Transcriber's Notes:

1. Page scan source:

https://archive.org/details/lastvendeeorshe00duma

(University of California Libraries)

2. The diphthong oe is represented by [oe]

Illustrated Sterling edition

THE LAST VENDÉE

OR, THE

SHE-WOLVES OF MACHECOUL

TWO VOLUMES IN ONE

BY

ALEXANDRE DUMAS

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1894,

By Estes and Lauriat.

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | |

| I. | Charette's Aide-de-camp. |

| II. | The Gratitude of Kings. |

| III. | The Twins. |

| IV. | How Jean Oullier, coming to see the Marquis for an Hour, would be there still if they had not both been in their Grave these ten years. |

| V. | A Litter of Wolves. |

| VI. | The Wounded Hare. |

| VII. | Monsieur Michel. |

| VIII. | The Baronne de la Logerie. |

| IX. | Galon-d'or and Allégro. |

| X. | In which Things do not Happen precisely as Baron Michel Dreamed they would. |

| XI. | The Foster-father. |

| XII. | Noblesse Oblige. |

| XIII. | A Distant Cousin. |

| XIV. | Petit-Pierre. |

| XV. | An Unseasonable Hour. |

| XVI. | Courtin's Diplomacy. |

| XVII. | The Tavern of Aubin Courte-Joie. |

| XVIII. | The Man from La Logerie. |

| XIX. | The Fair at Montaigu. |

| XX. | The Outbreak. |

| XXI. | Jean Oullier's Resources. |

| XXII. | Fetch! Pataud, fetch! |

| XXIII. | To whom the Cottage belonged. |

| XXIV. | How Marianne Picaut mourned her Husband. |

| XXV. | In which Love lends Political Opinions to those who have none. |

| XXVI. | The Springs of Baugé. |

| XXVII. | The Guests at Souday. |

| XXVIII. | In which the Marquis de Souday bitterly regrets that Petit-Pierre is not a Gentleman. |

| XXIX. | The Vendéans of 1832. |

| XXX. | The Warning. |

| XXXI. | My Old Crony Loriot. |

| XXXII. | The General eats a Supper which had not been Prepared for him. |

| XXXIII. | In which Maître Loriot's Curiosity is not exactly satisfied. |

| XXXIV. | The Tower Chamber. |

| XXXV. | Which ends quite otherwise than as Mary expected. |

| XXXVI. | Blue and White. |

| XXXVII. | Which shows that it is not for Flies only that Spiders' Webs are dangerous. |

| XXXVIII. | In which the Daintiest Foot of France and of Navarre finds that Cinderella's Slipper does not fit it as well as Seven-league Boots. |

| XXXIX. | Petit-Pierre makes the best Meal he ever made in his Life. |

| XL. | Equality in Death. |

| XLI. | The Search. |

| XLII. | In which Jean Oullier speaks his mind About young Baron Michel. |

| XLIII. | Baron Michel becomes Bertha's Aide-de-camp. |

| XLIV. | Maître Jacques and his Rabbits. |

| XLV. | The Danger of Meeting bad Company in the Woods. |

| XLVI. | Maître Jacques proceeds to keep the Oath he made to Aubin Courte-Joie. |

CONTENTS.

| I. | In which it appears that all Jews are not from Jerusalem, nor all Turks from Tunis. |

| II. | Maître Marc. |

| III. | How Persons travelled in the Department of the Lower Loire in May, 1832. |

| IV. | A little History does no Harm. |

| V. | Petit-Pierre resolves on keeping a Brave Heart against Misfortune. |

| VI. | How Jean Oullier proved that when the Wine is drawn it is best to drink it. |

| VII. | Herein is explained how and why Baron Michel decided to go to Nantes. |

| VIII. | The Sheep, returning to the Fold, tumbles into a Pit-fall. |

| IX. | Trigaud proves that if he had been Hercules He would probably have accomplished Twenty-four labors instead of twelve. |

| X. | Giving the Slip. |

| XI. | Mary is victorious after the Manner of Pyrrhus. |

| XII. | Baron Michel finds an Oak instead of a Reed on which to lean. |

| XIII. | The Last Knights of Royalty. |

| XIV. | Jean Oullier lies for the Good of the Cause. |

| XV. | Jailer and Prisoner escape together. |

| XVI. | The Battlefield. |

| XVII. | After the Fight. |

| XVIII. | The Chateau de la Pénissière. |

| XIX. | The Moor of Bouaimé. |

| XX. | The Firm of Aubin Courte-Joie & Co. does Honor to its Partnership. |

| XXI. | In which Succor comes from an Unexpected Quarter. |

| XXII. | On the Highway. |

| XXIII. | What became of Jean Oullier. |

| XXIV. | Maître Courtin's Batteries. |

| XXV. | Madame la Baronne de la Logerie, Thinking to serve her Son's interests, serves those of Petit-Pierre. |

| XXVI. | Marches and Counter-marches. |

| XXVII. | Michel's Love Affairs seem to be taking a Happier Turn. |

| XXVIII. | Showing how there may be Fishermen and Fishermen. |

| XXIX. | Interrogatories and Confrontings. |

| XXX. | We again meet the General, and find he is not changed. |

| XXXI. | Courtin meets with Another Disappointment. |

| XXXII. | The Marquis de Souday drags for Oysters and brings up Picaut. |

| XXXIII. | That which happened in Two Dwellings. |

| XXXIV. | Courtin fingers at last his Fifty Thousand Francs. |

| XXXV. | The Tavern of the Grand Saint-Jacques. |

| XXXVI. | Judas and Judas. |

| XXXVII. | An Eye for an Eye, and a Tooth for a Tooth. |

| XXXVIII. | The Red-Breeches. |

| XXXIX. | A Wounded Soul. |

| XL. | The Chimney-back. |

| XLI. | Three Broken Hearts. |

| XLII. | God's Executioner. |

| XLIII. | Shows that a Man with Fifty Thousand Francs about him may be much Embarrassed. |

| EPILOGUE |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

VOL. I.

Portrait of Dumas Frontispiece

VOL. II.

THE LAST VENDÉE;

OR,

THE SHE-WOLVES OF MACHECOUL

VOLUME I.

THE LAST VENDÉE;

OR,

THE SHE-WOLVES OF MACHECOUL

I.

CHARETTE'S AIDE-DE-CAMP.

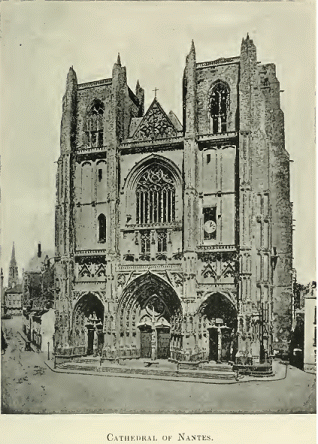

If you ever chanced, dear reader, to go from Nantes to Bourgneuf you must, before reaching Saint-Philbert, have skirted the southern corner of the lake of Grand-Lieu, and then, continuing your way, you arrived, at the end of one hour or two hours, according to whether you were on foot or in a carriage, at the first trees of the forest of Machecoul.

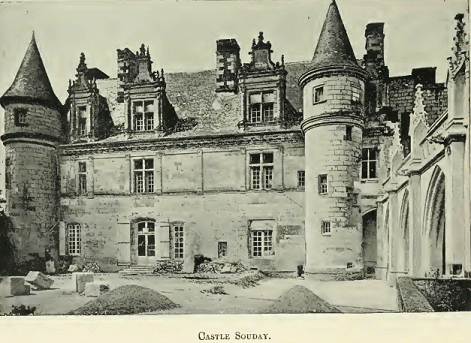

There, to left of the road, among a fine clump of trees belonging, apparently, to the forest from which it is separated only by the main road, you must have seen the sharp points of two slender turrets and the gray roof of a little castle hidden among the foliage.

The cracked walls of this manor-house, its broken windows, and its damp roofs covered with wild iris and parasite mosses, gave it, in spite of its feudal pretensions and flanking turrets, so forlorn an appearance that no one at a passing glance would envy its possessor, were it not for its exquisite situation opposite to the noble trees of the forest of Machecoul, the verdant billows of which rose on the horizon as far as the eye could reach.

In 1831, this little castle was the property of an old nobleman named the Marquis de Souday, and was called, after its owner, the château of Souday.

