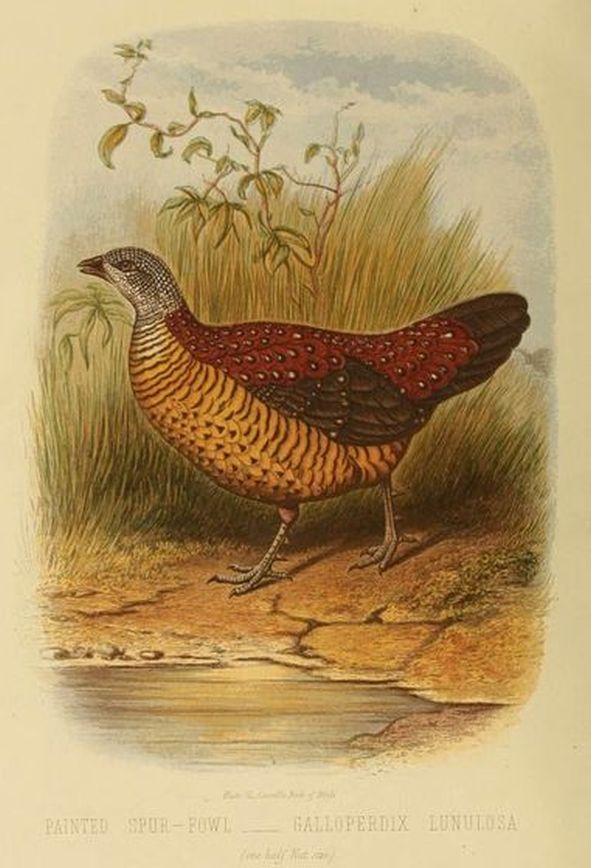

Plate 31. Cassell's Book of Birds

PAINTED SPUR-FOWL____GALLOPERDIX LUNULOSA

(one half Nat. size)

CASSELL'S

BOOK OF BIRDS.

FROM THE TEXT OF DR. BREHM.

BY

THOMAS RYMER JONES, F.R.S.,

PROFESSOR OF NATURAL HISTORY AND COMPARATIVE ANATOMY IN KING'S COLLEGE, LONDON.

WITH UPWARDS OF

Four Hundred Engravings, and a Series of Coloured Plates.

IN FOUR VOLUMES.

VOL. IV.

CASSELL, PETTER, & GALPIN,

LONDON, PARIS, AND NEW YORK.

CONTENTS.

ââ¦â

PAGE

THE STILT-WALKERS (Grallatores).

HE BUSTARDS (Otides):âThe Great BustardâThe Little BustardâThe HoubarasâThe Indian HoubaraâThe African Ruffled BustardâThe Florikin 1-9

THE COURSERS (Tachydromi):âThe Cream-coloured CourserâThe Trochilus, or Crocodile WatcherâThe Pratincoles, or Swallow-winged WadersâThe Collared Pratincole 9-14

THE THICK-KNEES (Ådicnemi):âThe Common Thick-knee, or Stone Curlew 14, 15

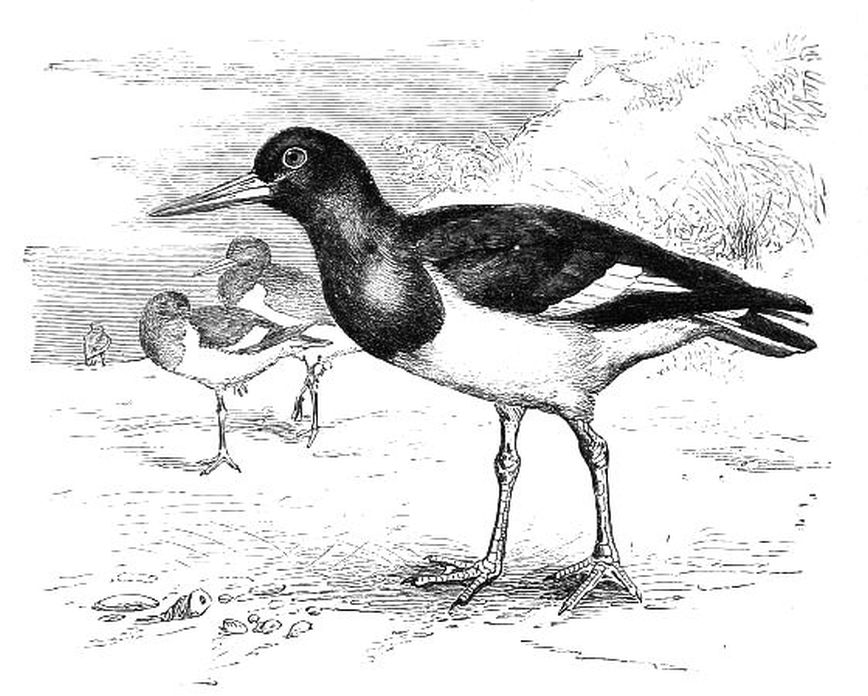

THE PLOVERS (Charadrii):âThe Golden PloverâThe Ringed PloverâThe Dotted PloversâThe Dotted Plover, or DotterelâThe Shore PloversâThe Little Shore Plover, or Little Ringed PloverâThe Lapwings, or PeewitsâThe Peewit, or LapwingâThe Spur-winged LapwingâThe Lappeted PeewitâThe TurnstoneâThe Pied Oyster-catcher, or Sea Pie 15-29

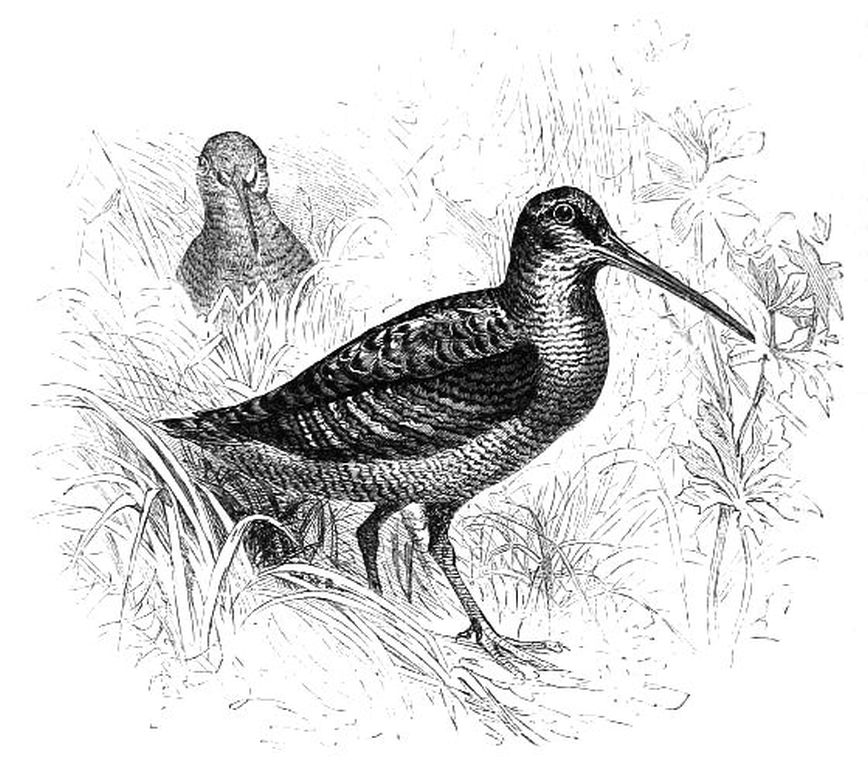

THE SNIPES (Limicolæ):âThe True SnipesâThe WoodcockâThe Marsh SnipesâThe Common SnipeâThe Moor SnipesâThe Jack Snipe 29-35

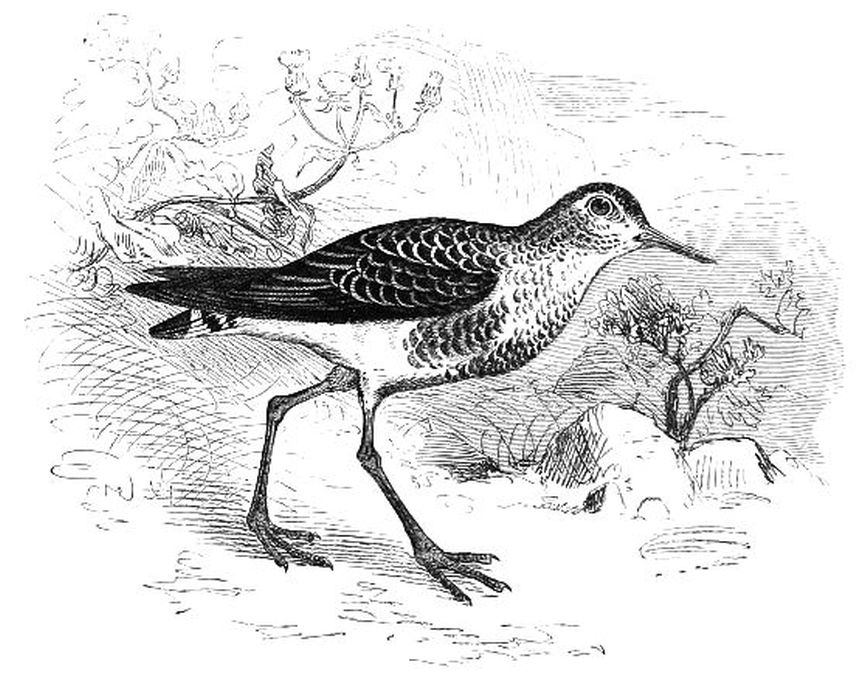

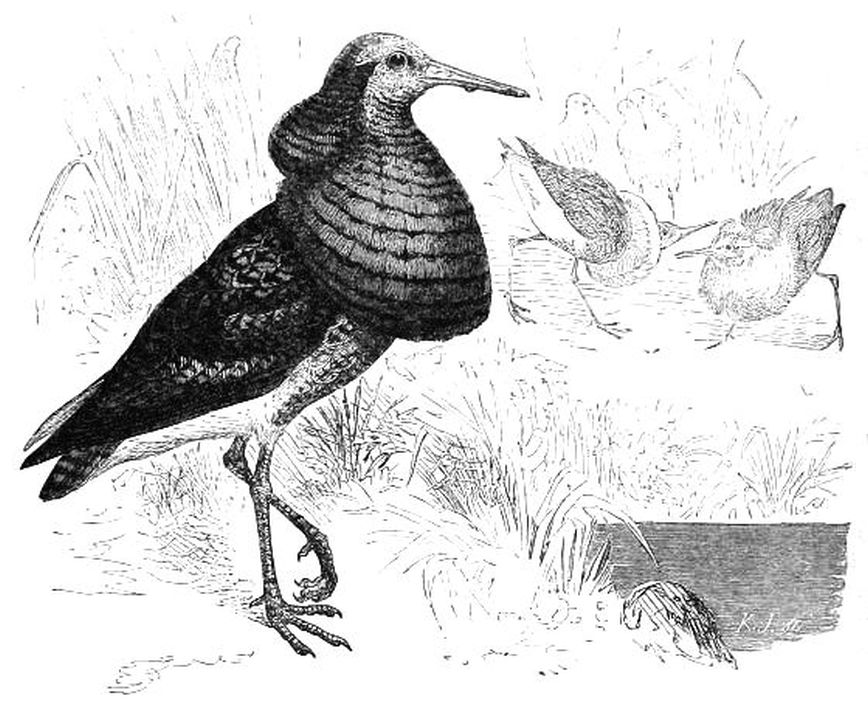

THE SANDPIPERS (Tringæ):âThe Curlew SandpipersâThe Pigmy Curlew SandpiperâThe SanderlingâThe Mud SandpiperâThe Dwarf SandpiperâThe Ruff 35-42

THE PHALAROPES (Phalaropi):âThe Hyperborean PhalaropeâThe Red Phalarope 42-44

THE LONGSHANKS (Totani) 44, 45

THE TRUE SANDPIPERS (Actitis):âThe Common SandpiperâThe Greenshank 45-47

THE GODWITS (Limosa):âThe Red or Bar-tailed GodwitâThe Black-winged Stilt 47-50

THE SCOOPING AVOCETS (Recurvirostræ):âThe Scooping Avocet 50, 51

THE CURLEWS (Numenii):âThe Great Curlew, or WhaapâThe Hard-billed WadersâThe IbisesâThe FalcinelsâThe Glossy IbisâThe Scarlet IbisâThe White, Egyptian, or Sacred Ibis [Pg iv] 51-58

THE SPOONBILLS (Plataleæ):âThe Common Spoonbill. The BOAT-BILLS (Cancromata):âThe Whale-headed Stork, or Shoe-beakâThe Savaku, or Boat-billâThe Hammer-head, or Shadow Bird 58-63

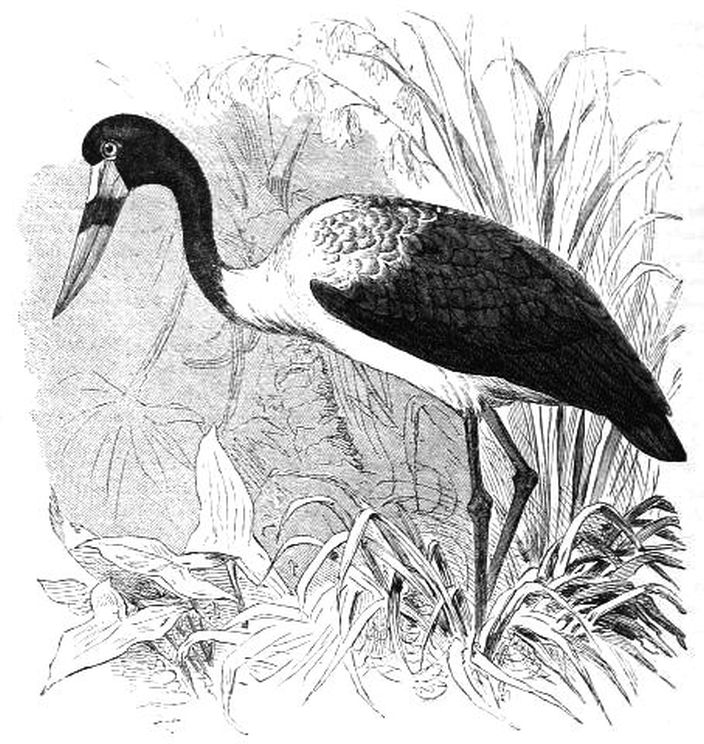

THE STORKS (Ciconiæ):âThe TantaliâThe Ibis-like TantalusâThe True StorksâThe White or House StorkâThe SimbilâThe Senegal JabiruâThe Jabiru 63-74

THE ADJUTANTS, ARGALAS, OR MARABOUS (Leptoptilos) The African MarabouâThe Indian Adjutant, or Argala 74, 75

THE CLAPPER-BILLED STORKS, OR SHELL-EATERS (Anastomus):âThe African Clapper-bill, or Shell-eater 75,76

THE HERONS (Ardeæ):âThe Common HeronâThe Giant Heron. The WHITE HERONS (Herodias):âThe Great White HeronâThe Lesser EgretâThe Cattle HeronâThe Night Heron 76-83

THE BITTERNS (Ardetta):âThe Little BitternâThe Common BitternâThe Sun Bittern, or Peacock Heron 83-87

THE MARSH-WADERS (Paludicolæ). The CRANES (Grues):âThe Common CraneâThe Demoiselle, or Numidian Crane. The AFRICAN CROWNED CRANES (Balearica):âThe Crowned African or Peacock Crane. The FIELD STORKS (Arvicolæ). The SNAKE CRANES (Dicholophus):âThe Brazilian Cariama, or Crested Screamer 87-94

THE TRUMPETERS (Psophia):âThe Agami, or Gold-breasted Trumpeter. The SCREAMERS (Palamedeæ):âThe Aniuma, or Horned ScreamerâThe Chauna, or Tschaja 94-98

THE RAILS (Ralli). The SNIPE RAILS (Rhynchæa):âThe Golden Rail, or Painted Cape SnipeâThe Water RailâThe ARAMIDES (Aramides):âThe SerrakuraâThe Land Rail, or Corn Crake. The JACANAS (Parræ):âThe Chilian JacanaâThe Chinese Jacana 98-103

THE WATER-HENS (Gallinulæ). The GALLINULES (Porphyrio):âThe Hyacinthine PorphyrioâThe Purple Gallinule. The WATER-HENS (Stagnicola):âThe Common Gallinule, or Moor-hen 103-110

THE COOTS (Fulica):âThe Common CootâThe FinfootsâThe Surinam Finfoot, or Picapare 110-113

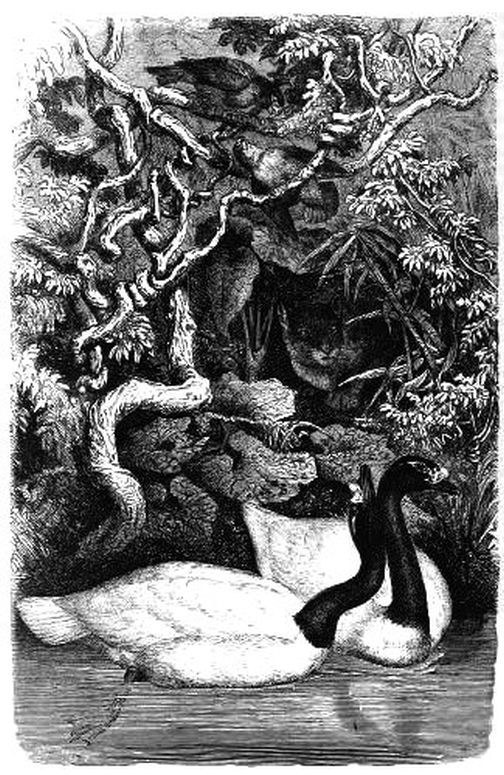

THE SWIMMERS (Natatores).

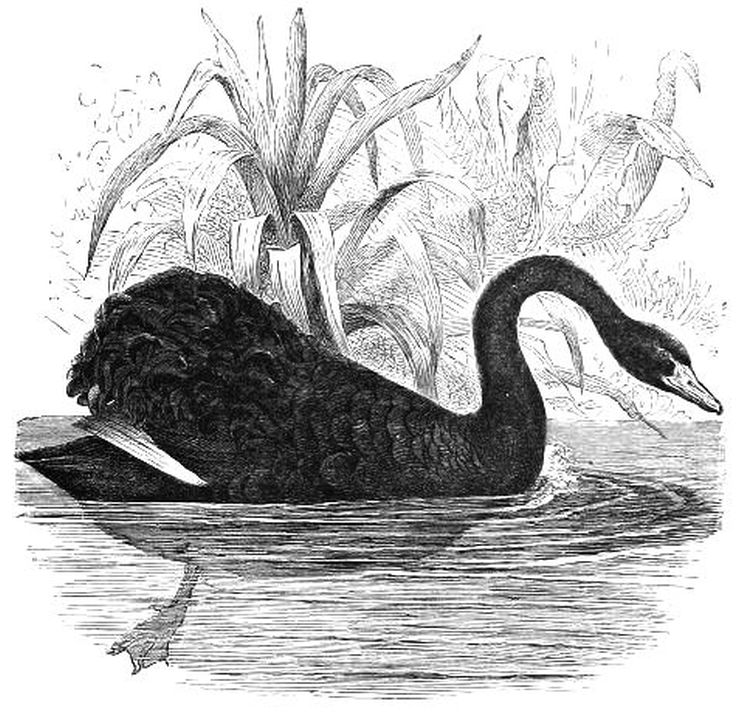

THE SIEVE BEAKS (Lamellirostres). The FLAMINGOES (PhÅnicopteri). The SWANS (Cygni):âThe Mute SwanâThe Whistling SwanâBewick's SwanâThe Black-necked SwanâThe Black Swan [Pg v] 114-129

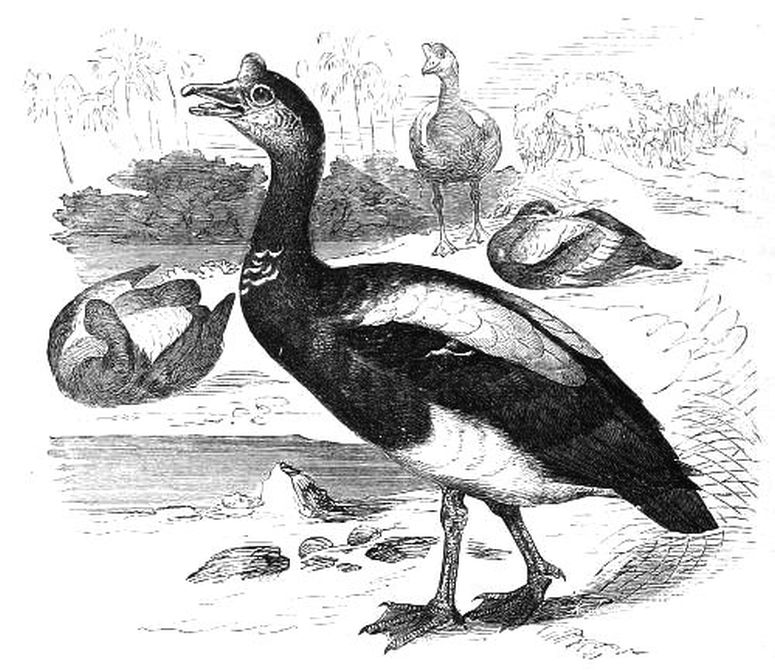

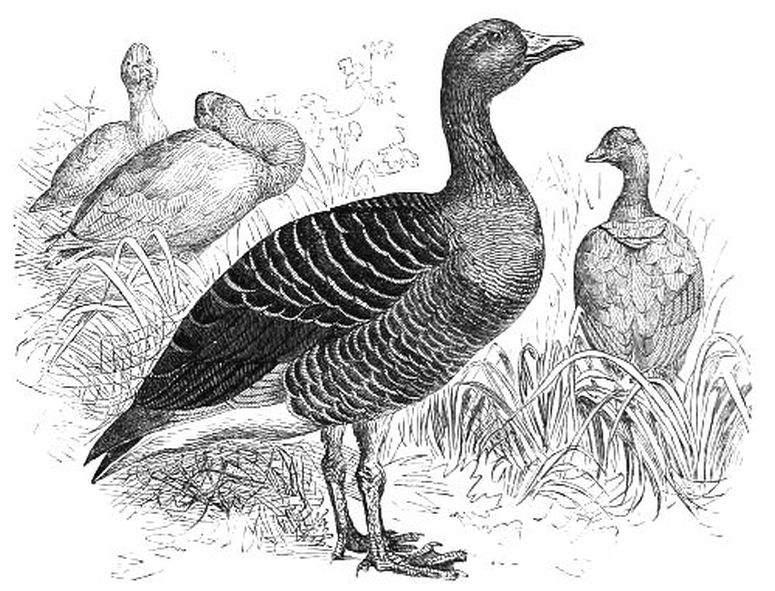

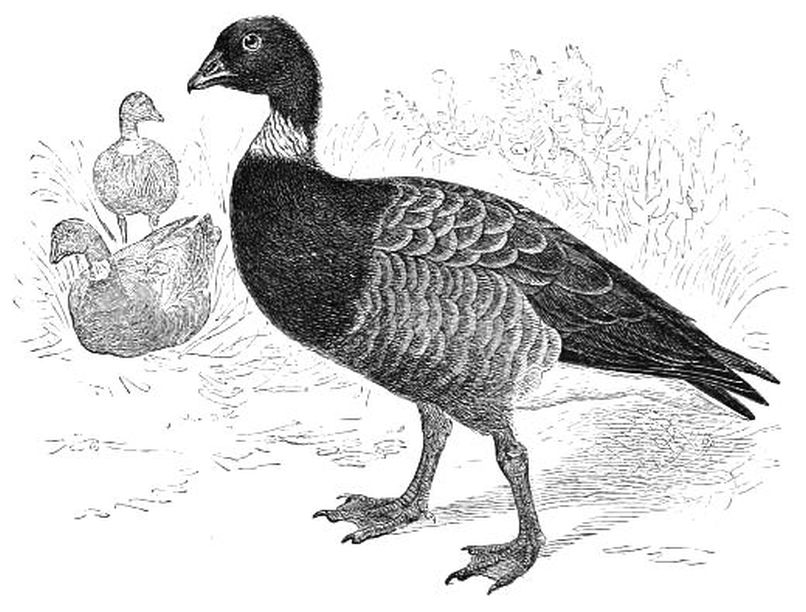

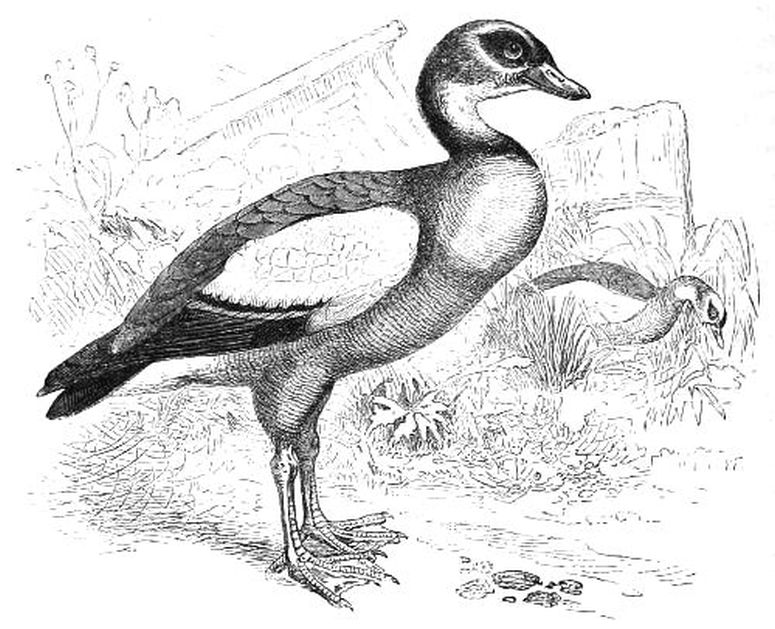

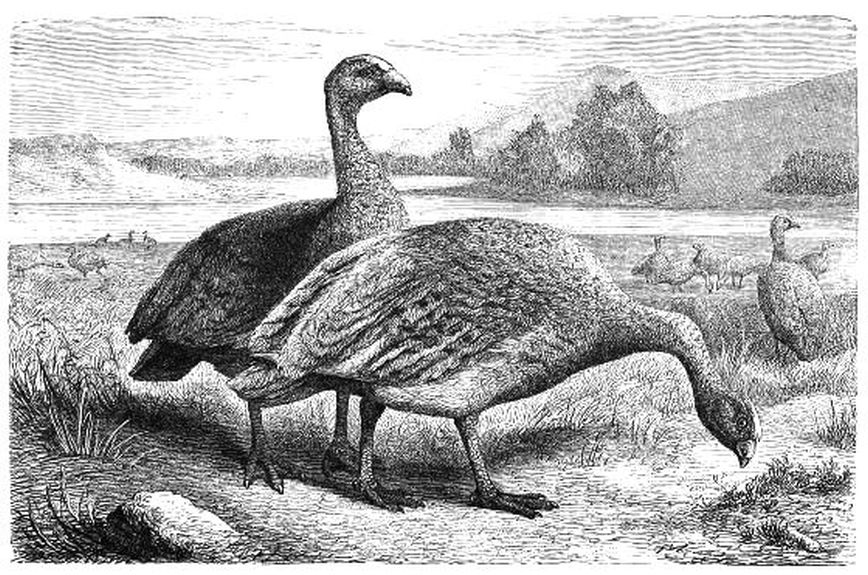

THE GEESE (Anseres):âThe Spur-winged GooseâThe Grey, or Wild GooseâThe Canada GooseâThe Snow Goose. The SEA GEESE (Bernicla):âThe Brent Goose. The FOXY GEESE (Chenalopex):âThe Nile Goose. The DWARF GEESE (Nettapus):âThe White-bodied Goose TealâThe Cereopsis Goose 129-143

