OR

SHE LOVED A HANDSOME ACTOR

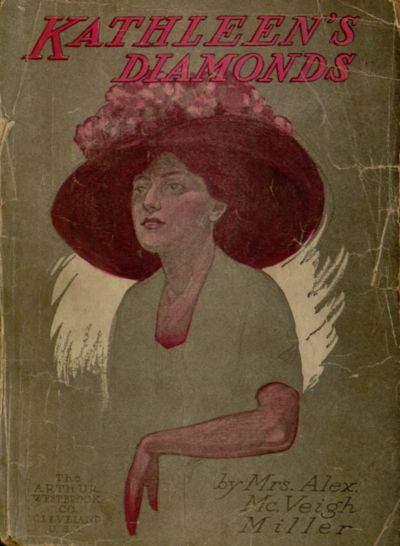

By Mrs. Alex. McVeigh Miller

HART SERIES No. 45

COPYRIGHT 1895 BY GEORGE MUNRO

(Printed in the United States of America)

Published by

THE ARTHUR WESTBROOK COMPANY

Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.A

| CHAPTER I. | PAGE |

| "Alas! Why Did She Do It?" | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| After Sixteen Years | 7 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| "This Prince Karl—This Ralph Chainey—is My Rescuer at Newport Last Summer," Whispered the Romantic Girl | 11 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| "I Distinctly Forbid You to Know this Actor," said Mrs. Carew | 15 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Mrs. Carew is Mysteriously Absent | 19 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Kathleen's Defiance | 23 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| "Mrs. Carew is Going to Make You Marry Her Son," said the Maid | 27 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| "Please Buy My Diamond Necklace," said Kathleen | 33 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Murdered! | 37 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| At Dead of Night | 40 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Fatal Telegram | 45 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| "Kathleen, I Swear that I Will Avenge Your Murder!" | 50 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Another Mystery | 53 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| A Strange Fate | 57 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Poor Daisy Lynn | 63 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Kathleen's Desperation and Her Escape | 70 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| "Will You be My Own Sweet Wife, Kathleen?" | 74 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Kathleen's Disappearance | 79 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| "Ralph Chainey is a Married Man!" | 83 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Kathleen Makes a Startling Discovery | 88 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Was Ralph Chainey a Villain? | 91 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Rescued | 93 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| "Papa, Darling, It is I, Your Little Kathleen!" | 97 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Turned Out Into the Storm | 102 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Teddy Darrell Again | 105 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| "I Would Lay Down My Life to Serve You!" said Teddy | 107 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| Alpine's Renewed Hopes | 111 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| Teddy Darrell's Plans | 115 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| Fedora's Escape | 119 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| "My Darling Girl, I'm as Fond of You as Ever!" | 122 |

| CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| Kathleen's Weary Waiting | 126 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| "We Have Met—We Have Loved—We Have Parted!" | 128 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| Ralph Chainey's Anger | 133 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| Alpine Sows the Seed of Jealousy | 135 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| Alpine's Falsehood | 138 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| A Cruel Stab | 142 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| Ralph Chainey is Driven to Desperation, and Turns on His Foe | 146 |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| "I Have Come for My Diamonds," Kathleen said to the Jeweler | 148 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| Kathleen Before Her Father's Portrait | 153 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| A New-found Relative | 157 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| Ralph's Letter | 160 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| "You Shall Not Marry Ralph Chainey!" Uncle Ben Cried Violently | 162 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| The Old Housekeeper's Story | 167 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| Grandmother Franklyn | 171 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| Ivan Receives a Check in His Career | 175 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| "I Have Betrayed Myself. You Know My Heart Now." | 177 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| A Terrible Crime | 181 |

| CHAPTER XLVIII. | |

| "Kathleen Has Mysteriously Disappeared." | 184 |

| CHAPTER XLIX. | |

| The Franklyns at Last! | 188 |

| CHAPTER L. | |

| "She Was My Mother." | 192 |

| CHAPTER LI. | |

| A Cousin for a Lover | 195 |

| CHAPTER LII. | |

| The Search for Kathleen | 198 |

| CHAPTER LIII. | |

| "Oh, Sir, Have Pity on Me!" prayed Daisy Lynn | 200 |

| CHAPTER LIV. | |

| "Is This Your Niece?" | 205 |

| CHAPTER LV. | |

| Kathleen and Daisy Meet at Last | 207 |

| CHAPTER LVI. | |

| "So Shines a Good Deed in a Naughty World." | 210 |

| CHAPTER LVII. | |

| Mrs. Carew Triumphs in Her Sweet Revenge Upon Kathleen | 212 |

| CHAPTER LVIII. | |

| "I Will Never Humble Myself to You Again." | 214 |

| CHAPTER LIX. | |

| Oh, Ralph Chainey, Wake! | 217 |

| CHAPTER LX. | |

| "My Love Shall Call Him Back from the Grave!" | 220 |

| CHAPTER LXI. | |

| She Loved Much | 223 |

| CHAPTER LXII. | |

| "God Bless Brave, Bonny Kathleen Carew!" | 225 |

| CHAPTER LXIII. | |

| Within Prison Bars | 227 |

| CHAPTER LXIV. | |

| "Your Father is George Harrison, the Convict!" | 231 |

| CHAPTER LXV. | |

| A Startling Dénouement | 234 |

| CHAPTER LXVI. | |

| "I Will Go to the Old Haunted Mill," said Kathleen Bravely | 239 |

| CHAPTER LXVII. | |

| Teddy's Love Letters | 242 |

| CHAPTER LXVIII. | |

| In Mortal Peril | 244 |

| CHAPTER LXIX. | |

| "I'll Take You Home Again, Kathleen." | 252 |

OR

SHE LOVED A HANDSOME ACTOR

"ALAS! WHY DID SHE DO IT?"

Incredible, you say?

Alas, it was too true!

She was dead by her own hand, the beautiful child-wife of Vincent Carew, the millionaire—dead in her youth and beauty, leaving behind her all that life held for a worshipped wife and loving mother; for upstairs at this moment in the silken nursery her child, the baby Kathleen, barely six months old, lay sweetly sleeping, watched by an attentive French bonne, while in the darkened parlor below, the girlish mother, not yet eighteen, lay pale and beautiful in her coffin, with white flowers blooming on the pulseless breast, hiding the crimson stain where the slight jeweled dagger from her hair had sheathed itself in her tortured heart.

She was so young, so ignorant, or surely she would have held back her suicidal hand—she would have taken pity on her child, the dark-eyed little heiress she was[Pg 6] leaving motherless in the wide, wide world that, whatever else it may give us, can not make up for the loss of the best thing life has to offer—a mother's love!

It is always a terrible misfortune to a young girl to be motherless, and it was going to be the tragedy of Kathleen Carew's life that she had no mother. The dagger-thrust that let out the life-blood of unhappy Zaidee Carew turned the whole course of her daughter's life aside into different channels.

But that lay in the future. Now all Boston wondered over the tragic death of Vincent Carew's wife, and people asked each other in dismay:

"Why did she do it?"

No one could answer that question.

The world thought that the young wife was perfectly happy.

And why not? Surely she had good cause.

Vincent Carew, the rich bachelor, who was a power in politics, and aspired to be governor of his state, had married Zaidee Franklyn out of a poverty-stricken home, lifting her at a bound to rank and fortune, and all for love of her fair face.

He had snapped his white fingers in the face of the world that called his marriage a mésalliance, and carried everything by storm. For his sake, society—cultured Boston society—had received his wife, the lovely young Southern girl, with her shy ways and neglected education, and for a time all went well.

So no one could answer the question why did she kill herself, but that was because Vincent Carew was too proud to admit the ubiquitous reporter inside his aristocratic portals. If one of these curious mortals had secured admittance to the house and questioned the servants,[Pg 7] they would have told him what they suspected and discussed in whispers among themselves—that madame was madly jealous of the teacher her husband had employed to finish her very imperfect education.

"She is a snake in the grass, that pretty widow, and she makes my mistress unhappy," said the housekeeper, the first month that Mrs. Belmont came, and her opinion was adopted by all the other servants. They all hated the stately young widow in her black garments, and when the grewsome tragedy of Mrs. Carew's death darkened the sunlight in that luxurious home, they whispered to each other that it was Mrs. Belmont who had worked their mistress such bitter woe that she could not bear her life.

If indeed she had schemed for anything like this, Mrs. Belmont had succeeded in her designs. Zaidee Carew, with her own dimpled, white hand, had cut the Gordian knot of life, and in a few more days a stately funeral cortège moved away from Vincent Carew's doors to the cemetery where his dead wife, in all her youthful beauty, was laid to rest beneath the grass and flowers.

