after me.”

“I have ceased to love your sister. I dare say she has forgotten me. Why do you insist on our marriage? Is it that she may be Lady Fenwick?”

“Look you, sir! I care nothing for lordships or ladyships; such things are matterless to me. But your desertion has set wicked suspicions loose about Miss Anneys; and the woman they dare to think her, you shall make your wife. By God in heaven, I swear it!”

“They have said wrong of Miss Anneys! Impossible!”

“No, sir! they have not said wrong. 81 If any man in Allerdale had dared to say wrong, I had torn his tongue from his mouth before I came here; and as for the women, they know well I would hold their husbands or brothers or sons responsible for every ill word they spoke. But they think wrong, and they make me feel it everywhere. They look it, they shy off from Aspatria,—oh, you know well enough the kind of thing going on.”

“A wrong thought of Miss Anneys is atrocious. The angels are not more pure.” He said the words softly, as if to himself; and William Anneys stood watching him with an impatience that in a moment or two found vent in an emphatic stamp with his foot.

“I have no time to waste, sir. Are you afraid to sup the ill broth you have brewed?”

“Afraid!”

“I see you have no mind to marry. Well, then, we will fight! I like that better.”

“I will fight both you and your brother, 82 make any engagement you wish; but if the fair name of Miss Anneys is in danger, I have a prior engagement to marry her. I will keep it first. Afterward I am at your service, Squire, yours and your brother’s; for I tell you plainly that I shall leave my wife at the church door and never see her again.”

“I care not how soon you leave her; the sooner the better. Will the eleventh of this month suit you?”

“Make it the fifteenth. To what church will you bring my fair bride?”

“Keep your scoffing for a fitter time. If you look in that way again, I will strike the smile off your lips with a hand that will leave you little smiling in the future.” And he passed his walking-stick to his left, and doubled his large right hand with an ominous readiness.

“We may even quarrel like gentlemen, Mr. Anneys.”

“Then don’t you laugh like a blackguard, that’s all.”

“Answer me civilly. At what church 83 shall I meet Miss Anneys, and at what hour on the fifteenth?”

“At Aspatria Church, at eleven o’clock.”

“Aspatria?”

“Ay, to be sure! There will be witnesses there, I can tell you,—generations of them, centuries of generations. They will see that you do the right thing, or they will dog your steps till you have paid the uttermost farthing of the wrong. Mind what you do, then!”

“The dead frighten me no more than the living do.”

“You will find out, maybe, what the vengeance of the dead is. I would be willing to leave you to it, if you shab off, and I am not sure but you will.”

“William Anneys, you are sure I will not. You are saying such things to provoke me to a fight.”

“What reason have I to be sure? All the vows you made to Aspatria you have counted as a fool’s babble.”

“I give you my word of honour. Between gentlemen that is enough.”

“To be sure, to be sure! Gentlemen can make it enough. But a poor little lass, what can she do but pine herself into a grave?”

“I will listen to you no longer, Squire Anneys. If your sister’s good name is at stake, it is my first duty to shield it with my own name. If that does not satisfy your sense of honour, I will give you and your brother whatever satisfaction you desire. On the fifteenth of this month, at eleven o’clock, I will meet you at Aspatria Church. Where shall I find the place?”

“It is not far from Gosforth and Dalton, on the coast. You cannot miss it, unless you never look for it.”

“Sir!”

“Unless you never look for it. I do not feel to trust you. But this is a promise made to a man, made to William Anneys; and he will see that you keep it, or else that you pay for the breaking of it.”

“Good-morning, Squire. There is no necessity to prolong such an unpleasant visit.”

“Nay, I will not ‘good-morning’ with you. I have not a good wish of any kind for you.”

With these defiant words he left the castle, and Fenwick threw off his pilot-coat and sat down to consider. First thoughts generally come from the selfish, and therefore the worst, side of any nature; and Fenwick’s first thoughts were that his yacht was ready to sail, and that he could go away, and stay away until Aspatria married, or some other favourable change took place. He cared little for England. With good management he could bring home and bury his father’s dust without the knowledge of William Anneys. Then there was the west! America was before him, north and south. He had always promised himself 86 to see the whole western continent ere he settled for life in England.

