THE HAUNTS OF

OLD COCKAIGNE

THE HAUNTS OF

OLD COCKAIGNE

BY

ALEX. M. THOMPSON

(DANGLE)

1898 . LONDON . THE CLARION OFFICE

72 FLEET STREET, E.C. . WALTER SCOTT

LTD., PATERNOSTER SQUARE, E.C.

AN EPISTLE DEDICATORY

My dear Will Ranstead,—

When, in our too infrequent talks, I have confessed my growing fondness for life in London, your kindly countenance has assumed an expression so piteous that my Conscience has turned upon what I am pleased to call my Mind, to demand explanation of a feeling so distressing to so excellent a friend.

My Mind, at first, was disposed to apologise. It pleaded its notoriously easy-going character: it had never met man or woman that it had not more or less admired,[8] nor remained long anywhere without coming to strike kinship with the people and to develop pride in their activities.

In its infancy it had been as Badisch as the Grossherzog of Baden, and had deemed lilac-scented Carlsruhe the grandest town in the world.

In blue-and-white Lutetia, it had grown as Parisian as an English dramatist.

When the fickle Fates moved it on to Manchester, it had learned in a little while to ogle Gaythorn and Oldham Road as enchanted Titania ogled her gentle joy, the loathly Bottom. It had looked with scorn on the returned prodigals who had been to London—"to tahn," they called it—and who came back to their more or less marble halls in Salford with trousers turned up round the hems, shepherds' crooks to support their elegantly languid totter, and words of[9] withering scorn for the streets of Peter and Oxford, which my Mind had learned to regard as boulevards of dazzling light.

Mine had always been a pliant and affable mind. Perhaps if it lived in Widnes it might prefer it to Heaven.

But the longer I remained in London the more convinced I became that never again should I like Widnes, or Manchester, or Paris, or Carlsruhe, as well as this tantalising, fascinating, baffling city of misty light—this stately, monstrous, grey, grimy, magnificent London.

Then I sought reason for my state, and the following papers—one or two contributed to the Liverpool Post, one to the Clarion, and the most part printed now for the first time—are the result of my inquiries.

One day I found cause for liking London,[10] another day the reverse. As the reasons came to me I wrote them down, and with all their inconsistencies upon their heads, you have them here collected.

I have addressed the papers to you, because:—

As you had inspired the book, it was only fair you should share the blame.

By answering you publicly, I saved myself the trouble of separately answering many other country friends who likewise looked upon my love of London as a deplorable falling from grace.

Thirdly, by this means, I save postages, and may actually induce a few adventurous moneyed persons to pay me for the work.

Lastly, and most seriously, I lay hold on this occasion to publish the respect and gratitude I owe to you, and which I[11] repay to the best of my ability by this small token of my friendship.—Sincerely yours,

ALEX. M. THOMPSON.

P.S.—You will naturally wonder after reading the book—should you be spared so long—why I call it Haunts of Old Cockaigne.

I may say at once that you are fully entitled to wonder.

It is included in the price.

INDEX

| PAGE | |

| An Epistle Dedicatory | 7 |

| London's Enchantment | 15 |

| London Charlie | 35 |

| London Ghosts | 57 |

| The Mermaid Tavern | 78 |

| Was Shakespeare a Scotsman? | 87 |

| Fleet Street | 116 |

| London's Growth | 135 |

| A Truce from Books and Men | 152 |

| A Rude Awakening | 161 |

| London Pride and Cockney Clay | 188 |

| My Introduction to Respectability | 202 |

| Paris Revisited | 215 |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

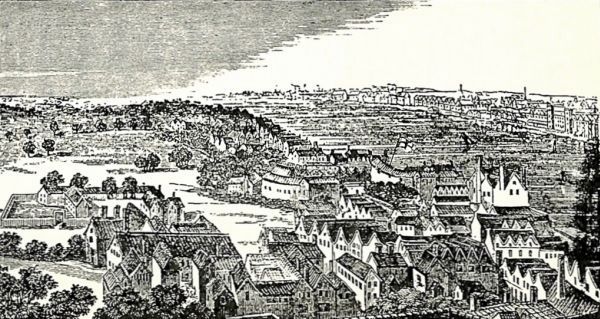

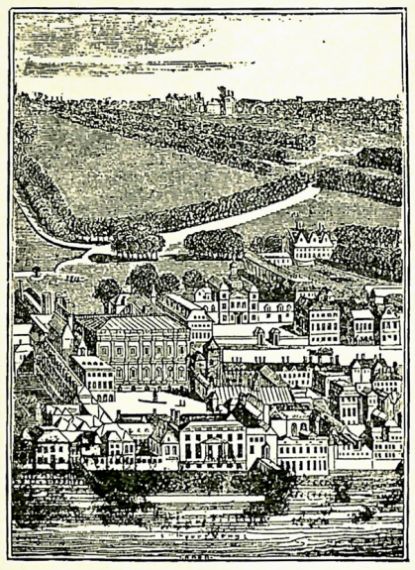

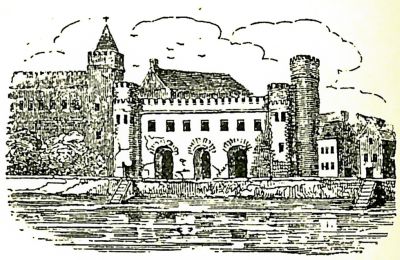

| Bankside in 1648 | Frontispiece |

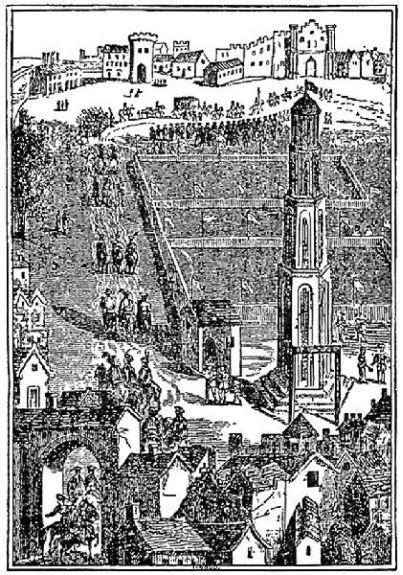

| Strand Cross, 1547 | 61 |

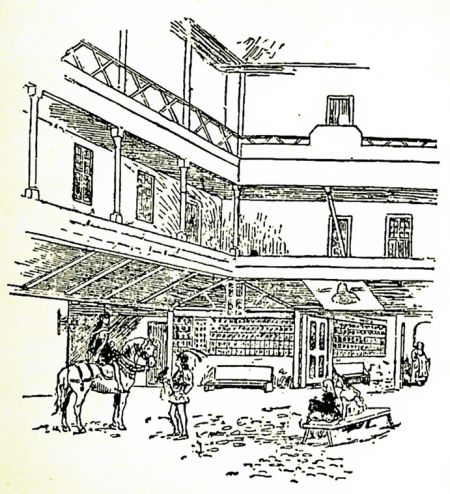

| Courtyard of an Old Tavern | 81 |

| A Barber's Shop in 1492 | 119 |

| Whitehall in the Reign of James I. | 137 |

| Old House in Southwark | 141 |

| The Strand, 1660 | 143, 144 |

| Whitefield's Tabernacle, 1736 | 147 |

| Gorleston Pier | 155 |

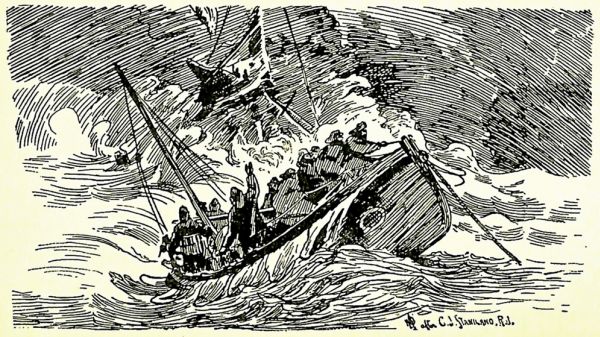

| The Lifeboat | 177 |

| The Champs-Élysées | 219 |

LONDON'S ENCHANTMENT

London bustle and London strife.

H. S. Leigh.

Let them that desire "solitary to wander o'er the russet mead" put on their clump boots and wander.

I prefer the Strand.

The Poet's customary meadow with its munching sheep and æsthetic cow, his pleasing daisies and sublimated dandelions, his ecstatic duck and blooming plum tree, are all very well in their way; but there is more human interest in Seven Dials.

Of a romantic mountain, forest crowned,

Sits coolly calm; while all the world without,

Unsatisfied, and sick, tosses at noon—

may have a very good time if his self-satisfaction suffice to shelter him from Boredom; but of what use is he to the world or to his fellow-creatures?

I have no patience with the long-haired persons whose scorn of the common people's drudgery finds vent in lofty exhortations to "fly the rank city, shun the turbid air, breathe not the chaos of eternal smoke, and volatile corruption."

By turning his back to "the tumult of a guilty world," and "through the verdant maze of sweetbriar hedges, pursue his devious walk," the Poet provides no remedy for the sin and suffering of human cities—especially if the Poet finds it inconvenient to his[17] soulful rapture to attend to his own washing.