AFTER SIXTEEN YEARS.

"I never saw such a forgetful girl as you, Kathleen Carew. Here you sit dreaming, instead of dressing for 'Prince Karl' to-night. Are you going to the theater, then, or not?"

"Of course I am going, Alpine. I did not know it was so late. What, you are dressed already? How sweet[Pg 8] you look! That blue crêpe de Chine is awfully becoming to you. Well, then, please ring the bell for my maid, won't you? I'll be ready in ten minutes."

"You'd better. Mamma will be furious if you keep her waiting," Alpine Belmont answered, crossly, as she touched the bell.

Then she looked back curiously at the graceful, indolent figure in the easy-chair, leaning back with white hands clasped on top of the bronze-gold head.

"Kathleen, what were you thinking about so intently when I came in? I had to speak twice before you heard me."

Kathleen raised her dark, passionate, Oriental eyes to the speaker's face, and, blushing vivid crimson, answered, dreamily:

"Alpine, I was thinking of that handsome young man who saved my life at Newport last summer. I was wondering who he was, and if we should ever see him again."

"It isn't likely we ever will," answered Alpine Belmont, carelessly. "I don't suppose he's in our set at all—some poor clerk spending all his winter's savings on a short summer outing, very likely. I wouldn't be thinking about him, like a romantic school-girl, if I were you, Kathleen. He didn't care about you, or he would have made himself known to you before this," and, with a low, taunting laugh, Alpine Belmont left the room just as Susette, the maid, came in.

"You'll have to do my hair in a hurry, Susie. There's no time for prinking," laughed her mistress; and while the maid brushed out the magnificent, rippling tresses, Kathleen relapsed into thoughts of the unknown hero whose handsome image haunted her thoughts.

"Is it true, as Alpine says, that he did not care for[Pg 9] me? It is strange he did not stay to inquire who I was, after I came so near drowning. If he was a poor young clerk, as Alpine believes, perhaps he was too proud to reveal himself, thinking I would scorn him because I was an heiress. Ah, how little he knew Kathleen Carew's heart!"

Her thoughts ran thrillingly on:

"Oh, how handsome he was when I first saw him in the water, that day at Newport! He kept watching me, and I could not help looking back. He seemed to draw my eyes. I know I wanted him to like me, for I wondered if my bathing suit was becoming, and I felt glad my hair was down, because I had been told it looked pretty that way, all wet and curling over my shoulders. His brown eyes said as plain as words that he admired me. Other men did, too, I know, but this time it seemed to thrill me with a new pleasure. As I splashed about like a mermaid in the waves, I kept thinking of him, wondering who he was, and hoping he would be at the ball that night. I wanted him to see how well I looked in my white lace and pearls. Then all at once came that treacherous undertow that swept me from my feet, down, down, down, under the heavy waves. Oh, how horrible it was! I thought I would be drowned, and my last thought was——"

"What gown, Miss Kathleen?" asked the maid.

"Anything, Susette. It don't matter how I look to-night. You can't decide? Oh, well, that new white cloth with the pink ostrich feather trimming, and diamonds. Alpine is wearing pearls and a blue gown, and we don't want to be dressed alike."

While Susette fastened the exquisite gown and clasped the diamonds, her thoughts ran on:

"He rescued me, the handsome, brave fellow, and as soon as he laid me, limp, but faintly conscious, upon the sands, he walked hastily away, and no one at Newport ever saw him again. Neither could any one ever find out who he was, although I'm afraid mamma did not try very hard. But he was certainly very modest. He did not want us to make a hero of him. Heigho, I do wish I knew his name—I do wish I could see him again! Alpine says I am foolish and romantic, and that I fell in love with him because he saved my life. Indeed, I think it was before—yes, at the very moment I first met his beautiful brown eyes gazing so eagerly into mine. A quick electric thrill seemed to dart through me, and——"

"Kathleen, aren't you ready yet?" asked Alpine, entering. "The carriage has been waiting ever so long, and mamma is getting furious over your delay."

"I'm ready," Kathleen answered, composedly, without hurrying the least bit. She drew her white opera-cloak leisurely about her ivory-white shoulders, and followed her step-sister down-stairs to where Vincent Carew's second wife, once the widow Belmont, poor Zaidee's governess, was waiting in impotent wrath at the detention.

"The first act will be quite over before we get there, and it will be entirely your fault, for Alpine and I have been ready for an hour," she fretted as they entered the carriage.

"THIS PRINCE KARL—THIS RALPH CHAINEY—IS MY RESCUER AT NEWPORT LAST SUMMER," WHISPERED THE ROMANTIC GIRL.

The first act had indeed begun when Mrs. Carew with her two daughters entered their box at the theater; but absorbing as was the interest in the popular play, "Prince Karl," many heads were turned to gaze admiringly at the trio of fair ones, for the matron, although fifty years old, looked much younger, and her stately charms were set off to advantage by black velvet and jet, with ruby ornaments on her neck and arms. Her silvery-white hair was arranged very becomingly, and Alpine felt quite proud of her mother's distingué appearance.

Alpine Belmont herself was a milk-white blonde, a trifle below the medium height, and with a rather too decided inclination to embonpoint. But the plumpness and dimples were rather fascinating, now in the heyday of youth—she was barely twenty—and with passable features, pale straw-gold hair, and forget-me-not blue eyes, Alpine passed as a belle and beauty.

But Kathleen Carew—Kathleen, with her slender, perfect figure just above medium height, and her vivid face as fresh as a flower, with her great, starry, passionate, Oriental eyes, veiled by thick curling lashes black as starless midnight, in such strong contrast to the rich bronze-gold of the rippling hair that crowned her queenly little head—Kathleen Carew was truly

"The Rose that all were praising."

"The house is crowded," Mrs. Carew observed in a[Pg 12] gratified tone, as she swept the brilliant horse-shoe with her lorgnette.

"Oh, of course. They say Ralph Chainey is a splendid actor," returned Alpine, as she threw back her blue-and-white cloak to give the crowd the benefit of her plump white arms and shoulders.

"Does Ralph Chainey play Prince Karl?" inquired Kathleen, with languid interest; and, forgetting to listen for the answer, turned her attention to the stage where the actors were strutting their brief day.

The play went on, and Kathleen, rousing with a start out of her languid mood, watched it with eager eyes.

Everybody knows the clever, fascinating play "Prince Karl." Mansfield has made it immortal in his rôle of the courier.

This new actor, whose name had brought out the fashionable world of cultured Boston, was no whit behind Mansfield in his clever impersonations. He was young, and had flashed upon the dramatic world two years before with the brightness of a star. Time was adding fresh laurels to his name, and Boston, critical as it was, did not hesitate to add its plaudits, for, be it known, Ralph Washburn Chainey was a Bostonian "to the manor born."

"Oh, it is splendid! And is he not perfectly magnificent?" exclaimed Alpine Belmont, turning eagerly to Kathleen, as the curtain fell upon the first act.

Then she started with surprise, for Kathleen was leaning back in her chair, breathing heavily, her face very pale, her eyes half veiled by the drooping lids.

"Kathleen, what is the matter? Are you going to sleep, or are you ill, or—what?" she demanded, in a high whisper.

Kathleen caught Alpine's hand and drew it against her side.

"Oh, Alpine, feel my heart how it beats!" she whispered. "I have had such a shock! Did you not recognize him, too?"

"I don't know what you are talking about, Kathleen."

"Don't you? Oh, Alpine, I have found him out at last—my hero!" whispered the romantic girl.

"Kathleen, you're dreaming!"

"I'm not. I knew him in a minute, and he recognized me, too. I saw it in his glance when his eyes met mine. He started, then I smiled—I could not help it, I was so glad."

Mrs. Carew had been listening to catch the whispered conversation. A heavy frown darkened her face. She leaned forward and muttered, harshly:

"Kathleen, you must be crazy!"

The girl shrugged her shoulders contemptuously, and took no other notice of the speech.

But Alpine's curiosity was awakened, and she whispered, eagerly:

"Where is he, then? Point him out to me."

"I can not. He has gone off. Wait till he returns," answered Kathleen, sitting up straight in her chair again. The color was coming back into her face again, her eyes flashed radiantly. Mrs. Carew regarded her with suppressed displeasure.

Some gentlemen acquaintances came into the box, and the subject of Kathleen's discovery was dropped. They chatted gayly until the time for the curtain to rise, then returned to their seats.

The curtain rose upon the second act of the play, and Alpine was so interested that she leaned eagerly forward,[Pg 14] quite forgetting, in her keen admiration of Prince Karl, her step-sister's interesting disclosure just now.