Such thoughts were naturally foremost, but he did not encourage them. He felt no lingering sentiment of pity or love for Aspatria, but he realized very clearly what suspicion, what the slant eye, the whispered word, the scornful glance, the doubtful shrug, meant in those primitive valleys. And he had loved the girl dearly; he had promised to marry her. If she wished him to keep his promise, if it was a necessity to her honour, then he would redeem with his own honour his foolish words. He told himself constantly that he had not a particle of fear, that he despised Will and Brune Anneys and their brutal vows of vengeance; but—but perhaps they did unconsciously influence him. Life was sweet to Ulfar Fenwick, full of new dreams and hopes set in all kinds of new surroundings. For Aspatria Anneys why should he die? It was better to marry her. The girl had been sweet to him, very sweet! After all, he was not sure but he preferred that she 87 should be so bound to him as to prevent her marrying any other man. He still liked her well enough to feel pleasure in the thought that he had put her out of the reach of any future lover she might have.

Squire Anneys rode home in what Brune called “a pretty temper for any man.” His horse was at the last point of endurance when he reached Seat-Ambar, he himself wet and muddy, “cross and unreasonable beyond everything.” Aspatria feared the very sound of his voice. She fled to her room and bolted the door. At that hour she felt as if death would be the best thing for her; she had brought only sorrow and trouble and apprehended disgrace to all who loved her.

“I think God has forgotten me too!” she cried, glancing with eyes full of anguish to the pale Crucified One hanging alone and forsaken in the darkest corner of the room. Only the white figure was visible; the cross had become a part of the shadows. She remembered the joyous, innocent prayers that had been wont 88 to make peace in her heart and music on her lips; and she looked with a sorrow that was almost reproach at her Book of Common Prayer, lying dusty and neglected on its velvet cushion. In her rebellious, hopeless grief, she had missed all its wells of comfort. Oh, if an angel would only open her eyes! One had come to Hagar in the desert: Aspatria was almost in equal despair.

Yet when she heard her brother Will’s voice she knew not of any other sanctuary than the little table which held her Bible and Prayer Book, and upon which the wan, sad ivory Christ looked down. In speechless misery, with clasped hands and low-bowed head, she knelt there. Will’s voice, strenuous and stern, reached her at intervals. She knew from the silence in the kitchen and farm-offices, and the hasty movements of the servants, that Will was cross; and she greatly feared her eldest brother when he was in what Brune called one of his rages.

A long lull was followed by a sharp call. It was Will calling her name. She felt it impossible to answer, impossible to move; and as he ascended the stairs and came 90 grumbling along the corridor, she crouched lower and lower. He was at her door, his hand on the latch; then a few piteous words broke from her lips: “Help, Christ, Saviour of the world!”

Instantly, like a flash of lightning, came the answer, “It is I. Be not afraid.” She said the words herself, gave to her heart the promise and the comfort of it, and, so saying them, she drew back the bolt and stood facing her brother. He had a candle in his hand, and it showed her his red, angry face, and showed him the pale, resolute countenance of a woman who had prayed and been comforted.

He walked into the room and put the candle down on a small table in its centre. They both stood a moment by it; then Aspatria lifted her face to her brother and kissed him. He was taken aback and softened, and troubled at his heart. Her suffering was so evident; she was such a gray shadow of her former self.

“Aspatria! Aspatria! my little lass!” Then he stopped and looked at her again.

“What is it, Will? Dear Will, what is it?”

“You must be married on the fifteenth. Get something ready. I will see Mrs. Frostham and ask her to help you a bit.”

“Whom am I to marry, Will? On the fifteenth? It is impossible! See how ill I am!”

“You are to marry Ulfar Fenwick. Ill? Of course you are ill; but you must go to Aspatria Church on the fifteenth. Ulfar Fenwick will meet you there. He will make you his wife.”