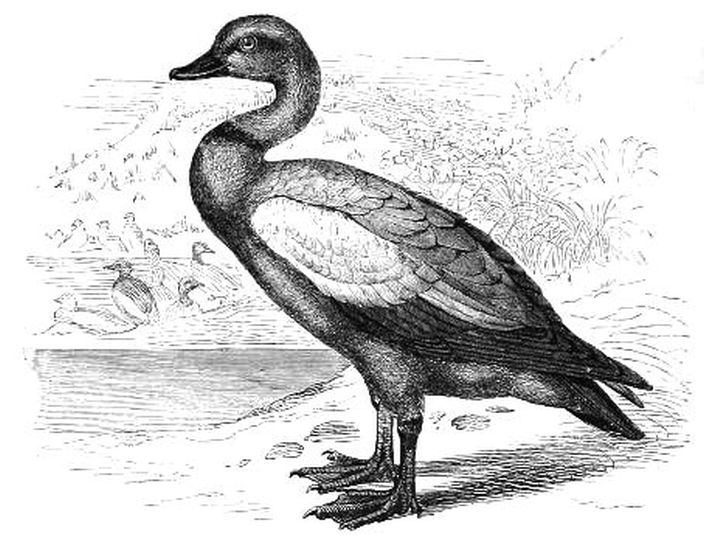

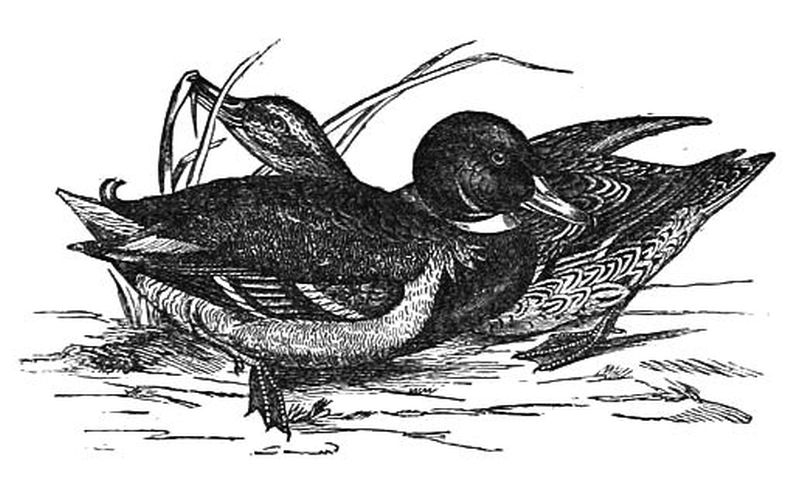

THE DUCKS (Anates):âThe Ruddy Sheldrake, or Brahminy Duck. The SHELDRAKES (Vulpanser):âThe Common Sheldrake. The TREE DUCKS (Dendrocygna):âThe Widow DuckâThe Wild DuckâThe Wood or Summer DuckâThe Chinese Teal, or Mandarin DuckâThe Shoveler DuckâThe Musk Duck. The DIVING DUCKS (Fuligulæ). The EIDER DUCKS (Somateria):âThe True Eider Duck, or St. Cuthbert's DuckâThe King Eider. The WESTERN or STELLER'S EIDER DUCK (Somateria or Heniconetta Stellerii). The SCOTERS (Oidemia):âThe Velvet Scoter. The FEN DUCKS (Aythya):âThe Red-headed Duck, Dunbird, or Pochard. The PIN-TAILED DUCKS (Erismatura):âThe White-headed Pin-tailed Duck 143-170

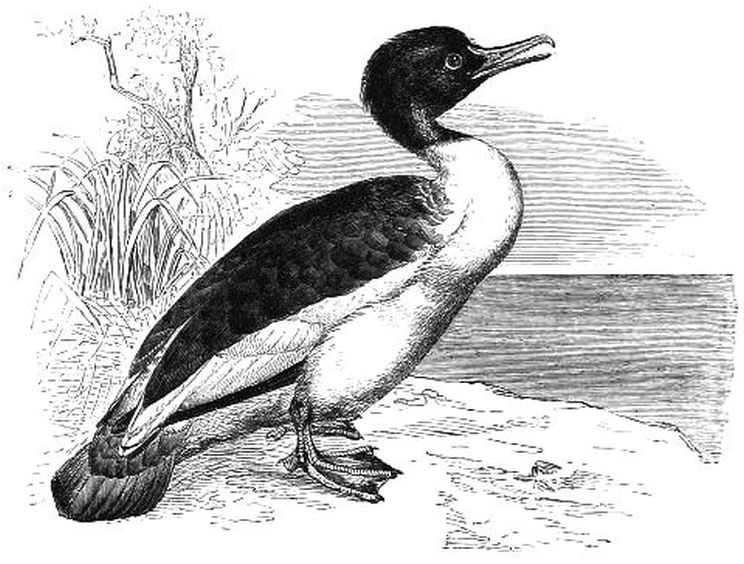

THE MERGANSERS, or GOOSANDERS (Mergi):âThe White-headed GoosanderâThe Green-headed Goosander 170-174

THE SEA-FLIERS (Longipennes).

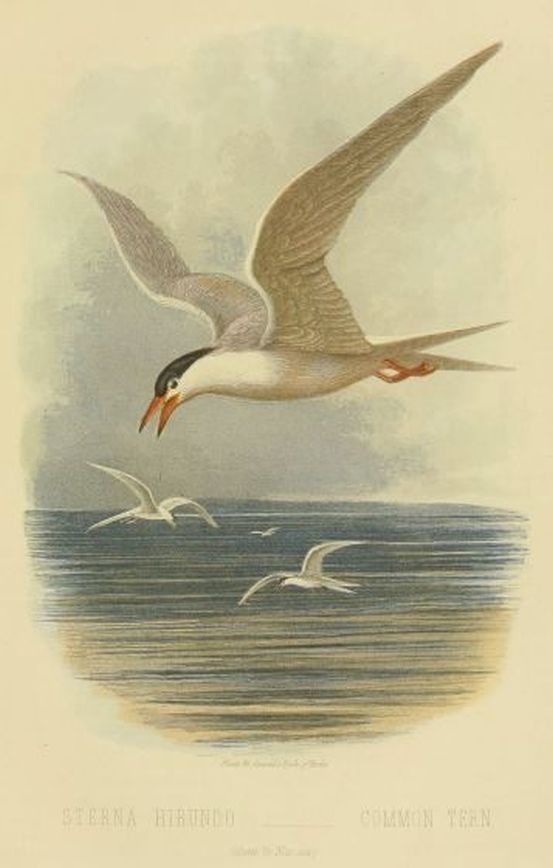

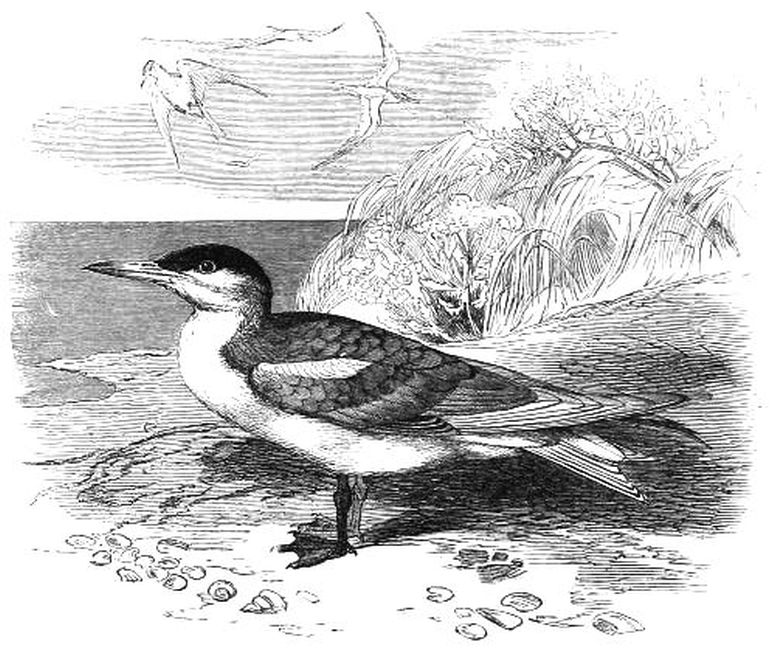

THE TERNS, or SEA SWALLOWS (Sternæ). The RAPACIOUS TERNS (Sylochelidon):âThe Caspian Tern. The RIVER TERNS (Sterna):âThe Common TernâThe Lesser Tern. The WATER SWALLOWS (Hydrochelidon):âThe Black Marsh TernâThe White-winged TernâThe White bearded TernâThe White or Silky TernâThe Noddy 175-185

THE SCISSOR-BILLS (Rhynchopes):âThe Indian Scissor-bill 185, 186

THE GULLS (Lari):âThe Fishing GullsâThe Great Black-backed GullsâThe Lesser Black-backed or Yellow-legged GullâThe Herring GullâThe Large or Glaucous White-winged GullâThe Lesser White-winged Gull. The ICE GULLS (Pagophila):âThe Ivory Gull 186-194

THE KITTIWAKES (Rissa). The BLACK-HEADED GULLS (Chroicocephalus):âThe Laughing GullâThe Great Black-headed GullâThe Lesser Black-headed GullâThe Little Gull 194-198

THE SKUAS (Lestres):âThe Common SkuaâBuffon's or the Parasite SkuaâRoss's Rosy Gull 198-203

THE PETRELS, or STORM BIRDS (Procellaridæ).âThe ALBATROSSES (Diomedæ):âThe Wandering AlbatrossâThe Yellow-billed AlbatrossâThe Sooty Albatross. The TRUE PETRELS (Procellariæ):âThe Giant PetrelâThe Fulmar PetrelâThe Cape PetrelâThe Broad-billed Prion, or Duck Petrel. The STORM PETRELS (Oceanides):âThe Common Storm PetrelâLeach's Storm Petrel 203-217

THE PUFFINS (Puffini):âThe Manx Puffin, or Shearwater [Pg vi] 217, 218

THE OAR-FOOTED SEA-FLIERS (Steganopodes).

THE TROPIC BIRDS (Phaëton):âThe White-tailed Tropic Bird. The Red-tailed Tropic Bird. The GANNETS (Sula):âThe Common GannetâThe Frigate Bird 219-227

THE CORMORANTS (Haliei). The DARTERS, or SNAKE-NECKS (Plotus):âThe AnhingaâLe Vaillant's Snake BirdâThe Common Cormorant 227-235

THE PELICANS (Pelecani):âThe White PelicanâThe Great Tufted or Dalmatian Pelican 235-239

THE DIVERS (Urinatores).

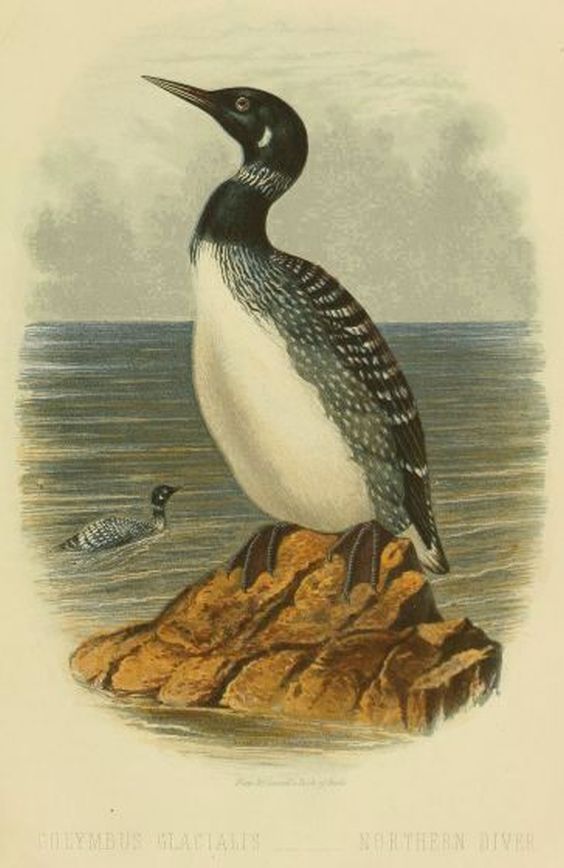

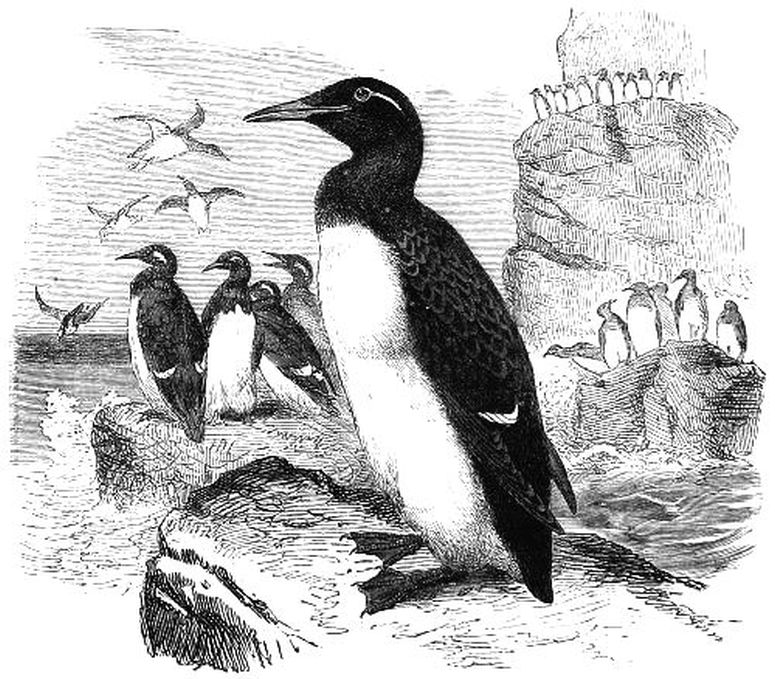

THE GREBES (Podicipites):âThe Crested GrebeâThe Little Grebe. The DIVERS (Colymbi):âThe Great Northern DiverâThe Black-throated DiverâThe Red-throated Diver. The LOONS (Uriæ): The Greenland Dove, or Black Guillemot. The TRUE GUILLEMOTS (Uria): The Common or Foolish GuillemotâThe Little Auk or Guillemot 240-255

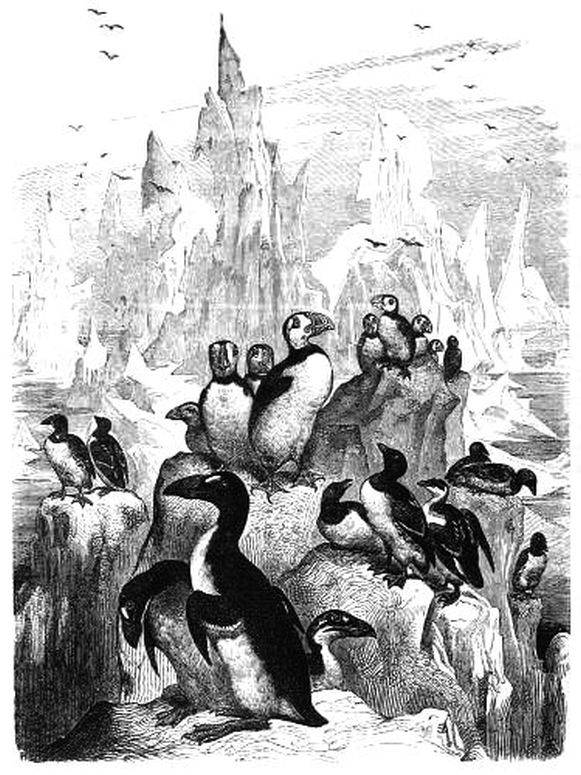

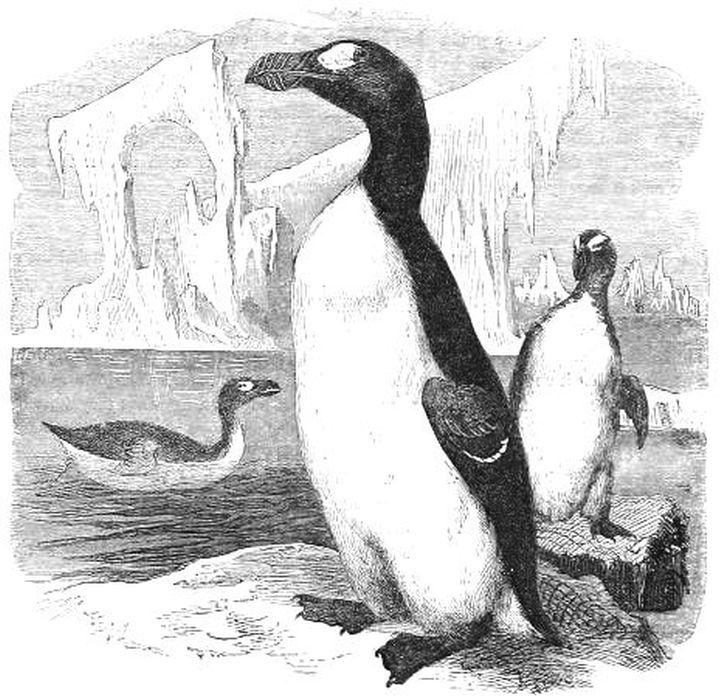

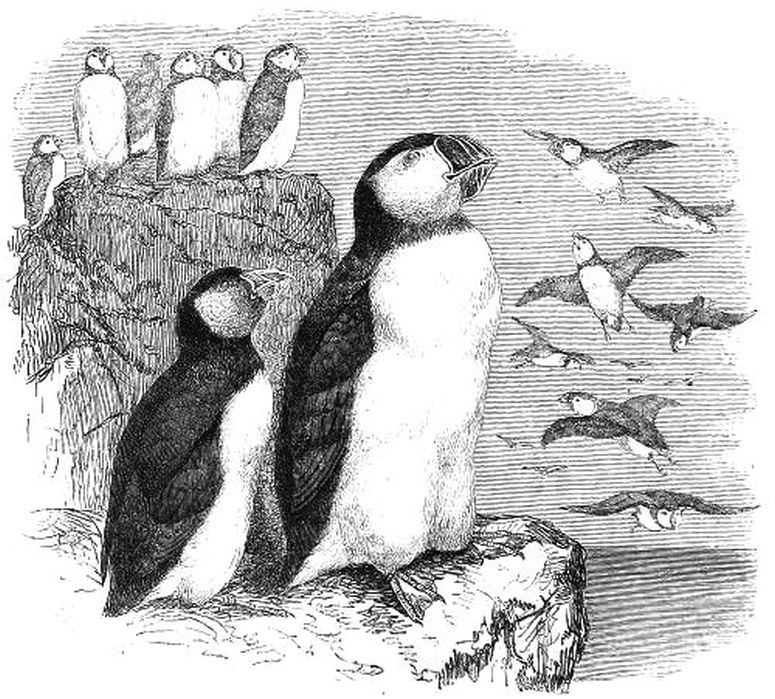

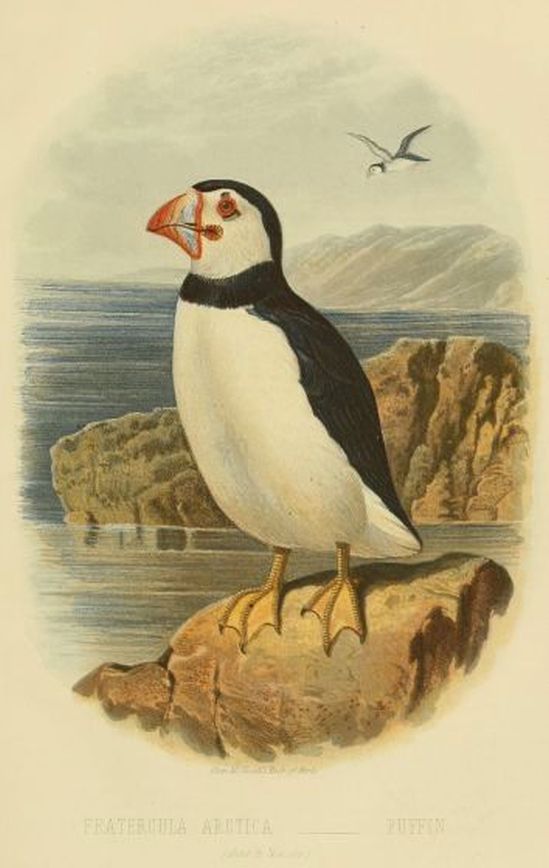

THE STARIKIS (Phaleres):âThe Stariki. The AUKS (Alcæ):âThe Razor-billâThe Great AukâThe Coulterneb, or Arctic Puffin 255-264

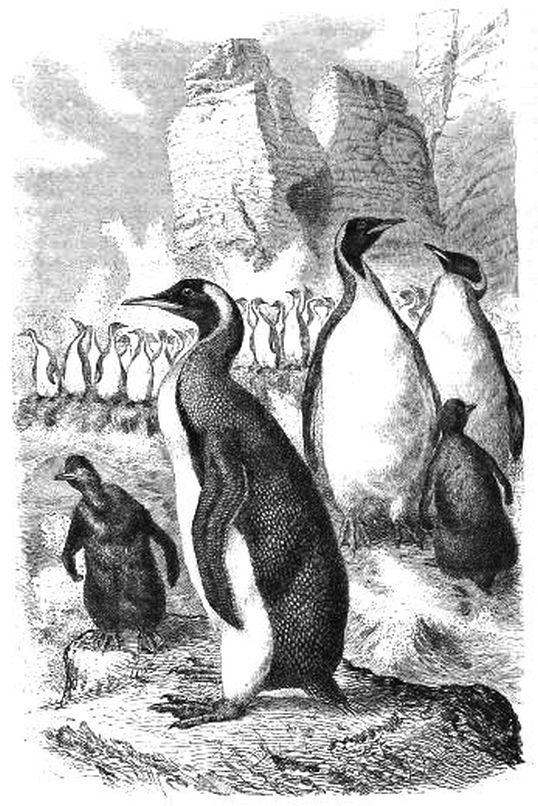

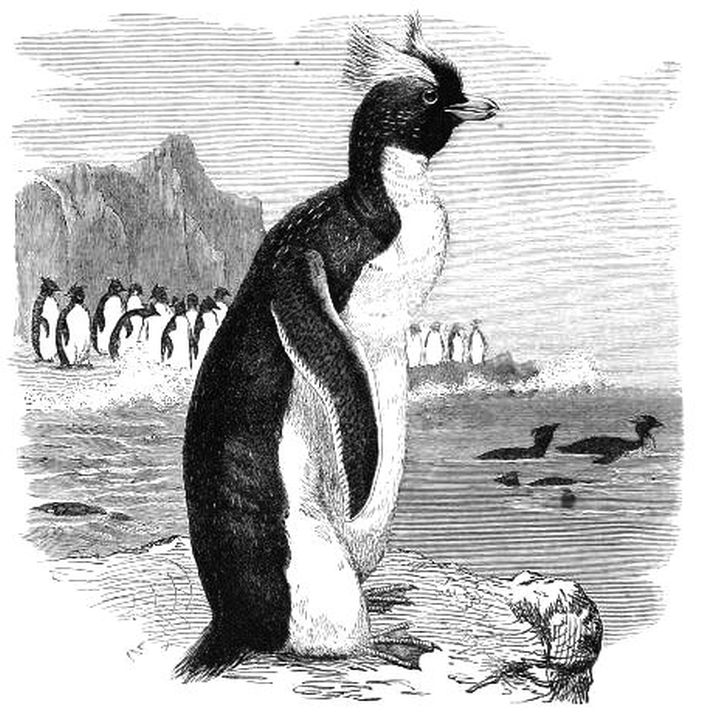

THE PENGUINS (Aptenodytes):âThe King Penguin. The TRUE PENGUINS (Spheniscus):âThe Spectacled, or Cape Penguin. The LEAPING PENGUINS (Eudypetes):âThe Golden or Crested Penguin 265-268

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

ââ¦â

COLOURED PLATES.