Let us now make known the owner, having described the château.

The Marquis de Souday was the sole representative and last descendant of an old and illustrious Breton family; for the lake of Grand-Lieu, the forest of Machecoul, the town of Bourgneuf, situated in that part of France now called the department of the Loire-Inférieure, was then part of the province of Brittany, before the division of France into departments. The family of the Marquis de Souday had been, in former times, one of those feudal trees with endless branches which extended themselves over the whole department; but the ancestors of the marquis, in consequence of spending all their substance to appear with splendor in the coaches of the king, had, little by little, become so reduced and shorn of their branches that the convulsions of 1789 happened just in time to prevent the rotten trunk from falling into the hands of the sheriff; in fact, they preserved it for an end more in keeping with its former glory.

When the doom of the Bastille sounded, and the demolition of the old house of the kings foreshadowed the overthrow of royalty, the Marquis de Souday, having inherited, not great wealth,--for nothing of that was left, as we have said, except the old manor-house,--but the name and title of his father, was page to his Royal Highness, Monsieur le Comte de Provence. At sixteen--that was then his time of life--events are only accidental circumstances; besides, it would have been extremely difficult for any youth to keep from being heedless and volatile at the epicurean, voltairean, and constitutional court of the Luxembourg, where egotism elbowed its way undisguisedly.

It was M. de Souday who was sent to the place de Grève to watch for the moment when the hangman tightened the rope round Favras's neck, and the latter, by drawing his last breath, restored his Royal Highness to his normal peace of mind, which had been for the time being disturbed. The page had returned at full speed to the Luxembourg.

"Monseigneur, it is done," he said.

And monseigneur, in his clear, fluty voice, cried:--

"Come, gentlemen, to supper! to supper!"

And they supped as if a brave and honorable gentleman, who had given his life a sacrifice, to his Royal Highness, had not just been hanged as a murderer and a vagabond.

Then came the first dark, threatening days of the Revolution, the publication of the Red Book, Necker's retirement, and the death of Mirabeau.

One day--it was the 22d of February, 1791--a great crowd surrounded the palace of the Luxembourg. Rumors were spread. Monsieur, it was said, meant to escape and join the émigrés on the Rhine. But Monsieur appeared on the balcony, and took a solemn oath never to leave the king.

He did, in fact, start with the king on the 21st of June, possibly to keep his word never to leave him. But he did leave him, to secure his own safety, and reached the frontier tranquilly with his companion, the Marquis d'Avaray, while Louis XVI. and his family were arrested at Varennes.

Our young page, de Souday, thought too much of his reputation as a man of fashion to stay in France, although it was precisely there that the monarchy needed its most zealous supporters. He therefore emigrated, and as no one paid any heed to a page only eighteen years old, he reached Coblentz safely and took part in filling up the ranks of the musketeers who were then being remodelled on the other side of the Rhine under the orders of the Marquis de Montmorin. During the first royalist struggles he fought bravely under the three Condés, was wounded before Thionville, and then, after many disappointments and deceptions, met with the worst of all; namely, the disbanding of the various corps of émigrés,--a measure which took the bread out of the mouths of so many poor devils. It is true that these soldiers were serving against France, and their bread was baked by foreign nations.

The Marquis de Souday then turned his eyes toward Brittany and La Vendée, where fighting had been going on for the last two years. The state of things in La Vendée was as follows:--

All the first leaders of the great insurrection were dead. Cathélineau was killed at Vannes, Lescure at Tremblay, Bonchamps at Chollet; d'Elbée had been, or was to be, shot at Noirmoutiers; and, finally, what was called the Grand Army had just been annihilated in Le Mans.

This Grand Army had been defeated at Fontenay-le-Comte, at Saumur, Torfou, Laval, and Dol. Nevertheless, it had gained the advantage in sixty fights; it had held its own against all the forces of the Republic, commanded successively by Biron, Rossignol, Kléber, and Westermann. It had seen its homes burned, its children massacred, its old men strangled. Its leaders were Cathélineau, Henri de la Rochejaquelein, Stofflet, Bonchamps, Forestier, d'Elbée, Lescure, Marigny, and Talmont. In spite of all vicissitudes it continued faithful to its king when the rest of France abandoned him; it worshipped its God when Paris proclaimed that there was no God. Thanks to the loyalty and valor of this army, La Vendée won the right to be proclaimed in history throughout all time "the land of giants."

Charette and la Rochejaquelein alone were left. Charette had a few soldiers; la Rochejaquelein had none.

It was while the Grand Army was being slowly destroyed in Le Mans that Charette, appointed commander-in-chief of Lower Poitou and seconded by the Chevalier de Couëtu and Jolly, had collected his little army. Charette, at the head of this army, and la Rochejaquelein, followed by ten men only, met near Maulevrier. Charette instantly perceived that la Rochejaquelein came as a general, not as a soldier; he had a strong sense of his own position, and did not choose to share his command with any one. He was therefore cold and haughty in manner, and went to his own breakfast without even asking Rochejaquelein to share it with him.

The same day eight hundred men left Charette's army and placed themselves under the orders of la Rochejaquelein. The next day Charette said to his young rival:--

"I start for Mortagne; you will follow me."

"I am accustomed," replied la Rochejaquelein, "not to follow, but to be followed."

He parted from Charette, and left him to operate his army as he pleased. It is the latter whom we shall now follow, because he is the only Vendéan leader whose last efforts and death are connected with our history.

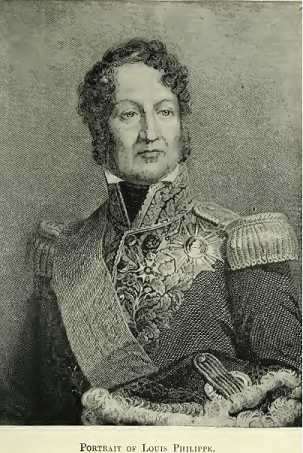

Louis XVII. was dead, and on the 26th of June, 1795, Louis XVIII. was proclaimed king of France at the headquarters at Belleville. On the 15th of August, 1795,--that is to say, two months after the date of this proclamation,--a young man brought Charette a letter from the new king. This letter, written from Verona, and dated July 8, 1795, conferred on Charette the command of the royalist army.

Charette wished to reply by the same young messenger and thank the king for the honor he had done him; but the young man informed the general that he had re-entered France to stay there and fight there, and asked that the despatch he had brought might serve as a recommendation to the commander-in-chief. Charette immediately attached him to his person.

This young messenger was no other than Monsieur's former page, the Marquis de Souday.

As he withdrew to seek some rest, after doing his last sixty miles on horseback, the marquis came upon a young guard, who was five or six years older than himself, and was now standing, hat in hand, and looking at him with affectionate respect. Souday recognized the son of one of his father's farmers, with whom he had hunted as a lad with huge satisfaction; for no one could head off a boar as well or urge on the hounds after the animal was turned with such vigor.

"Hey! Jean Oullier," he cried; "is that you?"

"Myself in person, and at your service, monsieur le marquis," answered the young peasant.

"Good faith! my friend, and glad enough, too. Are you still as keen a huntsman?"

"Oh, yes, monsieur le marquis; only, just now it is other game than boars we are after."

"Never mind that. If you are willing, we'll hunt this game together as we did the other."

"That's not to be refused, but much the contrary, monsieur le marquis," returned Jean Oullier.

From that moment Jean Oullier was attached to the Marquis de Souday, just as the marquis was attached to Charette,--that is to say, that Jean Oullier was the aide-de-camp of the aide-de-camp of the commander-in-chief. Besides his talents as a huntsman he was a valuable man in other respects. In camping he was good for everything. The marquis never had to think of bed or victuals; in the worst of times he never went without a bit of bread, a glass of water, and a shake-down of straw, which in La Vendée was a luxury the commander-in-chief himself did not always enjoy.

We should be greatly tempted to follow Charette, and consequently our young hero, on one of the many adventurous expeditions undertaken by the royalist general, which won him the reputation of being the greatest partisan leader the world has seen; but history is a seductive siren, and if you imprudently obey the sign she makes you to follow her, there is no knowing where you will be led. We must simplify our tale as much as possible, and therefore we leave to others the opportunity of relating the expedition of the Comte d'Artois to Noirmoutiers and the Île Dieu, the strange conduct of the prince, who remained three weeks within sight of the French coast without landing, and the discouragement of the royalist army when it saw itself abandoned by those for whom it had fought so gallantly for more than two years.

