|

Stories of Adventure in The Young United States By ALFRED BISHOP MASON Tom Strong, Washington's Scout Illustrated, $1.30 net Tom Strong, Boy-Captain Illustrated, $1.30 net Tom Strong, Junior Illustrated, $1.30 net Tom Strong, Third Illustrated, $1.30 net HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY Publishers New York |

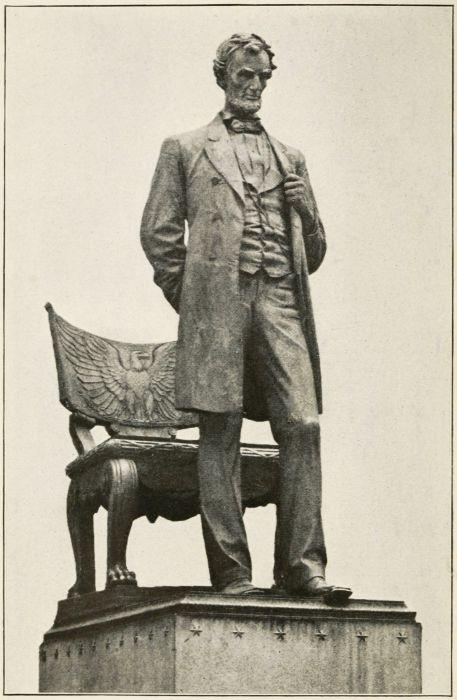

St. Gaudens' Statue of Lincoln

St. Gaudens' Statue of Lincoln

TOM STRONG,

LINCOLN'S SCOUT

A STORY OF THE UNITED STATES IN THE

TIMES THAT TRIED MEN'S SOULS

By

ALFRED BISHOP MASON

Author of "Tom Stron, Washington's Scout," Tom Strong,

Boy-Captain," "Tom Strong, Junior," and

"Tom Strong, Third"

Illustrated

NEW YORK

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

1919

Copyright, 1919

BY

HENRY HOLT AND COMPANY

The Quinn & Boden Company

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

RAHWAY NEW JERSEY

DEDICATED BY PERMISSION

TO

THEODORE ROOSEVELT

INSPIRER OF PATRIOTISM,

A GREAT AMERICAN

OYSTER BAY,

LONG ISLAND, N. Y.

August 31st, 1917.

Dear Mr. Mason:

All right, I shall break my rule and have you dedicate that book to me. Thank you!

|

|

Mr. Alfred B. Mason,

University Club,

New York City.

FOREWORD

Many of the persons and personages who appear upon the pages of this book have already lived, some in history and some in the pages of "Tom Strong, Washington's Scout," "Tom Strong, Boy-Captain," "Tom Strong, Junior," or "Tom Strong, Third." Those who wish to know the full story of the four Tom Strongs, great-grandfather, grandfather, father and son, should read those books, too.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

Tom Rides in Western Maryland—Halted

by Armed Men—John Brown—The Attack

upon Harper's Ferry—The Fight—John

Brown's Soul Goes Marching On

|

3 |

| CHAPTER II | |

Our War with Mexico—Kit Carson and His

Lawyer, Abe Lincoln—Tom Goes to Lincoln's

Inauguration—S. F. B. Morse, Inventor

of the Telegraph—Tom Back in

Washington

|

22 |

| CHAPTER III | |

Charles Francis Adams—Mr. Strong Goes

to Russia—Tom Goes to Live in the

White House—Bull Run—"Stonewall"

Jackson—Geo. B. McClellan—Tom

Strong, Second-Lieutenant, U. S. A.—The

Battle of the "Merrimac" and the

"Monitor"

|

40 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

Tom Goes West—Wilkes Booth Hunts Him—Dr.

Hans Rolf Saves Him—He Delivers

Despatches to General Grant

|

71 |

| [Pg x] CHAPTER V | |

Inside the Confederate Lines—"Sairey"

Warns Tom—Old Man Tomblin's "Settlemint"—Stealing

a Locomotive—Wilkes

Booth Gives the Alarm—A

Wild Dash for the Union Lines

|

90 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

Tom up a Tree—Did the Confederate Officer

See Him?—The Fugitive Slave

Guides Him—Buying a Boat in the Dark—Adrift

in the Enemy's Country

|

117 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

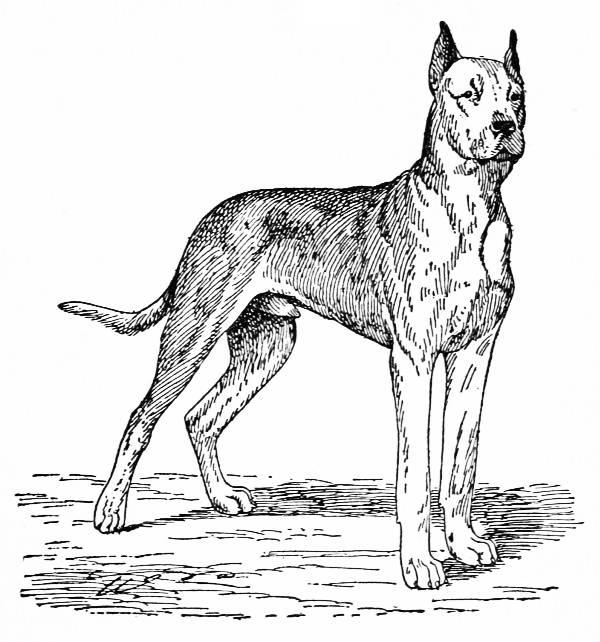

Towser Finds the Fugitives—Towser Brings

Uncle Moses—Mr. Izzard and His Yankee

Overseer, Jake Johnson—Tom Is

Pulled Down the Chimney—How Uncle

Moses Choked the Overseer—The

Flight of the Four

|

129 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

Lincoln Saves Jim Jenkins's Life—Newspaper

Abuse of Lincoln—The Emancipation

Proclamation—Lincoln in His

Night-shirt—James Russell Lowell—"Barbara

Frietchie"—Mr. Strong Comes

Home—The Russian Fleet Comes to

New York—A Backwoods Jupiter

|

160 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

Tom Goes to Vicksburg—Morgan's Raid—Gen.

Basil W. Duke Captures Tom—Gettysburg—Gen.

Robert E. Lee Gives

Tom His Breakfast—In Libby Prison—Lincoln's

Speech at Gettysburg

|

182 |

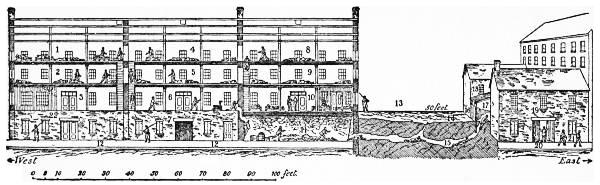

| [Pg xi] CHAPTER X | |

Tom Is Hungry—He Learns to "Spoon" by

Squads—The Bullet at the Window—Working

on the Tunnel—"Rat Hell"—The

Risk of the Roll-call—What Happened

to Jake Johnson, Confederate Spy—Tom

in Libby Prison—Hans Rolf

Attends Him—Hans Refuses to Escape—The

Flight Through the Tunnel—Free,

but How to Stay So?

|

213 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

Tom Hides in a River Bank—Eats Raw Fish—Jim

Grayson Aids Him—Down the

James River on a Tree—Passing the Patrol

Boats—Cannonaded—The End of

the Voyage

|

249 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

Towser Welcomes Tom to the White House—Lincoln

Re-elected President—Grant

Commander-in-Chief—Sherman Marches

from Atlanta to the Sea—Tom on

Grant's Staff—Five Forks—Fall of

Richmond—Hans Rolf Freed—Bob Saves

Tom from Capture—Tom Takes a Battery

into Action—Lee Surrenders—Tom

Strong, Brevet-Captain, U. S. A.