PLATE XXXI.âPAINTED SPUR FOWL (Galloperdix lunulosa).

" XXXII.âTHE HOUBARA (Otis Macquenii).

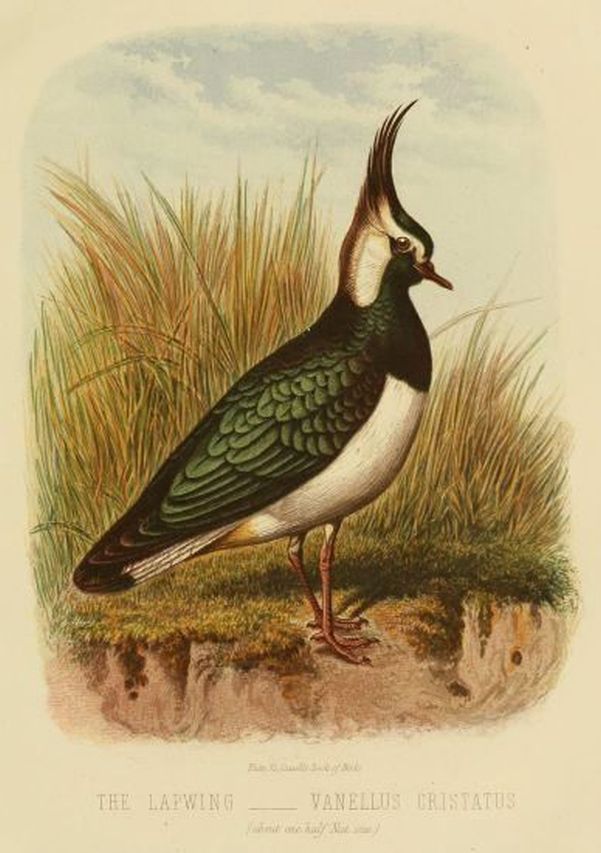

" XXXIII.âTHE LAPWING (Vanellus cristatus).

" XXXIV.âSQUACCO HERON (Buphus Comata).

" XXXV.âCHINESE JACANA (Hydrophasianus Sinensis).

" XXXVI.âRUDDY SHELDRAKE (Casarca rutila).

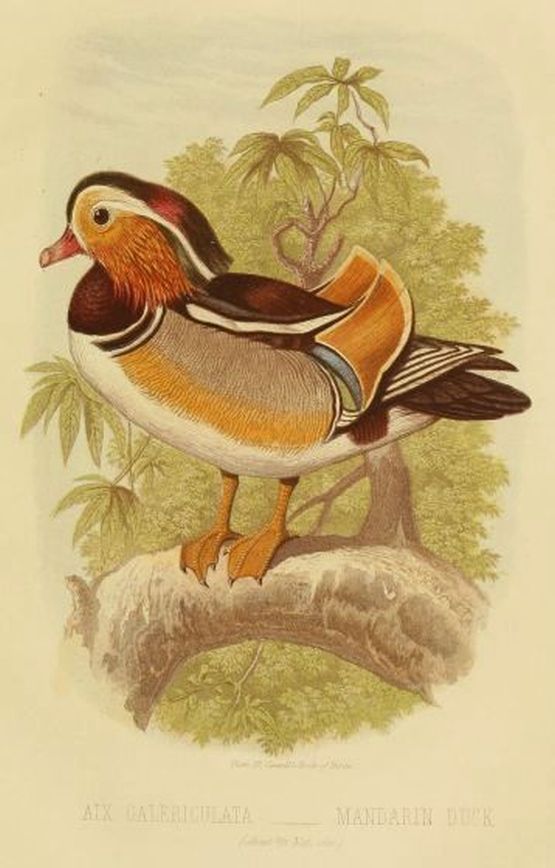

" XXXVII.âMANDARIN DUCK (Aix galericulata).

" XXXVIII.âTERN (Sterna Hirundo).

" XXXIX.âGREAT NORTHERN DIVER (Colymbus glacialis).

" XL.âPUFFIN (Fratercula Arctica).

WOOD ENGRAVINGS.

| FIG. | PAGE | |

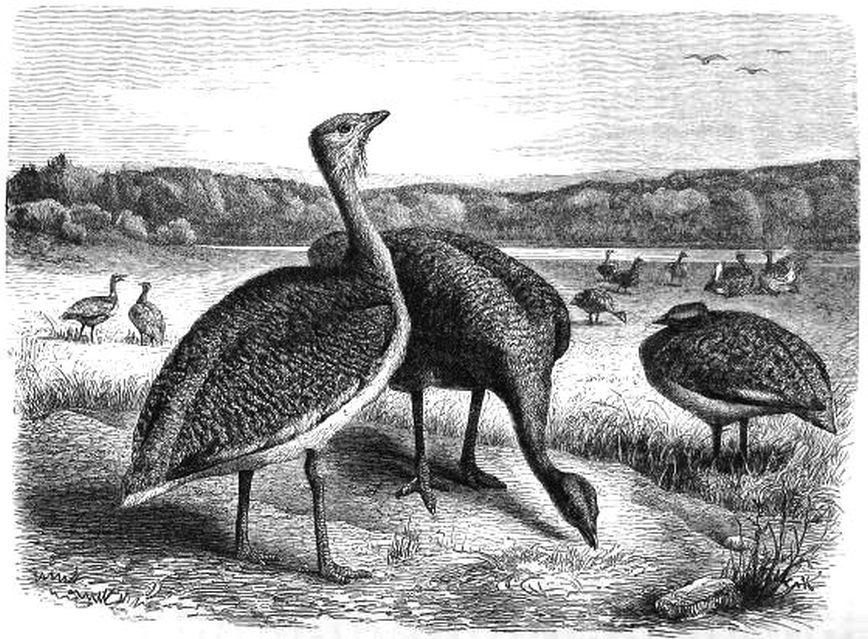

| 1. | Bustards (Otis tarda) | 4 |

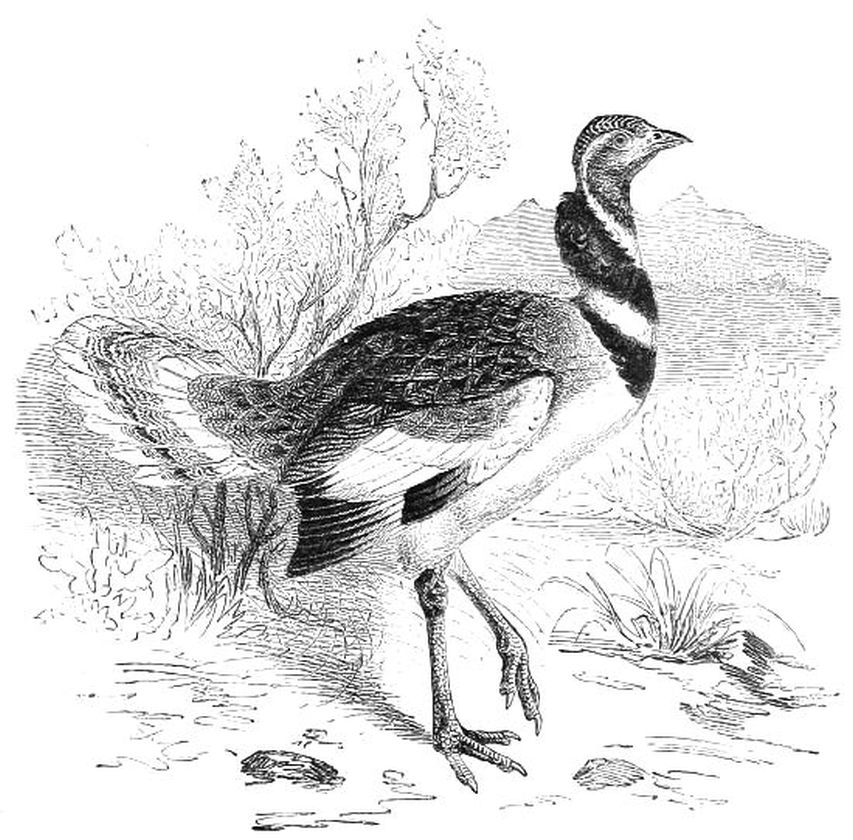

| 2. | The Little Bustard (Otis tetrax, or Tetrax campestris) | 5 |

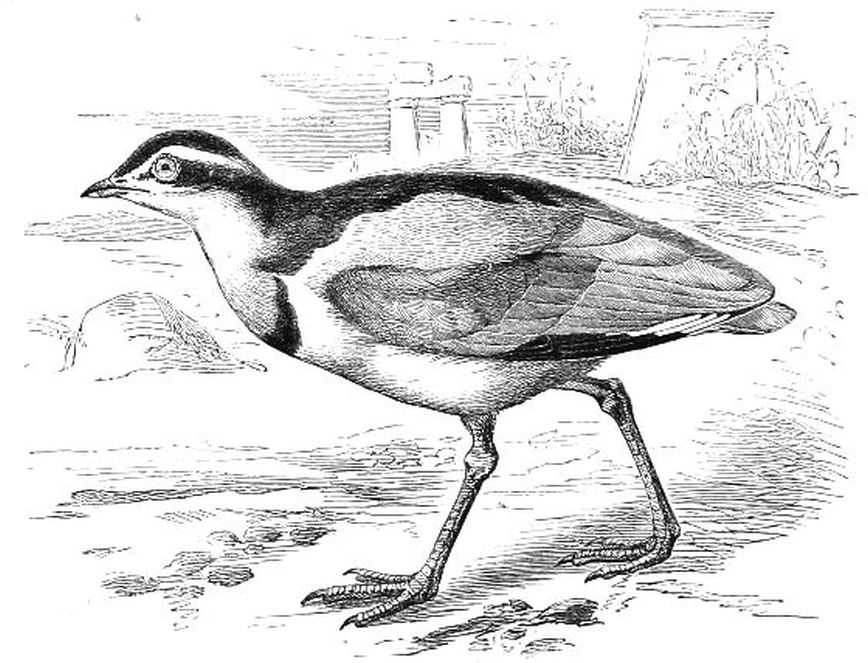

| 3. | The Trochilus, or Crocodile Watcher (Hyas Ãgyptiacus) | 9 |

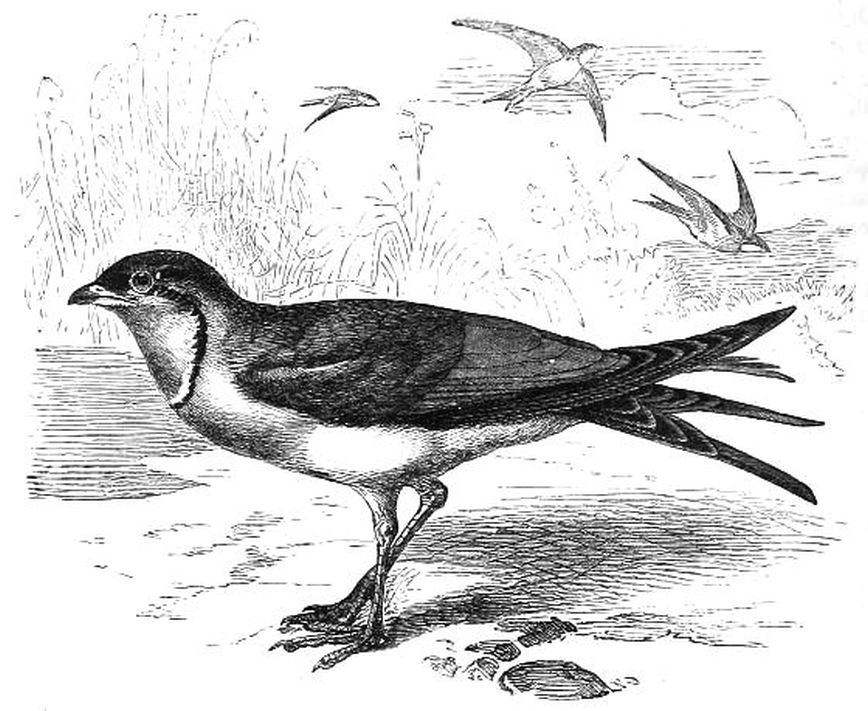

| 4. | The Collared Pratincole (Glareola pratincola) | 12 |

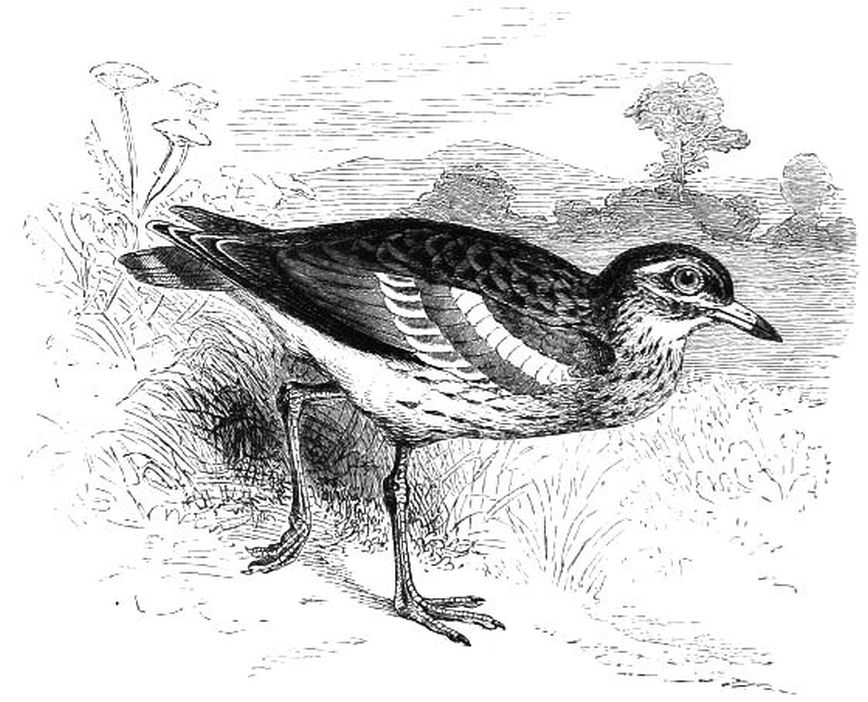

| 5. | The Common Thick-knee, or Stone Curlew (Ådicnemus crepitans) | 13 |

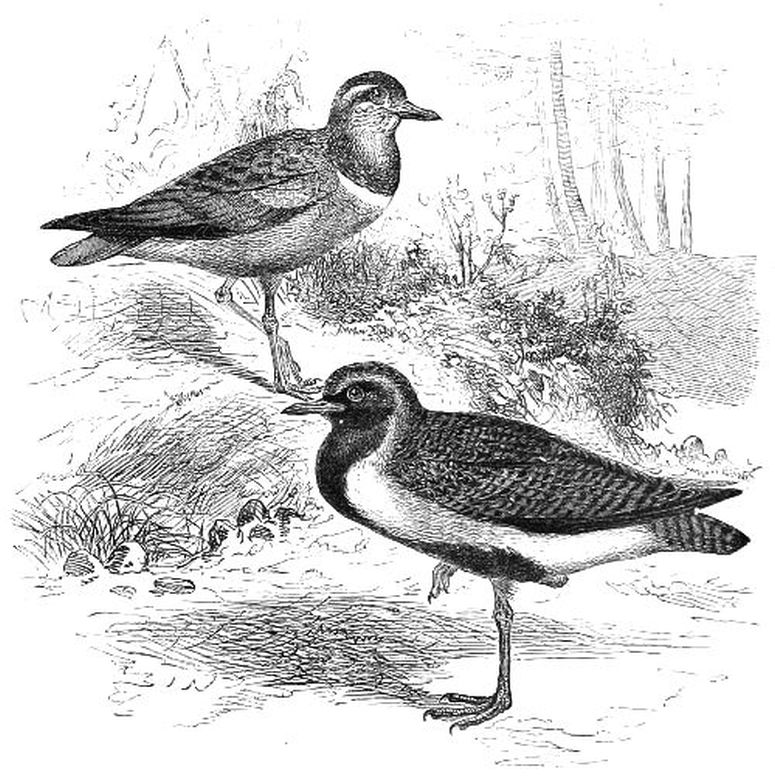

| 6. | The Golden Plover (Charadrius auratus), and the Dotterel (Eudromias Morinellus) | 17 |