In spite of which discouragement, however, Charette not long after won his terrible victory at Les Quatre Chemins. It was his last; for treachery from that time forth took part in the struggle. De Couëtu, Charette's right arm, his other self after the death of Jolly, was enticed into an ambush, captured, and shot. In the last months of his life Charette could not take a single step without his adversary, whoever he was, Hoche or Travot, being instantly informed of it.

Surrounded by the republican troops, hemmed in on all sides, pursued day and night, tracked from bush to bush, springing from ditch to ditch, knowing that sooner or later he was certain to be killed in some encounter, or, if taken, to be shot on the spot,--without shelter, burnt up with fever, dying of thirst, half famished, not daring to ask at the farmhouses he saw for a little water, a little bread, or a little straw,--he had only thirty-two men remaining with him, among whom were the Marquis de Souday and Jean Oullier, when, on the 25th of March, 1796, the news came that four republican columns were marching simultaneously against him.

"Very good," said he; "then it is here, on this spot, that we must fight to the death and sell our lives dearly."

The spot was La Prélinière, in the parish of Saint-Sulpice. But with thirty-two men Charette did not choose to await the enemy; he went to meet them. At La Guyonnières he met General Valentin with two hundred grenadiers and chasseurs. Charette's position was a good one, and he intrenched it. There, for three hours, he sustained the charges and fire of two hundred republicans. Twelve of his men fell around him. The Army of the Chouannerie, which was twenty-four thousand strong when M. le Comte d'Artois lay off the Île Dieu without landing, was now reduced to twenty men.

These twenty men stood firmly around their general; not one even thought of escape. To make an end of the business, General Valentin took a musket himself, and at the head of the hundred and eighty men remaining to him, he charged at the point of the bayonet.

Charette was wounded by a ball in his head, and three fingers were taken off by a sabre-cut. He was about to be captured when an Alsatian, named Pfeffer, who felt more than mere devotion to Charette, whom he worshipped, took the general's plumed hat, gave him his, and saying, "Go to the right; they'll follow me," sprang to the left himself. He was right; the republicans rushed after him savagely, while Charette sprang in the opposite direction with his fifteen remaining men.

He had almost reached the wood of La Chabotière when General Travot's column appeared. Another and more desperate fight took place, in which Charette's sole object was to get himself killed. Losing blood from three wounds, he staggered and fell. A Vendéan, named Bossard, took him on his shoulders and carried him toward the wood; but before reaching it, Bossard himself was shot down. Then another man, Laroche-Davo, succeeded him, made fifty steps, and he too fell in the ditch that separates the wood from the plain.

Then the Marquis de Souday lifted Charette in his arms, and while Jean Oullier with two shots killed two republican soldiers who were close at their heels, he carried the general into the wood, followed by the seven men still living. Once fairly within the woods, Charette recovered his senses.

"Souday," he said, "listen to my last orders."

The young man stopped.

"Put me down at the foot of that oak."

Souday hesitated to obey.

"I am still your general," said Charette, imperiously. "Obey me."

The young man, overawed, did as he was told and put down the general at the foot of the oak.

"There! now," said Charette, "listen to me. The king who made me general-in-chief must be told how his general died. Return to his Majesty Louis XVIII., and tell him all that you have seen; I demand it."

Charette spoke with such solemnity that the marquis did not dream of disobeying him.

"Go!" said Charette, "you have not a minute to spare; here come the Blues. Fly!"

As he spoke the republicans had reached the edge of the woods. Souday took the hand which Charette held out to him.

"Kiss me," said the latter.

The young man kissed him.

"That will do," said the general; "now go."

Souday cast a look at Jean Oullier.

"Are you coming?" he said.

But his follower shook his head gloomily.

"What have I to do over there, monsieur le marquis?" he said. "Whereas here--"

"Here, what?"

"I'll tell you that if we ever meet again, monsieur le marquis."

So saying, he fired two balls at the nearest republicans. They fell. One of them was an officer of rank; his men pressed round him. Jean Oullier and the marquis profited by that instant to bury themselves in the depths of the woods.

But at the end of some fifty paces Jean Oullier, finding a thick bush at hand, slipped into it like a snake, with a gesture of farewell to the Marquis de Souday.

The marquis continued his way alone.

II.

THE GRATITUDE OF KINGS.

The Marquis de Souday gained the banks of the Loire and found a fisherman who was willing to take him to Saint-Gildas. A frigate hove in sight,--an English frigate. For a few more louis the fisherman consented to put the marquis aboard of her. Once there, he was safe.

Two or three days later the frigate hailed a three-masted merchantman, which was heading for the Channel. She was Dutch. The marquis asked to be put aboard of her; the English captain consented. The Dutchman landed him at Rotterdam. From Rotterdam he went to Blankenbourg, a little town in the duchy of Brunswick, which Louis XVIII. had chosen for his residence.

The marquis now prepared to execute Charette's last instructions. When he reached the château Louis XVIII. was dining; this was always a sacred hour to him. The ex-page was told to wait. When dinner was over he was introduced into the king's presence.

He related the events he had seen with his own eyes, and, above all, the last catastrophe, with such eloquence that his Majesty, who was not impressionable, was enough impressed to cry out:--

"Enough, enough, marquis! Yes, the Chevalier de Charette was a brave servant; we are grateful to him."

He made the messenger a sign to retire. The marquis obeyed; but as he withdrew he heard the king say, in a sulky tone:--

"That fool of a Souday coming here and telling me such things after dinner! It is enough to upset my digestion!"

The marquis was touchy; he thought that after exposing his life for six months it was a poor reward to be called a fool by him for whom he had exposed it. One hundred louis were still in his pocket, and he left Blankenbourg that evening, saying to himself:--

"If I had known that I should be received in that way I wouldn't have taken such pains to come."

He returned to Holland, and from Holland he went to England. There began a new phase in the existence of the Marquis de Souday. He was one of those men who are moulded by circumstances,--men who are strong or weak, brave or pusillanimous, according to the surroundings among which fortune casts them. For six months he had been at the apex of that terrible Vendéan epic; his blood had stained the gorse and the moors of upper and lower Poitou; he had borne with stoical fortitude not only the ill-fortune of battle, but also the privations of that guerilla warfare, bivouacking in snow, wandering without food, without clothes, without shelter, in the boggy forests of La Vendée. Not once had he felt a regret; not a single complaint had passed his lips.

And yet, with all these antecedents, when isolated in the midst of that great city of London, where he wandered sadly regretting the excitements of war, he felt himself without courage in presence of enforced idleness, without resistance under ennui, without energy to overcome the wretchedness of exile. This man, who had bravely borne the attacks and pursuits of the infernal columns of the Blues, could not bear up against the evil suggestions which came of idleness. He sought pleasure everywhere to fill the void in his existence caused by the absence of stirring vicissitudes and the excitements of a deadly struggle.

Now such pleasures as a penniless exile could command were not of a high order; and thus it happened that, little by little, he lost his former elegance and the look and manner of gentleman as his tastes deteriorated. He drank ale and porter instead of champagne, and contented himself with the bedizened women of the Haymarket and Regent Street,--he who had chosen his first loves among the duchesses.

Soon the looseness of his principles and the pressure of his needs drove him into connections from which his reputation suffered. He accepted pleasures when he could not pay for them; his companions in debauchery were of a lower class than himself. After a time his own class of émigrés turned away from him, and by the natural drift of things, the more the marquis found himself neglected by his rightful friends, the deeper he plunged into the evil ways he had now entered.

He had been leading this existence for about two years, when by chance he encountered, in an evil resort which he frequented, a young working-girl, whom one of those infamous women who infest London had enticed from her poor home and produced for the first time. In spite of the changes which ill-luck and a reckless life had produced in the marquis, the poor girl perceived the remains of a gentleman still in him. She flung herself at his feet, and implored him to save her from an infamous life, for which she was not meant, having always been good and virtuous till then.

The young girl was pretty, and the marquis offered to take her with him. She threw herself on his neck and promised him all her love and the utmost devotion. Without any thought of doing a good action the marquis defeated the speculation on Eva's beauty,--the girl was named Eva. She kept her word, poor, faithful creature that she was; the marquis was her first and last and only love.