But suddenly Kathleen's taper fingers closed in a gentle pinch upon her plump arm.

"Look—now—don't you recognize him?" she murmured, triumphantly.

"Who? Where? Oh, for goodness' sake, Kathleen, don't bother me now! I don't want to lose a word of glorious Prince Karl!"

"But, Alpine, it is he, Prince Karl—my hero!"

"Good heavens, Kathleen! do you really mean it?"

"Yes, I do, Alpine. This Prince Karl—this Ralph Chainey—is my rescuer at Newport last summer. Watch him, Alpine, and perhaps you will catch him looking at us a little consciously, as I did just now."

"I see the likeness now!" answered Alpine, in a tone of suppressed dismay, whose import Kathleen could not understand. She said no more to her step-sister, but sat through the remainder of the play in a blissful dream.

The beautiful young heiress was intensely romantic, and for long months her fancy had been haunted by the image of the handsome young man who had saved her life. To find him again in the handsome young actor whose name was on every lip thrilled her with delight. He had recognized her, too, and the memory of his startled glance, so quickly withdrawn, thrilled her with keen delight, although he did not permit her to meet his eyes again.

Kathleen felt a little triumph, too, over Alpine, who had declared that her hero was doubtless a mere nobody—perhaps a clerk in a country store, than which position Alpine's contemptuous ideas could not descend lower.

Alpine was watching him now with such eager interest that Kathleen smiled and thought:

"I believe Alpine has fallen in love with him, herself. But she need not; he is mine, mine, mine!"

She was claiming him already in her thoughts, forgetting that she had never even spoken to the handsome stranger to whom she owed such a debt of gratitude. It seemed to her that she was as dear to him as he was to her, and she almost expected to see him waiting to hand her to her carriage when they left the theater.

But no; the faint, fluttering hope was soon extinguished. Other admirers were waiting obsequiously, eager for the honor of touching the small gloved hand of the beautiful belle, but when the curtain dropped on Prince Karl bowing to the applauding audience, Kathleen saw him no more that night.

When Mrs. Carew dismissed her maid that night she sent an imperative summons to her step-daughter to come to her room, and received in return a polite request to be excused. Kathleen was tired, and meant to retire immediately.

"I DISTINCTLY FORBID YOU TO KNOW THIS ACTOR," SAID MRS. CAREW.

Despite the message, Mrs. Carew, who went at once to Kathleen's room in a rage at her impertinence, found the young girl still in her ball-dress and jewels, sitting dreamily in an easy-chair, having dismissed Susette to arrange her bath. She yawned sleepily at her step-mother's entrance.

"I sent you word to wait till to-morrow," she said, petulantly.

"I did not choose to wait, Miss Impertinence!" and as Kathleen opened wide her big black eyes in a sort of contemptuous amazement, Mrs. Carew continued, angrily: "Alpine has told me how silly you were over that actor; how you love him, and long to get acquainted with him. Do you not know that it is very bold and coarse for a young girl to even think of a man that way until he has given some sign of liking for her? But Alpine declares that this man has never even noticed you."

"Alpine is a sneaking tell-tale, and you are a cruel woman!" Kathleen answered, indignantly. "And, madame, if I am ignorant, as you charge, of the proper feeling to observe toward men, who is to blame for that? Why did you not train me as carefully as you did your daughter Alpine? You took my poor dead mother's place before I was two years old. Why did you not do your duty by her orphan child?"

"How dare you speak to me like this?" demanded the angry woman. "Be silent, and listen to my commands!"

Her fingers itched to slap the cheek that dimpled with insolent amusement, but she clinched her hand and went on:

"Your father left you in my care when he went abroad for his health, and you shall obey my commands while he is gone. If you dare defy me, I shall lock you in your room, on bread and water, till you beg my pardon."

There was no answer. Kathleen looked her indignation, that was all.

"I distinctly forbid," said Mrs. Carew, "any further nonsense over this actor. Good heavens! an actor![Pg 17] What would your haughty father say?" contemptuously. "I will not take you to the theater again while he plays here. You disgraced yourself to-night, making eyes at him on the stage, and there shall be no more of it. I shall not permit him to make your acquaintance, even if he seeks to do so, which is very doubtful, as"—scornfully—"the infatuation seems to be all on one side."

Kathleen writhed with mortification, but she did not permit her foe to see how cruelly she was wounded. She held her queenly little head erect with that silent smile of maddening amusement on her scarlet lips. Years of wrong and injustice had made her scorn this woman who filled her dead mother's place so unworthily, and she made few efforts to conceal her feelings.

"I forbid any acquaintance with this Ralph Chainey—this actor. Do you understand me, Kathleen?" repeated her step-mother.

"I have heard you," answered the young girl, with a mutinous pout of her full lip.

"You will obey me?" a little anxiously, for Kathleen had never been so aggressively rebellious as to-night.

At the question, Kathleen rose to her feet and stood up like a young lioness at bay.

"I will not obey you, madame!" she replied.

"What?" almost shrieked Mrs. Carew.

"I will not obey you!" she repeated, with flashing eyes. "I will not run after Mr. Chainey, as you pretend so falsely that I am doing, and I will make no unmaidenly overtures toward his acquaintance, but if the proper opportunity offers for me to know and thank him for saving my life, I shall surely avail myself of it!"

They stood glaring at each other, the girl roused into furious rebellion, the woman speechless with fury, her[Pg 18] steel-blue eyes seeming to emit electric sparks from her deathly white face, so intense was her fierce wrath. Controlling herself with an effort, she turned to leave the room, and, pausing on the threshold, hissed back one significant sentence at the defiant girl:

"Forewarned is forearmed!"

"I do not fear you!" Kathleen answered; but Mrs. Carew never looked back.

"What will she do? What can she do? She will never dare lock me in my room, as she threatened!" Kathleen murmured, uneasily, and then her overstrained nerves gave way. She threw herself on the bed and sobbed aloud, in nervous abandonment to her outraged feelings.

God help that poor, motherless girl! She knew that the events of that night would only make her life harder than it had been before under the roof that her step-mother ruled with an iron hand.

The beautiful young heiress did not have a happy life, in spite of all the good gifts with which fate had so richly dowered her at her birth. Her step-mother had always hated her, and never relaxed her efforts to harden her father's heart against his only child. Perhaps she hated Kathleen the more because Heaven had denied any children to her second marriage, and she knew that to this girl would go the bulk of her father's great wealth.

Mrs. Carew had two children by her first marriage—a son, now twenty-three, called Ivan, and the girl Alpine. Her favorite scheme was to marry the hated Kathleen to this son, so that he might share her rich inheritance. Failing in this, she meant, if it lay in the power of a human devil to compass it, to have Kathleen disgraced and disinherited, so that she and her children might enjoy the whole of the great Carew fortune.

MRS. CAREW IS MYSTERIOUSLY ABSENT.

Mrs. Carew did not appear at breakfast the next morning and Alpine, with a reproachful glance at Kathleen, said that mamma was sick. She had been so worried last night that she could not sleep, and this morning she had such a terrible headache that she must lie abed all day.

Kathleen did not look either repentant or sorry. She simply said that in that case she would not practice her music this morning, and went off to her own little studio, where she painted a while with great ardor, then threw down her brush, and rang for Susette to bring up the morning papers.

Susette lingered a minute after she had put down the newspapers.

"Miss Kathleen, I don't think it will disturb Mrs. Carew the least bit if you practice your music," she said, significantly.

"But her head aches, Susette."

"No, it don't miss; she's not in the house, so there! She went away early—very early, in her traveling-dress, the Lord knows where; for James told me so on the sly." (James was the butler, and Susette's sweetheart.)

Kathleen looked a little startled as she said:

"You must be mistaken. Ellen has been with her mistress all day. I tapped at the door a while ago to ask how she was, and she reported Mrs. Carew as very low."

"They are all deceiving you, Miss Kathleen, but what for I don't know, only I'm sure and certain she ain't in this house," protested Susette, stoutly.

"Very well, Susette. Her absence has no more interest[Pg 20] for me than her presence," Kathleen answered, indifferently, as she opened The Globe and read the encomiums on Ralph Chainey's acting that filled a critical half column.

Her eyes sparkled and her cheeks glowed with pleasure.

"He plays 'Prince Karl' again to-night. Oh if I only could go again!" she thought, regretfully; then, throwing down the paper, she decided she would go and practice her music, since Mrs. Carew was not ill, as Alpine pretended.

She had played but a few bars when Alpine entered with reproachful eyes.

"Have you no feeling, Kathleen? You will kill mamma!"