|

265 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln

|

307 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

Tom Hunts Wilkes Booth—The End of the

Murderer—Andrew Johnson, President

of the United States—Tom and Towser

Go Home

|

315 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | ||

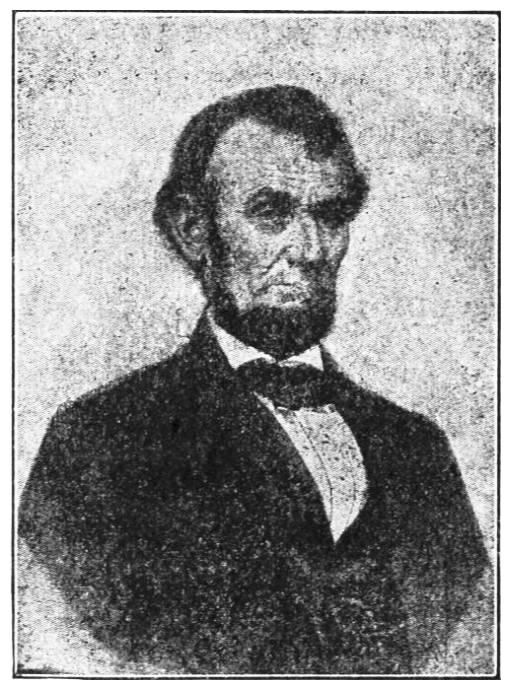

| Abraham Lincoln | Frontispiece | |

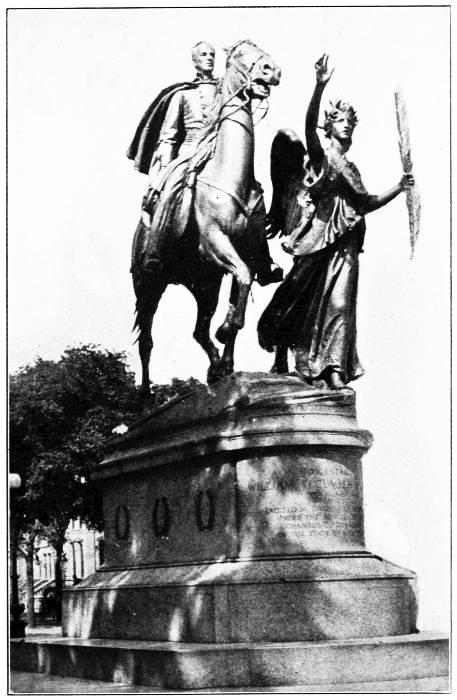

| St. Gaudens Statue, Lincoln Park, Chicago | ||

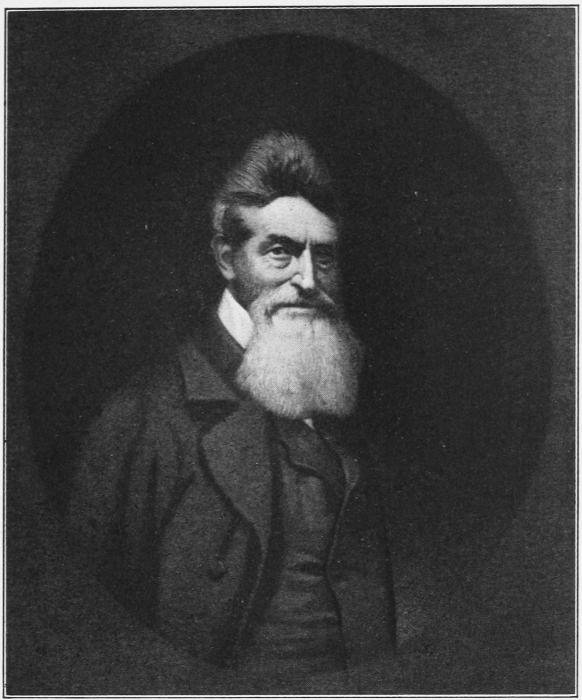

| John Brown | 10 | |

| The Attack upon the Engine House | 17 | |

| Battle of the "Monitor" and the "Merrimac" | 66 | |

| Admiral Farragut | 72 | |

| Mississippi River Gunboats | 85 | |

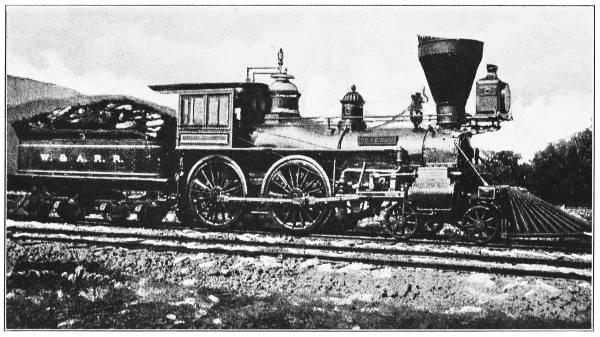

| The Locomotive Tom Helped to Steal | 106 | |

| Towser | 157 | |

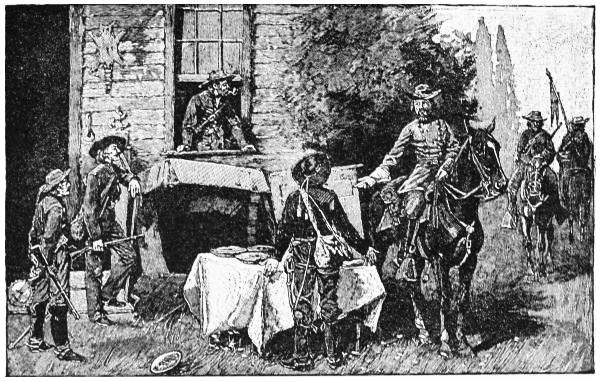

| General Duke Samples the Pies | 191 | |

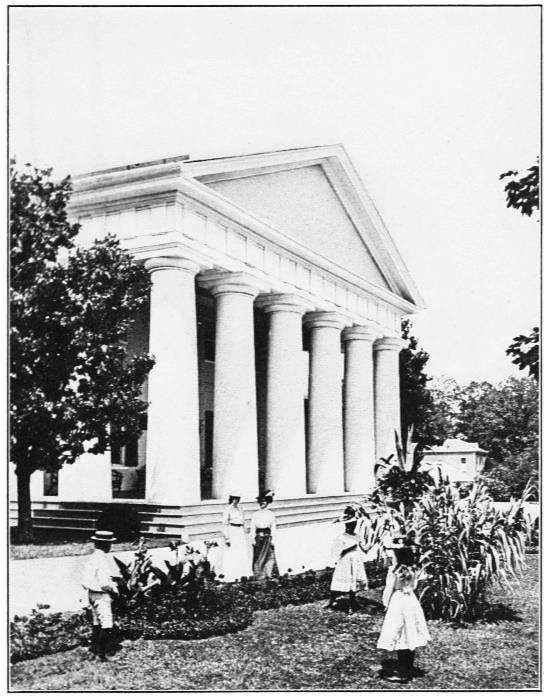

| Arlington | 198 | |

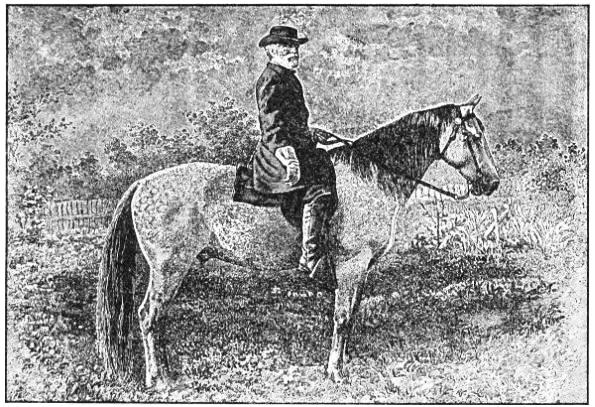

| Gen. Robert E. Lee on Traveler | 201 | |

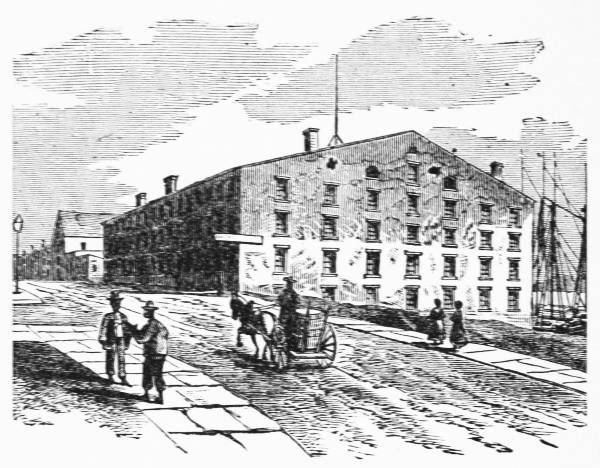

| Libby Prison after the War | 214 | |

| Fighting the Rats | 224 | |

| Libby Prison and the Tunnel | 229 | |

| Abraham Lincoln in 1864 | 269 | |

| Gen. W. T. Sherman | 272 | |

| St. Gaudens Statue, Central Park Plaza, New York | ||

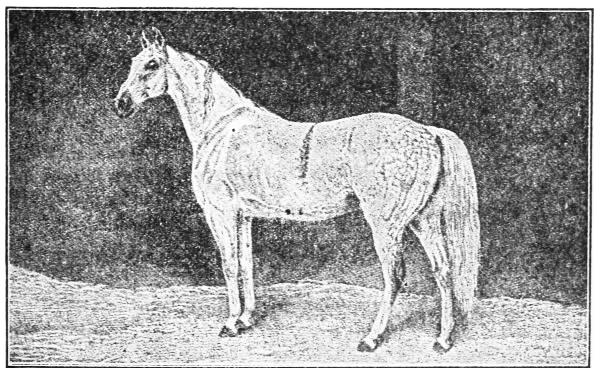

| Bob | 275 | |

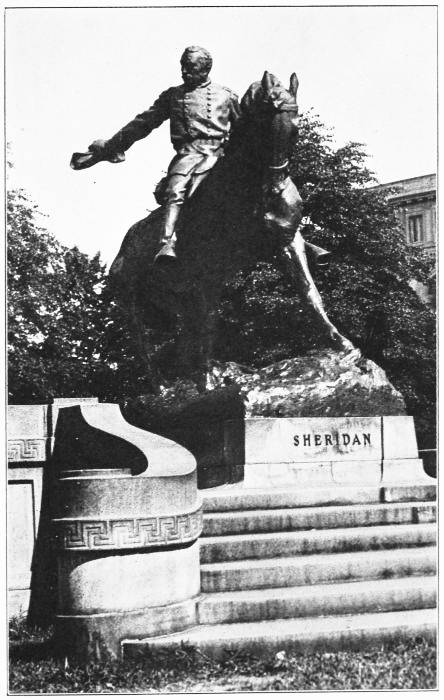

| Gen. Philip H. Sheridan | 278 | |

| Sheridan Square Statue, Washington, D. C. | ||

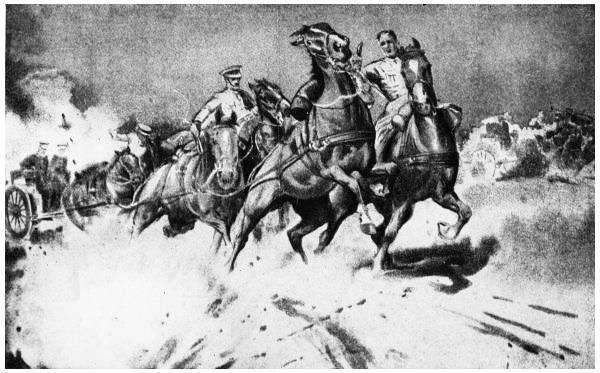

| Tom Takes a Battery into Action | 292 | |

| The McLean House, Appomattox Courthouse | 299 | |

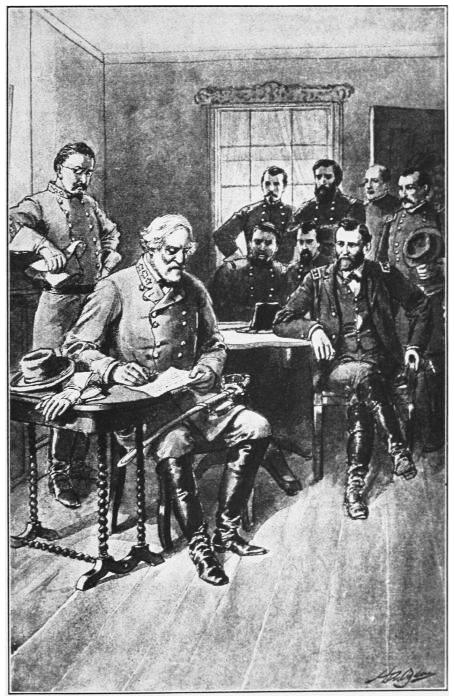

| Lee Surrenders to Grant | 302 | |

| Gen. U. S. Grant | 304 | |

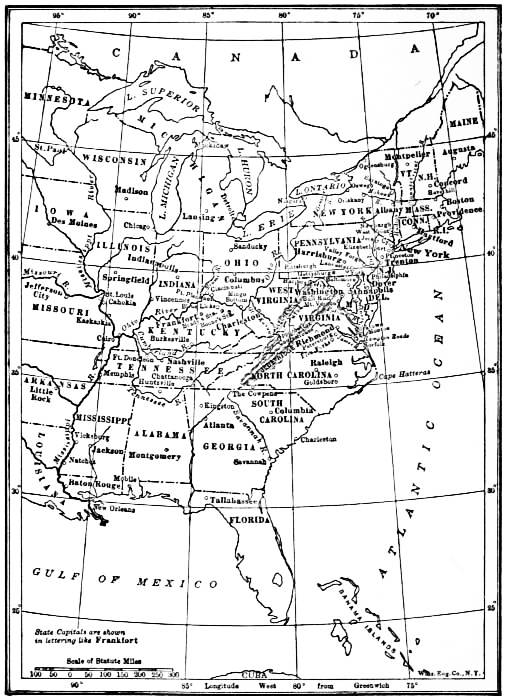

MAP

| Eastern Half of United States | 2 | |

TOM STRONG, LINCOLN'S SCOUT

THE EASTERN UNITED STATES

THE EASTERN UNITED STATES(Showing places mentioned in this book)

TOM STRONG, LINCOLN'S SCOUT

CHAPTER I

Tom Rides in Western Maryland—Halted by Armed Men—John Brown—The Attack upon Harper's Ferry—The Fight—John Brown's Soul Goes Marching On.