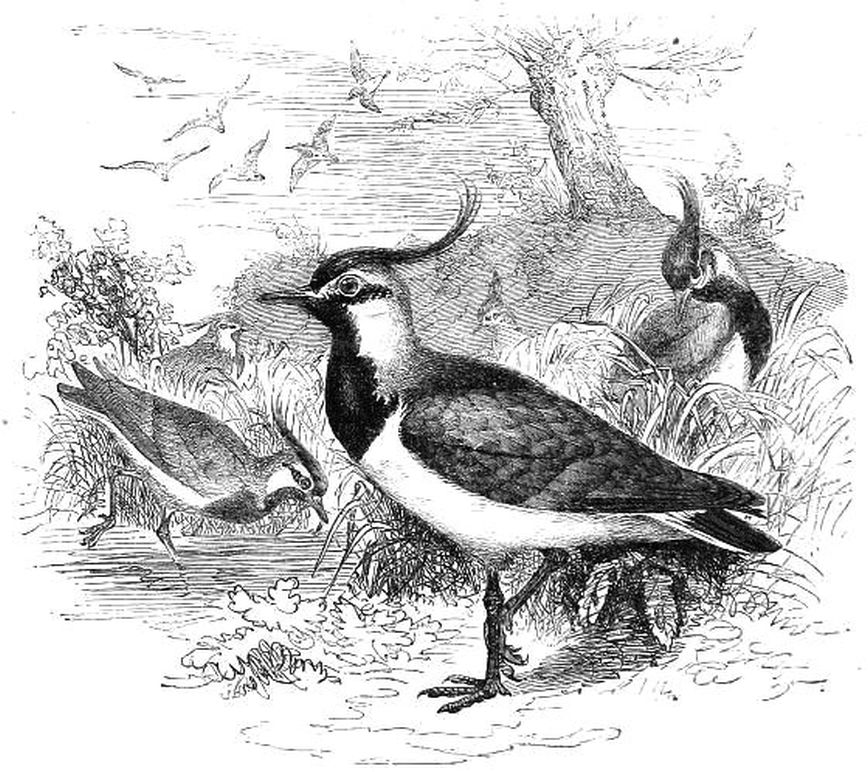

| 7. | The Lapwing, or Peewit (Vanellus cristatus) | 21 |

| 8. | The Spur-winged Lapwing (Hoplopterus spinosus) | 24 |

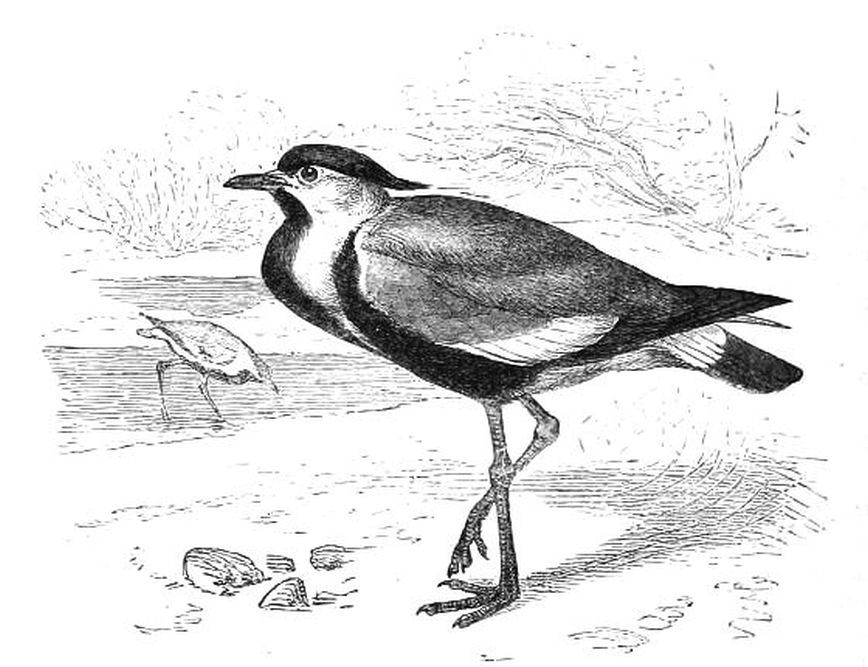

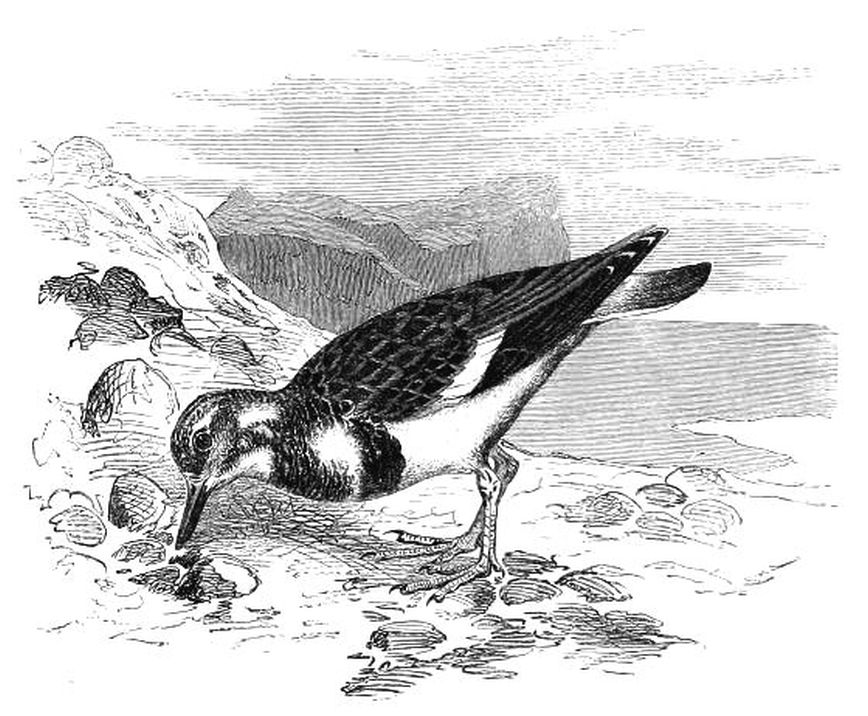

| 9. | The Turnstone (Strepsilas interpres) | 25 |

| 10. | The Pied Oyster-catcher, or Sea Pie (Hæmatopus ostralegus) | 28 |

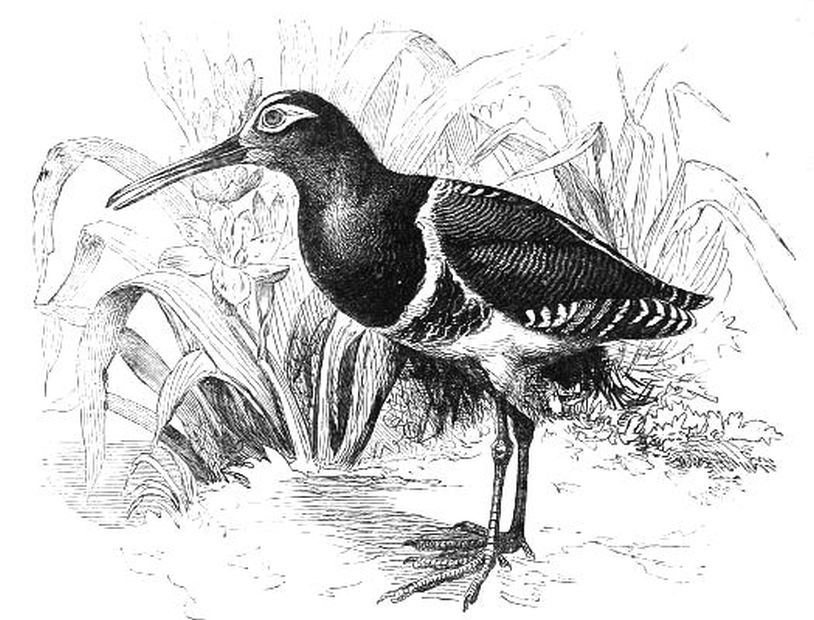

| 11. | The Woodcock (Scolopax rusticola) | 32 |

| 12. | The Sanderling (Calidris arenaria) | 37 |

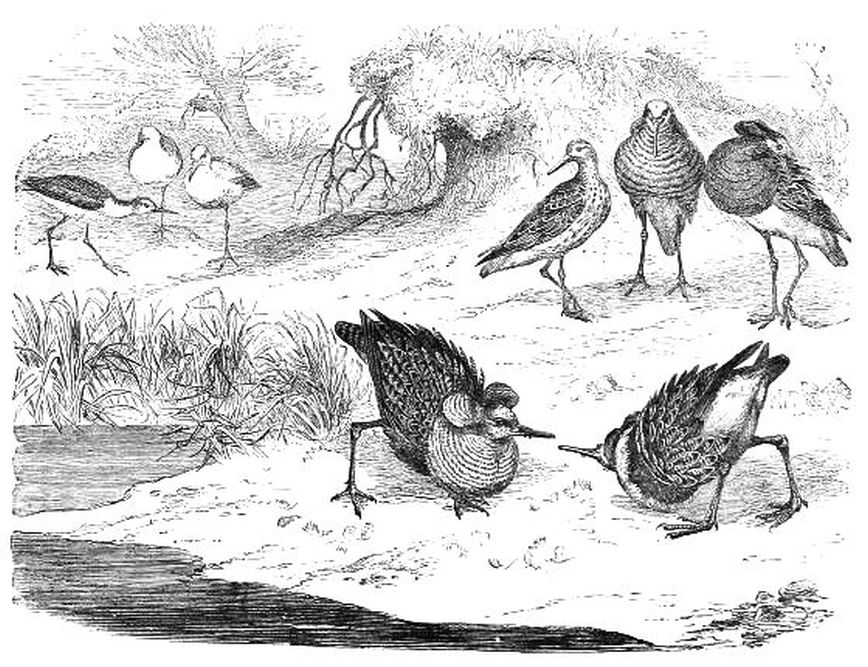

| 13. | The Ruff (Philomachus pugnax) | 40 |

| 14. | Ruffs Fighting | 41 |

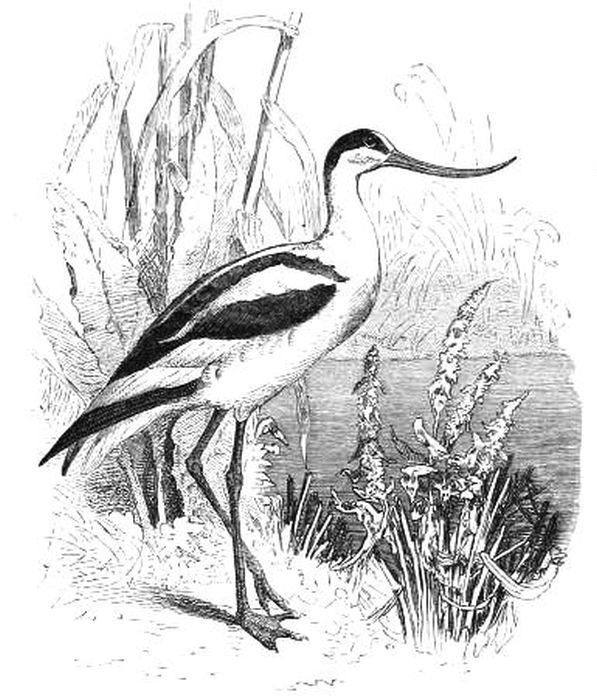

| 15. | The Scooping Avocet (Recurvirostra avocetta) | 52 |

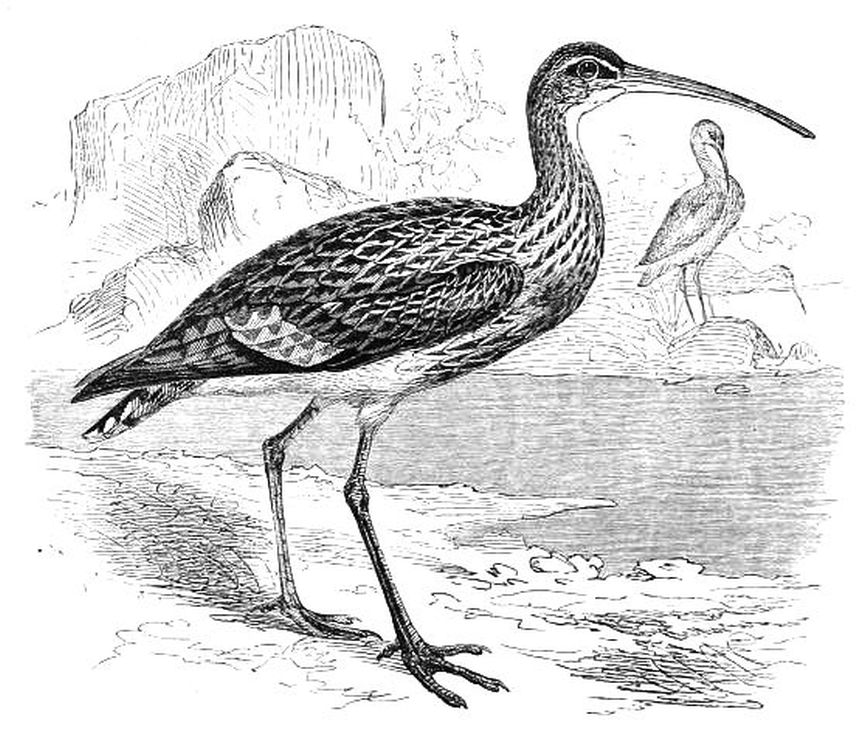

| 16. | The Great Curlew (Numenius arquatus) | 53 |

| 17. | The White or Sacred Ibis (Threskiornis religiosa) | 57 |

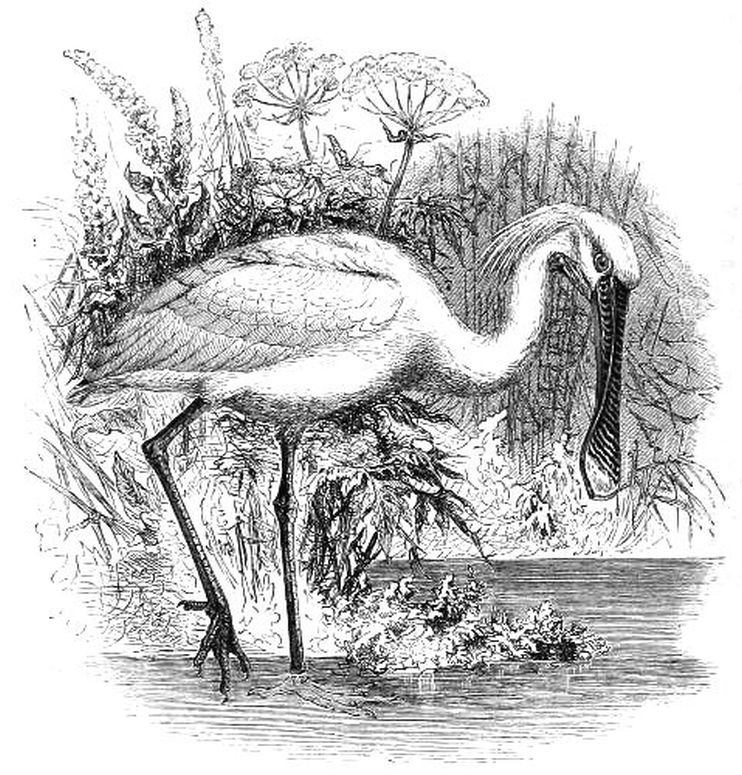

| 18. | The Spoonbill (Platalea leucorodia) | 60 |

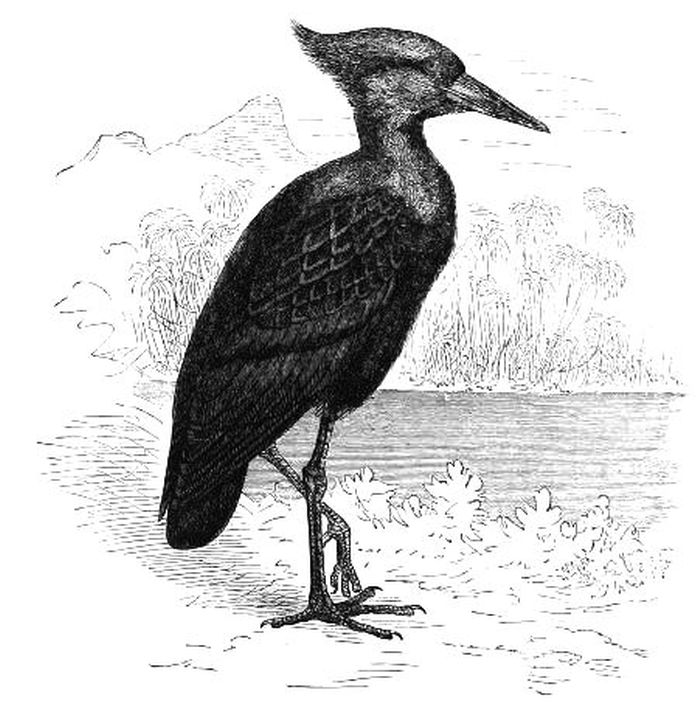

| 19. | The Whale-headed Stork, or Shoe-beak (Balæniceps rex) | 61 |

| 20. | The Savaku, or Boat-bill (Cancroma cochlearia) | 64 |

| 21. | The Hammer-head, or Shadow-bird (Scopus umbretta) | 65 |

| 22. | The Ibis-like Tantalus (Tantalus ibis) | 66 |

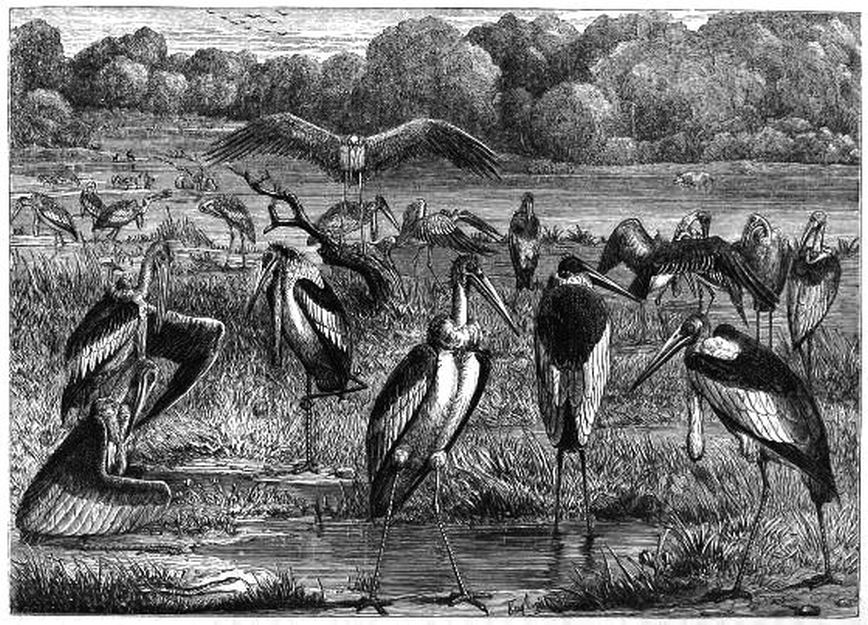

| 23. | Adjutants | 68 |

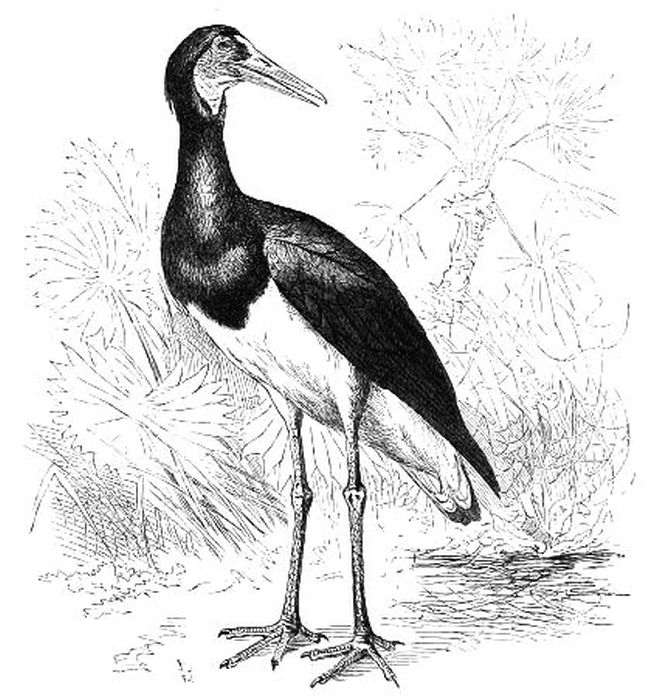

| 24. | The Simbil (Spenorhynchus Abdimii) | 69 |

| 25. | The Senegal Jabiru (Mycteria Senegalensis) | 72 |

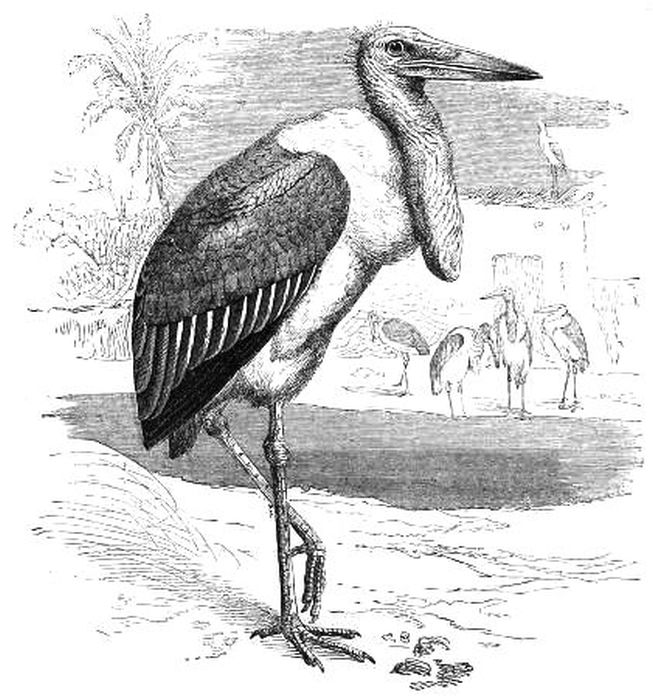

| 26. | The Marabou (Leptoptilos crumenifer) | 73 |

| 27. | The African Clapper-bill (Anastomus lamelligerus) | 76 |

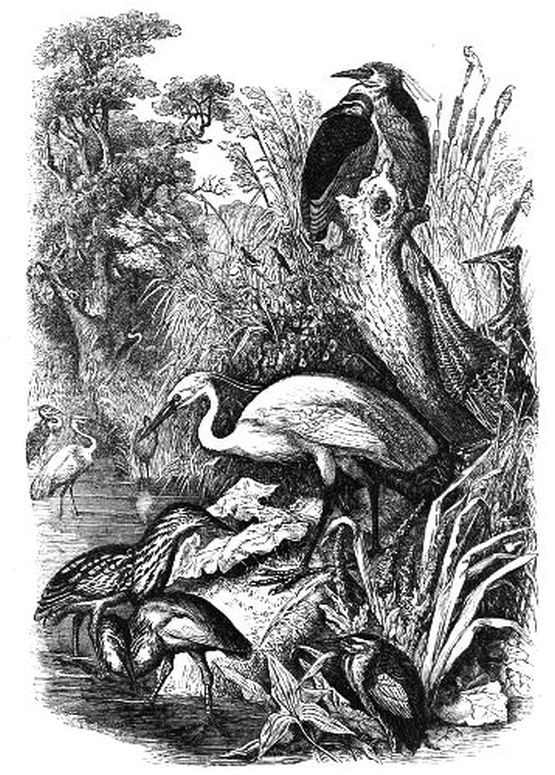

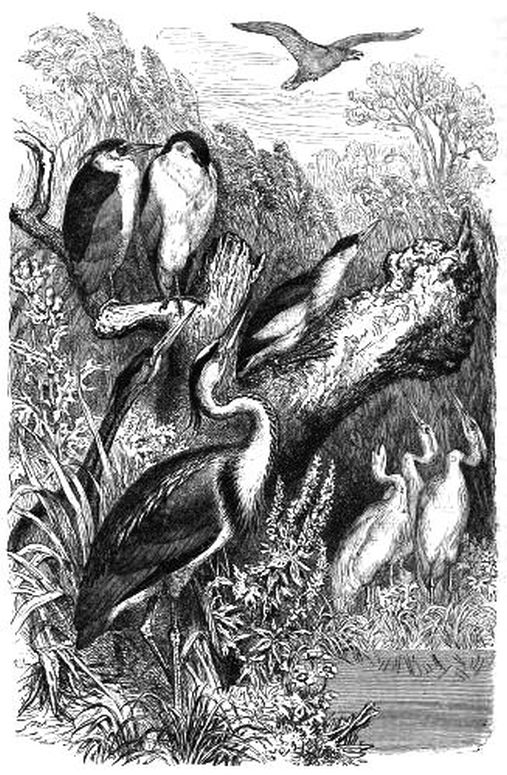

| 28. | Group of Herons | 77 |

| 29. | The Giant Heron (Ardea Goliath) | 79 |

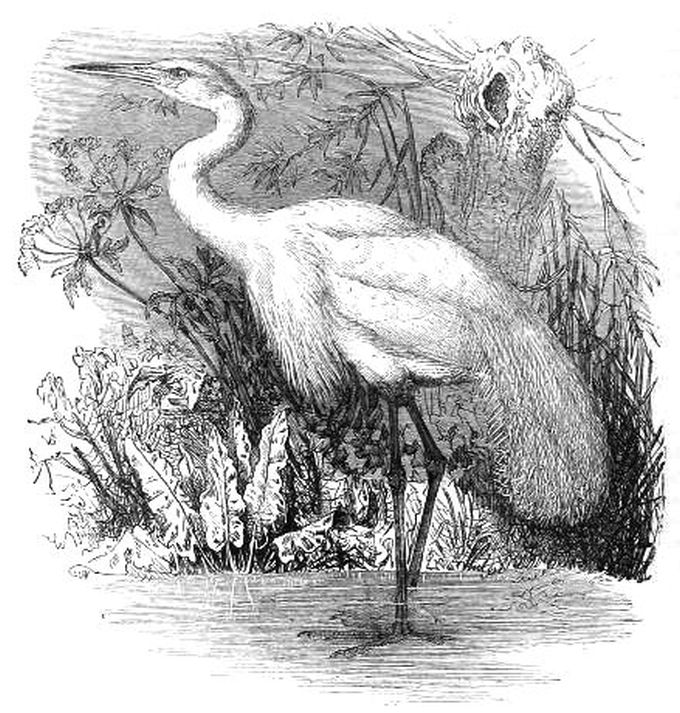

| 30. | The Great White Heron (Herodias alba) | 80 |

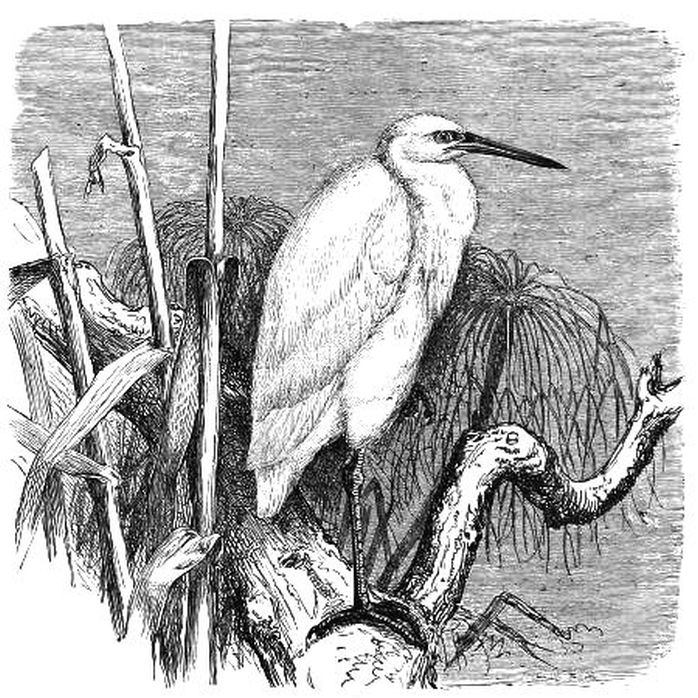

| 31. | The Lesser Egret (Herodias garzetta) | 81 |

| 32. | Day and Night Herons | 84 |

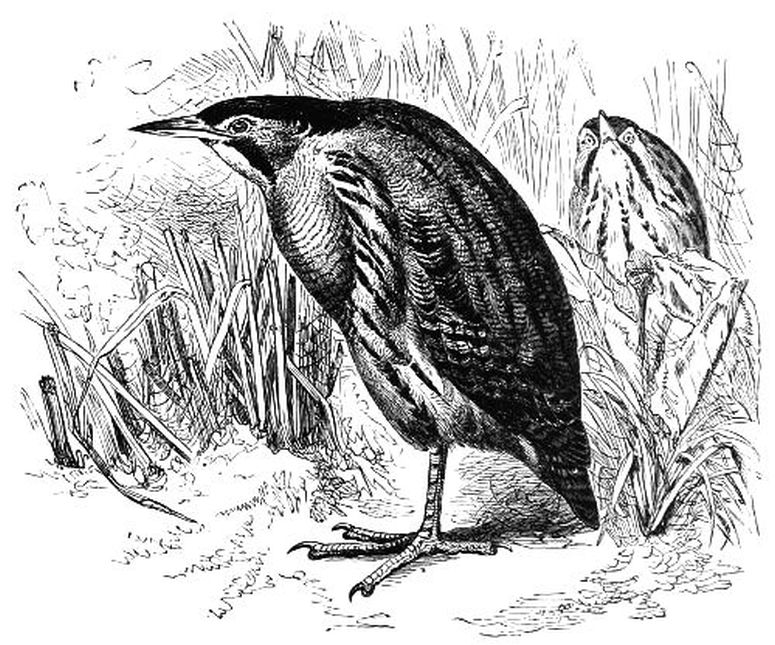

| 33. | The Common Bittern (Botaurus stellaris) | 85[Pg viii] |