"Since mamma went away this morning early and has not yet returned, there's no danger," Kathleen answered, coolly.

"It is false! Who told you so?"

"No matter how I found it out. I'm in possession of the mysterious fact."

"It's that prying Susette, I know! I shall advise mamma to dismiss her immediately."

"You'd better not, Alpine. Susette knows some of your secrets!" Kathleen answered, with a provoking laugh.

"I have no secrets!" snapped Alpine; but she left the room discomfited.

Kathleen practiced and read until the late luncheon, where she was surprised to find herself alone.

"Where is Miss Belmont, James?" she asked.

"Miss Belmont went out for a walk," he answered, respectfully.

While Kathleen was making up her mind to go for a walk, too, some callers were announced. She received the matron and her two gay young daughters, entertained them herself, with an apology for the absence of the other members of the family, and saw them depart with a sigh of relief.

"I will go for my walk now," she decided, but turning from the piano, she saw an open note lying on the floor. Her own name attracted her, and picking it up, she read, under date of that morning:

"Dear Alpine and Kathleen—Mamma wishes you to join us at an informal three-o'clock lunch to-day, to meet a distinguished guest. Brother George was at college with Prince Karl—Ralph Chainey, you know—and he is coming here to lunch with us to-day. Do come, girls! He's so handsome and talented I want you both to know him. There will be several others, too, but we want you especially. I want him to see our beautiful Kathleen."

The note bore the name of Helen Fox, one of their intimate girl friends, and Kathleen realized in a minute that she had been tricked by crafty Alpine, who had gone to the luncheon alone to meet Ralph Chainey.

A futile sob of bitter disappointment rose in the girl's throat, and crushing the note in her hand, she walked to the window, gazing blankly out into the handsome street through burning tears.

A light laugh startled her. There was Alpine Belmont, in elegant attire, walking toward the gate with a tall, handsome, distingué young man. Lifting his hat with a smile, he left the young lady there, and walked away with a hasty backward glance at the window that showed him a lovely, woful face staring in undisguised wonder[Pg 22] at the spectacle of Ralph Chainey walking home with deceitful Alpine Belmont.

"Alpine, you wicked girl, how could you treat me so unfairly?" she demanded, shaking with passion.

Alpine flung herself into a chair, flushed, laughing, insolent.

"You told mamma last night that I was a sneaking tell-tale, didn't you? Well, then, I paid you off, that's all! Besides, mamma does not allow you to know Ralph Chainey—a pity for you, my poor Kathleen, for he's the most fascinating young man I ever met. I made myself very agreeable to him, and I think he fell in love with me. You see yourself he walked home with me from Helen's luncheon. Would you like to know what I told him about you, my charming Kathleen?"

"No!" the girl answered, hotly.

"I don't believe you—you're dying to hear. Well, it was this: I said you did not recognize him in the least last night till I told you it was the man that saved you at Newport. Then I said you would not come to meet him at the luncheon to-day, because you said it would be such a bore having to thank him. Ha, ha! You'd like to murder me, I know!"

KATHLEEN'S DEFIANCE.

Helen Fox was one of those sweet, pretty, amiable girls that everybody loves. Her rosy lips were always wreathed in smiles, and the very glance of her roguish blue eyes invited confidence. She was the most popular[Pg 23] girl in her set, and the intimate friend of Kathleen Carew and Alpine Belmont.

Warm-hearted Helen had been sadly disappointed because Kathleen had not come to the luncheon, and the excuse that Alpine offered—namely, that her step-sister could not tear herself away from a new novel—seemed too shallow to entertain.

"I'm really mad with Kathleen, the lazy thing!" she said, frankly, to Ralph Chainey, who smiled, but made no comment. He was thinking about what Miss Belmont had told him just now. It rankled in his mind.

"I am anxious for you to meet her, she is such a beauty!" continued Helen, enthusiastically.

He gave some flattering answer that made her dimple and blush, but she answered, with a careless glance around:

"Oh, yes, we girls are well enough; but wait till you see my bonny Kathleen. Such lips, such hair, such eyes!"

Ralph Chainey laughed.

"You needn't be so sarcastic, Mr. Chainey. You haven't seen our beauty yet."

"I saw her last night at the theater."

"Oh, so you did. I forgot that. Well, isn't she charming?"

The handsome actor replied with a quotation:

"'Perfectly beautiful, faultily faultless.'"

"She is all that," Helen Fox replied; but she looked at him with puzzled eyes, and thought within herself that he was somehow piqued at Kathleen Carew. But why, since the two had never met?

Suddenly the reason presented itself to her mind.

"The great vain thing! He is piqued because the beauty didn't come to the luncheon. He is offended because she did not seem anxious to meet him."

And she was secretly amused at the young actor's palpable vanity, regarding it as a good joke, little dreaming of the seed that Alpine Belmont had been sowing in his mind.

Many envious glances followed Alpine, a little later, when she bore Ralph Chainey off in triumph as her escort home; but Helen was pleased, for she thought:

"If Alpine asks him into the house he will get acquainted with Kathleen, and then he will find out how lovable she is."

But when George Fox, who had also walked home with a young lady on Commonwealth Avenue, returned home he reported that Ralph Chainey had left Miss Belmont at the door.

Suddenly Helen remembered sundry small matters that were not at all to Alpine's credit.

"That girl is tricky, I know," she said to herself. "Perhaps she did not ask Mr. Chainey to go in. Perhaps she kept Kathleen from coming here to-day. She has been known to do shabby things to cut other girls out of their lovers. Not that Ralph Chainey is Kathleen's lover yet, but he ought to be. They are just suited to each other, both are so splendid. It may be that Alpine intends to catch him herself before her sister gets a chance." Helen laughed a sage little laugh to herself, and added: "I'll ask mamma to let us call at Mrs. Carew's and take Kathleen with us to the theater to-night."

"Oh, Alpine! where is Kathleen? George and mamma are waiting out here in the carriage. We have just one[Pg 25] seat left, and we stopped to ask Kathleen to go with us to the theater."

"Mamma is out, Helen, and she would not like it if Kathleen went without leave."

"But mamma is with us, Alpine. She would chaperon Kathleen."

"She can not possibly go," began Alpine, in a high tone of authority; but at that moment a light swish of silken draperies came through the hall, and a sweet voice said, clearly:

"Kathleen can go, Helen, and she will go, too, if you will wait till she gets on her things."

And Alpine beheld her step-sister, cool, calm, defiant, rustle up to Helen Fox and kiss that piquant, silk-robed damsel.

"Come upstairs with me, Helen, dear, while I dress," she said, radiantly, trying to draw her toward the stairway, for this colloquy had taken place in the hall.

Alpine followed them upstairs out of reach of the servants' ears, and then she said, sharply:

"You need not get ready, Kathleen, for I shall assume mamma's authority in her absence, and forbid your going."

"Oh, Alpine, where is the harm?" pleaded Helen.

"Mamma has forbidden her to go to the theater any more this week, because she caught her making eyes at an actor on the stage last night," Alpine answered, maliciously.

"It is false!" answered the young girl, stung to madness by Alpine's wickedness. Turning to Helen, she said, proudly: "I accept your invitation, Helen, and will accompany you to the theater, in spite of a hundred Alpine Belmonts! I am no slave to be domineered over in[Pg 26] this manner, and Alpine had better go and leave me alone before she arouses me any further."

"Very well, miss; take your own way and defy me; but mamma will make you repent it, be sure of that," snapped Alpine, withdrawing.

"Oh, Kathleen, I didn't know I was going to raise such a breeze! Perhaps you had better not go if Mrs. Carew objects," Helen said, uneasily.

Kathleen turned on her a face crimson with angry passion.

"I'd go if she killed me for it!" she cried, with an imperious stamp of her dainty foot. "Who is that woman to forbid my going to places of amusement, like other girls?" She rang the bell violently for Susette, and added: "Say nothing before my maid, Helen; but on our way to the theater I'll tell you how wickedly Alpine treated me this afternoon."

Presently Alpine, peeping through her door, saw the two girls going away, Helen a little uneasy looking, the other proud, defiant, beautiful as a dream.

"She will meet Ralph Chainey, after all," Alpine muttered, in a fury.

It was midnight when Mrs. Fox's carriage stopped again at the Carew mansion, and George handed Kathleen out and rang the bell for her at her own door.

The windows were closed, and not the faintest gleam of light shone through them. George waited a few moments, then rang the bell again.

"Every one must be asleep, they are so long coming," said Kathleen, shivering in the cold night air.

They rang again furiously; but there was no response. The locked door, the dark, forbidding windows seemed to frown on their frantic efforts to arouse the house.