It offends me to the soul to hear robustious, bladder-pated, tortured Bunthornes crying out for "boundless contiguity of shade" where they can hear themselves think, when they might be digging the soil or fixing gaspipes.

I would have such fellows banished to remote solitudes, where they should prove their disdain of the grovelling herd by learning to do without them. I would have them fed, clothed, nursed, caressed, and entertained solely by their own sufficiency. Let them enjoy themselves.

Erycina's doves, they sing, and ancient stream of Simois!

I sing the common people, and the vulgar London streets—streams of life, action, and passion, whose every drop is a human soul,[18] each drop distinct and different, each coloured by his or her own wonderful personality.

I never grow tired of seeing them, admiring them, wondering about them.

Beneath this turban what anxieties? Beneath yon burnoose what heartaches and desires? Under all this sartorial medley of frock-coats, jackets, mantles, capes, cloth, silk, satins, rags, what truth? what meaning? what purport? How to get at the hearts of them? how to evolve the best of them? how to blot out their passions, spites, and rancours, and get at their human kinship and brotherhood?

All day long these streets are crowded with the great, the rich, the gay, and the fair—and if one looks one may also see here the poorest, the most abject, the most pitiful, and most awful of the creatures that God[19] permits to live. There is more wealth and splendour than in all the Arabian Nights, and more misery than in Dante's Inferno.

Such a bustling, jostling, twisting, wriggling wonder! "An intermixed and intertangled, ceaselessly changing jingle, too, of colour; flecks of colour champed, as it were, like bits in the horses' teeth, frothed and strewn about, and a surface always of dark-dressed people winding like the curves on fast flowing water."

There is everything here, and plenty of it. As Malaprop Jenkins wrote to her "O Molly Jones," "All the towns that ever I beheld in my born days are no more than Welsh barrows and crumlecks to this wonderful sitty! Even Bath itself is but a fillitch; in the naam of God, one would think there's no end of the streets, but the Land's End. Then there's such a power of people going[20] hurry-scurry! Such a racket of coxes! Such a noise and halibaloo! So many strange sites to be seen! O gracious! I have seen the Park, and the Paleass of St. Gimeses, and the Queen's magisterial pursing, and the sweet young princes and the hillyfents, and pybald ass, and all the rest of the Royal Family."

In two minutes from Piccadilly Circus I can be at will in France, in Germany, in Italy, or in Jerusalem. Even at the loneliest hour of the night I can have company to walk with; for in Bond Street I meet Colonel Newcome's stately figure, in Pall Mall I encounter Peregrine Pickle's new chariot and horses, by the Thames I find the skulking figures of Quilp and Rogue Riderhood, in Southwark I am with Mr. Pickwick and Sam Weller, in Eastcheap with immortal Jack Falstaff, sententious[21] Nym, blustering Pistol, and glow-nosed Bardolph.

I float on London's human tide;

An atom on its billows thrown,

But lonely never, nor alone.

In a hundred yards I may jostle an Archbishop of the Established Church, a Prostitute, a Poet, a victorious General, the Hero of the last football match, a Millionaire, a "wanted" Murderer, a bevy of famous Actresses, a Socialist Refugee from Spain or Italy, a tattooed South Sea Islander, a loose-breeched Man-o'-War's man from Japan, Armenians, Cretans, Greeks, Jews, Turks, and Clarionettes from Pudsey.

The mere picturesque externals suffice to entrance me; but the spell grips like a vice when I look closer and discriminate between the types.

Such a commodity of warm slaves has civilisation gathered here! Such a fascinating rabble of addle-pated toadies, muddy-souled bullies of the bagnio, trade-fallen prize-fighters, aristocratic and other drabs, card and billiard sharpers, discarded unjust serving-men, revolted tapsters, touting tipsters, police-court habitués, cut-purses, area sneaks, and general slum-scum; pimpled bookmakers, millionaire sweaters and their dissipated sons; jerry-builders, members of Parliament, phosy-jaw and lead poisoners; African diamond smugglers, peers on the make, long-nosed company promoters, and old clo' men; Stock Exchange tricksters, fraudulent patriotic contractors, earthworms and graspers; fog-brained and parchment-hearted crawlers, pigeons, rooks, hawks, vultures, and carrion crows; the cankers of a base city and a sordid age; the flunkeys,[23] pimps, and panders of society; the pride and chivalry of Piccadilly; the carrion, maggots, and reptiles of an empire upon whose infamies the sun never wholly succeeds in hiding its blushing countenance.

There is no fear of my forgetting the misery and crime underlying London's splendour. I never invite Mrs. Dangle's admiration to the flashing lights of Piccadilly but she sharply reminds me of the pitiful sights which they illuminate. The ever-fresh and ever-wonderful magic of the Embankment's circle as seen by night from Adelphi Terrace does not efface the remembrance of Hood's "Bridge of Sighs," nor of Charles Mackay's "Waterloo Bridge."

Over the brink of it, picture it, think of it, dissolute Man!

Lave in it, drink of it, then, if you can!

I have seen our painted sisters standing for hire under the flaring gas-lamps. I have seen ghastly wrecks of humankind slinking by the blazing shop fronts as if ashamed of their hungry faces; and others, bloated out of womanly grace, tottering from gin-palace doors into side-dens that make one pale and sick to glance into.

And the interminable battalions of foolish-faced men in foolish frock-coats and foolish tall hats, who suck their foolish sticks as they foolishly amble by!

What tragic and comic contrasts! What variety!

Faces black and copper faces; yellow faces, rosy faces, and martyrs' faces ghastly white; cruel crafty faces, false and leering faces—faces cynical, callous, and confident; faces crushed, abject, bloodless, and woebegone; satyrs' faces, gross, pampered, impudent, and[25] sensual; sneering, arrogant, devilish faces; and shrinking faces full of prayer and meek entreaty; vulture faces—eager, greedy, ravenous; penguin faces—fat, smug, and foolish; faces of whipped curs, fawning spaniels, and treacherous hounds; wolves' faces and foxes' faces, and many hapless heads of puzzled sheep floating helpless down the current; faces of all tints and forms and characters; and not a few, thank Heaven! of faces strong and calm, of faces kind, modest, and intrepid! of faces blooming, healthy, pretty, and beautiful!

Gold and grime, purple and shame, squalor and splendour, contrasts and wonders without end. And all of it—all the flotsam and jetsam of these tumultuous streets—gallant hearts, heroes, criminals, millionaires, pretty girls, and wrecks—they are all charged, and overbrimming with interest, for, as[26] Longfellow says, "these are the great themes of human thought; not green grass, and flowers, and moonshine."

Yet flowers too can London show.

In the densest quarters of Whitechapel I have seen grass and trees as green as the best that can be seen in the choicest districts of Oldham or Bolton.

As for the West End, no richer, riper scenes of urban beauty are to be found in Europe than the stretch of park and garden spread out between the Horse Guards and Kensington Palace.

Stand on the steps of the Albert Memorial and feast your gaze on the woody vistas of Kensington Gardens; or, from the suspension bridge of fair St. James's Park, look over the water to the up-piled, towering white palaces of Whitehall; or, without exertion at all, lie down amongst the sheep in the wide green[27] fields of Hyde Park, and listen to the hum of the traffic.

Hyde Park's verdurous carpet is shot in its season with the golden lustre of the buttercup, dotted with the peeping white of the timorous daisy, and spangled with the flaunting, extravagant dandelion. Every tree is in spring a gorgeous picture, and every thorn bush a bouquet of fragrant flower.

As for London's outside suburbs, no English town can show such charming variety of wood and meadow, of hill and plain.

Smiling uplands and blooming slopes; bushy lanes, flowered hedges, and crystal streams; cottages overgrown, according to the season, with honeysuckle, roses, and creeping plants of gorgeous varying hues; smooth green lawns bedecked with flowers; bracken and woods upon the hills; scampering rabbits, scattered meditative cattle, placid[28] sheep, singing birds, swifts and swallows, rooks high sailing o'er tufted elms; and, above all, the sweet, blue, cloudless, southern sky;—all these may be found on a fine summer's day within an easy cycle-ride in any direction from London.

Where shall we find nobler views than those exposed from Muswell's woody slopes, or Sydenham's stately terraces; from happy Hampstead, or haughty Highgate; from rare Richmond, or, best of all, from glorious Leith?

Where are sweeter woods than those of Epping or Hadley? Where such glades as at Bushey or Windsor? Where so sweet a garden, or so gracious a stream to water it, as lies open to the excursionist in the valley of the Thames between Maidenhead and beautiful Oxford?

To hear the lark's song gushing forth to the[29] sun on Hampstead's golden heath, to see the bluebells making soft haze in the Hadley woods, to watch the children returning through Highgate to their feculent rookeries laden with the fair bloom of hawthorn hedges, to lie on Hyde Park's soft green velvet, is to bring home the knowledge to our tarnished hearts that even this city of fretful stir, weariness, and leaden-eyed despair, might be sweet and of goodly flavour—that even London's cruel face might be made to beam upon all her children like a maternal benediction, if they were wise enough to deserve and demand it!

But—

Monarch slavishly adored;

Mammon sitting side by side

With Pomp and Luxury and Pride,

Who call his large dominion theirs,

Nor dream a portion is Despair's.