On a beautiful October afternoon, a man and a boy were riding along a country road in Western Maryland. To their left lay the Potomac, its waters gleaming and sparkling beneath the rays of the setting sun. To their right, low hills, wooded to the top, bounded the view. They had left the little town of Harper's Ferry, Virginia, an hour before; had crossed to the Maryland shore of the Potomac; and now were looking for some country inn or friendly farmhouse where they and their horses could be cared for overnight.

The man was Mr. Thomas Strong, once Tom [Pg 4] Strong, third, and the boy was his son, another Tom Strong, the fourth to bear that name. Like the three before him he was brown and strong, resolute and eager, with a smile that told of a nature of sunshine and cheer. They were looking for land. Mr. Strong had inherited much land in New York City. The growth of that great town had given him a comfortable fortune. He had decided to buy a farm somewhere and a friend had told him that Western Maryland was almost a paradise. So it was, but this Eden had its serpent. Slavery was there. It was a mild and patriarchal kind of slavery, but it had left its black mark upon the countryside. Across the nearby Mason and Dixon's line, Pennsylvania was full of little farms, tilled by their owners, and of little towns, which reflected the wealth of the neighboring farmers. Western Maryland was largely owned by absentee landlords. Its towns were tiny villages. Its farms were few and far between. The free State was briskly alive; the slave State was sleepily dead.

The two riders were splendidly mounted, the father on a big bay stallion, Billy-boy, and the son on a black Morgan mare, Jennie. Billy-boy was a descendant of the Billy-boy General Washington had given to the first Tom Strong, many years before. Jennie was a descendant of the Jennie Tom Strong, third, had ridden across the plains of the great West with John C. Fremont, "the Pathfinder," first Republican candidate for President of the United States.

"We haven't seen a house for miles, Father," said the boy.

"And we were never out of sight of a house when we were riding through Pennsylvania. There's always a reason for such things. Do you know the reason?"

"No, sir. What is it?"

"The sin of slavery. I don't believe I shall buy land in Maryland. I thought I might plant a colony of happy people here and help to make Maryland free, in the course of years, but I'm beginning to think the right kind of white people won't come where the only work is done by [Pg 6] slaves. We must find soon a place to sleep. Perhaps there'll be a house around that next turn in the road. Billy-boy whinnies as though there were other horses near."

Billy-boy's sharp nose had not deceived him. There were other horses near. Just around the turn of the road there were three horses. Three armed men were upon them. Father and son at the same moment saw and heard them.

"You stop! Who be you?"

The sharp command was backed by uplifted pistols. The Strongs reined in their horses, with indignant surprise. Who were these three farmers who seemed to be playing bandits upon the peaceful highroad? The boy glanced at his father and tried to imitate his father's cool demeanor. He felt the shock of surprise, but his heart beat joyously with the thought: "This is an adventure!" All his young life he had longed for adventures. He had deeply enjoyed the novel experience of the week's ride with the father he loved, but he had not hoped for a thrill like this.

Mr. Strong eyed the three horsemen, who seemed both awkward and uneasy. "What does this mean?" he asked.

"Now, thar ain't goin' to be no harm done you nor done bub, thar, neither," the leader of the highwaymen answered, with a note almost of pleading in his voice. "Don't you be oneasy. But you'll have to come with us——"

"And spend Sunday with us——" broke in another man.

"Shet up, Bill. I'll do all the talkin' that's needed."

"That's what you do best," the other man grumbled.

"Well, Tom," said Mr. Strong, turning with a smile to his son, "we seem to have found that place to spend the night." He faced his captors. "This is a queer performance of yours. You don't look like highwaymen, though you act like them. Do you mean to steal our horses?" he added, sharply.

"We ain't no hoss thieves," replied the leader. "You've got to come with us, but you [Pg 8] needn't be no way oneasy. You, Bill, ride ahead!"

Bill turned his horse and rode ahead, Mr. Strong and Tom riding behind him, the other two men behind them. It was a silent ride, but not a long one. Within a mile, they reached a rude clearing that held a couple of log huts. The sun had set; the short twilight was over. Firelight gleamed in the larger of the huts. The prisoners were taken to it. A man who was lounging outside the door had a whispered talk with the three horsemen. Then he turned rather sheepishly; said: "Come in, mister; come in, bub;" opened the door, called within: "Prisoners, Captin' Smith," and stepped aside as father and son entered.

There were a dozen men in the big room, farmers all, apparently. They were all on their feet, eyeing keenly the unexpected prisoners. Their eyes turned to a tall man, who stepped forward and held out his hand, saying:

"Sorry the boys had to take you in, but you and your hosses are safe and we won't [Pg 9] keep you long. The day of the Lord is at hand."

There was a grim murmur of approval from the other men. The Lord's day, as Sunday is sometimes called, was at hand, for it was then the evening of Saturday, October 15, 1859. But that was not what the speaker meant. He was not what his followers called him, Captain Smith. He was John Brown, of North Elba, New York, of Kansas ("bleeding Kansas" it was called then, when slaveholders from Missouri and freedom-lovers under John Brown had turned it into a battlefield), and he was soon to be John Brown of Harper's Ferry, Virginia, first martyr in the cause of Freedom on Virginian soil. To him "the day of the Lord" was the day when he was to attack slavery in its birthplace, the Old Dominion, and that attack had been set by him for Sunday, October 16. His plan was to seize Harper's Ferry, where there was a United States arsenal, arm the slaves he thought would come to his standard from all Virginia, and so compass the fall of [Pg 10] the Slave Power. A wild plan, an impossible plan, the plan of an almost crazy fanatic, and a splendid dream, a dream for the sake of which he was glad to give his heroic life.

He had rented this Maryland farm in July, giving his name as Smith and saying he expected to breed horses. By twos and threes his followers had joined him in this solitary spot, until now there were twenty-one of them. The few folk scattered through the countryside had begun to be suspicious of this strange gathering of men. All sorts of wild stories circulated, though none was as wild as the truth. The men themselves were tense under the strain of the long wait. They feared discovery and attack. For the three days before "the day of the Lord" they had patrolled the one road, looking out for soldiers or for spies. Tom and his father had been their sole captives.

John Brown

John Brown

John Brown was one of Nature's noblemen and among his friends in Massachusetts and New York were some of the foremost men of their time, so he had learned to know a real man when he met one. He soon found out that Mr. Strong was a real man. He told him of his plans, and urged him to join in the projected foray on Harper's Ferry. But when Mr. Strong refused and tried to show him how mad his project was, the fires of the fanatic blazed within him.

"Did not Joshua bring down the walls of Jericho with a ram's horn?" he shouted. "And with twenty armed men cannot I pull down the walls of the citadel of Slavery? Are you a true man or not? Will you join me or not? Answer me yes or no."

"No," was the response, quiet but firm.

"You shall join me; you and your boy," thundered the crusader, hammering the table with his mighty fist. "Here, Jim, put these people under guard and keep them until we start."

Tom and his father were well-treated, but they were kept under guard until the next night and were then taken along by John Brown's [Pg 12] "army," which trudged off into the darkness afoot, while Billy-boy and Jennie and the other horses in the corral whinnied uneasily, sensing, as animals do, the stir of a departure which is to leave them behind. In the center of the little column the two captives marched the five miles to Harper's Ferry and started across the bridge that led to that tiny town.

A brave man, one Patrick Hoggins, was night-watchman of the bridge. He heard the trampling of many feet upon the plank-flooring. He hurried towards the strange sound.

"Halt!" shouted somebody in the column.

"Now I didn't know what 'halt' mint then," Patrick testified afterwards, "anny more than a hog knows about a holiday."

But he had seen armed men and he turned to run and give an alarm. A bullet was swifter than he, but not swifter than his voice. He fell, but his shouts had alarmed the town. There were two or three watchmen at the arsenal. They came forward, only to be made prisoners. The few citizens who had been [Pg 13] aroused could do nothing. The "army" seized the arsenal without difficulty.

Five miles from Harper's Ferry lived Col. Lewis W. Washington, gentleman-farmer and slave-owner, great-grand-nephew of another gentleman-farmer and slave-owner, George Washington. At midnight, Colonel Washington was awakened by a blow upon his bedroom door. It swung open and the light of a burning torch showed the astonished Southerner four armed men, one of them a negro, who bade him rise and dress. They were a patrol sent out by Brown. Their leader, Stevens, asked:

"Haven't you a pistol Lafayette gave George Washington and a sword Frederick the Great sent him?"

"Yes."

"Where are they?"

"Downstairs."

His four captors tramped downstairs with him. Pistol and sword were found.

"I'll take the pistol," said Stevens. "You hand the sword to this negro."

John Brown wore this sword during the fighting that followed. It is now in the possession of the State of New York. While its being sent George Washington by Frederick the Great is doubtful—the story runs that the Prussian king sent with it a message "From the oldest general to the best general"—its being surrendered by Lewis Washington to the negro is true.

Lewis was then on the staff of the Governor of Virginia, and had acquired in this way his title of Colonel. He was put into his own carriage. His slaves, few in number, were bundled into a four-horse farm-wagon. They were told to come and fight for their freedom. Too scared to resist, they came as they were bidden to do, but they did no fighting. At Harper's Ferry they and their fellow-slaves, seized at a neighboring plantation, escaped back to slavery at the first possible moment. Not a single negro voluntarily joined John Brown. He had expected a widespread slave insurrection. There was nothing of the sort. By Monday morning he knew he had failed, failed utterly.