Mrs. Fox put her head out of the carriage window and said:

"Kathleen, you had better come home with us to-night, my dear. I don't think you will be able to rouse any one there; and you will catch cold waiting in the cool night air."

"MRS. CAREW IS GOING TO MAKE YOU MARRY HER SON," SAID THE MAID.

Kathleen was annoyed by her failure to get into the house, but she did not attach any particular significance to it. She supposed that Alpine, out of spite, had caused the servants to lock up and go to bed; that was all. She went home willingly enough with her kind friends, intending to return the next morning.

And when she laid her beautiful head on the pillow that night, it was to dream of soft brown eyes that had looked thrillingly into hers, and of a warm white hand that had clasped hers, oh! so closely, when he said good-night; for Ralph Chainey, the actor—or Prince Karl, as Kathleen called him in her thoughts—had come into Mrs. Fox's box twice between the acts, and had been presented to the beautiful heiress whose life he had saved last summer, and from whose presence he had gone away incognito.

Prince Karl had been on his dignity at first. He had[Pg 28] remembered what Alpine Belmont had told him that afternoon.

He believed that beautiful Kathleen was cold, proud and ungrateful.

So, after bowing over her little hand when George Fox presented them, he turned his attention to the vivacious Helen, and scarcely looked at the radiant creature close to her side.

Kathleen bit her red lips and remained silent. She understood Ralph Chainey's mood, and knew that she had to thank Alpine for his indifference.

Her sweet lips quivered with a repressed sob, and her dark eyes swam in moisture that threatened to fall in blinding tears. It was hard—cruelly hard to have him believe her proud and ungrateful, and to see him resent it in this cavalier fashion.

He bowed himself out presently, and then Helen Fox turned to her, eagerly.

"How did you like him, Kathleen? Isn't he just splendid?" she exclaimed. Then she saw how grave and quiet the young girl looked, and remembered what Kathleen had told her in the carriage. "Oh! I forgot; he did not really pass one word with you. He was piqued and stiff over what Alpine told him," she cried, and added, consolingly: "Never mind; he'll come round. He admires you very much—I saw that in his eyes—and, of course, he is secretly very much interested in you, having saved your life! It is very romantic, Kathleen, and I shouldn't wonder if it's a match."

"Don't, Helen!" answered the girl, somewhat incoherently.

But Helen laughed gayly, and when the next act was over and the actor came again for a few minutes, he[Pg 29] found her whispering very mysteriously to her mother. She nodded at him, and went on confiding something to her mother's ear.

George Fox had gone out, so there was no one to speak to but Kathleen—trembling Kathleen—who blushed warmly when he came to her side, and murmured, tremulously:

"I want to thank you for—for last summer. It was so good of you, so noble, to risk your life for a—a stranger."

"Pray do not speak of it; it was nothing. I ran no risk; I am a good swimmer," he replied, a little stiffly.

But Kathleen went on, in that tremulous voice:

"I—I have always remembered you with gratitude—always longed to see you again, that I might thank you from my heart for your goodness. Papa, too, wanted to see you. Why did you go away so suddenly?"

Where was the arrogance, the indifference on which Alpine had expatiated? The sweet lips trembled; there was dew on the curling black lashes that shaded the splendid, luring black eyes. When Ralph Chainey had gazed into them a moment, he turned away his head like one dazzled by too much sunlight.

"Why did you go away so suddenly?" she repeated; and then he said:

"It was because I am an actor, Miss Carew. If I had stayed to receive your thanks, and disclosed my identity, the story would have got into the newspapers, and people would have said I did it to get some free advertising. Your name would have gone all over the country as the heroine of the rescue. You would not have liked the publicity, perhaps; and so I hurried away."

"It was very good of you to think of that," she answered,[Pg 30] simply; then added hastily, for the minutes were passing, and she knew he must soon return to the stage again: "Mr. Chainey, Alpine told me what she had told you this afternoon. It was—was—a joke on her part. I did recognize you last night as soon as I saw you. I told her who you were. She was jesting, believe me for I—I could not—be so ungrateful as to forget your face so soon."

It was time for him to go. He rose and held out his hand.

"Thank you," he said, in his deep, sweet voice, pressing her hand warmly. His magnetic brown eyes gazed deep into hers, and he murmured, inaudibly to the others: "It was the happiest moment I ever knew when I saved your life!"

Then he was gone. From the stage she met his eyes twice fixed on her, as if he could not resist the temptation of looking. When George Fox put them all into their carriage, he came out, still in his stage costume, to say good-night. He held her hand just a moment longer than Helen's, and he whispered:

"I hope we shall meet again."

His eyes, his words, his thrilling hand-clasp, haunted the motherless girl that night in the mystical land of dreams.

She arose early, after a rather restless night, and her first thought was that she had no morning-dress.

"I am taller than Helen, so I can not wear one of hers; neither can I wear the low-necked costume I wore to the theater last night," she murmured, in perplexity.

Her musings were cut short by a tap at the door. Susette, her maid, entered with a large bundle.

"Good-morning, Miss Kathleen. I've brought your[Pg 31] walking-dress for you to come home," she said, undoing the paper and displaying a black silk costume.

"Oh! how good of you, Susette! I was just thinking I would have to ask Mrs. Fox to send around for it."

"Mrs. Carew sent me," said Susette, pursing her lips.

"So she has returned?" asked Kathleen, resting her charming head on her elbow and looking down at the maid, who had seated herself on an ottoman close to the bed.

"She came home near midnight last night, Miss Kathleen."

"Near midnight? Why, then, some one must have been awake when I came home, Susette! Why did no one answer the bell?"

"The madame's orders," Susette replied, significantly.

The great dark eyes of Kathleen dilated in wonder.

"But why——" she began, and the maid interrupted:

"Miss Kathleen, I did some eavesdropping on your account last night, and if you'll not think the worse of me for it, I'll tell you Mrs. Carew's plans."

The woman was rather intelligent and quite well educated for one in her position. She had been in Kathleen's service five years, and loved her young mistress dearly. Her devotion to her interests had won her a warm place in Kathleen's heart.

"Go on," she said, and Susette continued:

"When madame went away yesterday it was somewhere into the country where there's a boarding-school, where you are to be sent to-day."

"Susette!"

"It's the gospel truth, miss! They packed your trunk last night, all ready for you to start. That's why they wouldn't let you in. You were not to know anything."

"To—send—me—back—to—school!" exclaimed the young girl in such amazement that the words came with difficulty from her lips. Her eyes flashed with anger. "I will not go! She can not force me!" she declared.

"She intends to make you go. I heard her tell Miss Belmont so," said the maid, looking very sad, for she knew that Mrs. Carew's will was law.

Kathleen's face grew scarlet with passion, and there was a dangerous light in her eyes, but she did not answer. Springing from the couch, she allowed Susette to attire her in her black silk.

"I thought maybe if I told you beforehand that maybe you could think of some way to outwit her," said the maid.

"And I will—I will! I will never be sent to school again!" cried the girl, in something almost like terror. She clasped her little hands and sighed: "Oh, why did papa ever go away and leave me here in that woman's power? She was always cruel to me, but she did not dare so much while he was here. Oh, I wish he would come home to his poor Kathleen!"

Bitter burning tears rolled down her cheeks and dropped on her heaving bosom. It was so hard to be ruled by this coarse woman, who envied and hated her in the same breath.

"She is going to make you marry her son, too. She told her daughter that she was determined to bring that about, so he might share your fortune," Susette remarked at this juncture.

"PLEASE BUY MY DIAMOND NECKLACE," SAID KATHLEEN.

Before Kathleen could reply, the door opened softly and Helen Fox came in with two letters in her hand. Kissing Kathleen good morning, she exclaimed:

"What do you think? The postman has just brought me a proposal!"

"From Loyal Graham?" queried her friend.

Helen blushed up to her eyes, but answered, gayly:

"No, indeed—from Teddy Darrell."

Kathleen arched her black eyebrows in surprise.

"Teddy Darrell! Why, he proposed to me last week," she said.

"And did he ask you to keep it a secret?" asked Helen, consulting her letter, her blue eyes dancing with fun.

"Yes, he did, now that I recall it. Oh, my! I'm sorry I mentioned it; but you took me by surprise."

"There's no harm done, my dear, and you need not look so conscience-stricken. Bless you, I don't mean to keep it a secret, although he prays me here to do so. Why, Teddy Darrell is the worst flirt in Boston, and proposes to a new girl every week, always trying to keep the new love a secret from the old one."

"But does no one ever accept him, Helen?"