The wealth and the poverty! the grandeur and the wretchedness!

Sir Howard Vincent, a Conservative M.P., lately told his Sheffield constituents, after a round of visits paid to "almost every state in Europe," that—

He had no hesitation in saying that in a walk of a mile in London, and in the West End too, they saw more miserable people than he met with in all the countries enumerated—more bedraggled, unhappy, unfortunate out-of-works, seeking alms and bread, and strong men earning a few pence loitering along with immoral advertisements on their shoulders. He granted that there were more people in London with palatial mansions, luxurious carriages, and high-stepping horses, but there was much greater poverty and dire distress among the aged.

As regards the luxury, this is true enough. As regards poverty, London's state is bad—God knows!—infinitely worse than that of Paris, which I know intimately; but not so[31] bad, according to my more travelled friends, as that of Russian, Italian, or even Saxon industrial regions. London's destitution at its worst is perhaps more brutal, and more repellent, but not more hopeless than the more picturesque poverty of sunnier climes.

Poplar, Stepney, Hoxton, Bethnal Green, and Whitechapel are as hideous tumours upon a fair woman's face.

They are vile labyrinths of styes, where pallid men and women, and skeleton children,—guileless little things, fresh from the hands of God,—wallow like swine.

Yet, except for vastness, London slums are not more shameful than the slums Sir Howard Vincent may find, if he will look in the town which he has the dishonour of representing in Parliament.

I saw the slum-scum sweltering in their[32] close-packed, fœtid East End courts during the great water famine last summer (miles of luxuriously appointed palaces in the gorgeous West standing the while deserted), but even then I found them cleaner, fresher, and sweeter than the slums of Manchester, Liverpool, Dublin, Dundee, Glasgow, Birmingham, or Darkest Sheffield.

For over all these London possesses one precious, inestimable advantage—the wide estuary and great air avenue of the Thames, through which refreshing winds are borne into the turbid crannies, bringing precious seeds of health and sweeping out the stagnant poisons.

I have beheld the great city in many aspects, fair and foul. I have seen St. Paul's pierce with ghostly whiteness through a mist[33] that swathed and wholly hid its lower parts, the great dome rising like a phantom balloon from out a phantom city. I have seen a blue-grey "London particular" transform a dingy, narrow street into a portal of mystery, romance, and enchantment. I have loitered on Waterloo Bridge to gaze on the magic of the river and listen to the eerie music of Time's roaring loom. I have heard the babel of Petticoat Lane on Sunday morning. I have surveyed the huge wen and contrasted it with the pleasant Kentish weald from Leith Hill's summit. And I would not go back from London to any place that I have lived in. I like London. I am bitten as I have seen all bitten that came under its spell—bitten as I vowed I never could be.

London's air is in my lungs and nostrils, its glamour in my eyes, its roar[34] and moan and music in my ears, its fever in my blood, its quintessence in my heart.

I came to scoff and I pray to remain.

LONDON CHARLIE

Our greatest evil, or our greatest good.

Moore.

The celebrated novelist Ouida has made a general indictment against the "cruel ugliness and dulness" of the streets of London.

The greatest city in the world, according to Mdlle. de la Ramé, has "a curiously provincial appearance, and in many ways the aspect of a third-rate town."

Even the aristocratic quarters are "absolutely and terribly depressing and tedious";[36] and as for decorative beauty, this is all she can find of it in London:—

An ugly cucumber frame like Battersea Park Hall, gaudily coloured; a waggon drawn by poor, suffering horses, and laden with shrieking children, going to Epping Forest; open-air preachers ranting hideously of hell and the devil; gin-palaces, music-halls, and the flaring gas-jets on barrows full of rotting fruit, are all that London provides in the way of enjoyment or decoration for its multitudes!

Instead of which, I am free to maintain that no town of my acquaintance has such diversity of entertainment.

Paris has the bulge in the trifling, foolish matter of theatrical plays and players. But London has more and finer playhouses; as good opportunities of hearing great music; and infinitely larger and better-appointed music-halls.

London has now the finest libraries,[37] museums, and picture-galleries; and as for out-door entertainment, no town possesses such remarkable variety as is offered at the Imperial Institute, the Crystal and Alexandra Palaces, Olympia, and Earl's Court. Thereby hangs a tale.

It must be that the provincial friends who visit me are not as other men. I hear of people receiving guests from the country and taking them out for nice walks to the National Gallery, South Kensington Museum, the Tower, and other places of cultured dissipation provided by the generous rate-payer to discourage and kill off the cheap-tripper; but I have no such luck.

To my ardent, blushing commendation of national eleemosynary entertainments, the rude provincials who assail my hospitality reply with a rude provincial wink.

Frequent failure has, I fear, stripped my[38] plausibility of its pristine bloom. Time was when I could boldly recommend Covent Garden Market at four o'clock in the morning as a first-rate attraction to the provincial pilgrim of pleasure, but your stammering tongue and quailing eye are plaguy mockers of your useful villainy.

Mrs. Dangle herself begins to look doubtfully when, on our periodical little pleasure trips, I repeat the customary: "Tower! eh? It will be such a treat!"

Ah me! Confidence was a beautiful thing. The world grows too cynical. Earl's Court is the thin end of the wedge by which the hydra-headed serpent of unbelief is bred to fly roughshod over the thin ice of irresolute dissimulation, to nip the mask of pretence in the bud, and with its cold, uncharitable eye to suck the very life-blood of that confidence which is the corner-stone and sheet-anchor[39] of friendly trust 'twixt man and man.

Be that as it may, my praise of County Council Parks and County Council Bands, of Tower history and Kensington culture, is as ineffectual as a Swedish match in a gale.

My visitors, as with one accord, reply, "That is neither here nor there. We are going to Earl's Court."

Thus, Captandem had come to town, and said "he wanted to see things."

I tempted him with the usual programme.

"I am told," I insinuated, "that the Ethnographical Section of the British Museum 'silently but surely teaches many beautiful lessons.'"

"I daresay," he sneered.

"The educational facilities furnished by South Kensington Museum"—

"Educational fiddlesticks," interrupted he.

"The Tower," I went on, "is improving to the mind."

"I have had some."

"The National Gallery"—

"Be hanged!" he snorted. "Do you take me for an Archæological Conference? or a British Association picnic?"

"Well," I began, in my most winning Board-meeting manner, "if you don't like my suggestions, you can go to"—

"Earl's Court," he opportunely snapped.

He then explained that he had been reading in The Savoy, a poem by Sarojini Chattopâdhyây on "Eastern Dancers," commencing thus:—

Drink deep of the hush of the hyacinth heavens that glimmer around them in fountains of light?

[41] O wild and entrancing the strain of keen music that cleaveth the stars like a wail of desire,

And beautiful dancers with houri-like faces bewitch the voluptuous watches of night.

And smiles are entwining like magical serpents the poppies of lips that are opiate-sweet,

Their glittering garments of purple are burning like tremulous dawns in the quivering air,

And exquisite, subtle, and slow are the tinkle and tread of their rhythmical slumber-soft feet.

Now wantonly winding, they flash, now they falter, and lingering languish in radiant choir,

Their jewel-bright arms and warm, wavering, lily-long fingers enchant thro' the summer-swift hours,

Eyes ravished with rapture, celestially panting, their passionate spirits aflaming with fire.

When I had finished reading this too-too all but morsel of exquisiteness, the Boy said[42] he'd be punctured if he could exactly catch the hang of the thing (the Philistine!), but he thought he would like some of those (the heathen!), and having seen an announcement that a troupe of Eastern Dancers were then appearing at Earl's Court, he had determined to let his passionate, with fire-aflaming spirit "drink deep of the hush of the hyacinth heavens."

On the way to Earl's Court, I filled up the Boy with such general information about Nautch Girls, as I had gathered in my studies.

I informed him that nothing could exceed the transcendent beauty, both in form and lineament, of these admirable creatures; that their dancing was the most elegant and gently graceful ever seen, for that it comprised no prodigious springs, no vehement pirouettes,[43] no painful tension of the muscles, or extravagant contortions of the limbs; no violent sawing of the arms; no unnatural curving of the limbs, no bringing of the legs at right angles with the trunk; no violent hops or jerks, or dizzy jumps.

The Nautch Girl's arms, I assured him, move in unison with her tiny, naked feet, which fall on earth as mute as snow. She occasionally turns quickly round, expanding the loose folds of her thin petticoat, when the heavy silk border with which it is trimmed opens into a circle round her, showing for an instant the beautiful outline of her form, draped with the most becoming and judicious taste.

She wears, I continued, scarlet or purple celestial pants, and veils of beautiful gauze with tassels of silver and gold. The graceful management of the veil by archly peeping[44] under it, then radiantly beaming over it, was in itself enough, I assured him, to make one's eyes celestially pant, but—

"Dis way for Indu juggler, Indu tumbler, Nautch Dance," at this moment cried a shrill voice at my side; and I perceived that we were actually standing outside the Temple where the passionate spirits in celestial pants drink deep of the hush of the hyacinth heavens!