“You have forced him to marry me. I will not go, I will not go. I will not marry Ulfar Fenwick.”

“You shall go, if I carry you in my arms! You shall marry him, or I—will—kill—you!”

“Then kill me! Death does not terrify me. Nothing can be more cruel hard than the life I have lived for a long time.”

He looked at her steadily, and she returned the gaze. His face was like a flame; hers was white as snow.

“There are things in life worse than death, Aspatria. There is dishonour, disgrace, shame.”

“Is sorrow dishonour? Is it a disgrace to love? Is it a shame to weep when love is dead?”

“Ay, my little lass, it may be a great wrong to love and to weep. There is a shadow around you, Aspatria; if people speak of you they drop their voices and shake their heads; they wonder, and they think evil. Your good name is being smiled and shaken away, and I cannot find any one, man or woman, to thrash for it.”

She stood listening to him with wide-open eyes, and lips dropping a little apart, every particle of colour fled from them.

“It is for this reason Fenwick is to marry you.”

“You forced him; I know you forced him.” She seemed to drag the words from her mouth; they almost shivered; they broke in two as they fell halting on the ear.

“Well, I must say he did not need forcing, when he heard your good name was in danger. He said, manly enough, that he would make it good with his own name. I do not much think I could have either frightened or flogged him into marrying you.”

“Oh, Will! I cannot marry him in this way! Let people say wicked things of me, if they will.”

“Nay, I will not! I cannot help them thinking evil; but they shall not look it, and they shall not say it.”

“Perhaps they do not even think it, Will. How can you tell?”

“Well enough, Aspatria. How many women come to Ambar-Side now? If you gave a dance next week, you could not get a girl in Allerdale to accept your invitation.”

“Will!”

“It is the truth. You must stop all this by marrying Ulfar Fenwick. He saw it was only just and right: I will say that much for him.”

“Let me alone until morning. I will do what you say.—Oh, mother! mother I want mother now!”

“My poor little lass! I am only brother Will; but I am sorry for thee, I am that!”

She tottered to the bedside, and he lifted her gently, and laid her on it; and then, as softly as if he was afraid of waking her, he went out of the room. Outside the door he found Brune. He had taken off his shoes, and was in his stocking-feet. Will grasped him by the shoulder and led him to his own chamber.

“What were you watching me for? What were you listening to me for? I have a mind to hit you, Brune.”

“You had better not hit me, Will. I was not bothering myself about you. I was watching Aspatria. I was listening, because I knew the madman in you had got loose, and I was feared for my sister. I was not going to let you say or do things you would be sorry to death for when you came to yourself. And so you are going to let that villain marry Aspatria? You are not of my mind, Will. I would not let him put a foot into our decent family, or have a claim of any kind on our sister.”

“I have done what I thought best.”

“I don’t say it is best.”

“And I don’t ask for your opinion. Go to your own room, Brune, and mind your own affairs.”

And Brune, brought up in the religious belief of the natural supremacy of the elder brother, went off without another word, but with a heart full to overflowing of turbulent, angry thoughts.

In the morning Will went to see Mrs. Frostham. He told her of his interview with Ulfar Fenwick, and begged her to help Aspatria with such preparations as could be made. But neither to her nor yet to Aspatria did he speak of Fenwick’s avowed intention to leave his wife after the ceremony. In the first place, he did not believe that Fenwick would dare to give him such a cowardly insult; and then, also, he thought that the sight of Aspatria’s suffering would make him tender toward her. William Anneys’s simple, kindly soul did not understand that of all things the painful results of our sins are the most irritating. The hatred we ought to give to the sin or to the sinner, we give to the results.

Surely it was the saddest preparation for a wedding that could be. Will and Brune were “out.” They did not speak to each other, except about the farm business. Aspatria spent most of her time in her own room with a sempstress, who was making the long-delayed wedding-dress. 97 The silk for it had been bought more than a year, and it had lost some of its lustrous colour. Mrs. Frostham paid a short visit every day, and occasionally Alice Frostham came with her. She was a very pretty girl, gentle and affectionate to Aspatria; and just because of her kindness Will determined at some time to make her Mistress of Seat-Ambar.