"Perhaps. I don't know, I'm sure I sha'n't, and I'm just dying to tell the girls. Why, only last week we were comparing notes over him, and out of seven girls in the crowd he had asked five to marry him. Maud Sylvester said I'd be the next one on his list, and you see I am."

"But how can he fall in love so often?" queried Kathleen, laughing.

"He's very susceptible, I suppose, or maybe it's all in fun. You know some young men like to be engaged to several girls at once, so they can boast of their conquests, and maybe he's one of them. Well, I must lacerate his poor heart by a refusal," with a mock sigh.

"Who will be his next victim?" asked Kathleen.

"Either Maud Sylvester or Katie Wells. One is an actress, the other a novelist. He is wild over both fraternities."

"How amusing!" laughed her friend. "But your other letter, Helen? Is it another proposal?"

"No; this is an invitation to attend a flower show."

"From Loyal Graham?"

"Ye-es," Helen answered, a little consciously. "But, Kathleen, how pale you are! Did you not sleep well?"

"No; I was restless," answered the girl.

She debated within herself whether she ought to tell Helen of the news Susette had brought. She concluded that she would not just yet.

"Come, we will go down to breakfast, dear," Helen said, drawing an arm through Kathleen's to lead her away.

"Susette, you need not go back yet. I shall want you after a while," said Kathleen, and the maid remained very willingly.

Down-stairs Kathleen smiled, talked, ate, and drank in a mechanical fashion. She was busy revolving schemes for escaping her threatening fate.

Kathleen had not been home from school more than six months. The idea of returning to it, and leaving the social whirl, that as yet was so new and charming, was not to be tolerated.

"And just as I had met Ralph Chainey, too," she said to herself, in keen dismay.

Her mind was on a rack of torture. She was afraid that open rebellion would not avail. Her foe was keen and subtle. She would employ strategy to compass her ends.

"I ought to meet her with her own weapons," she thought; and all at once she began to wonder if she could not quietly get away and go South to her dead mother's relatives, there to remain until the return of her father should make her safe from persecution.

Two hours later Kathleen bade her friends good-morning, and walked away with Susette, as they supposed, toward her home. Little did Helen Fox, as she gazed with loving eyes after her beautiful form, dream of the tragic doom hanging over Kathleen Carew.

"Susette, I am not going home with you," she said.

The maid looked inquiringly into the beautiful young face, and Kathleen added, determinedly:

"I am going straight to the station, where I shall take the train and go South to my mother's relatives, to remain until papa gets back to free me from that woman's tyranny."

"Oh, Miss Kathleen! do you think that will be for the best?" inquired Susette, timorously.

"Of course it will, Susette; for they will be kind to me for my dead mother's sake."

"And you will have me to pet you and care for you?" said the affectionate maid.

"I can not take you with me, Susette; for it might get you into trouble, you good soul, and I don't want to do that. I can take care of myself, never fear. No, you are[Pg 36] to go straight back home and say that I sent you, and will follow presently."

Susette began to sob dismally, and Kathleen had to draw her aside into a pretty little park where they seated themselves, and talked softly for some time. Then Kathleen arose, and pressed her sweet rosy lips to the woman's wet cheeks.

"Now good-bye for a few weeks only, Susette, dear; for as soon as papa returns I'll be back. If Mrs. Carew turns you out, go to Helen Fox and ask her to give you employment while I am away. She will do it for my sake, I know. And I'll write to you at Helen's as soon as I get to Richmond. How fortunate that I have my diamonds with me, for I can go to the jeweler's and sell enough to carry me on my journey. Oh, Susette, don't sob so, please, dear! Good-bye; God bless you!" She signaled a passing cab, gave the order: "Golden & Glitter's, Tremont Street," and was driven swiftly away.

It was a bright, cool morning in April, and Tremont Street was thronged with shoppers and business people as she stepped out of the cab in front of the jeweler's elegant shop.

Bidding the cab wait, the young girl drew down her lace veil and entered without noticing, in her preoccupation, the tall, blonde young man, with a small satchel in his hand, who was intently gazing into the jeweler's window with a covetous gleam in his pale, dull-blue eyes.

But the young man's eyes turned aside from the contemplation of the treasures displayed within the heavy plate-glass window and fastened on the beautiful young girl with her patrician air and elegant costume.

"Kathleen, as I live!" he exclaimed, with a violent start, and followed her stealthily into the shop.

The elegant place was thronged with shoppers, and he mingled with them, keeping close to Kathleen, although unobserved by the object of his espionage.

"I wish I had the money that lucky girl is going to spend!" he muttered, enviously, to himself.

Kathleen went immediately to the desk of Mr. Golden, the senior partner of the firm. Drawing a small black case from her pocket, she opened it, displaying a very pretty diamond necklace.

"Mr. Golden, of course you remember when papa bought this necklace here for me," she said, timidly. "He paid five thousand dollars for it, you know. Well, papa is away"—with a catch in her breath—"and—I—I need some money very much. Will you do me the favor of buying this back for whatever you will give me?"

The kindly white-haired gentleman, drew a check toward him and began to write rapidly.

"Will a thousand dollars do you, my dear young lady? Because you can take that, and leave the necklace as security for the loan. You can redeem it when your father gets back," he said, beaming genially upon her, for the Carews were among his best customers.

MURDERED!

When Kathleen had thanked Mr. Golden for his ready kindness, and gratefully accepted the check, she hastened to the bank, on the next block, and had it cashed in some large and a few bills of smaller denomination. She had left Cabby waiting for her in front of the jewelers, telling[Pg 38] him that as soon as she returned from the bank she wanted him to drive her to the station, to take the first train for the South.

Accordingly, she returned in a few minutes and sprung into the cab, little dreaming that she was watched and followed by the tall, blonde young man who had recognized her when she had alighted at Golden & Glitter's, and followed her into the store.

He had secured a cab for himself, and was following fast upon her track.

"Now, what is up with the heiress? Must be an elopement. Egad! Alpine told me she was in love with a handsome actor, and that the mater was going to take her back to school to save her for me. Deuce take her! I don't want her, only for the money she'll get from old Carew. I was always afraid of those snapping black eyes of hers. I'd rather have that little blue-eyed New York ballet dancer of mine, in spite of her extravagance. A thousand dollars—a cool thousand! That's what the little minx wants me to give her now, or——But I won't think of that; it makes me savage. A thousand dollars! That's what Kathleen Carew has in her purse this moment, besides the diamond on her finger, and her ear-rings—real diamonds inside the little gold balls she wears snapped over them in daytime. I wish I had 'em for my little duck! Wouldn't she be sweet with great sparklers in her pink ears! And to think that the mater refused me the check I begged her for this morning, and she rolling in old Carew's money, while her only son could not keep up any style at all only for gambling!" ran the tenor of his thoughts, as he pursued hapless Kathleen to the station, making up his mind that she was about to elope, and grimly determining that she should purchase his[Pg 39] silence with her money and jewels. "And cheap getting off like that, when I might take her back to mother and keep her for myself. Egad! maybe the actor will pay me something on his own account; d—n the lucky rascal!" he muttered.

To his amazement, no person met Kathleen at the station. She bought her ticket alone, and entered the parlor car of the vestibule train going South.

"To Richmond, hey? Running away alone, and to those poor relations of hers, I'll be bound. No chance, then, of getting any of her boodle for my dearie. She will need it all, for they say the Franklyns, her mother's relations, are poor as Job's turkey hen. Well, I'll follow, and we'll see if anything turns up to my advantage;" and, buying a ticket as far as Philadelphia, he entered the train, after first disguising himself by taking from his hand satchel and putting on a dark wig and dark, heavy whiskers.

The train rushed on and on through the land; but Kathleen, sobbing under her veil, took no heed of time. Day passed, and it was far into the night. The train rushed into a lonely woodland station, snorted and stopped, while the conductor shouted:

"Passengers for the South change cars here!"

Kathleen and a single gentleman seemed the only Southern passengers. They groped their way out into the darkness of the starless night. The other train was waiting on the other side of a small wooden depot. Kathleen, confused by the strangeness and darkness, staggered shiveringly forward on the muddy path, alone, and frightened at the solitude.

A stealthy step behind her, two throttling hands at her throat smothering her startled cry. She was thrown[Pg 40] violently down, the jewels wrenched from her hands and ears, the purse from her dress; then the black-hearted murderer fled toward the waiting train, leaving his victim for dead upon the ground.

AT DEAD OF NIGHT.