The performance had begun. An able-bodied, well-footed Christy Minstrel was doing a sort of shuffling walk-round, droning out the while a monotonous wail in a voice that might have been more profitably employed to kill cats.

"Lor'," the Boy complained, "will that suffering nigger last long? Couldn't they get him to reserve his funeral service for his[45] own graveyard? Ask them how soon they mean to trot out the exquisite, subtle Tremulous Dawns,—the swaying and swinging Sandalwood Slumber-soft Flutter in celestial pants,—the wantonly winding Lingering Languishers?"

I approached one of the artistes—a lean and dejected Fakir, picturesquely attired in a suit of patched atmosphere.

"That's very nice," I said conciliatorily, "very nice indeed, in its way. But we don't much care for Wagner's music, nor Christy Minstrels. We would prefer to take a walk until your cornerman is through: at what time will the Nautch Girls appear?"

"Yes, yes," the heathen Hindu replied, with a knowing leer, "Nautch Girl ver' good, ver' good; Lonndonn Charlee, he likee Nautch Girl, ver' good."

"Yes," I said. "What time do they kick off?"

"Yes, yes, ver' good, ver' good, Nautch Girl," the mysterious Oriental replied; "she Nautch Girl bimeby done now; me go do conjur, ver' good, ver' good."

"Nautch Girl nearly done?" I cried. "Why, where is the Nautch Girl!"

"That Nautch Girl is dance now, ver' good, ver' good. Lonndonn Charlee, he likee Nautch Girl, ver' good."

At last the horrible truth dawned on me!

The person we had taken for a Christy Minstrel was the wantonly winding, lingeringly languishing Nautch Girl!!!

After that we visited other "side shows," and saw more dejected Hindoos perform marvellous feats of jugglery and conjuring, with the aid of trained mongooses, monkeys,[47] and goats. Also an extraordinary game of football by Burmese players, who catch a glass ball on their necks and ankles as dexterously as Ranjitsinhji catches a cricket ball with his hands. Also we saw the acrobats who balance themselves on a bamboo pole by gripping it with their stomachs—a trick which I have since practised with but incomplete success.

We also saw the juggling of an Indian humorist with two attendants, who, if they did not realise all the wonders we have read about Indian conjurers, did at least perform miracles with the English language and the linked sweetness of music too long drawn out.

The attendants sat on the ground and beat monotonous drums, what time the conjurer walked to and fro and played a peculiarly baneful type of Indian bagpipe.

"Ram, ram, ram, ram, kurte heren ugh!" sang the conjurer.

"Ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh!" sang the chorus, rolling their eyes and swaying their shoulders.

"Baen, deina, juldee, chup, chup!" droned the conjurer.

"Chup, chup, chup, chup," wailed the chorus.

"Hum mugurer hue! hum padre hue! hum booker se mur jata hue!" cried the conjurer.

"Hue! hue! hue! hue!" replied the chorus.

Then, "one, two, three, four, five, nine, sumting, fifteen, twenty," cried the conjurer, fumbling with his conjuring gear; "see dere, dere de egg; Lonndonn chicken egg, chicken egg, chicken egg."

"Chicken egg, chicken egg," repeated the[49] chorus in triumphant tones; and banged the mournful drums.

By weird Hindu enchantment, they beguiled Captandem to the platform to assist, and having got him there, proceeded to make him wish he wasn't.

"Lonndonn Charlee," cried the conjurer, triumphantly introducing him; "Lonndonn Charlee, Lonndonn Charlee, say now uchmeechulouchuadmee," and grinned like a heathen.

"Uchmeechulouchuadmee," wailed the chorus.

"Uchmee—uchmee—oh! I can't say it," cried poor London Charlie, and the chorus, showing all its flashing teeth, victoriously droned a mocking "Bu-u-uh!" which obviously completed London Charlie's discomfiture and distress.

"Lennee me Lonndonn sixpence, Lonndonn[50] Charlee," cried the conjurer; and the youthful Captandem, after much inward searching, produced the coin demanded.

The conjurer took it in his hand, placed it under a flower-pot, and said: "Ulla ulla juldeechupalee"; and the chorus shouted, "Chupalee."

Then followed two or three more experiments and practical jokes on London Charlie's confiding innocence, till at last London Charlie, unwilling to bear any more ridicule, leaped from the platform and desperately fled the scene—looking as unlike the cocksure London Charlie that went up, as doth the tin-kettled feline maniac which has fallen amongst felonious boys, to the smug and purring pet of the ancient spinster's fireside.

Poor little London Charlie.

It was not till long afterwards that he remembered his sixpence.

Poor Captandem!

Still he enjoyed himself, and, if the truth must be told, there are moments when even I am less amused by the mummies and fossils of the museums than by the lights, the fountains, the colour, and the movement of Earl's Court.

I wonder why it never occurs to the philanthropists and municipalities which provide picture-galleries, libraries, and other elevating institutions for the people, to try the effect upon Whitechapel or Ancoats of a genuine place of amusement.

The class from which our philanthropists chiefly spring, regard with suspicion nearly everything in which the common people find spontaneous pleasure; and, instead of helping the development and improvement of such natural sources of delight, they only[52] aim to "elevate" the masses by mortifying their flesh and wearying their souls.

To "elevate" them, the philanthropists close their eyes to all that delights the common people, and thrust upon them, willy-nilly, something which interests them not at all, something which they cannot understand, something which nips and chills and infinitely bores them.

The philanthropists, when they give of their benefactions to the people, cannot, or will not, see that to teach a mouse to fly, it is needful for the teacher to begin by stepping down to the earth. They insist, as a condition of their generosity, that the people shall be thereby flabbergasticated, petriflummoxed, and aggrawetblankalysed with everlasting doldrums.

Show me, anywhere, 'twixt Widnes and Heaven—which is as wide a stretch as[53] imagination may compass—any public institution founded by private munificence for the people's delectation, to which the people flock with cheerful alacrity, or wherein the people bear themselves with anything like holiday jauntiness.

The public museums and picture-galleries are very fine institutions, but how much do they affect or brighten the lives of the mass? How do they touch the common people? How many of the Slum-scum come? and how often? Do they enjoy the painted and sculptured masterpieces presented to their admiration? Is it possible that, without guidance or explanation, they can understand the beauty of these, their treasures?

Behold the stragglers that come—how puzzled, awestruck, furtive, and ill-at-ease they are! There is fear of the Superior Person in their face, and of the policeman[54] in their tread. They stare at the frames, at the skylights, at the polished floors, at the attendants, and at the modified Minervas in No. 9 pince-nez who are the most regular frequenters of such places; but they scarcely see the pictures. They walk on their toes to prevent noise, cough apologetically, shrivel under the withering glances of the modified Minervas, and look ostentatiously unhappy.

The modified Minervas walk round with the air of exclusive proprietorship. They are at home. They pervade the place. The young ones stare with mild amazement or languid curiosity at the unaccustomed, aberrant hewer of wood or drawer of water, as if speculating as to which of the more remote planets he sprang from; the elder ones glare at him through their eyeglasses with such scathing disdain as to confirm[55] him in his opinion that his entrance there was an unpardonable liberty.

The public museums and picture-galleries are made, not for the common people of the seething slums, but for the modified Minervas of the genteel suburbs. These are the legatees of the public philanthropists. That which is given for the "elevation of the masses" tends in practice to elevate nothing except the already tilted tips of their particularly cultured noses. The benevolent Crœsus produces no happiness by his benefaction, except that which these ladies derive from the admiring contemplation of their refined superiority.

What the common people want is the glitter of spectacle, the intoxication of beauty and grace, of music and dance; the sensation of light and brightness and stirring movement.

The wisest thing to do with appetites so old-established and deep-rooted is, not to suppress, but to guide them.

Obstruct them, and they will run into dark and dirty channels out of sight; recognise and cultivate them in the clear light of day, and they may produce in every town even better sources of amusement than Earl's Court.

LONDON GHOSTS

In terrace or street or square,

I hear the rattle of chariots

And the sound of life on the air;

And up at the curtained windows,

Where the flaming gaslights glow,

I see 'mid the flitting shadows

Of the guests that come and go,

The paler and dimmer shadows

Of the ghosts of the Long Ago.

Charles Mackay.

Once upon a time, as the charmed books tell, there was a mountain covered with stones, of which each particular flint or pebble had been, "upon a time," a live and sentient man or woman.

The stones lay, with no attribute of life except a power to appeal in such wise to passers-by as to compel them to remain. But there came, one happy day, a beauteous maiden with a pitcher full of the Water of Life, and she, sprinkling the precious fluid over the stones, transformed them again into animated creatures of flesh and blood—"a great company of youths and maidens who followed her down the mountain."

As I take my walks in London-town, I think of that story and long for a pitcher of the magic Water of Life.

For if imagination may trace the noble dust of Alexander till he find it stopping a bung-hole, and if, as biologists tell us, the whole of our mortal tissue is unceasingly being shed and renewed, every brick and stone in London pavement, church, inn, and dwelling-house must have in it some part of[59] human greatness; for the flower of Britain's brain and valour, the heroes of her most glorious service and achievement—poets, philosophers, prelates, princes, statesmen, soldiers, scientists, explorers—the greatest of those who have "toiled and studied for mankind," have lived in London.