Before Monday's sun set, Harper's Ferry was full of soldiers, United States regulars and State militia. Brown, his men and his white captives, eleven of the latter, were shut up in the fire-engine house of the armory. The militia refused to charge the engine-house, saying that this might cost the captives their lives. Many of them were drunk; all of them were undisciplined; their commander did not know how to command. The situation changed with the arrival of the United States Marines led by Lieut.-Col. Robert E. Lee, afterwards the famous chief of the army of the Confederate States.

By this time Tom was beginning to think he had had enough adventure. He had enjoyed that silent tramp through the darkness beside his father. He had enjoyed it the more because they were both prisoners-of-war. Being a prisoner was an amazingly thrilling thing. He was sorry when brave Patrick Hoggins was shot and glad to know the wound was slight, but sharing in the skirmish, even in the humble capacity of [Pg 16] a captive, had excited the boy immensely. Now that there was almost constant firing back and forth, when two or three wounded men were lying on the floor, and when his father and he and Colonel Washington were perforce risking their lives in the engine-house, with nothing to gain and everything to lose, and when scanty sleep and little food had tired out even his stout little body, Tom felt quite ready to go home and have his adored mother "mother" him. His father saw the homesickness in his eyes.

"Steady, my son," said Mr. Strong. "This won't last long. No stray bullet is apt to reach this corner, where Captain Brown has put us. The only other danger is when the regulars rush in here, but unless they mistake us for the raiders, there'll be no harm done then. Steady." He looked through a bullet-hole in the boarded-up window and added: "Here comes a flag of truce. Listen."

The scattering fire died away. The hush was broken by a commanding voice, demanding surrender.

"There will be no surrender," quoth grim John Brown.

At dawn of Tuesday, two files of United States Marines, using a long ladder as a battering ram, attacked the door. It broke at the second blow. The marines poured in, shooting and striking. The battle was over. John Brown, wounded and beaten to the floor, lay there among his men. The captives were free. Their captors had changed places with them.

THE ATTACK ON THE ENGINE-HOUSE

THE ATTACK ON THE ENGINE-HOUSE

Colonel Washington took Mr. Strong and Tom home with him, for a rest after the strain [Pg 18] of the captivity. He was much interested when he found out that Tom's great-grandfather had visited General Washington at Mount Vernon and Tom was intensely interested in seeing the home and home life of a rich Southern planter. The Colonel asked his guests to stay until after the trial of their recent jailer. They did so and Mr. Strong, after some hesitation, decided to take Tom to the trial and afterwards to the final scene of all. He wrote to his wife: "Life is rich, my dear, in proportion to the number of our experiences and their depth. Ordinarily, I would not dream of taking Tom to see a criminal hung. But John Brown is no ordinary criminal. He is wrong, but he is heroic. He faces his fate—for of course they will hang him—like a Roman. I think it will do Tom good to see a hero die."

Whether or no his father was right, Tom was given these experiences. He sat beside his father and Colonel Washington at the trial. He heard them testify. He noted the angry stir of the mob in the court-room when Mr. Strong [Pg 19] made no secret of his admiration for the great criminal.

Robert E. Lee, who captured Brown, said: "I am glad we did not have to kill him, for I believe he is an honest, conscientious old man." Virginia, Lee's State, thought she did have to kill this invader of her soil and disturber of her slaves.

November 2, John Brown was sentenced to be hung December 2. The next day he added this postscript to a letter he had already written to his wife and children:

"P.S. Yesterday Nov. 2d I was sentenced to be hanged on Decem 2d next. Do not grieve on my account. I am still quite cheerful. God bless you all."

Northern friends offered to try to help him to break jail. He put aside the offer with the calm statement: "I am fully persuaded that I am worth inconceivably more to hang than for any other purpose."

December 2, John Brown started on his last [Pg 20] journey. He sat upon his coffin in a wagon and as the two horses paced slowly from jail to gallows, he looked far afield, over river and valley and hill, and said: "This is a beautiful country." He was sure he was upon the threshold of a far more beautiful country. The gallows were guarded by a militia company from Richmond, Virginia. In its ranks, rifle on shoulder, stood Wilkes Booth, a dark and sinister figure, who was to win eternal infamy by assassinating Abraham Lincoln. Beside the militia was a trim lot of cadets, the fine boys of the Virginia Military Institute. With them was their professor, Thomas J. Jackson, "Stonewall" Jackson, one of the heroic figures upon the Southern side of our Civil War.

When the end came, Stonewall Jackson's lips moved with a prayer for John Brown's soul; Colonel Washington's and Mr. Strong's eyes were wet; and Tom Strong sobbed aloud. Albany fired a hundred guns in John Brown's honor as he hung from the gallows. In 1859 United States troops captured him that he [Pg 21] might die. In 1899 United States troops fired a volley of honor over his grave in North Elba that the memory of him might live. Victor Hugo called him "an apostle and a hero." Emerson dubbed him "saint." Oswald Garrison Villard closes his fine biography of John Brown with these words: "Wherever there is battling against injustice and oppression, the Charlestown gallows that became a cross will help men to live and die."

CHAPTER II

Our War with Mexico—Kit Carson and His Lawyer, Abe Lincoln—Tom Goes to Lincoln's Inauguration—S. F. B. Morse, Inventor of the Telegraph—Tom Back in Washington.

In 1846, Mr. Strong, long enough out of Yale to have begun business and to have married, had heard his country's call and had helped her fight her unjust war with Mexico. General Grant, who saw his first fighting in this war and who fought well, says of it in his Memoirs that it was "one of the most unjust ever waged by a stronger against a weaker nation."

Much more important things were happening here then than the Mexican War. In 1846 Elias Howe invented the sewing-machine. In 1847 Robert Hoe invented the rotary printing press. Great inventions like these are the real milestones of the path of progress.

Mr. Strong served as a private in the ranks throughout the war. He refused a commission offered him for gallantry in action because he knew he did not know enough then to command men. It is a rare man who knows that he does not know. His regiment was mustered out of service at the end of the war in New Orleans. The young soldier decided to go home by way of St. Louis because of his memories of that old town in the days when he had followed Fremont. He went again to the Planters' Hotel and there by lucky accident he met again the famous frontiersman Kit Carson. Carson was away from the plains he loved because of a lawsuit. A sharp speculator was trying to take away from him some land he had bought years ago near the town, which the growth of the town had now made quite valuable. Carson was heartily glad to see his "Tom-boy" once more. He insisted upon his staying several days, took him to court to hear the trial, and introduced him to his lawyer, a tall, gaunt, slab-sided, slouching, plain person from the neighboring [Pg 24] State of Illinois. Everybody who knew him called him "Abe." His last name was Lincoln.

"I'd heard so much of Abe Lincoln," said Carson, "that when this speculator who's trying to do me hired all the big lawyers in St. Louis, I just went over to Springfield, Illinois, to get Abe. When I saw him I rather hesitated about hiring such a looking skeesicks, but when I came to talk with him, he did the hesitating. I asked him what he'd charge for defending a land-suit in St. Louis. He told me. I sez: 'All right. You're hired. You're my lawyer.'

"'Wait a bit,' sez he.

"'What for?' sez I. 'I'll pay what you said.'

"'That ain't all,' sez he. 'Before I take your money, Kit, I've got to know your side of the case is the right side.'

"'What difference does that make to a lawyer?' sez I.

"'It makes a heap o' difference to this lawyer,' sez he. 'You've got to prove your case to me before I'll try to prove it to the court. If [Pg 25] you ain't in the right, Abe Lincoln won't be your lawyer.'

"Darned if he didn't make me prove I was in the right, too, before he'd touch my money. No wonder they call him 'Honest Abe.'"

It took Lincoln a couple of days to win Kit Carson's suit. During those two days young Strong saw much of him and came to admire the sterling qualities of the man. Lincoln, too, liked this young college-bred fellow from the East, unaffected, well-mannered, friendly, and gay. There was the beginning of a friendship between the Westerner and the Easterner. Thereafter they wrote each other occasionally. When Lincoln served his one brief term in Congress, Mr. Strong spent a week with him in Washington and asked him (but in vain) to visit him in New York.

So, when this new giant came out of the West and Illinois gave her greatest son to the country, as its President, Mr. Strong went to Washington to see him inaugurated and took with him his boy Tom, as his father had taken [Pg 26] him in 1829 to Andrew Jackson's inauguration.

Washington was still a great shabby village, not much more attractive March 4, 1861, than it was March 4, 1829. The crowds at the two inaugurations were much alike. In both cases the favorite son of the West had won at the polls. In both cases the West swamped Washington. But in 1829 there was jubilant victory in the air. In 1861 there was somber anxiety. Seven Southern States had "seceded" and had formed another government. Other States were upon the brink of secession. Was the great democratic experiment of the world about to end in failure? Would there be civil war? What was this unknown man out of the West going to do? Could he do anything?

Mr. Strong and Tom, with a few thousand other people, went to the reception at the White House on the afternoon of March fourth. President Lincoln was laboriously shaking hands with everybody in the long line. Almost every one of them seemed to be asking him for [Pg 27] something. He was weary long before Tom and his father reached him, but his face brightened as he saw them. A boy always meant a great deal to Abraham Lincoln. "There may be so much in a boy," he used to say. He greeted the two warmly.

"Howdy, Strong? Glad to see you. This your boy? Howdy, sonny?"

Tom did not enjoy being called "sonny" much more than he had enjoyed being called "bub," but he was glad to have this big man with a woman's smile call him anything. He wrung the President's offered hand, stammered something shyly, and was passing on with his father, when Lincoln said:

"Hold on a minute, Strong. You haven't asked me for anything."

"I've nothing to ask for, Mr. President. I'm not here to beg for an office."

"Good gracious! You're the only man in Washington of that kind, I believe. Come to see me tomorrow morning, will you?"

"Most gladly, sir."

The impatient man behind them pushed them on. They heard him begin to plead: "Say, Abe, you know I carried Mattoon for you; I'd like to be Minister to England."

Boys and girls always appealed to the President's heart. When there were talks of vital import in his office, little Tad Lincoln often sat upon his father's knee. At a White House reception, Charles A. Dana once put his little girl in a corner, whence she saw the show. The father tells the story. When the reception was over, he said to Lincoln: "'I have a little girl here who wants to shake hands with you.' He went over to her and took her up and kissed her and talked to her. She will never forget it if she lives to be a thousand years old."

The next morning Tom followed his father into a room on the second floor of the White House. Lincoln sat at a flat-topped desk, piled high with papers. He was in his shirt-sleeves, with shabby black trousers, coarse stockings, [Pg 29] and worn slippers. He stretched out his long legs, swung his long arms behind his head, and came straight to the point.

"Strong, I'm going to need you. Your country is going to need you. I want you to go straight home and fix up your business affairs so you can come whenever I call you. Will you do it?"

"Yes, sir."