The matter was a fortunate thing for both of them. The marquis was getting very tired of cock-fights and the acrid fumes of beer, not to speak of frays with constables and loves at street-corners. The tenderness of the young girl rested him; the possession of the pure child, white as the swans which are the emblem of Brittany, his own land, satisfied his vanity. Little by little, he changed his course of life, and though he never returned to the habits of his own class, he did adopt a life which was that of a decent man.

He went to live with Eva on the upper floor of a house in Piccadilly. She was a good workwoman, and soon found employment with a milliner. The marquis gave fencing-lessons. From that time they lived on the humble proceeds of their employments, finding great happiness in a love which had now become powerful enough to gild their poverty. Nevertheless, this love, like all things mortal, wore out in the end, though not for a long time. Happily for Eva, the emotions of the Vendéan war and the frantic excitements of London hells had used up her lover's superabundant sap; he was really an old man before his time. The day on which the marquis first perceived that his love for Eva was waning, the day when her kisses were powerless, not to satisfy him but to rouse him, habit had acquired such an influence over him that even had he sought distractions outside his home he no longer had the force or the courage to break a connection in which his selfishness still found the monotonous comforts of daily life.

The former viveur, whose ancestors had possessed for three centuries the power of life and death in their province, the ex-brigand, the aide-de-camp to the brigand Charette, led for a dozen years the dull, precarious, drudging life of a humble clerk, or a mechanic more humble still.

Heaven had long refrained from blessing this illegitimate marriage; but at last the prayers which Eva had never ceased to offer for twelve years were granted. The poor woman became pregnant, and gave birth to twin daughters. But alas! a few hours of the maternal joys she had so longed for were all that were granted to her. She died of puerperal fever.

Eva's tenderness for the Marquis de Souday was as deep and warm at the end of twelve years' devotion as it was in the beginning of their intercourse; yet her love, great as it was, did not prevent her from recognizing that frivolity and selfishness were at the bottom of her lover's character. Therefore she suffered in dying not only the anguish of bidding an eternal farewell to the man she had loved so deeply, but the terror of leaving the future of her children in his hands.

This loss produced impressions upon the marquis which we shall endeavor to reproduce minutely, because they seem to us to give a distinct idea of the nature of the man who is destined to play an important part in the narrative we are now undertaking.

He began by mourning his companion seriously and sincerely. He could not help doing homage to her good qualities and recognizing the happiness which he owed to her affection. Then, after his first grief had passed away, he felt something of the joy of a schoolboy when he gets out of bounds. Sooner or later his name, rank, and birth must have made it necessary for him to break the tie. The marquis felt grateful to Providence for relieving him of a duty which would certainly have distressed him.

This satisfaction, however, was short-lived. Eva's tenderness, the continuity, if we may say so, of the care and attention she had given him, had spoilt the marquis; and those cares and attentions, now that he had suddenly lost them, seemed to him more essential to his happiness than ever. The humble chambers in which they had lived became, now that the Englishwoman's fresh, pure voice no longer enlivened them, what they were in reality,--miserable lodging-rooms; and, in like manner, when his eyes sought involuntarily the silky hair of his companion lying in golden waves upon the pillow, his bed was nothing more than a wretched pallet. Where could he now look for the soft petting, the tender attention to all his wants, with which, for twelve good years, Eva had surrounded him. When he reached this stage of his desolation the marquis admitted to himself that he could never replace them. Consequently, he began to mourn poor Eva more than ever, and when the time came for him to part with his little girls, whom he sent into Yorkshire to be nursed, he put such a rush of tenderness into his grief that the good country-woman, their foster-mother, was sincerely affected.

After thus separating from all that united him with the past, the Marquis de Souday succumbed under the burden of his solitude; he became morose and taciturn. As his religious faith was none too solid, he would probably have ended, under the deep disgust of life which now took possession of him, by jumping into the Thames, if the catastrophe of 1814 had not happened just in time to distract him from his melancholy thoughts. Re-entering France, which he had never hoped to see again, the Marquis de Souday very naturally applied to Louis XVIII., of whom he had asked nothing during his exile in return for the blood he had shed for him. But princes often seek pretexts for ingratitude, and Louis XVIII. was furnished with three against his former page: first, the tempestuous manner in which he had announced to his Majesty Charette's death,--an announcement which had in fact troubled the royal digestion; secondly, his disrespectful departure from Blankenbourg, accompanied by language even more disrespectful than the departure itself; and thirdly (this was the gravest pretext), the irregularity of his life and conduct during the emigration.

Much praise was bestowed upon the bravery and devotion of the former page; but he was, very gently, made to understand that with such scandals attaching to his name he could not expect to fulfil any public functions. The king was no longer an autocrat, they told him; he was now compelled to consider public opinion; after the late period of public immorality it was necessary to introduce a new and more rigid era of morals. How fine a thing it would be if the marquis were willing to sacrifice his own personal ambitions to the necessities of the State.

In short, they persuaded him to be satisfied with the cross of Saint-Louis, the rank and pension of a major of cavalry, and to take himself off to eat the king's bread on his estate at Souday,--the sole fragment recovered by the poor émigré from the wreck of the enormous fortune of his ancestors.

What was really fine about all this was that these excuses and hypocrisies did not hinder the Marquis de Souday from doing his duty,--that is, from leaving his poor castle to defend the white flag when Napoleon made his marvellous return from Elba. Napoleon fell again, and for the second time the marquis re-entered Paris with the legitimate princes. But this time, wiser than he was in 1814, he merely asked of the restored monarchy for the place of Master of Wolves to the arrondissement of Machecoul,--an office in the royal gift which, being without salary or emolument, was willingly accorded to him.

Deprived during his youth of a pleasure which in his family was an hereditary passion, the marquis now devoted himself ardently to hunting. Always unhappy in a solitary life, for which he was totally unfitted, yet growing more and more misanthropic as the result of his political disappointments, he found in this active exercise a momentary forgetfulness of his bitter memories. Thus the position of Master of Wolves, which gave him the right to roam the State forests at will, afforded him far more satisfaction than his ribbon of Saint-Louis or his commission as major of cavalry.

So the Marquis de Souday had been living for two years in the mouldy little castle we lately described, beating the woods day and night with his six dogs (the only establishment his slender means permitted), seeing his neighbors just enough to prevent them from considering him an absolute bear, and thinking as little as he could of his past wealth and his past fame, when one morning, as he was starting to explore the north end of the forest of Machecoul, he met on the road a peasant woman carrying a child three or four years old on each arm.

The marquis instantly recognized the woman and blushed as he did so. It was the nurse from Yorkshire, to whom he had regularly for the last thirty-six months neglected to pay the board of her two nurslings. The worthy woman had gone to London, and there made inquiries at the French legation. She had now reached Machecoul with the assistance of the French minister, who of course did not doubt that the Marquis de Souday would be most happy to recover his two children.

The singular part of it is that the ambassador was not entirely mistaken. The little girls reminded the marquis so vividly of his poor Eva that he was seized with genuine emotion; he kissed them with a tenderness that was not assumed, gave his gun to the Englishwoman, took his children in his arms, and returned to the castle with this unlooked-for game, to the utter stupefaction of the cook, who constituted his whole household, and who now overwhelmed him with questions as to the singular accession thus made to the family.

These questions alarmed the marquis. He was only thirty-nine years of age, and vague ideas of marriage still floated in his head; he regarded it as a duty not to let a name and house so illustrious as that of Souday come to an end in his person. Moreover, he would not have been sorry to turn over to a wife the management of his household affairs, which was odious to him. But the realization of that idea would, of course, be impossible if he kept the little girls in his house.

He saw this plainly, paid the Englishwoman handsomely, and the next day despatched her back to her own country.

During the night he had come to a resolution which, he thought, would solve all difficulties. What was that resolution? We shall now see.

III.

THE TWINS.

The Marquis de Souday went to bed repeating to himself the old proverb, "Night brings counsel." With that hope he fell asleep. When asleep, he dreamed.

He dreamed of his old wars in La Vendée with Charette,--of the days when he was aide-de-camp; and, more especially, he dreamed of Jean Oullier, his attendant, of whom he had never thought since the day when they left Charette dying, and parted in the wood of Chabotière.