| 34. | The Sun Bittern, or Peacock Heron (Eurypyga helias) | 88 |

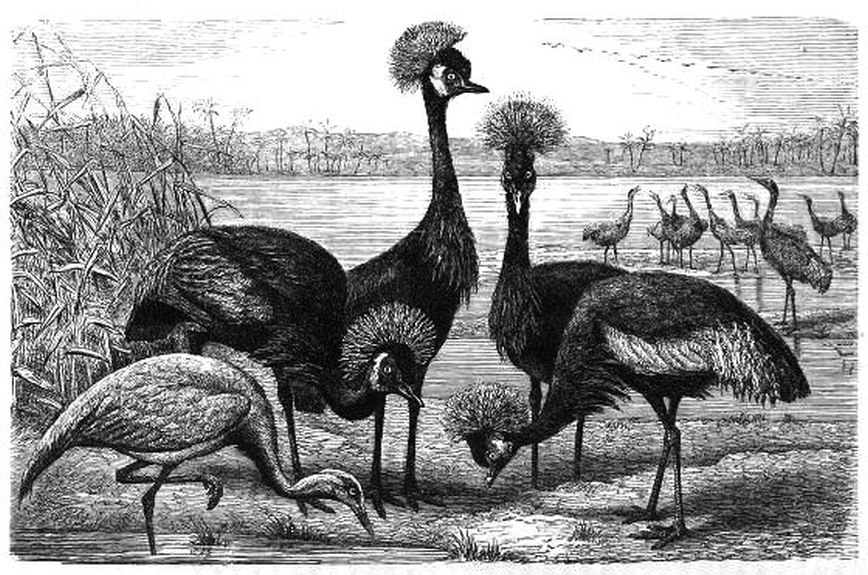

| 35. | Crowned, Demoiselle, and Common Cranes | 92 |

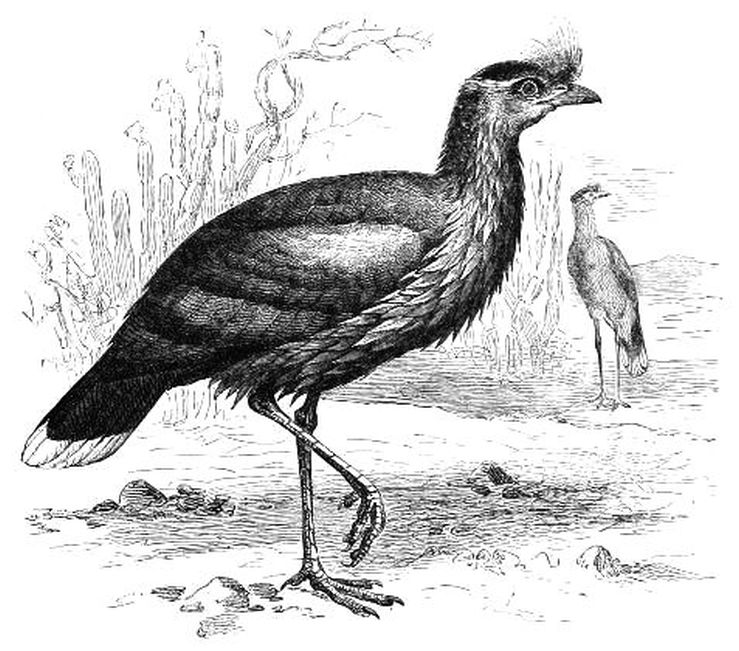

| 36. | The Cariama, or Crested Screamer (Dicholophus cristatus) | 93 |

| 37. | The Gold-breasted Trumpeter (Psophia crepitans) | 96 |

| 38. | The Aniuma, or Horned Screamer (Palamedea cornuta) | 97 |

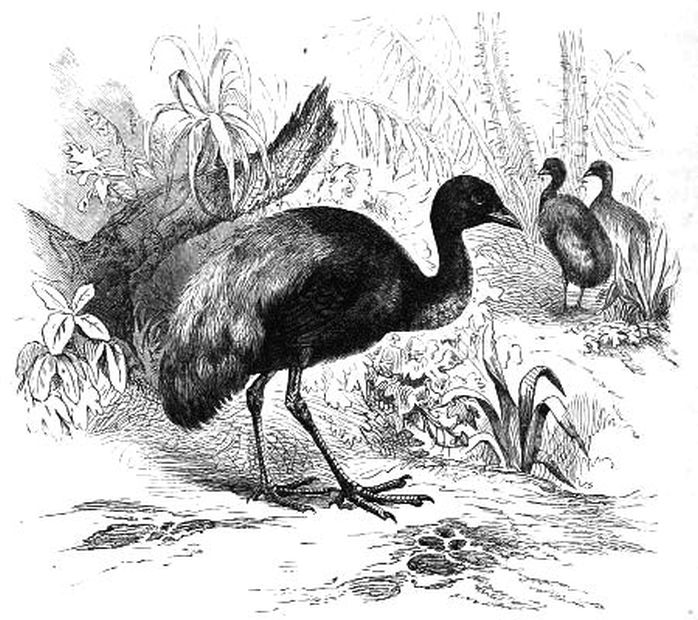

| 39. | The Golden Rail, or Painted Cape Snipe (Rhynchæa Capensis) | 100 |

| 40. | The Jacana (Parra Jacana) | 104 |

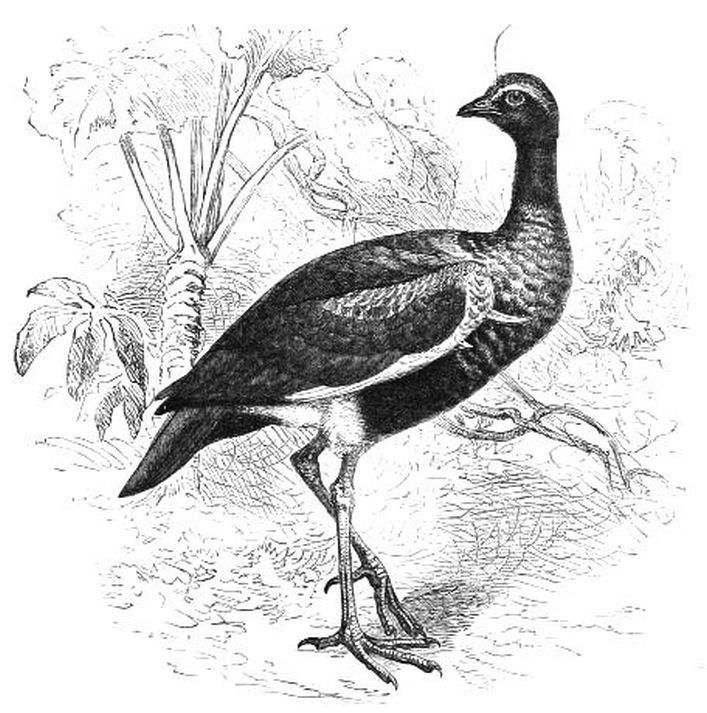

| 41. | The Hyacinthine Porphyrio (Porphyrio hyacinthinus) | 108 |

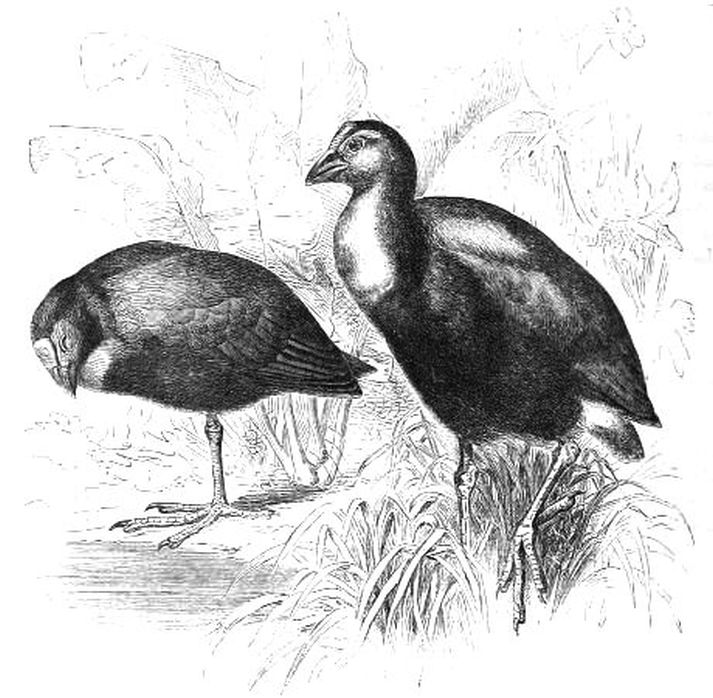

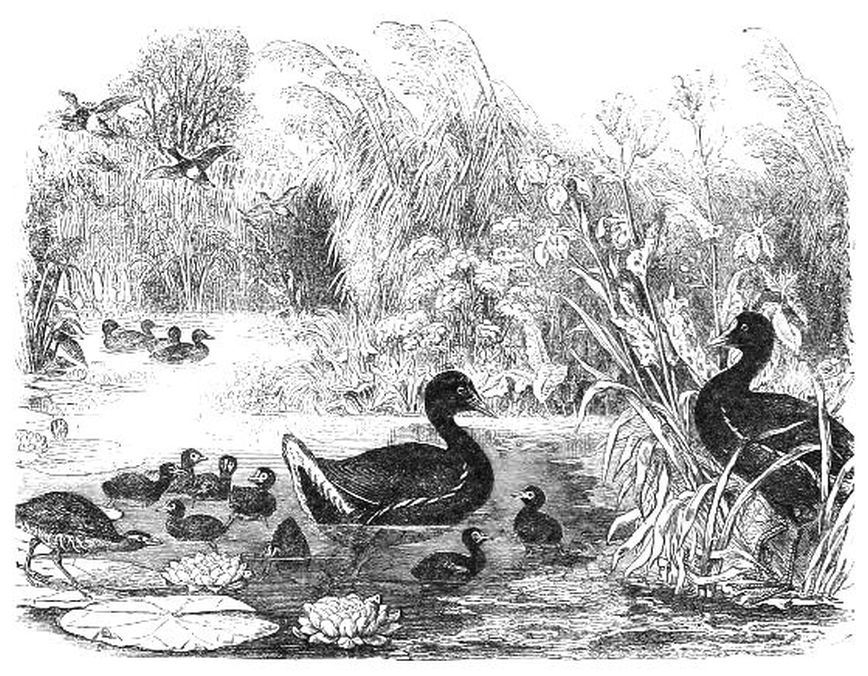

| 42. | Home of the Moor-hens (Gallinula chloropus) | 109 |

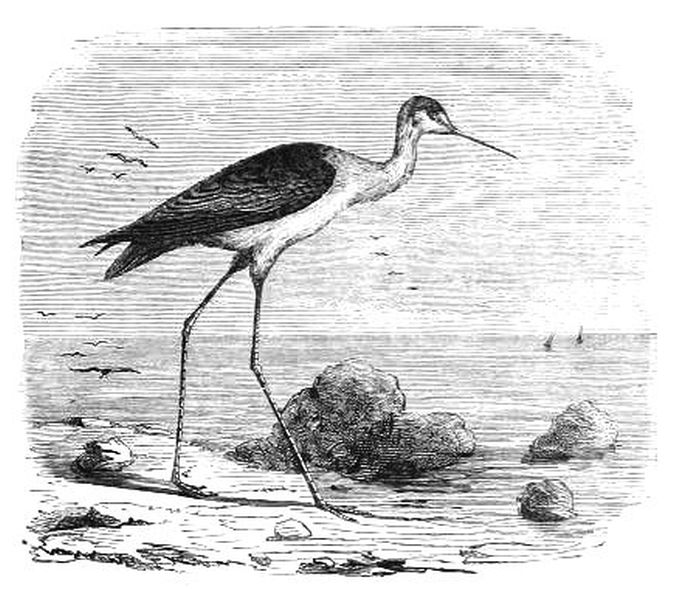

| 43. | The Stilt Bird (Charadrius himantopus) | 113 |

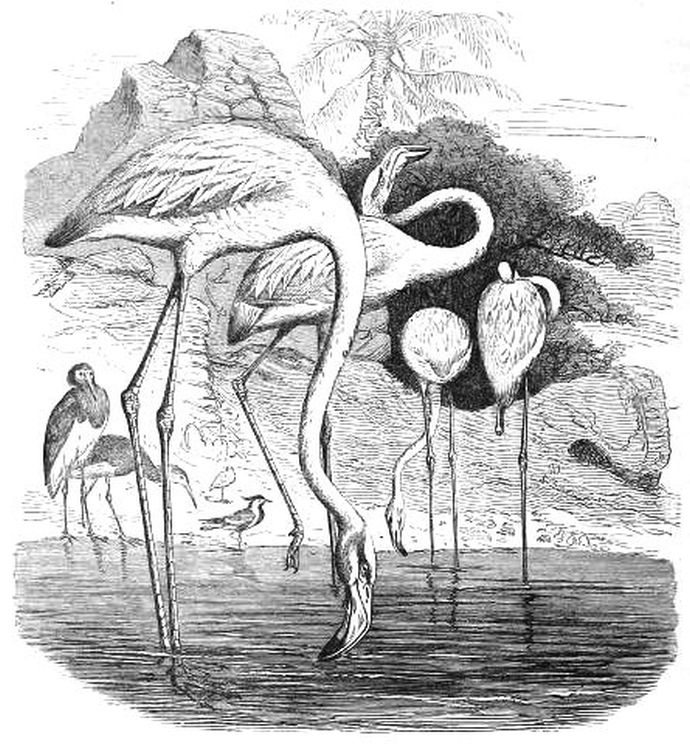

| 44. | The Flamingo (PhÅnicopterus roseus) | 116 |

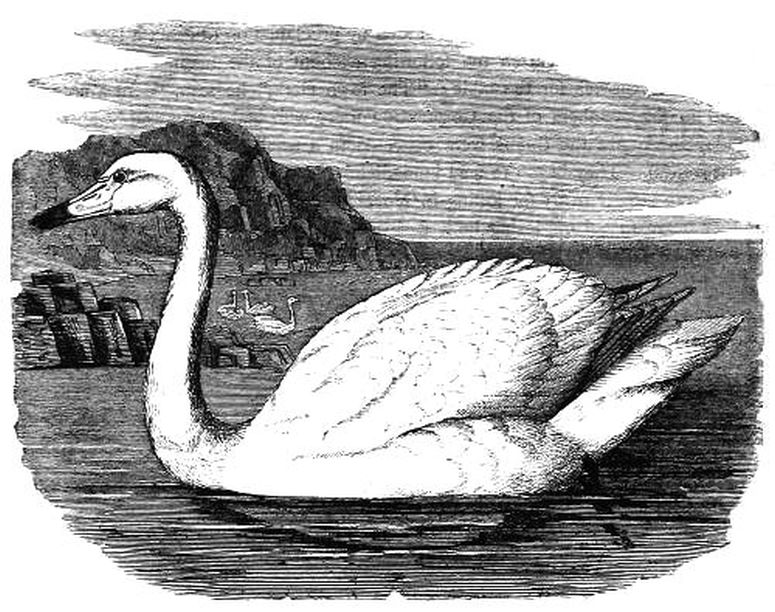

| 45. | The Whistling Swan (Cygnus musicus) | 124 |

| 46. | Black-necked Swans (Cygnus nigricollis) | 128 |

| 47. | The Black Swan (Cygnus or Chenopsis atratus) | 129 |

| 48. | The Spur-winged Goose (Plectropterus Gambensis) | 132 |

| 49. | The Grey or Wild Goose (Anser cinereus) | 133 |

| 50. | The Brent Goose (Bernicla torquata) | 137 |

| 51. | The Nile Goose (Chenalopex Ãgyptiacus) | 140 |

| 52. | Cereopsis Geese | 141 |

| 53. | The Ruddy Sheldrake, or Brahminy Duck (Casarca rutila) | 144 |

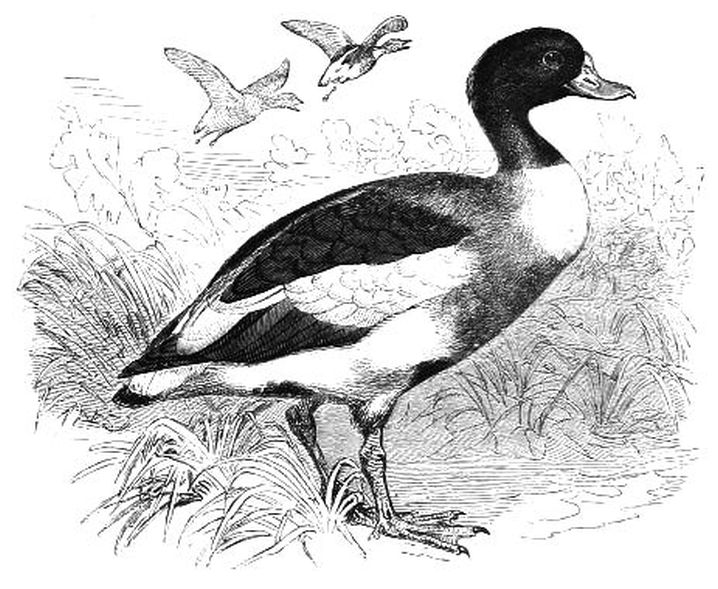

| 54. | The Sheldrake (Vulpanser tadorna) | 145 |

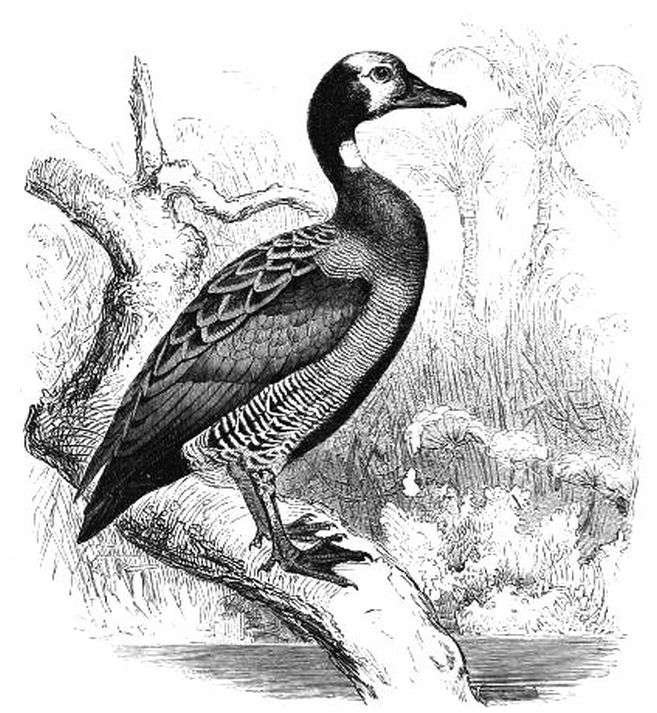

| 55. | The Widow Duck (Dendrocygna viduata) | 149 |

| 56. | The Wild Duck (Anas boschas) | 152 |

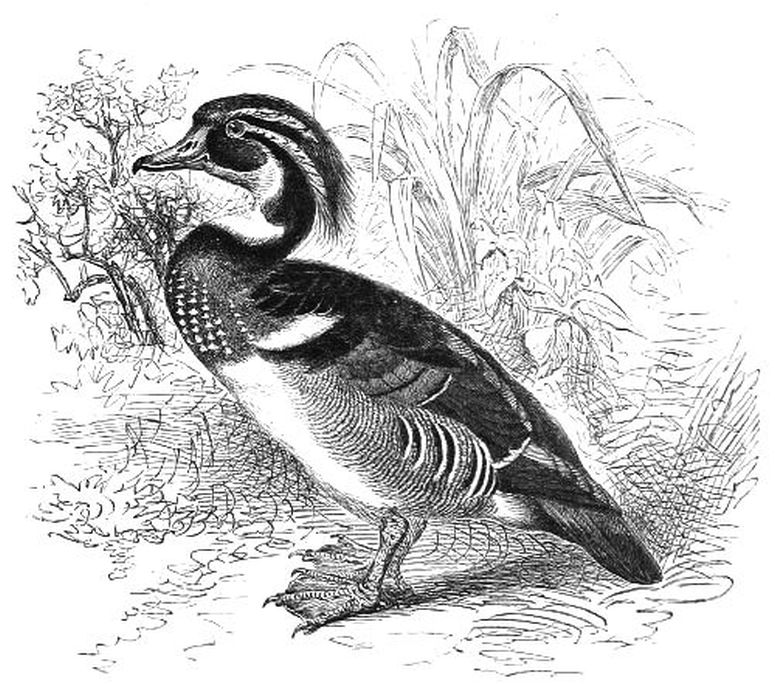

| 57. | The Wood or Summer Duck (Aix sponsa) | 153 |

| 58. | The Shoveler Duck (Spatula clypeata) | 157 |

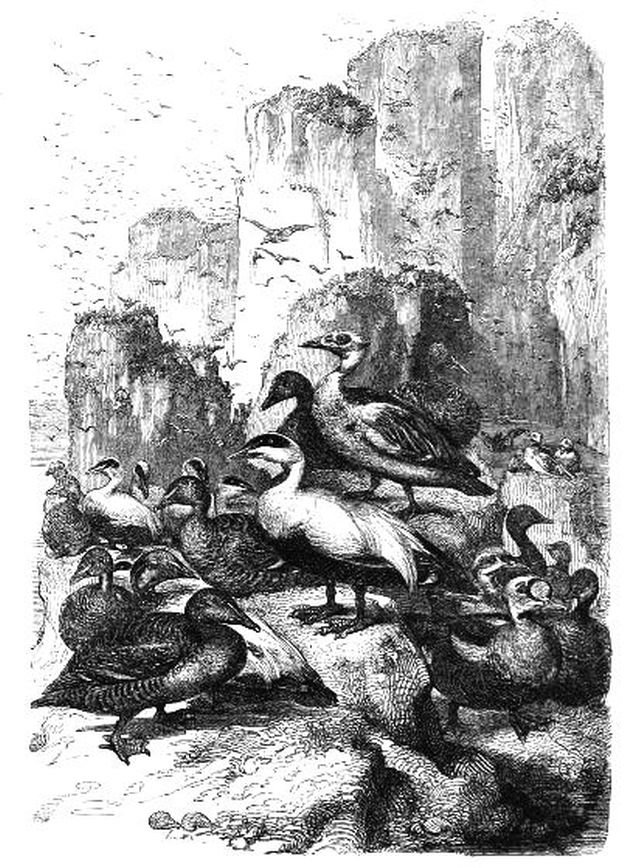

| 59. | Eider Ducks at Home | 161 |

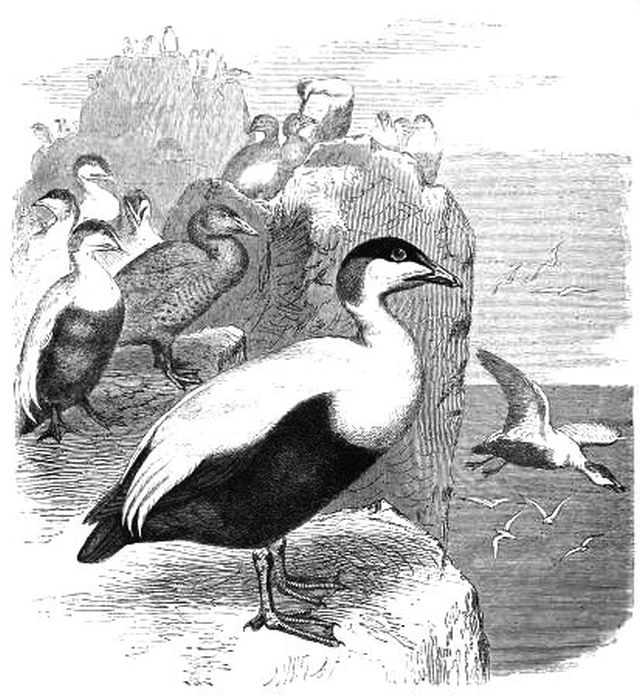

| 60. | The Eider Ducks (Somateria mollissima) | 164 |

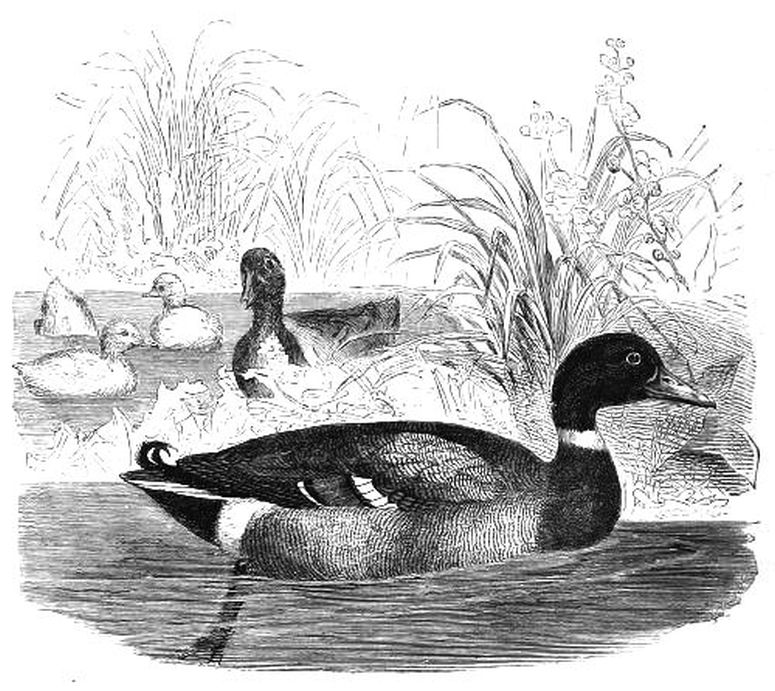

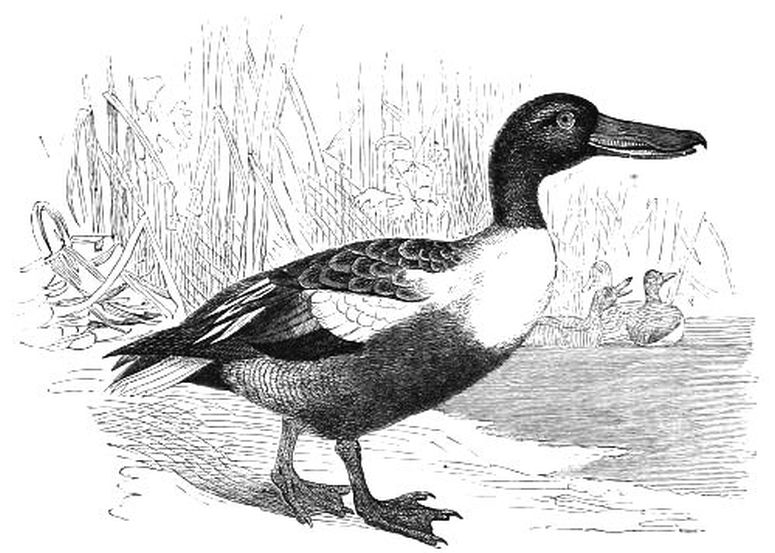