Milton used to thank God that he had been born in London. Shakespeare acted in Blackfriars and near London Bridge; his wit flashed nightly at the Mermaid; in the shadow of Whitehall, he broke his heart for Mary Fitton; and here he wove the magic of his plays.

That is the consideration which makes London's enchantment so irresistible. Here is the actual, visible scene of the most momentous deeds of our history, of the most memorable episodes in our country's fiction, and of the workaday, toiling, rejoicing, and sorrowing of[60] the greatest of our English brothers and sisters.

At Charing Cross the statue of Charles I. on his Rabelais horse faces the site of the scaffold "in the open street," on to which the king stepped one morning through a window of his palace of Whitehall. Pepys saw General Harrison hanged, drawn, and quartered at Charing Cross, he (Harrison) "looking as cheerful as any man could in that condition." And he gravely adds that Sir Harry Vane, about to be beheaded on Tower Hill, urgently requested the executioner to take off his head so as not to hurt a pimple on his neck.

Trooper Lockyer, a brave young soldier of

seven years' service, though only twenty-three

years old, having helped to seize General

Cromwell's colours at the Bull in Bishopsgate,

was shot in Paul's Churchyard by[61]

[62]

[63]

grim Oliver's orders. His crime was that

he was a Leveller or early Socialist, "with hot

notions as to human freedom, and the rate

at which millenniums are obtainable. He

falls shot in Paul's Churchyard on Friday,

amid the tears of men and women," says

Carlyle, Paul's Cathedral being then a horse-guard,

with horses stamping in the canons'

stalls, and its leaden roof melted into bullets.

On the following Monday the corpse having

been "watched and wept over" meantime

"in the eastern regions of the City," brave

Lockyer was buried "at the new churchyard

in Westminster":—

The corpse was adorned with bundles of Rosemary, one half stained with blood. . . . Some thousands followed in rank and file: all had sea-green and black ribbon tied on their hats and to their breasts; and the women brought up the rear.

How actual and visible and present they[64] are, as one stands on the spots where these great events were transacted! And such histories has nearly every street and every ancient building. London is not paved with gold. It is paved with the glory of England's mighty dead.

The name is Legion of the eminences whose last cumbrous clog of clay is buried here.

In Westminster's venerable and beautiful Abbey, where I saw Gladstone buried last June, I can look on the bury-hole of Edward the Confessor, King of our remote Anglo-Saxon ancestors, and one of the prime founders of English liberties; I see the tomb of that butcher Edward who subdued Wales and overthrew Scotland's Wallace; here, too, is the grave of the third Edward, who, by his raiding and stealing, laid the foundations of[65] England's glorious commerce. Here, under his Agincourt helmet, lies the valiant dust of Falstaff's Prince Hal, and of three other Royal Henrys. Bloody Mary rests from her fiery rage; Mary Queen of Scots is united in death to her terrible foe, Elizabeth of England; and two Stuart Kings repose uncomplainingly by the side of William of Orange.

Who swam to sov'reign rule through seas of blood;

The oppressive, sturdy, man-destroying villains,

Who ravag'd kingdoms, and laid empires waste,

And in a cruel wantonness of power

Thinn'd states of half their people, and gave up

To want the rest; now, like a storm that's spent,

Lie hushed.

From these crumbled majesties I turn with reverence to aisles hallowed by the mould of Darwin, Dickens, Thackeray,[66] Browning, Macaulay, Livingstone, Garrick, and Handel.

Beneath St. Paul's great dome my gratitude can tender homage to the names of Titanic Turner, Reynolds, Landseer, Napier, Cornwallis, Wellington, and Nelson.

Think what a procession if all these could be sprinkled with the Water of Life! If to each fragment of noble dust in this huge, unshapely, and overgrown wilderness of masonry, one could call back the soul that sometime quickened it, what a great city, in Walt Whitman's sense, would London be!

Every town cherishes the sacred memory of its own particular great man, but London bears in its bosom intimate and familiar tokens of them all. The city and its neighbourhood for miles round are marked with historic and literary associations. The[67] place is all composed of great men's fame and chapters of world-history. London Clay is made of London's Pride, and London Pride grows in the London Clay.

Not a quarter, not a suburb is free of hallowed associations.

Within half an hour's stroll from my home at Highgate I can visit the pleasaunce of which Andrew Marvell wrote—

But so with roses overgrown,

And lilies, that you would it guess

To be a little wilderness.

I cross the threshold of the adjoining house, and stand within the actual domicile of staid Andrew's improper neighbour, Mistress Nell Gwynne. It was from a window of this house she threatened to drop her baby, unless her Merry Monarch would there and then confer name and title on him; and[68] thus came England into the honour and glory of a ducal race of St. Albans.

When Nell Gwynne looked up from that signally successful jest, she may have seen, across the street, the two houses wherein, a few years before, had dwelt the stern Protector of the Commonwealth and the husband of his daughter, Ireton. I wonder what she thought of old Noll!

The houses stand there yet, substantial, square, their red brick "mellowed but not impaired by time."

The "restored" Charles had had the corpses of over a hundred Puritans, including Admiral Blake's, and that of Cromwell's old mother, dug up from their graves and flung in a heap in St. Margaret's Churchyard; he had hung in chains on Tyburn gallows the disinterred clay of Cromwell, Ireton, and Bradshaw.[69] I wonder he was not prompted to pull down these dwellings of his father's "murderers." He must have seen them often. Their windows overlooked the garden of his light-o'-love.

Did she intercede to have them preserved? As I linger there, I like to think so.

Still within a half-mile circle of my home, on the same Highgate Hill whereon stand the houses of Nell Gwynne and Ireton, I can show my children the "werry, indentical" milestone from which—ita legenda scripta—Dick Whittington was recalled by the sound of Bow Bells.

At the top of Highgate Hill, and on the slope of another hill where a man (since dead in the workhouse) saved Queen Victoria's life, stands the house where Samuel Taylor Coleridge lived. Here, and,[70] it is said, in a little inn near by, he entertained such company as Shelley, Keats, Byron, Leigh Hunt, and—surely not in the little inn?—Carlyle.

Coleridge lies buried in the churchyard hard by, and in Highgate Cemetery I find the graves of George Eliot, Michael Faraday, Charles Dickens' daughter Dora, Tom Sayers the prize-fighter, and Lillywhite the cricketer.

Harry Lowerison has a way of teaching children by taking them to see the streets and monuments of London; and I can think of no more interesting or promising mode of instruction.

For in these scenes English history is indelibly and picturesquely written, back to the date of our earliest records.

I stood one day in Cannon Street, when a passing omnibus-horse chanced to slip. The[71] vehicle swerved across the asphalt, and, to complete the catastrophe, the horse fell.

Then, hey, presto! in the twinkling of an eye, the street was blocked with a compact mass of "blue carts and yellow omnibuses, varnished carriages and brown vans, green omnibuses and brown cabs, pale loads of yellow straw, rusty red iron clanking on paintless carts, high white wool packs, grey horses, bay horses, black teams; sunlight sparkling on the brass harness, gleaming from the carriage panels; jingle, jingle, jingle."

A bustling, shuffling, pushing, wriggling, twisting wonder! One moment's damming of the stream had caused such a gathering as Imperial Cæsar never dreamt of.

I was pushed back against the wall, and then observed that I stood by the London Stone—a stone which "'midst the tangling[72] horrors of the wood" by Thames side, may have been drenched with the human gore of druidical sacrifices. Captives bound in wicker rods may have burned upon its venerable surface to glut the fury of savage gods.

That stone stood here when Constantine built the London Wall around the "citty."

It was here when, upon an island formed by a river which crept sullenly through "a fearful and terrible plain," which none might approach after nightfall without grievous danger, King Sebert of the East Saxons built to the glory of St. Peter the Apostle that church which is known to our generation as Westminster Abbey.

The London Stone stood when Sebert built a church on the ruins of Diana's Temple, where now stands St. Paul's Cathedral. London was built before Rome, before[73] the fall of the Assyrian monarchs, over a thousand years before the birth of Jesus Christ.

Who knows? Where I stood, old Chaucer may have stood to see his Canterbury Pilgrims pass. Falstaff, reeling home from Dame Quickly's Tavern with his load of sherris-sack, may have sat here to ponder on his honour. Shakespeare may have leaned on the old milestone as he watched the Virgin Queen's pageant to Tilbury Fort in Armada times. Through James Ball's and Jack Cade's uprising, through the Wars of the Roses, the Fire of London, the Plague, the Stuart upheaval, and Cromwell's stirring times—through all these the London Stone stood, "fixed in the ground very deep," says Stowe, "that if carts do runne against it through negligence the wheels be broken, and the stone itself unshaken." And now[74] it links the bustle and roar of modern London with the strife out of which London grew, and keeps our conceits reminded of the forefathers who lived and fought in Britain here to make the way more smooth for us.

Ere cabs or omnibuses were; ere telephones, telegraphs, or railways; ere Magna Charta; before William the Conqueror brought our ancient nobility's ancestors over from Normandy—London knew this stone.

It has endured longer than any king, it has survived generations and dynasties of monarchs. "Walls have ears," they say, and Shakespeare "finds tongues in trees, books in running brooks, and sermons in stones."