As well as he could remember, Jean Oullier before joining Charette's army had lived in the village of La Chevrolière, near the lake of Grand-Lieu. The next morning the Marquis de Souday sent a man of Machecoul, who did his errands, on horseback with a letter, ordering him to go to La Chevrolière and ascertain if a man named Jean Oullier was still living and whether he was in the place. If he was, the messenger was to give him the letter and, if possible, bring him back with him. If he lived at a short distance the messenger was to go there. If the distance was too great he was to obtain every information as to the locality of his abode. If he was dead the messenger was to return at once and say so.

Jean Oullier was not dead; Jean Oullier was not in distant parts; Jean Oullier was in the neighborhood of La Chevrolière; in fact, Jean Oullier was in La Chevrolière itself.

Here is what had happened to him after parting with the marquis on the day of Charette's last defeat. He stayed hidden in the bush, from which he could see all and not be seen himself. He saw General Travot take Charette prisoner and treat him with all the consideration a man like General Travot would show to a man like Charette. But, apparently, that was not all that Jean Oullier expected to see, for after seeing the republicans lay Charette on a litter and carry him away, Jean Oullier still remained hidden in his bush.

It is true that an officer with a picket of twelve men remained in the wood. What were they there for?

About an hour later a Vendéan peasant passed within ten paces of Jean Oullier, having answered the challenge of the sentinel with the word "Friend,"--an odd answer in the mouth of a royalist peasant to a republican soldier. The peasant next exchanged the countersign with the sentry and passed on. Then he approached the officer, who, with an expression of disgust which it is quite impossible to represent, gave him a bag that was evidently full of gold. After which the peasant disappeared, and the officer with his picket guard also departed, showing that in all probability they had only been stationed there to await the coming of the peasant.

In all probability, too, Jean Oullier had seen what he wanted to see, for he came out of his bush as he went into it,--that is to say, crawling; and getting on his feet, he tore the white cockade from his hat, and, with the careless indifference of a man who for the last three years had staked his life every day on a turn of the dice, he buried himself still deeper in the forest.

The same night he reached La Chevrolière. He went straight to his own home. On the spot where his house had stood was a blackened ruin, blackened by fire. He sat down upon a stone and wept.

In that house he had left a wife and two children.

Soon he heard a step and raised his head. A peasant passed. Jean Oullier recognized him in the darkness and called:--

"Tinguy!"

The man approached.

"Who is it calls me?" he said.

"I am Jean Oullier," replied the Chouan.

"God help you," replied Tinguy, attempting to pass on; but Jean Oullier stopped him.

"You must answer me," he said.

"Are you a man?"

"Yes."

"Then question me and I will answer."

"My father?"

"Dead."

"My wife?"

"Dead."

"My two children?"

"Dead."

"Thank you."

Jean Oullier sat down again, but he no longer wept. After a few moments he fell on his knees and prayed. It was time he did, for he was about to blaspheme. He prayed for those who were dead.

Then, restored by that deep faith that gave him hope to meet them in a better world, he bivouacked on those sad ruins.

The next day, at dawn, he began to rebuild his house, as calm and resolute as though his father were still at the plough, his wife before the fire, his children at the door. Alone, and asking no help from any one, he rebuilt his cottage.

There he lived, doing the humble work of a day laborer. If any one had counselled Jean Oullier to ask a reward from the Bourbons for doing what he, rightly or wrongly, considered his duty, that adviser ran some risk of insulting the grand simplicity of the poor peasant.

It will be readily understood that with such a nature Jean Oullier, on receiving the letter in which the marquis called him his old comrade and begged him to come to him, he did not delay his going. On the contrary, he locked the door of his house, put the key in his pocket, and then, as he lived alone and had no one to notify, he started instantly. The messenger offered him his horse, or, at any rate, to take him up behind him; but Jean Oullier shook his head.

"Thank God," he said, "my legs are good."

Then resting his hand on the horse's neck, he set the pace for the animal to take,--a gentle trot of six miles an hour. That evening Jean Oullier was at the castle. The marquis received him with visible delight. He had worried all day over the idea that Jean Oullier might be absent, or dead. It is not necessary to say that the idea of that death worried him not for Jean Oullier's sake but for his own. We have already informed our readers that the Marquis de Souday was slightly selfish.

The first thing the marquis did was to take Jean Oullier apart and confide to him the arrival of his children and his consequent embarrassment.

Jean Oullier, who had had his own two children massacred, could not understand that a father should voluntarily wish to part with his children. He nevertheless accepted the proposal made to him by the marquis to bring up the little girls till such a time as they were of age to go to school. He said he would find some good woman at La Chevrolière who would be a mother to them,--if, indeed, any one could take the place of a mother to orphaned children.

Had the twins been sickly, ugly, or disagreeable, Jean Oullier would have taken them all the same; but they were, on the contrary, so prepossessing, so pretty, so graceful, and their smiles so engaging, that the good man instantly loved them as such men do love. He declared that their fair and rosy faces and curling hair were so like those of the cherubs that surrounded the Madonna over the high altar at Grand-Lieu before it was destroyed, that he felt like kneeling to them when he saw them.

It was therefore decided that on the morrow Jean Oullier should take the children back with him to La Chevrolière.

Now it so happened that, during the time which had elapsed between the departure of the nurse and the arrival of Jean Oullier, the weather had been rainy. The marquis, confined to the castle, felt terribly bored. Feeling bored, he sent for his daughters and began to play with them. Putting one astride his neck, and perching the other on his back, he was soon galloping on all fours round the room, like Henri of Navarre. Only, he improved on the amusement which his Majesty afforded his progeny by imitating with his mouth not only the horn of the hunter, but the barking and yelping of the whole pack of hounds. This domestic sport diverted the Marquis de Souday immensely, and it is safe to say that the little girls had never laughed so much in their lives.

Besides, the little things had been won by the tenderness and the petting their father had lavished upon them during these few hours, to appease, no doubt, the reproaches of his conscience at sending them away from him after so long a separation. The children, on their side, showed him a frantic attachment and a lively gratitude, which were not a little dangerous to the fulfilment of his plan.

In fact, when the carriole came, at eight o'clock in the morning, to the steps of the portico, and the twins perceived that they were about to be taken away, they set up cries of anguish. Bertha flung herself on her father, clasped his knees, clung to the garters of the gentleman who gave her sugar-plums and made himself such a capital horse, and twisted her little hands into them in such a manner that the poor marquis feared to bruise her wrists by trying to unclasp them.

As for Mary, she sat down on the steps and cried; but she cried with such an expression of real sorrow that Jean Oullier felt more touched by her silent grief than by the noisy despair of her sister. The marquis employed all his eloquence to persuade the little girls that by getting into the carriage, they would have more pleasure and more dainties than by staying with him; but the more he talked, the more Mary cried and the more Bertha quivered and passionately clung to him.

The marquis began to get impatient. Seeing that persuasion could do nothing, he was about to employ force when, happening to turn his eyes, he caught sight of the look on Jean Oullier's face. Two big tears were rolling down the bronzed cheeks of the peasant into the thick red whiskers which framed his face. Those tears acted both as a prayer to the marquis and as a reproach to the father. Monsieur de Souday made a sign to Jean Oullier to unharness the horse; and while Bertha, understanding the sign, danced with joy on the portico, he whispered in the farmer's ear:--

"You can start to-morrow."

As the day was very fine, the marquis desired to utilize the presence of Jean Oullier by taking him on a hunt; with which intent he carried him off to his own bedroom to help him on with his sporting-clothes. The peasant was much struck by the frightful disorder of the little room; and the marquis continued his confidences with bitter complaints of his female servitor, who, he said, might be good enough among her pots and pans, but was odiously careless as to all other household comforts, particularly those that concerned his clothes. On this occasion it was ten minutes before he could find a waistcoat that was not widowed of its buttons, or a pair of breeches not afflicted with a rent that made them more or less indecent. However, he was dressed at last.

Wolf-master though he was, the marquis, as we have said, was too poor to allow himself the luxury of a huntsman, and he led his little pack himself. Therefore, having the double duty of keeping the hounds from getting at fault, and firing at the game, it was seldom that the poor marquis, passionate sportsman that he was, did not come home at night tired out.