| 61. | The Green-headed Goosander (Mergus merganser) | 173 |

| 62. | The Caspian Tern (Sylochelidon Caspia) | 177 |

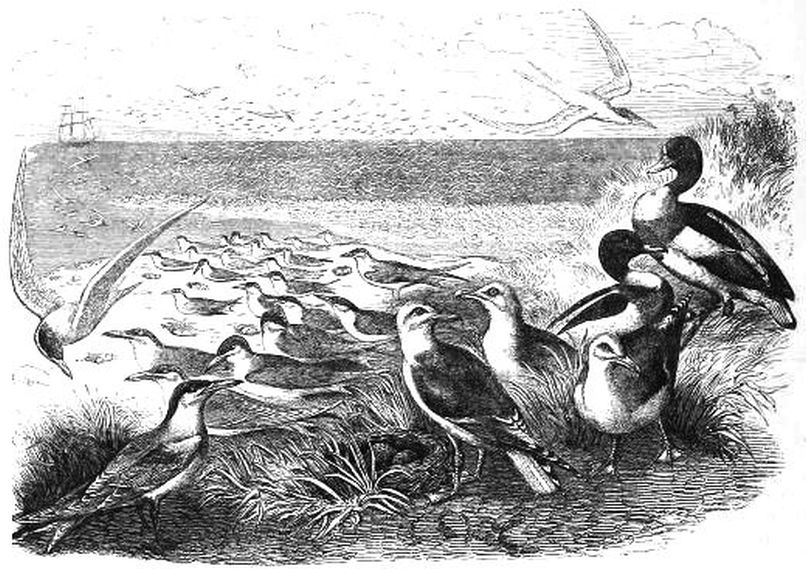

| 63. | Terns and their Nests | 180 |

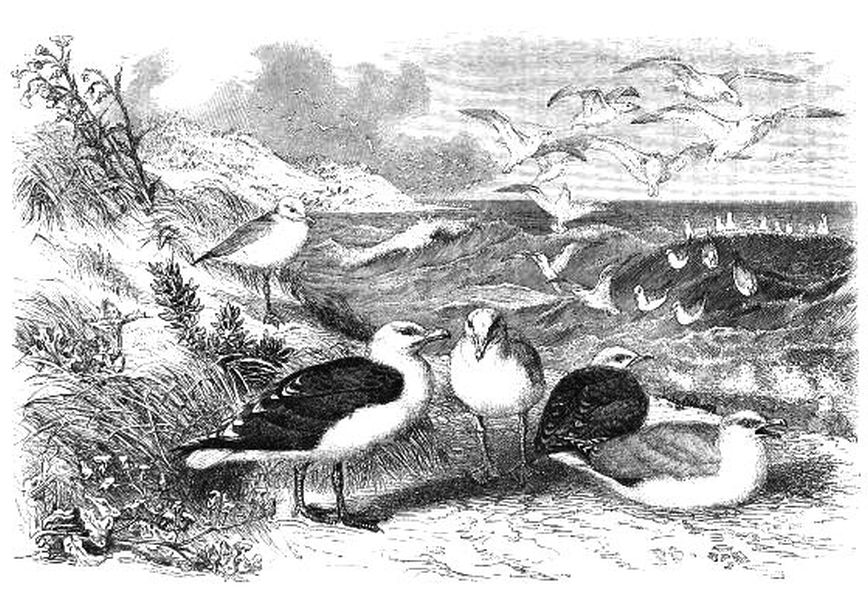

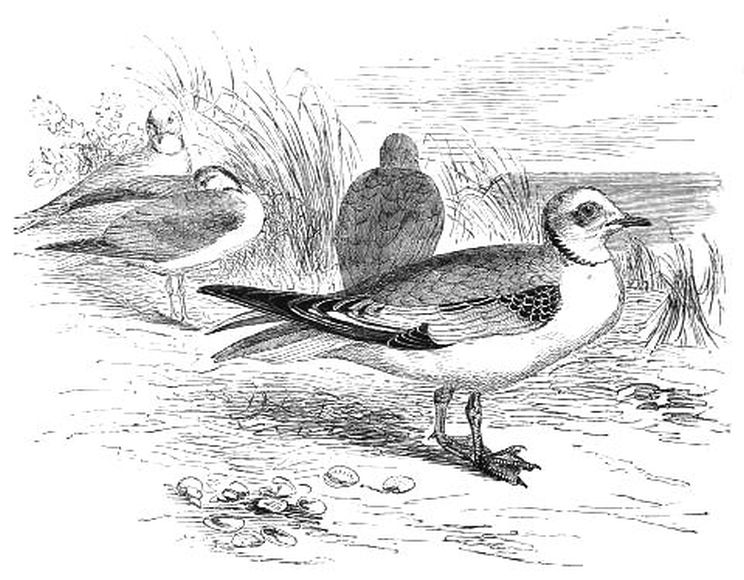

| 64. | Black-backed and Herring Gulls | 189 |

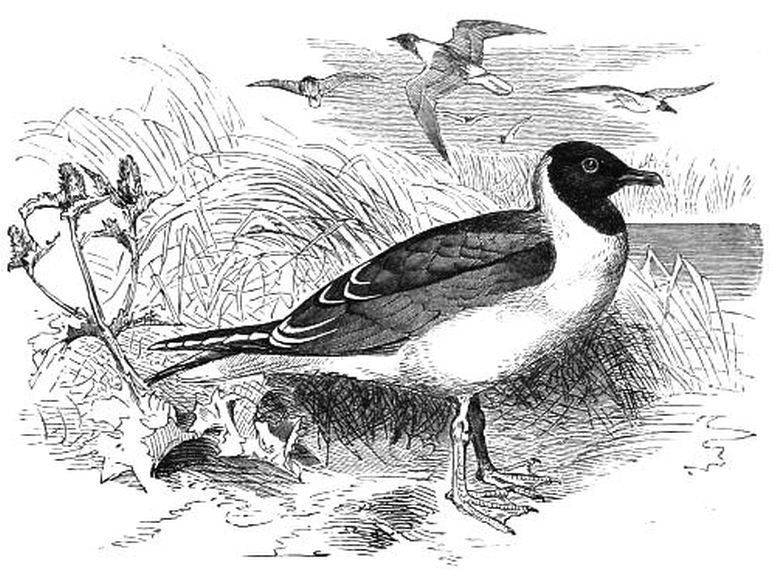

| 65. | The Laughing Gull (Chroicocephalus ridibundus) | 196 |

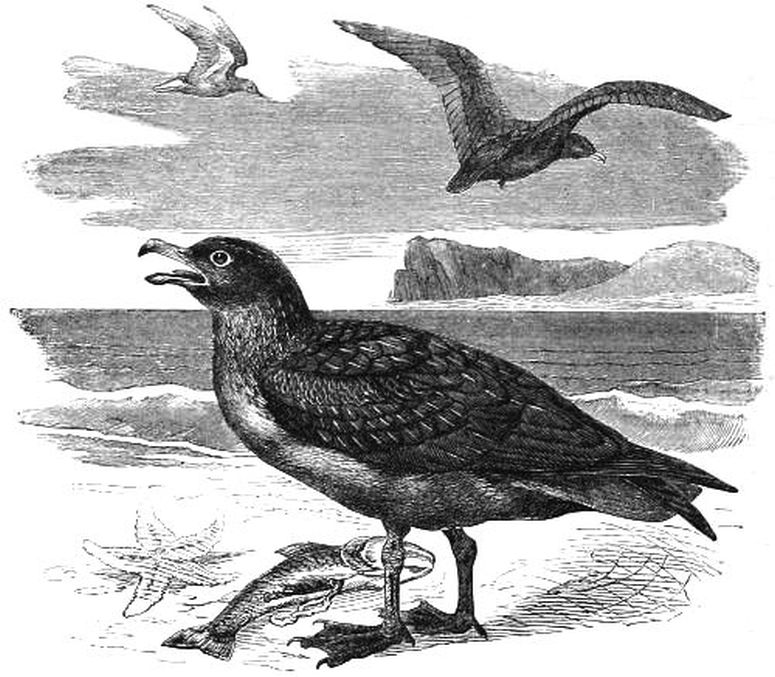

| 66. | The Common Skua (Lestris catarractes) | 200 |

| 67. | The Rosy Gull (Rhodostethia rosea) | 204 |

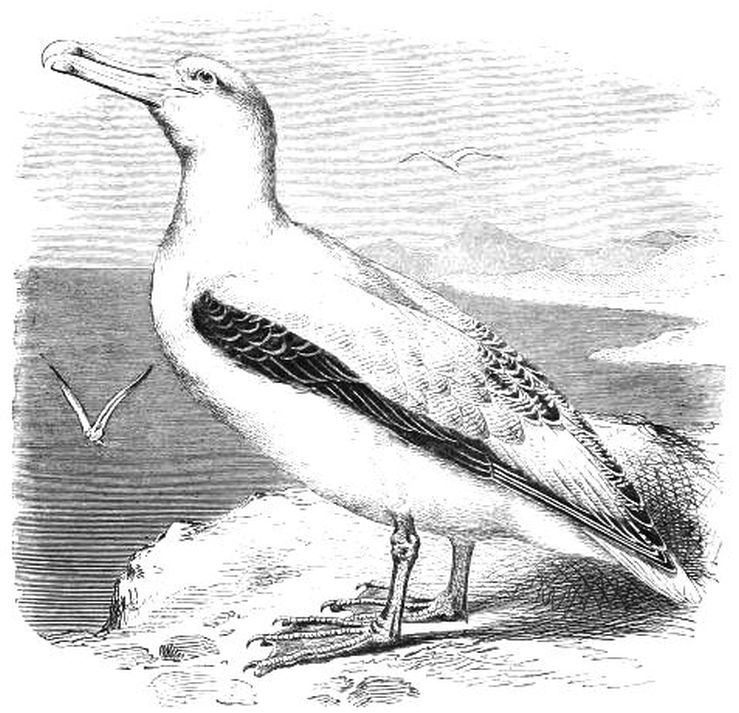

| 68. | The Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans) | 205 |

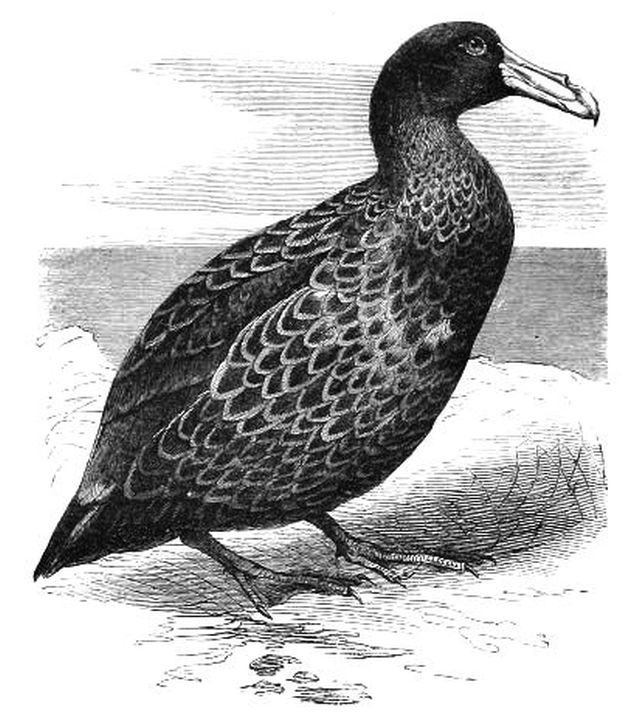

| 69. | The Giant Petrel (Procellaria or Ossifragus gigantea) | 208 |

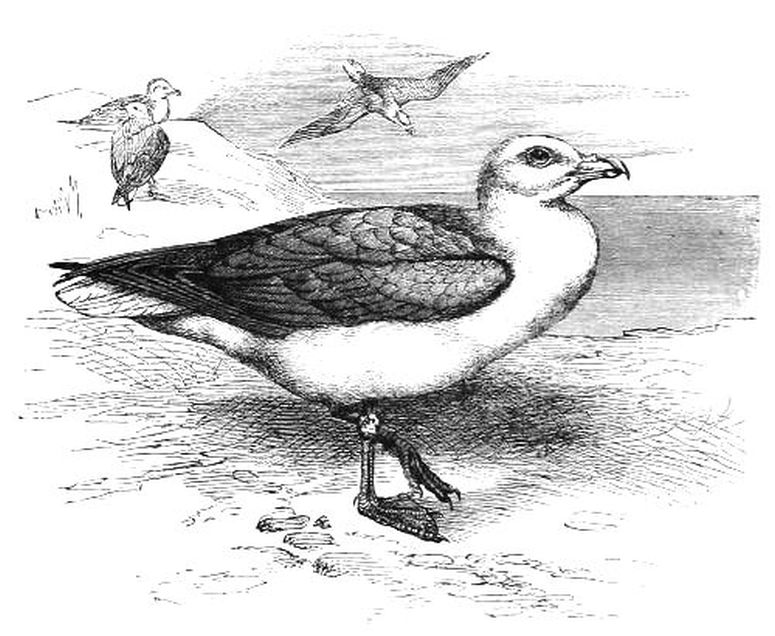

| 70. | The Fulmar Petrel (Procellaria glacialis) | 209 |

| 71. | The Cape Petrel (Procellaria or Daption Capensis) | 212 |

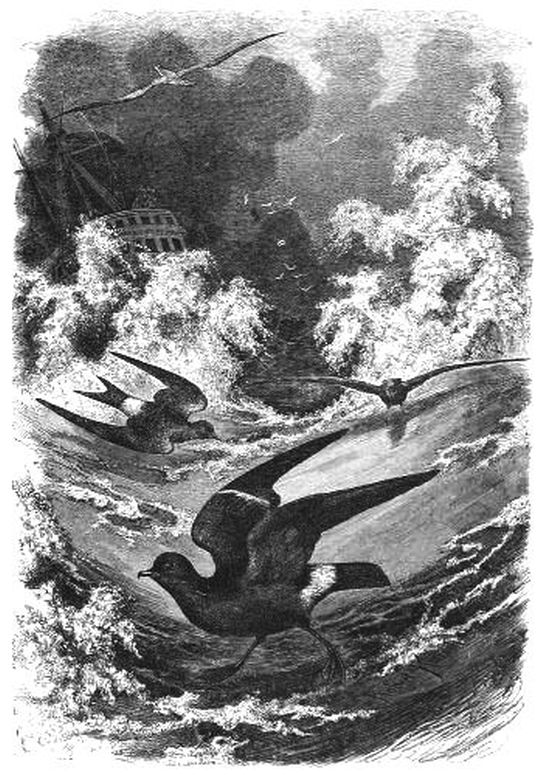

| 72. | Storm Petrels | 213 |

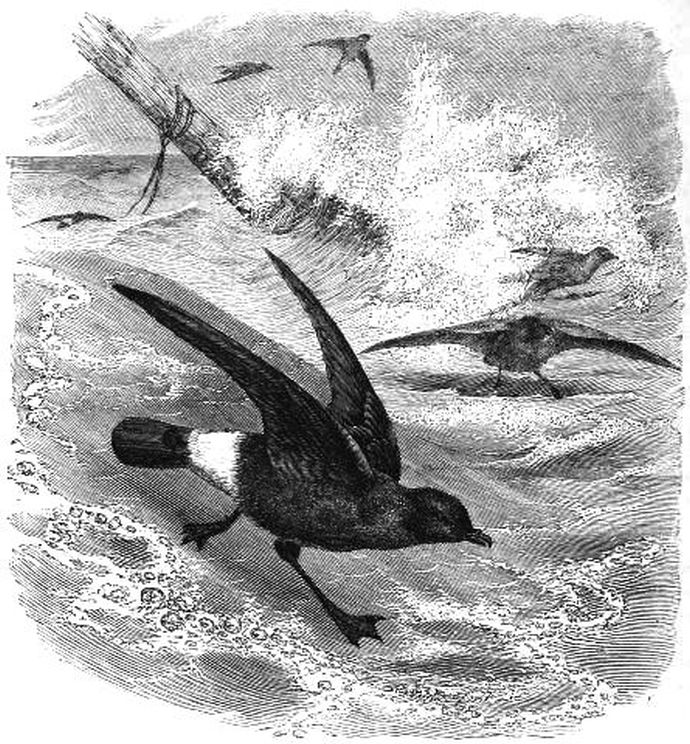

| 73. | The Storm Petrel (Thalassidroma pelagica) | 216 |

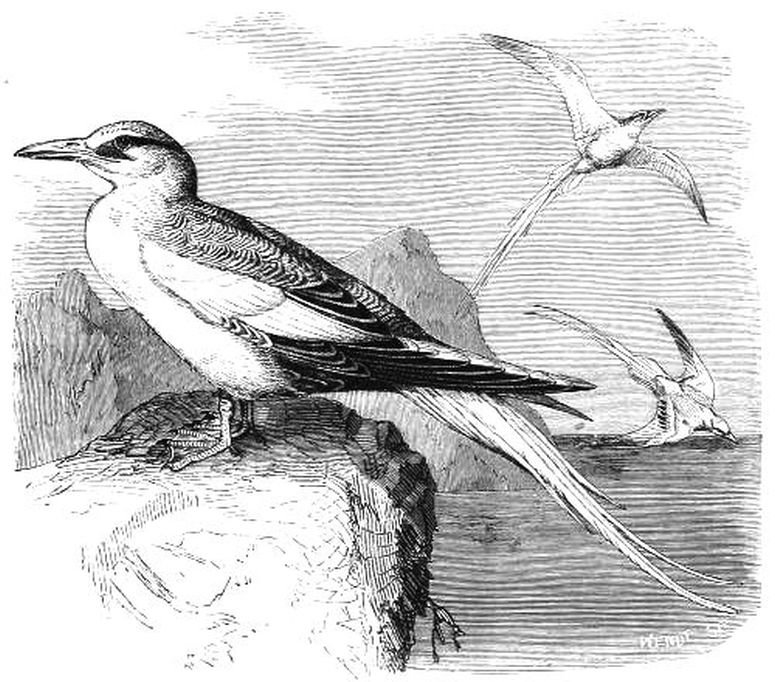

| 74. | The White-tailed Tropic Bird (Phaëton æthereus) | 221 |

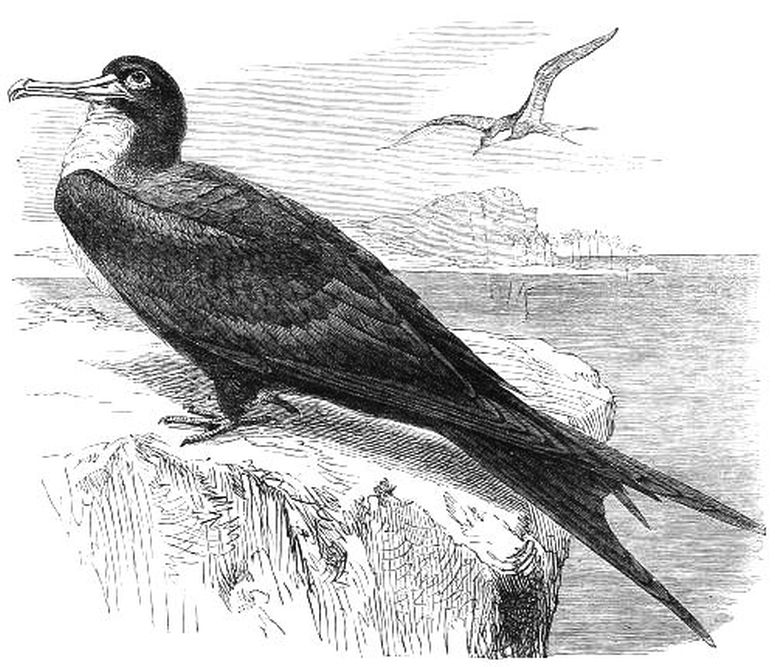

| 75. | The Frigate Bird (Tachypetes aquila) | 225 |

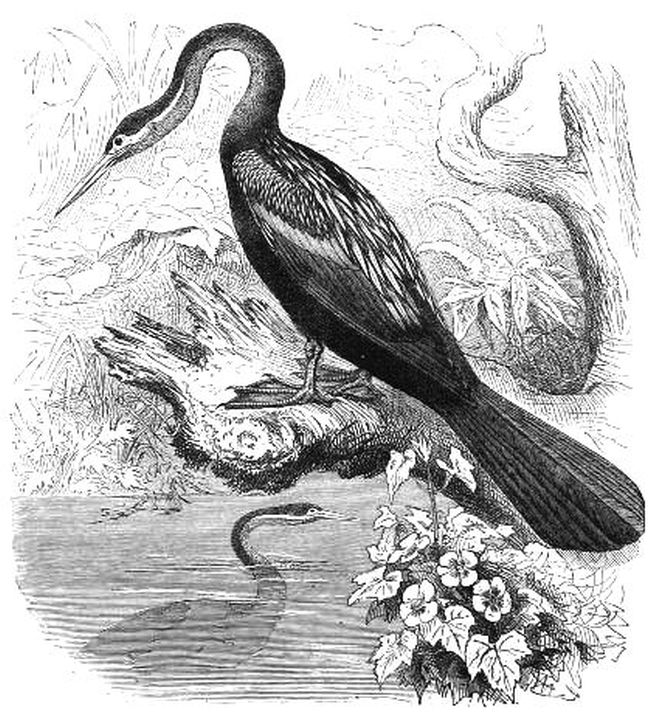

| 76. | Le Vaillant's Snake Bird, or Darter (Plotus Levaillantii) | 229 |

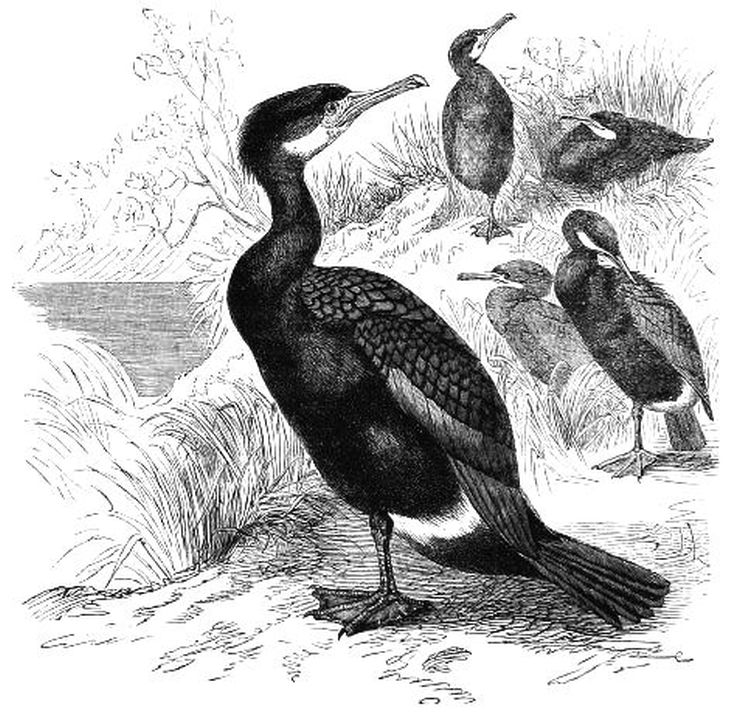

| 77. | The Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) | 233 |

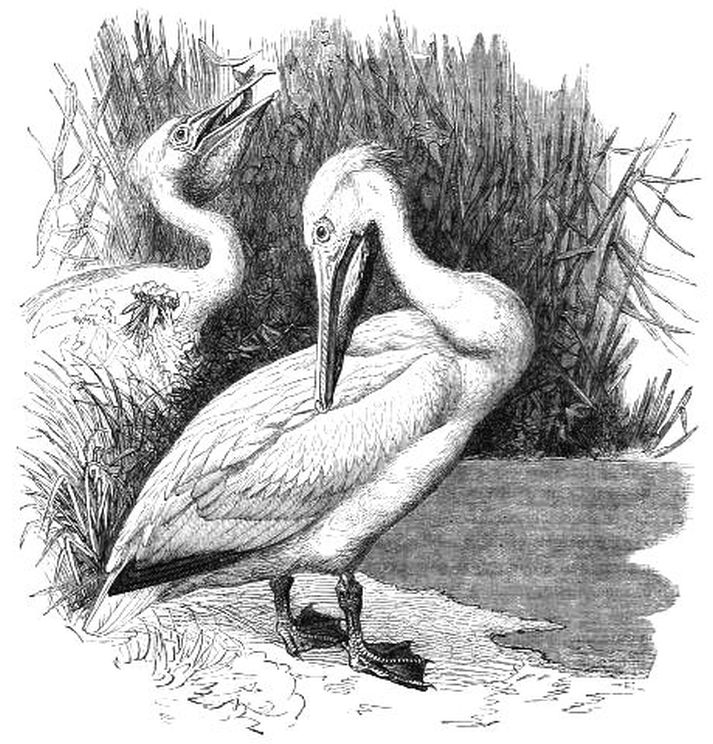

| 78. | The Pelican (Pelecanus onocrotalus) | 237 |

| 79. | The Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus) | 244 |

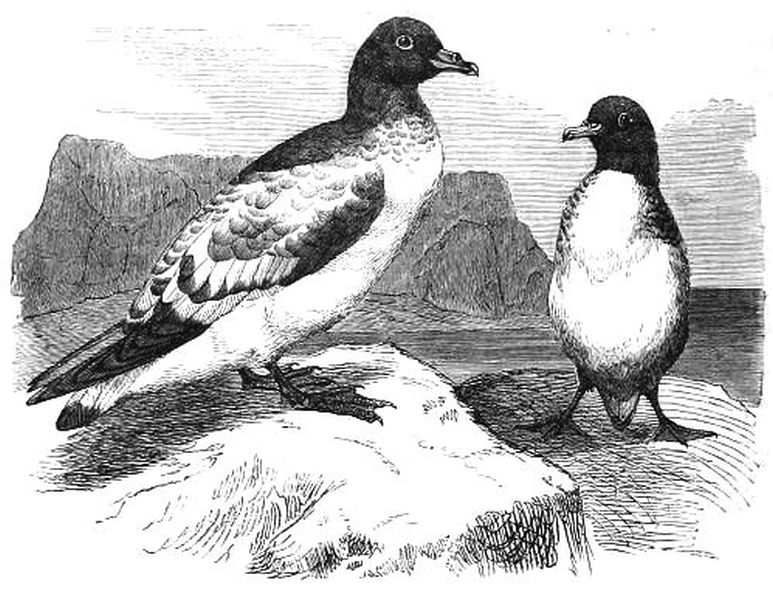

| 80. | The Common or Foolish Guillemot (Uria troile) | 253 |

| 81. | An Assemblage of Auks | 256 |

| 82. | The Great Auk, or Giant Penguin (Alca pinguinus) | 257 |

| 83. | Giant Penguins | 260 |

| 84. | The Coulterneb, or Arctic Puffin | 265 |

| 85. | The Golden Penguin (Chrysocome catarractes) | 267 |

CASSELL'S

BOOK OF BIRDS.

ââ¦â

THE STILT-WALKERS (Grallatores).