Kathleen lay still and white under the starless sky, like one dead, and there was no one to come to her rescue, for the telegraph operator, busy at his instrument, dreamed not of her proximity, and at this hour of the night there were no loiterers about in the village. Swiftly and silently had the fiend escaped, and it was most probable that day would dawn ere any one would discover the beautiful girl lying out there in the rear of the depot upon the damp, muddy ground, dead and cold.

But to return to Boston, which our heroine had so unceremoniously quitted.

Her last thought as the train steamed away with her was of Ralph Chainey, the handsome actor, who had looked so tenderly into her eyes, and who had whispered as he held her hand at parting: "I hope we shall meet again."

Her tears had started at the memory.

"It is all over," she sighed. "He will be gone away from Boston before I go back, and I shall never see him again."

But at that very moment events were shaping themselves in Ralph Chainey's life so as to bring him to her side again.

In his room at the Thorndike Hotel he was reading a telegram that said:

"Come at once. Fedora is ill—perhaps dying."

His handsome face grew grave and troubled. Throwing down the telegram, he sought his manager.

"Every engagement for this week must be canceled. I must go South on the first train."

"But, my dear Mr. Chainey, the loss will amount to thousands of dollars," expostulated the reluctant manager.

"No matter; let the loss be mine. A—some one—is—ill—dying. I must go."

"I am very sorry. We were having a splendid success here," sighed the manager; but his regrets did not deter the young man from going.

Two hours after Kathleen had left Boston, he drove up to the same station where she had taken the train for the South, and entered another one going in the same direction.

Meanwhile, Susette sauntered back to Beacon Street with the message Kathleen had dictated—she would be at home later on.

Mrs. Carew was indignant. She had been planning to take Kathleen away by the noon train. Her trunk, already strapped and corded, stood in the hall.

Susette received a severe scolding for leaving her young mistress, but she did not seem much affected by it.

"She is my mistress, and I should not dare to disobey her orders," she replied, and walked out of the room.

"What shall you do now?" asked Alpine, curiously.

"I must wait and take her on a later train."

Ringing a bell, she sent her own maid to Commonwealth Avenue, to bring home her tardy step-daughter.

Ellen returned with the news that Kathleen had left Mrs. Fox's several hours ago.

"And with Susette, too," said the elderly maid, sourly; for she cherished a secret grudge against Kathleen's maid, who was younger than herself, better looking, and had insnared the affections of James, the butler.

Susette was recalled. On being questioned, she readily admitted that Kathleen had started home with her, but sent her on ahead, promising to follow.

While the angry step-mother stormed and raved over Kathleen's willfulness, awaiting her return in impotent anger, the young girl was flying fast from her tyranny, and nearer to the fate that loomed darkly in the near future.

The flying train sped on through the night with Ralph Chainey. He had thrown himself down dressed upon his berth, for the porter had told him that he would have to change cars at midnight.

He was restless and troubled. No sleep visited his eyes. In spite of himself, his thought turned back to Boston—to Kathleen Carew. She haunted him with her musical voice and luring eyes. At last a deep groan forced itself through his lips.

"I would to Heaven we had never met!" he exclaimed, in a tone of deep despair.

Pushing back the light curtain, he looked out into the night. It had grown cold and bleak. A light patter of mingled rain and snow was beating against the window.

"How dreary!" the young man murmured, with a shudder; and added, in a sort of awe: "Dying! can that be true?"

The porter, who was very attentive—the result of a liberal tip—came and put his head between the curtains.

"We change cars at the next station, Mr. Chainey, and that's but a few miles away. You'd better be getting ready."

Ralph came into the little reception-room, and the man assisted him into his overcoat. A few minutes more, and the train was slowing up at the lonely station.

"You're the only person getting off, sir. Good-night, sir; a pleasant journey!"

The porter handed out Ralph's valise, and he stepped down into the darkness, while the train went its way.

"But where the dickens is the other one?" soliloquized the young man, standing still a moment, the light snow pelting his face, while he peered into the darkness for the locomotive's head-light. "It must be behind that little depot. Here goes for a tour of investigation!" and with his valise in hand, he strode forward in the darkness, hardly knowing where he went, and wondering at the scarcity of railway officials and light.

"The train can't be here. It is probably late," he thought, and then his foot tripped, and he fell headlong over a body lying in his path.

A shudder of nameless horror shook the young man as he scrambled to an erect position, muttering:

"Good heavens! a woman, I know, from the silken garments. Now, what is she doing out here on the ground in this Cimmerian darkness, with the snow coming down in a fury?" He raised his voice and shouted loudly: "Halloo, halloo!"

The closed door of the depot, with its one blinking lighted window, opened, and then the form of a man appeared in the opening.

"Who is it, and what's the matter?" he exclaimed, shortly.

"Bring a lantern out here. I've found a woman dead in the snow!" was the startling answer.

Ralph had knelt down and felt the face and hands of the motionless woman. They were cold as ice, and he realized that she was dead.

"Horrible!" he murmured, and while he waited for the man to come with the lantern little thrills of awe ran through him. The flesh he had touched was firm and young, the hair was soft and curly, the garments silken. Who was she, and why was she out here under the night sky, cold and dead?

The depot agent came hurrying out through the driving snow, and flashed the light of his lantern full into their faces, for Ralph was still kneeling down by the motionless form.

"Who are you, and what is the row?" he inquired, curiously, but Ralph did not reply.

He was gazing in terror at the silent face with its closed eyes that lay so pale and still before him, wet with the falling snow, the bronze curls tangled on the forehead, drops of blood congealed on the exquisitely-formed ears; and, oh, horror! the white throat and chin had dark crimson finger-marks upon them. The small velvet hat had fallen off, the dress pocket was turned inside out, one hand had the glove torn off, and was wounded where a ring had been wrenched from it.

"Oh, Heaven!" groaned Ralph Chainey, in a low voice of shuddering horror, and the man exclaimed:

"Why, this looks like robbery and murder! See, her pocket has been turned inside out, a ring has been torn from her finger—a diamond, very likely—and her ears[Pg 45] are bleeding where her ear-rings have been torn out! Look at the red marks on her throat! Good Lord; she has certainly been choked and robbed by some devil in human shape! Mister, who are you, and where did you come from, and how did you find her?"

Ralph Chainey, whose face had grown as white as the dead one before him, did not reply save by a second groan of unutterable horror. He was wringing his hands in dismay, and the expression of his eyes was one of bitterest anguish. Not until the man shook him by the shoulder, and plied him over and over with questions, did he reply, telling him in disjointed sentences the simple truth of how he came there, and adding:

"If I am not mistaken, she is Miss Carew, a young Boston lady, whom I met there only last night. How she came here, what is the mystery of this, I can not understand."

THE FATAL TELEGRAM.

"Poor thing! she must have been a beauty," the railway employé said, as he contemplated Kathleen's cold and beautiful face. "Come, let us carry her into the house and get a doctor. Maybe she ain't really dead, only swooned," he continued, hopefully; and between them they bore her in, and laid her on a bench made soft with their overcoats.

Then the man ran to his instrument, which was ticking busily away, and directly said:

"Your train is several hours late, sir; so if you'll stay here, I'll run and fetch a doctor."

He flashed out at the door, and in the illy-lighted, shabby little waiting-room Ralph Chainey was alone with beautiful dead Kathleen, so cruelly murdered.

He knelt down by her side in an agony of dumb despair. He gazed through blinding tears upon the sweet white face; he took her cold, white hand and kissed the wound upon it, and then he whispered, as if she could hear him:

"Beautiful Kathleen! you will never know now how dearly I have loved you since first I saw your face! You are dead—dead! and soon the dark earth will cover you away forever from the sight of men. Ah! if only those dead lips could unclose long enough to tell me the name of your dastardly murderer, I would pursue him to the ends of the earth, but that I would bring him to punishment!"

He bent his head until his pale lips touched the rigid ones of the dead girl. They were icy cold, but the soft curls of bright hair that lightly brushed his forehead, how soft, how silken, how alive, they felt! But she was dead—this girl who had blushed last night beneath his glance, whose voice had been so sweet and low when she spoke to him.

The shock and horror of the occasion began to overcome him, strong man as he was; and his head reeled; consciousness forsook him. He fell in a crouching position upon the floor, where he lay until the doctor entered, followed by his gentle, girlish wife.

"Oh, the dear, sweet, pretty creature! what an awful way for her to meet such a fate! The murderer ought to[Pg 47] be burned at the stake!" exclaimed the young wife, sorrowfully, and her tears fell fast on Kathleen's face.

Doctor Churchman examined the girl's throat carefully, and said, with a deep sigh:

"Poor thing, she is quite dead! There is nothing I can do for her but to carry her over to our house and take care of the body until her friends come."