What a tale would he tell that could find the tongue of the London Stone!

Think of all the men and women who[75] have passed it, seen it with their eyes, felt it with their hands; the millions of simple, faithful, anonymous people who have cheerfully slaved, and bled, and died, to help—as each according to his lights conceived—the honour, safety, and well-being of his country.

We have paid homage to the celebrated dead: what about those that have done their duty and have received neither fame nor monument? Their blood, too, cries out to me from the paving-stones of London.

And laud as gods the scourges of their kind!

Call each man glorious who has led a host,

And him most glorious who has murdered most!

Alas! that men should lavish upon these

The most obsequious homage of their knees—

That those who labour in the arts of peace,

Making the nations prosper and increase,

Should fill a nameless and unhonoured grave,

Their worth forgotten by the crowd they save—

[76] But that the Leaders who despoil the earth,

Fill it with tears, and quench its children's mirth,

Should with their statues block the public way,

And stand adored as demi-gods for aye.

But thanks to the efforts of Mr. G. F. Watts, R.A., and Mr. Walter Crane, London is at last in a fair way to pay homage also to these unsung and unhonoured heroes of lowly life.

During the Jubilee of 1887 Mr. Watts urged that cloisters or galleries should be erected throughout the country and frescoes painted therein, to record the shining deeds of the Democracy's great men and great women. Such a Campo Santo is now being prepared in the new Postmen's Park in Aldersgate Street, and one of the first frescoes to be painted there by Mr. Crane will commemorate the valiant act of one Alice Ayres, a young nurse-girl who rescued her three[77] young charges from a burning house, she herself perishing in the flames.

When I go to Paris, my favourite pilgrimage is to the Mur des Fédérés in the Père-la-Chaise Cemetery, where the last of the Communists were mowed down by the mitrailleuse.

My sincerest worship of the dead in London will be tendered in the Campo Santo of the Postmen's Park, and I hope one day to pay my homage there to the memorial of Trooper Lockyer.

THE MERMAID TAVERN

Besides beere, and ale, and ipocras fine,

In every country, region, and nation,

But chiefly in Billingsgate, at the Salutation;

And the Bore's Head, near London Stone,

The Swan at Dowgate, a taverne well known;

The Mitre in Cheape; and then the Bull Head,

And many like places that make noses red;

Th' Bore's Head in Old Fish Street, Three Crowns in the Vintry,

And now, of late, St. Martin's in the Sentree;

The Windmill in Lothbury; The Ship at th' Exchange,

King's Head in New Fish Street, where oysters do range;

The Mermaid in Cornhill, Red Lion in the Strand,

Three Tuns, Newgate Market; Old Fish Street, at the Swan.

(Newes From Bartholomew Fayre; an undated, anonymous black-letter poem.)

"Much time," says Andrews in his history of the sixteenth century, "was spent by the citizens of London at their numerous taverns."

The tavern was the lounging-place, not only of the idle and dissolute, but of the industrious also. It was the Club, the Forum, sometimes too the Theatre.

The wives and daughters of tradesmen collected here to gossip, and, strange as it now seems to us they came here, too, to picnic. An old song of the period describes a feast of this sort, and tells how each woman carried with her some goose, or pork, the wing of a capon, or a pigeon pie. Arrived at the tavern, they ordered the best wine. They praised the liquor, and, under its inspiriting influence, discussed their husbands, with whom they were naturally dissatisfied; and then went home by different streets,[80] perfidiously assuring their lawful masters that they had been to church.

This evidence is useful and seemly to be here set down, as indicating the true origin of habits for which much undeserved censure has been in these later days inflicted upon mere imitators.

The men, whose chiefest fault has ever been their too great readiness to follow the women, fell insensibly into the habit, and have been there ever since.

And what a glorious time they have had

of it! To recall only Fuller's description of

the "wit combates" between Shakespeare's

"quickness of wit and invention" against

Ben Jonson's "far higher learning," and

"solid, but slow performances," at the

historic Mermaid; and Beaumont's rapturous

praise in his epistle to Jonson

of the banquet of wit and admirable[81]

[82]

[83]

conversation which they had enjoyed at the

same place!

Oh to have been at the Mermaid on the night when Jonson had been burnt out at the Bankside Globe! or on the night of Shakespeare's first performance before Elizabeth—when he had first, perhaps, set eyes on Mary Fitton!

All the wits of that age of giants were wont to assemble, after the theatre, at the Mermaid, the Devil, and the Boar. Exuberant Fletcher and graver Beaumont would "wentle" in from their lodging on Bankside, wearing each other's clothes, and wrangling perhaps about their plots—a habit which on one occasion caused them to be arrested, a fussy listener having heard them disputing in a tavern as to whether they should or should not assassinate the king. Poor, drunken, profligate Greene, and his[84] debauched companions, Marlowe and George Peele,—all of whom ended their riotous courses with painful and shameful deaths,—are sure to have lurched in on many a razzling night. Regular visitors, too, were "Crispinus" Dekker, and his friend Wilson the actor, whom Beaumont mentions as a boon-companion over the Mermaid wine:—

Did Robert Wilson write his singing psalms.

From Whitehall, with "their port so proud, their buskin, and their plume," would swagger in Raleigh, Surrey, Spenser, and others of the wits from Elizabeth's ruffling Court. Drummond of Hawthornden came here at least once on a visit to Ben Jonson; but this must have been after Shakespeare had deserted the festive board for the crested pomp of a gentlemanly life at Stratford,[85] "coming up every term to take tobacco and see new motions."

Sombre John Webster would be here sometimes, sometimes Massinger, Thomas Middleton, Lilly, Thomas Heywood, William Rowley, Day, Wilkins, Ford, Camden, Ned Drayton, Fulke Greville, Harrington, Edmund Waller, Martin, Morley, Selden, the future Bishop of Winchester, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera!

What a galaxy! what a feast!

It is well for your peace of mind, my good wife, that the Mermaid and its company have vanished into the dark immensity. How long would I wait, and cheerfully, for so much as a peep through the window at that glorious company!

Dryden claims that the Mermaid did not receive such pleasant and such witty fellows[86] in the reigns of Bess and James as did the Royal Oak, the Mitre, and the Roebuck after the Restoration; but to me the haunts of Wycherley, Otway, Villiers of Buckingham, Wilmot of Rochester, and the periwigged bucks and bloods and maccaronies in velvets and lace of Charles the Second's dissolute Court, are, as compared with the Falstaffian Taverns of the Shakespeareans, but dull and dry dens.

So, if you will, of your grace, excuse the pun and the hasty skip, we will give these pretty gentlemen a miss, and jump at once into a fresh chapter and an account of a curious experience that once upon a time came in a tavern to me.

WAS SHAKESPEARE A SCOTSMAN?

Meet nurse for a poetic child.

Scott.

At last I was alone. The landlord, douce man, could stand no more; his conversation had been large and ample up to midnight, and had indeed left a fair remainder to spread a feast for solitude; but for the last two hours he had done nothing but alternately yawn and doze.

Now, thank goodness, he had gone, and I could read in peace.

Angels and ministers of grace defend us—Bacon's[88] Essays and Donnelly's Cryptogram!—in the parlour of a shabby old inn! Was mine host, then, of a literary turn? Ay, I had noted his gushing praise of Burns and Walter Scott; and, by the way, what was it he said about Shakespeare's visit to Edinburgh? He had shown me a letter in a book: I had been too intensely bored by his trowelled praise of Scottish lochs, Scottish mountains, haggis, parritch, usquebaugh, and Scottish poetry, to pay much heed—but yes, this must be it. Drummond's Sonnets, and here evidently was the letter, signed by Ben Jonson, indorsed "to my very good friend, the lairde of Hawthornden":—

Master vill,

quhen we were drinking at my Lordis on Sonday, you promised yat you would gett for me my Lordis coppie he lent you of my Lord Sempill his[89] interlude callit philotas, and qhuich vill Shakespeare told me he actit in edinburt, quhen he wes yair wit the players, to his gret contentment and delighte. My man waits your answer:

So give him the play,

And lette him awaye

To your assured friend

and loving servand,

Ben Jonson.

From my lodging in the canongait,

Mrch the twelft, 1619.

So here also had Shakespeare anticipated me? Had he been to Edinburgh too?

I might have known: but lo! I grow so used to our resemblances, I almost cease to notice them.

Donnelly too! I had never seen his book before—though I have taken keen interest in the subject ever since Delia Bacon arose in—well, the land where they do raise Bacon—and found Shakespeare out.

Could it indeed be true that Shakespeare[90] was an ignorant impostor, whose business it was to hold respectable gentlemen's horses at the stage-door of the theatre, instead of which he wickedly suborned the Lord High Chancellor of England to write his plays for him, and the same with intent to deceive?

To make sure, I read a few pages of Donnelly.

Even that failed to convince me: the more I read, the more I didn't know.

I saw Shakespeare's Works on the bookshelf, and reached the volume down. It opened at the Sonnets.

Ah! what exquisite music! But—what was this?

Though I, once gone, to all the world must die.

Again in Sonnet XXXVIII.—

The pain be mine, but thine shall be the praise.

And in the next:—

And what is't but mine own when I praise thee?