With Jean Oullier it was quite another thing. The vigorous peasant, in the flower of his age, sprang through the forest with the agility of a squirrel; he bounded over bushes when it took too long to go round them, and, thanks to his muscles of steel, he never was behind the dogs by a length. On two or three occasions he supported them with such vigor that the boar they were pursuing, recognizing the fact that flight would not shake off his enemies, ended by turning and standing at bay in a thicket, where the marquis had the happiness of killing him at one blow,--a thing that had never yet happened to him.

The marquis went home light-hearted and joyful, thanking Jean Oullier for the delightful day he owed to him. During dinner he was in fine good-humor, and invented new games to keep the little girls as gay as himself.

At night, when he went to his room, the marquis found Jean Oullier sitting cross-legged in a corner, like a Turk or a tailor. Before him was a mound of garments, and in his hand he held a pair of old velvet breeches which he was darning vigorously.

"What the devil are you doing there?" demanded the marquis.

"The winter is cold in this level country, especially when the wind is from the sea; and after I get home my legs will be cold at the very thought of a norther blowing on yours through these rents," replied Jean Oullier, showing his master a tear which went from knee to belt in the breeches he was mending.

"Ha! so you're a tailor, too, are you?" cried the marquis.

"Alas!" said Jean Oullier, "one has to be a little of everything when one lives alone as I have done these twenty years. Besides, an old soldier is never at a loss."

"I like that!" said the marquis; "pray, am not I a soldier, too?"

"No; you were an officer, and that's not the same thing."

The Marquis de Souday looked at Jean Oullier admiringly. Then he went to bed and to sleep, and snored away, without in the least interrupting the work of his old Chouan. In the middle of the night he woke up. Jean Oullier was still at work. The mound of garments had not perceptibly diminished.

"But you can never finish them, even if you work till daylight, my poor Jean," said the marquis.

"I'm afraid not."

"Then go to bed now, old comrade; you needn't start till you have mended up all my old rags, and we can have another hunt to-morrow."

IV.

HOW JEAN OULLIER, COMING TO SEE THE MARQUIS FOR AN HOUR, WOULD BE THERE STILL IF THEY HAD NOT BOTH BEEN IN THEIR GRAVE THESE TEN YEARS.

The next morning, before starting for the hunt, it occurred to the marquis to kiss his children. He therefore went up to their room, and was not a little astonished to find that the indefatigable Jean Oullier had preceded him, and was washing and brushing the little girls with the conscientious determination of a good governess. The poor fellow, to whom the occupation recalled his own lost young ones, seemed to be taking deep satisfaction in the work. The marquis changed his admiration into respect.

For eight days the hunts continued without interruption, each finer and more fruitful than the last. During those eight days Jean Oullier, huntsman by day, steward by night, not only revived and restored his master's wardrobe, but he actually found time to put the house in order from top to bottom.

The marquis, far from urging his departure, now thought with horror of parting from so valuable a servitor. From morning till night, and sometimes from night till morning, he turned over in his mind which of the Chouan's qualities was most serviceable to him. Jean Oullier had the scent of a hound to follow game, and the eye of an Indian to discover its trail by the bend of the reeds or the dew on the grass. He could even tell, on the dry and stony roads about Machecoul, Bourgneuf, and Aigrefeuille, the age and sex of a boar, when the trail was imperceptible to other eyes. No huntsman on horseback had ever followed up the hounds like Jean Oullier on his long and vigorous legs. Moreover, on the days when rest was actually necessary for the little pack of hounds, he was unequalled for discovering the places where snipe abounded, and taking his master to the spot.

"Damn marriage!" cried the marquis to himself, occasionally, when he seemed to be thinking of quite other things. "Why do I want to row in that boat when I have seen so many good fellows come to grief in it? Heavens and earth! I'm not so young a man--almost forty; I haven't any illusions; I don't expect to captivate a woman by my personal attractions. I can't expect to do more than tempt some old dowager with my three thousand francs a year,--half of which dies with me. I should probably get a scolding, fussy, nagging wife, who might interfere with my hunting, which that good Jean manages so well; and I am sure she will never keep the house in such order as he does. Still," he added, straightening himself up, and swaying the upper part of his body, "is this a time to let the old races, the supporters of monarchy, die out? Wouldn't it be very pleasant to see my son restore the glory of my house? Besides, what would be thought of me,--who am known to have had no wife, no legitimate wife,--what will my neighbors say if I take the two little girls to live with me?"

When these reflections came, which they ordinarily did on rainy days, when he could not be off on his favorite pastime, they cast the Marquis de Souday into painful perplexity, from which he wriggled, as do all undecided temperaments and weak natures,--men, in short, who never know how to adopt a course,--by making a provisional arrangement.

At the time when our story opens, in 1831, Mary and Bertha were seventeen, and the provisional arrangement still lasted; although, strange as it may seem, the Marquis de Souday had not yet positively decided to keep his daughters with him.

Jean Oullier, who had hung the key of his house at La Chevrolière to a nail, had never, in fourteen years, had the least idea of taking it down. He had waited patiently till his master gave him the order to go home. But as, ever since his arrival, the château had been neat and clean; as the marquis had never once missed a button; as the hunting-boots were always properly greased; as the guns were kept with all the care of the best armory at Nantes; as Jean Oullier, by means of certain coercive proceedings, of which he learned the secret from a former comrade of the "brigand army," had, little by little, brought the cook not to vent her ill-humor on her master; as the hounds were always in good condition, shiny of coat, neither fat nor thin, and able to bear a long chase of eight or ten hours, ending mostly in a kill; as the chatter and the pretty ways of his children and their expansive affection varied the monotony of his existence; as his talks and gossip with Jean Oullier on the stirring incidents of the old war, now passed into a tradition (it was thirty-six years distant), enlivened his dull hours and the long evenings and the rainy days,--the marquis, finding once more the good care, the quiet ease, the tranquil happiness he had formerly enjoyed with Eva, with the additional and intoxicating joys of hunting,--the marquis, we say, put off from day to day, from month to month, from year to year, deciding on the separation.

As for Jean Oullier, he had his own reasons for not provoking a decision. He was not only a brave man, but he was a good one. As we have said, he at once took a liking to Bertha and Mary; this liking, in that poor heart deprived of its own children, soon became tender affection, and the tenderness fanaticism. He did not at first perceive very clearly the distinction the marquis seemed to make between their position and that of other children whom he might have by a legitimate marriage to perpetuate his name. In Poitou, when a man gets a worthy girl into trouble he knows of no other reparation than to marry her. Jean Oullier thought it natural, inasmuch as his master could not legitimatize the connection with the mother, that he should at least not conceal the paternity which Eva in dying had bequeathed to him. Therefore, after two months' sojourn at the castle, having made these reflections, weighed them in his mind, and ratified them in his heart, the Chouan would have received an order to take the children away with very ill grace; and his respect for Monsieur de Souday would not have prevented him from expressing himself bluffly on the subject.

Fortunately, the marquis did not betray to his dependant the tergiversations of his mind; so that Jean Oullier did really regard the provisional arrangement as definitive, and he believed that the marquis considered the presence of his daughters at the castle as their right and also as his own bounden duty.

At the moment when we issue from these preliminaries, Bertha and Mary were, as we have said, between seventeen and eighteen years of age. The purity of race in their paternal ancestors had done marvels when strengthened with the vigorous Saxon blood of the plebeian mother. Eva's children were now two splendid young women, with refined and delicate features, slender and elegant shapes, and with great distinction and nobility in their air and manner. They were as much alike as twins are apt to be; only Bertha was dark, like her father, and Mary was fair, like her mother.

Unfortunately, the education of these beautiful young creatures, while developing to the utmost their physical advantages, did not sufficiently concern itself with the needs of their sex. It was impossible that it should be otherwise, living from day to day beside their father, with his natural carelessness and his determination to enjoy the present and let the future take care of itself.

Jean Oullier was the only tutor of Eva's children, as he was formerly their only nurse. The worthy Chouan taught them all he knew himself,--namely, to read, write, cipher, and pray with tender and devout fervor to God and the Virgin; also to roam the woods, scale the rocks, thread the tangle of holly, reeds, and briers without fatigue, without fear or weakness of any kind; to hit a bird on the wing, a squirrel on the leap, and to ride bareback those intractable horses of Mellerault, almost as wild on their plains and moors as the horses of the gauchos on the pampas.