But in the house there was a great depression, a depression that no one could avoid feeling. Will gave no orders for wedding-festivities; a great dinner and ball would have been a necessity under the usual circumstances, but there were no arrangements even for a breakfast. Aspatria wondered at the omission, but she did not dare to question Will; indeed. Will appeared to avoid her as much as he could.

Really, William Anneys was very anxious and miserable. He had no dependence upon Fenwick’s promise, and he felt that if Fenwick deceived him there was nothing possible but the last vengeance. 98 He had this thought constantly in his mind; and he was quietly ordering things on the farm for a long absence, and for Brune’s management or succession. He paid several visits to Whitehaven, where was his banker, and to Gosport, where his lawyer lived. He felt, during that terrible interval of suspense, very much as a man under sentence of death might feel.

The morning of the fifteenth broke chill and dark, with a promise of rain. Great Gable was carrying on a conflict with an army of gray clouds assailing his summit and boding 99 no good for the weather. The fog rolled and eddied from side to side of the mountains, which projected their black forms against a ghastly, neutral tint behind them; and the air was full of that melancholy stillness which so often pervades the last days of autumn.

Squire Anneys had slept little for two weeks, and he had been awake all the night before. While yet very early, he had every one in the house called. Still there were no preparations for company or feasting. Brune came down grumbling at a breakfast by candle-light, and he and William drank their coffee and made a show of eating almost in silence. But there was an unspeakable tenderness in William’s heart, if he had known how to express it. He looked at Brune with a new speculation in his eyes. Brune might soon be master of Ambar-Side: what kind of a master would he make? Would he be loving to Aspatria? When Brune had sons to inherit the land, would he remember his promise, and avenge the 100 insult to the Anneys, if he, William, should give his life in vain? Out of these questions many others arose; but he was naturally a man of few words, and not able to talk himself into a conviction that he was doing right; nor yet was he able to give utterance to the vague objections which, if defined by words, might perhaps have changed his feelings and his plans.

He had sent Aspatria word that she must be ready by ten o’clock. At eight she began to dress. Her sleep had been broken and miserable. She looked anxiously in the glass at her face. It was as white as the silk robe she was to wear. A feeling of dislike of the unhappy garment rose in her heart. She had bought the silk in the very noon of her love and hopes, a shining piece of that pearl-like tint which only the most brilliant freshness and youth can becomingly wear. Many little accessories were wanting. She tried the Roman cameos with it, and they looked heavy; she knew in her womanly 101 heart that it needed the lustre of gems, the sparkle of diamonds or rubies.

Mrs. Frostham came a little later, and assisted her in her toilet; but a passing thought of the four bridemaids she had once chosen for this office made her eyes dim, while the stillness of the house, the utter neglect of all symbols of rejoicing, gave an ominous and sorrowful atmosphere to the bride-robing. Still, Aspatria looked very handsome; for as the melancholy toilet offices proceeded with so little interest and so little sympathy, a sense of resentment had gradually gathered in the poor girl’s heart. It made her carry herself proudly, it brought a flush to her cheeks, and a flashing, trembling light to her eyes which Mrs. Frostham could not comfortably meet.

A few minutes before ten, she threw over all her fateful finery a large white cloak, which added a decided grace and dignity to her appearance. It was a garment Ulfar had sent her from London,—a long, mantle-like wrap, made of white cashmere, 102 and lined with quilted white satin. Long cords and tassels of chenille fastened it at the throat, and the hood was trimmed with soft white fur. She drew the hood over her head, she felt glad to hide the wreath of orange-buds and roses which Mrs. Frostham had insisted upon her wearing,—the sign and symbol of her maidenhood.

Will looked at her with stern lips, but as he wrapped up her satin-sandalled feet in the carriage, he said softly to her, “God bless you, Aspatria!” His voice trembled, but not more than Aspatria’s as she answered,—

“Thank you, Will. You and Brune are father and mother to me to-day. There is no one else.”