Curious, surely. What could these lines mean?

And again:—

My life hath in this line some interest.

What if the true cryptogram were concealed in this strangely emphasised and deeply noted line? What if it were left to me to solve the mystery?

By Jove! here was a discovery! Writing "interest" "interrest," as it would be written in the manuscript, the letters in the line spell the words

"Mistress Mary Fitton";

and Mistress Mary Fitton, as everybody[92] knows, is the Dark Lady of the Sonnets, the lady who had "her Will, and Will to boot, and Will in overplus"; to wit, Will Shakespeare; her young lover, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke; and the respectable elderly lover whom she was plighted to marry at his wife's death—Sir William Knollys, Comptroller of the Household to Queen Elizabeth!

Mary Fitton's identity with the lady of the Sonnets has been established beyond question by Lady Newdegate's publication of Passages in the Lives of Anne and Mary Fitton. The perfect anagram which I had accidentally discovered in the most pointedly accentuated line in the whole of the Sonnets, was therefore something more than curious.

I next took the entire passage:—

Which for memorial still with me shall stay.

After an hour's wrestling I had extracted from the letters forming these four lines, these words:—

"Learn ye that have a little wit yt Francis Bacon these lines to Mistress Mary Fitton, Elizabeth's maid of honour at Whitehalle, hath writt."

But the anagram was imperfect. Several letters included in the words of the sonnet, remained unused in my anagram.

It was maddening to arrive so near success, to touch it as it were with one's, finger tips, yet fail for a few foolish trifling alphabetic signs.

Desperately, frantically, I struggled to complete and perfect the anagram; but the more I juggled with the letters, the more bewildered, mazed, and helpless I became.[94] My blood was a-fire, my head a horrible ache, my brain a whirling tornado of dancing vowels and consonants.

The excitement, if still fed and unsatisfied, must lead, I felt, to brain fever or madness.

I tore myself from the intoxicating pursuit, and fell, restless, sleepless, yet painfully weary, upon the couch beneath the window.

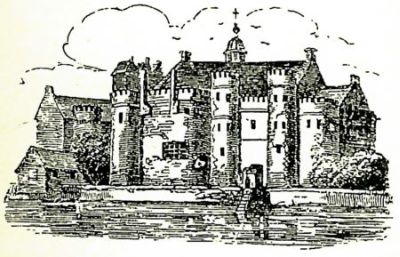

It was a wild winter's night, and the view outside was full of "fowle horror and eke hellish dreriment." The cordon of turrets girding the city bulged eerily through the heavy gloom like limbs of a skeleton starkly protruding through a lampblack shroud. A beam of lurid moonlight uncannily lit up a distant stretch of bluff, stern crags, and nearer spectral foreground of towers, gables, and bartisans.

Deep down in the hollow, dismal and desolate, under a sky of raven's feathers,[95] glowered murder-stained Holyrood, congenial to the night. The solitary glimmer on the thunder and battle-scarred Castle Rock, looked like a match held up to show the darkness.

The melancholy patter of the rain, and the discordant creaking and rattling of an iron shutter and rusty hinge, made music harmonious to the scene.

The air of the musty room added to the contagious heaviness. In vain I stretched the astral sceptre of the soul upon the incorporeal pavement of conjecture. Nothing came of it, except that I slipped off the couch. I was too restless to think. Even the dog, on the rug at my feet, uneasily twitched and growled in his sleep.

Suddenly, I became conscious of a creepy chill; my head, by some impulse foreign to my volition, was raised from its meditative[96] pose; and in the spluttering, dying beam of the lamp's light, I beheld an Apparition.

A grim and grisly goblin, of unwholesome oatcake hue, fluttered (no other word describes the wild and fitful unreliability of his movements) before my startled gaze; his eyes, like glassy beads, shone horridly.

My dog raised his head, and looked over his shoulder. When his gaze fell on the Apparition he bounded to his feet, his limbs shaking like jelly, his eyes projecting like shining stars, and his hair standing up round his neck like a frill.

He tried to growl, but the sound, shaken and softened by terror, issued to the night in lamb-like bleats. Yet more appalled by his vocal failure, he shrank, still feebly bleating, backwards under the sofa.

For my part, I believe I may say I was not afraid, but intensely excited. I felt that something[97] was about to be revealed to me; this was the reason why my hand trembled so as to knock Shakespeare, Bacon, and Donnelly in one commingled heap of fallen glory to the floor.

I was curious, fascinated, and highly wrought.

The wild and fitful little shape bewilderingly wriggled and flickered in the light, and his ghast and fixed eye was painful to endure. Yet I felt that we two had not met without reason. Instinct told me we should do business.

He was the jerkiest and perkiest little figure I had ever clapped eyes on. He bore his head with confident, nay impudent, erectness; his arms waved like a windmill's; and his shapeless little legs straddled all over the place in a succession of purposeless leaps and flings and prancings.

So quick and fidgety were his movements that it was not easy to catch the details of his dress; but I saw that his tartan was a spider's web, to whose check the slimy snail had imparted a variety of hue unknown to Macgregor or Macpherson; his bonnet was a flowering thistle; his philabeg was made of the beards of oat-florets; his buckle was a salmon's scale; and a blade of finest rye dangled proudly by his side.

"Ye'll know me the noo if ye'll speir lang enoo," he squealed ironically when I had stared for some moments. "Gape and glower till your lugs crack, but ye canna' alter the fact that a' great men are Scots. Burrrns was Scottish, and Allan Ramsay, and Blair, and Thomson, Smollett, and Hume, and Boswell, and Adam Smith, and Stewart, and Hogg, and Campbell; and ay, Sir Walter Scott, Tam Carlyle, and Lord Brougham; and[99] Chalmers, and Brewster, and Lyell, and Livingstone, and Macbeth, and McGinnis; Macchiaveli, the Maccabees; and Macaronis, the Macintoshes and Macrobes; and what reason hae ye to suppose that the author of Shakespeare's Plays was an exception?"

"Oh, I don't know," I said, "but—er—have I had the pleasure of meeting you before?"

"Bah!" said he, hastily dancing a strathspey, "ma fute is on ma native dew, ma name is Roderick; I am," he continued, drawing himself up to the full height of his figure, which was about six inches, "I am the Speerit o' Scottish Literature."

"Oh, I know you now," I said, "you're the spirit men call the Small Scotch."

"Where will ye find the Small Scotch that's fu' sax inches in height?" answered Roderick, with asperity.

"Oh, I beg your pardon," I said. "But I didn't ring for you, did I?"

"I'm no slave o' the ring," proudly answered Roderick, as he broke into the opening steps of a complicated sword-dance. "I came of my ain sweet will, just to improve your mind."

"That's very kind," said I; "will you take a chair, or a tumbler?"

The Spirit hissed angrily, as if a small soda had been poured over him, and I prudently abstained from further interruptions.

As some of my readers are perhaps less fluently acquainted with the Scotch than myself, I take the liberty of translating into English the conversation which ensued.

The Spirit began by asking whether I regarded Shakespeare as the greatest poet that ever lived, or as the meanest sweater that ever exploited the gifts of the helpless[101] poor—meaning in this case Francis Bacon.

I responded that I did not think Bacon a man of that sort.

"Well," continued the Spirit, "do you think that a man who could scarcely write his own name could write Hamlet?"

"It is a nice point," I said.

"Very well," said the Spirit, dancing a series of fantastic Highland flings in the unsubstantial air, and turning a double somersault at the finish; "if, as everybody admits, Bacon was one of the blackest scoundrels that ever lived, his mind could not have conceived the noble philosophy to which his name is attached. And if Shakespeare, as the signature to his will shows, could scarcely write his own name, he could not have written his own Plays."

"Same again," said I.

"Besides which," continued the Spirit, "neither Shakespeare nor Bacon was a Scotsman."

"That settles 'em," quoth I.

"Now, look at here," continued the Spirit, aggressively shaking his forefinger under my nose; "whoever wrote Shakespeare's Plays must have written Shakespeare's Sonnets."

"Undoubtedly," said I.

"And the Sonnets were dedicated by the publisher to 'W. H.,' who is styled 'the onlie begetter of these ensuing Sonnets.'"

"Well?"

"The publisher must have known who the author was."

"Very likely."

"And in referring to the 'onlie begetter,' he clearly implies that the authorship was claimed by many, and in furnishing no more than the initials of 'the onlie begetter,' he[103] indicates that the real author had reasons for concealing the authorship."

"That may be so."

"Well, why should a man desire to conceal his authorship of such exquisite sonnets—sonnets of whose surpassing excellence he himself is so convinced that he writes—

So long lives this,

—unless the Sonnets contained matter likely to bring him into trouble? For instance, if a man had, in the fervour of his youth, poured out such warm expression of his love as the Sonnets contain, and very earnestly desired, later on in life, to marry another lady, he might be anxious then that the authorship of the Sonnets should be temporarily forgotten. But Bacon never did marry. And Shakespeare married young, and deserted his wife; and she survived his[104] death. Therefore, no such motive for secrecy could have affected Bacon or Shakespeare."

At this point of his inductive reasoning, the Spirit paused for effect: he looked for all the world like a picture I had seen in the Strand Magazine.