The Marquis de Souday had seen all this without attempting to give any other direction to the education of his daughters, and without having even the idea of counteracting the taste they were forming for these manly exercises. The worthy man was only too delighted to have such valiant comrades in his favorite amusement, uniting, as they did, with their respectful tenderness toward him a gayety, dash, and ardor for the chase, which doubled his own pleasure from the time they were old enough to share it.

And yet, in strict justice, we must say that the marquis added one ingredient of his own to Jean Oullier's instructions. When Bertha and Mary were fourteen years old, which was the period when they first followed their father into the forest, their childish games, which had hitherto made the old castle so lively in the evenings, began to lose attraction. So, to fill the void he was beginning to feel, the Marquis de Souday taught Bertha and Mary how to play whist.

On the other hand, the two children had themselves completed mentally, as far as they could, the education Jean Oullier had so vigorously developed physically. Playing hide-and-seek through the castle, they came upon a room which, in all probability, had not been opened for thirty years. It was the library. There they found a thousand volumes, or something near that number.

Each followed her own bent in the choice of books. Mary, the gentle, sentimental Mary, preferred novels; the turbulent and determined Bertha, history. Then they mingled their reading in a common fund; Mary told Paul and Virginia and Amadis to Bertha, and Bertha told Mèzeray and Velly to Mary. The result of such desultory reading was, of course, that the two young girls grew up with many false notions about real life and the habits and requirements of a world they had never seen, and had, in truth, never heard of.

At the time they made their first communion the vicar of Machecoul, who loved them for their piety and the goodness of their heart, did risk a few remarks to their father on the peculiar existence such a bringing-up must produce; but his friendly remarks made no impression on the selfish indifference of the Marquis de Souday. The education we have described was continued, and such habits and ways were the result that, thanks to their already false position, poor Bertha and her sister acquired a very bad reputation throughout the neighborhood.

The fact was, the Marquis de Souday was surrounded by little newly made nobles, who envied him his truly illustrious name, and asked nothing better than to fling back upon him the contempt with which his ancestors had probably treated theirs. So when they saw him keep in his own house, and call his daughters, the children of an illegitimate union, they began to trumpet forth the evils of his life in London; they exaggerated his wrong-doing and made poor Eva (saved by a miracle from a life of degradation) a common woman of the town. Consequently, little by little, the country squires of Beauvoir, Saint-Leger, Bourgneuf, Saint-Philbert, and Grand-Lieu, avoided the marquis, under pretence that he degraded the nobility,--a matter about which, taking into account the mushroom character of their own rank, they were very good to concern themselves.

But soon it was not the men only who disapproved of the Marquis de Souday's conduct. The beauty of the twin sisters roused the enmity of the mothers and daughters in a circuit of thirty miles, and that was infinitely more alarming. If Bertha and Mary had been ugly the hearts of these charitable ladies and young ladies, naturally inclined to Christian mercy, would perhaps have forgiven the poor devil of a father for his improper paternity; but it was impossible not to be shocked at the sight of two such spurious creatures, crushing by their distinction, their nobility, and their personal charm, the well-born young ladies of the neighborhood. Such insolent superiority deserved neither mercy nor compassion.

The indignation against the poor girls was so general that even if they had never given any cause for gossip or calumny, gossip and calumny would have swept their wings over them. Imagine, therefore, what was likely to happen, and did actually happen, when the masculine and eccentric habits of the sisters were fully known! One universal hue-and-cry of reprobation arose from the department of the Loire-Inférieure and echoed through those of La Vendée and the Maine-et-Loire; and if it had not been for the sea, which bounds the coast of the Loire-Inférieure, that reprobation would, undoubtedly, have spread as far to the west as it did to the south and east. All classes, bourgeois and nobles, city-folk and country-folk, had their say about it. Young men, who had hardly seen Mary and Bertha, and did not know them, spoke of the daughters of the Marquis de Souday with meaning smiles, expressive of hopes, if not of memories. Dowagers crossed themselves on pronouncing their names, and nurses threatened little children when they were naughty with goblin tales of them.

The most indulgent confined themselves to attributing to the twins the three virtues of Harlequin, usually regarded as the attributes of the disciples of Saint-Hubert,--namely, love, gambling, and wine. Others, however, declared that the little castle of Souday was every night the scene of orgies such as chronicles of the regency alone could show. A few imaginative persons went further, and declared that one of its ruined towers--abandoned to the innocent loves of a flock of pigeons--was a repetition of the famous Tour de Nesle, of licentious and homicidal memory.

In short, so much was said about Bertha and Mary that, no matter what had been and then was the purity of their lives and the innocence of their actions, they became an object of horror to the society of the whole region. Through the servants of private houses, through the workmen employed by the bourgeoisie, this hatred and horror of society filtered down among the peasantry, so that the whole population in smocks and wooden shoes (if we except a few old blind men and helpless women to whom the twins had been kind) echoed far and wide the absurd stories invented by the big-wigs. There was not a woodman, not a laborer in Machecoul, not a farmer in Saint-Philbert and Aigrefeuille that did not feel himself degraded in raising his hat to them.

The peasantry at last gave Bertha and Mary a nickname; and this nickname, starting from the lower classes, was adopted by acclamation among the upper, as a just characterization of the lawless habits and appetites attributed to the young girls. They were called the she-wolves (a term, as we all know, equivalent to sluts),--the she-wolves of Machecoul.

V.

A LITTER OF WOLVES.

The Marquis de Souday was utterly indifferent to all these signs of public animadversion; in fact, he seemed to ignore their existence. When he observed that his neighbors no longer returned the few visits that from time to time he felt obliged to pay to them, he rubbed his hands with satisfaction at being released from social duties, which he hated and only performed when constrained and forced to do so either by his daughters or by Jean Oullier.

Every now and then some whisper of the calumnies that were circulating about Bertha and Mary reached him; but he was so happy with his factotum, his daughters, and his hounds, that he felt he should be compromising the tranquillity he enjoyed if he took the slightest notice of such absurd reports. Accordingly, he continued to course the hares daily and hunt the boar on grand occasions, and play whist nightly with the two poor calumniated ones.

Jean Oullier was far from being as philosophical as his master; but then it must be said that in his position he heard much more than the marquis did. His affection for the two young girls had now become fanaticism; he spent his life in watching them, whether they sat, softly smiling, in the salon of the château, or whether, bending forward on their horses' necks, with sparkling eyes and animated faces, they galloped at his side, with their long locks floating in the wind from beneath the broad brims of their felt hats and undulating feathers. Seeing them so brave and capable, and at the same time so good and tender to their father and himself, his heart swelled with pride and happiness; he felt himself as having a share in the development of these two admirable creatures, and he wondered why all the world should not be willing to kneel down to them.

Consequently, the first persons who risked telling him of the rumors current in the neighborhood were so sharply rebuked for it that they were frightened and warned others; but Bertha and Mary's true father needed no words to inform him what was secretly believed of the two dear objects of his love. From a smile, a glance, a gesture, a sign, he guessed the malicious thoughts of all with a sagacity that made him miserable. The contempt that poor and rich made no effort to disguise affected him deeply. If he had allowed himself to follow his impulses he would have picked a quarrel with every contemptuous face, and corrected some by knocking them down, and others by a pitched battle. But his good sense told him that Bertha and Mary needed another sort of support, and that blows given or received would prove absolutely nothing in their defence. Besides, he dreaded--and this was, in fact, his greatest fear--that the result of some quarrel, if he provoked it, might be that the young girls would be made aware of the public feeling against them.

Poor Jean Oullier therefore bowed his head before this cruelly unjust condemnation, and tears and fervent prayers to God, the supreme redressor of the cruelties and injustices of men, alone bore testimony to his grief; but in his heart he fell into a state of profound misanthropy. Seeing none about him but the enemies of his two dear children, how could he help hating mankind? And he prepared himself for the day when some future revolution might enable him to return evil for evil.

The revolution of 1830 had just occurred, but it had not given Jean Oullier the opportunity he craved to put these evil designs into execution. Nevertheless, as rioting and disturbances were not yet altogether quelled in the streets of Paris, and might still be communicated to the provinces, he watched and waited.

On a fine morning in September, 1831, the Marquis de Souday, his daughters, Jean Oullier, and the pack--which, though frequently renewed since we made its acquaintance, had not increased in numbers--were hunting in the forest of Machecoul.