President and citizen rose and shook hands upon it. The citizen was about to go when Tom, with his heart in his mouth, but with a fine resolve in his heart, suddenly said:

"Oh, Father! Oh, Mr. President——"

Then he stopped short, too shy to speak, but Lincoln stooped down to him, patted his young head and said with infinite kindness in his tone:

"What is it, Tom? Tell me."

"Oh, Mr. President, I'm only a boy, but can't I do something for my country, right now? Can't I stay here? Father will let me, won't you, Father?"

Mr. Strong shook his head. The boy's face fell. It brightened again when Lincoln told him:

"When I send for your father, I'll send for you, Tom."

With that promise ringing in his ears, Tom went home to New York City. Home was a fine brick house at the northeast corner of Washington Place and Greene Street. The house was a twin brother of those that still stand on the north side of Washington Square. Tom had been born in it. Not long after his birth, his parents had given a notable dinner in it to a notable man. Tom had been present at the dinner, and he remembered nothing about it. As he was at the table but a few minutes, in the arms of his nurse, and less than a year old, it is not surprising that he did not remember it. His proud young mother had exhibited him to a group of money magnates, gathered at Mr. Strong's shining mahogany table for dinner, at the fashionable hour of three P.M., to see another young thing, almost as young as Tom. [Pg 31] This other young thing was the telegraph, just invented by Samuel F. B. Morse, at the University of the City of New York, which then filled half of the eastern boundary of Washington Square.

While Tom waited in the old brick house and played in Washington Square, history was making itself. Pope Walker, first Secretary of War of the Confederate States, sitting in his office at the Alabama Statehouse at Montgomery, the first Confederate capital, said: "It is time to sprinkle some blood in the face of the people." So he telegraphed the fateful order to fire on Fort Sumter, held by United States troops in Charleston harbor. Sumter fell. Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers. Virginia, the famous Old Dominion, "the Mother of Presidents"—Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe were Virginians—seceded. The war between the States began.

Mr. Strong found in his mail one day this letter:

"The Executive Mansion,

Washington, April 17, 1861.

Sir:

The President bids me say that he would like to have you come to Washington at once and bring your son Tom with you.

Respectfully,

John Hay,

Assistant Private Secretary."

Tom and his father started at once, as the President bade them. At Jersey City, they found the train they had expected to take had been pre-empted by the Sixth Massachusetts, a crack militia regiment of the Old Bay State, which was hurrying to Washington in the hope of getting there before the rebels did. The cars were crammed with soldiers. A sentry stood at every door. No civilian need apply for passage. However, a civilian with a letter from Lincoln's secretary bidding him also hurry to Washington was in a class by himself. With the help of an officer, the father and son ran the [Pg 33] blockade of bayonets and started southward, the only civilians upon the train. It was packed to suffocation with soldiers. Mr. Strong sat with the regimental officers, but he let Tom roam at will from car to car. How the boy enjoyed it. The shining gun-barrels fascinated him. He joined a group of merry men, who hailed him with a shout:

"Here's the youngest recruit of all."

"Are you really going to shoot rebels?" asked Tom.

"If we must," said Jack Saltonstall, breaking the silence the question brought, "but I hope it won't come to that."

"The war will be over in three months," Gordon Abbott prophesied.

"Pooh, it will never begin,—and I'm sorry for that," said Jim Casey, "I'd like to have some real fighting."

Within about three hours, Jim Casey was to see fighting and was to die for his country. The beginning of bloodshed in our Civil War was in the streets of Baltimore on April 19, 1861, just [Pg 34] eighty-six years to a day from the beginning of bloodshed in our Revolution on Lexington Common. Massachusetts and British blood in 1775; Massachusetts and Maryland blood in 1861.

When the long train stopped at the wooden car-shed which was then the Baltimore station, the regiment left the cars, fell into line and started to march the mile or so of cobblestone streets to the other station where the train for Washington awaited it. The line of march was through as bad a slum as an American city could then show. Grog-shops swarmed in it and about every grog-shop swarmed the toughs of Baltimore. They were known locally as "plug-uglies." Like the New York "Bowery boys" of that time, they affected a sort of uniform, black dress trousers thrust into boot-tops and red flannel shirts. Far too poor to own slaves themselves, they had gathered here to fight the slave-owners' battles, to keep the Massachusetts troops from "polluting the soil of Maryland," as their leaders put it, really to keep them from saving Washington.

A roar of jeers and taunts and insults hailed the head of the marching column. Tom was startled by it. He turned to his father. The two were walking side by side, in the center of the column, between two companies of the militia. He found his father had already turned to him.

"Keep close to me, Tom," said Mr. Strong.

The storm of words that beat upon them increased. At the next corner, stones took the place of words. The mob surged alongside the soldiers, swearing, stoning, striking, finally stabbing and shooting. The Sixth Massachusetts showed admirable self-restraint, which the "plug-uglies" thought was cowardice. They pressed closer. With a mighty rush, five thousand rioters broke the line of the thousand troops. The latter were forced into small groups, many of them without an officer. Each group had to act for itself. Tom and his father found themselves part of a tiny force of about twenty men, beset upon every side by desperadoes now mad with liquor and with the lust [Pg 36] of killing. Jack Saltonstall took command by common consent. Calmly he faced hundreds of rioters.

"Forward, march!"

As he uttered the words, he pitched forward, shot through the chest. A giant "plug-ugly" bellowed with triumph over his successful shot, yelled "kill 'em all!" and led the mob upon them. But Mr. Strong had snatched Saltonstall's gun as it fell from his nerveless hands, had leveled and aimed it, and had shouted "fire!" to willing ears. A score of guns rang out. The mob-leader whirled about and dropped. Half-a-dozen other "plug-uglies" lay about him. This section of the mob broke and ran. Some of them fired as they ran, and Jim Casey's life went out of him.

"Take this gun, Tom," said Mr. Strong.

The boy took it, reloading it as he marched, while his sturdy father lifted the wounded Saltonstall from the stony street and staggered forward with the body in his arms. Casey and two other men were dead. Their bodies had to [Pg 37] be left to the fury of the mob. Saltonstall lived to fight to the end. As the survivors of the twenty pressed forward, the mob behind followed them up. Bullets whizzed unpleasantly near. Twice, at Mr. Strong's command, the men faced about and fired a volley. In both these volleys, Tom's gun played its part. He had hunted before, but never such big game as men. The joy of battle possessed him. Since it was apparently a case of "kill or be killed," he shot to kill. Whether he did kill, he never knew. The two volleys checked two threatening rushes of the rioters and enabled Mr. Strong to bring what was left of the gallant little band safely to the railroad station. An hour later the Sixth Massachusetts was in Washington. During that hour Tom had been violently sick upon the train. He was new to this trade of man-killing.

At Washington, once vacant spaces were soon filled with camps. Soldiers poured in on every train. Orderlies were galloping about. Artillery surrounded the Capitol. And from its [Pg 38] dome Tom saw a Confederate flag, the Stars-and-Bars, flying defiantly in nearby Alexandria.

Those were dark days. There were Confederate forces within a few miles of the White House. Sumter surrendered April 15th. Virginia seceded on the 17th. Harper's Ferry fell into Southern hands on the 18th. The Sixth Massachusetts had fought its way through Baltimore on the 19th. Robert E. Lee resigned his commission in our army on the 20th and left Arlington for Richmond, taking with him a long train of army and navy officers whose loyal support, now lost forever, had seemed a national necessity. Lincoln spent many an hour in his private office, searching with a telescope the reaches of the Potomac, over which the troop-laden transports were expected. Once, when he thought he was alone, John Hay heard him call out "with irrepressible anguish": "Why don't they come? Why don't they come?" In public he gave no sign of the anxiety that was eating up his heart. He had the nerve to jest about it. The Sixth Massachusetts, the Seventh [Pg 39] New York, and a Rhode Island detachment had all hurried to save Washington from the capture that threatened. When the Massachusetts men won the race and marched proudly by the White House, Lincoln said to some of their officers: "I begin to believe there is no North. The Seventh Regiment is a myth. Rhode Island is another. You are the only real thing." They were very real, those men of Massachusetts, and they were the vanguard of the real army that was to be.

CHAPTER III

Charles Francis Adams—Mr. Strong Goes to Russia—Tom Goes to Live in the White House—Bull Run—"Stonewall" Jackson—Geo. B. McClellan—Tom Strong, Second Lieutenant, U. S. A.—The Battle of the "Merrimac" and the "Monitor."

A few days passed before the President had time to see Mr. Strong and Tom. When they were finally ushered into his working-room, they found there, already interviewing Lincoln, the hawk-nosed and hawk-eyed Secretary of State, William H. Seward of New York, scholar, statesman, and gentleman, and a short, grizzled man, the worthy inheritor of a great tradition. He was Charles Francis Adams of Boston, son and grandson of two Presidents of the United States. He had been appointed Minister to England, just then the most important foreign [Pg 41] appointment in the world. What England was to do or not do might spell victory or defeat for the Union. Mr. Adams had come to receive his final instructions for his all-important work. And this is what happened.

Shabby and uncouth, Lincoln faced his two well-dressed visitors, nodding casually to the two New Yorkers as they entered at what should have been a great moment.

"I came to thank you for my appointment," said Adams, "and to ask you——"

"Oh, that's all right," replied Lincoln, "thank Seward. He's the man that put you in." He stretched out his legs and arms, and sighed a deep sigh of relief. "By the way, Governor," he added, turning to Seward, "I've this morning decided that Chicago post-office appointment. Well, good-by."

And that was all the instruction the Minister to Great Britain had from the President of the United States. Even in those supreme days, the rush of office-seekers, the struggle for the spoils, the mad looting of the public offices for partisan [Pg 42] purposes, was monopolizing the time and absorbing the mind of our greatest President. There is a story that one man who asked him to appoint him Minister to England, after taking an hour of his time, ended the interview by asking him for a pair of old boots. Civil Service Reform has since gone far to stop this scandal and sin, but much of it still remains. Today you can fight for the best interests of our beloved country by fighting the spoils system in city, state, and nation.

Adams, amazed, followed Secretary Seward out of the little room. Then Lincoln turned to the father and son.

Tom had more time to look at him now. He saw a tall man with a thin, muscular, big nose, with heavy eyebrows above deep-set eyes and below a square, bulging forehead, and with a mass of black hair. The face was dark and sallow. The firm lips relaxed as he looked down upon the boy. A beautiful smile overflowed them. A beautiful friendliness shone from the deep-set eyes.

"So this is another Tom Strong," he said. "Howdy, Tommy?"

The boy smiled back, for the welcoming smile was irresistible. He put his little hand into Lincoln's great paw, hardened and roughened by a youth of strenuous toil. The President squeezed his hand. Tom was happy.