"Ah!" I said, "I know you now; you are Sherlock Holmes, the detective."

At which he was so indignant that he angrily pirouetted himself right out of sight. But he re-appeared almost immediately, and went on as if nothing had happened:—

"Having proved to you that neither Bacon nor Shakespeare wrote his own works, I will now proceed to tell you who wrote them."

"What! The lot?"

"Certainly. The similarity of thought in Bacon's Essays and Shakespeare's Plays[105] prove that they were written by the same man. That man, as you may see by the legal knowledge betrayed alike in the Plays and the Essays, must have studied the law. But if he wrote all the books which I attributed to him, he could not have had time to practise it. Moreover, in the atmosphere of the law courts a man could have preserved neither the exquisite sweetness nor the human grandeur of the so-called Shakespeare's Plays."

"There's something in that," said I.

"Very well," continued Roderick, curveting so swiftly that even as one foot touched the floor the other seemed to be kicking the ceiling, "we have now established these facts:—

"First, that the initials of the author of the so-called Shakespeare's Plays are 'W. H.'

"Secondly, that he had an intensely painful[106] love affair in his youth, and married another woman in his later years.

"Thirdly, that he was a lawyer by education but not by practice.

"Now, who was he? We have yet more evidence to aid us in identifying him. There's Spenser's plaint that 'our pleasant Willy,' 'the man whom Nature's self had made to mock herself and truth to imitate,' had been 'dead of late,' and 'with him all joy and merriment.' We have also the lines in the Sonnets:—

And then thou lov'st me, for my name is Will.

The first name of 'W. H.,' therefore, is Will. And this Will had great trouble at one period of his life, which silenced all his joy and merriment. Again I ask you, Who was the man?"

And the Spirit, bubbling and shaking with eagerness, peered anxiously into my face.

"What great Scotsman of that great period," he continued, screaming rather than speaking, "was brought up to the law and abandoned it for the pursuit of literature and poetry? was driven nearly to distraction by the loss of a mistress whom he loved more dearly than life? went abroad to seek solace, and, returning after many years, married another lady? wrote and left extant in his own name, sonnets which are acknowledged to be perfect models of sweetness and delicacy, sonnets which have never been eclipsed since his death? who was the Scottish poet, friend of the London actors; friend of Ben Jonson; the man who has left on record in British literature the report of his conversations with Jonson; the man[108] who, as you have to-night seen by your landlord's letter, knew Shakespeare and lent him plays which are not known now by the names they then bore—come, come, man, who is this W. H.? Cannot you guess it even now?"

"William of Hawthornden?"

"Of course, of course," the Spirit cried. "Look you, now, how plain it is. William Drummond of Hawthornden was tinged with the conceits and romances of the Italian school, as was the author of Romeo and Juliet. He wrote histories, as did the author of The History of Henry VII., attributed to Bacon; as did the author of the historical plays, attributed to Shakespeare. He wrote many reflections on Death, as did the author of the Sonnets and the Plays. And who but a Scotsman, I would like you to tell me, could have furnished the local[109] colour and the Scottish character to the tragedy of Macbeth?"

"Why, man, it's as plain as a pikestaff. The greatest Englishman that ever lived was naturally a Scotsman. The greatest genius of any clime or time was William Drummond of Hawthornden."

And, in the frenzy of his exultation, Roderick leaped high again into the air, turned seventeen somersaults in succession, and, alighting upon my nose, danced a wild Highland fling of triumph and defiance.

It was certainly very plausible—as plausible, at least, as any argument that I had heard in support of the theory that Bacon wrote Shakespeare's Plays. I was almost persuaded: then a difficulty occurred to me.

"But," I said, "Drummond of Hawthornden was not born till 1585, and some[110] of Shakespeare's Plays appear to have been produced before 1593."

"Well," answered the Spirit, carelessly sticking his sword into my nose and sitting on it, "what has age to do with genius? Has not another poet said, 'He was not of an age, but for all time'? Besides, the Scottish are a precocious people and byordinar'. And furthermore, who told you that Drummond was born in '85?"

"English history says so."

"English history!" answered the Spirit, with a sneer; "try Scotch."

"But," I still objected, "if Shakespeare wrote nothing, why did Ben Jonson, who knew him well, praise his wit and his 'gentle expressions, wherein he flowed with that facility that sometimes it was necessary he should be stopped'?"

"Well," said Roderick, "and who said[111] that Shakespeare wrote nothing? I only said he did not write Shakespeare's Works. But he wrote other poetry—poetry which everybody knows—poetry as familiar in every child's mouth as butterscotch. There is nothing finer of its kind."

"It is strange," I muttered, "that I have never heard of it."

"What?" cried the Spirit, "never heard of 'Little Jack Horner'?

Eating a Christmas pie;

He pulled out a plum with his finger and thumb,

And said "What a good boy am I!"

"And is that Shakespeare's?" I exclaimed.

"And what for no'? It is a perfect specimen of pure Anglo-Saxon English, without corrupt admixture of Norman or Roman words. It is terse and dramatic.[112] The very first line, in its revelation of the hero's remote and solitary state, presents a powerful suggestion of a contemplative character. His voracity, tempered by intense conscientiousness, is indicated in a few clear, pertinent touches that unmistakably betoken the master-hand. Yet the author's name is lost in the dust of the centuries; it has eluded the vigilance of antiquarian research. Only I am acquainted with the secret. If you doubt it, turn the poem into an anagram, and the truth shall be clear even to you."

"But," I began, "if"—

"Bah! Look at here!" cried Roderick, jumping to his feet and brandishing his sword, "I came here to improve your mind; but if you are not amenable to reason, it's no use talking. So get out of it, ye puir, daft, gawkie Southron loon!"

And so saying, he struck me so terrible a blow across the nose with his sword that I sneezed, and lo, behold! he was gone, and in the place where he had been, was nothing but a great, busy, buzzing moth, that hovered round my nose as though it had been a joy-beacon.

It was a strange experience. I don't know what to make of it. But I don't think that Shakespeare was Bacon. And, as I hadn't the slightest trace of headache when I awoke, I think that, after all, the Scottish Spirit was right. Bacon hasn't a ham to stand on. Bacon is smoked. To honest nostrils Bacon hereafter is rancid.

Be that as it may, there can be no doubt henceforth as to the authorship of "Little Jack Horner." Following Roderick's[114] instructions, I have taken the letters of the lines of that poem, and have constructed with them an anagram which establishes beyond possibility of dispute that Shakespeare wrote them.

I am prepared to prove it to the British Association, and defy The Daily Chronicle. It is true the spelling is rather bad, but Shakespeare's was notoriously beastly, so that is another proof in my favour.

It is moreover a perfect anagram, in which each letter is used, and used once only. The letters are Little jack horner sat in a corner eating a christmas pie he pulled out a plum with his finger and thumb and said what a good boy am i.

Now, mark, hey presto! there's no deception; mix these letters and form them into new combinations, and you evolve this[115] remarkable, startling, conclusive, and scientifically historical revelation:—

Mistir Shakesper aloan was the Lyturery gent wich rote this Bootiful Pome in Elizabuth Raign, and Jaimce had Damn Good Lauph.

Could anything be clearer?

FLEET STREET

When I go up that quiet cloistered court, running up like a little secure haven from the stormy ocean of Fleet Street, and see the doctor's gnarled bust on the bracket above his old hat, I sometimes think the very wainscot must still be impregnated with the fumes of his seething punch-bowl.

Washington Irving.

My Bosom's Lord declares that it is more of a smell than a street; but there is not a journalist of any literary pretension in Britain who does not regard Fleet Street as the Mecca of his craft, and instinctively turn his face towards it when he has occasion to say his prayers.

It is the focus, the magnetic centre, and[117] very heart of London's Fairyland—the Capital of the Territory of Brick and Mortar Romance.

Its enchanted courts are the inner sanctuary of Haunted London. It is the most astonishing sensation to step out of the hum and moan and fret of the rushing and turbulent City's most bustling and roaring street, into the absolute, cloistered stillness of, for instance, the Temple; where, within fifty yards of Fleet Street, you may stand by Oliver Goldsmith's grave and hear no sound save the cooing of pigeons and the splashing of a fountain.

Fleet Street's air is the quintessence of English History. From the Plague and the Fire to the Jubilee Procession, everything has passed here. All the literary eminence of the day comes to do business here.[118] These paving-stones have felt the weight of George R. Sims, Clement Scott, Bernard Shaw, and the Poet Craig. It is the world's main artery, the centre of the Empire's nervous system, the brain and soul of England.

Be that as it may, I am conscious of an increase in my stature since I became a part of Fleet Street—a stretching of my boots since I began to walk in the footsteps of Swift, Steele, Pope, Goldsmith, Johnson, and all the other giants whose seething punch-bowls have impregnated the wainscot of the neighbouring taverns.

The chief of the ghosts, of course, is the

burly lexicographer—the man with the inky

ruffles, the dirty large hands, the shabby

brown coat, and shrivelled wig. Methinks I

see him now, clinging to his door in dingy

Bolt Court, and waking the midnight echoes[119]

[120]

[121]

with his Cyclopean laughter, as he listens

to a parting from fluent Burke or snuffy

Gibbon.