It was an occasion impatiently awaited by the marquis, who for the last three months had been expecting grand sport from it,--the object being to capture a litter of young wolves, which Jean Oullier had discovered before their eyes were opened, and which he had, being a faithful and knowing huntsman to a Master of Wolves, watched over and cared for for several months. This last statement may demand some explanations to those of our readers who are not familiar with the noble art of venery.

When the Duc de Biron (beheaded, in 1602, by order of Henri IV.) was a youth, he said to his father at one of the sieges of the religious wars, "Give me fifty cavalry; there's a detachment of two hundred men, sallying out to forage. I can kill every one of them, and the town must surrender." "Suppose it does, what then?" "What then? Why, I say the town will surrender." "Yes; and the king will have no further need of us. We must continue necessary, you ninny!" The two hundred foragers were not killed. The town was not taken, and Biron and his son continued "necessary;" that is to say, being necessary they retained the favor and the wages of the king.

Well, it is with wolves as it was with those foragers spared by the Duc de Biron. If there were no longer any wolves how could there be a Wolf-master? Therefore we must forgive Jean Oullier, who was, as we may say, a corporal of wolves, for showing some tender care for the nurslings and not slaying them, them and their mother, with the stern rigor he would have shown to an elderly wolf of the masculine sex.

But that is not all. Hunting an old wolf in the open is impracticable, and in a battue it is monotonous and tiresome; but to hunt a young wolf six or seven months old is easy, agreeable, and amusing. So, in order to procure this charming sport for his master, Jean Oullier, on finding the litter, had taken good care not to disturb or frighten the mother; he concerned himself not at all for the loss of sundry of the neighbors' sheep, which she would of course inevitably provide for her little ones. He had paid the latter several visits, with touching solicitude, during their infancy, to make sure that no one had laid a disrespectful hand upon them, and he rejoiced with great joy when he one day found the den depopulated and knew that the mother-wolf had taken off her cubs on some excursion.

The day had now come when, as Jean Oullier judged, they were in fit condition for what was wanted of them. He therefore, on this grand occasion, hedged them in to an open part of the forest, and loosed the six dogs upon one of them.

The poor devil of a cub, not knowing what all this trumpeting and barking meant, lost his head and instantly quitted the covert, where he left his mother and brothers and where he still had a chance to save his skin. He took unadvisedly to another open, and there, after running for half an hour in a circuit like a hare, he became very tired from an exertion to which he was not accustomed, and feeling his big paws swelling and stiffening he sat down artlessly on his tail and waited.

He did not have to wait long before he found out what was wanted of him, for Domino, the leading hound, a Vendéan, with a rough gray coat, came up almost immediately and broke his back with one crunch of his jaw.

Jean Oullier called in his dogs, took them back to the starting-point, and ten minutes later a brother of the deceased was afoot, with the hounds at his heels. This one however, with more sense than the other, did not leave the covert, and various sorties and charges, made sometimes by the other cubs and sometimes by the mother-wolf, who offered herself voluntarily to the dogs, delayed for a time his killing. But Jean Oullier knew his business too well to let such actions compromise success. As soon as the cub began to head in a straight line with the gait of an old wolf, he called off his dogs, took them to where the cub had broken, and put them on the scent.

Pressed too closely by his pursuers, the poor wolfling tried to double. He returned upon his steps, and left the wood with such innocent ignorance that he came plump upon the marquis and his daughters. Surprised, and losing his head, he tried to slip between the legs of the horses; but M. de Souday, leaning from his saddle, caught him by the tail, and flung him to the dogs, who had followed his doubling.

These successful kills immensely delighted the marquis, who did not choose to end the matter here. He discussed with Jean Oullier whether it was best to call in the dogs and attack at the same place, or whether, as the rest of the cubs were evidently afoot, it would not be best to let the hounds into the wood pell-mell to find as they pleased.

But the mother-wolf, knowing probably that they would soon be after the rest of her progeny, crossed the road not ten steps distant from the dogs, while the marquis and Jean Oullier were arguing. The moment the little pack, who had not been re-coupled, saw the animal, they gave one cry, and, wild with excitement, rushed upon her traces. Calls, shouts, whips, nothing could hold them, nothing stop them. Jean Oullier made play with his legs, and the marquis and his daughters put their horses to a gallop for the same purpose; but the hounds had something else than a timid, ignorant cub to deal with. Before them was a bold, vigorous, enterprising animal, running confidently, as if sure of her haven, in a straight line, indifferent to valleys, rocks, mountains, or water-courses, without fear, without haste, trotting along at an even pace, sometimes surrounded by the dogs, whom she mastered by the power of an oblique look and the snapping of her formidable jaws.

The wolf, after crossing three fourths of the forest, broke out to the plain as though she were making for the forest of Grand'Lande. Jean Oullier had kept up, thanks to the elasticity of his legs, and was now only three or four hundred steps behind the dogs. The marquis and his daughters, forced by the ditches to follow the curve of the paths, were left behind. But when they reached the edge of the woods and had ridden up the slope which overlooks the little village of Marne, they saw, over a mile ahead of them, between Machecoul and La Brillardière, in the midst of the gorse which covers the ground near those villages and La Jacquelerie, Jean Oullier, his dogs, and his wolf, still in the same relative positions, and following a straight line at the same gait.

The success of the first two chases and the rapidity of the ride stirred the blood of the Marquis de Souday.

"Morbleu!" he cried; "I'd give six years of life to be at this moment between Saint-Étienne de Mermorte and La Guimarière and send a ball into that vixen of a wolf."

"She is making for the forest of Grand'Lande," said Mary.

"Yes," said Bertha; "but she will certainly come back to the den, so long as the cubs have not left it. She won't forsake her own wood long."

"I think it would be better to go back to the den," said Mary. "Don't you remember, papa, that last year we followed a wolf which led us a chase of ten hours, and all for nothing; and we had to go home with our horses blown, the dogs lame, and all the mortification of a dead failure?"

"Ta, ta, ta!" cried the marquis; "that wolf wasn't a she-wolf. You can go back, if you like, mademoiselle; as for me, I shall follow the hounds. Corbleu! it shall never be said I wasn't in at the death."

"We shall go where you go, papa," cried both girls together.

"Very good; forward, then!" cried the marquis, vigorously spurring his horse, and galloping down the slope. The way he took was stony and furrowed with the deep ruts of which Lower Poitou keeps up the tradition to this day. The horses stumbled repeatedly, and would soon have been down if they had not been held up firmly; it was evidently impossible to reach the forest of Grand'Lande before the game.

Monsieur de Souday, better mounted than his daughters, and able to spur his beast more vigorously, had gained some rods upon them. Annoyed by the roughness of the road, he turned his horse suddenly into an open field beside it, and made off across the plain, without giving notice to his daughters. Bertha and Mary, thinking that they were still following their father, continued their way along the dangerous road.

In about fifteen minutes from the time they lost sight of their father they came to a place where the road was deeply sunken between two slopes, at the top of which were rows of trees, the branches meeting and interlacing above their heads. There they stopped suddenly, thinking that they heard at a little distance the well-known barking of their dogs. Almost at the same moment a gun went off close beside them, and a large hare, with bloody hanging ears, ran from the hedge and along the road before them, while loud cries of "Follow! follow! tally-ho! Tally-ho!" came from the field above the narrow roadway.[1]

The sisters thought they had met the hunt of some of their neighbors, and were about to discreetly disappear, when from the hole in the hedge through which the hare had forced her way, came Rustaud, one of their father's dogs, yelping loudly, and after Rustaud, Faraud, Bellaude, Domino, and Fanfare, one after another, all in pursuit of the wretched hare, as if they had chased that day no higher game.

The tail of the last dog was scarcely through the opening before a human face appeared there. This face belonged to a pale, frightened-looking young man, with touzled head and haggard eyes, who made desperate efforts to bring his body after his head through the narrow passage, calling out, as he struggled with the thorns and briars, "Tally-ho! tally-ho!" in the same voice Bertha and Mary had heard about five minutes earlier.

VI.

THE WOUNDED HARE.

Among the hedges of Lower Poitou (constructed, like the Breton hedges, with bent and twisted branches interlacing each other) it is no reason, because a hare and six hounds have passed through, that the opening they make should be considered in the light of a porte-cochère; on the contrary, the luckless young man was held fast as though his neck were in the collar of the guillotine. In vain he pushed and struggled violently, and tore his hands and face till both were bloody; it was impossible for him to advance one inch.