"You're to go to Russia, Strong," Mr. Lincoln said to the father. "England and France threaten to combine against us. You must get Russia to hold them back. We'll have a regular Minister there, but I'm going to depend upon you. See Governor Seward. He'll tell you all about it. Will you take Mrs. Strong with you?"

"Most certainly."

"Well, I s'posed you would. And how about Tom here?"

Tom's heart beat quick. What was coming now?

"Mrs. Strong must decide that. I suppose he had better keep on with his school in New York."

"Why not let him come to school in Washington?" asked Lincoln. "In the school of the world? You see," he added, while that irresistible smile again softened the firm outlines of his big man's mouth, "you see I've taken a sort of fancy to your boy Tom. S'pose you give him to me while you're away. There are things he can do for his country."

It was perhaps only a whim, but the whims of a President count. A month later, Mr. and Mrs. Strong started for St. Petersburg and Tom reported at the White House. He was welcomed by John Hay, a delightful young man of twenty-three, one of the President's two private secretaries. The welcome lacked warmth.

"You're to sleep in a room in the attic," said Hay, "and I believe you're to eat with Mr. Nicolay and me. I haven't an idea what you're to do and between you and me and the bedpost I don't believe the Ancient has an idea either. Perhaps there won't be anything. Wait a while and see."

The Ancient—this was a nickname his secretaries [Pg 45] had given him—had a very distinct idea, which he had not seen fit to tell his zealous young secretary. Tom found the waiting not unpleasant. He had a good many unimportant things to do. "Tad" Lincoln, though younger, was a good playmate. The White House staff was kind to him. Even Hay found it difficult not to like him. Then there was the sensation of being at the center of things, big things. He saw men whose names were household words. Half a dozen times he lunched with the President's family, a plain meal with plain folks. Even the dinners at the White House, except the state dinners, were frugal and plain. Lincoln drank little or no wine. He never used tobacco. This was something of a miracle in the case of a man from the West, for in those days, particularly in the unconventional West, practically every man both smoked and chewed tobacco. The filthy spittoon was everywhere conspicuous. We fiercely resented the tales told our English cousins, first by Mrs. Trollope and then by Charles Dickens, about our tobacco-chewing, [Pg 46] but the resentment was so fierce because the tales were so true. Those were dirty days. In 1860 there were few bathrooms except in our largest cities. Those that existed were mostly new. In 1789, when the present Government of the United States came into being, in New York City, there was not one bathroom in the whole town.

At these family luncheons, Tom was apt to become conscious that Lincoln's eyes were bent beneath their shaggy eyebrows full upon him. There was nothing unkind in the glance, but the boy felt it go straight through him. He wondered what it all meant. Why was he not given more work to do? Had he been weighed and found wanting? He waited in suspense a good many months.

The early months of waiting were not merry months. In July, 1861, the first battle of Bull Run had been fought and had been lost. Our troops ran nearly thirty miles. Telegram after telegram brought news of disgrace and defeat to the White House. In the afternoon Lincoln [Pg 47] went to see Gen. Winfield S. Scott, then commander-in-chief of our armies. The fat old general was taking his afternoon nap. Awakened with difficulty, he gurgled that everything would come out well. Then he fell asleep again. Before six o'clock it was known that everything had turned out most badly. Washington itself was threatened by the Confederate pursuit. Lincoln had no sleep that night. The gray dawn found him at his desk, still receiving dispatches, still giving orders. When he left the desk, Washington was safe.

It was at the beginning of the battle of Bull Run, when the Confederates came near running away but did not do so because the Union troops ran first, that "Stonewall" Jackson got his famous nickname. The brigade of another Southern soldier, Gen. Bernard Bee, was wavering and falling back. Its commander, trying to hearten his men, called out to them: "Look! there's Jackson standing like a stone wall!" The men looked, rallied, and went on fighting. It may have been that one thing of Jackson's example [Pg 48] that turned the tide at Bull Run, gave the battle to the South, and prolonged the war by at least two years. Stonewall Jackson's soldiers were called foot-cavalry, because under his inspiring leadership they made marches which would have been a credit to mounted men. It was his specialty to be where it was impossible for him to be, by all the ordinary rules of war. He was a thunderbolt in attack, a stone wall in defense.

In November of that sad year of 1861, the President made another noteworthy call upon the then commander-in-chief, Gen. George B. McClellan. President and Secretary of State, escorted by young Hay and younger Tom, called upon the General at the latter's house, in the evening. They were told he was out, but would return soon, so they waited. McClellan did return and was told of his patient visitors. He walked by the open door of the room where they were seated and went upstairs. Half an hour later Lincoln sent a servant to tell him again [Pg 49] that they were there. Word came back that General McClellan had gone to bed. John Hay's diary justly speaks of "this unparalleled insolence of epaulettes." As the three men and the boy walked back to the White House, Hay said:

"It was an insolent rebuff. Something should be done about it."

Lincoln's almost godlike patience, however, had not been worn out.

"It is better," the great man answered, "at this time not to be making a point of etiquette and personal dignity."

The President, however, stopped calling upon the pompous General. After that experience, he always sent word to McClellan to call upon him.

One day, at the close of a family luncheon, the President said to Tom: "Come upstairs with me."

In the little private office, Lincoln took off his coat and waistcoat with a sigh of relief and [Pg 50] lounged into his chair. He bade Tom take a chair nearby. Then he looked at the boy for a moment, while his wonderful smile overflowed his strong lips.

"I've been studying you a bit, Tom. I think you'll do. Now I'll tell you what I want you to do."

The smile died quite away.

"Are you sure you can keep still when you ought to keep still? Balaam's ass isn't the only ass that ever talked. Most asses talk—and always at the wrong time."

"The last thing Father told me," Tom answered, "was never to say anything to anybody 'less I was sure you'd want me to say it."

"Your father is a wise man, my boy. Pray God he does what I hope he will in Russia."

The serious face grew still more serious. The long figure slouching in the chair straightened and stiffened. The sloping shoulders seemed to broaden, as if to bear steadfastly a weight that [Pg 51] would have crushed most men. The dark eyes gleamed with a solemn hope. Tom longed to ask what his father was to try to do, but he was not silly enough to put his thought into words. Another good-by counsel his father had given him was never to ask the President a question, unless he had to do so. There was silence for a moment. Then Lincoln spoke again:

"You're to carry dispatches for me, Tom. This may take you into the enemy's country sometimes. If you were captured and were a civilian, it might go hard with you. So I've had you commissioned as a second lieutenant. If you should slip into a fight occasionally I wouldn't blame you much. Mr. Stanton, the Secretary of War, kicked about it. He said he didn't believe in giving commissions to babies. I told him you could almost speak plain and could go 'round without a nurse. Finally he gave in. I haven't much influence with this Administration"—here Tom looked puzzled until the President smiled over his own jest—"but [Pg 52] I did get you the commission. Here it is."

He laid the precious parchment on the desk, put on his spectacles, took up his quill pen, and wrote at the foot of it

The boy's heart thrilled and throbbed. He had never dreamed of such an opportunity and such an honor. He was an officer of the Union. He was to carry dispatches for the President of the United States. His hand shook a little as he took the commission, reverently.

"You've been detailed for special service, Tom. Stanton wanted to know whether your special service was to be to play with my boy, Tad. Stanton was pretty mad; that's a fact. Well, well, you must do your work so well that he'll get over the blow. You would have thought I was asking him for a brigadier's commission for a girl. Well, well. Being a war messenger is only one of your duties, son. You're to be my [Pg 53] scout. Keep your ears and eyes both open, Tom, and your mouth shut. Ever hear the story of what Jonah said to the whale when he got out of him? The whale said to Jonah: 'You've given me a terrible stomach-ache.' And Jonah said: 'That's what you got because you didn't have sense enough to keep your mouth shut.' But remember, Tom, to go scouting in the right way. What I want is the truth. It's a hard thing for a President to get. I don't want tittle-tattle, evil gossip, idle talk. When I was in Congress, there was a fine old fellow in the House from Florida. I remember he said once that the Florida wolf was 'a mean critter that'd go snoopin' 'round twenty miles a night ruther than not do a mischief.' Don't be a wolf, Tom,—but don't be a lamb either, with the wool pulled over your eyes and ears. Here's your first job. This envelope"—Lincoln took from the desk a sealed envelope, not addressed, and handed it to the boy—"this envelope is for the commander of the 'Cumberland,' in Hampton Roads. This War Department pass will [Pg 54] carry you anywhere. When Stanton signed it, he asked me whether he was to spend a whole day signing things for you to play with. Mrs. Lincoln has had a uniform made for you, on the sly. I rather think you'll find it in your room, Tom. You'd better start tomorrow."

"Mayn't I start this afternoon, Mr. President?"

"Good for you. Of course you may. I'll say good-by to the folks for you. God bless you, son."

Lincoln waved a kindly farewell as Tom, with drumbeats in his young heart, gave a fair imitation of an officer's salute—and strode out of the room with what he meant to be a manly step. Once outside, the step changed to a run. He flew along the halls and up the stairs to the attic. He burst into his room. On his narrow bed lay his new uniform. Mrs. Lincoln, kindly housewife that she was, had done her part in the little conspiracy for the benefit of the boy who was Tad Lincoln's beloved playmate. She had herself smuggled an old suit of Tom's to a [Pg 55] tailor, who had made from its measure the resplendent new blue uniform that now greeted Tom's enraptured eyes.

That afternoon, Lieutenant Tom Strong left the White House for Hampton Roads. A swift dispatch boat carried him there. He reached the flagship on a lovely, peaceful, spring day, and delivered his dispatches. The boat that had taken him there was to take him back the next morning. He was glad to have a night on a warship. It was a new experience. And his father had told him that experience was the best teacher in the world. The beautiful lines of the frigate were a joy to see. Her spick and span cleanliness, the trim and trig sailors and marines, the rows of polished cannon that thrust their grim mouths out of the portholes, these things delighted him. He was standing on the quarter-deck with Lieutenant Morris, almost wishing he could exchange his brand-new lieutenancy in the army for one in the navy, when from the Norfolk navy yard a rocket flared up into the air.

"What is that, sir?" asked Tom. "Is it a signal to you?"

"I fancy it is," Morris answered, "but it isn't meant to be. That's a rebel rocket. You know we lost the navy-yard early in the war and we haven't got it back—yet. That rocket went up from there. The Secesh are up to some deviltry. They've been signaling a good bit of late. I wish they'd come out and give us a chance at them. Hampton Roads is dull as ditchwater, with not a thing happening."