A deep groan startled him, and Ralph Chainey staggered dizzily to his feet.

"Ah, sir! so you have recognized this young woman, Dickson tells me. Well, please dictate a telegraph message to her friends at once," Doctor Churchman said to him, gently, for the despairing look on the young man's face touched him with sympathy.

"He must have been in love with the murdered girl," he said to himself.

Ralph went into the little office and sent a message off to Mrs. Carew's address:

"I have found Kathleen Carew here dead under very mysterious circumstances. Please come immediately, as I am compelled to leave."

By one of those strange rulings of fate that so startle us at times, a mistake was made at the Boston office in taking the message, and when received by Mrs. Carew the telegram ran thus:

"I have married Kathleen Carew, and nothing can change it. Please God in Heaven, I am comforted to know it."

Mrs. Carew raved with anger, and the very next day the Boston papers published, as a sensational item, Miss Carew's elopement and marriage to the handsome actor,[Pg 48] who charmed all women's hearts out of their keeping—Ralph Washburn Chainey.

Mrs. Carew's active malice could invent but one sting for the heart of her step-daughter at so short a notice. She cabled at once to Vincent Carew in London a garbled account of Kathleen's elopement with an actor, one of the lowest and most unprincipled professionals who had ever disgraced the stage.

Vincent Carew had just been buying his ticket to return to America. His health was restored, and his heart ached for a sight of his bonny Kathleen, his beloved daughter.

Close against his heart lay her picture, and her last sweet, loving letter, in which she implored him to come home to his unhappy child. She did not mention her step-mother's unkindness, but a vague suspicion stirred within him and prompted his speedy return.

His ticket was bought, his luggage, with so many beautiful gifts for Kathleen stored in it, was sent down to the steamer. He smiled as he thought of the surprise in store for his "home folks."

Upon this complacent mood came the malicious cablegram from his irate wife.

The revulsion from his pleasant mood to keen wrath was terrible.

Vincent Carew had a dislike to actors in general, of which no one understood the origin.

The thought of his bonny Kathleen married to one of this abhorred class drove the proud man beside himself with shame and rage. For an hour he raged and stormed about his room until he was on the verge of apoplexy.

Having exhausted the first fury of his anger, he flung himself into a cab and was driven in haste to a lawyer's office.

His last act on leaving England was to execute his last will and testament, in which he angrily disinherited Kathleen, his only child. Leaving the document with the lawyer for safe keeping, with instructions to forward it to America in case of his loss at sea, the angry man was driven down to the steamer, and embarked for home—the home that would be so lonely now without the light of Kathleen's starry, dark eyes.

Did he repent his harsh and hasty deed, that haughty man, as he paced the steamer's deck those long moonlight nights thinking of his dead wife—lovely, childish Zaidee—and the daughter she had left him—willful, spirited Kathleen? Did he shudder with fear as he remembered that should anything happen to him at sea, the cruel will that disinherited the young girl would be irrevocable? Or did he gloat over the prospect of her sufferings with her impecunious husband? No one knew, for in his bitter trouble and humiliation he stood proudly aloof from all, cultivating no one's friendship, seemingly absorbed in his own thoughts, until that night—that night of awful storm and darkness—when fatal disaster overtook the good ship Urania, and she was burned at sea, her fate sending a thrill of horror through the heart of the world when the tidings became known with Vincent Carew's name among the lost.

"KATHLEEN, I SWEAR THAT I WILL AVENGE YOUR MURDER!"

Gentle, womanly hands prepared lovely, hapless Kathleen for the grave, and she was laid upon a white bier in Doctor Churchman's pretty parlor. Very pale and beautiful she looked, and as Ralph Chainey bent over her for one farewell look, she did not seem like one dead, but just asleep. It even seemed as though the white flowers on her breast moved softly, as with a gentle breath; but when he hastened to hold a mirror over her lips, it remained clear, without any moisture. He laid it down with a bitter groan.

His delayed train would arrive in a few moments and he was compelled to leave the dead girl's side for a death-bed. He must leave Kathleen here with these kind, sympathetic people; but he would return as soon as he could; for there must be an inquest, at which he must be the chief witness.

He wondered how her relatives would take it—her stately step-mother, her pretty step-sister, who had told him such unblushing falsehoods about Kathleen.

"Helen Fox will be sorry, I know, for she loved Kathleen dearly," he murmured aloud. Tears fell from his beautiful brown eyes upon the angelic face, and he went on talking to the girl in a low monotone, almost forgetting that she could not hear him, or perhaps fancying that her gentle spirit hovered near: "My darling, you will never know how dearly I loved you, nor how I shall mourn you all my life long! Once I saved your life and oh! why did not Heaven give me that joy again? Why[Pg 51] did I come too late to-night?" With a groan, he laid his hand softly on the one that clasped the white flowers on her breast, and added: "Kathleen, I swear that I will avenge your murder, if it takes me all my life to do it and costs me all my fortune!"

He bent and pressed his lips on her white brow and her soft curls, took a white rosebud from under her pulseless hand and placed it in his breast, then he was gone. Presently, when the excited villagers began filing in to look at the murdered girl, they saw a tear-drop that had fallen from his eyes glittering like a pearl on the bosom of her black silk dress.

The little community was wild with horror and excitement at the finding of the murdered girl in their midst, and when it became known that she had been recognized as a great Boston heiress, the furore became even greater. The telegraph wires flashed the news from town to city, and the newspapers that one day had chronicled the news of Kathleen's elopement, printed twenty-four hours afterward in flaring head-lines the awful story of her robbery and murder.

Even Mrs. Carew, wicked as she was, paled to the lips as she read it, and Alpine fainted outright. Weak, selfish, cruel as the girl was, she had cared for Kathleen more than she knew. The girl's charms had won upon her, in spite of herself.

"Good heavens! that actor, he has robbed and murdered her, the fiend!" Mrs. Carew cried, violently. "He is even worse than I thought!"

"I do not believe it, mamma. There is some mistake—there must be. Ralph Chainey was a gentleman, and rich in his own right," Alpine answered, speaking the truth for once.

Like every one else, she admired the young actor, and though his preference for Kathleen had angered her, she was not prepared to do him the flagrant injustice of believing him as wicked as her mother asserted.

There was a moment's silence; then Mrs. Carew exclaimed, with a startled air:

"Good heavens, Alpine! think what this means to us! Kathleen dead, the whole Carew fortune is ours!"

Alpine had the grace to be ashamed.

"How can you think of that now?" she exclaimed, reproachfully. "I—I had rather know that—that Kathleen was alive than have the wealth of the Vanderbilts!"

Then she burst into tears and left the room in a hurry.

Mrs. Carew looked after her aghast.

"I did not think she would take it so hard, but then I always suspected her at times of a sneaking fondness for that black-eyed witch," she mused. "Well, I don't mind. It will look better in society, a little real grief on Alpine's part. As for me, I'm glad she's out of the way, and the Carew wealth assured to me and mine."

She gave a low laugh of satisfaction, but her hands were shaking with excitement, and her heart fluttered strangely. She was recalling the coincidence of Kathleen's and her mother's deaths—both at nearly the same age—sixteen—and both by violent means.

The maid came so suddenly into the room that it gave her a violent shock. She started and looked around angrily.

"Why do you enter the room so rudely, without knocking, Ellen?"

"I beg pardon, madame. I knocked, but you did not hear, so I made bold to enter, because Miss Belmont sent me in a hurry."

"Well?"

"She desires to know if I shall get your things ready to go after Miss Carew's body?"

The woman spoke in an unmoved tone. Her mistress had taught her to hate the fair young heiress.

"She means to go?" interrogated Mrs. Carew.

"She is getting ready, madame, and told me you were going."

"Yes, of course, Ellen. In the absence of my husband and son, it is my harrowing duty." Mrs. Carew put her handkerchief to her dry eyes and sighed: "Make haste, Ellen."

ANOTHER MYSTERY.

There was a little flutter of excitement at Doctor Churchman's pretty cottage.

The Carews had at last arrived, after being vainly looked for for more than two days, and their aristocratic airs and their stylish maid created quite a sensation.

Kathleen was waiting for them in the little parlor—Kathleen with shut eyes and pallid lips and folded, waxen hands—so unlike the brilliant beauty they remembered, with this awful calm upon her face.

They gazed upon her, and Mrs. Carew's lips twitched nervously, while Alpine wept genuine tears, remembering remorsefully how kind Kathleen had been, and how illy she had repaid her goodness.

Ralph had not come yet, but a telegram from Richmond had arrived announcing that he would come early[Pg 54] in the morning when arrangements had been made to hold an inquest.