THE birds belonging to this order have unusually long legs, formed in such a manner as to enable many of them to seek their food at a certain distance in the water; and are further characterised by their long thin neck, slender high tarsi, bare thighs, three or four toed feet, and fully-developed wings; but the construction of the bill, wings, and tail, and the coloration of the plumage is so various, as to render a general description almost impossible. The Grallatores are met with in every portion of our globe, and alike occupy open plains, mountain rangesâeven as high as the snow-lineâfertile valleys, or arid deserts, contesting possession of the sea-shore or river banks with the True Swimming Birds, and that in such extraordinary numbers, as often to render it a matter of wonder whence a sufficient supply of food can be obtained. During a three days' passage into the White Nile we have seen an almost uninterrupted line of birds of this description, numbering some fifty different species, running, fishing, and bathing, in thousands and tens of thousands, upon each side of the stream, and literally swarming in every lake, pond, or ditch in the vicinity. In Southern Asia and some of the islands of Southern and Central America they are equally numerous, and overspread the sea-shore for miles. Travellers in Southern India tell us that it is not uncommon to see them perched so thickly on the trees as to give these the appearance of being covered with magnificent white blossoms. Insects, worms, spawn, fishes, and various small animals and reptiles, constitute the principal food of these voracious birds; some also consume seeds, leaves, and tender shoots of plants. As regards their powers of locomotion considerable difference is observable, according to the situations which the various species have been created to occupy; for while some run with the utmost swiftness, and fly with an energy scarcely inferior to that displayed by the Raptores, others move but slowly over the surface of the ground, and make their way through the air with comparative labour and difficulty. Some few frequent the branches of trees, and only take to the water in emergencies; but, for the most part, they both dive and swim with extraordinary facility. The vocal powers of the Grallatores are extremely limited; indeed, some species are capable of producing nothing more than a hoarse, hissing note, while others endeavour to make up for their deficiency in this respect by clapping with their mandibles. No less various is the development of the senses, or the peculiarities of disposition observable in the members of this extensive section, and to these we must therefore allude more particularly when describing the different groups under which they have been classified. All such as inhabit the temperate zones migrate, whilst those occupying warmer regions make excursions with great[Pg 2] regularity at certain seasons, but probably do not venture to any great distance from their native haunts. Of the incubation of these birds it is impossible to speak in general terms.

The BUSTARDS (Otides) [Coloured Plate XXXII.] are of large size, with a heavy body, thick neck, moderately large head, and a powerful beak, almost as long as the head; this beak is of conical form, but compressed at its base, and slightly arched at the ridge of the upper mandible. The tarsi are high and strong, the feet furnished with three toes, the wings wedge-shaped, and formed of well-developed quills, of which the third is the longest; the tail is composed of twenty broad feathers; and the plumage is thick, smooth, and compact: in some instances, the feathers on the head and nape are prolonged or very brilliantly coloured. The male is recognisable from his mate by his superior size and brighter hues. The young resemble the mother after the first moulting. These birds are represented in every division of our globe, with the exception of America, and are especially numerous in the grassy steppes and barren tracts of Asia and Africa. In Europe they occupy the open cultivated country, but are never so numerously met with as in other parts of the Old World. They entirely avoid large forests, but occasionally take up their abode in woodland districts. Such as occupy warm latitudes do not migrate, whilst the natives of temperate zones either go south at the approach of winter, or at least wander forth and sweep the surrounding country. During the breeding season they live in small parties, but afterwards associate in large flocks, often numbering some hundreds. They are remarkably shy and wary, usually keeping to open ground, and in the summer endeavour to elude pursuers by their wonderful rapidity of foot, which enables them to scud along at a most extraordinary pace. At this season, if alarmed, they run for some distance before rising, but once on the wing, fly with strength and rapidity, always keeping near the ground. In the autumn, on the contrary, they rise with facility, and fly to a great distance. Some species of Bustards are capable of uttering clear resonant notes, while others are so deficient in this respect as to produce nothing more than an occasional dull and toneless sound. As regards the development of their senses, with the exception probably of that of smell, they are highly endowed, and in their intercourse with their feathered companions, or even with man himself, exhibit no slight degree of intelligence and courage.

THE GREAT BUSTARD.

The GREAT BUSTARD (Otis tarda), as it has been called, is distinguishable from all other species of the family by the beard-like tuft of feathers that adorns the chin of the male bird. The head, upper breast, and upper part of the wing, are light grey; the feathers on the back reddish yellow, striped with black; those of the nape rust-red, tipped with white, and decorated with a black stripe, the exterior being almost entirely white. The primary quills are dark greyish brown, with blackish brown tip and outer web, and yellowish white shaft; the secondaries are black with white roots, those at the exterior being nearly pure white. The beard consists of about thirty long, slender, and ragged greyish white feathers. The eye is deep brown, the beak blackish, and the foot grey. This fine and stately bird is from three feet and a quarter to three feet and a half long, and from seven feet and a half to eight feet broad; the wing measures two feet and a quarter, and the tail eleven inches. The female is much smaller than her mate, less striking in colour and without a beard; her length is at most two feet and three-quarters, and the expanse of the wings six feet.

These birds occupy the wild open parts of Europe and Asia, only occasionally visiting North-western Africa during the winter months. In Great Britain they were formerly abundant, but are now quite extinct; in France and Germany they are occasionally met with, and are more or less numerous throughout Southern Europe. Mr. Nicholson, who had an opportunity of studying the habits of the Bustard in the neighbourhood of Seville, where it is still common, tells us that[Pg 3] the stomachs of those he killed were literally crammed with stalks and ears of barley, and with the leaves of a large green weed, and a kind of black beetle. Such as he observed generally flew, when flushed, two miles or more at an elevation of at least a hundred yards. The same gentleman states that they never attempted to escape by running, and that if winged, they showed a disposition to remain and fight rather than to have recourse to their legs. An individual, kept by Mr. Bartley, lived principally upon birds, chiefly Sparrows, which it swallowed whole, feathers and all, with the greatest avidity; it also ate the flowers of charlock and the leaves of rape, as well as mice, and, indeed, any animal substance it casually met with. In disposition these Bustards are so shy and wild that, according to Schomburghk, they can never be approached except whilst eating. On the Continent they are often shot with a rifle. The flesh of the young is much esteemed, and is often exposed for sale in European markets. Like other members of the family, this species is not stationary in one place, but when it does not actually migrate, flies, at certain seasons of the year, to a considerable distance from its native haunts. When about to mount on the wing, it takes two or three springy steps, and then rises with slowly flapping pinions until it has reached a certain height, when it darts away with such rapidity as almost baffles the eye and gun of the sportsman. Whilst in flight the neck and legs are stretched forwards, and the hinder part of the body kept low, thus imparting an indescribable peculiarity to the bird when seen in the air. The voice of the Great Bustard is so low as to be scarcely audible except at a short distance. According to Naumann, during the breeding season it utters a deep dull sound, resembling the syllables "hah, hah, hah." In their habits these birds are strictly terrestrial; the whole day is passed upon the ground; the early morning hours being occupied in fighting, screaming, and feeding; at noon they repose for a time and dust themselves preparatory to going again in search of food before evening closes in. The pairing season is in April, and at that time desperate battles take place among the males. During these engagements the tails of the combatants are raised and spread out in the manner of a fan, the wings hang down to the ground, and they charge each other like Turkey-cocks. The strongest collects about him the largest harem, and pairing takes place in the same amusing way as among the Turkeys. The female lays two or three olive-grey eggs, marked with red and liver-brown spots, in a hole which she scratches in the ground. The period of incubation is said to be twenty-eight days, and as soon as the young are hatched, they are capable of following their mother in search of food.

The methods adopted for capturing the Bustard are various. From its extremely shy nature, and from its habit of keeping to the open country, it is not easy of approach. Of wayfaring people, however, it seems to have little apprehension; the usual plan, therefore, is for the sportsman either to clothe himself like a peasant, or to put on female apparel, and to make up to it with a basket on his back, and holding the gun closely by his side. Sometimes, also, these birds are chased with greyhounds, which are conveyed towards them in covered carts, until such time as they evince symptoms of alarm and begin to move off, when the dogs are slipped from their couplings.[Pg 4]

BUSTARDS (Otis tarda).

In the Catalogue of the Tradescant Museum, preserved at South Lambeth, bearing date 1656, is mentioned: "The Bustard, as big as a Turkey, usually taken by greyhounds on Newmarket Heath;" and Mr. Knox states in his "Systematic Catalogue of the Birds of Sussex," published in 1835, that he met with some very old people who, in their younger days, had seen flocks of these noble birds on the downs. Royston Heath is mentioned by Willughby as frequented by them, and White of Selborne, in his Journal records: "I spent three hours of this day, November 17, 1782, at a lone farmhouse in the midst of the downs, between Andover and Winton. The carter told us that, about twelve years before, he had seen a flock of eighteen Bustards on that farm, and once since only two." The authors of the "Catalogue of the Birds of Norfolk and Suffolk," published in 1827, affirm that Bustards, although much scarcer than formerly, still continue to breed in the open parts of both counties, and Yarrell gives other instances of their occurrence within a comparatively recent period. That they were formerly considered articles of special luxury for the table is evidenced by the price affixed to them in Dugdale's "Origines Judiciales," in an account of the various kinds of game consumed at a feast in the Inner Temple Hall on the 16th of October, 1555, namely: Bustards, 10s.; Swans, 10s.; Cranes, 10s.; while Turkeys are estimated only at 4s.[Pg 5]

THE LITTLE BUSTARD (Otis tetrax, or Tetrax campestris).

THE LITTLE BUSTARD.

The LITTLE BUSTARD (Otis tetrax, or Tetrax campestris) differs from the above species, not only in the inferiority of its size and general coloration, but in the curious prolongation of the feathers on the nape and throat. In the male bird the black throat is enlivened by white streaks, one of which passes from the ear to the gullet, and the other over the crop; the face is dark grey, the top of the head light yellow spotted and marked with black; the edges of the wings, feathers of the tail-covers and entire under side are white, the quills dark brown, and tail-feathers white, marked with two lines at their extremity. The eye is light or brownish, the beak horn-grey tipped with black,[Pg 6] and the foot straw-colour. The length of this species is from eighteen to nineteen inches, its breadth thirty-six inches, the wing measures ten and the tail five inches. The female is smaller than her mate, and has the side of her head of a yellowish hue; her throat is whitish; breast light yellow, striped with black; the spots upon her mantle are more clearly defined than in the plumage of the male; the feathers of her upper wing-covers are white spotted with black; her under side is white. The Little Bustard is met with principally in the southern parts of Europe, extending from the south of France, over Turkey, Greece, Italy, and Spain; it is particularly numerous in Sardinia, and is seen in large flocks upon the steppes of Southern Russia, particularly during the migratory season. According to Yarrell, this bird can only be regarded as an accidental or winter visitor to Great Britain, it having been killed here only between autumn and the middle of spring. The nest or eggs have never been found in the British Islands. In the course of its migrations, it occasionally visits the country round the Altai Mountains, and Syria. During our stay in Egypt, we saw but a single specimen. Unlike the larger species, the Little Bustard is not restricted to flat and open districts, but frequently inhabits mountainous regions; in Spain it principally occupies vineyards, wherever these may be situated. Although closely resembling the species last described in many respects, it yet differs from it considerably in the ease and comparative lightness of its movements. Its gait is more graceful, and its pace extraordinarily rapid; its flight is swift and capable of being long-sustained. In disposition it is cautious, but by no means so shy as the Great Bustard: if disturbed it seeks safety by squatting close to the ground among the grass or brushwood; and its voice is seldom heard except during the period of incubation. Insects, worms, beetles, grasshoppers, larvæ, and occasionally portions of plants or seeds constitute the food of this species; the young probably are reared exclusively on insect diet. The breeding season commences about the end of April, and is inaugurated by violent battles between the male birds; the eggs, from four to five in number, are about the size of those of the Domestic Fowl, and have a glossy yellowish brown or yellowish green shell more or less distinctly spotted with reddish brown; they are deposited in a slight hollow on the ground. The male seldom goes to any great distance from his mate whilst she is brooding, and beguiles the time by making short undulating flights in her immediate vicinity. We are almost without particulars respecting the rearing of the young.

The HOUBARAS (Hubara) constitute a distinct group, comprising but two species, both of which have been found in Europe. The distinguishing characteristics of these birds are their long beak, short foot, the crest upon their head, and the beautiful collar that adorns their neck.

THE INDIAN HOUBARA.

The INDIAN HOUBARA (Hubara Macquenii) is an inhabitant of Southern Asia, and from thence has occasionally visited Central Europe and even England. Upon the brow and sides of the head the plumage is of a reddish grey, powdered with brown; the long crest is black in front and white behind; the feathers on the nape are whitish, striped with brown and grey, and those on the back ochre-yellow delicately pencilled, and in some parts spotted with black; the throat is white above and brown below; the upper breast grey, and the belly yellowish white. The collar is composed of long streaming feathers situated on both sides of the neck; of these the lower ones are white, those higher up white with black tips and base, whilst those at the top are entirely black. The quills have white roots and black tips; the tail is of a reddish shade delicately spotted and decorated with two stripes; the eye is bright yellow; the beak slate-grey; and the foot greenish yellow. According to Jerdon, the length of the male varies from twenty-five to thirty inches, and its breadth from four to five feet; the wing measures from fourteen to fifteen, and the tail from nine to ten inches.[Pg 7] After the breeding season, the male moults his beautiful crest. According to Jerdon, the Indian Houbara is found throughout the plains of the Punjaub and Upper Scinde, occasionally crossing the Sutlej at Ferozepore; but no record exists of its occurrence eastward of Delhi. It is probably a permanent resident in the localities where it is found, as no notice is given of its appearance at any particular season. This bird inhabits open and sandy plains, or undulating sandy districts besprinkled with scattered tufts of grass; it also frequents fields of wheat and other grain, and is generally met with in open ground. Being very wary it is approached with difficulty, except in the heat of the day, when it lies down beneath a thick tuft or other shelter, and is easily secured. The Houbara is much hunted with Hawks both in the Punjaub and Scinde, the Falco sacer being generally employed for this purpose. The bird, however, occasionally baffles the Falcon by ejecting a horrible, stinking fluid, which besmears and spoils the plumage of his enemy; just as in Africa its congener is said to defend itself from the Sakr Falcon. Adams states that the Houbara is very destructive to wheat-fields, as it eats the young shoots; but insects of various kinds doubtless constitute its principal food. The flesh is exceedingly tender, and is often so loaded with fat that the skins are with difficulty dried and preserved. Captain Hutton tells us that this bird is common in the bare and stony plains of Afghanistan, where it is met with in parties of five or six together. It flies heavily, and for a short distance only, soon alighting and running over the ground. The Houbara has been found in Mesopotamia and other parts of Asia, and occasionally, but very rarely, in Europe. The stomach of a specimen killed in a stubble-field in Lincolnshire, in 1847, was filled with caterpillars of the common yellow underwing moth, small shelled snails, and beetles. The eggs of this species are from three to five in number, yellowish, spotted, and oval-shaped, and about the same size as those of the Turkey. Viera informs us that the eggs are deposited in a slight hollow, amongst the grass or corn; that the brood make their appearance within five weeks; and that they at once begin to run about after the manner of young chickens. The following graphic account of hawking the Houbara is given by Sir John Malcolm, in his "Sketches of Persia":â"We went," says that writer, "to see a kind of hawking peculiar, I believe, to the sandy plains of Persia, on which the Houbara, a noble species of Bustard, is found on almost bare plains, where it has no shelter but a small shrub called 'geetuck.' When we went in quest of these birds we were a party of twenty, all well mounted. Two kinds of Hawks are necessary for this sport: the first, the Cherkh (the same which is flown at the antelope), attacks them on the ground, but will not follow them on the wing; for this reason the Bhyree, a Hawk well known in India, is flown the moment the Houbara rises. As we rode along in an extended line, the men who carried the Cherkhs every now and then unhooded them and held them up that they might look over the plain. The first Houbara we found afforded us a proof of the astonishing quickness of sight of one of these Hawks; she fluttered to be loose, and the man who held her gave a whoop as he threw her off his hand, and then set off at full speed. We all did the same. At first we only saw our Hawk skimming over the plain, but soon perceived at the distance of more than a mile the beautiful speckled Houbara, with his head erect and wings outspread, running forward to meet his adversary. The Hawk made several unsuccessful pounces, which were either evaded or repelled by the beak and wings of the Houbara, which at last found an opportunity of rising, when a Bhyree was instantly flown, and the party were again at full gallop. We had a flight of more than a mile, and then the Houbara alighted and was killed by another Cherkh, which attacked him on the ground. This bird weighed ten pounds. We killed several others, but were not always successful, having seen our Hawks twice completely beaten during the two days that we followed the sport." When taken young, the Houbara is susceptible of being tamed, and has been reared among the fowls in a Farm-yard: when thus treated it is, however, very shy and timorous, hiding itself in holes and corners, and refuses to breed.[Pg 8]

THE AFRICAN RUFFLED BUSTARD.

The AFRICAN RUFFLED BUSTARD (Hubara undulata), though of larger size, closely resembles the above species in its general appearance, but has the back and wings of a deeper brown shade, and the crest entirely white.

Although rarely met with in Europe, this Houbara is plentiful in the sandy deserts of Arabia and North Africa, where its exquisitely-flavoured flesh is much prized. We are but imperfectly acquainted with its habits, and have no information respecting its eggs or nidification. Gould is of opinion that the crest of the female is either very small or entirely wanting, and that the male bird only wears his plume during the breeding season.

THE FLORIKIN.

The FLORIKIN (Sypheotidis Bengalensis), one of the most valued game-birds of India, is during the breeding season of a glossy black upon the head, nape, breast, and entire under side; the back, secondaries, rump, and feathers of the lower tail-covers are of a brownish hue, delicately marked with zigzag black lines, and each feather decorated with a black spot in its centre; the shoulder-feathers and quills are pure white; of the latter the three first are black upon the outer web, whilst the rest have black shafts and tips. The tail is black, spotted with brown, and tipped with white. The eye is brown, the beak black above, and yellow beneath; the foot is greenish yellow, and the heel blue. This species is from twenty-four to twenty-seven inches long, and from forty-four to forty-seven broad; the wing measures fourteen and the tail seven inches. After the breeding season the male appears in a different garb, in some degree resembling that of his mate. The head and entire upper portion of the body are, in the female, of a pale red, spotted, striped, and marked with black and brown; the feathers on the upper wing-covers are whitish, and those of the nape lined with black; the quills are striped dark brown and red. The female is from twenty-eight to twenty-nine inches long, and fifty inches broad. This fine bird, according to Jerdon, is found throughout Lower Bengal, north of the Ganges, extending to the south bank above the junction of the Jumna, and thence spreading through the valley of the Jumna into Rajpootana, the Cis-Sutlej States, and parts of the Punjaub; in the east it occurs in Dacca, Tipperah, Silhet, and Assam, and northwards to the foot of the Himalayas. It frequents large tracts of moderately high grass, whether interspersed with bushes or otherwise, grass charrs, or rivers, and occasionally cultivated ground; but it appears to be very capricious in its choice, several often congregating in certain spots to the exclusion of others that seemed equally favourable. From February to April it may be seen stalking about the thin grass early in the morning, and it is observed to be often found about newly-burnt patches; or one or more may be noticed winging their way to some cultivated spot, a pea-field, or mustard-field, to make their morning repast, after which they fly back to some thicker patch of grass to rest during the heat of the day. At this time, as well as during the earlier part of the year, they are usually met with singly, sometimes in pairs, male and female, not far distant from each other; or, as stated previously, three or four will be found in some favoured spot. According to Hodgson, the Florikin is neither monogamous nor polygamous, but the sexes live apart, at no great distance, and this would appear to be very probable. The Florikin breeds from June to August. At this season the cock bird may be seen rising perpendicularly into the air with a hurried flapping of his wings, occasionally stopping for a second or two, and then rising still higher, raising his crest at the same time, puffing out the feathers of his neck and breast, and afterwards dropping down to the ground; he repeats this manÅuvre several times successively, humming, as Hodgson asserts, in a peculiar tone. Such females as happen to be near obey this saltatory summons; and, according to Hodgson, when one approaches, he trails his wings, raises and spreads his tail like a Turkey-cock, humming[Pg 9] all the while. At this time the hen Florikin is generally to be found in lower ground and thicker grass, and is flushed with difficulty, as she conceals herself at the first approach of danger. She lays from two to four eggs in some sequestered spot, well hidden by the grass; these are of a dull olivaceous tint, more or less blotched, and covered with dark spots. Two females are said not unfrequently to brood near each other.

Plate 32. Cassell's Book of Birds

THE HOUBARA ____ OTIS MACQUEENII

(one quarter Nat. size)

The Florikin has a steady flapping flight, which is not very rapid, and is seldom prolonged to any considerable distance. When feeding, it is shy and wary, and will often rise at some distance, but speedily takes refuge in a thick patch of grass, and may then be easily approached. It is usually silent, but if suddenly startled rises with a shrill metallic "chik, chik," which is occasionally repeated during its flight. The food of the Florikin consists chiefly of insects, grasshoppers, beetles, and caterpillars; but it also eats small lizards, snakes, centipedes, and similar fare. According to Hodgson, it often consumes seeds and sprouts, but Jerdon is of opinion that these are not taken by choice, but swallowed with the insect diet. This bird is highly esteemed for the table, and by some numbered amongst the most delicate of Indian game. In all parts of India, therefore, the Florikin is eagerly sought for by sportsmen. It is frequently killed during a tiger-chase, and is occasionally taken by the help of the Falcon.

THE TROCHILUS, OR CROCODILE WATCHER (Hyas Ãgyptiacus).

The COURSERS (Tachydromi), a group in many respects closely resembling the smaller species of Otides, are slenderly-formed birds, with long legs, large, pointed wings, short tails, and a moderate-sized delicate beak of about the same length as the head, in most instances slightly curved, and[Pg 10] covered with a cere at its base. The leg is slender, the foot furnished with three toes, which are armed with delicately small claws, and almost entirely unconnected. The tolerably thick plumage is usually of a nearly uniform reddish brown colour, or sandy yellow, and varies according to the sex and age. These birds inhabit the arid plains and sandy deserts of Africa and Southern Asia, one species alone frequenting such spots as are in the vicinity of water, into which, however, it does not venture to wade. Their flight is rapid and powerful, and upon the ground they run with almost incredible ease and speed. Insects and larvæ constitute their diet; the seeds occasionally found in their stomachs being only accidentally swallowed in their hasty search for food. Except during the breeding season they live in small parties, and frequently associate with birds of similar habits. It is undetermined whether the Tachydromi should be regarded as stationary birds or not; some species certainly wander over the country, and occasionally appear at great distances from their native haunts.

THE CREAM-COLOURED COURSER.

The CREAM-COLOURED COURSER (Cursorius isabellinus) possesses a slender body and large wings, in which the second quill is longer than the rest; a comparatively short, broadly-rounded tail, composed of from twelve to fourteen feathers; a long, decidedly-curved bill, slender tarsi, and feet furnished with three toes. The thick, soft plumage is of a cream-colour, the upper parts of the body having a reddish and the under side a yellowish tinge; the nape is blueish grey, divided from the rest of the body by a white and a black line commencing at the eyes, and merging into a triangular patch on the nape; the secondaries are sand-yellow, with a black spot near the white tip, and a pale inner web. All the tail-feathers are reddish cream-colour, except two in the centre; these are tipped with white, and striped with black. The eye is brown, the beak blackish, and the foot straw-colour. This species is from eight inches and a half to nine inches long, and nineteen broad; the wing measures six inches, and the tail two inches and a half. The female closely resembles her mate; the young are at once recognised by the mottled and spotted appearance of their somewhat lighter plumage; their primary quills have yellow tips, and the nape is adorned by a whitish stripe bordered by a few black feathers.

The Cream-coloured Courser is a native of Africa, and is met with in Egypt, Nubia, and Abyssinia, being most numerous in the last-mentioned country; it appears in summer along the coast-line from Tangiers to Tripoli, and is seldom found north of the Mediterranean. This bird is one of the rarest visitors to our shores, but three or four specimens have occurred in Great Britain since 1785. Some years ago one was shot in Kent, whilst running over some light land. So little timidity did it exhibit that the gentleman who killed it had time to send for a gun, which did not readily go off, and he in consequence missed his aim. The report frightened the bird away, but after making a turn or two it again settled within a hundred yards, and was dispatched. It was observed to run with incredible swiftness, and at intervals to pick up something from the ground, and was so bold as to render it difficult to make it rise in order to shoot it while on the wing. The note was not like that of a Plover, nor, indeed, to be compared with that of any known bird.

From February to July these Coursers live in pairs, and are usually met with running together over the arid sands of their desert haunts. Travellers tell us that they frequently dart along with such extraordinary rapidity that, like the spokes in a swiftly-turned wheel, their limbs become invisible, so that at a distance they present the appearance of legless bodies darting through the air; if pursued by man, it is not uncommon for them thus to avoid his approach for hours together. If very sorely pressed, they rise upon the wing to a moderate height, and hover for a time before recommencing their wild career. They will allow a rider to come nearer than a man on foot; but even when mounted, it is extremely difficult to get a shot at them, as their many enemies soon render[Pg 11] them very timid. We learn from Bädeker that the eggs of this species are from three to four in number, short and broad, with a sand-coloured glossy shell, marked and dotted with a darker shade. These are deposited in a slight hollow in the ground amongst short grass or stones. We are unacquainted with further particulars respecting the nidification of the Cream-coloured Courser.