The gallant lieutenant yawned prodigiously. He little knew what terrible things were to happen on the morrow. That rocket meant that the rebel ram, the "Merrimac," the first iron-clad vessel that ever went into action, was to sail down Hampton Roads, where nothing ever happened, the next morning and was to make many things happen. The Confederates had converted the old Union frigate, the "Merrimac," into a new, strange, and monstrous thing. They had placed a battery of cannon of a size never before mounted on shipboard upon [Pg 57] her deck, close to the water-line; they had built over the battery a framework of stout timbers, covered with armor rolled from rails, and they had put a cast-iron bow upon this marine marvel. A wooden ship was a mere toy to her.

The next morning came—it was March 8, 1862—and the "Merrimac" came. As she emerged from distance and mist, our scout-boats came racing to the "Cumberland" with news of the danger that was fast nearing her. The news was a tonic to officers and to men. Here at last was something to fight. Here at last was something to do. They were all weary of having the flagship lie, week after week,

Upon a painted ocean."

The men sprang to quarters with a joyful cheer. The officers were at their posts. The gun-crews waited impatiently for the order to fire. And Tom, again upon the quarter-deck, thrilled with the thrill of all about him, was glad to know that the dispatch boat would not sail until that afternoon [Pg 58] and that he could see the fight. Everyone around him was sure of victory. The foe was soon to be sunk. The Stars-and-Bars, now flying so impudently at her stern, was to be hung up as a trophy in the ward-room of the "Cumberland." It never was.

The ram steered straight for the flagship. She did not fire a shot, though the flagship's cannon roared. A tongue of fire blazed from every porthole of the starboard side, towards which she came, silently and swiftly. Behind every tongue of fire there rushed a cannon-ball. Many a ball hit the "Merrimac." A wooden ship would have been blown to bits by the concentrated fury of the cannonade. Alas! the cannon-balls glanced from her armored sides "like peas from a pop-gun." They rattled like hail upon her and did her no more hurt than hail-stones would have done. She came on like an irresistible Fate. There had been shouts of savage joy below decks when the first order to fire had echoed through them. A burst of wild cheering from the gun-crews had almost [Pg 59] drowned the first thunder of the guns. There were no shouts or cheers now. Sharp orders pierced the clangor of artillery.

"Stand by to board!"

The marines formed quickly at the starboard bow of the "Cumberland." Then at last the guns of the "Merrimac" spoke. She was close upon her prey now. The sound of her first volley was the voice of doom. Her great cannon sent masses of iron through and through the pitiful wooden walls that had dared to stand up against walls of iron. The shrieks of wounded men, of men screaming their mangled lives away, rolled up to the quarter-deck. A messenger dashed up there.

"Half the gun-crew officers are dead. Send us others!"

"Go below," said Lieutenant Morris, turning to two young midshipmen who stood near Tom, "keep the guns manned."

The two middies bounded below and Tom bounded down with them. There was no hope of victory now, but the fight must be fought to [Pg 60] a finish. If the cannon could still be served, a lucky shot might strike the foe in a vital part, might disable her engines, might carry away her steering-gear, might—there was a long chapter of possible accidents to the "Merrimac" that might still save the "Cumberland" from what seemed to be her sure destruction. As the three boys raced down to the gun-deck, they saw a fearful scene. Dead and wounded men lay everywhere. The sawdust that in those days used to be strewn about, before entering action, in order to soak up the blood of the men who fell and keep the decks from growing slippery with it, had soaked up all it could, but there were thin red trickles flowing along the deck. Two or three of the cannon had been dismounted. Crushed masses that had been human flesh lay beneath them. A dying officer half raised himself to give one last command and fell back dead before he could speak. The men were standing to their task as American sailors are wont to do, but like all men they needed leaders. Three leaders came. The two middies and Tom [Pg 61] took command of these officerless cannon. The other two boys knew their work and did it. Tom knew that it was his business to keep his cannon at work and he did it. He repeated, mechanically:

"Load! Fire! Load! Fire!"

His men responded to the command. The cannon roared once, twice. Then there came a sickening shock. The rebel ram drove its iron prow home through the side of the "Cumberland." The good ship reeled far over under the deadly blow, righted herself, but began to sink. Her race was run. The black bulk of the "Merrimac" was just opposite the porthole of the gun Tom was handling. There was a last order. With the lips of their muzzles wet with the engulfing sea, the cannon of the "Cumberland" roared their last defiance of death. Down went the ship. The sea about her was black with wreckage and with struggling men. Boats from other ships and from the shore darted among them, picking them up. The dispatch boat that had brought Tom down was busy with [Pg 62] that good work. The "Merrimac" could have sunk her without effort, but of course the Confederates never dreamed of making the effort. Americans do not fire at drowning men. When Tom jumped into the water, as the ship sank beneath him, he swam to a shattered spar and clutched it. But other men who could not swim clutched at it too. It threatened to sink with their added weight and carry them down with it. So the boy, thoroughly at home in the water, let go, turned upon his back, floated with his nose just above the surface, and waited for the help that was at hand. A boat-hook caught his trousers at the waist-band. He was pulled up to the deck of the dispatch boat. It was not quite the way in which he had expected to board her. From her bridge, with the deck below him crowded with the rescued sailors of the "Cumberland," he saw the second sad act of that day's tragedy.

The "Merrimac" had backed away, after that terrible thrust of her iron ram, until she was free from the ship she had destroyed. Then she [Pg 63] laid her course for the "Congress," invincible yesterday, today helplessly weak in the face of this new terror of the seas. The "Congress" fought to the last gasp, but that last gasp came all too soon. Raked fore and aft by her adversary's guns, unable to fire a single effective shot in reply, she ran upon a shoal while trying to escape from being rammed and lay there, no longer a fighting machine, but a mere target for her foe. Her captain could not hope to save his ship. The only thing he could do was to save the lives of such of his crew as were still alive. And there was but one way to do that. The "Congress" surrendered. The Stars-and-Stripes fluttered down from her masthead. In place of the flag of the free, the Stars-and-Bars, symbol of slavery, flew above the surrendered ship. The "Cumberland," going down with her flag, had had the better fate of the two.

The "Merrimac," justly satisfied with her day's work and with the toll she had taken of the Union squadron, steamed proudly back to Norfolk, to repair the slight damages she had [Pg 64] suffered and to make ready to complete her conquest on the morrow. Three Union ships still lay in Hampton Roads, great frigates, the finest of their kind then afloat, perfectly appointed, fully manned,—and as useless as though they had been the toy-boats of a child. The "Minnesota," now the flagship, signaled Captain Lawrence's stirring slogan: "Don't give up the ship!" It might have been called a bit of useless bravery, but no bravery is useless. At least the officers and men of the three doomed ships would fight for the flag until they died. It was just possible that one of the three might so maneuver that she would strike the foe amidships and sink with her to a glorious death.

That night the wild anxiety at Hampton Roads was more than echoed at New York and Washington. The wires had told the terrible tale of the "Merrimac." It was thought she could go straight to New York, sink all the shipping there, command the city and levy tribute upon it. Lincoln's Secretary of the [Pg 65] Navy, Gideon Welles of Connecticut, wrote in his diary that night: "The most frightened man on that gloomy day was the Secretary of War. He was at times almost frantic.... He ran from room to room, sat down and jumped up after writing a few words, swung his arms, and scolded and raved." Hay records that "Stanton was fearfully stampeded. He said they would capture our fleet, take Fort Monroe, be in Washington before night."

Without consulting the Secretary of the Navy, Stanton had some fifty canal-boats loaded with stone and sent them to be sunk on Kettle Bottom Shoals, in the Potomac, to keep the "Merrimac" from reaching Washington. The canal-boats reached the Shoals, but the order to sink them was countermanded by cooler heads. They were left in a long row, tied up to the river bank.

The three doomed ships at Hampton Roads soon knew that at nine o'clock of that fateful night there had steamed in from the ocean a [Pg 66] Union iron-clad. Her coming, however, brought scant comfort.

"What is she like?" asked the first captain to hear the news.

"Like? She's like a cheese-box on a raft."

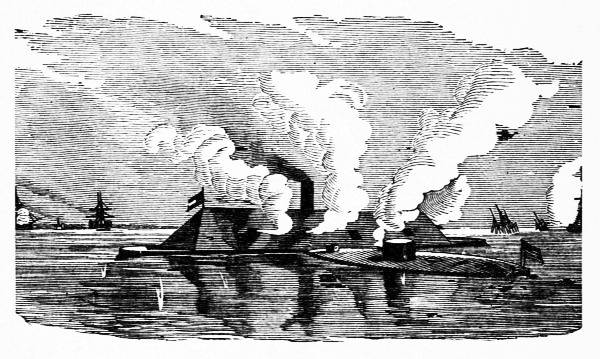

THE BATTLE OF THE "MONITOR" AND THE "MERRIMAC"

THE BATTLE OF THE "MONITOR" AND THE "MERRIMAC"

It was not a bad description. She was the "Monitor," an unknown boat of an unknown type that day, and on the morrow the most famous fighting craft that ever sailed the seas. She was born of the brain of a Swedish-American, Capt. John Ericsson, whose statue stands in Battery Park, the southern tip of the [Pg 67] metropolis, looking down to the ocean he saved for freedom's cause.

Lieut. A. L. Worden, commanding the "Monitor," was soon in consultation with the other commanders. They scarcely tried to disguise their belief that he had merely brought another predestined victim. His ship was tiny, compared with the "Merrimac." She was not built to ram, as was her terrible antagonist. Her guns were of a greater caliber, to be sure, than any wooden ship mounted, but there were but two of them and they could be brought to bear only by revolving the "Monitor's" turret,—a newfangled device in everyday use now, but then unknown and consequently despised. Men either fear or despise the unknown. They are usually wrong in doing either. The council of captains agreed upon a plan for the next day's fight. The plan was based upon the theory that the "Monitor" would be speedily sunk. Nevertheless, she was to face the foe first of all.

Again the next morning came and again there came the rebel ram. Decked out in flags as if [Pg 68] for a festival, proudly certain of victory, the "Merrimac" steamed down Hampton Roads. The cheese-box on a raft steamed out to meet her. It was David confronting Goliath. Goliath had fourteen guns and David had two. The iron-clads came nearer and the most famous sea-duel ever fought began. Tom saw it all from the bridge of the "Minnesota." Both vessels fired and fired again, without result. Their armor defied even the big guns they carried. Then the "Merrimac" tried to bring her deadly ram into play. The "Monitor" dodged into shoal water, hoping her foe would follow her and run aground. The "Merrimac" did not fall into the trap. On the contrary, she left her adversary and made a headlong course for the helpless "Minnesota." On board the latter, drums beat to quarters, shrill whistles gave orders, and the great ship moved forward to what seemed certain destruction. But the "Monitor" slipped away from the shoals and made after the "Merrimac," firing her guns as rapidly as her creaking turret could turn. The [Pg 69] "Merrimac" faced about, bound this time to make short work of this wretched little gnat that was seeking to sting her. This time the two came to close grips. Each tried to ram the other down. Each struck the other, but struck a glancing blow. They lay almost alongside and pounded each other with their giant guns. A missile from the "Monitor" came through a porthole of the "Merrimac," breaking a cannon and dealing death and destruction within her iron sides. She turned and ran for safety to the shelter of the Confederate batteries at Norfolk. The "Monitor" lay almost unharmed upon the gentle waves of Hampton Roads, the ungainly master of the seas. The "Merrimac" never dared again to try conclusions with her stout little rival. She stayed at her moorings until she was blown up there just before the Union forces captured Norfolk. The Union blockade was never broken. The "Monitor" survived the fight only to founder later in "the graveyard of ships," off Cape Hatteras.