THE TROCHILUS, OR CROCODILE WATCHER.

The TROCHILUS, or CROCODILE WATCHER (Hyas Ãgyptiacus, or Trochilus), differs in many essential particulars from the above group, to which, however, it is nearly allied. The body of this bird is compact, the neck short, and the head moderately large. The beak is not more than half as long as the head, compressed at its sides, and drawn in at the margins; the upper mandible rises gently from the base, and again curves downwards towards the tip; the lower mandible is straight; the leg is high, bare, and but three-toed; the wing, in which the first quill exceeds the rest in length, is so long, that it extends as far as the tip of the rounded tail. The secondary quills are also unusually developed. In this very beautiful bird, the top of the head, the broad cheek-stripes which unite at the nape, a wide stripe on the breast, and the long slender back-feathers are all black; the eyebrows, throat, gullet, and entire under side are white, shading into pale reddish brown on the sides and breast, and into brownish yellow in the region of the rump; the feathers on the shoulder and upper covers are pale slate-blue or grey; the quills, with the exception of the first (which has only a light border at the base of the outer web) are black in the centre and at the tip, the rest of the feathers being white, thus forming two broad stripes to the wings, which have a very fine appearance when fully spread. The tail-feathers are blueish grey tipped with white, and decorated with a black stripe. The eye is light brown, the beak black, and the foot light grey. The body is about eight inches and a half in length; the wing measures five inches, and the tail two inches and three-quarters. The female is but little smaller than her mate.

Herodotus gives the following quaint account of the supposed strange friendship between this species and the crocodile:â"All other beasts and birds," says that old Greek writer, "avoid the crocodile, but he is at peace with the Trochilus, because he receives benefits from it, for when the crocodile gets out of the water and then opens his jaws, which he does most commonly towards the west, the Trochilus enters his mouth and swallows the leeches which cling to his teeth. The huge beast is so pleased with this service that he never injures the little bird." This well-known account is still current in Egypt, with the addition of another tale traditional among the Nile boatmen concerning this bird, which they call the Zic-zac, in imitation of its call. The crocodile, they say, while reposing on a sandbank, often falls asleep, quite forgetful of his bird friend, who is busy within his large mouth clearing his teeth from their troublesome leech appendages. The Zic-zac, finding the huge door closely shut upon him, gives the crocodile a sharp reminder of his presence by striking his spurs into the mouth of the monster, who immediately sets the prisoner free. The Hyas Ãgyptiacus is met with throughout all the country watered by the Nile, and on the shores of all the rivers of Western Africa. It is very doubtful whether any stray specimens have really visited Europe as has been stated; this species, according to our own observations, being strictly stationary in its habits, and only quitting one sandbank for another when compelled to do so by the rising of the water. In all its movements this brisk and pretty little bird displays great ease and rapidity. During the course of its flight, which is never long sustained, it keeps close to the surface of the river, and frequently repeats its shrill whistling cry. Towards every living creature the Trochilus manifests the same utter fearlessness which he exhibits towards his neighbour the crocodile, over and around whose large body he constantly disports himself on the sandbanks, and gleans off the insect parasites that torment him. We can distinctly affirm that we have ourselves repeatedly seen the little creature[Pg 12] performing the tooth-clearing operation the ancients attributed to it, and which many modern writers have declared to be fabulous. Insects of all kinds, worms, small fish, mussels, and, according to some authorities, scraps of meat, and occasionally seeds, form the principal diet of the Crocodile-Watcher. Only once, in spite of all our endeavours, could we discover the carefully-concealed eggs. After many fruitless efforts our attention was attracted whilst looking through a telescope by a pair of birds, one of which was sitting in the sand, and the other running hither and thither in the immediate vicinity. Using every precaution we approached, but were no sooner observed than the brooding parent arose, and after going hurriedly to a short distance, joined its mate, and both together walked slowly from the spot with such a wonderful affectation of indifference, that we were completely taken in, and should not have carried our investigations any further had not a slight unevenness of the ground caught our eye. On removing the sand, two beautiful eggs were brought to light, having a reddish yellow shell, dotted and marked in a variety of ways.

THE COLLARED PRATINCOLE (Glareola pratincola).

The PRATINCOLES, or SWALLOW-WINGED WADERS (Tracheliæ), are recognisable at once by the swallow-like formation of their long wings, in which the first quill exceeds the rest in length; by their long, straight, or forked tail composed of fourteen feathers, and their slender bare legs. The toes, four in number, are very slender, the three in front are connected by a skin, and furnished with narrow, sharp, and almost straight claws. The plumage, which varies but little either in the sexes or at different seasons of the year, is very similar in all the species.

The Pratincoles, or Sea Partridges as they are called on the Continent, inhabit the temperate[Pg 13] and warm portions of the eastern hemisphere, and frequent the borders of lakes and rivers in the vicinity of mountains. Like the Swallow, they seek their insect prey whilst upon the wing, or from the surface of the ground, over which they run with great rapidity. The eggs, three or four in number, are deposited in a slight nest placed among rushes or thick marshy herbage.

THE COMMON THICK-KNEE, OR STONE CURLEW (Ådicnemus crepitans).

THE COLLARED PRATINCOLE.

The COLLARED PRATINCOLE (Glareola pratincola) is a beautiful bird, about ten inches long and twenty-two inches and a half broad, with the wing measuring seven inches, and the tail, at the centre of the fork, two inches and a half. The upper portions of the body are greyish brown, the wings, lower breast, and under side white; the reddish yellow throat is encircled by a brown ring, and the head is brownish grey; the tail-feathers and quills are tipped with black. The eye is dark brown, the beak black, with bright red corners, and the foot blackish brown. The male and female are almost alike in size. This bird inhabits Northern Africa, and the countries watered by the Don, the Volga, and the Caspian and Black Seas; and although it periodically visits France, is rarely seen in Great Britain. Everywhere it occupies the margins of rivers and lakes, equally frequenting the vicinity of fresh and salt water. The Collared Pratincole flies with great ease and swiftness, and indulges in a variety of graceful evolutions whilst on the wing; upon the ground its walk, though rapid, is seldom prolonged, and every step is accompanied by a constant whipping with the tail. Its food consists principally of aquatic insects, but it seizes its prey with equal facility on land, from the surface of the water or in the air; indeed, it is not uncommon to see one of these active little birds dart to a height of several feet into the air, in order to seize a passing fly. It consumes locusts in[Pg 14] great numbers, and, according to Jules Verreaux, is often to be found in the track of the hosts of these creatures that are met with in Southern Africa. The nest consists of a slight hollow in the ground, lined with fibres and blades of grass; the eggs, four in number, have a yellowish brown or greenish grey shell, spotted with grey, and variously marked with light brown and deep black. So great is the attachment of these Pratincoles for their mates and young that we are told, should one of a pair be shot, the other at once runs to its companion's side in utter disregard of its own safety. If the little family are intruded on, the parents frequently feign to be wounded, or by other devices entice the enemy from the nest. The helpless young, if alarmed, crouch to the ground, and are with difficulty detected, owing to the earthy colour of their downy feathers; they grow very rapidly, and soon attain the plumage of the adult birds.

The THICK-KNEES (Ådicnemi) constitute a sub-family whose members are at once recognisable by their comparatively large size, moderately long thin neck, thick head, large eyes, and a straight beak of about the same length as the head, with the culmen slightly depressed and swollen at the tip. The knees are very thick, the toes three in number, and the wings, in which the second quill is the longest, of moderate size; the secondary quills are of unusual length. The tail is wedge-shaped, and composed of from twelve to fourteen feathers. These birds are migratory, and are met with in all parts of the world, with the exception of North America; open moorlands are the localities they prefer, as affording them the largest supply of the small quadrupeds, reptiles, worms, and insects upon which they subsist, and which they seek during the evening or at night. In the daytime the Thick-knees remain closely squatted beneath a stone or any similar shelter, and if disturbed fly to a short distance, before running off rapidly to some place of concealment. The female deposits her two eggs on the bare ground; the young are able to follow their parents as soon as they quit the shell.

THE COMMON THICK-KNEE, OR STONE CURLEW.

The COMMON THICK-KNEE, or STONE CURLEW (Ådicnemus crepitans), is from sixteen to seventeen inches long and from twenty-nine to thirty broad; the wing measures eight inches and half, and the tail about five inches. The feathers upon the upper parts of the body are reddish grey, striped in the centre with blackish brown; the brow, a patch over the eyes and a line above and below the cere are white, the under side and a stripe on the upper wing are yellowish white, the quills black, and the tail-feathers bordered with black and white at their sides. The eye is golden yellow, the beak yellow with black tip, the foot straw-colour, and the eyelids yellow. The plumage of the young is principally of a rust-red. These birds are natives of the desert and barren districts of Northern Africa, Western Asia, and Southern Europe, being especially numerous in Syria, Persia, Arabia, and India. Such as occupy the most northern portions of their habitat go south late in the autumn and return to their former haunts early in spring, whilst such as dwell in the countries watered by the Mediterranean remain throughout the entire year in the same localities. In Egypt, notwithstanding their usual preference for barren tracts, the Stone Curlews not only venture into towns and perch upon houses, but occasionally make their nests on the roofs, always provided that the situation be such as to permit them to have a clear space about them, and an elevated perch from whence they can reconnoitre in order to elude the approach of danger. A nearly-allied species, residing in South Africa, frequents the outskirts of forests, selecting spots thickly covered with brushwood, in which it conceals itself if alarmed. The Common Thick-knee or Norfolk Plover, as it is called in England, is only a summer visitor to our country, appearing in April and departing in September or October. It is most numerous in the south and south-west parts of our island, and does not go north of Yorkshire. Ireland it rarely visits. According to Mr. Salmon, of Thetford, "it is numerously distributed all over[Pg 15] our warren and fallow lands during the breeding season, which commences about the second week in April, the female depositing her pair of eggs upon the bare ground, without any nest whatever; it is generally supposed that the males take no part in the labour of incubation; this I suspect is not the case. Wishing to procure for a friend a few specimens in their breeding plumage, I employed a boy to take them for me, this he did by ensnaring them on the nest, and the result was that all he caught during the day proved upon dissection to be males. They assemble in flocks previous to their departure, which is usually by the end of October; but should the weather continue open, a few will remain to a much later period. I started one as late as the 9th December, in the autumn of 1834. Montague records an instance of this bird being killed in Devonshire as early as February in 1807."

The Stone Curlew is singularly shy and cautious in avoiding observers, and should it be disturbed, at once seeks shelter by crouching to the ground; if still followed, it endeavours to escape by running, and is rarely forced to have recourse to its wings. Its flight is gentle and easy, but seldom long sustained. During the day it usually remains quiet, and in South Africa conceals itself from the presence of man almost after the manner of an Owl. No sooner, however, has night set in, than it appears in quite a new character, darting lightly about on rapid wing in search of food and water, or running swiftly over the surface of the ground. It is not uncommon for a pair of these birds to wander for miles in search of a drinking-place, returning before morning to their usual haunts. Whilst thus actively employed, their clear resonant call of "cur-lui" is constantly heard. Frogs, lizards, mice, and occasionally eggs and small birds form their principal food; field-mice they catch after the manner of a cat, and crunch the bones previous to swallowing their prey; insects they also kill before consuming them; grains of sand and pebbles are employed to assist the process of digestion. At the commencement of spring, battles between the males frequently occur in order to obtain a desired female. The eggs, from two to three in number, are deposited about April in a slight hollow in the sand, these are about the size of Hens' eggs and of the same shape, with a pale yellowish shell, spotted and streaked with deep yellow and blackish brown. The female broods and hatches her family in about sixteen days; during this time she is carefully guarded by her watchful mate. As soon as the young quit the nest, they follow their parent and receive instruction in the art of obtaining food: should danger be at hand, a cry warns them to seek shelter, and they at once conceal themselves by lying close to the ground. The Thick-knee exhibits considerable courage when protecting its family, and has been seen to defend its nest with vigour against the approach of sheep or dogs. One of these birds, kept by Brehm the elder, became extraordinarily tame and ran freely about the house, testifying the utmost attachment to his master, eating from his hand, and allowing himself to be caressed at pleasure.

The PLOVERS (Charadrii) constitute a family of short-necked, large-headed birds, of small size, with moderately long, slender, but thick-jointed legs, three-toed feet, the hinder toe being either entirely wanting or but slightly developed and much raised. The wings are pointed and slender, with the first or second quill longer than the rest, and the secondaries prolonged. The short tail is composed of twelve feathers, and slightly rounded at its extremity. The beak, which is rarely more than half as long as the head, is soft at its base and hard on the raised portion at its extremity. The thick compact plumage varies in the sexes, and according to the season of the year. The Plovers are met with in every quarter of the globe, and while some occupy the interior of the country, frequenting its plains and open grounds, others prefer the vicinity of the sea, or the margins of lakes and rivers, obtaining their food principally from the water; others, again, select desert tracts, marshes, or mountainous districts. During the breeding season all live in pairs, but near together; subsequently they collect together into large parties, which gradually increase in size as the season[Pg 16] for migrating approaches. In their habits the Plovers are usually active; they run and fly with equal facility, and though they rarely attempt to swim, are not altogether unsuccessful in that particular. Almost all the species utter a plaintive whistle, and during the breeding season can produce a few connected, pleasing notes. The three or four pear-shaped variegated eggs are deposited in a slight hollow in the ground, in which a few blades of grass are occasionally placed. Both parents assist in the work of incubation. Reptiles, worms, small quadrupeds, and insects constitute the food of these birds. Their flesh is regarded as a delicacy, and they are therefore objects of great attraction to the sportsman, although they often render themselves extremely troublesome by uttering their shrill cry, and thus warning their feathered companions of the approach of danger. From this habit they have received the name of "tell-tales." "The Charadrius carunculata, an African species," writes Livingstone, "a most plaguey sort of 'public-spirited individual,' follows you everywhere, flying overhead, and is most persevering in his attempts to give fair warning to all the animals within hearing to flee from the approach of danger."

THE GOLDEN PLOVER.

The GOLDEN PLOVER (Charadrius auratus, or pluvialis) is at once recognisable by its slender beak and feet, pointed wings, and golden plumage. The feathers on the upper portions of the body are black, thickly covered with small green or golden yellow spots, the entire under side is black. In the autumn, the throat and breast are spotted with yellowish grey; the belly is white; the black tail-feathers are streaked with white; and the black throat is decorated with a white stripe commencing at the brow and merging into the breast. The eye is dark brown, the beak black, and the foot blackish grey. This species is ten inches long and twenty-two broad; the wing measures seven inches, and the tail three inches and a half.

The Golden Plovers are especially numerous in the cooler portions of the globe, becoming gradually rarer towards 57° north latitude. In England they are generally distributed, but such as occupy the southern parts go northwards to the high hills and swampy ground of Scotland and the northern counties of England during the breeding season. These migrations usually take place at night, the birds flying at a considerable height from the ground. During the day they rest or seek for food, and, strangely enough, select not their usually favourite marshes, but fields and cultivated ground. These Plovers are brisk and nimble, running with great rapidity, and flying, not only swiftly, but gracefully. During the period of incubation they indulge in a variety of elegant gyrations in the vicinity of the nest, and their plaintive, clear whistle is heard to most advantage at that season. Worms, larvæ, beetles, snails, and slugs constitute their principal nourishment, and in order to assist digestion small pebbles are also swallowed. Water would appear to be a real necessary of life to these birds, as they love to wash and cleanse their feathers in it daily. The eggs, generally four in number, have a yellowish, stone-coloured shell, marked and spotted with brownish black. These are deposited in a slight hollow in the ground, lined with a few fibres or blades of grass. The young leave the nest immediately after quitting the shell, and follow their parents for about a month, after which time they are able to fly and seek for food on their own account. It is uncertain whether the father assists in the incubation of the eggs. Macgillivray gives the following graphic description of the parental affection observable in the male birds, as witnessed by himself on some heath-covered mountain. "Presently a breeze rolls away the mist, and discloses a number of these watchful sentinels, each on his mound of faded moss, and all emitting their mellow cries the moment we offer to advance. They are males, whose mates are brooding over their eggs, or leading their down-clad and toddling chicks among the (to them) pleasant peat-bogs that intervene between the high banks, clad with luxuriant heath not yet recovered from the effects of the winter[Pg 17] frosts, and little meadows of cotton-grass, white as the snow-wreaths that lie on the hills. How prettily they run over the grey moss and lichens, their little feet twinkling, and their full, bright, and soft eyes gleaming as they commence their attempts to entice us away from their chosen retreats." The attempts to lure intruders from their nest, above alluded to, consist in a most excellent feigning of being desperately wounded and unable to fly, or by affecting to have lamed a leg, and thus enticing the enemy to follow the cunning bird, as it slowly retreats in an opposite direction to that occupied by its beloved progeny. When the young are able to fly, the Plovers associate in flocks, which remain on the moors till winter begins, when they quit them for pasture lands. As the season advances, and the cold becomes severe, they descend to the coast, and usually remain in the vicinity of the sea during the winter. Occasionally they are so tame that, according to the authority above quoted, they will allow a sportsman to approach within fifteen yards, and even walk around them several times in order to drive them together before taking aim. "In windy weather," continues Macgillivray, "they often rest by lying flat on the ground, and I have reason to think that at night this is the general practice. In the Hebrides I have often gone to shoot them by moonlight, when they seemed as actively engaged as in the day, which was also the case with the Snipes, but I seldom succeeded in my object, it being extremely difficult to estimate the distance at night. The numbers that at this season frequent the sandy pastures and shores of the outer Hebrides is astonishing."

THE GOLDEN PLOVER (Charadrius auratus), AND THE DOTTEREL (Eudromias Morinellus).

The Golden Plover is in great request for the table, and is in perfection about September and October.

The specific name of pluvialis has been given to the Golden Plover on account of the extraordinary restlessness it exhibits before bad weather. A very remarkable instance of this characteristic is given by the Rev. R. Lubbock, in his "Fauna of Norfolk." According to that gentleman, he was much struck by the perpetual wheeling, now high, now low, of a large flock of these birds one fine bright day at the end of December. They were not still for a moment, and yet there appeared to be no cause for such unwonted disturbance. All next day they were in the same state of uproar, and on the following morning, which was as calm and mild as the preceding, the Plovers had all departed. About five o'clock in the morning, on the same day, the wind began to howl, signs of a severe tempest set in, and by the evening so much snow had fallen that in some places the drifts were six or seven feet in depth.

THE RINGED PLOVER.

The RINGED PLOVER (Charadrius hiaticula) is light brownish ash-colour on the upper parts of the body; the large wing-covers being tipped with white; the throat and belly are white, the former having a black patch upon its front; the cheeks are black, divided between the eyes by a white line; the quills are dusky, part of the shafts and the web at the base being white. Of the twelve feathers that compose the tail, the two centre ones are brown, with dark tips, the three next black towards the end, the next one only brown on the inner web, and the outer one entirely white. The claws are black, the eyes hazel, and the feet orange, the beak is orange, tipped with black. During the winter these colours are less bright and the black upon the throat comparatively very pale. The female has less white upon the front and more upon the wings, and her plumage generally is of a more cineraceous brown. The young are dusky black and without the white on the front; their bill is dusky, and their foot yellowish brown. The length of this species is seven inches and half, and the span of the wing, sixteen inches; the bill measures one inch and half.

The Ringed Plover is abundantly met with in Germany and Holland, and is also found in France and Italy; during the summer it visits Russia and Siberia, whilst in Great Britain it remains throughout the greater part of the year, being especially numerous in all such parts of our coast as are well covered with sand and shingle. This species has, however, been known to breed in the sandy warrens of Norfolk and Suffolk, at a considerable distance from the sea. The food of this Plover consists of insects, worms, and small crustaceans. The four eggs laid by the female are deposited near the sea, in a hole in the sand, above high-water mark; occasionally this cavity is lined with tiny stones, of about the size of a pea, and from this circumstance has been derived the name of "Stone Hatch," by which the bird is known in some parts of England. The eggs have a cineraceous brown shell, spotted with black and greyish blue. If disturbed while brooding, the parents at once feign lameness, and anxiously endeavour to lead intruders away from their little family. The note of the Ringed Plover is a shrill whistle.

The DOTTED PLOVERS (Eudromias) form a distinct group, having their high straight beak compressed in the centre of the upper mandible, and of greater length than their large head. A portion of the wing is much prolonged, and the tarsus covered with horny plates. The dotted plumage is very similar in the various species.[Pg 19]

THE DOTTED PLOVER, OR DOTTEREL.

The DOTTED PLOVER, or DOTTEREL (Eudromias Morinellus), has a garb well suited to the rocky haunts that it frequents. The feathers on the upper parts of the body are of a blackish shade, edged with rust-red; the grey head is separated from the rust-red breast by a narrow white and a black line; the lower breast is black in its centre, and the belly white; a broad light stripe passes over the eyes to the nape. The eye is dark brown, the beak black, and the foot greenish yellow. In autumn the upper portions of the body are deep grey, the feathers on the crown of the head black and rust-yellow, and the stripe over the eyes pale rust-yellow; the upper breast is grey and the rest of the under side white. The female resembles her mate, but is less beautifully coloured. This species is from eight inches and three-quarters to nine inches long, and eighteen broad; the wing measures five inches and three-quarters; and the tail two inches and three-quarters. The Dotterels inhabit the mountainous tracts of the northern portions of the globe, and are occasionally seen at an altitude of ten thousand feet above the level of the sea. During the winter they wander south; rarely, however, going beyond the countries bordering the Mediterranean. These migrations take place in August, and are carried on in flocks, which travel both by day and night. The homeward journey is not commenced earlier than April. The Dotterel visits Great Britain during the summer, appearing first in the south-eastern part of England. It seldom goes far west, but takes a northern course, and always inhabits high ground. Mr. Heysham, of Carlisle, gives the following account of the habits of this bird, drawn from his own observation:â

"In the neighbourhood of Carlisle, Dotterels seldom make their appearance before the middle of May, about which time they are occasionally seen in different localities in flocks which vary in number from five to fifteen, and almost invariably resort to heaths, barren pastures, fallow lands, &c., in open and exposed situations, where they continue, if unmolested, from ten days to a fortnight, and then retire to the mountains and the vicinity of lakes to incubate. The most favourite breeding haunts of these birds are always near to, or on the summits of, the highest mountains, particularly those that are densely covered with the woolly fringe-moss (Tricostomum lanuginosum), which, indeed, grows more or less profusely on nearly all the most elevated parts of this alpine district. In these lonely places they constantly reside the whole of the breeding season, a considerable part of the time enveloped in clouds, and daily soaked with rain or the drenching mist so extremely prevalent in these dreary regions. The Dotterel is by no means a solitary bird at this time, as a few pairs usually associate together, and live to all appearance in the greatest harmony. These birds do not make any nest, but deposit their eggs, which seldom exceed three in number, in a cavity on dry ground covered with vegetation, and generally near a moderate-sized stone or fragment of rock. In early seasons old females will occasionally lay their eggs about the 26th of May, but the greater part seldom commence before the first or second week in June; they appear, however, to vary greatly in this respect. The male assists in the incubation of the young.

"A week previous to their departure," continues the same observer, "they congregate in flocks, and continue together until they finally leave this country, which is sometimes during the latter part of August, at others not before the beginning of September. A few birds are, no doubt, occasionally seen after this period, but they are either late broods, or birds that are returning from more northern latitudes."

With regard to their manners, Mr. Heysham says:â"On the 3rd of July we found two or three pairs near the most elevated portion of this mountain; and on all our visits thither, whether early in the morning or late in the afternoon, the greater part were always seen near the same place, sitting on the ground. When first discovered, they permitted us to approach within a short distance without[Pg 20] showing any symptoms of alarm, and frequently afterwards, when within a few paces watching their movements, some would move slowly about and pick up an insect, others would remain motionless, now and then stretching out their wings, and a few would occasionally tug with each other, at the same time uttering a few notes which had some resemblance to those of the Common Linnet. In short, they appeared to be so very indifferent with regard to our presence, that at last my assistant could not avoid exclaiming, 'What stupid birds these are!' The female that had young nevertheless evinced considerable anxiety for their safety, whenever we came near the place where they were concealed, and as long as we remained in the vicinity, she constantly flew to and fro above us, uttering her note of alarm. As soon as the young birds were fully feathered, two were killed for the purpose of examining their plumage in this state, and we found that after they had been fired at once or twice they became more wary, and eventually we had some little difficulty in approaching sufficiently near to effect our purpose. The stomachs I dissected were all filled with the elytra and remains of small coleopterous insects, which in all probability constitute their principal food during the breeding season."

The pear-shaped eggs of the Dotterel are three or four in number, and have a smooth lustreless shell, of a pale yellowish brown or greenish hue, irregularly spotted with white. Upon one occasion we accidentally disturbed a brood, and having taken the young in our hand and shown them to the mother, she at once boldly ruffled her feathers, shook her wings, and endeavoured to excite pity by a variety of gesticulations. No sooner were the prisoners released than she uttered a cry of delight, and gathered them under her wings, after the manner of a Barn-door Fowl. The flesh of this Plover is extremely delicate.

The SHORE PLOVERS (Ãgialites) occupy the sandy or gravelly shores of rivers on the sea-coast, and are characterised by their comparatively small size, delicate beaks, long pointed wings, and the uniform hue of the sandy plumage on the upper parts of the body. The under side is white, and the neck encircled by a band.

THE LITTLE SHORE PLOVER, OR LITTLE RINGED PLOVER.