The wires had told the story of the famous [Pg 70] fight before Tom reached Washington, but he was the first eye-witness of it to reach there and he had to tell the tale many and many a time. His first auditors were Lincoln and Secretary Welles. The dispatch boat that carried him back put him on board the President's boat, south of Kettle Bottom Shoals, on the Potomac, in obedience to orders signaled to it. When he had finished his story, there was silence for a moment. The boy saw Lincoln's lips move, perhaps in prayer, perhaps in thanksgiving. Then the grave face relaxed and the pathetic eyes twinkled with humor. The President laid his hand upon the Secretary's arm and pointed to a long line of stone-laden canal-boats that bordered the bank.

"There's Stanton's navy," said Lincoln.

CHAPTER IV

Tom Goes West—Wilkes Booth Hunts Him—Dr. Hans Rolf Saves Him—He Delivers Dispatches to General Grant.

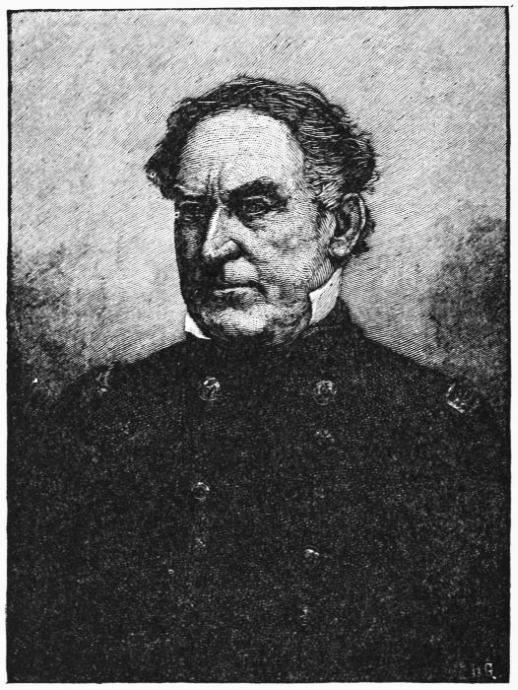

At the end of the next month, April, 1862, Admiral Farragut gallantly forced open the closed mouth of the Mississippi. He took his wooden ships into action against forts and iron-clad gunboats and captured New Orleans. Within fifteen months thereafter, the North was in practical control of the whole Mississippi. By July, 1863, the Confederacy had been split into two parts, east and west of the "Father of Waters." That was the poetic Indian name of the Mississippi. Farragut's fleet began the driving of the wedge. Grant's army drove it home. When the driving home had just begun, Tom, to his intense delight, was sent West with dispatches for Grant. He left on an hour's notice.

ADMIRAL FARRAGUT

ADMIRAL FARRAGUT

During that hour, a colored servant employed in the White House, whose heart was blacker than his sooty skin, had left the mansion, had sought a tumble-down tenement in the slums, [Pg 73] and had found there a vulture of a man, very white as to face, very black as to the masses of hair that fell to his shoulders.

"Dat dar boy Strong, he's dun sure goin'," said the darkey, "wid papers fur dat General Grant out West."

"How do you know?"

"Coz I listened to de door, when dey-uns wuz a-talkin'."

"He'll have to go West by Baltimore," mused the white man. "The next train leaves in half an hour. I can make it. Here, Reub, here's your pay."

He took a five-dollar gold piece from his pocket. The negro clutched at it. Then what was left of his conscience stirred within him. He said, pleadingly, hesitatingly:

"Massa, you knows I'se doin' dis coz old Massa told me to. You ain't a-goin' to hurt dat boy Strong, is you? He's a nice boy. Eberybody lubs him up dar."

"What is it to you, confound you!" snarled the man, "whether I hurt him or not? What's [Pg 74] a boy's life to winning the war? You keep on doing what old Massa told you to do, or I'll cut your black heart out."

With a savage gesture, he thrust the trembling negro out of the dingy room. With savage haste, he packed his scanty belongings. With a pistol in his hip pocket, with a bowie-knife slung over his left breast beneath his waistcoat, with a vial of chloroform in his valise, Wilkes Booth left Washington on the trail of Tom Strong.

Hunter and hunted were in the same car. Tom little dreamed that a few seats behind him sat a deadly foe, who would stick at nothing to get the precious papers he carried. Washington swarmed with Confederate spies. The face of everybody at the White House was well known to every spy. The hunter did not have to guess where the hunted sat.

General Grant had begun his career of victory in the West. It was all-important to the Confederacy to know where his next blow was to [Pg 75] be aimed. The papers in the scout's possession would tell that great secret. Wilkes Booth meant to have those papers soon. As the train bumped over the rough iron rails, towards Baltimore, Booth went to the forward end of the car for a glass of water and as he walked back along the aisle with a slow, lounging step, he stopped where Tom sat and held out his hand, saying:

"How do you do, Mr. Strong? I'm Mr. Barnard. I have had the pleasure of seeing you about the White House sometimes, when I have been calling on our great President. Lincoln will crush these accursed rebels soon!"

It was a trifle overdone, a trifle theatrical. Wilkes Booth could never help being theatrical. His greeting was one of the few times Tom had ever been called "Mister." He felt flattered and took the proffered hand willingly, but he searched his memory in vain for any real recollection of the striking face of the man who spoke to him. There was some vague stirring of memory about it, but certainly this had no relation to that happy life at the White House. [Pg 76] Something evil was connected with it. Puzzled, he wondered. He had seen Booth under arms at John Brown's scaffold, but he did not remember that.

The alleged Mr. Barnard slipped into the seat beside him and began to talk. He talked well. Little by little, suspicion fell asleep in Tom's mind as his companion told of adventures on sea and land. Booth was trying to seem to talk with very great frankness, in order to lure Tom into a similar frankness about himself. He larded all his talk with protestations of fervent loyalty to the Union. Tom bethought himself of a favorite quotation his father often used from Shakespeare's great play of "Hamlet." The conscience-stricken queen says to Hamlet, her son:

"The lady doth protest too much, methinks."

Wilkes Booth was protesting too much. The drowsy suspicion in Tom's mind stirred again. But he was but a boy and Booth was a man, skilled in all the craft of the stage. Once more his easy, brilliant talk lulled caution to sleep. [Pg 77] Tom, questioned so skillfully that he did not know he was being drawn out, little by little told the story of his short life. But the story ended with his saying he was going to Harrisburg "on business." He was still enough on his guard not to admit he was going further than Harrisburg.

"You're pretty young to be on the way to the State Capitol on business," said the skillful actor, hoping to hear more details in answer to the half-implied sneer. But just then Tom remembered what his father had advised: "Never say anything to anybody, unless you are sure the President would wish you to say it." He shut up like a clam. Booth could get nothing more out of him. But he meant to get those dispatches out of him. They were either in the boy's pocket or his valise, probably in his pocket. When he fell asleep, the spy's time would come. So the spy waited.

Darkness came. Two smoky oil-lamps gave such light as they could. The train rumbled on in the night. There were no sleeping cars [Pg 78] then. People slept in their seats, if they slept at all. Booth's tones grew soothing, almost tender. They served as a lullaby. Tom slept. The spy beside him drew a long, triumphant breath. His time had come.

Some time before, he had shifted his traveling-bag to this seat. Now he drew from it, gently, quietly, the little bottle of chloroform and a small sponge, which he saturated with the stupefying drug. Then he slipped his arm under the sleeping boy's head, drew him a little closer to himself, and glanced through the dusky car. Nearly everybody was asleep. Those who were not were trying to go to sleep. No one was watching. Booth pressed the sponge to Tom's nostrils. Tom stirred uneasily. "Sh-sh, Tom," purred the actor, "go to sleep; all's well." The drug soon did its work. The boy was dead to the world for awhile. Only a shock could rouse him.

The shock came. Booth's long, sensitive, skilled fingers—the fingers of a musician—ransacked his coat and waistcoat pockets swiftly, finding nothing. But beneath the waistcoat [Pg 79] their tell-tale touches had detected the longed-for papers. The waistcoat was deftly unbuttoned—it could have been stripped off without arousing the unconscious boy—and a triumphant thrill shot through Booth's black heart as he drew from an inner pocket the long, official envelope that he knew must hold what he had stealthily sought. He was just about to slip it into his own pocket and then to leave his stupefied victim to sleep off the drug while he himself sought safety at the next station, when one of those little things which have big results occurred. The sturdy man who was snoring in the seat behind this one happened to be a surgeon. He was returning from Washington, whither he had gone to operate on a dear friend, a wounded officer. Chloroform had of course been used, but the patient had died under the knife. It had been a terrible experience for the operator. It had made his sleep uneasy. A mere whiff from the sponge Booth had used reached the surgeon's sensitive nostril. It revived the poignant memories of the last few hours. He [Pg 80] awoke with a start that brought him to his feet. And there, just in front of him, he saw by the dim light a boy sunk in stupefied slumber and a man glancing guiltily back as he tried to thrust a stiff and crackling paper into his pocket. The sponge had fallen to the floor, but its fumes, far-spreading now, told to the practiced surgeon a story of foul play. He grabbed the man by the shoulder and awoke most of the travelers, but not Tom, with a stentorian shout: "What are you doing, you scoundrel?"

The scoundrel leaped to his feet, throwing off the doctor's hand, and sprang into the aisle, clutching the long envelope in his left hand, while his right held a revolver. He rushed for the door, pursued by half a dozen men, headed by the doctor. Close pressed, he whirled about and leveled his pistol at his unarmed pursuers. They fell back a pace. He whirled again, stumbled over a bag in the aisle, fell, sprang to his feet once more. A brakeman opened the door. He was hurrying to see what this clamor meant. Wilkes Booth fired at him pointblank. The [Pg 81] bullet missed, but it made the brakeman give way. Booth rushed by him, gained the platform and leaped from the slow train into the sheltering night.